Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 05/45/02. The contractual start date was in September 2007. The draft report began editorial review in February 2010 and was accepted for publication in September 2010. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

S Bhattacharya, K Cooper and P O’Donovan were authors of papers included in the individual patient data meta-analysis. K Cooper received support from Ethicon and Microsubs in the past (not since 2008). P O’Donovan is a member of the Medical Advisory Board of Microsubs since 2009 to the present. P Chien previously attended overseas meetings paid for by Hologic UK; he is also a member of the Clinical Reference Group for the National Audit of Patient Outcomes and Experience of Treatment for Women with Heavy Menstrual Bleeding. P Chien has published several manuscripts on menorrhagia.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2011. This work was produced by Bhattacharya et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) is a common problem1 which affects approximately 1.5 million women in England and Wales. 2 The condition causes 1 in 20 women of reproductive age to consult their general practitioners (GPs) and accounts for 20% of gynaecology outpatient referrals. HMB can cause significant distress to women by affecting their performance at work as well as their social activities, and leads to a measurable reduction in quality of life (QoL). 3 Surgery has been traditionally used as the definitive treatment of HMB such that, in the past, by the age of 55 years one in five women in the UK had a hysterectomy,4 over half of which were for HMB. 5

Definition of heavy menstrual bleeding

Although objectively defined as the loss of > 80 ml of blood per cycle,6 such measurement is impractical in most clinical settings. Between 35% and 60% of women who present with a subjective complaint of HMB have been shown to have normal levels of blood loss. 7,8 Conversely, many women with objectively demonstrable high blood loss do not seek help for associated symptoms. 9

Of various methods used to measure menstrual blood loss, the alkaline haematin technique has been considered to be the gold standard. 10 Despite the introduction of modifications in an effort to simplify it,11 this method remains laborious and involves extraction of haemoglobin from used sanitary wear. As such, it is unsuitable for regular clinical use.

A more practical method of assessing menstrual blood loss is the pictorial blood loss assessment chart (PBAC). 12 This takes into account the number of items of sanitary wear used and the degree of staining, which are in turn converted into a score. This technique is now more widely used than the alkaline haematin method although the correlation between actual measured blood loss and the PBAC score has been questioned. 13 Another indirect method for estimating menstrual blood loss is the ‘menstrual pictogram’,14 which is similar to the PBAC but additionally requires women to comment on the absorbency of the towel or tampon and any extraneous blood loss.

From a clinical perspective, HMB is defined as excessive menstrual blood loss which interferes with a woman’s physical, emotional, social and material QoL, and which can occur alone or in combination with other symptoms. 15

Causes of heavy menstrual bleeding

Possible causes of HMB are shown in Table 1. In most cases a definite cause is not found and the condition is labelled as dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB). 17

| Anatomical | Biochemical | Endocrine | Haematological | Iatrogenic | Associated factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fibroids | Prostaglandins | Hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal–adrenal axis dysfunction | Von Willebrand’s disease | IUDs | Obesity |

| Polyps | Oestrogen-producing tumours | Anticoagulants | Heavy smoking | ||

| Adenomyosis | Thyroid dysfunction | Leukaemia | Exogenous hormones | Excessive alcohol | |

| Infection | Increased endometrial fibrinolytic activity | Depression | |||

| Malignancies | Endometriosis |

Estimating the severity of heavy menstrual bleeding

Subjective estimates of menstrual blood loss do not correlate well with objective measures,13,18 and over half of women who have surgery for HMB do not experience a blood loss of 80 ml or more in each cycle. 8 Women’s expectations of normal menstrual loss can shape their perception of the gravity of their condition, inform their demand for treatment and influence their judgement about treatment success.

The presence of other menstrual symptoms may also have an impact on perceptions of bleeding and account for some of the differences between objective and subjective estimates of menorrhagia. Thus, many women presenting with HMB describe other additional symptoms such as painful periods while associated symptoms are more likely to encourage a diagnosis of HMB by clinicians. The impact of HMB is conventionally measured by means of a number of QoL measures. A systematic review of QoL measures in HMB described 15 generic and two condition-specific scales19 and suggested that there was scope for better ways of assessing the severity of the condition and its impact on women’s lives.

Generic scales allow comparison between different clinical conditions in terms of their impact on QoL and may provide a single score or scores across dimensions of QoL, but are relatively insensitive to specifics of a particular condition. Generic measures of QoL used in HMB include the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36), Nottingham Health Profile, health-status structured history and single global item. 16 SF-36 is generally a well-validated measure used to assess health-related QoL19 and includes items on global health perception, physical function, social function, role (physical and mental), pain, mental health and energy/vitality. 20 The SF-36 has been considered to be a feasible way of assessing QoL in women with HMB, but it has some limitations in this setting21 as some questions can be inappropriate for these women. In addition, internal reliability, as assessed by Cronbach’s statistic, has been shown to be lower in women with HMB, especially for general health perception and mental health scales.

Clark et al. 19 have also reported on the use of generic measures that address particular aspects of QoL such as physical (Modified Townsend Score), mental (General Health Questionnaire) and sexual health (Revised Sabbatsberg Sexual Rating Scale) and social function (Lifestyle Index) in studies of women with HMB bleeding.

Condition-specific scales have the advantage of incorporating attributes of QoL that are specifically affected by the condition of interest. They may therefore be more sensitive to small but important changes and may be considered to have greater face validity (that is, they include items that are of importance to sufferers and reflect their experience and concerns). Two condition-specific outcome measures have been developed for women with HMB. These include the Menorrhagia Outcomes Questionnaire22 and the Multi-attribute Questionnaire. 23 The Menorrhagia Outcomes Questionnaire includes items on symptoms and satisfaction with care, physical function, psychological and social well-being, global judgement of health and QoL, and personal constructs. The Multi-attribute Questionnaire includes items on practical difficulties, social function, psychological function, physical health, interruption to work and family life.

Preference-based measures elicit preferences for a given health state and, if appropriately scaled, provide weights that can be used in cost–utility analyses.

The EQ-5D™ (European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions; Euro Qol Group, Rotterdam, the Netherlands), which has been used in studies as a measure of QoL in HMB, includes a multi-attribute scale, with dimensions of mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression, and a global rating scale for QoL (visual analogue scale).

Measuring patient satisfaction

Patient satisfaction is widely used as a primary outcome measure in studies of treatments for HMB. 24 Satisfaction is a subjective and relative concept and represents the extent to which a service meets users’ expectations. It is not clear whether satisfaction can be measured on a continuum, from dissatisfied through to satisfied, or whether factors resulting in satisfaction are different from those leading to dissatisfaction. 16 Satisfaction is influenced by patient characteristics24 such as age and health status.

The extent to which these potential biases are addressed in the patient satisfaction measures used in studies of HMB is difficult to assess in the absence of detailed accounts of the development and validation of the measures used. While the use of a similar tool to measure subjective satisfaction for women in both arms of an RCT may provide a comparative measure between these groups, it may remain unclear exactly what is being measured for the reasons outlined above. 16 In addition, the range of techniques and scales used to elicit a measure of satisfaction across studies can limit any attempts to aggregate data by means of meta-analysis.

Current service provision

Treatment for HMB aims to improve women’s quality of life through reducing menstrual loss. The current National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline advocates full gynaecological examination followed by appropriate tests such as a full blood count and recognises the need for endometrial biopsy, ultrasound scan and hysteroscopy in specific cases. 15

Medical therapy

According to the recent NICE guideline on HMB,15 medical treatment should be considered where structural and histological abnormalities of the uterus have been excluded or for fibroids < 3 cm in diameter which do not appear to distort the cavity of the uterus. In addition, the contraceptive needs of the woman should be taken into consideration. In addition to being licensed as a contraceptive device, the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG IUS or Mirena®, Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Pittsburg, PA, USA) is an effective non-surgical treatment for HMB which is reversible and fertility sparing. The device, which has to be fitted by a qualified practitioner, has a T-shaped plastic frame and a rate-limiting membrane on the vertical stem which releases a daily dose of 20 µg of LNG. The effects of the LNG IUS are local and hormonal, including prevention of endometrial proliferation, thickening of cervical mucous and suppression of ovulation in a minority of women. It reduces estimated menstrual blood loss by up to 96% by 12 months, with up to 44% of users reporting amenorrhoea,25,26 at a cost which is a third of that for hysterectomy. 27 It has been recommended that LNG IUS should be considered before oral medication such as tranexamic acid, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or combined oral contraceptives. 15 Mirena can lead to troublesome spotting in some women, causing early discontinuation of the device. There are relatively few randomised trials comparing the relative effectiveness of LNG IUS with that of hysterectomy, as well as endometrial ablation (EA), or long-term follow-up data on Mirena use.

Surgical treatment

Despite the availability of a number of medical options, long-term medical treatment is unsuccessful or unacceptable in many cases and surgical alternatives such as EA techniques and hysterectomy may be required. 28 In a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of medical management versus transcervical resection of the endometrium (TCRE) in secondary care, total satisfaction with treatment was higher in women who were treated surgically (39% vs 61%; p = 0.01). 28 The current NICE guideline on HMB suggests that EA may be offered to women who do not desire future fertility and in whom bleeding is considered to have a major impact on QoL. The guideline development group felt that ablative surgery could be offered as the initial surgical treatment for HMB after full discussion about the risks and benefits of other options. 15

Incidence of surgical operations for heavy menstrual bleeding

Of 51,858 hysterectomies in the public sector in England in 1999–2000, it is likely that half were for HMB. 29 Between 1999–2000 and 2004–5, 6500 fewer hysterectomies were performed. 30 In contrast there were 826 hysteroscopic EAs in England in 1989, rising to 7173 in 1992–3, before falling to 3847 in 1997–8. In 2004–5, 9701 EAs were performed, of which over half (5457) used second-generation (non-hysteroscopic directed) methods. 30 With just 7179 hysterectomies performed for HMB over this period, the predominant operation for HMB was now ablation. The use of LNG IUS has increased concurrently, although the widespread use of this device for contraception as well as for the control of HMB across a number of clinical settings (primary care, sexual reproductive health as well as gynaecology clinics in secondary care) makes it difficult to gather accurate data on uptake rates.

Hysterectomy

Hysterectomy is defined as the surgical removal of the uterus. It offers a definitive treatment for menorrhagia and guarantees amenorrhoea, but is particularly invasive and carries risk of significant morbidity. 31 Hysterectomy can be performed through a number of routes. In abdominal hysterectomy the uterus is approached through the anterior abdominal wall, while vaginal hysterectomy involves surgical removal of the uterus through the vagina. In laparoscopic hysterectomy surgery is accomplished without the need for a laparotomy. Laparoscopic hysterectomy includes three subtypes: (1) laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy; (2) laparoscopic hysterectomy; and (3) total laparoscopic hysterectomy. In addition, laparoscopically assisted supracervical hysterectomy involves removal of the body of the uterus while the cervix is retained.

Hysterectomy can also be categorised on the basis of the extent of the operation and organs removed. Removal of the uterus and cervix constitutes total hysterectomy, while excision of the body of the uterus while conserving the cervix is defined as subtotal hysterectomy. Removal of the uterus alone is conventionally known as simple hysterectomy, while additional removal of the fallopian tubes and ovaries or ovaries alone is referred to as salpingo-oophorectomy or oophorectomy, respectively. Oophorectomy is usually performed in the presence of ovarian pathology but can also be carried out prophylactically to avoid the risk of cancer. Removal of the ovaries in cases of HMB is incidental. 15 Of 37,000 hysterectomies performed in the UK in 1994–5, two-thirds were abdominal (4% of these were subtotal hysterectomies) and 57% were accompanied by removal of tubes and ovaries. 5

Hysterectomy is generally performed as an inpatient procedure. The need for general anaesthesia, prolonged hospital stay and delayed recovery makes it a potentially expensive treatment. 32 Overall, 1 in 30 women suffers a major adverse event after hysterectomy, and the mortality rate is 0.4–1.1 per 1000 operations. Around 3% of women suffer from perioperative problems such as haemorrhage, trauma to other pelvic organs and anaesthetic problems. Immediate postoperative complications include sepsis, bleeding and venous thromboembolism. Adverse events following hysterectomy are summarised in Table 2. Although delayed complications including urinary incontinence, fatigue, pelvic pain, hot flushes and sexual problems have been reported,5,33–35 satisfaction rates following hysterectomy are very high. 31

| Very common (> 1 in 10) | Common (> 1 in 100, < 1 in 10) | Uncommon (> 1 in 1000, < 1 in 100) |

|---|---|---|

| Sepsis | Haemorrhage | Death |

| Pyrexia | Blood transfusion | Fluid overload |

| Wound haematoma | Anaemia | Visceral damage |

| Hypergranulation | Vault haematoma | Respiratory/heart complications |

| Urinary tract infection (UTI) | Anaesthetic | Deep-vein thrombosis |

| Diarrhoea | ||

| Ileus |

Endometrial ablation

Endometrial ablative techniques, which aim to destroy functionally active endometrium along with some underlying myometrium,36,37 offer a conservative surgical alternative to hysterectomy. The first-generation ablative techniques including endometrial laser ablation (ELA),38,39 TCRE40 and rollerball endometrial ablation (RBEA) were all endoscopic procedures. Although none guarantees amenorrhoea, their effectiveness (in comparison with hysterectomy) has been demonstrated in a number of RCTs. 41–46

National audits47,48 revealed that, although first-generation ablative techniques were less morbid than hysterectomy, they were associated with a number of complications, including uterine perforation, cervical laceration, false passage creation, haemorrhage, sepsis and bowel injury. In addition, fluid overload associated with the use of 1.5% urological glycine (non-ionic) irrigation fluid in TCRE and RBEA resulted in serious and occasionally fatal consequences due to hyponatraemia. 49,50 Mortality from these techniques has been estimated at 0.26 per 1000. 47,48

Second-generation ablative techniques represent simpler, quicker and potentially more efficient means of treating menorrhagia, which require less skill on the part of the operator. Examples of second-generation ablative techniques are fluid-filled thermal balloon EA (TBEA), radiofrequency (thermoregulated) balloon endometrial ablation, hydrothermal EA, 3D bipolar radiofrequency EA, microwave endometrial ablation (MEA), diode laser hyperthermy, cryoablation and photodynamic therapy. The most common techniques in the UK are TBEA (ThermaChoice®, Ethicon, Livingston, UK and Cavaterm™, Pnn Medical SA, Morges, Switzerland)51–53 and MEA,54,55 while the NovaSure® (Hologic Inc., Bedford, MA, USA) device56 is becoming more widely used.

First-generation endometrial ablation techniques

Early methods of EA which require direct hysteroscopic visualisation of the endometrial cavity such as TCRE, RBEA and ELA are known as ‘first-generation’ ablation techniques. 57 A national survey demonstrated that 99% of first-generation ablative procedures were performed under general anaesthetic. 47 Endometrial thinning agents are conventionally used prior to ablation in order to ensure an adequate depth of destruction. Drugs such as danazol and gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues have been shown to improve operating conditions for the surgeon and increase postsurgical amenorrhoea rates. 58 GnRHs were found to produce slightly more consistent endometrial thinning than danazol, although both produced satisfactory results. 58

Transcervical resection of the endometrium requires a hysteroscope with a fibre optic cable to transmit light from an external power source. The cervix is dilated prior to insertion of the resectoscope, which provides a 12° angle of view. A continuous-flow outer sheath circulates liquid (usually glycine) to provide a clear view of the uterine cavity. A cutting loop is used to remove the endometrial lining. TCRE provides good samples of endometrium for biopsy. 16 TCRE may also be used for the excision of small fibroids, and the operation17 is usually done as a day case.

Rollerball EA also requires visualisation and irrigation using a resectoscope. EA is achieved by means of a rollerball (RB) electrode rather than a cutting loop. A current is passed through the ball which is moved across the surface of the endometrium. 59 As the RB fits better within the cornua and decreases the chance of perforating this relatively thin-walled part of the uterus,47 some surgeons prefer to use the RB to treat this area. In the UK, it is usual for TCRE to be used to treat the uterine walls while RBEA is used for the fundus and cornua. 60

Potential perioperative adverse effects associated with TCRE and RBEA include electrosurgical vaginal and vulval burns, uterine perforation, haemorrhage, gas embolism, infection and fluid overload (which may cause congestive cardiac failure, hypertension, haemolysis, coma and death). Strategies for avoiding fluid absorption include maintaining the minimum intrauterine pressure compatible with safe surgery, using an efficient suction system to retrieve irrigation fluid and maintaining a strict fluid balance. 39

Possible adverse effects of first-generation ablation techniques are shown in Table 3.

| Common (> 1 in 100, < 1 in 10) | Uncommon (> 1 in 1000, < 1 in 100) |

|---|---|

| Haemorrhage | Death |

| Uterine perforation | Pregnancy |

| Sepsis | Cardiovascular/respiratory complications |

| Pyrexia | Visceral burn |

| Fluid overload | Haematoma |

| GI obstruction/ileus | |

| Laparotomy |

Second-generation endometrial ablation techniques

Since the 1990s, several new methods of EA have been developed. These are often referred to as second-generation techniques. They do not require direct visualisation of the uterine cavity and employ a variety of means to destroy the endometrium – circulation of heated saline within the uterine cavity, use of a diode laser [endometrial laser intrauterine thermo-therapy (ELITT)], punctual vaporising methods, photodynamic methods, radiofrequency, microwaves, a balloon catheter filled with heated fluid and cryotherapy. The treatments are much less dependent on the skill of the surgeon than first-generation techniques, and much more dependent on the reliability of the machines used to ensure safety and efficacy. Complications associated with second-generation techniques include equipment failure, uterine infection, perforation, visceral burn, bleeding and cyclical pain. A limited number of randomised trials indicate that these procedures appear to be as effective as first-generation ablative techniques. 61 In addition, some have the added benefit of being performed under local anaesthetic.

Microwave endometrial ablation

Microwave EA uses microwave energy (at a frequency of 9.2 GHz) to destroy the endometrium with a tissue penetration depth of 6 mm. An 8-mm applicator inserted through the cervix delivers the microwaves using a dielectrically loaded waveguide. 62 Power is controlled by the surgeon using a footswitch and the temperature inside the uterus is monitored by thermocouples on the surface of the waveguide. Prior to microwave ablation treatment, oral and vaginal thinning agents may be given. Immediately prior to MEA, hysteroscopy is performed to exclude false passages, wall damage and perforation.

Following measurement of uterine cavity length, the cervix is dilated to Hegar 8 or 9 under general or local anaesthetic and the uterine cavity length is measured again. Next, the microwave probe is inserted until the tip reaches the fundus. Graduated centimetre markings on the applicator shaft confirm the length and if these three measurements of uterine length are the same the device is activated. 63 When, after a few seconds, the temperature reaches 80 °C, the probe is moved laterally so that the tip is placed in one of the uterine cornua. The temperature briefly falls and rises again and when 80 °C is reached again the probe is moved to the other cornual region and the procedure is repeated.

Maintaining a temperature of 70–90 °C, the probe is withdrawn with side-to-side movements. The temperature measured by the thermocouple is actually the heat transmitted back from the tissue through the plastic sheath to the applicator shaft. Tissue temperature is higher than these measured levels during active treatment. As a marker on the probe appears at the external os, the applicator is switched off to avoid treating the endocervix. The procedure takes 2–3 minutes. 62 Postoperative analgesia is provided as required.

Thermal balloon endometrial ablation

Thermal balloon EA aims to destroy the endometrium by means of heated liquid within a balloon inserted into the uterine cavity, which should be of normal size and regular shape. Available devices such as ThermaChoice and Cavaterm have an electronic controller, a single-use latex or silicone balloon catheter with a heating element, thermocouples and an umbilical cable. As the balloon must be in direct contact with the uterine wall, the device is unsuitable for women with large or irregular uterine cavities.

In the case of the ThermaChoice device, following dilatation of the cervix to about 5 mm, the balloon is introduced within the uterus and filled with sterile fluid (5% dextrose in water) which causes it to expand to fit the cavity. Once intrauterine pressure is stabilised to 160–180 mmHg, the temperature of the fluid is raised to 87°C and maintained for 8 minutes. Pressure, temperature and time are continuously monitored and the device is switched off if safety parameters are breached. The heat produced by the device causes destruction of the endometrium. Postoperatively, oral analgesia is prescribed and the treated endometrium sloughs off over the following week to 10 days.

The Cavaterm device acts in a similar fashion. The cervix is dilated to about 6 mm and a silicone balloon is inserted and filled with sterile 5% glucose solution to a pressure of 230–240 mmHg. The liquid is heated at a target temperature of 78°C for 10 minutes.

Endometrial thinning agents are not recommended although curettage immediately prior to the procedure can be used. NSAIDs are given to reduce perioperative cramping.

Impedance-controlled bipolar radiofrequency (NovaSure)

The NovaSure system consists of a single-use bipolar ablation device which is inserted into the uterine cavity transcervically after dilatation to 8 mm. This is connected to a generator which functions at 500 kHz and has a power cut-off limit set at a tissue impedance of 50 Ω. The cavity and cervical length are measured and the difference in centimetres is determined; this setting is selected on the shaft of the device. The device is inserted and the trigger is deployed which delivers the bipolar triangular array into the cavity. With gentle tapping and slight rotation in both directions the array fully deploys with the tips sited in each cornua. The distance between the cornuae is displayed and then entered into the generator, and this determines the energy required. A cavity integrity test is then automatically performed, which must be passed before the energy is delivered. Active treatment times are under 2 minutes, during which time suction pulls the walls onto the device. After completion the array is retracted into the device sheath and withdrawn. While the device is versatile, it cannot effectively treat larger cavities (> 11 cm) or distorted cavities. Pre-treatment endometrial thinning is not required and the procedure can be performed under local anaesthetic. A number of randomised trials has been undertaken, one comparing with RBEA56 and the others with thermal balloon devices. 64,65 One of the trials has published follow-up to 5 years. 66 A randomised trial comparing NovaSure with microwave ablation has been completed and awaits publication. It has approval from NICE. 15 Results have been consistent through the trials, with amenorrhoea rates varying between 42% and 56%, high satisfaction rates of over 90% and low hysterectomy rates. Active treatment times vary between 90 and 120 seconds.

Adverse effects associated with second-generation EA devices include the following:16 uterine infection, perforation, visceral burn, bleeding, haematometra, laceration, intra-abdominal injury and cyclical pain.

Use of local anaesthetic

Use of local anaesthetic (LA) is a potential advantage of second-generation EA techniques, although this may not be suitable for all women. In a partially randomised trial of general anaesthetic (GA) and LA,67 the procedure was considered acceptable under GA in both preferred (100%) and randomised (97%) groups. However, under LA, 97% of those who chose this method and 85% of those allocated to LA found the procedure acceptable.

Selecting an appropriate treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding

The introduction of new EA techniques over the last two decades has been accompanied by a series of randomised clinical trials aimed at evaluating their clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Initially, first-generation EA techniques such as TCRE and laser EA were compared with hysterectomy. 31 Subsequent trials, which compared alternative first-generation techniques such as TCRE, laser EA and RBEA, established TCRE as the gold standard for this group of treatments. As less invasive and more user-friendly second-generation techniques such as MEA became available, these were compared with earlier methods of ablation like TCRE and RBEA. Although not all techniques have been subjected to head-to-head comparisons in the context of randomised trials, an overview of the literature demonstrates that MEA (second generation) has been shown to be comparable with TCRE (first generation) – which in turn has been shown to be an effective alternative to hysterectomy (gold standard). However, questions about the long-term clinical effectiveness and cost implications of alternative forms of surgical treatment remain unanswered. Published data report no more than 5 years of follow-up. 46,68 Inevitably, some women treated by EA will eventually require repeat ablation or hysterectomy. Following hysterectomy, a proportion of women will also develop further complications such as postsurgical adhesions and pelvic floor dysfunction, which may lead to further surgery. The necessity for a head-to-head comparison between the two most common second-generation methods – MEA and TBEA – has been identified. 15 Given the widespread use of ablative techniques as first-line surgical treatment for menorrhagia at the present time, it is uncertain whether it is either necessary or feasible to compare second-generation techniques directly with hysterectomy. At the same time, the need to obtain comparative information on long-term outcomes is clearly accepted, as is the need to identify the best technique for individual women.

From a clinical perspective, the most relevant research questions at the present time are:

-

How do the currently used ablative techniques compare with hysterectomy in the medium to long term?

-

Which among the commonly used second-generation ablation techniques is the most effective and cost-effective?

-

Are there subgroups of women who are most likely to benefit from either hysterectomy or specific types of ablation?

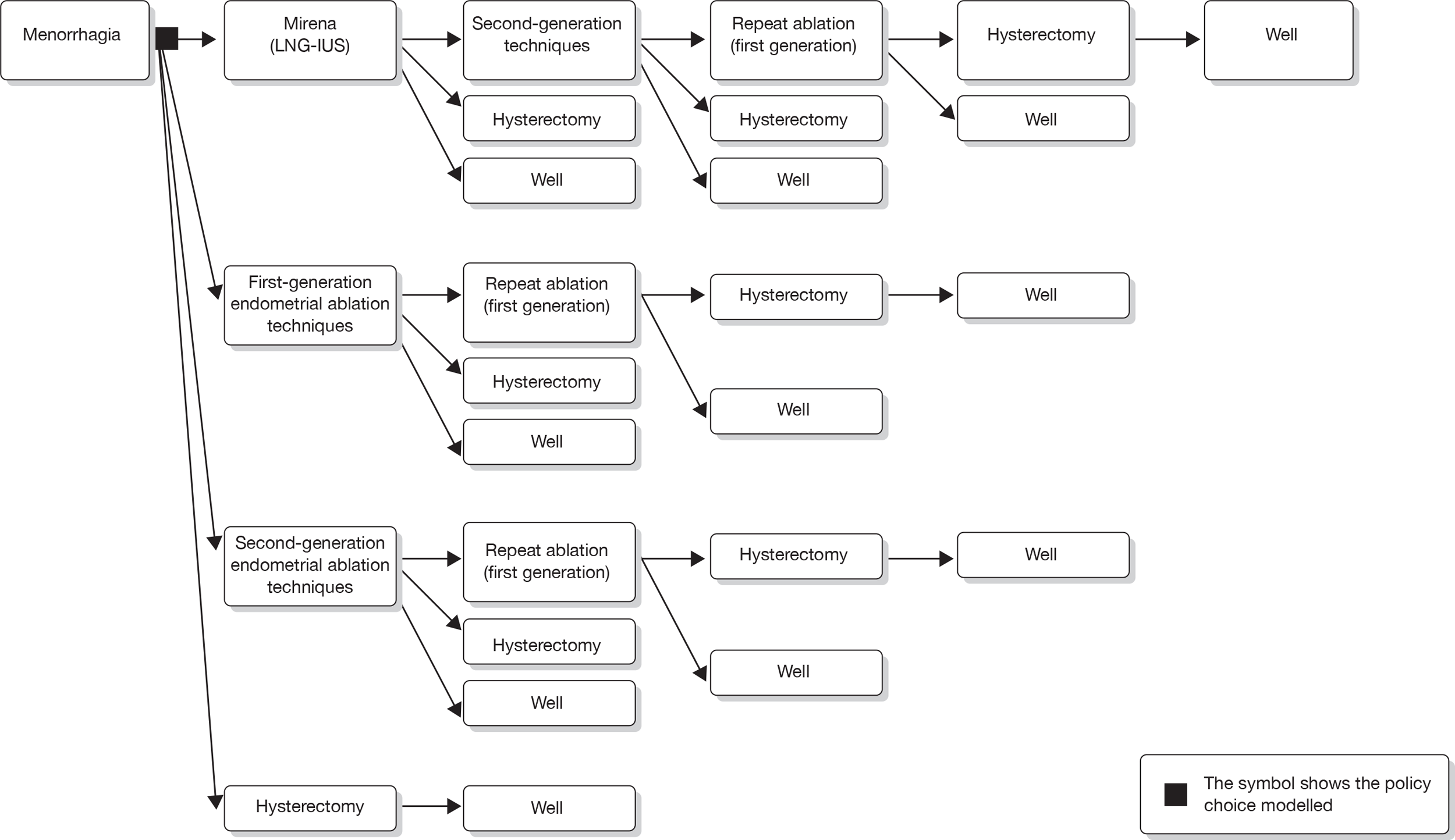

In this project we have performed a series of studies in order to address these questions by analysis of data from national data sets and randomised trials. Long-term outcomes following EA and hysterectomy in a national cohort have been explored by means of record linkage, while the effectiveness of Mirena, hysterectomy and EA have been determined by individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis of existing trials. The output has been used (along with other data from the literature) to create a model for the utilisation and costs of the different treatments.

Project objectives

-

To determine, using data from record linkage and follow-up of randomised and non-randomised cohorts of British women, the long-term effects of various second-generation ablative techniques and hysterectomy in terms of failure rates, complications, QoL and sexual function.

-

To determine, using IPD meta-analysis of existing RCTs, the short- to medium-term effects of various second-generation ablative techniques and hysterectomy, including the exploration of outcomes in clinical subgroups.

-

To undertake a model-based clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness analysis comparing various second-generation ablative techniques with hysterectomy using output from the above analyses and to conduct extensive sensitivity analyses to explore the robustness of the results to the assumptions made.

-

To devise an algorithm for clinical decision making regarding the choice of surgery for women with HMB in whom medical treatment has failed.

Chapter 2 Hysterectomy, endometrial ablation and Mirena for heavy menstrual bleeding: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis

Introduction

Many women with HMB are not satisfied with medical treatment and end up undergoing surgery. 69 Hysterectomy was once the only surgical option for HMB; indeed, almost half of the hysterectomies currently performed worldwide are for the treatment of HMB. 5 EA techniques, which aim to destroy or remove the endometrial tissue,70 have become increasingly popular alternatives, and, as a result, the number of hysterectomies in the UK has declined by 64% between 1995 and 2002. 71 EA techniques were introduced in the 1980s, with RB ablation and transcervical resection emerging as the predominant approaches under direct hysteroscopic vision. 30 Subsequently, a second generation of non-hysteroscopic techniques, which are easier to perform, have become available. Here, devices are sited and activated to treat the whole endometrial cavity simultaneously without visual control. Destruction is achieved through a variety of modalities, including high temperature fluids and bipolar electrical or microwave energy. Intrauterine coil devices were initially introduced as contraceptives, but the addition of progestogen resulted in reduced menstrual bleeding. Mirena, an LNG-releasing IUS, provides a non-surgical alternative, which is reversible and fertility sparing. 72

Women and clinicians now have greater choice of treatment, although evidence to support decision making is inadequate. In the UK, guidelines from NICE15 recommend the use of Mirena in the first instance for women with benign HMB, followed by EA if pharmaceutical treatments fail to resolve symptoms. Syntheses of evidence from RCTs comparing these treatments have been limited,31,61,73 partly because of the scarcity of head-to-head comparisons and variation in outcome measurements used to evaluate effectiveness. We undertook a meta-analysis of IPD from all relevant trials to address previous deficiencies in evidence synthesis. The aim of the study was to compare the relative efficacy of hysterectomy, first- and second-generation EA techniques, and Mirena in women with HMB using a primary outcome measure of patient dissatisfaction. IPD meta-analysis has a number of advantages over traditional published data reviews,74 including the ability to carry out data checks, standardise analytical methods and undertake subgroup analyses.

Methods

We sought IPD from RCTs of hysterectomy, EA techniques and Mirena to examine their relative efficacy as a second-line treatment of HMB. The systematic review was conducted based on a protocol designed using widely recommended methods75,76 that complied with meta-analysis reporting guidelines77 (see Appendix 10) (www.bctu.bham.ac.uk/systematicreview/hmb/protocol.shtml).

Literature search and study selection

The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE (1966–2010), EMBASE (1980 to May 2010) and CINAHL databases (1982 to May 2010) were searched using relevant terms and word variants for population [e.g. menorrhagia, hypermenorrhea, (excessive) menstrual blood loss, HMB, dysfunctional uterine bleeding] and interventions (e.g. hysterectomy, vaginal hysterectomy, total abdominal hysterectomy, subtotal abdominal hysterectomy, laparoscopic hysterectomy, LNG IUS, Mirena coil and all types and variants of first- and second-generation ablative techniques). Variant names (e.g. EA, resection) and different makes for EA (e.g. Microsulis Medical Ltd, Denmead, UK; Cryogen – now American Medical Systems, Minnetonka, MN, USA) were also searched (see Appendix 1). We also hand-searched the bibliographies of all relevant primary articles and reviews to identify any articles missed by the electronic searches. Experts were contacted to identify further studies. To identify any ongoing RCTs, the Meta-Register of Controlled Trials and the International Standard Randomised Control Trial Number register were searched. No language restriction was applied.

Studies were selected in a two-step process. Firstly, we scrutinised the citations identified by the electronic searches and obtained full manuscripts of all the citations that met, or were thought likely to meet, the pre-determined inclusion criteria based on patient entry criteria (women with HMB or abnormal/excessive/prolonged uterine bleeding that was unresponsive to other medical treatment) and study design, the latter limited to RCTs only. We then considered four categories of intervention with the intention of comparing them against each other: hysterectomy (performed abdominally, vaginally or laparoscopically); ‘first-generation’ EA techniques (using operative hysteroscopy, including endometrial laser ablation, TCRE and RBEA); ‘second-generation’ EA techniques [those that use a ‘blind’ device to simultaneously treat the whole cavity, including thermal balloon (Cavaterm, ThermaChoice and Vesta), microwave (Microsulis), laser (ELITT), bipolar radio frequency (NovaSure), cryoablation and hydrothermal ablation]; and LNG IUS (Mirena). Studies making a comparison within these categories could not contribute to the meta-analysis, but these data were also requested to allow further exploration of possible predictors of the primary outcome measure.

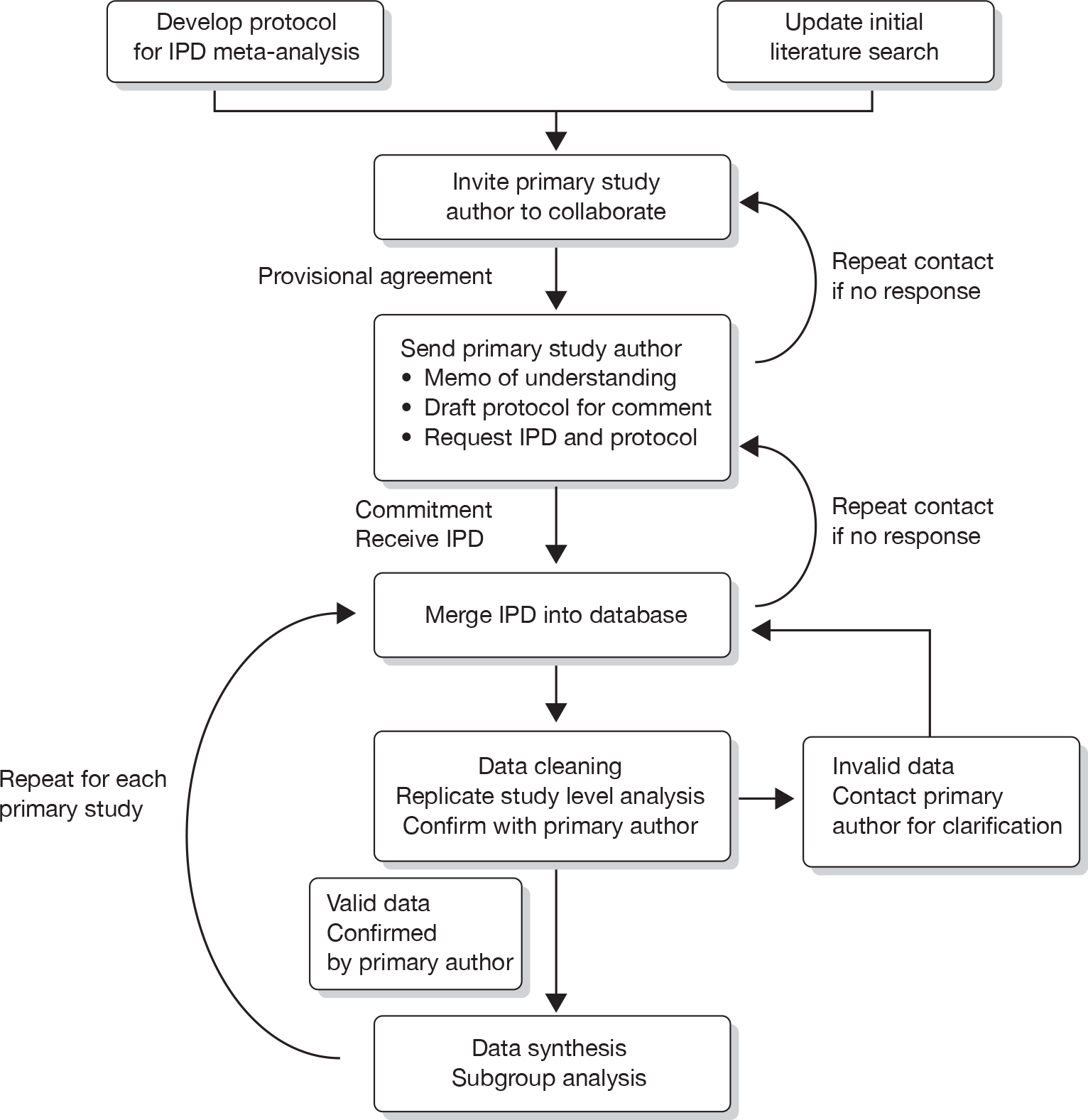

Data collection and study quality assessment

Repeated attempts were made to contact corresponding authors via post, email or telephone to access data. Where initial attempts failed, we attempted personal contact via our links through the British and European Societies for Gynaecological Endoscopy. Authors were asked to supply anonymised data for each of the pre-specified outcome measures (both published and unpublished to reduce the chance of selective reporting bias) and were invited to become part of the collaborative group with joint ownership of the final publication. Where the investigators declined to take part in the study or could not be contacted, published data were extracted from manuscripts using pre-designed proformas by two independent reviewers (RC and LJM). Any disagreements were resolved by consensus or arbitration by a third reviewer (JPD). Received data were merged into a master database, specifically constructed for the review. The data were cleaned and results were cross-checked against published reports of the trials. Where discrepancies existed authors were contacted for clarification.

Authors of the protocol reviewed all relevant outcome measures to be used in the meta-analysis from articles identified in the literature search. Level of satisfaction with treatment was the most frequently measured outcome across all identified studies, with 21 out of 30 (70%) using this measure, and was used as the primary outcome measure. Dissatisfaction rates are presented to simplify interpretation of statistical output. Responses of ‘very satisfied’ or ‘satisfied’ were taken as a positive response, likewise ‘very dissatisfied’ or ‘dissatisfied’ as a negative response. Where a ‘not sure’ or ‘uncertain’ response was given these were conservatively taken to be a negative rating of treatment, although sensitivity analysis was undertaken to test the robustness of this assumption. For a small number of studies,78–81 surrogate outcomes for satisfaction were used (major problem resolved/improvement of health state/menstrual symptoms successfully treated/degree of recommendation). This assumption was also tested by sensitivity analysis without these studies (indicated in the results section where important) (see Appendix 2). A more disease-specific QoL tool19 would have been the ideal choice for primary measure, but these data were not available from the studies identified. We have shown from the data in this review, though, that a strong relationship between dissatisfaction and patient QoL is apparent (see Results).

Other outcome measures were bleeding scores (ranging from a minimum of zero to no upper limit),12 amenorrhoea rate (converted from a bleeding score of zero where data existed, otherwise as reported), heavy bleeding rate (converted from bleeding scores of > 10012 where data existed, otherwise as reported), EQ-5D utility score,82 SF-36 scores,20 duration of surgery/hospital stay, general anaesthesia rates, postoperative pain score (standardised from visual analogue and ordinal scale scores onto a 0–10 scale), time to return to work/normal activities/sexual activity, dysmenorrhoea/dyspareunia rate and proportion undergoing subsequent ablation/hysterectomy or discontinuing use of Mirena. Pre-defined subgroups were age at randomisation (≤ 40 vs > 40 years), parity (nulliparous vs parous), uterine cavity length (≤ 8 vs > 8 cm), presence or absence of fibroids/polyps and, where available, severity of bleeding at baseline (bleeding score ≤ 350 or > 350).

All selected trials were assessed for their methodological quality, using received data sets where available in addition to the reported information. Quality was scrutinised by checking the adequacy of randomisation, group comparability at baseline (examining baseline characteristics for any substantive differences), blinding (where appropriate), use of intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis, completeness of follow-up, compliance, reliability using a priori sample size estimation and generalisability using description of the sample recruited. Adequacy of randomisation was assessed with subquestions examining information on sequence generation, the process of allocation and allocation concealment.

Statistical analysis

To minimise the possibility of bias IPD and aggregate data (AD) were combined in a two-stage approach. 83 IPD were reduced to AD to allow studies with AD only to be combined with those where IPD were obtained. Unless specifically stated in the text of the results section, all estimates shown are from all available data (both IPD and AD). Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for individual studies at each time point. For the primary outcome measure, differences in effect estimates between trials and the pre-defined subgroups of patients are displayed using odds ratio (OR) plots; results from other outcome measures are summarised in tables in the appendices for ease of reference. Heterogeneity was investigated using Cochran’s Q,84 I2 statistics24 and Higgins et al. 85 Subgroup analyses to explore the causes of heterogeneity were undertaken if the p-values of these tests were < 0.1. Differences between studies contributing IPD and those with AD only were examined in the same fashion to check that the latter results were consistent with those we received IPD for. Further details are given in the Results section if any inconsistency exists. Likewise, further details are given on any obvious publication bias if noted from the assessment of funnel plots. Only a limited amount of data were available for studies comparing Mirena with ED, so Mirena was compared with first- and second-generation studies combined as well as separately. Assumption-free ‘fixed-effect’ methods were used to combine dichotomous outcome measures and estimate pooled ORs using the method of Peto et al. ,86 and, for continuous variables, weighted mean differences (WMD) were calculated87 at each time point. Data at less than 12 months were combined and are described as results at 6 months. Results from the limited number of studies with follow-up longer than 2 years are not referred to in the text but are given in the appendices.

The primary outcome measure of dissatisfaction was investigated comprehensively using received data. Results at 12 months, where the majority of studies had collected data, were used as the focus for analysis. Where responses were not available at this time point, data were substituted in the first instance from 2 years and, failing that, from 6 months. If it was not possible to make a direct comparison between treatments (e.g. hysterectomy vs second-generation EA), indirect estimates were made88 using a logistic regression model89 allowing for trial and treatment. 90 Estimates using dissatisfaction at any time were also examined, along with an analysis allowing for the correlation of the repeated measurements using generalised estimating equations (IPD only). 91

Access to IPD also allowed the inclusion of patient-level covariates to examine possible predictors of dissatisfaction. First, covariates were considered individually, while allowing for differences between trial estimates. If considered statistically important (p < 0.1), covariate parameters were included together in a multivariate analysis to examine adjusted estimates. In addition to the analysis of the primary outcome measure described above, as a sensitivity analysis IPD were also used to explore the effect observed in compliance rates for comparisons between first- and second-generation EA (unfortunately there were insufficient data to extend this analysis to Mirena comparisons). For example, for those women ‘satisfied’ with treatment but subsequently undergoing a hysterectomy, positive responses were substituted with negative ones. The relationship between dissatisfaction and responses from the SF-36 QoL questionnaire was examined at the patient level using a regression model, allowing for trial. Given the number of analyses performed, any interpretation of p-values greater than the conservative threshold of 0.01 has been cautious owing to the likelihood of increased type 1 error rates. revman v5.0 (Cochrane Collaboration, Denmark) and sas v9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) software were used for analysis.

Results

Trials and patients

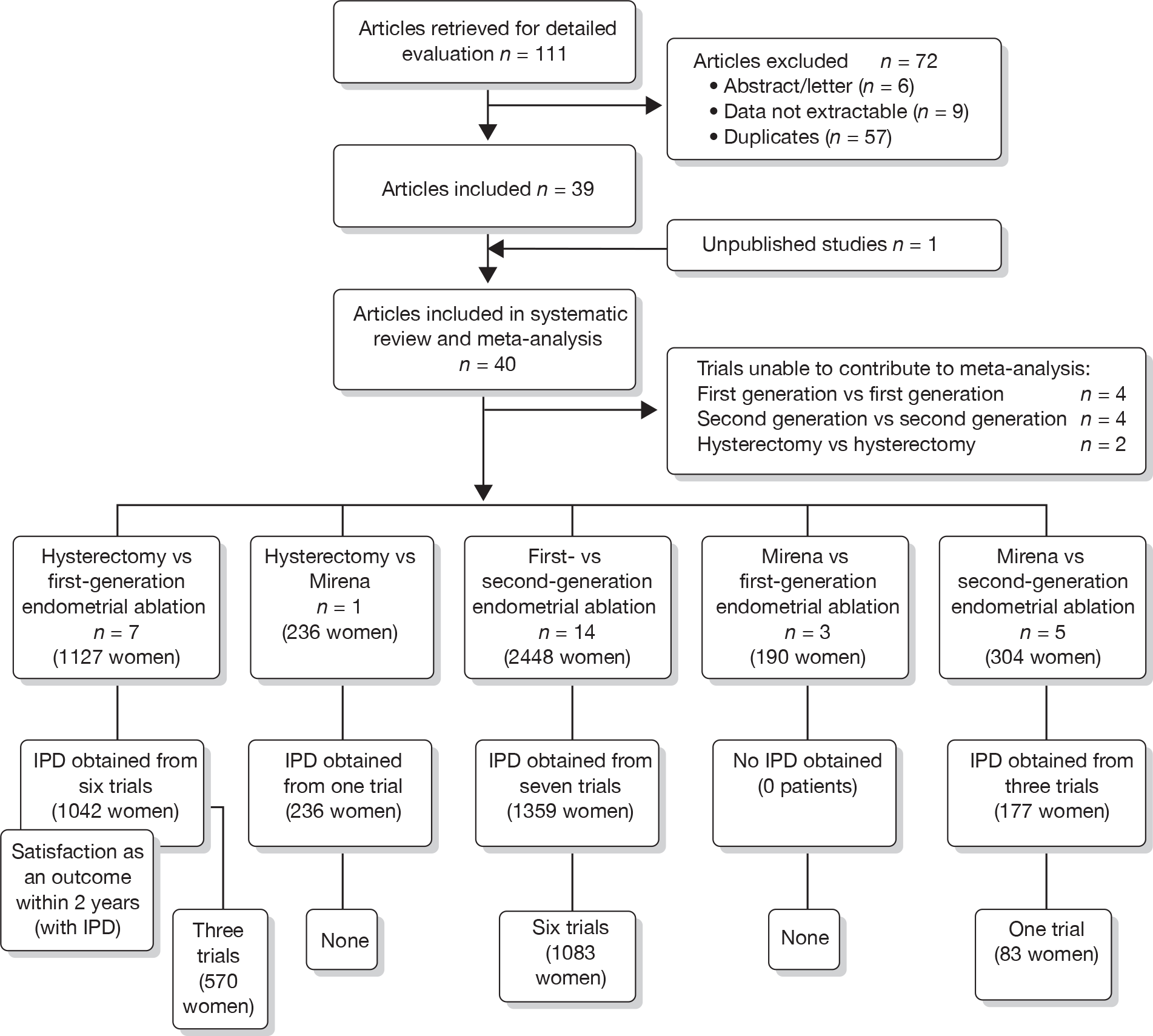

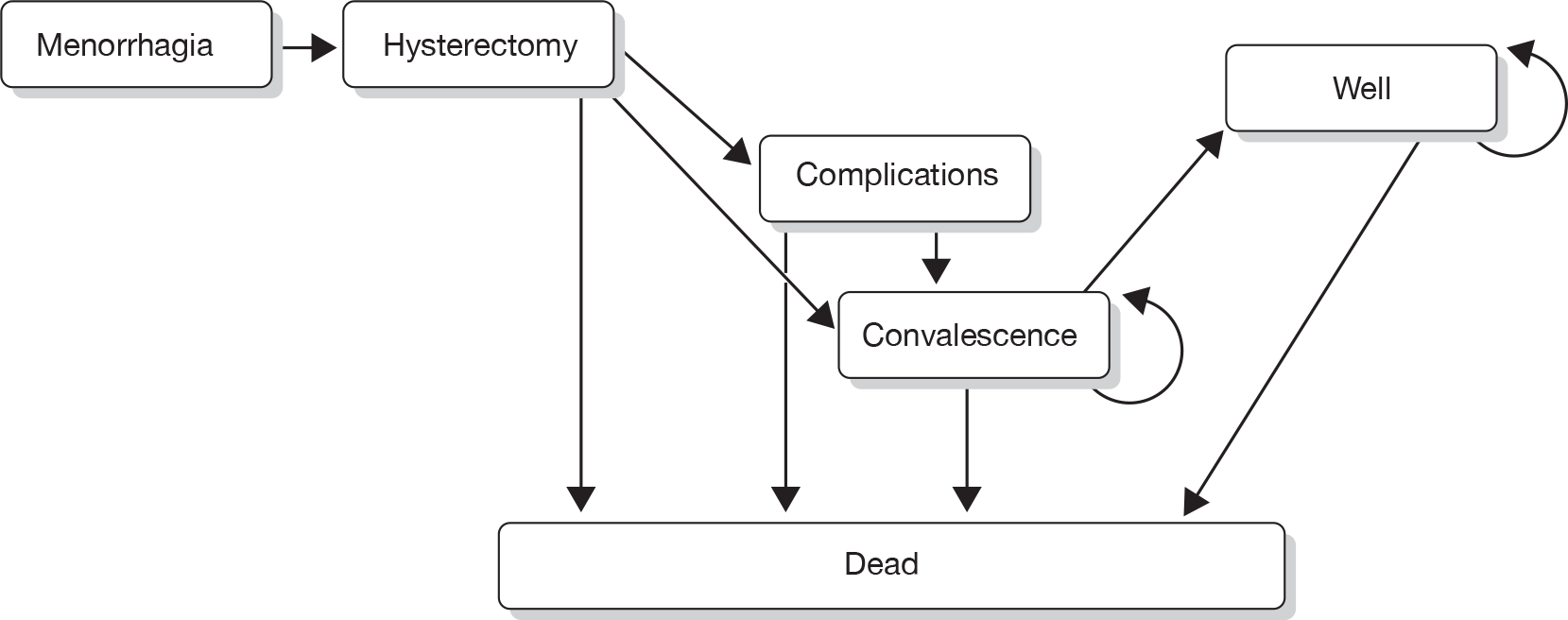

A total of 556 potentially relevant citations were identified by electronic searches. After detailed evaluation, 30 trials were eligible for inclusion in the review (Figure 1). Of these trials, seven compared hysterectomy with ED techniques. Six of these studies involved first-generation techniques. 41–45,78 The seventh study used a combination of first and second generation in equal proportions92 and was included here as a first-generation comparison, with a sensitivity analysis performed without the trial. One study compared hysterectomy93 with Mirena. Fourteen studies compared first-generation EA techniques with those of second generation53,54,56,79,94–103 and eight studies compared Mirena with EA, three of which were first generation80,104,105 and five second generation. 81,106–109 Characteristics of these studies are shown in Appendix 2. Data from a further five studies,64,65,110–112 which involved comparisons within first- and second-generation EA, were also received.

