Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 07/37/05. The contractual start date was in March 2009. The draft report began editorial review in December 2010 and was accepted for publication in May 2011. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2012. This work was produced by Thompson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2012 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Importance

Acute illness is one of the most common problems encountered in children attending emergency departments (EDs) as well as by primary-care services in the UK. Between 27% and 47% of patients who present to EDs in the UK do so for medical illness, rather than trauma. 1 In the case of children, the most common medical reasons for attending ED are breathing difficulty (31%), febrile illness (20%), diarrhoea/vomiting (16%), abdominal pain (6%), seizure (5%) and rash (5%). 1 Acute infections are responsible for four consultations per person-year in children aged < 1 year, and between one and two in children aged 1–15 years in the UK. 2 Children < 5 years of age also constitute a substantial part of the workload of urgent-access primary-care services. Indeed, the patient group which presents most commonly to out-of-hours clinics is children with acute infections. 3,4 Similarly, acute illness in children is also a major component of the work of NHS Direct, in which 22% of all telephone calls are related to children < 5 years of age. 5 Perhaps most importantly for the NHS, parents of unwell children are often concerned about their child and his/her risk of serious illness and need access to accurate and appropriate diagnostic clinical services. 6

Diagnostic difficulties in children with acute infections

One of the key tasks in both hospital EDs and primary-care settings is therefore to distinguish children who may have serious infections (e.g. meningitis, bacteraemia) or complications from infection (e.g. hypoxia from bronchiolitis, dehydration from gastroenteritis) from the vast majority with self-limiting or minor infections who can safely be managed at home. This task is challenging. With increasing ED attendance rates in the UK, hospital admission of children is becoming more common despite a falling incidence of serious infection. 7,8 At the same time, approximately half of children with meningococcal disease are missed at first consultation with a doctor, which results in a poorer health outcome. 9 Infections were responsible for 20% of childhood deaths reviewed in the recent Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health report Why children die,10 with the greatest number in the 1- to 4-year age group. One reason why recognition of serious infection in children is difficult is the low prevalence of serious illness. In a primary-care setting, < 1% of children assessed have a serious infection,8,11 while in the ED setting this can be as high as 25% of children referred by their GP for fever without source. 12 In addition, infections are dynamic illnesses, and children with serious illness may present at an early stage when severity is not apparent and deteriorate rapidly. Finally, assessment of children (particularly pre-verbal children) may be undertaken by staff with limited paediatric training or under high pressure because of large patient volumes. 13,14 Recent reductions in working hours may further reduce opportunities for trainees to gain experience of children with serious infections.

Clinical tests

Clinicians use several different combinations of clinical tools to identify children with serious infections in primary and emergency care. This primarily involves assessing symptoms reported spontaneously or elicited from parents and patients, overall or global assessment of severity of illness, as well as measurement of vital signs and findings from physical examination. 15 There has been no systematic assessment of which of these clinical features are most useful for identifying children with serious infection in ED or primary-care settings. Clinical prediction rules are a simple pragmatic technology that can potentially be used by clinical staff to assist them in assessment and clinical management. A widely implemented example which has been shown to reduce both resource use and missed diagnoses in EDs is the Ottawa Ankle Rule for ordering a radiograph. 16 There has been no systematic assessment of prediction rules for children with serious infection and, in particular, how well these rules have been validated or implemented in different clinical settings. These are necessary steps in the development of prediction rules, before widespread introduction in clinical care. 17

Additional testing

Some clinicians, particularly those working in EDs, have access to further diagnostic tests. These include urine dipsticks, blood tests for white blood cell counts (WBCs) and inflammatory markers, as well as imaging. Apart from urine dipsticks, most of these tests are carried out in hospital or ED settings, although several are now available as point-of-care tests which give an immediate result and could potentially be used in out-of-hours or other primary-care settings. EDs have the capability to use other tests in assessing children, for example additional biochemical and haematological tests, as well as microbiological cultures of blood, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and sputum, and a variety of imagining including plain radiographys, ultrasound, computerised tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. However, even the use of blood tests in identifying children with serious infections is not straightforward. In addition to the difficulties and discomfort of obtaining blood samples, particularly in younger children, the role of the test in the overall diagnostic pathway is important so that clinicians do not rely entirely on a test that does not have perfect discrimination. 18 Previous systematic reviews have assessed the value of selected inflammatory markers in either children only19 or children and adults20–22 for the diagnosis of various outcomes such as distinguishing viral from bacterial pneumonia23 or parenchymal involvement in children admitted with a urinary tract infection. 24 However, none has evaluated and compared all available laboratory tests for children with suspected serious infections in ambulatory care. In addition, most studies which evaluate blood tests neglect the available clinical information, which makes it difficult to determine their role in the clinical pathway, and their incremental value over clinical features. 18,25 In this monograph we will focus on urine and blood tests, which can potentially be used as initial diagnostic tests in most ED settings, rather than the more extensive list of all possible laboratory and imaging investigations.

Assessing the level of urgency

There are several triage systems currently in use in EDs in the UK. These are primarily designed to assess level of urgency for care, rather than as diagnostic tests for serious infections. The Manchester Triage System assigns the patient to one of five categories based on the maximum time that he/she can wait for full assessment. 26,27 It provides only modest sensitivity (63%) to detect emergency or very urgent cases, and is a generic instrument designed to deal with emergencies including trauma. 28,29 Other triage systems used internationally include the Emergency Severity Index, the Paediatric Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale, the Paediatric Risk of Admission Score and the Paediatric Emergency Assessment Tool. 30–34 A number of more specific ‘scoring systems’ for children presenting to EDs with medical illness have been developed. None has shown sufficient ability to rule out serious infection in children to be widely adopted in a NHS context. 35–38

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidance

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline for the management of children < 5 years of age with a fever was published in 2007. 39 It is an important starting point because its recommendations are based on a literature review utilising stakeholders to identify key documents. One of the main outputs from this guideline was a ‘traffic light’ system of clinical features that are designed to be used to assess the risk of serious infection in children. This system assigned clinical features to green, amber and red categories based on the risk of serious infection, and provides clinical guidance for actions needed according to these categories. The current project aims to contribute to the guidelines for the management of children, in a wider context than the NICE guideline, namely by including all children rather than only those < 5 years of age or with fever, but will also be used to update the NICE feverish child guideline. Moreover, we will identify clinical prediction rules relevant to children with acute infection and validate their performance in different clinical settings.

Chapter 2 Research objectives

The overall aim of this research study was to systematically identify clinical features, laboratory tests and clinical prediction rules which can be used to identify children with possible serious infection in acute paediatric settings, including paediatric ED, out-of-hours primary care and other primary-care settings. The clinical role of these diagnostic features includes not only identifying children with serious infection, but also equally identifying children with self-limiting illness who can be safely discharged home from emergency and primary-care settings although not missing any cases of serious infection.

The specific objectives of the systematic review were:

-

to identify the clinical features and prediction rules which have already been shown to have predictive value for identifying (or excluding) children with severe infection

-

to identify and compare the best performing prediction rules from the literature

-

to explore the added value of laboratory tests and vital signs to prediction rules based solely on clinical history and observation.

The focus of the diagnostic tests in this review includes symptoms, vital signs, findings from physical examination, urine analysis tests and blood levels of inflammatory markers.

The diagnostic value of individual features is important to identify, clinicians often refer to these as ‘red flags’ for serious illnesses. Indeed, this is the categorisation that NICE used in its guideline on serious infection in children. 39 However, the combination of several features, referred to as a clinical prediction rule (also known as clinical prediction tool or clinical decision rule), may have better diagnostic value than individual features. In general, clinical prediction rules are most likely to be helpful in situations in which ‘decision making is complex, the clinical stakes are high, or there are opportunities to achieve cost savings without compromising patient care’. 40 The management of children presenting to emergency and urgent-care settings with infections presents an ideal opportunity for application of a clinical prediction rule. The situation in which clinicians need to distinguish the very few seriously ill children from the vast majority of non-seriously ill children is very common; but individual experience with serious infections is more and more limited owing to the decreasing incidence and the consequences of missing a serious infection may be fatal. The ideal clinical prediction rules that this study aims to identify and validate will incorporate components of the history and basic examination findings including vital signs. This type of prediction rule is expected to be applicable to front-line clinicians, such as general practitioners (GPs), GP trainees, paramedics, practice nurses and ED medical and nursing staff. The advantage of the methods planned is that we intend to validate prediction rules in multiple clinical settings with varying prevalence of serious infection. This will form a test of the robustness of the prediction rules, and their generalisability and applicability to different acute paediatric settings in the NHS.

The marginal NHS cost of implementing a clinical prediction rule depends primarily on the cost of any additional staff time or investigations required. The prediction rules that we propose validating have very low marginal economic cost because the main components are an integral part of the standard clinical assessment of children that clinicians use in routine NHS practice (i.e. medical history, presenting complaints, vital signs and examination findings). In addition, we anticipate that the systematic review will complement the current NICE guideline on the assessment of feverish children39 by formally testing, simplifying and quantifying the accuracy of many of the clinical predictors used in that guideline.

This study focuses on children who are otherwise well and attending ED or primary-care settings. We will not address the important area of predicting infections in children with serious underlying health problems and particularly those who are immunocompromised and have markedly greater risks of morbidity and mortality from infections. In addition, we have limited this study to children older than 1 month as there are well-established guidelines for the management of infections in the neonatal period, and the clinical challenge of predicting infections in this period differs substantially in terms of clinical setting and expertise.

The main economic benefit to the NHS is the potential to reduce the need for urgent hospital admission by reliably identifying the vast majority of children who can safely be discharged home or to lower acuity care (e.g. GP follow-up). However, more effective triage using a formal prediction rule will also improve the care of children with serious infections (e.g. by signalling the need for emergency ambulance transfer to ED, for urgent diagnostic or therapeutic intervention, or for urgent paediatrician review), thus optimising the use and effectiveness of emergency services. In addition, identifying the optimal role of blood tests for inflammatory markers is important to ED settings in particular, as is balancing the diagnostic accuracy with the costs of these tests. If shown to discriminate effectively, such a prediction rule would be used at several levels of the emergency medical system in the UK, including by paramedics and in walk-in or out-of-hours surgeries, paediatric assessment units and EDs. Equally, of course, the consequence of a clinical prediction rule which is insufficiently specific is increasing inappropriate use of ED or secondary-care resources.

Chapter 3 Methodology of the systematic review

Literature search

We searched the literature in four electronic databases, MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, using search terms that included terms related to five components: serious infections, children, clinical history and examination, laboratory tests and ambulatory care settings (see Appendix 1). The searches were conducted in October 2008 with an update to the search in June 2009. We searched the Medion database (www.mediondatabase.nl) for systematic reviews using the ‘signs and symptoms’ component of our search strategy. Reference lists of included studies were searched for additional articles. We also checked reference lists of relevant NICE guidelines published prior to 200839,41 and asked clinical experts to report any studies that had been omitted. We did not limit the search based on language or time.

Selection process

After a pilot selection on a sample of 20 studies, two independent reviewers (AVDB and THH), identified articles based on title and abstract for full-text review. Any discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved by a third independent reviewer (MJT). We used six criteria to determine inclusion and exclusion: study design, participants, setting, outcome, diagnostic tests and reporting of data (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Design | Studies assessing diagnostic accuracy or deriving prediction rules | Narrative reviews, letters, editorials, comments and case series of < 20 subjects |

| Participants |

Age between 1 month and 18 years Studies including children spanning this age range included if they reported age-stratified analyses (so that children aged < 1 month or > 18 years could be excluded) or if the proportion of children out of range was < 50% |

Children with pre-existing immune suppression (such as HIV infection or neutropenia due to chemotherapy) Outwith age range |

| Setting |

Ambulatory care (defined as general or family practice, paediatric outpatient clinics, paediatric assessment units or EDs) Developed countries, defined using the United Nations list, which includes Europe, Canada, the USA, Australia, New Zealand and Japan |

Studies conducted in developing countries |

| Outcome | Serious infection, defined as sepsis (including bacteraemia), meningitis, pneumonia, osteomyelitis, cellulitis, gastroenteritis with dehydration, complicated urinary tract infection (positive urine culture and systemic effects such as fever) and viral respiratory tract infections complicated by hypoxia (e.g. bronchiolitis) | Diagnosis other than serious infection |

| Diagnostic features |

Clinical features Observation scales Clinical prediction rules Laboratory tests |

Imaging Invasive tests (e.g. lumbar puncture, joint aspirates) Microbiological tests |

| Data reported | Reconstruction of the 2 × 2 tables possible |

Quality assessment

We assessed quality using the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies (QUADAS) instrument. 42 This was performed by one reviewer (AVDB) and checked by a second (THH), with discrepancies resolved by discussion involving additional researchers when necessary. In addition, we contacted study authors if additional clarification was necessary. Two items from the QUADAS criteria were used as study exclusion criteria:

-

spectrum bias: this was considered present in case–control studies which used healthy controls or in studies in which participants were selected based on the performance of the reference standard

-

validity of the reference standard: this was assessed by a clinical review committee consisting of a minimum of three researchers.

When there were insufficient data to be able to confidently assess whether or not a quality criterion had been met, we assessed it as not being met. The overall quality of included studies was rated from high (A) to low (D) using the following criteria:

-

A: fulfilling all QUADAS criteria

-

D: lacking total verification with the reference standard or with interpretation of the index feature unblinded to the results of the reference standard

-

C: lacking an independent reference standard, with interpretation of the reference standard unblinded to the results of the index feature or with an unduly long time period between recording of the index feature and outcome

-

B: all other studies.

Data extraction and analysis

Data were extracted by one reviewer (AVDB) and checked by a second (THH), and any errors identified were corrected. Key characteristics of included studies were extracted, including year, study design, setting or country, number of participants, proportion with serious illness, quality rating, age range, and inclusion and exclusion criteria. We reconstructed 2 × 2 tables based on information in the article or from additional information obtained from the authors. Where empty cells were present in the 2 × 2 tables, we added 0.5 to each cell. We calculated likelihood ratios (LRs) for the presence (LR+) or absence (LR–) of each feature along with the pre- and post-test probabilities of the outcome. Confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated on the basis of the standard error of a proportion using Stata version 9.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Diagnostic features were categorised based on their diagnostic value as either red flags or as rule-out features for serious illness using the values of LR+ and LR–. Red flag (or rule-in) features were defined as those with a LR+ > 5.0. Rule-out features were defined as those with a LR– <0.2. 43 In cases in which studies reported more than one result on the same feature using different cut-off points, we presented the result with the highest LR+ or lowest LR–. We included features if at least one study reported a LR+ > 5 or a LR– < 0.2. Setting was used to categorise studies, as a proxy for prevalence of serious infection: < 5%, low-prevalence setting; 5–20%, intermediate-prevalence setting; and > 20%, high-prevalence setting.

The results of the LR+, LR–, pre- and post-test probability and prevalence were plotted on dumbbell plots. We report both the pre-test and post-test probabilities of serious infection for each study in dumbbell plots. We grouped studies based on (a) global clinical assessment features, (b) circulatory and respiratory features, (c) miscellaneous features, (d) inflammatory markers, (e) WBCs and (f) clinical prediction rules. The diagnostic value of temperature was explored using a plot of post-test values against pre-test prevalence on a log scale using R (www.r-project.org), using different cut-offs for temperature. Diagnostic meta-analysis of diagnostic markers across studies using multiple cut-points was carried out using the bivariate method of Dukic and Gatsonis,44 implemented in R.

