Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 05/11/02. The contractual start date was in December 2005. The draft report began editorial review in November 2009 and was accepted for publication in May 2010. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

None

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2010 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2010 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Introduction

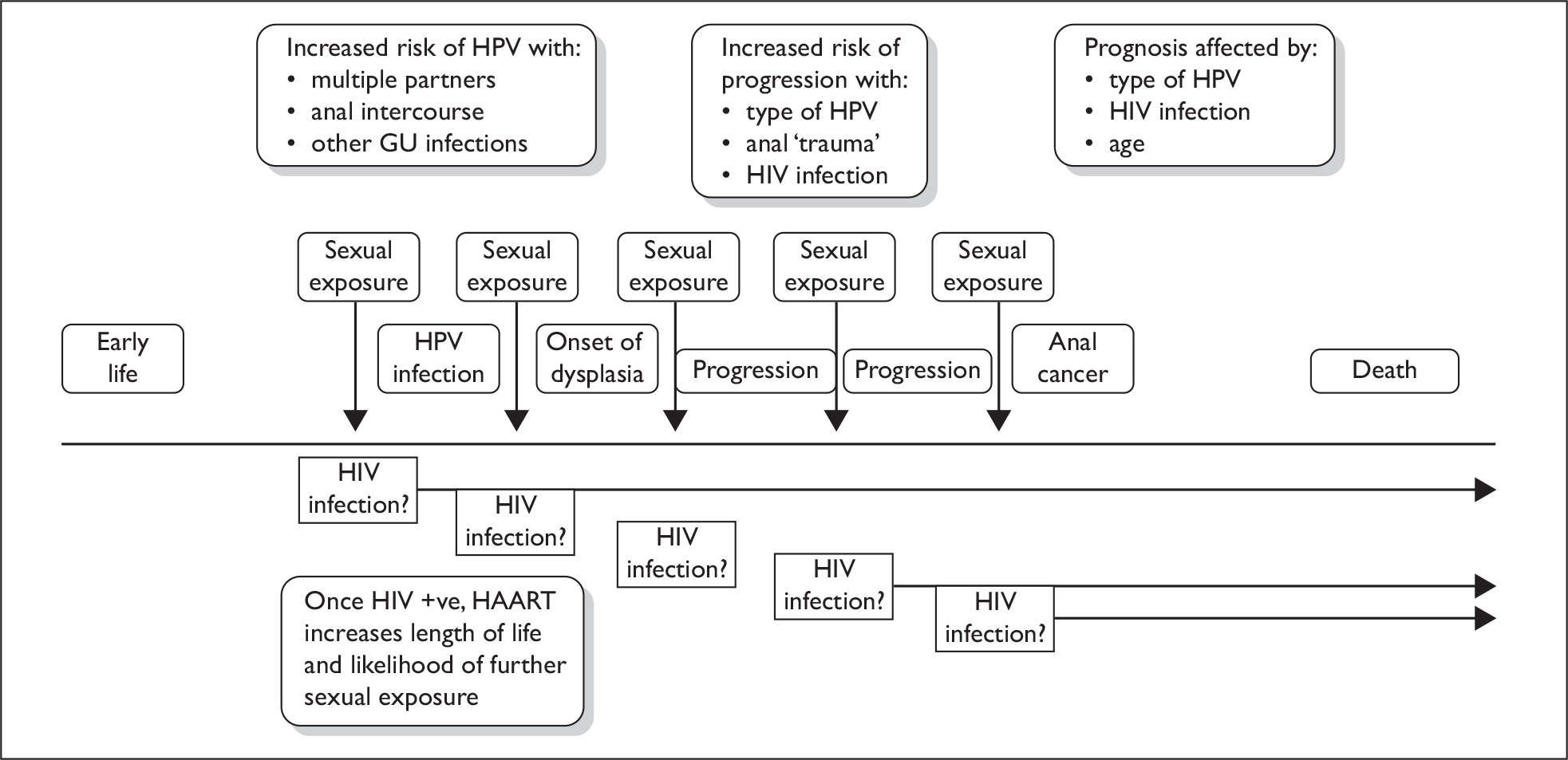

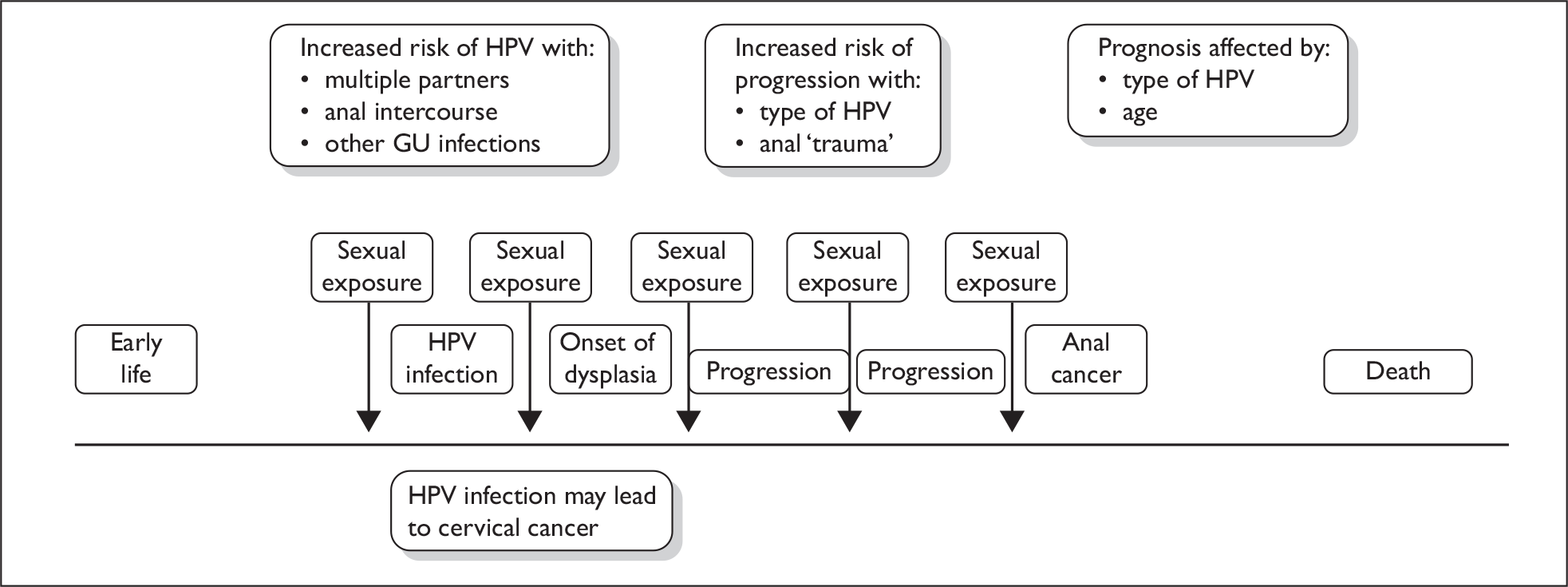

Anal cancer is an uncommon cancer. It is a disease in which cancer (malignant) cells are found in the anus. Like most cancers, anal cancer is best treated when it is diagnosed soon after it develops. Primary treatment is generally concomitant radiotherapy (RT) and chemotherapy (if tolerated) to preserve the anal sphincter, but, despite these approaches, local disease failure is considerable, and requires salvage radical surgery with associated high morbidity and mortality. Anal cancer is predominantly a disease of the elderly and is near to zero in early life. The human papillomavirus (HPV), has been implicated as a causal agent of anal cancer. HPV infection, for the majority of cases, is transmitted sexually. The vulnerability of individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) to HPV infections has seen an increase in the number of cases from this population presenting with anal cancer.

To decide whether the screening of groups of people for a specific condition is suitable, there are well-defined criteria that can be used to aid the decision process. 1 The condition should be an important health problem, and the natural history and epidemiology must be understood. The test itself should be safe, simple, accurate and acceptable to the general population.

Aim of the review

The aim of this review is to estimate the cost-effectiveness of screening for anal cancer in men and women who are HIV positive, and, in particular, men who have sex with men (MSM), who have been identified as being at greater risk of the disease, by developing a model that incorporates all of the above criteria.

Epidemiology

Cancer is predominantly a disease of the elderly, with overall crude rates of cancer registrations of 462 per 100,000 of the population for males and 451 per 100,000 of the population for females in England for 2003,2 with anal cancer being no exception. Anal cancer is a rare disease; in 2003 there were 722 registrations of newly diagnosed malignant neoplasm of anus and anal canal in England, with 291 of registrations being male and 431 female. 2 Anal cancer is also very much a cancer of the elderly, with 37% (108) of males with newly diagnosed anal cancer being aged 65 or over and 56% (241) of females with newly diagnosed anal cancer being aged 65 or over. 2 For anal cancer, the rate per 100,000 of the general population in England 2003 was 1.2 per 100,000 for males and 1.7 per 100,000 for females (Table 1). 2

| Rate per 100,000 | Total new cases | Percentage aged 65 years or over | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Males | 1.2 | 291 | 37 |

| Females | 1.7 | 431 | 56 |

Incidence of anal cancer

Johnson et al. 3 reported that the incidence rate for anal cancer in the USA was 2.04 per 100,000 for men and 2.06 per 100,000 women, based on data collected between 1973 and 2000 on diagnosis and outcomes of invasive and in situ anal cancer. The data came from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) programme (see Appendix 1), a system of population-based tumour registries in the USA. The rate for US males is almost double the rate of English males, whereas the rate for US females is slightly higher than that of English females.

Karandikar et al. 4 undertook a retrospective audit of the squamous (epidermoid) type of anal cancer diagnosed and treated in the principality of Wales over a 5-year period (1995–99), with follow-up until 2005. Patients diagnosed with anal cancer were identified from the Welsh Cancer Registry, Welsh Cancer Intelligence and Surveillance Unit (WCISU) database, and pathology records from 17 hospitals and five oncology units. Overall, 149 patients with anal cancer were identified from the WCISU and hospital pathology databases. Thirteen patients with adenocarcinoma involving the anal canal with or without involvement of the rectum, two patients with melanoma and one with a neuroendocrine tumour of the anal canal were excluded, leaving a cohort of 133 patients. The annual incidence rate of anal cancer from this audit of the principality of Wales was 1.3 per 100,000.

