Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 05/16/01. The contractual start date was in September 2006. The draft report began editorial review in June 2010 and was accepted for publication in October 2010. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

A Frost is a board member of the UK Water Treatment Association, consultant for the European Water Treatment Association and member of the Water Quality Association (USA). I Pallett was technical director and a board member of British Water until June 2009 and is now a technical consultant to British Water and also to Aqua Europa – the Federation of European Water Industry Associations.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

The problem of eczema

Atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) is the most common inflammatory skin disease in childhood, with a prevalence of around 20% in England, Australia and Scandinavia. There is recent evidence of a worldwide increase in atopic eczema symptoms in primary school-aged children. 1 The term atopic eczema is synonymous with atopic dermatitis. The World Allergy Organization now suggests that the phenotype of atopic eczema should be called just eczema unless specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies are demonstrated, and we will use the term eczema throughout this report.

The burden of eczema is wide-ranging. The child’s life is affected in many ways, including the suffering of intractable itch, sleep disturbance and ostracism by other children. Family disturbance is also considerable, including sleep loss and the need to take time off work for visits to health-care professionals. 2–4 Wider economic costs are considerable. Reviews of the socioeconomic impact of eczema reveal significant burdens worldwide, including the UK,5,6 the USA7 and Australia. 8

Treatment options for childhood eczema have traditionally focused on topical medications, with topical corticosteroids being the mainstay of treatment of skin inflammation and regular use of emollients for dry skin. 9 However, many parents of children with atopic eczema worry about the side effects of conventional topical medications. 10 Although the degree of public concern about the side effects of corticosteroids, such as skin thinning and growth retardation, has not been supported by long-term studies,2 it is important to recognise these concerns and continue to look for other ways of treating atopic eczema. Options that avoid the possible side effects of conventional pharmacological treatments would be a welcome addition to the management of eczema.

Water hardness and eczema

There is evidence from ecological studies linking increasing water hardness with increasing eczema prevalence in children of primary school age. This was first demonstrated in the UK in a study of 4141 primary school children. 11 The 1-year period prevalence of eczema was 17.3% in the hardest water category and 12.0% in the lowest [odds ratio (OR) 1.54, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.19 to 1.99 after adjustment for confounders]. Such a gradient was not seen in secondary school children in the same study. Similar results were subsequently reported in a large study in Japan of 458,284 children aged 6–12 years, in which the prevalence was 24.4% in the hardest water category and 22.9% in the lowest,12 and in a study in Spain of 3907 children aged 6–7 years, in which the lifetime prevalence was 36.5% in the hardest water category and 28.6% in the lowest. 13 There are also anecdotal reports from the patients themselves that water softeners are of benefit to eczema sufferers.

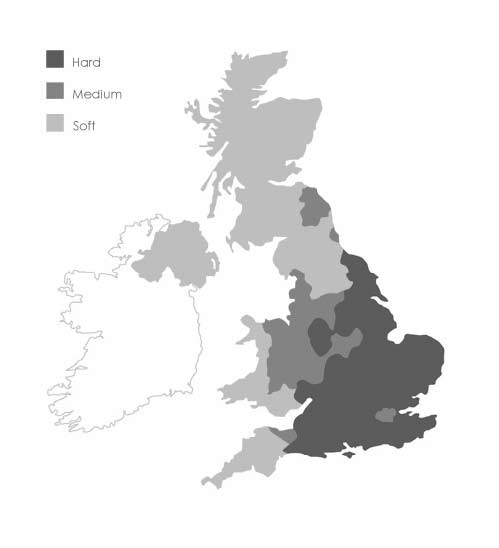

Hardness in water is due to a high mineral content, primarily calcium and magnesium ions. Calcium usually enters the water supply as calcium bicarbonate as the water passes through limestone or chalk rocks. Water hardness varies across the UK, but is generally classified as hard to very hard (> 200 mg/l calcium carbonate) throughout southern and central England (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Water hardness in the UK. Soft, < 100 mg/l calcium carbonate; medium, 100–200 mg/l calcium carbonate; hard, > 200 mg/l calcium carbonate.

If the association between water hardness and eczema prevalence is a causative one, a number of possible mechanisms can be put forward to suggest why hard water could exacerbate eczema. Perhaps the most likely explanation is increased soap usage in hard water areas, the deposits of which (‘soap scum’) can cause skin irritation in eczema sufferers. 14,15 This could be from direct skin contact with soap scum during washing or from the irritant effect of residual deposits in clothes and bedding. A direct chemical irritant effect from calcium and magnesium salts is also possible, or an indirect effect of enhanced allergen penetration from skin barrier disruption16 and increased bacterial colonisation of the skin. 14

Water softeners

Ion-exchange water softening is a well-understood and widely available technology. Water softeners are mainly used in households for reducing calcium deposits in appliances. They are usually installed under the kitchen sink and plumbed into the water supply to soften water to the whole house. A typical purchase price, including installation, would be approximately £600 ($900, €700). Ion-exchange water softeners remove calcium and magnesium ions, replacing them with sodium ions (from common salt). They reduce water hardness to < 20 mg/l calcium carbonate.

To fully soften water, calcium and magnesium ions must be removed, and domestic ion-exchange water softeners are the only products specifically designed to do this. Other technologies include water conditioners (also called ‘physical water conditioners’), which reduce limescale build-up by altering the physical properties of calcium and magnesium ions, but they do not affect the chemical composition of the water and therefore do not affect its hardness. For this reason ion-exchange water softeners were installed in the Softened Water Eczema Trial (SWET), and throughout this report the term ‘water softeners’ refers to ion-exchange technology.

Despite interest from people with eczema using water softeners, a Health Technology Assessment (HTA) systematic review of eczema treatments failed to identify any trials evaluating the use of water softeners for patients with eczema. 12 The only trials of possible relevance were an inconclusive one looking at the benefits of salt baths and another that examined the use of biological versus non-biological washing powders. The search for new, relevant studies was updated in 2010 and no new evidence on the use of softened water was found (see Appendix 1 for search strategy). The HTA systematic review identified a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of water softeners as one of six urgent research priorities in eczema. As a result of this, a feasibility study was run by the University of Nottingham in 2002 involving 17 families living in Nottingham, UK. This informed the design of SWET, in which ion-exchange water softeners were compared with usual eczema care in over 300 children recruited from seven hard water areas across England.

Objectives of the trial

The Softened Water Eczema Trial (SWET) had two main objectives: (i) to assess whether installation of an ion-exchange water softener reduces the severity of eczema in children with moderate-to-severe eczema; and, if so, (ii) to establish the likely cost and cost-effectiveness of this intervention.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

See also Chapter 3, Pilot study.

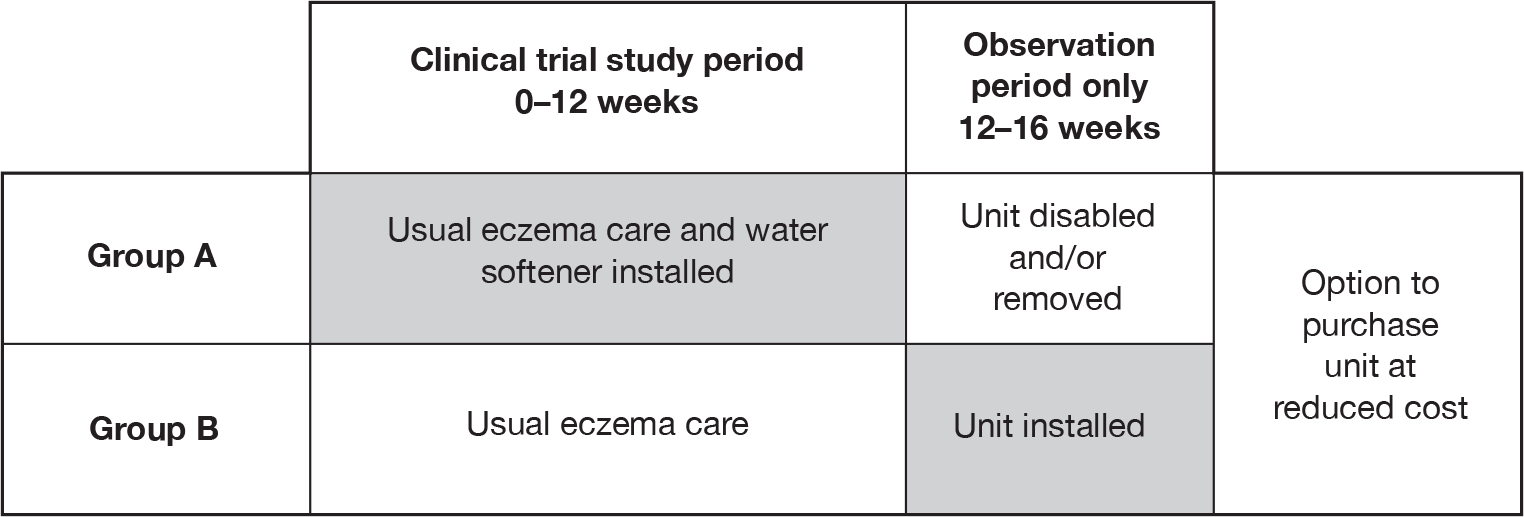

The Softened Water Eczema Trial (SWET) was a pragmatic, observer-blinded, parallel-group RCT of 12 weeks’ duration, followed by a 4-week observation period (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Trial design.

All participants were randomised to receive either immediate installation of an ion-exchange water softener, plus usual eczema care (group A), or usual eczema care, with delayed installation of a water softener after week 12 (group B). The primary outcome (eczema severity) was assessed at 12 weeks. The final 4-week period was included to provide further information on speed of onset of any effects, and to measure how quickly any benefits were lost once treatment was stopped. Feedback from the pilot study indicated that all participants would have liked to experience the intervention; hence, the inclusion of the opportunity for those not allocated to active treatment in the first 3 months to experience water softeners for the last month of the trial. In addition to helping recruitment, the provision of a water softener to group B after 12 weeks allowed a within-group comparison of speed of onset in group B if the softener was effective.

All families had the option of purchasing the water softener at reduced cost at the end of their child’s 16-week study period.

Recruiting centres

Recruitment took place at secondary and primary care referral centres in England, serving a variety of ethnic and social groups, and including both urban and periurban homes. All sites had predominantly hard water (> 200 mg/l calcium carbonate).

At the start of the trial children were recruited through four secondary care referral centres: Queen’s Medical Centre (Nottingham), Addenbrooke’s Hospital (Cambridge), Barnet and Chase Farm Hospitals NHS Trust (London) and David Hide Asthma and Allergy Research Centre, St Mary’s Hospital (Newport, Isle of Wight). As the trial progressed, a further four secondary care referral centres were opened: Leicester Royal Infirmary, United Lincolnshire Hospitals, the Royal London Hospital and St Mary’s Hospital (Portsmouth). All centres held designated paediatric clinics in which children with eczema were seen.

Participants were informed of the trial in a variety of ways. Principal investigators at each centre sent letters of invitation and information sheets to parents of children with eczema referred to these centres over the previous 12–18 months. Posters were displayed in centres, and SWET research nurses attended designated outpatient clinics, informing interested families about the trial. The National Eczema Society website included a link to the trial website. Information was included in primary school newsletters. Individual research nurses advertised the study through local radio and short articles in local newspapers. In addition, recruitment was obtained from primary care trusts local to three of the recruiting centres (Isle of Wight, Leicester and Cambridge), with letters of invitation and information sheets sent to targeted families by general practitioners (GPs) at practices within these primary care trusts.

Ethical considerations

The trial was approved by the North West Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (MREC, reference number 06/MRE08/77) and the local ethics research committee (LREC) for each participating centre prior to entering participants into the trial.

Participants

Eligibility criteria

Children were candidates for inclusion in the trial if they were aged 6 months to 16 years at recruitment visit, with moderate-to-severe eczema, and living in a property supplied by hard water. Eczema was defined by the UK refinement of the Hanifin and Rajka diagnostic criteria. 17

In order to qualify as a case of atopic eczema with the UK diagnostic criteria, the child must have:

-

an itchy skin condition in the last 12 months

-

plus three or more of:

-

onset below age 2 years (not used in children under 4 years)

-

history of flexural involvement

-

history of a generally dry skin

-

personal history of other atopic disease ( in children under 4 years, history of atopic disease in a first degree relative may be included)

-

visible flexural dermatitis as per photographic protocol.

Eczema was assessed using the Six Area, Six Sign Atopic Dermatitis (SASSAD) score. Moderate-to-severe eczema was defined as a SASSAD score of 10 or above. Children with a SASSAD score of < 10 were excluded in order to avoid floor effects, i.e. they had the potential to improve. Although children with a SASSAD score < 10 at baseline were not randomised into the trial, they were invited to contact the nurse again if their eczema worsened. The home where the child lived was assessed by a water engineer for technical suitability for the installation of an ion-exchange water softener, during a ‘home screening’ visit carried out prior to recruitment. Hard water was defined as containing ≥ 200 mg/l calcium carbonate, and was measured in the home by water engineers using the drop-count titration Hach test (counting the number of drops required to change the solution colour to determine water hardness). In order to be as inclusive as possible, approval for water softener installation was sought from local council housing departments, housing associations and private landlords.

Children were not admitted to the trial if:

-

they planned to be away from home for > 21 days during the 16-week study period, or had holidays scheduled during the 4 weeks prior to the primary outcome assessment date (to ensure adequate exposure to the intervention)

-

they had taken systemic medication (e.g. ciclosporin A, methotrexate) or ultraviolet light for their eczema within the previous 3 months (because of these treatments’ long-lasting effects)

-

they had taken oral steroids within the previous 4 weeks, or, as a result of seeing a health-care professional, had started a new treatment regimen for their eczema within the last 4 weeks

-

they lived in homes that already had a water treatment device installed, including ion-exchange softeners, polyphosphate dosing units or physical conditioners

-

they lived in a home that was unsuitable for straightforward installation of a water softener.

Screening

On expression of interest in the trial, a two-stage screening process was initiated.

