Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 06/06/03. The contractual start date was in July 2007. The draft report began editorial review in October 2010 and was accepted for publication in June 2011. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2012. This work was produced by Ewer et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2012 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Congenital heart defects

The term congenital heart defect (CHD) encompasses a variety of lesions with a wide spectrum of clinical importance, ranging from those of no functional or clinical significance to potentially life-threatening ‘critical’ lesions. If undiagnosed, infants with a critical lesion are at risk of acute cardiovascular collapse or death. At least 18 distinct types of CHD are recognised, with many anatomical variations. 1

Congenital heart defects are the most common group of congenital malformations, with a reported incidence of between 4 and 10 per thousand live-born infants. 1–3 CHDs are one of the leading causes of infant death in the developed world, accounting for more deaths than any other type of malformation; up to 40% of all deaths from congenital abnormalities,1,4 and 3–7.5% of infant deaths. 5,6 Apparent increases in the prevalence of CHDs7,8 are likely to be explained predominantly by the increased detection of relatively minor defects (which may never become clinically apparent), as echocardiography has become more sophisticated and widely available. 8,9

Most newborns with a CHD can be diagnosed using echocardiography and, if necessary, stabilised with prostaglandin infusion and treated with surgery or transcatheter intervention. 10 Surgery has resulted in marked improvements in survival, particularly for those infants with potentially life-threatening conditions. However, if such defects are not detected sufficiently early then severe hypoxaemia, shock, acidosis and death are potential sequelae. Such cardiovascular compromise, if not lethal, can have significant long-term effects as a consequence of significant multiorgan insults, including hypoxic–ischaemic brain injury. Timely recognition of these conditions is likely to improve outcome and therefore the evaluation of screening strategies to enhance early detection is of great importance.

Definitions

There is considerable variation in the definitions of severity of CHDs within the published literature. Terms such as major, critical, severe, complex, serious and significant are frequently used, but the lack of agreed definitions makes comparisons across studies difficult.

Because of the wide spectrum of severity, it is vital when evaluating the potential benefit of screening to be clear about the nature of CHDs that is considered important from the screening perspective. For the purposes of this report, and in keeping with previously published studies,8 we have defined a congenital heart defect as ‘a gross structural abnormality of the heart or intrathoracic great vessels that is actually or potentially of functional significance’. 11 We have further categorised CHDs according to echocardiographic findings and clinical course, in order to indicate the clinical importance of the lesion (Table 1).

| Normal | No echocardiographic abnormalities |

| Non-significant | Presence of any one of the following at birth and findings no longer detected at 6 months: small PDA; small interatrial communication (PFO/ASD); muscular VSD; mildly abnormal turbulence at branch pulmonary artery |

| Significant | Presence of any one of the following at birth and findings persist for longer than 6 months of age: small PDA/PFO/muscular VSD; mildly abnormal turbulence at branch pulmonary artery. Also any cardiac lesion that requires regular monitoring beyond 6 months or requiring drug treatment, but not categorised as serious or critical |

| Serious | Any cardiac lesion not defined as critical, which requires intervention (cardiac catheterisation or surgery) or results in death between 1 month and 1 year of age |

| Critical |

All infants with hypoplastic left heart, pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum, simple transposition of the great arteries or interruption of the aortic arch All infants dying or requiring surgery within the first 28 days of life with the following conditions: CoA; aortic valve stenosis; pulmonary valve stenosis; TOF; pulmonary atresia with VSD; total anomalous pulmonary venous connection |

Major CHDs resulting in death or requiring invasive intervention (surgery or cardiac catheterisation) during infancy are the lesions in which early detection by screening is most likely to improve outcome. We have further divided this group into two subcategories: critical and serious. Critical lesions are most likely to present in the first few days or weeks of life, usually as a result of closure of the ductus arteriosus. During fetal life the ductus is an important shunt between the aorta and the pulmonary artery, which allows blood to bypass the uninflated lungs in utero. After birth, once the lungs are inflated, alteration of blood flow to the lungs and an increase in blood oxygen levels causes the ductus to contract and close. This event usually takes place over the first few hours of life, but patency may persist for longer than this. In a CHD, in which normal blood flow to the lungs or to the systemic circulation is restricted, blood flow through the ductus can be vital. In these ‘duct-dependent’ circulations, closure of the ductus can be catastrophic and cause acute cardiac decompensation as previously described.

For the purposes of this study, we have defined critical CHDs in accordance with a previously published UK categorisation2 to include all potentially life-threatening duct-dependent conditions plus infants dying or undergoing invasive procedures (surgery or cardiac catheterisation) within the first 28 days of life, although it is accepted that death from undiagnosed CHDs can occur after that age. Serious CHDs are defined as those defects not classified as critical that result in death or invasive intervention within 12 months of age (see Table 1).

The prevalence of major defects remains essentially unchanged at around 2.5 per 1000 live births. 1,7,8 Critical lesions have an estimated incidence of 1–1.8 per 1000 live births2,12,13 and this group accounts for between 15% and 25% of all CHDs, depending on the definitions used. 2,10

Prognosis for congenital heart defects

In recent years there have been significant improvements in the survival of infants born with CHDs, mainly as a result of improved imaging and advances in surgical techniques. It is likely that the survival rates for infants operated upon in the 21st century will be even better than those for infants who received surgery 15–20 years ago. In the USA, between 1995 and 2005, the mortality rate from CHDs declined by 42%, and the recent aggregated postoperative mortality rate is estimated at 3.7%. 1

Most deaths from a CHD occur within the first year and these are commonly as a result of extracardiac anomalies (e.g. trisomies 13 and 18), cardiovascular collapse in the neonatal period or perioperative mortality. Mortality from specific cardiac defects varies depending on prevalence, association with extracardiac defects, likelihood of acute decompensation in the neonatal period and amenability to surgical intervention. For example, ventricular septal defect (VSD), the most common CHD, accounting for 37% of all defects8 and the highest proportion of deaths in infancy due to a CHD (17%), is more frequently associated with extracardiac defects, and most infants dying with VSD in the first year of life have non-cardiac cause of death. 14 By contrast, transposition of the great arteries (TGA) and hypoplastic left heart (HLH) account for 4% and 2% of CHDs, respectively, but account for 7% and 15% of all deaths in infancy; 82% of deaths with TGA and 79% of deaths from HLH are due to the cardiac condition alone. 14

The majority of children with major CHDs will require surgical intervention within the first year of life. The majority of CHDs are amenable to surgery and, in general, for infants with an isolated CHD surgical mortality rates are low. Some surgery, but by no means all, is corrective, resulting in an anatomically normal heart.

Whatever the mode of detection of CHDs, the definitive surgical procedure will be almost certainly the same. However, circulatory collapse prior to surgery, resulting in shock and acidosis, can have a significant effect on outcome. Poor clinical status at the time of operation increases surgical mortality and adversely affects outcome. 15 Evidence for worse surgical outcome associated with perioperative instability has also been shown for specific critical lesions such as TGA,16 coarctation of the aorta (CoA)17 and HLH. 18

At present, it is estimated that over 80% of babies born with a CHD will survive to 16 years of age,6 and this survival rate is likely to increase with increasing surgical expertise. Data on long-term sequelae, particularly neurodevelopmental outcome, are lacking, but it is estimated that severe neurological deficit occurs in 5–10% of patients and milder neurological problems occur in up to 25%. 6 Thus, for the majority of patients with CHDs the outcome is favourable, with survival to adulthood the norm, and quality of life is likely to be reasonable. 6 Detection of critical CHDs in a timely manner, i.e. a preoperative diagnosis prior to death or cardiovascular collapse, is highly likely to further improve survival and long-term outcome.

Detection of congenital heart defects

Primary prevention is not possible; therefore, detection of CHDs prior to the onset of symptoms allows the possibility of interventions that may influence the natural history of the condition and subsequent outcome. As previously stated, this is of particular importance in infants with potentially life-threatening, critical CHDs, most of whom are asymptomatic at birth2 and in whom deterioration or death can occur before the condition is recognised. 19

An undetected CHD is a significant cause of unexpected neonatal or infant death. In one UK study, 15% of infants with CHDs who died before 12 months of age had a CHD that was undiagnosed prior to death. 19 Failure to diagnose a critical CHD prior to discharge from hospital occurred in up to 26% of infants in a Swedish study over an 8-year period, with an increase in infants discharged without diagnosis over the study period. 20 In the same study, 20% of critical lesions were undetected prior to discharge. 20 In UK studies, 25–30% of infants with potentially life-threatening conditions2,15 and almost 80% of infants with obstructive left heart defects (the main causes of death from an undiagnosed CHD after discharge and before diagnosis) left hospital undiagnosed. 21 Similar data have been reported in the USA; 1 in 10 infants with a CHD dying in the first year of life did not have the malformation diagnosed before death and, of the infants who died in the first week of life, one-quarter did not have a diagnosis before death. 22 Death at home or in hospital emergency rooms occurred in 50% of infants with undetected critical CHDs. 23

Gold standard

Postnatal echocardiography is well established as the gold standard for diagnosing CHDs. However, it has to be remembered that, as studies of prevalence show, echocardiography may also contribute to an apparent rising incidence of CHDs mainly as a result of the detection of abnormalities which are of no functional or clinical significance. 7,8 As a result, echocardiography is likely to have significant limitations as a screening tool, mainly because of the high false-positive (FP) rate,6,10 but also as a result of cost and lack of availability of trained personnel to perform the examinations.

Screening procedures

A screening programme is directed at a population that may be at risk of a disease or its complications and offers one or more tests to identify those who need further investigation or treatment. Screening targets apparently healthy fetuses and newborn babies, and provides parents and health professionals with information with which to make informed choices about their health. It has the potential to reduce morbidity and improve quality of life through early diagnosis, but there can be disadvantages, and any screening programme should be systematically evaluated before implementation as a public health policy. Current screening strategies to detect CHDs in the UK include physical examination and antenatal ultrasound.

Physical examination

Current UK guidance recommends examination of the cardiovascular system in all infants shortly after birth and again at 6–8 weeks of age,24 and such practice has been in place for decades. 25 The cardiovascular component of the newborn screening clinical examination involves auscultation of the heart for murmurs and additional sounds, palpation of the peripheral pulses, particularly the femoral pulses, and observation for cyanosis.

A UK retrospective study of all infants with a CHD diagnosed in the first 12 months of life showed that routine neonatal examination failed to detect over half of the babies with a CHD and the later examination at 6 weeks missed one-third of babies. 26 Some CHDs are even more difficult to detect by examination; in a further UK study of 120 babies with CHDs causing obstruction to the systemic circulation – HLH, CoA, aortic stenosis (AS) and interrupted aortic arch (IAA) – 94 (78%) were discharged home without a diagnosis and, although an initial examination was noted in 34 babies, only 8 were referred. 21 The difficulties encountered when determining cardiovascular problems by physical examination are well known; many of the physical signs which may alert the clinician to CHDs are unreliable. Mild cyanosis is difficult to detect with the naked eye even if the examiner is very experienced,27 and peripheral pulses may still be palpable as a result of blood flow through the patent ductus arteriosus. The prevalence of murmurs detected during the neonatal examination is estimated to be between 0.6% and 4.2%. 10,28 The presence of a murmur has been shown to be associated with a 54% chance of a CHD. 28 However, they often do not occur in critical lesions such as valve atresias and TGA. 10 Murmurs associated with minor CHDs are common, and those associated with more complex lesions may become apparent only after the pulmonary vascular resistance has fallen, which may occur after discharge from hospital.

One of the main additional factors that is likely to influence early detection by physical examination is length of hospital stay following delivery. The sooner a baby is discharged, the lower the likelihood of the development of clinical signs or symptoms which could be detected by examination. Kuehl et al. 22 identified an increased risk of missing critical CHD if babies were discharged before 48 hours of age. However, there is an increasing trend towards earlier discharge in North America and Scandinavia. 29–32 In the UK, an increasing proportion of babies are being sent home within 12 hours after delivery, and this trend is likely to continue. 6 This is liable to have a further impact on the number of babies discharged from hospital before a CHD has been diagnosed.

Antenatal ultrasound (mid-trimester or anomaly scan)

The opportunity to perform a four-chamber ultrasound view of the fetal heart in order to diagnose fetal cardiac anomalies was recognised in the early 1980s. 33–35 Ultrasound is now established as a routine screening procedure, with 97% of all UK units offering second-trimester anomaly scans to all pregnant women between 18 and 22 weeks’ gestation. 36 Both the Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (RCOG) and the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) have issued guidelines relating to the nature of antenatal anomaly screening and have recommended that, in addition to the four-chamber view of the heart, the outflow tracts should also be visualised. 37,38 However, in the UK in 2002, only 57% of units reported routinely examining the outflow tracts and the range of units offering this service within health regions was 25–84%. 36

The identification of a cardiac anomaly at this stage of pregnancy allows time for appropriate counselling regarding the nature of the lesion and the management options that are available, for example termination of pregnancy or planned delivery and timely medical and surgical intervention. Cardiac defects diagnosed antenatally are frequently complex and associated with extracardiac abnormalities, such as chromosome disorders, genetic syndromes or are part of a multiple malformation disorder that may be associated with a poor outcome. However, antenatal diagnosis can improve the outcome for isolated critical conditions. 39 Antenatal detection of HLH,18 CoA17 and TGA40 has been reported as resulting in better surgical survival. This is likely to be as a result of better clinical state prior to surgery with reduction in preoperative acidosis, cardiovascular compromise and end-organ dysfunction as previously discussed. 15,41

The effectiveness of antenatal ultrasound screening to detect CHDs in low-risk populations at 18–23 weeks’ gestation is extremely variable with sensitivities ranging from 0% to 81%. 38,42 In the UK in 1999, the average national detection rate was reported as approximately 23%33 and similar figures have been reported more recently in the UK and in other countries. 18,40,43–49 Data from the north-east of England show that over the 20-year period from 1985 to 2004 an average of only 8% of life-threatening CHDs were diagnosed antenatally, and although there was an increase in the proportion of infants diagnosed antenatally over the time period, at best only 20% were picked up in this way. 2

In addition, it has to be remembered that a significant proportion of those babies detected antenatally have associated non-cardiac abnormalities that may themselves be life-threatening. The antenatal detection rate in isolated CHDs is lower. Prenatal detection also offers the opportunity for termination of pregnancy, which will reduce the prevalence of CHDs in the live-born population.

