Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 06/41/02. The contractual start date was in July 2007. The draft report began editorial review in March 2009 and was accepted for publication in October 2009. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Paul Abrams was involved in a trial of two surgical treatments for stress urinary incontinence conducted by the Bristol Urological Institute and funded by an educational grant by American Medical Services.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2010 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2010 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Description of underlying health problem

Continence mechanisms in health

Efficient mechanisms have evolved to ensure reliable urine storage and complete bladder emptying at socially convenient times. Mechanisms that prevent urine leakage involve the bladder, the urethra and the pelvic floor muscles, together with their controlling nerve pathways. The bladder is a highly compliant organ, allowing the storage of increasing quantities of urine without rise in pressure, a property underpinned by passive stretch and active relaxation of its smooth muscle (detrusor). Active central nervous control mechanisms in the pons and cerebrum inhibit detrusor contraction despite increasing sensation of bladder fullness until micturition is appropriate. Urethral mechanisms promoting continence are less well understood, but are thought to involve tonic contraction of smooth muscle in the urethral wall, together with a tight seal formed by the urethral lining (mucosa) and the highly vascular submucosal layer. Contraction of the pelvic floor striated muscles acts as an additional guarding mechanism, compressing the urethra and preventing leakage during actions that raise intra-abdominal pressure.

These features maintain continence during the storage phase of the micturition cycle by ensuring that bladder pressure is always lower than urethral closure pressure. Incontinence is therefore likely to result from deficiency of urethral closure mechanisms and/or involuntary detrusor activity, aggravated by factors that chronically increase intra-abdominal pressure. In general, maximal urethral closure pressure is higher in men and therefore incontinence is far more prevalent amongst women, who are the target population for this review. 1

Definition of urinary incontinence

The symptom of urinary incontinence is defined as the involuntary leakage of urine,2,3 and this can be subcategorised qualitatively according to the patient’s description (Box 1).

Involuntary leakage of urine associated with effort or exertion, or on sneezing or coughing

Urgency urinary incontinence (UUI)Involuntary leakage of urine accompanied, or immediately preceded, by urgency, which is a sudden compelling desire to pass urine that is difficult to defer

Mixed urinary incontinence (MUI)When complaints of both SUI and UUI coexist

This symptom categorisation2,3 is based on a detailed history and provides a useful basis for discussion of the problem with the patient, identification of patient-centred treatment goals and initiation of treatment pathways.

When the patient first reports the problem to a clinician it is usual for the clinician to define possible causative factors and commonly associated problems by further questioning, physical examination and performance of simple tests. The severity of incontinence and the degree of bother it causes the individual can be estimated by appropriate direct questioning, including pad usage, or can be quantified more objectively using validated symptom scores4 or bladder diaries.

Further categorisation of incontinence according to the underlying functional or anatomical cause requires simultaneous measurement of bladder and rectal pressure, together with observation of urine loss during bladder filling. This invasive clinical test, filling cystometry, requires catheterisation of the bladder and is therefore generally performed only when more accurate categorisation is required, for example prior to surgical treatment in women with MUI. This test will differentiate urodynamic stress incontinence (USI) due to bladder outlet weakness from detrusor overactivity (DO) incontinence due to involuntary contraction of the bladder muscle (Box 2).

Involuntary leakage of urine during increased abdominal pressure in the absence of a detrusor contraction

Detrusor overactivity (DO) incontinenceLeakage of urine due to an involuntary detrusor contraction

The test may be accompanied by radiographic visualisation of the bladder outlet to qualitatively subcategorise USI according to the degree of descent of the bladder neck on coughing (hypermobility) or loss of the sealing mechanism of the urethra (intrinsic sphincter deficiency). The diagnostic and prognostic usefulness of this additional imaging, together with related indices such as abdominal leak point pressure, is uncertain and currently not recommended for routine use by the International Continence Society. 2

Most people complaining of the symptom of SUI will have USI, which is demonstrable on cystometry, and this can be aggravated by conditions that chronically raise abdominal pressure, such as obesity and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In approximately 10–20% of cases, however, the symptom of SUI can result from DO provoked by coughing, for example, or from loss of bladder compliance due to fibrosis or neurological disease (low bladder compliance). It should therefore be noted that the symptom of stress incontinence does not always relate to weakness of the bladder outlet or urethral closure mechanism.

Practical definition of incontinence for outcome purposes requires a variable that can be measured before and after treatment. This presents a particular problem for evidence synthesis, as there is a lack of consensus on the most appropriate method, with a variety of variables being used to define improvement or cure (Box 3). It is also recognised that these variables may not capture outcomes of prime importance to individual women suffering SUI.

Self-report of outcome or change in symptom score

QuantifiedChange in reported episodes on bladder diaries

Weight of urine loss during exercise pad tests

Clinician definedDirect observation of urine loss

Cystometric diagnosis

Quality of life definedChange in generic ratings, such as EQ-5D

Change in condition-specific ratings, such as King’s Health Questionnaire

Epidemiology and natural history

Prevalence

Prevalence estimates vary depending on population sampled, definition of incontinence, severity threshold and survey methodology. 5 A recent longitudinal study from one county in the UK surveyed a random sample of over 15,000 community-dwelling individuals aged ≥ 40 years and found prevalences of 34% in women and 14% in men. 6 These data were in line with prevalence rates among adults living in the UK, summarised from previous studies, showing a mean (range) of 40% (2–69%) for women and 10% (2–25%) for men. 7 These ranges were consistent with findings from other developed countries, which documented rates of 10–72% for women and 3–20% for men. 7

The EPINCONT study surveyed over 34,000 community-dwelling Norwegian women and found that the prevalence of urinary incontinence increased during young adult life, reached a broad peak between the ages of 45 and 55 years, and then showed a further steady increase in the elderly (Figure 1). 8–12 This study also found that about one-quarter of women with incontinence rated it as severe, a proportion in line with previous reports. 13

FIGURE 1.

Prevalence of female urinary incontinence by age group and symptomatic type of incontinence. Compiled from data in Hannestad and colleagues (2000). 8

This study also provided differential prevalence rates for symptoms of stress, urge and mixed incontinence. 10 Overall, SUI was the most common type, experienced by 50% of incontinent women, whereas 11% reported urgency incontinence alone and 36% reported mixed symptoms (Figure 1). The pattern does vary, however, according to age group, with SUI alone being most frequently reported in women who are younger than 50–55 years, after which urgency incontinence is reported most often, either alone or in combination, possibly reflecting menopausal status. 12 This pattern was also found in a large cross-sectional European study using validated questionnaires, for which SUI was most often reported by women under 60 years old. 11 Overall prevalence rates for urinary incontinence amongst older women who are living in supported accommodation are usually much higher, reaching 40–50%. 14

This high community prevalence does not tend to lead to equivalent rates of consultation with a clinician. Studies estimate that only 15% of the women identified as suffering from SUI in cross-sectional surveys have consulted a health professional about the problem. 15,16 The reasons for this are unclear but may relate to social class, mild symptoms, lack of bother, embarrassment, disinclination towards treatment options and perceived lack of effective treatment. 17

Natural history

In comparison with the many cross-sectional prevalence surveys, fewer longitudinal studies have examined the incidence and remission of urinary incontinence symptoms. One study followed a large cohort of community-dwelling middle-aged women (mean age 46 years) for 2 years and documented an average annual incidence of new incontinence of 9%. 18 The incidence increased with age, with the majority reporting mild, non-disabling leakage (Figure 2). Subanalysis of type of incontinence showed an annual incidence of frequent or severe stress incontinence of about 2% (Figure 3). This study also documented a 7% annual remission rate among those women reporting urinary incontinence at baseline. Similar results were found from a cohort of older, postmenopausal women (mean age 64 years), followed for 2 years, and a further large cohort study of women aged > 65 years, with rates of annual incidence for SUI of 9% and 9.5%, respectively, and annual remission rates of 7% and 8%, respectively. 19,20

FIGURE 2.

Two-year incidence of urinary incontinence by severity. Based on a cohort of 33,952 American women. Any incontinence defined as leaking at least once per month; occasional incontinence defined as leaking one to three times per month; frequent incontinence defined as leaking at least once per week; severe incontinence defined as frequent leaking of quantities at least enough to wet the underwear. Adapted from Townsend and colleagues (2007). 18

FIGURE 3.