Families were initially contacted by telephone by their local SWET research nurse, who then administered a telephone screen checklist (Appendix 2) to assess eligibility for the trial. This generated a study number and a request for a home screen visit by a water engineer attached to the trial. The water engineer completed a home screen checklist (Appendix 2), which was faxed to the co-ordinating centre. If the home was supplied by hard water and was technically suitable for straightforward installation of an ion-exchange water softener, an appointment was made for the child to be assessed by their local SWET research nurse for recruitment into the trial.

Informed consent

Research nurses took written consent from the child’s primary carer at the initial recruitment visit for all children aged 15 years or less. Children aged 16 years consented in their own right. Children aged 15 years or younger were invited to sign the consent form if they wanted to. Consent included permission for on-site inspection of the installed water softener by the relevant water supply company, under their duties within the statutory water fitting regulations, should this be requested.

Consent to take part in the genetic part of the study (filaggrin status) was additional to consent for the main study, i.e. it was not necessary to participate in the genetic study in order to participate in the main trial.

Interventions

Participants received either an ion-exchange water softener plus usual eczema care (group A) or usual eczema care alone with delayed installation of a water softener at 12 weeks (group B).

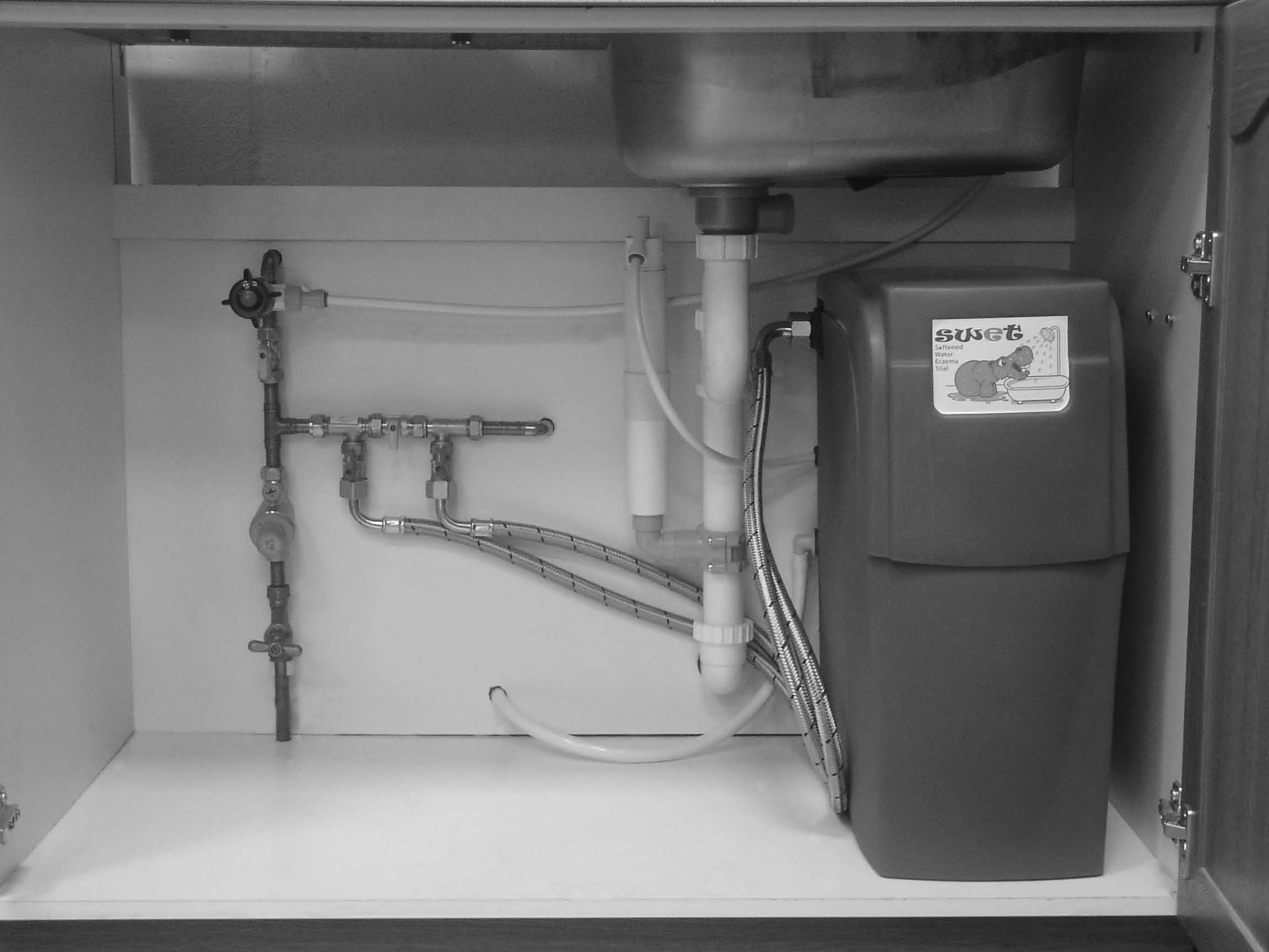

Ion-exchange water softeners use a synthetic styrene monomer resin to remove calcium and magnesium ions from hard household water, replacing them with sodium ions, thus removing the hardness. The resin becomes depleted of sodium and is recharged using sodium chloride (common salt). The units met all necessary regulatory standards, and were installed by trained water engineers according to the Water Regulations Advisory Scheme (WRAS) Information and Guidance Note18 and British Water’s code of practice. 19 In order to avoid favouring any one company, a generic unit was produced for the trial, which carried the SWET logo. Units were usually installed under the kitchen sink (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

The SWET ion-exchange water softener.

The standard procedure was to soften all water in the home, but to provide mains (hard) drinking water through an additional faucet-style tap at the side of the kitchen sink for drinking and cooking. (Occasionally, this was refused or was technically too difficult to install, in which case participants either purchased bottled water or used softened water for drinking and cooking for the duration of the study period.) Participants were therefore exposed to softened water for all washing/bathing/showering and washing of clothes, but continued to drink mains (hard) water. Participants were asked to shower/bathe and wash their clothes in their usual way. While using the water softener, participants were encouraged to reduce their soap use in line with general advice on the use of water softeners in the home (www.ukwta.org/watersofteners.php).

For those allocated to group A, a water softener unit was installed in the child’s main home as soon as possible after the baseline (recruitment) visit. Engineers were instructed to install water softeners within 10 working days, and parents were asked to be as flexible as possible when arranging suitable dates in order to achieve this. Participants allocated to group B received an active unit as soon as possible after the primary outcome had been collected at 12 weeks. Salt was supplied for all participants during the trial. Participants were reminded of the importance of replenishing the salt supply during a telephone call at 8 weeks (group A), and a weekly reminder was included in the daily symptom diary.

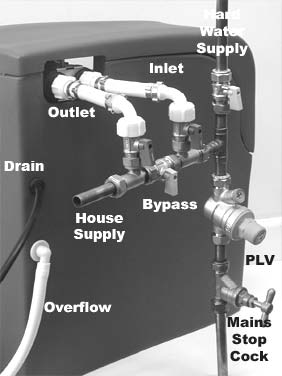

At week 12, group A participants were asked to switch their water softeners off, by turning three bypass levers to put the unit into ‘bypass mode’ (Figure 4) on the evening of the day they attended for their 12-week assessment (primary outcome), and reminded to do so with a telephone call the following day. A water engineer subsequently visited to remove the water softener and all associated pipework and fittings. However, if participants in group A indicated that they wished to purchase the water softener, the engineer ensured that the unit remained inactive for the final 4 weeks by removing the brine valve. Everything else remained in place, ready for subsequent reconnection.

FIGURE 4.

Water softener water supply and bypass levers.

Both groups received a ‘support telephone call’ from the co-ordinating centre at 8 weeks, and all participants continued with their usual eczema care for the duration of the trial. ‘Usual care’ was defined as any treatment currently being used in order to control the child’s eczema (e.g. topical corticosteroids, emollients). Newly introduced treatment regimens used during the study period were documented.

A Water Engineer’s Handbook was compiled by the trial manager in conjunction with the UK Water Treatment Association (UKWTA) giving background information about the trial and practical information about home screening and subsequent visits. The UKWTA provided engineers with SWET water softener installation instructions, based on the WRAS guidelines.

At installation, engineers gave parents a number of sampling pots, stamped addressed envelopes, and instructions for sending weekly samples taken from the hot tap in the bathroom for hardness testing. At the start of the trial (May 2007) parents were instructed to take the weekly water sample from the cold (softened) kitchen tap. Occasionally parents confused this with the new kitchen drinking faucet (mains hard water). In September 2008 a hardness alert visit revealed a home with unusual plumbing and a hard water supply to the bathroom despite a water softener installed in the kitchen. As a result parents were asked to take weekly water samples from the hot water tap in the main bathroom from October 2008 to the end of the trial. Samples were sent to Culligan UK Ltd (High Wycombe, UK) and analysed using a Palintest wavelength selection photometer (Palintest Ltd, Kingsway, Tyne & Wear, UK). Tests were carried out within 24 hours of receipt. Samples were split for analysis. The first sample was used for ‘blocking’ (setting the test unit), and the second was treated with Palintest Hardicol tablets. The test method was accurate to ± 5 mg/l calcium carbonate. If a sample contained > 20 mg/l calcium carbonate an alert was faxed through to the engineer’s co-ordinator, and copied to the co-ordinating centre. This triggered a standard procedure for dealing with the alert. If a unit was suspected to be malfunctioning, an engineer visited the home and replaced the unit. If there was an obvious reason for the hardness breakthrough (e.g. a bypass lever had been knocked out of position), this was rectified on site.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

As this was a single-blind trial, it was important to use an objective primary outcome measure that could be assessed by blinded observers (research nurses). 20 With this in mind, the primary outcome was the mean change in eczema severity at 12 weeks compared with baseline, as measured using the SASSAD severity scale –(see Appendix 3). SASSAD is an objective severity scale that was completed by the research nurses; it did not involve input from the participant in any way. 21 SASSAD includes assessment of the severity of six signs – erythema (redness), exudation (oozing of fluid), excoriation (scratch marks), cracking, lichenification (skin thickening) and dryness – in each of six areas, the head and neck, trunk, hands, arms, legs and feet. The theoretical range of the scale is 0 to 108, although in practice scores rarely exceed 70.

Nurses were trained in the use of SASSAD during a 2-day training event at the co-ordinating centre. With the exception of one study centre (Chase Farm Hospital) all SASSAD scores for each participant were obtained by the same nurse. In July 2008 the nurse at Chase Farm Hospital went on maternity leave. Prior to her departure she trained two Medicines for Children Research Network (MCRN)-funded nurses in SASSAD scoring. The MCRN-funded nurses attended a number of joint assessment visits by SWET participants, during which the nurses scored SASSAD independently and compared their final scores. Training was deemed complete when scores were within 10% or less of each other for three consecutive assessments.

In addition to the SASSAD score, nurses scored a representative site using the Three-Item Severity (TIS) scale. This measures three clinical signs – excoriation, erythema and oedema/population – at a single representative site. 22 Its simplicity makes it a suitable tool for research studies and clinical practice, and it has been suggested that the score provides as much information about eczema severity as more complex scoring systems. 23 In SWET, this score was recorded for two reasons: (i) to compare with SASSAD for research purposes; and (ii) to assess integrity of observer (nurse) bias (information bias) using digital images of a representative site of the participant’s eczema. These digital images were intended to be scored by two independent dermatologists using the TIS scale. The location of the representative site for TIS was agreed between the nurse, parent and child and photographed using a Samsung S630 CE digital camera (Chelsey, UK).

Secondary outcomes

Night-time movement

The difference between the groups in the proportion of time spent moving during the night was included as an objective surrogate for sleep loss and itchiness (two of the defining features of eczema). Previous research has suggested that this is a suitable objective tool for assessing itch,24,25 and it has been shown to correlate with objective clinical scores in children with atopic dermatitis. 26 Movement was measured using accelerometers (Actiwatch Mini™, CamNtech Ltd, Cambridge, UK) for periods of 1 week at week 1 and for 1 week at week 12. The unit was worn by the child in the same way as a wrist watch. Data were stored on the unit and uploaded on to a laptop computer at the subsequent assessment visit. Pilot work using these units suggested that it was unusual for participants to record complete data for an entire week. As a result, the first three nights of evaluable data were used at baseline and the last three nights of evaluable data were used at week 12, in order to tie data collection as closely as possible to the date at which the participants’ eczema severity was assessed by the research nurse. Evaluable data were defined as values > 5% and < 95% of the night spent moving to remove outliers. If there were fewer than three nights of evaluable data, this variable was considered missing.

Improvement in eczema severity

The difference between the groups in the proportion of children who had the same or worse outcome (≤ 0%) or a reasonable (> 0% and ≤ 20%), good (> 20% and ≤ 50%) or excellent (> 50%) improvement in SASSAD score at 12 weeks compared with baseline.

Topical medication use

The difference between the groups in the amount of topical corticosteroid/calcineurin inhibitors used during the study period was measured. Medications were weighed at each assessment visit, using digital scales. The scales were checked for accuracy before each visit, using standardised weights. Data were split into six types of medication: mild steroids, moderate steroids, potent steroids, very potent steroids, mild calcineurin inhibitors and moderate calcineurin inhibitors.

Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM, Appendix 3)

The difference between the groups in POEM data collected at baseline and at weeks 4, 12 and 16. This scale is a well-validated tool that has been developed to capture symptoms of importance to patients. 27 Parents were asked to state the number of days in the last week that their child had been affected by a range of symptoms. These were scored as follows: no days = 0, 1–2 days = 1, 3–4 days = 2, 5–6 days = 3 and every day = 4. The POEM score was then calculated as the sum of these seven individual scores (scale 0–28).