In 1990, Scholefield et al. 5 reported that anal cancer was a rare tumour in Britain, with no published epidemiology studies from this country. Scholefield et al. 5 reported 1988 statistics showing 250–300 cases of anal cancer per year. Scholefield et al. 5 undertook a retrospective study of anal cancer registrations, with colon cancer as controls, from Thames, West of Scotland and West Midlands Cancer Registries. Colorectal cancer was chosen as a control as there was no evidence that a sexual transmission agent is involved in its aetiology. Anonymous details for all anal and colorectal cancers for a 13-year period (1975–87) were obtained from the previously mentioned registries. Scholefield et al. 5 collected information on gender, marital status and 5-year age group.

Scholefield et al. 5 reported that from the Thames Cancer Registry (TCR) there were 846 cases of anal cancer and 26,359 cases of colon cancer, 182 cases of anal cancer and 9613 cases of colon cancer from the West of Scotland Registry and 288 cases of anal cancer and 11,905 cases of colon cancer from the West Midlands Cancer Registry. This gave a total of 1316 cases of anal cancer and 47,877 cases of colon cancer for the 13-year period.

In 1993, Frisch et al. 6 reported the findings of a descriptive epidemiological study based on data from the Danish Cancer Registry. The aim of the study was to examine long-term trends in incidence of anal cancer in a well-monitored, unselected population. The Danish Cancer Registry has recorded all cases of cancer in Denmark since 1943 (only invasive non-adenocarcinoma and non-melanoma anorectal cancers were included in the study) and 888 cases of anal cancers (303 men and 585 women) were identified.

Frisch et al. 6 reported that since around 1960 the incidence rates had nearly doubled in men and tripled in women. Data for 1983–7 gave incidence rates of 0.38 per 100,000 for men and 0.74 per 100,000 for women (world standardised).

Gatta et al. 7 gave details on survival and incidence from rare cancers (defined as those with an annual crude incidence rate of less than 2 per 100,000 for both sexes combined) in 2006, based on data of 39 adult cancer registries for 59,021 patients aged 15–99 years, diagnosed with a selected rare cancer between 1983 and 1994. Data were collected from 18 European countries. Gatta et al. 7 reported that for the UK (England, Scotland and Wales) there was a crude incidence rate of anal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of 0.73 per 100,000 and a world-standardised incidence rate of 0.51 per 100,000.

Table 2 displays the available evidence over the years of reported anal cancer incidence rates, and number of new cases. Care needs to be taken in evaluating the table as data are drawn from different sources and presented in different formats, for example age-standardised rates and non-standardised rates. Given that anal cancer is a rare disease, it would indicate that anal cancer is not a significant burden of disease in the population. The criteria for appraising screening programmes1 (Appendix 2) identify that the first criterion to be satisfied before screening for a specific condition is that the condition should be an important health problem. Screening for anal cancer would identify only a low number of cases.

| Study details | Study type | Country | New cases per year | Annual incidence per 100,000 population | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | Males | Females | ||||

| Scholefield et al. 19905 | Retrospective cohort study | Britain | 250–300 | – | – | – |

| Frisch et al. 19936 | Descriptive epidemiological study | World | – | – | 0.38a | 0.74a |

| Chiao et al. 20058 | Population-based analysis | USA, 1973–81 | – | 0.60b | – | – |

| USA, 1982–95 | – | 0.80b | – | – | ||

| USA, 1996–2001 | – | 1.00b | – | – | ||

| Office of National Statistics2 | Registry data | England, 2003 | 722 | 1.20 | 1.10b | 1.30b |

| Johnson et al. 20043 | Population-based analysis | USA, 1973–2001 | – | – | 2.04b | 2.06b |

| Karandikar et al. 20064 | Registry data | Wales, 1995–99 | – | 1.30 | – | – |

| Gatta et al. 20067 | Registry data | UK, 1983–94 | – | 0.51a | – | – |

Incidence rate by age and gender

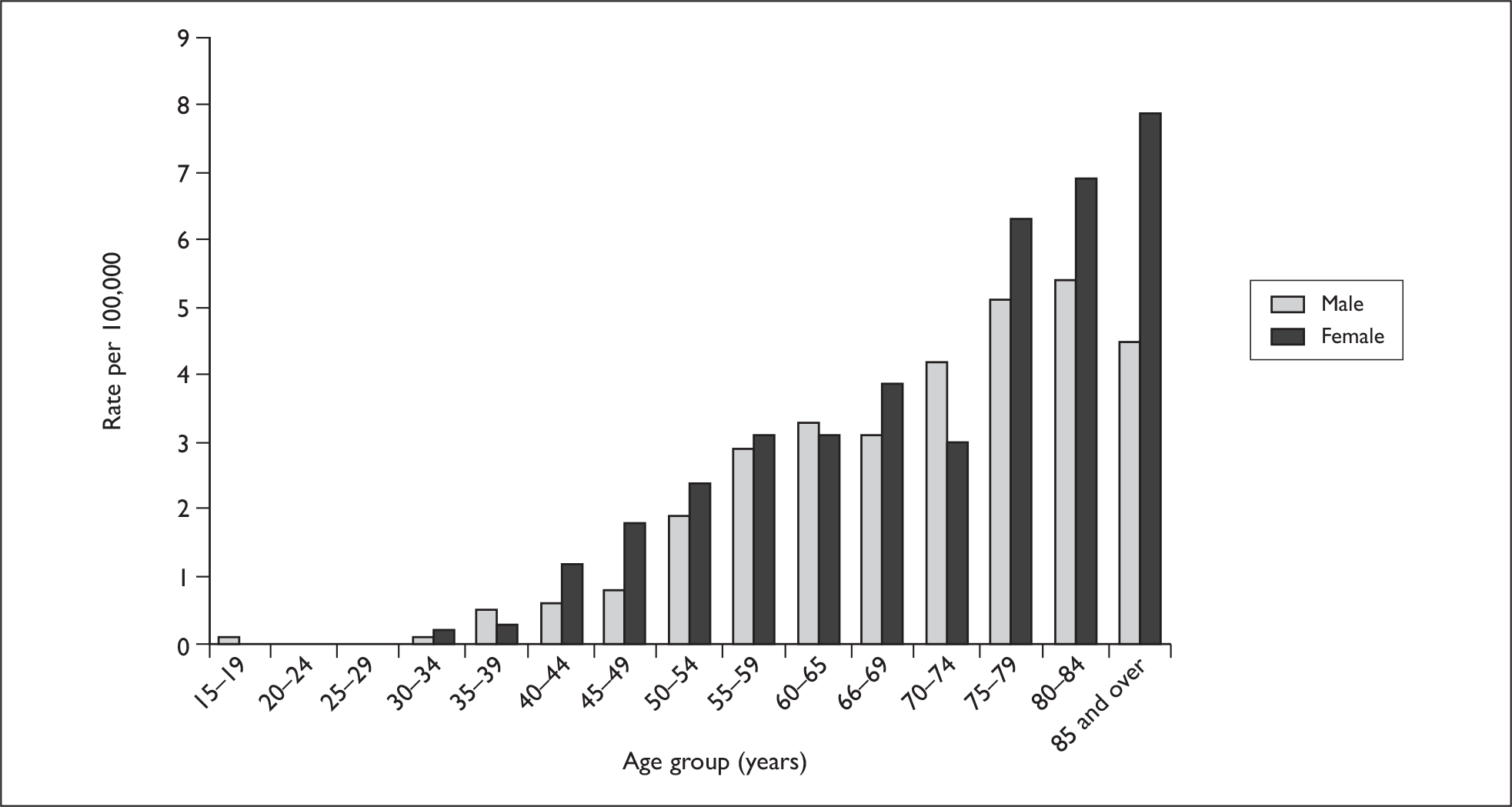

The probability of developing anal cancer rises sharply with age and the UK population is ageing. In young people, the risk is very low, but between the ages of 55 and 65 the annual incidence rate is approximately 3 per 100,000 for both males and females. Amongst those aged between 75 and 84 years, the annual incidence rate is over 5 per 100,000 and over 6 per 100,000 per year for males and females, respectively. Figure 1 shows the age-specific incidence rate for anal cancer, based on data from the Office of National Statistics. 2

FIGURE 1.

Annual incidence rate per 100,000 for newly diagnosed anal cancer by gender and age in England 2003. Compiled from data from the Office for National Statistics. 2

