Notes

Article history

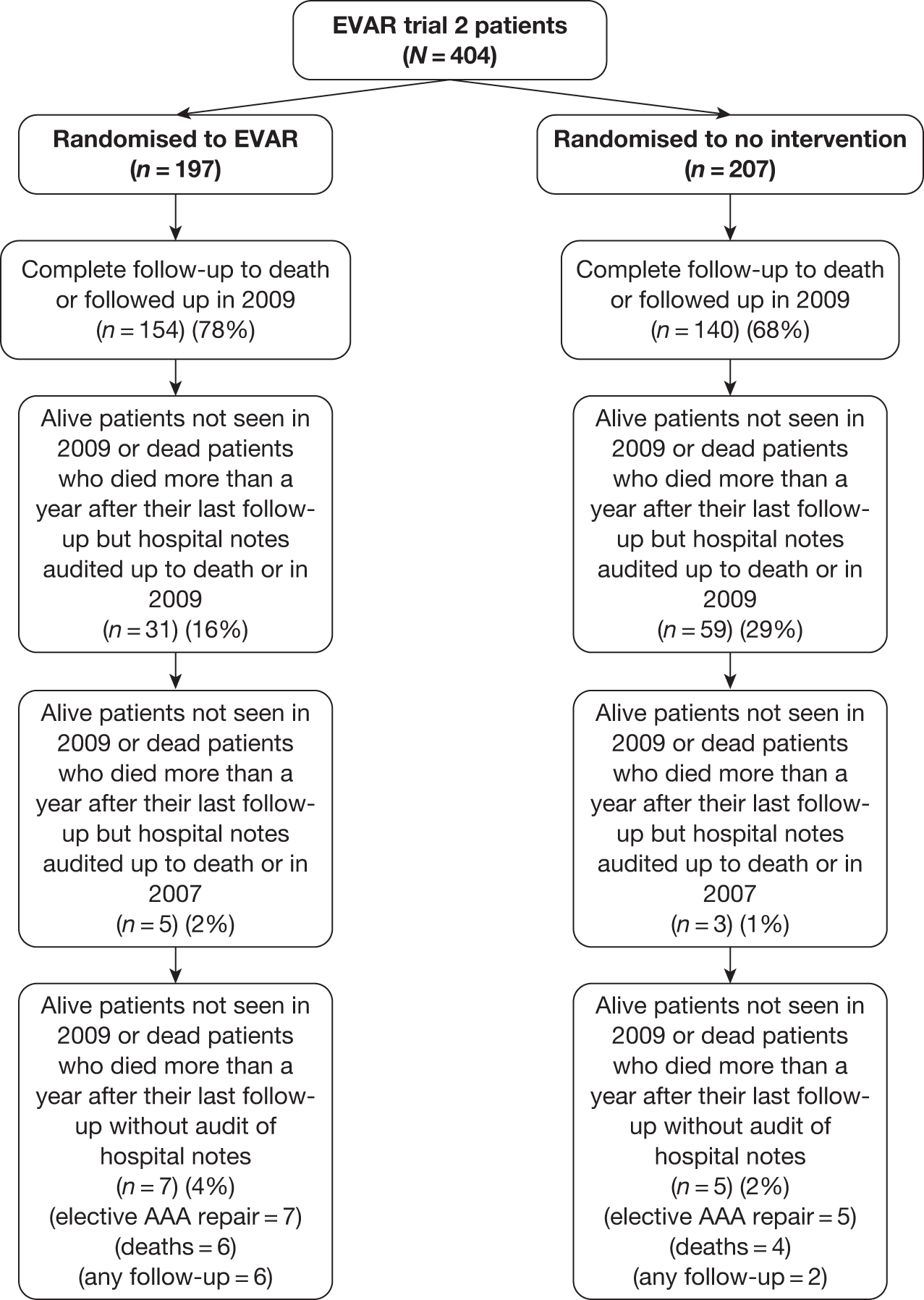

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 95/02/99. The contractual start date was in July 2005. The draft report began editorial review in December 2010 and was accepted for publication in May 2011. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

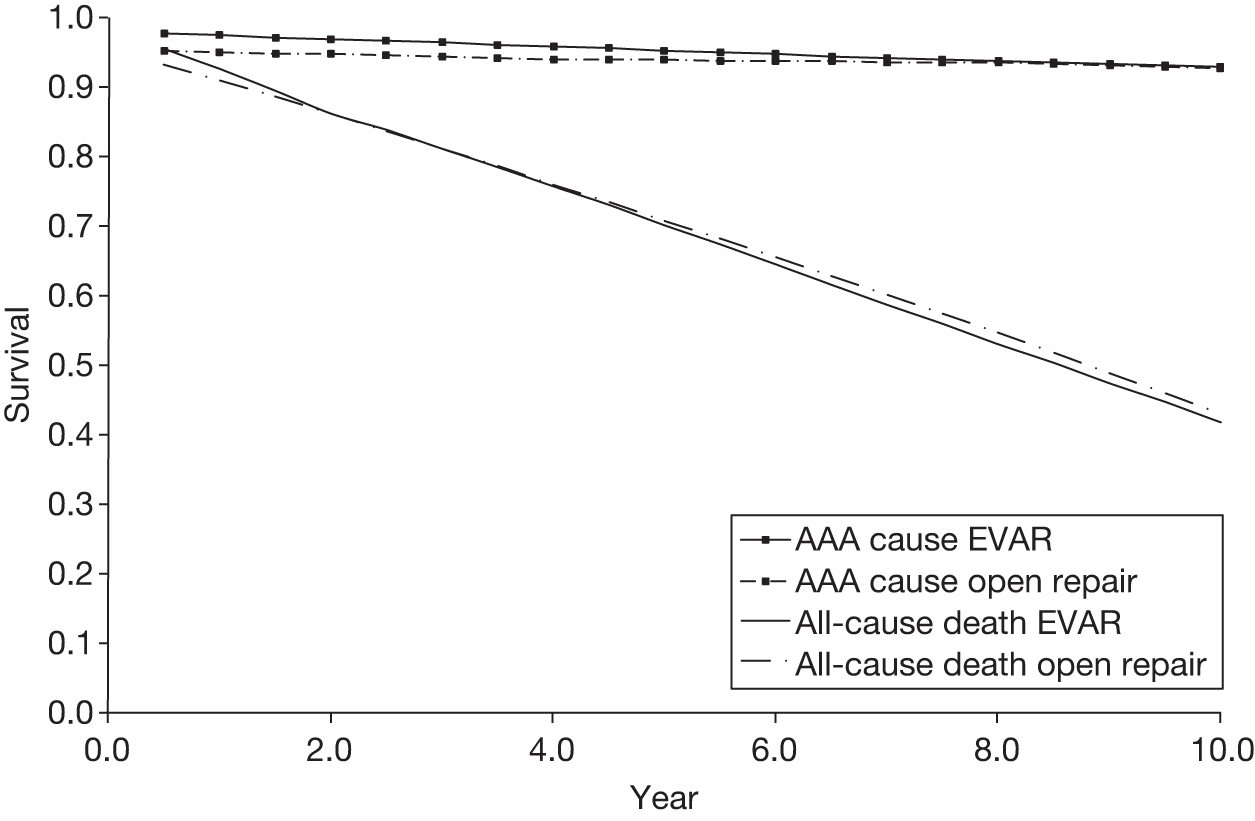

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2012. This work was produced by Brown et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

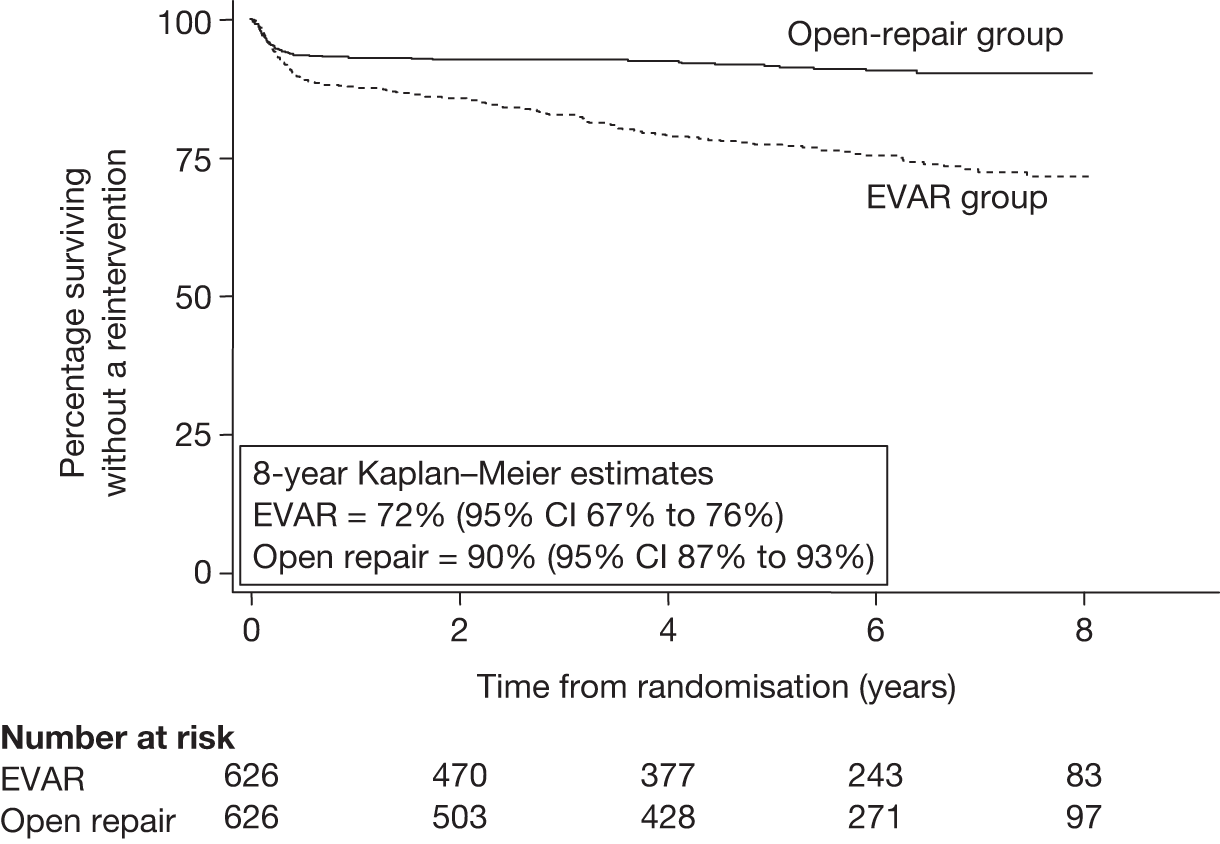

2012 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Abdominal aortic aneurysm

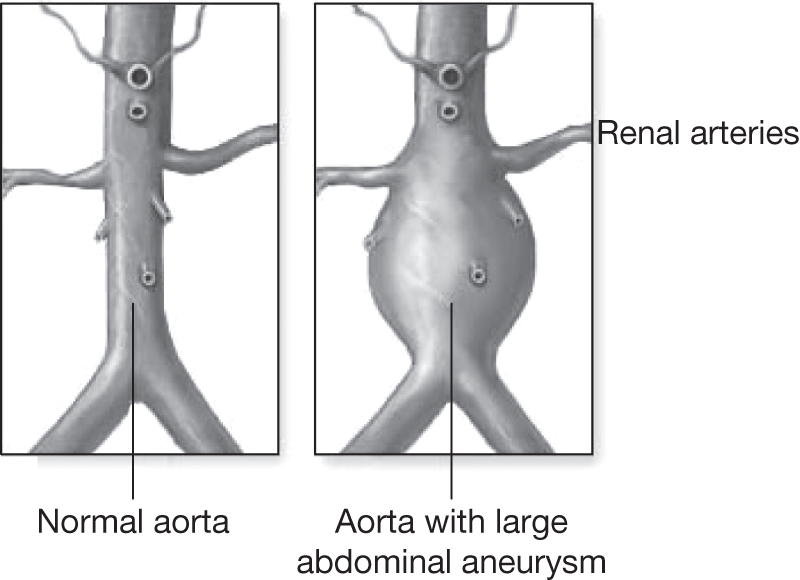

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a condition in which the abdominal segment of the aorta below the diaphragm becomes weakened and balloons outwards. Figure 1 shows a typically diseased aorta. This dilatation can continue for many years and in some cases it can lead to catastrophic rupture, which commonly results in death from internal haemorrhage unless emergency surgery can be performed in time to repair the damaged aorta. The aneurysmal dilatation of the aorta is commonly found below the renal arteries but expansion can also be found in the suprarenal segment and can sometimes extend upwards into the thoracic segment of the aorta above the diaphragm, and also downwards beyond the aortic bifurcation into the common iliac arteries.

FIGURE 1.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm.

The normal diameter of adult human abdominal aorta ranges from 1.0 to 2.5 cm at the level of the renal arteries and tapers as it approaches the aortic bifurcation. 1 Normal aortic diameters tend to be mainly dependent upon gender and body habitus, with narrower vessels in women and adults of smaller frame,2 although there is also some evidence to suggest variation between racial groups. 3–6 There have been a number of attempts to define the presence of an AAA7,8 but a common definition developed by McGregor et al. 9 classifies the abdominal aorta as aneurysmal if the diameter measures > 3.0 cm. Others have argued that a relative increase in diameter when compared with a proximal segment should be regarded as aneurysmal. 10,11 Currently, no universally accepted definition exists but, in clinical terms, if left untreated, AAAs have been known to grow to very large sizes, for example ≥ 15 cm, and in rare cases others have ruptured at more modest diameters as small as 3–4 cm.

Diagnosis of the condition is usually incidental as most aneurysms are asymptomatic. In some cases the aneurysm is known to become tender or lead to lower abdominal or back pain, and this can be exacerbated if the abdomen is pressed firmly. When the aneurysm becomes fairly large, AAA can be diagnosed by examining the abdomen of the supine patient and feeling for a large pulsatile mass, although diagnostic accuracy is reduced in obese subjects. Most AAAs are found when the patient is scanned for other conditions in the abdominal or pelvic areas. Given the asymptomatic nature of the disease, a considerable number of cases present as an emergency following rupture, which is thought to have only a 10–20% survival rate. 12 This is predominantly because many patients die rapidly in the community and only about a half of cases make it to hospital, with even fewer surviving an emergency operation.

Once diagnosed, non-ruptured aneurysms can be repaired surgically as a planned procedure but the successful management of AAA patients depends on the clinician finding the correct balance between careful surveillance of the aneurysm diameter until it enlarges to a point at which the risk of rupture exceeds the risk of death from elective surgery. However, making these kinds of predictions for an individual patient is extremely difficult and there is currently no proven medical therapy for primary prevention, cure or even retardation of expansion of the aneurysm.

Epidemiology of abdominal aortic aneurysm

Abdominal aortic aneurysm predominantly presents in later life and occurs in at least 5% of men aged > 65 years. 13 Larger screening studies in men aged between 65 and 85 years have found similar figures ranging from 4.5% to 7.7%. 14–18 Age appears to be the strongest factor relating to development of the disease, with the prevalence in males starting at about 2.6% in those aged 60–64 years and increasing to 6% in those aged 65–74 years and 9% in men aged ≥ 75 years. 19 However, these rates do not apply to women as the condition is three to four times more common in men than in women. 6,20,21 The reasons for this are not fully understood but are thought possibly to relate to the same biological mechanisms that lead to the higher rate of atherosclerotic disease in men than in premenopausal women. Further research has shown that, although women are rarely diagnosed with AAA, those who are found to have one experience significantly higher rupture, growth and operative mortality rates than men,20,22–25 and one laboratory study has shown a reduction in the tensile strength of female aortic tissue relative to male. 26

The prevalence of AAA is thought to differ between countries and racial groups, with the Asian subcontinent population exhibiting the lowest prevalence and Caucasians the highest. 27,28 One study from the USA suggests that although AAA is more prevalent in the white population, Afro-Americans with AAA show a higher mortality from the condition than Caucasians when adjusted for age. 5 Other studies have shown that the Asian population who tend to be of smaller stature than western Caucasians may be disadvantaged when being considered for endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR), as the presence of smaller vessels is not conducive to easy deployment or long-term durability of the grafts. 29,30

The incidence of AAA presenting as elective or emergency cases has also been shown to have increased in England and Wales31 over the last 40 years, a trend that, it has been concluded, cannot be fully explained by improvements in scanning modalities and training in elective surgical techniques. Other research from Sweden corroborates this finding by demonstrating a marked increase in the incidence of ruptured AAA from 5.6 to 10.6 per 100,000 person-years between 1971 and 2004 despite a 100% increase in the number of elective repairs. 32 Similar trends have also been shown in the USA5 and Australia. 33

Possibly the most important environmental factor associated with the development and prognosis of AAA is smoking. A number of studies have demonstrated a strong relationship between smoking and the development of an AAA, and this strength of association is even higher than that found between smoking and cardiovascular disease. 34–38 The odds ratio (OR) between smokers and non-smokers for development of at least a 4.0-cm aneurysm has been measured to be as high as 5.57 [95% confidence interval (CI) 4.24 to 7.31]. 39 Furthermore, once the AAA has been diagnosed, smoking has been shown to increase the rate of expansion of the AAA as well as the risk of rupture. 40,41 There is also some evidence of a dose-related effect as development of AAA has been shown to be significantly positively associated with the number of years of smoking as well as significantly negatively associated with the number of years after smoking cessation. 35 These are all strong arguments for encouraging the cessation of smoking.

A host of other risk factors such as greater height, high cholesterol, hypertension and poor lung function have been suggested to increase the risk of AAA development, but not all have not demonstrated consistent results in other cohorts. 39,42,43 Another notable observation is that patients with diabetes appear to have a reduced incidence of AAA,39,44 and this is particularly interesting given that the prevalence of diabetes is higher in the Asian population relative to the Caucasian population. 45 Also, diabetes has been associated with a slower AAA growth rate. 40

Management and treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysm

Detection, screening and surveillance

Most conventional scanning modalities can be used for the diagnosis and follow-up of AAA; however, the most common methods are computerised tomography (CT) or B-mode ultrasound scanning. In recent years duplex ultrasound (B-mode with colour flow imaging) has become the main imaging choice for surveillance of the aneurysm, but many aneurysms are still detected incidentally on CT scan. Although there is good correlation between AAA diameters measured by duplex and CT, there is not good agreement, and differences in sizes have been estimated to be as large as 5 mm between modalities. 46,47 Over the last 10 years, the development of EVAR has meant that CT scans have become essential for the planning of the EVAR procedure and many argue that this should remain the optimal method for post-EVAR surveillance despite the increase in radiation dosage to the patient. Increased radiation exposure and use of potentially nephrotoxic contrast agents have prompted some to move to duplex ultrasound surveillance after EVAR, but there is little evidence to justify this practice, and the sensitivity and specificity when compared with CT have been shown to be suboptimal. 48 Magnetic resonance imaging is also possible but tends to be limited for post-EVAR surveillance, as a number of endovascular stents contain ferrous material. Aortography is also used but this is felt to be too invasive for routine use and tends to be selected in an emergency situation or if postoperative graft problems are suspected.

