Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the National Coordinating Centre for Research Methodology (NCCRM), and was formally transferred to the HTA programme in April 2007 under the newly established NIHR Methodology Panel. The HTA programme project number is 06/91/06. The contractual start date was in March 2005. The draft report began editorial review in April 2009 and was accepted for publication in June 2009. The commissioning brief was devised by the NCCRM who specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

None

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2010 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK

2010 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Appropriate human resource management (HRM) policies and practices are vital if the UK NHS is to change the process of health care and improve outcomes for patients. The key issue is what ‘appropriate’ means in this context, and the evidence on which this can be based. This report presents findings from a series of systematic reviews of the literature linking HRM practices to performance outcomes in the NHS and wider organisational settings. It was commissioned by the National Coordinating Centre for Reseach Methodology (now part of the NIHR HTA programme under the NIHR Methodology Panel) and the NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation (SDO) Research and Development (R&D) Programme, and the reviews were undertaken between September 2005 and July 2007.

First, this chapter provides an overview of research in the field of HRM, exploring current debates and the rationale for the review. It then goes on to explain the research brief and detail the specific objectives for the review. Finally, the structure of the report and presentation of findings are described.

Context for the review: overview of the literature on HRM and organisational performance

Focus on high involvement and skill acquisition

The Department of Health (www.dh.gov.uk/en/index.htm) repeatedly singles out the crucial role of skill development, involvement, team working and morale to the modernisation of the NHS. In the words of the Department of Health’s website, ‘Successful human resources management improves efficiency through a culture that supports and develops its staff, allowing the workforce to share in the organisation’s objectives’ (www.dh.gov.uk/en/Policyandguidance/Humanresourcesandtraining/Buildingpeoplemanagementskills/index.htm).

The evidence offered to support the Department’s view that HRM is vital to the NHS is the finding that patient mortality rates improve in acute hospitals where an HRM director is a member of the Trust Board. In this, the Department of Health is mirroring a more general emphasis on employee development and involvement as key to maximising the human resource (HR) contribution to strategic objectives of organisations. This high-involvement management and human capital approach to HRM, sometimes referred to as ‘the HRM approach’, has been at the centre of the literature for the past two decades. For consistency, we refer to it as ‘the high-involvement management approach’, while acknowledging that not all of those who are referring to modern HRM necessarily place empowerment at its core, but rather emphasise the development of human skills and knowledge. The term ‘HRM’ is used whenever a potentially more all-embracing concept of personnel management is being considered.

The past 20 years have seen increasing attention given to both the general notion of HRM and the more specific high-involvement management approach as a major contributor to organisation performance, even in capital or technologically intensive industries. High-involvement management is assumed to contribute both in its own right and as a support for such other modern management practices as total quality management (TQM) and just-in-time (JIT). So, in the health context, high-involvement management adds to the human capital of the workforce and helps support new modes of organisation, technology and patient delivery. Its importance derives from an assumption that some forms of personnel management – and, particularly in the current context, approaches founded on involvement and development – have greater effects on the development, skills and motivation of employees than others.

Much of the attention given to the high-involvement or commitment HRM system has been advocatory. Contrasting it with a traditional control approach (sometimes known as Taylorist or Fordist), academics1–3 have championed high-involvement management as a progressive form of management that can remove past restrictions to both economic efficiency and the achievement of high-quality performance, thereby sharpening the competitive edge of Western organisations and improving public sector delivery. They contend that there is a unique set of practices or approaches to management that will, regardless of the context, outperform all others. Within the strategy literature, the resource-based theory of the firm4–6 highlights how human resources, and the knowledge embodied in them, may be decisive for long-term competitive advantage. In the operations management literature7–10 the emphasis is on how HRM practices and the knowledge and skills of workers are decisive in exploiting lean production11 and other modern management methods (e.g. see Dean and Bowen12 on TQM).

Research evidence

The last decade has witnessed a stream of research assessing high-involvement management and its associated concepts. The basic hypothesis underlying this work is that high-involvement HRM systems will have positive effects on organisational performance. As academics have sought to move beyond advocacy of high-involvement systems, they have focused on testing this hypothesis. A spate of research studies in the 1990s were motivated by this, with many surmising that high-involvement HRM systems do perform best. 13–20 Several overviews21,22 concluded that, on the basis of the first few studies, the universalistic hypothesis is supported. The increasing use of the term ‘high-performance’ model to describe the set of practices may imply that the matter is indeed settled, much as a drug might be named by the disease it is known to cure.

The initial overviews of these studies22,23 tended to present them in a homogeneous way, taking for granted that they are studying the same phenomenon and that the results are broadly the same, concluding they had successfully demonstrated the link between the human capital approach and key organisational outcomes. These reviews have led some to conclude that the main issue now is to explain the link between high-involvement management and performance, i.e. to assess the mechanisms between them or get inside the ‘black box’ between the HRM system and outcomes. A second issue might be the extent to which the link will be found in all contexts, and particularly in service industries such as health care. The majority of the early studies were in manufacturing, and it is significant that one of the few early studies in services24 found evidence of a contingent relationship between the human capital approach and performance, i.e. that the impact of human capital will vary between contexts. In the past few years, more studies have either been conducted singly in the service sector or included that sector within the scope of the study,15,25–27 and the results have been mixed. Studies specifically on health care are emerging, for example West et al. 28 have investigated the link between HRM and patient mortality.

Assessing the evidence

Notwithstanding the above, an increasing number of writers question whether the portrayal of the studies as providing conclusive evidence for a universal link between HRM and performance is premature, and that there is a clear need to delve more deeply – both into the studies and into the reality of high-involvement management and its links to other aspects and methods of management. There are a number of reasons for extending the debate.

First, the results of the various studies are neither as clear-cut nor as uniform as some have concluded (see Wood,29 particularly table 1 for a summary of the main results; and Wall and Wood30,31). Within studies, there is unevenness in the findings between performance measures; while some results point to universal effects, others do not. Moreover, in many studies only the universal hypothesis has been tested so one cannot rule out the contingency argument that the effects of high-involvement management on performance are contingent on a third factor, either a dimension of the context or the strategy of the organisation, even when a positive link between high-performance management and performance has been found.

Second, it is not always clear whether high involvement or performance management is being defined simply as the combined use of best practice in each domain of human resources, as a synergistic set of practices, or by a more fundamental managerial orientation. 32 In fact, the discussion so far has begged the question of how we define and identify a system. Most studies have defined an HRM system a priori, often with little theoretical justification, as the emphasis has been on testing the high involvement–performance link, rather than first investigating the relationship between practices or the nature of any systems. Researchers have measured HRM on the basis of differentiating organisations by their usage of a set of practices, the precise means varying between studies. Then they correlate these differences with performance measures. The problem of simply aggregating practices to provide an overall measure of HRM is that each practice is treated implicitly as if it were equally important. With only a few exceptions,33,34 studies have provided insufficient information about which individual or subset of practices has the strongest effects and which may be marginal or even irrelevant. In one case13 where this was done, and it was shown that only some of the practices affect performance, and, moreover, that their strength varied between industrial context, though the authors still framed their conclusions in terms of an overall (high-performance work) system yielding superior performance. Aggregating practices does not allow one to test whether the effects of one practice are enhanced by the use of another, i.e. whether they are synergistically related, and begs the question of whether they tend to be used together. 32,35

Third, there is considerable variability across studies in the practices included either in the model of high-involvement management or the set of practices used to test its link to performance. Some of the differences are terminological, perhaps reflecting disciplinary biases or a quest to differentiate one’s wares. But a core difference within the literature can be identified. On the one hand are those authors who see the core of high-involvement management as changes in work organisation, job design and employee involvement methods (particularly idea capturing), with the other practices acting as supports to help motivate and equip people to work in a new, more flexible and proactive way. On the other hand are those who do not prioritise the task system. They may then concentrate more on skill acquisition, following an emphasis on the resource-based theory of the firm, according to which genuine competitive advantage reflects an organisation having a unique capability or set of resources. Therefore, primacy is placed on the competencies of individuals, rather than whether they are empowered. Alternatively, they may treat high-involvement management as entailing the use of the whole gamut of sophisticated personnel management methods, and conceive them as primarily operating through people’s commitment or sense of whether they are being treated fairly and consistent with their psychological contract. The different approaches need not affect greatly the practices researchers include in their studies, but the inclusion of job design and work organisation practices is one major source of diversity between the studies, as Wood and Wall31 show. The other major difference is incentive systems, with some studies treating them as part of high-involvement management or at least performance management, whereas others do not.

Fourth, there has been insufficient empirical exploration of the mechanisms or intervening variables that might explain any link between HRM and performance. Of course it must be acknowledged that there is little point in investing resources in exploring the reasons for a link until it has been established. Yet, labels such as ‘high commitment’ and ‘involvement’ imply certain mechanisms that are concerned with the extent of commitment or engagement on the part of the work force, which is mirrored in the importance given to morale in statements about the modernisation of health care, and these could be explored more than they have been. Much of the theoretical justification that precedes the empirical studies also implies that skills, knowledge and learning might have an independent effect on performance as important as employees’ attitudes.

