Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 06/302/216. The contractual start date was in December 2007. The draft report began editorial review in June 2011 and was accepted for publication in December 2011. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design.The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2012. This work was produced by Sharples et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2012 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Lung cancer is the second most common cancer in the UK and is the most common cause of cancer death. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for 78% of all cases, with an overall 5-year survival of approximately 8% in the UK. 1 As treatment of lung cancer is influenced by stage, accurate staging is important to optimise treatment.

At present, the mainstay of lung cancer staging involves imaging and biopsy of areas that are suspicious for metastatic spread. The incorporation of positron emission tomography (PET) into staging algorithms has considerably reduced the number of unnecessary thoracotomies performed by identifying locoregional and distant metastases. Positron emission tomography–computerised tomography (PET–CT) is more accurate than computerised tomography (CT) for assessing mediastinal lymph node involvement. Although the negative predictive value (NPV) of PET–CT for mediastinal disease is around 93%, a positive predictive value of 74–90% makes pathological verification of 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (18-FDG)-avid mediastinal nodes necessary in order to determine whether or not they are malignant. 2 Making the assumption that FDG-positive nodes are malignant will potentially deny many patients potentially curative surgery as it is recognised that non-malignant mediastinal nodes can take up FDG in other pathological states, such as infection and inflammation.

Historically, surgical staging of enlarged and/or PET–CT-positive mediastinal lymph nodes has relied on procedures such as mediastinoscopy, mediastinotomy or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. These are invasive procedures requiring general anaesthetic and hospitalisation and have low, but well-recognised, morbidity and mortality. The accuracy of these procedures is variable and ranges between 80% and 90%. Although specificity is near 100%, sensitivity ranges between 66% and 90% (see Detterbeck et al. 2 and associated references, Pinto Filho et al. ,3 Anraku et al. 4). Thus, there is room for improvement in terms of the sensitivity of currently available surgical mediastinal staging investigations.

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) and, more recently, endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) are two relatively new, less invasive, diagnostic techniques that allow real-time controlled aspiration of mediastinal lymph nodes. These techniques are normally performed in an outpatient setting under moderate sedation. EUS-FNA and EBUS-TBNA are complementary techniques. EUS permits access to mediastinal lymph node groups 2L, 4L, 7, 8L/R, 9L/R, whereas EBUS gives access to mediastinal lymph node stations 2R/L, 4R/L and 7. Using the techniques in combination it is possible to access the majority of mediastinal lymph nodes. EBUS-TBNA also allows access to hilar and intrapulmonary nodal stations 10R/L and 11R/L. In addition, in selected cases, endosonography offers the possibility to assess whether or not a tumour is invading mediastinal structures (T4).

A number of non-randomised prospective studies using EBUS-TBNA have reported sensitivity of around 90% for diagnosis of hilar and/or mediastinal lymph nodes. 5–8 In 2009, two meta-analyses reported pooled sensitivity for EBUS-TBNA of 0.889 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.79 to 0.94] and 0.9310 (95% CI 0.91 to 0.94). In a systematic review, Varela-Lema et al. 11 reported that sensitivity for the diagnosis of malignancy ranged from 85% to 100%. In all three of these reports the specificity quoted was 1.00, but this figure is artificial, as positive TBNA results were not confirmed by surgical resection in any of these papers. In the case of EUS, reported sensitivity for mediastinal staging varies between 50% and 87%. 2,12–16 The lower figure may be a reflection of the fact that EUS is able to access only the left-sided mediastinal nodes along with the inferior posterior nodes.

To date, there have been three reports documenting a combined approach using both EBUS-TBNA and EUS-FNA for assessing the mediastinum. 17–19 In these series, sensitivity for detection of mediastinal disease ranged from 85% to 100%.

Taken together, it is clear that, although the reported sensitivity of EUS and EBUS for the detection of malignancy in mediastinal lymph nodes is similar to that of mediastinoscopy, there are no reported prospective randomised studies comparing the accuracy of EBUS-TBNA, EUS-FNA and surgical staging for assessment of the mediastinum in lung cancer. Furthermore, to date, no full economic evaluations investigating the cost-effectiveness of EBUS and EUS versus surgical staging have been published.

Therefore, in 2007, this group, led by clinical co-investigators in Ghent, Leiden, Leuven and Cambridge, undertook a prospective randomised controlled trial (RCT) comparing endosonography (combined EBUS-TBNA and EUS-FNA), followed by surgical staging if negative, with surgical staging alone for assessment of the mediastinum in (suspected) NSCLC. In addition to the clinical findings that were published in November 2010,20 data on patient-reported quality of life and the incremental costs and benefits from the perspective of a health-care provider were collected. Here we report resource-use data collection and a cost-effectiveness analysis from a UK NHS perspective.

Chapter 2 Study design

Study objectives

The final protocol is provided in Appendix 1. This RCT was designed to assess whether or not EBUS-TBNA combined with EUS-FNA, followed by surgical staging if these tests were negative, is better than standard surgical staging techniques in the staging of lung cancer in terms of sensitivity, diagnostic accuracy and NPV. The null hypothesis is that there is no difference between the two diagnostic strategies in these outcomes. The health economic study was designed to compare European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) utility and cost-effectiveness of the two diagnostic strategies.

Specific study objectives were as follows:

-

The primary research objective of the study was to determine whether or not EBUS-TBNA combined with EUS-FNA, followed by surgical staging if these tests were negative, is better than standard surgical staging techniques in terms of sensitivity for diagnosing and staging the mediastinum in lung cancer. The related NPV of the two diagnostic strategies was also calculated.

-

Determination of the sensitivity and accuracy of EBUS and EUS, followed by surgical staging if these tests were negative, compared with surgical staging for determining mediastinal tumour invasion (T4).

-

A comparative cost-effectiveness analysis of the diagnostic strategies of the two trial arms.

-

Assessment of the complication rates in each arm.

-

An estimation of the saving of surgical staging procedures that might be possible in the future if EBUS-TBNA/EUS-FNA, followed by surgical staging if these tests were negative, is shown to have greater sensitivity and diagnostic accuracy and becomes the new ‘gold standard’ staging approach.

-

Estimation of how many futile thoracotomies can be avoided by performing EBUS-TBNA and EUS-FNA, followed by surgical staging if these tests were negative, rather than surgical staging alone.

-

Assessment of interobserver variability of cytopathological evaluation of EBUS-TBNA and EUS-FNA samples.

Trial design

This was a prospective, international, multicentre, open-label randomised controlled study.

Trial centres

Four centres were involved in the trial: Ghent University Hospital, Belgium; Leuven University Hospitals, Belgium; Leiden University Medical Centre (LUMC), the Netherlands; and Papworth Hospital, UK. Details of the study, the main investigators, trial steering groups and data monitoring committees are provided in the Acknowledgements. In each centre there was a core team comprising a lung cancer physician, a thoracic surgeon and a research nurse. Data collection was completed at each centre using paper-based clinical report forms. All centres followed the same protocol, with the exception of Leuven, where ‘frozen-section’ histopathological analysis was performed in some patients during surgical staging procedures and proceeding directly to thoracotomy was possible if there was no evidence of mediastinal nodal malignancy.

Ethics

The trial was approved by the Cambridge 1 Local Research Ethics Committee in the UK and by the ethical committees of the three participating European hospitals (LUMC in the Netherlands, the University Hospitals of Ghent and Leuven in Belgium). The trial was registered with International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN 97311620) as ASTER (Assessment of Surgical sTaging versus Endosonographic ultrasound in lung cancer: a Randomised clinical trial).

Study population

All consecutive patients referred to the thoracic oncology clinics at the four participating hospitals for staging of lung cancer were considered for the study.

Inclusion criteria for the study were as follows:

-

known or suspected NSCLC and suspected mediastinal lymph node involvement (either N2 or N3), based on available thoracic imaging (CT or CT–PET)

-

pending the results of mediastinal staging, potentially suitable for surgical resection with an intention to cure

-

clinically fit for bronchoscopy, endosonography and diagnostic surgical procedures

-

no evidence of distant metastatic disease after routine clinical work-up

-

able to give informed consent.

Exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

previous treatment (chemotherapy, radiotherapy or surgery) for lung cancer

-

any known clinical reason for not undergoing, or a contraindication to, endosonography or a surgical staging procedure, unsuitability for definitive surgical resection by thoracotomy

-

based on available thoracic imaging, the likelihood that disease cannot be staged accurately by any surgical staging procedure (mediastinoscopy/-otomy, video-assisted thoracoscopic staging)

-

a concurrent malignancy at another site

-

an uncorrected coagulopathy

-

inability to give informed consent.

Study design

Patients who were potentially eligible for participation in the study according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria listed above were identified at the weekly multidisciplinary lung oncology meetings held at each of the centres. The initial diagnostic assessment involved the recording of medical history, a physical examination, full blood count, renal and liver function tests, CT of the chest and upper abdomen and whole-body PET–CT.

Patients were approached in the outpatient clinic by the local principal investigator and those who expressed interest in participating were given a copy of the patient information sheet. All patients were given at least 24 hours to consider participation, and those who indicated that they were willing to participate were consented and then were randomised to either surgical staging alone or endosonography (combined EUS-FNA and EBUS-TBNA) followed by surgical staging (if no nodal metastases were found at endosonography).

Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either surgical staging alone or endosonography followed by surgical staging. Group allocations were computer generated according to a simple randomisation strategy and were stratified for participating centre. A web-based program was developed, which, on registration of consented patients, provided the next, centre-specific group allocation.

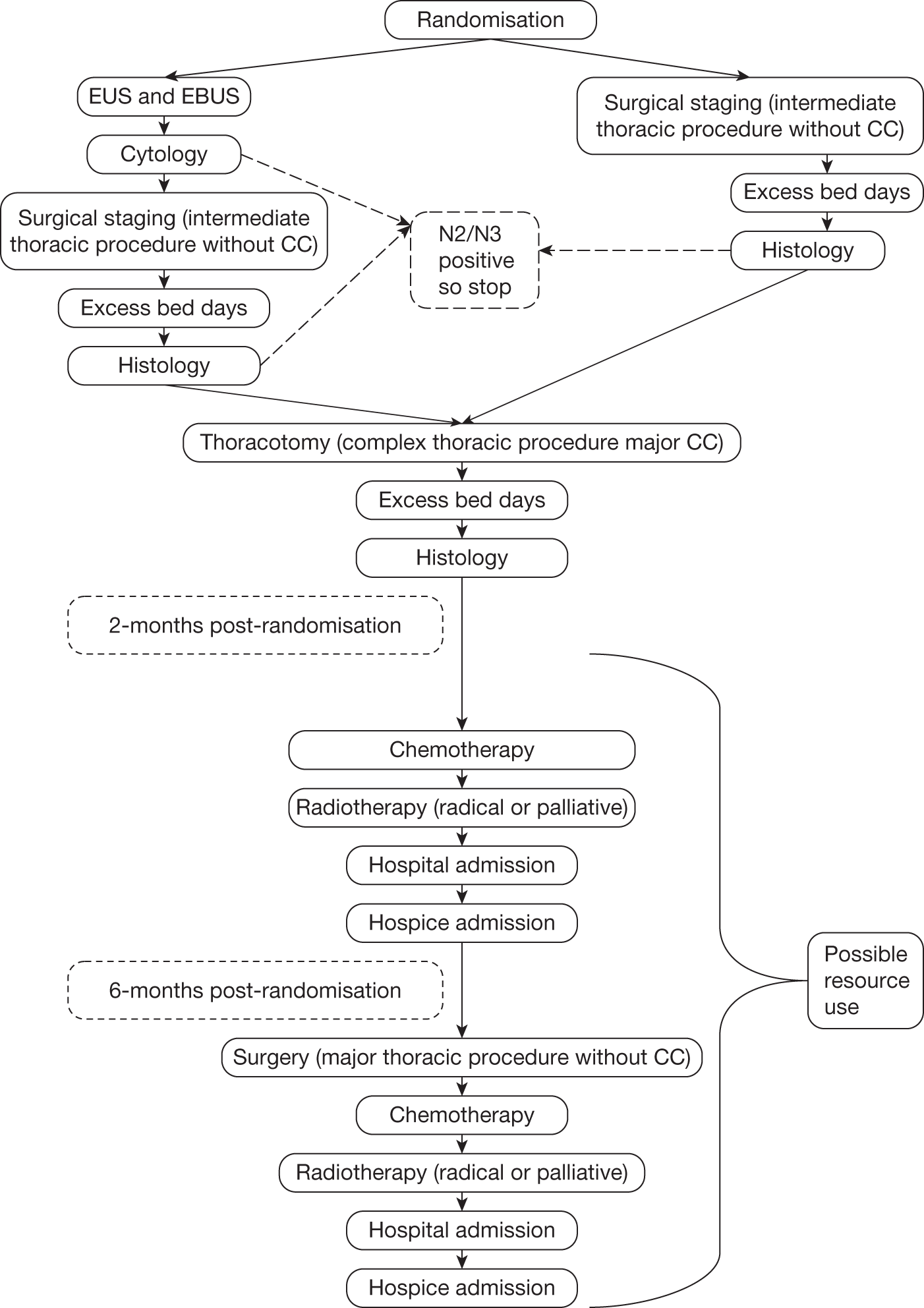

The study design is shown in Figures 1 and 2.

FIGURE 1.

Potential resource use in the first 6 months. CC, complication and comorbidity.

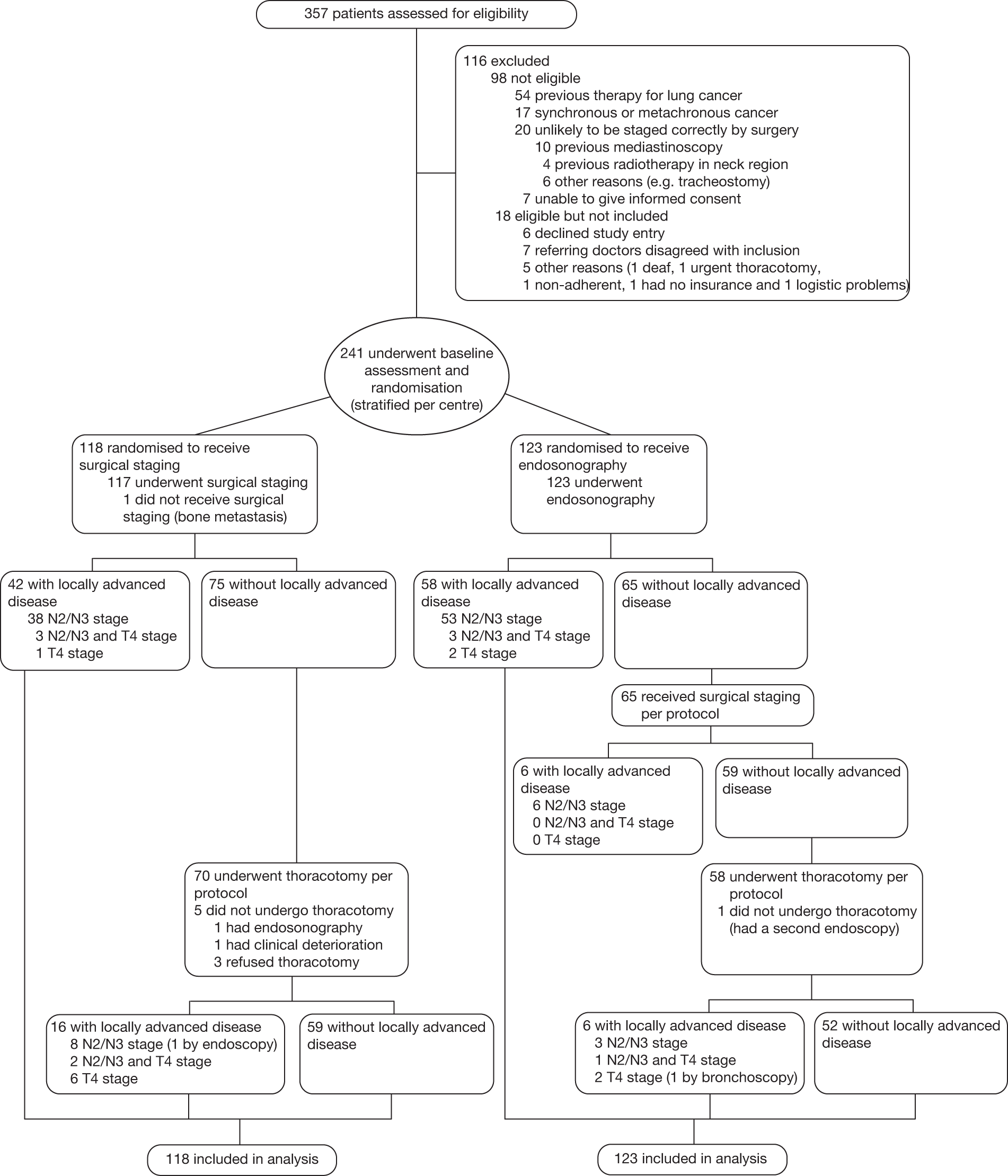

FIGURE 2.

Enrolment and randomisation of study patients.

Patients randomised to endosonography followed by surgical staging if negative

Patients underwent endosonography as detailed below (see Investigation protocols): if there was no evidence of mediastinal nodal metastases, surgical staging was performed as described. In the event of pathological evidence of mediastinal metastases (N2/N3) or mediastinal tumour invasion (T4), either after endosonography or after mediastinoscopy, patients were classified as having locally advanced disease (stage IIIA/B) and were referred for chemoradiotherapy. If after confirmatory surgical staging there was still no evidence of mediastinal nodal disease or direct tumour invasion, a thoracotomy with a systematic lymph node dissection was performed.

