Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 09/21/01. The protocol was agreed in October 2009. The assessment report began editorial review in March 2010 and was accepted for publication in October 2010. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2011. This work was produced by Hislop et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Description of health problem

Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) are tumours of mesenchymal origin that arise in the gastrointestinal tract (GI tract). Historically, and based upon morphological appearance alone, GISTs were considered to be of smooth muscle origin and regarded as leiomyomas or leiomyosarcomas. Subsequently, electron microscopic and molecular analysis has demonstrated that GISTs are a distinct tumour type arising from the interstitial cells of Cajal, and characterised by the expression of receptor tyrosine kinase KIT (CD117) protein demonstrated by immunohistochemistry. 1 CD117/KIT immunoreactivity now provides the diagnostic criteria for GISTs, although there is recognition that a small proportion of GISTs (4%) are KIT immunoreactive negative. 2,3

Aetiology, pathology and prognosis

Recent investigation has provided clinically significant insights into the molecular pathogenesis of GISTs. This has allowed the rational development of systemic therapies (including imatinib and sunitinib), provided robust diagnostic criteria for GISTs, and demonstrated the ability of certain pathogenic gene mutations to predict clinical behaviour and response to therapy in GISTs, therefore having potential application as predictive biomarkers.

Activating mutations in the KIT proto-oncogene are an early and key event in the pathogenesis of GISTs, and present in up to 95% of cases. 4–10 The protein product is a member of the receptor tyrosine kinase family and a transmembrane receptor for stem cell factor (SCF). 11 Extracellular binding of SCF to the receptor results in dimerisation of KIT and subsequent activation of the intracellular KIT kinase domain,9 leading to activation of intracellular signalling cascades controlling cell proliferation, adhesion and differentiation. KIT mutation is necessary but not sufficient for the pathogenesis of GISTs; other mutations are essential, and KIT mutation is absent in a minority of cases (< 5%). 12,13 In the majority of KIT mutation-negative cases, mutational activation of the closely related tyrosine kinase platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA) is the pathogenic event, and KIT and PDGFRA activation have similar biological effects. 12,13

It has been demonstrated that KIT and PDGFRA gene mutations are mutually exclusive7,8,10,14 and GISTs with no KIT mutations have either PDGFRA-activating mutations or no identified kinase mutations. 13 GISTs that lack KIT mutations may still have high KIT kinase activity and so may have KIT mutations that are not detected by conventional screening methods. Alternatively, KIT kinase activation may be due to non-mutational mechanisms. 6

Diagnosis of GIST is made when morphological and clinical features of the tumour are consistent and the tumour has positive KIT/CD117 protein expression. 15 However, as noted above, approximately 4% of GISTs have clinical and morphological features of GIST but have negative KIT immunoreactivity. 2 These KIT-negative GISTs are more likely to contain PDGFRA mutations. 2 It is important in these cases, when KIT/CD117 staining is negative, that other markers are investigated to confirm GIST diagnosis. Recent studies have shown that a novel protein DOG1 is highly expressed in both KIT and PDGFRA mutant GISTs,16,17 and immunostaining for DOG1 can be used in conjunction with CD117 staining, and diagnosis of GIST made on the basis of KIT and/or DOG1 immunoreactivity. 15 PDGRFA immunohistochemistry should also be performed and positivity can assist with diagnosis. Mutational analysis also plays a role in the diagnosis of KIT/CD117-negative suspected GISTs, as with consistent morphological and clinical features, positive mutation analysis for either KIT or PDGFRA is diagnostic. 15

Without treatment GISTs are progressive and will eventually metastasise to distant organs and so are invariably fatal without any intervention. GISTs are resistant to ‘conventional’ oncology treatments of cytotoxic chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Prognosis is highly dependent on the resectability of the tumour; however, only 50% of GIST patients have resectable disease at first presentation. 18,19 Ten-year survival for resectable/non-metastatic tumours is 30–50%, and at least 50% will relapse within 5 years of surgery, but for unresectable tumours prognosis is very poor, with survival generally < 2 years without further treatment. 18,19

Epidemiology and incidence

While GISTs are the most common mesenchymal tumour of the GI tract, overall they are a rare cancer, accounting for less than 1% of all cancers of the GI tract. 20 GISTs can occur anywhere in the GI tract from the oesophagus to the rectum, but most arise in the stomach or small intestine. 21 They are rare before the age of 40 years and very rare in children, with a median age at diagnosis of 50–60 years. 22,23 Some data show a slight male predominance but this is not a consistent finding. 22,24,25

Retrospective studies carried out using KIT immunoreactivity as a diagnostic criterion have shown that GISTs have been underdiagnosed in the past. 26,27 These retrospective population-based reclassification studies provide the most reliable and accurate current estimate of an annual incidence of 15 cases per million, which would equate to 900 cases in the UK. 15

Impact of health problem

The symptoms of GISTs depend on the size and location of the primary tumour and any metastatic deposits. While one-third of cases are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally during investigations or surgical procedures for unrelated disease, severe and debilitating symptoms occur in many patients and are invariable in those patients who have (or develop) metastatic disease. 28

Gastrointestinal stromal tumours of < 2 cm in size with no metastatic disease are usually asymptomatic. Larger primary tumours and those of patients with metastatic disease are usually symptomatic and the most common symptom is GI tract bleeding, which occurs in 50% of patients, 25% of these patients presenting as emergencies with acute GI haemorrhage, either into the intestine or peritoneum. 29 Abdominal discomfort is a feature of larger tumours. 30 Oesophageal GISTs typically present with dysphagia, which represents the main symptomatic problem in these cases, and colorectal GISTs may cause bowel obstruction. In metastatic disease, debilitating systemic symptoms, such as fever, night sweats and weight loss, are common.

Current service provision

Management of disease

There is wide consensus that the management of GISTs should be undertaken in the context of discussion of individual cases by a multidisciplinary team. 15,31

Management of resectable disease

Surgical resection is the primary treatment for GISTs and offers the only possibility of cure. Surgical resection is undertaken with the aim of achieving a complete microscopic resection (R0 resection). Evaluation of the suitability and possibility of a complete microscopic resection of a GIST is made after appropriate preoperative assessment to determine stage and also the fitness of the patient for the procedure required. Preoperative assessment for staging includes (as a minimum) a computerised tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, and, in specific circumstances, there is a role for endoscopic ultrasound, laparoscopy and angiography.

After resection patients are followed up with protocols involving clinical examination and/or surveillance imaging, based upon relapse risk stratification by means of histopathological criteria of the resected tumour. 15,32 Preliminary results from one randomised, placebo-controlled Phase III trial suggest that adjuvant therapy with imatinib (400 mg/day for 1 year) increases recurrence-free survival following resection, and it is therefore suggested that adjuvant imatinib may have an important role to play in the prevention of recurrence of GISTs after resection. 33 The results of other similar adjuvant trials are awaited. 15 At present imatinib is licensed for adjuvant treatment of patients who are at a significant risk of relapse,34 but although Scottish guidelines recommend adjuvant imatinib (400 mg/day) in patients considered to be of moderate or high risk of relapse, according to histopathological criteria,15 a National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) Technology Appraisal for this indication is still ongoing,35 and it is acknowledged that, until more data are available from ongoing adjuvant studies, there is still uncertainty regarding the optimal duration of treatment, and also the subgroups of patients who may or may not benefit from adjuvant therapy. The use of imatinib as an adjuvant therapy may have implications, for example with regard to the development of drug resistance, for the subsequent systemic treatment of GISTs upon recurrence. 36

Studies are ongoing to determine the role of imatinib as preoperative therapy in resectable tumours. 37 Nevertheless, the use of imatinib preoperatively to downstage tumours from unresectable to resectable is considered safe and clinically worthwhile. 15 Similarly, preoperative imatinib has also been recommended to limit the extent and (accordingly) morbidity of resection in specific circumstances, for example to facilitate sphincter-sparing resection in rectal GISTs.

Management of unresectable and metastatic disease

Conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy and radiotherapy are ineffective in the treatment of advanced GISTs. Similarly, initial debulking surgery is not recommended unless there is an immediate clinical need, such as to remove an obstructing tumour.

Imatinib (Glivec®, Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK) is a rationally designed small molecule inhibitor of several tyrosine kinases, including KIT and PDGFRA, and has provided the first clinically effective systemic therapy for GISTs. The European licence for imatinib was based on a Phase II study of 147 patients who were randomised to receive imatinib at either 400 or 600 mg orally taken once daily. 38 The treatment was well tolerated, objective response rate was the primary efficacy outcome and an overall partial response (PR) rate of 67% was demonstrated with no difference between treatment arms. Long-term results revealed median survival of 57 months for all patients. 39 A concurrent study investigated dose escalation and established 800 mg daily as the maximum tolerated dose. 40 Phase III trials performed both in Europe and Australasia [European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) 62005 study], and in North America (S0033 Intergroup study), confirmed the efficacy of imatinib in a larger patient population, and established the starting dose of 400 mg orally per day. 41,42

Primary resistance to imatinib is uncommon, but acquired resistance is highly likely, and manifest clinically by the observation of disease progression. 41–45 Guidelines suggest that patients should have a CT scan every 3 months while on therapy. 15 Measurement of response by conventional criteria, such as Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), based on objectively measured changes in tumour size, may not occur, or may happen only after many months of treatment. This means that definitive evidence of patient response, and therefore clinical benefit, can be difficult to ascertain (at least initially). This has been addressed by the development of alternate methods of GIST response assessment, such as the ‘Choi criteria’ based upon tumour density as well as tumour size. 46,47 Similarly, fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) has demonstrated some efficacy in predicting early response to imatinib therapy,48 although it should be noted that PET scanning is not widely available in the UK as very few NHS centres have access to this technology.

In addition, the assessment of progression of GISTs may be problematic if based on RECIST-based tumour size criteria, as tumour liquefaction (cystic degeneration) can occur, which may give the appearance of progressive disease (PD) although the tumour is actually responding. 47 Accordingly, it is recognised that experienced radiologists should assess CT scans before confirming progression.

It has been demonstrated that interruption of treatment results in rapid disease progression in many patients with advanced GISTs. 45 This includes patients with disease progression in whom a symptomatic worsening or ‘flare’ has been described. 49 Therefore, continuation of imatinib in these patients has been common practice despite progression, as part of best supportive care (BSC).

Several studies have reported further disease control after progression on an initial imatinib dose of 400 mg orally per day with dose escalation of imatinib to 800 mg orally per day, and this has also become common practice. 39,44 However, it should be noted that current NICE guidelines for imatinib do not actually recommend dose escalation for patients with unresectable and/or metastatic GISTs who progress on an initial dose of 400 mg/day. 50

Recently, sunitinib (Sutent®, Pfizer UK), another molecular-based treatment for GIST, became available, and has been approved by NICE for patients with unresectable and/or metastatic GIST who have progressed on treatment with imatinib. 51 The NICE advice follows a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre Phase II trial in which 312 patients, who were resistant or intolerant to imatinib, received either sunitinib (50-mg starting dose in 6-week cycles; 4 weeks on and 2 weeks off treatment) or placebo;52 the trial was unblinded early when interim analysis showed a significantly longer time to tumour progression (the primary end point) with sunitinib.

