Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the National Coordinating Centre for Research Methodology (NCCRM), and was formally transferred to the HTA programme in April 2007 under the newly established NIHR Methodology Panel. The HTA programme project number is 06/96/01. The contractual start date was in August 2008. The draft report began editorial review in March 2011 and was accepted for publication in August 2011. The commissioning brief was devised by the NCCRM who specified the research question and study design.The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

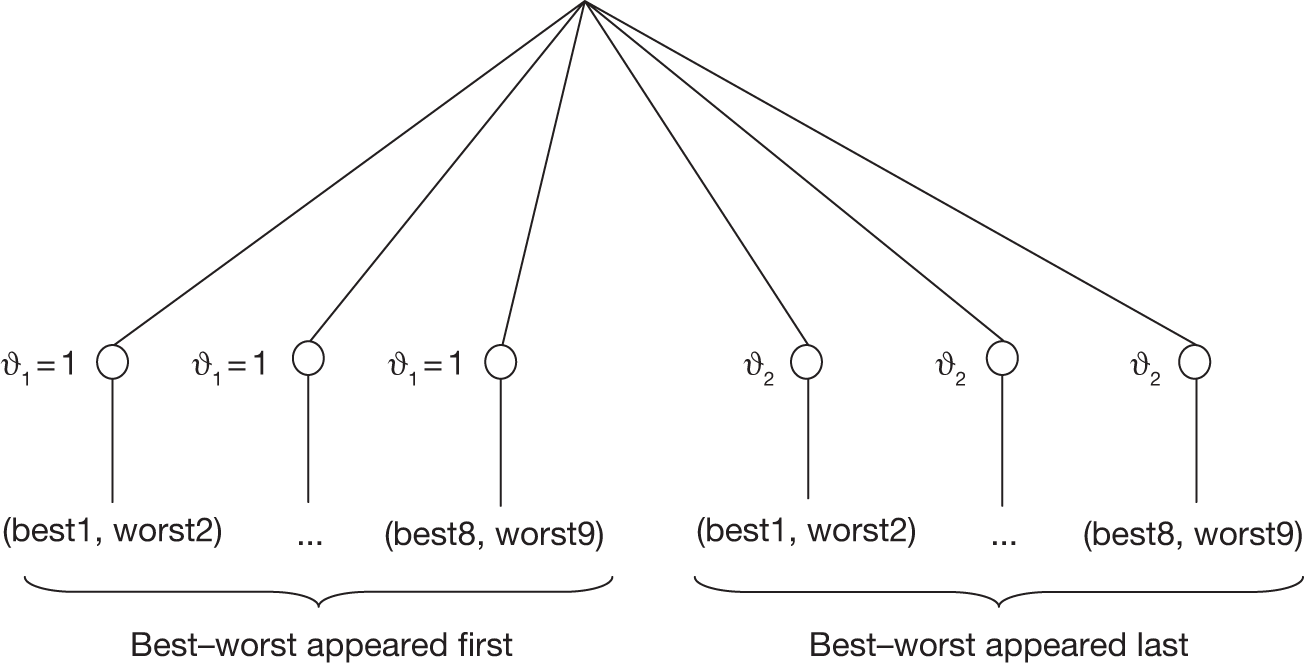

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2012. This work was produced by Netten et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2012 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Objective

The aim of this study was to develop a measure of social care outcome, an equivalent to the quality-adjusted life year (QALY) in health, which could be used in a range of circumstances.

Design

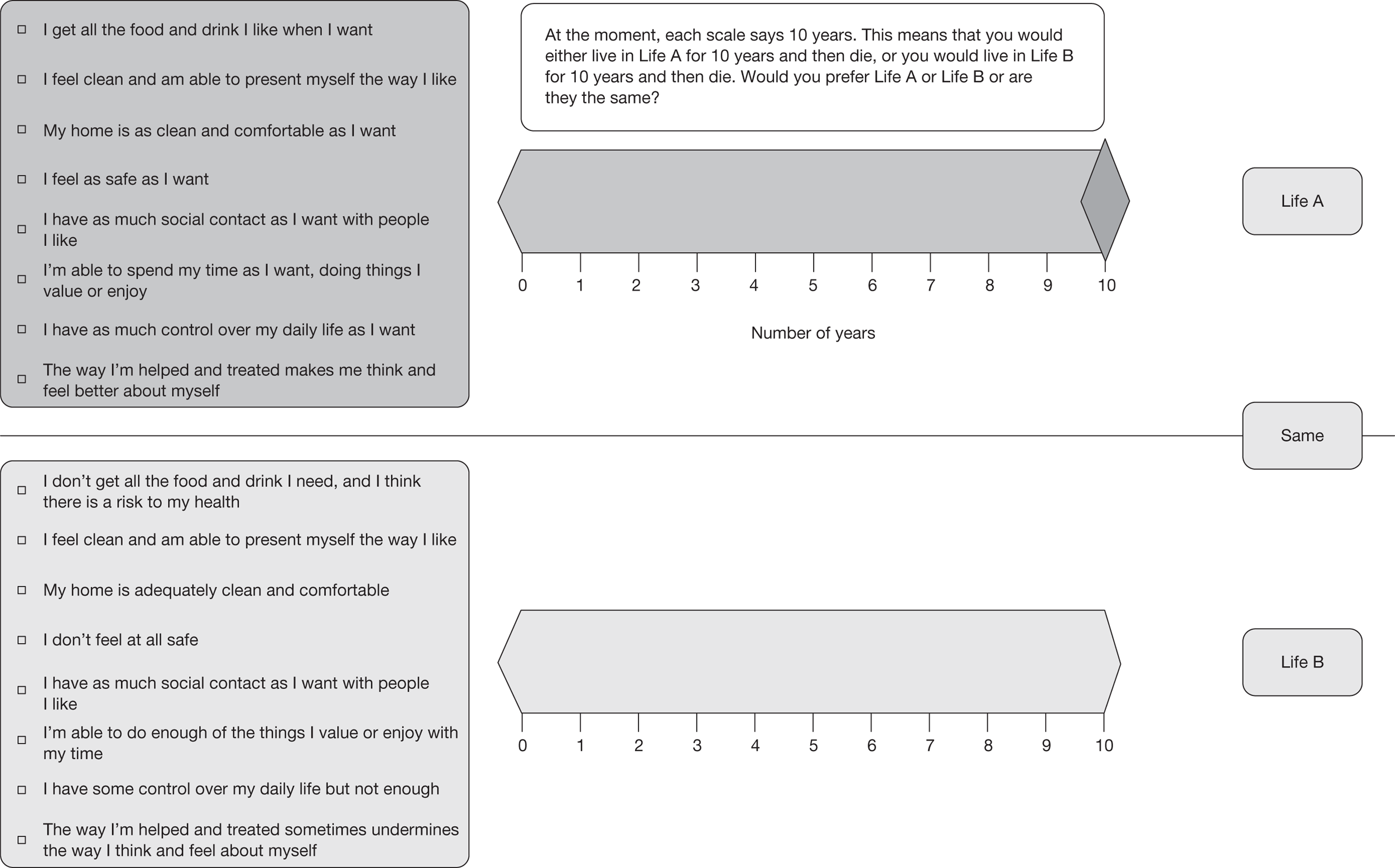

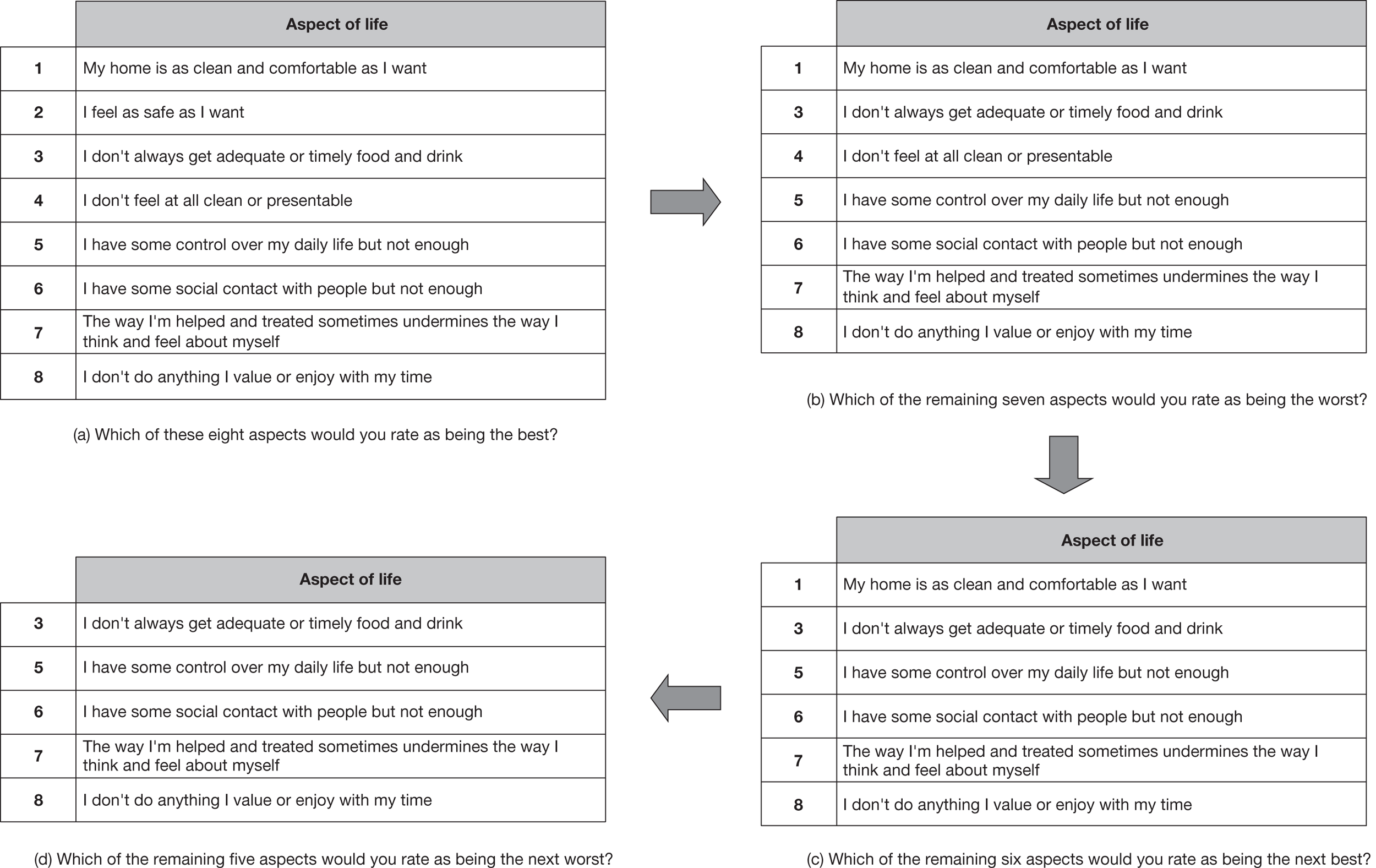

The project drew on previous and parallel work developing the Adult Social Care Outcome Toolkit and the national Adult Social Care Survey. We developed and tested an instrument designed to reflect service users’ social care-related quality of life (SCRQoL) and tested it with 30 service users from a variety of user groups and 300 older home care service users. In parallel, we explored discrete choice experiment (DCE) and best–worst scaling (BWS) approaches to preference elicitation with 300 members of the general population, and cognitively tested these with service users. We also cognitively tested a computer-aided time trade-off (TTO) exercise using SCRQoL attributes with members of the general population. In the second phase, using the finalised instruments, BWS interviews were conducted with 500 members of the general population, TTO interviews with a follow-up sample of 126 of these respondents, and BWS interviews with 458 people using equipment services.

Main outcome measures

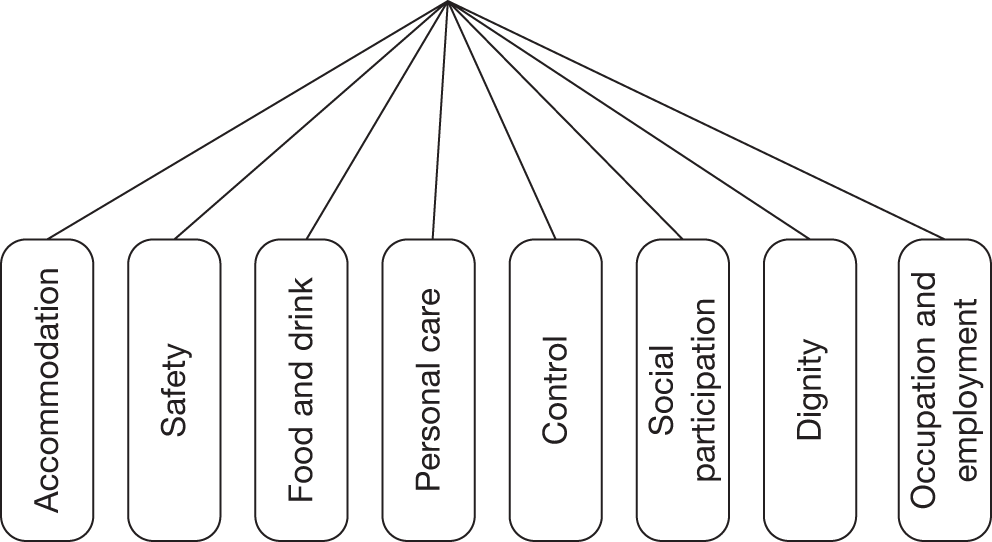

The final measure had eight domains: personal cleanliness and comfort, accommodation cleanliness and comfort, food and drink, safety, social participation and involvement, occupation, control over daily life and dignity. In addition to measuring current SCRQoL, the instrument includes questions used to establish service users’ views of their ‘expected’ SCRQoL in the absence of services. The difference between a person’s current and ‘expected’ SCRQoL provides an indicator of service impact.

