Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 02/41/06. The contractual start date was in February 2005. The draft report began editorial review in May 2009 and was accepted for publication in January 2010. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Ipsen Ltd provided the botulinum toxin type A used by the study free of charge. They also provided sponsorship for launch meetings at study sites. The design, analysis and reporting of the study were undertaken independently of Ipsen Ltd. LS, HR, CP, FvW, GF, PS and NS have no competing interests. MB and LG use botulinum toxin regularly in clinical practice. They have received sponsorship from Ipsen Ltd to attend and teach at conferences and meetings, but have no personal financial interest in botulinum toxin or any related product.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2010 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2010 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment programme identified the need to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of using botulinum toxin to treat chronic upper limb spasticity due to stroke in adults. This report describes the work commissioned to address this issue.

Overview of stroke

Stroke is a major cause of death and disability in the UK. In England, over 900,000 people are living with the consequences of stroke, 300,000 of them are moderately or severely disabled. 1 The direct cost of stroke to the National Health Service (NHS) is £2.8B per annum, although the overall cost to the economy is much higher (£7B per annum) once informal care costs and lost productivity are taken into account. 1

Upper limb problems following stroke

Upper limb impairments such as muscle weakness, spasticity, poor co-ordination and sensory disturbance are common after stroke. These impairments alone, or in combination, can result in a range of functional limitations. Between 50% and 70% of stroke patients have long-term upper limb functional limitations2–4 and many feel that insufficient attention is paid to upper limb rehabilitation. 5 In contrast, about 80% of stroke survivors are able to walk again. 6

Spasticity

Spasticity is traditionally defined as ‘a motor disorder characterised by a velocity-dependent increase in tonic stretch reflexes (muscle tone) with exaggerated tendon jerks, resulting from hyperexcitability of the stretch reflex, as one component of the upper motor neurone syndrome. 7 A recent definition, which is broader and perhaps more clinically relevant, is ‘disordered sensori-motor control, resulting from an upper motor neurone lesion, presenting as intermittent or sustained involuntary activation of muscles’. 8 However, put simply, spasticity is involuntary overactivity of muscles as a result of damage to the brain or spinal cord.

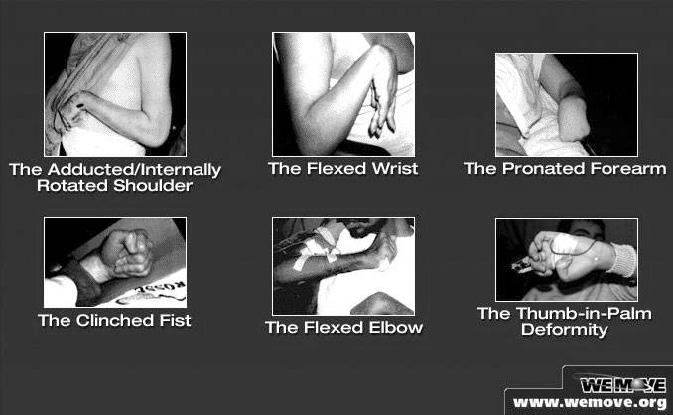

Spasticity may cause reduced function, pain and deformity, and in the longer term may lead to the development of contracture. 9 Patients with upper limb spasticity can develop abnormal limb posturing such as the classic adducted internally rotated shoulder, flexed elbow, flexed wrist and clenched fist10 (Figure 1). These positions can make washing of the axilla, elbow crease and hand difficult, leading to hygiene problems, which in turn can lead to skin breakdown, infections and pressure sores. 10 Dressing can also be a challenge. Activities such as opening the hand for washing and putting an arm down a sleeve may need the assistance of a carer or the unaffected limb if the patient cannot carry out the task voluntarily with the affected limb. Tasks completed by another person or the unaffected limb are commonly described as ‘passive’ functional tasks. 11

FIGURE 1.

Examples of severe upper limb spasticity. From Brashear and Mayer entitled ‘Spasticity and other forms of muscle overactivity in the upper motor neuron syndrome’. 14 Reproduced with permission from WeMove; New York, NY: 2009.

Although the relationship between spasticity and motor performance remains unclear,12,13 upper limb spasticity is thought to lead to reduced ‘active’ function as overactive muscles around the shoulder and elbow limit reaching activities and spastic finger flexors impair potential finger extension. 10

Upper limb spasticity after stroke is readily recognised clinically, but studies of the prevalence of the condition are lacking. The largest prospective cohort study to date (n = 106) found that 31% of patients had upper limb spasticity at 12 months. 15 A further study (n = 95) found that 20% of stroke patients had upper limb spasticity 5 days after stroke and 18% had upper limb spasticity at 3 months. 16 Despite the lack of prevalence or prospective cohort studies, upper limb spasticity after stroke is an important clinical issue and identification and treatment of spasticity is a key component of stroke rehabilitation. 17

Because of the complex multifaceted definition, measurement of spasticity is a challenge and no tool covers all aspects of the definition. 18 Clinicians and researchers often measure resistance to passive movement (muscle tone) using a clinical assessment scale, e.g. the Modified Ashworth Scale. 19 Resistance to passive movement (muscle tone) in addition to measuring some components of spasticity such as hyperactive tonic stretch reflexes also measures muscle biomechanical/viscoelastic changes. 20 Biomechanical measures have been developed to measure resistance to passive movement21 and the stretch reflex can be quantified using neurophysiological techniques,22 but neither have been widely used in clinical practice or trials.

Botulinum toxin

Botulinum toxins are proteins produced by the bacterial species Clostridium botulinum. Seven serotypes of toxin, labelled A–G, are produced from different strains of C. botulinum. 23,24 All serotypes of toxin can cause botulism, which is a life-threatening condition involving symmetrical flaccid paralysis, autonomic dysfunction and respiratory compromise. 25

The clinical syndrome of botulism was first accurately described in 1820 when Justinus Kerner published his observations of ‘sausage poisoning’. 26 Kerner correctly hypothesised that the syndrome was caused by a biological poison that interrupted nerve conduction. Although he was unable to isolate the toxin, he did suggest that it may be possible to use it therapeutically. 26

Botulinum toxins act by blocking the release of acetylcholine from cholinergic nerves leading to blockage of transmission at the neuromuscular junction and paralysis, and blockage of cholinergic autonomic nerves with resulting autonomic disturbance. 27 When given by intramuscular injection, botulinum toxin causes local and temporary paresis. It has been suggested that botulinum toxin may also block transmission of sensory neurotransmitters providing an analgesic effect independent of muscle relaxation. 27–29 The effects of botulinum toxins are not permanent. Each serotype has a different length of activity with that of botulinum toxin type A being the longest – lasting for 3–4 months. 30

Botulinum toxin was first used clinically in 1977 when it was given by local injection to treat a patient with squint due to overactive ocular muscles. 31 Since then, botulinum toxin has been used to treat various conditions including dystonia, tremor, spasticity, achalasia, migraine, incontinence and sweating. Three preparations of botulinum toxin type A [Dysport® (Ipsen Ltd), Botox® (Allergan Inc.) and Xeomin® (MerzPharmaceuticals)] and one preparation of botulinum toxin type B [Neurobloc® (Eisai Ltd)] are currently available in the UK. 32 Only Dysport and Botox currently have a licence for treating spasticity. The potency of each product is different and doses are not interchangeable. 32,33

Adverse effects following injection with botulinum toxin are generally mild and transient. 9,34 Local reactions such as erythema, rash and oedema have been reported at the injection site. Migration of toxin into adjacent tissues can lead to weakening of surrounding muscles and autonomic effects; for example, injections into the neck can result in dysphagia and dry mouth. Systemic effects such as fatigue, malaise and flu-like symptoms are reported and systemic transport of toxin to tissues distant to those injected can also occur. Systemic transport of toxin has given cases of botulism-like illness35 or cases of muscle weakness distant from the injection site,32 but these events are very rare.

Review of the evidence for treating upper limb spasticity due to stroke with botulinum toxin

Sixteen randomised controlled trials (RCTs)36–51 and five systematic reviews52–56 evaluating the clinical effectiveness of botulinum toxin as a treatment for upper limb spasticity after stroke have been published. Eight trials44–51 and four systematic reviews53–56 were published following the start of this study in 2005. Details of our literature search strategy, methodological appraisal of the papers, overview of the studies, and a summary of the systematic reviews can be found in Appendix 1.

Trials have reported that treating upper limb spasticity due to stroke with botulinum toxin results in a measurable reduction in resistance to passive movement (muscle tone), which is evident by 1–2 weeks post-treatment. The treatment effect usually lasts for 3–4 months. Although trials varied in the dose and type of botulinum toxin used, the magnitude of initial change in muscle tone/spasticity was approximately a one-point decrease on the Modified Ashworth Scale, which reflects a clinically significant improvement. 36,38–42,44–46,48,49,51

The main benefits of spasticity reduction appear to be in terms of improved global patient/physician ratings36,38,41,42,44,51 and itemised passive functional tasks, notably hand hygiene. 37,40,42 Only one trial reported an improvement in active upper limb function. 45

Botulinum toxin has also been shown to reduce shoulder pain associated with spasticity,46,47 but its role in preventing or treating other types of upper limb pain associated with spasticity is unclear. Only one trial found that upper limb pain was reduced in those who received botulinum toxin compared with those in the control group. 45 Trials reported no unexpected adverse events, however, the event reporting system was often unclear. No trial considered the cost-effectiveness of treatment.

As the treatment effect of botulinum toxin lasts for 3–4 months, injections may need to be repeated to offer sustained benefit. There is limited evidence to support the continued use of repeated botulinum toxin injections for spasticity reduction. Two RCTs considered the impact of repeat injections demonstrating a decrease in resistance to passive movement following a second injection. 44,51 One of the trials also demonstrated sustained improvement in global ratings and patient-selected goals. 51 Six uncontrolled studies have examined the effects of repeated injections. 57–62 These studies are summarised in Appendix 1, Table 36. Repeat injections decreased muscle tone by a similar amount after each injection and improved passive functional scores by a similar amount to the initial injection. 58–60,62 Two studies measured active function58,61 and one found improvement. 61

Botulinum toxin and upper limb rehabilitation

The use of botulinum toxin to treat spasticity forms only one part of upper limb rehabilitation following stroke. Guidelines for the use of botulinum toxin in the treatment of spasticity recommend that it should be used in combination with a rehabilitation programme to achieve optimal beneficial effect. 9,17,63 It is recommended that the rehabilitation programme should consist of 2–8 weeks of physical and/or occupational therapy. 17

Limitations of previous studies

Previous trials varied in methodological quality, size, type of patients included, muscles treated with botulinum toxin, dose of botulinum toxin delivered and outcome measures used. It was often unclear how randomisation was undertaken, whether blinding was robust and follow-up complete. A number of trials developed outcome measures specifically for their studies which were not assessed for validity or reliability and which focused on passive benefits rather than active function. Participants were significantly younger (average age 52–66 years) than typical stroke patients (the average age of incident stroke is 74 years64). Studies were mostly undertaken in specialist rehabilitation centres and were small, lacking statistical power.

Studies published to date have not attempted to standardise upper limb therapy and the amount and content of the therapy received was usually poorly described. It was also often unclear what concurrent medication or additional antispasticity treatments patients received.

Justification for the current study

Botulinum toxin is increasingly used to treat upper limb spasticity due to stroke. Although botulinum toxin does reduce muscle tone and facilitates activities such as hand hygiene and dressing, the impact of this treatment upon upper limb active function is unclear. In clinical practice, botulinum toxin injections may be repeated every 3–4 months, but the effectiveness of repeat injections has not been adequately studied. It is also important that botulinum toxin is evaluated as part of a rehabilitation programme which is clearly described. In addition, cost-effectiveness of treatment is not fully established.

Multidisciplinary care on a stroke unit is currently the gold standard for stroke care regardless of age or stroke severity. 65 Evaluations of botulinum toxin should recruit participants from stroke services rather than tertiary referral centres to avoid selection bias and ensure results are applicable to routine care.

The Botulinum Toxin for the Upper Limb after Stroke (BoTULS) trial was designed to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of botulinum toxin type A plus an upper limb therapy programme for the treatment of post-stroke upper limb spasticity.

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

The BoTULS trial was a multicentre open-label parallel-group RCT comparing the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of botulinum toxin type A plus an upper limb therapy programme with the upper limb therapy programme alone for the treatment of upper limb spasticity due to stroke in adults.

Primary objective

-

To compare the upper limb function of participants with spasticity due to stroke who receive botulinum toxin type A injection(s) to the upper arm and/or forearm flexors/hand/shoulder girdle plus a 4-week evidence-based upper limb therapy programme (intervention group) with participants who receive the upper limb therapy programme alone (control group) 1 month after study entry. Upper limb function was assessed using the Action Research Arm Test (ARAT). 66

Secondary objectives

-

To compare the upper limb function, impairment and activity limitation of participants with spasticity due to stroke who receive botulinum toxin type A injection(s) to the upper arm and/or forearm flexors/hand/shoulder girdle plus a 4-week evidence-based upper limb therapy programme (intervention group) with participants who receive the upper limb therapy programme (control group) 1, 3 and 12 months after study entry. Upper limb function, impairment and activity limitation was assessed by: ARAT,66 Nine-Hole Peg Test,67 basic upper limb functional activity questions used in previous upper limb spasticity studies,37,39,41 Modified Ashworth Scale,19 Motricity Index,68 grip strength69 and Barthel Activities of Daily Living (ADL) Index. 70

-

To compare attainment of participant-selected upper limb goals, upper limb pain, and stroke-related quality of life/participation restriction between intervention and control groups at 1, 3 and 12 months. The following measures were used: attainment of participant-selected upper limb goals (1 month only) – Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM);71 upper limb pain – numerical rating scales;72 stroke-related quality of life/participation restriction – Stroke Impact Scale,73 European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) measure of health-related quality of life74 and Oxford Handicap Scale. 75

-

To seek the experience and views of participants about treatment.