Over the last 20 years, the efficacy and feasibility of aneurysm screening has gained ground. In the UK, a national screening programme has been instigated for AAA in 65-year-old men. At present, this is being undertaken in a number of pilot centres in England and it is anticipated that a full national programme will be rolled out over the next 5–10 years. Initially, the feasibility of such a programme was demonstrated by the Gloucester Aneurysm Screening Programme (GASP), which has been running in the UK since 1990. 49,50 Subsequently, good evidence became available to support the implementation of a national screening programme for AAA, with two UK randomised trials demonstrating both clinical benefit (significant reduction in aneurysm-related mortality) as well as good cost-effectiveness with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) falling well within the limits of affordability recommended by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). 14,51–54 Similar clinical benefits and cost-effectiveness conclusions were drawn from another randomised screening trial based in Denmark. 55,56 In Western Australia, a further randomised trial also demonstrated clinical benefit but concluded that a national programme might be justified only in those who are at higher risk of developing an aneurysm, for example those with a family history of AAA or heavy smoking history. 17,57 A systematic review of the evidence for AAA screening was published in 200558 and a Cochrane review of all randomised trials was published in 2007. 59 Although there was some variation in the prevalence of AAA seen between studies, an overall clinical benefit was evident with a pooled 40% reduction in aneurysm-related mortality in the screened group. 59 Despite this, there is little evidence to suggest a reduction in all-cause mortality in any of the studies. In practical terms, aneurysms can be detected with good sensitivity and specificity using small portable ultrasound equipment in local general practitioner (GP) clinics. 60,61 Other research has shown that the optimal age for screening should be 65 years in men, as the probability of developing an aneurysm later in life is very low in aortas of normal size at this age. 19 There is come controversy over aneurysm screening in women, who have a three- to fourfold lower incidence of aortic aneurysm than men. Randomised evidence on aneurysm screening in women does not support the implementation of a national programme. 59,62 However, some have argued that screening might be cost-effective in women over time. 63

Medical therapy

A number of medical therapies have been proposed for the treatment of AAA but none has provided any consistent or sufficiently powerful evidence for the prevention or treatment of the disease. Given that a number of studies have found that hypertension is associated with the development of AAA, it is not surprising that antihypertensive therapies have been postulated as a potential medication for AAA. 64 One of the earliest groups of drugs to be tested for any association with AAA growth or rupture were beta-blockers, but although laboratory models65,66 provided encouraging evidence of a beneficial effect this has not translated convincingly into the general AAA population,67 although some benefit has been seen in patients with Marfan syndrome. 68 Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are also thought to provide benefit to patients with AAA69–71 but there is little evidence on their relationship with rupture and growth rates,64,72 and there is some evidence to suggest that the use of ACE inhibitors may be harmful in these patients. 73,74 Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and, in particular, cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors, have also been suggested as an agent for reducing AAA growth rate75 but this finding has not been reproduced consistently in other patient series. 76 Given the inflammatory nature of AAA, a number of randomised trials have investigated the impact of antibiotics on progression of the disease and a few small studies have generated encouraging results; however, larger studies are required to determine whether real benefit can be shown and whether long-term antibiotic use can be tolerated by most patients. 77–79

Currently, some of the most compelling evidence points towards statins as a potential treatment, with AAA growth rates shown to be reduced in patients taking statins,76,80 as well as a significant reduction in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality if patients are treated with statins prior to non-cardiac vascular surgery. 81 The mechanism for these effects is not understood, particularly as lipids have not been shown to have any impact on the development or progression of aneurysmal disease. 40,82 One study investigating the effects of statins has already been closed prematurely as recruitment of a sufficient number of control patients not taking statins was unfeasible. 83 In the absence of evidence from randomised trials on the effectiveness of statins it is difficult to draw any strong conclusions and, given the multiple unexplained coincidental benefits that statins appear to offer, it is unlikely that such a trial will ever be performed, particularly in elderly patients with other comorbidities.

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the impact of various medical therapies on growth rates of AAA has demonstrated little strong evidence for reduction in growth rates across a range of pharmaceutical products, including beta-blockers, other antihypertensive therapies, antibiotics and anti-inflammatory agents, including statin use. 84 Statins were the only therapy that showed encouraging results, with a random effects meta-analysis pooled difference in growth rate of –2.97 mm/year (95% CI –5.83 to –0.11 mm/year) between patients prescribed statins and control subjects.

Thus, given the lack of any proven benefit to medical therapy, current treatment methods are limited to interventional procedures, and at present three are available for the treatment of AAA: open surgical, endovascular or laparoscopic repair treatment.

Open surgical repair

This method is currently regarded as the standard surgical intervention for AAA and has been used since the early 1950s when Dubost et al. 85 presented the first case. The patient requires a general anaesthetic while a midline abdominal (or retroperitoneal) incision is made and the aneurysm is exposed. A clamp is fixed above the aneurysm, just below the renal arteries, and the aneurysmal sac is opened so that a synthetic piece of graft material, usually made from Dacron, can be sutured into place. The distal fixation is dependent upon the amount of aneurysmal disease and how far it extends beyond the aortic bifurcation. In most cases a straight tube graft is inserted, even if there is mild dilatation in the iliac system, but in some cases bifurcated or uni-iliac grafts are sutured beyond the aortic bifurcation. The old aneurysmal tissue is then loosely sewed back over the graft before surgical closure. The operation is regarded as a major procedure and carries a relatively high risk of mortality and morbidity, particularly in terms of cardiovascular end points.

However, elective repair is preferable to emergency repair, for which operative mortality rates have been estimated to range between 30% and 60%. 86–88 Many studies have estimated that the 30-day mortality of elective open repair and figures vary considerably within the UK and between countries. 89–94 Probably the most reliable source of unbiased data is randomised controlled trials (RCTs) but even here there is discrepancy between the UK Small Aneurysm Trial (UKSAT), which quotes a 30-day mortality of 5.6%,95 and the US Aneurysm Detection And Management (ADAM) trial, which quotes 2.7%. 96 National figures for 30-day operative mortality in the UK have been shown to be as high as 12% in district hospitals,91 whereas other cohorts from single-centre vascular specialist centres have quoted very small risks of < 2%. 97,98 Much of this variation is thought to relate to study design and measurement within hospital- or population-based cohorts;99 however, a review combining results from 64 studies estimated an average mortality rate of 5.5%. 100 Surgical training, operator experience and hospital volume are thought to be important factors, but UK practice at present allows open aneurysm repair to be performed by general surgeons who are not necessarily specialists in vascular surgery. 101–105 The Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland quotes the risk of 30-day death rate as 5% in their patient information documents,106 but it is stressed that there is considerable variation among patients as well as among hospitals within the UK. The most recent publication by Aylin et al. 107 compared the in-hospital elective AAA repair mortality using a number of sources, including the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) database and the National Vascular Database (NVD), and found alarmingly high rates of 6.8% in the NVD group and 8.7% in the HES group.

Further difficulty lies in disentangling the influence of individual patient selection, which is also thought to be very important. In particular, patient fitness for general anaesthesia is an influential factor, principally in terms of cardiac and respiratory disease; however, renal function also appears to play an important role and is consistently included in the numerous risk scores that have been developed for prediction of postoperative death after AAA repair. 108–114

Following the open procedure, most patients require a relatively long period of convalescence, typically up to 3 months. Beyond this time, open repair is regarded as durable and the patient can be discharged without long-term follow-up, as the graft is expected to last for the remainder of the patient’s life. Nevertheless, there remains a small risk of other related complications, including incisional hernia, aortoenteric fistula, impotence, graft thrombosis, graft infection and, in rare cases, graft rupture. However, there is a suspicion that many complications may remain unreported, as demonstrated by a recent publication reporting Medicare data in the USA, which found the rate of laparotomy-related complications to be as high as 10% at 4 years. 115 Despite this, postoperative complications are thought to be infrequent and mandatory long-term follow-up is not felt to be necessary.

Endovascular aneurysm repair

In the early 1990s, a new endovascular method for correction of AAA emerged. Two independent endovascular pioneers, Volodos et al. in the Ukraine116 and Parodi et al. in Argentina,117 each developed a stent–graft for correction of the aneurysm in patients who were not thought to be fit enough for an open surgical repair. The method is less invasive than open repair, as it requires only two small incisions in the groin to expose the femoral arteries. The stent–graft system is then fed into the aorta via catheters and guidewires so that it can be positioned correctly above and below the aneurysmal segment of aorta. The location of the graft is imaged using radiological methods, with patients being exposed to relatively large doses of radiation and contrast agent. The fixation mechanism for the stent–graft is held within a removable sheath and, as this is pulled back, the fixation devices open and become lodged within the aortic wall. Some grafts use hooks and barbs to take hold of the aortic wall, whereas others use expandable stents that can be either self-expanding or require balloon angioplasty to ensure a good seal with the aortic wall.

Since the early 1990s, EVAR technology has developed intensely, with manufacturers becoming the main producers of stent–graft systems, and some would argue that for relatively simple anatomy the technology is now reaching a plateau. However, there are still anatomical constraints and not all patients are suited to the devices available on the market at present. Defining suitability for EVAR is a complex issue and is dependent on both manufacturer guidelines as well as individual clinician judgement. Numerous studies have shown varying degrees of suitability for EVAR, ranging from 25% to 75%;118–124 however, most studies struggle when trying to collect data for a reliable consecutive series of patients with AAA. Suitability for EVAR at the proximal end of the device is predominantly dependent on having an adequately long aortic neck between the top of the aneurysm and the bottom of the lowest renal artery as well as a neck that is no more than approximately 2–3 cm in diameter, depending on which graft manufacturer is selected. Other considerations include assessment of neck angulation, as well as the extent of thrombus or calcification in the section where the stent is to be deployed. Similar anatomical considerations are required in the distal segments of the iliac arteries, and the tortuosity of the vessels, as well as the minimum vessel diameter for access of the device, is also important. More recently, fenestrated and branched graft designs have become available for aortas with more challenging anatomy but these are expensive and do not reflect current standard EVAR practice. 125–127

Over the last 15 years, various manufacturers have developed a number of grafts, but all of these have required some form of technical revision and some have been withdrawn from the market due to high complication rates. 128 Given that EVAR is still a relatively young treatment modality, the long-term efficacy remains unknown and this has meant that most clinicians still monitor their patients following EVAR. At present, most patients are followed indefinitely until there is good evidence to justify discharge. There is considerable speculation about the best method of surveillance following EVAR, with some clinicians believing that duplex ultrasonography with a plain radiograph is sufficient, whereas others argue that CT scanning should remain compulsory until the long-term durability is known. 129,130

Many studies have reported the 30-day operative mortality of EVAR, and this appears to be lower than that reported for open repair. However, a recent meta-analysis of 163 studies has estimated a pooled rate of 3.3% (95% CI 2.9% to 3.6%), with wide variation between studies ranging from close to zero up to over 10%. 131 When compared with open surgical repair, there tends to be a relatively shorter convalescence following EVAR, with less need for intensive care or high-dependency unit (HDU) stays. 121 However, hospital costs can escalate later if reinterventions are required to correct any graft complications. The main disadvantage of EVAR is that the long-term durability of the grafts remains uncertain. Certainly the risks of leaks and other graft complications appear to be higher in patients undergoing EVAR treatment than in those patients undergoing open-repair treatment. 132

The first report on the use of EVAR in the emergency situation was published in 1994133 and, since then, certain specialist centres have reported promising results for operative mortality when compared with the 40–50% rates seen following open emergency repair. 134–139 However, the results from one small RCT that was forced to close early suggest that the benefit is marginal and generalisable only to haemodynamically stable patients, with logistical difficulties making the method difficult to offer in all cases. 140 The anatomical limitations of EVAR still exist in the emergency situation, although they tend to be less stringent, and there remains a need for rapid radiological assessment or CT scanning to determine suitability for the device and 24-hour radiological staff, which are not usually available in current routine practice. A number of other randomised trials are in progress, in particular the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA)-funded Immediate Management of the Patient with Rupture: Open Versus Endovascular repair (IMPROVE) trial, which started recruitment in 2009 and will be the largest trial (600 patients) comparing EVAR with open repair for ruptured AAA.

Laparoscopic repair

The method of laparoscopic aneurysm repair was first published in the early 1990s by Dion et al. 141 but has not penetrated the vascular surgical world to the same extent as EVAR. The technique requires a high degree of skill and, despite encouraging results with very low operative mortality,142 is still performed in only a few specialist centres. The work presented in this report does not include any research on laparoscopic repair and thus will not be detailed further.

Size threshold for repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm

Currently, there is clear agreement that very small aneurysms measuring < 4.0 cm in diameter do not require surgical intervention, as the risk of rupture has been shown to be very low and certainly < 1% per year. 143,144 Small aneurysms in the larger range of sizes, typically between 4.0 and 5.5 cm, three large multicentre randomised trials – one in the UK, one in the USA and another in Canada – were instigated to determine whether or not open surgical repair should be offered to patients with small aneurysms. 145,146 The Canadian trial was forced to close after recruitment of just 100 patients but the UKSAT and the ADAM trial subsequently met recruitment targets and have published both short- and long-term results. 95,96,145,147,148 Both studies concluded that for people with small AAAs measuring between 4.0 and 5.5 cm, regular ultrasound surveillance until the aneurysm reached 5.5 cm, became tender or grew fast (> 1.0 cm per year) was a safe and less expensive management policy than immediate elective surgery. One meta-analysis has combined the results from the UKSAT and the ADAM trial with pooled hazard ratios (HRs) for all-cause and AAA-related mortality of 1.01 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.32) and 0.78 (95% CI 0.56 to 1.10), respectively. 149 There is little evidence to suggest any detrimental impact on quality of life in patients under surveillance and a reduction in impotence was also seen in this group. 150 Despite the findings of these trials, there are still those who feel that repair of small AAA was justified,151 and one cost-effectiveness modelling analysis performed in the USA has inferred that surgery may be cost-effective in patients aged < 72 years with AAAs between 4.5 and 5.5 cm in diameter. 152 During the 1990s, the use of EVAR became increasingly popular and some argued that EVAR may be justified in small AAA. This speculation led to the instigation of two further trials – the European Comparison of surveillance vs Aortic Endografting for Small Aneurysm Repair (CAESAR) trial153 and the American Positive Impact of endoVascular Options for Treating Aneurysm earLy (PIVOTAL) trial154 – both of which were company-funded randomised trials comparing EVAR against surveillance in patients with small AAAs (4.0–5.5 cm). The results from these trials have been released recently with no evidence to support EVAR in small AAA. 155,156 Thus, current evidence suggests that intervention for the aneurysm may be delayed until the aneurysm reaches 5.5 cm, becomes tender or grows fast (> 1.0 cm per year).

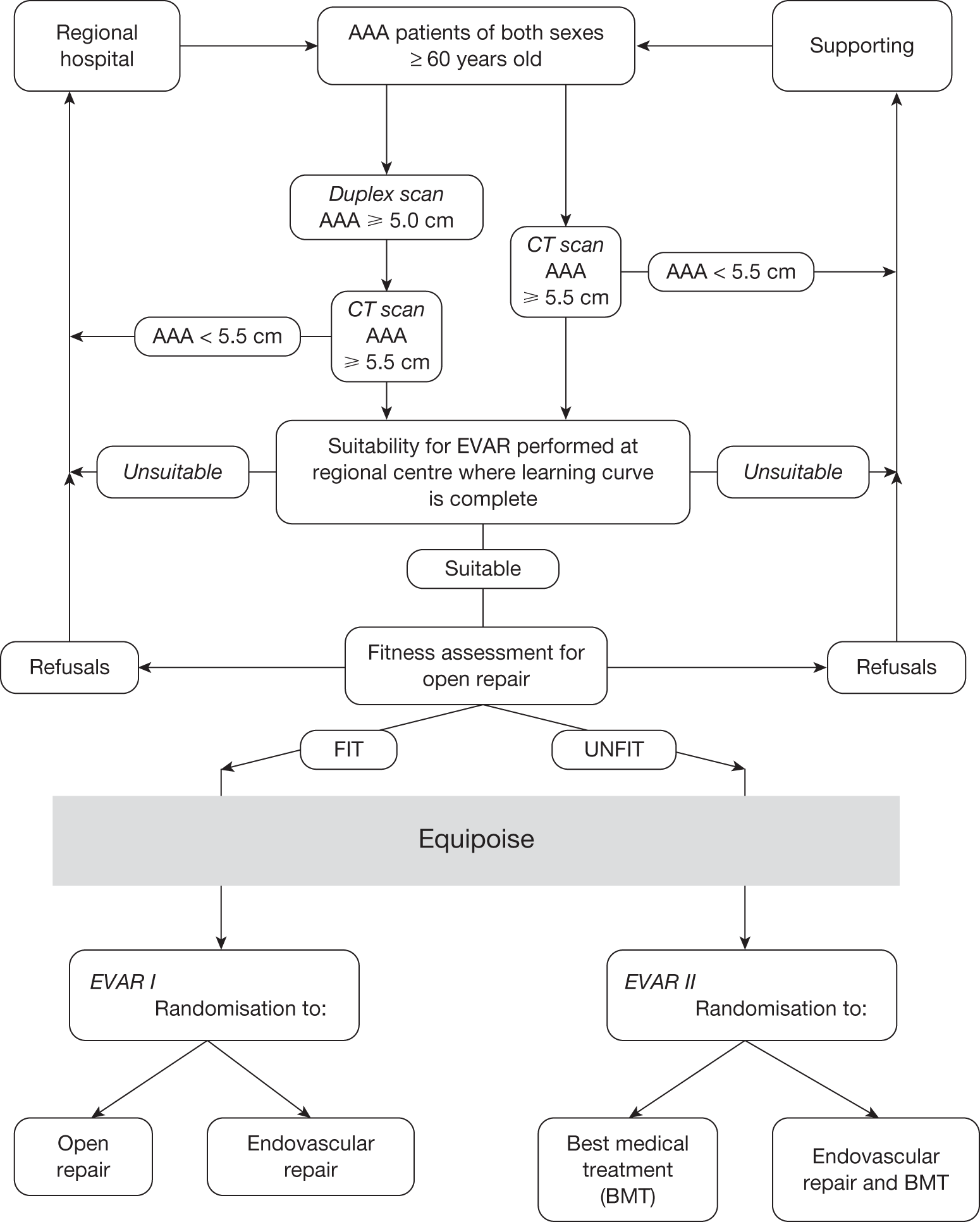

Current trials comparing treatments for large abdominal aortic aneurysm

The results of the trials in small aneurysms have provided evidence that small AAAs of < 5.5 cm can be monitored safely. The current debate relating to large aneurysms is, first, whether they should be treated with open or endovascular repair and, second, whether endovascular repair is justified in patients when open repair is not an option, usually on the grounds of poor anaesthetic fitness. A number of trials have been instigated to try and answer the first question but only one randomised trial (EVAR trial 2) has been set up to assess the role of EVAR in patients considered unfit for open repair. This report focuses on the results from the UK EVAR trials 1 and 2 but a brief summary of the other three trials follows, with Table 1 summarising all of the trials.

| EVAR trial 1 (UK) | DREAM trial (Netherlands) | ACE trial (France) | OVER trial (USA) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recruitment period | 1999–2004 | 2000–3 | 2003–8 | 2002–7 |

| Recruitment target | 900 | 400 | 600 | 900 |

| Final recruitment | 1252 | 351 | 306 | 881 |

| Age entry criteria | ≥ 60 years | Any | Any | Any |

| Gender entry criteria | Both | Both | Both | Mainly male |

| AAA diameter entry criteria | ≥ 5.5 cm | ≥ 5.0 cm | ≥ 5.0 cm for men | ≥ 5.0-cm AAA |

| ≥ 4.5 cm for women | ≥ 3.0-cm CIA | |||

| ≥ 4.5-cm AAA with fast growth | ||||

| Other entry criteria | None | Life expectancy > 2 years | Neck length > 15 mm | None |

| Neck angle < 60° |

The Dutch Randomised Endovascular Aneurysm Management (DREAM) trial

Soon after the EVAR trials began, a trial of similar protocol to EVAR trial 1 was started in the Netherlands and the trial methods have been published. 157 The target trial recruitment was 400 patients from 24 Dutch and four Belgian hospitals, but recruitment closed when only 351 patients had been randomised to receive either EVAR (n = 173) or open repair (n = 178). Trial entry criteria differed slightly from EVAR trial 1, with slightly smaller aneurysms (at least 5.0 cm) being eligible for inclusion. Operative mortality and longer-term results have been published. 158–160 Further data published on sexual dysfunction after each type of operation have shown that both treatments lead to some reduction in sexual function but this recovers more quickly following EVAR;161 however, this benefit is moderated somewhat by other data demonstrating a significant quality of life benefit in the open-repair group after 6 months. 162

The French Anévrisme de l’aorte abdominale, Chirurgie versus Endoprothèse (ACE) trial

This trial commenced in 2003 after experiencing significant bureaucratic start-up delays. 163 The trial struggled with recruitment, which was further hindered by the publication of favourable 30-day mortality results for EVAR in both EVAR trial 1 and the DREAM trial in 2004. EVAR funding issues continued to hamper recruitment, which eventually closed in 2008 when just over 300 patients had been recruited. In contrast to the three other trials there was no difference in operative mortality between the open and the endovascular repair arms, 0.6% versus 1.2%, respectively. 164

Open Versus Endovascular Repair (OVER) trial

This US trial recruited patients across 43 centres between October 2002 and 2008. Patients who were considered fit for a general anaesthetic with AAAs measuring at least 5.0 cm and who were anatomically suitable for EVAR were recruited from the Veterans Affairs Program and randomised to receive either EVAR (n = 444) or open repair (n = 437). The protocol is similar to the EVAR and DREAM trials, although the patients are predominantly male, marginally younger and have smaller aneurysms. Operative mortality and 2-year outcomes were published in 2009,165 and long-term results are due for release in 2013.

