Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 08/72/01. The contractual start date was in September 2009. The draft report began editorial review in December 2010 and was accepted for publication in March 2011. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

JS is Chief Medical Officer of the Fitness Industry Association (FIA). The FIA meets his receipted expenses. The post attracts neither a salary nor fees.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2011. This work was produced by Pavey et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Physical activity and health

Physical activity (PA) contributes to the prevention and management of over 20 medical conditions and diseases, including coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic back pain, osteoporosis, cancers, falls in the elderly, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), decline in physical and cognitive function, depression and dementia, as summarised in the Chief Medical Officer’s (CMO) report At Least Five a Week: Evidence on the Impact of Physical Activity and its Relationship to Health1 and, more recently, the US guidelines for physical activity. 2 Table 1 lists some of the key conditions in which exercise has been shown to be beneficial. The CMO report estimated the total cost of physical inactivity in England to be £8.2B per year.

| Mental health |

|---|

| Anxietya |

| Depressionb |

| Dementiab |

| Cancer |

| Breasta |

| Lunga |

| Prostatea |

| Colonc |

| Cardiovascular |

| MIa |

| Chronic heart failurea |

| Strokec |

| Peripheral vascular diseaseb |

| Hypertensiona |

| Metabolic |

| Hyperlipidaemiaa |

| Type 1 diabetesa |

| Type 2 diabetesb |

| Musculoskeletal |

| Low back paina |

| Osteoarthritisa |

| Rheumatoid arthritisa |

| Osteoporosisb |

| Other |

| Chronic kidney diseasea |

| Chronic obstructive lung diseasea |

| Chronic fatigue syndromea |

| Falls preventiona |

| Fertilitya |

| Obesitya |

| Parkinson’s diseasea |

| Asthmac |

| Human immunodeficiency virusc |

| Immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)c |

Current recommendations are for adults to aim to be active daily. Over a week, activity should add up to at least 150 minutes (2.5 hours) of moderate-intensity activity in bouts of 10 minutes or more – one way to approach this is to do 30 minutes on at least 5 days a week. Emerging evidence on the effects of time spent in sedentary activities (e.g. television viewing) on obesity, metabolic processes and type 2 diabetes, independent of PA, suggests that reducing time spent in sedentary activities may be an additional useful indicator of the effectiveness of interventions. Worldwide, over 20% of CHD4 has been attributed to physical inactivity, and the most active are at 30% lower risk for developing CHD than the least active,5 with a stepped reduction in risk. The dose for reducing risk in respect of other diseases and for promoting positive well-being is less clear, but the minimum target has been widely recommended as being reasonable for general health benefit at population level. 3

The Health Survey for England (HSE) provides national data on PA prevalence in England. The 2008 HSE report estimated that 39% of men and 29% of women meet the public health target of 5 × 30 minutes per week, with evident variations across age, sex, class and ethnicity. 6 The proportion achieving the targets for PA appears to have increased from 32% in 1997 to 39% in 2008 for men and from 21% to 29% for women. Nevertheless, there is a clear need to promote PA, particularly among the least active, who may have most to gain in terms of health. For adults, efforts in promoting PA have focused on changes in the environment (e.g. walking and cycle paths),7 mass media campaigns, web- and information technology-based communications at population and individual level,8 corporate and workplace initiatives,9 community programmes,10 and provision of individualised professional support11 and new health-care structures. 12

Reviews have also focused on the effectiveness of different PA interventions among specific groups in the population, such as the elderly13 and workers. 14 Systematic reviews suggest that no single approach can be wholly effective8 in helping sedentary people to maintain a physically active lifestyle, and that a wide variety of approaches can each facilitate small increments in behaviour change. The Foresight report on obesity15 reflected determinants of PA with regard to its influence on energy balance, and this is reflected in the cross-governmental policies in transport, health, schools and the built environment to tackle it.

Theories of behaviour change also support the need for multiple-level (e.g. targeting attitudes of both recipients and providers of health promotion messages) and multicomponent approaches (e.g. targeting different belief and attitudinal dimensions, such as the importance or salience of new behaviours, confidence to change, expectancy of benefits and beliefs of others). 16 The past 15 years have seen a growth in the understanding of physically active behaviour and in how to promote it with strategies matched to individual needs. 17 Achieving and maintaining a physically active lifestyle may require numerous and diverse changes in how individuals interact with the environment and with others, as well approaches such as self-monitoring of PA. 18 In evaluating the effectiveness of interventions, it is important to understand precisely what the intervention was and whether this was achieved, and also what process or mediating variables were implicated in changes in primary outcomes (i.e. behavioural and health outcomes). Many reviews and individual studies report the behavioural outcomes or biomedical markers yet very few describe the processes involved in behaviour change. 19

Physical activity promotion in primary care

Primary care has been recognised as a potentially important setting for the promotion of PA. 20 Over 85% of the population in the UK visit their general practitioner (GP) at least once a year, and almost 95% do so over a 3-year period,21 suggesting an opportunity to promote PA. Taylor22 identified, in a review of literature, several barriers that GPs perceived in promoting PA: (1) lack of time in the course of normal clinical interactions in primary care; (2) a lack of desire to pressure patients; (3) a belief that it may not be as beneficial as other therapies or other behavioural targets (e.g. smoking); (4) that patients would not follow advice; and (5) that PA promotion often seemed irrelevant for the needs of patients at the time of consultation. 22

Within the primary-care setting, there are broadly two models of PA promotion – exercise recommendation and EFSs. Although often referred to interchangeably, there are important differences between the two models:

-

Exercise recommendation Within the exercise recommendation framework, primary-care practitioners identify inactive adults and directly offer the advice or counselling regarding exercise, and/or a written prescription of exercise. In its guidance on PA promotion,23 the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommended that a validated tool, such as the Department of Health GP Activity Questionnaire (GPPAQ24), be used to identify inactive adults. Boxes 1 and 2 summarise the intervention description from two randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that illustrate the model of exercise recommendation.

-

Exercise referral schemes As in the exercise prescription approach, inactive adults are identified in the primary-care setting. In this case, instead of direct PA advice, the GP or health-care professional refers the patient to a third-party service, with this service taking responsibility for prescribing and monitoring an exercise programme tailored to the individual needs of the patient. NICE defines an exercise referral scheme (ERS) as a process whereby a health professional ‘directs someone to a service offering an assessment of need, development of a tailored PA programme, monitoring of progress and a follow-up. They involve participation by a number of professionals and may require the individual to go to an exercise facility such as a leisure centre’.

‘In a balanced 2 × 2 × 2 factorial design, the three factors were: booklet or no booklet; a counseling session given by a nurse based on attitudes, perceived control of behaviour and techniques for implementing behaviour, or no counseling session; an exercise prescription by the GP or no exercise prescription.’

Exercise prescription‘GPs briefly discussed the benefits of exercise, targets, how to start, and anticipating relapse, and wrote a prescription for 30 minutes, 5 times a week, of brisk walking (or equivalent).’

‘The intervention strategy was similar across the two intervention groups; the only difference was in the focus of the advice given. Patients recruited to the HP (health promotion) intervention group received materials and advice that encouraged them to be more active in order to protect or promote their general health. Patients recruited to the RF (risk factor) intervention group received materials and “medicalised” advice which focused on encouraging them to be more active as an adjunct to managing their hypertension. Physicians were encouraged to discuss the benefits of physical activity, to identify the patient’s preferred types of activity, and to negotiate a program of activity which was then recorded on an “Active Prescription”. The advice and prescription were then supplemented with one of two self-help booklets. The two control groups, HP control and RF control received only usual medical care from their physician. The “Active Prescription” was the same as that used by Smith et al. With the appearance of a clinical prescription; it included a precise prescription of the type, duration and frequency of activity suggested, plus additional space for other comments, a recommended review date and the physician’s signature. Carbon copy duplicates could be kept in the patient’s clinical notes to prompt review during subsequent consultations.’

Within this intervention model, the third-party service may often involve a referral to a local sport or leisure centre. However, the model can also include referral to a practice-based exercise specialist or physiotherapist. The interventions of two recent RCTs evaluating ERS are detailed in Boxes 3 and 4.

‘Patients were given a signed prescription card, with a reason for referral, resting heart rate and blood pressure, intensity of recommended exercise (three levels), and prohibited activity. They were instructed to take it to Hailsham Lagoon Leisure Centre, East Sussex, and arrange an appointment for an introductory session to start a 10 week programme with up to 20 sessions at £1.30 each (that is, half the normal admission price). The introductory session entailed a simple lifestyle assessment, a brief discussion about exercise perceptions and goals, an assessment of blood pressure, weight and height, and advice on use of the cycle ergometers, rowing machines, treadmills, stair climbing machines, and patient record cards. Patients were encouraged to progressively increase the duration and intensity of exercise during the referral period. Supervision was available when requested but patients attended informally between 9 am and 5 pm on weekdays, usually for up to an hour. A mid and end of programme individual assessments were the only formal sessions, though attendance was recorded by leisure centre staff.’

‘After receiving a referral form, the exercise officers telephoned clients to arrange a one-hour consultation at one of three leisure centres. During the consultation, the exercise officer gave person-specific advice and information with the aim of increasing the amount of physical activity clients carried out each week. This included tailored information to meet the needs o each client, taking account of their preferences and abilities, for different types of activity. All clients were offered a subsidized 12 week leisure pass, providing reduced entrance fees to any of the council-run physical activity facilities across the Borough, and were encouraged to attend at least two centre-based sessions a week. Participants were also given information about non-leisure-centre-based activities available across the Borough. At the end of 12 weeks, participants attending the first consultation were invited for an exit interview. This provided an opportunity to review their progress and to identify opportunities to maintain/increase physical activity through the longer term.’

Some trials have been conducted that have evaluated a primary care-based PA promotion including elements of both exercise prescription and ERS. One particular example is The New Zealand ‘green prescription’ (Box 5). In this model, the GP prescribes for the patient an exercise programme, and advises the patient that telephone support is available from the local sports foundation, if required. The failure to differentiate between different models has led to ambiguity within the literature, with different interpretations of these models, particularly in systematic reviews (see Chapter 3, Quality of previous systematic reviews, Scope of previous systematic reviews, and Findings of previous systematic reviews, for further discussion).

-

Primary-care clinicians are offered 4 hours of training in how to use motivational interviewing techniques to give advice on PA and the green prescription.

-

Patients who have been identified as ‘less active’ through screening at the reception desk and who agree to participate receive a prompt card, stating their stage of change, from the researcher, to give to the GP during consultation.

-

In the consultation, the primary care professional discusses increasing PA and decides on appropriate goals with the patient. These goals, usually home-based PA or walking, are written on standard green prescription and given to the patient.

-

A copy of the green prescription is faxed to the local sports foundation with the patient’s consent. Relevant details such as age, weight and particular health conditions are often included.

-

Exercise specialists from the sports foundation make at least three telephone calls (lasting 10–20 minutes) to the patients over the next 3 months to encourage and support them. Motivational interviewing techniques are used. Specific advice about exercise or community groups is provided if appropriate.

-

Quarterly newsletters from the sports foundations about PA initiatives in the community and motivational material are sent to participants. Other mailed materials, such as specific exercise programmes, are sent to interested participants.

-

The staff of the general practice is encouraged to provide feedback to the participant on subsequent visits to the practice.

Development of exercise referral schemes in the UK

Formal links between health care and promoting healthy living through opportunities to exercise are not new. For example, the Peckham Health Centre, in south London, was a bold departure in the medical field in the 1930s, concentrating on a preventative rather than a curative approach to health. To facilitate their grand project, two doctors housed in this purpose-built building engaged with over 900 families as part of ‘the Peckham Experiment’. For one shilling (£0.05 in today’s currency) a week, they relaxed in a club-like atmosphere: physical exercise, games, workshops or even simple relaxation were all encouraged.

The first contemporary ERS was set up around 1990, and over the past two decades there has been a significant and sustained growth in the number with possibly over 600 ERS operating across the UK. This rapid growth in the number of ERS has occurred, in part, in response to new legislation (e.g. compulsory competitive tendering and private management30) of such facilities. Leisure centres with swimming pools and other exercise facilities provide the opportunity to offer diverse options, as well as providing social facilities and became more business orientated, and broadening their clientele base and selling more direct debit-type memberships instead of ‘pay as you go’. The first evaluation of schemes was commissioned by the Health Education Authority in 1994. 31

In the 1990s, several limitations in ERS were indentified:32,33 (1) there were few of them, so they had little potential to impact on public health; (2) staff lacked the training to adapt exercise programmes to the specific health needs of patients; (3) there was little interest in the broader promotion of a more physically active lifestyle, but more interest in building leisure centre membership numbers; (4) GPs were reluctant to refer patients to exercise professionals who had unknown expertise and credentials; (5) there was only limited reference in key NHS policy documents to the promotion of PA; and (6) schemes were inadequately resourced for long-term evaluation. 34 As a result, and after broad consultation with health and exercise professionals, leisure industry operators and exercise scientists, a National Quality Assurance Framework (NQAF) was launched in the UK in 2001 to guide best practice and best value from ERS. 12 The document was aligned with the emerging range of NHS National Service Frameworks (e.g. for CHD, older people) that prioritise PA promotion.

The NQAF12 recommended a service-level agreement to drive the operational links between the primary-care referrer and the exercise or leisure provider, with exercise professionals on the Register for Exercise Professionals (www.exerciseregister.org/) at least at a level compatible with the needs of their clients (level 3: Instructing Physical Activity and Exercise). National Occupational Standards for level 4 (Specialist Exercise Instructor) in Health and Physical Activity were developed in 2007, with core units for CHD, mental health, obesity/diabetes, frailer older adults/falls prevention, after-stroke care and back pain. Despite the publication of the NQAF, capacity and resource constraints have largely dictated the extent to which schemes are meeting these standards. Furthermore, researchers have argued that the NQAF has failed to achieve consistency and comparability of standards, audit and evaluation mechanisms across the country. 33

The most recent survey of ERS programmes was undertaken by the British Heart Foundation National Centre for Physical Activity and Health (BHFNC34), from September 2006 to February 2008. In total, 158 schemes from England and Scotland provided information for the survey. Among these schemes, reported referral rates ranged from 20 to 6500 patients per year. Reported uptake rates (patients attending the initial consultation) ranged from 30% to 98%, with 82.5% of schemes having follow-up system for patients not attending initial consultations (telephone calls, letter/postcard). Scheme completion rates ranged between 20% and 90% depending on the ‘completion’ measure used. Although 95% of schemes reported collecting routine adherence data, adherence levels were not reported as part of the survey.

