Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 08/65/02. The contractual start date was in April 2009. The draft report began editorial review in April 2010 and was accepted for publication in November 2010. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2011. This work was produced by Brush et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Epidemiology

Worldwide, large bowel (colorectal) cancer (CRC) accounts for > 1 million cancers per year or 9% of all new cancer cases. 1 In the UK, CRC is the third most common malignancy (behind lung and breast cancer), with 37,514 new cases registered in 2006, of which around two-thirds (23,384) were in the colon and one-third (14,130) in the rectum. The proportions by gender are similar for colon cancer (M : F = 12,005 : 11,379) but for rectal cancer the number of cases is higher in men (M : F = 8425 : 5705). 2

Data from the EUROCARE (EUROpean CAncer REgistry-based study on survival and CARE of cancer patients)] analyses (2000–2) show that the age-adjusted 5-year relative survival for England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales ranges between 51.8% and 54.5%, rates that lag behind those of other European countries (e.g. Switzerland 63.8%) and the USA (SEER-13 registries 65.5%). 3 The reasons for these variations are multifactorial, but in part reflect variability in standards of care between regions and countries. In turn, these differences point to the continued need to improve the quality of diagnosis and treatment in patients with CRC – a theme central to this report.

Clinical presentation

For the purposes of clinical presentation and treatment, new cancer cases arising from the colon are distinct from those arising from the rectum (defined as the distal large bowel up to 15 cm from the anal verge). 4 In turn, clinical presentation may be considered as (1) elective and (2) emergency.

Symptomatic presentations of colon cancer in the non-emergency setting range from findings on surveillance for polyps or inflammatory bowel disease through abdominal discomfort, change in bowel habit and anaemia, to more advanced disease with weight loss, palpable tumour or metastatic disease. By contrast, rectal cancer typically presents with symptoms localised to the pelvis, including bleeding, diarrhoea and, in advanced cases, pain, fistulation to other adjacent viscera and/or tenesmus (a symptom characterised by the persistent sensation to defecate due to the presence of a rectal mass). Importantly, in general there is a poor correlation between symptoms and tumour stage.

A national CRC screening programme has been rolled out across the UK since 2007 using the faecal occult blood test as the primary screening modality. 5 Asymptomatic presentations of cancer of the colon or rectum will become increasingly more common as a result. Importantly, there is emerging evidence that screening substantially reduces the proportion of emergency cases at a population level – for example from 29% in 1999 to 16% in 2004 in the Coventry and North Warwickshire pilot studies. 6

Diagnosis and staging

Cancers of the colon and rectum are usually diagnosed either by direct endoscopic visualisation – for example colonoscopy for investigation of symptoms or flexible sigmoidoscopy, which is now widely used throughout the UK in ‘one-stop’ rectal bleeding clinics – or by a radiological investigation [barium enema has been largely replaced by computerised tomography (CT), plain imaging or CT colonography]. For the majority of cases, histological confirmation is obtained through endoscopic biopsy. Some 85% of CRCs are adenocarcinomas (not otherwise specified), 10% are mucinous adenocarcinomas and the remainder are rare histological types such as papillary carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma and signet ring cell carcinoma.

In the peri-operative period there should be comprehensive clinical and pathological assessment of the tumour, its invasion characteristics and its spread. This forms the basis of tumour ‘staging’. Traditionally in the UK, pathological staging of cancer of the colon and rectum comprised the Dukes’ staging system;7 this has increasingly been replaced by the internationally accepted tumour, node, metastasis (TNM) staging system. The TNM system classifies the extent of the tumour (T), the extent of spread to the lymph nodes (N) and the presence of metastases (M). 8

Treatment of primary tumour

For cancers of both the colon and the rectum, surgical resection is the mainstay of definitive treatment. However, the pathways before surgery differ for colon and rectal cancers. For most colon cancers, surgical resection is the primary treatment, followed by histopathological staging. Adjuvant chemotherapy is then standard care for patients with node-positive disease and for select cases of node-negative disease when there are adverse prognostic histological features, for example extravascular invasion.

For rectal cancer, the algorithms for treatment are more complex. For some T1 rectal tumours, a local surgical procedure (e.g. transanal endoscopic microsurgery) may be considered,9 but these tumours represent a small proportion of all cases. The majority of rectal cancers are larger yet confined within the anatomical boundaries of the mesorectal fascial plane and require major surgery, either as anterior resection [with total mesorectal excision (TME) for middle lower and third sections] or by total abdominoperineal resection (APR). These procedures are associated with considerable short- and long-term morbidity, including permanent colostomy if APR is required. Pre-operative radiotherapy has been shown to be superior to postoperative (salvage) radiotherapy, but there is no evidence that radiotherapy confers an overall survival advantage. Risk of local recurrence is a key issue for rectal cancer, and for this reason many patients in the UK receive pre-operative radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy, where radiotherapy and chemotherapy are delivered as a combination (CRT). 10 Pre-operative therapies are conventionally administered as either (1) short-course pre-operative radiotherapy (SCPRT) over 4–5 days followed by surgery within 10 days; or (2) long-course radiotherapy, usually in combination with chemotherapy [chemoradiotherapy (CRT)], and then a period to allow ‘tumour downstaging’ ranging from 6 to 12 weeks before surgery. The effectiveness of SCPRT11 and CRT12 in reducing local recurrence has been shown in randomised clinical trials (RCTs), but it is increasingly recognised that these adjuvant therapies are associated with long-term morbidities, for example sexual and bowel dysfunction. 13 However, the selection criteria for which pre-operative therapy is used varied between studies, but, in general, CRT is indicated for locally advanced rectal cancer where there is a high risk of local recurrence – for example a threatened resection margin (known as the ‘circumference’ margin) or several positive lymph nodes. 14 In modern clinical practice, these criteria are generally predicted from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). 15

In a small proportion of rectal cancers there is advancement of neoplastic disease locally beyond the mesorectal fascial plane to involve adjacent viscera. These cases require major complex surgery, often in the form of multivisceral exenteration and formation of colostomy and urostomy. These patients are generally treated within a centralised setting by the multidisciplinary surgical team (colorectal surgeon, urologist, gynaecologist and/or plastic surgeon). Cure rates are low to modest and morbidity is high; thus, pre-operative selection through staging is a key clinical process.

Treatment of recurrent disease

Locoregional recurrence is well recognised following initial treatment for colon and rectal cancers. The problem is best described for local pelvic recurrence following rectal cancer treatment. These cases require major complex ‘salvage’ surgery, often in the form of multivisceral exenteration with formation of colostomy and urostomy. Cure rates are low to modest and morbidity is high. 16

Treatment of metastatic disease

Cancer of the colon and rectum spreads via lymphatics and the blood system to the liver and lungs, the most common sites for ‘distant’ metastatic disease. A small proportion also spreads principally via the peritoneal lining and omentum (known as transcoelomic spread) to manifest as peritoneal deposits or ovarian masses in women (known as Krukenberg tumours).

Resections of metastatic tumour (referred to as ‘metastatectomy’), with or without pre-operative chemotherapy, are commonly performed in the UK for metastases of colorectal origin, with long-term cure rates greater than one-third. 17 Aggressive approaches to peritoneal deposits of colorectal origin are increasing recognised and involve major surgery known as cytoreductive surgery, and the administration of hyperthermic intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy.

Rationale for pre-operative staging

With the wide range of clinical scenarios, treatment options and their timings outlined above for colon and rectal cancer, the rationale for pre-operative staging becomes clearly apparent. Over the past two decades, a number of diagnostic tools have entered clinical practice and now facilitate the process of pre-operative staging. A number of imaging modalities are used in the pre-operative staging of CRCs including CT, MRI, ultrasound imaging and positron emission tomography (PET).

For this report, the focus is on imaging; the use of prognostic indicators, for instance blood-borne tumour markers, alone or in combination with imaging, is beyond the scope of the report.

Specifically, this report examines the role of CT in combination with PET scanning (‘hybrid’ scan) in pre-operative staging for CRC. The literature contains reports of the use of PET scanning alone compared with other imaging modalities for staging CRC, but as stand-alone PET technology is no longer commercially available, the present report is limited to the role of hybrid PET/CT scanning.

Pre-operative staging modalities

Computerised tomography

Computerised tomography is a cross-sectional technique using ionising radiation (X-rays) to produce images of sections of the body. Modern scanners are capable of producing high spatial resolution images with the ability to define anatomy and different tissues in great detail. However, one major drawback of CT is that it does not provide functional information and hence cannot reliably discriminate between active cancer cells and scar tissue following previous successful treatment. CT relies predominantly on morphology and size for diagnosis and it may be impossible to confidently detect cancer in small (< 1 cm) lymph nodes or, alternatively, to tell the difference between enlarged cancerous nodes and enlarged benign reactive nodes. 18

Modern CT scanners are capable of fast scanning and are the workhorse of modern imaging departments. Most protocols to stage CRC would involve injection of iodine-containing intravenous contrast, which also gives information on perfusion and the relationship of tumours to blood vessels and often makes metastases easier to discriminate from background tissues. Iodine-containing oral contrast is often used to highlight loops of bowel, allowing a higher degree of diagnostic certainty when evaluating adjacent soft tissue masses.

Computerised tomography scans can therefore be performed quickly [a total in-department time of approximately 30 minutes would be standard (not including administration of initial oral contrast), although actual scanning time is usually < 2 minutes].

Staging of CRCs uses CT as the first test and this test is capable of identifying the primary tumour, local and distant lymph nodes and the presence of liver and lung metastases.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging is a specialised investigation that is capable of producing very high spatial resolution images of targeted body parts. Unlike CT, MRI uses a powerful magnetic field and the properties of atoms within this field. A radiofrequency pulse allows a signal that can be measured and applied to an image. There is no radiation dose with MRI as X-rays are not used.

Magnetic resonance imaging is therefore capable of assessing the primary tumour and its relationship to the bowel wall, thus guiding surgeon and oncologist towards either curative surgery or radiotherapy, both to downstage the primary tumour and as palliation.

Magnetic resonance imaging scans take considerably longer than CT scans and require the patient to be still within the confined space of the magnet for prolonged periods. Claustrophobia can often result in incomplete imaging or the inability to even start the scan. MRI images are therefore best performed on parts of the body that are static, as motion can considerably degrade image quality. In CRC, imaging of the rectum is ideal as this segment of bowel is relatively fixed – peristaltic waves, although they obviously do affect the rectum, do not cause as much of a problem because the rectum is partly fixed by adjacent musculature forming part of the sphincter mechanism. For this reason, use of MRI to stage rectal cancers to assess the primary tumour and its relationship to the bowel wall is standard, whereas MRI is not used to assess primary colonic tumours elsewhere in the large bowel because of image quality degradation by peristalsis. In addition, the rectum, because of its relatively fixed position, can be targeted with radiotherapy with minimal risks to adjacent tissues – this is not the case with colonic tumours elsewhere. The use of MRI to pre-operatively stage rectal cancer is part of routine clinical practice in the UK and is recommended in UK clinical guidelines. 4,19

Magnetic resonance imaging can also be used to obtain high-quality, high spatial resolution images of the liver in the assessment of metastatic disease to the liver, and is capable of both identifying metastases that have not been seen by standard CT and providing a roadmap for surgery in the case of metastatic disease to liver being worked up for surgical resection. MRI to assess the liver is also excellent as a problem-solving tool in cases in which there is some doubt as to the nature of the liver lesion(s) present.

Ultrasound imaging

Standard transabdominal ultrasound has no role in assessment of primary CRCs, although it is possible to diagnose CRC with this modality. Transabdominal ultrasound is capable of identifying liver metastases and is a useful test to gain information on a liver lesion identified by cross-sectional imaging.

Transrectal ultrasound is a specialised test that is used to assess rectal cancers and is capable of producing high-resolution images of the tumour and its relationship to the bowel wall. This procedure is relatively invasive but can guide the surgeon and oncologist as to the presence or absence of extension through the wall. This may change the operative approach and may act as a guide in the use of pre-operative radiotherapy.

Positron emission tomography

Positron emission tomography has been in use for > 25 years as a research tool and during the last 15 years in a clinical role. The major clinical applications of PET are in the areas of oncology, cardiology and neurology, with by far the greatest use in oncology.

Positron emission tomography is a functional imaging technique that uses short-lived radioisotopes (with half-lives ranging from 2 to 110 minutes currently) attached to tracers to examine abnormal biochemical processes associated with disease. The most commonly used radiopharmaceutical in PET is fluorine-18-labelled deoxyglucose (FDG) – this acts as an analogue of glucose and can be used to identify tissues showing increased glucose transport and metabolism, such as cancer cells. There are potentially many more radiopharmaceuticals that can be used to investigate aspects of metabolism in the body, but currently FDG is the only readily available tracer.

The rationale behind PET is that biochemical changes caused by disease usually precede changes in size or structure of a particular organ or tissue. Hence, PET is capable of identifying cancer earlier than anatomical imaging techniques (such as CT and MRI).

A drawback of PET, however, is that the functional images obtained often lack fine anatomical definition, and it can be difficult, because of the inherently low spatial resolution of the technique, to accurately localise the abnormality.

Depending on the tumour type, PET can be highly effective as a prognostic indicator or as a technique for primary tumour staging, for assessing treatment response or for detecting disease recurrence. However, there are specific areas in which PET is not helpful, such as for specific subtypes of CRC with histological features consistent with mucinous carcinoma – PET scans can be falsely negative because of the inherent low metabolic rate of these tumours.

Positron emission tomography is also known to produce false-positive (FP) results when inflammation is present and can produce both FP and false-negative (FN) findings in people who have high plasma glucose levels as a result of poorly controlled diabetes. 20,21 Providing that the standard recommendations for PET are followed, the use of PET has already been shown to alter patient management in approximately one-third of cancer cases. 22

With regards to CRC, the main indications currently for PET are:

-

assessment of a residual mass following treatment

-

assessment of apparently isolated metastatic disease.

Combined positron emission tomography and computerised tomography imaging

Positron emission tomography and CT are complementary imaging techniques that, when combined, can maximise their individual advantages and minimise their disadvantages. The functional imaging provided by PET can be accurately superimposed on high spatial resolution CT images using combined FDG PET/CT imaging. Thus, when reporting a modern FDG PET/CT study, it is possible to analyse the functional PET study, the anatomical CT study and a combined fused image. A further advantage of this combination is that the CT component can be used to correct PET images for attenuation errors, thus further improving PET imaging quality and increasing scan speed.

The recommendation from the Royal College of Radiologists is that every new PET scanner should be a PET/CT scanner and that every cancer network should have access to FDG PET/CT services. 23

Combined PET/CT scanners using standard FDG allow scans to be acquired within approximately 30–40 minutes.

Several studies have shown FDG PET/CT to be more accurate than diagnostic CT and stand-alone PET for cancer staging, including staging of CRC. 24,25

It is also recognised that technology is rapidly changing and, although the first generation of combined PET/CT scanners used lower-specification CT scanners, modern scanners now use fast, multiple-slice CT components with technology as advanced as that of modern stand-alone CT scanners. This could obviously affect FDG PET/CT interpretation as higher-quality, more accurate scanners replace older technology.

Although the CT component of most FDG PET/CT scans is currently performed without oral and intravenous contrast agents (non-contrast-enhanced CT), the role of contrast-enhanced FDG PET/CT has been evaluated in more recent studies. 21 Currently, almost all patients with CRC who are undergoing FDG PET/CT studies will have had a diagnostic CT scan prior to referral for FDG PET/CT and there is, therefore, little to be gained by use of oral and intravenous contrast. It would be possible to perform an FDG PET/CT scan with oral and intravenous contrast to optimise the CT component if a role for use of FDG PET/CT in primary staging of CRC was identified. There is evidence that it may have a role in staging of primary rectal cancer. 21,26,27

Replacing diagnostic CT with FDG PET/CT as an imaging investigation has considerable resource and cost implications. However, the potential improvement in correctly diagnosing the extent of the disease could lead to a beneficial therapeutic impact in which unnecessary surgery and the prescribing of expensive chemotherapies are avoided. Cost and resource considerations currently limit FDG PET/CT use to an add-on test in most centres where the technology is available. 28

Information about safety is essential to guide clinicians’, patients’ and policy-makers’ decisions, and there are operational and pharmacological factors that need to be considered when FDG PET/CT scans are performed in hospital premises. These apply to all indications for FDG PET/CT scans, including CRC. A systematic review of potential harms from FDG PET/CT is outwith the scope of this research; however, we briefly outline below what is currently known about the safety of FDG PET/CT.

FDG is a radiopharmaceutical substance that contains a small amount of radioactivity. It has a short half-life of 110 minutes, after which it is rendered ‘safe’, and the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency supports its use in clinical practice. 29 However, there are some groups of patients for whom FDG is not advised: pregnant or lactating women should avoid FDG unless the benefits outweigh the risks. Nursing mothers are advised that breastfeeding should be stopped for 12 hours, and close contact between mother and infant is discouraged within 12 hours of the injection.

