Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 08/98/01. The protocol was agreed in July 2009. The assessment report began editorial review in December 2009 and was accepted for publication in July 2010. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2011. This work was produced by Hartwell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Description of underlying health problem

Hepatitis C is a slowly progressing infectious disease of the liver arising from the blood-borne hepatitis C virus (HCV). First identified in 1989, HCV belongs to the Flaviviridae family of viruses. It is a ribonucleic acid (RNA) virus, of which there are six genetic variations, known as genotypes (e.g. 1, 2, 3, etc.), the prevalence of which varies considerably between countries. 1,2 In England and Wales, the most prevalent genotypes are 1 and 3, representing more than 90% of all diagnosed infections. 3 Genotype 3a remains the most common, with a prevalence of 39%, followed by genotype 1a (22%). 3 Response to treatment is strongly influenced by HCV genotype (see Current service provision and Description of technology under assessment).

There are two main phases of infection: acute and chronic. Acute HCV refers to the period immediately after HCV infection, whereas chronic HCV (the focus of this report) is defined as infection persisting for > 6 months. Of those exposed to HCV, approximately 20% will clear the virus spontaneously, although the remaining 80% will go on to develop chronic infection. Chronic HCV is categorised as mild, moderate or severe according to the extent of liver damage, based on both the level of fibrosis (scarring) that has occurred in the liver as well as the degree of necroinflammation (inflammation and destruction of liver tissue) (see Disease progression and prognosis). Symptoms in people with chronic HCV are typically mild and non-specific, and include fatigue, flu-like symptoms, anorexia, depression, sleep disturbance, cognitive impairment, right upper quadrant pain, itching and nausea. 4,5 Although the symptoms are mild in some people, in others they can cause a significant decrease in quality of life (QoL) irrespective of the degree of liver damage. 6 Symptoms and signs of chronic HCV-related liver damage may occur later in the disease when scarring of the liver has progressed.

Aetiology

Hepatitis C virus is transmitted parenterally (i.e. via routes other than the digestive tract) and is acquired primarily through exposure to contaminated blood. The most common source of HCV transmission in the UK is through the sharing of injecting paraphernalia during illicit intravenous drug use, accounting for around 90% of cases. 3 Other less common sources of infection include mother–baby transmission, occupational exposure (e.g. via needlestick injury), tattooing and body piercing. Before the introduction of blood screening in 1991, it was also spread through the use of contaminated blood products or organ transplantation. In some resource-poor countries it is thought that infections may occur through the use of unsterilised needles in health-care settings. The risk of sexual transmission has been thought, traditionally, to be low. For example, the Health Protection Agency (HPA) estimates that only 1.4% of infections identified through laboratory reports between 1996 and 2007 were attributed to sexual exposure. 3 However, increasing numbers of acute infections in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive men who have sex with men (MSM) suggests potential for transmission associated with high-risk sexual practices probably involving blood (see below). 7

Epidemiology

Prevalence

The estimated global prevalence of chronic HCV is around 2%–3%, corresponding to about 130–170 million people. 1,8 In England and Wales, the HPA3 estimates that, based on statistical model data for the year 2003, around 191,000 [95% credible interval (CrI) 124.00 to 311.00] people aged 15–59 years are HCV antibody positive, with 142,000 people chronically infected, a prevalence of 0.44% (95% CrI 0.29% to 0.72%) in this age group.

Prevalence estimates vary geographically in England and Wales, with highest numbers of laboratory reports (from public health and UK NHS laboratories in England and Wales under a voluntary surveillance scheme) returned in the north-west, followed by London and the south-east of England. 3

The prevalence of chronic HCV also varies according to different population groups. For example, HCV is more common in men and in the 25–44 years age group. Estimates of the number of current injecting drug users (IDUs) in England vary between 100,000 and 217,000, and it is estimated that around 40% of IDUs are infected with chronic HCV, based on the Unlinked Anonymous Prevalence Monitoring Programme’s Survey of Injecting Drug Users in 2006. 9 There are limited data on prevalence in minority ethnic populations. However, it is thought that the prevalence of HCV is higher in migrants who will have acquired the infection while overseas, notably Pakistan. 3

Evidence suggests varying rates of HCV in people with HIV infection. For example, Mohsen and colleagues10 reviewed the international literature on the epidemiology of HCV/HIV co-infected patients. They included 12 HCV seroprevalence studies carried out in people infected with HIV-1 in Europe and the USA. HCV prevalence ranged from 7% to 57%, largely influenced by risk factors in the study populations. Prevalence was highest in people with a history of injecting drug use (> 80%). It has been suggested that up to 10% of all HCV-infected people are co-infected with HIV. 11

Prevalence is difficult to estimate because symptoms of HCV are frequently absent or non-specific and thus people can remain undiagnosed for many years. Between 1992 and 2007 there were 62,000 laboratory-confirmed diagnoses of HCV in England, and 3688 in Wales (from 1996). 3 It is thought that a proportion of those who are undiagnosed are ex-IDUs who used drugs transiently in the past. Sentinel surveillance by the HPA suggests that the number of people diagnosed with HCV in all settings is increasing, which may, in part, reflect awareness-raising campaigns to encourage uptake of testing. 3

Incidence

The incidence of chronic HCV is likely to be driven by two main sources – newly acquired infections in current UK residents (largely IDUs) and inward migration of chronically infected individuals from other countries. Up-to-date estimates of overall incidence are not yet available but recent studies in IDUs suggest that 3%–42% of susceptible injectors become infected each year. 3 The HPA reports that the number of laboratory-confirmed diagnoses of HCV in England and Wales in 2007 was 7540, representing a 12% increase from 2006. 3 This does not, however, necessarily represent an increase in rates of incidence but may be attributed to testing rates.

Recent rises in HCV infection in HIV-positive MSM have generated increased interest in the role of sexual transmission of HCV. HCV RNA can be detected in the semen of HCV-infected men, with higher levels in HIV-positive men, suggesting the possibility of transmission during certain sexual practices. Increases in cases of acute co-infection in HIV-positive MSM in urban centres in Europe and the USA have been reported in recent years. 12 A study of genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinics in London and the south-east of England found a 20% average annual increase in the number of HIV-positive MSM diagnosed with HCV between January 2002 and June 2006. 7 The prevalence of HCV in HIV-positive MSM is estimated to be between 4% and 11.5%. 12

Disease progression and prognosis

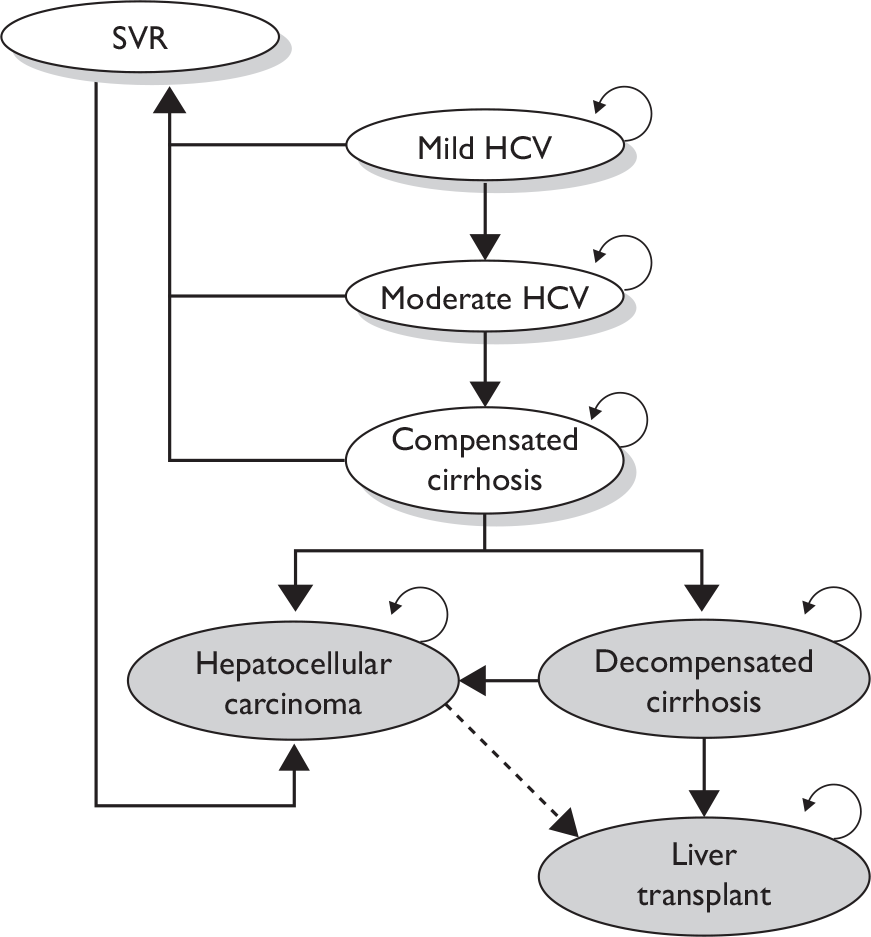

Chronic HCV infection is associated with progression to liver failure in some, but not all, people. Progressive liver disease is characterised by inflammation of the liver, which leads to gradual fibrosis, which, in its severe form, produces cirrhosis. Cirrhosis can progress from a compensated state (where the liver is still functioning despite the fibrosis) to a decompensated state (where the functioning of the liver is seriously impaired). Decompensation is characterised by complications such as ascites (large accumulations of fluid in the abdominal cavity), variceal bleeding (enlarged and bleeding veins around the oesophagus) and hepatic encephalopathy (neuropsychiatric abnormalities, such as cognitive impairment associated with liver dysfunction). There are a number of commonly used systems for classifying the severity of HCV-related liver disease from biopsy samples. Some share common characteristics and are derived from the same systems. 13 Three commonly cited systems are the Knodell histological activity index (HAI),14 the Ishak revised HAI15 and the METAVIR system. 16 The Ishak system,15 for example, classifies mild HCV as a fibrosis score of ≤ 2 and a necro-inflammation score of between 1 and 8, moderate HCV as a fibrosis score of 3–5 and a necro-inflammation score of 0–18 (moderate/severe), and severe HCV as a fibrosis score of 6 (cirrhosis). If the fibrosis score reaches ‘6’ the patient is classified as having severe HCV-related liver damage, irrespective of the necro-inflammation score (see our previous technology assessment report17 on antiviral treatment for mild HCV for further detail on liver biopsy classification systems).

Cirrhosis can develop rapidly, within 1–2 years of exposure (although this is rare), but more usually develops slowly over two to three decades. A recent Markov modelling study18 of three different observational cohorts in the UK estimated that between 6% and 23% of people will progress to cirrhosis after 20 years of infection. The estimates were highly sensitive to the type of cohort used, with lower estimates from the HCV National Register lookback cohort, comprising individuals identified from blood screening and donor surveillance schemes, and highest estimates from a London-based tertiary referral centre in which patients underwent a biopsy. Estimates of progression to cirrhosis from retrospective studies are higher, with between 17% and 55% of patients progressing between 10 and 30 years following infection. 19 It is estimated that 6%–10% of cirrhotic patients will progress to decompensated cirrhosis. 19

A recent modelling study estimated that in England the number of HCV-infected people living with compensated cirrhosis will rise from 3705 (95% CrI 2820 to 4975) in 2005 to 7550 (95% CrI 5120 to 116,400) in 2015. 20

Patients with HCV-related cirrhosis are at risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with an annual incidence of 1%–4%. 21 Some patients with decompensated cirrhosis or HCC may require liver transplantation. In 2007, 482 liver transplants were conducted in England, of which 13% (n = 64) were classified as first liver transplants with post-HCV cirrhosis at registration/HCV positive at registration or transplant. 3 However, demand for liver donors remains high and not all patients will be considered for transplantation. The number of people with decompensated cirrhosis and/or HCC is also estimated to rise from 1150 (95% CrI 1055 to 1250) in 2005 to 2540 (95% CrI 2035 to 3310) in 2015. 20

Risk factors associated with rapid disease progression include male gender, excessive alcohol consumption and age at infection. 19 For example, Poynard and colleagues22 studied a cohort of 2313 untreated patients and reported that increasing age at infection was independently associated with disease progression. Two per cent of those infected before the age of 20 years developed cirrhosis over a 20-year period compared with 6% of those infected between the ages of 31 and 40 years, 37% infected between 41 and 50 years, and 63% infected after the age of 50 years. HCV genotypes and HCV RNA viral load, although important in governing the effectiveness of treatment regimens (see Shortening the course of treatment), are not thought to influence the natural course of infection. 19

Co-infection with HIV is also associated with rapid HCV-related disease progression. 23–25 Since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in the mid to late 1990s, patients with HIV infection are living longer and therefore those who are co-infected are becoming at risk of long-term chronic HCV-related liver disease. Mohsen and colleagues26 reported a study of 153 HCV-infected and 55 HCV/HIV co-infected patients (72% of whom were receiving antiretroviral therapy at time of liver biopsy) from two London hospitals. The estimated median fibrosis progression rate was 0.17 units/year in HCV/HIV co-infected patients and 0.13 in HCV mono-infected patients (p = 0.01). This equates to estimated times from HCV infection to cirrhosis of 23 and 32 years, respectively. HIV positivity and a low CD4 cell count were among a number of factors that were independently related to fibrosis progression. A retrospective analysis by Poynard and colleagues27 of 4852 patients with chronic liver disease of a variety of causes found that HCV/HIV co-infection was associated with the fastest fibrosis progression compared with causes such as genetic haemochromatosis, primary biliary cirrhosis and alcoholic liver disease. Despite the findings of these studies it has been suggested that the effective immune restoration observed with HAART can, indirectly, reduce the rate of liver fibrosis to a value that is comparable with the rate of HCV mono-infected people,12 although a systematic review of natural history studies in co-infected patients concluded that this was not necessarily the case. 28

Given the slowing of HIV-related disease progression and extended survival associated with HAART29 it could be assumed that HCV is now one of the major causes of mortality in people with HIV. 11 However, although there has been an increase in liver disease-related deaths in co-infected patients, it is not clear whether this is associated with HAART-related toxicity or HCV-related liver disease, as studies have shown mixed findings. 30,31

Diagnosis

Presence of HCV infection may be detected through the identification of antibodies using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) and then confirmed through the identification of HCV RNA in serum. 32 The latter can be carried out using sensitive molecular assays, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR). A detectable HCV viral load of 50 international units (IU)/ml or above is generally considered indicative of infection, although newer assays have a lower threshold of detectability of 12–20 IU/ml. As part of the diagnostic process, patients receive testing to determine their genotype, as this is associated with the efficacy of treatment and will govern the duration of therapy (see Shortening the course of treatment). Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) biochemical tests are also used to indicate potential HCV-related liver damage, but are not necessarily used to determine eligibility for treatment.

Traditionally, a liver biopsy has been used to gauge the extent of HCV-related liver damage in order to guide treatment decisions. If the biopsy sample showed significant fibrosis or cirrhosis, clinicians would probably commence antiviral treatment. However, there has been a shift away from using biopsy in recent years for a number of reasons, including the risk of complications (e.g. a small risk of hepatic bleeding), the pain and discomfort to the patient, the lack of interobserver reliability between pathologists, and the suggestion that it may discourage some patients from presenting for assessment. Furthermore, guidance from organisations such as the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)33 to extend the provision of treatment to those with mild HCV means that it is no longer necessary to use biopsy to gauge disease severity in order to determine when to begin treatment.

Nevertheless, some clinicians find liver biopsy a useful tool to detect the presence or absence of steatosis (fatty liver) and other potential confounding liver diseases. This is reflected by NICE’s guidance, which states that clinicians may conduct a biopsy, if required, for other reasons,33 and also by Scottish guidelines on the management of HCV, which state that liver biopsy should be considered if there is concern about additional causes of liver disease. 32 Patients may also seek a biopsy to determine the extent of any fibrosis to help them decide whether or not to commence treatment.

The development of non-invasive serum markers and other technologies (e.g. ultrasound) as an alternative to biopsy has generated interest in recent years, although their clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness have not yet been appraised at policy level in England and Wales.