With intensive training, improvements in the detection rates of CHDs during the routine anomaly scan can be demonstrated; however, in the UK the proportion of CHDs detected antenatally still varies between 20% and 55%. 35

National standards for the anomaly scan published in 2010 by the NHS Fetal Anomaly Screening Programme state that a four-chamber view of the heart and views of the right and left ventricular outflow tracts should be performed. The use of colour-flow Doppler to improve detection is encouraged, but not a requirement. 50 The expected detection rate for serious CHDs is stated as 50%. 50

Fetal echocardiography

It is possible to detect most forms of CHDs even in the first trimester,51 using antenatal echocardiography; the main exceptions to this being milder obstructive lesions of the great arteries [AS, pulmonary stenosis (PS) and CoA], persistent patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), secundum atrial septal defects (ASDs) and some forms of VSD. 52 However, it is not a universal screening test. Tertiary obstetric centres will often offer fetal echocardiography to women at a high risk of a pregnancy complicated by a CHD – risk factors such as family history of CHDs, maternal diabetes and exposure to teratogens, such as lithium or phenytoin, would usually lead to fetal echocardiography by a paediatric cardiologist or individuals trained in the technique. However, despite the high risk, the absolute numbers of cardiac abnormalities in these groups are low and the majority of cases of CHDs occur in low-risk groups, as outlined in the previous section. Therefore, the majority of cardiac abnormalities detected antenatally will be identified in low-risk groups after a routine anomaly scan. 35 Even in tertiary centres the ability to detect specific defects varies with the nature of the defect. Four-chamber abnormalities are more readily detected than outflow tract lesions. For example, antenatal diagnosis has been reported as 81% for HLH in one tertiary centre, whereas TGA was diagnosed antenatally in only 25% of cases. 53

A systematic review of five studies comprising over 60,000 unselected and low-risk patients found that among the low-risk populations frequency of correct diagnosis ranged from 35% to 86%. However, the potential for ascertainment bias and the choice of reference standard that limited the validity of these findings was also reported, and the variation in sensitivity across studies was not explainable by clinical factors, such as scanning regime, operator skill and equipment. The review concluded that the evidence about the accuracy of fetal echocardiography did not lend support to its routine use among unselected and low-risk populations during the second trimester to detect congenital heart disease. 54 Additionally, expanding fetal echocardiography screening to include the low-risk population also has significant training and resource implications. 6,53,55

Pulse oximetry

The rationale for pulse oximetry screening is based on the fact that hypoxaemia is present, to some degree, in the majority of CHDs. This may result in obvious cyanosis; however, mild degrees of hypoxaemia cannot be detected by clinical observation, even by experienced clinicians. 27 The difficulty is exacerbated in infants with pigmented skin. 56

Pulse oximetry was developed as a non-invasive method to determine arterial oxygen saturations (SpO2) and has been widely used in intensive care, operating theatres and emergency units for over 30 years. The ability to detect the different absorption spectra oxygenated and deoxygenated haemoglobin allows pulse oximeters to measure the amount of oxygen-saturated haemoglobin in the capillaries of an extremity, such as a finger or an ear lobe in an adult, or a hand or foot in a baby. Pulse oximetry thus allows the detection of hypoxaemia that would not necessarily produce visible cyanosis; the technique correlates well with arterial blood gas measurements56 and does not require calibration.

Oximeters can measure either functional or fractional oxygen saturations. Functional saturation is the ratio of oxygenated haemoglobin to all haemoglobin capable of carrying oxygen; fractional saturation is the ratio of oxygenated haemoglobin to all haemoglobin (including that which does not carry oxygen). Fractional saturation is approximately 2% lower than functional saturation. 13,57,58

The fetus is hypoxic in utero, with oxygen saturations of 30–60%. 59 The events that follow delivery – clamping of the umbilical cord, initial inflation of the lungs allowing pulmonary gas exchange and an increase in pulmonary circulation – result in a rapid rise in the arterial oxygen tension. The mean preductal (right hand) and postductal (foot) saturations rise to 73% and 67%, respectively, within the first 2 minutes after birth, and to 92% and 89% by 10 minutes. 60 The difference between right hand and lower limb saturations reflects right-to-left shunting across the ductus arteriosus and this generally diminishes with time in most infants, with both pre- and postductal saturations reaching 95% by 1 hour of age. 60 Saturations are generally stable in the first 24 hours with a mean of 98% (similar to values obtained from older neonates); however, periods of desaturation may occur,61 and larger studies have shown that many healthy newborns (up to 5%) may have episodes of saturations of < 95% within the first 24 hours. 13

These findings have led to exploration of the possibility that pulse oximetry may be useful in detecting hypoxaemia associated with CHDs in apparently healthy newborns, and a number of studies have been published that have used pulse oximetry as a screen for CHDs in this group. 13,62–71

In a systematic review published in 2007, we reviewed the eight published studies available at that time. 72 We highlighted a number of problems when assessing the accuracy of this test as there was a wide variation in methodology, particularly patient selection, timing of saturation measurement, cut-off levels for a positive test result, nature of CHD screened for, rigour of follow-up and type of oximeters used (Table 2). In addition, most of the studies were relatively small and as a consequence the prevalence of CHDs was relatively low, particularly in the studies in which patients with an antenatally suspected CHD were excluded. None of the studies calculated power a priori and sample size was often inadequate to estimate sensitivity precisely. Since the publication of our systematic review, three more studies have been published,68–70 including two large Scandinavian studies69,70 (see Table 2).

| Author | Threshold | Functional/fractional | Single/repeat | Timing of testing | No. of patients | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | FP rate | Antenatal diagnosis included | Respiratory problems included | Follow-up post discharge completed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All CHDs | |||||||||||

| Richmond, 200213 | < 95% foot | FRAC | R | At 2 hours and at discharge | 5626 | 25 (12.7–41.2) | 99.6 (99.4–99.7) | 0.4% | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Arlettaz, 200571 | < 95% foot | FUNC | S |

6–12 hours Repeat 4–6 hours Median 8 hours |

3262 | 96.8 (73.6–100) | 99.7 (99.5–99.9) | 0.3% | Yes | Five PPHN only | No |

| Bakr, 200562 | < 94% hand and foot | FRAC | R |

Before discharge, three readings Average 32 hours |

5211 | 30.8 (9.1–61.4) | 100 (99.9–100) | 1/5006 | No | No |

Yes Not mortality |

| Meberg, 200869 | < 95% foot | FUNC | R |

First day Median 6 hours |

50,008 | 9.9 (7.3–13.2) | 99.4 (99.3–99.5) | 0.6% | No | Yes |

Yes Not mortality |

| Specified CHDs: cyanotic or critical | |||||||||||

| Hoke, 200263 |

< 92% in leg > 6% diff leg < arm |

FUNC | R |

< 6 hours 24 hours discharge |

2876 + 32 | 75 (57.8–87.9) | 87.9 (86.6–89.1) | 1.8% | Yes |

1 PPHN Nil else |

No |

| Koppel, 200364 | ≤ 95% foot | FUNC | S | > 24 hours | 11,281 | 60 (14.7–94.7) | 100 (100–100) | 1/11, 281 | No |

1 PPHN Nil else |

Yes |

| Reich, 200365 |

< 95% foot or hand ≤ 90% or > 3% difference |

FUNC | R | Before discharge | 2114 | 66.7 (9.4–99.2) | 99.9 (99.7–100) | 0.1% | No | No |

Yes 150 days |

| de Wahl Granelli, 200566 | < 95% hand and foot or > 3% difference | FUNC | S |

12–48 hours Median 24 hours |

266 | 89.4 (79.4–95.6) | 99 (96.4–99.9) | 1% | Yes | No | N/A |

| Rosati, 200567 | < 96% foot | FUNC | S |

> 24 hours Median 72 hours |

5292 | 66.7 (9.4–99.2) | 100 (99.9–100) | 0% | No | No |

Yes Not mortality |

| Sendelbach, 200868 | < 96% foot | FUNC | R |

4 hours Repeat at discharge |

15,233 | 75 (19.4 –99.4) | 94.4 (94–94.7) | 1/15, 233 | No |

Yes indirectly |

No |

| de Wahl Granelli, 200970 | < 95% hand and foot or > 3% difference | FUNC | R | Median 38 hours | 39,821 | 62.1 (42.3–79.3) | 99.8 (99.8– 99.9) | 0.17% | No | Yes | Yes |

| Meberg, 200869 | < 95% foot | FUNC | R |

First day Median 6 hours |

50,008 | 77.1 (59.4–89.0) | 99.4 (99.3–99.5) | 0.6% | No | Yes |

Yes Not mortality |

To date, only four studies have recruited more than 10,000 patients,64,68–70 although all of these excluded patients with antenatally diagnosed CHDs. In one study, this led to a significant reduction in the prevalence of CHDs with only 4/31 patients with critical CHDs receiving screening. 68 Sixteen out of 31 patients with critical CHDs (52%) were identified antenatally in this study cohort and therefore not screened, and 11 babies with critical CHDs were not screened for other reasons. 68 In the two largest studies, the antenatal diagnosis rate was comparatively low – only 3.3% of critical lesions detected in the Swedish study70 and 7% of total CHDs detected antenatally in the Norwegian study. 69

These two Scandinavian studies have significantly increased the number of patients screened by pulse oximetry69,70 and demonstrate sensitivity rates for critical CHDs in large cohorts of 62% and 77%, respectively. The Norwegian study also reported the sensitivity rate for all CHDs, but this was low at only 10%. When combined with physical examination both studies demonstrated an increase in sensitivity for pulse oximetry.

The methodological differences are important when comparing the results of studies and assessing test accuracy. There were various thresholds for abnormality of test results. Studies that screened for all CHDs generally had much lower sensitivity than those that screened specifically for critical or cyanotic lesions. Some studies with very high sensitivity rates66,71 tended to recruit lower numbers and therefore had a lower disease prevalence, which makes interpretation of these results more difficult (see Table 2). Ascertainment of missed cases (either those dying outside hospital or those presenting to other cardiac units) in order to identify false-negatives (FNs) was complete in only three studies. 13,64,70

In general, studies that screened later (24–72 hours)62,64,65,67,70 had lower FP rates; however, this has to be tempered by the fact that critical CHDs, if undiagnosed, may present with clinical deterioration in the first 48 hours of life; therefore, earlier testing may help to identify these patients before such an event can take place. The increasing trend towards earlier discharge for uncomplicated births also has to be taken into consideration when determining optimal timing. Some studies also included the detection of additional diagnoses such as respiratory problems and infections,13,69,70 which, although classified as FPs, were also potentially serious illnesses. These non-cardiac problems tended to present earlier and suggest a potential additional advantage to earlier screening.

Also important is the threshold for an abnormal saturation; the higher the percentage saturation thresholds the greater the sensitivity but the lower the specificity, and the converse is true for a lower cut-off. Although a number of levels have been proposed as the lower saturation threshold, the most frequently used in the published studies is around ≤ 95%. Most studies have used postductal saturations as a single measurement, although some studies used both pre- and postductal saturations and included a difference between the two in the definition of abnormality (see Table 2). Use of a differential criterion may increase the likelihood of detecting those obstructive left heart lesions, such as CoA, where the ductus supplies some of the systemic circulation and may result in a difference in saturation between the upper and lower limbs.

The two recent, large prospective studies discussed above69,70 demonstrate encouraging results, but were mostly limited to reporting the accuracy of pulse oximetry in detecting CHDs. Furthermore, they did not take into account the added influence of antenatal screening on the results, parents’ and health-care professionals’ acceptability of the test, psychosocial impact of FP results or identification of a non-critical CHD, and provided only limited analysis of the cost-effectiveness of such a screening programme.

Acceptability of pulse oximetry screening

When new antenatal or neonatal screening programmes are introduced, consideration should be given to the acceptability of screening to parents and to the psychological impact of the screening procedure. Any screening procedure is likely to raise anxiety as it raises the possibility, previously not considered by most parents, that a child may have a serious health condition. Our systematic review of pulse oximetry as a screening test identified no studies that evaluated the acceptability of screening to parents or the psychosocial impact of FP results. 72 It is important to address this as the literature on antenatal and neonatal screening more generally suggests that acceptability of screening has an impact on uptake and the effect of inaccurate results may extend over a considerable time period. 73–76 An earlier health technology assessment (HTA) review of newborn screening for congenital heart defects6 reported focus groups with parents in the results of the review. Although welcoming pulse oximetry as a screening method, these parents raised similar concerns to those found in studies of other types of neonatal and antenatal screening, particularly in relation to test accuracy and poor communication by health-care professionals. If screening is to be implemented as a standard procedure, it must also be acceptable to health-care staff; it is important to assess the impact of screening on the roles of staff involved.