FIGURE 1.

Study selection process for systematic review and IPD meta-analysis of randomised trials comparing hysterectomy, EA techniques and Mirena for HMB (details of selected trials in Appendix 2).

Trials comparing hysterectomy with EA and those comparing first- and second-generation ED involved women of a similar age, with average ages of 40.6 years [standard deviation (SD) 5.1 years] and 41.0 years (SD 4.9 years), respectively. Women involved in trials comparing Mirena with ED were slightly older, with an average age of 43.6 years (SD 3.5 years). Eligibility criteria for women with uterine pathology varied between trials; inclusion of women with fibroids was generally limited by size or number. Where included, they amounted to a maximum of 30% of the women in each individual study.

A high proportion of data was received from trials involving hysterectomy (seven of eight studies; 1278 of 1363 women), with less for trials of EA techniques (7 of 14 studies; 1359 of 2448 women) and those involving Mirena (three of eight studies; 177 of 494 women) (see Appendix 2). Overall, we received some IPD from 65% (2814/4305) of women involved in the trials, although only eight studies were able to provide all requested variables. 41,42,53,94,95,99,102,109 The remaining studies had some missing information, with limited details on patient follow-up covering subsequent operations (e.g. hysterectomy following Mirena). See the section on statistical analysis for details on how data from studies providing IPD were utilised.

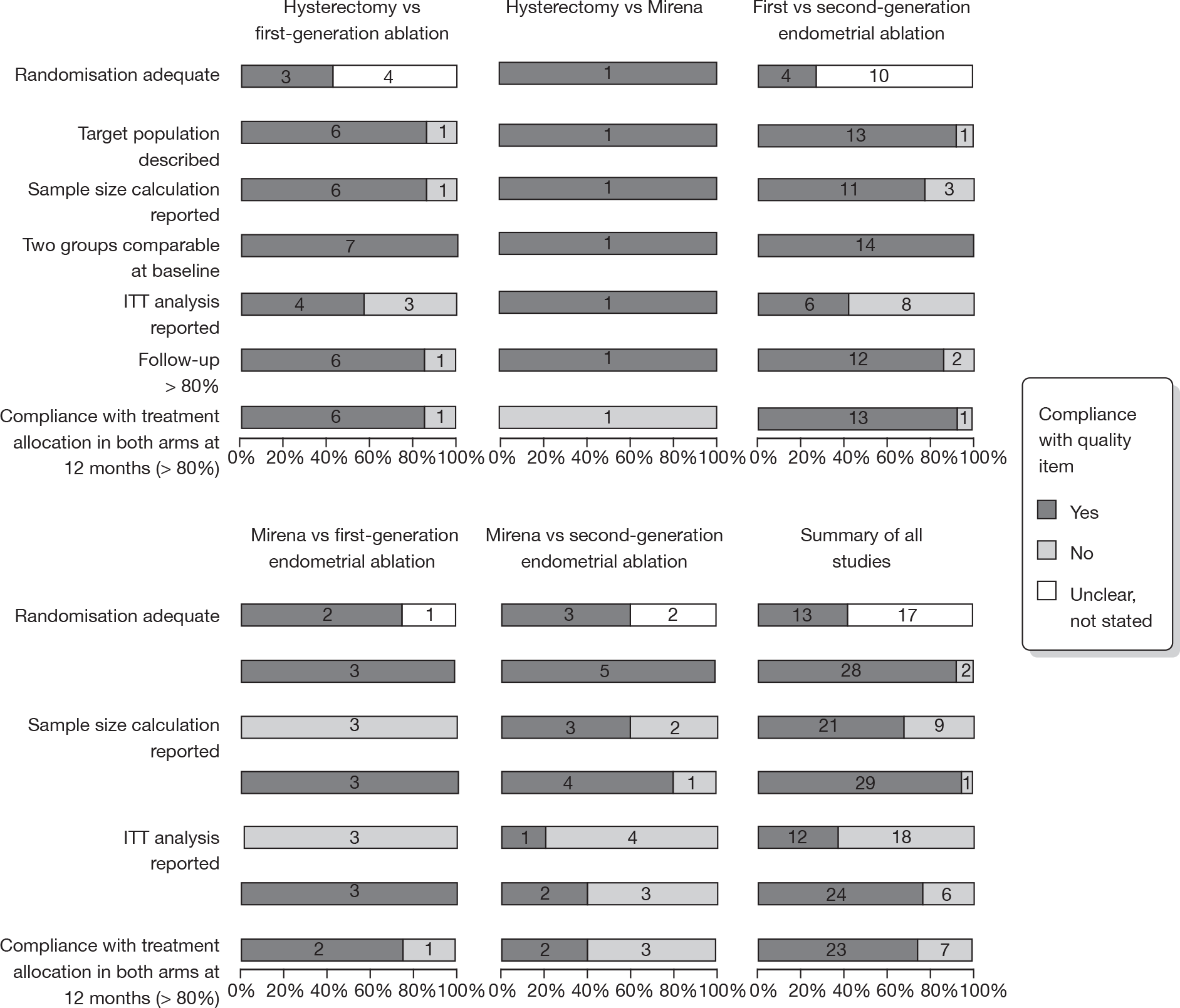

Study quality

The methodological quality of the published data from the studies was variable (Figure 2 and Appendix 3).

FIGURE 2.

Quality of studies included in systematic review and IPD meta-analysis of randomised trials comparing hysterectomy, EA techniques and Mirena for HMB. Numbers inside bars are numbers of studies (details given in Appendix 3).

Over half the studies failed to give adequate information about their randomisation procedure and details on allocation concealment. There was a general lack of true ITT analysis, with some studies stating that an ITT analysis had been performed but only analysing those women who had received treatment. For four studies that reported non-ITT analysis,53,95,99,107 ITT analyses were undertaken using the available IPD, although it was not always clear if protocol-deviant patients were followed up correctly in these cases. Small sample sizes often lacked a sensible justification, especially in studies involving Mirena. In the nine trials involving Mirena, only four had greater than 80% of women with Mirena in situ at 12 months post randomisation.

Dissatisfaction as an outcome measure

Data from four studies that provided IPD on both outcomes42,54,99,107 showed that satisfied patients had significantly increased scores in seven of eight domains of the SF-36 QoL questionnaire when compared with dissatisfied patients in the analysis of change from baseline scores, including the general health perception (7.4 points, 95% CI 3.1 to 11.8 points; p = 0.0008) and mental health (10.5 points, 95% CI 5.4 to 15.6 points; p < 0.0001) domains (Table 4). Differences from absolute differences (not adjusted for baseline score) were highly significant (p < 0.0001) in all eight domains in favour of satisfied patients.

| SF-36 domain | Change from baseline | Absolute | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD; n) | Differencea (95% CI) | p-value | Mean (SD; n) | Differencea (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| General health | Dissatisfied | –4.7 (14.2; 71) | 7.4 (3.1 to 11.8) | 0.0008 | 60.3 (20.5; 91) | 12.5 (8.5 to 16.6) | < 0.0001 |

| Satisfied | 5.7 (17.0; 507) | 77.7 (17.8; 642) | |||||

| Physical function | Dissatisfied | 0.4 (19.4; 70) | 2.8 (–2.6 to 8.3) | 0.3 | 78.1 (27.2; 89) | 10.9 (6.7 to 15.1) | < 0.0001 |

| Satisfied | 6.0 (20.7; 497) | 91.0 (16.6; 637) | |||||

| Role physical | Dissatisfied | 5.3 (51.6; 71) | 17.4 (5.3 to 29.4) | 0.005 | 60.8 (45.1; 90) | 24.0 (17.0 to 31.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Satisfied | 25.2 (44; 504) | 88.4 (27.9; 641) | |||||

| Role emotional | Dissatisfied | 4.2 (54.6; 71) | 15.0 (2.9 to 27.0) | 0.02 | 61.1 (44.2; 90) | 23.4 (16.3 to 30.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Satisfied | 18.2 (44.4; 505) | 87.4 (28.2; 641) | |||||

| Mental health | Dissatisfied | –2.1 (22.7; 71) | 10.5 (5.4 to 15.6) | < 0.0001 | 58.5 (21.6; 90) | 16.9 (12.8 to 21.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Satisfied | 7.6 (18.7; 504) | 76.9 (17.1; 638) | |||||

| Social function | Dissatisfied | 4.9 (26.2; 70) | 6.7 (0.9 to 12.5) | 0.02 | 61.0 (24.2; 90) | 17.6 (13.5 to 21.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Satisfied | 11.6 (21.2; 471) | 85.5 (18.6; 629) | |||||

| Vitality | Dissatisfied | 6.5 (23.7; 70) | 8.5 (2.4 to 14.6) | 0.006 | 43.6 (23.1; 91) | 18.9 (14.1 to 23.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Satisfied | 15.7 (22.9; 503) | 65.2 (21.0; 637) | |||||

| Pain | Dissatisfied | 6.4 (34.3; 71) | 9.1 (0.8 to 17.4) | 0.03 | 57.6 (27.2; 91) | 20.2 (14.7 to 25.6) | < 0.0001 |

| Satisfied | 20.1 (31.4; 504) | 81.0 (23.4; 642) | |||||

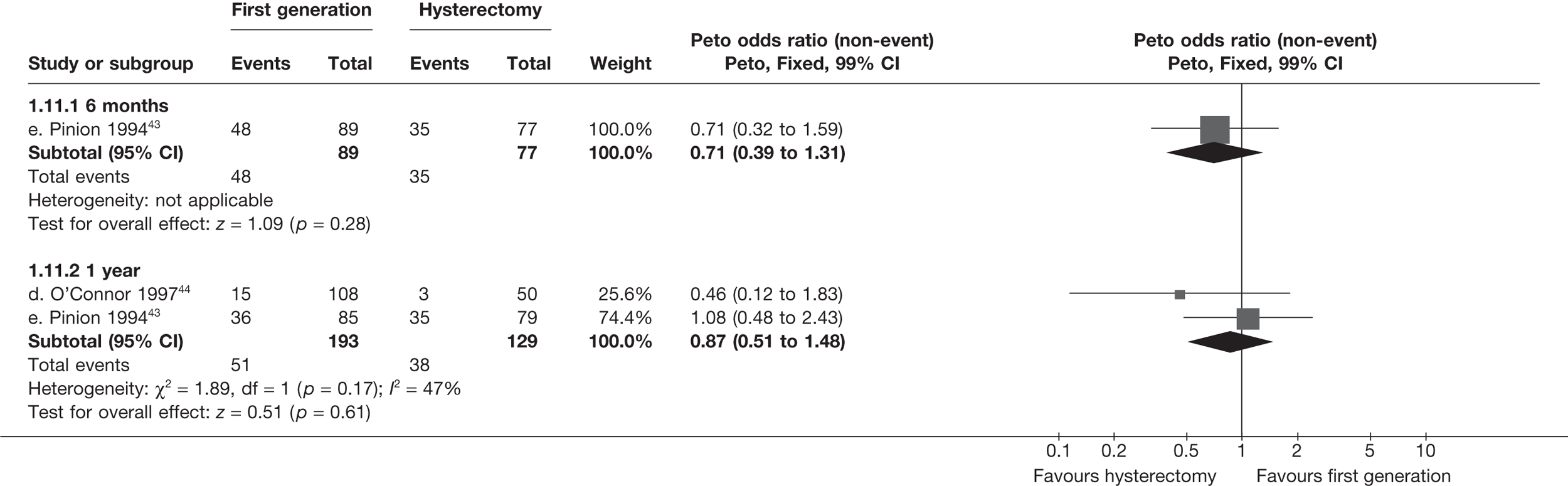

Effectiveness in reducing dissatisfaction with treatment

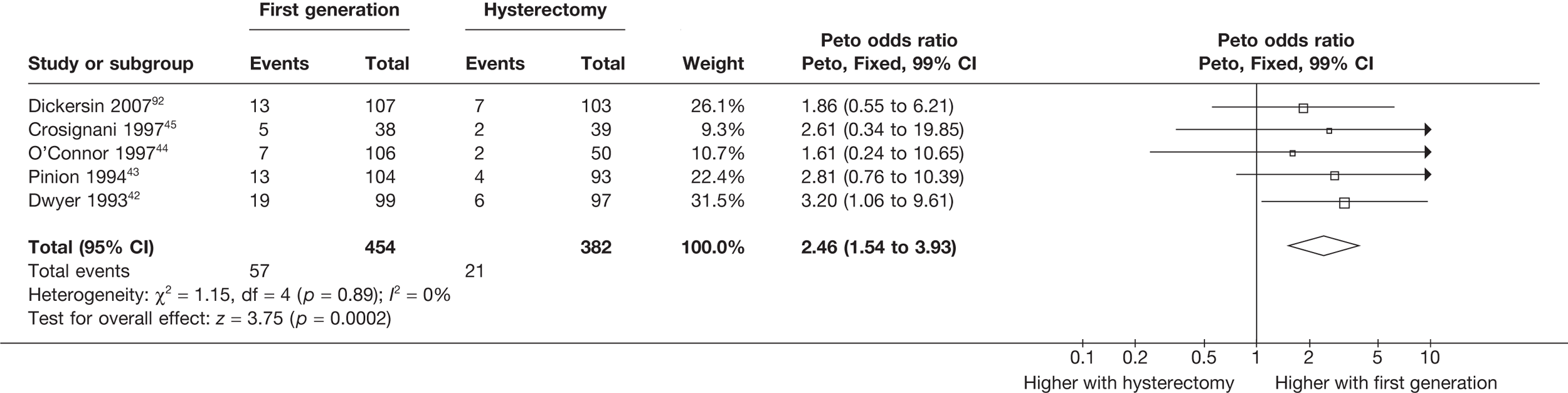

Hysterectomy versus first-generation endometrial ablation

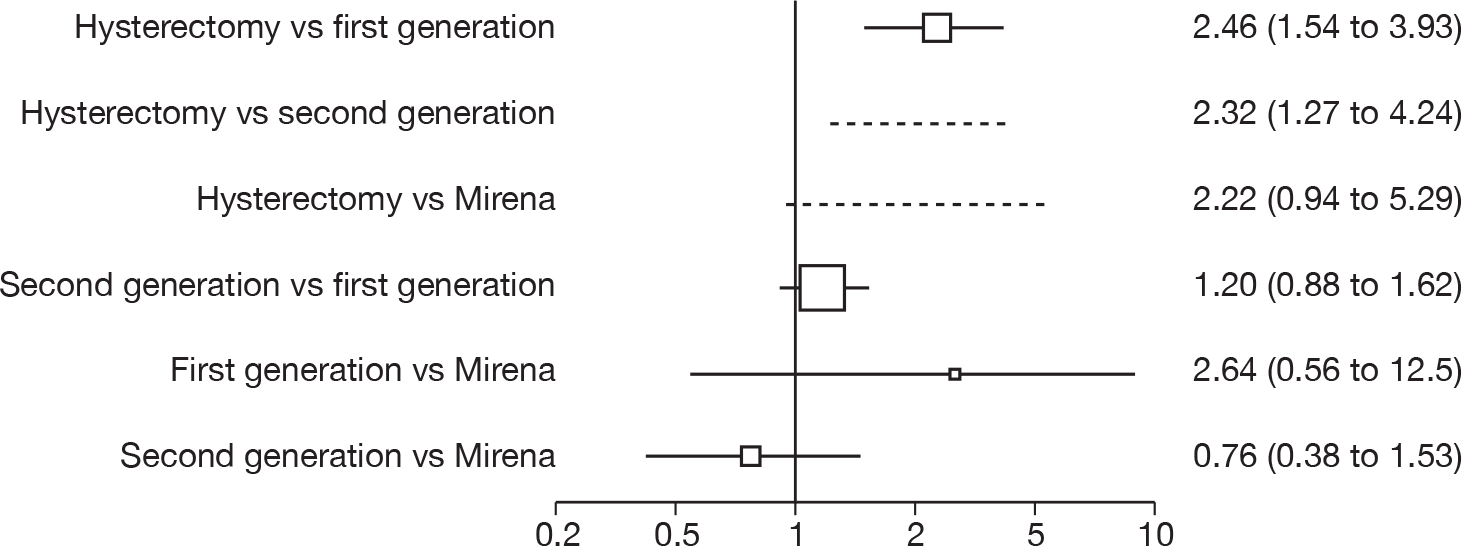

More women were dissatisfied at 12 months following first-generation EA than hysterectomy [12.6% vs 5.3%; (57/454 vs 23/432); OR 2.46; 95% CI 1.54 to 3.93; p = 0.0002] (Figure 3), with no significant heterogeneity between study estimates (p = 0.9; I2 = 0%). This estimate of effect size was consistent with, although slightly less than, the estimate from the repeated measures analysis (IPD only) over all time points (OR 3.75; 95% CI 2.18 to 6.46; p < 0.0001) and an analysis using dissatisfaction at any time point (OR 3.37; 95% CI 2.14 to 5.31; p < 0.0001). There was no evidence of any differences between subgroups (see the Data collection and study quality assessment section), including between studies providing IPD or AD (test for heterogeneity: p = 0.9).

FIGURE 3.

Dissatisfaction at 12 months – hysterectomy versus first-generation EA.

First- versus second-generation endometrial ablation techniques

Similar dissatisfaction rates were seen with first- and second-generation EA [12.2% vs 10.6% (123/1006 vs 110/1034); OR 1.20; 95% CI 0.88 to 1.62; p = 0.2; test for heterogeneity: p = 0.7)] (Figure 4). Comparison estimates were obtained from the repeated measures analysis of IPD (OR 1.21; 95% CI 0.84 to 1.74; p = 0.3), the analysis using dissatisfaction at any time (OR 1.22; 95% CI 0.91 to 1.62; p = 0.2), and also an analysis adjusting for patients who went on to receive a hysterectomy (OR 1.25; 95% CI 0.93 to 1.67; p = 0.1). Results were consistent over all subgroups, including those studies providing IPD or AD only (test for heterogeneity: p = 0.8).

FIGURE 4.

Dissatisfaction at 12 months – first- versus second-generation EA.

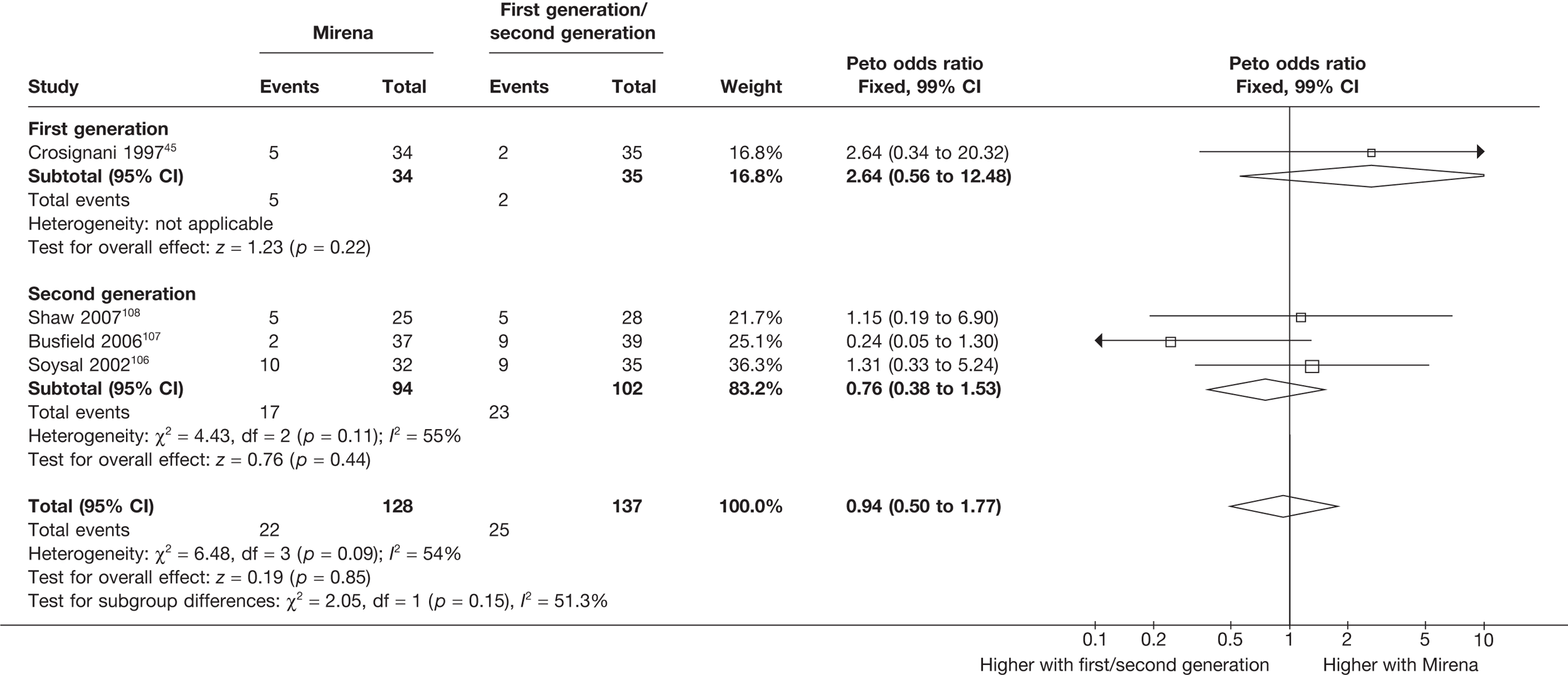

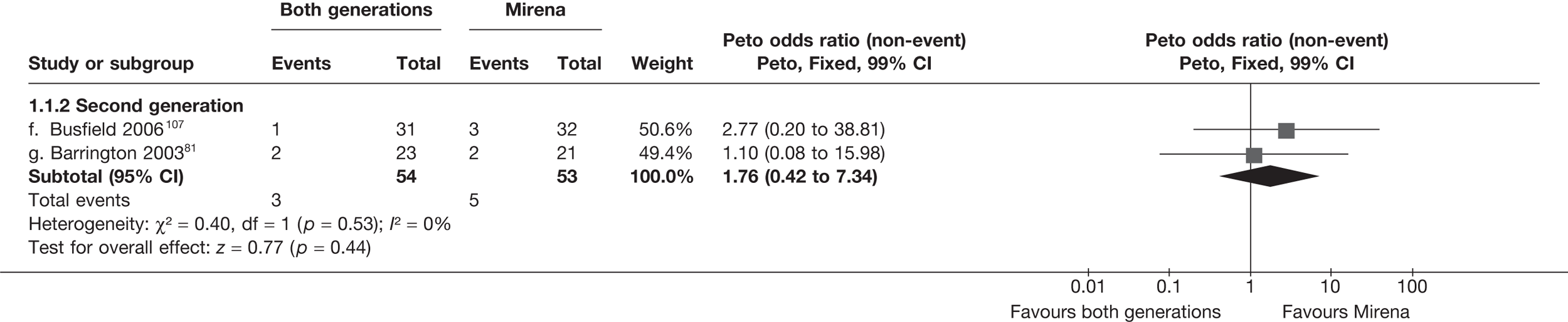

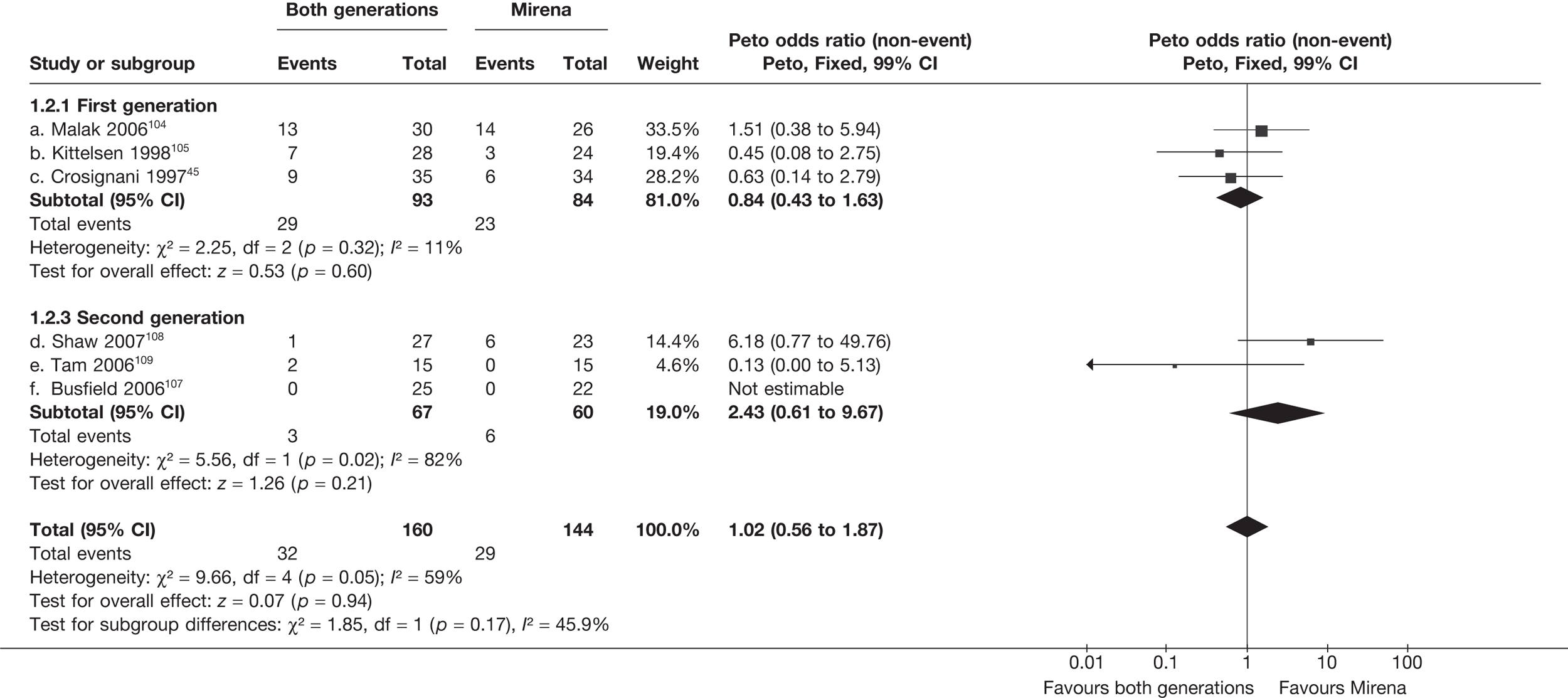

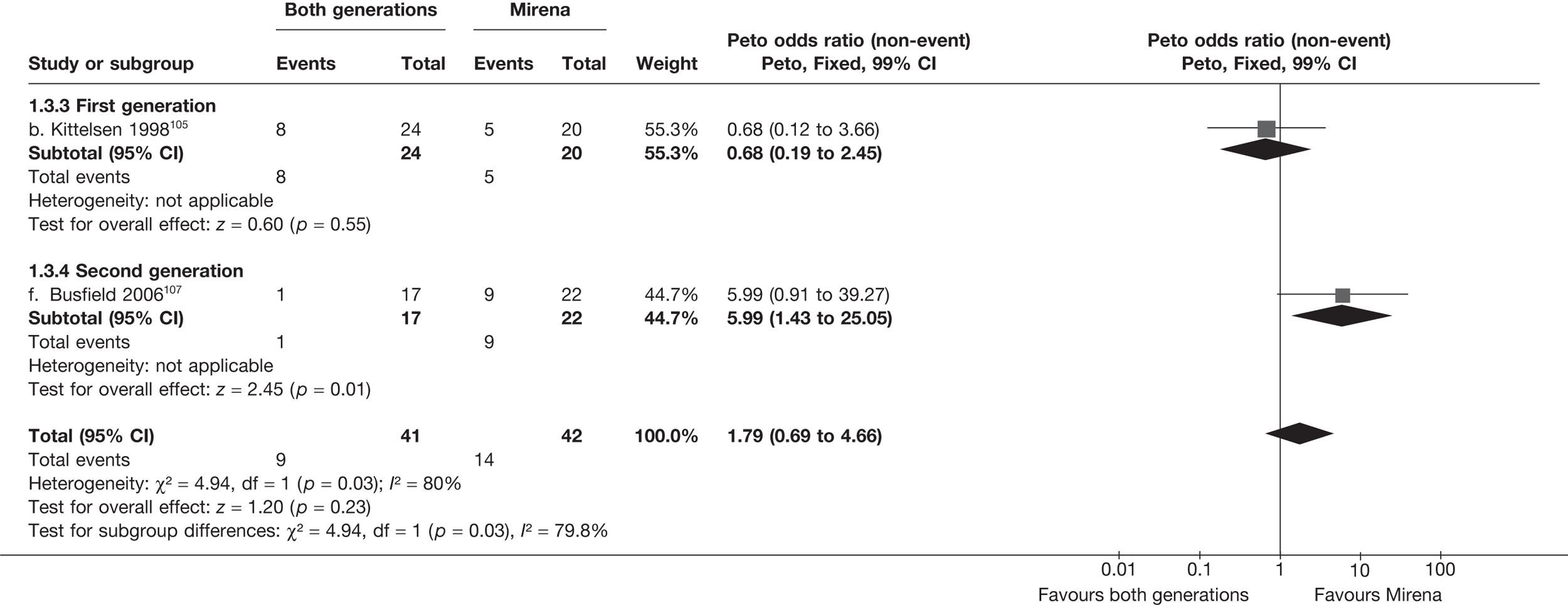

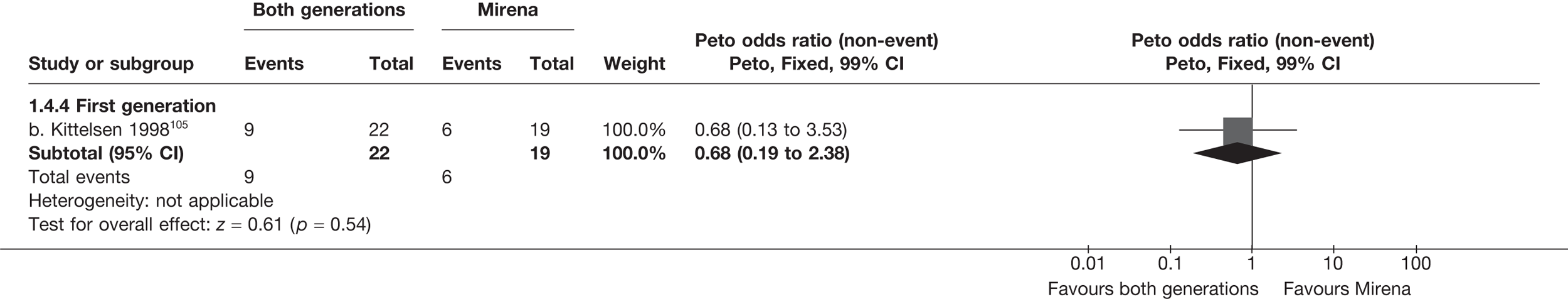

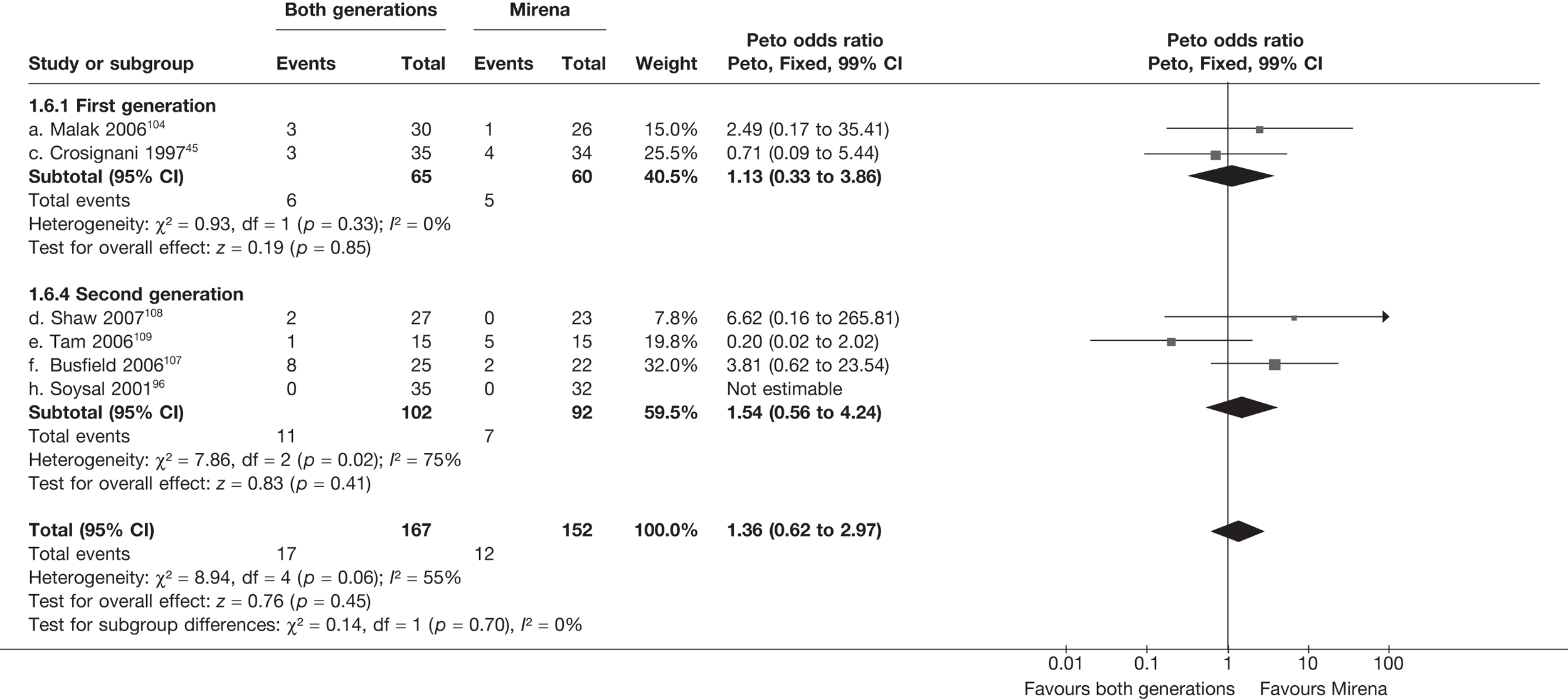

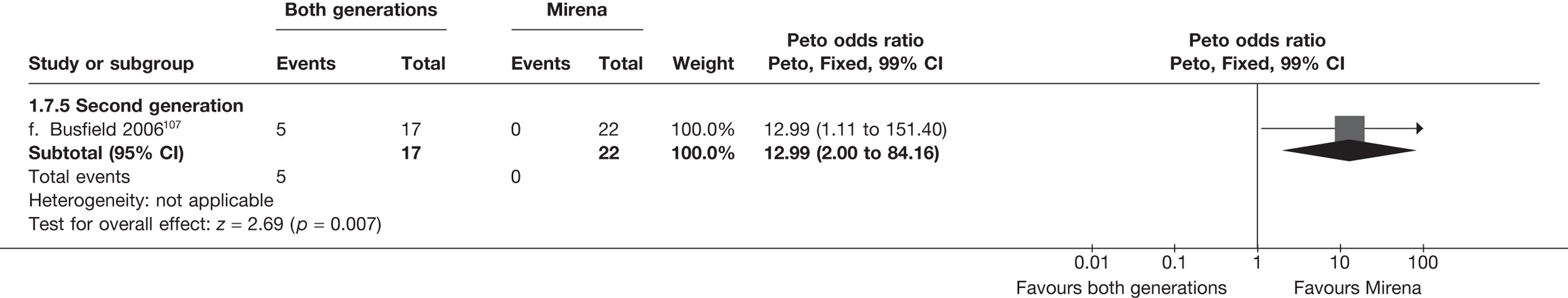

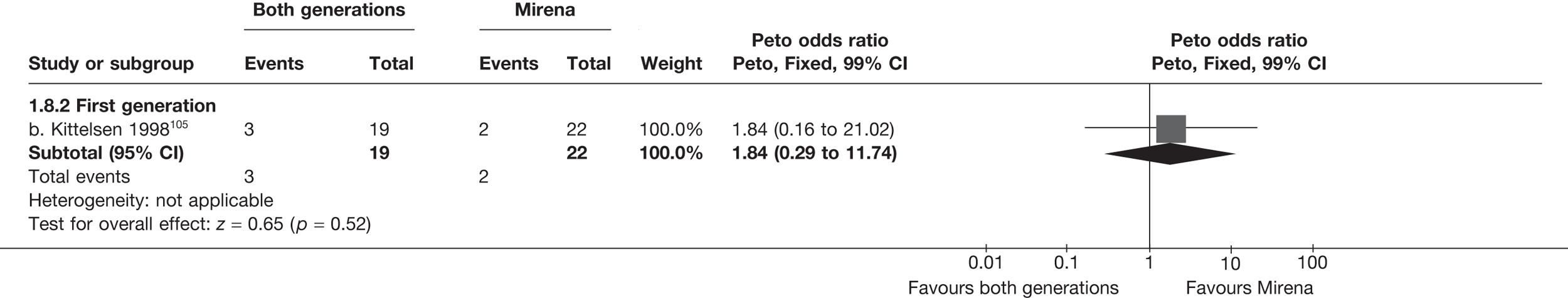

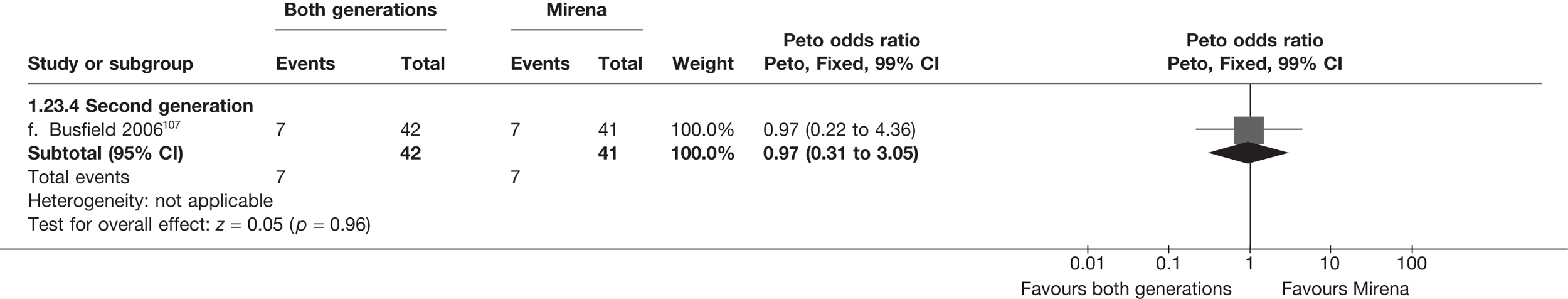

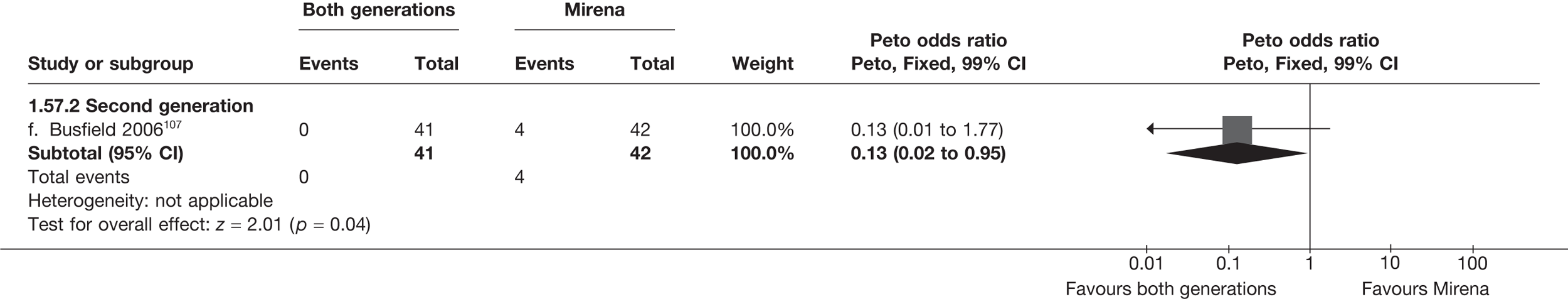

Mirena versus endometrial ablation techniques

Rates of dissatisfaction with Mirena and second-generation EA were similar [18.1% vs 22.5% (17/94 vs 23/102); OR 0.76; 95% CI 0.38 to 1.53; p = 0.4] (Figure 5), although the latter rate was twice as high as that seen for second-generation EA when it was compared with first-generation EA (see Figure 4). The slightly older age of women in these studies (see Trials and patients) could be a possible explanation for this increase, although given the small number of women studied in these trials this difference in rate could easily have arisen by chance. The combined estimate of this and the one study that compared Mirena with first-generation EA80 (test for differences between subgroups: p = 0.2) also showed no evidence of a difference (OR 0.94; 95% CI 0.50 to 1.77; p = 0.9). Heterogeneity of estimates overall was of borderline statistical significance (p = 0.09; I2 = 54%). Overall rates of dissatisfaction were 17.2% (22/128) for Mirena and 18.2% (25/137) for both first- and second-generation EA. Lack of IPD prohibited any further investigation of subgroups or repeated measures. Sensitivity analysis performed without two studies where surrogates for dissatisfaction were used significantly reduced the data available for analysis but did not change the findings.

FIGURE 5.

Dissatisfaction at 12 months – first- and second-generation EA versus Mirena.

Indirect comparisons of hysterectomy with second-generation endometrial ablation techniques and Mirena

Indirect estimates (Figure 6) suggest that hysterectomy is also preferable to second-generation EA [5.3% vs 10.6% (23/432 vs 110/1034); OR 2.32; 95% CI 1.27 to 4.24; p = 0.006) in terms of patient dissatisfaction. This is confirmed by the repeated measures analysis over all three time points, which per force only include IPD (OR 3.06; 95% CI 1.59 to 5.90; p = 0.0008). The evidence to suggest hysterectomy is preferable to Mirena was weaker [5.3% vs 17.2% (23/432 vs 22/128); OR 2.22; 95% CI 0.94 to 5.29; p = 0.07], but given the lack of precision from Mirena comparisons this was not a surprising result and should be cautiously interpreted.

FIGURE 6.

Dissatisfaction at 12 months summary. Odds ratios (95% CIs) are shown. Estimates > 1 indicate increased dissatisfaction for the second treatment listed. Indirect estimates are represented by a dotted line.