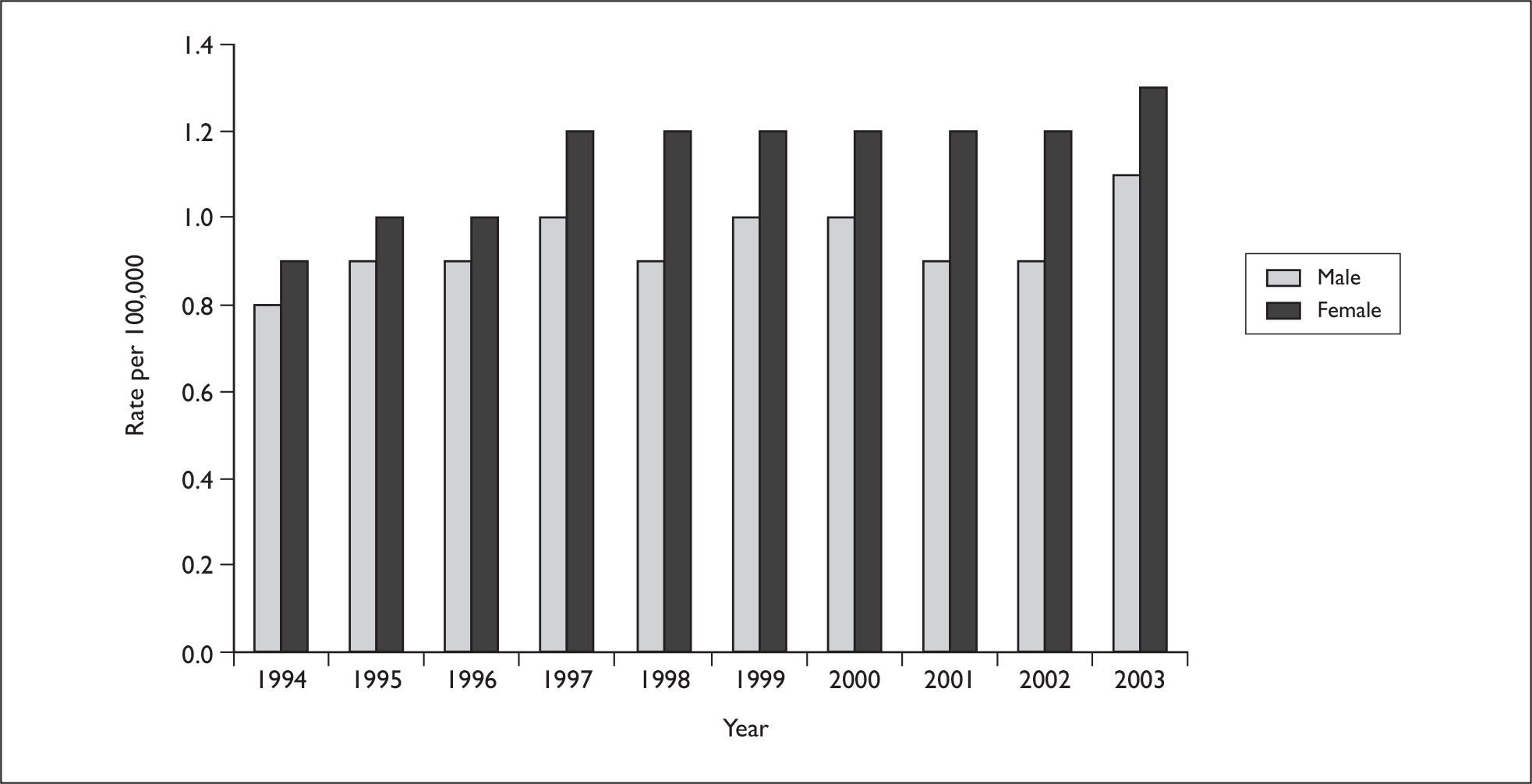

The annual incidence rate (directly age-standardised rates) has remained constant over the last decade, remaining at around 1.0 per 100,000 for males. For females, there has been a slight rise in directly age-standardised rates from the late 1990s, rising from around 1.0 per 100,000 to around 1.2 per 100,000 (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Directly age-standardised rate per 100,000 for newly diagnosed anal cancer by gender in England 1994–2003. Compiled from data from the Office for National Statistics. 2

In 2006, Brewster and Bhatti9 publicised the findings of their study describing secular trends in incidence of SCC of the anus in Scotland, before and during the HIV epidemic. Incidence cases of malignant neoplasms of the anus and anal canal were extracted from the Scottish Cancer Registry for the years 1975–2002. Brewster and Bhatti9 identified 757 cases of SCC (278 males and 479 females) registered, with an incident date falling within the 28-year period of the study. The authors found that in males the standardised incidence rate per 100,000 increased from 0.14 to 0.17 in the late 1970s to around 0.37 in the late 1990s, with a peak of 0.44 in the period 1993–7. For females, the incidence rate was generally higher, increasing from 0.23–0.27 in the late 1970s to a peak of 0.55 in the period 1998–2002.

Incidence by marital status

Scholefield et al. 5 reported that the odds ratio (OR) for never-married men compared with ever-married men was 2.2 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.8 to 2.8] and the OR for never-married women compared with ever-married women was 0.6 (95% CI 0.5 to 0.8). The authors concluded that there is a clear increase in the risk of anal cancer among never-married men.

Frisch et al. 6 examined incidence according to marital status, using a nested case-controlled design in which all anal cancer patients (n = 888) served as cases and all patients with colon cancer (n = 54,207) and stomach cancer (n = 58,198) were used as controls. The authors found that 17% (53 of 303) of men with anal cancer had never married, compared with 7% (1790 of 24,420) of never-married men with colon cancer and 9% (2877 of 33,248) of never-married men with stomach cancer. Among women the figures were 11% (64 of 585) anal cancer, 13% (3898 of 30,787) colon cancer, and 12% (2859 of 24,062) stomach cancer. The adjusted ORs were 2.7 (95% CI 2.0 to 3.6) for men and 1.0 (95% CI 0.8 to 1.3) for women, with colon cancer as control, and 2.1 (95% CI 1.5 to 2.8) for men and 1.2 (95% CI to 0.9–1.6) for women with stomach cancer as control. The authors of this study6 concluded that men who had never married were found at increased risk since the 1940s, indicating a potential association with male homosexuality.

Rabkin and Yellin10 reported in 1994 the results of a study to determine the types and rates of cancers occurring in excess in the presence of HIV-1 infection. The National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) SEER registry data (Appendix 1) was used to identify never-married men aged 25–54 years living in the San Francisco area and whom were HIV-1 seropositive as of late 1984. Age-, race- and sex-specific populations of San Francisco for the years 1973 to 1990 were obtained from Census data and for the period between Census dates they were estimated. For the study period of interest, there were 1,390,000 person-years of observation of the never-married men, 25–54 years of age, living in the San Francisco population. Expected cancers were calculated from age-, race- and period-specific cancer incidence rates of the entire male SEER population for the periods 1973–9 [defined as the pre-acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) period], 1980–4, 1985–7 and 1988–90.

Rabkin and Yellin10 study showed that in the pre-AIDS period, the incidence of anal cancer in the never-married, 25- to 54-aged San Francisco men group was 3.5 per 100,000. This was 9.9 (95% CI 4.5 to 18.7) times the expected rate of the total male SEER population for that period. By 1988–90, the standardised incidence had increased to 5.9 per 100,000 for the never-married 25- to 54-aged San Francisco men group. The SEER population rates, however, had similarly increased and the observed–expected ratio remained almost unchanged at 10.1 (95% CI 5.0 to 18.0). The authors concluded that HIV-1 is not related to the increase risk of anal cancer in homosexual men that antedated the AIDS epidemic.

Anal cancer and HIV/AIDS

In 2005, Diamond et al. 11 reported on a study that linked cancer registry data from 1988 to 2000 and AIDS registry data from 1981 to 2003 for San Diego County, USA. The authors defined 1991–5 as the pre-highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) era and 1996 to 2000 as the post-HAART era. The authors identified 42 men with SCC of the anus. The authors found that amongst men aged 25–64 years with AIDS, the average annual incidence of anal cancer pre-HAART was 88 per 100,000 and post-HAART, 190 per 100,000. They further reported that the annual incidence of invasive anal cancer increased from 0 per 100,000 men aged 25–64 years with AIDS in 1991 to 2224 per 100,000 in 2000. Pre-HAART, the average annual incidence of invasive anal cancer was 49 per 100,000 men aged 25–64 years with AIDS, whereas post HAART it was 144 per 100,000. It was also reported that patients diagnosed with anal cancer during the post-HAART era had a longer duration of diagnosed HIV infection (84 months vs 22 months pre-HAART).

For post-HAART anal cancer, both invasive and in situ, Diamond et al. 11 reported an average incidence of 190 per 100,000 men aged 25–64 years with AIDS (95% CI 209 to 646) compared with men without HIV/AIDS. The authors did acknowledge that the numbers of cases in the study were small but that the information had been collected for more than a decade from both registries.

In 2005, Chiao et al. 8 reported a population-based analysis of temporal trends in the incidence of squamous cell cancer of the anus (SCCA) in relation to the HIV epidemic. Chiao et al. 8 obtained data from the SEER programme, from 1973 to 2001 to characterise the primary site, histology [classified according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, version 3 (ICD-O3)], tumour site, stage at diagnosis, initial radiation therapy, patient demographics, age, gender, race and/or ethnicity, and mortality. Tumours with anatomic sites coded C21.0 through to C21.1 and C21.8 (anus, anal canal and anorectum) were included. The analysis was limited to cases with histological types coded as invasive non-in situ epidermoid cancers according to the ICD-O3. In situ cases were included only in the analysis describing stage at diagnosis.

Chiao et al. 8 used three eras to group the years of diagnosis. As the first case definition of AIDS was adopted in 1982, the period 1973–81 was defined as the pre-HIV era. The years 1982–95 were defined as the HIV era. HAART was widely introduced in 1996, and the years 1996–2001 were defined as the HAART era. A total of 4855 cases on invasive SCCA were reported from 1973 to 2001. The overall incidence from 1973 to 2001 was 0.8 per 100,000 population, an increase from 0.6 (95% CI 0.6 to 0.7) in the pre-HIV era to 0.8 (95% CI 0.8 to 0.8) in the HIV era, and to 1.0 (95% CI 1.0 to 1.1) in the HAART era.

The conclusions reached by Chiao et al. 8 were that the incidence of SCCA has increased steadily over the past three decades, and that since the introduction of HAART the incidence of SCCA has risen particularly among men and younger individuals – the groups most affected by HIV.

Grulich et al. 12 undertook a cohort study involving an Australian nationwide linkage of HIV, AIDS and cancer registry data to describe the incidence of non-AIDS-defining cancers in people with HIV infection before and after the occurrence of AIDS, and to examine the association of cancer risk with immune deficiency. In Australia, HIV and AIDS are reported with a name code (first two letters of first and last name), date of birth and sex. The authors attempted linkage for all of those individuals who had complete data for these three fields on either the national HIV or AIDS database. The procedure of linkage with the cancer register was not fully described, but a link to a paper giving details was given. Briefly, linkage was performed using a modified version of the National Cancer Register, with full names converted to name codes. A match was accepted if there was an exact match on all three fields, or there was a near match supported by consistency between the registers in dates of death and area of residence. Linkage was performed separately for the HIV and AIDS databases. HIV and AIDS data were available up to December 1999, and cancer data until 1995–98 depending on jurisdiction.

Grulich et al. 12 reported that 10 cases were observed for cancer of the anus compared with the expected number of cases of 0.27. The standard incidence rate (SIR) was 37.1 (95% CI 17.8 to 68.3), significant at p <0.05. The author’s conclusions were that, in this study, anal cancer rates increased from HIV diagnosis to the time around AIDS diagnosis, but there were no diagnoses more than 6 months after AIDS. Even in people with the mildest degree of immune deficiency the rates of this cancer were increased 20-fold above what was expected. The authors acknowledged that the data did not support an independent association between invasive anal cancer and HIV-associated immune deficiency but it may be that prolonged observation will be necessary.

In 2000, Frisch et al. 13 described a study looking at lifestyle factors associated with HPV-associated malignancies. The authors studied invasive and in situ HPV-associated cancers amongst 309,365 patients with HIV infection/AIDS in the USA, 5 years before the date of AIDS onset and 5 years after. Between 1995 and 1998, data from AIDS and cancer registries in 11 state and metropolitan locations were linked; these states and locations contained approximately one-third of the US population.

Among both male and female patients with AIDS, the majority were aged between 20 and 49 years at AIDS onset (88% and 86%, respectively). Of the males in the study, HIV infection was via homosexual contact (56%), homosexual contact and intravenous drug use (6%), intravenous drug use (26%), heterosexual contact (3%) or unknown/other (9%).