Current service provision

Antiviral treatment

The majority of people with chronic HCV will not clear the virus spontaneously and will need to be assessed for possible antiviral treatment. Patients with chronic HCV are generally managed in specialist hepatology centres. They may also be managed by gastroenterologists and specialists in infectious diseases. Specialist hepatology nurses are also involved, particularly in the administration of antiviral treatment.

The primary aim of treatment is to clear the virus from the blood, and success is usually taken to be a sustained virological response (SVR), defined as a drop in serum HCV RNA to undetectable levels (e.g. below 50 IU/ml) 6 months after the end of treatment. An SVR is generally considered to indicate permanent resolution of infection, although relapse may occur in around 5% of cases after 5 years. 34 Studies (mostly observational) have reported that people who achieve an SVR have a lower probability of developing HCC35 and liver-related death36 than those that do not. However, the validity of SVR as a surrogate for long-term clinical outcomes – such as decompensated liver disease, HCC and death – has been questioned. 37 It is suggested that this is because of an absence of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in which the effects of antiviral treatment, in terms of SVR, have been correlated with long-term clinical outcomes. The exception is for cirrhotic patients in whom some evidence of a correlation between SVR and HCC has been identified (based on studies of treatment with interferon alfa monotherapy). 37 It is recommended that several RCTs of antiviral treatment, with long-term follow-up over a number of years, are required to determine the validity of a surrogate outcome. 37 Given that this is unlikely to be practical, and the general acceptance of SVR as being the most reliable measure of HCV infection resolution, it is pragmatic to assume that an SVR, in most people, will reduce the likelihood of morbidity and mortality.

Interferon alfa, originally as monotherapy and then as combination therapy with ribavirin, was the mainstay of treatment until the pegylated forms of interferon (peginterferon alfa or α) were introduced in 2002. The peginterferons are cytokines, the mechanism of which is to assist the immune response by inhibiting viral replication. Two forms are available: peginterferon alfa-2a (Pegasys®, Roche Products) and peginterferon alfa-2b (ViraferonPeg®, Schering-Plough). Ribavirin is a synthetic nucleoside analogue that is available in three forms: Copegus® (Roche Products), Rebetol® (Schering-Plough) and Ribavirin Teva (Teva UK). Copegus is licensed only for combination therapy with peginterferon alfa-2a, whereas Rebetol and Ribavirin Teva are licensed only for combination therapy with peginterferon alfa-2b.

The current NICE guidance [Technology Appraisal (TA) 106,33 an extension of TA 7538] recommends combination therapy with ribavirin and either peginterferon alfa-2a or peginterferon alfa-2b for adult patients with chronic HCV, regardless of disease severity. Monotherapy with peginterferon alfa-2a or peginterferon alfa-2b is recommended for patients who are unable to tolerate ribavirin or for whom ribavirin is contraindicated. For those with mild HCV, the decision whether to treat immediately or adopt an approach of ‘watchful waiting’ is made by the patient and clinician on an individual basis. The standard duration of treatment is 24 or 48 weeks, depending on a combination of factors including the genotype, initial viral load, and rapid and early virological response (EVR) to treatment. Treatment is currently restricted to patients who:

-

are treatment naive

-

have previously been treated with non-peginterferon alfa combination therapy or monotherapy

-

have previously been treated with peginterferon alfa monotherapy but did not respond or subsequently relapsed.

It is not thought that there are substantial variations in practice across the country in terms of antiviral treatment, although clinical management of chronic HCV may vary according to the availability of hepatologists and specialist clinics.

There are a number of specific areas in which the clinical management of HCV infection is evolving, including prescribing shorter treatment courses, re-treating patients who have not responded or relapsed to a previous course, and treating patients who are co-infected with HCV/HIV. These areas are discussed in the following subsections.

Shortening the course of treatment

In recent years, one of the key aims of the management of HCV has been to maximise the likelihood of an SVR while minimising potential adverse effects of treatment. The adverse effects associated with interferon-based antiviral treatment (e.g. flu-like symptoms, nausea, vomiting, depression) and ribavirin (e.g. anaemia) can be significant, and some patients describe it as a very unpleasant experience, disrupting their social and family life, and, in some cases, impairing their ability to work. Sparing them the potential adverse effects through shorter but effective treatment courses will make therapy more tolerable, and may have the additional advantage of encouraging more people with suspected HCV to present for diagnosis, assessment and treatment.

To demonstrate the efficacy of shortened courses of treatment, clinical trials have measured viral response at interim time points after commencement of therapy to determine the likelihood of an SVR. An EVR is measured after 12 weeks of therapy and is generally defined as either a negative HCV RNA (complete EVR) or a minimum two log10 drop in quantitative HCV RNA levels (partial EVR). 39 EVR tends to be measured in genotype 1 patients to determine whether to stop treatment at 12 weeks in non-responders (patients who do not achieve an EVR generally do not go on to achieve an SVR with continued treatment) or to continue for 48 weeks in those who have responded.

Recently, there has been a focus on identifying responders earlier than 12 weeks. A rapid virological response (RVR) is measured at week 4 of therapy and is generally defined as a negative qualitative HCV RNA. Thresholds for negativity vary according to the assay, with some assays using a lower limit of detectability of 50 IU/ml, and others using thresholds as low as 12 IU/ml. RVR tends to be measured in genotype 2 or 3 patients in order to determine whether treatment can be shortened from 24 to 16 weeks, and in genotype 1 or 4 patients to determine whether treatment can be shortened from 48 to 24 weeks.

Decisions regarding the most appropriate length of treatment may also take into account baseline viral load in addition to genotype. Low viral loads (LVLs) have generally been associated with increased likelihood of an SVR in some clinical trials. 40,41 There does not appear to be a consensus regarding what constitutes a low or high viral load. However, the manufacturers of peginterferon alfa-2a and peginterferon alfa-2b consider LVL as being HCV RNA ≤ 800,000 and < 600,000 IU/ml, respectively. 42,43

Re-treatment of non-responders and relapsers

Given the fact that, on average, SVRs are achieved by between only 50% and 60% of patients receiving antiviral therapy17,44 (with variations according to factors such as genotype, baseline viral load and treatment regimen), it is important to establish the efficacy of re-treatment with a subsequent course for those who did not respond or who relapsed. A non-responder is a patient who has detectable HCV RNA throughout a course of antiviral treatment. A relapser is defined as a patient who achieves loss of detectable HCV RNA during treatment, but in whom HCV RNA reappears either while still on therapy or once therapy is stopped.

Current NICE guidance recommends the re-treatment of patients who have failed previous treatment with non-peginterferon alfa and ribavirin combination therapy or non-peginterferon alfa monotherapy, or peginterferon alfa monotherapy, providing they achieve an EVR (as defined above in Shortening the course of treatment). 33 However, the guidance does not currently make provision for patients who have not responded to, or failed, a previous course of, peginterferon alfa and ribavirin combination therapy.

If re-treatment with peginterferon alfa (with or without ribavirin, depending on contraindication) does not achieve an SVR, then it is unlikely that maintenance treatment to reduce progressive liver damage will be considered. At the present time there are no other licensed drugs that could be used as second-line treatment in patients with HCV.

Treatment of HCV/HIV co-infected patients

Effective clinical management of people co-infected with HCV and HIV is important, given the increased rate of HCV-related disease progression in this group (as discussed in Disease progression and prognosis). For example, treatment decisions need to take into account any possible drug interactions between HCV antiviral medication and HAART [e.g. didanosine (Videx®, Bristol–Myers Squibb), which is contraindicated in co-infected patients taking antiviral treatment for HCV]. 45 There is potential for significant HAART-associated hepatotoxicity in co-infected patients, which in serious cases may necessitate the withdrawal of HAART, with subsequent potential for the development of resistance to HIV medication. 11 The adverse effects of HCV antiviral medication may be more pronounced in co-infected patients, notably depression.

Given the complexity of managing both infections, clinical guidelines on the management of HCV/HIV co-infected people recommend that treatment be led by specialists in both HIV and HCV. 46 Treatment with peginterferon alfa and ribavirin in combination is recommended unless contraindicated. 45,46 Although HCV/HIV co-infected people were not the focus of NICE’s previous technology appraisals, the guidance does recommend antiviral treatment for this group, in common with that for HCV mono-infected people. 33,38

Description of technology under assessment

The intervention under assessment in this report is peginterferon alfa-2a and alfa-2b in combination with ribavirin (or as monotherapy if ribavirin is contraindicated). Peginterferon alfa-2a was licensed in June 2002, with extensions to the licence granted in June 2007. The recommended dose is 180 µg once per week, administered subcutaneously, for 16, 24 or 48 weeks, dependent on genotype, baseline viral load and treatment response. Peginterferon alfa-2b was licensed in February 2002, with extensions to the licence granted in May 2005. The recommended dose is 1.5 µg/kg body weight once per week, administered subcutaneously for 24 or 48 weeks, dependent on genotype, baseline viral load and treatment response.

The three forms of ribavirin (Rebetol, Copegus and Ribavirin Teva) were licensed in May 1999, November 2002 and March 2009, respectively. The recommended dose of ribavirin ranges from 800 mg to 1400 mg taken orally each day in two divided doses (200-mg capsules), with the dose depending on the patient’s body weight. The dose of Copegus also varies according to genotype [800 mg per day for genotype 2/3 and 1000–1200 mg per day (depending on body weight: 1000 mg for weight < 75 kg, 1200 mg for weight ≥ 75 kg) for genotype 1].

For both forms of peginterferon alfa, the therapeutic indication is the treatment of adult patients with chronic HCV who are positive for serum HCV RNA, including those with clinically stable HIV co-infection. The preferred indication is in combination with ribavirin, but monotherapy is indicated in cases of intolerance or contraindication to ribavirin. Patients may be treatment naive or may have failed previous monotherapy or combination treatment.

For peginterferon alfa-2a, genotype 1 patients with detectable HCV RNA at 4 weeks (i.e. no RVR) should receive 48 weeks’ treatment. Those with genotype 2/3 and detectable HCV RNA at 4 weeks should receive 24 weeks’ treatment. The licence extensions allow genotype 1 patients with LVL, an RVR and undetectable HCV RNA at week 24 to complete treatment at week 24 rather than receive the standard 48 weeks’ treatment. It also allows genotype 2/3 patients with LVL (≤ 800,000 IU/ml), an RVR and undetectable HCV RNA at week 16 to finish treatment at week 16 rather than receive the standard 24 weeks’ treatment. Those with genotype 4 may be treated as genotype 1, without the requirement for LVL. It is recommended that patients receiving peginterferon monotherapy be treated for 48 weeks.

For peginterferon alfa-2b, genotype 1 patients with an EVR (at week 12) should receive 48 weeks’ treatment. Those without an EVR are considered unlikely to achieve an SVR and consideration should be given to withdrawal of treatment. Genotype 2/3 patients should be treated for 24 weeks. Licence extensions permit genotype 1 patients with LVL (< 600,000 IU/ml) and an RVR and undetectable HCV RNA at week 24 to receive 24 weeks’ treatment rather than 48. The licence does not permit, however, shorter courses of treatment in genotype 2, 3 or 4 patients. Patients receiving peginterferon monotherapy who achieve an EVR should continue treatment for another 3 months. Extension of treatment to 1 year should be based on prognostic factors such as age and genotype.

For both peginterferon alfa-2a and alfa-2b, patients co-infected with HIV should be treated for 48 weeks, regardless of genotype. Full details of the indications, dosages and duration of treatment are given in the summaries of product characteristics (SPCs). 42,43

In terms of costs, a 180-µg prefilled syringe of peginterferon alfa-2a (the recommended weekly dose) costs £126.91. A 168 × 200 mg-tab pack of ribavirin (Copegus) costs £444.43. The weekly cost of Copegus would be £111 for genotype 1 (based on 1200 mg per day for an average body weight of 79 kg) and £74 for genotype 2/3 (based on 800 mg per day for an average body weight of 79 kg). A 120-µg prefilled injection pen of peginterferon alfa-2b costs £162.60. This would be the weekly cost for an average patient weighing 79 kg (1.5 µg per kg). A 168 × 200 mg-tab pack of ribavirin (Rebetol) costs £327. The weekly cost of for Rebetol would be £68, based on 1000 mg per day for an average body weight of 79 kg. All costs are from the British National Formulary (BNF), No. 58, September 2009. 47 [See Chapter 5 (Cost data) for full details of the drug costs estimated in our independent economic evaluation.]

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Interferon alfa (pegylated and non-pegylated) and ribavirin for the treatment of moderate to severe HCV was appraised by NICE in 2004 (TA75),38 and an appraisal specifically for mild HCV was carried out in 2006 (TA106). 33 Both appraisals were based on our independent assessment reports. 17,44 Since NICE’s clinical guidance was published, there have been extensions to the licences for peginterferon alfa-2a and alfa-2b. This health technology assessment (HTA) is a part-review of the current NICE guidance and is restricted to the patient subgroups that are affected by the licence extensions, as below.

Decision problem

The decision problem is based on the scope of the appraisal as set by NICE. The relevant intervention is peginterferon alfa (2a and 2b) in combination with ribavirin, or peginterferon alfa monotherapy where ribavirin is contraindicated. The population of interest is adult patients with chronic HCV infection in one or more of the following patient groups – those who (1) meet the licensed criteria for receiving shortened courses of combination therapy; (2) have been previously treated with peginterferon alfa and ribavirin in combination and who either did not respond or who responded but relapsed; and (3) are co-infected with HIV.

The relevant comparator for studies evaluating the efficacy of shortened treatment courses is standard treatment duration (e.g. 48 weeks for genotype 1 patients, 24 weeks for genotype 2/3 patients). For the other two patient groups the comparator is best supportive care (BSC). Relevant outcomes include virological response (e.g. during treatment, 6 months post treatment), biochemical response (e.g. ALT levels), histological improvement (fibrosis and inflammation), survival, adverse effects of treatment, and health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

The aim of this HTA is to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of peginterferon alfa and ribavirin for the treatment of chronic HCV in three specific patient groups: those eligible for shortened treatment courses; those eligible for re-treatment following previous non-response or relapse; and those who are co-infected with HIV.

Chapter 3 Methods

The a priori methods for systematically reviewing the evidence of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness were described in a research protocol (see Appendix 1), which was sent to experts for comment. Minor amendments were made as appropriate but no comments that identified specific problems with the methods of the review were received. The methods of the Southampton Health Technology Assessments Centre (SHTAC) economic evaluation can be seen in Chapter 5 (Methods for SHTAC independent economic analysis).

Identification of studies

A sensitive search strategy was developed and refined by an experienced information scientist and was based upon that used in previous technology assessment reports. 17,44 Separate searches were conducted to identify studies of clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, QoL, resource use/costs and epidemiology. The different search strategies are provided in Appendix 2.

Searches for clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness literature were undertaken from April 2007 (the date the most recent search was conducted48) to October 2009. References identified in the previous hepatitis C technology assessment reports17,44 in which literature searching extended back to the year 2000 were incorporated into the searches. Search filters were run, where possible, to locate RCTs and searches were restricted to the English language. The strategies were applied to the following databases:

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR)

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

-

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) (University of York) databases: Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) and the HTA database

-

MEDLINE (Ovid)

-

EMBASE (Ovid)

-

PREMEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (Ovid)

-

Web of Science with Conference Proceedings: Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE) and Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science (CPCI) (ISI Web of Knowledge)

-

Biosis Previews (ISI Web of Knowledge)

-

National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network Portfolio

-

ClinicalTrials.gov

-

Current Controlled Trials.

Bibliographies of retrieved papers were screened for relevant studies, and the manufacturers’ submissions (MSs) to NICE were assessed for any additional studies [see Appendix 3 for a critique of the clinical effectiveness section of the MS, and Chapter 5 (Review of manufacturers’ submissions) for further discussion of the cost-effectiveness section]. Experts who were contacted for advice and peer review were also asked to identify additional published and unpublished references. All search results were downloaded into a reference manager (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY, USA) database.

Key hepatitis C websites and symposia were also searched for completed or ongoing studies and background resources. These included:

-

European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL)

-

British Association for the Study of the Liver (BASL)

-

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)

-

British Viral Hepatitis Group (BVHG)

-

British Liver Trust

-

British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG)

-

International HIV and Hepatitis Co-infection workshop

-

Health Protection Agency

-

Hepatitis C Trust.