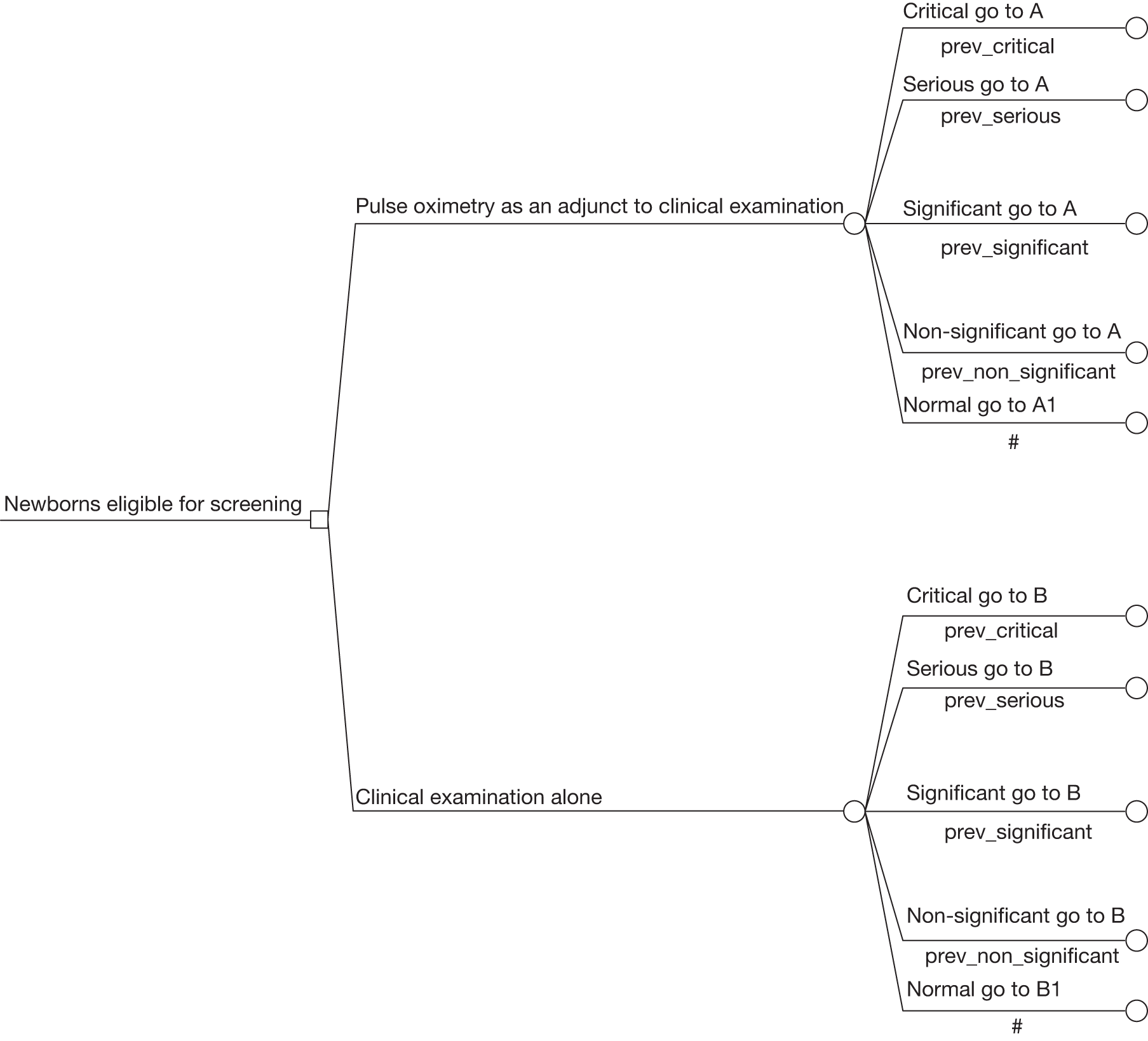

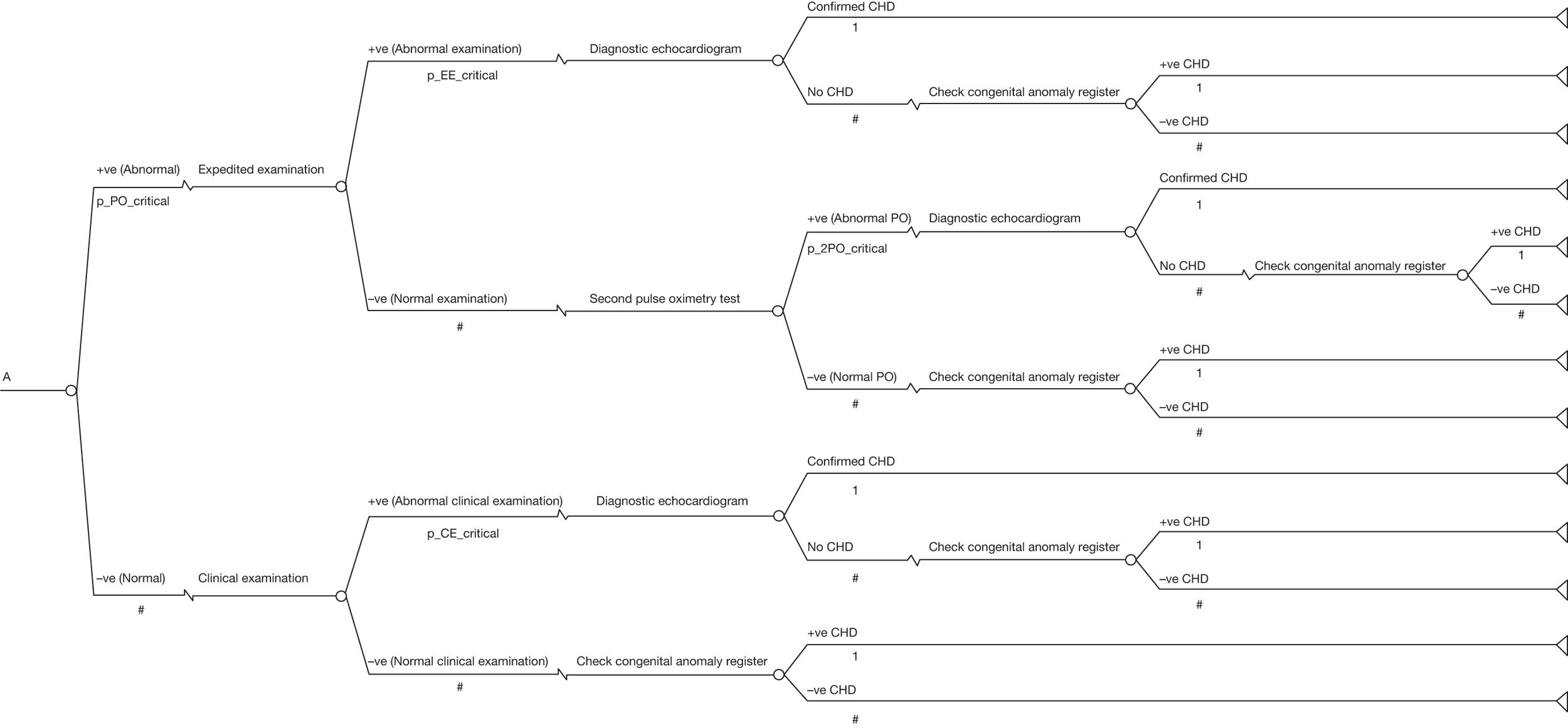

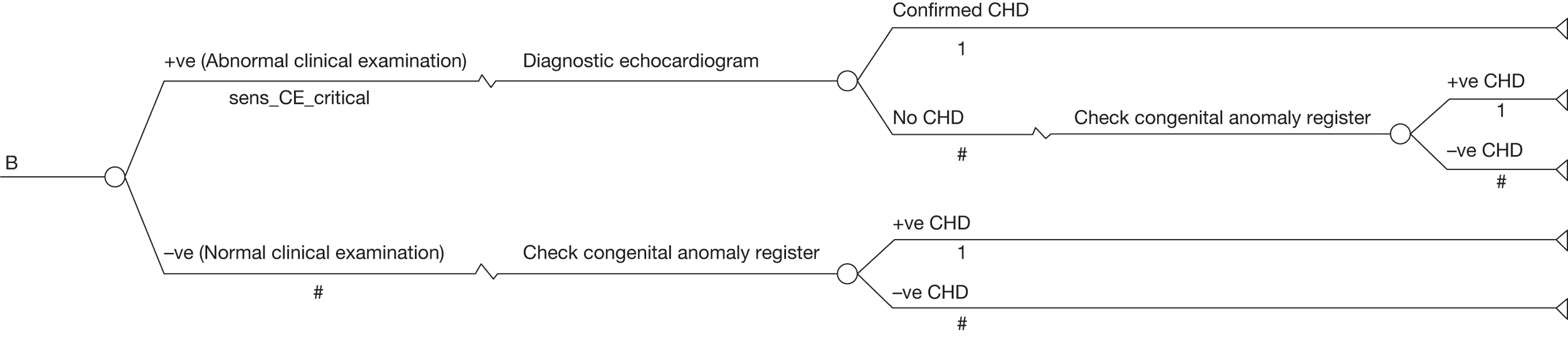

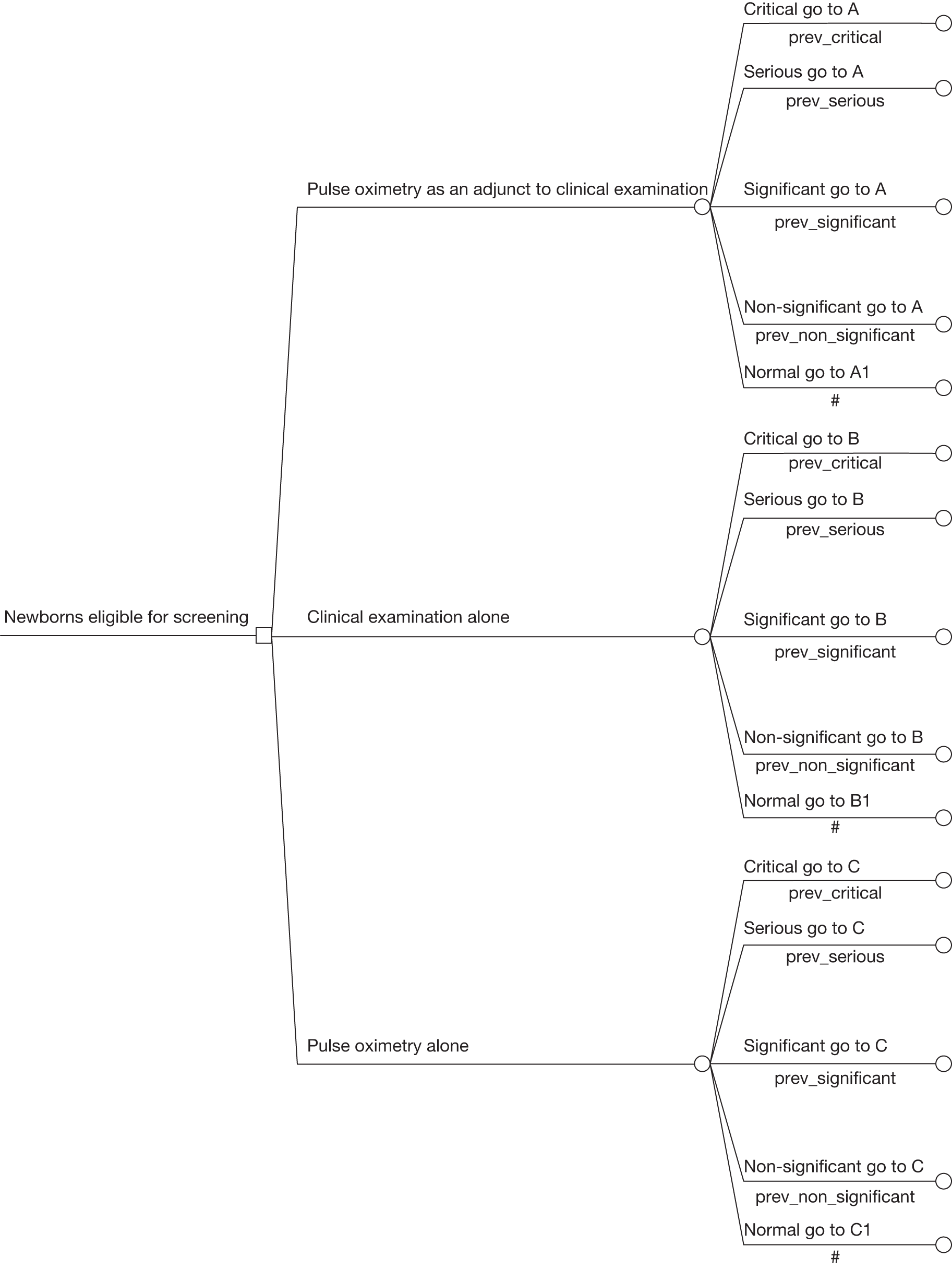

Cost-effectiveness of pulse oximetry screening

Adding the pulse oximetry test as an adjunct to the current practice of using clinical examination to screen for CHDs in newborn infants has the potential to improve the number of cases that receive a timely diagnosis. But such benefits need to be assessed against the additional costs that would be incurred and consideration of whether or not this is an appropriate use of limited health-care resources.

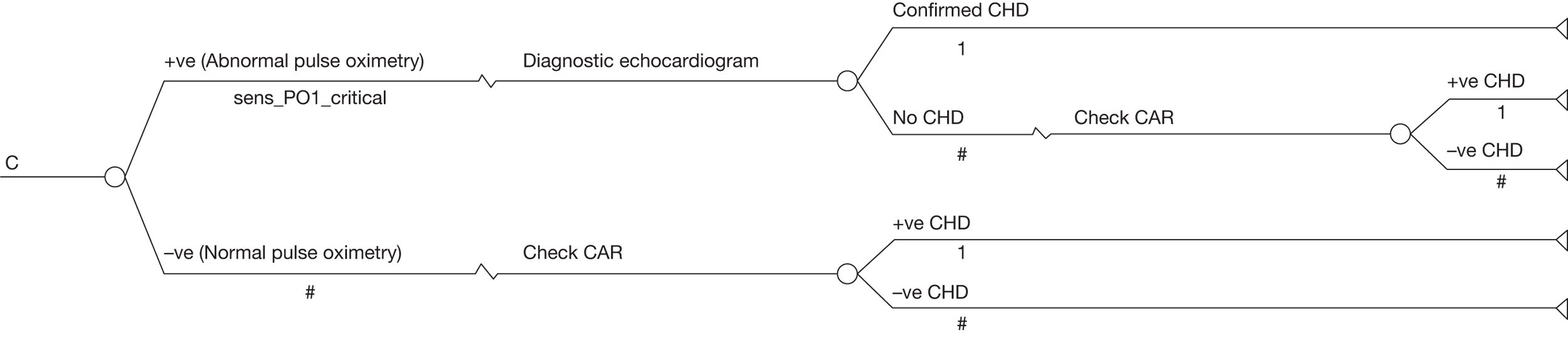

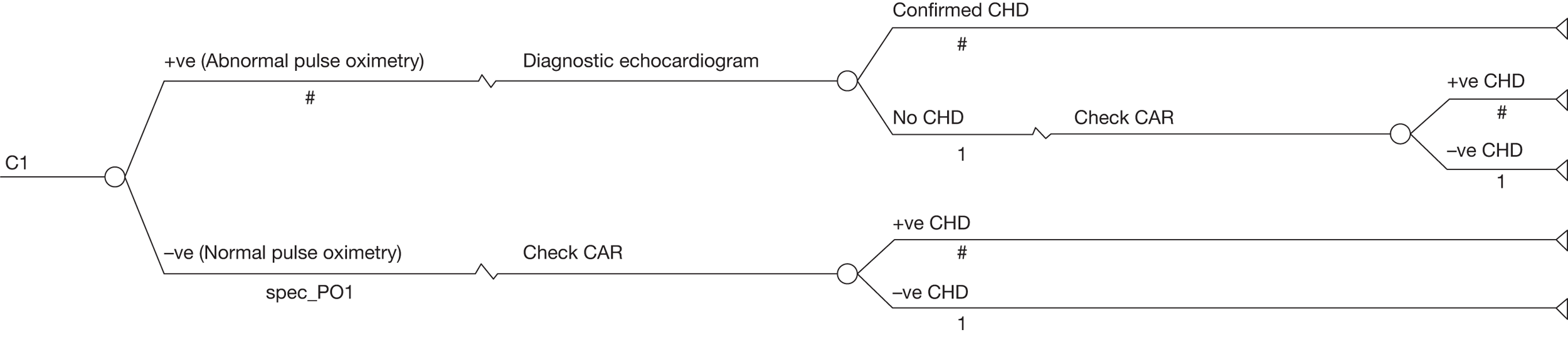

Knowles et al. 6 undertook a systematic review of the clinical and economic literature and used the data obtained to undertake a model-based economic evaluation of pulse oximetry to diagnose CHDs in the newborn. The authors developed a comprehensive model that suggested that pulse oximetry offered what could be considered a cost-effective screening test for detecting CHDs early in newborn infants. But the evaluation was based on secondary data from existing published sources and it was acknowledged that pulse oximetry required testing in a UK clinical setting to obtain primary data on its accuracy and associated costs. Against this background, we developed a new decision-analytic model based on the care pathways assessed in the current study and carried out an economic evaluation using new primary data on test accuracy and costs. The objective of the economic evaluation for this study was to assess the cost-effectiveness of pulse oximetry as an adjunct to current practice compared with current practice alone to ensure that decision-makers use available resources effectively.

Aims of the Health Technology Assessment project

The project was commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) HTA programme in 2007. The overall aim of the study was to evaluate the use of pulse oximetry as a screening procedure for the detection of serious and critical CHDs by assessing:

-

the accuracy of pulse oximetry against the reference standards of echocardiography, and interrogation of regional and national congenital anomaly and cardiac defect databases

-

the added value of pulse oximetry over routine antenatal ultrasound screening

-

the acceptability to parents and clinical staff of pulse oximetry testing

-

the cost-effectiveness of pulse oximetry testing compared with existing strategies of screening for CHDs.

The key objectives were:

-

to establish the feasibility of pulse oximetry as a screening test for CHDs among newborn infants

-

to determine the accuracy (sensitivity and specificity) of pulse oximetry using echocardiography and interrogation of regional and national congenital anomaly and cardiac defect databases as reference standards

-

to determine the acceptability of pulse oximetry testing among mothers whose babies tested positive and a selection of true-negative (TN) tests and also among health-care staff

-

to determine the cost and cost-effectiveness of pulse oximetry testing for CHDs and to compare this with other strategies for screening.

The accuracy study was designed and managed in such a way as to meet the Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (STARD) criteria for methodological quality. 77 Acceptability was assessed using a questionnaire survey and qualitative interviews. Cost-effectiveness analysis involved decision-analytic model-based economic evaluation.

Chapter 2 Diagnostic accuracy of pulse oximetry as a screen for congenital heart defects in asymptomatic newborn infants

Introduction

This chapter describes a test accuracy study (the PulseOx study) to determine the accuracy of pulse oximetry screening for serious and critical CHDs in asymptomatic newborns:

-

population apparently healthy asymptomatic newborn infants with a gestation ≥ 35 weeks prior to discharge from hospital

-

index test oxygen saturations from pulse oximetry readings from the right hand (preductal) and either foot (postductal)

-

reference standard echocardiography, clinical follow-up and follow-up through interrogation of regional and national clinical databases

-

target condition major CHDs (see Table 1).

Methods

Using recommended methods for diagnostic accuracy evaluation77 (see Appendix 1), a study protocol was developed for a prospective accuracy study using delayed verification for test negatives. 78,79

Research Ethics Committee (Trent Research Ethics Committee and local research ethics committees) and NHS Trust research governance approval was obtained for recruitment in six large obstetric units based in the UK: Birmingham Women’s Hospital; Birmingham Heartlands Hospital; City Hospital, Birmingham; New Cross Hospital, Wolverhampton; Royal Shrewsbury Hospital; and University Hospital of Coventry and Warwickshire – all serving large, socioeconomically and ethnically diverse populations. These hospitals represented a spectrum of activity from specialised tertiary referral centre to busy district general hospital.