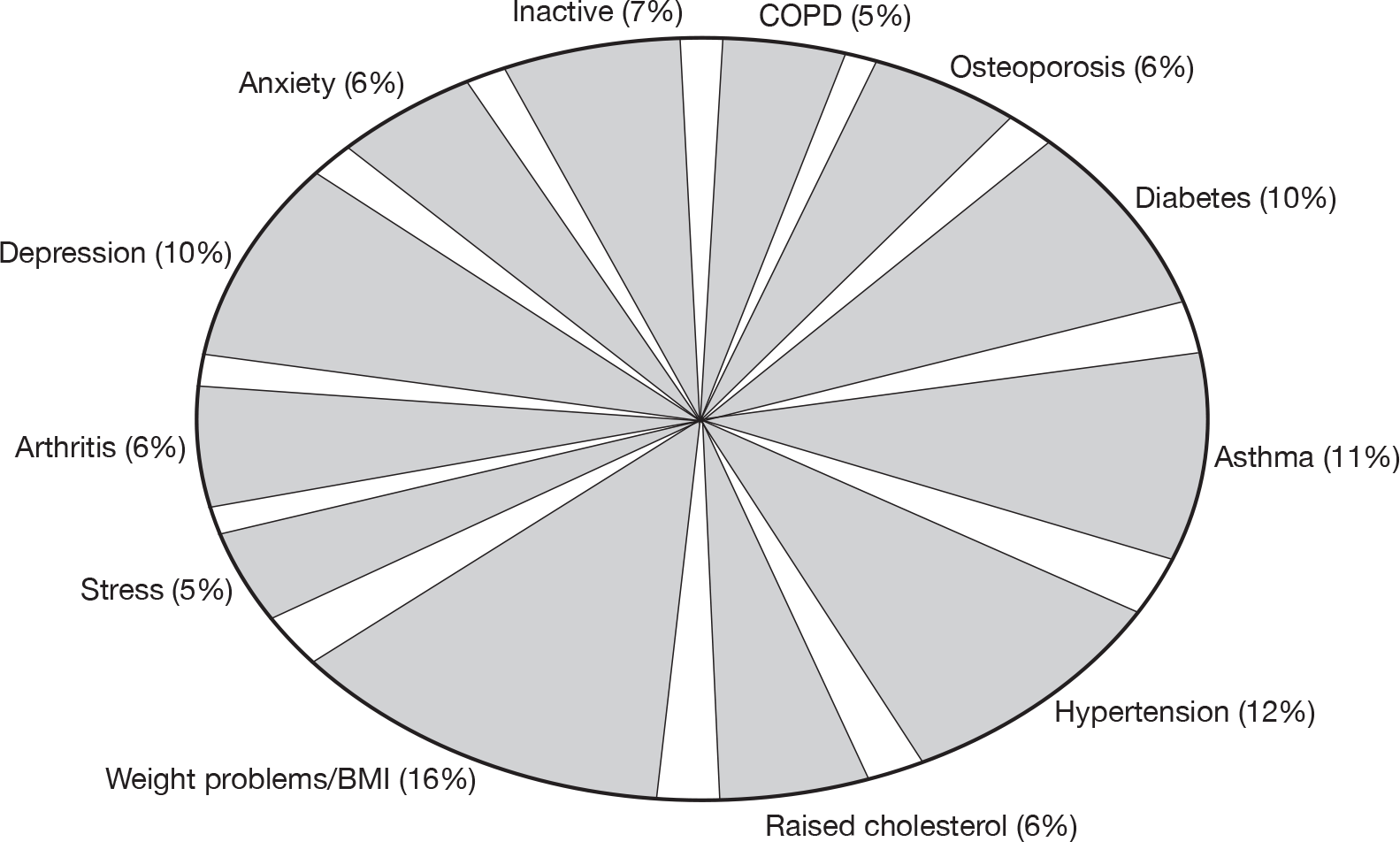

Fifty per cent of schemes had PA-based inclusion criteria, varying from less than 30 minutes’ activity per week or < 5 × 30 minutes of activity per week, with others using PA questionnaires (e.g. GPPAQ) to determine activity levels. Most schemes received patients with a range of medical conditions, including hypertension, weight problems, diabetes, arthritis, osteoporosis, anxiety and depression (see Appendix 1, Figure 21).

The survey reported further information regarding ERS in the UK that included how long schemes have been running; the aims of the scheme; the scheme characteristics (facilities and activities); the length of referral period (in 47% of schemes this was a 12-week period); and the extent to which the NQAF was used to inform the scheme. However, it was acknowledged that this information provided only a snapshot of operating EFSs, as an estimated 64% provided information.

Current guidance on exercise referral schemes in the UK

In 2006, the NICE Public Health Intervention programme undertook a review of the effectiveness of brief primary care-based intervention for PA promotion that included ERS. 35 NICE determined that there was insufficient evidence to recommend the use of ERS as an intervention to promote PA, other than as part of research studies where their effectiveness could be evaluated. NICE guidance35 recommended that:

Practitioners, policy makers and commissioners should only endorse exercise referral schemes to promote PA that are part of a properly designed and controlled research study to determine effectiveness. Measures should include intermediate outcomes, such as knowledge, attitudes and skills, as well as a measure of PA levels. Individuals should only be referred to schemes that are part of such a study.

Following NICE guidance, and in consultation with exercise referral professionals, commissioners and referring practitioners, the BHFNC published A Toolkit for the Design, Implementation & Evaluation of Exercise Referral Schemes. 34 As noted by its authors, this toolkit is not meant as a replacement for NICE or NQAF guidance, but aims to provide a set of guidance on the implementation and evaluation of ERS for referring health-care professionals, exercise referral professionals and ERS commissioners.

Summary

-

Physical activity contributes to the prevention and management of a number of medical conditions and diseases.

-

Currently, only 25–40% of adults in UK meet the CMO’s target for PA.

-

Primary care is a potentially important setting for the promotion of PA, resulting in the ERS model being developed.

-

Although variations in the model of delivery in ERS across the UK exist, common features include (1) identification of sedentary individuals at risk of lifestyle diseases by a health-care professional operating within a primary health-care setting; (2) referral to an exercise professional who seeks to develop a programme of exercise tailored to the needs of that individual patient; (3) monitoring of progress throughout the programme with appropriate feedback to the referring health-care professional; and (4) auditing to ensure adherence to quality assurance processes (e.g. appropriate staffing, health and safety procedures, ethical and data protection consideration).

-

Despite a NQAF for ERS, capacity and resource constraints have largely dictated the extent to which the majority of schemes are meeting these standards.

-

The NICE guidance in 2006 concluded that there was insufficient evidence to recommend the routine use of ERS to promote PA and called for further clinical effectiveness research.

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Decision problem

-

Interventions For the purposes of this report, an ERS was defined as comprising the following three core components:

-

– referral by a primary-care health-care professional to a service designed to increase PA or exercise

-

– PA/exercise programme tailored to individual needs

-

– initial assessment and monitoring throughout the programme.

-

-

Population including subgroups The population for this study was defined as people with a diagnosed condition known to benefit from PA. [Although the commissioned scope of this report was to focus on those with a diagnosed condition (known to benefit from PA), given the lack of evidence in this population, we broadened the scope of this report to include individuals without a medical diagnosis.] Subgroups of interest will be identified by diagnosed condition.

-

Relevant comparators All relevant comparators were considered including usual care (e.g. PA advice or leaflets), an alternative form of PA intervention or different forms of ERS.

-

Outcomes All relevant outcomes were sought. Given the nature of the intervention, we were particularly interested in changes in PA. PA can be assessed in number of ways [e.g. self-report or objective measures of PA, proportion of people meeting guideline recommendations, minutes per week of PA (total or moderate intensity), energy expenditure] and we considered all of these approaches. Other outcomes sought were uptake and adherence to ERS, physical fitness, clinical outcomes (e.g. blood pressure, serum lipids), psychological well-being, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), patient satisfaction, and potential adverse events of ERS (e.g. musculoskeletal injuries).

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

The overall aim of this review was to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ERS in people with a diagnosed condition known to benefit from PA. [Although the commissioned scope of this report was to focus on those with a diagnosed condition (known to benefit from PA), given the lack of evidence in this population, we broadened the scope of this report to include individuals without medical diagnosis.]

This aim is addressed through undertaking:

-

a systematic review of the clinical effectiveness of ERS

-

a systematic review of published economic evaluations of ERS

-

a systematic review to identify predictors of ERS uptake and adherence

-

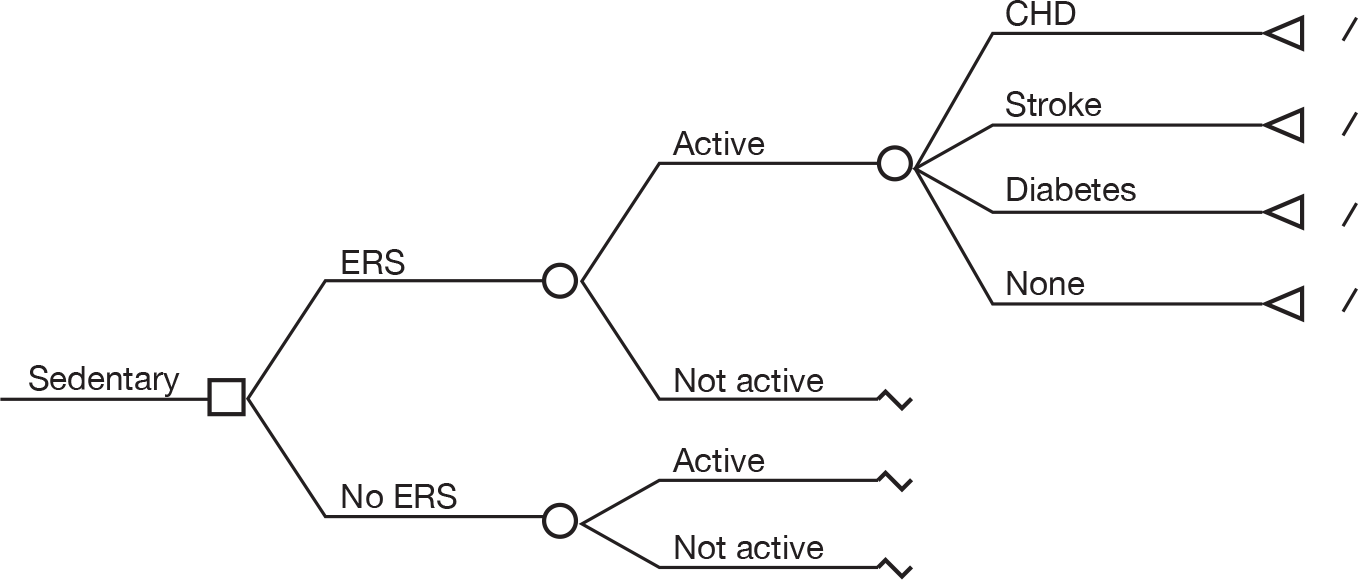

the development of a decision-analytic model to extend published results and to generate expected values for the health and cost gains/losses associated with ERS.

The specific objectives of the review are to:

-

assess the clinical effectiveness of ERS (see Chapter 3: includes individuals without a medical diagnosis – see note in parentheses above)

-

assess the cost-effectiveness of ERS (see Chapters 4 and 6: includes individuals without a medical diagnosis – see note in parentheses above)2

-

identify predictors of uptake and adherence to ERS (see Chapter 5)

-

explore the factors that might influence the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ERS (see Chapters 3 and 6: includes individuals without a medical diagnosis – see note in parentheses above)

-

identify priorities for future research in this area (see Chapters 7 and 8).

Chapter 3 Systematic review of the clinical effectiveness of exercise referral schemes

Methods

This clinical effectiveness review was conducted and reported in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement. 36

Search strategy

An experienced information scientist (TM) conducted an extensive scoping search that resulted in the utilisation of a two-part search strategy. Part 1 searched for ‘exercise referral’ and related synonyms within the title and abstract of articles. Part 2 expanded the terminology for ‘exercise referral’ within the title and abstract, and combined with ‘primary care’ search terms and a controlled trial filter. Limitations were also applied for English language and year of publication where possible (see Appendix 2 for full search strategies).

Both stages of the searches were run in the following databases:

-

Ovid MEDLINE(R) In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Ovid

-

MEDLINE(R) 1950 to October 2009

-

Ovid EMBASE 1980 to 2009 week 39

-

Ovid PsycINFO 1967 to September week 4 2009

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), NHS Health Technology Assessment (HTA), NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) via The Cochrane Library version 2009 v3

-

SPORTDiscus via Ebsco 1990 to October 2009

-

ISI Web of Knowledge 1900 to October 2009

-

Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE)—1900 to October 2009

-

Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) – 1898 to October 2009.

Records identified from the part 1 and part 2 searches were combined. The reference lists of included studies were then checked for any additional studies. Given the inception of contemporary ERS in the 1990s, any studies before 1990 were excluded from the search results.

Inclusion criteria

Studies were considered eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria.

Study design

Systematic reviews, meta-analyses, RCTs (cluster or individual) and non-randomised controlled studies. We excluded studies not published in a peer-reviewed journal (e.g. annual reports of UK ERS programmes), non-systematic reviews, editorials, opinions and reports published as meeting abstracts only (where insufficient methodological details are reported to allow critical appraisal of study quality).

Population

Any individual with or without a medical diagnosis and deemed appropriate for ERS.

Intervention

An ERS (as defined in the decision problem of this report: see Chapter 2).

The ERS exercise/PA programme was required to be more intensive than simple advice and needed to include one or a combination of counselling (face to face or via telephone); written materials; supervised exercise training. Programmes or systems of exercise referral initiated in secondary or tertiary care, such as conventional comprehensive cardiac or pulmonary rehabilitation programmes, were excluded. We excluded trials of exercise programmes for which individuals were recruited from primary care, but there was no clear statement of referral by a member of the primary care team.

Comparator

Any control, for example usual (‘brief’) PA advice, no intervention, attention control or alternative forms of ERS.

Outcomes

Physical activity (self-report or objectively monitored), physical fitness [e.g. maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max)], health outcomes (e.g. blood lipids), adverse events (e.g. musculoskeletal injury) and uptake and adherence to ERS. As we were also interested in patient (e.g. diagnosis, age) and programme factors (e.g. length of and intensity of the exercise programme) that might influence the outcome of ERS, we also extracted these factors from included studies.

Study selection process

Titles and abstracts were screened in a three-stage process. In stage 1, a single reviewer (TP) initially ruled out clearly irrelevant titles and abstracts. At stage 2, two reviewers (TP and RT or KF or MH or AT) then independently screened the remaining titles and abstracts. In stage 3, full papers of abstracts categorised as potentially eligible for inclusion were then screened by a consensus meeting of least two reviewers (TP and RT or KF or MH or AT) and disagreements were resolved in real time by consensus.

Data extraction

Data were extracted by one reviewer (TP) using a standardised data extraction form (see Appendix 3) and checked by another (RT). Discrepancies were resolved by discussion, with involvement of a third reviewer when necessary. Extraction included data on patient characteristics (e.g. age, disease diagnosis), intervention (e.g. duration, location, intensity and mode of the exercise intervention delivered), comparator, study quality, and reported outcomes pertinent to the review. All included study authors were contacted to seek information that was not available in the publication(s).

Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias criteria were derived from previous quality/risk of bias assessment instruments using published criteria relevant to controlled studies [Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) report 437 and Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions38].

Data analysis and synthesis

Given the heterogeneous nature of outcomes and variable quality of outcome reporting, the primary focus of our data synthesis was descriptive, and detailed tabular summaries are presented. For a small number of outcomes it was possible to consistently extract data across studies to allow quantitative summary using meta-analysis. Dichotomous outcomes were expressed as relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) calculated for each study. For continuous variables net changes were compared (that is exercise group minus control group to give differences) and a weighted mean difference (WMD) or standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI was calculated for each study. Heterogeneity was explored through consideration of the study populations, methods and interventions, by visualisation of results and, in statistical terms, by the chi-squared test for homogeneity and the I2-statistic. A fixed-effect model meta-analysis was used except where statistical heterogeneity was identified (χ2 p-value ≤ 0.05 or I2 ≥ 50%), in which case a random-effects model was used. Given the small number of studies consistently reporting outcomes in a format to allow meta-analysis, we were not able to undertake a funnel plot and publication-bias analysis. Analyses were conducted using RevMan version 5.0 (Cochrane IMS, London, UK).