Although the whole-body approach to FDG PET/CT imaging allows broad coverage of multiple organs, the radiation dose to the patient is potentially much higher than in conventional CT. 30 Staff working closely with patients undergoing an FDG PET/CT procedure may inadvertently receive a dose of radiation, and care in planning the FDG PET/CT procedure can reduce this. Staff radiation exposure can be maintained below regulatory limits by appropriate design, particularly shielding, and workflow in FDG PET/CT facilities. 30 The physical space in which FDG PET/CT scans are performed needs to shield equipment (syringes and vials) as well as rooms (walls, floors and ceiling), and to incorporate a ‘hot’ waiting area in which patients who have had an FDG injection can rest until the scan is performed. 30 In a study by Carson et al. ,31 a two-stage process involving a ‘cold’ pre-injection set-up session reduced the radiation received by radiotherapy radiographers working with small-cell lung cancer patients by a factor of three. 31 The staffing levels in radiography departments with FDG PET/CT equipment may necessarily be higher to reduce the exposure of individual staff to FDG. 31

Although the patient remains radioactive after the scan, this reduces quickly over time (the half-life of fluorine-18 is approximately 110 minutes); however, people who come into contact with the patient once he or she leaves the hospital will receive a small dose of radiation. The associated risk of harm from such low doses is thought to be low, although the risk to repeated contacts such as hospital transport drivers is unknown. NHS Scotland provides advice for patients’ friends and family members, and ambulance and taxi drivers who might accompany patients from the hospital after a scan. It recommends that there should be a space between the patients and other passengers whilst in a car or ambulance and suggests that drivers who may routinely transport patients from an FDG PET/CT facility may be at risk of higher than background doses of radiation (Dr Jim Hannan, Royal Infirmary Edinburgh, 2009, personal communication).

Chapter 2 Research objectives

The main objectives of the review are to compare the accuracy of FDG PET/CT scans with that of other staging modalities in the pre-operative staging of CRC, and to model the cost-effectiveness of these different diagnostic tests.

This study focuses on the use of FDG PET/CT for staging CRC in three different groups of patients:

-

those with primary CRC

-

those with recurrent CRC

-

those with metastatic CRC.

Research questions

The following questions were considered to reflect UK staging practice.

Primary colorectal cancer

How accurate is FDG PET/CT combined with pelvic MRI or routinely used imaging modalities compared with routinely used imaging modalities (CT chest/abdomen/pelvis combined with pelvic MRI) for pre-operative staging of primary rectal cancer?

How accurate is FDG PET/CT in addition to routinely used imaging modalities compared with routinely used imaging modalities for pre-operative staging of primary colon cancer?

Recurrent colorectal cancer

How accurate is FDG PET/CT combined with pelvic MRI compared with routinely used imaging modalities (CT chest/abdomen/pelvis combined with pelvic MRI) for pre-operative staging of patients with pelvic recurrence of rectal cancer?

How accurate is FDG PET/CT ± MRI compared with routinely used imaging modalities (CT chest/abdomen/pelvis ± MRI) for pre-operative staging of patients with recurrent colon cancer?

Metastatic colorectal cancers

How accurate is FDG PET/CT imaging compared with routinely used imaging modalities for pre-operative staging in patients with metastatic CRC?

Secondary objective

The secondary objective was to determine the impact of diagnostic information provided by FDG PET/CT over conventional imaging techniques on decisions about patient management. We also extracted data pertaining to adverse effects when these were reported in the included studies.

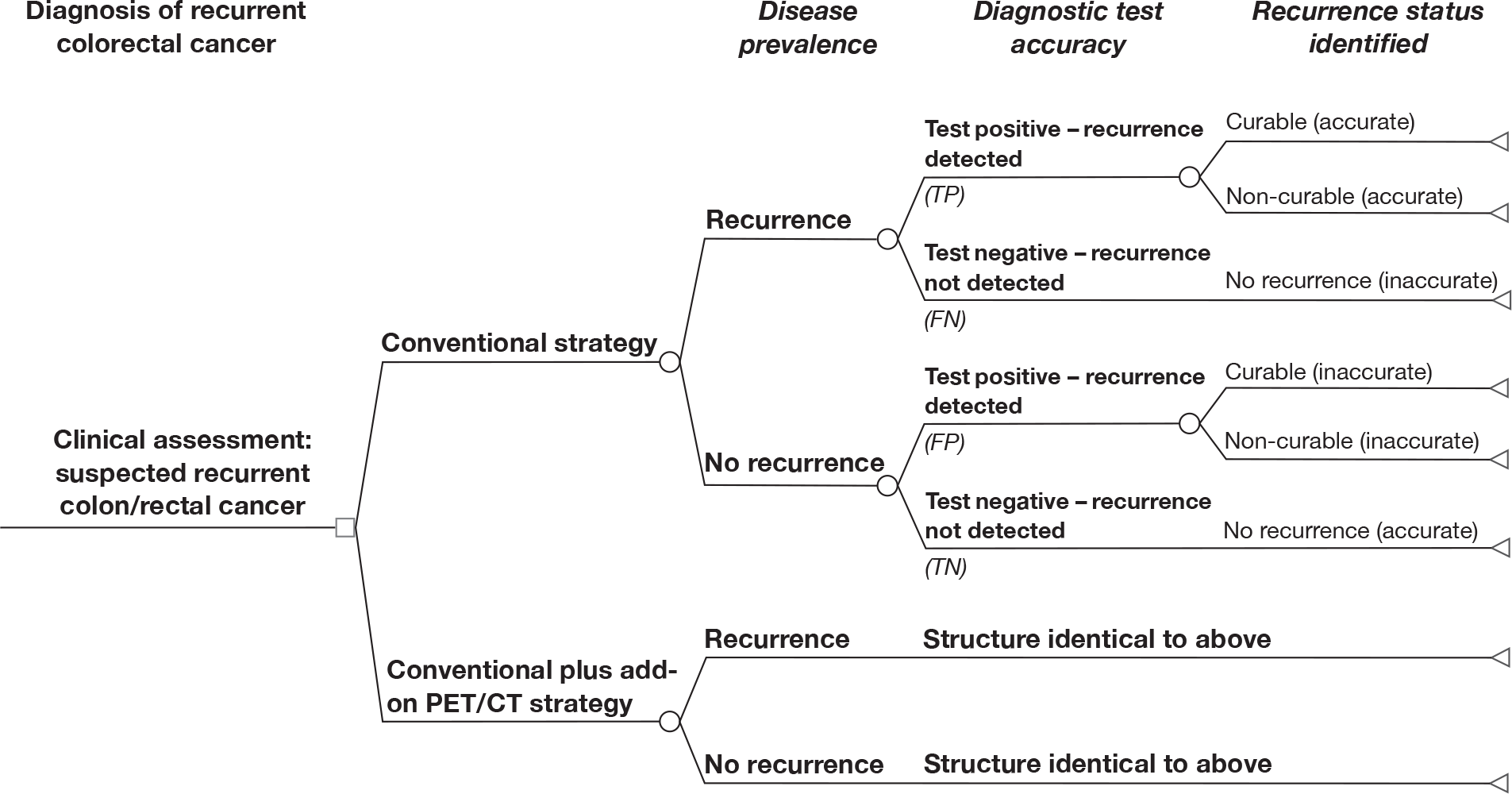

Economic evaluation

An economic evaluation of FDG PET/CT as an add-on test compared with routinely used imaging modalities for pre-operative staging in patients with primary, recurrent or metastatic CRC.

Chapter 3 Review methods

A steering committee was convened that included all the authors of this report plus three public partners from the South East Scotland Cancer Network (see Acknowledgements). The committee considered the current use of FDG PET/CT for the pre-operative staging of CRC in radiological and surgical practice in the UK, and the following methodological design was agreed following discussion.

Search methods for the systematic review(s)

A database was assembled from a comprehensive search for published and unpublished studies, which included database searches, reference list searches and contact with experts. The software used was Reference Manager version 10 (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA).

The search of online databases was performed combining the concepts ‘colorectal’, ‘neoplasm’ and ‘FDG-PET’ using a sensitive variety of free-text and subject heading terms. No limits, such as language or publication year, were used. The search histories were based on scoping searches and refined by adapting searches used in previous Cochrane reviews32,33 and optimal search strategies. 34,35 Available guidance on search methods for diagnostic accuracy tests was followed. 36 Intermediate search results were tested against known relevant publications and revised to ensure enough sensitivity to include those known publications with the intention that additional, unknown publications would not be missed.

The following online databases were searched for relevant studies from their inception until May 2009: BIOSIS Previews; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) Plus; The Cochrane Library; Compendex; ProQuest Dissertations and Theses; EMBASE; Global Health; Global Health Library regional indexes (comprising LILACS, AFRO, EMRO, PAHO, WHOLIS); Index to Theses; Inspec; MEDLINE; metaRegister of Current Controlled Trials; National Technical Information Services; OpenSIGLE (System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe); UK Clinical Research Network; and Web of Science, including Conference Proceedings Citation Index.

Reference lists in review publications identified by the database searches were obtained and had the review inclusion criteria applied. All conference abstracts reporting studies that met the inclusion criteria were followed up to obtain published full reports.

In addition to the main systematic review and quality of life searches, which were structured to include data on adverse effects, a supplementary search for reports of safety and adverse events of PET in CRC was performed in EMBASE. The sensitive floating subheading for adverse effects was used in combination with subject headings and keyword terms for CRC, and the principal subject heading for PET.

The main search strategy can be found in Appendix 1.

Study selection

One reviewer screened titles and abstracts for relevance, and a second screened a 25% sample of the titles identified by the search activities as resources permitted. It was intended that disagreements were resolved by discussion, but there was a high level of agreement (> 80%). Full papers of potentially relevant studies were obtained and assessed for inclusion by one reviewer, and the whole sample was double-checked by a second. Two different sets of criteria were used for studies evaluating the diagnostic test accuracy of FDG PET/CT and those evaluating its therapeutic impact. No language restrictions were applied in either type of review, and non-English-language studies were read by individuals with language-specific reading skills. These individuals are identified in the acknowledgements section of this report.

Studies evaluating the accuracy of FDG PET/CT in the pre-operative staging of primary, recurrent and metastatic colorectal cancer

Eligibility criteria

Types of studies

Prospective and retrospective patient series (diagnostic cohort), cross-sectional, before and after studies and RCTs were eligible for inclusion. Both consecutive series and series not explicitly reported as consecutive were included. Diagnostic case–control studies (two-gate design) were excluded because clinically relevant estimates of specificity and sensitivity can be derived only from an unselected sample of the clinical population.

Participants

Adults with known or suspected primary cancer of the colon or rectum undergoing pre-operative staging prior to curative surgery in a secondary care setting were eligible for inclusion. Patients with any stage of disease were included. Studies solely in patients with anal cancer were excluded because this rare cancer differs from CRCs both biologically and in terms of the treatment pathway. Studies that included colorectal and anal cancer patients in which data were not reported separately for the colorectal and anal cancer groups were included in the review only if < 20% of patients had anal cancer. It was intended that the effect of including these studies would be explored using sensitivity analysis where possible.

Index tests

Studies using only integrated FDG PET/CT equipment with both contrast-enhanced and non-contrast-enhanced CT were considered eligible for inclusion.

Comparator tests

Standard imaging tests including ultrasound, diagnostic CT, MRI and PET, alone or in combination.

Target conditions

Known or suspected primary, recurrent or metastatic CRC.

Reference standards

Histopathology of surgical resected specimens is the gold standard for tests used in CRC pre-operative staging; however, patients who do not undergo surgical resection (because tests show they have incurable disease) have their results verified by an alternative standard. These include histopathology based on biopsy and follow-up, which can include both clinical examination and imaging tests, but wide variations in practice for CRC follow-up are well recognised. Although it was intended to restrict the eligibility criteria to surgical histopathology and follow-up, so few studies met these criteria that we deviated from the original protocol to include studies using any reference standard either singly or mixed. Any duration of follow-up and frequency of follow-up were permitted.

Data extraction and management

Data were extracted by two reviewers (HMc and FCr) independently using a standard form, which included the quality assessment criteria, and disagreements were resolved by discussion. Data to populate 2 × 2 contingency tables consisting of the numbers of true positives (TP), true negatives (TN), FPs and FNs using the studies’ own definitions were extracted as reported, including both patient- and lesion-level data, and qualitative and quantitative definitions of diagnostic thresholds. Numbers of uninterpretable test results were also extracted when these were reported.

Data that described the clinical characteristics of FP and FN FDG PET/CT findings, and additional cases detected and cases re-staged by the use of FDG PET/CT, actual changes in planned management directed by FDG PET/CT findings and the clinical consequences of the changes were also collected. Data on mortality, adverse events (including how these were monitored and recorded) and technical failures for both index and comparator tests were also extracted.

To facilitate our interpretation of the results, we extracted data on comorbidities (e.g. diabetes) and previous treatment in the study population; the FDG PET/CT system; fasting duration; FDG dose and time between administration of FDG and performance of the scan; comparator imaging test system(s), patient preparation and test interpretation; interval between index and comparator tests (more or less than 3 months); assessors (number, expertise, experience, consensus procedures and learning effect data); and, in regard to the reference standard, whether histopathology was by surgery or biopsy, the duration, frequency, type and interpretation of clinical and imaging follow-up tests, and the numbers of patients whose results were confirmed by each type of reference standard.

Non-English-language studies had data extracted by one reviewer (FCr) during face-to face discussions with fluent individuals who translated all available data outlined above.

The assessment of methodological quality of studies evaluating the accuracy of FDG PET/CT in the pre-operative staging of colorectal cancer

Fourteen items from the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS) checklist were used to assess the methodological quality of the included studies. Two reviewers (HMc and FCr) applied the criteria independently and resolved disagreements by discussion. We intended to use the results of the quality assessment for descriptive purposes to provide an evaluation of the overall quality of the included studies and to investigate potential sources of heterogeneity. 37

The classification of responses to each of the QUADAS items is summarised in Appendix 2.

Statistical analysis and data synthesis of studies evaluating the accuracy of FDG PET/CT in the pre-operative staging of colorectal cancer

We intended to analyse data pertaining to the accuracy of FDG PET/CT in the following way. Because of methodological problems, particularly those caused by the difficulty of estimating within-study variance when patients contribute more than one data point, and when the individual patient data are not available, it was our intention that the 2 × 2 tables should report the lesion-level data, but that the analyses be restricted to patient-level data.

The 2 × 2 tables for the patient-level data were used to calculate sensitivity and specificity with confidence intervals (CIs). Depending on the degree of heterogeneity, data were plotted graphically in forest plots to give an indication of the extent of heterogeneity between studies. 38

A random effects meta-analysis was planned to fit the bivariate summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curve model38 with the within-study variances fitted as binomial. The DiagMeta package in R was used for all meta-analyses and forest plots (www.r-project.org). In the event that the data were not amenable to bivariate random effects meta-analyses, separate meta-analyses for sensitivity and specificity were presented instead, using fixed or random effects as appropriate, depending on the degree of heterogeneity. Estimates include the average sensitivity and specificity for each test.

Investigation of sources of heterogeneity

Several potential sources of heterogeneity were identified in other systematic reviews and meta-analyses of diagnostic imaging techniques in CRC. 39–44 These were considered by the clinical authors of this report, who identified the factors most likely to affect diagnostic accuracy in studies of FDG PET/CT from these previously published systematic reviews and also from their own clinical and surgical experience.

We planned to investigate the following potential sources of heterogeneity, using subgroup analysis where possible: academic (e.g. university hospital) versus non-academic setting; indication known or suspected; study conducted up to 2005 and post 2005 (reflecting differences in FDG PET/CT technology); blinding of index and reference standard test interpretation. It was also our intention that heterogeneity in the statistical analysis would be initially assessed graphically where possible using meta-regression (see Investigations of heterogeneity).

Investigations of heterogeneity

We intended to explore heterogeneity due to individual diagnostic studies using different diagnostic thresholds as a standard part of fitting the bivariate SROC curve model. Investigations of heterogeneity due to other study characteristics were planned using meta-regression, but only if the data were adequate for such analyses. In either case, we planned graphical displays of estimates from individual studies grouped according to the pre-specified sources of heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analyses

We planned to conduct sensitivity analysis where possible by including only prospective studies (excluding retrospective) with explicitly consecutive samples (excluding non-consecutive or unclear), studies with a histopathology (surgical specimen or biopsy) reference standard for all participants (excluding studies in which some or all participants received only clinical or imaging follow-up as the reference standard) and studies that included only rectal and colon cancer patients (excluding anal cancer).

Studies evaluating the therapeutic impact of pre-operative staging of FDG PET/CT for primary, recurrent and metastatic colorectal cancer

For studies evaluating the therapeutic impact (changes in management) of FDG PET/CT, we adapted our methodological approach detailed above. The main differences were the eligibility criteria and the quality assessment processes; it was no longer necessary for the studies to include 2 × 2 data and this was dropped as an eligibility criterion, and the items used in the quality assessment process were assembled from three different sources in recognition of the different study designs required to evaluate changes in management arising from the use of diagnostic tests. 37,45,46

Eligibility criteria

Types of studies

We included case series, cross-sectional studies, before and after designs and RCTs.

