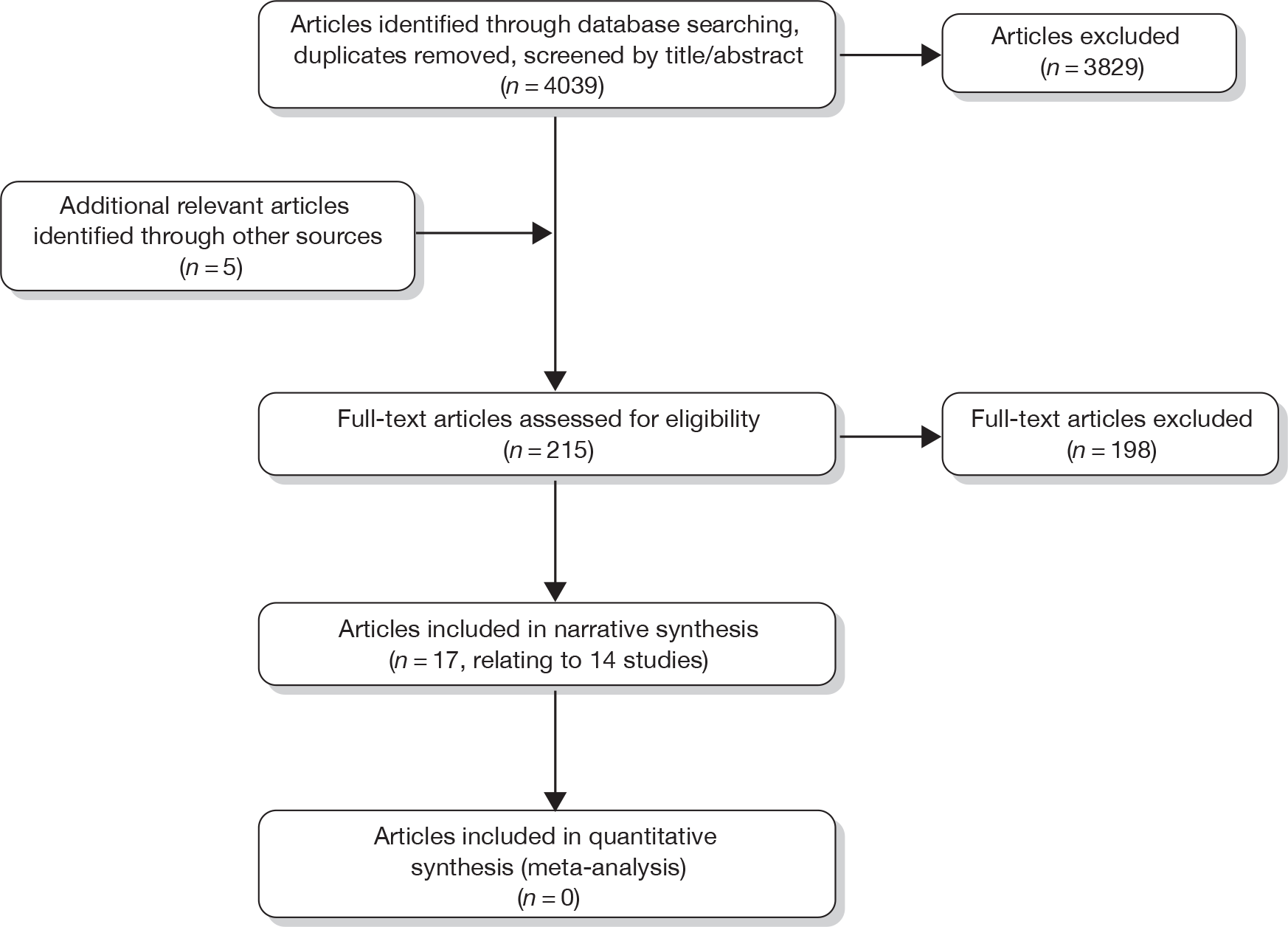

Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 09/62/01. The contractual start date was in December 2009. The draft report began editorial review in July 2010 and was accepted for publication in March 2011. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draftdocument. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2012. This work was produced by Stevenson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2012 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Description of health problem

Alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) is the term used to describe changes within the liver that develop as a result of excess alcohol consumption. Included within this spectrum are hepatic steatosis (alcoholic fatty liver), alcoholic hepatitis, alcoholic cirrhosis, and hepatocellular cancer (HCC). 1–3 Although patients with cirrhosis may remain free of major complications for several years, once such complications develop survival is usually short. 4

In 2008, 4764 deaths registered in England and Wales were attributed to ALD. 5

Aetiology, pathology and prognosis

Aetiology

Alcohol-related liver disease is caused by the consumption of substantial quantities of alcohol. In the UK, alcoholic drinks are measured in units corresponding to approximately 10 ml (8 g) of ethanol. 6 Previously, the minimum alcohol intake associated with significant liver damage was thought to be around 20 units a day for 5 years and the likelihood of light to moderate drinkers developing cirrhosis was considered very remote. 7 More recently, it has been suggested that all people whose daily alcohol consumption exceeds 80 g (10 units) will eventually develop steatosis; 10–35% will develop alcoholic hepatitis, and approximately 10% will develop cirrhosis. 8 However, because steatosis is usually, and hepatitis and cirrhosis sometimes, asymptomatic, many will be unaware that they have ALD; indeed, 30–40% of cases of cirrhosis are not discovered until autopsy. 1

Pathology

As noted above, the term ALD covers a spectrum of illness. The majority of individuals who abuse alcohol will develop steatosis,9 a condition characterised by the accumulation of excess fat within the liver cells. 10 Steatosis is usually asymptomatic, but may manifest as changes in liver function test results; it is reversible if alcohol consumption is stopped or significantly reduced. 1 However, approximately 20% of people with alcoholic steatosis who continue long-term alcohol consumption are likely to develop fibrosis and cirrhosis. 2

In a minority (perhaps < 20%) of alcohol misusers, alcoholic steatosis evolves with the development of inflammation and cell death within the liver. This phase of injury is known as alcoholic hepatitis. 10 The majority of patients who develop alcoholic hepatitis are asymptomatic, but others suffer non-specific symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, whereas others present with acute alcoholic hepatitis (AAH), which is characterised by abdominal pain/discomfort, fever, a high white blood cell count, abnormalities of blood clotting, jaundice, and other features of liver failure. 1 Patients with mild alcoholic hepatitis will recover well, with reversal of the liver damage, if they stop drinking. Progression to cirrhosis is more likely in women than in men, and in individuals of both sexes who have severe alcoholic hepatitis on presentation, irrespective of their future drinking behaviour.

Repeated episodes of alcoholic hepatitis may result in the development of scar tissue known as fibrosis; this can be localised or diffuse, and can eventually lead to distortion of the architecture of the liver by broad fibrous bands and the development of regenerative nodules, which are the hallmark of cirrhosis. Patients with cirrhosis may be asymptomatic, and their liver function tests may show few if any abnormalities; such patients are described as having compensated disease. 10,11 In a recent Danish study, 24% of patients diagnosed with alcoholic cirrhosis had no complications. 12 Patients with cirrhosis may, however, develop a number of complications as a result of hepatocellular failure and the development of portal hypertension (PHt). Hepatocellular failure results in loss of the liver’s ability to deal with waste products (e.g. bilirubin from red blood cells, toxins produced in the bowel such as ammonia, and drugs) and impairment of its synthetic function leading to low levels of body proteins such as albumin and the factors responsible for blood clotting. PHt develops when the passage of blood from the intestine and the spleen, which is usually cleansed and detoxified in the liver, is impeded because of the presence of fibrosis. As a result, collateral vessels develop to bypass the liver to ensure that the blood gets back to the heart. These collateral vessels may develop in the stomach and oesophagus and may rupture when the pressure gradient within the portal system [the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG)] exceeds 12 mmHg. 13 Hepatocellular failure and PHt result in the development of several problems, including jaundice, ascites, variceal bleeding, and hepatic encephalopathy (HE). 4 Patients with these complications are described as having decompensated cirrhosis. Each year, approximately 5–7% of patients with compensated cirrhosis will develop decompensated disease. 4 Approximately 20% of patients with cirrhosis will go on to develop HCC; this is more common in men than in women and in those who have stopped drinking (Dr Marsha Morgan, Royal Free Hospital, London, 2010, personal communication).

Alcoholic hepatitis and cirrhosis may co-exist within the same patient: thus, it has been reported that 50–60% of patients diagnosed with AAH already have cirrhosis at the time of diagnosis. 14

Measurement of disease

Traditionally, liver biopsy has been used to obtain histological samples from patients suspected of having ALD. These biopsy samples are used to confirm the diagnosis of ALD, exclude other or additional liver pathologies, and provide accurate staging of the degree of liver injury in order to enable the prediction of prognosis and inform treatment decisions.

Various semi-quantitative scoring systems have been developed to measure and categorise disease progression in biopsy samples. The most widely used system, the METAVIR system, has a grading system that scores the degree of inflammation from 0 to 4 (where 0 is no activity and 4 is severe activity) and a staging system that categorises the degree of architectural change and consequent severity of the underlying liver disease15 from none (F0) to mild (F1), moderate (F2), severe (F3), and cirrhosis (F4). It should be noted that METAVIR, and other similar systems, have been described as being, at best, ordered categorical data;16 they do not represent an arithmetic progression, and consequently, for example, a METAVIR score of F4 does not involve twice as much scarring as a score of F2. For further details of the various scoring systems referred to in this review, see Appendix 1.

In clinical practice, various boundaries are said to be significant. These are the boundaries between no-to-mild fibrosis (F0–F1) and significant fibrosis (F ≥ 2),17 and between mild-to-moderate fibrosis (F1–F2) and severe fibrosis or cirrhosis (F3–F4). 18 However, the former seems primarily relevant in viral hepatitis, where F2 fibrosis forms the threshold for the initiation of interferon therapy;19 it arguably has less relevance in ALD, where the boundary between F0–F3 and F4 appears more important as it forms the threshold for the initiation of regular screening for varices and HCC.