Eczema control

The difference between the groups in the number of totally controlled weeks (TCWs) and well-controlled weeks (WCWs) was recorded. This outcome was based on a systematic review looking at ways of assessing long-term control for chronic conditions such as eczema, asthma and rheumatoid arthritis. 28 The terms TCW and WCW have been adopted for use by researchers in the field of asthma and appear to be a useful and intuitive means of capturing disease activity over time. Using this definition, a TCW is one in which symptoms are controlled throughout the week without the need to ‘step up’ treatment beyond normal maintenance care (such as emollients). A WCW is one in which symptoms and the need for ‘step-up treatment’ occurred on 2 days of the week or less. Each family was asked to keep a daily symptom diary throughout the trial. The information from this diary was used to calculate the number of TCWs and WCWs.

Dermatitis Family Impact questionnaire (Appendix 3)

The difference was measured between the groups in the mean change in the questionnaire at 12 weeks compared with baseline. This scale measures how much the child’s eczema has affected the whole family over the previous week, based on 10 questions. 29 Questions were scored as follows: not at all = 0, a little = 1, a lot = 2 and very much = 3. The Dermatitis Family Impact (DFI) score was calculated as the sum of these 10 individual scores (scale 0–30).

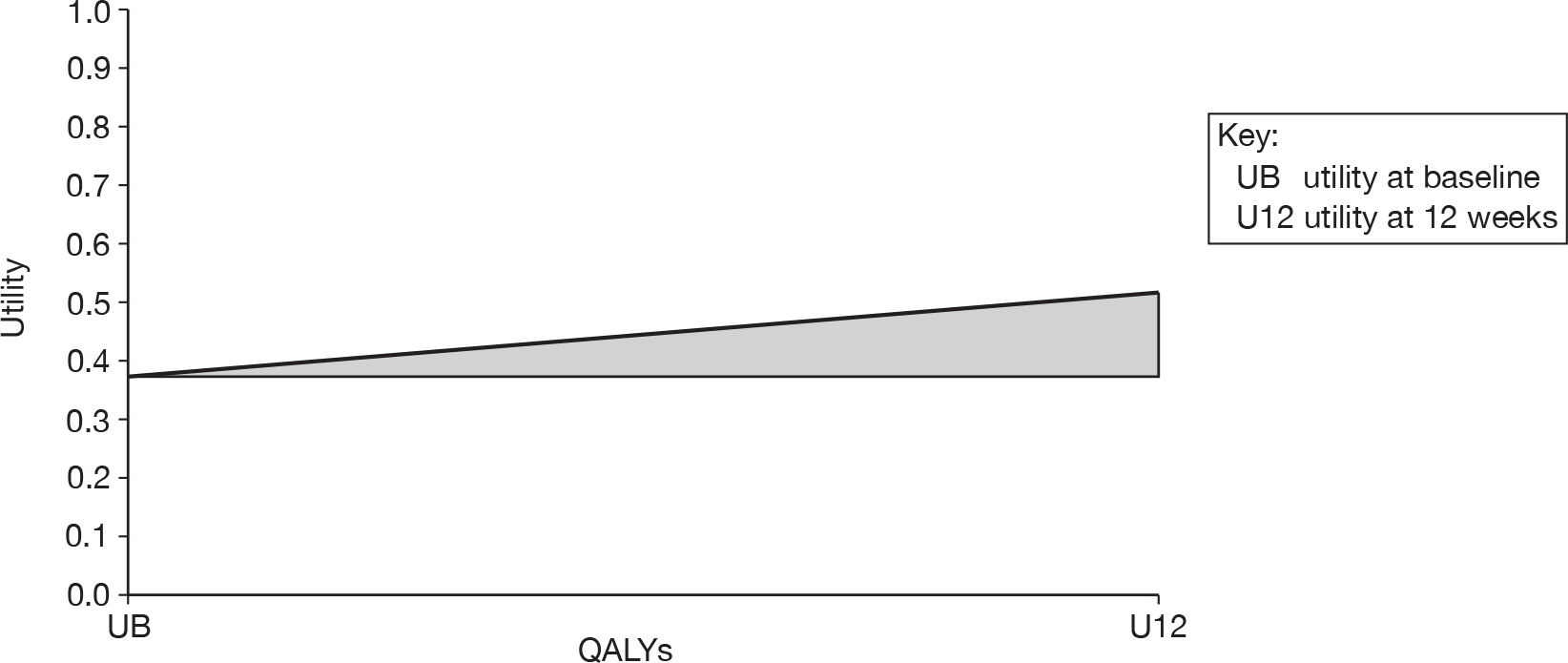

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (Appendix 3)

In order to assess whether the intervention had an impact on generic health-related quality of life, health utility was captured using the children’s version of the EQ-5D for children aged 7 years and over, or the proxy version of the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) for children aged 3–6 years. 30,31 A utility weight was attached to the health state descriptions using the currently accepted UK adult tariff, calculated using the York A1 tariff. 32 The mean change in utility score from baseline to 12 weeks was compared for group A against group B.

Filaggrin status

The role of filaggrin gene (FLG) mutations as a predictor of treatment response was assessed. Mutations of the epidermal barrier protein filaggrin have been shown to be a predisposing factor for eczema. 16,33 Saliva samples were collected during the trial. If children were unable to spit into the container, swabs were taken from inside the cheek. Samples were shipped to the Human Genetics Unit at the University of Dundee, Dundee, UK and analysed for FLG genotyping for the common null alleles according to published protocols. 34

Assessment visits

Assessment visits were carried out in paediatric dermatology clinic rooms in one of the SWET secondary care referral centres. Occasionally the research nurse agreed to see the child in the family home for the initial recruitment visit, but parents were informed that follow-up visits would all need to take place in the local SWET referral centre, to avoid unblinding of the nurse once the child had been randomised into the trial. SWET research nurses were trained in defining eczema at an initial training session run by a dermatology nurse consultant, by attending eczema clinics run by their principal investigators and consultant colleagues, and by self-testing using the online diagnostic criteria manual (www.nottingham.ac.uk/scs/divisions/evidencebaseddermatology/methodologicalresources/diagnostictools.aspx). Assessments took place at baseline and at 4 weeks and at 12 weeks (primary outcome) and at 16 weeks (Table 1).

| Baseline | Week 4 | Week 12 | Week 16 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eligibility criteria checked | SASSAD/TIS | SASSAD/TIS | SASSAD/TIS |

| Baseline characteristics | POEM | POEM, DFI, EQ-5D | POEM |

| SASSAD/TIS | Medications weighed | WTP questionnaire | Medications weighed |

| POEM, DFI, EQ-5D | Digital photo of index site (TIS score) | Medications weighed | Digital photo of index site (TIS score) |

| WTP questionnaire | Week 1 Actiwatch data downloaded and watch reissued | Digital photo of index site (TIS score) | |

| Medications weighed | Diary 2 issued | Week 12 Actiwatch data downloaded | |

| Digital photo of index site (TIS score) | Diary 3 issued | ||

| Saliva sample | |||

| Actiwatch issued | |||

| Diary 1 issued | |||

| Consent taken, child randomised into trial |

Data collection and monitoring

Data generated by all centres were collected on study case report forms, which were entered on to the password-protected SWET database that was created and maintained by the Nottingham Clinical Trials Unit (CTU). Data were entered by the research nurses and by staff at the co-ordinating centre. A 100% check was conducted for the primary outcome (eczema severity) and the time spent moving, and discrepancies were resolved. All other data were subject to a 10% check, which was assumed to be adequate if the maximum error rate was, < 1 in 200 (in practice it was much lower than this). Data were also checked for consistencies in range and missing data. Missing and/or ambiguous data were queried with individual research nurses and resolved wherever possible.

Randomisation

Participants were randomised using web-based randomisation, and allocated on a 1 : 1 basis according to a computer-generated code, using random permuted blocks of randomly varying size. The program was created by the Nottingham CTU in accordance with its standard operating procedure and held on a secure server. Randomisation was stratified by disease severity (baseline SASSAD score ≤ 20 or SASSAD score > 20) and recruiting centre. Access to the sequence was confined to the CTU data manager. The allocation group was indicated to the trial manager only after baseline data had been irrevocably entered into the randomisation programme by the research nurse. The sequence of treatment allocations was concealed until interventions had all been assigned, recruitment and data collection were complete, a signed-off statistical analysis plan had been received and the database locked.

Blinding/bias

Research nurses were blinded to treatment allocation throughout the trial and statisticians analysed the results based on treatment code, using an analysis plan that had been finalised prior to locking the database and prior to the blinded data analysis. The only study personnel in direct contact with study participants were the research nurses and water engineers. The trial manager and study support staff at the co-ordinating centre in Nottingham had telephone contact with parents of participants. Trial participants continued to see health-care professionals for their usual eczema care.

Participants were discouraged from discussing their treatment allocation with the research nurse and the importance of maintaining ‘blinding’ was highlighted in the participant information sheets. Records were kept of all instances when the nurses believed they had become unblinded.

Sample size

Sample size calculations, based on the results of the pilot study and previously published eczema trials, supported a target of 310 participants (155 in each group) in order to show a minimum clinically relevant difference of 20% in the change in SASSAD score between the two groups [assuming a mean baseline SASSAD score of 20 and a standard deviation (SD) in change scores of 10]. This sample size provided 90% power, assuming a significance level of 5% and dropout rate of 15%.

For the planned subgroup analysis, including children with at least one mutation in the gene coding filaggrin, a total of 90 children with the mutation was assumed to be sufficient to detect a 30% difference between the treatment groups in the primary outcome, with 80% power, 5% significance and a SD of 10.

Statistical analysis

Primary outcome

The full statistical analysis plan is included in Appendix 4. The primary efficacy end point was an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis including all participants with evaluable data (if < 5% missing values). If > 5% of data were missing, then a general linear model was to be used to handle the missing values.

Baseline characteristics were summarised and, if any major imbalance existed, the analyses were to be adjusted to account for this, along with an adjusted analysis including the stratification variables (recruiting centre and eczema severity).

A secondary, per-protocol analysis was performed in order to establish proof of principle, and subgroup analysis was conducted, based on those with at least one mutation of the gene coding for filaggrin.

Per-protocol analysis excluded the following participants:

-

those who were randomised into the study, but who failed to receive their allocated treatment

-

those who were deemed to be major protocol violators as defined by the Protocol Violators Group [including independent members of the Trial Steering Committee (TSC)].

Criteria for protocol violators were defined prior to breaking of the code relating to treatment allocation. They were as follows:

-

missing SASSAD score at week 12

-

group A: exposed to fully softened water for < 75% of the time that their home had an active water softener in place (i.e. sleeping at home + unit fully working for < 75% of the time that their home had an installation)

-

group A: participant away from home or with partially functioning water softener for > 2 days/week for each of the 4 weeks prior to the primary outcome assessment

-

group B: participant away from home for > 2 days/week for each of the 4 weeks prior to the primary outcome assessment

-

unblinding of research nurse prior to primary outcome measurement (which could have caused observer bias)

-

participants starting new treatment prior to primary outcome assessment were examined by a dermatologist on a case-by-case basis to determine if they were violating protocol.

Sensitivity analyses

Three sensitivity analyses were planned in relation to the primary outcome: (i) including all randomised participants by replacing missing values; (ii) excluding those for whom the research nurse had become unblinded; and (iii) excluding outliers. For the analysis including all randomised participants, missing values at baseline were replaced by the maximum score from the other five areas of the SASSAD score that were completed. Missing values at week 12 were replaced by the SASSAD score at baseline or week 4, depending on which was greater. For the analysis excluding outliers, these were defined as change scores outside the range of ± 3 SD.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary end points were analysed using a complete case analysis.

In order to aid clinical interpretability, SASSAD scores were grouped into those reporting no change or worse, a reasonable reduction (> 0% and ≤ 20%), a good reduction (> 20% and ≤ 50%), or an excellent reduction (> 50%).

The average percentage of the night spent moving was calculated by taking the average of the first three nights of usable data at baseline and the last three nights of usable data at week 12. Usable data were defined as values between 5% and 95% of the night spent moving to exclude outliers.

The total amount of medication used during the 12-week study period was measured by weighing the medication at each visit. Nurses recorded how confident they were in the measurement.

The number of TCWs and WCWs were compared during the first 12 weeks of the trial. A TCW was defined as a week with zero days with an eczema bother score above 4 and zero days on which ‘stepping up’ of treatment was required. Stepping up of treatment was defined as treatment over and above that defined as ‘normal’ for an individual participant in the daily symptom diaries. Bother scores were assessed on a scale of 0–10 in answer to the following question: ‘How much bother has your child’s eczema been today?’ A WCW was defined as a week with ≤ 2 days with an eczema bother score > 4 and ≤ 2 days on which stepping up was required.

All other outcomes were scored according to the guidelines for the scale, and compared the mean change from baseline to week 12. Continuous data were analysed using a t-test and categorical data were analysed using a chi-squared test for trend.

Analyses of all secondary end points and adjusted analyses were considered to be supportive to the primary analysis, so no adjustments for multiple comparisons were made.

Analyses were performed in stata 10.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and all p-values reported are two sided, with a significance level of 5%.

Summary of changes to the protocol

A full copy of the final trial protocol and statistical analysis plan are given in Appendix 4. Changes to the protocol following MREC approval in January 2007 include minor amendments to trial documents: the inclusion of amounts of topical medications as an additional secondary outcome measure and an end of trial follow-up questionnaire. One of the secondary outcomes (patient-assessed global improvement in eczema) was replaced with broad categories as defined by the SASSAD score [the proportion of children who had a reasonable (≤ 20%), good (> 20% and ≤ 50%) or excellent (> 50%) improvement in SASSAD score], as this was felt to be more appropriate in a single-blind study. All amendments were implemented prior to breaking of the treatment allocation code and prior to finalising the analysis plan.

Trial conduct

Trial organisation

The trial was managed and co-ordinated from the Centre of Evidence Based Dermatology, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK. Data management was conducted through the Nottingham CTU. Statistical analysis was overseen by Professor Andrew Nunn and conducted at the Medical Research Council (MRC) CTU in London.

The Trial Management Group (TMG) was responsible for overall management of the trial. The TSC had an independent chairperson and vice chairperspon and met annually to provide overall supervision of the trial on behalf of the trial sponsor (University of Nottingham). Training sessions were held for research nurses and water engineers prior to starting the trial, and ongoing training was provided at individual sites as required.