Results

Identification and selection of studies

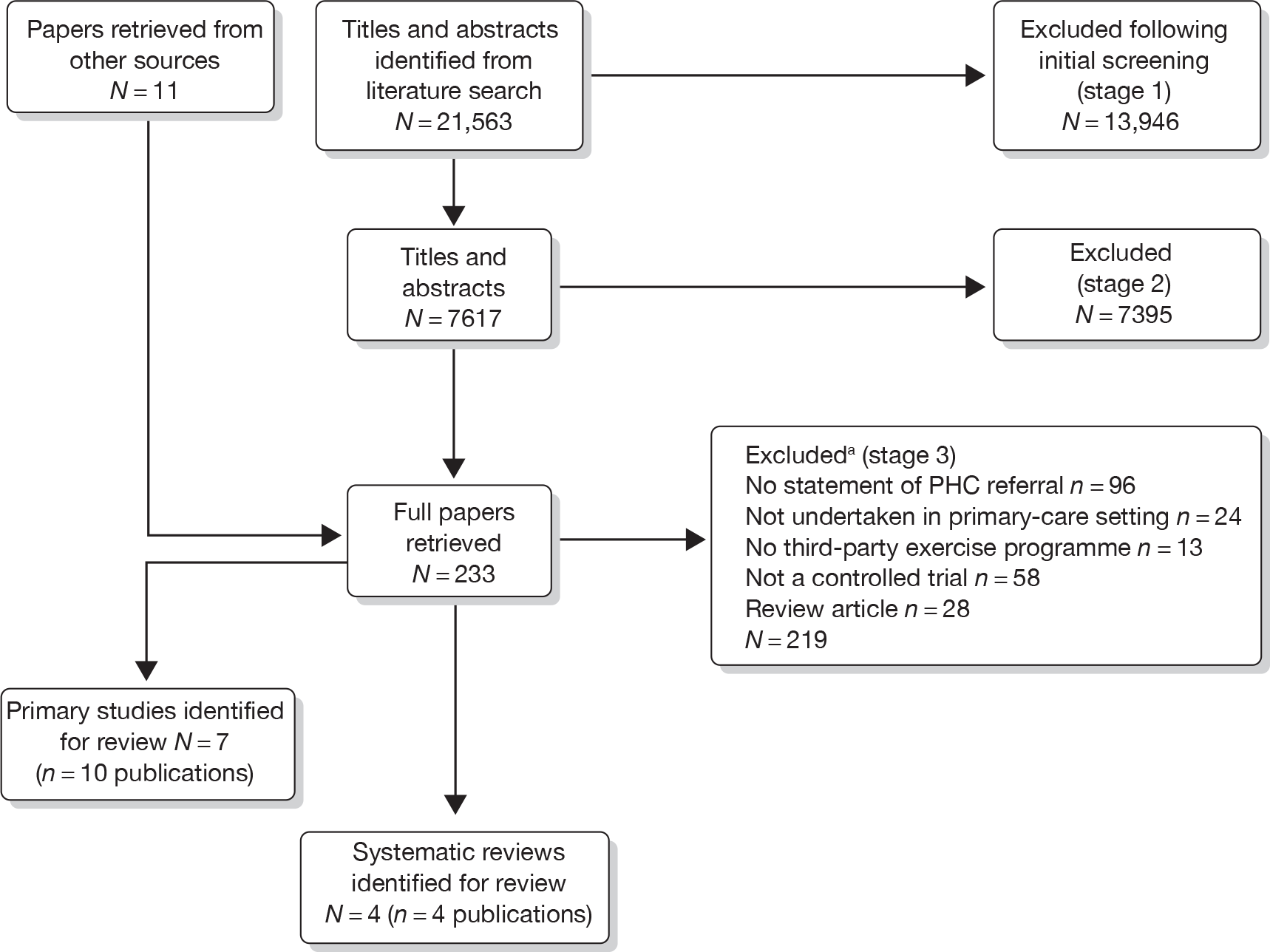

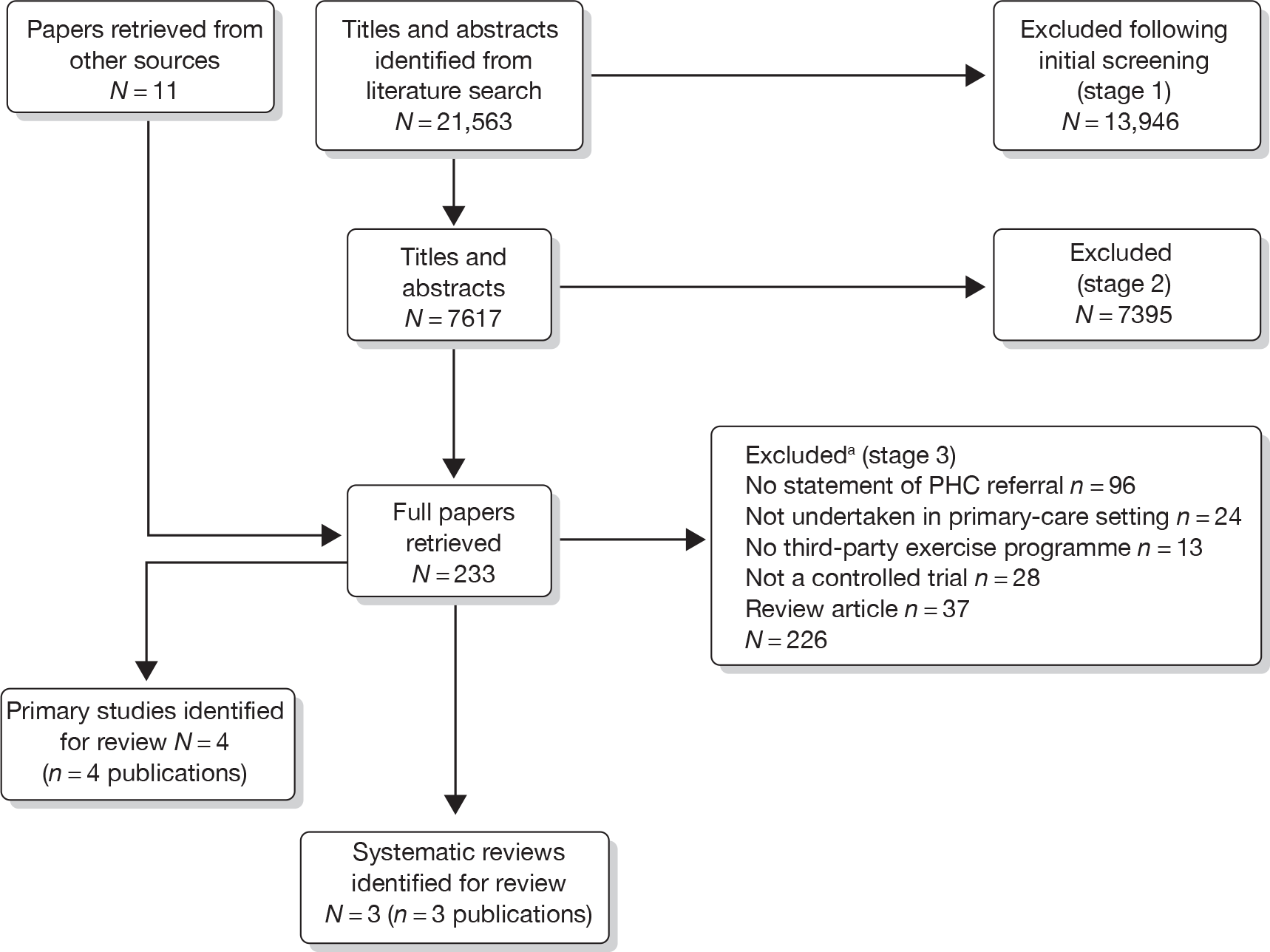

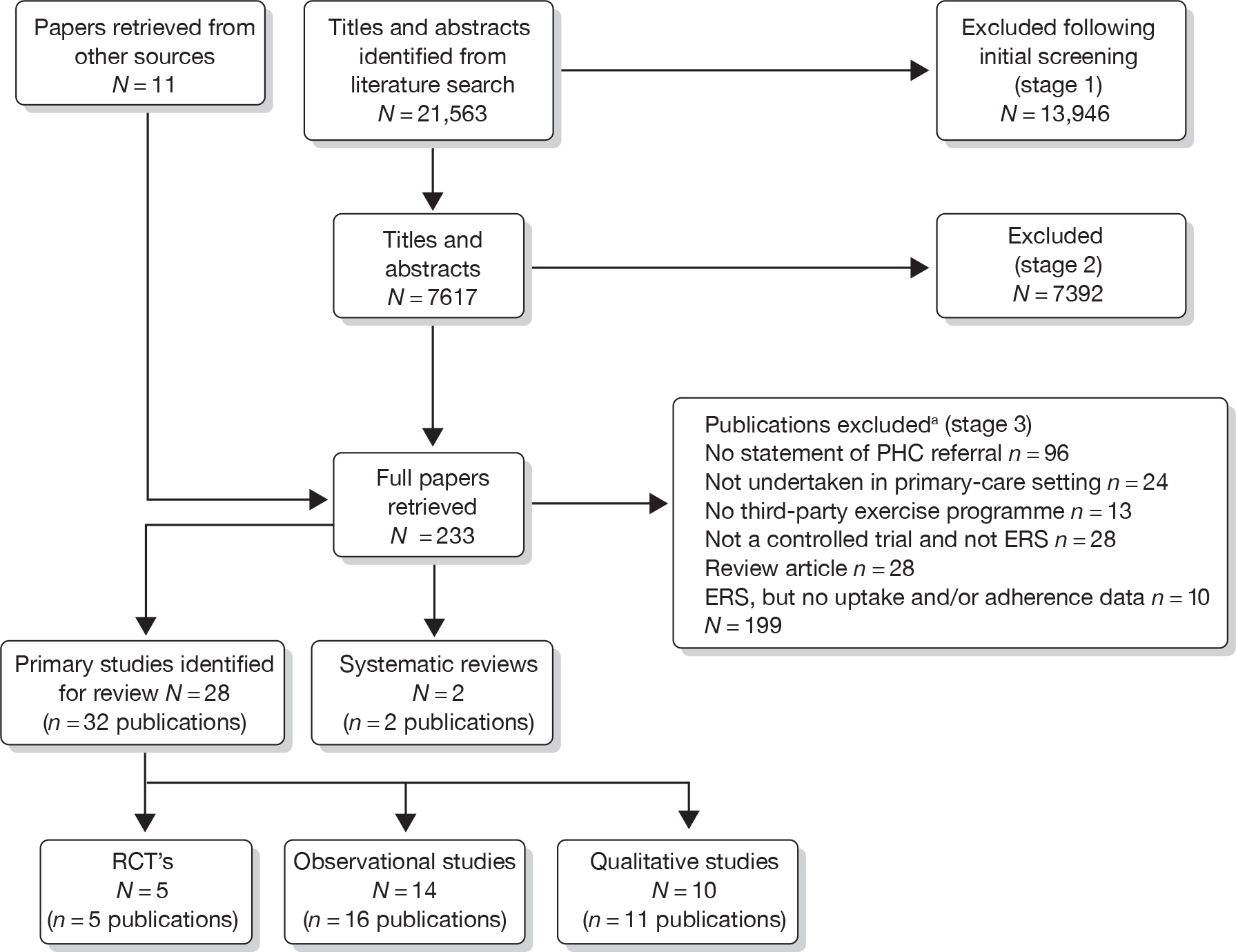

Our bibliographic search yielded 21,563 titles, of which seven primary studies and five systematic reviews were judged to meet the inclusion criteria. Figure 1 summarises the selection and exclusion process.

FIGURE 1.

Study inclusion process for ERS effectiveness systematic review. a, Primary exclusion criteria identified. PHC, primary health care.

Previous systematic reviews of exercise referral scheme effectiveness

A review of previous systematic reviews of the effectiveness of ERS was undertaken to gain an understanding of the evidence for the effectiveness of ERS and information scope and methods of the present systematic review.

Description of included reviews

Four previous systematic reviews of the effectiveness of ERS were identified. 35,39–41 Details of these systematic reviews are summarised in Tables 2–4. 35,39–41 There was considerable variation in the ERS definition applied by these reviews and the type of study design that they included (see Table 2). The systematic reviews by Morgan,39 Sorensen et al. 40 and NICE35 focused on the effectiveness of ERS and included only RCTs. In contrast, Williams et al. 41 included RCTs, non-RCTs, and observational and qualitative studies.

| Authors | Objectives of review (stated by authors) | Databases/end date of searches | ERS definition | Inclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morgan (2005)39 | Review current evidence of the effectiveness for ERS | MEDLINE; EMBASE; CINAHL 2002 | Interventions providing access to exercise activities or facilities and studies based in a primary-care setting | Experimental or quasi-experimental studies, with control groups. Studies including an exercise component with measures of PA or adherence |

| Sorensen et al. (2006)40 |

|

MEDLINE; WinSPIRS; NLM Gateway 2005 | Exercise prescribed by GP or other primary-care staff where EoP included more than just simple advice |

Sedentary adults with signs of lifestyle disease Peer-reviewed studies Reported PA or maximal oxygen uptake Follow-up ≥ 6 months |

| NICE (2006)35 | Examine the evidence for the effectiveness of ERS in increasing PA levels in adults | MEDLINE; PubMed; EMBASE; CINAHL; PsycINFO; SPORTDiscus 2005 | Referral by appropriate professional to a service with formalised process of assessment; development of tailored PA programme; monitoring of progress |

Controlled study design Measurement of PA outcomes or physical fitness at baseline and at least 6 weeks post intervention |

| Williams et al. (2007)41 | Assess whether ERS are effective in improving exercise participation in sedentary adults | MEDLINE; AMED; EMBASE; CINAHL; PsycINFO; SPORTDiscus; The Cochrane Library; SIGLE 2007 | Referred adults from primary care to intervention where encouraged to increase PA; initial assessment; tailored programme; monitoring |

RCT; non-RCT; observational; process evaluation; qualitative Any outcome |

| Studies | Morgan (2005)39 | Sorensen et al. (2006)40 | NICE (2006)35 | Williams et al. (2007)41 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCTs | ||||

| King et al. (1991)45 | ✓ | |||

| Marcus and Stanton (1993)46 | ✓ | |||

| McAuley et al. (1994)47 | ✓ | |||

| Munro et al. (1997)48 | ✓ | |||

| Bull and Jamrozik (1998)49 | ✓ | |||

| Taylor et al. (1998)27 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Stevens and Hillsdon (1998)50 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Dunn et al. (1998, 1999)51,52 | ✓ | |||

| Goldstein et al. (1999)53 | ✓ | |||

| Harland et al. (1999)43 | ✓ | |||

| Naylor et al. (1999)54 | ✓ | |||

| Halbert et al. (2000)55 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Writing Group for the Activity Counselling Trial (2001)56 | ✓ | |||

| Dubbert et al. (2002)57 | ✓ | |||

| Lamb et al. (2002)58 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Petrella et al. (2003)59 | ✓ | |||

| Elley et al. (2003)29 | ✓ | |||

| Harrison et al. (2005)28 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Marshall et al. (2005)26 | ✓ | |||

| Jimmy and Martin (2005)60 | ✓ | |||

| Isaacs et al. (2007)61 | ✓ | |||

| Non-randomised trials | ||||

| Robertson et al. (2001)62,63 | ||||

| Fritz et al. (2006)64 | ✓ | |||

| Authors | No. of included studies | Method of data synthesis | Key findings (as reported by author) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morgan (2005)39 |

UK (n = 4) Non-UK (n = 5) |

Narrative |

1. ERS appears to increase PA levels, particularly for those already partially active, older adults and those overweight (not obese) 2. Increases may not be sustained 3. Need strategies to increase long-term adherence |

| Sorensen et al. (2006)40 |

Effectiveness (n = 12) Total (n = 22) |

Narrative, included assessment of quality |

4. Most studies reported moderate improvements in PA or physical fitness for 6–12 months 5. EoP patients displayed 10% improvement in PA compared with control |

| NICE (2006)35 | (n = 4) | Narrative, included, quality appraisal; study type; applicability |

6. Insufficient evidence to make conclusions/recommendations about ERS 7. More research required (e.g. long-term effects) |

| Williams et al. (2007)41 |

Meta-analysis (n = 5) Total (n = 18) |

Narrative and meta-analysis (heterogeneity, quality) |

8. Significant increase in participants doing moderate exercise (number needed to treat: 17 sedentary adults would need referring for one to become moderately active) 9. Poor uptake and adherence to ERS |

