Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 96/03/99. The contractual start date was in January 2008. The draft report began editorial review in April 2010 and was accepted for publication in September 2010. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

None

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Epidemiology

Breast cancer is the commonest cancer in the world, with over 1.15 million new cases per year. 1 Breast cancer in older patients is a major and rising health-care burden, due to demographic changes in the population. 2 In 2007, of the 45,695 new breast cancer patients in the UK, 45% were older than 65 years. 3 Based on 2007–9 mortality rates,4 the life expectancy of a woman reaching 65 years during this period is another 20 years. This will place an increasing burden on providers of cancer care and complicate the medical management of many older women. There is now great interest in educating primary care physicians on the management of cancer care in the elderly.

Breast cancer in the older population

Despite this substantial number of older patients with breast cancer, the evidence base for the treatment of these patients is weak, given that, historically, patients older than 70 years were excluded from randomised trials. In general, the results of the principal treatments for early breast cancer in younger patients [surgery, radiotherapy (RT) and systemic therapy] have been extrapolated to older patients. There has, therefore, been a need to establish clinical trials specifically to address the role of these different therapies, alone or in combination with the older age group,5 to strengthen the evidence base and inform the development of evidence-based guidelines. Acquiring data related to breast cancer in older women is a priority to optimise their management, with both physical and psychosocial dimensions being taken into consideration in selecting treatment. 6

Quality of life

The issue of quality of life in older patients undergoing anticancer treatment for breast cancer is an important one. Primary therapies for breast cancer may adversely affect quality of life. In the older patient group, independent physical and social functioning may be fragile and easily imbalanced by treatment-related toxicity. In addition, as patients age, they experience increasing numbers of comorbidities which may contribute to competing risks of non-breast cancer mortality. 7,8 For example, a 80-year-old female without comorbidity has a life expectancy of 12 years compared with a patient of a similar age with four comorbid diseases who has, on average, 2 years to live. 9

Role of post-operative radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery

Post-operative RT after breast-conserving surgery (BCS) in combination with systemic treatment reduces the absolute risk of 5-year local recurrence from 25.9% to 7.3% (p < 0.0001), and reduces 15-year absolute breast cancer mortality risk from 35.9% to 30.5% (p = 0.0002). 10 A number of randomised controlled trials with different types of local surgery have shown a four- to fivefold reduction in local recurrence at 5 years from the addition of whole breast radiotherapy (WBRT). 11–15 Some trials have found age to be a factor that predicts for a lower risk of local recurrence after whole breast irradiation compared with conservative surgery alone. 12–14,16–18 Therefore, in older, lower-risk patients the absolute reduction in local recurrence from post-operative RT may be very small,19 and the need for WBRT has been questioned. 20

The PRIME (Post-operative Radiotherapy In Minimum-risk Elderly) trial was established in 1997 to assess the impact of adjuvant WBRT or its omission on quality of life and cost-effectiveness in women aged ≥ 65 years at low risk of local recurrence after breast-conserving therapy and adjuvant endocrine therapy. The eligibility criteria, end points and powering of the trial are described in our first report to the NHS Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Board. 21 The European Organisation for Research in the Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) general cancer and breast cancer quality of life modules were used to assess quality of life. These have been widely validated and used in breast cancer, although their application on older patients with early breast cancer has been limited. To our knowledge, the PRIME trial is the first to have used them to assess the impact of adjuvant RT in an older low-risk population. The trial, therefore, provides a unique insight into the impact of breast RT in this population. A much larger trial (PRIME II22), funded by the Chief Scientist’s Office for Scotland with similar eligibility to PRIME, focusing on the impact of the omission of WBRT on local control, reached its target accrual of 1300 patients in November 2009 and is due to report in 2011.

In our first report in 200721 we reported on the impact of RT or its omission on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and cost-effectiveness up to 15 months following surgery as per the research protocol. 23 At that time point we showed no difference in overall HRQoL, although there were some differences in the subscales of the EORTC modules. The quality of life data were collected by a research nurse, mainly in the patient’s home. We recognised that 15 months was a relatively short period of follow-up and that the acquisition of longer-term data would be important to establish the impact on quality of life changes over time. In addition, local recurrences might occur in both irradiated and non-irradiated patients that might adversely affect their HRQoL. We therefore designed a postal questionnaire to determine HRQoL, which was sent to patients at 3 and 5 years after surgery. In this report, we provide longer-term data on the primary end points of the trial and comment on any changes we have identified to our original report to the HTA in 2007. 21 Our report is deliberately shorter than the original report, partly to avoid repetition and partly because the conclusions are broadly similar to those of our earlier report. We have focused the discussion on any differences we have observed in the longer term compared with the 15-month follow-up time point.

Chapter 2 Methods

Objectives

The primary objectives were to assess whether the omission of post-operative RT in older women with ‘low-risk’, axillary node-negative breast cancer (T0–2, N0–1, M0) treated by breast conservation with wide local excision and endocrine therapy (1) improves quality of life and (2) is more cost-effective.

Design

PRIME was a randomised controlled clinical trial comparing the quality of life, functional status, cosmesis and cost-effectiveness of low-risk older breast cancer patients treated with or without breast RT. The original design envisaged the trial being conducted entirely within Scotland, over a recruitment and follow-up period of 5 years. The geographical restriction reflected the support of the trial by the Scottish Cancer Trials Breast Group, and feasibility of patient interviews by a research nurse located in Edinburgh. Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (now superseded by the Integrated Research Application System) approval was granted by the Scotland Committee on 15 October 1998. However, following initial slow recruitment, this area was extended to include centres in England – firstly in the north of England, which was relatively accessible to the research nurse, and subsequently to centres further south. These centres provided their own interviewers and worked to a set of instructions provided by the trial research nurse.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusions

-

Age of ≥ 65 years, receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy.

-

Medically suitable to attend for all treatments and follow-up.

-

Histologically confirmed unilateral breast cancer of TNM stages T0–2, N0 and M0.

-

No axillary node involvement on histological assessment.

-

Had breast-conserving surgery with complete excision on histological assessment.

-

Able and willing to give informed consent.

Exclusions

-

Past history of pure in situ carcinoma of either breast or previous or concurrent malignancy within the past 5 years other than non-melanomatous skin cancer or carcinoma in situ of cervix.

-

Grade III cancer with lymphovascular invasion (LVI) (because of a higher risk of local recurrence).

Changes made since previous report

A detailed description of the methods employed in the first phase of the trial (up to 15 months after surgery) may be found in the original 2007 HTA report,21 and is not repeated here. Patients were offered the opportunity to opt out of the postal questionnaires at the time of the 15 months postsurgery questionnaire, as well as at any time subsequently.

This report deals with the longer-term effects of RT on quality of life, anxiety and depression, morbidity and, to a lesser extent, local recurrence and overall survival.

Questionnaire-based measures

The questionnaires, sent to the patients after 3 and 5 years, were a shortened version of the questionnaire that had been completed with the research nurses. Both the EORTC scales (QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23)24,25 were retained, as were the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)26 and the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D). 27 These measures are discussed in depth in the previous report. 21 The open questions ‘Could we again ask you to say in your own words how breast cancer is affecting you now?’ and ‘Apart from breast cancer, have there been any events since the last visit/questionnaire which have had a major impact on your life?’ remained, as did the opportunity to give any further information that patients felt was important.

It was decided to omit the Clackmannan Scale because of its complexity and the Barthel Index because of its known ceiling effects, which would become more extreme as patients hopefully returned to their normal living. In addition, several patients had commented that these functional indices needed updating to take into account changes in lifestyles, such as use of a washing machine and shopping home delivery services. As neither of these scales had been informative during the first 15 months following surgery, it was decided to exclude them.

The questions in the Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale were considered to be too vague by many patients, with the word ‘things’ (e.g. ‘Do things keep getting worse as you get older?’) highlighted by many patients as being too non-specific to be able to reply to the question meaningfully. As there had been no evidence to suggest that there was any difference between the treatment groups in this scale, we reasoned that it could be removed.

Clinical measures

No changes were made to the clinical measures of morbidity [Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) scales] since the previous report. However, although data on lung and bone problems were requested, very few problems were recorded, and the data were considered to be unreliable, as few of the clinical tests required (e.g. chest X-ray to detect rib fractures) were performed. Therefore, these results will not be reported. It should be noted that the observers were clinicians and were not blinded to the randomisation.

Data collection

As before, data were entered twice to minimise the risk of errors. Before each questionnaire was sent to the patient, the research nurse contacted the patient’s general practitioner (GP) to ascertain the health status and current address of the patient. Questionnaires were sent directly to patients at the third and fifth anniversaries of their surgery, with a replacement questionnaire and reminder being sent a month later if it had not yet been returned. Patients received questionnaires only if they had previously consented to be included in the long-term analysis, and were given the opportunity to decline at each subsequent questionnaire.

The same coding frame was used to categorise the open question responses as was used for the first four questionnaires, with a few additions to reflect issues that patients had identified in the longer term.

Statistical analysis

As in the previous report,21 the main emphases were on the quality of life aspects. The principal analysis was based on repeated measures methods, using baseline levels of each variable as a covariate. Analyses were conducted in sas 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC) using mixed models (PROC MIXED), as this overcomes many of the problems associated with missing values, if these can be assumed to be missing at random. The analysis of binary response data, such as the presence of clinical anxiety and depression, used generalised linear mixed models by means of the glmm8.sas macro as composed by Wolfinger and O’Connell. 28

Local recurrence and overall survival were analysed using Kaplan–Meier plots and log-rank (Mantel–Cox) tests, with Cox proportional hazards.

All analyses were based on the intent-to-treat principle, and all confidence intervals (CIs) and significance tests were two-sided. Given the large number of hypothesis tests performed, CIs were reported following adjustment for multiple testing using the Bonferroni method; p-values, on the other hand, were reported as for single tests, as any non-significant result adjusted for multiple testing resulted in a p-value of 1.0, which is singularly uninformative. For the most part, the number of degrees of freedom used was 248. Where this is not the case, a note in the results was made.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

Only a basic exploratory analysis was undertaken as no funding was available for the cost-effectiveness analysis of the 5-year data. The EQ-5D scores were used to derive quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) for the 5-year time horizon. Regression analysis was used to adjust for baseline difference in utility scores. Detailed data on resource use were collected for the first 15 months only. The previous report showed that there were no statistically significant differences in resource use other than RT between the two arms of the trials. 21 It is reasonable to assume that health service use across the two groups will remain similar after 15 months unless there is a difference in local recurrence rates. The extended analysis, therefore, incorporated the costs of local recurrence only. Karnon et al. 29 estimated the first-year costs after locoregional recurrence as £11,701, with very few costs in subsequent years. These costs include all secondary care costs. Costs and QALYS are discounted at 3.5%.

The non-parametric technique of bootstrapping was used to construct 95% CIs for the differences in QALYs and costs between the two arms of the trial. The bootstrap samples were used to construct a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve. This showed the probability that having no RT is cost-effective relative to current practice (having RT) at various thresholds of cost-effectiveness. The threshold represents the decision-maker’s willingness to pay for an additional QALY. Missing data were common in the 15-month follow-up data and as expected are even more common in the 5-year follow-up. Complete data were available for only 168 out of 254 patients. Mean imputation was used to obtain values for the missing data. The results were reported for both the 168 complete cases and all 254 patients.

Chapter 3 Characteristics of the trial population

Demographic data at randomisation

The randomised group were well balanced to the treatment arms of RT or no RT with respect to centre, age, grade of cancer, LVI and pre-operative endocrine therapy (pre-op ET), all of which were used in the minimisation programme. Table 1 summarises these factors, along with axillary surgery and side of cancer. Good balance was achieved for all of these variables.

| Baseline demographic and clinical data | Randomised (n = 255) | |

|---|---|---|

| RT (n = 127) | No RT (n = 128) | |

| Mean age at surgery (SD) | 72.3 (5.0) years | 72.8 (5.2) years |

| n (%) | ||

| Tumour grade | ||

| 1 | 48 (37.8) | 48 (37.5) |

| 2 | 72 (56.7) | 71 (55.5) |

| 3 | 7 (5.5) | 9 (7.0) |

| LVI | ||

| No | 121 (95.3) | 122 (95.3) |

| Yes | 6 (4.7) | 6 (4.7) |

| Pre-op ET | ||

| No | 110 (86.6) | 106 (82.8) |

| Yes | 17 (13.4) | 22 (17.2) |

| Axillary surgery (one unknown) | ||

| Clearance | 30 (23.6) | 36 (28.1) |

| Sample | 95 (74.8) | 90 (70.3) |

| Sentinel node | 2 (1.6) | 1 (0.8) |

| Side | ||

| Right | 63 (49.6) | 59 (46.1) |

| Left | 61 (48.0) | 67 (52.3) |

| Not given | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.5) |

Quality of life scores at baseline

The mean scores at entry to the trial for the EORTC QLQ-C30 are shown for each dimension and for the combined functionality and symptom scores by the randomised treatment group in Table 2. There were no substantial differences in any variable between the randomised groups. Functionality and symptoms were summary variables of the mean scores of the other variables.

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | RT (n = 125) | No RT (n = 128) |

|---|---|---|

| Functionality | 83.4 (14.3) | 81.7 (15.7) |

| Symptoms | 14.0 (10.5) | 14.9 (12.0) |

| Physical functioning | 82.6 (17.2) | 80.4 (19.1) |

| Role functioning | 78.0 (23.6) | 74.0 (28.3) |

| Emotional functioning | 83.3 (19.2) | 83.9 (18.4) |

| Cognitive functioning | 84.5 (19.9) | 85.3 (18.2) |

| Social functioning | 88.4 (19.0) | 85.0 (22.7) |

| Quality of life | 72.4 (16.4) | 70.3 (19.0) |

| Fatigue symptoms | 26.8 (19.3) | 27.7 (22.2) |

| Nausea and vomiting | 4.8 (11.0) | 5.3 (12.5) |

| Pain symptoms | 24.7 (25.1) | 29.0 (25.5) |

| Dyspnoea | 12.0 (19.6) | 10.9 (21.0) |

| Insomnia | 28.8 (29.4) | 28.9 (32.0) |

| Appetite loss | 10.4 (20.5) | 13.3 (23.0) |

| Constipation | 12.5 (24.2) | 9.1 (19.9) |

| Diarrhoea | 3.7 (15.4) | 6.0 (17.0) |

| Financial difficulties | 1.9 (7.7) | 3.4 (12.4) |

The mean scores at entry to the trial are shown in Table 3 for the variables obtained from the EORTC QLQ-BR23 for the two randomised treatment groups. The number of subjects answering the questions relating to sexual matters is substantially less than the total and only for the few subjects who responded to the questions relating to sexual enjoyment are there significant differences between the treatment groups. Similarly, both hair loss and cough are subject to a screening question and only those patients who reported problems of this nature were asked the relevant question.

| EORTC QLQ-BR23 | RT | No RT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | |

| Body image | 125 | 94.7 (10.1) | 128 | 93.5 (12.4) |

| Sexual functioning | 78 | 10.3 (18.9) | 81 | 6.6 (15.5) |

| Sexual enjoyment | 18 | 51.9 (28.5) | 9 | 63.0 (26.1) |

| Future perspective | 125 | 21.9 (24.0) | 128 | 26.0 (24.7) |

| Arm symptoms | 125 | 15.3 (14.6) | 128 | 17.5 (18.4) |

| Breast symptoms | 125 | 23.1 (19.5) | 128 | 19.8 (18.4) |

| Systemic therapy side effects | 125 | 12.1 (11.4) | 127 | 12.9 (12.8) |

| Hair loss | 20 | 21.7 (19.6) | 14 | 16.7 (17.3) |

| Cough | 37 | 35.1 (22.2) | 40 | 36.7 (21.1) |

The results at entry to the trial for the HADS are summarised in Table 4. The two treatment groups are well balanced, with the levels of anxiety and depression generally low (a higher score indicates higher levels of anxiety or depression).

| HADS (maximum score) | RT (SD) (n = 125) | No RT (SD) (n = 128) |

|---|---|---|

| Depression (21) | 2.4 (2.4) | 2.8 (2.6) |

| Anxiety (21) | 4.6 (3.5) | 4.7 (3.4) |

Demographic data of patients in longer follow-up

Most patients agreed to complete the postal questionnaires, so there is a distinct imbalance between the groups in terms of size (Table 5). Any perceived imbalance in the clinical factors is likely to be the result of this disparity, and not a true effect on the decision to complete the postal questionnaires.

| Baseline demographic and clinical data | Randomised (n = 255) | |

|---|---|---|

| Agreed to complete postal questionnaires (n = 240) | Declined completing postal questionnaires or deceased (n = 15) | |