Chapter 4 Number and characteristics of studies included in the systematic review

Numbers of included studies

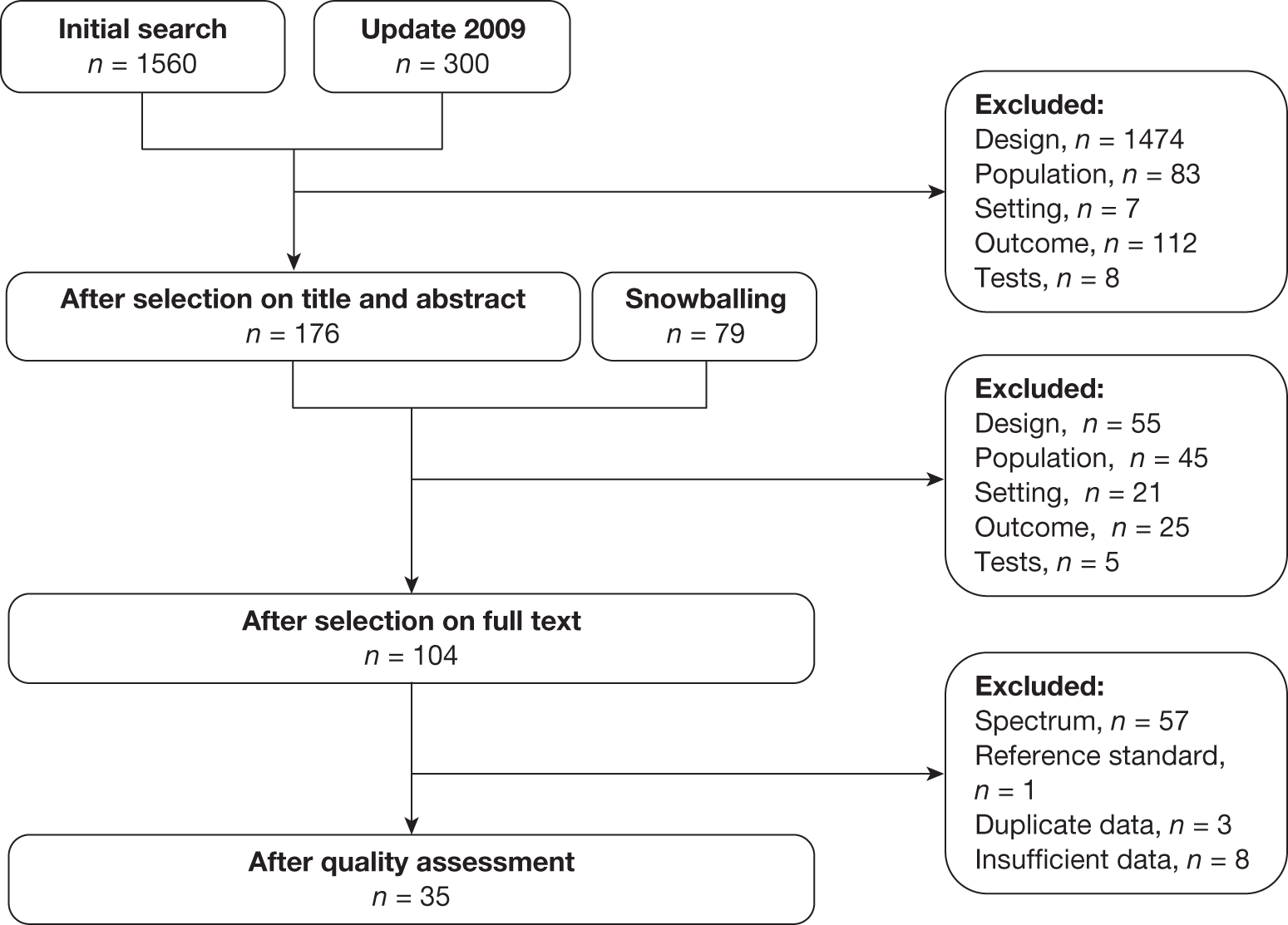

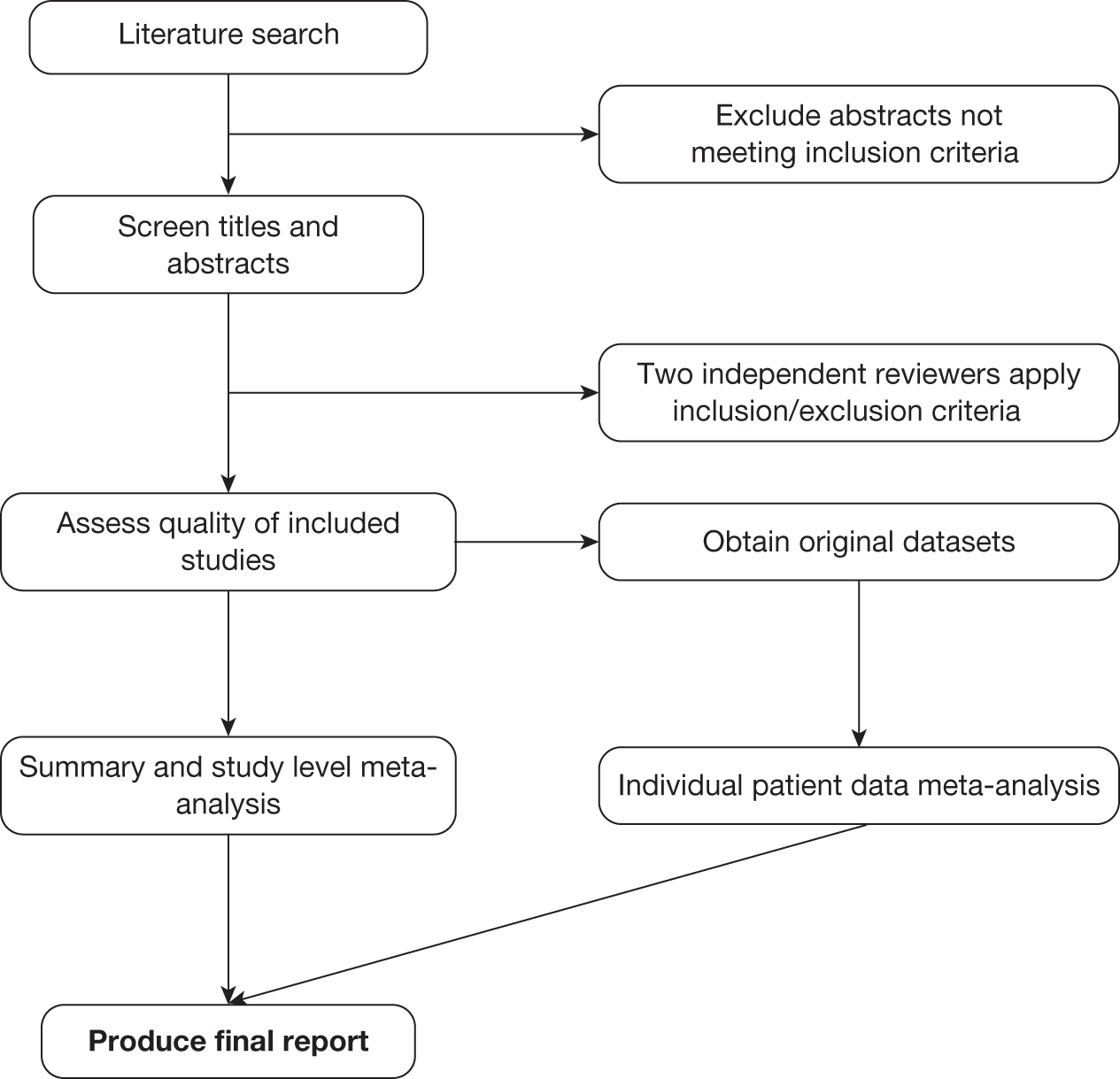

The electronic search of databases identified 1560 articles at the initial search date (October 2007) and a further 300 at the June 2009 update (Figure 1). After reviewing titles and abstracts, 176 of these articles were selected for full-text review. An additional 79 articles were identified based on reference lists of included studies, systematic reviews and NICE guidelines, and from content experts (‘snowballing’). Following the review of the full text of these articles, we included 104 for quality assessment, of which 35 were selected for inclusion in the review. The most common reason for exclusion was spectrum bias.

FIGURE 1.

Flow of literature search.

One study77 was excluded during the analysis stage because the 2 × 2 tables could not be reconstructed.

Setting of included studies

The majority of the studies were performed in the USA (16), with a further five from the UK, four from the Netherlands, three from Switzerland, two from Canada, and one each from Belgium, Italy, Australia, Denmark and Spain. Full details of the 35 included studies are shown in Table 2. There was only a single trial from general practice (which also recruited non-referred patients from ambulatory paediatric care and the ED in Belgium). 11 All other studies were performed in EDs, with four of these in paediatric departments (one a paediatric assessment unit). 29,59,60,75

| Study | Design | Setting, country | n | % serious illness | Quality rating | Age range | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serious infections, composite outcome | ||||||||

| 1. Andreola 200745 | Prospective, Cx, consecutive | ED, IT | 408 | 23.0 | C | < 3 years | Fever of uncertain source and increased risk of SBI, namely all infants aged 7 days to 3 months with rectal temperature > 38 °C and children aged 3–36 months with ill/toxic appearance or with rectal temperature > 39.5 °C | Antibiotics or vaccination in 48 hours prior to enrolment, known immunodeficiencies, any chronic pathology, fever > 5 days |

| 2. Baker 199346 | Prospective, Cx, consecutive | ED, USA | 747 | 8.7 | D | 29–56 days | Temperature (rectal) ≥ 38.2 °C and immunocompetent | Not stated |

| 3. Baker 199947 | Prospective, Cx, consecutive | ED, USA | 422 | 10.2 | D | 29–60 days | Temperature (rectal) ≥ 38.0 °C and immunocompetent | Not stated |

| 4. Baker 199048 | Prospective, consecutive | ED, USA | 126 | 29.4 | C | 26–56 days | Temperature (rectal) > 38.2 °C | Not stated |

| 5. Berger 199649 | Prospective, Cx, consecutive | ED, NL | 138 | 23.9 | B | 2 weeks to 1 year | Temperature (rectal) ≥ 38.0 °C measured on the ward | Gestational age < 37 weeks; perinatal complications; antibiotics or vaccination in previous 48 hours; known previous or underlying disease |

| 6. Bleeker 200750 | Prospective, Cx, consecutive | ED, NL | 381 | 26.0 | D | 1–36 months | Referred to ED for fever without source, i.e. temperature ≥ 38 °C for which no clear focus could be identified after evaluation by the GP or after history taking by paediatrician | Not referred by GP; immune deficiencies |

| 7. Bonadio 199351 | Prospective, Cx; consecutive | ED, USA | 534 | 4.5 | D | 4–8 weeks | Temperature (rectal) ≥ 38 °C at triage, previously healthy | Not stated |

| 8. Galetto-Lacour 200152 | Prospective, Cx | ED, CH | 124 | 22.6 | D | 7 days to 36 months | Temperature (rectal) > 38.0 °C and no localising signs of infection from history or physical examination | Fever > 7 days, neonates < 1 week of age, children treated with antibiotics during the 2 preceding days, children with known immunodeficiencies |

| 9. Galetto-Lacour 200353 | Prospective, Cx | ED, CH | 99 | 29.3 | D | 7 days to 36 months | Temperature (rectal) > 38 °C and without localising signs of infection in their history or at physical examination | Fever > 7 days, neonates < 1 week of age, children treated with antibiotics during the 2 preceding days, children with known immunodeficiencies |

| 10. Galetto-Lacour 200854 | Prospective, Cx | ED, CH | 202 | 26.7 | D | 7 days to 36 months | Temperature (rectal) > 38.0 °C and without localising signs of infection in their history or at physical examination | Fever > 7 days, neonates <1 week of age, children treated with antibiotics during the 2 preceding days, children with known immunodeficiencies |

| 11. Garra 200555 | Prospective, Cx, consecutive | ED, USA | 181 | 21.6 | C | 29–56 days | Temperature (rectal) ≥ 38.1 °C | Likely bacterial source for his or her fever on physical examination including cellulitis, mastitis, omphalitis, abscess, otitis media or septic arthritis |

| 12. Grupo de Trabajo 200156 | Prospective, Cx, consecutive | ED, ES | 739 | 19.9 | D | 0–36 months | Temperature (rectal) ≥ 38 °C | Antibiotics or DTP within 48 hours or MMR within 10 days; systemic central nervous condition; concomitant analytical changes in blood that interfere with interpretation of full blood count; fever duration > 72 hours; chronic illness |

| 13. Hsiao 200657 | Prospective, Cx, consecutive | ED, USA | 429 | 10.3 | C | 57–180 days | Temperature (rectal) > 37.9 °C | Not stated |

| 14. McCarthy 198758 | Prospective, Cx, consecutive | ED, USA | 143 | 19.6 | C | < 24 months | Temperature ≥ 38.3 °C | Not stated |

| 15. McCarthy 198236 | Prospective, Cx, consecutive | ED, USA | 165 | 15.8 | C | < 24 months | Temperature ≥ 38.3 °C | Not stated |

| 16. Nademi 200159 | Prospective, Cx, consecutive | PAU, UK | 141 | 29.1 | D | 0–16 years | Temperature ≥ 38 °C | Temperature < 38 °C |

| 17. Thayyil 200560 | Prospective, Cx, consecutive | PD, UK | 72 | 11.1 | D | 1–36 months | Temperature > 39 °C without localising signs | Antibiotics 72 hours prior to enrolment, immunodeficiencies, fever > 7 days |

| 18. Thompson 200929 | Prospective, Cx, consecutive | PAU, UK | 700 | 55.3 | C | 3 months to 16 years | Suspicion of acute infection | Children with diseases liable to cause repeated serious bacterial infection, and infections resulting from penetrating trauma |

| 19. Trautner 200661 | Prospective, Cx, | ED, USA | 103 | 19.4 | C | < 17 years | Temperature (rectal) ≥ 41.1 °C | None |

| 20. Van den Bruel 200711 | Prospective, Cx, consecutive | GP-APC-ED, BE | 3981 | 0.78 | C | < 17 years | Acute illness for a maximum of 5 days | Traumatic or neurological illness, intoxication, psychiatric or behavioural problems without somatic cause, exacerbation of a chronic condition |

| Bacteraemia | ||||||||

| 21. Crocker 198562 | Prospective, Cx, consecutive | ED, USA | 201 | 10.5 | C | 6 months to 2 years | Temperature (rectal) ≥ 39.4 °C | Viral exanthem, enanthem, croup, vomiting, diarrhoea, admitted with a diagnosis of meningitis or sepsis |

| 22. Haddon 199963 | Prospective, Cx, | ED, AU | 526 | 3.4 | C | 3–36 months | Temperature (tympanic) ≥ 39 °C | Varicella, croup or herpes gingivostomatitis |

| 23. Jaffe 199164 | Prospective, Cx | ED, CA | 955 | 2.8 | C | 3–36 months | Temperature (rectal) ≥ 39.0 °C | Focal infection requiring immediate antibiotic; clinical appearance necessitating immediate hospitalisation; specific viral infections; known immune-deficiency condition or chronic illness; antibiotic or DTP within preceding 48 hours |

| 24. Osman 200265 | Prospective, consecutive | ED, UK | 1547 | 38.0 | D | 0–14 years | All children with an infectious illness | Not stated |

| 25. Teele 197566 | Prospective, Cx, consecutive | ED, USA | 600 | 3.2 | C | 4 weeks to 2 years | Temperature (rectal) ≥ 38.3 °C | Prior medical evaluation or referral from other physician or from other clinic |

| 26. Waskerwitz 198167 | Prospective, Cx, consecutive | ED, USA | 292 | 5.8 | B | < 24 months | Temperature (rectal) ≥ 39.5 °C | Not previously healthy: weight less than third percentile or known chronic disease |

| Gastroenteritis causing dehydration | ||||||||

| 27. Gorelick 199768 | Prospective, Cx | ED, USA | 186 | 33.4 | C | 1 month to 5 years | Chief complaint of vomiting, diarrhoea or poor oral fluid intake | Symptoms > 5 days; history of cardiac or renal disease or diabetes mellitus; malnutrition or failure to thrive: treatment within 12 hours in other health facility; hyponatraemia or hypernatraemia; tonsillectomy within 10 days; no telephone or beeper for follow-up |

| 28. Shavit 200669 | Prospective | ED, CA | 83 | 15.7 | C | 1 month to 5 years | History of diarrhoea (with or without vomiting) for ≤ 5 days and judged by the ED triage nurse to have some degree of dehydration | History of cardiovascular or renal disease; judged by the triage nurse to require emergent medical intervention |

| Meningitis | ||||||||

| 29. Joffe 198370 | Retrospective | ED, USA | 241 | 5.4 | D | 6 months to 6 years | First episode of fever and seizures | Did not undergo lumbar puncture and final outcome was not available; children with a predisposition to meningitis |

| 30. Offringa 199271 | Retrospective, consecutive | ED, NL | 309 | 7.4 | C | 3 months to 6 years | First episode of fever and seizures | Not stated |

| 31. Oostenbrink 200172 | Retrospective | ED, NL | 256 | 38.7 | C | 1 month to 15 years | Signs of meningeal irritation | Patients with a history of severe neurological disease or ventricular drainage, and those referred from other hospitals |

| Pneumonia | ||||||||

| 32. Mahabee-Gittens 200573 | Prospective, Cx | ED, USA | 510 | 8.6 | A | 2–59 months | Cough and more than one of laboured, rapid or noisy breathing, chest or abdominal pain, or fever | Currently taking AB, smoke inhalation, foreign body aspiration or chest trauma; known diagnoses of asthma, bronchiolitis, sickle cell disease, cystic fibrosis, chronic cardiopulmonary disease |

| 33. Taylor 199574 | Prospective, Cx, consecutive | ED, USA | 572 | 7.3 | D | < 2 years | Temperature ≥ 38.0 °C | Acute wheezing and/or stridor, history of chronic pulmonary disease, chest radiograph interpreted as indeterminate by both radiologists (n = 2), clinical diagnosis of pneumonia with no radiograph obtained (n = 2) |

| Meningococcal infection | ||||||||

| 34. Nielsen 200175 | Prospective, Cx, consecutive | PD, DK | 208 | 18.8 | C | > 1 month to < 16 years | Haemorrhages in the skin detected at admission or during hospital stay, plus rectal temperature > 38 °C within 24 hours of admission | Second or more inclusion in the study |

| 35. Wells 200176 | Prospective, Cx, consecutive | ED, UK | 218 | 11.0 | C | ≤ 15 years | Non-blanching rash | Not stated |

