Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 09/142/01. The contractual start date was in January 2011. The draft report began editorial review in July 2011 and was accepted for publication in November 2011. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2012. This work was produced by Tappenden et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2012 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Description of the health problem

In old age, reduction in physical function can lead to loss of independence, the need for hospital and long-term nursing home care, and premature death. The importance of physical, functional, psychological and social factors in realising a healthy old age is recognised by older people,1 health-care professionals,2 policy advisors3 and decision-makers.

As the number of older people increases, the needs of older people are expected to become an increasingly important health issue. It has been estimated that by the year 2025, around 20% of the population in industrial countries will be aged 65 years and over as a consequence of people living longer. Changing family structures and greater mobility in the working population mean that many more older people will be living alone, and social isolation and loneliness are likely to become increasingly widespread. It has been suggested that the number of older people with mental health problems will also grow; estimates suggest that, by the year 2021, more than 1 in every 15 people will be an older person experiencing a mental health problem. 4

The objective of enabling older people to remain in their own homes has been a cornerstone of government policy for several decades. In recent years, considerable emphasis has been placed on health promotion and other preventative measures as a means of delaying the onset of illness and dependency that eventually lead older people to need long-term care. 5

Home-based health promotion programmes for older people, carried out by nurses and other health-care professionals (such as occupational therapists and physiotherapists), have the potential to positively affect health and functional status, and may promote independent functioning of older people. Such programmes may also aim to reduce hospital and nursing/residential home admissions. A substantial number of studies have examined the effects of preventative home-visiting programmes on older people living in the community. Since 2000, 10 systematic reviews of the clinical effectiveness of home- or community-based programmes have been published. 6–15 However, these reviews have reported inconsistent and conflicting results. Subgroup analyses of the largest published meta-analysis suggested that effective home-visiting programmes include multidimensional assessment and numerous follow-up visits and were targeted at individuals who were at lower risk of death. 8 However, none of the existing reviews included an assessment of the cost-effectiveness of home-visiting programmes nor did they limit the analysis to the UK context. This assessment seeks to address these gaps and to explore what is known about the factors that may contribute to the effectiveness of this type of complex intervention.

Current service provision

Older people potentially have a great deal to gain from effective preventative programmes and from health promotion. Prevention services may lead to better health outcomes and a more efficient use of resources over the long term, with decreased demand on costly acute and social care services. However, there is evidence of an uneven uptake of health-promoting services such as immunisation and screening programmes in older people. 16 Furthermore, general practitioners (GPs) may be less likely to discuss lifestyle changes such as weight reduction, smoking, alcohol and safe drinking with older people than with younger people. 17

Nurses may play an important role in promoting health and preventing ill health in older people, who may experience a range of health and social care problems. The NHS Improvement Plan18 described a new clinical role for nurses. Known as community matrons, these experienced skilled nurses use case management techniques with patients who meet criteria denoting very high-intensity use of health care. With special intensive help, these patients are able to remain at home longer and to have more choice about their health care. Community nurses, including practice nurses, health visitors (public health nurses) and district nurses, are also well placed to promote health in older people. A recent survey of community nurses suggested that they recognise health promotion as part of their role but may be limited by a range of factors including organisational constraints, the absence of specific training, variable knowledge and the unplanned approach to this area of work, suggesting that nurses working in primary care may currently be ill equipped to enable older people to increase or maintain their levels of physical activity and function. 19

Description of the intervention under assessment

The World Health Organization defines health promotion as ‘the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve, their health. It moves beyond a focus on individual behaviour towards a wide range of social and environmental interventions’ (www.who.int/topics/health_promotion/en/). Health promotion can take a variety of forms including provision of advice and education for improving health and avoiding ill health, the implementation of service improvements and policy agenda-setting. Hubley and Copeman20 have put forward a framework for describing the range of activities that may be encompassed within health promotion programmes. This is comprised of three main types of activity: (1) health education, which involves communication directed at individuals, families and communities to influence; (2) service improvement, which involves quality and quantity of service; and (3) advocacy, which involves agenda-setting for healthy public policy.

Given the range of possible ways of implementing a home-based, nurse-led health promotion programme, the intervention under consideration within this assessment would be best described as a complex intervention, in that it that may comprise multiple, potentially interacting components. The focus within this assessment is principally on nurse-led health promotion activities undertaken within the subject’s home. It should be noted, however, that within several of the studies included within this assessment, the home-based intervention did not consist solely of health promotion activities for the prevention of illness, but also extended to treatment and other care-related elements of nursing activity.

Chapter 2 Description of decision problem

Research question

The commissioning brief for the assessment sought to address the following questions:

-

Do home-based, nurse-led interventions work, and if so what do they prevent or promote?

-

If these interventions work effectively, what features of the intervention are crucial to their effectiveness and how much will the beneficial effects cost?

Aims and objectives of this assessment

The main research question addressed by this study is ‘What is the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of nurse-led health promotion intervention delivered at home for older people at risk of admission to hospital, residential or nursing care in the UK?’ The specific objectives of this assessment are to:

-

evaluate the clinical effectiveness of home-based, nurse-led health promotion programmes in the UK

-

review existing health economic evaluations of home-based, nurse-led health promotion programmes from the perspective of the NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS)

-

explore, as far as existing evidence allows, those elements of this form of complex intervention that may contribute to its clinical effectiveness and

-

identify key gaps in current evidence and to identify areas in which future research may be warranted.

The main facets of the decision problem addressed by the review are detailed below:

-

Intervention Structured home-based, nurse-led health promotion.

-

Population Older people > 75 years of age with long-term medical or social needs at risk of admission to hospital, residential or nursing care.

-

Setting Interventions delivered at home, relating to a UK context.

-

Comparator Standard care including joint health and social assessment. Health promotion delivered in a different setting or not delivered by a nurse.

-

Design This assessment report includes two related systematic reviews: (1) a systematic review of clinical effectiveness studies (see Chapter 3) and (2) a systematic review of cost-effectiveness studies (see Chapter 4). A de novo cost-effectiveness model was not developed as part of this study.

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Introduction

This chapter presents the methods and results of a systematic review of the clinical effectiveness of home-based, nurse-led health promotion programmes.