To date, no randomised trial has been conducted comparing imatinib and sunitinib. One had been planned but was stopped owing to poor recruitment. 53 As new options for management of patients with unresectable and/or metastatic GIST have developed since the initial 2004 publication of NICE guidance for GIST treatment with imatinib, a review of the evidence available on treatments currently used in clinical practice is required.

Current service cost and anticipated costs associated with the intervention

As GIST affects mostly the middle-aged and older age population, the loss of productivity from the middle-aged population suffering from GIST is of concern. The median age of the GIST patients was found to be between 50 and 60 years,22,23 and incidence of GIST was found to increase with increase in age. 54 The cost of different treatment strategies needs thorough investigation in a robust economic evaluation.

Treatment with imatinib per patient within an NHS setting has been estimated at £18,896 and £24,368 annually for patients on 400 and 600 mg/day, respectively. 55 Other associated annual costs of treatment (including the treatment of adverse events) were estimated at £2730 (price year not stated). Estimates from previous disease models suggest that in 2 years it would cost the NHS approximately £31,160 to treat a patient with imatinib, and for 10 years this figure would be £56,146 (2002 price year). 54,55 Costs would differ when patients who fail to respond to imatinib are provided with higher doses or alternative treatments (e.g. sunitinib). 50

The costs of treating patients with unresectable and/or metastatic GIST using imatinib were estimated at between £1557 and £3115 per month per patient, resulting in a cost to the NHS (England and Wales) of between approximately £5.6M and £11.2M per year (2002 price year). 55 Another study estimates that the total costs over 10 years for managing GIST patients with molecularly targeted treatment would be between £47,521 and £56,146 per patient compared with a cost of between £4047 and £4230 per patient when managed with BSC (price year not stated). 54

Variation in service and uncertainty about best practice

The treatment of GISTs after progression on imatinib is generally decided on a case-by-case basis by multidisciplinary teams, and the alternatives are dose escalation of imatinib, sunitinib at 50 mg/day (4 weeks out of 6 weeks) or, alternatively, BSC only (although due to the ‘symptomatic flare’ already mentioned this may include continuation of imatinib at 400 mg/day). Many clinicians advocate initial dose escalation of imatinib and then consider sunitinib on subsequent progression, but there will be variation in clinical practice depending on the specific needs of individual patients.

Description of technology under assessment

Summary of intervention

Imatinib

Imatinib (Glivec) is a rationally designed small molecule inhibitor of several oncogenic tyrosine kinases: c-Abl, PDGFRA and the KIT tyrosine kinases. Its therapeutic activity in GISTs relates to inhibition of KIT, although in cases with no KIT mutation the inhibition of PDGFRA is likely to be of therapeutic importance. 2 Imatinib is a derivative of 2-phenylaminopyrimidine, and a competitive antagonist of adenosine triphospate (ATP) binding, which blocks the ability of KIT to transfer phosphate groups from ATP to tyrosine residues on substrate proteins. This interrupts KIT-mediated signal transduction, which is the key pathogenic driver for many GISTs. The inhibitory activity of imatinib on KIT is highly selective, and minimal inhibition of other kinases that are important in normal cell function occurs, thereby affording a good toxicity and safety profile.

Imatinib is licensed and approved for use in the UK NHS in KIT-immunoreactive positive advanced/unresectable GISTs. 50,57

Sunitinib

Sunitinib malate (Sutent), is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting KIT, PDGFRA, all three isoforms of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF-1R) and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor receptor. 58 Sunitinib activity in GISTs may predominantly relate to inhibition of KIT and/or PDGFRA, and ex vivo investigation has shown that sunitinib can inhibit the kinase activity of KIT molecules harbouring secondary mutations conferring imatinib resistance. 59 However, the potent antiangiogenic activity of sunitinib as a consequence of strong VEGFR inhibition may also be important for clinical activity in GISTs.

Best supportive care

Best supportive care is not well defined or standardised, and can also be referred to as ‘supportive care’ or ‘active symptom control’. 55 It usually involves interventions to manage pain and treat fever, anaemia (due to GI haemorrhage) and GI obstruction,50 and can include palliative measures. 60 A Cochrane review of supportive care for patients with GI cancer defined supportive care as ‘the multi-professional attention to the individual’s overall physical, psychosocial, spiritual and cultural needs’. 61 It was argued that this type of care should ethically be made available to all treatment groups, meaning that treatment with imatinib or sunitinib could not be provided without concomitant supportive care as well in clinical practice for patients with GIST, although it is possible that treatment with BSC could be provided without additional drug treatment with either imatinib or sunitinib. It should be noted that the amount of care required as part of BSC is likely to increase as the disease progresses and symptoms become worse.

Identification of important subgroups

The differential benefit from imatinib and sunitinib in subgroups of patients with GIST, whose tumours have different primary and secondary KIT mutations, has suggested possible benefits in personalising first- and second-line therapy.

Primary KIT mutations are those that are pathogenic and present before any systemic treatment, while secondary mutations are those that have been identified after imatinib treatment and confer resistance to imatinib. Identification of secondary mutations requires rebiopsy of tumours, and studies have suggested that the emergence of secondary (or acquired) imatinib resistance is polyclonal, so patients with GIST may acquire more than one secondary KIT mutation. 62

A meta-analysis of 1640 patients revealed that patients with KIT exon 9 primary mutations have a better outcome if treated at the escalated dose of 800 mg daily. 63 Similarly, objective response rates to imatinib 400 mg/day are higher in patients with exon 11 primary mutations than in those with exon 9 mutations, or those with no detectable KIT or PDGFR mutation. 14,41 Therefore, advanced GIST patients with exon 9 mutations may benefit from immediate dose escalation of imatinib, and the benefit of dose escalation on progression may be more significant in this subgroup of patients and thereby have implications for therapeutic alternatives and choices on progression in different groups of patients defined by KIT mutations. Recent studies have indicated that plasma monitoring in GIST patients could assist clinicians’ decision-making with regard to whether or not dose escalation of imatinib is required for particular patients, including those with mutations in KIT. 64–66

Secondary mutations in KIT exons 13, 14, 17 and 18 are associated with acquired resistance to imatinib. 43 Sunitinib activity after progression on imatinib has been demonstrated in GIST patients with imatinib resistance conferring secondary KIT mutations. 62 However, both the primary KIT mutation genotype and secondary KIT mutations may influence the clinical benefit effect of sunitinib in GIST patients who have progressed on imatinib. 62 Interestingly, in contrast to imatinib, greater benefit from sunitinib (after imatinib failure) is seen in patients with primary exon 9 mutations or wild-type KIT as opposed to primary exon 11 mutations. 62 However, it is not clear how dose-escalated imatinib (800 mg/day) compares with sunitinib in patients with primary exon 9 KIT mutations. While the polyclonal emergence of resistance is an investigational and clinical challenge, it appears that GIST patients with secondary KIT mutations associated with acquired imatinib resistance in exons 13 or 14 (which involve the KIT–ATP binding pocket) appear to gain greater clinical benefit from sunitinib after imatinib failure than those patients with exon 17 or 18 imatinib resistance secondary mutations (which involve the KIT activation loop). 62

Changes in FDG (fluorodeoxyglucose) avidity of GISTs measured by FDG-PET occur earlier than anatomical changes in GISTs and so may also have a role as a predictive biomarker for imatinib response, and also for detecting early disease progression49 in the future as the technology becomes more widely available in NHS settings.

Current usage in the NHS

Current practice is to commence patients on imatinib 400 mg/day, and on confirmed disease progression the options are dose escalation of imatinib up to 800 mg/day or sunitinib, or BSC only. Practice is variable, and decided on a case-by-case basis. Some clinicians proceed with dose escalation of imatinib initially and then, on further progression, use sunitinib. Some guidelines and clinicians advocate returning to imatinib for symptomatic benefit, when there are no other therapeutic options, and the cessation of imatinib in the absence of alternative treatment options is not recommended owing to the tumour flare phenomenon, with rapid deterioration in symptoms observed in some patients.

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Decision problem

Specific information on the population, interventions, comparators and relevant outcomes considered for this review are discussed in detail in Chapter 4 (see Identification of studies).

Until the licensing of imatinib, the prognosis for people with unresectable and/or metastatic GISTs was poor. 19 Since 2002, the clinical effectiveness of treatment for GIST with imatinib at a dose of 400 mg/day has been well documented. 50,55 There is also clinical trial evidence showing that patients with unresectable and/or metastatic GIST can also respond to higher doses of imatinib, up to a maximum tolerated dose of 800 mg/day,40 and that patients with different exon mutations in the KIT gene may differ in their response to imatinib at both standard and escalated doses. 14

Guidance from NICE does not currently recommend the prescription of escalated doses of imatinib upon progression on the standard 400 mg/day dose,50 although it is common in clinical practice. 15,32 Most of the evidence relating to dose-escalated imatinib comes from randomised trials where participants were randomised to doses greater that 400 mg/day, as opposed to receiving these higher doses upon disease progression on the 400 mg/day dose. However, evidence suggests that tolerability of higher doses may depend on the extent of prior exposure to the drug,66 and if in clinical practice escalated doses are prescribed only upon progression, these trial data may not provide reliable estimates of response, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), quality-of-life effects or the extent of adverse event occurrence. In addition, if patients with unresectable and/or metastatic GIST are likely to attain different levels of clinical benefit from different imatinib doses then clinicians’ decision-making on appropriate dosages for individual patients should be informed by the best available evidence.

The development of imatinib has represented a paradigm shift in the treatment of unresectable and/or metastatic GIST, as, prior to its introduction onto the market, the only available treatment remaining for this population group was BSC, which, given the severity of this disease, represents essentially palliative intervention. Since the introduction of imatinib, other new treatments for unresectable and/or metastatic GIST have become available, including sunitinib, which has been recommended by NICE as the second-line treatment for the population of interest, after failure on treatment with imatinib. 51 As there are now various options available for treating unresectable and/or metastatic GIST, it is therefore necessary to review the available evidence on imatinib at escalated doses, when compared with sunitinib, for patients with unresectable and/or metastatic GIST, whose disease has progressed on the standard imatinib dose of 400 mg/day.

Overall aims and objectives

The aim of this review was to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of imatinib at escalated doses (i.e. 600 or 800 mg/day) within its licensed indication,67 for the treatment of patients with unresectable and/or metastatic GISTs, who have progressed on imatinib at a dose of 400 mg/day.

The objectives of this review will help facilitate decision-making on the most appropriate treatment(s) for patients with unresectable and/or metastatic GIST who have progressed on imatinib at a dose of 400 mg/day, by:

-

conducting a systematic review of the evidence available on the clinical effectiveness of imatinib at dosages of 600 or 800 mg/day compared with sunitinib and/or BSC

-

conducting a systematic review of the cost-effectiveness of imatinib at dosages of 600 or 800 mg/day compared with sunitinib and/or BSC

-

analysing available outcome data for particular subgroups of interest (e.g. patients with different KIT mutations) in order to establish any differences in clinical effectiveness for specific groups

-

developing an economic model to compare the cost-effectiveness and cost–utility of imatinib at a dose of 600 or 800 mg/day with those of sunitinib (within its recommended dose range) or BSC only.

This report contains reference to confidential information provided as part of the NICE appraisal process. This information has been removed from the report and the results, discussions and conclusions of the report do not include the confidential information. These sections are clearly marked in the report.