Age and prevalence of serious infection

The age of eligible children also varied among the studies, with an upper age limit ranging from 3 months to 18 years. The median prevalence of serious infection was 15.8% (interquartile range 8.66–22.06%), ranging from 0.8% in the general practice study11 to 55.3% in one study at a paediatric assessment unit. 29

Outcomes reported

The majority (20/35) of studies reported on a composite outcome of serious infection, which included sepsis, bacteraemia, meningitis, pneumonia and urinary tract infection (and in some cases additional infections such as cellulitis, osteomyelitis and abscess). 11,29,36,45–61 All but two18,20 of these included children based on the presence of fever and six cases45,50,52–54,60 were based on the absence of localising signs or focus of infection. A further six studies reported outcomes on bacteraemia,62–67 and five of them62–64,66,67 included children with fever. Three studies used an outcome of meningitis,70–72 of which two included children with first episode of fever and seizures,70,71 and one based on signs of meningeal irritation. 72 Two studies used an outcome of gastroenteritis causing dehydration,68,69 one of which included children with clinical gastroenteritis68 and the other children with diarrhoea with or without vomiting and evidence of dehydration. 69 Two studies used an outcome of pneumonia,73,74 and included febrile children and children with clinical signs of respiratory infection. Finally, two studies75,76 used meningococcal infection as an outcome, both of which included haemorrhagic or non-blanching rash as inclusion criteria.

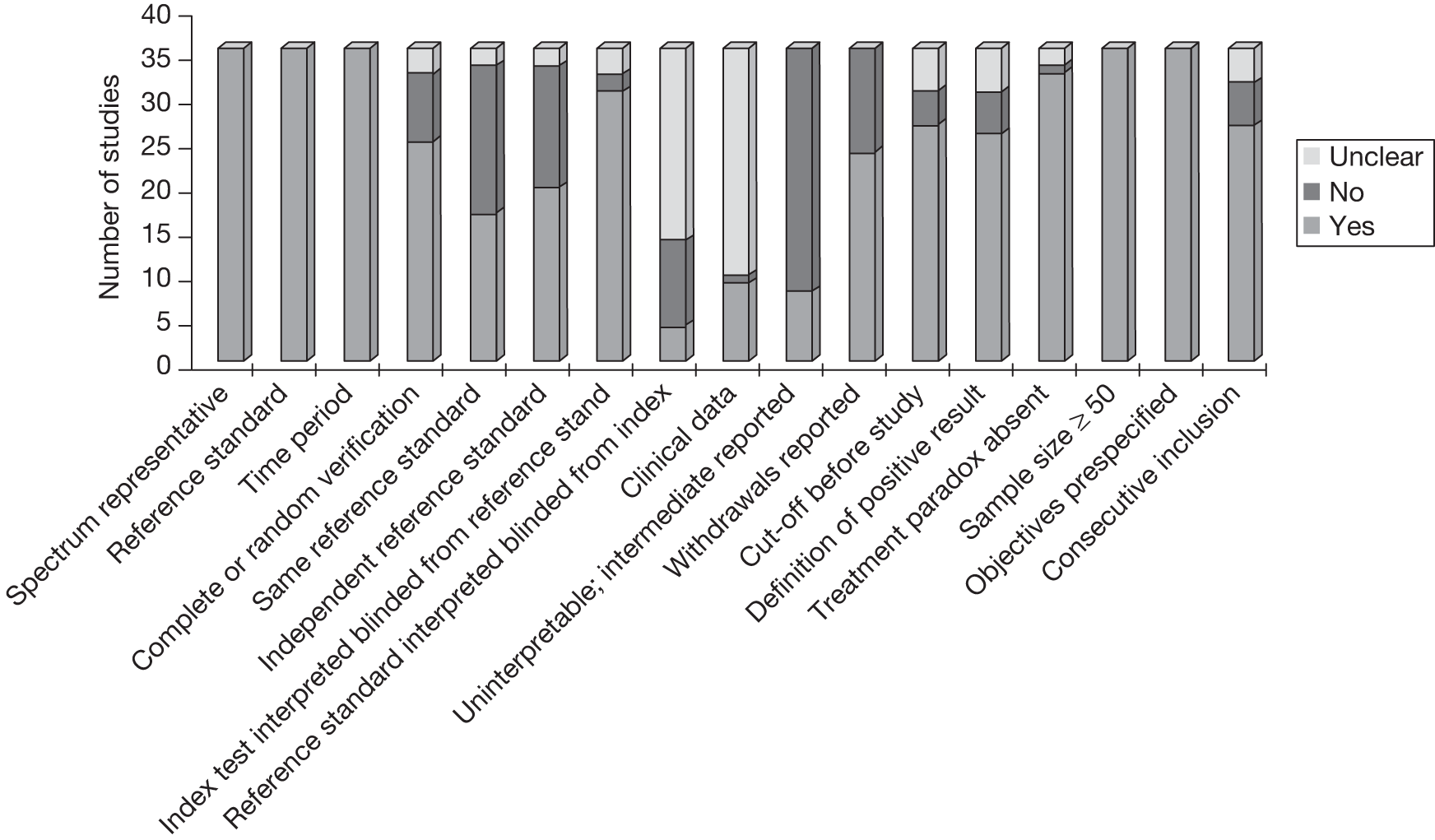

Quality of included studies

All but three of the studies used prospective designs; the remainder were retrospective. The majority (24) used consecutive recruitment. The quality of the included studies was modest (Figure 2). As representativeness of spectrum and valid reference standard were used as inclusion criteria, all studies met these quality criteria. The majority of studies were scored as yes or unclear for the criteria of index text interpreted blinded from reference standard, cut-offs were defined before study, definitions of positive results provided, treatment paradox absent, sample size exceeding 50, pre-specified objectives, and consecutive inclusion. The quality criteria filled by the fewest studies were blind reading of the reference standards which was explicitly mentioned in four studies, and scored as unclear in 21 studies.

FIGURE 2.

Summary of QUADAS features of studies included in systematic review.

Chapter 5 Results of systematic review of clinical features

A total of 3011,29,36,45,48–50,52,53,56–76 studies identified in the systematic review presented the diagnostic value of clinical features for serious infections as a composite outcome or for a specific infection. Clinical features included global assessment, child behaviour, circulatory and respiratory signs, neurological signs or petechial rash, fever, miscellaneous other clinical features and clinical prediction rules. The results of this analysis have also been published in The Lancet. 78

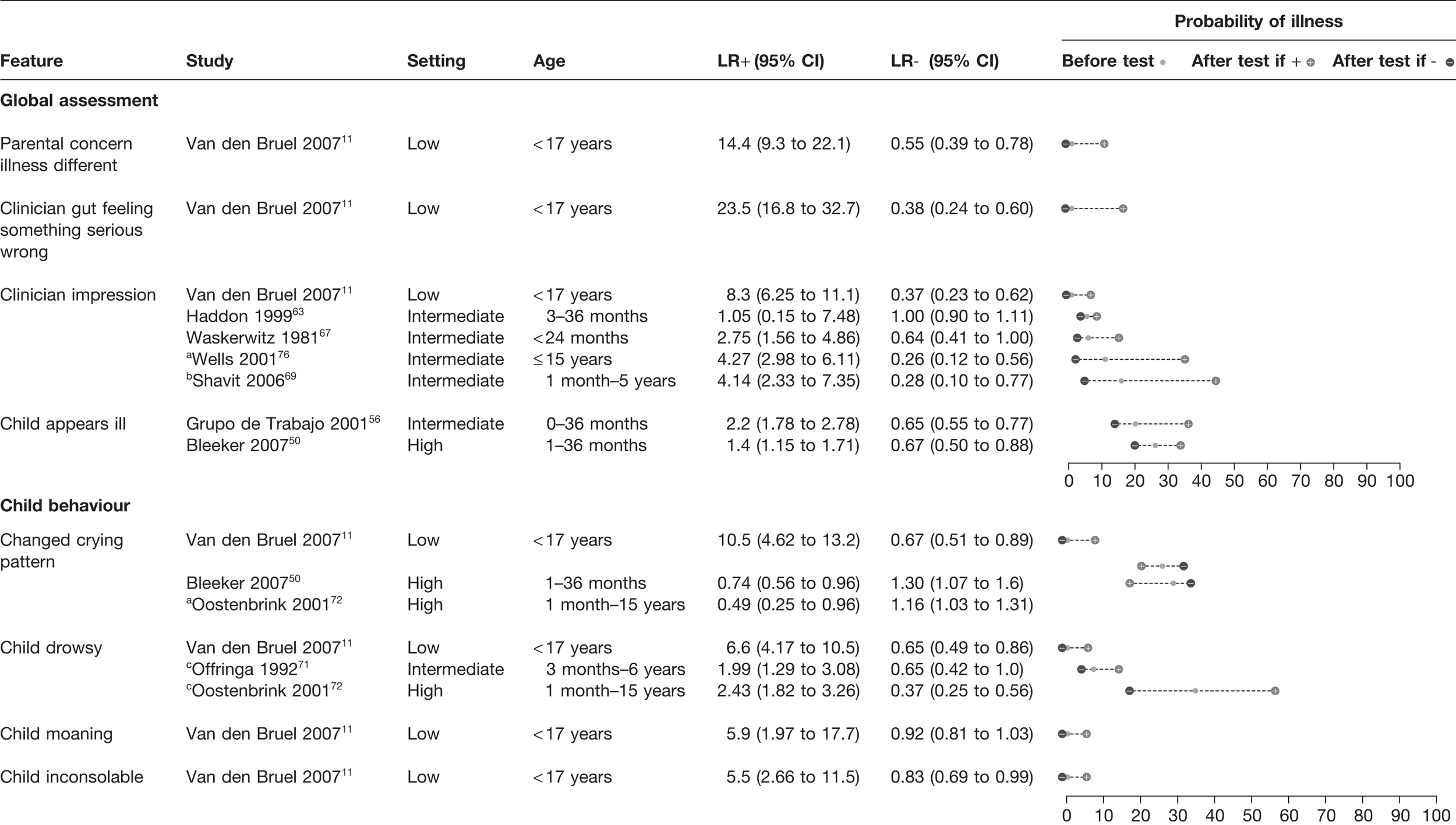

Global assessment

Parental concern that the illness is different from previous illnesses (LR+ 14) and the clinician’s gut feeling that something is wrong (LR+ 23) were important red flags in a single study from a low-prevalence setting (Figure 3). 11 Overall assessment of severity based on clinical impression or the child appearing ill from six further studies50,56,63,67,69,76 (all but one in intermediate-prevalence setting) provided weaker LRs+ and LRs–.

FIGURE 3.

Potential red flag features for serious illness (LR+ > 5 in at least one study): global assessment and behavioural features. Setting: low, low prevalence of serious illness (< 5%); intermediate, intermediate prevalence of serious illness (5–20%); high, high prevalence of serious illness (> 20%). a, Meningococcal infection; b, gastroenteritis causing dehydration only; c, meningitis only.

Child behaviour

Change in the child’s crying pattern, drowsiness, moaning or inconsolability all had a LR+ > 5.0 and thus potential red flags, but again all were from the sole low-prevalence study. 11 In an additional three studies from intermediate or high prevalence settings,50,71,72 these features provided weak LRs+ and LRs– and, paradoxically, changed crying reduced the probability of serious disease in a high-prevalence setting.

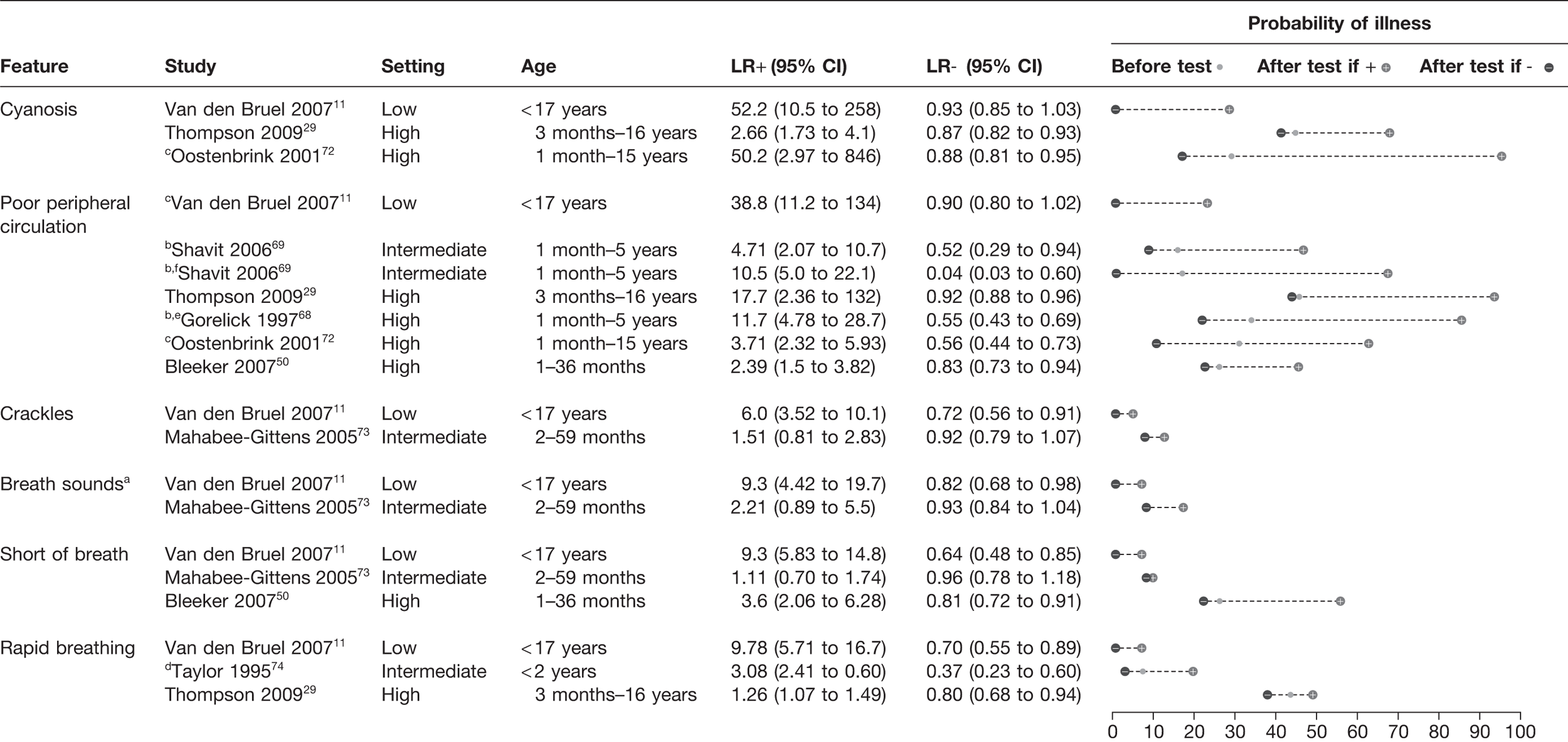

Circulatory and respiratory clinical features

The presence of cyanosis had a LR+ ranging from 2.66 to 52.2 in three studies,11,29,72 suggesting a rule-in value (Figure 4). Poor peripheral circulation was noted in six studies, with a LR+ ranging from 2.39 to 38.8. 11,29,50,68,69,72 There did not appear to be a clear relationship between the prevalence of infection in the study setting and LR+. Rapid breathing and shortness of breath provided greatest LR+ in the single low-prevalence study,11 with a LR+ of 9.3–9.7. In the four other studies that assessed these features, the LR+ was weaker, ranging from 1.11 to 3.6. 29,50,73,74 The presence of crackles on auscultation and diminished breath sounds again provided a LR+ > 5 in the low-prevalence setting (LR+ 6.0–9.3),11 but little value in the single study conducted in an intermediate-prevalence setting. 73

FIGURE 4.