Patients randomised to surgical staging

Surgical staging was performed as described below (see Investigation protocols). In the event of pathological evidence of mediastinal metastases (N2/N3) or direct mediastinal tumour invasion (T4), patients were classified as having locally advanced disease (stage IIIA/B) and were referred for chemoradiotherapy. If there was no evidence of mediastinal metastases, a thoracotomy with a systematic lymph node dissection was performed.

Investigation protocols

Endosonography

Endosonography of the mediastinum was performed under moderate sedation. For reasons of convenience and patient comfort, EUS-FNA (Pentax 34UX/38UX, Pentax, Tokyo, Japan or Olympus GF-UCT140-AL5, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was performed prior to EBUS-TBNA (Olympus BF-UC160F-OL, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). A systematic examination of at least left and right paratracheal, subcarinal and paraesophageal mediastinal nodes, as described above, was performed. Nodes that were suspicious on PET–CT or ultrasound imaging were sampled under real-time ultrasound guidance with 22-gauge needles and labelled according to the Mountain–Dresler lymph node classification. 21 When the primary lung tumour was visible by endosonography, the presence or absence of direct mediastinal tumour invasion (T4) was recorded. The cytology preparations were analysed using either May–Grünwald–Giemsa or Papanicolaou stains, dependent on local practice, with additional preparation of cell blocks for histological analysis when appropriate. At completion of the study, all EUS and EBUS samples were re-evaluated by an independent reference pathologist (AGN) to assess interobserver agreement.

Surgical staging

Surgical staging was performed by a (video-) mediastinoscopy according to current guidelines. 2,22 A systematic (five lymph node stations) assessment of left and right higher (2L and 2R) and lower paratracheal (4L and 4R) and subcarinal (7) nodes was performed. If necessary, a left parasternal mediastinotomy or video-assisted thoracoscopy was performed to allow access to nodal stations 5 and 6 or 7–9, respectively. Combinations of the above procedures were permitted. The approach(es) taken were left entirely to the surgeon’s discretion. Nodal samples were labelled and sent for pathological examination. Any evidence of direct mediastinal invasion by the primary tumour (T4) was noted.

Thoracotomy

Thoracotomy with nodal dissection was considered to be the reference in both study arms for patients without N2/N3 nor T4 involvement after mediastinal staging. Thoracotomy was performed when there was no mediastinal nodal metastasis or direct mediastinal tumour invasion following surgical staging in both groups and was carried out according to current guidelines. 23 At the time of lung resection a systematic lymph node dissection (at least three mediastinal stations, including the subcarinal station) was performed according to current guidelines. All hilar and intrapulmonary (N1) lymph nodes were counted as a single station. Histological examination of the resected nodes/resection specimen and pTpN classification were performed according to current guidelines. 24

Histology

Cytology preparations were analysed using either May–Grünwald–Giemsa or Papanicolaou stains, dependent on local practice, with additional preparation of cell blocks for histological analysis where appropriate.

Sample size

The sample size calculation was based on demonstrating a 20% increase in sensitivity [the rate of detecting mediastinal nodal metastases (N2/N3)] from 70% with surgical staging alone to 90% with endosonography followed by surgical staging. Assuming 80% power and a two-tailed α-value of 5%, the required sample size was calculated to be 62 patients per group, total 124. It was further assumed that the prevalence of mediastinal nodal metastases would be 70% and the dropout rate 5%, giving a required sample size of 93 per group, or 186 in total. However, as interim monitoring revealed the prevalence of mediastinal nodal metastases to be 55% rather than 70%, the sample size was increased to 240 patients.

Outcome measures

The primary clinical outcome was the sensitivity of each diagnostic strategy for detection of mediastinal nodal (N2/N3) metastases. The denominator for the calculation of sensitivity was taken to be the number of patients in whom histological examination of nodal tissue biopsied during any procedure was positive for cancer (EUS/EBUS, mediastinoscopy, thoracotomy). The numerator was the number of patients in whom histology was positive during the diagnostic phase (EUS/EBUS and/or mediastinoscopy, depending on group). Patients with tumour-positive nodal findings at EUS, EBUS or surgical staging were regarded as true-positives, as further validation of these findings was judged unethical. The final reference status of the patient was positive if any diagnostic test was positive or if nodal involvement was detected after thoracotomy. The related NPV was also calculated as the number of patients who were free of nodal involvement as a proportion of the number of patients with negative tests during the diagnostic phase. This is interpreted as the probability of a final diagnosis of no metastases given the diagnostic tests were all negative.

Other outcome measures were:

-

determination of the sensitivity of EBUS and EUS (followed by surgical staging) compared with surgical staging alone for determining mediastinal tumour invasion (T4)

-

EQ-5D items and associated utility at end of staging (before thoracotomy) and 2 and 6 months after randomisation

-

cost–utility of the endosonography diagnostic strategy (including surgical staging if negative) relative to surgical staging alone up to 6 months after randomisation

-

complication rates

-

the rate of futile thoracotomies that could be avoided by performing EBUS-TBNA and EUS-FNA rather than surgical staging alone, defined as nodal metastases, tumour invasion, distant metastases, non-malignant disease or death within 30 days of procedure

-

interobserver variability of cytopathological evaluation of EBUS-TBNA and EUS-FNA samples.

Statistical analysis

In the primary analysis, estimation of sensitivity and NPVs was performed on an intention-to-treat basis. Patients in whom diagnostic tests were negative and who did not undergo thoracotomy did not have a reference standard. For these patients, multiple imputation based on the binomial distribution was used for the missing reference standard. An additional worst-case scenario analysis assumed that patients who were staged node negative, but in whom surgical verification was missing, were considered to be false-negatives. A κ-value was calculated to assess the interobserver variability of EUS and EBUS cytology samples. In exploratory analysis, the groups were compared using Fisher’s exact test for binary categorical variables, the chi-squared test for other categorical variables and the independent Student’s t-tests for continuous normally distributed variables. EQ-5D utilities were compared using linear models that included the baseline value as well as the group allocation. Survival rates from randomisation to death or last known survival date were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and compared using a log-rank test. Details of statistical methods used in the cost-effectiveness analysis are given below.

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions analysis

The EQ-5D questionnaire consists of five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. For each dimension, the patient indicates the level of problems experienced by one of three responses: no problems (score 1), some problems (score 2) or extreme problems (score 3).

The EQ-5D questionnaire was completed using standard pro forma at baseline, at the end of staging (after surgical staging but before thoracotomy) and after 2 months and 6 months for all patients recruited at Papworth Hospital. 25 This information was collected for patients in the continental European centres who were recruited after April 2008. For these patients the established Dutch- or Flemish-language versions of the EQ-SD were used. Between February 2007 and April 2008 EQ-5D, data were not available from the continental European centres. As this represented a block of time for which no patient completed the EQ-5D, this information was reasonably assumed to be missing at random.

The social tariff for the EQ-5D, as estimated by Dolan et al.,26 was applied to each patient’s self-reported classification in order to calculate utility values for each patient. 26 Although European tariffs exist for the EQ-5D, this report is from a UK perspective so the UK tariff was applied to all responses. Utilities were scaled so that full health = 1 and death = 0. In the case of patients in whom between one and four dimensions (out of five) of the EQ-5D were missing, a single imputation using an ordinal logistic regression model was used to impute the missing values.

Initially, utilities were summarised according to the nominal times of completion (baseline, end of staging, 2 months, 6 months) of the questionnaires. In order to estimate EQ-5D values at the same times after randomisation for each patient, the exact dates that the questionnaires were completed were used and linear interpolation between the recorded EQ-5D values on these dates gave an estimate at specific days post-randomisation. This allowed estimation of utilities at times 0, 7, 61 and 183 for all patients, and these were summarised. If EQ-5D questionnaire dates were not available, end of staging, 2- and 6-month questionnaires were assumed to have been completed at 7, 61 and 183 days after randomisation, respectively.

In the case of patients who died within 183 days of randomisation (four EUS/EBUS and seven surgical patients), EQ-5D was assumed to be ‘0’ at the date of death and thereafter. Interpolation between the last recorded EQ-5D and an EQ-5D of ‘0’ at the date of death was carried out to obtain EQ-5Ds for each time point (0, 7, 61 and 183 days).

For patients who died after 183 days but did not have EQ-5Ds recorded for all dates up to day 183, interpolation was again performed between the last known EQ-5D and an EQ-5D of ‘0’ at the date of death (two EUS/EBUS and two surgical patients).

For patients who had monotonic missing EQ-5D values (i.e. had an EQ-5D value up to a certain time point, but all subsequent EQ-5D values missing) and did not die within or after the study, the last recorded EQ-5D value was carried forward. One patient (randomised to the endosonography strategy) had the baseline EQ-5D value carried forward to 6 months. Two patients (one EUS/EBUS and one surgical staging) had the end of staging EQ-5D carried forward. Four patients (one EUS/EBUS and three surgical staging) had the 2-month value carried forward to 6 months. The analysis was repeated using a subset of data that excluded these patients from the quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) calculations and the results were very similar.

For the patients who had an EQ-5D recorded at each time point and did not die within or after the study but the 6-month EQ-5D was earlier than 183 days after randomisation, the last EQ-5D was carried forward. Twelve people from the EUS/EBUS group and 13 from the surgical staging group were included in this group. All had last dates recorded that were within 10 days of the end of the study, except one patient who had the final follow-up at 155 days. This was considered to be a reasonable method to use, as the EQ-5D for these patients would have been unlikely to change dramatically without the investigators knowledge in such a short time period.

Exploratory cost-effectiveness analysis

The 6-month QALY was estimated for each patient using the area under the curve (AUC) method. The maximum QALY achievable was therefore 0.5 years. As the groups were randomised, adjustment for baseline utility was unnecessary in the exploratory analysis.

Costs were estimated from a health-service provider viewpoint using resource use from all of the patients in the trial and, in the base case, costs from a UK NHS perspective. For resource use, a study-specific data collection form was designed (see Appendix 2). Data were recorded prospectively after April 2008 and retrospectively for patients recruited before April 2008. Forms were returned to the Papworth Hospital research and development (R&D) unit for data processing and analysis.

Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of resource use for the ASTER trial.

The following resource-use components were recorded: EBUS/EUS, surgical staging, thoracotomy, surgery other than planned thoracotomy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hospital stays and hospice stays.

The final costs assigned to each component of resource use are summarised in Table 1. For standard treatments and procedures the NHS Reference Costs 2008–0927 was used, with specific procedures as shown in Table 1. For EBUS-TBNA and EUS-FNA there were no NHS reference costs, so they were estimated by Papworth Hospital finance department. The costs included staff time, bed occupancy, and hospital costs and equipment, which were assumed to have a 5-year lifetime. Full details of the costing of the endosonography procedures are given in Table 2. Similar unit costs for staging using EBUS/EUS were elicited by the finance departments at the centres in Ghent (€671.8) and Leiden (€1506).

| NHS resource | Mean unit cost (quartiles) (£) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital/hospice costs | ||

| EUS/EBUS procedure | 1237 | Papworth NHS finance department estimates |

| Surgical staging procedure | 3056 (2360 to 3652) | Code DZ04B27 |

| Surgical staging procedure cost from day 10 | 329 (217 to 424) | Code DZ04B27 |

| Thoracotomy (lobectomy or pneumonectomy) with lymph node dissection | 6525 (5917 to 6903) | DZ02B27 |

| Thoracotomy cost from day 44 | 318 (218 to 458) | Code DZ02B27 |

| Deliver simple parenteral chemotherapy at first attendance1 | 272 (98 to 234) | Code SB12Z27 |

| Deliver subsequent elements of a chemotherapy cyclea | 227 (121 to 236) | Code SB15Z27 |

| Radical radiotherapy (very first fraction) | 274 (123 to 415) | Code SC02Z27 |

| Subsequent radical radiotherapy fractions | 112 (68 to 137) | Code SC22Z27 |

| Palliative radiotherapy (very first fraction) | 274 (123 to 415) | Code SC02Z27 |

| Subsequent palliative radiotherapy fractions | 112 (68 to 137) | Code SC22Z27 |

| Hospital admission | 2126 (1543 to 2475) | Code DZ17B27 |

| Cost of hospital admission per day from day 32 | 224 (168 to 256) | Code DZ17B27 |

| Hospice admission per day | 399 (337 to 406) | Code SD01A27 |

| Surgery | 4120 (3197 to 4677) | Code DZ03B27 |

| Laboratory costs | ||

| Following EUS/EBUS procedure | 17 (9 to 22) | Code DAP83827 |

| Following surgical staging procedure | 26 (7 to 36) | Code DAP82427 |

| Following thoracotomy (lobectomy or pneumonectomy) with lymph node dissection | 26 (7 to 36) | Code DAP 82427 |

| Component | Total cost including VAT (£) | Equipment life (years) | Activity | Unit cost (£) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBUS scope | 61,000 | 5 | 150 | 81 | Assumes 5-year life |

| EUS scope | 92,500 | 5 | 100 | 185 | Assumes 5-year life |

| Ultrasound processor | 58,300 | 5 | 150 | 78 | Assumes 5-year life |

| Two consultants | 300,000 | 3404 | 88 | Assumes 1-hour procedure | |

| Two Band 6 nurses | 60,510 | 3404 | 18 | Assumes 1-hour procedure | |

| One health-care assistant | 15,500 | 1702 | 9 | Assumes 1-hour procedure | |

| Aspiration needle | 155 | 2 | 310 | As per consumables schedule | |

| Balloon | 15 | 1 | 15 | As per consumables schedule | |

| Single-use suction valve | 3 | 1 | 3 | As per consumables schedule | |

| Sterilisation of scopes | 16 | 2 | 32 | ||

| Maintenance contract | 19,000 | 150 | 127 | Assumes maintenance for above equipment only | |

| Day ward bed-day | 150 | 1 | 150 | ||

| Hospital overheads, including capital charges – 15% | 945 | 15% | 142 | Trust overhead included in annual trust costing exercise | |

| Total | 1237 |

The total expected costs from randomisation to 6 months were estimated by summing the resource use multiplied by its unit cost and taking the sample average for each group. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (difference in costs divided by difference in effects) was calculated using the sample differences.

A first analysis was restricted to ‘completers’, i.e. individuals for whom both complete cost and QALY information was available. All patients completed a resource-use questionnaire and data surrounding the initial diagnostic strategy was complete. However, because subsequent treatment was often administered in a patient’s local oncology centre (distant from the tertiary diagnostic referral centre), some resource-use information was missing. The number of missing data for each category was:

-

EBUS/EUS (0 missing)

-

surgical staging (0 missing)

-

thoracotomy (0 missing)

-

surgery other than planned thoracotomy (28 missing)

-

chemotherapy (35 missing for 0–2 months, 30 missing for 2–6 months)

-

radiotherapy (22 missing for 0–2 months, 26 missing for 2–6 months)

-

hospital stays (34 missing for 0–2 months, 28 missing for 2–6 months)

-

hospice stays (26 missing for 0–2 months, 29 missing for 2–6 months).

Values were imputed for these missing resource-use items. In this exploratory analysis, a single imputation was performed as follows. Patients were divided by centre, randomisation group and stage (N2-/N3-positive or N2-/N3-negative, as determined at the end of the surgical staging procedure in both groups – i.e. for the EUS/EBUS group, this was the number of people who were found to be N2/N3 positive after endosonography added to the number found to be N2/N3 positive after endosonography followed by surgical staging). Within each of these subgroups, the mean cost for each item was calculated from cases with available information and imputed for those with missing values.

To estimate the standard errors and CIs for the mean cost and QALY, bootstrap samples were generated and the results plotted on the cost-effectiveness plane and as a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC).

Full data cost-effectiveness analysis

Bayesian parametric modelling28 was used to estimate expected costs and QALYs. This allowed the estimation of cost-effectiveness to include information from all of the patients rather than just patients for whom complete cost and QALY data were available. The methods are unbiased under the assumption that the missing data were ‘missing at random’; in other words, whether or not an observation is missing depends on other variables for which we adjust, but not on the missing value itself. The QALY can be assumed to be missing ‘completely at random’, as quality-of-life data collected were collected only for patients recruited at later time points.

Overall, QALYs over 6 months were missing for 97 out of 241 patients. The model used for imputation of the missing QALYs was a truncated normal distribution (see Table 3). The mean before truncation was modelled in terms of predictors (randomisation group, centre and baseline EQ-5D) and the resulting posterior distribution for the expected QALY over 6 months was used in the cost-effectiveness estimate.

| Parameter | Imputation model |

|---|---|

| Observed QALYs between randomisation and 6 months | Truncated normal, truncated between the theoretical minimum (–0.297) and maximum (0.5) |

| Day in hospital for EBUS/EUS (0 or 1) | Bernoulli |

| Days in hospital for surgical staging | Beta-binomial |

| Days in hospital for thoracotomy | Beta-binomial |

| Surgery other than planned thoracotomy (0 or 1) | Binomial |

| Chemotherapy cycles | Poisson |

| Radiotherapy fractions | Poisson-gamma |

| Days in hospital | Beta-binomial |

| Days in hospice | Binomial |

As described in the exploratory analysis, some resource-use costs were missing As these costs arise as counts of events (multiplied by a fixed unit cost), a model was defined for each of these event counts. Different parametric models were used to represent the distribution of the event counts for each component.

Although there were no missing data for EUS/EBUS, it was modelled as a binary outcome in order to include it in the model for total mean cost. Surgery other than the planned thoracotomy was modelled as a binary outcome. For the remaining events, owing to the high number of zero counts, a hurdle count-data model was used. 29 In this methodology, a proportion of the patients did not have the event and so were given a value of zero, whereas the remaining patients did have the event and were given a value greater than zero to reflect, for example, the number of days in hospital or the number of fractions of radiotherapy. The non-zero count was assumed to come from a standard count model such as the binomial or Poisson distribution truncated below to be greater than zero. Overdispersed equivalents of these models were used where the counts had a high variance. Binomial or beta-binomial distributions were used for count data with theoretical maximum values. In this case, the number of days spent in hospital over 6 months has a theoretical maximum of 183 days. The beta-binomial is an overdispersed version of the binomial, whereby the outcome probability is allowed to vary according to a beta prior. Poisson distributions were used for theoretically unbounded count data, with a gamma prior assigned to the rate parameter when necessary to allow for overdispersed counts. Specific models for the resource-use components are summarised in Table 3.