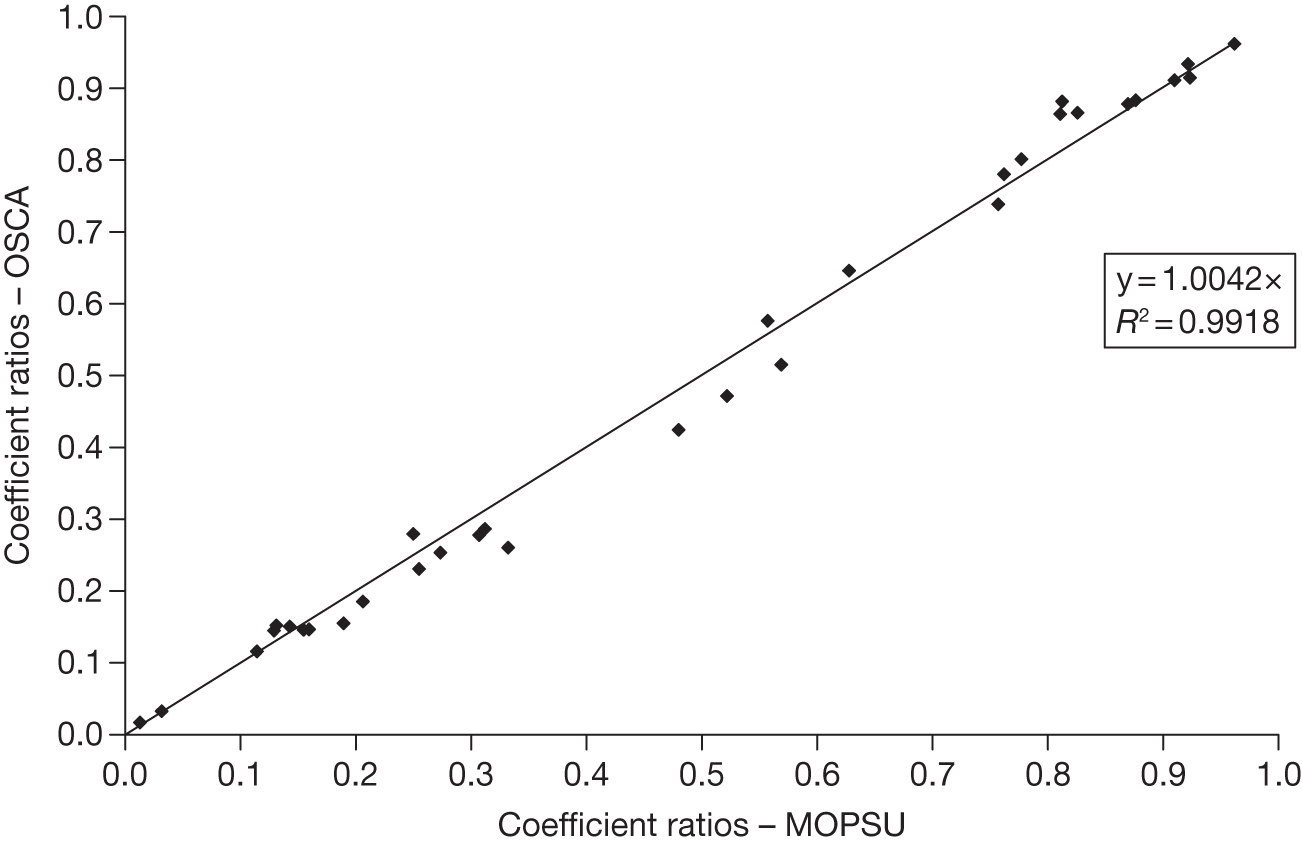

Results

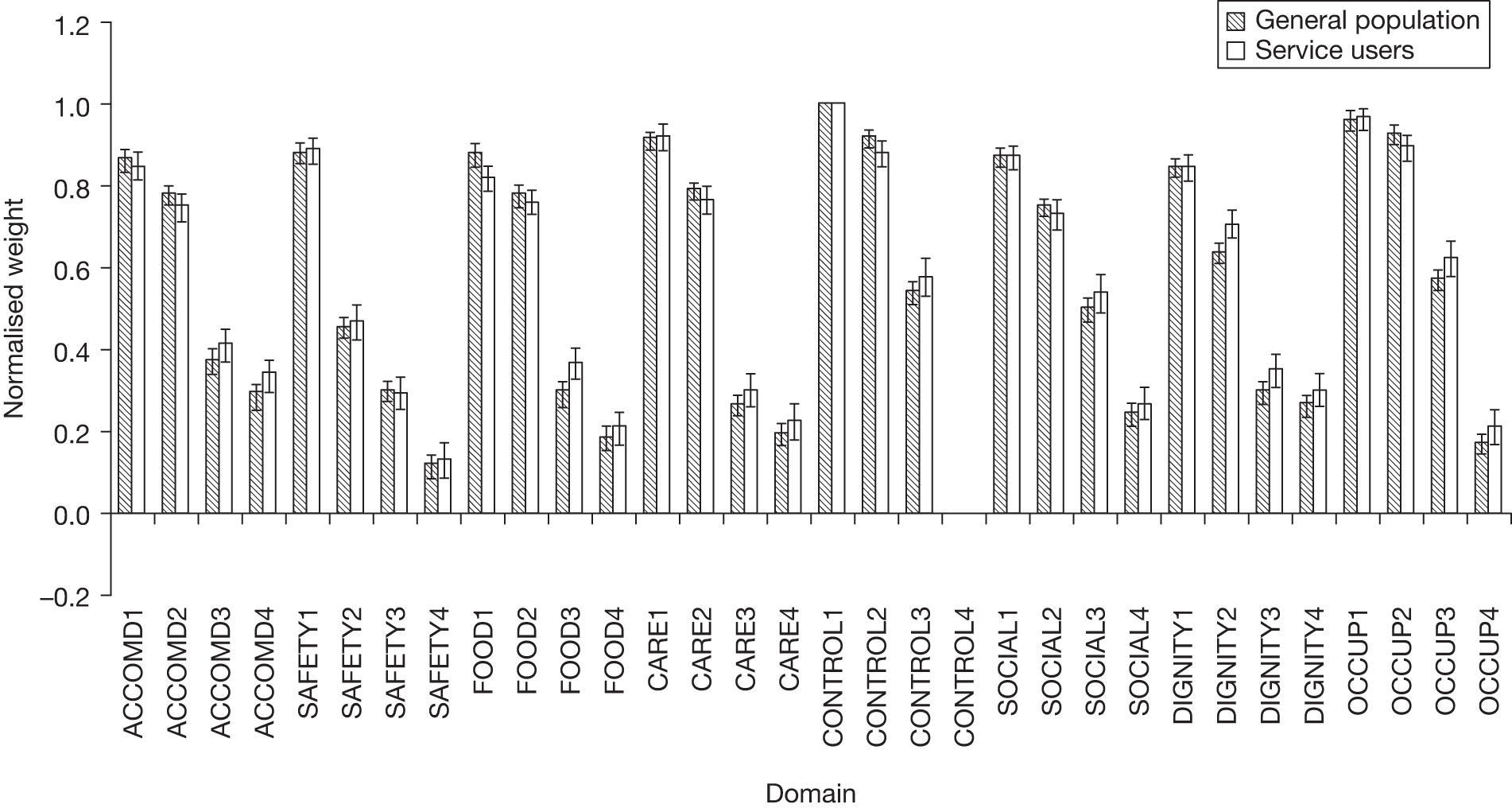

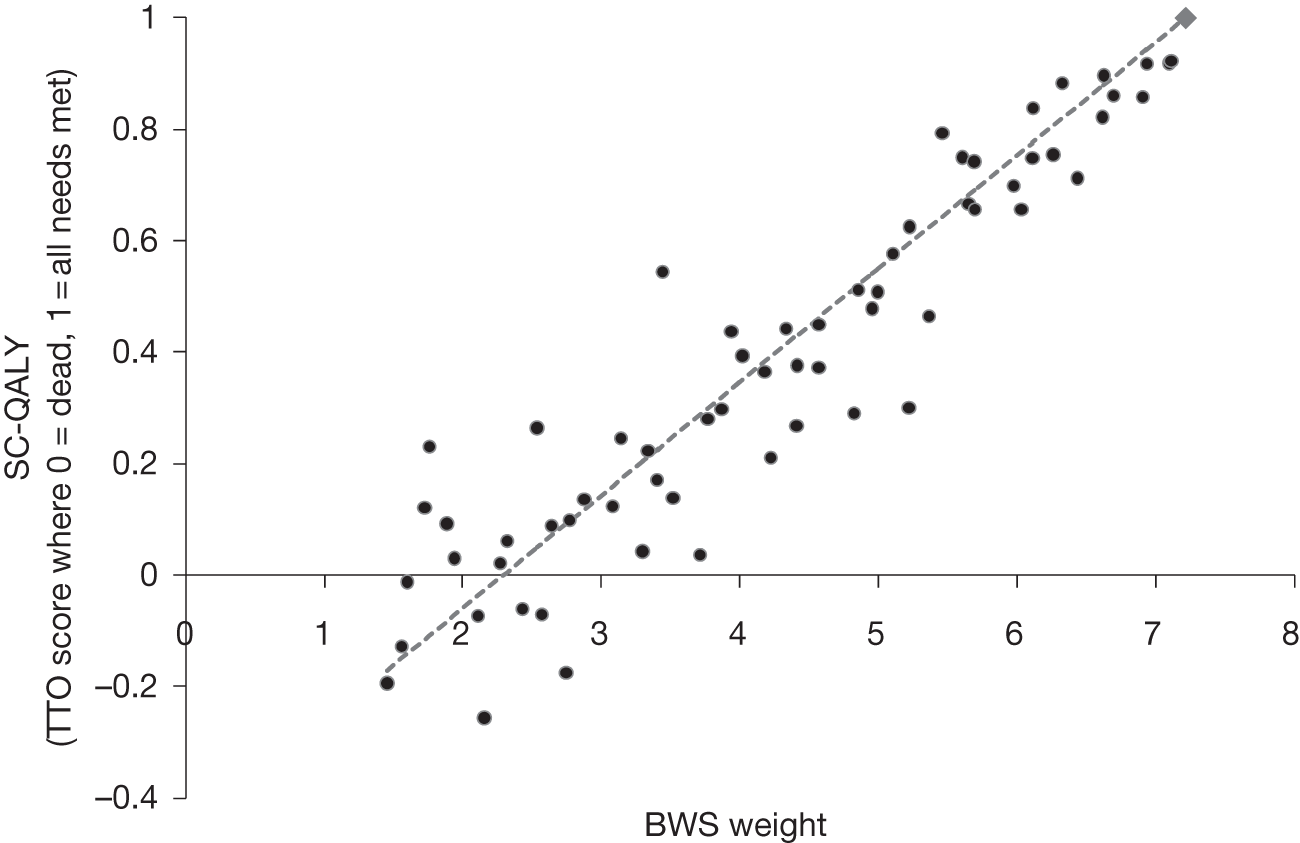

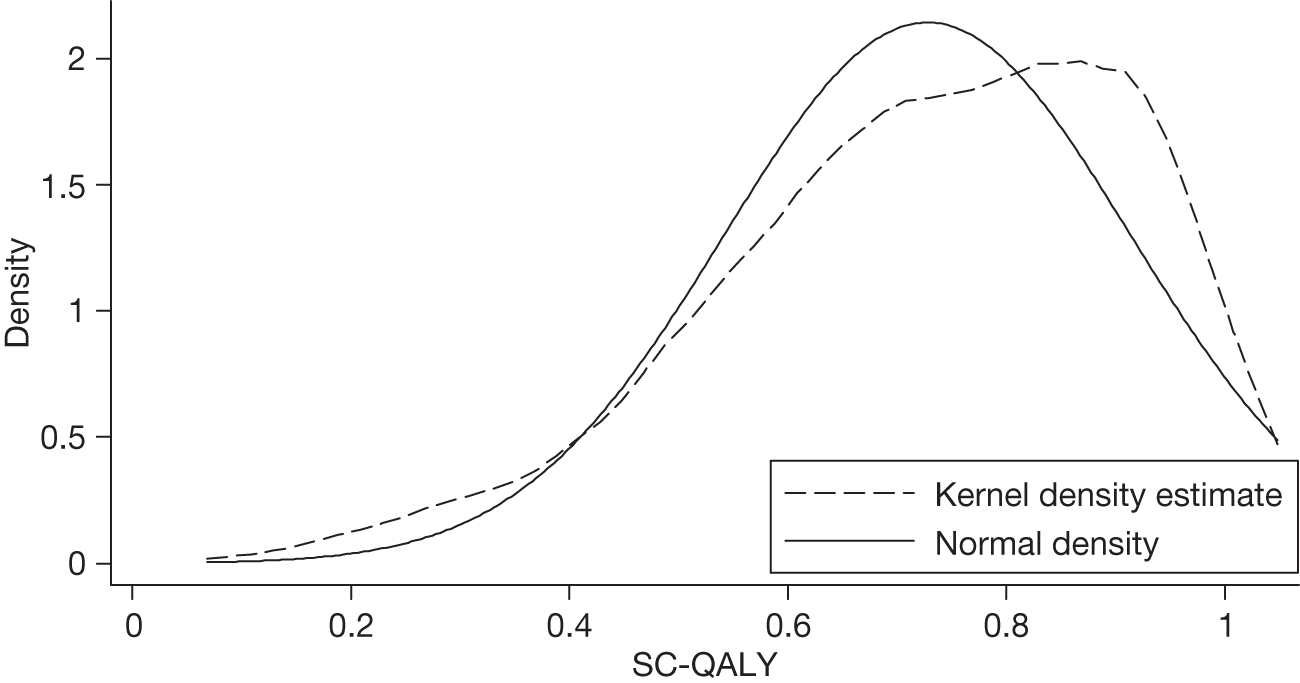

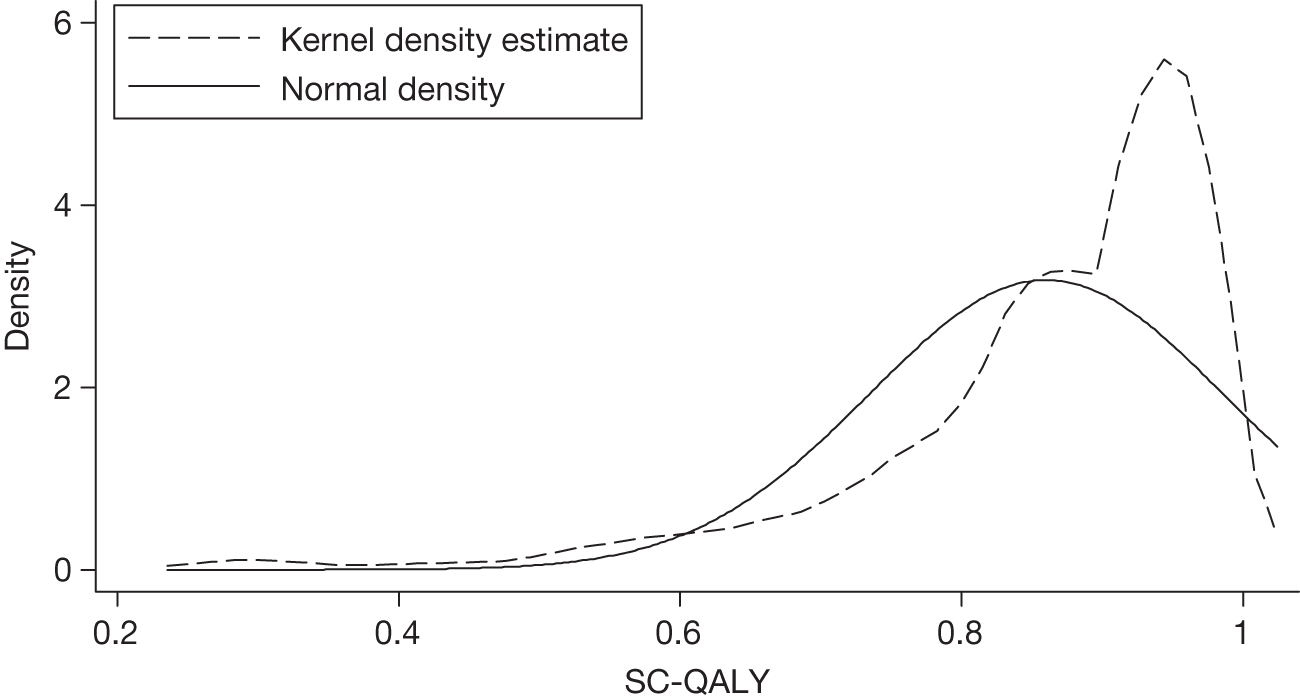

There was good evidence for the validity of the descriptive system and the validity of the current, expected and SCRQoL gain scales. The DCE and BWS approaches yielded similar results and, once introductions made clear, were understood by service users. BWS was used for the main stages, as it had technical and cognitive advantages. The computer-aided approach to TTO worked well, and respondents found questions acceptable and understandable. There were no substantive differences in the preferences of service users and the general population. The key domain was control over daily life, with the lowest and highest levels strongly estimated in all models. After allowing for observable heterogeneity, service users’ preferences appeared to be more closely associated with their own SCRQoL than with those of the general population. The consistency of the results with the results of a previous study allowed the final model to be based on the preferences of 1000 members of the general population. A formula based on the relationship between TTO and BWS values was estimated for a social care QALY, with ‘0’ equivalent to ‘being dead’ and ‘1’ being the ‘ideal’ SCRQoL state. Members of the population experienced significantly higher SCRQoL than service users.

Conclusions

Although further work is needed, particularly to develop an equivalent measure for informal carers and to explore the links with health QALYs, the measure has considerable potential. A number of methodological advances were achieved, including the first application of TTO in a social care context and use of BWS to establish service user preferences.

Funding

The National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

There is increasing policy focus on outcomes in the field of health and social care in England. 1,2 This reflects a wider emphasis on the importance of reflecting outcomes of publicly funded services, which has been evident for some time, for example in reflecting productivity of public services in National Accounts. 3 In times of financial stringency it is particularly important to estimate the impact of different interventions accurately if we are to identify cost-effective alternatives and make the best use of limited resources. In the field of health, the quality-adjusted life year (QALY) is widely accepted as the measure of health outcome used to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of new health interventions. There is no such equivalent for social care, which has fundamentally different objectives to health care, making it difficult to assess accurately the impact of interventions that are closely aligned with, and can have direct impacts on, the demand for health care. The Wanless review4 used an early social care outcome measure to comment on future resource needs, but identified the need for much more development of outcome tools in this area. Ideally, commissioners and providers should have outcome information to draw on as a management tool for allocating resources to ensure good productivity and efficient use of those resources.

This report describes the results of a study designed to develop an equivalent measure to the health QALY, which reflects the particular characteristics of social care and can be used in a range of circumstances to reflect the impact and value of social care interventions. This first chapter describes the aims and objectives of the study, provides a broad overview of the design and describes the conceptual basis of the measure. In Chapter 2 we describe the basis for, and development of, the items that make up the instrument, and in Chapter 3 we outline how we tested the validity of the measure. Chapter 4 discusses how we tested a variety of approaches to preference elicitation and developed the methods used for the basis of the utility weights. The results of this work are reported in Chapter 5. The report ends with an overview of the final measure, discusses the potential uses and value of the measure, and suggests future work needed.

Aims and objectives

The aim of the study was to generate a preference-weighted measure of social care outcomes that could be used in a variety of circumstances, including social care evaluations, cost–utility analyses, weighted output of government-funded social care for National Accounts,3 and policy analyses.

The objectives were to:

-

develop a measure of social care outcome that captures all relevant domains, has credibility in the social care community, has been cognitively tested and demonstrates good psychometric properties

-

test a variety of approaches to establishing preferences for methodological soundness and practical application with the general population

-

investigate the applicability of these methods to a service user population

-

conduct a population preference study

-

develop a set of weights for calculating social care quality-adjusted life years (SC-QALYs) and weighting measures of social care output

-

explore how service users’ views differ from those of the general population, and establish alternative preference weights if appropriate

-

identify the factors that affect preferences among the general population and service users.

Research design

The project comprised two phases. The first covered development and feasibility work to inform the design for a main phase in which preference weights for the final measure were derived from a study of both the general population and service users. The project undertook and drew on a number of different data collections, summarised in Table 1 and described below.