Predictors of dissatisfaction

For second-generation EA, IPD showed that uterine cavity length was the strongest predictor of dissatisfaction (p = 0.02), with shorter uterine cavity length (≤ 8 cm vs > 8 cm) associated with reduced rates (OR 0.59; 95% CI 0.38 to 0.93; p = 0.02) (Table 5). Absence of fibroids/polyps also showed a trend towards reduced dissatisfaction (p = 0.07), although no further adjusted estimates including both parameters were attempted as only three studies had data on fibroids/polyps. There were no convincing associations with any of the variables for hysterectomy or first-generation EA.

| Hysterectomy | First-generation EA | Second-generation EA | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI)a | n | p-value | OR (95% CI)a | n | p-value | OR (95% CI)a | n | p-value | |

| Individual estimatesb | |||||||||

| Uterine cavity length, cm (≤ 8 vs > 8) | – | – | – | 0.97 (0.38 to 2.44) | 418 | 0.9 | 0.59 (0.38 to 0.93) | 817 | 0.02 |

| Age, years (≤ 40 vs > 40) | 2.28 (0.66 to 7.89) | 239 | 0.2 | 1.21 (0.81 to 1.81) | 971 | 0.4 | 1.30 (0.87 to 1.93) | 942 | 0.2 |

| Fibroids/polyps (absence vs presence) | 0.51 (0.14 to 1.93) | 233 | 0.3 | 1.15 (0.55 to 2.38) | 476 | 0.7 | 0.36 (0.12 to 1.07) | 302 | 0.07 |

| Parity (nullparous vs parous) | – | – | – | 1.27 (0.36 to 4.43) | 778 | 0.7 | 0.84 (0.33 to 2.16) | 734 | 0.7 |

| Baseline bleeding score (≤ 350 vs 350) | – | – | – | 0.73 (0.27 to 1.97) | 328 | 0.5 | 0.96 (0.48 to 1.91) | 551 | 0.9 |

