Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 98/34/05. The contractual start date was in October 2001. The draft report began editorial review in May 2007 and was accepted for publication in October 2009. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

see Acknowledgements

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2011. This work was produced by Price et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

Asthma is a condition of the bronchial airways, characterised by airway hyper-responsiveness (or airway irritability) and reversible airway obstruction. In 2002, an estimated 3 million people, or 5% of the UK population, had asthma. 1,2 Asthma is caused by chronic inflammation of the small, or bronchial, airways. This inflammation causes the production of mucus, oedema formation, and nerve end exposure, and leads to an increase in airway hyper-responsiveness. Increased airway hyper-responsiveness causes narrowing of the airways (or bronchoconstriction), which may lead to coughing, wheezing, chest tightness and shortness of breath. In asthma, airway bronchoconstriction can be substantially reversed with a short-acting β2-agonist or reliever medication.

Untreated chronic inflammation in the airways may lead, in some individuals, to structural changes (or airway remodelling), irreversible bronchoconstriction and persistent symptoms. The recognition that airway inflammation is present even in patients with mild asthma has led to a shift towards introducing anti-inflammatory therapy earlier in the management of asthma,2,3 with increased prescribing of inhaled corticosteroids4,5 in patients requiring daily use of a short-acting β2-agonist [step 2 of British Thoracic Society (BTS) Asthma Guidelines]. 4,5 However, while there is some evidence of reduced morbidity, many patients with asthma still have considerable symptoms and lifestyle limitation. 6 Possible reasons for this include lack of disease recognition, poor adherence to inhaled steroids, poor inhaler technique, untreated rhinitis, smoking, and an inability of inhaled steroids alone to fully control asthma, with an increasing emphasis on the role of adding additional therapy to inhaled steroids rather than routinely increasing inhaled steroid dose. As a result these patients end up being treated at step 3 of the BTS Asthma Guidelines. 4

Efficacy studies of antiasthma therapies have traditionally used measures of airways function, such as spirometry [forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)]7,8 and domiciliary peak expiratory flow (PEF),7 or measures of airway hyper-reactivity, such as methacholine bronchial challenge testing,9–12 to demonstrate therapeutic effectiveness. While these measures provide objective information on airway function, they provide no information on patient perceived effectiveness of an asthma treatment or asthma control. Indeed, the ‘real-life’ control of asthma is now regularly assessed in terms of changes in patient-reported quality of life (QOL), symptoms, exacerbations and rescue medication use. As the correlation is often poor between objective measures of airway function (e.g. domiciliary PEF) and measures of asthma control, international guidelines encourage the collection of measures of both airway function and disease control. 5

Anti-inflammatory treatments with the potential to treat mild to moderate asthma are inhaled corticosteroids and leukotriene receptor antagonists. Corticosteroids work by suppressing the production of inflammatory mediators by airway epithelial and smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells and fibroblasts. 13 However, inhaled steroids have been shown to have limited impact on suppressing the production or release of the cysteinyl leukotrienes LTC4, LTD4 and LTE4, biologically active mediators derived from arachidonic acid, which collectively account for the biological activity known as slow-reacting substance of anaphylaxis. 14,15 These leukotrienes mediate many responses that are associated with asthma, including mucus production, decreased mucociliary clearance, changes in vascular permeability, inflammatory cell influx and smooth muscle contraction. 16 Thus, leukotriene receptor antagonists that act to reduce the production or block the action of leukotrienes may be important in asthma management and complementary to inhaled corticosteroids.

Leukotriene receptor antagonists

Montelukast and zafirlukast are orally active, potent selective leukotriene CysLT1 receptor antagonists. The safety and tolerability of both of these leukotriene antagonists are well established. 17,18 Compared with placebo they have been shown to improve airway function and symptoms, and decrease short-acting β2-agonist use. 19–21 They also inhibit early- and late-phase bronchoconstriction that is induced by inhaled allergen,22,23 and attenuate exercise-induced bronchoconstriction at a level at least comparable to long-acting β2-agonist. 24 Montelukast has also been shown to decrease sputum and peripheral blood eosinophil levels. 25 Results from adult Phase III clinical studies demonstrate that, compared with placebo, montelukast21 and zafirlukast19 improve FEV1, daytime symptoms, total daily β2-agonist use, nocturnal asthma, morning and evening PEF, asthma-specific QOL, patient and investigator global evaluations, and asthma exacerbation rate in patients using short-acting β2-agonist only. Other studies have demonstrated the additive effects of montelukast in patients taking inhaled steroids. 26 Additionally, results from a chronic exercise study demonstrate the ability of montelukast to attenuate exercise-induced bronchoconstriction at the end of the dosing interval over a 12-week period without loss of effect27 and a comparable effect to long-acting β2-agonist. 24 Montelukast also reduces blood21 and sputum eosinophils. 25

Leukotriene antagonists could potentially be used at step 2 or step 3 of the asthma guidelines. At step 2, leukotriene antagonists would be used as an alternative to inhaled steroids, while at step 3 leukotriene antagonists would be used as an alternative to long-acting β2-agonists as add-on therapy to inhaled steroids in patients who are not controlled on inhaled steroids alone.

Recent studies evaluating the use of montelukast or zafirlukast against inhaled steroids at step 2 suggest that leukotriene antagonists are inferior to inhaled steroids in short-term double-blind double-dummy studies and in patients with significant asthma severity. In a meta-analysis, Ducharme28 reported that patients randomised to a leukotriene antagonist had a 60% increased risk of exacerbation compared with a patient receiving 400 µg of the inhaled steroid beclometasone dipropionate. Those randomised to inhaled steroid had a significantly increased FEV1 compared with leukotriene antagonist. However, Israel et al. 29 reported that although 400 µg beclometasone significantly improved FEV1 compared with montelukast, they found no significant difference in the number of exacerbations, possibly indicating that leukotriene antagonists may confer benefits in asthma control which are equivalent to those of inhaled steroids.

In patients with unstable asthma currently receiving an inhaled steroid, the addition of montelukast or zafirlukast leads to clinically important improvements in airway function, asthma exacerbations, attacks and symptoms, as reviewed by Currie and McLaughlin. 30 All inhaled steroids have debilitating side effects; although these are largely associated with high doses, local side effects appear to be more common at lower doses than previously recognised. 31 Indeed guidelines advocate tapering inhaled steroids to the minimum effective dose. 4,5 Although neither montelukast nor zafirlukast is licensed for steroid sparing (i.e. minimising the dose of inhaled steroid), Lofdahl et al. ,32 Price et al. 33 and Riccioni et al. 34 have reported some evidence that this may be possible.

Two recent meta-analyses have examined the effects of leukotriene antagonists as add-on therapy to inhaled steroids. 35,36 Ducharme et al. ,35 compared the effects of adding leukotriene antagonist versus long-acting β2-agonist to inhaled steroid therapy in trials of 28 days or longer, and found a 17% lower risk of asthma exacerbation with add-on long-acting β2-agonist: 38 patients receiving inhaled steroid had to be treated for 48 weeks with add-on long-acting β2-agonist rather than add-on leukotriene antagonist to prevent one exacerbation. Lung function, symptoms and the use of rescue short-acting β2-agonist were also better with long-acting β2-agonist. The authors note that while the internal validity of their findings is supported by the homogeneity of studied patients and trials, the external validity or generalisability of their findings is an issue. 35 Indeed, a limitation of the majority of the studies performed to date is that they are not ‘real world’, and do not necessarily reflect the issues of poorer compliance and adherence to inhaled medications compared with oral medications observed in primary care. They also rarely take a true intention-to-treat approach with patients who cease study therapies and drop out of the study at that point. 37

The second systematic review (pooling of data by meta-analyses performed when feasible) looked only at studies of ≥ 12 weeks’ duration that compared montelukast as add-on to inhaled steroid with inhaled steroid monotherapy or with salmeterol as add-on to inhaled steroid. 36 Compared with inhaled steroid monotherapy, add-on montelukast to inhaled steroid improved control of mild to moderate asthma. Compared with add-on salmeterol, add-on montelukast to inhaled steroid was less effective with regard to most clinical outcomes in the medium term; however, over 48 weeks the proportions of patients with ≥ 1 exacerbation were similar, as were hospitalisation and emergency treatment rates. The rate of serious adverse events over 48 weeks was significantly higher with add-on salmeterol; thus, montelukast may have a better long-term safety profile. 36

At the time of commissioning this study, the data regarding the cost-effectiveness of leukotriene antagonists in primary care were limited. In one primary care centre, a prospective audit of outcomes and cost associated with montelukast suggested that as an add-on option in patients at step 3, there might be significant clinical benefits at little additional cost. 38 Recent studies have suggested that, at step 2 of the asthma guidelines, use of a leukotriene antagonist compared with an inhaled steroid is associated with higher health-care resource utilisation. 39 However, this study did not evaluate clinical outcomes or patient reported measures of disease control.

Hypotheses

In older children and adult patients with chronic asthma, initiation of a leukotriene receptor antagonist will provide, at no greater cost to the National Health Service (NHS) and patients, clinical improvements in QOL and other important asthma parameters that are at least equal to the alternative treatment options of inhaled corticosteroid at step 2 and adding a long-acting β2-agonist at step 3. This study was designed as two separate, but concurrent, equivalence trials to determine whether a leukotriene antagonist is an equal choice to inhaled steroid as monotherapy, and to long-acting β2-agonist as add-on therapy, for a real-world population of patients with perhaps milder asthma and who are less likely to adhere to therapy than those enrolled in classical clinical trials.

Rationale for this study

Need for cost-effectiveness data

In response to growing pressure on health-care budgets, and the availability of a choice of different therapeutic interventions for many diseases, evidence on the relative value for money of new or different therapeutic interventions is becoming increasingly important. In recognition of this, the UK Department of Health has provided guidelines to encourage the evaluation of therapeutic interventions from an economic perspective, in parallel with traditional investigations into efficacy and safety. 40 Indeed the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), established in 1999, evaluates medicines (new and current) for use within the NHS by reviewing both clinical and economic evidence.

Asthma is a condition for which economic evaluation of therapeutic interventions is particularly relevant; the prevalence is high, with reported treatment prevalence rates for the UK ranging from 2% to 5% for adults and up to 10% for school-aged children,1 and a range of different therapeutic interventions are available. 4 The high-prevalence chronic nature of the disease, along with the range of therapeutic interventions, make the management of asthma a considerable financial burden on the NHS. 41 However, published investigations into the costs of asthma management either have focused on isolated components of treatment, such as specific medications, or have used limited retrospective data for estimates of health-care utilisation. 41–45 Only minimal information is available on the ‘real-world’ cost of asthma management, including costs to primary and secondary care, the patient, and the indirect cost of lost productivity to the economy.

Leukotriene receptor antagonists could potentially be used at both steps 2 and 3 of the asthma guidelines. 4,5 Although leukotriene antagonists are more expensive to prescribe, in terms of drug acquisition costs, than low-dose inhaled steroids (∼£24 per 28 days versus ∼£8 per 28 days, respectively46), and although less effective in terms of objective measures of lung function, they appear to produce comparable overall asthma control29 and are associated with superior adherence. 37,47 Leukotriene antagonists may therefore result in significant health gain and savings in other areas of health and patient costs, which might justify additional prescribing costs. There is some evidence from long-term trials that this may be the case. 48 However, markers of cost-effectiveness in asthma clinical trials have included cost per asthma-free day or cost to achieve a given improvement in lung function. 49 Outcomes such as asthma-free days and improvement in lung function are good clinical measures. However, the latter is not necessarily correlated with meaningful changes in overall QOL for the patient, and the former does not cover all aspects of health-related QOL that may be of relevance to the patient. More appropriate markers are required.

The purpose of this study was to compare the long-term effectiveness and total cost of asthma management to the NHS, patients and society in two groups of patients – one group receiving leukotriene antagonist and the other group receiving the most effective evidence-based alternatives at step 2 (inhaled steroid) and step 3 (long-acting β2-agonist). It is important to provide a convincing investigation of the cost-effectiveness of prescribing leukotriene antagonists. To this end, we proposed a long-term study, taking the wider costs of asthma management into account, to be conducted in a manner reflecting real clinical practice. The primary efficacy variable for this study was the validated Juniper disease-specific asthma QOL scale – the Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (MiniAQLQ). 50 This was chosen because it captures outcomes of relevance to patients and their primary caregivers, thus reflecting ‘real life’. We regarded a difference of > 0.3 in MiniAQLQ score as a meaningful difference because although 0.5 has been regarded in individuals as a minimum clinically important difference,51 many studies, even versus placebo, have found smaller differences of 0.3–0.421 to be associated with clinical benefit. Therefore, we have opted for this more conservative figure for a population difference.

Evaluation of effectiveness at step 2 of asthma guidelines

Many patients are not fully controlled by inhaled steroids, due to a mixture of lack of complete clinical effectiveness and poor adherence with regular treatment. Alternative treatments for inhaled steroids, such as the leukotriene receptor antagonists zafirlukast and montelukast, may have a role, with some studies suggesting fairly similar overall asthma control and proportion of responders to inhaled steroids,52,53 greater patient preference54 and higher adherence rates. 55

At the time of designing and commissioning of this study, UK guidelines for the management of asthma in older children and adults (written in 1995) did not propose a clear role for leukotriene antagonists. 56 However, the latest Global Initiative For Asthma (GINA)/World Health Organization and UK guidelines suggest they may be used at step 2 as an alternative to inhaled steroids. 4,5

Evaluation of effectiveness at step 3 of asthma guidelines

Many patients taking inhaled steroids continue to have symptoms, reduced asthma-specific QOL and excessive relief treatment use, and thus require additional treatment. 57 BTS and GINA guidelines suggest two options: increasing the dose of inhaled steroid or adding a long-acting β2-agonist. 4,5 However, some view the safety, tolerability and compliance with high doses of inhaled steroids with some concern,5,58,59 and most studies suggest that adding a long-acting β2-agonist may be most likely to be clinically effective. 60,61

Adding in a leukotriene antagonist may be useful at this step for two reasons (1) steroids do not appear to suppress leukotriene production14,15 and (2) montelukast and zafirlukast have both been shown to give add-on benefit to inhaled steroid. 26,30 Leukotriene antagonists may enable inhaled steroid tapering and thus maintenance on a lower dose of inhaled steroid. 32

Chapter 2 Methods

This study comprised two separate randomisations, thus two pragmatic randomised controlled trials, powered for equivalence, comparing leukotriene antagonists with (1) inhaled steroids for patients initiating controller therapy at step 2 and (2) long-acting β2-agonists on a background of inhaled steroids for patients at step 3 of the asthma guidelines with regard to disease-specific QOL and resource use in the short term (2 months) and the long term (2 years) on an intention-to-treat basis. The trials were conducted with minimal interference with routine clinical care to evaluate real-life outcomes for patients with asthma in general practice. Patients and health-care providers were not blinded to treatment allocations; however, data collection and statistical analyses were blinded.

The study was reviewed and approved by the Eastern Multi Centre Research Ethics Committee (Ref. 00/5/13) and local (research consortia and primary care trust) ethical and research governance committees, and was conducted in accordance with appropriate research guidelines.

Participants

In the BTS British Guideline on the Management of Asthma4 the therapy of patients from the age of 6 years upwards follows the same strategy as for adults, except for alterations in dosage ranges to adjust for differences in body mass. Since exactly the same strategy is used across the age range of older children and adults, the findings of studies will have greater generalisability if they enrol patients from that entire range. Owing to limitations of validity of the MiniAQLQ and the Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ),62 we were unable to study children below the age of 12 but did allow children over this age, as well as adults of all ages, to be included to maximise generalisability of the study findings.

In the initial design of the study, participant recruitment was to be by primary care practice staff, as they conducted acute and routine respiratory care visits, identifying patients who met the entry criteria, informing them of the study and, if appropriate, consenting and enrolling them into the study. However, recruitment by this strategy was slower than originally anticipated owing to changes in clinical practice resulting from delays in study funding and changes in national asthma guidelines. The protocol and the process of identification of eligible patients were therefore modified, as described below, to allow prospective identification of possible study participants. All patients entering the study met the same eligibility criteria and follow-up was identical.

Further recruitment into the study was via a three-stage process.

Recruitment stage 1

Patients aged 12–80 years, attending 53 participating primary care (or general) practices in Norfolk, Suffolk, Essex, Cambridgeshire, Bedfordshire, Hampshire and Dorset, in the UK, who had received a prescription of short-acting β2-agonist in the previous 2 years, were invited, by letter, to provide data allowing eligibility for the studies to be determined. Patients were asked to provide information on their current asthma status and inhaler usage. The case notes of patients whose asthma status was consistent with eligibility in the study were reviewed by practice and study staff against the following eligibility criteria.