| Project | Nature of the sample | Sample size | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| OSCA | People who use services (all service user groups) See Chapter 2 | 30 | Cognitive testing of ASCOT measure items, cognitive testing of DCE and BWS questions |

| OSCA | Older home care service users (see Chapter 3) | 301 | Psychometric testing of the ASCOT measure |

| ASCS development study8 | People who use services (all service user groups) | 25 | Cognitively testing new versions of problematic ASCOT items |

| ASCS pilot study9 | People who use services (all service user groups) | 1364 | Checking distribution of final version of all ASCOT items |

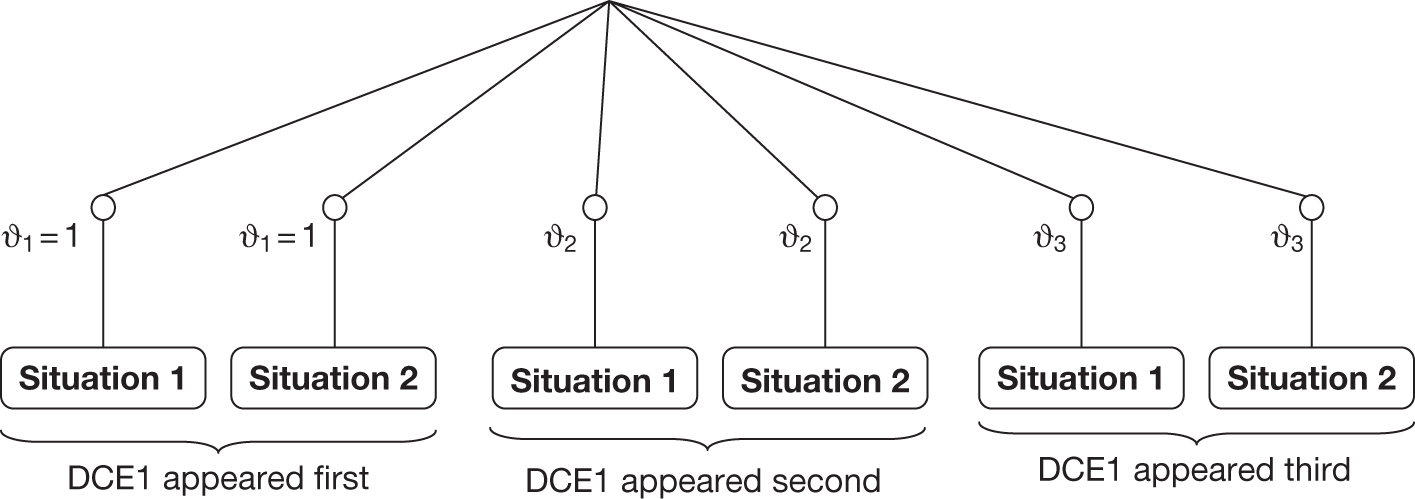

| OSCA | General population (see Chapter 4) | 300 | Pilot preference elicitation study (comparing BWS and DCE) |

| OSCA | General population (see Chapter 4) | 19 | Cognitively testing TTO technique with ASCOT measure |

| MOPSU preference study10 | General population (see Appendix 6) | 513 | BWS preference elicitation survey comparing three- and four-level versions of ASCOT measures |

| OSCA | General population (see Appendix 6) | 500 | BWS preference elicitation survey of final ASCOT measure |

| OSCA | General population (see Appendix 6) | 126 | TTO preference elicitation survey of final ASCOT measure |

| OSCA | Users of equipment services (see Appendix 6) | 458 | BWS preference elicitation survey of final ASCOT measure |

| OSCA | Users of equipment services (see Appendix 6) | 100 | Follow-up interviews using final ASCOT instrument |

There were two strands to the development and feasibility work, conducted in parallel:

-

the development and psychometric testing of the measure itself

-

exploration of the feasibility of different approaches to establishing preferences.

The aim was to refine and develop the measure, while testing a number of elicitation approaches with the general population. The results of these exercises could then feed into testing the measure and piloting preference elicitation with service users. This allowed us to evaluate both the measure itself and the preference elicitation methods.

The development of the measure included conceptual development, a focused literature review, analysis of data sets that incorporated previous versions of the measure, cognitive testing of items with service users, and a survey of older people using home care services (see Table 1, and Chapters 2 and 3). The preference elicitation feasibility work involved testing alternative discrete choice approaches through a survey of the general population and cognitively testing these approaches with service users. In addition, we wanted to explore the feasibility of anchoring the measure to the state of ‘being dead’, permitting equivalent cost–utility analyses as those used in health care. To this end, we cognitively tested the use of time trade-off (TTO) techniques with respect to social care-related quality-of-life (SCRQoL) attributes with members of the general population (see Table 1 and Chapter 4).

We built on previous work in the field of outcome measurement in social care, and the project both contributed to, and drew on, other work that fed into the development of the Adult Social Care Outcome Toolkit (ASCOT) (www.pssru.ac.uk/ASCOT). The measure drew on earlier attempts to develop a measure of social care outcome for older people,5 which was then extended through a number of studies to be applicable to a wider group of social care service users. The extension to other groups was undertaken partly as a result of an interest in developing an approach to developing outcome-based quality weightings for publicly-funded outputs for the purposes of National Accounts,3 in which the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) took the lead on developing an approach for Personal Social Services (PSS). 6 This work led to a Treasury-funded study led by the Office for National Statistics (ONS),7 as part of which the ASCOT was developed, drawing on a study of care homes,8 low-level services9 and a preference study. 10 The preference study drew on the development work undertaken as part of this study and provided a helpful test of the measure during its developmental stage (see Chapters 3 and 4). In addition, development work for the national Adult Social Care Survey (ASCS), which now includes the ASCOT measure, provided other opportunities for testing the measure (see Chapter 3). 11

The second phase drew on this iterative work and, for the final version of the instrument, involved a main preference study of the general population using the best–worst scaling (BWS) approach, and a follow-up TTO study with a subsample of this population. We also conducted a preference study of people who use equipment services, and a follow-up study with a subsample of these to test further the final version of the instrument (see Table 1 and Chapter 5).

An important element of the work was the involvement of local councils, and other authorities in the field were recruited as ‘critical friends’ to the project. In the early stages of the work, to assist in ensuring the acceptability of the approach being developed, they were invited to comment on our thinking with respect to the conceptual basis of the measure and were later kept informed on its practical application. 12 The councils also provided access to service users who were interested in participating in various stages of the study through the annual User Experience Surveys (UESs) that councils are required to conduct. 13 Service users were also consulted through the user and carer group at the PSSRU, London School of Economics (LSE).