Prognosis

Prognosis in patients with ALD is strongly linked to the degree of disease progression. In an early UK study, Saunders et al. 20 found that 5-year survival in adults identified between 1959 and 1976 as having alcoholic cirrhosis was only 36%; most already had decompensated cirrhosis at diagnosis. More recently, Jepsen et al. 12 found that the median survival in Danish patients diagnosed between 1993 and 2005 with alcoholic cirrhosis without complications was 48 months. The 1-year mortality ranged from 17% in those who presented with no complications to 64% in those who presented with HE; the equivalent 5-year mortality figures were 58% and 85%, respectively. More generally, median survival times for patients diagnosed with compensated and decompensated cirrhosis have been estimated at over 12 years and around 2 years, respectively; most patients originally diagnosed with compensated cirrhosis die only after the development of decompensation. 4

In patients with cirrhosis, the presence of superimposed alcoholic hepatitis and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma significantly reduced survival. Verrill et al. 21 found that 30-day mortality in patients with cirrhosis and alcoholic hepatitis was 27%, while Orrego et al. 22 found that the 1-year and 5-year mortality were significantly higher than in those of patients who had alcoholic cirrhosis alone, and Chedid et al. 23 found that 65% of patients with concurrent alcoholic hepatitis and cirrhosis died within 4 years of diagnosis, mostly within the first year. Alcoholic cirrhosis substantially increases the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma,1 which, again, has a poor prognosis: 1-year survival after diagnosis of HCC is about 20%, 5-year survival about 5%,24 and approximately 15% of patients who develop alcohol-related cirrhosis will die of HCC. 9

However, the outcome for patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis is substantially determined not only by the degree of decompensation at presentation but also by subsequent drinking behaviour. In 2004, Tome and Lucey25 suggested that, in people with clinically compensated cirrhosis, the 5-year survival was about 90% in those who abstained compared with about 70% in those who did not, whereas in 2003 Mann et al. 1 suggested that, in patients with late-stage, decompensated cirrhosis, the 5-year survival was 60% in those who abstained, but only 35% in those who did not. In a recent study, Verrill et al. 21 found that patients who reported being abstinent from alcohol 30 days after receiving a diagnosis of alcoholic cirrhosis had a 7-year survival of 72% compared with 44% in those who continued to drink. A considerably older study by Saunders et al. 20 found that 10-year survival in patients who abstained completely from alcohol was nearly 60% in those who presented with compensated cirrhosis and around 50% in those who presented with decompensated cirrhosis, compared with around 30% and < 10%, respectively, in those who continued drinking. It is currently estimated that a middle-aged man who presents with compensated cirrhosis and subsequently abstains from alcohol has a 60–80% chance of being alive in 10 years, whereas a similar individual who presents with, for example, variceal bleeding, and who survives the initial presentation but who continues to drink, is unlikely to survive more than a year or two (Dr Marsha Morgan, Royal Free Hospital, London, 2010, personal communication).

A small study by Day,26 of 96 patients with biopsy-proven ALD and a weekly alcohol intake of 135 ± 8 units, suggests that a reduction in alcohol intake may also be beneficial. No difference was found between abstainers and mild/moderate drinkers in either mortality (total or liver-related) or the development of new liver complications; however, continued heavy drinking (> 50 units/week for men and > 35 units/week for women) was predictive of both total and liver-related mortality.

Alcohol consumption also has a marked impact on prognosis in patients with milder forms of ALD. With abstinence, hepatic steatosis appears to be completely reversed within several weeks and AAH usually improves. 25 Patients with hepatic steatosis who stop drinking have a near-normal lifespan; future drinking behaviour is the most important determinant of outcome in this patient group. Their prognosis has improved over time as the treatment of their complications has become more successful. Moreover, as Chedid et al. have shown,23 these patients tend to die as a result of their alcoholism rather than their liver disease. Thus, although the 2-year survival in patients with alcoholic steatosis is only 70%, those who die do so as a result of other alcohol-related events such as accidents, injuries, suicide, and homicide, not their liver disease. However, although some patients with alcoholic hepatitis who abstain from alcohol make a complete recovery, others develop cirrhosis despite abstinence. 10

Although only a minority of patients with ALD abstain from alcohol following diagnosis, the proportion may be increasing; although only 19% of patients in a UK study who were diagnosed with alcoholic cirrhosis between 1959 and 1976 abstained from alcohol after hospital discharge,20 36% of patients in a Danish study who received a hospital diagnosis of cirrhosis between 1993 and 2005 maintained abstinence,12 and 46% of participants in a UK study who were diagnosed with biopsy-proven alcohol-related liver cirrhosis between 1995 and 2000 reported abstinence both at 30 days post diagnosis and at follow-up a mean of 3.4 years later (although some admitted to lapses during that period). 21 However, the precise diagnosis given may influence subsequent drinking behaviour. Thus, Day26 studied 96 patients with biopsy-proven ALD referred to unit between August 1991 and August 1993: 76% had established cirrhosis or fibrosis, 23% had alcoholic hepatitis and 8% steatosis. At follow-up, 50% were still drinking heavily, although 21% were completely abstinent, and 21% had mild and 8% moderate alcohol intake. The only predictor of continued heavy intake was the absence of cirrhosis; continued heavy drinking was reported in 59% of patients without, and 38% of patients with, cirrhosis (p = 0.04). By contrast, a study of patients receiving liver transplants for ALD found that a number of factors were independently associated with a significantly increased risk of resumption of harmful alcohol consumption after transplantation: these were pre-transplant diagnosis of an anxiety or depressive disorder, a pre-transplant period of abstinence < 6 months, and a total score of > 3 on the high-risk alcoholism relapse (HRAR) scale (Table 1). Over a mean follow-up period of 61.2 months, the overall relapse rate was 11.9%; however, it varied from 5% to 100% depending on the number of relevant factors (Table 2). 27

| Item | Score |

|---|---|

| Duration of heavy drinking, in years | |

| ≤ 11 | 0 |

| 11–25 | 1 |

| ≥ 25 | 2 |

| Number of daily drinks (one drink = 12 g of ethanol) | |

| ≤ 9 | 0 |

| 9–17 | 1 |

| ≥ 17 | 2 |

| Number of prior alcoholism inpatient treatments | |

| 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 |

| ≥ 1 | 2 |

| Number of relevant factorsa | Number resuming harmful alcohol consumption | Rate % (95% CI) | Mean time to relapse (months) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 13/272 | 5 (2 to 7) | 45 |

| 1 | 16/92 | 17 (10 to 25) | 30 |

| 2 | 14/22 | 64 (44 to 84) | 32 |

| 3 | 3/3 | 100 | 23 |

It has therefore been suggested that, in patients with ALD, the degree of fibrosis may have less prognostic importance than other factors such as the severity of alcoholic hepatitis, severity of liver dysfunction as assessed by tools such as the Child–Pugh score, the MELD (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease) score, or the Glasgow score and subsequent drinking behaviour. 28

Epidemiology demographic factors (age, sex, ethnicity, income, and regional variation)

Current government guidelines state that women should drink no more than 2–3 units of alcohol a day, and men no more than 3–4 units; the recommended weekly limits are 14 and 21 units, respectively. 29 However, in 2007, a health survey for England found that 31% of women and 42% of men in England aged ≥ 16 years reported drinking more than the government recommended maximum on at least 1 day in the preceding week. 30,31 The figures reported to the Welsh health survey in 2008 were higher, at 38% of women and 52% of men. 32

Hazardous drinking has been defined as an established pattern of drinking that carries a risk of physical or psychological harm. Harmful drinking has been defined as drinking at a level where damage to physical or mental health is considered likely. 31 A score of 8–15 on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) is held to represent hazardous drinking, and an AUDIT score of ≥ 16 as harmful drinking (for the AUDIT tool, see Appendix 2). 31 A total of 20.4% of individuals in England aged ≥ 16 years living in private households who participated in the 2007 Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey reported established patterns of alcohol consumption that were categorised as hazardous, and a further 3.8% reported patterns categorised as harmful (Table 3). 31 These figures are probably underestimates as they are likely to under-represent both alcohol-dependent individuals, who are more likely than non-alcohol-dependent individuals to be homeless or living in an institution, and problem drinkers living in private households, who may be less likely than those who are not problem drinkers to participate in surveys. 31

| AUDIT score | Men (%) | Women (%) | All (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–7: not hazardous | 66.8 | 84.3 | 75.8 |

| 8–15: hazardous, not harmful | 27.4 | 13.8 | 20.4 |

| 16–40: harmful | 5.8 | 1.9 | 3.8 |

| 8–40: hazardous or harmful | 33.2 | 15.7 | 24.2 |

In England, rates of hazardous or harmful drinking vary by ethnic group, being highest in white people and lowest in people of South Asian origin31 (Table 4). However, there is evidence both that alcohol problems may be increasing in the South Asian community in the UK, and that they may be particularly vulnerable to ALD. 33,34

| AUDIT score | Ethnicity (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Black | South Asian | Othera | |

| Men | ||||

| 0–7: not hazardous | 64.2 | 81.4 | 88.0 | 84.1 |

| 8–15: hazardous, not harmful | 29.6 | 15.6 | 9.9 | 13.8 |

| 16–40: harmful | 6.2 | 3.0 | 2.1 | 2.1 |

| 8–40: hazardous or harmful | 35.8 | 18.6 | 12.0 | 15.9 |

| Women | ||||

| 0–7: not hazardous | 83.4 | 95.4 | 96.9 | 84.5 |

| 8–15: hazardous, not harmful | 14.5 | 4.6 | 3.1 | 13.9 |

| 16–40: harmful | 2.0 | 0 | 0 | 1.6 |

| 8–40: hazardous or harmful | 16.6 | 4.6 | 3.1 | 15.5 |

In England, levels of hazardous or harmful drinking vary by region. In 2007, they were lowest for women in the East of England (12.2%) and highest in Yorkshire and the Humber (21.1%), whereas they were lowest for men in the East Midlands (27.8%) and highest in the North East (42.4%) (Table 5). 31

| AUDIT score | Government Office region (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North East | North West | Yorkshire and the Humber | East Midlands | West Midlands | East of England | London | South West | South East | |

| Men | |||||||||

| 0–7: not hazardous | 57.6 | 61.9 | 59.4 | 72.2 | 67.0 | 65.9 | 70.0 | 68.9 | 71.2 |

| 8–15: hazardous, not harmful | 32.2 | 31.7 | 34.4 | 23.8 | 26.2 | 27.9 | 25.6 | 25.5 | 23.4 |

| 16–40: harmful | 10.2 | 6.4 | 6.2 | 4.0 | 6.7 | 6.2 | 4.4 | 5.7 | 5.4 |

| 8–40: hazardous or harmful | 42.4 | 38.1 | 40.6 | 27.8 | 33.0 | 34.1 | 30.0 | 31.1 | 28.8 |

| Women | |||||||||

| 0–7: not hazardous | 79.2 | 80.6 | 78.9 | 82.9 | 84.5 | 87.8 | 86.2 | 85.7 | 87.7 |

| 8–15: hazardous, not harmful | 17.0 | 17.1 | 18.4 | 15.0 | 13.5 | 11.5 | 12.5 | 12.7 | 10.4 |

| 16–40: harmful | 3.7 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 0.6 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.9 |

| 8–40: hazardous or harmful | 20.8 | 19.4 | 21.1 | 17.1 | 15.5 | 12.2 | 13.8 | 14.3 | 12.3 |

