Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 06/34/02. The contractual start date was in May 2007. The draft report began editorial review in June 2008 and was accepted for publication in January 2009. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

None

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2009 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO. This monograph may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK. 2009Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Infant feeding and health

Breastfeeding is a source of complete nutrition that changes to meet each infant’s growing needs, and confers active immunity to disease. The use of breastmilk substitutes is detrimental to the health and development of the infant and child, and to the health of the mother. Despite longstanding methodological challenges in this field, it is now recognised nationally and internationally that the public health implications of infant feeding are important in industrialised countries as well as in resource-poor countries. 1–3 Good-quality, large cohort studies, a large randomised controlled trial and a good-quality systematic review have shown that the absence of breastfeeding increases the risk of short-, medium- and long-term ill health in infants in industrialised countries (e.g. refs 4–8), and adversely affects long-term outcomes in mothers (e.g. ref. 9). Further, data from prospective studies and a large randomised controlled trial show that infants who are not breastfed have worse neurodevelopmental outcomes. 10–13

Particular care is needed in the interpretation of studies of health outcomes and infant feeding among infants in neonatal units. Studies of infant feeding can seldom be randomised, and there are confounding variables related to the socioeconomic factors associated with infant feeding behaviour. Outcomes measured are often short-term indicators of milk intake or time to discharge, and longer-term health and development outcomes are seldom measured. 14 Studies are often small, as there are relatively limited numbers of infants requiring care in these settings. Because formula feeding and bottle feeding have been standard care for many years, breastfeeding and breastmilk feeding and the techniques required to support them are novel and staff may be unfamiliar with them. Formula is not a standard product across time or across countries or hospitals. Neither can breastmilk be assumed to be standard; even when breastfed, infants can be supplemented with formula or other breastmilk substitutes, and breastmilk is often ‘fortified’ with commercial preparations depending on the nutritional status of the baby and the policy and practice of the country, unit or individual neonatologist. 15–18 Despite inconclusive evidence of effectiveness and safety,19 ‘fortification’ is such a common procedure in some countries (e.g. the USA) that not all studies report whether or not it is used. Breastmilk can also be enriched by maximising the intake of high-fat components of expressed breastmilk,20,21 although this is not common practice. Expressed breastmilk can also vary; fresh or stored mother’s milk differs from donor milk, which may be derived from one or more mothers at different stages of lactation. Expressed milk may be treated in different ways before being given to the baby. Each of these products is likely to have a different impact on outcomes. Further complicating interpretation is the use of different methods for the oral feeding of both formula and breastmilk. Gavage feeding, bottles and cups may each be associated with different outcomes regardless of the content of the feed. 22–24

Despite these methodological challenges, it has been shown that for preterm, growth-restricted and sick neonates including those requiring surgery, the use of breastmilk substitutes is associated with increased short- and long-term adverse outcomes including mortality and serious morbidity. Epidemiological studies,25,26 and randomised and quasi-randomised controlled trials18,27 in high-risk environments have found that the incidence of invasive infection is higher in low birthweight infants who are fed formula. A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials28 has shown that formula-fed low birthweight infants have five times the risk of necrotising enterocolitis (NEC), a condition associated with a mortality of approximately 20% and significant long-term health-care costs amongst survivors. 29 In a UK randomised controlled trial, formula feeding resulted in later transition from parenteral nutrition,30 increasing the associated cost and infection risk. The studies of neurodevelopmental outcomes cited above indicate a larger deficit in low birthweight infants fed on formula (see, e.g., ref. 31). This finding is particularly important in this group where cognitive impairment is a frequent adverse outcome. 14

Deaths and serious morbidity as a result of infants in neonatal units consuming contaminated powdered formula have also been highlighted in the US press (www.cfsan.fda.gov/∼dms/inf-warn.html). In light of the epidemiological findings and the fact that powdered infant formulas are not commercially sterile products, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) now recommends that ‘powdered infant formulas not be used in neonatal intensive care settings unless there is no alternative available’ (www.cfsan.fda.gov/∼dms/inf-ltr3.html; 12 April 2002). The UK Food Standards Agency has informed consumers that powdered infant formula is a non-sterile product (www.food.gov.uk/news/newsarchive/2007/jul/nonsterile; 4 July 2007).

Following discharge from hospital, infants who are not breastfed continue to be exposed to hazards including contamination of feeds and feeding equipment, and errors of reconstitution of formula. 32–35

Feeding from the breast may facilitate other beneficial outcomes, for example a reduction in procedural pain36–38 and earlier discharge. 39,40

Finally, it has been argued that supporting mothers in breastfeeding and providing breastmilk is an essential part of a package of humane care, and assists in promoting attachment. 41 Such care includes gentle touch, decreased negative stimulation, exposure to the mother’s scent, skin-to-skin care and family involvement in care,42 all of which are inherent in breastfeeding. Breastfeeding/breastmilk feeding adds the important factor that the mother’s unique involvement in the nutrition and care of her infant may help to ease the inevitable shock, fear and grief following the birth, and decrease estrangement from her baby in the process of care in the high-tech environment of a neonatal unit. 43–46

Breastfeeding rates

Breastfeeding rates vary widely internationally. High incidence and prevalence are found in many resource-poor countries,2 although socioeconomic and geographic differences are apparent and these high rates can be disrupted by factors including conflict and displacement, maternal mortality and ill health. 47 Exclusive breastfeeding, which results in the biggest health gains, is far from universally practised; only 39% of infants are reported as being exclusively breastfed for 4 months following birth. 2 In industrialised countries, the first six or seven decades of the twentieth century saw breastfeeding rates decline steeply. Countries that have successfully reversed this decline include Sweden, Norway and Japan; Australia and Canada have also seen significant recent increases. Several industrialised countries have, however, not yet achieved such a reversal. These include the USA, France, Ireland and the UK, where low rates of initiation, duration and exclusivity have been observed for several decades. 48 Recent data suggest that initiation rates are increasing in the UK and the USA, although cessation rates have not improved. 49,50

There is also a marked contrast in breastfeeding rates across different socioeconomic groups in resource-poor countries compared with industrialised countries. The wider availability and promotion of formula is associated with increased formula feeding among the more affluent urbanised populations in resource-poor countries (e.g. ref. 51); recent developments in China, where tens of thousands of infants have become ill as a consequence of substandard formula use, demonstrate the potential adverse consequences of this (www.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/337/oct01_1/a1890). In industrialised countries, those most likely to formula feed are from the lowest income families (e.g. ref. 49).

Breastfeeding rates in the UK

Initiation rates in UK countries in 2005 were 78% in England, 70% in Scotland, 67% in Wales and 63% in Northern Ireland,49 indicating an increase in the previous 10 years. This increase is attenuated but not abolished if data are standardised for the age and socioeconomic composition of the survey sample.

In the same 2005 national survey, the rate of women breastfeeding at all in the UK at 6 weeks after birth was 48% (50% in England, 37% in Wales, 44% in Scotland and 32% in Northern Ireland), demonstrating that the rapid discontinuation of breastfeeding in the first few weeks persists. Exclusive breastfeeding rates are also very low; in 2000 only a quarter of those breastfeeding were breastfeeding exclusively at 2 months. In 2005, 27% of those breastfeeding were breastfeeding exclusively at 2 months, 17% at 3–5 months, 21% at 3 months and 5% at 5 months for the UK overall. 49

Incidence and prevalence are lowest amongst families from lower socioeconomic groups,49 particularly among white women compared with those of Asian, black or mixed ethnicity. 49,52 Teenage, young mothers and those least educated are also vulnerable groups, being half as likely as older mothers to initiate any breastfeeding. The increased prevalence of formula feeding in low-income families is an important contributor to inequalities in health. 53

Breastfeeding rates in neonatal units

One challenge in measuring breastfeeding rates in neonatal units is that, for these infants, feeding directly from the breast may not be possible. They may instead have breastmilk feeds, which can include fresh or stored mother’s own milk, or donor milk, and this milk may be fed by methods including bottle, cup and tube. It is important to distinguish between types of milk and methods of feeding, as they may each have a different impact on health outcomes. This is not always the case in surveys of rates, however, and the information available is limited in this respect. Throughout this report, we use the term ‘breastfeeding/breastmilk feeding’ whenever it is not possible to differentiate.

The absence of a definition of initiation of breastfeeding and breastmilk feeding specifically for infants admitted to neonatal units in the UK raises further difficulties for measurement of breastfeeding rates among this population. The UK definition for the initiation of breastfeeding is as follows: ‘The mother is defined as having initiated breastfeeding if, within the first 48 hours of birth, either she puts the baby to the breast or the baby is given any of the mother’s breast milk’. 54

In the case of infants admitted to neonatal units, it is particularly important to measure both of these components where they occur, namely, the baby receiving human milk (directly through breastfeeding, or with milk expressed by the mother or donor milk) and the mother having initiated breastfeeding or expression of breastmilk. Furthermore, the initiation of breastfeeding may be most usefully measured at the point at which the baby receives a nutritive breastfeed, an event which is likely to involve several occasions of the baby being put to the breast and may occur within days or weeks from birth. The time points for the most appropriate routine measurement of each of these components also require consideration to ensure consistency and to aid comparison with initiation rates among term, healthy infants.

Mothers responding to the 2005 national UK study of infant feeding49 reported that 5% of their infants were admitted to ‘special care’. No difference was found in initiation of breastfeeding/breastmilk feeding (the survey did not distinguish) according to whether or not the baby started life in a neonatal unit. Infants starting life in a neonatal unit were slightly more likely to be breastfed/have breastmilk both at 1 week (68% of neonatal unit infants compared with 64% of other infants) and at 2 weeks (63% compared with 60%), indicating that mothers were at least as motivated to produce breastmilk for these infants, or that staff encouraged them to do so, or both. This differential increased with the length of time spent in the neonatal unit, with 73% of infants spending at least 4 days in a neonatal unit being breastfed/having breastmilk at 1 week compared with 61% of infants spending only 1 day and 64% not in a neonatal unit at all. Similarly the prevalence of breastfeeding/breastmilk feeding at 2 weeks increased from 58% of infants spending up to 1 day in a neonatal unit to 67% spending 4 or more days. 49

Policy and infant feeding

The United Nations Global Strategy on Infant and Young Child Feeding2 recommends that all infants should be exclusively breastfed until 6 months, and that breastfeeding should continue at least until age 2 years. This report states that ‘Infants who are not breastfed, for whatever reason, should receive special attention from the health and social welfare system since they constitute a risk group.’ These international recommendations on duration and exclusivity of breastfeeding are supported by the governments of England, Wales and Northern Ireland, and there have been a series of policy developments intended to tackle low breastfeeding rates across the four countries in the UK (e.g. ref. 55). Breastfeeding is recognised as contributing to several Public Service Agreement targets and as an important part of the strategy to tackle inequalities in health. 53 Targets have been set to raise both initiation and duration rates. 56 Breastfeeding has been recognised as an important factor in reducing health inequalities in infant mortality,57 and infants in neonatal care are those most at risk of mortality and serious morbidity. Breastfeeding is also recognised as having a role to play in meeting the Every Child Matters agenda by improving children’s health. 58

Professional bodies and UK NHS organisations have long endorsed breastfeeding as appropriate for all infants (e.g. ref. 1), and recently the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommended a series of interventions across the NHS to raise initiation and duration rates. 3,59 Statements on breastfeeding/breastmilk for preterm and sick infants are more limited. Strong support is given for breastfeeding/breastmilk for high-risk infants by the American Association of Pediatrics. 60 Recently, the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH)61 specifically recommended that mothers with diabetes should be encouraged to breastfeed for both their own and their infants’ metabolic control; these infants are more likely to require care in a neonatal unit. Further, advice that mothers and infants in specific high-risk situations, such as human immunovirus (HIV)-positive mothers, those on antidepressants and substance users, should avoid breastfeeding is now being re-examined in the light of new evidence (e.g. refs 62,63).

There has never been a national UK policy initiative specifically intended to increase breastfeeding uptake and duration for infants in neonatal units, and information about such initiatives in other countries is lacking.

Factors affecting infant feeding rates in neonatal units

Reasons for the low prevalence of breastfeeding overall include the influence of societal and cultural norms, poor continuity of care in the health services, and a lack of effective care by health professionals in hospital and community. 64–66 These factors are likely to be amplified in the highly medicalised environment of neonatal units, making continuation of breastfeeding/breastmilk feeding difficult for those who do start. Specific factors examined here include the medical condition of infants, the health and well-being of mothers, the neonatal unit environment, the organisation of care, staff training, and the lack of consistent availability of care that would enable breastfeeding in this challenging environment.

Infants in neonatal units

Infants cared for in special care baby unit (SCBU)neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) settings include:

-

Infants born prematurely: these will range from very preterm births, down to 23 weeks, through to those born up to 36 completed weeks. These infants are likely to be low birthweight (LBW; birthweight < 2.5 kg). Some will be of appropriate birthweight for gestational age (AGA), others will be small for gestational age (SGA).

-

Infants born SGA: these are infants whose birthweight falls below a chosen threshold for gestation, most commonly the 10th centile. Some will be preterm infants who are also small for their gestational age, and some term or near term but who are growth restricted. Twins and multiple births will be over-represented in this group, and are more likely to be both preterm and SGA.

-

Infants born with or acquiring a health problem that requires additional care: this could include a variety of single or multiple system disorders, congenital malformations (particularly those requiring surgical intervention) and infections. It also includes infants of mothers with problems, for example, they may be infected with HIV or be substance users whose babies may exhibit neonatal abstinence syndrome,67 and infants admitted with feeding problems and/or weight loss.