Chapter 3 Critique of the manufacturer submission

The manufacturer of imatinib (Novartis) did not provide an economic analysis in their submission, stating that, owing to the limited amount of data available from the key clinical studies and the dearth of data comparing imatinib dose escalation with sunitinib and BSC, they were unable to submit a sufficiently robust economic analysis that met the scope for the appraisal. However, they did provide a summary of clinical evidence and implications for the economic analysis. With the exception of the Executive Summary section, and most of the References section, a large proportion of the submission document was highlighted as commercial in confidence (CiC). Electronic copies of all the papers cited in the References section, including two labelled as CiC by the manufacturer, were provided. Apart from both of the CiC documents, these studies had already been retrieved by our searching process and are discussed in Chapter 4.

Of the two CiC reports provided, one (CiC information has been removed) was a report on the randomised, Phase II, B2222 trial comparing imatinib at doses of 400 and 600 mg/day. Patient data from this trial that are relevant to this review have since been published by Blanke et al. 39 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. The remaining CiC report (CiC information has been removed) provided a meta-analysis of data from the randomised, Phase III, intergroup S0033 trial comparing imatinib at doses of 400 and 800 mg/day, and the randomised, Phase III, EORTC-ISG (Italian Sarcoma Group)-AGITG (Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group) trial, also comparing imatinib at these doses. Crossover data from the S0033 trial have been published separately,41,68 as have crossover data from the EORTC-ISG-AGITG trial. 44 (CiC information has been removed.)

(CiC information has been removed.) All relevant results pertaining to the population of interest for this review have been provided in Chapter 4(Assessment of clinical effectiveness). (CiC information has been removed) but as more recent results for the study population of interest have been published, only study characteristics information was used in Chapter 4 of this review.

The key points made in the manufacturer submission were as follows:

-

The limited number of data available from the key clinical studies and the paucity of data comparing imatinib dose escalation with sunitinib and BSC prevent, in the opinion of the manufacturer, the submission of a sufficiently robust economic analysis which meets the scope of the appraisal.

-

There are currently no head-to-head trial data comparing imatinib with sunitinib.

-

Sunitinib represents a third-line treatment, rather than second line as per the scope of the evaluation, making it difficult, if not impossible, to conduct a robust and plausible indirect comparison of the two technologies. UK National GIST Guidelines56 recommend that changing treatment to sunitinib should be considered only after patients have shown progression on imatinib dose escalation.

-

Since the publication of TA86 clinical practice has evolved to consider dose escalation to a daily dose of 600 or 800 mg, when patients progress on the standard daily dose of 400 mg, and this change in clinical practice is reflected within UK National GIST Guidelines. 56

-

(CiC information has been removed.)

-

(CiC information has been removed.)

-

(CiC information has been removed.)

Chapter 4 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Methods for reviewing effectiveness

Identification of studies

Extensive sensitive electronic searches were conducted to identify reports of published and ongoing studies on the clinical effectiveness of imatinib. The searches were also designed to retrieve clinical effectiveness studies of the comparator treatments (sunitinib and BSC). In addition, reference lists of retrieved papers and submissions from industry and other consultees were scrutinised to identify additional potentially relevant studies.

The databases searched were MEDLINE (1966 – September, week 3, 2009), MEDLINE In-Process (25 September 2009), EMBASE (1980 – week 39, 2009), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (September 2009), Science Citation Index (SCI) (2000 – 26 September 2009), BIOSIS (2000 – 24 September 2009), Health Management Information Consortium (September 2009), and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register for primary research and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (October 2009), the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) (Issue 3, 2009) and the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database (October 2009).

Ongoing and recently completed trials were searched in the following databases: current research registers, including Clinical Trials, Current Controlled Trials (CCT), National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Portfolio, World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations (IFPMA) Clinical Trials and the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) database. Recent conference proceedings of key oncology and GI organisations, including the American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO), European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and the European Cancer Organisation, were screened. Websites of the GIST Support International, and the drug manufacturers Pfizer and Novartis were also scrutinised.

Full details of the search strategies used are reproduced in Appendix 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Types of studies

An initial scoping search suggested that there would be few studies looking specifically at either of the named interventions (imatinib 600 or 800 mg/day). Therefore, we considered all of the following types of studies for the assessment of clinical effectiveness:

-

randomised controlled trials (RCTs)

-

non-randomised comparative studies, and

-

case series.

If the number of studies meeting our inclusion criteria was sufficiently large, consideration was to be given to limiting them by type of study design, and also possibly other factors (e.g. sample size). Additionally, we planned to exclude non-English language papers, and/or reports published as meeting abstracts, if the evidence base of English language and/or full-text reports was sufficiently large.

Types of participants

Participants considered were people with KIT (CD117)-positive unresectable and/or metastatic malignant GISTs, whose disease had progressed on treatment with imatinib at a dose of 400 mg/day. If sufficient evidence was available, subgroup analysis was to be undertaken for those patients with different mutations of CD117, as there is some evidence to suggest this may affect their response to escalated doses of imatinib14,41,63 (see Chapter 1, Identification of important subgroups). In addition, subgroup analysis was also to be undertaken on methods used to identify response or resistance (e.g. FDG-PET or CT scanning) and the use of imatinib in a neoadjuvant or adjuvant setting for patients with previously resectable GIST, where sufficient data were available.

Types of intervention and comparators

The interventions considered were imatinib at escalated doses of 600 and 800 mg/day, respectively, being prescribed with BSC. The comparators considered were sunitinib, prescribed within its recommended dose range of 27–75 mg and provided with BSC, and BSC only. As previously stated, BSC is defined as ‘the multi-professional attention to the individual’s overall physical, psychosocial, spiritual and cultural needs’. 61

Types of outcomes

For the assessment of clinical effectiveness, the following outcomes were considered:

-

overall response

-

overall survival

-

disease-free survival

-

progression-free survival

-

time to treatment failure

-

health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [e.g. European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) scores]

-

adverse effects of treatment (e.g. number of discontinuations due to adverse events).

Exclusion criteria

We excluded studies of animal models, preclinical and biological studies, reviews, editorials, opinions, case reports and reports investigating technical aspects of the interventions.

Data extraction strategy

The titles and abstracts (where available) of all records identified by the search strategy were screened by two reviewers independently. Full-text copies of all potentially relevant reports were retrieved. The full-text reports were assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria by two reviewers independently. Full-text papers and conference abstracts were assessed using a screening form that was developed and piloted for this purpose. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus or arbitration by a third party. A copy of the screening form used can be found in Appendix 2.

A data extraction form was developed and piloted (Appendix 3). One reviewer extracted details of the study design, participants, intervention, comparator and outcomes, and a second reviewer checked the data extraction for accuracy. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus or arbitration by a third party.

Quality assessment strategy

Two reviewers independently assessed the methodological quality of the included full-text studies. Non-randomised comparative studies were assessed using an 18-question checklist, with the same checklist minus four questions used to assess the methodological quality of case series. This checklist for non-randomised studies and case series was adapted from several sources, including the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination’s guidance for those carrying out or commissioning reviews,69 Verhagen et al. ,70 Downs and Black,71 and the Generic Appraisal Tool for Epidemiology (GATE). It assesses bias and generalisability, sample definition and selection, description of the intervention, outcome assessment, adequacy of follow-up, and performance of the analysis. The checklist was developed through the Review Body for Interventional Procedures (ReBIP). ReBIP is a joint venture between Health Services Research at Sheffield University and the Health Services Research Unit at the University of Aberdeen, and works under the auspices of the NICE Interventional Procedures Programme.

We planned to assess the quality of RCTs using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias. 72 The tool addresses six specific domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other issues. Each quality assessment item had three possible responses: ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘unclear’, with space for additional comments. Disagreements between reviewers over study quality were to be resolved by consensus and, if necessary, arbitration by a third party. Abstracts were not quality assessed because they were considered unlikely to provide sufficient methodological information to enable an accurate assessment of study quality. Methodological quality did not form part of the criteria for the inclusion or exclusion of studies. A copy of the quality assessment tool can be found in Appendix 4.

Data analysis

The type of data analysis considered was dependent on the number of studies meeting the specified inclusion criteria, and study design. Where a quantitative synthesis was considered inappropriate or not feasible, it was planned that a narrative synthesis of results would be provided instead.

For relevant outcomes from randomised comparisons, it was decided that meta-analysis (where appropriate) would be used to estimate a summary measure of effect. Dichotomous outcome data for the overall response outcome would be combined using the Mantel–Haenszel relative risk (RR) method, and continuous outcomes by using the inverse variance weighted mean difference (WMD) method. For both of these estimates, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values would also be calculated. Chi-squared tests and I2-statistics were to be used to explore statistical heterogeneity across studies, with possible reasons for heterogeneity explored using sensitivity analysis. Where no obvious reason for heterogeneity was found, the implications would be explored using random effects methods.

The pooled weighted ratio of median survival would be derived for OS, disease-free survival and PFS. The hazard ratio (HR) is the most appropriate statistic for time-to-event outcomes (i.e. for time to treatment failure). If available, the HR would be extracted directly from the trial publications, but if not reported it would be extracted if possible from other available summary statistics or from data extracted from published Kaplan–Meier curves using methods described by Parmar et al. 73 A pooled HR from available RCTs could then be obtained by combining the observed (O) minus expected (E) number of events and the variance obtained for each trial using a fixed effects model. 74 A weighted average of survival duration across studies was to be calculated. The chi-squared test for heterogeneity was to be used to test for statistical heterogeneity between studies.

Where no RCT data were available, but non-randomised studies had reported relevant data for survival outcomes, assessment of the risk of bias and heterogeneity was to be undertaken using meta-regression analysis.

It was expected that few studies, if any, would report direct comparisons of the intervention and comparators, so (depending on feasibility and appropriateness) it was decided that, where non-randomised evidence was available, meta-analysis models would be used to model survival rates for interventions and comparators. A ‘cross-design’ approach was to be adopted to allow non-randomised evidence to be included, while avoiding the strong assumption of the equivalence of studies. Evidence suggests that this approach would allow data from RCTs, non-randomised comparative studies and case series to be included. 75 Differences between treatments for survival outcomes were to be assessed via the corresponding odds ratio and 95% credible intervals. These results are ‘unadjusted odds ratios’, but meta-analysis models adjusting for study type were also to be used. The results from these models produce ‘adjusted’ odds ratios. 76 Winbugs software (MRC Biostatics Unit, Cambridge, UK) was to be used for the analysis.

Any reported data on adverse effects of treatment and quality of life (QoL) that were collected were to be combined, using standardised mean difference, where appropriate.

In addition, and taking into account the type of evidence, the feasibility of using a mixed treatment comparison model for indirect comparisons was to be considered.