Participants

Adults with known or suspected primary cancer of the colon or rectum undergoing pre-operative staging prior to curative surgery in a secondary care setting were eligible for inclusion. Patients with any stage of disease were included. Studies solely in patients with anal cancer were excluded. Studies that included colorectal and anal cancer patients in which data were not reported separately for the colorectal and anal cancer group, were included in the review only if < 20% had anal cancer. It was intended that the effect of including these studies would be explored using sensitivity analysis where possible.

Index tests

Studies using only integrated FDG PET/CT equipment with either contrast-enhanced or non-contrast-enhanced CT were considered eligible for inclusion.

Comparator tests

Standard imaging tests including ultrasound, diagnostic CT, MRI and PET, alone or in combination.

Target conditions

Known or suspected primary, recurrent or metastatic CRC.

Reference standards

Surgically resected specimens, histology and clinical and imaging follow-up were considered for inclusion, and studies using these reference standards singly or mixed were eligible for inclusion. Any duration of follow-up and frequency of follow-up testing were included.

Data extraction and management

Data were extracted by two reviewers (HMc and FCr) independently using a standard form, which included the quality assessment criteria, and disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Additional cases detected and cases restaged by the use of FDG PET/CT were collected, as were the actual changes in planned management directed by FDG PET/CT findings and the clinical consequences of the changes. Data on mortality, adverse events (including how these were monitored and recorded) and technical failures for both index and comparator tests were also extracted.

To facilitate interpretation of the findings, we extracted data on comorbidities (e.g. diabetes) and previous treatment in the study population; the FDG PET/CT system; fasting duration; FDG dose and time between administration of FDG and performance of the scan; comparator imaging test system(s), patient preparation and test interpretation; interval between index and comparator tests (more or less than 3 months); assessors (number, expertise, experience, consensus procedures and learning effect data); and, in regard to the reference standard, whether histopathology was by surgery or biopsy and the duration, frequency, type and interpretation of clinical and imaging follow-up tests, and the numbers of patients whose results were confirmed by each type of reference standard. Diagnostic findings, changes in management or treatment intent, appropriateness of management decisions or patient outcomes, adverse events, numbers of patients with each type of event, and consequences, for example withdrawal from the study, were all sought from each report. Non-English-language studies had data extracted by one reviewer (FCr) during face-to-face discussions with fluent individuals who translated all available data outlined above.

Contact with authors

When necessary, authors of studies identified by our search activities were contacted to request points of clarification in assessing a study’s eligibility for inclusion in the review or to request specific data.

Search methods for FDG PET/CT economics, decision-making and quality of life

Additional database searches for studies with data on economics, decision-making and quality of life were undertaken. The searches used a sensitive combination of subject headings and free-text search terms, constructed by drawing on key terms identified by the expert health economists in combination with adaptations of the Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network’s published search filters (www.sign.ac.uk/methodology/filters.htmlwww.sign.ac.uk/methodology/filters.html).

The following databases were also searched: Cost-effectiveness Analysis Registry; CINAHL; The Cochrane Library; EMBASE; Health Management Information Consortium; MEDLINE; and Web of Science. The search strategies used can be found in Appendix 3.

FDG PET/CT as an add-on imaging test versus routinely used imaging modalities for pre-operative staging in patients with primary, recurrent or metastatic colorectal cancer

Handsearch study

Systematic reviews adopt an approach of searching extensively for studies to ensure as much available evidence as possible can inform the review and to minimise bias, including publication bias. Handsearching has formed part of the extensive search approach for systematic reviews of effects.

Guidance for conducting Cochrane systematic reviews of effects evidence and more recently diagnostic test accuracy studies recommends that handsearching should be considered to enhance the retrieval of relevant studies, but there is sparse research evidence for the value of this approach. We therefore designed a complementary but distinct research project to exploit the opportunity to explore the value of handsearching to inform an imaging systematic review and to contribute to our understanding of the role of handsearching in the identification of reports of diagnostic test accuracy studies. A full report of the method employed and the results obtained can be found in Appendix 4.

A copy of the protocol for the systematic review can be found in Appendix 5.

Chapter 4 Included and excluded studies identified by the search strategy

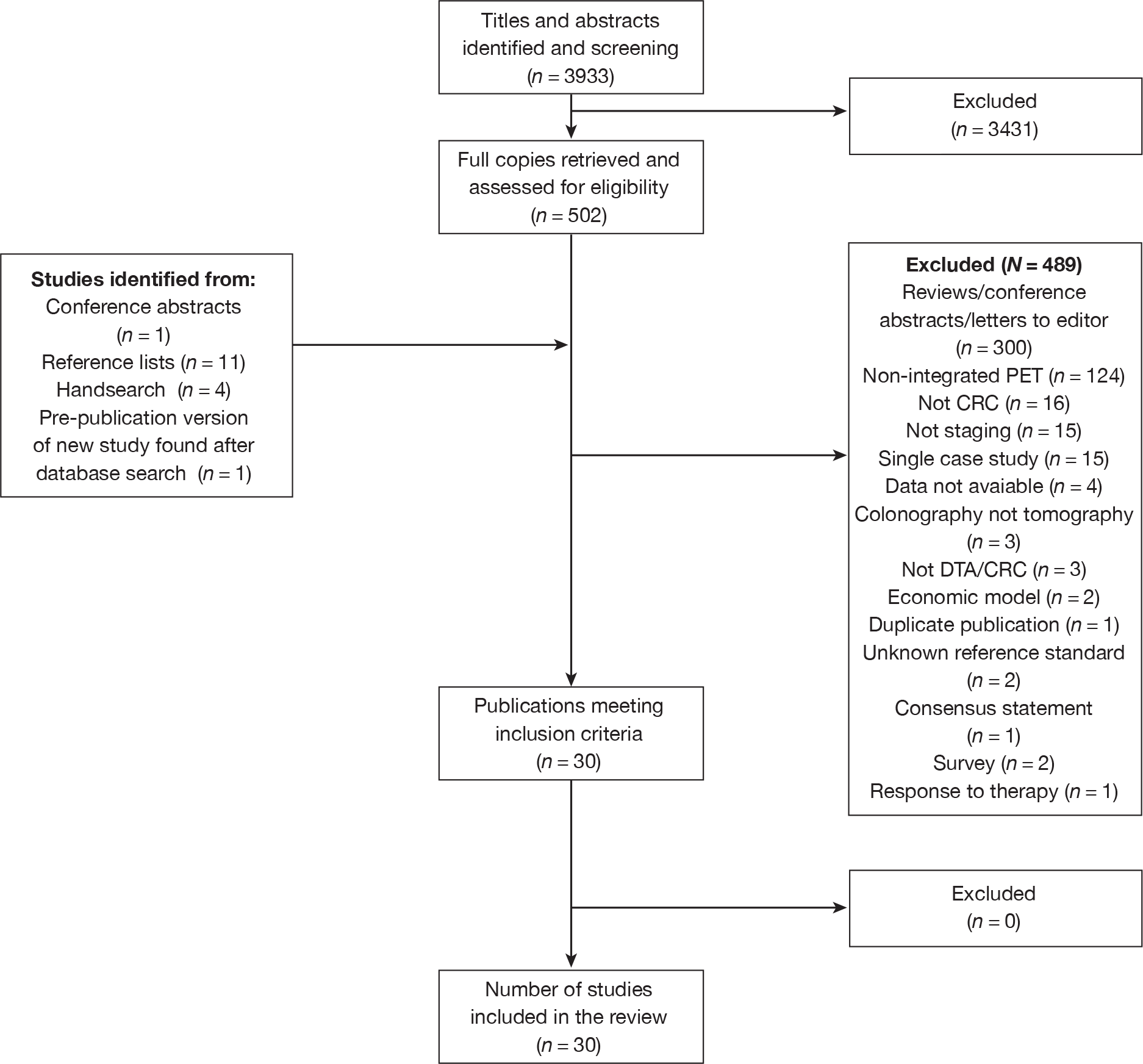

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of study selection process for studies of diagnostic test accuracy and therapeutic impact. CRC, colorectal cancer; DTA, diagnostic test accuracy.

A table of excluded studies with reasons for exclusion can be found in Appendix 6.

Chapter 5 FDG PET/CT for the pre-operative staging of primary colorectal cancer

Recent statistics on the incidence of CRC report that 37,514 new cases of large bowel cancer were registered in the UK in 2006. Primary colonic tumours (any part of the colon other than the rectum) outnumber primary rectal tumours by approximately 2 : 1. 47

After the first diagnosis of a new CRC with colonoscopy and biopsy, and occasionally following an incidental finding on radiological imaging performed for another reason, more sophisticated medical imaging tests are required to accurately stage the tumour to determine the extent to which other tissues might be involved. The aim of radiological imaging is to obtain information regarding the primary tumour (T stage), local and distant nodal involvement (N stage) and distant metastatic disease (M stage).

The containment of the tumour to the mucosa or the muscularis propria is associated with improved survival. 48 However, because of delayed presentation before development of symptoms, it is not uncommon for CRCs to have either spread locally through the colonic wall, with involvement of local and distant nodal groups, or metastasised. Metastases tend to occur to the liver and lung.

For staging primary cancer of the colon, CT with spiral acquisition through the chest, abdomen and pelvis following intravenous contrast administration is the conventional imaging technique and is readily available and reproducible. MRI is not currently used for assessment of primary colonic tumours because of image degradation by peristalsis, and does not add any value to standard CT imaging in this area.

Magnetic resonance imaging is used as standard for staging of rectal cancers, with the benefits of imaging a part of the bowel that is not degraded by peristaltic motion resulting in more accurate assessment of the primary tumour and relationships to bowel wall. MRI is also capable of identifying involved local nodal groups, although, currently, standard practice is to rely on size criteria to suggest involvement. This results in a large inherent inaccuracy, as many studies have shown that size alone is a poor indicator of disease status within nodal groups. Spiral CT is also used to give information on local and distant nodal involvement and the presence or absence of metastatic disease, again usually to the liver and lungs.

FDG PET/CT is currently recommended only for the assessment of suspected recurrence of CRC and in pre-operative staging prior to metastectomy, and clinical opinion on the role of FDG PET/CT in the routine management of primary colon cancer varies. Some investigators suggest that in certain clinical circumstances it should be considered as part of the standard pre-operative assessment and acknowledge it may have an up-and-coming role in the initial staging of primary rectal cancer. 21,26–28 More recently, small studies have suggested that FDG PET/CT may offer a clinically useful addition for the routine staging of rectal cancers. 27 In one study, FDG PET/CT was able to identify involved nodes outwith the mesorectal fascia not seen with standard imaging, particularly with low rectal tumours in which iliac and inguinofemoral nodal involvement was a common finding. 49 This resulted in a change in planned management in 27% of patients, improving the accuracy of pre-treatment staging.

As 11% of the CRC population present with metastases at the time of first diagnosis,50 the early identification of those with advanced disease might lead to improved survival. Replacing diagnostic CT with FDG PET/CT as the initial imaging investigation has considerable resource and cost implications; in a cost-effectiveness study in 2005, a single PET scan (using non-integrated equipment) was estimated to cost €1038 compared with €313 for a single CT scan. 51 These cost considerations currently limit FDG PET/CT use to an add-on test in most centres where the technology is available.

The rationale for using FDG PET/CT (or PET/contrast-enhanced CT) as a replacement test, at the outset of the CRC diagnostic pathway, is the avoidance of unnecessary and expensive surgery in individuals who have advanced incurable disease at the time of the first diagnosis. 50

Replacing the diagnostic CT scan with FDG PET/CT implies that the CT component of both investigations should be of a similar standard. Modern FDG PET/CT systems tend to use low-dose spiral CT to localise a functional abnormality – this is because the patient has already undergone a high-quality, higher-dose spiral CT scan with intravenous contrast in almost all cases. Using FDG PET/CT as a replacement should involve performance of the CT component to the same standards as the diagnostic scan – this increases the complexity of the FDG PET/CT study but may have a role in the future.

It is anticipated that there will be a knock-on effect from the UK CRC screening programmes on NHS CRC radiology services, and this also deserves consideration. 50,52 Results from the second round of the UK CRC screening programme show that the majority of detected cancers are early tumours, classified as Dukes A or B. FDG PET/CT is more commonly used for the detection of recurrence and liver metastases, and the value of its use in the detection of small, contained primary CRCs remains under-researched. The limitation of the spatial resolution of modern scanners (5–8 mm) is a potential issue here and, although modern FDG PET/CT systems are capable of identifying primary CRCs, the standard roles for this imaging modality are concerned with disease spread, rather than assessment of the primary tumour.

Aim

The aim of this systematic review is to compare FDG PET/CT imaging with routinely used imaging modalities for pre-operative staging in patients with a primary diagnosis of CRC.

Objectives

The primary objective is to determine the diagnostic accuracy of integrated FDG PET/CT over (in addition to) conventional imaging for the pre-operative staging of primary CRC. The comparisons of interest are:

-

PET/CT combined with pelvic MRI or routinely used imaging modalities versus routinely used imaging modalities (CT chest/abdomen/pelvis combined with pelvic MRI) for pre-operative staging of primary rectal cancer.

-

PET/CT in addition to routinely used imaging modalities versus routinely used imaging modalities for pre-operative staging of primary colon cancer.

Results

Our search did not identify any systematic reviews to evaluate the diagnostic test accuracy of integrated FDG PET/CT in the pre-operative staging of primary CRC.

We found no studies that met the stated objectives, but have presented all studies that included patients with primary CRC who received FDG PET/CT for pre-operative staging.

Number of included studies

The search identified two studies53,54 that evaluated the diagnostic test accuracy of integrated FDG PET/CT for the detection of primary CRC.

Study characteristics and study designs

The study characteristics are shown in Table 1 and accuracy data are shown in Table 2.

| Study | Population | Index test | Comparator(s) | Reference standard |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tsunoda 200853 Country: Japan Year: 2004–5 Study design: prospective/retrospective: unclear; consecutive sample: unclear Setting: national cancer centre Aim: to assess the value of FDG PET/CT for detection of LN metastases |

88 patients (52 men, 36 women), mean age 60.6 years (range 23–89 years) Indication: pre-operative nodal diagnosis Exclusion criteria: NR Disease: primary CRC; colon (n = 37), rectum (n = 51) Comorbidities: NR Previous treatment: NR |

FDG PET/CT Discovery LS8® (GE Healthcare, Fairfield, CT); fasting duration at least 6 hours; FDG 370 MBq, scan 60 minutes later; non-contrast-enhanced CT Image interpretation Assessors: two observers experienced in interpreting FDG PET/CT, blind to clinical information, disagreement resolved by discussion to reach consensus Qualitative: LN metastases diagnosed by abnormal uptake regardless of node shape or size (visual diagnosis) Quantitative: maximal nodal diameter (size diagnosis) cut-off value 10 mm; SUVmax of LNs with greater uptake than normal organs or surrounding tissue (SUV diagnosis): the optimal cut-off value was where accuracy was greatest; when more than one LN in the proximal or distant region was malignant, the one with the highest SUV was used in the analysis |

None | Histopathology; all patients had surgical resection and regional LN dissection |

|

Tateishi 200754 Country: Japan Year: NR Study design: retrospective; consecutive sample: unclear Setting: cancer centre hospital Aim: to compare contrast-enhanced FDG PET/CT and non-contrast-enhanced FDG PET/CT for nodal staging of rectal cancer |

53 patients (32 men, 21 women), mean age 61 years (range 27–79 years) Indication: pre-operative staging of rectal cancer Exclusion criteria: evidence of distant metastases, diabetes, pregnancy, lactation; performance status other than 0 (fully active) or 1 (restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory) Disease: histologically proven rectal cancer; rectosigmoid (n = 6), upper rectal (n = 26), lower rectal (n = 21); Stage I (n=12), Stage IIA (n = 5), Stage IIB (n = 2), Stage IIIA (n = 6), Stage IIIB (n = 24), Stage IIIC (n = 4); mucinous tumour (n = 6) Comorbidities: NR Previous treatment: NR |

FDG PET/CT Biograph® (Siemens Health Care Diagnostics, Surrey, UK); fasting duration at least 6 hours; FDG 370–555 MBq, time to scan NR; non-contrast-enhanced CT Image interpretation Assessors: a certified radiologist and a nuclear medicine specialist, blind to clinical information and results of other studies, in consensus Qualitative: Abnormal LN: focal increased uptake at a location corresponding to LN chains on CT scans; abnormal uptake: focal increased activity higher than that of the background soft tissue Quantitative: SUVmax; no further details |

CE FDG PET/CT CT as index test with IV contrast agent Image interpretation As index test Time between index and comparator tests: sequential; time between assessment of the two data sets 3 months |

