Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 08/49/01. The contractual start date was in July 2009. The draft report began editorial review in February 2010 and was accepted for publication in June 2010. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Overweight and obesity are defined as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that may impair health. A complex relationship between genetic,1 biochemical, neural and psychological factors, and environmental aspects2 can come into play in the development of overweight and obesity. Studies have shown that age, gender and ethnicity are key risk factors for weight gain. 3–5 Without intervention, reversal of overweight and obesity is uncommon. 4

The most commonly used measure for classifying overweight and obesity is the body mass index (BMI). This is a simple ratio that is defined as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in metres (kg/m2). Overweight in adults is most commonly defined as a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or over, and obesity as a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or over (Table 1).

| Classification | BMI (kg/m2) |

|---|---|

| Underweight | < 18.50 |

| Normal range | 18.50–24.99 |

| Overweight | ≥ 25.00 |

| Pre-obese | 25.00–29.99 |

| Obese | ≥ 30.00 |

| Obese class I | 30.00–34.99 |

| Obese class II | 35.00–39.99 |

| Obese class III (morbid obesity) | ≥ 40.00 |

Description of the underlying health problem

It has been estimated that globally, in 2005, approximately 1.6 billion adults (aged 15 years and over) were overweight and at least 400 million adults were obese. 7 A recent systematic review estimated that across European countries the prevalence of obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2) ranged from 4% to 28.3% in men, and 6.2% to 36.5% in women. 8 A 2009 NHS Information Centre report,9 drawing on data from the Health survey for England 2007 (HSE)10 states that in England in 2007, 65% of men and 56% of women were overweight or obese. In Wales in 2007, 57% of adults were classified as overweight or obese, including 21% obese. 11 In 2008, 68.5% of men and 61.8% of women aged 16 years or over in Scotland were overweight or obese. 12 Data from Northern Ireland in 2005/6 show that 59% of adults were either overweight (35%) or obese (24%), and rates were similar across genders. 13

Prevalence of obesity varies by age as well as by gender. In the 2009 NHS Information Centre report9 prevalence of overweight and obesity varied by age, with high rates in older age groups (Table 2). In the Northern Ireland health and social wellbeing survey 2005/06, obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2) was most prominent among those aged between 35 and 64 years. 13

| Overweight or obese | Age (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16–24 years | 25–34 years | 35–44 years | 45–54 years | 55–64 years | 65–74 years | 75 + years | All ages | |

| All adults | 33 | 49 | 65 | 68 | 74 | 73 | 69 | 61 |

| Men | 33 | 54 | 71 | 75 | 79 | 77 | 71 | 65 |

| Women | 32 | 44 | 58 | 62 | 68 | 69 | 67 | 56 |

Overweight or obesity in women is more common in lower income households (defined using equivalised household income which takes account of the number of people in the household) than in women in the highest income households. 9 In men this pattern is not seen. Other demographic characteristics potentially associated with overweight and obesity include urbanisation, marital status and ethnicity. Available data for rates of obesity from the HSE 2004 report showed that men from Bangladeshi and Chinese minority ethnic groups had the lowest prevalence (both 6%) while Black Caribbean and Irish men had the highest prevalence (both 25%). 9 There are also regional differences in England in the prevalence of overweight and obesity, with generally higher levels in the North. 14 Estimates from survey data also suggest these geographical differences are widening in women but not in males (based on Health Survey data from 1993 and 2004). 14

The prevalence of obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2) among adults is increasing. Estimates from England in 2007 reported obesity prevalence was 24% for both men and women. This shows a clear increase from the figures shown in 1993, which were 13% for men and 16% for women. 9 In Wales there has also been an upward trend in obesity over time among people aged over 16 years. 10 Data from Scotland also show that there has been a steady upward trend (data is for overweight and obesity) in adults since 1995 (55.6% of men and 47.2% of women aged 16–64 years in 1995 compared with 66.3% and 59.6%, respectively in 2008). 12

The prevalence of obesity is predicted to rise in the future. The World Health Organization (WHO) has projected that by 2015 more than 700 million adults worldwide will be obese. A projection of the UK prevalence of obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2) extrapolating data from 1993 to 2004 onto 2012, showed that the prevalence would be 32.1% in men and 31.0% in women, suggesting nearly 13 million people will be obese by 2012. 15 The projected prevalence for adults was higher for those in manual social classes (48%) than non-manual social classes (35%). Another estimate of obesity prevalence, modelled in the UK’s Foresight project ‘Tackling obesities: future choices’, showed that if current trends persist, 36% of men and 28% of women aged 21–60 years will be obese in 2015. 16

Health consequences of overweight or obesity

Obesity can cause a variety of adverse health consequences. An increased risk of health problems starts when someone is only very slightly overweight; this risk increases as someone becomes more and more overweight. 7,17 The predominant serious health consequences associated with overweight and obesity include Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, musculoskeletal disorders such as osteoarthritis, and many cancers (Table 3).

| Greatly increased risk (relative risk > 3)a | Moderately increased risk (relative risk 2–3)a | Slightly increased risk (relative risk 1–2)a |

|---|---|---|

| Type 2 diabetes | Coronary heart disease | Cancer (breast cancer in postmenopausal women, endometrial cancer, colon cancer) |

| Gallbladder disease | Hypertension | Reproductive hormone abnormalities |

| Dyslipidaemia | Osteoarthritis (knees) | Polycystic ovary syndrome |

| Insulin resistance | Hyperuricaemia and gout | Impaired fertility |

| Breathlessness | Low back pain due to obesity | |

| Sleep apnoea | Increased risk of anaesthesia complications | |

| Fetal defects associated with maternal obesity |

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 89 studies reporting incidence of comorbidities related to obesity and overweight found statistically significant associations for multiple comorbidities. 18 Being overweight (BMI 25.00–29.99 kg/m2) was associated with the increased incidence of Type 2 diabetes, most cancers (except oesophageal in females, pancreatic and prostate cancer), all cardiovascular diseases, asthma, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis and chronic back pain. Being obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) was associated with an increased incidence of Type 2 diabetes, all cancers (except oesophageal and prostate), all cardiovascular diseases, asthma, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis and chronic back pain. The associations were most strongly observed for the incidence in Type 2 diabetes in females, for those overweight and those obese.

A recent meta-analysis of prospective observational studies19 assessed the association between increases in BMI and the incidence of common adult cancers. Positive and strong associations with a 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI in men were identified for cancer of the oesophagus [relative risk (RR) 1.52], thyroid cancer (RR 1.33), colon cancer (RR 1.24) and renal cancer (RR 1.24). In women, positive and strong associations with a 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI were seen for endometrial cancer (RR 1.59), gallbladder cancer (RR 1.59), oesophageal cancer (RR 1.51) and renal cancer (RR 1.34). Weaker positive associations were identified for rectal cancer and malignant melanoma in men, postmenopausal breast cancer, pancreatic, thyroid, and colon cancers in women, and leukaemia, multiple myeloma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in both sexes. These findings are similarly reflected in a recently published report on the relationship between food, nutrition, and physical activity and the prevention of cancer by the World Cancer Research Fund. 20 Based on a series of systematic reviews this report shows evidence of a convincing risk of oesophageal, pancreatic, colorectal, breast, endometrial and kidney cancers with increased body fatness. The association with oesophageal cancer noted in these latter studies is in contrast to that of the systematic review noted above and may reflect differences in the analysis.

The relationship between BMI and mortality has also recently been investigated in an analysis of 57 prospective studies. 17 Deaths of known cause during a mean of 8 years of follow-up (adjusted for age, gender, smoking status and study) showed that in both sexes and at all ages, mortality was lowest in people with a BMI of about 22.5–25 kg/m2. A progressive excess mortality above this range was shown, with each 5 kg/m2 higher BMI being associated with approximately 30% higher overall mortality {hazard ratio [HR] per 5 kg/m2 1.29 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.27 to 1.32]}. For vascular mortality, diabetic, renal and hepatic mortality the HRs were 1.41 (95% CI 1.37 to 1.45), 2.16 (95% CI 1.89 to 2.46), 1.59 (95% CI 1.27 to 1.99) and 1.82 (95% CI 1.59 to 2.09), respectively (ranging from 40% to 120% higher mortality). There were no specific causes of death that were inversely associated with a BMI above the range 22.5–25 kg/m2. This study showed that mortality from cancer was 10% higher with each 5 kg/m2 higher BMI [HR 1.10 (95% CI 1.06 to 1.15)]. 17 In this study there was a greater proportional increase in the risk of mortality at younger ages (35–59 years) with each 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI, but the trend for higher overall mortality per increment in BMI was still seen in the older age groups. This is different to the findings of an earlier systematic review21 of elevated BMI in those aged 65 years or over. The conclusions of this latter study suggested that a BMI in the overweight range was not associated with a significantly increased risk of mortality. 21

Psychosocial consequences of overweight and obesity

Alongside the health consequences of overweight and obesity a number of self-perceived problems such as low self-esteem and disturbance of body image can also affect an individual. Socially, obese people often encounter discrimination and prejudice at work and in public. 22 This can lead to negative economic and social consequences such as low educational attainment and lower income. 23,24 In general, quality of life (QoL), whether physical, psychological or social, is lower in those who are overweight or obese. 23 There is growing evidence to show that there is a strong negative correlation between degree of overweight and QoL; greater impairments in QoL are associated with greater degrees of weight increase. 22,23 One recent analysis based on surveillance data25 found that being obese was associated with a significant deterioration in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) but being overweight was not. Reduced physical health and QoL associated with obesity can contribute to impaired mental well being. 25 This may also be influenced by gender as excess weight among women has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of depression, suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts, whereas this is less common in males. 24 A recent large population study (n = 43,534)26 investigated the relationship between depression and BMI. This study noted that there was a significant U-shaped association between BMI categories and depression such that being obese and being underweight were associated with depression.