Results

Number of studies identified

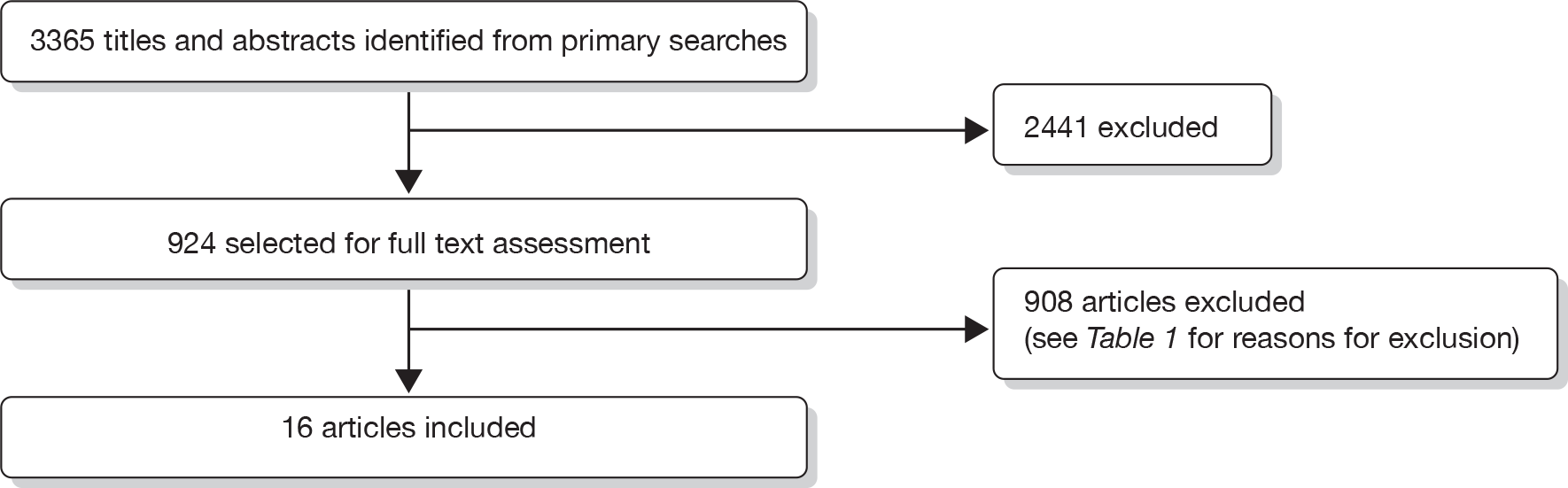

We identified 3365 records from the primary searches for the review of clinical effectiveness. After title and abstract screening, 2441 articles were considered not to be relevant for this review and were excluded. The full-text papers of 924 records were obtained and screened. One hundred and twenty-three of these full-text papers were non-English language publications. In total, six full-text papers and 10 abstracts reporting four separate clinical trials and one additional retrospective cohort met our inclusion criteria. An additional 49 papers were retained for background information. The reasons for exclusion of assessed full-text papers are given in Table 1. A flow diagram of the screening process is outlined in Figure 1. Information on the reasons for excluding individual studies is provided in Appendix 5.

| Reason for exclusion | No. of studies excluded |

|---|---|

| Patient had resectable GIST | 24 |

| Outcomes not reported separately for patients with GIST | 10 |

| < 10 patients in relevant study population | 46 |

| Imatinib dose is 400 mg/day | 13 |

| No/insufficient data reported for escalated dose patients | 65 |

| No imatinib dose reported | 84 |

| No relevant interventions | 15 |

| Treatment not evaluated | 11 |

| No outcomes of relevance | 10 |

| Other reason | 61 |

| 339 | |

| Retained for background information | 49 |

| Review articles | 169 |

| Letter/editorial/correspondence/symposium articles/meeting reports/expert views/comments | 117 |