Potential red flag features for serious illness (LR+ > 5 in at least one study): circulatory and respiratory features. Setting: low, low prevalence of serious illness (< 5%); intermediate, intermediate prevalence of serious illness (5–20%); high, high prevalence of serious illness (> 20%). a, Meningococcal infection; b, gastroenteritis causing dehydration only; c, meningitis only; d, pneumonia only; e, capillary refill > 2 seconds; f, digitally measured capillary refill.

Neurological signs or petechial rash

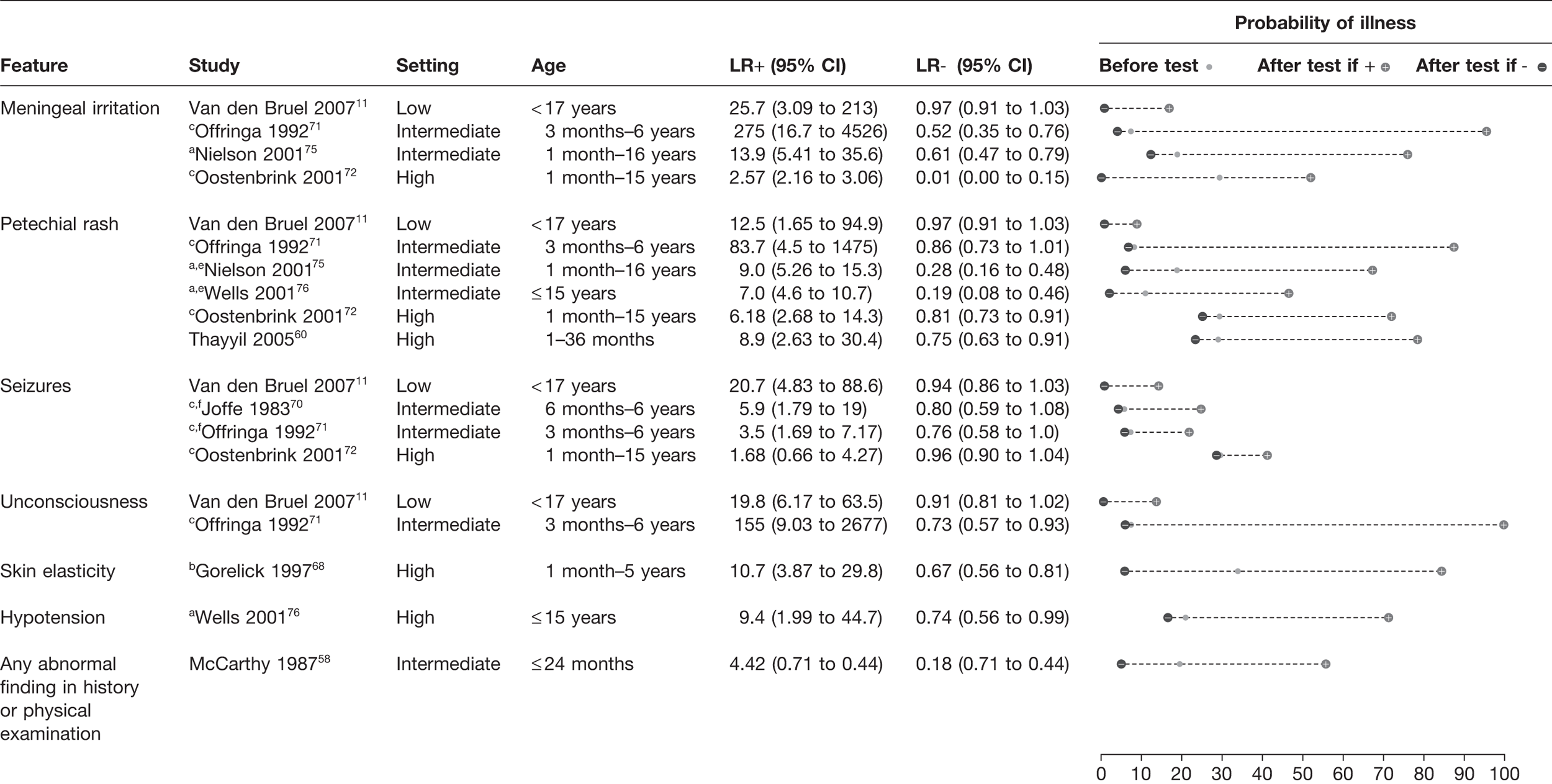

The presence of meningeal irritation, petechial rash, decreased consciousness and seizures all had a LR+ > 5 in the majority of the eight studies which assessed these features (Figure 5). 11,60,70–72,75,76 This effect appeared to be relatively consistent across all settings. Meningeal irritation had a LR+ ranging from 2.57 to 275 in four studies. 11,71,72,75 The presence of a petechial rash had a LR+ of 6.18–83.7 in six different studies. 11,60,71,72,75,76 Seizures were a useful red flag in the study11 in a low-prevalence setting (LR+ 20.7),11 whereas in three studies in intermediate- or high-prevalence settings it was less useful (LR+ 1.68–5.9). 70–72 Loss of consciousness was assessed in only two studies, in which it had a LR+ of 19.8–155. 11,71

FIGURE 5.

Potential red flag features for serious illness (LR+ > 5 in at least one study): neurological and miscellaneous features. Setting: low, low prevalence of serious illness (< 5%); intermediate, intermediate prevalence of serious illness (5–20%); high, high prevalence of serious illness (> 20%). a, Meningococcal infection; b, gastroenteritis causing dehydration only; c, meningitis only; d, pneumonia only; e, diameter > 2 mm; f, during examination.

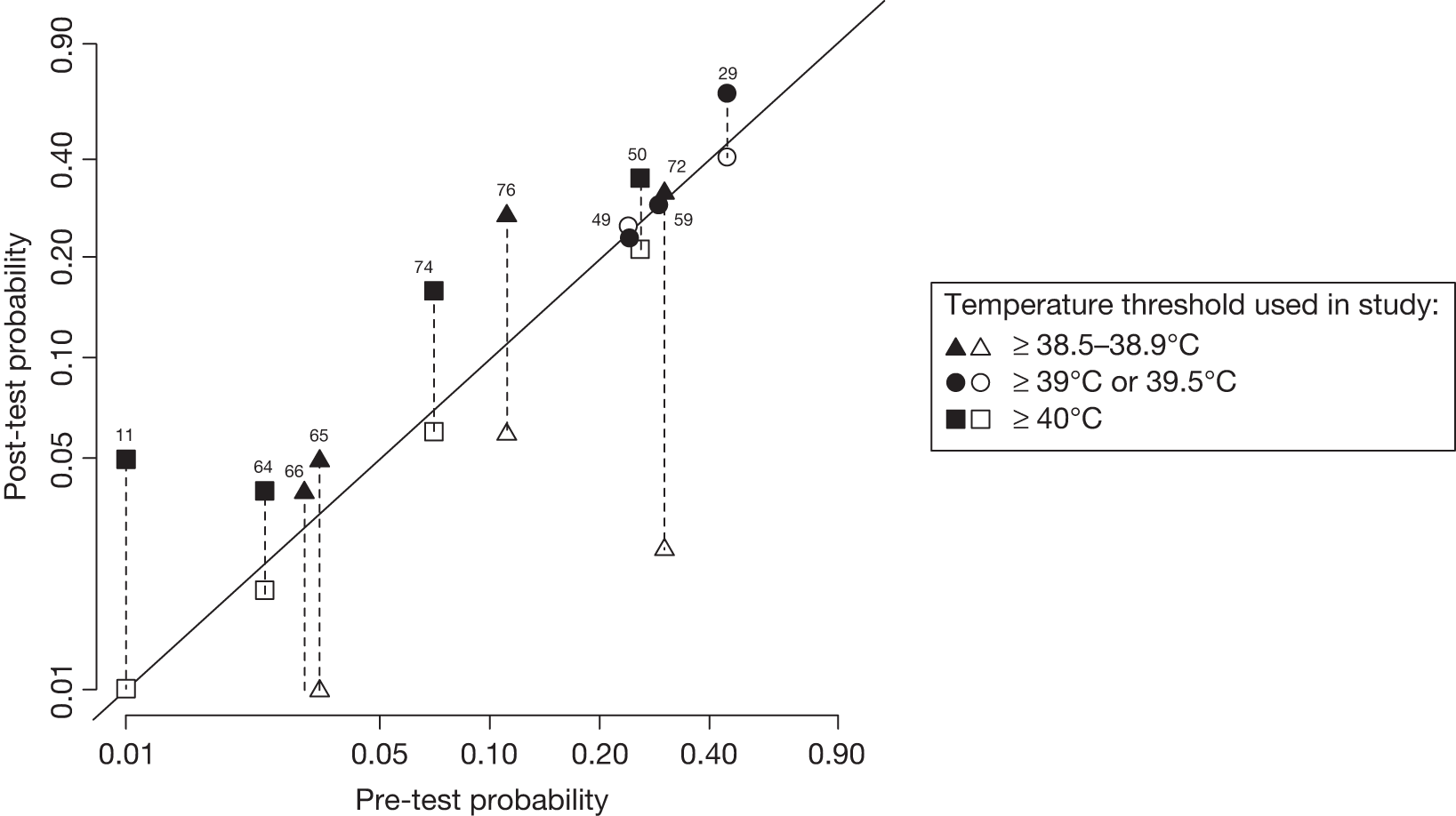

Fever

Data from 11 studies11,29,49,50,59,64–66,72,74,76 were available to plot on a graph of pre-test probability (i.e. prevalence) versus poste-test probability (Figure 6) using cut-offs with the highest LR+. The highest rule-in value was obtained in the setting with the lowest prevalence, where a temperature of 40 °C or more increased the likelihood of disease from 0.8% to 5.0%. 11 By contrast, the absence of high temperature (< 38.5 °C to 38.9 °C) had greatest rule-out value in a study with prevalence of serious infection of 29.1%. 59 However, this rule-out potential was not seen in any of the other five studies29,49,50,65,72 with prevalence > 20% and temperature had no rule-in value in these high prevalence settings.

FIGURE 6.

Probability of serious illness in children with temperature above (closed symbols) or below (open symbols) threshold in 11 studies11,29,49,50,59,64–66,72,74,76 carried out in health-care settings with different pre-test probabilities of serious infection and using different temperature thresholds. The distance of the symbol from the 45 °-line indicates the diagnostic value of temperature measurement in the study (applying the specified threshold). The figure is plotted on a log scale to achieve visual separation of the studies carried out in low-prevalence settings (Teele et al. ,66 the estimated post-test probability if the temperature was < 38.5 °C was 0%, which cannot be plotted on a log scale, so there is no lower symbol).

When we repeated the analysis using additional cut-offs (data not presented in Figure 6), results were very similar to the results presented in Figure 2. In the low-prevalence study,11 temperature ≥ 38 °C had a LR+ of 1.5 and a LR– of 0.38 and temperature ≥ 39 °C has a LR+ of 2.3 and a LR– of 0.59.

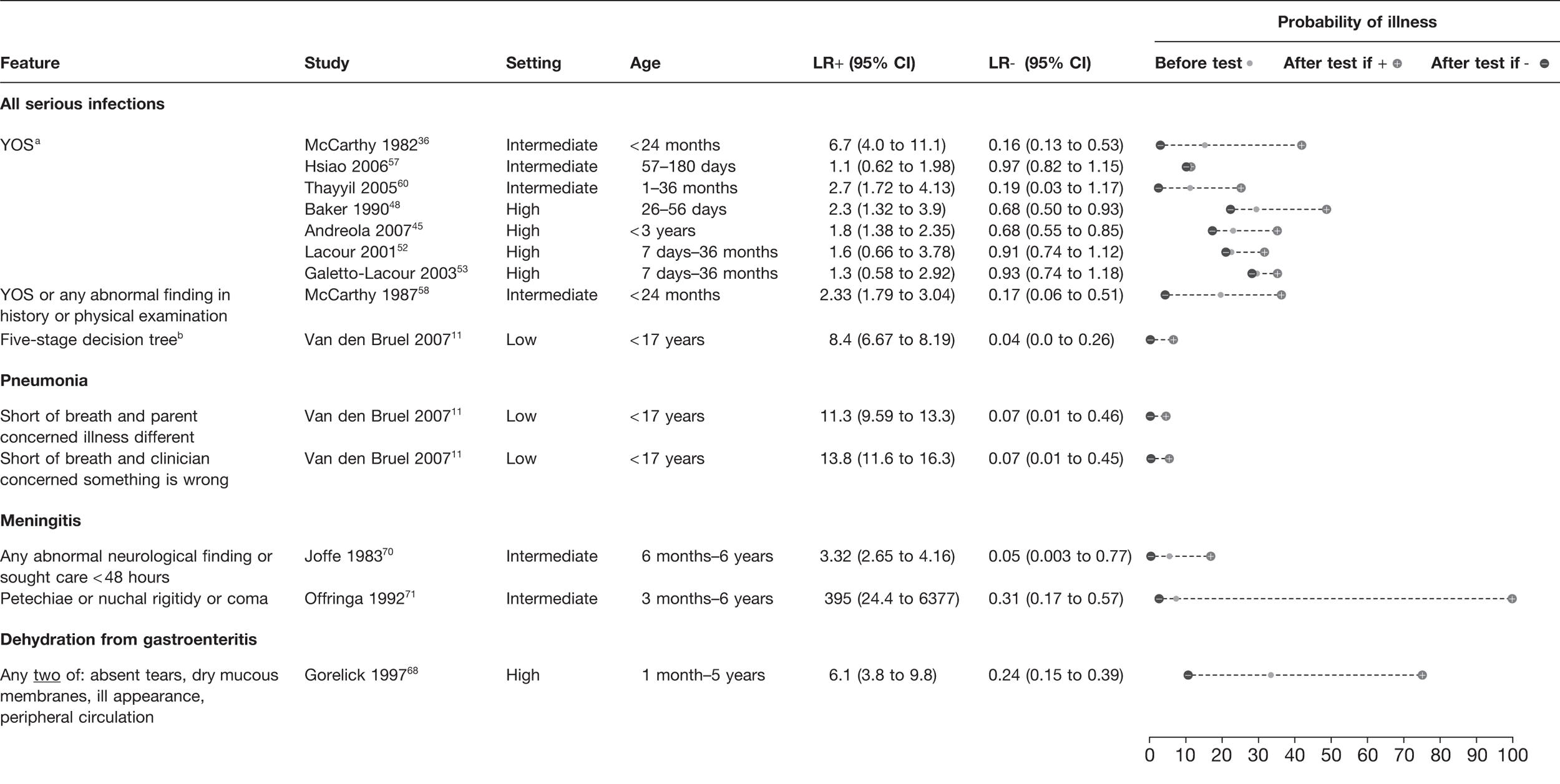

Clinical prediction rules

We identified clinical prediction rules which had been applied to a composite outcome of serious infection, pneumonia, meningitis and dehydration from gastroenteritis (see Appendix 2). The Yale Observation Scale (YOS) was assessed in seven studies (Figure 7). It provided a LR– < 0.2 in two studies,36,60 whereas in five other studies it varied from 0.68 to 0.94,45,48,52,53,57 associated with post-test probabilities ranging from 10% to 28%. The YOS was derived in the McCarthy et al. 1982 study36 at a time prior to routine vaccination against Haemophilus influenzae and pneumococcus, possibly explaining its better results. This would not explain the similar low LR– of the Thayyil et al. study,60 which was performed on a similar patient population in 2003. For meta-analysis, there was significant heterogeneity present (p = 0.002), which remained (p = 0.026) after exclusion of the McCarthy et al. study,36 but disappeared (p = 0.093) after exclusion of both studies. The summary sensitivity of the five remaining studies45,48,52,53,57 was 32.5% (95% CI 21.7% to 45.5%) and specificity was 78.9% (95% CI 73.9% to 83.1%), theoretically corresponding to a LR+ of 1.54 and a LR– of 0.86. An additional study58 assessed the YOS or the presence of any abnormal finding on history or clinical examination in an intermediate population; again it provided a rule-out value with a LR– of 0.17.