Ethical permission was obtained from the Social Care Research Ethics Committee (SCREC) for all stages of the work that involved service users. The Association of Directors of Adult Social Services (ADASS) supported the study, and research governance approval was obtained from all participating local councils. For elements of the study that involved only members of the general population, ethical approval was obtained from the University of Kent ethics committee. All participants were given gift vouchers to thank them for their involvement.

Conceptual basis of the measure

Before we can develop a measure of outcome, we need to be clear about exactly what it is we are intending to measure. We have discussed the conceptual basis of outcome measurement in social care in more detail elsewhere. 14–16 Here, we summarise what we mean by social care, describe the implications of that for what we wanted to be able to reflect in our measure, and briefly consider the implications of the objective of a measure that can be seen as a SC-QALY equivalent.

Social care

Social care is a term used in the UK to describe a range of long-term care activities, including providing help with personal hygiene, dressing and feeding, as well as help with shopping, getting out and about, socialising, and keeping the home tidy and clean. Social care is usually provided in response to needs arising from physical or sensory impairments, learning difficulties and mental health problems, including those associated with older age. 17 It is provided in people’s homes, in day centres and care homes, and includes support purchased by individuals themselves through personal budgets or direct payments.

Most people using social care services have conditions that involve a permanent (and often declining) loss of functional ability, for example neurological conditions, arthritis and most intellectual disabilities. In these situations, the primary aim of social care interventions is to compensate a person for their lost functional ability, rather than try to restore it. Therefore, interventions focus primarily on maintaining service users’ quality of life (QoL) by helping them with – or enabling them to accomplish – the types of tasks and activities associated with daily living described above. Frequently, because of the nature of a person’s condition, this type of help is required continuously, often on a daily basis, until a person dies. For many service users, this means that the service is often an integral part of their life; indeed, and particularly in cases where the service helps with very personal tasks, the way the care is delivered (its process) can have a significant effect on the user’s well-being. 15,18

These characteristics of social care have important consequences for how we think about outcomes. Qureshi and Nicholas19 identified three types of outcomes relevant to social care interventions: ‘change’ outcomes, which are rare and tend to be associated with rehabilitation; ‘maintenance’ outcomes, which are more common; and ‘process’ outcomes, which are related to how services are delivered and are important in their own right because of the ongoing and personal nature of much social care. To these, we might add ‘prevention’, which is increasingly being seen as important. 20,21 For each outcome type, it is important to ask ‘of what?’ For the most part, the answer is about well-being or QoL: maintaining, improving or preventing deterioration in well-being.

Social care is not unique in having the objective of improving QoL. Health, housing and other public services also have the goal of improving or maintaining QoL. If we use too broad a measure of QoL, we may fail to pick up on effective social care interventions because of the confounding effects of these and other such factors. The extra-welfarist approach addresses the problem by identifying the outcomes agreed by decision-makers as important. 22–25 For example, the government could decide that the aim of the health service is solely to improve population health. So, although health services have effects that go beyond people’s health, the outcome of health care would be assessed only in these terms.

Extra-welfarist health outcome measures identify specific aspects of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in order to ensure that they are sensitive to the impact of health-care interventions. Such measures have proved very powerful in generating an evidence base in health. Although social care is related to health care, its compensatory nature is fundamentally different, so HRQoL measures will likely be insensitive to the impact of social care interventions. Moreover, if we accept an extra-welfarist approach that puts weight on improving population health then we might conceive of an equivalent goal for social care. We might lack a familiar goal such as health improvement in social care, but government policy has indicated that the goal for social care is improving well-being. 26 In order to reflect the impact of social care with respect to well-being, we need to define and measure an equivalent to HRQoL: SCRQoL.

Social care-related quality of life

If we are to define an equivalent to HRQoL for social care, we need to be more specific about what it is that social care does and aims to do. The Social Production of Welfare (SPOW) framework27,28 puts individuals and their care networks at the heart of the production process. This draws on household economics29,30 and the capabilities framework, put forward by Sen31,32 as an alternative to standard welfare economics. Household economics propose that we are all in the business of producing welfare for ourselves and others in our households by using our resources, goods and services to produce what Sen defines as ‘functionings’ – such as social contact or being well fed – from which we directly derive utility or well-being. Impairment of a person in the household results in changes in the household production processes and can result in drawing others, including people, usually family members who are not resident in that household, into a ‘care network’. Social care services and support become necessary when the resources of individuals and their care networks are insufficient to produce necessary levels of ‘functioning’ for network members’ well-being, whether that of the person with impairments or of those caring for him/her.

From an extra-welfarist perspective, what are regarded as legitimate functionings for interventions or ‘SCRQoL’ can be deduced by observation of what services do, and consultation with those in receipt of services and support. The nature of the SPOW means that the impact of social care services will be experienced both by people with impairments and those caring for them. Informal carers can be represented as both providers of care and beneficiaries of social care services. 33 Provision specifically targeted on carers tends to take the form of providing respite from the caring task, substituting for the role that they are playing in the care network. The biggest impact, however, will come from ongoing services that have the well-being of the individual with impairment as their primary objective. These services will generate outcomes for both individuals and their carers, whose utility and well-being are inter-related. 34

While acknowledging this, our focus here is on the impact on the primary recipient of social care services, whatever the source or nature of the care. In general, publicly funded services for individuals with impairment in England are primarily involved in the production of nutrition, personal care and safety, and, to a lesser extent, employment, social contact and participation, and household cleanliness and comfort. However, the focus of services is culturally defined, and varies both over time and across client groups. 4,27 For example, in England, home help services for older people used to be focused primarily on household cleanliness and comfort, with some personal care. In the 1990s, there was a policy shift away from what was seen as ‘low-level’ household support to more intensive services focused on personal care and safety. 5 Recently, there has been a move to more emphasis on ‘prevention’, social inclusion and on giving people choice and control. 26,35,36

This shift in emphasis to choice and control has implications beyond the description of SCRQoL. Sen31 argues that utility (or experienced QoL derived from functionings) is not the sole object of value; rather, it is capability – understood as the substantive opportunities an individual has to be, or to do, a range of things – that is the prime object of value. The importance of the capability-functioning distinction is that it differentiates, for example the person who does not go to the cinema out of choice from the person who does not go because he/she cannot for health or social reasons. Sen31 argues that the latter person experiences a loss of utility associated with their lack of choice. This distinction is not recognised where functionings are the focus of analysis, but where capabilities are the focus it is recognised in a reduced capability set for the person who is restricted in what he/she can do. Although Sen31 developed this theory in the context of poverty, it is apposite in the social care context, as people with social care needs frequently face barriers that constrain their choices. 37,38

Sen’s argument31 for capabilities as the focus of measurement is supported by the social model of disability and the shift in policy in this area. 38 Traditionally, social care has been concerned with meeting needs, which could be represented as particular functioning states (such as being well-fed or safe). The social model of disability places contextual barriers in the foreground, giving them precedence over individual impairments, to emphasise that disability is a consequence of the environment rather than an intrinsic characteristic of a disabled person. 39 In keeping with this view, policies for younger disabled people have tended to focus on ‘enablement’ by, for example, changing the built environment and giving disabled people greater flexibility and freedom in their daily lives. In England, the emphasis has increasingly been on broadening opportunities for people with disabilities and developing ‘independence’, ‘choice’ and ‘control’. 26,35,36 This more aspirational agenda has been reflected in policy documents, such as Putting people first: a shared vision and commitment to the tranformation of adult social care20 and, more recently, A vision for adult social care: capable communities and active citizens. 40 This focus on choice and control encourages us to aim to measure what people can do, rather than what they actually do, across all aspects of SCRQoL. Thus, when thinking about basic aspects of QoL, such as personal grooming, outcomes are not just about whether or not people have their personal care needs met but whether or not they can dress as they would like. Similarly, when considering occupation, we should be able to identify not solely whether or not people are employed or doing activities at all, but whether or not they are involved in work or activities that they value or enjoy.

Measuring social care outcomes

Clearly, key to ensuring that any measure is a valid and sensitive measure of social care outcomes is establishing that all relevant domains of SCRQoL are covered, and that the way these domains are described reflects the objectives of social care in terms of capabilities and functionings. We describe our approach to establishing these domains of the measure in Chapter 2. A further issue is how the measure might be used in practice to establish outcome: the contribution of any given intervention to SCRQoL.

In many fields the standard approach is to measure the QoL state of a person before and again after an intervention is used, with the pre-test score acting as a proxy for what would have happened in the absence of the intervention. However, this approach assumes both that there is a clear start and end point to the intervention, and that the type of outcome observed displays (it is hoped) positive change. But social care interventions tend to be ongoing, so there is often no clear start or end point. In addition, people rarely approach services in a high-need state with no support, and if they did so it would be not only impractical, but also unethical, to ask them to participate in research before addressing those needs. This means that we cannot directly observe the SCRQoL state in the absence of the intervention, and the ‘before’ measurement tends to be taken when a person is already in receipt of social care. It is also likely that, over time, there will be an exacerbation of the underlying impairment and therefore functional ability of a person. As functional ability declines, the resources required to maintain their SCRQoL are greater, and it can become much harder to compensate them fully for their loss of functioning. Good long-term social care should maintain people’s QoL, flexibly responding in the face of deteriorating or varying levels of impairment. With a ‘before and after’ measurement of SCRQoL, we would therefore expect to see either no change in SCRQoL where QoL has been maintained, or a decline in SCRQoL where it has not been possible to fully compensate the person for his or her declining functional ability. These factors mean that ‘before’ measures act as a poor proxy for ‘absence of intervention’.

As with any evaluation, research designs (such as randomised controlled trials), observational data and analytical techniques can be used to disentangle and compare marginal effects, whether one intervention is superior to another for a specified group of people with particular characteristics. Such designs that enable comparisons across interventions are clearly critical in this case to help interpret the observed lack of improvement in ‘before and after’ measurements. Such designs are very expensive, however, and are rarely conducted in social care. This means that there is a lack of data with which to inform decisions about targeting resources in a cost-effective manner.

The ongoing nature of most social care provides us with an advantage in terms of evaluating the QoL in the absence of services: people themselves daily face the possibility that the help and support on which they rely may not be forthcoming. For example, a care worker may be late or even not turn up at all. Because of these possibilities, social care service users are arguably uniquely well-qualified to identify for themselves what their SCRQoL would be in the absence of services.

In previous work,5 and as part of ASCOT, we have therefore been developing a pragmatic approach to establishing outcomes, which builds on the nature of social care to establish an estimate of the full benefit of interventions. In the interview version of ASCOT, this involved asking people to estimate, for each domain, what their situation would be in the absence of the intervention and then comparing this estimate to their current state to generate a measure of SCRQoL gain from the intervention. Elsewhere,16 we describe the rationale for the approach in more detail. In Chapter 2 we describe the cognitive testing of the approach, and in Chapter 3 we examine the evidence for validity.

The ongoing nature of social care interventions and the underlying conditions that services and support help to overcome mean that adaptation behaviour may be a particular issue when we are trying to evaluate social care. Generally speaking, where people have adjusted their expectations downwards when adapting to their circumstances (negative adaptation), we would expect people with low capability to rate their situation as better than if they had not adapted. 41,42 Similarly, people who have adapted to having a higher level of capability (positive adaptation) might find this situation less fulfilling than if they had not adapted. Adaptation is likely to mean we find a smaller effect of services than if adaptation did not occur: in the absence of services, service users who have negatively adapted might be expected to rate their QoL as higher than without adaptation. And with services that improve people’s capability, service users might rate their QoL as lower than they would have without positive adaptation. The difference with adaptation is lower than the difference without adaptation.

In measuring the utility associated with (different levels of) capability, most QoL measures will be susceptible to this adaptation effect. Theoretically, we might argue that this problem is avoided if we are able to measure capability directly, but this would have to be done in an objective way so that respondents, in rating their capability, had no opportunity to allow their own preferences and expectations to colour their response. Designing the descriptive content of such an instrument would seem virtually impossible in practice. Potentially, a set of highly specific and verifiable metrics could be used (e.g. regarding social contact, we might measure the number, duration and types of contacts people made), but the set would need to be extremely large to comprehensively reflect all aspects of capability that might be affected by services. For more abstract aspects of capability, such as having control over daily life, it is hard to imagine how a set of objective metrics might be specified.

Given these challenges and the lack of a robust method to measure the extent of adaptation, we acknowledge that inevitably our measure will reflect (in so far as adaptation occurs) a person’s adapted utility. We return to this issue in Chapter 6.

Quality-adjusted life year equivalence

We have stated that one of our objectives was to develop a measure that could be used as a QALY equivalent. This requires that our measure is preference weighted, reflecting the relative importance of different aspects of SCRQoL and thus the value of the different states described by the measure. Preference weighting raises the issue of whose preferences, those of the general public or those of service users? There is an ongoing debate on this issue. 43 Seeking the general public’s preferences has the important advantage that the preferences of members of the general public will be largely free of the influence of or adaptation to the circumstances of service users, particularly where those circumstances are affected by services. In other words, experience of a long-term condition and of how services support people with care needs is likely to shape the preferences of service users.

The disadvantage of using general population rather than service user preferences is that non-service users have to hypothesise what a situation of reduced functioning and capability is like. As Dolan and Kahneman43 argue, general population respondents might focus on the short-term implication of transitioning into a poor functioning state, the transitional loss in utility.

We can also argue these points from a normative perspective. In particular, it might be regarded as important to establish preferences for the general population on the grounds that the population pays for health care through taxes, and decisions about funding (ultimately) are made at the ballot box. 44 However, there is also an argument that whose preferences should be addressed depends on why those preferences are being sought45 and, in the field of social care, service users’ views increasingly play a central role in policy and practice development. It is therefore important to establish if their views are systematically different to those of the general population and, if so, in what way.