| Case study/case series < 10 patients | 64 |

| Non-English language exclusions | 123 |

| Not obtained | 47 |

| Total | 908 |

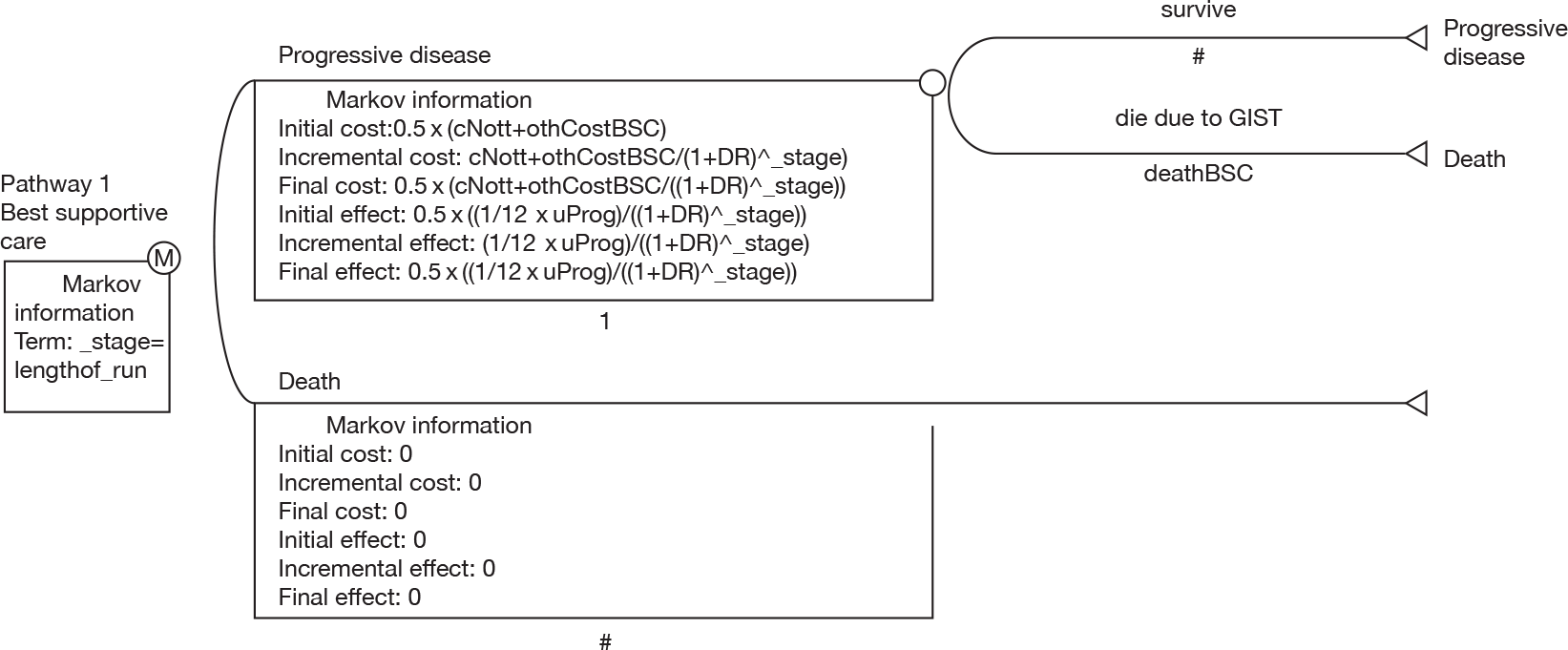

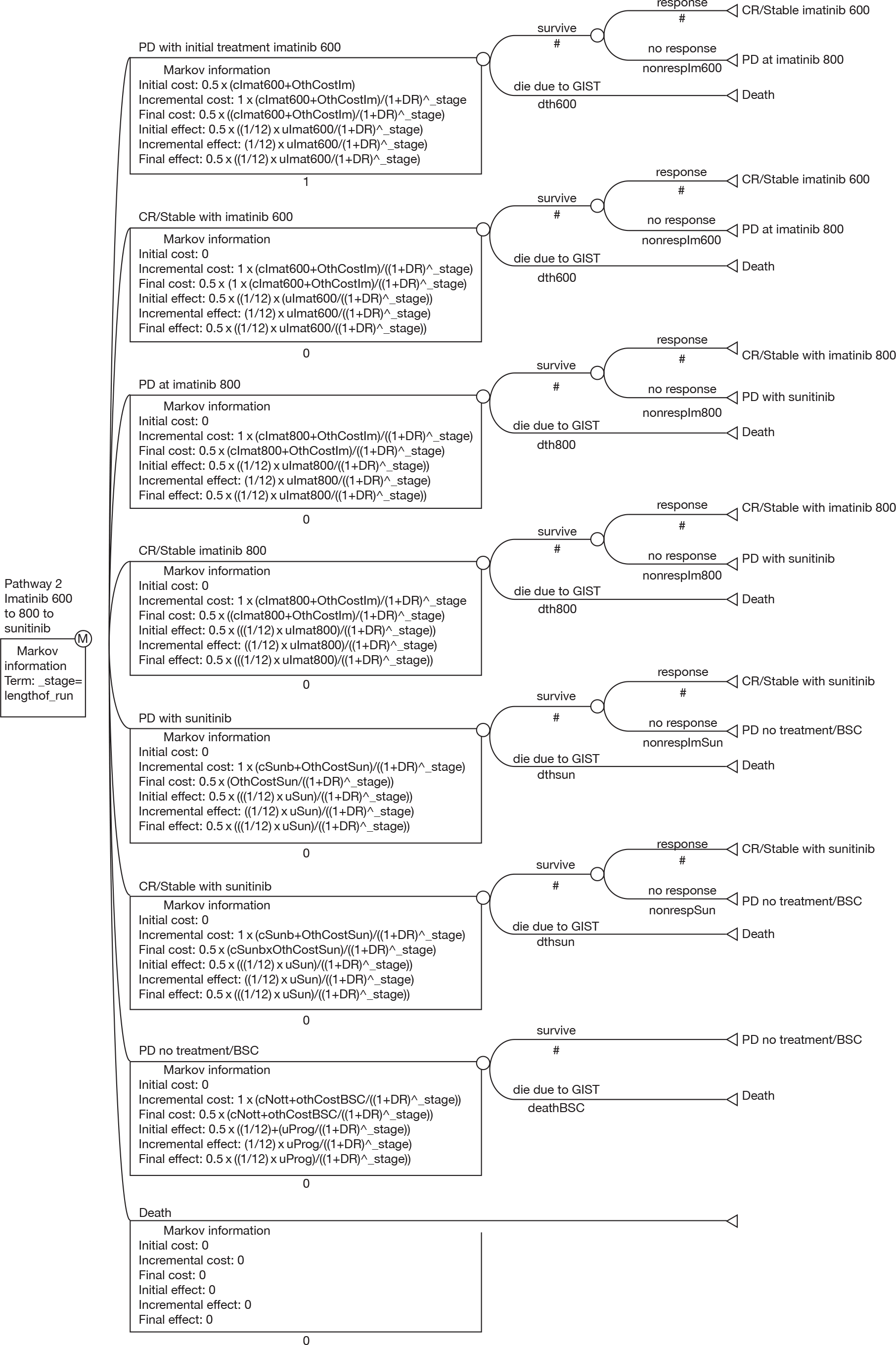

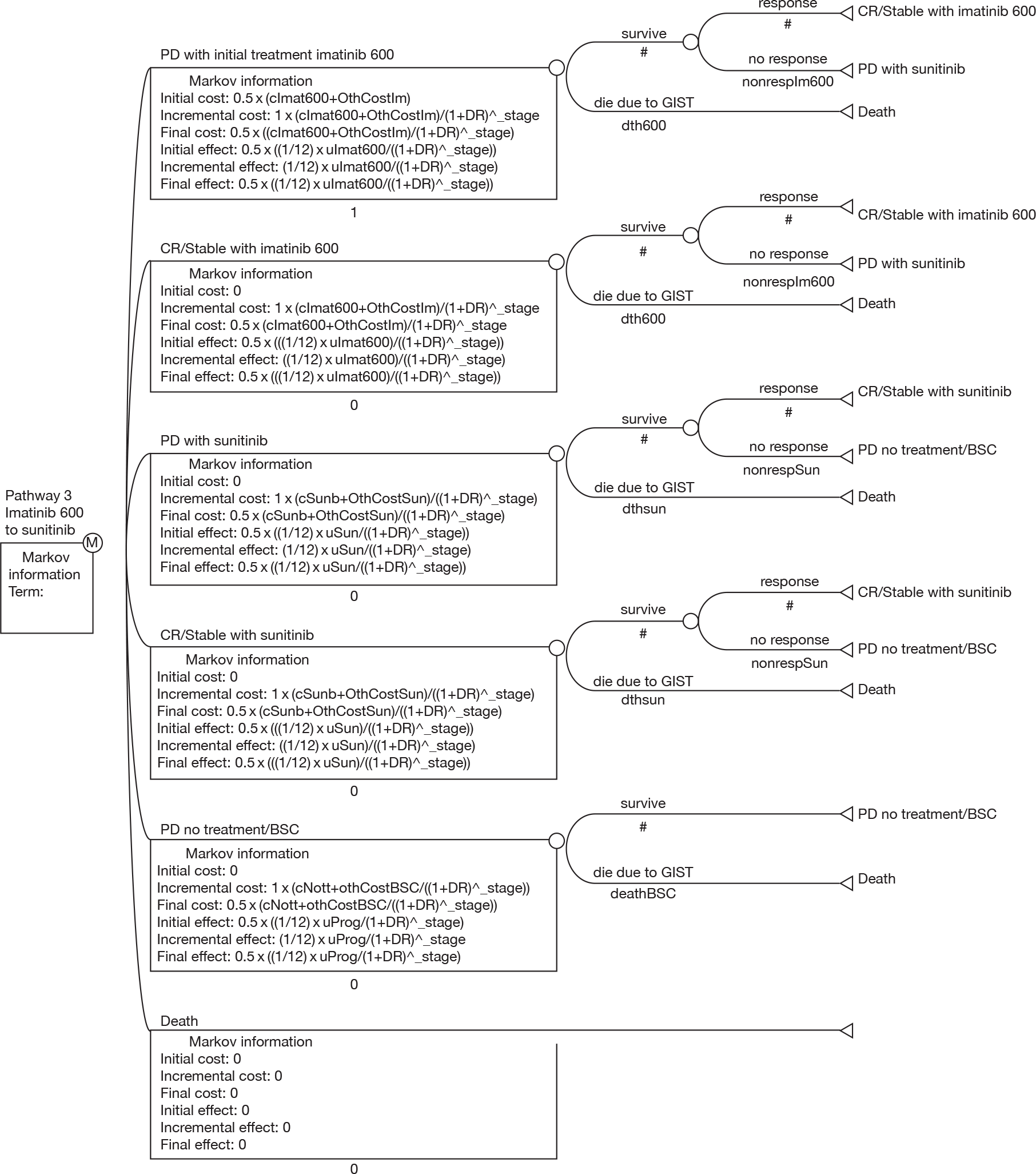

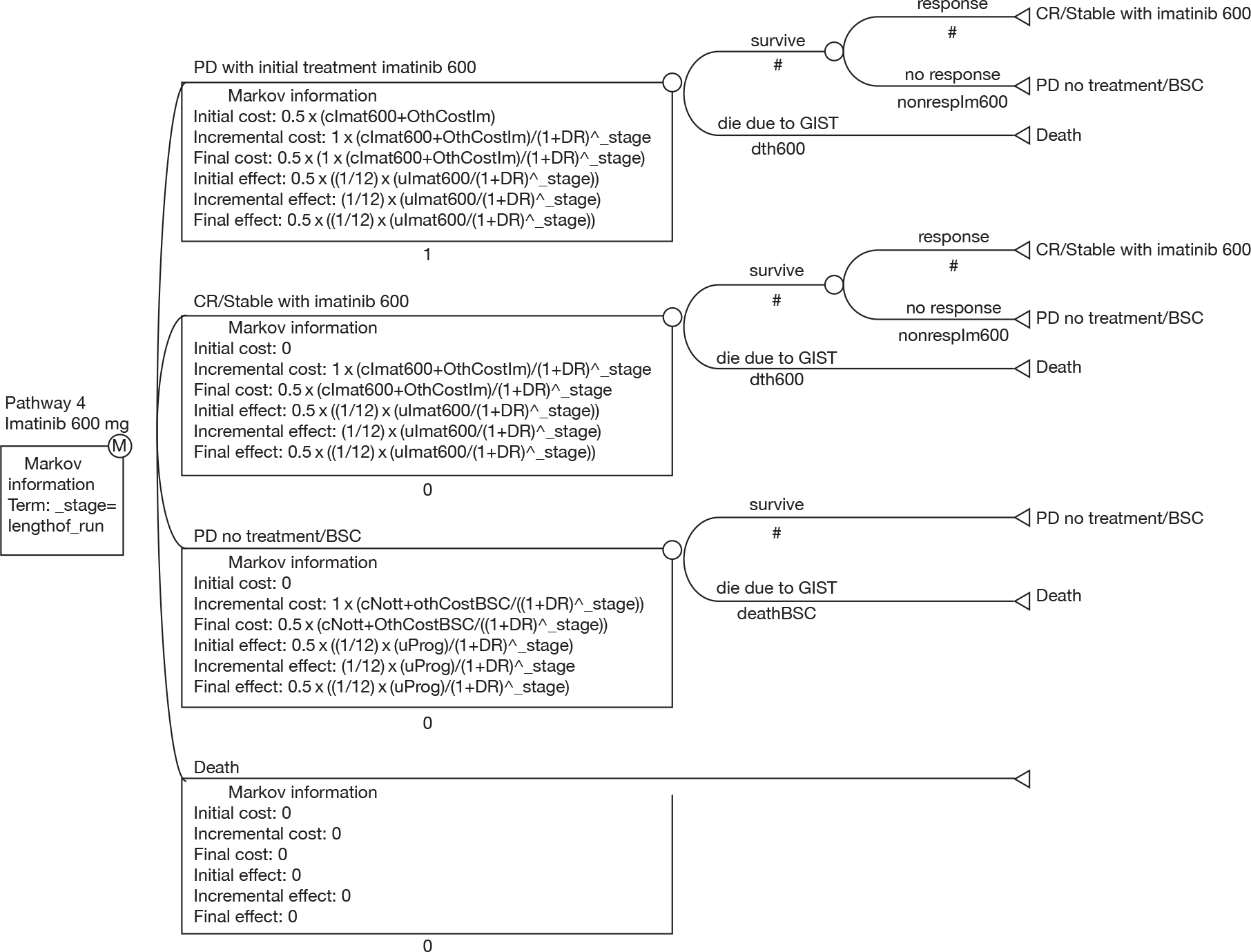

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram outlining the screening process for the review of clinical effectiveness.

Included studies

See Appendix 6 for a list of studies that were included in the review of clinical effectiveness. We did not identify any RCTs, or non-randomised comparative studies, comparing the effectiveness of escalated doses of imatinib (600 or 800 mg/day) with sunitinib or BSC that met our inclusion criteria. One ongoing trial was identified comparing imatinib and sunitinib. However, this study was stopped owing to poor recruitment. 53 We identified five full-text reports of three randomised trials of imatinib that contained relevant data for this review. 14,38,39,41,44 The studies by Zalcberg et al. ,44 Blanke et al. (S0033)41 and Blanke et al. (B2222)39 were designated as the primary reports for the EORTC-ISG-AGITG (62005) trial, the S0033 trial and the B2222 trial, respectively. The study by Debiec-Rychter et al. 14 met our inclusion criteria and provided additional information from the EORTC-ISG-AGITG (62005) study on response following crossover, while the study by Demetri et al. 52 met our inclusion criteria and provided interim data from the B2222 trial on response following crossover.

An additional three abstracts were identified, with two68,77 reporting interim data for the S0033 trial, and one reporting interim data for the EORTC-ISG-AGITG 62005 trial. 78

All of these included studies contained a treatment arm of 400 mg/day, and reported data separately for participants who received an escalated dose of imatinib upon progression at this randomised dose. One additional full-text paper detailing the results of a non-randomised retrospective study by Park et al. 79 was also included. This study met our inclusion criteria as it also provided separate outcome data for patients with metastatic or unresectable GIST, who received escalated doses of imatinib on progression at an initial dose of 400 mg/day.

For the comparator treatment of sunitinib, we identified seven abstract reports meeting our inclusion criteria. All were interim results of an ongoing, open-label sunitinib trial reporting information on participants recruited to the trial following failure at different doses of imatinib, including doses of ≤ 400 mg/day. 80–86 We designated the abstract by Seddon et al. 86 to be the primary report for this trial, as it was thought to contain its most recent results.

For the comparator treatment of BSC, no randomised, non-randomised or case series studies were identified that compared either of the interventions (imatinib at a dose of 600 mg/day or imatinib at 800 mg/day) with BSC, or provided data on relevant outcomes for the population of interest for BSC only. It should be noted that studies published on the clinical effectiveness of BSC prior to the licensing of imatinib18,19 were not eligible for this review as our population of interest was those who had failed on imatinib at 400 mg/day; therefore all studies published prior to the availability of imatinib automatically failed to meet our inclusion criteria because BSC at that time could not possibly have been provided following failure of treatment with imatinib at a dose of 400 mg/day.

Corresponding authors for each of the included trials were contacted in order to determine whether any additional data could be provided specifically for the population of interest (i.e. those participants failing on an imatinib dose of 400 mg/day and receiving either an escalated dose of imatinib 600 or 800 mg/day or, alternatively, sunitinib). For the ongoing, open-label sunitinib study, the corresponding author replied that no further information could be provided as the study was an official, ongoing trial by the manufacturer (Pfizer). For the imatinib trials, in the case of both studies by Blanke et al. 39,41 our requests for information were forwarded to the statistics team involved in the trials. The requested data for the S0033 trial were provided on 17 February 2010. For the study by Zalcberg et al. ,44 a response to our request was received, explaining that an official data request form must be completed. This was submitted, and a further response was received on 9 April 2010 explaining that the data could not be provided until September 2010 (and then only if the request were approved). It was decided not to pursue the request for data further, given the timelines for this project.

Two additional reports (CiC information has been removed) to the ones identified through our search strategy were provided for this review by the manufacturer and have been discussed in Chapter 3, and are also discussed below. Both of these reports were marked as CiC.

Excluded studies

A list of 340 studies, originally identified as potentially relevant but subsequently failing to meet our inclusion criteria, is provided in Appendix 5. The studies were excluded because they failed to meet one or more of the inclusion criteria in terms of the type of study, participants, intervention, comparator or outcomes reported. It should be noted that all full-text screened studies on plasma monitoring, as well as those on the use of FDG-PET technology for evaluating PD, did not meet our inclusion criteria. In addition, the types of participants were limited to an adult population, therefore studies involving children with GIST were excluded. However, it should be noted that the age range provided in the baseline data for the included study by Seddon et al. 86 indicates that at least one child was recruited on to this trial, but, as the median age reported indicates that the majority of patients in this trial were adults, the study was not excluded.

Studies with a relevant population of fewer than 10 patients were also excluded. Changes to our original protocol were reported to NIHR in a progress report submitted on 9 December 2009.