Benefits of weight loss

Overweight and obesity together are the second leading cause of preventable death, primarily through effects on cardiovascular disease risk factors (hypertension, dyslipidaemia and Type 2 diabetes). 27 Weight loss improves these risk factors, and some evidence suggests that benefits can persist as long as weight loss is maintained. 28,29 A systematic review30 found that weight loss from various interventions was associated with decreased risk of development of diabetes, and a reduction in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, total cholesterol and blood pressure (BP) in the long term. The results of weight loss on mortality are however less certain. One systematic review31 undertaken in 2007 suggests that weight loss has long-term benefits on all-cause mortality, particularly for women and for those with diabetes. However, a recent (2009) meta-analysis32 showed that weight loss had a neutral effect on all-cause mortality. This study did find evidence of benefit in terms of mortality in those classified as ‘unhealthy and obese’. A recent evidence synthesis of surgery for obesity compared with non-surgical options found that weight loss in the longer term reduced the incidence of risk factors such as metabolic syndrome, hypertriglyceridaemia and hyperuricaemia, and increased the proportion of people with remission from Type 2 diabetes. 33

After weight loss, HRQoL has also been shown to be improved, even when weight loss has been small to moderate. 23,24 Participants in one cohort study showed improved HRQoL after a 1-year weight loss programme, and a strong relationship between the amount of weight lost and the change in QoL was also seen. This suggests that greater weight loss leads to greater improvement in HRQoL. 34

In addition to health benefits resulting from weight loss there are cost implications to the health service. As many of the factors making up this cost are attributable to comorbidities [such as stroke, coronary heart disease (CHD), hypertension and diabetes mellitus], any reduction in the incidence of these conditions as a consequence of weight loss is likely to produce a cost saving to the health service.

However, for many people the lifestyle factors that have contributed to weight gain are difficult to change in order to lose weight. Although attempts at weight loss are often successful in the short term, sustaining the weight loss can be difficult.

Current service provision

Management of disease

Overweight and obesity are initially managed within the general practice setting. The recommendation within the clinical section of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) obesity guideline35 is that the level of intervention discussed with patients should be based on patient BMI, waist circumference measurement, and presence of comorbidities (Table 4).

| BMI classification | Waist circumference | Comorbidities present | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | Very high | ||

| Overweight (BMI 25.00–29.99 kg/m2) | General advice on healthy weight and lifestyle | Diet and physical activitya | Diet and physical activity; consider drugs | |

| Obesity I (BMI 30.00–34.99 kg/m2) | ||||

| Obesity II (BMI 35.00–39.99 kg/m2) | Diet and physical activity; consider drugs | |||

| Obesity III (BMI 40 kg/m2 and above) | Diet and physical activity; consider drugs; consider surgery | |||

Non-surgical interventions based on a combination of diet and physical activity, accompanied by strategies to support behavioural (lifestyle) changes, form the cornerstone of overweight and obesity treatment. Recommendations regarding lifestyle interventions (LIs) for overweight and obesity have been provided within the clinical section of recommendations within the NICE guideline. 35 These recommendations state that ‘Multicomponent interventions are the treatment of choice. Weight management programmes should include behaviour change strategies to increase people’s physical activity levels or decrease inactivity, improve eating behaviour and the quality of the person’s diet and reduce energy intake’. 35 It is also recommended that treatments should be individualised, both in terms of the type of treatment suggested and the level of support provided.

The guidelines give some indication of the information or content within a multicomponent intervention that should be provided for the weight loss, behavioural and physical activity aspects. For weight loss, adults should be informed that a realistic maximum weekly weight loss target is 0.5–1 kg (1–2 lb), and the overall aim should be to lose 5–10% of original weight. Diets that have a 600 kcal/day deficit (that is, they contain 600 kcal fewer than the person needs to stay the same weight) or that reduce calories by lowering the fat content (low-fat diets), in combination with expert support and intensive follow-up, are recommended for sustainable weight loss. The guidance states that low-calorie diets (1000–1600 kcal/day) may be considered, but are less likely to be nutritionally complete. Very-low-calorie diets (VLCD) (< 1000 kcal/day) may be used for a maximum of 12 weeks continuously, or intermittently with a low-calorie diet (for example, for 2–4 days per week), by people who are obese and have reached a plateau in weight loss. There should be clinical supervision of any diet of < 600 kcal/day.

Behavioural therapy interventions should be delivered with the support of an appropriately trained professional. The strategies included in behavioural therapy interventions need to be appropriate for the person, and can include:

-

self-monitoring of behaviour and progress

-

stimulus control

-

goal-setting

-

slowing rate of eating

-

ensuring social support

-

problem solving

-

assertiveness

-

cognitive restructuring (modifying thoughts)

-

reinforcement of changes

-

relapse prevention

-

strategies for dealing with weight regain.

The physical activity recommendation is for at least 30 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity on 5 days or more a week. To prevent obesity, people may need to do 45–60 minutes of moderate-intensity activity a day, particularly if they do not reduce their energy intake.

The NICE guideline35 also states that the distinction between losing weight and maintaining weight loss should be explained and stresses the importance of developing skills for both phases. The change from losing weight to maintenance typically happens after 6–9 months. In the longer term, people should move towards eating a balanced diet, consistent with other healthy eating advice and continue with regular physical activity to avoid regaining weight.

In addition to the clinical recommendations the NICE guideline35 also provides recommendations for the wider public health setting. In this section the guideline states that weight loss programmes (including commercial or self-help groups, slimming books or websites) are recommended only if they are based on a balanced healthy diet, encourage regular physical activity, and expect people to lose no more than 0.5–1 kg (1–2 lb) a week. The guidance indicates that programmes that do not meet these criteria are unlikely to help people maintain a healthy weight in the long term and that people with certain medical conditions – such as Type 2 diabetes, heart failure or uncontrolled hypertension or angina – should check with their general practitioner (GP) or hospital specialist before starting a weight loss programme.

In some people who are overweight or obese, in particular those with other comorbidities or class I obesity, a prescription for weight control drugs can be considered. Surgery is usually only considered as a last resort if a number of criteria are fulfilled (e.g. BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 or between 35 kg/m2 and 40 kg/m2 with other significant disease and all appropriate non-surgical measures have been tried previously).

Current service cost

Estimating the costs of overweight and obesity has been approached in different ways. The impact of BMI on prescribing costs in the UK has been recently reported. 36 This study found that the attributable cost of overweight and obesity accounted for 23% of spending on all drugs, with 16% attributable to obesity. The minimum annual cost of any drug prescriptions at BMI 20 kg/m2 rose from £50.71 for men and £62.59 for women by £5.27 and £4.20, respectively, for each unit increase in BMI to a BMI of 25 kg/m2. Increases for each BMI unit were greater to BMI 30 kg/m2, and greater still, £8.27 (men) and £4.95 (women) to BMI 40 kg/m2, giving total annual prescribing costs at this level of obesity of £63.59 (men) and £27.16 (women).

A House of Commons Health Committee report37 included an update of the National Audit Office estimate of obesity costs for England in 1998 using cost data for 2002 (Table 5). This update estimated that the direct treatment costs of obesity for 2002 were between £46M and £49M. The costs included in calculating this estimate were those for GP consultations, ordinary admissions, day cases, outpatient attendances and prescriptions. The costs of treating the consequences of obesity (comorbidities) lay between £945M and £1075M. Combining the total costs of treating obesity with the total costs of treating the consequences of obesity results in total direct costs of £990–1225M (2.3%–2.6% of net NHS expenditure in 2001–2). When indirect costs are also included the costs of obesity rise further.

| Included costs | 2002 (£M) |

|---|---|

| GP consultations | 12–15 |

| Ordinary admissions | 1.9 |

| Day cases | 0.1 |

| Outpatient attendances | 0.5–0.7 |

| Prescriptions | 31.3 |

| Total cost of treating obesity | 45.8–49.0 |

| Consequences of obesity | |

| GP consultations | 90–105 |

| Ordinary admissions | 210–250 |

| Day cases | 10–15 |

| Outpatient attendances | 60–90 |

| Prescriptions | 575–625 |

| Total cost of treating the consequences of obesity | 945–1075 |

| Lost earnings due to attributable mortality | 1050–1150 |

| Lost earnings due to attributable sickness | 1300–1450 |

| Total indirect costs | 2350–2600 |

| Total cost of obesity | 3340–3724 |

These figures were based on people with a BMI of 25 kg/m2 and over and the Health Committee report stresses that these figures are likely to underestimate the true cost of treating obesity and its consequences. A more recent study, which included a wider range of costs, estimated the direct cost of overweight and obesity to the UK NHS at £3.2B per year. 38 The majority of the costs attributable to overweight and obesity were from treating stroke, CHD, hypertensive disease and diabetes mellitus. The cost estimate from this study may be higher than those of other published sources because cost estimates are sensitive to the chosen cut-off point for BMI. In this case people with a BMI of 22 kg/m2 and above were included, whereas some other studies have taken a BMI cut-off of 25 kg/m2.

The UK’s Foresight project ‘Tackling obesities: future choices’16 estimated that in 2007, overweight and obesity would account for £4.2B of the overall £17.4B estimated total annual cost to the NHS of diseases for which elevated BMI is a risk factor. The only factor considered in the model used to provide these estimates was BMI.

It has not been possible to determine the costs of adult weight management schemes within a primary care trust (PCT). There are a number of reasons for this but chiefly a lack of any centralised reporting of such information. When cost information for individual PCTs is found, for example on PCT websites or within press releases, the costs quoted are very variable. This variation in costs is because of factors that include:

-

Differences between PCTs in the proportion of adult weight management schemes provided within different settings such as leisure centres, primary care, pharmacies and schemes delivered in partnership with commercial weight loss organisations.

-

Costs for adult weight management services may be reported within an overall value that includes adult, child, and family-centred weight management services.

-

Differences in the target adult population: some schemes are only available to those who are obese, others are available to the overweight and the obese.

In general it appears that these weight management schemes are provided by PCTs to eligible adults who are not charged for using the service.

Variation in services

The large numbers of people in the population who are overweight and/or obese place a high demand on services from primary care. However, at the same time many practices have limited capacity to manage these people, and few evidence-based interventions to choose from. This has led to variation across the UK in the service offered to overweight and obese people. In 2001 a National Audit Office report39 concluded that approaches to weight management were inconsistent and that effective strategies for weight management were needed. This view was similarly echoed in a report of the House of Commons Health Committee in 2004. 37 More recently a survey by the Dr Foster organisation published in 200540 showed that primary care organisations employ a number of innovative approaches to the management of obesity; however, there is considerable national and regional variation in the service provided. The survey also showed that while more organisations had established weight management clinics than in their previous survey in 2003 (up by 5%), in the majority of general practices (69%) there was still no organised weight-management clinic.