Frisch et al. 13 reported that invasive and in situ anal cancers were present in 360 patients (239 were invasive cancer and 121 in situ), with a mean age at onset of 41 years for invasive anal cancer and 37 years of in situ anal cancer. For invasive anal cancer, the relative risk (RR) was 6.8 (95% CI 2.7 to 14.0) for females and 37.9 (95% CI 33.0 to 43.4) for males. For in situ anal cancer, the RR was 7.8 (95% CI 0.2 to 43.6) for females and 60.1 (95% CI 49.2 to 72.7) for males.

Anal cancer and HPV

Hemminki and Dong14 used the Swedish Family-Cancer Database to analyse the spectrum of cancers diagnosed in husbands of women with in situ or invasive cervical cancer, and compared these to second carcinogenic events in women presenting with these cancers. The author’s hypothesis was that there was increased cancer susceptibility from HPV. The Swedish Family-Cancer Database (which includes all persons born in Sweden after 1934 with their biological parents, some 9.6 million individuals). From this database the authors identified 313,602 men with cancer after the birth of their last child; 6839 were men whose wife was diagnosed with in situ cervical cancer, and 2813 were men whose wife was diagnosed with invasive cervical cancer. Women (117,921 with in situ cervical cancer and 17,579 with invasive cervical cancer) were followed for second events (i.e. first cancer after in situ cancer and second primary cancer after first primary cancer) until the end of 1996, resulting in 7455 women with first cancers (after in situ cervical cancer) and 1990 women with second primaries (after invasive cervical cancer).

Hemminki and Dong14 reported that for wives with in situ cervical cancer, the husbands had an excess of cancer at six sites: upper aerodigestive tract (including mouth, tongue, larynx and pharynx), stomach, anus, lung, kidney and connective tissue, with anal cancer showing the highest SIR of 1.75. Penile cancer showed an SIR of 1.30 (95% CI 0.91 to 1.77). These sites agreed with first cancers of women who had suffered from an in situ cervical cancer. SIRs for female cancers were high for anus (3.60), lung (2.08) and other tobacco-related sites. The authors concluded that the results suggest that female cervical cancer, probably through HPV infection, is associated with anal and, weakly, with penile cancer in husbands. There was a consistency in husbands’ anal cancers irrespective of wives’ in situ or invasive cervical cancer. The authors reported that the findings are consistent with the demonstrated associations between HPV infection, sexual activity and anal cancer in men and women.

In 2002, De Sanjose and Palefsky15 undertook a review to summarise recently published epidemiological information that contributed to understanding the natural history of cervical and HPV infection and their associated lesions among HIV-infected women and men. De Sanjose and Palefsky15 concluded that HIV-positive women and men are more likely to be infected with oncogenic HPV types and to have cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) or anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) lesions that may lead to invasive cervical and anal cancer, respectively.

Anal cancer and homosexual partnerships

In 2003, Frisch et al. 16 undertook a retrospective cohort study of 1614 women and 3391 men in Denmark for cancer from their first registration for marriage-like homosexual partnership between 1989 and 1997. The authors used data from the population-based Danish Cancer Registry to investigate the cancer profile of all men and women in Denmark who had one or more records of registered homosexual partnership between 1989 and 1997. The Civil Registration System in Denmark has kept continuously updated files on basic demographic variables of its citizens. The system uses a unique 10-digit personal identification number as key – recorded information includes name, date of birth, marital status, emigration and vital status since 1968.

Frisch et al. 16 reported that for women in registered homosexual partnerships, no incidences of anal cancer were identified and that overall cancer incidence among this group differed little from that of Danish women in general (RR = 0.9, 95% CI 0.6 to 1.4, n = 24 cancers). For men, the overall risk of cancer among 3391 men in registered homosexual partnerships increased twofold (RR = 2.1, 95% CI 1.8 to 2.5, n = 139). The authors reported that this excess was almost entirely due to high numbers of Kaposi’s sarcoma (RR = 136, 95% CI 96 to 186, n = 38) and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (RR = 15.1, 95% CI 10.4 to 21.4, n = 32) cases. A statistically significant excess was also seen for anal squamous carcinoma (RR = 31.2, 95% CI 8.4 to 79.8, n = 4).

Frisch et al. 16 concluded that apart from HIV/AIDS-associated cancers and anal squamous carcinoma in men, Danish men and women in registered homosexual partnerships appear not to be at any unusual cancer risk compared with the general population.

In 1999, Lacey et al. 17 reported on a prospective cohort study of HIV-positive homosexual men. A total of 57 subjects were recruited from a larger cohort [300 patients, 33% Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) group C] attending North Manchester General Hospital for their HIV care in January 1994 and were followed for 18 months.

The participants in the Lacey et al. 17 study were interviewed and underwent screening for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), anal cytology and HPV at enrolment and at subsequent follow-up visits, with anoscopy and biopsy at the final visit. The study end point with anoscopy and biopsy was reached by 38 participants. The average follow-up was 17 months (range 14–21 months, total 650 months); 184 outpatient visits were attended and 184 cytology and HPV specimens were available for analysis.

Lacey et al. 17 concluded that AIN and infection with multiple oncogenic HPV types are very common among immunosuppressed HIV-positive homosexual men. Apparent progression from low to high-grade cytological changes occurred over a short follow-up period, with no cases of carcinoma. All 23 cases of high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia (HG-AIN) were predicted by cytology and/or anoscopy. The authors further concluded that it appears that anoscopy and cytology could be a useful screening procedure in the detection of high-grade disease in immunosuppressed HIV-positive homosexual men, but questions remain to be answered about the significance of HG-AIN in this group of patient, it seems wise to urge caution when considering screening programmes until more data about the natural history and efficacy of treatment options are known.

HPV infection

The natural history of HPV infection is complex, and clearance and persistence of viral DNA, along with progression to squamous intraepithelial lesions (SILs), vary depending on the viral type and patient characteristics, such as age and immune status. 18

Palefsky et al. 19 reported in 1998 the findings of a cohort study to characterise the prevalence of 29 different HPV types and the mixture of 10 additional types in the anal canal among HIV-positive and HIV-negative men. Palefsky et al. 19 recruited 346 HIV-positive and 262 HIV-negative men from among homosexual and bisexual men in the San Francisco Men’s Health Study (SFMHS) in the San Francisco General Hospital Cohort Study (SFGH) and the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), responding to newspaper advertisements. The participants were interviewed regarding their medical history, prescribed drug use, X-ray exposure, hospitalisation, transfusions, history of sexually transmitted diseases, intestinal parasites, hepatitis anal conditions (such as fissures and fistulas) and symptoms related to HIV. The participants were also asked about sexual practices, cigarette smoking, drinking and recreational drug use. Participants also tested underwent HPV testing. Palefsky et al. 19 reported no differences between HIV-positive and HIV-negative men.

Kreuter et al. 20 conducted a prospective cohort study in Germany to determine the clinical spectrum of AIN and lesional HPV colonisation in a cohort of homosexual men who were HIV-positive and had a history of receptive anal intercourse. Between December 2003 and July 2004, 103 homosexual men with a laboratory-confirmed diagnosis of HIV were recruited for a screening programme for AIN. The participants underwent a standardised interview on medical history, STDs, history of HPV-related diseases and tobacco use before screening.

Kreuter et al. 20 reported that of all patients 86% had anal HPV infection at their first visit. AIN was diagnosed in 20 (19.4%) of the 103 participants. The authors concluded that their data confirmed the high incidence and prevalence of inpatients with AIN who are HPV positive with HIV infection. The authors of this paper were of the opinion that standardised screening programmes for anal cancer prevention and treatment protocols for AIN in patients infected with HIV must be implemented.

Watson et al. 21 in 2006 reported on a prospective cohort of 72 patients (52 women, 20 men) who were diagnosed with AIN between January 1996 and December 2004. These 72 patients, from a single institution in New Zealand, were identified from a prospective database. Data collected from the database were supplemented with information from patient chart review, which included data on age, sex, HIV/AIDS infection, chronic immunosuppression, disease presentation, management and follow-up. All patients underwent biopsy or perianal skin excision between January 1996 and July 2005; 17 patients were initially diagnosed with AIN 1, 10 with AIN 2, and 45 with AIN 3 on first biopsy. A total of 42 patients also had pathological changes that were consistent with HPV infection. Seven patients were recipients of renal transplants and were on immunosuppressive therapy. Five patients were HIV positive and 10 others were on long-term immunosuppressive therapy for other causes.

Watson et al. 21 detailed that, during the study period, 193 procedures were carried out (127 were biopsies only and 66 were perianal skin excisions). Eight patients progressed to develop SCC during the study period (median time 42 months). There was histological evidence of progression in 11 patients, with six patients having AIN 3 progressing to have anal SCC. Two patients with AIN 2 developed cancer and 25 patients with AIN had regression of dysplasia. The conclusion reached by Watson et al. 21 was that their study suggested that patients with HG-AIN are at a higher risk of developing anal SCC than previously thought and surveillance is indicated. The authors also concluded that the patients who are particularly at risk are the immunocompromised, and that the treatment available at present does not prevent AIN in some patients from progressing to invasive cancer and carries the associated risk of faecal incontinence. Watson et al. 21 further concluded that as a result of their study they could not recommend screening of asymptomatic high-risk populations, but that there is a need for research into more effective and less morbid treatments for this disease.

Prognosis

The staging system for anal cancer is the TNM (tumour, node, metastasis) staging system. 22 The TNM staging system is useful for surgical purposes, such as providing guidelines on the extent of resection, it is described in more detail below.

The TNM staging system is based on the anatomical extent of spread, where, T refers to the extent of the primary tumour, N refers to the extent of nodal metastases and M refers to the presence or absence of distant metastases. Each of these three factors is given a number: for T, the number indicates how large the tumour is; for N, the number informs which lymph nodes have cancer cells in them; and for M, the number informs as to whether the cancer has spread to other parts of the body – in general, the higher the number, the more serious the cancer. There are five stages of tumour size in the current TNM classification of anal cancer: T1–T4 and a very early stage called Tis or carcinoma in situ. Anal cancers are not usually found at this very early stage, as they do not cause any symptoms when they are so small. Below are descriptions of each T stage for anal cancer:

-

Tis or carcinoma in situ The earliest stage of anal cancer, when the cancer cells are found only inside the lining of the anus and have not spread elsewhere.

-

T1 The tumour measures 2 cm across or less.

-

T2 The tumour is larger than 2 cm but smaller than 5 cm.

-

T3 The tumour is larger than 5 cm.