Effectiveness in improving other outcomes

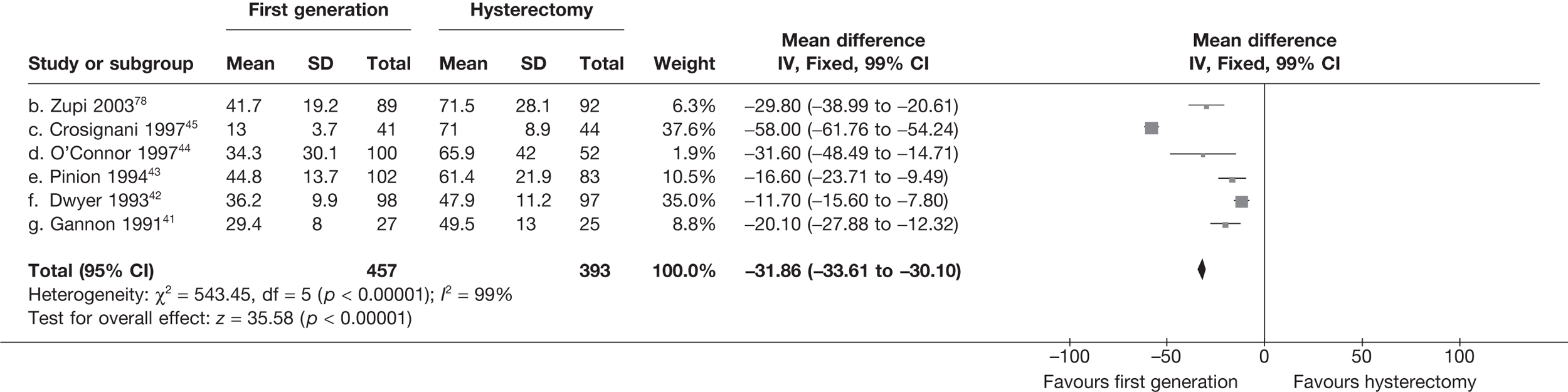

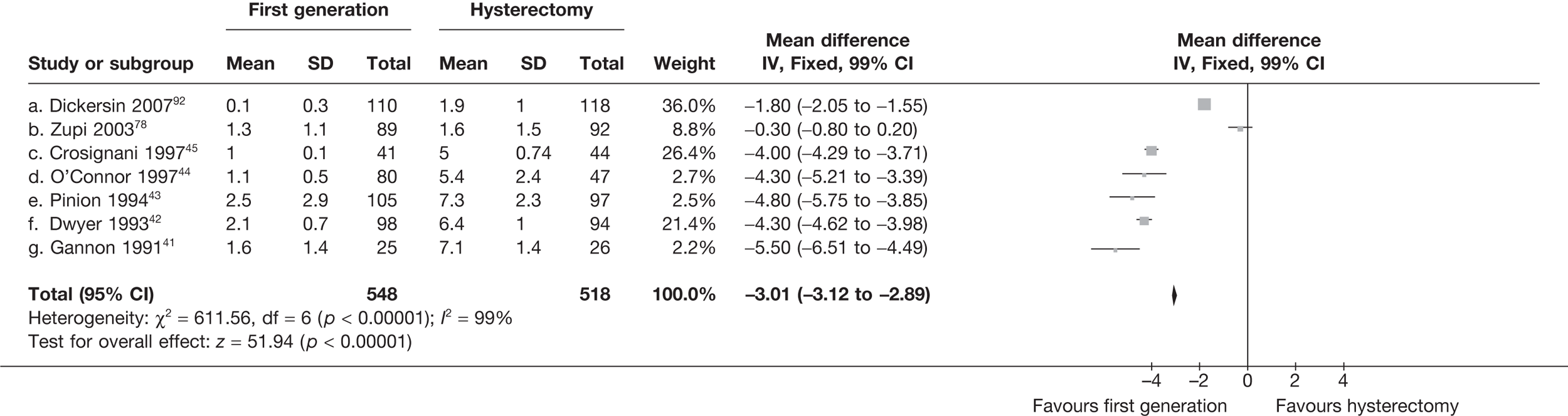

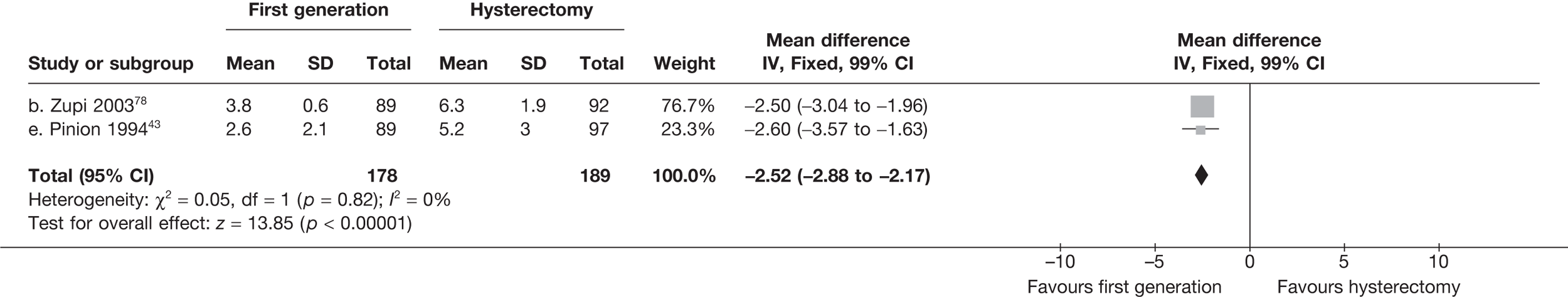

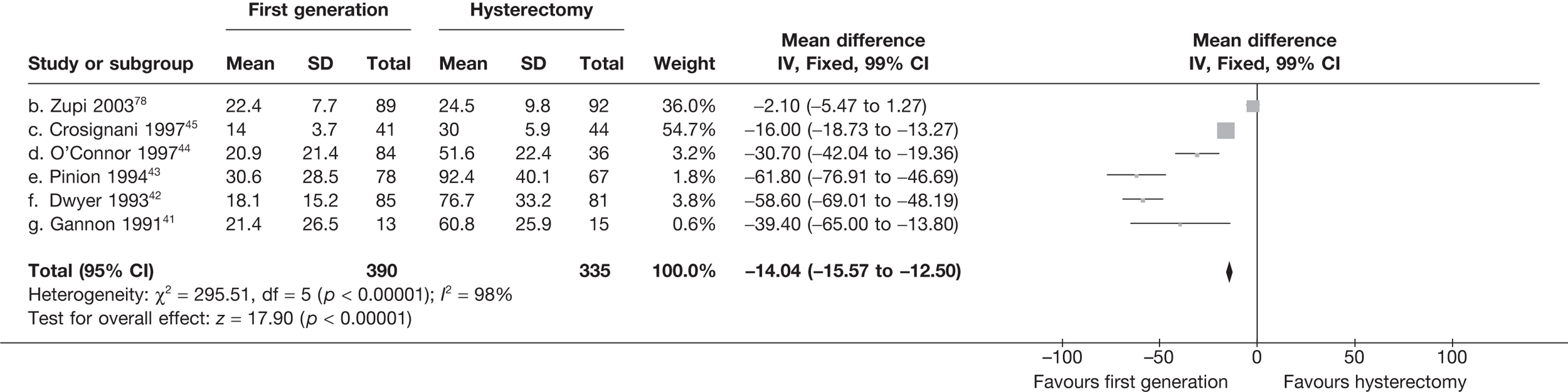

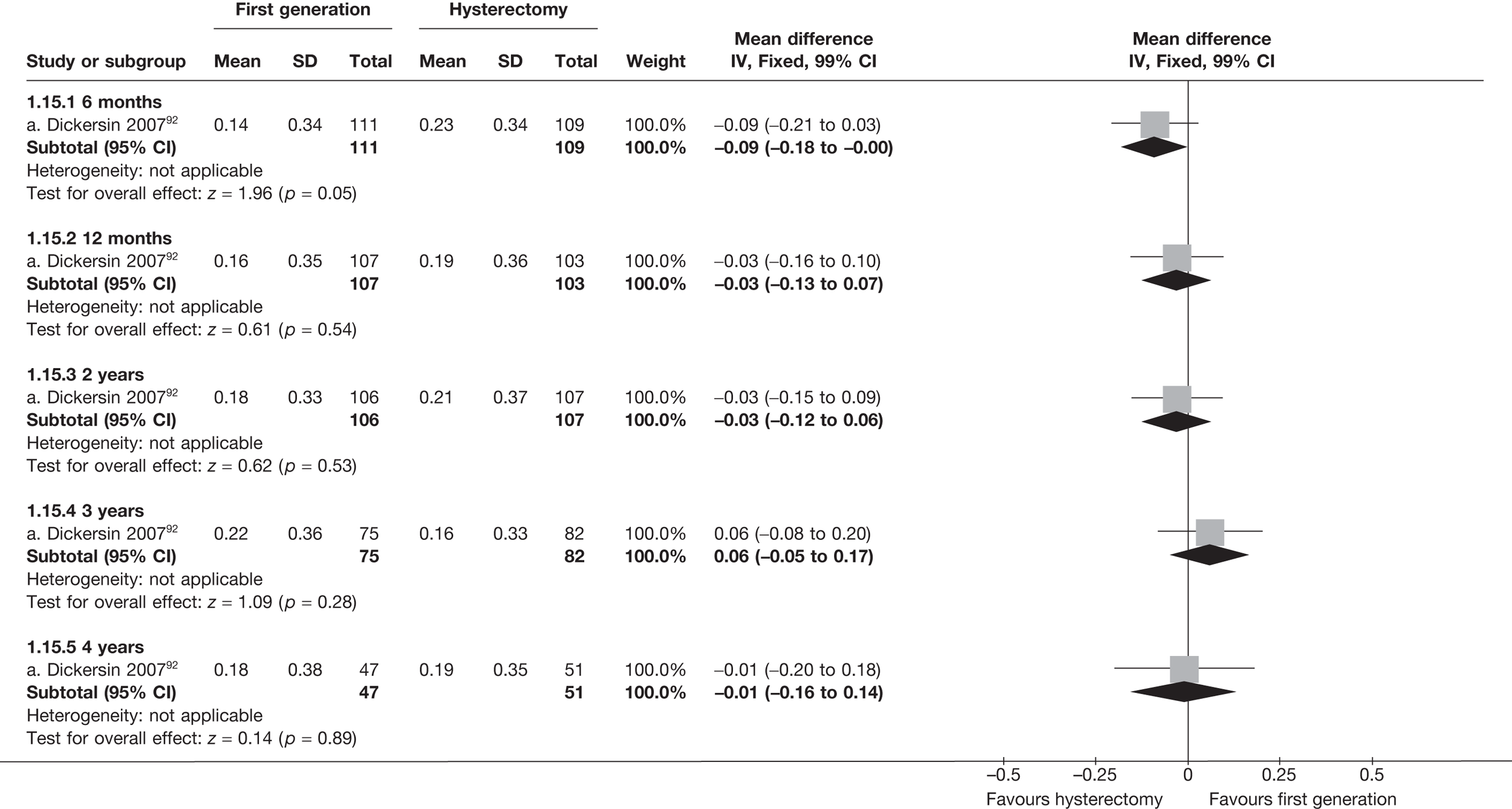

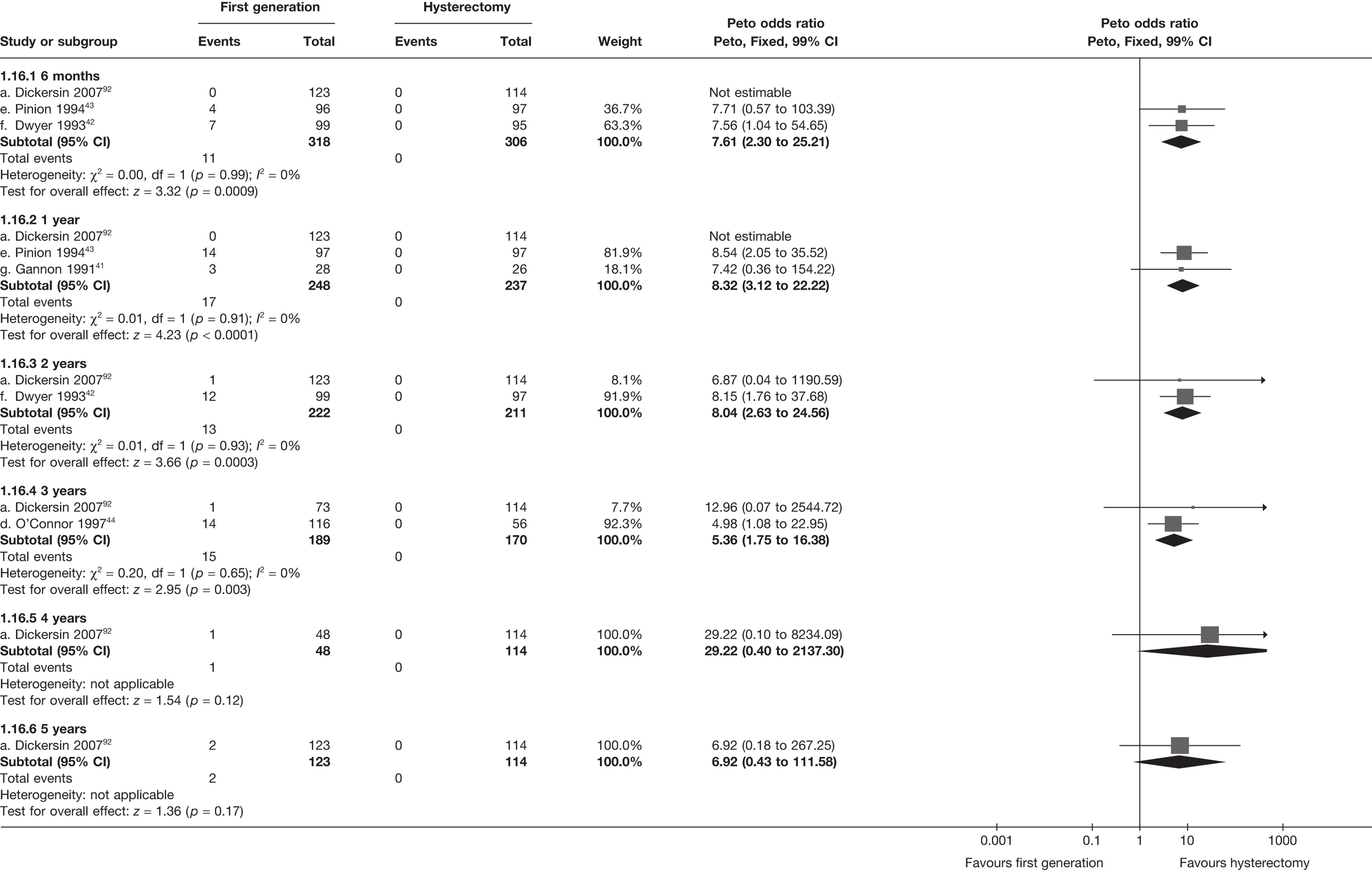

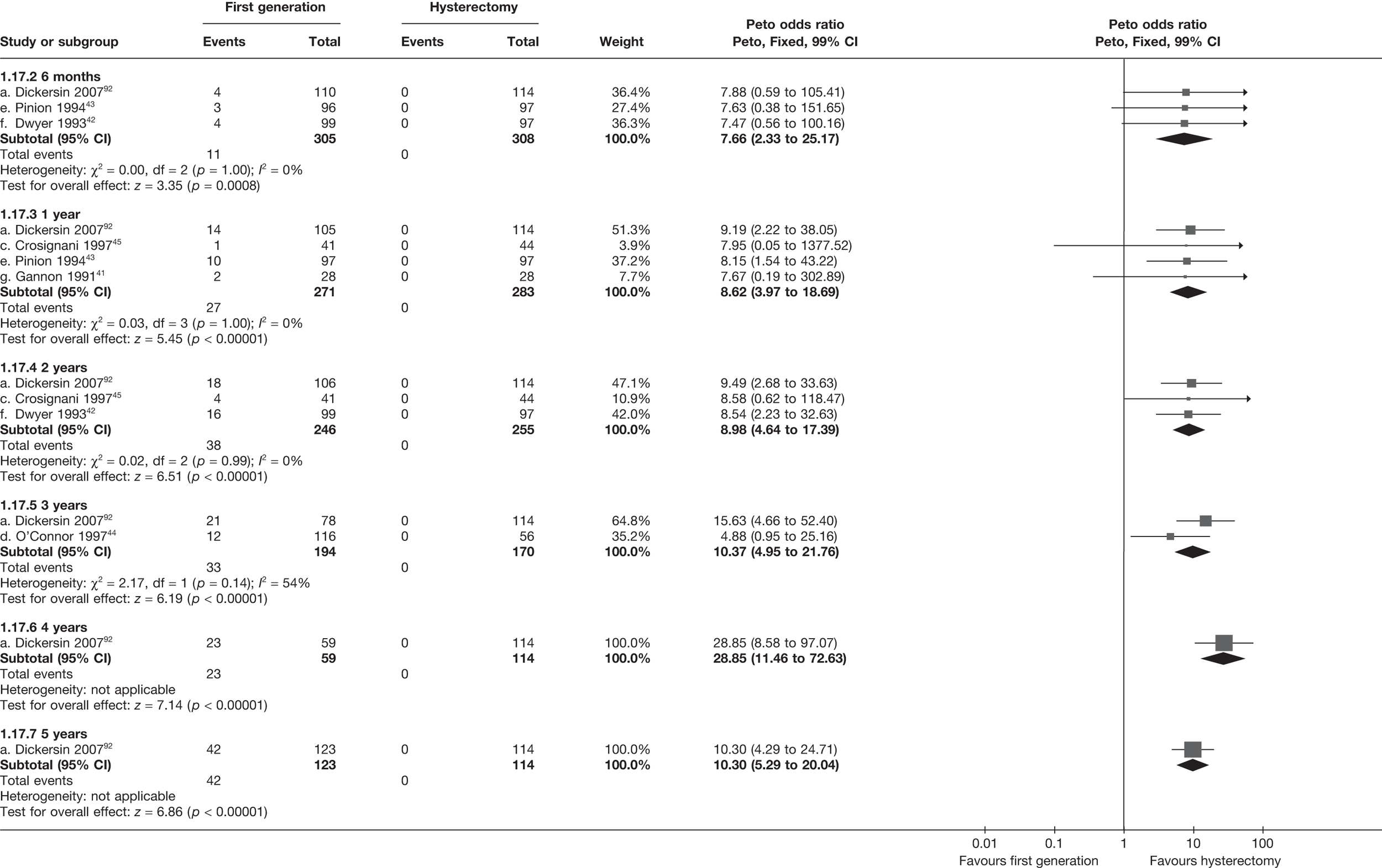

Hysterectomy versus endometrial ablation and Mirena

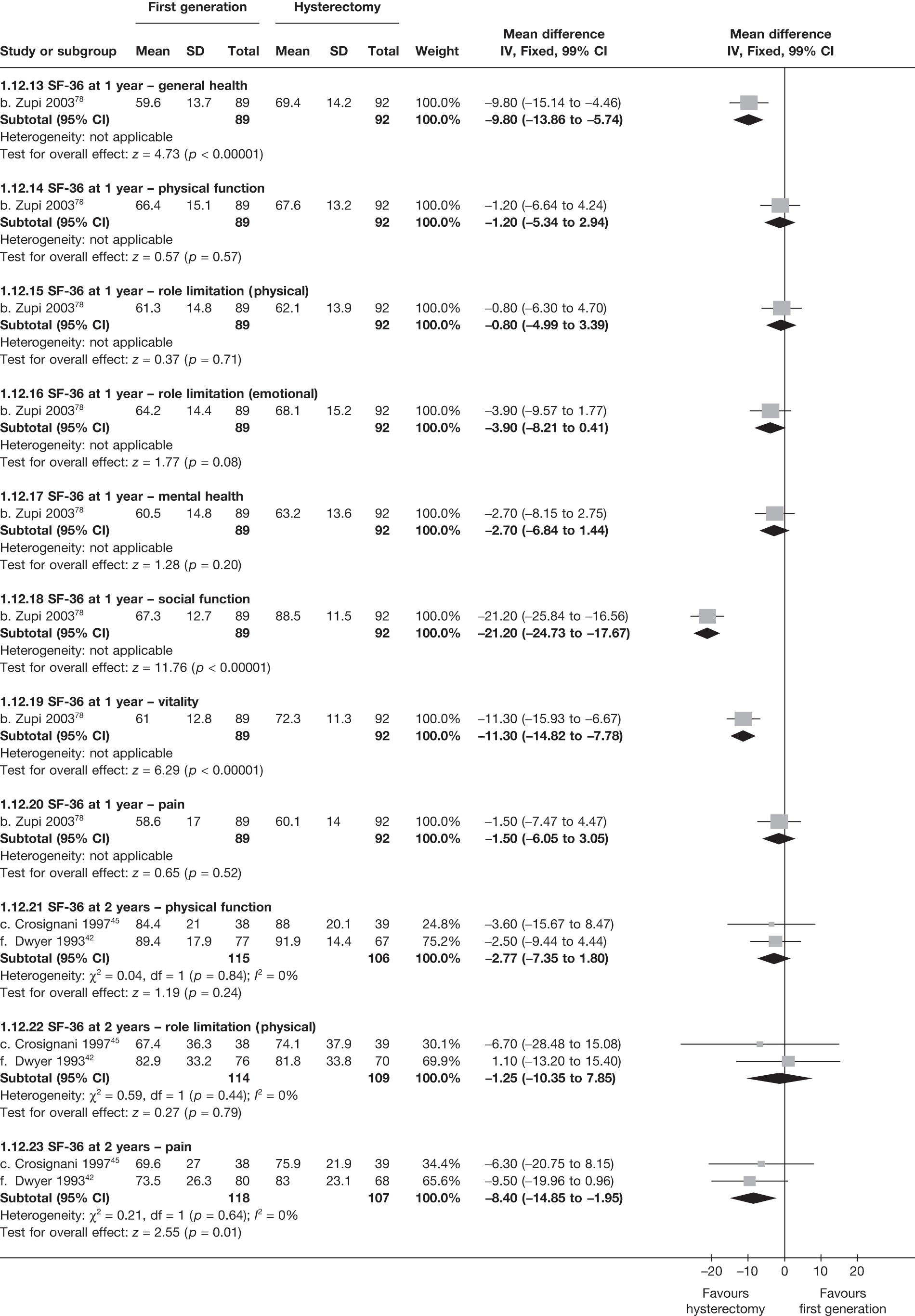

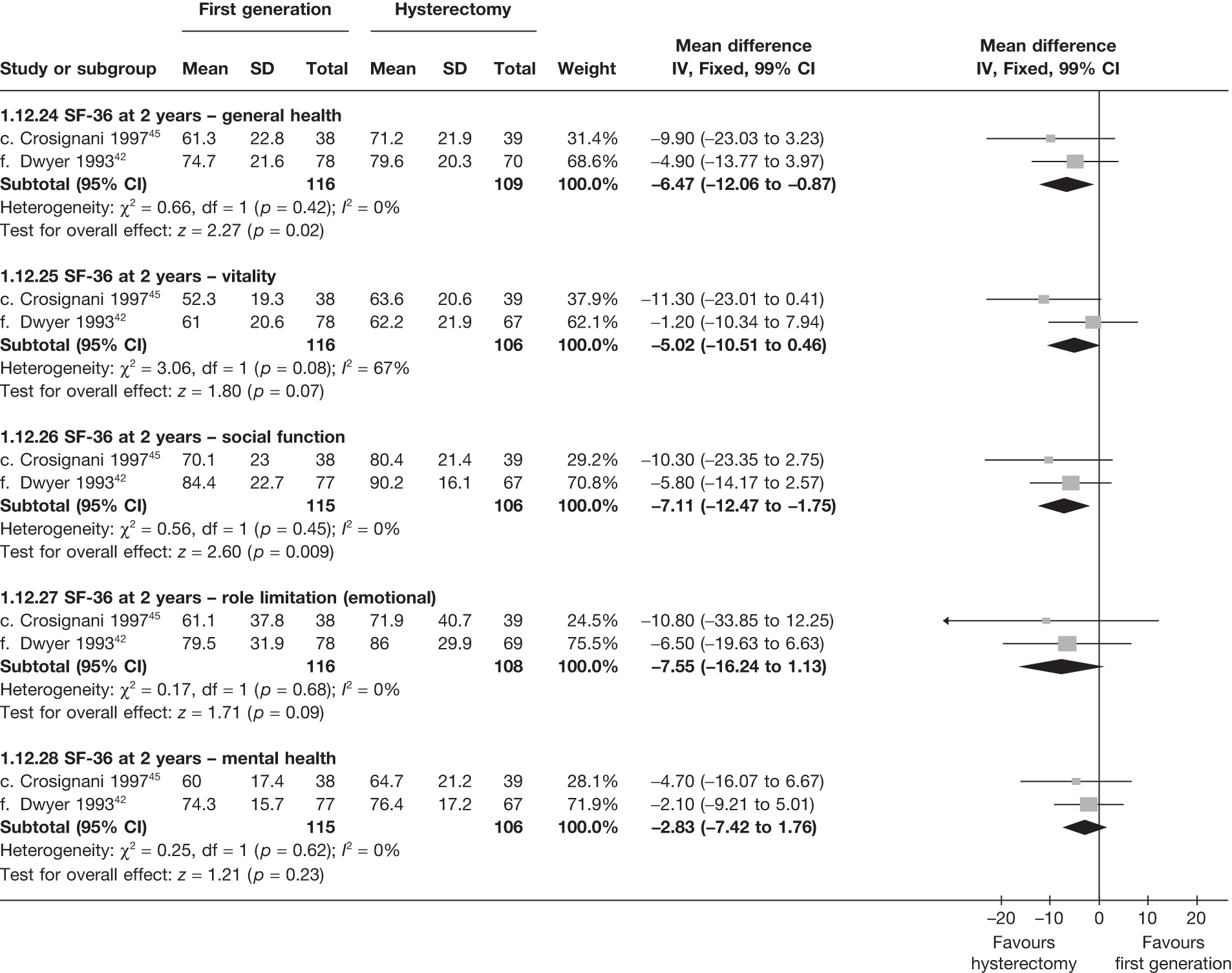

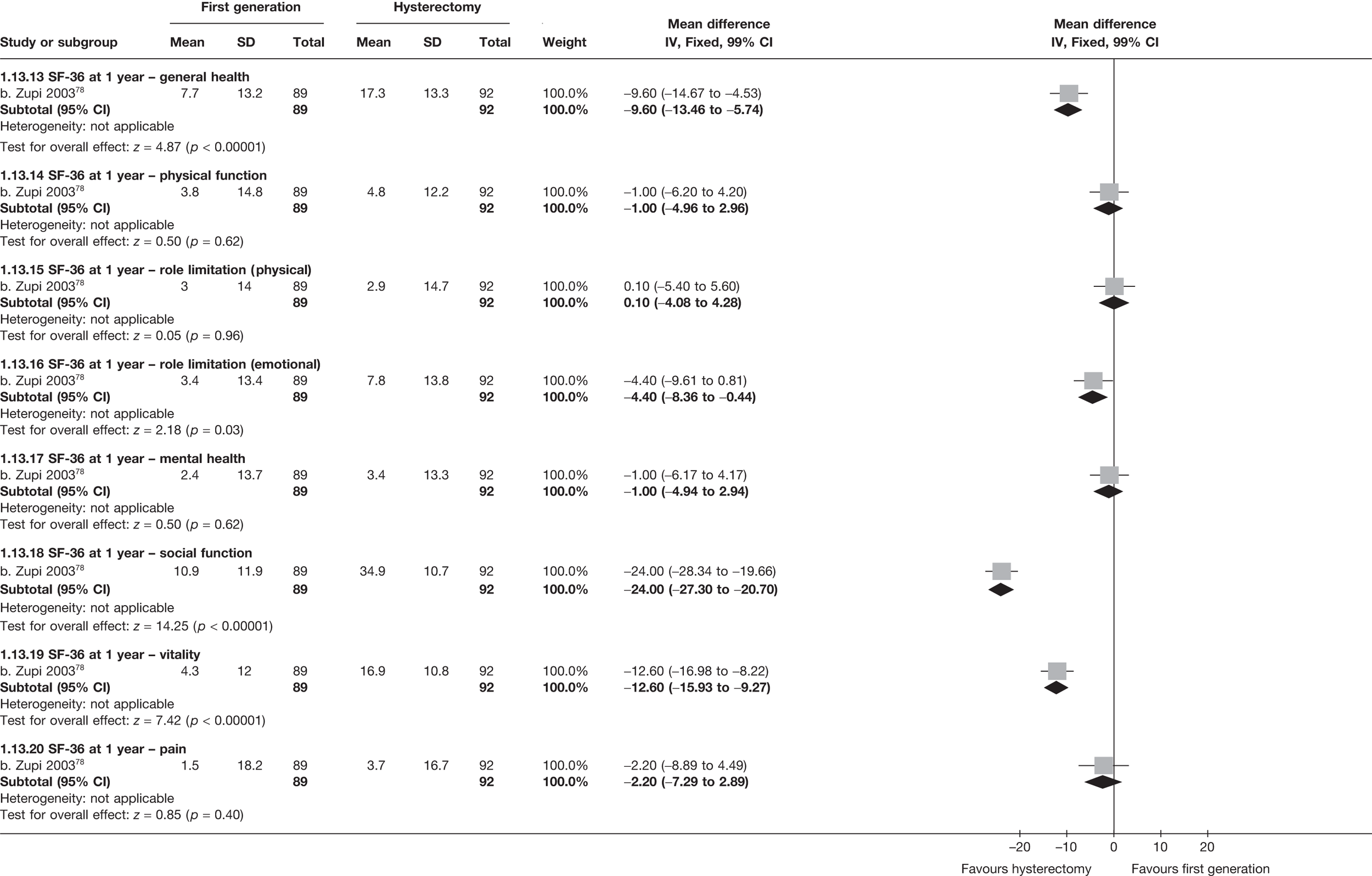

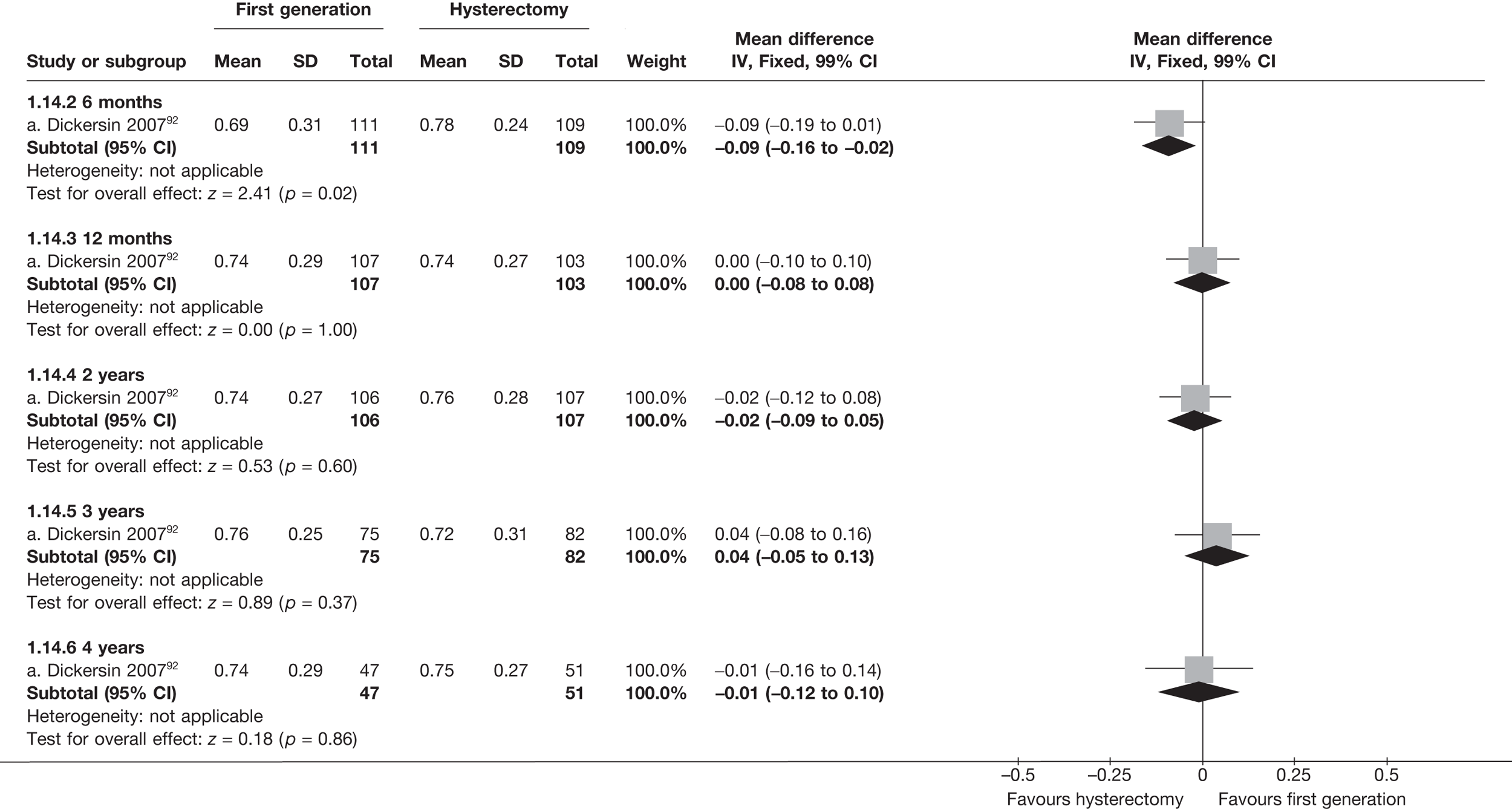

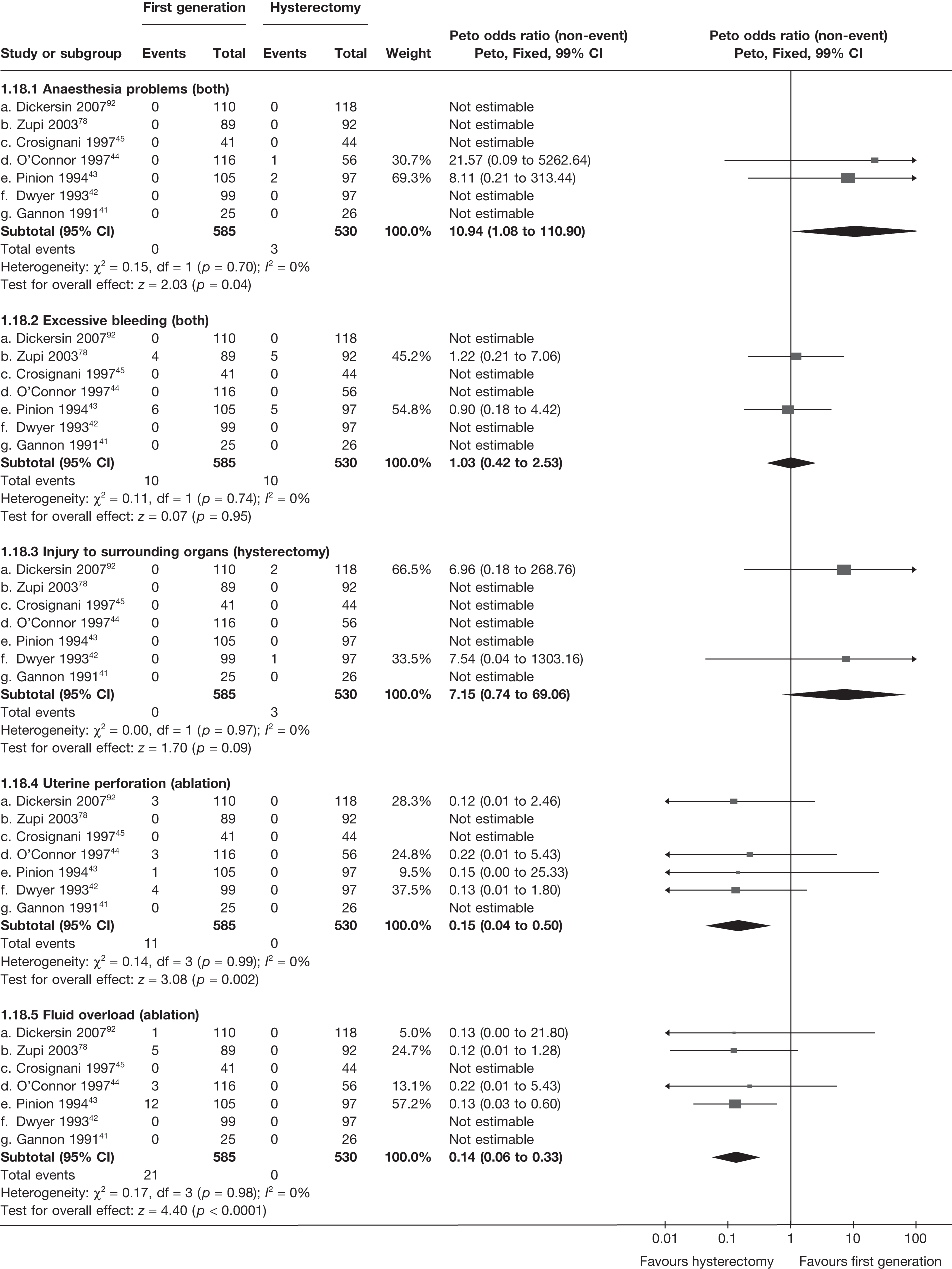

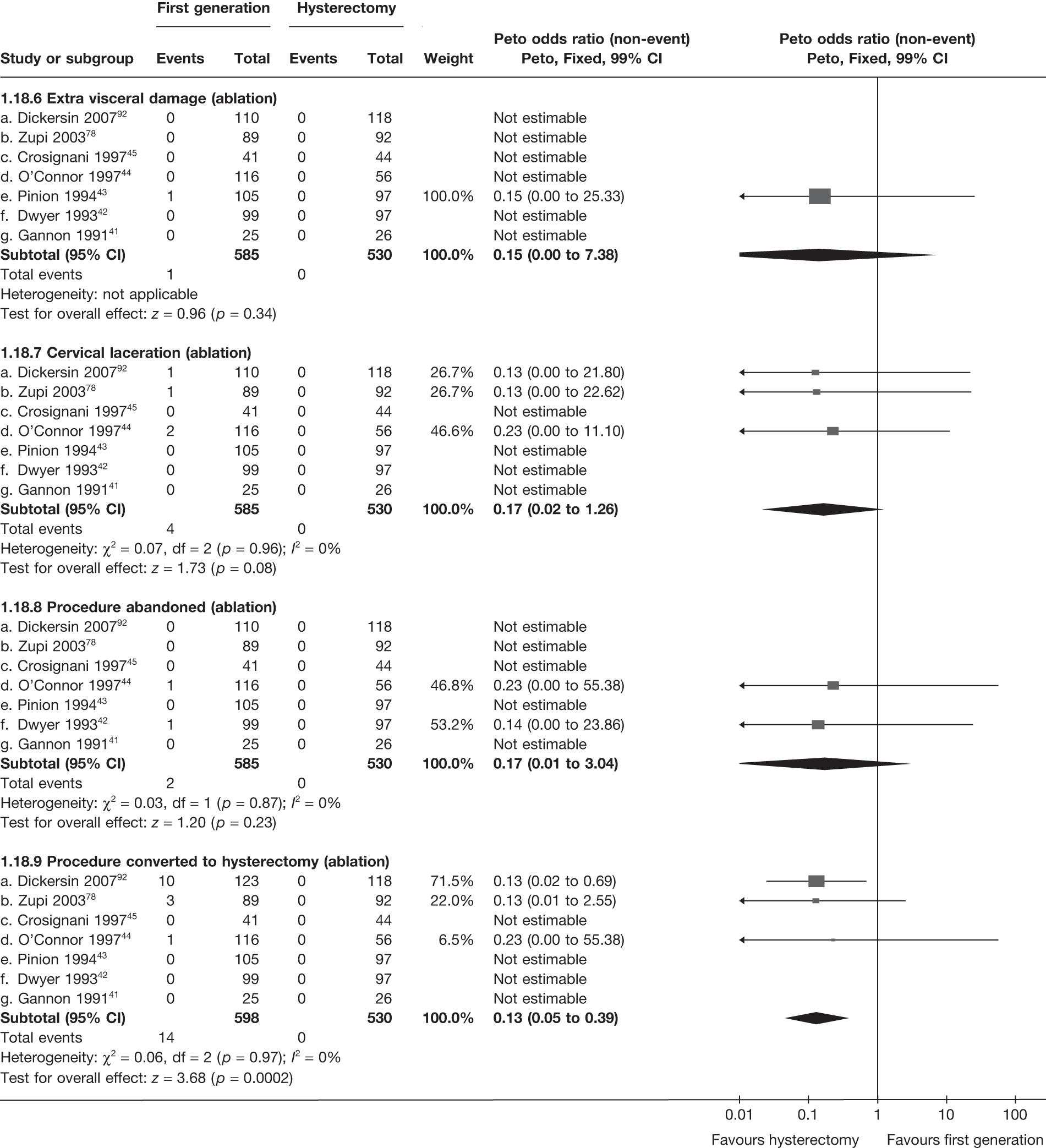

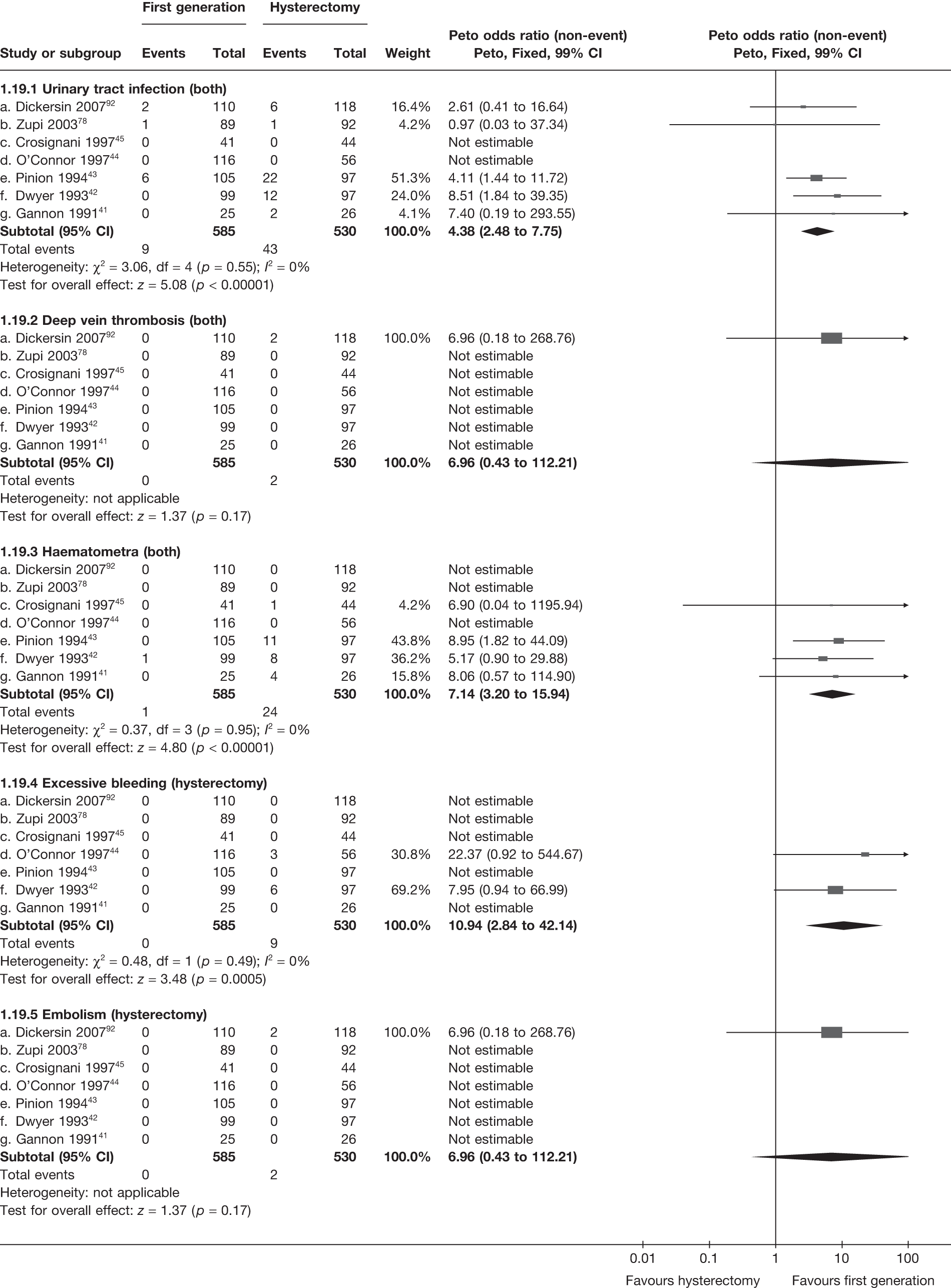

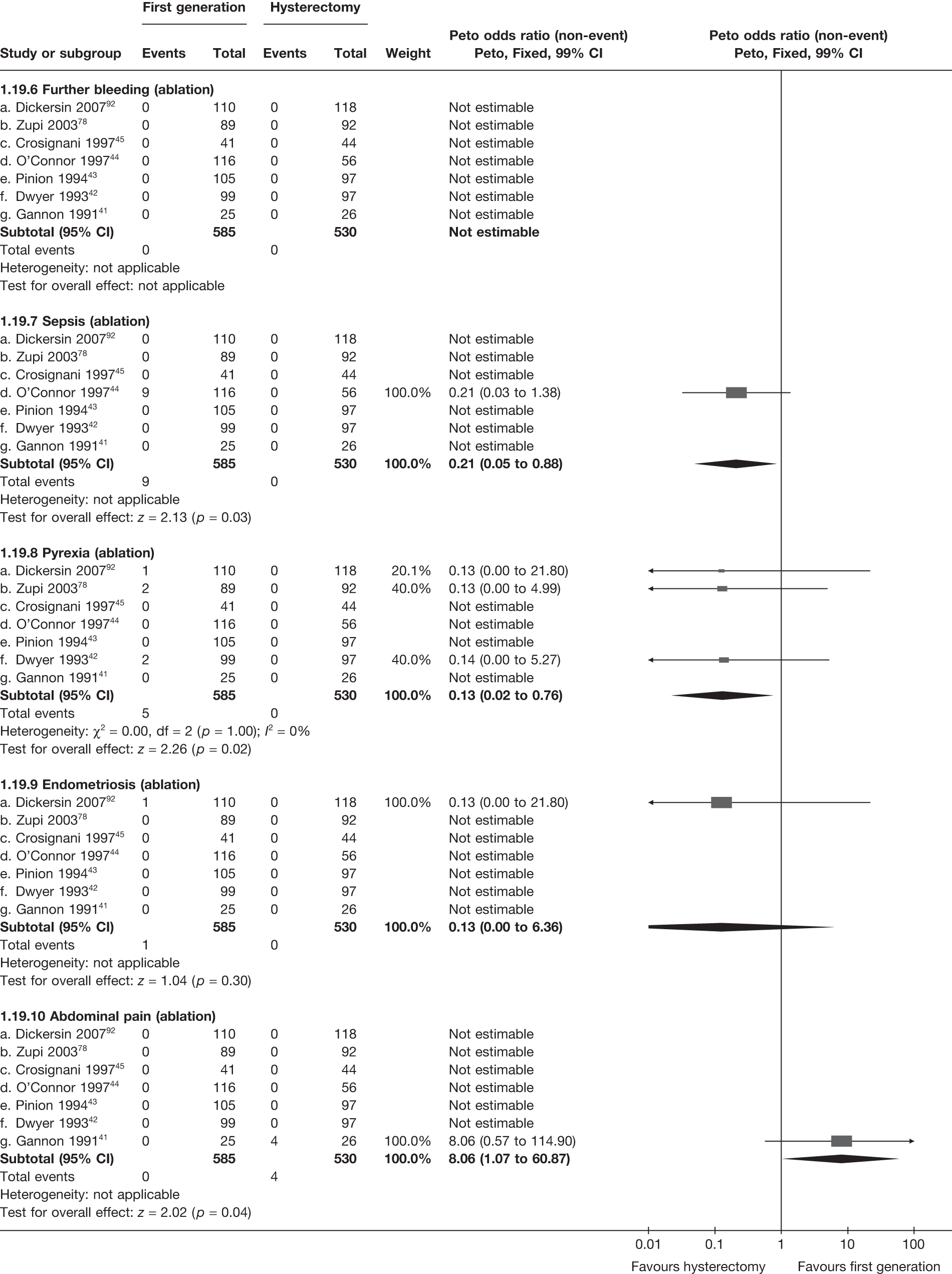

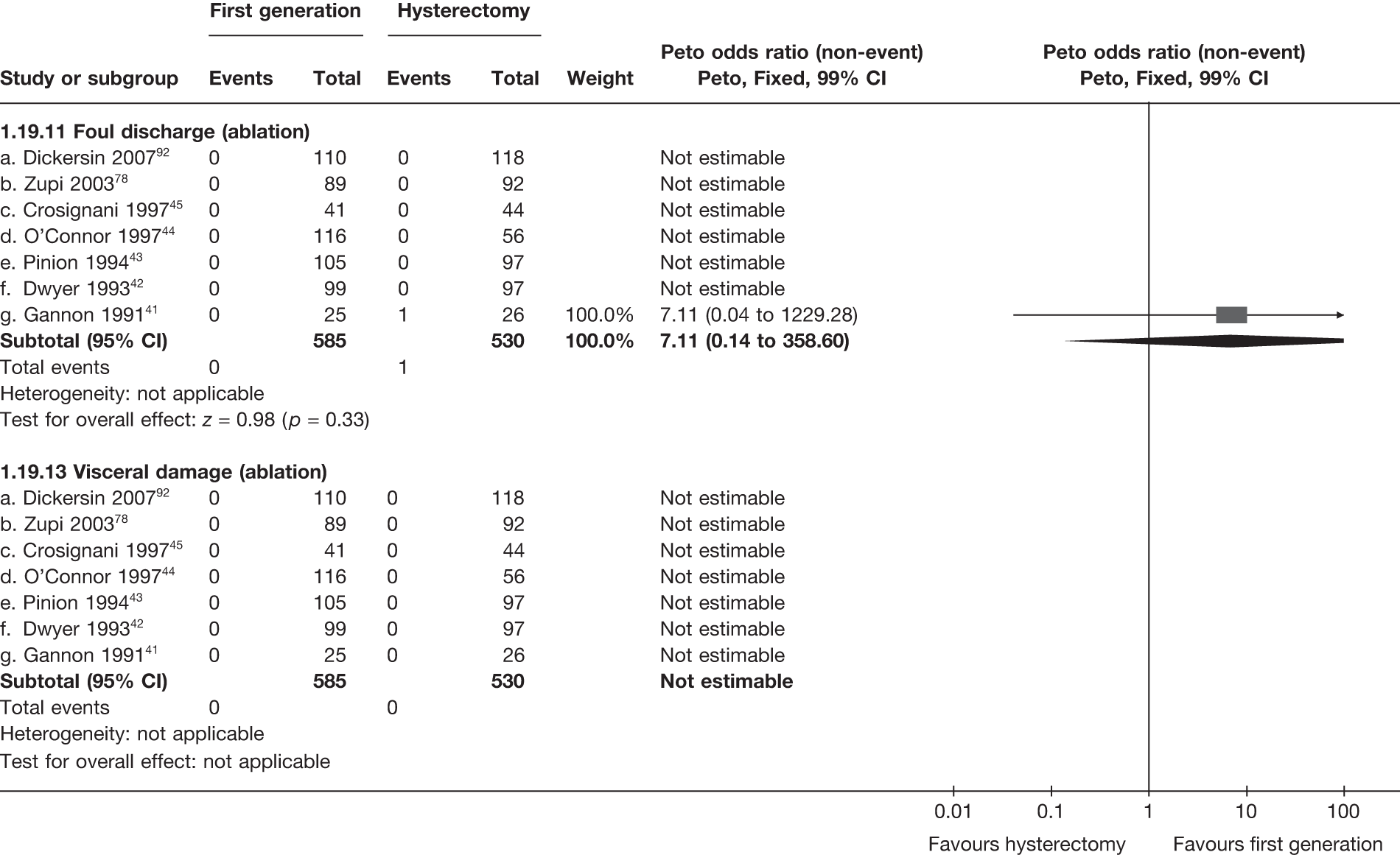

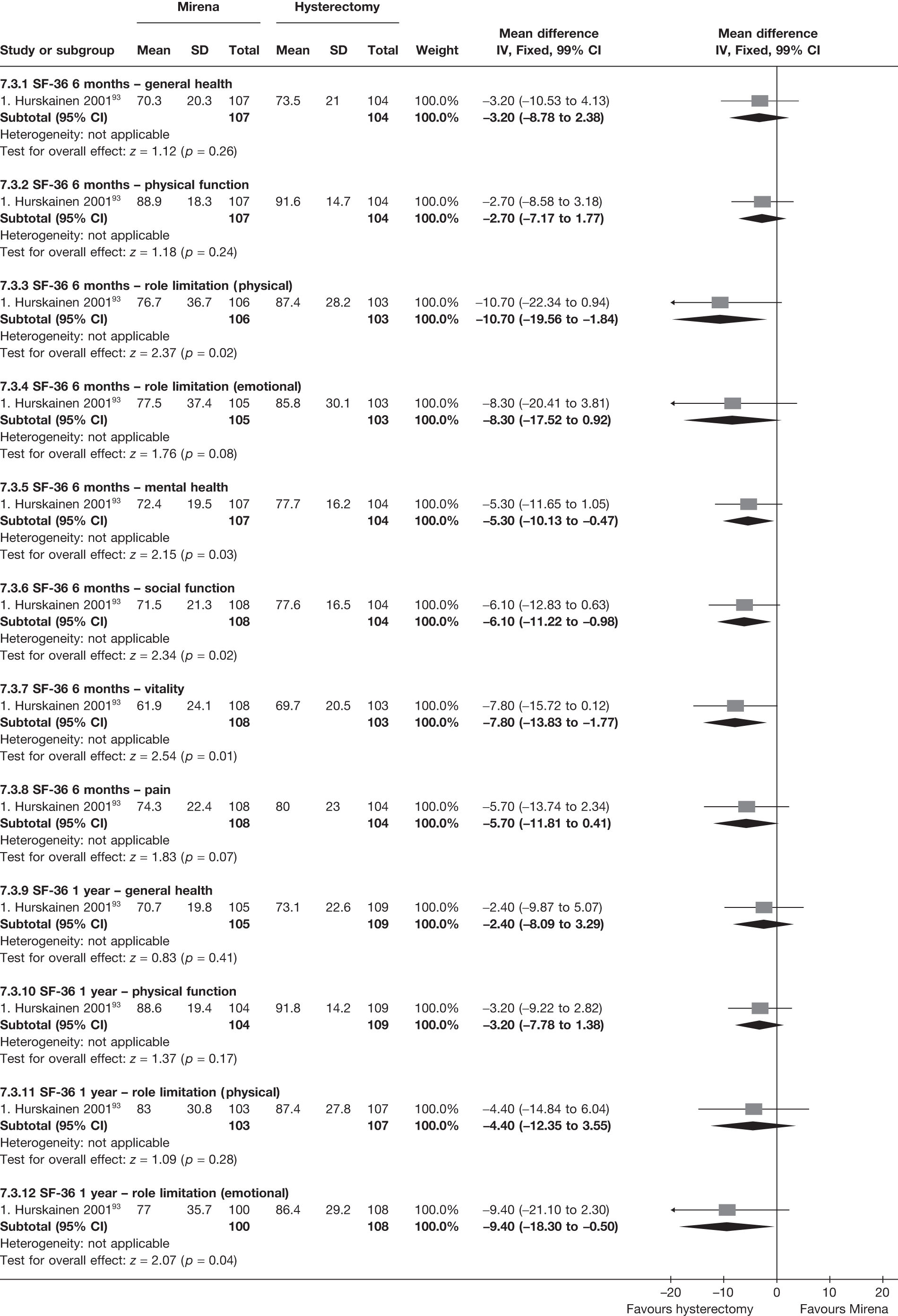

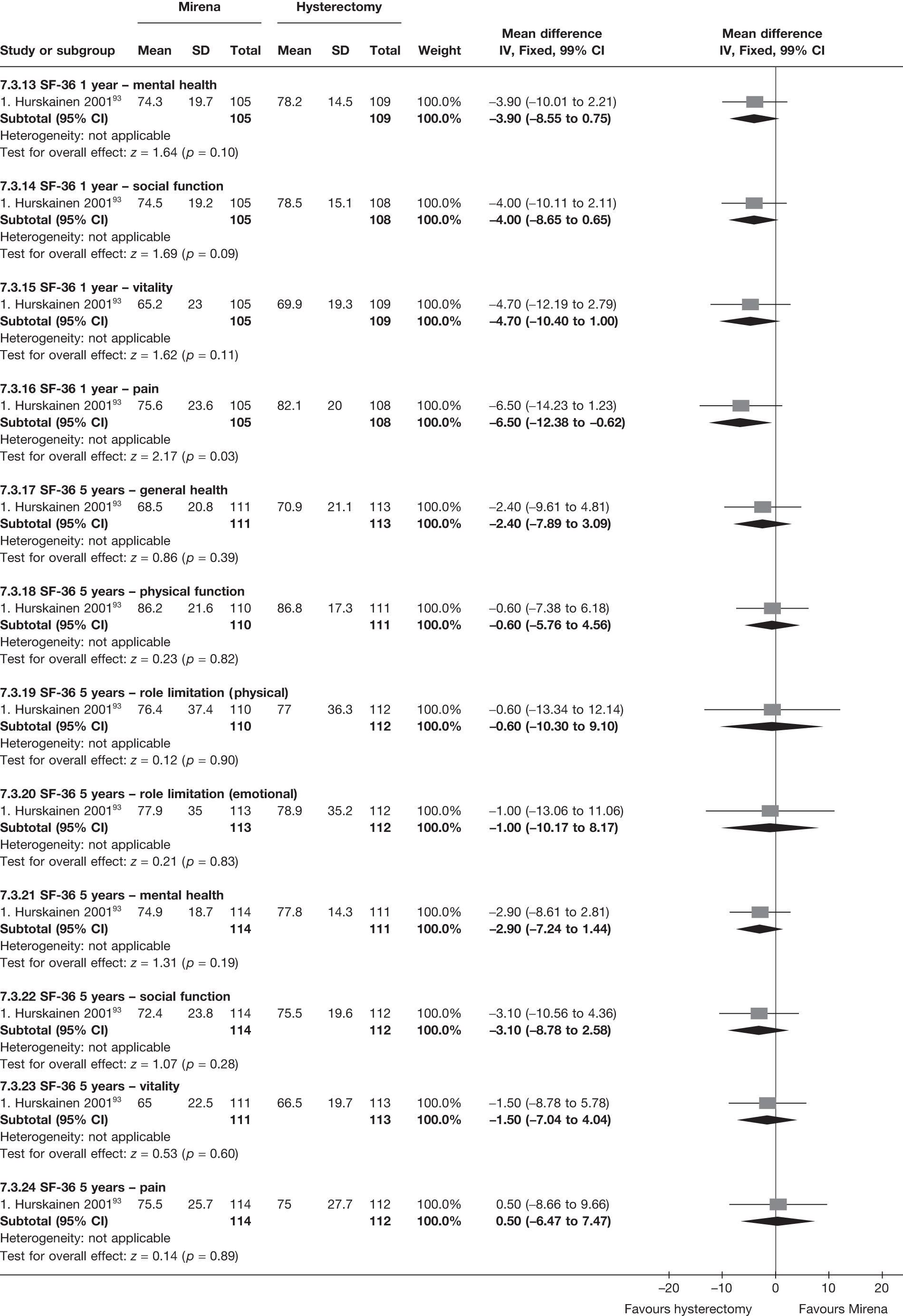

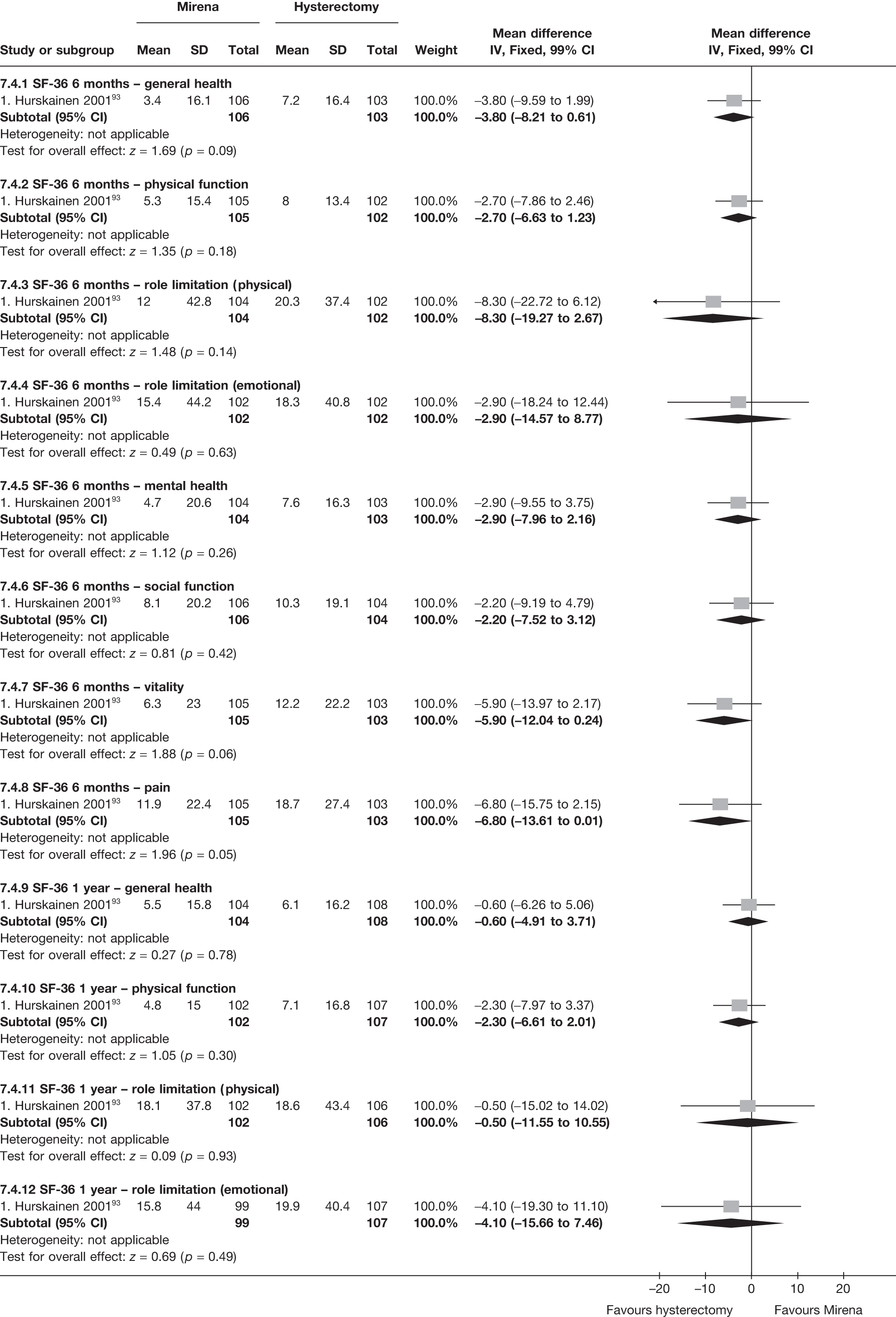

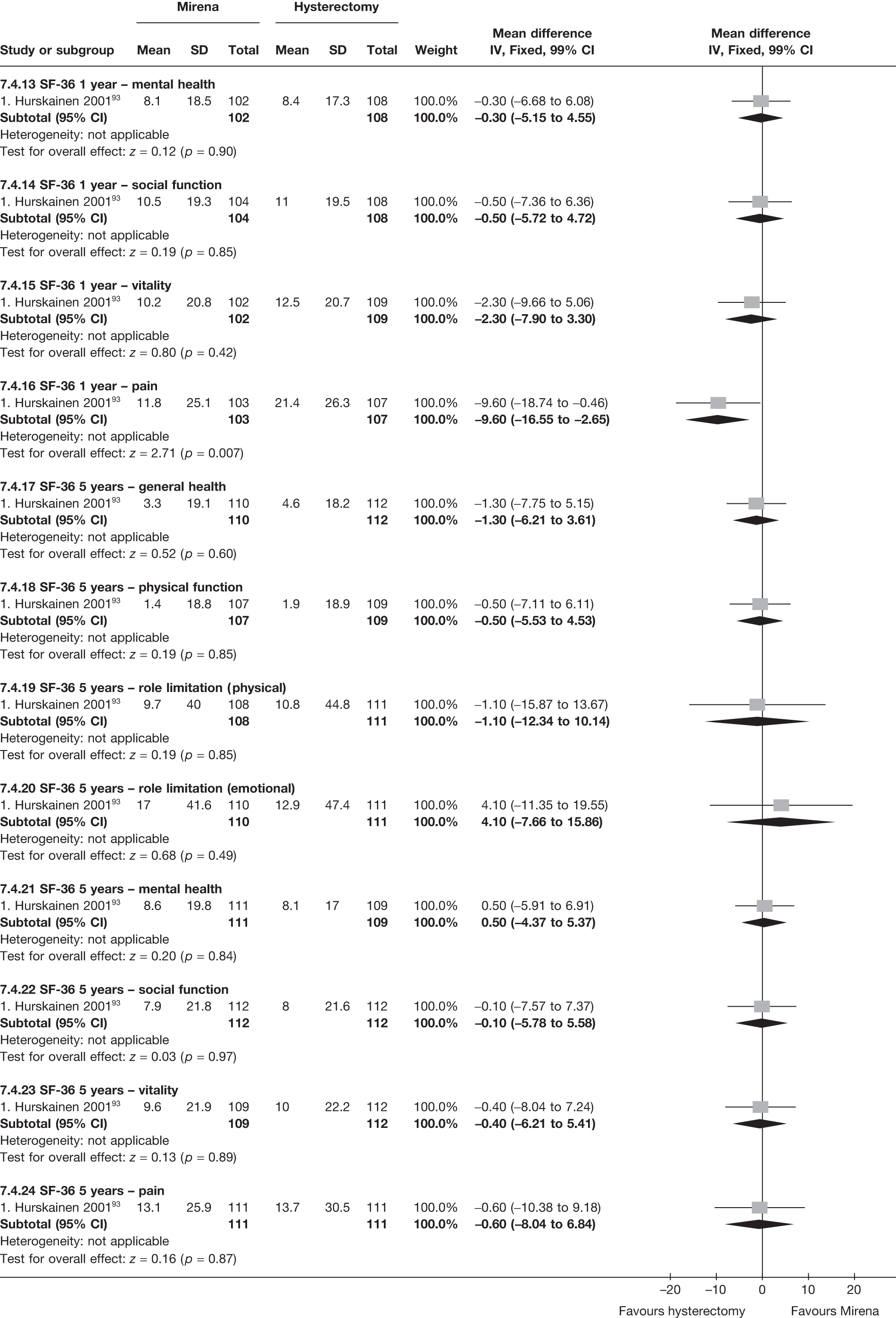

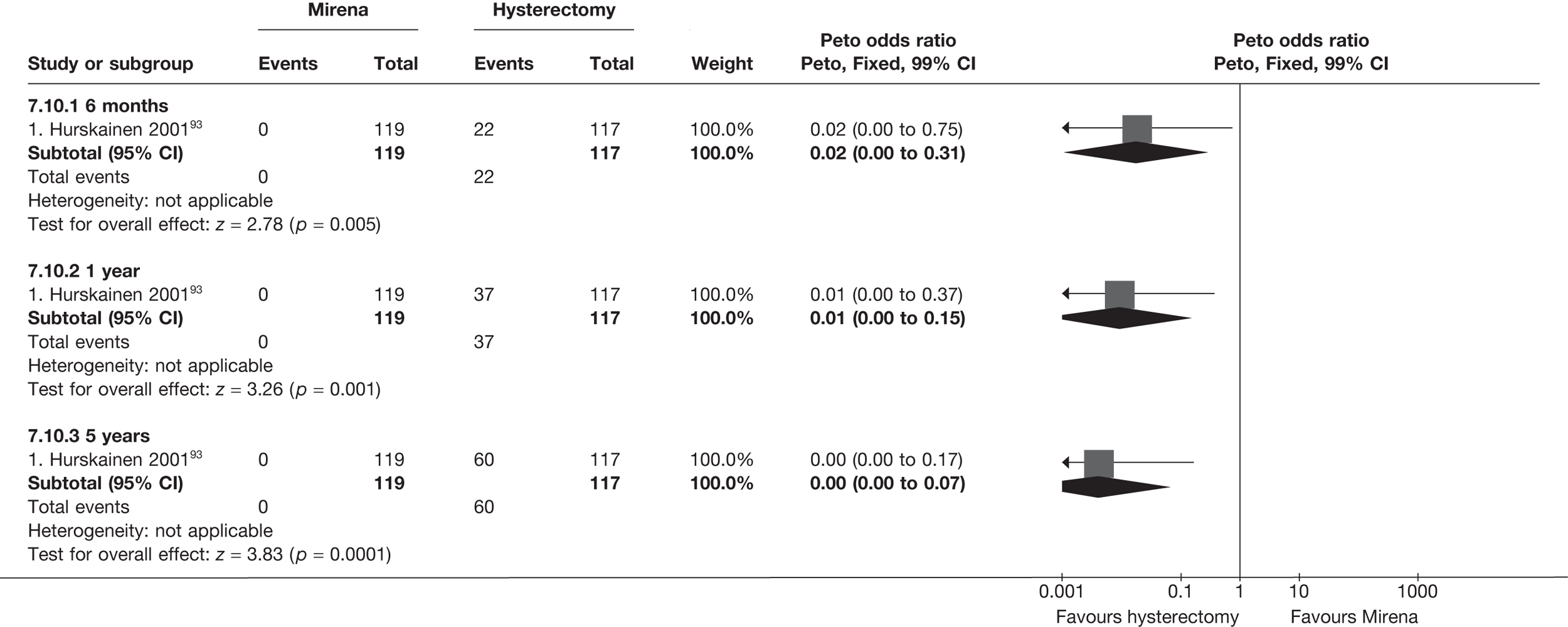

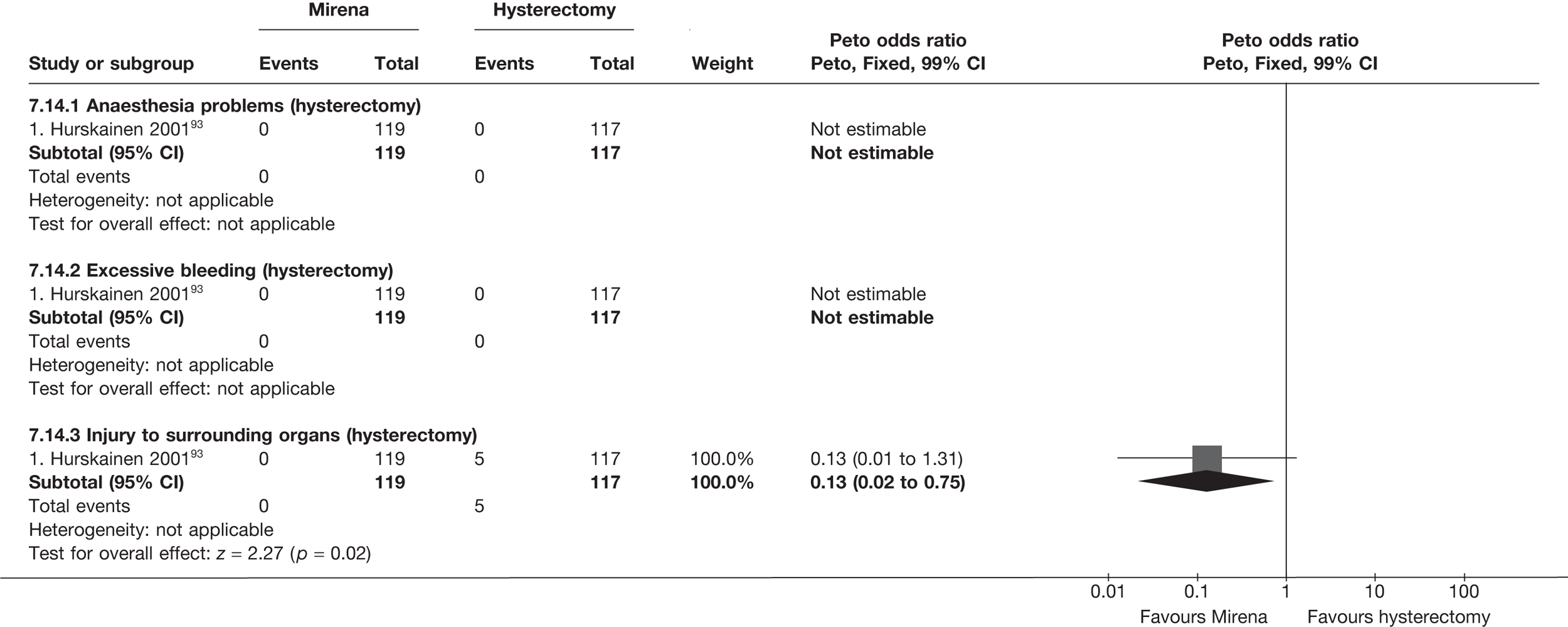

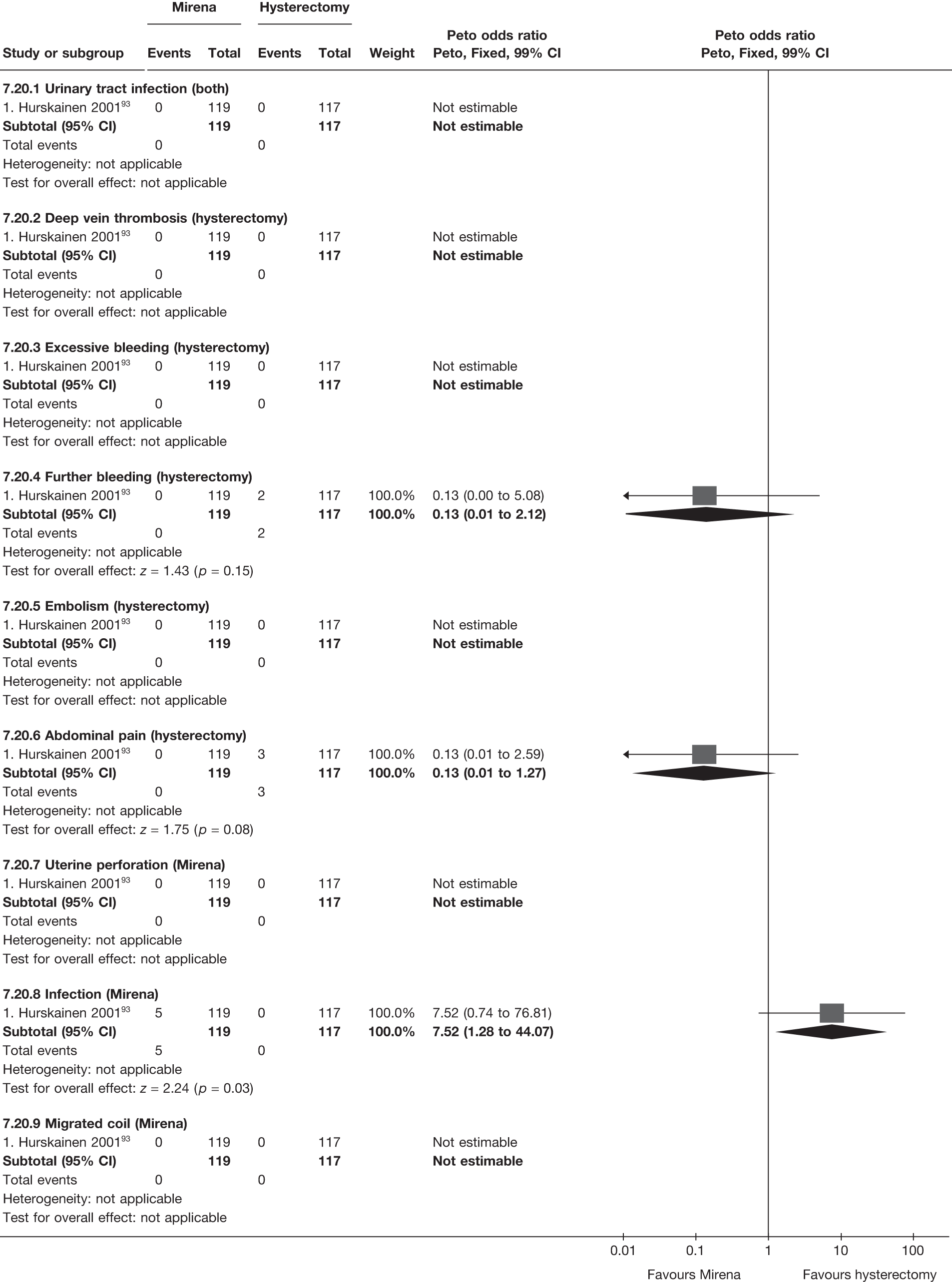

These comparisons focused on recovery times and QoL, as estimates of postoperative menstrual blood loss are redundant after hysterectomy (see Appendix 4). EA offered quicker surgery (WMD 32 minutes; 95% CI 30 to 34 minutes; p < 0.0001), shorter hospital stay (WMD 3.0 days; 95% CI 2.9 to 3.1 days; p < 0.00001), faster recovery periods (time to return to normal activities: WMD 5.2 days; 95% CI 4.7 to 5.7 days; p < 0.00001) and less pain postoperatively (WMD 2.5 points; 95% CI 2.2 to 2.9 points; p < 0.0001), although estimates of differences for some of these parameters should be used with caution given the high variability between studies (see Appendix 4). One study92 suggested no obvious difference in EQ-5D utility scores, while another78 suggested differences in favour of hysterectomy in the general health (WMD 9.6 points; 95% CI 5.7 to 13.5 points; p < 0.0001), social function (WMD 24 points; 95% CI 21 to 27 points; p < 0.0001) and vitality (WMD 13 points; 95% CI 9.3 to 16 points; p < 0.0001) domains of the SF-36 questionnaire. Perioperative adverse events associated with hysterectomy were relatively few (0.5%–2.0% each), but UTIs were more common with hysterectomy (43/530; 8.1%) than with EA (9/585; 1.5%). Of the women who were initially treated with EA, 15% had undergone a hysterectomy within 2 years.

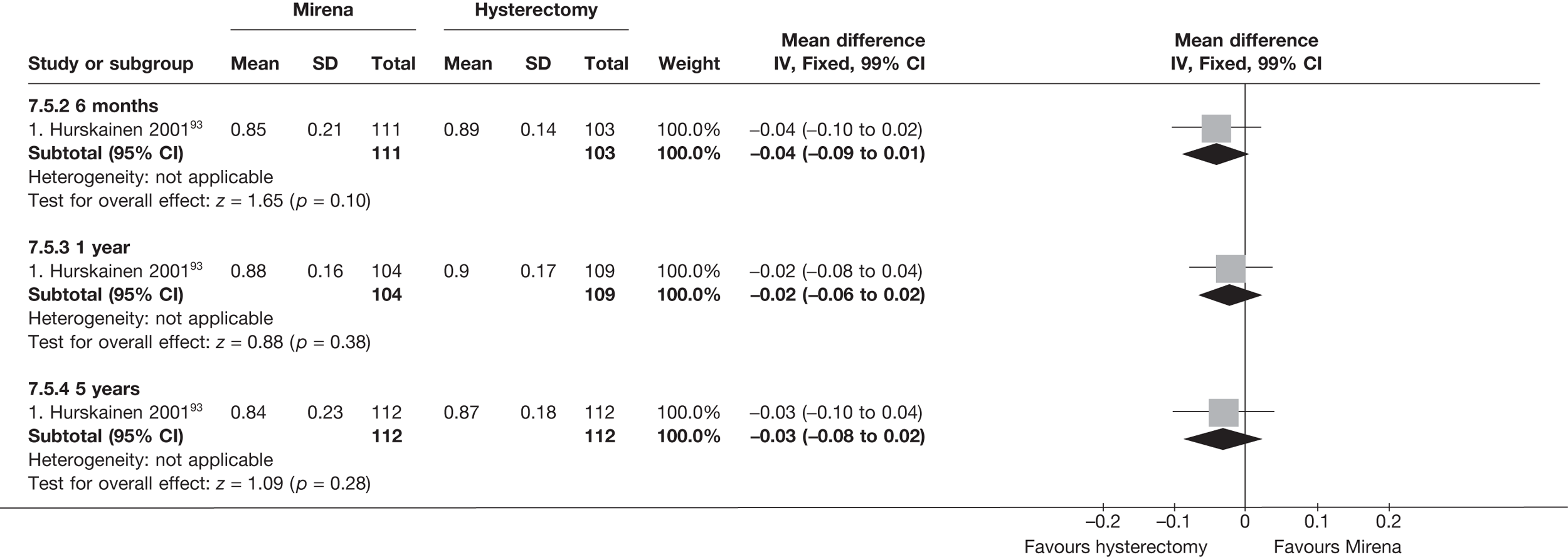

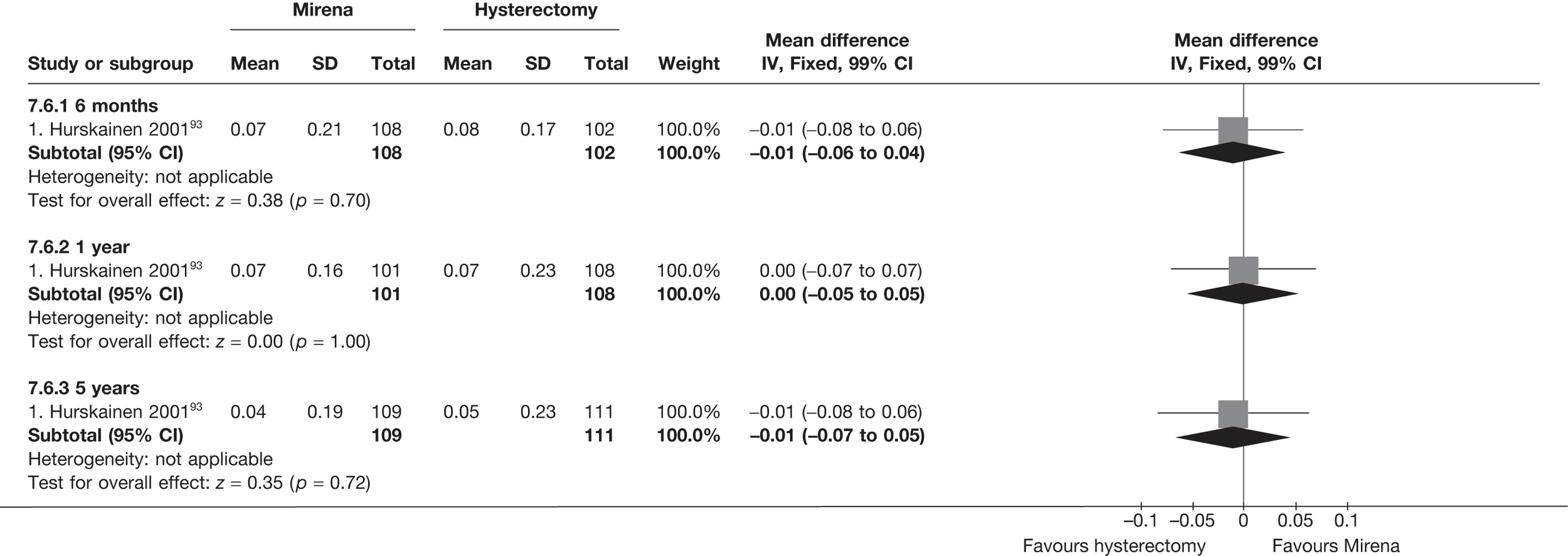

No differences in EQ-5D scores were seen at 6 or 12 months in the single study comparing hysterectomy with Mirena (see Appendix 5), while the only statistically significant effect observed in the SF-36 questionnaire was in the pain domain, which favoured hysterectomy (WMD 9.6 points; 95% CI 2.7 to 16.6 points; p = 0.007). All results were consistent over subgroups.