FIGURE 7.

Clinical prediction rules with the potential to rule in or rule out serious infection (LR+ > 0.5 or LR– < 0.2 in at least one study). Setting: low, low prevalence of serious illness (< 5%); intermediate, intermediate prevalence of serious illness (5–20%); high, high prevalence of serious illness (> 20%). a, Cut-off used: > 8, study 48; > 9, study 45; > 10, studies 36, 52, 53, 57, 60. b, If yes to any of five sequential questions: (1) clinician instinct that something is wrong; (2) dyspnoea; (3) temperature > 39.5 °C; (4) diarrhoea; (5) age 15–29 months.

The clinical prediction rule that performed best for ruling out serious infection (LR– 0.04) involved five sequential questions, but was assessed in only a single low-prevalence study. 11 Two prediction rules were identified which potentially ruled out pneumonia, with LR– 0.07, both involved the absence of shortness of breath and either parental or clinician concern. Again, these were assessed in only a single low-prevalence study. 11 We identified two prediction rules for meningitis derived in intermediate settings. One provided a rule-out value (LR– 0.05) if there was no abnormal neurological finding and care was not sought within 48 hours, whereas the other provided rule-in ability (LR+ 395) if any of petechiae, nuchal rigidity or coma was present. Finally, a single rule was identified for dehydration from gastroenteritis, which provided modest LR+ (6.10) and LR– (0.24) from a single high-prevalence study. 68

Features of limited help in ruling in or ruling out serious infections

Features that had a LR+ < 5.0 and/or a LR– > 0.2 (i.e. less helpful in either ruling in or ruling out serious infection) for any serious infection are listed in Table 3. The NICE traffic light system and the Manchester Triage System score were of little value in a single study with a high-prevalence setting. Symptoms that are common in children, such as cough, headache, tummy ache, vomiting, diarrhoea, poor feeding and coryza, had little diagnostic value. Two features, namely failure to smile (LR+ 4.2) and changed breathing pattern (LR+ 4.4), were just below the arbitrary LR+ cut-off of 5, but both had a weak LR–, suggesting no rule-out value (LR– 0.6–0.7). The behavioural features of a reactive child (i.e. moving, reaching for objects, looking around the room), lack of irritability and lack of sleepiness did not provide a rule-in or rule-out value based on three studies. 11,49,59 Although cyanosis and poor peripheral perfusion (which causes mottling and pallor) are red flag symptoms as described above, the report of abnormal skin colour (described as cyanotic, pallor or flushed/mottled) in three studies of low and high prevalence did not provide a useful LR. 11,49,50

| Feature | Study | Setting | LR+ | LR– |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global assessment | ||||

| No obvious source of fever | Hsiao 200657 | Int | 3.04 | 0.87 |

| Prediction rulea | Bleeker 200750 | High | 2.1 | 0.38 |

| NICE traffic light systemb | Thompson 200929 | High | 1.20 | 0.50 |

| Manchester triage system | Thompson 200929 | High | 1.35 | 0.43 |

| Prediction rulec | Thompson 200929 | High | 1.31 | 0.52 |

| Child behaviour | ||||

| Child no longer smiles | Van den Bruel 200711 | Low | 4.24 | 0.64 |

| Child is irritable | Van den Bruel 2007,11 Nademi 200159 | Low and high | 1.33–2.34 | 0.57–0.86 |

| Child is somnolent | Van den Bruel 200711 | Low | 2.25 | 0.81 |

| Child is reactived | Berger 199649 | High | 1.33–1.97 | 0.56–0.79 |

| Respiratory signs | ||||

| Changed breathing pattern | Van den Bruel 200711 | Low | 4.43 | 0.67 |

| Cough | Van den Bruel 200711 | Low | 1.30 | 0.73 |

| Signs of URTI | Van den Bruel 2007,11 Trautner 200661 | Low and int | 0.46–0.99 | 1.01–2.21 |

| Gastrointestinal signs | ||||

| Diarrhoea | Van den Bruel 2007,11 Berger 1996,49 Trautner 200661 | Low, int and high | 0.99–2.91 | 0.69–1.00 |

| Vomiting | Van den Bruel 2007,11 Bleeker 2007,50 Nademi 2001,59 Trautner 200661 | Low, int and high | 0.83–1.60 | 0.69–1.10 |

| Signs of dehydratione | Van den Bruel 2007,11 Bleeker 200750 | Low and high | 1.07–2.49 | 0.98 |

| Poor feeding | Van den Bruel 2007,11 Nademi 200159 | Low and high | 1.37–1.54 | 0.51–0.83 |

| Other signs | ||||

| Age | Berger 1996,49 Hsiao 2006,57 Trautner 200661 | Int and high | 0.98–2.49 | 0.77–1.01 |

| Underlying condition | Trautner 200661 | Int | 2.42 | 0.76 |

| Duration of fever/illness | Van den Bruel 2007,11 Andreola 2007,45 Berger 1996,49 Bleeker 2007,50 Trautner 200661 | Low, int and high | 0.76–2.18 | 0.74–1.53 |

| Abnormal skin colour | Van den Bruel 2007,11 Berger 1996,49 Bleeker 200750 | Low and high | 1.59–1.95 | 0.61–0.97 |

| Tummy ache | Van den Bruel 200711 | Low | 0.41 | 1.15 |

| Headache | Van den Bruel 200711 | Low | 0.23 | 1.20 |

| Tachycardiaf | Thompson 200929 | High | 1.49–2.05 | 0.65–0.85 |

The clinical features that were of limited rule-in or rule-out value for specific infections are listed in Table 4. Several clinical features in a single study of dehydration from gastroenteritis (low urine output, sunken eyes, dry mucous membranes, tachycardia, abnormal respiration) all had modest LRs (LR+ 1.8–3.8). The presence of paralysis or paresis had only a modest LR+ for meningitis (3.48).

| Feature | Study | Setting | LR+ | LR– |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteraemia | ||||

| Child is irritable | Crocker 198562 | Int | 1.48 | 0.61 |

| Child is lethargic | Crocker 198562 | Int | 0.64 | 1.10 |

| Functional statusa | Waskerwitz 198167 | Int | 1.21–2.57 | 0.26–0.55 |

| Age (various cut-offs) | Teele 197566 | Low | 0.33–1.83 | 0.66–1.13 |

| Referral status | Haddon 199963 | Low | 1.74 | 0.79 |

| Meningitis | ||||

| Child is irritable | Oostenbrink 200172 | High | 0.76 | 1.05 |

| Vomiting | Offringa 199271 | Int | 2.53 | 0.64 |

| Duration of fever/illness | Offringa 199271 | Int | 1.43 | 0.81 |

| Sought care in previous 48 hours | Joffe 1983,70 Offringa 199271 | Int | 2.28–2.92 | 0.64–0.73 |

| Paresis or paralysis | Offringa 199271 | Int | 3.48 | 0.76 |

| Meningococcal infection | ||||

| Cough | Nielsen 200175 | Int | 0.41 | 1.35 |

| Vomiting | Nielsen 200175 | Int | 1.08 | 0.94 |

| Pneumonia | ||||

| Grunting | Mahabee-Gittens 200573 | Int | 0.56 | 1.02 |

| Wheezing | Mahabee-Gittens 200573 | Int | 1.25 | 0.95 |

| Duration | Mahabee-Gittens 200573 | Int | 1.03 | 0.93 |

| Dehydration from gastroenteritis | ||||

| Abnormal respirations | Gorelick 199768 | High | 3.10 | 0.66 |

| Tachycardia | Gorelick 199768 | High | 2.18 | 0.68 |

| Abnormal radial pulse | Gorelick 199768 | High | 3.10 | 0.66 |

| Sunken eyes | Gorelick 199768 | High | 3.71 | 0.47 |

| Dry mucous membranes | Gorelick 199768 | High | 3.62 | 0.26 |

| Decreased urine output | Gorelick 199768 | High | 1.82 | 0.27 |

Chapter 6 Results of the systematic review of laboratory tests for serious infections

A total of 14 studies45–47,49–55,57,59–61 identified in the systematic review reported the diagnostic value of laboratory tests for serious infections. (Published in Van den Bruel et al. Diagnostic value of laboratory tests in identifying serious infections in febrile children: a systematic review. BMJ 2011;342:D3082.)

Diagnostic value of laboratory tests for composite outcome of serious infection

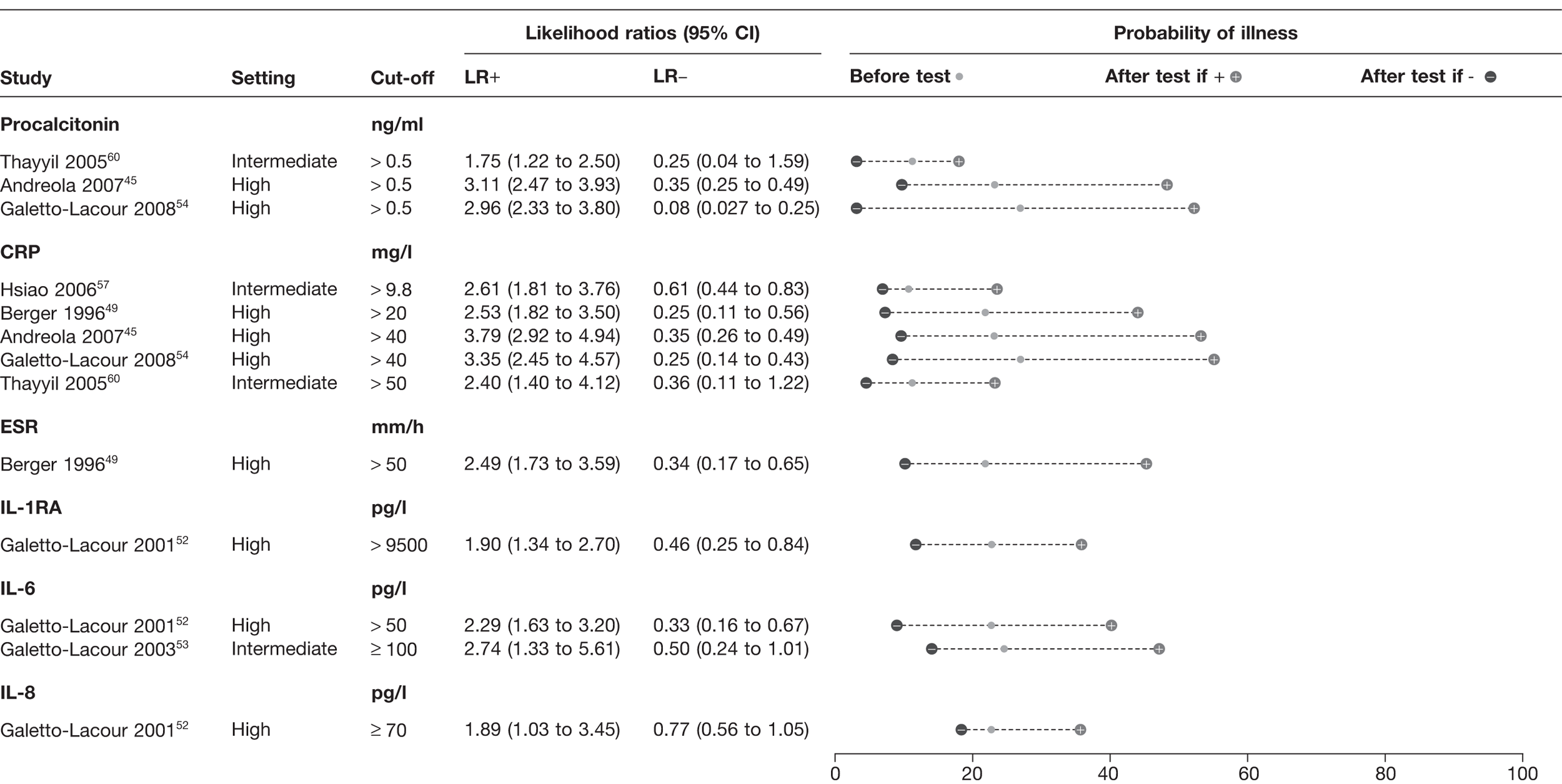

Inflammatory markers

Seven studies identified in the systematic review45,49,52–54,57,60 provided data on the diagnostic value of six inflammatory markers: procalcitonin (PCT), C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), interleukin-6, interleukin-8 and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (Figure 8). None of the studies was performed in low-prevalence settings. The three studies45,54,60 which reported the results of PCT all used the same cut-off (0.5 ng/ml) and demonstrated a LR+ of 1.75–2.96, with a LR– of 0.08–0.35. The five studies of CRP45,49,54,57,60 had cut-offs ranging from 9.8 to 50 mg/l, and provided a LR+ of 2.53–3.79 and a LR– of 0.25–0.61. Pooling of CRP results was possible and using bivariate meta-analysis of CRP yielded a pooled LR+ of 3.15 (95% CI 2.67 to 3.71) and a pooled LR– of 0.33 (95% CI 0.22 to 0.49) across all cut-offs.

FIGURE 8.

Diagnostic value of inflammatory markers for serious infection. IL-1RA, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist; IL-6, interleukin-6; IL-8, interleukin-8. Setting: low, low prevalence of serious illness (< 5%); intermediate, intermediate prevalence of serious illness (5–20%); high, high prevalence of serious illness (> 20%).

