Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the National Coordinating Centre for Research Methodology (NCCRM), and was formally transferred to the HTA programme in April 2007 under the newly established NIHR Methodology Panel. The HTA programme project number is 05/516/08. The contractual start date was in December 2007. The draft report began editorial review in June 2010 and was accepted for publication in September 2010. The commissioning brief was devised by the NCCRM who specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

The number of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of medicines for children is increasing as initiatives are put in place to improve access to medicines licensed for use in children. 1–3 Significant resources are invested in the design and set-up of these trials, yet experience shows that many children’s trials struggle to enrol and retain sufficient participants. This results in trials being delayed or abandoned4,5 or publishing with very small sample sizes. 6 Numerous studies have reported interventions to improve recruitment to adult trials. 7–9 However, ‘children are not small adults’10 and their recruitment involves greater complexity, such as gaining proxy consent from a parent or guardian. Therefore, we cannot extrapolate directly from research in adults. While difficulties in enrolling sufficient participants to clinical trials of medicines for children need to be addressed if improvements in treatment are to be realised, it is also important to ensure that recruitment is conducted in a way that is appropriate to families and practitioners and is ethically sound. Concern to ensure adequate accrual therefore needs to be balanced with the concern to ensure good conduct in recruitment to clinical trials and that prospective participants feel able to make informed and voluntary decisions. 11

Recruitment to trials of medicines for children involves three key groups: the young people themselves, their parents and the practitioners who are responsible for the trial. This chapter gives an overview of the existing research on the recruitment process as relevant to each of the groups before presenting the rationale and objectives of the current study.

Parents

Recruitment, information and understanding

By far the largest body of evidence on recruitment to children’s trials has been gathered from parents, and largely from paediatric oncology (specifically leukaemia) and neonatology. There is little work beyond these specialties. Research on parents is dominated by quantitative investigations of the recruitment process in terms of the information families receive and how much of that information they understand and recall. 12–15

Information can affect parents’ satisfaction and willingness to participate in a trial. 16–18 However, what constitutes the ‘right’ level and type of information is probably impossible to define,19 not least because information can simultaneously serve different functions20 and parents can vary in their preferences for trial information. 21,22 More information is not necessarily better: Miller and colleagues23 reported a trend for more information to be associated with greater parental anxiety and less control. While a baseline level of information may be necessary for informed consent and informed decline,24 research suggests that parents benefit from an approach in which practitioners select and tailor information according to individual need and preference. 23,25

Researchers consistently report that parents’ understanding of trials is poor. 26–28 Families whose first language is different from that used by practitioners, minority group members and those from disadvantaged backgrounds may experience particular difficulties. 27 It can also be a struggle for patients and families to separate discussions about treatment options and management from those about trial participation,29–31 particularly when faced with serious illness. 24,32 Based on a series of investigations of paediatric oncology trial discussions, followed by assessments of parents’ understanding, Simon and colleagues33 emphasised the need for a clearer distinction between trial-related issues and standard treatment issues, along with clearer explanations of randomisation, confirming findings from previous studies. 12

Interventions to improve understanding

When asked for feedback on how to improve informed consent discussions, parents of children with leukaemia who were approached about trial entry advocated a sequenced or staged approach to informed consent,21,34 including scheduling discussion of the trial after patients have achieved a basic understanding of the disease and treatment. An intervention based on this feedback, and on studies stressing the importance of encouraging parental participation,12,23,33 was used to train practitioners in communication techniques, such as simplifying information, prompting parents’ interactions and encouraging them to ask questions. 35 The training was evaluated using researcher-assessed measures of parental understanding. Improvements were found in parents’ understanding of the voluntary nature of the trial but not in their understanding of randomisation. Parents found nurse–family research education sessions helpful to prepare them for the trial discussion with their doctor, and felt that the sessions helped them ask questions and understand the information provided by the doctor. 36

Qualitative work on the recruitment of adults into trials has also indicated that patients find trials hard to understand; concepts such as voluntariness, equipoise and randomisation can be particularly difficult for patients to grasp. 37–39 These studies further indicated that a failure to understand these concepts can result in patients becoming distrustful of the trial or the doctor, and simple interventions to provide more or ‘better’ information may not always be sufficient to ameliorate these difficulties. 37–39 Adaptations to the practitioners’ communication, such as changing the way in which the trial arms were presented to emphasise their equivalence, increased the perceived acceptability of a trial to patients39 and its randomisation rate. 7 Wade and colleagues40 reported that styles of consultation that were participant led rather than practitioner led, and which involved practitioners using open questions, pauses and ‘ceding the floor’, enabled participants to express their concerns more easily.

The context and experience of trial recruitment

While these adaptations to practitioner presentation and communication about trials may be transferable to the paediatric context, parents considering trial entry for their child have a very different role from the adult considering trial entry for him or herself. 41 Parents are responsible for their child and are entrusted to act in the child’s best interests, a difficult and complex position when trials, by their nature, cannot promise to act in the best interests of the individual child. 42–44 Consent can often be sought soon after diagnosis, at birth or when the child is very ill and the parents are distressed and vulnerable. 30,45,46 Despite such challenges, parents have reported that they, rather than doctors or nurses, should be the ones who make the decision about whether a child should enter a trial,15,32,43,47,48 although parents value doctors’ advice. 49 Making a decision for one’s child is further complicated by the need to make the ‘right decision’ and the anticipation that one might later regret a decision. 31,50,51

The generally high rates of recruitment to trials in neonatology52 and childhood cancer53 suggest that the threat of a child’s illness and parents’ consequent need for hope could be important influences on how parents view trials. Parents of chronically ill children may, in general, be prepared to take greater risks in treatment in the hope of helping their child42 than the parents of healthy children considering participation in vaccine research, who have been found to believe that children should take part in research only when the medical benefits outweigh any potential risk. 54

Influences on parents’ decision to enter their child into a trial

Most studies on the reasons why parents choose whether or not to enter their child in a trial have used questionnaire and survey methods. Particularly common worries for parents when considering a trial are that their child might be randomised to the treatment arm that they perceive to be less effective50,55 and the responsibility that they would feel if the child later deteriorated. 56 Nevertheless, parents do perceive several benefits of trial participation for their own child, such as receiving extra medical attention. 57–60 Such benefits can be influential in their decision. However, evidence indicates that parents’ primary concern when considering a trial is their child’s safety61 and to protect their child from harm. 43 Altruism, although frequently cited by parents as a motivation for participation in trials,49,62,63 may be a secondary consideration in their decision. 26,45,64

The seriousness of the child’s condition and the urgency surrounding trial entry and parents’ resulting sense of vulnerability have also been found to be important influences on how parents experience recruitment to trials. 31,32,55,65 However, the relationship between anxiety, vulnerability and trial decisions may be mediated or moderated by factors such as trust in medical research66 and the parent–practitioner relationship. 23,56,67–70 The practicalities of trial participation are less commonly mentioned;71 this may reflect the fact that most studies have been conducted in neonatology and oncology, when the child is usually in hospital at the time of the trial approach.

Summary

A relatively large body of work has been conducted on parents and trial recruitment within oncology and neonatology; however, other areas have been largely overlooked, including trials in other specialties and studies investigating the experiences of parents who decline trials. The quantitative nature of much of the existing literature reflects the priorities of researchers and presupposes what is important to parents when they are approached about a trial. 72 In adult clinical trials, the information content of the trial discussion and the patient ratings of the interpersonal aspects of communication, such as a belief that the doctor listened to them, has been found to influence the trial decision and the patient’s confidence in that decision. 73 With a few notable exceptions, little research has addressed how the trial approach is experienced by parents in a way that allows them to define what they consider meaningful and important during this process. 21,30,55,74 Finally, no studies have compared parents’ experience of trial recruitment with the actual content of the trial discussion.

Young people

Young people’s experiences of trial recruitment cannot be considered in isolation from their parents’; it is usually necessary to obtain parental consent, which ultimately guarantees that the parent will be involved in the discussion and decision. However, although parents give consent on behalf of their children, when young people are old enough to have an opinion then their assent to trial entry should be sought. 75,76 This means that when a parent’s and young person’s wishes differ, they must discuss the decision. While interventions to improve parental understanding of trials have been reported,35,36 we are not aware of any studies investigating interventions to promote young people’s understanding of research.