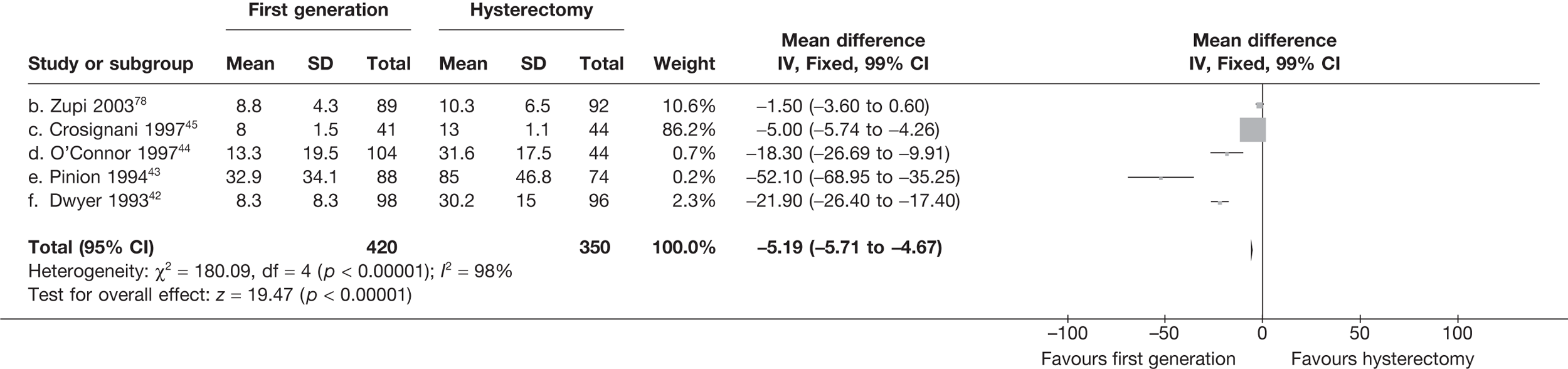

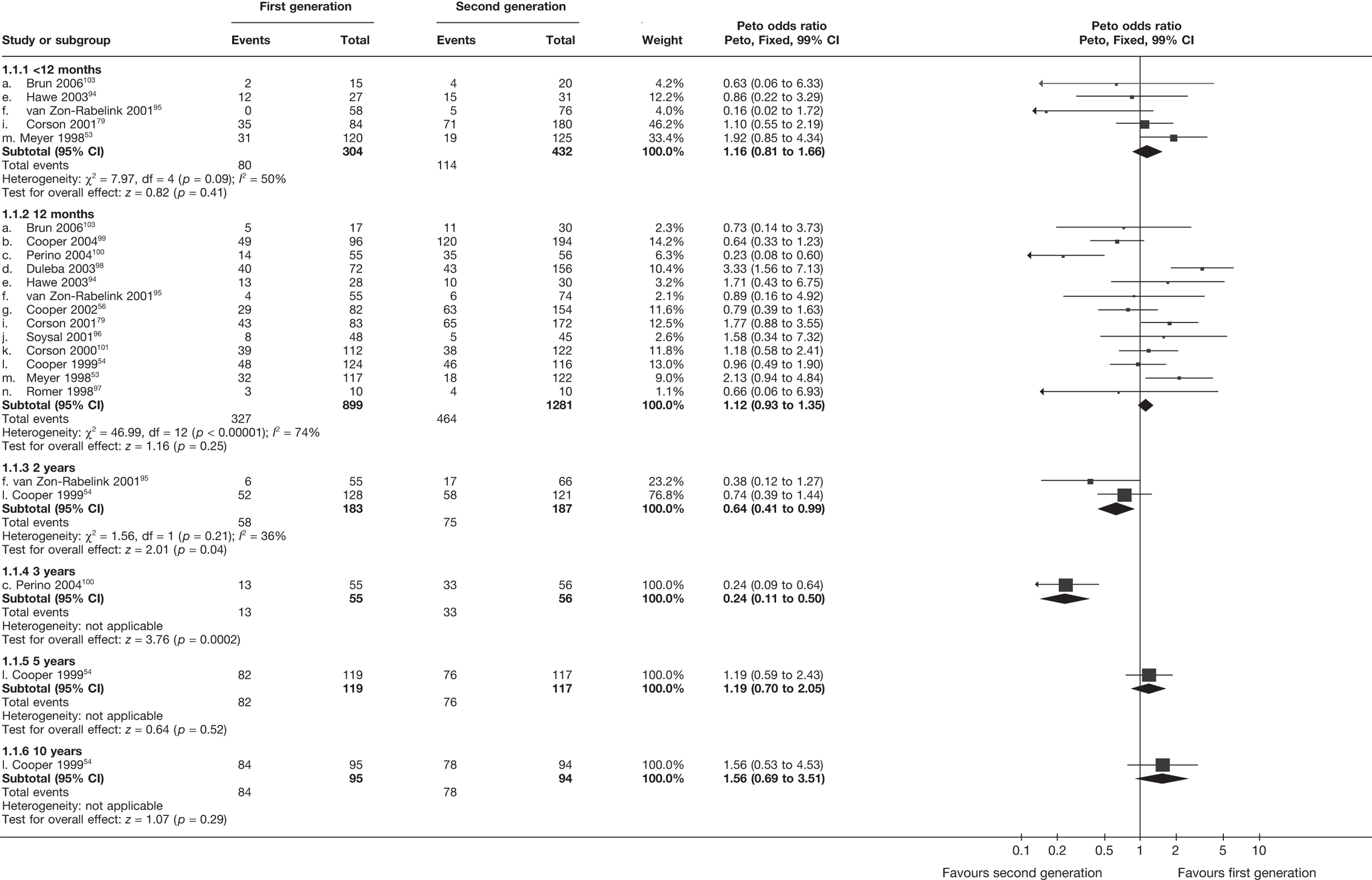

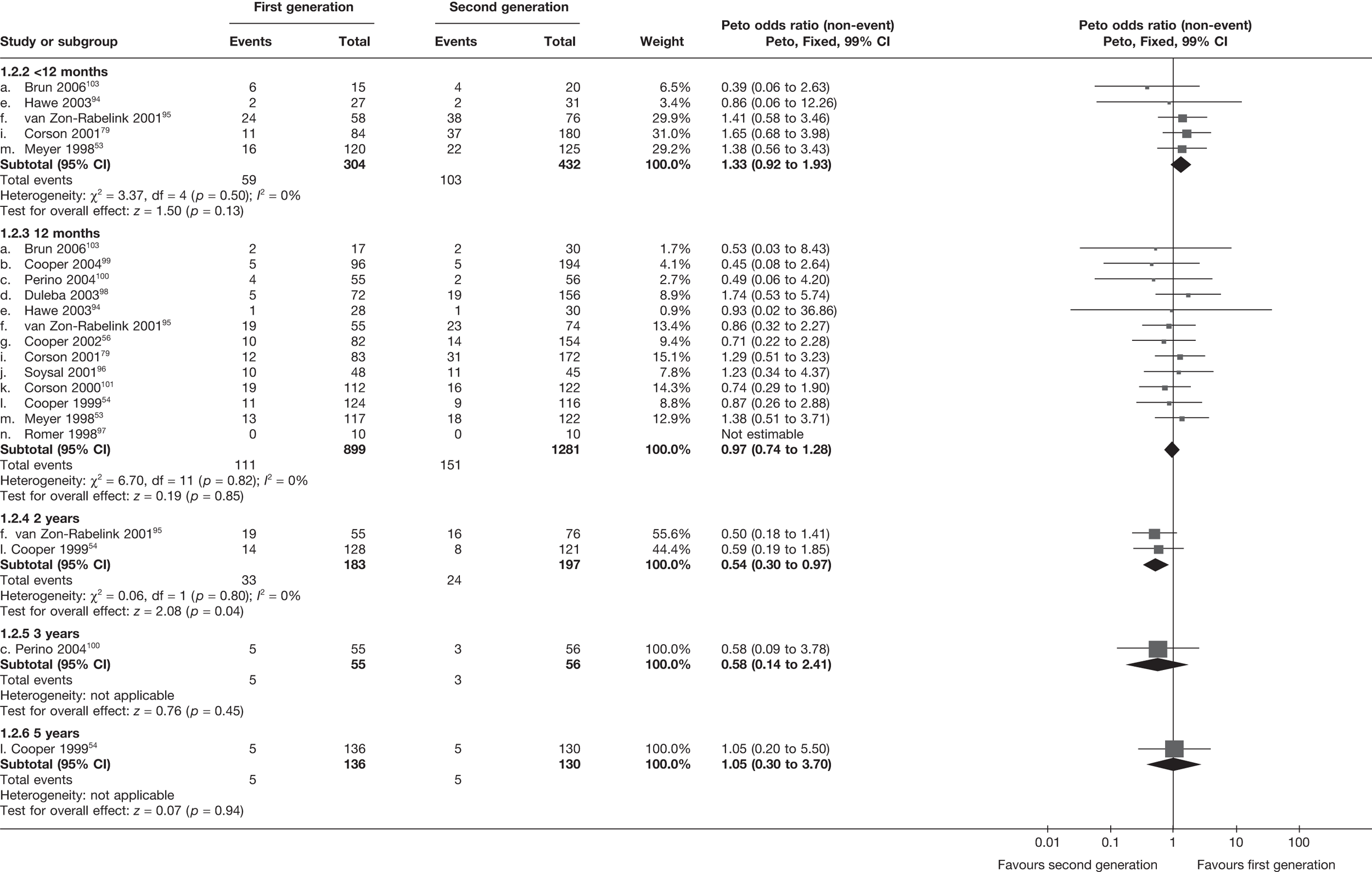

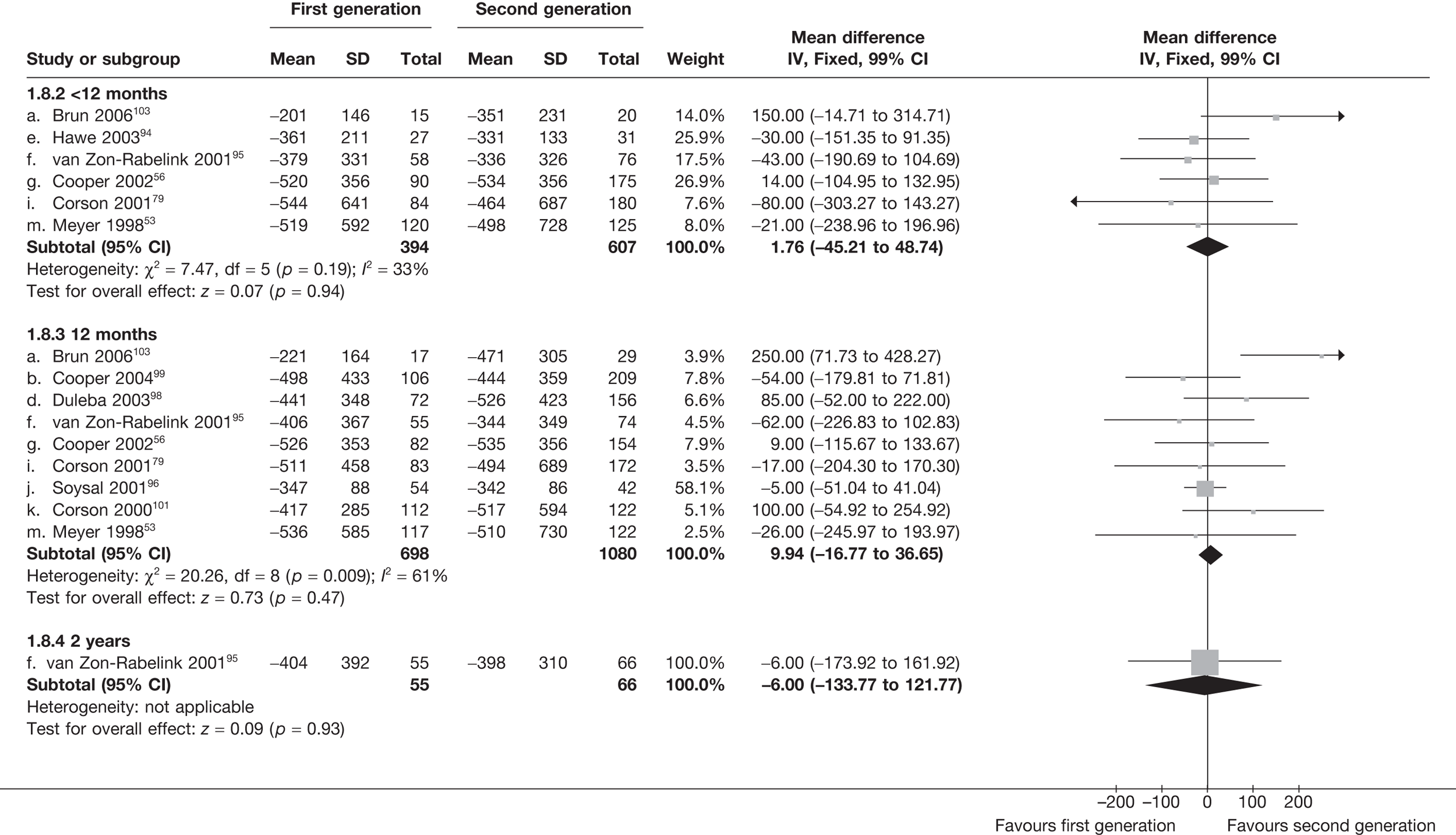

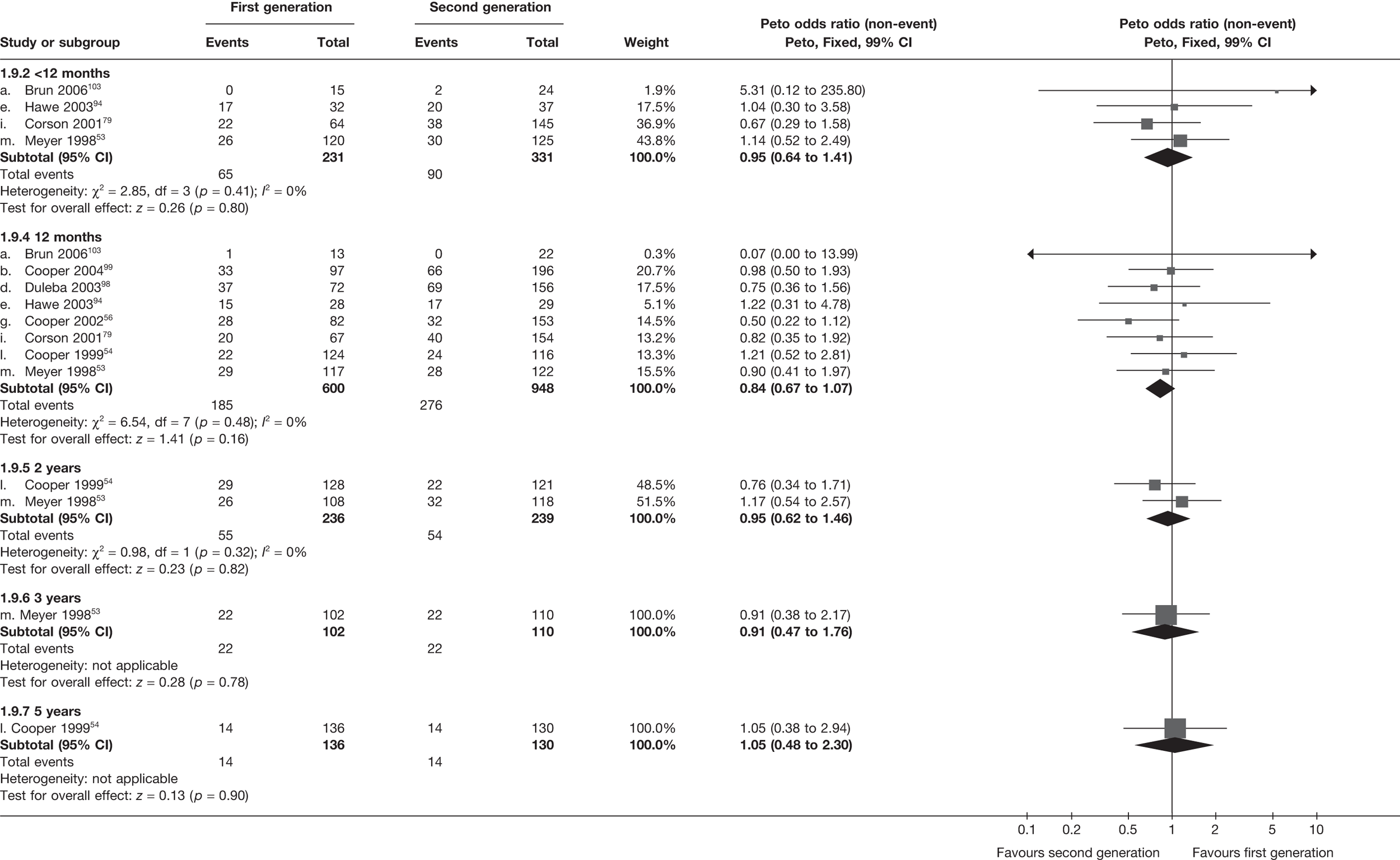

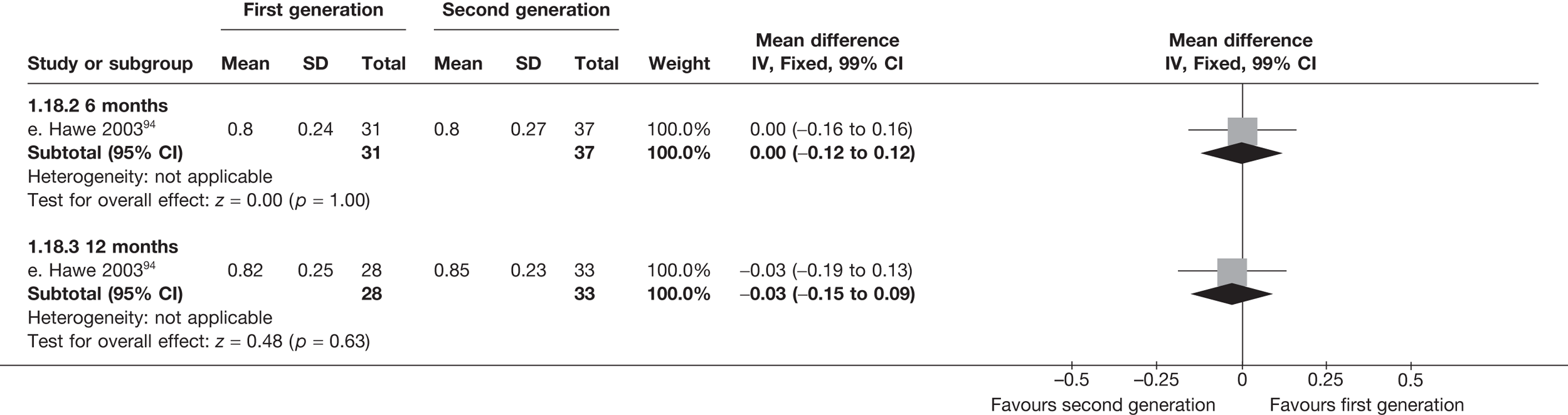

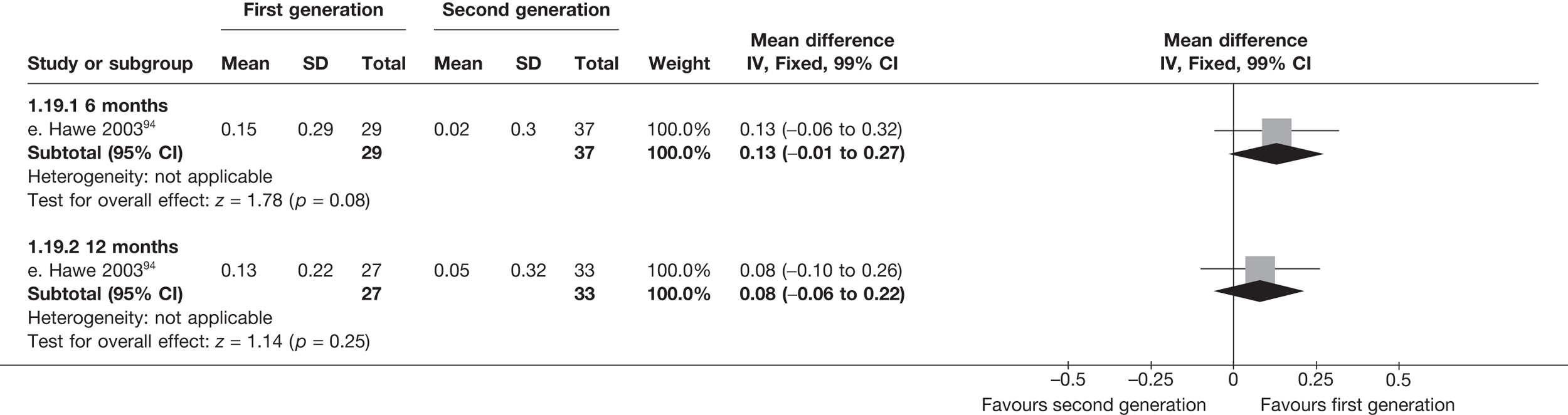

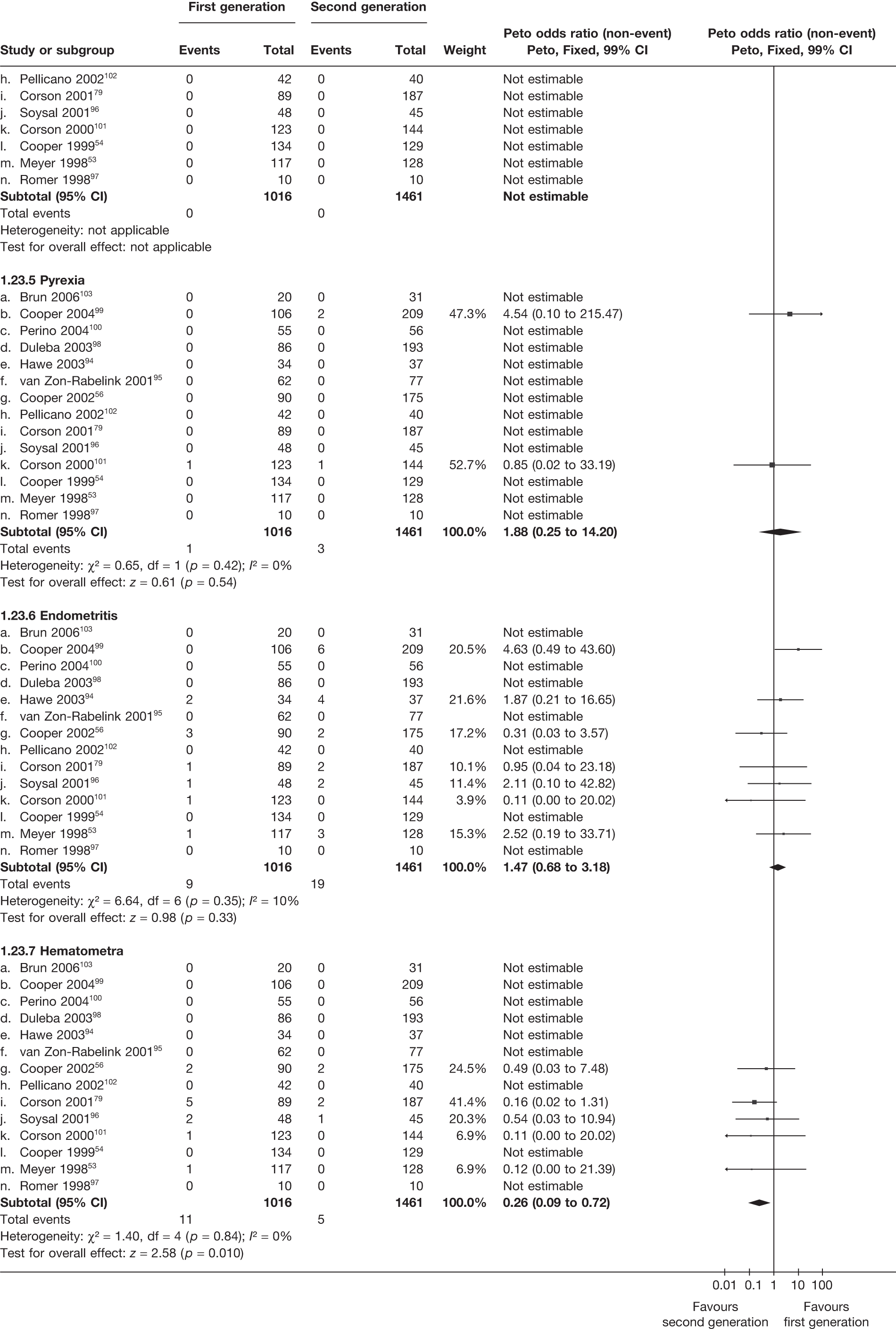

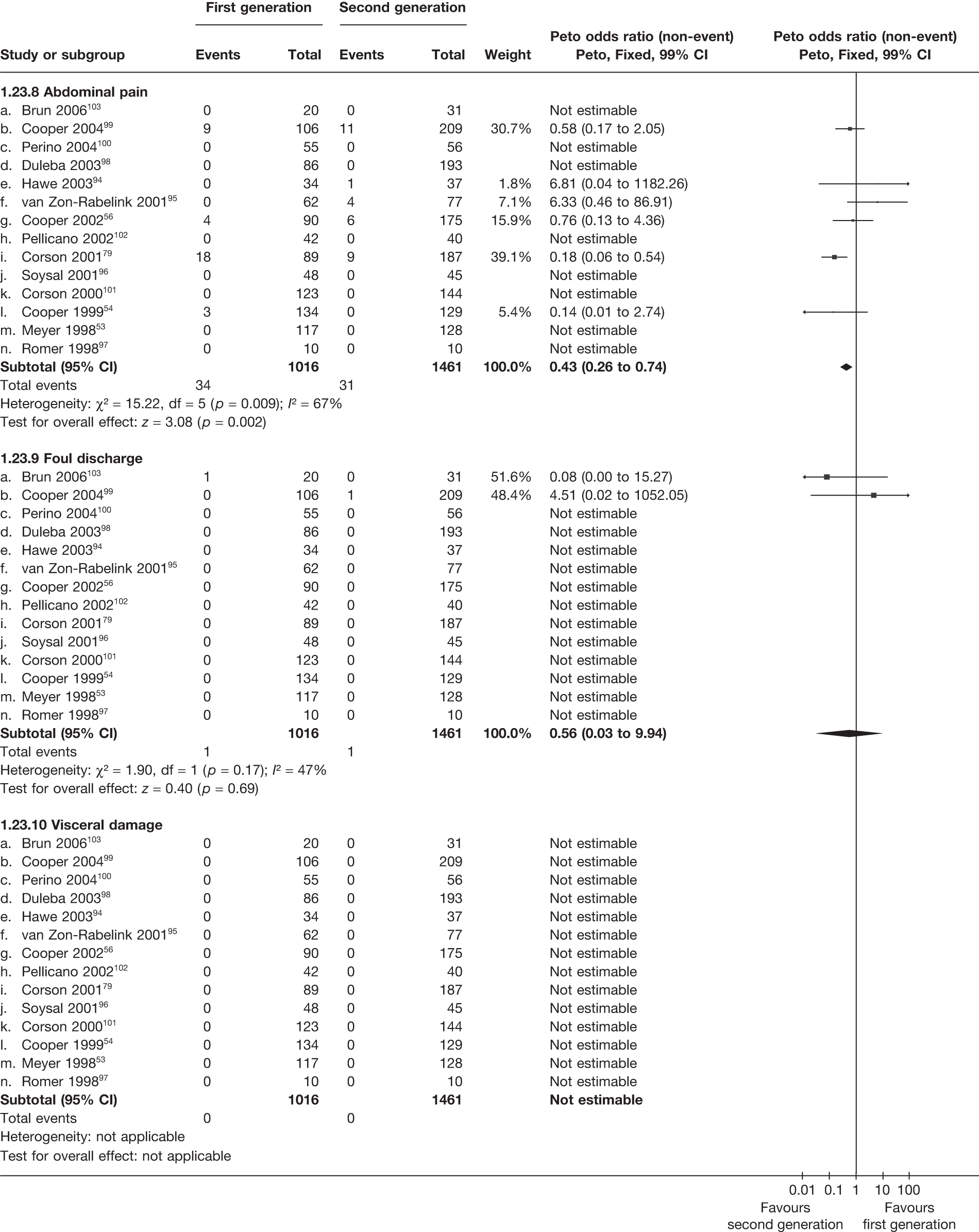

First- versus second-generation endometrial ablation techniques

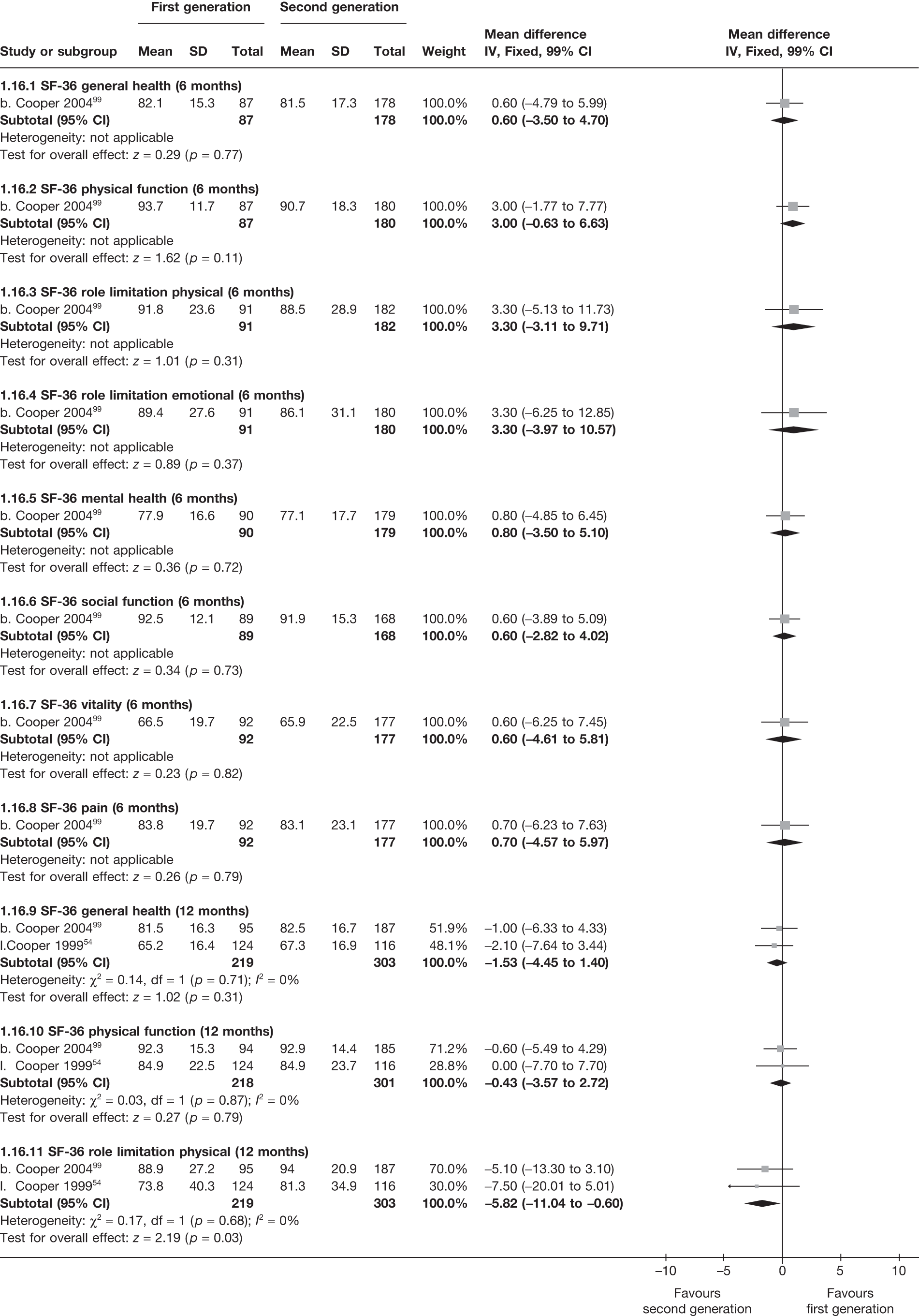

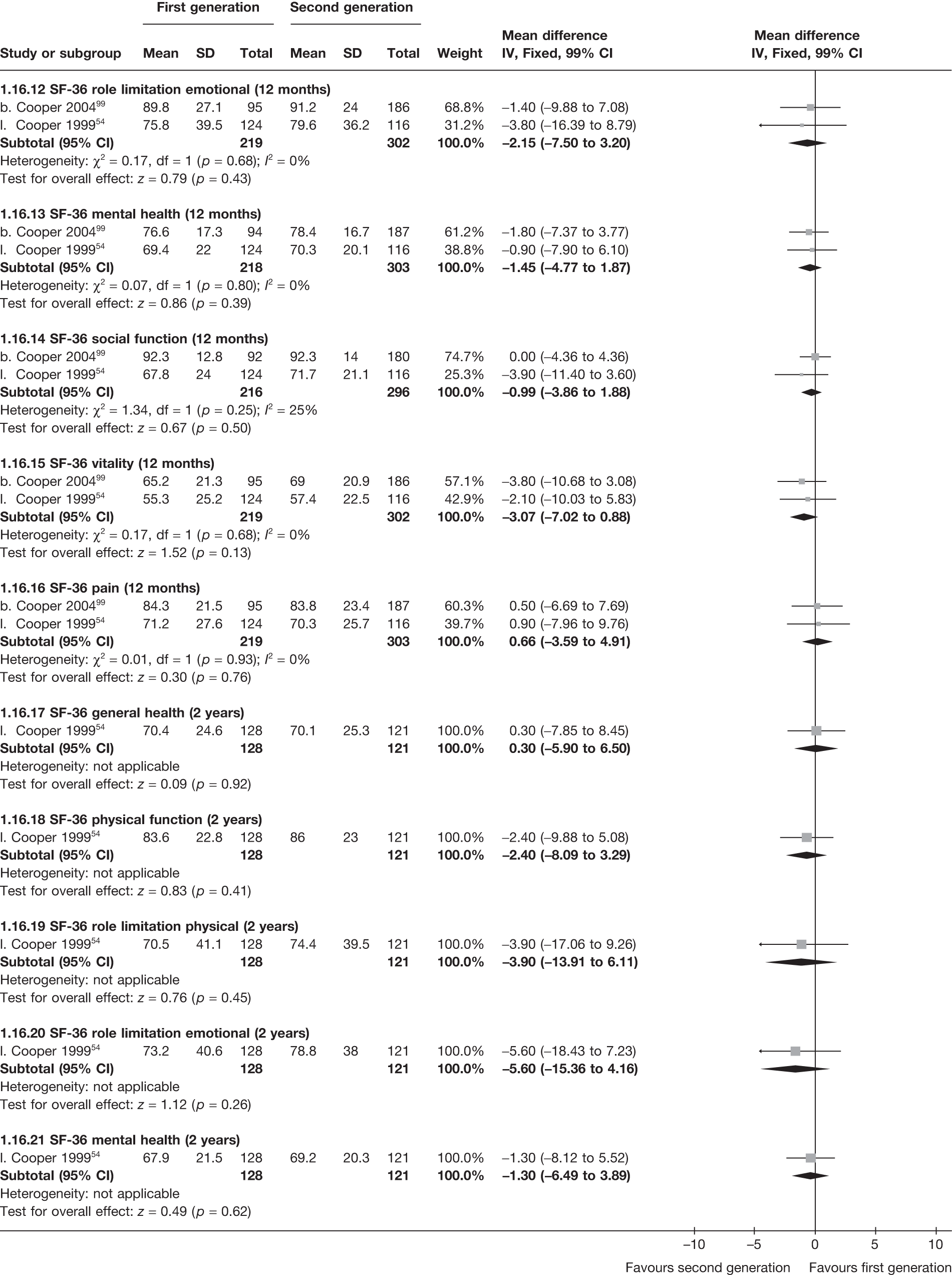

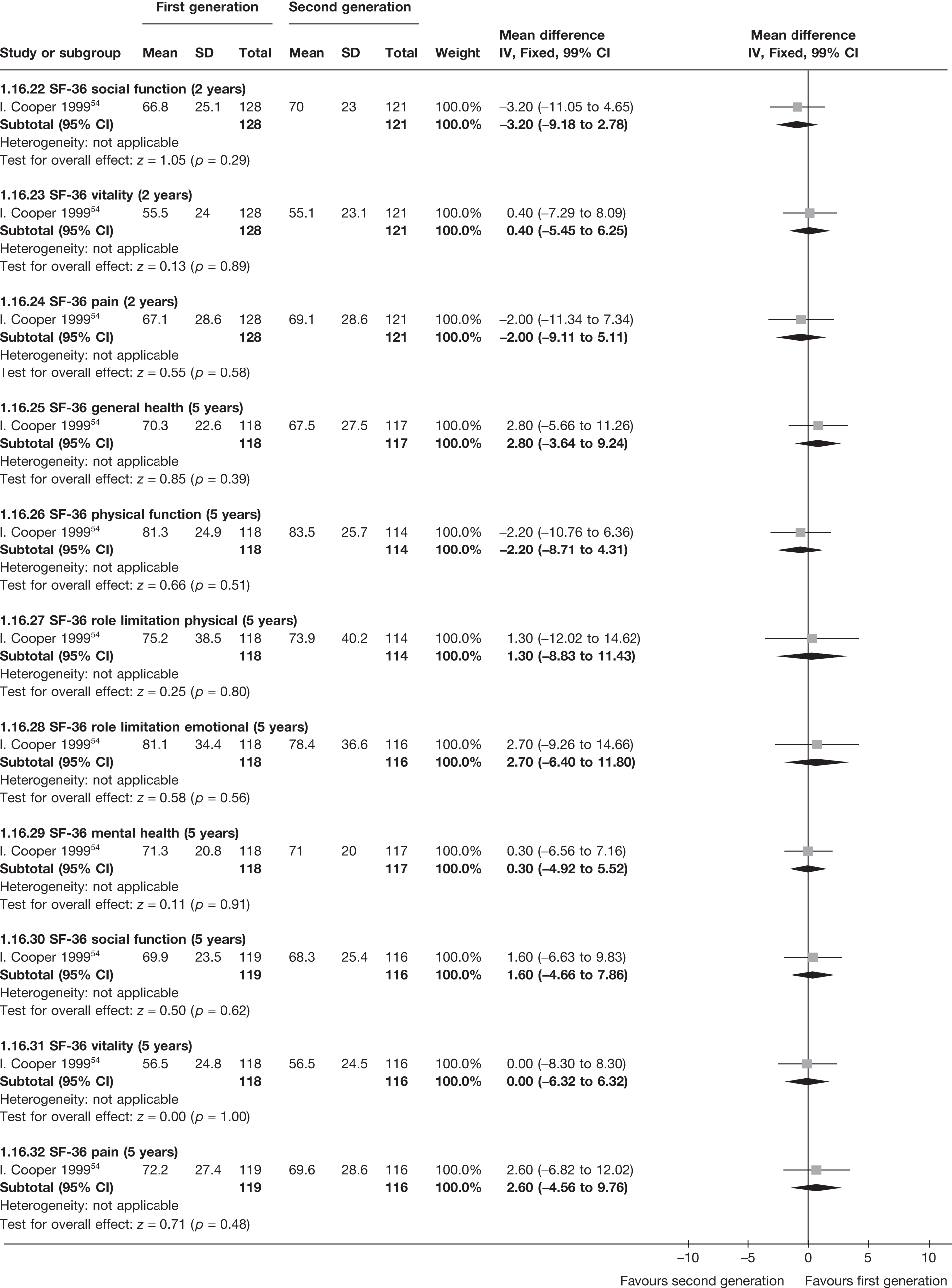

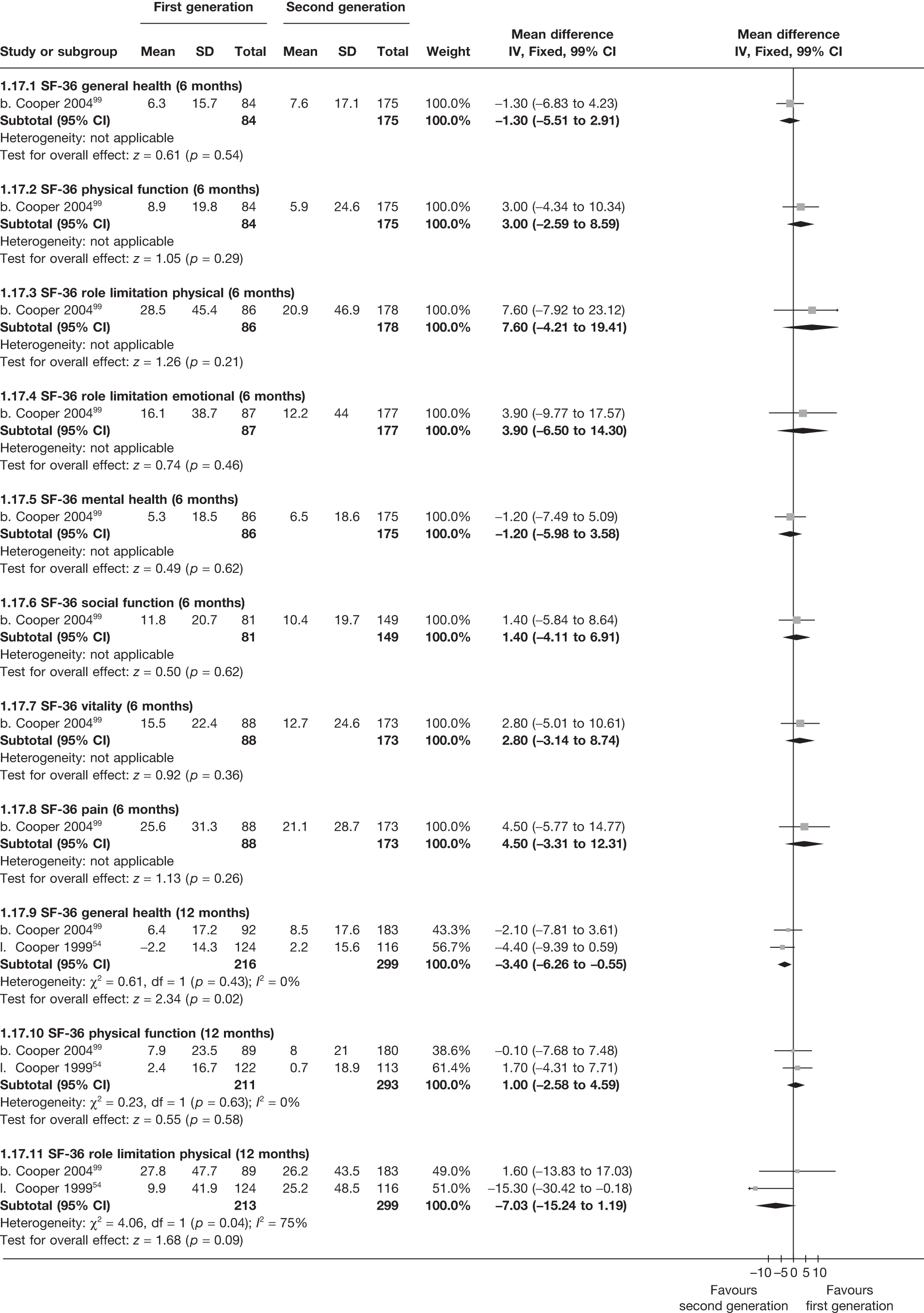

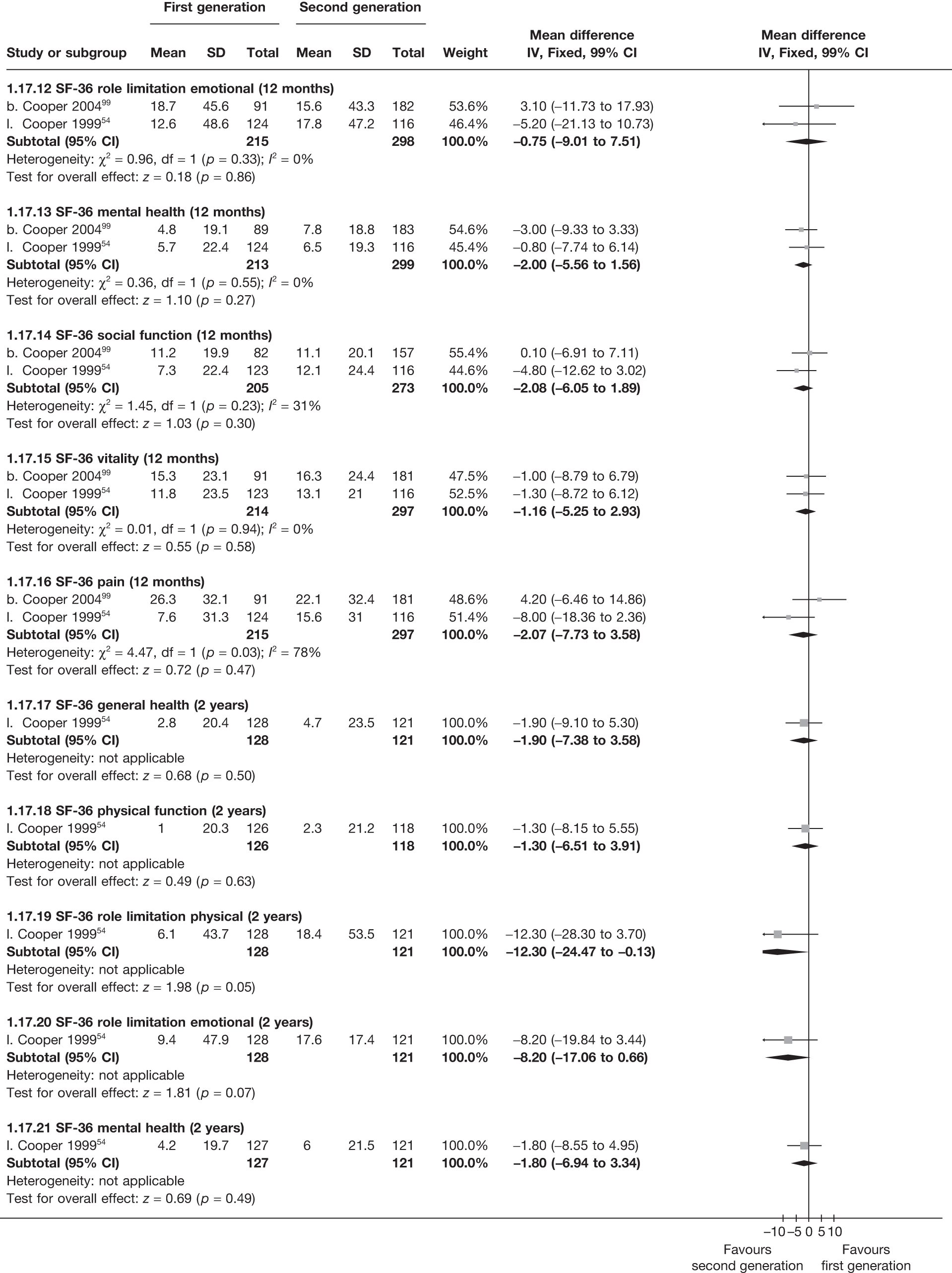

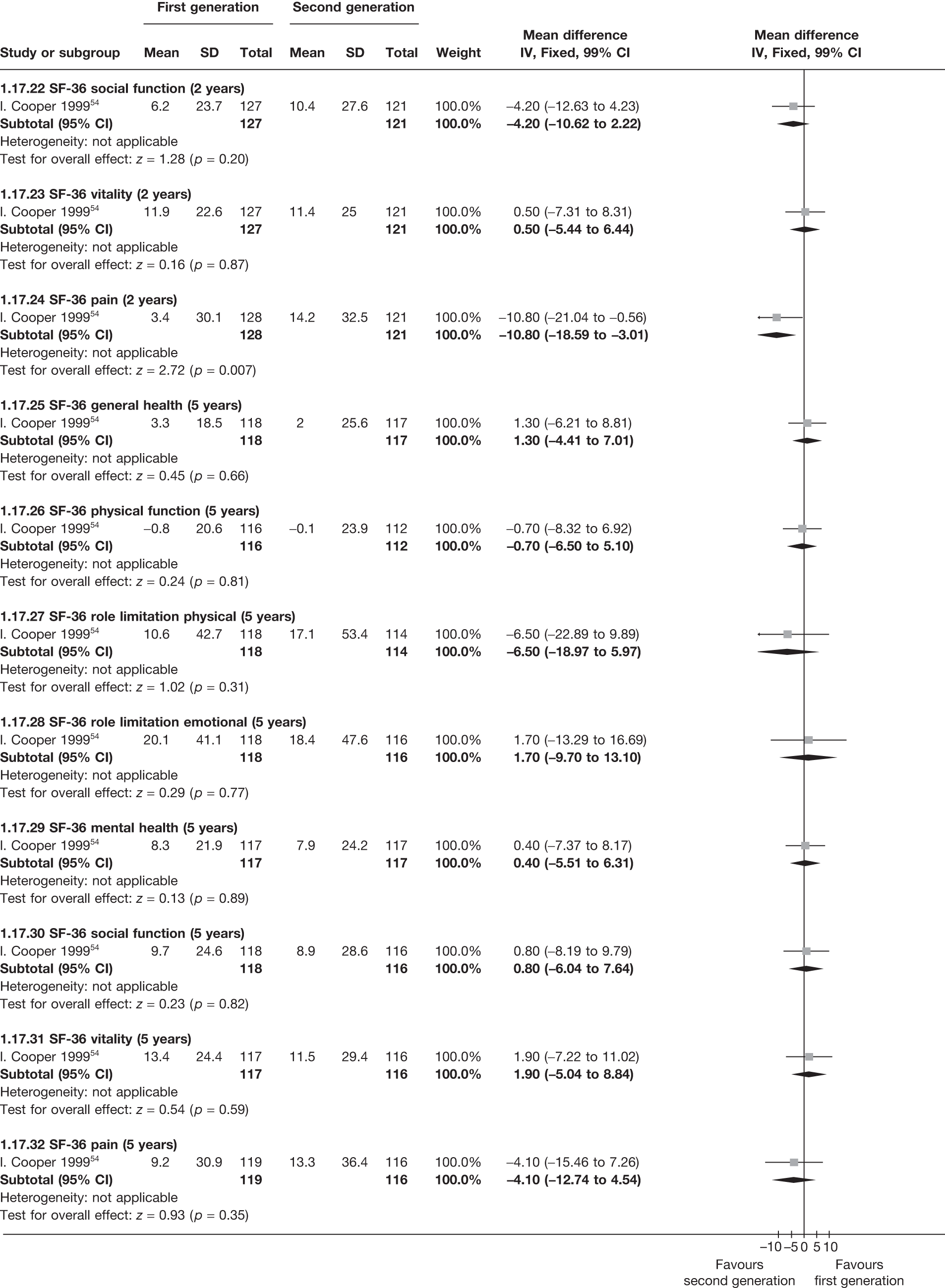

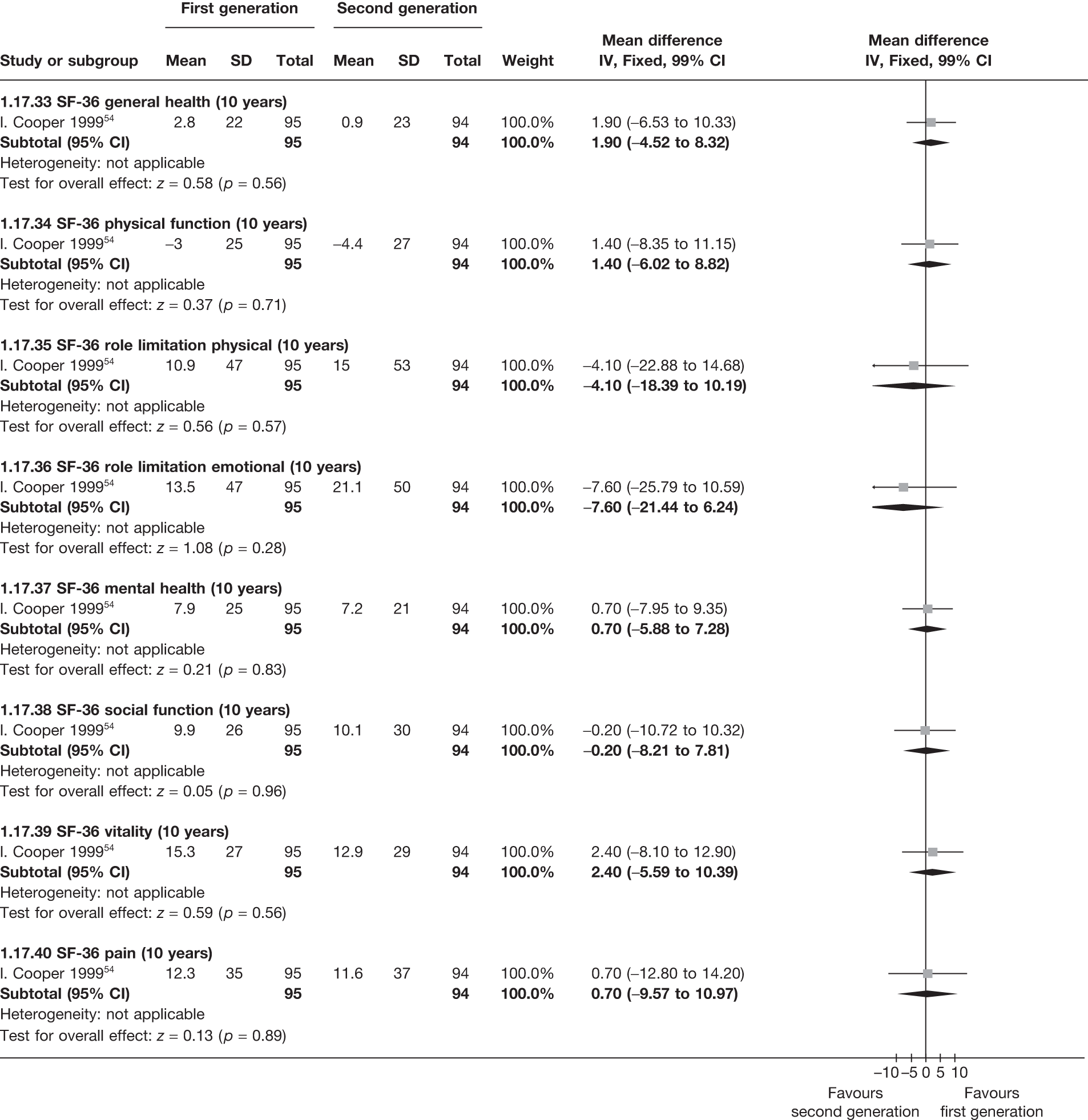

The proportion of women with amenorrhoea or still experiencing heavy bleeding was similar in both groups at all time points apart from at 2 years, where there was a borderline significant difference in favour of second-generation techniques (amenorrhoea: OR 0.64, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.99, p = 0.04; HMB: OR 1.85, 95% CI 1.04 to 3.32, p = 0.04) (see Appendix 6). High heterogeneity for the estimate of amenorrhoea rate at 12 months (OR 1.12, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.35, p = 0.3) appeared to be due to two outlying studies (Duleba98 and Perino100), the results of which could not be verified as IPD were not available. However, analysis without these studies gave very similar results (OR 1.10, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.35, p = 0.4) with lowered heterogeneity (p = 0.1; I2 = 36%). Change from baseline analysis of bleeding scores showed no evidence of a difference at any of the time points. Inconsistency of estimates for this outcome at 12 months was due to a single study;103 sensitivity analysis without this study also showed no change to the overall result (WMD –0.3; 95% CI –27.5 to 27.0; p = 1.0; heterogeneity: p = 0.4; I2 = 10%). Two studies54,99 using the SF-36 questionnaire and one small study94 using the EQ-5D questionnaire showed no consistent difference between first- and second-generation techniques, in terms of change from baseline results.