Data about levels of hazardous or harmful drinking are not available for Wales. Although, in 2008, 45% of all adults in Wales reported drinking above the government-recommended sensible levels on at least 1 day in the preceding week,32 not all of these would necessarily have drinking patterns that equate to an AUDIT score of ≥ 8.

Incidence and prevalence

Alcohol-related liver disease is a major cause of death in England and Wales. In 2008, 4764 deaths registered in England and Wales were attributed to ALD5 – 0.95% of all deaths registered in people aged ≥ 20 years.

Although ALD mortality in England and Wales appears to have risen by 450% over the past 30 years,35 this rise in registrations may be at least in part because of the under-reporting of alcohol-related deaths during the earlier part of that period. This may be explained by the then requirement for post-mortem examinations and coroners’ inquests following alcohol-related deaths, and the potential invalidation of life insurance (Dr Marsha Morgan, Royal Free Hospital, London, 2010, personal communication). It may also be due in part to the increases in obesity and type 2 diabetes observed during the later part of the period. In a prospective study in France, Raynard et al. 36 found that body mass index (BMI) and fasting blood glucose were risk factors for histologically confirmed fibrosis in ALD, independent of age, gender, daily alcohol intake, and total duration of alcohol misuse, whereas, in Scotland, two prospective cohort studies found that raised BMI and alcohol consumption had a supra-additive effect on liver disease mortality. 37 The proportion of adults in England with a BMI ≥ 30 (i.e. categorised as obese or morbidly obese) rose from 13% of men and 18% of women in 1993, the first year for which data are available, to 25% and 28%, respectively, in 2008, whereas the proportions with raised waist circumference (i.e. > 102 cm for men and > 88 cm for women) rose from 20% of men and 26% of women in 1993 to 34% and 44%, respectively, in 2008,38 and, between 1991 and 2006, the prevalence of diagnosed type 2 diabetes increased by 65% in men and by 25% in women. 39

In 2008, over twice as many deaths were attributed to ALD in men than in women (Table 6).

| Age group (years) | Male | Female | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of deaths | Percentage of total deaths | Number of deaths | Percentage of total deaths | |

| All ages | 3200 | 1.3 | 1564 | 0.6 |

| 20–24 | 2 | 0.2 | 5 | 1.1 |

| 25–29 | 25 | 1.8 | 10 | 1.7 |

| 30–34 | 83 | 4.9 | 36 | 4.2 |

| 35–39 | 173 | 6.5 | 85 | 6.0 |

| 40–44 | 339 | 9.0 | 172 | 7.2 |

| 45–49 | 408 | 7.8 | 217 | 6.4 |

| 50–54 | 562 | 8.0 | 252 | 5.2 |

| 55–59 | 534 | 5.0 | 256 | 3.6 |

| 60–64 | 471 | 2.9 | 225 | 2.0 |

| 65–69 | 289 | 1.4 | 143 | 1.1 |

| 70–74 | 176 | 0.6 | 105 | 0.5 |

| 75–79 | 89 | 0.2 | 41 | 0.1 |

| 80–84 | 32 | 0.07 | 10 | 0.02 |

| 85–89 | 14 | 0.04 | 7 | 0.01 |

| 90–94 | 3 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.0 |

| ≥ 95 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Between 1992 and 2001, 3360 incident cases of cirrhosis in patients aged ≥ 25 years were reported to the UK General Practice Research Database, which contains data relating to over 13 million patients in the UK40 (approximately 20% of the UK population). Of the reported cases, 1287 (38.3%) were judged, on the basis of records of problem drinking in the GP notes, to be alcoholic cirrhosis. 40 These figures suggest an annual incidence of alcoholic cirrhosis in the UK of approximately 25,740. During the 10 years from 1992 to 2001, the incidence of alcoholic cirrhosis rose by 75% in men and by 34% in women,40 and in 2000 it was claimed that around 80% of all cases of liver cirrhosis seen in district general hospitals in the UK could be attributed to alcohol. 8

Impact of health problem

Significance for patients in terms of ill-health (burden of disease)

Alcohol-related liver disease is often asymptomatic. However, cirrhosis is associated with a number of complications, the more common of which include variceal bleeding, ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and encephalopathy;41 these are associated with a significant burden of disease. Moreover, approximately 20% of patients with cirrhosis will go on to develop HCC (Dr Marsha Morgan, Royal Free Hospital, London, 2010, personal communication).

Portal hypertension is a major complication of chronic liver disease. It contributes to the development of ascites and HE, and forms a direct cause of variceal bleeding. Clinically significant PHt (i.e. PHt associated with a risk of such complications) has been defined as a HVPG measurement above about 10 mmHg. 42 Patients with clinically significant PHt should be offered treatment to reduce the risk of complications. 42

Approximately 40% of patients with liver cirrhosis have oesophageal varices, and approximately one-third of these will suffer variceal bleeding within 2 years of diagnosis. Such bleeding is associated with a mortality rate of 20–40% per episode43 and a 1-year mortality of 57%;4 nearly half of the deaths occur within 6 weeks of the initial episode of bleeding. 4

Over a 10-year period, approximately 50% of patients with compensated cirrhosis will develop ascites (excessive fluid within the peritoneal cavity). 44 This is associated with a poor quality of life, increased risk of infections, renal failure, and poor long-term outcomes. 45

Cirrhosis is also associated with HE, a condition that encompasses mental alterations ranging from mild (trivial lack of awareness, a shortened attention span, or euphoria or anxiety) to more obvious mental alterations including lethargy or apathy, occasional disorientation, personality change, and inappropriate behaviour, and in more severe cases to somnolence, confusion, gross disorientation and bizarre behaviour, and ultimately coma. Motor function is also impaired. 46 Patients who do not display any overt neurological abnormalities may nonetheless display subtle abnormalities of cognition and/or neurophysiological variables; this condition is termed minimal HE. Minimal HE appears to be associated with a reduction in health-related quality of life and in the ability to perform complex tasks such as driving a car. 46 It has been suggested that approximately 35–40% of cirrhotic patients will develop overt HE at some point, whereas approximately 20–60% with liver disease will develop minimal HE. 47

Significance for the NHS

The number of patients admitted to NHS hospitals in England with ALD has risen year on year from around 25,700 in 2002–3 to approximately 38,300 in 2007–8, an increase of around 49%. In approximately 14,300 of these patients (37%), ALD was the primary diagnosis (Table 7). 48

| Hospital admissions related to ALD | Number of admissions, rounded to nearest hundred | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002–3 | 2003–4 | 2004–5 | 2005–6 | 2006–7 | 2007–8 | |

| Patients admitted with ALD | 25,700 | 28,600 | 31,500 | 34,400 | 37,700 | 38,300 |

| Patients admitted primarily because of ALD | 11,500 | 12,200 | 13,100 | 13,800 | 14,500 | 14,300 |

| Alcoholic fatty liver | 100 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 |

| Alcoholic hepatitis | 1100 | 1200 | 1200 | 1300 | 1400 | 1400 |

| Alcoholic fibrosis and sclerosis of liver | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Alcoholic cirrhosis of liver | 3100 | 3400 | 3800 | 4200 | 4800 | 4800 |

| Alcoholic hepatic failure | 800 | 800 | 900 | 1000 | 1100 | 1100 |

| Alcoholic liver disease, unspecified | 6300 | 6500 | 6800 | 7000 | 7000 | 6700 |

In 2006, liver disease was responsible for approximately 1600 hospital admissions in Wales. 49 No information was provided regarding the proportion of these admissions that could be attributed specifically to ALD.

The number of patients admitted to adult, general critical/intensive care units (ICUs) in England and Wales with ALD is estimated to have increased from 550 in 1996 to 1513 in 2005, and the number of ICU bed-days which they occupied to have increased from around 3100 to > 10,000. These figures are likely to be underestimates, as they exclude admissions to specialist liver critical-care beds and also any ICU patients with ALD who did not have ALD recorded as a primary or secondary reason for admission. 50

Current service provision

Diagnosis and subsequent management of disease

Diagnosis

The diagnostic pathways for suspected ALD are complex. Many people with ALD have no signs or symptoms of disease, the first indication of liver disease often coming from routine liver function tests. Others first come to medical attention when they report relatively mild symptoms (e.g. nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort, or diarrhoea). Sometimes, ALD is identified when people present voluntarily for detoxification, or when they require treatment for alcohol-related injuries or pneumonia, or alcoholic damage to organs other than the liver (e.g. the pancreas, heart, brain or peripheral nerves). 8 Yet other patients do not present until they have advanced liver disease characterised by more severe symptoms, such as jaundice, ascites, encephalopathy, or upper gastrointestinal bleeding. 8

The variability in the diagnostic pathways, caused by the varying reasons for presentation, is complicated by the absence of a single test that differentiates ALD from liver disease of other aetiologies. Rather, the patient’s history is obtained to identify risk factors (alcohol and other) for liver disease, and liver function tests, blood counts, and hepatitis serology are performed to exclude liver diseases of other aetiologies. 51 Ultrasound may also be used. 9 Because patients without clinical evidence of decompensated cirrhosis may have histologically advanced ALD but normal, or only mildly abnormal, liver function test results, liver biopsy may be required to confirm the diagnosis and the stage of the disease by assessing the degree of fibrosis. 9,52

There is a lack of consensus about the role and the timing of biopsy in patients with suspected ALD. 51 This derives in part from the absence of high-quality evidence for the accuracy of liver biopsy specifically in the diagnosis of ALD, together with the fact that its status as the ‘gold standard’ diagnostic and staging tool has been called into question for several reasons. There are also concerns relating to the safety of liver biopsy. For further details, see Summary of diagnostic tests.