-

T4 The cancer can be any size, but is growing into the surrounding tissues or organs, such as the urethra, the vagina or bladder.

Staging is a process that tells the clinician how widespread the cancer may be at the time of diagnosis. It will show whether the cancer has spread and how far. The treatment and outlook for anal cancer depends, to a large extent, on its stage.

In 2004, Johnson et al. 3 reported 5-year survival figures of 58% for males and 64% for females, based on data collected between 1973 and 2000 on diagnosis and outcomes of invasive and in situ anal cancer. The data came from the SEER programme in the USA. Lower 5-year survival figures were reported by Bower et al. 23 for a cohort of English patients with HIV (25 MSM and 1 heterosexual woman) with confirmed cases of invasive anal cancer. Bower et al. 23 reported a 5-year overall survival figure of 47%.

In 2006, Karandikar et al. 4 reported a 5-year overall survival figure of 45%, based on a cohort of patients with anal cancer who were identified from a 5-year audit (1995–9) of anal cancer in Wales.

Also in 2006, Jeffreys et al. 24 reported the results of a study that was based on all first, primary, invasive malignant cancers of the rectum and anus – excluding anal margin and skin – that were diagnosed in adults (15–99 years) and registered in the National Cancer Registry for England and Wales between 1986 and 1999. The aims of the study were to investigate the effects of tumour and patient characteristics on trends in the survival of patients with cancer of the anus or rectum in England and Wales. A total of 132,542 adults who were diagnosed during the 14 years were followed up to 2001 through the National Health Service Central Register. Results were given for patients diagnosed during the calendar periods 1986–90, 1991–5 and 1996–9. Relative survival up to 5 years after diagnosis was estimated, using deprivation-specific life tables. Five-year relative survival rose by about 10% overall, from 38% (1986–90) to 48% (1996–9) in men, and 39% (1986–90) to 51% (1986–90) in women.

Gatta et al. 7 gave details on survival and incidence from rare cancers using data collected from 18 European countries. They reported that the overall 5-year relative survival for anal SCC was good at 53.1% (95% CI 51.5 to 54.8); the authors also reported absolute survival figures, with 53.1% (95% CI 51.7% to 54.4%) for 3-year survival and 43.3% (95% CI 41.9% to 44.6%) for 5-year survival.

For the UK, Gatta et al. 7 reported a 5-year relative survival of 51.9% (95% CI 49.7% to 54.2%). Data for the UK (England, Scotland and Wales) came from national cancer registries or from regional cancer registries.

Quality of life

Allal et al. 25 undertook a study to assess long-term quality of life (QoL) in patients treated by RT with or without chemotherapy. The study population was drawn from 165 patients with anal carcinoma who received sphincter-conserving treatment using RT, with or without chemotherapy, between January 1976 and December 1994. Patients were considered for the study’s QoL assessment if they were 80 years old or less and were alive without disease activity at least 3 years after completion of treatment with a functioning anal sphincter. In total, 52 patients satisfied the inclusion criteria – 49 patients were contacted by telephone to request their participation in the study and three were contacted by mail. Of these patients, 46 patients agreed to participate, one refused, two were assessed to be ineligible because of serious comorbidities and the three contacted by mail did not respond. Among the 46 patients who received the two questionnaires, five refused to complete them for different reasons (two ‘unclear’, two ‘number of questions’, one ‘questions relating to sexual aspects’). This left 41 patients for the analysis.

The QoL questionnaires used by Allal et al. 25 were developed by the QoL Study Group of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). One was a validated questionnaire assessing cancer-specific QoL (EORTC QLQ-C30) (Aaronson et al. 1993) and one assessing site-specific (colorectal) QoL (EORTC QLQ-CR38), which at the time of the study was in the process of validation.

The EORTC QLQ-C30 is a patient self-rating questionnaire that comprises six multi-item function scales measuring physical, role, social, emotional and cognitive functions, along with overall QoL. Separate symptom scales are included to assess pain, fatigue and emesis, and five single items to measure gastrointestinal symptoms, dyspnoea, appetite loss and sleep disturbances. A final item evaluates the perceived economic consequences of the disease.

The EORTC QLQ-CR38 is a patient self-rating questionnaire that comprises 38 questions, of which 19 are completed by all patients and the remaining by a subset of patients (males or females, patients with or without a stoma). The general structure comprises four multi-item/single-function scales, seven multi-item symptom scales and one single symptom item. The functioning scales assess effects on micturition, chemotherapy, side effects, gastrointestinal general symptoms, defecation problems, stoma-related problems and sexual dysfunction in males or females. The single symptom item assesses weight loss.

The result reported by Allal et al. 25 for the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire was that the physical function scale scores did not differ significantly in the subgroups, although older patients tended to report lower scores (p = 0.08). For the role function scale, while non-significant, the severity of late complications and poor MSK (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Center anal function criteria) anal function appear to have a negative effect (p = 0.08 for both). For the emotional and the social function scales, no significant differences were noted between the different subgroups. However, the overall QoL score was significantly affected by the severity of late complications (p = 0.005) and the anal function score (p = 0.04). This score did not differ with the current age and pain symptom scales, particularly according to the length of follow-up.

The results of the EORTC QLQ-CR38 questionnaire used by Allal et al. 25 were that body image function score was significantly lower only in patients with advanced T stage (p = 0.003). For the future perspective function scale, no significant differences were noted between subgroups, while lower scores were reported in patients with higher grade of late complications (p = 0.1). The sexual functioning score was significantly lower only in the advanced-age subgroup (p = 0.01). None of the function scale scores seemed to be influenced by the length of follow-up. A significantly higher defecation problems score was reported in patients who were treated with brachytherapy for the boost (p = 0.03).

Allal et al. 25 concluded that in patients treated with sphincter conservation for anal carcinomas, long-term QoL, as measured by the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-CR38, appeared to be acceptable, with the exception of diarrhoea and, perhaps, sexual function. The subset of patients who presented with severe complications and/or anal dysfunction showed poorer scores in most scales.

In 2005, Pachler and Wille-Jorgensen26 reported on a systematic review of QoL after rectal resection for cancer, with or without permanent colostomy. The objective of the review was to evaluate the QoL in patients treated for rectal cancer with either abdominoperineal excision (APE), with a permanent stoma or rectal anastomosis anterior resection (AR) with preservation of the sphincter function.

The criteria for considering studies to use in the review by Pachler and Wille-Jorgensen26 were:

-

All controlled clinical trials and observational controlled studies in which QoL in patients with rectal cancer, having either APE or AR were studied using a multidimensional QoL instrument.

-

The participants were individuals with verified cancer of the rectum, which had been treated with either APE or AR.

-

No discriminatory criteria concerning age, gender, race or social status.

-

Quality-of-life assessments using validated multidimensional questionnaire, self-reported questionnaires completed by the patient – a relative or independent rater was considered eligible for inclusion.

-

Assessments of functional results or one-dimensional aspects of QoL (e.g. sexual function, urinary function, pain) were not included in the review.

Pachler and Wille-Jorgensen26 reported that 30 potential studies were identified, 11 of these, including 1412 participants (range 23–372), met the inclusion criteria. None was randomised, nine were retrospective and two prospective. Overall, six studies found that patients undergoing APE did not have poorer QoL than patients undergoing AR. One study found that a stoma only slightly affected the patient’s QoL; four found that after APE patients had significantly poorer QoL than after AR. The authors concluded that it was not possible to draw conclusions whether the QoL measures of stoma patients are poorer than for non-stoma patients. However, the results challenge the assumption that people with stoma fare less well than non-stoma patients.

Chapter 2 Methods

Systematic reviews were conducted to identify and assess all literature relating to the screening of anal cancer in high-risk groups.

Search strategies

A comprehensive literature search was undertaken in January 2006 (updated in November 2006) to identify relevant literature pertaining to screening high-risk groups for anal cancer. Four major searches were conducted, which were designed to retrieve papers:

-

describing the epidemiology of anal cancer

-

on the effectiveness of screening technologies for anal cancer

-

on the effectiveness of different screening programmes/policies for anal cancer

-

on the cost-effectiveness and comparative costs of candidate technologies/programmes/policies identified from effectiveness searches. Searches were also undertaken to retrieve papers on the effectiveness of different treatments for anal cancer.

The following electronic bibliographic databases were searched:

-

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA)

-

BIOSIS previews (Biological Abstracts)

-

British Nursing Index (BNI)

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL)

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR)

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

-

EMBASE

-

MEDLINE

-

MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations

-

NHS Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE)

-

NHS Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Database

-

PsycINFO

-

Science Citation Index (SCI)

-

Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI).

Attempts were also made to identify ‘grey’ literature by searching appropriate databases (e.g. the King’s Fund, DH-Data) current research registers [e.g. National Research Register (NRR), Current Controlled Trials (CCT) register]. A general internet search was also conducted using a standard search engine (Google) and a meta-search engine (Copernic).

The reference lists of included studies and relevant review articles were also checked.

No date or language restrictions were applied to these searches. The search strategies used in MEDLINE (Ovid) are displayed in Appendix 3.