| Number given RT (%) | 117 (49) | 10 (67) |

| Mean age at surgery (SD) | 71.9 (5.03) | 75.1 (4.91) |

| n | ||

| Tumour grade | ||

| 1 | 92 | 4 |

| 2 | 135 | 8 |

| 3 | 13 | 3 |

| LVI | ||

| No | 229 | 14 |

| Yes | 11 | 1 |

| Pre-op ET | ||

| No | 206 | 10 |

| Yes | 34 | 5 |

| Axillary surgery | ||

| Clearance | 64 | 2 |

| Sample | 172 | 13 |

| Sentinel node | 3 | 0 |

| Side | ||

| Right | 113 | 9 |

| Left | 123 | 5 |

| Not given | 1 | 1 |

Chapter 4 Quality of life questionnaires

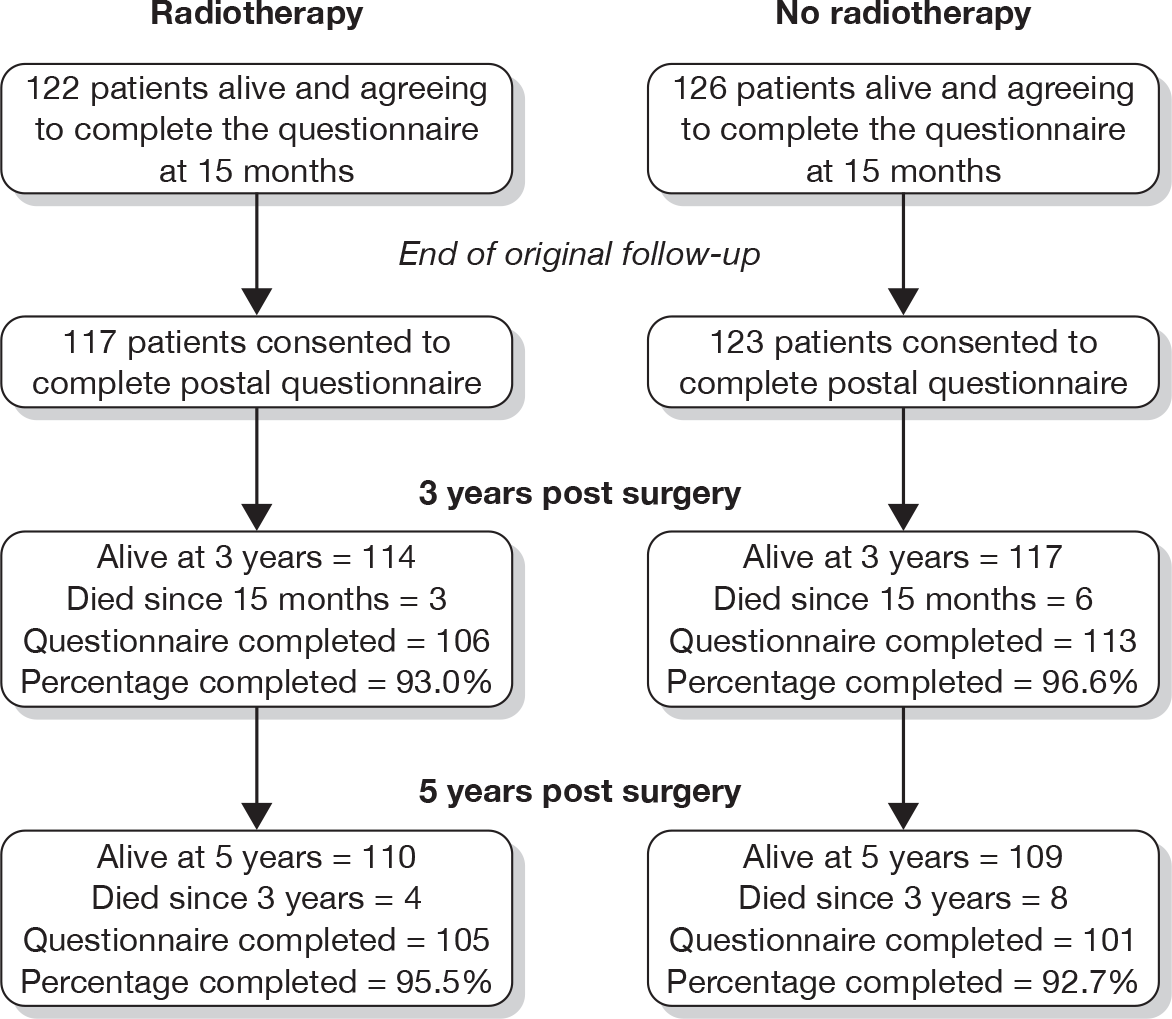

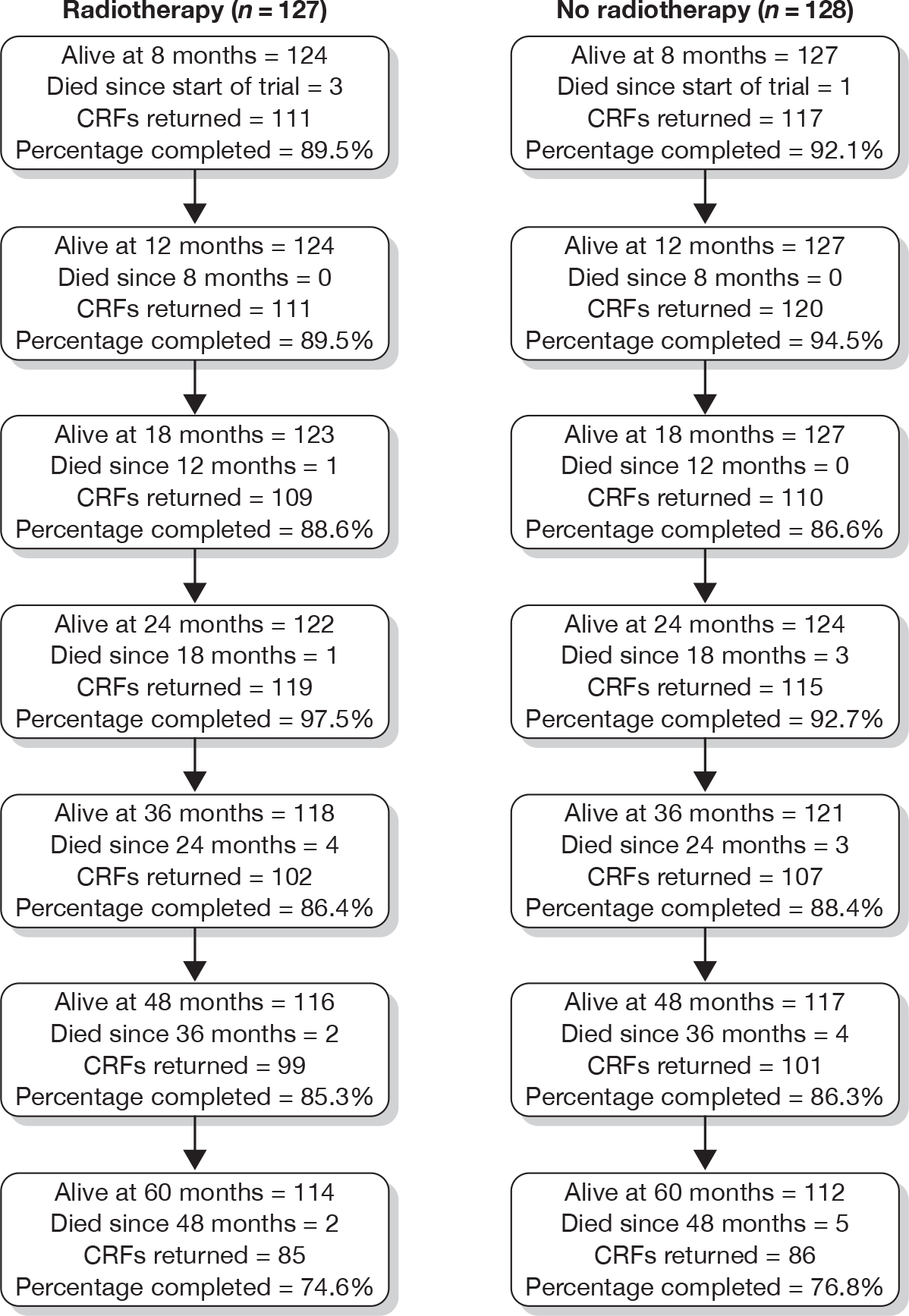

Figure 1 shows the number of questionnaires available for analysis at each time point.

FIGURE 1.

Number of evaluable questionnaires at the time of each postal questionnaire.

A summary of the interpretation of the EORTC and HADS scores may be found in Appendix 1.

The European Organisation for Research in the Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30 scale

The QLQ-C30 scale is a multi-item scale which may be collapsed into 15 subscales and two summary scales, and refers to the patient’s quality of life over the previous week. For each variable, the corresponding baseline score was used as a covariate, in a repeated measures analysis of covariance with an unstructured covariance pattern. The major scales, and those subscales with interesting or significant explanatory variables, are illustrated with a graph. In order to show changes over time as clearly as possible, only part of the scale on the y-axis is shown, and in the interpretation of the graphs the scales should be read carefully. As the treatment means at each time point have been adjusted for the baseline, a common baseline at the mean of all subjects is shown.

Functioning

For the functioning scales, a higher score indicates a higher level of functioning. Mean differences have been calculated by taking the mean of the patients who received RT from the mean of the patients who did not receive RT (i.e. no RT – RT). Thus, a positive mean indicates that those patients who did not receive RT had, on average, higher levels of functionality, and vice versa. ‘Adjusted’ refers to the p-values following adjustment due to the Bonferroni correction. All CIs were calculated following adjustment.

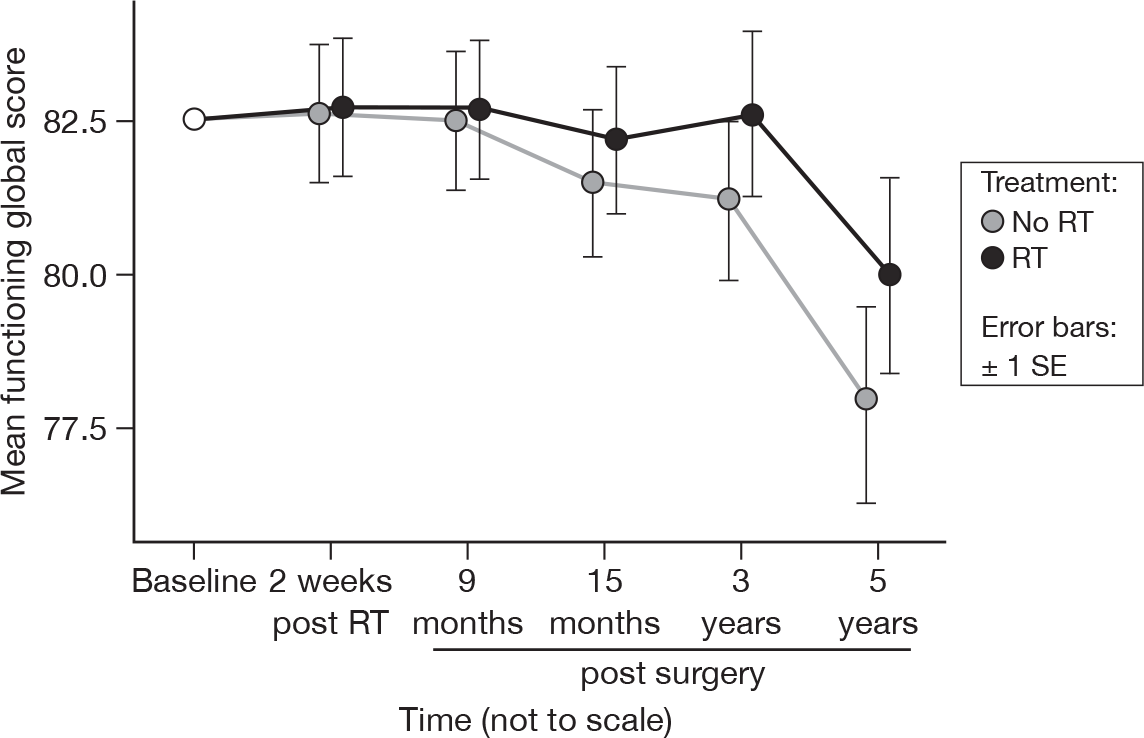

Functionality (mean of physical, role, emotional, cognitive and social functioning)

Whereas at 15 months there was no evidence of a difference over time, by 5 years this difference is significant (p = 0.002, adjusted p = 0.22), and follows the downwards trend evidenced by many of the individual items that constitute this summary statistic (Figure 2). The fall in means was 4.7 units for those patients without RT and 2.6 units for those who received RT. There is still no evidence of a statistically significant difference between the treatments, however. The mean difference was –0.90 and the adjusted 95% CI was –5.97 to 4.17.

FIGURE 2.

Mean scores of functionality by questionnaire. SE, standard error.

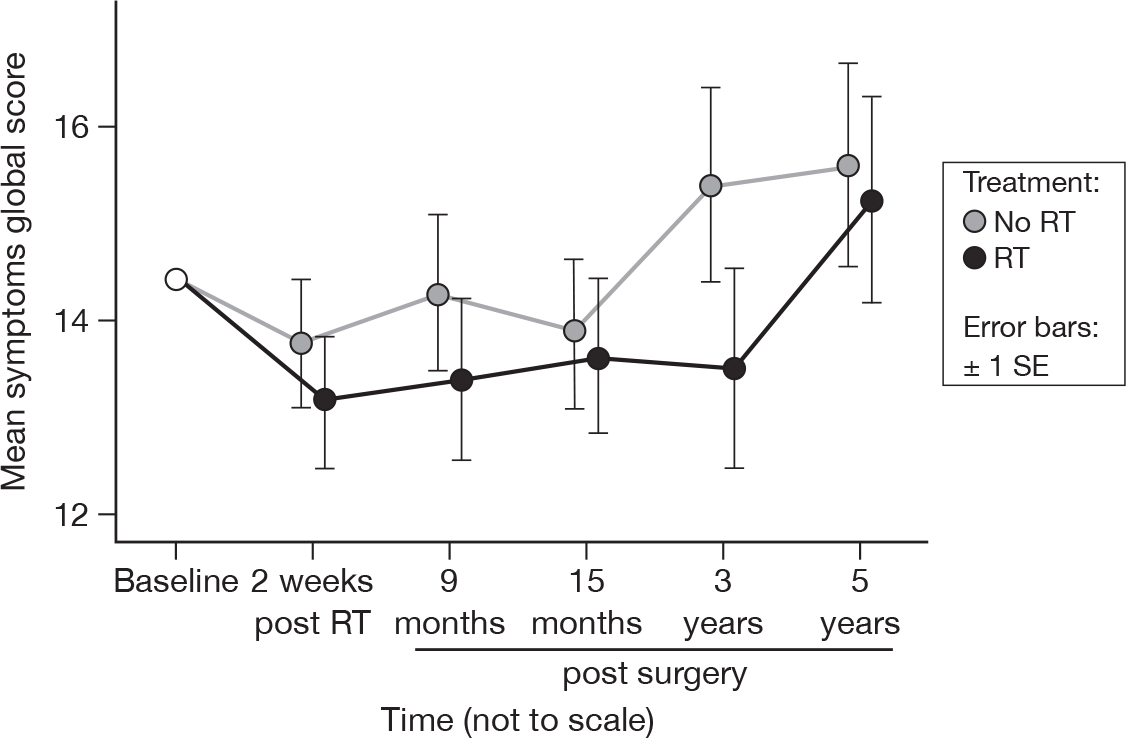

Symptoms (mean of fatigue, nausea/vomiting, pain, dyspnoea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhoea and financial difficulties)

An increase in score indicates an increase in symptoms. There was no evidence of a time or treatment effect (Figure 3). This did not differ from the results at 15 months. The mean difference was 0.80 and the 95% CI was –2.39 to 3.99.

FIGURE 3.

Mean scores of symptoms by questionnaire. SE, standard error.

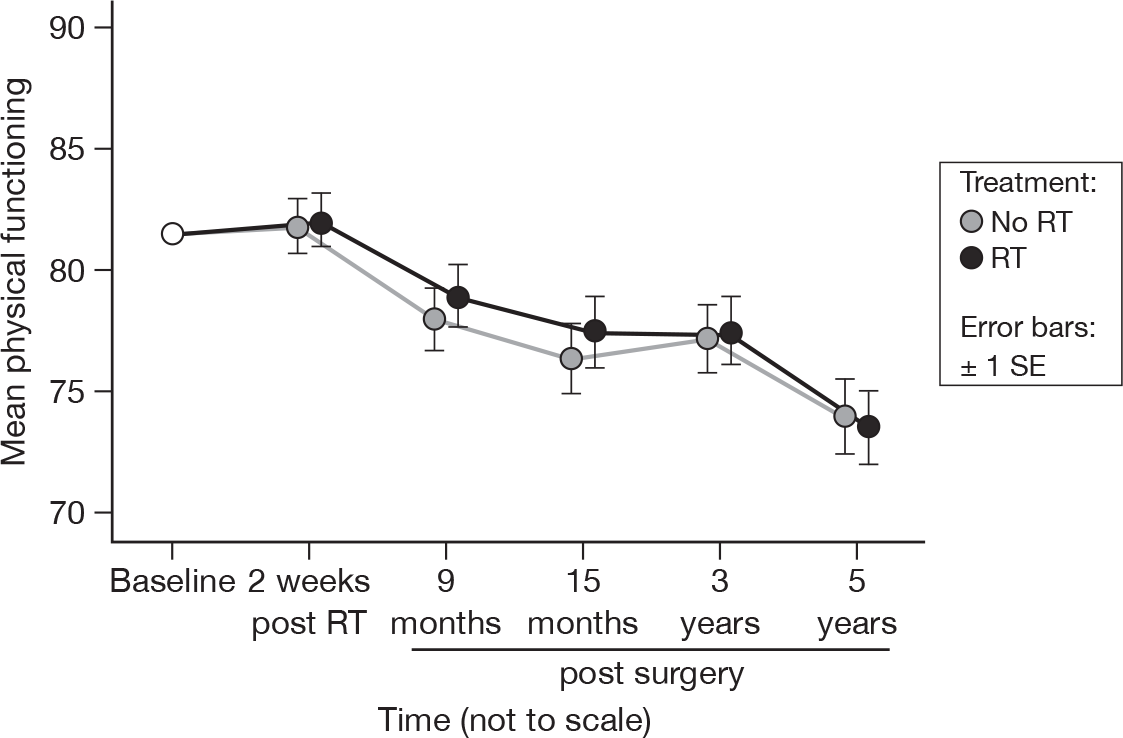

Physical functioning

-

Do you have any trouble doing strenuous activities, like carrying a heavy shopping bag or a suitcase?

-

Do you have any trouble taking a long walk?

-

Do you have any trouble taking a short walk outside of the house?

-

Do you have to stay in a bed or a chair during the day?

-

Do you need help with eating, dressing, washing yourself or using the toilet?

There was a significant change over time (p < 0.0001, adjusted p < 0.0001), but no evidence of a treatment effect, in accord with what was seen in the previous report (Figure 4). The mean difference was –0.45 and the 95% CI was –5.63 to 4.74.

FIGURE 4.

Mean scores of physical functioning by questionnaire.

Role functioning

-

Were you limited in doing either your work or other daily activities?

-

Were you limited in pursuing your hobbies or other leisure-time activities?

As in the previous report,21 there was no evidence of a time or treatment effect. The overall mean score was 77.6, with a standard error (SE) of 0.8. The mean difference was –1.47, with a 95% CI of –10.89 to 7.95.

Emotional functioning

-

Did you feel tense?

-

Did you worry?

-

Did you feel irritable?

-

Did you feel depressed?

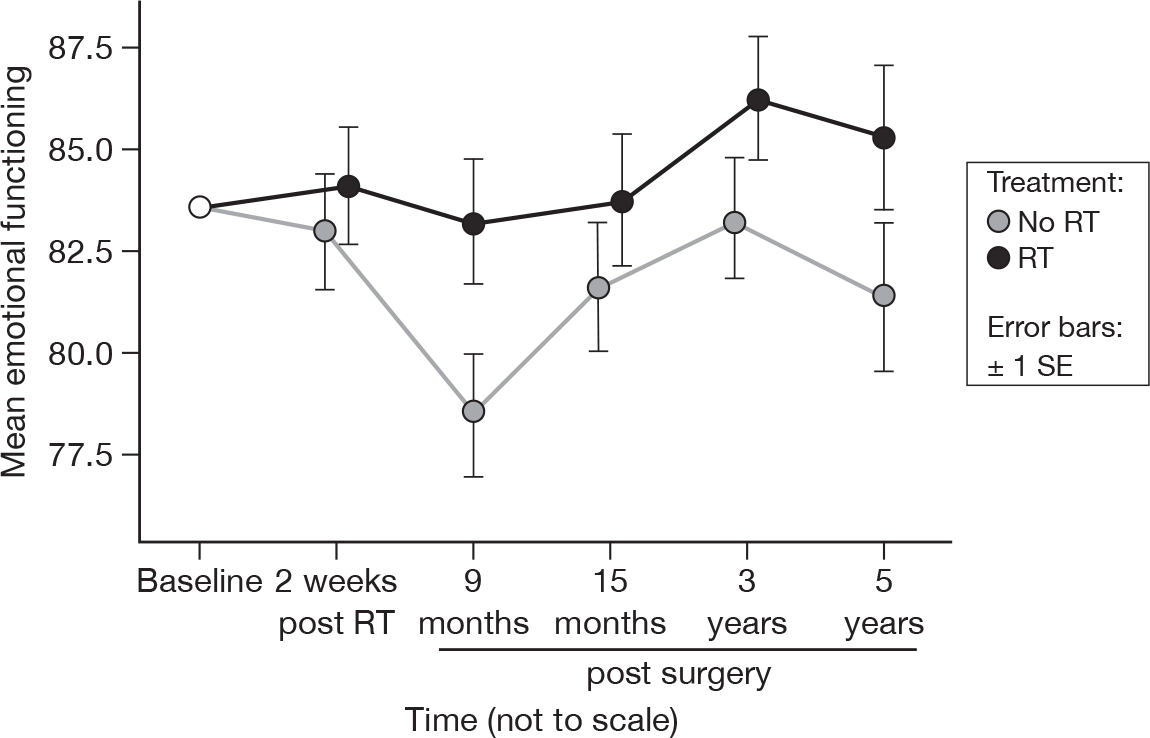

There was slight evidence to suggest a time (p = 0.04, adjusted p = 1.0) and treatment (p = 0.06, adjusted p = 1.0) effect (Figure 5). At 15 months, these were p = 0.07 and p = 0.12, respectively (adjusted p = 1.0 for both). However, this difference in treatment effect was still only of the order of approximately 4 units at 5 years, which is not large. Mean difference was –2.96 and the 95% CI was –8.57 to 2.64.

FIGURE 5.

Mean scores of emotional functioning by questionnaire.

Cognitive functioning

-

Have you had difficulty concentrating on things like reading a newspaper or watching television?

-

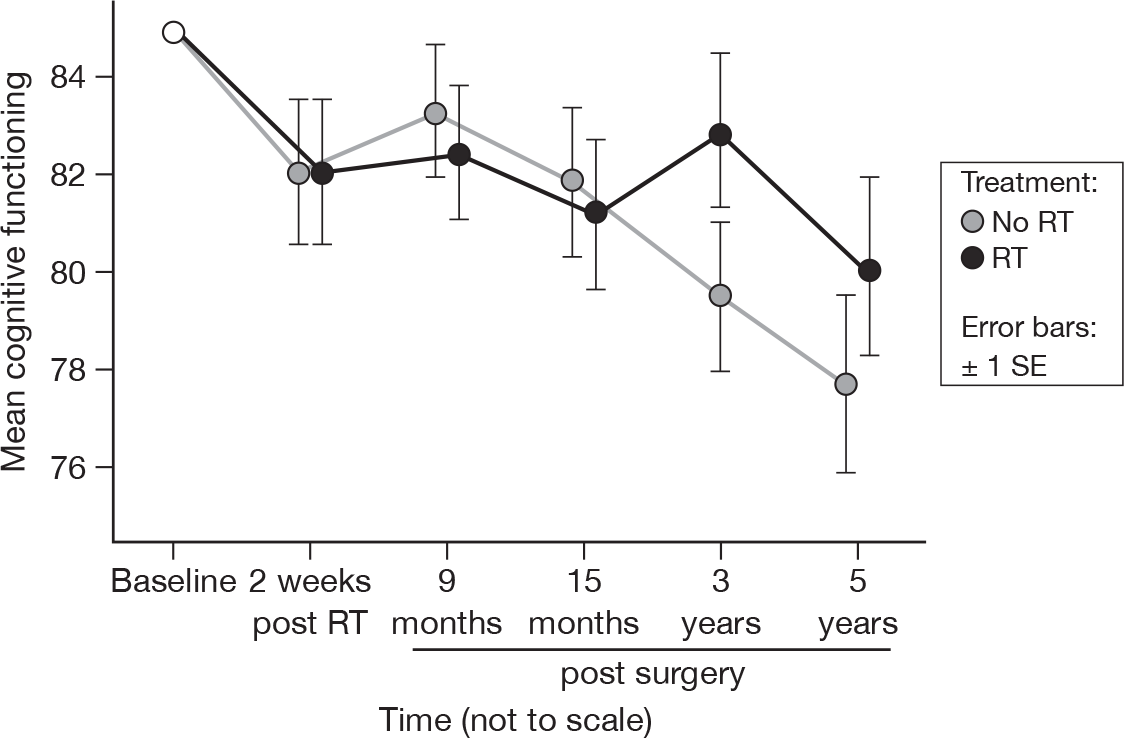

Have you had difficulty remembering things?

There was no evidence of a treatment effect, in accord with the previous report (Figure 6). 21 There was some slight evidence that cognitive functioning is declining over time, with a mean fall of 0.6 units per questionnaire (p = 0.04, adjusted p = 1.0), adjusted for baseline. Mean difference was –0.87 and the 95% CI was –6.48 to 4.73.