Relevant national guidelines

The most comprehensive guideline for the prevention and management of obesity in adults in England and Wales is the NICE guideline. 35 This guideline, referred to in detail above, covers both primary and secondary care. Other guidelines which are relevant to the prevention and management of obesity in adult populations in the UK have been produced by the National Obesity Forum41 and the Northern Ireland Clinical Resource Efficiency Support Team. 42 They are consistent with the NICE guideline35 but focus on either primary care41 or secondary care. 42 Several UK guidelines are also available on the prevention and management of obesity in children and young people [e.g. the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network guideline43 (currently being updated; spring 2010)], and on the management of obesity using pharmacological and surgical approaches. However, these populations and interventions are outside the scope of the current assessment (see Chapter 2).

There are currently no National Service Frameworks (NSFs) that specifically focus on overweight or obesity. Guidance on avoiding obesity, with a focus on healthy diet and exercise, is included in the current NSF for CHD. 44

Existing systematic reviews

Weight management interventions have been the focus of a number of systematic reviews in recent years. Ten systematic reviews, published between 1997 and 2009, have included studies with weight management or weight maintenance interventions that comprised diet, exercise and/or behavioural components and reported weight outcomes for adults, and are summarised in Table 6. 30,45–53 Seven of these systematic reviews were restricted to randomised controlled trials (RCTs)30,45–50 and three focused on RCTs but also permitted inclusion of other study designs. 51–53 The minimum follow-up for weight management outcomes required for studies to be included in the systematic reviews was 12 months in the majority (n = 7), 12 weeks (n = 1), 24 months (n = 1) or was not specified (n = 1) (Table 6).

| Authors and date | Goal | Principal inclusion criteria | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design and intervention | Population | Follow-up | ||

| Glenny et al. 199751 | Determine effectiveness of interventions for obesity prevention and treatment, weight loss and weight maintenance | RCTs (other study designs accepted for prevention goal) | Overweight and obese adults and/or children | ≥ 12 months |

| McLean et al. 200345 | Evaluate family involvement in weight control or weight loss | RCTs with at least one family-based intervention | Adults and/or children | ≥ 12 months |

| McTigue et al. 200347 | Determine effectiveness of adult obesity screening and treatment | RCTs of fair or good quality | BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 | ≥ 12 months |

| Avenell et al. 200446 | Systematically review effectiveness of exercise ± diet ± and behaviour therapy for weight loss and other outcomes | RCTs; specific details of interventions required; weight change an explicit outcome | Adults with minimum, mean or median BMI 28 kg/m2 | ≥ 12 months from randomisation |

| Avenell et al. 200430 | Systematically review obesity treatments in adults to identify therapies that achieve weight reduction, risk factor modification or improved clinical outcomes | RCTs; sufficient details of interventions required | Adults with minimum, mean or median BMI 28 kg/m2 | ≥ 12 months from randomisation |

| Franz 200448 | Not clearly stated but focus on weight management interventions targeting women | RCTs of weight loss and maintenance | Women, BMI > 25 kg/m2 | ≥ 12 months |

| Tsai et al. 200553 | Describe major commercial and self-help weight loss programmes in the USA that provide structured in-person or online counselling | RCTs (other designs permitted); ≥ 10 participants; assessed intervention under same conditions as offered to public | Adults | ≥ 12 weeks |

| Söderlund et al. 200949 | Determine effectiveness of exercise ± diet ± behaviour therapy in overweight and obese healthy adults | RCTs; minimum n = 15 per intervention | Overweight or obese otherwise healthy adults | ≥ 12 months (or intervention ≥ 12 months) |

| Turk et al. 200950 | Summarise findings of RCTs that tested strategies for weight loss | RCTs with weight maintenance intervention after initial weight loss | Adults | Follow-up not stated |

| Brown et al. 200952 | Determine the effectiveness of long-term lifestyle interventions for the prevention of adult weight gain and morbidity | RCTs and controlled before–after studies | Adults, BMI < 35 kg/m2 | Weight reported ≥ 24 months after randomisation |

Eligible interventions varied between these systematic reviews. Their inclusion criteria required interventions to comprise diet, exercise and/or behavioural components, but not necessarily all three together. None of the systematic reviews precisely matched the ‘multicomponent’ approach supported in the NICE guidelines. The goal of the systematic review by Söderlund and colleagues49 appears the most similar, but this review did not formally require interventions to include diet or behavioural components. The remaining nine systematic reviews also included some interventions with diet, exercise and/or behavioural components but the reviews all had different goals (Table 6) from assessing multicomponent approaches per se. For example, the systematic review by Avenell and colleagues46 focused on interventions that included exercise, behaviour therapy and/or drugs and was not limited to those that also contained a diet component. In addition, many of their included studies provided limited details of their interventions and many were of relatively short-term follow-up.

The conclusions of the 10 systematic reviews were mixed, which in part reflects their differing objectives and inclusion criteria. Some reviews (including Söderlund and colleagues49) suggested that the most effective weight loss interventions are those that combine diet, exercise and behaviour components to achieve weight loss. 30,49,51 There was also some support for interventions that contained only one or two of these three elements. 30,48,52 However, it is difficult to draw any firm conclusions regarding the long-term benefits of multicomponent weight management approaches from these systematic reviews due to their different objectives and inclusion criteria.

There is therefore a need to systematically synthesise all relevant evidence from good-quality studies that report long-term results, in order to compare the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different weight management programmes in delivering sustained weight loss.

Description of technology under assessment

Weight management programmes aim to improve the eating behaviour and the quality of a person’s diet, to reduce energy intake, and to also increase people’s physical activity levels or decrease inactivity. 35 A multicomponent intervention is defined as one which combines more than one mutually reinforcing strategy to achieve a common outcome. It is thought that addressing multiple influences on overweight and obesity will be an effective way to reduce and maintain healthy weight. The components may be distinguished from each other in terms of setting, location, provider, format, media and content. As previously stated, good practice guidelines promote weight management programmes that are multicomponent interventions that usually involve a combination of diet, exercise and behavioural therapy with ongoing support. In this sense the components differ primarily in terms of content (i.e. focus on diet or physical activity), but may also differ, to varying extents, in terms of setting (e.g. clinics, leisure centres), provider (e.g. dietitians, behavioural therapists) and other attributes. They work towards the common goal of encouraging weight loss and maintenance.

Dietary approaches incorporated in weight management programmes used in the UK may involve strategies such as calorie restriction, VLCDs, low fat, low carbohydrate, high fibre, meal replacement, food combining, or low glycaemic index foods. As described above (see Current service provision), dietary goals, in terms of the number of kilocalories per day permitted, may be set according to the type of diet followed. Nutritionists, dietitians or trained nurses may deliver dietary interventions. Broader lifestyle approaches may also accompany dietary goals, including education around food labelling, cookery skills and identifying where healthier foods can be purchased.

Physical activity elements of weight management programmes include exercise training and endurance exercises (e.g. running, swimming) and resistance training (e.g. use of weights). Physiotherapists, specially trained staff or fitness coaches may deliver physical activity sessions to individuals or groups with differing degrees of supervision in settings such as leisure centres or community centres. Physical activity may also be self-supervised, with participants given exercise goals to be reached through activities of their own choosing, for example daily living activities, walking or cycling.

Behavioural therapy may include a number of specific techniques including: self-monitoring (e.g. systematically observing and recording one’s own behaviour); problem analysis (e.g. dealing with situations that might interfere with reaching dietary or exercise goals); alteration of cognitive patterns such as cognitive reframing and coping imagery; cognitive strategies for replacing negative thinking with positive statements (e.g. modifying self-defeating thoughts about dieting, constructive self-statements); relapse prevention (e.g. identifying when lapses might occur in diet or physical activity and how to deal with high-risk situations); goal-setting; menu planning; stimulus control (e.g. avoiding stimuli that might encourage eating, such as reducing the visibility of food in the home, slowing the pace of eating, avoiding fast food restaurants); and may be delivered by psychologists, trained interventionists and counsellors. Ongoing support may take the form of personal contact, meetings, telephone calls and internet technology, and be individual, group or family based. Therapy may be theoretically based, for example drawing on the stages of change (SOC) approach of the Transtheoretical Model, or Social Cognitive Theory. 54–56 However, it is recognised that definitions of behavioural techniques are not always standardised, or explicitly linked to a theoretical model of behaviour change. 57

Multicomponent interventions may also include surgery and prescribed or over-the-counter (OTC) weight loss drugs, although this is more often as a second-line treatment if weight loss goals have not been attained through diet, physical activity and behavioural therapy strategies. There has been recent interest in the use of OTC drugs for obesity and their place within multicomponent approaches to weight management. In 2009 the European Union approved the use of 60 mg orlistat per day (Alli™, GlaxoSmithKline) for purchase following consultation with a pharmacist for people with a BMI over 28 kg/m2. It is possible that people participating in multicomponent interventions may use OTC orlistat as an additional weight loss strategy, though it has been suggested that some may use it in place of diet and exercise. Research is needed to establish how it might be best used in practice. 58

Weight management programmes may be delivered in the primary care setting, by GPs supported by specialists as mentioned above, and tutors trained specifically to deliver such programmes, or through professionals in specialist hospital clinics. For example, the Counterweight Programme54 is a primary care-based programme in the UK that aims to help obese people to achieve weight loss (e.g. 5%–10% over 3–6 months) and weight maintenance through changes in diet and exercise. In addition to NHS-based programmes, commercial and self-help programmes are available such as Weight Watchers®, Slimming World, Rosemary Conley™, LighterLife™ and others. LIs in overweight working populations are also available. 59