Inclusion criteria

-

Capable of understanding the study and study procedures (and parent/guardian’s capability of understanding the study and study procedures for patients aged under 16 years).

-

Patient had a diagnosis of asthma [defined as (1) documented reversibility after inhaled short-acting β2-agonist and/or (2) PEF variability on PEF diary and/or (3) physician-diagnosed asthma and/or (4) physician diagnosis of asthma plus history of response to treatment].

-

Step 2 trial Patient was not currently receiving, and had not received, inhaled steroid or leukotriene antagonist within the previous 12 weeks.

-

Step 3 trial (1) Patient had received inhaled steroid for at least the last 12 weeks, as ascertained from prescribing records and patient self-report and (2) had not received a long-acting β2-agonist or leukotriene antagonist in the previous 12 weeks.

Exclusion criteria

-

Patient had participated in a clinical trial involving an investigational or marketed drug within 90 days.

-

Patients had received a substantial change in antiasthma medication within the previous 12 weeks.

-

Patient was a current, or recent past, abuser (within past 3 years) of alcohol or illicit drugs.

-

Patient had any other active, acute or chronic pulmonary disorder or unresolved respiratory infection within previous 12 weeks.

-

Patient had a history of any illness that was considered to be immediately life threatening, would pose restriction on participation or successful completion of the study or would be put at risk by any study drugs (e.g. allergy to leukotriene antagonist).

-

Patient had received systemic, intramuscular or intra-articular corticosteroids within the previous 2 weeks (artificial baseline).

Patients who met those entry criteria that could be assessed by a records review in their general practice were invited for a screening visit (visit 1 – see Figure 1 and Table 1). All patients had at least 24 hours to review the patient information sheet prior to attending the visit. Patients attending for at least visit 1 will, from here on, be referred to as ‘participants’.

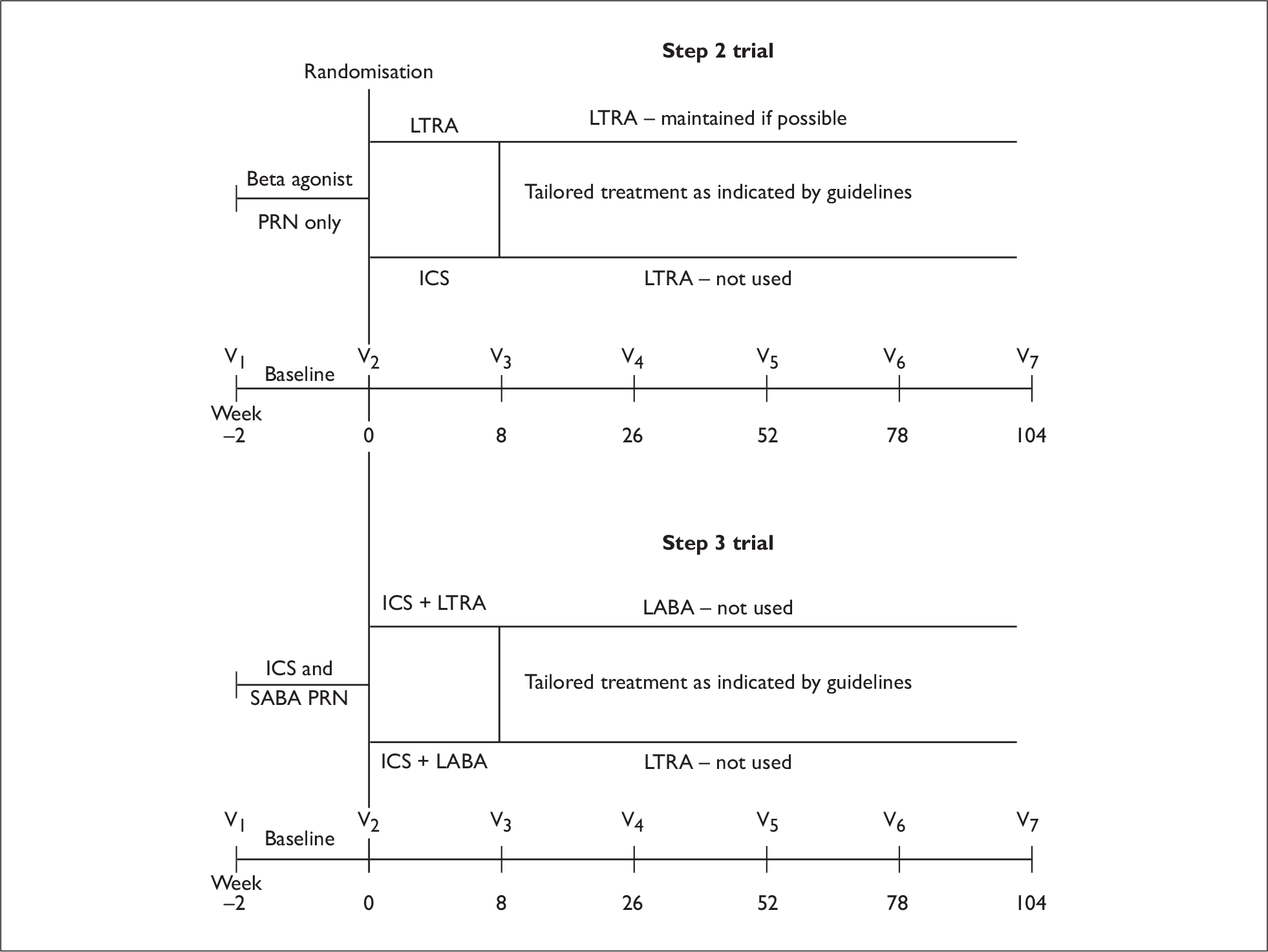

FIGURE 1.

Study flow charts, Patients at step 2 received initial controller therapy with leukotriene antagonist or inhaled steroid, Patients at step 3 received leukotriene antagonist or long-acting β2-agonist as add-on to inhaled steroid, ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; LTRA, leukotriene receptor antagonist; LABA, long-acting β2-agonist; PRN, ‘pro re nata’ – as needed; SABA, short-acting β2-agonist.

| Visit | Baseline | Trial period | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Study timescale (weeks) | –2 | 0 | 8 | 26 | 52 | 78 | 104 |

| Leeway allowed (days)a | ± 7 | ± 21 | ± 21 | ± 21 | ± 21 | ± 21 | |

| GP and/or practice asthma nurse procedures | |||||||

| Assess inclusion/exclusion criteria | ✓ | ||||||

| Informed consent | ✓ | ||||||

| Record clinical/asthma history and prior medications | ✓ | ||||||

| Review clinical data and asthma therapy (per clinical need) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Check patient has/can adequately use PEF meter | ✓ | ||||||

| Treatment arm randomisation by dial-up centre | ✓ | ||||||

| Review action plan for worsening asthma | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Review any adverse experiences | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Record PEF (no inhaled β2-agonist for 4 hours if possible) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Confirm patient resource utilisation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Blinded research assistant/study office | |||||||

| Collect completed patient symptom diary card | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Collect data on patient costs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Asthma QOL and EQ-5D (quality of life) questionnaries | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Rhinitis questionnaires | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Dispense patient diary card for subsequent visit | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Collect resource use data from practice records | ✓ | ||||||

Recruitment stage 2

At visit 1, participants (and parent or guardian if appropriate) gave written informed consent and were allocated a unique study number. Participants were reviewed for the following additional entry criteria:

-

Peak expiratory flow, while withholding β2-agonist for at least 4 hours, of > 50% predicted.

-

Females of child-bearing potential agreed to use adequate contraception throughout the study.

Participants meeting the above criteria completed a 2-week PEF diary,63 ACQ,64 and asthma-specific QOL questionnaire (MiniAQLQ)50 prior to returning for visit 2.

Recruitment stage 3

At visit 2, participants scoring ≥ 1 on the ACQ (range 0–6, with ≤ 0.75 being optimal65) and/or ≤ 6 (out of a maximum best score of 7) on the MiniAQLQ were registered and randomised within the step 2 or step 3 study by an automated ‘dial-up’ centre at the University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK. A computer responded to the telephone calls from practices by recording identification information. It then used input from the practice about the step at which the patient was to enter the study to perform a look-up into predefined tables of randomisation allocations (see Randomisation, below) and then inform the caller of the allocation for that participant.

Interventions

Using a pragmatic, randomised controlled trial design, leukotriene antagonist prescription was compared with (1) inhaled steroid prescription at step 2 of the guidelines and (2) long-acting β2-agonist against a background of inhaled steroid at step 3 (Figure 1). Patients and health-care providers were aware of treatment allocations, while study data collection and statistical analyses were blinded.

-

Leukotriene receptor antagonist montelukast 10 mg, once daily (as Singulair®; Merck, Sharp & Dohme Ltd, Hoddesden, UK) or zafirlukast 20 mg, twice daily (as Accolate™, AstraZeneca Ltd, Kings Langley, UK).

-

Inhaled corticosteroid – step 2 study inhaled beclometasone dipropionate, budesonide or fluticasone propionate.

-

Long-acting β2-agonist – step 3 study salmeterol (as Serevent®, GlaxoSmithKline, Uxbridge, UK) or formoterol (as Foradil®, Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd, Camberley, UK; or Oxis®, AstraZeneca Ltd, Kings Langley, UK); these are also available in fixed dose combinations with inhaled steroid (as Seretide™, GlaxoSmithKline, Uxbridge, UK and Symbicort®, AstraZeneca Ltd, Kings Langley, UK).

All individual drug and device choices within treatment allocations were made according to normal clinical practice by the health professional involved (and bearing in mind BTS guidelines), subject to the restrictions outlined below.

Other asthma medications

-

Inhaled short-acting β2-agonist was permitted throughout the study ‘as needed’.

-

Theophylline, cromoglycate, nedocromil and ipratropium were permitted if clinically appropriate.

-

Inhaled steroids were permitted after randomisation in both arms in the step 2 trial. However, if clinically acceptable, participants within the leukotriene antagonist arm were to be given every chance to manage without inhaled steroid.

-

In step 2 and step 3 trials, practices were asked to use leukotriene antagonists only within that treatment arm assigned to them.

-

Long-acting β2-agonists were permitted in both arms of the step 2 trial. Practices were asked not to use them in the leukotriene antagonist step 3 arm.

-

If participants required a disallowed asthma medication, this fact was noted, the medication was given and the patient was continued in the study. As the planned analysis was on an intention-to-treat basis, participants were not discontinued for receiving a disallowed medication.

Allowed allergic rhinitis and conjunctivitis medications

-

Topical treatment or antihistamines were preferred.

Excluded therapy

-

β-Receptor blocking agents (including ocular preparations).

-

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, when a patient had a known or suggestive history of aspirin-sensitive asthma.

Objectives

Primary objective

To compare QOL with leukotriene receptor antagonist against alternative treatments at steps 2 (inhaled corticosteroid) and 3 (long-acting β2-agonist) of the guidelines, comparing resource use in the short term (over 2 months) and the long term (2 years) to the NHS and society (on an intention-to-treat basis), using cost–utility and cost-effectiveness approaches.

Secondary objectives

To compare two markers of asthma control: (1) the validated ACQ, which evaluates symptoms of asthma and reliever treatment usage, and (2) asthma exacerbations requiring oral steroid therapy or hospitalisation. Other outcomes compared between the two treatment groups at 2 months and throughout the 2-year study period included respiratory tract infections, consultations for respiratory tract infection, short-acting β2-agonist prescriptions, daily inhaled steroid dose (step 3 study only), per cent predicted PEF (%PPEF) at clinic visits, secondary QOL measures, 2-week domiciliary diary cards of symptoms and PEF, and time off work because of asthma. As the design was pragmatic in nature, and to ensure minimal dropouts, the major focus in terms of data collection were the primary study end points and the markers of asthma control (ACQ and exacerbations).

Outcome measures

-

Primary outcome measure: The primary outcome was a between-group comparison of disease-specific QOL (described in Health status measures, below) and cost to achieve this to the NHS and patient at 2 months (the primary time point) and 2 years (described in section Resource use assessment, below).

-

Secondary outcome measures:

-

– ACQ score

-

– number of asthma exacerbations – defined as requiring at least one course of oral corticosteroids or hospitalisation for asthma; when a patient received more than one course of oral steroid during the course of the study, any two courses of oral steroid prescribed within a 14-day period were considered as a single exacerbation, irrespective of the fact the patient required ≥ 2 courses of oral steroid.

-

– attendance at primary care practice for upper and/or lower respiratory tract infections (number of total respiratory tract infections and number of primary care practice attendances for those respiratory tract infections)

-

– short-acting β2-agonist prescriptions

-

– change in inhaled steroid dose (for step 3 participants only)

-

– clinic PEF, percentage of predicted normal values calculated using the Roberts equation66

-

– Mini Rhinitis Quality of Life Questionnaire (mRQLQ) scores67

-

– Royal College of Physicians – three (RCP3) asthma questions scores68,69

-

– personal objectives scores

-

– changes in treatment after randomisation

-

– adherence with prescribed therapy.

-

Safety was evaluated by the analysis of the overall incidence of adverse experiences.

Health status measures

Participants completed the following self-administered questionnaires at visit 2, and prior to attending visits 3–7. Participants were asked to return completed questionnaires to the study office.

-

Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (age-specific version50) The MiniAQLQ is a validated 15-item asthma-specific QOL questionnaire, which is a self-administered shortened version of the 32-item AQLQ,51,70 used to evaluate the impact of asthma on QOL. Eleven questions assess the presence of asthma-related symptoms rated from 1 (all of the time) to 7 (none of the time); and four questions assess specific activity limitations as a result of asthma, rated from 1 (totally limited) to 7 (not at all limited). The final score is a mean of the responses ranging from 1 (worst) to 7 (best), and the minimum clinically important difference in MiniAQLQ score is 0.5. 51

-

Asthma Control Questionnaire The validated ACQ assesses five asthma-related symptoms, judged by international consensus to be the most important in evaluating asthma control. 62 These are night-time awakenings by asthma, severity of asthma symptoms on awakening, daily activity limitations because of asthma, shortness of breath and wheezing; patients score each question on a 7-point scale from 0 (best) to 6 (worst). A sixth question categorises daily number of puffs of short-acting bronchodilator from 0 (none) to 6 (more than 16 puffs most days). The overall score is the mean of the responses from 0 (totally controlled) to 6 (severely uncontrolled). A shortened version of the ACQ, excluding airway calibre, was used in this study. 64 An ACQ score of ≤ 0.75 is considered to represent well-controlled asthma, whereas a score of ≥ 1.5 respresents asthma that is not well controlled. 65 The minimum clinically important difference in ACQ score is 0.5. 64

-

– In addition, as mentioned under Participants, above, the ACQ and MiniAQLQ were completed by patients prior to, or at, visit 1 as part of the screening process.

-

-

European Quality of life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire The EQ-5D comprises five questions (dimensions) on aspects of overall health (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression) and a visual analogue scale, recording the respondents’ self-rated health status on a vertical graduated (0–100) ‘thermometer’. 71 The five questions are converted into a single utility index representing overall health, using equations relevant to the UK population. 72 Alternatively, direct measurements from the visual analogue scale can be used.

-

Mini Rhinoconjunctivitis Quality of Life Questionnaire The Mini Rhinoconjunctivitis Quality of Life Questionnaire is a shortened 14-item version of the 28-item Rhinoconjunctivitis Quality of Life Questionnaire that assesses how troubled the patient has been by rhinoconjunctivitis – from 0 (not troubled) to 6 (extremely troubled) – with regard to five domains: activity limitations, practical problems, nose symptoms, eye symptoms and other symptoms. 73,74

-

RCP3 questions The RCP recommends three questions to use to evaluate the impact of disease severity on quality of life in asthma patients (RCP3). 68,69 The questions are (1) Do you have difficulty sleeping because of asthma symptoms (including cough)? (2) Have you had usual asthma symptoms (cough, wheeze, chest tightness, shortness of breath) during the day? and (3) Has your asthma interfered with your usual activities (housework, work/school, etc. )?

-

Personal objectives At visit 2, participants were asked to identify three activities that occurred regularly (not seasonally) in their life, and which they found difficult to do because of their asthma. These activities were events (e.g. cleaning, walking to work, aerobics), and not things or places avoided (e.g. cats, smoky rooms), as these do not count as activities. At each visit, participants graded their ability to undertake their chosen activities on a visual analogue scale of 0–100.