Methods for reviewing clinical effectiveness

Identification of studies

A comprehensive literature search was undertaken across 12 different databases and research registers between February and March 2011. Information on the provider and coverage dates of the sources are detailed in Table 1.

| Database | Provider/interface | Coverage |

|---|---|---|

| MEDLINE and MEDLINE in Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations | Ovid | 1948–present |

| EMBASE | Ovid | 1980–present |

| Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE) | Web of Science | 1899–present |

| Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) | Wiley InterScience | 1996–present |

| Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CCRCT) | Wiley InterScience | 1898–present |

| NHS Health Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) | Wiley InterScience | 1995–present |

| Health Technology Assessment database (HTA) | Wiley InterScience | 1995–present |

| Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) | Wiley InterScience | 1995–present |

| Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) | EBSCO | 1982–present |

| UK Clinical Research Network (CRN) Portfolio Databasea | National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) | 2001–present |

| ClinicalTrials.gov | United States-National Institutes of Health (US-NIH) | 2000–present |

| Health Economics Evaluations Database (HEED) | OHE-IFPMA database | 1967–present |

Where applicable, sensitive search filters were applied to identify three study designs: (1) randomised controlled trials (RCTs), (2) systematic reviews and (3) economic evaluations (Table 2; see also Appendix 1). MEDLINE and MEDLINE in Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, EMBASE and the Web of Science were searched for all three study designs. Completed and unpublished studies were identified through searches in the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database and two web-based research registers, including the UK Clinical Research Network (CRN) Portfolio Database and ClinicalTrials.gov. Searches for economic evaluations were supplemented by searching MEDLINE and EMBASE, HTA database, NHS Health Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL).

| Database | Study design | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| RCTs | Systematic reviews | Economic evaluations | |

| MEDLINE and MEDLINE in Process & Other Non-Indexed citations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| EMBASE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| SCIE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| CDSR | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| HTA and DARE | ✓ | – | ✓ |

| CCRCT | ✓ | – | ✗ |

| NHS EED | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| CINAHL | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| UK CRN | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| ClinicalTrials.gov | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| HEED | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

It was agreed among the research team that the searches would be limited by date from 2001 onwards and that an English-language limit would also be applied as only UK-specific studies were relevant to the scope of the assessment. Other studies published prior to this date were identified by hand-searching existing systematic reviews. RCT filters were not applied to searches in The Cochrane Library [HTA and Cochrane controlled trials reports (CCTR)] and research registers (UK CRN and ClinicalTrials.gov), as these are trial-based sources. Similarly, the economic evaluation filter was not applied to the NHS EED and the Health Economic Evaluations Database (HEED) as these constitute the largest collection of economic evaluations. Given that the largest number of records was retrieved from the RCT searches compared with the systematic reviews and economic evaluation searches, a geographic filter was applied to identify studies that were related to the UK setting.

All citations were imported into Reference Manager, version 12 (Thomson Reuters, Philadelphia, PA, USA) software and duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts of all unique citations were then screened by one reviewer (FC) using the inclusion criteria outlined in Chapter 3 (see Inclusion/exclusion criteria). Any uncertainty regarding possible inclusion of studies was resolved by discussion between the members of the research team, or through retrieval and subsequent examination of the full study publication. The full papers of all potentially relevant citations were retrieved to enable an in-depth assessment concerning study inclusion in the review. In the event that published papers did not report potentially relevant data, corresponding authors were contacted by e-mail; where further relevant data were made available through this route, they were included in the analysis.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for the systematic review of clinical effectiveness were as follows:

-

Population Older people (> 75 years or > 70 years when considered a vulnerable population on the basis of age) with long-term medical or social needs at risk of admission to hospital, residential or nursing care.

-

Interventions Structured home-based, nurse-led health promotion.

-

Comparators Standard care including joint health and social assessment. Health promotion delivered in a different setting or not delivered by a nurse.

-

Setting Interventions delivered in the home setting, undertaken in the UK.

-

Outcomes Admission to hospital, residential or nursing care, mortality, morbidity including depression, falls, accidents, deteriorating health status, patient satisfaction.

-

Study design RCTs.

Studies were excluded from the review if the effectiveness of the intervention was not assessed within a UK setting, if the intervention was not predominantly delivered by nurses, if the population did not include a substantial proportion of individuals aged over 75 years, or if the intervention did not include any discernible elements of health promotion. In instances whereby all inclusion criteria were met except for the age-restriction criterion, this was sometimes relaxed based on subjective judgement and discussions among the research team. Non-randomised studies were also excluded from the review.

Data extraction strategy

Data were extracted independently by one reviewer using a standardised data extraction form.

Quality assessment strategy

The methodological quality of studies included in the review was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (available from www.cochrane.org/). In particular, consideration of study quality included the following factors:

-

timing, duration and length of follow-up of the study

-

method of randomisation

-

method of allocation concealment

-

blinding

-

numbers of participants randomised, excluded and lost to follow-up (LTFU)

-

whether or not intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis has been performed.

Methods of analysis and evidence synthesis

Data from included studies were tabulated and discussed in a narrative review. Where appropriate, statistical meta-analysis was undertaken to estimate a summary measure of effect on relevant outcomes based on ITT analyses. Meta-analysis was undertaken using random-effects models using Review Manager (RevMan) software, version 5.0 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). The results of these analyses were reported as odds ratios (ORs). Heterogeneity was explored through consideration of the study populations, methods and interventions, by visualisation of analysis results and through consideration of the I2-statistic.