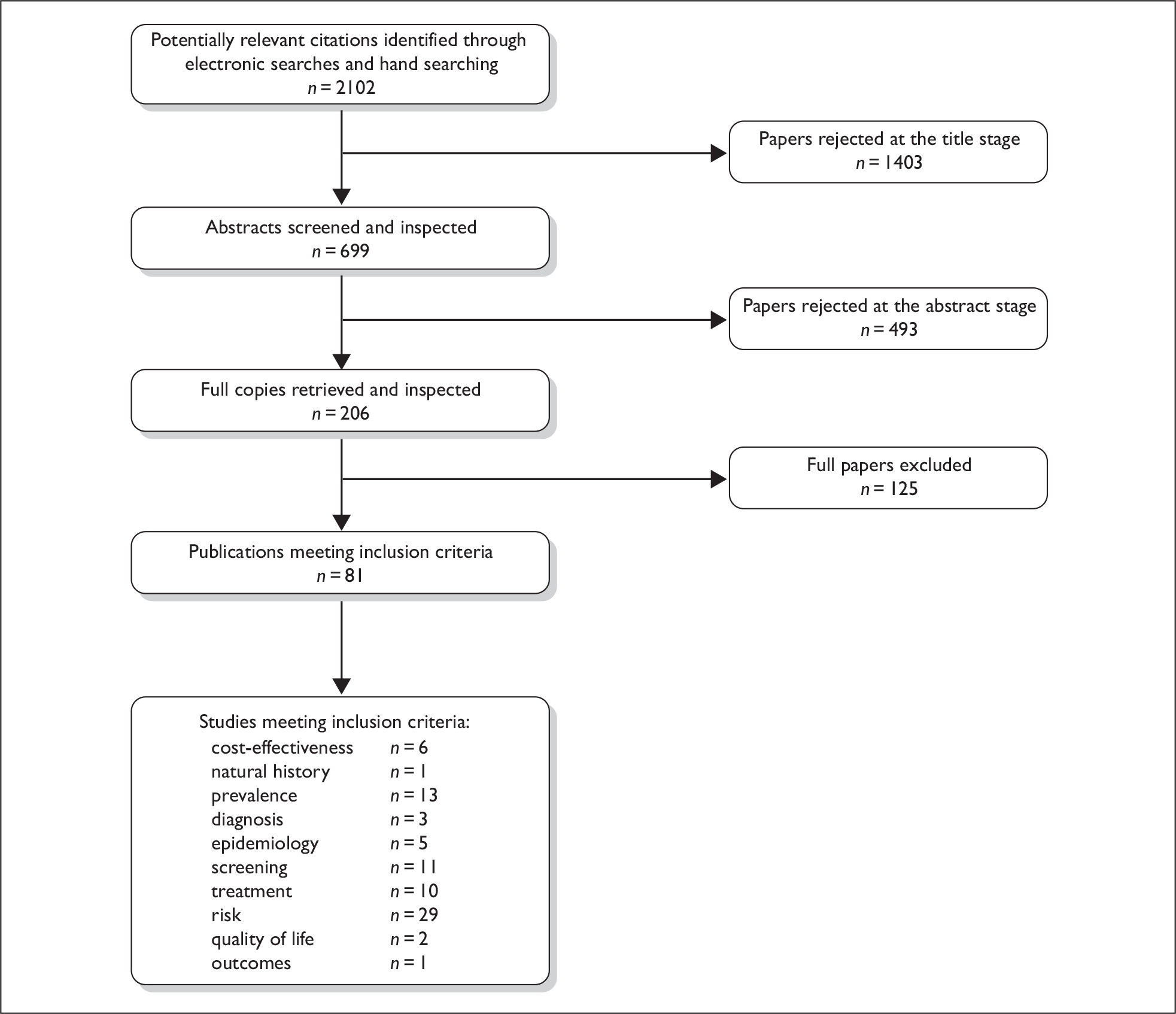

All prospective and retrospective primary studies groups who were at high risk of anal cancer were included in the review. An assessment was conducted of published literature identified by the search strategy by all four reviewers. All publications were divided into the following broad categories based initially on their titles and abstracts (where available): cost-effectiveness, natural history, prevalence, diagnosis, epidemiology, screening, treatment, risk, QoL, and not relevant – excluded. A paper could be included in more than one category. The reviewers then obtained copies of all papers not excluded. Some papers were reclassified after reading the full text, additional papers were subsequently excluded. Each paper not excluded after the initial readings was given a unique identifier. Hand searching of included papers was conducted to identify any relevant papers not detected by the electronic searches. A quality of reporting of meta-analyses (QUOROM) trial flow chart is displayed in Appendix 4.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Papers were selected if they met the following inclusion criteria:

-

contained data on population incidence, effectiveness of screening, health outcomes or screening and/or treatment costs of anal cancer

-

described defined suitable screening technologies

-

prospectively evaluated a test, or a combination of tests, to detect anal cancer.

Papers were excluded if they were a foreign language publication.

Data abstraction

Data from all of the studies meeting the inclusion criteria were extracted into data extraction forms by the clinical effectiveness reviewer.

Chapter 3 Results

Screening

This section reviews studies that evaluated screening procedures for the detection of AIN, anal squamous intraepithelial lesion (ASIL) or anal cancer. Ten studies were identified for inclusion on screening; Table 3 shows the studies characteristics and Appendix 5 gives details on study quality. Nine studies were cohort studies27–35 and one was a systematic review. 36

| Study details | Objective | Population | Inclusion/exclusion criteria | Study type | Screening test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| de Ruiter 199427 | To compare anal cytology with histology as a method of detecting AIN | Homosexual or bisexual men (n = 215) | Homosexual and bisexual men attending a central London department of GU medicine for routine follow-up of their HIV infection or with newly diagnosed anal condylomata | Cohort study | Anal cytological smear performed under standard conditions |

| Palefsky et al. 199728 | To assess the sensitivity, specificity, and positive and NPVs of anal cytology | HIV-positive (n = 407) and HIV-negative (n = 251) homosexual and bisexual men | HIV-positive and HIV-negative homosexual and bisexual men, who were participating in a natural history study of ASIL | Cohort study | Anoscopically directed anal biopsy as standard. Anal cytology results were classified using standard Bethesda criteria38 for cervical cytology |

| Mathews et al. 200429 | To estimate agreement between consecutive anal cytological examinations, between concurrent cytological examination and histopathology, and between HRA visual impression and histopathology and to estimate the prevalence of severe dysplasia by concurrent cytological category | Patients with HIV (n = 1864) | HIV-infected patients receiving anal dysplasia screening as part of routine care for HIV at the University of California at San Diego Owen Clinic, with a history of anal receptive intercourse, anogenital warts or anal/cervical dysplasia | Prospective observational cohort study | Anal Pap test with a repeat Pap test and biopsy performed for patients with a screening Pap diagnosis of ASCUS, LSIL or HSIL |

| Panther et al. 200430 | To determine the accuracy of anal Pap smear as a predictor of paired anal histology results, as well as whether HIV serostatus had an impact on findings | MSM (n = 153) | MSM referred to an anal dysplasia clinic | Cohort study | Anal Pap smears |

| Fox et al. 200537 | To establish whether anal cytology has value as a screening tool and to validate the Palefsky method based on a UK population | Homosexual/bisexual males who underwent high-resolution anoscopy (n = 99) | Cohort study | Dacron swab was inserted blindly 3 cm into the anal canal and rotated using a spiral motion | |

| Arain et al. 200531 | To assess the usefulness and limitations of anal smears in screening for ASILs | Males that had anal smears collected in liquid medium (n = 198) | Anal smears retrieved from files of the pathology department at Cedars-Sinai Medical Centre, Los Angeles | Cohort study | Anal smears collected in liquid medium compared with results of surgical biopsies or repeat smears |

| Friedlander et al. 200332 | To evaluate anorectal cytology as a screening tool and to correlate anorectal cytology with anoscopic and histological findings | Patients that had anorectal specimens on file (n = 51) | Anorectal specimens retrieved from the files of the cytology service at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York | Cohort study | Retrieved smears stained with Papanicolaou stain |

| Lampinen et al. 200633 | To compare self- vs clinician-collection procedures with respect to specimen adequacy for cytological evaluation | HIV-1 seronegative MSM aged 18–30 years (n = 222) | Men involved in a study of HIV incidence and risk behaviours among young HIV-1 seronegative MSM conducted in Vancouver | Cross-sectional study | Self- and clinician- collected anorectal Dacron swabs for liquid-based cytological evaluation were collected |

| Cranston et al. 200436 | To assess the performance of results collected by study participants at home compared with samples collected by experienced research clinicians in a clinic of MSM with a high prevalence of AIN | HIV-positive and HIV-negative MSM (n = 125) | HIV-positive and HIV-negative MSM, enrolled at the University of California at San Francisco Anal Neoplasia Study; criterion: who previously had an anal cytology sample taken by a practitioner | Cohort study | Self-collection kit and standard clinician-collected samples |

| Varnai et al. 200536 | To examine methods that may enable the routine diagnosis of HPV-induced changes in the anal rim and the consequences of such detection of a more sensitive diagnosis of AIN | Patients that had tissue samples from anal lesions, which had been archived (n = 87) | Patients who had been diagnosed with the following: invasive anal carcinoma, AIN of varying severity and condylomatous lesions | Cohort study | Tissues samples from anal lesions, which had been archived, were retrospectively examined, for histological examination; the tissue was completely embedded in paraffin and processed according to the usual methods of diagnostic histology |

| Chiao et al. 200636 | To evaluate and summarise indirect evidence concerning anal Pap smear screening for HIV-infected patients | HIV-infected individuals | Studies were excluded if they did not include HIV-infected individuals or did not include original data | Systematic review | Anal Pap smear |

The reporting quality of the screening studies is generally poor, making it difficult to assess the true quality of the work undertaken. Only one of the studies is randomised. The remaining studies are cohort studies. The data tend not to be analysed on an intention-to-treat basis and assessors are not blinded.

Anal cytology

De Ruiter et al. 27 reported on a cohort study that recruited 215 homosexual/bisexual men. The perianal area and anal canal were then examined using a colposcope, and areas macroscopically suggestive of intraepithelial neoplasia were biopsied.

The anal cytology and histology methods used by De Ruiter et al. 27 were:

-

Cytology Patients were examined in the lithotomy position. Anal smears were obtained by blindly inserting a cytobrush 1.5–2.0 cm into the anal canal, rotating through 360°, transferring to a glass slide and fixing with 96% ethanol.

-

Histology An oblique-viewing Graeme Anderson proctoscope was inserted into the anal canal.

The findings from De Ruiter et al. 27 were:

-

Cytology A total of 126 (81.8%) of the 154 patients had macroscopic anal condylomata and 28 (18.2%) had no macroscopic evidence of anal condylomata; 46 patients were found to have features of both HPV and AIN, 85 (55.2%) had evidence of HPV alone and 23 (14.9%) were found to be negative.

-

Histology A total of 169 (78.6%) had macroscopic anal condylomata, 46 (21.4%) did not have macroscopic anal condylomata and 176 (81.9%) were biopsied; 76 patients (35.4%) had histological evidence of both HPV and AIN, 91 (42.3%) had features suggestive of HPV alone and 9 (4.2%) were normal.

-

Comparison between anal cytology and histology Of the 154 patients with an adequate anal smear, 56 (36.4%) had both HPV and AIN on histology; 67 (43.5%) had evidence of HPV alone; and 31 (20.1%) were negative.

The conclusions reached by De Ruiter et al. 27 were that anal cytology is a sensitive but non-specific method of identifying patients with biopsy-proven AIN if cytological features of HPV alone are included as abnormal smears. The authors reported that specificity is improved by restricting abnormal smears to those with features of both HPV and AIN but it markedly lowers the sensitivity of the test. The authors further concluded that at the time of the study, anoscopy and histology are required in addition to anal cytology to differentiate between patients who simply have anal condylomata and those who also have AIN.