Study sample

Recruitment was organised and supported by research midwives, who worked with local community and antenatal clinics, midwifery teams and obstetrics leads. A dedicated co-ordinating midwife was employed at each centre with responsibility for overseeing staff training, consent, testing and data collection in her centre. In addition, a lead research midwife at Birmingham Women’s Hospital liaised with all the co-ordinating midwives at each centre, providing training for consent procedures, trouble-shooting of recruitment and midwifery problems.

All pregnant women booked for delivery at one of the six participating units were approached for consent to be recruited into the study. Study information leaflets were given to mothers at the time of their antenatal booking visit or at the mid-trimester scanning visit. The leaflet emphasised that pulse oximetry was introduced for routine use in the participating hospitals for the duration of the study, but that parents are entitled to choose whether or not they want their baby screened. Whenever possible, the written consent of the women was sought between 20 and 24 weeks or at least prior to labour and reconfirmed postnatally prior to testing eligible babies. The information leaflet and consent forms were also provided in minority languages (Arabic, Bengali, Chinese, French, Kurdish, Polish, Punjabi, Somali and Urdu) and also as audio-recordings on CD. Consent was supported by interpreters whenever possible.

All consecutive asymptomatic newborns with a gestation of 35 weeks or more were eligible for inclusion in the study. This included babies who were suspected antenatally of having a CHD. We excluded mothers who were unable to give consent through incapacity or lack of interpreter. Any newborn who showed symptoms of cardiovascular abnormalities at birth (such as overt cyanosis, dyspnoea or tachypnoea) was excluded from the study.

Index test

Pulse oximetry was performed after delivery and prior to discharge in all eligible, consented cases and was embedded in routine postnatal care provided by the midwife on the postnatal ward. We aimed to test early (within 3–6 hours of age), but in practice expected a range of testing times prior to discharge from hospital.

Clinical examination was not performed independently of the pulse oximetry result as ethically midwives would be expected to alert the medical staff of low saturations. This precluded a comparison of clinical examination with pulse oximetry on account of work-up bias.

Standardisation of pulse oximetry and feasibility pilot study

The Radical-7® pulse oximeter (Masimo, Irvine, CA, USA) was used in the study with the reusable probe LNOP YI. These have been shown to produce recordings free from motion artefact and to be capable of achieving stable, accurate readings of functional saturations in an active subject and also when perfusion is low with extremely low intra- and interobserver variability. 66 Five oximeters were available for each unit in order to ensure that readings could be taken at all times and babies were not missed because of faulty or misplaced machines. Oximeters were available on both the postnatal ward and delivery suite.

An initial technical feasibility study was carried out to establish the most practicable methods of testing and reporting results in the clinical setting. This allowed us to develop programmes for quality assurance and training. Testing was carried out by midwives and midwifery assistants depending on the availability of staff and working pattern preferences within each hospital. All staff involved in obtaining pulse oximetry readings were trained and their technique observed by the research midwife to ensure standard proficiency in testing. The importance of obtaining a high-quality, stable reading before documenting saturations was emphasised. If the saturation fluctuated between two or more readings and the signal quality was acceptable then the lower of the readings was documented.

Pulse oximetry was performed at a time deemed appropriate to clinical staff and after written informed consent was obtained. If consent had been obtained antenatally, then verbal confirmation of consent was obtained at the time of testing. An observational assessment of the baby was made prior to testing to ensure that the baby was asymptomatic. Either the oximeter was taken to the baby’s cot on a trolley or the detachable front section of the oximeter was removed to allow handheld testing. The reusable probe was used on the right hand and either foot in a non-specified order and remained on the limb until a satisfactory trace and consistent saturation reading was obtained. The date and time of the test and the results – expressed as percentage functional saturation for each limb – were recorded on the patient data sheet. The reusable probe was cleaned with an alcohol swab before and after each patient test.

A saturation of < 95% in either limb or a difference of > 2% between the limb readings was considered to be abnormal. This threshold was chosen in an attempt to increase the sensitivity to detect left heart obstructive lesions, such as AS, CoA and IAA – treatable conditions that were most commonly missed in earlier studies with different thresholds.

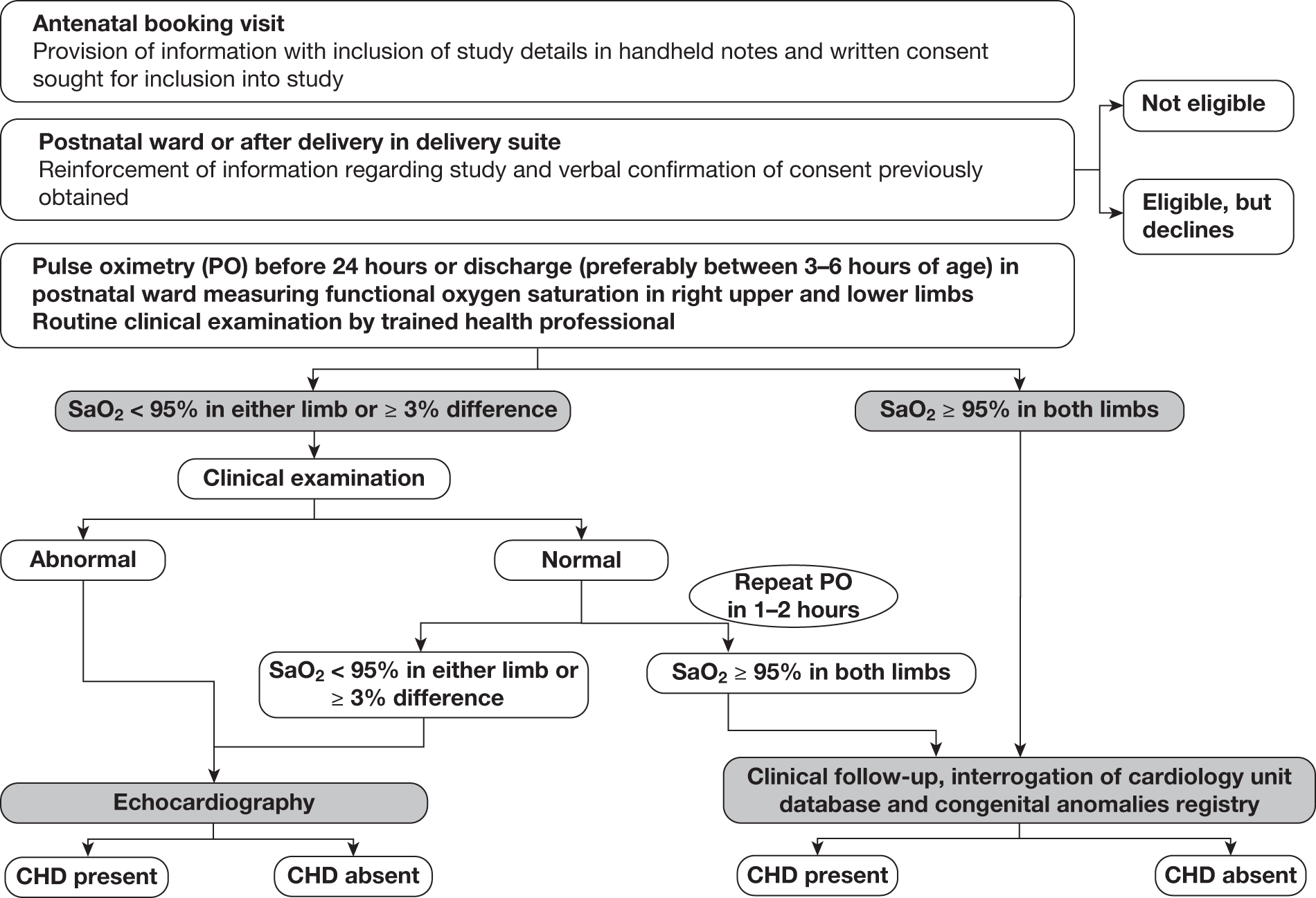

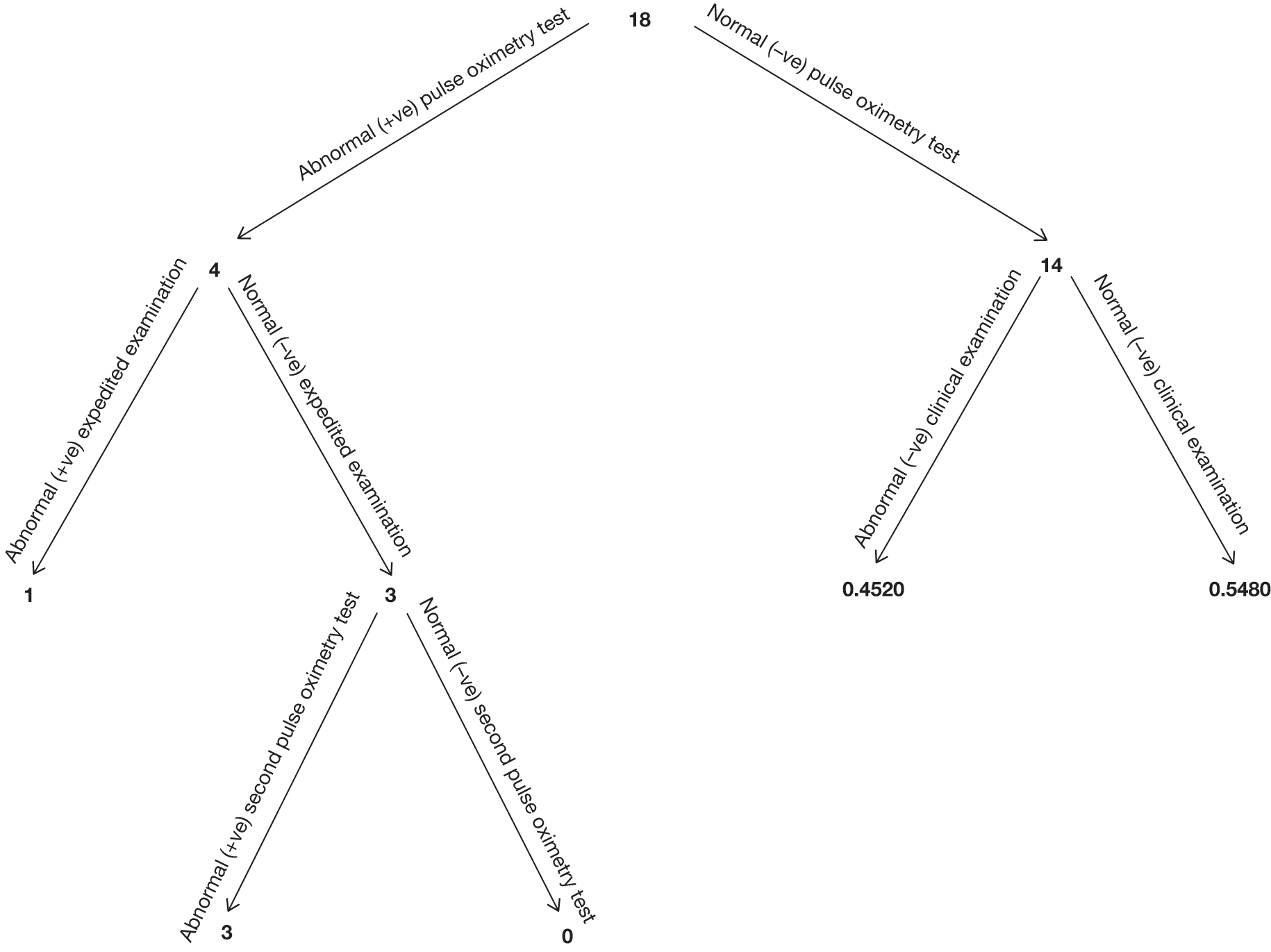

If the oxygen saturations were considered abnormal, an expedited clinical examination (ECE) was performed by an individual trained in examination of the newborn. If this clinical examination was unremarkable, pulse oximetry was repeated 1–2 hours later. If the saturations remained abnormal on this second occasion, or if abnormalities of the cardiovascular system were identified on the ECE, these babies were classified as test positive and underwent echocardiography (Figure 1).

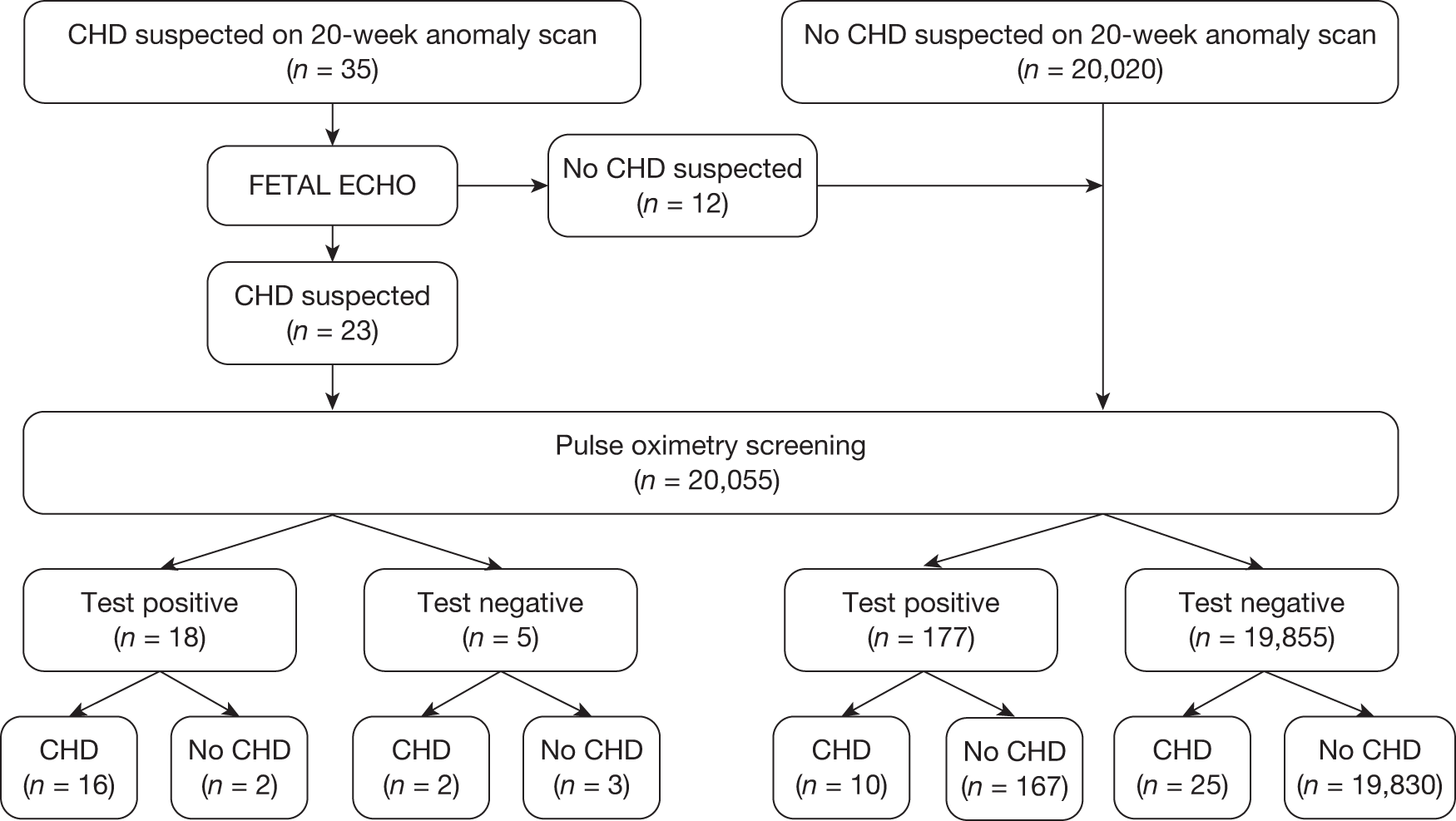

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of study organisation.

