Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 04/07/06. The contractual start date was in June 2005. The draft report began editorial review in January 2007 and was accepted for publication in June 2008. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

None

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2009 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO. This monograph may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2009 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Aim of the review

The aim was to provide a systematic literature review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of breaks in care for informal carers of frail and disabled older people living in the community. The review includes a synthesis of both quantitative and qualitative data pertaining to the impact of respite care on users and carers.

Background

The ageing population

In 2002 4,464,000 people in the UK were aged 75 years and over1 and it is projected that the number of people over pensionable age will increase to over 15 million by 2040. 2 This will impact on health-care systems as age-related conditions become more common. In 2001 46% of people over the age of 75 years reported having a limiting long-standing illness. 3 The most frequently reported chronic conditions in people aged 65 years and over in 2001 were heart and circulatory diseases and musculoskeletal ailments. 4 Dementia is a particularly debilitating problem associated with ageing, with around one in 20 people aged 65 years and over having the condition, rising to around one in five people over 80 years of age. 5 Stroke is also one of the most prevalent causes of morbidity in older people. In the UK around 110,000 people per year experience a first stroke and a further 30,000 have recurrent strokes. 6

Provision of care for people with disabilities

Many older people with chronic conditions are cared for in the community, with their main source of support coming from informal carers. Such informal carers of the frail and elderly are frequently in mid- to later life themselves, being spouses or adult children of the care recipient. In 2001 almost 2.8 million people in England and Wales aged 50 years and over provided unpaid care for family members, friends or neighbours. In total, 24% of carers in the 50- to 60-year age group spend 50 hours per week or more on caring activities. 3,4 Although people from white British or white Irish backgrounds were more likely to be carers than other ethnic groups, this probably reflects the older age structure of the white UK-born population. However, Bangladeshi and Pakistani carers were just as likely to spend 50 hours a week or more on caring activities as their white UK counterparts, and numbers of ethnic minority carers will increase in the future as these populations age.

According to the General Household Survey3 women were more likely to be carers than men and have a heavy caring commitment of over 20 hours per week. About one-third of carers were the only means of support for the care recipient. In total, 21% of carers had been in a caring role for at least 10 years and 45% for 5 years or more; 62% of carers were looking after someone with a physical disability only, 6% with a mental disability only and 18% with both physical and mental disabilities; 14% reported caring for a person simply because they were ‘old’.

The types of help given by informal carers consisted mainly of practical help with activities of daily living (ADL) such as meal preparation, shopping and household tasks. A total of 60% reported that they ‘kept an eye’ on the person they cared for and 55% reported providing company; 26% gave more personal care such as personal hygiene and 35% reported helping with mobility.

Impact of caring on carers’ health and well-being

Caring can have a direct effect on health, such as physical strain and musculoskeletal problems, as well as causing emotional strain. It can also have an indirect effect on health status through lower earnings or income or increased costs when the recipient of care takes up residence with the carer. 7 As a result, carers tend to report poorer health than their peers who are not carers. Health is particularly poor among those who devote at least 20 hours a week to caring, with around half reporting a long-standing illness. 4 In many cases poor health is directly attributed to the caring role. In total, 39% of carers report that their physical or mental health has been impaired as a result of caregiving. Other complaints include tiredness, depression, loss of appetite, disturbed sleep, stress and short temper. Such complaints were higher in those caring for someone who lived in the same household than in those caring for someone living elsewhere, probably reflecting the number of hours spent caring and the level of care needed. 3,8,9

The impact of caring on mental health was explored in a survey carried out by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) for the Department of Health. 10 Neurotic symptoms were measured using the revised version of the Clinical Interview Schedule (CIS-R). Psychiatric morbidity was related to hours spent caring, with only 13% of those caring for less than 20 hours a week having a CIS-R score of 12 or more, compared with 27% of those spending 20–34 hours caring. Sole carers were more likely to have mental health problems than those not having the main responsibility for the care recipient. Mental health was also related to the ability to take a break from caring, with 36% of carers who had not had a break experiencing high levels of neurotic symptoms, compared with 17% of those able to take a break. Over half of the carers reported worrying about their caring responsibilities and one-third felt that caring had made them depressed. Relationships and social life were also adversely affected in around one-third of carers, which again was related to high levels of neurotic symptoms.

To capture the caring impacts on these different aspects of health and well-being, research studies have focused on the concept of ‘carer burden’. This is an all-encompassing term that refers to the financial, physical and emotional impact of caring. It may include factors such as restrictions to social activity of the carer, lack of privacy, impaired sleep, feelings of stress, satisfaction with the caregiving relationship, effects on family/job, etc. Carer outcome measures often include a general health measure and/or a standard measure of anxiety and depression. But it should also be noted that not all outcomes of caring are negative. Qualitative studies have reported positive feelings related to caring such as pride, gratification and a sense of closeness to the person being cared for. 8

The concept of carer burden is complex and is mediated by many factors. It is not necessarily the case that the carers of the most impaired patients experience the greatest stress and burden. 11 Factors such as age, gender and ethnicity play a role. Female carers experience greater burden than male carers. White carers have been reported to experience greater burden than African American carers. However, relationship may be a confounding factor in this context as white carers are more likely to be spouses and African Americans tend to be adult children of the care recipient, and it has been reported that spouses experience greater burden. 12 Other factors include carer support, carer health status, coping abilities and quality of the previous relationship with the care recipient. The type of problems displayed by the care recipient are also an important factor as it is suggested that carers of dementia patients experience greater stress than carers of individuals with physical disabilities, and it is specifically behaviour problems rather than cognitive impairment that cause most stress. 13

Definition of respite care

Respite care is traditionally defined as the provision of a temporary break in caregiving activities for the informal carer to reduce carer distress and promote well-being. 14 Respite care can be provided in a number of different ways. These include care as an inpatient of a care home or hospice, typically for 1 or 2 weeks, or adult day care (ADC) or in-home or sitting services. There are also some night-sitting services available. Care may be provided by a variety of bodies including voluntary services, social services or the NHS. However, operationalising a definition of respite care in a review is not straightforward. There are a number of situations when the carer may be physically separated from the caring role and the care recipient but the aim is not to achieve respite. For example, if the care recipient is admitted to hospital for medical treatment this may provide ‘respite’ for the carer; however, the aim of the intervention is to deal with a health event of the care recipient. The intervention will be focused on changing the health state of the care recipient and not the carer. The health and well-being of the carer may also be improved but it is difficult to determine to what extent this is due to a temporary relief in the caring responsibility or to an improvement in the care recipient’s health, functional abilities or dependence.

In an attempt to identify the specific effects of respite itself rather than interventions aimed at changing the state of the care recipient, this review takes a fairly restricted definition of respite care. The view is taken that respite is aimed at changing the well-being of the carer and so focuses on studies that explicitly state that the intervention is designed to provide respite for the carer and that assess carer outcomes. This also includes studies which evaluate interventions that have the potential to provide respite (such as day care or in-home service provision) without explicitly expressing the aim as being respite, but which focus on carer outcomes. It excludes studies that provide interventions whose primary purpose is to change the health state of the care recipient (e.g. rehabilitation interventions or highly medicalised interventions as in some palliative care contexts), as in this case it is more difficult to distinguish the effects of confounding factors. The aim was to include studies in which the normal care carried out by the informal carer is taken over for a set period of time by another person to allow the carer a break. However, it does not require the care recipient to be physically removed from the informal care context; for example, in-home care may provide respite without the carer actually leaving the home.

Definition of frail elderly

Frail elderly was defined as anyone over the age of 65 years in receipt of informal care from a relative or friend. In defining the older care recipient a cut-off of 65 years is common and most likely to be identified in studies of respite care. Frailty is not a concept that is consistently reported or defined in the relevant literature and so in this instance, with the focus on carers, it is assumed that anyone over the age of 65 years identified as having an informal carer can be defined as frail. The need for informal care suggests a certain level of disability whether it be cognitive or physical.

Questions addressed by the review

The questions addressed by the review are as follows.

-

How effective and cost-effective are respite interventions compared with no respite or other interventions?

-

What is the impact of respite interventions on care recipients?

-

What are the barriers to uptake of respite care?

-

What are carers’ expressed needs in relation to respite care?

Chapter 2 Review methods

The primary aims of the review were to identify and evaluate the quantitative and qualitative evidence base for the effectiveness of respite care for community resident frail elderly and to estimate the cost-effectiveness of respite care provided in various settings. The methods used to achieve these aims are outlined in the following sections and are based on guidance provided by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD). 15

Operational definition of respite care in the frail elderly

Based on the discussion in Chapter 1 on the definition of respite care, the following operational definition will be used in the review (Box 1).

| Definition | Implications for the review |

|---|---|

| Care that aims to improve the well-being of the carer by providing substitution for the normal caring duties of the informal carer and not care that is aimed primarily at providing therapeutic intervention for the care recipient | Studies must report carer outcomes |

| Studies must explicitly state that the intervention aims to provide respite for the carer or the intervention provides substitution of care and carer outcomes are measured, e.g. day care | |

| Interventions intended to change the health state of the care recipient are excluded, e.g. rehabilitation | |

| Care is provided for a set period of time | |

| Care can be provided in the home or in day or institutional care settings | All care contexts included, i.e. day care, home care and institutional |

| Care recipient is aged 65 years or older and is identified as having an informal carer | Outcomes for carers of care recipients aged 65 years or older must be discernible in the findings |

The definition of respite care focused primarily on the benefits to the carer and considered the outcome for carer well-being as not only the primary outcome but also the defining criterion for respite care. This placed some limitations on measuring outcomes for the care recipient, as only studies that reported carer outcomes were included. There is the possibility that a paper examining a respite intervention may report outcomes for the care recipient only (as in some cases in which studies are ‘salami sliced’). However, the inclusion of all studies that report only care recipient outcomes (for example, of day care) would prove problematic as it would be unclear whether all recipients of the service actually had or depended on an informal carer. It would therefore be difficult to establish if these samples were equivalent to those who were reported as having informal carers. It was felt most appropriate, therefore, to accept the possible loss of a small number of studies, rather than have broader inclusion criteria and include a potentially large number of articles of dubious relevance.

It must also be acknowledged that not all included interventions are ‘pure respite’ in that formal care provision will never map exactly to care provided by the informal carer. There may be activities undertaken that are designed to benefit the care recipient (for example, directed group activities such as reminiscence or occupational therapy), but there may also be changes in care that may prove to be a disbenefit (such as lack of exercise and mobility). These are confounders that are poorly described in studies and are not measurable and cannot therefore be accounted for in study selection or analysis, although the selection criteria aimed to exclude studies in which the intervention predominantly provided individual treatments (usually of a medical nature) to the care recipient.

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for quantitative studies

Inclusion criteria for quantitative studies were as follows:

-

study mentions an intervention designed to provide the carer with a break from caring

-

care recipient population is aged 65 years or over (or analyses carried out on a subsample of population aged 65 years or over)

-

carer outcomes are measured

-

respite intervention is compared with either no respite or another intervention (this included regression analyses in which respite was used as a predictor of carer outcome such as carer burden, and within-group longitudinal comparisons that reported carer outcomes before and after the delivery of a respite intervention)

-

articles written in any language.

Two additional criteria were used to identify any quantitative papers including cost data:

-

include all papers costing informal care, respite, carer outcomes or service usage (even if respite component not specifically costed)

-

include above only if costs are directly measured.

Exclusion criteria for quantitative studies

-

Exclude studies in which the intervention is designed to change the state of the care recipient (e.g. stroke rehabilitation).

-

Palliative care/hospital-at-home interventions to be excluded unless stated aim is to provide respite for carer and carer outcomes are measured.

-

Exclude if care recipient population is under 65 years, age of care recipient population is not discernible or outcome data cannot be identified for those in the care recipient sample who are aged 65 years and over.

-

Exclude if only care recipient outcomes are measured.

-

Exclude qualitative studies and observational studies having no comparison group, e.g. surveys providing descriptive data only.

Inclusion criteria for qualitative studies

A broader set of inclusion criteria were devised for assessing qualitative studies as it was felt important to assess both care recipient and carer views of their needs and preferences for respite care even if they were not actually in receipt of respite. Inclusion criteria for qualitative studies were as follows:

-

study employs qualitative methods (face-to-face semistructured/in-depth interviews; focus groups; open questions in questionnaires)

-

care recipients have a mean age of 65 years or over (or analyses carried out on a subsample aged 65 or over)

-

study reports views of carers and/or recipients

and either:

-

study reports views of respite care or study reports respite as a theme in relation to other types of care, e.g. care aimed to change the state of the care recipient

or:

-

views of respite include:

-

respite care service provision/satisfaction with services

-

impact of respite on the carer and/or care recipient

-

unmet needs/perceived needs for respite care

-

reasons for utilising or not utilising respite care.

-

Exclusion criteria for qualitative studies

-

Quantitative data reported as part of a qualitative or quantitative study, e.g. descriptive statistics.

-

Data not reporting themes or concepts related to views of respite care, respite needs, use of respite or impact of respite care on carer and/or care recipient, e.g. data reporting general experiences of caring.

-

Studies using direct observation methods, e.g. participant observation.

-

Care recipients are under 65 years of age or data relating to those over 65 years are not discernible in the study findings.

-

Non-English language papers.

In the qualitative synthesis all foreign language papers were excluded as the issue of translation and interpretation is of greater significance and would have a potential impact on the findings. It was felt that these difficulties outweighed the potential limitation of excluding relevant studies. The impact of these exclusions would depend on the similarity of the different health-care systems and any cultural differences. Although many of the good-quality European studies are published in English journals there is the possibility of relevant studies being published in the language of origin.

Qualitative studies involving direct observation were excluded to maintain comparability of the type of data included in the synthesis,15 i.e. self-reported views rather than inferences made from observation. However, no observational studies were identified in the searches.

Year of publication

The year of publication was defined by the databases searched. All years were searched for each database.

Data sources and search strategy

Search strategy

The remit of the current review is very broad: respite care might feasibly occur within both community and institutional settings and across many different conditions (e.g. dementia, palliative care, stroke, etc.). In addition, interventions or services designed to give carers a break from their caring role may not be explicitly labelled as respite care. Therefore, an inclusive and broad search strategy was felt most appropriate to capture all potentially relevant literature and specificity was sacrificed to some degree to maximise sensitivity.

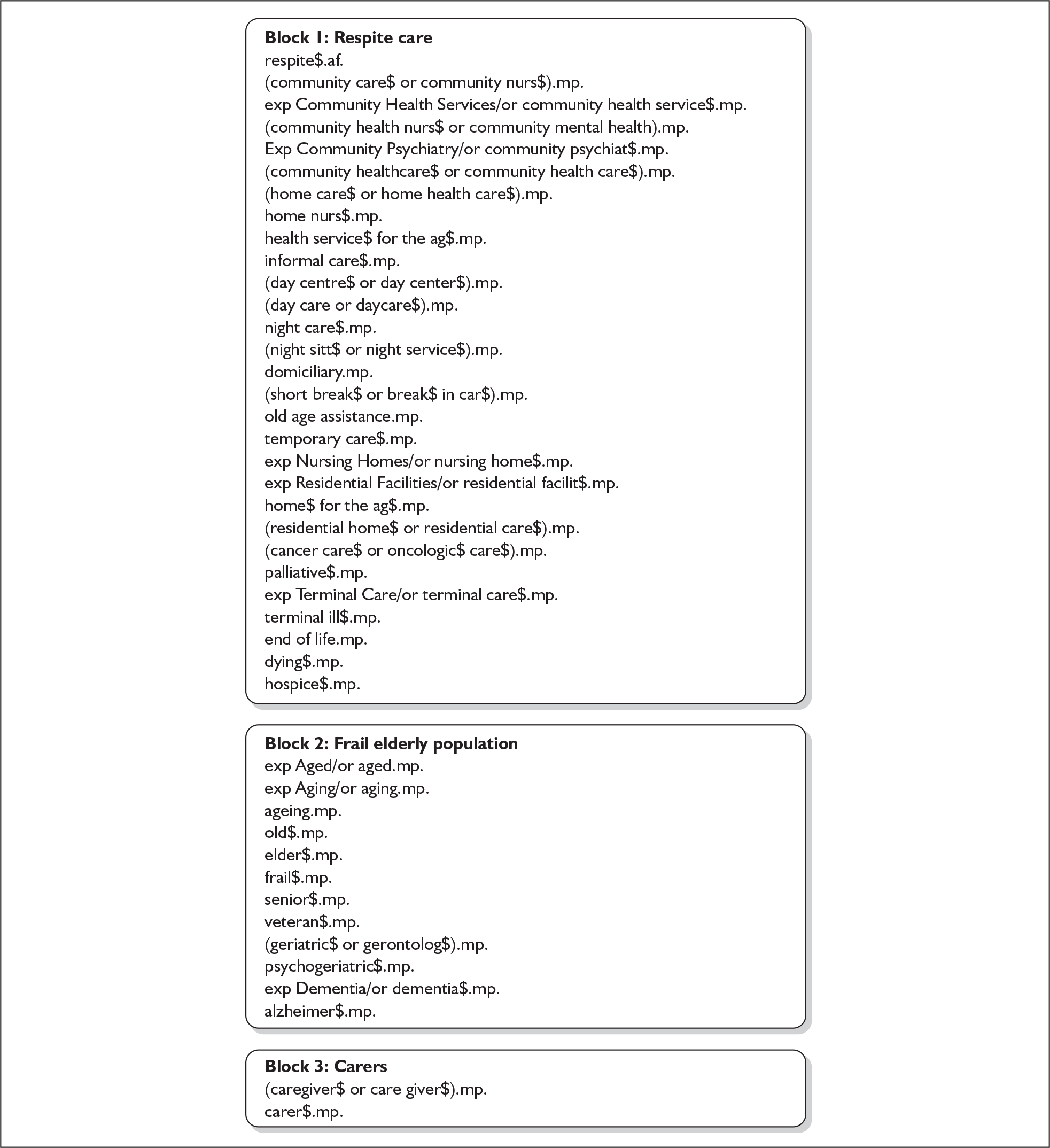

The final search strategy was developed iteratively following discussion with the review management group (all investigators, listed as authors of this review) and carer representatives (Carers Wales). This was based on the most appropriate definitions of respite care, the target population (i.e. frail elderly) and possible respite settings. The search strategy comprised three distinct blocks: the first set of terms were designed to capture all studies reporting respite care; the remaining two sets were included to limit results to studies carried out within elderly populations and those specifically citing carers or the caring role respectively. Words and phrases within each set were combined using the Boolean OR operator; the three sets were then combined using the AND operator. Search terms were trialled initially on MEDLINE, mapping words and phrases to MeSH headings (using the .mp operator). Keywords using the .mp operator were used either in addition to MeSH headings or in place of them when they produced the same or additional hits. Input on the appropriateness and comprehensiveness of the search terms was sought from an information specialist, all members of the review group and user representatives from two UK charities. The final MEDLINE search terms are shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

MEDLINE search terms.