In addition to preference weighting, we argue that if we can establish a common anchor and scale, this would allow economic evaluation of the impact of health and social care interventions, facilitating a broader perspective when evaluating the most effective use of health and social care resources. This would mean that interventions whose effects can be fully captured by a SCRQoL measure can be evaluated in a similar manner to those currently evaluated using a HRQoL one. Thus, the cost per social care-related QALY gained could be estimated and compared with the threshold(s) used by decision-makers. The base anchor used for QALYs is the state of ‘being dead’. This is potentially challenging in the context of social care where mortality historically has rarely been identified as a relevant outcome but is clearly worth investigating to provide a more widely applicable and useful measure.

Conclusion

The project was designed to establish a preference-weighted and ideally anchored generic measure of social care outcomes that could be used for a variety of purposes. The first task was to clarify exactly what it is we are attempting to measure. Drawing on the concepts identified above, in the next chapters we now turn to the development and validation of the instrument.

Chapter 2 Development of items

Introduction

As noted in Chapter 1, we did not start from scratch in developing the measure: we were building on previous work and indicators that had been developed specifically to measure outcomes in social care. We made use of previous studies to review the domains and levels, both empirically and in the light of our conceptual thinking, which had moved on since the earlier measures had been developed. Although service users had been involved in previous work, early versions were based on the perspective of those observing (e.g. researchers), commissioning and providing social care. We consulted with service users through general advice (the LSE PSSRU user and carer advisory group), a review of the literature16 and in the cognitive testing stages of this work and linked studies. 46

In this chapter, we describe the reviews of the previous measures and our conclusions in terms of the domains, levels and wording requirements needed for the development of the individual items for our instrument. We then describe the results of the cognitive testing of those new items taken through to the next validation stage.

Previous development and review of Adult Social Care Outcome Toolkit

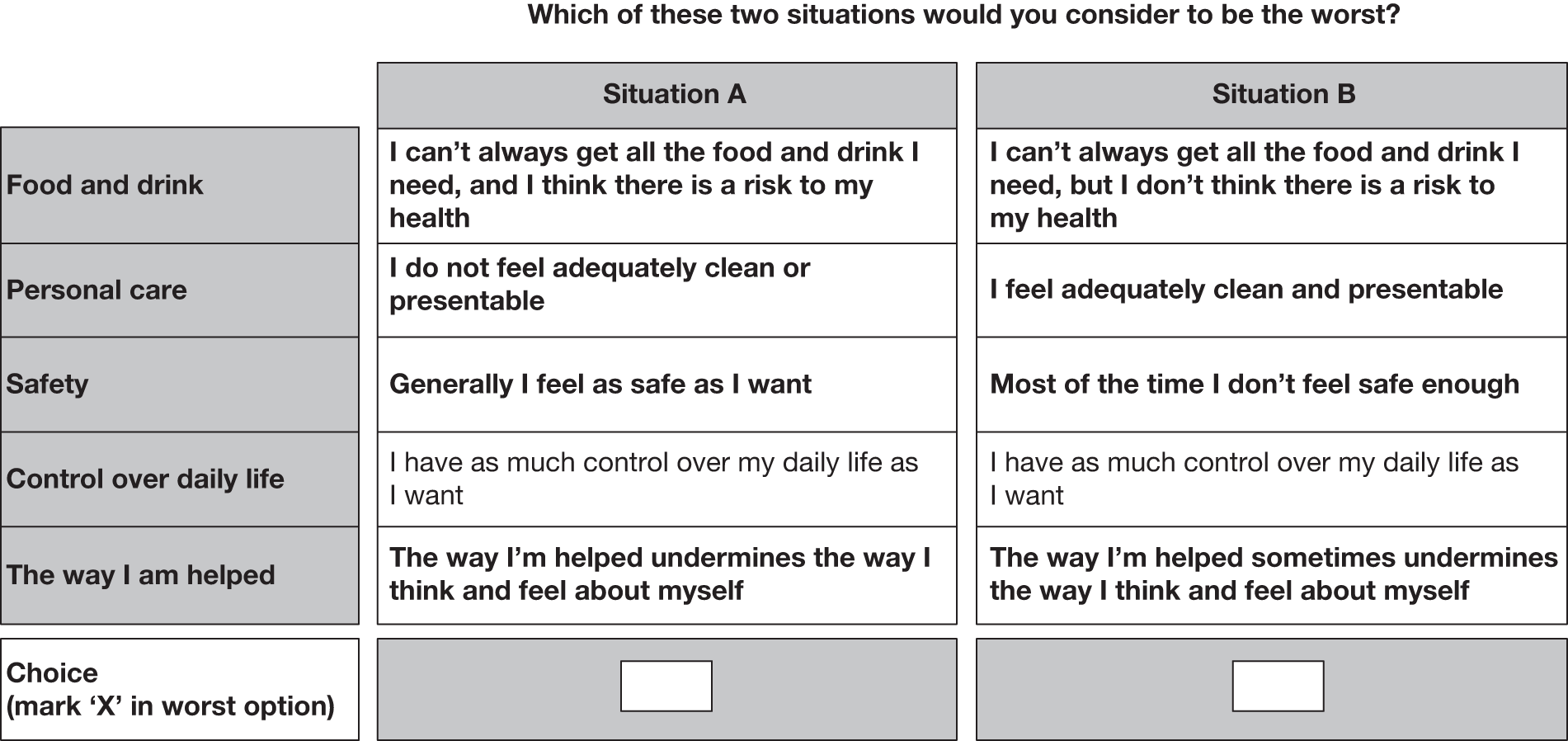

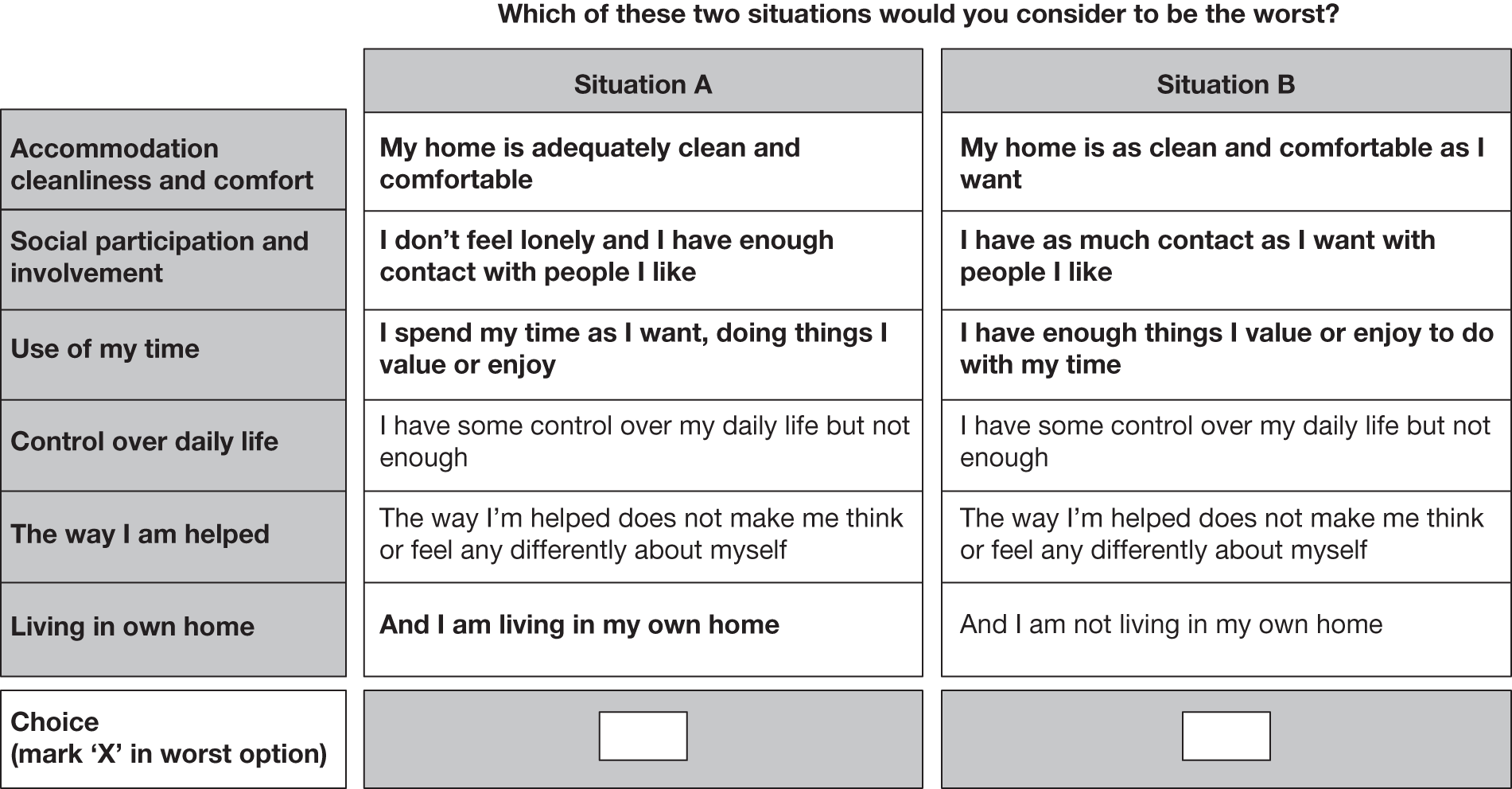

The ASCOT measure was originally based on the Older People’s Utility Scale (OPUS), a preference-weighted measure of social care outcomes for older people. 5 A Delphi exercise, asking respondents to focus on the key domains of outcome for older people, identified five domains (food and drink, personal care, safety, social participation and involvement, and control over daily living). Drawing on the literature and expert opinion, the OPUS measure was later extended to adults aged < 65 years, and included the domains occupation, accommodation cleanliness and comfort, caring for others and living in own home. 47 These reflected both the concerns of social care for younger age groups, such as parenting, and the objective of moving beyond ‘key’ domains to a more comprehensive measure covering all aspects of social care. A single question was used to reflect each domain, with the exception of living at home, which was simply recorded, reflecting whether the person was living in their own home or in a care home setting. The wording of the individual items was cognitively tested and changed as part of development work for a survey of younger adults. 46 A pilot preference study was conducted, providing provisional preference weights anchored to a financial attribute using discrete choice experiments (DCEs). 10 This version of the measure has been used in a number of studies,4,46,48 including a major evaluation of the policy of individual budgets, a new form of consumer-directed support, in England. 49

As part of the Outcomes of Social Care for Adults (OSCA) review of the conceptual basis for the measure, we noted that the ongoing and intimate nature of most social care interventions meant that care itself became a part of people’s lives, which meant that the process of care-giving is important for people’s QoL. The literature review found 15 studies in which aspects of process were identified as important to people’s QoL, including such factors as being valued and treated with dignity and respect,49–54 being listened to/having a say,49–51 having kind staff with whom one can have good relationships55–58 and receiving a service that is both responsive and reliable. 59–61 For the most part, we would expect these aspects of process to be reflected in the SCRQoL domains. For example, people report that the reliability of a service affects their sense of control62 and may have consequences for having needs met in other domains. We would expect the impact of abuse and neglect to be picked up primarily in people’s sense of personal safety. However, some effects of the process of delivering care were unlikely to be captured, in particular those that have an impact on the psychological well-being of service users or their sense of personal dignity. We therefore decided to include in our measure an additional dignity domain, which captured the effect of the process of care-giving on a service user’s sense of self-esteem. Appendix 1 shows a table summarising the development of the domains through the different studies.

Conceptual work undertaken as part of the MOPSU study14 (Measuring Outcomes for Public Service Users) had identified the importance of distinguishing between reflecting Sen’s ‘capabilities’ and ‘functionings’. 31,32 Wording of early versions of the measure had tended to reflect ‘functioning’ states most closely. One version of ASCOT developed for low-level interventions had focused on reflecting capabilities. 9 We wanted our measure to reflect the full range from the very fundamental level where functioning levels are so low they could lead to mental and physical health implications, through to ‘capability’ states, in which people have real choice and their circumstances can be seen to reflect the objectives of the ‘personalisation’ agenda in social care. 11,40

Analysis of previous versions of Adult Social Care Outcome Toolkit

At the time of the review for this study, the instrument had most recently been used in two studies: (1) a postal UES in 2007 of 2228 people with physical and sensory impairments (PWPSI) aged 18–64 years receiving help to enable them to live in their own homes and (2) in an evaluation of the use of individual budgets in social care, in which interviews were conducted with 959 people from all service user groups (the study evaluating the use of individual budgets – IBSEN). The data sets from these studies were analysed to explore empirically, first, whether there were any problems with the items as phrased and, second, the choice of domains. The data sets and analysis are described in detail in Appendix 2. Here we summarise the results and implications for the development of the measure.

In both data sets the domains included:

-

control over daily life

-

personal cleanliness and comfort

-

food and nutrition

-

accommodation

-

safety

-

social participation

-

occupation.

In addition, the data sets included an item on ‘caring for others’, but we did not include this in our analyses as it was not seen as relevant by a very high a proportion of service users. In the IBSEN study, each item had three levels, reflecting:

-

No needs Where any needs experienced are minor or the type of variation in experience people might normally expect in the absence of impairment.

-

Low or some needs Where there are needs that lead to lower levels of well-being, but that are not likely to have any long-term consequences if unmet.

-

High needs Where the needs are of such a level of severity or number that mental or physical health problems are likely to ensue in the short or longer term.