Some studies have included intervening variables, which have either centred on intermediate HR outcomes (e.g. labour turnover in Huselid18) or on commitment and satisfaction. 36,37 Several authors hint at, but do not explore in depth, other mechanisms; for example, Guest and Conway38 imply that procedural justice may be important. In addition to morale and staff development, an important emphasis in statements on the modernisation of health care is what might be termed the strategic integration of individuals into the organisation, so that they both understand and share the goals that achieving patient care entails and, consequently, orientate their behaviour towards common visions. Studies outside the narrow confines of the HRM studies, particularly building on the job redesign and lean production literature, point to the importance of the kinds of attitudes that advocates of total quality management and other modern management methods highlight, including quality consciousness,39 continuous improvement orientation40 or flexible work orientation. 41

Finally, the majority of studies have concentrated on a narrow range of HRM practices in isolation, the exception being those that have included TQM in their analysis,20,31,34 but there is a general failure to assess the effectiveness of HRM and related practices relative to both key elements of management, such as leadership, and practices further afield, such as R&D expenditure.

In addition, despite the differences in focus and measures, most of the studies share a basic research design, which has a number of weaknesses. These include:

-

The use of cross-sectional designs, which limits the ability to make causal inferences (e.g. to decide whether HRM practices promote performance, or rather better performance encourages greater investment in HRM).

-

A reliance on a single data source (e.g. a chief executive or HRM director) for information on HRM practices and performance, which may result in measures of unknown reliability and common-method bias (see, for example, the debate between Huselid and Becker42 and Gerhart et al. 43 on the reliability of measures based on single respondents).

-

Many have small samples, low response rates and concentrate on a limited range of sectors.

However, even the most searching reviews that have highlighted problems in the studies have concluded that there is nonetheless sufficient promise in the body of evidence to consider major investments in the area. 30 It is thus timely to invest in detailed assessment of what we know.

Review aim, scope and objectives

The overall aim of this series of related systematic reviews is to provide a picture of HRM practices in use in the UK, to identify evidence on the relationships between HRM practices and a variety of individual and organisational outcomes, and to assess the reliability of measures of some outcomes of HRM.

The brief for the review was that its scope should be broad, covering, where feasible, evidence from non-health sectors, although evidence from the health sector should be emphasised.

The objectives of the review (source: NHS/SDO Invitation to Tender 2004) are to:

-

describe HRM practices and measure the fidelity with which they may be implemented

-

review the reliability of methods of measuring particular intermediate outcomes (intended outcomes of HRM that may affect patient care, e.g. morale)

-

review the literature on the correlation of intermediate outcomes to each other

-

investigate the correlation of intermediate outcomes with final outcomes

-

investigate the sensitivity of intermediate outcomes to individual HRM practices.

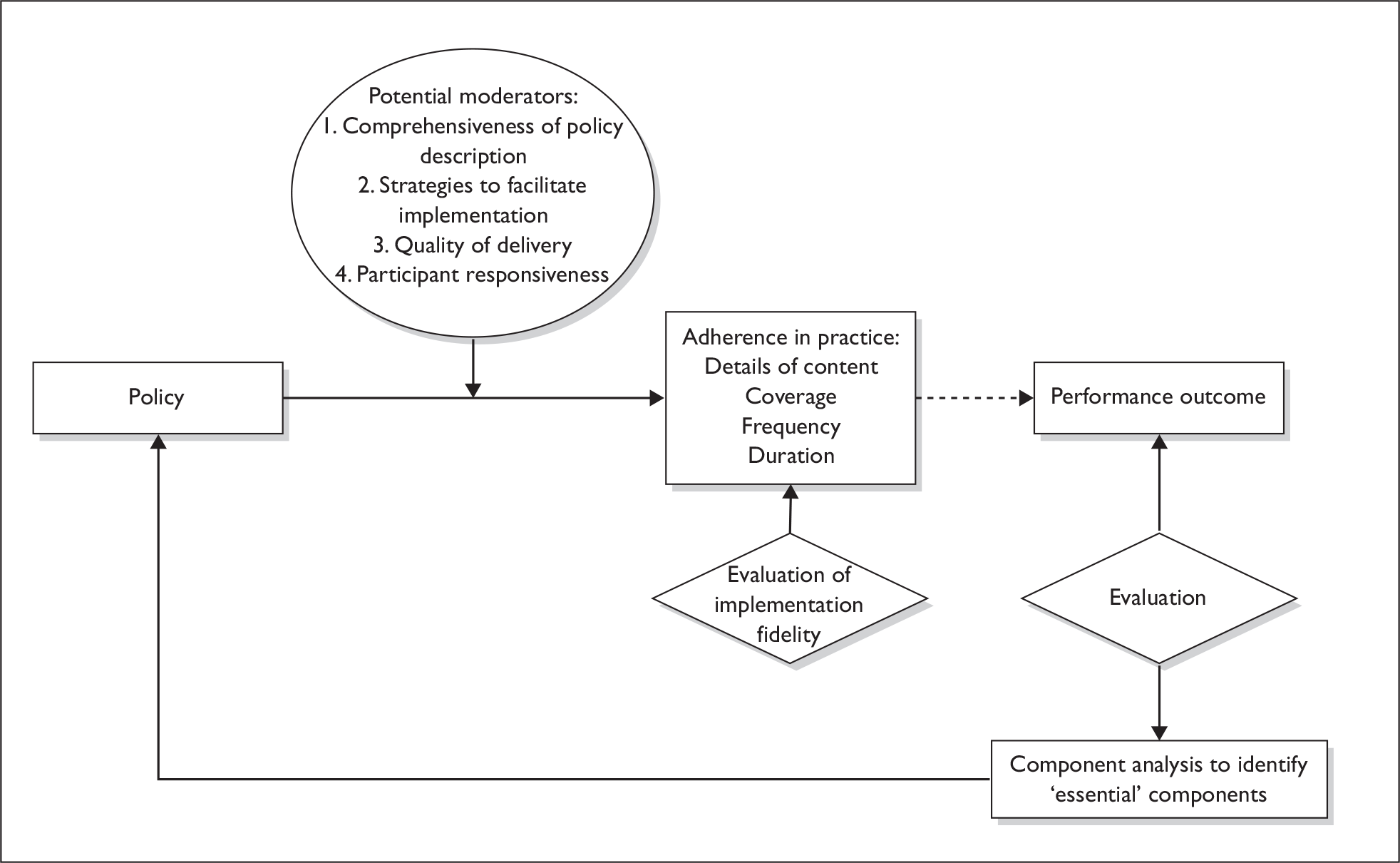

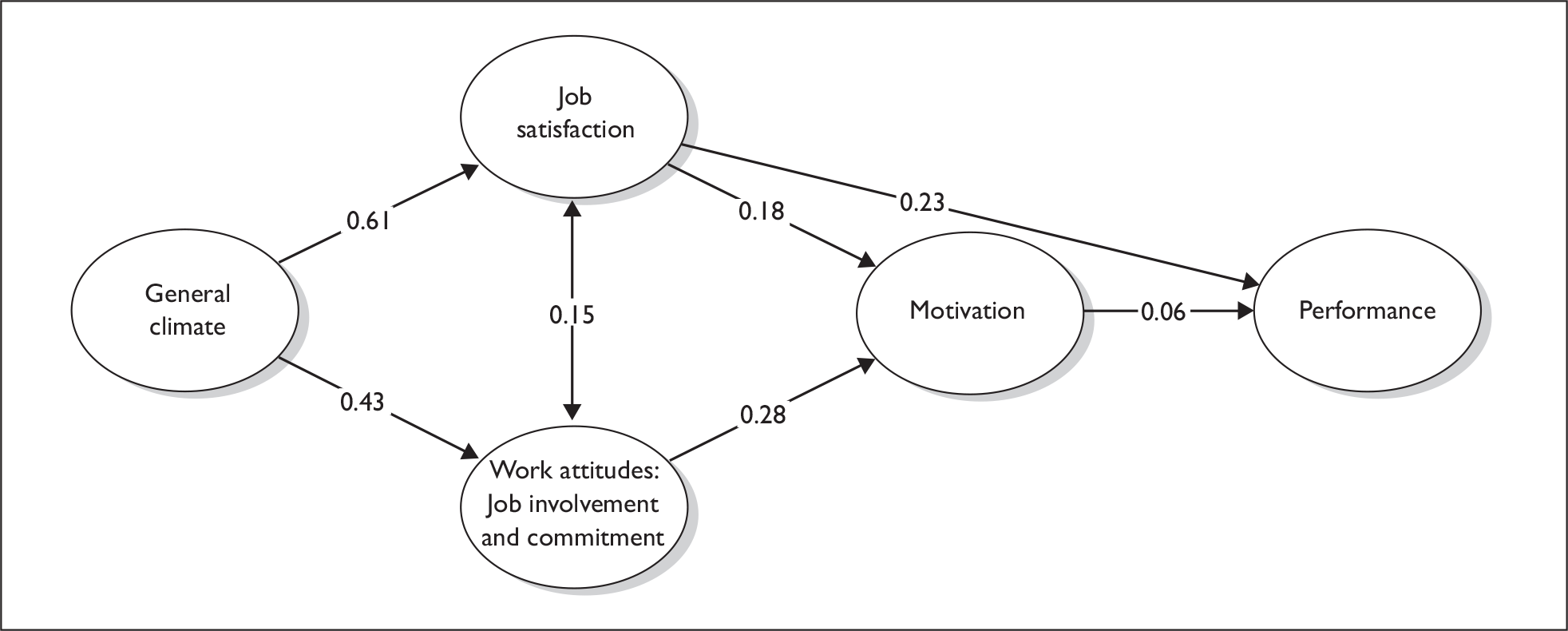

A pictorial summary of the project and its objectives (adapted from that provided in the original brief) is shown in Figure 1 (for details of the full proposal see Appendix 1).