Quality of previous systematic reviews

A modified version of the Oxman and Guyatt42 Overview Quality Assessment Questionnaire (OQAQ) assessment tool and scale was used to assess the quality of reviews (see Table 5), with total scores for the reviews ranging from 10 to 18 points. All of the reviews provided a comprehensive search strategy, inclusion/exclusion criteria and risk of bias measure for the included primary studies, with conclusions supporting the data reported in the overview. Three of the reviews35,39,40 were lacking in the application of the quality criteria to inform the review analysis, and the reporting and subsequent application of methods used to combine the findings of included studies. Only the review by Williams et al. 41 fulfilled all of the criteria.

| Quality assessment items | Morgan (2005)39 | NICE (2006)35 | Sorensen et al. (2006)40 | Williams et al. (2007)41 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Were the search methods used to find evidence on the primary question(s) stated? | Yes: 2 points | Yes: 2 points | Yes: 2 points | Yes: 2 points |

| 2. Was the search for evidence reasonably comprehensive? | Yes: 2 points | Yes: 2 points | Yes: 2 points | Yes: 2 points |

| 3. Were the criteria used for deciding which studies to include in the review reported? | Yes: 2 points | Yes: 2 points | Yes: 2 points | Yes: 2 points |

| 4. Was bias in the selection of articles avoided? | No: 0 points | Yes: 2 points | Can’t tell: 1 point | Yes: 2 points |

| 5. Were the criteria used for assessing the validity for the studies (i.e. meeting inclusion criteria) reviewed reported? | Yes: 2 points | Yes: 2 points | Yes: 2 points | Yes: 2 points |

| 6. Were study quality assessment criteria used to inform the review analysis? | No: 0 points | Yes: 2 points | Partially: 1 point | Yes: 2 points |

| 7. Were the methods used to combine the findings of the relevant studies (to reach a conclusion) reported? | No: 0 points | No: 0 points | No: 0 points | Yes: 2 points |

| 8. Were findings of the relevant studies combined appropriately relative to the primary question of the overview? | No: 0 points | No: 0 points | No: 0 points | Yes: 2 points |

| 9. Were the conclusions made by the author(s) supported by the data and/or analysis reported in the overview? | Yes: 2 points | Yes: 2 points | Yes: 2 points | Yes: 2 points |

| Total | 10/18 points | 14/18 points | 12/18 points | 18/18 points |

Scope of previous systematic reviews

Table 3 highlights the lack of consistency in the studies included by these four previous systematic reviews of ERS. Although some of this variation reflects the inclusion of non-randomised studies, the principal reason for this difference is in the scope of inclusion criteria for the interventions. The systematic review by Sorensen et al. 40 assessed what the researchers called ‘exercise on prescription’ (EoP) and included studies that involved physician-delivered PA advice (i.e. exercise recommendation). As discussed in the Background section of this report, such interventions do not meet the standard definition of ERS in the UK.

A number of studies included in these previous systematic reviews did not appear to formally involve a referral from a primary-care health-care practitioner to a third party. For example, the study by Harland et al. 43 took place in primary care and involved an exercise intervention delivered by a third party/service. The methods section of the study publication states:

the researcher (JH) approached all patients aged 40–64 attending routine surgeries. Patients completed a recruitment card, signed by their general practitioner, which they returned to the researcher before leaving

(Harland et al. ,43 p. 828)

Thus, no referral from the GP was made; the researcher recruited subjects opportunistically from the waiting room. Indeed, in response to correspondence following publication of this trial, the authors confirmed that ‘our scheme was not an exercise prescription scheme’ (p. 1470). 44

The study of Lamb et al. 58 has been included in three previous systematic reviews,35,39,41 including the review by NICE. 35 In this study, the participant recruitment process involved several stages: the practice manager initially identified a random sample from computerised records; individuals in this sample were sent a questionnaire and covering letter from GPs to assess inclusion criteria and willingness to participate in a PA promotion trial; eligible patients who returned the questionnaires were sent a second letter explaining the trial in more detail; positive responses were followed up with a telephone call to gain consent and registration. However, there is no actual referral from the GPs, with the researchers using the primary-care setting as a gateway to recruit patients for their PA promotion trial. Finally, Elley29 (included in one of the previous reviews) is an example of an alternative model of PA intervention, i.e. the ‘green prescription’ PA model. In this model, the GP prescribes the patient’s exercise programme and advises the patient that telephone support is available from the local sports foundation, if required, but third-party service provision is not an essential component.

Findings of previous systematic reviews

These previous systematic reviews35,39–41 appear to conclude that ERS have a small effect in increasing PA in the short term, with little or no evidence of long-term sustainability (i.e. 12 months or longer) (Tables 4 and 5). The one review that undertook a meta-analysis (of five UK-based RCTs) reported that participants in the ERS were 20% more likely to be moderately physically active at the threshold of 90–150 minutes/week) than those not participating in ERS [odds ratio (OR) 1.20, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.35]. 41 These reviews provide limited consideration of either the impact of ERS on disease-specific groups or outcomes other than PA.

Primary exercise referral scheme studies

As shown in Figure 1, the most frequent reason for exclusion from the present review was that studies used primary care as means of recruiting individuals into exercise programmes, but there was no clear statement of a referral by a member of the primary-care team to a third-party exercise provider. Examples of three such studies are presented in Boxes 6–8. A full list of excluded papers is provided in Appendix 3.

‘Participants were drawn from a patient electronic database at a local health centre.’

‘A total of 1439 patients were contacted by mail with an invitation letter and information sheet telling them about the study. Three hundred and fifty-eight (28%) accepted the invitation to enter the study by completing a form and returning it in a stamped addressed envelope.’

‘General practitioners at participating practices were asked to identify women in the age group from their practice register, excluding patients deemed inappropriate for participation in a physical activity trial. The general practitioners sent letters to those identified as suitable, inviting them to participate in a lifestyle study. The invitation letter requested that women contact the research team if they were interested in learning more about the study using the reply slip and prepaid envelope supplied.’

‘Two research assistants recruited patients through three primary care practices from different socioeconomic regions of Auckland, New Zealand, from June 2003 to March 2004. The primary care physicians identified and screened all those aged 65 and older on the practice databases (from their files). Those for whom physical activity was not contraindicated and were contactable at the address and telephone number on the practice database (N = 831) were invited to participate in the study via a letter from their primary care physician and follow-up telephone call from the practice where necessary.’

Characteristics of included primary studies

The characteristics of the seven included ERS studies are summarised in Table 6. 26,27,49,60,67–69 These studies included a total of 3030 participants. All studies were RCTs: five undertaken in the UK,27,28,50,61,68 one in Denmark69 and one in Spain. 70 The studies of Jolly et al. 68 and Gusi et al. 70 used cluster allocation (i.e. allocating participants to ERS and control at the ERS provider and general practice level, respectively). The other included studies undertook participant level randomisation. Studies had a median sample size of 347 (range 54–943) and follow-up duration ranged from 2 to 12 months. The GP was the main referrer, usually using a bespoke referral form to a fitness or exercise instructor/officer.

| Study | No. of GP practices | Date study conducted | RCT design | Overall n | Randomised (n) (ERS/control) | Comparator group description | Follow-up periods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

UK |

3 | January to December 1994 | Individual | 142 | 97/45 |

Initial screen No exercise programme |

8, 16, 26 and 37 weeks |

|

Stevens et al. 50 UK |

1 | Not stated | 714 | 363/351 | No exercise programme; sent exercise promotion materials | 8 months | |

|

Harrison et al. 28 UK |

46 | March 2000 to December 2001 | 545 | 275/270 | No exercise programme; sent a written information pack | 6, 9 and 12 months | |

|

Isaacs et al. 61 UK |

88 | October 1998 to April 2002 | 943 | 317/315/311 |

Initial assessment No exercise programme, advice only or 10-week walking scheme, 2 × 45 minutes/week, 60–80% of heart rate max., group setting |

10 weeks, 6 and 12 months | |

|

Denmark |

14 | 2005–6 | Individual | 52 | 28/24 |

Initial health profile and motivational counselling (45–60 min/session) No exercise programme |

4 and 10 months |

|

Gusi et al. 70 Spain |

Four | Not stated | Cluster | 287 | 127/160 | Best care in general practice, which consisted of routine care and a recommendation of PA | 6 months |

|

Jolly et al. 68 UK |

Not reported (13 leisure centre sites) | November 2007 to July 2008 | 347 | 184/163 | ERS plus SDT programme | 3 and 6 months |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Most studies determined their inclusion and exclusion of participants based on criteria of the ERS they were evaluating (Table 7). Four studies27,50,68,70 excluded patients with any form of heart condition. Gusi et al. 70 excluded patients with severe obesity or major depression and Taylor et al. 27 excluded patients with diabetes. All excluded individuals were considered to be at especially high risk [e.g. systolic blood pressure (SBP) of > 200 mmHg, insulin-dependent diabetes].

| Study | Age range of patients (years) | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Inclusion/exclusion criteria determined/evaluated by | No. of participants excluded |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Taylor et al. 27 UK |

40–70 | Smokers, hypertension (140/90 mmHg), overweight (BMI > 25) | SBP > 200 mmHg, history of MI or angina pectoris, diabetes mellitus, musculoskeletal condition preventing PA, previous ERS referral | Research team and GP determined and evaluated | 44 |

|

Stevens et al. 50 UK |

18+ | Sedentary–less than 20 × 30 minutes of moderate-intensity PA or less than 12 × 20 vigorous-intensity PA in the last 4 weeks | Medical reasons for exclusion, e.g. registered disabled, diagnosis of heart disease | Research team determined and evaluated | 113 |

|

Harrison et al. 28 UK |

18+ | Sedentary, participating in < 90 minutes of moderate/vigorous PA a week, additional CHD risk factors; obesity, previous MI, on practice CHD risk management register, diabetes | GP identified contradiction to PA, SBP > 200 mmHg, not sedentary, only one family member (to avoid contamination–research team criterion) | GP evaluation using the trial’s ERS-determined criteria | 285 |

|

Isaacs et al. 61 UK |

40–74 | Not active (no definition reported), raised cholesterol, controlled mild/moderate hypertension, obesity, smoking, diabetes, family history of MI at early age | Pre-existing overt CVD, uncontrolled hypertension, uncontrolled insulin-dependent diabetes, psychiatric or physical conditions preventing PA, conditions requiring specialist programme | GP evaluation using criteria determined by an existing ERS | Not reported |

|

Sorensen et al. 69 Denmark |

18+ | Patients must meet all criteria: (1) having medically controlled lifestyle diseases or at risk of developing lifestyle diseases; (2) motivated to change lifestyle; (3) believed by the GP to be able to improve health from an increased PA level; and (4) willing to pay 750 Danish krone (€100) for the intervention | Not meeting the inclusion criteria | GP evaluation using the trial’s ERS-determined criteria | Not reported |

|

Gusi et al. 70 Spain |

60+ | Moderately depressed (6–9 points on the Geriatric Depression Scale), overweight (BMI 25–39.9), capable of walking for more than 25 minutes | Severe obesity, major depression, debilitating medical condition, known unstable cardiac condition, attention or comprehension problems | Research team determined, GP evaluation | 32 |

|

Jolly et al. 68 UK |

18+ | People with two or more major risk factors of coronary heart disease:

|

Angina pectoris, moderate-to-high (or unstable) hypertension ≥ 160/102 mmHg Poorly controlled insulin-dependent diabetes, history of MI within the last 6 months – unless the patient has completed stage III cardiac rehabilitation, established cerebrovascular disease, severe chronic obstructive airways disease, uncontrolled asthma |

GP evaluation using the trial’s ERS-determined criteria | Not reported |

Trial participants

Studies mainly recruited sedentary, middle-aged white adults who had no medical diagnosis and evidence of at least one lifestyle risk factor, i.e. high blood pressure, raised serum cholesterol, smoking or being overweight (Tables 7 and 8). Studies also included a number of individuals with a medical diagnosis that included diabetes, hypertension, depression, CHD and obesity. However, all included studies reported outcomes aggregated across all participants (see Findings, below). Only Gusi et al. 70 reported a rural population with 66% of participants living in a rural area.

| Study | Age (mean, years) | Gender (% male) | Ethnicity (%) | Reported diagnosed conditions or risk factors (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Comparator | |

|

Taylor et al. 27 UK |

54.1 | 54.4 | 37 | 38 | Not reported | Not reported |

Smokers: 43% Overweight: 77% Hypertensive: 46% |

Smokers: 40% Overweight: 71% Hypertensive: 58% |

|

Stevens et al. 50 UK |

59.1 | 59.2 | 40 | 44 |

White: 87 Black: 5 Asian: 4 Other: 4 |

White: 83 Black: 4 Asian: 6 Other: 5 |

BMI > 25: 46 Smoker: 18 |

BMI > 25: 42 Smoker: 17 |

|

Harrison et al. 28 UK |

18–44 = 111 45–59 = 101 > 60 = 63 |

18–44 = 107 45–59 = 98 > 60 = 65 |

33 | 34 | White: 71.9 | White: 74.1 |

Smoker: 24.4 At least one CHD risk factor: 75.3 |

Smoker: 20.7 At least one CHD risk factor: 75.2 |

|

Isaacs et al. 61 UK |

57.1 |

Usual care: 57 Walk: 56.9 |

ERS: 35 |

32 Walk: 31 |

White: 75.7 Asian:16.7 |

(Control/walking) White: 76.5/75.9 Asian: 14/12.2 |

(Exercise/walking) Raised cholesterol: 24.0 Hypertension: 44.5 Obesity: 65.9 Smoking: 10.4 Type 2 diabetes: 12.3/11.3 Family history of MI: 13.9 |

(Control/walking) Raised cholesterol: 17.1/21.5 Hypertension: 43.5/46.3 Obesity: 63.5/58.5 Smoking: 8.3/12.2 Diabetes: 15.6/11.3 Family history of MI: 16.2/12.9 |

|

Sorensen et al. 69 Denmark |

53.9 | 52.9 | 43 | 37 | Not reported | Not reported |

Metabolic syndrome: 36 Type 2 diabetes: 18 CVD: 32 Other diseases: 14 |

Metabolic syndrome: 25 Diabetes: 21 Heart disease: 42 Other diseases: 13 |

|

Gusi et al. 70 Spain |

71 | 74 | 0 | 0 | Not reported | Not reported |

Overweight (BMI>25): 80 Type 2 diabetes: 39 Moderate depression: 34 |

Overweight: 86 Type 2 diabetes: 37 Moderate depression: 38 |

|

Jolly et al. 68 UK |

< 30: 19 30–49: 76 50–64: 64 65+: 25 |

< 30: 11 30–49: 77 50–64: 50 65+: 25 |

24 | 30 |

White: 74.9 Black: 10.6 Asian: 9.5 Other: 5 |

White: 67.5 Black: 14.9 Asian: 14.9 Other: 2.6 |

Smoker: 22.1 Hypertension: 38 Overweight (BMI > 25): 25.3 Obese (BMI > 30): 52.3 Morbidly obese (BMI>40): 12.1 Probable anxiety: 34.2 Probable depression: 21.9 |

Smoker: 23.1 Hypertensive: 37.5 Overweight: 26.3 Obese: 51.9 Morbidly obese: 13.5 Probable anxiety: 31.9 Probable depression: 15.3 |

Exercise referral scheme intervention

The ERS intervention of all studies, except that of Gusi et al. ,70 undertook an initial consultation by the third-party provider, such as an exercise professional (Table 9). The consultations varied in content, but all contained information and advice about being physically active. Other components of the screen (dependent on study outcomes) included lifestyle and health questionnaires and physical fitness measures. Scheme length was typically 10–12 weeks, and took place in a leisure centre,27,28,50,61,68 a clinic, public parks or forest tracks (Table 10). Exercise sessions were usually twice per week, lasted between 30 and 60 minutes per session, and were conducted at either a moderate or individually tailored intensity. Two studies69,70 provided group-based exercise sessions, and four27,28,61,68 provided a combination of group and individual exercise sessions. Only three studies28,50,68 reported an assessment at the end of the ERS programme.