Several individuals had a particular cost component observed for 0–2 months, but missing for 2–6 months, and vice versa. For these cases, this component was modelled as right censored at the observed cost value.

The probability of a non-zero cost was modelled in terms of covariates using logistic regression. For hospice admission, the only covariate used in this part of the model was randomisation group. For all other events, randomisation group, centre and stage were included as covariates. Where appropriate, the mean of the Poisson(-gamma) or (beta-)binomial non-zero component is also modelled in terms of randomisation group, centre and stage, except for radiotherapy, for which there was insufficient information to be able to model any covariates. For the Poisson distribution, log-linear regression on the rate was assumed, and, for the beta-binomial distribution, adjustment was based on logistic models.

The total expected cost was calculated as the sum of the component-specific expected costs for each randomisation group, while averaging over the other patient characteristics.

As a Bayesian model was used, uncertainty about the unit costs could be acknowledged. The UK mean unit cost estimates and upper and lower quartiles were available for each resource (see Table 3). These were used to define gamma prior distributions for each unit cost. 30 The point estimates of the unit cost in Table 2 were assigned to the mean, and the variance was estimated as the variance of the normal distribution with the same mean and interquartile range (IQR), so that IQR = 1.35 standard deviation (SD).

The freely available software package WinBUGS31 (MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK) was used to estimate the joint posterior distribution of all unknown parameters involved in the cost and QALY models, hence the posterior distributions of expected total cost and QALY. The ‘WBDev’ add-on to WinBUGS was used to calculate the lower tail probabilities and conditional tail expectations of the binomial distribution, which was required because of the time-dependent change in costs for certain components, for example after 32 days in hospital.

Deterministic sensitivity analysis

One potential alternative diagnostic strategy was identified a priori for investigation. The value of using endosonography as the only diagnostic modality to exclude nodal involvement was assessed by excluding the costs of the confirmatory surgical staging in this group, but adding in costs for additional futile thoracotomies that would have resulted from the lower sensitivity of these tests when used alone. The QALYs were not adjusted, as the difference between groups was very small and the proportion of patients for whom utilities would change is also small.

Chapter 3 Clinical outcomes

Trial progress

Between February 2007 and April 2009, 357 consecutive patients with potentially resectable (confirmed or suspected) NSCLC were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 98 patients did not meet the inclusion criteria owing to previous therapy for lung cancer (n = 54), concurrent cancer at another site (n = 17), improbability of being staged correctly by surgery (n = 20) or inability to give informed consent (n = 7). Eighteen patients were eligible but not included because the patient refused consent (n = 6), referring doctors were unwilling to include the patient (n = 7), the patient was too deaf to complete study requirements (n = 1), urgent thoracotomy was required (n = 1), the patient was known to be non-compliant (n = 1), the patient had no health insurance (one continental European patient) or there were logistic problems (n = 1). The remaining 241 patients were randomised, 118 (49%) to surgical staging and 123 (51%) to endosonography followed by surgery if negative [Figure 2, the CONSORT (CONonsolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials) diagram]. Of the 241 patients recruited, 88 were from Ghent, 81 from Leiden, 44 from Leuven and 28 from Papworth.

Baseline characteristics

The average age of patients was 64.5 years [standard deviation (SD) 8.9 years] and men were in the majority in both groups (74% men in the surgical staging arm and 80% men in the endosonography arm). Further clinical characteristics can be found in Table 4.

| Baseline variable | Surgical staging alone (n = 118) | Endosonography and surgical staging (n = 123) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age, years | 64.5 (9.1) | 64.6 (8.7) |

| No. (%) men | 87 (74) | 99 (80) |

| Centre, no. (%) | ||

| LUMC | 39 (33) | 42 (34) |

| Ghent | 43 (36) | 45 (37) |

| Papworth | 14 (12) | 14 (11) |

| Leuven | 22 (19) | 22 (18) |

| Indication for staging, no. (%) | ||

| Quamous cell carcinoma | 44 (37) | 46 (37) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 21 (18) | 28 (23) |

| Adenosquamous | 2 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Large cell carcinoma | 3 (3) | 6 (5) |

| Bronchoalveolar cell carcinoma | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Carcinoma not specified | 18 (15) | 16 (13) |

| Suspected NSCLC | 29 (25) | 24 (20) |

| Tumour location, no. (%) | ||

| Left lower lobe | 17 (14) | 27 (22) |

| Left upper lobe | 18 (15) | 25 (20) |

| Right upper lobe | 30 (25) | 28 (23) |

| Middle lobe | 9 (8) | 10 (8) |

| Right lower lobe | 44 (37) | 33 (27) |

| Tumour stage on PET/CT, no. (%) | ||

| T1 | 26 (22) | 22 (18) |

| T2 | 66 (56) | 80 (65) |

| T3 | 11 (9) | 11 (9) |

| T4 | 15 (13) | 10 (8) |

| Nodal status on PET/CT, no. (%) | ||

| N0 | 15 (13) | 9 (7) |

| N1 | 17 (14) | 20 (16) |

| N2 | 66 (56) | 78 (63) |

| N3 | 20 (17) | 16 (13) |

| Mean (SD) short axis of largest lymph node (mm) | 12.3 (5.1) | 13.2 (4.2) |

| ACCP class, no. (%) | ||

| Massive enlargement (A) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Discrete enlargement (B) | 73 (62) | 76 (62) |

| Central tumour or hilar node (C) | 35 (30) | 33 (27) |

| Nodes < 10 mm (D) | 10 (8) | 14 (11) |

| Final histopathology grade, no. (%) | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 47 (40) | 51 (41) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 40 (34) | 40 (33) |

| Adenosquamous | 5 (4) | 6 (5) |

| Large cell carcinoma | 6 (5) | 2 (2) |

| Bronchoalveolar carcinoma | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Carcinoma not specified | 12 (10) | 19 (15) |

| Small cell carcinoma | 1 (1) | 4 (3) |

| Benign lesion | 5 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Unknown | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

Surgical staging alone

Surgical staging was performed in 117 out of the 118 randomised patients. A distant metastasis was found in one patient after randomisation but before the surgical staging procedure could be performed. Cervical mediastinoscopy was performed in 116 of the 117 (99%) which was combined with parasternal mediastinoscopy in three and a thoracoscopy in two. Only one patient underwent a thoracoscopy. Of the 117 who underwent mediastinoscopy, data on mediastinal nodal status were incomplete in seven patients for the following reasons:

-

In one patient, mediastinal invasion (T4) was found during mediastinoscopy without verification of the nodal status.

-

Three patients in whom surgical mediastinoscopy staging was negative, declined verification by thoracotomy.

-

In one patient in whom surgical mediastinoscopy staging was negative, thoracotomy was not possible because of rapid clinical deterioration.

-

One patient underwent an open–close thoracotomy without nodal verification because of haemodynamic instability.

-

In one patient, direct mediastinal invasion was observed at thoracotomy and the surgeon decided to close the thorax without taking nodal biopsies.

In the 110 patients in whom staging was complete, a median of four (range 1–5) mediastinal nodal stations were sampled at surgical staging.

Overall, during staging, mediastinal metastases (N2/N3) were found in 41 out of 118 (35%) patients. In four patients, one without nodal metastases, direct mediastinal invasion of the lung tumour in the mediastinum (T4) was found. Thus, 42 patients had either mediastinal metastases (N2/N3) or mediastinal invasion (T4), or both. Thoracotomy was performed in 70 patients, and two patients underwent further diagnostic tests or had clinical evidence of metastatic disease. Of these patients, 10 had nodal metastases (of whom two also had mediastinal tumour invasion) and a further six had mediastinal invasion alone . Three patients who did not have evidence of mediastinal node involvement after surgical staging refused thoracotomy, so that their final nodal status was not confirmed.

Endosonography followed by surgical staging

Endosonography was performed in 123 patients and detected mediastinal nodal metastases in 56 out of 123 (46%). In five patients it was obvious on endosonographic imaging that the primary lung tumour invaded the mediastinum (T4); two of the five did not have nodal verification. Thus, surgical staging was avoided due to endosonography findings in 47% of patients (58/123). Sixty-five patients without evidence of mediastinal nodal metastases or mediastinal tumour invasion underwent surgical staging showing nodal metastases in six additional patients. These missed mediastinal metastases were located in stations 4R (n = 3), 5 (n = 1), 6 (n = 1) and 7 (n = 1), with those in stations 5 and 6 being out of reach for endosonography.

Fifty-eight (out of 59) patients in whom endosonography or surgical staging revealed no evidence of nodal metastases underwent thoracotomy with nodal dissection. One patient was found to have undeniable mediastinal invasion based on a second endosonography, but did not have nodal verification. In the 58 patients who underwent thoracotomy, nodal metastases were found in four, one of whom also had mediastinal tumour invasion; two others were found to have mediastinal tumour invasion without confirmation of nodal metastases. At endosonography and surgical staging a median of three (range 1–7) different mediastinal nodal stations were sampled. For 121 patients in the endosonography group, the interobserver agreement in relation to cytological diagnosis of samples was assessed by an independent pathologist (Table 5) with κ = 0.97 (95% CI 0.92 to 1.00).

| Local result | Reference observer’s result | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benign | Malignant | ||

| Benign | 63 | 2 | 65 |

| Malignant | 0 | 56 | 56 |

| Total | 63 | 58 | 121 |

Final diagnosis and false-negative findings

Of the 241 patients, 229 (95%) were diagnosed with NSCLC, five (2%) with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and five (2%) with other diagnoses, such as sarcoidosis; in two patients (1%), the diagnosis could not be ascertained during the study. Overall, the prevalence of mediastinal nodal metastases (N2/N3) was 49% (117/241). At thoracotomy, a median of five (range 0 to 10) lymph node stations were obtained in both study arms. At pre-operative staging, nodal metastases were missed in 10 patients in the surgical staging arm (stations 4L, 4R, 5 and 7) and in four patients in the endosonography arm (stations 3A, 4L, 4R, 5, 8L and 8R). In eight patients (7%) in the surgical staging arm, negative lymph node findings at staging were not verified by surgery. One of these eight patients had bone metastases before staging and in one surgical staging revealed clear T4 disease and so nodes were not sampled; in a further four of the eight patients, mediastinoscopy was negative and they received no further treatment (three refused thoracotomy and one deteriorated clinically) and in two patients who underwent thoracotomy lymph node confirmation of stage was not performed. There were three patients (2%) in the endosonography arm in whom negative lymph node findings at staging were not verified by surgery: in two of these endosonography clearly demonstrated T4 disease and in one T4 disease was diagnosed by bronchoscopy.

Diagnostic accuracy

Mediastinal nodal (N2/N3) metastases were found in 41 out of 118 patients (35%) by surgery alone compared with 62 out of 123 patients (50%) by endosonography followed by surgical staging if negative (p = 0.02). In the intention-to treat analysis, sensitivity for detecting mediastinal nodal metastases by each of the staging strategies was 79% (41/52, 95% CI 66% to 88%) versus 94% (62/66, 95% CI 85% to 98%) (p = 0.02; Table 6). The corresponding NPVs were 86% (66/77, 95% CI 76% to 92%) and 93% (57/61, 95% CI 84% to 97%) (p = 0.18; Table 6). In the worst-case scenario of treating cases with no surgical verification of negative staging as false-negatives, the sensitivity of surgical staging alone was 68% (41/60, 95% CI 57% to 80%) compared with 90% (62/69, 95% CI 81% to 95%) for endosonography with surgical staging if negative, respectively (p = 0.006), with corresponding NPVs of 75% (58/77, 95% CI 66% to 85%) and 87% (53/61, 95% CI 78% to 94%), respectively (p = 0.08).

| Nodal invasion (N2/N3) | Surgical staging (n = 118) | Endosonography and surgical staging (n = 123) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) positive on endosonography | – | 56/123 (46%) | – |

| No. (%) positive on surgical staging | 41/117 (35%) | 6/65 (9%) | – |

| No. (%) positive on thoracotomy | 10/70 (14%) | 4/58 (7%) | |

| Sensitivity of initial strategy | 41/52a (79%) | 62/66 (94%) | 0.02 |

| NPV of initial strategy | 66/77 (86%) | 57/61 (93%) | 0.18 |

Detection of locally advanced disease

In addition to the patients with N2/N3 involvement identified above, the tumour was observed to have invaded the lymph nodes (T4) in one patient in the surgical staging group and in two patients in the endosonography strategy group. Tumour invasion alone was detected by thoracotomy in a further six patients in the surgical staging group and two in the endosonography strategy group. One further patient in the endosonography strategy group was referred for thoracotomy but underwent a second endosonography before planned surgery, which showed clear tumour invasion. Thus, 42 patients (36%) in the surgical staging arm were found to have locally advanced diseases (nodal metastases and/or unforeseen direct mediastinal invasion) during staging, compared with 65 patients (53%) in the endosonography arm (p = 0.009). When the one patient in the endosonography arm who had a second endosonography was removed, the difference remained significant (p = 0.01).

Unnecessary thoracotomies and complications

There were 21 unnecessary thoracotomies among the 118 patients randomised to surgical staging (18%), compared with nine unnecessary thoracotomies in 123 patients randomised to endosonography followed by surgical staging if negative (7%; p = 0.02) (Table 7).

| Reason | Surgical staging (n = 118) | Endosonography and surgical staging (n = 123) |

|---|---|---|

| N2/N3a | 5 | 2 |

| N2/N3/death within 30 days | 1 | 1 |

| N2/N3/M1 | 1 | 0 |

| N2/N3/T4 | 2 | 0 |

| N2/N3/T4/death within 30 days | 0 | 1 |

| T4 | 6 | 1b |

| M1 | 0 | 2 |

| SCLC | 0 | 1 |

| Benign lesions | 2 | 0 |

| Exploratory thoracotomy | 2 | 0 |

| Death within 30 days | 2 | 1 |

| Total | 21 | 9 |

The overall complication rate was 7 out of 118 (6%) in the surgical staging arm compared with 6 out of 123 (5%) in the endosonography arm (p = 0.78; Table 8). There was one pneumothorax that was considered to be directly related to endosonography. This occurred during a EUS-FNA procedure, during which the primary tumour was biopsied. With pleural drainage, full lung expansion was achieved.

| Complication | Surgical staging (n = 118) | Endosonography and surgical staging (n = 123) |

|---|---|---|

| Persistent hoarseness | 2 | 4 |

| Pneumothorax | 1 | 1 |

| Mediastinitis | 0 | 1 |

| Major bleeding | 3 | 0 |

| Conversion to thoracotomy | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 7 | 6 |

The remaining 12 complications were all directly related to the surgical staging procedure. The most common adverse event was persistent hoarseness as a result of recurrent nerve palsy, which was considered to be a severe complication if it lasted at least 6 months and was attributable to the mediastinoscopy. One patient presented with fever 24 hours after mediastinoscopy and mediastinitis was diagnosed; treatment with antibiotics resulted in full recovery.

Endosonography alone versus surgical staging

It is possible to estimate the diagnostic accuracy of endosonography alone using the first part of the endosonography arm strategy (i.e. without additional surgical staging). Of the 66 patients identified with mediastinal nodal involvement, this was observed during endosonography in 56 cases. The sensitivity estimates for surgical staging alone and endosonography alone were 79% (41/52; 95% CI 68% to 89%) and 85% (56/66; 95% CI 74% to 92%), respectively (p = 0.62). The corresponding NPVs were 86% (66/77; 95% CI 75% to 92%) and 85% (57/67; 95% CI 74% to 92%) (p = 1.00), respectively. Complications occurred in 7 out of 118 patients (6%) after surgical staging and in 1 out of 123 patients (1%) following endosonography alone (p = 0.03). Endosonography alone would have resulted in an additional six cases of unnecessary thoracotomy.

Summary

The clinical component of this RCT showed that a strategy of using combined EUS–FNA and EBUS-TBNA (followed by surgical staging only if these tests were negative) had higher sensitivity (94% vs 79%) and negative predicted probability (93% vs 86%) than surgical staging alone, and resulted in a lower rate of unnecessary thoracotomy (7% vs 18%). Other benefits of endosonography include less invasive testing, with no requirement for general anaesthesia or open surgery, and the small number of minor complications (1%).