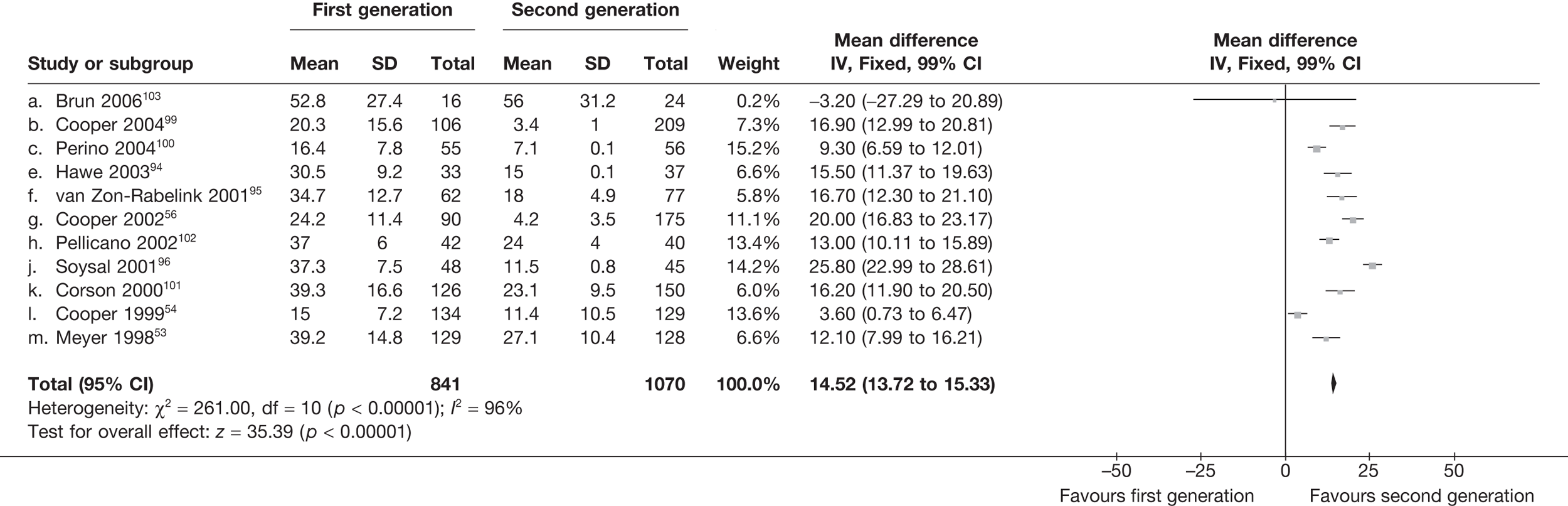

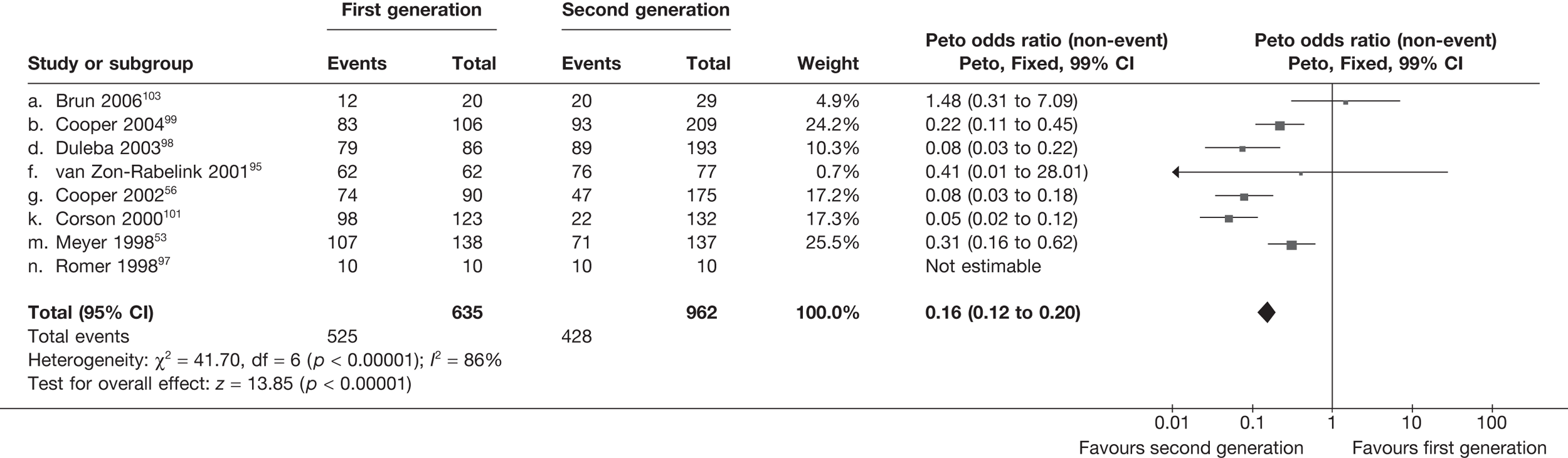

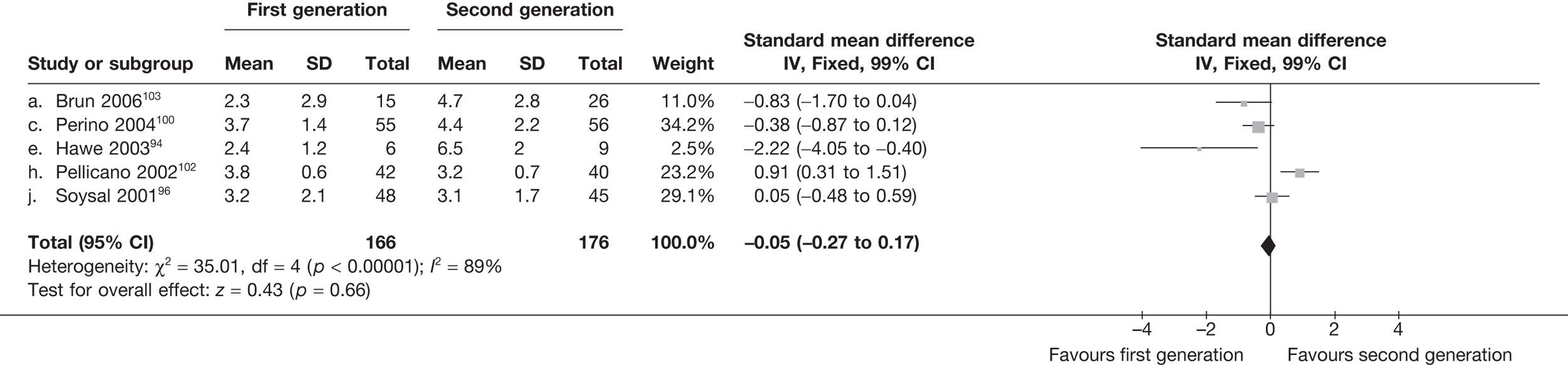

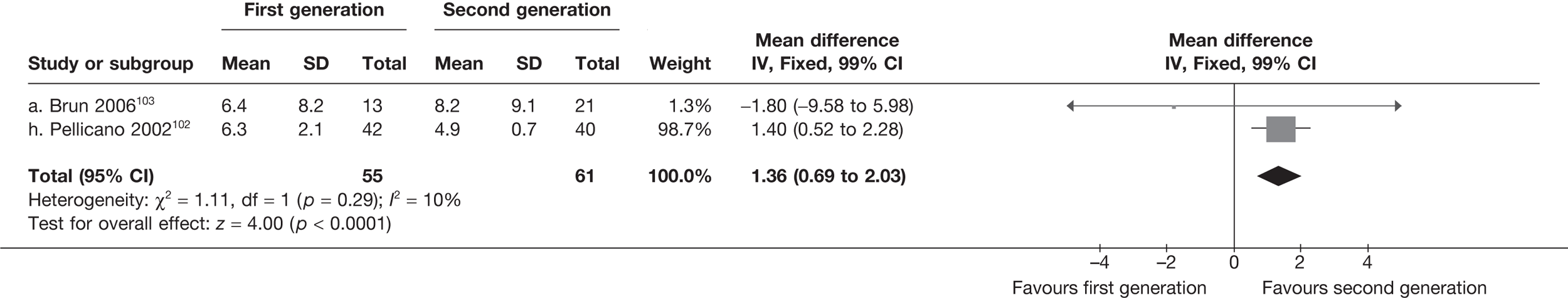

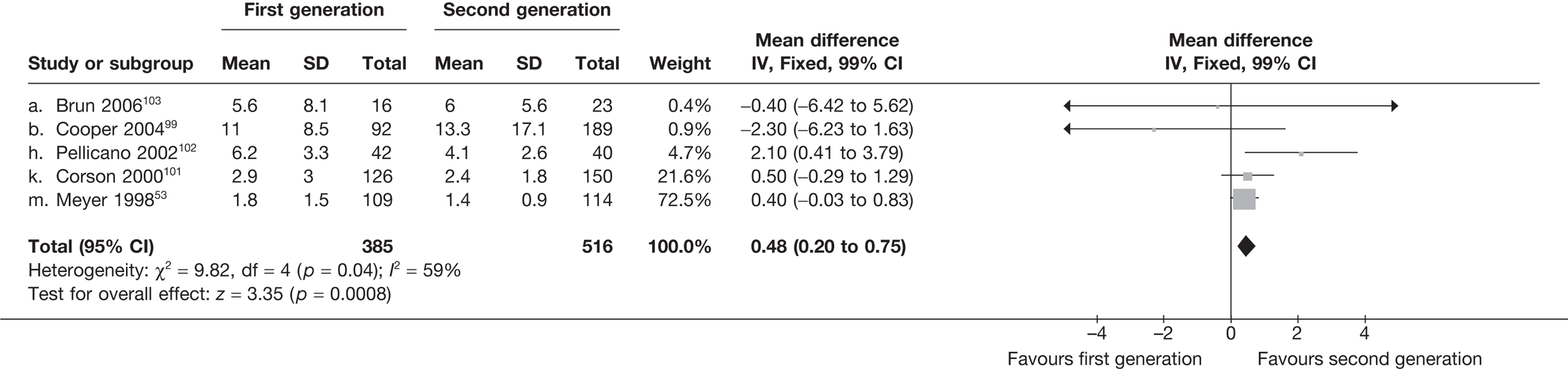

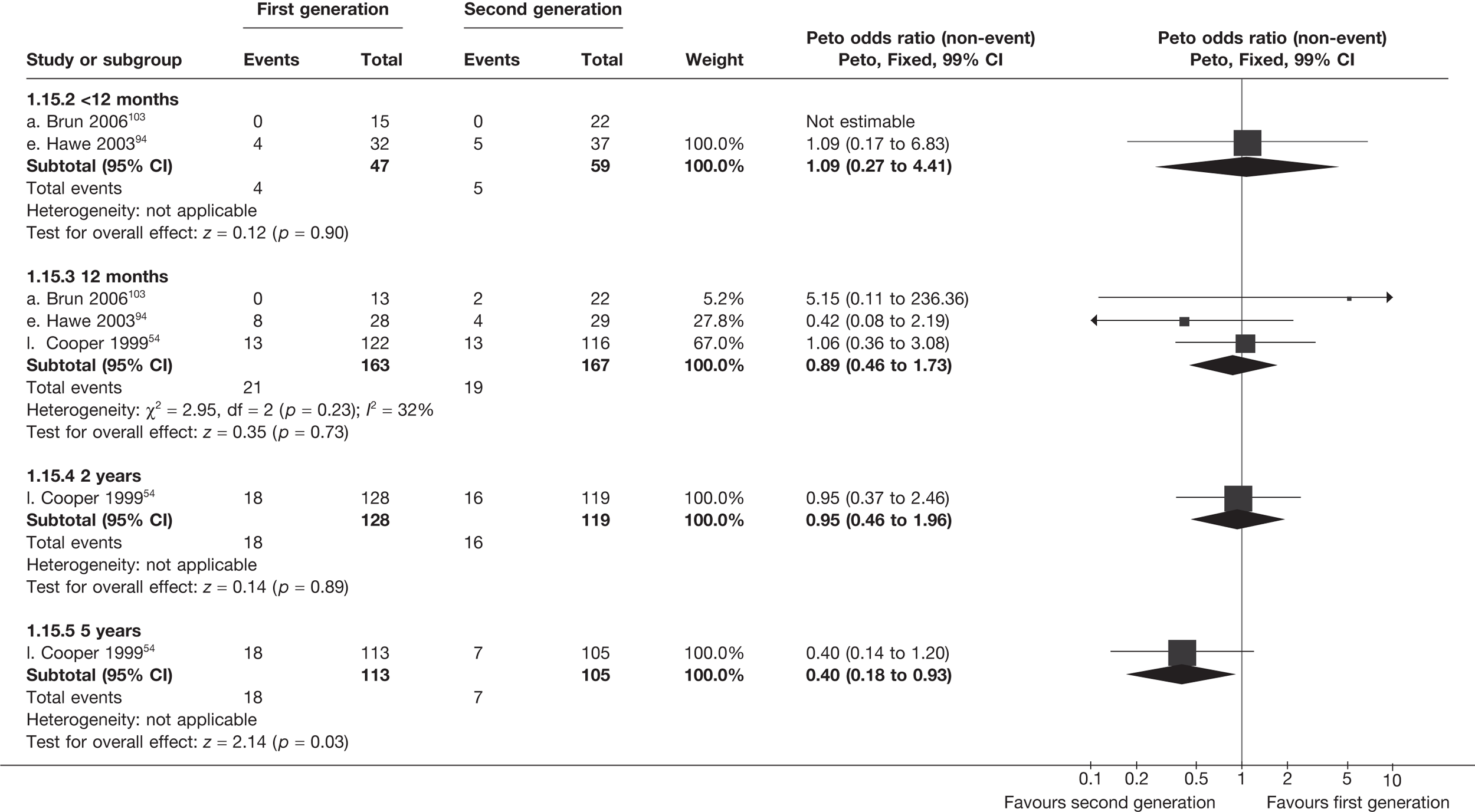

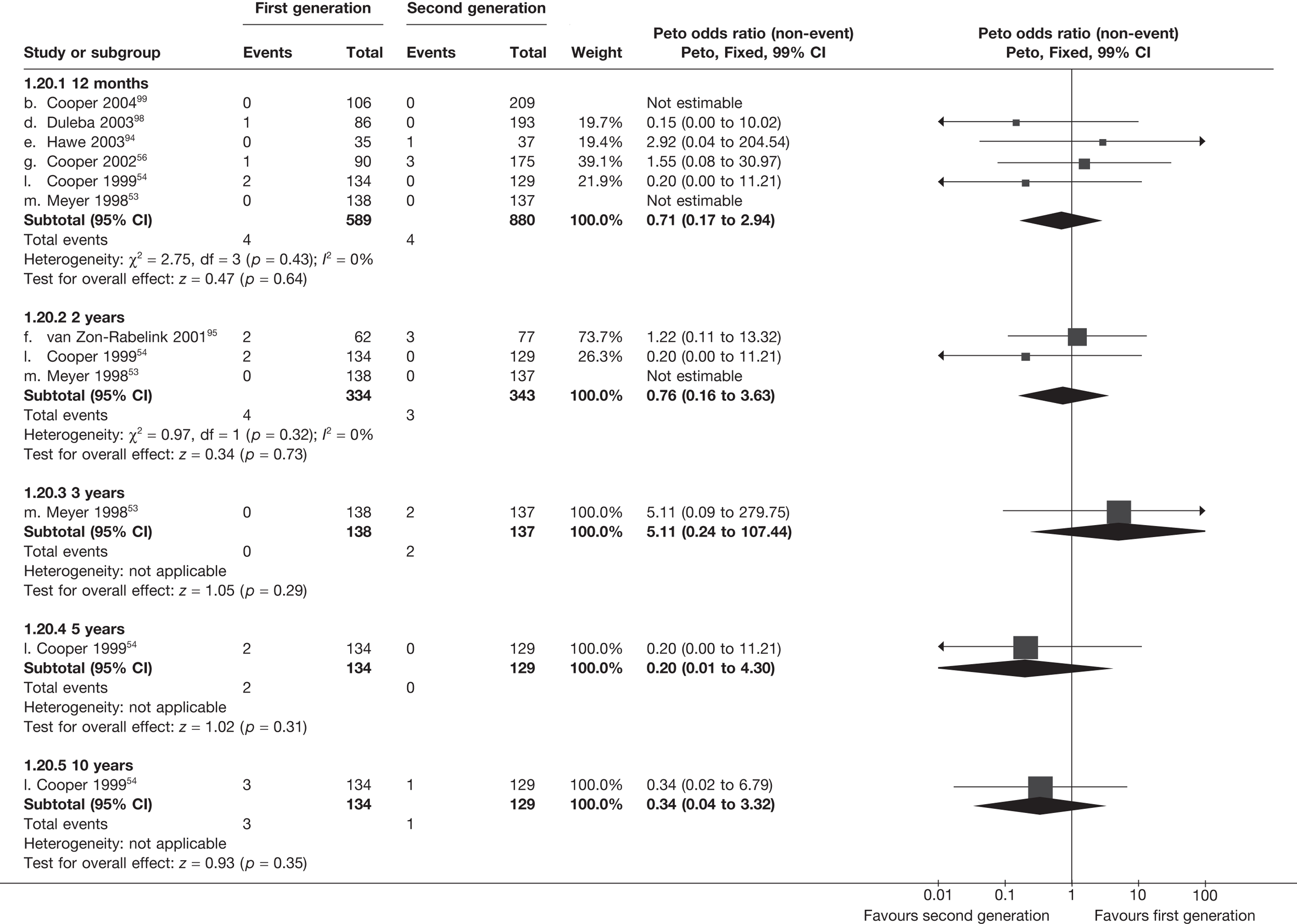

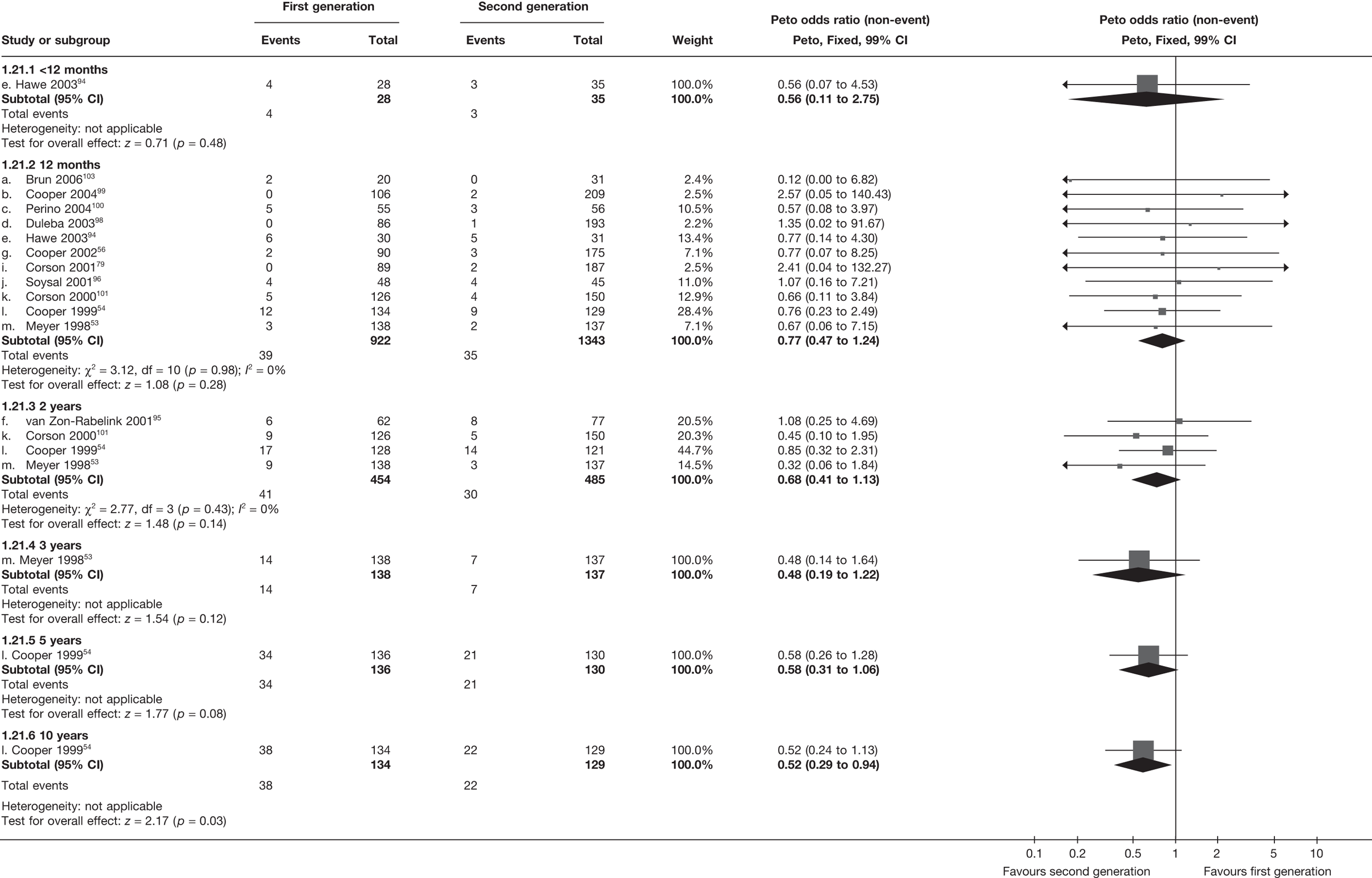

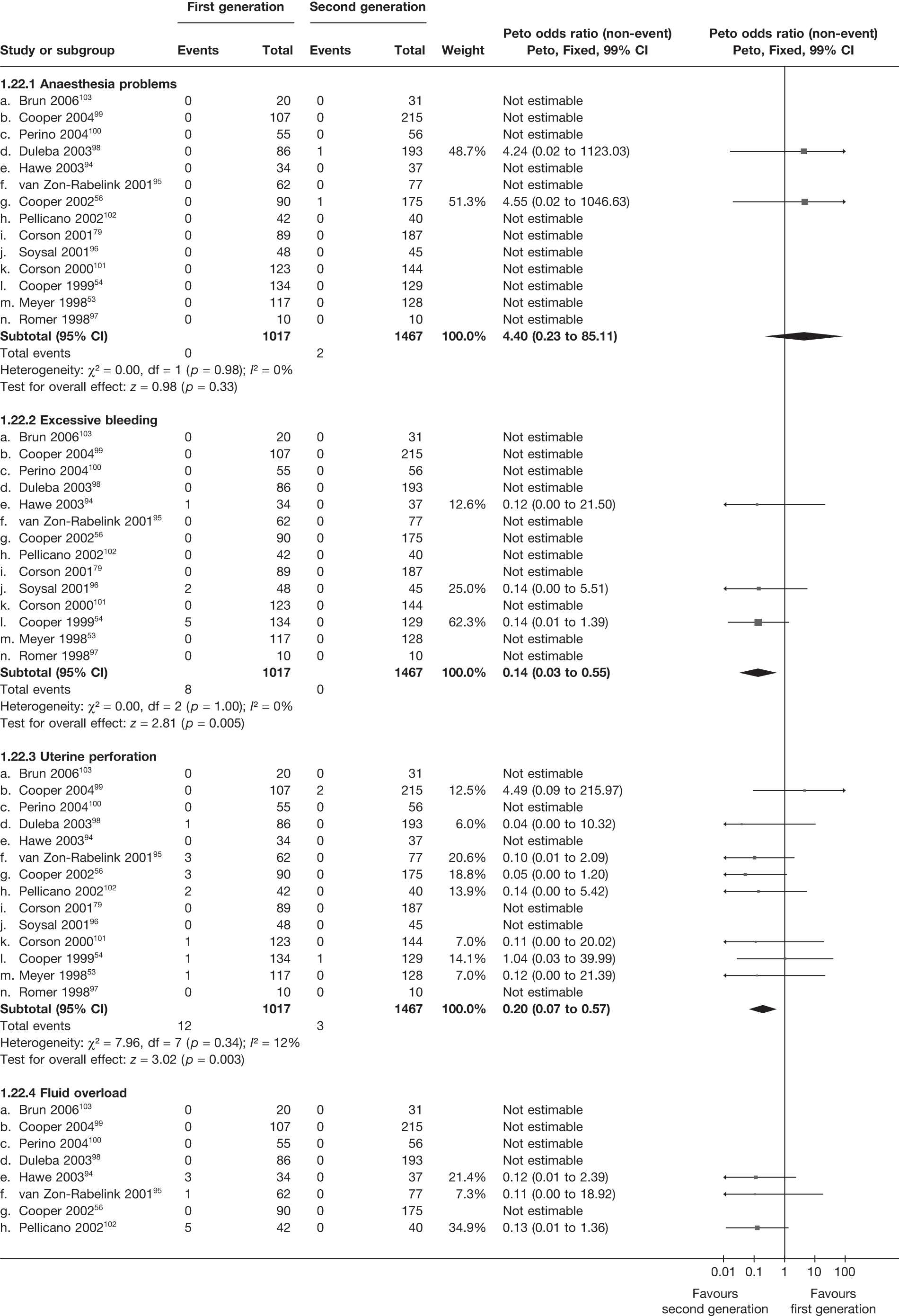

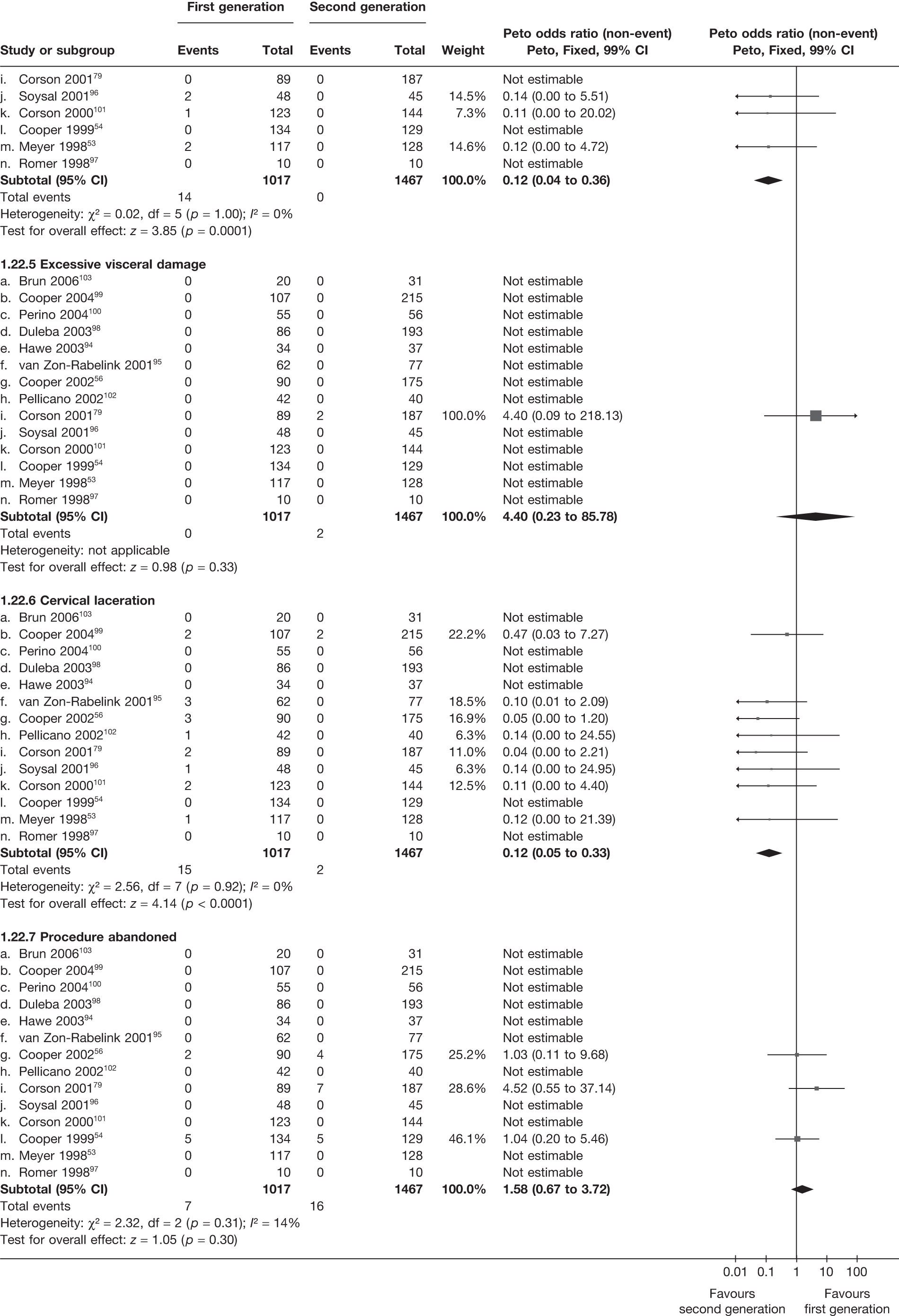

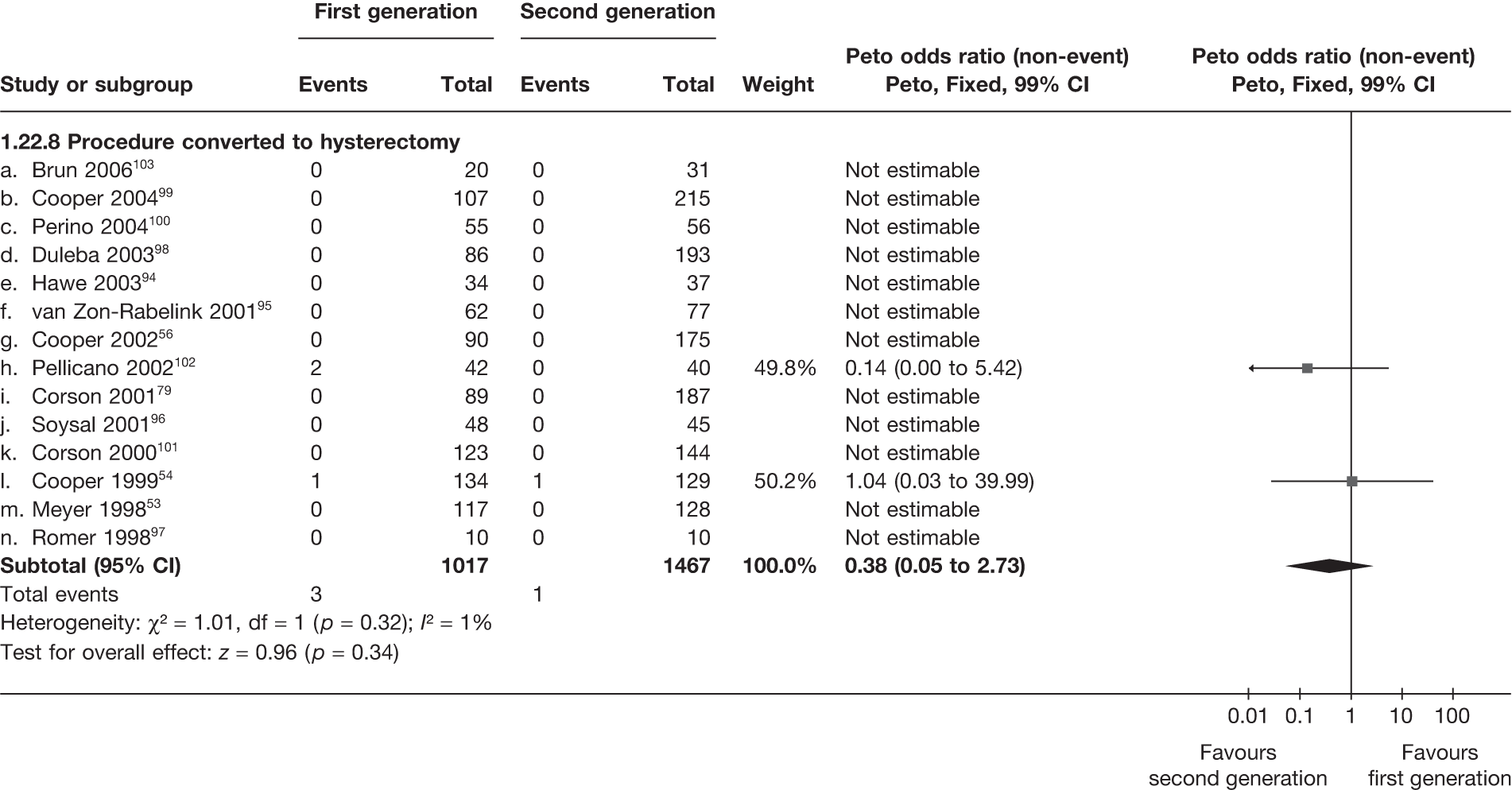

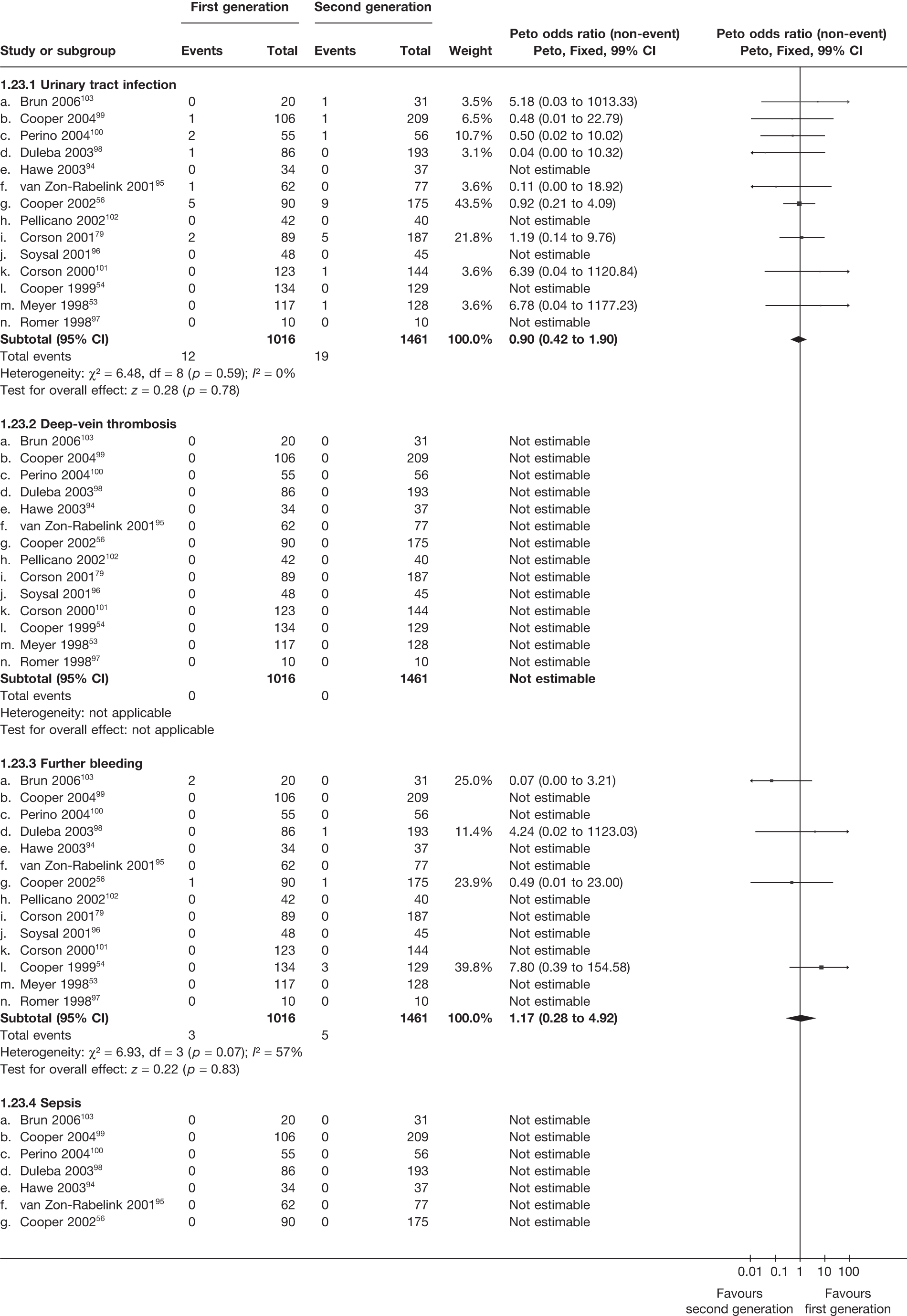

Second-generation EA was quicker (WMD 15 minutes; 95% CI 14 to 15 minutes; p < 0.0001) and less likely to need general anaesthesia than first generation (OR 0.16; 95% CI 0.12 to 0.20; p < 0.0001), although highly significant heterogeneity makes estimates difficult to interpret. Less frequent use of general anaesthesia with second-generation EA translated to a slightly quicker time to return to work (WMD 1.36 days; 95% CI 0.69 to 2.03 days; p < 0.0001) and time to return to normal activities (WMD 0.48 days; 95% CI 0.20 to 0.75 days; p = 0.0008), although the overall estimate for the latter was somewhat inconsistent (heterogeneity: p = 0.04; I2 = 59%). Postoperative pain was similar following either method of EA, although estimates from different studies varied widely (heterogeneity: p < 0.0001; I2 = 89%) without any obvious explanation. Adverse events were relatively low in both groups (each < 2%), but perioperative complications such as uterine perforation (OR 0.20; 95% CI 0.07 to 0.57; p = 0.003), excessive bleeding (OR 0.14; 95% CI 0.07 to 0.55; p = 0.005), fluid overload (OR 0.12; 95% CI 0.04 to 0.36; p = 0.0001) and cervical laceration (OR 0.12; 95% CI 0.05 to 0.33; p < 0.0001) were lower with second-generation EA. The number of women requiring a subsequent hysterectomy was lower for second-generation EA, but these differences were not large enough to be statistically significant within the first 2 years (12 months: OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.24, p = 0.3; 2 years OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.41 to 1.13, p = 0.1). Overall rates were 3.3% (74/2265) and 7.6% (71/939) at these time points. Any differences amongst subgroups were confined to single time points only. Results from studies providing IPD were consistent with those with AD only.