Other screening tests

Antenatal screening ultrasound

It was routine practice in each participating centre to perform screening mid-trimester anomaly ultrasound at between 18 and 22 weeks, including a four-chamber assessment of the fetal heart. Any pregnant woman in whom a suspected fetal cardiac anomally was identified at this stage was referred to a fetal medicine centre for fetal echocardiography. In addition to this, in one of the centres (BWH), women at high risk of fetal cardiac anomaly [i.e. those with a family history of CHDs, maternal diabetes, increased nuchal translucency, taking medication known to increase the risk of CHDs (e.g. antiepileptic drugs), fetal dysrhythmias] were also tested by fetal echocardiography. In order to identify the results of antenatal anomaly ultrasound we reviewed all fetal echocardiography results of study participants in order to identify screening scans that detected a suspicion of a CHD. We assumed that every woman received an anomaly scan and that all fetuses, in whom there was concern about cardiac abnormality, underwent fetal echocardiography.

Clinical examination

Patients who tested negative on the initial pulse oximetry test underwent a routine clinical examination, usually within the first 24–36 hours or prior to discharge, whichever was sooner. Patients who tested positive on initial testing underwent the ECE of the cardiorespiratory systems as described above. All patients receiving this examination also had the routine neonatal screening examination prior to discharge. No examination was performed without knowledge of the saturation result as we felt this would be unethical. It was not possible, therefore, to compare directly the accuracy of oximetry testing with examination. Only details of the expedited examination were recorded on the patient data sheet. Details of the routine clinical examination were collected retrospectively only if a CHD was suspected as a result.

Reference standard

A composite reference standard combining echocardiography and follow-up was used to identify immediate- and late-presenting cases of CHDs. Echocardiography was performed in all test-positive cases by trained individuals and the timing of the procedure was decided by the senior clinician responsible for the care of the baby; whenever possible, this was on the same day and always no longer than 72 hours after a positive pulse oximetry test result. In a small number of cases and at the discretion of the responsible clinician, infants perceived to be at low risk of a CHD despite a positive test were allowed to go home prior to echocardiography.

All echocardiograms were stored on videotape, collated, reviewed and ratified by a paediatric cardiologist. If there was disagreement then a second echocardiogram was produced.

The echocardiography result was categorised into one of the following groups: critical, serious, significant, non-significant or normal (see Table 1). We were particularly interested in the accuracy of diagnosing critical (potentially life-threatening conditions requiring invasive intervention within 1 month of life) and serious (requiring invasive intervention within 12 months of life) CHDs. Any baby with significant echocardiographic findings was followed up by a cardiologist in a routine manner. Those with non-significant findings were followed up until 6 months to establish non-significance.

All babies were also followed up through information obtained from regional and national registries. At 12 months after the end of recruitment, the regional congenital anomalies registers (CARs) and mortality registers for the West Midlands and surrounding regions [East Midlands and South Yorkshire (EMSYCAR), Oxfordshire, Berkshire and Buckinghamshire (CAROBB), South West (SWCAR) and Wales (CARIS)] were interrogated using diagnostic codes for cardiac abnormalities. Birmingham Children’s Hospital paediatric cardiology database (HeartSuite) and the national Central Cardiac Audit Database (CCAD) were also interrogated to identify all CHD cases requiring intervention within 1 year (i.e. critical and serious cases).

Sample size and power consideration

The sample size of at least 20,000 neonates was calculated on the basis that the lower limits of the confidence intervals (CIs) for both sensitivity and specificity would exceed certain values for an estimated prevalence of 2 per 1000. For an assumed sensitivity of 75% and specificity of 99.5%, the study had 80% power to prove that the sensitivity was at least 52% and over 90% power to prove that the specificity was above 99.3% (both using a one-tailed significance level of 2.5%). Estimates were calculated by simulation (using 10,000 repetitions) to account for both the sampling variability in the observed number of cases of CHDs and also the observed sensitivity and specificity. Binomial exact methods were incorporated to estimate CIs and a range of higher and lower prevalence rates were used to explore the effect on power and size of CIs.

An independent monitoring committee confidentially reviewed interim analyses to determine whether or not our assumptions for sample size were borne out at 3–4 months after commencement of recruitment in the accuracy study. It determined if the principal question on index test accuracy had been answered and monitored any adverse scenarios. The monitoring committee also reviewed reports of recruitment, compliance and estimated completeness of verification at 6-monthly intervals. 80 They met on two occasions and recommended continuing recruitment until the target recruitment of 20,000 babies was met.

Data analysis

For the analysis, the subjects were divided into two main cohorts. The first included all recruited babies, with the second excluding those individuals with an antenatal suspicion of a CHD from anomaly ultrasound screening that was subsequently confirmed by fetal echocardiography. This was undertaken in order to identify those in whom a positive pulse oximetry test result could make a difference to subsequent testing (most likely using echocardiography) and contingent health care. Those who underwent fetal echocardiography for a reason other than an abnormal anomaly scan were not excluded from the full cohort, as fetal echocardiography screening in this manner is not currently available as a routine test across the UK.

The diagnostic accuracy for the cohorts detailed above was evaluated by calculating sensitivity, specificity and predictive values for critical cases alone and for critical plus serious cases combined (see Table 1 for definitions). The 95% CIs for each estimate were calculated using binomial exact methods. 81 The accuracy of anomaly scan alone was evaluated in a similar fashion. The accuracy of pulse oximetry according to the timing of test was evaluated using a logistic regression model allowing for time from birth to the first stage of the pulse oximetry testing as a continuous variable.

Results

Between February 2008 and January 2009, there were 26,513 deliveries within the participating hospitals. Mothers of 20,055 eligible babies (75.64%) consented to the study; 685 infants were ineligible for inclusion (2.58%); 2005 infants were not included because consent was declined (7.56%); and in 3768 the opportunity for screening was missed (14.21%). The main reason babies were missed was insufficient staffing levels to obtain informed consent and/or to undertake the screening. The total percentage recruitment of eligible babies whose parents consented to the study was 84%. Demographic details of the mothers included in the study are described in Table 3.

| Total consented, 20055 | |

|---|---|

| Characteristic | n (%) |

| Age (years) | |

| < 20 | 1474 (7) |

| 20–24 | 4541 (23) |

| 25–29 | 5833 (29) |

| 30–34 | 4784 (24) |

| 35–39 | 2766 (14) |

| ≥ 40 | 657 (3) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 11,158 (56) |

| Asian | 4956 (25) |

| Black | 1323 (7) |

| Other | 1550 (8) |

| Not known | 1068 (5) |

| Gestational age (weeks) | |

| 35–36 | 731 (4) |

| 37–38 | 4396 (22) |

| 39–40 | 11,029 (55) |

| > 40 | 3899 (19) |

| Gravidaa | |

| 1 | 7500 (37) |

| 2 | 5708 (28) |

| 3 | 3273 (16) |

| 4 | 1707 (9) |

| 5+ | 1866 (9) |

| Missing | 1 |

| Parity | |

| 1 | 9197 (46) |

| 2 | 5800 (29) |

| 3 | 2834 (14) |

| 4+ | 2224 (11) |

| Pregnancy type | |

| Singleton | 19,537 (97) |

| Twins | 518 (3) |

| Baby gender | |

| Female | 9874 (49) |

| Male | 10,181 (51) |

| Birthweight (kg) | |

| Mean (SD) | 3.33 (0.52) |

| No. recruited in each centre | |

| Birmingham Women’s | 5708 |

| Birmingham Heartlands | 3378 |

| City Hospital | 1845 |

| New Cross | 2460 |

| UHCW | 3300 |

| Royal Shrewsbury | 3364 |

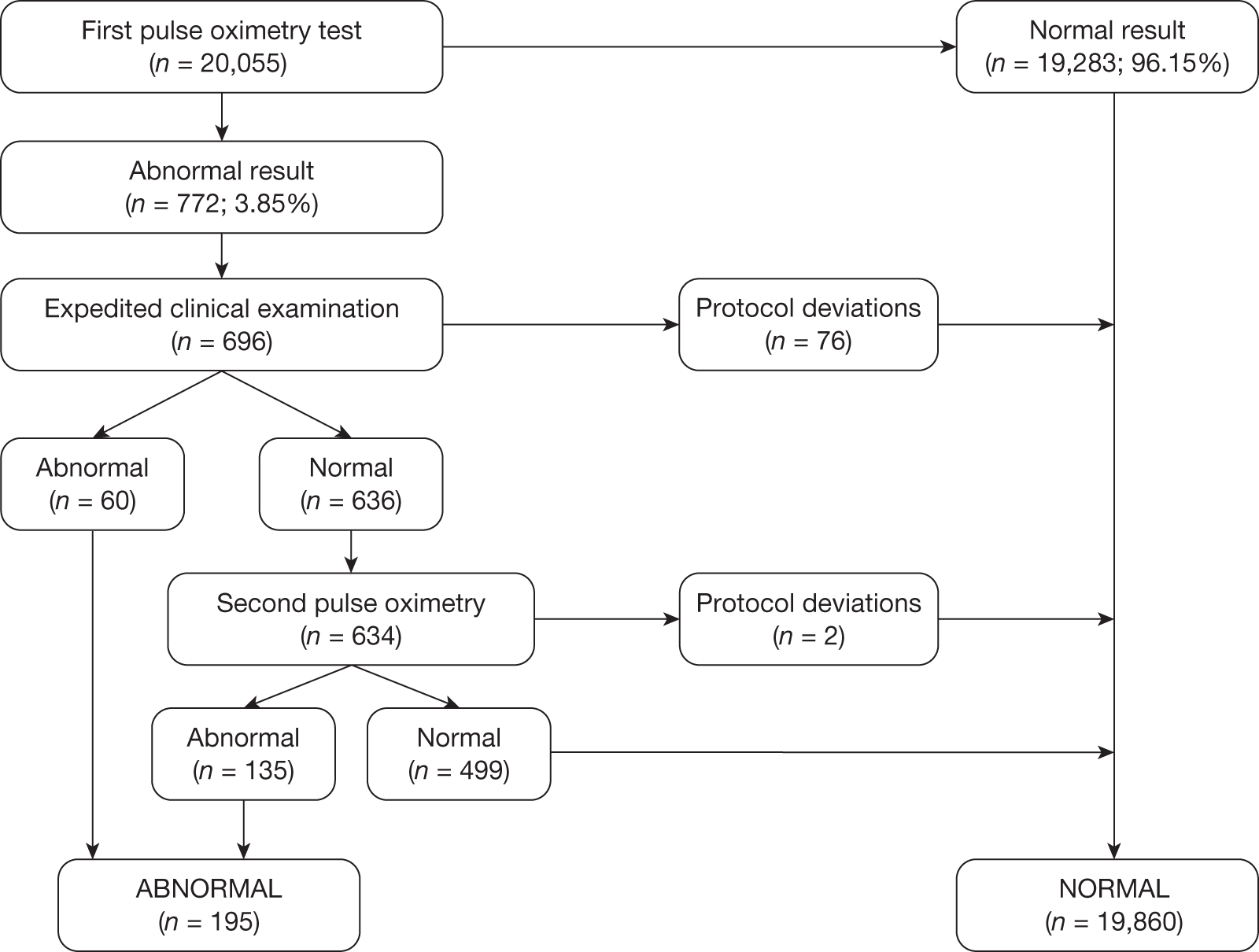

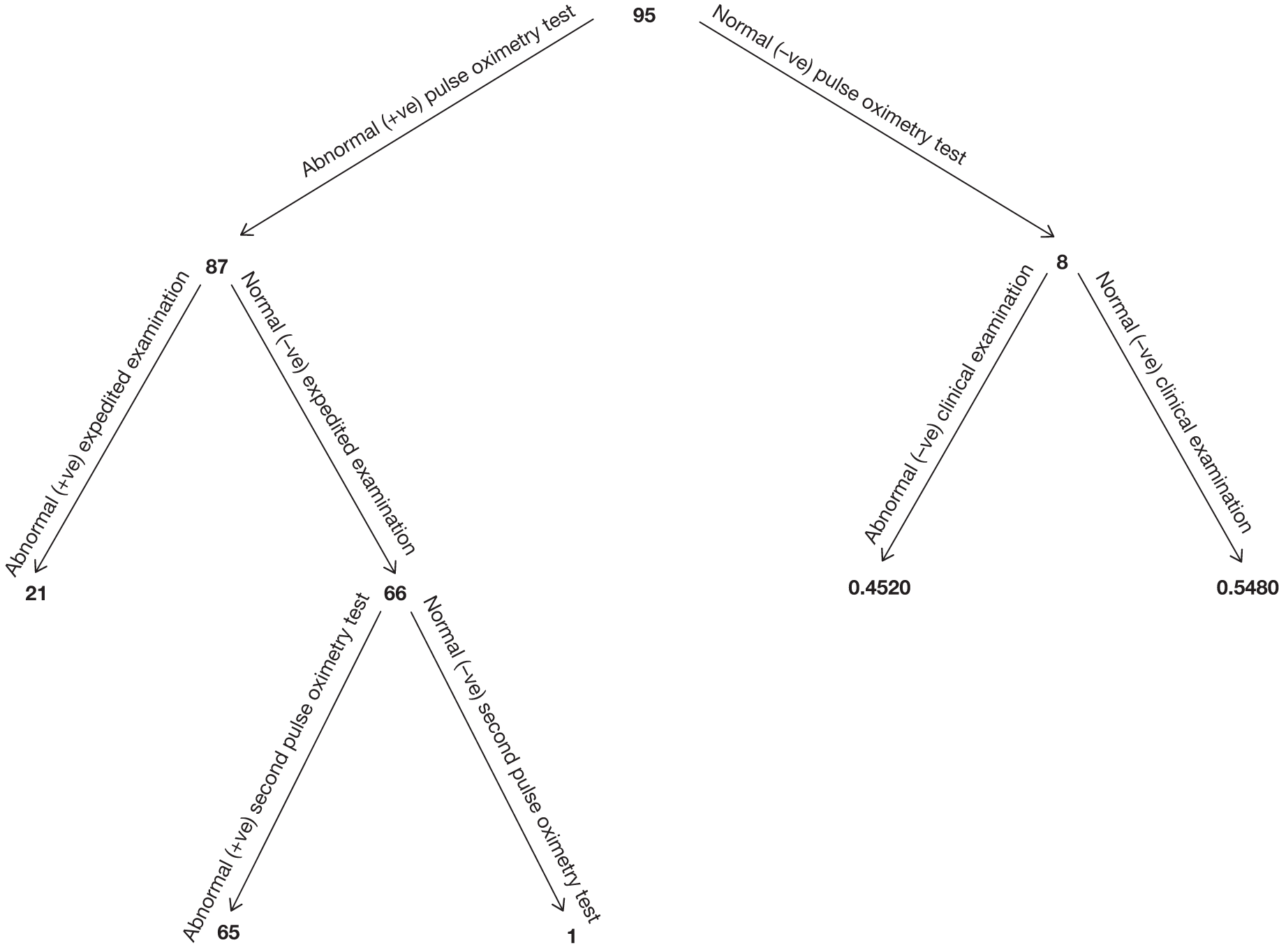

Seven hundred and seventy-two babies (3.85%) had an abnormal result with the first test, with 696 proceeding to an ECE (Figure 2). Seventy-six babies were wrongly classified at the time as test negative and therefore the expedited examination did not take place; these babies were followed up as per reference standard for a normal result. Of the 76 babies, 70 had both hand and foot saturation readings of > 94% and a difference of 3%; one had both saturation readings of > 94% and a difference of 4%. A further five cases correctly classified as test positive did not have the expedited clinical examination; in two cases the mothers declined the examination and for the remaining three the examination was not done for unknown reasons. None of these 76 babies was found to have any evidence of a CHD and they were classified as TN on an intention-to-test basis given that they did not complete testing.