| Study | Referrer | Format of referral | Referred to where | Participant cost | Referred to who |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Taylor et al. 27 UK |

GP | Signed prescription card | Leisure centre | Half-price admission | Fitness instructor |

|

Stevens et al. 50 UK |

GP | Letter | Leisure centre | Not reported | Exercise development officer |

|

Harrison et al. 28 UK |

GP | Faxed referral form | Leisure centre | ‘Subsidised ’ | Exercise officer |

|

Isaacs et al. 61 UK |

GP or practice nurse | Specially prepared ‘prescription pad’ – referral form | Leisure centre | Free | Fitness instructor |

|

Sorensen et al. 69 Denmark |

GP | Not reported | Clinic | Pay €100 | Physiotherapist |

|

Gusi et al. 70 Spain |

GP | Not reported | Supervised walks in a public park or forest tracks | Not reported | Qualified exercise leaders |

|

Jolly et al. 68 UK |

Member of the primary-care team | Not reported | Leisure centre | Not reported | Health and fitness adviser |

| Study | Initial screen/assessment | Scheme duration | Exercise programme | Exit assessment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provider | Exercise sessions per week | Exercise session intensity | Group or individual | ||||

|

Taylor et al. 27 UK |

Yes | 10 weeks | Leisure centre | 2 × 30–40 minutes | Moderate intensity | Group and/or individual | Not reported |

|

Stevens et al. 50 UK |

Yes | 10 weeks | Leisure centre | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Yes |

|

Harrison et al. 28 UK |

Yes | 12 weeks | Leisure centre | 2 × 1 hour | Individually based | Group and/or individual | Yes |

|

Isaacs et al. 61 UK |

Yes | 10 weeks | Leisure centre | 2 × 45 minutes | Not reported | Group and/or Individual | |

|

Sorensen et al. 69 Denmark |

Yes (and motivational counselling) | 4 months | Clinic |

First 2 months 2 sessions × 1 hour Second 2 months 1 session × 1 hour |

More than 50% of heart rate reserve for a minimum of 20 minutes | Group | |

|

Gusi et al. 70 Spain |

Not reported | 6 months | Walking scheme | 3 × 50 minutes | Not reported | Group | |

|

Jolly et al. 68 UK |

Yes | 12 weeks | Leisure centre | Individually based | Individually based | Group and/or Individual | |

Control/comparator group

Five studies27,28,50,61,70 compared ERS with a ‘usual care’ control group, which consisted of no exercise intervention or simple advice on PA (see Table 6). Sorensen et al. 69 compared ERS with motivational counselling aimed at increasing daily PA. In addition to a no-exercise group, the Isaacs et al. study61 also included an instructor-led walking programme. The Jolly et al. study68 compared two forms of ERS, i.e. standard ERS versus a combined ERS plus self-determination theory (SDT)-based intervention.

Risk of bias

Table 11 summarises the risk of bias for each of the included studies. Most included a power calculation and allocated participants using an appropriately generated random number sequence. However, the reporting of concealment of trial group allocation was poor, although there was good evidence of participant characteristics of intervention and control groups at baseline. Although blinding of participants and intervention providers in these studies was not feasible, blinding of outcome assessment was possible. Outcome blinding is particularly important in preventing assessment bias in the case of outcomes that require observer judgement or involvement (e.g. blood pressure measurement or exercise testing). However, only the study of Jolly et al. 68 reported outcome blinding, i.e. self-reported PA using the 7-Day Physical Activity Recall Questionnaire was assessed via telephone to maintain blinding. The reporting and handling of missing data was detailed for most studies, and all studies, except one,27 reported the use of intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis. The level of missing data at follow-up ranged across studies from 16.5% to 50%. Most studies used imputation methods (last observation carried forward or complete case average values) to replace missing data values at follow-up. Overall, three studies were judged to be at moderate overall risk of bias27,28,50 and four to be at low overall risk of bias. 61,68–70

| Risk of bias criterion | Taylor et al.27 UK |

Stevens et al.50 UK |

Harrison et al.28 UK |

Isaacs et al.61 UK |

Sorensen et al.69 Denmark |

Gusi et al.70 Spain |

Jolly et al.68 UK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power calculation reported? | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Method of random sequence generation described? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes+ |

| Method of allocation concealment described? | Yes+ | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Method of outcome (assessment) blinding described? | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | Unclear | Unclear | Yes |

| Were groups similar at baseline? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was ITT analysis used? | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was there any statistical handling of missing data? | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were missing data (dropout and loss to follow-up) reported? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Exercise referral scheme eligibility, uptake and adherence

There was a considerable range in the proportion of individuals randomised compared with those deemed eligible (Table 12). In both the Sorensen et al. 69 and Jolly et al. 68 studies, of those deemed eligible for ERS, a substantial number refused participation in the trial. For Sorensen et al. 69 this low number maybe reflective of the €100 payment by patients as part of a standard Danish EoP.

| Study | No. deemed eligible (n) | Total n randomised | ERS (n) | Control (n) | ERS uptake |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Taylor et al. 27 UK |

345 | 142 (41%)+ | 97 | 45 | 85 (88%) |

|

Stevens et al. 50 UK |

827 | 714 (86%)+ | 363 | 351 | 126 (35%) |

|

Harrison et al. 28 UK |

830 | 545 (66%)+ | 275 | 270 | 232 (84%) |

|

Isaacs et al. 61 UK |

1305 | 949 (73%)+ | 317 | 315 + 311 | 293 (92%) |

|

Sorensen et al. 69 Denmark |

327 | 52 (16%)+ | 28 | 24 | 28 (100%) |

|

Gusi et al. 70 Spain |

160 | 127 (79%)+ | 64 | 63 | Not reported |

|

Jolly et al. 68 UK |

1683 | 347 (21%)+ | 184 | 163 | Not reported |

Uptake was defined as the proportion of those individuals offered entry to ERS who attended an initial consultation with an ‘exercise professional’ or attended a first exercise session. Although Taylor et al. ,27 Issacs et al. 61 and Sorensen et al. 69 reported uptake rates in excess of 85%, in the Stevens et al. 50 study only 126 (35%) of the 233 randomised to ERS attended the first consultation. Stevens et al. 50 discussed how the low uptake they experienced may have been reflective of the nature of the invitation letter sent to participants and the point of randomisation (pre-invitation letter). Furthermore, they hypothesise that a change in the format of the letter (e.g. including a specific appointment date for the first ERS appointment) would have improved participation. Uptake was not reported by Jolly et al. 68 or Gusi et al. 70

Harrison et al. 28 and Jolly et al. 68 failed to provide information on participants’ adherence to the ERS intervention. Stevens et al. 50 and Gusi et al. 70 reported ERS programme completion rates of 25% and 86%, respectively. However, these rates do not reflect the number of sessions attended, only those who attended a second consultation50 or follow-up assessment. 70

Sorensen et al. 69 reported that an average 18 of a total of 24 ERS exercise sessions were attended and 68% and 75% of participants attended the counselling sessions at 4 and 10 months, respectively. Both Taylor et al. 27 and Isaacs et al. 61 provide a detailed description of ERS programme adherence. Taylor27 reported 13% attending no exercise sessions and 28% attending 75–100% of exercise sessions, with an average of 9.1 out of 20 prescribed exercise sessions attended. Isaacs et al. 61 reported 7.6% attending no exercise sessions and 42% attending 75–100% of exercise sessions in the leisure centre group. In the walking group, 23.5% attended no exercise sessions, with 21.5% attending 75–100% of exercise sessions. As shown in Table 13, there was no consistent difference in attendance rates between those in at-risk groups and the overall study population in the studies of Taylor et al. 27 and Isaacs et al. 61 In the Isaacs et al. 61 study, the 60- to 69-year age group had the highest adherence in both the ERS (53.3%) and the walking (24.2%) groups. There were no significant differences in attendance rate with employment status, educational level, socioeconomic status, ethnicity or relationship status. Adherence was lower for those without access to private transport in both the ERS and walking groups.

Findings

Only Isaacs et al. 61 reported all outcome domains applicable to this systematic review (Table 14). Outcome results are reported according to the three categories of comparator, i.e. ERS versus usual care; ERS versus alternative exercise intervention and ERS versus alternative form of ERS.

| Study | PA | PA measure | Physical fitness | Clinical outcomes | Psychological well-being | HRQoL | Patient satisfaction | Adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Taylor et al. 27 UK |

Yes |

Self-report 7-day PAR |

Yes Sub-max HR |

Yes BP, BMI, BF%, waist to hip |

Yes PSW |

No | No | No |

|

Stevens et al. 50 UK |

Yes |

Self-report 7-day PAR |

No | No | No | No | No | No |

|

Harrison et al. 28 UK |

Yes |

Self-report 7-day PAR |

No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

|

Isaacs et al. 61 UK |

Yes |

Self-report Minnesota LTPAQ |

Yes Sub-max bike test Sub-max walking test |

Yes BP, cholesterol, lipoproteins, triglycerides, weight, BMI, BF%, waist-to-hip ratio, FEV, PEF |

Yes Anxiety, depression |

Yes SF-36 mental |

Yes |

Yes GP records |

| Sorensen et al.69 Denmark | Yes |

Self-report Unspecified |

Yes Sub-max bike test |

Yes Weight, BMI |

No |

Yes SF-12 mental, physical |

No | No |

|

Gusi et al. 70 Spain |

Not reported | N/A | No |

Yes BMI |

Yes Anxiety, depression |

Yes EQ-5D |

No | No |

|

Jolly et al. 68 UK |

Yes |

Self-report 7-day PAR |

No |

Yes BMI |

Yes Anxiety, depression |

Yes Dartmouth QoL |

No | No |

Physical activity

All studies, with the exception of Gusi et al. ,70 provided a measure of self-reported PA. Self-reported measures included the validated 7-Day Physical Activity Recall Questionnaire,27,28,50,68 a modified version of the validated Minnesota Leisure Time Activity Questionnaire61 and an invalidated questionnaire designed by the research team. 63 No studies reported assessed PA using objective methods. A summary of the main PA outcomes at follow-up is provided in Table 15.

| Study and time of follow-up | Patients achieving PA guidance (90–150 minutes/at least moderate-intensity per week) | Minutes per week at least moderate intensity | Total PA (minutes per week) | Energy expenditure (kcal/kg/day)a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERS, n/N | Usual care, n/N | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | |||

| ERS vs usual care | ||||||||||

| Taylor et al.27 | ||||||||||

| (Moderate) | (Vigorous) | (Moderate) | (Vigorous) | |||||||

| 8 weeksb | 51/63 | 20/31c,d | 247 (174) | 49 (60) | 145 (178)e | 21 (61)e | Not reported | Not reported | 34.6 (1.2) | 33.7 (1.7)e |

| 16 weeksb | 51/57 | 18/31d,e | 226 (252) | 59 (72) | 160 (262)c | 21 (72)e | Not reported | Not reported | 34.6 (1.2) | 33.9 (1.7)e |

| 26 weeksb | 39/47 | 18/31d,e | 183 (234) | 56 (108) | 206 (251)c | 34 (111)c | Not reported | Not reported | 34.4 (1.8) | 34.3 (1.2)c |

| 37 weeksb | 39/57 | 19/c,d | 158 (228) | 42 (96) | 162 (245)c | 23 (106)c | Not reported | Not reported | 34.1 (2.4) | 33.9 (2.2)c |

| Stevens et al.50 | ||||||||||

| 8 monthsf | 204/363 | 174/351c,d | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | ||

| Harrison et al.28 | ||||||||||

| 6 monthsb | 38/168 | 22/162d,e | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | ||

| 9 monthsb | 36/149 | 31/140c | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | ||

| 12 monthsb | 40/155 | 32/157c | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | ||

| Isaacs et al.61 | ||||||||||

| 10 weeksg | 48/164 | 29/157d,e | 93 (115) | 79 (114)c | 584 (479) | 668 (555)c | 34 (26) | 36 (32)c | ||

| 6 monthsg | 70/179 | 66/200c,d | 65 (106) | 58 (98)c | 692 (496) | 647 (463)c | 38 (27) | 35 (27)c | ||

| Gusi et al.70 | ||||||||||

| Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | |||

| Study and time of follow-up | Patients achieving PA guidance (90–150 minutes/at least moderate-intensity per week) | Minutes per week at least moderate intensity | Total PA (minutes per week) | Energy expenditure (kcal/kg/day)a | ||||||

| ERS, n/N | Alternative PA, n/N | ERS, mean (SD) | Alternative PA, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Alternative PA, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Alternative PA, mean (SD) | |||

| ERS vs alternative PA intervention | ||||||||||

| hSorensen et al.69 | ||||||||||

| 4 monthsb | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 63 (114) | 23 (107)c | 43 (2.4) | 41 (4.8) | ||

| 10 monthsb | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 20 (124) | 20 (152)c | 41 (2.1) | 40 (5) | ||

| Isaacs et al.61 | ||||||||||

| 10 weeksg | 48/164 | 53/92d,e | 93 (115) | 113 (291)c | 584 (479) | 863 (1026)e | 34 (26) | 43 (38)e | ||

| 6 monthsg | 70/179 | 62//141c,d | 65 (106) | 89 (150)e | 692 (496) | 759 (539)c | 38 (27) | 42 (27)c | ||

| ERS, n/N | ERS plus SDT, n/N | ERS, mean (SD) | ERS plus SDT, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | ERS plus SDT, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | ERS plus SDT, mean (SD) | |||

| ERS vs ERS plus SDT | ||||||||||

| Jolly et al.68 | ||||||||||

| 3 monthsg | Not reported | Not reported | 319 (338)c | 331 (336)c | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | ||

| 6 monthsg | 66/156 | 83/169c,d | 249 (356)c | 246 (343)c | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | ||