Management of disease

Following a diagnosis of ALD, the aims of management are to treat the underlying cause, prevent disease progression, and manage complications. By far the most important management aim in all patients is to ensure long-term abstinence from alcohol. As noted in Aetiology, pathology and prognosis, a small UK study found that ≤ 50% of patients with ALD either abstained completely from alcohol or significantly reduced their intake following simple advice from a physician during their initial presentation. 26 Additional pharmacological or non-pharmacological interventions may also be used to promote abstinence. 8,52 Other aspects of management include lifestyle changes to reduce cigarette consumption and obesity,10 if relevant.

In patients with relatively mild alcoholic hepatitis, the focus of treatment is the achievement of abstinence. Corticosteroid therapy may be used to treat severe AAH,9 but there is no conclusive evidence that it leads to significant improvements in survival. 53 As most patients with AAH have some degree of malnutrition, nutritional therapy may also be offered. 25

A range of therapies may be used to treat the various complications of alcoholic cirrhosis. 8,52 Complications such as fluid retention, HE, and variceal bleeding are treated symptomatically. Because prophylactic treatment with non-selective beta-blockers or band ligation reduces the risk of first bleeding in patients with medium or large varices by 50%, all patients with cirrhosis should be screened regularly by endoscopy for signs of PHt (particularly the presence of oesophageal varices), and, if necessary, offered preventative treatment against gastrointestinal bleeding. Current guidance recommends that all patients diagnosed with cirrhosis should be offered such endoscopic screening every 2 years if they have no varices and annually if they have small varices54 or decompensated disease with or without varices. 42 Abdominal Doppler ultrasound may be used to screen for liver and portal abnormalities (especially HCC). 11

Orthotopic liver transplantation has a place in the management of patients with decompensated alcohol-related cirrhosis who have failed to improve despite well-documented abstinence from alcohol and expert medical treatment for a period of approximately 6 months. Survival rates are similar to those observed in patients transplanted for non-alcoholic cirrhosis, although recidivism rates are still unacceptably high in some centres. Transplantation is also considered the optimal treatment for early HCC. 55 However, the supply of donor livers is limited. 8

Current service cost

The current service cost has been limited to the cost of diagnostic liver biopsy, which has been estimated at £894 for a percutaneous biopsy56 and £1500 for a transjugular biopsy. 9 It is recognised that there are associated costs that have not been estimated, but that are assumed to be independent of the strategy employed.

No evidence has been identified regarding the number of diagnostic liver biopsies undertaken each year in England and Wales specifically as a consequence of suspected ALD.

Relevant national guidelines, including national service frameworks

The following relevant national guideline was issued in 2010:9

Alcohol use disorders: diagnosis and clinical management of alcohol-related physical complications.

The National Clinical Guideline Centre for Acute and Chronic Conditions

Variation in services and uncertainty about best practice

It became apparent, during the course of this project, that rates of referral to secondary care of patients with suspected ALD vary considerably in different parts of the country and that there is some uncertainty about best practice.

Description of technology under assessment

Summary of diagnostic tests

This review assesses four non-invasive tests for liver fibrosis: three blood tests [the Enhanced Liver Fibrosis (ELF™) test (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostic Inc., Tarrytown, NY, USA), FibroTest (BioPredictive, Paris, France) and FibroMAX (BioPredictive, Paris, France)] and transient elastography (FibroScan®; produced by EchoSens, Paris, France and distributed in the UK by Artemis Medical Ltd, Kent, UK). The reference standard with which they are generally compared is liver biopsy, but HVPG measurement and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy have also been considered. All these tests are discussed in turn below.

The Enhanced Liver Fibrosis Test

The Enhanced Liver Fibrosis Test is a blood test that uses an algorithm combining three biomarkers [hyaluronic acid (HA), tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) and aminoterminal propeptide of procollagen type III (PIIINP)] to assess the stage and rate of progression of liver fibrosis. 57 The biomarkers are direct markers of extracellular matrix metabolism/degradation indicative of liver fibrosis. A higher concentration of the individual biomarkers leads to a higher ELF score and indicates a higher probability of more severe fibrosis.

The test requires a minimum of 0.3 ml of serum. 58 Blood samples are collected in a clinic and analysed at a central laboratory. 51

As alcohol affects many of the variables used in the ELF test,59,60–62 individuals should ideally be abstinent before the blood sample is taken.

The ELF test was CE marked in May 2007. 51

Cautions and contraindications for the Enhanced Liver Fibrosis Test

No cautions and contraindications have been identified by the manufacturer. However, because the test uses direct markers of fibrogenesis (HA and TIMP-1), the results will be unreliable in patients with chronic diseases characterised by fibrogenesis in organs other than the liver. 63

FibroTest and FibroMAX

FibroTest and FibroMAX are proprietary algorithms that use serum biochemical markers to assess the stage of liver fibrosis. 64 FibroTest (marketed in the USA as FibroSure) combines one direct marker of extracellular matrix metabolism/degradation (alpha-2-macroglobulin) and four indirect markers (apolipoprotein A1, haptoglobin, total bilirubin and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase) with the patient’s age and sex. 65

Blood samples are not analysed at a central laboratory, but it is recommended that the individual components of the test are analysed using the same techniques and analysers as used by the reference laboratory that developed FibroTest. 66 The individual values are then entered into BioPredictive’s website (www.biopredictive.com) and an algorithm calculates the results, which are presented as numeric estimates on a continuous scale ranging from 0.00 to 1.00. Table 8 displays the correspondence proposed by Morra et al. 67 between FibroTest scores and the fibrosis stages identified by the METAVIR, Knodell, and Ishak fibrosis staging systems.

| FibroTest | METAVIR | Knodell | Ishak |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00–0.21 | F0 | F0 | F0 |

| 0.22–0.27 | F0–1 | F0–1 | F1 |

| 0.28–0.31 | F1 | F1 | F2 |

| 0.32–0.48 | F1–2 | F1–3 | F2–3 |

| 0.49–0.58 | F2 | F1–3 | F5 |

| 0.59–0.72 | F3 | F3 | F4 |

| 0.73–0.74 | F3–4 | F3–4 | F5 |

| 0.75–1.00 | F4 | F4 | F6 |

FibroMAX combines the components of FibroTest with alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, total cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting blood glucose, height and weight, and presents on one sheet the scores for FibroTest, SteatoTest (which measures hepatic steatosis) and AshTest (which measures the degree of necroinflammatory activity of alcoholic origin). 68

FibroTest and FibroMAX are validated for use in patients with chronic viral hepatitis (B or C), ALD, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The manufacturer recommends the use of FibroTest in patients with hepatitis B or C and FibroMAX in those with alcoholic or metabolic liver disease. 69

Although FibroTest may be performed on blood samples from fasting or non-fasting patients, FibroMAX must be performed on samples from fasting patients. 67 As in the case of the ELF test, alcohol affects many of the variables used in FibroTest; therefore, individuals should ideally be abstinent before the blood sample is taken (Dr Marsha Morgan, Royal Free Hospital, London, 2010, personal communication).

FibroTest and FibroMAX are said to yield consistent results, with a reproducibility > 95%. 70,71 However, this has been questioned. A small study by Gressner et al. 72 suggests that FibroTest scores may vary by up to two METAVIR stages as a result of possible interlaboratory differences in measurements of the individual test components, even when the laboratories fulfil BioPredictive’s technical requirements and the measurements lie within a quality-controlled, analytically acceptable range. Moreover, Poynard et al. ’s73 prospective analysis of discordance between the FibroTest and biopsy results in patients with hepatitis C demonstrated that critical interpretation of every FibroTest result is required in order to avoid false-positive (FP) or false-negative (FN) results.

The FibroTest and FibroMAX algorithms are patented, but not CE marked; they have not been published. 66 However, there are CE-marked kits for assessing the individual components.

Cautions and contraindications for FibroTest and FibroMAX

No cautions or contraindications relating to patient safety have been identified. However, for reasons relating to test accuracy, FibroTest is not recommended for use in patients who have intercurrent illness (particularly acute inflammation, haemolysis, or Gilbert’s syndrome), or who are taking medications that can cause elevated bilirubin levels11 (these include allopurinol, anabolic steroids, some antibiotics, antimalaria medications, azathioprine, chlorpropamide, cholinergics, codeine, diuretics, adrenaline, meperidine, methotrexate, methyldopa, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, morphine, nicotinic acid, birth control pills, phenothiazines, quinidine, rifampin, steroids, sulfonamides, and theophylline74).

FibroScan

FibroScan is produced by EchoSens, Paris, France, and distributed in the UK by Artemis Medical Ltd., Kent, UK75 It is a non-invasive test that uses a specialised probe, an ultrasound and elastography system, and specialised software. The probe is placed on the skin over the right lobe of the liver and generates a mechanical pulse that sends a shear wave to the liver through the intercostal spaces. 76,77 The wave’s velocity is measured by ultrasound and is determined by the stiffness of the liver, which is correlated with the degree of fibrosis. 76

The procedure, which is painless, can be performed by trained medical or paramedical staff. Each test typically takes < 15 minutes. 75 The result is the median of 10 individual ‘shots’, reported as a numerical measure in kilopascal (kPa);78 it is available immediately. 76 If a shot is unsuccessful, the machine provides no result and the whole process is deemed to have failed if no value is obtained after ≥ 10 shots. 79 In addition, the manufacturer recommends that, to be considered reliable, successful measurements should meet the following three criteria:

-

at least 10 valid shots

-

a success rate (the ratio of valid shots to total number of shots) of at least 60%

-

an interquartile range < 30% of the median value. 79

FibroScan values range from 2.5 to 75 kPa; normal values are around 5.5 kPa. 80 A cut-off value of about 12.5 kPa has been proposed as optimal for discriminating between fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. 81 As the threshold for cirrhosis appears to be higher in patients with ALD, it is important that disease aetiology should be established before testing.