As technology has allowed infants to survive at younger gestations, the very preterm, born before 28 weeks, have distinct challenges to their survival, health and development. These infants have had a major impact on the work of neonatal units as they have more complex problems, will require intensive care, and will have an increased length of stay in neonatal units. 68

There is a strong association between prematurity and multiple births; about 40–50% of twins and 90% of triplets are born prematurely. 69 With improvements in fertility treatment, the already established trend of increasing multiple pregnancies is likely to continue. The issues in relation to breastfeeding twins and multiples are complex and range from simple difficulties relating to the additional time it takes to breastfeed two or more infants, to more complex questions about fulfilling nutritional requirements.

The needs of infants born between 34+0 and 36+6 weeks’ gestation also require consideration. Although less physiologically and metabolically mature than term infants, they are usually well enough not to need admission to a neonatal unit and are often looked after on the postnatal ward in order to avoid maternal separation. These infants have relatively low oromotor tone and function so are more likely to have feeding difficulties, especially if breastfed, and to require readmission in the first month of life. 70,71

Mothers of infants in neonatal units and their families

Mothers of infants in neonatal units are more likely than mothers of term infants to have experienced a complicated labour and/or birth, to be prescribed medication, to have a range of pre-existing social and medical problems, and to be anxious about their children’s well-being and even survival. 72 They may have been prescribed antenatal corticosteroids if recognised to be at risk of preterm birth, and this may have a negative impact on milk production. 73 They may have health problems, such as HIV, that require careful consideration of feeding options. They are more likely than mothers of term infants to be from a low-income background74 and therefore less likely to choose to breastfeed; and, as their pregnancies may be curtailed by preterm labour, they are likely to miss out on the antenatal education that could influence their feeding decision. 75 Women with lifestyle challenges, such as smoking, use of non-prescription drugs and alcohol, will also be over-represented, as these factors predispose to preterm birth and to intrauterine growth retardation. 76 This group of mothers is less likely to have made a decision to breastfeed prior to the often unexpected early birth of their baby.

Mothers will be anxious and concerned about the health and survival of their infant or infants, and they may even be in a different hospital, or discharged home while the infant/infants remain in hospital. They may have to take care of older children, or even return to work if the infant’s stay is prolonged. For mothers of twins and multiples, there may be a healthy infant in addition to a sick infant/infants, and it is possible that one infant may be transferred to another hospital for specialist care, resulting in the mother having to choose which baby to spend most time with. Mothers of infants in neonatal units have described being exhausted, feeling insecure bonds with their infants, and experiencing unresolved grief,45 and the experience of having a small and preterm baby has been described as ‘a complete shock’, and ‘an unnerving experience’. 43 These experiences are likely to have an impact on trying to establish breastfeeding or breastmilk expression. 46

Family members, especially fathers and grandparents, are likely to be anxious and concerned about the baby, as well as the health and well-being of the mother. 77

Neonatal units: organisation of care, staff and ethos

Markedly improved survival rates at all gestations, as well as many more survivors at the extremes of prematurity, mean that there are increasing numbers of infants in neonatal units with complex problems. 14 In addition, the organisation of neonatal care in the UK has undergone substantial reorganisation in the last 5 years with the creation of neonatal networks and the centralisation of neonatal intensive care. 43 These factors combine to give rise to large populations of very small infants with complex needs in big tertiary neonatal units. Almost all units examined in a recent survey reported that they commonly exceeded their capacity, with three-quarters being closed to admissions at some time in the 6 months prior to the survey. 43 This system of care also requires transport of infants, with reported problems related to lack of specialised transport, and communication with parents.

Although the centralisation of care has delivered benefits including streamlining of care, shared meetings, staff training and shared protocols,43 the promotion of breastfeeding still requires attention. Staff working in neonatal units include neonatal nurses (who are likely to have diverse backgrounds including general nursing, adult intensive care and midwifery), paediatricians, speech therapists, nursery nurses and health-care assistants. Mothers will be cared for by a different set of staff in different settings, including hospital and community midwives, obstetricians, staff in critical and intensive care, health visitors and GPs. A recent learning needs assessment found that NHS staff were not adequately prepared to support breastfeeding among the general population,78 and that paediatricians were particularly ill-prepared to promote and support breastfeeding. 79 The problems of staff training for breastfeeding have been recognised recently, and NICE has recommended that the Baby Friendly Initiative becomes the minimum standard for care for NHS trusts. 3,59,80 However, although neonatal units are assessed to a limited degree as part of the Baby Friendly assessment of the maternity unit, there is as yet no Baby Friendly accreditation process for standards of care in neonatal units. Neonatal nurses and medical staff are therefore likely to be poorly trained in the complexities of supporting breastfeeding in this environment, including the skills needed to work with mothers of multiples;81 midwives and health visitors are unlikely to have the skills to support women to express breastmilk over long periods of time; and each discipline is likely to differ in their preparation for and approach to infant feeding, resulting in inconsistencies in approach.

These problems are compounded by understaffing. The national shortage of neonatal nurses means that the British Association of Perinatal Medicine guidelines82 of one nurse to one NICU patient are seldom adhered to; only 4% of neonatal units meet these standards, and the nurse workforce is understaffed by one-third. 43

Neonatal units are stressful for staff and students, as well as families. All the infants are ill or very small, parents are visibly anxious, staff are busy and concerned about the infants’ well-being and even survival. The atmosphere has been described as ‘stressful’, ‘frightening’ and ‘difficult’. 83 Parents need support from staff; some parents have described themselves as ‘completely overwhelmed’, and that ‘it felt like [their baby] belonged to the NHS and not to us’. 43 Equipment is essential and pervasive, including incubators, monitors and pumps.

Facilities may not be ideal for providing appropriate care. Finding space for parents to sit quietly with each other, to talk with staff, or to sit beside the baby and take in the fact of an unexpected preterm birth, a congenital problem, or an episode of worsened health status, can be problematic. In a recent survey, 25% of mothers reported that units had no facilities for them to stay in or close by the unit. 43 The lack of space beside incubators can make prolonged skin-to-skin care difficult or even impossible. The same report found that 25% of mothers ‘never’ had skin-to-skin care with their infants, and 60% sometimes felt they were ‘in the way’. 43

In such settings, the promotion of humane care becomes problematic. 41–44 It is widely accepted in the care of healthy, term infants that close contact between baby and mother is essential for breastfeeding, for attachment and for the well-being of the baby and the mother,84 and the lack of this contact adds to the vulnerability of mothers and infants in neonatal units. A system of care that includes reducing noise and light, minimal handling, and giving longer rest periods, known as developmental care (NIDCAP), has been instituted in some units internationally. Although the evidence base examining this form of care is limited, outcomes identified include decreased moderate–severe chronic lung disease and NEC, and improved family outcomes. 85

Breastfeeding/breastmilk feeding in neonatal units

Several factors influence breastfeeding/feeding with breastmilk in neonatal units.

Breastmilk production, and in particular the copious production of milk known as lactogenesis II, is delayed in women having a preterm birth, and this may be further complicated in women who have had antenatal corticosteroids. 73 Mammary growth may be incomplete, and the placental lactogen required for mammary development could also be impaired. 86 Establishing and sustaining lactation is much more complex than for mothers of healthy infants,87 expressing milk without the satisfaction of having a baby to feed can be demanding and disheartening,21 and expression often needs to be sustained over a prolonged period of time – the mean length of stay for infants in neonatal units in the UK is 55 days. 43

Mothers who have had a complicated birth including caesarean section, or who are themselves ill, will have major problems in expressing milk and visiting their infant, and will be unable to spend the close and intimate time needed to help establish breastfeeding/breastmilk supply. 88

It becomes increasingly hard for the mother to sustain milk production in the absence of direct feeding from the breast, often resulting in poor weight gain and growth. In order to promote growth clinicians either increase the volume of milk an infant is fed or supplement breastmilk. This is done by ‘fortification’ using a multinutrient breastmilk fortifier or individual supplements (protein, carbohydrate, fat and minerals) or supplementing intake with a preterm infant formula. Evidence on short- and long-term benefits and adverse effects of these practices is inconclusive. 19 Practice on this issue differs internationally and across different units in the UK, and there are concerns about the increased osmolality that results when breastmilk has commercial products added. 89 The psychological impact of implying to a mother that her milk is nutritionally inadequate is unknown but could be profound. Some units offer increased concentrations of hindmilk as a method of fortification,90 although evidence is lacking on the consequences for the infant in terms of growth, development and health.

Treatment and storage of mother’s own expressed breastmilk, whether fresh, frozen or pasteurised, is critical both for the baby’s intake and for the mother’s motivation to continue to express. Staff need to be trained and to have the facilities to ensure proper storage and use. 3

When mother’s own milk is not available or not sufficient, donor milk can provide a high-quality substitute. A recent unpublished study at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital in London found that the establishment of a donor human milk bank was associated with a substantial increase in the provision of maternal breastmilk to infants with a birthweight of less than 1500 g at the time of discharge. Fifty per cent of infants received breastmilk at discharge before the milk bank opened, whereas 78% received breastmilk on discharge 18 months after their milk bank opened (Dr Camilla Kingdon, St Thomas’ Hospital and Association for Milk Banking, personal communication, 2008). An efficient milk bank system is not widely available in the UK;91 NICE is currently examining this issue (www.nice.org.uk/guidance/index.jsp?action=byID%26o=11973).

The transition to oral feeds is challenging as a result of the unco ordinated suck and swallow pattern of preterm and low birthweight infants. 92–94 Infants may not be able to tolerate oral feeds, will have problems of temperature control, may be difficult for parents to handle, and may have respiratory, cardiac, neurological or other problems that make oral feeding complicated. They may have nasogastric tubes and intravenous (i.v.) lines in place. Difficulties exist for all oral feeding methods,95 but breastfeeding is especially challenging if conducted in an environment where staff do not have the special skills needed, women are anxious about handling a fragile baby, facilities are not available for privacy, and milk supply may not be well established. 81,96 There is concern that giving the baby bottle teats or pacifiers may complicate the transition to feeding directly from the breast as the feeding action is different from breastfeeding,97,98 and alternatives including cups and nasogastric and orogastric tubes have been used to avoid this. 99 However, staff may find it more time consuming to help a mother to breastfeed or support her to express and store her milk than using formula or feeding from a bottle as these have been standard practice for some time.

Hospital protocols may interfere with breastfeeding/breastmilk feeding; these may relate to infants’ expected weight gain and growth, feeding frequency or mode of feeding. Such protocols are likely to be based on current standard care, which in the UK is more likely to be formula feeding.

A consistent strategy to promote breastfeeding/breastmilk feeding in neonatal units is lacking. 100 Without such a strategy at national and unit levels, the combination of the stressful environment and the lack of skills needed to support breastfeeding/breastmilk feeding in these vulnerable infants and their mothers is likely to result in inconsistent and ineffective care.

Conclusion

It is in this complex context that this review and economic analysis are set. The work is both timely and important, as this topic has the potential to have an impact on the mortality and morbidity of preterm and low birthweight infants, and the health and well-being of mothers, and to have considerable resource implications for the health service. Recognising the range of factors that affect the mother, infant, caregivers and the health service, and the potential of this topic to have an impact on inequalities in health, we sought to examine not only the clinical interventions that might work but also the public health context. This study includes work to examine both the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions.

Chapter 2 Aims and objectives of the study

Aims

This study, which includes a systematic review and a decision model, was commissioned by the NIHR Health Technology Assessment programme. The specific aim was to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions that promote breastfeeding or feeding with breastmilk for infants admitted to neonatal units.

This study aimed to evaluate the impact of all types of breastfeeding promotion intervention among infants admitted to neonatal units. These could range from national policies that aim to support the mother in her role as prime carer, such as paid maternity leave, through to clinical interventions such as interim feeding methods, and education and support programmes that aim to increase women’s understanding of, and ability to, breastfeed their infants. The decision model focused on evaluating the impact of support, specifically enhanced staff support, on the long-term health of the infant.

Objectives

The specific objectives of this study were to:

-

identify and describe health promotion activity intended to increase breastfeeding or feeding with breastmilk for infants admitted to neonatal units

-

evaluate the effectiveness of any such health promotion activity, in terms of changing the number of women who breastfeed or feed with breastmilk, using the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion framework101

-

analyse the cost-effectiveness of health promotion activity, specifically enhanced staff support, using a critical review of the existing cost-effectiveness literature and the development of a decision model

-

collate expert opinion on best practice, using the views of Advisory Group members and information from neonatal unit settings nationally and internationally where breastfeeding/breastmilk feeding rates are high

-

identify implications for policy, practice and education based on the findings of this study

-

identify an agenda for future research that will inform key gaps in knowledge.

This study was informed by an Advisory Group including academic, clinical and service user/consumer colleagues and a subgroup of clinical advisers (Appendix 1).

Chapter 3 Scope and methods of the effectiveness and health economics reviews

Effectiveness review

A systematic review of the literature was undertaken using guidelines published by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. 102

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for studies in the effectiveness review

Participants

This review included only studies that recruited infants or the mothers of infants who were admitted to neonatal units. The eligible infant population included preterm infants (both healthy and sick) and full-term infants who were growth restricted and/or sick. Twins and multiple births were eligible for inclusion, as were infants with congenital abnormalities, feeding problems, hypoglycaemia or jaundice, and those requiring surgery.

Studies recruiting population subgroups of mothers of eligible infants, such as mothers from low-income groups or different ethnic groups, were also eligible. Studies of interventions targeting other people were also considered: these participants included those linked to women who may breastfeed, such as partners, other family members or health professionals.