Results

Quantity and quality of research available

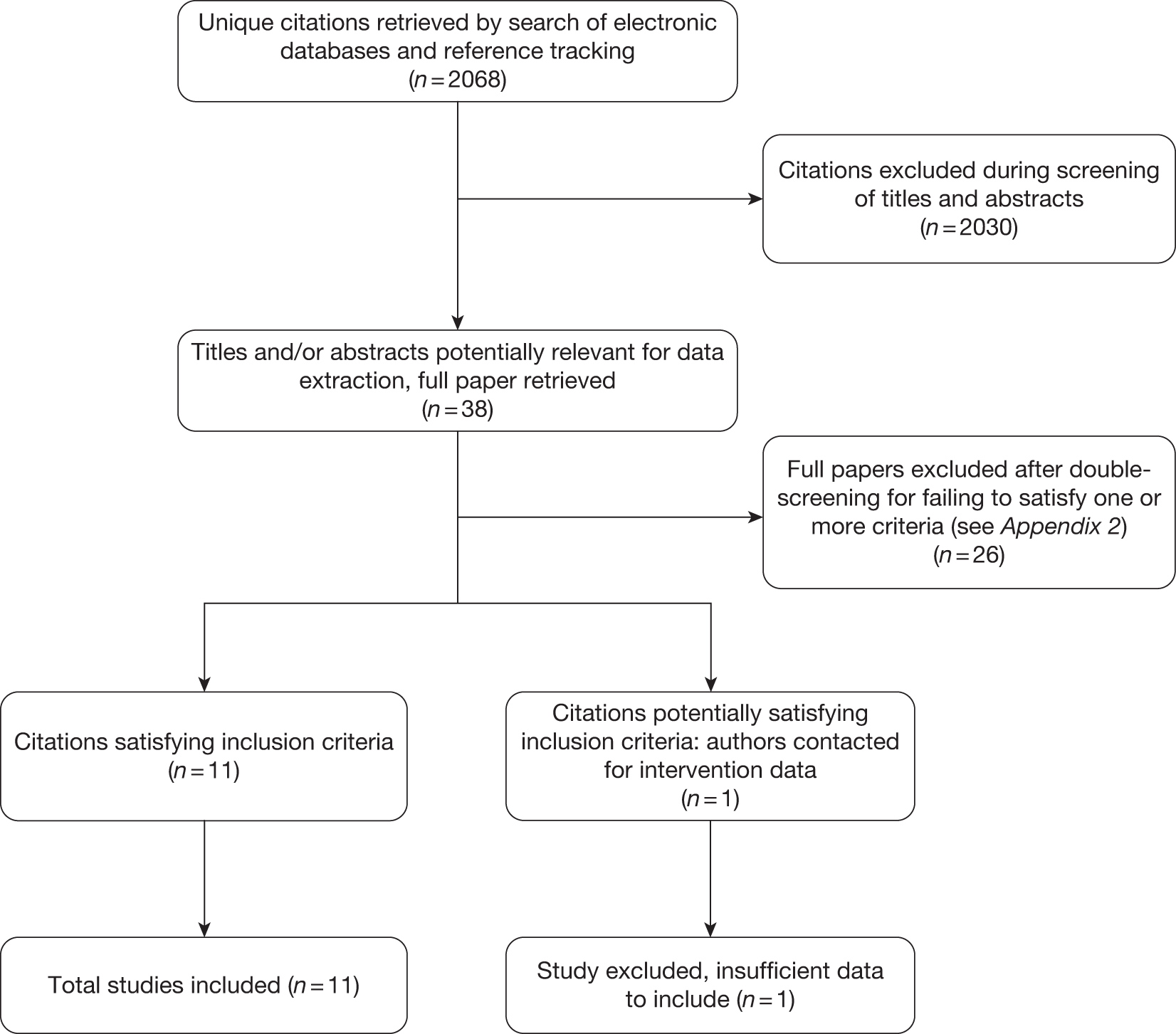

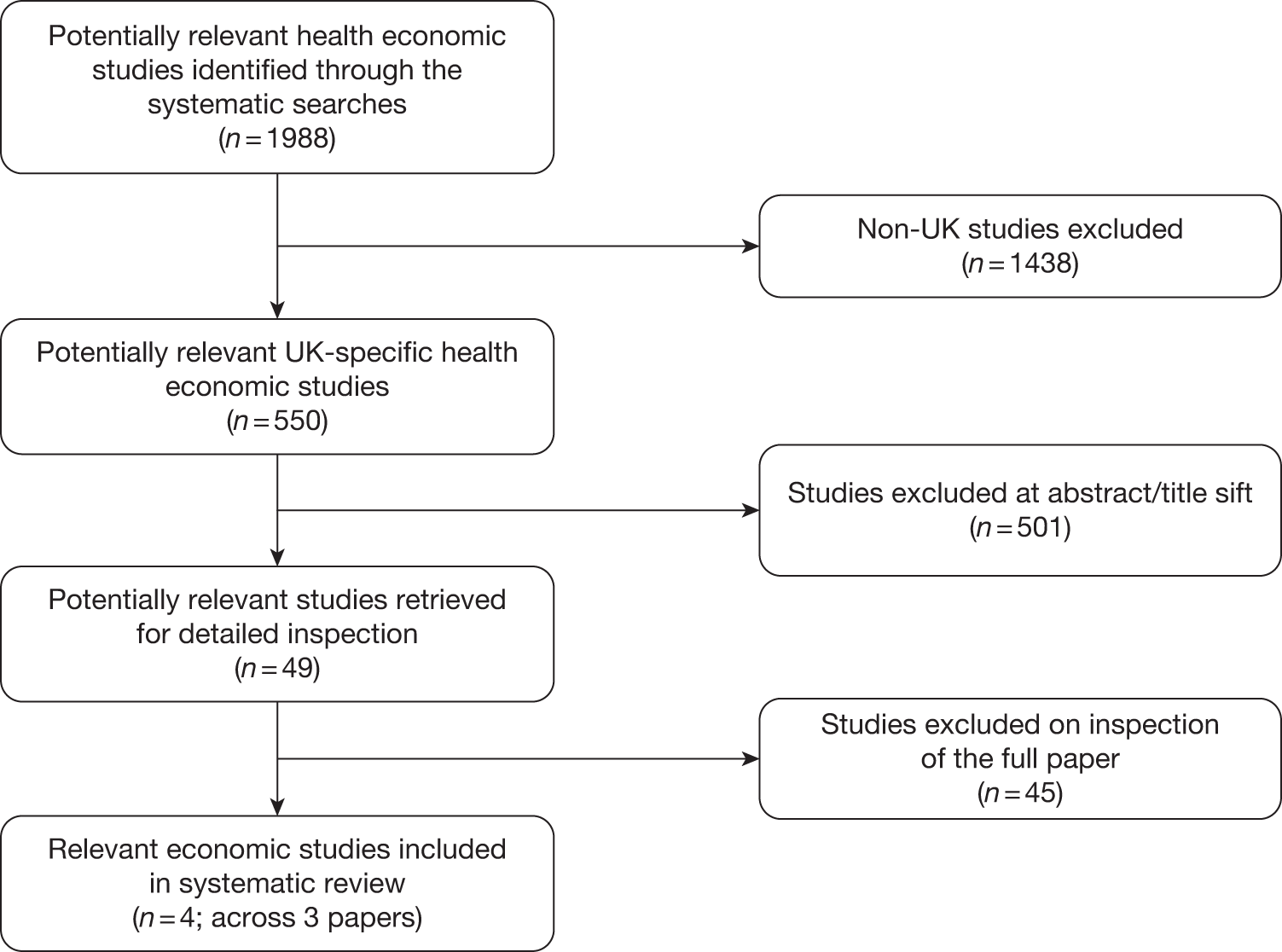

Following the removal of duplicate citations, the systematic searches for RCTs and systematic reviews identified 2068 potentially relevant records. Of these, 38 were retrieved for a more detailed inspection. Of these, 26 studies were excluded from the review. In total, 11 studies were included in the final review of clinical effectiveness. This information is summarised in the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram presented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram.

Characteristics of included studies

Eleven studies21–31 were included in this review, with the number of participants ranging from 51 to 1286. The total number of participants was 5761. All of the included studies were conducted in the UK. The characteristics of the included studies in terms of study subjects and interventions are reported in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. The 11 studies included RCTs which differed in terms of the target population and the purpose of the health promotion intervention. Four studies were designed to evaluate home-based, nurse-led interventions for particular groups of older people with existing morbidities; these included patients populations with chronic heart failure,21 Parkinson’s disease22 or venous leg ulcers,23 and individuals who had suffered a stroke. 24 The focus of health promotion was to slow or prevent further deterioration or complications of the conditions. Four studies25–28 focused on preventing falls in older people by providing home-based nursing assessment and health promotion. Two studies29,30 evaluated programmes that provided home-based screening and health promotion by nurses to older populations. One study31 assessed the effectiveness of a home-based rehabilitation programme.