-

To compare the health-care and social services resources used by control and intervention groups during 3 months following study entry.

-

To report adverse events and compare the use of other antispasticity treatments between intervention and control groups.

-

To investigate the influence of severity of initial upper limb function and time since stroke upon the efficacy of the intervention.

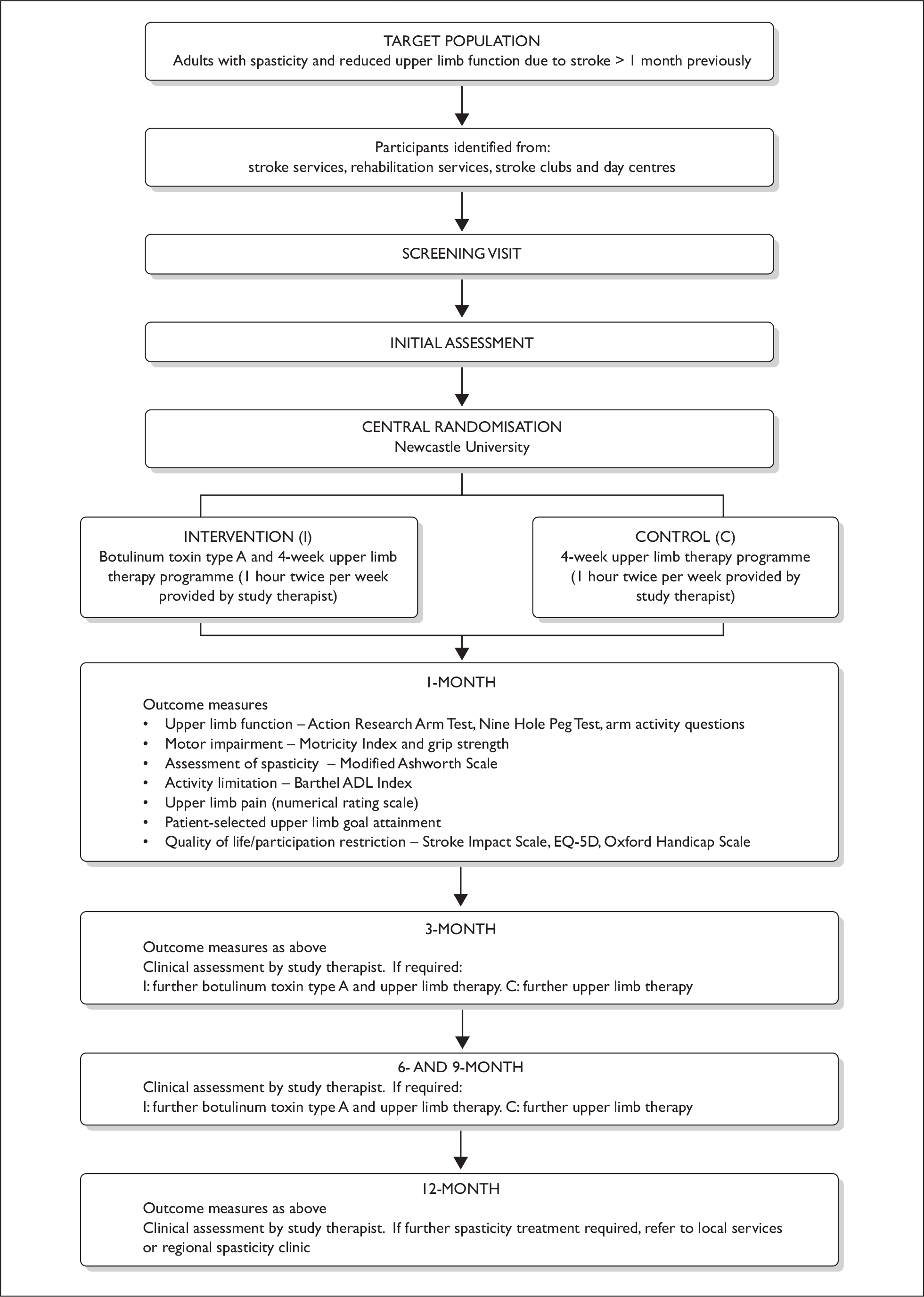

Summary of design of randomised controlled trial

Figure 2 summarises the study method.

FIGURE 2.

Study method.

A list of all case record forms used in the study is shown in Appendix 2.

Setting

The study involved a collaborative network of 12 stroke services in the north of England. Expertise in the management of spasticity and use of botulinum toxin was provided by the regional spasticity clinic based at the International Centre for Neurorehabilitation, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. This model, i.e. stroke units with close links to a specialist spasticity service, enabled stroke patients to access specialist care (both in terms of stroke and spasticity management) and could be replicated in other settings.

Case ascertainment

Potential participants were identified from a number of sources in each study centre which were components of locally organised stroke services (stroke unit, outpatients, day hospital and community rehabilitation teams). They were given an information leaflet and had an opportunity to discuss the study with a member of the clinical team. Training was given to clinical teams about the project and research governance. A member of the research team then arranged to see the participant to discuss the study. Consent was sought at the screening visit.

Some potential participants were not in contact with rehabilitation or stroke services. Local community stroke clubs and day centres were given information about the study and individuals were able contact a member of the study team directly.

Inclusion criteria

Adults with a stroke more than 1 month previously who had moderate/severe spasticity and reduced upper limb function who fulfilled all of following criteria were eligible:

-

age over 18 years

-

at least 1 month since stroke

-

upper limb spasticity [Modified Ashworth Scale19 > 2 at the elbow and/or spasticity at the hand, wrist or shoulder (there is no validated measure of spasticity at these sites)]

-

reduced upper limb function (ARAT66 score 0–56)

-

able to comply with the requirements of the protocol and upper limb therapy programme

-

informed consent given by participant or legal representative.

Exclusion criteria

-

Significant speech or cognitive impairment which impeded ability to perform the ARAT66 assessment.

-

Other significant upper limb impairment, e.g. fracture or frozen shoulder within 6 months, severe arthritis, amputation.

-

Evidence of fixed contracture.

-

Pregnancy or lactating.

-

Female at risk of pregnancy and not willing to take adequate precautions against pregnancy for the duration of the study.

-

Other diagnosis likely to interfere with rehabilitation or outcome assessments, e.g. registered blind, malignancy.

-

Other diagnosis which may contribute to upper limb spasticity, e.g. multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy.

-

Contraindications to intramuscular injection.

-

Religious objections to blood products [botulinum toxin type A (Dysport) contains human albumin].

-

Contraindications to botulinum toxin type A, which include bleeding disorders, myasthenia gravis and concurrent use of aminoglycosides.

-

Use of botulinum toxin to the upper limb in the previous 3 months.

-

Known allergy or hypersensitivity to any of the test compounds.

-

Previous enrolment in this study.

Screening assessment

Having sought consent, the screening assessment was completed by a study therapist or clinical research associate. The assessment consisted of demographic details, review of medical history and medication, handedness, Abbreviated Mental Test Score,76 Sheffield Aphasia Screening Test,77 prestroke limitations (Oxford Handicap Scale),75 time since stroke, stroke type and subtype,78 self-reported current neurological impairment and activity limitation (Barthel ADL Index70), quality of life (EQ-5D74), assessment of spasticity (Modified Ashworth Scale19) and measurement of upper limb function (ARAT66). Details of antispasticity treatment and concomitant medications were recorded.

Baseline assessment

The baseline visit was undertaken within 2 weeks of the screening visit by a study therapist or clinical research associate. The inclusion/exclusion criteria were reviewed to ensure that the participant was still eligible. Participants underwent a clinical assessment and were asked to complete the following assessments: Modified Ashworth Scale,19 Motricity Index,68 grip strength,69 ARAT,66 Nine-Hole Peg Test,67 upper limb functional activity questions,37,39,41 Stroke Impact Scale73 and upper limb pain. 72 Female participants with child-bearing potential (i.e. those who were not either surgically sterile or at least 1 year post last menstrual period) had to have a negative urine pregnancy test to be included in the study. Such participants agreed to use adequate contraception throughout the study if they were randomised to receive botulinum toxin type A. Participants were randomised once the baseline assessment was completed.

Randomisation

Randomisation was by a central independent web-based randomisation service from the Clinical Trials Unit, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. Participants were stratified according to research site and level of upper limb function (ARAT 0–3, ARAT 4–28, ARAT 29–56), and randomised to intervention or control in a 1 : 1 ratio using permuted block sequences.

Botulinum toxin

Participants in the intervention group received botulinum toxin type A (Dysport). Dysport is available as a white lyophilised powder for reconstitution containing 500 units of C. botulinum type A toxin–haemagglutinin complex together with 125 µg of a 20% albumin solution and 2.5 mg lactose in a clear glass vial.

The range of muscles and dosages injected were as described in ‘The management of adults with spasticity using botulinum toxin: a guide to clinical practice’. 9 The maximum dose of botulinum toxin type A (Dysport) that could be administered at any one time point was 1000 units. All injectors were clinicians trained in the assessment and injection of botulinum toxin in the context of upper limb spasticity.

The use of aminoglycosides was prohibited during the study because they enhance the effects of botulinum toxin, thereby increasing the risk of toxicity. Clinicians were advised to use muscle relaxants with caution because the effects of botulinum toxin are enhanced by non-depolarising muscle relaxants. The international normalised ratio of participants taking warfarin was checked before injection. Information about concomitant drug use was given in the patient information sheet and in letters to consultants and general practitioners.

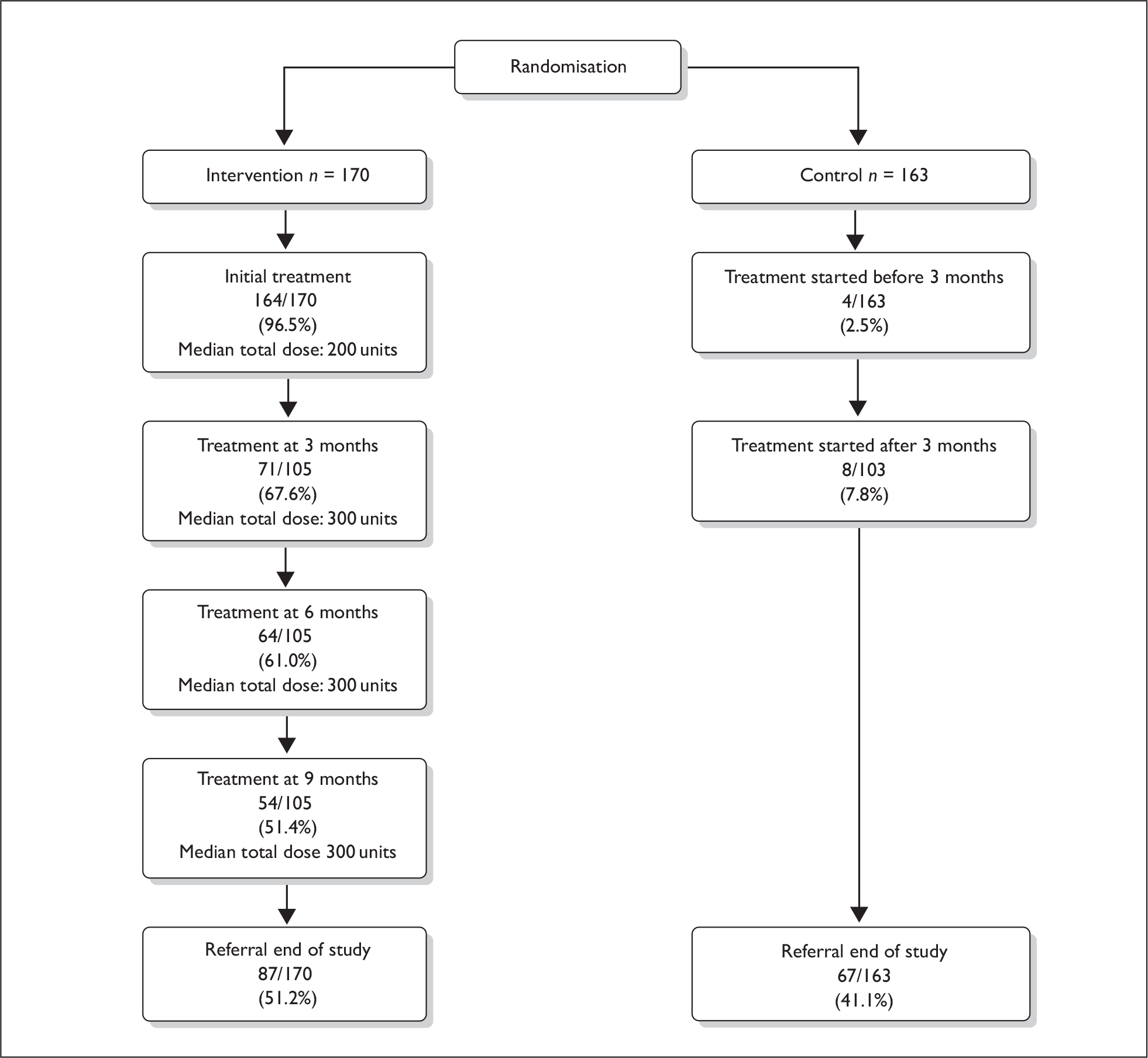

If further treatment was necessary at 3, 6 or 9 months, further injections were provided to those in the intervention group. At each visit a letter was sent to the participant’s stroke physician, general practitioner and physiotherapist. At the 12-month review, participants in both the intervention and control groups who required botulinum toxin were referred to the spasticity clinic.