FIGURE 6.

Mean scores of cognitive functioning by questionnaire.

Social functioning

-

Has your physical condition or medical treatment interfered with your family life?

-

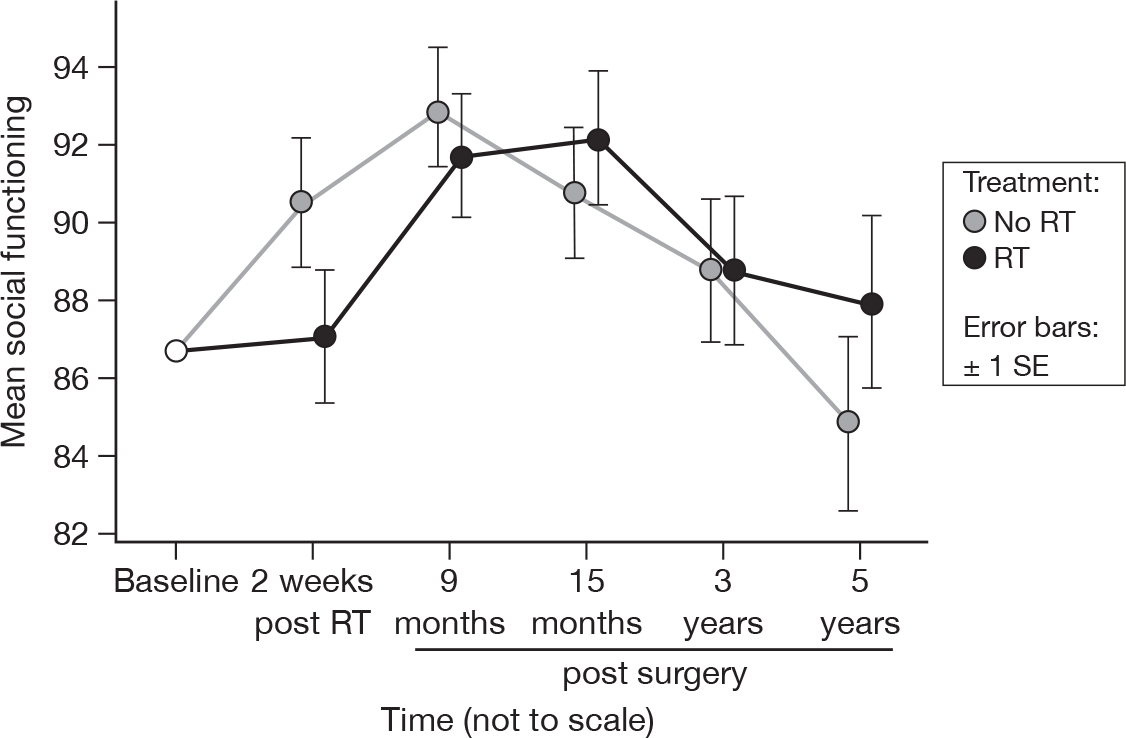

Has your physical condition or medical treatment interfered with your social life?

There were significant differences between the questionnaires (p = 0.0009, adjusted p = 0.10), but no evidence of a treatment effect (Figure 7). This was no different to the results at 15 months, although the suggestion is that the RT group may be one time point behind the no RT group. Mean difference was 0.018 and the 95% CI was –6.34 to 6.38.

FIGURE 7.

Mean scores of social functioning by questionnaire.

Quality of life

-

How would you rate your health during the past week?

-

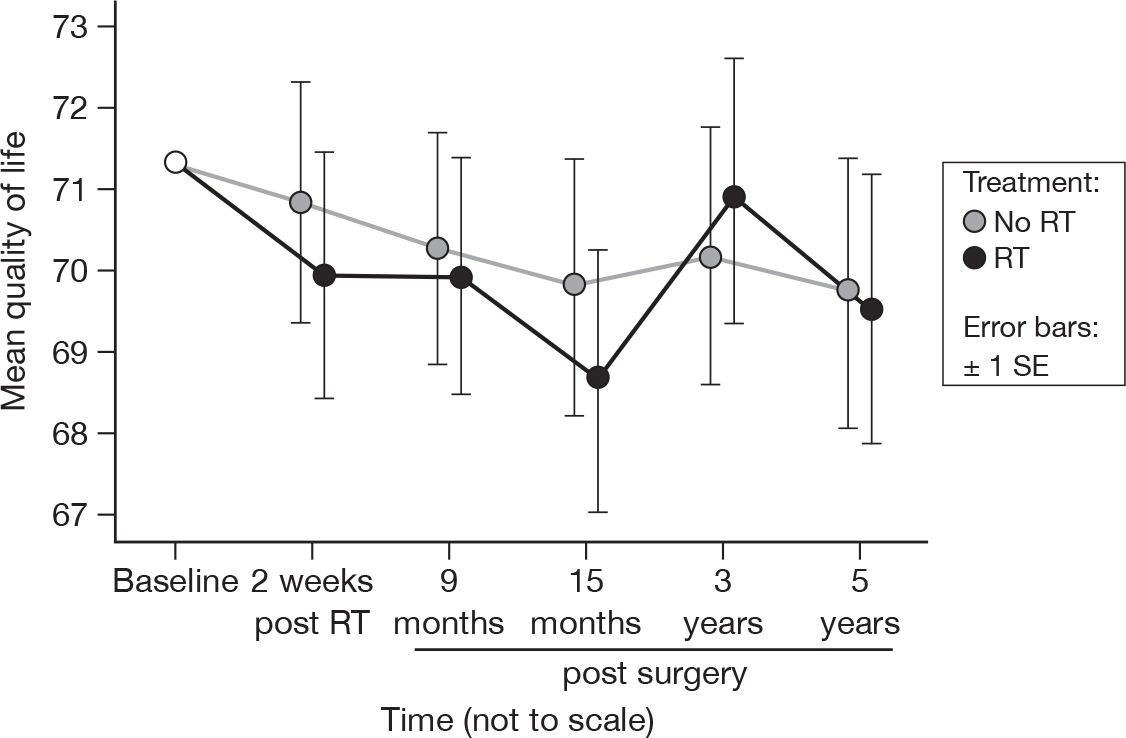

How would you rate your overall quality of life during the past week?

There was no evidence of a time or treatment effect in overall quality of life, which was unchanged from the previous report (Figure 8). 21 The overall mean score was 70.4 with an SE of 0.5. Mean difference was 0.36 and the 95% CI was –5.09 to 5.81.

FIGURE 8.

Mean scores for quality of life by questionnaire.

For the following symptom scales, a higher score indicates a higher level of problems. As above, mean differences were calculated by subtracting the mean of the patients who received RT from the mean of the patients who did not receive RT (i.e. no RT – RT). Thus, a positive mean indicates that those patients who did not receive RT had, on average, higher levels of problems, and vice versa. ‘Adjusted’ refers to the p-values following adjustment due to the Bonferroni correction. All CIs were calculated following adjustment.

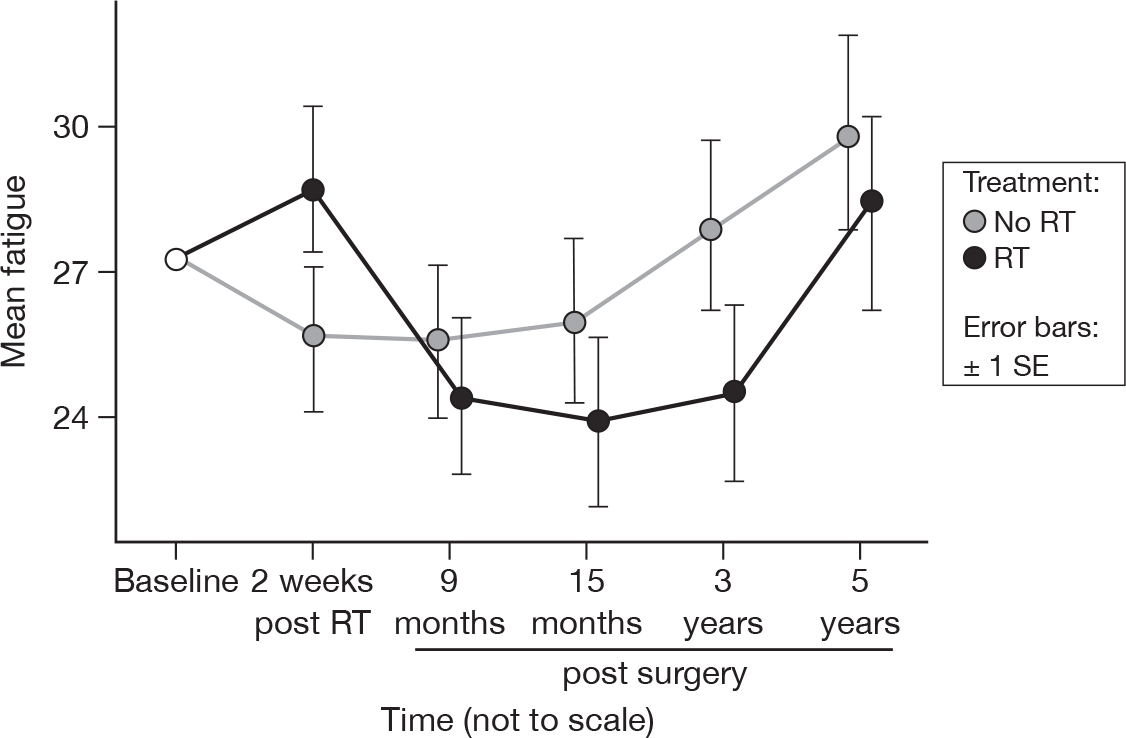

Fatigue

-

Did you need to rest?

-

Have you felt weak?

-

Were you tired?

There were significant differences between the questionnaires (p = 0.01, adjusted p = 1.0), a feature that was not present at 15 months. Apart from the spike in fatigue immediately following RT, the irradiated group had consistently lower (but not significantly lower) levels of fatigue (Figure 9). Mean difference was 1.08 and the 95% CI was –5.57 to 7.72.

FIGURE 9.

Mean scores of fatigue by questionnaire.

Nausea and vomiting

-

Have you felt nauseated?

-

Have you vomited?

As before, there was no evidence of a time or treatment effect. The overall mean score was 3.6, with an SE of 0.3. Mean difference was –0.25 and the 95% CI was –2.72 to 2.23.

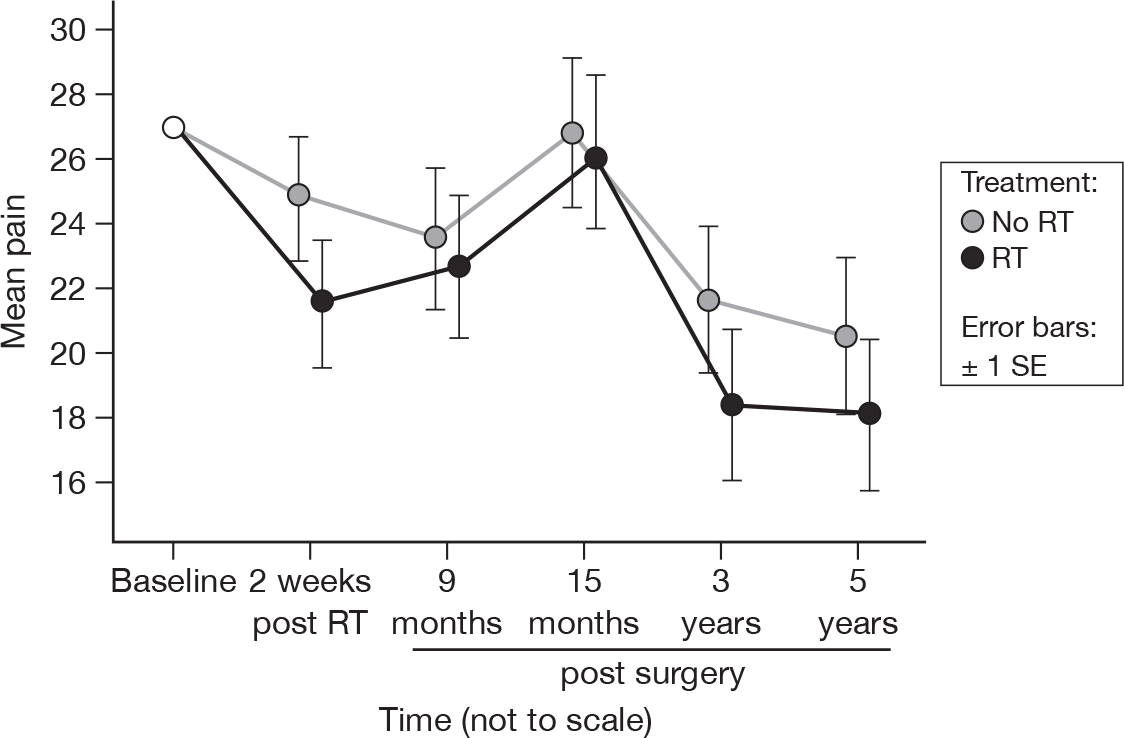

Pain

-

Have you had pain?

-

Did pain interfere with your daily activities?

There were significant differences between the time points (p = 0.002, adjusted p = 0.22), which have become more pronounced since the results at 15 months (p = 0.09, adjusted p = 1.0). There was still no evidence of a treatment difference and the pattern of change in the pain scores was very similar between treatment groups (Figure 10). Mean difference was 2.08 and the 95% CI was –5.74 to 9.90.

FIGURE 10.

Mean scores of pain by questionnaire.

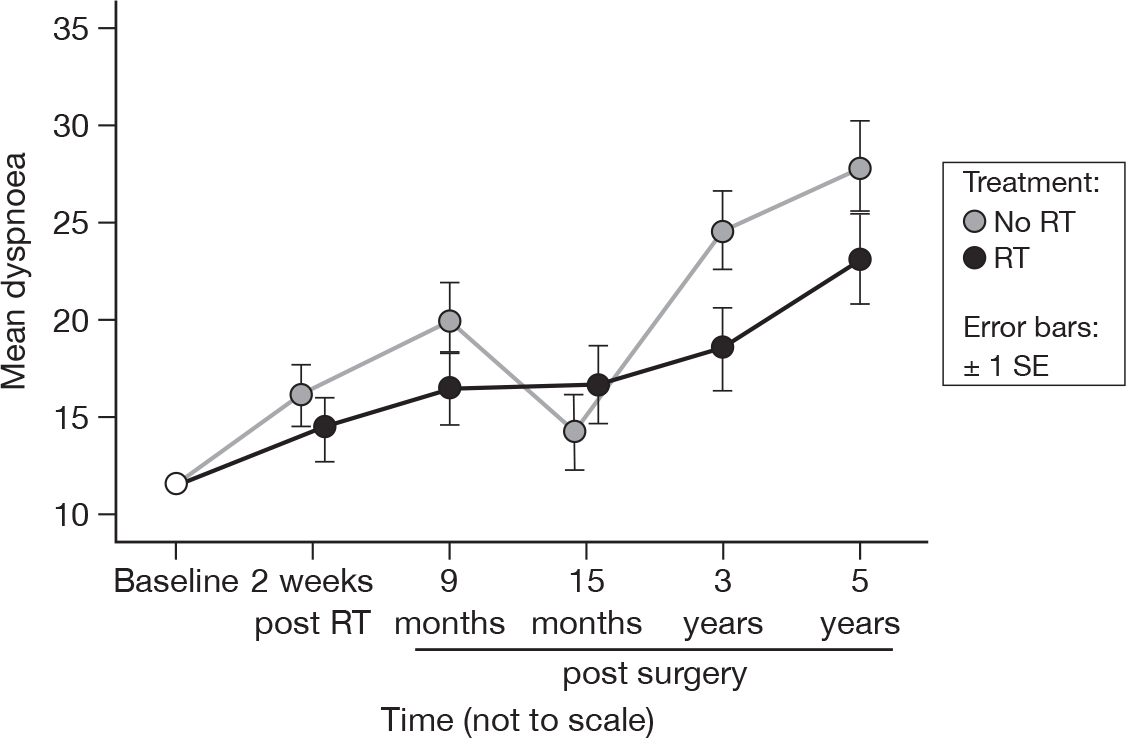

Dyspnoea

-

Were you short of breath?

There were significant differences over time (p < 0.0001, adjusted p < 0.0001), which have become more marked from 15 months (p = 0.07, adjusted p = 1.0). As before, there was no evidence of a difference between treatment groups (Figure 11). Mean difference was 2.77 and the 95% CI was –4.05 to 9.60.

FIGURE 11.

Mean scores of dyspnoea by questionnaire.

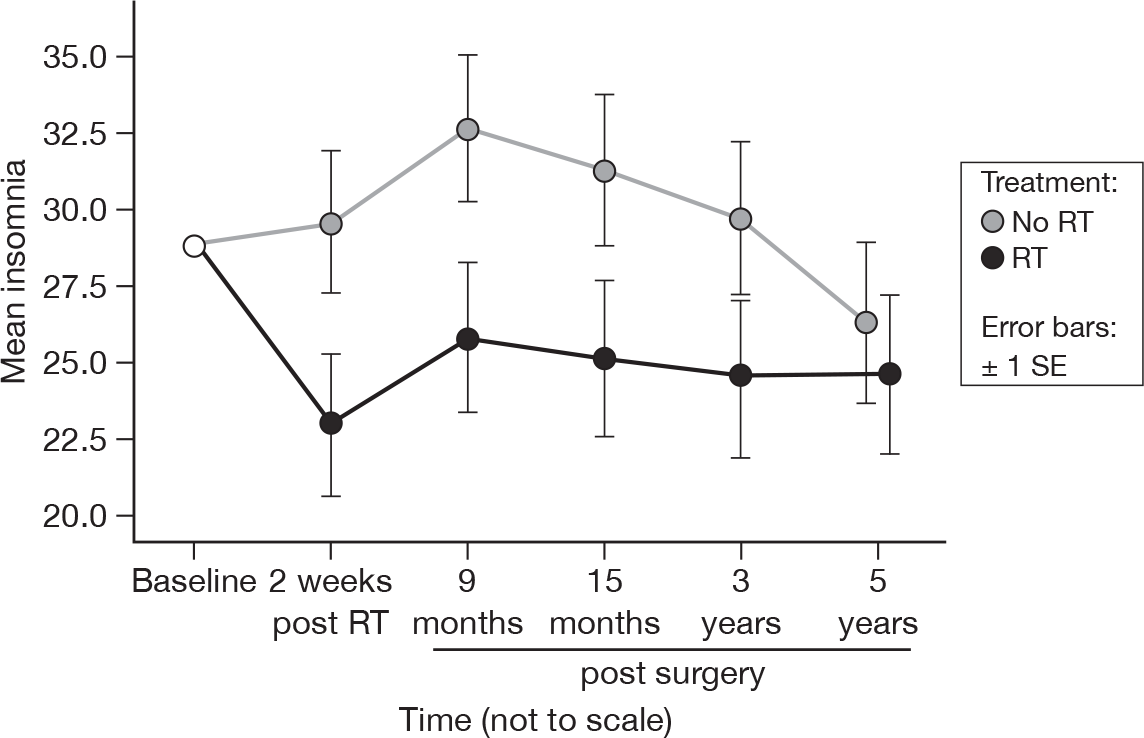

Insomnia

-

Have you had trouble sleeping?

Differences between the treatment groups remained significant (p = 0.03, adjusted p = 1.0), although by 5 years the significance was lower than that at 15 months (p = 0.01, adjusted p = 1.0). This was most likely due to the lessening of the difference at 5 years, which was only 1.7 units at that point (Figure 12). Mean difference was 5.30 and the 95% CI was –3.56 to 14.16.

FIGURE 12.

Mean scores of insomnia by questionnaire.

Appetite loss

-

Have you lacked appetite?

As before, there was no evidence of a time or treatment effect. The overall mean score was 9.5, with an SE of 0.5. Mean difference was 0.74 and the 95% CI was –4.64 to 6.13.

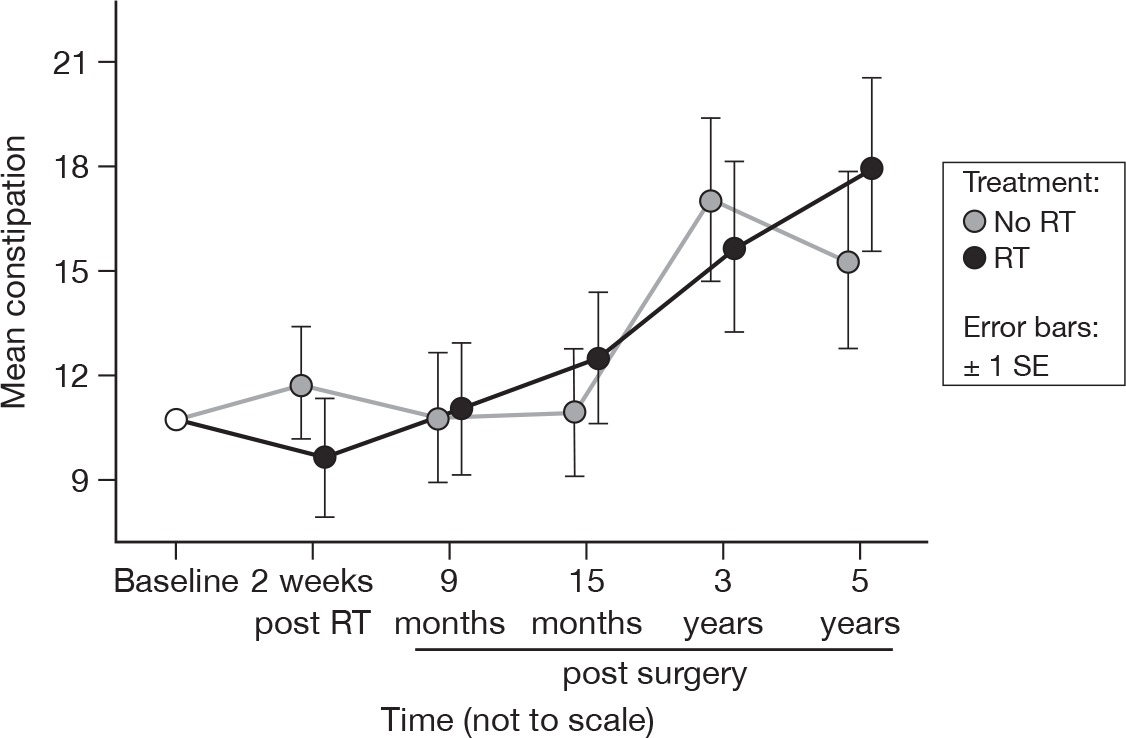

Constipation

-

Have you been constipated?