Registry data

Registries act as an important and necessary complement to RCTs and this is certainly the case with developing technologies such as EVAR. Numerous registries have been set up around the world, usually to monitor national case load and outcome; however, there is enthusiasm to collaborate on an international registry that has recently tested the practicalities of managing such an extensive database by starting with AAA repairs. 166 In the UK, generic national registries for all treatments include the HES database, as well as the Dr Foster registry, which provides data on clinicians and hospitals across the UK. In 2000, The Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland instigated the NVD, which is specific to vascular surgery, with reports available online. 167 There are also a number of registries that are exclusively for endovascular repair of AAA. The Registry for Endovascular Treatment of Aneurysms (RETA) was based in Sheffield, overseen by the Registry Committee of the Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland. It began collating data on endovascular repairs performed in the UK in 1996 and reports were available via the Vascular Society website. Follow-up has now closed for this registry but the results have been published widely and the organisers were very involved in the setting up of the UK EVAR trials. 168–170 One of the largest registries that started in 1996 is The EUROpean collaborators on Stent–graft Techniques for abdominal aortic Aneurysm Repair (EUROSTAR), which collates EVAR data from over 20 European countries and has been used extensively as a data source for many publications. 171,172 The EUROSTAR Secretariat is based in Eindhoven, the Netherlands, and data on over 6000 EVAR cases have been collected.

Other international registries include the commercially funded Lifeline registry in the USA, which has been running since 1998 and concentrates on pooling the data from trials on different manufactured EVAR devices, but it also holds data on corresponding open surgical controls. 173–175 In Australia in 1999, the Medical Services Advisory Committee (MSAC) and the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing recommended that a registry, rather than a RCT, should be used to monitor the impact of endovascular repair in their country. This is managed at present by the Australian Safety and Efficacy Register of New Interventional Procedures–Surgical (ASERNIP-S) and, to date, just under 1000 cases have been registered, with regular data reports available on the internet. 176

Although these registries are very helpful in providing summary data and preliminary results about the performance of hospitals, surgeons and types of procedure, none of them is mandatory and selection bias is a common problem with registry data. The reliability of the data is often further compromised by insufficient funding, which can lead to poor data collection and reduced enthusiasm of the participants to submit new cases or follow up old ones. Despite validation of the databases, none have been able to document all cases of interest, and a recent audit of the NVD reported that only about a half of all vascular cases have been submitted. 107 It has also been suggested that missing cases tend not to be missing at random, with the worst outcome data often excluded. 177 For these reasons, registries are not able to answer all the pertinent questions relating to treatments but, in combination with well-conducted RCTs, are likely to provide the best evidence for making public health decisions.

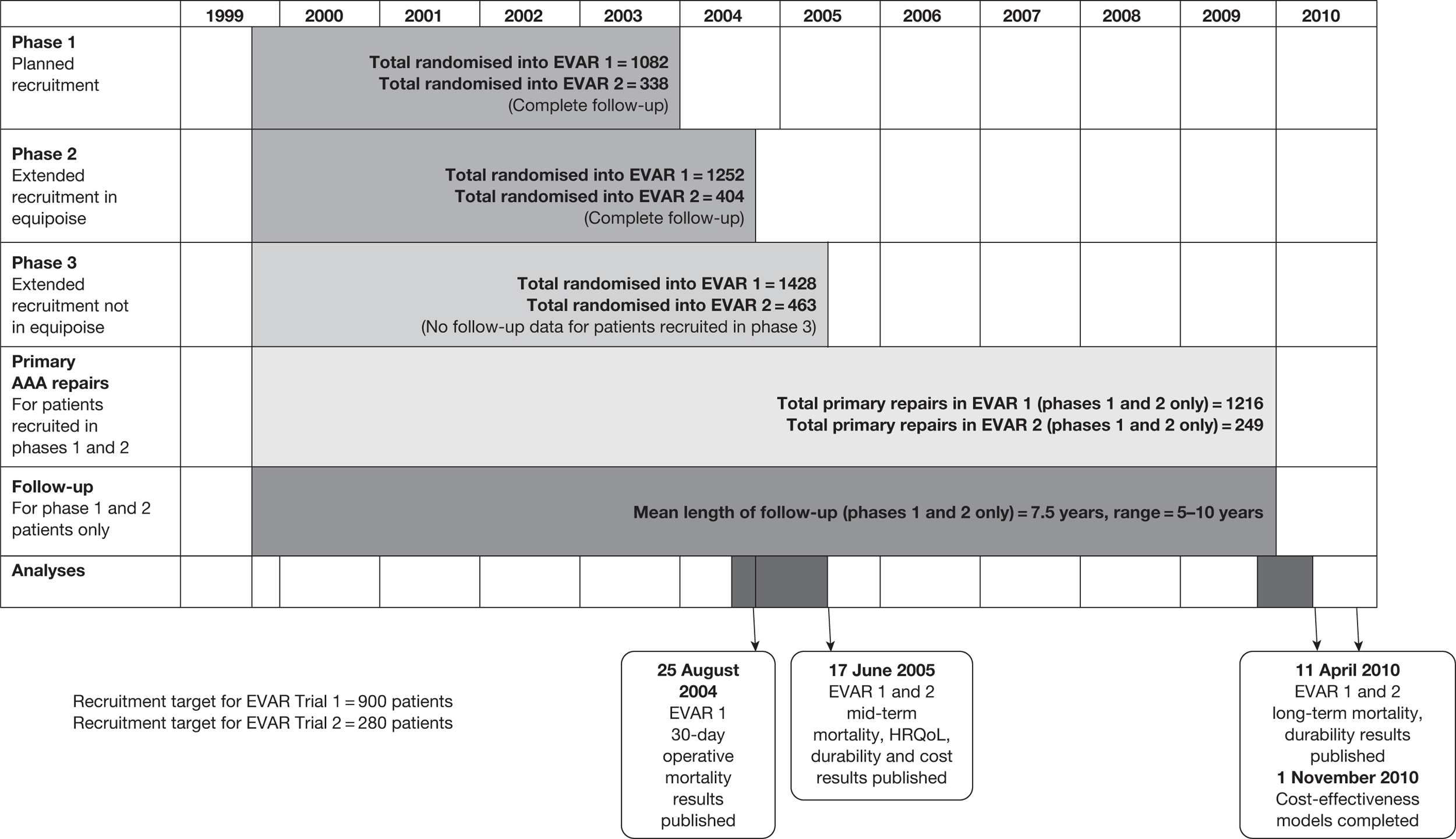

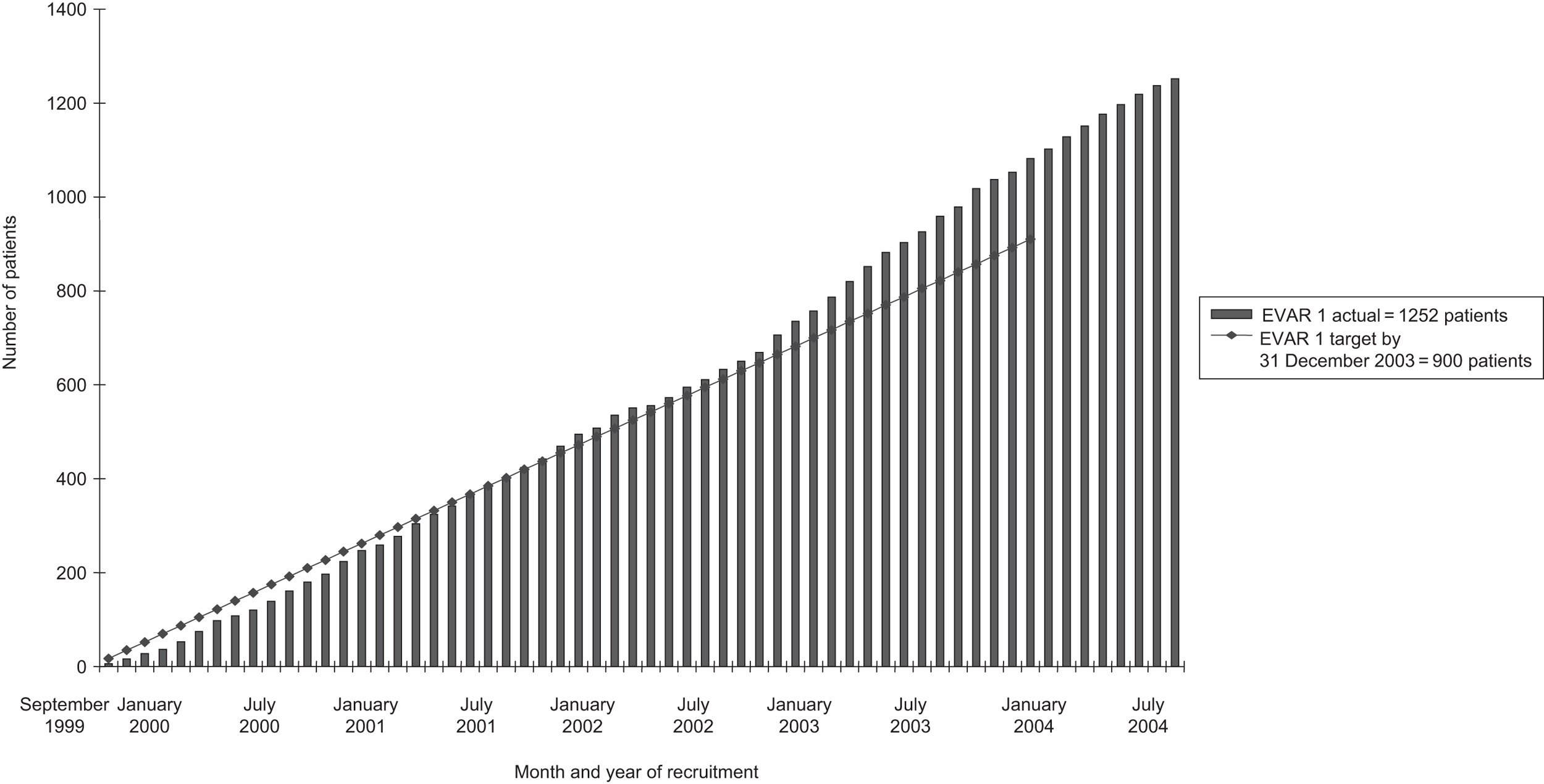

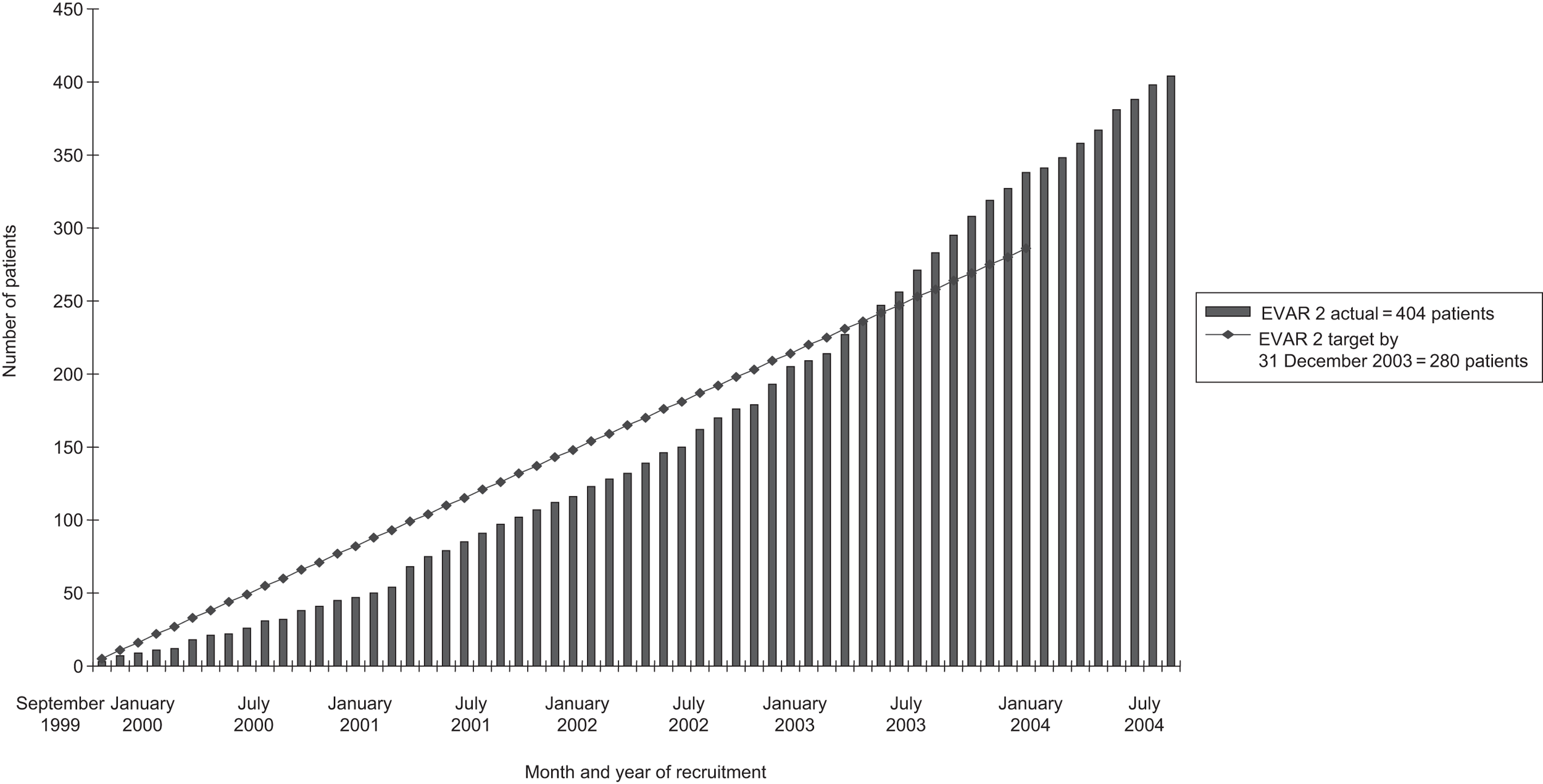

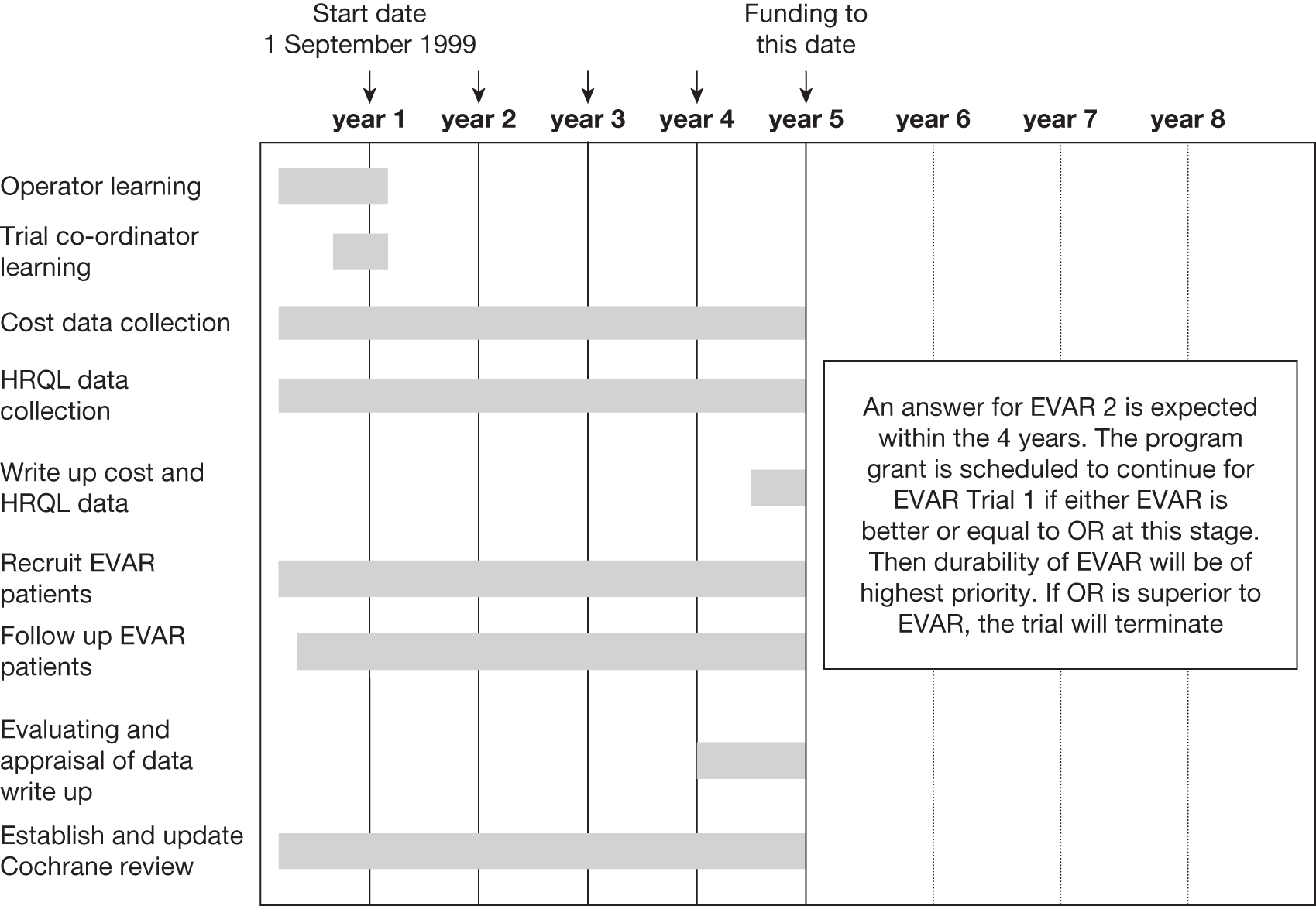

Objectives of the UK EVAR trials

In 1996, the Department of Health issued a call for research into the efficacy of EVAR. This was followed by a number of years of consultation on study design and ethical issues, and in July 1999 the UK EVAR trials were commissioned by the NHS Research and Development Health Technology Assessment Programme, now renamed as the NIHR Health Technology Assessment programme. Initially, the trials were funded for 4 years, from July 1999 to 2003. A 2-year extension was granted to ensure that recruitment targets were met and subsequently a long-term follow-up grant was awarded for a further 5 years of follow-up until July 2010. The trial objectives were to assess the safety and efficacy of EVAR against current standard treatment in the management of large AAAs measuring at least 5.5 cm in diameter according to a CT scan. Two trials were instigated: EVAR trial 1 would compare EVAR against open repair in patients who were considered fit and suitable for both procedures and EVAR trial 2 would compare EVAR against no intervention for patients who were considered suitable for EVAR but unfit for open repair. The primary outcome was mortality for both trials with secondary outcomes of graft-related complications and reinterventions as well as health-related quality of life (HRQoL), adverse events, renal function, costs and cost-effectiveness.