FIGURE 1.

Human resource management policy, performance model and project objectives.

Report

This report presents findings from a series of systematic reviews of the relationship between HRM practices and performance. The reviews presented two principal challenges to the research team. First, the literature on HRM and performance, and possible intervening variables linking the two, is diffuse, considerable and complex. For example, the research literature contains contributions from several disciplines, using different types of research designs, and what constitutes HRM and performance can vary considerably from study to study. Second, systematic review methodology has not been used much in the HRM field. As the literature is heterogeneous on a number of dimensions, we use a reflective approach, adapting and developing the review methodology to meet the particular demands of each research objective rather than using an identical methodology throughout the project.

Chapter 2 of the report describes the methodological context for the review, detailing recent developments in thinking and methodology that we have drawn upon. It then provides a methodological summary, including a description of the systematic review methodologies used in this research, the process by which research objectives were translated into specific research questions and an overview of the range of methods used in relation to each research question.

Chapter 3 addresses some of the research questions relating to Objective 1 of the review, specifically detailing:

-

the range of HRM practices described in the literature

-

evidence on the extent to which these practices are used in UK organisations.

Chapter 4 considers implementation fidelity (Objective 1), i.e. the extent to which HRM practices are actually put into practice, and the extent to which this is measured and how it could be measured, based on a critical review of the literature.

Chapter 5 explores current understanding of the linkages between HRM practices and performance outcomes. It outlines the identification of intermediate and final outcomes, and provides a context for interpreting the review findings.

Chapters 6–8 investigate the sensitivity of intermediate outcomes to individual HRM policies (Objective 5) and present findings from a series of systematic reviews of the evidence on the impact of HRM practices on intermediate and final outcomes in the general and health literature:

Chapters 6 and 7 focus on evidence from the health sector:

-

Chapter 6 presents a synthesis of evidence on the extent to which HRM practices affect intermediate outcomes in the health sector.

-

Chapter 7 outlines the findings of a systematic review of the impact of HRM practices on health sector outcomes.

Chapter 8 reports on findings from a systematic review in the general HRM literature to identify and synthesise evidence on the links between HRM practices and both intermediate and final outcomes. It details specific search strategies and presents a narrative synthesis of results.

Chapter 9 describes the pattern of intercorrelations found in the literature both between intermediate outcomes (Objective 3) and between intermediate and final outcomes (Objective 4).

Chapter 10 presents evidence on the reliability and validity of measures of intermediate outcomes (Objective 2). Generic and health sector-specific measures of intermediate outcomes are identified, and the best available evidence on their reliability is presented.

Chapter 11 comprises the conclusions and recommendations, based on the evidence in this report.

Chapter 2 Methodology

Introduction

Chapter 2 provides a broad description of the methodological approaches used at different stages in the review. First, the research context is considered and the challenges of applying systematic review methodology to the HRM literature are discussed. Next, the systematic review approaches used are explained and the specific questions for the review established. The combinations of search terms and databases used are detailed and a summary of the methodological approaches used in addressing each of the specific research questions is presented.

Applying systematic review methodology within the HRM literature

Systematic review methodology has a very limited pedigree within HRM, which has only comparatively recently begun to adopt some of the tools of evidence-based practice. 44 Nevertheless, some key studies do exist. For example, Levy and Williams45 conducted a systematic review of 300 studies examining the social context of performance appraisal and Taris46 examined 16 studies dealing with the burnout–performance relationship. The lack of a significant body of exemplars within HRM has limited the capacity of this particular field to develop tailored methods of systematic review and to stimulate methodological innovation in the identification, assessment and synthesis of this type of data. As a consequence, there are very few instances of methodological papers on conducting systematic reviews within HRM. The review team, therefore, faced a number of challenges in conducting this series of systematic reviews and in leading the adaptation and development of methods to tackle practical problems generated by these review questions. The challenges were compounded by a corpus of literature that conceives the concepts of both HRM and performance (and indeed their intersection) in different ways, asking comparable but not identical questions, and using different types of research design. Furthermore, the literature that is examined in this review is multidisciplinary and heterogeneous. Finally, the review is composed of five (subsequently six) distinct and yet related objectives – not a single well-focused research question but rather a series of separate and equally elusive questions.

Systematic review was the method of choice because the methodology offers a number of models to be applied or modified depending on the questions being asked. Systematic review is an evolving methodology, primarily designed to answer questions regarding the effectiveness of interventions by synthesising findings from large numbers of studies. As such systematic reviews are ‘a scientific tool which can be used to summarise, appraise and communicate the results and implications of otherwise unmanageable quantities of research. They differ from traditional reviews and commentaries produced by “content experts” in that they use a replicable, scientific and transparent approach that seeks to minimise bias.’47 Systematic reviews follow a process of constructing a clearly defined research question with inclusion and exclusion criteria, comprehensive searching to identify all relevant literature, quality assessment of selected studies, extraction of relevant data from these studies, and synthesis of the study results. In cases where there is sufficient similarity in the focus of studies, in terms of interventions and outcomes researched, a meta-analysis may be performed: a quantitative synthesis. The final result of the review is thus a conclusion based on a critical synthesis of the comprehensive, unbiased selection and appraisal of the best available research examining the topic under consideration, which typically, in the health area, is an intervention.

This methodology was originally developed for analysing the effectiveness of pharmaceutical interventions in medicine, based on quantitative data from randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Systematic reviews in the medical field now have an accepted, standardised methodology. 47,48 In recent years, the advantages of systematic review over more conventional forms of literature review have been recognised and examples have appeared in other fields. 49,50 This has led to the piloting and development of methodologies for the review of qualitative research and the review of literature in disciplines, such as the social sciences,51 where there is no accepted hierarchy of study design or accepted criteria for quality assessment. 52–57

Despite the challenges presented by heterogeneous types of research, systematic review methods are characterised by transparency of approach, along with comprehensiveness, reliability and reproducibility of methods and techniques.

Recent commentators on systematic review methods endorse the adoption of flexible, exploratory and reflective approaches, especially (as is the case here) when the fields of evidence being considered are both complex and multidisciplinary. 56,58,59 The team therefore decided that rather than adhere strictly to any one systematic review methodology in answering the different questions posed by this review a more reflective approach should be taken, which would allow the development of the methodology as new challenges within the literature were encountered.

Overview of systematic review methodology

Each systematic review attempts to follow the standard model:

-

consultation exercise to define research question(s)

-

scoping exercise to define elements of research question (population, intervention, outcomes) and establish inclusion criteria

-

production of protocol document specifying population, intervention, outcomes, and inclusion/exclusion criteria (study design, quality assessment, language, date)

-

identification of potentially relevant literature (literature search)

-

study selection and quality assessment

-

data extraction

-

data synthesis.

This chapter goes on to describe the broad systematic review approach adopted by this research. It outlines how each stage of the review was conducted for the series of reviews that were undertaken, and ultimately presents a summary of the review questions and methodologies.

Applying the systematic review methodology

As described in Chapter 1, the five primary research objectives are concerned with the evidence at each stage in a model of HRM and performance. The model identifies final outcomes (such as patient care and performance) as well as intermediate outcomes – conceptualised as the factors that link HRM practices to final outcomes. Hence, the review aims to identify evidence on the nature of the causal links between, on the one hand, HRM practices and intermediate outcomes and, on the other, intermediate and final outcomes. However, this clear-cut distinction between final and intermediate outcomes is not reflected in the literature. The team identified that evidence generated from studies falling outside the five stated objectives would also be informative, namely:

-

studies that attempt to examine the whole HRM to performance chain, and

-

studies that examine the impact of HRM on final outcomes.

As a result, a sixth objective was added to the list:

-

to review the literature investigating the impact of HRM on final outcomes.

Developing research questions

Getting the question right is ‘the most important step in doing a review … [because] poorly focused questions lead to unclear decisions about what research to include and how to summarise it’. 48 The first stage is to develop specific research questions for the review.

The initial steps for this project involved breaking down the research objectives into their specific component questions. The aim was to provide questions that would form the basis of the series of systematic reviews that followed. The process of formulating precise, answerable questions from the research objectives was achieved through consultation within the team and with the expert advisers.

The six research objectives (that is, the five that were originally commissioned and the sixth added following consultation with experts) were broken down into 10 specific questions, as shown in Table 1.

| Research objectives | Research questions |

|---|---|

| Describe HRM methods and measure the fidelity with which they may be implemented |

What HRM practices are described in the literature? How widespread is the use of HRM practices in UK organisations? How can the fidelity with which an HRM practice is implemented be measured? |

| Review the reliability of measures of particular intermediate outcomes (intended outcomes of HRM) | What is the evidence on the reliability of measures of intermediate outcomes covered by this review? |

| Review the literature on the correlation of intermediate outcomes to each other | What is the evidence on the intercorrelation of intermediate outcomes with each other? |

| Review the literature investigating intermediate outcomes with final outcomes (be these business or patient centred) |

What is the evidence for the impact of intermediate outcomes on non-health final outcomes? What is the evidence for the impact of intermediate outcomes on patient care outcomes? |

| Investigate the sensitivity of intermediate outcomes to individual HRM methods alone or in conjunction with each other | What is the evidence for the impact of HRM practices on the intermediate outcomes identified for this review? |

| Review the literature investigating the impact of HR methods on final outcomes |

Which HRM practices have an impact on performance outcomes? Which HRM practices have an impact on patient outcomes? |

Once this had been done, each research question was then typically broken down into the components of ‘population’, ‘intervention’, ‘comparators’ and ‘outcome’; this ‘PICO model’ provides a structure for devising research questions, constructing search strategies and defining the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review. 47 It is not necessary for all of the elements of the PICO model to be present in every question. Where a PICO model has been used in these reviews, it is detailed in the specific methodology for that chapter.