Although there was no evidence of a time effect at 15 months, there was a significant difference at 5 years (p = 0.003, adjusted p = 0.29). There was a linear relationship between mean score and questionnaire, with an increase of 1.1 units per questionnaire. As at 15 months, there was no evidence of a treatment effect (Figure 13). Mean difference was –0.20 and the 95% CI was –7.88 to 7.48.

FIGURE 13.

Mean scores of constipation by questionnaire.

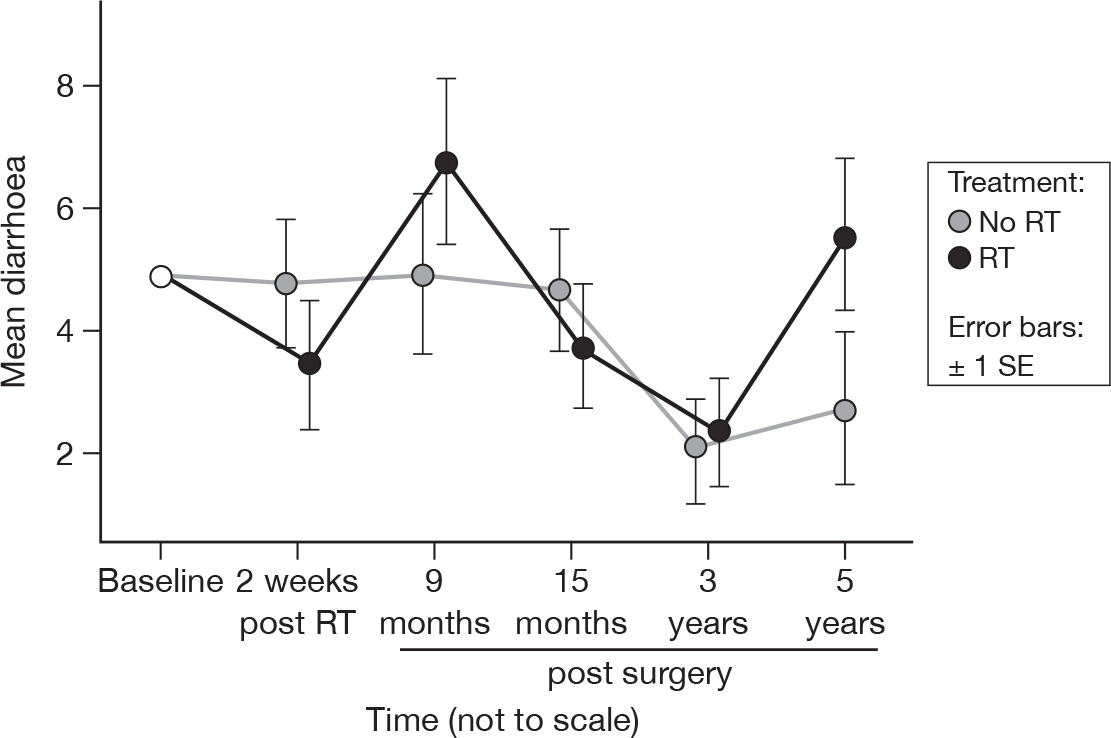

Diarrhoea

-

Did you have diarrhoea?

As with constipation, there was no evidence of a time effect at 15 months, but there was a significant effect at 5 years (p = 0.01, adjusted p = 1.0). Unlike constipation, however, there was no evidence of a trend in any direction, and we suggest that it was an entirely spurious effect owing to the small number of patients reporting diarrhoea at any point. There was no evidence of a treatment effect, as before (Figure 14). Mean difference was –0.54 and the 95% CI was –3.82 to 2.73.

FIGURE 14.

Mean scores of diarrhoea by questionnaire.

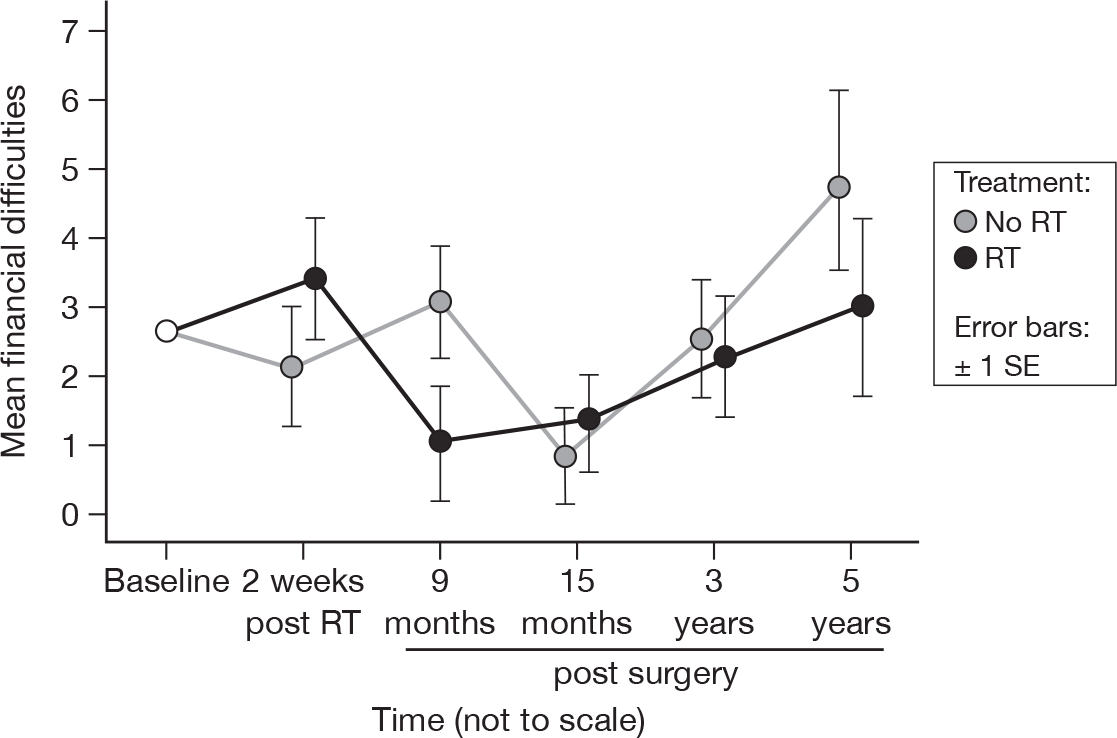

Financial difficulties

-

Has your physical condition or medical treatment caused you financial difficulties?

The difference between time points was significant at 5 years (p = 0.04, adjusted p = 1.0), having been not significant at 15 months (p = 0.09). This factor may have been demonstrating the same time-shift behaviour seen in social functioning, although the scores remained very low. There remained no evidence of a difference between treatments (Figure 15). Mean difference was 0.48 and the 95% CI was –2.20 to 3.16.

FIGURE 15.

Mean scores of financial difficulties by questionnaire.

The European Organisation for Research in the Treatment of Cancer QLQ-BR23 scale

This scale is specific to patients suffering from breast cancer and consists of 23 questions which may be collapsed into eight subscales. In addition, a question on the presence of a cough was introduced by the trial team using the same format, in order to capture information on a potential side effect of breast irradiation. As with the EORTC QLQ-C30, each measure relates to the previous week, except for the questions dealing with sexual functioning and enjoyment, which relate to the previous 4 weeks.

Again, mean differences were calculated by subtracting the mean of the patients who received RT from the mean of the patients who did not receive RT (i.e. no RT – RT). Thus, a positive mean indicates that those patients who did not receive RT had, on average, higher levels of problems/activity/etc., and vice versa. ‘Adjusted’ refers to the p-values following adjustment due to the Bonferroni correction. All CIs were calculated following adjustment.

Body image

-

Have you felt physically less attractive as a result of your disease or treatment?

-

Have you been feeling less feminine as a result of your disease or treatment?

-

Did you find it difficult to look at yourself naked?

-

Have you been dissatisfied with your body?

As with the results at 15 months, there was no evidence of a time or treatment effect. The overall mean score was 92.9, with an SE of 0.4. Mean difference was 0.01 and the 95% CI was –4.10 to 4.11.

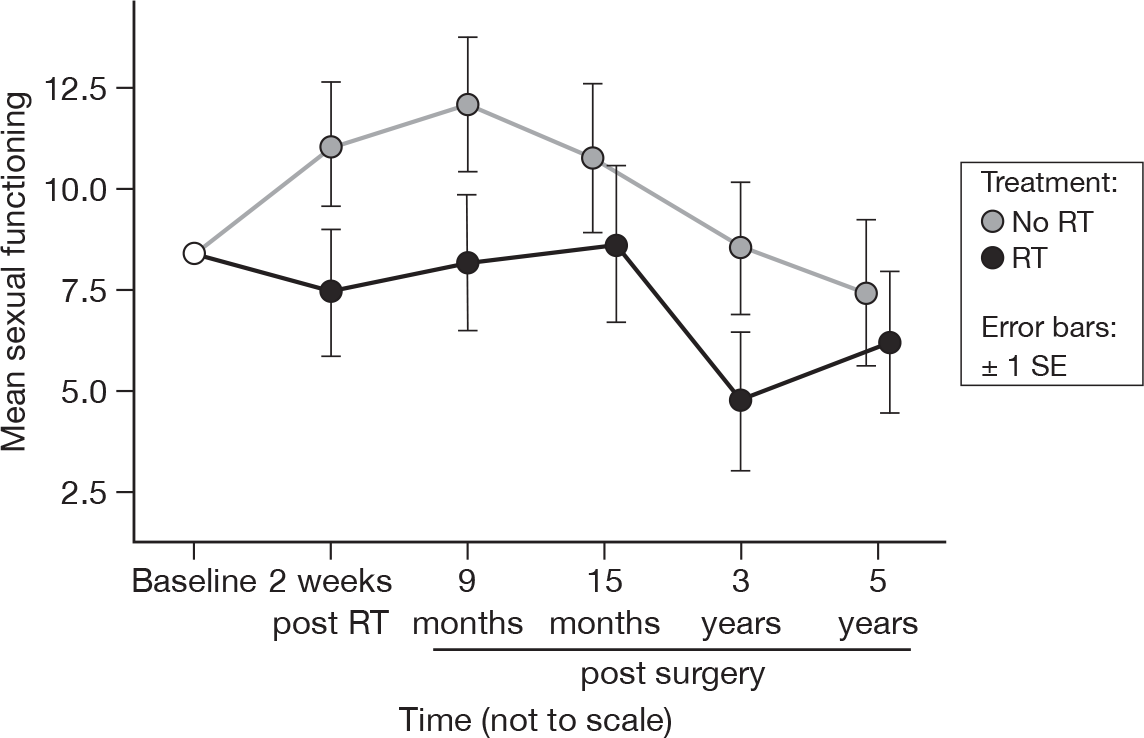

Sexual functioning

-

To what extent were you interested in sex over the last month?

-

To what extent were you sexually active (with or without intercourse) over the last month?

As before, this question was optional, with patients given the choice on whether to answer any part of it. There was some slight evidence that there was a treatment difference (15 months p = 0.05, 5 years p = 0.07, adjusted p = 1.0 for both), but it must be remembered that not all patients answered this question, and interpretation of the result should be cautious (Figure 16). On average, per questionnaire, 118 patients who gave an answer at baseline answered these questions. The number of degrees of freedom used in the calculation of the 95% CI was 151. Mean difference was 2.93 and the 95% CI was –2.78 to 8.64.

FIGURE 16.

Mean scores of sexual functioning by questionnaire.

Sexual enjoyment

-

To what extent was sex enjoyable for you?

This question was completed only if the patient had indicated that he or she had been sexually active. Of the patients who had answered this question at baseline, on average 14 answered this question per subsequent questionnaire. Only 17 degrees of freedom were available for this analysis. As with the results at 15 months, there was no evidence of a time or treatment effect. The overall mean score was 57.8, with an SE of 1.9. Mean difference was 3.93 and the 95% CI was –19.42 to 27.29.

Future perspective

-

Were you worried about your health in the future?

In accordance with the results at 15 months, there was no evidence of a time or treatment effect. The overall mean score was 21.4, with an SE of 0.6. Mean difference was 1.54, and the 95% CI was –5.33 to 8.41.

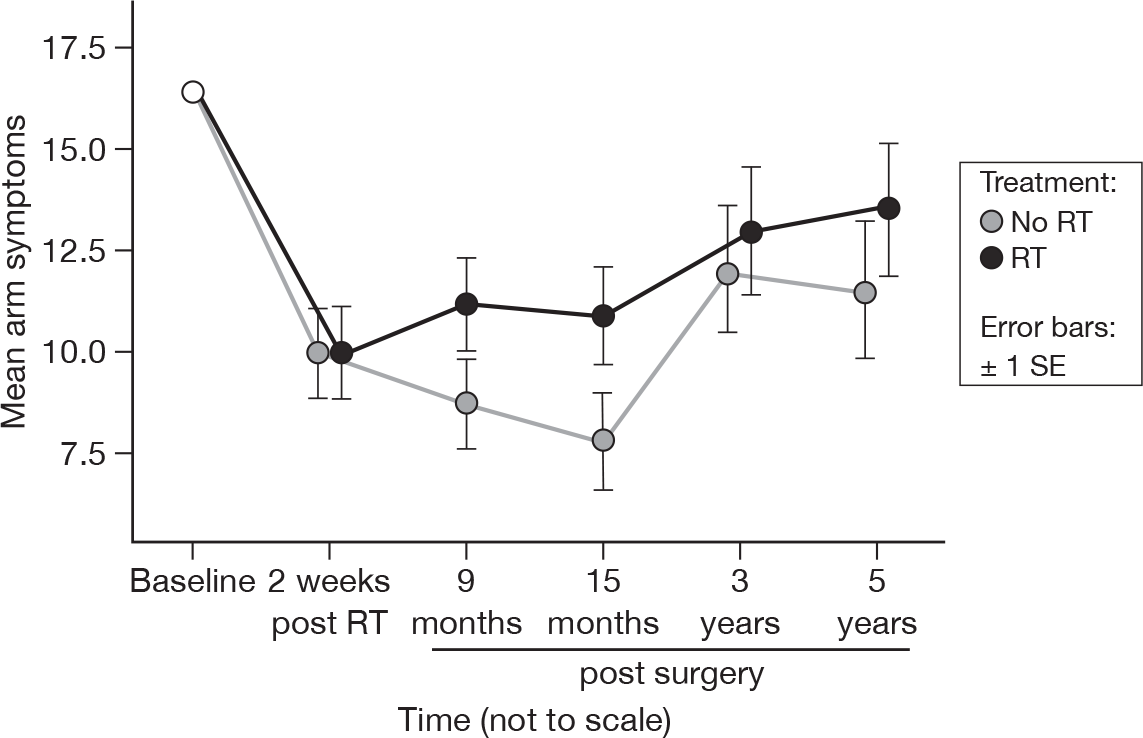

Arm symptoms

-

Did you have any pain in your arm or shoulder?

-

Did you have a swollen arm or hand?

-

Was it difficult to raise your arm or move it sideways?

Despite no significant differences over time at 15 months (p = 0.73), by 5 years a significant difference appeared (p = 0.01, adjusted p = 1.0; Figure 17). There was no evidence to suggest a difference in treatments (p = 0.22, adjusted p = 1.0). Mean difference was –1.69 and the 95% CI was –6.60 to 3.22.

FIGURE 17.

Mean scores of arm symptoms by questionnaire.

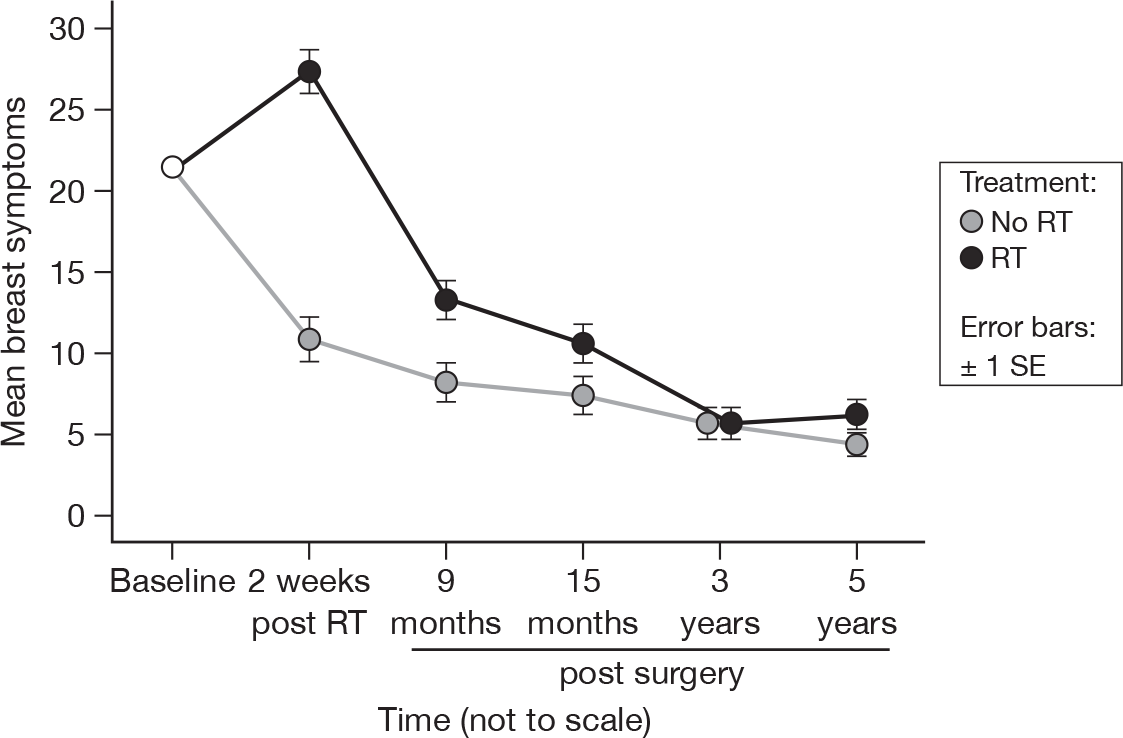

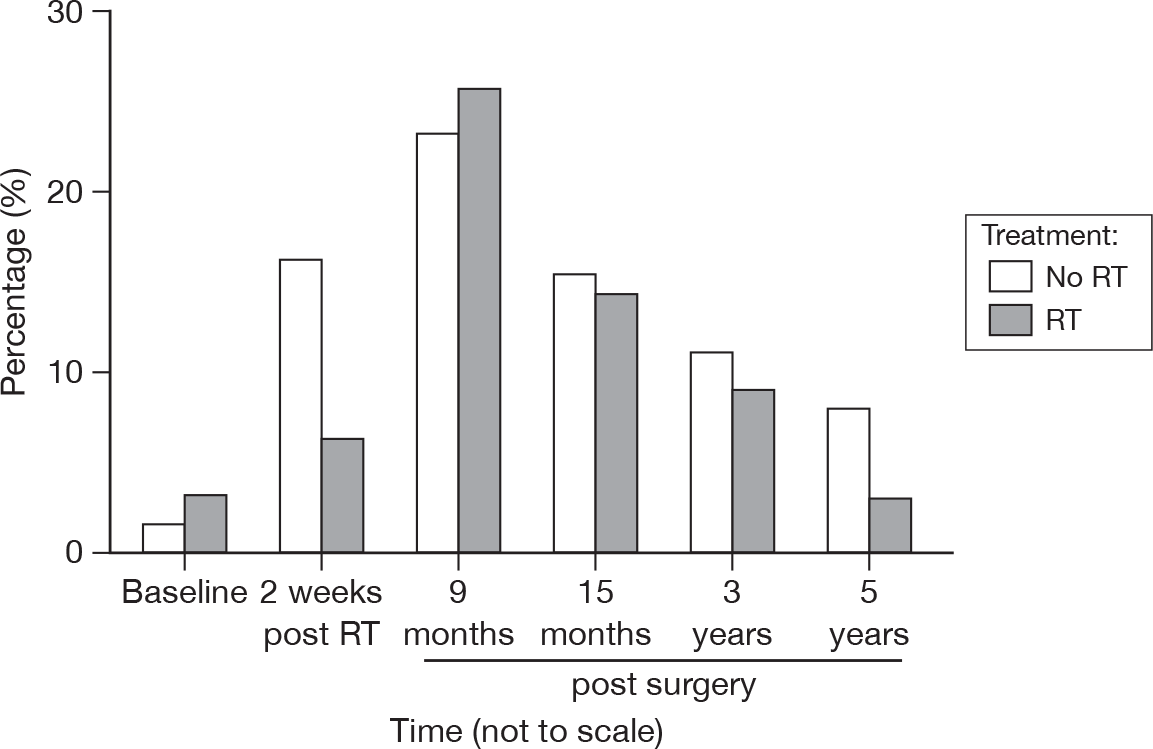

Breast symptoms

-

Have you had any pain in the area of your affected breast?