FIGURE 2.

Simplified flow of patients through the PulseOx study.

The ECE raised a suspicion of cardiac abnormality in 60 out of 696 (8.62%) babies. Of the remaining 636 infants who were apparently normal on examination, 634 went on to have a second pulse oximetry test, and an abnormal result occurred on this occasion in 135 (21.23%). Two babies from this group did not have a second test because of parental refusal.

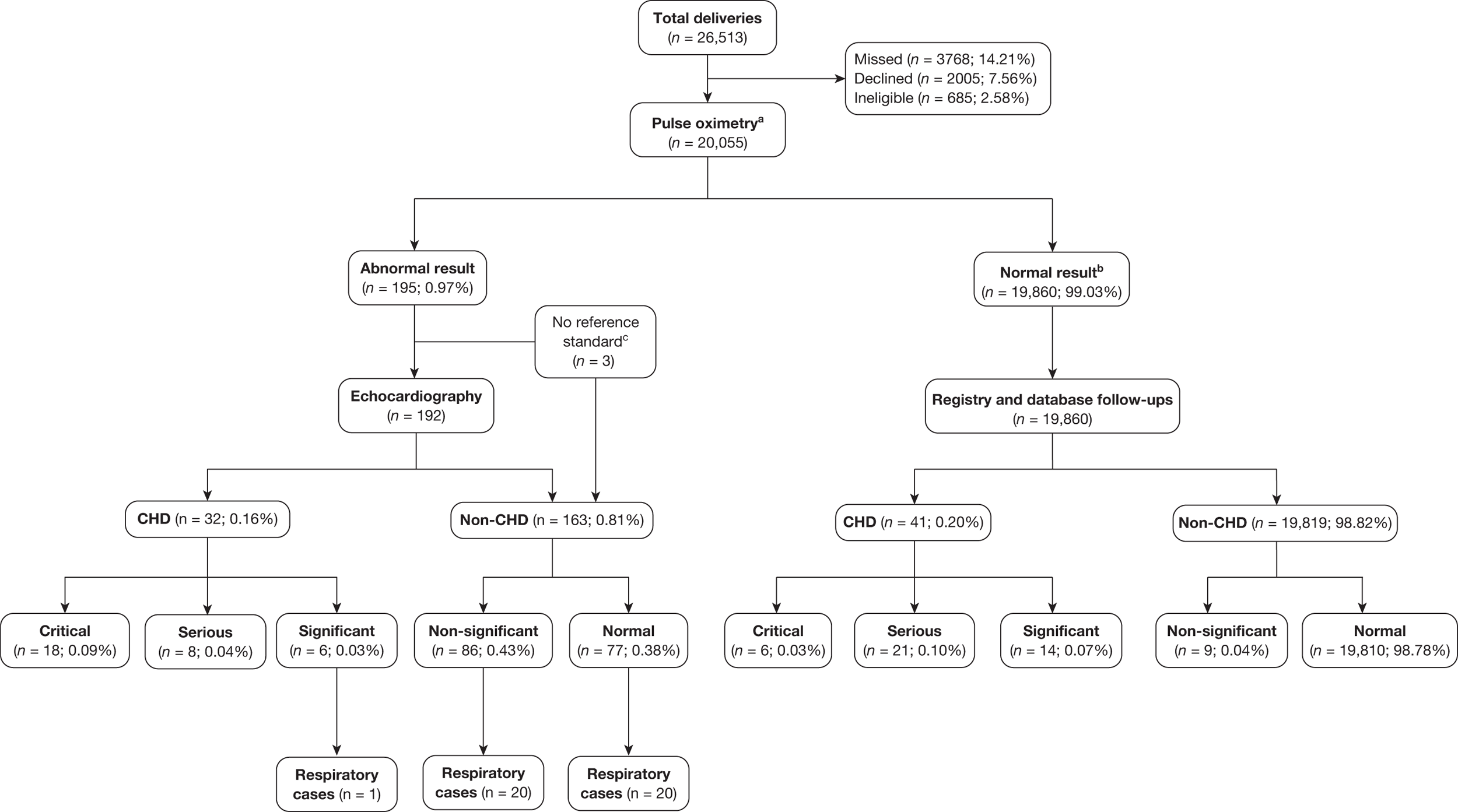

Of the resulting 195 babies (0.97% of the total cohort) who were test positive, 193 proceeded to reference standard of echocardiography (Figure 3). Two babies missed any echocardiography testing, despite repeated attempts to arrange this, and in one case the tape of the echocardiography result was lost and so the provisional normal echocardiographic diagnosis could not be ratified. These three babies were followed up via clinical databases and were not found to have evidence of CHDs.

FIGURE 3.

Flow of participants through the study. Percentages quoted are as of a proportion of the total recruited (n = 20,555). a, See test methods for details of index text; b, this includes 78 babies who missed some or all of the stages of the index test after the first pulse oximetry stage; these were followed up as per reference standard for normal result and have been confirmed as non-CHD; c, these were followed up as per reference standard for normal result and have been confirmed as non-CHD.

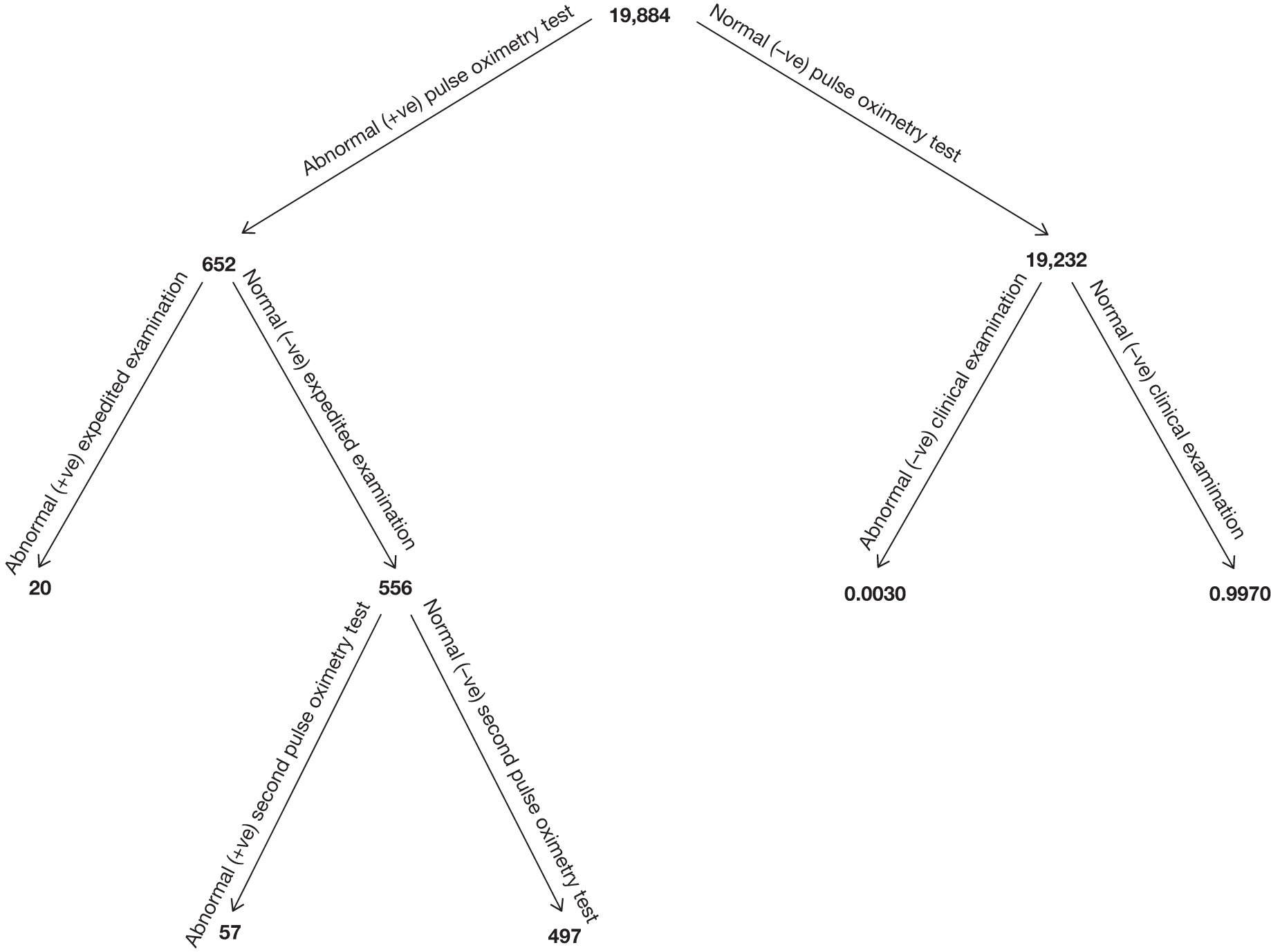

In the total cohort, 24 babies were ultimately diagnosed via echocardiography or clinical database follow-up as having a critical CHD (0.12%), and 29 babies were diagnosed as having a serious CHD, making 53 in total (2.6 per 1000 live births) (see Figure 3 and Appendix 2). In addition, 20 babies were found to have a significant CHD, although for the purposes of our main analysis these were classified as six FPs (see Figure 3 and Appendix 2) and 14 TNs (see Figure 3).

Assessment of test accuracy

Accuracy of pulse oximetry

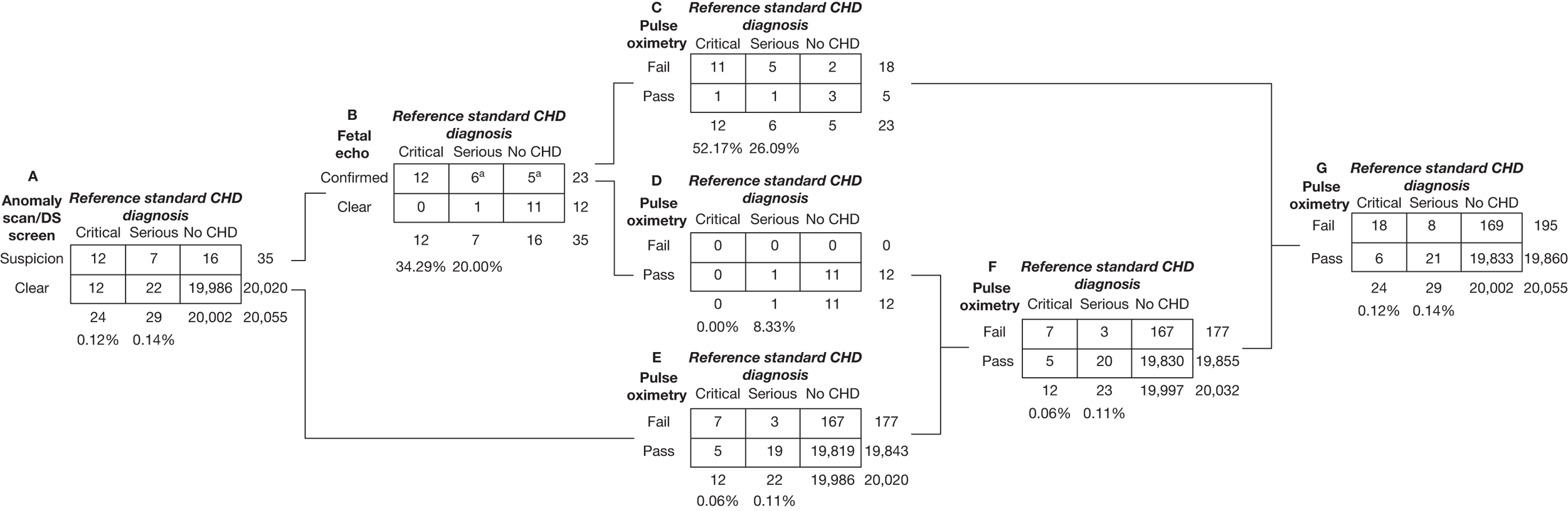

Of the 20,055 babies screened, 53 had major CHDs (24 critical and 29 serious) – a prevalence of 2.6 per 1000 live births (see Figure 3). As stated previously, we examined the test accuracy both for the full cohort and then for the cohort excluding those suspected of having a CHD after routine anomaly scan and fetal echocardiography in order to assess the added value of pulse oximetry. Details of testing outcomes for these two cohorts are shown in Figure 4 (cohorts F and G).

FIGURE 4.

Results of antenatal and pulse oximetry testing all participants recruited to the study are in cohort A. Thirty-five individuals (cohort B) were identified by prenatal screening for anomalies and Down syndrome to have suspicion or high likelihood of a CHD (all 35 were in fact based on anomaly scans with zero prenatally diagnosed Down syndrome cases). CHDs were confirmed in 23 of these 35 by fetal echocardiography (cohort C) – echocardiography would be undertaken after birth regardless of pulse oximetry results. Combining the 12 who were clear on fetal echocardiography (cohort D) with the 20,020 who had no suspicion on prenatal screening (cohort E) defines the group (cohort F) in whom a positive pulse oximetry test result could make a difference to subsequent testing (most likely using echocardiography) and contingent health care. In settings without antenatal testing the whole cohort (cohort G) would benefit from pulse oximetry testing. In settings with antenatal testing, but without fetal echocardiography those in cohort E are the appropriate group. a, two babies (one a serious case, the other without a CHD) had missing fetal echocardiography results; we have made the assumption that these babies would undergo echocardiography after birth.

Full cohort

Of the 195 babies who had an abnormal result following pulse oximetry testing, 26 had major CHDs, with 18 critical and 8 serious cases. For the full cohort, pulse oximetry had a sensitivity of 75.00% (95% CI 53.29% to 90.23%) for critical cases and 49.06% (95% CI 35.06% to 63.16%) for critical plus serious cases combined (Table 4). Six critical and 21 serious cases were not identified by pulse oximetry (FNs).

| Critical cases alone | Critical plus serious cases | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of TPs | 18 | 26 |

| No. of FNs | 6 | 27 |

| No. of FPs | 177 | 169 |

| No. of TNs | 19,854 | 19,833 |

| % Sensitivity (95% CI) | 75.00 (53.29 to 90.23) | 49.06 (35.06 to 63.16) |

| % Specificity (95% CI) | 99.12 (98.98 to 99.24) | 99.16 (99.02 to 99.28) |

| % Positive predictive value (95% CI) | 9.23 (5.56 to 14.20) | 13.33 (8.90 to 18.92) |

| % Negative predictive value (95% CI) | 99.97 (99.93 to 99.99) | 99.86 (99.80 to 99.91) |

Cohort in which congenital heart disease was not suspected antenatally

Of the 20,055 babies who took part in the study, following retrospective review of all cases of CHDs identified, we found that 12 out of 24 with critical CHDs (50.00%) had already been suspected by prenatal screening as having a high likelihood of anomaly (sensitivity 50.00%, 95% CI 29.12% to 70.88%) (Table 5), whereas 19 out of 53 critical and serious cases combined were detected (sensitivity 35.85%, 95% CI 23.14% to 50.20%). Sixteen out of 20,002 babies without critical or serious CHDs were incorrectly identified at this stage (specificity 99.92%, 95% CI 99.87% to 99.95%), although this was reduced to five cases after fetal echocardiography examination of these babies was undertaken (cohort B; see Figures 4 and 5). It was noted that one serious case was incorrectly diagnosed as a non-CHD after fetal echocardiography (cohort D; see Figure 4).

| Critical cases alone | Critical plus serious cases | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of TPs | 12 | 19 |

| No. of FNs | 12 | 34 |

| No. of FPs | 23 | 16 |

| No. of TNs | 20,008 | 19,986 |

| % Sensitivity (95% CI) | 50.00 (29.12 to 70.88) | 35.85 (23.14 to 50.20) |

| % Specificity (95% CI) | 99.89 (99.83 to 99.93) | 99.92 (99.87 to 99.95) |

| % Positive predictive value (95% CI) | 34.29 (19.13 to 52.21) | 54.29 (36.65 to 71.17) |

| % Negative predictive value (95% CI) | 99.94 (99.90 to 99.97) | 99.83 (99.76 to 99.88) |

FIGURE 5.