Scoping exercise

The scoping exercise defines key issues for a review as clearly as possible in terms of the population, interventions and outcomes to be studied, and the inclusion and exclusion criteria to be applied. Together with the definition of the research question, this constitutes the ‘problem formulation stage, which involves the development of key research questions, construction of the definitions of the key concepts … and the establishment of inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review’. 60

For each review, a series of scoping exercises was undertaken to identify the best search terms with regard to the balance of specificity (relevance) and sensitivity (inclusivity). The nature of the HRM literature made the identification of specific intervention and outcome terms particularly challenging. Chapter 3 details the process of identifying HRM practice terms, and the specific intervention and outcome terms used by the respective reviews are given in Chapters 6–8.

Developing the protocol

The protocol provides an explicit outline and plan to be followed by the review. Conventional systematic review methods require that a protocol describe clearly defined populations, interventions and outcomes for the review, and provide details of the literature-searching procedure, quality assessment, and data extraction and synthesis to be conducted. 47 As the outcome of the scoping process, the protocol specifies the exact content and processes of the review, from which there should be no deviations. It facilitates the performance of the review by itemising exactly what the review does and does not include, and specifying the methods of quality assessment and synthesis. It should also state any language or geographical restrictions that might lead to bias in the review. 61,62

It is increasingly recognised that protocols for reviews in disciplines where the literature is a less known quantity, i.e. potentially heterogeneous, qualitative, and lacking the tradition of a recognised hierarchy of study design and quality assessment criteria,54,55,60,63 may be required to be broad, flexible and open to change. In short, as Eakin and Mykhalovskiy64 suggest, the question is to be viewed as a compass rather than an anchor, continually being enhanced and refined until completion of the review. Management is typical of such a discipline. 56 In such cases, it may be necessary to revisit and redefine interventions and outcomes in response to findings, and conduct iterative and purposive searching of the literature to address questions that arise or gaps identified in the literature. 52,58,60,63 This is often the case where the overall intent of the review is interpretive, not aggregative, and where the terminology and concepts are neither secure nor predefined. 65 The starting point, defined by the protocol, can therefore be broad and inclusive, rather than narrow and exclusive, in contrast with that required by more traditional systematic reviews.

In order to manage the diffuse HRM literature, simple, broad protocols were developed for each search. Protocols were reviewed regularly during the search process to help shape the eventual body of literature included in the data synthesis.

Identifying literature

After the scoping exercise, which is naturally exploratory, imaginative and purposive, the approach adopted is required to become more systematic, transparent and reproducible. A literature search for a review aims ‘to provide as comprehensive a list as possible of primary studies, both published and unpublished, which may be suitable for answering the question posed by the review’. 47 Systematic review methods almost unequivocally advocate an extensive and multimethod approach to identifying relevant literature. The intention is to identify all published and unpublished literature of relevance to the review that satisfies the review’s inclusion criteria. The principal means for achieving this is the searching of electronic databases. Search strategies follow the PICO model, which, as mentioned previously, breaks a search query down into four separate elements: population, intervention, comparator and outcome, a now-standard approach within health care. 66 Critical in this, was a time-consuming process designed to identify both the interventions (HRM practices) and the outcomes (whether intermediate outcomes, such as job satisfaction or final outcomes, such as reduction in mortality). The resulting lists and classifications inform most of the subsequent questions. This process is described in more detail in Chapter 3 (HRM practices) and Chapters 5 and 7 (intermediate and final outcomes).

Identifying longitudinal studies

A further component of the review was restriction by study design. This was used for sections of the review that sought to establish a causal link between interventions, in this case HRM practices, and either intermediate or final outcomes. While longitudinal studies in themselves do not prove causality, it is widely recognised that longitudinal analyses do provide better evidence for causation than cross-sectional analyses that use the same variables. 67,68 Indeed, contemporaneous systematic reviews of HRM have reported that they are limited in their ability to draw conclusions by their dependence on cross-sectional data. 69 The project team decided to limit the searches to longitudinal study designs only, as the intention was to identify those studies that could demonstrate causal links between HRM practices and outcomes, rather than simple associations. It is believed that this literature would offer evidence with greater capacity for answering the questions set by this review. No limitations of language were applied in order to avoid known biases produced by language and location. 61,62 There were no limitations by date other than those of the databases themselves.

Operationalising the search

For much of this particular review, only terms pre-specifying an intervention and an outcome were required. Searches aimed to optimise use of free-text searching and keyword terms, along with synonyms and variant spellings. This improves the chances of identifying all literature relevant to a topic, and is particularly necessary within social sciences where indexing and abstracting quality falls short of standards encountered within health care. 70

Literature searching requires more than interrogation of electronic databases with search strategies based on the protocol. It should use other formal methods, such as citation tracking and scanning the reference lists of selected papers, and hand searching of relevant journals. Informal methods of study identification can also be utilised, such as personal communications from peer reviewers or expert advisors and serendipity. Supplementary formal and informal methods may account for many, or even a majority, of studies included in non-quantitative reviews. 52,53,60,63 Such additional approaches are especially valuable if concepts are imprecise or if the literature is widely dispersed and inconsistently indexed.

In conventional review methodology, literature searching is refined by the scoping process and then carried out once. 47 However, where concepts or interventions are evolving or cannot be easily defined, supplementary, purposive literature searches may be performed. This may reflect an increasing understanding of the topic or the subsequent identification of specific questions raised by the findings of the review. 52,63 Searching becomes an iterative rather than one-off process, the so-called ‘spiral approach’ as described by Grant et al. 71 This was often how we had to proceed in this review, where pre-defining outcomes could have limited the findings. However, such a process is still systematic and consistent with the principles of systematic review methods. All search strategies and sources for all included papers are documented to make the process transparent, auditable and reproducible.

Developing the search terms

Scoping searches were performed using two of the less ambiguous categories from the list of HRM practices generated for the review: pay and training. Even relatively non-sensitive scoping searches of the principal health and psychology databases (MEDLINE and CINAHL) produced large numbers of research studies, which, although they used these terms, were not the focus of the review and would provide no data on HR performance linkages. Additionally, the scoping searches indicated that even larger numbers of citations would be retrieved by the more sensitive searches planned for the full review. Table 2 provides an illustration of the number of hits from three databases using standard and more sensitive versions of the pay and training filters. The number of potential HRM categories and practices was very large. A complete and formal process of reciprocal translation to produce a more clearly defined list would have been an extremely resource-intensive task and would have produced an unmanageable number of results from any searches performed. On account of the multifaceted nature of our study, with its multiple questions, it was decided that the approach of leading the review by specific HRM interventions was not viable. The original idea of structuring this review by HR intervention was therefore rejected.

| HR practice | Database | Hits | + Patient outcomes | – Comments, editorials, letters, reviews | English only | + Longitudinal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pay systemsa | MEDLINE | 1350 | 417 | 379 | 367 | 55 |

| Pay | MEDLINE | 58,126 | 7443 | 6387 | 5572 | 1385 |

| EMBASE | 40,179 | 5882 | 4873 | 4213 | 914 | |

| CINAHL | 13,909 | 1344 | 1283 | 1247 | 209 | |

| Traininga | MEDLINE | 11,607 | 939 | 823 | 793 | 163 |

| Training | MEDLINE | 178,806 | 10,028 | 8804 | 8269 | 1341 |

| EMBASE | 209,317 | 28,908 | 21,084 | 19,283 | 4001 | |

| CINAHL | 9968 | 1274 | 1219 | 1198 | 160 |

Problems encountered using particular HRM terms required an alternative approach to the intervention terminology. The team tested the viability of constructing an intervention search filter using only generic HRM terms, such as human resource, HRM, HR and high-performance work practices or management, and database keywords, such as ‘personnel management’. This removed the problem posed by constructing strategies using potentially non-HRM-related terms, such as ‘training’, ‘communication’ or ‘pay’, which retrieved large numbers of studies and were, arguably, as generic and non-specific as this overarching terminology. Scoping searches using this approach produced manageable numbers of potentially more relevant studies and, therefore, this method was adopted. The resulting HRM search strategy is discussed more fully in Chapters 5–7, and example searches are provided in Appendices 6 and 7.