-

Was the area of your affected breast swollen?

-

Was the area of your affected breast oversensitive?

-

Have you had skin problems on or in the area of your affected breast

Although time and treatment remained significantly different (both p < 0.0001, adjusted treatment p = 0.003, adjusted time p < 0.0001), by 3 years the levels of breast symptoms were similar in both treatment groups, and they remained similar at 5 years (Figure 18). Mean difference was –5.27 and the 95% CI was –9.07 to –1.46.

FIGURE 18.

Mean scores of breast symptoms by questionnaire.

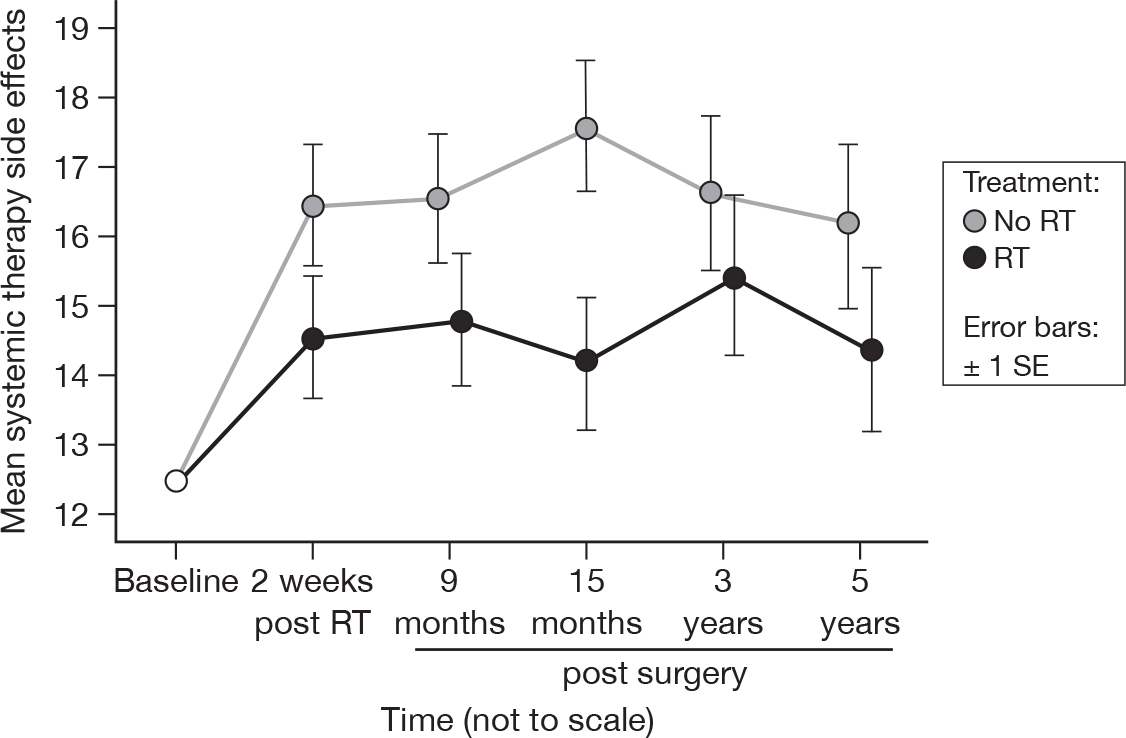

Systemic therapy side effects

-

Did you have a dry mouth?

-

Did food and drink taste different from usual?

-

Were your eyes painful, irritated or watery?

-

Have you lost any hair?

-

Did you feel ill or unwell?

-

Did you have hot flushes?

-

Did you have headaches?

The differences between treatments have become less significant over time (up to 15 months p = 0.03, up to 5 years p = 0.07, both adjusted p = 1.0), most likely owing to the large difference at 15 months being mitigated by the smaller differences at later time points (Figure 19). There was no evidence of a time effect, however (p = 0.80). Mean difference was 2.00 and the 95% CI was –1.86 to 5.86.

FIGURE 19.

Mean systemic therapy side effect scores by questionnaire.

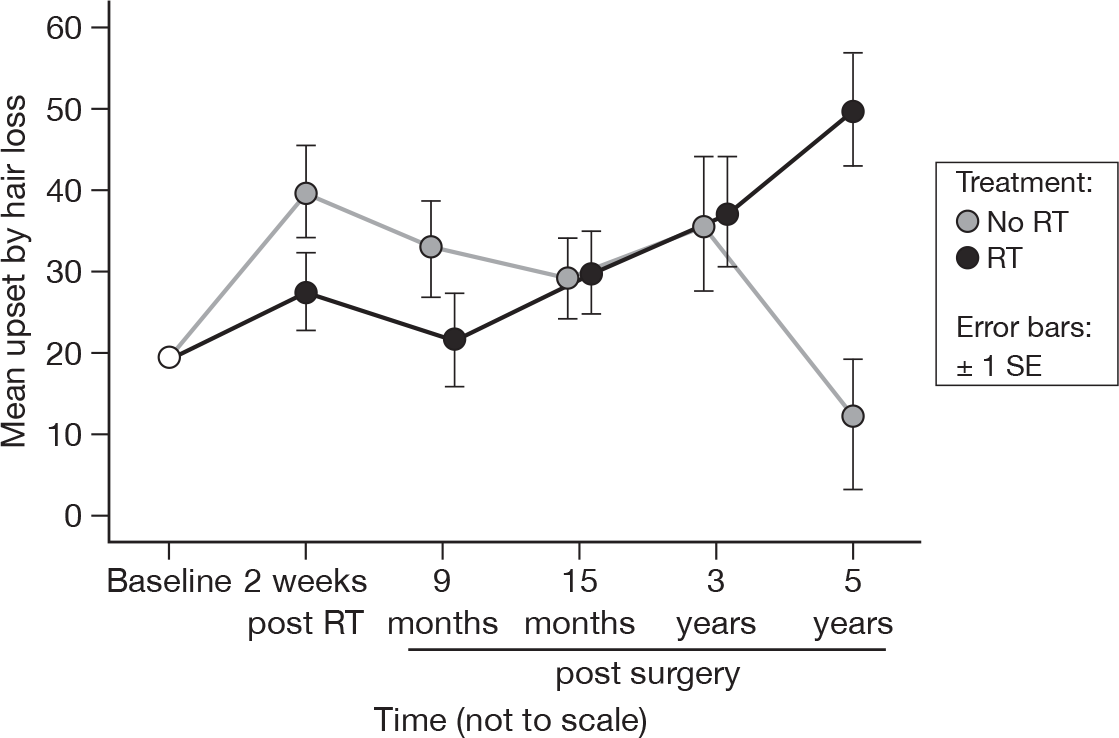

Hair loss

-

Were you upset by the loss of your hair?

As with the sexual questions, very few patients answered this question. The mean scores were based only on those patients who acknowledged that they had encountered hair loss (Figure 20). Only 28 degrees of freedom were available for this analysis. Mean difference was –3.47 and the 95% CI was –24.52 to 17.59.

FIGURE 20.

Mean upset by hair loss scores by questionnaire.

If we include those patients who did not respond with any hair loss as being not upset by hair loss, then the mean difference was 0.06 and the 95% CI was –5.51 to 5.64. No variables were significant.

Cough

-

Did you have a cough?

-

(If yes) How much has it affected you?

As with hair loss and sexual enjoyment, only patients who answered ‘yes’ to the question ‘Did you have a cough?’ were included, so the degrees of freedom were 62. In accordance with the results at 15 months, there was no evidence of a time or treatment effect. The overall mean score was 37.1, with an SE of 1.2. Mean difference was 4.74 and the 95% CI was –15.53 to 25.02.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

The HADS is designed to investigate psychiatric and psychological morbidity with respect to health. It comprises 14 questions, scored 0–3, and is subdivided to provided separate scores for anxiety and for depression. Higher scores are indicative of higher anxiety/depression. Scores of ≥ 10 on either scale are indicators of significant problems, with a possible maximum of 21 for each scale.

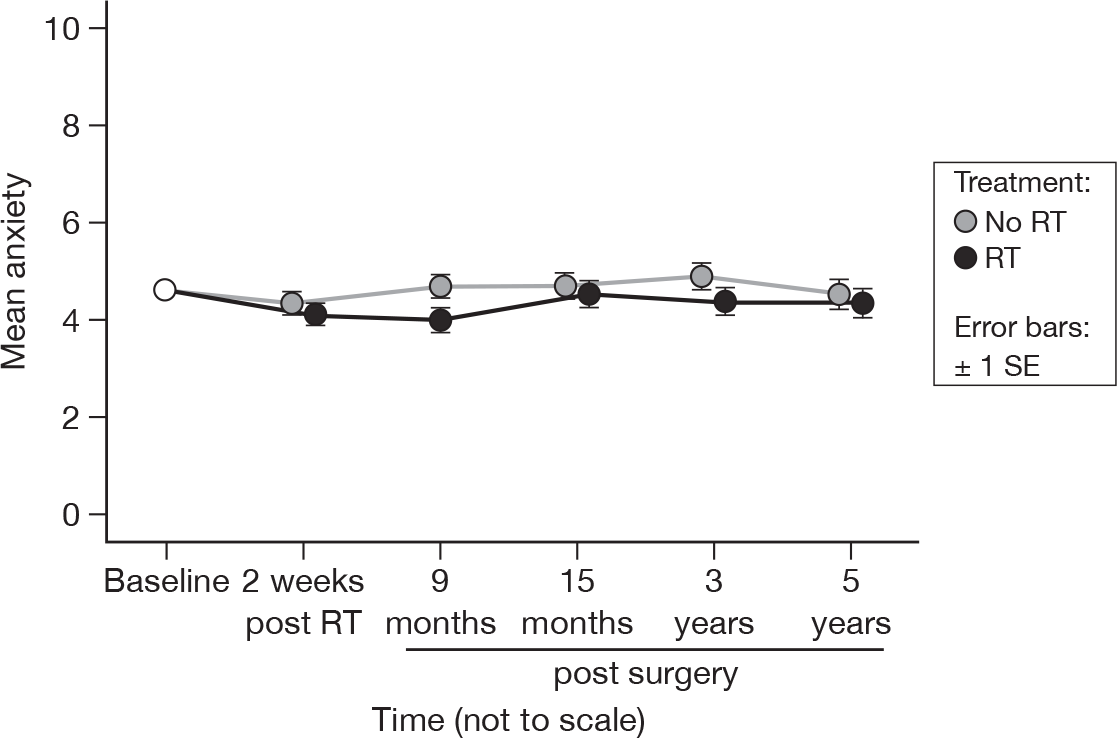

Anxiety

There was no evidence of a time (p = 0.09) or treatment (p = 0.16) effect (adjusted p = 1.0 for both). This did not differ from the results at 15 months. There was a suggestion that anxiety levels were lower in the RT group (Figure 21), but the difference was still not significant. Mean difference was 0.35 and the 95% CI was –0.55 to 1.26.

FIGURE 21.

Mean scores of anxiety by questionnaire.

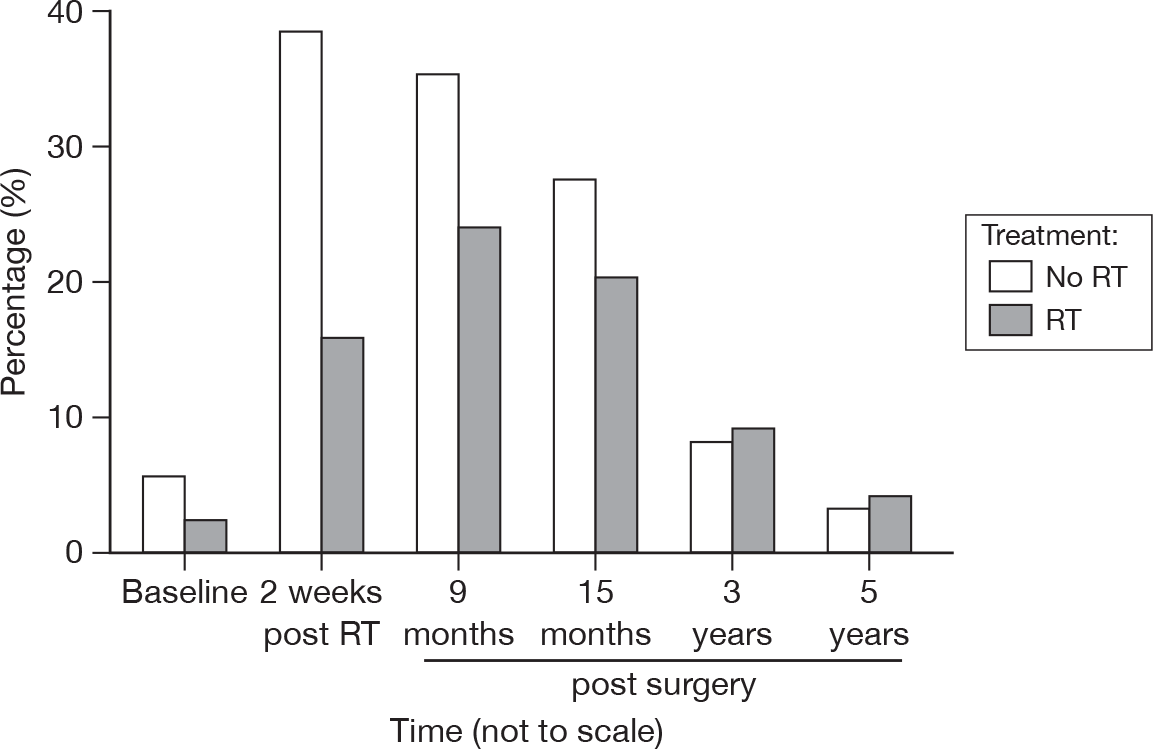

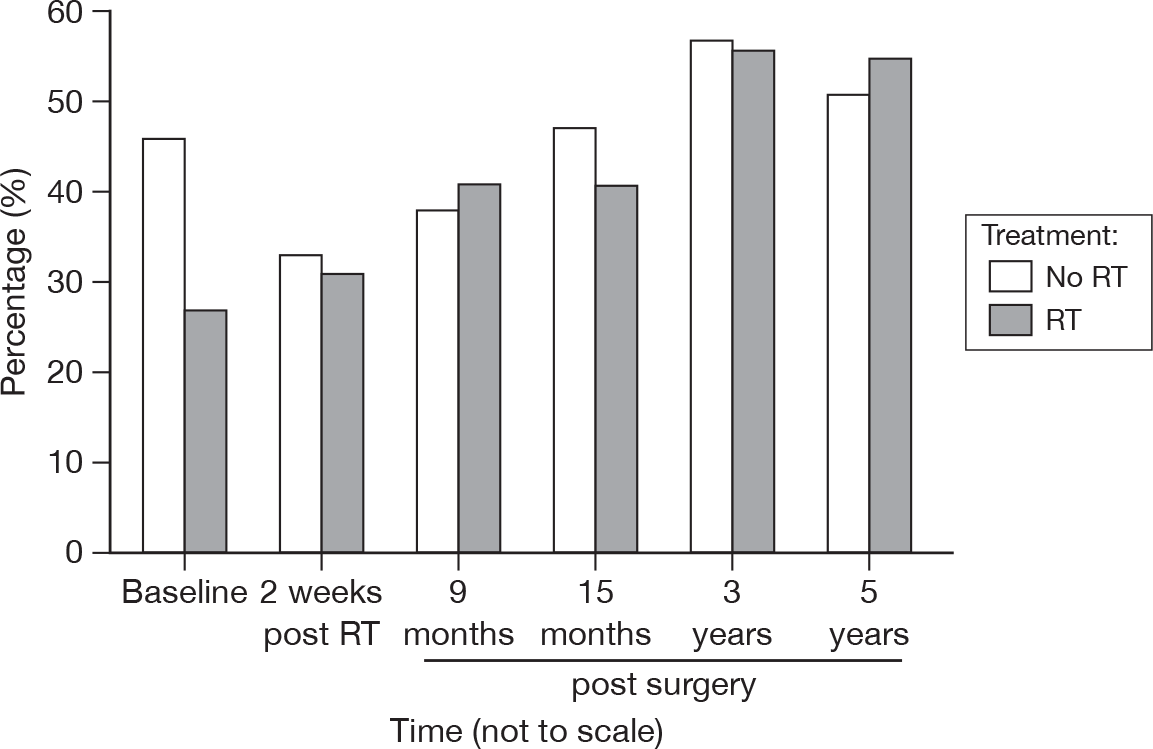

It must be remembered that in order for anxiety to be considered a clinical issue, it must equal or exceed a score of 10. As can be seen in Table 6, there was no evidence of a difference over time (p = 0.37), and once we take into account the correlation due to the fact that the patients at each point were not independent, there was no evidence to suggest that there was a significant difference between treatments (p = 0.17).

| RT | Questionnaire (% with a score ≥ 10) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 2 weeks post RT | 9 months post surgery | 15 months post surgery | 3 years post surgery | 5 years post surgery | |

| No | 9.4 | 8.7 | 10.4 | 11.3 | 12.4 | 11.9 |

| Yes | 8.8 | 8.1 | 5.0 | 9.2 | 3.8 | 8.7 |

| Total | 9.1 | 8.4 | 7.7 | 10.3 | 8.2 | 10.2 |

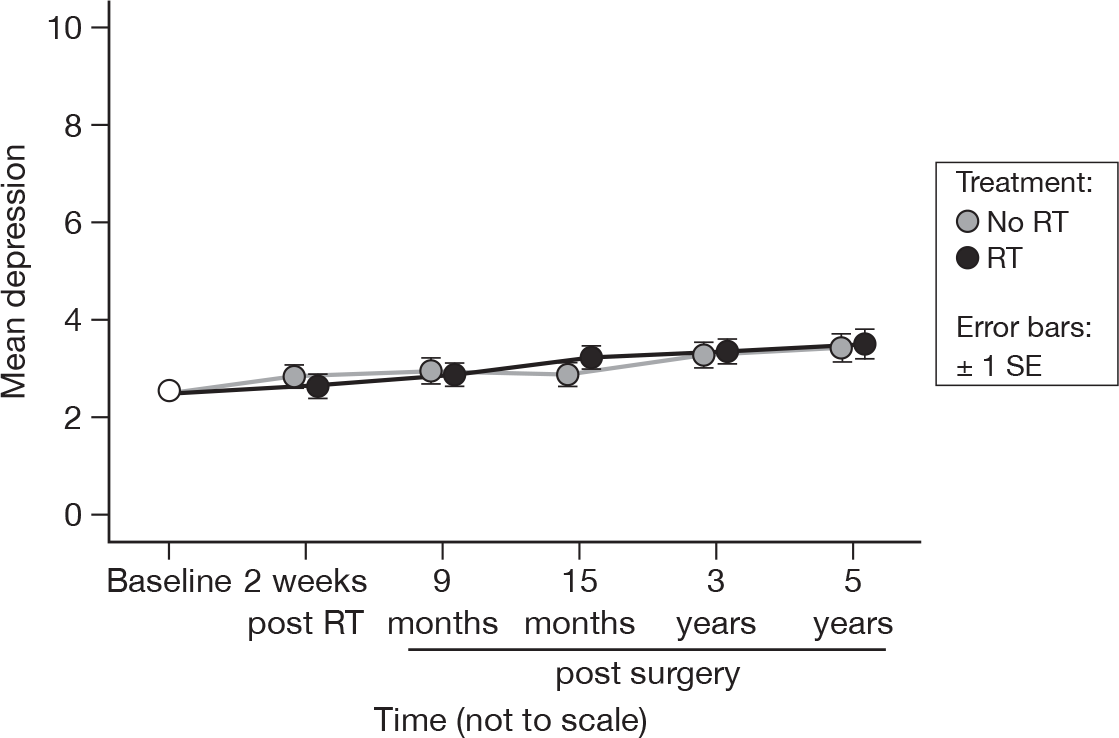

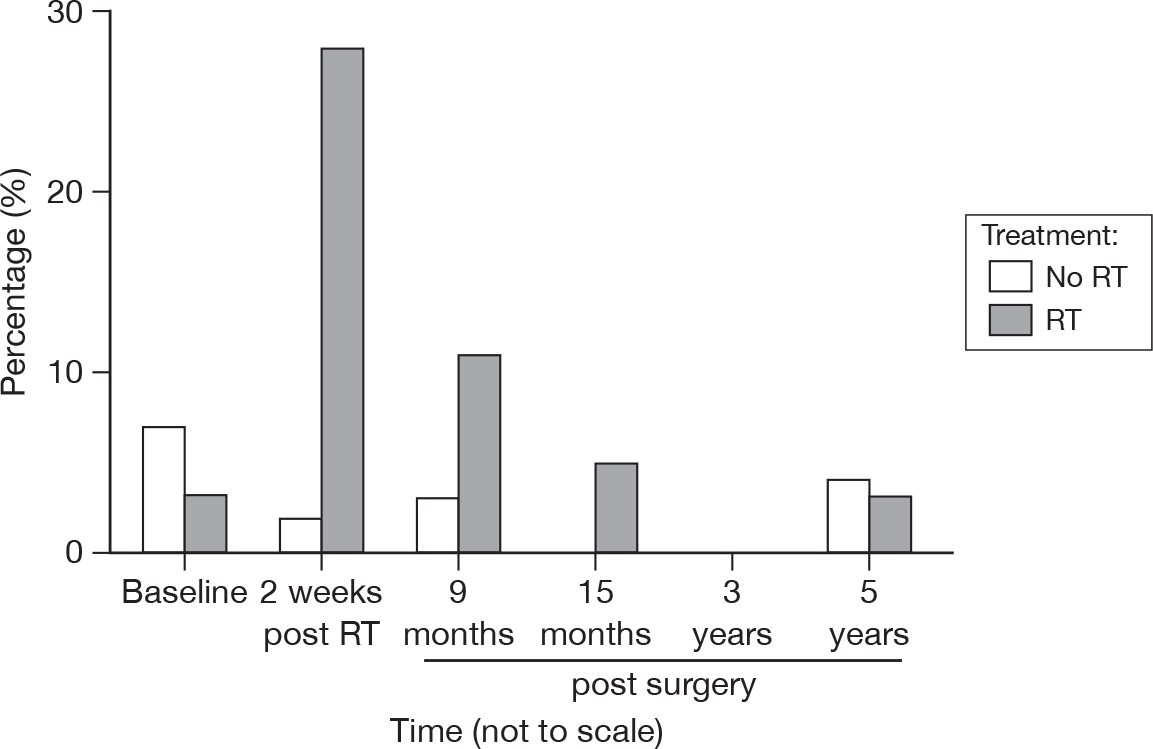

Depression

As before, there was a significant change over time (p < 0.0001, adjusted p = 0.005). However, these differences are small (approximately 1 unit over 5 years), and are unlikely to be of clinical interest (Figure 22). There was no evidence of a difference between treatment groups (p = 0.78). Mean difference was –0.06 and the 95% CI was –0.88 to 0.75.