In the UES self-completion version, an additional level was included that was intended to distinguish whether ‘no needs’ was due to those needs already being met by services.

The response rates for the items in both data sets were generally good. However, the number of missing data was higher for the occupation and social participation items, suggesting that these could be improved. Response rates also varied across client groups; they were particularly good for PWPSI, and poor for people with learning difficulties (PWLD) and people with mental health problems (PWMH). It is possible that this pattern arose because the phrasing of the items used in both studies was developed in cognitive interviews with PWPSI. 46

Across both of the data sets, the majority or the largest proportion of respondents chose the ‘no needs’ response option. [It should be noted that the distribution of some of the items (control over daily life, safety and food and nutrition) was better in the IBSEN than in the UES sample, which could be explained by the lack of the second ‘service help’ level in the IBSEN data set. This level could have been ‘taking’ respondents from the lower response options as well as the ‘no needs’ response option.] In addition, for the accommodation cleanliness and comfort, food and nutrition and personal care items, very few people in either data set chose the lowest response option. On both counts, this situation is desirable, as it implies that services are successful in compensating people for their impairments. However, it also means that the distribution of scores for any scale composed of these items is likely to be highly skewed, with most people to be found towards the high SCRQoL end of the scale and very few people towards the low SCRQoL end. The concentration of respondents at the high end of the measure could make the measure insensitive among populations with high SCRQoL. As we assumed that we would be unlikely to observe many people in poor SCRQoL situations, given the existence of services and the availability of help from other sources (family, friends and privately paid-for help), it is important to have high sensitivity at the high SCRQoL end of the scale.

In both data sets a similar relationship was observed between pairs of items. The social participation and occupation items had strong correlations, as did the personal cleanliness and comfort item with both food and nutrition and accommodation cleanliness and comfort. The strong correlation may indicate some conceptual overlap in these domains, which might cause problems in the preference elicitation study. In the case of the personal cleanliness and comfort, food and nutrition and accommodation cleanliness and comfort items, this explanation seemed unlikely, as the wording of the domains and the ideas the domains represent do seem conceptually distinct. A more likely explanation of the strong correlations noted is that they are all areas of life for which poor outcomes would have severe health implications, and service users (and service providers) are likely to express a preference towards having needs in these areas met. In other words, the strong correlation is a result of the similarity in users’ preferences and the response of services to needs in these areas. There is more similarity in the concepts expressed by the social participation and occupation domains, and it was possible that there was some conceptual overlap between them. However, these two areas tend not to be priorities for social care services, so it may have been this perspective that was causing the strong correlation between these two items. Factor analysis for both data sets seemed to indicate that the items formed a weak unidimensional scale, with many of the items having high unique variances, suggesting that the items were conceptually distinct.

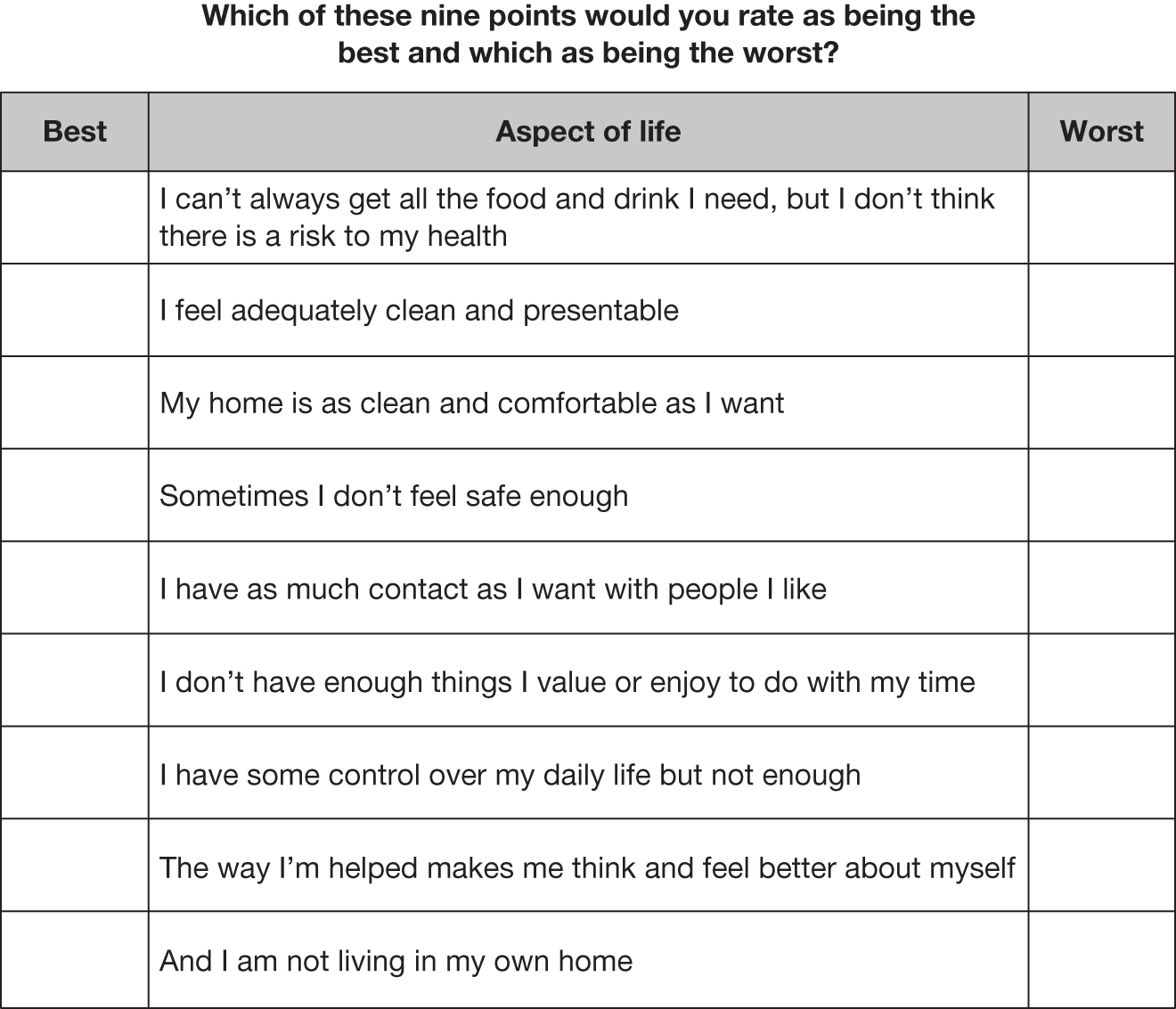

Development of the new Adult Social Care Outcome Toolkit questions

The findings from the theoretical and literature review of the previous ASCOT instrument identified the need to develop a new dignity domain, and to ensure that Sen’s31 concept of capability was incorporated in the measure. From the empirical analysis we concluded there was a need to develop greater sensitivity at the high SCRQoL end of the scale by attempting to split the ‘no needs’ response option into two options: one representing the ideal situation, the other in which there are no real needs but the person considers the situation to be just adequate rather than completely satisfactory. In addition, the empirical work identified the need to improve the wording of the social participation and occupation domains, as well as to improve all the domains so that they were more applicable to older people, PWLD and PWMH. In summary, therefore, the literature and empirical review of the previous version of the measure suggested developing a version of ASCOT composed of nine domains, summarised in Table 2, where each question (excluding living in own home) has four responses. The meaning of these response options is summarised in Box 1.

Ideal. The preferred situation, in which needs are met to the desired level

No needs. Where needs are met, but not to the desired level

Low-level needs. Where there are needs, but these do not have an immediate or longer-term health implication

High-level needs. Where there are needs and these have an immediate or longer-term health implication

| Domain | Definition |

|---|---|

| Personal cleanliness and comfort | The service user feels that he/she is personally clean and comfortable and looks presentable or, at best, is dressed and groomed in a way that reflects his/her personal preferences |

| Accommodation cleanliness and comfort | The service user feels that his or her home environment, including all the rooms, is clean and comfortable |

| Food and drink | The service user feels that he/she has a nutritious, varied and culturally appropriate diet with enough food and drink that he/she enjoys at regular and timely intervals |

| Safety | The service user feels safe and secure. This means being free from fear of abuse, falling or other physical harm, and fear of being attacked or robbed |

| Social participation and involvement | The service user is content with his or her social situation, where social situation is taken to mean the sustenance of meaningful relationships with friends and family, and feeling involved or part of a community should this be important to him/her |

| Occupation | The service user is sufficiently occupied in a range of meaningful activities, whether formal employment, unpaid work, caring for others or leisure activities |

| Control over daily life | The service user can choose what to do and when to do it, having control over his/her daily life and activities |

| Dignity | The negative and positive psychological impact of support and care on the service user’s personal sense of significance |

| Living in own home | The service user is living in his/her own home |

In developing a new set of questions, we set out what each of the response options would look like for each of the domains. This is summarised in Appendix 3. This activity helped us to think about appropriate wording, and ensured that the whole team was clear about what each domain meant and what situation each response option was intended to represent. Where possible, we used terms such as ‘want’ or ‘like’ and ‘adequate’ to distinguish between the preferred situation and the ‘needs met’ or ‘mustn’t grumble’ state, the aim being to reflect capability differences. Need states were described using terms that reflected amount or frequency of events, closer to functioning states. Once the items had been developed, we assessed them using the questionnaire appraisal system63 before testing them with service users. We explain how the questions were tested, and present the results of this testing in the next section.

Testing the revised Adult Social Care Outcome Toolkit instrument

Method

The questions that form the basis of the current and expected SCRQoL scales, as well as the two methods for eliciting preferences (see Chapter 4), were tested and the wording developed so that it made sense to service users in cognitive interviews. Cognitive interviewing is a technique that has gained popularity over recent years as a way of exploring the validity of questions, in particular the aspect of standardisation in the meaning of the question across respondents. 64,65 The technique draws on cognitive psychology and separates the process of responding to the questions into four tasks or components: comprehension, retrieval (from memory using strategies), judgement and response (includes mapping the judgement to a response category and any editing of the response that may be required to present the respondent in a positive light). 66 These components are used by the interviewers as a guide during the interview process in order to uncover differences in the interpretation of questions by respondents.

Thirty cognitive interviews were undertaken during February, March and April 2009, with participants from a range of backgrounds, in three waves of 10 interviews across England. Service users were recruited through councils that had volunteered to act as ‘critical friends’ to the project. All participants had some contact with social care services, although some arranged their own support through a direct payment or personal budget. Most (20) were female and were white (29). About half of the sample were older (aged ≥ 65 years) – although eight were aged 40–64 years – and most lived alone. Only two were in full-time employment, although five were involved in unpaid work. They suffered from a range of conditions, including depression and anxiety, stroke, Parkinson’s disease and arthritis.

After each wave of interviews, the three field researchers met to discuss the issues that arose for the interviewees as they tried to respond to the questions. 67 Discussion between the researchers centred on issues that allowed insight into the interviewees’ thought processes as indicated by the cognitive model, and any problems in the wording were rectified and the questions retested in subsequent waves of interviews.

Results

Measurement domains

Identifying the aspects of QoL that matter most was an important part of developing the questionnaire. As we were trying to measure social care outcomes, the most important aspects were those that are affected by the provision of social care. The sensitivity of the measure depends on capturing the aspects that are affected by social care and matter to people. Everyone we interviewed agreed that the questions captured important aspects of their QoL.

Wording of questions

We tested the wording of the questions and the answer options in order to come up with ways to express each aspect of SCRQoL in everyday language. We also wanted to find words for the answer options that captured the states in Box 1.

For accommodation cleanliness and comfort, we used the wording ‘my home is clean and comfortable’. Important aspects were having clean, dust-free surfaces and hygienic kitchens and bathrooms, but people also mentioned the state of the décor, whether or not their home was neat and tidy, whether or not their home had their own ‘stuff’ in it that they could get to easily, and also whether or not or not they could get around their home easily. For example, a number of people mentioned the problems posed by stairs, or how they had had their home adapted to make it easier for them to move around without help.

The term control over daily life was understood by the people we interviewed. They often distinguished between making decisions and carrying out those decisions. Most of the people we spoke to depended to some extent on help from others to see these decisions through. Having control over their daily life depended on them having someone – and, importantly, the right someone – to help them.

Dignity can mean many things to people, but ‘the way I think and feel about myself’ captured a person’s sense of self and significance well. Including ‘the way I’m helped and treated’ forced people to consider the way their care and support packages had an impact on their sense of self and significance. However, this was not the case for everyone. Some people felt negatively about themselves, not because of how they were treated but because it was difficult for them to accept that they needed help. Some of these people chose the ‘no needs’ answer, but others chose one of the ‘low- or high-level needs’ answers. In order to allow investigation of the impact of this on responses and interpretation of these, an additional question was asked about the impact of having help at all on how people felt about themselves.

We used the term ‘food and drink’ to express the aspects of meals and nutrition. Including ‘drink’ was very important, as people drink more often than they eat, and many people discussed how they managed their lives to ensure that they had the drink they needed. Initially the wording was ‘I can get … the food and drink …’, but we found that some people interpreted the ‘can’ too literally as being physically able to get food and drink without help. We changed the wording to ‘I get … the food and drink …’, which did not have the same problems.

‘Doing things I value and enjoy’ seemed to capture the type of things we intended for the occupation domain. People talked about voluntary work and paid work; activities they did with others, such as going out shopping or to eat; and activities they did on their own, such as reading, needlework or making cards. The answer options changed significantly from the first draft to capture the frequency of doing things, the quality of the things done, and the number of things people had to do. This is important, as for some people the problem was not that they did not have enough to do or things they enjoyed doing, but because they were not able to do as many things as they would like to do because of health limitations.