Chapter 4 Survival and health-related quality of life

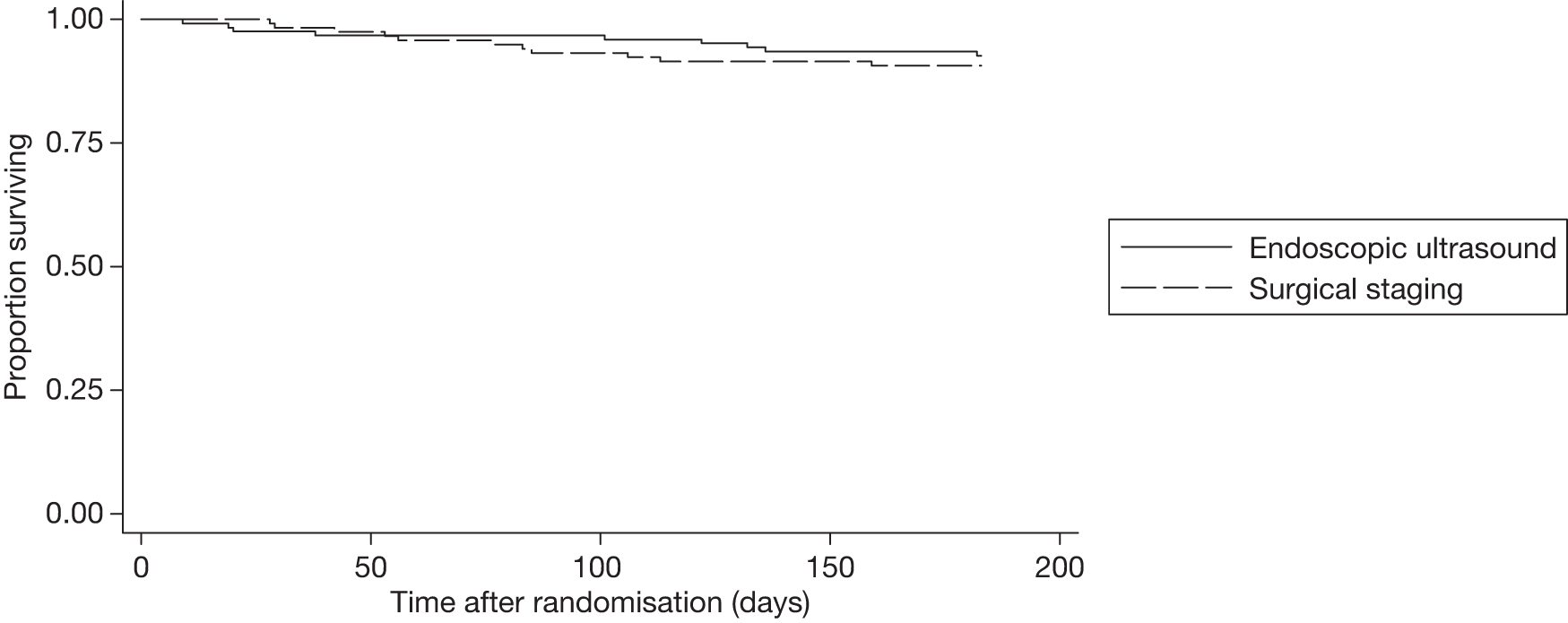

Patients were followed up for survival for 6 months after staging, during which period there were 20 deaths: nine in the endosonography strategy group and 11 in the surgical staging group. Kaplan–Meier estimates in Figure 3 show no difference in survival rates over the 6-month period (log-rank test, p = 0.57).

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival estimates for time (in days) to death.

Compliance

Of the 241 patients randomised into the study, 144 (60%) randomised after April 2008 were asked to complete the EQ-5D questionnaire at baseline, at the end of staging and 2 months and 6 months post-randomisation. All 144 patients completed the questionnaire at baseline. At end of staging and 2 months and 6 months post-randomisation, 139 (97%), 132 (92%) and 124 (86%) patients, respectively, completed the questionnaires. This gave a total of 539 completed questionnaires.

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions

Of the 539 completed questionnaires, one or more of the dimensions of the EQ-5D was missing in six (1.1%). The missing values were imputed using a single imputation based on an ordinal logistic regression model, including the five dimensions of the EQ-5D.

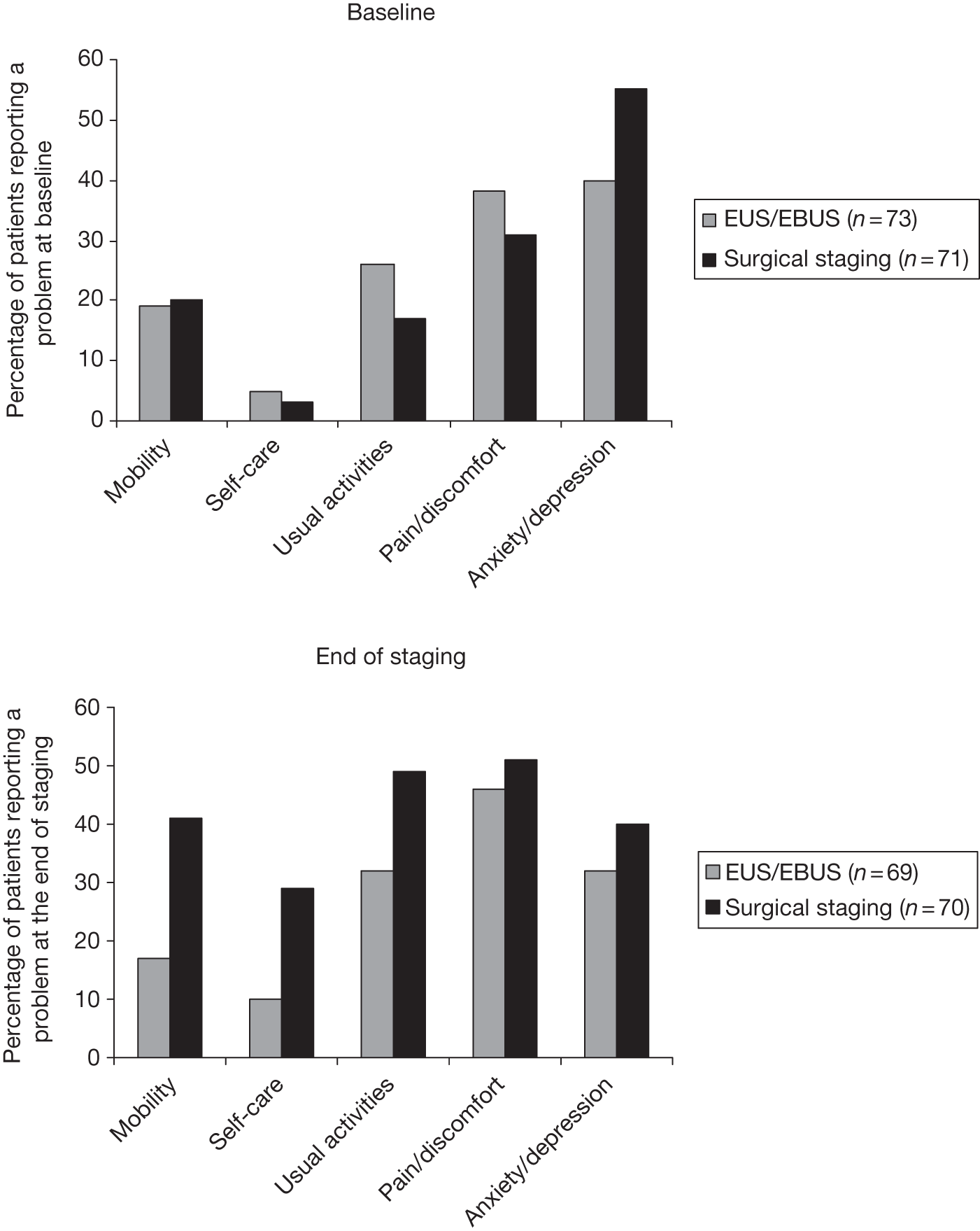

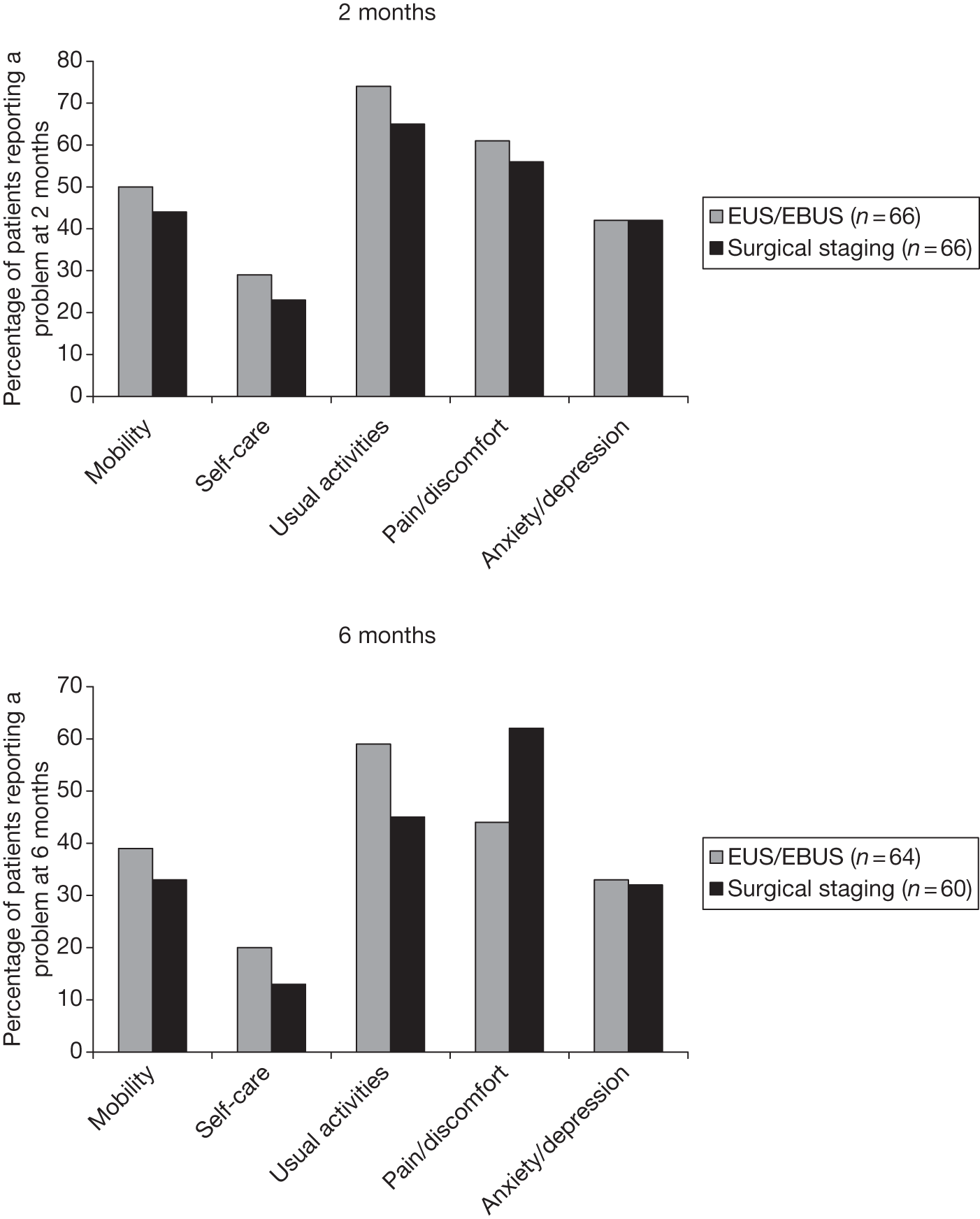

Figure 4 shows the percentage of patients reporting a problem in each dimension (i.e. those patients indicating some/moderate or extreme problems – score 2 or 3). At baseline, anxiety/depression was the most common problem in both groups, and the surgical group had approximately 15% more patients experiencing these symptoms. In all other dimensions, there was a < 10% difference between the groups. At the end of staging (for the endosonography group after surgical staging if the EBUS/EUS was negative or after the EBUS/EUS if it was positive), the surgical group reported more problems in every dimension than the endoscopic group. This was particularly noticeable in the mobility dimension, for which > 20% more patients in the surgical group reported problems. By 2 months the situation was reversed, with those in the endoscopic group faring worse in each dimension, although the differences were < 10%. At 6 months, the endoscopic group reported slightly more problems with usual activities, whereas the surgical group reported more problems with pain/discomfort. The other dimensions were similar between the groups.

FIGURE 4.

Percentage of patients reporting at least some problems on the EQ-5D dimensions. a, Baseline; b, end of staging; c, 2 months; d, 6 months.

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions utility

The mean (SD) of the EQ-5D utility, by group, at each stage is summarised in Table 9. The values shown are for the nominal time points of baseline, end of staging, and 2 months and 6 months post-randomisation, not the actual dates that the questionnaires were collected. Therefore, there may be some inaccuracies in these estimates if, for example, the surgical staging group completed the end of staging questionnaire at a different time to the EUS/EBUS strategy group. Furthermore, this analysis includes only patients for whom questionnaires were completed. It does not make any attempt to impute missing EQ-5D information. The average age of patients was 65 years (SD 9 years) in both arms, and both groups had a majority of men (74% for the surgical staging arm vs 80% for endosonography and surgical staging). For a population with similar age and sex characteristics to patients in this study, the average EQ-5D score was 0.78. 32

| Time point | EUS/EBUS | Surgical staging |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n = 73, n = 71) | 0.81 (0.18) | 0.83 (0.14) |

| End of staging (n = 69, n = 70) | 0.77 (0.26) | 0.63 (0.34) |

| 2 months (n = 66, n = 66) | 0.65 (0.26) | 0.70 (0.24) |

| 6 months (n = 64, n = 60) | 0.74 (0.26) | 0.75 (0.22) |

At baseline, the groups were very similar with values slightly above the population average. However, by the end of staging, the average value for the surgical staging group had decreased by 0.20 compared with only 0.04 for the EUS/EBUS group. By 6 months, both groups were again similar but now slightly lower than the population average values.

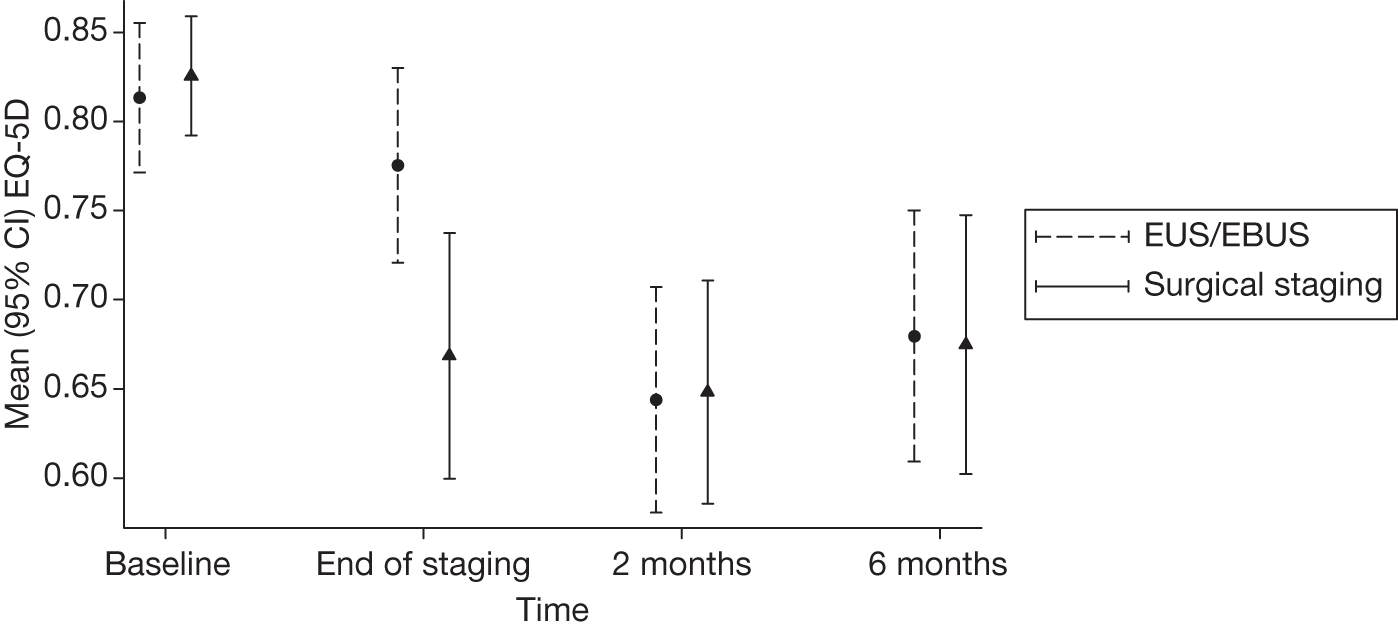

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions index at specified time points

Table 10 and Figure 5 show the estimated mean (SD) EQ-5D utility at days 0, 7, 61 and 183 after randomisation for all patients. This allows for a more accurate comparison between groups. There are 73 and 71 patients in the endosonography (followed by surgical staging if negative) group and surgical staging groups, respectively. All patients who completed a questionnaire at baseline had an EQ-5D calculated at each subsequent time point, with zero utility representing death. When compared with Table 9, the average value for the surgical staging group at the end of staging decreased from baseline to a similar extent. By 6 months, the average value had decreased from baseline by 0.13 and 0.16 for the EUS/EBUS and surgical staging groups, respectively.

| Time point | EUS/EBUS (n = 73) | Surgical staging (n = 71) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline (day 0) | 0.81 (0.18) | 0.83 (0.14) |

| End of staging (day 7) | 0.78 (0.23) | 0.67 (0.29) |

| 2 months (day 61) | 0.64 (0.27) | 0.65 (0.26) |

| 6 months (day 183) | 0.68 (0.30) | 0.67 (0.31) |

FIGURE 5.

Mean (95% CI) EQ-5D utility at each time point in each group.