FIGURE 22.

Mean scores of depression by questionnaire.

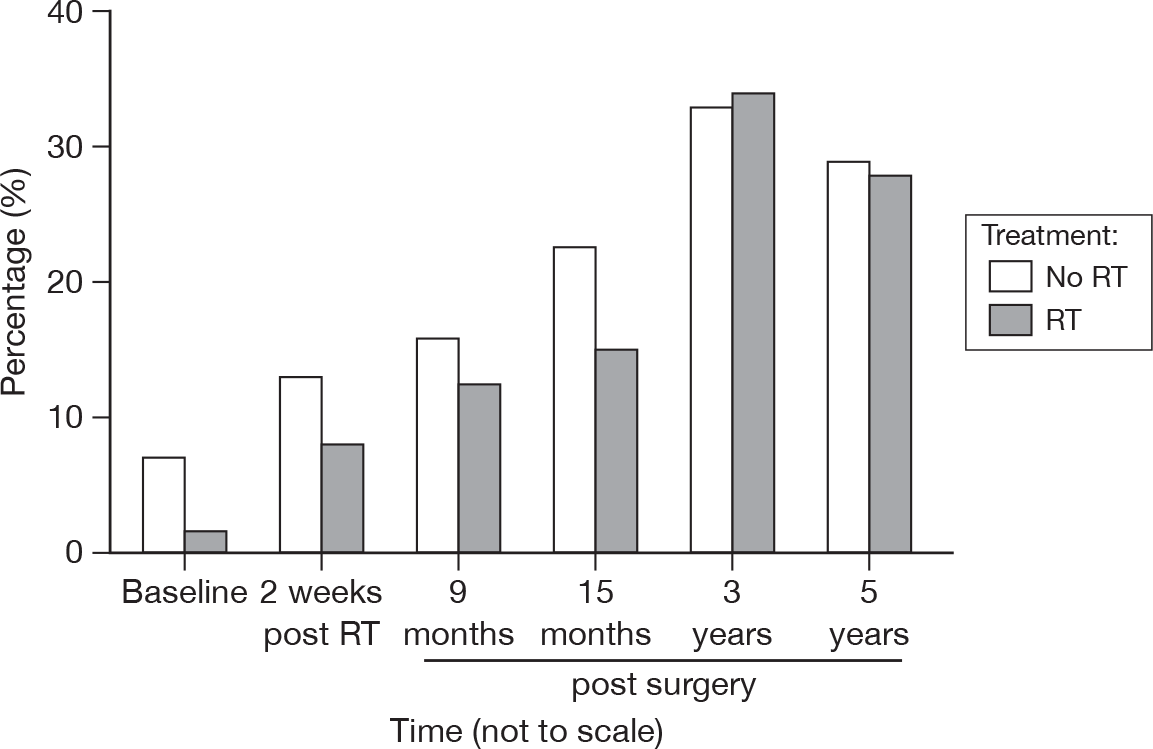

As with anxiety, depression becomes clinically important only if the score is ≥ 10. As can be seen from Table 7, there were very few patients with significant depression. There was no evidence to suggest that there was a difference between treatments (p = 0.84), with only a weak suggestion that there was a difference over time (p = 0.07, adjusted p = 1.0).

| RT | Questionnaire (% with a score ≥ 10) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 2 weeks post RT | 9 months post surgery | 15 months post surgery | 3 years post surgery | 5 years post surgery | |

| No | 3.9 | 3.2 | 4.0 | 3.2 | 0.9 | 3.0 |

| Yes | 1.6 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 3.4 | 1.9 | 1.0 |

| Total | 2.8 | 3.6 | 4.1 | 3.3 | 1.4 | 2.0 |

Summary of results at 15 months versus 5 years

In terms of the treatment effect, very little changed between 15 months and 5 years post surgery (Table 8). Both sexual functioning and systemic therapy became non-significant at 5 years, having been significant at 15 months. However, the proportion of patients answering the sexual functioning question is lower at each questionnaire, which brings into question the reliability of the results. The trend to non-significance for the systemic therapy side effects (unadjusted) reflects the mitigating effect of smaller differences between the groups at later times. Otherwise, the conclusions remain the same as at 15 months, with only insomnia (unadjusted only) and breast symptoms still showing significant differences between the groups at 5 years.

| Scale variable | 15 months (p-value) | 5 years (p-value) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Treatment | Time | Treatment | |

| C30 | ||||

| Functioning (global measure) | 0.53 | 0.82 | 0.002 | 0.53 |

| Symptoms (global measure) | 0.76 | 0.50 | 0.12 | 0.38 |

| Physical functioning | < 0.0001 | 0.61 | < 0.0001 | 0.76 |

| Role functioning | 0.32 | 0.89 | 0.30 | 0.58 |

| Emotional functioning | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| Cognitive functioning | 0.49 | 0.79 | 0.07 | 0.58 |

| Social functioning | 0.02 | 0.54 | 0.0009 | 0.99 |

| Quality of life | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.85 | 0.82 |

| Fatigue symptoms | 0.11 | 0.95 | 0.01 | 0.56 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 0.67 | 0.21 | 0.92 | 0.72 |

| Pain symptoms | 0.09 | 0.55 | 0.002 | 0.35 |

| Dyspnoea | 0.07 | 0.57 | < 0.0001 | 0.15 |

| Insomnia | 0.33 | 0.01 | 0.39 | 0.03 |

| Appetite loss | 0.50 | 0.94 | 0.05 | 0.62 |

| Constipation | 0.76 | 0.97 | 0.003 | 0.93 |

| Diarrhoea | 0.21 | 0.84 | 0.01 | 0.55 |

| Financial difficulties | 0.09 | 0.95 | 0.04 | 0.53 |

| BR23 | ||||

| Body image | 0.37 | 0.59 | 0.74 | 0.99 |

| Sexual functioning | 0.67 | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.07 |

| Sexual enjoyment | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.50 | 0.47 |

| Future perspective | 0.32 | 0.53 | 0.19 | 0.43 |

| Arm symptoms | 0.73 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.22 |

| Breast symptoms | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| Systemic therapy side effects | 0.84 | 0.03 | 0.80 | 0.07 |

| Hair loss (distress) | 0.36 | 0.16 | 0.40 | 0.52 |

| Cough | 0.11 | 0.69 | 0.05 | 0.39 |

| HADS | ||||

| HADS – anxiety | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.16 |

| HADS – depression | 0.04 | 0.82 | < 0.0001 | 0.78 |

There are still several measures with significant changes over time, even taking the Bonferroni correction into account. This would suggest that the quality of life of patients in this population will change over 5 years, regardless of treatment.

Chapter 5 Clinical outcomes

Treatment-related morbidity

Figure 23 summarises the number of forms returned to the trial office at each of the standard clinical follow-up visits.

FIGURE 23.

Number of morbidity forms completed and returned. CRFs, Clinical Record Forms.

As in the previous report,21 late morbidity is recorded using the RTOG/EORTC scales, at 8, 12 and 18 months post surgery, then at 2, 3, 4 and 5 years post surgery. The first two time points (8 and 12 months) have been reported in detail in the previous report.

In order to summarise the data in their simplest form, any report of a morbidity (i.e. a score of > 0) will be considered to be an ‘event’, an outcome of interest.

Breast oedema

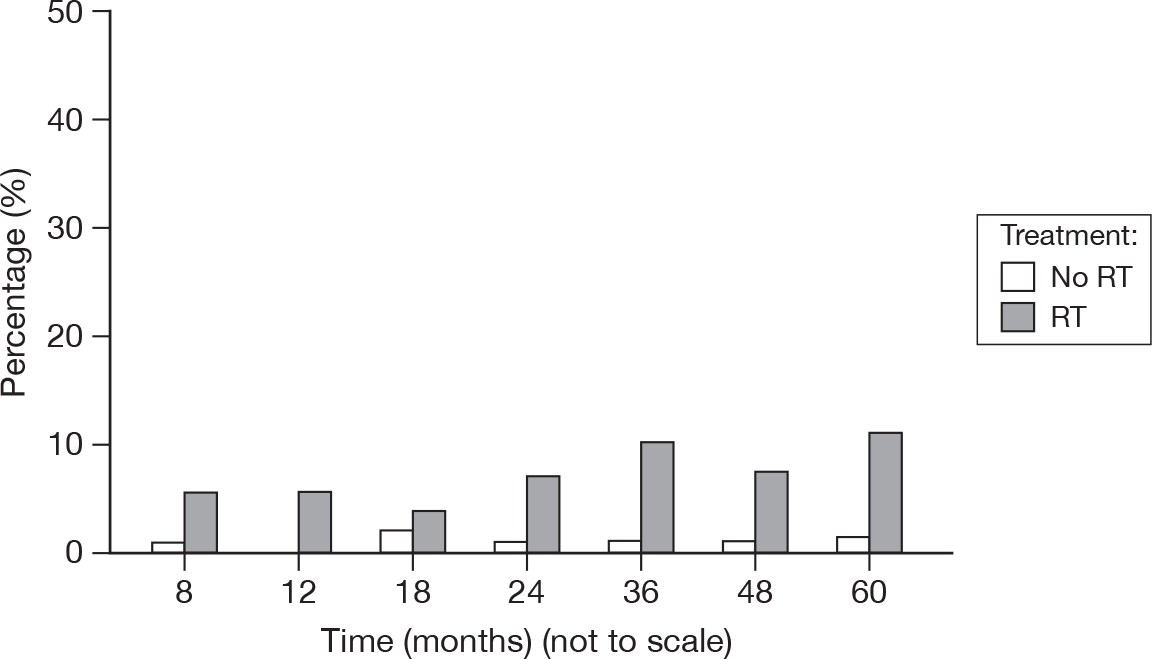

An abnormal collection of fluid in the tissues, causing a puffy swelling (Figure 24).

FIGURE 24.

Percentage of patients with oedema score > 0.

-

0: None

-

1: Asymptomatic

-

2: Symptomatic

-

3: Secondary dysfunction.

Only one patient recorded a score of 3, which was reported at 8 months and from a patient treated with RT. Across all time points, patients who received RT had < 5% of scores > 1 (other than at 8 months, 6.3%), with only 1% of scores > 1 for those patients who did not receive RT.

It is not unexpected to see continued evidence of breast oedema as late as 4 and 5 years after surgery.

Telangiectasia

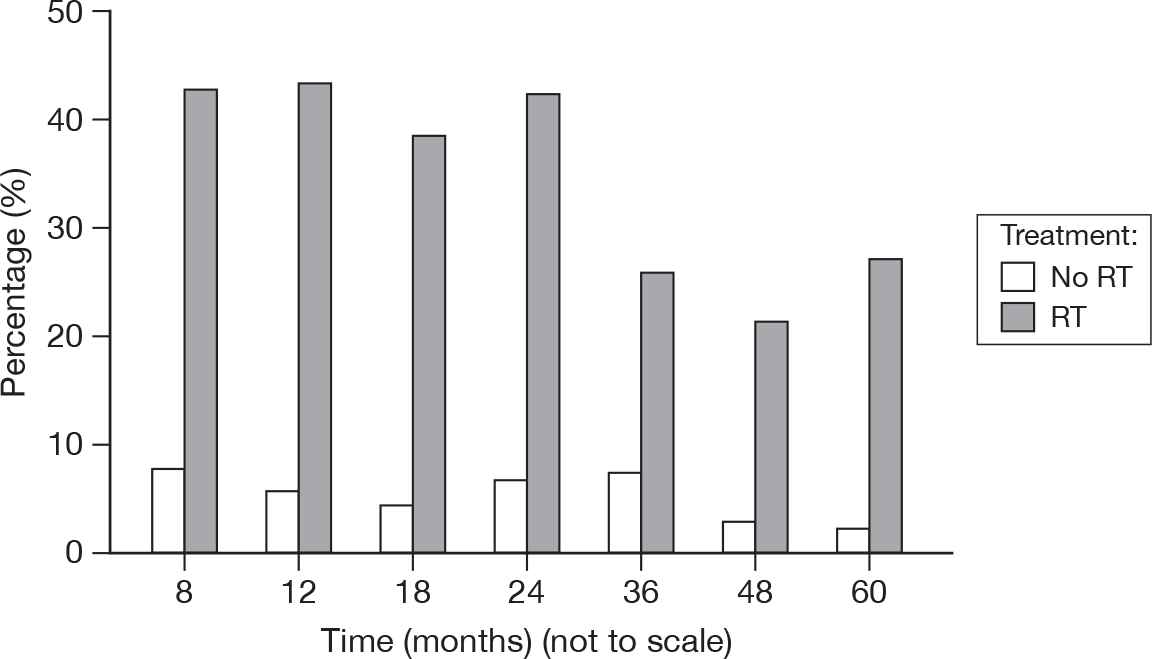

The formation of a lesion in the breast consisting of a number of dilated capillaries which have a web-like appearance. The categories are based on the size of area affected (Figure 25).

FIGURE 25.

Percentage of patients with telangiectasia score > 0.

-

0: None

-

1: < 1 cm2

-

2: 1–4 cm2

-

3: > 4 cm2.

As would be expected, only patients who received RT had any scores of 3, ranging from 0% to 3.5% (at 24 months). There were two scores of 2 in the no RT group, at 48 and 60 months. Telangiectasia is a morbidity that would be expected to increase over time, although it is odd that there was evidence of the lesion in the no RT group.

Fibrosis

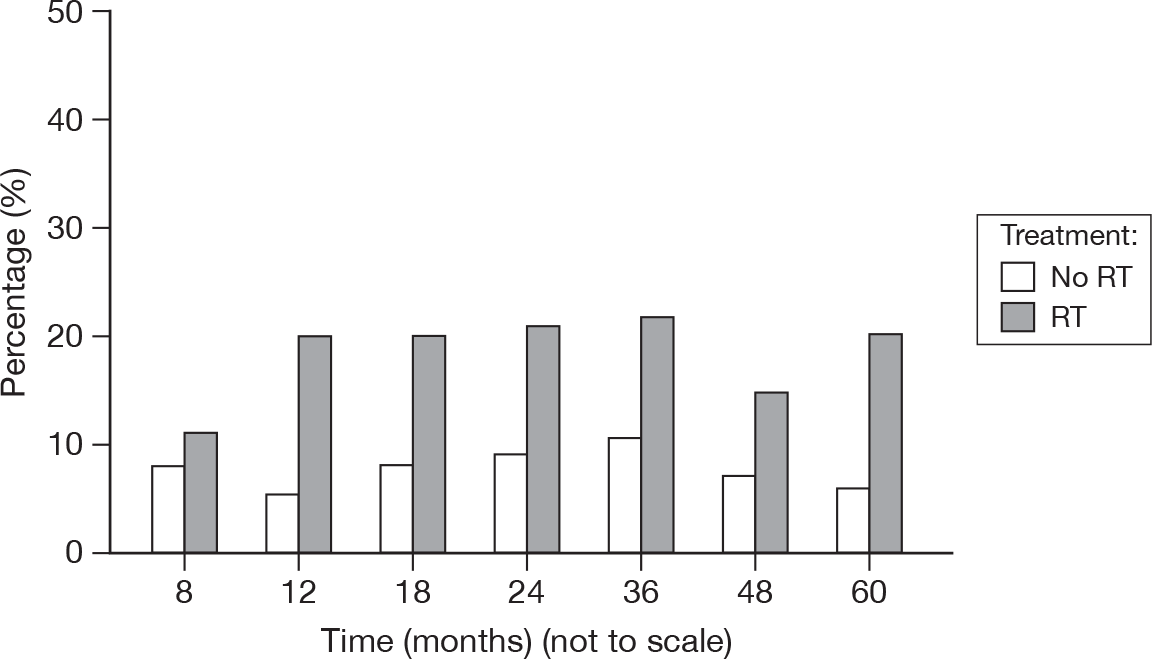

A measure of the formation of fibrous connective tissue in the breast (Figure 26).

FIGURE 26.

Percentage of patients with fibrosis score > 0.

-

0: None

-

1: Barely palpable increased density

-

2: Definite increased density and firmness

-

3: Very marked density, retraction and fixation.

There were two patients with a score of 3, both in the RT group, at 24 months and 36 months. There were also comparatively few scores of 2 in the no RT group (mean of 1.3% vs 12%). Although fibrosis is generally due to RT, there may be a surgical component. Despite the high levels of fibrosis still evident at 5 years, it appeared to be diminishing.

Retraction/Atrophy

A wasting of the tissues, pulling back from the wound. Again, the categories are based on the proportion of the breast affected (Figure 27).

FIGURE 27.

Percentage of patients with retraction/atrophy score > 0.

-

0: None

-

1: 10%–25%

-

2: > 25%–40%

-

3: > 40%–75%

-

4: Whole breast.

Only one score of 3 was recorded for retraction/atrophy, at 24 months for an RT patient. The number of patients with scores of ≥ 2 was similar between the treatment groups (0.8% with no RT vs 1.2% with RT). As above, it is possible that some of the retraction was due to surgical procedures.

Ulcer

A region where there is a breach in the continuity of the epithelium.

-

0: None

-

1: Epidermal only, ≤ 1 cm2

-

2: Dermal, > 1 cm2

-

3: Subcutaneous

-

4: Bone exposed, necrosis.

Very few patients were reported to have developed an ulcer. Of those treated with no RT, there was a record of one patient with an ulcer at 24 months, and another at 36 months. Of those treated with RT, there was one ulcer at 8 months and another at 48 months. These were all singular and were for four different patients.

Pain management

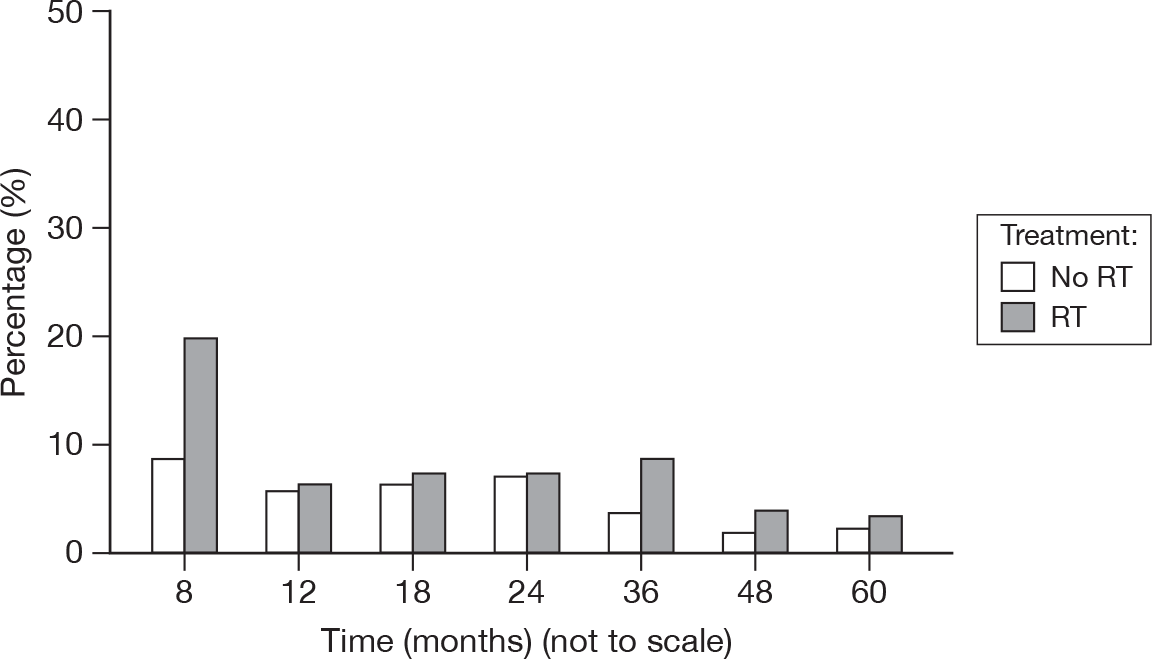

Records the actions taken to resort to control any breast pain that the patients may have experienced (Figure 28).