Inclusion process

Titles and abstracts identified by the search strategy for the clinical effectiveness section of the review were assessed for possible eligibility by one reviewer using an inclusion worksheet (see Appendix 4) based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria detailed below. The full texts of relevant papers were then obtained and inclusion criteria were applied independently by two reviewers. Any disagreements over eligibility were resolved by consensus. References identified from our previous searches were rescreened according to the inclusion criteria for the current review.

Titles and abstracts identified by the search strategy for the cost-effectiveness section of the review were assessed for potential eligibility by two reviewers independently. Economic evaluations were considered for inclusion if they reported both health service costs and effectiveness, or presented a systematic review of such evaluations. Full papers were formally assessed for inclusion by two reviewers independently. Data extraction was undertaken by one reviewer and checked by a second.

Inclusion criteria

Study design

Randomised controlled trials were included for the clinical effectiveness review. Trials published as abstracts or conference presentations from 2007 onwards were included only if sufficient details were presented to allow an appraisal of the methodology and the assessment of results to be undertaken. Systematic reviews were used only as a source of references. For the systematic review of cost-effectiveness, studies were eligible for inclusion if they reported the results of full economic evaluations [cost-effectiveness analyses (reporting cost per life-year gained), cost–utility analyses or cost–benefit analyses]. For studies reporting QoL and epidemiology/natural history, a range of study designs were eligible (e.g. cohort studies, cross-sectional surveys).

Interventions

-

Combination therapy comprising ribavirin and either peginterferon alfa-2a or peginterferon alfa-2b.

-

Peginterferon alfa-2a or peginterferon alfa-2b monotherapy (for patients who are unable to tolerate or are contraindicated to ribavirin).

Comparators

For patients who have been previously treated with combination therapy, and for HCV/HIV co-infected patients:

-

BSC (e.g. symptomatic treatment, monitoring, treatment without any form of interferon therapy).

For patients who meet the criteria for receiving shortened courses of combination therapy:

-

standard-duration courses of peginterferon alfa and ribavirin combination therapy (up to 24 or 48 weeks, as appropriate).

Population

Adults with chronic HCV, restricted to people who:

-

have been previously treated with peginterferon alfa and ribavirin in combination but who relapsed/did not respond

-

have HCV/HIV co-infection

-

meet the criteria within the marketing authorisation for receiving shortened courses of peginterferon alfa and ribavirin in combination, namely patients with:

-

– genotype 2 or 3 with LVL* at the start of treatment and an RVR (defined as HCV RNA undetectable by week 4) – shortened course of 16 weeks†

-

– genotype 1 with LVL* and an RVR (defined as HCV RNA undetectable by week 4 and at week 24) – shortened course of 24 weeks

-

– genotype 4 with an RVR (defined as HCV RNA undetectable by week 4 and at week 24) – shortened course of 24 weeks.†

-

(*For peginterferon alfa-2a, LVL is defined as ≤ 800,000 IU/ml;42 for peginterferon alfa-2b, LVL is defined as ≤ 600,000 IU/ml. 43 †Applies only to peginterferon alfa-2a.)

Outcomes

Studies had to report SVR (defined as undetectable HCV RNA at least 6 months after treatment cessation). The following outcomes were also included:

-

virological response (e.g. during treatment)

-

biochemical response (e.g. ALT levels)

-

histological improvement (fibrosis and inflammation)

-

survival

-

adverse effects of treatment

-

HRQoL

-

cost-effectiveness (incremental cost per life-year gained) or cost–utility [incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained].

Data extraction and critical appraisal strategy

Data from included studies were extracted by one reviewer using a standardised data extraction form and checked by a second reviewer. The quality of included RCTs was assessed using criteria recommended by CRD49 (see Appendix 5). Quality criteria were applied by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer. At each stage, any differences in opinion were resolved through discussion.

Methods of data analysis/synthesis

Data were synthesised through a narrative review with tabulation of results of all included studies. Full data extraction forms are presented in Appendix 6. It was not considered appropriate to combine the RCTs in a meta-analysis owing to differences in the drug regimens and also because the population of interest (i.e. patients with LVL and RVR) were often subgroups of the main treatment arms. Any meta-analyses would therefore compromise intention-to-treat (ITT) principles and the data may be biased and not valid.

Consideration was given to performing a pairwise indirect comparison of peginterferon alfa with or without ribavirin with a trial featuring no active treatment (analogous to BSC). For this to be possible, an RCT featuring an arm in which patients were treated with peginterferon alfa would be required, in addition to an RCT featuring a ‘no active treatment’ (e.g. placebo) in patients with HCV/HIV co-infection or previous non-responders or relapsers. A comparator arm common to both RCTs would be necessary, such as non-peginterferon alfa. However, as will be discussed in the following chapter, we did not identify any such studies from our database of RCTs of both peginterferon and non-peginterferon alfa (which we have amassed from our previous technology assessment reports on antiviral treatment for hepatitis C for NICE since 2000). Furthermore, none of the systematic reviews of HCV/HIV co-infected patients identified in our search identified any trials in which a non-active treatment arm was included. 50,51

As antiviral treatment for HCV has been available for some time – first with interferon alfa monotherapy, followed by the addition of ribavirin as combination therapy, and latterly with the introduction of peginterferon alfa and ribavirin – it is unlikely that any studies, whether randomised or not, will have included a non-active treatment arm, as withholding treatment would not be considered ethical.

Chapter 4 Clinical effectiveness

Results

Quantity and quality of research available

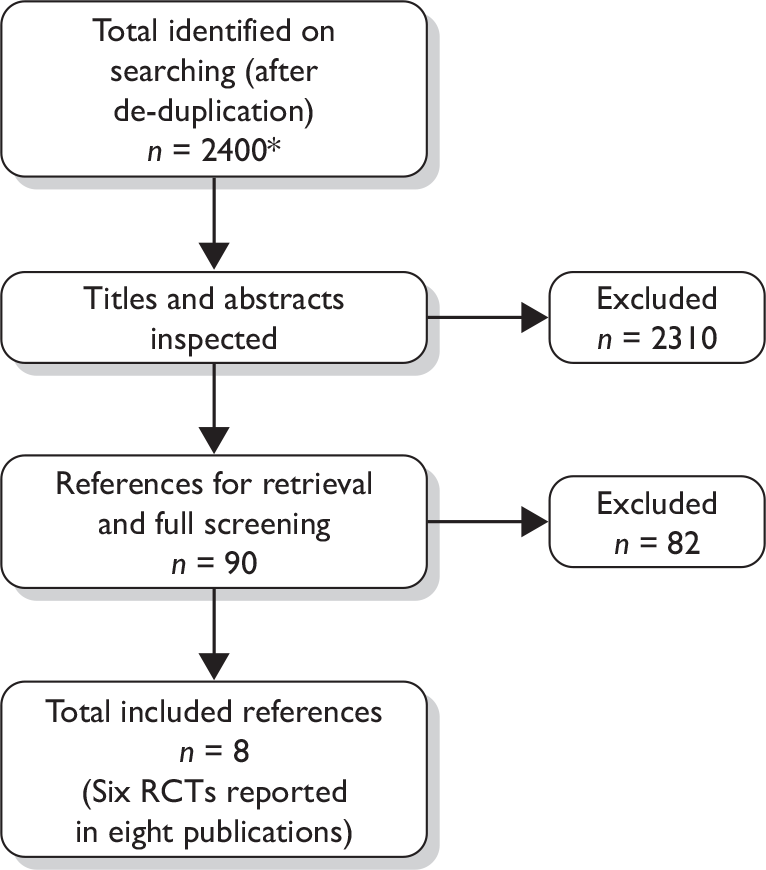

Literature searches identified 1317 references, after the removal of duplicates. A further 1389 references identified from searches conducted for our previous hepatitis C technology assessment reports17,44 were screened according to the inclusion criteria for the present review. After further de-duplication, the total number of records screened was 2400. Following initial screening of titles and abstracts, 2310 references were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria and full copies of 90 articles were retrieved. Of these, 82 were excluded on further inspection, leaving eight included studies. The total number of published papers included at each stage of the systematic review is shown in the flow chart in Figure 1; the list of excluded studies can be seen in Appendix 7.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of identification of studies for inclusion in the review. *Includes total number of studies identified in updated searches and searches from previous hepatitis C assessment reports (n = 2706); further de-duplication left n = 2400 for screening.

Eight publications describing six RCTs met the inclusion criteria of the review. 52–59 Two of the articles were abstracts57,58 linked to full publications. 53,60 All of the included studies report peginterferon and ribavirin combination therapy in patients eligible for shortened treatment duration (i.e. those with specific genotypes as described in Chapter 3, Inclusion crtieria). No RCTs comparing peginterferon alfa with or without ribavirin compared with BSC for the other two population groups specified in the NICE scope (i.e. re-treatment following previous non-response or relapse, and HCV/HIV co-infection) were identified through our searches. A number of RCTs comparing peginterferon alfa with or without ribavirin to active treatment comparators were identified (e.g. peginterferon alfa and ribavirin vs non-peginterferon alfa and ribavirin) but these did not meet the inclusion criteria for the review, which was based on the scope of the appraisal issued by NICE. 61

The remainder of this chapter describes the six trials in patients who were eligible for shortened courses of treatment.

Description of the included trials

The key characteristics of the RCTs are shown in Table 1. Four of the included studies evaluated peginterferon alfa-2a in combination with ribavirin,53–56 one trial (Berg and colleagues59) evaluated peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin, and one trial evaluated peginterferon alfa-2a or peginterferon alfa-2b in combination with ribavirin (Mangia and colleagues52). The comparator in all the studies was the same intervention for a shorter duration. The dose of peginterferon alfa-2a was the same in all the trials (180 µg/week, subcutaneously), as was the dose of peginterferon alfa-2b (1.5 µg/kg/week). Ribavirin was administered orally, according to body weight, at a dose of 1000 mg/day for patients weighing ≤ 75 kg and 1200 mg/day for patients weighing > 75 kg in four studies,52–55 or 800 mg/day for patients weighing ≤ 65 kg, 1000 mg/day for patients weighing 65–85 kg, and 1200 mg/day for patients weighing > 85 kg in one study. 56 Berg and colleagues59 reported only that patients received 800–1400 mg/day ribavirin and it is assumed that the dose was administered according to body weight. It should be noted that in two trials,55,56 the doses of ribavirin used are higher than those stipulated in the current licence for peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin combination treatment (800 mg/day for genotype 2/342,62) owing to changes in the licence since these studies were carried out.

| Study | Methods | Key inclusion criteria | Key patient characteristics | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berg and colleagues 2009 59 |

Design: open-label, multicentre RCT No. of centres: 19 Country: Germany Sponsor: Essex Pharma (subsidiary of Schering-Plough), Bayer Diagnostics, German Competence Network for viral hepatitis Interventions: PEG α-2b + RBV for 48 weeks vs PEG α-2b + RBV for 18, 24, 30, 36, 42 or 48 weeks Follow-up: 24 weeks after treatment cessation No. of participants: n = 433 |

Inclusion criteria: Treatment-naive adults with compensated chronic HCV, genotype 1 Anti-HCV positive HCV RNA > 1000 IU/ml by quantitative reverse transcription PCR Increased ALT levels at screening Liver biopsy consistent with chronic HCV within preceding 24 months Neutrophils ≥ 1500 µl Platelets ≥ 80,000 µl Hb ≥ 12 g/dl for women, ≥ 13 g/dl for men Creatinine < 1.5 mg/dl |

Mean viral load (log10 IU/ml): 5.7 Group 1, 5.7 Group 2 Mean serum ALT × ULN, IU/l: 2.6 Group 1, 2.6 Group 2 Fibrosis score 0–2: 87% Group 1, 85% Group 2 Genotype 1: 100% Mean age: 42 years Gender: 55% male Mode of infection: NR Ethnicity: NR |

Primary outcome: SVR Secondary outcomes: Biochemical responsea On-treatment virological response (RVR, EOT) Relapse rate Adverse events |

| Mangia and colleagues 2008 52 |

Design: multicentre RCT No. of centres: 11 Country: Italy Sponsor: NR Interventions: PEG α-2a or PEG α-2b + RBV for 48 weeks vs PEG α-2a or PEG α-2b + RBV for 24, 48 or 72 weeks Follow-up: 24 weeks after treatment cessation No. of participants: n = 696 |

Inclusion criteria: Treatment-naive adults with compensated chronic HCV, genotype 1 HCV RNA positive Anti-HCV positive Neutrophils ≥ 1500 µl Platelets ≥ 90,000 µl Hb ≥ 12 g/dl for women, ≥ 13 g/dl for men Creatinine < 1.5 mg/dl |

Serum HCV RNA < 400,000 IU/ml: 26% Group 1, 22% Group 2 Serum ALT ≥ 3 ULN: 19% Group 1, 16% Group 2 Fibrosis score 0–2: 62% Group 1, 65% Group 2 Genotype 1a: 9%, 1b: 91% Mean age: 52 years Gender: 56% male Mode of infection: blood transfusion 21%, drug abuse 7%, unknown 72% Ethnicity: NR Treatment: PEG α-2a 46% Group 1, 49% Group 2; PEG α-2b 53% Group 1, 51% Group 2 |

Primary outcome: SVR Secondary outcomes: RVR EOT virological response SVR according to virological response at weeks 4, 8 and 12 Relapse rate Adverse events |

| Liu and colleagues 2008; 53 2008 abstract 57 |

Design: multicentre RCT No. of centres: 5 Country: Taiwan Sponsor: National Taiwan University Hospital, National Science Council & Department of Health, Executive Yuan, Taiwan Interventions: PEG α-2a + RBV for 24 weeks vs PEG α-2a + RBV for 48 weeks Follow-up: 24 weeks after treatment cessation No. of participants: n = 308 |

Inclusion criteria: Treatment-naive adults with chronic HCV, genotype 1 Liver biopsy consistent with chronic HCV within previous 3 months Detectable HCV RNA for > 6 months Presence of anti-HCV antibody Serum ALT > ULN |

Mean viral load (log10 IU/ml): 5.7 Group 1, 5.8 Group 2 Mean serum ALN × ULN: 3.2 Group 1, 3.0 Group 2 Fibrosis score ≥ 3: 77% Genotype 1a: 2%, 1b: 94%, 1a and 1b: 4% Mean age: 54 years Gender: 57% male Mode of infection: NR Ethnicity: 100% Asian |

Primary outcome: SVR Secondary outcomes: RVR EVR EOT virological response Relapse rate Biochemical response Histological response Adverse events |

| Yu and colleagues 2008; 54 2007 abstract 58 |

Design: open-label, multicentre RCT No. of centres: 4 Country: Taiwan Sponsor: Taiwan Liver Research Foundation Interventions: PEG α-2a + RBV for 24 weeks vs PEG α-2a + RBV for 48 weeks Follow-up: 24 weeks after treatment cessation No. of participants: n = 200 |

Treatment-naive adults with chronic HCV, genotype 1 Liver biopsy consistent with chronic HCV within ≤ 1 year of study entry HCV RNA positive Positive for HCV antibodies Elevated serum ALT ≥ 2 measurements within ≤ 6 months of study entry Neutrophils ≥ 1500 mm–3 Platelets ≥ 90,000 µl Hb > 12 g/dl for women, > 11 g/dl for men Creatinine < 1.5 mg/dl |

Mean viral load (log10 IU/ml): 5.43 Group 1, 5.66 Group 2 Serum HCV RNA < 400,000 IU/ml: 55% Serum ALT IU/l: 156 Group 1, 137 Group 2 Fibrosis score 0–2: 75% Group 1, 81% Group 2 Genotype 1: 100% Mean age: 49 years Gender: 57% male Mode of infection: NR Ethnicity: NR |

Primary outcome: SVR Secondary outcomes: RVR EVR EOT virological response Relapse rate Adverse events |

| Yu and colleagues 2007 55 |

Design: open-label, multicentre RCT No. of centres: 4 Country: Taiwan Sponsor: Taiwan Liver Research Foundation Interventions: PEG α-2a + RBV for 24 weeks vs PEG α-2a + RBV for 16 weeks Follow-up: 24 weeks after treatment cessation No. of participants: n = 150 |