Young people’s understanding of research

Like their parents, young people may struggle to understand trials. 77–79 The voluntary nature of research and the right to withdraw were understood by young people in some studies78,80 but not in others. 81 In their study of young people with cancer or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Chappuy and colleagues81 link this difference to the young people’s lack of information and understanding of their life-threatening condition and proximity to diagnosis. Like parents, young people may find it difficult to distinguish between their treatment and research,82 and this may be particularly true in the cancer setting, where the two are particularly entwined. One study reported that young people with diabetes were much better able to differentiate between the research they were involved in and their treatment regimen than those with cancer,82 whereas one-half of the young people participating in one oncology research project did not know that their treatment was part of a clinical research study. 83

Young people’s reasons for participation in research

Like the available studies in parents, most studies on the reasons why young people choose whether or not to participate in research has been conducted using questionnaire and survey methods. Personal benefit is the most popular reason cited by young people consenting to an actual or hypothetical trial; the desire to help others is significantly less influential in young people’s decisions than perception of personal benefit,84–86 as it also is for their parents,87 although occasionally young people cite benefit to others as more important than personal benefit. 88,89 Young people give a number of reasons for declining a trial, including worries about blood or urine samples or the doctor’s examination,89 extra clinic visits,90 belief that the trial will take up too much time,88 belief that the ‘research methods are too involved or too burdensome’ and lack of interest in the research topic. 91 Refusal rates have been found to be higher in studies that include blood sampling, and higher in boys than in girls. 91

Young people’s role in the trial discussion

Discussions about young people’s participation in a trial entail more complex dynamics than is usually typical of adult trial recruitment. 92,93 Compared with adult trials, such dynamics are likely to present additional challenge to paediatric trial recruiters in managing the consultation and balancing the involvement of each party. 94 However, studies of health-care consultations, in general, report that young people often play little active part. 95,96 While few studies have investigated their role in discussions about trial entry, Olechnowicz and colleagues94 reported that young people recently diagnosed with cancer said very little in the trial discussion. There was considerable variability in the extent to which practitioners directed the discussion towards the patient. Older patients spoke more than younger ones, largely because they asked more questions, but few of their questions were about the trial.

Young people’s role in the trial decision

The role of young people in the decision about trial entry is complex. Some researchers have argued that while young people’s dissent should be respected, they are not in a position to make a decision on trial entry without significant guidance from their parents,97,98 and that, while it is important that they are consulted, they should be protected from decisions that they are unwilling, or unable, to make. 99 A key complexity in considering research in this area is that much of it has investigated young people’s decision-making about entry into hypothetical trials or non-therapeutic clinical research,87,100–105 rather than focusing on young people who have been approached about a ‘real’ clinical trial. Moreover, some research in this area has been conducted with samples of healthy children, rather than children who have recent experience of illness. Because of the uncertainties in interpreting the relevance of such research, we have limited our discussion of it in this section; we draw on it only where other evidence is unavailable.

Young people approached for assent to clinical anaesthesia and surgery research80 or to clinical trials of treatments for cancer or HIV81 are strongly influenced by their parents when making a decision on trial entry. This probably stems from young people’s reliance on their parents to guide and protect them, and from both parties’ concern to make the ‘right’ decision. 92 Sometimes, parents encourage or persuade children to take part in research if they think it is in their child’s best interests. 57,85

The potential for tension between young people and parents regarding decisions about research participation, and the difficulty for practitioners in balancing their needs, is highlighted by several studies. A survey of 7- to 14-year-olds who were enrolled in clinical research or receiving clinical care for cancer or asthma reported that approximately 90% of young people felt that they should be involved in decisions, whereas only approximately 60% of parents agreed. 84 Just over 40% of parents were against or unsure about whether children should have decisional authority over participation in non-therapeutic clinical research,100 while nearly 70% of parents responding to a hypothetical research scenario said that they would impose their own views on research participation regardless of their child’s wishes. 102

Particularly where the child has a life-threatening illness, some parents report excluding the child from the decisions about research altogether in order to protect them from distressing information, or including their child in discussions but making the trial decision themselves. 94,106 In a departure from much of the decision-making literature, which has largely focused on young people in hypothetical research scenarios, Unguru83 presented the views of young people in relation to the cancer research in which they were participating. Many young people in Unguru’s study felt minimally involved in decision-making. They had wanted to be involved but did not want to make the decision on their own – rather they wanted to decide jointly with their parents and doctors. By contrast, some healthy young people102,104 and those with a chronic condition (asthma, diabetes or epilepsy) responding to hypothetical research scenarios want the ultimate decision to be theirs, although other research has indicated that some young people feel that their parents ‘know best’ and take the view that if their parents did not want them to participate then they would not do so. 105

Among the challenges for triallists when considering the young person’s role in decision-making are the conflicting legislative frameworks governing consent for research versus those governing consent for treatment. While legislation governing consent to treatment recognises young people’s agency and autonomy,107 Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations give power of legal consent to parents. The wishes of under-16-year-olds are ‘considered’ but they do not have legal force in the context of clinical trials of medicines. 76 Interestingly, evidence provides some support for this legislation. Young people are more willing to take part in above-minimal-risk hypothetical studies than their parents,87 and adolescents are particularly more likely to ‘consent’ than parents. 87 If they are less risk averse than their parents in actual clinical trials, parental consent may serve a valuable function in helping to protect young people from accepting inappropriate research risks. 105 Where family decisions are initially discordant about hypothetical research scenarios, the final decision usually reflects the parents’ opinions, although the young people are less happy with the final family decision as a result. 101

Summary

Considered alongside the legislative frameworks governing consent for children’s trials,108,109 data on hypothetical scenarios and non-therapeutic clinical research can alert us to some important considerations. However, as we outline above, the applicability of these findings to families of seriously ill children approached about a real clinical trial is questionable. Moreover, the survey nature of much research on young people means that, like the literature on parents, it assumes rather than explores what is important to young people when they are invited to join a clinical trial.

Practitioners

Research involving practitioners has focused in two key areas: their role as information givers in trial discussions and their views on barriers to trial recruitment. Rarely have studies asked practitioners about their own priorities for, and experiences of, discussing trials with families.

Practitioners’ communication in the trial discussion

Clinical trials have a long and successful history in paediatric oncology. It is no surprise then that almost all research on practitioners’ communication about clinical trials has been conducted in this area. In an early survey of clinicians’ practice and parents’ opinion, practitioners noted the need for a flexible and adaptable approach to accommodate families’ individual needs, but they also sometimes noted a conflict between the need to start treatment and the ‘deliberate pace necessary for an optimal consent’. 46 However, practitioners’ concerns about informed consent were not shared by parents, who were generally more satisfied with the consent process than practitioners, 50% of whom felt that families were given too much information. 46 These disparities between parents and practitioners are important. However, the brief survey data gathered from this and similar studies limit interpretation. In response to an open-ended question in another survey, one-quarter of practitioners’ suggestions for improving the informed consent process related to simplifying information for parents, while suggestions for improving the timing and staging of the discussions were a close second. 110

Barriers to recruitment

A relatively large body of work has investigated so-called barriers to recruiting adults and children to clinical research. Evidence from adult trial recruitment suggests that, when offered a trial, most patients accept,73 and some paediatric practitioners described selectively approaching those families who they thought most likely to consent. 111 Non-invitation of eligible participants is therefore likely to contribute to trial recruitment difficulties in trials in all specialties. In paediatric trials, where the pool of eligible participants may already be relatively small,111 this source of recruitment difficulty is an important concern.