If during the course of the trial the study therapist decided that a participant in the control group had an unacceptable degree of symptomatic spasticity, further management was discussed with the stroke physician, physiotherapist, occupational therapist and/or a member of the local or regional spasticity team and the participant could then be referred to a local spasticity service for botulinum toxin.

The upper limb rehabilitation programme

Guidelines highlight that it is important that botulinum toxin is not used in isolation but as part of a comprehensive rehabilitation programme. 9,17,63,79,80 Focal reductions in upper limb spasticity from any pharmacological intervention are unlikely to translate into sustained improvements in function or patient-selected rehabilitation goals without a targeted therapy programme.

The upper limb therapy programme was based upon available research evidence from the stroke rehabilitation and skill acquisition literature as well as clinical practice80–98 and consisted of two menus. Participants with ARAT 0–3 received menu 1, which was designed specifically for participants with no active upper limb function. Menu 1 aimed at improving and maintaining range of movement, encouraging active assisted upper limb movement in the context of functional activities, along with hand hygiene and positioning88–93. Menu 2 was for participants with some retained active upper limb movement (ARAT 4–56) and was piloted in a previous study. 99 Following stretching of soft tissues affected by spasticity, this menu specifically concentrated on task-orientated practise aimed at patient-centred goals. Upper limb goals were measured by the COPM. 71 Each menu standardised the category of tasks, the number and order of repetitions as well as the amount of feedback for each session, but within these parameters the therapist was able to tailor the specifics of each activity to the ability of the patient. Manuals and training programmes were developed for both upper limb therapy menus and all therapists were trained in the delivery of the programme.

The upper limb therapy programme was provided by study therapists and each participant received 1 hour per day, twice a week for 4 weeks, in addition to their other rehabilitation needs. The study therapist could transfer participants between menu 1 and menu 2 according to their clinical opinion. Participants were given a written exercise programme, which was based on the content of the face-to-face sessions with the therapist, to carry out by themselves or with a carer (following training) on the weekdays on which they were not attending therapy.

If the participant was already receiving rehabilitation, then the upper limb therapy programme was delivered in that setting, e.g. stroke unit, outpatients, day hospital or home. In each case, the study therapist liaised closely with the rehabilitation team to ensure the participant’s needs were addressed and therapy was well co-ordinated. At the end of the 4-week intervention period participants were given advice by the study therapist regarding maintenance of upper limb function.

Participants were reviewed by the research team every 3 months. If further therapy was required, this was provided by a study therapist. Those in the intervention group could also receive further botulinum toxin type A injections. Participants in both the intervention and control groups who had symptomatic spasticity at the 12-month follow-up appointment were referred to the spasticity clinic.

Participants who made a good recovery before completing the 4-week upper limb therapy programme could be discharged from the programme provided that they had achieved a maximum score on the ARAT66 and achieved their upper limb goals.

Outcome assessments

Outcomes were measured 1 month (+/– 3 days), 3 months (+/– 5 days) and 12 months (+/– 5 days) after study randomisation.

Each outcome assessment consisted of two stages – stage 1 outcome assessment was a self completion postal questionnaire (Barthel ADL Index,70 Oxford Handicap Scale,75 Stroke Impact Scale,73 EQ-5D,74 upper limb functional activity questions37,39,41 and resource utilisation) which was sent to participants 1 week before stage 2. Participants were asked to bring the completed proforma to their stage 2 appointment.

Stage 2 outcome assessments consisted of assessment of upper limb impairment and function (Modified Ashworth Scale,19 Motricity Index,68 grip strength,69 ARAT,66 Nine-Hole Peg Test67 and upper limb pain72) and face-to-face interview seeking participant’s experience and views of the study treatment. Information was sought about side effects, use of other antispasticity treatment and any change in the participant’s concomitant medications. Any new adverse events or changes in existing adverse events that had occurred since the previous visit were sought. The stage 1 questionnaire was checked for completeness. The stage 2 assessment was completed by a study therapist or clinical research associate.

Blinding

Outcome assessments were undertaken by an assessor who was blinded to the randomisation group. Participants and the study therapists who provided the upper limb therapy programme were not blind to the randomisation group. To enable blinding to be achieved, study therapists undertook screening and baseline assessments and provided the upper limb therapy programme in one research centre and undertook outcome assessments in adjacent centres. As it was possible for assessors to become unblinded, at each outcome assessment an evaluation of blinding was performed.

Participant withdrawal criteria

No specific withdrawal criteria were defined for the study. If a participant discontinued the study prematurely (i.e. before completion of the protocol), the primary reason for discontinuation was recorded when given. In all cases the investigator ensured that the participant received medical follow-up as necessary. Withdrawn participants were not replaced.

Study completion/early termination visit

Study completion was the last outcome visit. If a participant discontinued from the study prematurely, every effort was made to perform an early termination visit consisting of all outcome assessments. At the participant’s last study visit details of their completion of the study/withdrawal from the study were recorded. Female participants of child-bearing potential (i.e. those who were not either surgically sterile or at least 1 year post last menstrual period) in the intervention group were asked to undertake a urine pregnancy test.

Safety evaluation

Side effects of botulinum toxin type A are generally mild and transient. Local muscle weakness may occur as a result of toxin spread to nearby muscles. Five per cent experience flu-like symptoms 1 week to 10 days after injection. Pain at the injection site and a dry mouth can occur. Transient dysphagia has been reported. Anaphylaxis rarely occurs. Excessive doses may produce distant and profound neuromuscular paralysis. Respiratory support may be required where excessive doses cause paralysis of respiratory muscles.

The safety of botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of participants with upper limb spasticity post stroke was evaluated by examining the occurrence of all adverse and serious adverse events as defined by the Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations, 2004. 100 Follow-up of each adverse event continued until the event or its sequelae resolved or stabilised at a level that was acceptable to the investigator.

Study schedule

Table 1 summarises the study schedule.

| Time point | Screening < 2 weeks | Baseline | Visit 3 Month 1a | Visit 4 Month 3b | Visit 5 Month 6 | Visit 6 Month 9 | Visit 7 Month 12b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informed consent | ✗ | ||||||

| Record demographics and handedness | ✗ | ||||||

| Review inclusion/exclusion criteria | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Review medical history | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Details of stroke | ✗ | ||||||

| Prestroke limitation (inc. Oxford Handicap Scale) | ✗ | ||||||

| Abbreviated Mental Test Score | ✗ | ||||||

| Sheffield Aphasia Screening Test | ✗ | ||||||

| Action Research Arm Test | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Motricity Index | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Grip strength | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Nine-Hole Peg Test | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Modified Ashworth Scale | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Upper limb pain | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Patient selects upper limb goals | ✗ | ||||||

| Review upper limb goal attainment | ✗ | ||||||

| Oxford Handicap Scalec | ✗ | ✗c | ✗c | ✗c | |||

| Barthel ADL Indexc | ✗ | ✗c | ✗c | ✗c | |||

| Upper limb functional activity questionsc | ✗ | ✗c | ✗c | ✗c | |||

| Quality of life – Stroke Impact Scalec | ✗ | ✗c | ✗c | ✗c | |||

| Quality of life – EQ-5Dc | ✗ | ✗c | ✗c | ✗c | |||

| Resource utilisation questionsc | ✗ | ✗c | ✗c | ✗c | |||

| Pregnancy testd | ✗ | ✗f | ✗f | ✗f | |||

| Randomisation | ✗ | ||||||

| Treatment with Dysporte | ✗ | ✗g | ✗g | ✗g | |||

| Commencement of 4-week upper limb therapy programme | ✗ | ✗g | ✗g | ✗g | |||

| Clinical assessment by study therapist | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Concomitant medications (inc. antispasticity treatment) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Adverse events | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Participants’ views and experience | ✗ | ✗ |

Resource utilisation and economic evaluation

This is discussed in Chapter 4.

Data completeness

Data quality checks were performed regularly throughout the study. Missing data and data queries were discussed with the local site teams and collected/resolved as possible.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were undertaken on an ‘intention-to-treat’ basis; participants were analysed in the group to which they were randomised. Data were exported from the study microsoft access database to spss for analysis. All available data were analysed, missing data were not imputed.

The primary end point was the ARAT score at 1 month. For each participant it was determined if there had been a significant improvement in function based on the change in ARAT score from baseline. It is suggested that the minimal clinically important difference for the ARAT is 10% of its range (six points);101 however, we estimated that a smaller treatment effect would be clinically beneficial in those with poor initial upper limb function (ARAT 0–3) compared with those with some retained active function (ARAT 4–56).

A successful outcome was defined as:

-

a change of three or more points on the ARAT scale for a participant whose baseline ARAT score was between 0 and 3

-

a change of six or more points on the ARAT scale for a participant whose baseline ARAT score was between 4 and 51

-

a final ARAT score of 57 for a participant whose baseline ARAT score was 52–56.

The proportion of ‘successes’ in each group was compared using Fisher’s exact test and an interval estimate of the effect of the intervention in the form of an approximate 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for the relative risk was calculated.

Secondary outcomes providing binary data were compared using Fisher’s exact test (or chi-squared test if unable to compute exact form). Secondary outcomes providing ordinal or continuous data were compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test (exact form where possible). Two-tailed p-values are reported. All secondary outcomes were analysed using scale score at follow-up and change in scale score from baseline to follow-up. Change in score was believed to be the key analysis and is presented in the Results section. Scale score at follow-up is presented in Appendix 3.

Although the Mann–Whitney U-test gives an indication of statistical significance it does not provide any information about the magnitude of difference between the groups or whether the difference is clinically important. For some outcomes, the presentation of median values was not helpful in determining clinical importance because of the presence of skewness (changes in the tail of the distribution may not result in any change in the median score). To address this we used resampling methods (bootstrapping) to generate an interval estimate of the effect of the intervention on the group means for each outcome (changes in the tails of the distribution will affect the mean score). The 2.5 and 97.5 percentiles of the bootstrap distribution based on 10,000 replications are reported. This analysis was not prespecified in the study protocol because it was not anticipated to be necessary before viewing the results of planned non-parametric tests.

To enable comparison with previous studies, the basic upper limb functional activity questions were also analysed by comparing the proportion of participants in each randomisation group who had improved by one or more points on the scale from baseline.

As a secondary analysis, logistic regression modelling was used to estimate the effect of the intervention on the primary outcome (ARAT ‘success’) adjusting for randomisation strata (research site and baseline upper limb function).

There were two prespecified subgroup analyses. Response to treatment was compared for:

-

participants who had a stroke ≤ 1 year ago and those who had a stroke > 1 year ago

-

participants with no initial active upper limb function (with a baseline ARAT score of 0–3) and participants with some initial upper limb function (baseline ARAT 4–56).

Subgroup analysis of the primary outcome was undertaken using logistic regression procedures by adding a subgroup by treatment interaction term to a model that already included the main effects. For secondary outcomes, subgroup analysis was only undertaken where the difference between treatment groups in the main analysis had been statistically significant. For these secondary outcomes, resampling procedures were used to estimate the difference between the treatment effects in the two subgroups.

A power calculation was performed before the start of the study using prognosis based methodology. 102 A clinically important treatment effect was defined as a difference in good outcomes between intervention and control groups of 15% where a good outcome was defined as listed above for each ARAT group; it was expected to see 20% of the control group achieve good outcomes and 35% of the intervention group achieve good outcomes. Using Fleiss’s method for a binary outcome103 and inflating the sample size by 10% to allow for attrition, we needed to recruit a total sample of 332 participants to give 80% power to detect a 15% difference in good outcomes assuming a two-tailed test and a significance level of 5%. The study aimed to recruit 50% of the sample from the ARAT 0–3 group and 50% from the ARAT 4–56 group.

Ethical arrangements and research governance

Multicentre Research Ethics Committee approval was granted. For each individual centre, a site-specific approval was obtained from the appropriate local research ethics committee. Research and development approval was obtained from each participating Trust. The trial was commenced subsequent to the UK Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations, 2004100 and was one of the first investigator-led trials of an investigational medical product to be undertaken in the UK following the introduction of this legislation. Regulatory approval was granted by the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency and the trial was conducted in accordance with the legislation, the International Conference on Harmonisation–Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP),104 and the Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care. 105

A Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) following Medical Research Council guidelines were established. 106 The TSC comprised an independent chairperson, two independent researchers (all of whom had expertise in rehabilitation research and clinical trials), a consumer representative and three members of the study team.

The DMEC was chaired by a clinical academic with expertise in RCTs of complex interventions in the field of stroke. A biostatistician with expertise in multicentre trials, a researcher experienced in running rehabilitation trials and the study statistician were also members.