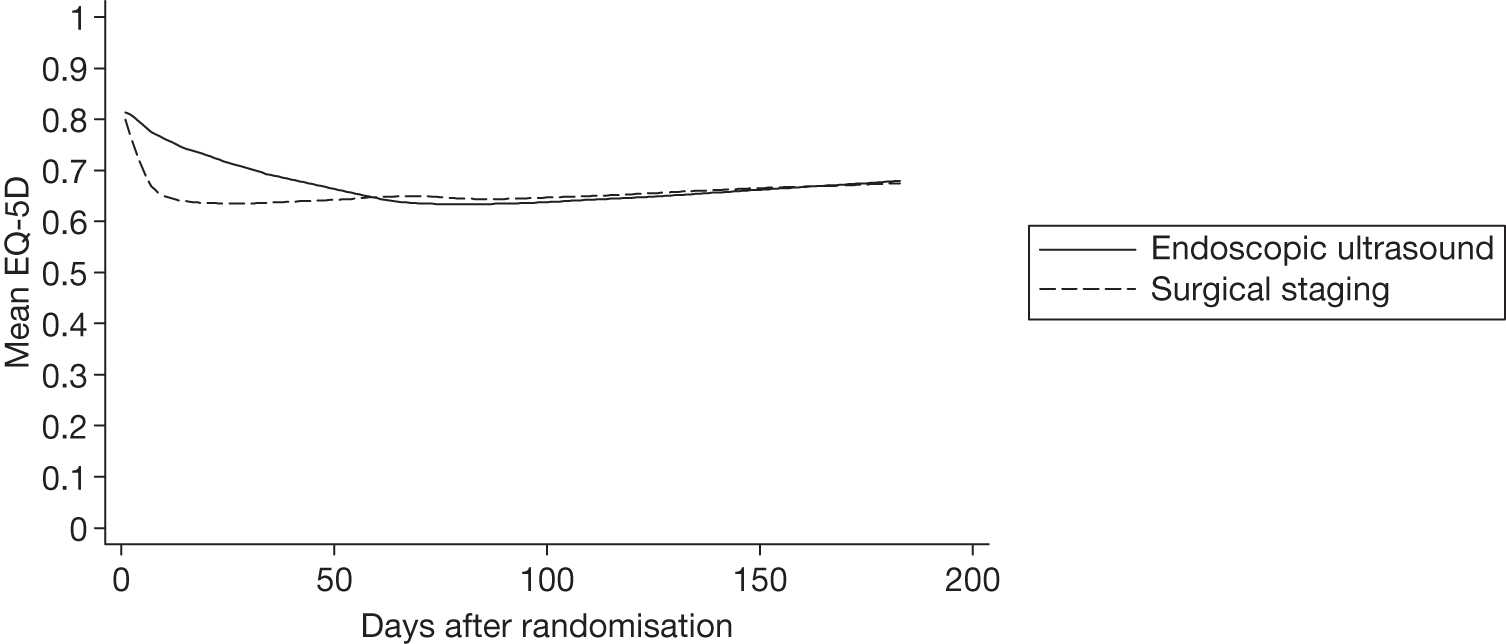

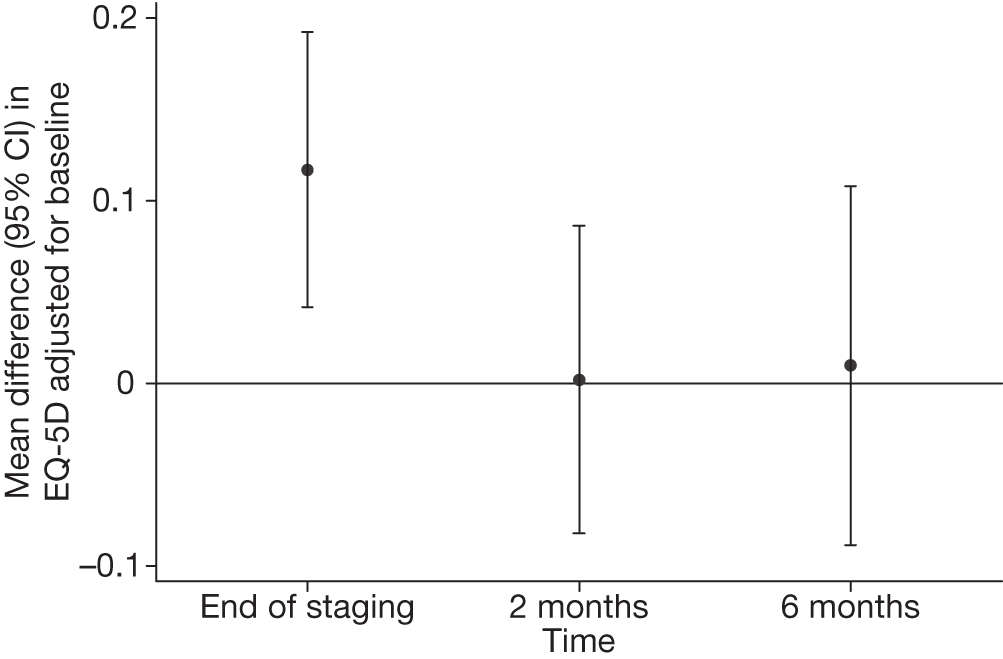

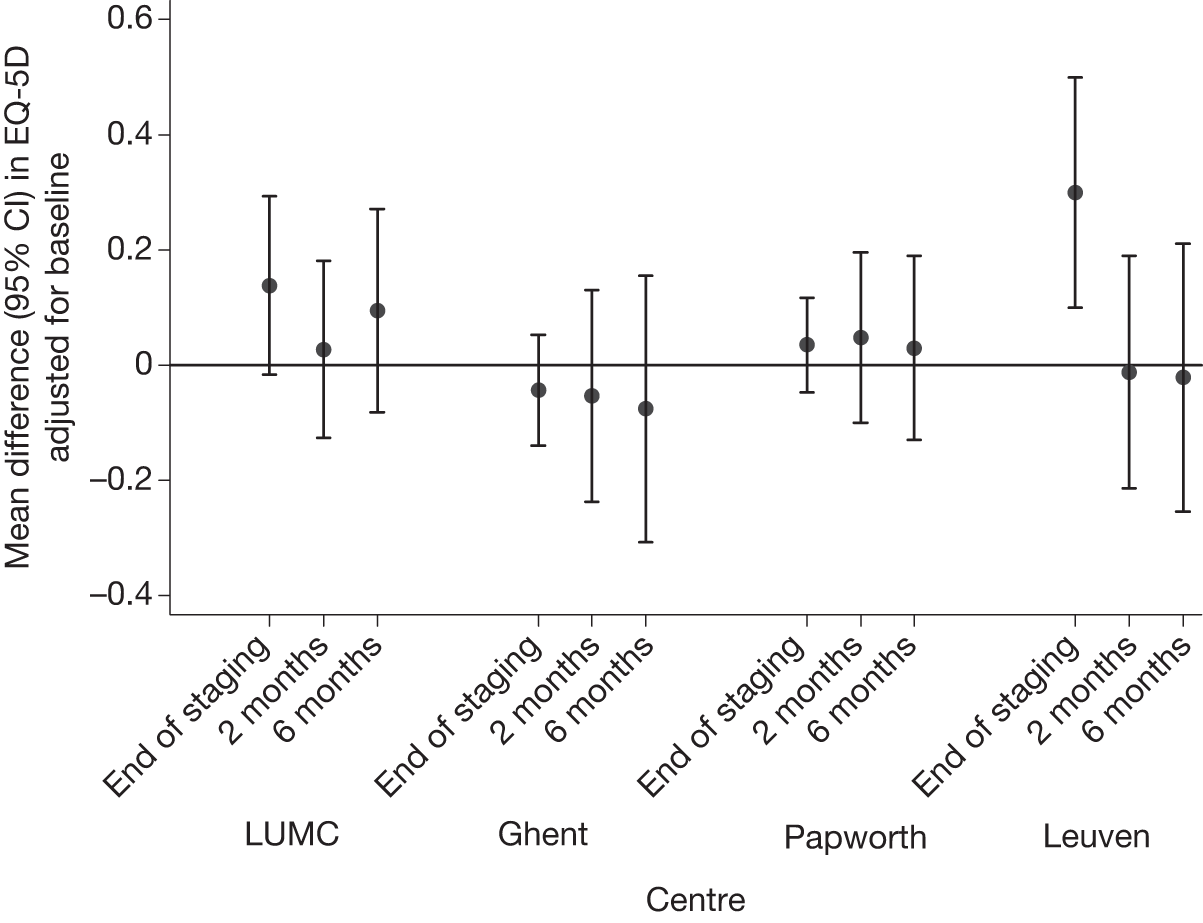

Table 11 shows the difference in EQ-5D between surgical staging and EUS/EBUS groups, both unadjusted and adjusted for baseline. In both analyses, there was a statistically significant difference between the groups at the end of staging, with those patients randomised to EUS/EBUS having a higher utility than those in the surgical staging group. However, at the other time points, there was little difference between the groups (Figure 6).

| Time point | Difference between EUS/EBUS and surgical staging (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | ||

| End of staging | 0.107 (0.020 to 0.194) | 0.02 |

| 2 months | –0.004 (–0.092 to 0.084) | 0.92 |

| 6 months | 0.005 (–0.096 to 0.105) | 0.92 |

| Adjusted for baseline | ||

| End of staging | 0.117 (0.042 to 0.192) | 0.003 |

| 2 months | 0.002 (–0.082 to 0.086) | 0.96 |

| 6 months | 0.010 (–0.089 to 0.108) | 0.84 |

FIGURE 6.

Mean EQ-5D utility by day after randomisation.

Figure 7 shows the mean difference (95% CI) in EQ-5D values between surgical staging and EUS/EBUS groups adjusted for baseline. This highlights the statistically significant difference between the groups at the end of staging (p = 0.003) when surgical staging patients had a worse quality of life than EUS/EBUS patients.

FIGURE 7.

Difference in mean EQ-5D (95% CI) between EUS/EBUS (followed by surgical staging if negative) and surgical staging alone, adjusted for baseline. Values > 0 favour the EUS/EBUS group.

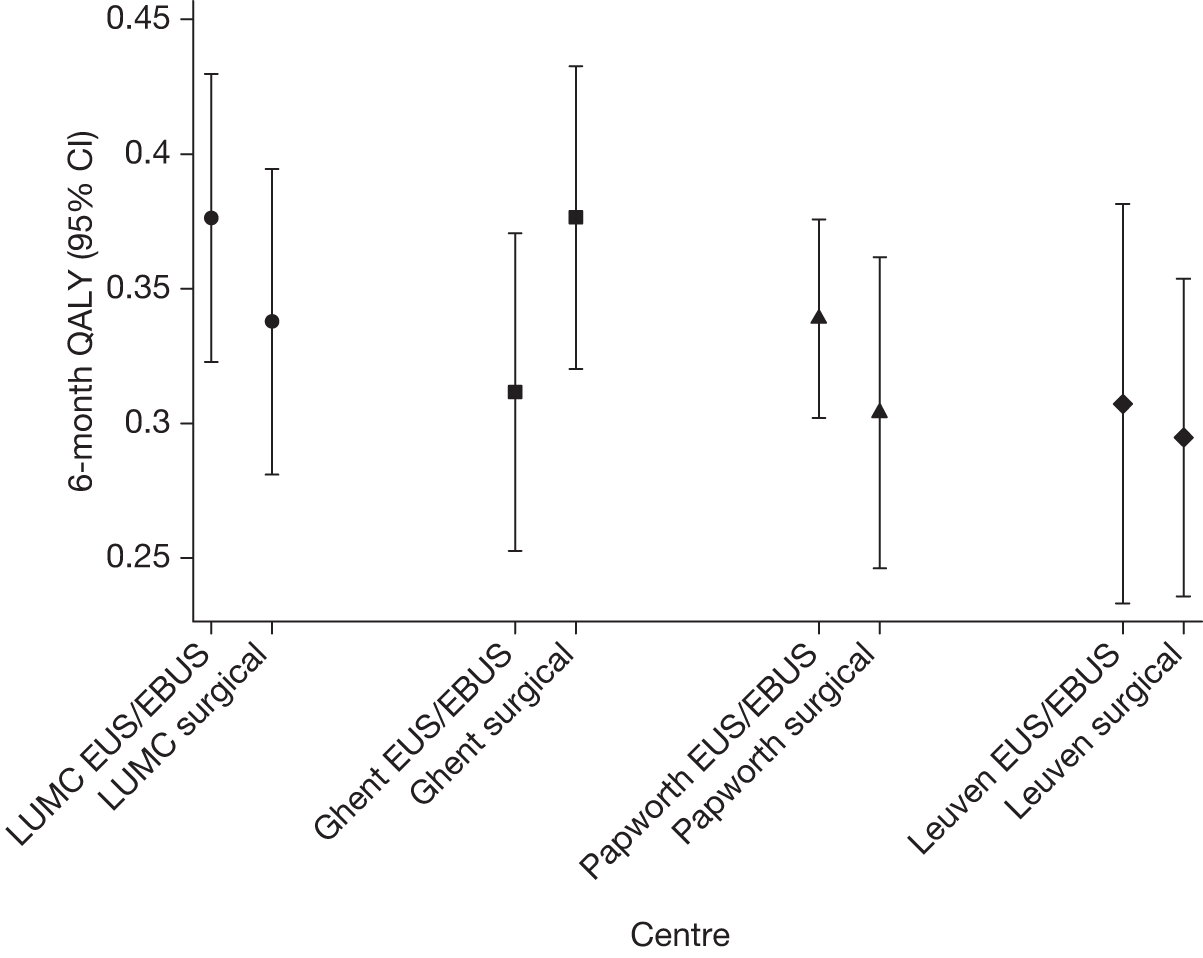

Quality-adjusted life-year results by randomisation group

Table 12 shows that the mean (SD) 6-month QALY gain was very similar in the two randomisation groups. Once adjusted for baseline EQ-5D utility, the surgical staging group had a mean QALY gain that was 0.011 less than that of the EUS/EBUS group. The difference was not clinically or statistically significant (p = 0.55; Table 13).

| Measurement | EUS/EBUS (n = 73) | Surgical staging (n = 71) |

|---|---|---|

| 6-month QALY | 0.34 (0.12) | 0.33 (0.12) |

| Analysis | Mean (95% CI) difference in QALY between surgical staging and EUS | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | 0.008 (–0.032 to 0.047) | 0.70 |

| Adjusted for baseline EQ-5D | 0.011 (–0.026 to 0.048) | 0.55 |

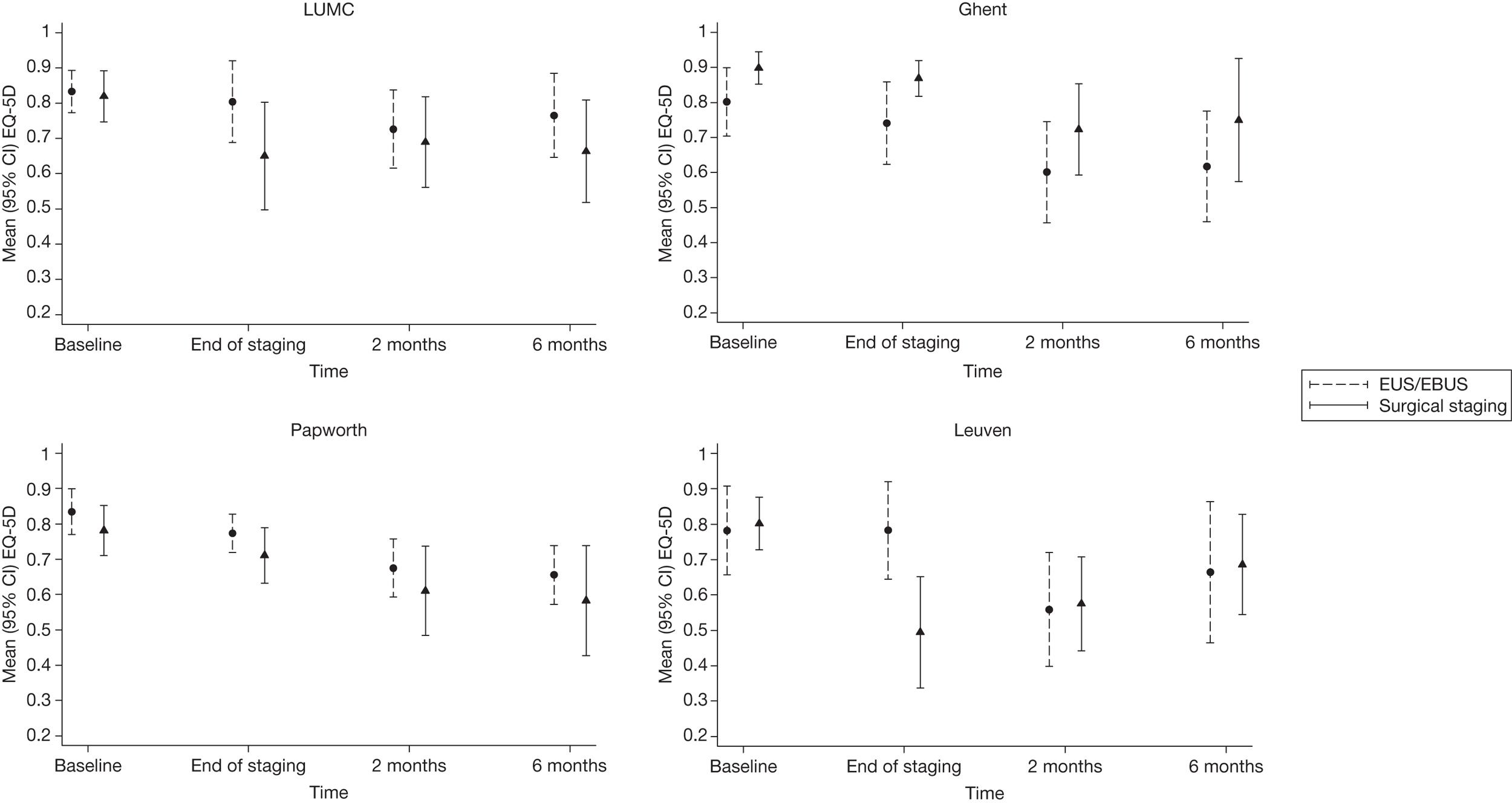

Comparison of European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions and quality-adjusted life-year between centres

There were some differences in the EQ-5D scores between the centres (see Appendix 3). In all centres except Ghent, EQ-5D values at the end of staging were lower in patients undergoing surgical staging than in those who had been allocated to EUS/EBUS. This was particularly apparent at Leuven, where the difference in average values was almost 0.30. By 6 months, EUS/EBUS patients from LUMC and Papworth were doing slightly better, on average, than the surgical patients, whereas the opposite was the case in Ghent and Leuven. However, this was an unadjusted analysis and simply reflects the fact that, at LUMC and Papworth, baseline EQ-5D scores were slightly higher in EUS/EBUS patients than in surgical patients, whereas in Ghent and Leuven baseline EQ-5D scores were slightly better in the surgical staging group than the EUS/EBUS group. The number of patients in each randomisation group, in each centre, was small so that these differences were consistent with between-centre variation. There were no significant differences in QALY gains between the surgical staging and the EUS/EBUS staging strategy in any of the centres. Details for each centre are given in Appendix 3.