The trial manager was responsible for day-to-day management of the trial. Details of individual participants were kept in a password-protected access database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). This included unblinded information relating to home screen outcomes, installation and removal of water softeners and hardness alerts.

As the trial involved the use of a commonly available domestic water softening unit, and did not involve the use of a medicinal product, there was no need for a Data Monitoring Committee.

Membership of the TMG and the TSC are given in Appendix 5.

Engineer co-ordination

Water engineers were subcontracted by the UKWTA. All water engineering aspects on the Isle of Wight were handled by a single subcontractor (MG Heating Ltd, Oxford, UK). Homes on the mainland were assessed by a number of local independent subcontractors co-ordinated by Lorraine Doran at European Water Care Ltd (Essex, UK, May–October 2007) and John Kyle at Kinetico UK Ltd (Hampshire, UK, October 2007 to September 2009). Fourteen subcontractors carried out water engineering aspects over the course of the trial. The majority of the work was done by the following nine subcontractors: Aquastream, Capital Softeners, Clearwater Softeners, European Water Care, Greens Water Systems, Kinetico UK, MG Heating Ltd, Silkstream and Simply Soft Water Softeners.

Consumer involvement

A consumer panel of five service users with experience of living with eczema assessed patient information sheets, symptom diaries and publicity material prior to submission for ethical approval. The panel members shared these documents with children with eczema aged 4 and 13 years. Mr David Potter acted as consumer panel representative on the TSC. Several participants from the trial assisted with trial publicity by agreeing to take part in media interviews (once their direct involvement in the trial was over). The National Eczema Society (NES) and the Nottingham Support Group for Carers of Children with Eczema (NSGCCE) helped with publicity during the recruitment phase of the trial.

Trial finances

This trial was funded by the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) HTA programme. Subcontracts were established between the University of Nottingham and the MRC CTU, the consortium of water treatment companies (through the UKWTA) and the University of Portsmouth. In addition to the funding provided by the NIHR HTA programme, representatives from the water-softening industry covered the costs of the design, testing and supply of generic ion-exchange water softeners, salt supplies, hardness testing of water samples and supervision of water engineers.

Trial participants were offered a standard inconvenience allowance of £5–10 per visit in the form of gift vouchers.

Trial insurance and indemnity

The usual NHS indemnity arrangements for negligent harm applied. The University of Nottingham acted as sponsor for the trial and had third-party liability insurance in accordance with all local legal requirements, including cover for children under the age of 5 years. In addition, study engineers carried their own third-party liability insurance. The water softeners used in the study were covered by product warranty.

SWET website

The SWET website (www.swet-trial.co.uk, Figure 5) was active from May 2007 when recruitment began. The website included a password-protected researcher section where all current trial documentation was accessible for download by research nurses at individual study sites.

FIGURE 5.

Screenshot of the home page of the SWET website.

Chapter 3 Working with industry

Pilot study

A pilot study funded by Kinetico UK Ltd was carried out in 2002 by Professor Hywel Williams and his research team at the University of Nottingham. This was a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group pilot study of 12 weeks’ duration. The aims of the pilot study were (i) to test the appropriateness of the recruitment methods and trial procedures; (ii) to inform sample size calculations for the main RCT; and importantly and; (iii) to assess whether or not it was possible to blind participants to their treatment allocation (given that softened water typically produces more lather when using cleaning products).

Participants in the pilot study received either an ion-exchange water softener or a specially modified ‘placebo’ water softener, in which the internal resin beads had been replaced with inactive polypropylene. Technical difficulties meant that, for the purposes of the pilot trial, only homes with a gravity-fed boiler were eligible to take part (families with a combination boiler were excluded). Participants were instructed to continue treating their eczema according to their usual practice for the duration of the trial.

Seventeen children aged 1–10 years with moderate or severe eczema from the Nottingham area were randomised into one of two treatment groups for a period of 12 weeks.

At the end of 12 weeks, the children’s eczema was assessed, and parents/carers were asked whether they thought they had received a real or a placebo unit.

Lessons from the pilot study.

-

The pilot trial generated a lot of interest, although many families were ineligible because their homes were unsuitable for the installation of a water softener; or they had a combination boiler in the home. This led to modifications in the RCT design so that both gravity-fed and combination boiler types were eligible, and an additional home screen visit was introduced prior to randomising the participants into the trial.

-

It proved to be extremely difficult to blind participants to their treatment allocation and, as might be expected, this was particularly marked for those who received the real water softener. However, there was no evidence to suggest that the research nurse had been compromised, and so a single-blind study was recommended (with mechanisms in place to record instances when the research nurses had become aware of the treatment allocation).

-

In order to maximise exposure to the intervention, it was recommended that water softener units were installed as soon as possible after a child had been randomised into the study, and records kept of periods away from the home.

-

The number of technical difficulties experienced with the units during the 12-week study period was higher than expected. For the full study, it was recommended that engineers be employed to work exclusively for the trial, and that regular water testing be introduced.

-

Measuring chlorine content of the water proved problematic due to rapid evaporation. For the full study it was recommended that we measure water hardness only.

-

Participants randomised to receive a placebo unit expressed regret at not being able to try a ‘real’ unit for themselves. It was felt that this might impact on our ability to recruit into the main RCT, and so an additional 4-week period was introduced between weeks 12 and 16, when the control group would have a water softener installed.

Experiences from the main trial

The Softened Water Eczema Trial (SWET) was an unusual eczema clinical trial in that the intervention was not another skin cream, but altering one aspect of the child’s normal home environment (water hardness). The intervention was a piece of widely available specialised non-medical equipment, which plumbed into the mains water supply to the child’s home. This required a level of specialist knowledge and expertise that could be achieved only by close collaboration with the water-softening industry.

Water-softening industry and their trade associations

British Water is a corporate membership association covering all sectors of the water industry, and was closely involved with the pilot study and setting up the main study. Ian Pallett (Technical Director at British Water) was a co-applicant on the funding application and served as the industry representative on the TSC.

A number of meetings were held with representatives from British Water and the water-softening industry prior to setting up the main trial. These informed practical logistics, including the design of a generic water-softening unit encased in a special SWET cabinet.

Representatives from the following companies gave input to meetings prior to and during the trial: Aqua Focus Ltd (Newport, UK), Aquademic Ltd (Derby, UK), Aqua Nouveau Ltd (Basingstoke, UK), Coleman Water Ltd (Ipswich, UK), Culligan International (UK) Ltd (High Wycombe, UK), EcoWater Systems Ltd (High Wycombe, UK), Harvey Softeners Ltd (Surrey, UK), Kennet Water Components Ltd (Newbury, UK) and Kinetico (UK) Ltd (Hampshire, UK).

The UKWTA was formed in March 2006 and is a national trade organisation for companies involved in the sale and use of water treatment chemicals and equipment in the UK. The UKWTA was closely involved with delivery of the SWET trial, and Tony Frost served as the UKWTA representative on the TMG.

There was a great deal of goodwill in the industry towards the trial; an early example was the professional redrawing of a draught logo by artists working in the publicity department of Aqua Nouveau Ltd. This became the instantly recognisable SWET hippo logo, which was a great hit with children on the trial.

Engineer employment

The intention had been to employ a small number of water engineers, one for each study centre, and to pay each engineer a salary for a fixed number of days/week devoted to SWET. However, this plan was set aside in March 2006, when the UKWTA was formed. By liaising directly through the UKWTA, the trial was able to have a more flexible approach to securing water engineer expertise and cover a wider geographical area extending across south-east and central England, from the Isle of Wight to Lincolnshire. Tony Frost acted as representative on the TMG for the UKWTA, which took over responsibility for subcontracting work to a number of smaller water softener companies.

Engineer training

Over the lifetime of the study, more than 20 water engineers from over 10 companies were involved in the installation and/or removal of study units. It was felt that the advantage of increased flexibility and engineer cover outweighed the disadvantage of losing direct contact with individual engineers. A downside was the effect on engineer training. Information about the trial was passed on through engineer co-ordinators on the Isle of Wight and the mainland, rather than directly in face-to-face training sessions with members of the TMG. In response to a few instances where engineers became involved in unwarranted discussions with parents about softened water and eczema, the trial manager wrote a SWET engineer’s handbook. This was distributed to all engineers in March 2008, and included background information and a list of important ‘dos’ and ‘don’ts’.

Individual engineers’ levels of expertise and professionalism were very high. There were a few occasions when water engineers did not have the skills necessary to adequately screen homes, or to carry out installations, e.g. one engineer underestimated water hardness at home screen by not giving sufficient time for the Hach drop-count test to develop. Action to resolve the situation was swiftly implemented in all cases.

Water engineers work to tight deadlines, often driving many miles between homes and only visiting their company depot/offices as required. As a result, it was difficult for individual engineers to work to good clinical practice (GCP) standards in terms of paperwork trails. The co-ordinating centre spent many hours chasing paperwork, confirming home screens and installations/removals. In an effort to improve rapid communication between engineers and the co-ordinating centre, a dedicated telephone answering machine was introduced for engineers to leave messages whenever they had done anything for SWET.

Understanding research terminology and methodology

In order to collaborate effectively, industry colleagues needed to understand clinical methodology and terminology such as the difference between RCTs and other types of research, and the statistical interpretation of RCT blinded and unblinded outcomes. This was important both during the trial itself in terms of working to GCP standards (data protection, paperwork trails, etc.) and at the end of the trial when understanding trial results and statistical terminology. Hywel Williams, in his role of Chief Investigator, agreed to talk to a meeting of industry colleagues after the trial ended, in order to explain the results.

While the water-softening industry helped inform study design and assisted with the trial conduct by carrying out home screen visits, installing devices and monitoring water samples, it had no involvement in data collection, analysis or interpretation.

Publicity issues

The UKWTA companies involved with SWET were asked to take a responsible approach to publicity about the study on their own websites. While all additional publicity about the trial was welcomed (because it would aid recruitment) it was important that companies remained neutral and did not give any misleading information. Routine monitoring of company websites occasionally revealed problems which were rapidly resolved on our behalf by the UKWTA.

Ongoing commitment to the trial

There were numerous examples of good practice which put the needs of the trial foremost. During the first 6 months of the study the number of homes failing the ‘home screening visit’ was higher than expected, and this was addressed in meetings held within the industry, and in collaborative meetings with staff at the co-ordinating centre. As the trial progressed, the number of samples needing routine analysis for hardness levels increased, and this extra work was absorbed by Culligan UK Ltd. Kinetico UK Ltd had responsibility for building the generic SWET ion-exchange water softeners. Originally the company had been told that 100 units would be required across the 2-year recruitment period, but owing to higher than expected numbers of units being purchased by families, this number increased to 197. At an individual level, engineers attached to the SWET trial were often working in very different environments from usual. This sometimes involved installing softeners into tight or unusual spaces, and finding creative ways to solve technical problems. One engineer discovered additional pipework to a bathroom during a visit to investigate a hardness ‘alert’. As a result of this, the procedure for routine weekly water testing and home screening was changed. Other examples included staff at the co-ordinating centre contacting parents to let them know about a recent hardness alert only to be told that water engineer had already visited and rectified the problem.

Option to buy the water softener

All participants had the option of buying the water softener at a reduced price at the end of their child’s 16-week study period.

To avoid potential conflict of interest, staff at the co-ordinating centre did not get involved in payment arrangements. Standard information was included in the letter sent out after recruitment, and all requests to purchase units were directed to the UKWTA (responsible as intermediary) and Kinetico UK Ltd (responsible for invoicing and warranty).

Chapter 4 Results

Recruitment

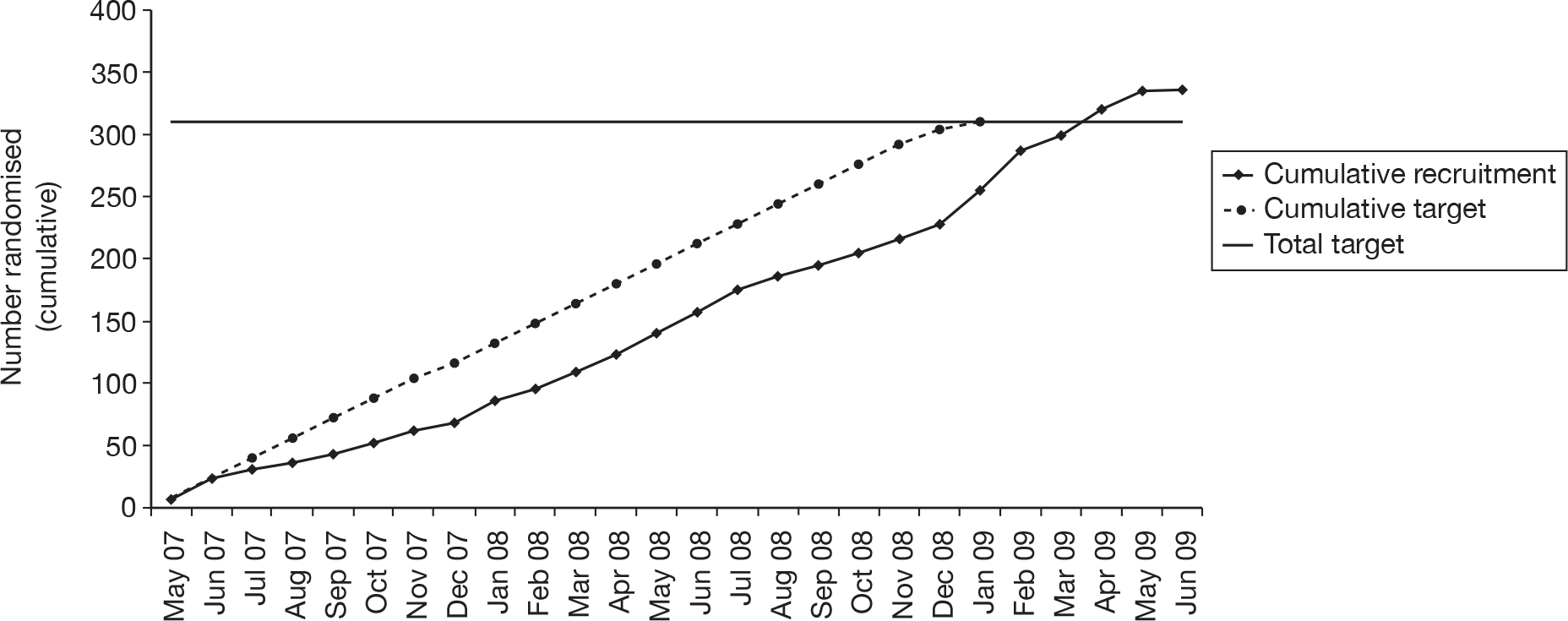

Recruitment took place between May 2007 and June 2009 (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Cumulative recruitment.