Data sources

The terms provided in Figure 1 were adapted as appropriate to search an additional 24 electronic databases from the earliest possible date to the end of September 2005. Searches were rerun until the end of 2005, resulting in an additional 332 references not previously identified. All databases searched (and number of hits retrieved from each) are shown in Table 1.

| Electronic data source | Hits |

|---|---|

| Allied and Complementary Medicine (AMED) | 278 |

| Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) | 599 |

| BIDS International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS) | 59 |

| British Nursing Index (BNI) | 284 |

| Cochrane Database of Methodology Reviews | 1494 |

| Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) | |

| Cochrane Methodology Register (CMR) | |

| Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) | |

| Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) | |

| Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA) | |

| NHS Economic Evaluation Databasea | |

| Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) | 3467 |

| Computer Retrieval of Information on Scientific Projects (CRISP)a | 28 |

| EconLit | 22 |

| EMBASE | 2402 |

| Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC, including King’s Fund) | 1024 |

| MEDLINE | 5118 |

| MEDLINE (in progress and non-indexed citations) | 81 |

| National Research Register (NRR)a | 478 |

| PsychInfo | 2662 |

| PubMed Cancer Citations (maintained by NCI/NLM – formerly CancerLit) | 631 |

| Scopus | 1210 |

| Social Care Online (previously CareData) | 782 |

| Sociological Abstracts | 302 |

| Web of Science (including Social Science Citation Index) | 523 |

Once duplicates were removed a total of 12,992 unique references were identified. Overlap between databases was substantial. Taking four of the major electronic data sources as an example, 64% of citations were identified on MEDLINE and original citations on EMBASE accounted for a further 24%, PsychInfo for 11% and the British Nursing Index for just 1%.

Hand searching of the following journals was also undertaken from the earliest possible date to the end of 2005: Gerontologist, Journal of Gerontology, Age and Ageing, International Psychogeriatrics, Journal of Palliative Medicine and Stroke.

Study selection

A preliminary title sift of all 12,992 references was undertaken by two reviewers. Obviously irrelevant titles such as those relating to respite for carers of children or pharmacological interventions were excluded at this stage. For any titles on which disagreements occurred the abstracts were assessed, along with all of the remaining abstracts, by two reviewers. When disagreements occurred papers were selected for full retrieval. Inter-rater agreement ranged from fair to moderate (kappa coefficient range 38–52). 16 At the full paper stage all exclusions were checked by a second reviewer selected from within the project management team. Inclusions of papers in the meta-analysis were checked by group discussion of the statistical team (RM, KH, KA), and inclusions of papers in the narrative syntheses (longitudinal and cross-sectional observational studies and qualitative studies) were checked by CS. The number of studies included at each of these stages is shown in Table 2.

| Sift stage | Number of articles |

|---|---|

| Initial search (duplicates removed) | 12,992 |

| Irrelevant titles excluded | 8042 |

| Included articles following abstract sift | 928 |

Before full paper retrieval all quantitative, qualitative and cost papers were grouped together. Following full paper retrieval papers were categorised according to their content (i.e. quantitative/qualitative). All full papers were assessed against the inclusion criteria by a single reviewer, with any excluded papers checked by a second reviewer. The number of papers categorised into each component of the review on full paper retrieval and second-stage inclusion assessment are shown in Table 3.

| Review component | Papers retrieved | Included at second-stage assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | 374 | 104 |

| Qualitative | 226 | 71 |

| Cost | 125 | |

| Reviews | 59 | N/A |

| Grey literature | 144 | N/A |

| Total | 928 |

A much greater number of qualitative studies was retrieved than originally anticipated. This is due in part to the wider remit and less stringent inclusion criteria adopted for qualitative studies and in part to reliance on qualitative methods in an area in which it is difficult to carry out controlled trials for ethical reasons.

Quality assessment

Methods for assessing the quality of both quantitative and qualitative studies are outlined in the following sections.

Quality assessment of quantitative studies

Numerous tools are available for the quality assessment of randomised controlled trials (RCTs), with at least 25 currently in use. 17 However, a MEDLINE search from 1990 to 1997 did not identify any quality checklists for assessing cohort and case–control studies. 18 A brief review of the literature by the current authors to the end of 2005 indicated that this situation has changed very little. Given the broad and inclusive nature of the current review it was important to identify a tool that could be used to assess the quality of varied quantitative designs simultaneously (i.e. RCTs and cohort and case–control studies).

Two particularly relevant quality checklists were identified from a brief review of the available literature. 18,19 Downs and Black18 developed a tool to assess the quality of both randomised and non-randomised designs. The tool comprises a 27-item checklist and an overall score pertaining to the quality of the study. Checklist items relate to the appropriateness and adequate description of the hypotheses, study design, intervention, main outcomes and methods of analysis. The checklist demonstrated good inter-rater reliability, although further development and testing of the tool was recommended. The tool devised by Kmet et al. 19 was also intended for quality assessment of both randomised and non-randomised designs and was produced following a review of the relevant literature and discussion of issues central to internal validity. The checklist provides an overall summary score, although the authors acknowledge this approach is inherently prone to bias. In addition, inter-rater reliability appeared somewhat limited (a subsample of 10 studies scored by two reviewers). The Kmet et al. 19 checklist contains 14 items relating to study design, intervention, outcome measurement and methods of analysis.

Within the context of the current effectiveness review both tools were felt to contain useful elements but each had particular drawbacks. For example, the Downs and Black18 checklist is heavily weighted towards randomised designs (likely to be small in number in the current review) and is also lengthy at 27 items. Although more concise, comprising just 14 items, the Kmet et al. 19 checklist is less detailed (e.g. adequate description of the intervention is not included). In addition, previously developed tools did not accommodate particular issues relevant to this review, such as the presence of two samples of interest (carer and care recipient). A single quality checklist was therefore created, in line with CRD recommendations,15 specifically designed for the current review (see Appendix 1) but likely to be of value in reviews of similarly complex areas encompassing few randomised trials.

The current tool was also developed within the framework recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force. 20 The first of three strata within this framework relates to quality assessment at the individual study level. The framework does not give a quantifiable score but provides an indication of quality based on certain parameters. Study designs are first organised into a hierarchy [RCT, non-RCT, cohort, case–control, observational (i.e. multiple time series, case studies, opinion of experts)] and are then classified as ‘good’, ‘fair’ and ‘poor’ according to criteria specific to the particular study design.

The final checklist contains 18 items, with three levels of quality assessment: good (2), fair (1) or poor (0). Some items within the list are relevant only to RCTs; therefore, a ‘non-applicable’ option is provided for other study designs. Scores across items are summed to create a quality score, which is represented as a percentage to account for any non-applicable (i.e. missing) items.

Quality assessment of qualitative studies

There is some debate as to the appropriateness of formal quality assessment in qualitative research and the use of such tools is comparatively new. Qualitative research is extremely useful in addressing patient-centred views in health-care research and as such is a valuable and often expected study component. Controversy relating to the appropriateness of quantifiable quality assessment arises from the belief that this serves to stem the interpretative and creative aspects of qualitative study. 21 Nonetheless, many believe that some form of quality assessment is necessary if qualitative research is to be taken seriously within the wider research community. 22–24 Within the context of the current review, equal weight and importance are given to both the quantitative and the qualitative components and therefore a common approach to assessing study quality was needed.

To maximise consistency across these two aspects of the review, the aim was to develop a quality tool similar in structure to that of the quantitative tool previously described, keeping in mind the different aims of qualitative and quantitative research. Quantitative research seeks to eliminate bias to render results generalisable to the wider population, whereas qualitative research is context bound and seeks to expose and discuss bias. For these reasons it has been proposed that a common language may be misleading. 22 Alternatives to terms such as internal and external validity, reliability and objectivity have been proposed, for example credibility, dependability, transferability and confirmability. 25 Others, however, feel that issues of validity and relevance are appropriate to qualitative research even though the concepts supporting them may be dissimilar to those pertaining to quantitative research. 22,23

However, it has been pointed out that there is a need to qualify this by ensuring that the different paradigms within qualitative research are acknowledged. 26 Qualitative research is not a unitary activity and aims and methods will vary according to the philosophical underpinnings and requirements of the study. This could be considered similar to the varied approaches in quantitative research with the resultant difficulty of establishing a quality assessment tool that is appropriate to all types of study. However, a number of concepts are relevant across study types, if interpreted somewhat differently. To identify items for inclusion in the assessment tool, a review was undertaken of papers that presented either a quality checklist or a narrative account of quality assessment. This scoping review followed a similar approach to that used by Walsh et al. ,27 who adopted such a scoping method designed to assess commonalities between quality assessment tools and eliminate redundant items. The review by Walsh et al. 27 was based on seven existing checklists: the checklist that they produced was included in the present scope.

The scope of the quality assessment literature revealed considerable overlap and agreement between studies in terms of the relevant criteria for assessing quality. Items to be included in the tool were chosen based on their frequency of occurrence in the articles reviewed, their appropriateness to the requirements of the current review and their generalisability across different qualitative methods. However, the types of study likely to occur within the context of respite care will largely comprise thematic analysis, such as grounded theory or phenomenology (direct observational studies or data from sources other than focus groups, interviews or open-ended questions were excluded). Some quality checklists were quite broad and vague although they had the advantage of appearing shorter and more succinct than others. A more detailed and structured approach was preferred in order to give clear definitions to facilitate interpretation and increase inter-rater reliability. The rating format was based on the checklist developed by Kmet et al. 19 for quality assessment of qualitative research, in line with the format used for the quantitative tool. The tool was piloted and amended; items included in the final version are shown in Appendix 2. Three levels were assigned to each item in the tool, which were scored from 2 to 0. The scores could then be summed to produce an overall quality rating.

Data extraction

Data extraction was carried out as a two-stage process for both the quantitative and qualitative sections of the review. These stages are outlined in the following sections.

Data extraction for quantitative studies

A paper version of a quantitative data extraction form was circulated to all members of the review group for comment and revised appropriately. Members of the study team could use either a paper or an electronic version of the data extraction form at this stage. The electronic version comprised an Access database with identical fields to the paper version. When extraction was completed using the paper version the information extracted was entered into the Access database to enable a direct comparison of all data. The use of Access forms for data entry also aided in ensuring consistency of the extracted data by allowing only certain types of options to be entered in any one field, thus ensuring that all data were categorised in a similar way.

At the first stage of data extraction detailed information relating to study methods was extracted, which included information about the intervention (e.g. type, setting, duration and length of follow-up), carer and recipient characteristics, and types of outcomes measured (including information on the tool used to measure each outcome). The first-stage data extraction form is given in Appendix 3.

The second stage involved more detailed extraction of appropriate numerical data for all studies categorised as either randomised trials or quasi-experimental designs into an Excel spreadsheet. The same procedure was followed for all longitudinal studies in which participants served as their own control (i.e. outcomes measured before and after an intervention in a single group). Summary tables detailing the observational studies (both longitudinal and cross-sectional) were also created (see Appendices 6 and 7 respectively)

Data extraction for qualitative studies

The qualitative review followed a similar pattern with an initial meta-methods analysis in which data were extracted to a summary table (see Appendix 9). A meta-data analysis was then carried out on a subsample of papers; the findings from the qualitative papers were extracted into a software package specifically designed for qualitative analysis (NUDIST version 6). Data extracted comprised the concepts identified in the results sections of the papers but not the themes defined by the researchers or their conclusions derived from their analyses, usually presented in the discussion sections of the papers.

Data analysis and synthesis

Methods of analysis and approaches to data synthesis for the quantitative and qualitative components of the review are outlined in the following sections.

Quantitative data synthesis

When appropriate and possible, quantitative results from individual studies were synthesised using meta-analysis techniques, taking account of statistical, clinical and methodological heterogeneity. 28 To account for the variety of ways in which some outcomes such as carer burden and depression are measured, standardised effect sizes were used.

Initially, between-study heterogeneity was investigated within randomised and quasi-experimental studies. Separate meta-analyses were carried out for each carer outcome using the following study-level covariates when possible: length of follow-up, length of intervention (i.e. brief versus sustained) and respite setting (e.g. day versus home care). A number of studies measured outcomes at two or more follow-up periods; therefore, additional separate meta-analyses were carried out splitting studies into short- and longer-term follow-up groups.