Chapter 2 Methods for UK EVAR trials

Organisational structure of the trials and relevant committees

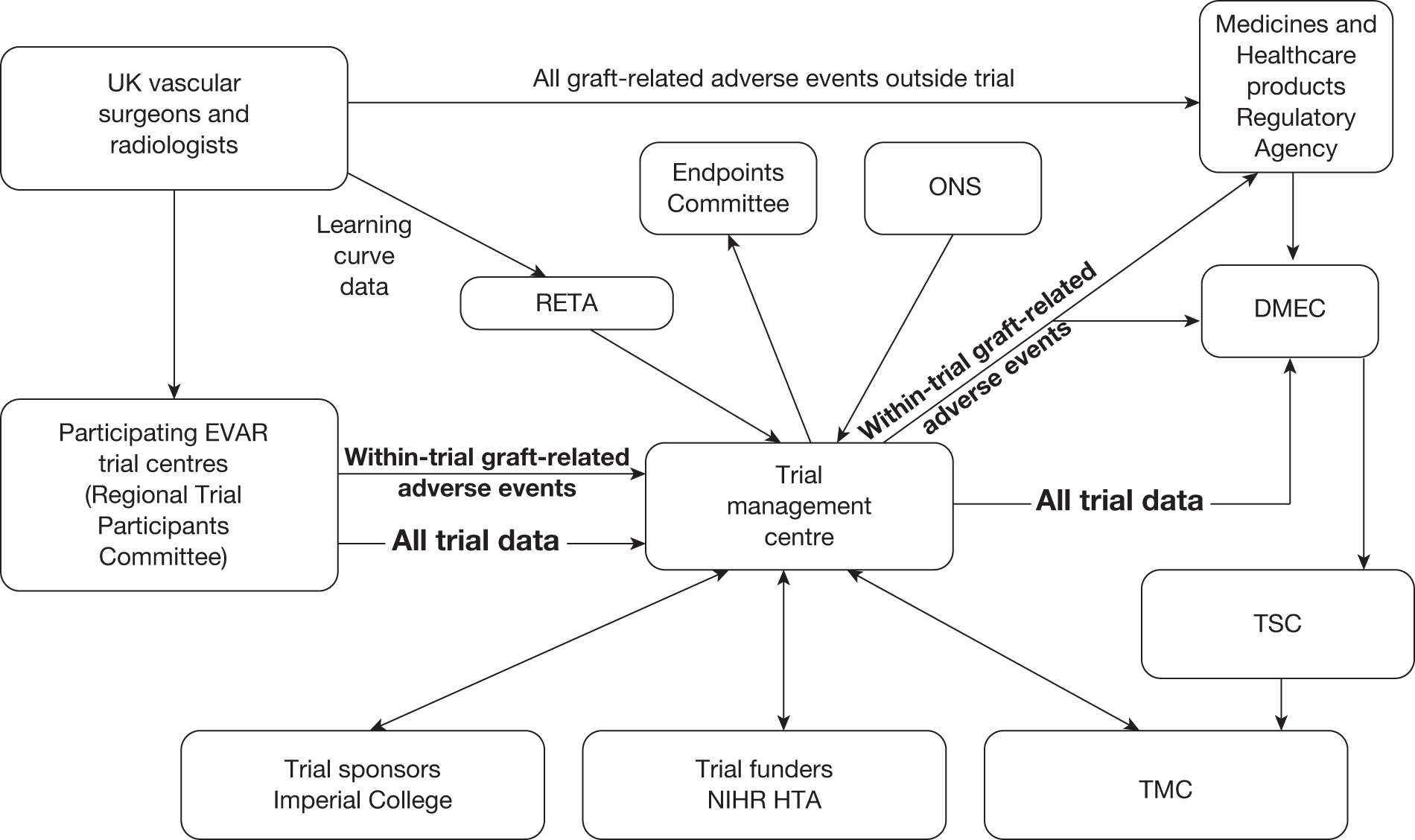

The trials are a joint collaboration of many surgeons, radiologists, clinical trials specialists and vascular health professionals. A full list of trial participants is provided in Appendix 1. The trials were managed centrally by the principal investigator (Professor Roger Greenhalgh), the trial manager (Dr Louise Brown) and Professor Janet Powell (co-applicant), who are based at the Charing Cross Hospital site of Imperial College London. Statistical expertise was provided by Professor Simon Thompson, Director of the Medical Research Council Biostatistics Unit in Cambridge, and costs and cost-effectiveness expertise were provided by Professor Mark Sculpher and Mr David Epstein from the University or York, with input from Professor Martin Buxton from the Centre for Health Economics at the University of Brunel. Figure 2 presents the structure of the trial committees in relation to the sponsor and regulatory bodies. The minutes of all of the committee meetings are archived at the central trial office. Dates of the meetings are provided in Appendix 2. The protocol is provided in Appendix 3.

FIGURE 2.

Structure of EVAR trial committees.

Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee

We are indebted to the late Professor PA Poole-Wilson (Professor of Cardiology, National Heart & Lung Institute, Imperial College London), who chaired this committee on behalf of the trials. Membership included two representatives of The Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland, namely Professor CV Ruckley (Edinburgh) and Mr WB Campbell (Exeter) and also two representatives of The British Society of Interventional Radiology (BSIR), namely Dr MRE Dean (Shrewsbury) and Dr MST Ruttley (Cardiff), as agreed with their councils. Dr EC Coles (Cardiff) acted as the statistical representative for the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC). Data on trial progress as well as mortality results at prespecified time points were provided to DMEC by the trial manager and audit of these data was confidential and never disclosed outside the committee. The DMEC communicated with the Trial Steering Committee (TSC).

Trial Steering Committee

This was chaired by Professor Richard Lilford (University of Birmingham) and included Roger Greenhalgh for the applicants and Trial Management Committee (TMC), as well as surgical and radiological input supplied by Professor Sir Peter Bell (Leicester) and Dr Simon Whitaker (Nottingham). The role of the committee was to liaise between the DMEC and TMC and oversee any issues relating to the progress of the trials or needs for additional funding.

Trial Management Committee

This was concerned with the day-to-day running of the EVAR trials and related to both the DMEC and TSC committees. It was chaired by Roger Greenhalgh and included Simon Thompson (statistics), Janet Powell (vascular biology), Ian Russell (HRQoL), Jonathan Beard (RETA), Peter Harris (EUROSTAR), John Rose (interventional radiology) and Martin Buxton (costs). During the course of the trial, Ian Russell moved to another institution and his role was replaced by Mark Sculpher and his colleague David Epstein from the University of York, who collaborated with Martin Buxton on the cost and cost-effectiveness issues relating to the trials. Louise Brown (Trial Manager) attended all meetings to present on trial progress and any problematic issues.

Regional Trial Participants Committee

This included a surgical and radiological representative as well as a co-ordinator from each participating centre and was convened at the request of trial centres or the trial management centre whenever the need arose, but usually the members met at the annual meetings of The Vascular Society and BSIR to update participants on trial progress or obtain feedback on any pragmatic running issues.

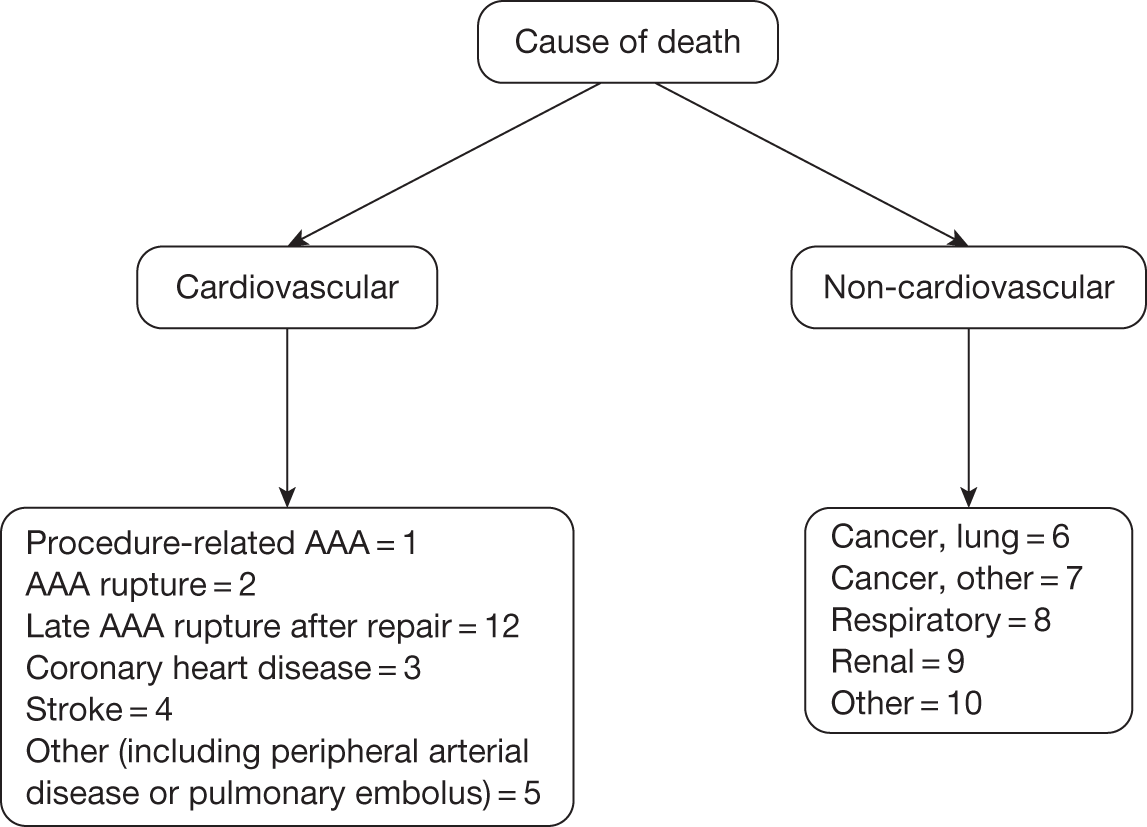

Endpoints Committee

This committee was chaired by Professor Janet Powell and consisted of an independent vascular surgeon who was not participating in trial recruitment (Professor Alison Halliday) and a consultant cardiologist (Dr Simon Gibbs). All death certificates were centrally coded at the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and these were reviewed by this committee in relation to any aneurysm-related procedures. The committee were blinded to randomised group but all available data relating to the death and a primary underlying cause of death were classified according to the groupings presented in Figure 3, where death codes 1, 2 and 12 were classified as aneurysm related. Aneurysm-related deaths were defined as all deaths occurring within 30 days of the primary AAA repair or any reintervention for a graft-related complication unless over-ruled by post-mortem findings or a separate procedure (unrelated to the AAA) that took place between the aneurysm intervention and death (code 1); all deaths from rupture of an unrepaired AAA (code 2) and all deaths from rupture of a repaired AAA, usually endograft rupture (code 12). In addition, late complications of AAA repair, such as aortoduodenal fistula or bowel obstruction, were recorded as procedure-related deaths (code 1).

FIGURE 3.

Classification of deaths codes assigned by the Endpoints Committee.

Learning curve and eligibility of participating centres

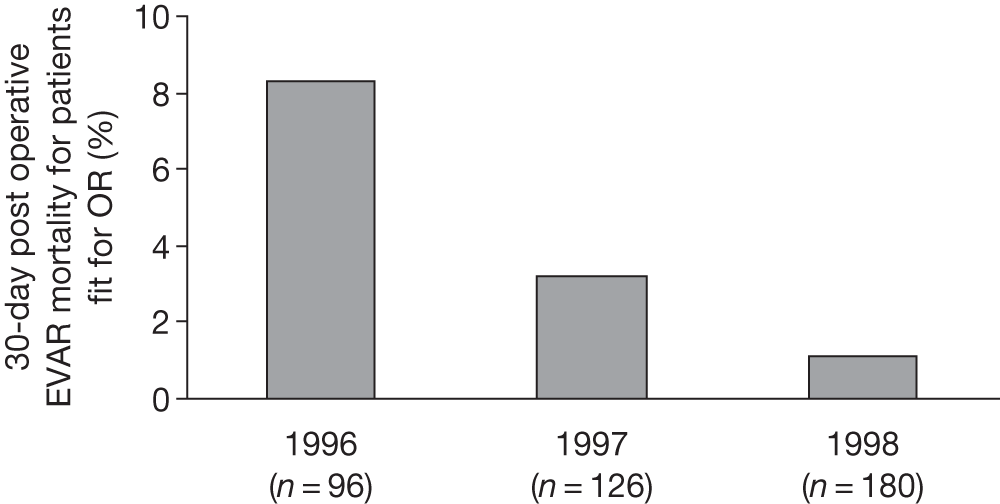

The setting up of the trials used invaluable data provided by the two main registries that had been running since 1996 and monitoring the performance of EVAR in the UK and the rest of Europe, namely the RETA and the EUROSTAR collaboration. There was representation from both of these registries on the EVAR TMC.

The UK Registry for Endovascular Treatment of Aneurysms

The national RETA registry, based at the Northern General Hospital in Sheffield, was initiated in January 1996 to audit ‘in-house’ and commercially available EVAR systems deployed within the UK. Annual audits were conducted and reports made available to the EVAR TMC, principally to be advised when centres were trained. As the EVAR technique was felt to be highly operator and hospital dependent, it was felt that a learning curve of training should be established to ensure that basic expertise had been acquired by the operators before EVAR could compete realistically with open repair as part of a trial comparison. Four specialist vascular centres were nominated as training hospitals to offer expertise and support in getting other hospitals through this learning curve, namely The Queens Medical Centre in Nottingham, The Royal Liverpool University Hospital, The Freeman Hospital in Newcastle and Leicester Royal Infirmary. Thus, the EVAR TMC met regularly to monitor progress of the trials and demanded that each centre had performed at least 20 EVAR procedures according to RETA before they were able to participate in the trials. It was also felt strongly that endovascular repair would achieve the best results if it was regarded as a multidisciplinary procedure with good collaboration between vascular surgeons and interventional radiologists. Therefore, each centre was required to nominate a vascular surgeon, interventional radiologist and trial co-ordinator as trial participants for their hospital. At the start of the trials in 1999, only 13 centres were eligible for participation in the trials but during the 5 years of recruitment a further 28 centres met the eligibility criteria. However, although 41 centres were eligible, only 38 centres actually entered patients into the trials before recruitment closed in August 2004.

EUROpean collaborators on Stent–graft Techniques for abdominal aortic Aneurysm Repair (EUROSTAR)

The EUROSTAR project was launched in 1996 to audit prospectively the performance of EVAR across 14 European countries. 171 At the start of the EVAR trials, a long-term durability analysis of EVAR (up to 4 years of follow-up) was performed on 2464 patients from the EUROSTAR registry and this demonstrated a 1% annual rupture rate for EVAR devices deployed in small and large aneurysms across Europe. 178 A similar rupture rate had been observed during surveillance of patients randomised in the UKSAT,179 and although these cohorts of patients were quite different there was concern that EVAR may do little to improve upon the natural history of AAA. Subsequent reports from EUROSTAR and other EVAR series have not provided any evidence of a substantial reduction in this rupture rate and there is concern that the long-term rupture rate may be even higher. 180,181

The role of the UK Small Aneurysm Trial (UKSAT)

The results of the UKSAT have been reported in a number of publications over the last 10 years, with the final statement on the role of early elective open repair in small AAA being published recently. 148 This trial was instrumental in defining the aneurysm diameter for inclusion in the EVAR trials, as it had shown that aneurysms could be safely monitored until they grew to 5.5 cm, when intervention could be considered. The trial showed that although there was a slight increase in the 30-day operative mortality for patients who underwent elective or emergency surgery later on in the surveillance group (7.2%), this increase was not statistically significantly different from that seen in patients who went for immediate elective surgery soon after randomisation into the trial (5.5%), χ2 (p-value = 0.28). Further corroborating evidence has also come from the ADAM96 trial and thus the aneurysm diameter for inclusion in the trials was set at 5.5 cm, although the measurement modality had switched from ultrasonography in the UKSAT to CT scan in the EVAR trials.