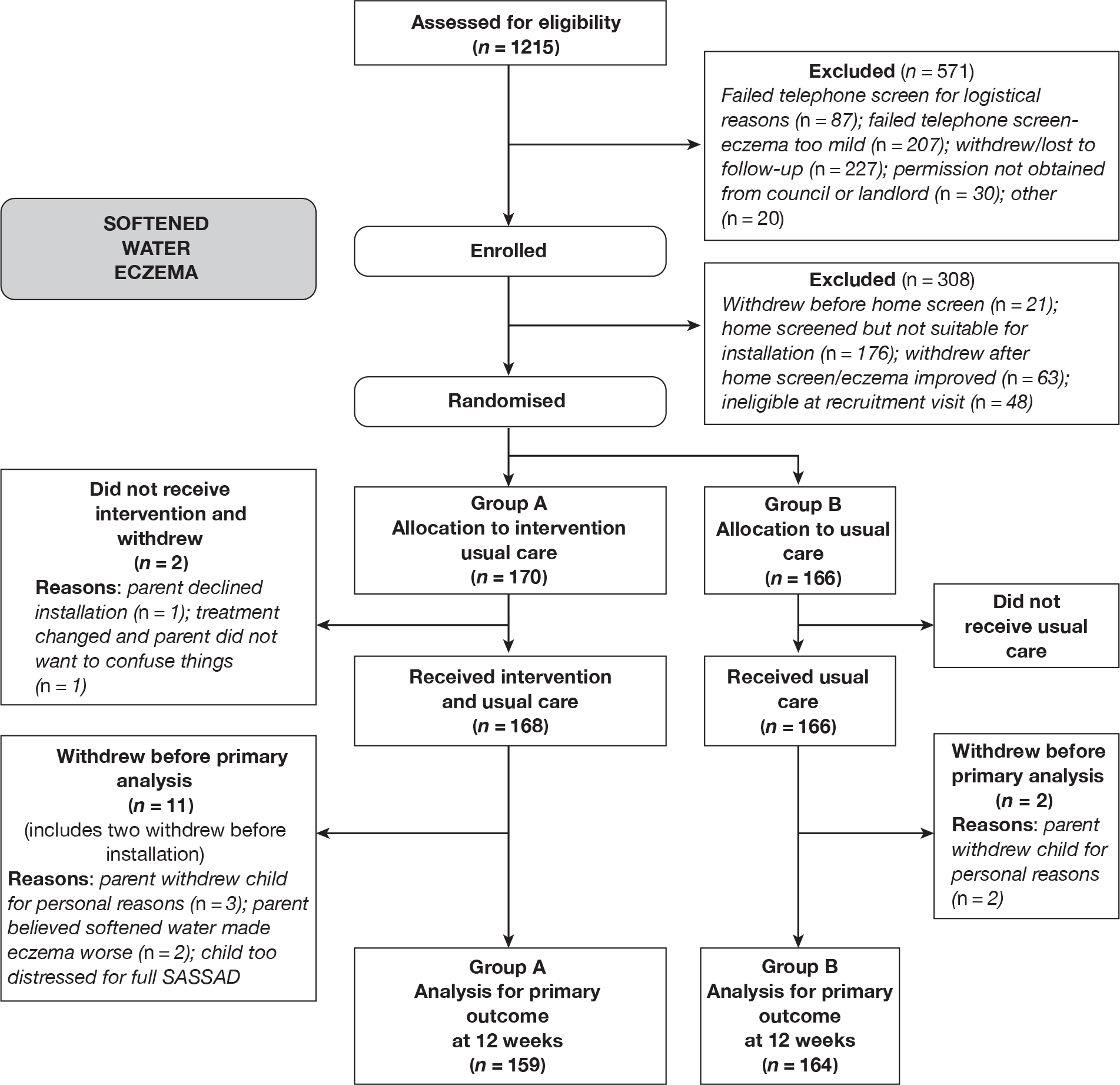

Enrolment into the trial was a two-stage process (Figure 7). All those who passed the initial telephone screen were issued a study number (n = 644). Of these, 308 failed to meet the full inclusion criteria and were not randomised into the trial. The main reasons for excluding participants at this stage were that it was not possible to install a water-softening device in the child’s home or that the child’s eczema was too mild. Further details on home screening outcomes are given in Appendix 6.

FIGURE 7.

CONSORT diagram of participant flow.

A total of 336 participants were randomised into the study (170 in group A and 166 in group B). This is higher than the original target (n = 310), as a number of families had been issued study numbers and were in the process of having home screening visits or were awaiting landlord/council decisions when the 310th participant was recruited into the trial. The ITT population consisted of the 323 participants with evaluable data (96% of all randomised participants). This included 159 in group A (water softener + usual care) and 164 in group B (usual care). Multiple imputation of missing values was not felt to be appropriate in this context owing to the very low levels of missing data.

Baseline data

The groups were generally well balanced for all baseline characteristics, although to group A (water softener + usual care) included a slightly higher proportion of older children (aged ≥ 7 years) and members of group A, were more likely to use higher potency topical therapy (potent steroids, very potent steroids or calcineurin inhibitors) and slightly more likely to use biological washing powders (Table 2). The possible impact of these differences was explored in sensitivity analysis (primary outcome).

| Baseline characteristics | Group A (water softener + usual care) | Group B (usual care) |

|---|---|---|

| Number enrolled | 170 | 166 |

| Number in ITT population | 159 | 164 |

| Age | ||

| Mean age, years (SD) | 5.8 (4.2) | 5.1 (4.0) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 89 (56) | 96 (59) |

| Female | 70 (44) | 68 (41) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White | 124 (78) | 125 (76) |

| Non-white | 34 (21) | 38 (23) |

| Not stated/unknown | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Previous treatment history, n (%)a | ||

| High strength corticosteroids/calcineurin inhibitors | 91 (57) | 80 (49) |

| Low strength corticosteroids/calcineurin inhibitors | 57 (36) | 73 (45) |

| None | 11 (7) | 11 (7) |

| Filaggrin status, n (%) | ||

| Presence of mutation | 45 (28) | 47 (29) |

| Absence of mutation | 103 (65) | 109 (66) |

| Unknown | 11 (7) | 8 (5) |

| Food allergy, n (%)b | ||

| No | 97 (63) | 102 (64) |

| Yes | 58 (37) | 58 (36) |

| Baseline SASSAD score, n (%)c | ||

| Mean (SD) | 24.6 (12.7) | 25.9 (13.8) |

| Median (IQR) | 21 (15–32) | 22.5 (15.5–33.5) |

| 10–19 | 72 (45) | 68 (41) |

| > 20 | 87 (55) | 96 (59) |

| Water hardness (mg/L-1 calcium carbonate) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 309 (50) | 310 (58) |

| Median (IQR) | 308 (274–342) | 300 (270–340) |

| Washing powder, n (%)d | ||

| Biological | 20 (13) | 12 (7) |

| Fabric softener, n (%)e | ||

| Yes | 69 (44) | 81 (49) |

| Bathing frequency at home, times per weekf | ||

| Median (IQR) | 5 (3–7) | 4 (3–7) |

| Bathing frequency away from home, times per weekg | ||

| Median (IQR) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–0) |

| Swimming frequency, n (%)h | ||

| Never | 56 (35) | 66 (40) |

| Less than once a month | 53 (34) | 52 (32) |

| More than once a month | 49 (31) | 46 (28) |

Intervention – duration of exposure to softened water

Engineers were instructed to carry out installation of water softeners within a maximum of 2 weeks (10 working days); parents were asked to be as flexible as possible when arranging suitable dates, in order to achieve this. The average duration of exposure to softened water in group A was 10.6 weeks (range 7.6–16.4 weeks) (Table 3).

| Group | Installation status | Days (including weekends), mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Group Aa (n = 168) | Time from randomisation to installation | 12.4 ± 5.5 (range 2–32) |

| Duration of installation prior to primary outcome assessment | 74 ± 7.6 (range 53–115) | |

| Group Bb (n = 156) | Time from week 12 visit to installation | 9.2 ± 6.5 (range 0–34) |

| Duration of installation prior to assessment at 16 weeks | 24.5 ± 9.0 (range 0–78) |

Primary analysis

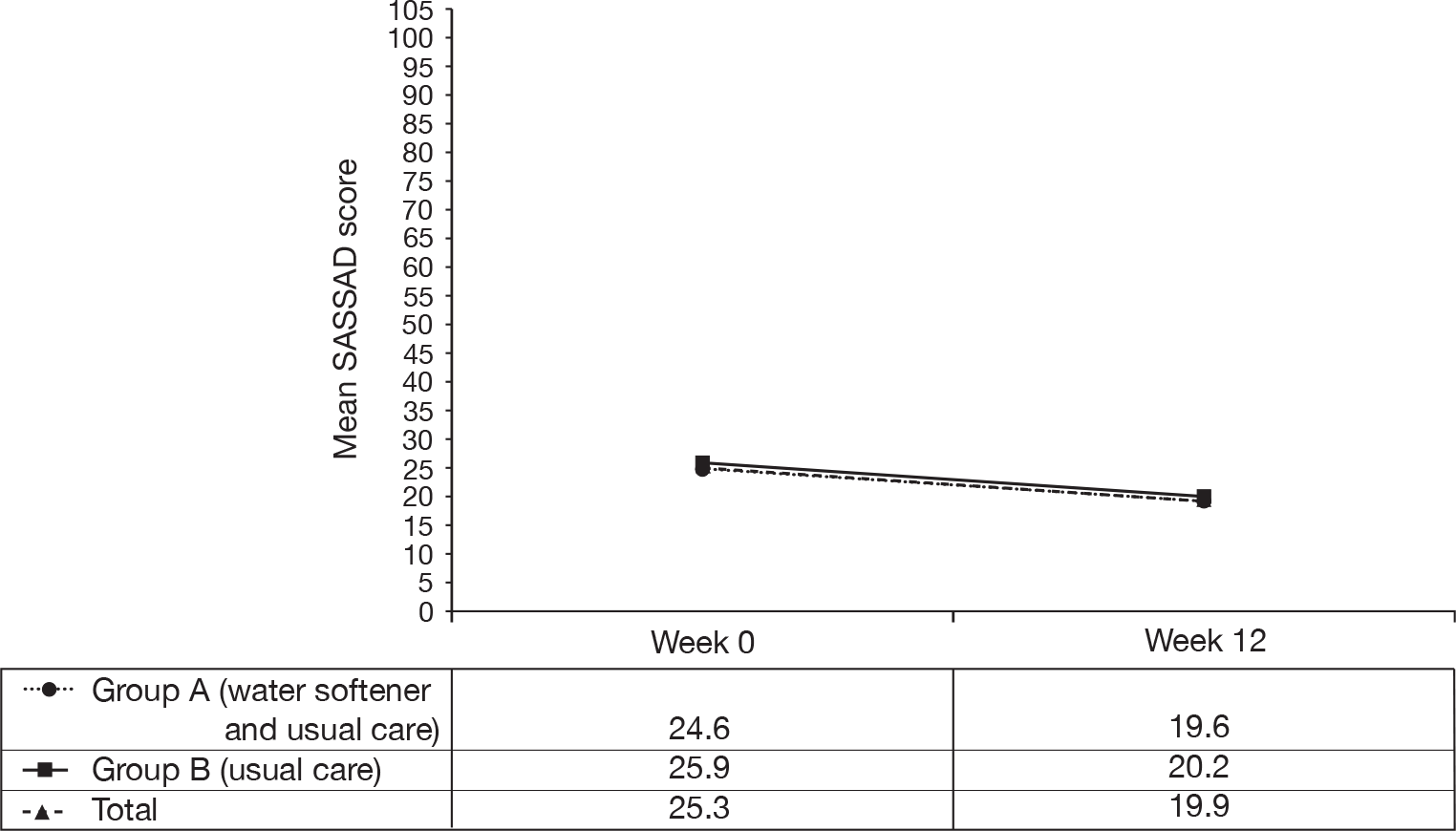

Intention-to-treat analysis

The primary end point of change in disease severity is shown in Table 4. Group A showed a mean reduction of 20% (5.0 points) in SASSAD score from an average of 24.6 at baseline to 19.6 at week 12. Group B showed a reduction of 22% (5.7 points) in SASSAD score from an average of 25.9 at baseline to 20.2 at week 12. The difference between the two groups at week 12 was 0.66 in favour of group B (95% CI –1.37 to 2.69) and was not statistically significant (p = 0.53). An additional analysis adjusting for stratification variables (baseline SASSAD score and centre) was performed, but this did not alter the conclusion. The difference between the two groups was reduced to 0.34 (95% CI –1.65 to 2.33, p = 0.74), in favour of group B.