Treatment-naive adults with chronic HCV, genotype 2 Liver biopsy consistent with chronic HCV within ≤ 1 year of study entry Seropositive for HCV RNA Seropositive for HCV antibodies Increased serum ALT ≥ 1.5 × ULN for ≤ 2 measurements within 6 months before study entry Neutrophils > 1500 mm–3 Platelets > 9 × 104 mm–3 Hb > 12 g/dl for women, > 11 g/dl for men Creatinine < 1.5 mg/dl |

Mean viral load (log10 IU/ml): 4.88 Group 1, 4.98 Group 2 Serum ALT IU/l: 108.9 Group 1, 107 Group 2 Fibrosis score 0–2: 80% Group 1, 78% Group 2 Genotype 2: 100% Mean age: 50 years Gender: 60% male Mode of infection: NR Ethnicity: 100% Asian (Taiwanese) |

Primary outcome: SVR Secondary outcomes: RVR EOT virological response Relapse rate Adverse events |

| von Wagner and colleagues 2005 56 |

Design: multicentre, Phase IIIb RCT No. of centres: 6 Country: Germany Sponsor: Hoffmann-La Roche and German Hepatitis Network of Competence (Hep-Net) Interventions: PEG α-2a + RBV for 16 weeks vs PEG α-2a + RBV for 24 weeks (RVR) vs PEG α-2a + RBV for 24 weeks (no RVR) Follow-up: 24 weeks after treatment cessation No. of participants: n = 142 |

Treatment-naive adults with compensated chronic HCV, genotype 2 or 3 Liver biopsy consistent with chronic HCV within ≤ 18 months before study entry HCV RNA positive (> 600 IU/ml) Positive for anti-HCV antibodies Elevated serum ALT at screening or study entry Neutrophils > 1500/µl Platelets > 90,000/µl Hb ≥ 12 g/dl for women, ≥ 13 g/dl for men |

Mean viral load (log10 IU/ml): 5.8 Group 1, 5.8 Group 2 Serum ALT × ULN IU/l: 2.8 Group 1, 2.8 Group 2 Mean fibrosis score: 1.6 Group 1, 1.6 Group 2 Genotype 2: 27%, genotype 3: 73% Mean age: 38 years Gender: 65% male Mode of infection: NR Ethnicity: NR |

Primary outcome: SVR Secondary outcomes: RVR EOT virological response Biochemical response Adverse events |

Four trials evaluated treatment in patients with genotype 1,52–54,59 with two of these53,54 comparing the standard 48 weeks’ treatment duration with a shorter 24 weeks’ treatment duration. The other two genotype 1 studies52,59 randomised patients to the standard 48 weeks’ treatment duration or to a variable treatment duration based on the time when HCV RNA first became undetectable. In the Mangia and colleagues trial,52 patients who were first HCV RNA negative at weeks 4, 8 and 12 were treated for 24, 48 and 72 weeks, respectively; in the Berg and colleagues trial,59 time to first HCV RNA negativity was multiplied by a factor of 6, such that patients who were first HCV RNA negative at weeks 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 or 8 were treated for 18, 24, 30, 36, 42 or 48 weeks, respectively. One trial by Yu and colleagues55 assessed treatment in patients with genotype 2, comparing the standard 24 weeks’ treatment duration with a shorter 16 weeks’ treatment duration. The sixth trial by von Wagner and colleagues56 evaluated treatment in patients with genotypes 2 and 3 and had three treatment arms. All patients were treated with combination therapy for an initial period of 8 weeks, and those with an RVR at week 4 were randomised (at week 8) to receive either a further 8 or 16 weeks’ treatment (giving a total treatment duration of 16 vs 24 weeks, respectively). Patients without an RVR at week 4 were allocated (at week 8) to receive a further 16 weeks’ treatment (giving a total treatment duration of 24 weeks).

In five of the RCTs,53–56,59 patients had LVL at baseline (based on the mean viral load) ranging from 4.98 log10 HCV RNA (95,500 IU/ml) to 5.8 log10 HCV RNA (631,000 IU/ml). In the trial by Mangia and colleagues,52 only 24% of patients were reported to have LVL (HCV RNA < 400,000 IU/ml) at baseline. However, the study was included because results were reported for the subgroup of patients with LVL and RVR. The two trials of genotype 2/3 patients55,56 used a cut-off HCV RNA level of ≤ 800,000 IU/ml to differentiate LVL and high viral load. The Berg and colleagues trial59 in genotype 1 patients also used a cut-off of < 800,000 IU/ml, although it should be noted that this threshold for LVL is higher than the threshold of < 600,000 IU/ml specified in the SPC for peginterferon alfa-2b. 43 Two of the trials in genotype 1 patients52,54 used a cut-off of < 400,000 IU/ml. The sixth genotype 1 trial (Liu and colleagues53) presented results for viral load of between 400,000 and 1,000,000 IU/ml, at 200,000 IU/ml intervals, but in the published paper the authors appear to use a cut-off of < 800,000 IU/ml to define LVL. The trials varied in their lower limits of detection of serum HCV RNA. For RVR, a lower limit of < 50 IU/ml was used in three trials,52,54,55 < 25 IU/ml was used in one trial,53 < 600 IU/ml in one trial56 and < 615 IU/ml in the sixth trial. 59 For SVR, most of the trials had a threshold of < 50 IU/ml,52,54–56 whereas Liu and colleagues53 used a lower limit of < 25 IU/ml. In the Berg and colleagues trial,59 HCV RNA negativity was verified using a highly sensitive transcription-mediated amplification (TMA) assay with a detection limit of < 5.3 IU/ml.

All of the included studies were multicentre trials (ranging from 4 to 19 centres), recruiting patients from medical centres, hospitals and/or tertiary referral centres in Taiwan,53–55 Italy52 and Germany. 56,59 The trial by Mangia and colleagues52 was the largest, recruiting 696 patients, followed by Berg and colleagues (n = 433)59 and Liu and colleagues (n = 308). 53 The numbers of participants in the three smaller trials ranged from 142 to 200. Two of the studies received partial funding from the drug manufacturers: von Wagner and colleagues56 were partially sponsored by Hoffmann-La Roche, and Berg and colleagues59 were partially sponsored by Essex Pharma (a subsidiary of Schering-Plough).

All of the trials were based on middle-aged (mean age range 39–53 years) adult patients, with the proportion of male participants ranging from 55% to 73%. Patients were treatment naive in all studies. Two of the studies53,55 reported that 100% of patients were of Asian ethnicity, and it can be assumed that this was also the case for the third Taiwanese study. 54 The ethnicity groups of the three European studies52,56,59 were not reported. Only one trial52 reported the source of infection, although for nearly three-quarters of patients this was unknown: approximately 20% were infected by blood transfusion and 7% via intravenous drug use. The proportion of patients with a fibrosis score of 0–2 was similar in four trials52,54,55,59 (range 62%–87%), with one-fifth56 reporting a mean fibrosis score of 1.6. In contrast, more than three-quarters of patients in the study by Liu and colleagues53 had a fibrosis score of ≥ 3, indicating a greater degree of liver damage.

In general, all six trials had similar inclusion criteria, with patients required to have chronic HCV (as determined by liver biopsy in five trials53–56,59), be positive for anti-HCV antibodies, be HCV RNA positive and have elevated serum ALT levels. 53–56,59 The other primary inclusion criterion was a specific HCV genotype, with patients required to have HCV genotype 1,52–54,59 genotype 255 or genotype 2 or 3. 56

Exclusion criteria were similar across the included trials. All six trials excluded patients with significant comorbidities, such as chronic hepatitis B or HIV infection, autoimmune liver disease or other causes of liver disease, as well as organ transplant, excessive alcohol intake or pregnancy. All except one study52 excluded patients with psychiatric conditions, and four studies52,53,56,59 excluded patients with drug abuse. Further details on exclusion criteria can be found in the data extraction forms in Appendix 6.

All of the trials stipulated certain laboratory readings in their inclusion/exclusion criteria, most of which are related to conditions that are consistent with decompensated liver cirrhosis, such as thrombocytopenia, anaemia and neutropenia. Patients were required to have a neutrophil count of > 1500 cells/mm3, a platelet count ranging from at least 70,000 cells/mm3 to at least 90,000 cells/mm3, haemoglobin (Hb) levels of ≥ 11–12 g/dl for women and ≥ 12–13 g/dl for men, and creatinine level of < 1.5 mg/dl. 53–55,59,63

All six RCTs reported SVR as the primary outcome measure. In terms of secondary outcomes, RVR and end-of-treatment (EOT) virological response were reported by all six trials, with some trials also reporting EVR at week 12 of therapy53,54 and relapse rate. 53–55,59 Biochemical response (ALT levels) was reported by two trials53,56 and histological response by one trial. 53 Five RCTs52–54,56,59 presented SVR rates according to RVR and viral load. All six trials reported adverse events in some way but none reported HRQoL.

Characteristics for the third treatment arm in the von Wagner and colleagues trial56 are not discussed here, as this group did not achieve an RVR and thus is not relevant to this review. It is not possible to report baseline characteristics for the 24-week subset of the variable treatment duration groups in the trials by Mangia and colleagues52 and Berg and colleagues,59 as these were not reported separately by the authors.

Quality assessment of included studies

The methodological quality of reporting in the included studies was assessed using criteria set by CRD at the University of York,49 and is shown in Table 2. On the whole, the methodological quality of the trials was good, particularly for the two studies by Yu and colleagues. 54,55 Four trials explicitly reported a computer-generated randomisation procedure that assured true random assignment to treatment groups, while in two studies56,59 details were not reported. The use of a central randomisation procedure assured adequate concealment of allocation in only two trials. 54,55

| Quality criteria | Berg 200959 | Mangia 200852 | Liu 200853 | Yu 200854 | Yu 200755 | von Wagner 200556 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adequate randomisation | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Adequate allocation concealment | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Similarity of baseline prognostic factors | Yesa | Yesa | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Blinding of outcome assessors | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Blinding of care provider | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Blinding of patient | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Unexpected imbalances in dropouts | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| More outcomes measured than reported | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| ITT analysis included: | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Appropriate | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Missing data accounted for | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

The groups appeared similar at baseline on demographic, biochemical and virological characteristics, with most presenting supporting statistical comparisons. However, in the studies by Berg and colleagues59 and Mangia and colleagues,52 the comparability of the standard-treatment-duration group (48 weeks) versus the 24 weeks’ subset of the variable-treatment-duration group is unknown, as characteristics for this subset were not presented. Neither patients nor caregivers were blinded to treatment in any of the trials, but this would not be possible given the treatment regimens. Although the blinding of outcome assessors was unclear in all trials, the possibility of detection bias would be minimal, given the objective hard end point of virological response.

There were no unexpected imbalances in dropouts between groups in any of the studies, nor was there any evidence to suggest that the authors measured more outcomes than they reported, with the exception of the Berg and colleagues study,59 where sustained biochemical response was reported by the authors as a secondary outcome but no results were presented in the publication. All six RCTs undertook an appropriate ITT data analysis for the primary efficacy outcome, although appropriate methods were used to account for missing data in only three trials. 54–56 All of the trials were statistically powered (at 80%) for the primary outcome of SVR between treatment groups as a whole. However, none performed a power calculation for patient subgroups (such as those with RVR and LVL), and therefore these results in the following sections should be interpreted with caution.

Assessment of clinical effectiveness

The results in the following sections relate to the included trials of patients eligible for shortened courses of treatment with the focus on the subgroup of patients with an RVR and LVL, where reported. Results presented in the tables are ordered by genotype.

Sustained virological response

Sustained virological response was defined as undetectable serum HCV RNA (< 50 IU/ml,52,56 25 IU/ml,53 < 5.3 IU/ml59) at the end of 24 weeks’ follow-up in four trials, and as HCV RNA negative (< 50 IU/ml) at the end of treatment and end of follow-up in two trials. 54,55

Sustained virological response was the primary outcome in all six included RCTs. Four of the trials52–54,56 separately reported SVR in the subgroup of patients who achieved an RVR and had LVL at baseline, which is the patient subgroup meeting the licensed criteria for receiving shortened courses of combination therapy (Table 3). Yu and colleagues55 reported SVR for patients who achieved an RVR, but did not further stratify this subset by baseline viral load. However, it can be assumed that rates would be similar to SVR by RVR rates, as the mean baseline viral load was low for both treatment arms, and approximately 83% of the study population had LVL at baseline (< 800,000 IU/ml). Although the trial by Berg and colleagues59 reported SVR in the subgroup of patients who achieved an RVR and had LVL at baseline, the threshold used was either ≤ 800,000 IU/ml or > 800,000 IU/ml, which differs from the threshold of < 600,000 IU/ml specified in the SPC for the study drug peginterferon alfa-2b. 43 For this reason we do not present the results for this subgroup, but instead present the SVRs for the subgroup that achieved an RVR irrespective of the baseline viral load. As the mean viral load for the study sample, as a whole, was log10 5.7 IU/ml (calculated to be around 500,000 IU/ml), these SVRs can be considered, overall, to reflect LVL in accordance with the SPC.

| Study details | Group 1 | Group 2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype 1 | ||||

| Berg and colleagues 2009 59 | PEG α-2b + RBV a | PEG α-2b + RBV | ||

| 48 weeks, n = 225 | 24 weeks, n = 28 b | |||

| SVR by RVR, % (n/N ) | 42 (8/19) | 57 (16/28) | NR | |

| Mangia and colleagues 2008 52 | PEG α-2a or α-2b + RBV | PEG α-2a or α-2b + RBV | ||

| 48 weeks, n = 237 | 24 weeks, n = 123 c | |||

| SVR by RVR and baseline viral load,% (n/N ) | < 400,000 IU/ml | 83.3 (20/24) | 84.4 (38/45) | 0.83 |

| ≥ 400,000 IU/ml | 86.8 (33/38) | 73.1 (57/78) | 0.14 | |

| Liu and colleagues 2008 53 | PEG α-2a + RBV | PEG α-2a + RBV | ||

| 48 weeks, n = 154 | 24 weeks, n = 154 | |||

| SVR by RVR and baseline viral load,% (n) | < 400,000 IU/ml | 100 (42) | 94 (49) | 0.25 |

| < 600,000 IU/ml | 100 (50) | 93 (61) | 0.13 | |

| < 800,000 IU/ml | 100 (57) | 94 (69) | 0.13 | |

| < 1,000,000 IU/ml | 100 (61) | 92 (71) | 0.03 | |

| Yu and colleagues 2008 54 | PEG α-2a + RBV | PEG α-2a + RBV | ||

| 48 weeks, n = 100 | 24 weeks, n = 100 | |||

| SVR by RVR and baseline viral load, % (n/N ) | < 400,000 IU/ml (n = 52) | 100 (24/24) | 96.4 (27/28) | 1.000d |

| ≥ 400,000 IU/ml (n = 35) | 100 (18/18) | 76.5 (13/17) | 0.045 | |

| Genotype 2/3 | ||||

| Yu and colleagues 2007 55 | PEG α-2a + RBV | PEG α-2a + RBV | ||

| 24 weeks, n = 100 | 16 weeks, n = 50 | |||

| SVR by RVR, % (n/N ) | RVR | 98 (85/87) | 100 (43/43) | 1 |

| No RVR | 77 (10/13) | 57 (4/7) | 0.610 | |

| von Wagner and colleagues 2005 56 | PEG α-2a + RBV | PEG α-2a + RBV | ||

| 24 weeks, RVR n = 71 e | 16 weeks, RVR n = 71 e | |||

| SVR by RVR and baseline viral load, % (n/N ) | ≤ 800,000 IU/ml (n = 66) | 87 (27/31) | 94 (33/35) | NR |

| > 800,000 IU/ml (n = 75) | 75 (30/40) | 69 (24/35) | NR | |

Results for SVR for treatment groups as a whole, SVR by RVR, and SVR by viral load can be seen in the data extraction forms in Appendix 6.

In patients with LVL (≤ 800,000 IU/ml) who attained an RVR, SVR rates were comparable between groups who received the standard duration of treatment and those who received shortened courses, for both genotype 1 and genotypes 2 and 3. Rates were similar in five trials, ranging from 83% to 100% for standard treatment duration compared with 84%–96% for shortened treatment duration, with no statistically significant differences between treatment arms. In addition, SVRs were broadly similar regardless of genotype with the exception of the trial by Berg and colleagues,59 in which SVRs were lower than in the other studies. This may be due to the fact that these rates are only for those who first became HCV RNA negative at week 4 and do not include those who became HCV RNA negative during weeks 1–3 (as a consequence of the study design), whereas in all of the other trials the rates reflect all patients who became negative up to week 4. It should also be noted that patient numbers in these subgroups were small, and none of the trials was powered for this subgroup analysis. In the trial by Mangia and colleagues,52 in particular, only 10% of patients had an RVR and LVL.