Search process

Literature search strategies were developed and performed by a systematic review information specialist on the following databases: Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), British Nursing Index (BNI), Business Source Premier, Campbell Collaboration, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE), DH-Data, EMBASE, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC), International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS), King’s Fund database, MEDLINE, NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), National Research Register (NRR), PREMEDLINE, PsycINFO, ReFeR, Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) and Science Citation Index (SCI). Search strings were modified for the different databases to take account of the different keywords and thesauri they use. Searching of electronic databases using pre-designed search filters was supplemented by reference tracking of selected studies. Searches were conducted in May/June 2006. Table 3 provides details of the search filters and databases used for different areas of the review.

| Report chapter | Search filter | Database | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRM | IOs | POs | Longitudinal | Meta-analysis/review | IO measures | MEDLINE, CINAHL | PsycINFO | Business Source Premier | SSCI | ASSIA, SCI, EMBASE, Cochrane library | HMIC, King’s Funda | IBSS,a BNI | DH-Data, NRR, ReFeR | PREMEDLINE | |

| Linking HRM practices to outcomes (Chs 7 and 8) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| HRM practices to patient outcomes (POs) (Ch. 6) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Linking IOs to IOs (Ch. 8) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Linking IOs to FOs (Ch. 8) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Linking IOs to POs (Ch. 8) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Reliability of IO measures (Ch. 9) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓a | ✓a | ||||||||

Use of generic HRM terms is not ideal in identifying relevant studies. Papers that examined an HRM practice, such as employee feedback, could be missed if no mention of human resources, personnel or a synonym is made in the title, abstract or database designated keywords. However, this was the only way to operationalise HRM as a search strategy, given the extensive problems of using single practice terms. This search string was modified for different databases recognising the different keywords and thesauri they utilise. Additionally, the ‘HRM’ searches were supplemented by reference tracking and citation searching.

Study selection

This stage aims to identify articles that ‘help to answer the questions being addressed by the review’. 47 Study selection should be systematic, replicable and free from bias. Sifting is informed by criteria reflecting the population, intervention, outcome, study design, language and other criteria defined in the protocol. Titles and abstracts of retrieved articles are sifted by two reviewers or by one reviewer after an acceptable inter-rater reliability score is achieved. 47 Where a question remains over whether or not to include a study it is referred to a third reviewer (or a consensus is reached by two reviewers).

Conventional systematic review methods advocate the application of a quality threshold in determining study inclusion. 47 The aim is to evaluate the internal validity of studies by assessing selection, performance, measurement and attrition bias. The intention is to include only those studies that achieve the highest standards of methodology and reporting. Many tools or checklists have been developed for the critical appraisal of study quality based on study design, but each has limitations and there is no accepted standard set of tools. 72 Nevertheless, such tools are principally designed for specific types of medical research; surveys and case studies, for example, are less easily assessed, although quality assessment checklists have been developed. 58

However, there is a case for not excluding studies on the basis of quality, but simply to use assessment criteria to weight the findings of the studies in the review. 52,54,55,63,73 Quality assessment may act as a guide to interpreting findings and determining the strength of inferences, as well as enabling weighting of study results. It has been argued that qualitative studies cannot and should not be appraised formally,54,57 and that quality assessments may be evaluating limitations of reporting rather than methodology. 74 Quality assessment thus depends on the type of studies being reviewed. Controversy remains on whether or not to exclude ‘weak papers’. 75 In this review assessment of quality is used to moderate the messages from included research, and not as a quality threshold.

This review had already imposed a longitudinal criterion on the studies selected for review – a fairly high threshold for studies in the HRM field (in which cross-sectional, self-report design is common). Further weighting of studies by study design was applied and this is reflected in the relative weight given to the various studies in the data synthesis.

Data extraction

This is the process ‘by which reviewers obtain the information they need from what is reported by primary investigators’. 47 The aim is to collect from the selected studies the most important data for answering the research question. A data extraction form is piloted on several studies to ensure that reviewers are recording the same data and to develop forms of optimal length so that all key data are recorded. 47 In this review, data are primarily extracted and presented in the form of evidence tables.

Data synthesis

Synthesis aims to ‘draw together, contextualise and interpret the findings from the separate [studies]’. 53 Methods of synthesis are determined by whether data are qualitative or quantitative, and by the questions being asked of the data. 75 Meta-analysis is ‘the quantitative synthesis of data, in which evidence is pooled using statistical techniques’. 75 A narrative review seeks to ‘capture and describe, rather than “average out” the heterogeneity between studies’, and its choice as a method of synthesis may be ‘predicated on the diversity and complexity of the field’. 53 Several methods of synthesising qualitative data are being developed, such as thematic analysis, grounded theory, meta-ethnography and realist synthesis. 75 The method applied to each review is determined by the heterogeneity of the included studies and their data. In this review, synthesis is primarily descriptive and quantitative in recording the studies that meet specific characteristics, and is accompanied by a narrative synthesis. 76 There were very few studies in this review that addressed the same basic research question (i.e. examining the same relationship or set of relationships) precluding the use of meta-analysis for most intervention groups. Narrative synthesis was retained to ensure consistent synthesis across all interventions and enabling comparisons to be made.

Summary of specific research questions and methodological approaches

The review team drew on the most recent developments in systematic review methodology in identifying and then resolving the challenges of this evidence base.

A number of different research methods were used to identify evidence in relation to each of the specific research questions. This section provides a summary of the methodological approaches used in relation to each of the objectives and specific research questions.

Objective 1

Objective 1 is a mapping exercise involving both the identification of the range of HRM practices documented in the literature and the HRM practices actively reported in use reported by management practitioners. It is necessary to triangulate findings from these two sources in order to identify any gaps between research and practice.

-

Question 1.1 What HRM practices are described in the literature?

Method Content analysis was performed on six, recent major reviews of HRM practices, supplemented by additional literature identified for Objective 6. Practices were then categorised under broad headings of HRM, using accepted definitions of these categories, for example work design, performance management.

-

Question 1.2 How widespread is the use of HRM practices in UK organisations?

Method Evidence was drawn from the best available surveys of HRM practices in the UK. These surveys were identified from the expert knowledge of members of the project team, personal communications from colleagues, and systematic searching of electronic databases and relevant websites. Surveys were included if they contained UK data. They were then weighted according to specific criteria. Results were tabulated.

-

Question 1.3 How can the fidelity with which an HRM practice is implemented be measured?

Method A critical review was undertaken of research on implementation fidelity and relevant studies from the field of HRM. Studies were identified by systematic searching of electronic databases and informal methods, such as serendipity. A model, a measure and a guidance document were developed, based on this literature review.

Objective 2

-

Question 2.1 What are the most reliable measures of the intermediate outcomes identified for this review?

Method The intermediate outcomes to be assessed by this review were identified by content analysis of the relevant literature and a Delphi process involving HRM experts. The existing review and theory literature on the measures of these intermediate outcomes was examined to identify candidate measures. This literature was identified from a combination of systematic searching of electronic databases and informal methods, such as expert knowledge.

Objective 3

-

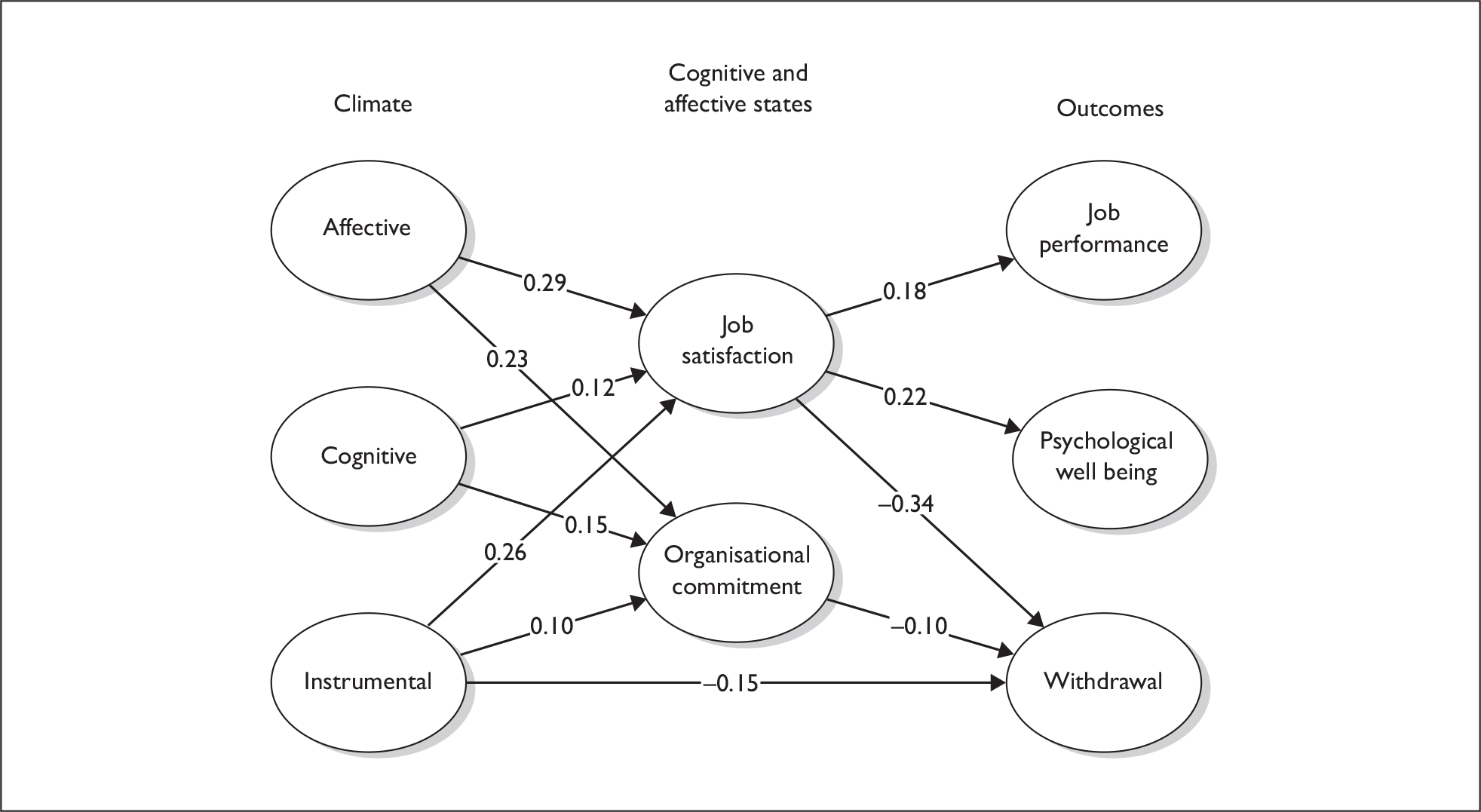

Question 3.1 What is the evidence on the intercorrelation of intermediate outcomes with each other?