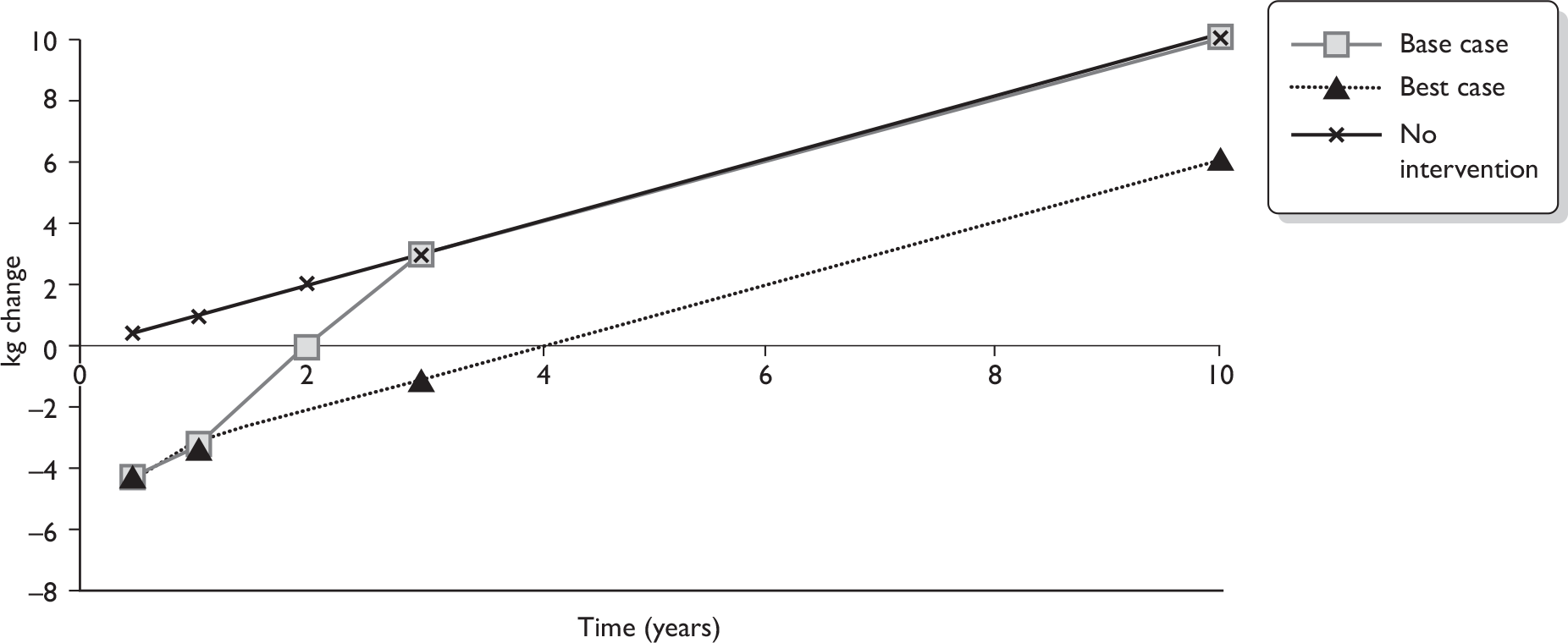

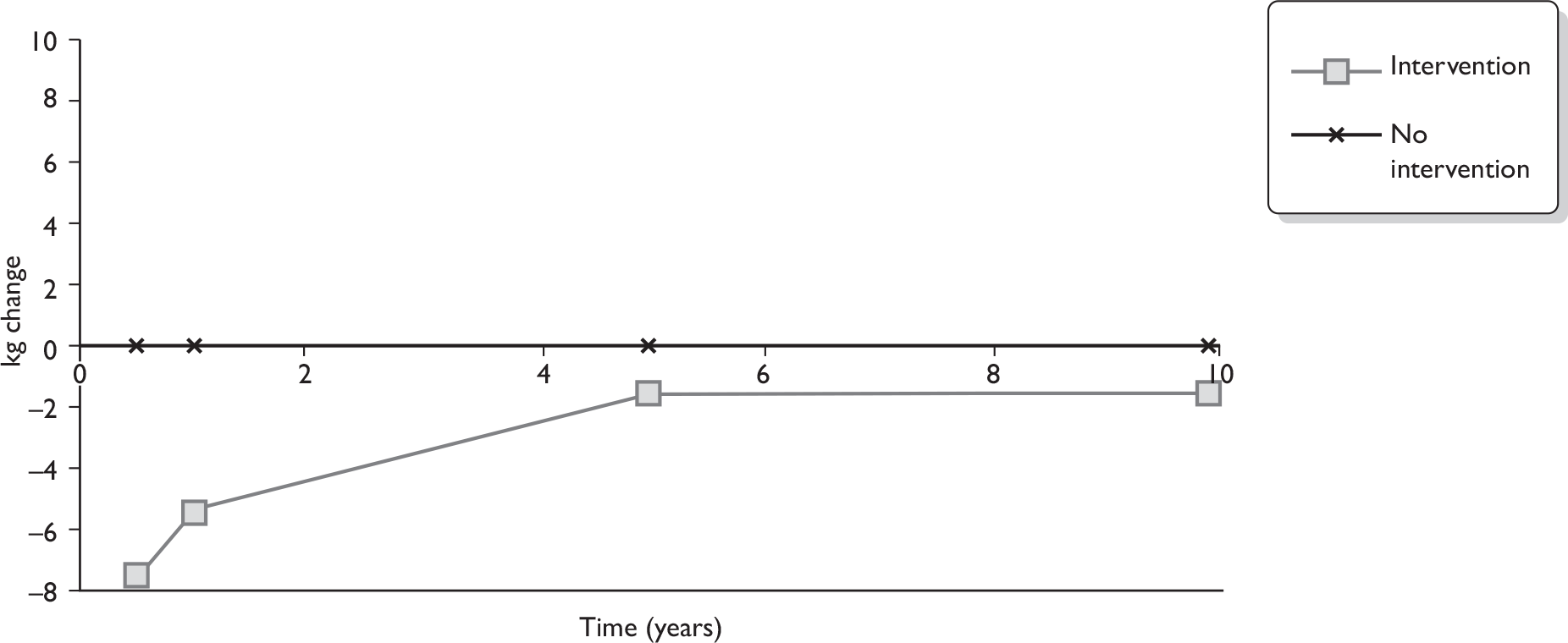

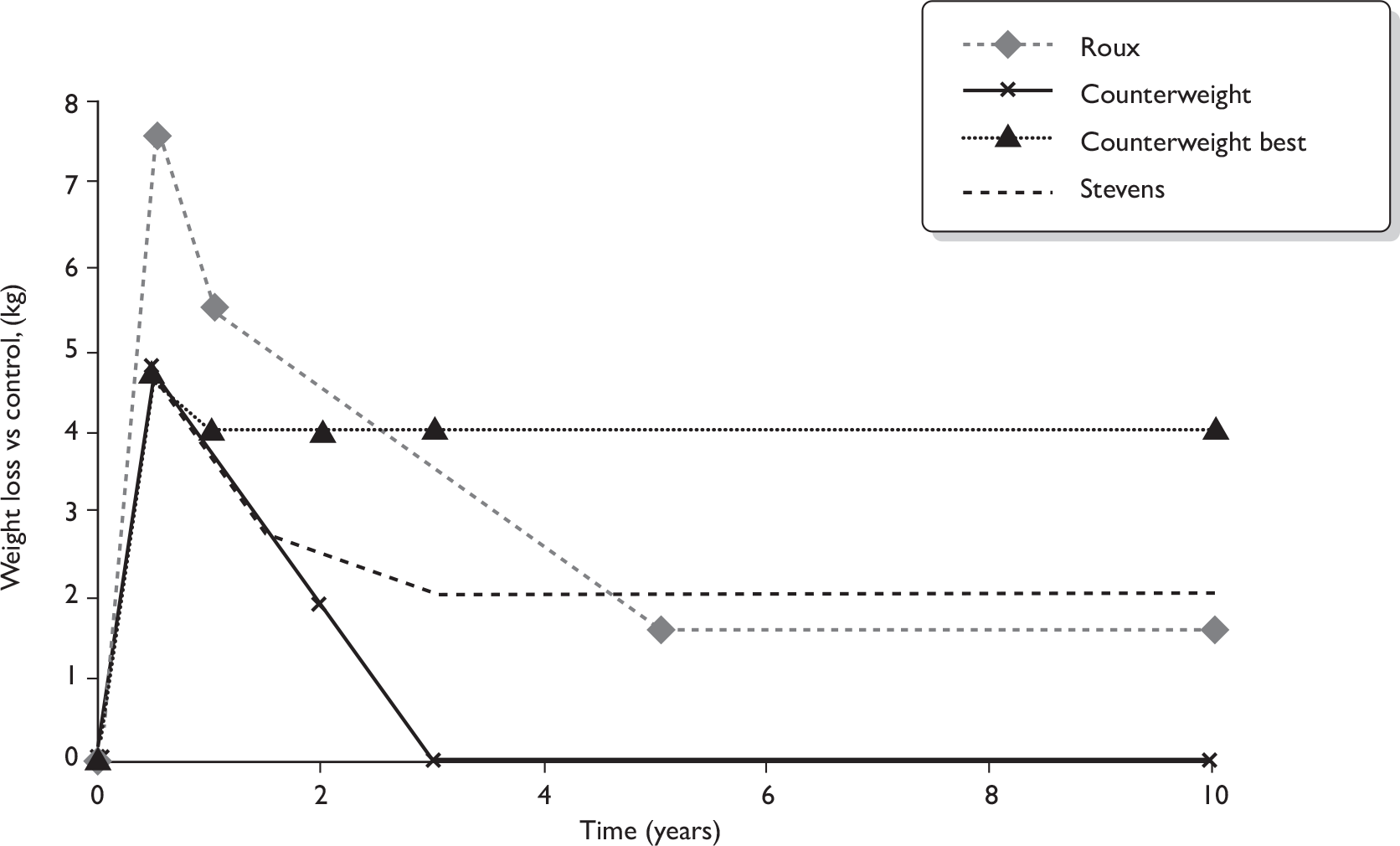

Weight management programmes vary in terms of their duration. Generally there will be an initial period where the aim is to achieve a desired weight loss goal (e.g. 6–12 months). Thereafter there may be a weight maintenance phase where the aim is to sustain weight lost in the first stage. There is some evidence to suggest that weight is lost rapidly at first, and the point of greatest loss occurs 6 months after beginning treatment; weight is then slowly regained and often reaches near the original level. 60 For example, approximately a third of lost weight may be regained in the first year after treatment and often continues with the average loss of about 1.8 kg remaining at 4 years after treatment. 60 Therefore, it is important that any weight management scheme facilitates weight maintenance after the target weight has been reached. Resulting changes to lifestyle must become part of everyday life for long-term health benefits to be realised. 35 It is important to acknowledge, however, that weight gain in the general population may occur throughout life and therefore people who have participated in a weight loss intervention may still be at lower weight than if they have not participated.