‘Clean and presentable’ was the term used for personal cleanliness and comfort, which was understood well by people. People talked about how frequently they washed, showered or bathed, and also about whether or not they were able to do their hair as they liked and wear the clothes they liked. Many of the women we interviewed talked about the difficulties they had with jewellery and make-up, and how important it was for them to be able to wear them.

Feeling safe was understood by everyone, although some people questioned whether we meant their feeling safe outside or only inside their home. We therefore recommended a prompt for interviewers to make it clear that we mean both outside and inside the home.

We had some difficulty finding a good way of expressing social participation and involvement, but settled on the phrase ‘social contact with people I like’. Similarly to the occupation aspect, it is important to reflect the quality of contact, the frequency of contact and the number of people known to the person being interviewed. However, it was not possible to reflect all three aspects throughout the question, and the quality part – ‘people I like’ – was dropped from the last three options. This did not seem to matter: people continued to talk about contact with friends and family. They also mentioned phone, e-mail and letter contact, as well as face-to-face contact.

The original answer options also included the phrase ‘I feel lonely’, but this was taken out as it was confusing. As one person explained, ‘it depends on whether you mean personal or social life, as a person can be lonely because they don’t have a special person in their life or lonely because they don’t know many (or any) people’. Given the areas over which social care can be expected to have an impact, we felt it was important to focus the question on the social – rather than the personal – side. We chose to use the term ‘socially isolated’ to denote social loneliness, which seemed to work well.

We also tested including a time frame in the answer options of ‘the past couple of weeks’. We found, however, that it made the question difficult for people to follow and, because many people had conditions that fluctuated, they tended to ignore the instruction even when it was pointed out to them. Most people preferred to answer according to an ‘average’ day. We decided to leave these instructions out.

In the original instrument living in own home was also included. This was not asked as a question but was assessed by the interviewer according to where the person lived. It was, however, included in the preference elicitation tasks as an attribute. The team hypothesised that there may be well-being effects from living in your own home over and above those derived from the other aspects of SCRQoL. In the testing, when service users imagined not living in their own home, they tended to imagine living in a care home. When we asked them to describe what this was like, they described it in terms of the other aspects of QoL that were already included in the measure, such as control over daily life, social participation and involvement, and so on. This seemed to be evidence that this attribute was not distinct from the other aspects of SCRQoL, and therefore would not meet condition of preference independence. 68 We therefore decided to exclude this attribute from the measure.

Response options

As well as understanding the domains as expected, people also seemed to interpret the response options as we had intended. However, for the dignity and safety questions, we felt that there was not enough difference in meaning between some of the levels (and these findings were confirmed by the preference elicitation feasibility study). For dignity, the problem was for the bottom two levels, which were changed from ‘sometimes undermines’ and ‘undermines’ to ‘sometimes undermines’ and ‘completely undermines’. The bottom two levels of safety were also seen as quite similar. These were changed to ‘feel less than safe’ and ‘don’t feel at all safe’ from ‘sometimes I don’t feel safe enough’ and ‘most of the time I don’t feel safe enough’. The top two levels of safety were also changed, with the second level amended to emphasise the sense of adequacy that is intended to be conveyed by this response option.

The impact of services on quality of life: expected social care-related quality-of-life questions

As described in Chapter 1, we wanted to test a pragmatic approach to reflect the outcome of care services. In this, we asked people to assess, in addition to their current status, what their QoL within each domain would be like without services. In the cognitive testing, we tested these questions with service users. For the most part, people could visualise this ‘hypothetical’ situation in the absence of services, and their reasoning made sense and seemed plausible. Some examples of the reasoning of interviewees to these questions are given in Box 2.

A woman who had help with bathing and carrying washing to laundry was very worried about falling and a lack of bowel control. In the absence of services, she chose the high-level needs option for the safety domain, arguing that she would feel very unsafe bathing and walking about

A woman who had help with both shopping and cooking chose the high-level needs option for the food and drink domain in the absence of services, as she perceived that her health would be at risk as she is diabetic

A woman who had help with the accommodation cleanliness and comfort domain chose the high-level needs option in the absence of services, as she said she would be unable to do any housework because of her mobility problems. Interestingly, this issue was reflected in her responses to the social participation domain, where she chose high-level needs in the absence of services. She argued that, without services, she would not want anyone to come to her home, as it would be dirty from the lack of housework, and she would not be able to go to her bridge club as she needs someone to take her there

For the personal cleanliness and comfort domain, a woman who had help with personal care and washing clothes chose the high-level needs option in the absence of help from carers because she felt she would not be able to wash her back, take clothes out of the washing machine and hang them out

A woman who had help in the personal cleanliness and comfort domain chose the ‘no needs’ option in the absence of services (her current situation was the preferred situation). She argued that she would struggle to make herself as clean and presentable as she wished. She would not be able to shower, so would strip wash every time. She did add that this is what made her collapse before, as trying to manage these activities exhausts her. She ended up in hospital relatively recently and the doctors told her she needed to have a carer. Interestingly, this was reflected in the safety domain, where she said that in the absence of services she would have high-level needs as she would ‘be in hospital more than out’ because she would ‘wear [herself] out trying to do things’

For the social participation domain, the same lady argued that, without her carers taking her out, as well as the contact she has with friends, she would not have the same kind of social life: people would come to her but she would not go out. For this reason she chose the low-level needs option in the absence of services

Despite evidence that these questions seemed to work on the whole, there were some examples where people responded in unexpected ways. In one case, a respondent chose low-level needs as the current SCRQoL state and ‘needs met in the absence of services’ arguing that ‘they did not want lots of people coming in to provide help’. This response seems to be driven by a wish to send a message to those organising the care package, despite the fact that the interview findings were not shared with the relevant care manager.

It was also clear from the interviews that the task required a level of cognitive ability that some of the interviewees did not possess. As the interviews also included testing of the preference elicitation tasks, we were able to compare the cognitive ability required for each of the tasks (current SCRQoL questions, expected SCRQoL questions and preference elicitation study). One interviewee provided unclear reasoning for a number of the responses to the expected SCRQoL questions. For example, for the personal cleanliness and comfort domain, this person chose needs met in the absence of services arguing that, without help, it would not be possible to wash or shower but it would be possible to get dressed. This same person was incapable of understanding the preference elicitation task, and the interview had to be curtailed. It would seem that a similar level of cognitive ability is required for both the preference elicitation study and expected SCRQoL questions.

Another difficulty encountered was trying to get the interviewees to answer questions without imagining someone else stepping in, for instance a family member or private support. For example, a lady who had help from her carers to get and prepare food argued that in the absence of services she would have low-level needs, as she would find a way to manage even if it was difficult for her on her own. She might ask someone to deliver food to her, so she would get enough food to sustain her, although it might not be the right food. When interviewers ask these questions, it is important to emphasise that interviewees should not try to imagine what other types of services or people could step in to help them out.

Another issue apparent from the cognitive interviews was that, prior to asking certain questions, it is important to clarify what services a person is receiving. Depending on the types of services the interviewees were receiving, we varied the services they should be thinking about in this testing phase. We asked people to include help from social services and specified exactly what services they should include, i.e. home care, day centres and so on. Where the interviewees did not receive help from social services, we asked them to think about any help they purchased privately. We also asked people to think about equipment they had, although this was more difficult for people to consider. What is included as ‘services’ and the precise wording will depend on the purpose of the study.

Finally, the importance of the specific words chosen was underlined by these interviews. People conceptualised ‘support and services’ very differently. For instance, few participants included equipment or adaptations when thinking about services. The researchers were able to identify such ‘mistakes’ only because they had asked each service user what services they were receiving before asking these questions. It is also important to tailor instructions to the service user. Thus, although the precise nature of wording will always depend on the nature of the study, in operationalising the measure we include detailed questions on service receipt, which can be used to tailor the wording to each individual’s situation.

Conclusions

The OSCA project built on previous versions of the ASCOT measure, drawing on conceptual developments, the literature, consultations with stakeholders and empirical evidence to cognitively test a revised measure with service users. This measure included a new domain (dignity) and a fourth level for all of the domains intended to increase sensitivity and reflect capabilities. The cognitive testing suggested that in taking the dignity domain forward it would be helpful to include an additional question that allowed respondents to reflect their general attitude to receiving any help, as some people have problems coming to terms with needing help at all. The living in own home domain was dropped as it appeared to be double-counting other domains, rather than reflecting an additional care setting or location dimension to our measure. The next step was to explore the validity of the revised measure.

Chapter 3 Testing validity

Introduction

Validity assesses the extent to which an instrument measures what it is intended to represent. In Messick’s words,69 it is ‘an integrated evaluative judgement of the degree to which empirical evidence and theoretical rationales support the adequacy and appropriateness of interpretations and actions based on test scores or other modes of assessment’. The ASCOT measure is intended to be of use in economic evaluations and to provide information for decisions about resource allocation across social care. It should enable decision-makers to compare the value of different types of social care provision, such as a meals service with a home care worker. Validating ASCOT is therefore about identifying the extent to which the instrument captures the value of social care. 70

The ASCOT consists of several components to capture the value of social care. The main instrument is composed of two types of questions. The first set of questions asks people to rate their current SCRQoL state in terms of eight domains or attributes. A second set of questions then requires people to rate their current SCRQoL state in the absence of the ‘intervention’, within seven of the eight attributes, where ‘intervention’ can be defined variously according to the purpose of the study. The dignity attribute does not have an item for the second set of questions because it is process based and it cannot be asked when people are not receiving services. We refer to the second set of questions as the ‘expected’ SCRQoL items and the first set as the ‘current’ SCRQoL items. The third component of ASCOT is a set of preference weights that can be used to attach a value to each SCRQoL state. (The generation of preference weights is described in Chapters 4 and 5.)

The different sets of questions serve different purposes and can be used in a variety of contexts. The current items capture the prevailing SCRQoL state of the individual and could be used to compare the states of otherwise equivalent groups (such as matched samples). They could also be used for evaluation of interventions, where they could be administered before and after an intervention, to generate pre- and post-test scores, where the pre-test scores act as a proxy for the expected SCRQoL state in the absence of the intervention and the difference in the estimated effect. The alternative, pragmatic approach proposed in Chapter 1 is to ask individuals what their expected SCRQoL in the absence of services is directly, with the difference between that and currently experienced SCRQoL representing the contribution that social care makes to a person’s SCRQoL. For the expected score, dignity is assumed to be at the second level – where the care process has no impact on the person’s sense of self-worth. All of the SCRQoL measures (current, expected and gain) can be preference weighted.

The psychometric criteria of ‘construct under-representation’ (the failure to capture important aspects of the concept being measured) and ‘construct-irrelevant variation’ (when responses to the measure are influenced by factors irrelevant to the concept being measured) are useful for thinking about validity in the context of valuing social care. 71,72 However, as Brazier et al. 70 recognise, the psychometric approaches used to determine validity need modification to make them applicable to a preference measure. Brazier et al. 70 identify three aspects of preference measures that require validation: the descriptive system, the valuations or utility weights, and the empirical validity of the instrument, which refers to whether people, through their behaviour in practice, appear to value the different states in the way that they are valued in the measure.

Here we focus our assessment of validity on the validity of the descriptive system, which refers to the choice of domains, the specification of the items in the instrument, and the ability of the instrument to detect changes or known differences in SCRQoL. This was achieved in four separate sets of analysis. We first examined the construct validity of the individual items in terms of whether or not they reflect the concepts as intended. We then evaluated the construct validity of the three preference-weighted scales by exploring their ability to detect known differences in SCRQoL. In this we wanted to establish:

-

current SCRQoL scale as a measure of social care-related QoL

-

expected SCRQoL scale as a measure of social care need

-

gain in SCRQoL scale as a measure of the contribution of services to SCRQoL.

Methods

Data collection

Throughout the project, in order to access service user samples, we made use of the annual UES conducted by local councils. The main data collection conducted to test the validity of the instrument with service users took place in 2009 when the UES was of older people (aged > 65 years) using home care services. 13 Ten councils across England took part, covering a variety of regions and local authority (LA) types: six shire counties, two London boroughs, one metropolitan district and one unitary authority. A sampling frame was generated from respondents who had indicated that they were happy to be approached to take part in further research. Data were collected face to face through computer-aided personal interviews (CAPIs). Interviewers were briefed prior to interviewing. Data collected included sociodemographic information; service receipt and informal support; QoL and psychological well-being; health; functional ability; control and autonomy; nature of the locality and environment; social contact and support; and participation in groups and volunteering.

Analysis

The content of the instrument is clearly an important aspect of the validity of the descriptive system. If key aspects of SCRQoL relevant to a person’s utility function are absent, the instrument will not provide an adequate valuation of social care. We followed the method used by Coast et al. ,73 who assessed validity by observing relationships between the items of their measure (ICECAP, now renamed ICECAP-O) and other factors thought to be related to it. Variables were divided into thematic groups for testing associations between these and items in the ASCOT measure. We examined the statistical significance of associations, and considered patterns of percentages and means to form a judgement about the strength or otherwise of relationships.

To demonstrate the validity of the current scale as a measure of SCRQoL, the aim was to explore its relationship with other variables that capture the same construct. However, because of the uniqueness of this measure – in its focus on SCRQoL – it was difficult to find measures with which to compare its performance. We therefore examined its relationship with other measures capturing related constructs. These included HRQoL, where we would expect a moderate relationship with SCRQoL, and psychological well-being, where we might expect a closer relationship.