Two-year incidence of frequent (at least once weekly) urinary incontinence by incontinence type. Cases of incident frequent incontinence; missing data on incontinence type symptoms are excluded from these calculations. Adapted from Townsend and colleagues (2007). 18

A number of studies have reported questionnaire follow-up of numerically smaller cohorts of younger women (mean age 26–30 years) before and after their first vaginal delivery and reported the annual incidence of new urinary incontinence to be 5%, 1% and 4% over periods of 4, 10 and 12 years, respectively. 21–23

Factors associated with SUI

The main risk factors for female SUI are pregnancy, vaginal delivery, increasing parity, increasing age, obesity and postmenopausal status. 24–26 In older women, particularly those requiring social care, age-related changes to the lower urinary tract (such as reduced bladder capacity) and comorbidity in other organ systems (such as cardiac or cognitive impairment treated with drugs such as diuretics) can precipitate or worsen incontinence. Consideration of these multiple factors, together with the increasing preponderance of mixed urgency and stress incontinence symptoms, makes effective management of the problem in the elderly more difficult. 14

Postpartum SUI

Childbearing is the main predisposing factor that is specific for SUI, although the exact mechanism of pelvic floor injury that contributes to the development of outlet weakness during pregnancy and vaginal delivery is unclear. 26,27 Longitudinal studies have reported that two-thirds of women with SUI during their first pregnancy continue to have symptoms at a follow up of 15 years. Having antenatal SUI doubles this risk. 28 Immediately after childbirth women may expect to have higher levels of incontinence, which can often resolve spontaneously over the first 6 months. As this natural resolution might confound the effect of any intervention, data from trials in women in the immediate postpartum period were not included in the main body of the systematic review or in the cost-effectiveness analysis (results are reported in Appendix 20).

Other risk factors

In a large population-based cross-sectional study of premenopausal women, high body mass index (BMI > 30), diabetes mellitus and previous urinary incontinence surgery were identified as significant risk factors for severe SUI. 29 A history of gynaecological surgery for prolapse increased the risk of developing stress leakage over twofold, and hysterectomy and other gynaecological procedures also doubled the risk. 30,31

Significance in terms of ill health

Effect on well-being

Embarrassment associated with urinary incontinence may cause withdrawal from social situations and reduce quality of life. 32 Women with a severe or frequent problem find the leakage distressing and socially disabling. They may avoid going away from home, using public transport and sexual activity. 33 SUI does not generally lead to deterioration in physical health but can be associated with depression and other psychological morbidity. 33 The problem may also lead to withdrawal from regular physical activities, potentially harming general health. 34

Extent of problem in the UK

Assuming an overall prevalence for SUI of 15% among women aged over 20 years, it can be estimated that there are 3.3 million sufferers in the UK. 35

Cost to society

The high prevalence of urinary incontinence results in a high overall cost of treatment and containment. Precise cost is difficult to define but a recent study suggested an estimated figure for combined health care, personal and societal expenditure of £248 per person per year in the UK, which would equate to a total annual cost of £818M for SUI. 36 A further estimate, assuming that SUI accounts for 50% of cases, suggested a health care cost to the UK National Health Service (NHS) of £117M per year. 37

Description of interventions

The treatment options for SUI can be classified as non-surgical and surgical. Lifestyle changes, such as weight loss, smoking cessation, control of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, timed voiding and oral fluid management, may reduce risk of leakage but all need continued adherence to the required adjustments in order to maintain response. Specific non-surgical interventions, such as pelvic floor muscle training and biofeedback (BF), also require long-term adherence to the taught programmes in order to produce continued benefit. However, these interventions have few or no adverse events. Surgical treatment, on the other hand, may have a higher rate of benefit but has a greater risk of complications. 38 Alternatively, the leakage can be contained using absorbent pads, an indwelling urinary catheter or, very rarely, urinary diversion.

The choice of treatment depends on patient preference and professional advice and will take into account factors, such as symptom severity, degree of interference with lifestyle, presence of related problems and degree of comorbidity. The importance of patient preference as the primary consideration in selecting a particular treatment for SUI was underlined by the findings of a recent survey which reported that most preferred less invasive treatment and management options. 39 From a health service perspective it is important to balance short- and long-term efficacy against potential adverse events and costs.

Existing guidelines

Epidemiological studies consistently demonstrate that proportionally few women who experience urinary leakage approach clinicians for advice and treatment. 15,16 It is likely that most women first seek advice from family, friends and the media and, for individually varying reasons, decide to manage the problem themselves. Those who present their problem to health-care professionals tend to have more severe symptoms, which cause interference to their social activities and they are therefore generally seeking active treatment. Most countries, such as the UK, have attempted to standardise the assessment and initial management of women with incontinence by publication of consensus documents and guidelines. 40–44 Despite this, uniformity of care remains lacking and will depend on individual clinician opinion and local service provision.

Current UK NHS care pathway

In the UK, the first port of call is likely to be the general practitioner (GP – primary care physician). An initial assessment will document the severity of the problem and the degree to which it bothers the women, and make sure that there are no more immediate health-threatening problems. Lifestyle advice, such as smoking cessation and weight loss, to modify risk factors may be offered. It is then possible that conservative therapy, in terms of bladder training (BT) or pelvic floor education and therapy, will be suggested, with referral to a practice nurse, physiotherapist or continence nurse specialist. Alternatively, or if these approaches subsequently fail, the woman will be offered referral to secondary care, to a urologist, urogynaecologist or gynaecologist, depending on local service arrangements. Such referrals will mostly result in further investigation, further conservative treatment including the use of drugs and eventually the offer of surgery to those with predominant SUI.

Lifestyle changes

Symptomatic SUI may be improved or cured by changing lifestyle factors. This can be achieved by interventions, such as weight loss, fluid restriction, reduction of caffeine or alcohol intake, limiting heavy activity, stopping smoking and treatment of constipation (Table 1). The effect of weight loss has been most intensively studied, with evidence summarised in a recent systematic review. 45 Successful weight-loss programmes require intensive therapy, involving diet, exercise and behavioural modification over a prolonged period.

| Lifestyle change | Methods | Evidence of effectiveness for SUIa |

|---|---|---|

| Weight loss | Diet | Level 1a |

| Exercise | ||

| Behavioural modification | ||

| Adjustment of fluid intake | Reduced volume | Level 2b |

| Avoidance of caffeine | ||

| Avoidance of carbonated drinks | ||

| Smoking cessation | Behavioural modification | Level 4 |

| Nicotine replacement | ||

| Exercise modification | Avoidance of provocative exercise | Level 4 |

| Regularisation of bowel habit | Interventions to prevent constipation and straining to defecate | Level 4 |

Setting

In the context of a consultation in primary care, the possible benefit of lifestyle modifications, such as weight loss, would be discussed and reinforced by a patient information leaflet, together with the offer of further therapeutic help. Intensive weight-loss programmes are not widely available at present but are most likely to be community based.

Personnel involved

Weight loss or smoking cessation therapy is most likely to be effective if it is supervised, preferably on a weekly basis, by a therapist who has undergone recognised training and obtained appropriate qualifications. Such programmes are frequently run as group sessions.

Costs

The cost of lifestyle changes will vary according to the intensity of the intervention. It might range from simple provision of information at a primary care consultation with a specialist nurse (£13.95)46 to the taking of active steps to lose weight. For example, a 6-month supervised group weight-reduction programme with the leading commercial provider in the UK, WeightWatchers®, would currently cost £152,47 with possible additional costs to the individual related to dietary changes and exercise programme.

Pelvic floor muscle training

Recommendations for the standardisation of these treatments have been published by the UK Chartered Society of Physiotherapists. 40

Basic pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT basic)

Popularised by Arnold Kegel,48 basic pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) is generally the first-line non-surgical management for SUI. The principle behind this intervention is to condition and strengthen the striated pelvic floor muscles in order to improve the urethral sphincter closure mechanism during provocative activity (such as coughing) that raises intra-abdominal pressure. There is a variety of regimens to provide PFMT to women. The simplest involves education about pelvic floor structure and function, together with demonstration, using digital vaginal examination by the therapist or woman herself, of a correct and effective pelvic floor muscle contraction. A regular exercise programme schedule is then agreed between the woman and her therapist, with intermittent checks of progress and benefit over a 3- to 4-month period. The schedule suggested by Kegel was five contractions performed every waking hour,49 whereas that recommended by recent guidelines is a sequence of eight contractions three times daily. 43 A summary of current recommendations is given in Box 4.

-

Pelvic floor muscle awareness is taught

-

The pelvic floor is assessed and exercised in functional positions

-

The use of anticipatory pelvic floor muscle contraction immediately prior to an activity that causes urine leakage (‘The Knack’) is taught

-

A programme of pelvic floor muscle exercises is tailored to individual patients and includes exercises for both fast- and slow-twitch muscle fibres

-

Pelvic floor muscle exercises are performed several times a day until the muscle fatigues

-

Pelvic floor muscle exercises are practised for 15–20 weeks

-

Patients are initially seen weekly, but account may need to be taken of their circumstances and/or the available resources

-

Pelvic floor muscle exercises are continued on a maintenance programme

Recommendation from Laycock and colleagues (2001). 40

Augmented PFMT

The addition of BF as a teaching and performance-enhancing device, in the form of vaginal pressure recording using a perineometer or electromyographic demonstration of muscle activity, can be helpful to visually demonstrate to the patient when they are performing a correct pelvic contraction and to quantify improvement. This feedback should encourage and motivate perseverance with a regular exercise programme. Digital BF is the practice of assessing pelvic muscle strength by vaginal examination, with verbal feedback concerning correctness and strength of the contraction. Once benefit is established and the woman is discharged from the therapist’s care, a continued exercise programme is encouraged.