FibroScan is claimed to measure liver stiffness in a cylinder approximately 1 cm in diameter and 4 cm long, between 25 and 65 mm below the surface of the skin. 82 The volume of this cylinder is at least 100 times that of a percutaneous liver biopsy sample, and is therefore far more representative of the whole liver, reducing the risk of sampling error. However, the claim that it may be performed satisfactorily on non-fasting patients82 has recently been called into question by the finding that liver stiffness values increase substantially after food intake in both patients with hepatitis C infection and healthy controls. 83

FibroScan appears to have good reproducibility. In a series of 195 patients with chronic liver disease of various aetiologies and without ascites, using the FibroScan ultrasonography guide to identify a suitable portion of the liver for examination, Fraquelli et al. 84 found that overall agreement between two operators was 0.98 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.977 to 0.987], and intraobserver agreement was 0.98 for both operators. Increased BMI (> 25 kg/m2), steatosis (> 24% of fatty liver cells), and histological evidence of no to mild fibrosis (METAVIR stage < F2) were all significantly associated with reduced interobserver agreement, and the most marked variability was seen in mild fibrosis (F0/F1), where interobserver agreement fell to 0.60 (95% CI 0.455 to 0.719).

FibroScan is CE marked. Because it is designed specifically to test for liver fibrosis, and does not produce an image, it cannot be used for any other diagnostic purpose. 56

Cautions and contraindications for FibroScan

No cautions or contraindications relating to patient safety have been identified. However, because elastic waves do not travel through liquids, FibroScan has no value in patients with ascites, even if it is clinically undetected. 77 Although this limitation has been claimed to be of little practical importance because the diagnosis of cirrhosis is clinically obvious in most patients with ascites,85 patients with portal vein or hepatic vein block may present with ascites although not having appreciable hepatic fibrosis (Dr Marsha Morgan, Royal Free Hospital, London, 2010, personal communication).

More importantly, it is difficult or impossible to use FibroScan in obese patients because the probe is calibrated for a specific distance between the liver and the chest wall,79 and the low-frequency vibration induced by the probe and/or the ultrasound wave can be strongly attenuated by the fatty tissue. 85 This limitation is particularly unfortunate as obese patients form an increasing proportion of the population and appear to be at increased risk of disease progression. However, a special probe with a measurement depth of 35–75 mm17 is currently being developed for use in patients who are morbidly obese. 77 It is also impossible to use FibroScan in patients whose intercostal spaces are too narrow for the 9-mm-diameter probe to fit between the costal bones. 85

Finally, FibroScan results may be influenced by factors such as acute liver injury, which will result in an overestimation of the degree of fibrosis. 79

Liver biopsy

The true gold standard for assessing the degree of liver fibrosis is histological analysis of the whole liver. As this is not possible in living patients, liver biopsy has been adopted as the reference standard.

Liver biopsy has a number of disadvantages. It is an invasive test: a hollow needle is used to remove a small sample of tissue from the patient for examination in the laboratory. It is performed in the fasting patient and is generally preceded by ultrasonography of the liver. 86 In most cases, liver biopsy is performed percutaneously, through the skin over the liver. However, in order to reduce the risk of complications associated with bleeding, it may be performed transvenously in patients with conditions such as ascites or coagulation defects, which are relatively common in ALD, and which form contraindications to percutaneous biopsy. In transvenous biopsy, a catheter carrying the biopsy needle is inserted through a vein (most commonly the jugular vein in the neck) and guided to the veins inside the liver. 87 Liver biopsy is also occasionally performed laparoscopically. 9

Liver biopsy often involves a hospital stay. Patients should undergo liver biopsy on an outpatient basis only if they have no conditions that may increase the risk of the procedure, and then only in locations with easy access to a laboratory, blood bank, and inpatient facilities, and with staff who can observe the patient for 6 hours following the procedure. In addition, the patient should be able to return easily within 30 minutes to the hospital where the biopsy was undertaken, and should have a reliable individual to stay with on the first night post biopsy. If any of these criteria cannot be met, biopsy must be undertaken on an inpatient basis. Moreover, patients who undergo outpatient biopsy should be hospitalised if there is any significant complication, including pain that requires more than one dose of analgesic. 88 In the USA, where liver biopsy is generally performed on an outpatient basis under local anaesthetic, 1–3% of patients subsequently require hospital care for the management of complications (predominantly pain or hypotension); 60% of these complications occur within 2 hours of the biopsy and 96% within 24 hours. 86

Because fibrosis is not evenly distributed throughout the liver, liver biopsy, which samples only 1/25,000–50,000 of the liver, carries a substantial risk of sampling error. Regev et al. 89 found a difference of at least one fibrosis stage between biopsy samples from the right and left hepatic lobes in 33% of patients with hepatitis C. Such sampling errors usually produce a low FP rate but a relatively high FN rate but, in the case of liver biopsy, inclusion of elements such as capsular or connective tissue will lead to overestimation of the degree of fibrosis. 16 Factors that affect the degree of sampling error include the length of the biopsy sample and the number of samples taken. Bedossa et al. 90 demonstrated experimentally in liver samples from patients with hepatitis C that correct staging was achieved for only 65% of cases when the biopsy sample was 15 mm in length; this figure rose to only 75% when samples 25 mm in length were analysed, and the proportion of samples which were correctly identified did not increase significantly with longer specimens. Abdi et al. 91 found that a single biopsy correctly identified cirrhosis in only 80% of cases (16/20) at post-mortem, but that 100% accuracy was achieved when three samples were taken,91 while Maharaj et al. 92 also found that a single sample was unreliable: when three consecutive samples were taken through a single entry site, all three samples identified cirrhosis in only 50% of cases.

In addition to sampling error, liver biopsy results may be affected by intra- and inter-pathologist variation in the interpretation of samples. 93 Levels of inter- and intra-observer discrepancies as high as 10–20%89,94 have been reported.

However, liver biopsy has the advantage that it provides information not only on liver fibrosis but also on other factors such as inflammation, necrosis, and steatosis, and permits the identification of potentially unexpected cofactors and comorbidities. 95

Cautions and contraindications for liver biopsy

As an invasive procedure, liver biopsy carries a risk of morbidity and mortality. Morbidity associated with liver biopsy may be broadly divided into minor complications, including transient discomfort at the biopsy site, post-procedural pain, and mild transient hypotension, and major complications, including more severe hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg), bleeding into the peritoneal or thoracic cavity, haemobilia, pneumothorax, perforation of the gall bladder or another organ, myocardial infarction, and death. 96

Murtagh and Foerster93 have suggested that one-third of patients who undergo liver biopsy report pain, and that complications occur in 3 per 1000 biopsies (0.3%) and death in 3 per 10,000 (0.03%). A systematic review of the adverse effects of liver biopsy undertaken as part of this project suggests that the overall rates of severe adverse events including death, and of death, in patients undergoing biopsy are higher at 0.81% (95% CI 0.71% to 0.90%) and 0.09% (95% CI 0.06% to 0.13%), respectively, for percutaneous biopsy, and 1.45% (95% CI 0.62% to 2.57%) and 0.18% (95% CI 0.02% to 0.85%), respectively, for transjugular biopsy (for details, see Appendix 3). The higher rates seen in patients undergoing transjugular biopsy presumably reflect the fact that they are at higher risk of adverse events because of the complications that form contraindications for percutaneous biopsy.

The systematic review found rates of any minor adverse events substantially lower than Murtagh and Foerster’s93 figure for pain alone, at 7.51% (95% CI 7.12% to 7.93%) for percutaneous biopsy and 9.14% (95% CI 6.51% to 12.37%) for transjugular biopsy. However, these results are less reliable than those for more severe adverse events because of greater variability in the definitions of minor adverse events used in the different studies (see Appendix 3). Moreover, the majority of included studies were retrospective audits of clinical notes that presumably only identified cases where the pain was sufficiently severe to require attention from medical or nursing staff.

The management of bleeding from internal biopsy sites has improved over the last 15–20 years because of the use of non-invasive arterial embolisation, which has a much lower associated morbidity and mortality than the open surgical procedures that were previously necessary to deal with this complication (Dr Marsha Morgan, Royal Free Hospital, London, 2010, personal communication). However, because of the particularly high risk of adverse effects in patients with alcoholic hepatitis and cirrhosis, both of which are associated with coagulation problems,8 current UK guidance recommends that biopsy is not required for confirmation of diagnosis in patients with a high clinical suspicion of ALD in whom other causes of liver disease have been excluded using blood tests, unless it is necessary to confirm a diagnosis of AAH in order to inform specific treatment decisions. 9 In other words, in these patients, liver biopsy should be performed only if the risks it poses are outweighed by the potential benefits of improved patient outcomes consequent on changes in management which would not be possible without information that could only be obtained by biopsy.