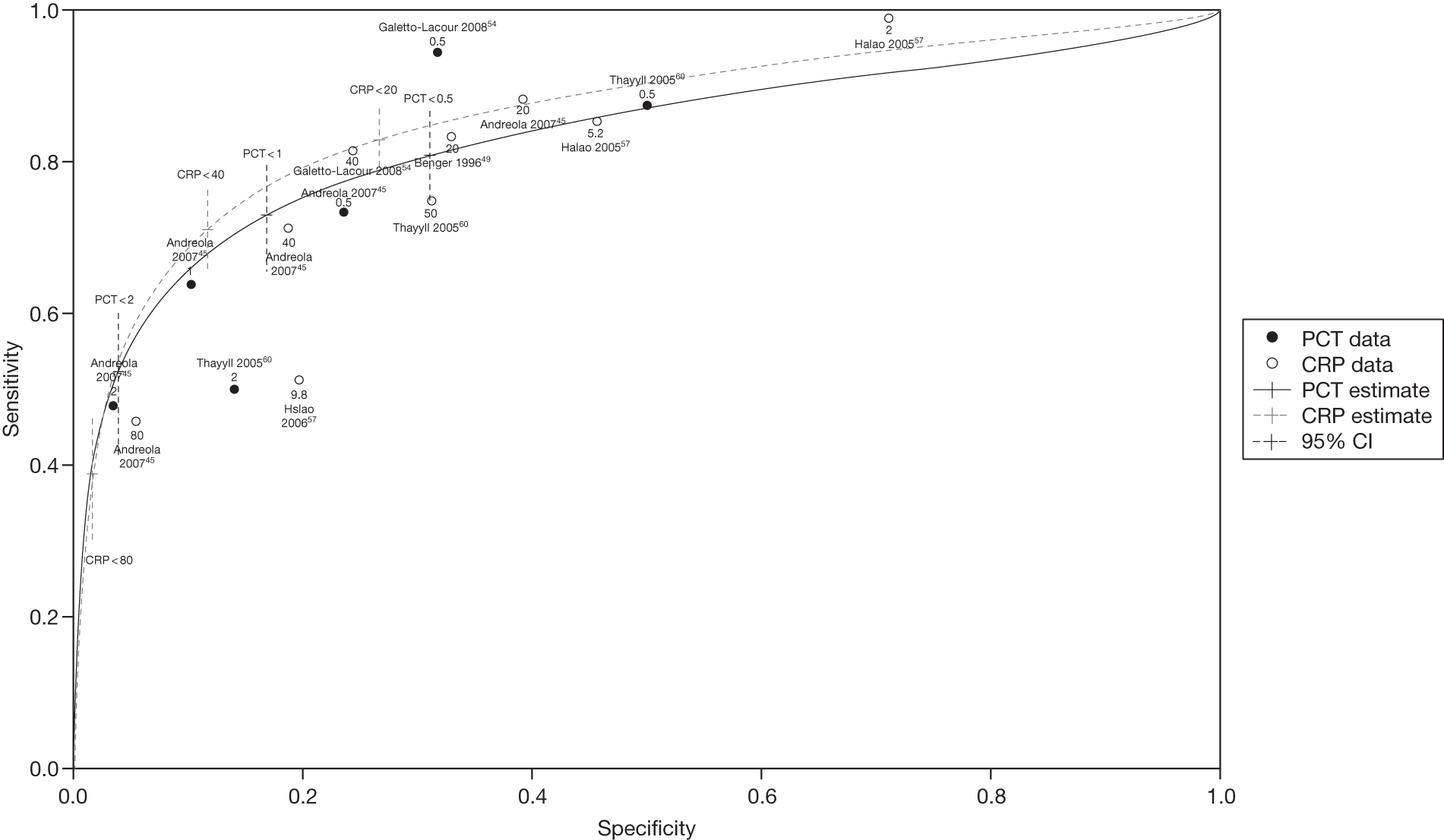

The summary receiver operator characteristics curve plots of CRP and PCT (Figure 9) confirm that the markers have similar diagnostic accuracy as the shapes of the curves are very similar and the CIs are overlapping. We plotted the LRs of CRP and PCT identified in the systematic review by cut-off value and disease prevalence to identify the optimal cut-off points to apply. To rule in serious infection, cut-off levels of 2 ng/ml for PCT or 80 mg/l for CRP both provide good diagnostic value (a LR+ of ≥ 4) but poor rule-out value. To rule out effectively, cut-offs of 0.5 ng/ml for PCT or 20 mg/l for CRP may be a better choice (a LR– of ≤ 0.2).

FIGURE 9.

Summary receiver operator characteristic curves for CRP and PCT.

The performance of ESR in a single study49 (cut-off of 50 mm/hour) provided LR+ 2.49 and LR– 0.34. The two studies investigating the three interleukins demonstrated somewhat inferior diagnostic values to CRP or PCT. 52,53

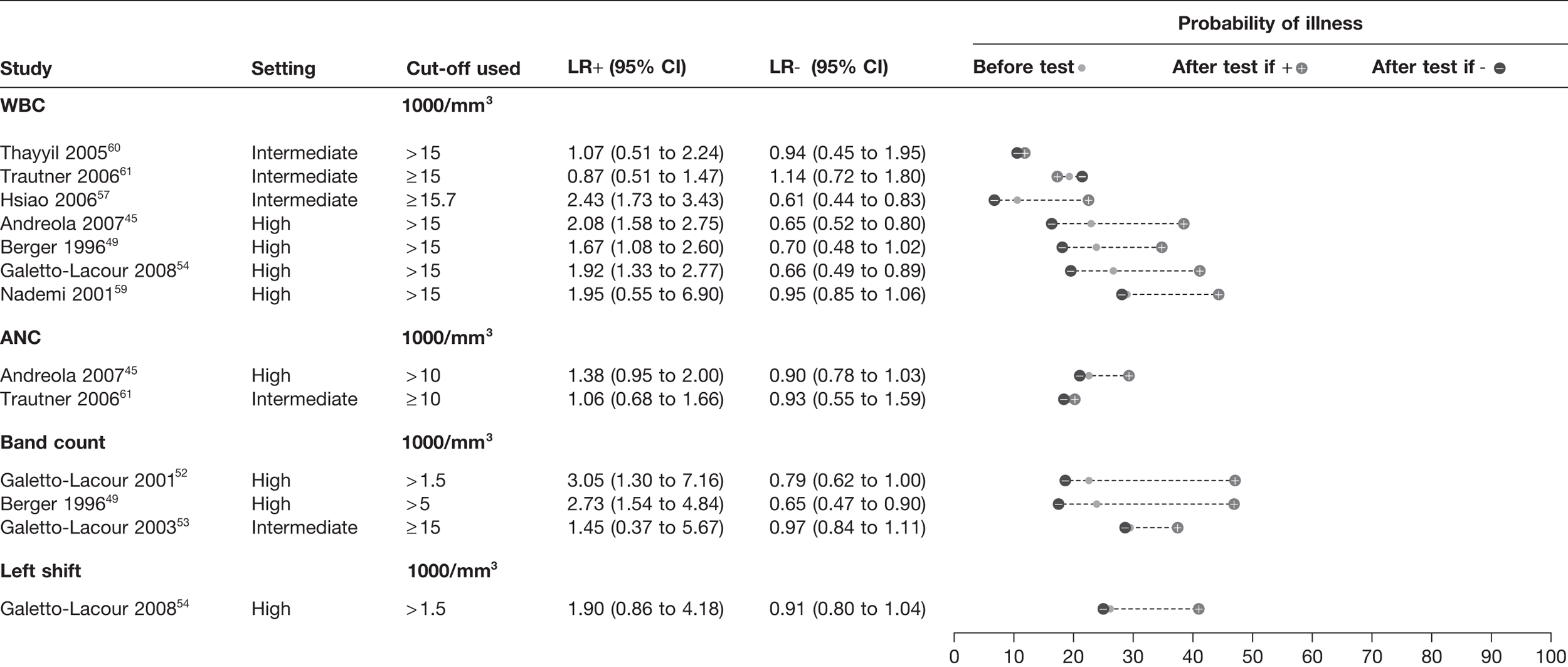

White blood cell counts

A total of nine studies45,49,54,57,59–61 provided data on either total WBC (seven studies45,49,54,57,59–61), absolute neutrophil count (two studies45,61), band count (three studies49,52,53) or left shift (single study54); all were from intermediate- or high-prevalence settings (Figure 10). All four WBC indices demonstrated little diagnostic value in ruling out serious infection: the minimum LR– is 0.61 with the 95% CI in most studies crossing 1.0. The LRs+ were also weaker than the inflammatory markers, with values ranging from 0.87 to 3.05. There was little evidence to determine whether or not any of the WBC markers offered superior diagnostic value. The results of one study61 appeared to show paradoxical results for WBC: the likelihood of disease was lower in children with a WBC ≥ 15,000/mm3.

FIGURE 10.

Diagnostic value of WBCs for serious infection. ANC, absolute neutrophil count. Setting: low, low prevalence of serious illness (< 5%); intermediate, intermediate prevalence of serious illness (5–20%); high, high prevalence of serious illness (> 20%).

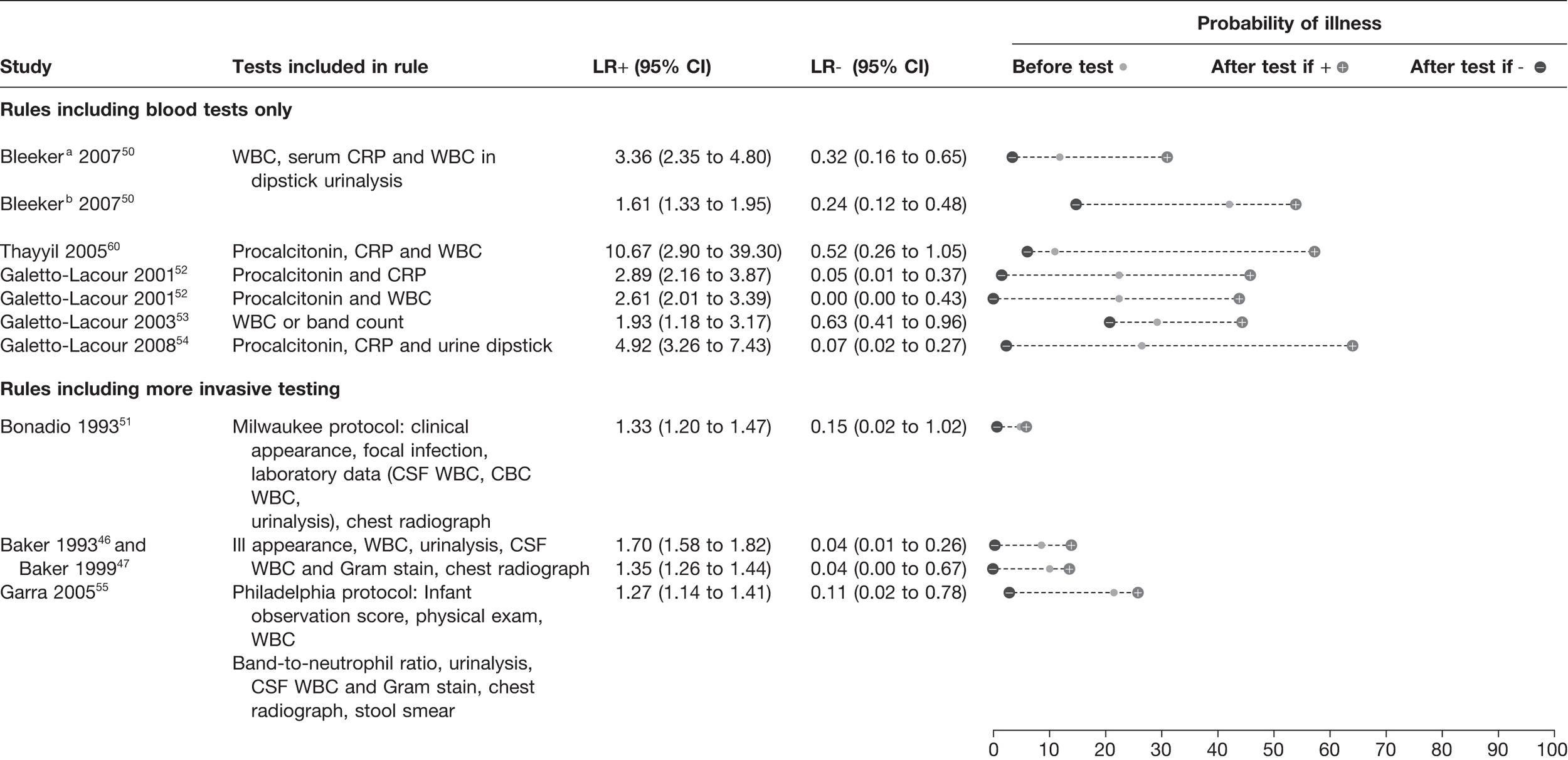

Added value of combinations of blood tests and clinical features

We identified eight studies46,47,50–55,60 which reported the diagnostic value of prediction rules consisting of a single blood test or combinations of blood tests, with or without clinical features (Figure 11). The clinical features, laboratory tests and cut-offs used are provided in Appendix 3.

FIGURE 11.

Prediction rules combining CRP, WBC and PCT with clinical features. a, In patients negative on a clinical prediction rule; b, in patients positive on a clinical prediction rule. ANC, absolute neutrophil count. Full details of cut-off points applied are given in Annex 3 (Van Den Bruel et al. Diagnostic value of laboratory tests in identifying serious infections in febrile children: a systematic review. BMJ 2011;342:D3082).

Bleeker et al. 50 determined the added value of laboratory markers in patients testing high or low risk for a prediction rule of clinical symptoms. The clinical rule included duration of fever, history of vomiting, ill appearance, chest-wall retractions and/or tachypnoea, and decreased capillary refill. Their results showed that in children testing high risk on their clinical prediction rule, a combination of WBC, CRP and urinalysis lowered the probability from 42% to 15% when negative, but the probability was not increased substantially when positive (54%), indicating a greater ability to rule out than rule in serious infection. In contrast, the use of WBC, CRP and urine analysis in children who tested low risk on the clinical prediction rule lowered the probability of serious infection (from 12% to 4%) if negative and increased the probability to 31% if positive.

The laboratory clinical prediction rule reported by Thayyil et al. 60 provided the highest LR+ (10.67) based on the results of PCT, CRP and WBC. However, this offered little rule-out value with a LR– of 0.52. The best performing prediction rule by Galetto-Lacour et al. 54 reported a LR+ of 5 and a LR– of 0.07 and involved urine dipstick as well as measuring a score based on the levels of PCT and CRP. This rule had good rule-in and rule-out potential, a high score increasing the likelihood of a serious infection from 27% to 64%, and a below threshold score decreasing it to 2%. The inclusion criteria for both the studies of Thayyil et al. 60 and Galetto-Lacour et al. 54 included the presence of fever.