Simplified results of antenatal and pulse oximetry testing.

Therefore, for the cohort in whom pulse oximetry results could affect postnatal management as they had not been suspected prenatally, pulse oximetry had a sensitivity of 58.33% (95% CI 27.67% to 84.83%) for critical cases (12 babies) and 28.57% (95% CI 14.64% to 46.30%) for critical plus serious cases combined (35 babies) (Table 6). One in 119 babies (0.84%) without a serious or critical CHD had a FP pulse oximetry result (specificity 99.16%, 95% CI 99.02% to 99.28%); this was similar for both the full cohort and those not diagnosed prenatally.

| Critical cases alone | Critical plus serious cases | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of TPs | 7 | 10 |

| No. of FNs | 5 | 25 |

| No. of FPs | 170 | 167 |

| No. of TNs | 19,850 | 19,830 |

| % Sensitivity (95% CI) | 58.33 (27.67 to 84.83) | 28.57 (14.64 to 46.30) |

| % Specificity (95% CI) | 99.15 (99.01 to 99.27) | 99.16 (99.03 to 99.29) |

| % Positive predictive value (95% CI) | 3.95 (1.60 to 7.98) | 5.65 (2.74 to 10.14) |

| % Negative predictive value (95% CI) | 99.97 (99.94 to 99.99) | 99.87 (99.81 to 99.92) |

Timing of pulse oximetry

For the full cohort (cohort G; see Figure 4), earlier testing showed a strong association with increased sensitivity [odds ratio of true-positive (TP) to FN with hours to testing as the explanatory variable 0.93 (95% CI 0.88 to 0.98; p = 0.008)], although when those babies suspected antenatally of having a CHD were not included (cohort F; see Figure 4) this association was weaker and non-significant (odds ratio 0.97, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.02; p = 0.2) (Table 7). There was evidence of an increased rate of FP outcomes from earlier timings [odds ratio FP to TN 0.988 (95% CI 0.977 to 0.998; p = 0.02)]. This result did not change when babies suspected of having a CHD antenatally were excluded.

| Cohort where positive test would influence subsequent testing (n = 20,032, F in Figure 4) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–6 hours (n = 4937, 25%) | 6–12 hours (n = 4822, 24%) | 12–24 hours (n = 5320, 27%) | > 24 hours (n = 4953, 25%) | |

| No. of TPs | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| No. of FNs | 6 | 1 | 7 | 11 |

| No. of FPs | 59 | 40 | 37 | 31 |

| No. of TNs | 4869 | 4778 | 5273 | 4910 |

| % Sensitivity (95% CI) | 33.33 (7.49 to 70.07) | 75.00 (19.41 to 99.37) | 30.00 (6.67 to 65.25) | 8.33 (0.21 to 38.48) |

| % Specificity (95% CI) | 98.80 (98.46 to 99.09) | 99.17 (98.87 to 99.41) | 99.30 (99.04 to 99.51) | 99.37 (99.11 to 99.57) |

| Full cohort (n = 20,055, G in Figure 4) | ||||

| 0–6 hours (n = 4956, 25%) | 6–12 hours (n = 4823, 24%) | 12–24 hours (n = 5323, 27%) | > 24 hours (n = 4953, 25%) | |

| No. of TPs | 18 | 3 | 4 | 1 |

| No. of FNs | 7 | 1 | 8 | 11 |

| No. of FPs | 60 | 40 | 38 | 31 |

| No. of TNs | 4871 | 4779 | 5273 | 4910 |

| % Sensitivity (95% CI) | 72.00 (50.61 to 87.93) | 75.00 (19.41 to 99.37) | 33.33 (9.92 to 65.11) | 8.33 (0.21 to 38.48) |

| % Specificity (95% CI) | 98.78 (98.44 to 99.07) | 99.17 (98.87 to 99.41) | 99.28 (99.02 to 99.49) | 99.37 (99.11 to 99.57) |

False-positives

There were 169 babies in the full cohort (see Table 4) who tested positive, but did not have a critical or serious CHD. Of these, six babies had a significant CHD and a further 40 cases had respiratory or infective conditions that required medical intervention (antibiotic treatment, oxygen therapy or respiratory support). Thus, the total number of test-positive infants in whom there was neither a significant CHD nor intercurrent illness requiring treatment was 123 [63.08% of those who were test positive (195) or 0.61% of the total cohort].

The study by de Wahl Granelli et al. 70 used both pre- and postductal saturations < 95% and a difference of > 3% as the test-positive threshold rather than the single measurement < 95% and the > 2% difference used in this study. If de Wahl Granelli et al. ’s threshold70 had been used as an alternative in our study, this would have reduced the number of FPs by 61; however, one critical case [hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), which had been suspected antenatally], one serious case (truncus arteriosus) and one significant case (Ebstein’s anomaly) – neither suspected antenatally – and 13 respiratory conditions would have been missed.

Similarly, using a threshold of < 95% in the foot only – the most frequently used test in previous studies13,64,67–69,71 – would have reduced the number of FPs by 84, but three critical cases (two with HLH identified antenatally and one with CoA not diagnosed antenatally) and one serious case (truncus arteriosus not diagnosed antenatally) would have been missed. Two babies with significant CHDs and nine with respiratory conditions would also have been missed.

False-negatives

Six babies from the full cohort with critical CHDs were not detected by pulse oximetry testing (see Figure 3 and Appendix 2). One of these (a baby with congenitally corrected TGA and PS) had a suspected diagnosis of CHD following antenatal anomaly screening, and in a further three babies a CHD was identified prior to discharge from hospital because of an abnormal routine clinical examination. Two babies (one with TGA, VSD and a coarctation and one with a hypoplastic aortic arch and coarctation) were discharged home after both the pulse oximetry screen and postnatal examination were normal. Both presented with clinical symptoms relating to the CHD and one of the babies (hypoplastic aortic arch and coarctation) presented in a collapsed state. Both went on to have a surgical correction of the lesion. No baby died with an undiagnosed CHD in our study cohort.

A further 21 babies with normal pulse oximetry screening were diagnosed with serious CHDs (see Figure 3 and Appendix 2). In this cohort, two babies had CoA, one had a hypoplastic aortic arch with a PDA, two had tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), five had PS (one with a VSD) and one had an atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD). In addition, seven babies had an isolated VSD; one had persistent PDA, one had anomalous coronary artery and one had aortopulmonary window, all of whom received invasive intervention within 12 months. One baby from this group was identified by abnormal clinical examination prior to discharge (one PS); the remaining 20 were identified by interrogation of the relevant databases.

Discussion

Summary of main findings

This is the largest UK test accuracy study using pulse oximetry in the detection of major CHDs. The study has demonstrated the feasibility and accuracy of pulse oximetry testing in a cross-section of UK maternity units. In asymptomatic infants, pulse oximetry screening had a sensitivity of 75.00% (95% CI 53.29% to 90.23%) for critical lesions and a sensitivity of 49.06% (95% CI 35.06% to 63.16%) for critical plus serious lesions.

For the cohort in which the test results could affect postnatal management as a CHD had not been suspected prenatally, pulse oximetry had a sensitivity of 58.33% (95% CI 27.67% to 84.83%) for critical cases and 28.57% (95% CI 14.64% to 46.30%) for critical plus serious cases combined.

When combined with the standard screening of antenatal ultrasound and physical examination 22/24 cases of critical CHDs were detected prior to discharge from hospital, with pulse oximetry alone identifying seven cases. FP results occurred in 1 in 119 babies (0.84%) without serious or critical CHDs (specificity 99.16%, 95% CI 99.02% to 99.28%); however, out of the FP cohort of 169 babies, 46 (27%) had additional medical problems requiring intervention (specifically significant CHDs, respiratory disorders and infections).

The timing of pulse oximetry testing varied, with the majority of testing occurring in the first 24 hours. There was a significant association of increased sensitivity with earlier timing, but this is likely to be owing to the fact that those with an antenatal suspicion of a CHD were tested much earlier. Earlier testing was associated with a higher FP rate.

Strengths and limitations of methods

The validity of our findings relies on the quality of the study. We complied with and reported all criteria for a high-quality test accuracy evaluation77 (see Appendix 1). The study population and recruitment criteria were well defined. Recruitment of consecutive eligible subjects was representative of a spectrum of maternity activity. A sample size calculation was performed to ensure that the study had sufficient power to exclude clinically unacceptable accuracy and the study recruited to that target. The rationale for the index test was clarified and it was performed by trained staff. The initial reference standard of echocardiography was performed by independent, trained individuals. The robustness of the data has been facilitated by the rigorous follow-up to 1 year of age of all recruited babies.

This study used a composite reference standard of echocardiography and database interrogation, therefore, not all babies entered into the study underwent the gold standard reference of echocardiography. This would have been impracticable and we are confident that the database follow-up was sufficiently rigorous to account for all potential FNs. Because only those testing positive underwent echocardiography, it was not possible to blind the echocardiographers to the index test result; however, all echocardiograms were ratified by an independent cardiologist. Echocardiography is an objective test and unlikely to be influenced by bias; in addition, the independent cardiologists allocated the final echocardiography category after clinical data on outcomes (such as surgery) were available.

In general, pulse oximetry screening took place before routine clinical examination and we felt that it was unethical for the results of pulse oximetry readings to be withheld from clinical staff. This lack of blinding meant that we were unable to compare the accuracy of the physical examination with that of pulse oximetry. As we described in Chapter 1, the published evidence relating to the accuracy of the physical examination shows that it has a relatively low sensitivity. 2 A large Swedish study compared CHD detection in different regions and showed that the rate of critical CHDs diagnosed after discharge in those regions which did not use pulse oximetry was significantly higher than in those that used examination alone. 70

We included those infants who had been suspected of having a CHD following antenatal ultrasound; this increased the prevalence of CHDs in our study cohort and simplified study recruitment. We tested those infants who fulfilled the eligibility criteria in order to ascertain if pulse oximetry would have identified them had the condition not been suspected and we undertook further sensitivity analysis after excluding these patients. The antenatal detection rate in our cohort was relatively high compared with other published studies, for example in de Wahl Granelli et al. ’s study70 of almost 40,000 babies undergoing pulse oximetry testing, only 3.3% of critical lesions were detected antenatally compared with 50% in our study. We feel that our findings represent the value of pulse oximetry when antenatal detection rates are high and this implies that in regions where antenatal detection rates are lower, the added value of pulse oximetry is likely to be even greater.

We were unable to access directly the anomaly scan data for all study participants and we made two assumptions – that all women recruited into the study had undergone an anomaly scan and all anomaly scans in which there was a suspicion of a CHD were referred for fetal echocardiography. This is standard practice in the region where the study was performed and we believe that these assumptions are reasonable. With this additional information we were able to calculate the added value of pulse oximetry over anomaly scan screening.

There were a number of protocol violations in our study which are described in detail. The likelihood that all protocol violations would have resulted in a negative test and the robustness of the subsequent clinical follow-up makes it extremely unlikely that these violations would have had any impact on the outcome of the test accuracy study.

The FP rate for the test accuracy study was relatively high compared with some previous studies, and there are a number of explanations for this. The initial test was performed in the first 24 hours in a significant proportion of babies, and this has been shown in previous studies to be associated with a higher FP rate. However, as an increasing number of newborn babies in the UK and elsewhere are discharged from hospital in the first 24 hours, we felt that it was important to collect data in this crucial time window in order to inform test accuracy within current clinical practice. In addition, the threshold for a test-positive case in our study using pre- and postductal saturations and a > 2% difference between the two was more conservative than in any previous published work. This was an attempt to increase the sensitivity of the test with particular reference to those lesions that are commonly missed, such as obstruction of the aortic arch. In previously published pulse oximetry studies these lesions have been the most commonly reported lesions undetected by saturation testing. In our study, 3/7 (43%) babies with critical CoA or IAA were detected by pulse oximetry, which compares with 3/14 (21%) in de Wahl Granelli et al. ’s study,70 which used a difference of > 3%. Analysis showed that a threshold of > 2% resulted in the detection of one additional critical case, but at the expense of a higher FP rate.

The failure to detect a significant number of serious CHD lesions can partly be explained by the fact that the majority of babies with these conditions were likely to be acyanotic at the time of testing and, therefore, would not be expected to test positive. Increasingly early intervention for VSD – which accounts for 14–16% of CHDs requiring intervention within 12 months1 – also increased the number categorised as serious.

Some technical problems were identified with the pulse oximeters (see Chapter 3), particularly relating to battery life. The same oximeters were used in all centres; however, it became apparent that some experienced problems, whereas others did not. On investigation, it became clear that in some units testing was undertaken with the oximeter as a full unit connected to the mains and in others the detachable front of the oximeter was used as a portable device taken to the baby. This had not been specified in the training and either was felt to be acceptable at the start of the study. The detachable front relies on a rechargeable internal battery and the centres using this method encountered problems with battery life, which occasionally resulted in inadequate saturation readings and a delay in testing. This situation was resolved at the time by using another oximeter within the hospital. The likely cause of this problem was felt to be that the machines were used so frequently, in a way for which they were not designed, that they were not able to fully charge and over time the battery gradually became discharged. Once this problem was identified further recommendations and training significantly reduced the frequency of these events. Occasionally, saturation readings were unobtainable because of ‘wear and tear’ to the reusable oximeter probe; this was easily identifiable and the probes were replaced. In general, the reusable probes lasted approximately 6 months. The problem with both the batteries and probes resulted in an unobtainable saturation result and so no (potentially unreliable) data were recorded in these situations; a functioning, alternative oximeter was used in each case.

Interpretation of findings

When combined with the routine anomaly scan and newborn physical examination screening, 92% of critical CHDs were detected in our study cohort and no baby died with an unidentified CHD. The detection rate of critical CHDs by pulse oximetry was 75% in the full cohort, which is comparable with other large studies. 69,70 The detection rate for serious lesions is lower; however, it has to be remembered that a significant proportion of the serious lesions not identified by screening were non life-threatening acyanotic conditions (VSD, PDA, etc.), which would not usually be associated with hypoxaemia and therefore would not be expected to be detected by low oxygen saturations. The consequences of missing such lesions are important, but not as potentially devastating as missing the life-threatening critical lesions. The critical lesions most likely to be missed by pulse oximetry screening were those causing obstruction to the aortic arch (such as CoA and IAA), which is consistent with findings in other studies. 69,70

If the results from this study were applied to a population of 100,000 babies, approximately 264 babies would have critical or serious CHDs. Of these, pulse oximetry testing would identify 130. Approximately 120 babies would have life-threatening critical lesions and pulse oximetry testing would detect 90 of these.