FIGURE 28.

Percentage of patients with pain management score > 0.

-

0: None

-

1: Occasional non-narcotic

-

2: Regular non-narcotic

-

3: Regular narcotic

-

4: Surgical intervention.

The sole record of a score of 3 was from a patient who was not treated with RT and occurred at 48 months.

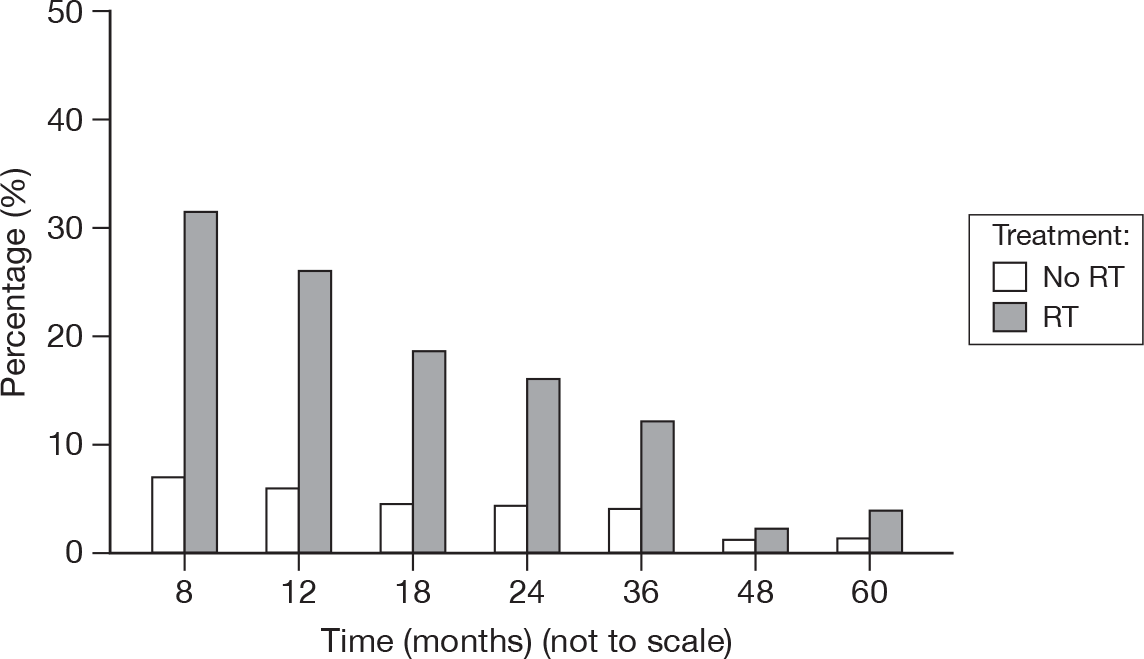

Local recurrence

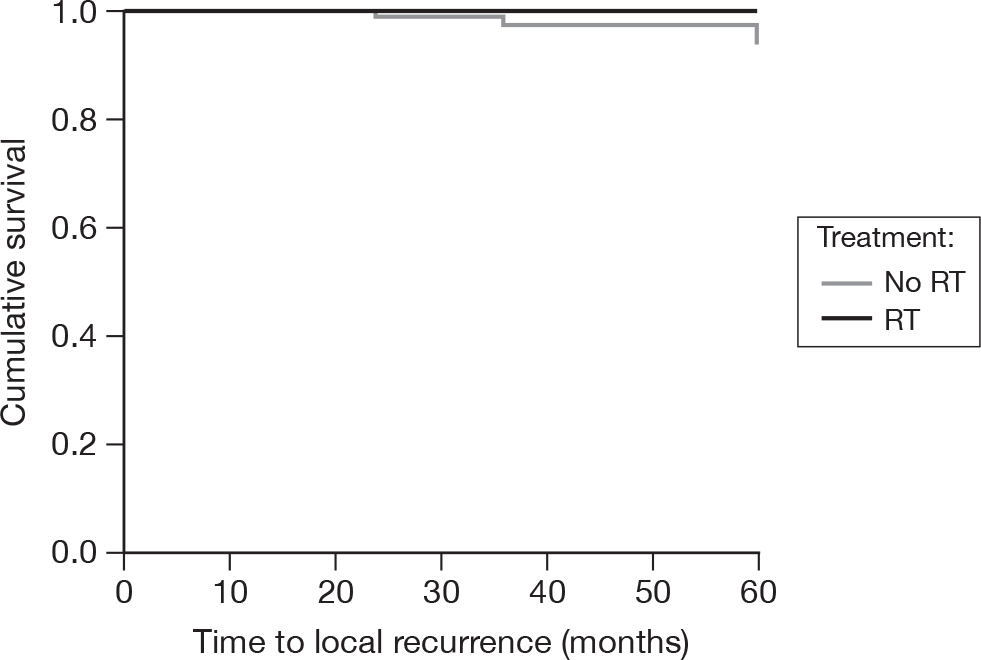

As of 18 February 2010, there were six local recurrences in the no RT group by 5 years of follow-up (from time of randomisation) and none in the RT groups. This equates to 5-year actuarial local recurrence-free survival rates of 94% (SE = 3%, 95% CI 88% to 100%) and 100% (CI not calculable), respectively (Figure 29). By the log-rank test, this was a significant difference (p = 0.014). However, as there were no events in the RT group, the Cox regression model was unreliable and is not reported.

FIGURE 29.

Time to failure of local control.

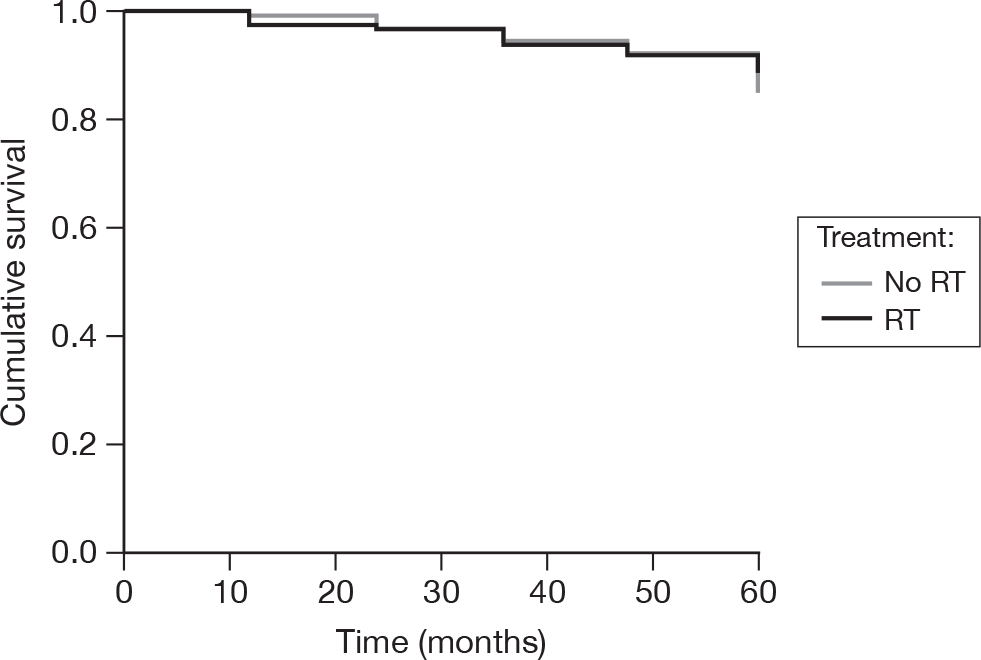

All-cause mortality

As above, the data were frozen on 18 February 2010. At that point, there were 16 deaths in the no RT group and 13 in the RT group at 5 years of follow-up from randomisation. This equates to 5-year actuarial rates of 85% (SE = 4%, 95% CI 77% to 93%) and 89% (SE = 3%, 95% CI 83% to 95%), respectively (Figure 30). There was no evidence to suggest that there was a significant difference between the treatment groups (log-rank p = 0.65), with a hazard ratio (RT compared with no RT) of 0.85 (95% CI 0.42 to 1.72, p = 0.65).

FIGURE 30.

Time to death.

Causes of death (up to 5 years)

-

Radiotherapy (n = 13):

-

– breast cancer: 3

-

– other cancer: 1 (second primary, believed related to breast cancer)

-

– intercurrent disease: 9.

-

-

No RT (n = 16):

-

– breast cancer: 5

-

– other cancer: 3

-

– intercurrent disease: 8.

-

Cost-effectiveness

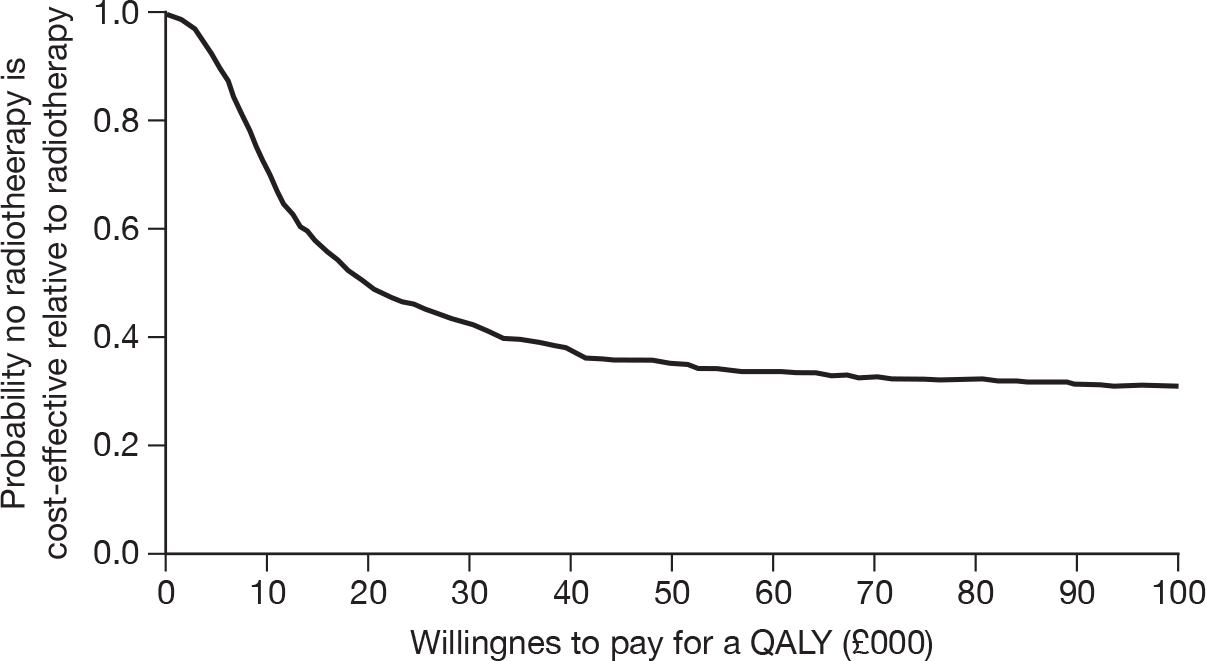

The difference in baseline-adjusted QALYs has increased since the previous report21 as a result of considering the longer time horizon. The mean QALYs in the no RT arm are 0.06 lower than the mean QALYs in the RT arm (Table 9). However, the difference in QALYs has a wide CI and is statistically insignificant. The difference in costs has reduced as a result of the higher level of recurrences in the no RT arm, but remains statistically significant. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio is £19,981.26 per QALY. It should be noted that this is a ratio of two negatives, that is, the no RT option is less costly but also less effective.

| RT (n = 126), mean (95% CI) | No RT (n = 128), mean (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| EQ-5D | ||

| Baseline | 0.77 (0.73 to 0.80) | 0.75 (0.72 to 0.79) |

| 3.5 months | 0.78 (0.75 to 0.81) | 0.77 (0.74 to 0.80) |

| 9 months | 0.76 (0.72 to 0.80) | 0.75 (0.71 to 0.78) |

| 15 months | 0.74 (0.70 to 0.77) | 0.75 (0.71 to 0.78) |

| 36 months | 0.82 (0.78 to 0.85) | 0.78 (0.74 to 0.82) |

| 60 months | 0.79 (0.75 to 0.83) | 0.79 (0.75 to 0.82) |

| Unadjusted QALYs | 3.39 (3.22 to 3.55) | 3.29 (3.13 to 3.45) |

| Difference in adjusted QALYs: –0.06 (–0.27 to 0.14) | ||

| Difference in costs: –1265.74 (–2107.43 to –216.75) | ||

The cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (Figure 31) shows that at the conventional threshold of £30,000 per QALY the no RT option was unlikely to be cost-effective compared with the RT option. The results should be treated with caution as only a basic exploratory analysis was performed.

FIGURE 31.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve.

Similar results were found when the analysis was repeated for the complete cases only. However, the difference in cost between the two arms of the trial was no longer statistically significant (Table 10).

| RT (n = 85), mean (95% CI) | No RT (n = 83), mean (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| EQ-5D | ||

| Baseline | 0.78 (0.74 to 0.81) | 0.74 (0.70 to 0.78) |

| 3.5 months | 0.79 (0.75 to 0.83) | 0.77 (0.74 to 0.81) |

| 9 months | 0.78 (0.74 to 0.83) | 0.73 (0.69 to 0.78) |

| 15 months | 0.76 (0.72 to 0.80) | 0.75 (0.71 to 0.79) |

| 36 months | 0.82 (0.77 to 0.87) | 0.78 (0.72 to 0.84) |

| 60 months | 0.79 (0.73 to 0.85) | 0.77 (0.71 to 0.82) |

| Unadjusted QALYs | 3.44 (3.24 to 3.64) | 3.24 (3.03 to 3.45) |

| Difference in adjusted QALYs: –0.10 (–0.34 to 0.15) | ||

| Difference in costs: –1028.55 (–2254.52 to 640.25) | ||

Chapter 6 Subjective views of patients (open-ended questions)

Introduction

As in earlier questionnaires, participating women were given the opportunity to record how breast cancer was affecting them at each time point. They were also asked if they had had any additional life experiences that had significantly affected their lives.

The headings of the following sections reflect the categories for the response content in the first report to 15 months. A few additions to the categories were made at the 3- and 5-year questionnaires as patients identified additional effects that were being experienced in the longer term, such as breast cancer recurrence. Some response types were not mentioned at all in the postal questionnaires. Only where a fair proportion of patients mention a particular response, or interesting trends or treatment differences were identified are comments or graphics provided.

Longer-term effects of breast cancer

-

How is breast cancer affecting you now?

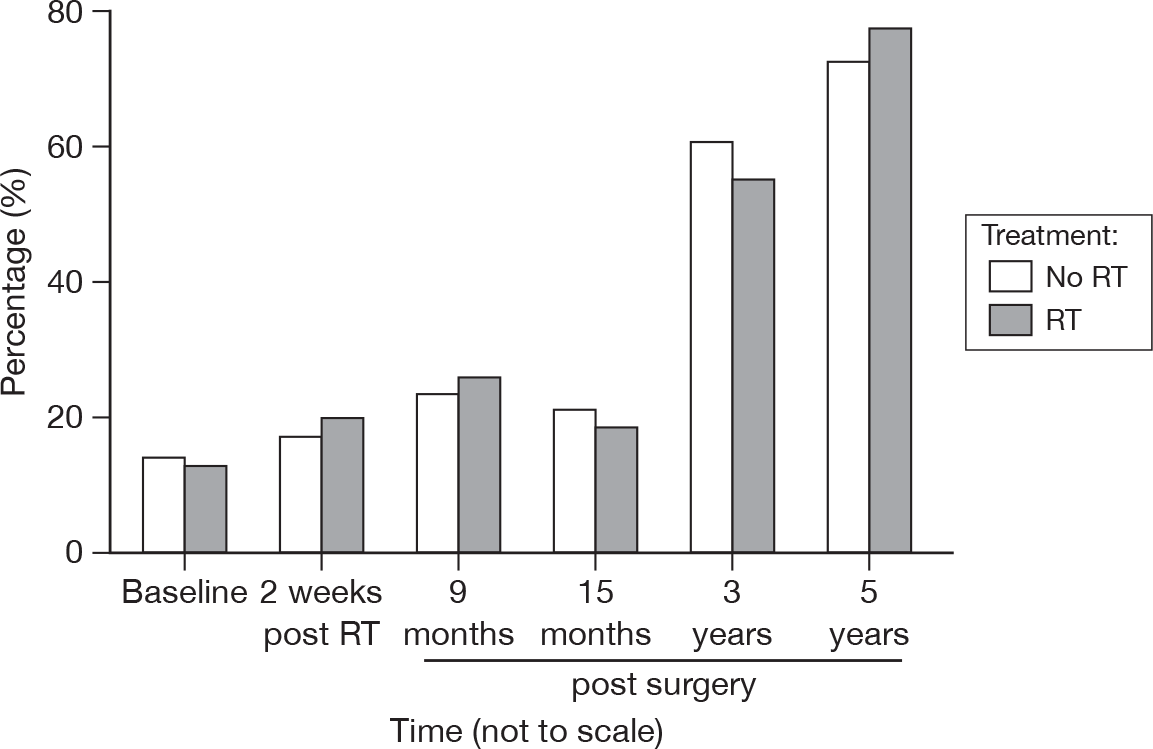

Compared with baseline and the 15-month stage, the proportions of patients answering that breast cancer was no longer affecting them has increased to > 70% at 5 years from surgery (Figure 32). As before, the proportions are similar in both treatment groups. Of those who considered breast cancer was still affecting them in some way, there were multiple causes. However, endocrine therapy side effects were the most frequently mentioned (see Endocrine therapy effects). At 3 and 5 years, the following themes were not commented upon at all: shock/relief at diagnosis or RT. Themes mentioned much less frequently were surgery, fatigue, coping mechanisms, negative impact of the media, change in life perspective and discomfort in bra.

FIGURE 32.

Percentage of patients reporting that breast cancer had no effect on them by questionnaire.

Endocrine therapy effects

Figure 33 illustrates the finding of no significant difference between groups at the 3- and 5-year questionnaires. This is in contrast to our earlier findings where the RT group offered considerably fewer comments about endocrine side effects. In general, the number of comments diminished as time progressed, although a significant proportion (approximately 40%) of patients would have very recently discontinued tamoxifen or other endocrine therapy by the 5-year questionnaire completion time.

FIGURE 33.

Percentage of patients reporting negative physical effects due to endocrine therapy by questionnaire.

At 3 years, 2% of patients reported some emotionally negative effect as a consequence of hormone therapy, which had reduced to 1% by 5 years. No differences between the groups were evident.

In addition, at 3 years 7% of the RT and 1% of the no RT group commented on complications from therapy such as abnormal liver function or allergy which had resulted in the treatment being terminated or replaced by an alternative. By 5 years, 2% in the RT and none in the control group remarked on treatment complications.

Radiotherapy

No specific comments about ongoing effects of RT were made in either the 3- or 5-year postal questionnaires.

Fatigue

At 3 years none of the responses in either group were about fatigue or tiredness, while at 5 years 3% in the RT group and 4% in the no RT group mentioned this symptom (Figure 34). This does not tally with the results of the fatigue score in the EORTC QLQ-C30 scale.

FIGURE 34.

Percentage of patients reporting fatigue by questionnaire.