Hepatic venous pressure gradient measurement

Hepatic venous pressure gradient measurement is the gold standard for assessing the presence and severity of PHt in patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis, in whom splenomegaly, the clinical hallmark of PHt, is a less useful sign. HVPG measurement is an invasive procedure in which a balloon-tipped catheter is inserted into a hepatic vein via the femoral or jugular route. The pressure is measured with the balloon deflated, and again when it has been inflated to occlude the hepatic vein. The HVPG is the difference between the two measurements; a result > 5 mmHg indicates PHt, and a result > 10–12 mmHg indicates clinically significant PHt associated with a risk of complications such as ascites, HE, and variceal bleeding. 42

Hepatic venous pressure gradient measurement is reliable only when performed by an experienced operator. 97

Cautions and contraindications for hepatic venous pressure gradient measurement

Although invasive, HVPG measurement appears to be safe. No reports of mortality or serious complications have been published. The most common complications appear to be related to local injury to the vein used to gain access to the hepatic vein; they include leakage and haemorrhage. Other complications, such as vagal reactions and arteriovenous fistulae, are more rare. The risk of such complications is greatly reduced if deep-venous puncture is performed under Doppler ultrasound guidance, and this is particularly recommended in obese patients, or when arterial palpation is difficult. Finally, passage of the catheter through the right atrium may cause supraventricular arrhythmias; in over 90% of cases, these are self-limiting. 98

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy involves the insertion of a thin, flexible viewing instrument, called an endoscope through the mouth into the oesophagus, stomach, and duodenum. It is used in patients with cirrhosis to identify medium or large varices in those areas so that prophylactic treatment may be initiated to reduce the risk of bleeding.

Endoscopy is expensive to perform. 99 Patients must have had nothing to eat or drink for 4–8 hours prior to the procedure.

Cautions and contraindications for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is invasive and unpleasant for the patient if done without deep sedation. 100 When performed for diagnostic purposes, it has a small, but not insignificant, risk of complications. These include:

-

Cardiopulmonary complications related to sedation. These range from minor changes in vital signs to respiratory depression, shock/hypotension, and myocardial infarction, and account for approximately 40% of complications associated with diagnostic endoscopy.

-

Infectious complications resulting either from the procedure itself or from the use of contaminated equipment; these are relatively uncommon.

-

Perforation of the gastrointestinal tract; this is also relatively uncommon, but is associated with a mortality rate of approximately 25%.

-

Significant bleeding; this is rare, although individuals with thrombocytopenia and/or coagulopathy are at increased risk of bleeding. 101

Identification of important subgroups

Potentially important subgroups include:

-

obese patients (i.e. those with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 or a waist circumference > 102 cm for men and > 88 cm for women)

-

patients with metabolic syndrome

-

patients with concurrent alcoholic hepatitis

-

patients who are not abstinent from alcohol.

All of these subgroups are important because their characteristics may affect the performance or results of the non-invasive tests assessed in this report; in addition, obese patients with ALD appear to be at increased risk of disease progression. Thus, FibroScan is more likely to fail, or to provide unreliable measurements, in patients with ALD who are obese or rotund, whereas it has been shown in apparently healthy individuals that liver stiffness measurements (LSMs) are higher in those with metabolic syndrome than in those without. 80 The inflammation associated with alcoholic hepatitis will result in an overestimation of the degree of fibrosis using FibroScan. 79 Finally, current alcohol consumption affects many components of the ELF test and FibroTest, so that the tests will provide different results in patients who are abstinent from alcohol and in those who are still drinking, even though they may have the same degree of fibrosis.

Current usage in the NHS

None of the four tests are currently routinely performed within the NHS. However, in April 2008, FibroScan machines were said to be installed in 12 NHS hospitals (implicitly in the UK rather than in England and Wales). 75 By 2009, this figure had risen to 17 NHS hospitals and five private hospitals in England, and six NHS hospitals in Scotland; there were none in Wales. 102 The majority of FibroScan machines in place in 2008 were funded by pharmaceutical companies and/or charitable donations. 75

In 2008, the manufacturers predicted that initial uptake would be confined to the major hepatology centres and would be limited to approximately 35 systems, but that FibroScan might subsequently expand into district general hospitals with gastroenterology departments. 75

Anticipated costs associated with non-invasive testing

There are no good data relating to the costs of non-invasive testing. The best data relate to the ELF test, where currently the favourable price for early adopters in the NHS is £45 per test for a volume of 100 tests a month (1200 a year), i.e. a total cost of £54,000/year (Dr Marsha Morgan, Royal Free Hospital, London 2010, personal communication). There is no indication as to what the price is likely to be for subsequent customers.

In 2007, Morra et al. 67 stated that the cost of FibroTest ranged from €90 to €300 and that of FibroMAX from €150 to €500. However, it seems likely that FibroTest will in the future be priced more competitively in relation to the ELF test. The cost of FibroMAX is likely to be somewhat higher than that of FibroTest as it incorporates more components and provides additional information.

The ancillary costs associated with the ELF test, FibroTest, and FibroMAX are those associated with any diagnostic blood test.

No cost data have been identified for FibroScan.

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Decision problem

Population

Patients with suspected liver fibrosis related to alcohol consumption.

Diagnostic tests under assessment

The non-invasive tests for liver fibrosis assessed in this review take the forms of either blood tests:

-

ELF test

-

FibroTest

-

FibroMAX

or transient elastography:

-

FibroScan.

Reference standard tests

The reference standard test for liver fibrosis is liver biopsy. However, HVPG measurement and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy are used to identify conditions associated with liver fibrosis, namely PHt and oesophageal varices respectively, which are of clinical importance and which can also be used as surrogates for the diagnosis of cirrhosis.

As noted in Chapter 1, Liver biopsy, liver biopsy carries a substantial risk of sampling error, and may also be affected by intra- and inter-observer variation in the interpretation of samples. It can, therefore, only be regarded as an imperfect reference standard.

Outcomes

Relevant outcomes include:

-

the diagnostic accuracy of the index test compared with the reference standard, as indicated by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC), for a specified fibrosis stage, and/or the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value, compared with the reference standard for the diagnosis of a specified fibrosis stage based on a specified cut-off point, or the data required to calculate those values [i.e. numbers of true-positive (TP), FN, true-negative (TN) and FP results]

-

numbers of test failures or other withdrawals

-

adverse effects associated with testing

-

long-term patient outcomes (disease progression, complications related to liver disease, need for liver transplantation, mortality)

-

health-related quality of life

-

cost-effectiveness and cost–utility.

Studies of diagnostic or predictive accuracy are included only if they report numbers of TP, FN, TN and FP results, or measures of diagnostic accuracy (e.g. sensitivity and specificity) calculated from those values, relating to the index test in comparison with either a reference standard test or a clinical outcome (e.g. survival or adverse clinical events).

Discussion of outcomes measuring test accuracy

In studies of diagnostic tests, patients are generally classified by the index test (i.e. the diagnostic test being investigated) as either positive or negative (i.e. as having or not having the condition that the test is designed to identify). The same patients are also assessed using the reference standard (an established diagnostic test assumed to have 100% sensitivity and specificity), and the latter result is taken to identify the patients’ true health status. If both the index test and the reference standard are positive, the result is described as a TP. If the index test is positive but the reference standard is negative, the result is termed a FP. If both the index test and the reference standard are negative, the result is termed a TN, whereas if the index test is negative and the reference standard is positive it is termed a FN. These results can be presented in a 2 × 2 table (Table 9).

| Index test result | Reference standard positive | Reference standard negative |

|---|---|---|

| Index test positive | TP | FP |

| Index test negative | FN | TN |

| Sensitivity = [TP/(TP + FN)]× 100 | Specificity = [TN/(TN + FP)] × 100 |

The sensitivity of a test (the proportion of patients with the condition of interest who have a positive test result – i.e. TPs), indicates how good it is at correctly identifying the condition of interest, whereas its specificity (the proportion of patients without the condition of interest who have a negative test result – i.e. TNs) indicates how good it is at correctly classifying people as free of that condition. The sensitivity and specificity are expressed as simple percentages (see Table 9). Both FP and FN results may be harmful: FP results may cause patients to undergo further tests or receive unnecessary treatment, whereas FN results may deprive them of the treatment they need. Ideally, therefore, diagnostic tests would have both high sensitivity and high specificity. In practice, however, they often have high sensitivity at the expense of low specificity or vice versa. The optimum balance between sensitivity and specificity varies from test to test because of differences in the relative consequences of FP and FN results in the context of the condition of interest.

In practice, the situation may be more complex than indicated in Table 9, as the results of the index test may be neither positive nor negative, but uninterpretable. It is important that such uninterpretable results should be included in the calculations. Their inclusion will lower the sensitivity and specificity of the index test (Table 10). In the absence of full data relating to uninterpretable results, sensitivity analyses may be used to explore the impact of such results on sensitivity and specificity.

| Index test result | Reference standard positive | Reference standard negative |

|---|---|---|

| Index test positive | TP | FP |

| Index test uninterpretable | Uninterpretable (U1) | Uninterpretable (U2) |

| Index test negative | FN | TN |

| Sensitivity = [TP/(TP + U1 + FN)] × 100 | Specificity = [TN/(TN + U2 + FP)] × 100 |

The positive predictive value of a test is the proportion of patients with positive test results who are correctly diagnosed. In clinical practice, this is generally the most important measure of test accuracy as it reflects the probability that a positive test reflects the underlying condition being tested for. Consequently, its value depends on the prevalence of the disease, which may vary, and indeed in real life situations may differ considerably from that seen in study populations. The negative predictive value is the proportion of patients with negative test results who are correctly diagnosed. The negative predictive value may be more important than the positive predictive value if the test is being used as a triage test to identify those patients who may have the condition of interest so that they may undergo further, more expensive or invasive, testing.

Although fibrosis has, for convenience, been divided into grades of severity using a number of different scales, the most common being the METAVIR scale (see Chapter 1, Measurement of disease), it actually forms a continuum that ranges from very mild fibrosis to severe fibrosis (cirrhosis). Consequently, the non-invasive tests for fibrosis reviewed in this report also yield continuous measurements and, therefore, diagnostic thresholds must be deliberately selected to define positive and negative results. The sensitivity and specificity of the tests will vary depending on the thresholds that have been selected. If several thresholds have been used in one data set, the diagnostic characteristics of the test in question may be illustrated using a receiver operating characteristic plot of the TP rate (sensitivity) against the FP rate (1 – specificity). 103

The AUROC may be used as an overall measure of the performance of a surrogate test when compared with the reference standard. Bedossa and Carrat104 state that the AUROC represents the probability that the surrogate will correctly rank two randomly chosen patients, one of whom has been classified by the reference standard as having, and the other as not having, the condition that the index and reference tests are intended to identify. Unlike sensitivity and specificity, the AUROC does not vary according to the threshold set for identification of a positive result. It therefore represents a loss of information, as compared with sensitivity and specificity, as it provides no indication of the degree to which any departure from 1.00 (a perfect result) is because of FPs, and the degree to which it is because of FNs. Moreover, Lambert et al. 105 have noted that, in the context of liver fibrosis, the AUROC has two main drawbacks:

-

Because it assumes that the reference standard yields a binary result whereas, as has been seen, liver biopsy uses an ordinal scoring system, the fibrosis stages have to be aggregated into two groups.