An informal interim analysis was performed at the request of the DMEC following recruitment of 50% of the required sample size. Only the DMEC had access to these data. They were able to recommend discontinuation of the study if significant ethical or safety concerns arose, or if there was clear evidence of benefit (clinical or statistical).

The study was monitored for compliance with ICH-GCP by an independent monitor from the Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit.

Amendments to the study following commencement

Objectives

The initial study protocol included measurement of spasticity at the elbow by a biomechanical device that had been used in a previous pilot study. 107 This was to be used in addition to clinical measures. Unfortunately, the device was not at a stage of development where it could be used in a multicentre study.

Setting

Initially the trial was planned in four geographical areas within the UK: North Tyneside, Wansbeck, Newcastle upon Tyne and Sunderland. As a result of low recruitment rates, eight further areas were added (Gateshead, South Tyneside, Durham, Hexham, Carlisle, Bishop Auckland, Hartlepool, North Tees).

Case ascertainment

This was widened to include identification of participants from stroke clubs and day centres (in addition to clinical settings) because of initial low recruitment rates.

Inclusion criteria

Prospective studies of upper limb recovery have shown that baseline impairment is a strong predictor of outcome. To demonstrate whether botulinum toxin plus upper limb therapy can improve upper limb function (primary outcome) it was initially thought important to exclude those participants with no retained upper limb function (ARAT 0–3). Because of the initial low recruitment and following reconsideration of the evidence of effectiveness of botulinum toxin in this group, this was later reviewed and a decision was taken in conjunction with the TSC and the Health Technology Assessment programme that it would be valuable to include stroke patients with all levels of reduced upper limb function (ARAT 0–56).

The study also initially excluded participants with cognitive impairment or significant speech problems measured by the Abbreviated Mental Test Score and Sheffield Aphasia Screening Test. This was felt to be too restrictive, excluding patients who were keen to participate. This inclusion criterion was relaxed to include all participants capable of performing the ARAT and complying with the upper limb therapy programme.

Upper limb therapy programme

A second menu was developed for the upper limb therapy programme after the eligibility criteria were widened to include participants with no active upper limb function. This alternative menu was designed because the original menu contained activities that these participants would not have been able to undertake.

Statistical analysis

Inclusion of participants with lower ARAT scores required revision of the primary analysis and power calculation. In the original protocol, the primary analysis was comparison of ARAT scores and 390 participants were required to provide 80% power to detect a difference of six points on the ARAT between intervention and control groups. However, participants with a baseline ARAT of 0–3 could not be expected to improve as much as those with a baseline ARAT of 4–56. This led to the definition of successful treatment as improvement by three points on the ARAT for those with a starting ARAT of 0–3, six points by those with a starting ARAT of 4–51 and a final score of 57 for participants whose baseline ARAT was 52–56. Comparison of the proportions of successes between the groups (control/intervention) became the primary analysis. The power calculation was revised for the new binary outcome and 332 participants were required to provide 80% power to detect a 15% difference in treatment successes.

Follow-up period

Participants recruited after 2 July 2007 were followed for 3 months only. This was a pragmatic decision taken because the trial was behind schedule as a result of initial low recruitment rates. Curtailing 12-month follow-up allowed the trial to be completed within the initial study timetable.

The initial study protocol specified comparison of health-care and social services resource usage between the randomisation groups for 12 months. Because of the curtailing of 12-month follow-up, it was felt more appropriate to compare health-care and social services resource usage over 3 months to include all study participants.

Chapter 3 Results

Study recruitment

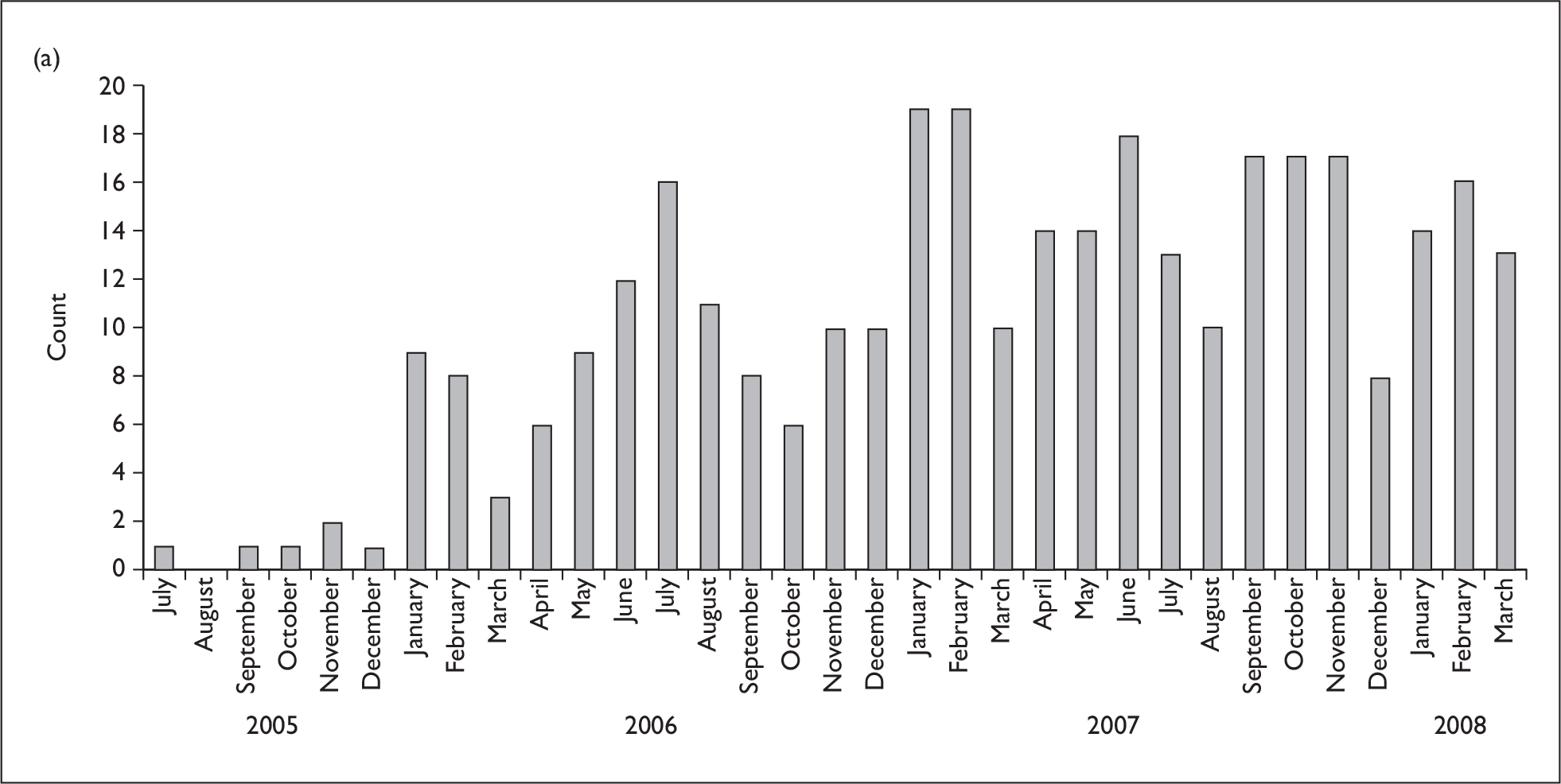

Between July 2005 and March 2008, 333 participants were recruited to the BoTULS trial. One hundred and seventy were randomised to the intervention group and 163 to the control group. Monthly and cumulative recruitment are shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

BoTULS trial recruitment: (a) monthly recruitment, and (b) cumulative recruitment.

Two hundred and eight (62%) participants were randomised before July 2007 and entered the trial for 12 month follow-up. The remaining 125 (38%) participants were followed for 3 months. Details of recruitment in each study site are given in Appendix 4.

Study attrition

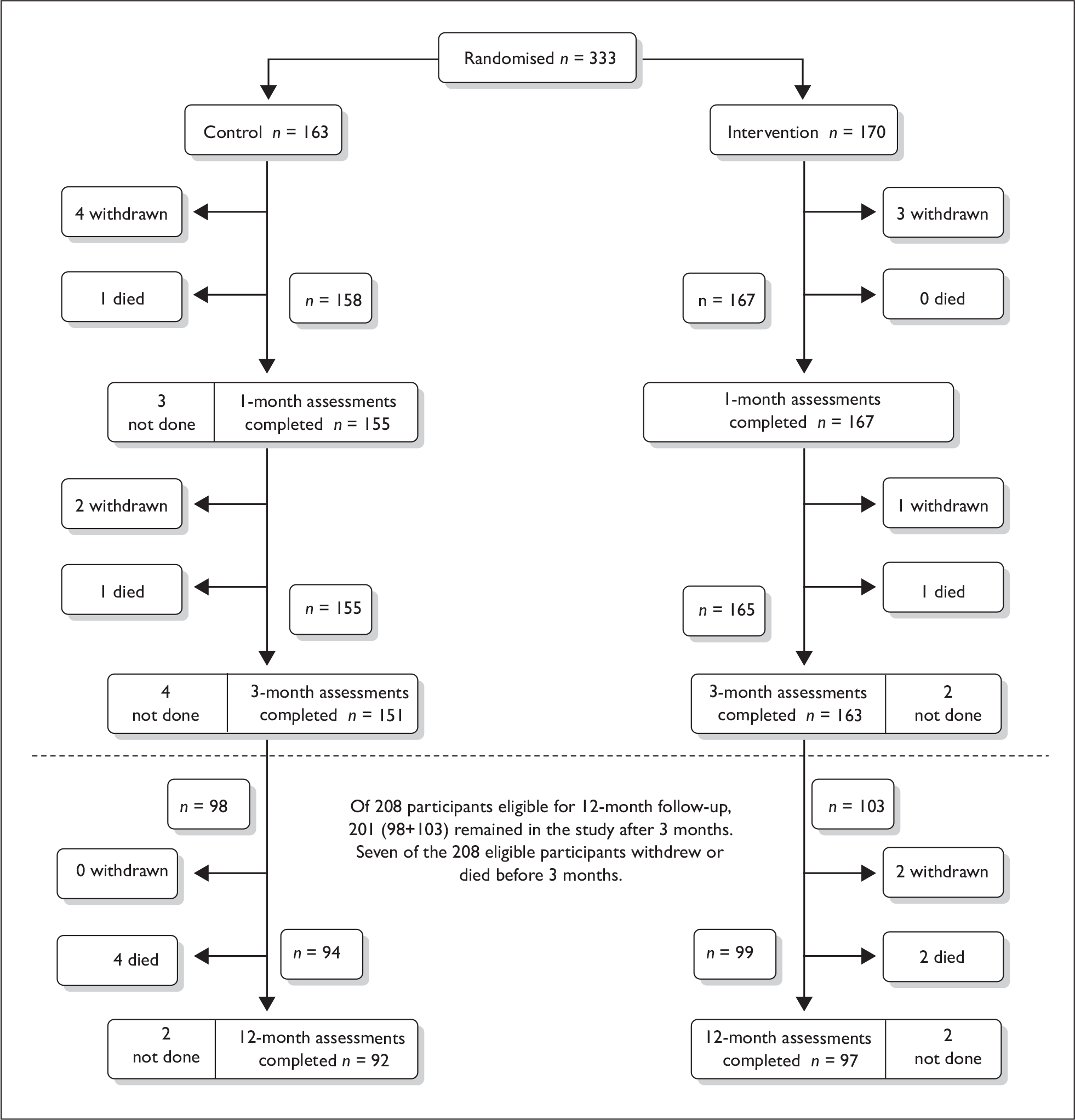

Figure 4 shows participant flow through the trial. There were nine deaths during the study period and 12 participants withdrew. Reasons for attrition are described in Table 2.

FIGURE 4.

BoTULS participant flow chart.

| Control (n and reasons) | Intervention (n and reasons) | |

|---|---|---|

| Withdrawn | ||

| 0–1 month | 4; wanted injection; did not want to continue; wife unwell; no reason recorded | 3; did not want injection; unwell; in another trial |

| > 1–3 months | 2; wanted injection; thought no benefit | 1; unwell |

| > 3–12 months | 0 | 2; unwell; no reason recorded |

| Death | ||

| 0–1 month | 1; myocardial infarction | 0 |

| > 1–3 months | 1; pneumonia | 1; pneumonia |

| > 3–12 months | 4; pneumonia; further stroke; cancer; cause unknown | 2; pneumonia; further stroke |

| Assessment not done | ||

| 1 month | 3; unwell (n = 2);administrative error | 0 |

| 3 months | 4; unwell (n = 3); unable to contact | 2; unwell |

| 12 months | 2; assessment recorded as done but data missing | 2; unable to contact |

One participant withdrew consent shortly after randomisation and asked for their data to be excluded from the analyses. Baseline data are therefore presented for 332 participants. The 1-month assessment was completed by 155/163 (95%) participants in the control group and 167/170 (98%) participants in the intervention group. The 3-month assessment was completed by 151/163 (93%) participants in the control group and 163/170 (96%) in the intervention group.

Of the 332 participants randomised into the study, 208 (63%) were enrolled for 12-month follow-up. The 12-month assessment was completed by 92/103 (89%) participants in the control group and 97/105 (92%) in the intervention group. Outcome data were missing at all time points for one study participant only.