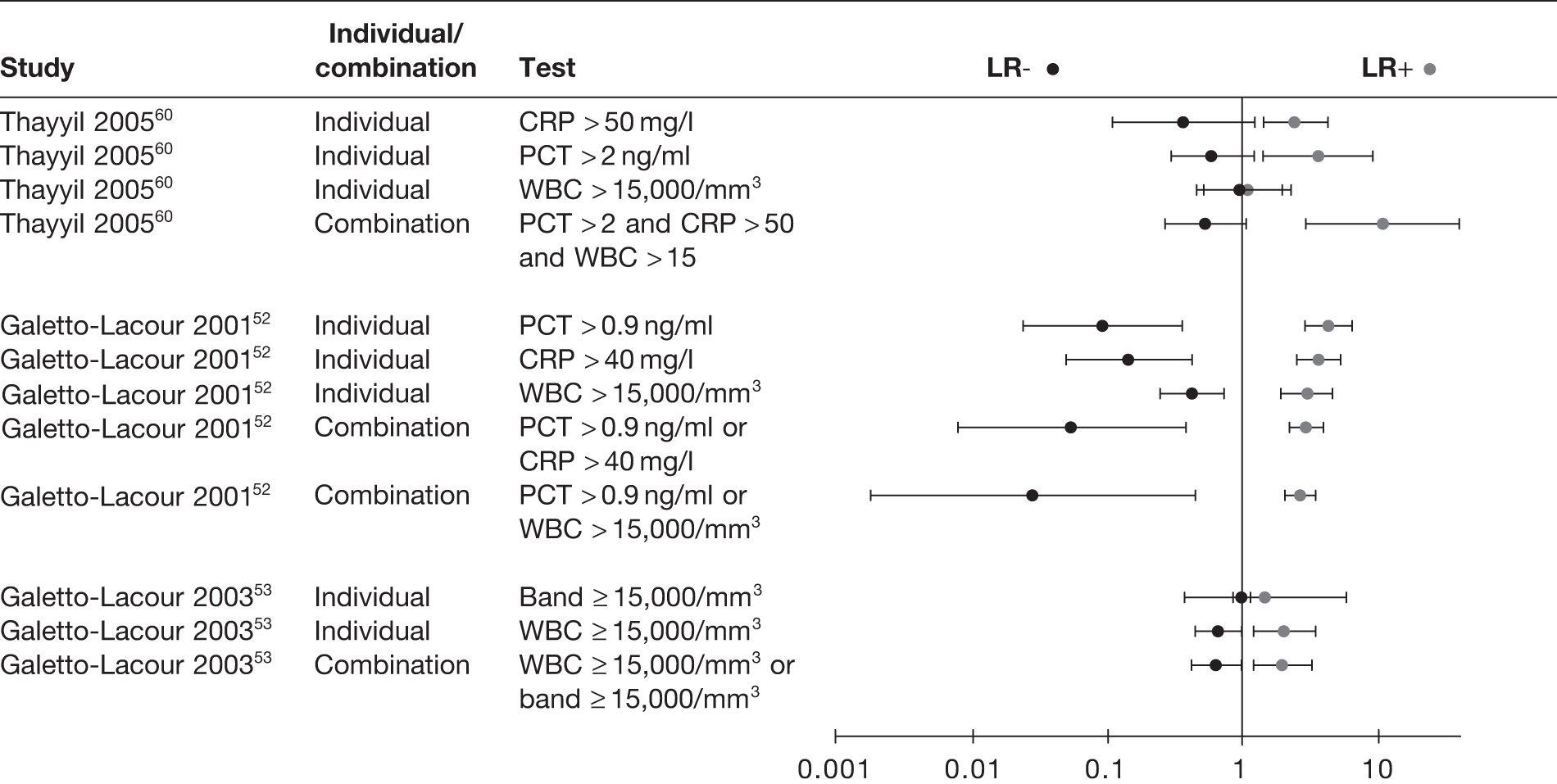

We also found that combinations of inflammatory markers offered little additional diagnostic value to the individual tests, with all the CIs of the combinations largely overlapping with those of the individual tests (Figure 12). In general, combinations in which all tests had to be positive increased the ability to rule in serious infection, whereas combinations in which at least one test had to be positive increased the ability to rule out serious infection.

FIGURE 12.

Likelihood ratios of individual and combinations of inflammatory markers and WBCs.

Although clinical prediction rules which involve a series of clinical features as well as more invasive investigations (i.e. cerebrospinal fluid parameters and chest radiography) are not within the scope of this review, the results of the clinical prediction rules identified are presented in Appendix 3. These rules were derived for use in infants < 3 months of age presenting to the ED with fever. The dumbbell plots show they provide little diagnostic value in ruling in serious infection (LR+ 1.27–1.70), but provide LR– ranging from 0.04 to 0.15 (pooled LR– 0.06; 95% CI 0.018 to 0.19), indicating good rule-out value.

Diagnostic value of laboratory tests for meningitis and/or bacteraemia

Only one study evaluating CRP for the diagnosis of meningitis and/or bacteraemia was available that showed CRP is able to rule out meningococcal infection if normal (LR– 0.05). 76 Two studies on meningococcal infection75,76 evaluated the value of coagulation markers, i.e. activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), international normalised ratio (INR) and platelets, and found good diagnostic value at ruling in the disease (LR+ 2.05–13.08), except for platelets (LR+ 3.20). Normal coagulation markers do not exclude the possibility of meningococcal infection.

Six studies evaluated the value of WBC, all with bacteraemia as outcome. 62–64,66,67,76 None of the studies reported a LR+ > 3.0 or a LR– < 0.3, suggesting that WBCs were of very little use in diagnosing or excluding bacteraemia. Indeed, after pooling these studies, the summary sensitivity of abnormal WBC was 62.71% (95% CI 52.60% to 71.81%), summary specificity was 69.27% (95% CI 62.71% to 75.13%), summary was LR+ 2.04 (95% CI 1.51 to 2.75) and summary LR– was 0.54 (95% CI 0.40 to 0.73). Absolute neutrophil count was reported in two studies, one on bacteraemia62 and one on meningococcal infection. 76 Both reported low LRs (LR+ 1.65–2.57 and LR– 0.40–0.60).

Five studies reported prediction rules for meningitis and bacteraemia which combined clinical features with inflammatory markers. 62,66,67,72,75 The rules by Teele et al. ,66 Crocker et al. 62 and Waskerwitz67 did not increase or decrease the probability of bacteraemia significantly (LR+ 1.21–2.92). Two prediction rules, those of Nielsen et al. 75 and Oostenbrink et al. ,72 combined clinical features with CRP, and both were able to rule out meningococcal disease and meningitis respectively (LR– 0.01–0.05). The Nielsen rule also increased the likelihood of meningococcal infection at higher cut-offs (LR+ 17.33). The Nielsen rule consists of the presence and characteristics of haemorrhages, general condition nuchal rigidity, band count and CRP. The Oostenbrink rule consists of duration of the main complaint, vomiting, meningeal irritation, cyanosis, petechiae, disturbed consciousness and CRP.

Chapter 7 Methods used for validation of prediction rules

We aimed to perform a multiple external validation analysis of the clinical prediction rules identified from the systematic review using existing data sets on populations of children attending ED or primary care. The details of the clinical prediction rules which were validated and the variables included in each prediction rule have been presented in previous chapters. This chapter describes the methods of the validation of the prediction rules.

Identification of data sets

We identified existing data on children attending ED, urgent-access primary care or primary care from two sources. Firstly, we identified data sets included in the systematic review. We approached authors of data sets published within the last 10 years and invited them to contribute data and expertise to the multiple external validation study. Secondly, we contacted content experts in this clinical area and asked them to identify other existing data sets. The criteria we used to include data sets were modified from those used as inclusion criteria for the systematic review (Table 5).

| Characteristic | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Design |

Studies which had recorded clinical features, laboratory tests Prospective or retrospective cohort study design |

Unclear methods |

| Participants |

Age between 1 month and 18 years Studies including children spanning this age range included if they reported age (or age could be calculated) |

Children with pre-existing immune suppression (such as HIV infection or neutropenia due to chemotherapy) Outwith age range |

| Setting |

Ambulatory care (defined as general or family practice, paediatric outpatient clinics, paediatric assessment units or EDs) Developed countries, defined using the United Nations list, which included Europe, Canada, USA, Australia, New Zealand and Japan |

Studies conducted in developing countries |

| Outcome | Serious infection, defined as sepsis (including bacteraemia), meningitis, pneumonia, osteomyelitis, cellulitis, gastroenteritis with severe dehydration, complicated urinary tract infection (positive urine culture and systemic effects such as fever) and viral respiratory tract infections complicated by hypoxia (e.g. bronchiolitis) | Diagnosis other than serious infection |

| Data availability | Agreement to share data |

Identification of clinical prediction rules

The systematic review identified clinical prediction rules which have been applied to a composite outcome of serious infection, pneumonia, meningitis and dehydration from gastroenteritis (see Appendix 2): the YOS, a five-stage decision tree, two prediction rules for pneumonia, two prediction rules for meningitis and a rule for dehydration from gastroenteritis.

To determine which data sets could be used to validate the prediction rules, we constructed a matrix of all variables recorded in the available data sets. Consensus through group discussion was reached on which clinical prediction rules we could validate based on the available data sets.

Exploring heterogeneity

Given that the analysis was performed on an individual patient data level, it was essential to tabulate heterogeneity and mark up similarities between studies. This heterogeneity may be related to patient characteristics, setting, geographical characteristics, test characteristics or study design.

Characteristics of included data sets

Key characteristics of each of the data sets were extracted, including inclusion and exclusion criteria, setting, age of participants and individual variables (see Table 6). The variables used in each data set were translated to English if necessary, and clarifications for variables were obtained from the researcher responsible for each data set. Coding of all key variables was checked not only on statistical grounds but also on clinical grounds, with the responsible researcher (i.e. meaning of the variable label ‘unknown’ in relation to missing observations). A merged data set was then created and checked for internal and external validity. The translation, the synopsis, the recoding and the data checking were carried out by one member of the study team (JV) and the results of each step were discussed with every responsible researcher when necessary.

| Data set | Year | Setting | Country | n | Prevalence serious infection, % (95% CI) | Mean age, years (range) | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Van den Bruel et al.11 | 2004 | GP/AP/ED | BE | 4102 | 0.78 (0.51 to 1.05) | 5.00 (0.02–16.93) | Children ≤ 16 years with acute illness for a maximum of 5 days | Traumatic or neurological illness, intoxication, psychiatric or behavioural problems without somatic cause or an exacerbation of a chronic condition. No repeated inclusion of same infant within 5 days. Exclusion of physicians if the assumption of consecutive inclusion was probably violated |

| Oostenbrink et al.72 | 2001 | ED | NL | 593 | 44.35 (40.34 to 48.36) | 3.66 (0.08–16.08) | Children aged 1 month to 16 years, meningeal signs at GP, paediatrician or self-referred with neck pain | Comorbidity, VP-drain |

| Roukema et al.28 | 2005 | ED | NL | 1772 | 12.97 (11.40 to 14.55) | 2.88 (0.09–15.69) | All children with fever (T > 38 °C) at ED, without meningeal irritation | Chronic disease, immunodeficiency |

| Bleeker et al.50 | 2006 | ED | NL | 595 | 23.53 (20.11 to 26.95) | 0.94 (0.00–2.99) | Children with fever T > 38 °C at ED, no clear focus identified after evaluation GP of history by paediatrician | Chronic disease, immunodeficiency |

| Thompson et al.29 | 2005 | PAU | UK | 700 | 44.71 (41.02 to 48.41) | 4.62 (0.00–16.00) | Children age 3 months to 16 years with suspected acute infection | Children with diseases liable to cause repeated serious bacterial infection, and infections resulting from penetrating trauma |

| Brent et al.79 | 2001 | ED | UK | 2777 | 13.43 (12.16 to 14.70) | 3.32 (0.18–18.39) | All children presenting with a medical problem to the paediatric emergency care unit whatever their age | Children who required immediate resuscitation. Comorbidity and chronic illness |

| Berger et al. | 2005 | GP | NL | 506 | 6.52 (4.36 to 8.68) | 2.16 (0.27–5.88) | Children aged 3 months to 6 years, contacting a GP co-operative after hours with fever as the presenting complaint | Language barriers, no repeated inclusion within the last 2 weeks |

Where variables were not entirely comparable, proxies were identified from other variables contained in the data sets and fitted to perform the analysis. If too few variables were present in one data set to allow cross-validation, that data set was excluded from the specific analysis (e.g. fewer than three variables present for a composite clinical prediction rule of six variables was deemed unsuitable). In addition to approximations on the variables, approximations to sum scores had to be used as well. For example, the YOS assigns points at three levels for each variable, depending on the severity of abnormality of that variable. For example, a normal reaction to parent stimulation is given one point, a moderately abnormal reaction is given three points and a severely abnormal reaction given five points. Some data sets had only dichotomous results for the variables included in the score, for which one point was awarded to a normal variable and five to an abnormal variable. Consequentially, the total sum score differs from the original sum score, and different cut-offs for defining an abnormal YOS were explored (i.e. cut-offs of 10 and 8).

Statistical analysis

The accuracy of the clinical prediction rules identified in the systematic review was assessed in each of the data sets in which this was possible. The outcome used to validate the prediction rule was as similar as possible to that of the original prediction rule derivation. For each prediction rule, we used dumbbell plots to display results of sensitivity, specificity, LR+, LR– and pre- and post-test probabilities. This analysis was performed for all children in each data set, as well as the subgroup analyses of only children who had been referred from primary care to the ED, and for children who had not been referred. When a data set had been used to derive a prediction rule, we did not use this data set to validate that same prediction rule. Because there were considerable missing data on key variables (see Appendix 6), several specialised methods (i.e. multiple imputation techniques by the Markov chain Monte Carlo method or by chained equation) were evaluated but none was feasible, because the condition of observations assumed to be missing at random was almost certainly violated, and also because in some cases the problem was that variables were missing completely. All analyses were performed with Stata (version 11).

Chapter 8 Results of external validation of clinical prediction rules

Description of included data sets

We identified seven data sets (Table 6) for the multiple external validation. 11,28,29,60,72,79 Two had been collected in the UK,29,79 four were from the Netherlands and one was from Belgium,11 providing data on a total of 11,045 children. Two data sets had been collected from primary care,11 the remainder from ED settings. Four of the data sets were included in the systematic review (Van den Bruel et al. ,11 Thompson et al. ,29 Bleeker et al. 50 and Oostenbrink et al. 72). Inclusion criteria for the data sets were children with fever (three), acute illness (two), or acute infection (one) and referred children with meningeal signs (one). Six of the data sets excluded children with various types of comorbidity, and in one case children who required immediate resuscitation. The mean age of children ranged from 0.94 to 5.0 years, and the prevalence of serious infection ranged from 0.78% to 44.71%.

Clinical predictor variables included in data sets

The variables recorded in each data set varied (see Appendix 4). Most data sets included basic demographic characteristics such as age, duration and severity of illness, or referral status. Presenting symptoms were recorded in almost all data sets, apart from two gastrointestinal symptoms. Temperature was recorded in all data sets, followed by heart rate (five data sets), respiratory rate (five data sets), capillary refill time (five data sets) and oxygen saturations (four data sets). Investigations in all data sets were performed at the discretion of the clinical team and none had performed a complete set of investigations on all children.

A matrix was created to determine which of the data sets could be used to validate the clinical prediction rules. Consensus was reached for four clinical prediction rules: YOS, a five-stage decision tree, a pneumonia rule and a meningitis rule. Appendix 5 presents the variables used for external validation of the clinical prediction rules, either original ones or approximations of the predictor variables.

For the YOS, three data sets had variables which were identical to the original Yale scoring (Berger et al. , Brent et al. 79 and Thompson et al. 29). Two data sets (Van den Bruel et al. 11 and Oostenbrink et al. 72) required recoding of dichotomous variables to the YOS, in which cases we assigned a score of 1 for a normal value and 5 for an abnormal value. We considered using the intermediate value of 3 instead of 5 to indicate a normal value, but this did not provide any differences in distribution of the outcome variables. Different cut-offs (8 and 10) were used to validate the YOS, which was consistent with the cut-offs identified by the systematic review. Four data sets were available to validate the YOS using a cut-off of 10 (Van den Bruel et al. ,11 Berger et al. , Thompson et al. 29 and Brent et al. 79), and an additional data set when using a cut-off of 8 (Oostenbrink et al. 72).

One of the data sets had been used to derive the five-stage decision tree (Van den Bruel et al. 11), and an additional six data sets were suitable for validation (Berger et al. , Roukema et al. ,28 Brent et al. ,79 Bleeker et al. ,50 Thompson et al. 29 and Oostenbrink et al. 72). One variable in the derivation study (‘physician’s gut feeling that something is wrong’) was not recorded in any of the validation data sets. We, therefore, used a proxy variable of ‘clinical impression’ in the validation data sets. In addition, we compared the diagnostic characteristics of the rule in the derivation data set using both the original and the proxy variable. Four data sets had all variables present (with approximations, such as nasal flaring for dyspnoea); two data sets (Bleeker et al. 50 and Oostenbrink et al. 72) had up to two missing variables (diarrhoea and/or dyspnoea).