Histopathology, all patients had total mesorectal resection and lymphadenectomy performed within 2 weeks of the radiological tests; 14 nodal stations were examined in each patient |

| Study | Test and outcome level | TP | FP | TN | FN | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP/TP + FN | TN/TN + FP | TP/TP + FP | TN/TN + FN | ||||||

| Tsunoda 200853 | FDG PET/CT, nodal staging, LN group level (proximal, distal), visual diagnosis | 14 | 9 | 118 | 35 | 0.286 | 0.929 | 0.609 | 0.771 |

| FDG PET/CT, nodal staging, LN group level, size diagnosis | 15 | 6 | 121 | 34 | 0.306 | 0.953 | 0.714 | 0.781 | |

| FDG PET/CT, nodal staging, LN group level, SUV diagnosis 1.5 | 26 | 12 | 115 | 23 | 0.531 | 0.906 | 0.684 | 0.833 | |

| FDG PET/CT, nodal staging, LN group level, SUV diagnosis 2.5 | 19 | 7 | 120 | 30 | 0.388 | 0.945 | 0.731 | 0.800 | |

| FDG PET/CT, nodal staging, LN group level, SUV diagnosis 3.5 | 12 | 0 | 127 | 37 | 0.245 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.774 | |

| FDG PET/CT, proximal nodal group staging, patient level, SUV diagnosis 1.5 (optimal cut-off value) | 21 | 7 | 40 | 20 | 0.512 | 0.851 | 0.750 | 0.667 | |

| FDG PET/CT, distant nodal group staging, SUV diagnosis 1.5 (optimal cut-off value) | 5 | 6 | 74 | 3 | 0.625 | 0.925 | 0.455 | 0.961 | |

| Tateishi 200754 | FDG PET/CT, nodal staging, patient level | 29 | 11 | 8 | 5 | 0.853 | 0.421 | 0.725 | 0.615 |

| Contrast-enhanced FDG PET/CT, nodal staging, patient level | 29 | 6 | 13 | 5 | 0.853 | 0.684 | 0.829 | 0.722 | |

| FDG PET/CT, pararectal nodal staging, patient level | 24 | 10 | 11 | 8 | 0.750 | 0.524 | 0.706 | 0.579 | |

| Contrast-enhanced FDG PET/CT, pararectal nodal staging, patient level | 29 | 5 | 16 | 3 | 0.906 | 0.762 | 0.853 | 0.842 | |

| FDG PET/CT, internal iliac nodal staging, patient level | 5 | 7 | 30 | 11 | 0.313 | 0.811 | 0.417 | 0.732 | |

| Contrast-enhanced FDG PET/CT, internal iliac nodal staging, patient level | 12 | 5 | 32 | 4 | 0.750 | 0.865 | 0.706 | 0.889 | |

| FDG PET/CT, obturator nodal staging, patient level | 8 | 16 | 25 | 4 | 0.667 | 0.610 | 0.333 | 0.862 | |

| Contrast-enhanced FDG PET/CT, obturator nodal staging, patient level | 8 | 2 | 39 | 4 | 0.667 | 0.951 | 0.800 | 0.907 |

One study54 reported using a retrospective design. In the second study53 the study design was unclear.

Study setting and country in which the research was conducted

Both studies were conducted in cancer centres in Japan.

Patient populations

The studies reported outcomes for a total of 141 patients, who were mostly men. The mean age of the patients in the two studies was 6053 and 6154 years, respectively, with a range of 23–89 years. Rectal cancer affected 104 patients and cancer of the colon affected 37.

Indication for FDG PET/CT

FDG PET/CT was undertaken in order to pre-operatively stage the primary CRC, and was reported to be specifically for the diagnosis of nodal disease in one study. 53

FDG PET/CT equipment and patient preparation

Full details of all the equipment used in the studies can be found in Table 1. FDG PET/CT equipment was manufactured by GE Healthcare (Fairfield, CT) and Siemens Medical Solutions (Surrey, UK). The fasting duration prior to the scan was at least 6 hours in both studies.

A range of injected FDG doses was reported with units ranging from 370 to 555 MBq. Where the information was reported, patients were scanned 60 minutes after the administration of the radioactive tracer. 53 Neither study used contrast-enhanced CT.

Image interpretation

The index and comparator tests, when one was performed,54 were assessed by at least two individuals blind to clinical information. The qualitative and quantitative image interpretations were conducted in similar ways in each of the studies.

In one study,53 lymph node metastases were qualitatively diagnosed by abnormal uptake regardless of node shape or size (visual diagnosis). A maximal nodal diameter (size diagnosis) cut-off value of 10 mm was used; maximum standardised uptake value (SUVmax) of lymph nodes with greater uptake than normal organs or surrounding tissue (SUV diagnosis): the optimal cut-off value was where accuracy was greatest; when more than one lymph node in the proximal or distant region was malignant, the one with the highest SUV was used in the analysis.

In the second study54 the qualitative assessment judged lesions positive if there was an abnormal focal uptake at a location corresponding to lymph node chains on CT scans. Abnormal uptake was defined as a focal increased activity higher than that of the background soft tissue. The authors also reported using SUVmax in the quantitative diagnosis but did not report any other details.

Reference standard

Both studies reported histopathology from surgically resected specimens and lymph node resection as the reference standard in all patients.

Data synthesis – diagnostic performance

FDG PET/CT versus none

In proximal nodal staging based on patient-level analysis with an SUV threshold of 1.5, FDG PET/CT demonstrated a sensitivity of 51% (95% CI 36% to 66%) and a specificity of 85% (95% CI 72% to 92%). For distal nodal staging using an SUV threshold of 1.5, the sensitivity of FDG PET/CT was 62% (95% CI 30% to 86%) and specificity was 92% (95% CI 84% to 96%).

In analysis based on group-level data and compared with findings from surgical excisions and region lymph node dissection,FDG PET/CT was found to have a sensitivity of 28% (95% CI 18% to 42%) and specificity of 92% (95% CI 87% to 96%) when used for nodal staging of proximal and distal lymph nodes (n = 176).

In the detection of lymph nodes based on size (nodal maximum axial diameter) and a threshold of ≥ 10 mm, the authors found FDG PET/CT to have a sensitivity of 30% (95% CI 19% to 44%) and a specificity of 95% (95% CI 90% to 97%).

For SUV diagnosis using the optimal cut-off value of 1.5, the sensitivity of FDG PET/CT was 53% (95% CI 39% to 66%) and the specificity was 90% (95% CI 84% to 94%). At a threshold of 2.5, the sensitivity of FDG PET/CT was 38% (95% CI 26% to 53%) and the specificity was 94% (95% CI 89% to 97%), and, at a threshold of 3.5, the sensitivity was 24% (95% CI 15% to 38%) and the specificity was 100% (95% CI not calculable).

FDG PET/CT versus contrast-enhanced FDG PET/CT

Accuracy in diagnosing nodal staging appeared to be improved by adding contrast enhancement to the FDG PET/CT in 53 patients. FDG PET/CT had a sensitivity of 85% (95% CI 69% to 93%) and a specificity of 42% (95% CI 23% to 67%), and the respective accuracy of contrast-enhanced FDG PET/CT was 85% (95% CI 69% to 93%) and 68% (95% CI 46% to 84%).

FDG PET/CT produced poorer estimates of accuracy than contrast-enhanced FDG PET/CT in imaging all lymph nodes: a sensitivity of 75% (95% CI 57% to 87%) and a specificity of 52% (95% CI 32% to 71%) for FDG PET/CT compared with 90% sensitivity (95% CI 76% to 97%) and 76% specificity (95% CI 55% to 89%) for contrast-enhanced FDG PET/CT for pararectal nodes; a sensitivity of 31% (95% CI 14% to 55%) and specificity of 81% (95% CI 66% to 90%) for FDG PET/CT but 75% sensitivity (CI 95% 50% to 90%) and 86% specificity (95% CI 72% to 94%) for contrast-enhanced FDG PET/CT for internal iliac nodes; and a sensitivity of 67% (95% CI 39% to 86%) and a specificity of 61% (95% CI 46% to 74%) for FDG PET/CT compared with a sensitivity of 67% (95% CI 39% to 86%) and a specificity of 95% (95% CI 84% to 99%) for contrast-enhanced FDG PET/CT for obturator nodes.

Quality assessment

Fourteen items from the QUADAS checklist were used to assess the methodological quality of the results and the findings from this process are shown in Table 3.

| Study | Spectrum of patients’ representative? | Selection criteria clearly described? | Reference standard likely to classify the target condition? | Time between the reference standard and index test short enough? | Whole or a random sample receives verification using a reference standard? | Patients received the same reference standard regardless of the index test result? | Reference standard independent of the index test? | Execution of the test described in sufficient detail to permit replication? | Execution of the reference standard described in sufficient detail? | Index test results interpreted without knowledge of the reference standard results? | Reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the index test results? | Same clinical data available when tests results were interpreted as in clinical practice? | Uninterpretable intermediate test results reported? | Withdrawals from the study explained? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tateishi 200754 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | UC | UC | UC | N | UC | Y |

| Tsunoda 200853 | Y | N | Y | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | UC | UC | UC | N | UC | Y |

Only one study reported including a consecutive series of patients nor a random sample of adults undergoing pre-operative staging of primary CRC. 53 In both studies the assessors were blind to the clinical information and results of other studies. The reference standard test of histopathology was applied to all patients and is therefore likely to be 100% sensitive and specific, but neither study gave details of the execution of the reference standard. The reviewers considered 6 weeks to be the time limit after which disease progression might occur, and the time between the reference standard and the index test was reported to be ≤ 6 weeks in one study. 53 The withdrawals from the study were explained for both studies.

In addition to selection bias, the validity of the findings from these studies is also potentially compromised by review bias arising from the lack of information about the ‘blinding’ of individuals reviewing the scans.

Summary

-

The accuracy data to support the use of FDG PET/CT or contrast-enhanced FDG PET/CT in the pre-operative staging for primary CRC are very limited and both studies53,54 include small samples of patients. Furthermore, cross-tabulation of results of different tests for patients contributing to the same study was not available. This meant that significance testing for differences between the sensitivity and specificity of different tests was not carried out.

-

Both studies53,54 produced estimates of accuracy for the detection of lymph node disease associated with primary CRC, but the lack of comparisons with other tests makes it difficult to place a value on the use of this test in clinical practice.

-

An analysis based on lymph node size showed FDG PET/CT to have a sensitivity of 30% and a specificity of 85% for tumours > 10 mm.

-

The patient population was not well described in terms of disease, and the accuracy estimates from both studies may be compromised by reviewer bias.

-

In one study,53 patients had a primary diagnosis of both rectal and colon cancer, which makes the clinical interpretation of this study difficult because colon cancer and rectal cancer are regarded as two distinct pathologies, and are investigated and treated differently.

-

There is a suggestion that contrast-enhanced FDG PET/CT is more accurate for pre-operative staging of primary CRC than non-contrast-enhanced FDG PET/CT, but the poor quality of the data makes a reasonable interpretation difficult.

-

Both studies53,54 suggest that FDG PET/CT is able to identify nodal disease remote from the primary site, and this may suggest a future role for FDG PET/CT in the pre-operative staging of primary rectal cancer.

-

There is a lack of data to support the use of FDG PET/CT in the routine staging of all patients diagnosed with primary CRC.

Chapter 6 FDG PET/CT in the pre-operative staging of recurrent colorectal cancer

The rate of recurrence of CRCs is high, and long-term postoperative surveillance of patients is regarded by many as essential to identify relapsing malignancy early. 55,56 Estimates suggest that 40% of patients who have undergone a surgical resection of primary cancer in the colon or rectum will have recurrent disease confirmed during a follow-up period of 2–3 years. 56,57 Recurrent lesions may occur locally at the site of the previous tumour or in distant tissues, typically the liver or lungs. Two main classification systems are used to stage CRCs – the Dukes’ and TNM systems – and survival diminishes as numeric values increase. 21,25 This chapter reports the evidence that FDG PET/CT accurately stages local recurrence of CRC pre-operatively.

Local recurrence of colon cancer is less common than recurrent rectal cancer because the surgical removal of primary tumours of the colon involves extensive resection and the removal of lymph nodes. 58 Most primary rectal tumours are confined to the pelvis, and the prognosis is improved in this group of patients compared with those with worse TNM stages. 59 TME is the procedure used to remove both the tumour and the surrounding mesorectal fat, and this is currently the standard surgical treatment for all patients with primary rectal cancer. This technique is associated with a reduction in rates of recurrence and mortality. 60

Although successful surgical outcomes can increase life expectancy for some patients, secondary surgical resections often result in considerable morbidity and greatly diminished quality of life for survivors. 56 Accurate pre-operative re-staging is essential to distinguish those most likely to benefit from additional, sometimes drastic, surgery. 60

The procedures used in the routine follow-up of patients with a history of CRC vary but generally include blood testing to detect rising levels of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), imaging tests (predominantly CT) and clinical examination. 55,56 When recurrence is suspected, combinations of MRI, CT, chest radiography and ultrasound are used to confirm the presence or absence of disease and allow pre-operative staging to reclassify the disease status. MRI is regarded by many as the best method to image the rectum. 56 In hospitals with access to FDG PET/CT, this imaging test is now used alongside conventional imaging techniques and is widely believed to have an important role in the detection and the delineation of the extent of recurrent colorectal tumours. 21,55

The accuracy of all radiological imaging tests used for pre-operative staging of recurrent CRC is hampered by the gross disruption to the pelvic anatomy arising from the first surgery and associated chemotherapy. 56 The ability of individual imaging tests to differentiate between fibrous scar tissue and tumour is considered to be especially valuable in staging recurrent CRC.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies evaluating the diagnostic test accuracy of PET without a CT integrated component42 reported a sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 98% in 366 patients with locally recurrent rectal cancer. When data pertaining to changes in the management of these patients were pooled, 29% (95% CI 25% to 34%) of management decisions were changed, the majority of which were the avoidance of surgery as a result of the upstaging of the patients’ disease classification.

Aim

The aim of this systematic review is to compare FDG PET/CT imaging with routinely used imaging modalities for pre-operative staging in patients with a local recurrence of CRC.

Objectives

The primary objective is to determine the diagnostic accuracy of integrated FDG PET/CT over (in addition to) conventional imaging for the pre-operative staging of recurrent CRC. The comparisons of interest are:

-

DG PET/CT combined with pelvic MRI versus routinely used imaging modalities (CT chest/abdomen/pelvis combined with pelvic MRI) for staging of patients with pelvic recurrence of rectal cancer.

-

PET/CT ± MRI versus routinely used imaging modalities (CT chest/abdomen/pelvis ± MRI) for staging of patients with recurrent colon cancer.

Results

Our search did not identify any systematic reviews evaluating the diagnostic test accuracy of integrated FDG PET/CT in the pre-operative staging of recurrent CRC.

We found no studies that met the stated objectives but have presented all studies that included patients with suspected recurrent CRC who received FDG PET/CT for pre-operative staging.