To reflect HRQoL we used the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D),74,75 a widely used indicator that has preference weights that generate a measure of health value. For psychological well-being we used the 12-item version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12). Although originally developed as a measure of mental ill health, with a cut-off score below which it is likely the person is clinically depressed,76–78 GHQ-12 has been tested as a measure of positive mental health in the general population. 79 In addition, as ASCOT attempts to capture capability, we anticipated a moderate relationship with measures of concepts such as control, autonomy and independence. To reflect these concepts, we used the control and autonomy subscale of the CASP-12,80 a reduced form of CASP-19, which is a theoretically based needs satisfaction measure of quality of life for older people. 81 The items capturing expected SCRQoL in the absence of services can be viewed as measuring the need for social care services, as the items capture what a person’s life would be like without the compensatory action of services. We would therefore expect the expected SCRQoL scale to be associated with other measures that capture need for help in activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL). These measures capture the functional ability and are frequently used in needs assessments for social care.

The SCRQoL gain measure is designed to capture the contribution of services to SCRQoL, so construct validity was explored in relation to service receipt. ‘Services’ here were any publicly funded service and included home care, day centres and meals services, as well as newer forms of service delivery, such as direct payments. We would expect the gain in SCRQoL measure to have a positive correlation with intensity of service receipt, although the strength of the correlation will depend on a number of factors that affect the production of welfare, including the quality of the care delivered and other factors that may influence the ability of workers to deliver optimal care, such as the design of the person’s home or challenging behaviour of the individual. It is also possible that the relationship is non-linear, as increasing levels of service input deliver diminishing marginal returns. Therefore, we would not necessarily expect a strong relationship, but merely that the correlation is significant and positive.

We examined the relationships with our individual SCRQoL items using chi-squared tests (for unordered or ordered categorical variables) or one-way analysis of variance (for continuous variables). For comparisons with the SCRQoL current, expected and gain scales, we used a series of Pearson correlations with continuous variables and one-way analysis of variance (for unordered or ordered categorical variables).

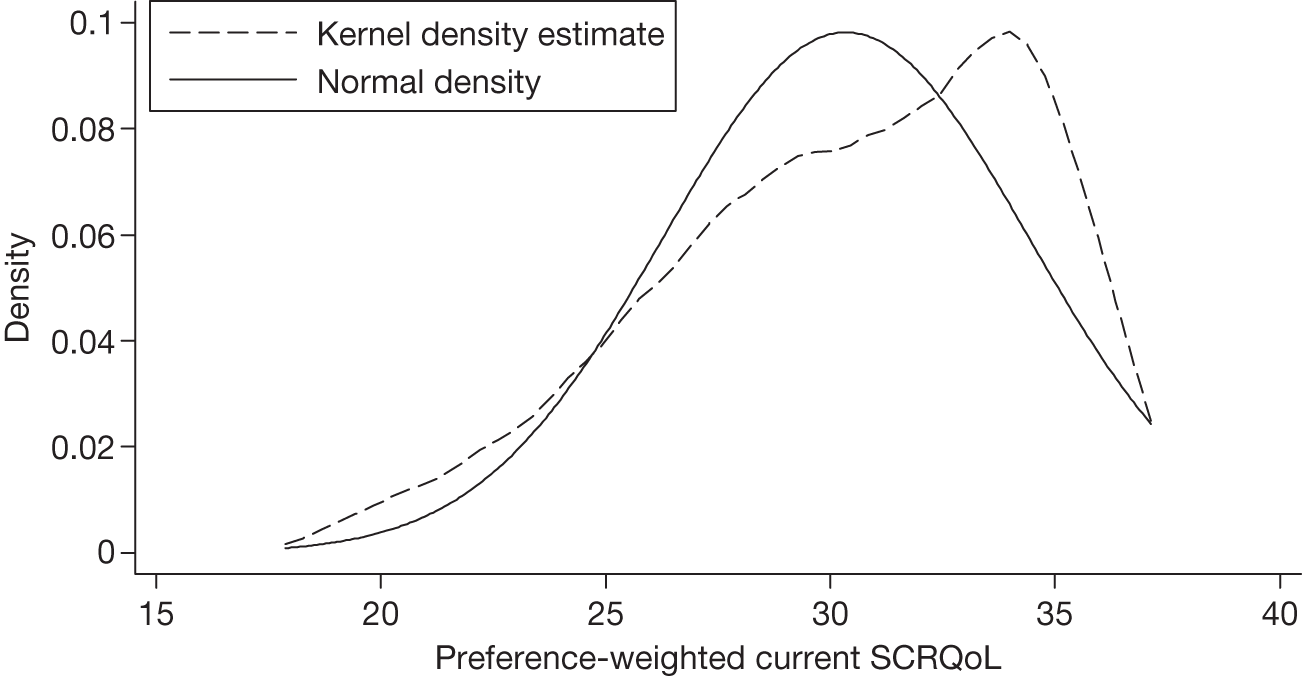

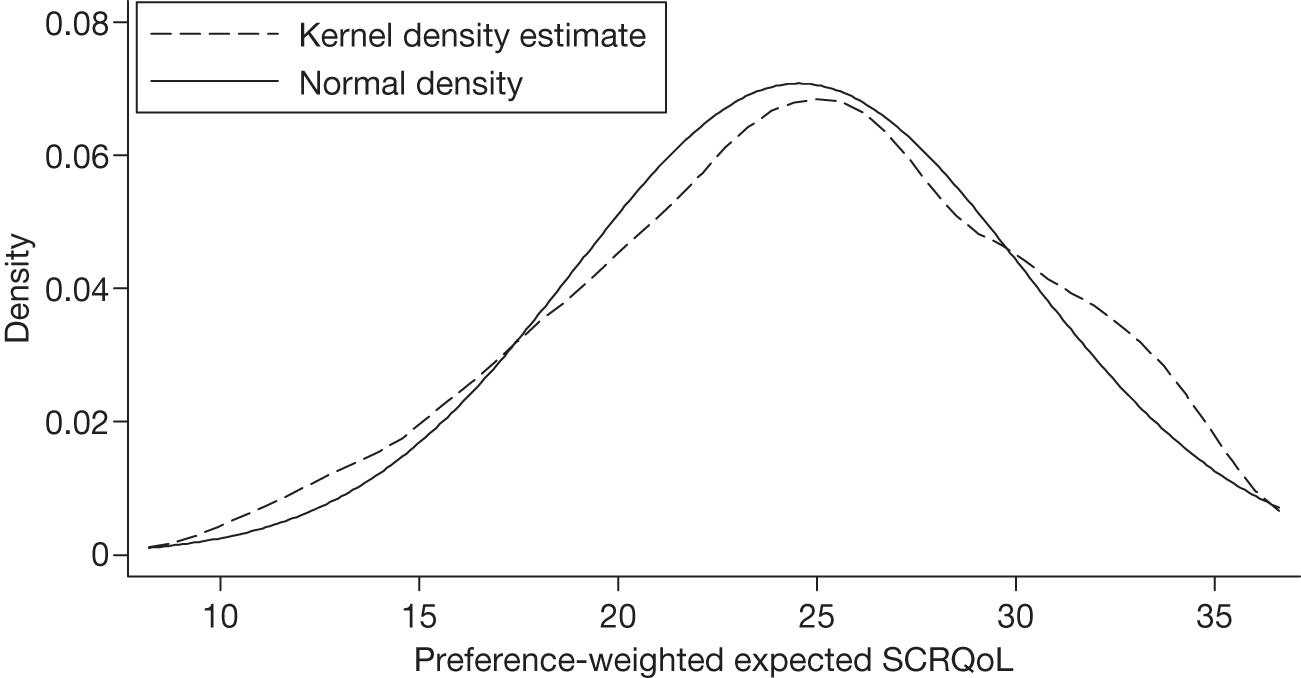

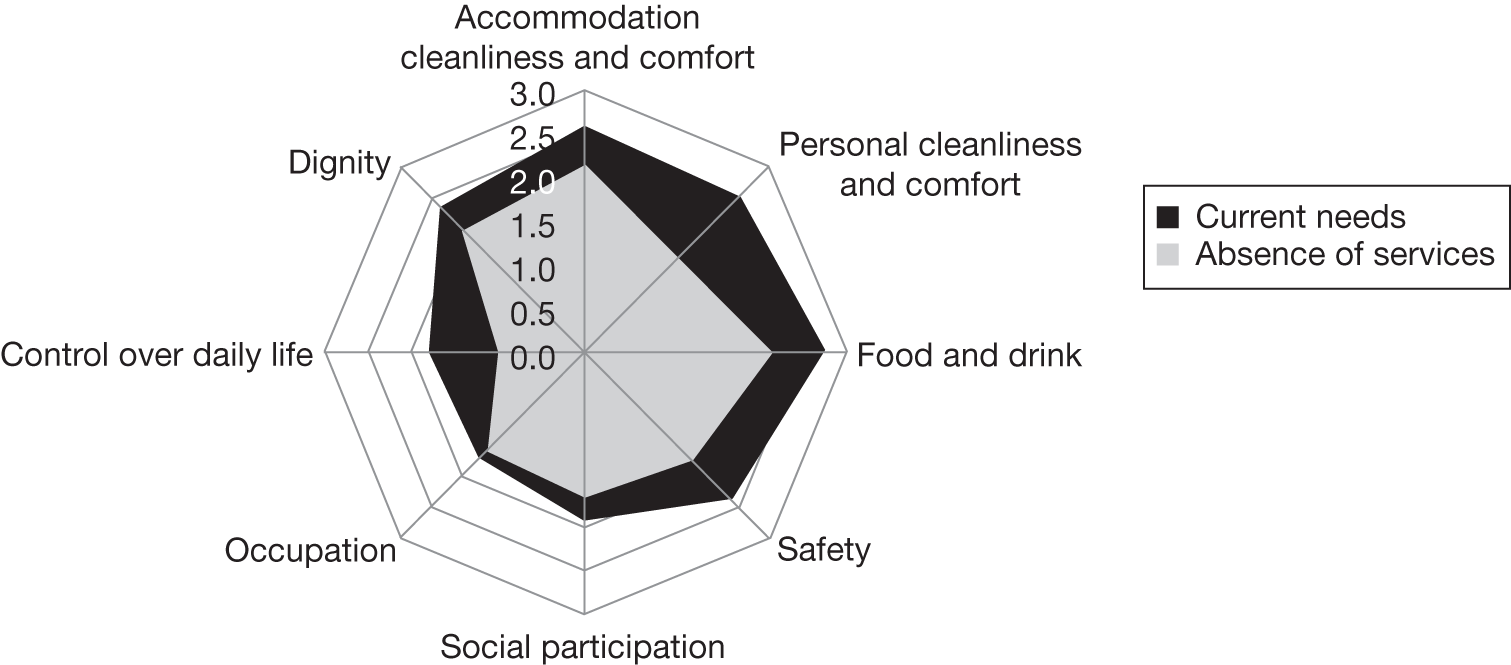

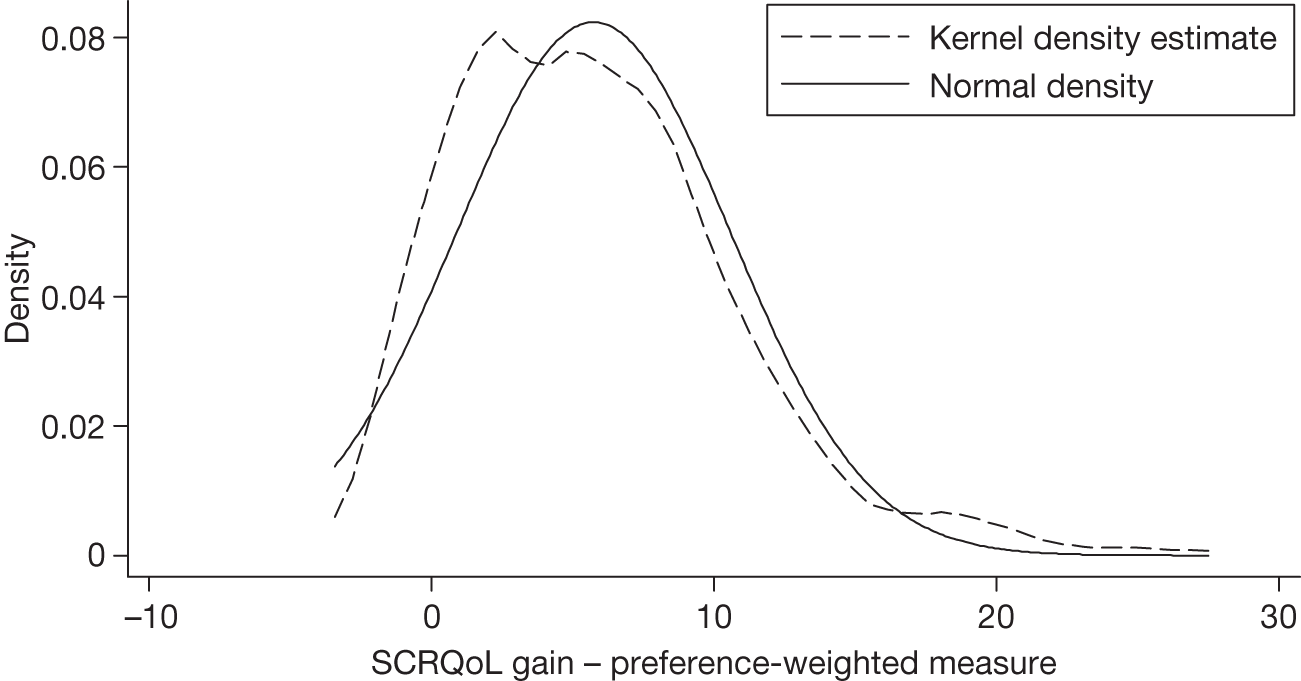

Description of sample