Many studies in adult care settings cite practitioners’ time constraints as one of the most common barriers to recruitment or involvement in research at all. 112–115 However, based on a study of general practitioners (GPs) who declined to facilitate an adult trial, Salmon and colleagues112 pointed out that such justifications may be markers of the low priority that practitioners give to research and the perception that research has limited relevance to their clinical work. Other evidence on practitioners’ reasons for not approaching patients about research has indicated that practitioners do not recruit to studies because they see their patients as vulnerable,113 in need of protection;116 have concerns about the impact of research on the doctor–patient relationship,113,117 which may be a particular difficulty in community-based trials;52 or have strongly held preferences for one treatment over another118 and perceive other ethical difficulties. 115

Practitioners also cite time constraints as a barrier to recruitment in paediatric trials. 119 They are also concerned about the impact of research on the doctor–patient relationship,119,120 the use of placebo and randomisation,111,119 the practical burden of participation for families,111 potential harms to participants and unpleasant procedures, such as venepuncture. 111,119 Some practitioners describe an allegiance to the patient, which they regard as being in conflict with the uncertainty inherent in trials,120 and believe that families are liable to be confused by, or mistrust, trials. 119

Particular barriers exist in paediatric research in critical care settings where parents may be unavailable for consent or be so emotionally distraught as to make an approach about research untenable. 121 In a personal account of avoiding approaching vulnerable families, Walterspiel122 described the ‘emotional burden’ of obtaining informed consent under such circumstances. Particularly in critical situations, as is often the case in neonatal trials, practitioners express concern about parents’ competence to give informed consent because of their vulnerable position and emotional state, as well as their lack of knowledge and time to decide. 32

Practitioners may also have concerns over their own skill and confidence in approaching patients. 113 While some practitioners regard trials more positively, for example as a chance to offer their patients potentially effective therapies at an early stage,115 a prominent feature of much of the research on practitioners is the negative way in which they construct trials and oppose the interests of trials and the interests of the doctor–patient relationship. One study123 reported that a significant proportion of clinicians in adult cancer care rated seeking consent to clinical trials as their main communication problem – ranking it as more difficult than breaking news of serious illness to patients. In one focus group study, some paediatricians described how they disliked approaching parents and felt ‘rejected’ if parents said ‘no’ to a trial, while others described discomfort at expressing uncertainty because they were concerned it might damage parents’ trust in their expertise. 119

Summary

Recruiting to children’s trials brings additional complexities compared with recruiting adults to trials, which probably affects the practitioner’s experience of recruitment. Paediatric trials also confer specific potential risks – such as patient discomfort, pain and fear of separation from parents or familiar surroundings – that are either absent in adult trials or harder to assess in paediatric settings. 124 Much of the research on practitioners in both adult and paediatric settings indicates that they construct trials in rather negative ways, but evidence directly comparing practitioners’ and parents’ constructions of the same trials is limited.

Rationale and objectives

While there are strands of evidence relevant to the three different stakeholder groups – young people, parents and practitioners – involved in recruitment to trials, much of this has been collected in a way that assumes rather than explores what is important to the groups. None of the evidence has been collected in a way that directly compares the perspectives of the three groups, which means that it is impossible to identify where their perspectives converge and diverge and to use this to inform clinical trial recruitment. Also missing from the existing literature are studies that have linked the experience of trial recruitment to the actual conduct of trial discussions. This is an important omission because we cannot assume that the ‘look’ of trial recruitment consultations, from the viewpoint of third-party researchers, is the same as the ‘feel’ of these consultations from the viewpoint of those involved. Finally, much of the existing evidence comes from neonatology and paediatric oncology trials, or from hypothetical trials or non-therapeutic clinical studies. It is important to extend the evidence base to families who have been approached about ‘real’ clinical trials across a range of different specialties and to include the perspectives of those who decline as well as those who consent. Existing interventions to improve recruitment and its conduct in children’s trials have generated some promising findings,35,36 although these are in the early stages of development. This study is therefore important to provide a comprehensive investigation of the processes of recruitment, with the aim of identifying strategies to improve recruitment and its conduct that can be applied across the spectrum of trials of medicines for children.

As stated in the original protocol, the data for our study were (1) trial recruitment discussions between families and trial recruiters; (2) follow-up semi-structured interviews with families (young people and parents); and (3) follow-up semi-structured interviews with practitioners. Our specific objectives were to describe:

-

how recruitment consultations (trial discussions) between families and trial recruiters (practitioners) are conducted and how information about trials is exchanged during these encounters

-

from the perspective of families, the experience of trial recruitment and the communication needs and other priorities that are served or thwarted by recruitment consultations

-

from the perspective of trial recruiters, the goals of recruitment consultations, the functions of these goals, how they interface with the conduct of the consultation, and families’ communication needs and other priorities.

In the next chapter we describe the study methods, and, in keeping with recommendations in qualitative research,125 how these evolved over the course of the study.

Chapter 2 Methods

Sampling of trials and sites

RECRUIT [processes in recruitment to randomised controlled trials of medicines for children] ran alongside four placebo-controlled, double-blind RCTs of medicines for children. All trials were National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) – Medicines for Children Research Network (MCRN) portfolio trials and were selected to represent different conditions, disease status and trial design to maximise the transferability of findings. The trials also differed in the timing and circumstances of the approach for recruitment and in the relationship between family and the practitioners responsible for recruitment. Where circumstances allowed, we selected sites in the north-west of England in preference to other regions for logistical reasons, but where north-west sites were unavailable we included sites in other regions. Two or three teams from each trial facilitated RECRUIT. MCRN local research networks (LRNs) helped to facilitate the research and development (R&D) process and assisted in liaison with the trial teams. Brief details of the four participating trials are given in Table 1 and further outlined below.

| Trial title | Age range | Disease status | Medicine delivery |

|---|---|---|---|

| MASCOT | 6–15 years | Chronic | Inhaled and oral |

| MENDS | 3–15 years | Chronic | Oral |

| POP | 4–18 years | Chronic | Oral |

| TIPIT | Infants born < 28 weeks’ gestation | Acute | i.v. |

MASCOT – Management of Asthma in School-aged Children On Therapy

-

This was an RCT comparing the add-on treatments salmeterol (long-acting β2-agonist) and montelukast (leukotriene receptor antagonist) for young people whose asthma was poorly controlled with fluticasone (low-dose inhaled corticosteroid).

-

The initial approach about the trial was usually via a letter from the GP (interested families returned a slip to the trial team) or a personal approach when the child was attending a secondary care centre. Interested families received participant information leaflets (PILs) and a telephone call from a research nurse before attending an appointment with a respiratory consultant and research nurse, specifically arranged to discuss trial entry.

-

The parent PIL was 12 pages long (approximately 5500 words), excluding consent forms.

-

Prior to randomisation, there was a 4-week run-in period, during which families were provided with information about asthma and its management. All young people were prescribed the same low-dose inhaled corticosteroid (fluticasone), which was continued throughout the trial period. Families also completed an asthma diary throughout the trial period. Young people whose asthma control had not improved after the run-in phase were randomised to one of the three treatment arms. There was a 48-week treatment period. Including the screening and baseline assessments, families made five clinic visits and received one telephone call. There was a genetic substudy for which consent was taken separately after the run-in phase.

-

At the time this report was prepared, 772 patients had been assessed for eligibility, 151 had registered for the trial, 54 had declined the trial, and 567 were ineligible or excluded for other reasons.

MENDS – the use of MElatonin in children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders and impaired Sleep

-

This was an RCT of melatonin in young people with neurodevelopmental disorders and impaired sleep.

-

The initial approach about the trial was usually made by community paediatricians at a routine clinic visit. Interested parents received PILs from their community paediatrician or by post, and had a telephone conversation with a research nurse before attending an appointment with a consultant neurologist and research nurse, specifically arranged to discuss trial entry.

-

The parent PIL was 11 pages long (approximately 5500 words), excluding consent forms. Melatonin was not licensed in the UK for children at the time the trial was conducted, and this was stated in the parent PIL.

-

Prior to randomisation there was a 4-week behavioural intervention using established techniques to reduce the child’s sleeping problems. During the trial parents completed a sleep diary every day and the child wore an ActiGraph (Ambulatory Monitoring Inc., Ardsley, NY, USA; www.ambulatory-monitoring.com) watch to record movement. Saliva samples were collected before randomisation and towards the end of the treatment phase to measure melatonin levels. There was a 12-week treatment period. Families made three additional hospital visits, and received four home visits by the research nurse and three telephone calls. There was a genetic substudy for which separate consent was taken.