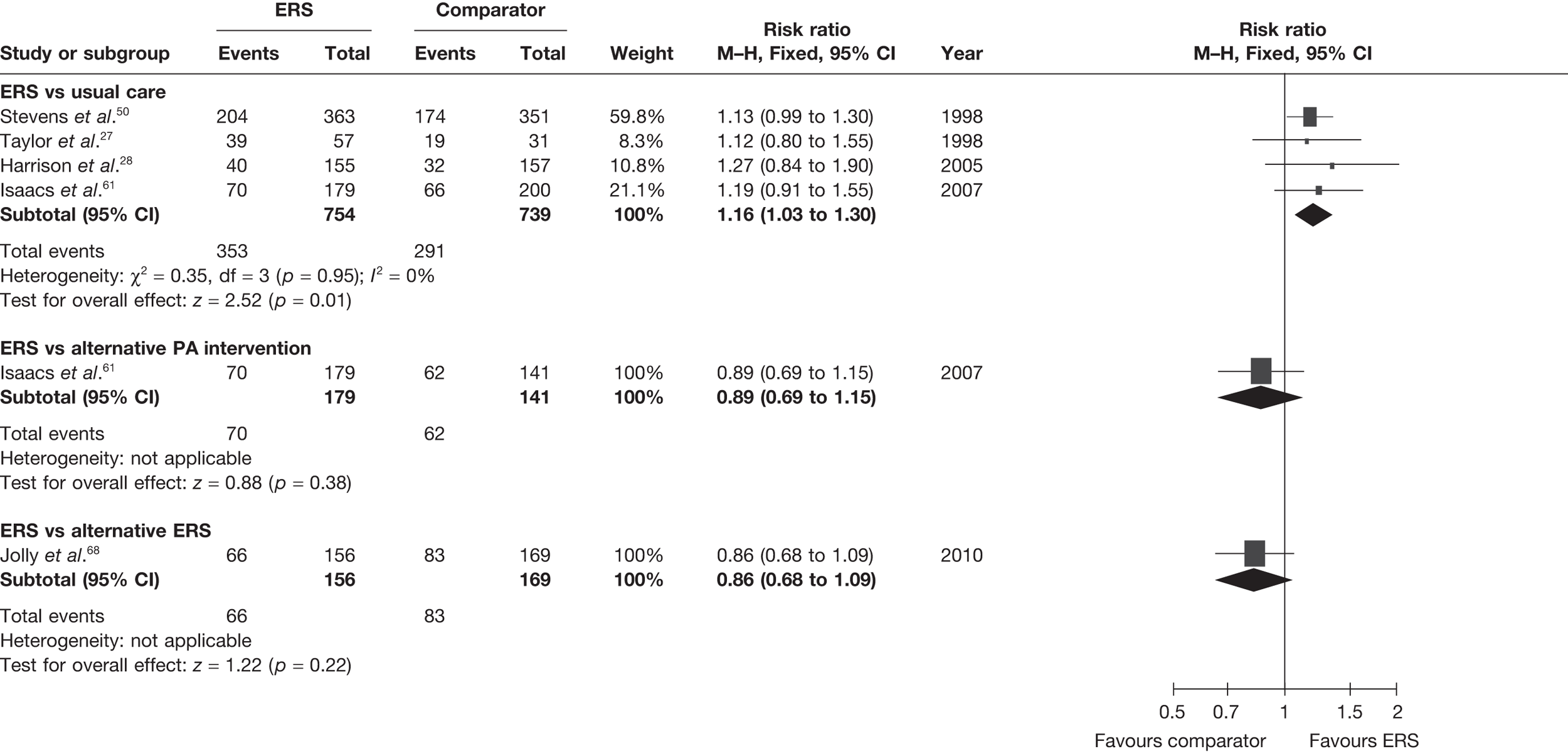

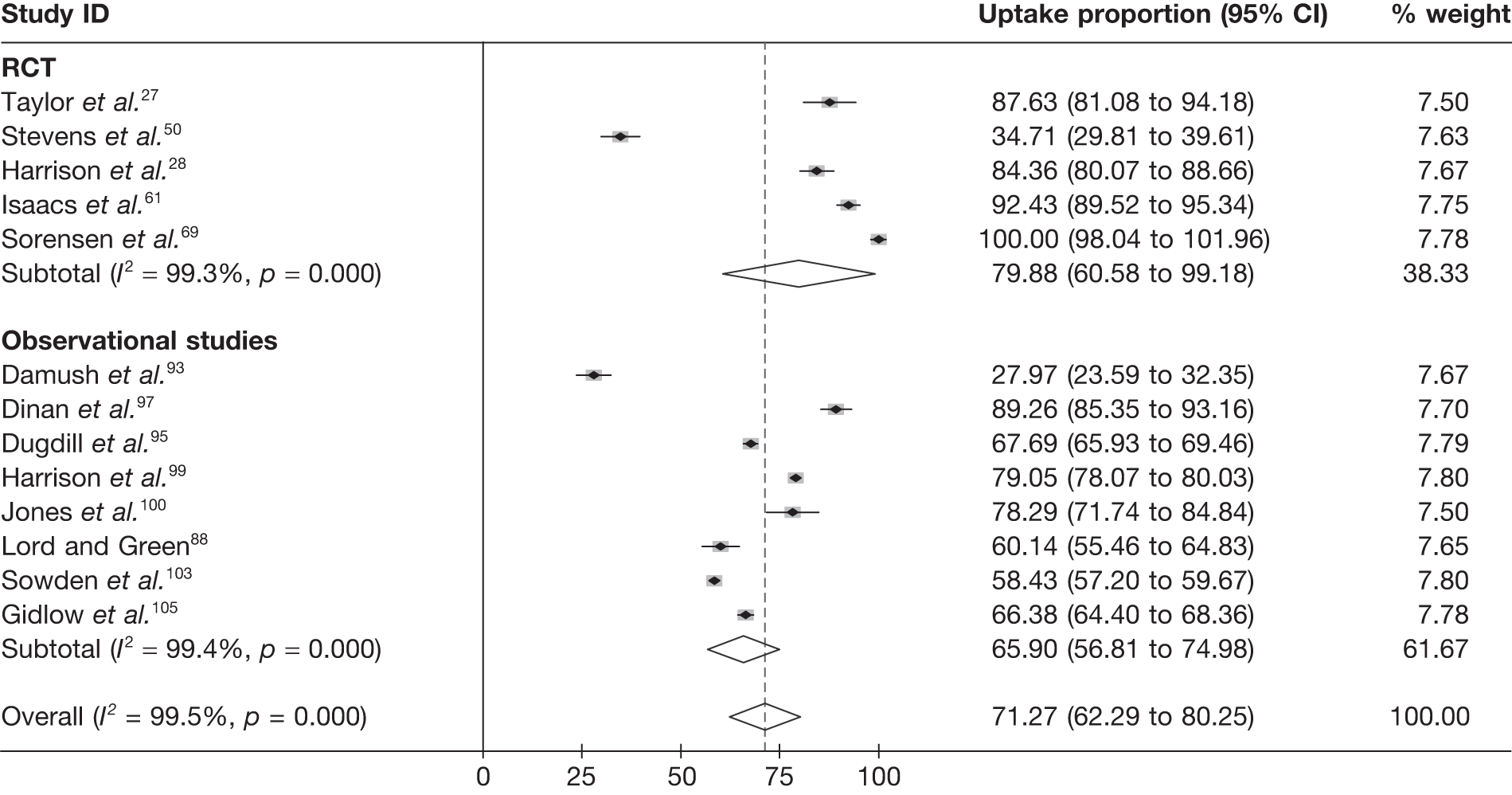

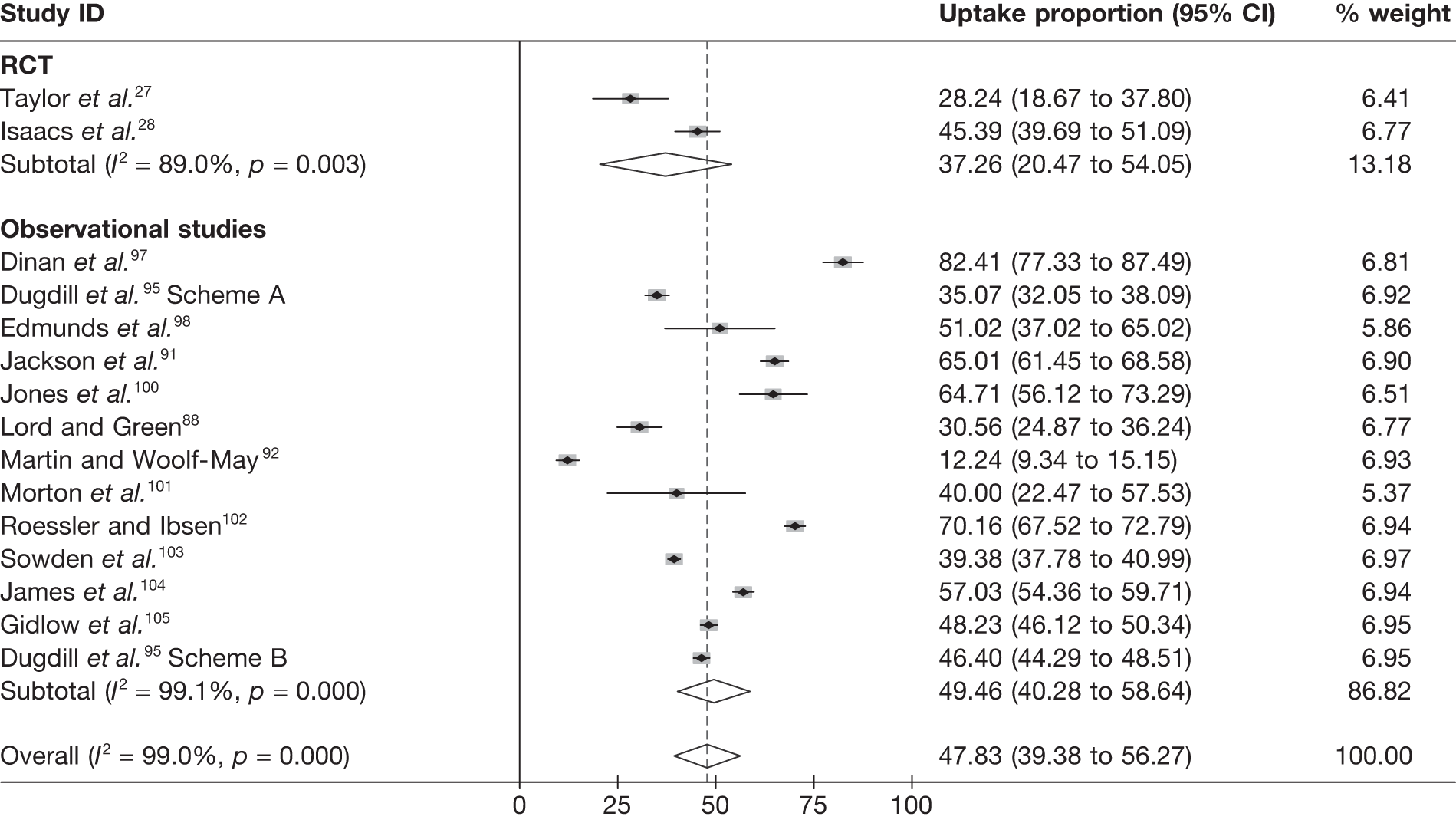

The most consistently reported PA outcome across studies was the proportion of individuals achieving 90–150 minutes of at least moderate-intensity activity per week. (The use of 90–150 minutes of at least moderate-intensity PA/week is pragmatic with the included studies.) When pooled across studies there was a 16% (95% CI 3% to 30%) increase in the RR of achieving this outcome with ERS compared with usual care at 6–12 months’ follow-up (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Meta-analysis of the number of patients achieving 90–150 minutes of at least moderate-intensity PA per week at 6–12 months’ follow-up (denominators as reported by authors).

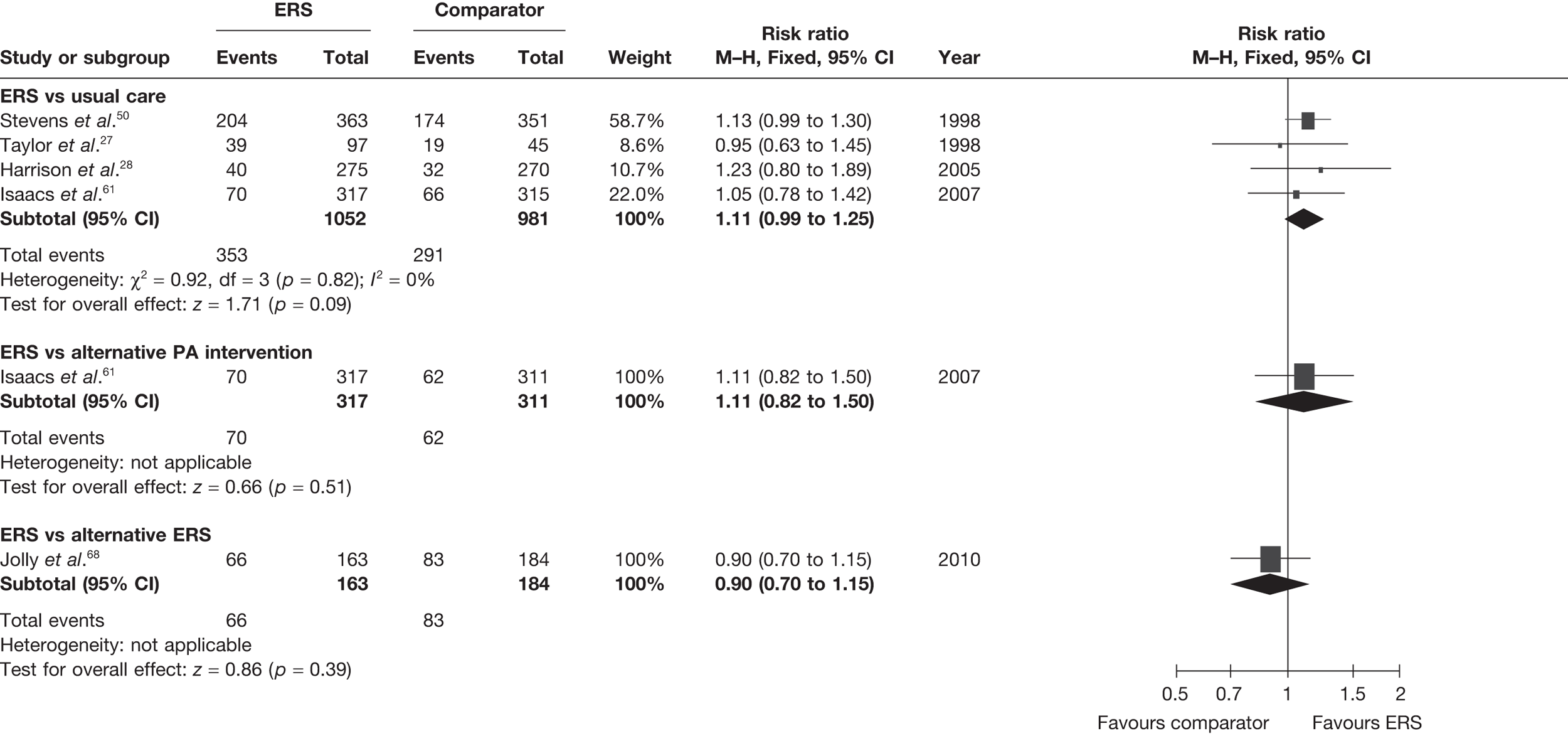

The studies of Taylor et al. 27 and Harrison et al. 28 reported this outcome based on the number of individuals who were available at follow-up. In order to assess the potential (attrition) bias in using completers, we adjusted the denominators of these two studies to all individuals randomised – an ITT analysis (Figure 3). We assumed that all missing cases did not meet the PA threshold. In the pooled ITT analysis, the proportion achieving the PA threshold with ERS than usual care (11%, 95% CI –1% to 45%) this effect was no longer statistically significant.

FIGURE 3.

Meta-analysis of the number of patients achieving 90–150 minutes of at least moderate-intensity PA per week at 6–12 months’ follow-up (denominators adjusted to all randomised – ITT analysis).