Study population

Randomisation groups were well matched at baseline with regard to demography, stroke characteristics and comorbidity (Table 3). The median age of participants was 67 years [interquartile range (IQR) 59–74], 225 (67.8%) were male and the majority were living at home. One hundred and eighty-one participants (54.5%) were randomised within 1 year of stroke.

| Control (n = 162)a | Intervention (n = 170)a | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex: n (%) | ||

| Male | 115 (71.0) | 110 (64.7) |

| Female | 47 (29.0) | 60 (35.3) |

| Age: median (IQR) | ||

| All | 66 (59.8 to 72.3) | 67 (58.8 to 74) |

| Male | 67 (61 to 73) | 68 (59 to 74) |

| Female | 64 (54 to 72) | 67 (56.3 to 74) |

| Current residence: n (%) | ||

| Own house | 133 (82.1) | 129 (75.9) |

| Living with family/friends | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.4) |

| Sheltered | 3 (1.9) | 4 (2.4) |

| Residential care/nursing home | 7 (4.3) | 5 (2.9) |

| Hospital | 19 (11.7) | 28 (16.5) |

| Stroke type: n (%) | ||

| Infarct | 131 (81.9) | 140 (82.8) |

| Intracerebral haemorrhage | 21 (13.1) | 25 (14.8) |

| Subarachnoid haemorrhage | 3 (1.9) | 2 (1.2) |

| Unknown | 7 (4.3) | 3 (1.8) |

| Stroke subtype: n (%) | ||

| Total anterior circulation stroke | 68 (42.0) | 75 (44.1) |

| Partial anterior circulation stroke | 61 (37.7) | 57 (33.5) |

| Lacunar stroke | 26 (16.0) | 33 (19.4) |

| Posterior circulation stroke | 3 (1.9) | 2 (1.2) |

| Uncertain | 4 (2.5) | 3 (1.8) |

| Time from stroke to randomisation: median (IQR) days | 280 (148.8 to 1145.8) | 324 (128.5 to 1387.5) |

| Time from stroke to randomisation: n (%) | ||

| 1–6 months | 49 (30.2) | 60 (35.3) |

| > 6 months to 1 year | 43 (26.5) | 29 (17.1) |

| > 1–2 years | 19 (11.7) | 16 (9.4) |

| > 2–5 years | 29 (17.9) | 31 (18.2) |

| 5+ years | 22 (13.6) | 34 (20.0) |

| Comorbidity: n (%) | ||

| Previous stroke/transient ischaemic attack | 48 (29.6) (n = 162) | 49 (28.8) (n = 170) |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 36 (22.4) (n = 161) | 39 (23.1) (n = 169) |

| Peripheral arterial occlusive disease | 8 (5.0) (n = 160) | 6 (3.6) (n = 168) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 22 (13.6) (n = 162) | 22 (13.1) (n = 168) |

| Hypertension | 119 (73.5) (n = 162) | 124 (74.3) (n = 167) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 103 (64.4) (n = 160) | 111 (65.7) (n = 169) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 21 (13.3) (n = 158) | 24 (14.5) (n = 166) |

Randomisation groups were well matched for the distribution, severity and current treatment of upper limb spasticity (Table 4). The majority of participants had spasticity present throughout the upper limb and the median score on the Modified Ashworth Scale at the elbow was two. Previous treatment with botulinum toxin was not an exclusion criterion provided that it was given more than 3 months before study entry and potential participants were prepared to temporarily relinquish further upper limb injection(s) should they be randomised to the control group. Botulinum toxin treatment had been previously received by 27 (16.7%) of the control group compared with 21 (12.4%) of the intervention group. Randomisation groups were also well matched for other measures of upper limb impairment (Table 4).

| Control (n = 162) | Intervention (n = 170) | |

|---|---|---|

| Upper limb affected by spasticity: n (%) | ||

| Right | 65 (40.1) | 75 (44.1) |

| Left | 97 (59.9) | 95 (55.9) |

| Dominant hand affected: n (%) | ||

| Yes | 64 (39.5) | 80 (47.1) |

| No | 98 (60.5) | 90 (52.9) |

| Area affected by spasticity: n (%) | ||

| Shoulder | 95 (58.6) | 111 (65.3) |

| Elbow | 156 (96.3) | 161 (94.7) |

| Wrist | 141 (87.0) | 141 (82.9) |

| Hand | 140 (86.4) | 138 (81.2) |

| Distribution of spasticity: n (%) | ||

| Shoulder and elbow | 9 (5.6) | 15 (8.8) |

| Elbow and wrist | 8 (4.9) | 2 (1.2) |

| Wrist and hand | 5 (3.1) | 4 (2.4) |

| Shoulder and elbow and wrist | 1 (0.6) | 9 (5.3) |

| Shoulder and elbow and hand | 4 (2.5) | 4 (2.4) |

| Elbow and wrist and hand | 47 (29.0) | 43 (25.3) |

| Shoulder and elbow and wrist and hand | 80 (49.4) | 81 (47.6) |

| Other | 8 (4.9) | 12 (7.1) |

| Antispasticity treatment: n (%) | ||

| Total | 67 (41.4) | 64 (37.6) |

| Dantrolene | 2 (1.2) | 3 (1.8) |

| Baclofen | 16 (9.9) | 20 (11.8) |

| Tizanidine | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.8) |

| Gabapentin | 16 (9.9) | 14 (8.2) |

| Methocarbanol | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Shoulder brace | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Upper limb sling | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.2) |

| Thumb strap | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Elasticated glove | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Functional electrical stimulation machine | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) |

| Upper limb splint | 42 (25.9) | 36 (21.2) |

| Botulinum toxin treatment > 3 months before study entry: n (%) | ||

| Total | 27 (16.7) | 21a (12.4) |

| Arm | 12 (44.4) | 4 (19.0) |

| Leg | 7 (25.9) | 5 (23.8) |

| Both arm and leg | 8 (29.6) | 11 (52.4) |

| Modified Ashworth Scale at elbow: n (%) | ||

| 0 | 7 (4.3) | 8 (4.7) |

| 1 | 16 (9.9) | 20 (11.8) |

| 1 + | 53 (32.7) | 44 (25.9) |

| 2 | 57 (35.2) | 68 (40.0) |

| 3 | 28 (17.3) | 30 (17.6) |

| 4 | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 2 (1 + to 2) | 2 (1 + to 2) |

| Motricity index: median (IQR) | ||

| Arm | 40 (29 to 62) | 40 (24 to 61) |

| Total | 47 (34.5 to 64.3) | 50 (33.5 to 64.5) |

| Grip strength (kg): median (IQR) | 1.8 (0.0 to 6.0) | 0.7 (0.0 to 5.0) |

One hundred and eighty-four participants (55.4%) had no active upper limb function (ARAT 0–3) and 148 (44.6%) had some retained active function (ARAT 4–56) at randomisation. The median initial ARAT in both intervention and control groups was three (Table 5). Most participants had no or poor dexterity and were unable to complete the Nine-Hole Peg Test. Participants experienced moderate difficulty with upper limb functional activities such as putting their arm through a sleeve or opening the hand to clean the palm and the majority were unable to use cutlery as a result of their stroke. The control group had a lower level of participation restriction when assessed using the Oxford Handicap Scale, but it is unlikely that this possible imbalance at baseline is clinically important or had an impact upon outcome assessments.

| Control (n = 162)a | Intervention (n = 170)a | |

|---|---|---|

| ARAT: median (IQR) | ||

| Total | 3 (3 to 16) | 3 (3 to 16) |

| Grasp | 0 (0 to 5) | 0 (0 to 5) |

| Grip | 0 (0 to 4) | 0 (0 to 3) |

| Pinch | 0 (0 to 0) | 0 (0 to 0) |

| Gross | 3 (3 to 5) | 3 (2.8 to 4) |

| Nine-Hole Peg Test (pegs placed in 50 seconds): median (IQR) | 0 (0 to 0) | 0 (0 to 0) |

| Upper limb functional activities: median (IQR) | ||

| Put arm through sleeve | 3 (2 to 4) (n = 142) | 3 (2 to 4) (n = 159) |

| Open the hand for cleaning your palm | 3 (2 to 4) (n = 142) | 3 (2 to 4) (n = 159) |

| Open the hand for cutting fingernails | 2 (1 to 4) (n = 141) | 2 (1 to 3.3) (n = 158) |

| Use cutlery | 1 (1 to 1) (n = 140) | 1 (1 to 1) (n = 155) |

| Barthel ADL Index: median (IQR) | 15 (10 to 17) (n = 162) | 15 (10 to 17) (n = 170) |

| Stroke Impact Scale: median (IQR) | ||

| Strength | 31.3 (18.8 to 43.8) (n = 141) | 31.3 (18.8 to 43.8) (n = 157) |

| Memory | 82.1 (64.3 to 92.9) (n = 143) | 78.6 (57.1 to 92.9) (n = 159) |

| Emotion | 66.7 (52.8 to 80.6) (n = 141) | 66.7 (55.6 to 77.8) (n = 159) |

| Communication | 89.3 (67.9 to 100) (n = 142) | 85.7 (60.7 to 100.0) (n = 159) |

| ADL | 42.5 (32.5 to 57.5) (n = 142) | 40.0 (30.0 to 55.0) (n = 159) |

| Mobility | 50.0 (30.6 to 69.4) (n = 139) | 47.2 (25.0 to 64.3) (n = 158) |

| Hand function | 0.0 (0.0 to 10.0) (n = 139) | 0.0 (0.0 to 15.0) (n = 158) |

| Participation / handicap | 40.6 (21.9 to 65.6) (n = 141) | 34.4 (15.6 to 53.1) (n = 158) |

| Physical domain | 33.3 (22.7 to 42.5) (n = 143) | 30.5 (20.1 to 43.1) (n = 159) |

| Stroke recovery | 50.0 (30.0 to 60.0) (n = 136) | 40.0 (25.0 to 53.5) (n = 157) |

| EQ-5D: median (IQR) | ||

| Mobility | 2 (2 to 2) (n = 162) | 2 (2 to 2) (n = 170) |

| Self-care | 2 (2 to 2) (n = 162) | 2 (2 to 2) (n = 170) |

| Usual activities | 3 (2 to 3) (n = 162) | 3 (2 to 3) (n = 170) |

| Pain/discomfort | 2 (1 to 2) (n = 162) | 2 (1 to 2) (n = 170) |

| Anxiety/depression | 2 (1 to 2) (n = 162) | 2 (1 to 2) (n = 170) |

| Good/bad health scale | 60 (50 to 70) (n = 161) | 60 (50 to 70) (n = 169) |

| Oxford Handicap Scale: median (IQR) | 3 (3 to 4) | 4 (3 to 4) |

The median rating for pain was moderate in both groups. The median pain score was 5/10 in both the intervention and control groups (Table 6).

Primary outcome

Improved upper limb function (predefined treatment success on the ARAT) at 1 month was achieved by 30/154 (19.5%) participants in the control group and 42/167 (25.1%) in the intervention group. This difference was not significant (p = 0.232). The relative risk of having a ‘successful treatment’ in the intervention group compared with the control group was 1.3 (95% CI 0.9 to 2.0).

Secondary outcomes

Impairment

Changes in impairment from baseline to 1, 3 and 12 months are shown in Tables 7a and 7b. At 1 month, muscle tone at the elbow (Modified Ashworth Scale) decreased in the intervention group compared with the control group; the median change from baseline to 1 month in the control group was zero; the median change in the intervention group was – 1 (p < 0.001). The corresponding differences in change in muscle tone between intervention and control groups seen at 3 and 12 months were not statistically significant.