| Author | n | Mean age (years) | Living alone | Health condition | No. (%) male |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue et al.21 | 165 | I, 74.4 (8.6); C, 75.6 (7.9) | 76/165 (46.1%) | Patients with heart failure | 95/165 (57.6%) |

| Brooks et al.23 | 51 | 80 | NR | Patients had suffered from venous leg ulcers | 22/51 (43.1%) |

| Burton and Gibbon24 | 176 | 75.3 | NR | Patients discharged from hospital following a stroke | 92/176 (52.3%) |

| Jarman et al.22 | 1859 | NR but 577/1836 (31.4%) aged > 77, 649/1836 (35.3%) aged 70–77 and 610/1836 (33.2%) aged < 70 | NR | Patient’s with Parkinson’s disease | 1044/1859 (56.2%) |

| Lightbody et al.28 | 348 | Median 75 (IQR range 70–81) | 153/348 (44.0%) | Patients discharged from A&E, Barthel Index (SD): I, 19 (2.0)/171; C, 19 (2.3)/177 | 89/348 (25.6%) |

| Kingston et al.27 | 109 | 71.9 | NR | Patients who had attended an A&E department following a fall | NR |

| Vetter et al.25 | 674 | Patients > 70 recruited | NR | 41% no disability | NR |

| Vetter et al.30 | 1286 | Patients > 70 recruited | NR | General elderly | NR |

| Spice et al.26 | 516 | C, 83 (6.6)/159; I1, 83 (6.7)/136; I2: 81 (6.6)/210 | NR | Median Barthel Index (IQR): I1, 18 (11 to 20); C, 18 (5 to 20) | 133/516 (25.8%) |

| McEwan et al.29 | 296 | NR | NR | Nottingham Health Profile: Mobility: I, 17.5 (SD)/132; C, 21.8 (SD)/130 | NR |

| Cunliffe et al.31 | 370 | Median (IQR) 80 (73–85) | 123/370 (33.2%) | Median Barthel Index (IQR):18 (17–20) | 114/370 (30.1%) |

The mean age of participants, where reported in the paper, ranged from 71.9 years to 83 years across the included studies. The health status of participants at baseline was not directly comparable between studies. Three studies26,28,31 recorded Barthel Index scores (a tool designed to assess independence with a 0 to 20 score range) at baseline; these studies reported average scores of 19,26 1828 and 1831 (see Glossary). Three studies21,28,31 reported the number of older people living alone. These results also suggested fairly similar populations, with the proportion of older people living alone ranging from 33.2% to 46%. The number of male participants ranged from 25.8% to 58%, with greater proportions of men in the groups with a pre-existing morbidity. 21–24

Description of the interventions

The interventions were delivered by nurses, although the background experience and additional training requirements required for the practitioners was not consistently described in the included studies. In three RCTs,25,27,30 the intervention was delivered by health visitors; these are public health nurses, working in the community, whose role concerns the protection and promotion of health. In two studies26,29 community nurses were given additional training before the study commenced. In one study,24 a specialist stroke nurse was given additional training to provide continuity of care in the community following the study subjects’ discharge from hospital. In five studies, the authors simply state that nurses were given additional training but do not provide further information with respect to their grade or level of qualification. 21–23,28,31 In one study,31 the nurse worked within a multidisciplinary team including physiotherapists and occupational therapists (not doctors). In the other 10 studies,21–30 the nurses worked independently, referring to other health- and social-care professionals as necessary.

The number of home visits made by the nurses also varied between the studies; this quantity was not consistently reported within the study publications. Those home-based interventions delivered to older people discharged from hospital with an existing morbidity received the most visits. In the study reported by Cunliffe et al. ,31 up to four visits were made per day, 7 days per week, for up to 4 weeks. Burton and Gibbon24 reported an average of three visits per patient. Blue et al. 21 did not report how many visits were made to each patient, but these were of decreasing frequency over time and were supplemented by telephone contact as judged necessary. In other studies26,28–30 single visits were made, with additional visits as judged necessary, but follow-up continued over 12 months. In four studies,22,23,25,27 the number of visits was not reported.

Control interventions were consistently described as usual care. In all of the 11 studies21–30 this was care managed by the GP once the patient was discharged from hospital and did not involve a home visit from a nurse. The nature of ‘usual care’ may have differed considerably between studies, but there is insufficient information to evaluate the heterogeneity of care in the control groups between studies.

The nature of the health promotion intervention itself also varied between the included studies (Table 4). For those home-based interventions delivered to patients with existing morbidities, the focus of the intervention was related to managing and monitoring their condition to prevent exacerbation of their disease. The intervention also focused on improving recovery and therefore regaining health following discharge from hospital. Education about medications, recognising symptoms, ensuring appropriate follow-up, encouraging concordance with medications, and health advice and providing advice about healthy lifestyle were features of the intervention in those studies in which the subjects had existing morbidities;21–24,31 in these instances the focus of the intervention was concerned with promoting recovery. Information was delivered verbally but also supported by written information21,23,29 and contact by telephone. 22 The nurses’ roles also included supporting the carers, and where necessary, instigating respite and day hospital care. 28 The nurses’ roles could also involve other health-promoting activities, such as assessing entitlement to social security benefit. 22 Those interventions targeting older people who had experienced falls were designed to reduce risk of future falls and involved in-depth assessments of health state and environmental hazards with appropriate referral to other services. 25–29 This might include working with local councils to raise awareness of local hazards for older people.

| Author | n | Study purpose | Intervention | Nurse | No. of visits | Control | Duration of intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue et al.21 | 165 | To determine whether or not specialist nurse intervention improves outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure | Nurses provided education about heart failure and its treatment, optimisation of drug treatments, diet, exercise, monitoring electrolyte concentrations, teaching self-monitoring and management. Nurses liaised with other health-care and social workers as required and provided psychological support. They also provided booklets containing an explanation of heart failure and its treatment, dietary advice, contact details for the heart failure nurses, a list of their drugs, weights, blood test results and details of planned visits (dates and times) | Training for nurses in role before start of the study | Planned home visits of decreasing frequency, supplemented by telephone contact as needed | Usual care, managed by the admitting physician and subsequently the GP | 12 months |

| Burton and Gibbon24 | 87 | The study aimed to test the hypothesis that expanding the stroke nurse role to provide continuity in care to stroke survivors and carers after discharge from hospital would improve recovery from stroke | Experimental groups received a follow-up visit from the stroke nurse at the place of discharge within 2 days of discharge. A holistic assessment was undertaken, with the stroke nurse specifically reviewing ‘health promotion’. Subsequent input was flexible, determined by the stroke nurse in consultation with the patient and carer | A bespoke training programme was provided for the stroke nurse prior to the study | The average number of contacts between the patient and stoke nurse was three (range 0–28). Contact was typically maintained every 2 months (range 0–12 months) | Control group members received usual care on discharge from the rehabilitation unity. Those in the control group did not receive home visit or any further intervention from the stroke nurse | 12 months |

| Brooks et al.23 | 51 | The study evaluated the effects of a structured nurse-led education programme that aimed to improve patient concordance and prevent venous leg ulcer recurrence | Qualified nurses and nursing auxiliaries in this group attended a 3-hour education session that focused on enhancing patient concordance on leg ulcer prevention. Patients were given information leaflets on prevention and exercise leaflets developed by the researcher. These explained seven key ways that they could prevent ulcer recurrence. The nurses emphasised the importance of the prevention strategies described in the leaflets. This was reinforced every 3 months. Where possible, relatives and carers were also encouraged to reinforce concordant behaviour | Qualified nurses and nursing auxiliaries in this group attended a 3-hour education session that focused on enhancing patient concordance with leg ulcer prevention | NR | Patients received ‘usual’ care. Qualified nurses caring for this group received mandatory 1-day training for leg ulcer management. Compression hosiery used in both groups was changed weekly and replaced every 3 months | Data were collected weekly for 52 weeks |