Biofeedback may also be used as a training device or as an aid to pelvic floor muscle exercising. Women use a pressure perineometer to monitor strength and endurance of a series of pelvic floor muscle contractions over a period of time, typically 20–30 minutes, at weekly or monthly intervals.

As an adjunct to standard pelvic floor training programmes, women can be instructed to retain graded cone-shaped weights [vaginal cones (VCs)] within the vagina to improve pelvic floor muscle strength. Starting with the lightest weight, women are advised to hold a cone in their vagina and prevent it from slipping out, while standing, moving around or coughing. It is suggested that the use of cones improves compliance with the exercise schedule, individualises the exercise regimen, gives BF and improves knowledge of the functional anatomy of the vagina and pelvic floor. Cones may also be used as a standalone treatment at home for women who do not wish to, or cannot, access a health professional. 50

A further possible adjunct to PFMT is electrical stimulation (ES). This causes the pelvic floor muscles to contract, either directly or indirectly, by excitation of the motor efferent fibres of the pudendal nerve. The electrodes can be placed on the perineal skin, within the vagina or within the anus. The vaginal route is recommended with set stimulation parameters (Box 5). It is thought that ES may be particularly useful for women who are unable to contract their pelvic floor muscles voluntarily, or to help build up muscle strength prior to a supervised PFMT programme. The reported advantages of this intervention include high patient acceptability, little or no discomfort and home-managed delivery of the treatment. 51

-

Frequency: 35 Hz

-

Pulse width: 250 microseconds (0.25 milliseconds)

-

Current type: biphasic rectangular

-

Intensity: maximum tolerated

-

Duty cycle: 5 seconds on/10 seconds off. Very weak muscles: 5 seconds on/15 seconds off

-

Treatment daily/twice daily (home treatment)

-

Treatment time: 5 minutes initially, gradually increasing to 20 minutes

Recommendation from Laycock and colleagues (2001). 40

Setting

These interventions are organised through a primary care continence or physiotherapy service, which may be located in a primary health care centre or local hospital department. The patient will typically attend weekly or fortnightly sessions over a 3- to 4-month period, depending on compliance and improvement. They will be instructed to continue the exercise programme at home, during daily activity between visits to the therapist, and to continue the programme themselves, lifelong, after discharge from the therapist’s care.

Personnel involved

These treatments will be typically supervised by a chartered physiotherapist who has undergone education to degree level and has undertaken a recognised professional training programme leading to the relevant professional registration. In some cases sessions may be delegated to trainees or assistants under supervision. Alternatively, the treatment will be administered by a continence nurse specialist who has undergone training in the provision of pelvic floor exercise programmes and has achieved appropriate competencies signified by additional qualifications.

Costs

Based on Personal and Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) figures, the average cost for a consultation with a physiotherapist is approximately £13. 46 Additional costs for PFMT programmes would include overheads and consumables for basic intervention (£4), and additional equipment for BF (£35) and ES (£11). VCs are not provided by the UK NHS, and women would have to purchase them commercially at a cost of £20. 52 The total cost of all these interventions is determined by the number of sessions the women receive. For basic PFMT, the average cost for a 3-month cycle of treatment is £189, for BF it is £224 and for ES it is £398. These costs are similar if the programme is provided by a continence nurse specialist. 43

Bladder training

Bladder training to regain control of micturition is more predominantly used for UUI or those women with mixed symptoms. Typical programmes involve a gradually progressive voiding schedule to delay micturition, together with distraction and relaxation techniques to suppress urgency. This would generally involve an initial assessment consultation and subsequent visits or telephone follow-up over a period of 8–12 weeks. Bladder diaries are often used as additional BF and outcome tools. 53

Setting

The initial assessment would take place in a primary health care centre, with follow-up visits in the health centre, patient’s home or by telephone as appropriate.

Personnel involved

This type of therapy is generally supervised in primary care by a designated member of the district nursing team with expertise in continence promotion or by a continence nurse specialist.

Costs

UK NHS reference costs for district nursing contacts (CN301AF) average £31 (range £26–40), while continence nurse specialist contacts (CN204AF) are costed at between £48 and £114. This would give an approximate total cost, assuming fortnightly visits for 12 weeks, of £180–540. 54

Pharmacotherapy

Serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor

Experimental studies in animals suggest that noradrenaline and serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) act on efferent neurons in the sacral spinal cord (Onuf’s nucleus) to encourage contraction of the periurethral striated muscle of the urethral sphincter and relaxation of the bladder wall muscle (detrusor muscle), thereby promoting urine storage and continence. Duloxetine hydrochloride, a balanced serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), was tested as an antidepressant but found to have an effect on reducing stress incontinence in women. It is now licensed as a continence-promoting drug in women with SUI. 55 Although it has been shown to improve symptoms of SUI, the usefulness of duloxetine is limited by side effects, particularly nausea, which result in up to 20% of women being unable to tolerate the drug. 56 There is some evidence to suggest that this drug may be more useful as an adjunct to other conservative therapies, such as PFMT. 57 Despite poor tolerability and modest efficacy, the prescribing of this drug appears to be increasing in the UK (Figure 4). Further details on the current use of SNRI’s were obtained from a survey of members of the Association of Continence Advisors (ACA). The ACA provided a copy of their e-mail distribution list and members were surveyed during January and February 2009. Out of approximately 650 ACA members on the distribution list, 86 responded (a 13.2% response rate). Of these, 57 provided details of their SUI caseload, of which 15/57 (26.3%) advisors reported that they had patients using duloxetine for the treatment of SUI. The number being treated was 92 out of a caseload of 1234 patients (7.5%); the majority of these, however, came from the caseloads of two respondents.

FIGURE 4.

Serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor prescriptions for stress urinary incontinence. UK NHS prescribing data obtained from NHS information centre. 58

The drug is generally prescribed in divided doses, totalling 40–80 mg per day, and the response is assessed over a 12-week period. The relatively high risk of side effects requires initial close monitoring by the specialist or GP.

The poor tolerability profile of this drug has resulted in it mainly being prescribed by specialists through hospital clinics.

The drug is predominantly initiated by hospital specialists for women with SUI, who are unsuitable for surgery or do not wish to undergo surgery.

The cost of a 56 × 40-mg tablet pack of duloxetine is £30.80. 59 This equates to an average annual cost per patient, for drugs alone, of £402. If two visits to the GP are included the total annual cost rises to £474.

Estrogen

Estrogens are thought to affect female continence through several modes of action, including maintenance of pelvic floor musculature and enhancement of urethra mucosal sealing. It was therefore considered that therapeutic estrogen supplementation in postmenopausal women would be beneficial delivered either locally or systemically. Overall, there is a high level of evidence that oral estrogen replacement therapy appears to increase incontinence symptoms amongst postmenopausal women,60–62 and its use for this indication is therefore not recommended. Recent appraisal of evidence for topical vaginal estrogen therapy suggests that it may benefit women with incontinence but not to any consistent degree,63 and it is currently only recommended for women with overactive bladder symptoms that are associated with mucosal atrophy. 43 The opinion from the expert group for the current review was in agreement with this guidance and so oral or topical estrogen were not included as a treatment option for SUI.

Adrenergic agonists

Despite a theoretical and experimental expectation that alpha-adrenergic drugs should improve urethral and bladder neck smooth muscle activity, no consistent clinical benefit was found in women with stress incontinence. 63,64 These drugs are neither licensed for this treatment indication nor recommended by current guidance,43 and were considered to be very rarely used in practice by our expert group. On this basis, the use of adrenergic agonists as a treatment option for SUI was not considered further.

Mechanical devices

Consideration of the underlying urodynamic changes that result in SUI has continued to encourage the design and testing of intraurethral or intravaginal mechanical devices to prevent leakage. The mechanism of action of intravaginal devices is either by compression of the urethra against the inferior margin of the pubis or adjunctive bladder neck support with tampons such as Contrelle™. 65 Intraurethral devices, such as NEAT Expandable Tip Continence Device™,66 and FemSoft™,67 plug the urethral lumen. The clinical effectiveness of these devices in comparison with no treatment or other conservative methods of managing stress incontinence was the subject of a recent systematic review. 68 This review included six trials with a total of 286 participants. The mechanical devices used were five intravaginal devices and five intraurethral devices. The included trials either compared a mechanical device with no treatment or with an alternative device. There were no published data comparing devices with other non-surgical interventions for the treatment of SUI. The published data were unsuited to meta-analysis and the individual trials had small sample sizes and poor methodology ratings. The review therefore concluded that there was insufficient evidence to estimate the effect of mechanical devices for the treatment of women with SUI. In summary, although these devices are conceptually attractive, they do not appear to be widely used at present. 49 Some further information was obtained from the previously described survey of ACA members. The respondents had a total caseload of 1187 women. A total of 80 women were using mechanical devices, although 35 (43.8%) of these came from the caseload of a single respondent. The vast majority of devices used were vaginal devices, used by 78/80 women (97.5%). The most popular of these was pessaries, used by 77.5% (62/80) of the women. The Contrelle Activeguard was used by 7/80 (8.8%) women, tampons by 4/80 (5%) women, the Incostress device by 2/80 (2.5%) women, and vaginal sponges by 3/80 (3.8%) women. The only non-vaginal device used was an anal plug used by 2/80 (2.5%) women.