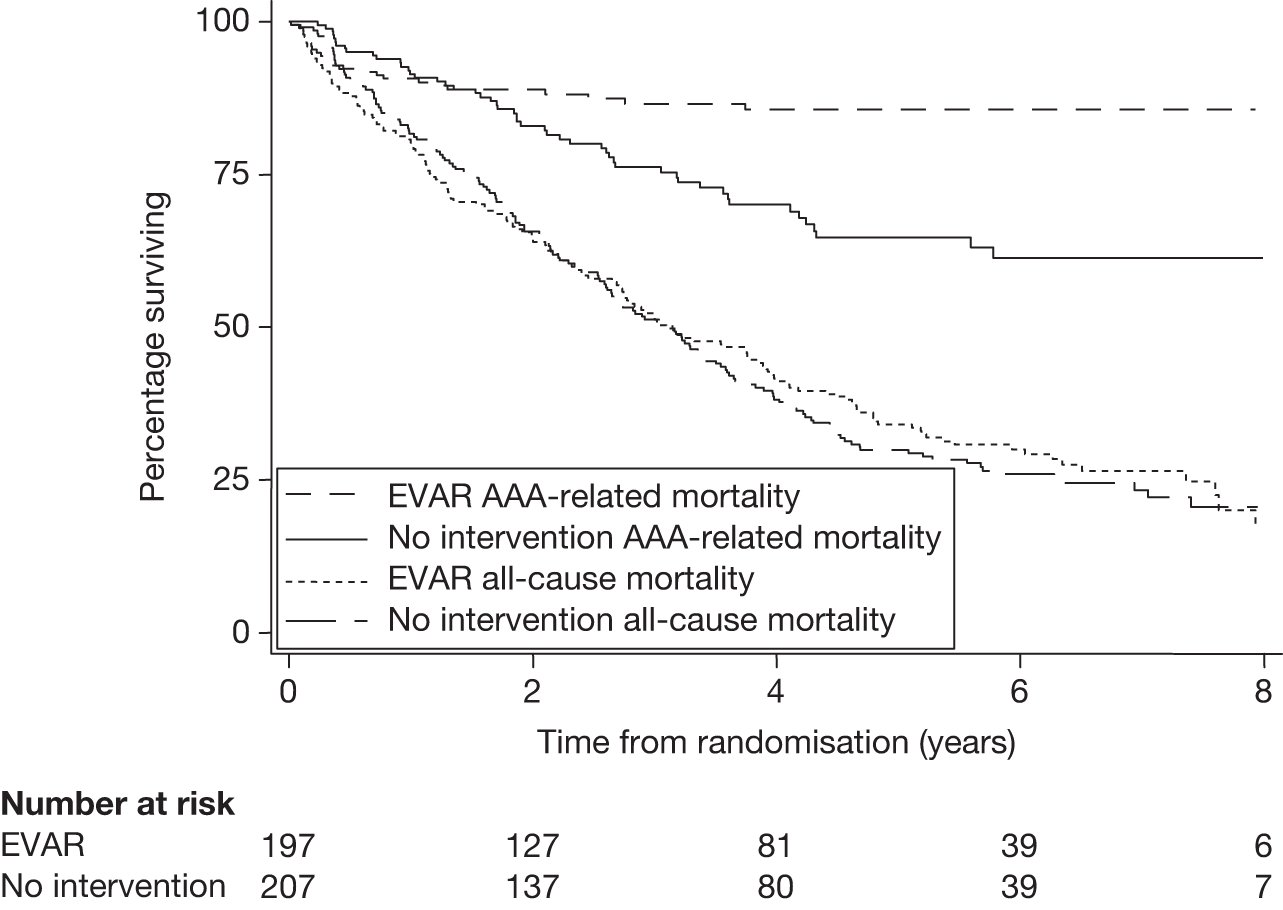

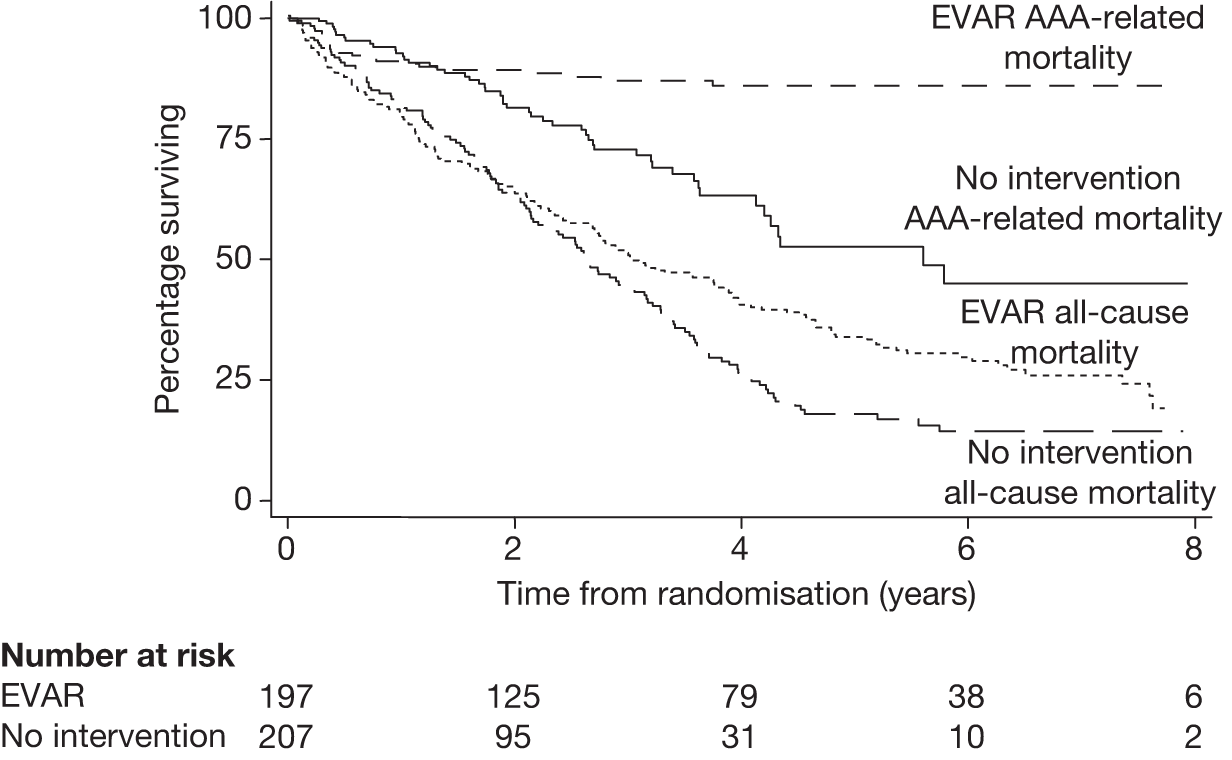

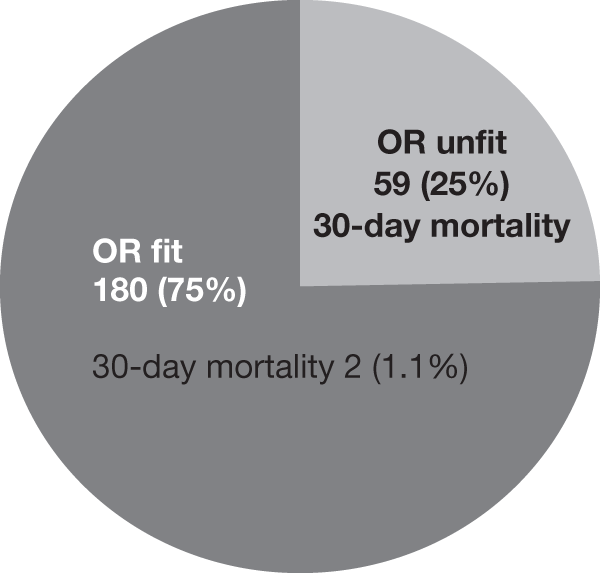

The need for two separate trials: EVAR trials 1 and 2

Endovascular repair was originally intended for use in patients who were regarded as too unfit for a conventional open procedure but, as the technology advanced, clinicians started offering it to fitter patients as the use of hospital facilities and the length of postoperative recovery seemed to be much improved over the conventional open operation. By the time the EVAR trials began in 1999 it was estimated that approximately 75% of patients undergoing EVAR were fit, whereas the remaining 25% were considered unfit for an open repair. Consequently, it was thought appropriate to pose two separate questions: first, whether or not EVAR was at least as good as open repair in patients considered fit for an open repair, and, second, whether or not EVAR with best medical therapy offered any benefit over best medical therapy alone in patients considered unfit for an open repair. Unfortunately, by the time EVAR trial 2 reported in 2005, it was clear that best medical therapy had not been implemented very successfully, with only 56% of patients on aspirin and 39% on a statin. Thus, it was decided that the description ‘EVAR versus no intervention’ was more appropriate for the EVAR trial 2 comparison.

Outcome measures

The primary end point for both trials was mortality, which included assessment of all-cause, aneurysm-related and 30-day operative mortalities.

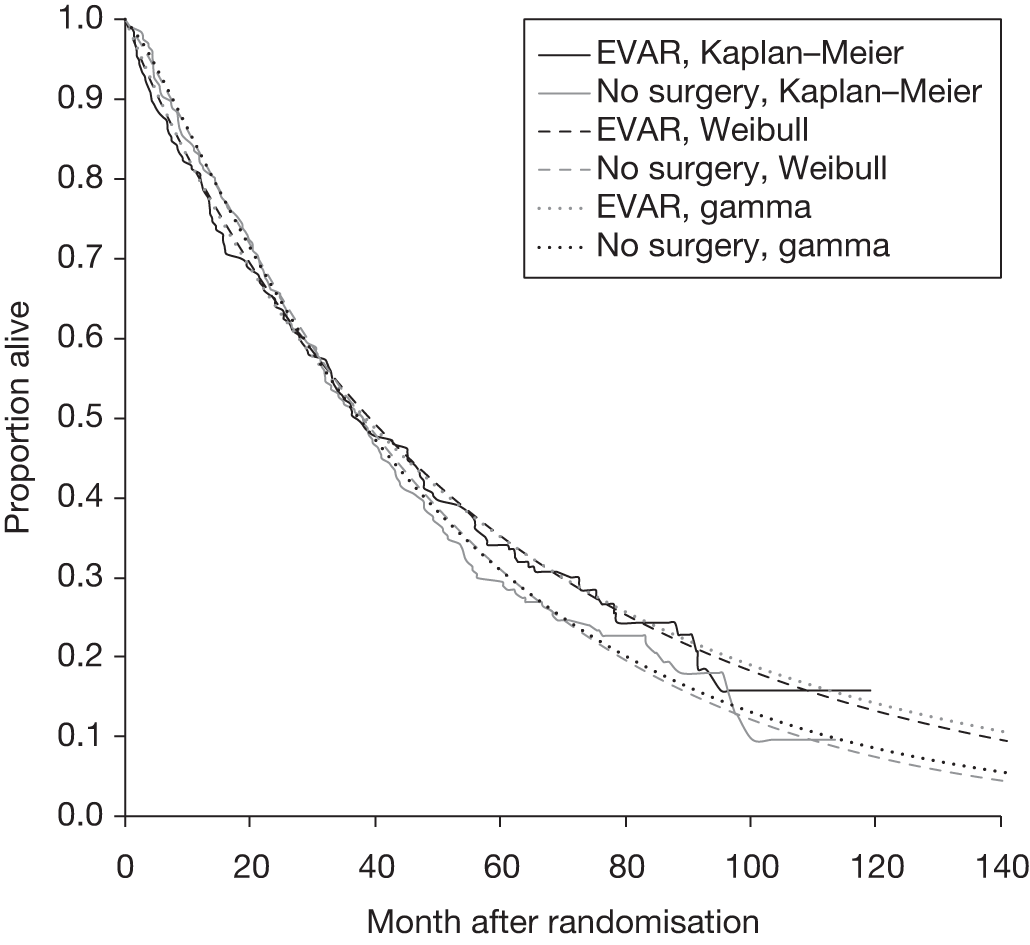

All-cause mortality for EVAR trial 1

When the EVAR trials were being devised, the UKSAT patient data were used to estimate expected mortality rates for patients with AAA. Patients randomised to open repair in the UKSAT experienced an annual all-cause mortality of 7.1%. In the EVAR trials, patients were undergoing AAA repair for larger aneurysms and thus an annual mortality rate of 7.5% was assumed. If EVAR could reduce this mortality to 5% per year then EVAR might be justified as a viable treatment alternative for AAA. Similar mortality results had been reported in the EUROSTAR and RETA registries. At the start of the trials, funding was requested for follow-up to April 2005 and this would accumulate an average of 3.33 years’ follow-up per patient. To achieve 80% power at the 5% significance level, a total of 900 patients would be required to detect this 2.5% difference in annual mortality between the groups.

All-cause mortality for EVAR trial 2

Patients with large AAAs who were considered unfit for open repair in the UKSAT had been followed up for AAA growth and rupture and were shown to have an annual all-cause mortality of 25%. The RETA registry provided data on patients who were considered unfit for open repair and who had been treated with EVAR and these data showed that such patients experienced an annual all-cause mortality of 15%. To be consistent with EVAR trial 1, it was decided that patient follow-up would continue until April 2005, when an average of 3.33 years’ follow-up had been accrued per patient. To achieve 95% power at the 5% significance level, a total of 280 patients would be required to detect this 10% difference in annual mortality between the groups.

Thirty-day operative mortality

From the UKSAT data, 30-day operative mortality was calculated for patients who were randomised to observation but whose aortic aneurysms subsequently grew to > 5.5 cm, at which point surgery was performed (n = 191). Eleven were dead at 30 days, leading to a 30-day operative mortality of 5.8%. Power calculations for 30-day operative mortality in EVAR trial 1 were based on 90% power at the 5% significance level using 5.8% for open repair and 1.5% for EVAR, and these indicated that 443 patients would be required in each arm, leading to a total of 900 patients to detect this difference, should it exist.

Aneurysm-related mortality

To increase the power of the trials, it was decided that disease-specific mortality should also be used as an outcome measure to complement the all-cause mortality results, as this is often a more sensitive measure of effect. An Endpoints Committee was convened to scrutinise all of the death certificates and ascribe the cause of death according to a predefined protocol. The underlying cause of death on the death certificates provided by the ONS was centrally coded by ONS according to the International Classification of Diseases and Health Related Problems, Version 10 (ICD-10). The Endpoints Committee defined an aneurysm-related death as a death from any cause within 30 days of any intervention for the aneurysm or if the underlying cause of death on the death certificate was coded using ICD-10 codes 713–719, which includes ruptured AAA.

Graft durability

The incidence of graft-related complications and reinterventions was monitored for both types of AAA repair. Annual CT scans were selected as the method of surveillance to record the aneurysm sac and other postoperative aortic and iliac measurements for all patients in the trials.

Endoleaks in EVAR patients were classified according to an amended version of the White and May classification:182

-

endoleak type 1 perigraft leak, perigraft channel or graft-related endoleak at proximal or distal end

-

endoleak type 2 retrograde endoleak, collateral flow, retroleak or non-grade-related endoleak, leak from patent lumbar, inferior mesenteric or intercostal arteries

-

endoleak type 3 fabric tear, modular disconnection or poor seal between subparts, stent fracture or separation

-

endotension presence of continued sac expansion without any detected graft complication.

Incidence of graft migration, rupture, anastomotic aneurysm, thrombosis, stenosis, graft infection and renal infarction was also monitored. Collaboration with the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) was instigated early in the trial. At the time the trials commenced, the reporting of graft-related complications to the MHRA was not mandatory and in order to ensure complete reporting of these events it was agreed that the trial manager would send details of any graft-related complications detected in the trials to the MHRA, which also established links with DMEC to alert them of any potentially important safety issues relating to particular EVAR devices.

Renal function

Serum creatinine was measured at baseline and annually for all patients in both trials to investigate whether or not the use of contrast agents in the deployment of EVAR devices has a detrimental effect on renal function.

Health-related quality of life

The HRQoL assessment was completed by patients in the form of a full questionnaire at recruitment and subsequently 1, 3 and 12 months after surgery or at the beginning of medical treatment as appropriate. For long-term economic evaluation, a EuroQol questionnaire continued to be completed each year until follow-up closed at the end of 2009. The full questionnaire includes three generic instruments: the Short-Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) Health Survey,183 European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) version 2 (visual analogue scale and utility index),184 and the State–Trait Anxiety questionnaire, selected to assess patient anxiety. Unfortunately there is no specific instrument designed to measure HRQoL in patients suffering from AAA. Thus, it was proposed that the most relevant specific instrument would be the Patient-Generated Index (PGI). This quasi-specific HRQoL instrument focuses on the concerns of the individual patient with a given condition rather than the concerns derived by the investigator for the typical patient with that condition. 185

Economic evaluation

Hospital inpatient data for aneurysm-related procedures were collected for all patients from randomisation. Resource use was estimated from the results of a survey questionnaire that was sent to trial centres in May 2004 requesting information on the costs of their chosen endovascular devices, theatre occupation time, blood products used, contrast agent used, radiological and theatre facility costs (including staff and consumables), and costs of stay on standard wards and in intensive treatment units and HDU. These costs were applied to patient-specific data for the primary AAA repair as well as any subsequent aneurysm-related inpatient procedures. Given the limited trial resources for data collection, we were not able to collect data for non-aneurysm-related admissions or for the number of GP, outpatient or day-case appointments. Similarly, data on admissions for laparotomy-related complications after open repair, such as incisional hernia or wound infections, were excluded.

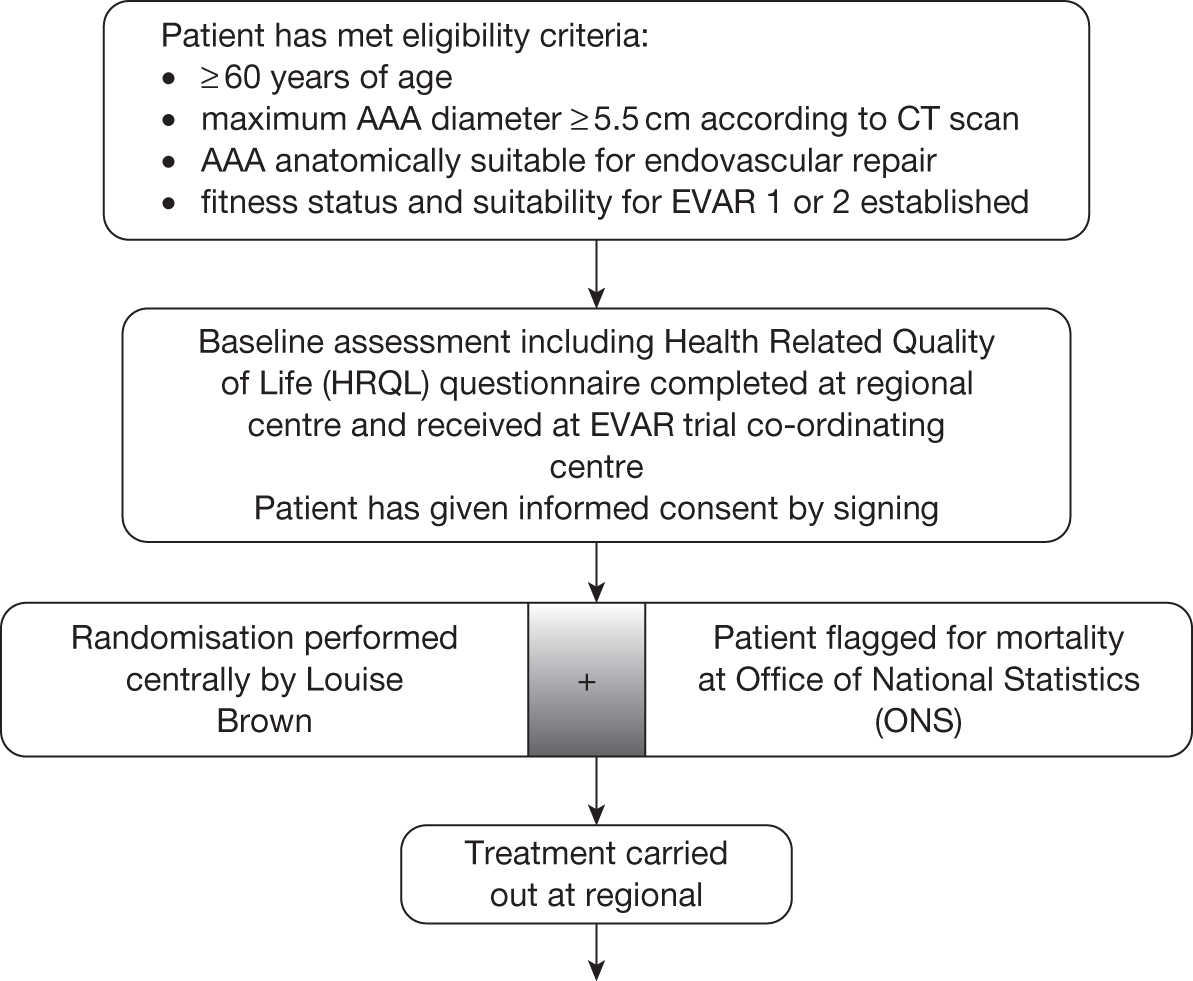

Trial recruitment procedure

Ethical approval and informed consent procedure

The trials are registered with international trial number ISRCTN 55703451. National ethical approval was obtained from the North West Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (MREC), subsequently to become the Integrated Research Application System (IRAS), based in Manchester (MREC references 98/8/26 and 98/8/27). Once approved, all participating centres were required to obtain local ethical approval and copies of the approval documents were sent to the main trial office at Charing Cross Hospital before any patient could be entered into the trials. Patients were provided with a patient information sheet and counselled regarding their possible recruitment into the trial. In addition, they were encouraged to spend as much time as they wished discussing their involvement in the trial with family, friends and their GP, and asked to sign their consent form only when they fully understood the implications of the trial. Patients could not be entered into the trial until a signed copy of the consent form had been received at the central trial office. The patient information sheets and consent forms are provided as Appendices 4 and 5.