| Jarman et al.22 | 1859 | The study aimed to determine the effects of community-based nurses specialising in Parkinson’s disease on health outcomes and health-care costs | Nine nurses who were trained in meeting the special needs of people with Parkinson’s disease and their carers. Nurses were advisory to the GP. Each nurse was supplied with a leased car and a mobile telephone, and assumed areas of responsibility under the guidance of a nurse manager. Nurses’ roles included counselling and educating patients and carers about Parkinson’s disease in their homes, at health centres, and GP clinics, in hospital outpatients departments, and via telephone; providing information on drugs; monitoring clinical well-being and response to treatment; instigating respite/day hospital care where appropriate; assessing entitlement to social security benefit; and liaising with local multidisciplinary primary care teams for ongoing assessment and therapy | Nurses were given additional training | NR | Patients in the control group were not provided with additional services until the end of the 2-year intervention. They were subsequently offered one assessment by a nurse specialist | 2 years |

| Lightbody et al.28 | 348 | The study aimed to assess a nurse-led intervention for older people discharged from the A&E department, requiring a single visit, through which action on falls, risk factor modification could be taken through usual channels | The intervention group was assessed for risk factors for falls at home by the falls nurse 2–4 weeks after the index fall. Medication, ECG, blood pressure, cognition, visual acuity, hearing, vestibular dysfunction, balance, mobility, feet and footwear were assessed using adapted versions of the falls checklist. The environmental assessment identified inadequate lighting, tripping hazards and education about safety in the home, and simple modifications were made with consent. Risk factors requiring further action were referred to relatives, community therapy services, social services and/or the primary care team. Direct referrals were not made to hospital outpatients or day hospital | Nurses were given criteria for initial assessment and onward referral developed in consultation with therapists and clinicians | Single visit | Usual care | 6 month follow-up |

| Kingston et al.27 | 109 | The study aimed to test the hypothesis that a health-visiting intervention delivered within 5 working days of attending an A&E department with a fall would improve the medium-term self-reported functional status of older women who had fallen | The health visiting intervention included pain control and medication, including advice on appropriate analgesia. Advice from the health visitor also included the type of analgesics to use and the correct times at which they should be taken; how to get up after a fall; individuals were also educated about risk factors for falls both in terms of environmental risks and risk factors related to drugs, alcohol, etc. Patients were also given advice on diet and exercise. The intervention group received a rapid health visiting intervention within 5 working days of the index fall. All individuals within the intervention group were care managed on an individual requirement basis for 12 months post fall | Health visitor | NR | The control group received standard post-fall treatment administered in the A&E. This consisted of a letter from the A&E department to their GP detailing the clinical event, and any follow-up | 12 months |

| Spice et al.26 | 516 | The study examined two interventions in community-dwelling older recurrent fallers, who had not attended an A&E department for their most recent fall, comparing effectiveness in preventing falls against usual care within a cluster RCT design |

Group 1: Primary care intervention group participants received an assessment by a designated trained nurse to identify risk factors for falls. If problems were identified referrals to appropriate professionals in primary or secondary care were made Group 2: Secondary care intervention group participants attended a one-stop multidisciplinary clinic with referral for investigations, interventions (including home check) and follow-up if necessary Intervention assessments in the primary and secondary groups were standardised: further management of each participant was then individualised |

Designated trained nurse working in the community, using a risk factor review and subsequent targeted referral to other professionals | Not described – appears to be one-off assessment | The usual care group received a baseline assessment but were managed by their primary care team without specific guidance: referral to routine services made was at the discretion of the primary care clinicians | Unclear |

| Vetter et al.25 | 674 | RCT. Households, rather than individuals were randomised | A health visitor was employed in the practice with the task of reducing the incidence of fractures within the intervention group. This was to be achieved by visiting the households at least once per year for those not presenting any problems, assessing patients risk of falls or fractures and intervening in those who had obvious risk characteristics or who had a history of such problems. Those older people who had problems were visited as often as deemed necessary by the health visitor. The health visitor also referred people with problems to other professionals. The health visitor first obtained a history of illness and then concentrated on four factors:

|

Health visitor | Older people who had problems were visited as often as was thought necessary by the health visitor | Usual care | 4 years |

| Vetter et al.30 | 1286 | The study assessed the effectiveness of using health visitors to visit and monitor of a caseload of older individuals within their respective general practices | Health visitors were instructed to interview patients and to keep notes according to usual health visiting practice. In addition, a problem sheet and procedure form had to be completed at each interview. These were copied on to a card which was placed in the patients practice notes and this acted as a means of communication between the practitioners and the health visitor. No major changes in either the membership of the general practices or of their policies with regard to older patients occurred during the study | Health visitors, already working with older people | Health visitors made one unsolicited visit a year. They followed up patients who were in trouble at that visit and they were also alerted by the other professionals in the practice if one of their patients had any difficulties | Usual care | 2 years |

| McEwan et al.29 | 296 | This study evaluated the effectiveness of a primary care-linked screening programme to resolve health and related problems and to improve the quality of life of older people | Home visit from one of the care plan nurses. An assessment lasting about 45 minutes was undertaken, which included the following: activities of daily living, social functioning, sensory functions, mental and emotional assessment, current medical problems, measurement of blood pressure, urinalysis and haemoglobin level, and apparent compliance with medication. The requirements for care were decided on the basis of the findings at this consultation and appropriate referrals were made. The intervention consisted of a special screening assessment and referrals and/or advice based on the results. A booklet which described the health social and voluntary services available locally for older people was left with each test group participant | Community nurse trained in interviewing techniques | Single visit | The control group received the usual pattern of care from the primary care team | Not described. Follow-up at 20 months |

| Cunliffe et al.31 | 370 | This study examined the effect of an EDRS in Nottingham, UK | The ERDS was staffed by two occupational therapists, two physiotherapists, three nurses, a community care officer (liaising with social services), seven rehabilitation assistants, and secretarial support. There were no doctors in the EDRS: medical care was provided by the hospital team while in hospital and by the GP when at home. The EDRS aimed to assess the patient and arrange discharge as soon as possible. Up to four visits per day could be provided, up to 7 days per week, between the hours of 8 am and 10 pm. The package of care could last up to 4 weeks and was tailored to individual needs. Some patients when assessed in hospital by the EDRS were deemed not to require any further input. All standard after-care services were available, if required for those allocated to the EDRS | Part of team with occupational therapists, rehabilitation assistants and physiotherapists | Up to four visits per day, 7 days per week | Usual care – patients were managed in hospital until fit for home, using existing after-care services as required. After-care services comprised hospital outpatient rehabilitation, geriatric day hospitals and usual social services | Up to 4 weeks |