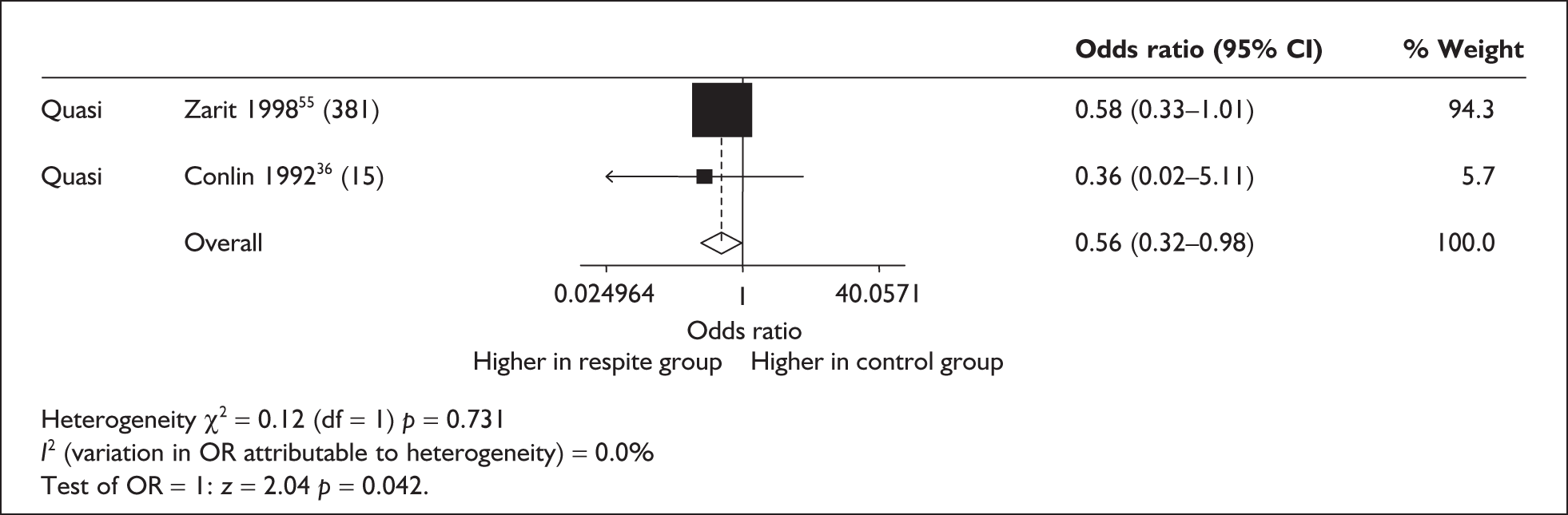

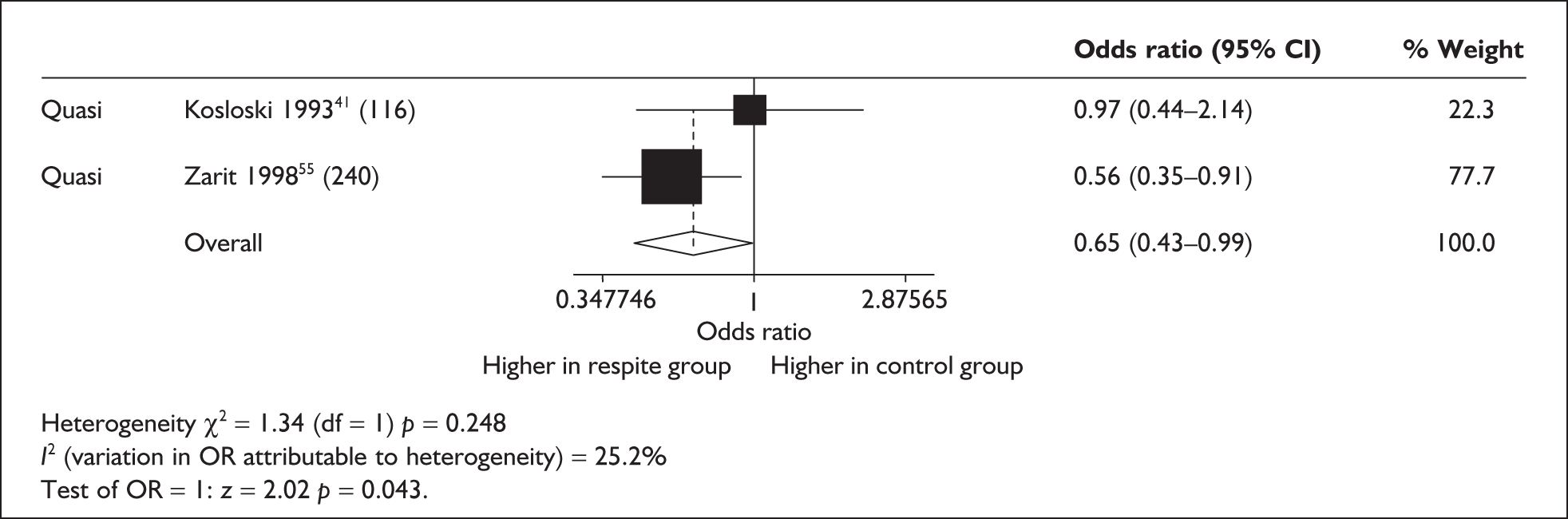

Meta-analyses were carried out both on follow-up data only and on change scores. However, standard deviations for change scores (change SDs) were rarely provided. Change SDs were therefore estimated using two previous assumptions: first, that the correlation between baseline and follow-up scores is zero and, second, that the correlation between baseline and follow-up scores is likely to be 0.6, based on data from the Rothman et al. 29 study. This study reported correlation coefficients for a large number of outcomes from baseline to both short- and long-term follow-up. Outcomes for carers were the primary focus of the meta-analyses: however, likelihood of institutionalisation was also assessed to represent a patient outcome relative to either positive or negative effects of a respite intervention. This was felt to be an important step as a preliminary scoping of the qualitative literature indicated that a common reason for non-uptake of services is concern on the part of the carer that respite may be detrimental to the care recipient. All meta-analyses were carried out in Stata (version 9).

Studies in which outcomes were measured in a single group before and after delivery of an intervention were analysed separately.

It was intended to assess negative publication bias by funnel plots but there were few studies eventually included in each analysis and so this was not feasible. To assess any potential for publication biases the country of origin and year of publication were examined across the different types of study design.

Observational studies identified by the review (both cross-sectional and longitudinal) formed the basis of a narrative synthesis, with particular reference to the rate of institutionalisation amongst those accessing respite compared with non-users and the impact on carer burden and mental health. However, much of the observational work in the area tends to focus on use of respite as a generic, dichotomous outcome and so differentiating between the effects of diverse respite settings (i.e. home care, day care) is problematic.

Qualitative data synthesis

The methods used to review the qualitative literature followed those used in carrying out primary qualitative research and were based on the methods of meta-study described by Paterson et al. 30 The synthesis aimed to be both interpretive, to provide further explanation of the research findings in the quantitative review, and aggregative, to identify the extent of the literature and gaps that need to be addressed. To do this a three-stage process was adopted by, first, carrying out a meta-method analysis, second, a meta-data analysis and, finally, meta-synthesis.

Meta-method analysis assesses both the quality of the research methods of the primary research papers and the ways in which the methodological context may have influenced the study findings. 31 Each paper was summarised into a table under the headings shown in Appendix 9. Separate tables were constructed depending on the country in which the research was conducted, and the factors influencing study findings could then be explored. For example, as well as differences in sampling procedures, variation in data collection methods might have an impact on study findings, such as data collected by face-to-face interview versus focus groups. Such tables may also provide information about the generalisability of findings if consistent results are found across samples and contexts (such as place of care) and also about the extent of the literature and any gaps for future research. The listing of sampling procedures could reveal the types of carers and care recipients whose views were not sought, giving an indication of the representativeness of the findings. These tables also give a view of the literature over time, as preferred methods have changed and developed, and how the field of research is likely to develop in the future.

Because of the large number of studies identified in the qualitative literature search, a purposive sampling technique was used in the meta-data analysis stage. At the outset of the study we had intended to sample according to type of respite provision (e.g. institutional care, day care, home care) and characteristics of the care recipients (e.g. dementia, physically impaired, palliative care). However, such categorisations were not possible as the majority of studies reported a mix of respite use and often a mix of care recipients. We therefore decided, in the first instance, to focus on the organisational context of studies and relevance to UK policy. Accordingly, all UK studies were included. Although there were a substantial number of studies carried out in the UK, studies carried out in the USA were also prominent and tended to be of higher quality, with a more direct focus on respite care issues. We considered that the concerns of carers of older people in the USA would be similar, within the Medicare system, to those of carers in the UK and so these too were included, along with all studies conducted in Canada, where the health-care system is more similar to that in the UK. Also included were studies carried out in Australia and New Zealand, where there are similarities with the UK in culture and health-care systems.

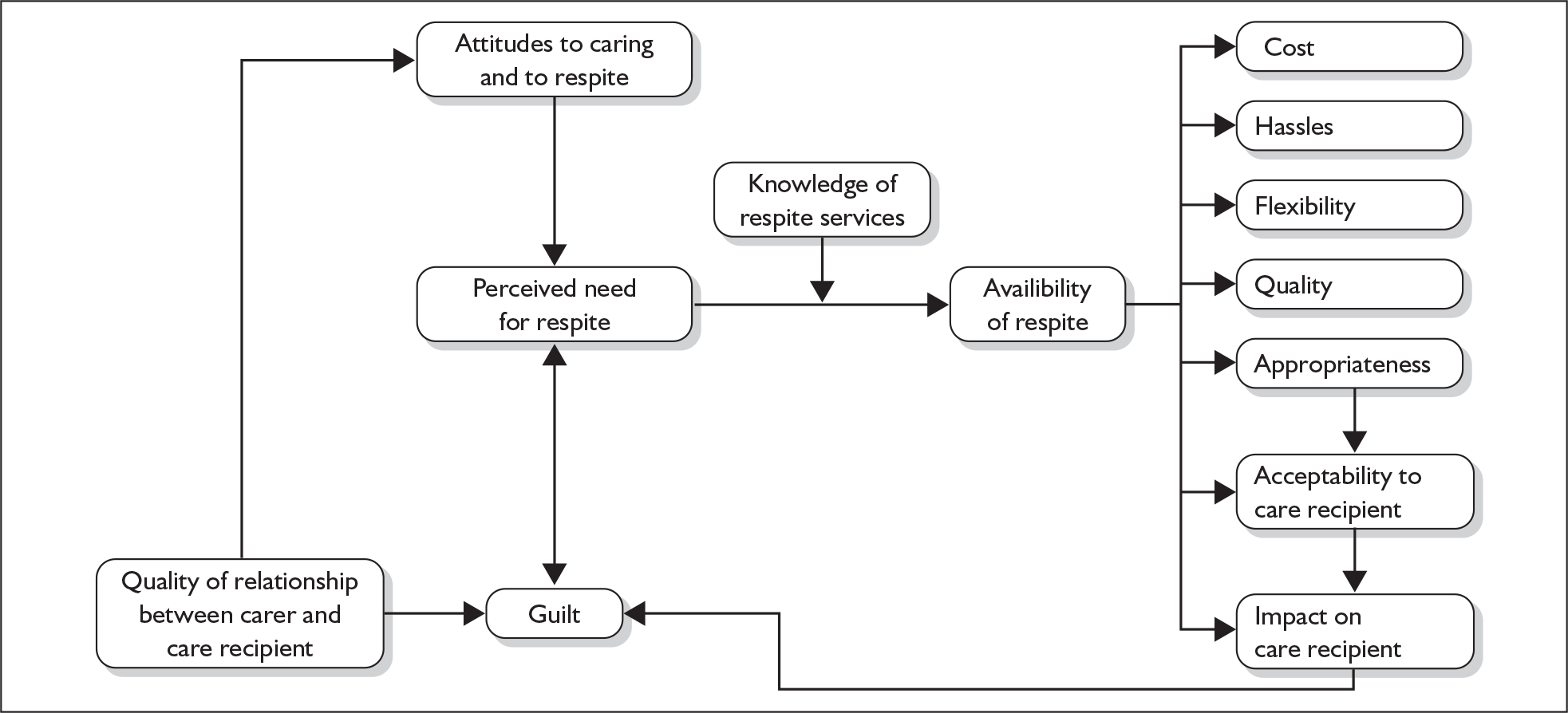

The meta-data analysis stage was carried out using similar methods to those used in primary qualitative studies,31 with each study representing a case. This was based on a grounded theory approach31 although certain aspects of the study had limitations in relation to grounded theory methodology. Because a discrete set of studies was available, theoretical sampling could not be carried out, and therefore data saturation may not necessarily have been achieved for all categories and themes. In addition, although a wide range of studies was included, representing general views of respite care, and coding aimed to focus on emergent themes rather than themes identified a priori, it is likely that the coding process was influenced by the main research question related to identifying barriers to uptake. However, there were no previous assumptions concerning the nature of barriers or other views of respite care.

The findings from each study (the concepts as reported by the authors) were extracted. Category codes were developed using a constant comparative technique. 31 Common categories were extracted from the studies by comparing for similarities and differences between the concepts expressed in each study. As concepts emerged that did not fit the coding frame a new category was instigated. The data within each category code were then compared to identify subcategories describing the range of the general properties of each main category. Characteristics of the studies were coded as base data, for example quality rating, type of data collection, characteristic of care recipient, etc. A sample of texts was coded by two reviewers to assess the reliability of the coding framework. The coding demonstrated a high level of concordance, showing good reliability. By comparing the data in the categories across groups of cases (i.e. studies) and in relation to other categories, hypotheses concerning the causal, contextual and intervening relationships between categories and subcategories were developed in a process of ‘axial coding’. 31 Data were then sought across the different studies that either supported or refuted these hypotheses.

Finally, in the meta-synthesis stage of the analysis ‘selective coding’31 was carried out, whereby a core category was identified (i.e. barriers to respite), which became the central focus of the analysis, and a theory developed concerning the causal relationships between this and the other major categories. This core category was to some extent defined by the research question as studies were selected based on their ability to answer this question. However, the category ‘barriers to respite’ did fulfil the criteria for a core category31 and related to all of the other major categories apart from three, which are reported separately (i.e. ethnicity, positive aspects of respite and palliative care). In addition to this, and for completeness, a descriptive analysis of the data occurring under the category ‘carer needs’ is reported separately although these data also related to the core category.

The final stage of the analysis described above provides a theory of the barriers to the uptake of respite over and above that described in individual studies. It is based on integration and interpretation of the data (rather than merely aggregation) and takes account of the methodological aspects of the studies reviewed by including design features, such as carer and care recipient characteristics and quality ratings, as categories within the coding frame. As such it can be considered to represent a synthesis of the data, although there are limitations concerning the contribution of meta-theory analysis (analysis of the theoretical approaches underpinning primary studies) prescribed by Paterson et al. 30 for meta-synthesis.

These findings were then integrated with the findings of the quantitative review. One important feature was to identify whether the outcomes addressed in the quantitative studies were consistent with those identified in the qualitative studies as being important for both care recipients and carers. The findings from the qualitative review were used to shed further light on findings in the quantitative review and aid interpretation.

Chapter 3 Quantitative synthesis

Organisation of the presentation of results

The results will be presented under headings according to the level of evidence, i.e. RCTs and quasi-experimental studies, single-group longitudinal before-and-after studies, observational longitudinal studies and cross-sectional studies. Meta-analyses are carried out on RCTs and quasi-experimental studies and the longitudinal before-and-after studies and so these two levels of evidence will be presented together and form the main source of evidence related to the effectiveness of respite care. Before presentation of the meta-analyses narrative summaries are provided of studies unsuitable for inclusion in the meta-analyses, pertaining to both trials and longitudinal before-and-after studies.

Following the meta-analyses narrative summaries of all of the observational studies (longitudinal and cross-sectional) are presented. A narrative synthesis will also be presented of care recipient outcomes across the different types of study. No meta-analyses were carried out on care recipient outcomes because the inclusion/exclusion criteria for the review were based on studies reporting carer outcomes; there may be studies focusing only on care recipient outcomes of respite services that are not included in this review and so meta-analysis was not felt to be appropriate. A section relating to the economic review follows the quantitative synthesis and, finally, the synthesis of qualitative studies is presented.

Within each section the evidence relating to particular outcomes will be presented separately, for example carer burden, carer depression. The review focuses on outcomes reported by more than one study, which mainly includes carer burden, carer depression and institutionalisation. A discussion relating to each outcome across all of the levels of evidence, in combination with how this relates to findings from the qualitative review, will be presented in the discussion section.

Studies included in the review

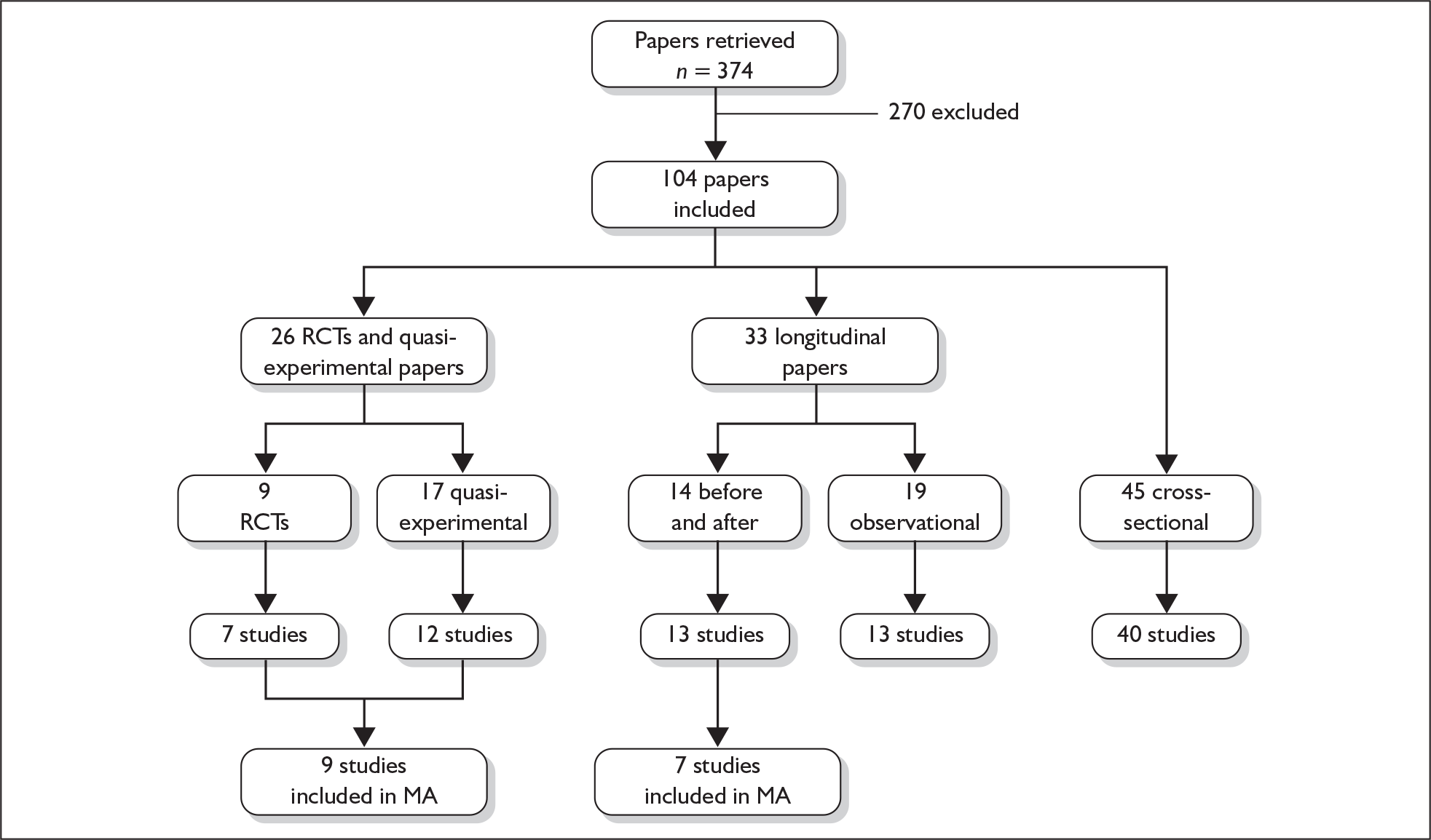

A total of 374 full quantitative papers were selected for retrieval following the abstract and title screening stages (including one identified from bibliographies); 270 of these were excluded following screening of the full papers.