Method Intermediate outcomes covered by this question were identified as described under Objective 2. The existing review and meta-analysis literature was reviewed to identify correlations between individual intermediate outcomes. This literature was identified by a combination of systematic searching of electronic databases and reference tracking.

Objective 4

-

Question 4.1 What is the evidence for the impact of intermediate outcomes on non-health final outcomes?

Method Once again, the intermediate outcomes covered by this question were devised as for Objective 2. The existing review and meta-analysis literature was identified and reviewed to evaluate correlations between individual intermediate outcomes and final outcomes, such as performance, turnover and absenteeism. This literature was identified by a combination of systematic searching of electronic databases and reference tracking.

-

Question 4.2 What is the evidence for the impact of intermediate outcomes on patient care outcomes?

Method Intermediate outcomes were again identified as for Objective 2. The aim was to produce a synthesis of the longitudinal literature for each intermediate outcome as it relates to the patient care outcomes identified for this review. This literature was identified by a combination of formal methods, such as systematic searching of electronic databases and reference tracking.

Objective 5

-

Question 5.1 Do any HRM practices have a significant impact on the intermediate outcomes identified for this review?

Method Again, each intermediate outcome identified under Objective 2 was examined in a systematic review of the longitudinal HRM literature. This literature was identified from Objective 6, Questions 6.1 and 6.2, which included longitudinal research examining the impact of HRM practices on various intermediate outcomes. A qualitative, narrative synthesis of the literature was produced.

Objective 6

-

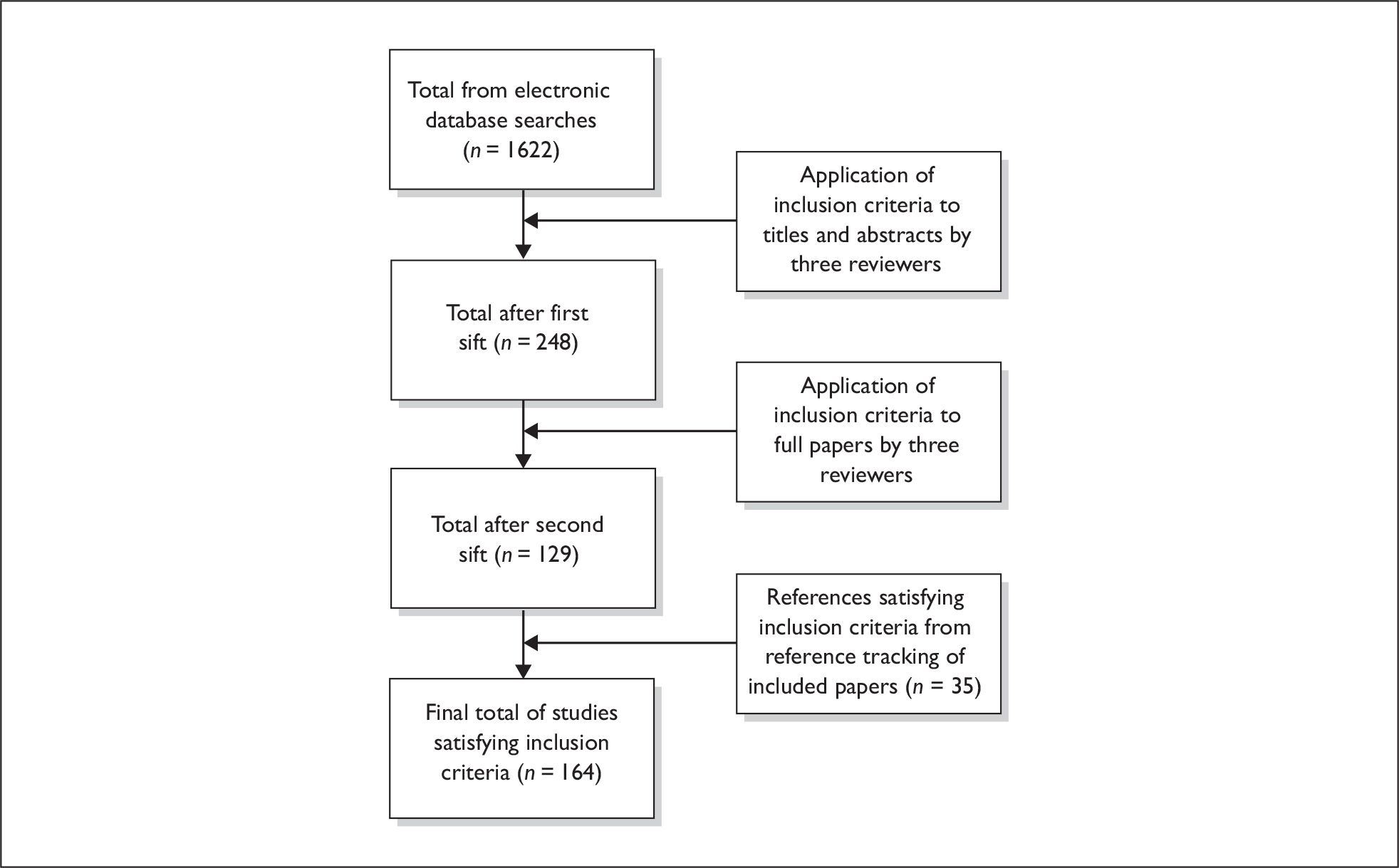

Question 6.1 Which HRM practices have an impact on performance outcomes?

Method A systematic review was undertaken of longitudinal research examining HRM practices and both intermediate and final outcomes. Studies were identified by the systematic searching of electronic databases and reference tracking, and by informal methods such as expert advice. The literature was mapped to the category framework developed in response to Question 1.1 and a qualitative, narrative synthesis of the literature was produced.

-

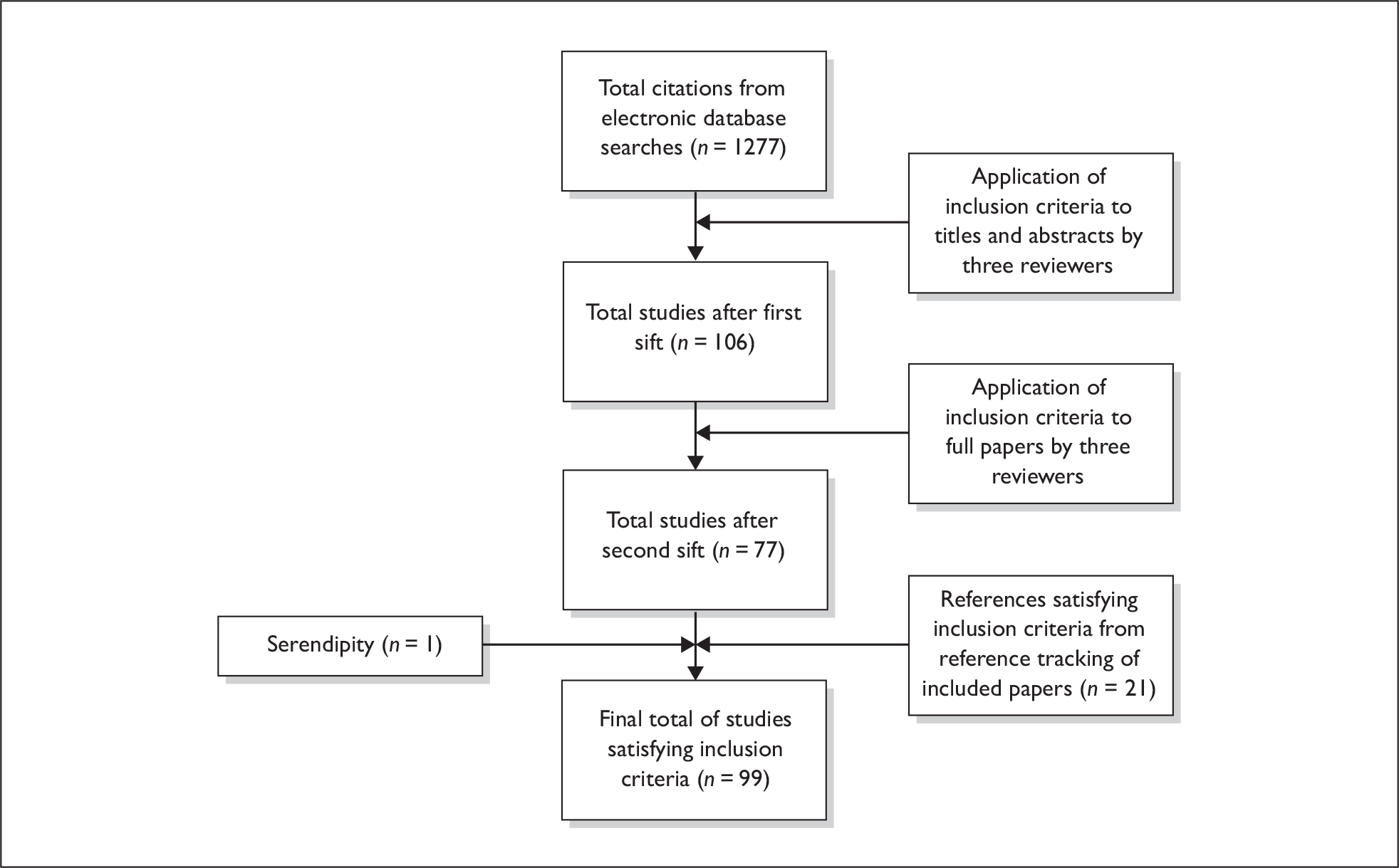

Question 6.2 Which HRM practices have an impact on patient care outcomes?