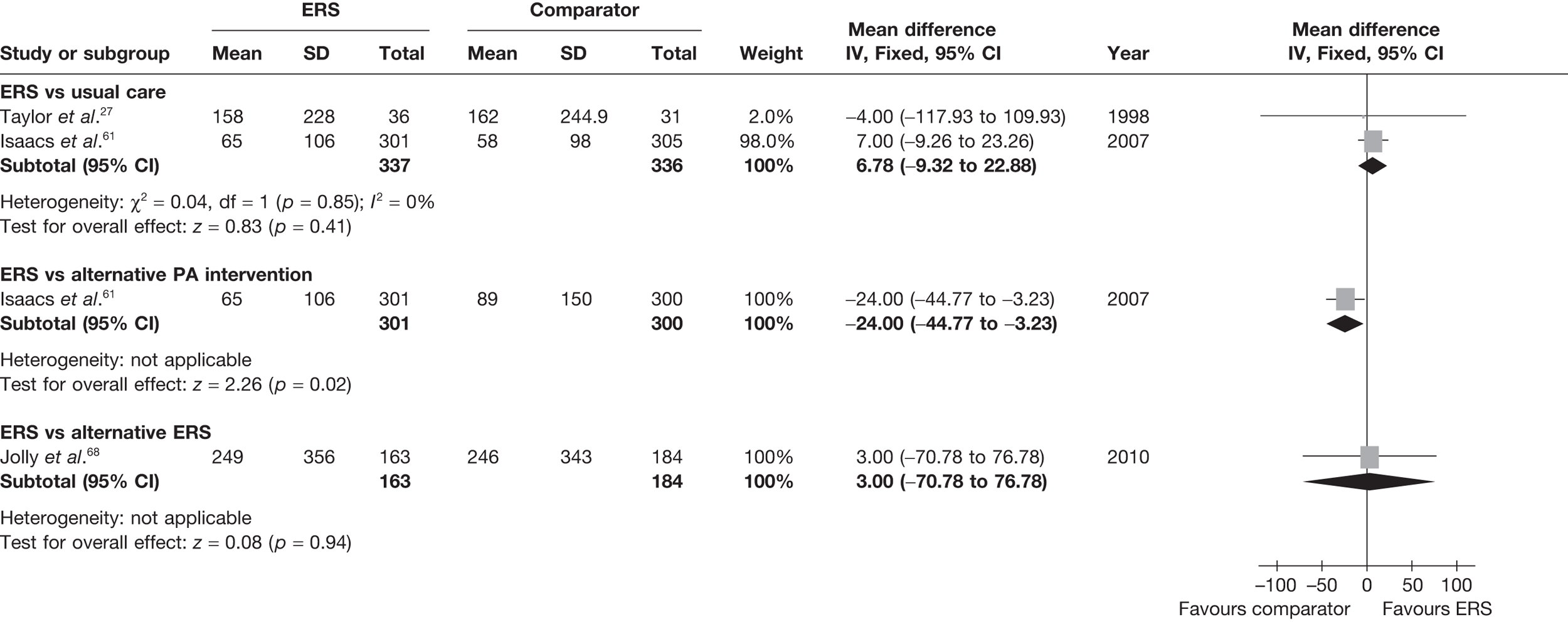

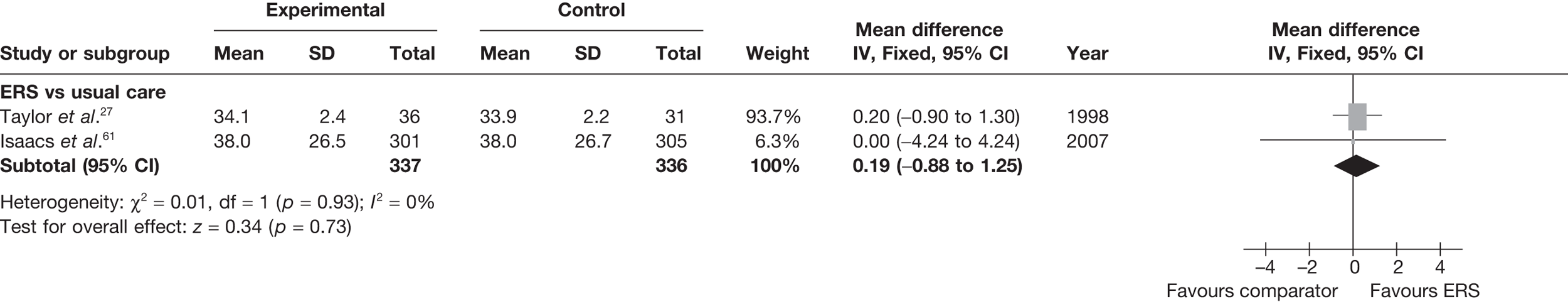

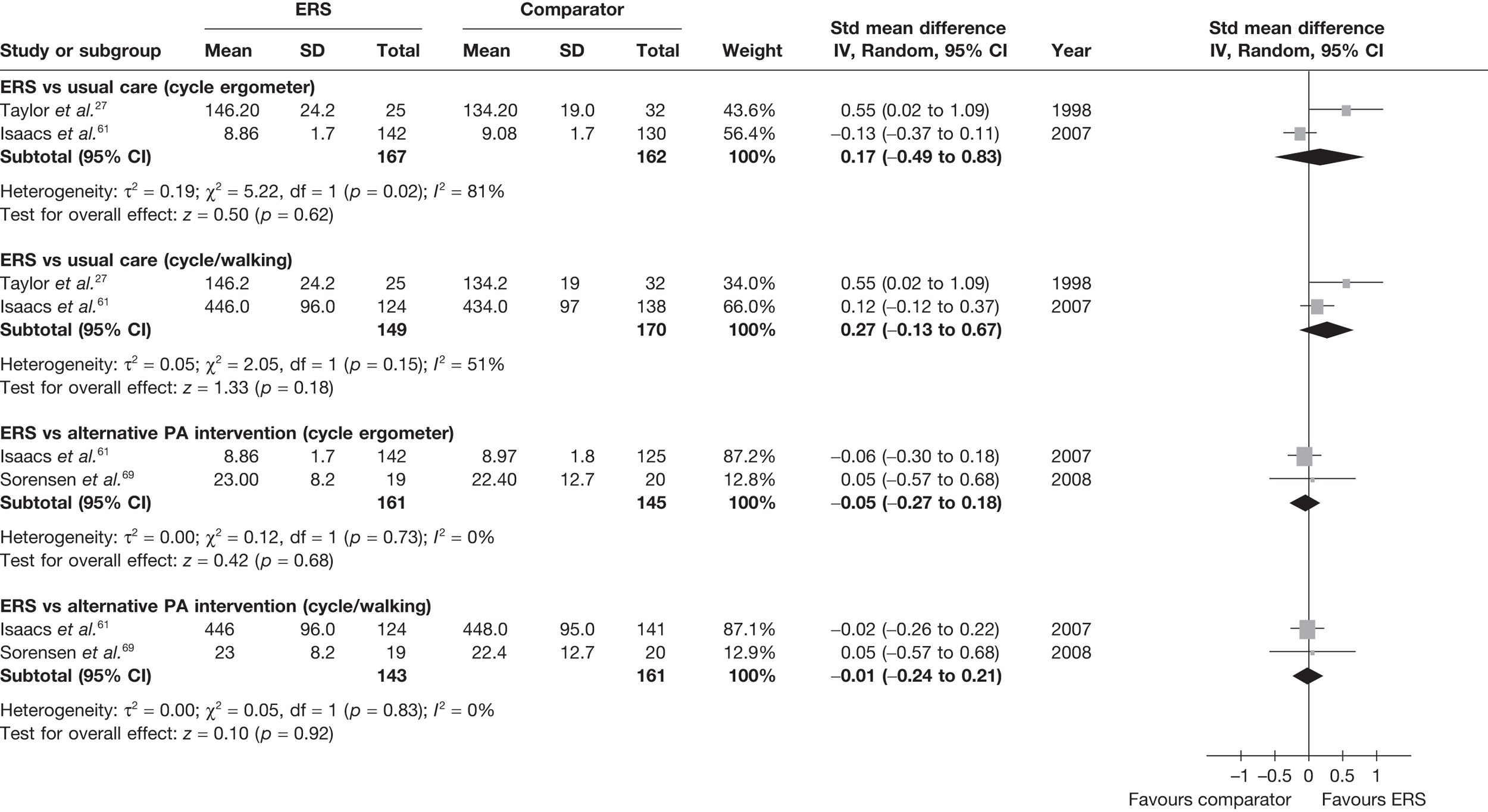

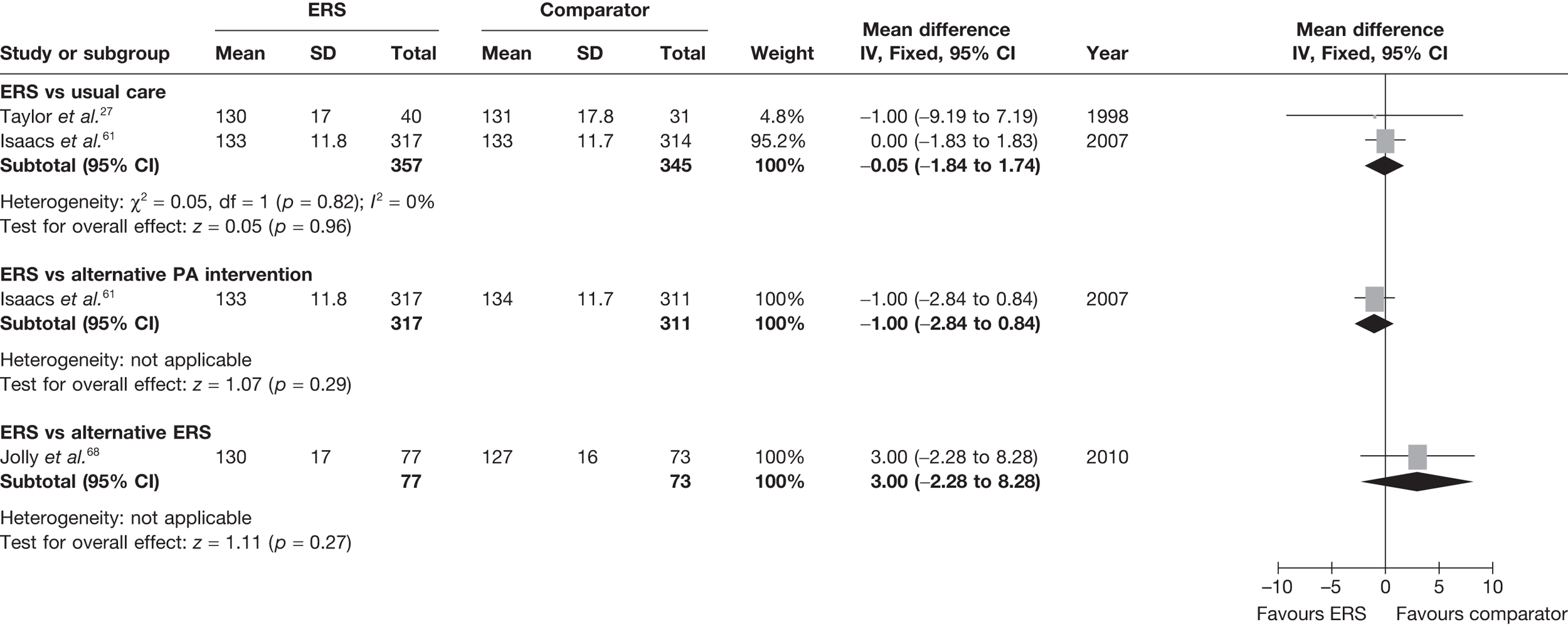

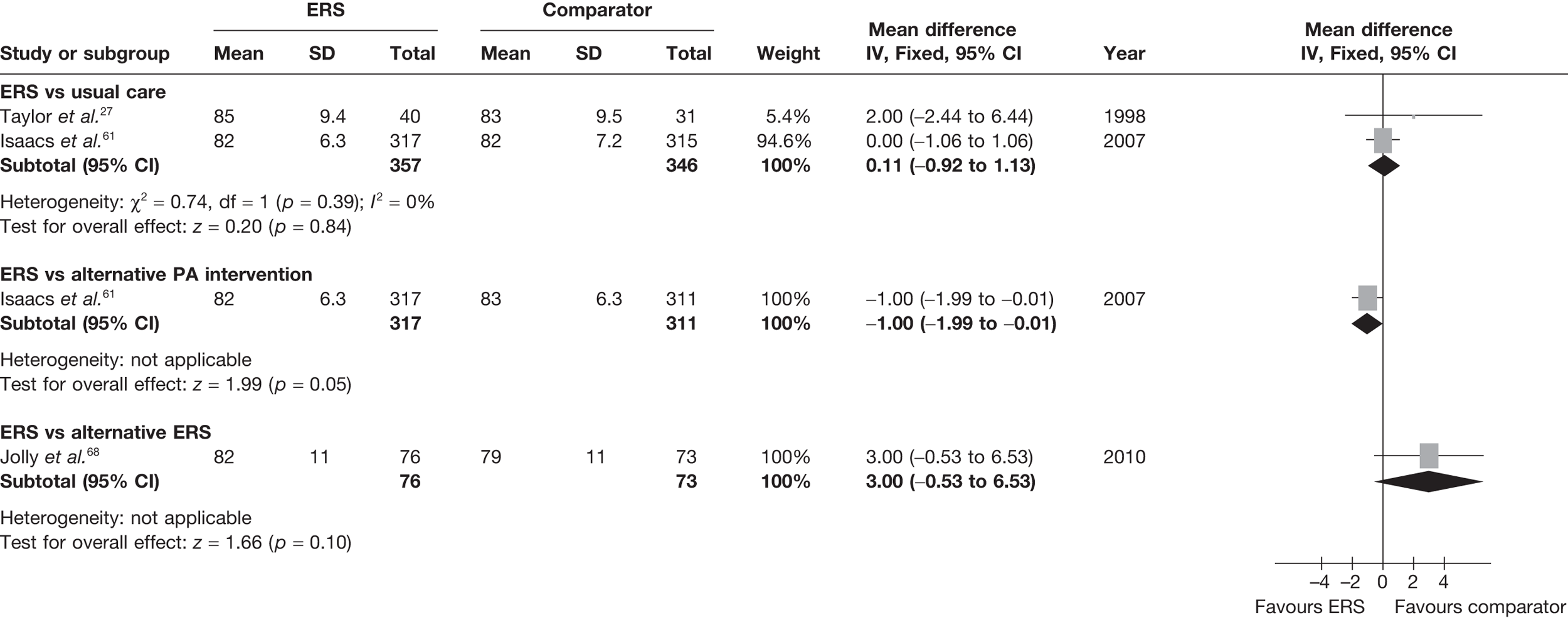

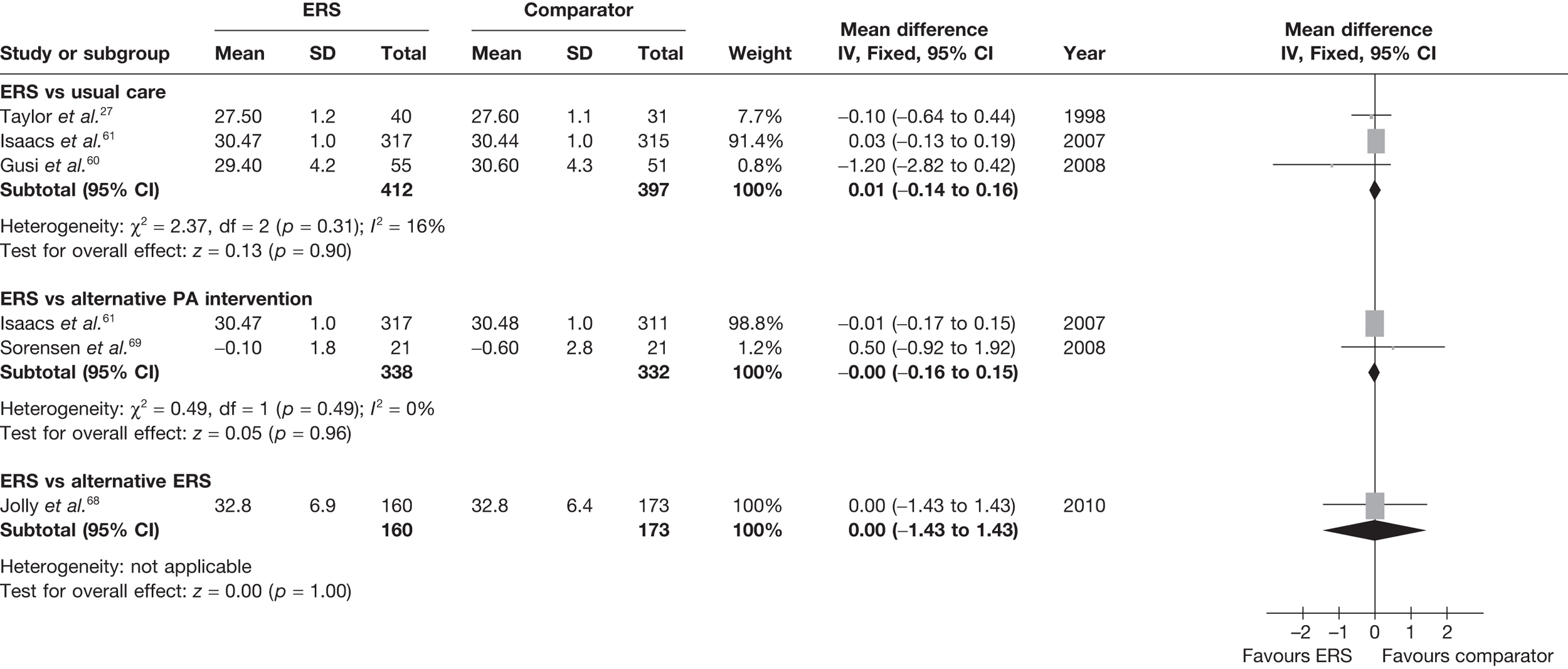

There was no difference between ERS and usual care in either the minutes spent in at least moderate-intensity PA/week or estimated PA-induced energy expenditure (Figures 4 and 5).