Well-managed, multicomponent weight management schemes are not thought to lead to any specific adverse events for participants;35 however, there are some suggestion that negative outcomes for some participants may occur from weight management programmes. This appears to be largely based on ‘dieting’ in general, where evidence suggests that for some people dieting can lead to eating disorders, negative psychological and emotional effects and increased social stigma. 61

Overall aims of this assessment

The aim of this review was to assess the long-term clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of multicomponent weight management schemes for adults in terms of weight loss and maintenance of weight loss.

Chapter 2 Methods

The a priori methods for systematically reviewing the evidence of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness are described in the research protocol (see Appendix 1), which underwent comment by our expert advisory group. Although helpful comments were received relating to the general content of the research protocol, there were none that identified specific problems with the methods of the review. The methods outlined in the protocol are briefly summarised below.

Search strategy

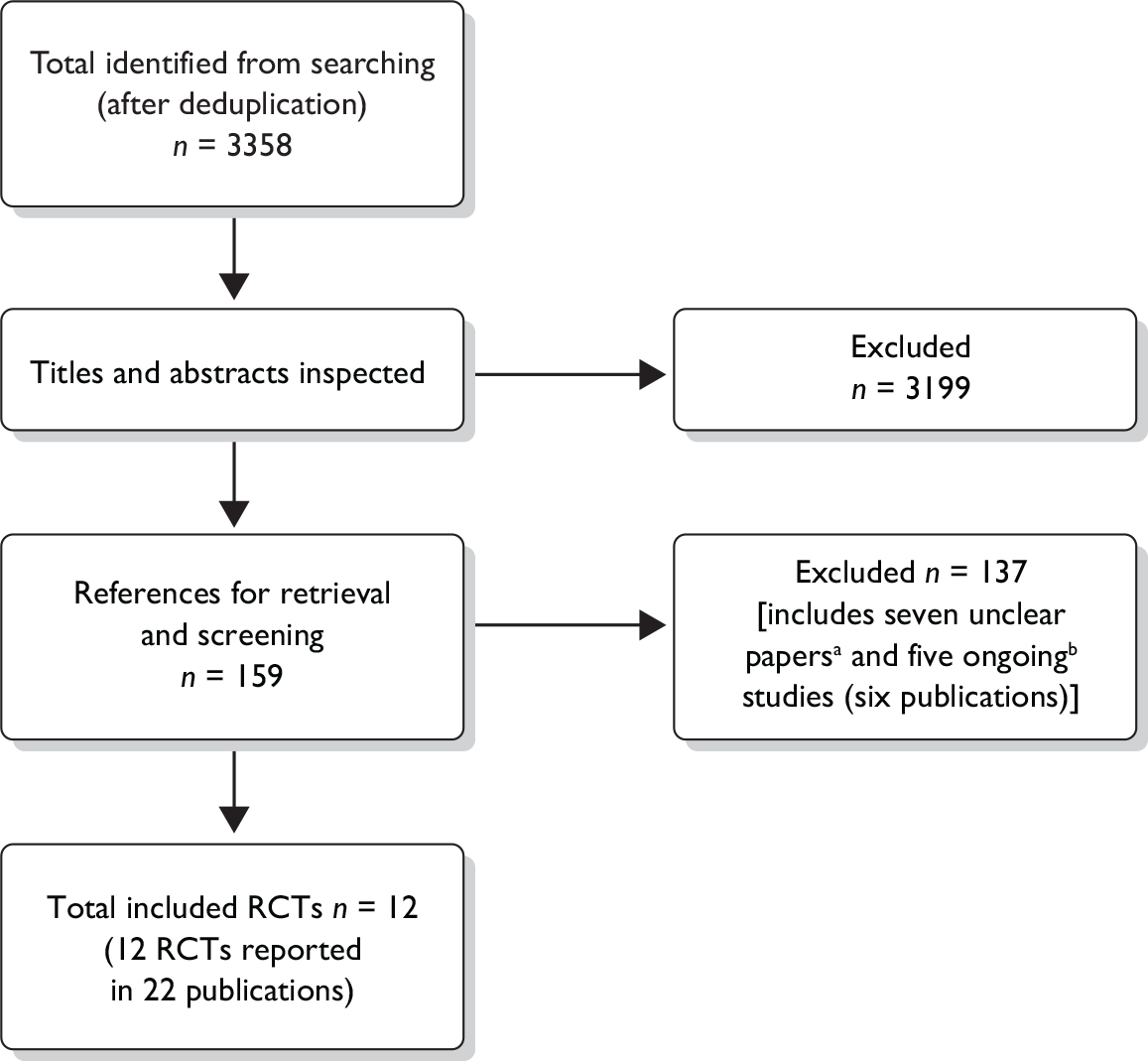

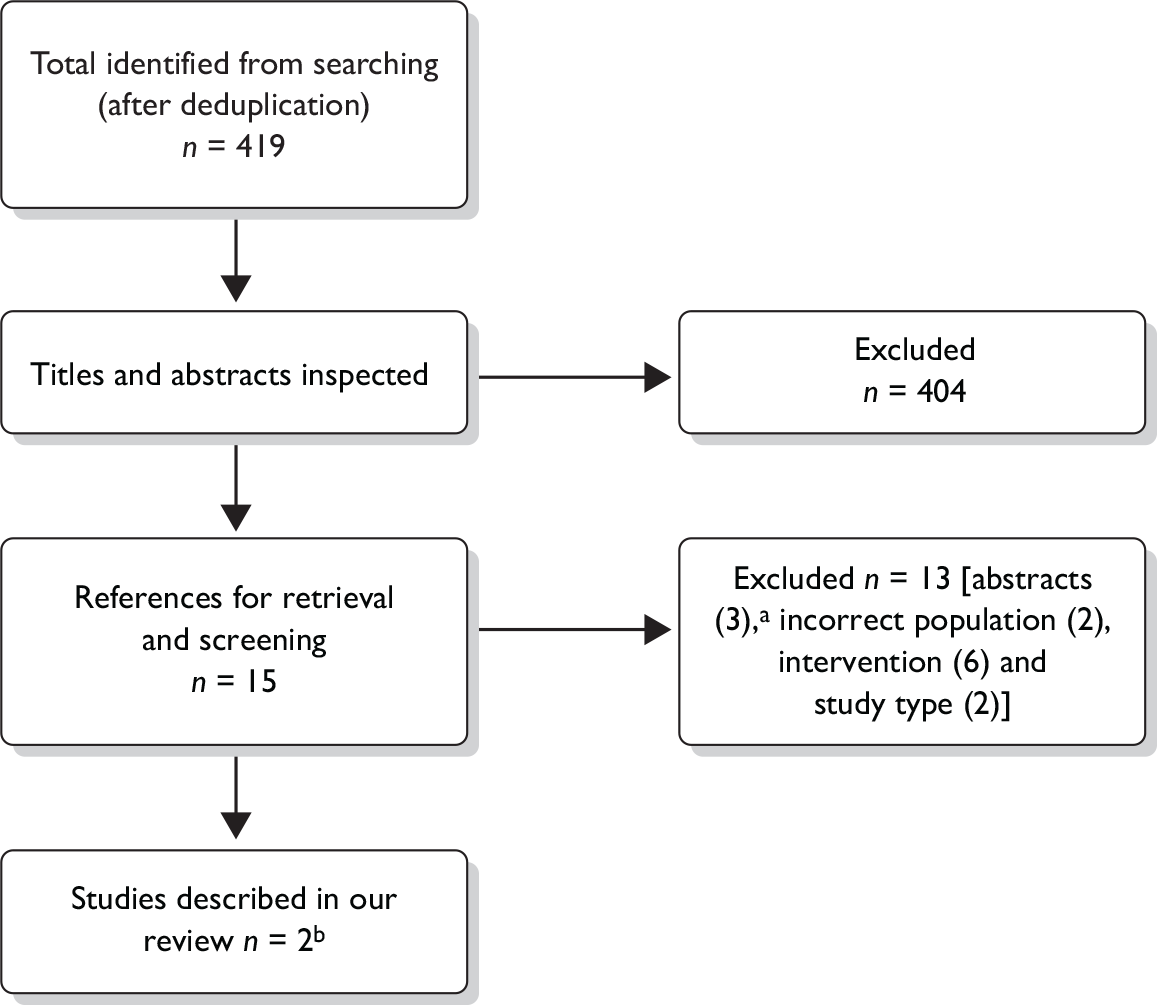

The search strategy was developed, tested and refined by an experienced information scientist. Separate searches were conducted to identify studies of clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and epidemiology. Sources of information and search terms are provided in Appendix 2 and a flow chart of identification of studies can be seen in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of identification of studies for inclusion in the review. (a) Details of the interventions in six RCTs (seven publications) nearly met our threshold of containing enough detail (see Methods). (b) Five studies (six publications) were assessed as ongoing and are described as such in Assessment of effectiveness of multicomponent interventions versus non-active intervention comparators.

Searches for clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness literature were undertaken from database inception to December 2009. Electronic databases searched included: MEDLINE; EMBASE; MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations; The Cochrane Library including the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, NHS Economic Evaluation Database and HTA databases; Web of Science; PsycINFO; BIOSIS; and databases listing ongoing clinical trials.

Searches were restricted to the English language. Bibliographies of related papers were screened for relevant studies, the expert advisory group were also contacted for advice and peer review and to identify additional published and unpublished references.

Inclusion process

Titles and abstracts identified by the search strategy for the clinical effectiveness section of the review were assessed for possible eligibility by two reviewers independently. The full texts of relevant papers were then obtained and inclusion criteria were applied by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer using a previously piloted inclusion flow chart (see Appendix 3). Any disagreements over eligibility were resolved by discussion or by recourse to a third reviewer.