A total of 104 quantitative papers met the inclusion criteria for the review. 29,32–134 These are summarised in tabular format in Appendices 4–7, classified according to study design (26 RCT/quasi-experimental papers;29,32–56 14 longitudinal before-and-after papers;57–70 19 longitudinal papers;71–89 and 45 cross-sectional observational papers90–134). In some cases more than one paper refers to the same study and so the number of studies at each level of evidence was seven RCTs, 12 quasi-experimental studies, 13 longitudinal before-and-after studies, 13 observational longitudinal studies and 40 observational cross-sectional studies. Figure 2 shows the numbers of papers identified at each level of evidence.

FIGURE 2.

Number of papers retrieved and identified as eligible for inclusion in the quantitative review. MA, meta-analysis; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

A subset of these papers was included in a series of meta-analyses (split by outcomes). A number of studies have been excluded from the meta-analyses as it was not always possible to extract appropriate data. A total of nine RCTs and quasi-experimental studies (detailed by 14 papers) and seven longitudinal before-and-after studies were included in the meta-analyses. When studies could not be included the reasons for exclusion are indicated in the final column of the summary tables in Appendices 4 and 5; the reasons for exclusion are also listed in Table 6.

Quality assessment

The previously described quality checklist was used to assess the quality of all of the 104 included quantitative papers (quality scores are given in the appropriate tables). Quality scores were divided into tertiles (low, moderate, high) to allow the relative quality of included studies to be assessed; this is discussed in more detail in the appropriate sections.

First and second level of evidence: RCTs/quasi-experimental studies and longitudinal before-and-after studies

Characteristics of RCTs/quasi-experimental studies and longitudinal before-and-after studies

The majority of randomised and quasi-experimental studies assessed day care and mixed respite care interventions, followed by in-home care and then institutional care (Table 4). Most studies were carried out in the USA or UK, with the USA having nine studies and the UK having five; none of these studies assessed institutional care. The remaining studies were carried out in Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Germany.

| Country | Type of respite care | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day care | Institutional | In-home | Mixed | Total | |

| UK | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | |

| USA | 3 | 2 | 4 | 9 | |

| Canada | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Australia | 1 | 1 | |||

| New Zealand | 1 | 1 | |||

| Germany | 1 | 1 | |||

| Total | 7 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 19 |

Similarly, the majority of longitudinal before-and-after studies were carried out in the USA and UK. These studies were more evenly spread across the different types of respite, although only one study (carried out in the UK) assessed in-home respite (Table 5).

| Country | Type of respite care | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day care | Institutional | In-home | Mixed | Total | |

| UK | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| USA | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | |

| Canada | 2 | 2 | |||

| Australia | 1 | 1 | |||

| Hong Kong | 1 | 1 | |||

| Total | 5 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 13 |

Studies excluded from the meta-analyses

Table 6 summarises the reasons why RCTs and quasi-experimental studies and longitudinal before-and-after studies (identified for inclusion in the review) were excluded from the meta-analyses. Ten randomised and quasi-experimental studies were excluded, as well as six longitudinal before-and-after studies. A narrative summary of the studies excluded from the meta-analyses is presented first, followed by the meta-analyses according to each outcome.

| Study | Reason for exclusion from meta-analyses |

|---|---|

| Randomised and quasi-experimental studies | |

| Brodaty et al. 199733 | No other studies measuring mean time to institutionalisation identified |

| Burch et al. 199934 | Could not derive mean values |

| Burdz et al. 198835 | Could not derive mean values |

| Lawton et al. 198942; Lawton et al. 199143 | No follow-up data provided |

| Montgomery and Borgatta 198945; Montgomery 198846 | Not possible to extract means |

| Riordan and Bennett 199849 | No SDs |

| Rolleston and Ball 199450 | Study assessing effect of temporary closure of existing service |

| Schwarz and Blixen 199752 | Data not given for experimental and control groups separately |

| Wells and Jorm 198753 | Comparison of respite vs institutional care (comparison group not appropriate) |

| Zank and Schacke 200254 | Not possible to extract means |

| Longitudinal before-and-after studies | |

| Adler et al. 199357 | No means given |

| Chi and Wong 199458 | Outcomes not measured in any other study (attitudes to care recipient and caring) |

| Cox 199859 | No SDs |

| Deimling 199260 | No SDs |

| Gilleard 198762; Gilleard et al. 198463 | No suitable comparison group |

| Johnson and Maguire 198968 | No SDs |

Narrative review of randomised and quasi-experimental studies excluded from the meta-analyses

The effectiveness of respite for carer well-being

Zank and Schacke54 evaluated the effects of specialist geriatric day care on the well-being of carers. After 15 months of service use no significant differences between the respite and control groups were observed in terms of well-being and burden. However, semistructured interviews indicated that carers of day care recipients reported a more positive change than those in the control group. Conlin et al. 36 demonstrated a positive effect of respite (either in-home or day care) on carer stress levels at both 5 and 10 weeks following service use. Carers not receiving respite reported greater stress at follow-up. However, no difference in the rate of institutionalisation (included in meta-analysis) between respite and control groups was observed, although the follow-up period is likely to be too short to detect any meaningful difference.

In contrast, Lawton and colleagues42,43 did not find that the use of a mixed respite service significantly impacted on carer burden or psychological health. However, satisfaction with the service at 12 months was reported to be high, and families accessing respite services maintained the care recipient in the community for significantly longer (22 days on average) than those not accessing such a service. Schwarz and Blixen52 also failed to detect any positive effects of in-home respite services on depression and strain relative to the control group at 3 months. No significant differences in positive caregiving appraisal were found between the two groups.

Riordan and Bennett49 examined the effectiveness of a dementia-specific augmented domiciliary service on levels of psychological well-being and carer strain after 6 months of service use. Use of the service was not found to be of significant benefit to carers in terms of psychological well-being; however, service users remained in the community significantly longer than matched control subjects.

The interaction of respite effectiveness and reason for frailty

Burdz et al. 35 examined the effects of inpatient respite care on carer strain after 5 weeks of service use. Although it was hypothesised that non-dementia patients and their carers would benefit most from the respite intervention, results indicated a significant decrease in carer burden in the respite condition (relative to a waiting list control group) regardless of diagnosis.

The effectiveness of respite care relative to other supportive interventions

Montgomery and Borgatta45,46 followed up carers of frail elderly receiving several different service interventions, one of which comprised a mixed respite intervention (day care, home care, night inpatient care), after 12 months of service eligibility. It was not possible to include the results in the meta-analysis (means not given) but results suggest that subjective burden was significantly reduced in all intervention groups at 12 months relative to the control group who received no intervention. However, there were no significant differences in subjective burden between any of the intervention groups, indicating that various other supportive interventions (i.e. educational interventions and support groups) are just as effective in reducing burden as respite care.

Comparison of two or more respite interventions

Burch et al. 34 carried out a RCT comparing day hospital and day centre interventions. Although carer strain was reduced in both groups at 3 months, no significant differences were found between the two interventions in terms of outcomes for carers.

The impact of service closure on carer well-being

Rolleston and Ball50 measured levels of general carer well-being before and following a 2-week closure of a psychiatric day hospital. The results indicate that the removal of existing respite services is detrimental to carer well-being, although well-being regressed to preclosure levels on assessment at 3 weeks following reopening of the unit.

Comparison of respite and institutional care

Wells and Jorm53 carried out a randomised comparison of permanent institutional care and periodic respite care in terms of carer outcomes. Levels of anxiety and depression were significantly reduced in carers who institutionalised the care recipient, whereas those accessing periodic respite care continued to demonstrate high levels of emotional distress. Wells and Jorm53 also noted no detrimental effects of institutionalisation on care recipients (all dementia sufferers) in terms of behavioural symptoms.

Respite as a predictor of institutionalisation

Brodaty et al. 33 carried out a randomised trial comparing a carer training programme (either immediate or waiting list control subjects) with a 10-day respite intervention with no training. The 8-year survival analysis indicated that carer training delayed both death and institutionalisation; the respite intervention, in comparison, although coupled with memory retraining for dementia patients, was associated with a shorter mean time to institutionalisation.

Narrative review of longitudinal (before-and-after) studies excluded from the meta-analyses

Six studies (reported in seven papers) were excluded from the meta-analyses of single-group longitudinal comparisons (i.e. before-and-after studies).

Adler et al. 57 found that levels of carer burden and depression were reduced during a 2-week inpatient respite intervention, but that levels returned to baseline once patients had returned home, which suggests that the effects of respite may be short-lived in some instances.

Johnson and Maguire68 examined the impact of the use of day care on a range of carer outcomes and found no difference in carer stress between baseline and follow-up (2 and 4 months).

Chi and Wong58 studied the effect of institutional respite on carer attitudes at 1 month. They found that carers were less likely to express a wish to institutionalise recipients following respite; however, perceptions of the caring role as stressful actually increased following respite.

Gilleard and colleagues[62,63] examined the effects of carers’ psychological well-being and self-reported strain and also the number of care recipient problems on community status after 3 and 6–7 months of day care. Institutionalisation was predicted by the number of patient problems and carer psychological distress. Day care itself was associated with reduced distress for the majority of carers; for those in whom day care did not help to alleviate psychological distress, institutionalisation had a significant positive impact in terms of this outcome.

Cox59 examined a mixed respite programme for carers of dementia sufferers, which allowed families to buy up to 164 hours of respite, consisting of in-home care, institutional care (4–5 days) or day care. Follow-up was carried out at 6 months and African American participants were compared to white participants. There was no reduction in anxiety or depression in either group but there was a decline in carer burden in both groups.

Deimling60 also examined a mixed respite programme for dementia carers, consisting of short institutional stays, day care and home health aides. Follow-up was carried out at 4–6 months and assessed depression, symptoms of health problems and relationship strain. Comparisons were made between carers of those with stable conditions and carers of those with declining conditions. Carers of stable recipients had decreases in depression, health problems and relationship strain whereas outcomes for carers of recipients with declining conditions either stabilised or deteriorated.

Summary

Two of the studies reported respite to be associated with a delay in institutionalisation whilst having no effect on carer well-being. One of these studies, however, had too short a follow-up to give a meaningful result. In addition, one further study found respite to be associated with a shorter time to institutionalisation when compared with carer training interventions. There was no clear effect of type of respite in these studies.

The results pertaining to the impact of respite on carers’ well-being were variable although it would appear that, in the main, there was not a substantial effect on carer well-being; effects that were seen were beneficial with no evidence for negative effects. The longest length of follow-up was around 12–15 months. Studies that did show a positive effect of respite tended to be either short term or studies comparing respite with other types of intervention. In these studies respite reduced burden to a similar extent as the other interventions. It was not clear whether any particular type of respite was more effective than another, although the two studies examining mixed respite showed beneficial effects.

Meta-analysis: the effectiveness of respite care on carer well-being

The effectiveness evidence for respite care in terms of carer well-being is outlined in the following sections, presented for each outcome separately. Meta-analyses of randomised and quasi-experimental studies are given first, followed (when applicable) by the results from meta-analyses of single-group comparisons (longitudinal before-and-after studies) to examine any differences in terms of effects. All results from meta-analyses (Cohen’s method) are based on change scores and, when the change standard deviation is missing, a 0.6 correlation between baseline and follow-up is assumed. 29 Fixed models were initially fitted, except when tests for heterogeneity were statistically significant at the 5% level. In this instance a more conservative random-effects model is presented and resulting changes discussed. When significance was between the 5% and 10% levels both fixed and random models are shown. Appropriate descriptive findings are also summarised at the end of each section (outcome). Results are therefore presented in terms of a hierarchy of evidence quality; the relative quality of included studies is also discussed within each outcome.