Number of included studies

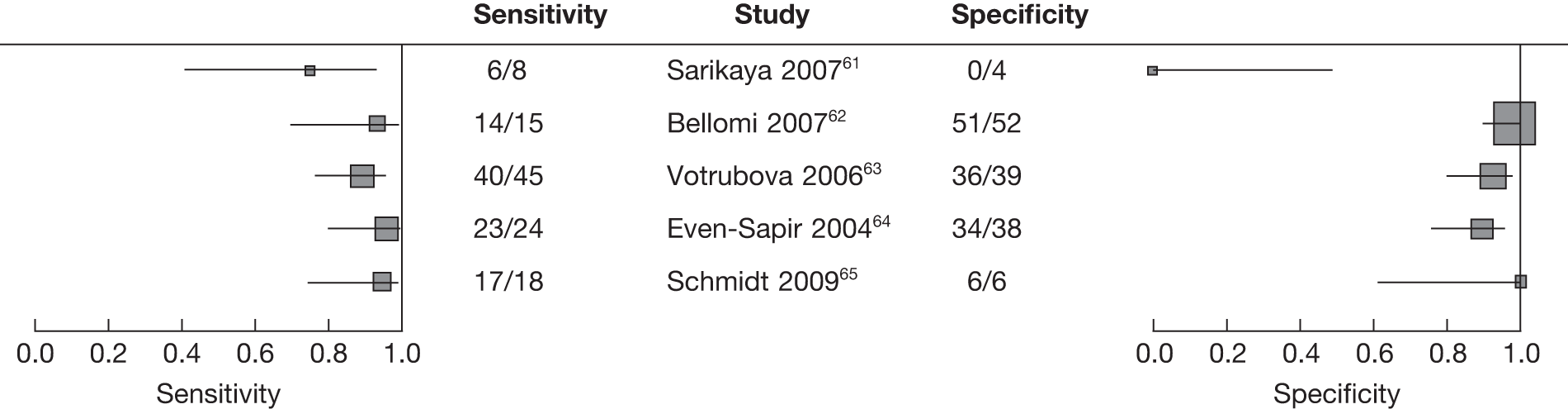

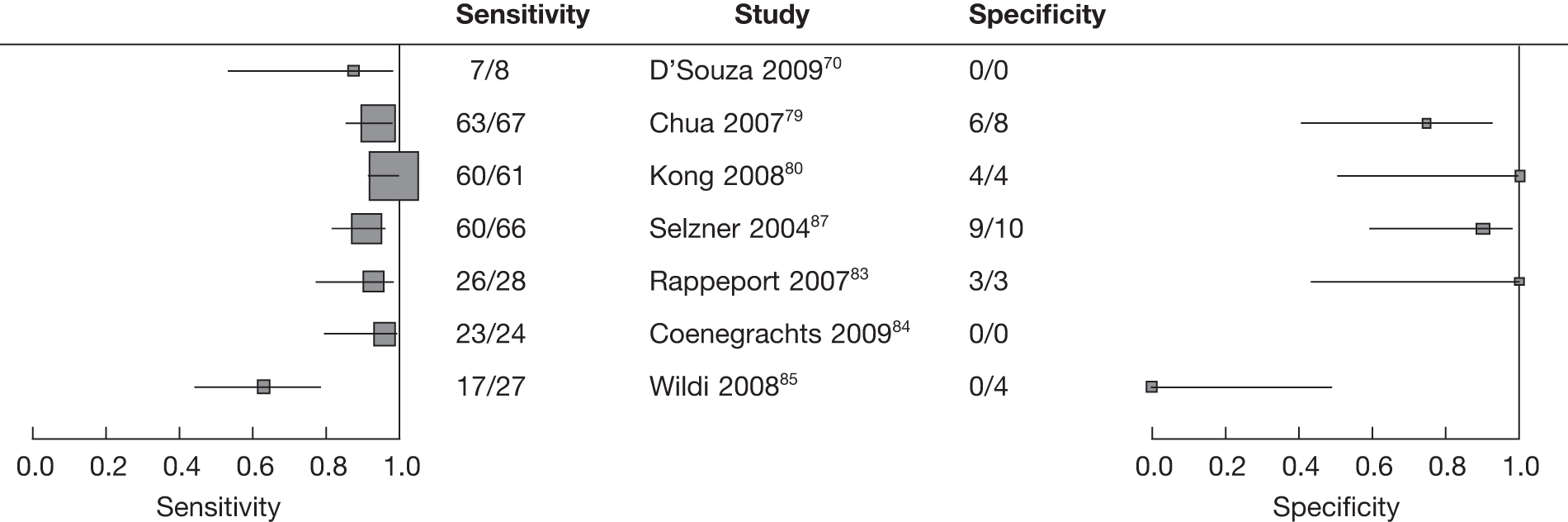

The search identified eight studies61–68 that evaluated the diagnostic test accuracy of integrated FDG PET/CT for the detection of colorectal recurrence.

Study characteristics and study designs

The study characteristics are shown in Table 4 and accuracy data are shown in Table 5. All eight studies used a retrospective design. Three62,65,67 studies reported recruiting patients consecutively.

| Study | Population | Index test | Comparator(s) | Reference standard |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sarikaya 200761 Country: USA Year: 2005–6 Study design: retrospective; consecutive sample: unclear Setting: university hospital Aim: to assess the value of FDG-PET in patients with suspicion of CRC recurrence but with normal CEA |

39 patients who had PET (n = 27) or FDG PET/CT (n = 12); mean age 55 years (range 33–91 years) Indication: clinical and/or radiological suspicion of recurrence but normal CEA (0–5 ng/ml); suspicion based on history and physical exam (n = 20), equivocal lesions on CT (n = 17), barium study (n = 2) Exclusion criteria: no histopathological evaluation following PET scan Disease: NR Comorbidities: NR Previous treatment: surgical resection alone, or chemotherapy and/or RT before or after resection (numbers NR) |

FDG PET/CT Biograph 16® (Siemens Health Care Diagnostics, Surrey, UK); fasting duration approximately 6 hours; FDG 370–555 MBq, scan approximately 60 minutes later; CT: non-contrast-enhanced CT Image interpretation Assessors: two certified nuclear medicine physicians, no further details Qualitative: positive or suspicious: abnormal or non-physiological activity; focal hypermetabolic activity in the liver greater than adjacent normal liver; isometabolic liver lesions identified with the help of the CT component; diffuse mild activity in bowel considered normal physiologic uptake Quantitative: mean SUVmax compared between PET TPs and FPs but not used as a threshold |

None | Histopathology, surgery within 2 months of FDG PET/CT scan |

|

Bellomi 200762 Country: Italy Year: NR Study design: retrospective; consecutive sample: yes Setting: university hospital Aim: to compare MDCT and FDG PET/CT for detection of local and distant recurrence of rectal cancer |

67 patients (gender NR), age NR Indication: suspicion of local or distant recurrence on routine follow-up (CEA, abdominal and pelvic MDCT, chest radiography or colonoscopy) following radical surgery Exclusion criteria: diabetes Disease: local recurrence (n = 15), distant recurrence (n = 27); hepatic metastases (n = 17); local recurrence and hepatic metastases (n=7); lung metastases (n = 8); local recurrence and lung metastases (n = 2) Comorbidities: NR Previous treatment: all underwent radical surgery; pre-surgical RT (n = 20); post-surgical RT (n = 5); pre-surgical chemotherapy (n = 5); post-surgical chemotherapy (n = 18); post-surgical RT and chemotherapy (n = 19) |

FDG PET/CT Discovery LS® (GE Medical Systems, Fairfield, CT); fasting duration 6 hours; FDG 5 MBq/kg, scan approximately 60 minutes later; non- contrast-enhanced CT Image interpretation Assessors: experts in nuclear medicine, aware of other clinical, laboratory and diagnostic investigations results, who had just started interpreting FDG PET/CT images at the time of the study Qualitative: Local recurrence: any new tissue at or close to anastomosis with asymmetrical, irregular, inhomogeneous contrast enhancement or changes compared with previous findings; hepatic or lung metastases: lesions not present at pre-operative CT Quantitative: SUV not used |

MDCT Lightspeed scanner® (GE Medical Systems, Fairfield, CT); intravenous contrast agent Image interpretation Assessors: expert radiologists with several years’ experience of reading MDCT scans Qualitative: as index test Quantitative: NR Time between index and comparator tests: within 30 days, mean 22 days |

Histology (biopsy or surgical) or follow-up of at least 2 years; independently compared with FDG PET/CT and MDCT findings |

|

Votrubova 200663 Country: Czech Republic Year: NR Study design: retrospective; consecutive sample: unclear Setting: hospital PET centre Aim: to compare PET and FDG PET/CT for detection of CRC recurrence |

84 patients (54 men, 30 women), mean age 64 years (range 41–78 years) Indication: suspected recurrence of CRC Exclusion criteria: NR Disease: NR Comorbidities: NR Previous treatment: colonic resection or rectal amputation |

FDG PET/CT Biograph Duo LSO® (Siemens Health Care Diagnostics, Surrey, UK); fasting duration at least 6 hours; FDG 370 MBq, scan 60–90 minutes later; CT: 30 patients received intravenous contrast agent; patients who previously underwent contrast-enhanced CT received oral contrast agent only Image interpretation Assessors: a skilled radiologist and a nuclear physician, in consensus; assessors first analysed CT and PET corrected and uncorrected images blind but aware of results of patients’ other investigations, then CT and FDG PET/CT images read with knowledge of previous PET reading Qualitative: positive: lesions with increased uptake and CT abnormality; pulmonary/liver nodules < 1 cm, even in absence of FDG uptake; clearly increased focal uptake in normal structures; pathological structures with slightly higher uptake than in the liver Quantitative: NA |

PET component of FDG PET/CT: using attenuation-corrected and -uncorrected images Image interpretation As index test Time between index and comparator tests: sequential |

Histopathology within 4 weeks (no further details) and/or follow-up, mean duration 6.5 months (range 5–8 months) |