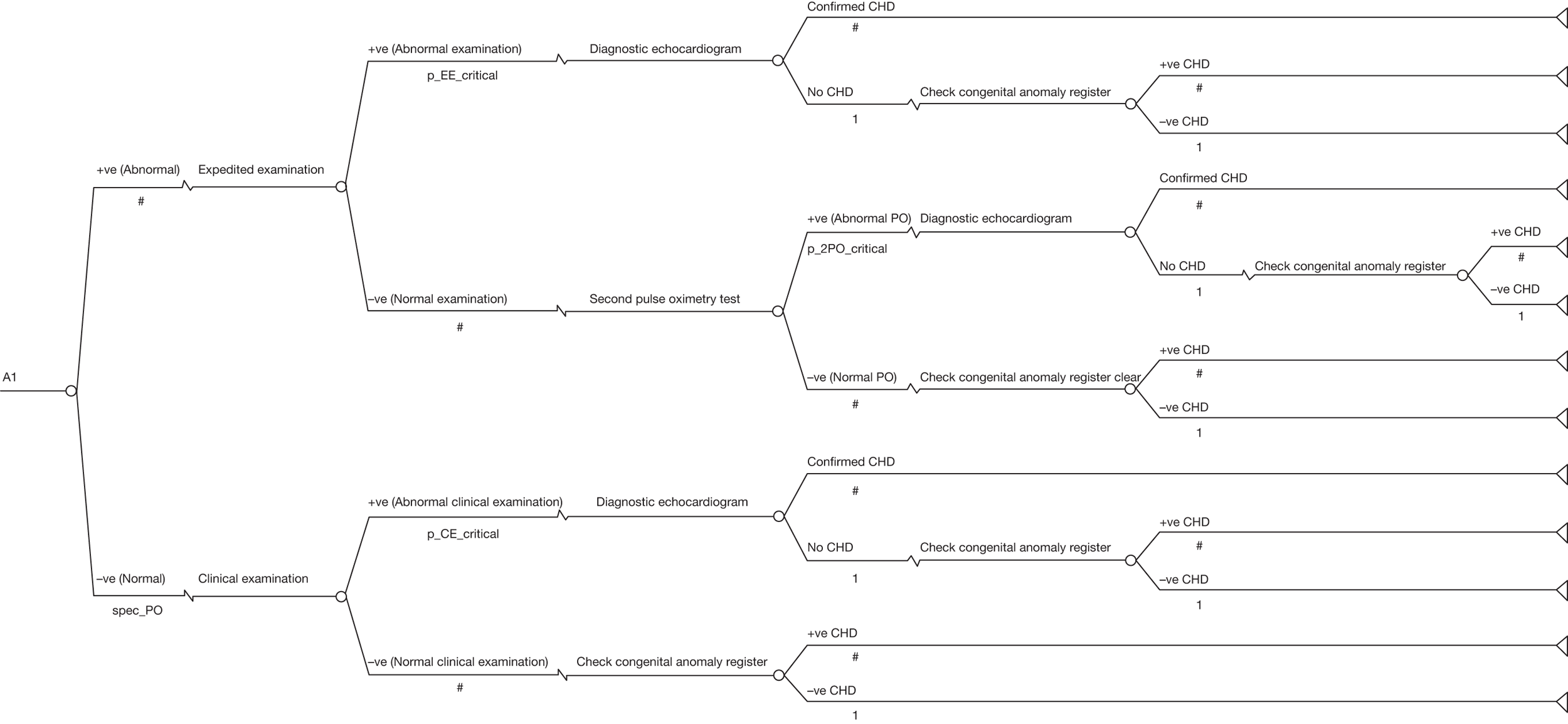

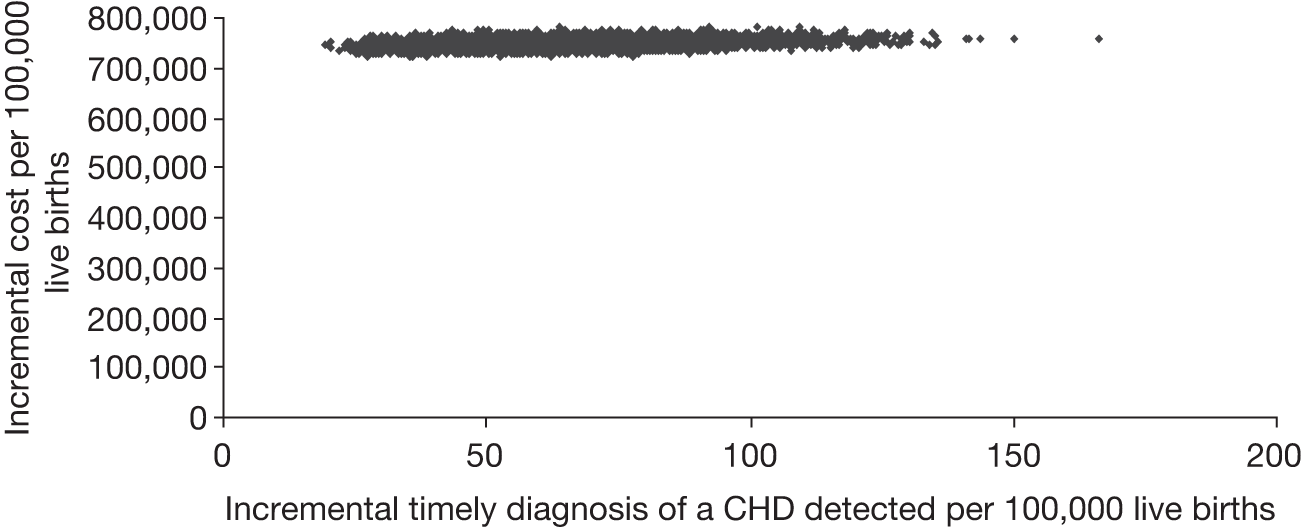

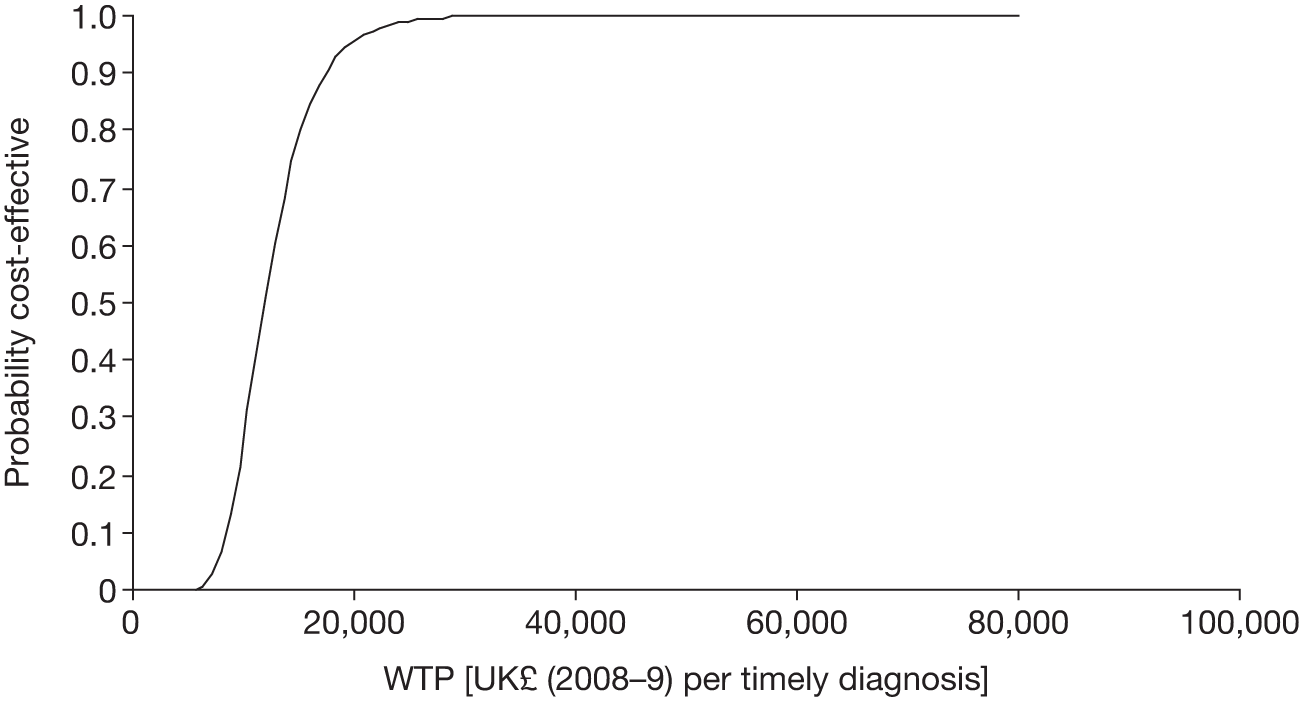

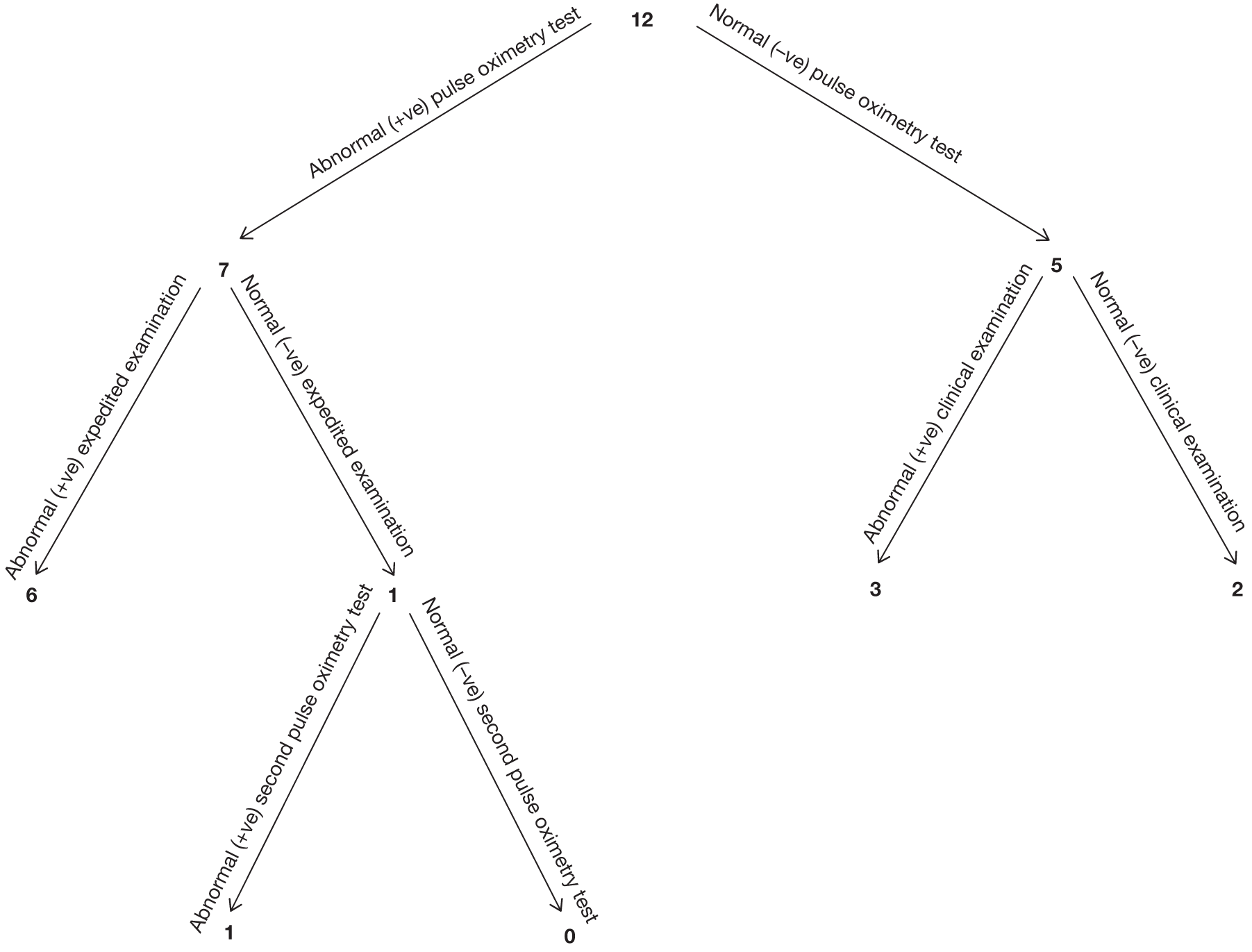

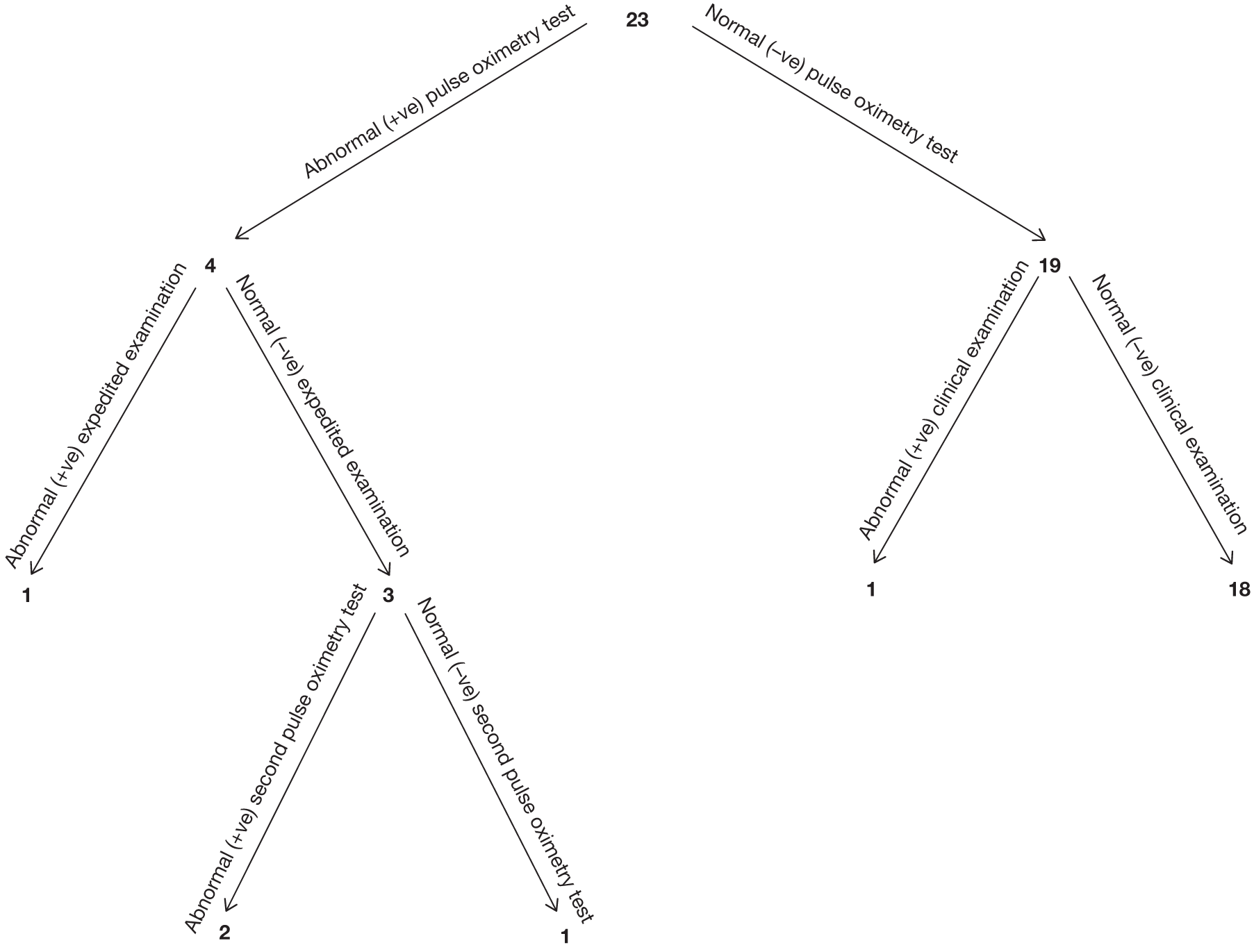

In our cohort, 50% of critical lesions were detected by antenatal anomaly scan. In a cohort of 100,000 babies with a similar antenatal detection rate pulse oximetry testing could, on average, detect an additional 35 cases of critical CHD. This figure is likely to be higher in areas where the rates of detection by antenatal ultrasound are lower.