Carer burden

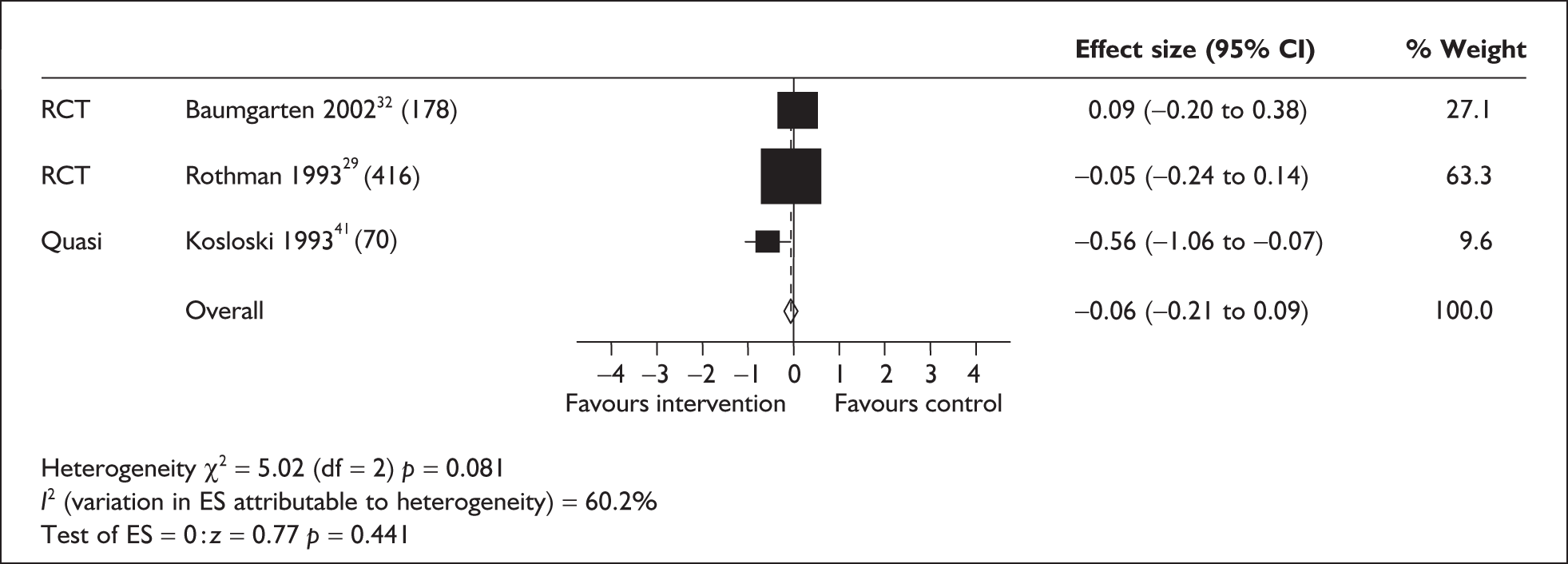

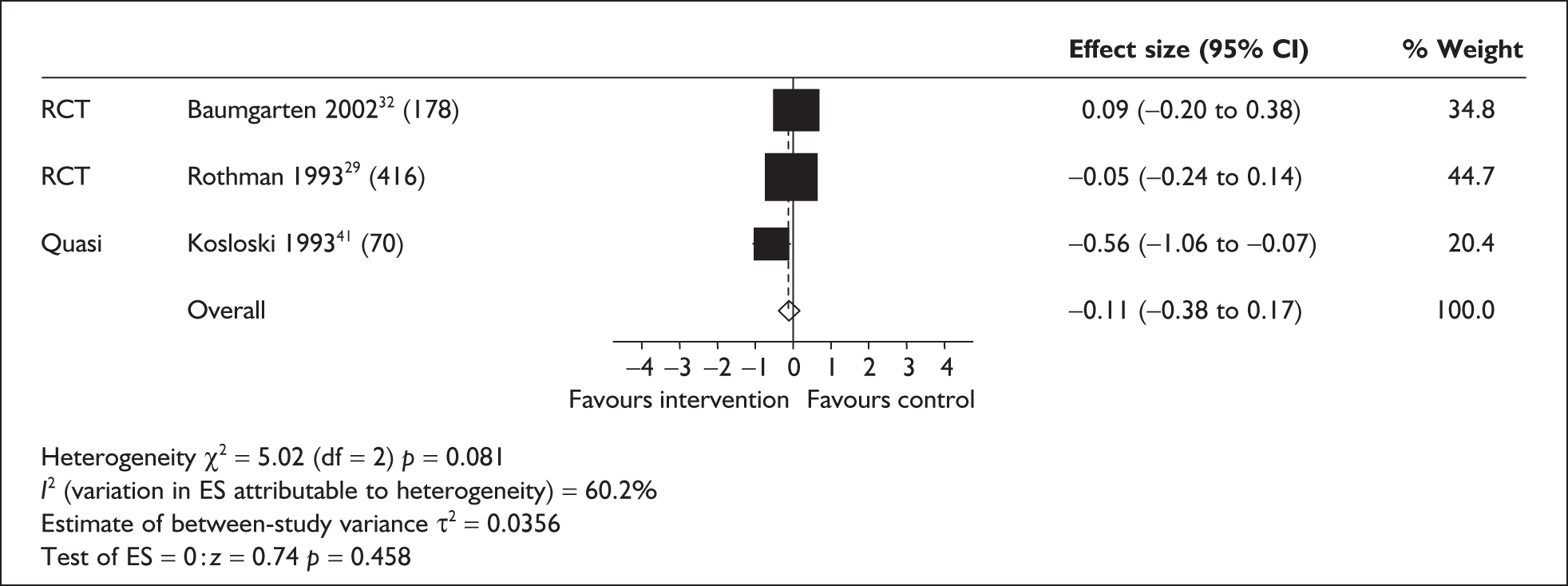

Carer burden in randomised and quasi-experimental studies

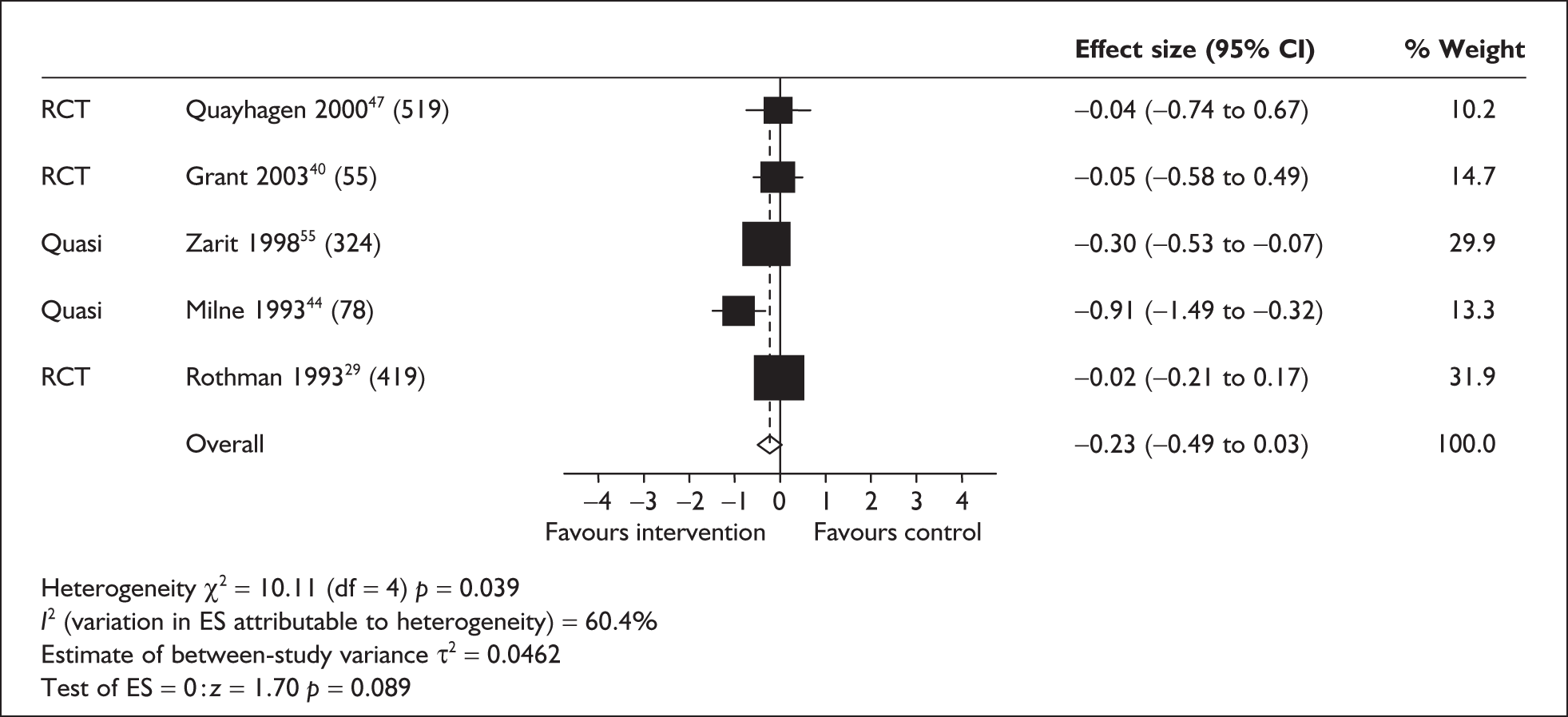

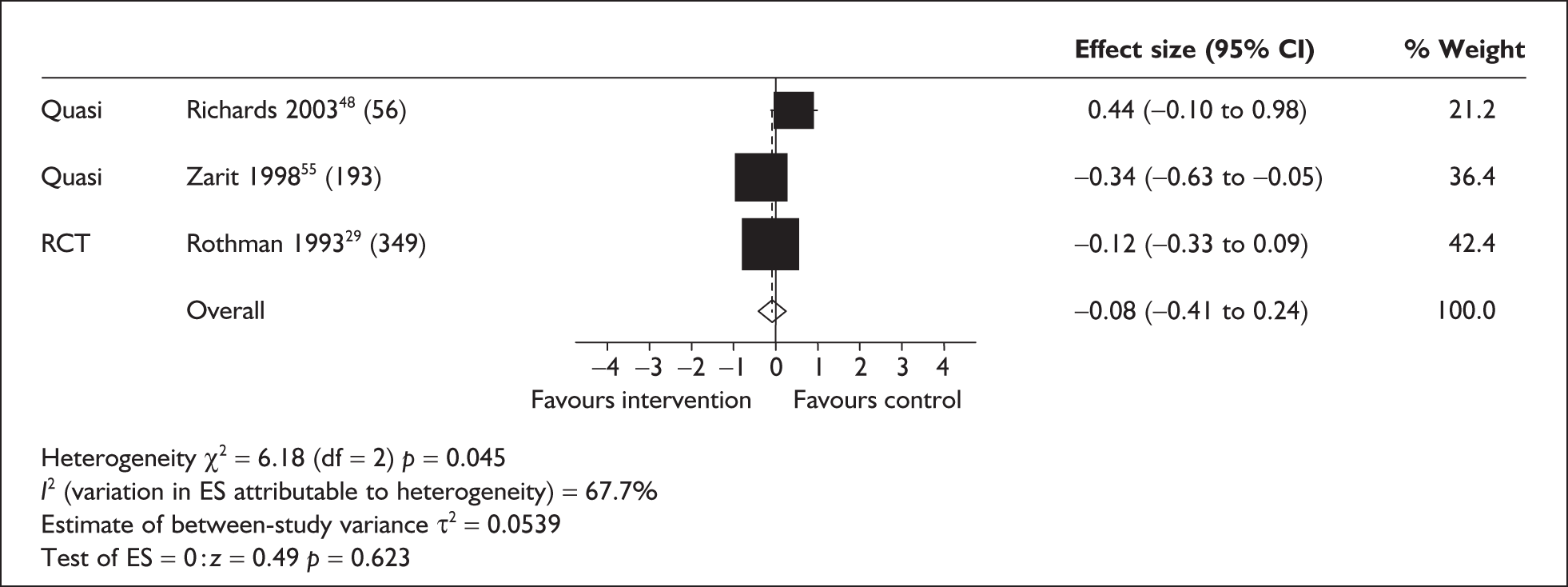

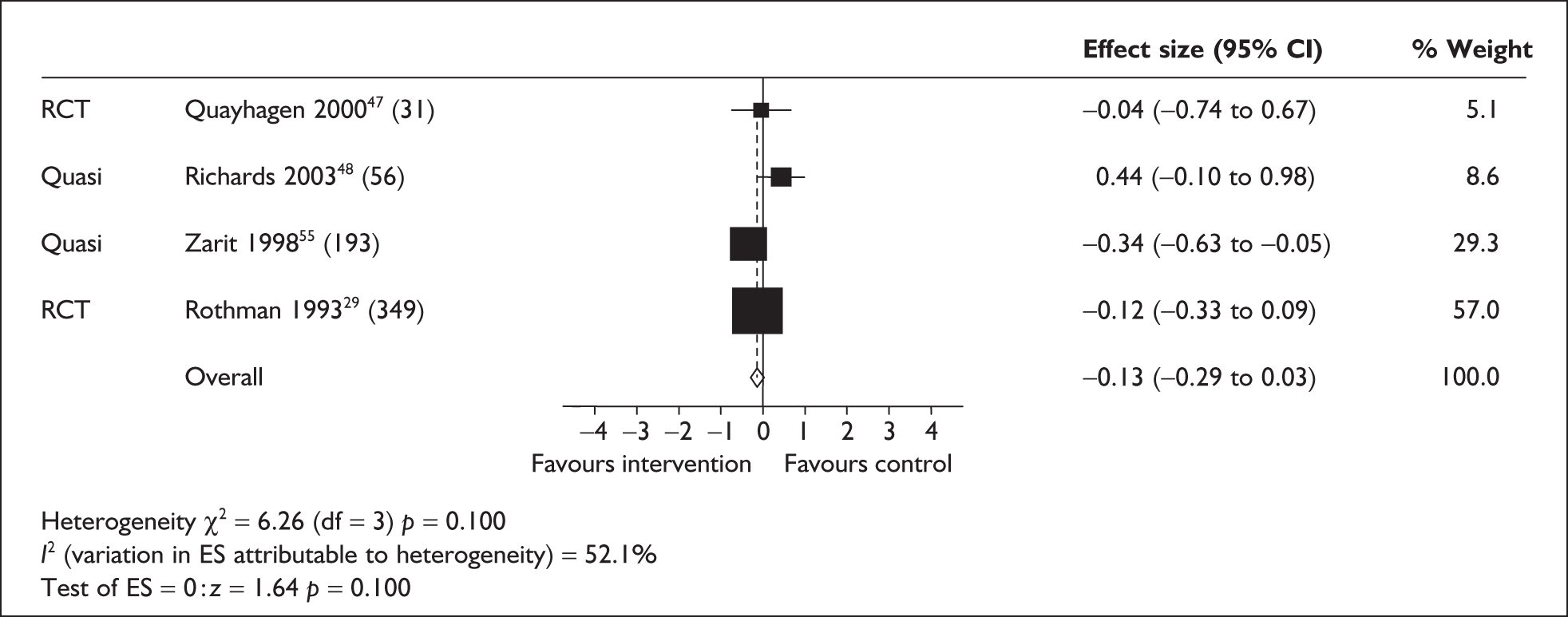

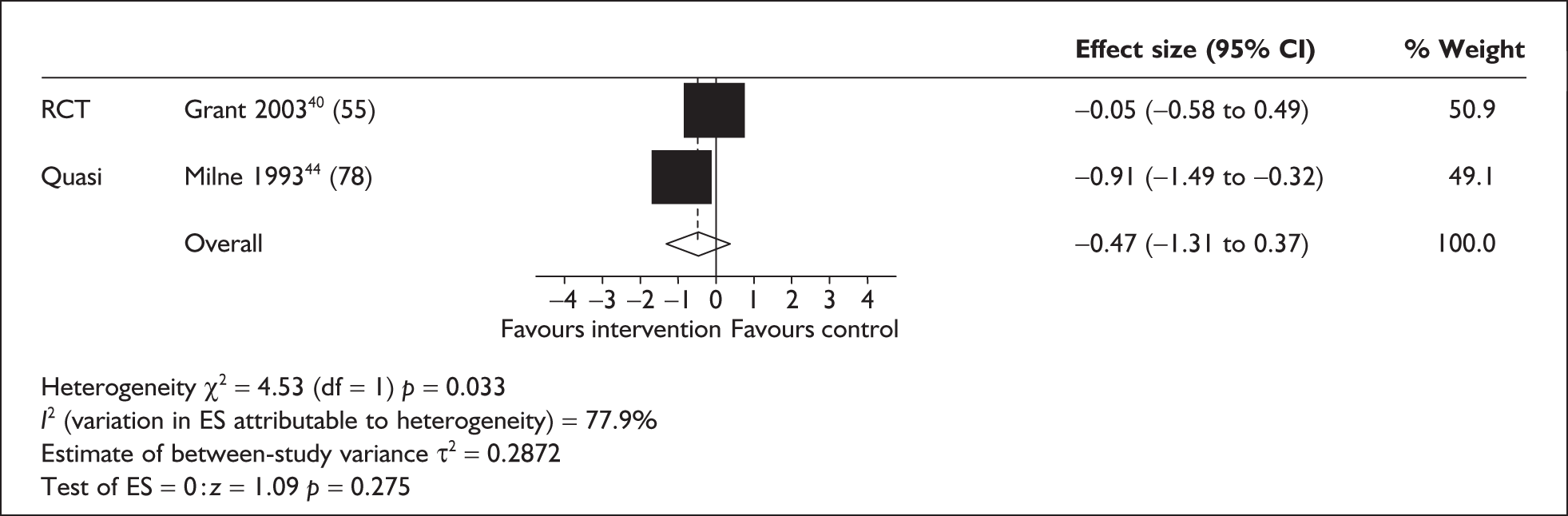

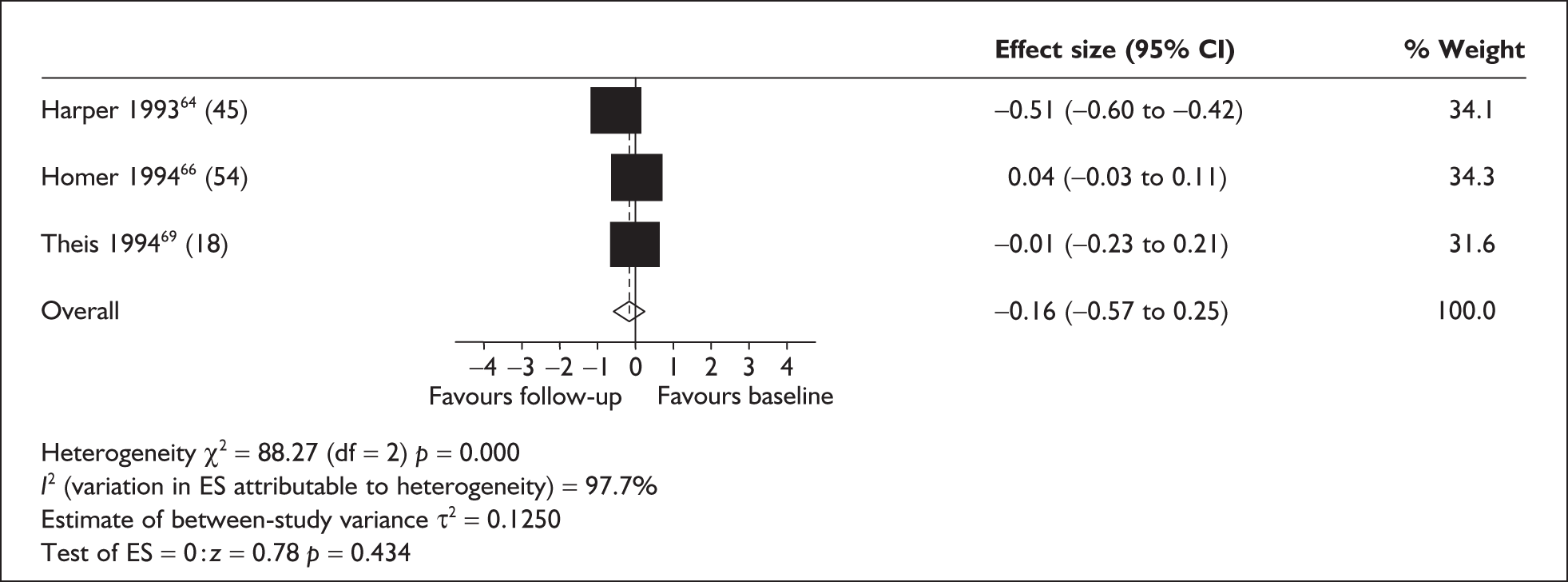

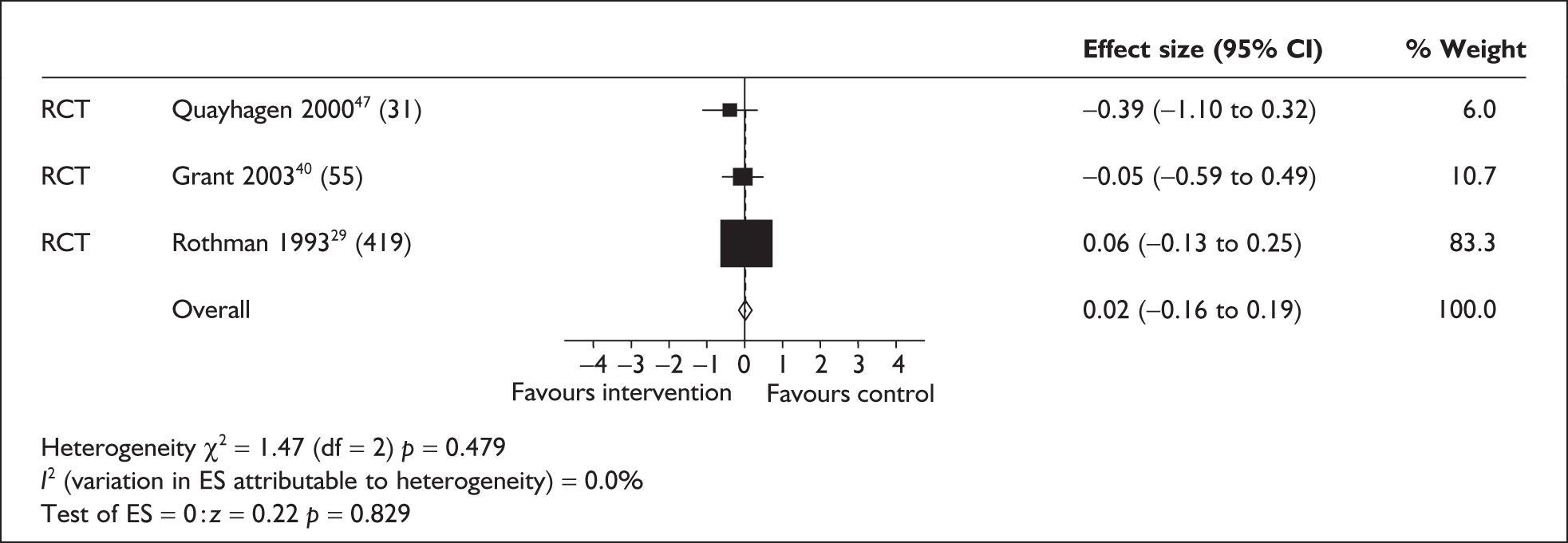

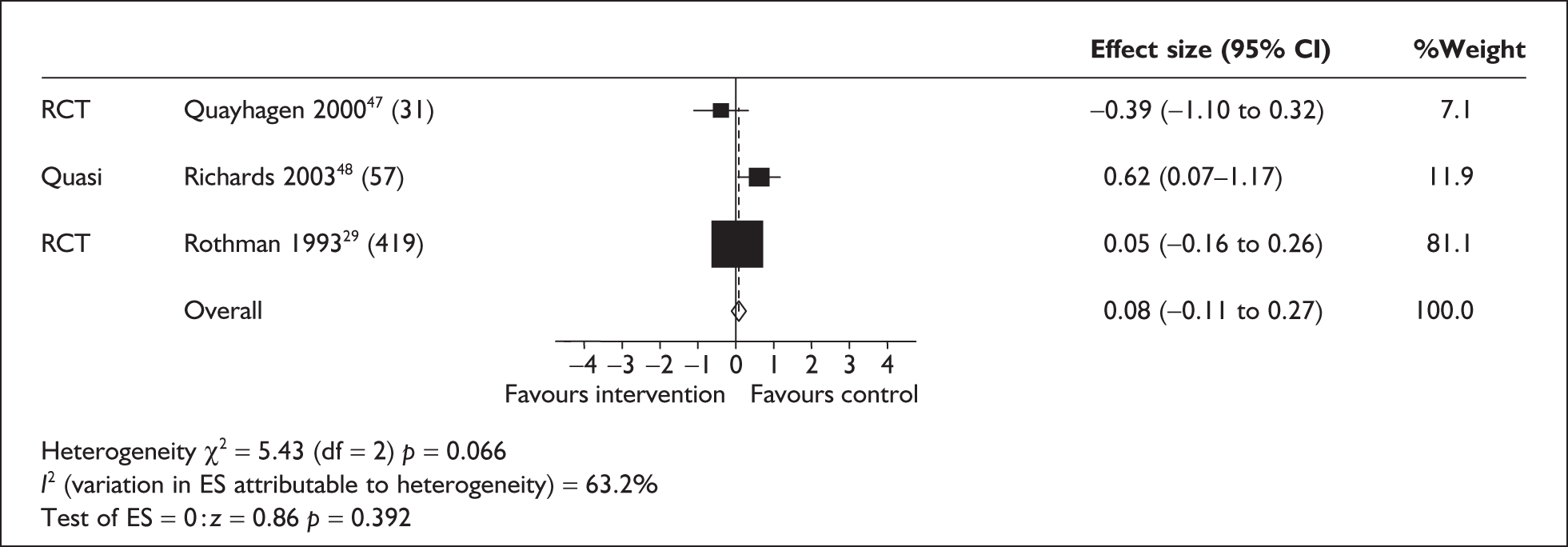

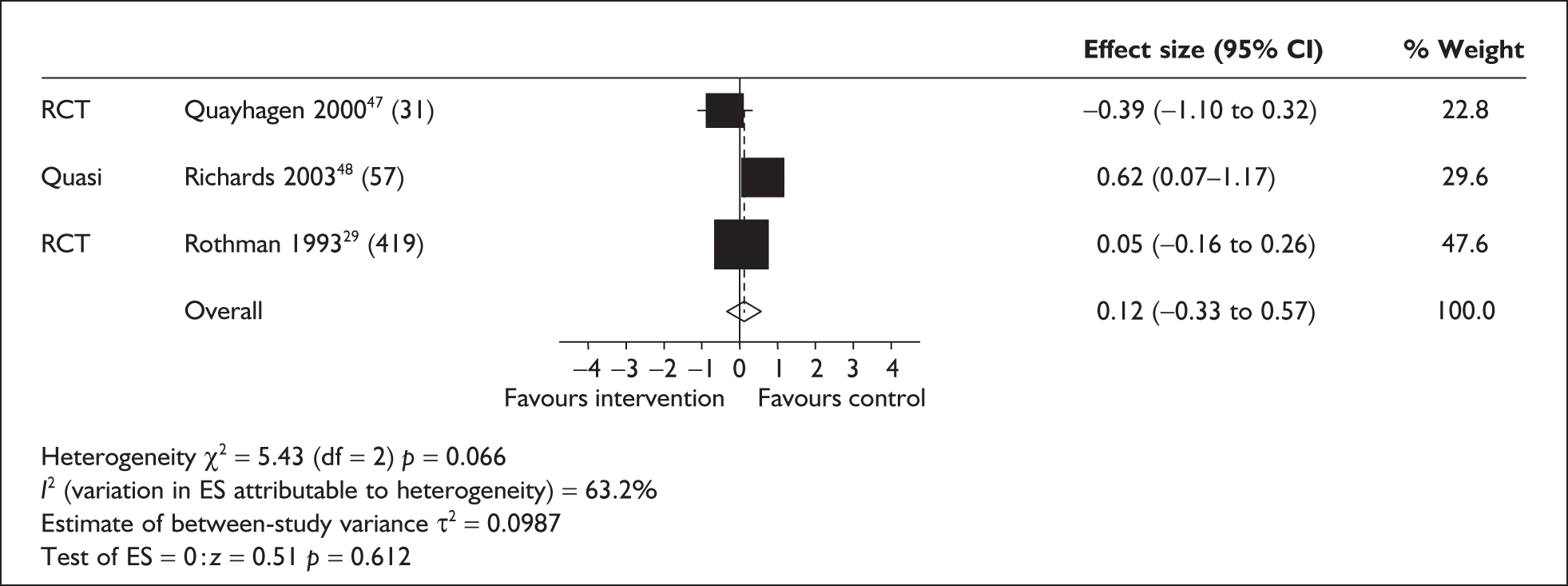

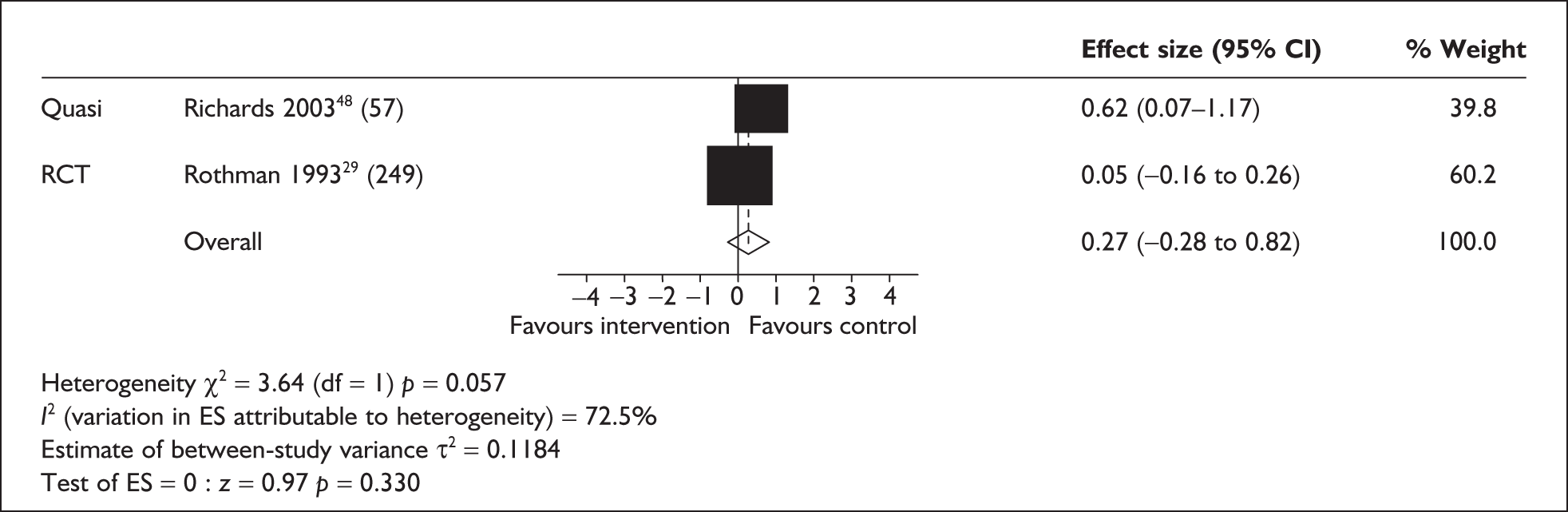

Three studies provided sufficient data on carer burden for inclusion in the meta-analysis: two RCTs29,32 and a single quasi-experimental study. 41 Two studies29,32 assessed day care interventions and the other41 both day and home care. Care recipients were frail elders,29 elders with dementia41 and elders experiencing mixed problems. 32 Two of the studies were carried out in the USA29,41 and one in Canada. 32 Carers in one study29 were followed up at 6 and 12 months; the length of follow-up for the other two studies32,41 was 3 and 6 months and, therefore, only the 6-month follow-up period in the Rothman et al. 29 study was included in the meta-analysis. All interventions comprised day care and were delivered continuously over the respective follow-up periods. No significant effects of respite care on carer burden were observed (Figures 3 and 4) in either fixed or random models. The two RCTs can be seen to be closer to the line of no effect than the quasi-experimental study.

FIGURE 3.

Carer burden in randomised controlled trials/quasi-experimental studies (fixed model) – 6-month follow-up (sample sizes in brackets). CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

FIGURE 4.

Carer burden in randomised controlled trials/quasi-experimental studies (random model) – 6-month follow-up (sample sizes in brackets). CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