Quality of the included studies

Quality assessment of the included studies is presented in Table 5. Seven studies21,22,24–26,30,31 were judged to be at low risk of bias. These studies adopted appropriate methods of randomisation, described the numbers of participants lost to follow-up, reported ITT analyses and reported well-balanced patient groups at study baseline. Two studies24,31 attempted to overcome the challenges of blinding by ensuring that outcome assessors were blinded to the allocation groups of the participants. Two studies27,28 that did not adopt an ITT analysis were judged to be at medium risk of bias. Only one study, by Brooks et al. ,23 was judged to be at high risk of bias, as it failed to use a randomisation process; in particular, this introduces the possibility of selection biases that may influence the observed effectiveness of the intervention. It appears in this study that subjects within the experimental group were in a better health state at baseline; however, the potential impact of this imbalance was not examined statistically.

| Author | Randomisation procedure | Allocation concealment | Blinding | ITT/LTFU | Baseline comparability | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue et al.21 | Central computerised randomisation | Yes | No |

Yes Withdrawals Details given. Only one withdrawal from the intervention group C: Six died before discharge I: One died before discharge and one died after discharge to a hospice |

Yes | Low |

| Burton and Gibbon24 | Randomisation was stratified by admitting hospital, first or subsequent stroke, destination on discharge and levels of functional dependence on discharge. Randomisation used a computer database | Yes | Yes, of outcome assessors |

Yes ITT: 12 months Withdrawals I, 6/87; C, 5/89 Died I, 7/87; C, 8/89 LTFU I, 10/87; C, 14/89 |

Yes | Low |

| Brooks et al.23 | Allowed manipulation and some controls, but not random assignment of individual subjects to treatment conditions. Patients in the two arms were from six regions in Oxfordshire, which were divided to produce two demographically similar groups | No | Staff were unaware the trial had two arms | Experimental group appear in a better health state at baseline. No randomisation. No test of similarity | High | |

| Lightbody et al.28 | Consecutive block randomisation | No | NR |

No Four patients LTFU |

There were no differences between intervention and usual care groups in baseline characteristics except total number of medications | Medium |

| Jarman et al.22 | 438 general practices in nine randomly selected English health authority areas. Health authorities were stratified by three factors that influence service organisation and accessibility: size, population density and area deprivation score. Randomisation was performed centrally by an independent organisation. Patients were randomised within practice using block randomisation lists that reflected the randomisation ratio of the health authority area | NR | NR |

Yes LTFU I, n = 163; C, n = 116 |

No differences observed between treatment groups for age, sex, accommodation, social class, disease duration, disease severity or drugs | Low |

| Kingston et al.27 | NR | NR | NR |

No 17 patients LTFU |

Both intervention and the control group had the same mean age (71.9 years) and could undertake the same activities of daily living before the fall. However, the control group reported significantly greater levels of treatment for depression (p = 0.04) and angina (p = 0.04) in the 12 months prior to the fall | Medium |

| Vetter et al.25 | RCT randomisation by household. A group practice of five GPs took part in the study. Randomisation was undertaken using random number tables with subjects study numbers and without direct contact with the subjects | NR | NR | Yes | Similar age and gender distributions. Greater degree of disability in the intervention group was different from that in the control group: 159 (45%) of the intervention group and 117 (36%) of control subjects had no initial disability | Low |

| Vetter et al.30 | Method not described | Method not described | NR | NR | No significant differences in physical disability, scores for anxiety | Unclear |

| Spice et al.26 | Cluster RCT. Practices were stratified into urban and rural and randomly allocated to the three arms, in blocks of three, using a random number generator | NR | Blinding to the intervention group of those collecting and analysing data were impractical, but all data collected were entered without alteration | Yes | Groups were very similar but more participants were recruited to the secondary care arm owing to differences in the underlying demography of participating practices | Low |

| McEwan et al.29 | 296 people were stratified into the age–sex groups 75–84 years and ≥ 95 years, then randomly allocated to the test (151 patients) and control groups (145 patients) | NR | NR |

No I, LTFU n = 17; C, LTFU n = 11 |

No significant differences in mental test scores, in the proportion living alone, in sheltered housing or residential care and the proportion consulting a general practitioner in the last 6 months | Medium |

| Cunliffe et al.31 | Telephone randomisation services were used for allocation using computer-generated balanced randomisation within strata. Stratification was by diagnostic group and by Barthel Index at randomisation | NR | Outcomes were assessed blind | Yes | Well matched at baseline | Low |

Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Mortality

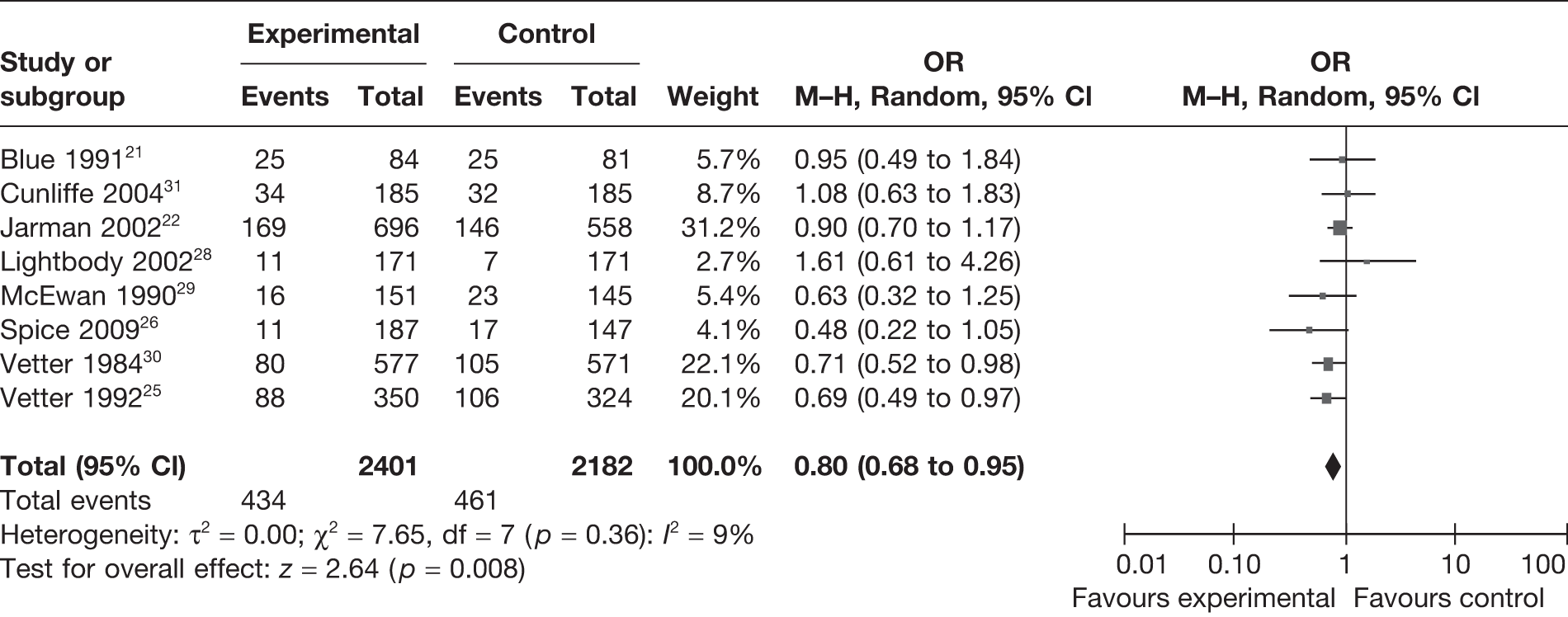

Eight studies21,22,25–31 reported mortality rates, with a total of 4583 participants included in the analysis. Random-effects meta-analysis (Figure 2) suggests that the intervention significantly reduced the risk of death [odds ratio (OR) = 0.80, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.68 to 0.95]. There was little heterogeneity present in this analysis (I2 = 9%).