For those with high baseline viral load, lower SVR rates were observed in patients who were treated for a shorter duration, although this was reported to be statistically significant in only two trials (100% vs 92%, p = 0.03, at < 1,000,000 IU/ml;53 100% vs 76.5% , p = 0.045, at ≥ 400,000 IU/ml54 for standard vs shortened treatment, respectively).

Virological response during treatment

The included trials varied in their lower limits of detection, with RVR defined as undetectable serum HCV RNA (< 25 IU/ml),53 serum HCV RNA negative (< 50 IU/ml),52,54,55 serum HCV RNA < 600 IU/ml56 or < 615 IU/ml,59 all at week 4 of therapy.

Table 4 presents RVR rates for each of the six included RCTs. There were no statistically significant differences between treatment groups who received the standard duration of treatment compared with those who received shortened courses, for both genotype 1 and genotypes 2 and 3.

| Study details | Group 1 | Group 2 | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype 1 | |||||

| Berg and colleagues 2009 59 | PEG α-2b + RBV | PEG α-2b + RBV | |||

| 48 weeks, n = 225 | 24 weeks, n = 28 a | ||||

| Percentage with response (n/N ):b RVR | 8.4 (19/225)c | 13.5 (28/208)c | NR | ||

| 35 (78/225)d | 37 (76/208)d | ||||

| Mangia and colleagues 2008 52 | PEG α-2a or α-2b + RBV | PEG α-2a or α-2b + RBV | |||

| 48 weeks, n = 237 | 24 weeks, n = 123 e | ||||

| Percentage with response (n/N ): RVR | 26.2 (62/237) | 26.8 (123/459)f | 0.90 | ||

| 100 (123/123)g | |||||

| Liu and colleagues 2008 53 | PEG α-2a + RBV | PEG α-2a + RBV | |||

| 48 weeks, n = 154 | 24 weeks, n = 154 | ||||

| Percentage with response (n): RVR | 63 (97) | 68 (104) | 0.47 | ||

| Yu and colleagues 2008 54 | PEG α-2a + RBV | PEG α-2a + RBV | |||

| 48 weeks, n = 100 | 24 weeks, n = 100 | ||||

| Percentage with response (n): RVR | 42 | 45 | NR | ||

| Genotype 2/3 | |||||

| Yu and colleagues 2007 55 | PEG α-2a + RBV | PEG α-2a + RBV | |||

| 24 weeks, n = 100 | 16 weeks, n = 50 | ||||

| Percentage with response (n/N ): RVR | 87 (87/100) | 86 (43/50) | NR | ||

| von Wagner and colleagues 2005 56 | PEG α-2a + RBV | PEG α-2a + RBV | PEG α-2a + RBV | ||

| 24 weeks, RVR n = 71 h | 16 weeks, RVR n = 71 h | 24 weeks, no RVR, n = 11 h | |||

| Percentage with response: RVR | 100 | 100 | 0 | NR | |

There was a large range in reported RVR between the studies, with rates in genotype 1 patients generally being lower than in genotype 2/3 patients. In the four genotype 1 trials,52–54,59 26%–68% of patients achieved an RVR, although in the subset of patients treated for 24 weeks in the Mangia and colleagues trial52 all of the patients achieved an RVR as per the study design (see Description of the included trials). The rates in this trial were lower than in the other five trials, and this may be due to the smaller proportion of patients (24%) having LVL at baseline. In the trial of genotype 2 patients by Yu and colleagues,55 rates were much higher at 86%. In the study of genotype 2/3 patients,56 two of the three treatment arms had RVR rates of 100% owing to the nature of the study design, whereby patients who achieved an RVR at week 4 were randomised (at week 8) to a total of 16 or 24 weeks’ treatment. In the trial by Mangia and colleagues,52 it is also reported that RVR rates were not significantly different between those treated with peginterferon alfa-2a compared with peginterferon alfa-2b (24% vs 29%, respectively, p = 0.14) (see Appendix 6), although results were not reported for the different treatment arms for the two peginterferons.

Early virological response rates and EOT response rates were similar for patients receiving shortened and standard duration treatment, with no statistically significant differences (where significance values were reported). As these results were presented for all patients rather than the subgroup of patients with RVR and LVL of interest to this systematic review, we have not presented these data here. However, for information they can be found in Appendix 6.

Relapse rate

Relapse was defined as the re-appearance of serum HCV RNA during the 24-week follow-up period in patients who achieved an EOT response. The RCT by Yu and colleagues54 was the only included trial to report the relapse rate in the subgroup of patients with an RVR and LVL (Table 5). In this subgroup, rates of relapse were low and were not statistically significantly different between treatment arms [3.6% vs 0% for 24 vs 48 weeks, respectively, difference 3.6%, 95% confidence interval (CI) –7.2 to 6.6, p = 1.000]. In those with an RVR and high viral load, shortening the duration of therapy resulted in higher rates of relapse, reaching statistical significance (23.5% vs 0 for 24 weeks vs 48 weeks, respectively, p = 0.045).

| Study details | Group 1 (PEG α-2a + RBV 48 weeks, n = 100) | Group 2 (PEG α-2a + RBV 24 weeks, n = 100) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relapse rate by RVR and baseline viral load, % (n/N ) | < 400,000 IU/ml (n = 52) | 0 (0/24) | 3.6 (1/28) | 1.000a |

| ≥ 400,000 IU/ml (n = 35) | 0 (0/18) | 23.5 (4/17) | 0.045 | |

Relapse rates for the other included RCTs can be found in Appendix 6. These have not been presented here because they were reported for the study groups as a whole rather than the subgroup of patients of relevance to this systematic review (i.e. those with both LVL and an RVR).

Biochemical response

Two RCTs reported biochemical response rate (normalisation of ALT levels) (Table 6). 53,56 In one trial of genotype 1 patients (Liu and colleagues53), data were analysed for 248 patients with available paired ALT levels (baseline and end of follow-up). Treatment for 24 weeks resulted in a lower ALT normalisation rate compared with 48 weeks of treatment, with the difference being statistically significant (51% vs 72%, respectively, p < 0.001). However, the study did not report the response rate for the subgroup of patients with an RVR or RVR and LVL. In the trial of genotype 2/3 patients (von Wagner and colleagues56) there was no statistically significant difference in sustained biochemical response rates between groups who achieved an RVR.

| Study details | Group 1 | Group 2 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype 1 | |||

| Liu and colleagues 2008 53 | PEG α-2a + RBV | PEG α-2a + RBV | |

| 48 weeks | 24 weeks | ||

| Percentage with response (n) | 72 (107) | 51 (75) | < 0.001 |

| Genotype 2/3 | |||

| von Wagner and colleagues 2005 56 | PEG α-2a + RBV | PEG α-2a + RBV | |

| 24 weeks, RVR n = 71 | 16 weeks, RVR n = 71 | ||

| Percentage with response | 87 | 89 | NR |

Histological response

Histological response was reported by one trial in patients with genotype 1 HCV (Liu and colleagues53), and was analysed for 295 patients with available paired liver biopsy specimens (baseline and end of follow-up). However, the numbers in each treatment arm were not reported by the authors. Patients who received the shortened treatment regimen had a significantly lower histological response than those treated for the standard duration of 48 weeks (59% vs 78%, respectively, p = 0.001). Again, the study did not report the response rate specifically for the subgroup of patients with an RVR or RVR and LVL (Table 7).

| Study details | Group 1 (PEG α-2a + RBV 48 weeks) | Group 2 (PEG α-2a + RBV 24 weeks) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage with response (n) | 78 (97) | 59 (71) | 0.001 |

Adverse events

Adverse events for the included studies are presented in Table 8. All of the trials presented adverse events for treatment groups as a whole, not for the subgroup of patients achieving an RVR and with LVL.

| Reported adverse events: % (n) of patients affected | Genotype 1 | Genotype 2 | Genotype 2/3 | ||||||||||