Interventions

This review included evaluations of any type of intervention that addressed breastfeeding/feeding with breastmilk in neonatal units, and studies that comprised a domiciliary care component following discharge from the unit. Control groups could receive standard or routine care or an alternative breastfeeding promotion intervention.

As the aim of this review was to examine breastfeeding-/breastmilk-related interventions in neonatal units, evaluations of interventions that were implemented during the antenatal period were excluded.

Studies that examined the effectiveness of breastmilk on clinical outcomes (e.g. studies that examined associations between breastmilk consumption and the incidence of necrotising enterocolitis, NEC), studies that evaluated the nutritional content of formula and breastmilk fortifiers, and studies of the establishment and maintenance of milk banking were outside the scope of this review of effectiveness.

Outcomes

A study must have reported a breastfeeding-/breastmilk-related outcome to be included in this review of effectiveness. These may have included breastmilk composition and volume, tasting dripped breastmilk, number of sucks, initiation of breastfeeding, any breastfeeding, exclusive breastfeeding and rates of breastfeeding at discharge and beyond. Studies that did not report a breastfeeding-/breastmilk-related outcome were excluded.

Secondary outcomes of interest included clinical/health outcomes (e.g. NEC, gastrointestinal disease, weight), process outcomes (e.g. time of hospital discharge, readmission, time spent by mother in contact with baby), psychosocial outcomes (e.g. views of mothers, fathers, families, health-care staff) and cost-effectiveness outcomes.

Outcomes were examined to assess the different gestational ages of the infant and/or ability to coordinate sucking and swallowing: for example, practice and outcomes for skin-to-skin care may be different for extremely low birthweight infants compared with low birthweight infants, and for infants with specific neurological problems.

Study designs

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and non-RCTs with concurrent controls were included in this review. For categories of interventions where evidence was limited and in recognition of the difficulties inherent in evaluating certain types of health promotion intervention, exceptions to this rule were considered. For example, multifaceted changes to organisation of care may have been conducted using a comparative study with retrospective controls or a before- and after-intervention design. Before/after studies that had utilised a cohort or cross-sectional study design were eligible for this review. It is important to note that results from these studies are likely to be less robust than those from RCTs and non-RCTs, and any reported effect on breastfeeding outcomes may not be solely attributable to the intervention(s). Studies without any form of control group (i.e. descriptive studies) and case studies were excluded.

We identified systematic reviews to assist with identification of eligible primary studies. Findings from identified systematic reviews were not included as a source of evidence for this review. This was due to differences in quality and methodological approaches across reviews for the analysis of primary studies, which may have been included in more than one review.

Identification of studies

The search strategies were devised in collaboration between the information officer (KM) and members of the research team familiar with the topic area. There was no limit by language or country of origin. Studies in this review were identified by searching a wide range of medical, nursing, psychological, sociological and grey literature databases. Each search strategy was developed for MEDLINE and adapted for use with other databases (see Appendix 2.1). In order to minimise potential publication bias for the effectiveness review, the search process aimed to identify published research, unpublished research or research reported in the grey literature, through the following four stages:

Search to identify systematic reviews

Searches were carried out to identify systematic review literature published in this field. Databases were searched for studies dated from 2006 to January 2008. Searches were limited to retrieve only systematic reviews. A total of 115 references were retrieved.

The following databases were searched:

-

MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process Citations

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness

-

Health Technology Assessment Database

-

National Research Register

-

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network

-

National Guidelines Clearinghouse

-

Health Services/Technology Assessment Text

-

Turning Research into Practice

-

Health Evidence Bulletins Wales

-

Clinical Evidence.

Search to identify primary studies

All databases were systematically searched for primary studies dating from inception to August 2007. A pragmatic search of selected databases was undertaken in January 2008. The databases marked below (*) were identified for update searching based on yield of included studies. A total of 14,729 references were retrieved by both original and update searches.

The following databases were searched:

-

*MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process Citations

-

*EMBASE

-

*CINAHL

-

*Maternity and Infant Care

-

*PsycINFO

-

*British Nursing Index and Archive

-

*Health Management Information Consortium

-

*Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

-

*Science Citation Index

-

*Pascal

-

*Inside Conferences

-

*Dissertation Abstracts

-

Sociological Abstracts

-

Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences

-

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts

-

Index to Theses

-

MetaRegister of Controlled Trials

-

National Research Register.

Search for studies evaluating galactagogues

As part of an iterative approach to searching, an additional search was undertaken to identify studies of galactagogues. Databases were searched for studies dated between 1991 and February 2008. Searches were not limited by study design. A total of 4045 references was retrieved.

The following databases were searched:

-

MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process Citations

-

Embase

-

CINAHL

-

Maternity and Infant Care

-

PsycINFO

-

British Nursing Index and Archive

-

Health Management Information Consortium

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

-

Science Citation Index.

To identify grey literature and unpublished studies and to check for completeness, bibliographies of studies retrieved were hand searched, and experts on the Advisory Group were asked to assist with the identification of other published or unpublished studies.

Data handling process

Titles and abstracts of bibliographic records were imported into endnote 9 bibliographic management software and duplicate records removed. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts of identified records. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus. This process identified 138 potentially relevant studies. Full papers were ordered and assessed for inclusion using a prescreen form (see Appendix 3) by one reviewer and checked by a second. Any disagreement on whether a paper was relevant to the review was resolved by a third reviewer.

The five areas of health promotion action identified in the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion101 were used as a framework to assist in classification of the different types of intervention to promote breastfeeding among infants in neonatal units. These were:

-

public policy such as legislation, fiscal measures (e.g. maternity leave)

-

supportive environments that protect natural resources and generate healthy living and working conditions (e.g. private rooms for expressing, provision of pumping equipment to express at home)

-

community action that uses existing human and material resources to enhance self-help and social support (e.g. social support through family, peers)

-

development of personal skills through the provision of information, education for health, and enhancing life skills (e.g. education programmes, clinical support)

-

reorientation of health services to promote health (e.g. staff training, the BFI).

Standardised data extraction and quality appraisal tables were adapted from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) Report 4. 102 Data were extracted and appraised for quality by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer (see Tables 26–73 in Appendix 4.1). An overall quality rating was awarded to each study based on NICE guidance development methodology103 and the Cochrane Handbook (2008)104 (see Tables 74–87 in Appendix 5). Any disagreements in data extraction or quality appraisal were resolved by discussion or, if necessary, by a third reviewer. Details of studies that were excluded at either the prescreening or data extraction stage are shown in Appendix 6.1.

Five relevant systematic reviews were identified in the course of the searches. These were used to identify studies. Data extraction forms for these reviews are given in Appendix 7.

Analysis and presentation of results

Quality ratings for each study have been presented in the text (Chapter 4) using the following definitions:

-

Good quality – most or all criteria being fulfilled and where they were not met, the study conclusions were thought very unlikely to alter.

-

Moderate quality – some criteria being fulfilled and where they were not met, the study conclusions were thought unlikely to alter.

-

Poor quality – few criteria were fulfilled and the conclusions of the study were thought very likely to alter. Serious caution is warranted in interpretation of the results of these trials.

Details of the individual quality ratings for each study are provided in Appendix 5.

Within each topic area, results are presented first for RCTs and then for other study designs.

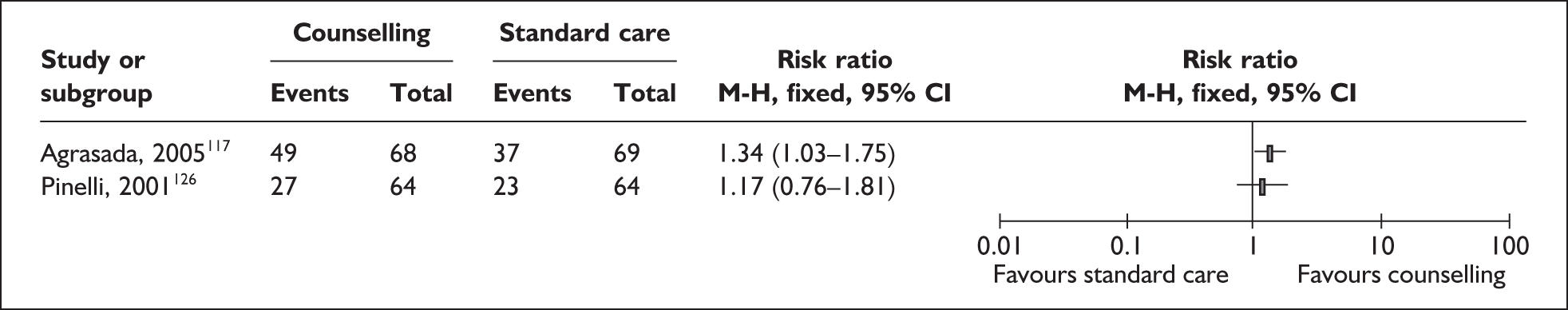

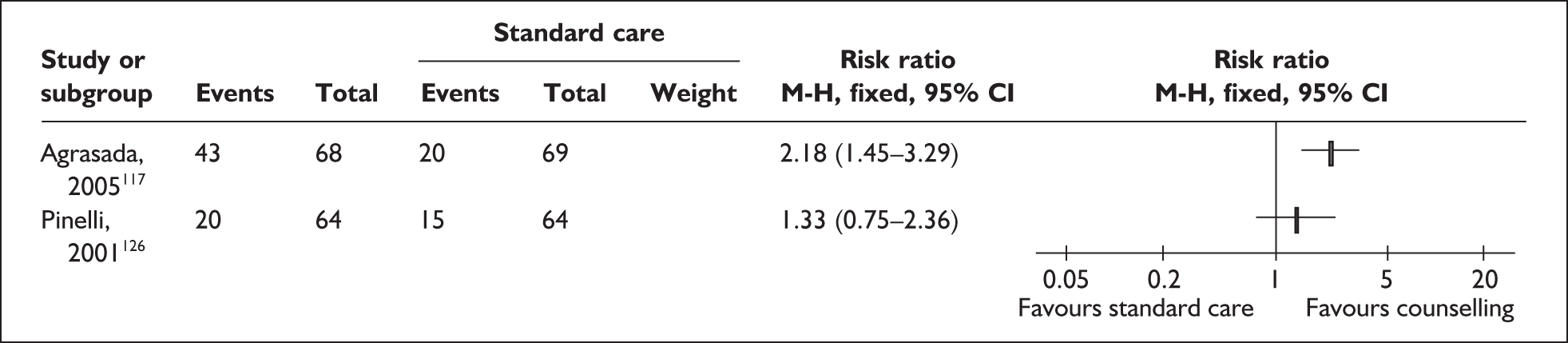

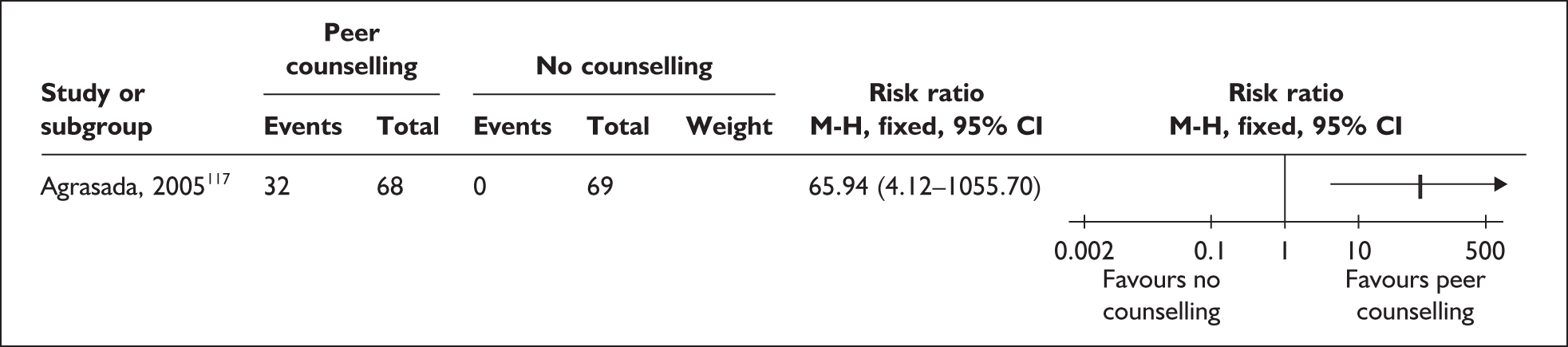

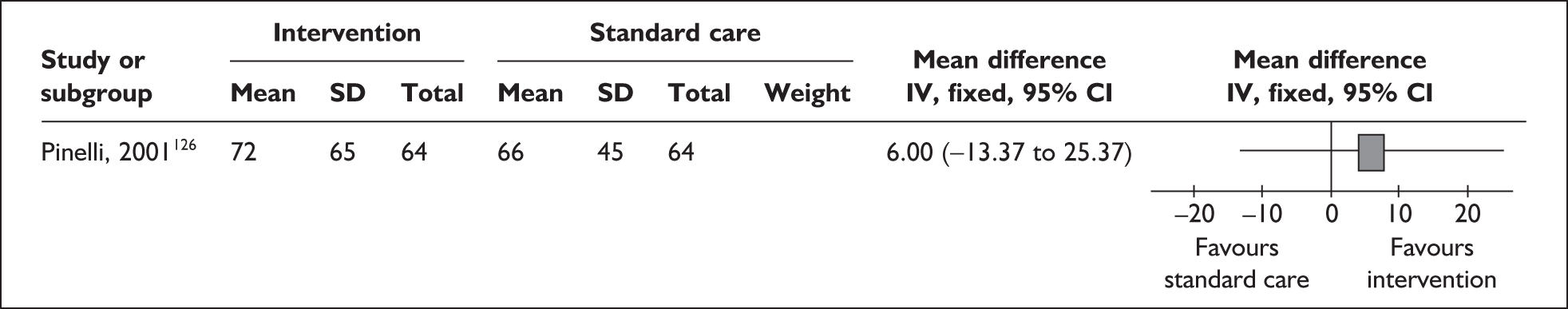

Results from all primary studies were assessed and summarised in a qualitative synthesis for each type of intervention (Chapter 4) and across types of intervention (Chapter 7). Meta-analysis was not considered appropriate due to the heterogeneity between studies for type of intervention, standard care, characteristics of participants, outcome measures, feeding intention and country settings. Relative risks for outcomes have been estimated for individual studies on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis where appropriate outcome data were reported. Given the relatively high clinical risk among the target population, the ITT analysis was adjusted for legitimate postrandomisation exclusions. These were calculated as infants who were lost to the study due to death, not achieving predefined clinical stability to participate in the intervention, or other clearly defined inclusion or exclusion criteria such as discharge to original hospital. Data from studies rated as good or moderate quality have been presented in forest plots where appropriate. In the absence of meta-analyses, funnel plots and sensitivity analyses were not considered appropriate methods to assess publication bias.