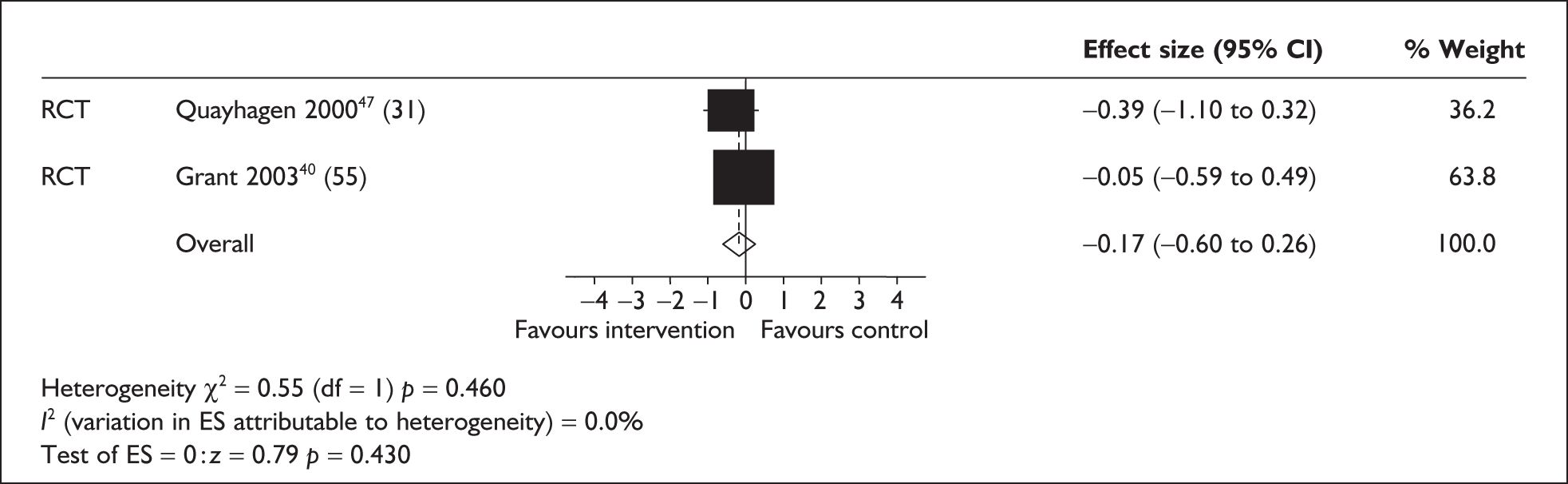

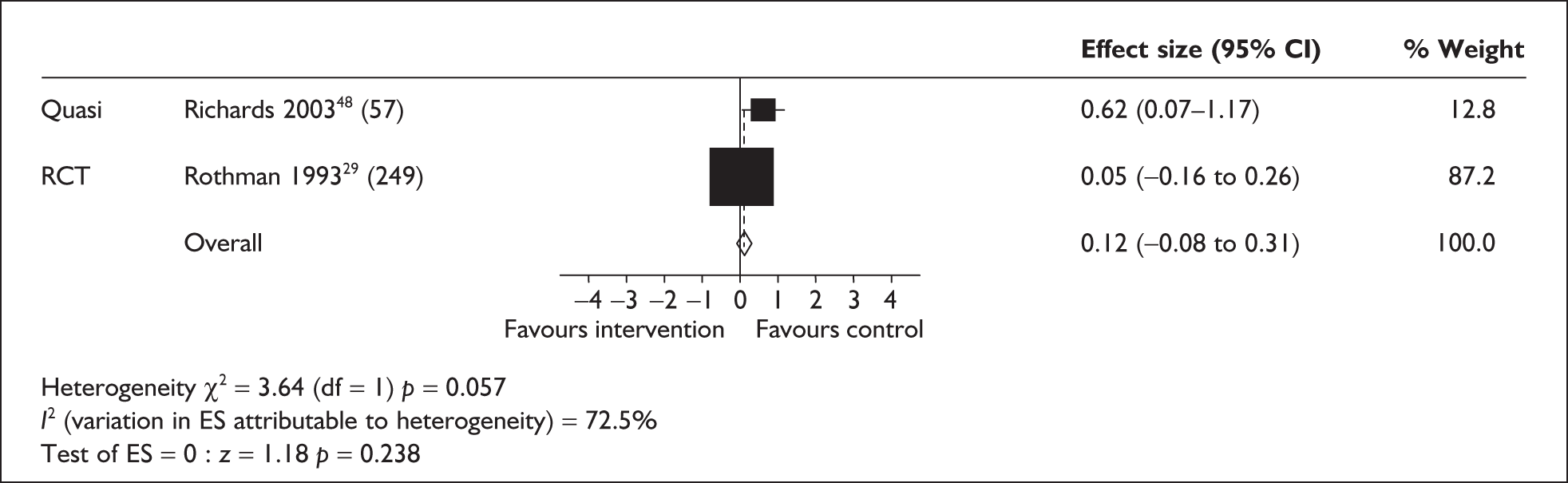

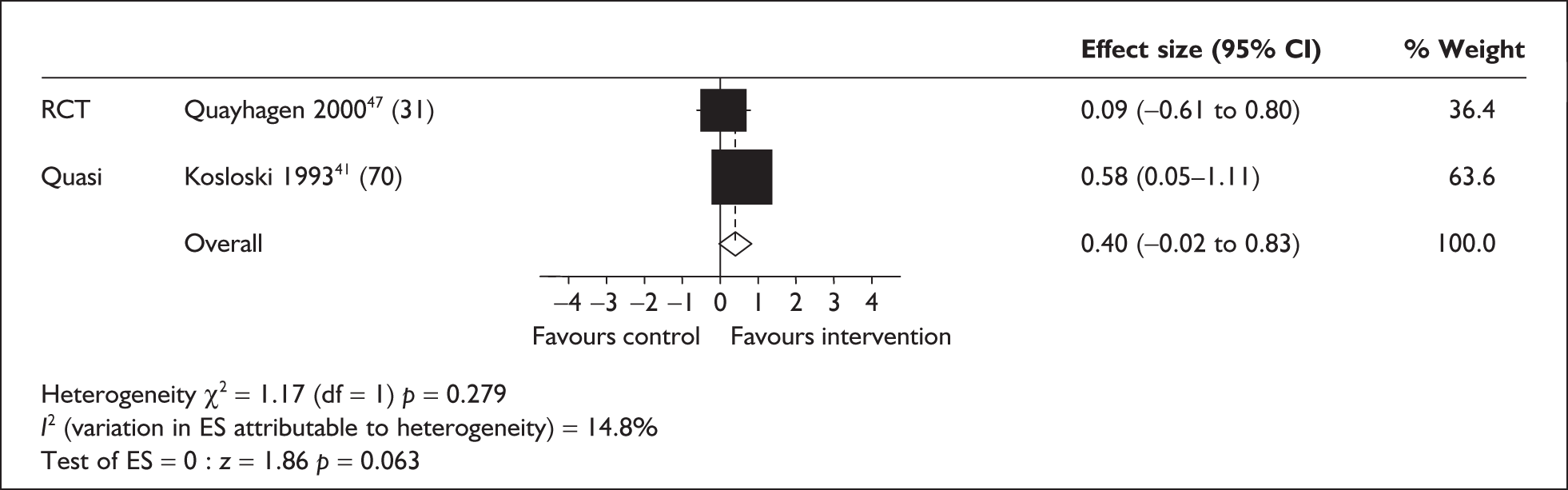

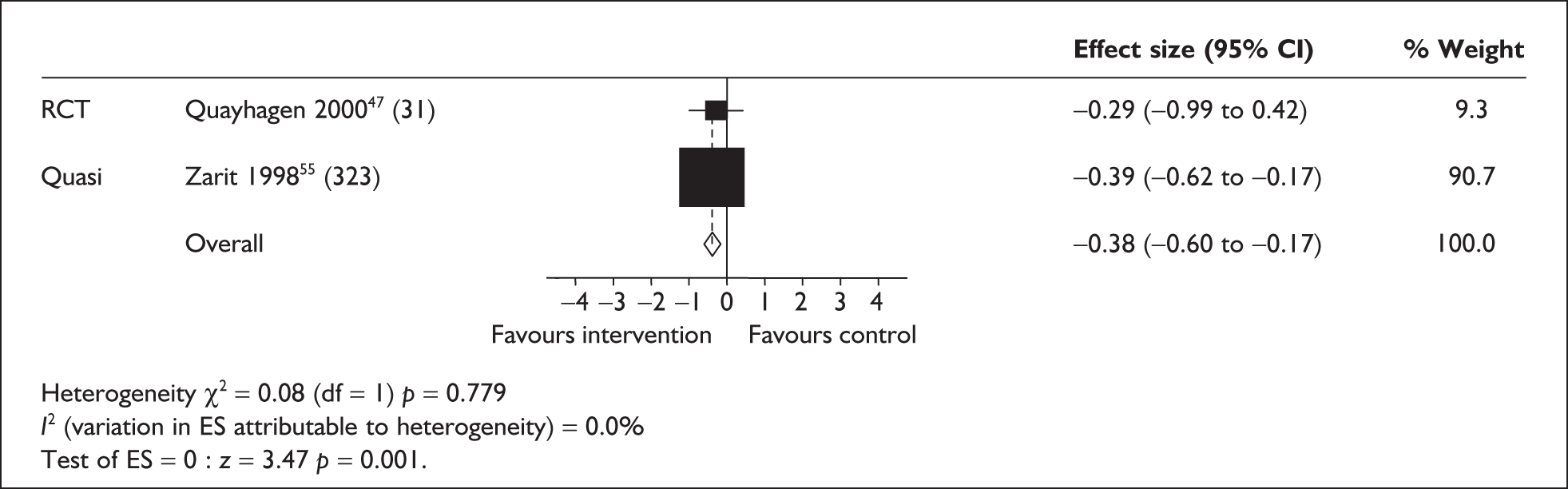

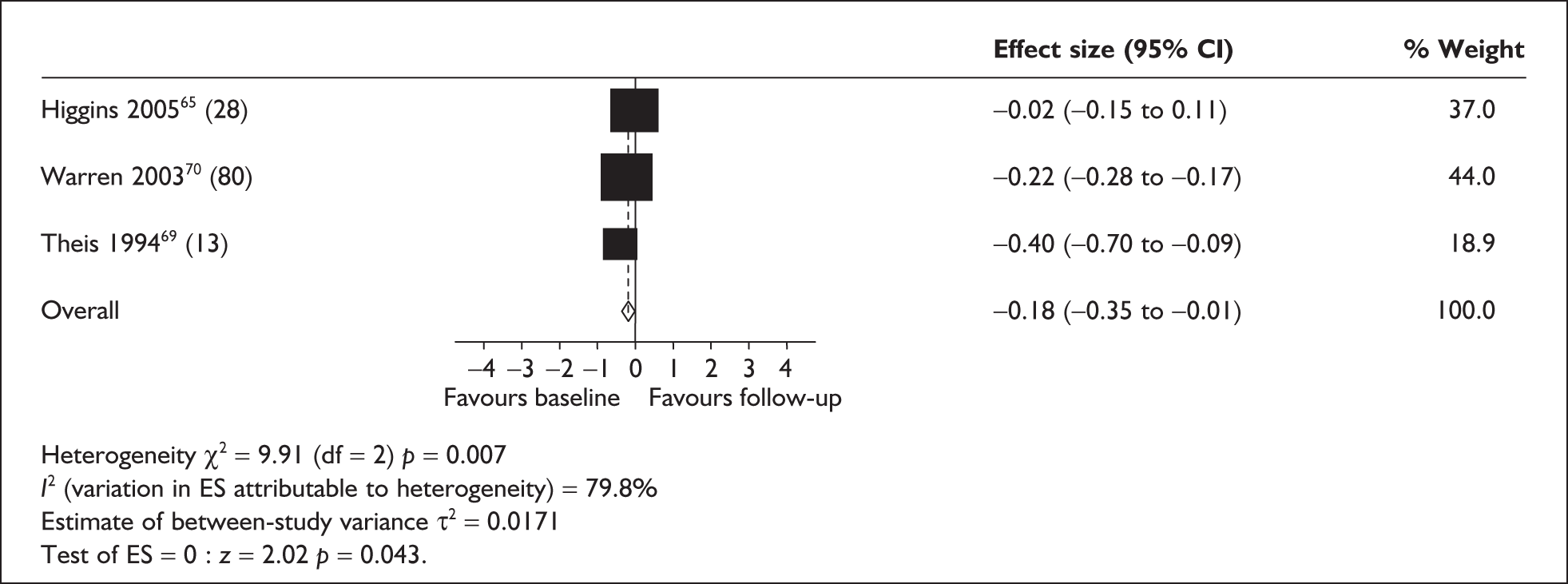

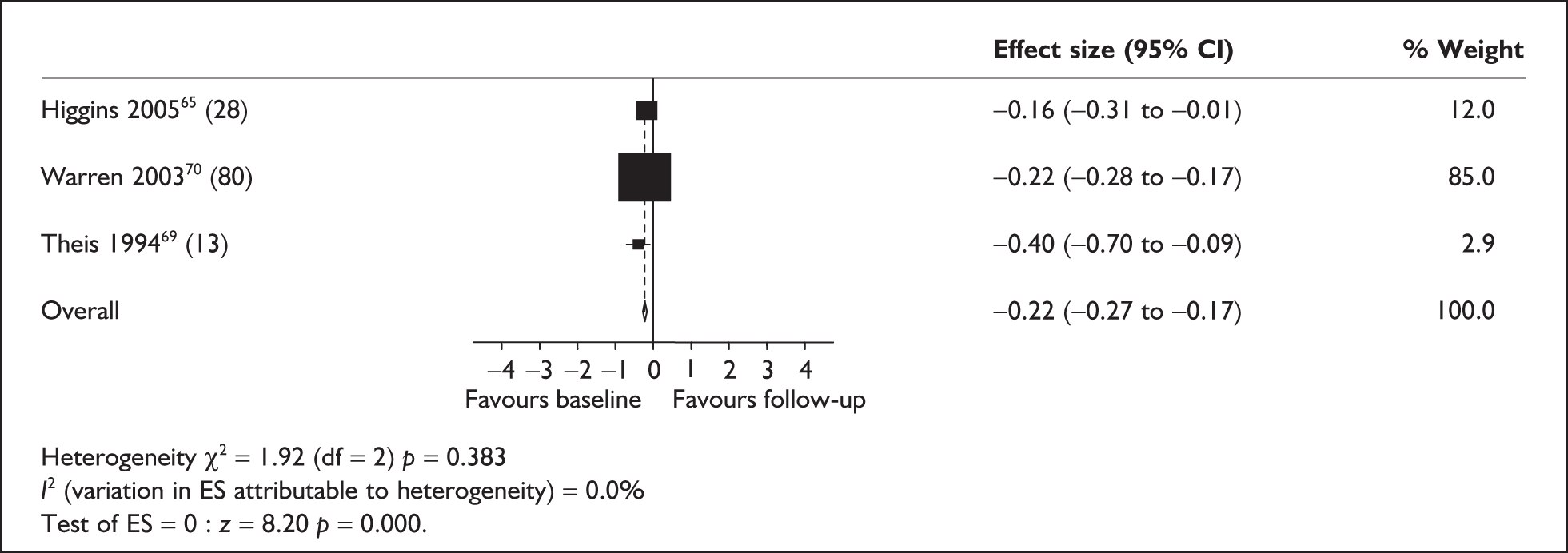

Carer burden in longitudinal before-and-after studies

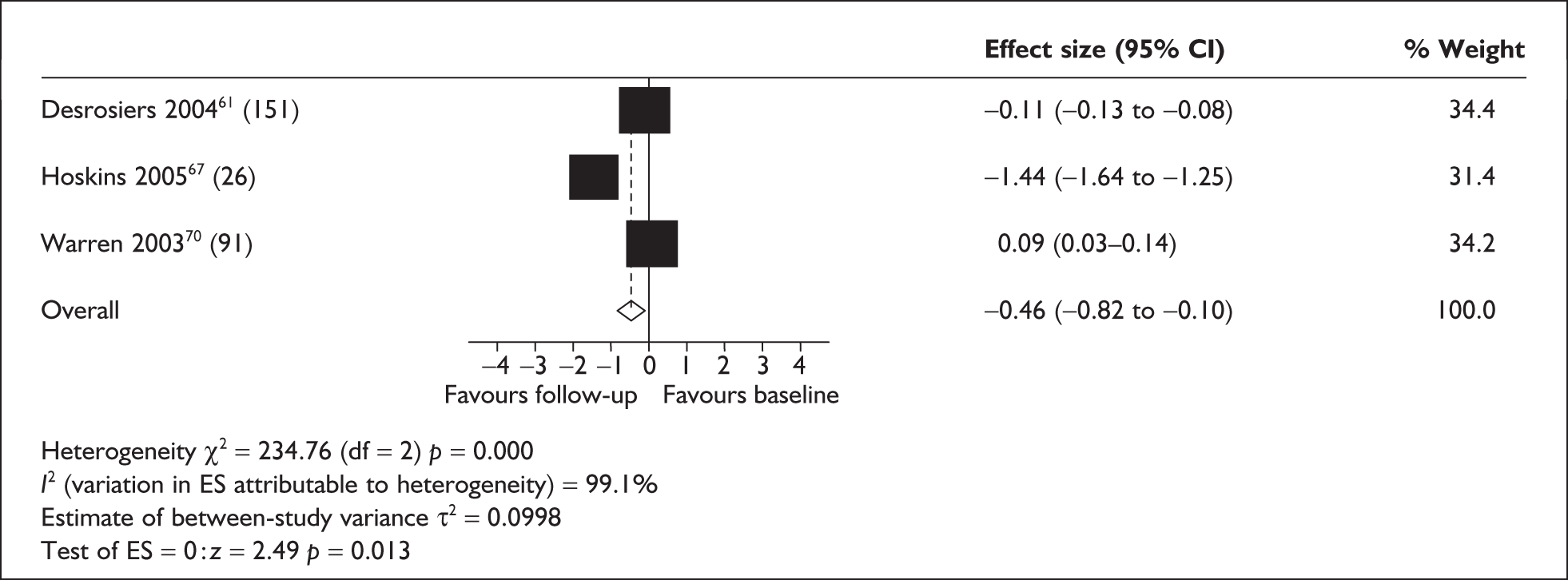

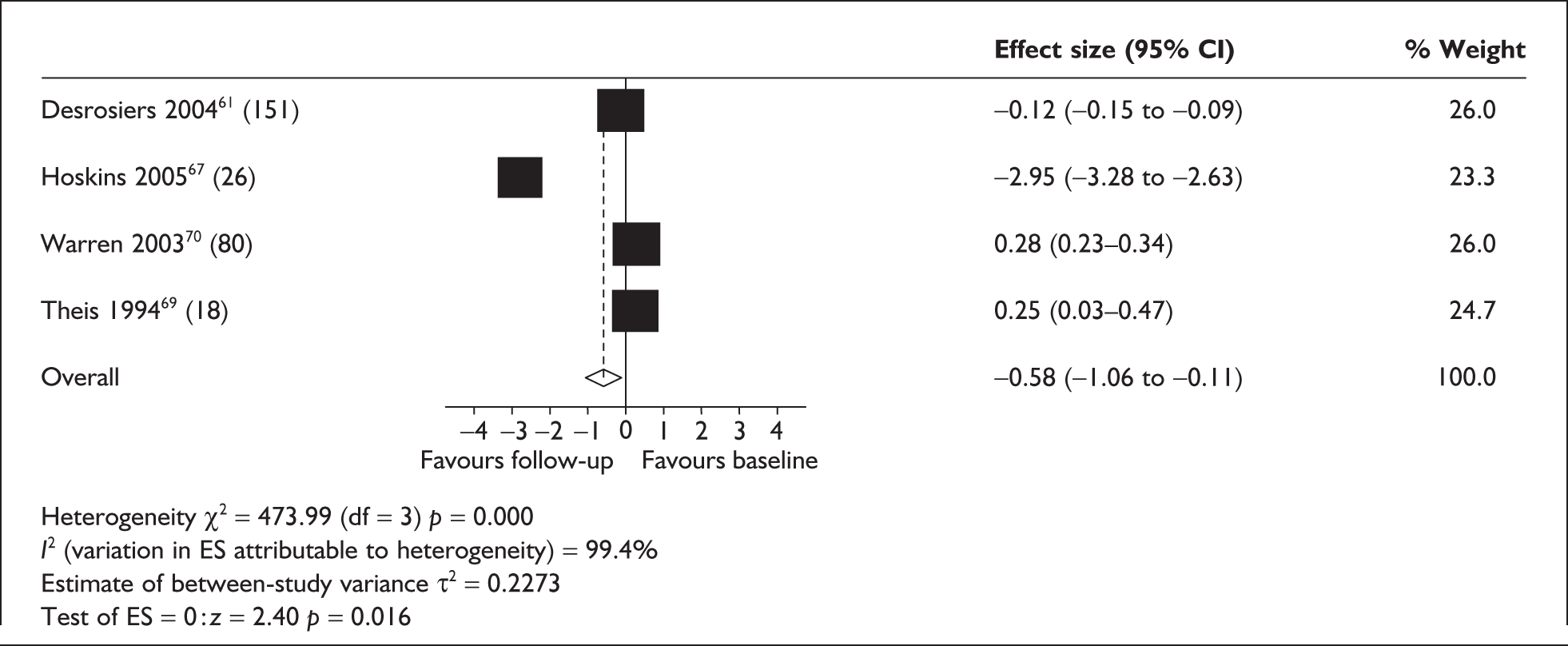

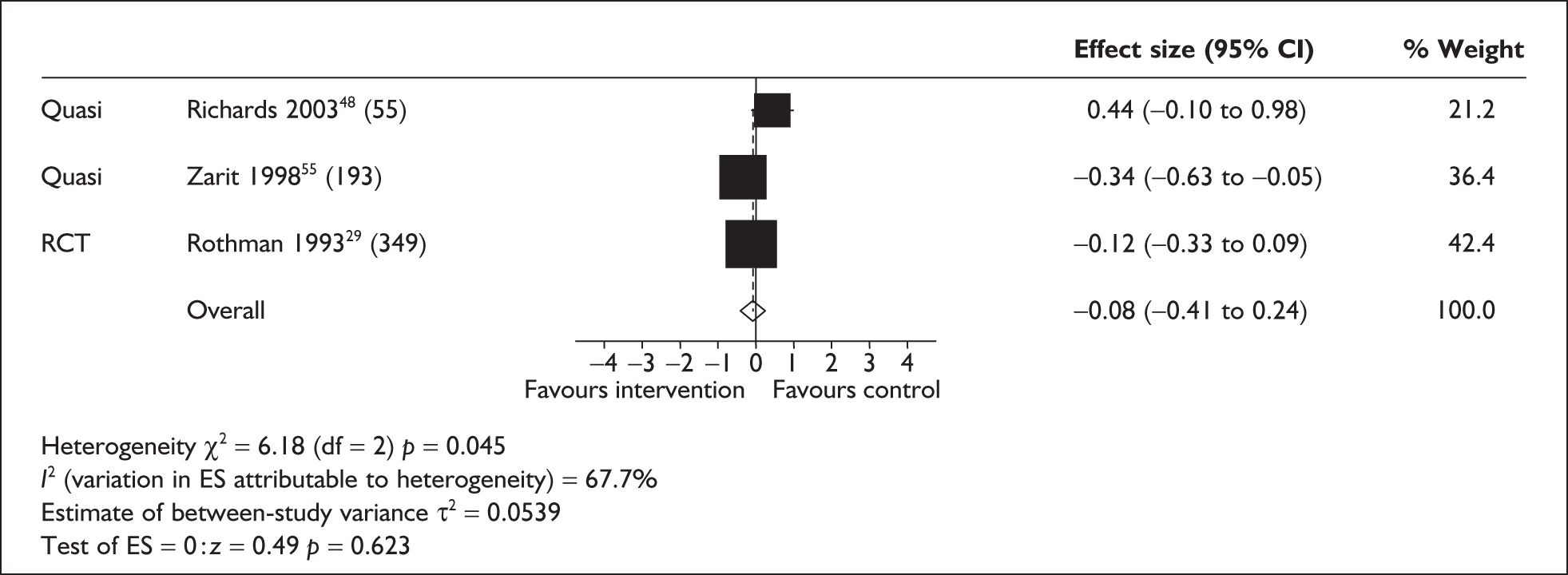

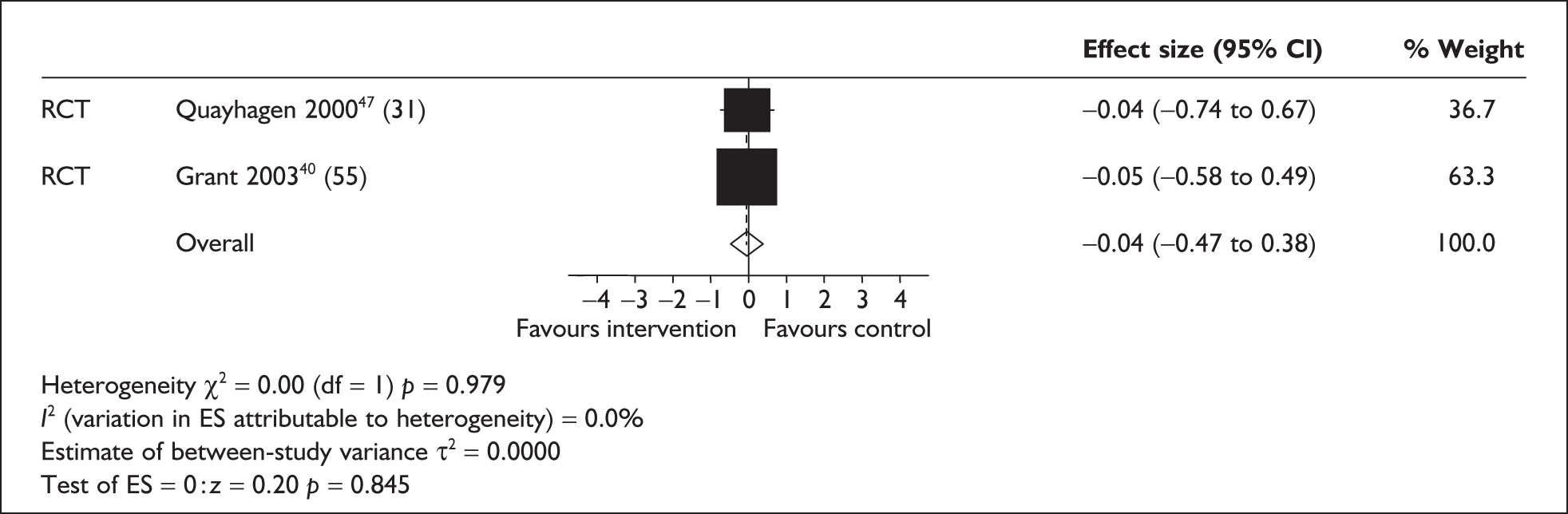

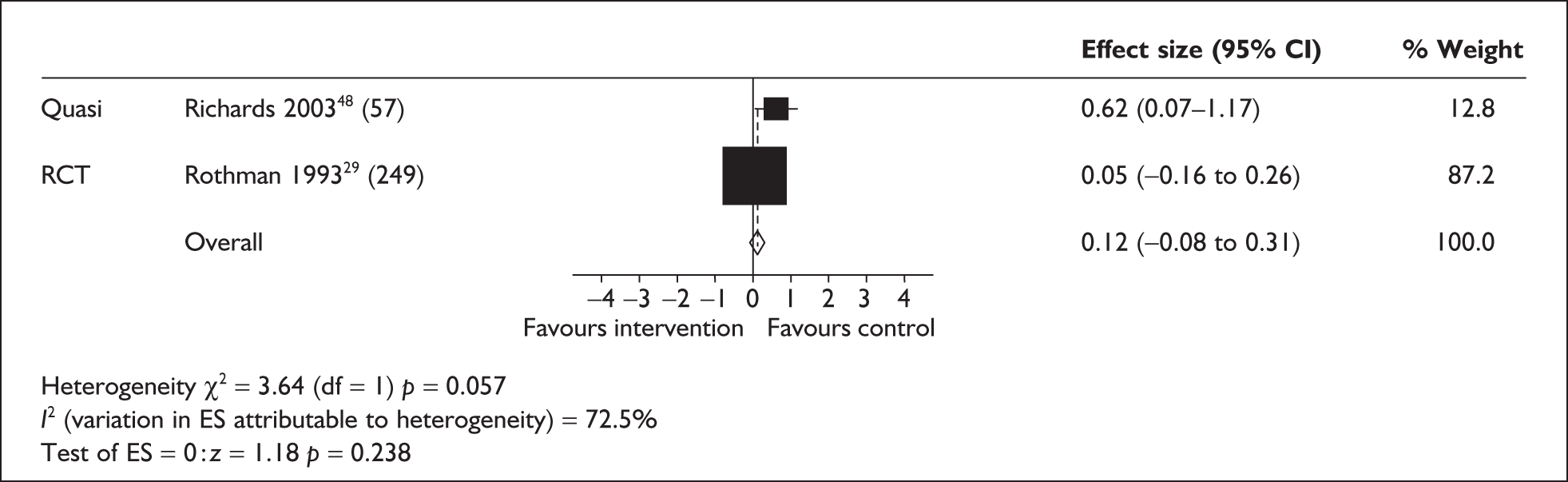

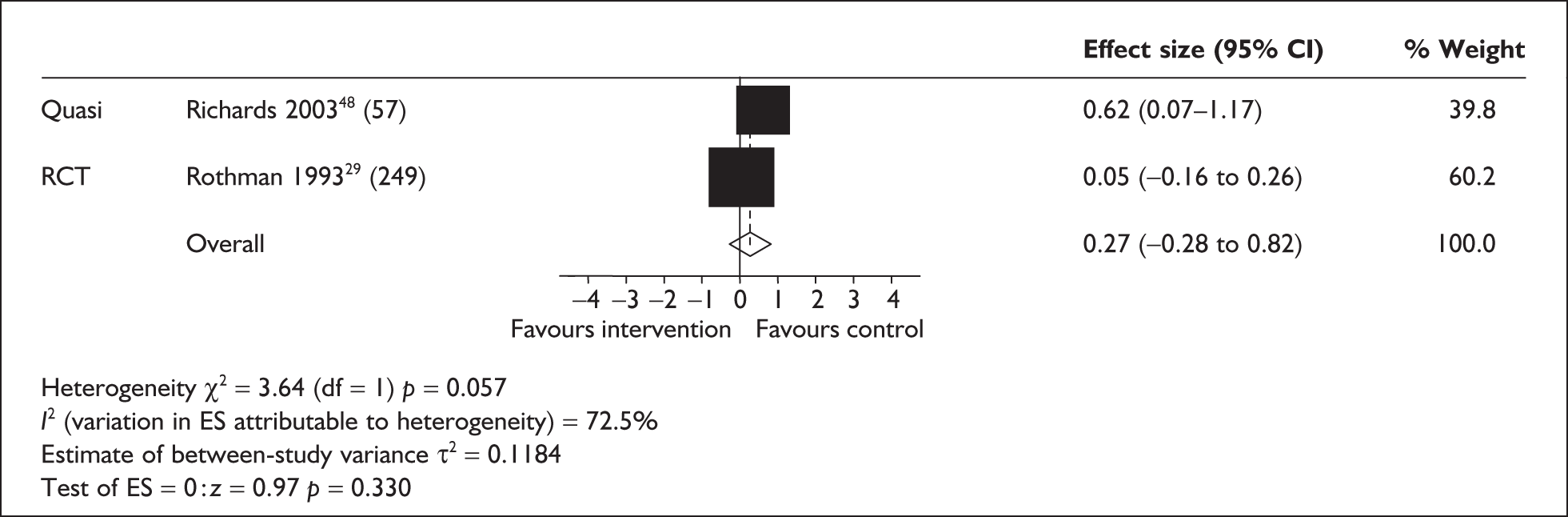

Four longitudinal studies comprising a single-group (before-and-after studies) were included in a meta-analysis of carer burden. 61,67,69,70 Two studies were carried out in Canada using a day care intervention;61,70 one in the UK on a combination of institutional and day care;67 and one in the USA on a combination of home and institutional care. 69 The two studies focusing on day care gave similar levels of respite of around 2 days per week, but the study using a combination of day and institutional care did not give any information on the amount of respite provided. Three of the studies focused on frail elders61,69,70 and one on care recipients with dementia. 67 All studies measured burden at multiple time points (3 and 6 months;61,67 2 and 6 months;70 6 and 12 months69). Warren et al. 70 also measured burden at 2 weeks post-respite; this follow-up measurement was excluded from the meta-analysis. Therefore, two meta-analyses were carried out, one at short-term follow-up (2–3 months) and one at longer-term follow-up (6 months); the 12-month follow-up69 was not included in the meta-analysis. At both short- and longer-term follow-up tests for heterogeneity fitting a fixed model were significant (p = 0.0000); therefore, results of random models are presented (Figures 5 and 6). The only individual study with a positive significant effect at either follow-up67 was focused on care recipients with dementia rather than frail elderly more generally and used a combination of institutional and day care.

FIGURE 5.

Carer burden in longitudinal before-and-after studies at 2–3 months’ follow-up (random model) (sample sizes in brackets). CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size.

FIGURE 6.

Carer burden in longitudinal before-and-after studies at 6 months’ follow-up (random model) (sample sizes in brackets). CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size.

Quality and design characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis of carer burden

As seen in the analysis presented above, only two RCTs29,32 assessed carer burden. Neither of these studies found a significant effect of day care on carer burden. Only one of these trials was rated as high quality,32 having scored highly on all attributes on the quality assessment. This study examined a day care programme that included some functional and psychosocial activities, although these were group based, which is common in many day care facilities. The day centres did have access to a range of staff such as nurses, recreation technicians, special care counsellors and drivers, with possibly a rehabilitation technician, occupational therapist and psychosocial worker in some facilities. The intervention was fairly active but the main aim was of support rather than medical intervention. In addition, any attendees who required individual intervention were excluded from the analysis, thus excluding those who were having more treatment-focused interventions. However, there were some limitations in relation to external validity as only 34% of participants attended the facility at least once a week. The majority, therefore, had low exposure to the intervention, which may have been insufficient to exert any effects on carers. A subgroup analysis was carried out of high attendees (those attending at least once a week) and those attending less often. Carers of high attendees were substantially less burdened post-intervention whereas carers of low attendees had a slight increase in burden, although the difference was not statistically significant. Although the authors acknowledge that little weight can be placed on conclusions as there may be confounding factors in such an analysis, they suggest that future studies should aim to encourage a level of attendance that would be felt to be of consequence for carers. In addition to this, both intervention and control groups could access other services involving respite if they desired, but this was not measured or accounted for in the analysis.