Resource use assessment

Resource use was divided into four groups: prescribed medications and devices, over-the-counter medications, primary and secondary care activity, and lost productivity. Data were extracted from primary care practice databases using miquest (www.connectingforhealth.nhs.uk/miquest) and apollo sql suite (www.apollo-medical.com/products/sql.htm). Where it was not practical to use automated extraction, a researcher transposed the data from the practice record system to the project database manually. Extraction was by the miquest query system at 34 practices and apollo sql suite at seven practices; manual retrieval was performed at 17 practices. At four practices, data were collected using both manual and miquest systems during the development of the data extraction and collection tools. Duplicate data were removed. Data were extracted manually for 97 participants, and from miquest or apollo data systems for 586. For all participants, 100% of the records were reviewed by a research associate to ensure that the records represented a cost attributable to asthma or asthma-related care as described in the section Prescribed medications, below. Data were also obtained from patient-completed diary cards, as detailed below. The price year for this analysis was 2005, and all costs incurred in the second year post randomisation were discounted by 3.5%.

Prescribed medications

Prescribed medications data were extracted from primary care practice records for the following conditions:

-

asthma

-

chest infections and/or bronchitis

-

other respiratory tract infections

-

eczema, hay fever, rhinitis and allergic conjunctivitis

-

any adverse events considered to be related to asthma medication, for example oral thrush treatment.

Details recorded were:

-

name of medication (brand name if branded medication prescribed) or device

-

dosage

-

formulation

-

amount prescribed

-

indication

-

date prescribed.

After confirmation of the data in the practice, records were mapped from the various coding systems used by each of the primary care practice software systems (including Read codes), using further information about the product description as given in the miquest ‘Rubric’ field, to a single table of unit costs indexed using the British National Formulary46 code with unique extensions for each distinct product found [P. Richmond, prescribing data analyst, Broadland Primary Care Trust (PCT): List of unique product descriptions and codes; modified from the ePACT (Electronic Prescribing Analysis and CosT) codes from the Prescription Pricing Authority, 7 July 2005, personal communication]. From this a total quantity and cost were calculated.

Over-the-counter medications

Over-the-counter medication use data were extracted from patient diary cards. Prices were taken as stated by the patient (88%), or, if not stated (12%), from retail pharmacy websites (www.boots.com and www.sainsburys.com). All prices were adjusted to 2005 values using the Retail Prices Index (www.statistics.gov.uk).

NHS activity

All consultations with health-care professionals for conditions listed in Prescribed medications, above, were extracted from primary care records. Consultations initiated for another indication in which these problems were addressed (e.g. a regular consultation for contraception at which asthma problems were reported) were assigned 50% of the time of the consultation. Consultations were divided into the following categories:

-

Primary care regular attendance at asthma clinic with nurse or GP.

-

Primary care – patient initiated GP and nurse clinic/home visits, out-of-hours visits and telephone consultations.

-

Secondary care outpatient, inpatient, day case, emergency medicine and diagnostic procedures.

Study visits were timed to coincide with routine patient follow-up as per normal clinical practice for the management of asthma. Study visits (e.g. those clinical consultations that occurred for routine patient follow-up and therefore study data collection) were excluded from the analysis, as stated in the study protocol. However, where part of the study visit was used for non-routine patient follow-up, for example treatment of an exacerbation, 50% of the visit time was allocated to acute management of asthma rather than routine care. Unit costs and sources for the consultation scenarios are detailed in Appendix 1 (Unit costs table).

Indirect costs

Data on lost productivity were extracted from patient diaries where participants had noted the number of hours or days taken off work due to hospitalisation, primary care visits or other (asthma exacerbations, etc.). A day was counted as 8 hours.

Secondary outcome measures

At visit 1, and prior to visits 3–7, patients were given a validated diary card containing questions on asthma, to be completed in the 2 weeks immediately prior to the next visit. 63 As the duration between study visits was usually longer than 2 weeks, participants were contacted 2 weeks before study visits by the study office to remind them to complete the diary. The diary captured daytime and overnight symptoms, β2-agonist use and resource utilisation. Diary cards were explained to study participants at visit 1 and reviewed by their practice nurse at each study visit. Diary cards were inspected by the GP to ensure that (1) the patient demonstrated proper use of the diary card in the baseline period at visit 2 and (2) the participant’s symptoms were severe/mild enough to justify a treatment change when the patient reported unstable/stable asthma. Outcome measures collected in the diary were as follows.

Peak expiratory flow

Peak expiratory flow was measured prior to medication in the morning and evening during the 2-week baseline assessment and for 2 weeks before study visits. The best of three blows was recorded. Participants were asked to refrain from using short-acting β2-agonist during the 4 hours immediately prior to PEF measurement.

Daytime asthma symptoms

Prior to going to bed, participants scored his/her asthma symptoms against a validated four-question daytime symptom score (marked on a 6-point scale of 0–5):

-

How often did you experience asthma symptoms today? (‘none’ to ‘all of the time’).

-

How much did your asthma symptoms bother you today? (‘not at all’ to ‘severely bothered’).

-

How much activity could you do today? (‘more’ to ‘less than usual’).

-

How often did your asthma affect your activities today? (‘none’ to ‘all of the time’).

Overnight asthma symptom score

Upon arising, and before taking any medications, participants answered the following question:

-

Did you wake-up with asthma during the night or on arising at normal time? (yes or no)

‘As needed’ short-acting β2-agonist use

Participants recorded the total number of ‘puffs’ of ‘as needed’ short-acting β2-agonist used during the day (from waking to time of going to bed) and at night. Salbutamol that was used during study visits to assess airway reversibility was excluded. If nebulised β2-agonist was used then this was recorded as six puffs.

Change in treatment

Numbers of patients with treatment changes, and reasons for change, were tabulated for all patients who were not lost to follow-up, who did not use a self-management treatment plan, and who had 18-month or 2-year treatment data. In addition, the days to treatment change were recorded.

Perception of therapy and adherence

Comparisons between objective measures of adherence and perceptions of oral therapy post-randomisation provide important complementary data to the cost-effectiveness analysis. Detailed patient interviews were conducted at intervals of between 3 and 6 months on 28 participants within the study time period to elucidate information on participants’ perceptions of inhaled and oral therapy and adherence to long-term therapy.

Adherence to treatment was further analysed for patients who had at least 6 months of treatment without any change. Actual prescriptions issued versus prescribing instructions for periods in which they were valid were examined.

Safety monitoring and measurements

Action plan for treatment of worsening of asthma (self-management plan)

All participants had a personal asthma action plan provided, which adhered to asthma management guidelines and included information on self-treatment, when to seek help and how urgently to do so.

Evaluating and recording adverse experiences

Adverse experiences were monitored throughout the study and during the 14 days after completion of the study, and were recorded at each examination according to Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Adverse experiences were defined as any unfavourable and unintended change in structure, function or chemistry of the body temporally associated with any study medication, whether or not considered related. Clinically significant worsening of any pre-existing condition is also included. Serious adverse experiences were reported within 24 hours to the sponsor, the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme Coordinating Centre and Multi Centre Research Ethics Committee.

Discontinuation

Criteria for patient discontinuation during the study

Participants could discontinue study medication or participation at any time. Participants were discontinued from the study medication or participation if any of the following criteria were met:

-

An adverse event occurred that suggested the patient’s health could have been in jeopardy from continued study participation or that the patient was unable to complete study procedures successfully.

-

The patient became pregnant.

Withdrawal of participants from the study

Participants who were withdrawn post randomisation from the study due to procedural errors (but were not discontinuations) continued to receive normal routine clinical care from their GP following withdrawal from the study.

Sample size and power calculation

This was based on the published literature50,75 regarding sample sizes for assessing treatment differences in QOL. Treating this as an equivalence study, and assuming no true difference between the treatments in QOL for a two-tailed alpha of 0.05 and an upper limit of 0.3 for the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the difference between arms, a sample size of 142 participants was required. To allow for a 20% dropout rate, we aimed to recruit 178 participants to each study arm, resulting in a total of 356 participants at each of steps 2 and 3 (totalling 712 participants).

Randomisation

Participants were registered for entry into the study after giving written informed consent and returning completed QOL questionnaires. At visit 2, participants eligible for entry into step 2 or step 3 studies were randomised into the study. Randomisation into the study was stratified by practice, with a block size of 6. Practice nurses were informed of the randomised treatment to be given to their patient via an automated telephone centre (see Participants, above).

Blinding

This was a single-blind randomised controlled trial. General practitioners (GPs)/practice asthma nurses and participants were aware of the randomisation, while study research assistants were blinded to the randomisation. The role of the GPs/practice asthma nurses and research assistants in the conduct of the study is described below:

-

General practitioners/practice asthma nurses GPs/practice asthma nurses had minimal involvement in data collection except baseline prior to randomisation, implementing the randomisation allocation and thereafter in administering the resource data collection sheet with participants. This allowed clinical freedom to change treatment as per normal management. Randomisation allocation was given directly to the GPs/practice asthma nurses by an independent automated telephone answering system.

-

Research assistants Research assistants were non-clinical personnel who worked with practice staff to ensure proper completion of the diaries and self-completed QOL and disease-related questionnaires. They collected resource use information from participants, data from prescribing records, and clinical resource utilisation data for the participants at the end of the study period. When collecting resource data the research assistants were blind to the randomised allocation of the participants.

Data and statistical analysis

All analyses were performed blind to study arm allocation. This section outlines the statistical analysis procedures that were performed.

Effectiveness analysis

Baseline comparability between treatment groups

Baseline comparability between the treatment groups was evaluated by summarising and comparing the following parameters:

-

Demographics age, sex, race, education, employment, disease history, weight, height, PEF, %PPEF, and PEF reversibility after salbutamol.

-

Efficacy outcome measures primary and secondary outcome measures.

For the outcomes recorded on patient diary cards (nocturnal awakenings, symptom score, diurnal variation, etc.), the baseline was defined as the average of all values obtained during the 14 days between visits 1 and 2. For the other continuous efficacy end points, baseline was defined as the last value obtained before the start of randomised therapy. For binary outcomes, the baseline value was the sum of events occurring within the baseline period. For outcome measures obtained from the patient diary card, the baseline period was defined as the 14 days (or, if < 14 days, as many days of data as were available). For data obtained from the electronic patient record, the baseline period was defined as the 12 months prior to randomisation.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome analysis was an intention-to-treat analysis of the MiniAQLQ score using multiple imputation where data were missing and including all patients with data at baseline and one post-randomisation time point. Analysis of covariance was used, with treatment as a fixed effect, and baseline value as covariate, to analyse MiniAQLQ scores at 2 months (the primary time point) and 2 years. A 95% CI for the difference between treatment mean scores was derived. The treatments were deemed to be equivalent if the 95% CI excluded a mean difference > 0.3 on the MiniAQLQ score (thus, 95% CI between –0.3 and 0.3), a difference chosen using an a priori conservative approach, based on 0.3 being substantially less than the 0.5 minimum clinically important difference for the MiniAQLQ.

This study was designed as two equivalence trials to determine whether leukotriene receptor antagonist is an equal choice to inhaled corticosteroid as monotherapy, and to long-acting β2-agonist as add-on therapy, for a real-world population of patients with perhaps milder asthma and less likely to adhere to therapy than those enrolled in classical clinical trials.

In addition, a one-sided 95% CI (i.e. the lower bound from a 90% CI) was constructed for the difference in MiniAQLQ score. This was a secondary analysis to examine non-inferiority (rather than equivalence) of leukotriene antagonist versus control.

Secondary outcomes

The ACQ score analysis, like that for MiniAQLQ score, was an intention-to-treat analysis using multiple imputation for missing data, including all patients with data at baseline and one post-randomisation time point. The PEF values as percentage of predicted normal values were calculated using the Roberts equation and were compared between treatment groups at 2 months and 2 years using the Mann–Whitney test. Rates of asthma exacerbations, respiratory tract infections, and consultations for respiratory tract infections were compared using the Wald chi-squared test from the Poisson model. For other secondary end points, the last-observation-carried-forward approach was used for patients with missing follow-up data, again including only those with data for at least one post-randomisation time point; and an analysis of covariance was used, including treatment arm and baseline value as covariate.

-

Frequency of exacerbations requiring hospitalisation, GP attendances and oral steroid courses The count of exacerbations included all events where data indicated that the participant had a prescription for oral corticosteroids and/or a hospital admission for asthma. Issues of oral steroids related to asthma exacerbations were identified from primary care practice records. Where two or more consecutive courses of oral steroids were issued within 3 days of one course completing and a second being issued, this was regarded as a single exacerbation.

-

Frequency of consultations for respiratory tract infections The count of respiratory tract infections included all events where the Read code (or the rubric in the case of manually entered items) was for any diagnosed infection or combination of symptoms that strongly suggested an acute infection of either viral or bacterial aetiology. The combination of symptoms included ‘productive cough with green sputum’, and ‘fever, cough, sore throat’. Events with descriptions such as ‘allergic…’ or ‘chronic…’ were excluded. All free text associated with the records was searched for the same phrases. In the case of entries where a single less specific symptom was recorded, such as ‘cough’, the database was searched for other records that could provide further clarification, for example the acute prescription of an antibiotic on that date. For both exacerbations and respiratory tract infections, when all such records were flagged, multiple records (e.g. clinic visits or courses of oral steroids) for a patient within a period of 14 days were considered to be a single event. Participants were considered to have multiple separate events if the duration between events was > 14 days.

-

Short-acting β2-agonist consumption (prescribing records) Number of inhalers of short-acting β2-agonist over the 2-year duration of the study was determined by totalling the number of issues requested, adjusting where appropriate for multiple inhalers of short-acting β2-agonist being prescribed within a single issue.

-

Daily inhaled corticosteroid dose for step 3 trial only Daily dose of inhaled steroid was calculated from prescription records for the year prior to randomisation and the following 2 years. Daily dose of inhaled steroid was normalised to the efficacy of beclometasone dipropionate by multiplying daily dose of fluticasone propionate and beclometasone delivered as QVAR® (Ivax Laboratories, Aylesbury, UK) by 2. Budesonide was considered to have equivalent efficacy to beclometasone on a microgram per microgram basis.

-

Asthma symptoms from diary card (for 2 weeks before each study visit) Data for the 14 days immediately prior to each visit (or as much as was available if less than 14 days) were averaged or, for binary variables, the percentage of days with a positive response was taken.

-

Clinic and diary PEF records (for 2 weeks before each study visit).

-

Diurnal variation in PEF Diurnal variability was calculated according to the BTS Guidelines:4 [(highest PEF–lowest PEF)/highest PEF].

-

mRQLQ.

-

Need for further treatment intervention beyond initial treatment.

The record of any participant whose medication dosage or device was changed after randomisation was reviewed by research assistants to determine the recorded reason for the change. Reasons for change were categorised as: associated with an asthma exacerbation (a change within 14 days of the use of or written reference to a use of short course of oral steroids or symptoms requiring use of secondary care services); to address poor symptom control (notes of respiratory symptoms); a report or suspicion of a side effect; after an adverse event; patient preference: to decrease the dosage; because of practice-based administrative policies; and/or reason unknown.

To confirm the results of the intention-to-treat analysis, we repeated the analyses after limiting to those participants who completed the study as per protocol and who were on an entirely fixed treatment regime. The population included in these analyses strictly included only participants whose prescribed therapy at randomisation was a fixed dose (not a prescribed range to be adjusted) and who did not have any change in either the initial drug prescribed at randomisation or the prescribed daily dose of that drug, or the addition of any other preventive asthma therapy at any time during the study, including the study final visit.

Planned secondary analysis

Planned subgroup analyses identified in the study protocol and in the minutes of study steering committee meetings are listed in Appendix 2.