Throughout the report, included studies are referred to using the name of the first author and the date, e.g. Jones 2001, or the citation number.

Results of the effectiveness review are presented in full in Chapter 4, and for the economic modelling in Chapter 5. Due to the inter-related nature of results from each topic area, results are summarized and discussed together in Chapter 7.

Methods of health economics literature review

Inclusion criteria

Studies were eligible if they were full economic evaluations (i.e. they included an explicit comparison of both costs and effects for an intervention and at least one comparator), and were considered to be useful in answering the research question relating to cost-effectiveness.

Identification of potential economic evaluations

The search strategies were devised in collaboration with an information specialist. There was no limitation by language or country of origin. A search strategy was developed for NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) and adapted for use with other databases. Full details are presented in Appendix 2.1.

The search process was undertaken in three stages:

1. Searches of health economics resources The following resources were searched to identify economic evaluations:

-

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) (up to 2007/08/8) (internal CRD interface)

-

Health Economic Evaluations Database (HEED) (up to 2007/08/08) (internet)

-

Pediatric Economic Database Evaluation (PEDE) (1980–2003) (internet) http://pede.bioinfo.sickkids.on.ca/pede.search.jsp.

A total of 294 references were retrieved.

2. Subset search of Clinical Effectiveness Endnote Library An Endnote Library containing 10,262 references, identified by the search undertaken for the evidence of effectiveness review search detailed above, was searched to identify potentially relevant cost/economic studies. After deduplication, 1176 records were identified.

The following terms were entered line-by-line (_ indicates a space):

-

_cost_

-

_costs

-

_cost-

-

_costly

-

_costing

-

_econom

-

_budget

-

_price

-

_pricing

-

_expenditure

-

value for money

A total of 1176 references were retrieved and scanned for relevance.

3. Further searches to populate the decision model A series of focused supplementary searches were undertaken to identify data to populate the model. These searches were limited to a small collection of ‘core’ databases, as specified by the health economists:

-

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) (up to 2008/02/28 (internal CRD interface)

-

Health Economic Evaluations Database (HEED) (up to 2008/02/28) (internet)

-

MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process Citations (2003–2008/02/wk 2) (OVID)

-

Embase (2003–2008/wk 7) (OVID)

-

EconLit (2003–2008/01) (OVID).

Searches were undertaken for three supplementary topics:

-

long-term outcomes of NEC or sepsis

-

quality of life in infants with NEC, sepsis, meningitis, etc.

-

economic evaluations of NEC, sepsis, meningitis, etc. in preterms or neonatal units.

Totals of 713 (topic 1), 99 (topic 2) and 487 (topic 3) references were retrieved for the searches and scanned for relevance.

Results of health economics review

No economic evaluations that met the inclusion criteria were identified. Had suitable studies been identified, data would have been extracted (Appendix 4.2). Details of excluded studies are presented in Appendix 6.1, along with information on the planned quality appraisal process.

Framing recommendations

To inform implications for policy, practice and education, and to identify gaps in the evidence base and priorities for future research, two additional approaches were used:

-

Seven expert clinical advisors from neonatal units in Sweden, the USA and the UK (Appendix 1) were asked to identify key factors in their experiences of introducing successful breastfeeding-/breastmilk feeding-related change into their units (Chapter 6). This information was used to reflect on the findings of the study (Chapter 7).

-

After reading the findings of the study, Advisory Group members were asked to agree implications for policy, practice and education (Chapter 8) and to agree prioritisation of suggestions for future research studies (Chapter 9). Studies with methodological weaknesses, which were considered likely to have potentially misleading results, were not used in framing the implications for policy, practice and education.

Chapter 4 Results of the effectiveness review

Summary of review flow

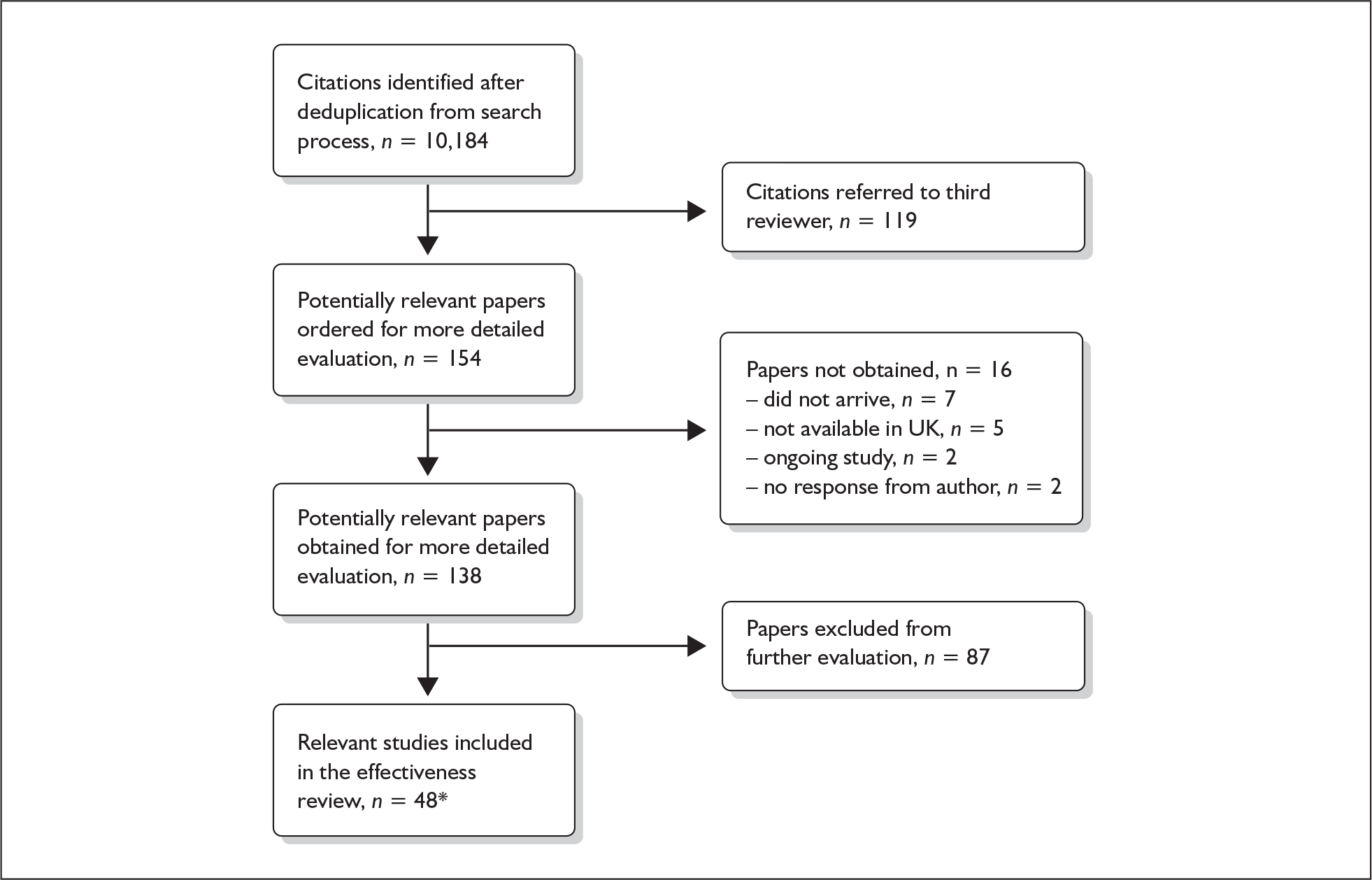

The flowchart (Figure 1) is based on the QUOROM statement flow diagram105 to summarise the results of the methodology described in Chapter 3.

As detailed above, only 1% (119/10,184) of the total citations identified following deduplication were referred to a third reviewer for resolution regarding their potential relevance to this effectiveness review. Decisions regarding these citations were largely uncontroversial and, where any uncertainty remained, full papers were sought for further evaluation. Decisions regarding exclusions during the prescreening process were largely uncontroversial with the exception of one study (Sisk et al. 2006),110 which was excluded on the grounds that this study was not an evaluation of an intervention.

FIGURE 1.

QUOROM statement flow diagram summarising the methodology. *Reported in 51 papers.

Summary of evidence base

A total of 48 studies evaluating the effectiveness of interventions to promote breastfeeding in neonatal units met the inclusion criteria for this review. Of these studies, 65% (31/48) were randomised controlled trials (RCTs). The results of two studies were reported in two separate papers107–110 and Hill was reported in three separate papers. 111–113 One paper reported findings for two types of intervention presented in this review, with each intervention having been evaluated by a different study design method. 114 For the purposes of this review, this paper has been counted as two studies.

The five identified systematic reviews assisted with the identification of a total of 29 included primary studies including 22 RCTs,107–110,114–133 one randomised crossover study134 and six other forms of controlled studies. 135–139

A further 19 primary studies were identified through our independent search methods for inclusion in this review. These included nine RCTs,113,140–147 two randomised crossover studies114,148 and eight other forms of controlled studies. 20,81,149–154

Definitions of topic areas

The 48 included studies were grouped into nine topic areas, considered in detail in the following sections. Definitions of these topic areas and related issues are as follows:

Increased mother and infant contact interventions

Relevant interventions are those that promote warmth, developmental care, and early and successful breastfeeding for infants in need of special care. This includes skin-to-skin contact, which is defined as any contact between the mother’s and the infant’s skin over any period of time, usually from birth,155 and kangaroo mother care (KMC). KMC was originally developed in Colombia and comprises three components: (1) ongoing skin-to-skin contact in the kangaroo position, namely, between the mother’s breasts in an upright position; (2) kangaroo feeding policy, which is frequent and exclusive breastfeeding; (3) kangaroo discharge policy, which is early discharge from hospital regardless of weight or gestational age. 107 The use of KMC to optimise extrauterine transition in term154 and preterm157,158 infants is generally accepted as a safe intervention with multiple physiological advantages. 159 The potential of KMC to increase breastfeeding rates, resulting in associated physiological and emotional benefits, is, however, less established.