One data set was used to derive the pneumonia rule (Van den Bruel et al. 11) and five were available to validate it (Berger et al. , Oostenbrink et al. ,72 Roukema et al. ,28 Thompson et al. 29 and Brent et al. 79). As with the five-stage decision tree, this rule used clinical impression in the validation data sets as a proxy for the physician’s gut feeling that something is wrong. The same variables and approximations for clinical impression and dyspnoea were used as for the five-stage decision tree.

Four data sets were available to validate the meningitis rule (Van den Bruel et al. ,11 Thompson et al. ,29 Brent et al. 79 and Oostenbrink et al. 72). The variable petechiae was available in all data sets, nuchal rigidity in one data set (Oostenbrink et al. 72) with the proxies meningeal irritation, neck stiffness and AVPU (alert, responds to voice, pain, unresponsive) score of 3 in three of the data sets, whereas coma was approximated with unconsciousness and AVPU score of 4 in all four data sets.

Results of external validation

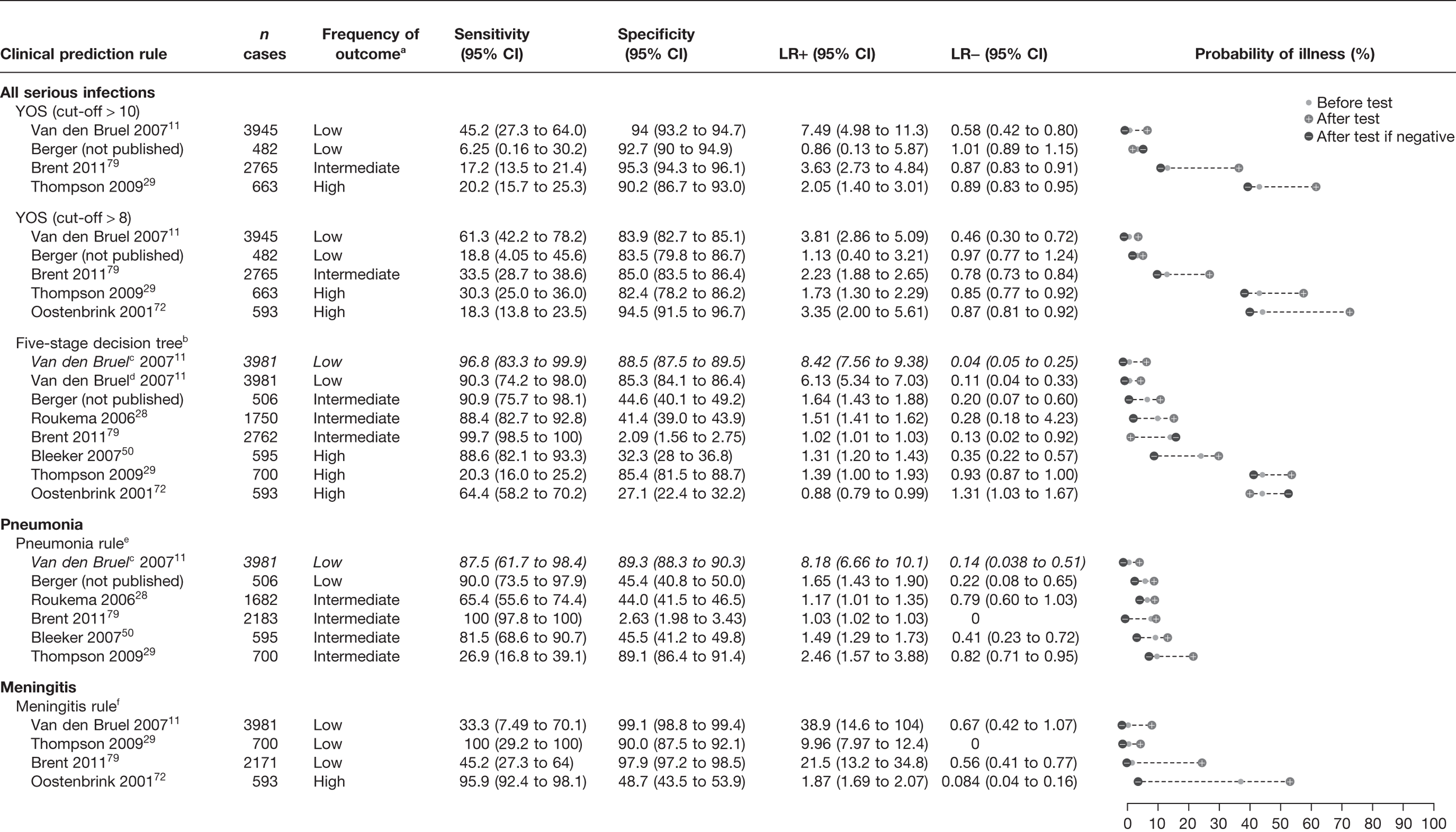

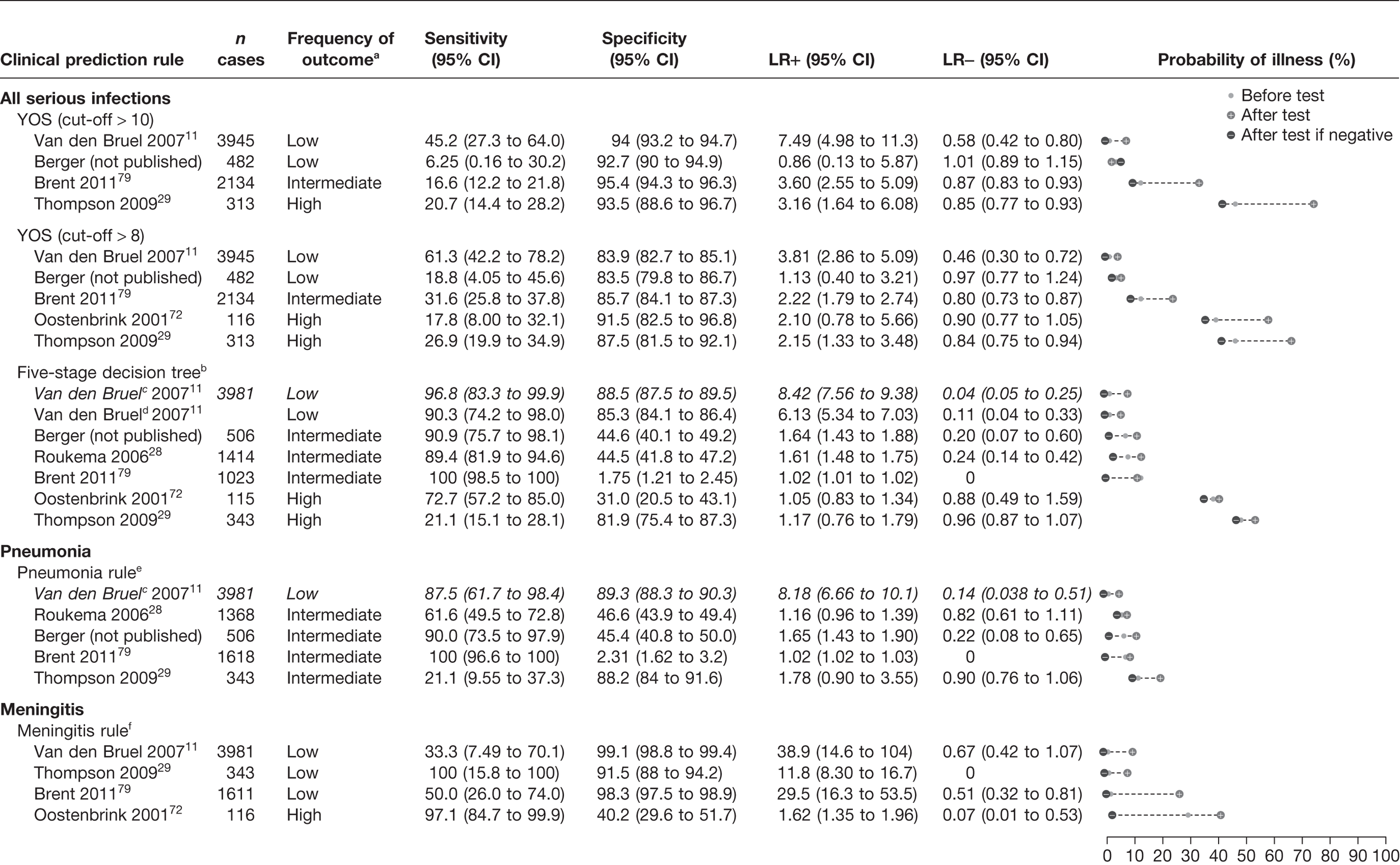

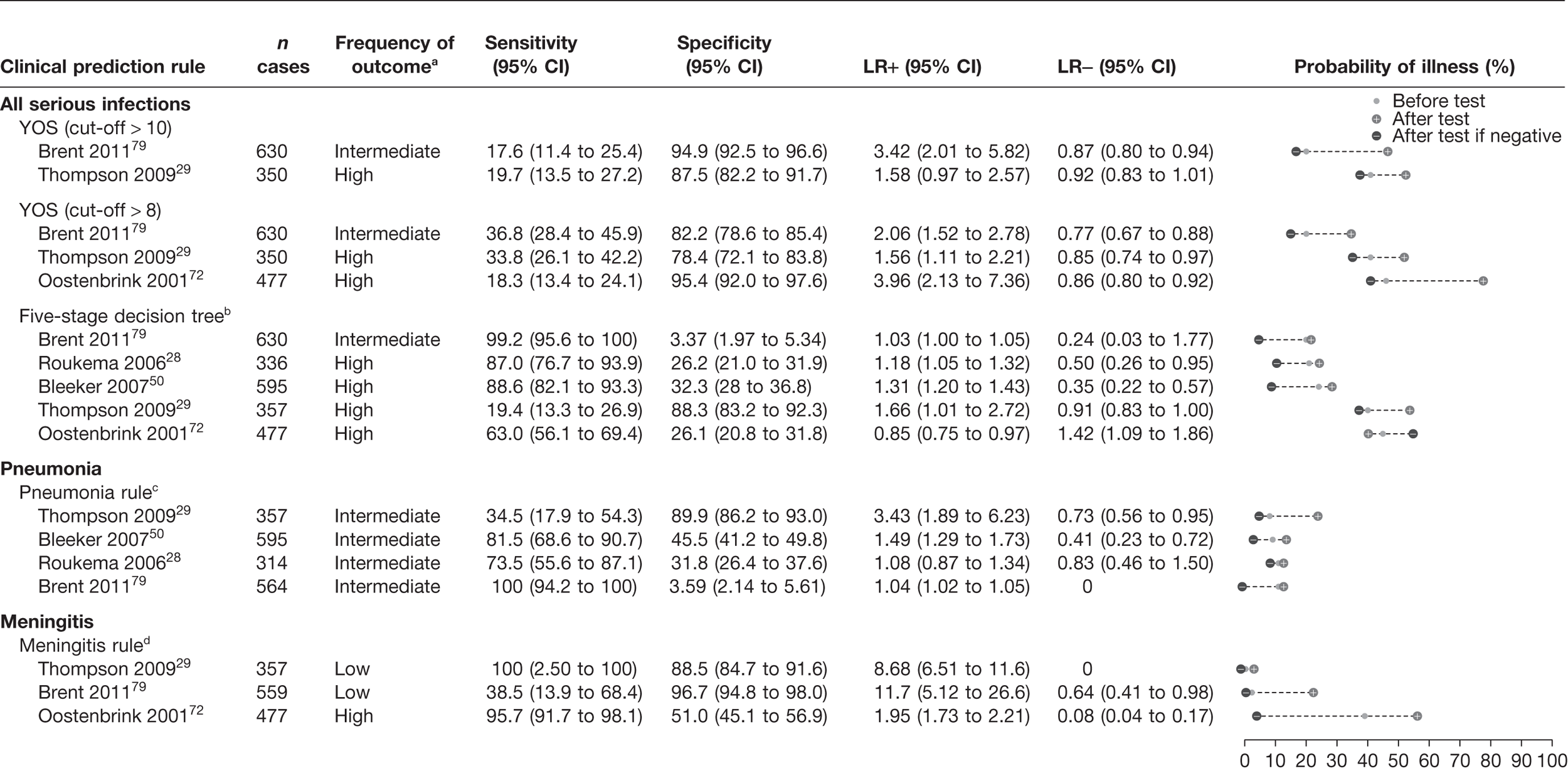

The results of the validation of the four clinical prediction rules for all children, those who were not referred and those who were referred are provided in Figures 13–15, respectively.

FIGURE 13.

Results of multiple external validation of clinical prediction rules with potential to rule or rule out serious infection in all children. a, Setting: low frequency (< 5%), intermediate frequency (5–20%) and high frequency (> 20%) of the selected outcome measure for serious infection in all children. b, If yes to any of the five sequential questions: (1) clinical instinct that something is wrong, (2) dyspnoea, (3) temperature > 39.5 °C, (4) diarrhoea and (5) age 15–29 months. c, Italic denotes a derivation study. d, ‘clinical instinct that something is wrong’ replaced by ‘clinical impression’. e, If yes to any of (1) shortness of breath and (2) clinicians concern. f, If yes to any of (1) petechiae, (2) nuchal rigidity and (3) coma.

FIGURE 14.

Results of multiple external validation of clinical prediction rules in non-referred children. a, Setting: low frequency (< 5%), intermediate frequency (5–20%) and high frequency (> 20%) of the selected outcome measure for serious infection in all children. b, If yes to any of the five sequential questions: (1) clinical instinct that something is wrong, (2) dyspnoea, (3) temperature > 39.5 °C, (4) diarrhoea and (5) age 15–29 months. c, Italic denotes a derivation study. d, ‘clinical instinct that something is wrong’ replaced by ‘clinical impression’. e, If yes to any of (1) shortness of breath and (2) clinicians concern. f, If yes to any of (1) petechiae, (2) nuchal rigidity and (3) coma.

FIGURE 15.

Results of multiple external validation of clinical prediction rules in referred children. a, Setting: low frequency (< 5%), intermediate frequency (5–20%) and high frequency (> 20%) of the selected outcome measure for serious infection in all children. b, If yes to any of the five sequential questions: (1) clinical instinct that something is wrong, (2) dyspnoea, (3) temperature > 39.5 °C, (4) diarrhoea and (5) age 15–29 months. c, If yes to any of (1) shortness of breath and (2) clinicians concern. d, If yes to any of (1) petechiae, (2) nuchal rigidity and (3) coma.

A normal YOS score, i.e. below a threshold of 8 or 10, provided little or no rule-out value, i.e. none of the LRs– were smaller than 0.46 (Figure 13). In one low-prevalence setting,11 the score was moderately to highly specific with a LR+ of 3.81–7.49, depending on the score cut-off selected. In two studies (intermediate and high prevalence) it provided a marginally useful rule-in value (LR+ 3.35–3.63). 72,79 Subgroup analysis of the children who had not been referred (Figure 14) indicated similar results, again with a marginally useful LR+ (3.16–3.81) depending on the cut-off selected, and again with no useful LR–. In children who had been referred (Figure 15), only two data sets were available to validate results, and again indicated a marginally useful LR+ in one study (LR+ 3.42),79 and no useful LR–.

We first compared the performance of the five-stage decision tree in the data set in which it had been derived (Van den Bruel et al. 11), substituting one variable used to derive this rule (physician’s gut feeling that something is wrong) with a proxy variable (clinical impression). Using this proxy variable, both the LR+ and LR– were slightly lower, although the CIs of the latter were overlapping. Using the five-stage decision tree with the proxy variable of clinical impression, we found that the rule had no rule-in value in any of the validation data sets, regardless of whether all children, referred children or non-referred children were considered. However, we found a marginally useful rule-out value in four data sets (LR– 0.13–0.35),28,50,79 but with wide CIs. When the rule was validated on the subgroups of children who had not been referred (see Figure 14) and had been referred (see Figure 15), results were similar: marginally useful LR– of 0.20–0.24 in non-referred children in two data sets,28 and LR– of 0.35 in referred children in one data set. 50