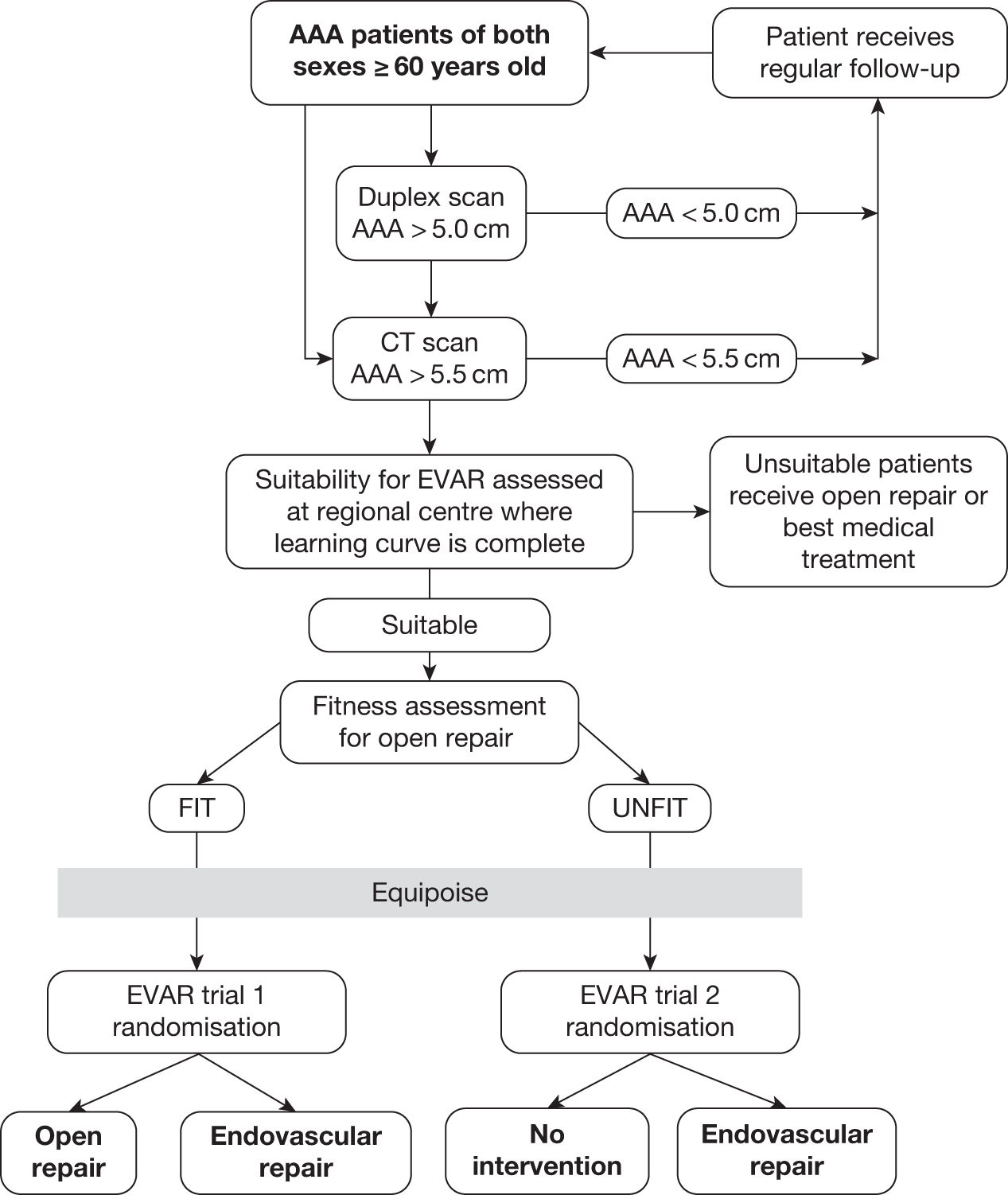

Generalisability and the EVAR study

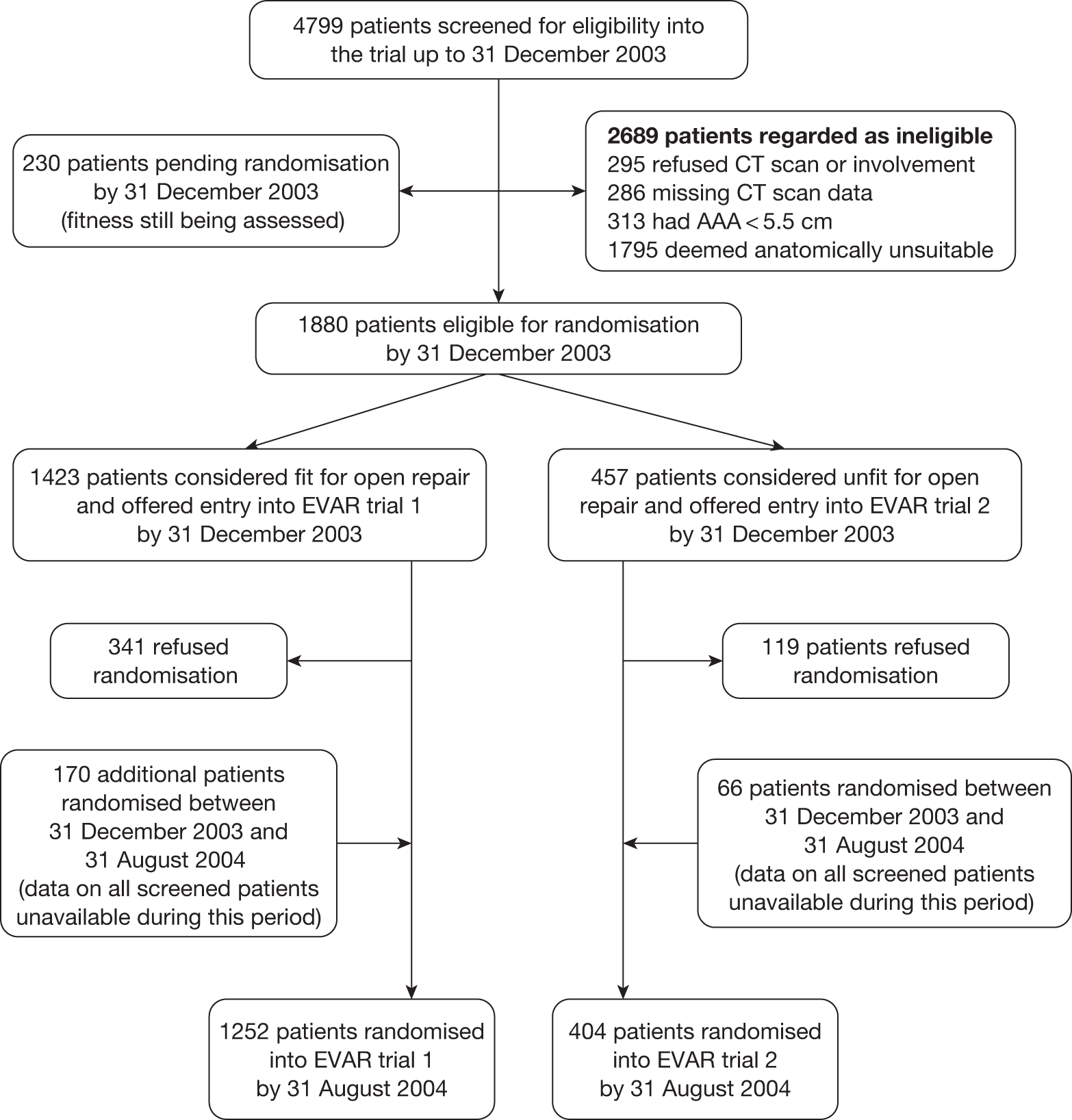

It was of particular importance that patients found to be unsuitable for an EVAR device were recorded. Numbers of unsuitable patients were logged and reasons for unsuitability were recorded in order to determine what proportion of patients with AAA were anatomically suitable for an EVAR device at the national level. Thus, all patients registered for assessment of anatomical suitability for an EVAR device formed the ‘EVAR Study’ and trial patients were drawn from this pool of patients with AAA. Some of the eligible centres acted as both the ‘local’ and ‘regional specialist’ centres for their area. Figure 4 demonstrates the trial recruitment procedure.

FIGURE 4.

Summary of recruitment procedure for EVAR trials.

Entry criteria

Age of at least 60 years

A minimum age of 60 years was chosen, as surgeons often manage patients of < 60 years in a different way because there may be an associated genetic reason why expansion rates and extent of aortic aneurysm may be extreme, such as Marfan syndrome. No upper age limit was thought to be necessary as it was felt that very elderly patients may benefit from the use of an EVAR device and their additional recruitment would be important for achieving the numbers required.

Size of abdominal aortic aneurysm

The criterion for entry into both trials was an aneurysm diameter measuring ≥ 5.5 cm according to a CT scan. However, reproducibility differences between duplex ultrasound and CT scanners can lead to significant variation in AAA diameters. Duplex scanning can produce smaller AAA diameters than CT scanning and therefore it was recommended that patients presenting with a ≥ 5.0-cm aneurysm on duplex should be sent for a CT scan to determine whether or not the aneurysm was ≥ 5.5 cm in any diameter on CT scan and thus suitable for EVAR trial entry. It was decided that tender aortic aneurysms or contained ruptures could be included providing the aneurysm measured at least 5.5 cm on a CT scan and suitable EVAR equipment was available at short notice.

Anatomical suitability for EVAR

This was assessed by spiral CT, conventional CT or, if necessary, with conventional angiography where a marked catheter could be used to measure aortic length. The trial co-ordinator was required to work closely with the local radiologist and document how the aneurysm was assessed and how the size and type of EVAR device were selected.

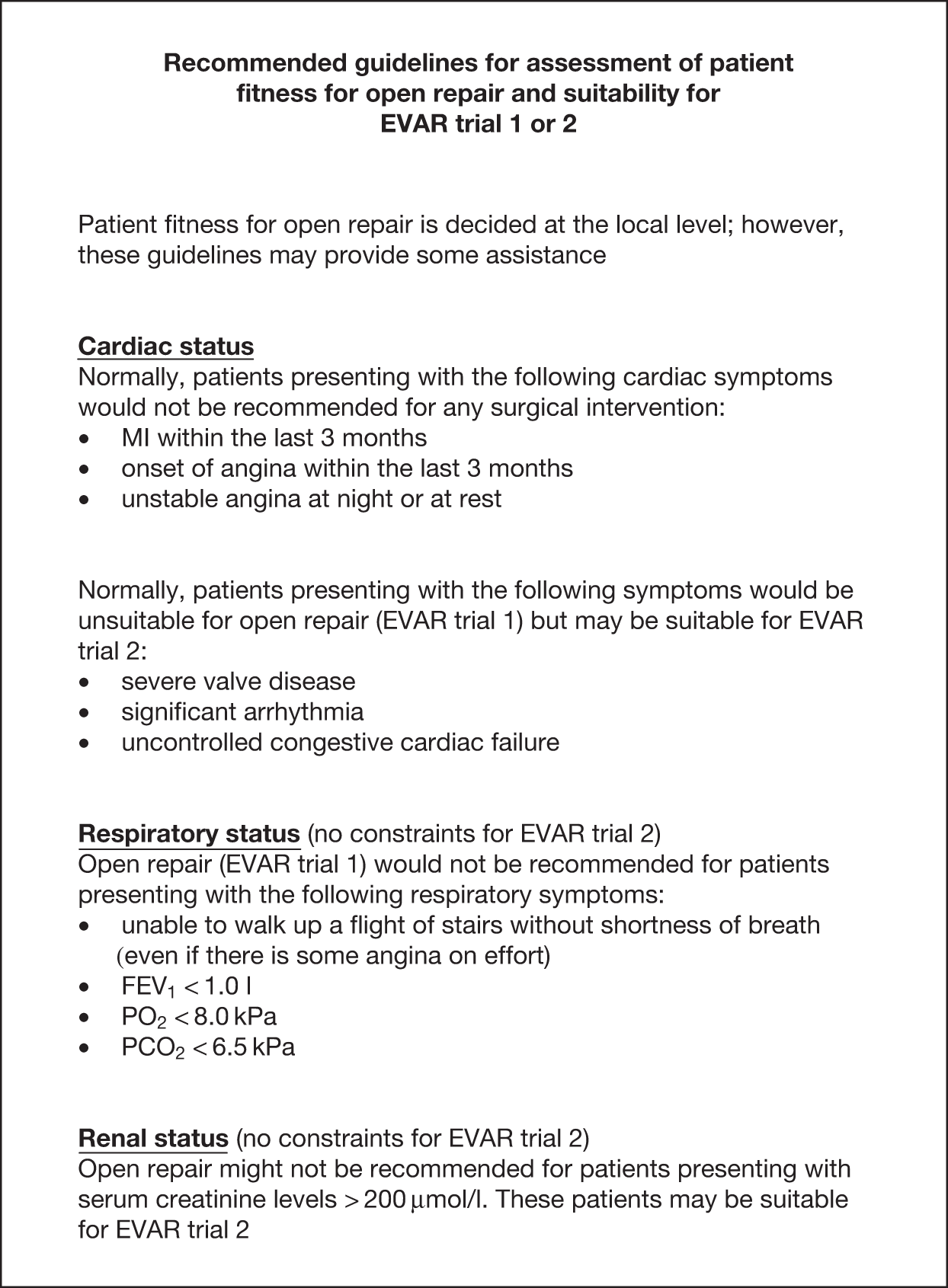

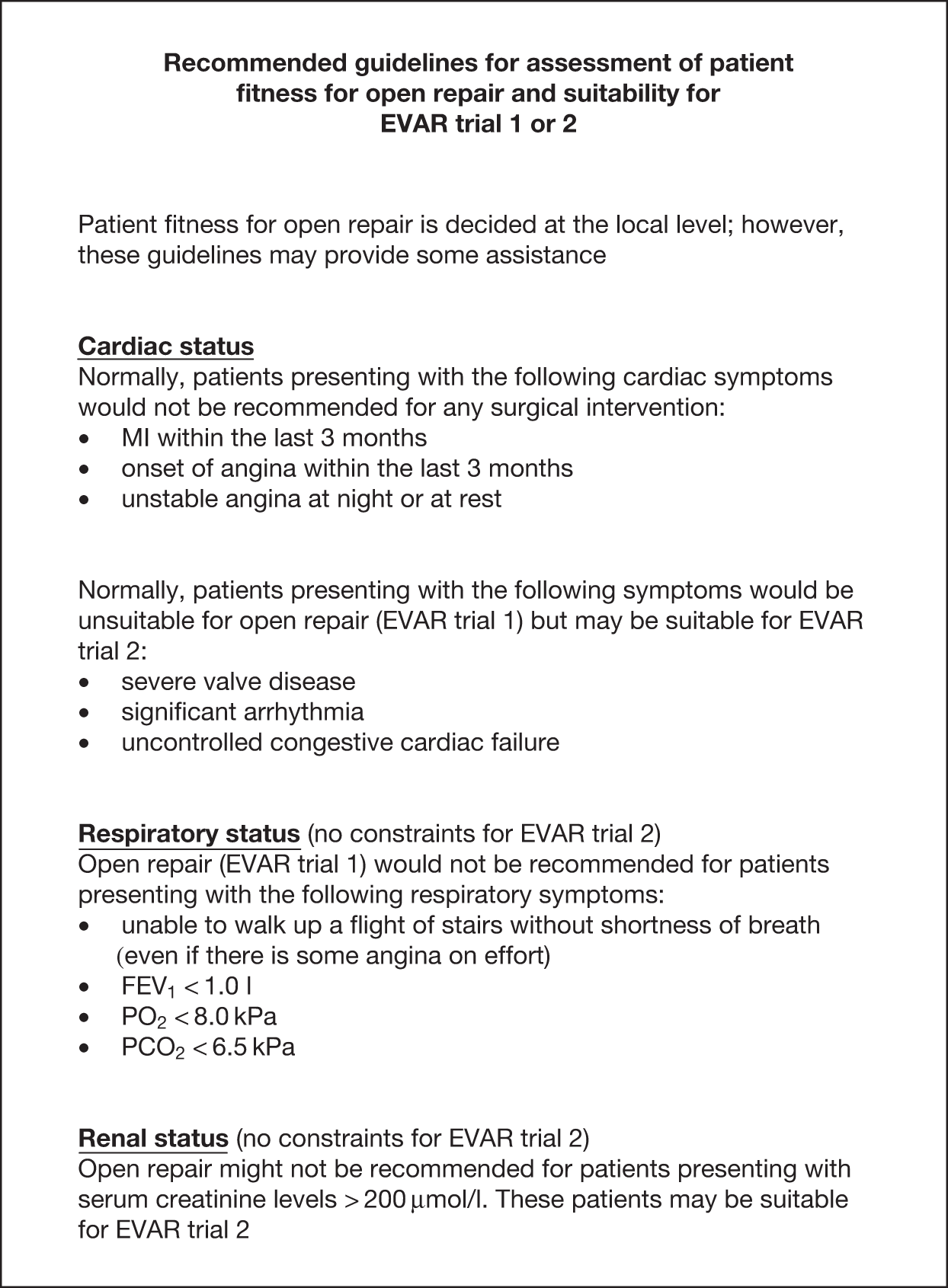

Fitness for open surgery

This was determined locally by the surgeon, radiologist, anaesthetist and cardiologist. It was originally thought that American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) grades I, II and III would indicate entry to EVAR trial 1, and ASA grade IV patients would permit entry into EVAR trial 2. However, despite the simplicity of ASA grading it can be open to wide interpretation at each centre and thus it proved too difficult to use as a classification system for EVAR trial 1 or 2. It had also been appreciated during the UKSAT that fitness ‘inflation’ emerged with respect to the size of aneurysm. Patients who were earlier described as ‘unfit for open repair’ and later developed a larger aneurysm were suddenly deemed ‘fit for the procedure’. It was believed that this could happen equally for these trials and for the purposes of pragmatism, fitness was determined at the local level. Recommended cardiac, respiratory and renal guidelines were provided as outlined in Figure 5, and baseline data were collected to allow assessment of patient fitness in the final analyses. It was felt that these guidelines would help provide some conformity of fitness classification for EVAR trial 1 or 2. Furthermore, randomisation was stratified by centre and this would also ensure that any differences in assignment of fitness status between centres would not lead to any considerable differences between randomised groups. In hindsight, it would appear that these guidelines were good at separating patients into the EVAR 1 and 2 cohorts, and further assessment on classification of fitness will be made in Chapter 4, Results for EVAR trial 1, Chapter 5, Results for EVAR trial 2 and Chapter 9, Discussion.