The other RCT29 was of moderate quality and details had to be gleaned from a number of papers reporting different aspects of this large study. The sample in the analysis included here was not representative of the carer population generally as the trial was carried out in Veteran Administration facilities; the majority of care recipients (96%) were therefore men. The care recipient population further differed from a general community population in that 66% were in hospital at recruitment and were at high risk of nursing home placement on discharge, with the intervention being offered as an alternative to residential care. There were limited details of care recipients’ characteristics or context, but it is likely that there were more carer and care recipient dyads in crisis situation than in the population in general. There was little description of the services provided although, as in the previous study, some additional services were offered such as occupational, physical and recreational therapy. There were also some more individualised services, such as monitoring of complex medications. However, the overall aim of the intervention was focused on support, to allow people to remain at home by providing respite, motivation for self-care and stabilisation of health status. Uptake of the intervention was said to vary considerably with some not attending at all or for very few days; however, actual uptake in the group was not specified, and neither was use of other support services during the time period of the study. The control group received customary care but it was unclear what this involved, although it was apparent that this could be nursing home as well as community care.

The only study in this particular analysis reporting a positive effect of respite on carer burden was a quasi-experimental study,41 which was rated to be of high quality. The main difference between this and the other two studies is that the intervention included more flexibility of respite options. At three sites in-home and day care respite were offered with no limitations on access; two sites offered in-home care, both day and evening with a flexible schedule, and two sites offered only day care on weekdays from 8am to 5pm. It was reported that respite workers received special training but beyond this there was no further definition of the intervention. A further notable difference in this study is that all participants used the respite services, with mean use being 220 hours over the period of the study (range 4–1137 hours). A major issue with quasi-experimental studies is the potential for bias in sampling. In this study waiting list control subjects were used but the majority were recruited from just one site. This had an impact on comparability of the intervention and control groups as they differed on race and income (the control group had more ethnic minorities and a lower income). There were no other statistically significant differences between the groups. Consequently, race and household income were controlled in the analysis, and the positive effect of respite remained. Use of other services was not restricted but was also controlled in the analysis. Finally, the sample of care recipients in this study were people with dementia, whereas care recipients in the other two studies had a range of physical and cognitive disabilities.

Four before-and-after studies assessed carer burden, only one of which was rated as being of high quality and which found no effect of day care. 61 One was rated as being of moderate quality67 and demonstrated a positive effect of institutional and day care, and two were rated as being of lower quality,69,70 both showing no effect. The high-quality study61 assessed burden following ADC in a geriatric day hospital. The aim of the programme was to maintain people in their living environments, but being a day hospital as opposed to a day centre participants had access to a more medicalised support team of nurses, physicians, physical therapists, occupational therapists, recreational therapists, a neuropsychologist and a gerontopsychiatrist. All participants in the study had received services from at least two of these categories, which may or may not have involved medical intervention. However, description of the study intervention was incomplete, which was reflected in the quality assessment scoring. Whereas this study assessed a range of physical and cognitive disorders, the study rated as being of moderate quality67 focused on care recipients with dementia. This study showed a positive impact of the intervention on carer burden but again the intervention was poorly described, which in this instance was more problematic, as a range of services were offered, not all of which necessarily involved a respite element. Those specifically aimed at respite provision involved day care and institutional care; 50% of participants received institutional respite and 69% day care, although these were not received in isolation. Other interventions included a social care worker scheme, home help, inpatient access, carers group and B-grade nurse. Participants were assessed by a social worker or community psychiatric nurse on entry to the intervention and an individualised programme of care was devised. As well as poor description of the intervention characteristics and the amount and type of intervention received by participants, other aspects rated on the quality assessment form received only moderate scores (i.e. caregiver characteristics poorly described, incomplete control for population characteristics and methods of analysis inadequately described). As it was not possible to identify which particular aspects of the intervention had a positive effect, a logistic regression analysis was carried out, which suggested that only institutional respite had a positive effect. Those receiving day care appeared to be negatively affected. It is not clear if any other factors were included in this analysis and so there may be some confounding.