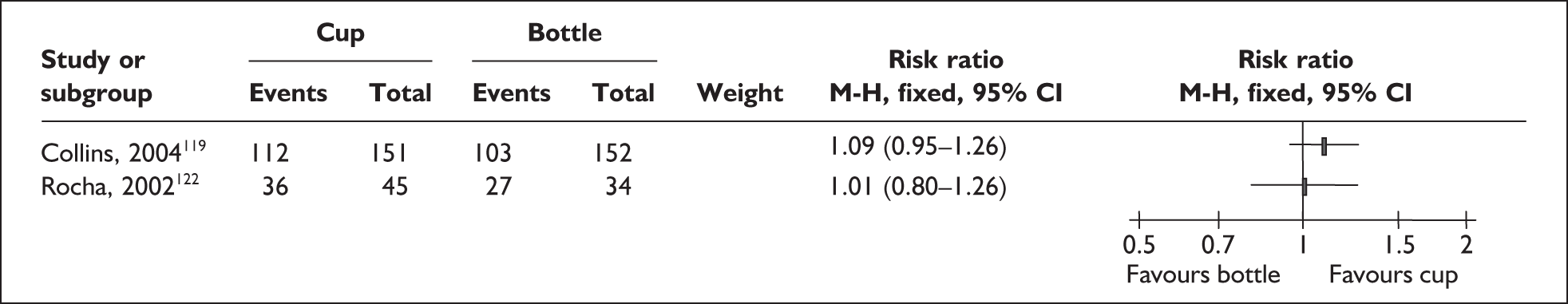

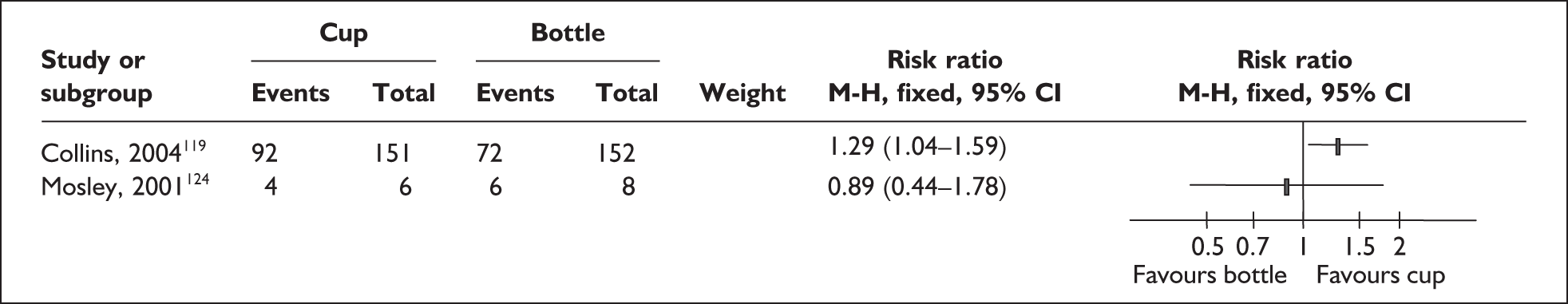

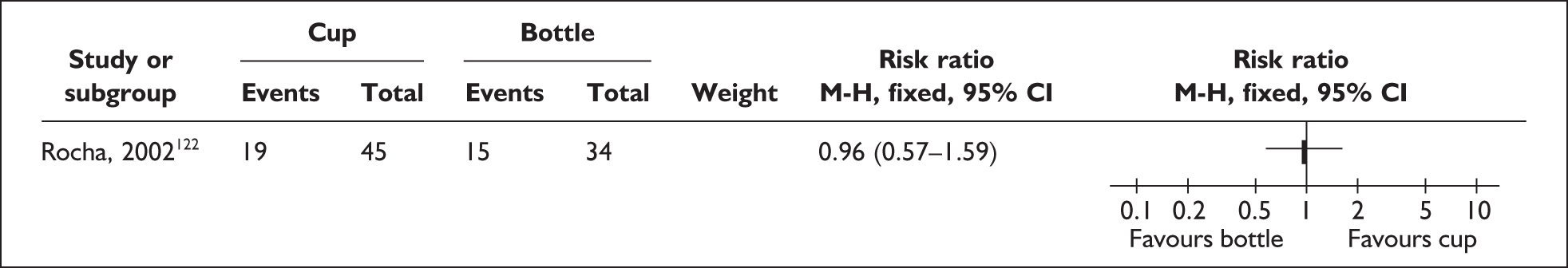

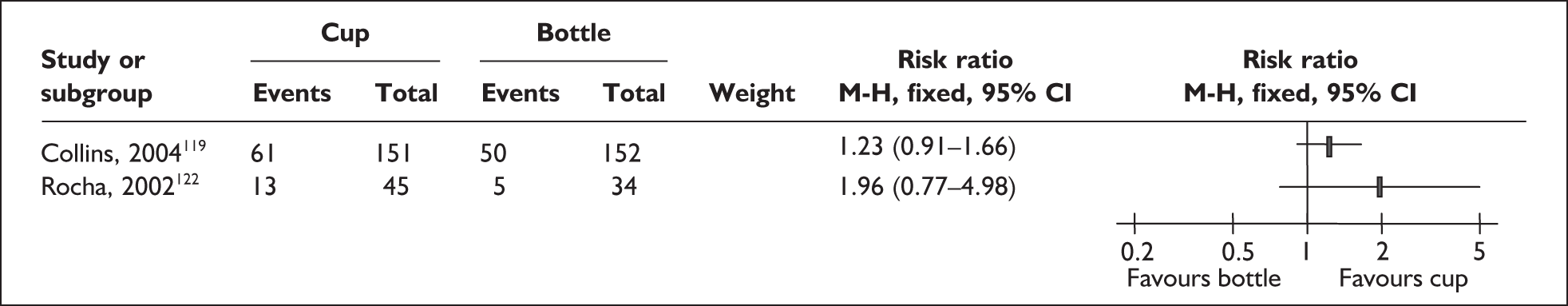

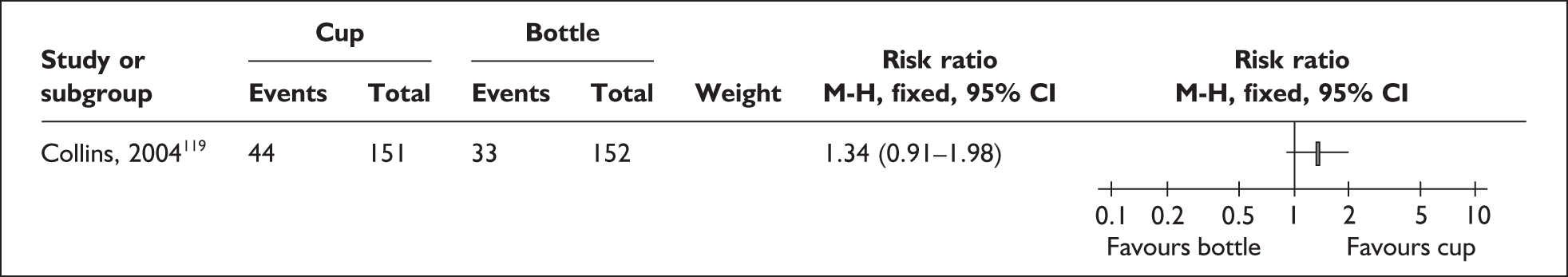

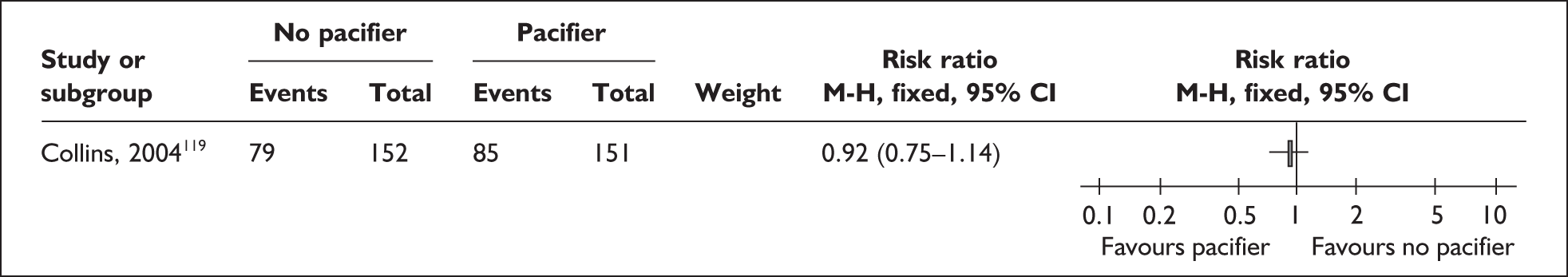

Interim feeding methods and related interventions

‘Interim feeding methods’ refers to the range of enteral feeding methods used to give babies either breastmilk or other fluids until feeding from the breast is possible. Enteral feeding is the administration of any feed into the gastrointestinal tract. 155 Feeding from vessels other than the breast may be necessary if the infant is too small or sick to take the breast directly or because the mother is unavailable; thus such methods may be used to replace or supplement feeding from the breast.

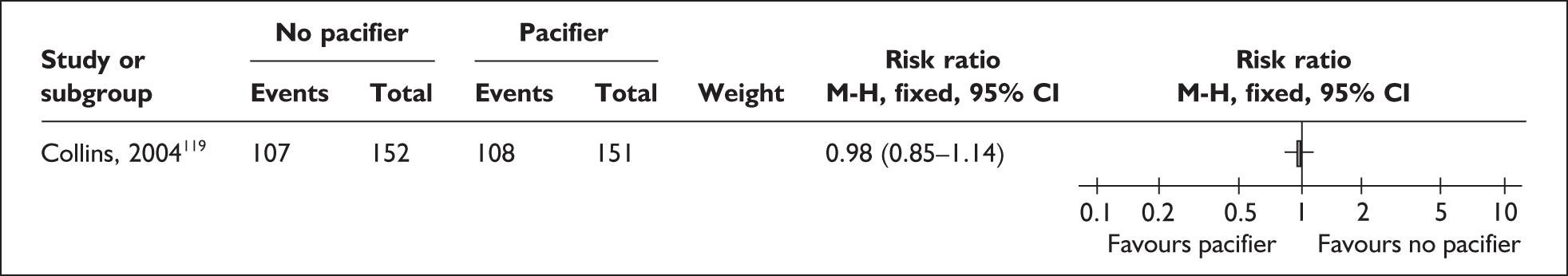

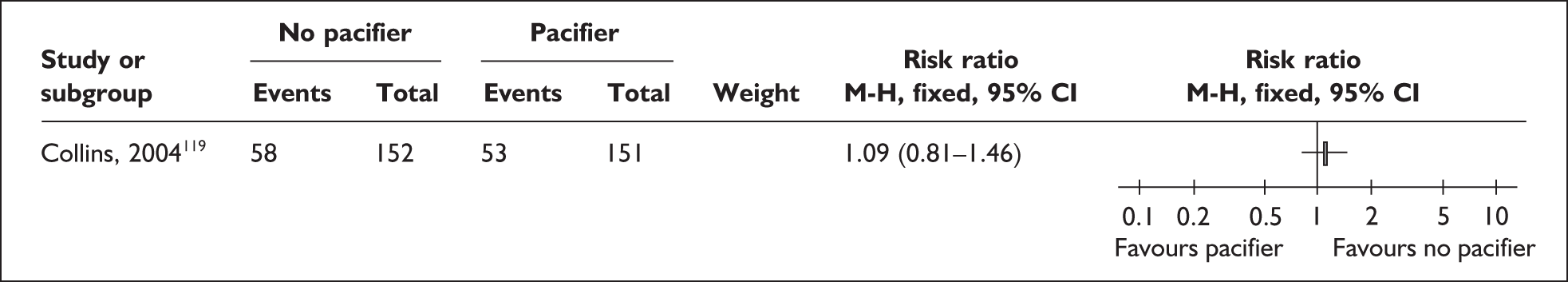

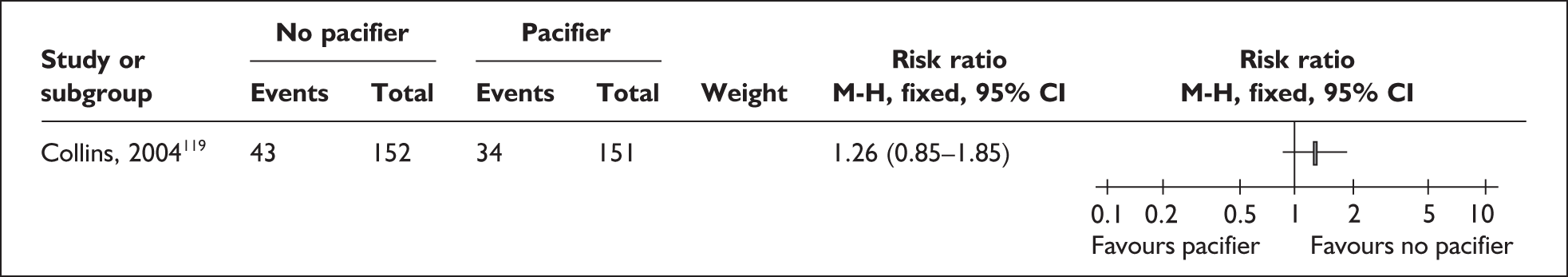

Interim feeding methods used include feeds given by nasogastric or orogastric tube or from vessels including bottles, cups, spoons and syringes. Some methods specifically aim to avoid the use of artificial teats on the rationale that learning to feed using a teat may make the transition to the breast more difficult. Such methods include cups, spoons and syringes, as well as ‘finger feeding’, where a nasogastric tube is attached to the finger of the carer and inserted in the infant’s mouth. Nipple shields are sometimes used with the aim of making feeding directly from the breast easier for small and sick babies.

‘Related interventions’ describes interventions used with the aim of enhancing feeding behaviours. This includes the use of pacifiers, which can be used for the purpose of enhancing non-nutritive sucking or in an effort to calm the infant. One alternative offered is the use of carers’ fingers.

Expressing breastmilk interventions

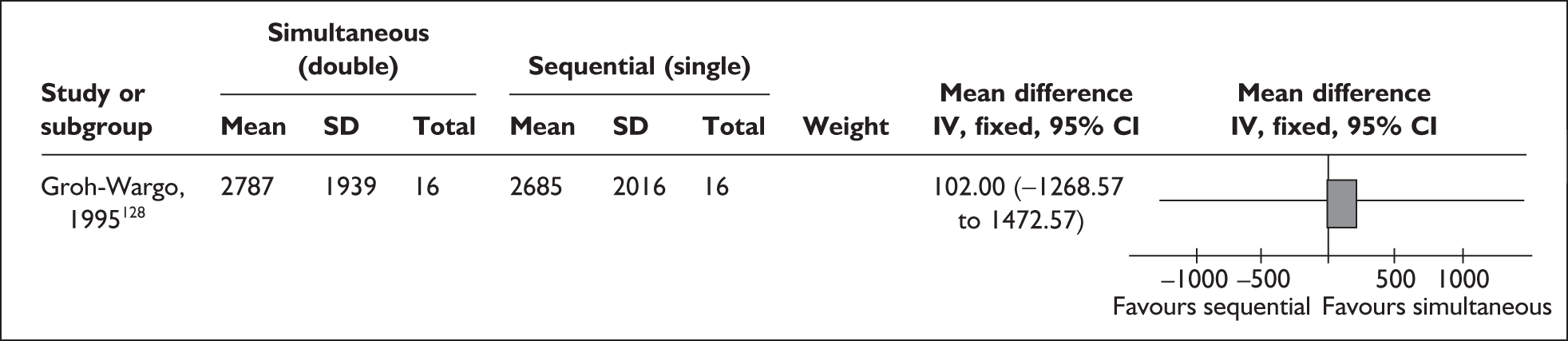

Relevant interventions include those that mothers may use to remove breastmilk from their breasts. The purpose of expression is normally twofold: to stimulate milk production, and to provide breastmilk for infants until they are able to satisfy their nutritional needs by feeding directly from the breast or until they are no longer receiving breastmilk. Variables of interest in the expression of breastmilk include both the equipment or technique that mothers may use for milk removal and the regimens for their use. Breastmilk may be expressed by hand and/or by pump; pumps may be hand- or foot-operated, or battery or electrically powered. Regimens may specify how, how often, how long or how much to express.