Setting and personnel

These devices require a preliminary assessment by a trained health-care professional, who will also instruct the patient on their use. However, this could occur in primary or secondary care settings.

Costs

The Contrelle device costs £50 and can be reused, whereas the FemSoft urethral insert costs £1.50 and has to be changed for a new device after urination.

Electromagnetic stimulation

Experimental studies have shown that electromagnetic stimulation of the S3 and S4 sacral nerves increases maximum urethral closing pressure by 34% compared with baseline. 69 However, few randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have reported on the cure or improvement of SUI using electromagnetic stimulation compared with placebo,69,70 and the intervention is not in current clinical use. It will not be considered further in this review.

Periurethral injectable bulking agents

Stress urinary incontinence can be treated by periurethral injections of agents that bulk the urethral wall to encourage sealing during urine storage and hence improve continence. Conceptually, they occupy a ‘grey’ area between truly non-surgical treatments and operations. We chose to define periurethral injection therapy as surgical treatment, as this is carried out by surgically qualified clinicians, in an operating room environment, with the standard precautions and care process that this entails. This treatment modality will not therefore be included in treatment pathways, but a summary of a recently updated Cochrane review of the subject is included here for completeness. 71 This review looked at the effects of periurethral or transurethral injection therapy for the treatment of women with urinary incontinence. It identified 12 relevant trials, including 1318 participants in total, and examined eight types of injectable material (Box 6) along with one dummy injection (saline).

Macroplastique™ – silicon particles

Durasphere™ – carbon particles

Contigen™ – glutaraldehyde cross-linked bovine collagen

Coaptite™ – calcium hydroxylappatite

Uryx™ – ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer

Permacol™ – porcine dermal collagen

Experimental useSilicon microballoons

Dextran copolymer

Alginate gels

Autologous chondrocytes

Autologous myoblasts

DiscontinuedAutologous fat

Polytef™ – polytetrafluoroethylene

Zuidex™ – dextranomer/hyaluronic acid copolymer

Full details available from Keegan and colleagues (2007). 71

One study comparing periurethral injection to dummy treatment with saline was terminated due to safety concerns, although early results had not indicated any significant difference in treatment effect prior to this. 72 There were no relevant studies comparing periurethral injection to conservative management of urinary incontinence. However, in two studies comparing periurethral injection with surgery, surgery was reported to result in significantly greater improvement as measured by clinical observation. Comparisons between different types of agents used for periurethral injection suggested a variety of new agents to be as effective as collagen, and porcine dermal implant as effective as silicone, although confidence intervals (CIs) were wide and longer-term data were required. In general, approximately 50% of patients were satisfied in the short term (less than 1 year) after injection therapy. The review concluded that methodologically robust trials were needed, particularly with longer follow-up data and when using non-surgical treatments, such as PFMT, as comparators. Currently, the lack of useful high-quality evidence makes it difficult to draw conclusions regarding the place of periurethral injection therapy in the care pathway for women with SUI and it will not be used in the care pathways described in this review.

Surgery for SUI

Since the introduction of the first surgical procedure, anterior colporrhaphy with plication of the urethra by Kelly and Dumm in 1911,73 the number of different surgical procedures used to treat stress incontinence has grown to about 100. They are covered by six published Cochrane reviews (Box 7).

Open Burch retropubic colposuspension – Lapitan and colleagues (2005)38

Laparoscopic colposuspension – Dean and colleagues (2006)74

Suburethral slings – Bezerra and colleagues (2005)75

Anterior colporrhaphy – Glazener and Cooper (2001)76

Needle urethral suspension – Glazener and Cooper (2004)77

Tension-free transvaginal tape (TVT) – Ogah and colleagues78

Tension-free transobturator vaginal tape (TVT-O) – Ogah and colleagues78

The development of a novel theory of causation of SUI by Petros and Ulmsten79 has clarified the rationale for different surgeries. Older abdominal techniques, such as Burch colposuspension and pubovaginal sling insertion, aim to reduce mobility of the bladder neck and proximal urethra by providing fixation to the pubis. Newer techniques popularised by Ulmsten aim to increase support to the mid-urethra, typically using a synthetic tape introduced through the vagina and fixed either suprapubically or in the obturator fossa without tension. 80,81 These latter two procedures – TVT and TVT-O – are currently the most popular surgical techniques for treatment of SUI in women, having the advantages of a vaginal approach, minimally invasive insertion and a favourable adverse event profile. 82 The procedures involve blind passage of a length of monofilament macroporous polypropylene tape to provide a ‘hammock’ for the mid-urethra. The tape is positioned without tension using specially designed curved needles through suprapubic (TVT) or medial groin (TVT-O) incisions, and an incision in the anterior vaginal wall beneath the mid-urethra. The procedure can be performed under local anaesthetic and sedation or, more usually, a general or regional anaesthetic, and can be accomplished within a 24-hour hospital stay. The TVT variant also requires cystoscopy to detect and correct bladder perforation. Burch colposuspension or pubovaginal sling insertion, on the other hand, are open surgical procedures requiring a formal suprapubic incision. They require a general anaesthetic and a 2- to 3-day hospital stay. The main risk of all such procedures is transient (10%) or permanent (1%) voiding difficulty requiring intermittent self-catheterisation. Surgical success rates after 1–5 years of follow-up vary between 51% and 87% for Burch colposuspension/pubovaginal sling and between 63% and 85% for TVT/TVT-O, according to definition of cure/improvement and length of follow-up. 80

Setting

All procedures require an appropriately equipped hospital or clinic environment for safe surgical conduct. This will include a preoperative area, a fully equipped operating room and facilities for postoperative recovery. The newer minimally invasive procedures, such as TVT and TVT-O, can be carried out in an ambulatory care unit that is designed for stays of up to 24 hours.

Personnel

The procedures require staff for preoperative preparation, a surgical team including an anaesthetist and appropriately trained surgeon, and postoperative recovery staff. Staff and facilities to monitor residual urine and teach intermittent self-catheterisation when required are also needed.

Cost

UK National Health service reference costs54 for TVT and TVT-O, classified as ‘lower genital tract minor procedures without complications’, are, on average (interquartile range), £1135 (£741–1357) for inpatient treatment (mean stay of 2 days) and £629 (£456–828) for day-case treatment. Colposuspension classified as an ‘open bladder neck procedure in women’ has an average (interquartile range) cost of £1396 (£1011–2013) for inpatient treatment (mean stay of 2 days). 54

Criteria for treatment

Women with incontinence who choose to seek clinician advice generally have more severe symptoms that are bothersome and therefore desire treatment to improve their continence and lessen the impact on their day-to-day life. It is the clinician’s responsibility to gather evidence of the severity, type and degree of bother suffered by the individual in order to suggest the most appropriate first-line treatment options for the patient to consider. Selection of the initial treatment is then negotiated according to patient choice, clinician opinion and local availability. Subsequent consultations will decide on the need for further trials of treatment if the initial outcome is unsatisfactory. This assessment requires the exclusion, by examination and simple testing, of complicating factors, such as relevant neurological dysfunction, impaired voiding, infection and pelvic organ prolapse. Those with modifiable lifestyle factors, such as high body mass index and smoking, should be encouraged and helped to address these either before, or concurrent with, more active treatment. The selection for active treatment then depends on the individual’s desire and motivation, the presence of comorbidity and local service availability.

For women with a predominant symptom of SUI, education about their pelvic floor anatomy and function, and supervised training to improve pelvic floor muscle function, are the most used first-line treatments in the UK. This may sometimes be augmented by transvaginal ES or BF techniques, including use of VCs. To benefit from these therapies, women require sufficient mobility, motivation and the ability to attend frequent therapy sessions. Following a trial of PFMT, the next step is likely to be referral to a specialist for consideration of surgery.