|

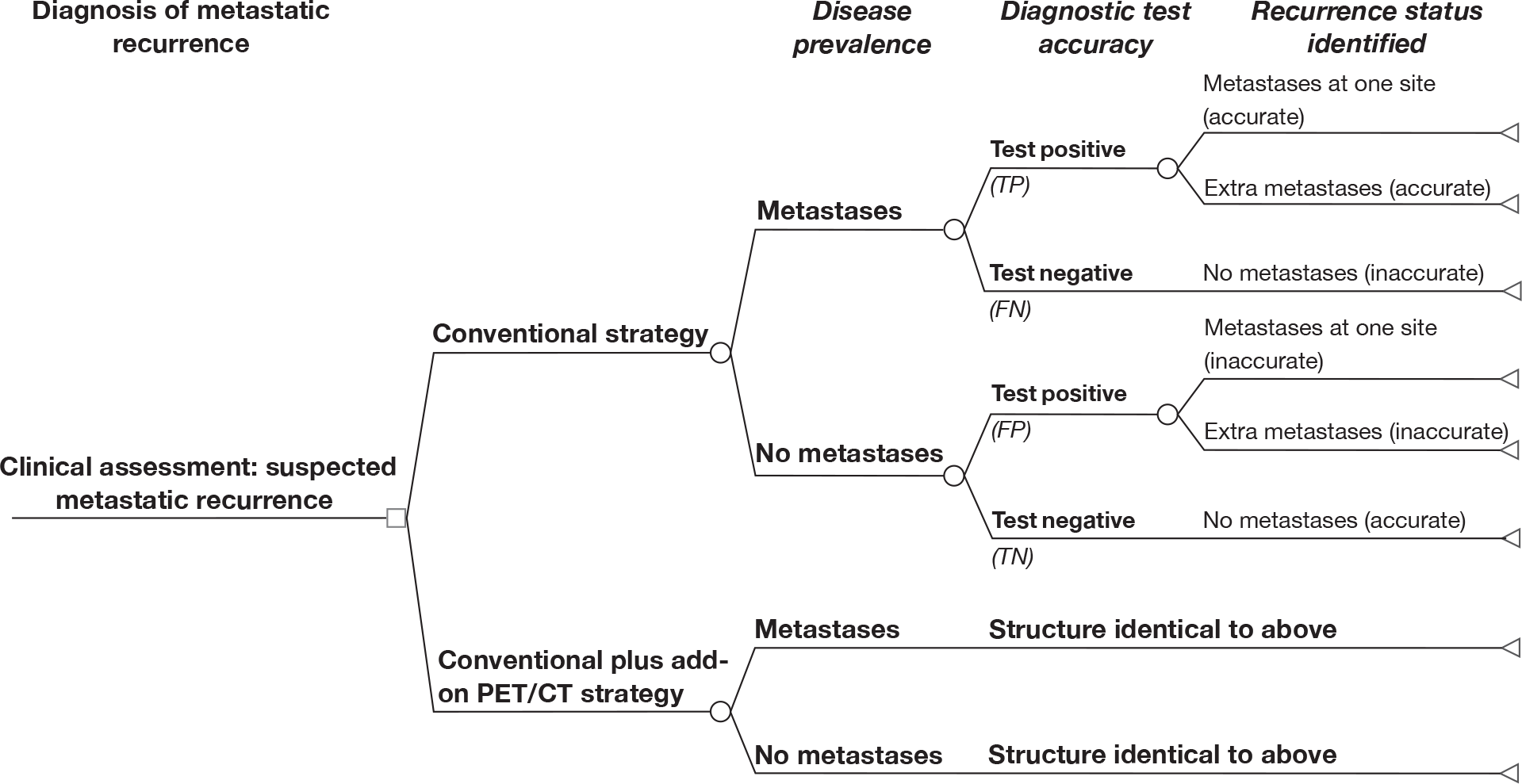

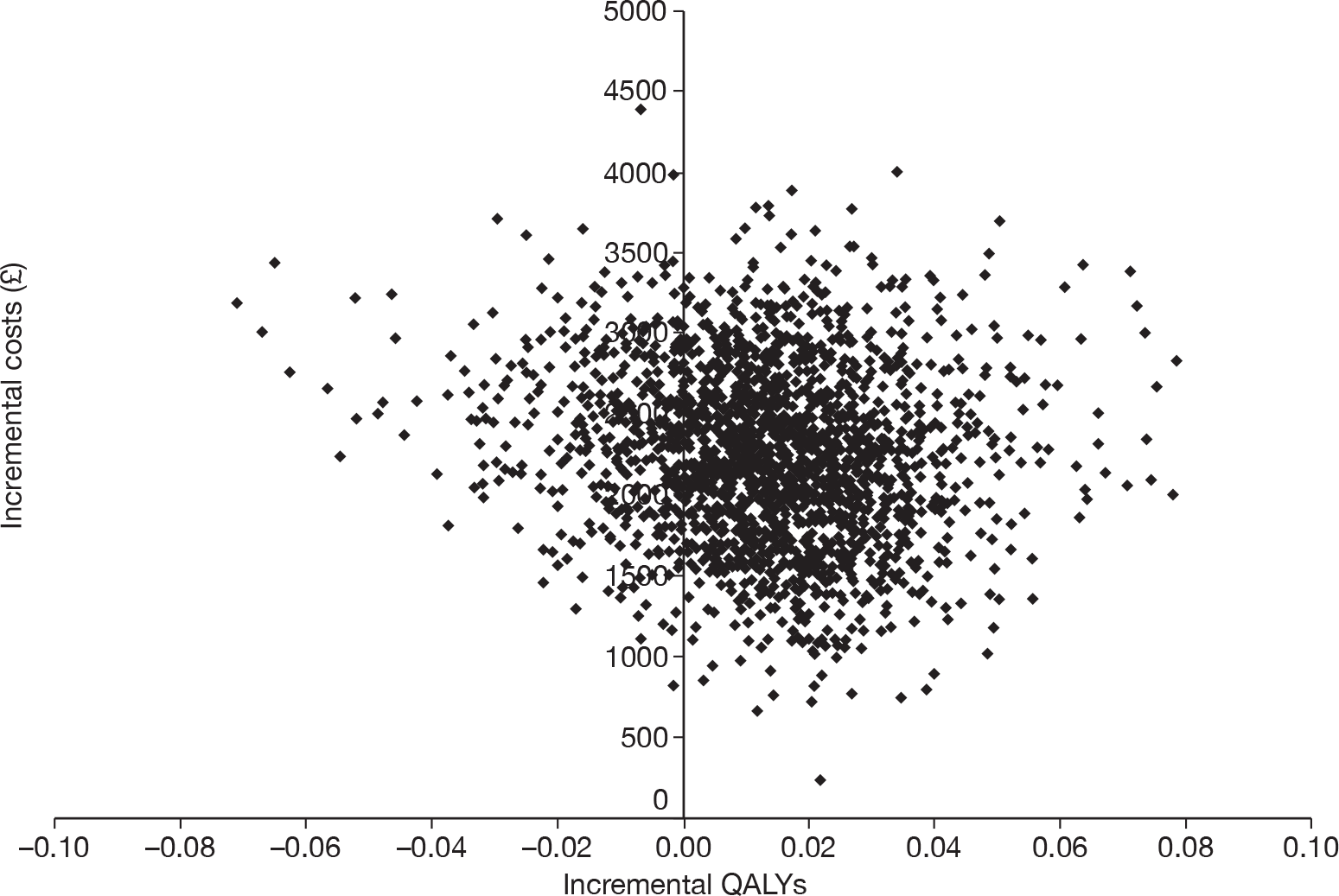

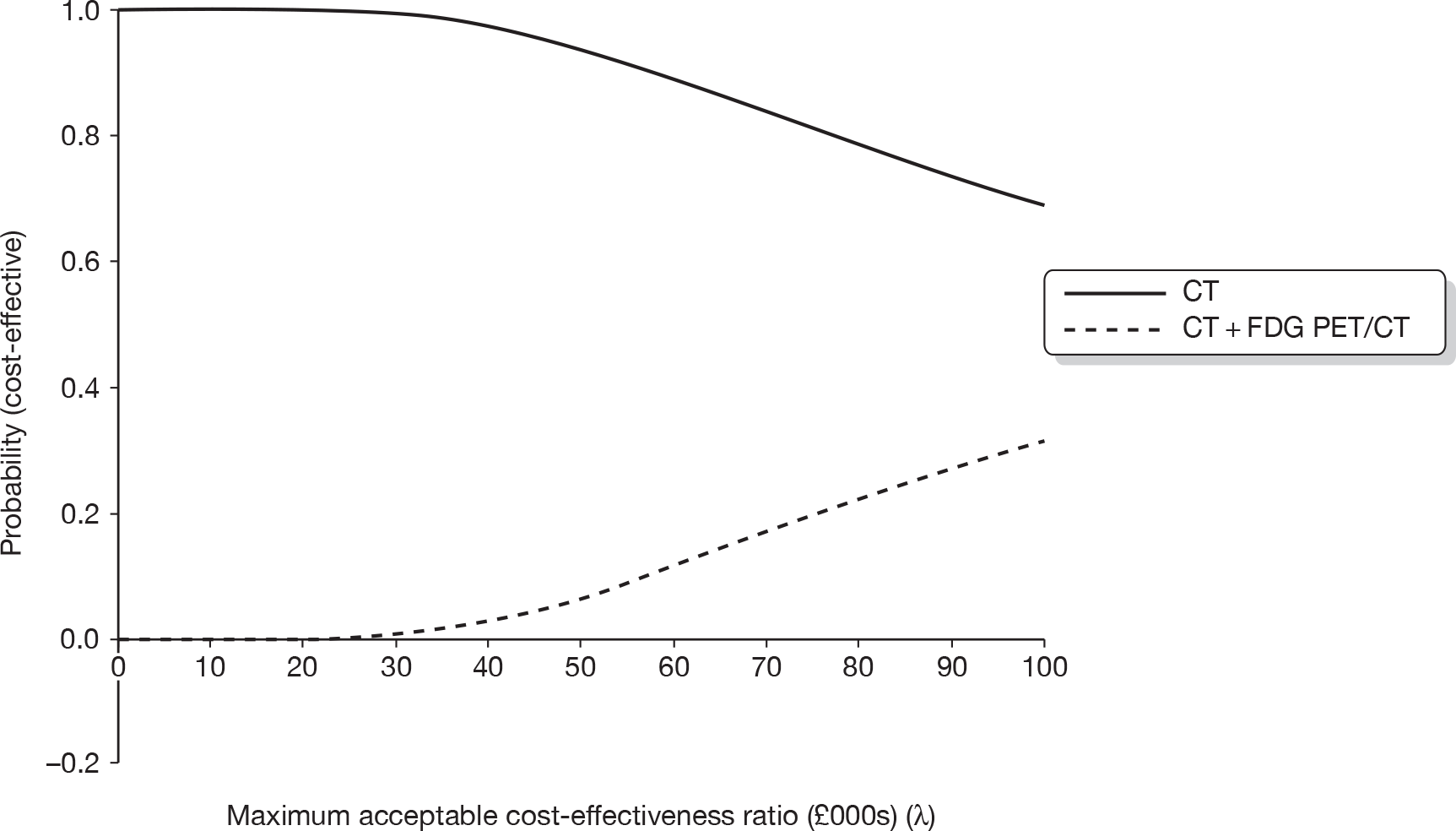

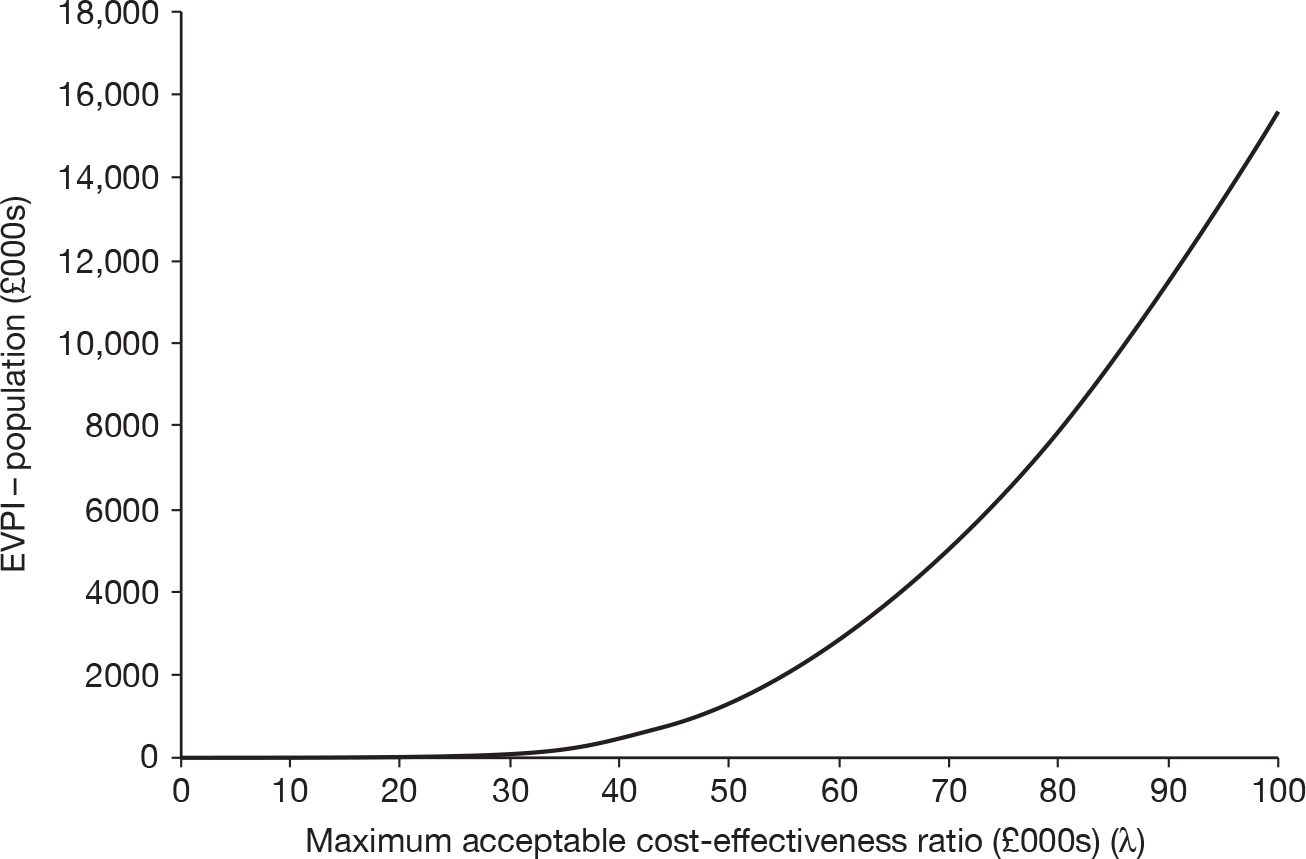

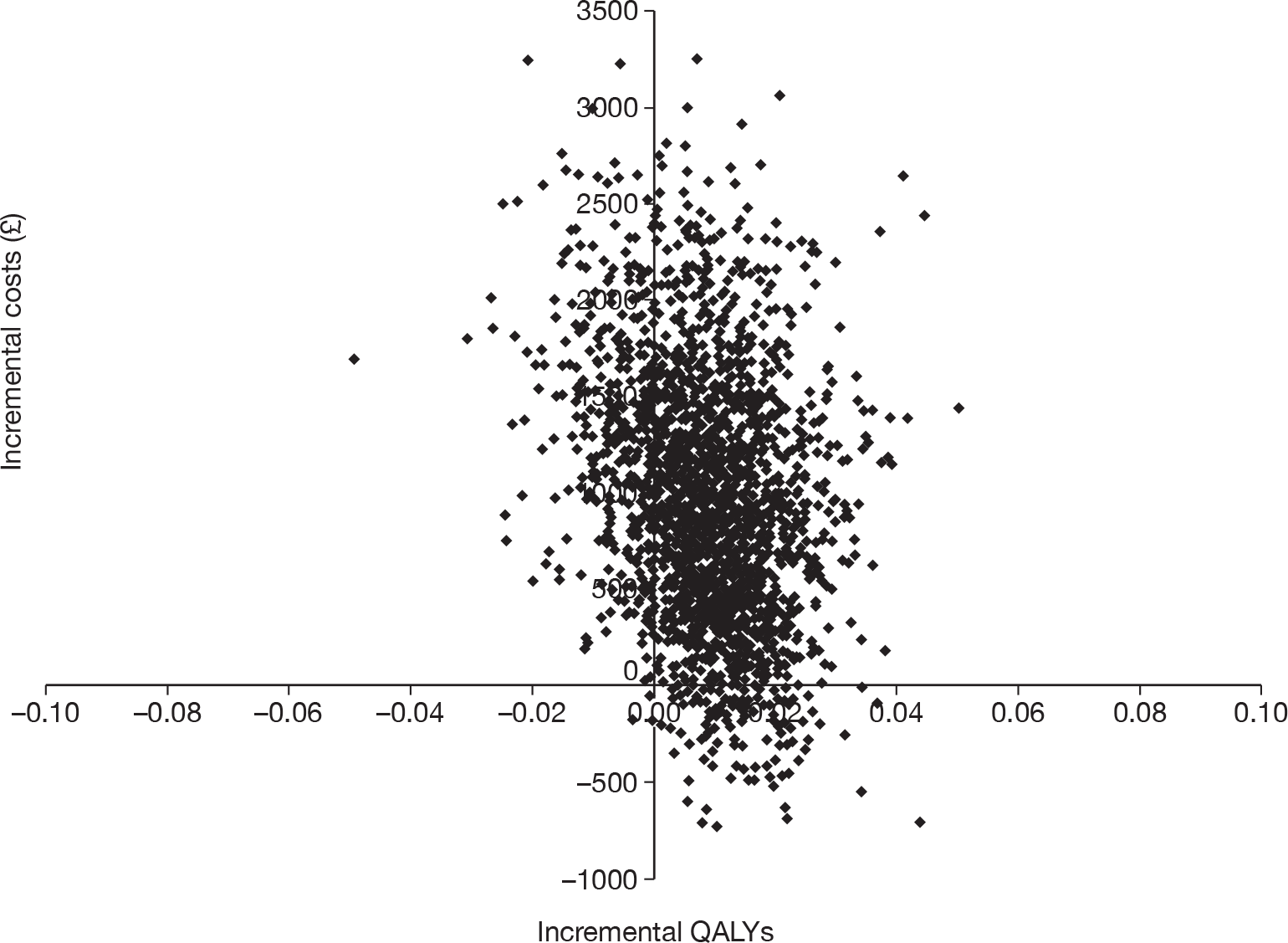

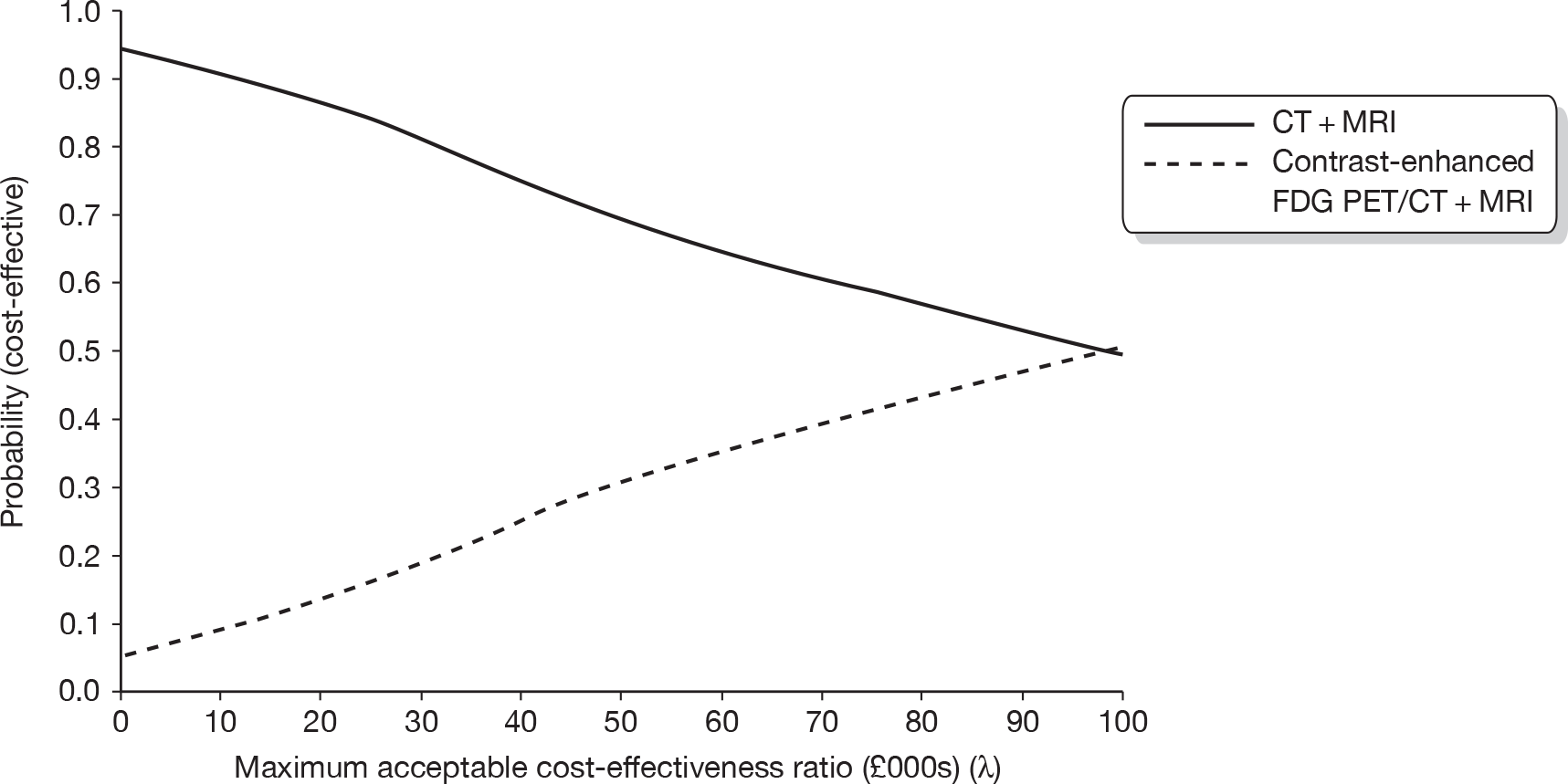

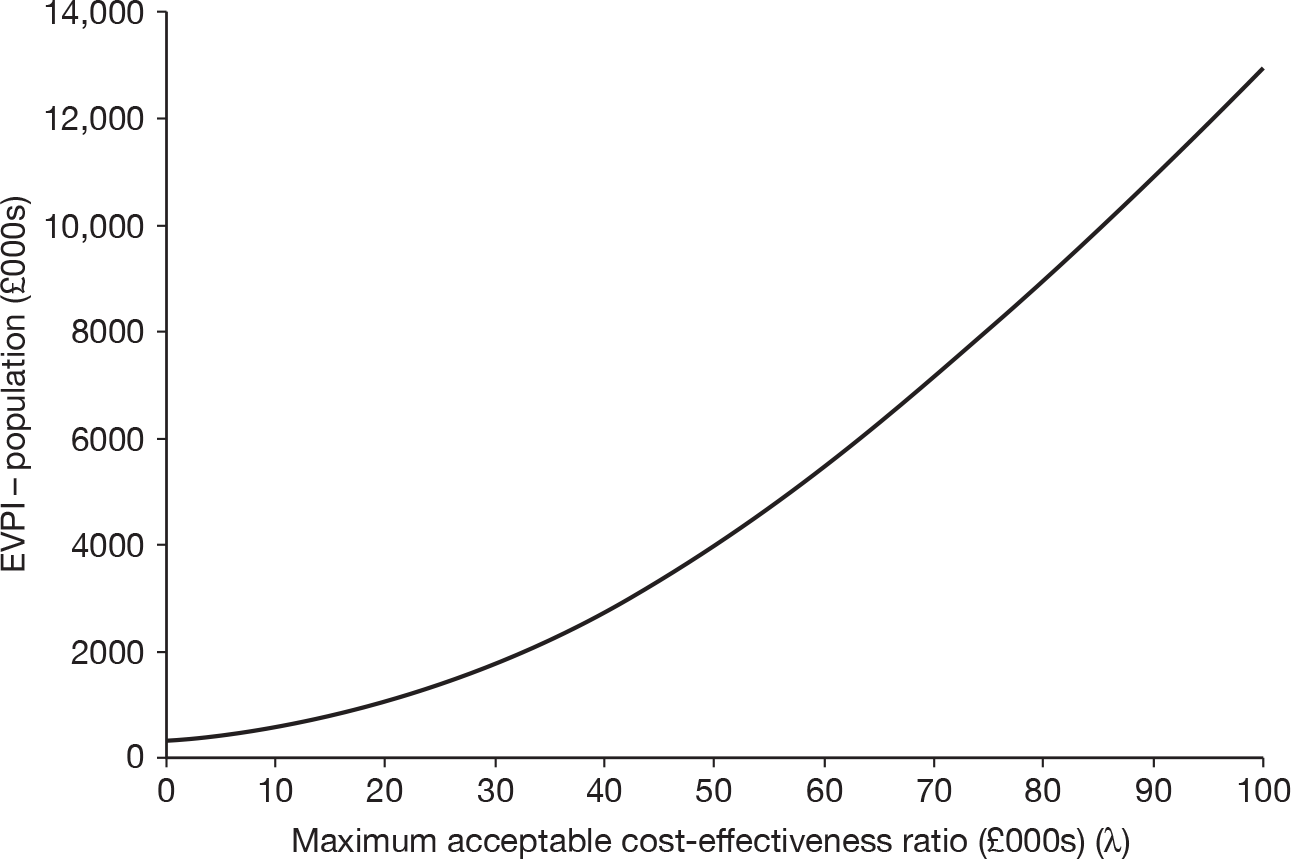