Method A systematic review was undertaken of longitudinal research examining HRM practices and their impact on patient-care outcomes. Studies were identified by the systematic searching of electronic databases and reference tracking, and by informal methods, such as serendipity. The literature was mapped to the category framework developed in response to Question 1.1 and a qualitative, narrative synthesis of the literature was produced.

Against this methodological backdrop, the specific details of each review are described in the corresponding section of the report and justification is given for methods used.

Chapter 3 HRM practices and their reported use in the UK

Introduction

This chapter of the report presents findings in relation to Objective 1. Specifically, it addresses the first two research questions identified under Objective 1 (Question 1.3, on implementation fidelity, is dealt with in Chapter 11):

-

Objective 1: 1.1 What HRM practices are described in the literature?

-

Objective 1: 1.2 How widespread is the use of HRM practices in UK organisations?

The chapter first describes the process by which HRM practices were identified, and then goes on to report findings on the extent of use of these practices in the UK.

What HRM practices are described in the literature?

This phase of the research sought to audit the main HRM practices described in the literature. The aim was to identify a complete list of HRM practices to be developed into a search strategy. Data from three sources were used to develop the list.

Step 1

The research team and expert advisers generated a list of 13 headings. Eleven of these were broad HRM categories under which it was anticipated that the majority of individual HRM practices could be grouped, which could then be used as a framework to shape the reviews. Initial HRM practice terms are presented in Table 4.

| 1 | Work design |

| 2 | Training and development |

| 3 | Communication |

| 4 | Single status/harmonisation/status differentials |

| 5 | Appraisal/performance management |

| 6 | Higher-level concepts (HPWPs, HI, HC, etc.) |

| 7 | Administration |

| 8 | Recruitment and selection (including placements) |

| 9 | Compensation and reward systems |

| 10 | Family friendly |

| 11 | Employee representation/involvement/participation |

| 12 | Total quality management |

| 13 | Miscellaneous |

It was recognised from the outset that HRM practices were unlikely to all fall into neat categories. In addition to the 11 broad categories of HRM practice identified, two further categories were used to group individual practices:

-

The ‘Miscellaneous’ category was used to group practices that were not subject to direct manipulation by the HR department, or were too broad to be influenced by HR policies/practices alone, but were of potential interest to the review for their impact on organisational or individual performance. Examples include bullying/harassment, socialisation, etc.

-

A sizeable number of HR policies/practices, 29 in total, were considered to be part of HR maintenance functions (i.e. administration) rather than proactive HR practices aimed at enhancing performance. Examples include equal opportunity, dispute resolution policies, and health and safety policies.

The classification of HRM practices into broad categories was reviewed by the expert advisers. As a result, the terms were refined according to the most appropriate HR category as defined and used in the literature and additional HRM practice terms were suggested, which had not been identified in the review of reviews:

-

The higher level concepts category was renamed ‘bundles’ of practices. Over the last 10–15 years there has been a growing body of research on ‘bundles’ of practices. This category was therefore intended to capture research that focused on combinations of HRM practices that were intentionally designed to be used in concert as well as for multiple practices opportunistically used together.

-

Articles in the ‘Miscellaneous’ category were reappraised and either recategorised under one of the main headings or excluded from this assessment of the main HRM practices described in the literature.

Step 2

In a parallel process, a list of HRM practices was compiled from six major recent reviews of the HRM literature. 30,35,77–80 This process identified 245 practices.

A process of reciprocal translation81 was applied to the 245 practices identified by the review of reviews, with the intention of building a consensus about the main HRM practices covered in the literature. Reciprocal translation involves the comparison of themes across papers and an attempt to establish whether there is equivalence in the themes of one paper with those from another. The aim is to ensure that a key theme captures similar policies or practices from different papers. In this exercise, the reciprocal translation was approached by two of the researchers independently attempting to compare HRM practice terms across review papers and group them under one of the broad HRM categories listed in Table 4.

Initially, a substantial number of practices did not appear in any of the categories or could be allocated to more than one. For example, appraisal-based pay can be seen as a part of the broad HRM category of appraisal/performance management and of compensation and reward systems. Likewise, introducing autonomous work teams can be seen as both an employee involvement strategy and a work design approach.

The process of reciprocal translation made it apparent that the same term could be used to describe different practices in different papers (e.g. ‘goal setting’ to mean performance management in one context and employee involvement in another).

At this stage in the research, it became apparent that the diffuse nature of the HRM literature, in particular the inconsistency of terminology and the blurred boundaries of some of the concepts, meant that the broad categories identified through this process would not be a suitable as the sole basis for the subsequent review of evidence. Ultimately, a combination of broader search terms and study design criteria were used (which are described in Chapters 2, 5 and 6).

Step 3

The systematic reviews undertaken to meet Objectives 3–5 generated over 450 papers (see Chapter 5 for a description of these searches). The individual HR practices, policies or interventions that had been the focus of these studies were mapped on to the list of HR practices generated by Steps 1 and 2. This was done in order to identify any gaps in the list of HR practice terms and further refine the categories. The exercise revealed that:

-

A large body of literature in the health sector focused on specific HR practices not commanding much attention in the non-health sector – specifically ‘working hours’, ‘staff levels’ and ‘skill mix’. These practices were included under the ‘staffing’ practice category along with selection and recruitment.

-

All TQM practices identified (a separate category on the original list) were, in fact, training interventions, so were included under the broad ‘training’ heading.

The final list of 10 broad HRM categories is as follows:

-

work design

-

staffing

-

training and development

-

compensation and rewards

-

communication

-

family friendly

-

single status/status harmonisation

-

employee representation, involvement and participation

-

appraisal/performance management

-

bundles.

Appendix 2 contains a list of these broad HRM categories with definitions. Appendix 3 presents the specific HRM practices identified in the literature grouped under these 10 broad categories.

How widespread is the use of these HRM practices in the UK?

Aim

As part of Objective 1, the review sought to document evidence on the extent of use of HRM practices within UK organisations or workplaces. The intention is to:

-

provide a comprehensive report of the percentage of organisations using the HRM practices identified for this review and to identify gaps in the survey literature

-

relate findings of the review of the research literature to actual practices used within UK organisations. For example, research may demonstrate that a practice has a significant beneficial impact on job satisfaction or patient outcomes, while survey data may indicate that this practice is not actually widespread.

The first aim is addressed in this chapter and the implications for the overall conclusions of the review are considered in Chapter 11.

Methods

Findings from the highest-quality and most up-to-date HR surveys were used to generate these data. Surveys were identified using several strategies. The Workplace Employment Relations Survey (WERS) and other survey organisations were identified by members of the project team. Searches were conducted to identify appropriate publications on the websites of relevant organisations, including: Community Innovation Survey (CIS), Continuing Vocational Training Survey (CVTS), European Survey on Working Time and Work–Life Balance (ESWT), PASO (Panel Survey of Organisations), Employee Direct Participation in Organisational Change (EPOC Project), and Workplace and Employee Survey (WES) Canada. Searches of the SSCI and King’s Fund electronic databases were used to identify additional surveys, particularly for the UK health sector. Search strategies used combinations of the following terms and their variants: survey(s) and practice(s) and either human resource(s), staffing, work or personnel. To be included, the survey data had to relate to UK workplaces.

Surveys were ordered in a hierarchy, based on the following quality assessment criteria. The survey reported data that:

-

were weighted and representative of UK workplaces (i.e. data were collected or adjusted so that the resulting figures do not simply represent large organisations or organisations from particular sectors or industries)

-

were based on the unit of the workplace (this can be a self-contained entity or a unit of a larger organisation) rather than an individual employee

-

included the UK public sector and/or health sector.

Data from surveys that were weighted were preferred to data from surveys that were not representative of UK workplaces but simply reported data based on the unit of the workplace. Data from such surveys were, in turn, preferred to those that simply reported UK private or public sector data. If data on a practice were available in a survey that was weighted and representative of UK workplaces then these data were used in preference to data on that practice from a more limited survey.