FIGURE 4.

Meta-analysis of patient’s minutes spent in at least moderate-intensity PA per week at 6–12 months’ follow-up. SD, standard deviation.

FIGURE 5.

Meta-analysis of energy expenditure (kcal/kg/day) ERS vs usual care at 6–12 months’ follow-up. SD, standard deviation.

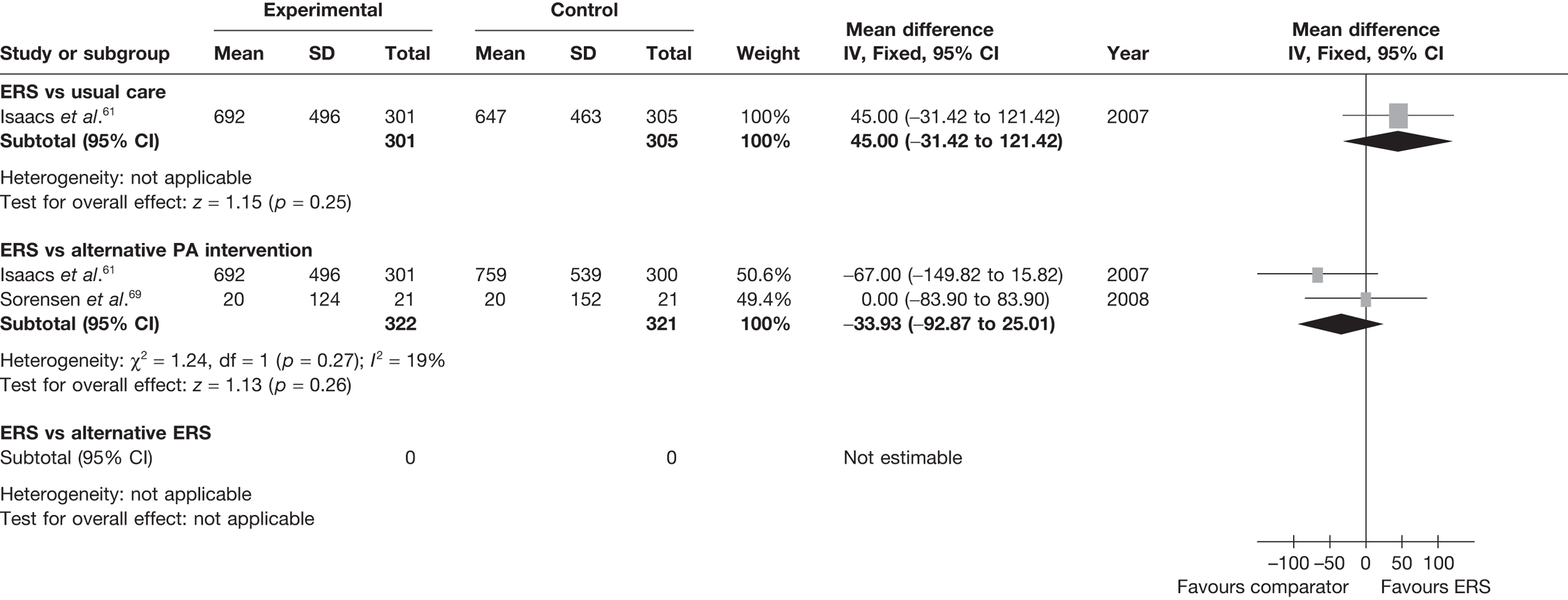

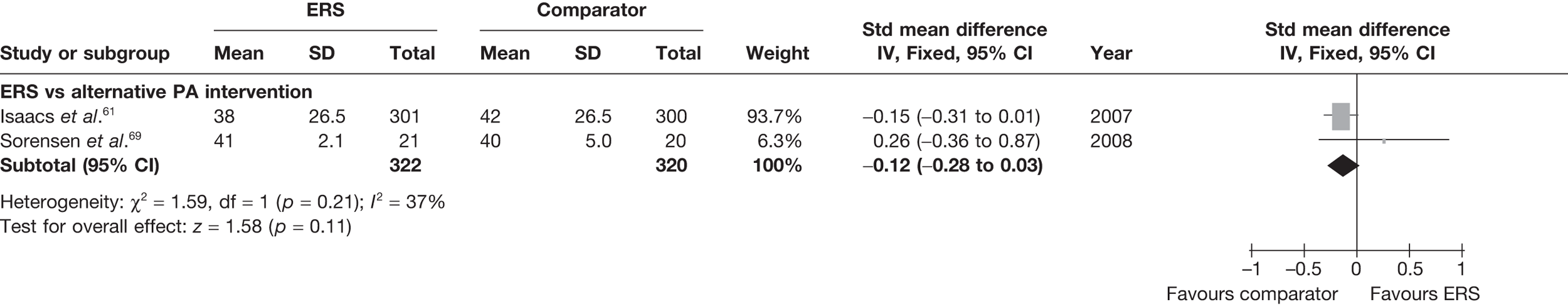

Sorensen et al. 69 reported a higher level of energy expenditure with ERS than with PA counselling. In contrast, the study by Isaacs et al. 61 observed a higher level of PA (minutes of total and moderate-intensity activity, and energy expenditure) in those in the walking programme than in the ERS group. When pooled across studies, there was no significant difference in the total amount of physical or energy expenditure between ERS and alternative PA interventions (Figures 6 and 7).

FIGURE 6.

Meta-analysis of patient’s minutes of total PA/week at 6–12 months’ follow-up. SD, standard deviation.

FIGURE 7.

Meta-analysis of energy expenditure ERS vs alternative PA intervention at 6–12 months’ follow-up. SD, standard deviation.

In the Jolly et al. study,68 the proportion of patients achieving at least 150 minutes of moderate PA per week increased in the standard ERS group from 27% at baseline to 63% at 3 months and 46% at 6 months. There were no significant differences in these proportions between the standard ERS and ERS-plus-SDT groups (Table 15).

Harrison et al. 28 reported no statistically significant interaction effects between the ERS effect and pre-specified baseline variables (i.e. CHD risk factors, sex and age). Comparing high adherers (≥ 75% attendance at ERS) with low adherers (< 75% attendance at ERS) in the Isaacs et al. study,61 32 high adherers and 16 low adherers were achieving ≥ 150 minutes of moderate PA per week at 10 weeks. At 6 months, 41 high adherers and 29 low adherers were achieving ≥ 150 minutes of moderate PA per week. However, these proportions were not significantly different. In the Jolly et al. study,68 age, gender, deprivation (Index of Multiple Deprivation score), ethnicity, depression at baseline and level of PA at baseline were assessed by regression methods as predictors of PA at 6 months. Only PA at baseline was associated with PA at the 6-month follow-up (p < 0.001).

Physical fitness

The studies by Taylor et al. ,27 Isaacs et al. 61 and Sorensen et al. 69 reported physical fitness outcomes (Table 16).

| Study and time of follow-up | Mean predicted heart rate at a workload of 150 W | VO2max (ml/kg/minute) | Submaximal bike ergometer (minutes) | Submaximal shuttle walk (m) | Isometric knee strength (N) | Leg extension power (W) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Usual care, mean (SD) | |

| ERS vs usual care | ||||||||||||

| Taylor et al.27 | ||||||||||||

| 16 weeksa | 138.6 (23.0) | 147.2 (29.7)b | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| 26 weeksa | 136.3 (22.6) | 142.3 (28.5)b | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| 37 weeksa | 134.2 (19.0) | 146.0 (24.2)c | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Isaacs et al.61 | ||||||||||||

| 10 weeksa | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 9.65 (1.5) | 8.87 (1.5)c | 456 (102) | 434 (104)b | 277 (54) | 265 (56)b | 174 (31) | 165 (31)b |

| 6 monthsa | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 8.86 (1.7) | 9.08 (1.7)b | 445 (96) | 434 (97)b | 265 (58) | 267 (66)b | 173 (66) | 167 (68)b |

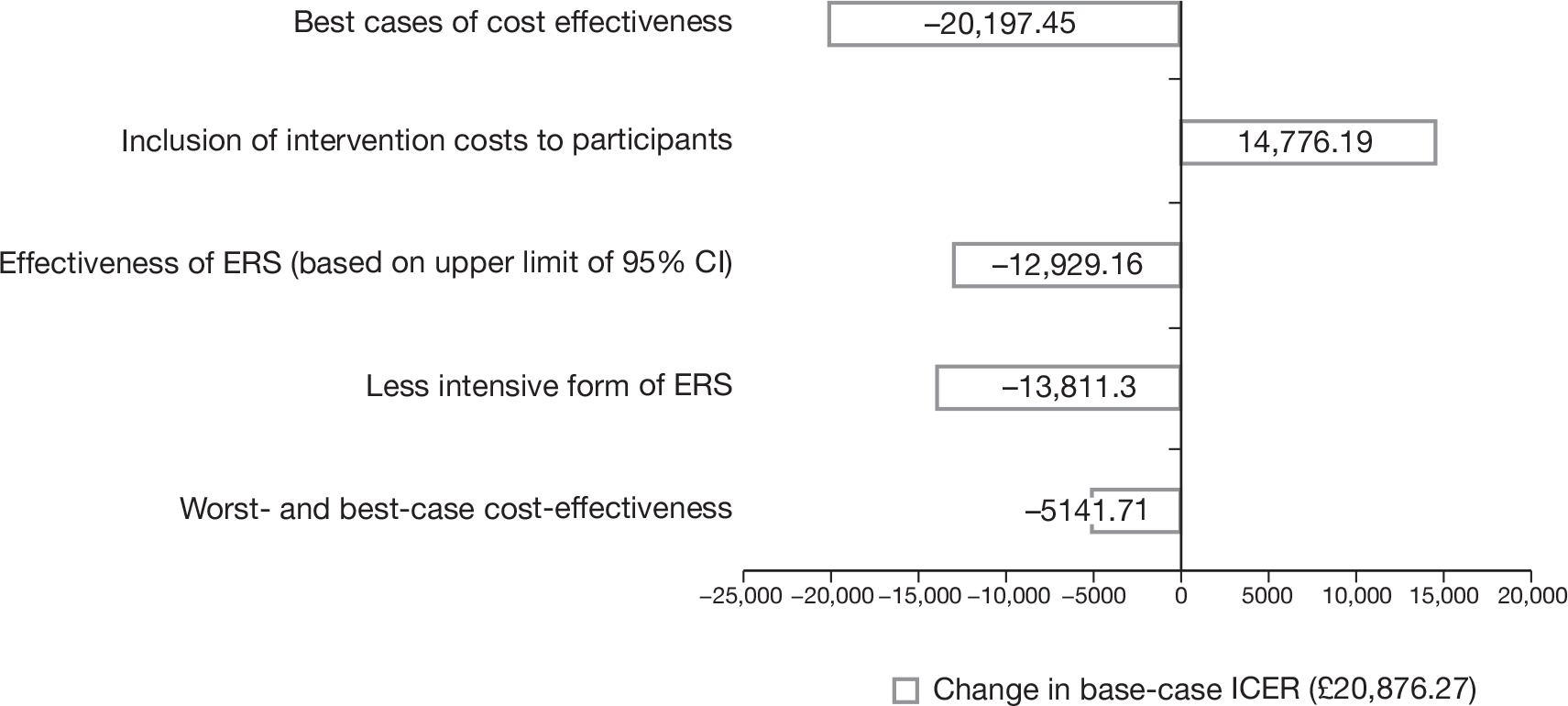

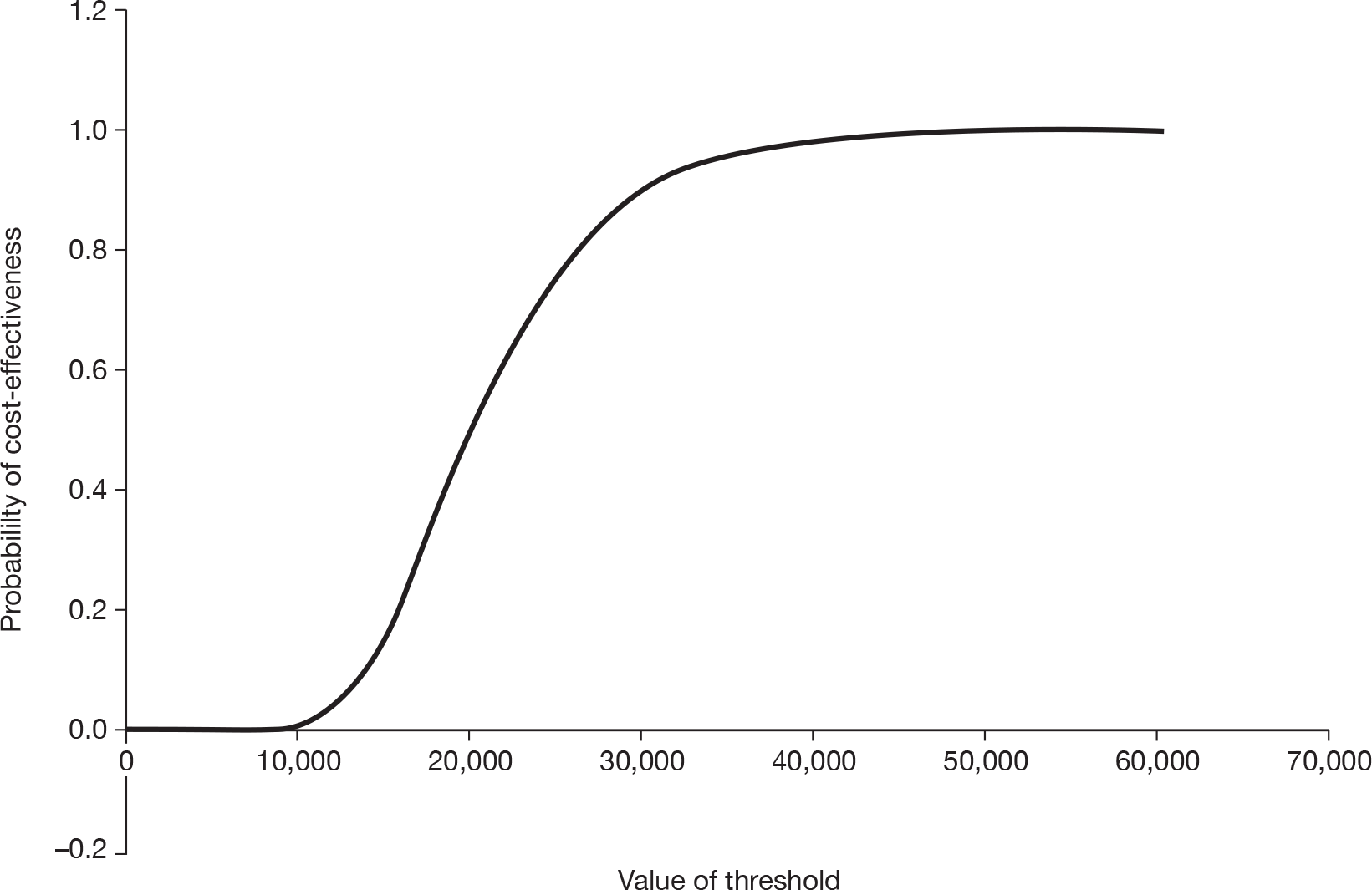

| ERS, mean (SD) | Alternative PA, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Alternative PA, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Alternative PA, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Alternative PA, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Alternative PA, mean (SD) | ERS, mean (SD) | Alternative PA, mean (SD) | |