FIGURE 5.

Recommended guidelines for assessment of patient fitness for open repair and suitability for EVAR trial 1 or 2. PCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PO2, partial pressure of oxygen.

Baseline assessment

Patients who met the entry requirements of the trial underwent a full baseline assessment, during which data were collected for basic demographics (age, gender, postcode, occupation, level of education, source of referral and marital status), physical fitness in terms of cardiac disease [history of myocardial infarction (MI), angina, cardiac revascularisation, severe cardiac valve disease, uncontrolled congestive cardiac failure or significant arrhythmia sourced from hospital notes], respiratory disease [forced expiration volume in 1 second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity from a hand-held spirometer] and renal function (serum creatinine from trial hospital laboratory), as well as other markers of mortality such as body mass index (BMI), ankle–brachial pressure indices (ABPIs) (ratio of blood pressure in ankle to arm), blood pressure (standard cuff sphygmomanometry), pulse rate, total serum cholesterol (from trial hospital laboratory), smoking status (patient reported), diabetes (insulin controlled or not), and medication history for aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, cholesterol-lowering drugs, statins and beta-blockers. These baseline data were subsequently used to calculate the customised probability index (CPI) score for each patient. This score is a validated prognostic score for fitness for open repair and uses data on cardiac, renal and respiratory function, as well as use of medical therapies, to generate a score such that higher scores indicate poorer fitness. 108,109 This score was used as a marker of general fitness for all the patients. A full collection of anatomical aortic measurements was also taken from the baseline CT scan.

Randomisation

Randomisation was performed for each trial using 1 : 1 ratio randomly permuted block sizes constructed by the Stata package version 7.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Randomisation was stratified by centre and performed only when all necessary baseline data had been received at the central trial office based at Charing Cross Hospital, London. This enabled patients to be randomised into the relevant trial and simultaneously flagged for mortality at the ONS. Centres were encouraged to perform surgery within 1 month of randomisation.

Choice of EVAR device and reimbursement of treatment costs

Participating centres were free to decide which commercial or ‘in-house’ device to use, although the use of commercially available devices was favoured. These all carry the CE (Conformité Européenne) mark and are therefore freely available on the market and have undergone certain checks before being released. It was assumed that each centre would take the time to discuss the evidence for the safety of each device with the company. The anatomical suitability of EVAR devices would therefore be very centre specific depending on the number of devices that they chose to use in that hospital. It was not feasible for the trial protocol to intrude on the choice of device at each centre and this was left as a pragmatic decision for the participating clinicians.

It had been anticipated that the cost of the EVAR procedure would incur significantly greater treatment costs over open repair and there was concern that this may impede recruitment into the trials as local trusts would refuse to pay these additional costs. Following negotiations with the NHS Executive (North Thames London Region) it was agreed that treatment costs may be reimbursed to each trial centre on randomisation to an EVAR device. It was agreed that additional service costs would not be funded, as EVAR may be associated with a reduction in length of stay and particularly intensive treatment unit (ITU) and HDU usage. An assessment of costs was carried out to ascertain the excess treatment expenditure associated with an EVAR repair over an open repair for EVAR trial 1 and the additional costs of EVAR over medical treatment alone in EVAR trial 2. Estimates were made and a fixed figure was agreed with the Department of Health such that randomisation to an EVAR device in EVAR trial 1 triggered £5418 of additional funding and randomisation to an EVAR device in EVAR trial 2 triggered £8102 of additional funding. It is thought that this payment incentive contributed greatly to achieving the excellent recruitment rates into both trials.

Trial follow-up protocol

All trial patients were flagged for mortality at the UK ONS, which provided death certificates on which the underlying cause of death was assigned using ICD-10 codes. A trial Endpoints Committee was convened to confirm this underlying cause of death as well as determine whether or not the death was aneurysm related.

All centres were required to nominate a local trial co-ordinator, who was responsible for all aspects of trial recruitment and follow-up at that hospital. The co-ordinator was required to attend a 1-day training course in trial protocol, recruitment and data collection procedures at the main trial headquarters at Charing Cross Hospital. All patients were required to have baseline CT scan and fitness assessment data collected prior to randomisation and these data needed to be sent to the central trial office where randomisation was performed. After randomisation, data were collected for the primary AAA repair operation as well as for any further admissions for aneurysm-related complications that required at least one night in hospital. Admission details were obtained on theatre time and blood product usage as well as length of stay in ITU, HDU and standard bed wards. HRQoL data were collected at baseline and then at 1, 3 and 12 months following treatment with a further EuroQol questionnaire annually until the end of the trial to be used for cost-effectiveness evaluation. Further data were collected on the incidence of any of the following adverse events: ruptured AAA for patients without AAA repair, conversion from EVAR to open repair, MI, stroke, renal failure and amputation (above or below knee). Annual creatinine measurements were taken to assess renal function over time. CT scans were used for assessment of growth rates, persistent endoleaks and graft durability with all graft-related adverse events for EVAR patients reported to the MHRA. Centres were encouraged to provide data from as many CT scans as possible, but the minimum requirement for CT scan follow-up was at 1 and 3 months post EVAR procedure for EVAR patients and then annual scans for all randomised patients in each arm of both trials. Centres were free to utilise any additional imaging modality beyond CT scan if it is felt appropriate; however, data were not collected for any additional imaging, as the CT scan form could be used to record any problems that had been identified with the AAA or graft.

Data collection and management

Data were entered into an Access database version 10 (2002) (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) by the trial manager based at Charing Cross Hospital, who remained as the trial manager for the whole duration of the trial and was the only person responsible for data entry. Data entry errors were assessed using consistency checks on time between dates and on unreasonable or outlier values. The trial case record forms are provided in Appendix 6. To encourage good data retrieval, the departments of each trial co-ordinator were paid a small amount of money on receipt of clean and complete data at Charing Cross Hospital. The payment could be spent at the discretion of each local centre, but centres were encouraged to use the funds as an incentive for the co-ordinator, for example as funding to attend conferences or relevant training courses. An estimate was made of the length of time a trial co-ordinator would take to complete the forms (1 hour for a baseline assessment and 20 minutes for a follow-up appointment). A £25 payment was made for each complete baseline assessment and a further £25 payment for any operation or reintervention forms. A £25 payment was also made on receipt of each complete set of follow-up data.

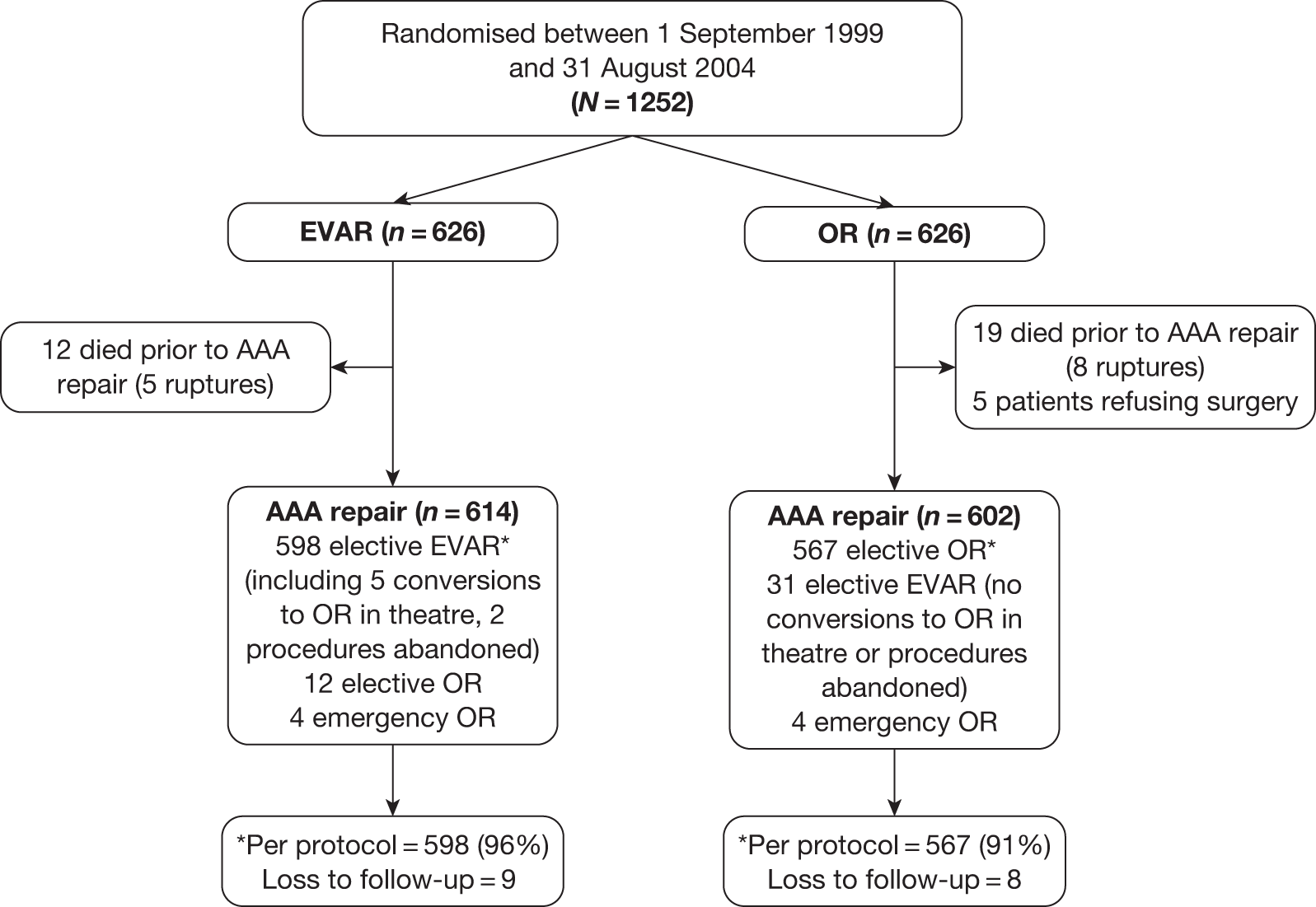

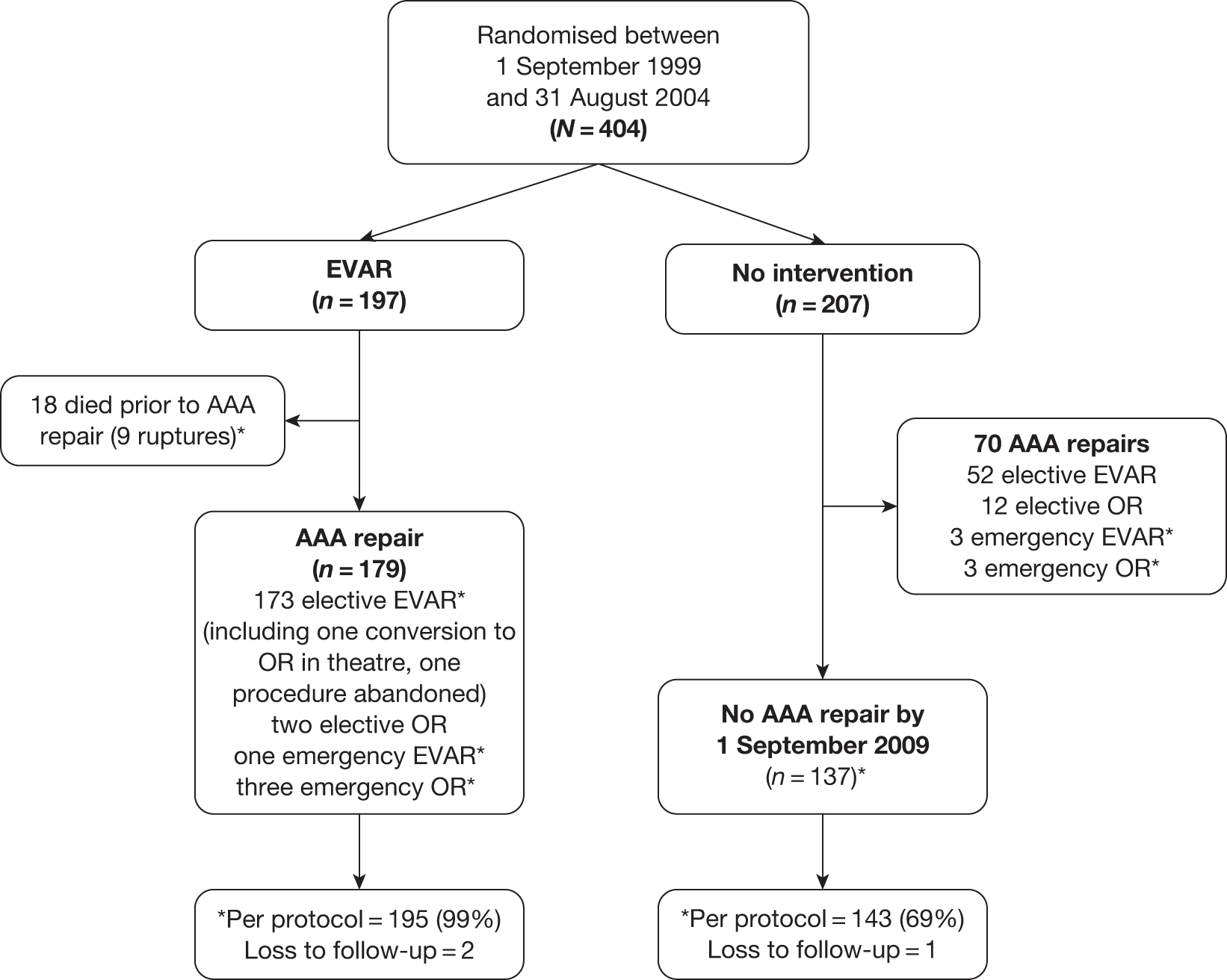

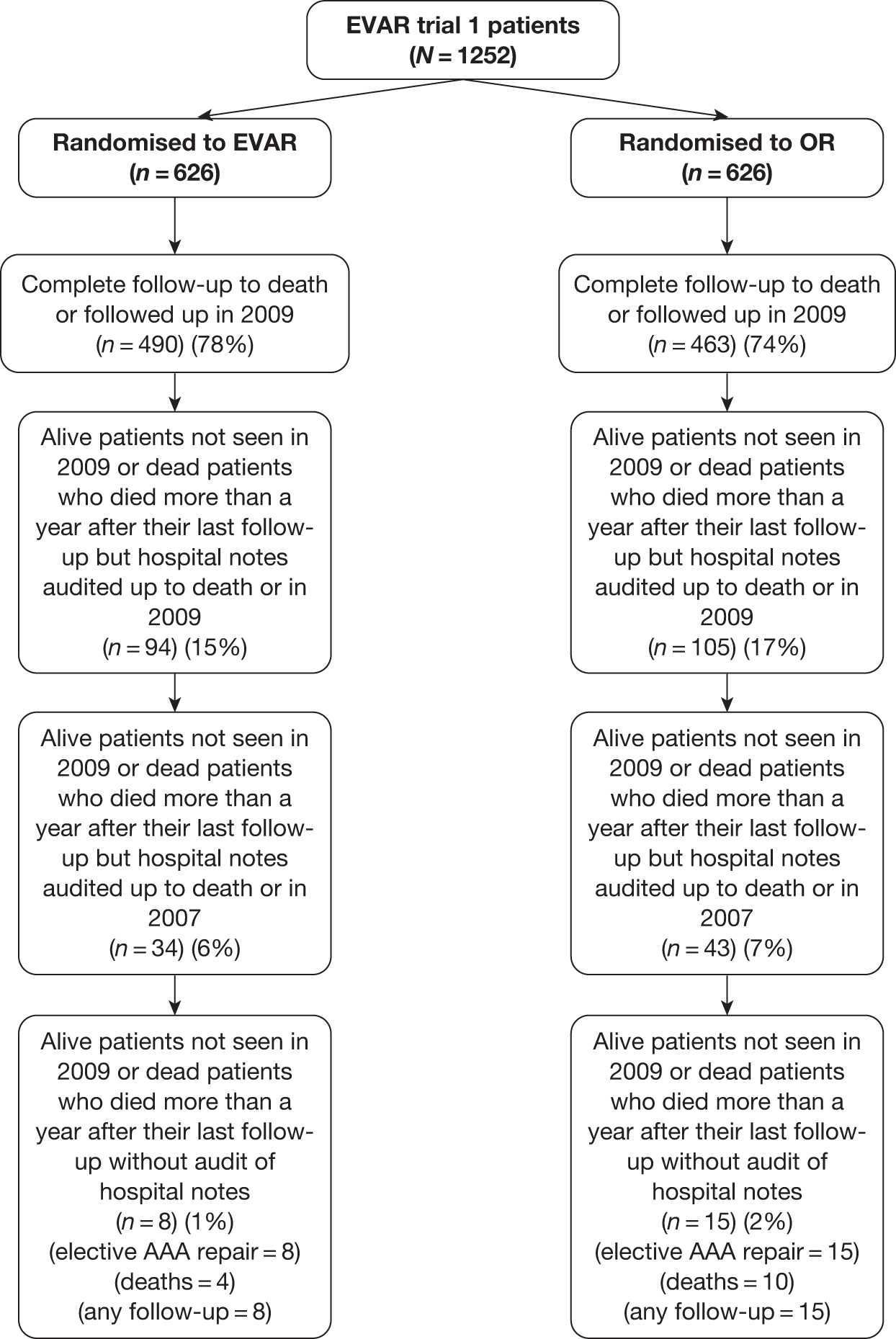

Quality assurance and data audit

To check that all adverse events, graft-related complications and reinterventions had been reported, a data clerk was employed to audit the trial case record notes (completed by the local co-ordinators) against the local hospital notes. Two periods of audit were conducted: one in 2007 and one in 2009. A total of 1052 (84%) patient notes were audited in EVAR trial 1 with the remaining 200 sets of notes unavailable in archive. A total of 308 (76%) patient notes were audited in EVAR trial 2, with the remaining 96 sets of notes unavailable in archive. All reported events were confirmed and a small number of unreported events were detected and included in the main database.

Methods specific to renal function analyses

For details, see Chapter 4, Renal function, Chapter 5, Renal function and Chapter 6, Factors associated with development of serious graft-related complications and reinterventions.