Additional interventions to enhance breastmilk production

Relevant interventions are those that mothers may use, usually in association with expressing breastmilk and/or breastfeeding, with the intention of increasing the volume of breastmilk produced. Such interventions include pharmacological (galactagogue medication) or dietary interventions, or interventions aimed at facilitating the mother’s let-down reflex with relaxation techniques or use of items such as photographs that she associates with her infant.

Interventions to support optimal nutritional intake from breastmilk

Relevant interventions include those that aim to optimise the quality and/or quantity of the breastmilk fed to infants in neonatal units and following discharge. Interventions may include test weighing infants before and after feeds, measuring the fat content of expressed breastmilk, and feeding hindmilk to increase the energy content of milk.

Breastfeeding education and support interventions

Relevant interventions include those that aim to offer support, education and/or counselling to parents of babies in neonatal care settings, and to take place either in hospital or at home during an infant’s hospital stay, or following discharge. Interventions may be offered by professionals or peers on a one-to-one or group basis and using a range of strategies including oral communication via face to face or telephone methods or written information via leaflets and other materials.

Staff training interventions

Interventions that aim to improve health-care professionals’ knowledge, skills and behaviour in relation to lactation and breastfeeding, and practices to support and promote breastfeeding and breastmilk production by mothers of infants in neonatal units.

Early hospital discharge with home support interventions

Early hospital discharge with home support intervention refers to discharge of infants prior to those infants having met standard weight gain criteria and/or having moved from gavage to full oral feeds. In most, but not necessarily all, cases, this intervention is conducted among clinically stable infants, defined as ones without cardiorespiratory compromise and maintaining normal body temperature when fully clothed in an open cot. Education and support of parents may be provided in the community setting following such discharge. Early discharge as part of comprehensive KMC is discussed below under ‘Increased mother and infant contact intervention’.

Organisation of care interventions

Relevant interventions are those that change care at the level of the individual unit (intra-unit) or between units (inter-unit). Both groups of intervention aim to improve the organisation of a single or allied health service or care within that service, to promote and support breastfeeding. These interventions are mostly, but not necessarily, conducted in hospital settings and may have several components implemented at one time. The changes to organisation of care may be implemented at the level of the hospital or the neonatal care unit or between hospitals or neonatal care units, as in the case of a managed clinical network.

Standard care

Standard or routine care was highly variable between studies and settings and often described in insufficient detail. Details of standard care or comparison group(s), where available, are provided for each study within each of the results sections below.

Initiation and duration of breastfeeding or feeding with breastmilk

The specific time points at which outcomes (such as initiation or duration of breastfeeding) were assessed varied between studies and in some cases were inadequately described. Definitions used by study authors are reported in the results sections below. These may or may not be consistent with the definitions adopted for the purposes of this review in accordance with the Department of Health definition for initiation of breastfeeding for the general population (see Glossary).

Included studies, the topic addressed, and whether or not they have been included in previous systematic reviews, are summarised in Table 1.

| Topic | Subgroups of intervention | No. of systematic reviews (SRs) | No. of studies in SRs (no of RCTs) | No. of extra primary studies (no of RCTs) | Total no. of primary studies (RCTs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased mother and infant contact | Kangaroo care, skin-to-skin | 3 | 9a (7) | 3 (2) | 12 (9) |

| Interim feeding methods and related interventions | Nasogastric tube, bottle, cup, nipple shields, pacifiers | 3 | 6 (5) | 0 | 6 (5) |

| Expressing breastmilk | Electric and pedal pumps, manual, frequency of expressing | 1 | 4b (3) | 2 (2) | 6 (5) |

| Enhancing breastmilk production | Galactagogues, relaxation, therapeutic touch | 2 | 3 (3) | 4b (2) | 7 (5) |

| Supporting optimal nutritional intake from breastmilk | Mothers’ measures of creamatocrits, breastmilk intake weights, hindmilk feeds | 0 | 0 | 3 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Breastfeeding education and support | Peer or professional support, community or hospital based. Education for mothers | 2 | 3 (2) | 3 (1) | 6 (3) |

| Staff training | Training or education of health professionals | 0 | 0 | 2 (0) | 2 (0) |

| Early hospital discharge with home support | Home visits and support including home gavage feeding | 3 | 2c (2) | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Organisation of care | Policy, protocol-based care, BFI or non-BFI standard(s) | 1 | 2 (0) | 2 (0) | 4 (0) |

| TOTAL | 5d | 29 (22) | 19 (9) | 48 (31) |

Increased mother and infant contact interventions

A total of 12 primary studies evaluating mother and infant contact interventions were identified. As detailed in Table 2, nine primary studies were included in at least one of the three identified systematic reviews. Seven115,121,129,135,139,147,150 of the 12 studies were conducted in industrialised country settings including one in the UK. 147

| Primary paper | Study design No. analyseda | Inclusion in existing systematic review | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cattaneo 1998131 | RCT | Conde-Agudelo 2003164 | Ethiopia, Indonesia and Mexico |

| n = 100 (site 1) | Edmond 2006155 | ||

| n = 104 (site 2) | McInnes 2006161 | ||

| n = 79 (site 3) | |||

| Charpakb 1997107 | RCT | Conde-Agudelo 2003164 | Colombia |

| n = 746 | Edmond 2006155 | ||

| McInnes 2006161 | |||

| Charpakb 2001108 | Edmond 2006155 | Colombia | |

| McInnes 2006161 | |||

| Sloan 1994132 | RCT | Conde-Agudelo 2003164 | Ecuador |

| n = 300 | Edmond 2006155 | ||

| McInnes 2006161 | |||

| Rojas 2003121 | RCT | McInnes 2006161 | USA |

| n = 57 | |||

| Blaymore Bier 1996115 | RCT | McInnes 2006161 | USA |

| n = 41 | |||

| Roberts 2000129 | RCT | McInnes 2006161 | Australia |

| n = 30 | |||

| Kadam 2005118 | Pilot RCT | McInnes 2006161 | India |

| n = 89 | |||

| Hurst 1997139 | Before/after | McInnes 2006161 | USA |

| n = 23 | |||

| Wahlberg 1992135 | Before/after | McInnes 2006161 | Sweden |

| n = 66 | |||

| Wilhelm 2005150 | Crossover | No | USA |

| n = 25 | |||

| Whitelaw 1988147 | RCT | No | UK |

| n = 63 | |||

| Boo 2007141 | RCT | No | Malaysia |

| n = 126 |

Results from randomised controlled trials

Nine randomised controlled trials of mother and infant contact interventions were identified107,108,115,118,121,129,131,132,141,147 (Tables 26–34 in Appendix 4.1).

Characteristics of participants

Four of the trials were conducted in industrialised country settings including one in the UK,147 two in the USA115,121 and one in Australia. 129 Of the remaining five trials, one was a multicentre trial conducted in Ethiopia, Indonesia and Mexico131 and one was a pilot RCT conducted in India. 118 The other three trials were conducted in Colombia,107,108 Ecuador132 and Malaysia. 141

All trials recruited infants according to criteria of birthweight or gestational age. Four trials115,121,141,147 focused on infants with the internationally recognised definition of very low birthweight (< 1500 g). The remaining trials used a variety of birthweight criteria, including infants with a birthweight of 2000 g or less,107,108,132 1000–1999 g131 and < 1800g. 118 The Colombian trial (Charpak 1997, 2001)107,108 included some infants [intervention (I):132/382; control (C): 155/364) who had a birthweight of 2000 g or less and were eligible to participate in the intervention but were not admitted to the neonatal unit. The remaining trial focused on infants at ≥ 30 weeks’ gestation. 129

All trials focused on infants who were clinically stable. Two trials included infants on minimal ventilatory support. 121,141 The remaining trials included infants who did not require oxygen equipment147 and were gavage fed,115 on oral feeds,118 tolerant of enteral feeds129,131,132 or demonstrating a satisfactory suck and swallow reflex. 107,108

Characteristics of maternal participants are limited and variable across trials. One of the nine trials focused on mothers from a range of social and economic settings. 131 Of the remaining trials that reported socioeconomic data, two trials comprised participants who were mostly high-level professionals115 or on medium to high incomes. 141 Maternal participants in the trial performed in the UK were mostly white (n = 50/63, 79%) with small numbers of Asian and Afro-Caribbean participants. 147

Two trials focused on mothers who intended to115 or had started to118 express breastmilk or breastfeed their infants. Two further trials reported participants’ intention to breastfeed147 and exclusive breastfeeding behaviour at enrolment131 by comparison groups.

Characteristics of interventions

Eight trials evaluated the skin-to-skin component of KMC where the infant is held upright between the mother’s breasts in a nappy and hat, usually covered by a blanket, and in a private setting, compared with traditional care where contact between mother and infant is fully clothed and privacy is not the norm. 115,118,121,129,131,132,141,147 The remaining trial evaluated a more comprehensive KMC intervention,107,108 namely, skin-to-skin contact together with early hospital discharge and regular, but not exclusive, breastfeeding. As characteristics of these studies vary, they are summarised in Table 3.

| Study | Country | Components of intervention | Total period of intervention | Duration of each daily contact | Inclusion criteria for infants by BW or GA | Other criteria for eligible infants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boo 2007141 | Malaysia | Kangaroo skin-to-skin contact | Up to hospital discharge | 1 hour | < 1500 g | Minimal ventilatory support |

| Kadam 2005118 | India | Kangaroo skin-to-skin contact | Up to hospital discharge | 1 hour | < 1800 g | On oral feeds |

| Rojas 2003121 | USA | Kangaroo skin-to-skin contact | Up to hospital discharge | Up to 8 hours in two 4-hour periods | < 1500 g | Minimal ventilatory support |

| Roberts 2000129 | Australia | Kangaroo skin-to-skin contact | Up to hospital discharge | Not reported | ≥ 30 weeks | On enteral feeds |

| Cattaneo 1998131 | Mexico | Kangaroo skin-to-skin contact | Up to 40th week postnatal age | 20 hours | 1000–1999 g | On enteral feeds |

| Blaymore Bier 1996115 | USA | Kangaroo skin-to-skin contact | 10 days | 10 minutes | <1500g | Gavage fed |

| Sloan 1994132 | Ecuador | Kangaroo skin-to-skin contact | Up to hospital discharge | Not reported | < 2000 g | On enteral feeds |

| Whitelaw 1988147 | UK | Kangaroo skin-to-skin contact | Up to and beyond hospital discharge | At hospital visits (mean 2.1 hours daily visiting) | < 1500 g | No oxygen equipment |

| Charpak 1997, 2001107,108 | Colombia | Kangaroo skin-to-skin contact; early hospital discharge; regular breastfeeding | Up to 41 weeks corrected age | 24 hours | < 2000 g | Satisfactory suck and swallow reflex |

The total period during which kangaroo skin-to-skin contact was promoted varied considerably across trials, and between participants within trials; however, data on this were not reported in two trials. 129,132 Four trials reported the mean period of skin-to-skin contact during the hospital stay as 4.6 (range 0–40),107,108 8.5 (SD 4.4),118 11 (range 2–85), 17 (range not available)141 and 61 (SD 28)121 days. Two trials reported the median period of kangaroo skin-to-skin contact during the hospital stay as 11 (range 2–85)131 and 30 (range 5–83)147 days.

The large ranges around the average further highlight the heterogeneity of the total periods of kangaroo skin-to-skin contact between participants within an intervention group. This can be attributed in part to the range of birthweights of infants included in each trial and the inverse relationship between birthweight and length of hospital stay and in part to the diverse criteria for hospital discharge between trials.

The duration of each kangaroo skin-to-skin contact also varied considerably between trials. Three trials evaluated ‘short’ individual periods of contact of 10 minutes per weekday115 and one hour daily. 118,141 A further trial evaluated the promotion of kangaroo skin-to-skin contact at all visits during and beyond hospital stay,147 reporting a mean of 2.1 hours visiting per day. Data on actual contact time is not reported. 147

One trial evaluated a ‘medium’ level of skin-to-skin kangaroo care contact of up to 8 hours per day in two 4-hour periods. 121 Prolonged periods of contact were evaluated in two trials, defined as 24 hours per day until no longer tolerated by infant107,108 and reported as a mean of 20 hours per day during hospital stay. 131 Two trials did not define or report the duration of individual kangaroo skin-to-skin contacts. 129,132

The detail of standard care provided in control groups was limited. Incubators were available in all trials with the exception of one of the three study sites in the multicentre trial:131 standard care in Addis Ababa was open cribs in a warm room. 131 The Colombian trial specified visiting as restrictive for mothers in the control group107,108 while the UK trial specified open visiting practice as standard care. 147 Clothing of infants while being cuddled or fed was reported as standard care for the four trials conducted in industrialised countries. 115,121,129,147

Outcome assessment

One RCT reported the initiation of breastfeeding or receiving expressed breastmilk141 assessed between enrolment and hospital discharge. Another trial evaluated the timing of the initiation of breastfeeding118 assessed by the infant’s mean age in days when breastfeeding started.