-

At the time this report was prepared, 241 patients had registered for the trial. A further 147 had not proceeded to registration because of an inappropriate referral, or ineligibility at screening or because the family was not contactable; 170 had refused screening.

POP – Prevention and treatment of steroid-induced OsteoPenia in children and adolescents with rheumatic diseases

-

This was an RCT to establish if the bisphosphonate risedronate or the vitamin D analogue 1-alphahydroxycholecalciferol was better than placebo in preventing/reducing bone loss in young people (aged 4–18 years) with rheumatic diseases who were treated with corticosteroids.

-

Usually the trial was briefly introduced to families by a doctor from the rheumatology clinical team. The trial design allowed considerable flexibility so practitioners could select an appropriate time to approach the family. After the initial introduction, a more formal discussion would be arranged to coincide with a routine hospital appointment with the rheumatology team. Research nurses and doctors had trial discussions with families, although only doctors took consent.

-

The parent PIL was 6.5 pages long (approximately 3500 words), excluding the consent forms.

-

There was no run-in phase and the treatment phase lasted for 1 year. All groups received calcium and vitamin D supplementation daily. Young people were seen seven times over the course of the year. However, this was timed to coincide with routine clinic visits where possible. Blood samples were also taken, but at the same time as routine visits and tests. Young people gave regular urine samples and had three DEXA (dual-emission X-ray absorptiometry) scans and two bone radiographs taken as part of the trial. There was a genetic substudy that was discussed at the time of consent; young people could participate in the main trial without consenting to the storage of their genetic material.

-

At the time this report was prepared, 318 patients had been screened for the study, 132 had been recruited, 63 had declined the trial, 60 were potential future participants, 42 were ineligible and 41 did not take part for another or unstated reason.

TIPIT – Thyroxine In Preterm Infants Trial

An RCT of thyroxine in preterm infants under 28 weeks’ gestation.

-

As the trial name indicates, this was a trial of thyroid hormone supplementation in babies born before 28 weeks’ gestation. The primary outcome related to brain growth.

-

Necessarily, the initial trial discussion was often conducted either on the neonatal unit or at the mother’s bedside and with a practitioner unknown to the parents. A research nurse was not usually present during these discussions.

-

The PIL was three pages long (approximately 1700 words), excluding the consent forms.

-

Trial medication commenced within 5 days of birth and was given every day, through intravenous or feeding tube, until the baby was 32 weeks old, with follow-up until the baby went home. The mother had a single blood test and bloods were taken at several points from the baby alongside those for routine care (no bloods were taken from the baby specifically for the trial). There was a brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study for which there was a separate consent, taken at a later date.

-

The trial closed to recruitment in 2009 when target accrual was reached. In total, 153 babies took part in the trial (20 twin pairs) and the parents of 210 babies were approached for the trial.

Procedure for recorded trial discussions

Practitioners facilitating RECRUIT sought permission to audio-record the trial recruitment discussions from families whom they approached for their trials. Families often had more than one discussion about the trial but only one was recorded. If permission was declined, the audio-recorder was not activated and the trial discussion progressed as normal. If permission was given, the practitioner activated a digital recorder. The practitioner briefly described RECRUIT, gave parents and young people the RECRUIT PIL and asked the family for permission to pass their contact details to the RECRUIT team. A member of the RECRUIT team subsequently discussed the study in full with the family and sought their consent to participate, explaining RECRUIT’s independence from the trial and clinical team. Audio-recordings of the trial discussions were released to the RECRUIT team only after the written consent of participants had been obtained. If the family declined RECRUIT, the recorded trial discussion was erased. Where families were approached without a recorded trial discussion, the practitioner described the RECRUIT study and asked for permission to pass the family’s contact details to the RECRUIT team.

Procedure for interviews

Parents

We asked parents to describe the trial discussions from their perspective, how they felt about the encounter, the recruiter, the written and verbal information exchanged, whether there was anything that was unclear or surprising about this information, and whether anything might have been handled differently. Each interview was informed by the interviewers’ detailed knowledge of the features of the particular trial concerned. The interviewers used this knowledge to develop specific prompts about, for example, what the trial involved for families such as hospital visits, or about the trial run-in period.

Parents were also prompted about (1) other (unrecorded) experiences of family–practitioner discussions about the trial; (2) their broader views on clinical research involving children; (3) their prior knowledge and experience of such research; (4) how they saw trial participation in the context of the child’s illness and future well-being and their relationships with health professionals; and (5) how trial decision-making was negotiated within the family. We consulted with the RECRUIT steering group, which included two parent representatives, on the content of the parent and practitioner prompt guides. We also consulted with the study steering group and MCRN young persons’ advisory group on the prompt guides for young people.

Young people

Where possible we interviewed parents and young people separately. This was to avoid the difficulties of interpreting individual experiences from data collected at joint interviews, which may be particularly difficult in the case of young people interviewed in the presence of their parents.

Individual interviews with young people followed the same topics as those with their parents, although the number and complexity of prompts was greatly reduced, particularly for younger participants (7–10 years). We explored young people’s feelings about particular aspects of the trial and the extent to which they felt involved and able to influence trial decision-making.

Prior to the interviews, we usually consulted with parents about how best to approach interviewing their child and to select a time for the interview that would be convenient for the young person. Where possible we met with the young person some days before the interview so that we were not complete strangers to them by the time the interviews took place. On the day of the interviews we spent some time building rapport with the young person before starting the interview and we used various activities to conduct the interviews in a developmentally appropriate and child-friendly way. With younger children we sometimes used a ‘spidergram’ to find out about their likes and dislikes prior to starting the interview. Here the young person is shown a picture of a ‘friendly’ spider’s body and together with the interviewer they suggest four likes and four dislikes, making up the spider’s legs. To demystify and allay any potential fears that younger participants might have had about the audio-recording we encouraged them to listen to a short sample recording that was made during the warm-up questions if they wanted to, and help to switch on and off the digital recorder.

Interviews with older children and adolescents were very similar in style to the parent interviews and, where appropriate, followed the same prompt guide or one that was slightly simplified. However, with younger members, if they chose to, we introduced picture cards so as to vary the question-and-answer format; this also provided a shared reference point for the young person and the interviewer and avoided the young person potentially feeling ‘in the spotlight’ by an exclusive focus on him or herself. Each card had a familiar picture on one side, and a question on the other. These were spread on the floor and the interviewer asked the young person to find the card with a certain picture on it. Depending on the individual’s preference and reading ability, the young person or the researcher would ask the question out loud. The researcher then used additional prompts to explore the topic further. When the topic was finished, the young person could choose a sticker to place on the card to mark it as complete.

Irrespective of their age or developmental level, for all of the young people we took particular care to emphasise that:

-

their responses to the questions would not get anyone into trouble

-

there were no right or wrong answers and we were interested in their thoughts and feelings.

Practitioners

Interviews with practitioners followed a similar course to the parent interviews, but we steered these using a separate topic guide. We prompted practitioners to (1) contrast their experiences of this trial discussion with their experiences of other trial discussions [although, as we describe later (see Other clarifications and changes to the methodology), this was often not possible]; (2) describe their experiences of families who declined and those who agreed to trials; (3) describe what information children and parents required to inform their decision-making, and their experiences of managing the involvement of each party; (4) describe how they responded to the needs and requirements of families; (5) describe their experiences of deciding which families to approach, including their accounts of deciding not to approach eligible families; and, finally, (6) compare their role in approaching families about trials with other aspects of their role as clinical practitioners or researchers.

General interview and transcription procedure

The pace, sequencing and duration of all the interviews were shaped by the participants. All participants were given the opportunity to ask questions before and after their interviews. We audio-recorded and then transcribed all of the interviews, reviewed the transcripts for accuracy and pseudoanonymised them. Transcription was verbatim, recording all words spoken, as well as hesitation and overlapping speech; for the recorded trial discussions we also recorded markers of disfluency. We continually reviewed the transcripts from trial discussions and interviews, as the study was ongoing, to develop the prompt guides and thereby ground and inform subsequent interviews. VS and ES conducted all of the interviews and kept reflexive notes to record systematically the contextual details of the interviews and to inform the analysis.