Most high-level evidence for the effectiveness of each of these treatments is based on randomised trials with set inclusion and exclusion criteria. It is uncertain how the results of these trials and meta-analysis of multiple trials relate to individual patients, particularly those who would not meet the inclusion criteria (Table 2).

| Treatment | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| PFMT83 | SUI | Urinary tract infection |

| USI | Incomplete voiding | |

| More than two episodes of incontinence per week | Neurological disorders | |

| 18–75 years | Cognitive impairment | |

| BT53 | Age > 35 | Previous surgery for incontinence |

| Urgency or MUI | Neurological disease | |

| DO (urodynamic diagnosis) | Urinary tract infection | |

| Predominant stress incontinence | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | ||

| Inability to reach toilet unaided | ||

| Duloxetine56 | Age 30–80 years | Pregnancy |

| SUI | Breastfeeding | |

| USI | Urinary tract infection | |

| Arrhythmias or liver disease | ||

| Advanced pelvic organ prolapse | ||

| Continence surgery within 1 year | ||

| Prior hip fracture or replacement | ||

| Prior formal PFMT | ||

| Surgery38,74–77 | SUI | Age < 21 years |

| USI | Age > 65 years | |

| Non-ambulatory | ||

| Pregnancy | ||

| Current cancer treatment | ||

| Systemic disease affecting bladder function | ||

| Urethral diverticulum | ||

| Recent pelvic surgery | ||

| Grade III incontinence | ||

| DO | ||

| Urinary tract infection | ||

| Severe medical disease |

Containment options

Methods for containment of urinary incontinence do not constitute a means of treatment and are therefore not included in the systematic review. It is acknowledged, however, that pads are widely used by women in all phases of management of their incontinence problem and that methods for urinary diversion form the ‘last resort’ for women with severe incontinence who cannot be treated, or have failed repeated attempts at curative treatment, typically following multiple surgical procedures. As such, the use of containment products is included in the economic evaluation as they form part of the care that a woman might receive over her lifetime.

Absorbent pads

The most commonly used method of incontinence management is absorbent pads. The total expenditure on such products is large and, although not altering the underlying condition, it can be a satisfactory option for women with minimal or predictable leakage, or for those who are unsuited to treatments or have failed to benefit from treatment. The products range from thin panty-liners to large nappy (diaper)-type pads. Despite their widespread use, little research has been conducted concerning patient satisfaction or effectiveness, although recent evidence summarised in a Cochrane review does suggest that specifically designed pant insert pads are superior to those designed for menstrual loss. 84,85 Containment-using pads was also the subject of a previous UK Health Technology Assessment (HTA) monograph. 86

Urinary diversion

Some women with severe intractable incontinence that has not responded to corrective methods of management may choose to undergo urinary diversion. The simplest method is transurethral or suprapubic insertion of an indwelling catheter, with continuous drainage into a collection bag. Summarised evidence regarding types of catheter and policies for their use has previously been published. 87,88 Generally, indwelling catheters are unsuited for women with long life expectancy, who are often better served with a formal surgical urinary diversion procedure. This can be performed using an ileal conduit or continent diversion. The techniques, benefits and adverse events have been described in a Cochrane review. 89

Chapter 2 Aims and objectives

The aim of this study was to estimate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of non-surgical treatment for women with SUI.

The objectives are to:

-

develop a series of management pathways that describe potential sequence of non-surgical and surgical treatments for SUI

-

determine the clinical effectiveness of the different individual treatments for SUI

-

determine the safety in terms of the magnitude of any risks or side effects of treatments for SUI

-

estimate the cost-effectiveness of the alternative management pathways

-

identify areas for future research.

The remainder of the report is structured as follows:

-

Chapter 3 describes the definition of the decision problems and the patient treatment pathway.

-

Chapter 4 presents the results of a survey performed on women with SUI to identify the outcomes of importance to them.

-

Chapter 5 describes the methods used for reviewing clinical effectiveness and provides information on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, search methods for identification of studies, data collection and analysis.

-

Chapter 6 describes the studies included in the systematic review of clinical effectiveness.

-

Chapter 7 assesses the clinical effectiveness of the major treatments using direct pair-wise (head-to-head) comparisons.

-

Chapter 8 assesses the clinical effectiveness of the treatment using a mixed-treatment comparison (MTC) model.

-

Chapter 9 assesses the cost-effectiveness using an economic model; this chapter describes the basics of the modelling approach and the key assumptions underpinning the estimates of cost-effectiveness results.

-

Chapter 10 discusses the results of the study.

-

Chapter 11 is the conclusion, which highlights the implications of the findings for the NHS, women and research.

Chapter 3 Definition of the decision problem

The impact of SUI on individual women with the condition, their families and carers, and on the NHS, as a whole, is huge. 43 There are many potential methods for treating SUI which might be used alone or as part of a management strategy. However, while there is some evidence of the relative effectiveness of individual treatments, there is a lack of evidence on how the various interventions might be combined into management strategies. We therefore sought to identify plausible treatment strategies comprising sequences of non-surgical and surgical interventions. The clinical pathways were based on advice from the health-care professionals and patient group representatives who were involved in the study on what interventions patients could receive and the sequencing of the interventions. Even though the focus of this study is on non-surgical treatments, surgery is considered, as it may form part of a treatment strategy. For example, it may be a viable alternative for some women seeking treatment for SUI. For other women, surgery may be resorted to if a non-surgical intervention fails to satisfactorily resolve symptoms.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)90 and the third International Consultation on Incontinence91 have published a comprehensive literature review and consensus opinion of treatment guidelines for therapeutic interventions for SUI (the AHRQ has declared its guidelines obsolete). It is generally accepted that there is no ‘perfect’ therapy for all patients with SUI. Many factors should be considered when determining the optimal therapy for SUI in women. These include the aetiology and type of SUI, bladder capacity, renal function, sexual function, severity of the leakage and degree of bother to the patient, the presence of associated conditions – such as vaginal prolapse – or concurrent abdominal or pelvic pathology requiring surgical correction, prior abdominal and/or pelvic surgery, and, finally, willingness to accept the costs, risks, morbidity and success (or failure) rates associated with each intervention.

For most women with SUI it is sensible to discuss first the most reversible, simplest, least invasive and least expensive service-provider interventions, such as lifestyle changes and PFMT. The clinical consensus appears to be that the initial treatments for SUI involve a variety of non-surgical interventions, including lifestyle modification, PFMT with or without BF, and other accessory teaching aids, such as electronic devices and VCs. Further strategies can be formulated, which would consist of sequences of non-surgical and surgical interventions. These strategies will take into account the mechanism by which the treatment works and will also place limits on the number of retreatments allowed, based on current concepts of the use and effectiveness of the different procedures. More invasive or expensive interventions, such as surgery, are pursued if the clinician and patient decide that the current therapy is either ineffective or otherwise undesirable.

The importance of patient preference as the primary consideration in selecting a particular treatment for SUI was underlined by the findings of a recent survey which reported that most women preferred less invasive options. 92,93 From a health service perspective it is important to balance short- and long-term effectiveness against the potential adverse events and costs. Compared with surgical treatments, non-surgical treatments, such as lifestyle changes and physical therapies (such as PFMT), are associated with limited side effects and do not preclude future changes in management. Hence, non-surgical procedures have been considered to be the choice of primary treatments for SUI. 43 In developing the care pathways we have categorised treatments as being either non-surgical or surgical procedures and then considered how these treatments might be combined into management strategies for women presenting with SUI. While it is true that the specific treatment strategy adopted will vary from woman to woman, broad exemplars of specific strategies can be defined. In the following sections, descriptions of possible management strategies of women with SUI are presented, which vary in terms of the type and sequences of treatments that might be offered.

Descriptions of the patient treatment pathways

Figure 5 describes the treatment pathways that are compared within the economic model reported in Chapter 9. Potentially there are a very large number of alternative pathways that might be considered, and the pathways selected were derived following discussion with the health-care professionals and patient representatives involved in this study. They represent plausible care pathways that women might follow and might also be used to infer the value of other potential pathways not otherwise considered.

FIGURE 5.

Description of patient care pathways

Patient treatment pathway 1

Patient treatment pathway 1, in Figure 5, details one plausible strategy of care for a woman presenting with SUI. The first line of treatment that women presenting with SUI are offered is lifestyle modification. Lifestyle modification may involve a combination of one or more elements. These are dietary factors, reduction of caffeine intake, fluid intake, smoking, weight, physical exercise, alcohol consumption and limiting heavy activity (it may be possible that there are several ways lifestyle modifications can be performed so that they can be considered as different treatments, therefore allowing someone to get more than one lifestyle modification treatment). There are three states that could arise after treatment: ‘continent’, ‘incontinent’ or ‘dead’ (from natural causes). The continent state includes women who report that they are completely cured and those that feel that their condition has improved to the extent that they require no further treatment at the present time. Women could remain continent and hence require no further treatment, but some of them may experience a return or worsening of symptoms of SUI at some point in the future and then require further treatment. The women who report that they are not cured are said to be in the incontinent state. These women could either require or not require further treatment. The women who require further treatment get the next treatment option in the pathway they are following. In the first care pathway, all of the women who need further treatment are offered the second line of treatment: physical therapy. There are different forms of physical therapies that women can receive. These include PFMT alone or in combination with an adjunct, such as BF, ES or VCs. Based on the number of sessions women receive, PFMT can be classed as ‘basic’, when a patient has a maximum of two sessions per month, or ‘PFMT with extra sessions’, when the patient receives more than two sessions per month. This pathway offers only basic PFMT without any adjunct. Women who are not cured and do not receive any further treatment may use containment products, such as pads, to manage symptoms.

If women are not cured after PFMT they progress to the third line of treatment, which is surgery. Those who are not cured and need further treatment are offered a second surgical procedure. If the second surgical procedure does not work then women use containment products until they die. It is appreciated that women may also use containment products even when they are receiving other possible interventions. Figure 6 provides a detailed description of pathway 1. Similar figures could have been developed for all of the other pathways.