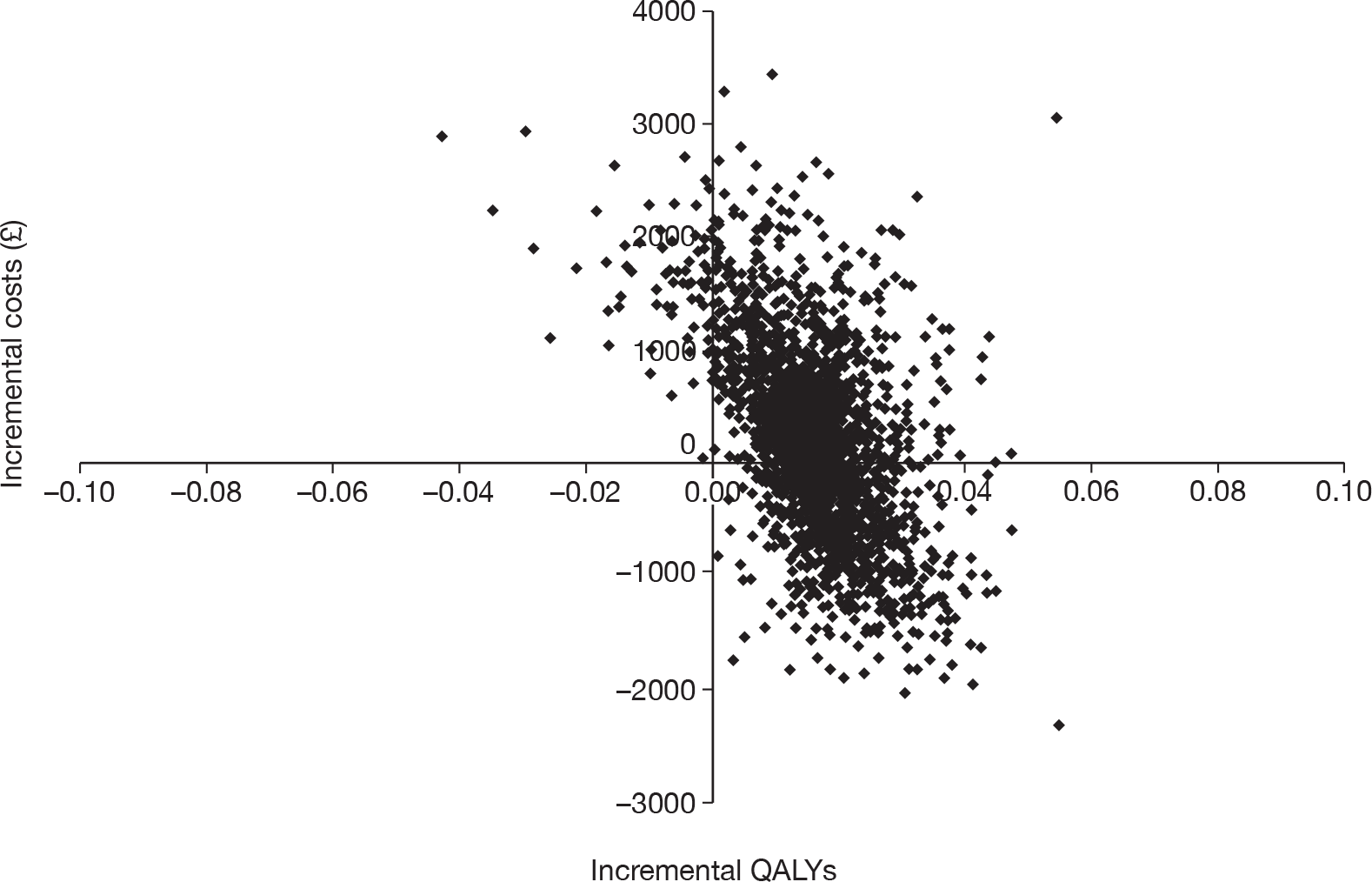

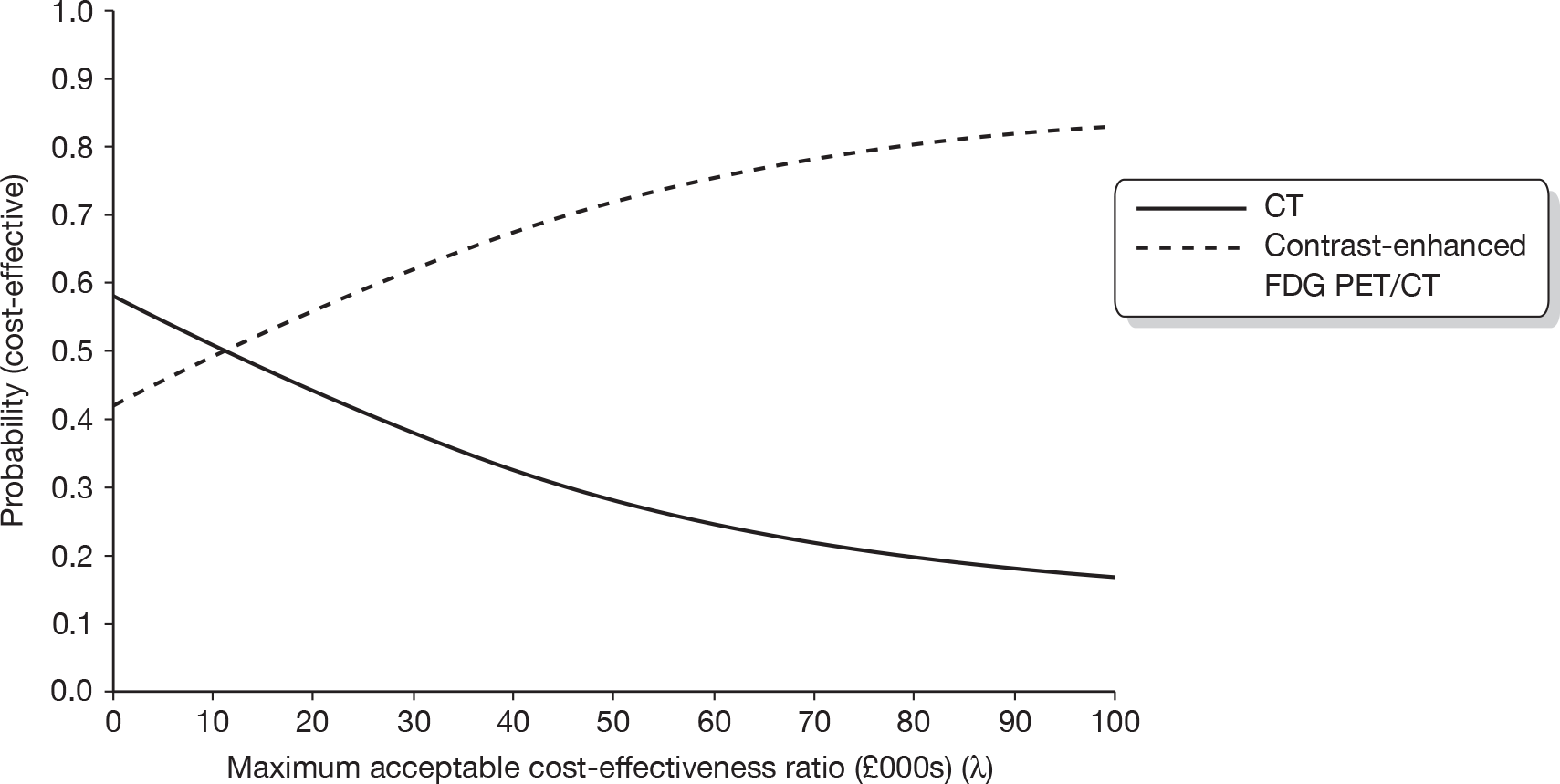

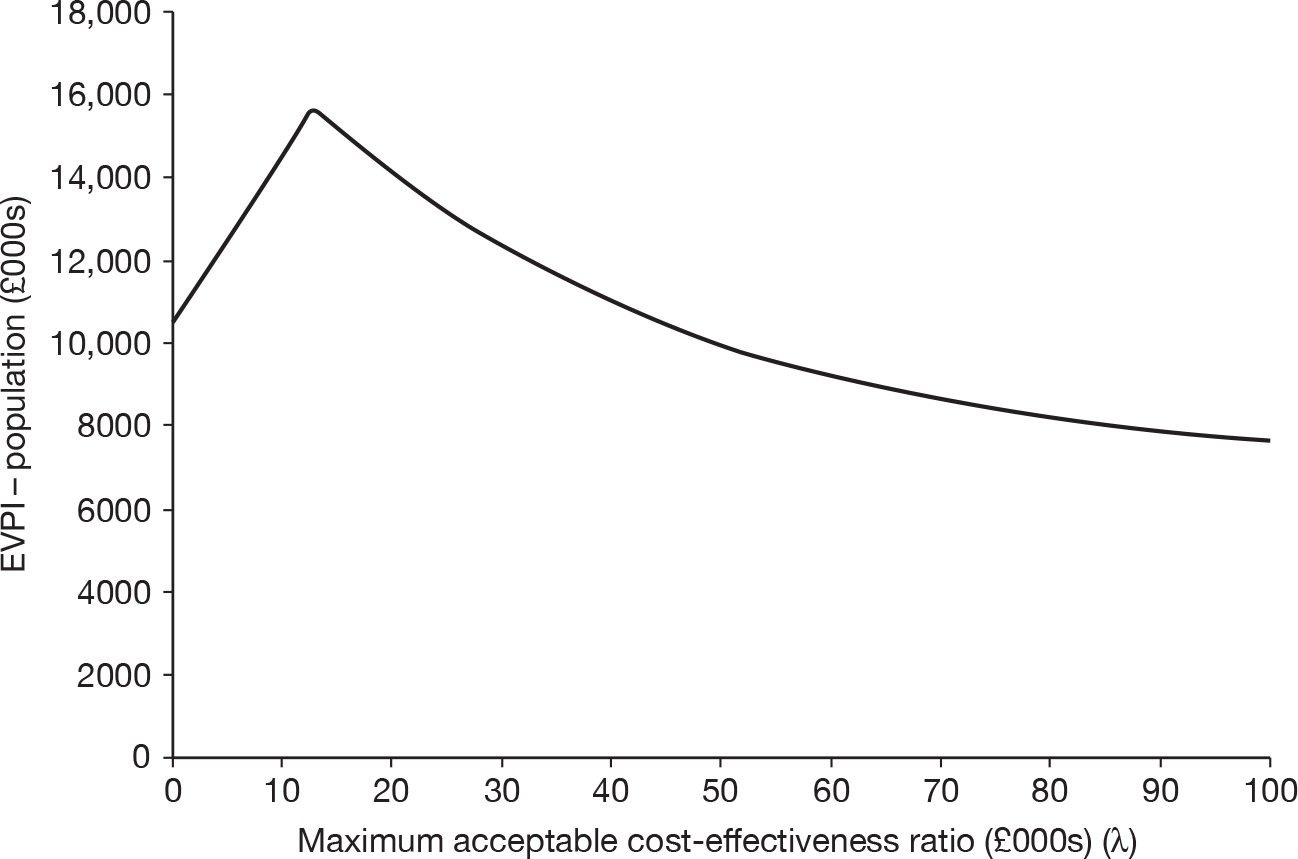

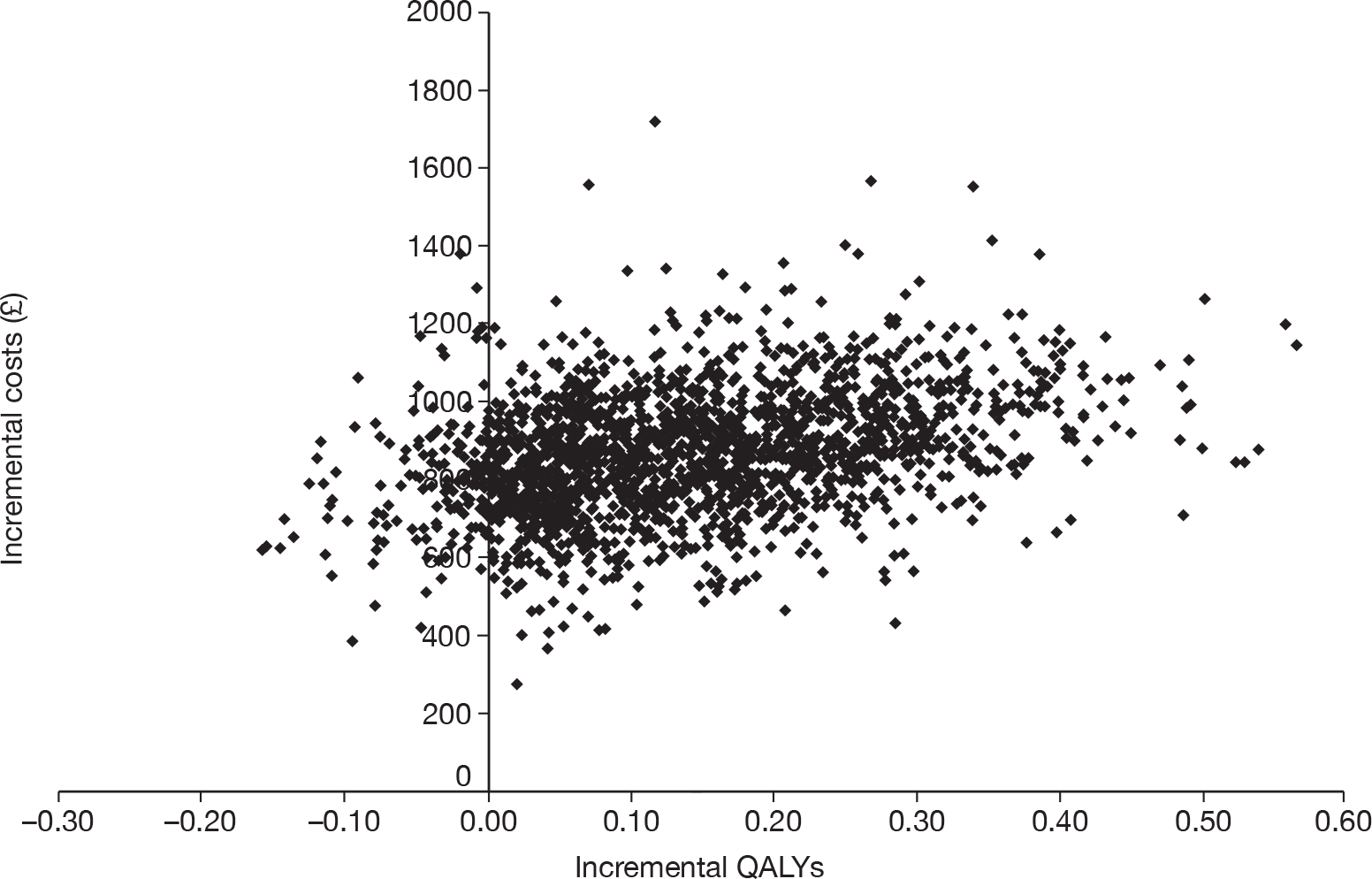

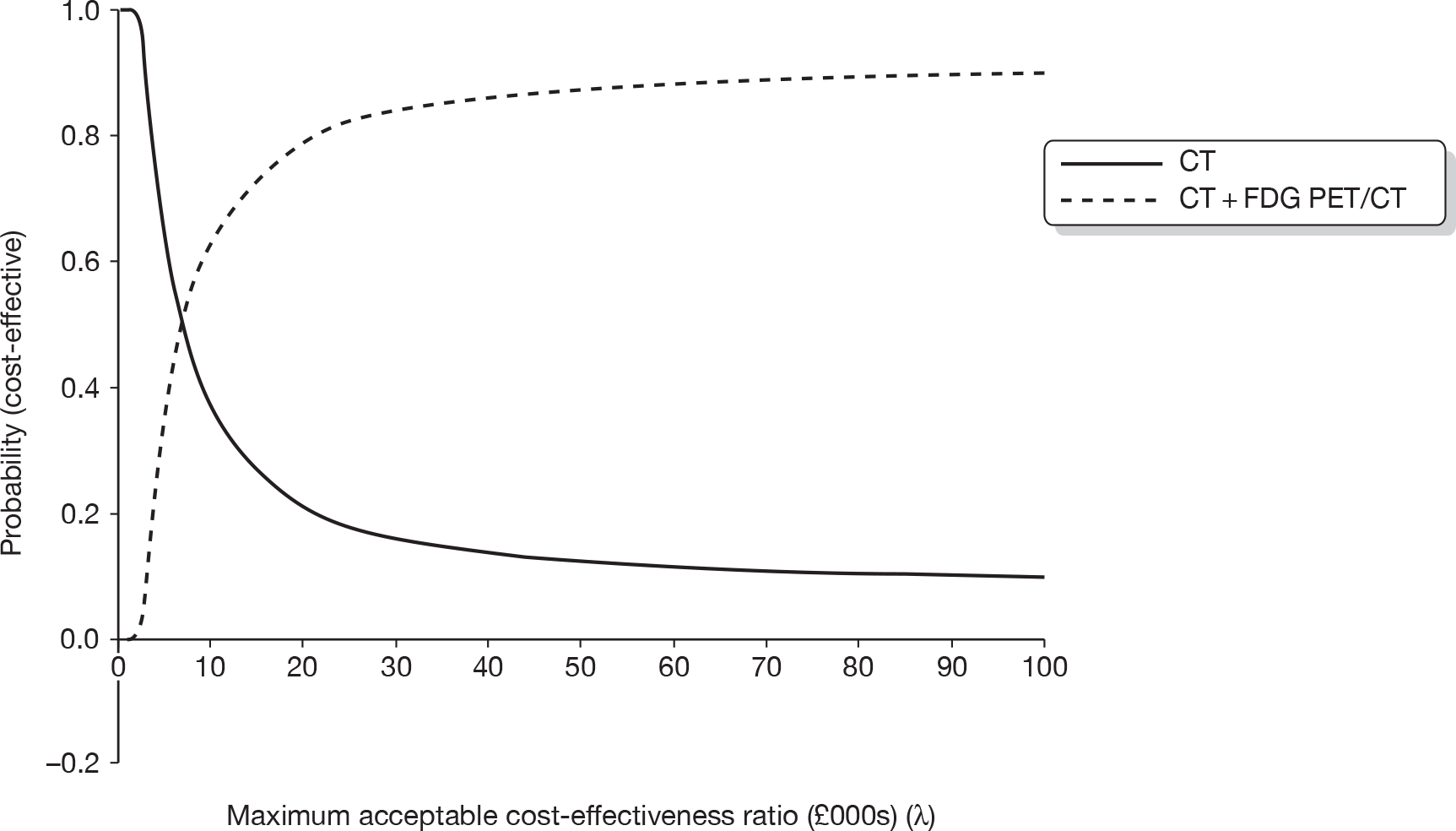

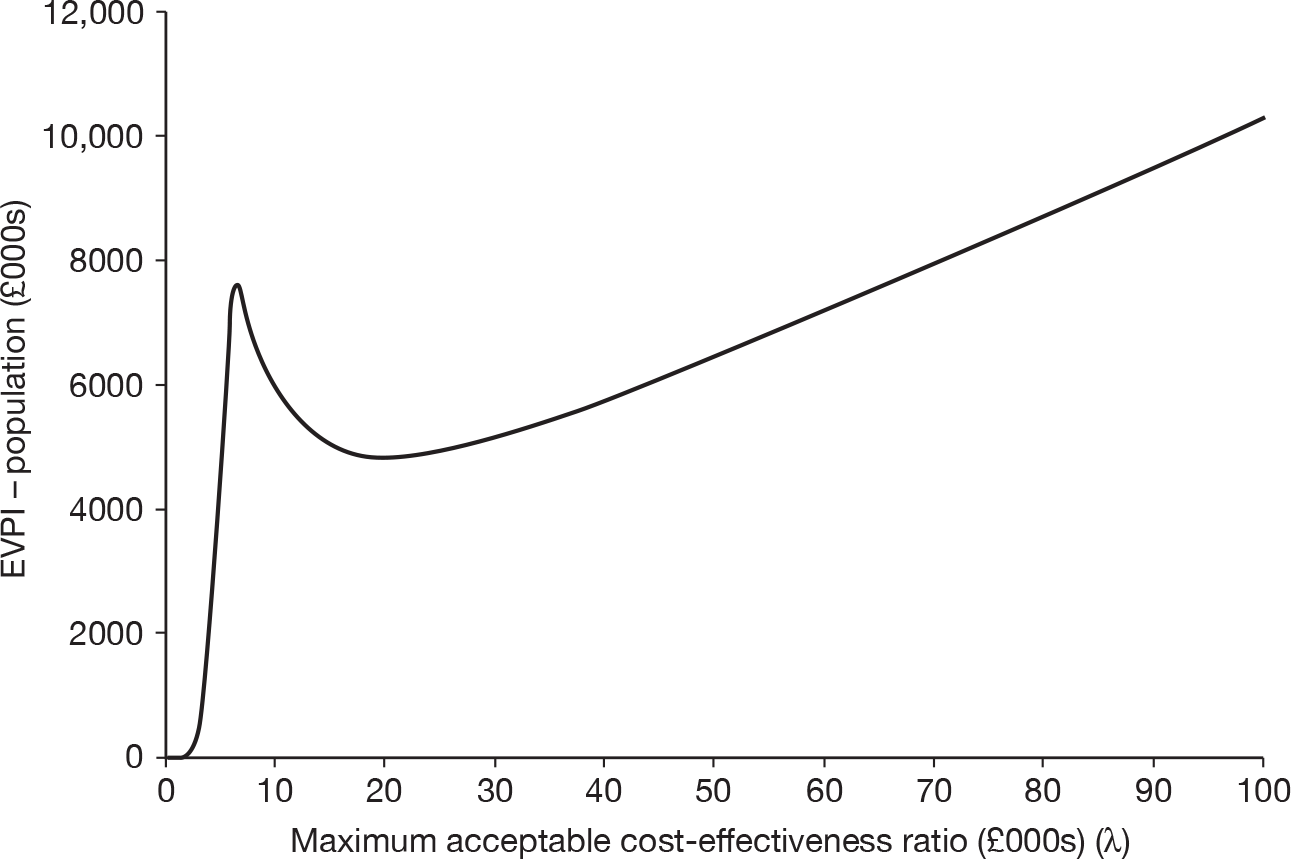

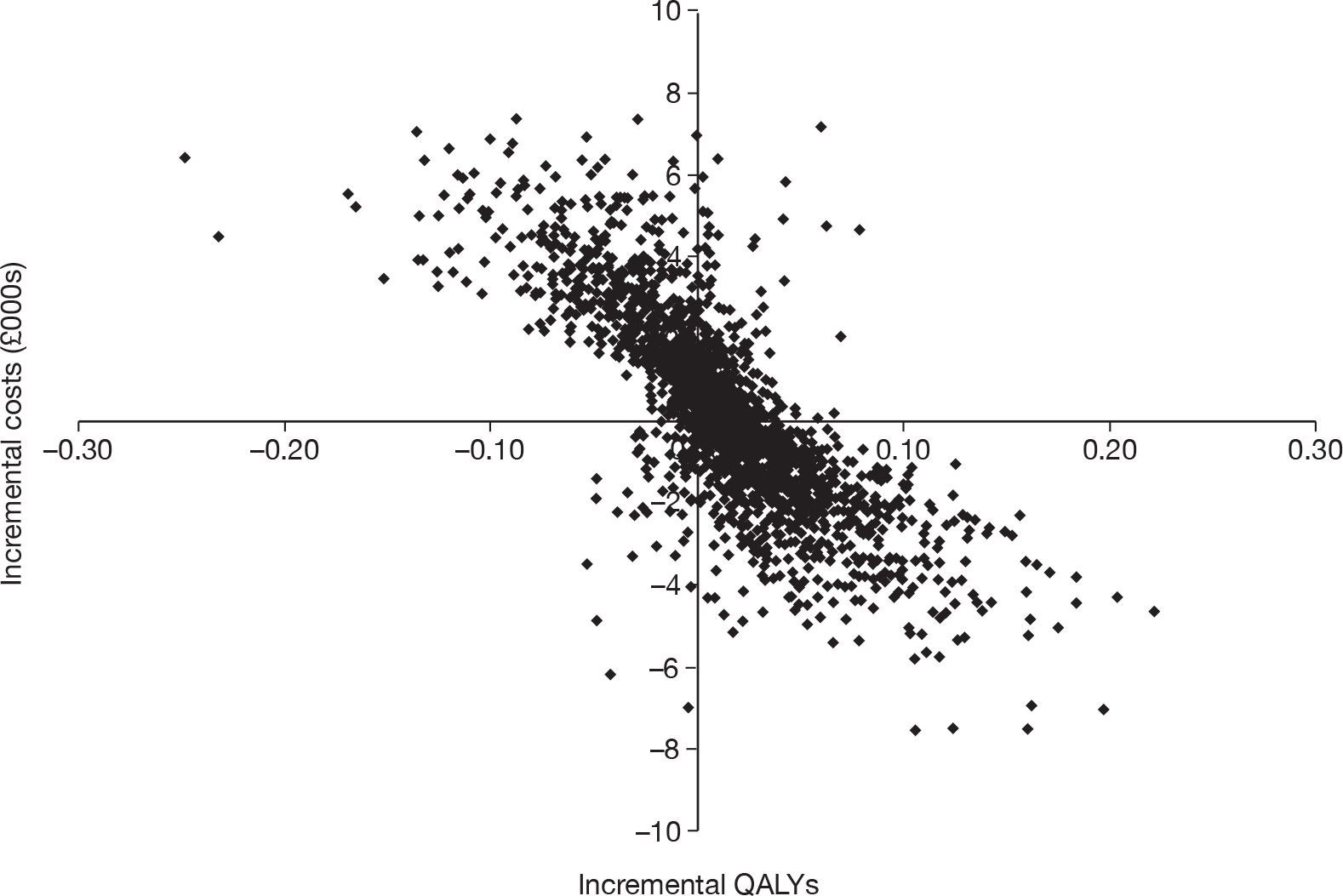