In addition to the included studies identified above, nine studies (reported in 14 papers) reported sufficient information with regard to our inclusion criteria to be considered for potential inclusion in this review, subject to clarification from the study authors regarding specific aspects of the study. Corresponding authors for each of the nine studies were therefore contacted. Responses were received from four corresponding authors (GD Demetri, Ludwig Center at Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center and Sarcoma Center, Boston, MA, USA, 2010; YK Kang, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, 2010; P Rutkowski, Sklodowska-Curie Memorial Cancer Center and Institute of Oncology Department of Soft Tissue/Bone Sarcoma and Melanoma, Warsaw, Poland, 2010; P Wolter, UZ Leuven, Leuven, Belgium, 2010; personal communication). In the cases of two responses, this resulted in the exclusion of the studies (five papers in total) from the review (P Rutkowski, P Wolter, personal communication) In the remaining two studies (four papers), the responses did not result in clarification, as the authors requested that we wait for a further response from them or their colleagues (GD Demetri, YK Kang, personal communication). In the case of correspondence with YK Kang, it was decided that the study by Park et al. 79 could be included in the review without further clarification from the corresponding author.

Of the correspondences that did not result in responses, one e-mail could not be sent successfully87 and the remaining four authors did not respond. 88–91

Characteristics of the included studies

Study characteristics data were available for the four full-text included imatinib studies39,41,44,79 and the primary report of the included sunitinib trial. 86 However, of these studies, only the studies by Zalcberg et al. 44 and Park et al. 79 gave specific baseline information for the crossover subgroup of interest. Therefore, Table 2 provides details of all characteristics information provided for each crossover group, while Table 3 provides details of the same characteristics for all patients in the treatment arms of interest (initial randomisation to a dose of 400 mg/day). In the case of the EORTC-ISG-AGITG trial reported by Zalcberg et al. ,44 relevant study characteristic data for participants initially randomised to the 400 mg/day dose were not available. However, these data were reported in a paper by Verweij et al. 42 for the same trial. The paper by Verweij et al. 42 failed to meet the inclusion criteria for this review as it did not provide any outcome data for patients receiving an escalated dose of 800 mg/day imatinib upon progression at a 400 mg/day dose, but as it provides information on the characteristics of all randomised patients (of whom a proportion went on to receive an escalated dose of 800 mg/day and formed the study population of the included study by Zalcberg et al. 44), it was felt that the baseline data from this excluded study could still be used.

| Zalcberg 200544 | Blanke S003341 | Blanke B222239 | Park 200979 | Seddon 200886 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug assessed | Imatinib | Imatinib | Imatinib | Imatinib | Sunitinib |

| Doses given | 400 mg/day, 800 mg/day | 400 mg/day, 800 mg/day | 400 mg/day, 600 mg/day | 600 mg/day, 800 mg/day | Cycle of 50 mg/day for 4 weeks, then 0 mg/day for 2 weeks |

| Start date | (CiC information has been removed) | December 2000 | July 2000 | June 2001 | Unspecified |

| End date | April 2004 | (CiC information has been removed) | May 2006 | June 2006 | December 2007 |

| Study countries | Australia, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, Singapore, Spain, Switzerland, UK | Canada, USA | Finland, USA | Seoul, South Korea | Unspecified but ‘worldwide’ and ‘multicentre’ |

| No. of institutions involved (no. of countries involved) | (CiC information has been removed) | 148 (2) | 4 (2) | 1 (1) | 96 (33) |

| Length of follow-up at time of analysis | Median of 25 months (maximum of 35 months) | Median of 4.5 years | Median of 63 months (maximum of 71 months) | Median of 8 months (range 1.4–22.3) | Median of 51 weeks (range 0.1–159) |

| Number receiving escalated dose of imatinib after failure of imatinib at 400 mg/day, out of all of those randomised to receive 400 mg/day | 133/473 (28.1%) | 118/345 (34.2%) | 43/73 (58.9%) | 24/24 (100.0%) | NA |

| Number receiving sunitinib after failure of imatinib at ≤ 400 mg/day, out of all of those receiving sunitinib | NA | NA | NA | NA | 351/1117 (31.4%) |

| Included in this analysis | aEORTC-ISG-AGITG42 | Blanke S003341 | Blanke B222239 (CiC information has been removed) | Park 200979 | Seddon 200886 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All those randomised to 400 mg/day | All those who received escalated doses of imatinib on progression at a dose of 400 mg/dayb | All those receiving sunitinib | ||||

| Number included | 473 | 345 | 73 | 24 | 1117 | |

| Age in years: median (range) | 59 (49–67) | 61.9 (18–87) | (CiC information has been removed) | 52 (31–73) | 59 (10–92) | |

| Sex: M/F | 283/190 | 187/158 | (CiC information has been removed) | 18/6 | 665/451 | |

| ECOG/WHO Performance Status Score: | 0 | 217 | (CiC information has been removed) | 4 | 420 | |

| 1 | 191 | (CiC information has been removed) | 18 | 515 | ||

| 2 | 48 | (CiC information has been removed) | 2 | 134 | ||

| ≤ 2 | (456) | 332 | (CiC information has been removed) | (1069) | ||

| > 2 | 17 | 13 | (CiC information has been removed) | 38 | ||

| Missing | 10 | |||||

| Race/ethnicity (n) | NR | NR | NR | |||

| White | 273 | CiC information has been removed) | ||||

| Black | 37 | (CiC information has been removed) | ||||

| Asian | 25 | (CiC information has been removed) | ||||

| Other/unknown | 10 | (CiC information has been removed) | ||||

| Number having previous chemotherapy | 156 (32.9%) | NR | (CiC information has been removed) | 3 (12.5%) | 225 (26.8%) | |

| Number having previous radiotherapy | 26 (5.5%) | NR | (CiC information has been removed) | NR | 78 (7.9%) | |

| Number having prior surgery | 410 (86.7%) | (CiC information has been removed) | 20 (83.3%) | NR | ||

Four of the included trials reported data for imatinib,39,41,44,79 while the remaining trial reported data for sunitinib. 86 Two of the imatinib trials randomised patients to imatinib doses of either 400 or 800 mg/day,41,44 one randomised patients to imatinib doses of either 400 or 600 mg/day,39 and the other was a retrospective study looking only at patients with GIST who had received escalated doses of imatinib at either 600 or 800 mg/day on progression at a dose of 400 mg/day. 79 The sunitinib trial is an ongoing, non-randomised, open-label study and participants are provided with a 6-week cycle of sunitinib, at a dose of 50 mg/day for 4 weeks followed by 2 weeks without the drug. 86

The study start date was reported for three out of the four included imatinib trials39,41,79 and was made available for the study by Zalcberg et al. 44 by the manufacturer (CiC information has been removed). From this it can be seen that the earliest study start date is that of the study (CiC information has been removed)39 (CiC information has been removed). The included sunitinib abstract did not report a start date.

Three out of the four included imatinib studies reported an end date,39,44,79 and in the case of the sunitinib study by Seddon et al. 86 a date was reported for the most recent analysis. The manufacturer also made this information available for the study by Blanke et al. 41 (CiC information has been removed). The ongoing sunitinib trial has the most recent update, while the study by Zalcberg et al. was completed first, in April 2004. 44

With the exception of the study by Park et al. ,79 which involved one centre in one country, all trials were international and multicentre,39,41,44,86 with the sunitinib trial involving the most countries85 and the S0033 trial involving the most institutions. 41 The B2222 trial involved the fewest countries and fewest institutions. 39

The longest length of follow-up occurred in the B2222 trial reported by Blanke et al. ,39 in which patients were followed up for a median of 63 months, while the shortest length of follow-up was found in the study by Park et al. ,79 which gave a median follow-up for the study population of 8 months.

Among the imatinib trials, 133/473 (28.1%), 118/345 (34.2%) and 43/73 (58.9%) of those initially randomised to imatinib at 400 mg/day progressed and were given an escalated dose. 39,41,44 In the imatinib study by Park et al. ,79 the study population comprised only those who were given escalated doses of imatinib so 24/24 (100%) received an escalated dose. In the sunitinib study by Seddon et al. ,86 351/1117 (31.4%) of those who failed on imatinib and were entered into the trial had failed on a dose of 400 mg/day or less. Therefore, the study with the largest relevant population was the sunitinib trial,86 while the study by Park et al. 79 had the smallest study population.

The Park study79 had the youngest population, whereas the S0033 trial41 had the oldest study population. In (CiC information has been removed) studies, the number of male patients was higher than the number of female patients, which concurs with the epidemiological trends in gender associated with this disease (see Chapter 1, Epidemiology and incidence).

(CiC information has been removed) studies reported data on the performance status score of participants, although the study by Blanke et al. for the S0033 trial41 had combined the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status categories 0–2. Doing the same for the remaining studies shows that the vast majority of participants, 456/473 (96.4%), 332/345 (96.2%), (CiC information has been removed), 24/24 (100%) and 1069/1107 (96.6%) in the EORTC-ISG-AGITG trial,42 S0033 trial,41 B2222 trial,39 (CiC information has been removed) Park study79 and the sunitinib trial,86 respectively, had a performance status score of ≤ 2.

(CiC information has been removed.)

In terms of prior treatment, (CiC information has been removed) two reported the number having previous radiotherapy,42,86 (CiC information has been removed). For the imatinib studies, 3/24 (12.5%), 156/473 (32.9%) and (CiC information has been removed) of participants had undergone previous chemotherapy in the study by Park et al. ,79 the EORTC-ISG-AGITG trial42 and the B2222 trial39 (CiC information has been removed), respectively, while 26.8% (225/1117) of patients had received prior chemotherapy in the study by Seddon et al. 86 With regard to radiotherapy, 26/473 (5.5%) of patients in the EORTC-ISG-AGITG trial42 and 78/1117 (7.9%) of patients in the sunitinib trial86 had received prior radiotherapy. (CiC information has been removed) of participants involved in the B2222 trial reportedly had received prior surgery, (CiC information has been removed) while this figure was 86.7% (410/473) for participants in the EORTC-ISG-AGITG trial,42 and 83.3% (20/24) in the study by Park et al. 79