-

Because the proportion of each fibrosis stage in the sample can affect the AUROC, comparisons of AUROCs from populations with different distributions of fibrosis stages may be flawed. To overcome this, Poynard et al. 106 recommend standardising the AUROC according to the prevalence of fibrosis stages, but this method is complex and has not yet been statistically validated. 105

As noted above, calculation of the sensitivity and specificity of the index tests involves the assumption that the reference standard has 100% sensitivity and specificity. Unfortunately, this is not true of liver biopsy (see Chapter 1, Summary of diagnostic tests). If the results of the reference test are not very close to the truth, the performance of the index tests will be poorly estimated. 103 In an attempt to address this problem, a number of the studies included in this review have looked in detail at cases in which the index test and reference standard have yielded discrepant results, to determine which test is more likely to have provided the correct result in each individual case.

Another serious problem relating to the use of liver biopsy as the reference standard is its relevance to the different types of non-invasive tests. On the one hand, liver biopsy is arguably a more appropriate reference standard in relation to transient elastography than in relation to tests based on serum markers because it seeks directly to identify the degree of fibrosis present in the liver at a fixed point in time, whereas transient elastography measures the stiffness of the liver, a surrogate for fibrosis, also at a fixed point in time. By contrast, tests such as the ELF test and FibroTest, which are based on combinations of serum markers, seek to assess dynamic processes taking place within the liver. Consequently, their results may be discordant with the liver biopsy results either because the fibrotic process is highly active but fibrotic tissue has not yet developed (thus the serum tests will yield a higher result than the biopsy), or because fibrotic activity is temporarily discontinued even though there are clusters of fibrotic tissue in the liver (thus the serum tests will yield a lower result than the biopsy). 107 In such circumstances, the test results may be discordant even though both tests have yielded correct results in terms of the parameter that they set out to measure. On the other hand, it has been argued that liver biopsy is a more appropriate reference standard in relation to serum marker algorithms such as FibroTest and the ELF test, which have been designed to match histological stages of liver fibrosis as assessed by liver biopsy irrespective of biopsy accuracy, than in relation to transient elastography, which measures stiffness, a single genuine characteristic of liver tissue. 104

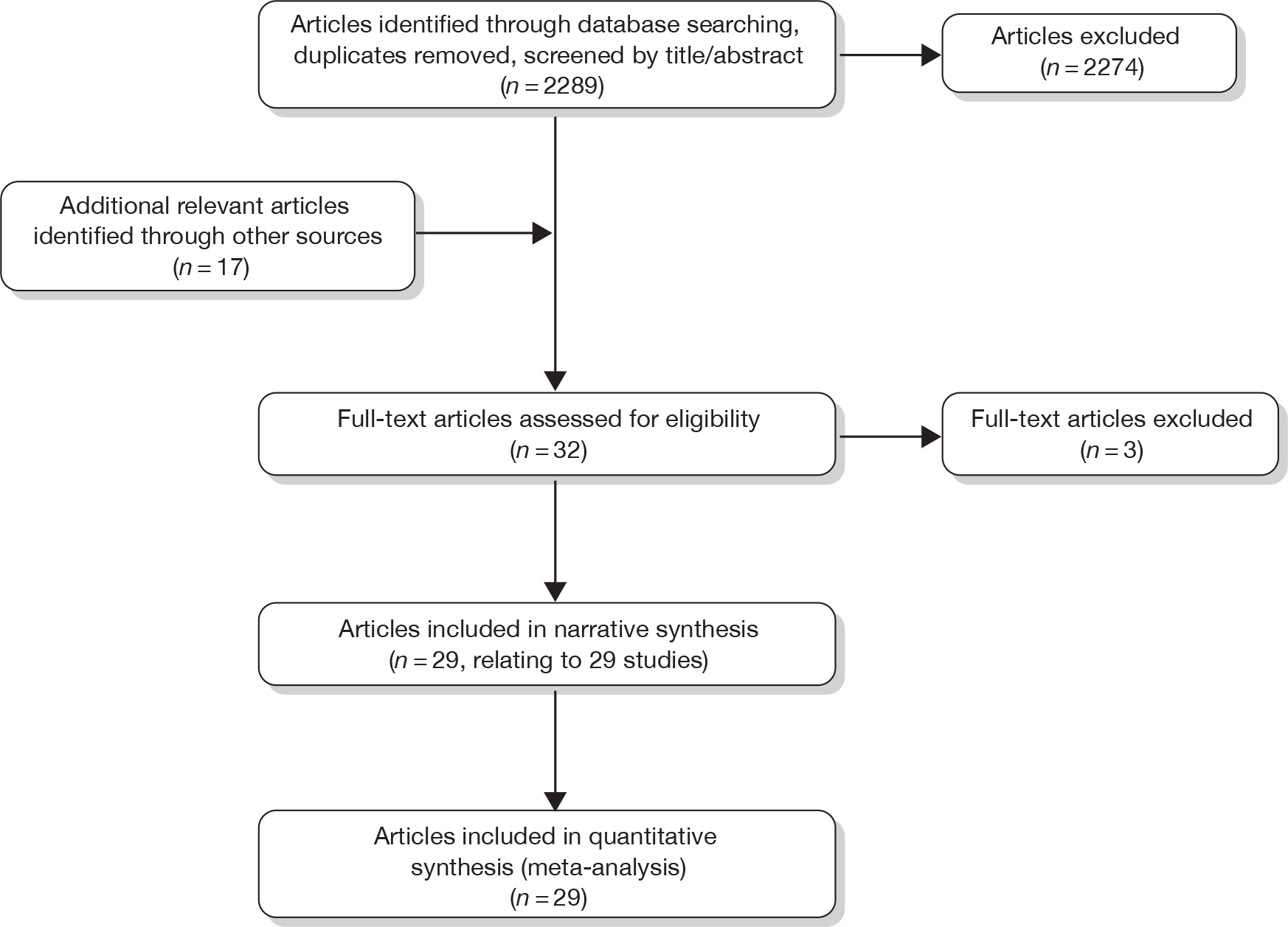

Study design

The best available level of evidence, with priority given to controlled studies, if available.

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

The overall aim of the assessment is to assess the diagnostic accuracy, effect on patient outcomes, and cost-effectiveness of the specified non-invasive tests for liver fibrosis in patients suspected of having liver fibrosis related to alcohol consumption. The tests are assessed firstly as a replacement for liver biopsy, and secondly as an additional test prior to liver biopsy.

The objectives of the assessment are:

-

To conduct a systematic review of the published evidence on the diagnostic accuracy and cost-effectiveness of the specified non-invasive tests for the assessment of liver fibrosis in patients suspected of having ALD.

-

To develop a decision model to investigate the benefits, harms, and cost-effectiveness of non-invasive testing, either as a replacement for liver biopsy or as an additional test in the diagnostic pathway for assessing liver fibrosis. Outcomes from the model will be expressed in terms of net health benefit and cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY).

Chapter 3 Cost-effectiveness: model structure and methodology

As previously discussed, the use of non-invasive liver tests (NILTs) for assessing the fibrosis levels of patients with suspected ALD has been posited owing to the fact that the current assessment method, biopsy, is associated with morbidity and mortality. If NILTs were of sufficient accuracy in determining the level of fibrosis, then they could be used cost-effectively to either filter those patients in whom biopsy would not be appropriate, or indeed replace biopsy for some patients. Henceforth strategies aimed at filtering patients will be referred to as ‘triaging strategies’ and strategies aimed at replacing biopsy will be referred to as ‘replacement strategies’.

The focus of the model is to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of different strategies involving NILTs when compared with biopsying all patients. Within this remit, it has been assumed that there is sufficient infrastructure for the identification and referral of patients with suspected ALD and subsequent treatment to be performed to a satisfactory level. Additional details on providing such services are contained in Alcohol use disorders: diagnosis, assessment and management of harmful drinking and alcohol dependence108 and the references contained therein.

During the process of undertaking the evaluation, it became apparent that data regarding the use of NILTs within primary care were extremely scant. Pivotal studies assessing test accuracy were all undertaken in secondary or tertiary care as a gold standard (liver biopsy) was needed. As it is unethical to undertake liver biopsy in those with minimal risk of fibrosis, the trials would be subject to considerable spectrum bias and the resultant sensitivities and specificities could not be assumed to apply in primary care. Clinical experts (comprising primary, secondary and tertiary care physicians) who provided advice to the assessment groups were unanimous that there was currently insufficient evidence to appraise the tests in primary care. This advice, in conjunction with the considerable uncertainty that is prevalent with regards to the cost-effectiveness of NILTs in secondary care, was the rationale for the results of this study to focus on the cost-effectiveness of NILTs solely within secondary and tertiary care.

Owing to the uncertainty in both management and prognosis following a diagnosis of cirrhosis, advanced fibrosis or of their absence, there were few data from the systematic reviews that could be utilised within the modelling evaluation. The key parameters that were used were the sensitivity and specificity of the tests.

The population simulated within the model will be those patients that a hepatologist would wish to biopsy. Guidance from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)9 indicates that biopsy, because of the potential for causing morbidity and mortality, should only be used when it would affect the management of the patient. It is assumed that within the model, management would only be altered where a patient had been diagnosed with cirrhosis, in which case the patient would be monitored for HCC, HE and oesophageal varices. In contrast, it is assumed that the management strategy would not change for those patients without cirrhosis, where the clinician would continue to stringently attempt to persuade the patient to become abstinent or reduce alcohol intake.

The prevention of further fibrosis (and ultimately cirrhosis) is of great importance and the model assumes that a proportion of those patients who continue to drink heavily will progress to cirrhosis, in which case the greater cost implications and reduced life expectancy will be taken into consideration.