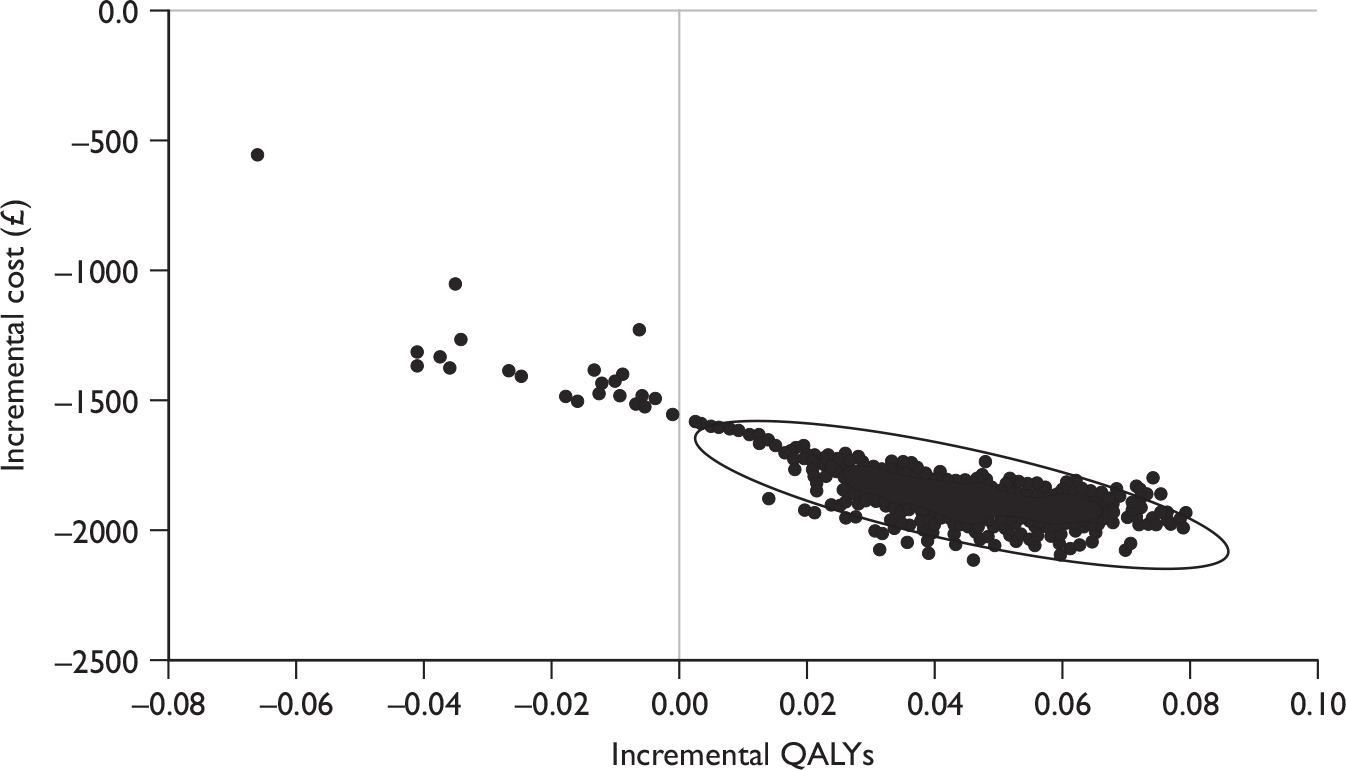

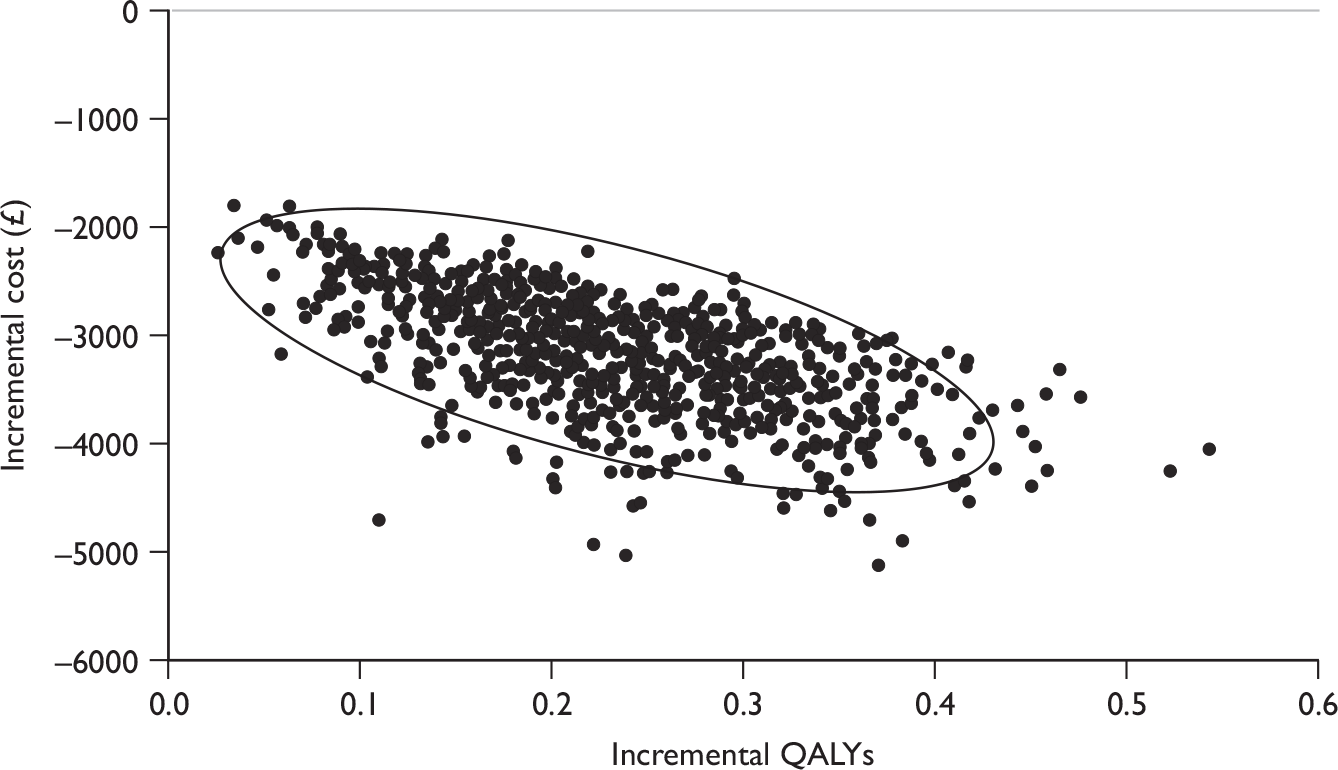

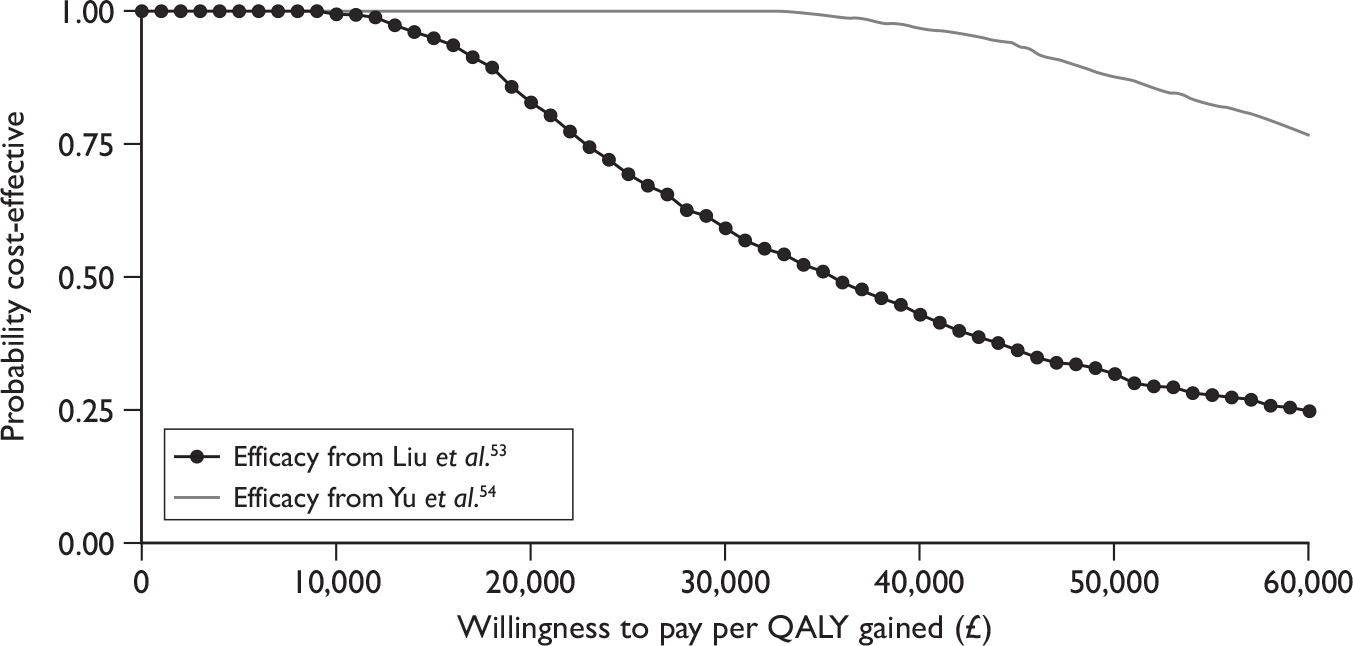

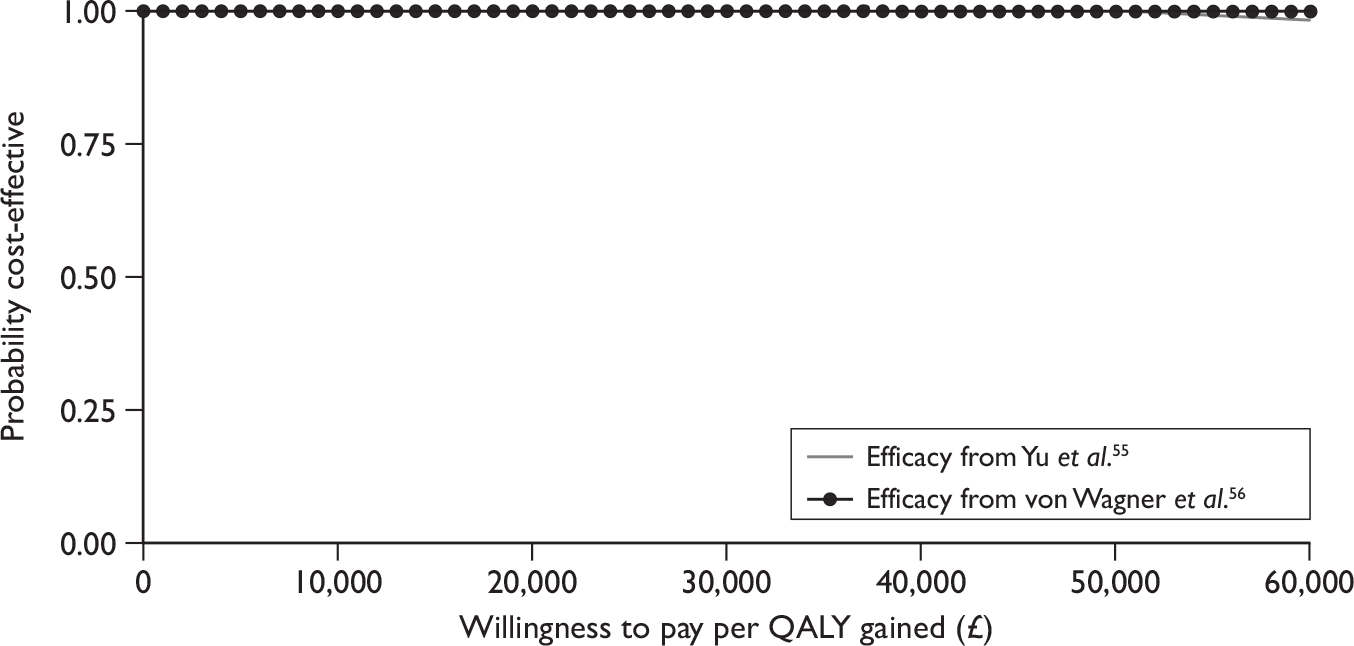

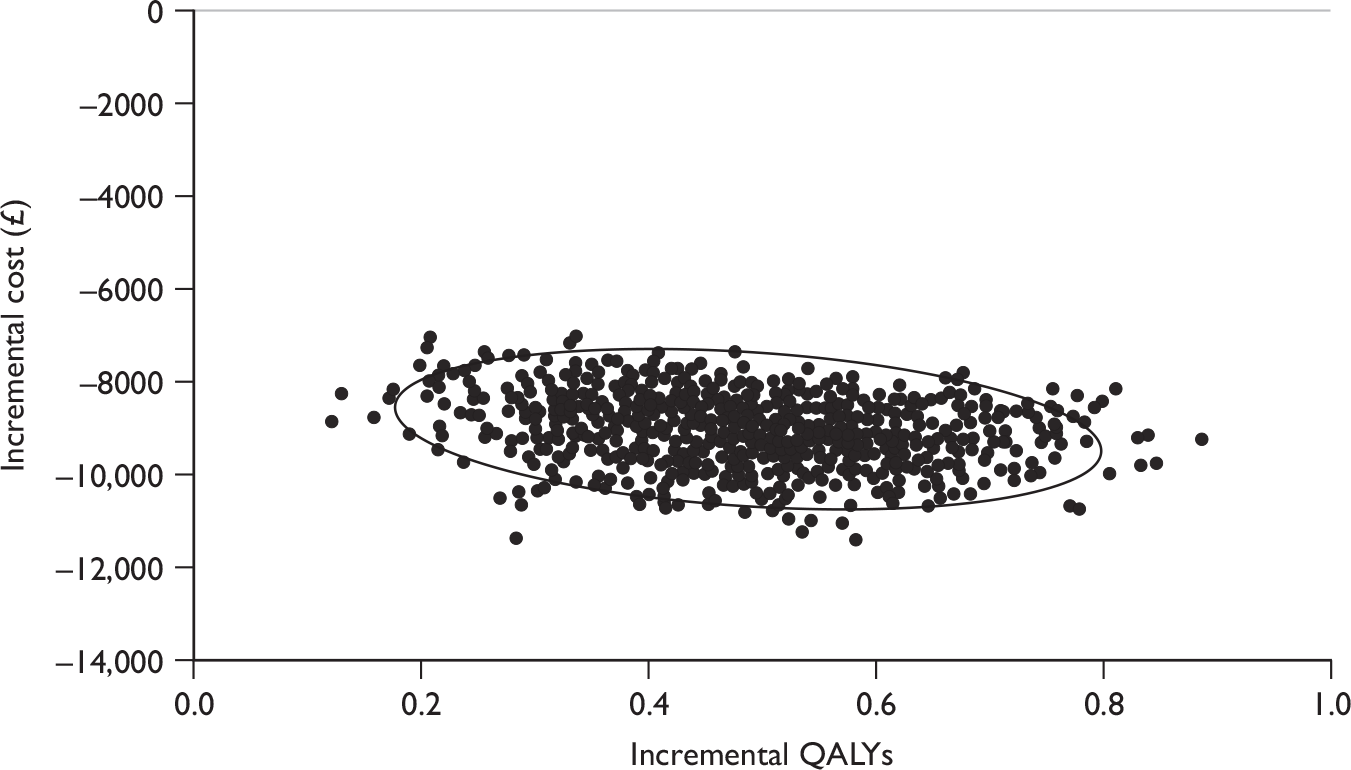

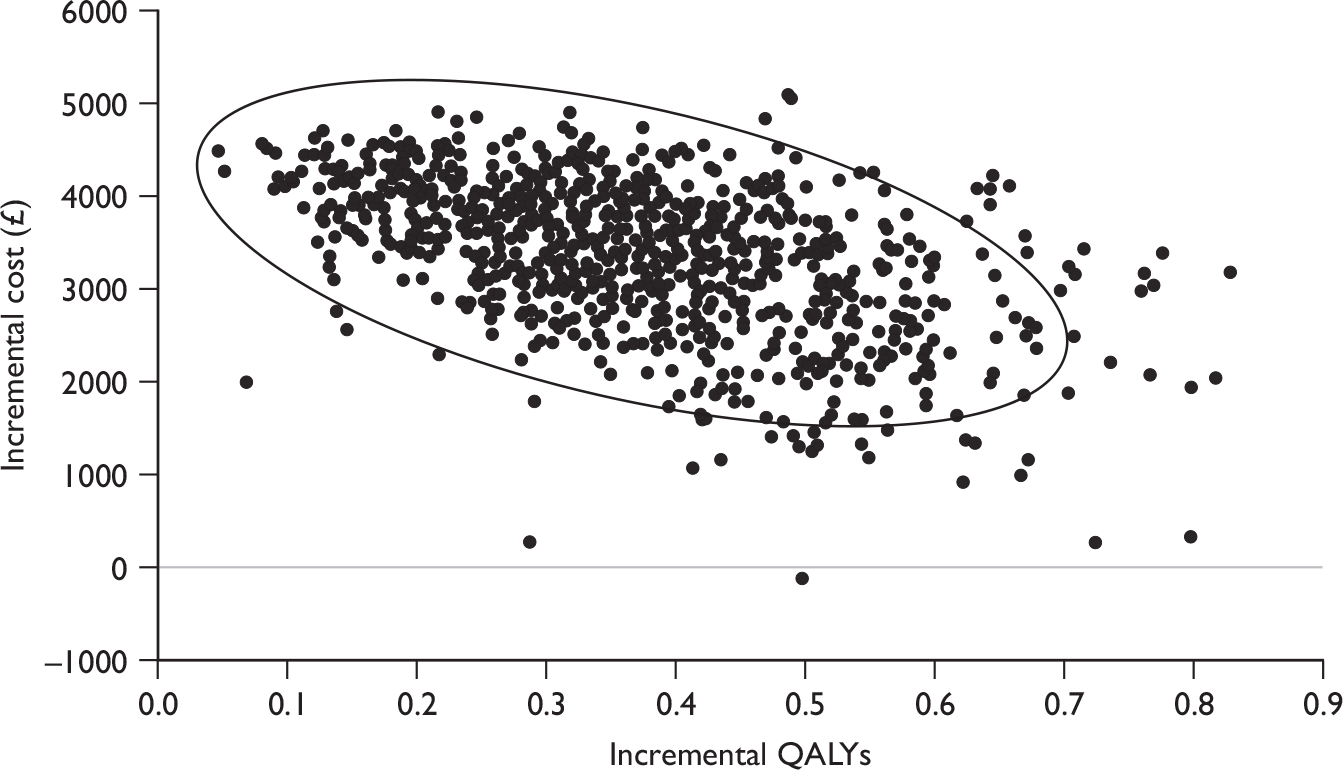