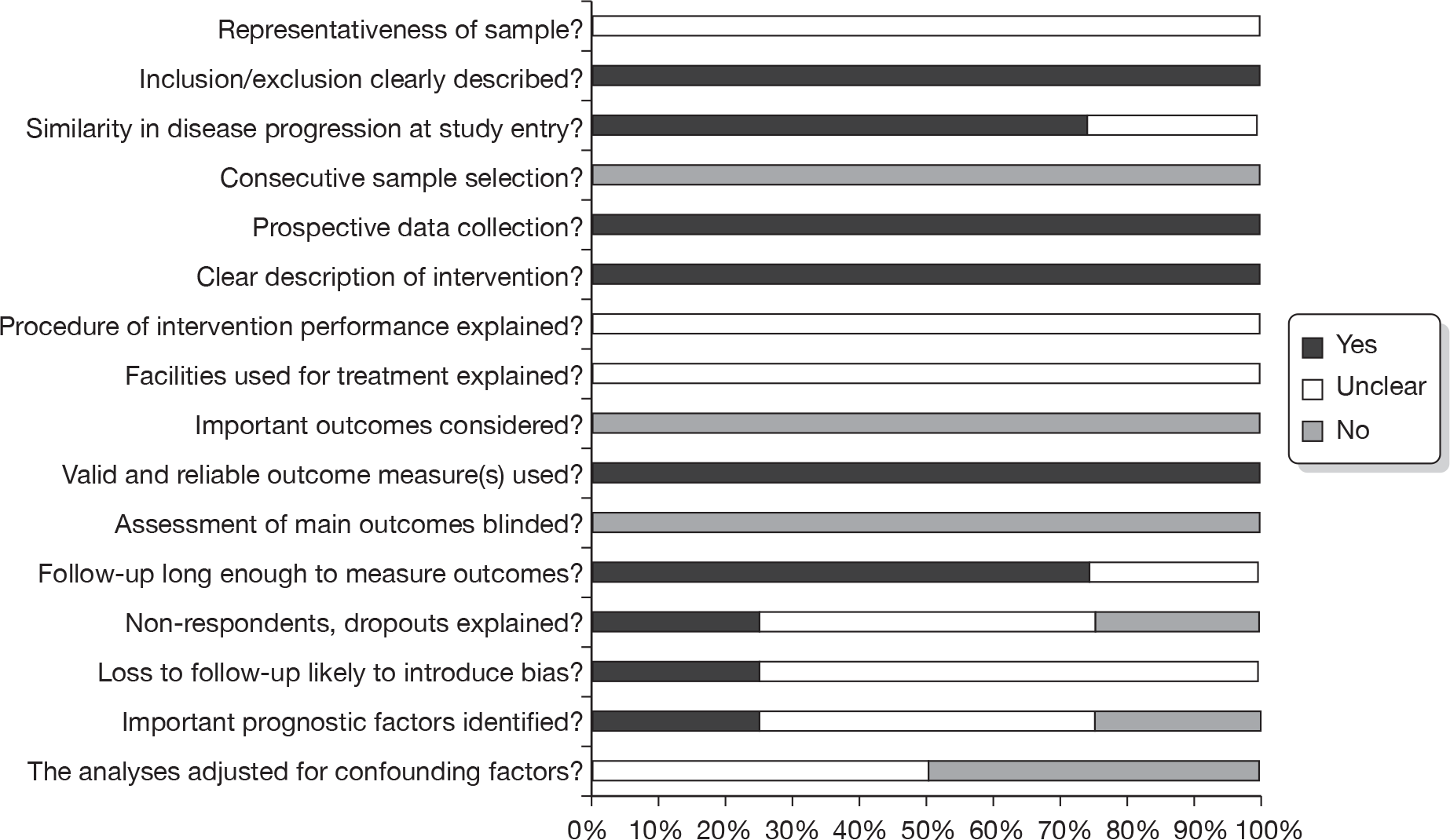

Quality of the included studies

Results of the quality assessment for all four included full-text papers are summarised in Figure 2. No third party arbitration for quality assessment was required. The results of the quality assessment for each individual study are provided in Appendix 9. Three full-text studies assessed for quality assessment were included in the review because they provided crossover data on a subset of patients who were originally randomised to a dose of 400 mg/day, but progressed and received an escalated dose of either 600 mg/day39 or 800 mg/day. 41,44 The fourth study79 was assessed for quality because it included a retrospective analysis of a subgroup of a cohort of patients given treatment with imatinib at 400 mg/day. The subgroup were patients who received escalated doses of 600 mg/day and/or 800 mg/day after progression on the 400 mg/day dose.

FIGURE 2.

Quality assessment results summary.

As the study populations of interest were not the original randomised populations, but the crossover subgroup in three studies,39,41,44 and a subgroup of consecutively treated patients in the remaining study,79 quality was assessed using the checklist for non-randomised studies (detailed in Methods, above). Questions within this checklist that were specific to non-randomised comparative groups (i.e. Q6 and Q16) were not considered applicable to the crossover subset population included in our review, and were therefore not summarised (see Appendix 4).

However, two specific domains were assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias, namely sequence generation and allocation concealment, as these would check for selection bias at trial level.

Sample definition and selection

In three studies39,41,44 the included subgroups of participants were randomised at trial level, but crossover patients were not randomly selected, and so it is unclear the extent to which this group can be considered representative of the relevant patient population (Q1). The other study provided inadequate information to allow judgement of the representativeness of the sample. 79 With regard to the randomisation process at trial level, the studies by Blanke et al. 41 and Zalcberg et al. 44 used methods that adequately generated the allocation sequence to avoid influence of confounding factors while Blanke et al. 39 did not report sufficient data on the randomisation process. In the study by Zalcberg et al. ,44 allocation to treatment was not concealed. Both the B222239 and S003341 studies by Blanke et al. reported inadequate information on allocation concealment. All four studies adequately described inclusion and exclusion criteria (Q2). To consider whether participants entered the study at a similar point in their disease progression, we looked at data on their performance status. Three of the studies39,41,79 involved participants whose performance status at the time of study entry was similar, while the study by Zalcberg et al. 44 included participants with different performance status at study entry (Q3), although most of the participants in all populations had a performance status of < 2, meaning they were ambulatory and awake for at least 50% of their waking hours. None of the studies undertook consecutive selection of patients (Q4). Data were collected prospectively in all of the four studies (Q5).

Description of the intervention

The intervention was adequately defined by all studies (Q7). However, no study provided sufficient data describing supervision of the intervention (Q8) and no information was provided describing the types of staff involved, or the facilities used (Q9).

Outcome assessment

The quality of all four studies was similar in terms of outcome assessment (Q10). None of the studies had considered all of the outcomes of interest, but all reported the objective response of escalated imatinib dosing in patients with GIST, while one41 reported OS and two41,44 measured PFS. The study by Park et al. 79 reported time to progression, and the study by Zalcberg et al. 44 was the only study that also reported adverse events for those on an escalated dose of imatinib. No study reported outcomes related to QoL.

All four studies used valid and reliable outcome measures (Q11), such as RECIST to assess objective response or Kaplan–Meier methods to estimate survival curves, minimising detection bias. Assessment of main outcomes was not blinded in any of the studies (Q12).

Follow-up and attrition bias

Follow-up was considered long enough to detect important effects on outcomes of interest in all but one study where follow-up information was not provided and so this was unclear79 (Q13). Information on those lost to follow-up was either not provided39 (and thereby likely to introduce bias) or not provided at a sufficient level of detail41,44,79 to judge whether those lost to follow-up would be likely to introduce bias (Q14 and Q15).

Performance of the analysis

For both studies by Blanke et al. ,39,41 important prognostic factors such as sex, performance status, neutrophils counts, etc., were investigated and multivariate analyses were performed at trial level but this was not carried out for the subset of patients who crossed over. Similarly, Park et al. 79 identified possible prognostic factors (but did not adjust for confounding factors during analysis). The study by Zalcberg et al. 44 also did not identify any prognostic factors or their effect on analyses, or adjust for confounding factors (Q17 and Q18). Hence we considered the quality of reporting ambiguous in terms of the performance of the analyses.

Assessment of effectiveness

Response

For imatinib at an escalated dose of 600 mg/day following progression at a dose of 400 mg/day, response is reported in the B2222 study by Blanke et al. 39 and the study by Park et al. 79 In the study by Blanke et al. ,39 the median follow-up at this time was 63 months (maximum 71 months), and, at that time, 43 patients had crossed over from 400 to 600 mg/day. Of these 43 patients, 11 (25.6%) showed either PR or stable disease (SD). However, it should be noted that one patient showed response only after further escalation from 600 to 800 mg/day. Some of the 43 patients who crossed over would have had an initial response to 400 mg/day before progression, as only 11 patients in the 400 mg/day arm showed a best response of PD. 39 Interim data for this study population are provided in the study by Demetri et al. ,38 where, after a median follow-up of 288 days (maximum 9 months), nine patients had crossed over, with one showing PR at that point, and two with SD. 38

In the study by Park et al. ,79 median follow-up was eight months (range 1.4–22.3 months) and, of the 12 patients who received an escalated dose of 600 mg/day of imatinib, five (41.7%) showed either PR or SD.

With regard to response data provided by the manufacturer, (CiC information has been removed). As a result, these data from the manufacturer’s submission were not used in our review.

For imatinib at a dose of 800 mg/day following progression at a dose of 400 mg/day, response data are available from the S0033 study by Blanke et al. ,41 the EORTC-ITG-AGITG trial by Zalcberg et al. 44 and the study by Park et al. 79 Of the crossover populations in the S003341 and EORTC trials44 (117 and 133 patients, respectively), three patients in each trial (i.e. six in total) had a PR, while 33 patients in the S0033 trial41 and 36 patients in the EORTC-ISG-AGITG trial44 had SD as a best response. This means that out of a total of 250 patients, 75 (30%) had a response after escalation from 400 mg to 800 mg/day.

Response information from the study by Park et al. 79 did not provide separate data for those with SD and those achieving PR. However, it did state that four out of the 12 patients (33.3%) receiving an escalated imatinib dose of 800 mg/day upon progression at the 400 mg/day dose achieved either PR or SD. 79

Some of the patients receiving dose-escalated imatinib to 800 mg/day would have had an initial response to the 400 mg/day dose, because only 42/345 patients (12.2%) in the S0033 trial 400-mg arm had a best/only response of PD (or ‘early death’),41 and in the study by Zalcberg et al. 44 this figure was 61/473 (12.9%). 42

Interim data for the EORTC-ISG-AGITG trial were provided for a data cut-off point of 7 December 2003, at which point there were 2/97 (2.1%) patients showing a PR, 30/97 (30.9%) patients with SD, and 65/97 (67.0%) patients with PD. 78 Interim data for the S0033 trial, also from December 2003, showed that there were 5/68 (7.4%) patients with PR, and 20/68 (29.4%) patients with SD, during crossover treatment with 800 mg/day of imatinib, following failure of treatment at 400 mg/day. 68

In addition, secondary analysis for the EORTC-ISG-AGITG trial in the study by Debiec-Rychter et al. 14 indicated, without stating the number of patients involved, that response following crossover was significantly more likely to occur in patients with wild-type GIST than with KIT exon 11 mutation (p = 0.0012), and response following crossover was also significantly more likely to occur in patients with KIT exon 9 mutation compared with exon 11 mutation (p = 0.0017). 14

No response data were provided for treatment with sunitinib at a dose of 50 mg/day (as part of a 4 weeks-on-treatment/2 weeks-off-treatment 6-week cycle), following progression on an imatinib dose of 400 mg/day.

Overall survival

For imatinib at an escalated dose of 600 mg/day following progression at a dose of 400 mg/day, OS data were not reported by Blanke et al. 39 (CiC information has been removed) for the B2222 trial.

For imatinib at a dose of 800 mg/day following progression at a dose of 400 mg/day, the EORTC-ISG-AGITG trial by Zalcberg et al. 44 did not report OS outcomes. However, the S0033 trial by Blanke et al. 41 reported relevant outcome data, and at the time of the analysis (median follow-up of 4.5 years) noted that 76/118 (64.4%) of patients had died. 41 Median OS was 19 months (95% CI 13 to 23 months) starting from the commencement of crossover. Interim data for the S0033 trial were also provided in the study by Rankin et al. ,68 which stated that median OS at December 2003 was 19 months. 68

(CiC information has been removed.)

(CiC information has been removed.)

(CiC information has been removed.)

(CiC information has been removed.)