| Time assessed | Group A (water softener + usual care) | Group B (usual care) | Difference and 95% CI (A–B) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number randomised | 170 | 166 | |||

| N analysed a | 159 | 164 | |||

| Week 0 | Mean ± SD | 24.6 ± 12.7 | 25.9 ± 13.8 | ||

| Week 12 | Mean ± SD | 19.6 ± 12.8 | 20.2 ± 13.8 | ||

| Change | Mean ± SD | –5.0 ± 8.8 | –5.7 ± 9.8 | 0.66 (–1.37 to 2.69) | 0.53 |

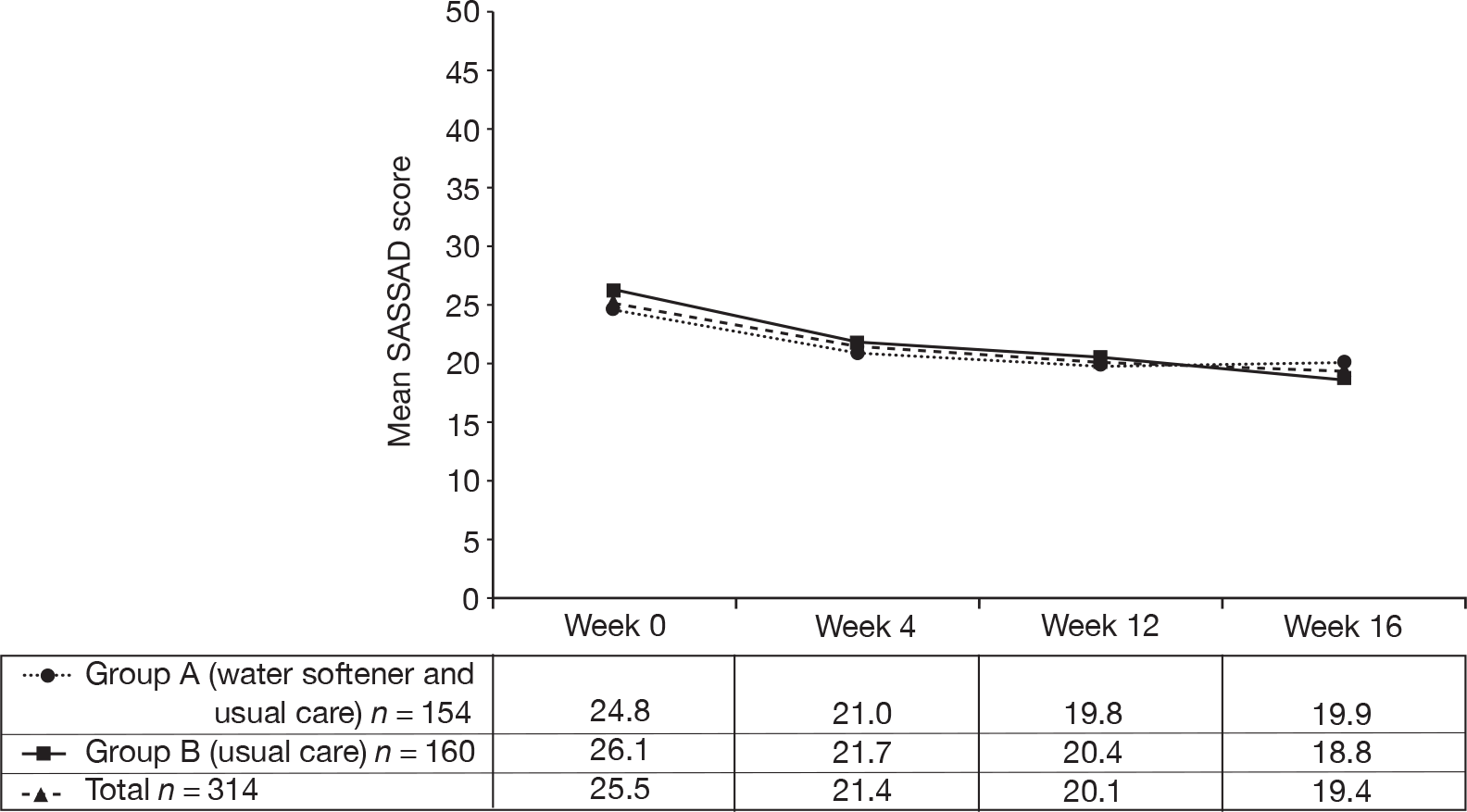

These results are shown graphically in Figure 8 based on those with complete data at all time points.

As a result of the slight imbalance between the two groups at baseline in relation to age, previous treatment history and use of biological washing powder, a generalised linear model (GLM) was performed that adjusted for these baseline differences. This analysis gave similar results to the univariate t-test analysis. The difference between the two groups was 0.54 (95% CI –1.54 to 2.62, p = 0.61). (More detailed information is given in Appendix 7.)

FIGURE 8.

Six Area, Six Sign Atopic Dermatitis scores to week 12.

Per-protocol analysis

The planned per-protocol analysis supported the findings of the primary ITT analysis (Table 5). There was an 18% reduction (4.5 points) in group A and a 24% reduction (6.3 points) in group B. This represented a difference of 1.87 in favour of group B (95% CI –0.73 to 4.47), which was not statistically significant (p = 0.16).

| Time assessed | Group A (water softener + usual care) | Group B (usual care) | Difference and 95% CI (A–B) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number randomised | 170 | 166 | |||

| N analysed a | 99 | 115 | |||

| Week 0 | Mean ± SD | 25.3 ± 13.7 | 26.3 ± 14.5 | ||

| Week 12 | Mean ± SD | 20.8 ± 13.6 | 20.0 ± 13.4 | ||

| Change | Mean ± SD | –4.5 ± 9.3 | –6.3 ± 9.9 | 1.87 (–0.73 to 4.47) | 0.16 |

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses were performed (i) including all randomised participants by replacing missing values; (ii) excluding participants for whom the outcome assessor had been unblinded; and (iii) excluding participants with scores that were defined as being outliers (Table 6).

| Time assessed | Group A (water softener + usual care) | Group B (usual care) | Difference and 95% CI (A–B) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number randomised | 170 | 166 | |||

| N – all participants a | 170 | 166 | |||

| Week 0 | Mean ± SD | 25.5 ± 13.7 | 26.0 ± 13.9 | ||

| Week 12 | Mean ± SD | 20.7 ± 13.8 | 20.4 ± 13.9 | ||

| Change | Mean ± SD | –4.9 ± 8.7 | –5.6 ± 9.7 | 0.76 (–1.22 to 2.74) | 0.45 |

| N – excluding participants where nurse became unblinded b | 153 | 159 | |||

| Week 0 | Mean ± SD | 24.7 ± 12.8 | 26.0 ± 14.0 | ||

| Week 12 | Mean ± SD | 19.8 ± 12.9 | 19.9 ± 13.7 | ||

| Change | Mean ± SD | –4.9 ± 8.7 | –6.1 ± 9.4 | 1.26 (–0.77 to 3.28) | 0.22 |

| N – excluding outliers c | 157 | 163 | |||

| Week 0 | Mean ± SD | 24.7 ± 12.7 | 25.5 ± 12.8 | ||

| Week 12 | Mean ± SD | 19.3 ± 12.5 | 20.2 ± 13.8 | ||

| Change | Mean ± SD | –5.4 ± 8.2 | –5.3 ± 8.3 | –0.11 (–1.93 to 1.70) | 0.90 |

Results from analysis of all randomised participants supported the primary result, as the mean change in SASSAD score was 0.76 in favour of group B (95% CI –1.22 to 2.74; p = 0.45).

Results from analysis excluding unblinded participants showed a difference between the two groups of 1.26 in favour of group B (95% CI –0.77 to 3.28), which was not statistically significant (p = 0.22), and again supported the primary result.

Results from analysis excluding outliers gave a mean difference of –0.11 in favour of group A (95% CI –1.93 to 1.70) and was not statistically significant (p = 0.90).

Planned subgroup analysis – filaggrin status

The laboratory screened for the two most common mutations in the filaggrin gene (loss-of-function mutations R501X and 2282del4); variants (mutations) were either heterozygous or homozygous affected. A sample size of 90 children with at least one mutation was required for this subgroup analysis (see Chapter 2 for further details).

Of the 314 participants with test results, 94 (30%) had at least one mutation in the filaggrin gene. These were affected as follows:

-

11 wild type/heterozygous

-

71 heterozygous/heterozygous

-

12 wild type/homozygous affected.

The p-value for the interaction between the filaggrin status and the intervention was 0.87, indicating no evidence that the treatment effect varied between those with and without the mutation.

The analysis by filaggrin status is given in Table 7. The change in SASSAD score between baseline and week 12 in those in whom the mutation was absent was –5.1 in group A and –5.8 in group B. This represented a difference of 0.68 in favour of group B (95% CI –1.87 to 3.23, p = 0.60). The change in SASSAD score between baseline and week 12 in those in whom the mutation was present was –5.2 in group A and –6.3 in group B. This represented a difference of 1.05 in favour of group B (95% CI –2.36 to 4.47, p = 0.54).

| Time assessed | Group A (water softener + usual care) | Group B (usual care) | Difference and 95% CI (A–B) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number randomised | 170 | 166 | |||

| Na – mutation absent | 103 | 109 | |||

| Week 0 | Mean ± SD | 23.2 ± 12.3 | 25.4 ± 14.2 | ||

| Week 12 | Mean ± SD | 18.1 ± 12.5 | 19.6 ± 13.9 | ||

| Change | Mean ± SD | –5.1 ± 8.0 | –5.8 ± 10.6 | 0.68 (–1.87 to 3.23) | 0.60 |

| Nb – mutation present | 45 | 47 | |||

| Week 0 | Mean ± SD | 27.2 ± 13.4 | 26.7 ± 13.4 | ||

| Week 12 | Mean ± SD | 22.0 ± 13.4 | 20.4 ± 13.9 | ||

| Change | Mean ± SD | –5.2 ± 9.5 | –6.3 ± 6.8 | 1.05 (–2.36 to 4.47) | 0.54 |

Secondary analyses

Categories of improvement in Six Area, Six Sign Atopic Dermatitis score

The SASSAD scores grouped into categories of improvement are shown in Table 8. There was no evidence of a difference between the groups (p = 0.62), which supported the primary ITT analysis.

| Level of improvement | Group A (water softener + usual care) | Group B (usual care) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number randomised | 170 | 166 | 336 |

| N analysed a | 159 | 164 | 323 |

| Same or worse (≤ 0%) | 39 (25%) | 42 (26%) | 81 (25%) |

| Reasonable (> 0% and ≤ 20%) | 37 (23%) | 30 (18%) | 67 (21%) |

| Good (> 20% and ≤ 50%) | 53 (33%) | 56 (34%) | 109 (34%) |

| Excellent (> 50%) | 30 (19%) | 36 (22%) | 66 (20%) |

Night-time movement

The percentage of the night spent moving was measured using accelerometers (Table 9). Both groups showed an increase in the percentage of the night spent moving: 3.5% in group A and 4.1% in group B. The difference between the two groups was –0.64 in favour of group A (95% CI –4.68 to 3.40) and was not statistically significant (p = 0.76). Both groups showed an increase in night-time movement during the trial. This is in contrast to the other reported outcomes, which all showed improvements over time in both groups. As a result an exploratory sensitivity analysis was conducted (see below). The correlation between the SASSAD score and the first three nights of usable data from the accelerometers at baseline was 0.11 (p = 0.06), suggesting weak evidence of a weak correlation. Comparing the change in SASSAD score from baseline to week 12 with the change in the percentage of the night spent moving from the accelerometer data gave a correlation of –0.02 (p = 0.77), suggesting no evidence of any correlation.

| Time assessed | Group A (water softener + usual care) | Group B (usual care) | Difference and 95% CI (A–B) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number randomised | 170 | 166 | |||

| N analysed a | 114 | 121 | |||

| Week 0 | Mean ± SD | 21.2 ± 7.7 | 22.4 ± 9.7 | ||

| Week 12 | Mean ± SD | 24.7 ± 15.9 | 26.5 ± 17.9 | ||

| Change | Mean ± SD | 3.5 ± 14.5 | 4.1 ± 16.8 | –0.64 (–4.68 to 3.40) | 0.76 |

| Nb – same watch at baseline and 12 weeks | 75 | 85 | |||

| Week 0 | Mean ± SD | 20.7 ± 7.8 | 22.8 ± 10.5 | ||

| Week 12 | Mean ± SD | 26.0 ± 17.2 | 26.8 ± 18.2 | ||

| Change | Mean ± SD | 5.3 ± 16.0 | 4.0 ± 16.2 | 1.30 (–3.73 to 6.34) | 0.61 |

| Nc – participants with > 5 sleep bouts and wearing watch all night (according to diaries) | 94 | 104 | |||

| Week 0 | Mean ± SD | 21.1 ± 7.3 | 22.1 ± 9.1 | ||

| Week 12 | Mean ± SD | 23.1 ± 12.1 | 25.7 ± 17.9 | ||

| Change | Mean ± SD | 2.0 ± 11.1 | 3.6 ± 17.1 | –1.62 (–5.70 to 2.46) | 0.44 |

Sensitivity analyses

Owing to possible differences between the watches, a sensitivity analysis was performed restricted to those who wore the same watch at baseline and week 12 (n = 160). The difference between the two groups was 1.30 (95% CI –3.73 to 6.34), and was not statistically significant (p = 0.61), which supported the main analysis. Given that the direction of change for this outcome was different to that of all other reported outcomes (i.e. participants moved more rather than less during the trial), a post hoc sensitivity analysis was conducted restricted to those for whom we had the most confidence in the accuracy of the data. This was restricted to those who had five or more sleep ‘bouts’ during the analysis period (which would suggest that the units had been worn correctly), and those whose parents indicated that the watch had been worn throughout the night (information taken from diaries, n = 198). This analysis continued to show an increase in movement during the trial and the difference between the groups remained non-significant (Table 9).