Analysis

Analysis was interpretative, followed the general principles of the constant comparative method126,127 and was informed by several procedural steps to ensure its quality. 128–131 VS led a process of ‘cycling’ between the developing analysis and new data in consultation with BY. The complete team developed and tested the analysis by periodic discussion, based on detailed reports of the analysis containing extensive data extracts.

Initially, a member of the team read each transcript several times before developing open codes to describe each relevant unit of meaning. VS usually did this, although ES and BY also contributed. Broadly, interview transcripts were analysed for evidence of the families’ experiences, needs and priorities when approached about a trial, with reference to their different trajectories in relation to the trials; for practitioners we analysed for evidence about their goals in discussing the trials with families and how they responded to families’ cues. Through comparison within and across the whole transcripts, VS, ES and BY developed the open codes into theoretical categories and subcategories to reflect and test the developing analysis. VS organised the categories into a framework to code and index the transcripts using nvivo software (QSR International, Doncaster, VIC, Australia), and VS, ES and BY continually checked and modified the framework categories to ensure an adequate ‘fit’ with the data in relation to the interview as a whole, as well as the proximal content, while also accounting for deviant cases. A second member of the project team checked the categories and the assignment of data to them. A record was kept of the analysis process, including definitions of the categories and their application.

We initially focused on participants’ expressed accounts whether in trial discussions or interviews. However, as the study progressed, we interpreted the accounts to theorise beyond what participants made explicit, for example we considered participants’ overall stance in their interviews and what they chose not to focus on in their responses as well as what they did focus upon.

We linked transcripts from trial discussions and interviews to compare our observations of exchanges during trial discussions, with families’ interpretations and experiences of these exchanges. Thereby we compared the ‘look’ and ‘feel’ of the trial discussions. In this way, we also identified discrepancies between interpretations and observations to inform our analysis of how communication could go awry and lead to misunderstandings. We produced summaries of the verbal interactions during the trial discussion to capture the ‘look’ of these in terms of parents’ and young people’s spoken interactivity. We calculated the proportion of speech and number of questions asked by parents and young people as indicators of their ‘observed’ level of interactivity, and recorded the frequency of practitioners’ use of open and closed questions. We particularly focused on practitioners’ invitations to elicit parents’ thoughts and questions about the trial and explore their understanding.

In the following results chapters, extracts from parents’ interviews and trial discussions are followed by identification codes beginning ‘F’, those from practitioners beginning ‘P’. Where extracts from trial discussions are included this is indicated in the text and the parent’s identification code beginning ‘F’ is used. When the extract is from a young person, the codes identify their age as 8–10 years, 11–14 years or 15–16 years. For all extracts, square brackets containing three dots […] indicate short sections of omitted speech; square brackets containing text indicate explanation added during transcribing or analysis, usually to replace a name; double parentheses signify expressions such as laughter. While original transcription recorded hesitation, overlapping speech and disfluency, for ease of reading we edited out most of these markers from the excerpts that we present in Chapters 3 and 4.

Sampling of trial discussions, families and practitioners and participant characteristics

Trial discussions

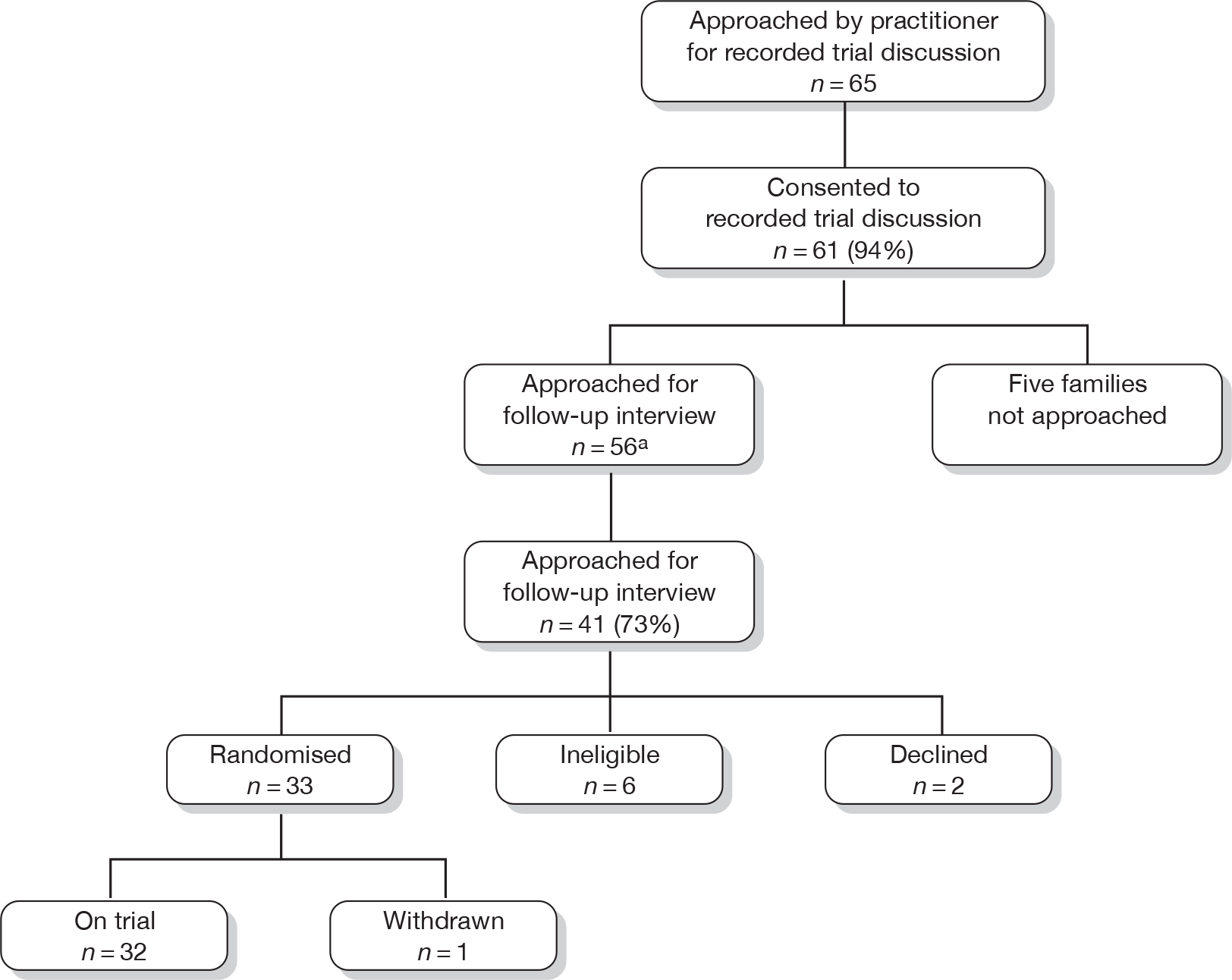

In order to link trial discussions and interviews, the sample of families interviewed largely comprised those for whom recorded trial discussions were available. However, during the course of the study we also included families for whom there was no recorded trial discussion but who had potentially informative experiences of recruitment. The recruitment of families is summarised in Figure 1, which shows the numbers of families with and without recorded trial discussions.

FIGURE 1.

(a) Recruitment of families with recorded trial discussion to RECRUIT, showing families’ trajectory in relation to the trials. a, Five families with recorded discussions from TIPIT were not approached for interview. Two had transferred to another hospital before they could be approached. Three babies had died; the RECRUIT steering group advised the team not to approach bereaved parents. (b) Recruitment of families without recorded trial discussion to RECRUIT, showing families’ trajectory in relation to the trials.