Summary

The survival and quality-of-life components of this RCT show that a strategy of using combined EUS–FNA and EBUS-TBNA (followed by surgical staging only if these tests are negative) has no significant impact on survival to 6 months after randomisation and is only slightly more effective, with an increase in QALYs (over 6 months) of 0.011 (95% CI –0.026 to 0.048). However, we found that patients undergoing the endosonography staging strategy (including surgical staging if negative EUS/EBUS) had better quality of life at the end of staging than those who underwent surgical staging alone (mean difference 0.117; 95% CI 0.042 to 0.192). At all other time points, quality of life was similar in the two groups.

Chapter 5 Economic evaluation

A cost–utility analysis of surgical staging alone compared with EUS/EBUS and surgical staging (if the former was negative) from a health service perspective was undertaken. The time horizon was 6 months post-randomisation and all costs were reported in 2008–9 prices (£).

In terms of resource use, all patients followed the protocol for their group with the following exceptions:

-

One patient randomised to surgical staging did not have the procedure because of bone metastases.

-

Three patients randomised to surgical staging had a negative surgical mediastinoscopy staging, but refused thoracotomy.

-

In one patient randomised to surgical staging mediastinoscopy was negative, but because of rapid clinical deterioration the patient did not undergo thoracotomy.

-

One patient randomised to surgical staging who had a negative mediastinoscopy underwent endosonography rather than having a thoracotomy.

-

One patient in the EUS/EBUS group who had negative surgical staging underwent a second endosonography instead of having a thoracotomy.

-

Two patients in the EUS/EBUS group underwent additional surgical staging off protocol.

In addition, where both thoracotomy and surgical resection were recorded within 2 months of randomisation, this was assumed to be the same procedure unless there was evidence to the contrary.

Cost breakdowns for patients who had complete information on each resource item

The number and percentage of patients in each group using each resource item is shown in Table 14. Aside from the initial procedure (EUS/EBUS followed by surgical staging if negative, or surgical staging alone), the main difference in resource use was in the number of thoracotomies, 57 out of 87 (66%) patients in the surgical staging group compared with 45 out of 85 (53%) in the endosonography strategy group. Resource use was similar between the groups in all other items.

| Resource item | No. of patients using each resource item (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| EUS/EBUS (n = 85) | Surgical staging (n = 87) | |

| EUS/EBUS procedure | 85 (100) | 1 (1) |

| Surgical staging procedure | 47 (55) | 86 (99) |

| Thoracotomy (lobectomy or pneumonectomy) with lymph node dissection | 45 (53) | 57 (66) |

| Chemotherapy in the first 2 months | 43 (51) | 39 (45) |

| Radiotherapy in the first 2 months | 10 (12) | 9 (10) |

| Hospital admission in the first 2 months | 18 (21) | 19 (22) |

| Hospice admission in the first 2 months | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Surgery between months 2 and 6 | 7 (8) | 9 (10) |

| Chemotherapy between months 2 and 6 | 40 (47) | 43 (49) |

| Radiotherapy between months 2 and 6 | 32 (38) | 27 (31) |

| Hospital admission between months 2 and 6 | 28 (33) | 25 (29) |

| Hospice admission between months 2 and 6 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

The total mean costs for each resource item are presented in Table 15 for those patients who had complete information on all resource items. This includes 85 out of 123 (69%) in the endosonography arm and 87 out of 118 (74%) in the surgical staging arm.

| Resource item | Mean cost per patient (£) | Difference (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EUS/EBUS (n = 85) | Surgical staging (n = 87)a | ||

| EUS/EBUS procedureb | 1254 | 14 | 1240 (1211 to 1268) |

| Surgical staging procedurec | 1712 | 3058 | –1346 (–1682 to –1010) |

| Thoracotomy (lobectomy or pneumonectomy) with lymph node dissectiond | 3543 | 4292 | –749 (–1737 to 239) |

| Total chemotherapy cost in the first 2 months | 528 | 401 | 127 (–35 to 288) |

| Total radiotherapy cost in the first 2 months | 225 | 292 | –68 (–318 to 183) |

| Total hospital admission costs in the first 2 months | 450 | 464 | –14 (–279 to 250) |

| Hospice admission in the first 2 months | 0 | 0 | 0 (0 to 0) |

| Surgery between months 2 and 6 | 339 | 426 | –87 (–449 to 275) |

| Total chemotherapy cost between months 2 and 6 | 493 | 574 | –80 (–289 to 128) |

| Total radiotherapy cost between months 2 and 6 | 1082 | 884 | 198 (–249 to 645) |

| Total hospital admission costs between months 2 and 6 | 766 | 747 | 19 (–436 to 473) |

| Hospice admission between months 2 and 6 | 97 | 0 | 9 (–9 to 28) |

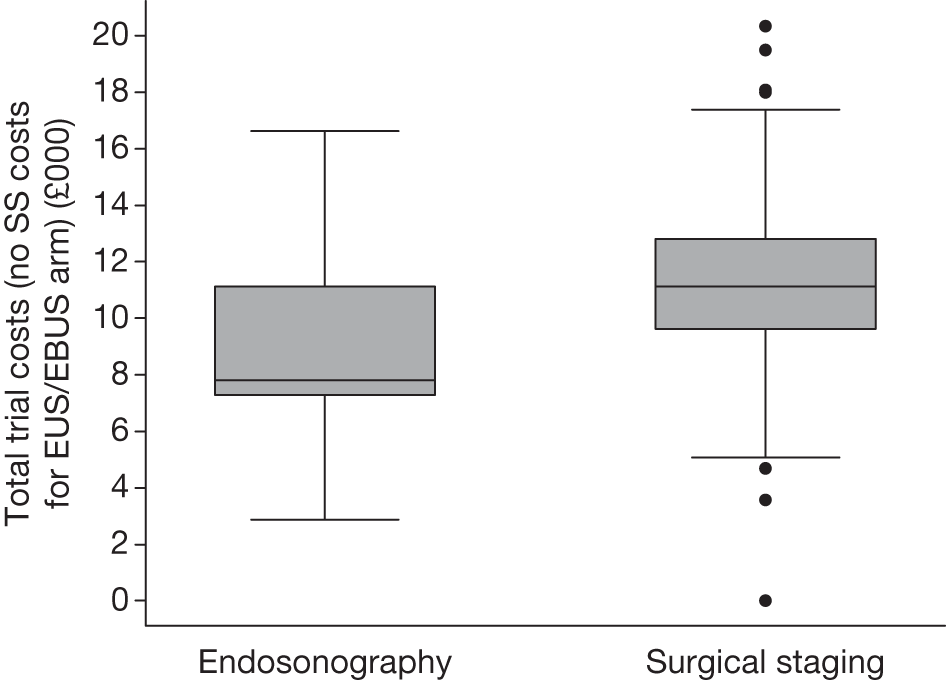

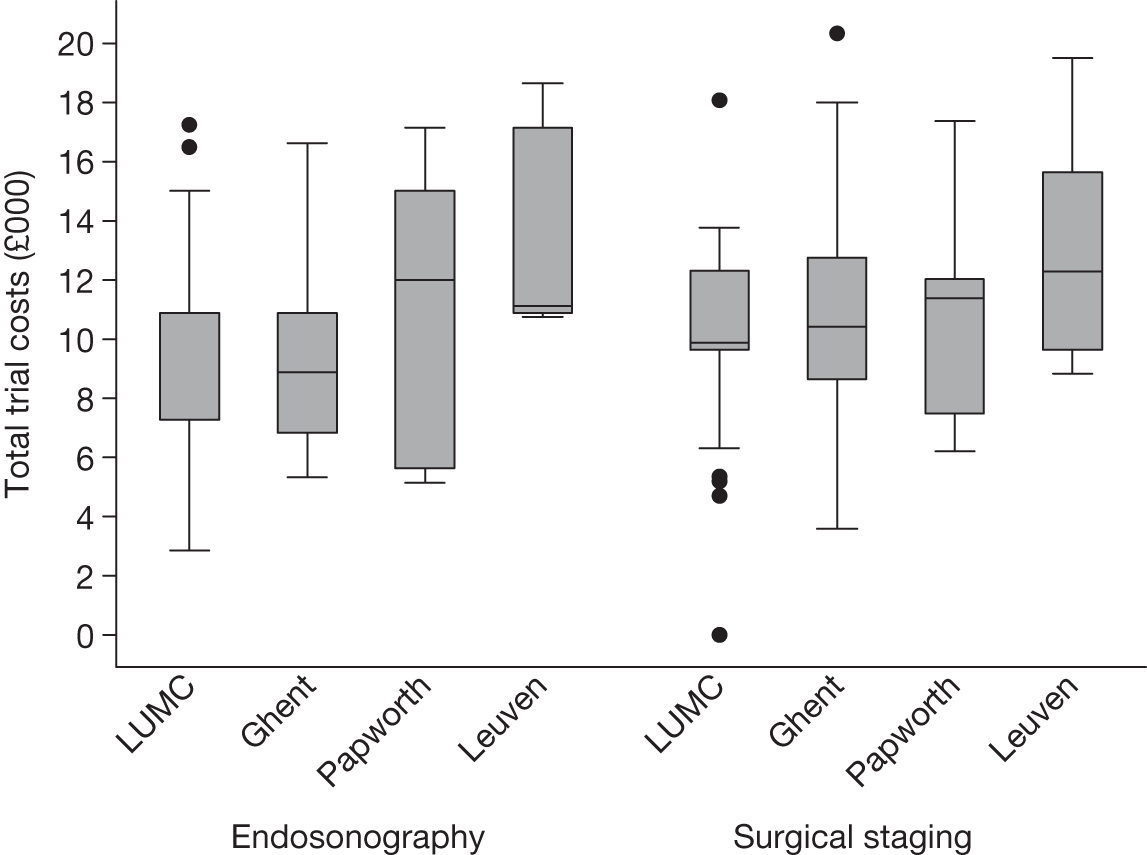

Total trial costs for patients who had complete information on each resource item

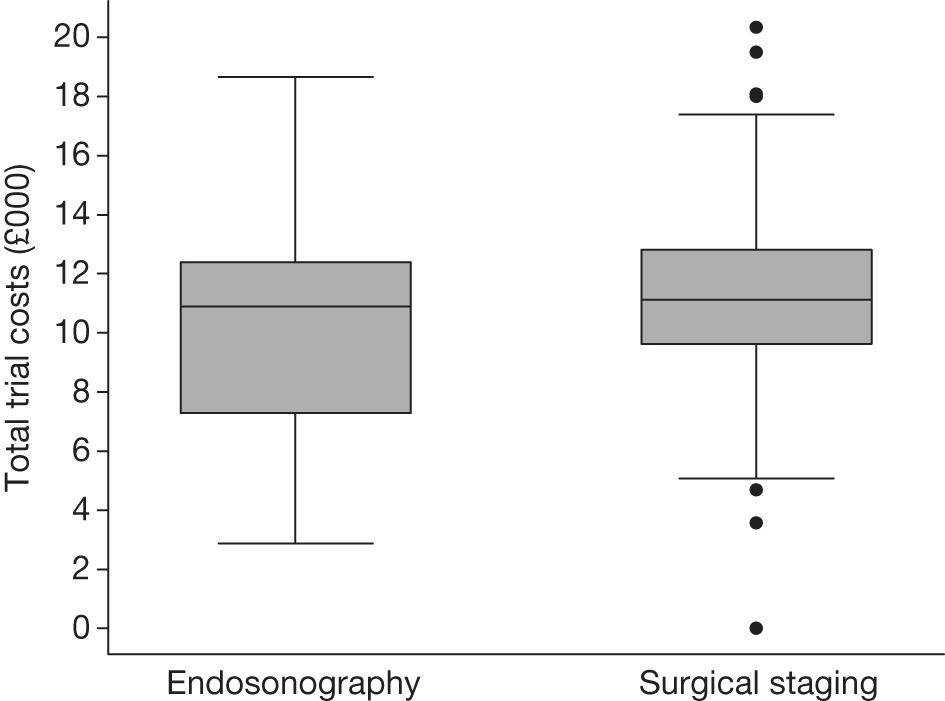

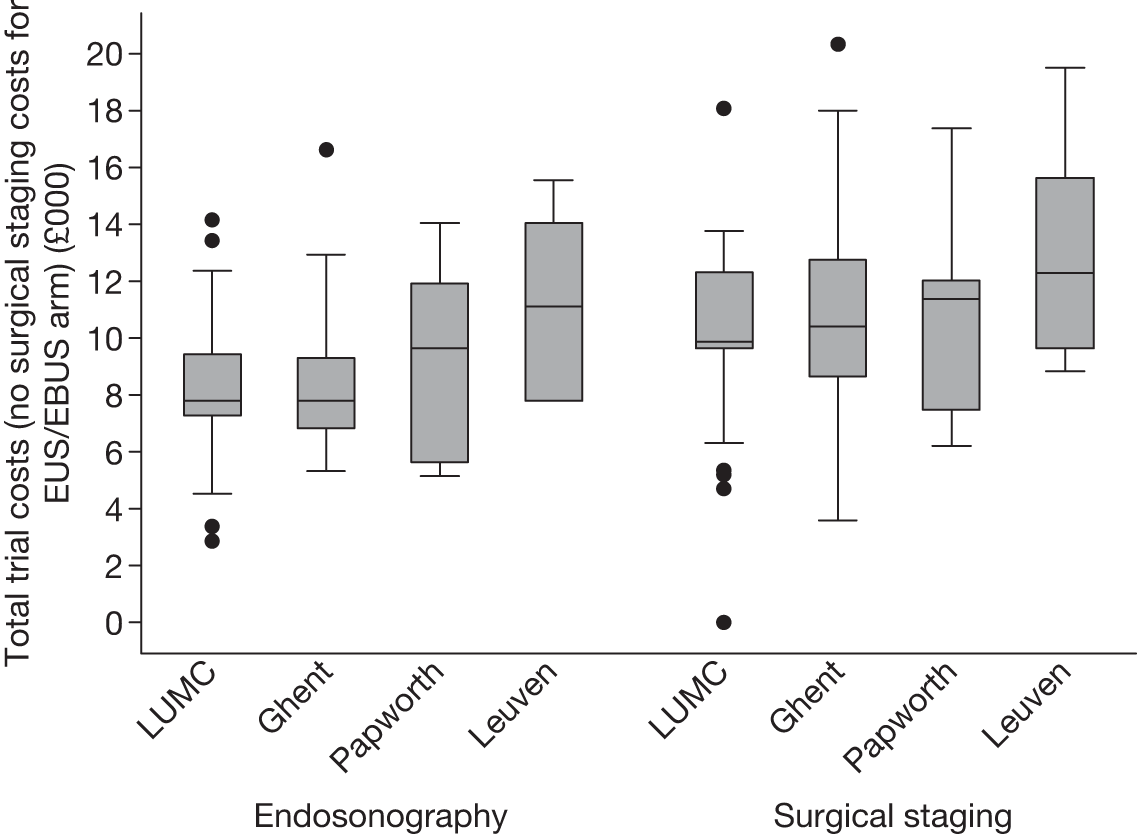

The total mean (SD) and median (IQR) trial costs are presented in Table 16 and Figure 8 for those patients who had complete information on all resource items.

| Randomisation group | Mean (SD) total cost (£) | Median (quartiles) total cost (£) |

|---|---|---|

| EUS/EBUS (n = 85) | 10,402 (3639) | 10,887 (7279 to 12,384) |

| Surgical staging (n = 87) | 11,154 (3567) | 11,130 (9633 to 12,801) |

FIGURE 8.

Box plot of total trial costs for patients who had complete information on all resource items: endosonography, n = 85; surgical staging, n = 87.

Cost–utility for completers (patients who have both complete costs and a quality-adjusted life-year estimate)

Both complete cost and QALY information was available for 58 out of 123 (47%) patients in the endosonography (followed by surgical staging if negative) group and 56 out of 118 (47%) in the surgical staging group.