Amount of medication used

Group A used on average 58.4 g (SD = 96.8 g) of medication over the 12-week period and group B used on average 67.3 g (SD = 97.3 g, Table 10). The difference between the two groups was –8.90 g (95% CI –30.50 to 12.70 g) and was not statistically significant (p = 0.42).

| Steroid strength | Group A (water softener + usual care) | Group B (usual care) | Difference and 95% CI (A–B) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number randomised | 170 | 166 | |||

| N analysed | 160 | 153 | |||

| Mild steroids (g) | Mean ± SD | 12.0 ± 29.9 | 18.2 ± 35.6 | ||

| Moderate steroids (g) | Mean ± SD | 19.7 ± 69.3 | 25.3 ± 59.1 | ||

| Potent steroids (g) | Mean ± SD | 21.5 ± 41.4 | 18.4 ± 39.7 | ||

| Very potent steroids (g) | Mean ± SD | 2.2 ± 11.7 | 1.8 ± 20.7 | ||

| Mild calcineurin inhibitors (g) | Mean ± SD | 1.9 ± 7.9 | 2.7± 12.0 | ||

| Moderate calcineurin inhibitors (g) | Mean ± SD | 1.1 ± 9.1 | 1.0 ± 7.9 | ||

| Total medications (g) | Mean ± SD | 58.4 ± 96.8 | 67.3 ± 97.3 | –8.9 (–30.50 to 12.70) | 0.42 |

Sensitivity analyses

Two further sensitivity analyses were performed based on strength of medication and confidence of the nurses in the measurements. Detailed information is given in Appendix 8. Both analyses supported the main findings.

Patient Oriented Eczema Measure scores

Group A showed a drop of 34% (5.7 points) from 16.8 at baseline to 11.1 at week 12 and group B showed a drop of 22% (3.6 points) from 16.6 at baseline to 13.0 at week 12 (Table 11). The difference between the two groups was –2.03 (95% CI –3.55 to –0.51) which was statistically significant (p < 0.01).

| Time assessed | Group A (water softener + usual care) | Group B (usual care) | Difference and 95% CI (A–B) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number randomised | 170 | 166 | |||

| N analysed a | 161 | 162 | |||

| Week 0 | Mean ± SD | 16.8 ± 6.0 | 16.6 ± 5.6 | ||

| Week 12 | Mean ± SD | 11.1 ± 7.1 | 13.0 ± 6.7 | ||

| Change | Mean ± SD | –5.7 ± 7.2 | –3.6 ± 6.7 | –2.03 (–3.55 to –0.51) | < 0.001 |

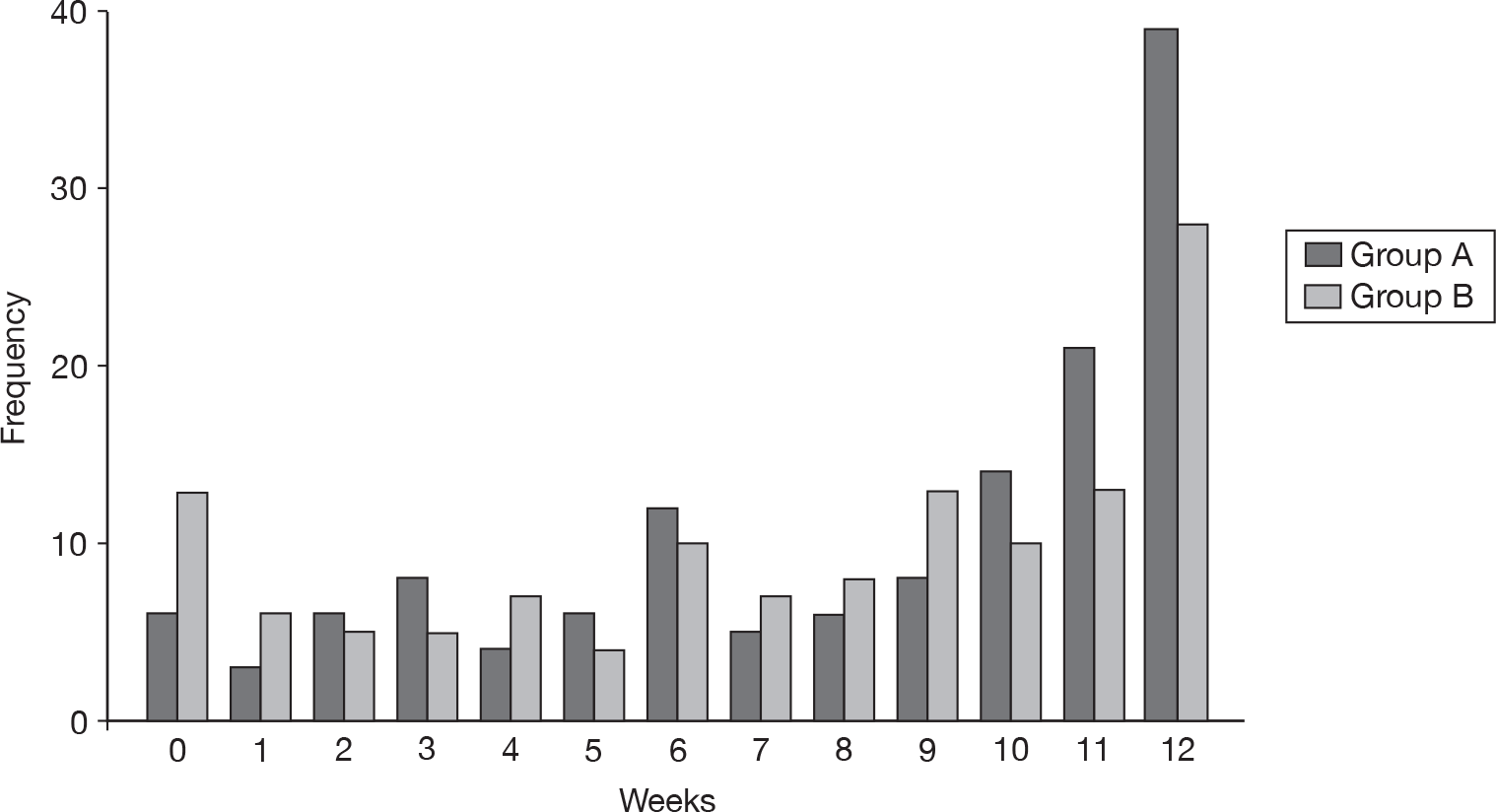

The difference between the two groups is shown visually in Figure 9.

FIGURE 9.

Change in POEM scores.

The POEM scores at week 4 also showed a difference in favour of group A, but this was not statistically significant. Group A showed a drop of 22% (3.8 points) from 16.9 at baseline to 13.1 at week 4, and group B showed a drop of 17% (2.8 points) from 16.8 at baseline to 13.9 at week 4. The difference between the two groups was –1.0 (95% CI –2.25 to 0.30), which was not statistically significant (p = 0.13).

Totally controlled weeks and well-controlled weeks

Group A had an average of 8.3 (SD 3.8) WCWs and group B had an average of 7.3 (SD 4.1) WCWs over the 12-week study period. The difference between the groups was 0.99 (95% CI 0.04 to 1.95). This difference of just under 1 week was statistically significant (p = 0.04).

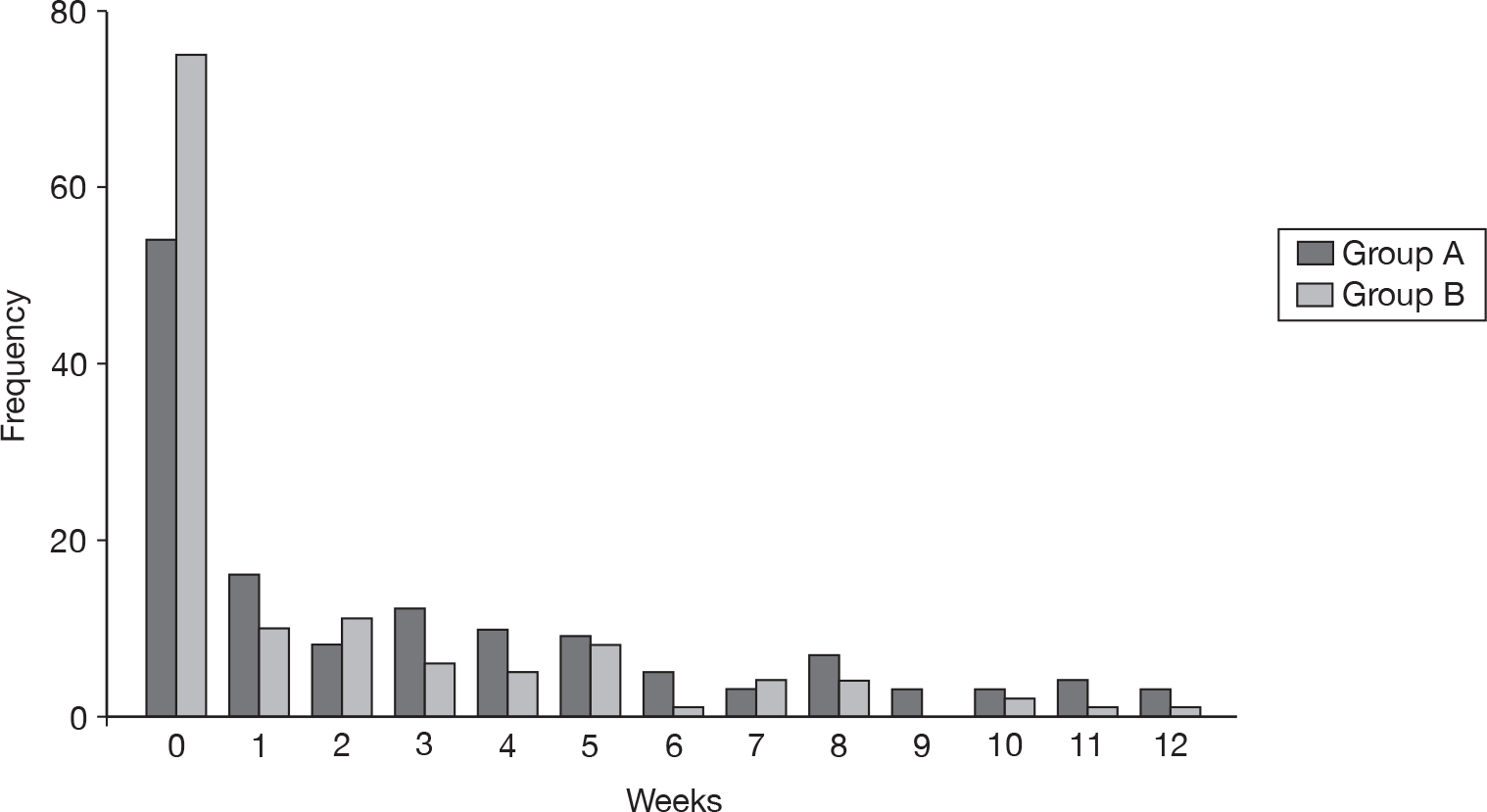

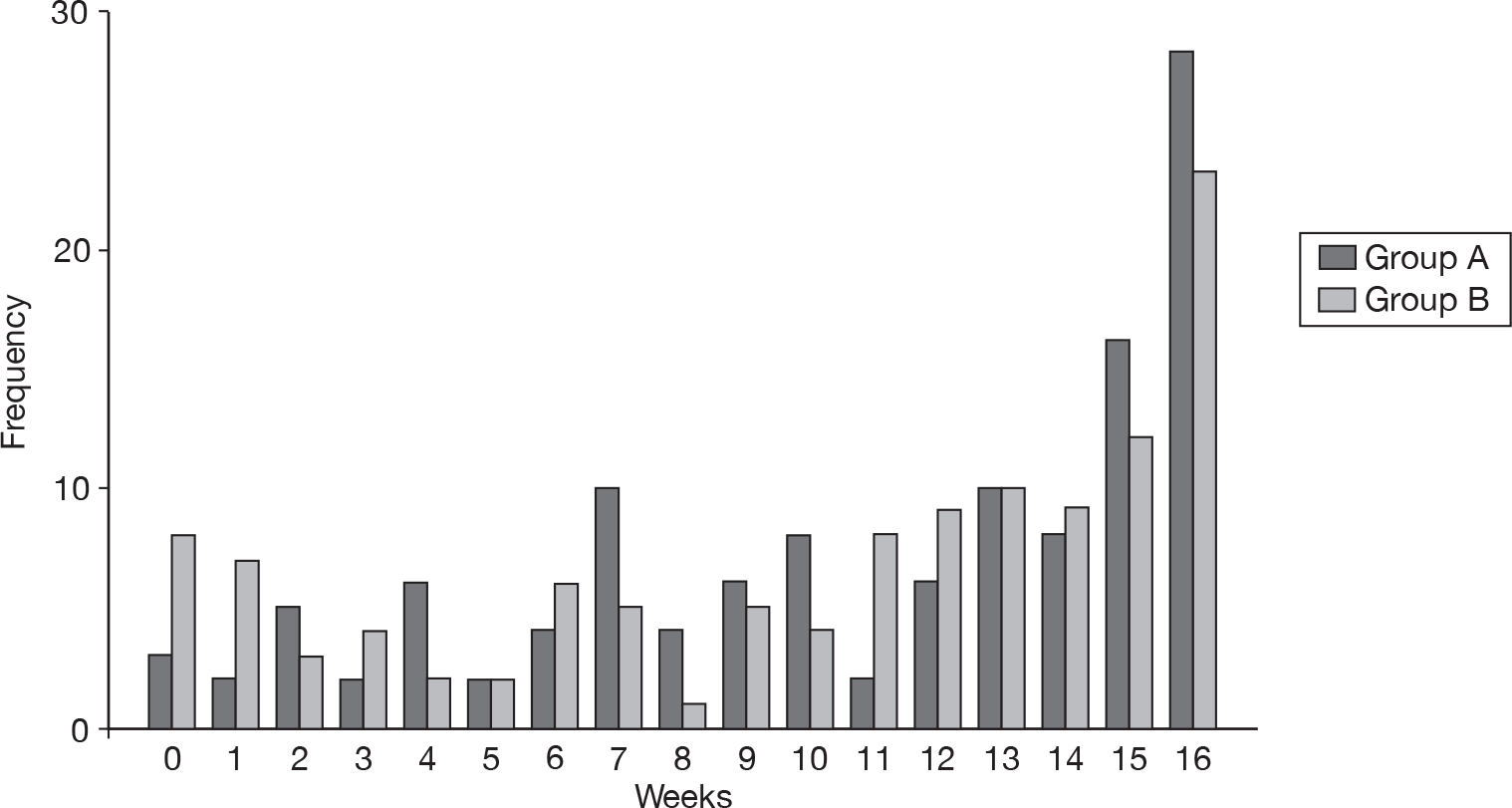

The difference between the two groups can be seen in Figure 10.