| Control | Intervention | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modified Ashworth Scale at elbow: median change (IQR) | |||

| 1 month | 0 (– 1 to 1) (n = 154) | – 1 (– 1 to 0) (n = 167) | 0.001 |

| 3 months | 0 (– 1 to 0) (n = 151) | 0 (– 1 to 0) (n = 163) | 0.145 |

| 12 months | 0 (– 1 to 1) (n = 91) | 0 (– 1 to 0) (n = 97) | 0.333 |

| Motricity index: median change (IQR) | |||

| Arm | |||

| 1 month | 0 (– 9 to 11) (n =153) | 3 (– 5 to 11) (n = 167) | 0.138 |

| 3 months | 0 (– 6 to 11) (n = 151) | 4 (– 4 to 14) (n = 164) | 0.055 |

| 12 months | 5 (– 3 to 11) (n = 92) | 5 (0 to 13) (n = 97) | 0.597 |

| Total | |||

| 1 month | 1.5 (– 5.5 to 8.8) (n = 153) | 2.5 (– 4.5 to 11) (n = 167) | 0.277 |

| 3 months | 0 (– 6.6 to 9) (n = 151) | 4 (– 4.5 to 11.5) (n = 162) | 0.042 |

| 12 months | 2 (– 5.9 to 9.4) (n = 92) | 3 (– 2.5 to 9.5) (n = 97) | 0.588 |

| Grip strength (kg): median change (IQR) | |||

| 1 month | 0.0 (– 0.4 to 2.0) (n = 154) | 0.0 (– 0.7 to 1.3) (n =167) | 0.233 |

| 3 months | 0.0 (– 0.7 to 2.0) (n = 151) | 0.0 (– 0.0 to 2.7) (n = 163) | 0.139 |

| 12 months | 0.5 (– 0.5 to 3.9) (n = 92) | 0.0 (– 0.2 to 3.0) (n = 97) | 0.764 |

| Control | Intervention | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modified Ashworth Scale at elbow: mean change (95% CI) | |||

| 1 month | – 0.1 (– 0.2 to 0.1) | – 0.6 (– 0.8 to – 0.4) | – 0.5 (– 0.8 to – 0.3) |

| 3 months | – 0.1 (– 0.3 to 0.1) | – 0.3 (– 0.4 to – 0.1) | – 0.2 (– 0.5 to 0.1) |

| 12 months | – 0.2 (– 0.5 to 0.1) | – 0.3 (– 0.5 to – 0.1) | – 0.1 (– 0.4 to 0.2) |

| Motricity Index: mean change (95% CI) | |||

| Arm | |||

| 1 month | 1.4 (– 0.9 to 3.7) | 3.6 (1.5 to 5.7) | 2.2 (– 0.9 to 5.4) |

| 3 months | 1.7 (– 0.6 to 4.1) | 5.2 (2.8 to 7.6) | 3.5 (0.1 to 6.8) |

| 12 months | 3.6 (0.7 to 6.4) | 6.1 (3.5 to 8.8) | 2.5 (– 1.4 to 6.3) |

| Total | |||

| 1 month | 1.4 (– 0.3 to 3.1) | 2.6 (0.9 to 4.3) | 1.2 (– 1.2 to 3.7) |

| 3 months | 1.2 (– 0.7 to 3.1) | 4.3 (2.5 to 6.2) | 3.2 (0.4 to 5.8) |

| 12 months | 2.4 (0.1 to 4.8) | 3.6 (1.6 to 5.8) | 1.3 (– 1.9 to 4.4) |

| Grip strength (kg): mean change (95% CI) | |||

| 1 month | 0.6 (0.2 to 1.1) | 0.5 (0.0 to 1.0) | – 0.2 (– 0.8 to 0.5) |

| 3 months | 0.9 (0.4 to 1.5) | 1.9 (1.1 to 2.8) | 1.0 (0.0 to 2.0) |

| 12 months | 1.6 (0.7 to 2.6) | 1.5 (0.7 to 2.4) | – 0.1 (– 1.4 to 1.1) |

The differences between the groups for change in upper limb motor impairment (Motricity Index) from baseline to 1 or 12 months were not significant. However, at 3 months the intervention group had improved by a median of four compared with a median of zero in the control group. This difference approached statistical significance when groups were compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test (p = 0.055). Examination of the difference between the mean change in the groups confirmed a similar magnitude of effect (3.5, 95% CI 0.1 to 6.8), which was statistically significant. Total motor impairment was also improved at 3 months in the intervention group compared with the control group (p = 0.042). There were no significant differences between intervention and control groups for change in grip strength at any assessment.

Upper limb function and activity limitation

At 3 months, predefined treatment success (improvement in upper limb function) on the ARAT was achieved by 37/151 (24.5%) participants in the control group and 54/161 (33.5%) in the intervention group (p = 0.083). At 12 months treatment success was achieved by 27/92 (29.3%) participants in the control group and 36/97 (37.1%) in the intervention group (p = 0.282). The relative risk of having a ‘successful treatment’ in the intervention group compared with the control group was 1.4 (95% CI 0.9 to 1.9) at 3 months and 1.3 (95% CI 0.8 to 1.9) at 12 months.

The effect of botulinum toxin upon upper limb function was also examined by analysing change in ARAT score from baseline to each assessment (Tables 8a and 8b). No significant differences were seen between intervention and control groups at 1 or 12 months. At 3 months, although the median change in upper limb function in both randomisation groups was zero, the Mann–Whitney U-test reached statistical significance (p = 0.049). Examination of the difference between the mean change in the groups showed that the intervention group had improved by a mean of 1.8 (95% CI 0.4 to 3.2) points on the ARAT compared with the control group. Although this demonstrates improved upper limb function in the intervention group compared with the control group, the size of the improvement is small and therefore of doubtful clinical significance.

| Control | Intervention | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ARAT: median change (IQR) | |||

| 1 month | 0 (0 to 3) (n = 154) | 0 (0 to 4) (n = 167) | 0.427 |

| 3 months | 0 (0 to 3) (n = 151) | 0 (0 to 5) (n = 161) | 0.049 |

| 12 months | 0 (0 to 3) (n = 92) | 1 (0 to 5) (n = 97) | 0.227 |

| Nine-Hole Peg Test (pegs placed in 50s): median change (IQR) | |||

| 1 month | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 155) | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 166) | 0.150 |

| 3 months | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 151) | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 162) | 0.062 |

| 12 months | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 92) | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 97) | 0.498 |

| Upper limb functional activities: median change (IQR) | |||

| Put arm through sleeve | |||

| 1 month | 0 ( to 0.5 to 1) (n = 125) | 0 (0 to 1) (n = 144) | 0.004 |

| 3 months | 0 (0 to 1) (n = 122) | 0 (0 to 1) (n = 142) | 0.127 |

| 12 months | 0 ( to 1 to 1) (n = 79) | 0 ( to 0.3 to 1) (n = 86) | 0.956 |

| Open the hand for cleaning your palm | |||

| 1 month | 0 (0 to 1) (n = 124) | 0 (0 to 1) (n = 143) | 0.071 |

| 3 months | 0 (– 1 to 1) (n = 122) | 0 (–1 to 1) (n = 142) | 0.047 |

| 12 months | 0 (– 1 to 1) (n = 79) | 0 (0 to 1.3) (n = 86) | 0.029 |

| Open the hand for cutting fingernails | |||

| 1 month | 0 (0 to 0.5) (n = 125) | 0 (– 1 to 1) (n = 143) | 0.526 |

| 3 months | 0 (– 1 to 1) (n = 122) | 0 (– 1 to 1) (n = 141) | 0.342 |

| 12 months | 0 (– 1 to 1) (n = 78) | 0 (– 0.3 to 2) (n = 86) | 0.097 |

| Use cutlery | |||

| 1 month | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 123) | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 141) | 0.376 |

| 3 months | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 120) | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 140) | 0.595 |

| 12 months | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 77) | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 83) | 0.066 |

| Barthel ADL Index: median change (IQR) | |||

| 1 month | 0 (– 2 to 1) (n = 134) | 0 (– 2 to 1) (n = 142) | 0.335 |

| 3 months | 0 (– 2 to 1) (n = 130) | 0 (– 2 to 2) (n = 143) | 0.260 |

| 12 months | – 1 (– 2 to 1) (n = 75) | – 1 (– 3 to 1.3) (n = 82) | 0.833 |

| Control | Intervention | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ARAT: mean change (95% CI) | |||

| 1 month | 1.5 (0.8 to 2.2) | 2.2 (1.3 to 3.0) | 0.7 (– 0.4 to 1.8) |

| 3 months | 1.3 (0.4 to 2.1) | 3.0 (2.0 to 4.2) | 1.8 (0.4 to 3.2) |

| 12 months | 2.0 (– 0.5 to 0.1) | –3.1 (1.7 to 4.5) | 1.1 (– 0.7 to 2.9) |

| Nine-Hole Peg Test (pegs placed in 50s): mean change (95% CI) | |||

| 1 month | 0.1 (– 0.1 to 0.3) | 0.3 (0.0 to 0.5) | 0.2 (– 0.1 to 0.5) |

| 3 months | 0.1 (– 0.1 to 0.3) | 0.5 (0.2 to 0.9) | 0.5 (0.1 to 0.8) |

| 12 months | 0.2 (0.0 to 0.3) | 0.3 (0.0 to 0.7) | 0.1 (– 0.2 to 0.6) |

| Upper limb functional activities: mean change (95% CI) | |||

| Put arm through sleeve | |||

| 1 month | 0.0 (– 0.2 to 0.2) | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.6) | 0.4 (0.1 to 0.6) |

| 3 months | 0.1 (– 0.1 to 0.3) | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.5) | 0.2 (– 0.1 to 0.5) |

| 12 months | 0.1 (– 0.2 to 0.3) | 0.1 (– 0.2 to 0.3) | 0.0 (– 0.4 to 0.4) |

| Open the hand for cleaning your palm | |||

| 1 month | 0.1 (– 0.1 to 0.3) | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.6) | 0.3 (0.0 to 0.6) |

| 3 months | 0.0 (– 0.3 to 0.2) | 0.3 (0.0 to 0.5) | 0.3 (– 0.1 to 0.7) |

| 12 months | – 0.1 (– 0.4 to 0.2) | 0.4 (0.1 to 0.8) | 0.5 (0.0 to 1.0) |

| Open the hand for cutting fingernails | |||

| 1 month | 0.1 (– 0.1 to 0.4) | 0.2 (– 0.1 to 0.4) | 0.1 (– 0.3 to 0.4) |

| 3 months | 0.0 (– 0.3 to 0.2) | 0.1 (– 0.2 to 0.3) | 0.1 (– 0.3 to 0.5) |

| 12 months | 0.0 (– 0.4 to 0.4) | 0.3 (– 0.1 to 0.7) | 0.3 (– 0.2 to 0.9) |

| Use cutlery | |||

| 1 month | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.2) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.3) | 0.1 (– 0.1 to 0.3) |

| 3 months | 0.2 (0.0 to 0.3) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.4) | 0.1 (– 0.1 to 0.3) |

| 12 months | – 0.1 (– 0.3 to 0.1) | 0.2 (0.0 to 0.2) | 0.3 (0 to 0.5) |

| Barthel ADL Index: mean change (IQR) | |||

| 1 month | – 0.6 (– 1.0 to 0.2) | – 0.4 (– 0.8 to 0.1) | 0.2 (– 0.4 to 0.8) |

| 3 months | – 0.3 (– 0.8 to 0.1) | 0.0 (– 0.5 to 0.4) | 0.3 (– 0.3 to 0.9) |

| 12 months | – 0.5 (– 1.1 to 0.2) | – 0.4 (– 1 to 0.2) | 0.1 (– 0.8 to 1.0) |

Although the median change in score from baseline to 1 month for the ability put the affected arm through a sleeve was zero in both the control and intervention groups, comparison of scores reached statistical significance (p = 0.004). Examination of the difference between the mean change in the groups showed that the intervention group had improved by 0.4 (95% CI 0.1 to 0.6) compared with the control group (Tables 8a and 8b). Similarly, at 3 and 12 months there were statistically significant differences between intervention and control groups in ability to open the hand for cleaning the palm despite the median change from baseline being zero in both groups. Further examination of the data showed that the intervention group had improved by 0.3 (95% CI – 0.1 to 0.7) compared with the control group at 3 months and by 0.5 (95% CI 0.0 to 1.0) at 12 months. As self-reported arm function was assessed using an ordinal scale of 1 (unable to perform) to 5 (no difficulty), a mean improvement of 0.3–0.5 is of doubtful clinical importance.

To enable comparison with previous studies, responses to basic upper limb functional activity questions were also analysed by comparing the proportion of participants in each randomisation group who had improved by one or more points on the scale from baseline (Table 8c). For the ability to dress a sleeve, this improvement was seen for 65/144 (45.1%) of participants in the intervention group compared with 38/125 (30.4%) in the control group at 1 month (p = 0.017). No significant differences were seen at 3 and 12 months. For opening the hand to clean the palm and opening the hand to cut fingernails, significant differences in favour of the intervention group were seen at 1, 3 and 12 months. No significant differences were seen between the groups for improvement in ability to use cutlery.