Families

We interviewed 84 members of 60 families: 58 mothers, 4 fathers and 22 young people. Figure 1 illustrates the recruitment process, recruitment rates and families’ trajectories in relation to the trials, i.e. those who consented to the trial, declined, were ineligible or withdrew. Table 2 shows family demographics and trial participation status for each of the four trials. Each trial had an initial target to enrol 15 families in RECRUIT. The MENDS trial reached this target in January 2009 and from that point we purposively sampled only those families who declined MENDS, as decliners were under-represented in the wider RECRUIT sample. Families who declined MENDS did so before attending a clinic appointment and, as such, no recorded trial discussions were available for them.

| MASCOT | MENDS | POP | TIPIT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (% of total 60) | 10 (17) | 22 (37) | 16 (26) | 12 (20) |

| n | ||||

| Randomised | 5 | 9 | 13 | 11 |

| Declined | 1 | 8 | 0 | 1 |

| Ineligible at consent | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Ineligible after run-in | 3 | 3 | NA | NA |

| Withdrawn | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Median (range) age of child (years) | 10 (8–14) | 7 (4–13) | 13 (4–16) | – |

| n (%) not self-identified as white British | 0 | 2 (9) | 1 (6) | 6 (50) |

| n (%) Index of Multiple Deprivation132 quintile | ||||

| Lowest | 5 (50) | 15 (68) | 2 (13) | 9 (75) |

| Highest | 2 (20) | 1 (5) | 2 (13) | 0 |

| Doctorsa | 2 | 4 | 3 | 5 |

| Research nurses | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1 |

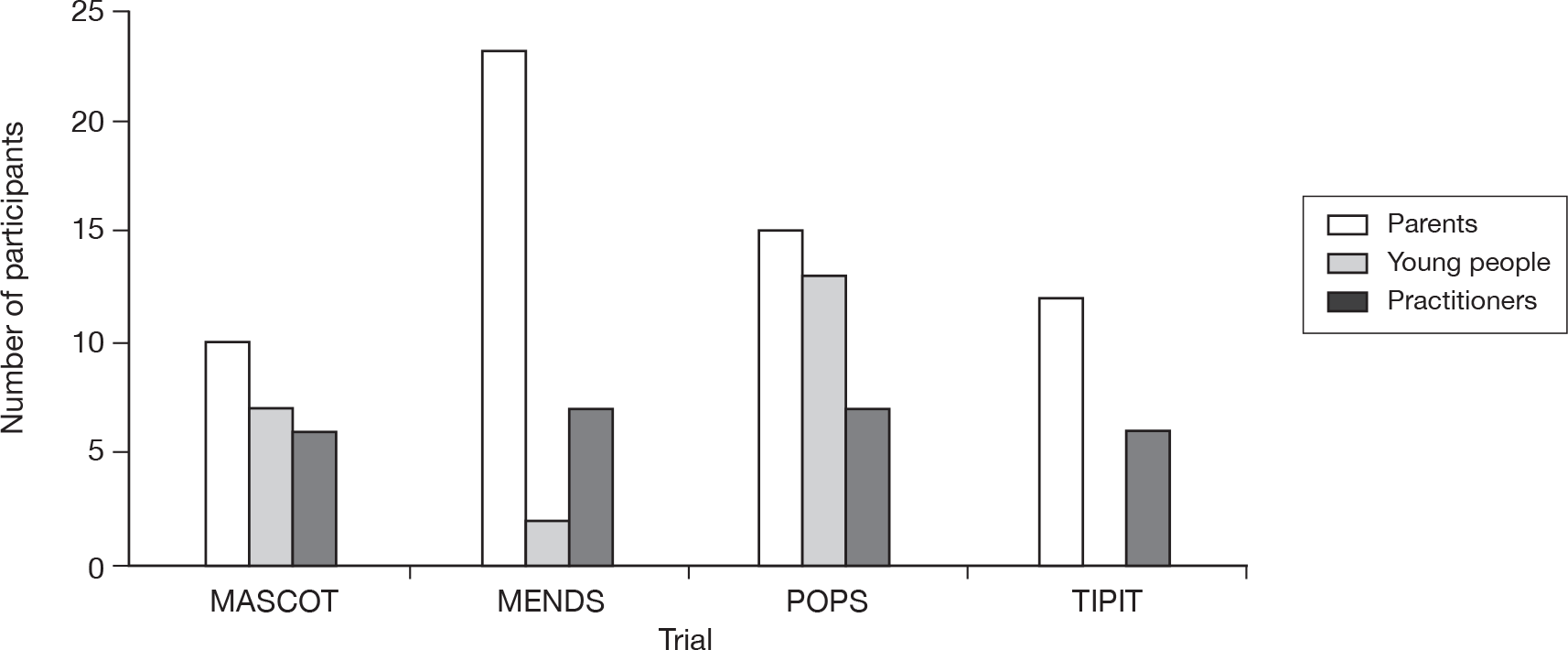

In total, 22 young people were interviewed, with the permission of their parents. [Through the remaining chapters of this report, we usually use the terms ‘young person/people’ in preference to ‘child/children’ unless the term child/children is used by the parent or patient themselves or is necessary for accuracy (e.g. when referring to the child of a parent).] Our protocol stated that, in the case of children < 7 years old, only the parents would be interviewed, as very young children are more likely to experience difficulties in articulating their experiences in interviews. Of the 22 young people interviewed, two were from MENDS, both of whom were aged 9 years, seven were from MASCOT, with a median age of 10 years (range 8–14 years), and 13 from POP, median age 13 years (range 8–16 years). We did not interview any 7-year-olds. Figure 2 shows the number of parents and young people interviewed by trial.

FIGURE 2.

Number of parents, young people and practitioners by trial. We interviewed 84 members of 60 families (58 mothers, 4 fathers and 22 young people). In one MENDS family and two POP families, both parents were interviewed. In one POP family, the parent declined to be interviewed but the young person was. Five doctors were also interviewed who regularly recruited to trials but were not recruiting to the four participating trials.

Interviews with families took place a median of 42 days after the recorded trial discussion (range 14–126 days). Table 3 shows the time lag between the recorded discussion and the RECRUIT family interviews by trial. We interviewed 48 of the 60 families in their homes, nine at the trial site and three by telephone interview. Interviews with parents lasted approximately 45–60 minutes and those with young people lasted approximately 15–30 minutes. Of the 22 young people interviewed, eight chose to be interviewed with one of their parents (sometimes for pragmatic reasons if the interviews were being conducted in the hospital). An interview with one young person was excluded from analysis as it contained no content relating to the trial.

| MASCOT | MENDS | POP | TIPIT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (range) days between recorded discussion and interview |

35 (30–69) n = 6 |

38 (14–69) n = 15 |

42 (14–119) n = 8 |

52 (20–126) n = 12 |

Practitioners

We interviewed 31 practitioners: 12 were research nurses who were part of the trial teams for one of the four trials and 19 were doctors (14 of whom were also members of the trial teams). Twenty practitioners were directly involved in approaching the families who participated in RECRUIT; of these, 11 had audio-recorded trial discussions included in the study; nine were directly involved in approaching families within the study but were not present during or did not lead the recorded trial discussion. A further six were directly involved in recruiting families to the participating trials but had not been involved in the recruitment of specific families within this study. The remaining five practitioners did not recruit families to any of the participating trials, but we interviewed them because they had considerable experience of recruiting families to other trials. These were practitioners who responded to a request at one of the participating centres inviting those with extensive experience of recruitment to children’s trials to be interviewed. Table 2 and Figure 2 show the numbers of practitioners by trial, alongside those for families. The majority of interviews with practitioners were conducted at the trial site and lasted approximately 45–60 minutes.

Changes to protocol

The North West 5 Research Ethics Committee (REC) approved the study on 2 March 2007 (ref. 07/MRE08/6). The study was subsequently given R&D approval to run in 10 Trusts (seven hospital, three primary care). Two amendments were made to the protocol during the study, both of which aimed to increase access to data or participants.

The REC approved a substantial amendment to the protocol on 28 October 2008:

-

Under the original protocol, families gave verbal permission for the practitioner to audio-record the trial discussion. Full written consent for the release of this recording to the RECRUIT team was sought at the same time as consent to be interviewed for the RECRUIT study. The original version of the protocol required these recordings to be destroyed if the family declined the RECRUIT interview. The substantial amendment allowed us to seek separate written consent from families who declined RECRUIT interviews to include their recorded discussions in the analyses, hence avoiding the unnecessary destruction of potentially valuable data.