FIGURE 10.

Number of well WCWs.

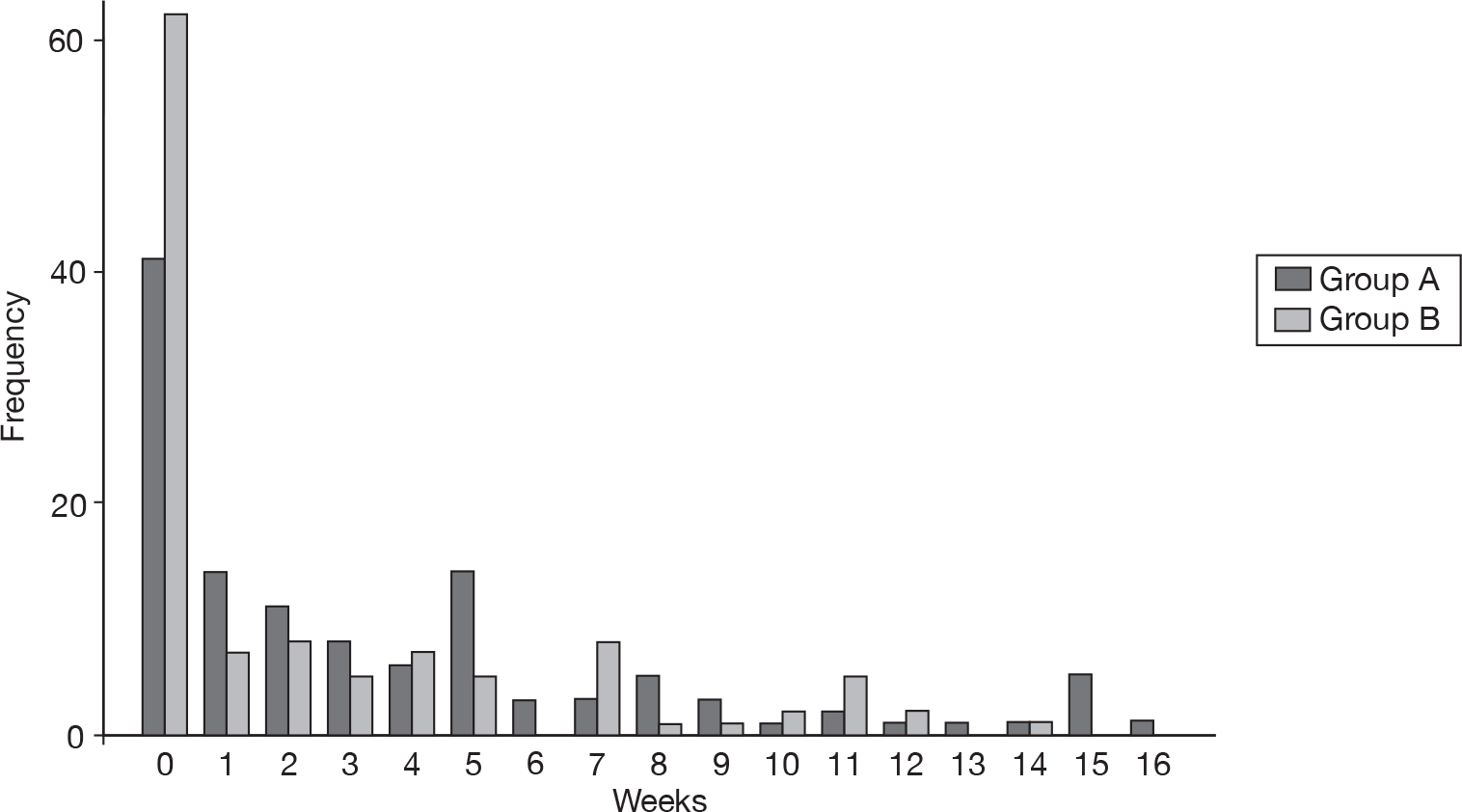

This result was also reflected in the number of TCWs. Although the majority of participants had no weeks when the eczema was totally controlled (Figure 11), group A had an average of 2.9 (SD 3.5) TCWs compared with 1.7 (SD 2.8) in group B. This represented a difference of 1.19 (95% CI 0.43 to 1.95), which was statistically significant (p < 0.01).

FIGURE 11.

Number of TCWs.

Graphs showing the number of WCWs and TCWs for the entire 16-week trial period are shown in Appendix 9.

Dermatitis Family Impact questionnaire

Both groups showed a reduction in DFI score (Table 12). Scores in group A dropped by 32% (3.2 points) and in group B by 16% (1.8 points). This represented a difference of –1.33 points in favour of group A (95% CI –2.63 to –0.03), which just achieved statistical significance (p = 0.05).

| Time assessed | Group A (water softener + usual care) | Group B (usual care) | Difference and 95% CI (A–B) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number randomised | 170 | 166 | |||

| N analysed a | 151 | 158 | |||

| Week 0 | Mean ± SD | 10.0 ± 6.8 | 11.2 ± 7.3 | ||

| Week 12 | Mean ± SD | 6.8 ± 6.0 | 9.3 ± 7.1 | ||

| Change | Mean ± SD | –3.2 ± 6.2 | –1.8 ± 5.4 | –1.33 (–2.63 to –0.03) | 0.05 |

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions

Both groups showed a small improvement in health-related quality of life. Scores in group A increased by 0.119 points and in group B by 0.066 points. The difference between the two groups was 0.054 (95% CI –0.015 to 0.122) and was not statistically significant (p = 0.12, Table 13).

| Time assessed | Group A (water softener + usual care) | Group B (usual care) | Difference and 95% CI (A–B) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number randomised | 170 | 166 | |||

| N analysed a | 112 | 112 | |||

| Week 0 | Mean ± SD | 0.690 ± 0.298 | 0.693 ± 0.274 | ||

| Week 12 | Mean ± SD | 0.810 ± 0.236 | 0.759 ± 0.245 | ||

| Change | Mean ± SD | 0.119 ± 0.269 | 0.066 ± 0.250 | 0.054 (–0.015 to 0.122) | 0.12 |

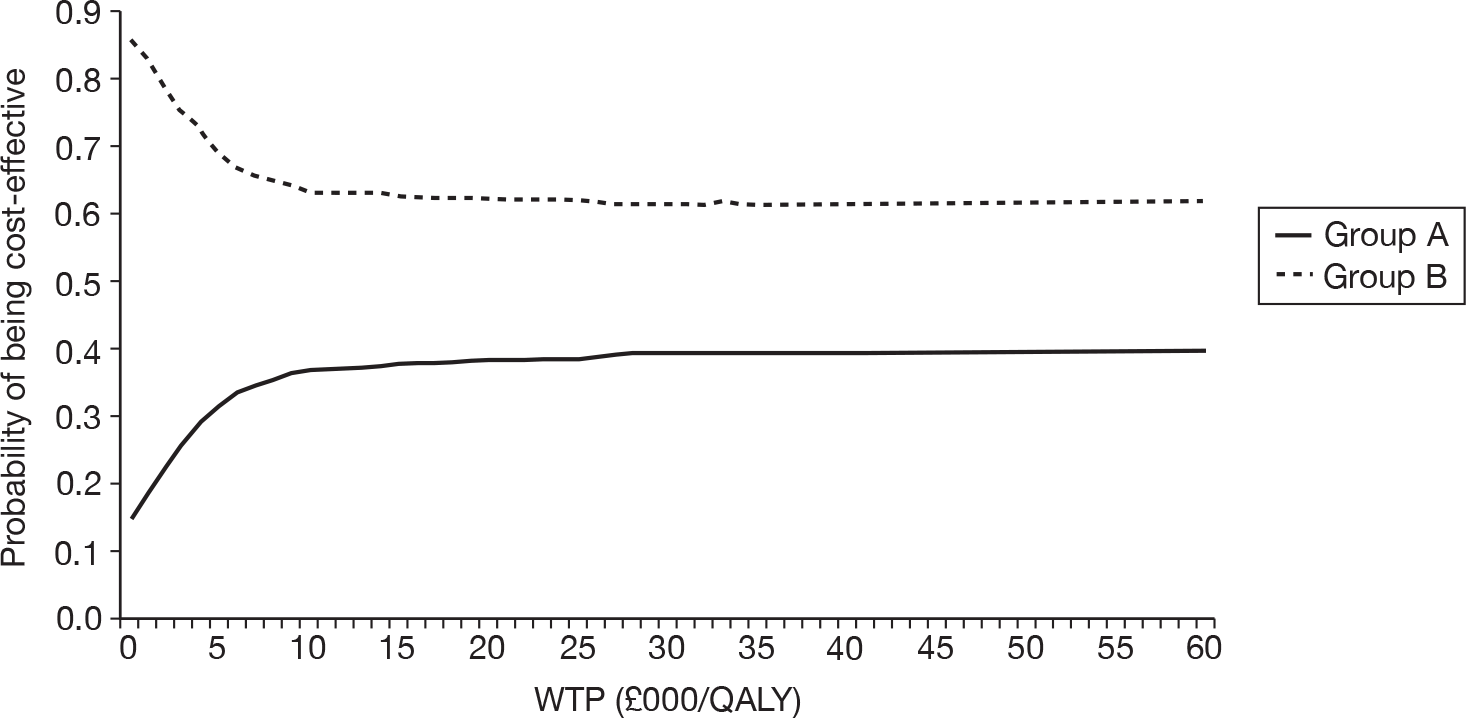

Tertiary analyses

It was not appropriate to conduct analyses looking at possible duration of benefit or speed of onset of benefit, as there was no primary treatment effect. Nevertheless, the SASSAD scores collected between weeks 12 and 16 are shown for interest (when the softeners had been turned off for group A, and installed for group B) (Figure 12).

FIGURE 12.

The SASSAD scores during trial period (weeks 0–16).

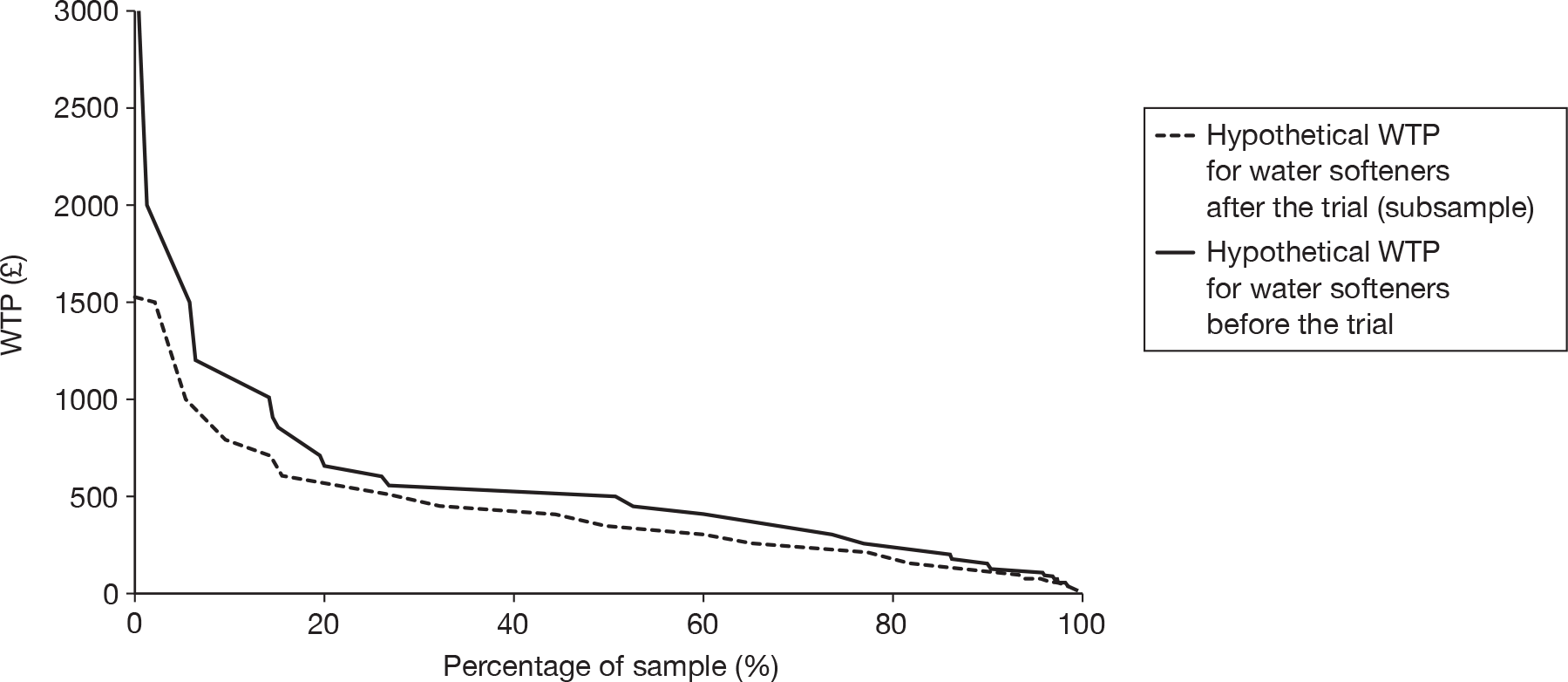

Purchase of water softener

Participants had the opportunity to purchase the water softener at the end of the study period. Water softeners were purchased by 55% of participants (179 purchases from 324 installations). Purchase rates in group A (93/168 installs; 55%) were the same as purchase rates in group B (86/156 installs; 55%), even though group A had an average 10.5-week installation period prior to deciding whether to purchase, whereas group B only had an average 3.5-week installation period.

Post hoc end of trial questionnaire

Participants were sent an end of trial follow-up questionnaire once all participants had completed the study. This sought information about current eczema status, whether they had a functioning water softener and, if so, their reasons for purchase. Non-responders were followed up by telephone.