A subset of patients will be suspected of having severe alcoholic hepatitis and/or decompensated liver disease; these will not be considered within the model. The rationale for this decision is twofold. Firstly, those patients with alcoholic hepatitis are likely to require treatment with steroids to reduce the risks of mortality; however, if the patient has decompensated cirrhosis, which can be determined by biopsy but not by any of the current NILT, then the course of steroids can cause mortality. Secondly, patients with alcoholic hepatitis will have inflammation of the liver, which can affect the validity of diagnosis provided by a NILT. There may be additional patients in whom the clinician believes that a biopsy would be unnecessary, for example where the clinical manifestations clearly indicate that the patient has cirrhosis; these patients are also not considered within the model with the assumption that the clinician would treat the patient as he or she deemed appropriate.

The strategies analysed

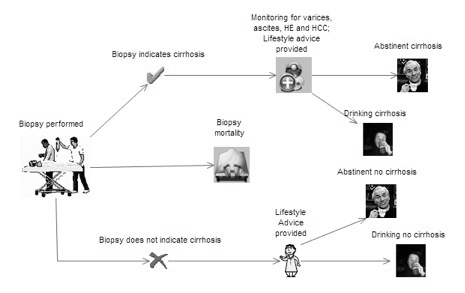

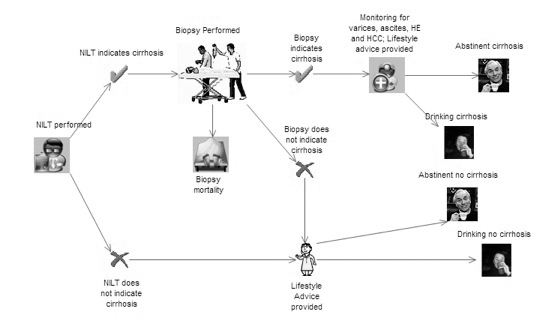

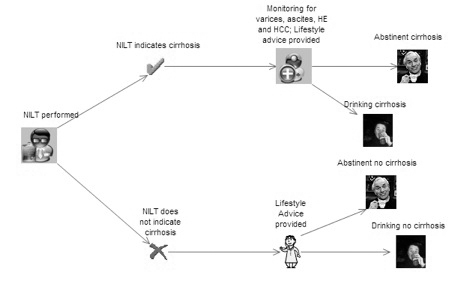

Ten strategies will be considered:

-

biopsy all patients (assumed current practice)

-

triage patients with FibroScan and biopsy all those in whom cirrhosis is indicated

-

triage patients with FibroTest and biopsy all those in whom cirrhosis is indicated

-

triage patients with the ELF and biopsy all those in whom cirrhosis is indicated

-

triage patients using clinical experience and biopsy all those in whom cirrhosis is indicated

-

use FibroScan and assume that the result is definitive

-

use FibroTest and assume that the result is definitive

-

use the ELF and assume that the result is definitive

-

use clinical experience and assume that the result is definitive

-

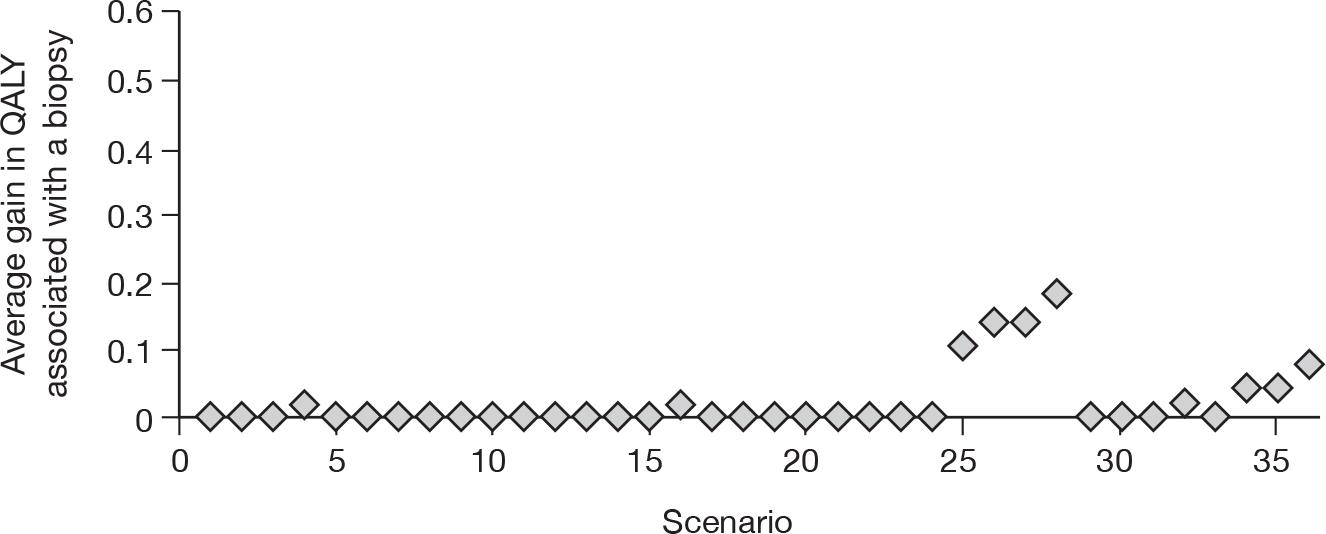

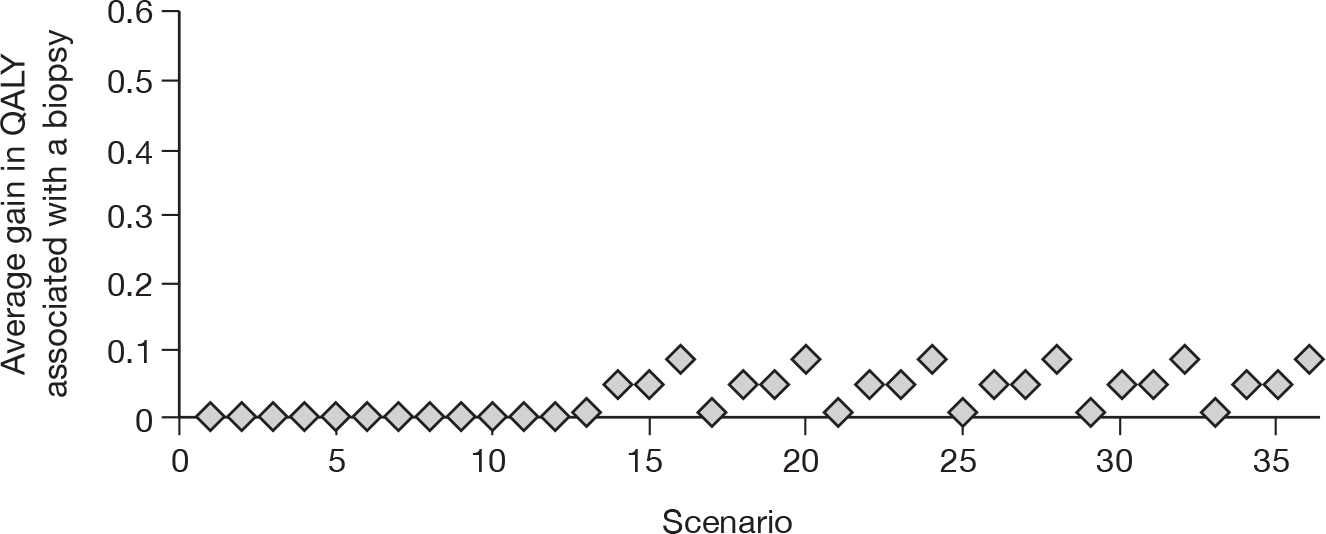

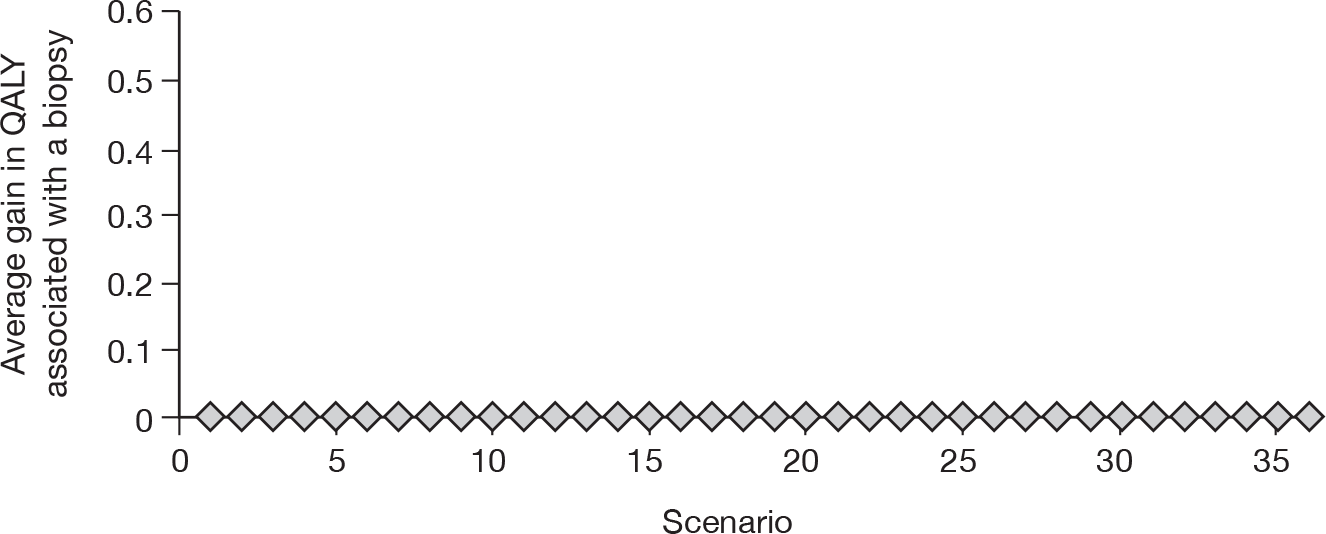

diagnose all patients as having cirrhosis.