FIGURE 6.

Description of alternative treatment strategies (note: women may choose not to seek further treatment at any point).

Patient treatment pathway 2

The treatment pathway option 2 is similar to that depicted in option 1. The only difference is that PFMT with extra sessions is offered as an additional non-surgical treatment between basic PFMT and surgery.

Patient treatment pathway 3

Pathway 3 extends pathway 2 by adding a drug therapy (an SNRI) between PFMT with extra sessions and surgery.

Patient treatment pathway 4

The treatment pathway 4 is substantially the same as pathway 1. The difference is that women receive PFMT with extra sessions straight away, instead of PFMT basic.

Patient treatment pathway 5

Pathway 5 extends pathway 4 by adding SNRI therapy between PFMT extra sessions and surgery.

Patient treatment pathway 6

In this pathway women would, as in all other pathways, initially receive the relevant advice or treatment aimed at modifying lifestyle. If they experienced a recurrence, had insufficient improvement or no improvement, they would proceed straight to surgery. Such a strategy might be appropriate for some subgroups of women. Alternatively, it may be popular with some women because it gives the prospect of relatively rapid relief from symptoms.

Patient treatment pathway 7

This treatment pathway is similar to pathway 1 but with VCs as a treatment option between basic PFMT and surgery.

Patient treatment pathway 8

This treatment pathway is similar to pathway 1 but with ES as a treatment option between basic PFMT and surgery.

These patient care pathways will be used in the study to inform the economic model reported in Chapter 9. These pathways will also assist in identifying outcomes of interest for the systematic review of effectiveness and identify the data required to populate the model. The key outcome of these pathways is that any need for further treatment is heavily influenced by whether the prior treatment has resulted in sufficient resolution of symptoms.

Chapter 4 Identification of outcomes of importance to women with stress urinary incontinence

Introduction

It has been recognised for many years that the embarrassment associated with urinary incontinence may cause withdrawal from social situations and reduce quality of life. 32 Many women with SUI show symptoms of depression and introverted behaviour, together with dysfunctional interpersonal relationships. 33 Furthermore, SUI may lead to withdrawal from regular physical activities and hence impair women’s general health. 34 One of the problems with the assessment of incontinence is that outcome measures frequently used in primary research may not perfectly map on to outcomes of importance to women. For example, the commonly reported outcome measure in clinical trials is ‘cure’, which is the satisfactory resolution (or near resolution) of symptoms. Using this definition usually means the patient self-report of the absence of incontinence. However, the ideal measure of how women are after treatment should reflect the ability to lead a normal social life, which may be compatible with improvements in the level of continence.

Given that much of the available literature focuses on clinical outcomes, which, as a result, may have limited relevance to the lives of women with SUI, the aim of this survey was to provide evidence on outcomes of importance to women.

The purpose of this work was to prospectively survey women with SUI to provide information on outcomes of importance to them; a secondary aim was to identify additional outcomes that ought to be collected in future primary studies and hence to define relevant outcomes for systematic reviews of the literature.

Methods

In order to identify the areas of importance to women who suffer from SUI, a questionnaire was designed. A Patient Generated Index (PGI)94 was used to allow respondents to state and evaluate the areas of their life affected by SUI. In addition to the PGI, the questionnaire included the King’s Health Questionnaire,95 the EQ-5D, and questions relating to socioeconomic and demographic information. The rationale for choosing the PGI was that as it is an individualised instrument – it would provide information on the specific concerns of women with SUI. In addition, these outcomes could then be compared with generic measures, such as the King’s Health Questionnaire and the EQ-5D.

The questionnaire

The PGI is an individualised patient-reported health instrument that allows the respondent to select, weight and rate the importance of a particular health outcome. 96 The PGI was designed with the aim of producing a valid measure of outcome that reflected areas of importance to patients’ lives. 94 The PGI involves the respondent deciding what factors are important to her. Examples of the types of factors that may be important are included to provide guidance. The aim of the PGI is therefore to capture the diverse range of concerns or priorities of respondents. Using the PGI, respondents can vary the weight they attach to these concerns or priorities, which provides researchers with an insight into each respondent’s viewpoint. An overall score for the PGI for each respondent can then be calculated by multiplying the rating for each health area by the proportion of points allocated to that particular area.

The PGI is completed in three stages. In the first stage, respondents are asked to identify up to five areas of their life that are affected by their SUI. Respondents are given a list of outcomes to act as prompts to help them think about which areas of their life might be affected by their condition. Respondents can then choose from these options or provide their own examples. In addition to the five boxes, there is a sixth box that enables respondents to rate all other areas of their life affected by their SUI. Examples of the factors to include as prompts on the PGI were drawn from three sources. The first of these was the King’s Health Questionnaire,95 which was used to generate a list of outcomes under the broad headings of: ‘role limitations’, ‘physical limitations’, ‘social limitations’ and ‘personal relationships and emotions’. These outcomes were supplemented from Cochrane reviews of non-surgical treatments. 56,75,83,97 Finally, a general literature search was also conducted, although this did not provide further additions to the 17 different outcomes identified from the King’s Health Questionnaire and the Cochrane reviews. These outcomes were then narrowed down to broad categories of those considered most relevant by members of the project team. These were ‘work’, ‘household tasks’, ‘social activities’, ‘feeling depressed/anxious’, ‘personal hygiene’ and ‘affecting sleep’. In addition to the methods used to generate the prompt list, further qualitative work could have been conducted. This could have included a focus group of women with SUI to further refine the areas to include in the prompt list. This is an area that could be considered in future use of the PGI.

In stage two of the PGI, respondents were asked to score each area listed in stage one of the PGI on a scale ranging from 0 to 6. The score given in stage two was intended to reflect how the individual was affected by their SUI in the past month. A score of 0 would signify that the effect on their life was as bad as it could possibly be and a score of 6 would correspond to an effect that was as good as it could possibly be.

Finally, in stage three, respondents were asked to ‘spend’ 10 points to indicate the relative importance of each of the areas mentioned in stage one. Respondents were requested to spend more points on areas that were the most important to them.

As noted above, in addition to the PGI, the questionnaire also contained the King’s Health Questionnaire and the EQ-5D. The King’s Health Questionnaire is a condition specific questionnaire that aims to assess the impact of urinary incontinence on an individual’s quality of life. It contains questions set in nine domains relating to: general health perception, incontinence impact, role limitations, physical limitations, social limitations, personal relationships, emotions, sleep and energy, and severity. With the exception of the final part of the questionnaire (severity measures) scores can be calculated for each domain (0–100). The higher the score the worse off an individual feels they are and the lower they perceive their quality of life to be.

The EQ-5D is a standardised instrument used to measure quality of life. The EQ-5D is applicable to a wide range of health conditions and treatments and it provides a simple descriptive profile and a single index value for health status. 98 The EQ-5D has five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression) that can be converted into a utility score.

Sample

The Bladder and Bowel Foundation (formerly ‘InContact’ and the ‘Continence Foundation’) is a national charity that provides information and support to people with bladder and bowel problems, representing the interests of people with continence problems with the aim of ensuring they have access to the latest information and services available. 99 In 2006 a survey conducted by InContact was completed by 755 people affected by bladder and bowel problems. 100 Of these, 188 women with SUI gave consent for future contact about relevant research and formed the sample for the current study. In July 2007 these women were sent questionnaires for the current study by InContact. Given that this is a self-selected sample of women suffering from SUI and not a random sample of the population, it is not known how representative this sample is of the wider population.

Ethical issues

The 2006 survey in which the participants were originally identified was a service evaluation in which The Bladder and Bowel Foundation surveyed people who had previously been in touch with the charity. As such, no ethical approval was necessary. The 2006 survey materials contained an explicit assurance that confidentiality would be maintained and that identifiable data would not be passed on to third parties. Respondents were asked if they were willing to be contacted in the future for research purposes. For this study questionnaires were sent in July 2007 to 188 women with SUI who gave their consent for further contact relating to research. The questionnaires were returned directly to the charity and, after screening only anonymous data, were subsequently forwarded to the authors in accordance with the Medical Research Council’s guidance on the use of personal information in medical research and the Data Protection Act 1998. 101,102

Results

All data were analysed in spss version 17.0. Descriptive statistics and correlations of the sample were analysed and EQ-5D and PGI scores were calculated. In total, 105 out of 188 respondents (55.9%) completed and returned the questionnaire. Table 3 shows the areas of an individual’s life that they reported to be affected by their SUI, divided into four different themes. These themes were: (1) activities of daily living (work, home and social); (2) sex, hygiene and lifestyle issues; (3) emotional health; and (4) services. In total, 38 different areas were reported by respondents. Activities of daily living were the most frequently reported areas to be affected by SUI, followed by sex, hygiene and lifestyle issues and emotional health.