Economic analyses

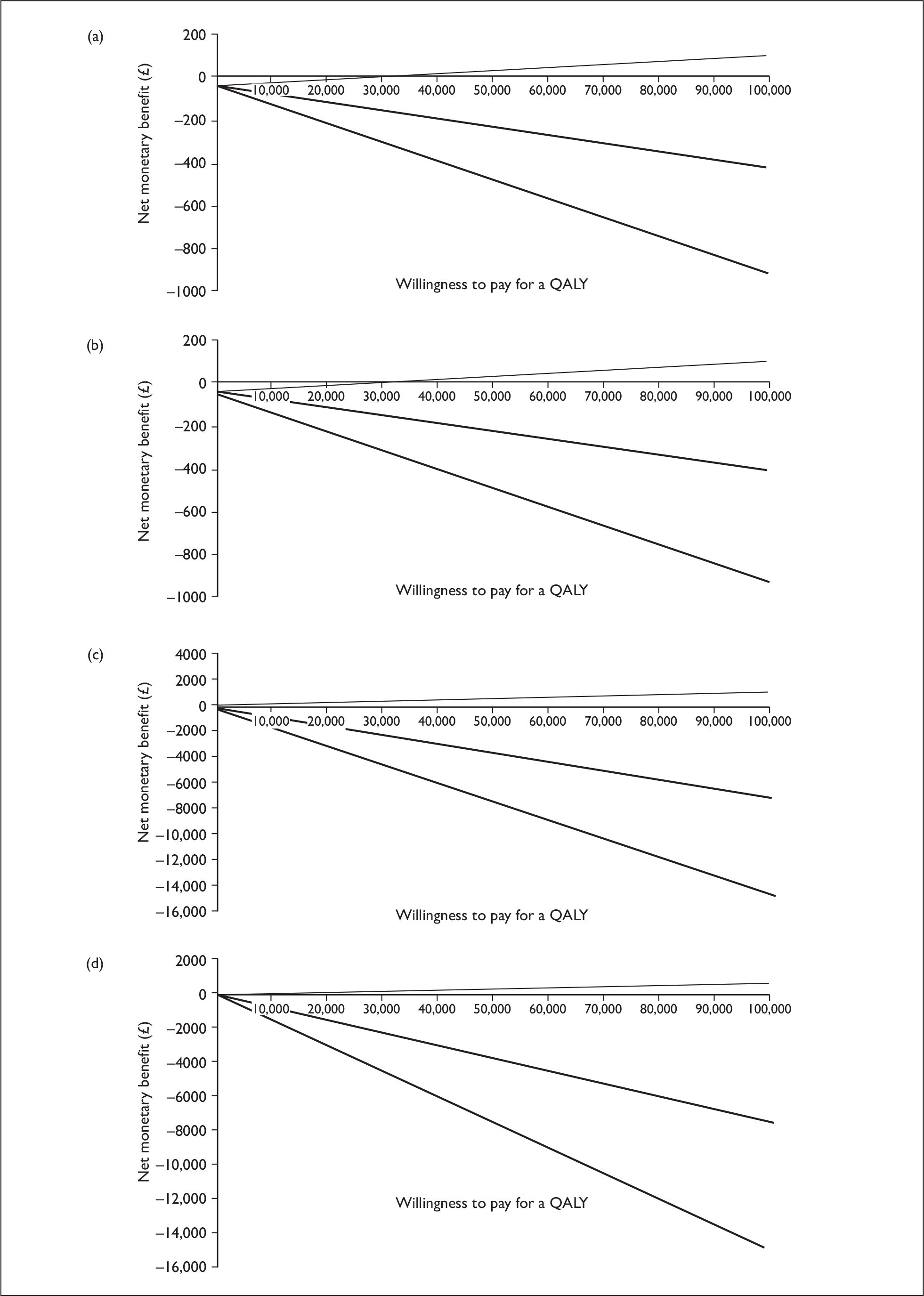

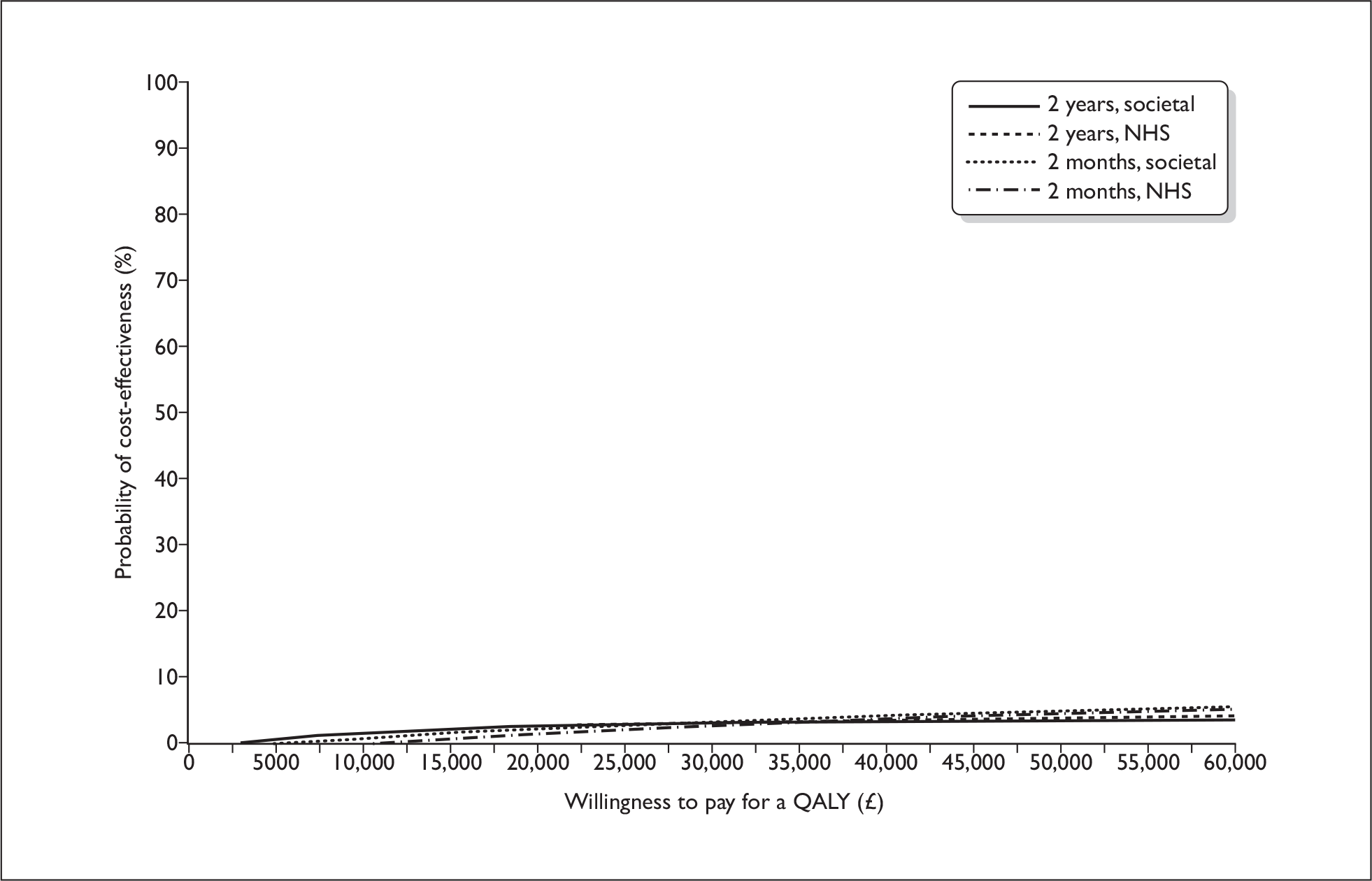

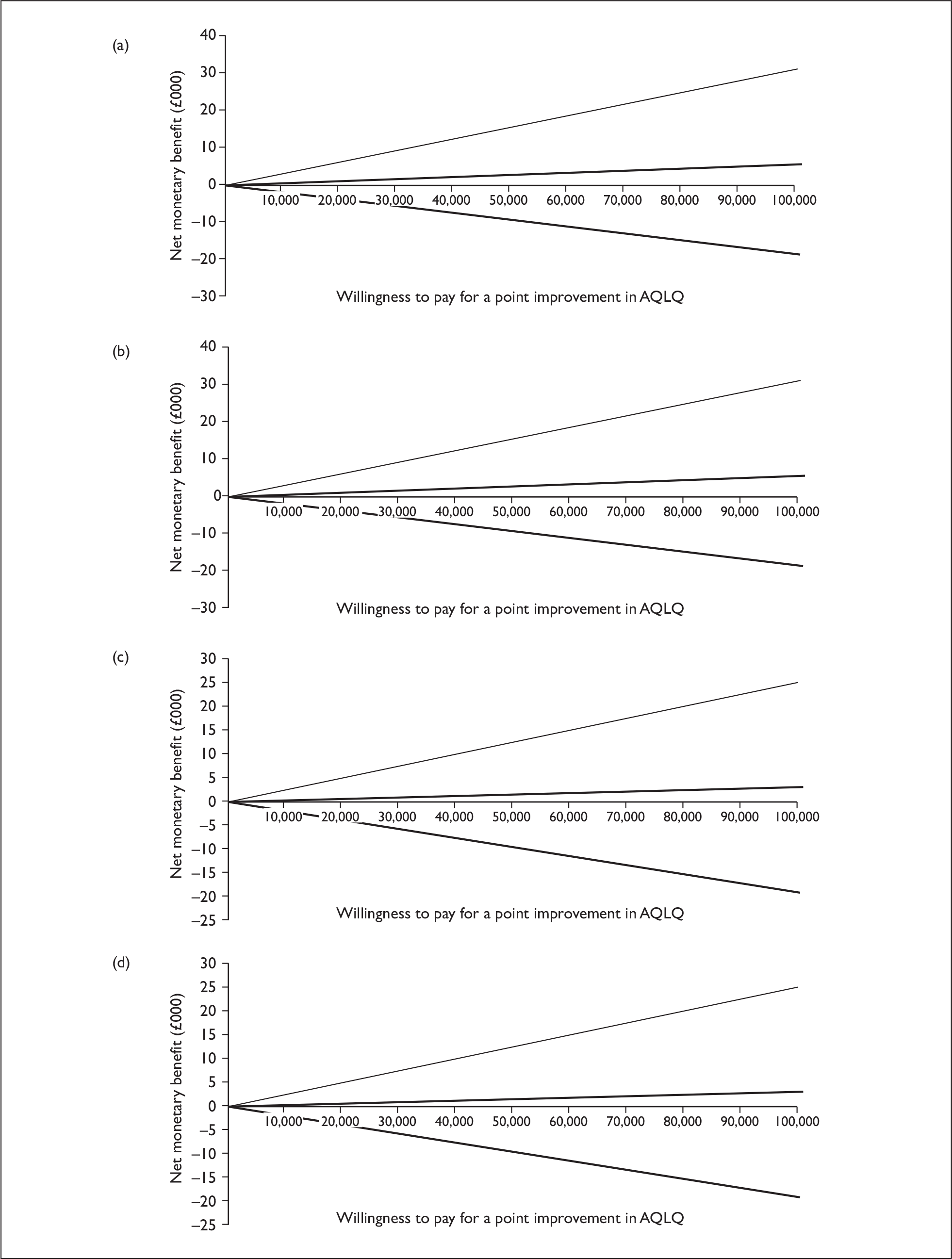

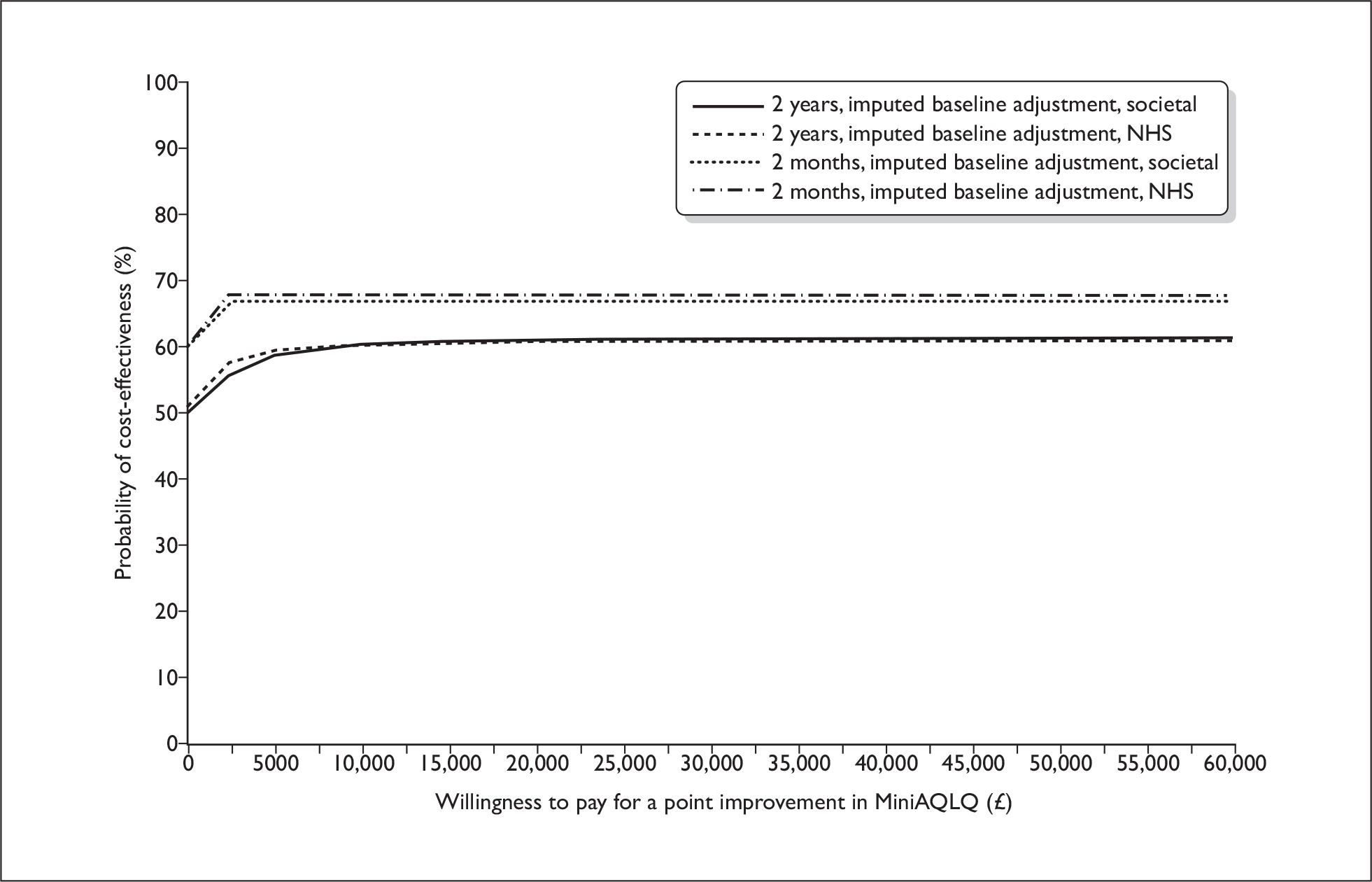

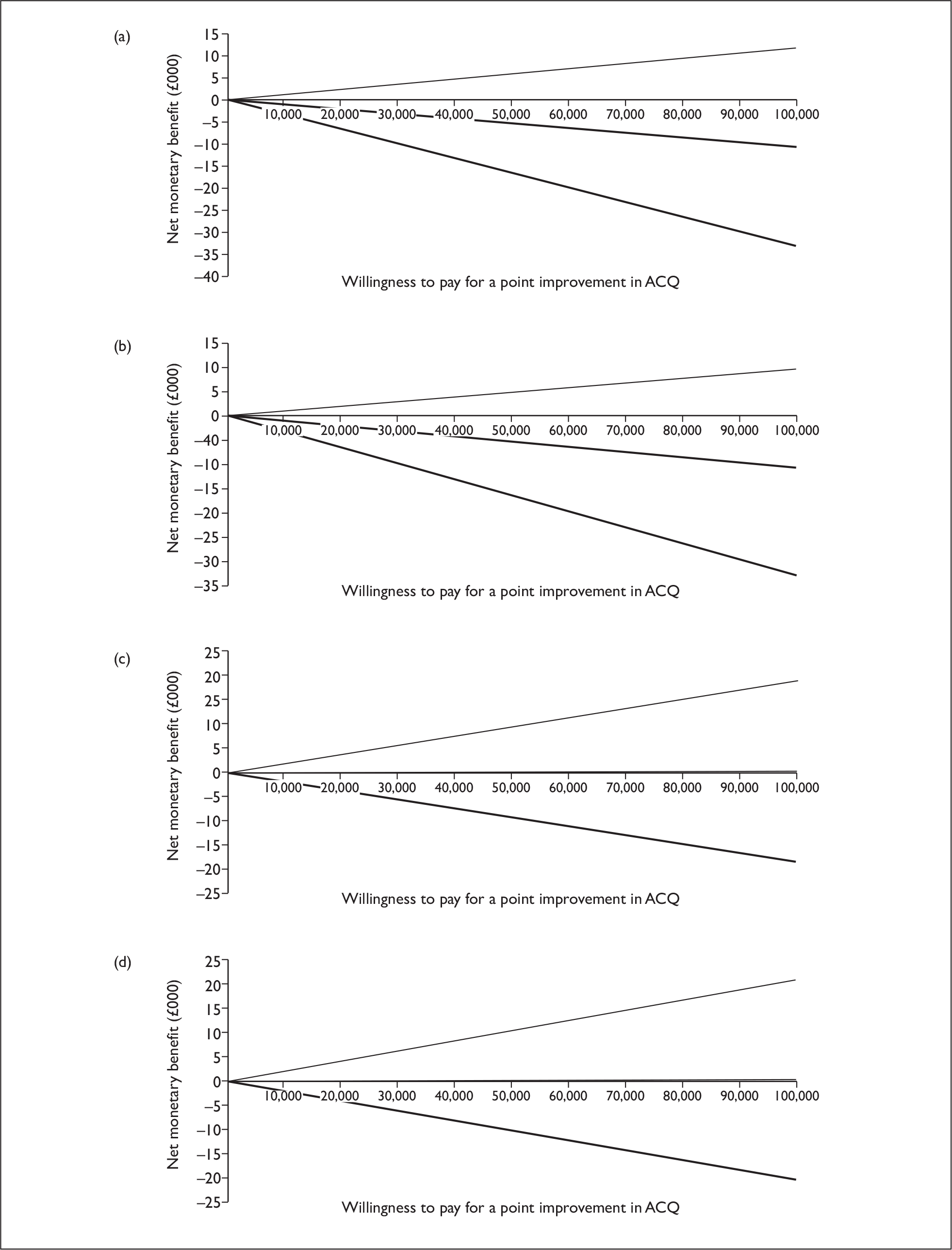

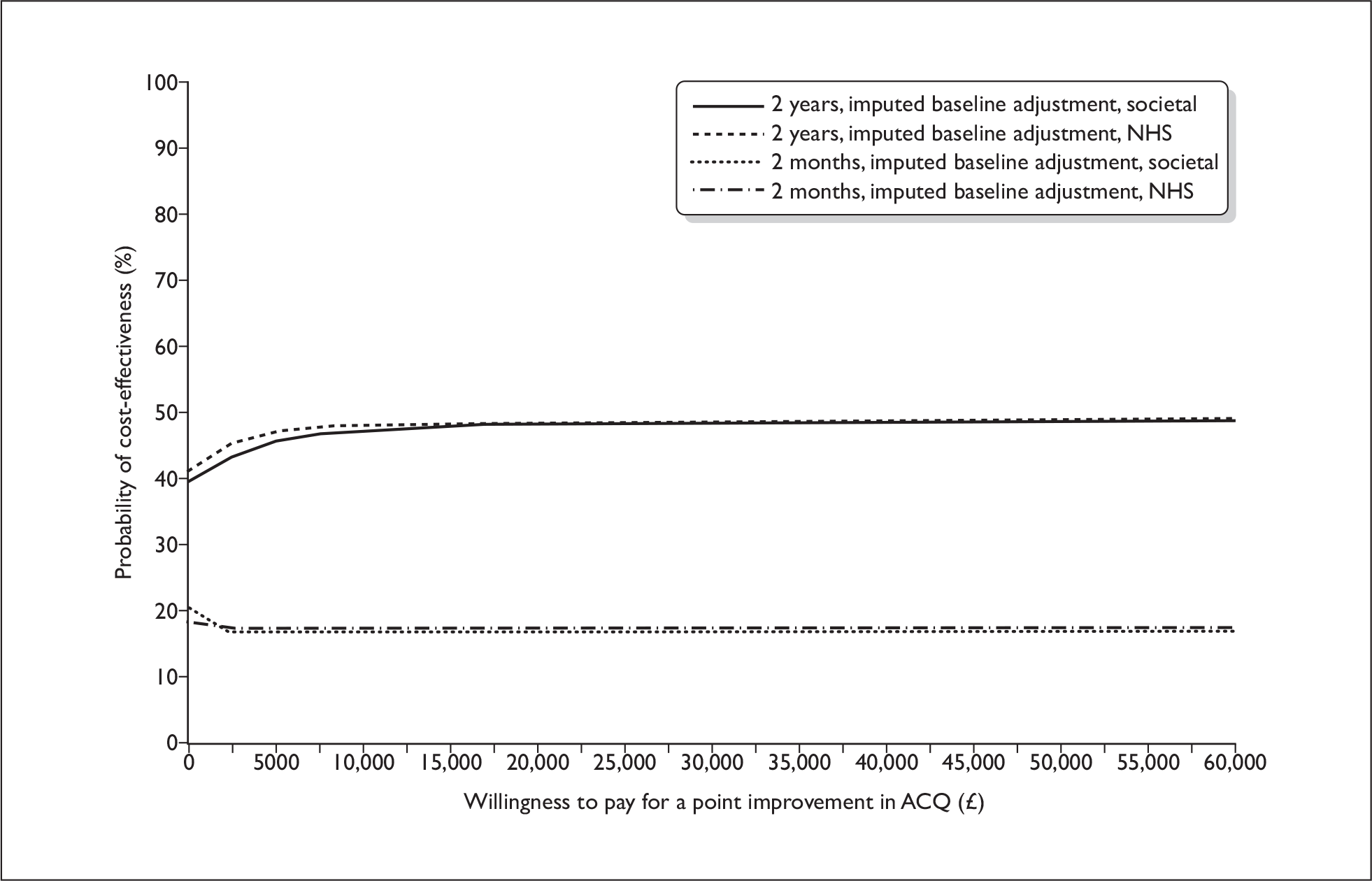

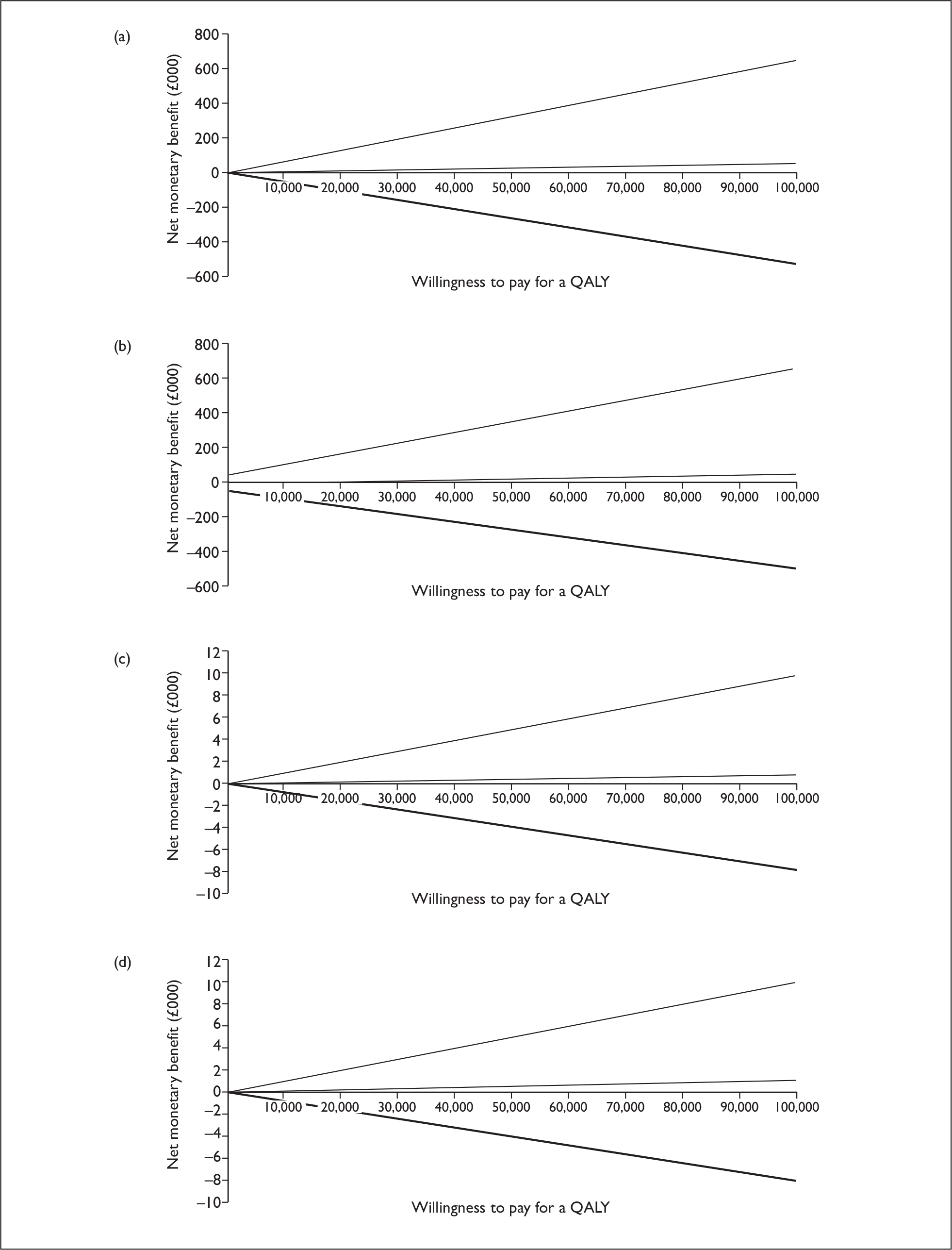

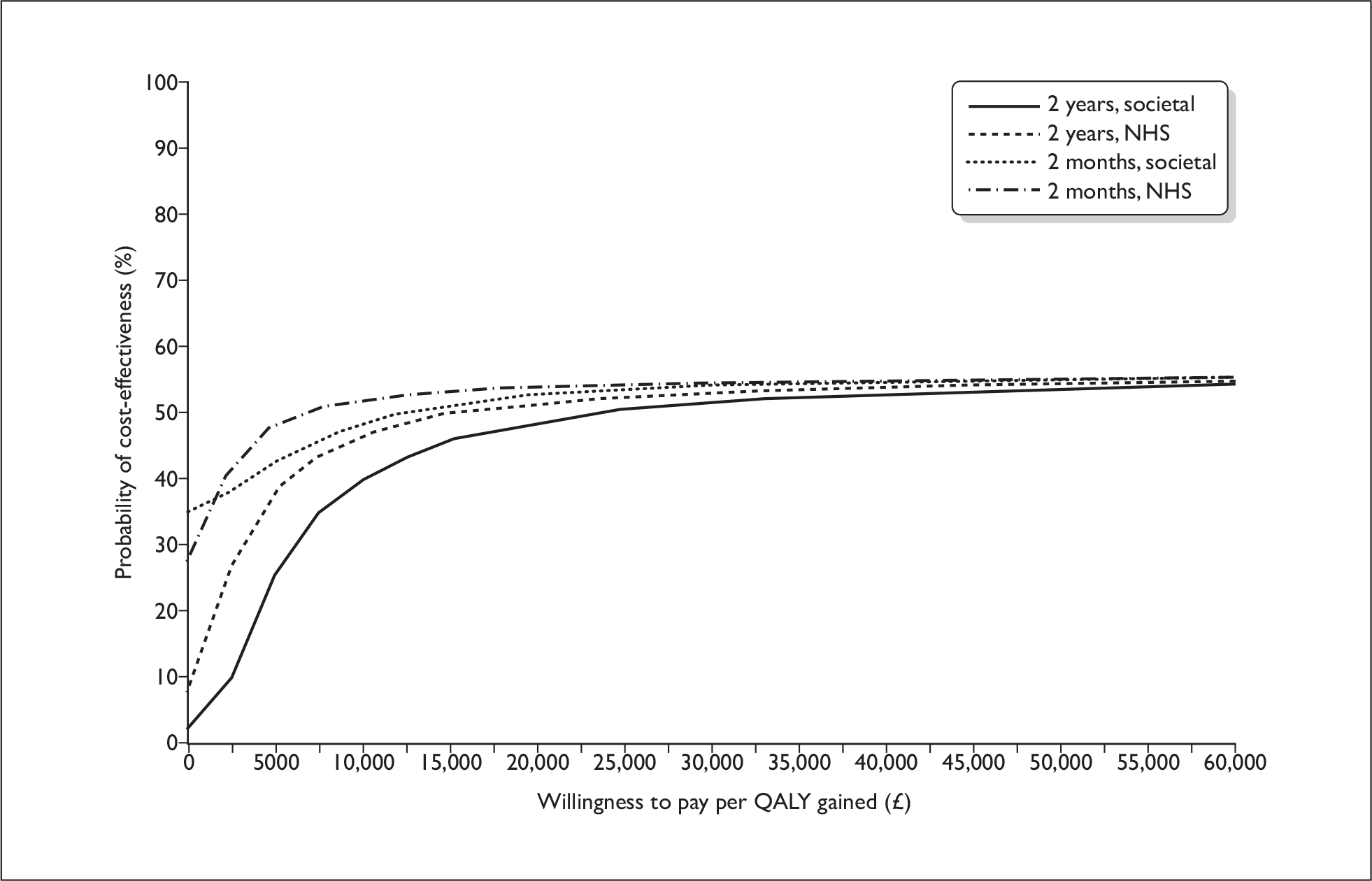

The protocol stated that where equivalence was demonstrated, a cost-minimisation analysis would be performed. As the results suggested ‘near-equivalence’ and, furthermore, as the study was powered to detect a difference in MiniAQLQ only (and not costs or other outcome measures), we present both comparisons of cost and cost-effectiveness analyses on MiniAQLQ, ACQ and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained, showing which of the treatments has the highest probability of being cost-effective.