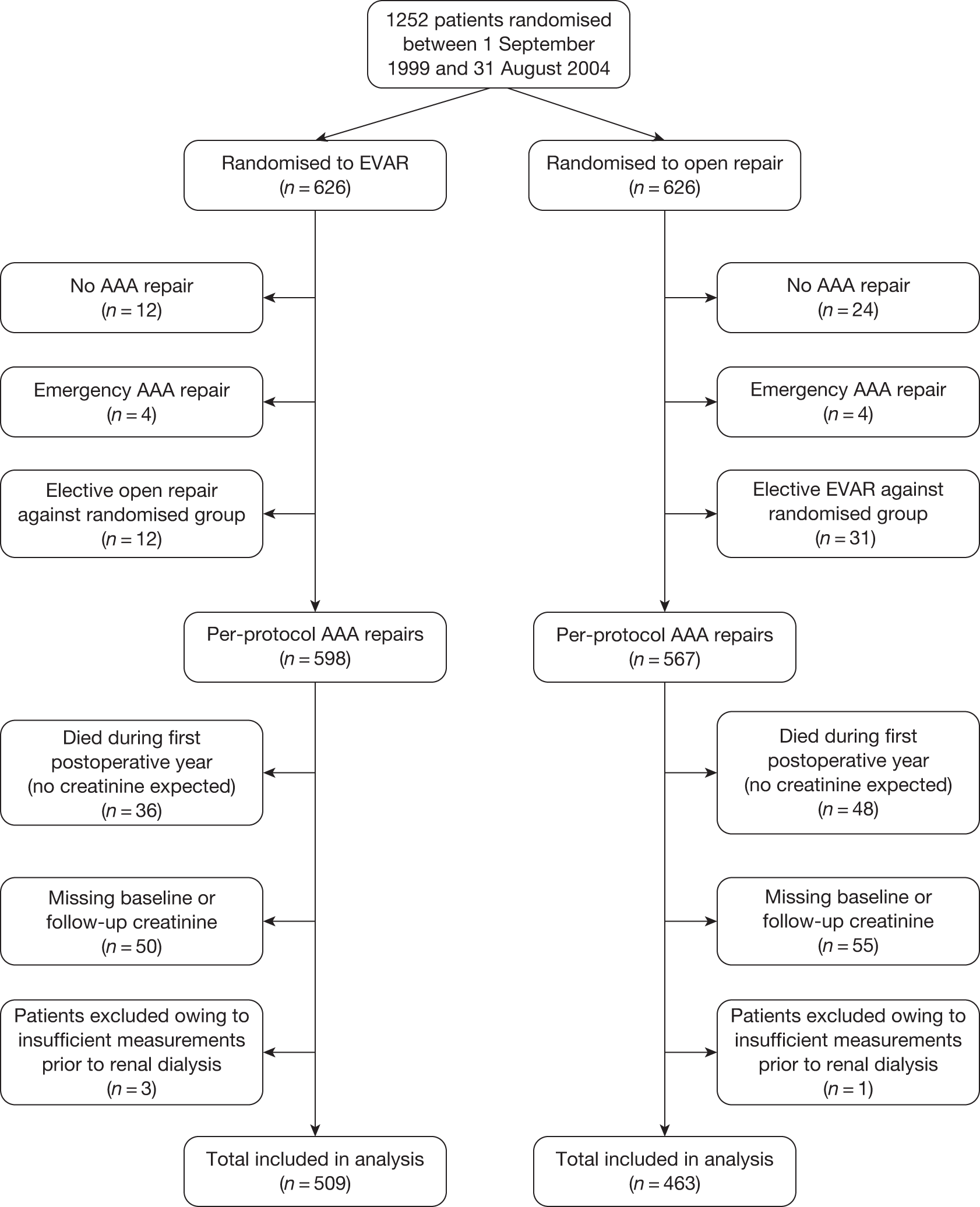

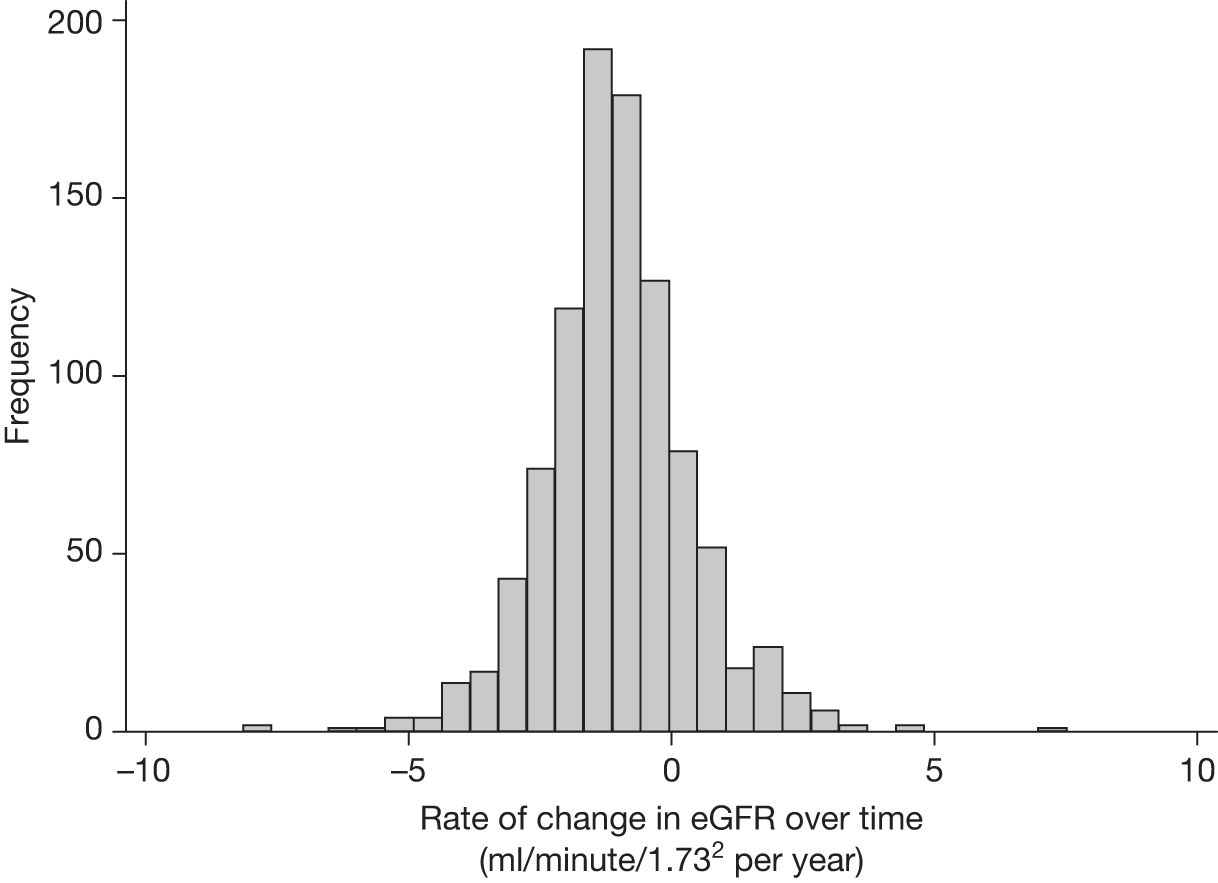

Serum creatinine measurements were collected for all patients at baseline and as part of their annual follow-up. Available measurements were included up to March 2008, when the analyses were undertaken. For this investigation, a priori inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined as follows: (1) only elective cases of aneurysm repair would be included as the impact of emergency repair on renal function may distort the results; (2) for similar reasons, renal function data collected after non-compliance with randomised management would be excluded; and (3) creatinine measurements during the 6-month period after the AAA repair were not included in the analysis to allow renal function to stabilise after any acute kidney injury associated with the initial procedure.

In both trials, the analyses were timed from randomisation as the baseline creatinine measurements had been collected at that time. Patients without a baseline and at least one follow-up estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) measurement were excluded. As the trial protocol specified that creatinine measurements needed to be collected only annually, survival to 1 year became an indirect inclusion criterion for the analysis. However, these analyses focused on the long-term consequences of different aneurysm management policies on renal function, relevant only to those who survive beyond 1 year. In EVAR trial 1, annual follow-up measurements were used to compare changes in eGFR over time between those who received an elective EVAR in the EVAR randomised group and those who received an elective open repair in the open-repair randomised group. In EVAR trial 2, changes in eGFR over time were compared between those who received an elective EVAR in the EVAR group with those who remained under surveillance in the no-intervention group. Patients without AAA repair in the EVAR group were excluded and eGFR measurements after any AAA repair in the no-intervention group were excluded. For both trials, patients who required chronic renal dialysis during the course of follow-up were censored at the time of commencing dialysis, as their creatinine results would be unreliable after this date.

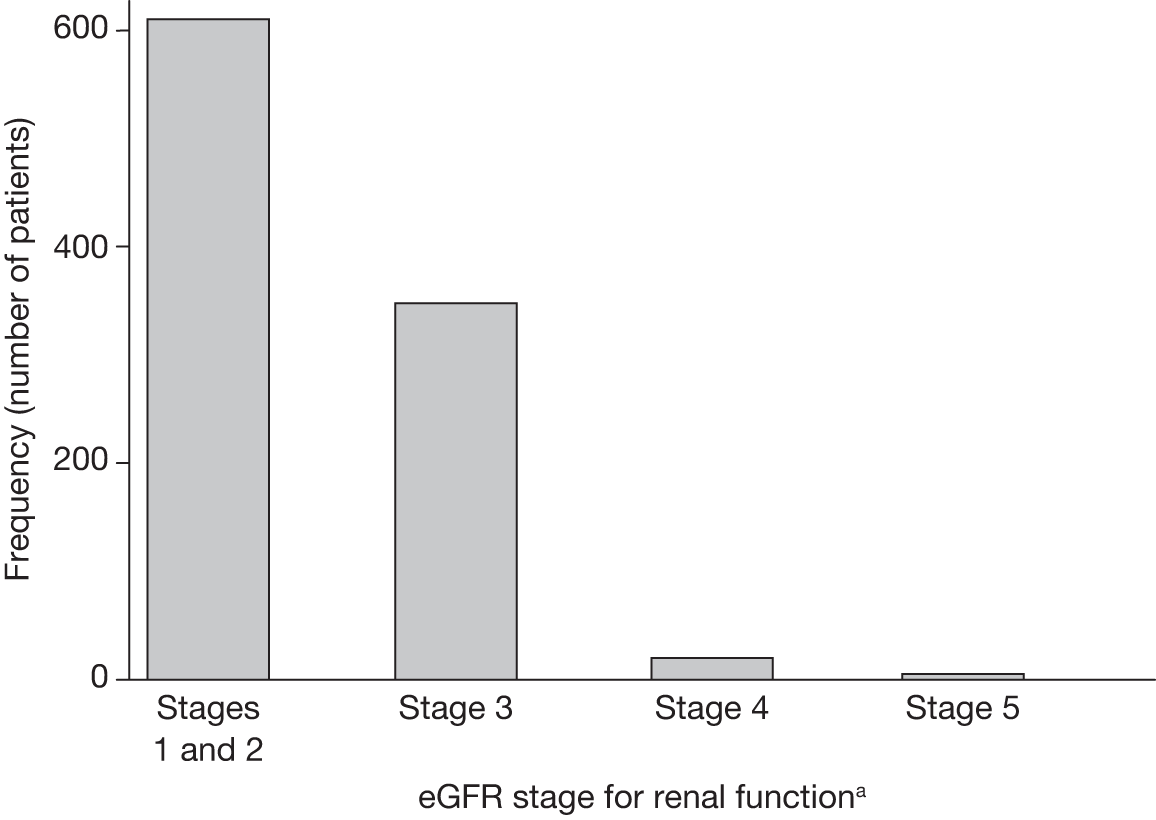

Assessment of renal function

Estimated glomerular filtration rate was selected to represent renal function as it has been recommended as a more sensitive determinant of renal function in patients with AAA. 186 As the Cockcroft–Gault equation requires weight at each creatinine measurement (and only baseline weight was available), we used the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease calculation,187 sourced from the website of the Renal Association for UK professional renal physicians and scientists,188 which includes creatinine in units of micromoles per litre, age in years, sex and ethnicity:

Data on ethnicity were not available in the EVAR trials’ data sets, but after consultation with local co-ordinators it was clear that very few patients (< 1%) were of black origin and application of the 1.210 correction factor to all of their eGFR measurements would be unlikely to change the overall results or the within-patient changes over time. Another potential source of error is the fact that laboratory standards for measurement of creatinine vary across the UK. As creatinine was measured by the same hospital for each patient, this would not affect the analyses based upon within-patient changes over time. Once eGFR was calculated, patients were classified according to the National Kidney Foundation Kidney Dialysis Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) staging for renal impairment. 189 Statistical methods for the renal analyses are provided below (see Multilevel modelling statistical methods for renal function analyses).

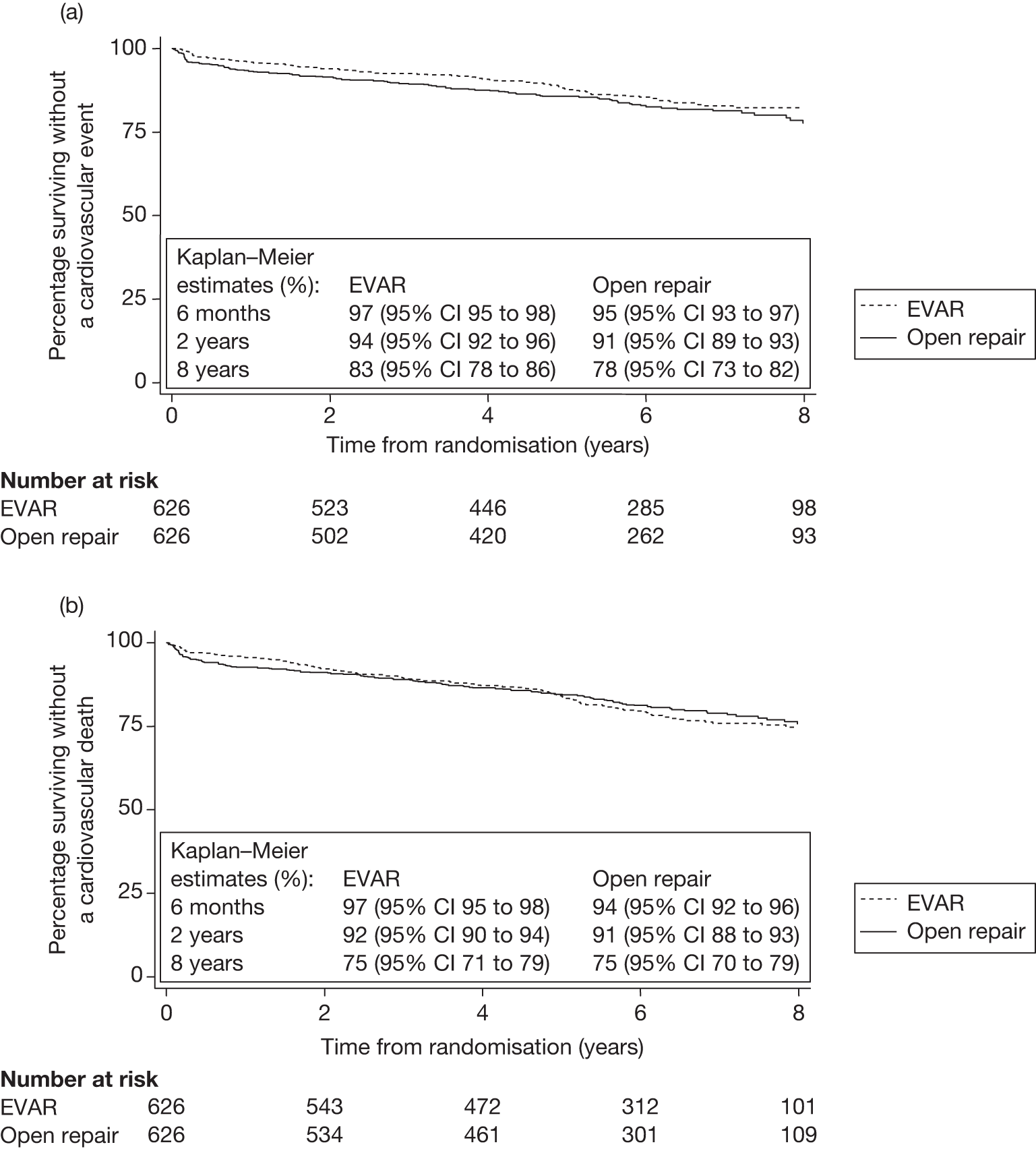

Methods specific to analysis of cardiovascular mortality and events

For details, see Chapter 4, Cardiovascular mortality and events and Chapter 5, Cardiovascular events.

The local trial co-ordinators had collected data prospectively on MI and stroke events throughout the trial, although World Health Organization (WHO) criteria were not required. Two outcomes were analysed: time from randomisation to first cardiovascular event (fatal or non-fatal MI or stroke) and time from randomisation to cardiovascular death (which was defined according to ICD-10). In addition, the numbers of multiple cardiovascular events in patients were summated to calculate a crude overall event rate.

Definition of fatal MI Primary cause of death on the death certificate assigned under ICD-10 MI codes I210 to I238.

Definition of non-fatal MI Any report of a non-fatal MI from the co-ordinator at the participating hospital or any mention of ICD-10 codes I210 to I238 on the death certificate, providing that they were not attributed as the original underlying cause of death. In the latter cases, the date of death was used as the date of event and the events were audited by two independent assessors blinded to randomised group.

Definition of fatal stroke Primary cause of death on the death certificate assigned under cerebrovascular disease leading to stroke, ICD-10 codes I600 to I640.

Definition of non-fatal stroke Any report of a non-fatal stroke from the co-ordinator at the participating hospital or any mention of ICD-10 codes I600 to I640 on the death certificate using the same criteria as those for non-fatal MIs.

Definition of cardiovascular death All death certificates were reviewed by an Endpoints Committee, who ascribed the following underlying primary causes of death as cardiovascular: death within 30 days of an aneurysm-related procedure, aortic aneurysm rupture (before or after aneurysm repair), cardiac (including all coronary deaths), cerebrovascular disease or stroke, other cardiovascular disease such as peripheral vascular disease or pulmonary embolism.

The timing of events and censoring of patients was slightly different for cardiovascular events and deaths, and predefined according to the following rules.

-

For patients with a new cardiovascular event recorded since randomisation:

-

If the patient had a baseline/follow-up appointment or had been audited within 18 months prior to a first recorded event then the event was defined as the first event.

-

If the patient had a baseline/follow-up appointment or had been audited more than 18 months prior to the event then it could not be assumed that this was the first event and the patients were censored without an event on the date last seen or audited. This removed events in a small number of patients (n = 3) who were not seen for at least 18 months and then died with a fatal or non-fatal mention of MI or stroke on their death certificate.

-

-

For patients without any new cardiovascular event recorded since randomisation, censoring occurred at the latest of these dates:

-

For patients who were alive on 1 September 2009, the date of last follow-up appointment or the date of audit.

-

For patients who were dead, the date of death (without mention of MI or stroke cause) was used providing that the death occurred within 18 months after the last follow-up or date of audit. For patients dying more than 18 months after their last follow-up or date of audit, the date of follow-up or audit was used for censoring.

-

-