| Theme/specific issue | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Activities of daily living: work, home and social | ||

| Going out/socialisinga | 58 | 13.7 |

| Sleepa | 47 | 11 |

| Shoppinga | 33 | 7.8 |

| Physical activity | 30 | 7.1 |

| Worka | 24 | 5.7 |

| Travel | 18 | 4.2 |

| Going on holiday/staying away from home | 12 | 2.8 |

| Household tasks | 10 | 2.4 |

| Family activities | 4 | 0.9 |

| Travelling on public transport | 1 | 0.2 |

| Being housebound | 1 | 0.2 |

| Inability to study/write | 1 | 0.2 |

| Activities outside the home | 1 | 0.2 |

| Total | 56.6 | |

| Sex, hygiene, lifestyle issues | ||

| Personal hygienea | 53 | 12.5 |

| Sexual relationships | 10 | 2.4 |

| Personal relationships | 7 | 1.7 |

| Sneezing/coughing/laughing | 7 | 1.7 |

| Affecting choice of clothes | 6 | 1.4 |

| Infections/skin irritations | 4 | 0.9 |

| Loss of independence | 3 | 0.7 |

| Limiting liquid intake | 2 | 0.5 |

| Continually going to toilet when not necessary | 1 | 0.2 |

| Feeling cold | 1 | 0.2 |

| Worry about leaving wet stains | 1 | 0.2 |

| Total | 22.4 | |

| Emotional health | ||

| Depressiona | 32 | 7.5 |

| Anxietya | 24 | 5.7 |

| Bladder controlling life | 2 | 0.5 |

| Embarrassment | 2 | 0.5 |

| Affecting confidence | 1 | 0.2 |

| Body image | 1 | 0.2 |

| Feeling unfeminine | 1 | 0.2 |

| It annoys me | 1 | 0.2 |

| Long-term effect it is having on me | 1 | 0.2 |

| Failure | 1 | 0.2 |

| Total | 15.6 | |

| Services | ||

| Lack of public toilets | 11 | 2.6 |

| Need to use products/pads | 8 | 1.9 |

| Time spent at doctor’s surgery/hospital | 3 | 0.7 |

| Public queues | 1 | 0.2 |

| Total | 5.4 | |

Out of 105 respondents, 73 respondents were categorised as having answered the PGI correctly. A further nine respondents made mistakes in the PGI and 23 respondents did not fully complete it (Table 4). Of the 73 respondents who correctly completed the questionnaire, 61 answered the PGI with no mistakes (all sections were completed satisfactorily). The remaining 12 respondents made a small error in completion of the PGI. This small error always occurred in section three of the PGI, where respondents had to spend 10 points. These respondents did in fact spend 10 points but they missed out spending points in area 6 (all other areas of their life affected by SUI) and totalled to 10 in box 6. This error is likely to have occurred due to the layout of the PGI. An example of the PGI used can be seen in Appendix 1.

| Responses | Frequency | Percentage | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| PGI answered correctly | 73 | 69.5 | PGI correct: 61 |

| PGI put total in box 6: 12 | |||

| Mistake in PGI | 9 | 8.6 | |

| PGI not fully completed | 23 | 21.9 | |

| Total | 105 | 100.0 |

Table 5 shows the demographic information of the sample, as a whole and for those individuals who correctly and incorrectly completed the PGI. The mean age for the sample as a whole was 57 years (range 28–89). As can be seen in Table 5, those respondents who correctly completed the PGI were, on average, younger than those who completed it incorrectly. In addition, those who correctly completed the PGI appear to be better educated and in higher-income groups.

| Variable | Total sample (n = 105) | Correct PGI (n = 73) | Incorrect PGI (n = 32) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age of respondents (range, years) | 56.90 (28–89) | 55.16 (28–89) | 60.84 (37–87) |

| Age ranges (%) | |||

| 25–34 | 3 (2) | 3 (4) | – |

| 35–44 | 15 (14) | 11 (15) | 4 (13) |

| 45–54 | 39 (37) | 28 (38) | 11 (35) |

| 55–64 | 21 (20) | 15 (21) | 6 (19) |

| 65–74 | 8 (8) | 6 (8) | 2 (6) |

| 75+ | 19 (18) | 10 (14) | 9 (28) |

| Income (valid %) | |||

| £6000 | 10 (11) | 7 (11) | 3 (11) |

| £6001–10,000 | 16 (17) | 12 (19) | 4 (15) |

| £10,001–15,000 | 20 (22) | 11 (17) | 9 (33) |

| £15,001–20,000 | 13 (14) | 9 (14) | 4 (15) |

| £20,001–25,000 | 5 (5) | 3 (5) | 2 (7) |

| £25,001–30,000 | 10 (11) | 7 (11) | 3 (11) |

| £30,001–35,000 | 8 (9) | 6 (9) | 2 (7) |

| £35,001+ | 10 (11) | 10 (15) | – |

| Education (%) | |||

| None | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (3) |

| Secondary school | 39 (37) | 22 (30) | 17 (53) |

| College | 29 (28) | 21 (29) | 8 (25) |

| University | 35 (33) | 29 (40) | 6 (19) |

In addition to listing the outcomes of importance to women who suffer from SUI, a score of overall quality of life can also be calculated from the PGI. The score ranges from 0 to 6, with 0 reflecting a very low quality of life (‘it’s as bad as it could possibly be’) and 6 reflecting a very high quality of life (‘it’s as high as it could possibly be’). An example of the PGI and the method used to calculate the score is given in Table 6. For the respondents who successfully completed the PGI the mean score was 2.4 (SD 1.4, range 0–6). Given that a score of 6 on the PGI reflects the highest quality of life, a mean score of 2.4 in this population reflects that their quality of life falls significantly short of their hopes and expectations. In total, 101 out of 105 returned questionnaires had a fully completed EQ-5D. Scores on the EQ-5D ranged from –0.17 to 1. The mean EQ-5D score was 0.598 (SD 0.339). Correlation between the mean PGI score and the mean EQ-5D score was, as expected, positive and statistically significant.

| Part 1: list areas of life affected by urinary incontinence | Part 2: score (0–6) | Part 3: spend your 10 points | Final PGI score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Interrupted sleep | 1 | 3 | 0.3 |

| 2. Affects my social life | 6 | 1 | 0.6 |

| 3. Affects my work | 3 | 2 | 0.6 |

| 4. Personal relationships | 2 | 2 | 0.4 |

| 5. It makes me feel depressed | 4 | 1 | 0.4 |

| 6. All other areas of your life affected by your urinary incontinence | 5 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Total | 2.8 |

Scores (out of 100) for each domain in the King’s Health Questionnaire can be seen in Table 7. The higher the score, the worse off an individual feels. In addition to the domains of the King’s Health Questionnaire, it also contains a section detailing the respondent’s bladder problems and how much they affect the individual’s life.

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KHQ scores for role limitation | 101 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 53.30 | 30.64 |

| KHQ physical limitation scores | 100 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 61.83 | 30.09 |

| KHQ social limitation | 95 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 45.61 | 30.98 |

| KHQ score for personal relationships | 73 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 37.90 | 35.92 |

| KHQ score for emotions | 98 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 60.32 | 31.67 |

| Sleep energy | 100 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 60.67 | 31.02 |

| Severity measures | 98 | 6.67 | 100.00 | 68.50 | 22.55 |

Correlations of the PGI and seven domains of the King’s Health Questionnaire were also performed. Given the scoring system of the King’s Health Questionnaire we would expect to find a negative correlation between the PGI and King’s Health Questionnaire. All correlations were negative but only two were statistically significant: personal relationships (p = 0.004) and severity measures (p = 0.003).

In addition, correlations between the EQ-5D score and the domains of the King’s Health Questionnaire were also calculated. We found all seven of the King’s Health Questionnaire domains to be significantly (negatively) correlated with the EQ-5D. This result is to be expected, as many of the EQ-5D and King’s Health Questionnaire domains are similar.