Seven trials reported the duration of breastfeeding. 107,108,115,121,129,131,141,147 Two of these trials reported the duration of lactation where the mother, and not the infant, was the unit of allocation and analysis. 115,147 Exclusive rates of breastfeeding were reported in two trials. 107,108,132 One trial also evaluated the primary outcome of production of expressed breastmilk. 115 Interpretation of findings and further analysis are limited, however, due to lack of any numerical data to report this outcome (see Table 26 in Appendix 4.1).

Assessments of duration of breastfeeding varied between studies and included the following: 40–41 weeks’ corrected age,107,108 hospital discharge,115,121,129,141 1 month after hospital discharge,115 6 weeks,129 more than 6 weeks,147 3 months,107,108,129 6 months,107,108,129 9 months107,108 and 12 months107,108 and mean weeks’ lactation. 147 Exclusive breastfeeding was assessed at 40–41 weeks’ corrected age,107,108 at hospital discharge and 1 and 6 months. 132 With the exception of one trial,121 it is not clear whether the measures of breastfeeding started at the point of non-nutritive or nutritive breastfeeding.

All nine RCTs reported data on secondary outcomes including health,107,108,115,118,121,129,131,132,141 process,107,108,115,118,121,129,131,132,141,147 psychosocial 118,131,141 and cost-effectiveness outcomes. 108,109,131

One trial observed and monitored the predefined short duration of kangaroo skin-to-skin contact time. 115 This is unlikely to be possible for interventions promoting continuous or prolonged contact. The amount of enhanced kangaroo skin-to-skin contact is likely to be variable therefore between participants within each trial.

Methodological quality of included trials

No trials were rated as ‘good’ quality overall. Eight trials were rated as ‘moderate’ quality. 107,108,115,118,121,131,132,141,147 The remaining trial was considered to be ‘poor’ quality. 129 Serious caution is warranted in interpretation of the results of this trial. Details of the quality ratings for each trial are provided in Table 74 in Appendix 5.

Effectiveness of interventions

Primary outcomes

Complete outcome data for all those originally enrolled were provided in three trials,118,141,147 including data for postrandomisation exclusions where appropriate. 141 Relevant data have been sought and/or extracted to perform intention-to-treat analysis using postrandomisation exclusion data for five trials. 107,108,115,121,131,132 It was not possible to estimate the relative risk for primary outcome data for one study due to lack of denominator data. 129

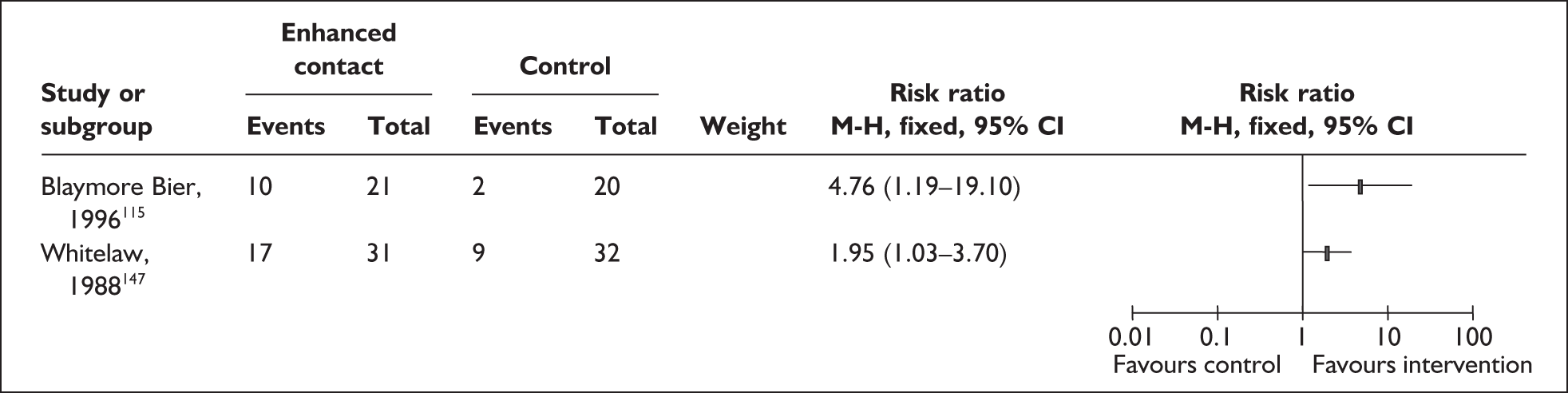

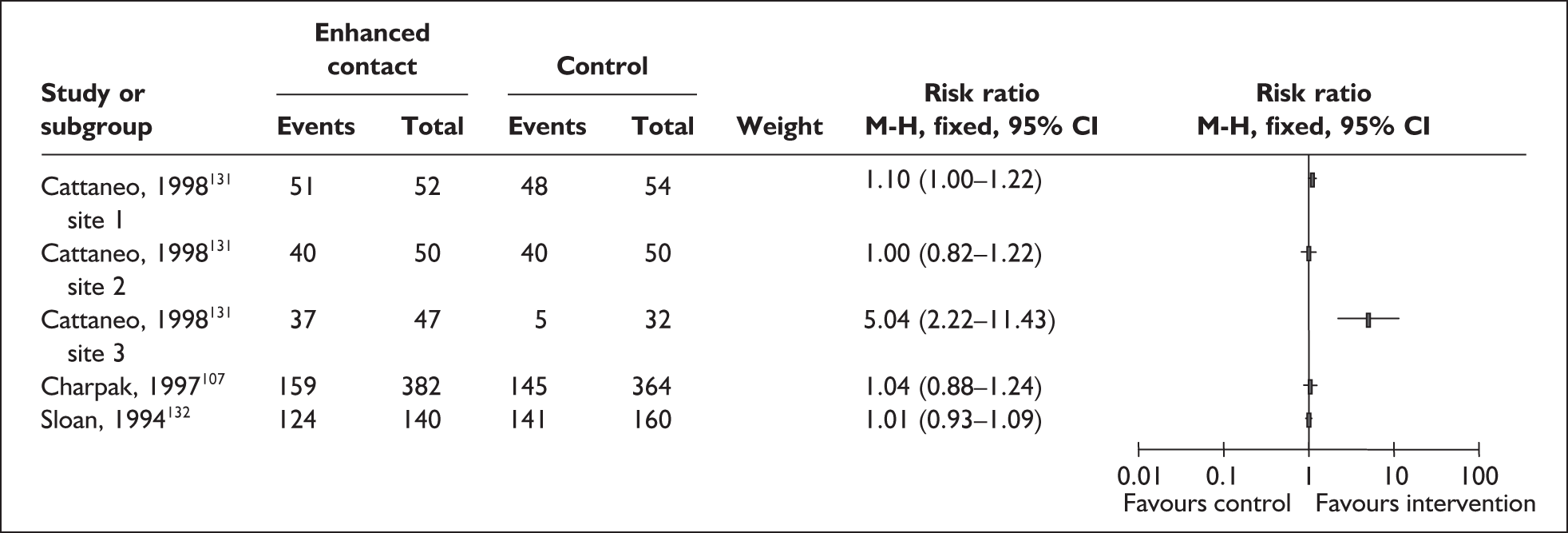

Individual relative risk estimates for primary outcomes in trials that did not receive a poor overall quality rating are presented in forest plots. 107,108,115,118,121,131,132,147 These have been calculated on an ITT basis.