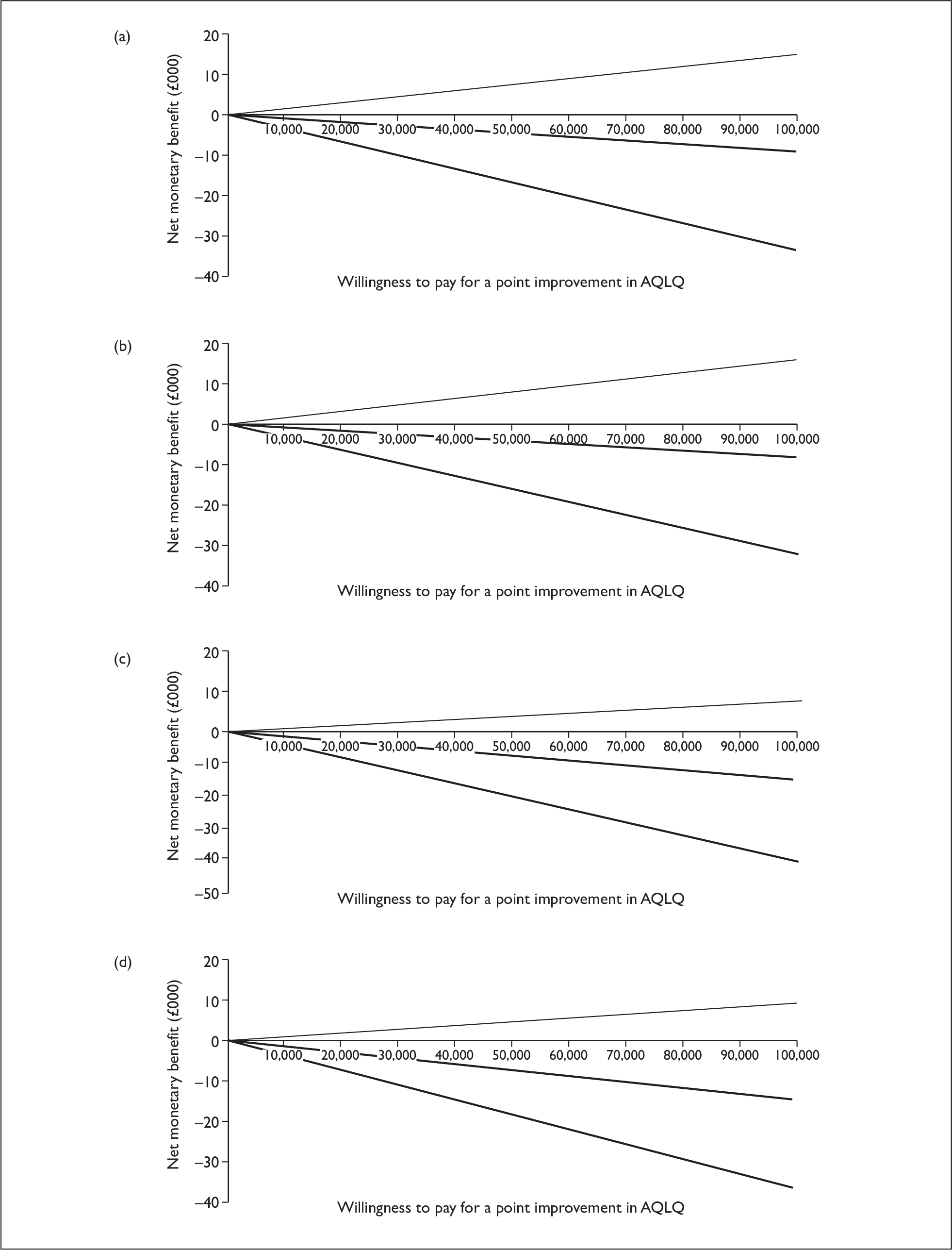

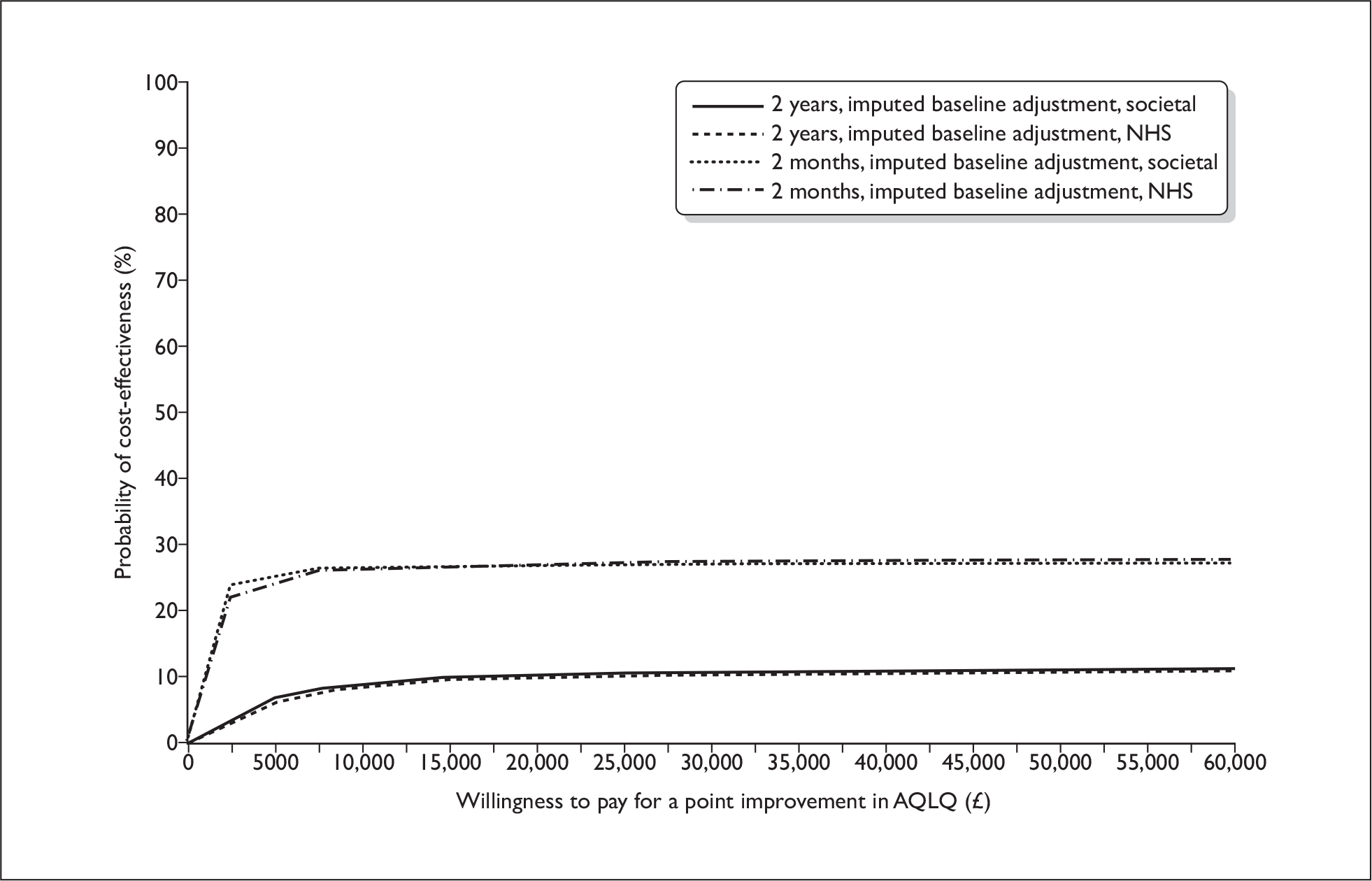

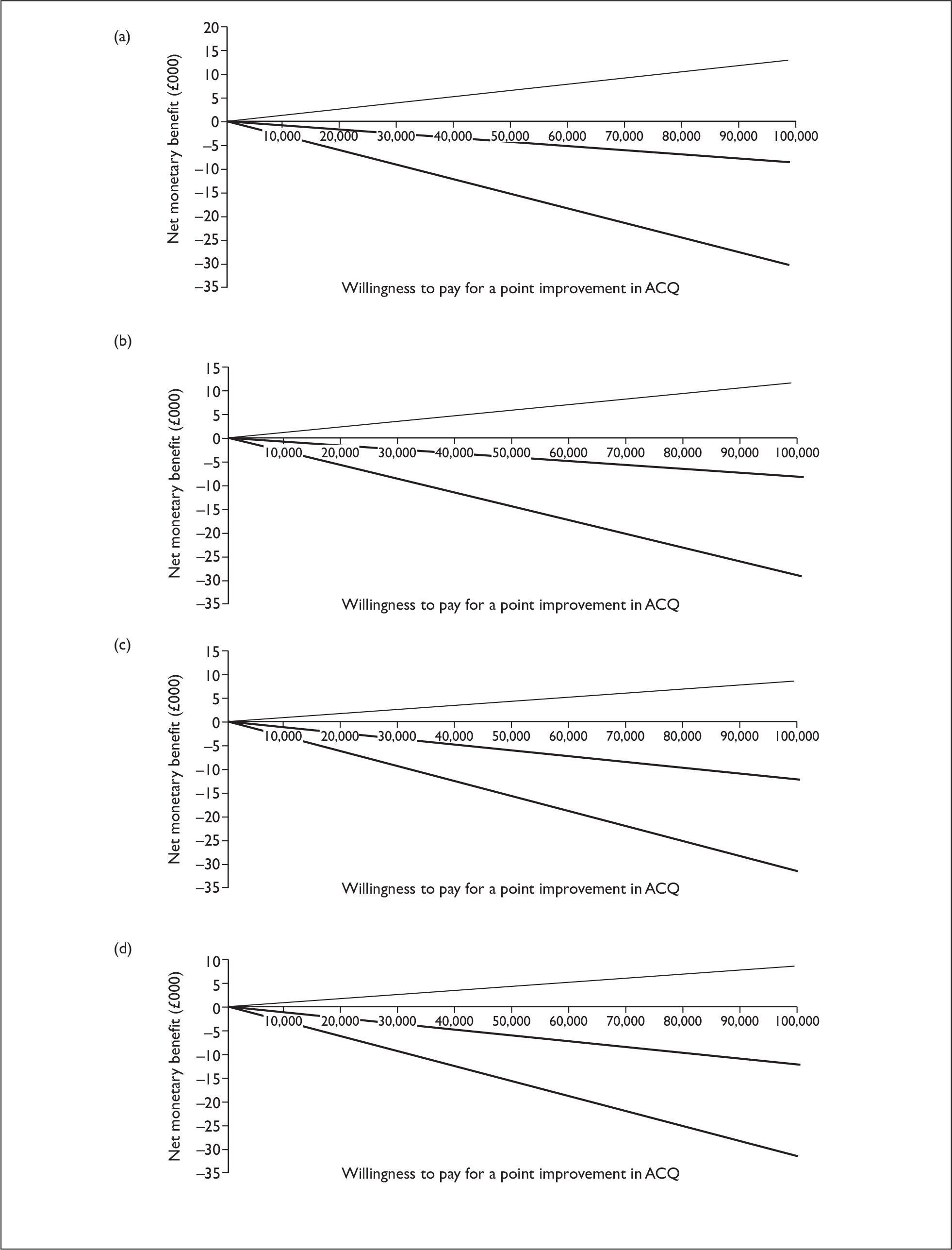

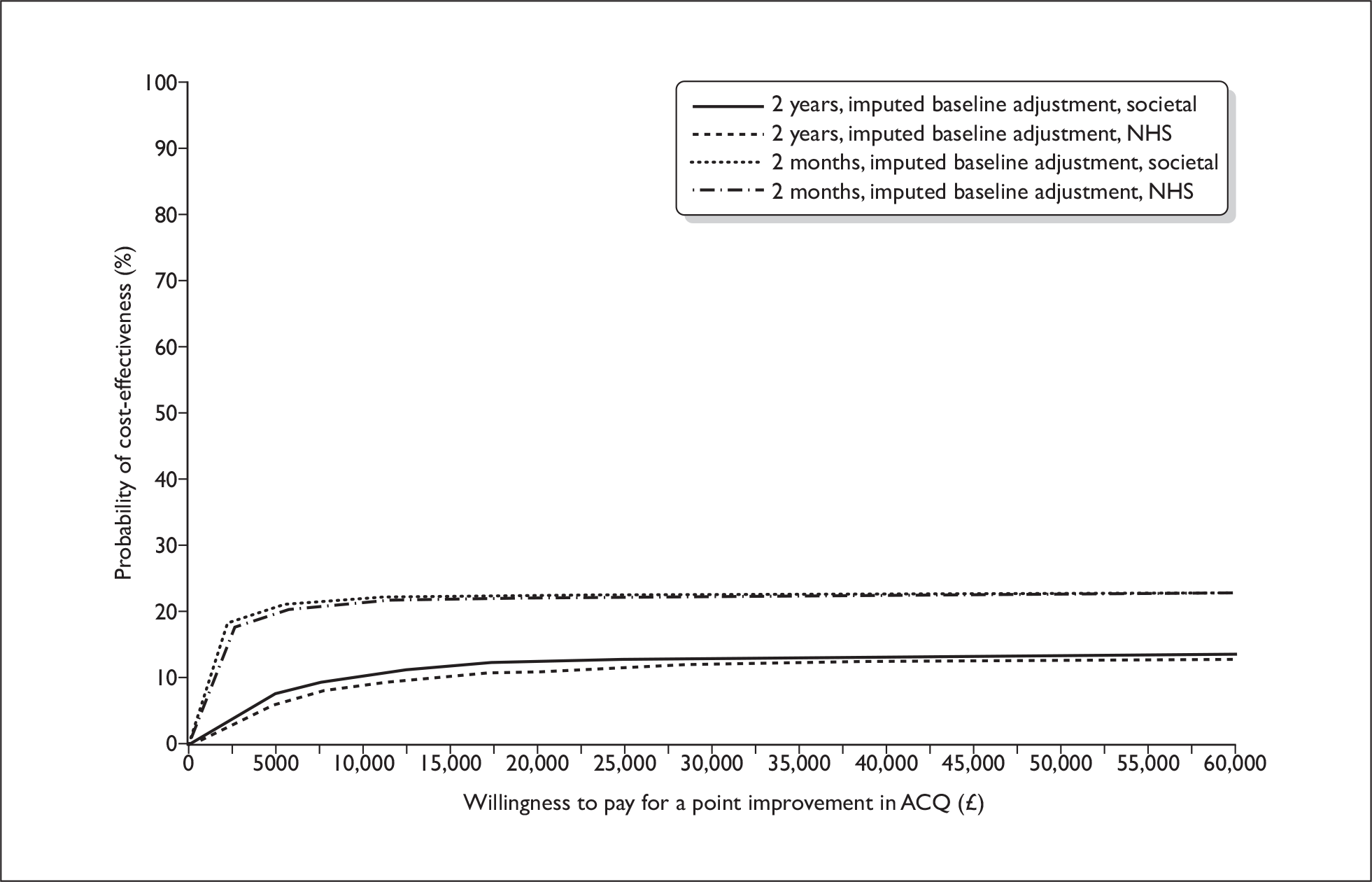

Three cost-effectiveness analyses were performed: (1) comparison of incremental cost with incremental point improvement in MiniAQLQ score; (2) comparison of incremental cost and incremental point improvement in ACQ score; and (3) comparison of incremental cost and incremental QALYs gained (i.e. cost–utility analysis). Each analysis was conducted at 2 months’ and 2 years’ follow-up, from the NHS and societal perspectives.

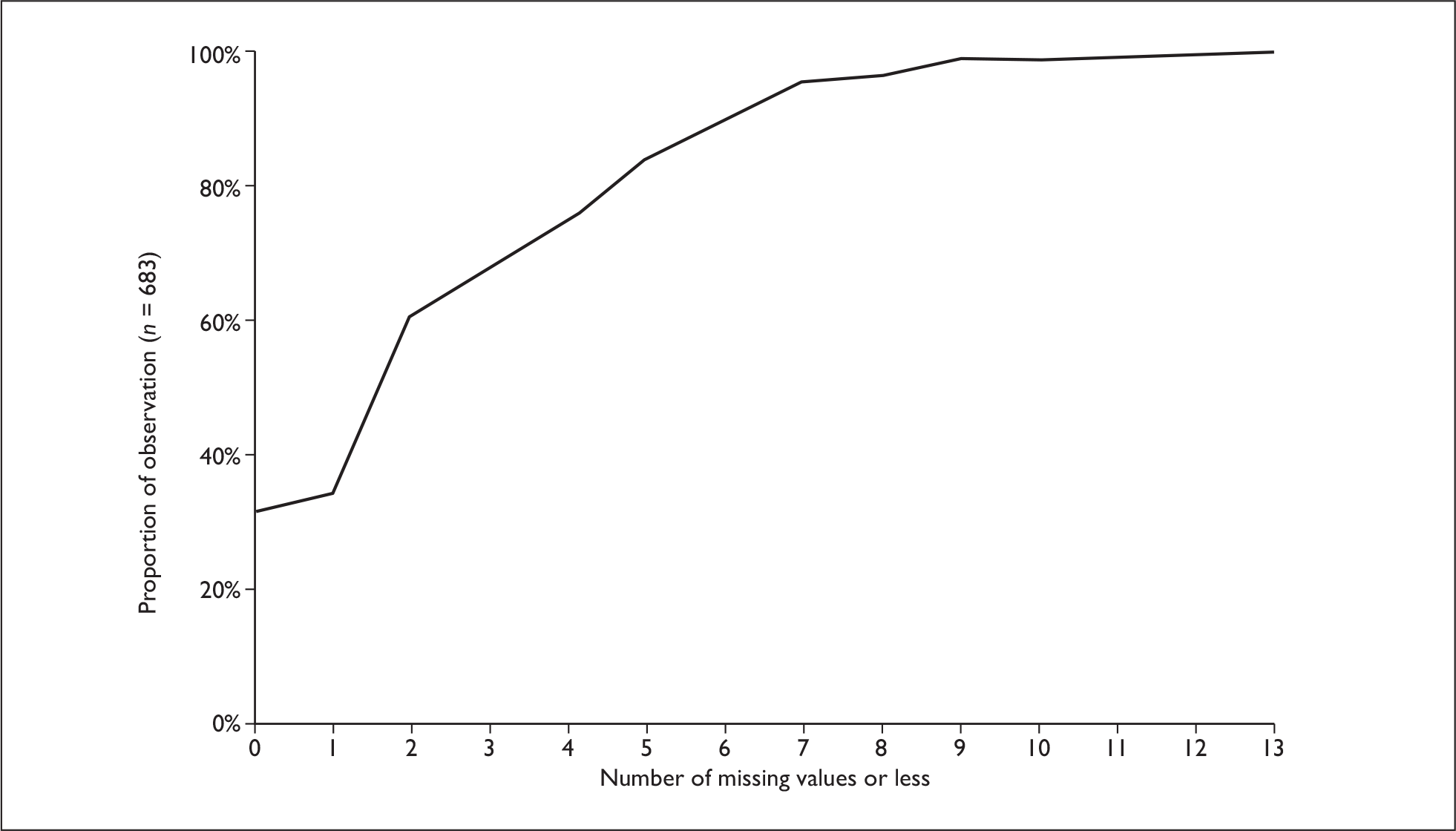

Analyses were undertaken, based on complete case analysis, an imputed dataset, and imputed dataset adjusted for baseline MiniAQLQ, ACQ, or utility as appropriate. The imputed data comprised the complete case analysis plus imputed values for missing observations using Rubin’s Multiple Imputation approach. This is preferable to single imputation approaches, as it takes account of uncertainty in the missing values themselves, and therefore better characterises the associated uncertainty. 76

Multiple imputation was carried out on variables at an aggregate level (Appendix 1, Table 55) using solas software (Statistical Solutions, Cork, Republic of Ireland). In each case, data were imputed with five iterations using the propensity score method, with all other variables used as potential covariates as well as age, education, employment and gender. The imputed variables were visually reviewed to ensure that predicted values were within logical limits. Summary statistics were generated from the five imputed datasets using Rubin’s rule76 (this is simply the mean of the estimates for each of the imputed data sets). See Appendix 1 (Imputation approach for economic analyses) for a more detailed summary of the imputation technique.