For sunitinib, OS data were available for those on 50 mg/day of sunitinib who failed on a prior imatinib dose of ≤ 400 mg/day from two abstracts of the same trial, taken at different follow-up periods. 82,86 The data from the study by Reichardt et al. 82 were analysed after a median of four cycles. Median survival at this point was 93 weeks (95% CI 72 to 100 weeks) and 231/339 (68.1%) of patients were still alive. 82 The data from the report by Seddon et al. 86 were analysed after a median of 51 weeks (range 0.1–159 weeks). Median survival at that time was 90 weeks (95% CI 73 to 106 weeks) and 193/351 (55%) were still alive. 86 It should also be noted that further interim OS data were provided in another study by Seddon et al. ,85 but although the date of analysis is the same month as that reported by the studies by Reichardt et al. 82 and Rutkowski et al. ,83 the median OS reported differed, at 80.4 weeks (95% CI 60.3 to NA weeks), while the population who had failed on doses of imatinib of ≤ 400 mg/day was also less (307 patients). 85

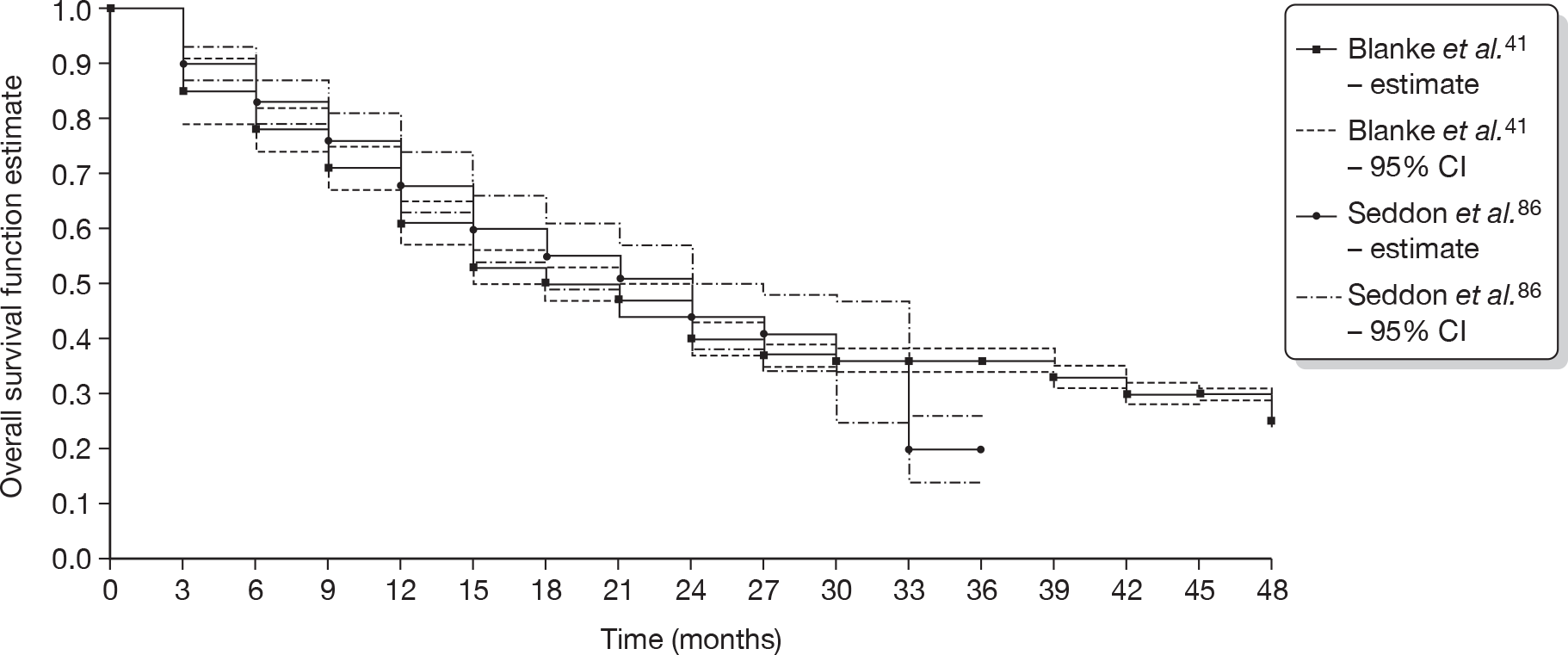

It was possible to compare OS with an escalated dose of 800 mg/day, from the S0033 trial reported by Blanke et al. ,41 with that with sunitinib at a dose of 50 mg/day (provided in 4 weeks-on/2 weeks-off cycles of 6 weeks), for patients who had progressed on imatinib at a dose of 400 mg/day. Quarterly OS estimates for the sunitinib participants reported in a Kaplan–Meier chart by Seddon et al. 86 were obtained using the method proposed by Parmar et al. 73 and compared with OS estimates for the S0033 trial provided by the authors. The results are provided in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Comparison of OS estimates for imatinib at 800 mg/day and sunitinib at 50 mg/day.

The study by Zalcberg et al. did not report information on OS and was therefore not included in the comparison in Figure 3. However, data are available from the (CiC information has been removed), and data from the study by Seddon et al. 86 on treatment with sunitinib are provided in Table 6.

| No. years elapsed | Seddon 200886 (n = 351) | (CiC information has been removed) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival estimate | 95% CI | (CiC information has been removed) | (CiC information has been removed) | ||

| 1 | 0.684 | 0.626 to 0.741 | (CiC information has been removed) | (CiC information has been removed) | (CiC information has been removed) |

| 2 | 0.441 | 0.379 to 0.503 | (CiC information has been removed) | (CiC information has been removed) | (CiC information has been removed) |

| 3 | 0.200 | 0.140 to 0.261 | (CiC information has been removed) | (CiC information has been removed) | (CiC information has been removed) |

| 4 | NR | (CiC information has been removed) | (CiC information has been removed) | (CiC information has been removed) | |

Disease-free survival

No data were reported for this outcome on account of no patient in any of the included studies having a complete response.

Progression-free survival

For imatinib at an escalated dose of 600 mg/day following progression at a dose of 400 mg/day, PFS data were not reported by Blanke et al. 39 (CiC information has been removed) for the B2222 trial.

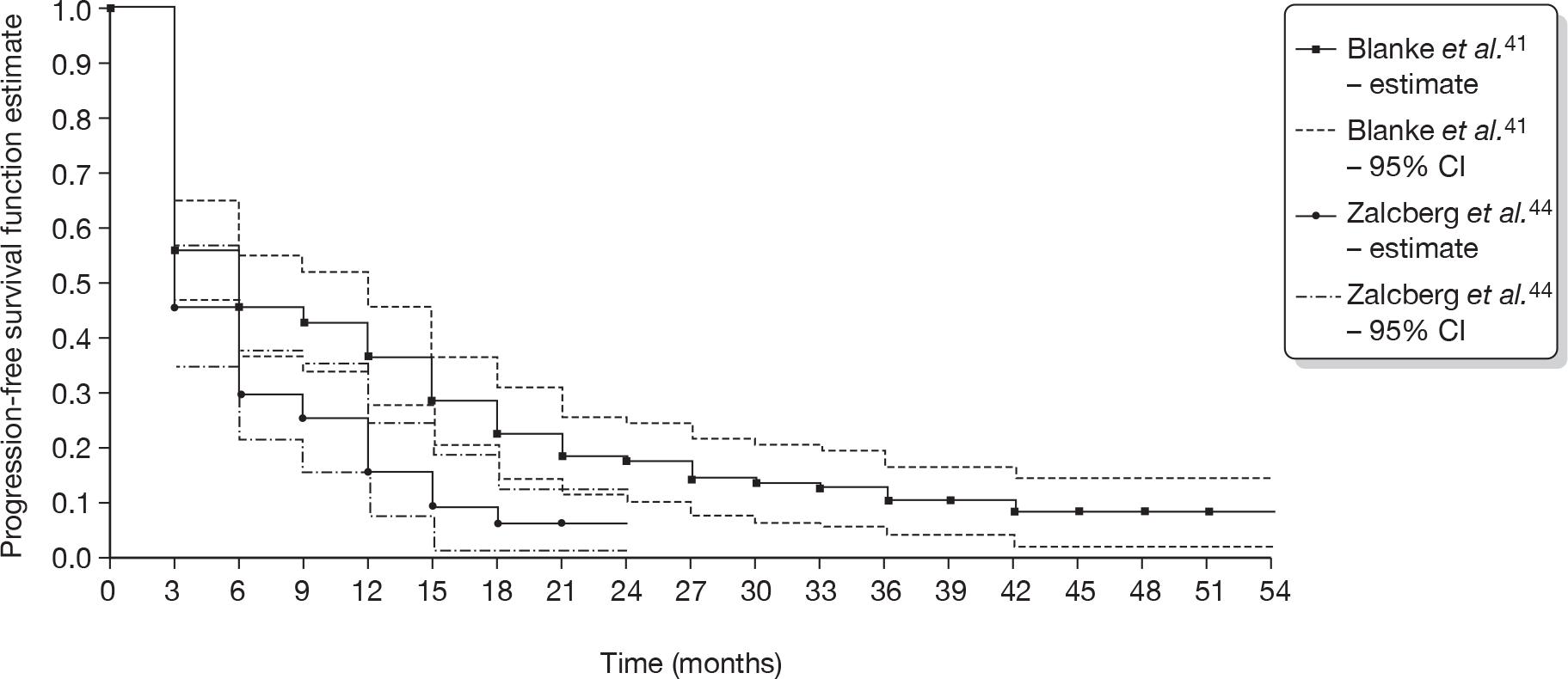

For imatinib at an escalated dose of 800 mg/day following progression at a dose of 400 mg/day, data were reported for the S0033 trial by Blanke et al. ,41 and for the EORTC-ISG-AGITG trial by Zalcberg et al. 44

For the S0033 trial, at the time of the analysis, median follow-up of 4.5 years (54 months), 99/118 (83.9%) of the crossover cohort for whom data were available had progressed. 41 Median PFS was estimated to be 5 months (95% CI 2 to 10 months). Of the 99 patients who had PD or had died at the time of the analysis, 23/99 (23.2%) had progressed but were still alive. Interim data from this trial, at a data cut-off point of December 2003, gave median PFS to be 4 months following crossover, for 68 patients. 68

For the EORTC-ISG-AGITG trial, median follow-up was 25 months (maximum follow-up was 35 months), and, at that time, 108/133 (81.2%) of the crossover cohort with data available had progressed. Median PFS was 81 days. Sixty-seven patients (50.4%) had progressed or died within 3 months (Kaplan–Meier survival estimate 0.467). At 1 year, the Kaplan–Meier survival estimate was 0.181. 44

(CiC information has been removed.)

The estimates of PFS provided at 3-month intervals by the authors of the S0033 study,41 and available as a Kaplan–Meier chart in the published paper of this study by Blanke et al. ,41 were compared with PFS estimates at 3-month intervals that were measured from an enlarged copy of the plot of the Kaplan–Meier survival function estimate given in the paper by Zalcberg et al. 44 The number of events in each time period was then calculated using the method proposed by Parmar et al. ,73 corrected to ensure that the total number of patients censored was consistent with the number reported in the published paper. 44 For both trials the standard error of the survival function estimates was estimated from the quarterly numbers for events and patients at risk using Greenwood’s formula. Figure 4 shows the survival functions from each trial, together with 95% CIs for each.

FIGURE 4.