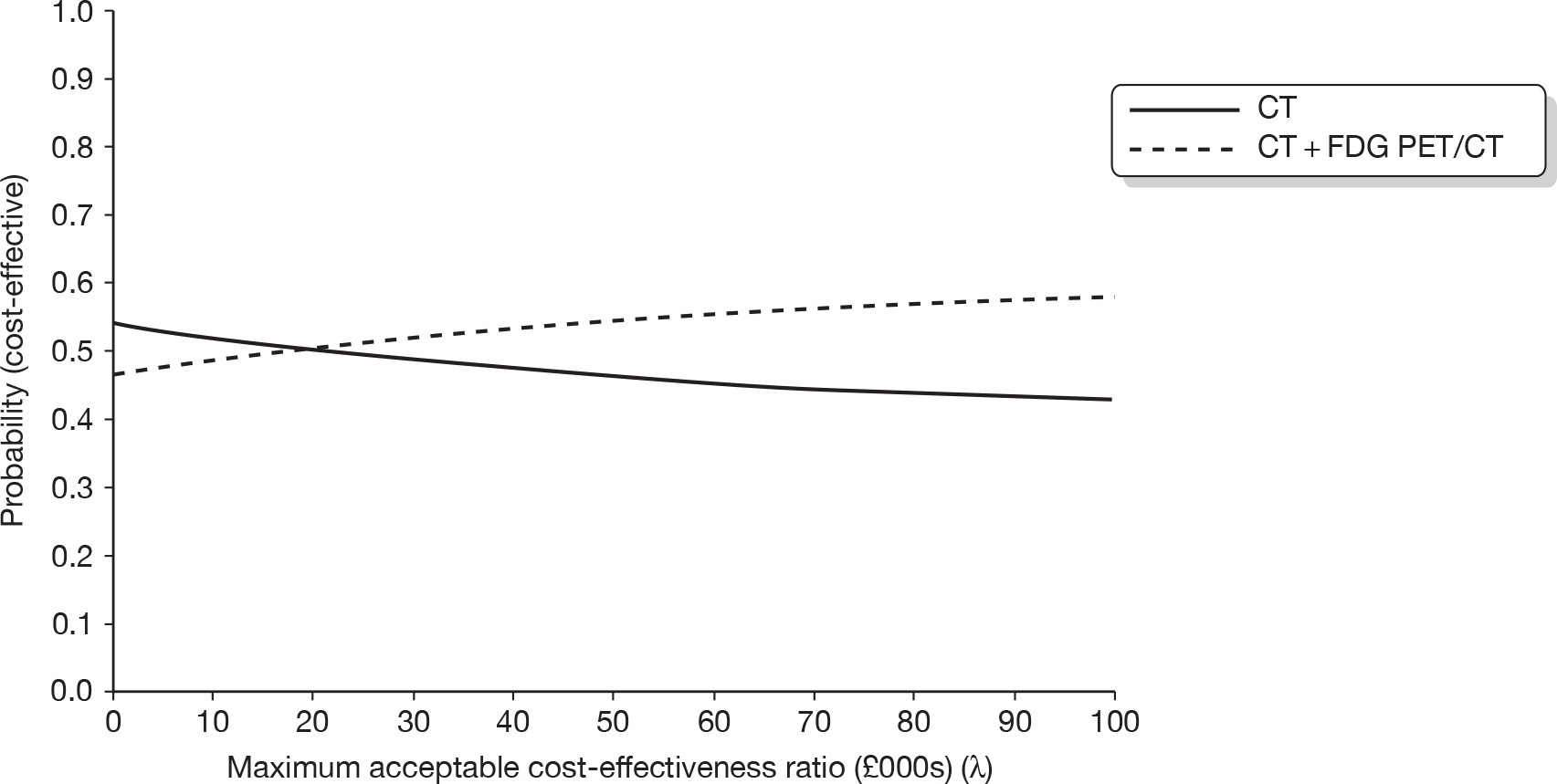

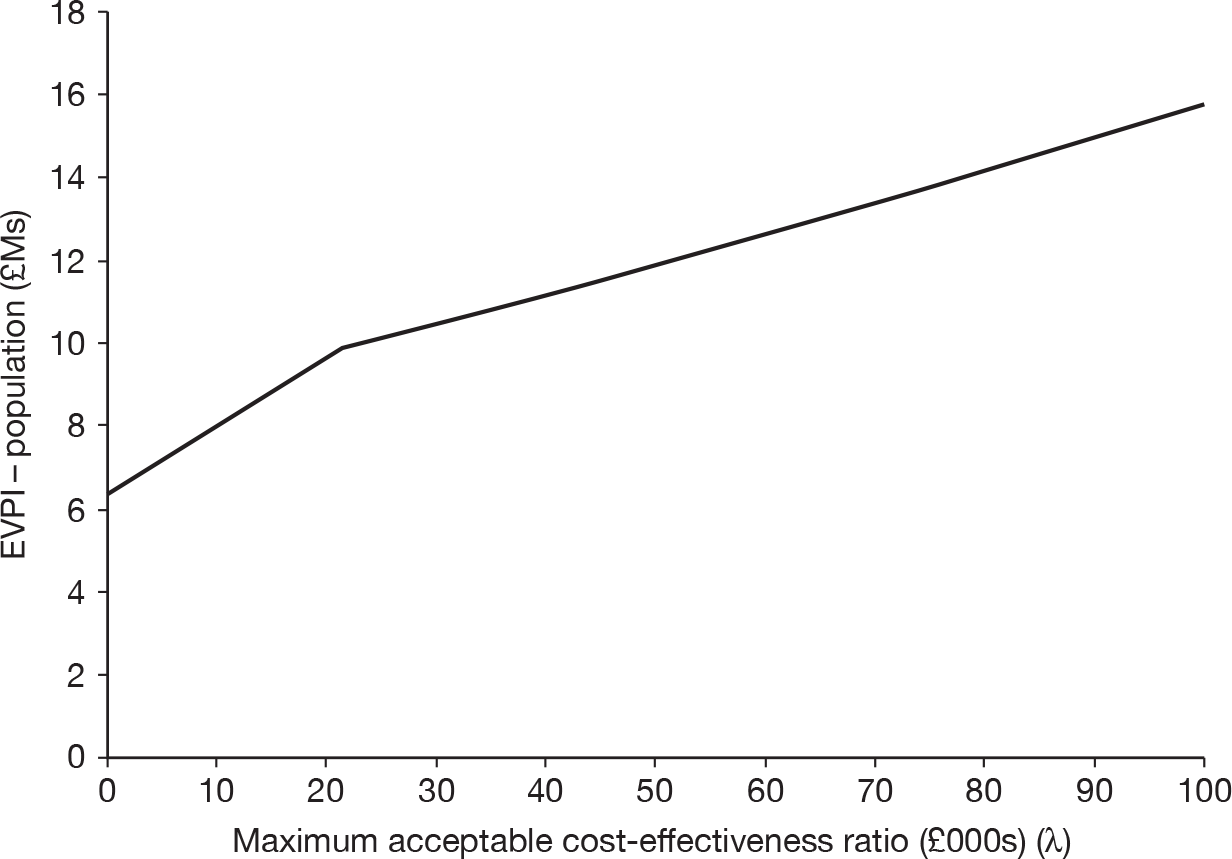

Kim 200568 Country: USA Year: 2002–3 Study design: retrospective; consecutive sample: unclear Setting: university hospital Aim: to compare PET and FDG PET/CT for restaging recurrent CRC |