Results are presented as total cost per patient, mean MiniAQLQ, ACQ or total QALYs per patient, increments, and incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) defined as the difference in cost divided by the difference in outcome:

If this is below a threshold of ‘willingness to pay’ for a point improvement in outcome score (λ), the intervention is deemed cost-effective in relation to the comparator.

Incremental net benefit (INB) was calculated by rearranging the ICER equation:

(Note that λ is now on the right-hand side, and thus INB depends on the value of λ being known. We therefore present charts plotting INB for a variety of plausible values of λ.)

A non-parametric bootstrap approach was used to generate CIs around INB and to generate cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs), showing the probability that leukotriene receptor antagonists are cost-effective compared with inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting β2-agonist, given varying thresholds of willingness to pay for a point improvement in outcome (MiniAQLQ, ACQ or QALY gained).

Resource use

All items of resource use in the four areas (prescribed medications, over-the-counter medications, NHS activity, and indirect costs) were allocated to one of three time points: 0–2 months post randomisation, > 2 months to 1 year and > 1 year to 2 years. Where primary care record data were truncated, the patient’s follow-up was counted as missing for that and subsequent periods (for example, where a patient’s record was truncated after 36 weeks of follow-up, period 1 data were counted as present, but periods 2 and 3 were counted as missing).

Unit costs were assigned for each scenario from a variety of relevant sources (Appendix 1, Unit costs table), with prices taken from 2005 sources or adjusted to 2005 values using the Retail Price Index as appropriate. Quantities were multiplied by unit costs to calculate the total and per-patient cost. All costs incurred in the third time period (> 1 year to 2 years) were discounted by 3.5%.

Indirect costs were valued by multiplying the number of hours off work by a unit cost of £13.13, the national average gross wage in 2005. 77 For many of the indirect cost observations, the date the event took place was not reported. For these events, the date of the activity was taken as the date the patient diary was completed.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

Two cost-effectiveness analyses were performed comparing incremental cost with incremental point improvement in (1) MiniAQLQ score and (2) ACQ score. For both analyses, the primary analyses were based on complete case analysis. Secondary analyses were performed, based on an imputed data set, and the imputed data set adjusted for baseline MiniAQLQ and ACQ, respectively. Results are presented as total cost per patient, mean ACQ/MiniAQLQ score at visits 3 (2 months) and 7 (2 years), increments (95% CIs) and ICER.

Cost–utility analysis

The EQ-5D health profiles were converted into utilities using standard conversion algorithms that were relevant to the UK population. 72 QALYs were calculated from utilities by computing the area under the curve. Where 2-month and 2-year follow-up dates varied from target date, straight-line imputation was used to estimate the utility on the appropriate day. QALYs gained during the second year post randomisation were discounted at 3.5%.

Analyses were based on complete case analysis, the imputed data set and imputed data set adjusted for baseline utility. Observations were included in the complete case analysis for the 2-month follow-up if there was at minimum a valid EQ-5D reading at visit 2 (baseline) and visit 3 (2 months). Missing values for the interim visits (visits 4–6) were estimated using straight-line imputation.

Safety analyses

All randomised participants were included in the safety analyses. The primary variables for the safety analysis were the overall incidence of adverse experiences and incidences of common adverse experiences reported by participants.

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment

All patients with any evidence of asthma from 53 participating practices were sent a postal asthma symptom questionnaire (adapted from the ACQ), which was used to evaluate initial eligibility. For patients meeting these initial criteria, a review of the their notes was undertaken to confirm eligibility. A further 80 patients from the practices were identified as meeting study entry criteria at the time of clinical visits by general practice staff. Of those patients considered potentially eligible, 449 (step 2) and 482 (step 3) responded positively to an invitation and were booked to attend a screening visit (Figures 2 and 3).

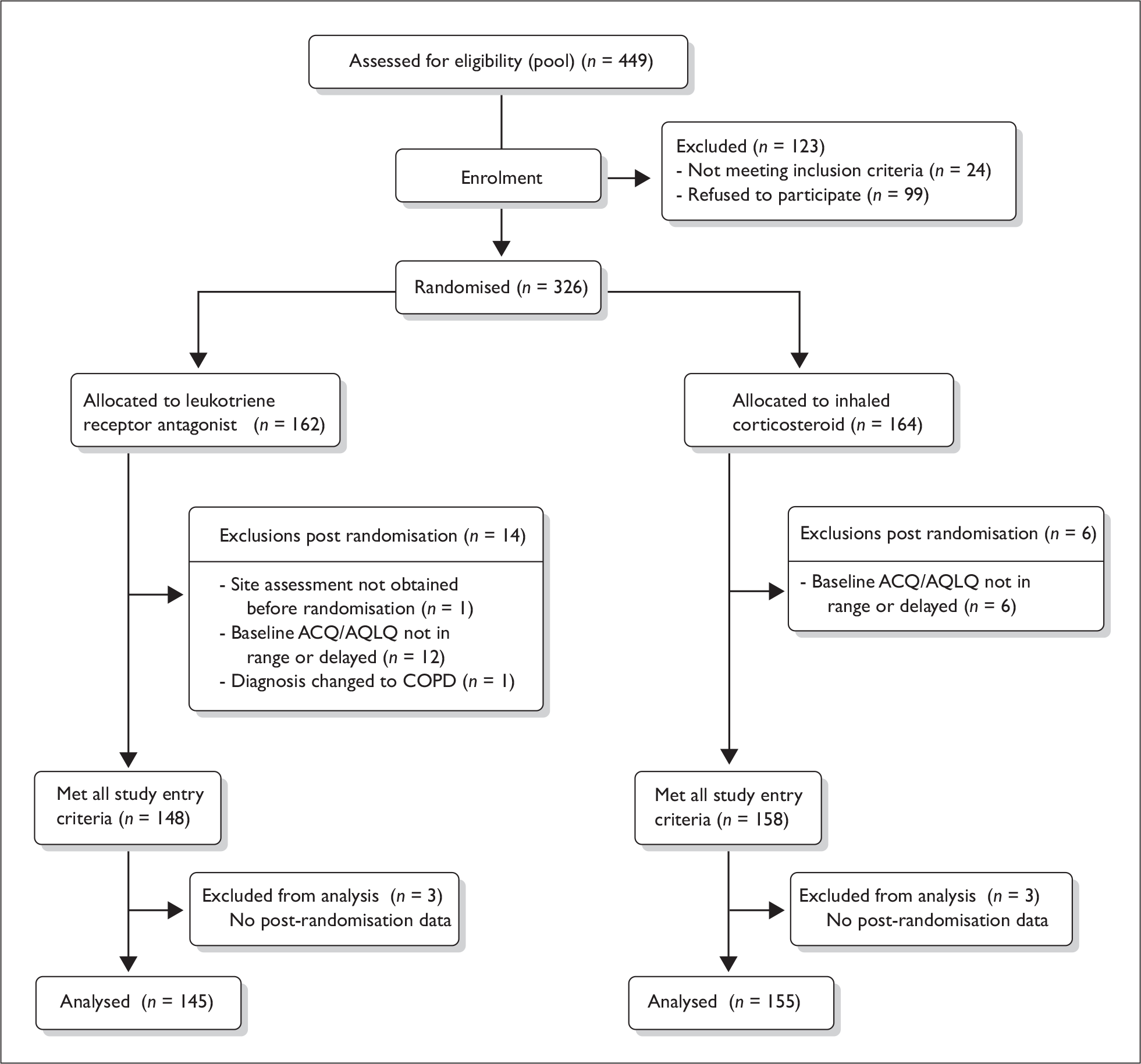

FIGURE 2.

Step 2, the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) e-flowchart for primary end point.

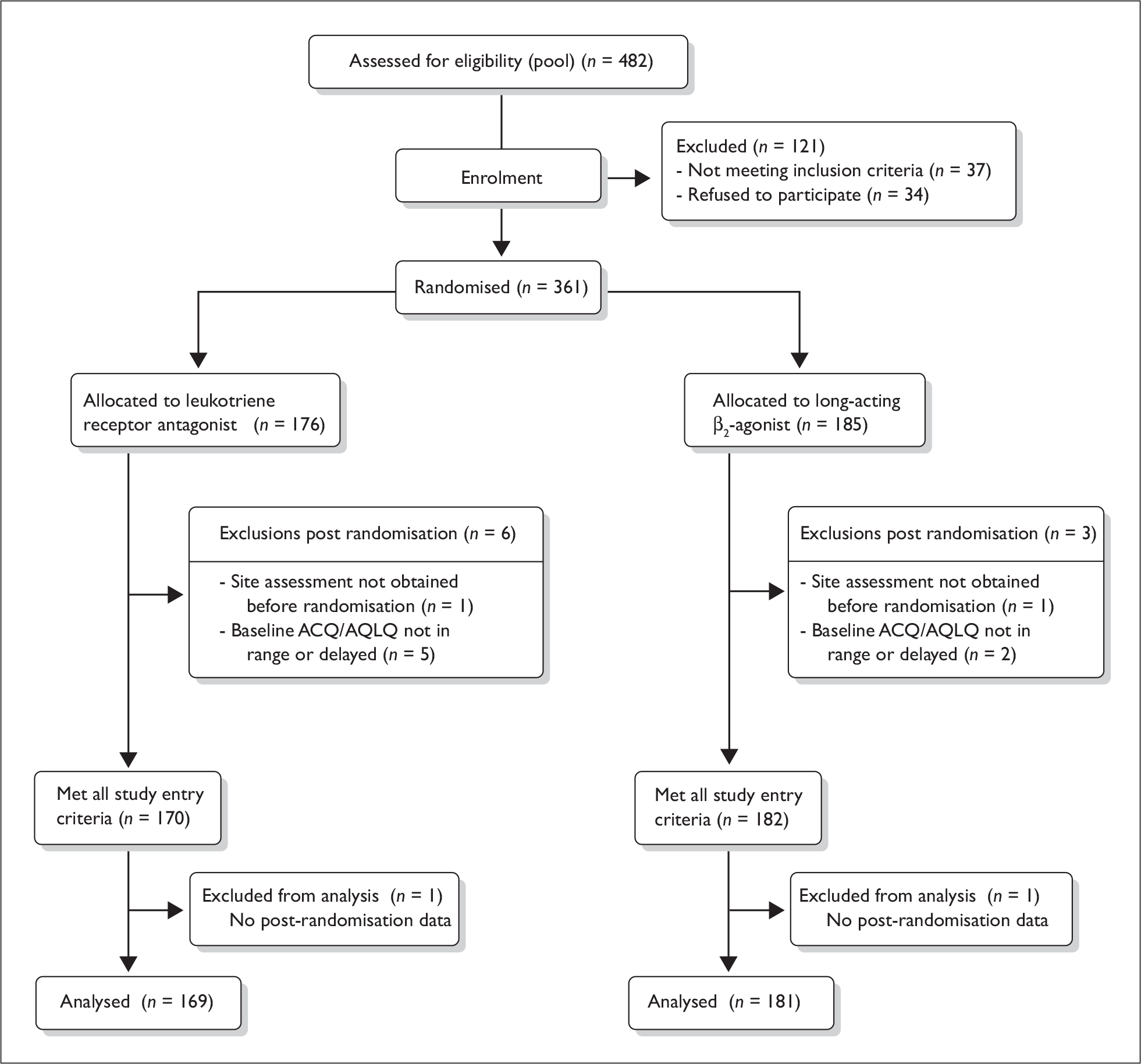

FIGURE 3.

Step 3, the CONSORT e-flowchart for primary end point.

Work began on the study in October 2001, with initial piloting in one practice of study procedures completed by May 2002. Further practices were recruited from October 2001 through to September 2004. The first patient was enrolled on 3 May 2002 with the last step 3 patient being enrolled on 18 February 2004. The last step 2 patient was enrolled on 4 February 2005. The last clinical and QOL follow-up data were collected on 8 January 2007. The last resource data collection was in the same week.

Numbers analysed versus screened

For the step 2 trial, of the 449 screened, 123 participants were excluded (99 declined to participate and 24 were identified prior to randomisation as ineligible) and 326 participants were randomised (compared with the target of 356). No significant difference was found in mean age between excluded and analysed populations. There were more females among those excluded than those analysed (Table 2). For the step 3 trial, of the 482 screened, 121 participants were excluded (84 declined to participate and 37 were identified prior to randomisation as ineligible) and 361 participants were randomised (compared with the target of 356). No significant difference was found in either the sex distribution or mean age between excluded and analysed populations (Table 2).

| Total n with sex available | Males (%) | Total n with age at screening available | Mean (SD), age (years) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 2 patients screened = 449 | ||||

| Excluded | 114 | 40 (35.1) | 96 | 47.30 (17.34) |

| Analysed | 326 | 162 (49.7) | 326 | 44.74 (16.49) |

| Total | 440 | 202 (45.9) | 422 | 45.32 (16.70) |

| Step 3 patients screened = 482 | ||||

| Excluded | 119 | 52 (43.7) | 115 | 49.74 (17.34) |

| Analysed | 361 | 136 (37.7) | 361 | 50.02 (15.93) |

| Total | 480 | 188 (39.2) | 476 | 49.95 (16.84) |

Duration of follow-up in the study for analysed groups

No significant differences were observed in the duration of follow-up in the study between analysed groups in the step 2 or step 3 studies (Table 3).

| Mean days (SD) | Median days | Maximum days | Minimum days | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 2 trial | ||||

| LTRA | 746 (75) | 743 | 1260 | 447 |

| ICS | 748 (64) | 740 | 1092 | 526 |

| Step 3 trial | ||||

| LTRA | 753 (76) | 739 | 1201 | 611 |

| LABA | 748 (76) | 733 | 1308 | 573 |

Numbers analysed

At step 2, 20 patients were excluded post-randomisation (Figure 2), and 13 of the remaining 306 patients (4.2%) were lost to follow-up. Post-randomisation data were available for 7 out of the 13 lost to follow-up; thus, 300/306 patients (98%) had post-randomisation data and were included in the primary intention-to-treat analyses. The per-protocol population, who received an entirely fixed treatment regime throughout the study, included 65/145 (45%) patients in the leukotriene antagonist group and 82/155 (53%) patients in the inhaled steroid group.

In the step 3 trial, nine patients were excluded post randomisation (Figure 3). Twelve of the remaining 352 patients (3.4%) were lost to follow-up; however, post-randomisation data were available for 10 out of these 12 and thus a total of 350 patients were included in the primary intention-to-treat analysis, including 169 and 181 in leukotriene antagonist and long-acting β2-agonist groups, respectively. Patients who met the per-protocol definition of a fixed treatment regime and no therapeutic change of any kind and were included in the MiniAQLQ analyses numbered 60/169 (36%) and 80/181 (44%), respectively.

Randomisation data

For the step 2 trial, this process resulted in an almost equal distribution of participants between leukotriene antagonist and inhaled steroid arms (162 and 164 participants, respectively). However, for the step 3 study, 9 fewer participants were randomised to leukotriene antagonist than to long-acting β2-agonist (176 and 185 participants, respectively). This difference is likely to have arisen for two reasons. Firstly, a small number of practices had one or two more participants randomised to long-acting β2-agonist than leukotriene antagonist. Secondly, because of an error in the way that the randomisation telephone calls were performed, practice 12 had four more participants randomised to long-acting β2-agonist than to leukotriene antagonist (13 and 9 participants, respectively). There was never any prior or biasing knowledge of the allocation on the part of the nurse performing the randomisation, but the result was an excess of four participants receiving long-acting β2-agonist at that practice.