The cohort members of the 1997 cohort study by Palefsky et al. 28 were participating in a natural history study of ASIL, using anoscopically directed anal biopsy as the standard. Overall, 658 homosexual or bisexual male subjects were studied: 407 (62%) were HIV positive and 251 were HIV negative. The mean age of HIV-positive men was 41 years, range 21–66 years, whereas for HIV-negative men the mean was 44 years with a range of 25–73 years.

Palefsky et al. 28 reported that, defining abnormal cytology as including atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) and ASIL, the sensitivity of anal cytology for detection of biopsy-proven ASIL in HIV-positive subjects was 69% (95% CI 60 to 78), specificity 59% (95% CI 53 to 65), the positive predictive value (PPV) was 38% (95% CI 31–45) and the negative predictive value (NPV) was 84% (95% CI 79–89). A PPV is the proportion of those with a positive test who actually have the disease, whereas a NPV is the proportion of those with a negative test who actually do not have the disease.

For HIV-negative subjects, Palefsky et al. 28 reported that, using the previous definition, the sensitivity of anal cytology for detection of biopsy-proven ASIL was 47% (95% CI 26–68), specificity 92% (95% CI 89–95), the PPV 35% (95% CI 15–54) and the NPV was 95% (95% CI 93–98). The authors concluded that anal cytology may be a useful screening tool to detect ASIL, particularly in HIV-positive men. The grade of disease on anal cytology did not always correspond to the histological grade, and anal cytology should be used in conjunction with histopathological confirmation.

Between July 2000 and September 2003, Mathews et al. 29 identified 1864 patients who underwent 2918 Pap tests: 8.4% were female, 11.5% were black, 21.5% were Hispanic, 60.4% were white and 6.6% from other ethnic groups; 68.4% were MSM, 15.4% related to injection drug abuse, 9.4% were related to heterosexual transmission and 6.8% were related to other risk factors. Median age was 39 years (35–45 interquartile range). The authors suggested that the reproducibility of key screening measures is moderate at best but of similar magnitude to that of other studies of anal and cervical dysplasia screening.

Panther et al. 30 accounted the results of a study that looked at comparing the pathological diagnoses obtained by anal Pap smear with those obtained by anal biopsy or by surgical excision for 153 MSM. The medical histories, high-resolution anoscopy (HRA) findings and pathology reports of these MSM were recorded. Of the 153 MSM, 100 (65%) were HIV positive and 53 (35%) were HIV-negative. The basis for referral was an abnormal screening anal Pap smear finding [24 (24%) of 100 HIV-positive and 22 (42%) of 53 HIV-negative subjects], HG-AIN on pathological examination of surgically removed anogenital condylomata [19 HIV-positive subjects (19%) and six HIV-negative subjects (11%)], or a history of internal and/or external anal condylomata for 40 HIV-positive subjects (40%) and 14 HIV-negative subjects (26%). The remainder of the cohort was referred for anal bleeding, palpable internal and/or external anal mass, or screening.

Panther et al. 30 stated that the detection of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) on an anal Pap smear had a sensitivity of 47% (95% CI 35–59) and specificity of 90% (95% CI 81–96) for detection of a high-grade histological finding (AIN level 2, AIN level 3 or SCC) in the paired specimen. Panther et al. 30 believe that the cross-sectional data presented in their article independently confirmed a substantial incidence of histologically proven high-grade anal dysplasia in MSM who present with minimally abnormal anal Pap smear findings. The authors also stated that their study independently confirmed that a substantial proportion of low-grade dysplasia on anal Pap smears occurs with HG-AIN in MSM, and that it confirmed that abnormal anal cytological findings of any grade should suggest the possibility of high-grade histological findings.

Fox et al. 37 prospectively collected data from 99 consecutive homosexual/bisexual male patients who underwent HRA at the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital anoscopy clinic. Data from follow-up visits on this group of patients were also included in the study. The anoscopy procedure used by Fox et al. 37 utilised the cytology method developed by Palefsky, whereby a Dacron swab was inserted blindly 3 cm into the anal canal and rotated, using a spiral motion, outward pressure was applied on the anal canal and the swab was gradually withdrawn. They reported that 160 anoscopic procedures were reviewed from 99 homosexual or bisexual men in whom both cytological and histological examinations were planned. Eighty-nine (90%) patients were HIV positive and 10 were known to be HIV negative. They concluded that anal cytology by the Palefsky method is simple to undertake, and can therefore be used as the basis of a pilot screening project in centres with large cohorts of HIV-positive homosexual men who have a high risk of developing anal carcinoma. HPV genotyping is not a useful adjunct to cytological screening.

Arain et al. 31 studied the cytomorphological features of 200 consecutive anal smears collected in liquid medium from 198 patients, and the findings were correlated with results of surgical biopsies and/or repeat smears that became available for 71 patients within 6 months. They concluded that liquid based anal smears had a high sensitivity (98%) for detection of ASIL but a low specificity (50%) for predicting the severity of the abnormality in subsequent biopsy, and suggested that all patients with a diagnosis of ASCUS should be recommended for HRA with biopsy.

Anorectal cytology

Friedlander et al. 32 collected 78 consecutive anorectal specimens representing 51 patients: 33 patients were HIV positive (27 males, six females). All HIV-positive females also had a history of gynaecological (vulvar, vaginal or cervical) intraepithelial neoplasia. The mean age of the patients was 43 years (range 26–74 years). The results from this study were that with histology as the gold standard, the sensitivity of cytology to distinguish benign from dysplasic or malignant lesions was 92% but the specificity was only 50%. Friedlander et al. 32 concluded that anorectal cytology is an accurate method for screening patients for anal squamous lesions. Atypical parakeratotic cells represent a potential pitfall. Anoscopy is important in confirming the presence of a lesion, but only a biopsy can accurately determine the grade of a lesion.

Self-screening

In 2006, Lampinen et al. 33 evaluated self-screening for anal cancer by MSM. Paired self- and clinician-collected anorectal Dacron swabs for liquid-based cytological evaluation were collected in random sequence from this cohort of young MSM. Each participant provided at the same study visit two anorectal swab specimens: one self-collected and one collected by the study clinician. Specimens collected by clinicians were more adequate than those collected by men who were wholly naive to the procedure; however, it was found that the vast majority of self-collected anorectal swab specimens from MSM were adequate for cytological evaluation. The conclusion reached by Lampinen et al. 33 was that self-collection of anorectal swab specimens for cytological screening in research and possibly clinical settings appears feasible, particularly if specimen adequacy can be further improved. The severity of biopsy-confirmed anorectal disease is seriously underestimated by cytological screening, regardless of collector.

A total of 125 MSM were invited to take part in the study by Cranston et al. ,34 and 102 were included in the analysis: 82 were HIV positive and 20 HIV negative. The participants in the study by Cranston et al. 34 were given a cytology self-collection kit, with written instructions for use, and requested to collect the sample 1 month after the clinic visit. Cranston et al. 34 reported that the sensitivity of any grade of anal cytology abnormality for detection of AIN 1, AIN 2, or AIN 3 was comparable between clinician-collected (70%) and self-collected (68%) samples. The sensitivity of any grade of anal cytology abnormality for detection of a high-grade lesion (AIN 2 or 3) was also comparable between clinician-collected (74%) and self-collected (71%) samples. The sensitivity of anal cytology to detect AIN in self-collected samples was higher among HIV-positive men than among HIV-negative men. Among the 57 HIV-positive men, anal cytology to detect AIN overall or AIN 2 or 3 specifically was also higher for HIV-positive men in the clinician-collected samples, and the magnitude of these differences in sensitivity was similar to those seen in self-collected samples (p = 0.15 for AIN overall; p = 1.0 for AIN 2 or 3). The conclusions reached by Cranston et al. 34 were that MSM with biopsy-proven AIN can self-collect anal cytology samples with sensitivity comparable with that of experienced clinicians, and that this may facilitate screening for AIN.

Histological markers

Varnai et al. 35 retrospectively examined biopsy samples from 87 patients for microscopic indications of HPV infection. After microdissection, additional HPV analysis via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was carried out. Varnai et al. 35 reported that in 38 of 47 cases of anal carcinoma, HPV DNA could be detected via PCR (80.9%), the majority of which were HPV 16 (33 out of 38 = 86.8%). In 29 of the 33 cases of AIN, HPV DNA was detected (87.9%), most of these in AIN 3 (15 out of 16 = 93.8%). Histological markers of HPV infection were detected in all 87 cases. The authors recommended any histological reports on excision of anal lesions to include a statement as to whether histological markers of HPV infection were detected. In individual cases, that, validation via HPV PCR must be considered.

Anal Pap smear screening for HIV-infected patients

Chiao et al. 36 systematic review of the English-language literature published from July 1996 through to July 2005 noted that the natural history of progression from anal intraepithelial neoplasia to anal cancer is unknown, and although low-grade anal dysplasia has been shown to progress to high-grade dysplasia (HGD) in a majority of HIV-infected men within 2 years after initial diagnosis, the true rate of progression from HGD to invasive anal cancer remains unclear.

Chiao et al. 36 commented that the data published to date highlight limitations to current anal Pap smear screening-related research, no randomised or cohort studies exist to determine if there are improved survival or outcomes for those who have been screened with anal Pap smears, and that there have been no ecological studies to correlate use of screening and the incidence or outcomes of SCCA.