The REC approved a second substantial amendment to the protocol on 24 February 2009:

-

The amendment allowed us to post an invitation letter and information sheet to families in certain circumstances, rather than relying exclusively on a personal approach by a practitioner. Invitation letters contained a reply slip and postage-paid envelope, which interested families returned directly to the RECRUIT team. Recruiters to the trials could therefore identify and post invitation letters to eligible families.

This approach was to be used if, for example, RECRUIT had not been discussed with the family when they were approached about a trial, where the trial discussion was held prior to the RECRUIT study opening at a particular centre. We were particularly keen to explore if this method would allow us to access more decliners. For example, in the MASCOT trial the approach about the trial was itself made by a postal invitation letter. We sent a RECRUIT mailshot to 100 families from three general practices who did not respond to the original MASCOT mailshot and hence had declined the trial. However, we abandoned this strategy when we received no responses from families who had declined MASCOT and wished to participate in RECRUIT.

Other clarifications and changes to the methodology

-

Compared with other qualitative studies, RECRUIT was a large and complex study. It had 156 data collection points and required numerous additional visits and discussions with trial teams. The data consisted of approximately 111 hours of audio-recording, which produced an estimated 2200 pages of transcript. Simultaneously co-ordinating the study across four trials and 11 trial teams, obtaining R&D approval and conducting the data collection and analysis was a challenging task. At RECRUIT’s outset it took some time to win the confidence of the trial teams. Because RECRUIT was to run contemporaneously alongside the trials rather than retrospectively, it also took several months to clarify with the National Research Ethics Service and the Trust R&D departments the nature of the relationship between the trials and RECRUIT. It was eventually established that RECRUIT was a separate entity to the trials, rather than an add-on or nested study. This clarification was fundamental to RECRUIT’s progress. Owing to the slow recruitment and delayed starts to some of the trials (e.g. one trial was delayed by > 1 year), and delays in obtaining R&D approvals, we were not able to concentrate sampling at particular sites in time-limited blocks as planned. Because of these delays we were unable to use maximum variation sampling and we pragmatically used a mix of purposive and consecutive sampling instead. Delays to the trials also resulted in uneven recruitment between trials.

-

The protocol stated that most RECRUIT interviews would be conducted within a few days of the recorded trial discussion and within an outside limit of 2 weeks. This element of the protocol was not acceptable to three of the four trial teams. In MENDS and MASCOT there was a run-in period, meaning that trial discussions were recorded 4 weeks before randomisation. To avoid any actual or perceived impact on recruitment to the main trial, it was necessary to delay interviewing families until after the randomisation appointment. In TIPIT, discussions were recorded within days of the birth of a critically ill premature baby. The mother was often unwell herself. Mothers were not approached by the RECRUIT team until the TIPIT teams were happy that mother and baby were stable. In many cases this entailed a lag of several weeks between the trial discussion and RECRUIT interview.

-

For each trial our goal was to enrol approximately equal numbers of families who consented to the trial and families who declined. This proved unachievable within the original design of the study, which relied on practitioners introducing RECRUIT to families during the face-to-face trial discussion. We found that for all trials participating in RECRUIT except TIPIT, families who attended a face-to-face trial discussion almost always consented to the trial. Families who declined often did so prior to this discussion in a number of ways: by not responding to written invitation, by telephone or by not attending an appointment. Throughout the study we sought every opportunity to recruit families who declined, and this necessitated several changes to our methodology, some of which required ethical approval. These in turn brought delays which further hindered our efforts to recruit declining families. In the case of TIPIT, the REC amendment (see Changes to Protocol) was sought to access declining families where RECRUIT had not been discussed with the family when they were approached about the trial because the trial discussion was held prior to RECRUIT opening at a particular centre. However, practitioners felt unable to send letters to families who were no longer in their care, and this route for accessing TIPIT decliners was therefore impossible to implement. We explored alternative ways of enrolling participants who declined the trials without a face-to-face discussion. These involved approaching families who (1) declined during a telephone call with the research nurse prior to the main trial discussion; (2) declined to be referred to the trial team when the study was initially mentioned to them by the community paediatrician; and (3) did not respond to an invitation letter from their GP regarding the MASCOT trial. Of these three strategies, only the first was successful, yielding 11 trial decliners who expressed an interest in RECRUIT, seven of whom entered the study.

-

We initially intended to link practitioners’ interviews to the specific trial discussions that they recorded with families participating in RECRUIT. This proved to be impractical as some practitioners recorded several of their trial discussions, while others were unable to draw to mind a particular discussion. Instead, we adapted the interview topic guide. For example, the interviewers prompted practitioners to describe specific trial discussions that they felt exemplified the ‘easier’ and the ‘more difficult’ trial discussions.

Chapter 3 Analysis strand 1: communication about trials as observed and experienced

Summary of objectives

This chapter is about the way in which families were approached to consider a clinical trial. Using data from audio-recorded trial discussions and interviews with parents, young people and practitioners, we compare the experience of trial recruitment for these groups with the conduct of the discussion itself.

As well as the linked trial discussion and interview data, the analysis also includes interview data from the 20 parents (of 19 children) and nine young people for whom we had no recorded trial discussions but whose insights add to our understanding of the experience of being approached to take part in a trial. These included families who declined or withdrew from the trial and the young people for whom we had no recorded trial discussion.

This chapter is organised into several sections. First, we discuss the features of communication, specifically the percentage of speech contributed by the parents and young people and the number and type of questions each party asked during the trial discussion. We also examine parents’ misunderstandings of the trial discussions and trial methodology. In the second part of the chapter we bring in data from interviews with parents and young people (including those for whom we had no recorded trial discussion) to discuss the trial approach ‘as experienced’ by all parties, the function and value of the PIL, and the impact of different types of relationship with the trial team on the recruitment experience. Finally, we present some suggestions from parents and young people on ways to improve the trial approach.

Communication as observed

Parents’ interactivity in the trial discussion

A striking finding from the trial discussions was that parents’ observed level of interactivity was generally low – the median percentage of speech by parents was 16% and ranged from just 1% to 49%. We categorised the discussions into three groups according to the amount of speech contributed by the parents: those discussions where parents contributed ≤ 10% of the speech (n = 12), those where parents contributed 11%–24% (n = 16) and those where parents contributed 25%–50% of the speech (n = 13) (Table 4).

| Group | Low interactivity | Medium interactivity | High interactivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 12 | 16 | 13 |

| Median percentage speech by parent (range) | 5 (1–7) | 16 (11–21) | 29 (25–49) |

| Median number of questions (range) | 1 (0–4) | 2 (0–6) | 1 (0–7) |

| Mean duration of discussion (SD and range) | 8.5 minutes (3.48, 5–16) | 13 minutes (6.21, 5–23) | 13 minutes (5.46, 6–19.5) |

| No. in which more than one practitioner present | 3 | 9 | 11 |

| No. in which more than one parent/adult present | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| No. in which young person presentb | 6 | 10 | 12 |

Typically, a ‘low-interactivity’ discussion was the first time that a family had heard about the trial in any great detail – sometimes it was the first time the trial had been mentioned to them – and its purpose was to impart information. Often families had not received the information sheet in advance. In three cases consent was taken after one of these discussions. These discussions, which were usually very brief, typically began with an explanation of the rationale for the trial and moved on to cover the key procedural and methodological aspects of the trial. Practitioners presented trial information in a systematic way and did not actively try to involve the parent. A frequent goal of these discussions was to set the scene for future discussion, and invariably they concluded with the practitioner encouraging the parent to read the PIL and discuss it with his/her family.