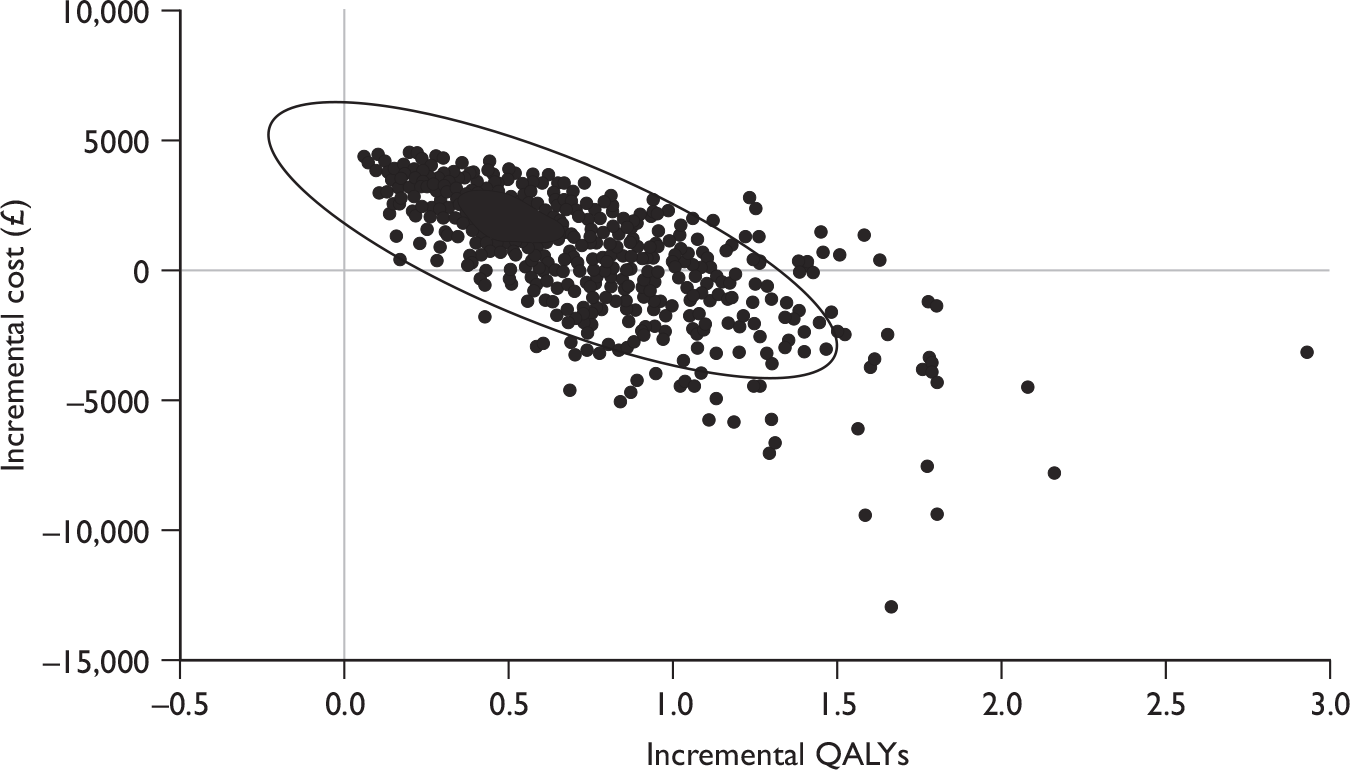

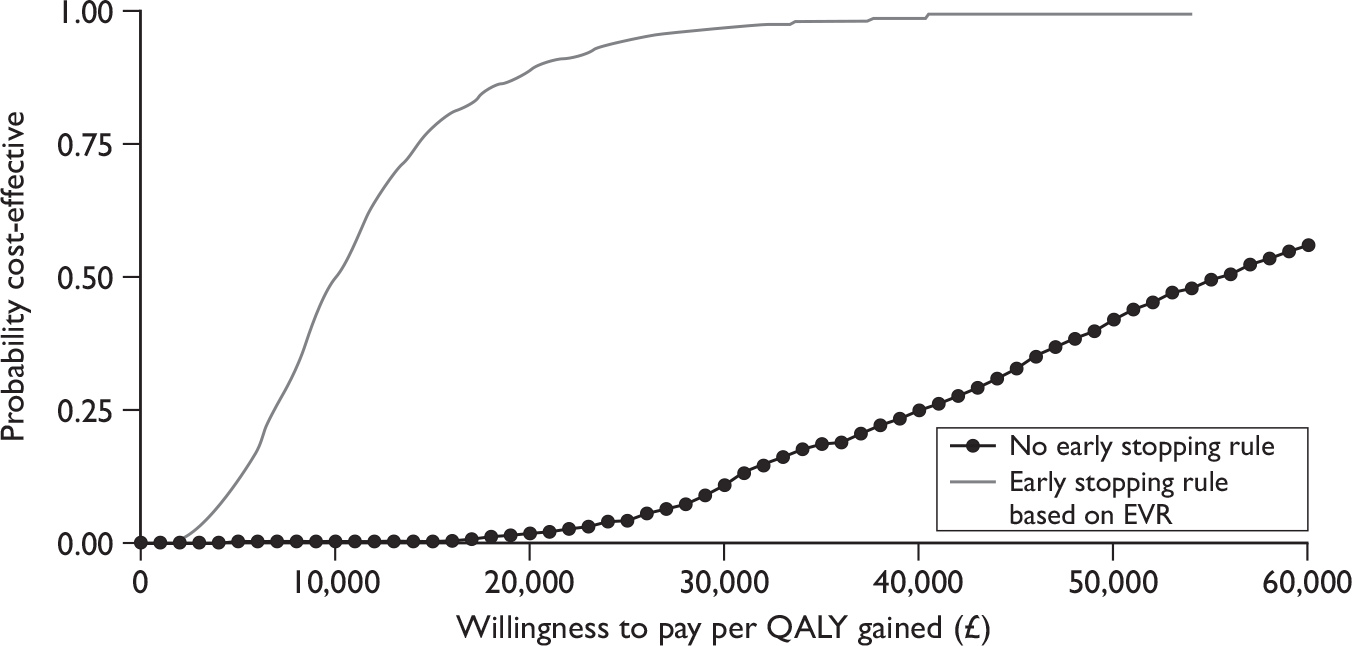

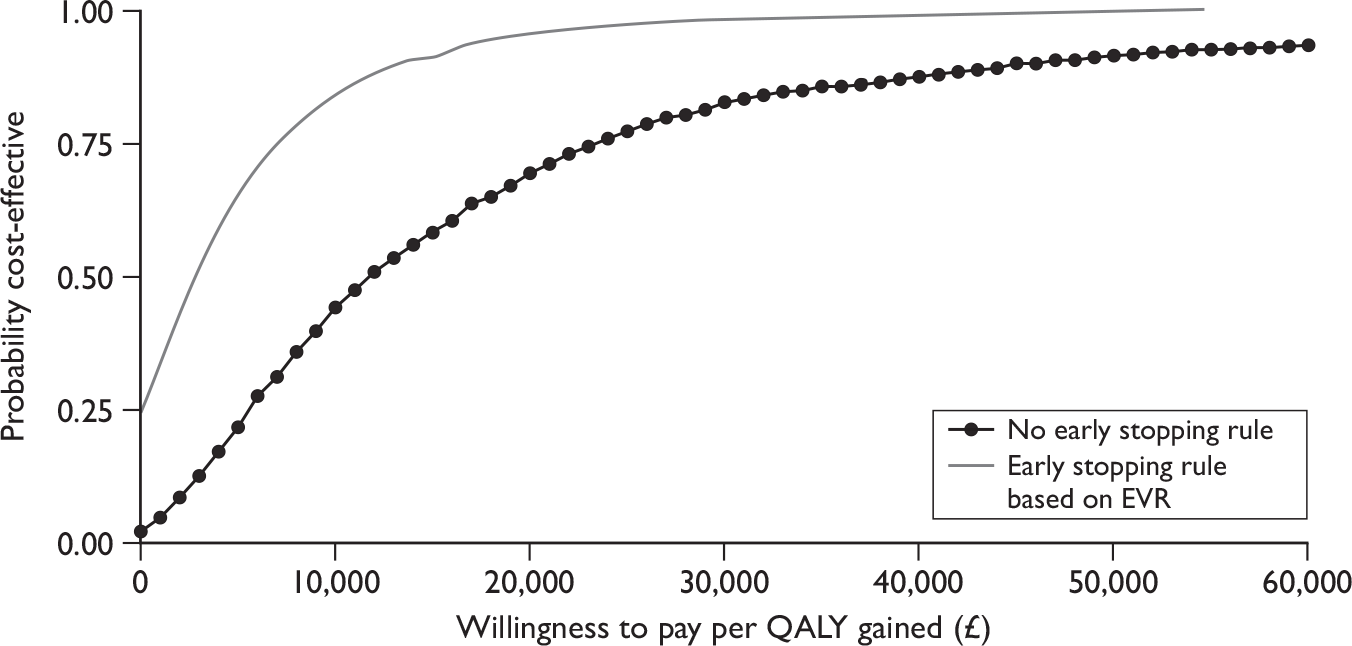

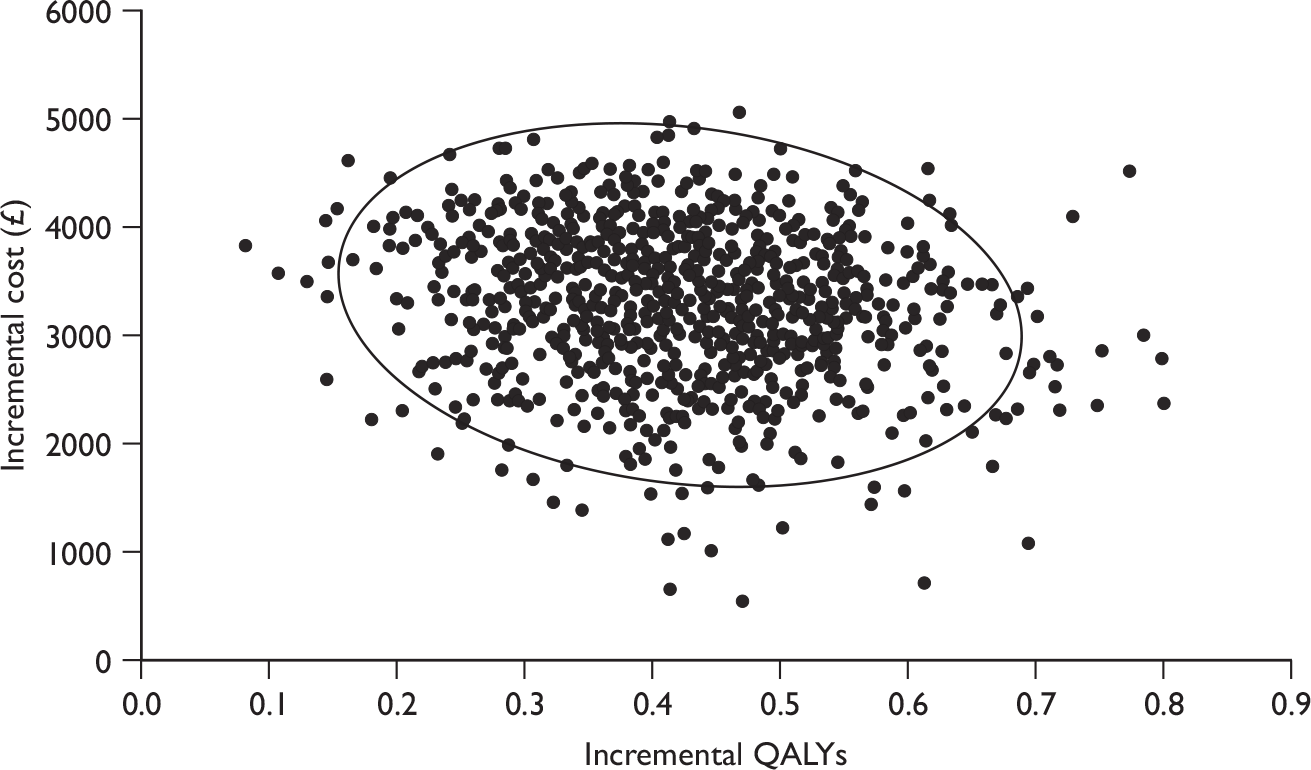

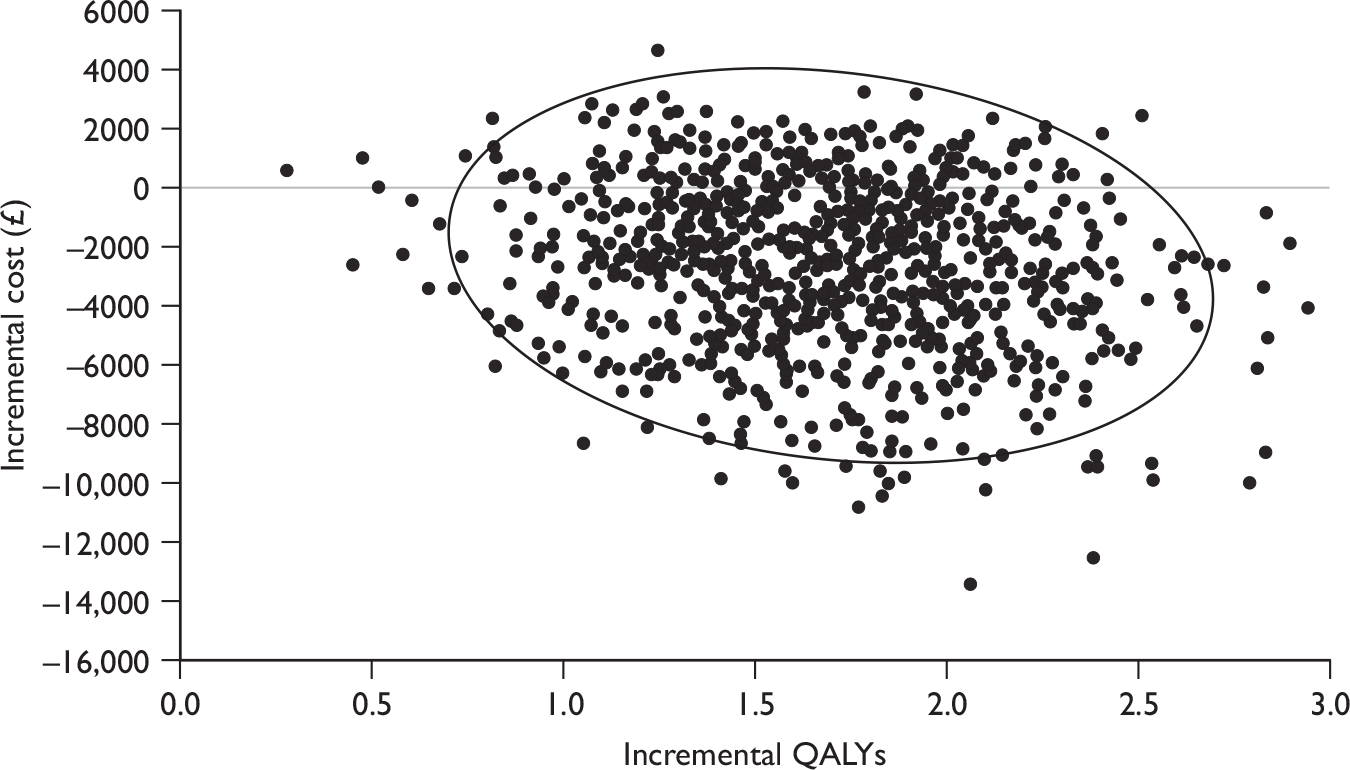

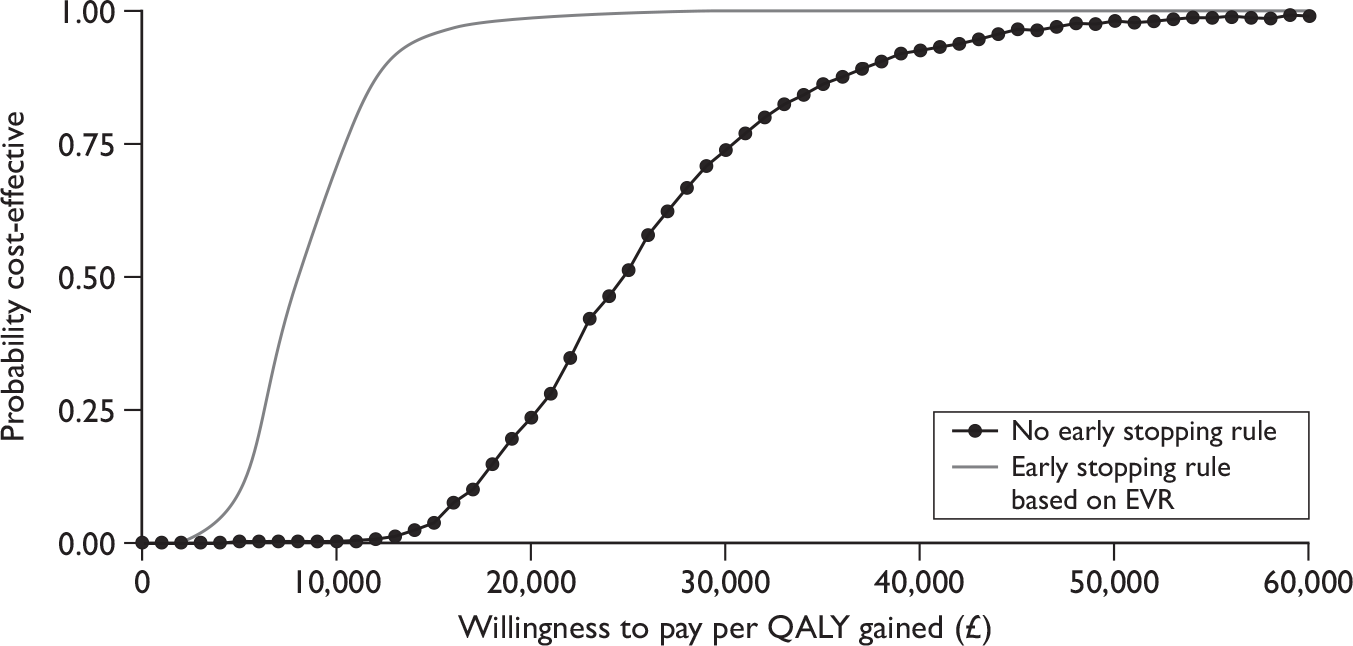

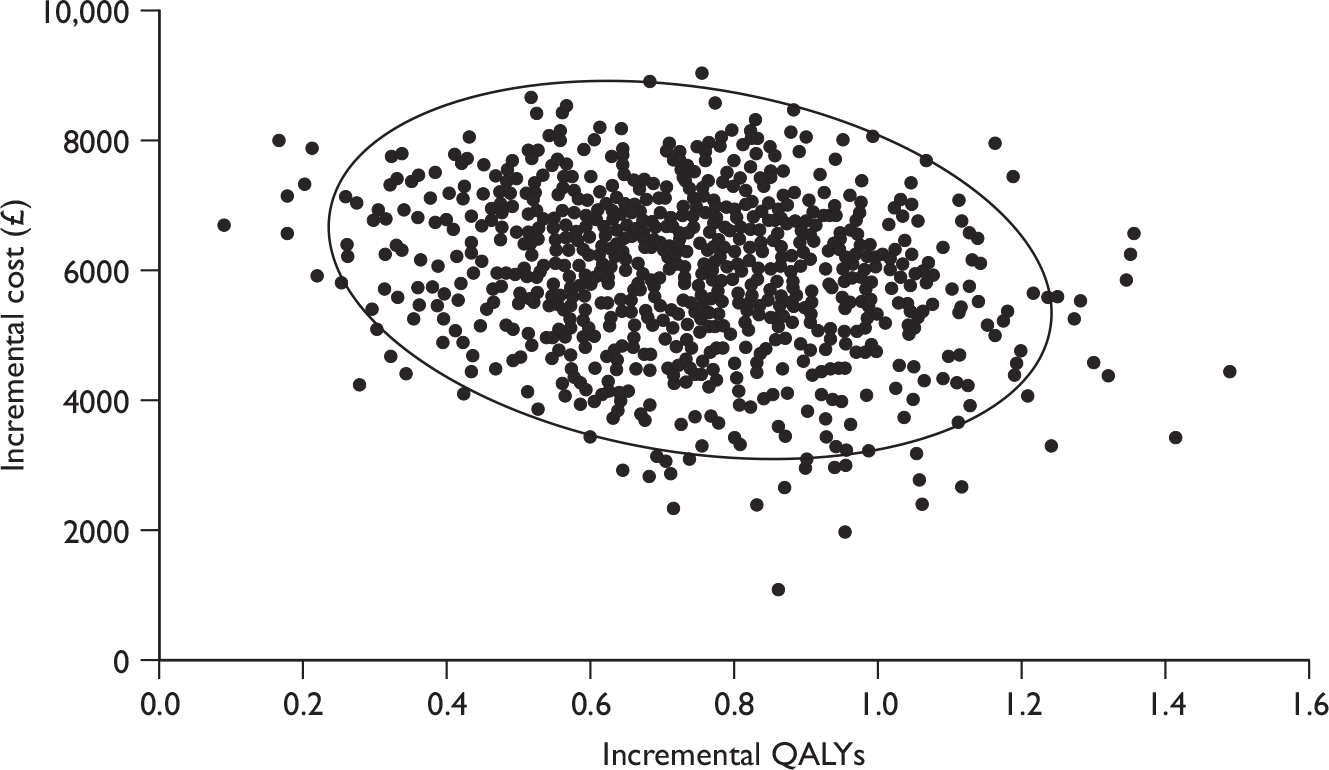