FIGURE 2.

Random-effects meta-analysis results for mortality.

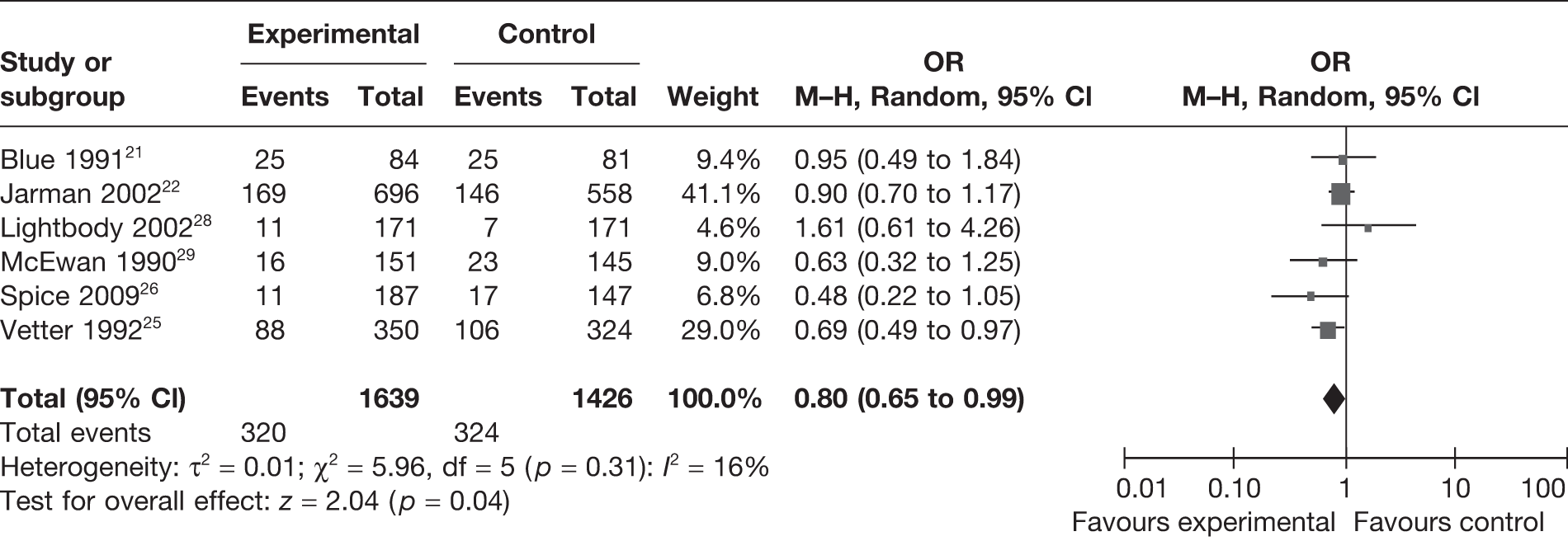

Exclusion of the two studies – Cunliffe et al. 31 and Vetter et al. 30 – from the above random-effects meta-analysis (Figure 3) did not differ significantly in reducing the overall risk of death (OR = 0.80, 95% CI 0.65 to 0.99). However, the degree of heterogeneity increased in this analysis (I2 = 16%).

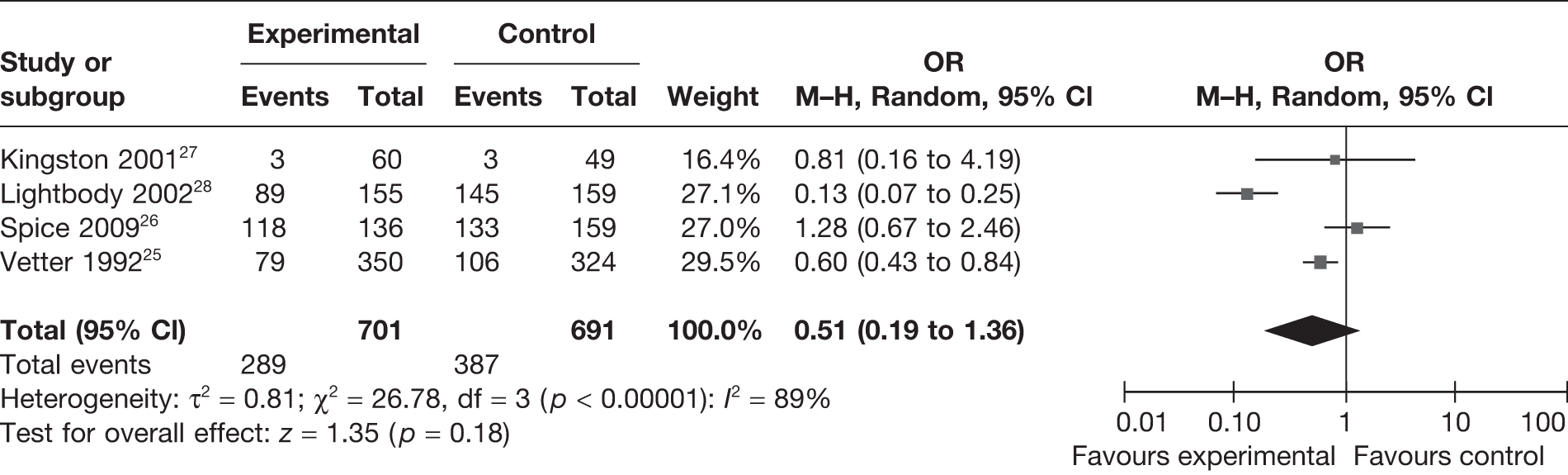

Falls

Four studies25–28 reported the number of falls experienced within the intervention and control groups. Assessment of risk and health promotion activities designed to reduce future falls were objectives of these studies. A total of 1392 participants were included in this analysis (Figure 4). Although there appears to be a trend favouring the intervention, with fewer falls occurring in the intervention group compared with usual care, this difference was not statistically significant at the 95% level (OR = 0.51, 95% CI 0.19 to 1.36). There was evidence of considerable heterogeneity in this analysis (I2 = 89%).

FIGURE 4.

Random-effects meta-analysis results for incidence of falls.