Practitioners rarely asked families any questions other than to gain required information, such as the date of next appointments or discharge, although occasionally they asked questions pertinent to the trial which might have allowed parents to influence the direction of the discussion, for example ‘do you know much about thyroid at all?’ (F10). It was relatively unusual for practitioners in these discussions to elicit parents’ thoughts or questions about the trial, although 6 out of 12 discussions had at least one such instance, for example ‘That’s a lot of information so far. Have you any questions you want to ask me?’ (F42). (The 41 recorded trial discussions were made by 16 practitioners. The 12 discussions in which parents contributed ≤ 10% of the speech were recorded by five different practitioners.) Practitioners in this group often imparted a ‘chunk’ of trial information and then loosely checked back with the parents for confirmation that they were happy with what they had been told, often in one word such as ‘alright?’ or ‘OK?’. These questions generally elicited one-word responses from parents, such as ‘OK’, ‘right’ or ‘yeah’. For some parents, these responses formed the main content of their turn taking in the discussion. Practitioners made few enquiries to explore whether the parent had understood the information, this being the case in only 3 out of 12 discussions, for example ‘Obviously there’s a one in two chance he may get the dummy medicine. Um, do you understand that part?’ (F29).

For ‘high-interactivity’ discussions, parents had typically received the PIL prior to the discussion and had taken part in at least one brief conversation about the trial prior to the recorded discussion. Where the parent had received the PIL in advance, practitioners often used it as a starting point for the discussion and to offer parents the opportunity to ask questions at an early stage (n = 6), for example ‘You’ve had the information sheets […] about the study? And what did you think of that when you, you read through it?’ (F18). In five of the six discussions that began in this way, the practitioner also asked questions later in the discussion, for example ‘so, reading over it, were there any concerns you had?’ (F20).

When the parent had not read the PIL in advance, the discussion was initially much closer in style to those of the low-interactivity group, but, over time, it gradually became more interactive as the focus shifted to the child’s condition. In all four discussions, the practitioner asked questions that appeared to be aimed at exploring the parents’ understanding, but because the discussion had not been preceded by a written information sheet, the questions were necessarily more closed, for example ‘In a nutshell, does that make sense?’ (F3), ‘Are you with me so far?’ (F2).

In all 13 of these high-interactivity discussions, the practitioners asked parents lots of questions. These were almost all related to the child’s condition and seemed aimed at establishing eligibility rather than eliciting parents’ thoughts or questions about the trial. Although the agenda was always set by the practitioner, the parents in this group were more able to influence the direction of the discussion because they had valuable input about their child’s condition to contribute. Conversation directly related to the trial was dominated by practitioners.

Irrespective of their level of interactivity in the trial discussion, parents asked few questions. Ten families asked no questions at all and a further 13 asked just one. Questions asked by families were most often concerned with the practical and procedural requirements of the study (n = 37) although questions relating to safety and potential side effects (n = 16) and to clarify aspects of methodology and rationale (n = 17) were also common. Parents rarely asked questions relating to potential benefits to their child (n = 4). Examples of the types of questions parents asked are shown in Box 1.

‘Is there not a chance that it could go wrong and something could harm, harm him or something like that?’ (F41)

Practical and procedural

‘Does it stay on all day, or is it just on the evenings?’ (F15)

‘And would it be mouth form or injection?’ (F25)

Methodology and rationale

‘[At] the end of the study? Do we get told whether she had the dummy?’ (F17)

‘What is it meaning by here, to be randomised?’ (F22)

Benefit to child

‘What my question is, if they say he’s gonna take the placebo, […], the dummy one what is he going to benefit from the study?’ (F32)

Practitioners always gave reassurances on safety and absence of procedures that might be distressing to a child, irrespective of the level of a parent’s interactivity in the discussion, for example:

All the treatments that we are using in the study are licensed in children of [your child’s] age […] They’re all fully available so there’s nothing new or unusual about them.

(F48)

But if she wasn’t having bloods normally she wouldn’t give bloods for the study.

(F37)

It is therefore possible that in some cases practitioners’ reassurances pre-empted parents’ questions and contributed to their relatively low number.

Mismatches and misunderstandings

In this section we present several cases in which parents appeared to have misunderstood some aspect of the trial. We identified potential misunderstandings by reading the parent interview transcripts several times to search for descriptions or explanations that were not consistent with the trial rationale or methodology. We then cross-referenced these with the transcripts from the recorded trial discussions to examine whether the source of the misunderstanding could be potentially linked to the trial discussion. In most cases no direct link could be identified; however, in a few cases it was conceivable that a misunderstanding could have had its origins in the trial discussion, although other sources cannot be excluded. These misunderstanding cases are intended to indicate topics that might warrant particular attention from practitioners when recruiting families. An important aspect of our interviews was that they were led by parents and their beliefs. We explored their beliefs or misunderstandings sensitively as our aim was to describe parents’ experiences in a way that avoided influencing, ‘testing’ or altering their beliefs about the trials.

Parents often made general statements about having experienced a sense of misunderstanding and confusion that they linked to their emotional situation at the time of the trial approach (e.g. F12 and F25). Three parents in the neonatal trial told us that they were comfortable with the limitations of their understanding because they felt that their baby was in safe hands (F41, F45 and F46). However, we have identified several possible cases in which parents had specific misunderstandings had the potential to influence families’ decisions on trial entry.

A number of parents, particularly from the TIPIT and MENDS trials, had some degree of misunderstanding linked to equipoise and/or the rationale for the trial. In TIPIT particularly, a number of parents did not seem to recognise that the trial had been designed to test whether or not the trial medication was beneficial to that group of babies; rather they saw the trial as an opportunity to receive a medication that would be of benefit to their child, and which was otherwise unavailable to them.

Her only real way of getting it is to go and take part in the trial because then, I’ve got sort of a 50/50 chance of either she gets the drug or she gets the placebo. But she wouldn’t be getting it otherwise.

(F21)

These ‘therapeutic misconceptions’ represent a misunderstanding of the rationale of the trial but do not represent a direct misunderstanding of what parents had been told; practitioners often began the trial discussions by mentioning previous positive research. Therefore, the framework for parents’ understanding was that they had a 50 : 50 chance of ‘getting the right medication’ (F31). Indeed, the practitioner’s use of the term ‘I’m afraid’ in one trial discussion might have indicated to the parent that the practitioner was not in equipoise.

So we are running this study for the last year now, where I’m afraid half the [babies] get the supplement and half the [babies] doesn’t get it.

(F29)

In the MENDS trial, parents most common area of ‘misunderstanding’ also comprised a general lack of equipoise. Additionally, parents were often under the impression that the trial medication was not available outside the trial. One family told us:

We’d already made our mind up that we were going to. Before we’d even got the information […] we just weren’t getting sleep […] it’s like, we have to do something.

(F22)

Like a number of other parents, they entered the trial as a means, albeit randomised, of accessing the trial medication ‘in order to get that tablet he has to participate in the trial’ (F32). In fact, the trial medication was regularly prescribed outside the trial; in the trial discussion with one of these families the practitioner explained:

We’ve been using it for […] ten years or so […] and the whole idea of this study is to do it properly and to get the proof that it works so that we can use it more widely and for many more doctors to prescribe it, if it, if it is successful.

(F22)

This potentially sent mixed messages about the efficacy and availability of medication to parents who, in some cases, had asked for help and felt that trial participation was the only option open to them.

A few parents were confused about randomisation. Here, a practitioner explains randomisation to a parent during the trial discussion:

We will randomise [your son] into the study […] which means there’s a lottery as to whether he gets the trial medication […] or a thing called placebo dummy […] and they look exactly the same […] and no one knows which one contains [trial medication] and which one contains placebo.

(F1)

But in her interview the parent wondered whether the allocation of medicine might be more individually tailored:

You do kind of think ‘I wonder who does actually make the decision, who goes on what and who doesn’t’. I mean, do they actually look at all the information before they decide who goes on what?

(F1)

A second parent seemed to grasp the concept of randomisation in the trial discussion:

And by randomised, what we mean is that we just randomly pick one. So it’s almost like a sort of, it’s usually a computer program that just sort of.

A lucky dip?

Yeah it is exactly like that. Like a lucky dip […] so it’s almost like just, you know, saying well we just picked this out of a hat and [your son]’s got this treatment.

However, this parent’s comments in her interview indicate that she had misunderstood the explanation to mean that the drugs to be studied would be selected at random:

A bit wary, […] because I thought, ‘Oh what’s, just going to give him some random tablets or anything’.

(F48)