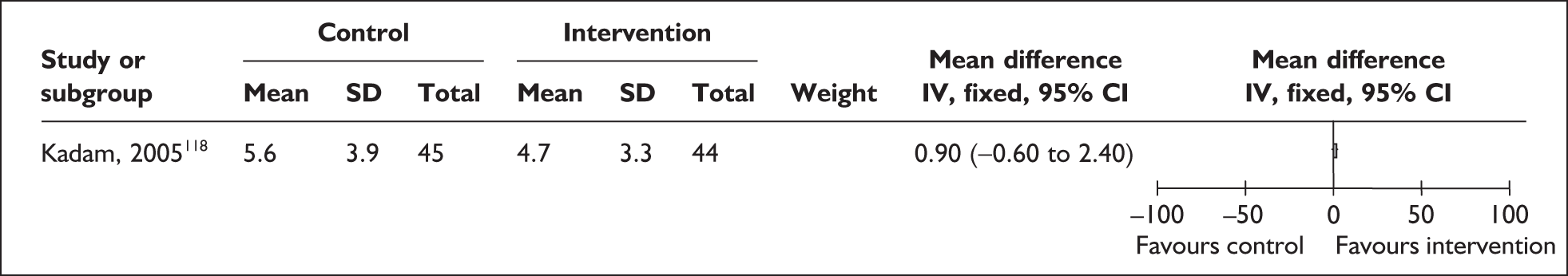

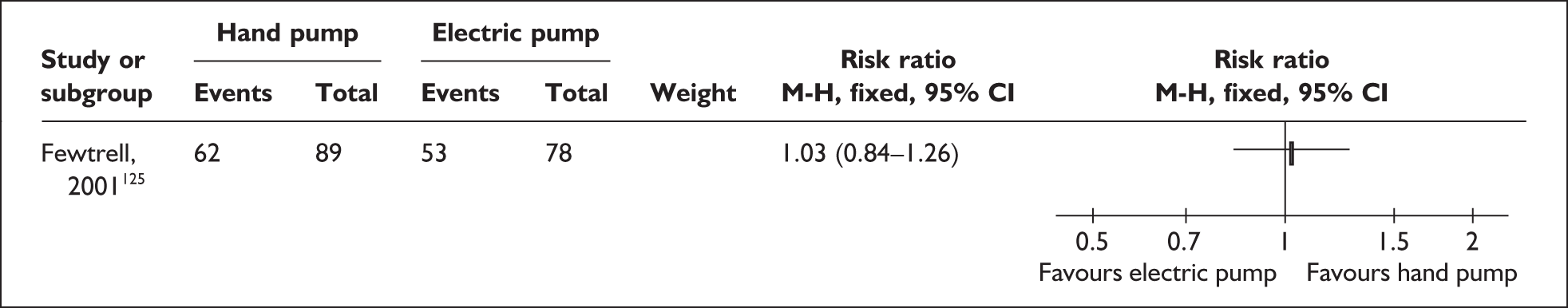

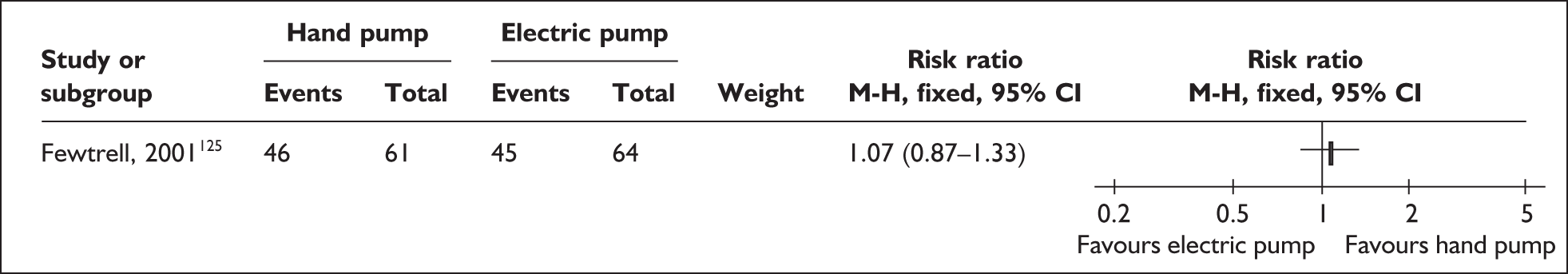

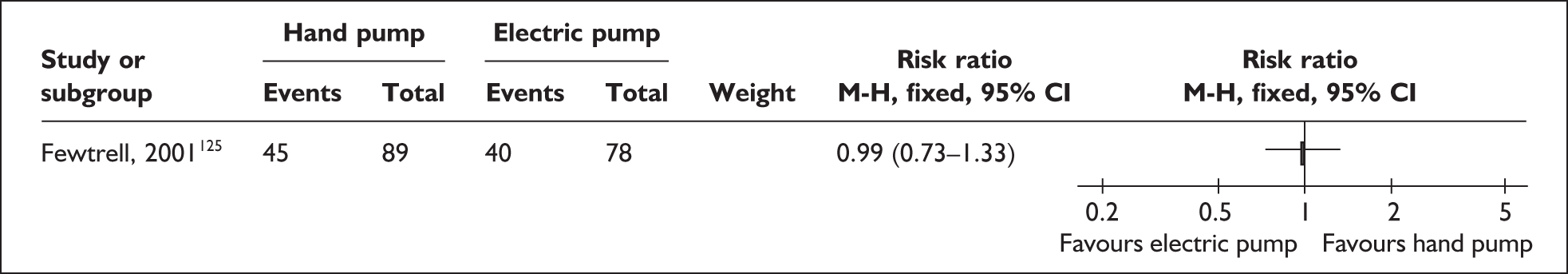

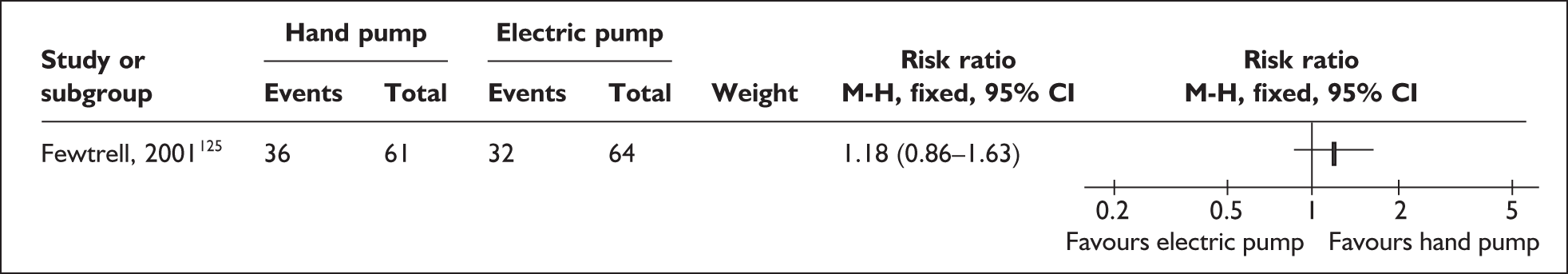

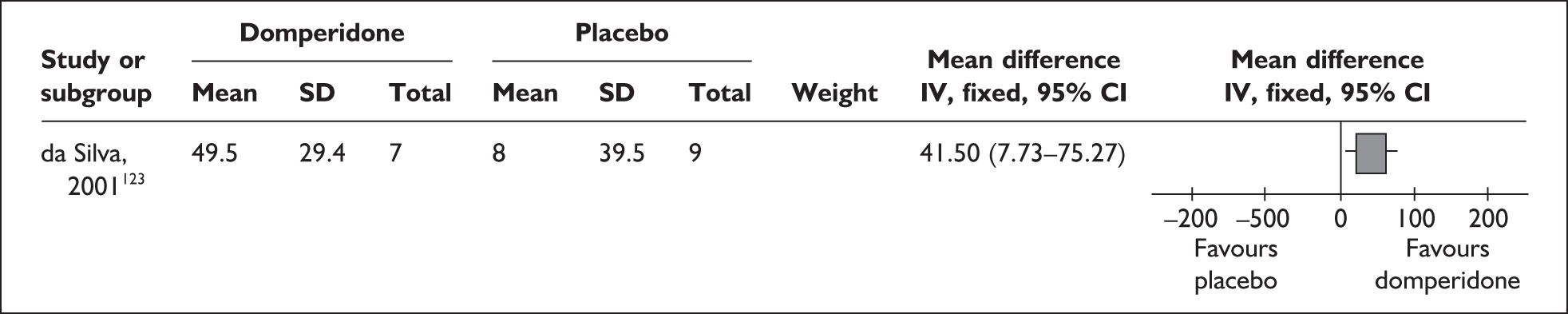

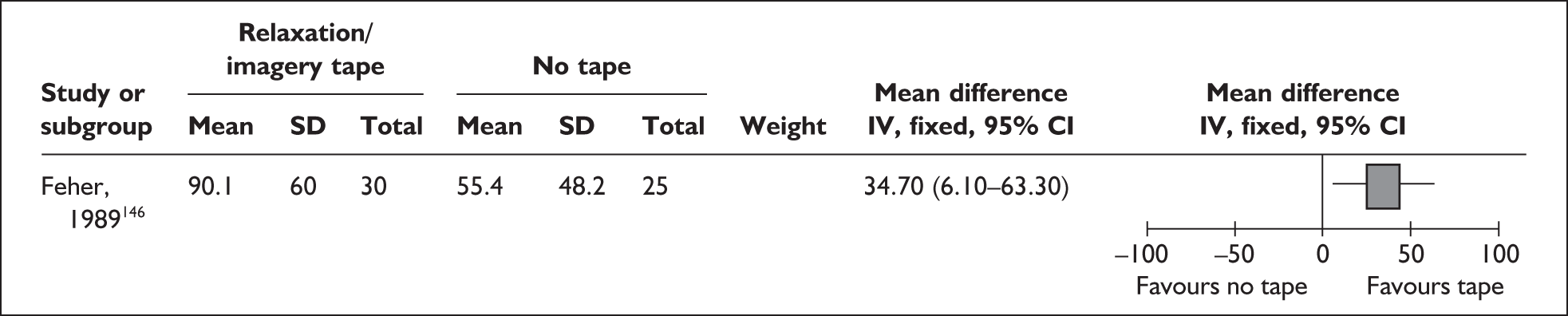

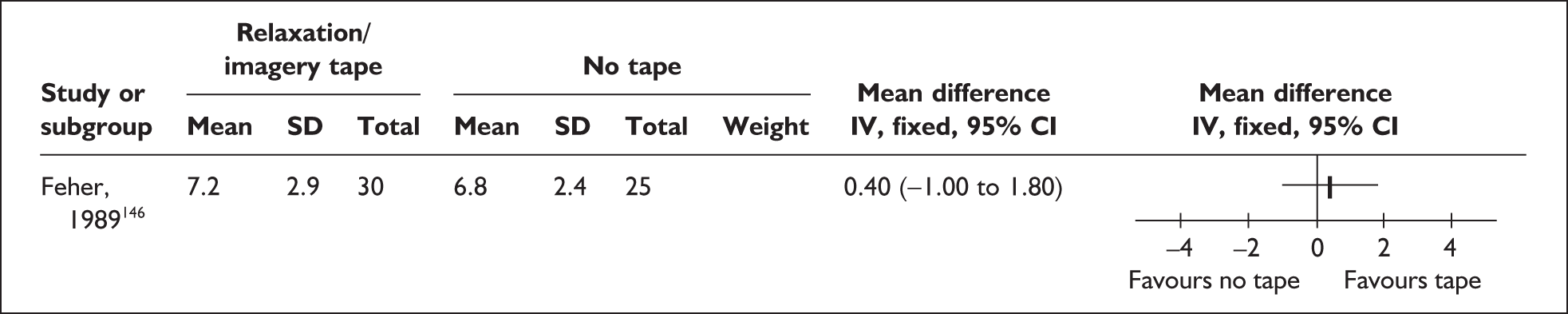

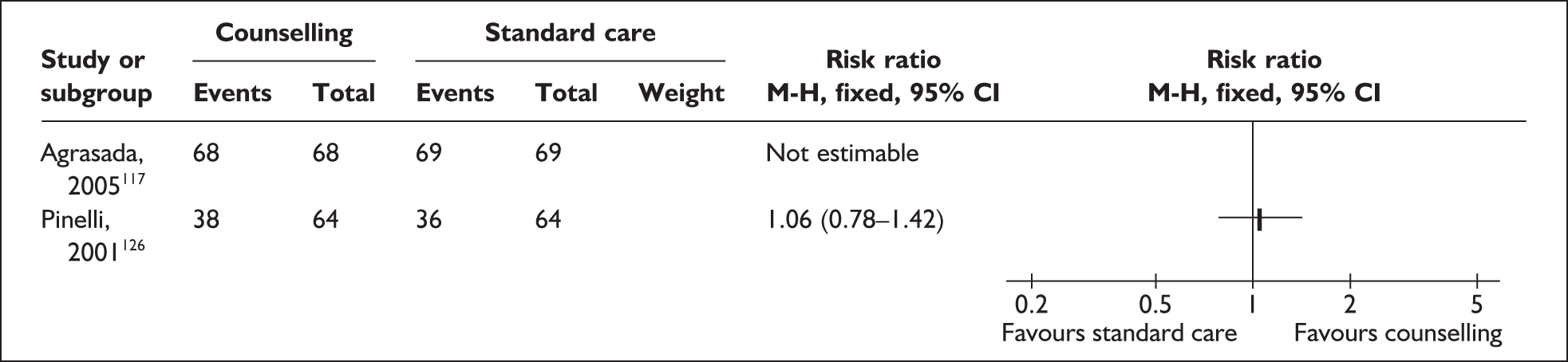

No trials evaluated the effect of mother and infant contact on the primary outcome of initiation of breastfeeding or oral feeding of expressed breastmilk. One small trial in India shows that kangaroo skin-to-skin contact for 1 hour a day has no effect on the age of initiation of breastfeeding among infants with birthweights of less than 1800 g118 (Figure 2). Some caution in interpretation of findings is required as age of the infants at enrolment is not reported by comparison group and between-group differences may affect this outcome. All infants in this study received only human milk and were either breastfed or spoon-fed.

FIGURE 2.

Kangaroo skin-to-skin contact vs standard care: age at initiation of breastfeeding (ITT).

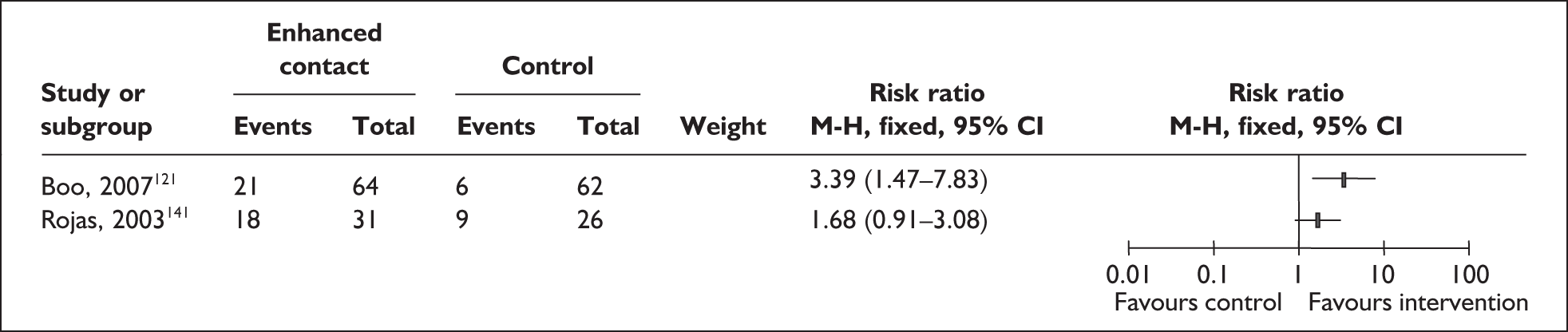

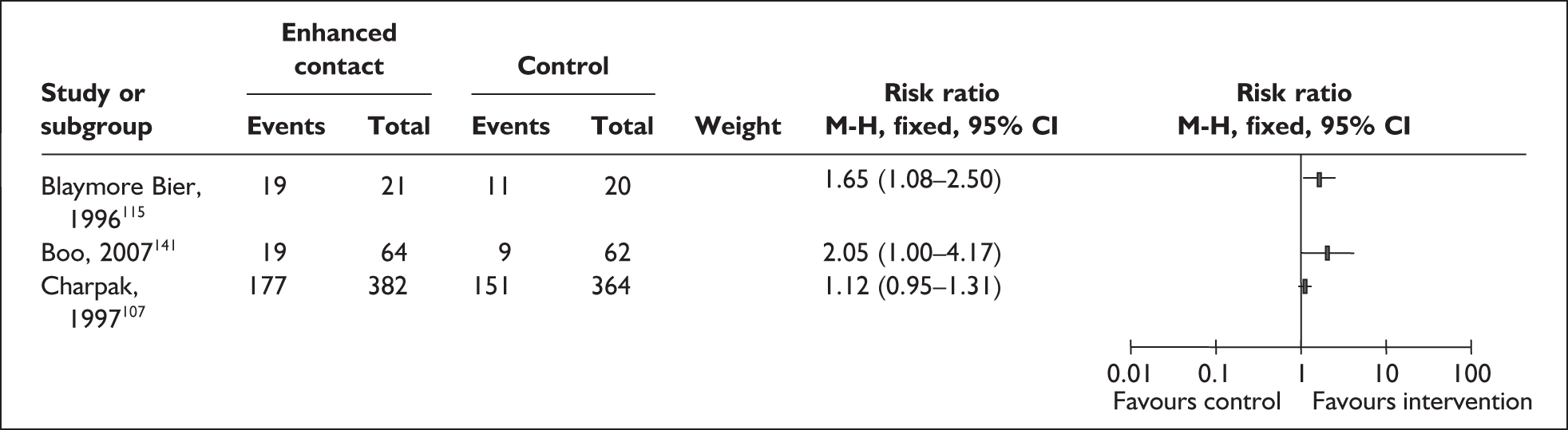

Two trials that evaluated the effect of kangaroo skin-to-skin contact on the duration of any breastfeeding before hospital discharge in industrialised settings showed a positive effect of the intervention compared with standard care121,141 (Figure 3). Both trials were conducted among infants of very low birth weight and among populations with typically low breastfeeding rates (30% in 2000 census of study neonatal unit141 and 74% initiation in the USA nationally. 165

FIGURE 3.

Kangaroo skin-to-skin contact vs standard care: duration of any breastfeeding before hospital discharge (ITT).

Results from one large trial have shown a statistically significant between-group difference (p = 0.004) as a result of the intervention. 141 This trial promoted kangaroo skin-to-skin contact for 1 hour a day with a mean hospital stay of 17 days (no range available). Some caution is required in interpretation of these findings as infants in the intervention group were of significantly later postmenstrual age, and intervention mothers had significantly more years of education, than their respective control groups. 141

A US-based trial reported no effect of the intervention. Findings of this trial are based on samples that are underpowered both as a total and as a subgroup sample for each comparison group and are not conducted on an ITT basis,121 and compliance was low in both groups.