Titles and abstracts identified by the search strategy for the systematic review of cost-effectiveness were assessed for potential eligibility by two reviewers independently. Economic evaluations were considered for inclusion if they reported both health service costs and effectiveness of multicomponent adult weight management programmes, or presented a systematic review of such evaluations. Two reviewers formally assessed full papers independently, with respect to their potential relevance to the research question. Any differences in judgement were resolved through discussion.

Inclusion criteria

Population

-

Adults (≥ 18 years) classified as overweight or obese, i.e. people with a BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2 and ≥ 30 kg/m2, respectively.

-

Studies in children and people with eating disorders were not included, nor were studies specifically in people with a pre-existing medical condition such as diabetes, heart failure, uncontrolled hypertension or angina.

Intervention

-

Structured, sustained multicomponent weight management programmes (i.e. the intervention had to be a combination of diet and physical activity with a behaviour change strategy to influence lifestyle).

-

Components of the programme had to be clearly specified (i.e. details provided of the diet, behavioural definition, and exercise components; see below).

-

Programmes that included a long-term follow-up of more than 18 months.

-

The programme was delivered by the health sector, in the community or commercially.

-

Multicomponent programmes that involved the use of OTC medicines that are licensed in the UK for overweight or obesity were also included. Programmes that involved non-OTC drug therapies or surgery for obesity were not included.

-

Interventions incorporating other lifestyle changes such as efforts at smoking cessation or reduction of alcohol intake were not included.

Comparators

-

Normal practice (as defined by the study).

-

Single-component weight management strategies.

-

Other structured multicomponent weight management programmes.

Outcomes

-

Studies were required to include a measure of weight loss.

-

Data on the following outcomes were also eligible for extraction where reported in the included studies: study-defined success rates at more than 18 months, attrition rates at more than 18 months, barriers and facilitators of weight loss and maintenance of weight loss.

-

Outcomes of cost-effectiveness studies were costs, benefits in terms of weight loss and cost-effectiveness.

Types of studies

-

For the systematic review of clinical effectiveness RCTs were included.

-

For the systematic review of cost-effectiveness eligible study types were full cost-effectiveness analyses, cost–utility analyses, cost–benefit analyses and cost–consequence analyses.

-

Studies published as abstracts or conference presentations were only included if sufficient details were presented to allow an appraisal of the methodology and the assessment of results to be undertaken.

-

Case series, case studies, cohort studies, narrative reviews, feasibility studies, editorials and opinions were not included.

-

Systematic reviews were used as a source of references.

-

Non-English language studies were excluded.

As stated above, all three components of the intervention had to be clearly specified for a trial to meet the inclusion criteria. This was firstly to ensure that interventions were ‘multicomponent’ (providing evidence of the three components rather than simply reporting that an intervention had a diet, exercise and behavioural component) and secondly to ensure that included interventions were, as far as possible, reproducible. It has been proposed that interventions that include a behaviour change element should clearly describe the content, the characteristics of the providers, the setting, the mode of delivery, the intensity, the duration and adherence to protocols. 62 There have also been calls for greater standardisation of specific behavioural techniques used, including explicit links to guiding theory. 57 Where details of these attributes of the included interventions were available these have been reported.

In many cases discussion as regards study selection were straightforward as one or more of the components were absent or no details whatsoever were provided for one or more of the components. In other cases a decision had to be made whether the level of detail about the component was sufficient. In these cases the following criteria were looked for in each of the three components:

-

diet

-

– type of diet

-

– calories

-

– proportion of diet (e.g. proportion of diet made up of fats, protein, carbohydrate)

-

monitoring

-

-

exercise

-

– mode

-

– type

-

– frequency/length sessions

-

– delivered by

-

– level of supervision

-

– monitoring

-

-

behaviour modification

-

– mode

-

– type

-

– content

-

– frequency/length sessions

-

– delivered by.

-

Using these criteria any studies that provided detail on only one aspect of one (or more) of the three main components were excluded (e.g. only the type of diet, but no detail of calorie goals, proportions of diets, or how the diet was monitored), and studies which referred to a secondary source for the description of their interventions were marked as unclear and authors were contacted for further information.

Data extraction and quality assessment strategy

Data were extracted by one reviewer using a standardised and pre-piloted data extraction form and checked by a second reviewer. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion, if necessary involving a third reviewer.

Within the clinical effectiveness review the quality of included studies was assessed using criteria based on those recommended by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD)63 (see Appendix 4). Each RCT was assessed by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion, if necessary involving a third reviewer. The reviewers assessed the adequacy of reporting: randomisation; allocation concealment; population baseline characteristics; blinding of assessors, care providers and participants; imbalances in attrition; outcomes; intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses; and analyses of missing data. For ease of presentation and interpretation of the quality assessment of RCTs the responses were then translated into judgements of ‘high’, ‘low’ or ‘uncertain’ risk of bias based on the Cochrane risk of bias criteria. 64 For example, where a positive response to a question indicated an adequate procedure to minimise bias (e.g. ‘was the allocation adequately concealed?’) this was translated into a ‘low’ risk of bias. Similarly, where a positive response to a question indicated an inadequate procedure to minimise bias (e.g. ‘is there any evidence to suggest that the authors measured more outcomes than they reported?’) this was translated into a ‘high’ risk of bias.

For the systematic review of cost-effectiveness, the methodological quality of the cost-effectiveness studies was assessed using a critical appraisal checklist based on that by Philips and colleagues,65 Drummond and Jefferson66 and the NICE reference case requirements. 67 These checklists were combined to include the key elements that were relevant to internal and external validity, and the generalisability of the studies to the UK NHS.

Data synthesis

Data were synthesised through a narrative review with tabulation of results of all included studies. Full data extraction forms for the clinical effectiveness review are presented in Appendix 5. Within the clinical effectiveness section studies using similar interventions were grouped together to aid interpretation. Studies were categorised according to which of the intervention components (diet, exercise, and/or behaviour modification) were of primary interest and how they differed from the comparator intervention. This led to four groups: studies in which the comparator was a non-intervention group; studies in which the intervention focused on the diet aspect versus another active comparison; studies in which the intervention focused on the exercise aspect versus another active comparison; and studies where other variables were the focus of the study.

Where trials reported several interventions, decisions were made by consensus among the review group as to which was the ‘key’ intervention of relevance to the scope of this review (as noted above, these are multicomponent interventions involving a combination of diet, exercise and behavioural therapy) and which comparators were relevant. For some trials there was little discernible difference between the interventions tested and as such the focus of our report is limited to those which appeared to be the most relevant to our research protocol, with complete details of all interventions reported (see Appendix 5).

Our pre-defined inclusion criteria excluded studies with < 18 months’ follow-up from randomisation, in order to focus the review on long-term weight loss and maintenance of weight loss given that weight regain in the long term is an intractable problem. Therefore, where included studies report interim data before 18 months’ follow-up these have not been included. However, we do provide comment in the text where these data are available in the primary studies.

It was considered inappropriate to combine the results of the studies in a meta-analysis due to differences in the interventions, comparators and populations in the included studies.

Chapter 3 Clinical effectiveness

Quantity and quality of research available

Searching identified 3358 references after deduplication. After initial screening of titles and abstracts, 159 references were retrieved for further inspection. The total number of published papers included at each stage of the systematic review is shown in the flow chart in Figure 1. References to the studies retrieved for further inspection but subsequently excluded can be seen in Appendix 6. The most common reason for exclusion was the inadequate length of follow-up (54 studies); lack of, or only minimal, detail reported on one or more of the components of the intervention (see Chapter 2) led to 20 studies being excluded; another 21 were not deemed to be multicomponent interventions, and 19 were not RCTs. In addition, one study did not have an appropriate comparator; two studies did not report weight loss outcomes and the participants in seven studies did not meet the inclusion criteria. The level of agreement between reviewers assessing study eligibility was generally good although this was not formally measured.

Six RCTs (seven publications) appeared to meet all of the inclusion criteria except that the details of the multicomponent interventions were judged to be below our threshold (see Chapter 2). Authors of these six studies were contacted for further detail. A response from one author was received; however, the information provided did not clarify any further whether the interventions did indeed meet our criteria. These studies were undertaken between 2 and 15 years ago, which may explain the poor response from the authors. As such there were six studies that we were unable to identify whether they met the inclusion criteria of the review. These studies can be seen in Appendix 7.

Twelve RCTs met all of the inclusion criteria,68–79 of which five had two intervention arms, one had three arms, four had four arms and two had five arms (Table 7). In many of these RCTs data were reported in multiple publications; for ease of presentation the primary reference is used here, with full details of all secondary publications given in Appendix 5. Not all of the intervention arms were considered relevant to the scope of the current review; this is outlined in the subsequent sections where this is the case. The key methodological attributes of these trials are summarised in Table 8, with full details of the interventions, outcomes and quality assessments provided in Appendix 5. All included trials were individual-level interventions; no community-level interventions met the inclusion criteria.

| Study details | Study armsa | Target population and selected baseline characteristics |

|---|---|---|

|

Burke et al. 200871 Country: USA Design: RCT Follow-up: 18 months |

Preference for standard diet (pref STD-D), n = 48 Preference for lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet (pref LOV-D), n = 35 No preference for standard diet (no pref STD-D), n = 48 No preference for lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet (no pref LOV-D), n = 45 Total n = 176b |

Target population: overweight men and women aged 18–55 years Mean age (years): pref STD-D 43.2; pref LOV-D 44.3; no pref STD-D 43.2; no pref LOV-D 43.2 Sex (% M : F): pref STD-D 12.5 : 87.5; pref LOV-D 20 : 80; no pref STD-D 12.5 : 87.5; no pref LOV-D 9 : 91 Mean BMI (kg/m2): pref STD-D 34.5; pref LOV-D 34.1; no pref STD-D 32.9; no pref LOV-D 33.7 Mean weight (kg): pref STD-D 97.2; pref LOV-D 96.7; no pref STD-D 92.4; no pref LOV-D 91.8 |

|

Tate et al. 200777 Country: USA Design: RCT Follow-up: 30 months |

High physical activity (HPA), n = 109 Standard behavioural treatment (SBT), n = 93 Total n = 202 |