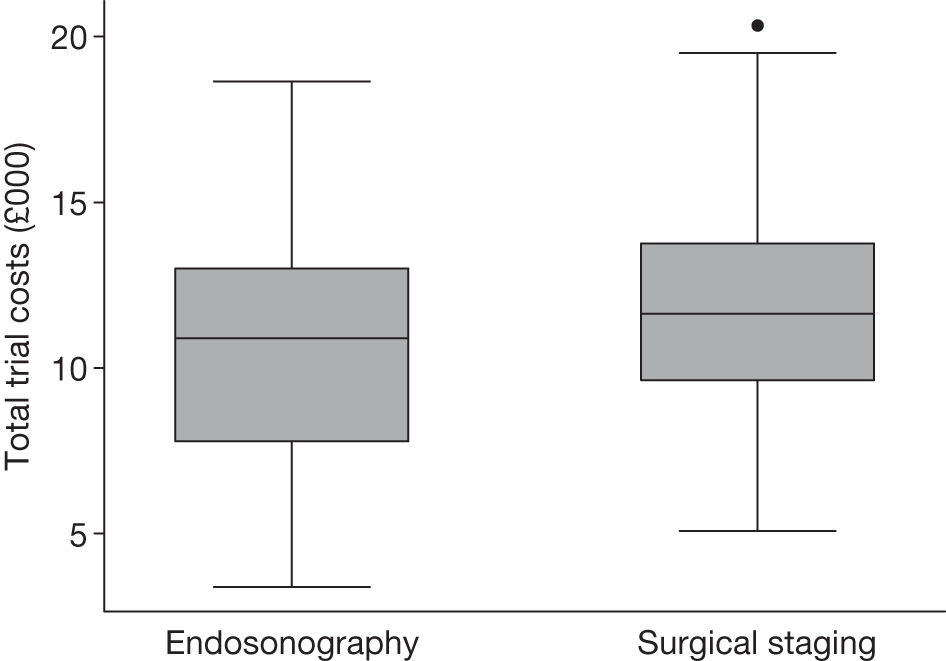

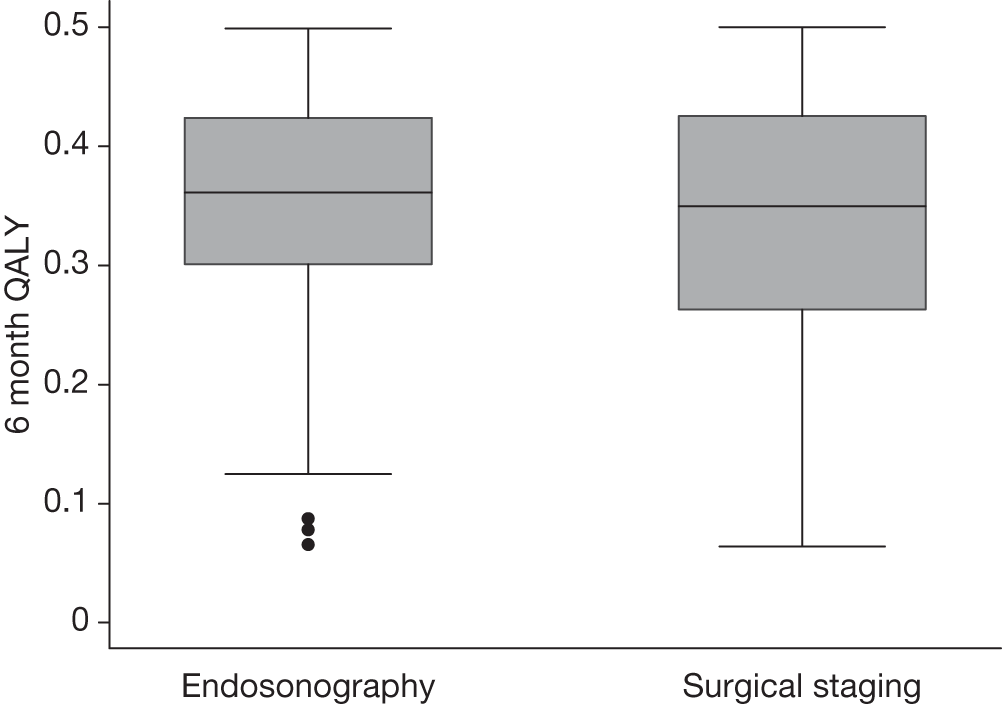

Table 17 and Figure 9 show summaries of total costs for these patients. Figure 10 shows a box plot for the 6-month QALYs by group.

Endosonography (followed by surgical staging if negative) was cheaper overall than surgical staging (Table 18). However, the CI for the mean difference goes from it being cheaper by £2246 to being £394 more expensive. The difference in QALY between the groups is very close to zero. This would make any estimation of the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) extremely unreliable.

| Randomisation group | Mean (SD) total trial cost (£) | Median (IQR) total trial cost (£) |

|---|---|---|

| EUS/EBUS (n = 58) | 10,808 (3787) | 10,887 (7778 to 13,013) |

| Surgical staging (n = 56) | 11,735 (3477) | 11,629 (9633 to 13,755) |

| Parameter | Mean | Median | SD | 95% CI for mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Costs (£) | ||||

| Endosonography and surgical staging | 10,808 | 10,887 | 3787 | 9843 to 11,764 |

| Surgical staging | 11,735 | 11,629 | 3477 | 10,843 to 12,674 |

| Cost comparisons (£) | ||||

| Endosonography – surgical staging | –927 | 5141 | –2246 to 394 | |

| QALY | ||||

| Endosonography and surgical staging | 0.348 | 0.361 | 0.103 | 0.321 to 0.373 |

| Surgical staging | 0.342 | 0.350 | 0.100 | 0.316 to 0.367 |

| QALY comparisons | ||||

| Endosonography – surgical staging | 0.00652 | 0.143 | –0.0298 to 0.0418 | |

| Cost per QALY gained | ||||

| Endosonography – surgical staging (from sample) | Dominance | |||

| Bootstrapped mean ICER | Dominance | |||

FIGURE 9.

Total trial costs for patients who had both complete cost and QALY information: endosonography, n = 58; surgical staging, n = 56.

FIGURE 10.

Six-month QALY for patients who had both complete cost and QALY information: endosonography, n = 58; surgical staging, n = 56.

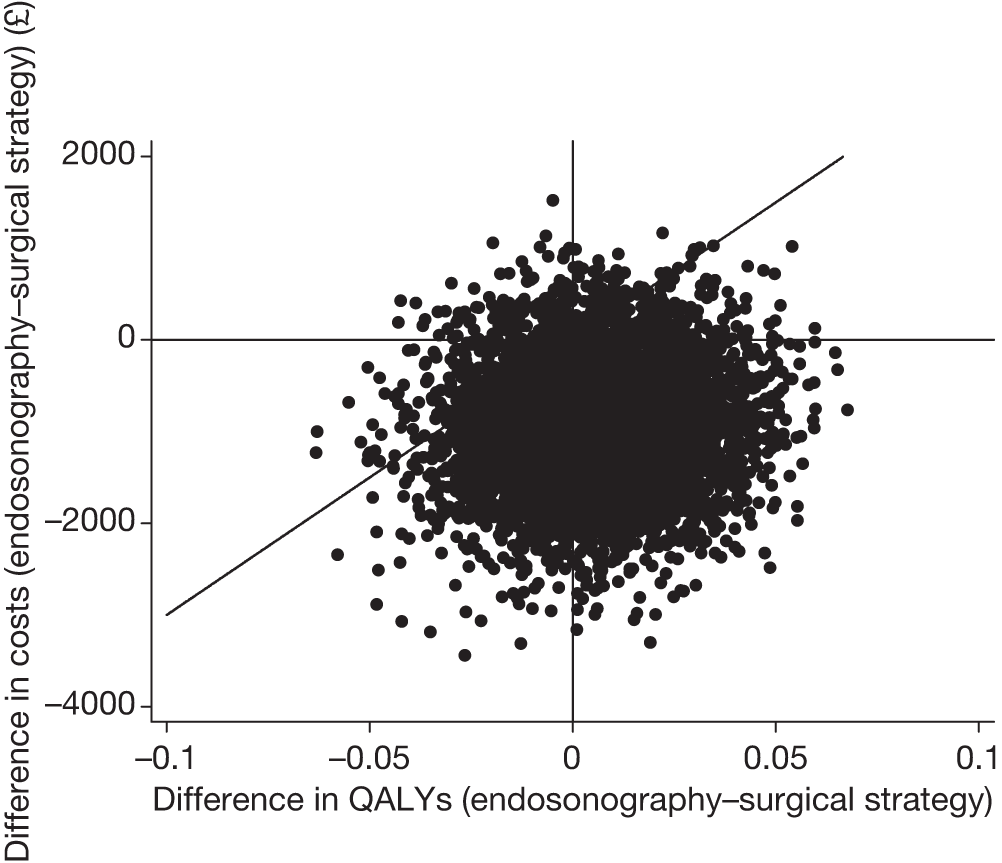

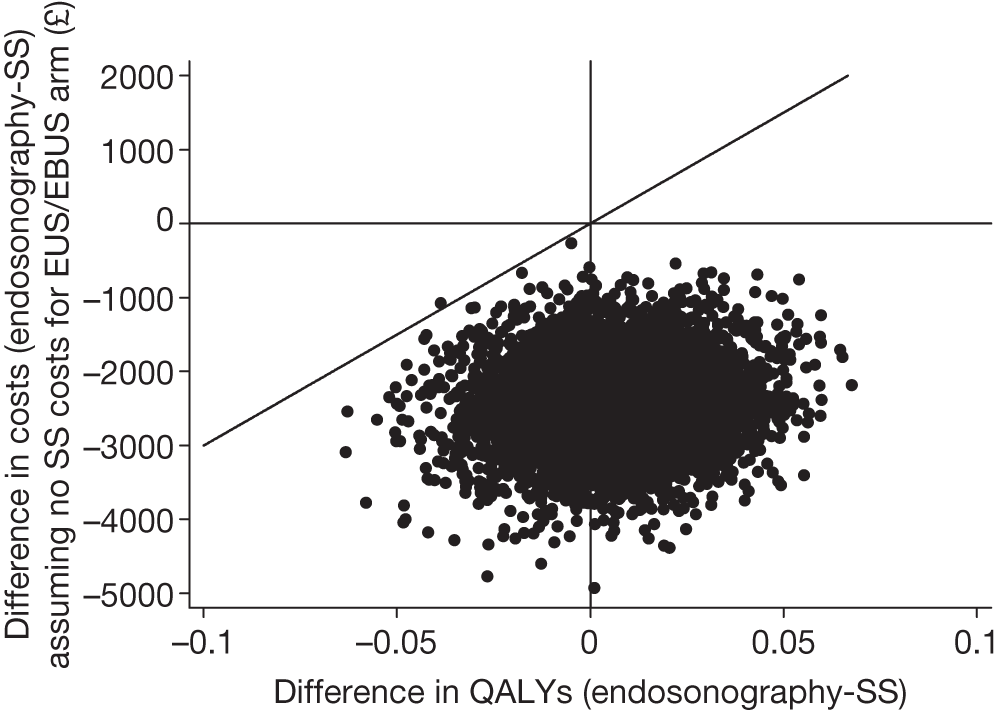

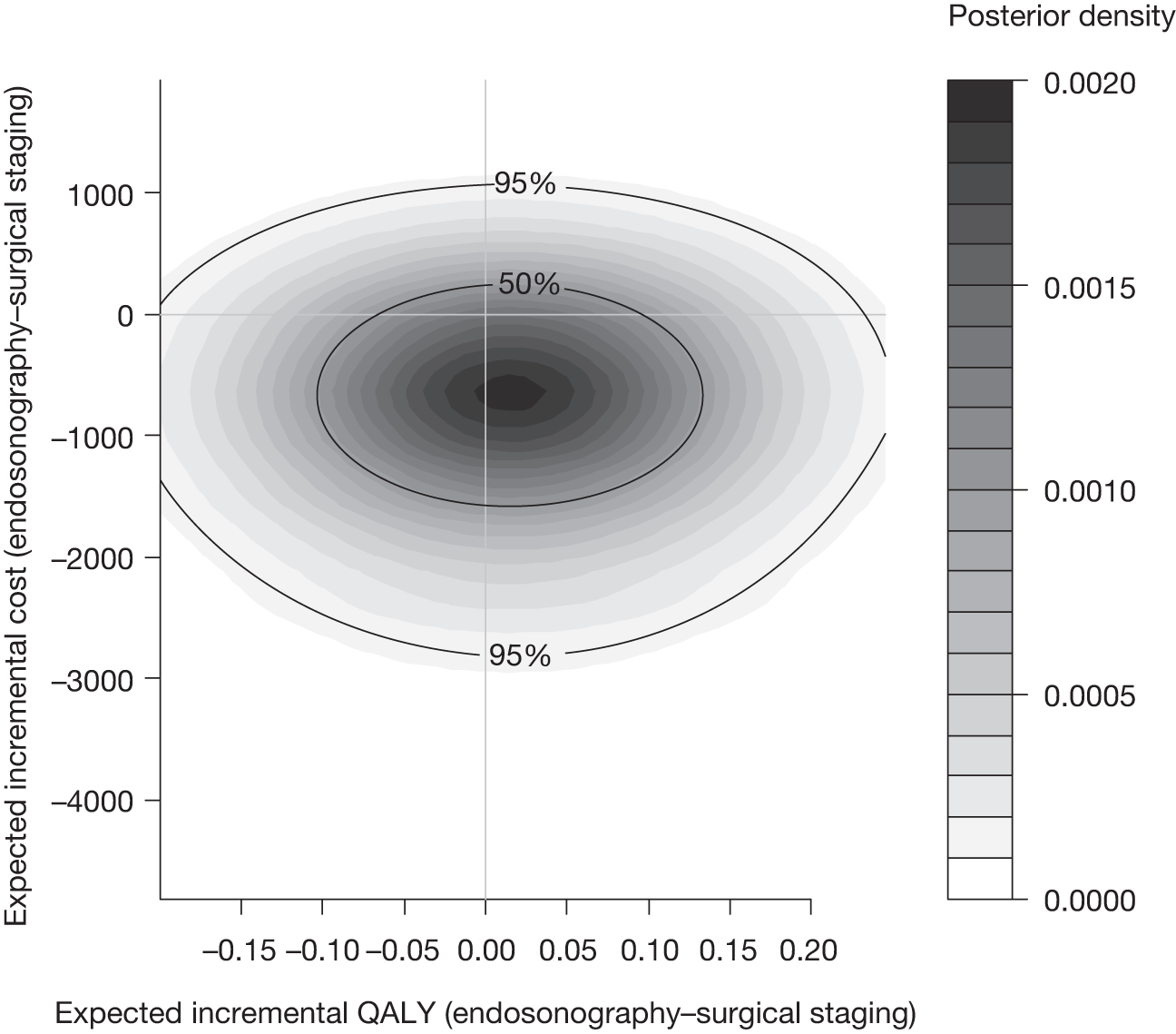

Figure 11 shows 5000 bootstrapped estimates of the cost and QALY differences: 2917 out of 5000 (58%) points show that endosonography, followed by mediastinoscopy if negative, is dominant, i.e. less costly and more effective (bottom right-hand quadrant); 1687 out of 5000 (34%) points show that the endosonography strategy is less costly and less effective (bottom left-hand quadrant); 253 out of 5000 (5%) points show that the endosonography strategy is more costly and more effective (top right-hand quadrant); and 143 out of 5000 (3%) points show that the endosonography strategy is dominated, i.e. more costly and less effective (top left-hand quadrant).

FIGURE 11.

Five thousand bootstrapped samples from the joint distribution of the difference in costs (endosonography strategy – surgical staging) and the difference in QALYs. Positive values indicate that endosonography (followed by surgery if negative) costs more and has greater QALYs. The line shows an ICER of £30,000 per QALY.