Step 2 trial

Demographics and baseline characteristics

Characteristics of participants screened and found eligible for the step 2 trial are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

| Leukotriene antagonist (N = 148) | Inhaled steroid (N = 158) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 73 (49%) | 83 (53%) |

| Male | 75 (51%) | 75 (47%) | |

| Age | Mean (SD) | 47.6 (16.5) | 44.1 (16.4) |

| Race | Caucasian | 144 (97%) | 153 (97%) |

| Non-Caucasian | 0 | 1 (1%) | |

| Not known | 4 (3%) | 4 (3%) | |

| Height (cm) | Mean (SD) |

n = 138 169.6 (9.2) |

n = 153 169.1 (9.6) |

| PEF (l/min) | Mean (SD) |

n = 147 438 (139) |

434 (127) |

| %PPEF (%) | Median (IQR) |

n = 134 85.97 (77.43 to 94.16) |

n = 150 85.07 (73.92 to 95.42) |

| Salbutamol PEF reversibility (%) | Mean (SD) |

n = 128 9.20 (10.7) |

n = 142 8.74 (9.17) |

| SABA puffs/day | Mean (SD) |

n = 140 3.0 (3.2) |

n = 145 2.9 (3.1) |

| Asthma exacerbations in last year | Mean (SD) | 0.13 (0.036) | 0.10 (0.029) |

| Asthma Control Questionnaire | Mean (SD) | 1.99 (0.70) | 2.06 (0.84) |

| MiniAQLQ | Mean (SD) | 4.75 (0.92) | 4.72 (0.95) |

| mRQLQ | Mean (SD) |

n = 113 1.58 (1.29) |

n = 131 1.78 (1.35) |

| EQ-5D utility | Mean (SD) |

n = 118 0.795 (0.245) |

n = 131 0.830 (0.195) |

| Personal objectives (0–100 VAS) | Mean (SD) |

n = 99 42.59 (18.03) |

n = 118 38.89 (18.15) |

| RCP3 | Mean (SD) |

n = 133 2.07 (0.81) |

n = 146 2.06 (0.79) |

| Sleep difficulty | Yes | 79 (58%) | 86 (56%) |

| No | 58 (42%) | 67 (44%) | |

| Missing | 11 | 5 | |

| Day symptoms | Yes | 125 (93%) | 142 (94%) |

| No | 10 (7%) | 9 (6%) | |

| Missing | 13 | 7 | |

| Interferes with activities | Yes | 65 (49%) | 74 (49%) |

| No | 69 (51%) | 76 (51%) | |

| Missing | 14 | 8 | |

| LTRA (N = 148) | ICS (N = 158) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Continued education > 16 | Yes | 72 (50%) | 81 (53%) |

| No | 70 (49%) | 67 (44%) | |

| Student | 2 (1%) | 4 (7%) | |

| Not known | 4 | 6 | |

| Professional qualification | Yes | 45 (33%) | 50 (35%) |

| No | 88 (64%) | 84 (59%) | |

| Student | 4 (3%) | 8 (6%) | |

| Not known | 11 | 16 | |

| Employment position | Employer | 5 (5%) | 8 (7%) |

| Employee | 74 (73%) | 90 (84%) | |

| Self-employed | 21 (21%) | 9 (8%) | |

| Disabled | 1 (1%) | 0 | |

| Not known | 47 | 51 | |

| Smoking habit | Current smoker | 37 (25%) | 30 (19%) |

| Ex-smoker | 54 (37%) | 54 (35%) | |

| Never smoked | 56 (38%) | 71 (46%) | |

| Not known | 1 | 3 | |

| Current smoker over age 45 | 15 (10%) | 11 (7%) | |

No substantial differences were identified between the arms. A small female preponderance was noted in the inhaled steroid arm, but not in the leukotriene antagonist arm of the study. Most participants were Caucasian. Mean %PPEF was indicative of airflow obstruction consistent with untreated asthma of mild to moderate severity. Most participants had daytime asthma symptoms, with half having additional night-time symptoms. Half of participants felt that their asthma symptoms interfered with their daily activities. Education and occupation status of participants is shown in Table 5.

Most participants were in employment. Only 40% of participants had never smoked. Approximately 20% of participants were active smokers at randomisation into the study, including 26 (9%) who were over the age of 45 (Table 5). Baseline diary card data for these participants are shown in Table 6.

| LTRA (N = 148) | ICS (N = 158) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) morning waking with symptoms |

0.48 (0.36) n = 129 |

0.48 (0.34) n = 147 |

| Mean (SD) puffs of reliever at night |

0.78 (0.88) n = 125 |

0.99 (1.37) n = 141 |

| Mean (SD) morning PEF |

408.9 (99.1) n = 127 |

402.5 (100.2) n = 146 |

| Mean (SD) daytime asthma symptom score (0–6)a |

1.88 (1.18) n = 129 |

1.81 (1.29) n = 145 |

| Mean (SD) score for daytime ‘bother from asthma symptoms’ (0–6)a |

1.63 (1.18) n = 128 |

1.48 (1.23) n = 145 |

| Mean (SD) daily activity score (0–6)b |

2.68 (1.12) n = 126 |

2.38 (1.27) n = 145 |

| Mean (SD) score for interference on activities from asthma (0–6)a |

1.38 (1.24) n = 128 |

1.28 (1.33) n = 147 |

| Mean (SD) puffs of reliever during the day |

2.26 (1.67) n = 126 |

2.18 (1.99) n = 145 |

| Mean (SD) evening PEF |

420.6 (101.1) n = 127 |

413.9 (103.0) n = 147 |

| Mean (SD) diurnal variation in PEF (%) |

7.1 (4.8) n = 127 |

7.7 (5.4) n = 147 |

Primary analyses

Change in QOL

Mini asthma quality of life questionnaire

Mean MiniAQLQ score increased (improved) from baseline in both leukotriene antagonist and inhaled steroid randomised groups (Table 7 and Figure 4).

| Treatment duration | Outcome measure | LTRA | ICS | Difference (95% CI) LTRA–ICS | Adjusted differencea (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 months (visit 3) | n | 122 | 132 | 0.0 (–0.25 to 0.26) | –0.02 (–0.24 to 0.20) |

| Mean | 5.25 | 5.28 | |||

| SD | 1.03 | 1.10 | |||

| 2 yearsb | n | 145 | 155 | –0.10 (–0.35 to 0.17) | –0.11 (–0.35 to 0.13) |

| Mean | 5.52 | 5.63 | |||

| SD | 1.07 | 1.16 |

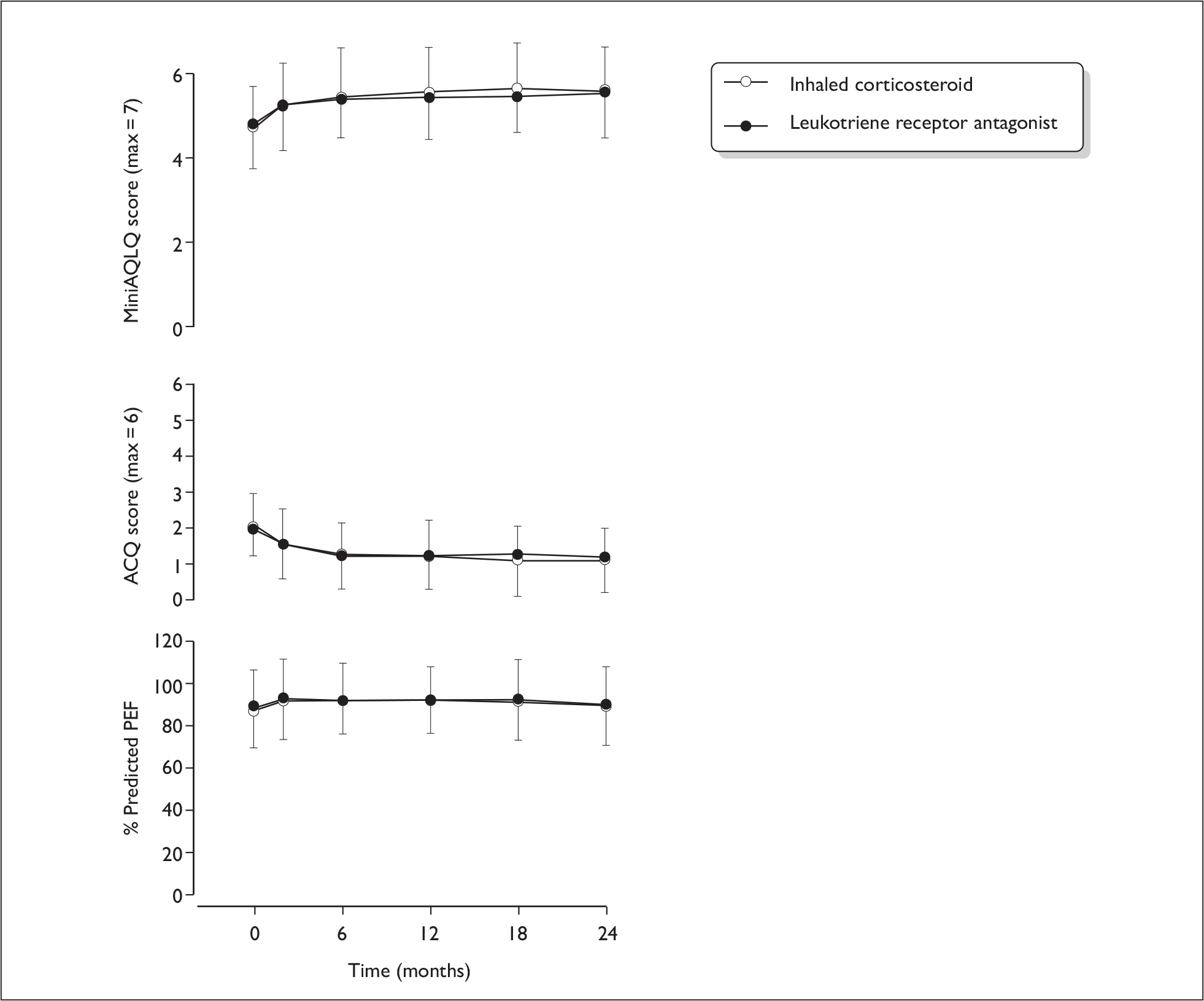

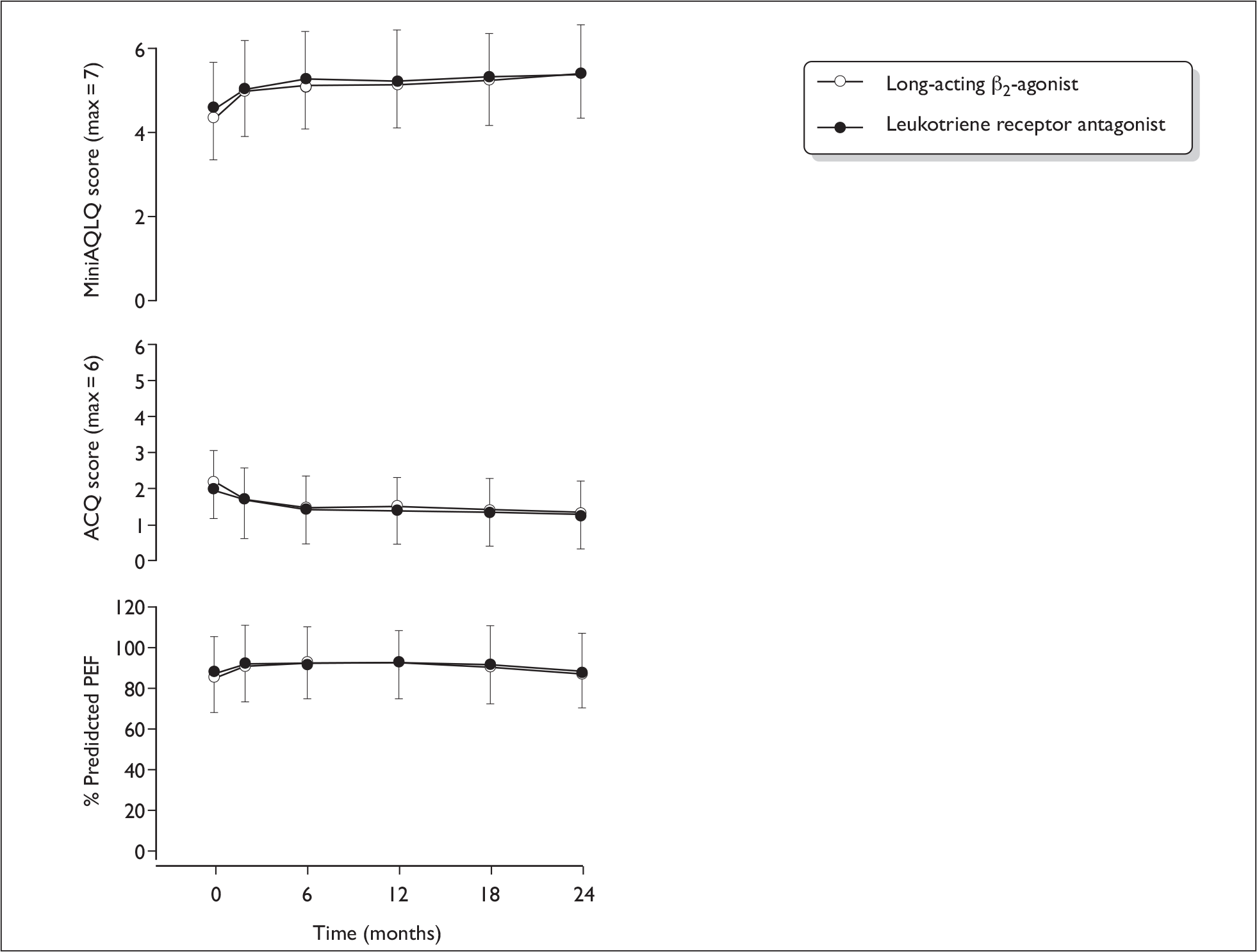

FIGURE 4.

Step 2: ACQ, MiniAQLQ and %PPEF over 2 years of treatment. Mean (standard deviation) ACQ (from 0 ‘best’ to 6 ‘worst’) and MiniAQLQ (from 1 ‘worst’ to 7 ‘best’) scores and median (interquartile range) %PPEF at baseline and over 2 years of treatment with leukotriene antagonist or inhaled steroid.

No statistically significant between-group differences in MiniAQLQ score were found at the 2-month time point, either unadjusted or adjusted for baseline values. At 2 months, the 95% CIs for both the unadjusted and adjusted differences in MiniAQLQ score were within the limits for equivalence: (–0.25 to 0.26) and –0.02 (–0.24 to 0.20), respectively, i.e. excluding 0.3. The limit of the one-sided 95% CI for the unadjusted difference was –0.25, and –0.18 for the adjusted difference.

At the 2-year visit, while the difference was again not statistically significant, and the estimated difference between groups was small, the 95% CI did include the equivalence value of 0.3, favouring inhaled steroid [imputed results, unadjusted difference (95% CI) –0.10 (–0.35 to 0.17), adjusted difference (95% CI) –0.11 (–0.35 to 0.13)]. The limit of the one-sided 95% CI for the unadjusted difference was –0.32 and was –0.31 for the adjusted difference, i.e. inferiority could not be excluded.

Asthma Control Questionnaire

Mean ACQ score decreased (improved) substantially from baseline in both leukotriene antagonist and inhaled steroid randomised groups (Table 8 and Figure 4). Again, no significant between-group differences in ACQ score were found at either the 2-month or 2-year time points, whether unadjusted or adjusted for baseline values. At 2 years (imputed results), the adjusted difference (95% CI) was 0.13 (–0.07 to 0.33). The CI is well within the minimum clinically important difference of 0.5.

| Treatment duration | LTRA | ICS | Difference (95% CI) LTRA–ICS | Adjusted differencea (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 months (visit 3) | n | 123 | 132 | –0.02 (–0.24 to 0.21) | 0.01 (–0.20 to 0.22) |

| Mean | 1.54 | 1.53 | |||

| SD | 0.93 | 1.00 | |||

| 2 yearsb | n | 145 | 155 | 0.10 (–0.11 to 0.32) | 0.13 (–0.07 to 0.33) |

| Mean | 1.23 | 1.15 | |||

| SD | 0.95 | 0.92 |

Quality-adjusted life-years

Leukotriene antagonist participants experienced a mean of 0.122 QALYs over the 2-month period, compared with 0.132 in inhaled steroid participants, a mean (95% CI) difference of approximately 0.01 (–0.019 to 0.001) QALYs, falling to 0.001 (–0.005 to 0.002) QALYs after adjustment for baseline utility (Table 9). Over 2 years, leukotriene antagonist participants experienced 0.153 (–0.274 to –0.032) fewer QALYs than inhaled steroid participants. However, after adjusting for baseline utility, the difference falls to 0.050 (–0.126 to 0.026) QALYs, equivalent to 2.5 weeks of perfect health.

| LTRA | ICS | Difference (95% CI) LTRA–ICS | Adjusted differencea (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | |||

| EQ-5D utility | ||||||

| Baseline | 118 | 0.795 (0.245) | 131 | 0.830 (0.195) | – | – |