Target population: overweight men and women aged 25–50 years Mean age (years): overall 42.2 Sex (% M : F): overall 42 : 58 Mean BMI (kg/m2): overall 31.7 Mean weight (kg): approximately 90.5 for both interventions |

|

Logue et al. 200572 Country: USA Design: RCT Follow-up: 24 months |

Transtheoretical model and chronic disease paradigm (TM-CD), n = 329 Augmented usual care (AUC), n = 336 Total n = 665 |

Target population: overweight men and women aged 40–69 years Age (years): mean not reported. In both arms ≥ 80% aged 40–59 years Sex (% M : F): TM-CD 29 : 71; AUC 33 : 67 BMI (kg/m2): not reported Weight: not reported |

|

Stevens et al. 200170 Country: USA Design: RCT Follow-up: 36 months |

Weight loss (WL), n = 595 Usual-care control group (C), n = 596 Total n = 1191 |

Target population: overweight men and women with non-medicated diastolic blood pressure (BP) of 83–89 mmHg and systolic BP < 140 mmHg and aged 30–54 years Mean age (years): WL 43.4; C 43.2 Sex (% M : F): WL 63 : 37; C 68 : 32 Mean BMI (kg/m2): men: WL 31.0; C 31.0; women: WL 31.0; C 30.8 Mean weight (kg): WL 93.4; C 93.6 |

|

Jeffery et al. 199876 Country: USA Design: RCT Follow-up: 18 months |

Standard behavioural therapy (SBT), n = 40 SBT + supervised exercise (SBTE), n = 41 SBT + trainer (SBTT), n = 42 SBT + incentive (SBTI), n = 37 SBT + trainer + incentive (SBTTI), n = 36 Total n = 196 |

Target population: overweight men and women aged 25–55 years Mean age (years): SBT 40.0; SBTE 41.5; SBTT 41.0; SBTI 42.6; SBTTI 40.7 Sex (% M : F): SBT 18 : 82; SBTE 17 : 83; SBTT 21 : 79; SBTI 14 : 86; SBTTI 14 : 86 Mean BMI (kg/m2): SBT 31.4; SBTE 31.5; SBTT 31.4; SBTI 31.5; SBTTI 30.6 Mean weight (kg): SBT 85.6; SBTE 87.1; SBTT 84.7; SBTI 87.7; SBTTI 85.7 |

|

Simkin-Silverman et al. 199873 Country: USA Design: RCT Follow-up: 54 months |

Lifestyle intervention (LI), n = 260 Assessment-only control group (C), n = 275 Total n = 535 |

Target population: perimenopausal women, aged 44–50 years, of whom a subgroup were overweight Mean age (years): LI 47; C 47 Sex (% M : F): LI 0 : 100; C 0 : 100 Mean BMI (kg/m2): LI 25; C 25 Mean weight, lb (kg)c: LI 148.0 (67.1); C 147.6 (67.0) |

|

Weinstock et al. 199878 Country: USA Design: RCT Follow-up: 96 weeks |

Diet plus combined strength and aerobic training (DSA), n = 29d Diet plus strength training (DS), n = 31d Diet plus aerobic training (DA), n = 31d Diet alone (D), n = 29d Total n = 120d |

Target population: overweight women Mean age (years): DSA 42.8; DS 40.0; DA 40.8; D 41.0 Sex (% M : F): 0 : 100 in all arms Mean BMI (kg/m2): DSA 35.3; DS 36.5; DA 37.3; D 36.4 Mean weight (kg): DSA 92.4; DS 96.8; DA 98.7; D 96.3 |

|

Skender et al. 199679 Country: USA Design: RCT Follow-up: 2 years |

Diet + exercise (D + E), n = 42 Diet (D), n = 42 Exercise (E), n = 43 Waiting list (n = 38; data not reported) Total n = 127 (165) |

Target population: overweight men and women aged 25–45 years Age (years): not reported Sex (% M : F): D + E 50 : 50; D 52 : 48; E 53 : 47 BMI (kg/m2): not reported Mean weight (kg): D + E 97.60; D 97.65; E: 93.92 |

|

Jeffery and Wing 199575 Country: USA Design: RCT Follow-up: 30 months |

Standard behavioural treatment (SBT), n = 40 SBT + food provision (SBT + FP), n = 40 SBT + incentives (SBT + I), n = 41 Combined intervention (SBT + FP + I), n = 41 Control group (no intervention) (C), n = 40 Total n = 202 |

Target population: overweight men and women aged 25–45 years Mean age (years): SBT 37.5; SBT + FP 38.5; SBT + I 38.1; SBT + FP + I 37.6; C 35.7 Sex (% M : F): Not reported by intervention group BMIe (kg/m2): SBT 30.9; SBT + FP 30.8; SBT + I 31.1; SBT + FP + I 31.1; C 31.1 Weighte (kg): SBT 89.4; SBT + FP 88.1; SBT + I 92.3; SBT + FP + I 91.1; C 88.2 |

|

Stevens et al. 199374 Country: USA Design: RCT Follow-up: 18 months |

Weight loss (WL), n = 308 Usual-care control group (C), n = 256 Total n = 564 |

Target population: overweight men and women, average diastolic BP of 80–89 mmHg and aged 30–54 years Mean age (years): WL 43.1; C 42.4 Sex (% M : F): WL 73 : 27; C 63 : 37 Mean BMI (kg/m2): WL 29.5; C 29.5 Mean weight (kg): WL 90.2; C 89.3 |

|

Wadden et al. 198869 Country: USA Design: RCT Follow-up: 3 years |

Behaviour therapy (BT), n = 18 Combined treatment (BT + VLCD), n = 23 Very-low-calorie diet (VLCD), n = 18 Total n = 59 |

Target population: overweight men and women Mean age (years): BT 44.3; BT + VLCD 43.6: VLCD 44.3 Sex (% M : F): BT 19 : 81; BT + VLCD 11 : 89; VLCD 13 : 87 BMI (kg/m2): not reported Weightf (kg): BT 112.2; BT + VLCD 108.0; VLCD 106.4 |

|

Dubbert and Wilson 198468 Country: USA Design: RCT Follow-up: 30 months after end of intervention (circa 34 months after randomisation) |

Individual treatment with weekly (distal) goalsf Individual treatment with daily (proximal) goalsf Couples’ treatment with weekly (distal) goalsf Couples’ treatment with daily (proximal) goalsf Total n = 62 |

Target population: overweight married men and women currently living with spouse; spouse willing to attend sessions Age (years): not reported Sex (M : F): overall 23 : 77 BMI (kg/m2): not reported Weightf lb (kg)c: individual, distal 207.7 (94.2); individual, proximal 208.9 (94.8); couples, distal 190.4 (86.4); couples, proximal 195.0 (88.5) |

| Study | Randomisation sequence | Allocation concealment | Similarity of groups | Blinding of assessors | Blinding of care providers | Participant blinding | Dropout imbalance | Missing outcomes | ITT analysis | Missing data explained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burke et al. 200871 | ? | ? | High | ? | ? | ? | Low | High | High | High |

| Tate et al. 200777 | ? | ? | Low | ? | ? | ? | ? | Low | ? | ? |

| Logue et al. 200572 | Low | ? | Low | ? | ? | ? | Low | High | Low | Low |

| Stevens et al. 200170 | Low | Low | Low | Low | ? | ? | Low | Low | High | ? |

| Jeffery et al. 199876 | ? | ? | Low | ? | ? | ? | ? | Low | High | High |

| Simkin-Silverman et al. 199873 | Low | Low | Low | Low | ? | ? | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Weinstock et al. 199878 | ? | ? | Low | ? | ? | ? | Low | Low | High | High |

| Skender et al. 199679 | Low | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | High | Low | ? | High |

| Jeffery and Wing 199575 | ? | ? | Low | ? | ? | ? | ? | High | ? | ? |

| Stevens et al. 199374 | ? | Low | Low | ? | ? | ? | ? | Low | ? | ? |

| Wadden et al. 198869 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | Low | Low | ? | High |

| Dubbert and Wilson 198468 | ? | ? | Low | ? | ? | ? | ? | Low | ? | High |

All RCTs that met the inclusion criteria were conducted in the USA. Most (83%) of these were published between 1993 and 2008, with two older RCTs, published in 198468 and 1988. 69 The total number of participants randomised ranged from 5969 to 1191,70 while the number of participants per intervention group ranged from 1869 to 596. 70 Only four of the 12 RCTs had sample sizes > 100 participants per intervention group. 70,72–74 The earliest of the RCTs68 did not report the number of participants randomised. Power analyses to calculate the necessary sample sizes were reported in only five trials. 70–74

In all but one73 of the 12 RCTs the target population was stated as being overweight. The RCT by Simkin-Silverman and colleagues73 enrolled middle-aged women and aimed to prevent the rise in weight and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol observed during the menopause. The baseline weight, however, indicated that participants were overweight (mean BMIs > 25 kg/m2). The two trials reported by Stevens and colleagues70,74 were conducted as part of a larger study of risk factors for hypertension [Trials of Hypertension Prevention (TOHP)] and included overweight participants.

Nine of the 12 RCTs reported the starting BMI of their participants. 70–78 According to the international classification of overweight or obesity,6 participants would be considered overweight (pre-obese) in two RCTs,73,74 class I obese in five RCTs,70,71,75–77 and class II obese in one RCT. 78 The remaining RCT72 contained a mixture of pre-obese (18%–22%), class I obese (32%–36%), class II obese (21%–24%) and class III obese (22%–24%) participants (see Appendix 5). Seven of the 12 RCTs specified that their participants, aside from being overweight, were in good health. 68,70,73–77 One RCT, by Weinstock and colleagues,78 excluded women with bulimia but not those with binge eating disorder. The remaining four RCTs69,71,72,79 did not include health status as an inclusion criterion.

Three studies did not mention age among their inclusion criteria (however participants were all adults). 68,69,78 The upper age limit specified for inclusion of participants was 45 years in two RCTs,75,79 50 years in two RCTs,73,77 54 years in two RCTs,70,74 55 years in two RCTs,71,76 and 69 years in the remaining RCT. 72 None of the trials specifically included elderly populations.