Overall, at 1 month 109/144 (75.7%) of the intervention group and 79/125 (63.2%) of the control group had improved by at least one point on any of the four tasks (p = 0.033). At 3 months the corresponding proportions were 102/142 (71.8%) of the intervention group and 71/122 (58.2%) of the control group (p = 0.027). No significant difference was seen at 12 months [intervention group 59/86 (68.6%), control group 51/79 (64.6%), p = 0.622].

| Control | Intervention | p-value | Relative risk Intervention: Control (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dressing sleeve improvement by ≥ 1: n (%) | ||||

| 1 month | 38 (30.4) (n = 125) | 65 (45.1) (n = 144) | 0.017 | 1.5 (1.1 to 2.0) |

| 3 months | 39 (32.0) (n = 122) | 62 (43.7) (n = 142) | 0.057 | 1.4 (1.0 to 1.9) |

| 12 months | 32 (40.5) (n = 79) | 30 (34.9) (n = 86) | 0.521 | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.3) |

| Opening hand for cleaning palm improvement of ≥ 1: n (%) | ||||

| 1 month | 41 (33.1) (n = 124) | 65 (45.5) (n = 143) | 0.045 | 1.4 (1.0 to 1.8) |

| 3 months | 34 (27.9) (n = 122) | 64 (45.1) (n = 142) | 0.005 | 1.6 (1.2 to 2.3) |

| 12 months | 25 (31.6) (n = 79) | 41 (47.7) (n = 86) | 0.040 | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.2) |

| Opening the hand for cutting nails improvement of ≥ 1: n (%) | ||||

| 1 month | 31 (24.8) (n = 125) | 52 (36.6) (n = 142) | 0.047 | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.2) |

| 3 months | 31 (25.4) (n = 122) | 52 (36.9) (n = 141) | 0.048 | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.2) |

| 12 months | 21 (26.9) (n = 78) | 39 (45.3) (n = 86) | 0.016 | 1.7 (1.1 to 2.6) |

| Ability to use cutlery improvement of ≥ 1: n (%) | ||||

| 1 month | 22 (17.9) (n = 123) | 31 (22.0) (n = 141) | 0.444 | 1.2 (0.8 to 2.0) |

| 3 months | 25 (20.8) (n = 120) | 31 (22.1) (n = 140) | 0.880 | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.7) |

| 12 months | 10 (13.0) (n = 77) | 17 (20.5) (n = 83) | 0.291 | 1.6 (0.8 to 3.2) |

Stroke-related quality of life/participation restriction

Tables 9a and 9b show stroke-related quality of life/participation restriction at 1, 3 and 12 months. For the EQ-5D question about pain and discomfort, although the median change in score from baseline to 3 months was zero in both groups, comparison of scores between the groups reached statistical significance (p = 0.025). Examination of the difference between mean change in the groups showed that the intervention group had improved (decreased) their score by 0.2 points compared with the control group. Similarly, the median change in score from baseline to 3 months on the Oxford Handicap Scale was zero in both groups, but comparison of scores between the groups reached statistical significance (p = 0.015). The mean change in the groups showed that the intervention had improved (decreased) their score by 0.3 points compared with the control group.

| Control | Intervention | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke Impact Scale domains: median change (IQR) | |||

| Strength | |||

| 1 month | 0.0 (– 6.3 to 12.5) (n = 124) | 0.0 (– 6.3 to 12.5) (n = 142) | 0.544 |

| 3 months | 0.0 (– 12.5 to 6.3) (n = 117) | 0.0 (– 12.5 to 6.3) (n = 140) | 0.784 |

| 12 months | 0.0 (– 12.5 to 12.5) (n = 76) | 0.0 (– 12.5 to 10.9) (n = 84) | 0.408 |

| Memory | |||

| 1 month | 0.0 (– 7.1 to 7.1) (n = 125) | 0.0 (– 6.3 to 7.1) (n = 144) | 0.204 |

| 3 months | 0.0 (– 10.7 to 10.7) (n = 122) | 0.0 (– 7.1 to 10.7) (n = 143) | 0.674 |

| 12 months | – 3.6 (– 14.3 to 0.0) (n = 79) | 0.0 (– 10.7 to 7.1) (n = 86) | 0.060 |

| Emotion | |||

| 1 month | 0.0 (– 5.6 to 8.3) (n = 123) | 0.0 (– 8.3 to 8.3) (n = 143) | 0.831 |

| 3 months | 0.0 (– 8.3 to 8.3) (n = 120) | 0.0 (– 12.6 to 8.3) (n = 140) | 0.771 |

| 12 months | – 5.6 (– 13.9 to 5.6) (n = 78) | 0.0 (– 8.3 to 8.3) (n = 86) | 0.092 |

| Communication | |||

| 1 month | 0.0 (– 7.1 to 3.6) (n = 125) | 0.0 (– 3.6 to 3.6) (n = 144) | 0.519 |

| 3 months | 0.0 (– 7.1 to 3.6) (n = 122) | 0.0 (– 3.6 to 7.1) (n = 141) | 0.115 |

| 12 months | – 3.6 (– 10.7 to 3.6) (n = 79) | 0.0 (– 7.1 to 7.1) (n = 86) | 0.023 |

| ADL | |||

| 1 month | 0.0 (– 7.5 to 5.0) (n = 125) | 0.3 (– 5.0 to 10.0) (n = 143) | 0.078 |

| 3 months | 0.0 (– 7.5 to 7.5) (n = 122) | 0.0 (– 6.3 to 7.5) (n = 142) | 0.642 |

| 12 months | – 2.5 (– 10.0 to 5.0) (n = 79) | 0.0 (– 7.5 to 10.0) (n = 85) | 0.189 |

| Mobility | |||

| 1 month | 0.0 (– 8.3 to 5.6) (n = 124) | 0.0 (– 5.6 to 8.3) (n = 142) | 0.217 |

| 3 months | 2.8 (– 8.3 to 11.1) (n = 119) | 2.8 (– 5.6 to 8.3) (n = 140) | 0.686 |

| 12 months | – 1.4 (– 11.1 to 8.3) (n = 78) | 0.0 (– 8.8 to 8.3) (n = 86) | 0.686 |

| Hand function | |||

| 1 month | 0.0 (0.0–10.0) (n = 124) | 0.0 (0.0 to 10.0) (n = 142) | 0.387 |

| 3 months | 0.0 (0.0–5.0) (n = 120) | 0.0 (0.0 to 10.0) (n = 141) | 0.908 |

| 12 months | 0.0 (– 2.5 to 0.0) (n = 77) | 0.0 (0.0 to 11.3) (n = 86) | 0.096 |

| Participation/Handicap | |||

| 1 month | – 2.3 (– 12.5 to 9.4) (n = 124) | 0.0 (– 9.4 to 13.5) (n = 142) | 0.122 |

| 3 months | 0.0 (– 18.7 to 14.5) (n = 122) | 3.1 (– 9.4 to 21.9) (n = 140) | 0.091 |

| 12 months | 0.0 (– 18.0 to 12.5) (n = 76) | 3.1 (– 12.5 to 18.8) (n = 85) | 0.241 |

| Physical domain | |||

| 1 month | 1.0 (– 5.0 to 6.2) (n = 126) | 2.0 (– 2.7 to 7.5) (n = 144) | 0.125 |

| 3 months | 1.1 (– 5.6 to 7.1) (n = 123) | 2.0 (– 4.6 to 7.0) (n = 143) | 0.790 |

| 12 months | – 1.8 (– 6.8 to 5.0) (n = 79) | – 0.4 (– 7.1 to 6.9) (n = 86) | 0.534 |

| Stroke recovery | |||

| 1 month | 0.0 (– 10.0 to 5.0) (n = 121) | 0.0 (– 12.5 to 10.0) (n = 141) | 0.352 |

| 3 months | 0.0 (– 10.0 to 10.0) (n = 117) | 0.0 (– 10.0 to 15.0) (n = 141) | 0.464 |

| 12 months | 0.0 (– 20.0 to 10.0) (n = 74) | 0.0 (– 20.0 to 20.0) (n =86 ) | 0.369 |

| EQ-5D: median change (IQR) | |||

| Mobility | |||

| 1 month | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 138) | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 151) | 0.914 |

| 3 months | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 134) | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 151) | 0.445 |

| 12 months | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 83) | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 87) | 0.542 |

| Self-care | |||

| 1 month | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 138) | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 151) | 0.255 |

| 3 months | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 134) | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 152) | 0.256 |

| 12 months | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 82) | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 87) | 0.576 |

| Usual activities | |||

| 1 month | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 138) | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 149) | 0.764 |

| 3 months | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 134) | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 151) | 0.311 |

| 12 months | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 83) | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 86) | 0.443 |

| Pain/discomfort | |||

| 1 month | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 137) | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 150) | 0.247 |

| 3 months | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 133) | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 152) | 0.025 |

| 12 months | 0 (0 to 1) (n = 83) | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 87) | 0.270 |

| Anxiety/depression | |||

| 1 month | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 133) | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 149) | 0.138 |

| 3 months | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 132) | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 151) | 0.818 |

| 12 months | 0 (0 to 1) (n = 81) | 0 (– 1 to 0) (n =86 ) | 0.002 |

| Good/bad health scale | |||

| 1 month | – 5 (– 20 to 10) (n = 135) | – 1 (– 18 to 10) (n = 149) | 0.663 |

| 3 months | – 1 (– 22.5 to 15) (n = 133) | – 5 (– 20 to 10) (n = 148) | 0.755 |

| 12 months | 0 (– 25.8 to 18.8) (n = 80) | – 5 (– 20 to 10) (n = 84) | 0.749 |

| Oxford Handicap Scale: median change (IQR) | |||

| 1 month | 0 (– 0.5 to 0) (n = 137) | 0 (–1 to 0) (n = 152) | 0.359 |

| 3 months | 0 (0 to 0) (n = 133) | 0 (–1 to 0) (n = 151) | 0.015 |

| 12 months | 0 (– 1 to 0) (n = 83) | 0 (–1 to 0) (n = 87) | 0.045 |

| Control | Intervention | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke Impact Scale domains: mean change (95% CI) | |||

| Strength | |||

| 1 month | 0.9 (– 1.6 to 3.4) | 1.7 (– 1.1 to 4.4) | 0.8 (– 2.9 to 4.6) |

| 3 months | – 1.6 (– 5.1 to 1.8) | – 0.2 (– 3.4 to 3.0) | 1.4 (– 3.3 to 6.2) |

| 12 months | 0.2 (– 4.2 to 4.5) | – 2.2 (– 6.5 to 2.2) | – 2.3 (– 8.3 to 4.0) |

| Memory | |||

| 1 month | – 1.1 (– 3.7 to 1.5) | 1.3 (– 1.6 to 4.2) | 2.4 (– 1.5 to 6.3) |

| 3 months | – 2.0 (– 5.0 to 1.0) | – 0.8 (– 2.3 to 4.0) | 2.8 (– 1.5 to 7.2) |

| 12 months | – 5.6 (– 9.6 to – 1.5) | – 1.8 (– 5.6 to 1.8) | 3.8 (– 1.7 to 9.2) |

| Emotion | |||

| 1 month | 0.6 (– 2.0 to 3.1) | 0.3 (– 1.8 to 2.4) | – 0.3 (– 3.6 to 3.0) |

| 3 months | – 0.1 (– 2.8 to 2.6) | – 1.0 (– 3.4 to 1.5) | – 0.9 (– 4.6 to 2.8) |

| 12 months | – 3.5 (– 6.9 to – 0.1) | – 1.0 (– 4.0 to 1.9) | 2.5 (– 2.0 to 7.0) |