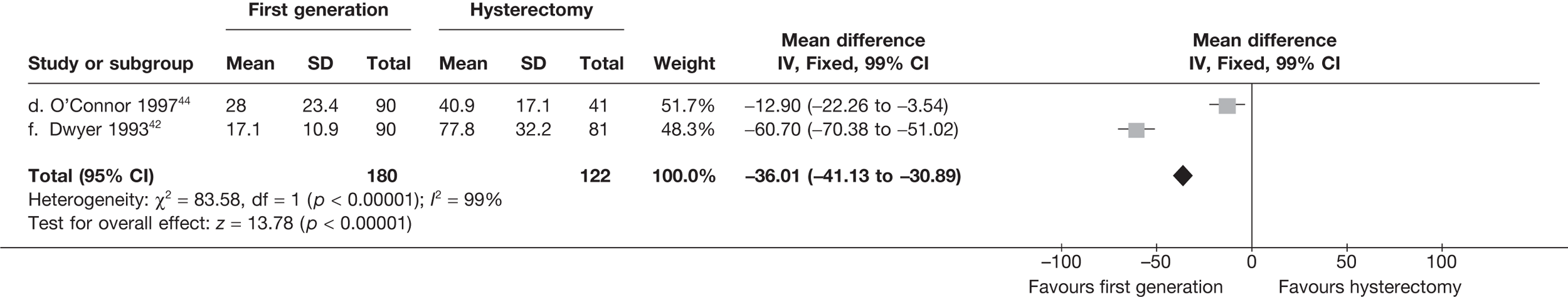

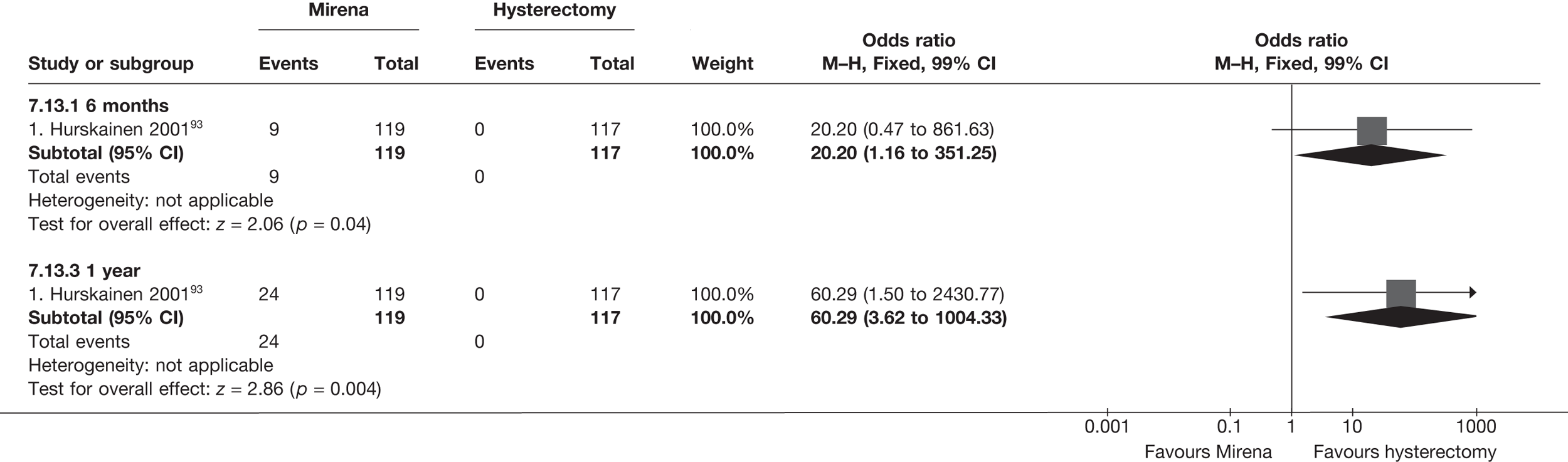

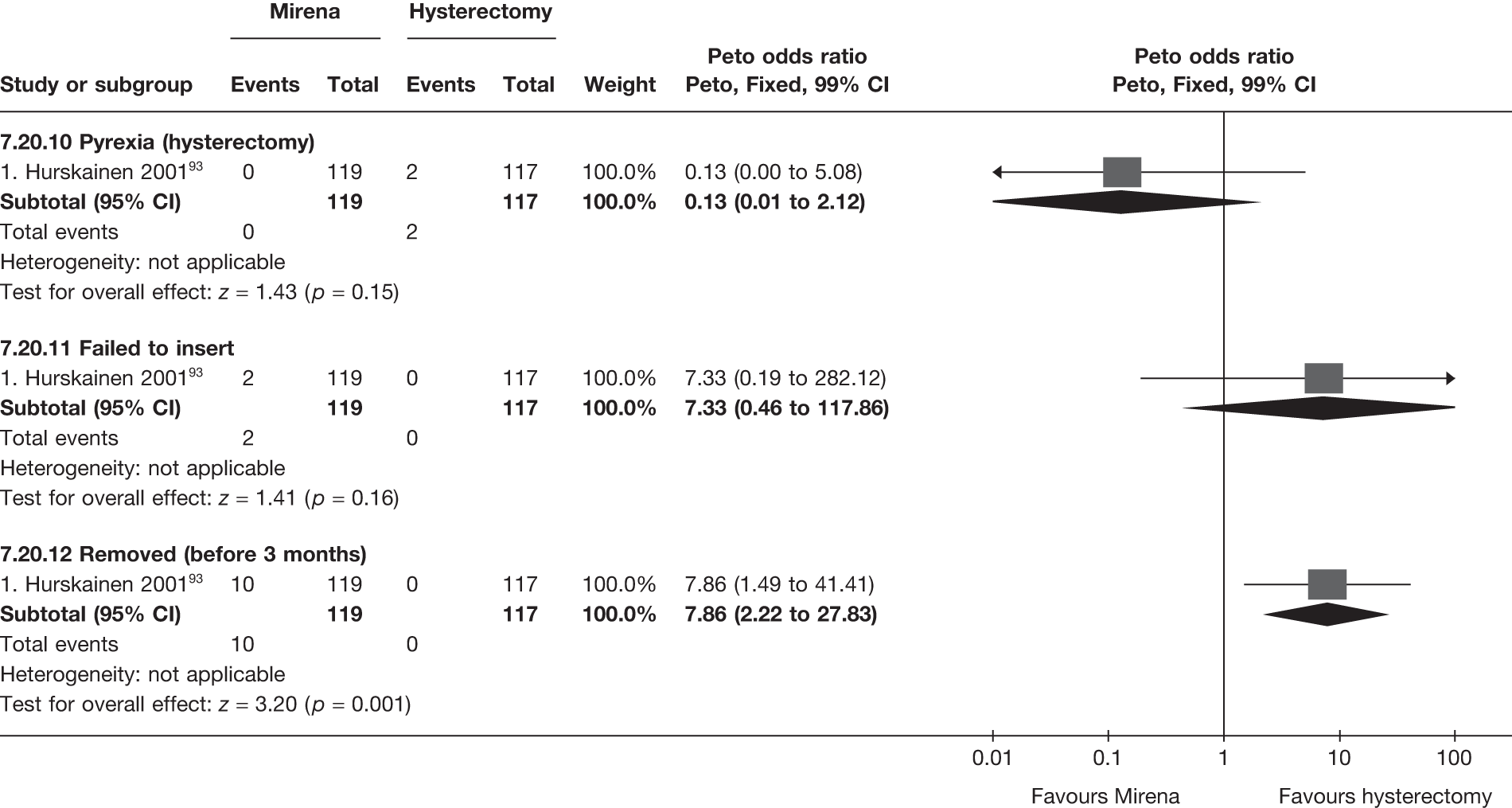

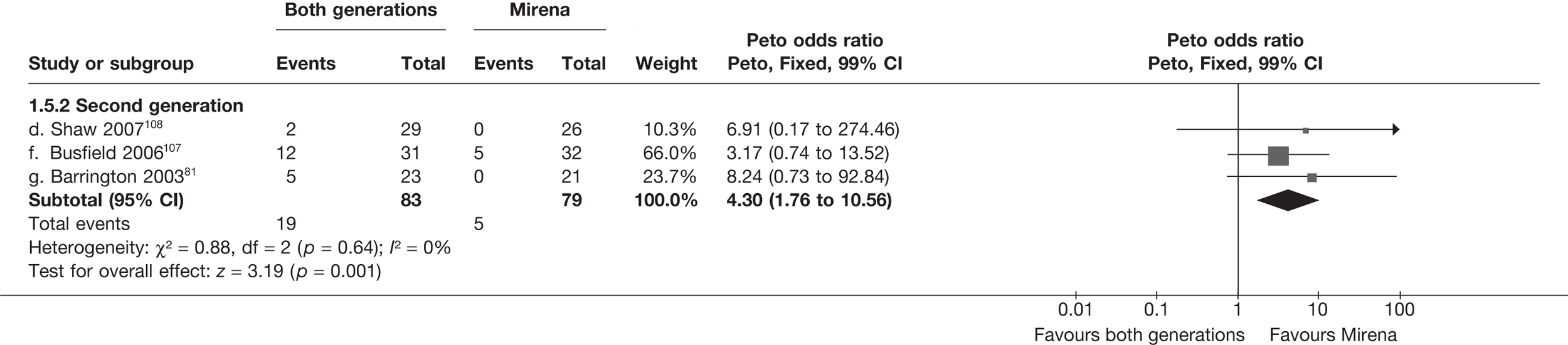

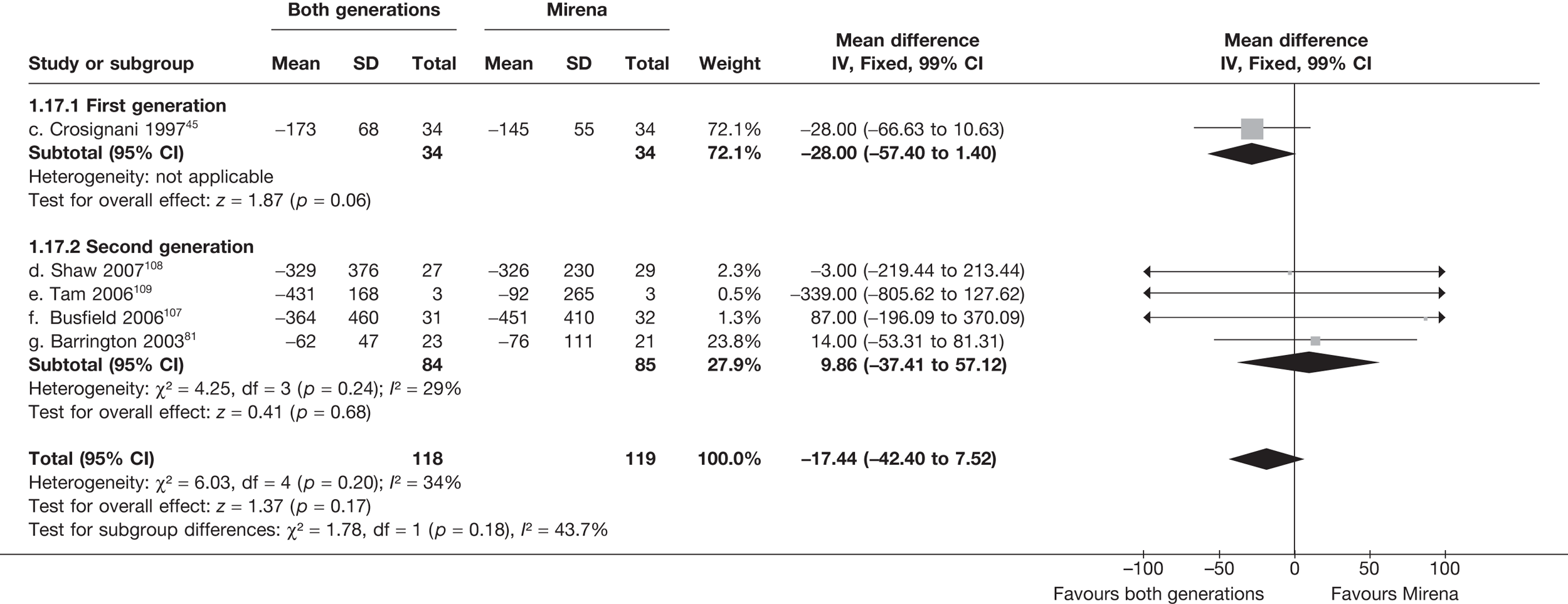

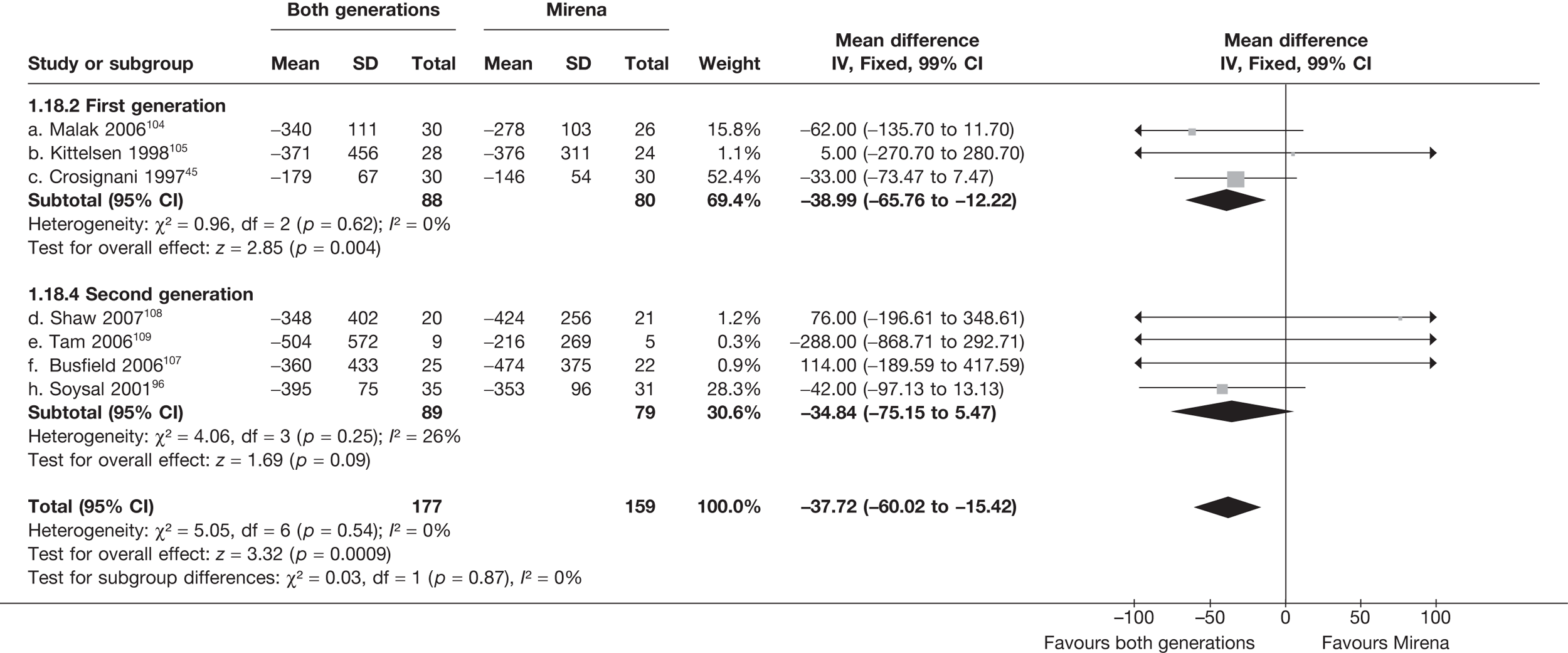

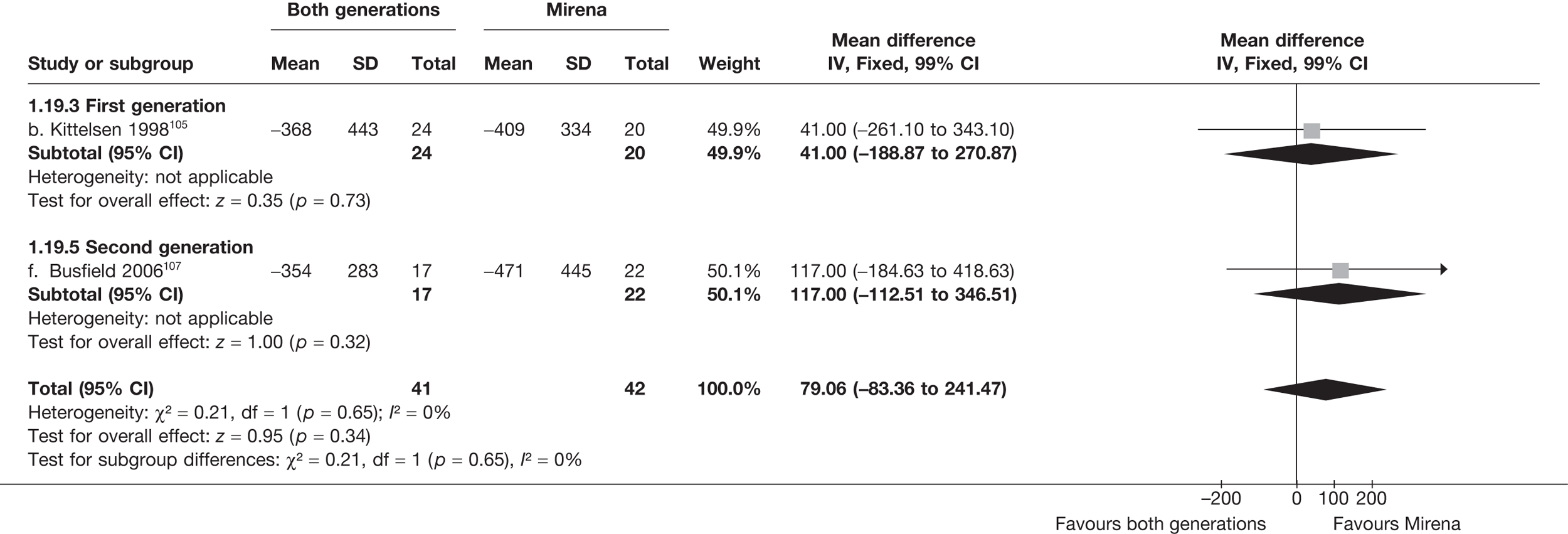

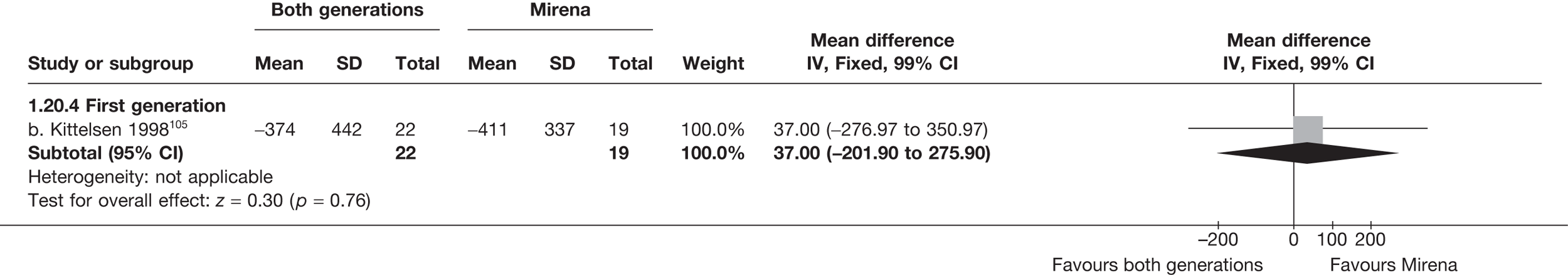

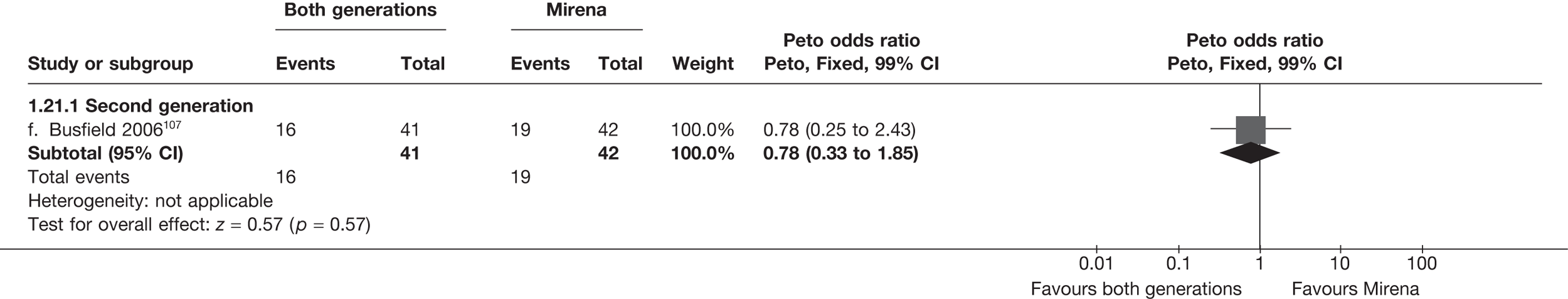

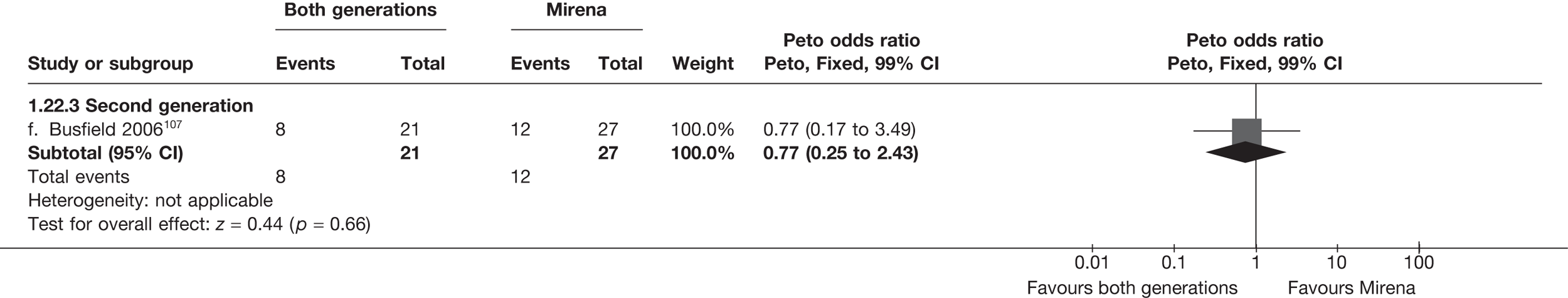

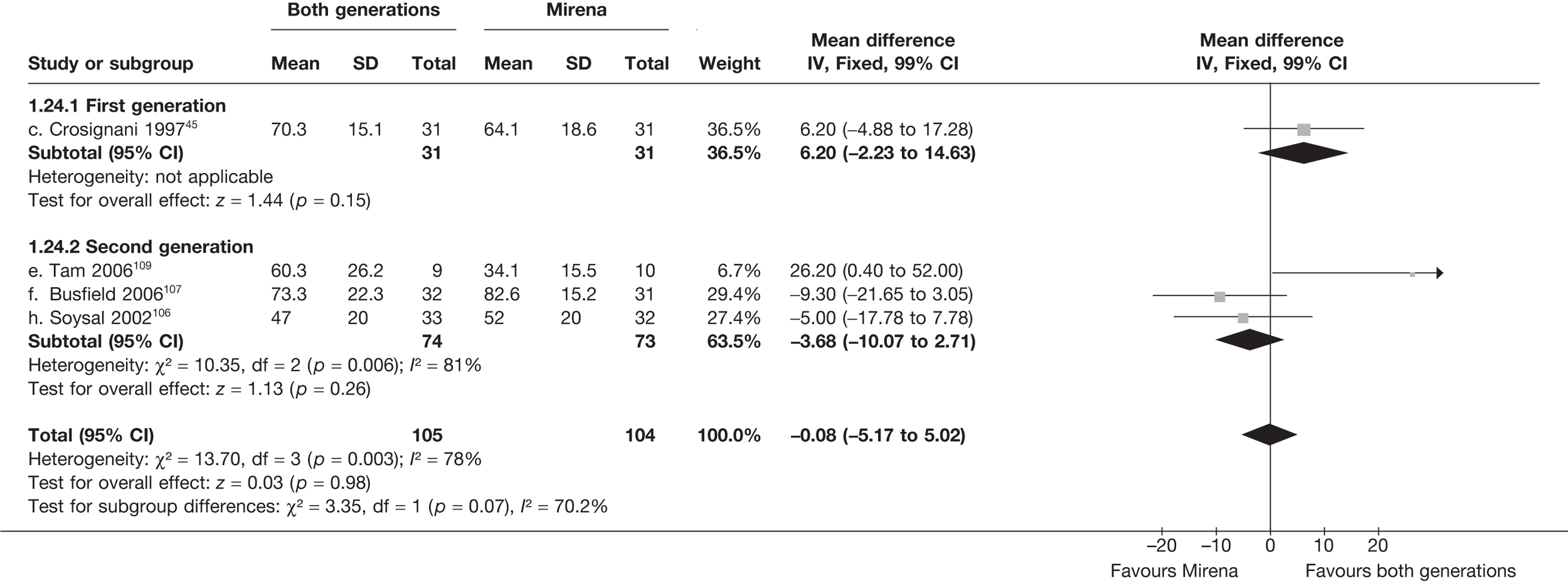

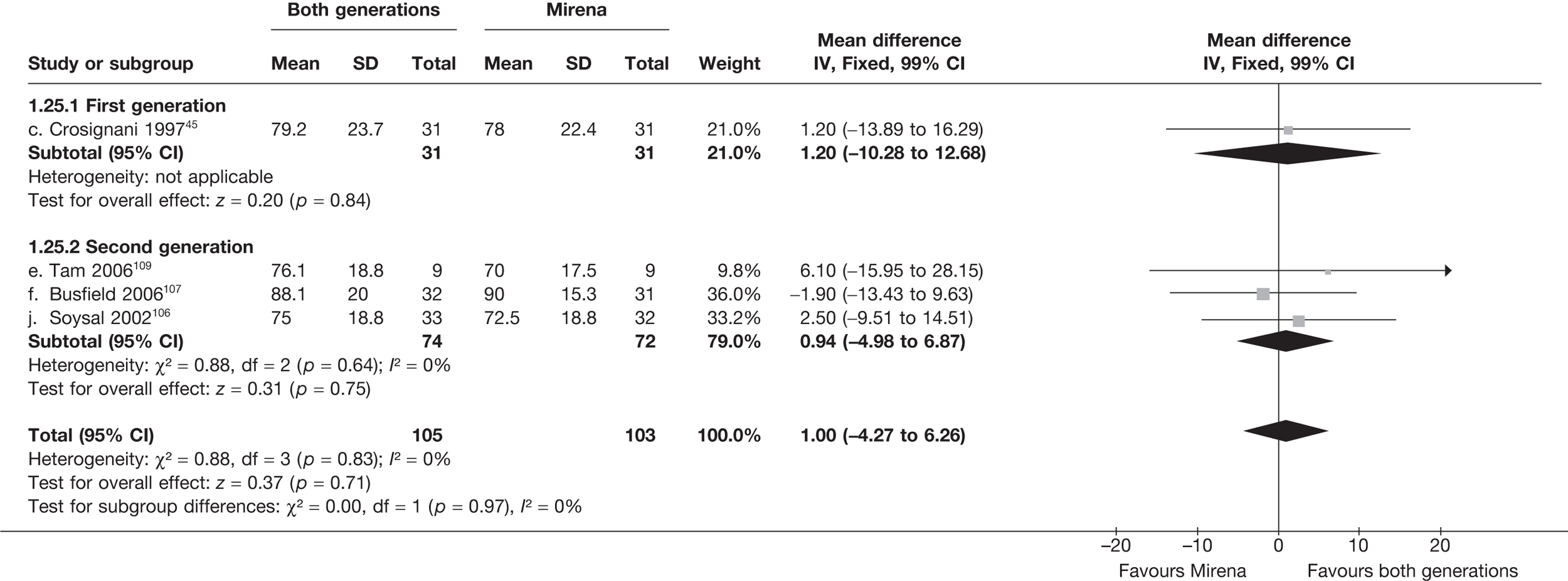

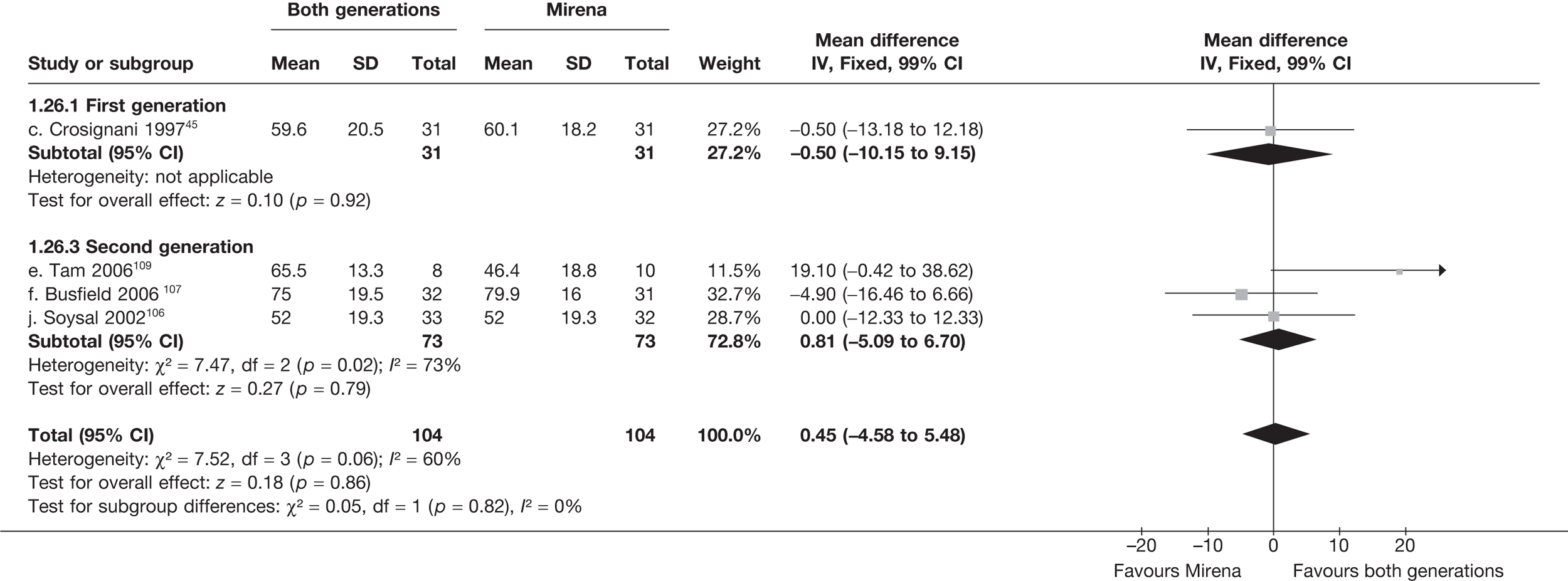

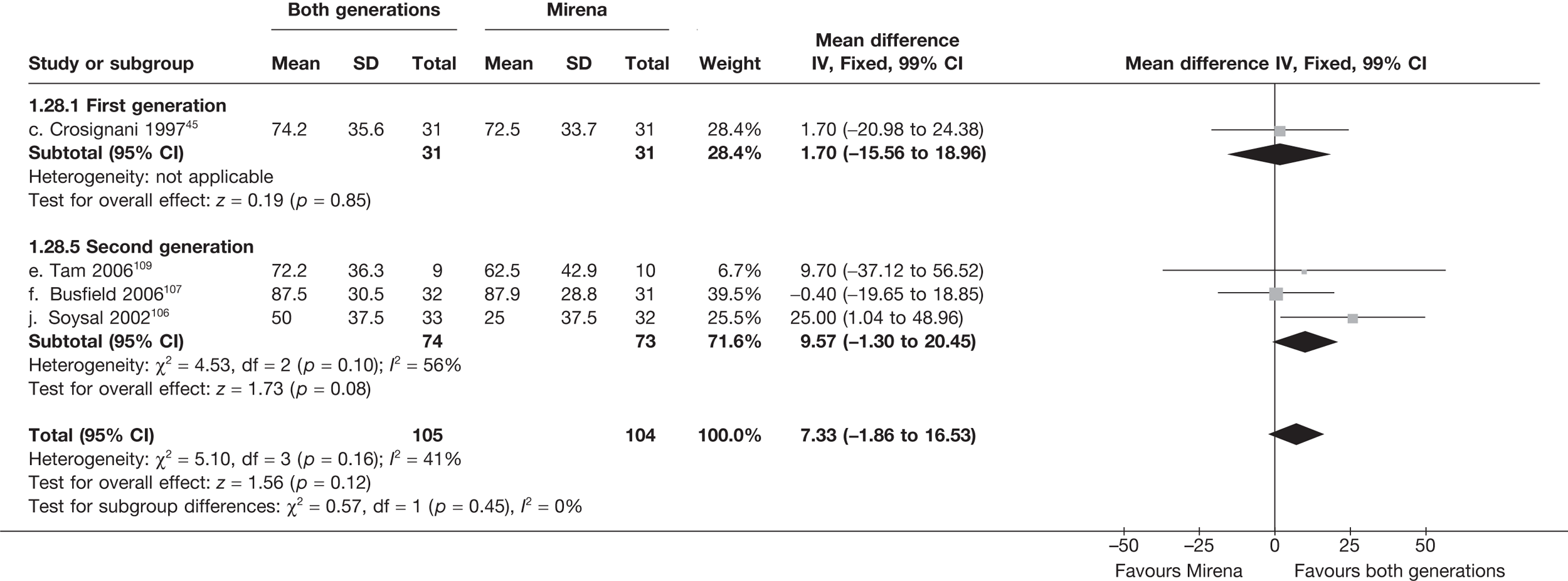

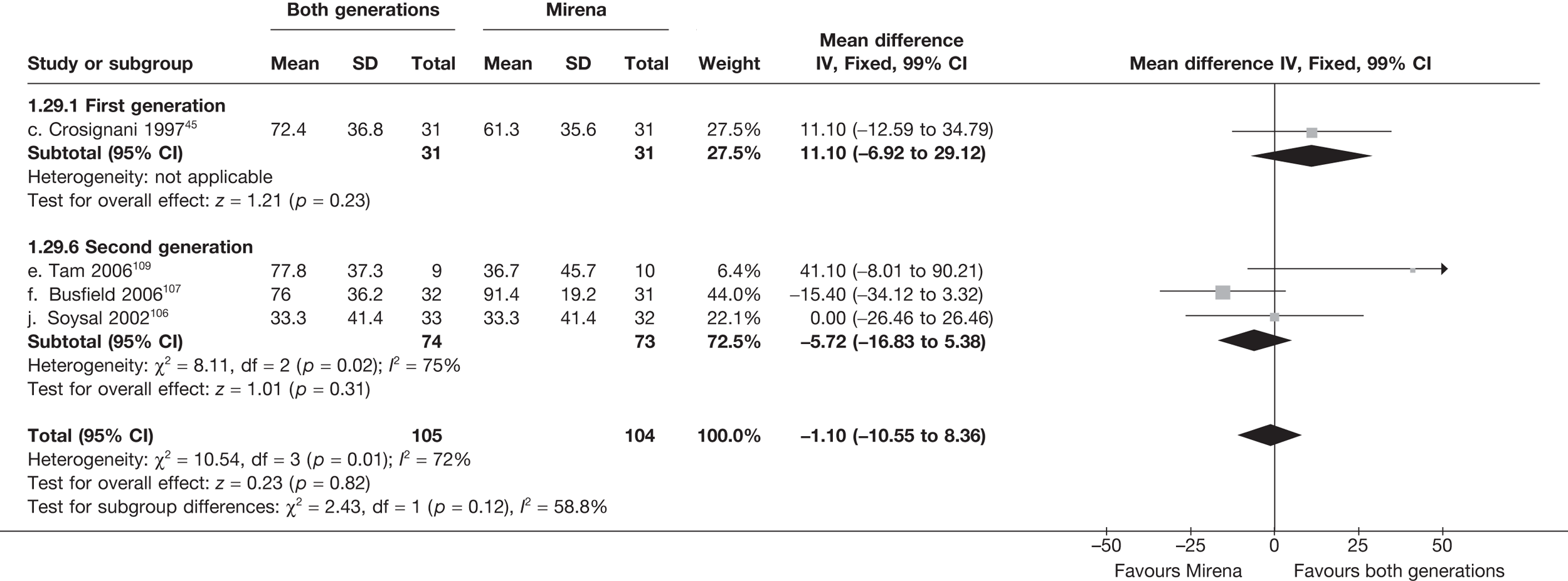

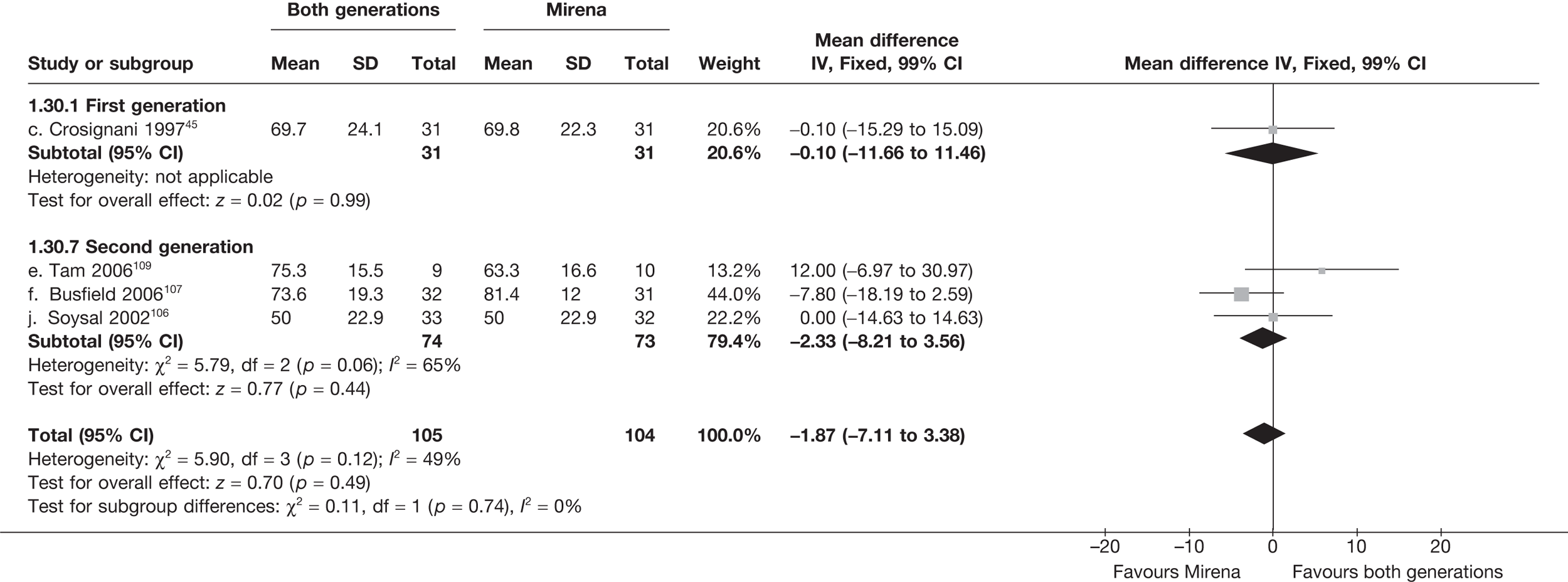

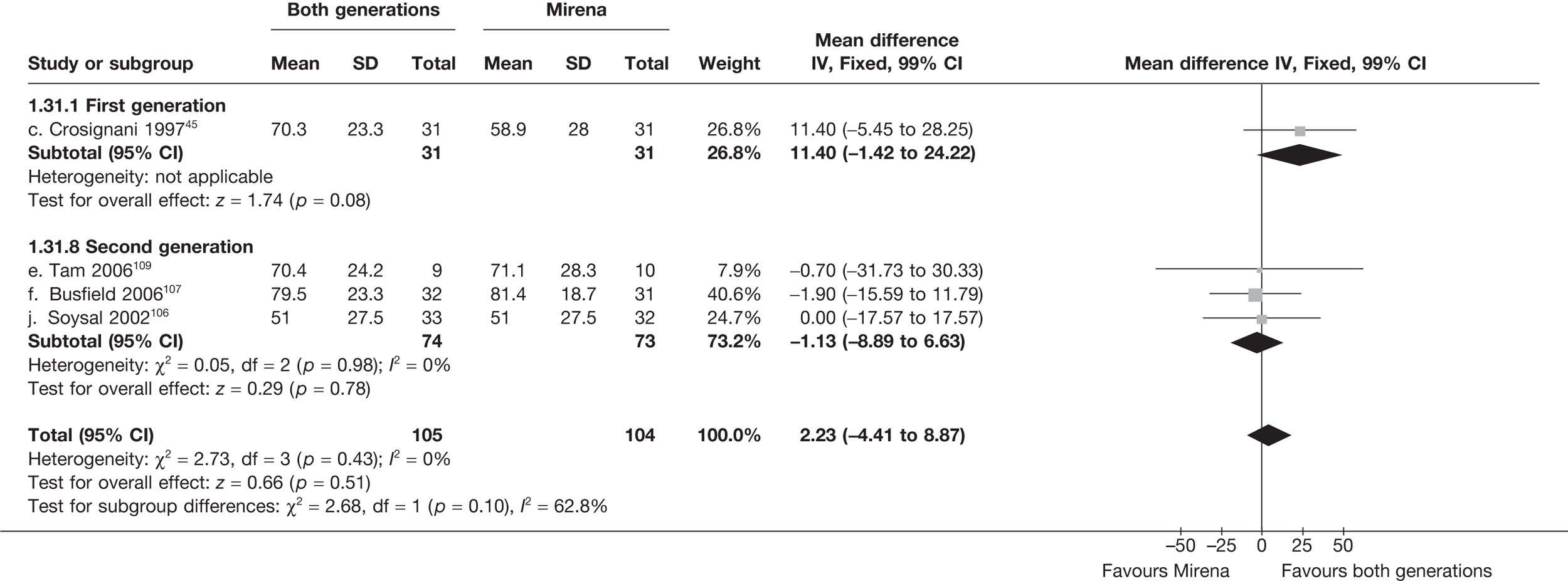

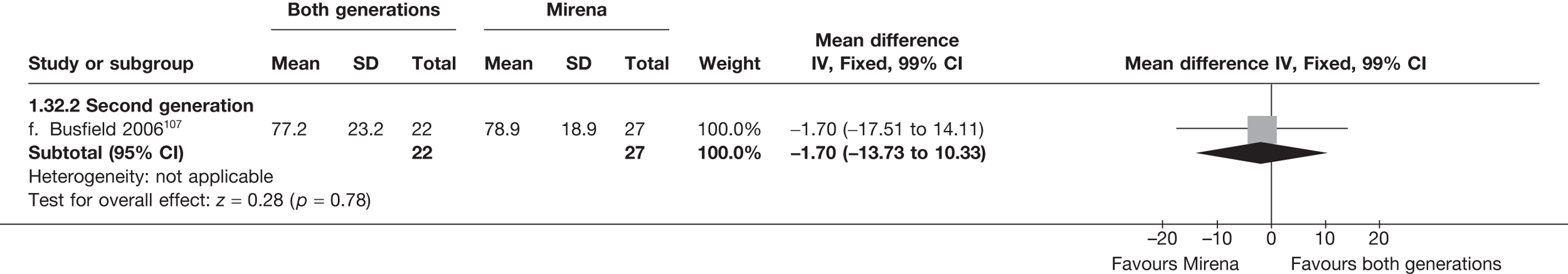

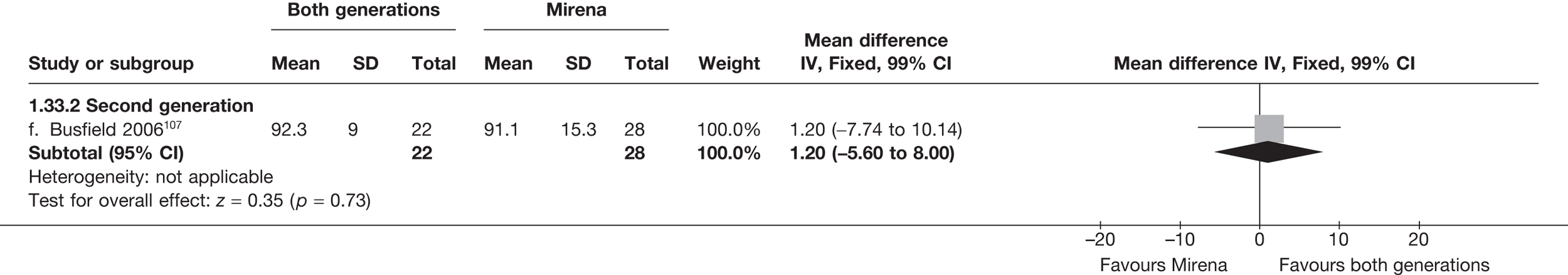

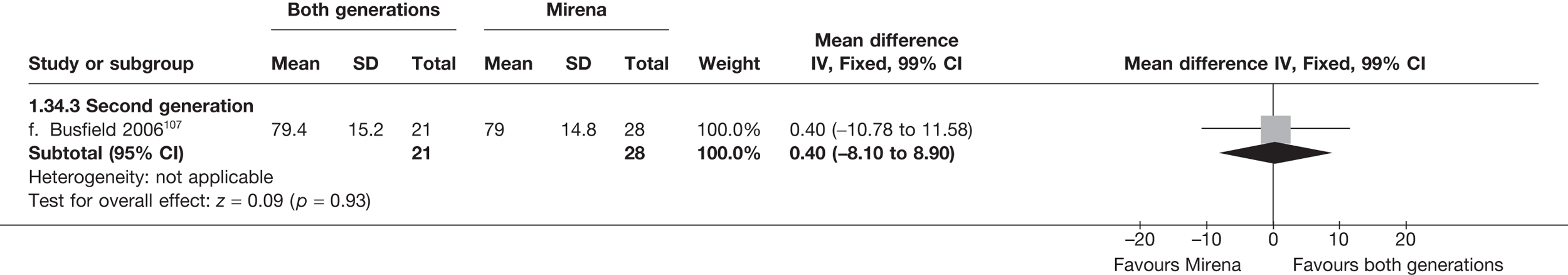

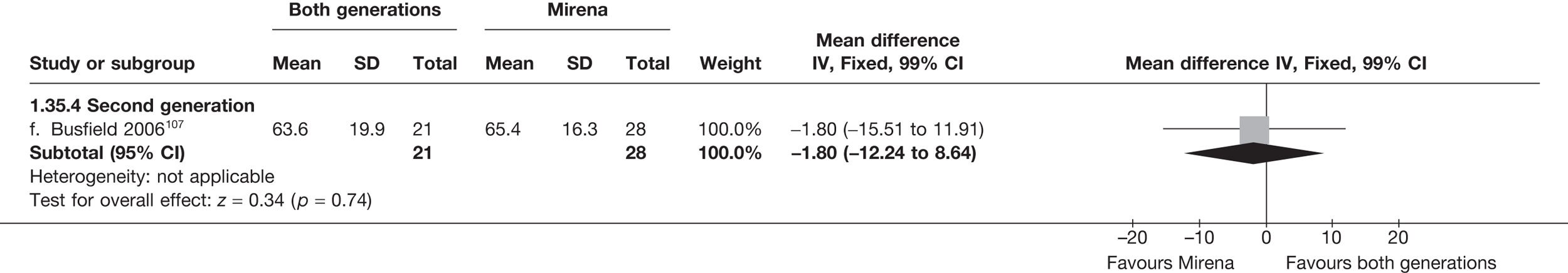

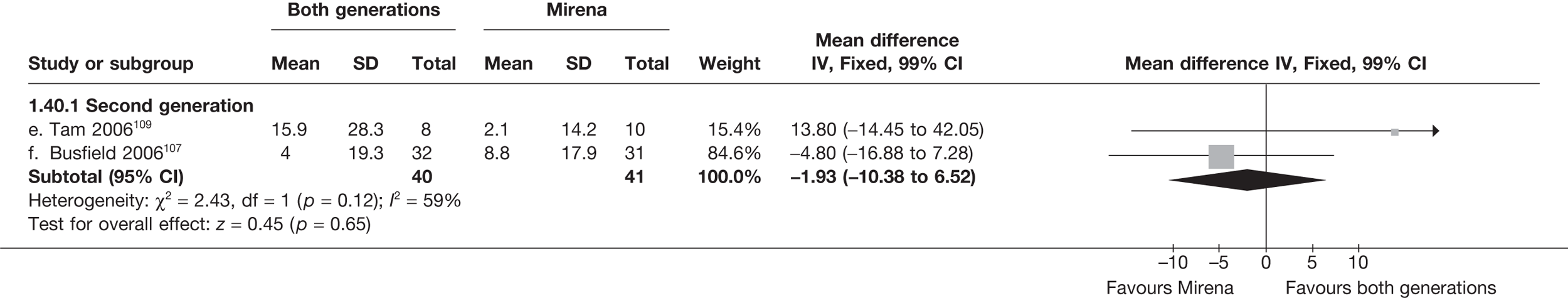

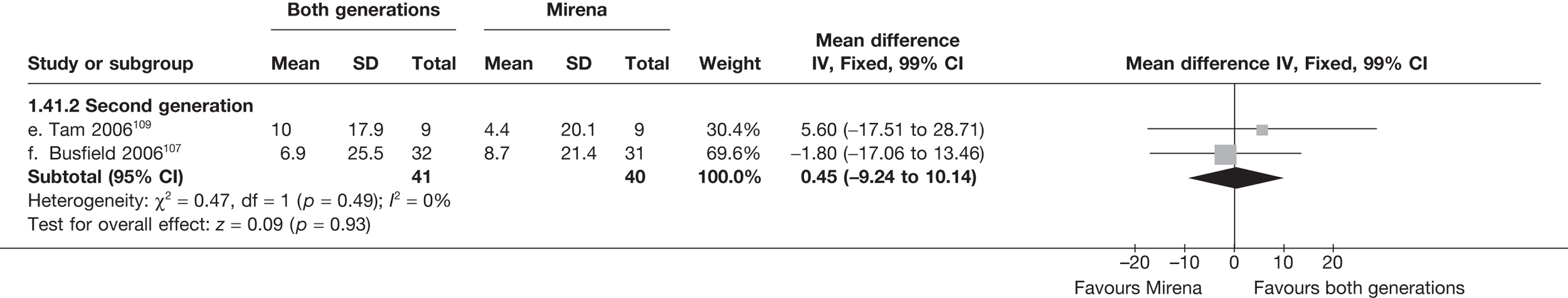

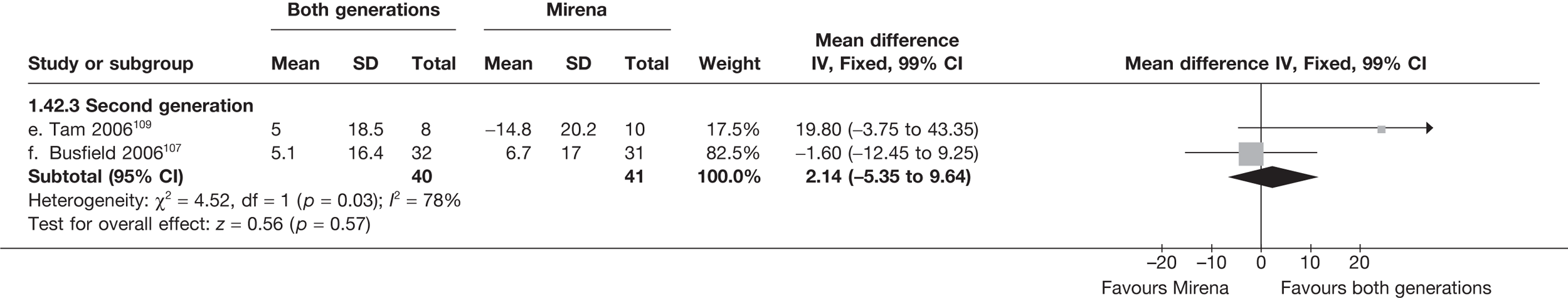

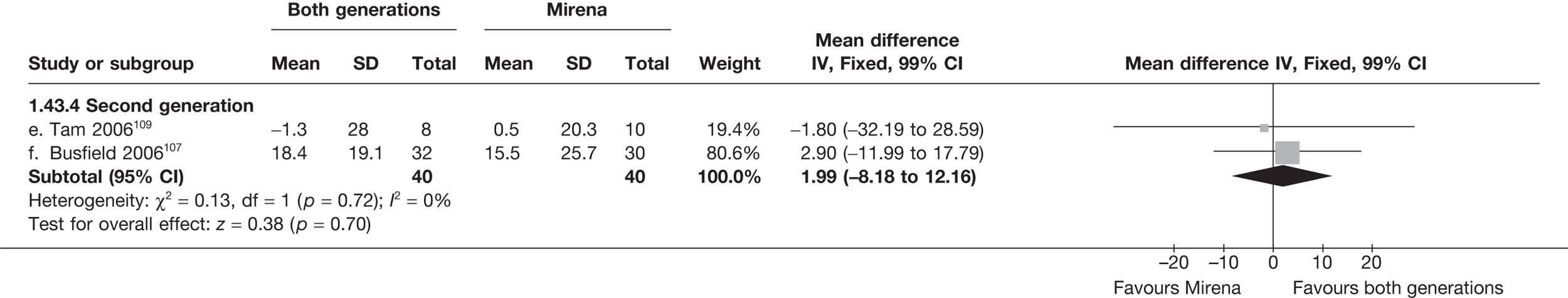

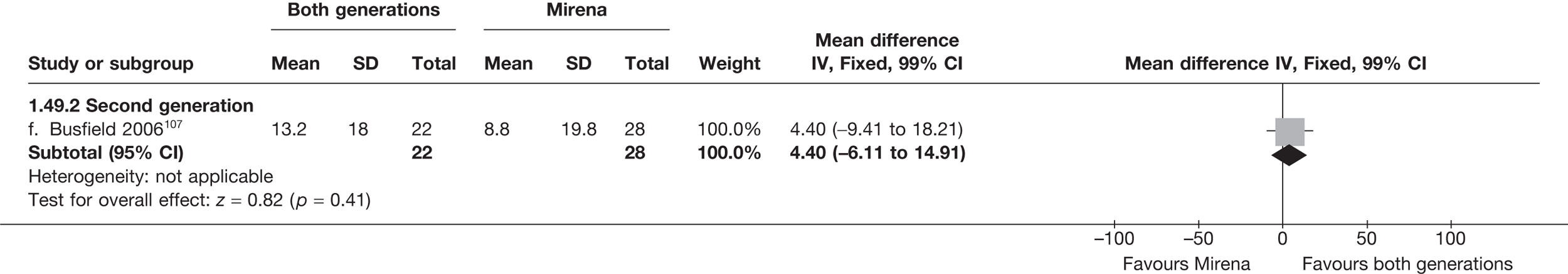

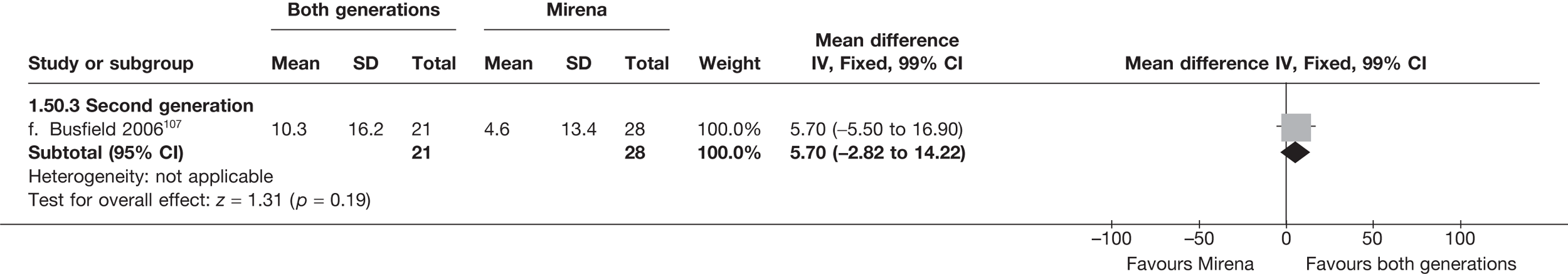

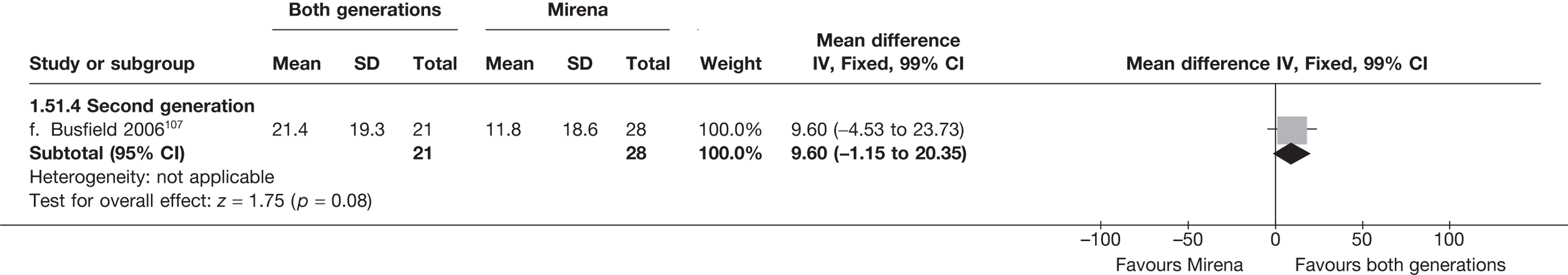

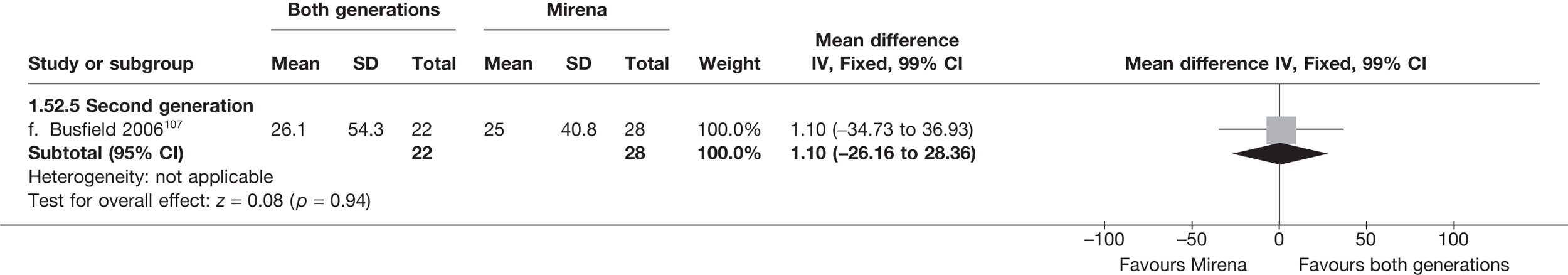

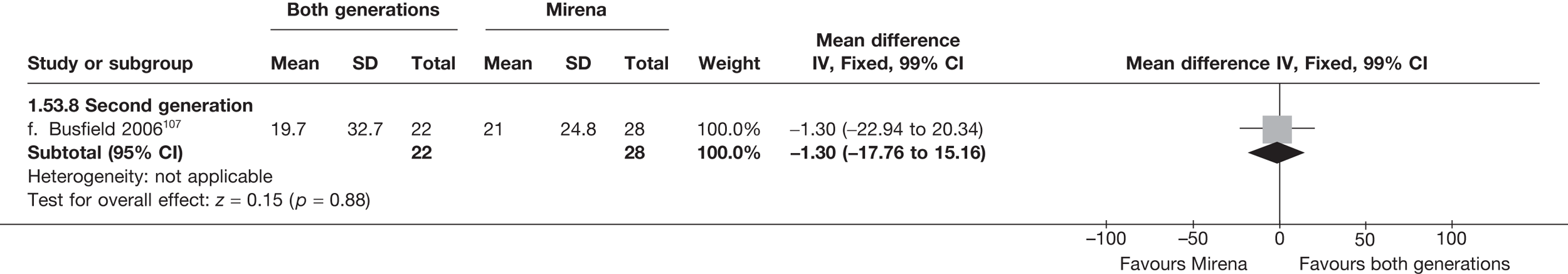

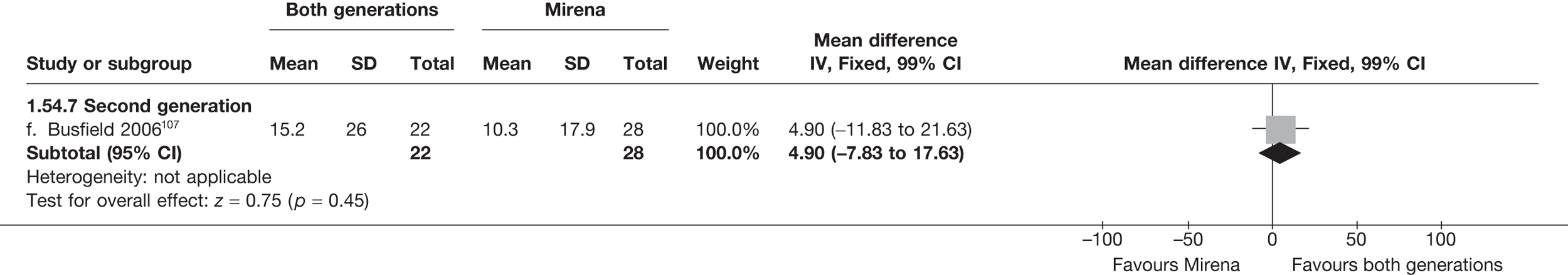

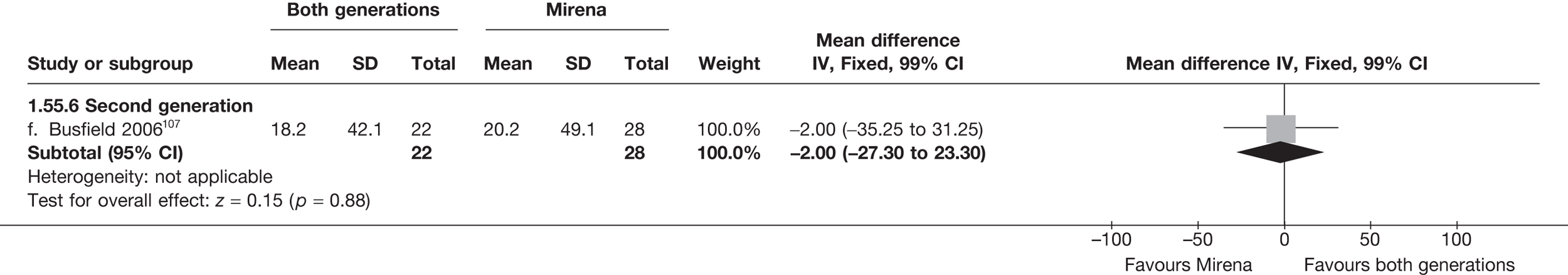

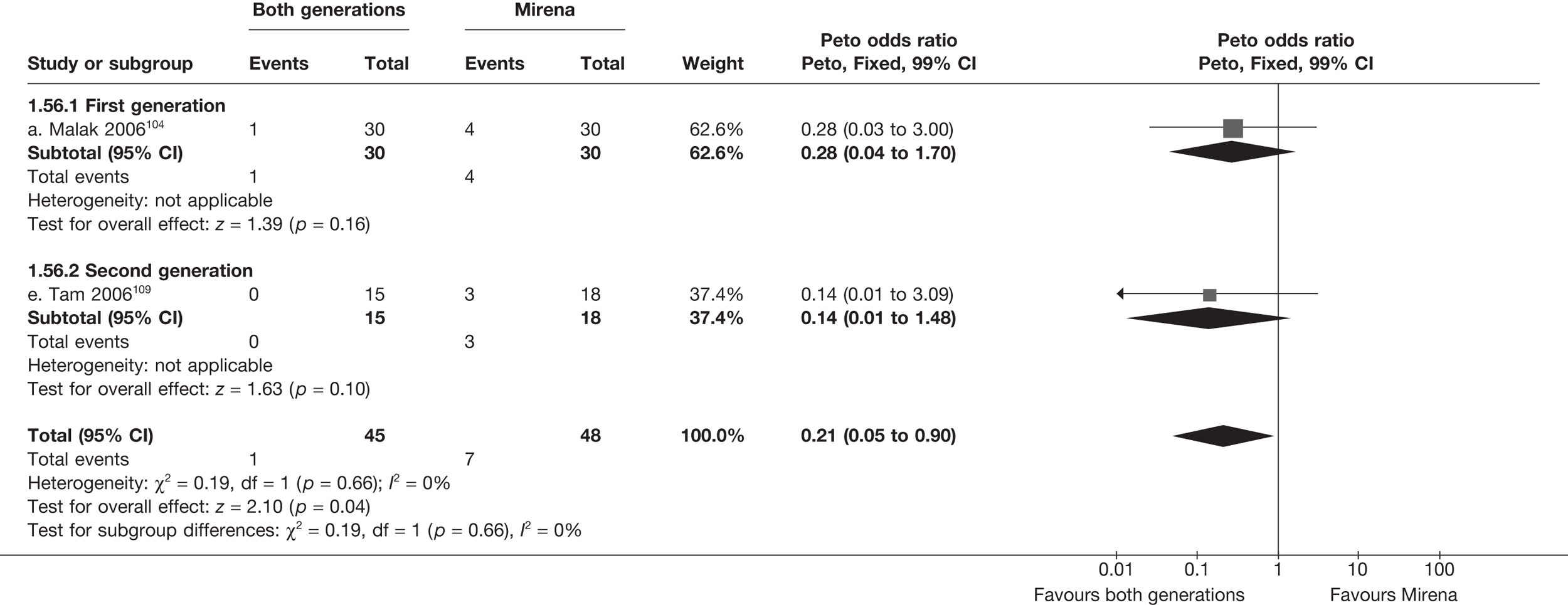

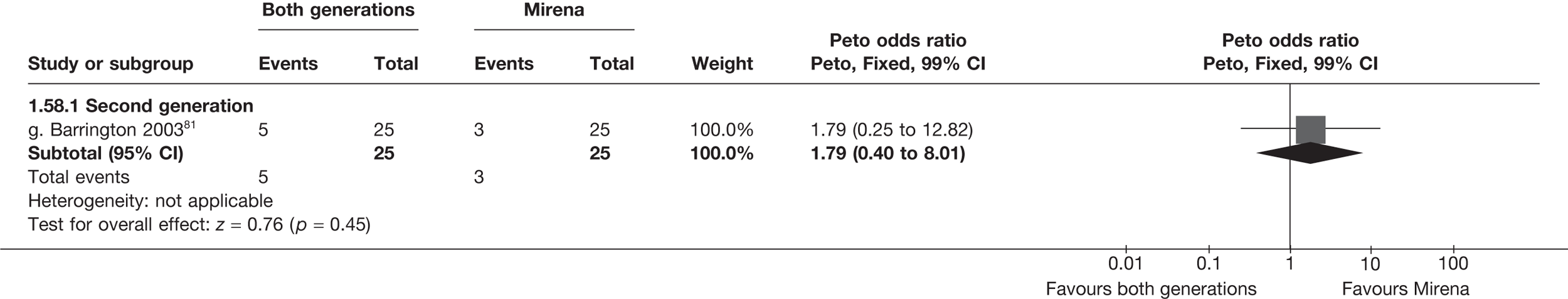

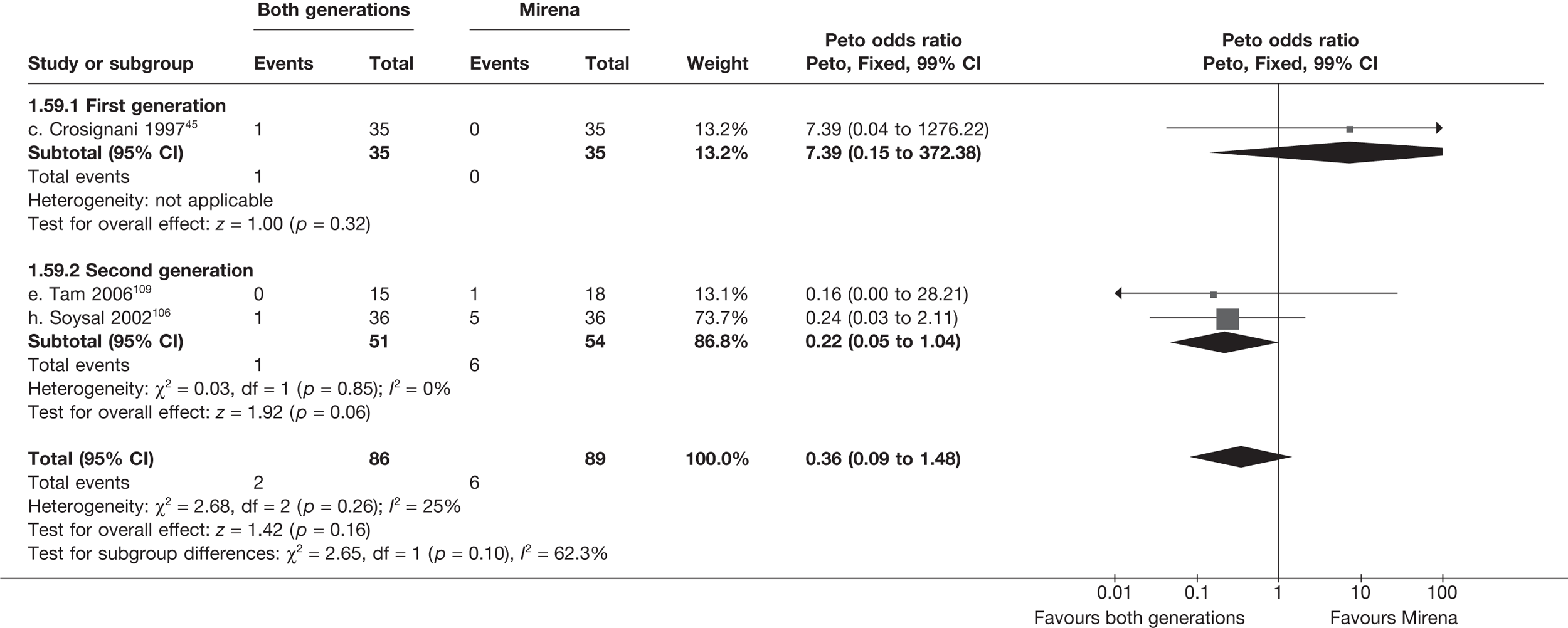

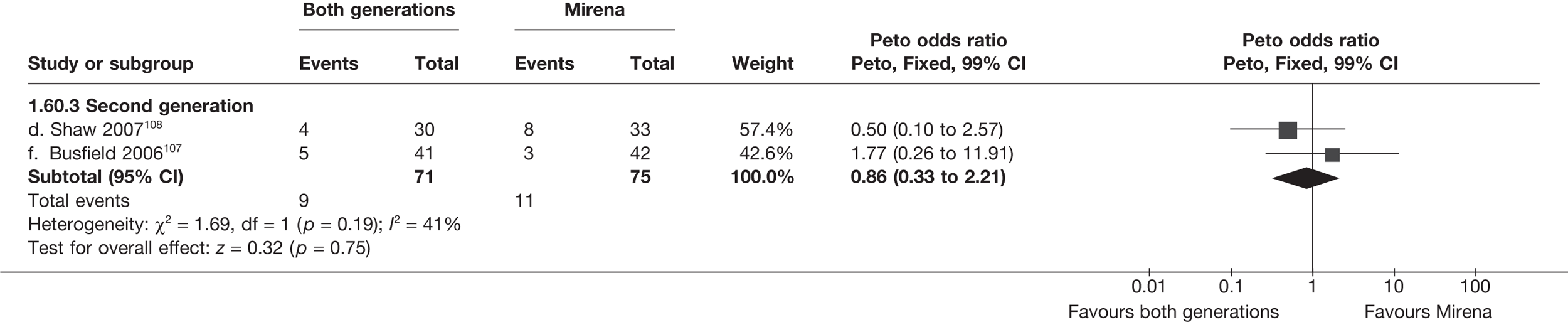

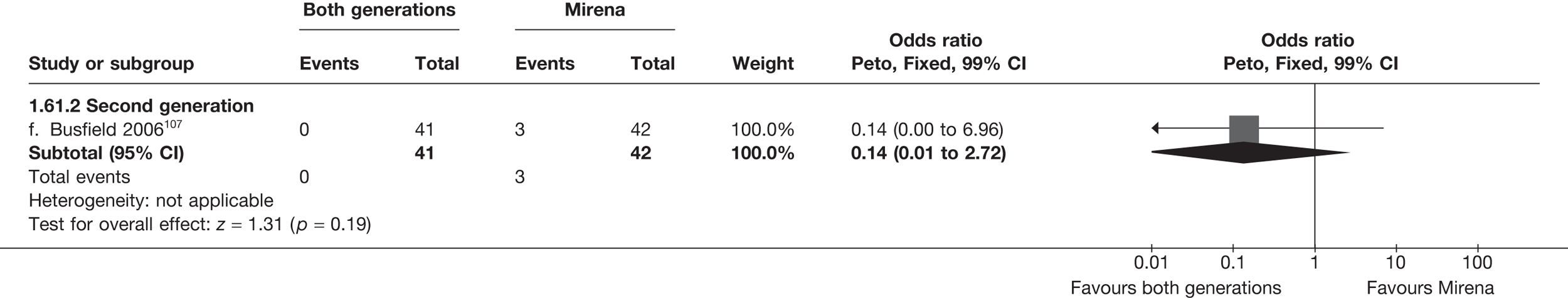

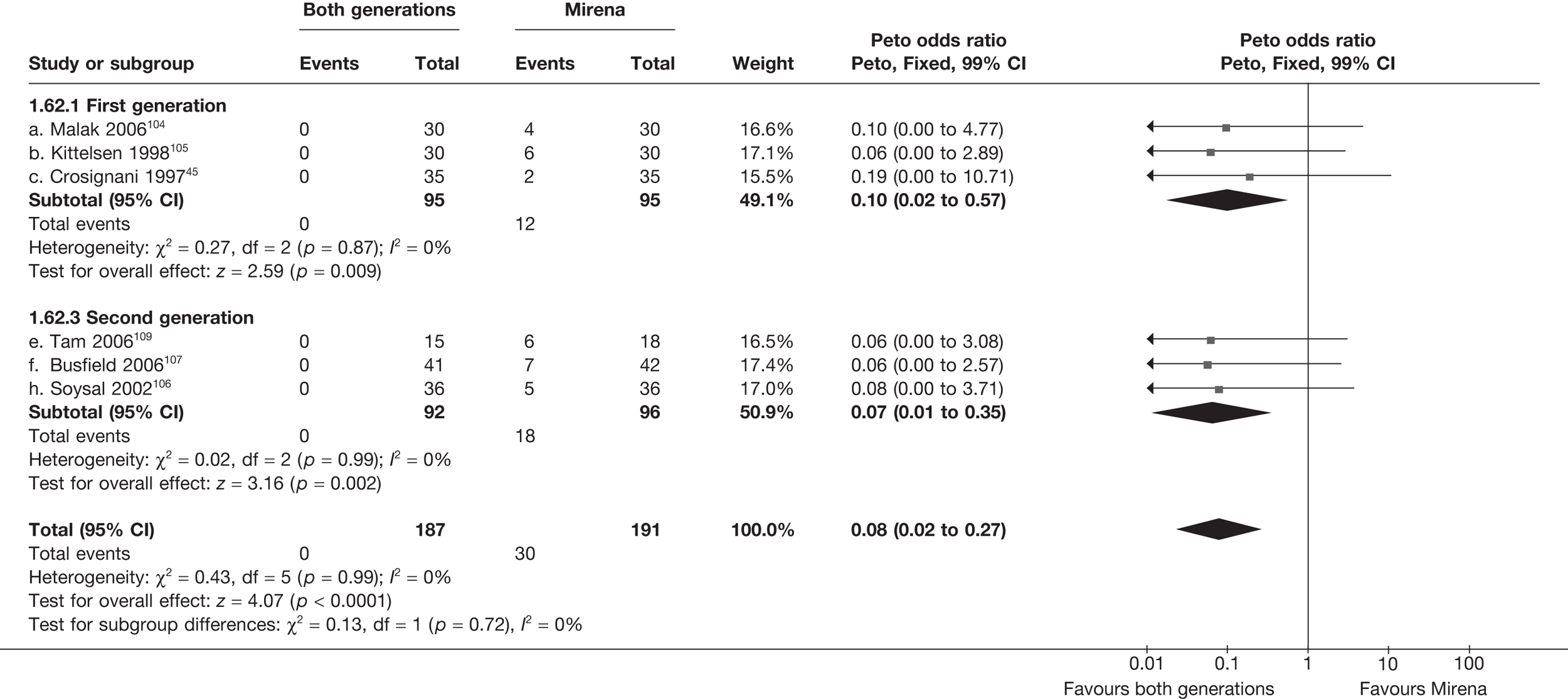

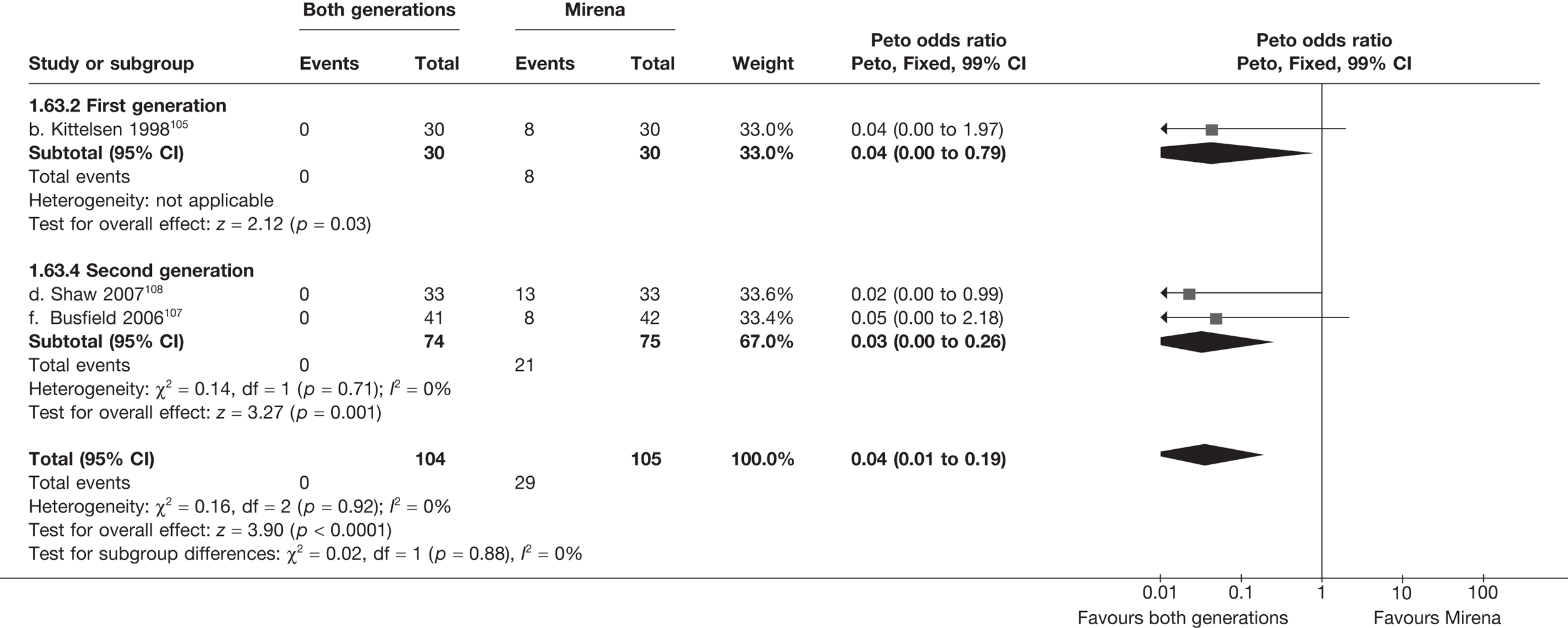

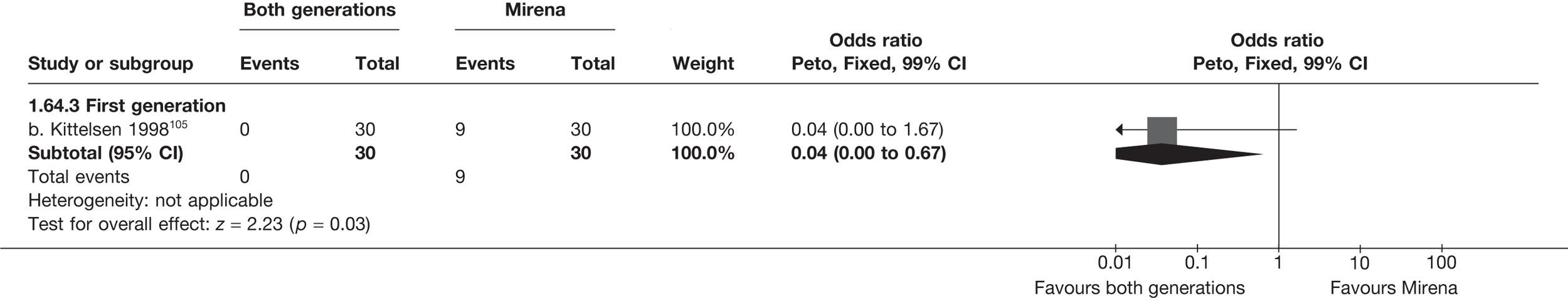

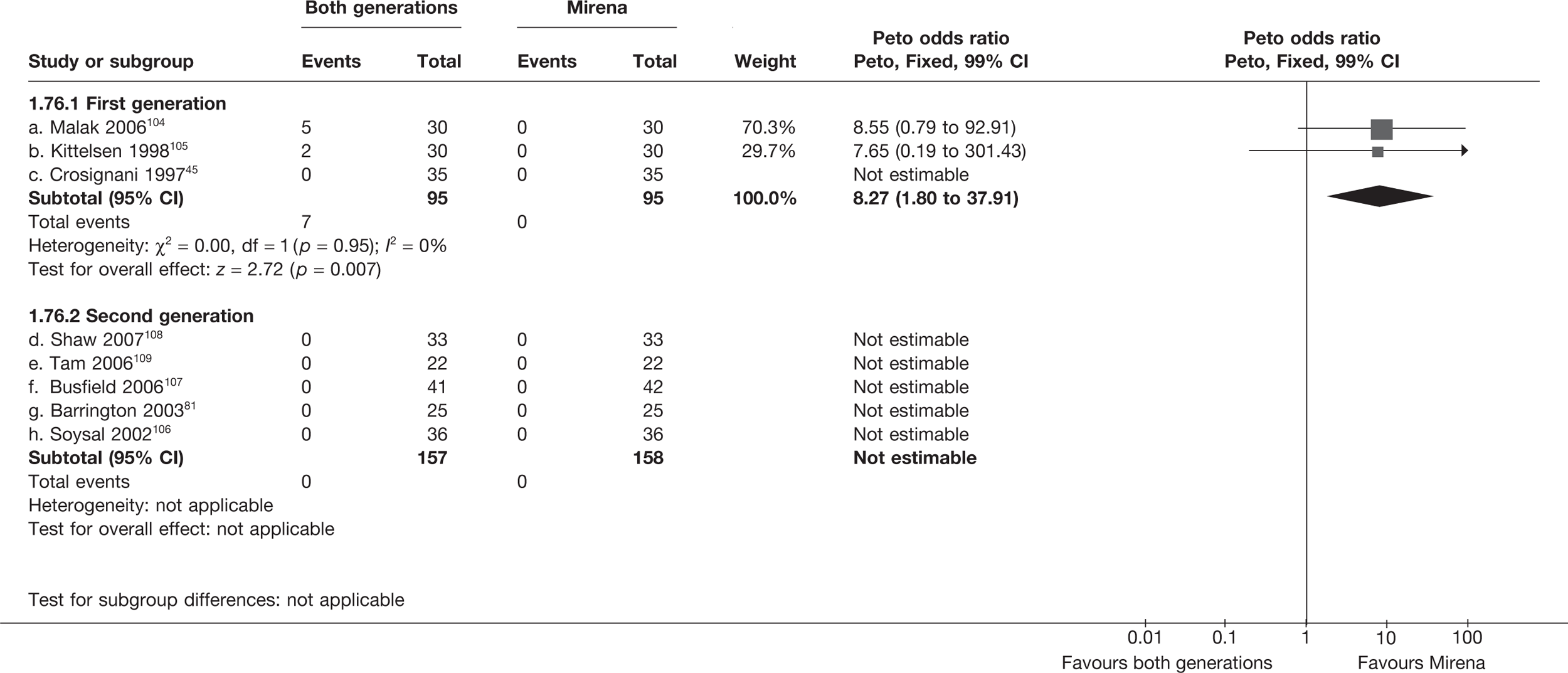

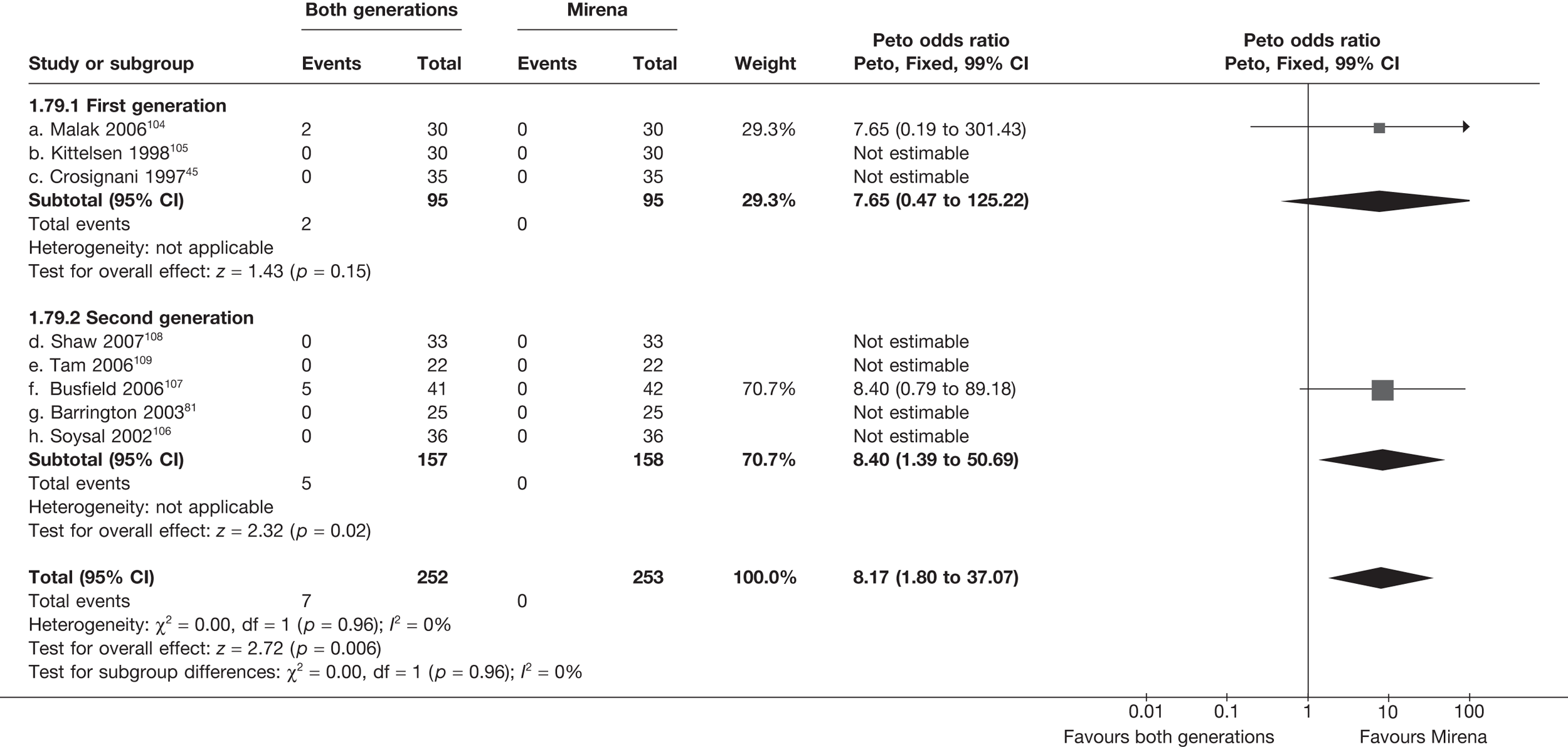

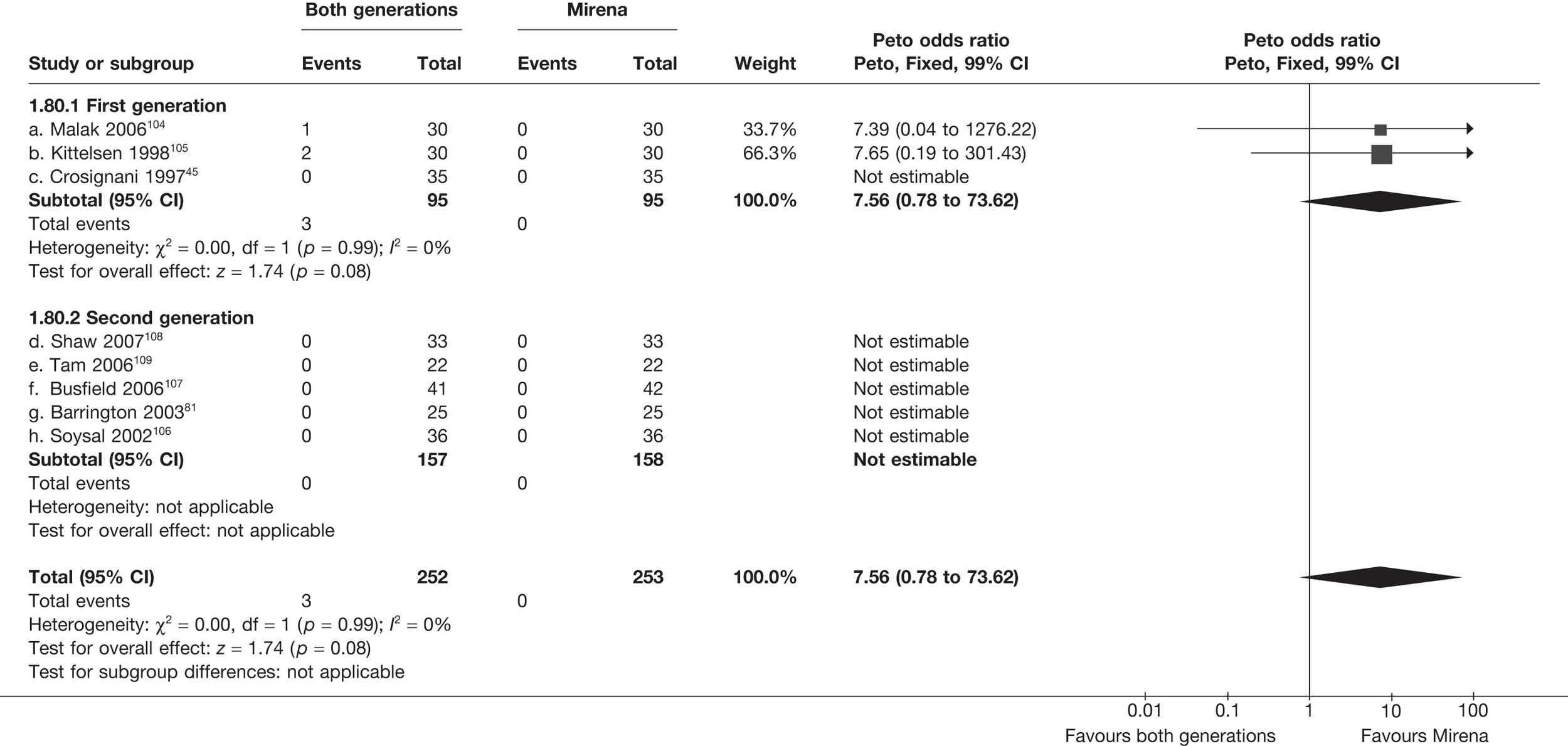

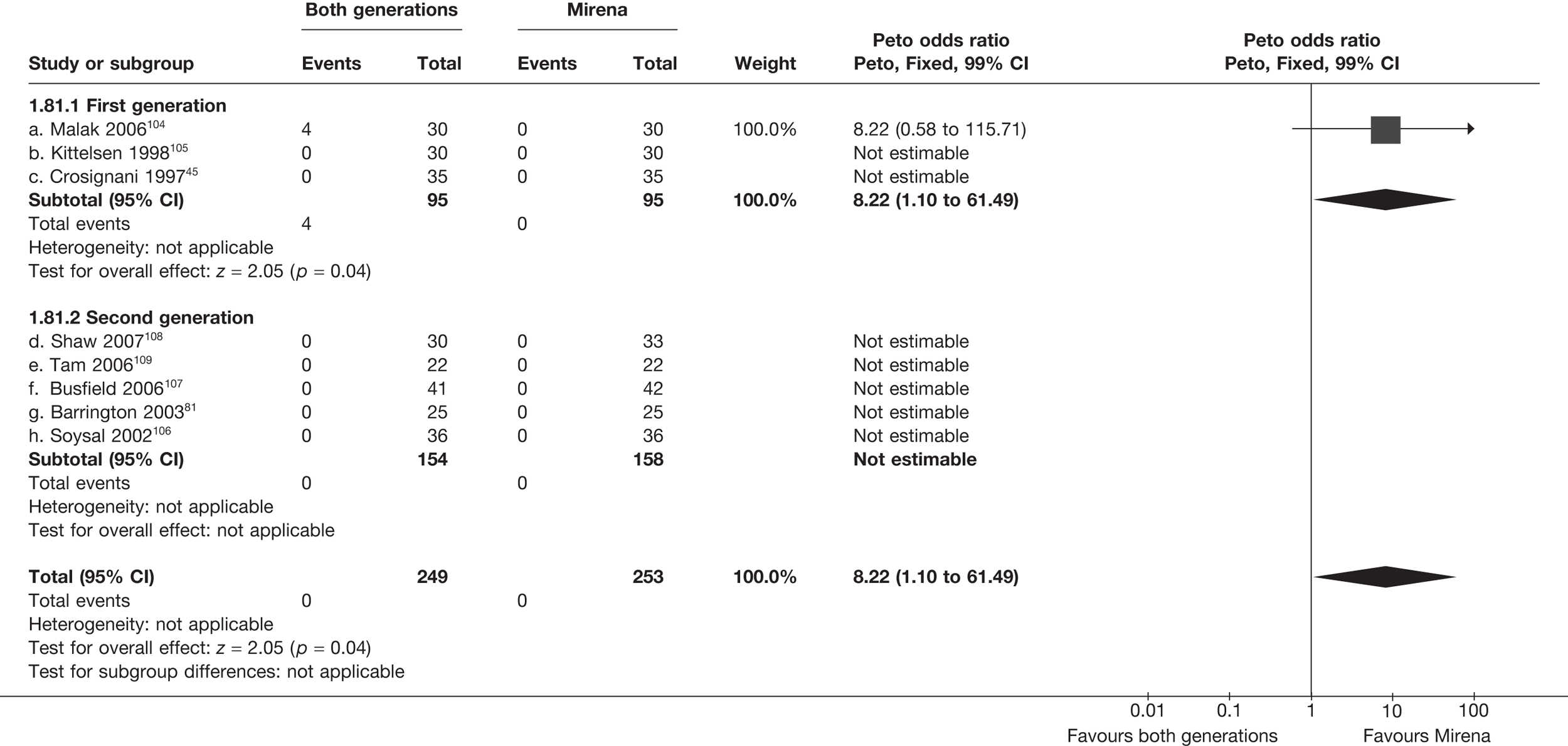

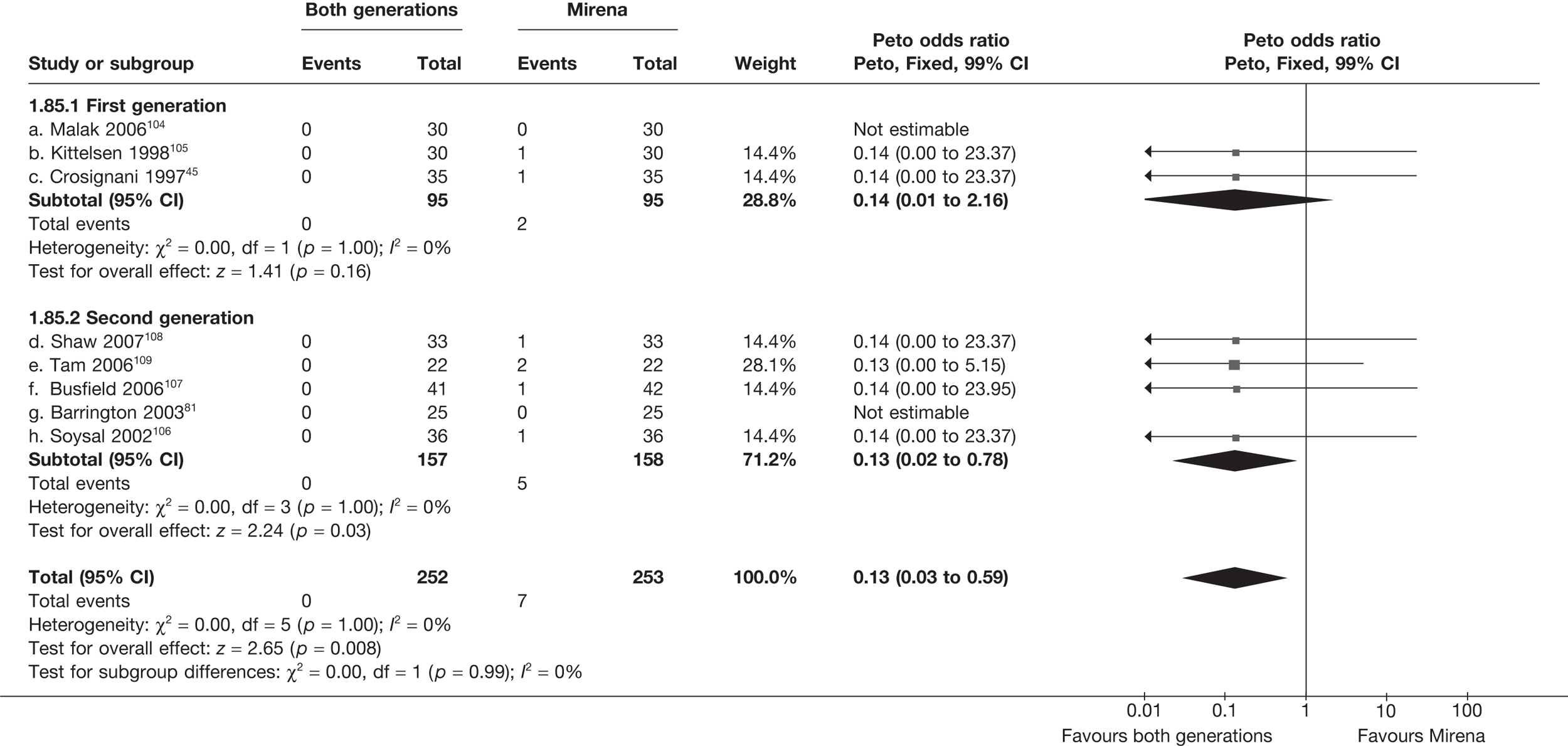

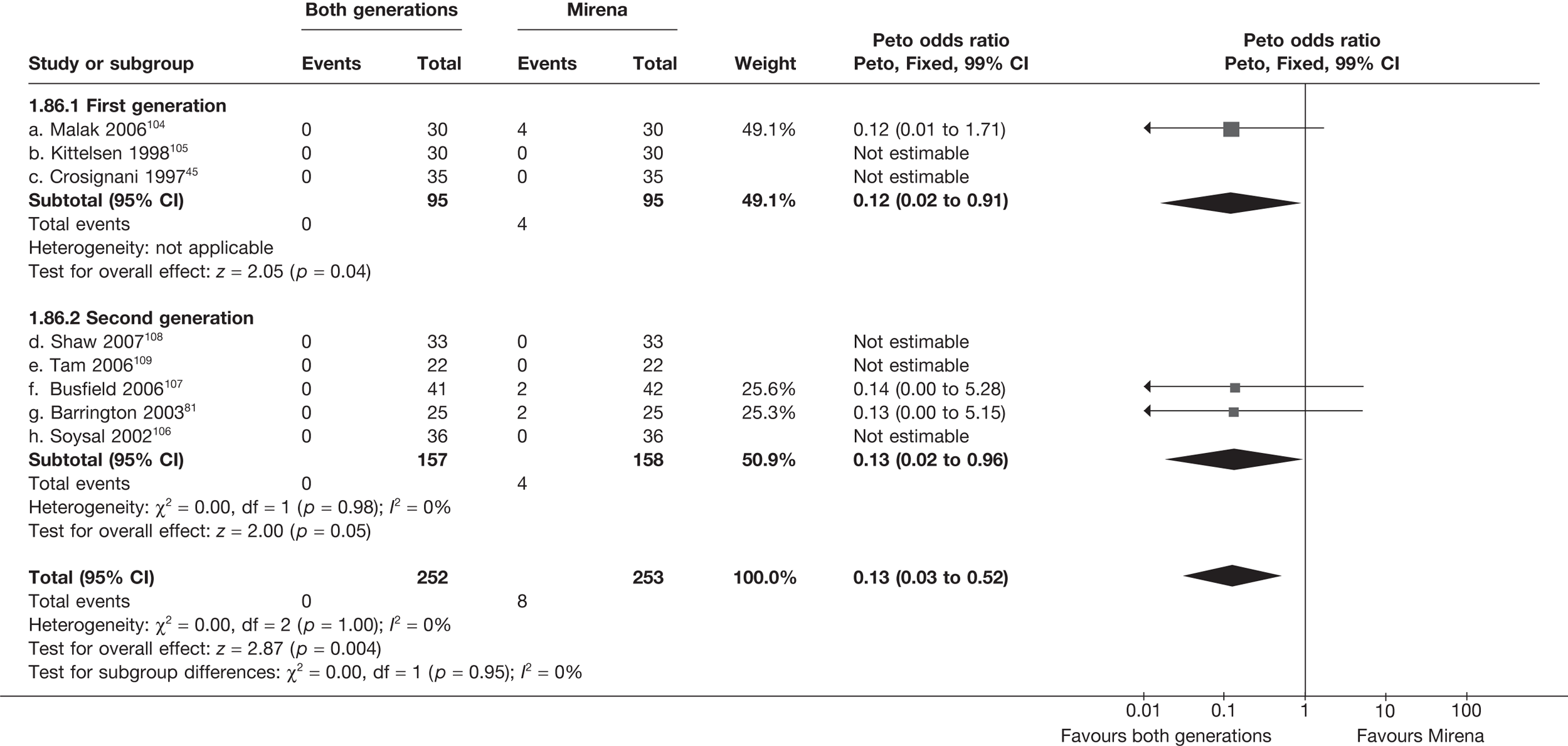

Mirena versus endometrial ablation techniques

Fewer women experienced HMB after Mirena at 6 months (OR 0.23; 95% CI 0.09 to 0.57; p = 0.001) and at 2 years (OR 0.08; 95% CI 0.01 to 0.50; p = 0.007), although total numbers here were small compared with the estimate at 12 months, where there was no evidence of any difference (OR 0.74; 95% CI 0.34 to 1.61; p = 0.5) (see Appendices 7 and 8). Amenorrhoea rates were similar at all time points, although the overall estimate at 12 months, along with the estimate for HMB, was somewhat inconsistent (heterogeneity: p = 0.05 and 0.06, respectively; I2 = 59% and 55%, respectively). Changes in bleeding scores favoured EA at 12 months only (WMD 38 points; 95% CI 15 to 60 points; p = 0.0009), a result consistent over all studies (heterogeneity: p = 0.5; I2 = 0%). Other outcome measures could not separate the two treatments. Two studies107,109 provided SF-36 changes from baseline scores, and no differences were found in any of the domains. The number of women subsequently undergoing a hysterectomy was slightly higher for Mirena, although total numbers in this comparison were very small; rates at 12 months were 2.3% (2/86) for EA and 6.7% (6/89) for Mirena. A high proportion of women originally prescribed Mirena discontinued use of this treatment – 15.7% (30/191) at 12 months, rising to 27.6% (29/105) by 2 years. Reported adverse events were low with Mirena; around only 3% reported an expelled/migrated coil within the first month. These results were from studies of first- and second-generation studies combined where first-generation data existed, and were consistent over both types of EA.

Discussion

Principal findings

In this review, access to IPD enabled a more rigorous analysis than is possible from published data from trials comparing second-line treatments for HMB. The primary outcome measure of dissatisfaction was shown to be strongly related to increased QoL. Based on direct and indirect comparisons using all available data, the review found that both first- and second-generation EA techniques were associated with greater dissatisfaction than hysterectomy, although rates were low for all treatments and absolute differences were small. Recovery times and length of hospital stay were longer for hysterectomy. Dissatisfaction levels with second-generation techniques were slightly lower than those associated with first-generation techniques. In addition, second-generation methods of EA were quicker, had faster recovery times, were associated with fewer adverse procedural events and could be offered under local anaesthetic. Fewer women subsequently underwent hysterectomy after second-generation EA than with first-generation EA, but this difference was not statistically significant. Shorter uterine cavity length was associated with lower levels of dissatisfaction for second-generation EA. Comparisons of EA with Mirena suggest comparable efficacy, although studies involving the latter treatment were generally small and consequently imprecise. Substantial discontinuation of Mirena use was noted and makes interpretation of findings for this treatment difficult.

Strengths and limitations of the review

We used optimal methodology, complying with guidelines on reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. 113 An extensive literature search was conducted, with no language restrictions, minimising the risk of missing information. The collection of IPD allowed us to use previously unreported data, improve the assessment of study quality, standardise outcome measures, undertake ITT analysis and use optimal analytical methods. Subgroup, repeated measures and multivariable analyses would not have been possible without the collection of IPD, and, along with the indirect measures analysis, previously have not been reported.

The review was hampered by the unavailability of IPD from at least 35% of randomised women, which could not be accessed as a number of triallists did not agree to collaborate or could not be contacted. Received data were sometimes incomplete and on occasion failed quality checks and so were unusable. The review’s inferences are also limited by the inconsistent outcome measure used across trials; studies involving ED and Mirena focused on comparing reduction in bleeding, while hysterectomy trials focused on patient satisfaction, QoL and resource usage.

Interpretation

In this review we found that more women were dissatisfied following EA than following hysterectomy, although this should be placed in context of longer operating time, total hospital stay and recovery period for hysterectomy. Rates of dissatisfaction are relatively low for EA and it is an effective alternative for women with abnormal uterine bleeding who do not seek amenorrhoea. While this review has shown that hysterectomy is a relatively safe operation, other studies with a more comprehensive follow-up of large populations have shown higher levels of morbidity following hysterectomy. 6 In contrast, EA has low rates of complication. 47 All these factors need to be taken into consideration when considering any potential benefit of hysterectomy.

We found that second-generation techniques, such as thermal balloon ablation (ThermaChoice and Cavaterm),51–53 the NovaSure device56 or microwave (Microsulis),54,68 were not significantly different to first-generation techniques in terms of patient dissatisfaction. Moreover, they are simpler and quicker, require less skill on the part of the operator and can be attempted under local anaesthetic. Importantly, fewer operative complications have also been recorded. Thus, they are clearly preferable to first-generation techniques. The association of shorter uterine cavity length and lower dissatisfaction with second-generation EA could be because endoscopic treatment is technically more difficult, although given the borderline statistical significance it could also have arisen by chance.