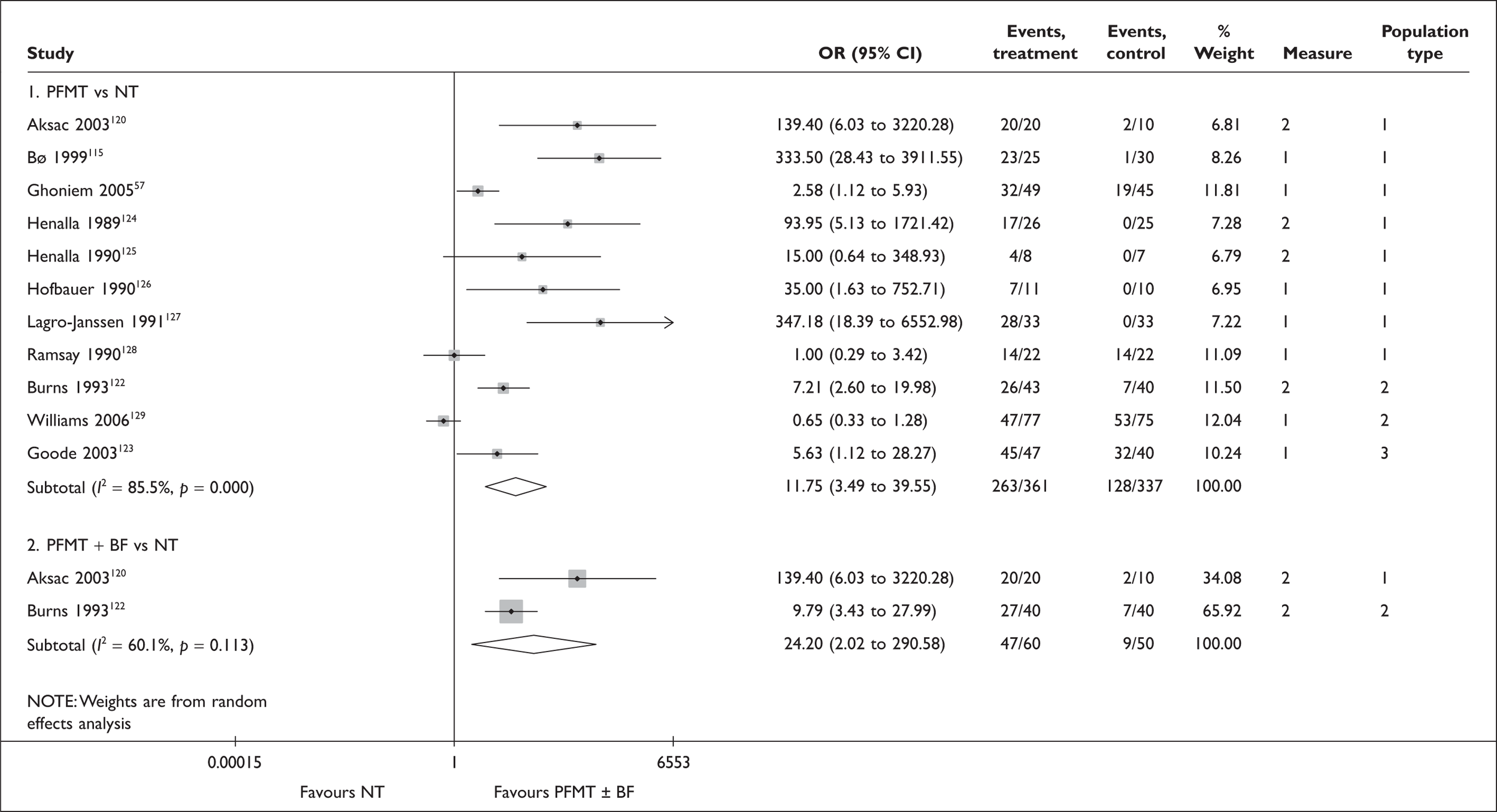

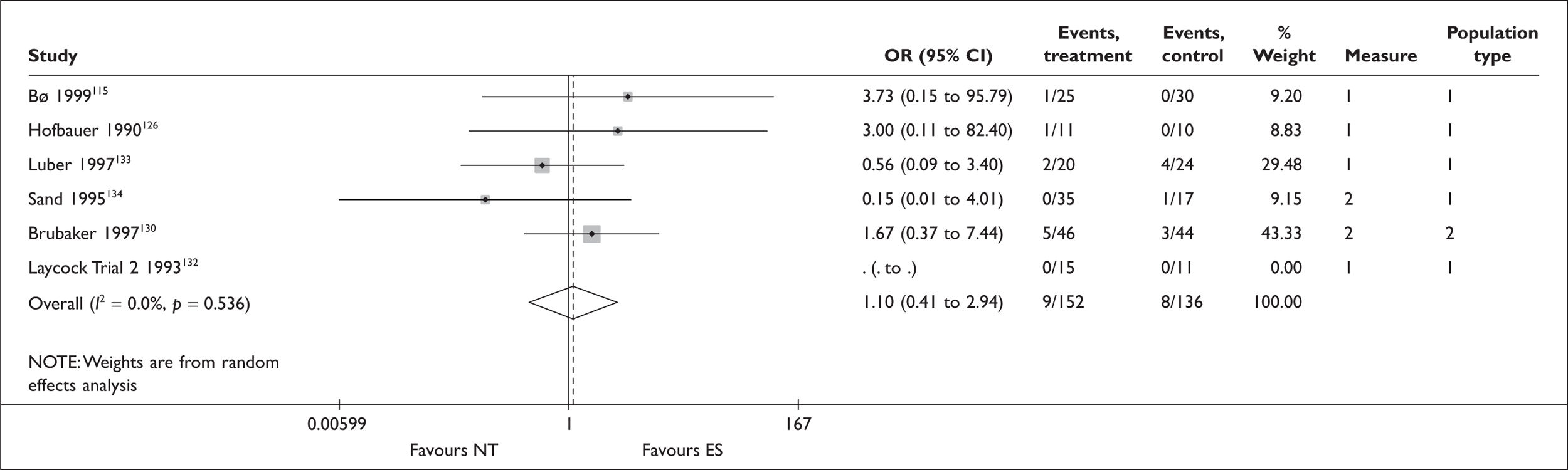

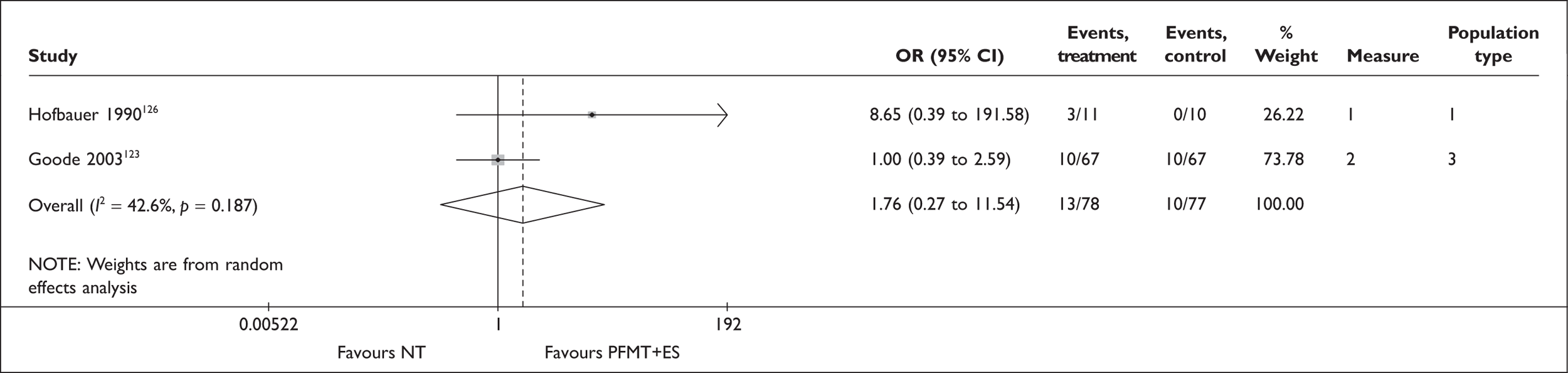

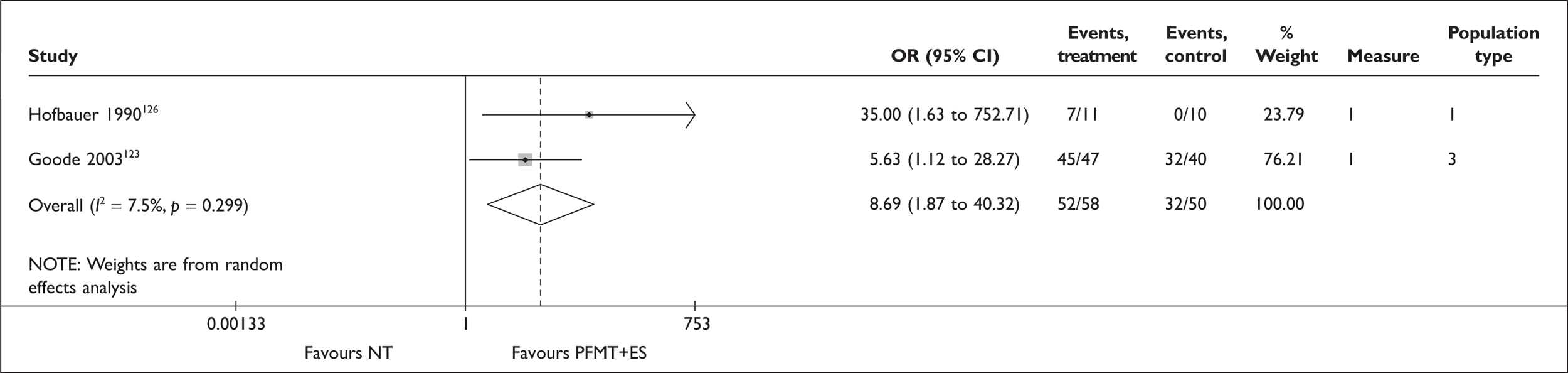

Summary