| Communication | |||

| 1 month | – 1.6 (– 3.6 to 0.4) | 0.6 (– 1.7 to 2.8) | 2.1 (– 0.9 to 5.1) |

| 3 months | – 2.4 (– 5.3 to 0.3) | 0.3 (– 2.2 to 2.7) | 4.7 (1.1 to 8.5) |

| 12 months | – 4.2 (– 8.1 to – 0.5) | 1.2 (– 2.4 to 4.7) | 5.3 (0.2 to 10.6) |

| ADL | |||

| 1 month | – 1.6 (– 3.8 to 0.5) | 1.8 (– 0.5 to 4.1) | 3.4 (0.4 to 6.6) |

| 3 months | – 1.0 (– 3.7 to 1.4) | 2.5 (0.0 to 5.0) | 1.4 (– 2.2 to 4.9) |

| 12 months | – 2.4 (– 5.5 to 0.7) | 0.8 (– 2.3 to 3.8) | 3.2 (– 1.1 to 7.5) |

| Mobility | |||

| 1 month | – 1.0 (– 3.6 to 1.7) | 1.1 (– 1.4 to 3.5) | 2.1 (– 1.5 to 5.7) |

| 3 months | 1.7 (– 1.3 to 4.7) | 2.9 (– 0.5 to 6.2) | 0.8 (– 3.1 to 4.6) |

| 12 months | – 2.0 (– 5.4 to 1.4) | – 0.8 (– 3.9 to 2.2) | 1.2 (– 3.5 to 5.8) |

| Hand function | |||

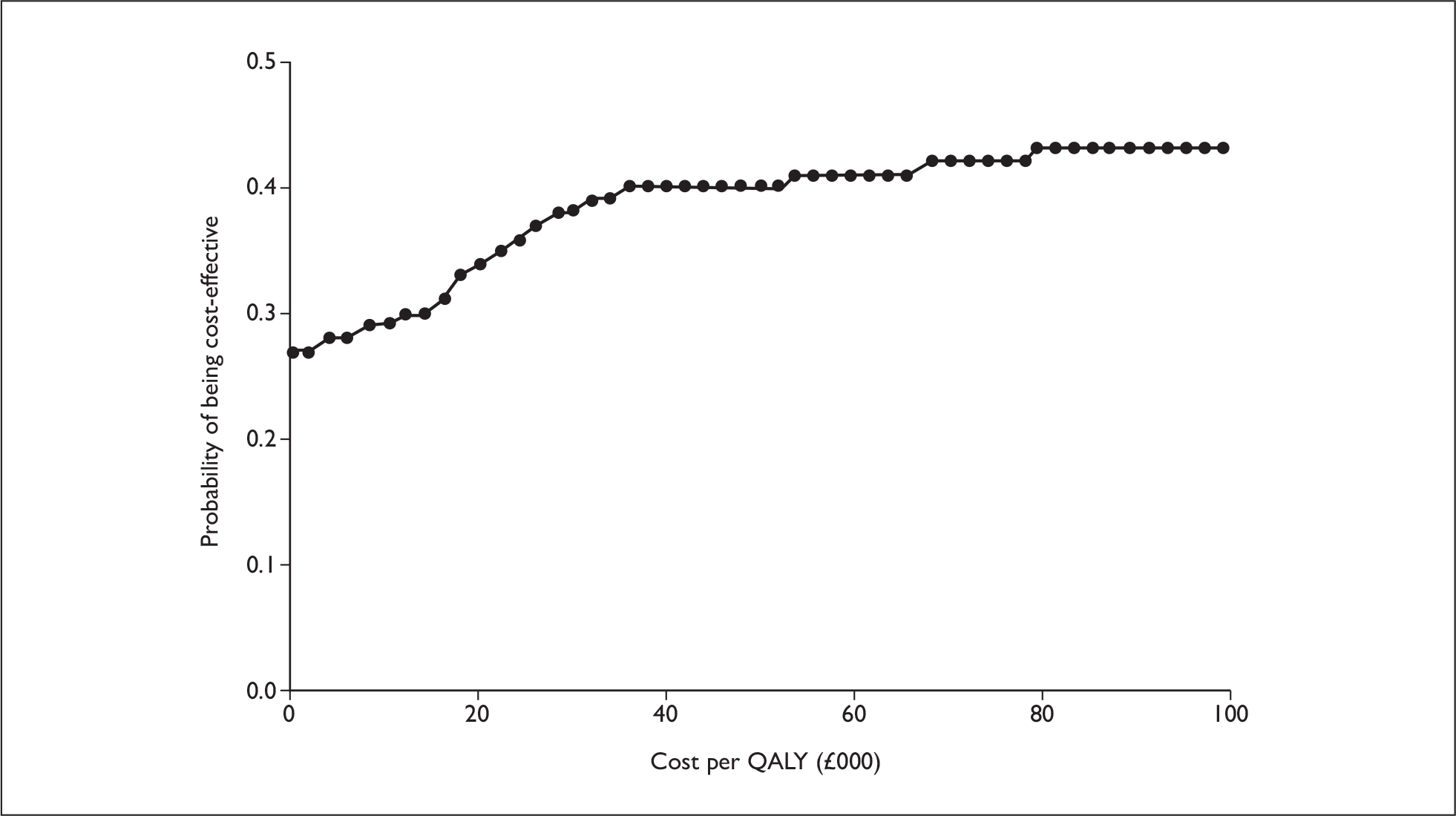

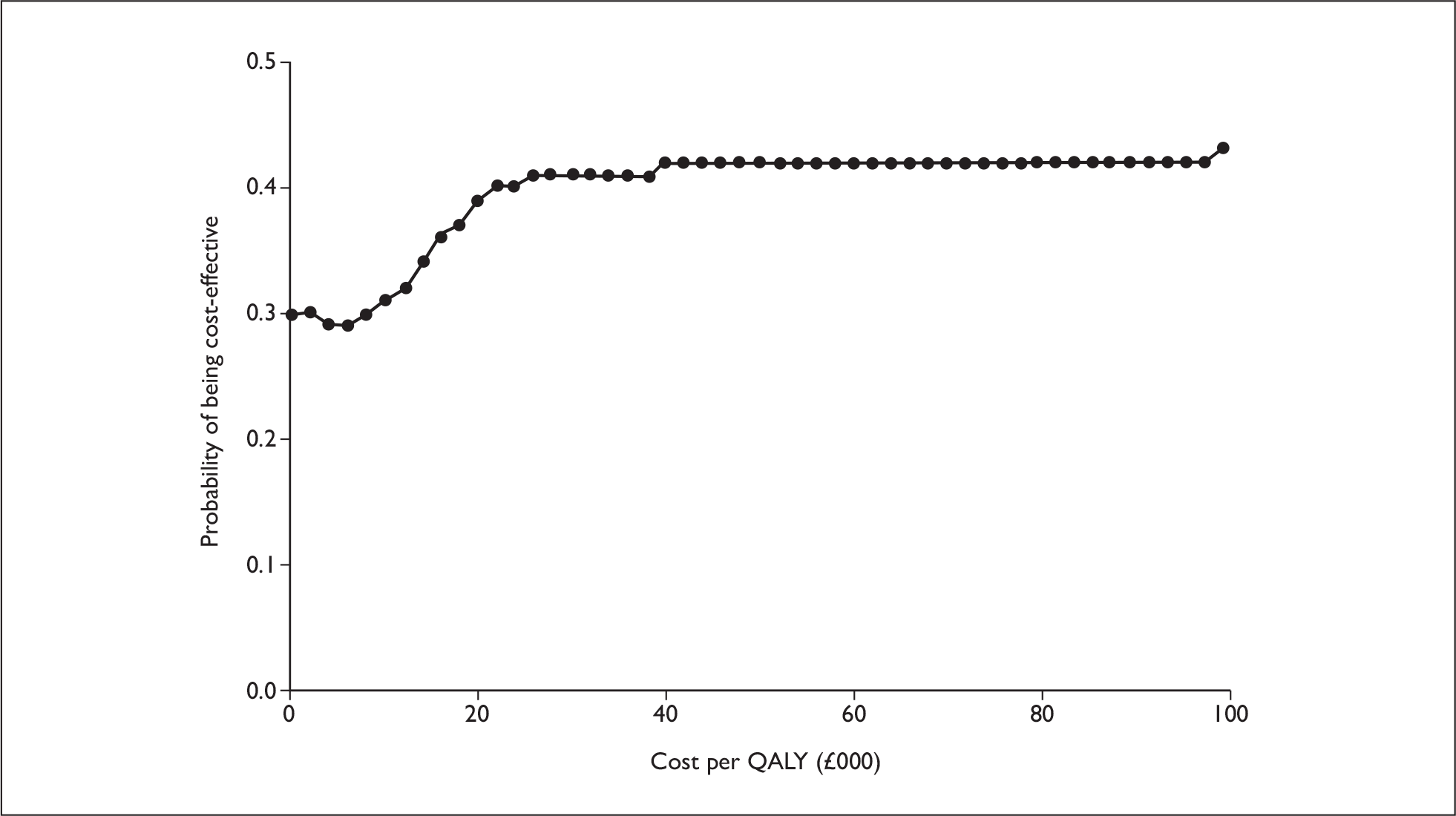

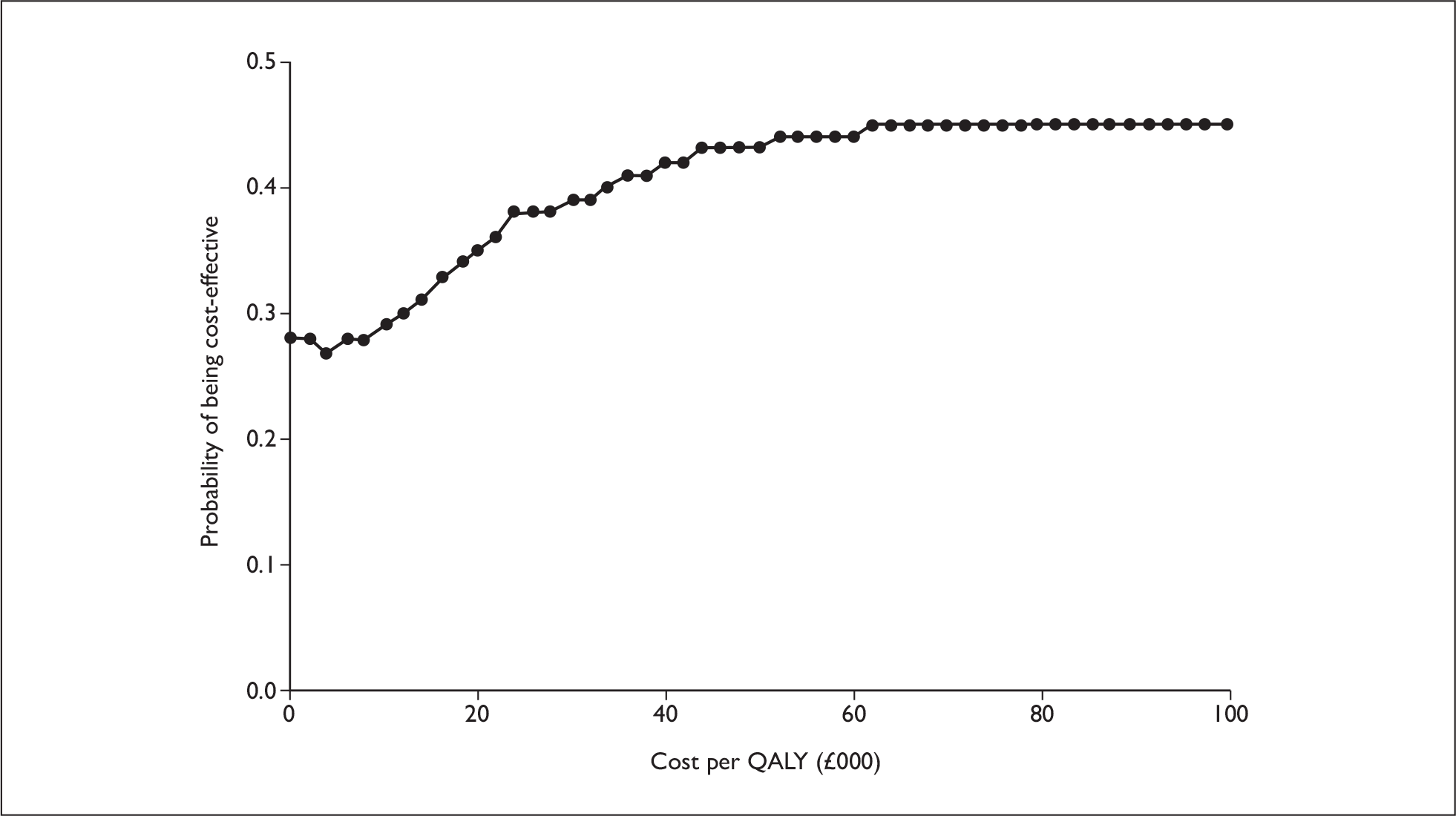

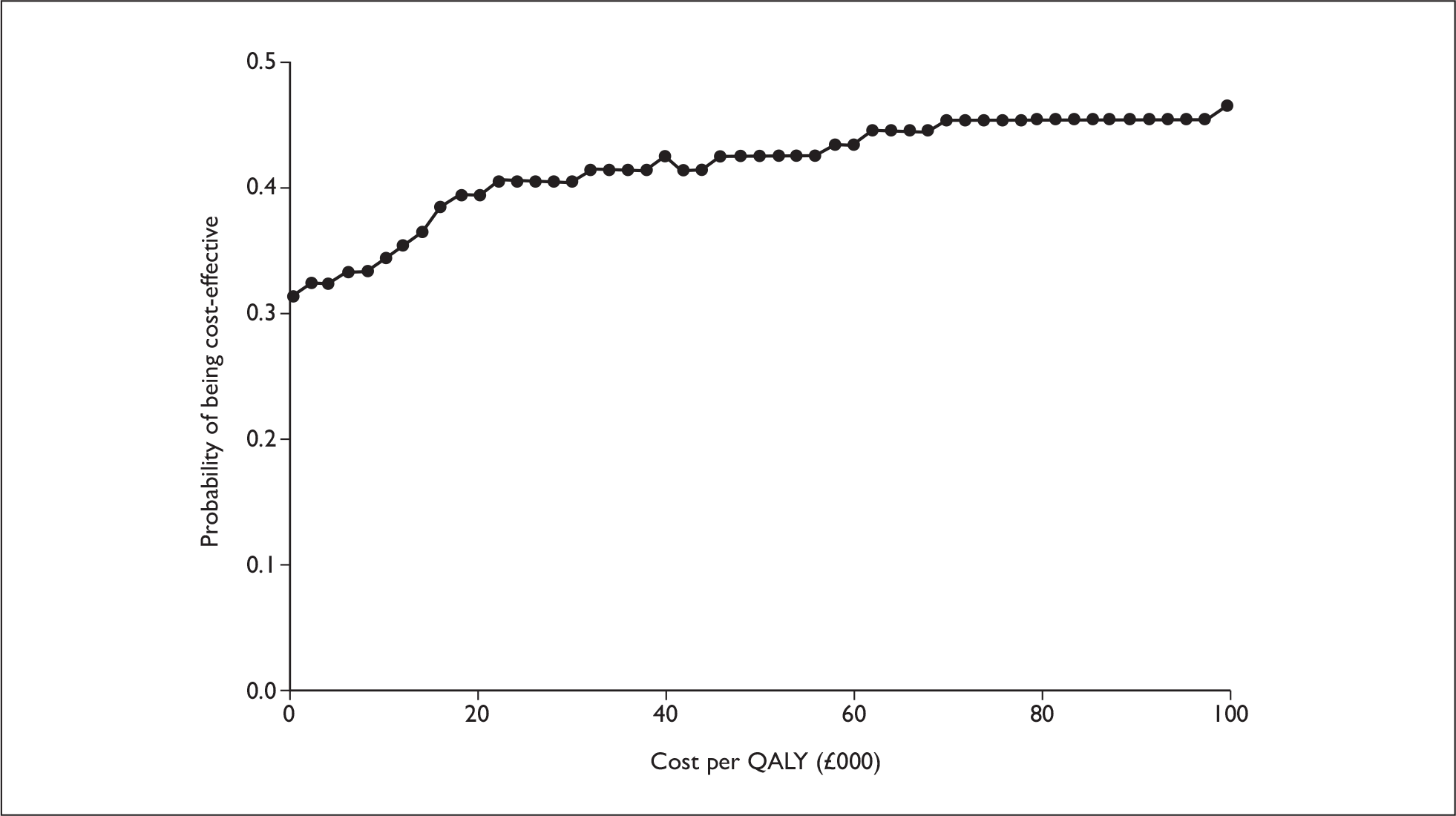

| 1 month | 3.3 (0.2 to 6.1) | 4.7 (1.3 to 8.0) | 1.5 (– 3.0 to 5.8) |