Screening summary/discussion

The sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV (where given) of the studies reported in Chapter 3 (see Screening) are displayed in Table 4. The PPV will depend on the prevalence rate of the disease: if the disease (such as anal cancer) has a low prevalence rate then we would expect to have a low PPV. Where reported, 95% CIs are included.

| Study details | Screening test | n | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| de Ruiter et al. 199427 | Anal cytology | 154 | 88 | 16 | 37 | 70 |

| Histology | 215 | 34 | 73 | 41 | 66 | |

| Palefsky et al. 199728 | Anal cytology (ASCUS and above) HIV-positive patients | 407 | 69 (95% CI 60 to 78) | 59 (95% CI 53 to 65) | 38 (95% CI 31 to 45) | 84 (95% CI 79 to 89) |

| Anal cytology (ASCUS and ASIL) HIV-negative patients | 251 | 47 (95% CI 26 to 68) | 92 (95% CI 89 to 95) | 35 (95% CI 15 to 54) | 95 (95% CI 93 to 98) | |

| Anal cytology ASIL, HIV-positive patients | 407 | 46 (95% CI 36 to 56) | 81 (95% CI 76 to 85) | 46 (95% CI 36 to 57) | 80 (95% CI 76 to 85) | |

| Anal cytology ASIL, HIV-negative patients | 251 | 26 (95% CI 5 to 47) | 98 (95% CI 96 to 100) | 56 (95% CI 22 to 89) | 94 (95% CI 91 to 97) | |

| Fox et al. 200437 | Anal cytology | 99 | 83 | 38 | 86 (95% CI 78 to 91) | 33 (95% CI 19 to 51) |

| Cranston et al. 200434 | Self-collected anal cytology samples | 102 | 68 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Clinician-collected anal cytology samples | 102 | 70 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | |

| Panther et al. 200430 | Anal Pap smear (HG-AIN) | 153 | 47 (95% CI 35 to 59) | 90 (95% CI 81 to 96) | 81 (95% CI 66 to 92) | 65 (95% CI 55 to 74) |

| Anal Pap smear (LSIL) | 68 (95% CI 56 to 78) | 48 (95% CI 36 to 59) | 59 (95% CI 48 to 69) | 57 (95% CI 44 to 70) | ||

| Arain et al. 200531 | Anal Pap smear | 71 | 98 | 50 | Not reported | Not reported |

|

Varnai et al. 200635 |

Histology | 87 | 94 | 80 | 85 | 91 |

Since the late 1990s, the sensitivity and specificity of reported screening tests for anal cancer appear to have improved (Table 4). Within recent years, sensitivity values of 70–98% have been reported,31,34,35 which would highly suggest that screening techniques have improved. However, the reported PPVs are mixed while a number of studies fail to report these values (Table 4). This reflects the relative rarity of anal cancer. Large numbers would need to be screened to identify a relatively small number of affected individuals. Table 4 allows comparisons to be made between the historical data and the positive and NPVs. ROC (receiver operating characteristic) curves have not been generated for this review.

The two studies by Lampinen et al. 33 and Cranston et al. 34 reported that self-collected samples (anorectal swabs or anal cytology) are adequate for interpretation, although further research is needed before using self-collected samples in a screening programme. However, both the De Ruiter et al. 27 and Palefsky et al. 28 studies put forward that anal cytology should be used in conjunction with histopathological confirmation.

Treatment

Six studies40–45 were identified and included in this review: Table 5 displays characteristics of the studies and Appendix 6 gives details on study quality. The criteria of the National Screening Committee (NSC) for appraising the viability, effectiveness and appropriateness of a screening programme (Appendix 2) states that there should be an effective treatment or intervention for patients identified through early detection, with evidence of early treatment leading to better outcomes than late treatment. Therefore, survival from treatment options is of interest. For completeness, comments from an editorial38 and Effective Health Care bulletin issued in March 200439 are included at the end of this section.

| Study details | Study type | Design | Patient group | Study objectives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UKCCCR Anal Cancer Working Party 199640 | RCT |

Multicentre RCT with a main end point of local failure whether due to disease or complications of treatment, as indicated by the need for major surgical intervention. Five-year survival was a secondary end point. Eligible patients had epidermoid carcinoma (squamous, basaloid or cloacogenic) of the anal canal or margin, no evidence of major hepatic or renal dysfunction, and normal blood counts From 856 patients considered for entry to the multicentre trial, 585 patients were randomised to receive initially either 45-gray (Gy) RT in 20 or 25 fractions over 4–5 weeks (290 patients) or the same regimen of RT combined with 5-FU by continuous infusion during the first and final weeks of RT and mitomycin (12 mg/m2) on day 1 of the first course (295 patients). Clinical response was assessed 6 weeks after initial treatment: good responders were recommended for boost RT and poor responders for salvage surgery. The main end point was local failure rate (≥ 6 weeks after initial treatment); secondary end points were overall and cause-specific survival. Analysis was by intention to treat |

Any patient with anal cancer | To compare the most promising regimens of RT alone with CMT |

| Cummings et al. 198441 | Case series | A subset (25 patients) of 51 anal canal carcinoma patients treated by radical external beam radiation alone (RT) between 1958 and 1978, were compared with 30 patients with anal canal carcinoma treated by combined 5-FU, mitomycin C and radical radiation therapy (FUMIR) between 1978 and 1982 | Any patient with anal cancer | The results and toxicity of treatment of anal canal carcinoma by radiation therapy or radiation therapy and chemotherapy in a single centre |

| Doniec et al. 200642 | Case series | From 1993 to 2001, 50 patients with histologically confirmed primary cancer of the anal canal (n = 38) and the anal margin (n = 12) without evidence of distant metastases were treated at the University Clinic Kiel with curative intention. Prior to treatment, all patients underwent staging, consisting of digital and EUS investigation of the anus and the rectum (7-MHz transducer, BandK Medical), sphincter manometry, total colonoscopy, ultrasound of the abdomen and the inguinal region, and CT scan of the pelvis. Forty-five patients were admitted and examined | Any patient with anal cancer | To optimise local tumour control by TRUS-guided brachytherapy and thereby minimise the risk of local recurrence, resulting in a reduced rate of salvage abdominoperineal resection |

| Brown et al. 199943 | Between 1989 and 1996, 46 patients were identified with HG-AIN; 34 underwent local excision of all macroscopically abnormal disease and the resulting defect was left open, closed primarily or skin grafted. Regular follow-up subsequently included anoscopy and biopsy of any suspicious lesions. All patients diagnosed in one hospital with HG-AIN between 1989 and 1996 were included | Any patient with anal cancer | ||

| Edelman and Johnstone 200644 | Case series | Retrospective review of the records of 17 HIV-positive patients with anal SCC treated with CMT of RT and concurrent chemotherapy, between 1991 and 2004, at a single institution | HIV-positive patients | To report the toxicity and survival data of HIV-positive patients with anal SCC treated with CMT of RT and concurrent chemotherapy |

| Place et al. 200145 | Case series | This was a retrospective cohort study, which identified 73 patients with anal SCC, treated at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center-affiliated hospitals; 23 were HIV positive. In the HW-positive group, nine had in situ squamous carcinomas and 14 had invasive SCCs. Data collected included age, CD4 count, treatment, complications and survival | HIV-positive patients | To determine the outcome of HIV-positive patients with anal SCCs |

RT alone vs a combination of RT/chemotherapy

Two studies reported on the treatment of anal cancer by RT alone or a versus combination of RT/chemotherapy: there was one randomised controlled trial (RCT)40 and one cohort study. 41

In 1996, the United Kingdom Co-ordinating Committee for Cancer Research (UKCCCR) Anal Cancer Working Party40 reported on a trial to compare combined modality therapy (CMT) with RT alone in patients with epidermoid anal cancer. The aim was to compare the most promising regimens of RT alone with CMT, within a multicentre RCT. The main end point of the trial was local failure whether due to disease or complications of treatment, as indicated by the need for major surgical intervention, with 5-year survival as a secondary end point. Patients were eligible if they had epidermoid carcinoma (squamous, basaloid or cloacogenic) of the anal canal or margin, no evidence of major hepatic or renal dysfunction, and normal blood counts. The Working Party40 reported that from 856 patients considered for entry to the multicentre trial, 585 patients were randomised to receive initially either 45 Gy RT in 20 or 25 fractions over 4–5 weeks (290 patients) or the same regimen of RT combined with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) (1000 mg/m2 for 4 days or 750 mg/m2 for 5 days) by continuous infusion during the first and the final weeks of RT and mitomycin (12 mg/m2) on day 1 of the first course (295 patients). Clinical response was assessed 6 weeks after initial treatment: good responders were recommended for boost RT and poor responders for salvage surgery.

The UKCCCR Anal Cancer Working Party40 findings were that, after a median follow-up of 42 months (interquartile range 28–62), 164 of 279 (59%) patients receiving RT had a local failure compared with 101 of 283 (36%) of patients receiving CMT. This gave a 46% reduction in the risk of local failure in the patients receiving CMT (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.69, p < 0.0001). The risk of death from anal cancer was also reduced in the CMT arm (0.71, 95% 0.53 to 0.95, p = 0.02). There was no overall survival advantage (0.86, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.11, p = 0.25). Early morbidity was significantly more frequent in the CMT arm (p = 0.03), but late morbidity occurred at similar rates. There was no statistically significant difference in overall survival between the two groups, with a 58% 3-year survival rate for the RT arm and 65% for the CMT arm.

The authors reported that the UKCCCR Anal Cancer Working Party trial40 showed that the standard treatment for most patients with epidermoid anal cancer should be a combination of RT and infused 5-FU and mitomycin, with surgery reserved for those who fail on this regimen.

In 1984, Cummings et al. 41 reported on the results and toxicity of treatment of anal canal carcinoma by radiation therapy or radiation therapy and chemotherapy in a single centre. In this study, a subset (25 patients) of 51 patients with anal canal carcinoma, treated by radical external beam radiation alone between 1958 and 1978, were compared with 30 patients with anal canal carcinoma treated by combined 5-FU, mitomycin C and radical radiation therapy (FUMIR) between 1978 and 1982.

Cummings et al. 41 reported that the uncorrected 5-year survival rate in each group was approximately 70%, but primary tumour control was achieved in 93% (28 of 30 patients) in the FUMIR group compared with 60% (15 of 25 patients) treated with RT. The authors further reported that colostomies were needed as part of treatment for residual carcinoma or for the management of treatment-related toxicities in 11 of the 25 patients treated by radiation alone, and required (at the date of the study) in 4 out of the 30 patients treated by FUMIR.

The conclusion reached by Cummings et al. 41 was that the improvement in the primary tumour control rate, and the reduction in the number of patients requiring colostomy when compared with the results of RT, favour combined chemotherapy and radiation as the initial treatment for anal canal carcinoma.

RT combined with chemotherapy

One prospective cohort study42 and two retrospective cohort studies44,45 reported on patients treated with RT combined with chemotherapy.

Doniec et al. 42 reported using CMT of anal cancer and transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)-guided high dose rate (HDR) after-loading therapy on 50 patients with histologically confirmed primary cancer of the anal canal (n = 38) and the anal margin (n = 12) with curative intention. Prior to treatment, all patients underwent staging consisting of digital and endosonographic ultrasonography (EUS) investigation of the anus and the rectum (7-MHz transducer, BandK Medical), sphincter manometry, total colonoscopy, ultrasound of the abdomen and the inguinal region, and CT scan of the pelvis. All patients underwent follow-up examination 3 months after completion of brachytherapy, including clinical examination and TRUS. This was repeated at 3-month intervals for 1 year, followed by 6-month intervals during the second year, and annually thereafter. The median follow-up was 34 months (range 6–96). Relapse rates, disease-specific survival and overall survival were calculated according to the Kaplan–Meier method.