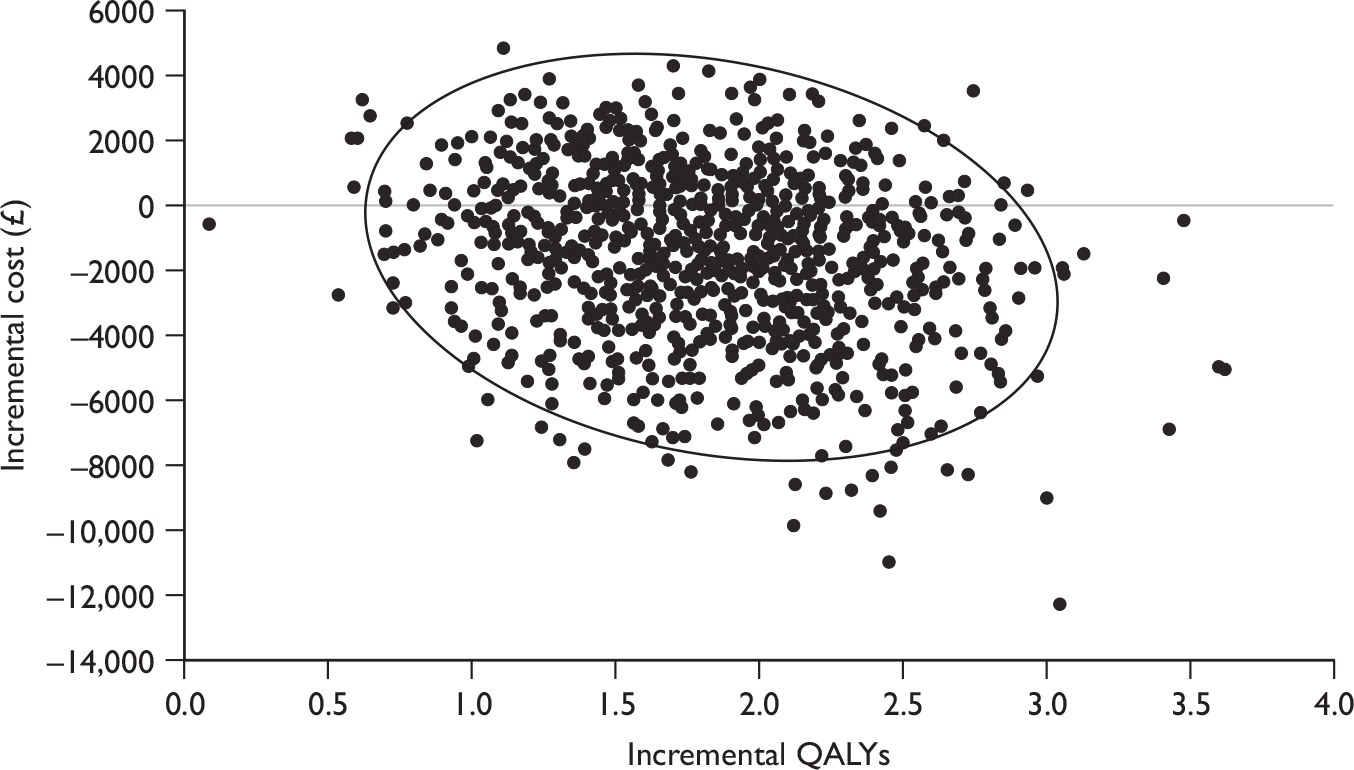

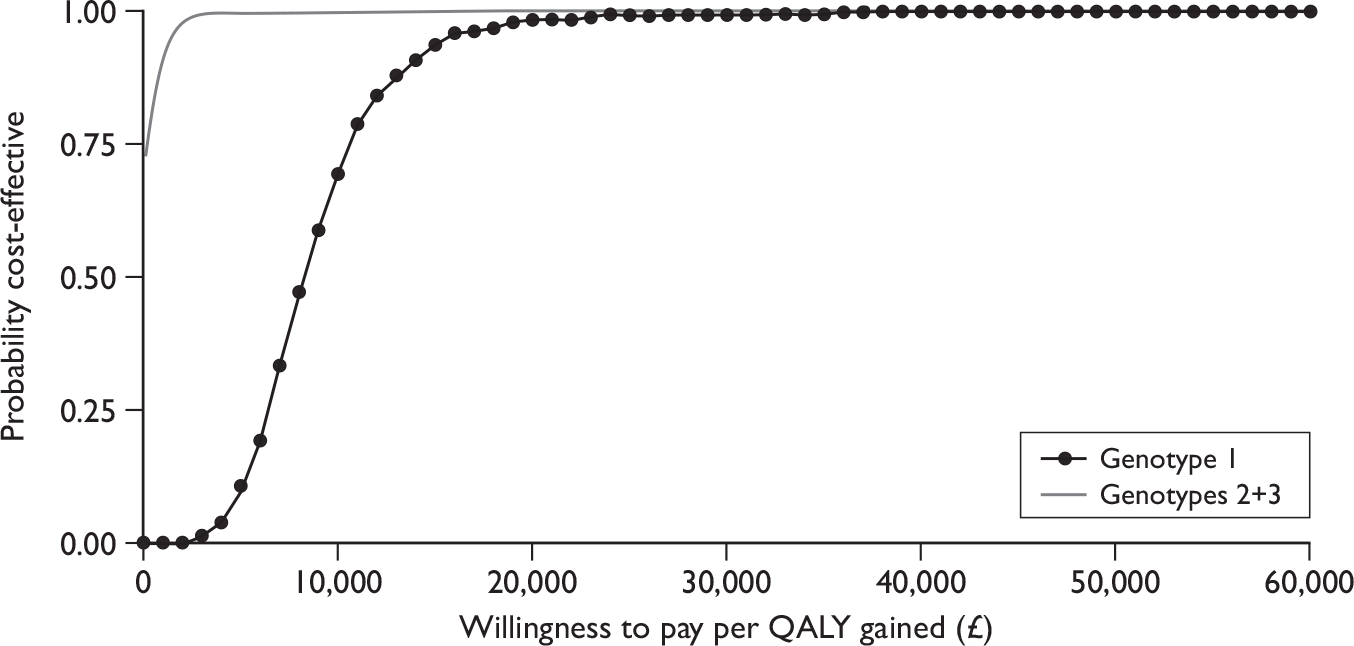

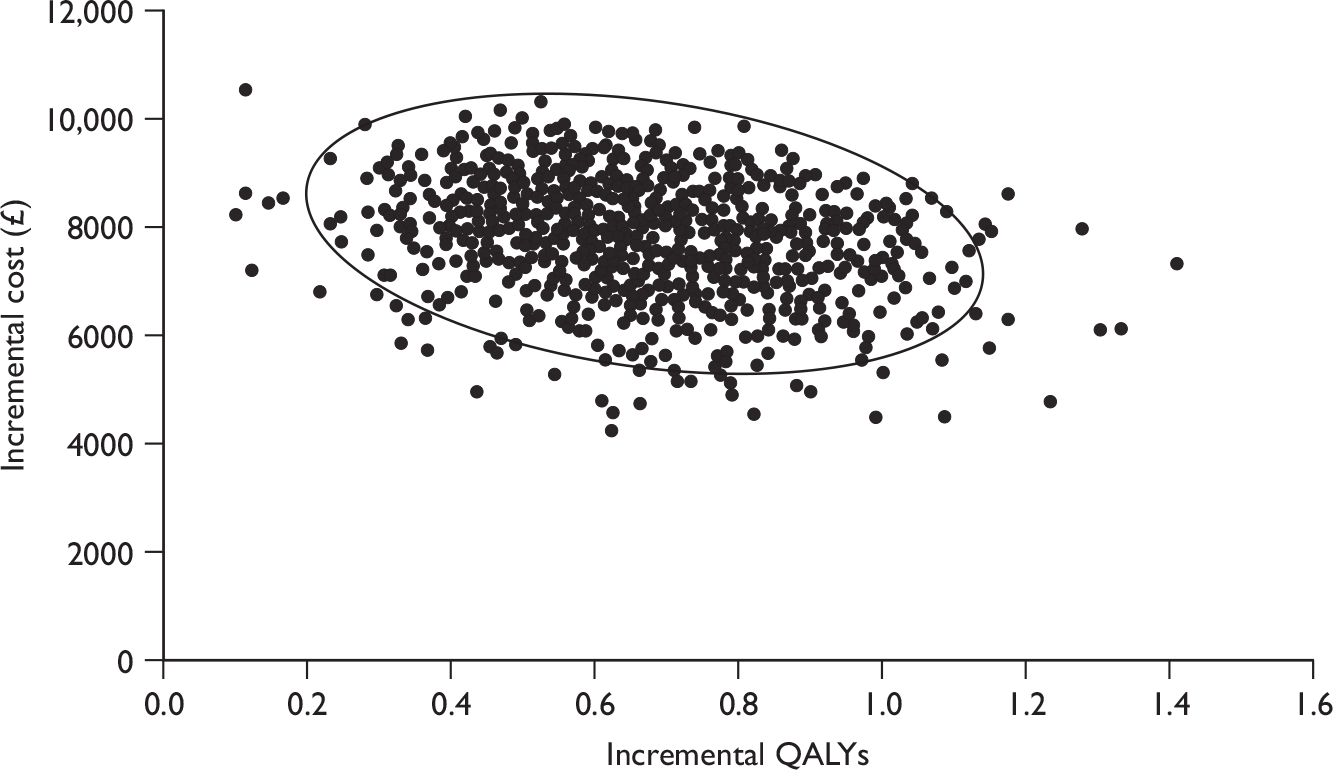

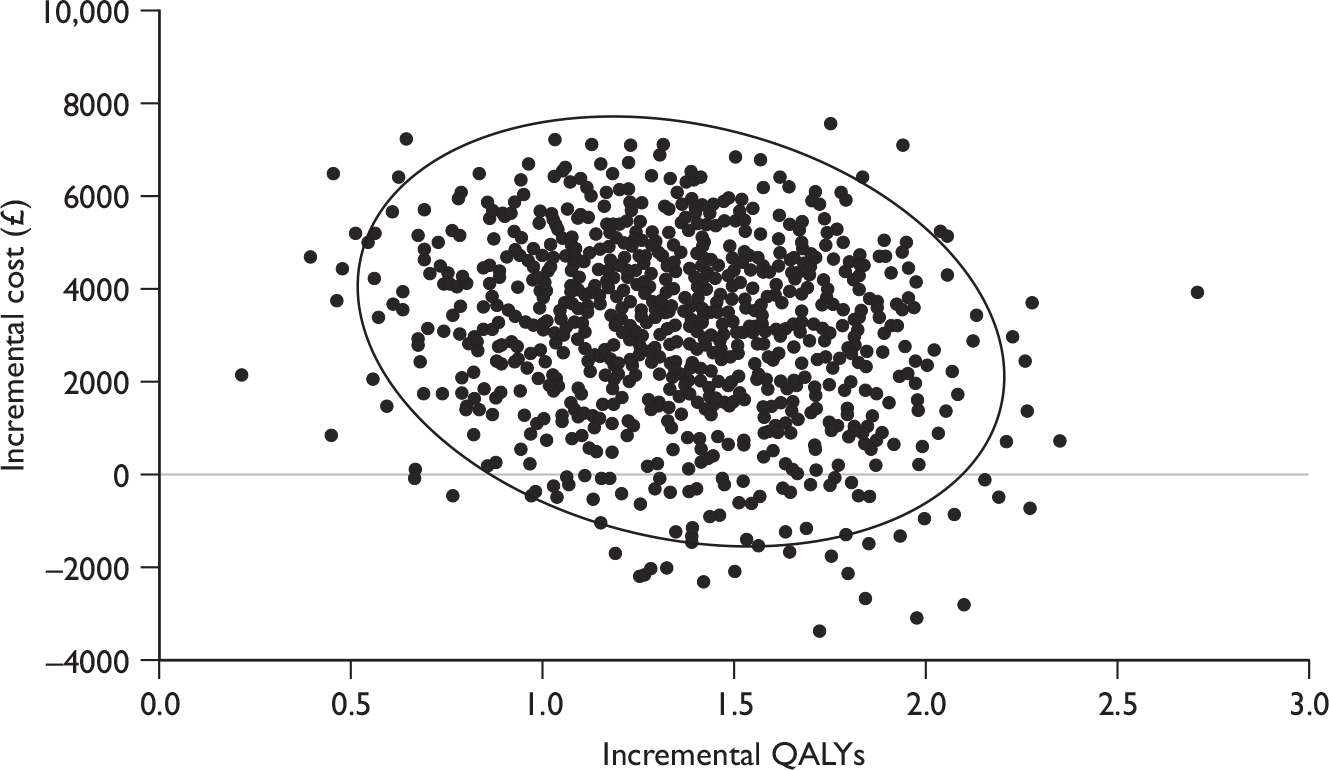

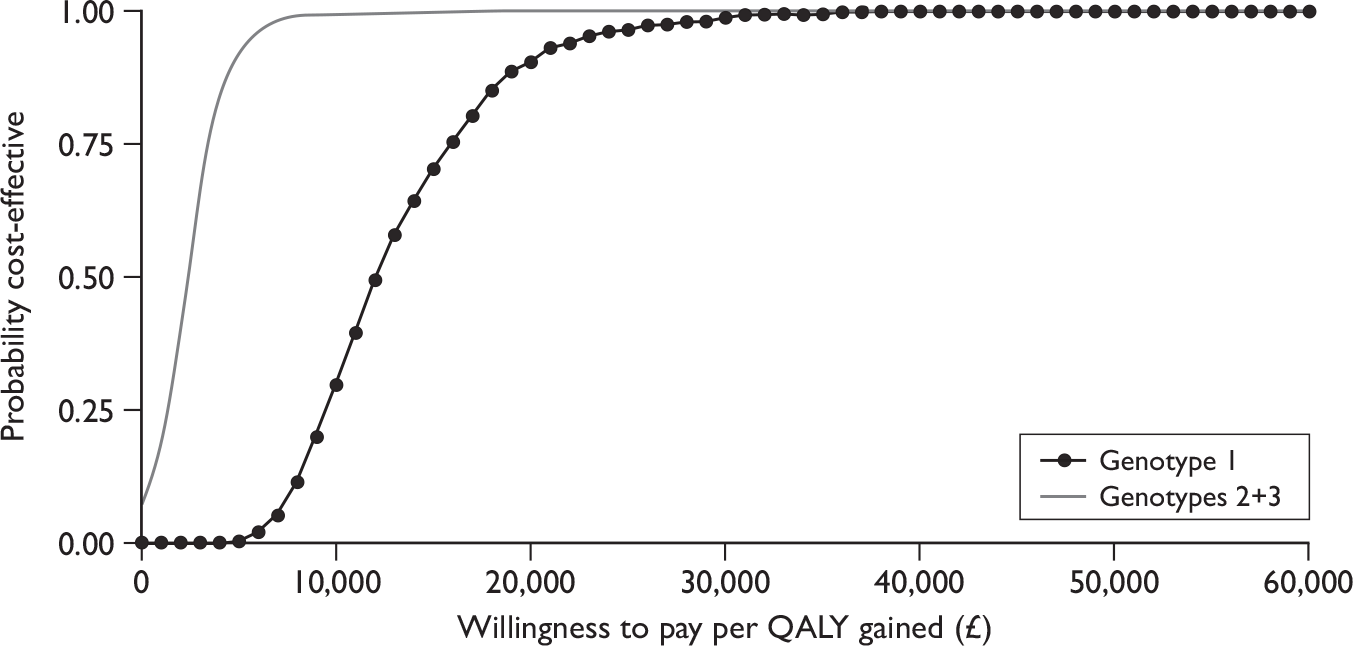

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|