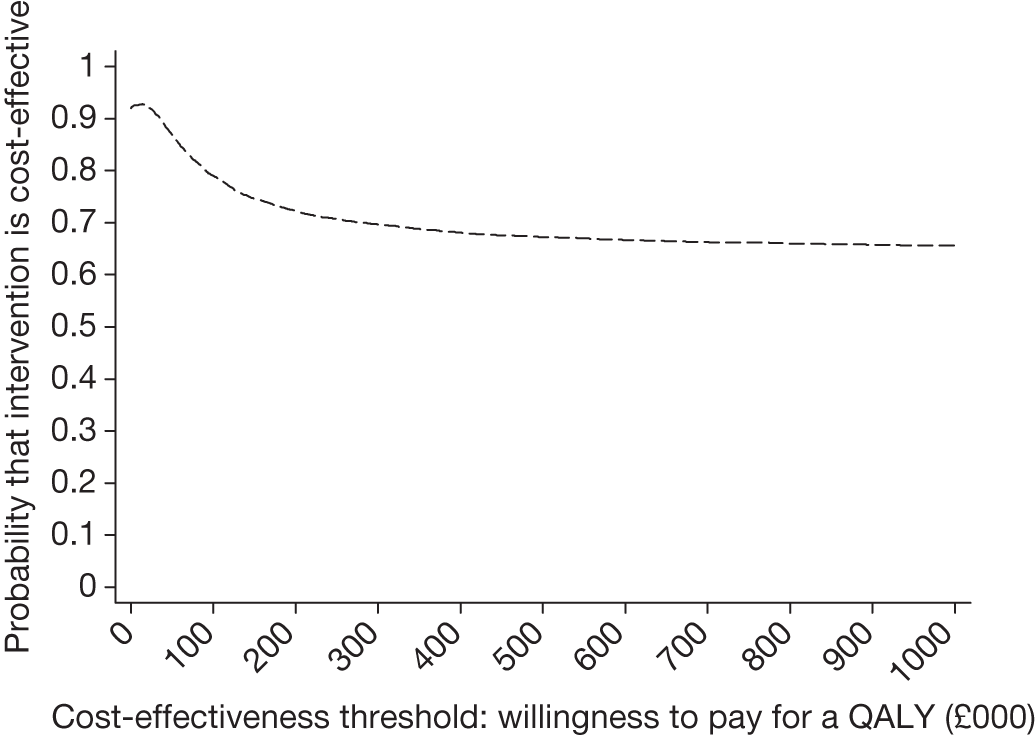

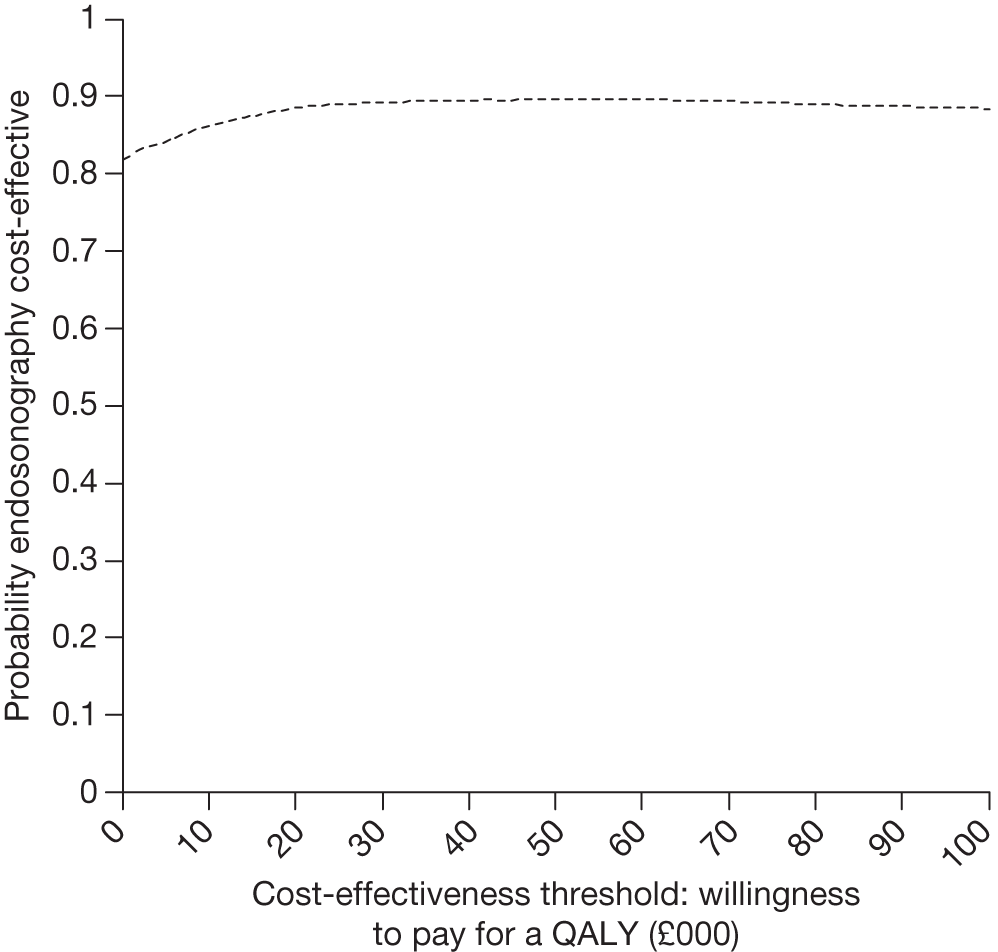

The CEAC for endosonography followed by surgery if negative (Figure 12) crosses the y-axis at 0.92, meaning that 92% of the density involves cost savings. It is a decreasing function of the willingness to pay because not all of the joint density involves health gains, hence the CEAC asymptotes to a value of < 1. At a willingness to pay of £30,000, there is a 91% chance that endosonography strategy compared with surgical staging strategy is cost-effective. The corresponding probability of cost-effectiveness for a willingness to pay of £20,000 is 92%.

FIGURE 12.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve for endosonography (with surgical staging if negative) relative to surgical staging alone, based on completers only (endosonography strategy, n = 58; surgical staging, n = 56).

Deterministic sensitivity analysis

The only a priori defined scenario analysis was used to compare surgical staging with endosonography alone, hence assuming that patients randomised to EUS/EBUS did not incur any surgical staging costs, but would be more likely to have a futile thoracotomy. In the case of patients who underwent EUS/EBUS and surgical staging but not thoracotomy, the mean thoracotomy cost was added to the total trial cost to reflect the fact that EUS/EBUS was negative in these patients and they would have then gone on to receive thoracotomy. The total mean (SD) and median (IQR) trial costs, assuming that the EUS/EBUS patients did not undergo surgical staging, are shown in Table 19 and Figure 13.

| Randomisation group | Mean (SD) total cost (£) | Median (IQR) total cost (£) |

|---|---|---|

| EUS/EBUS (n = 85) | 8922 (2785) | 7805 (7279 to 11,123) |

| Surgical staging (n = 87) | 11,154 (3567) | 11,130 (9633 to 12,801) |

FIGURE 13.

Total costs complete case analysis ignoring the costs of surgical staging and increasing the futile thoracotomy rate for the EUS/EBUS group.

The corresponding cost-effectiveness results (Table 20) show that in this scenario endosonography is £2413 cheaper than surgical staging, and there remains very little difference in mean QALY. Because of the very small QALY difference, the ICER cannot be estimated reliably and the analysis reduces to a cost comparison.

| Parameter | Mean | Median | SD | 95% CI for mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Costs (£) | ||||

| Endosonography alone (n = 58) | 9322 | 7822 | 2958 | 8551 to 10,079 |

| Surgical staging (n = 56) | 11,735 | 11,629 | 3477 | 10,843 to 12,674 |

| Cost comparisons (£) | ||||

| Endosonography – surgical staging | –2413 | 4565 | –3605 to –1271 | |

| QALY | ||||

| Endosonography alone | 0.348 | 0.361 | 0.103 | 0.321 to 0.373 |

| Surgical staging | 0.342 | 0.350 | 0.100 | 0.316 to 0.367 |

| QALY comparisons | ||||

| Endosonography – surgical staging | 0.00652 | 0.143 | –0.0298 to 0.0418 | |

| Cost per QALY gained (£) | ||||

| Endosonography – surgical staging | Dominant | |||

| Mean ICER from bootstrapping | 50,688 | |||

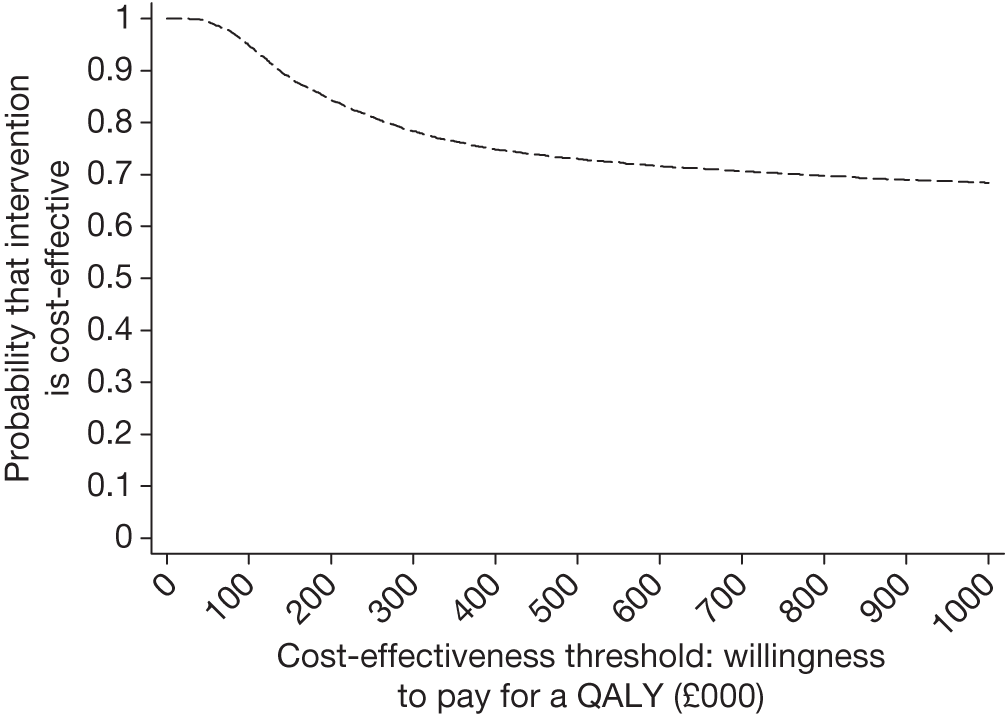

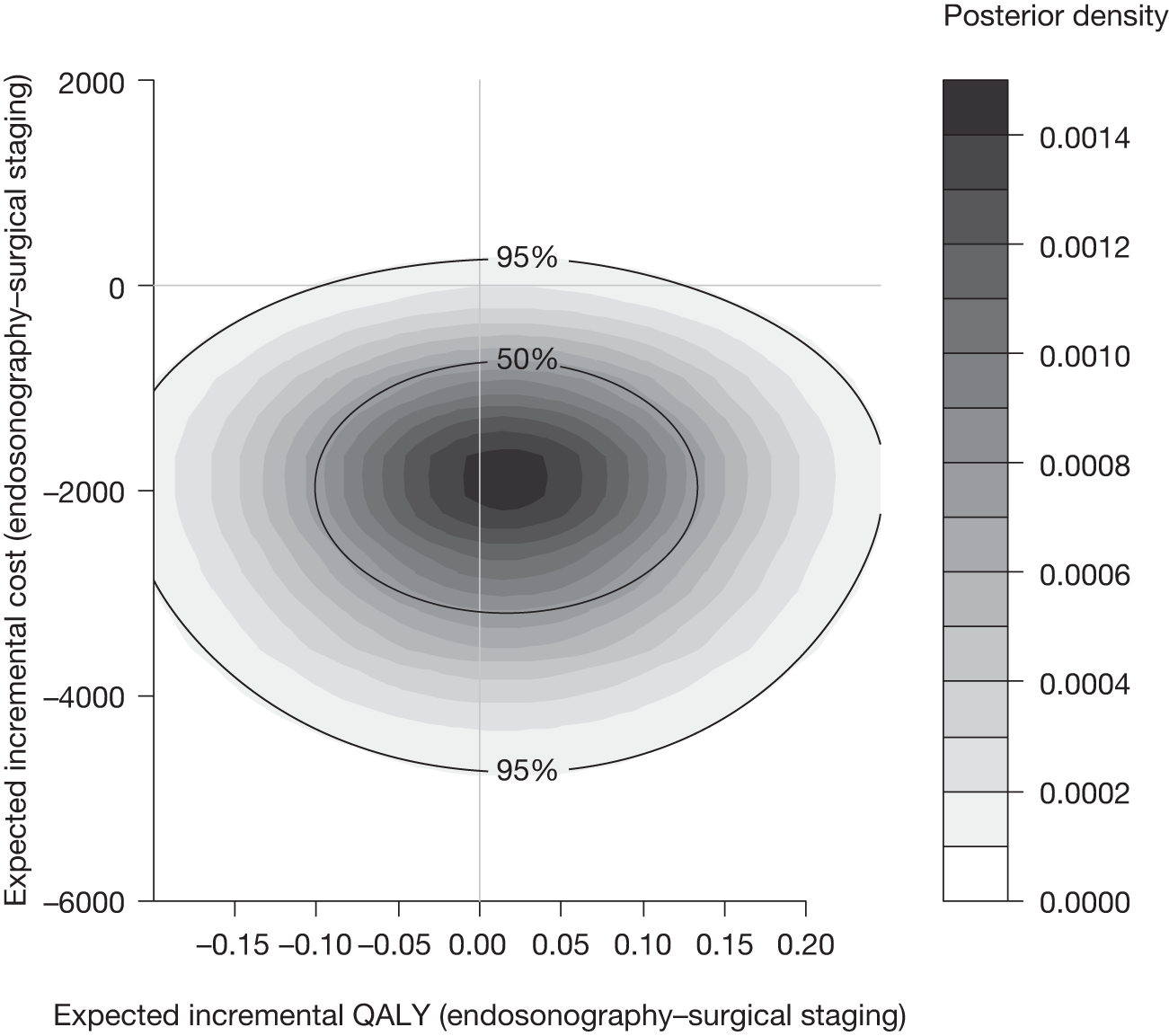

Figure 14 shows the bootstrapped estimates plotted on the cost-effectiveness plane and Figure 15 shows the corresponding CEAC. In the cost-effectiveness plane (see Figure 14), 3170 out of 5000 (63%) of the bootstrapped samples show that endosonography alone is less costly and more effective than surgical staging (bottom right-hand quadrant); 1830 out of 5000 (37%) points show that endosonography is less costly and less effective (bottom left-hand quadrant); and 4999 out of 5000 (99.98%) points are below the £30,000 ICER line.

FIGURE 14.

Five thousand bootstrapped samples from the joint distribution of the difference in costs and the difference in QALY, assuming no surgical staging costs but increased thoracotomy rate for EUS/EBUS patients. Positive values indicate that endosonography costs more and has greater QALYs. The line shows an ICER of £30,000 per QALY.

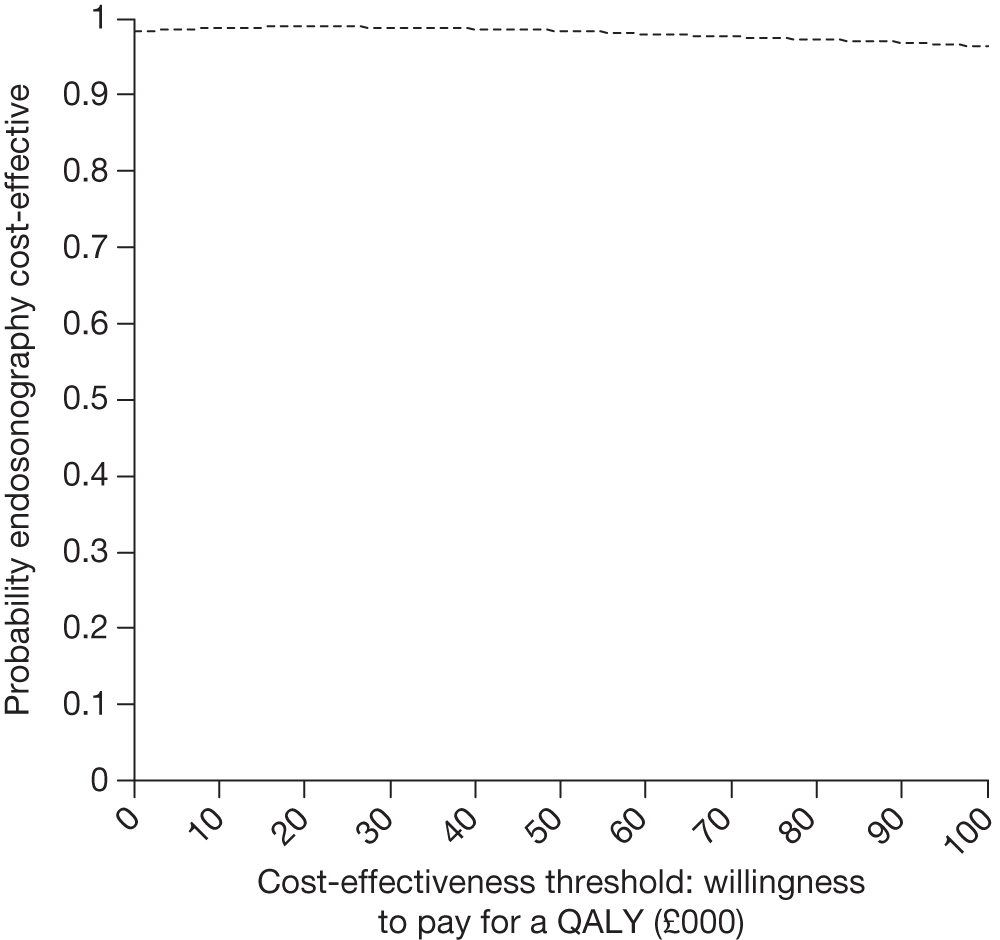

FIGURE 15.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve for complete cases (endosonography, n = 58; surgical staging, n = 56) assuming no surgical staging costs, but increased futile thoracotomy rate for the EUS/EBUS group.

The CEAC (see Figure 15) crosses the y-axis at 1 with a willingness to pay per QALY of £0.00 showing that EUS/EBUS as the sole staging modality will result in cost savings with probability close to 100%.

Comparison of resource use and cost-effectiveness between centres for patients with complete data

There were some differences between the centres in resource use (see Appendix 3). The two Belgian centres were the most different, in that Leuven had the highest percentage (77%) of EUS/EBUS randomised patients going on to have surgical staging, whereas Ghent had the lowest (42%). Leuven also had the highest percentage of EUS/EBUS patients (77%) undergoing thoracotomy compared with Ghent, which had the lowest (39%). The percentage of patients in the surgical staging group undergoing thoracotomy was similar in all centres. Radiotherapy in the first 2 months was used more often in LUMC and Ghent – no patients from Papworth, and only one patient from Leuven, underwent this treatment in the first 2 months. The percentage of patients who required hospital admission was much higher in Leuven (62% in EUS/EBUS and 60% in surgical staging) than in the other centres, where the rate was ≤ 20%. LUMC showed consistently lower rates of chemotherapy, both in the first 2 months and between 2 and 6 months, compared with the other centres. These differences represent the diversity of practice in tertiary centres and the number of patients in each randomisation group, in each centre, was too small to reliably estimate centre-specific results.

Full Bayesian economic analysis

Base-case analysis

Table 21 presents cost-effectiveness of the two strategies using the fully Bayesian model that combines information from all 241 patients, including those with complete data alongside those for whom some or all resource usage or health-related quality of life data were missing. The expected 6-month costs under both strategies were around £1000 less than those that were calculated using the 114 patients with complete data only. Again there was no significant difference in expected cost between the two strategies – the posterior mean expected cost under endosonography (followed by surgical staging if negative) was £746 less than under surgical staging alone, but the 95% credible interval (CrI) for the difference spanned zero. Similarly, expected QALYs were substantively the same between the two strategies, with only a very small increase for the endosonography arm, therefore an ICER for endosonography (followed by surgical staging if positive) would not be meaningful.

| Parameter | Posterior mean | Posterior 95% CrI |

|---|---|---|

| Expected costs (£) | ||

| Endosonography and surgical staging | 9713 | 7209 to 13,307 |