Descriptions of the baseline characteristics of the populations included in the RCTs varied considerably in their detail (see Table 7). In eight (67%) of the RCTs the mean age of participants within each intervention group was in the range 35.7–47.0 years. 69–71,73–76,78 Two RCTs did not report the age by intervention group but stated that the overall mean age was 42.2 years77 or that most participants (≥ 80%) were aged 40–59 years. 72 The remaining two RCTs did not report the age of their participants. 68,79 In two of the RCTs the participants were all female,73,78 in five RCTs they were mostly (67%–91%) female,68,69,71,72,76 in two RCTs they were mostly (63%–73%) male,70,74 and in two RCTs the gender balance was nearly equal (42%–53% male). 77,79 One RCT75 did not report the gender balance of its participants.

Weight change from baseline was reported as a primary outcome in 11 RCTs68–77,79 and as a secondary outcome in one RCT. 78 Two RCTs also reported changes in BMI, either as a primary outcome75 or as a secondary outcome. 71 The proportion of participants maintaining weight loss was also a primary outcome in one RCT69 (see Table 7).

In one study the setting of the intervention was reported to be in primary care. 72 Six studies70,71,73,74,76,78 reported that their study was clinic based; in some cases these were clinical practice-based research units within universities. Five studies68,69,75,77,79 did not report the setting of their intervention.

The duration of follow-up (post randomisation) ranged from 18 to 54 months. Eight68,69,71,72,74,76,78,79 of the 12 RCTs provided weight outcome follow-up data for a single time point after randomisation, three RCTs70,75,77 provided follow-up data for two time points, and one RCT70 provided follow-up data for four time points. Six68–70,73,75,77 of the RCTs included follow-up beyond 2 years (see Table 7). The duration of interventions is discussed more fully in the following three sections.

The methodological detail reported varied considerably among the RCTs. As an indication of methodological rigour, the risk of bias was assessed for each of the 10 methodological criteria (see Table 8). Quality assessment of each individual trial can be seen in Appendix 5.

Trials that do not properly randomise their participants or conceal the allocation of interventions could be at risk of selection bias. Trials were assessed according to whether they used an adequate method to generate random allocations and to conceal their intervention allocations. Four trials provided information on their randomisation sequence70,72,73,79 and three described their allocation concealment,70,73,74 and all of these were judged to have a low risk of selection bias (see Table 8). For the remaining trials there is an uncertain risk of bias as there was either inadequate or no information reported from which this could be assessed.

Blinding of participants, care providers and outcome assessors can help to reduce the risk that participants and trial personnel become aware of intervention assignment, so potentially influencing their performance in the trial (detection bias). None of the trials clearly reported blinding of their participants or care providers, so it is unknown whether blinding occurred. It seems unlikely that care providers and participants would have been blinded as it would have been difficult to conceal the identity of the weight loss interventions without substantial spatial and/or temporal separation of the care providers and participant groups that were allocated to different interventions. Blinding of outcome assessors, however, is more feasible but was only reported in two trials. 70,73 In both of these the method of blinding was judged as adequate, with a low risk of bias (see Table 8).

Sources of measurement bias in clinical trials include losses of participants to follow-up, unequal dropout rates between interventions, selective reporting of outcomes (missing outcomes) and failure to explain why participants are missing (e.g. whether they are missing at random). Six RCTs were judged to have low risk of bias from dropout (no dropout imbalance);69,73,78 five, however, provided inadequate or no information to assess risk of bias from dropout,68,74–77 and one had unequal dropout between interventions, indicating a high risk of bias. 79 All 12 trials provided sufficient information to permit an evaluation of reporting bias,68–79 of which three had a high risk of bias (some outcomes not reported)71,72,75 and nine had a low risk of bias (all outcomes were adequately reported). 68–70,73,74,76–78,79 Four trials were judged to have a high risk of bias because they did not report an ITT analysis,70,71,76,78 and seven trials were judged to have a high risk of bias because their analysis and interpretation did not account for missing data68,69,71,73,76,78,79 (see Table 8).

Given the lack of methodological information reported it was not possible to rank the RCTs according to their methodological rigour or risk of bias. The extent to which methodological criteria were reported did not appear to show any patterns in relation to the publication date, suggesting there has not been an obvious improvement or deterioration in rigour through time. Where appropriate, the implications of risk of bias are considered in more detail for specific trials in the following three sections of this report.

The 12 RCTs varied considerably in the structure and content of their interventions and comparators and were consequently grouped into four categories (see Chapter 2). The four categories are: trials in which the comparator was a non-active intervention group, for example described as usual care (five trials);70,72–75 trials where the focus of the study was predominantly on diet (two trials);69,71 trials where the focus of the study was predominantly on exercise (four trials);76–79 trials where the focus was on other factors (one trial). 68 Studies are reported in the following sections grouped in these four categories. In these subsequent sections of the report we describe the key aspects of the interventions and results of the studies. As described above there were differences between studies in terms of quality, follow-up, participant characteristics and sample sizes that are referred to where relevant in the subsequent sections. Studies were statistically powered to detect a difference between groups unless stated.

Assessment of effectiveness of multicomponent interventions versus non-active intervention comparators

Five trials70,72–75 compared multicomponent interventions against a non-active intervention comparator group, and can be seen in Table 9. The nature of the comparator differed slightly between these studies. In two of the RCTs, reported by Stevens and colleagues,70,74 the comparator was described only as a usual-care control group, with no further details provided. In one RCT, reported by Jeffery and Wing,75 the comparator was a control group whose participants received no instruction or guidance and were free to act independently to achieve weight loss. The remaining two RCTs, reported by Logue and colleagues72 and Simkin-Silverman and colleagues,73 provided participants in their comparator group with limited general guidance on improving diet72 or reducing cardiovascular risk factors73 (see Table 9). The trial by Jeffery and Wing75 differed in that it had five arms (four active interventions and one non-active comparator), with only 40 or 41 participants randomised per arm. The four active intervention arms reported by Jeffery and Wing75 were standard behavioural therapy/treatment (SBT) alone, or SBT in combination with food provision (FP) and/or incentives (see Table 7). For the purpose of this review we consider SBT as the multicomponent intervention of most relevance. Details of the other interventions can be found in Appendix 5.

| Logue et al. 200572 | |

|---|---|

| Length of intervention: 24 months, follow-up immediate | |

| Transtheoretical model applied to chronic disease | Augmented usual care |

|

Diet: Calorie goal: reduce calories Proportions diet: increase fruit and vegetables, and reduce fat Exercise: Energy expenditure goal: increase activity and exercise but no details provided Type: not reported Behaviour modification: Mode: not reported explicitly but assume individual Frequency: face-to-face counselling once every 6 months. Telephone counselling every month Content – see Table 10 Delivered by: Registered dietitian and weight loss advisor Ongoing support: Written materials mailed on request |

Diet: Calorie goal: reduce calories Proportions diet: increase fruit and vegetables, and reduce fat Exercise: Energy expenditure goal: not reported Type: not reported Behaviour modification: Mode: not reported Frequency: counselling once every 6 months Delivered by: Registered dietitian Ongoing support: None reported |

| Stevens et al. 200170 | |

| Length of intervention: intensive phase – 14 weeks; transitional phase – 16–18 months; follow-up 36 months | |

| Weight loss intervention | Usual-care control |

|

Diet: Calorie goal: men: < 1500 kcal/day. Women: < 1200 kcal/day Proportions diet: decreasing consumption of excess fat, sugar and alcohol Exercise: Energy expenditure goal: approximately 40%–55% of heart rate reserve. From initially 10–15 minutes at least 3 days per week to 30–45 minutes per day, 4–5 days per week Type: primarily brisk walking (moderate intensity) Behaviour modification: Mode: individual then groups of 11–34 Frequency: weekly for 14 weeks (intensive phase) then six biweekly meetings and then monthly meetings for additional 3–4 months (transitional phase) Content – see Table 10 Delivered by: Dietitians and health educators and some psychologists Ongoing support: Variety of options including refreshing or redelivering the intervention content. Biweekly contacts for three to six sessions, offered six times a year (participants expected to attend at least three) |

No description provided |

| Simkin-Silverman et al. 199873 | |

| Length of intervention: phase 1 – 20 weeks; phase 2 – 6–54 months; follow-up 54 months | |

| Lifestyle intervention | Control |

|

Phase 1: Diet: Calorie goal: 1300–1500 kcal/day meal plan in the first month. When weight goal met, intake increased gradually until weight stabilised Proportions diet: for the first month dietary fat reduced to 25%, saturated fat to 7% of daily calories, and cholesterol to 100 mg/day Exercise: Energy expenditure goal: expend 1000 kcal per week from week 3. Already active women to expend 1500 kcal per week, those already expending 1500 kcal per week encouraged to maintain this Behaviour modification: Mode: group, size ≈ 20 Frequency: weekly for 10 weeks, biweekly for 10 weeks Content – see Table 10 Delivered by: Behavioural psychologists and nutritionists Ongoing support Phase 2: Meetings in months 6, 7, 8, 10, 12 and 14. After month 14 participants offered refresher programmes to help with maintenance of behaviour change |

Assessment only (received a health education pamphlet on reducing cardiovascular risk factors and for those who were smokers, advice to quit) |

| Jeffery and Wing 199575 | |

| Length of intervention: 18 months; follow-up 30 months | |

| Standard behavioural treatment | Control |

|

Diet: Calorie goal: 1000 or 1500 kcal per day on the basis of baseline body weight to produce an estimated weight loss of about 1 kg per week Proportions diet: not stated Exercise: Energy expenditure goal: 50 kcal per day for 5 days a week to increase to a final goal of 1000 kcal per week Type: Walking or cycling Behaviour modification: Mode: group, size ≈ 20 Frequency: weekly for first 20 weeks and then once a month Content – see Table 10 Delivered by: Trained interventionists with advanced degrees in nutrition or behavioural science Ongoing support: Not specifically mentioned but content of monthly group meetings noted above may fill this role |

No intervention. Participants could do whatever they wished to lose weight on their own |

| Stevens et al. 199374 | |

| Length of intervention: phase 1 – 6 months; phase 2 – 12 months; follow-up 18 months | |

| Weight loss intervention | Usual-care control |

|