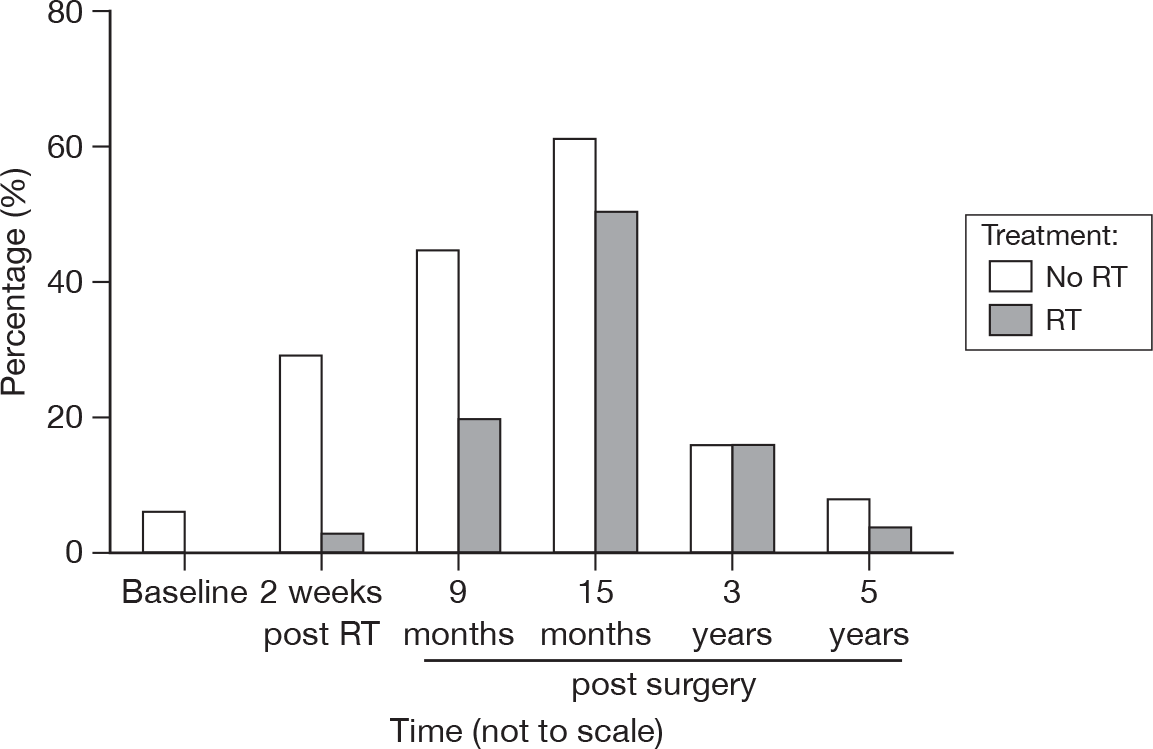

Concern about cancer recurrence

Gradually fewer patients voluntarily expressed such concerns at 3 and 5 years (Figure 35). No significant difference between the groups was found.

FIGURE 35.

Percentage of patients expressing concerns about recurrence by questionnaire.

Anxiety about the process of clinical follow-up

As time progressed, the difference between groups was not as marked as in the earlier questionnaires (Figure 36). As before, this trend reflects the proportions expressing concerns about cancer recurrence.

FIGURE 36.

Percentage of patients expressing anxiety about clinical follow-up.

Other breast cancer effects

Other topics that occurred only up to 3 years and in < 5% of patients in either group were:

-

the negative impact that the media had on the women

-

a change in life perspective as a result of breast cancer

-

experiencing discomfort from wearing a bra.

Other life-impacting events

-

Apart from breast cancer have there been any events in the last 6 months that have had a major impact on your life?

Except at baseline, the groups are very well balanced in terms of events which could potentially have had an impact on their quality of life. However, the proportion of reported events increased as time progressed (Figure 37).

FIGURE 37.

Percentage of patients reporting major life-impacting events by questionnaire.

The most frequently cited category for a life-impacting event was comorbidity, with slightly more than 30% in each group indicating that this was the cause at 3 years and slightly less than 30% at 5 years (Figure 38).

FIGURE 38.

Percentage of patients reporting comorbidity to have a major impact on life by questionnaire.

Next in frequency was bereavement, at around 10% at 3 years and 5% at 5 years. Finally, family illness was the life-impacting event in about 10% and 6% of cases at 3 and 5 years, respectively.

Comorbidity

At baseline, patients were asked to identify any health problems that they had, apart from breast cancer, and at each subsequent questionnaire any new ones that had arisen since the previous questionnaire.

In our first report,21 comorbidity categories were based on the Charlson et al. 30 list of comorbid diseases. Given that this information was provided by patients, no scores of severity were incorporated. We had added a few new categories and subcategories of comorbidity that we judged might affect quality of life.

For this report we have expanded the categories to further reflect life impact rather than survival and have recategorised the baseline comorbidities using this framework. These new categories have again been marked with an asterisk in Table 11. For example, in the first report, at baseline, a patient may have mentioned that only urinary incontinence was a problem, but as it was not included as a Charlson Score disease it was therefore categorised as ‘no comorbidity.’ In the 3- and 5-year postal questionnaires, patients increasingly mentioned that a comorbidity was having more effect on their quality of life than breast cancer (see Figure 38), which made it all the more important that this information was recorded as completely as possible.

| Disease group | Baseline | At 5 yearsa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT (n = 125) | No RT (n = 128) | RT (n = 105) | No RT (n = 101) | |

| None | 12 | 15 | 3 | 1 |

| Dermatological problemb | 7 | 5 | 16 | 14 |

| Endocrine: diabetes | 6 | 9 | 11 | 20 |

| Endocrine: overactive thyroidb | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Endocrine: underactive thyroidb | 14 | 11 | 14 | 14 |

| Gastrointestinal: hiatus herniab | 4 | 16 | 8 | 17 |

| Gastrointestinal: inflammatory bowel disease | 16 | 12 | 19 | 17 |

| Gastrointestinal: other | 11 | 2 | 29 | 33 |

| Gastrointestinal: peptic ulcer | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Genito-urinary: otherb | 1 | 6 | 8 | 12 |

| Genito-urinary: polyuriab | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Genito-urinary: prolapseb | 1 | 3 | 9 | 11 |

| Genito-urinary: urinary incontinenceb | 8 | 4 | 15 | 13 |

| Genito-urinary: vaginal problemsb | 2 | 3 | 6 | 9 |

| Haematological diseasesb | 4 | 2 | 8 | 2 |

| Hepatic disease | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Mental health: depressionb | 10 | 8 | 17 | 17 |

| Mental health: ‘nervous breakdown’b | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Mental health: otherb | 2 | 1 | 2 | 9 |

| Mental health: phobiasb | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Mental health: schizophreniab | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Miscellaneous: allergiesb | 1 | 0 | 9 | 3 |

| Miscellaneous: auditory problemsb | 5 | 6 | 8 | 8 |

| Miscellaneous: auto immune disorderb | 1 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Miscellaneous: fall, no specific causeb | 1 | 1 | 14 | 17 |

| Miscellaneous: fatigueb | 0 | 0 | 7 | 10 |

| Miscellaneous: lethargyb | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Miscellaneous: obesityb | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Miscellaneous: ongoing infectionsb | 0 | 1 | 17 | 15 |

| Miscellaneous: visual problemsb | 9 | 16 | 30 | 41 |

| Miscellaneous: weight gainb | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Miscellaneous: weight lossb | 2 | 1 | 4 | 6 |

| Musculoskeletal: damaged ligament/tendonb | 1 | 2 | 5 | 14 |

| Musculoskeletal: fractureb | 1 | 2 | 9 | 10 |

| Musculoskeletal: osteoarthritisb | 45 | 52 | 71 | 75 |

| Musculoskeletal: osteoporosisb | 3 | 8 | 11 | 18 |

| Musculoskeletal: otherb | 9 | 11 | 38 | 29 |

| Musculoskeletal: rheumatological diseaseb | 2 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| Myocardial: angina | 17 | 10 | 19 | 13 |

| Myocardial: arrhythmia | 4 | 9 | 14 | 17 |

| Myocardial: congestive cardiac failure | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Myocardial: myocardial infarction | 4 | 4 | 6 | 5 |

| Myocardial: valvular disease | 2 | 5 | 5 | 8 |

| Neurological: dementiab | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Neurological: otherb | 4 | 8 | 13 | 16 |

| Neurological: Parkinson'sb | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Neurological: tinnitusb | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Neurological: vertigob | 6 | 2 | 11 | 6 |

| Pulmonary: asthmab | 8 | 4 | 12 | 5 |

| Pulmonary: chronic obstructive airways diseaseb | 1 | 6 | 3 | 7 |

| Pulmonary: otherb | 1 | 1 | 10 | 9 |

| Pulmonary: tuberculosisb | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Renal disorders | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Tumour: benign | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Tumour: cancer | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Tumour: skin cancers | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Vascular: cerebrovascular | 1 | 4 | 10 | 6 |

| Vascular: hypercholesterolaemiab | 9 | 10 | 14 | 12 |

| Vascular: hypertension | 56 | 43 | 65 | 51 |

| Vascular: otherb | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Vascular: peripheral | 8 | 8 | 25 | 25 |

There were few differences between groups at baseline or at 5 years (see Table 11). As expected 5 years on, the number of coexisting diseases has increased. At 5 years, as at baseline, the largest frequencies are in the musculoskeletal category, particularly osteoarthritis. Hypertension is the next most frequently recorded in the corresponding questionnaires.

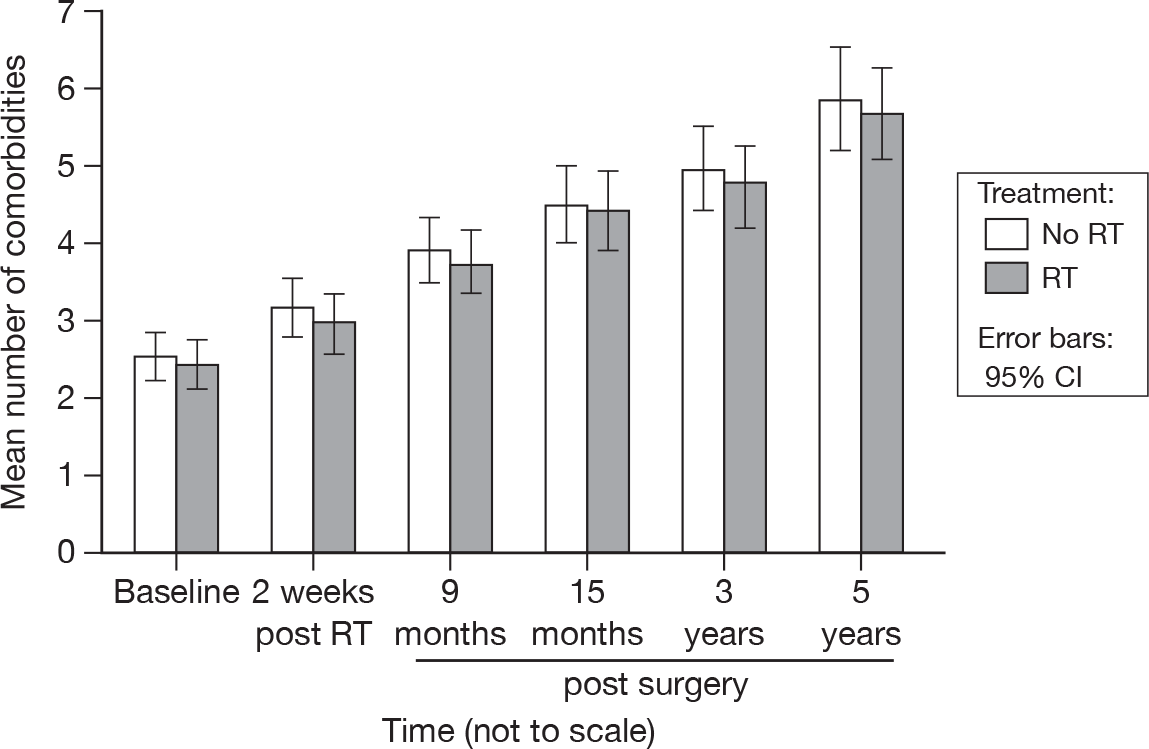

As can be seen in Figure 39, over the 5-year period the mean number of comorbidities rose from slightly more than 2 to just below 6 in both groups. The no RT group had a consistently higher mean number of comorbidities, but this was not statistically significant.

FIGURE 39.

Mean number of comorbidities reported by patients by questionnaire.

Chapter 7 Discussion

The rising proportion of older patients presenting with early breast cancer (now > 50%) in the UK presents an increasing health-care challenge for the NHS in the twenty-first century. With the expansion of the upper age limit of the UK breast screening programme to 69 years, increasing numbers of patients are being diagnosed with small tumours suitable for BCS and post-operative RT. Despite the importance of both quality of life to patients and costs of post-operative RT to the NHS, there remains a paucity of level I evidence examining these issues in patients aged 65 years and over.

We have previously reported the results for the first 15 months of follow-up in the PRIME trial, which evaluates the impact on quality of life and cost-effectiveness of the omission of post-operative WBRT after BCS. 21 In the initial report to the NHS HTA programme we found no overall difference in global quality of life between irradiated and non-irradiated patients using the EORTC quality of life modules. We did, however, find significant differences in some subscales.

The natural history of breast cancer is very long, such that follow-up is normally required for a minimum of 5 years to assess the impact of treatment interventions on outcomes. We recognised that follow-up to 15 months was too short and that longer-term follow-up was needed to determine if the differences in quality of life were maintained. We also acknowledged that local recurrences in either arm of the PRIME trial could have an impact on patients’ quality of life. In this update on the trial we highlight differences in the results compared with our initial report and, where relevant, results that have remained unchanged. Our aim is to complement and not duplicate our initial report.

Quality of life

Our finding that global quality of life is not significantly different between treatments at 3 and 5 years from surgery is in line with our findings at 15 months. This confirms that our observations are robust and durable. We are confident that our findings are real as the level of completion of questionnaires at 3 and 5 years was high (94.8% and 94.1%, respectively).

Changes in UK breast radiotherapy practice

Since our first report,21 mature results have been published of two randomised trials which have shown equivalent local control and cosmesis from the use of shorter (hypofractionated) courses of RT. 31,32 Although only 40% of patients were over the age of 60 years, the following trials may be pertinent to the application of the results of the PRIME trial. The START (Standardisation of Radiotherapy) breast trials tested the hypothesis that breast cancer may be sensitive to dose per fraction. The authors compared the international standard of 50 Gy in 25 fractions over 5 weeks with two shorter regimes (39 Gy in 13 fractions and 41.6 Gy in 13 fractions) in START trial A,31 and in START trial B32 the same control dose regime was compared with 40 Gy in 15 fractions over 3 weeks. No statistically significant difference between regimes was found in local control or cosmesis at 5 years of follow-up.

A Canadian trial33 randomised > 1200 patients with early breast cancer after BCS to a hypofractionated dose fractionation schedule of 42.5 Gy in 16 fractions or the same control as in the START trials (50 Gy in 25 fractions over 5 weeks). Mature data at 10 years of follow-up showed no difference in local control or cosmesis between the two arms of the trial.

Since the publication of these trials, there has been a substantial change in breast RT practice in the UK with the wider adoption of the hypofractionated dose fractionation regime of 40 Gy in 15 fractions after BCS, including in older patients, and some of these changes were seen during the period of recruitment to the PRIME trial from 1999 to 2004. The majority of patients in the PRIME trial were treated before the results of the UK START trial were published. However, within the PRIME trial, 21% of patients were treated with 40 Gy in 15 fractions, 52% with 45 Gy in 20 fractions and 3% with 50 Gy in 25 fractions over 5 weeks. Other regimes were 41.6 Gy in 13 fractions (7%) and 42.5 Gy in 20 fractions (6%). We specified in the protocol that eligible patients could be treated with 40–50 Gy in 15–25 daily fractions. This permissive approach reflected the diversity of dose and fractionation regimes used within participating centres before the trial began in 1999. We acknowledge that our data on quality of life and cost-effectiveness are generalisable only to dose and fractionation regimes used within the trial. The adoption of shorter dose fractionation regimes of RT could have a lower impact on quality of life than longer regimes used for some patients in the trial. We cannot estimate this impact. However, we do not think that it would have made a substantial difference as 21% of patients were treated with the shorter 40 Gy in 15 fractions regime within the trial.

Subscales of the European Organisation for Research in the Treatment of Cancer quality of life measures

Functionality

In the first report we observed no difference between treatment groups in the mean values of overall functionality (physical, role, emotional, cognitive and social functioning) at 15 months. 21 However, between 3 and 5 years there was a decline in the mean global scores of functioning. This is likely to reflect the impact of ageing on the older population under study. Given that no difference was seen at 15 months, and that there is no statistically significant difference in score between groups, we think it highly unlikely that the decline was in any way related to RT treatment.

Physical functioning

The decline from baseline continued beyond 15 months. Again we believe that this was due to the ageing process and was broadly in line with what would be expected over a period of 5 years in this age group. 34 There was no evidence of a treatment effect.

Emotional functioning

There was a small change in emotional functioning between 15 months and 5 years. However, the treatment effect was extremely small and we did not consider it to be clinically significant.

Cognitive functioning

Between 15 months and 5 years there was further decline in cognitive functioning. There was no evidence of a treatment effect and we believe that the pattern was related to the ageing process, again broadly similar to the reference data. 34

Fatigue

Fatigue is a well-recognised feature of post-operative WBRT. Its severity and intensity are highly variable. Some patients experience no fatigue after RT, while others experience prolonged fatigue over months and sometimes years. Its pathogenesis is unclear. For the first 15 months we found no evidence of a time, treatment or time by treatment effect. Beyond 15 months we observed significant differences in fatigue between questionnaires, although once adjusted for multiple testing these differences were no longer significant. The irradiated group had consistently, but not statistically significantly lower levels of fatigue. However, there was still no evidence of a treatment effect. The upwards trend in fatigue is again probably related to ageing and progressive acquisition of new comorbidities or exacerbation of existing ones.

Dyspnoea

Greater levels of dyspnoea were observed between 15 months and 5 years than before 15 months. Again there was no evidence of a treatment effect. Any late radiation-induced lung toxicity would have manifested itself by 15 months. This trend was likely to be due to new or existing comorbidities such as anaemia or cardiac or pulmonary disease.

Insomnia

One of the most intriguing findings in our original report was the higher level of insomnia in the non-irradiated group. This was statistically significant. It is noteworthy that this difference persists to 5 years even though the difference is less than at 15 months, although following adjustment with Bonferroni’s correction, this is no longer statistically significant. We speculated in our initial report that this might have been due to greater concern among non-irradiated patients that breast cancer might recur. As this difference disappears following adjustment, it is possible that this result is merely an artefact of multiple testing.

Financial difficulties

In our first report21 we observed no time-related difference in the reporting of financial difficulties. However, with longer-term follow-up, there was slight evidence of a time effect, although the size of the differences was very small, and not significant following adjustment. There remained no evidence of a treatment effect. The increase in financial difficulties might be related to greater costs of personal care as a result of acquisition of more comorbidities and the erosion of older patients’ financial resources with the passage of time. The findings are relevant to cancer support services such as Macmillan Cancer Support in estimating the additional financial support these older patients with breast cancer may require.

Arm symptoms

Despite no difference between the trial arms at 15 months, there is a suggestion of a time, but not treatment effect by 5 years (unadjusted only). We think that this is likely to be related to the acquisition of musculoskeletal comorbidities such as osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis with age (see Table 11).

Breast symptoms

The decline in breast symptoms in both arms of the trial seen at 15 months continues up to 5 years. This probably reflects the settling of breast symptoms seen after surgery. Sharp pains in the breast known to be related to surgery usually settle by 2 years after surgery. RT-related pain is also likely to have settled by 5 years in the majority of patients. A significant difference between the treatment options is still evident following adjustment for multiple testing.

Systemic therapy side effects

In our initial report21 we observed a significantly higher level of side effects of endocrine systemic therapy in the no RT group, although by 5 years this difference is no longer statistically significant. By the final questionnaire, 40% of patients had recently discontinued endocrine therapy, as per protocol. We speculated in the previous report that this might have been due to the greater attention given to irradiated patients in addressing these toxicities during review during RT, but this is not a reasonable explanation in the long term.

Most patients had been receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy for 5 years from the time of surgery. Some of the patients had changed endocrine therapy during the follow-up period, most commonly owing to intolerance of the first endocrine agent, which may be the reason for the lessening of the side effects over time.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

Anxiety

We did not observe any time or treatment effect in relation to anxiety up to 15 months. The same is true up to 5 years. There was a slightly lower level of anxiety among irradiated patients, although this was not statistically significant. We might speculate that this difference was due to higher degrees of anxiety about recurrence in non-irradiated patients. However, the population under study was at low risk of recurrence and this would have been explained to patients at entry to the trial. Levels of anxiety about recurrence even in the non-irradiated group may persist over time, but are likely to be modest. There was, however, no statistical evidence of a treatment effect.

Depression

At 15 months we observed a small time-related increase in depression in both arms of the trial. This trend continued up to 5 years, and was significant even following adjustment for multiple testing. There remained no evidence of a treatment effect. Other life events such as the acquisition of comorbidities and bereavement become increasingly common with advancing age and may in large part explain this continuing trend.

Radiotherapy-related morbidity

Breast oedema

There was a progressive decline in clinical reports of breast oedema in both irradiated and non-irradiated patients. At 5 years, < 5% of irradiated patients reported oedema scores > 1. These findings are compatible with the expected resolution of these symptoms between 3 and 5 years.

Breast fibrosis

Levels of breast fibrosis were predictably higher in the irradiated group up to 15 months. It is well recognised that breast fibrosis plateaus around 3 years after RT. 35 Our results show that between 15 months and 5 years, clinical reporting of breast fibrosis declined. This may reflect the stabilisation of this clinical feature.

Local recurrence and survival

Impact of local recurrence

In the first 5 years after randomisation, six patients (2.4% of the trial accrual of 255 patients) developed a local recurrence, all in the non-irradiated arm of the trial. Recurrence is likely to have an adverse affect on the quality of life of patients, particularly if they were randomised to RT, as a further course of RT is not possible and the surgical option is then mastectomy. However, the numbers of patients with local recurrence were very small and have not had any impact on the difference in quality of life of patients at 3 and 5 years after surgery.

In the low-risk group of patients included in the PRIME trial, it is likely that the annual risk of ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence will be about 0.5%, similar to that reported in the British Association of Surgical Oncology (BASO) trial. 36

Survival