The comparisons involving Mirena were encouraging and, given that it is a relatively cheap and minimally invasive procedure, it could be considered first if drug treatment for heavy bleeding fails. 114 It may even be an alternative to oral drug treatment as a first-line agent, but we did not address this question in our review. However, the current body of evidence comparing Mirena with more invasive techniques is limited and prohibits us from making any strong conclusions about the current findings of this treatment. Furthermore, research on Mirena presents some specific difficulties in interpretation owing to the high proportion of women discontinuing treatment. This can be seen in the trial by Hurskainen et al. ,93 which compared Mirena with hysterectomy. While the study was well conducted and reported, the lack of further investigation into the analysis of the primary outcome measure (EQ-5D QoL measure) made the interpretation that there was no evidence of a difference questionable. Of the women allocated Mirena, 20% had received hysterectomy before the main analysis time point at 12 months, with a further 12% no longer using the Mirena. Unfortunately, missing IPD from this trial meant we could not examine further.

Implications for practice

Our review provides evidence that hysterectomy reduces dissatisfaction compared with EA, and this information should be used as part of a consultation with women making a choice about treatment options when initial drug treatment fails to control HMB. EA is satisfactory for a very high proportion of women, but, if complete cessation of bleeding is sought, then hysterectomy may be offered.

Despite the relative paucity of trials evaluating Mirena (particularly in comparison with hysterectomy), it is available in primary care and is less invasive than surgical options. In view of this we can concur with a recent NICE recommendation that women should be offered Mirena before more invasive procedures. 15

Implications for research

This review has shown that further investment in an RCT comparing hysterectomy with second-generation EA would be of limited value given the similar efficacy of first- and second-generation techniques. Questions remain about the long-term clinical effectiveness of all the treatments; evidence from trials with longer term follow-up (≥ 4 years) is limited to a handful of studies involving differing comparisons. 92,93,115,116 Mirena in particular versus alternative forms of surgical treatment requires further research. While the small studies included in this review have indicated promising results for this treatment, the substantial levels of non-compliance makes interpretation of outcomes difficult and casts some doubt on the equivalent efficacy conclusions.

Individual patient data meta-analysis is an extremely powerful tool if used correctly117 and provides the most definitive synthesis possible of the available evidence. Such collaborative meta-analyses are well established in cancer and have greatly influenced clinical practice, resulting in striking improvements in, for example, breast cancer survival. 84 Clinicians in speciality groups, such as gynaecology, need to be aware that contributing study results to an IPD is certainly as important as conducting the original research, if not more so. Consensus on optimal outcome measures would also be helpful for meta-analysis.

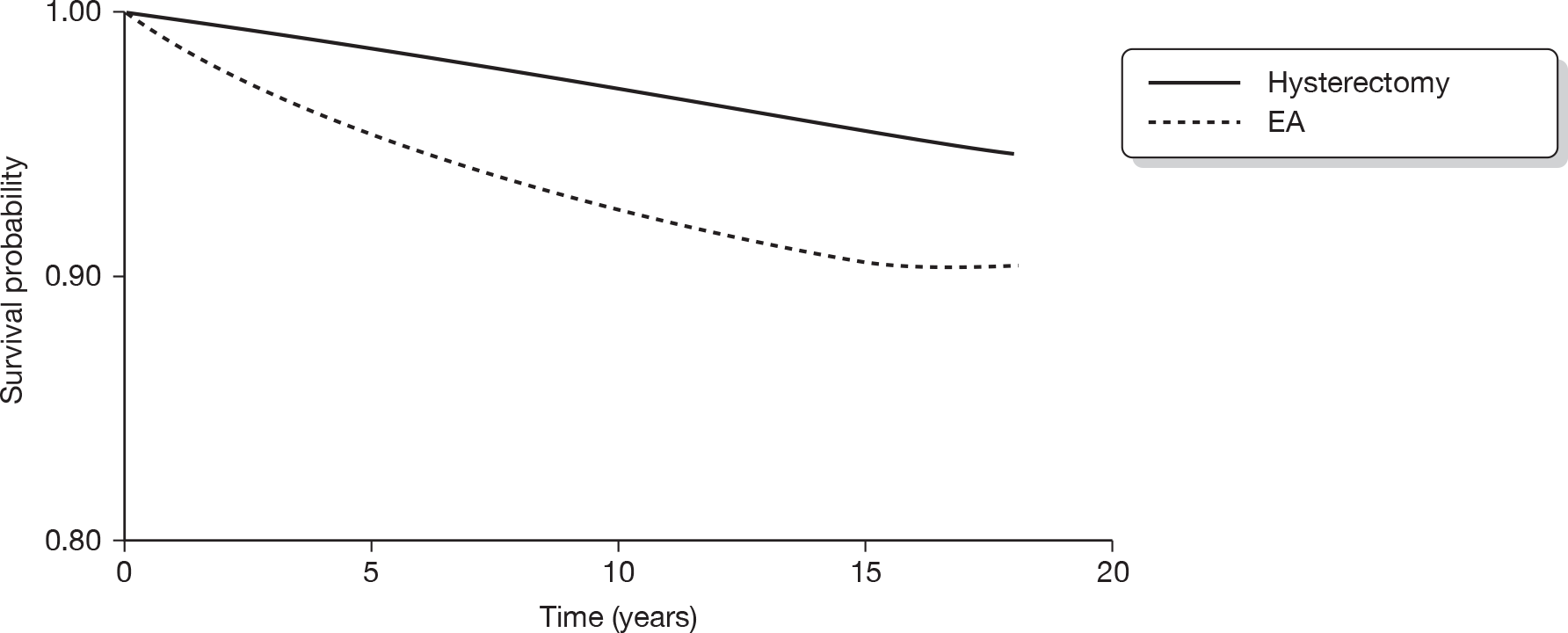

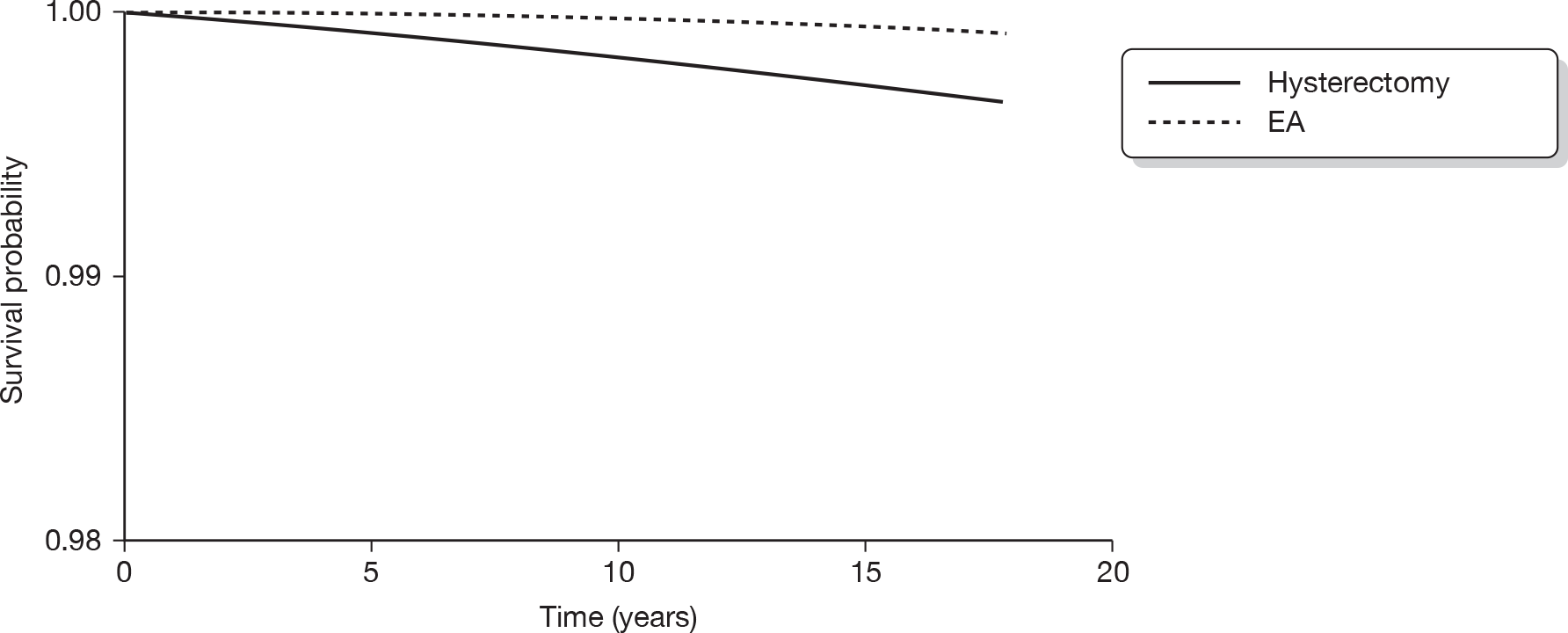

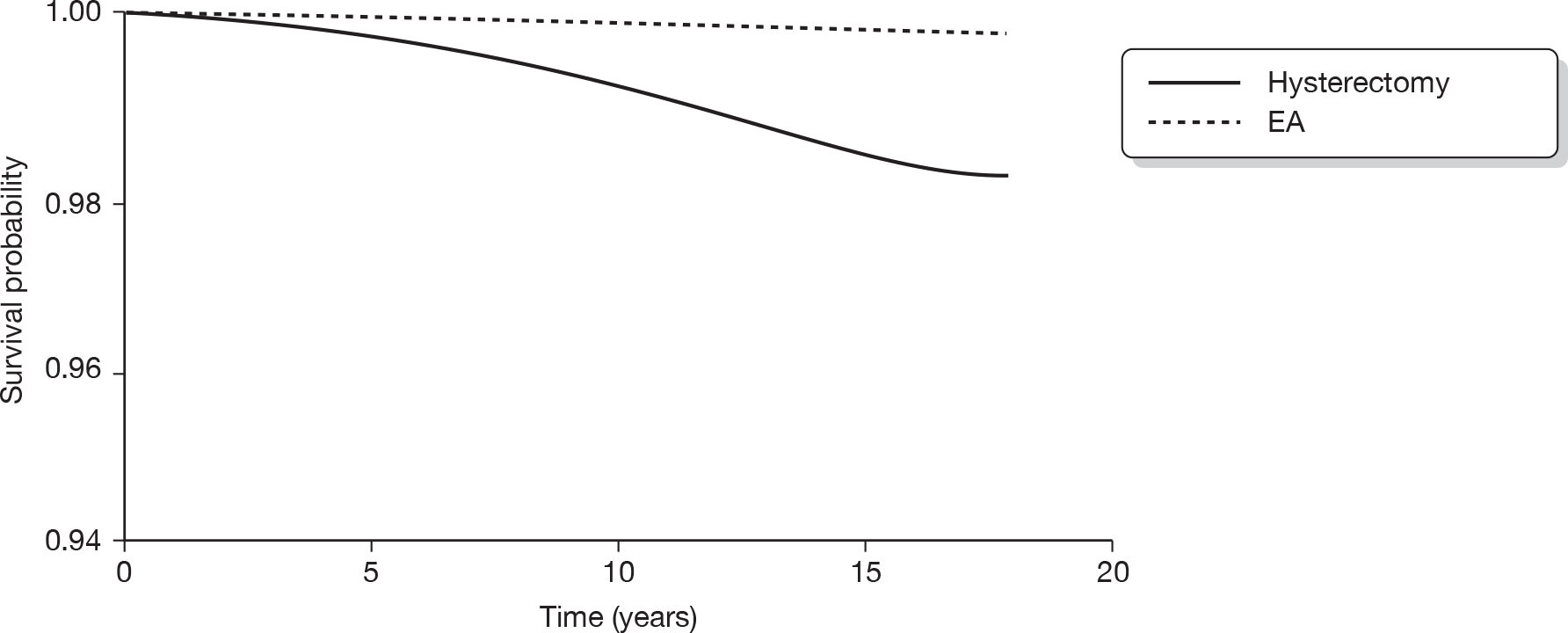

Chapter 3 Long-term sequelae following hysterectomy or endometrial ablation in Scotland

Introduction

The last two decades have seen the emergence of EA as a conservative surgical alternative to hysterectomy. While the results of hysterectomy are good and amenorrhoea is guaranteed, hysterectomy is invasive and can carry significant short-term morbidity. 31 Overall, 1 in 30 women suffers a major adverse event, and the mortality rate is 0.4–1.1 per 1000 operations. The need for general anaesthesia, prolonged hospital stay and delayed recovery also makes hysterectomy potentially a more expensive treatment. 32 Recent national data from England suggest that EA is now more common than hysterectomy for HMB and second-generation methods are now more commonly performed than hysteroscopic EA. 30

Endometrial ablative techniques do not guarantee amenorrhoea, but their effectiveness (in comparison with hysterectomy) has been demonstrated in a number of RCTs41–44 (Aberdeen Endometrial Ablation Trials Group, 199946). National audits of first-generation EA (Scottish Hysterectoscopy Audit Group, 199548) have revealed a number of short-term complications including uterine perforation, fluid overload, cervical laceration, false passage creation, haemorrhage, sepsis and bowel injury. 49,50 Mortality from these techniques has been estimated at 0.26 per 1000. 47,48 Second-generation ablative techniques represent simpler, quicker and potentially more efficient means of treating menorrhagia, which require less skill on the part of the operator but are associated with complications such as equipment failure, uterine infection, perforation, visceral burn, bleeding and cyclical pain. A number of randomised trials indicate that these procedures appear to be as effective as first-generation ablative techniques. 61

Studies on outcomes after hysterectomy have mainly concentrated on short-term outcomes (in unselected groups of women undergoing the procedure for different underlying reasons118). Similarly, most evaluative studies on first- and second-generation EA have reported short-term complications, although some have included medium- and long-term outcomes (there have been few long-term controlled comparisons of hysterectomy with ablation techniques in women with HMB116).

Objective

To determine, using population-based data from record linkage, long-term effects of ablative techniques and hysterectomy in terms of failure rates and complications.

Research questions

-

What is the risk of further gynaecological surgery following EA compared with that following hysterectomy in women with HMB?

-

What is the risk of further gynaecological surgery following different types of hysterectomy in women with HMB?

-

What is the risk of gynaecological cancer following EA compared with that following hysterectomy in women with HMB?

-

What is the association of age with risk of further gynaecological surgery following EA compared with that following hysterectomy in women with HMB?

Methods

Anonymised patient-based data for inpatient and day case activity from the whole of Scotland which are routinely collected as Scottish Morbidity Returns (SMR) by the Information Services Division (ISD) were used for this study. More information on the ISD is available at www.isdscotland.org. The SMR register is subjected to regular quality assurance checks and has been shown to be more than 99% complete since the late 1970s. 119 Approval to perform the study was granted by the Privacy Advisory Committee of the ISD. As researchers had no access to any patient identifiers, the North of Scotland Research Ethics Service were of the opinion that formal ethical approval was not necessary.

The original database supplied by ISD contained a total of 549,223 records. From this, records with an International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10) diagnostic code beginning with either N92 (excessive, frequent and irregular menstruation) or N93 (other abnormal uterine and vaginal bleeding excluding neonatal vaginal haemorrhage and pseudo menses) plus any record with ICD, Ninth Edition (ICD-9) codes of –6226, –6270 and –6268 were selected. This identified 61,880 records (29,100 records with relevant ICD-10 codes and 32,780 with relevant ICD-9 codes). A total of 791 subjects who were aged < 25 or > 55 years were then excluded to avoid clinically implausible diagnoses and those unlikely to have dysfunctional bleeding, leaving 61,089 records. Thirty-seven records were subsequently excluded from women recorded as implausibly having EA following a hysterectomy, leaving 61,052 records. We also excluded 9891 women who had a hysterectomy before 1989 (after making sure that no EA was lost) to ensure a comparable time frame (1989–2006) of initial operation in both the EA and hysterectomy groups. This left 51,198 records (14,078 in the EA group and 37,120 in the hysterectomy group). A total of 2779 women (19.7%) in the EA group went on to have a hysterectomy. We excluded these women since it would be difficult to determine whether subsequent sequelae should be attributed to the initial EA or to the subsequent hysterectomy. The median (interquartile range, IQR) duration between the date of EA and subsequent hysterectomy for these 2779 women was 1.25 (0.66–2.67) years. Similarly, of the original 14,078 women undergoing EA, 379 (2.7%) went on to have a repeat EA procedure within a median (IQR) of 1.17 (0.66–2.83) years. These 379 women have been retained in the EA group.