Results

Surveys: a comparison

Searches identified 18 surveys from 1996 to 2006 that satisfied the criteria. A comparison of included surveys is seen in Table 5. The best available survey is the 2004 WERS:82 WERS data were ‘weighted and are representative of [workplaces with 10 or more employees], which accounts for 18% of all workplaces and 80% of all employees in Britain’. With the exception of the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) surveys on performance pay or rewards, this was also the only major survey to record data from the public sector, and the only survey to compile specific health sector data. Therefore, if WERS covered a practice, then only WERS data were used, even if other surveys provided data on the same practice; WERS was considered the best evidence. Where duplicate data existed, those from only the best survey were reported.

| Survey | UK data | Representative of UK workplaces | Unit = workplace or equivalent | Public sector data | Health sector data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WERS (1998, 2004, 2006)82–85 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| ESWT (2006)86 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| CVTS (2001)87 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| EPOC (1996)88 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Newton et al. (1996)102 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| CIPD (2006)89 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| IPD (1999)90 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| NESS (2005)91 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| CIPD surveys (2002–6)92–98 | ✓ | ✓a | |||

| Wood et al. (2004)99 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| CRANET (2003)100 | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| IPD (1999)101 | ✓ |

Three further surveys also claimed to be representative, although they did not acknowledge weighting of these data. For example, the ESWT survey stated that ‘the survey data in the ESWT are representative of establishments with 10 or more employees from all sectors of activity’ 86 and the EPOC survey88 claimed to be ‘representative of workplaces in ten countries of the European Union’. The remaining surveys were not representative, although several did offer public sector or health sector data, which were absent from the representative surveys.

Seven surveys sampled the workplace, all of which reported UK data (although three surveys were Europe wide). In the remaining surveys, CIPD members were being surveyed rather than actual workplaces, limiting the potential value of these sources. Only one specific health sector survey of HRM practices was identified by this review. 102 The study reported on a non-representative sample of general practices in the UK. Some HRM practices, which duplicate those covered by other surveys, are included because this was the only specific health service survey.

This section examines evidence on the extent of use of HRM practices among UK employers. As a result, the focus is on the most recent data for any practice rather than on all available data. For example, only the most recent WERS82 data were recorded here. Data from an earlier WERS83 survey were recorded only if the information was not collected for the subsequent survey. Also, it was outwith the remit of this review to examine developments in coverage of practices over time.

Health sector-specific surveys

The most comprehensive surveys within the health sector are those conducted by the Healthcare Commission (HCC). Whilst providing extensive information about staff experiences of working within the NHS, the annual staff survey differs considerably from the HR surveys reviewed here in that:

-

It is targeted at the individual employee, rather than the HR function.

-

It asks questions about individual staff perceptions or experiences rather than the absence or presence of specific HR practices.

-

The nature of the data means that findings are reported at the individual level (i.e. percentage of all staff responses to a particular item) for the NHS as a whole, or by type of Trust [e.g. all Primary Care Trusts; all Ambulance Trusts, etc.], or by Strategic Health Authority, or by individual Trust, rather than at the organisational level (i.e. percentage of Trusts/organisations reporting the presence of an HR practice).

Comparing such data with HR practice measures is extremely problematic. For example, the proportion of employees reporting that they have had an appraisal in the last 12 months may not bear a strong relation to the proportion of NHS organisations with appraisal policies in place, or to the existence of an appraisal policy in any specific organisation. Accepting these limitations, it is possible to interpret some of the NHS Staff Survey findings as a proxy indicator for staff experience of particular HR practices in the NHS.

Analysis of data from the NHS Staff Survey focuses on 26 key areas (key scores). These are a mixture of attitudinal and experiential measures, the latter providing an indication of the percentage of NHS staff who have experienced a particular HR practice (i.e. a proxy indicator).

Where a proxy indicator for staff experience of an HR policy is available from the National NHS Survey 2007,103 this has been indicated in the right-hand column of Table 6. Findings from the survey are summarised later (see Table 17) and discussed below (see Data from the NHS Staff Survey 2007, below).

| WERS 200682 | ESWT 200686 | CVTS 200187 | EPOC 199688 | CIPD 200689 | IPD 199990 | NESS 200591 | CIPD 200292 | CIPD 200393 | CIPD 200594 | CIPD 200595 | CIPD 200696 | CIPD 200697 | CIPD 200698 | NHS103 Staff Survey 2007 proxy indicator | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work design | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Staffing: recruitment and selection | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Training and development | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Compensation and rewards | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Communication | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Family friendly/work–life balance | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Single status/harmonisation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Employee involvement | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Performance management | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Bundles of practices/HPWPs | ✓ |

Categorisation of practices

Practices recorded by HR practice surveys are reported using our categories of HRM practices (as presented above: see What HRM practices are described in the literature?). These groupings are used to structure the following tables reporting the survey data (Tables 7–16). Figures in these tables represent the percentage of workplaces that report using a particular practice. Data are from the National NHS Staff Survey 2007103 as presented later in the chapter (Table 17).

| Category | Practice: interview or survey question/report definition, where available | Percentage of workplaces with practice [overall (public/private/health)] | Data collection method | Sample size; workplace size | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job characteristics |

Formal job description Percentage of workplaces answering ‘yes’ to the question, ‘What percentage of your staff has a formal written job description?’ |

72 (na/na/na) | Manager telephone survey | 27,172 managers/establishments | NESS (2005: 84)91 |

| Job rotation | Job rotation (used frequently, occasionally or rarely) | 77 (na/na/na) | Postal survey | 635 CIPD members in UK organisations; no limit | CIPD (2006: 6)97 |

| Team working | Some use of team-based working | na (80/na/79) | Manager telephone survey | 1115 UK organisations; more than 150 employees | Wood et al. (2004: 426)99 |

| Team working |

Any employees working in teams Percentage of workplaces with some or all staff in teams answering the question, ‘What proportion, if any, of the [largest occupational group] in this workplace work in formally designated teams?’ |

72 (88/68/na) | Manager interviews | 2050 managers; 10 or more employees | WERS (2006: 90)82 |

| Empowerment | Empowerment | na (70/na/73) | Manager telephone survey | 1115 UK organisations; more than 150 employees | Wood et al. (2004: 426)99 |

| Category | Practice: interview or survey question/report definition, where available | Percentage of workplaces with practice [overall (public/private/health)] | Data collection method | Sample size; workplaces size | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selection |

Personality tests used routinely for some occupations Percentage of workplaces answering ‘yes’ to the question, ‘When filling vacancies at this workplace do you ever conduct any type of personality or attitude test?’ |

19 (18/20/17) | Manager interviews | 2024 managers; 10 or more employees | WERS (2006: 77)82 |

|

Performance tests used routinely for some occupations Percentage of workplaces answering ‘yes’ to the question, ‘When filling vacancies at this workplace do you ever conduct any type of performance or competency test?’ |

46 (63/42/50) | Manager interviews | 2024 managers; 10 or more employees | WERS (2006: 77)82 | |

|

Preference for internal applicants Percentage of workplaces specifying the answer to the question, ‘Which of these statements best describes your approach to filling vacancies as internal applicants are given preference, other things being equal, over external applicants?’ |

22 (12/25/na) | Manager interviews | 2024 managers; 10 or more employees | WERS (2004) p. 984 | |

| Open internal job market | 93 (na/na/na) | Postal survey | 732 HR and career management practitioners; no limit | CIPD (2003: 19)95 | |

| Formal promotion policies | 18 (na/na/na) | Postal survey to practice manager | 477 general practices | Newton et al. (1996: 83)102 | |

| Recruitment |

Special recruitment procedures to attract women returning to work after having a child Percentage of workplaces answering ‘yes’ to this choice in the question, ‘When filling vacancies do you have any special procedures to encourage applications from the following groups?’ |

8 (12/8/na) | Manager interviews | 2056 managers; 10 or more employees | WERS (2006: 243)82 |

|

Special recruitment procedures to attract women in general Percentage of workplaces answering ‘yes’ to this choice in the question, ‘When filling vacancies do you have any special procedures to encourage applications from the following groups?’ |

6 (10/5/na) | Manager interviews | 2056 managers; 10 or more employees | WERS (2006: 243)82 | |

|

Special recruitment procedures to attract members from minority ethnic groups Percentage of workplaces answering ‘yes’ to this choice in the question, ‘When filling vacancies does you have any special procedures to encourage applications from the following groups?’ |

9 (21/6/na) | Manager interviews | 2056 managers; 10 or more employees | WERS (2006: 243)82 | |

|

Special recruitment procedures to attract older workers Percentage of workplaces answering ‘yes’ to this choice in the question, ‘When filling vacancies do you have any special procedures to encourage applications from the following groups?’ |

5 (6/5/na) | Manager interviews | 2056 managers | WERS (2006: 243)82 | |

|

Special recruitment procedures to attract disabled workers Percentage of workplaces answering ‘yes’ to this choice in the question, ‘When filling vacancies do you have any special procedures to encourage applications from the following groups?’ |

10 (29/5/na) | Manager interviews | 2056 managers; 10 or more employees | WERS (2006: 243)82 | |

|

Special recruitment procedures to attract people who have been unemployed for 12 months or more Percentage of workplaces answering ‘yes’ to this choice in the question, ‘When filling vacancies do you have any special procedures to encourage applications from the following groups?’ |

5 (8/5/na) | Manager interviews | 2056 managers; 10 or more employees | WERS (2006: 243)82 | |

| Advertising in different sources to widen interest from under-represented groups | 41 (65/33/na) | Postal survey | 659 HR professionals; no limit | CIPD (2006: 15)98 | |

| Using images and words that appeal to a wider audience | 39 (45/37/na) | Postal survey | 659 HR professionals; no limit | CIPD (2006: 15)98 | |

| Checking tests used are culture free and tested on diverse norm groups | 37 (44/33/na) | Postal survey | 659 HR professionals; no limit | CIPD (2006: 15)98 | |