Measures of independence

Four studies24,26,28,31 reported outcomes using the Barthel Index (Table 6). The results were not presented in sufficient detail across the trials to enable meta-analysis to be performed. Two studies24,28 reported a significant difference, with those participating in the intervention group demonstrating greater independence than those in the control group. Spice et al. 26 and Cunliffe et al. 31 did not report a significant difference between the intervention and control groups. The differences in these findings are not attributable to the baseline conditions of the participants or the frequency of contact with the nurse during the intervention period.

| Study | Time of measurement (months) | Intervention, mean (SD) | Control, mean (SD) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burton and Gibbon24 | 12 | Median 17, IQR 10 (n = 63); change score from 3–12 months 0.0 (2.0) (n = 63) | 13 (7.25) (n = 62); change score from 3–12 months: 0.0 (1.0) (n = 62) | NS (p = 0.049)a |

| Lightbody et al.28 | 6 | 18.5 (2.37) (n = 155) | 17.8 (3.6) (n = 159) | p < 0.04 |

| Spice et al.26 | 12 | Difference from the control group at 12 months: 0.07 (–0.54 to –0.67) | NR | p = 0.824 |

| Cunliffe et al.31 | 12 | Mean difference at 12 months 0.2 (–0.7 to 1.1) | NR | NS |

Other outcomes

A number of other outcomes were measured and recorded in the included studies (Table 7). These included admission to hospital, moving to residential care, leg ulcer recurrence, the Nottingham Health Profile, the Beck Depression Inventory, Caregiver Strain Index, the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) and Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36). Brooks et al. 23 found a significant reduction in leg ulcer recurrence in participants in the intervention group (4% vs 36%, p = 0.004). During the intervention, participants were encouraged to perform leg exercises and to keep his or her legs elevated for a prescribed period during the day. Interventions were also successful in improving Nottingham Health Profile scores,24 reducing caregiver strain,24 improving health and well-being as measured by the GHQ,31 and using a global health question. 22

| Study | Time of measurement | Intervention | Control | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admission to hospital | ||||

| Blue et al.21 | 12 months | 47/84 (56%) | 49/81 (60%) | p = 0.27 |

| No. moving to residential care | ||||

| Spice et al.26 | 12 months | 3/113 (3%) | 7/133 (5%) | p = 0.39 |

| Leg ulcer recurrence | ||||

| Brooks et al.23 | 12 months | 1/25 (4%) | 15/42 (36%) | p = 0.004 |

| Nottingham Health Profile (higher scores reflect greater difficulty) | ||||

| Burton and Gibbon24 | 12 months | Median (IQR): 134.9 (133.47)/63 | Median (IQR): 177.51 (184.05) | p = 0.012 |

| McEwan et al.29 | 20 months | 97.4 (SD)/101 | 130 (SD)/92 | NR |

| Beck Depression Inventory | ||||

| Burton and Gibbon24 | 12 months | Median (IQR): 8(6)/61 | Median (IQR): 10 (7)/56 | p = NS |

| Caregiver Strain Index | ||||

| Burton and Gibbon24 | Median (IQR): 4 (3.5)/37 | Median (IQR): 5.5 (3.8)/36 | Significant when measured as change from 3 to 12 months | |

| Global health question | ||||

| Jarman et al.22 | 24 months | Mean (SD) 4.79 (1.50)/696 | Mean (SD) 5.02 (1.38)/558 | p = 0.008 |

| GHQ (high score unfavourable) | ||||

| Cunliffe et al.31 | 3 months | Mean difference at 2.4 (–4.1 to 0.7) favouring intervention | ||

| SF-36 (36–0) | ||||

| Kingston et al.27 | 12 weeks | 1.6 (SD) | 3.1 (SD) | p = 0.81 |

Statement of principal findings

Eleven studies21–31 with a total of 5761 participants were included in the clinical effectiveness review. The studies varied in the nature of the interventions: four21–24 targeted participants with pre-existing morbidities (heart disease, Parkinson’s disease, stroke, venous leg ulcers), one31 provided care at home for patients recently discharged from hospital, two29,30 undertook assessment visits of older people and four25–28 delivered interventions to older people with the purpose of preventing falls. The nature of the interventions varied, with some delivered by nurses visiting more frequently over a limited period of time, whereas others included one visit, with future visits as deemed necessary, and patients being followed up for a longer period of time. The background training and experience of the nurses also varied between studies. Some interventions were delivered by health visitors, stroke nurse specialists or nurses who had been given training specific to the role required for delivering the intervention. Interventions comprised information provision, reinforcement of prescribed treatment and health behaviour, healthy lifestyle information, support for carers, psychological support and referral to other health- and social-care professionals.

Ten21,22,24–31 of the studies were judged to be of medium or low risk of bias. The consistency of high methodological quality in the studies facilitated meta-analysis using a random-effects model.

Eight studies21,22,25,26,28–31 reported mortality rates. These results were pooled in the meta-analysis, using a random-effects model owing to the heterogeneous nature of the intervention and participants. Home-based nursing significantly reduced the risk of death (OR = 0.80, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.95). There was little heterogeneity present in this analysis (I2 = 9%). Four studies25–28 reported the number of falls experienced by participants; a random-effects meta-analysis found a non-significant trend to improved outcomes in the intervention group, but the results were not statistically significant (OR = 0.51, 95% CI 0.19 to 1.36). There was evidence of considerable heterogeneity in this analysis (I2 = 89%). Other outcomes were measured and reported differently between studies preventing meta-analysis. Barthel Index scores were reported in four studies. 24,26,28,31 Two26,28 of these reported a statistically significant effect favouring the intervention, whereas the other two24,31 found no evidence of beneficial effect. Other outcomes measured showing a statistically significant effect favouring the intervention included leg ulcer recurrence,23 Nottingham Health Profile,24,29 Caregiver Strain Index,24 the GHQ31 and a global health question. 22 The following outcomes failed to demonstrate a statistically significant difference: admission to hospital,21 number of individuals moving into residential care,26 the SF-3627 and the Beck Depression Inventory. 24

Four existing systematic reviews8,10,14,32 incorporated meta-analysis. These were reviews of home- or community-based interventions to support older people. The reviews were not limited to nurse-led interventions and were not focused on the UK context. Three of these reviews8,14,32 did not find a significant reduction in mortality. However, the results from the review by Elkan et al. 10 concur with the findings of the meta-analyses presented here. They found a significant reduction in mortality (OR = 0.76, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.97). Stuck et al. 8 and Beswick et al. 14,32 both reported statistically significant benefits for the intervention group in terms of reduced nursing home admission, risk of hospital admissions, falls and functional decline. Stuck et al. 8 found, however, that the effect on functional decline was dependent on the number of home visits performed during follow-up. The positive effects seen in these reviews are mirrored in our review, supporting the conclusion that home visits to older people can reduce mortality and appear to improve the health and well-being in older people.

Chapter 4 Assessment of cost-effectiveness

Introduction

This chapter presents the methods and results of a systematic review of existing UK-based economic evaluations of home-based, nurse-led health promotion programmes.

Methods for reviewing cost-effectiveness

The systematic review was undertaken to identify existing economic analyses of the use of home-based, nurse-led health promotion interventions specifically from the perspective of the UK NHS and PSS. The purpose of this review was to identify, appraise and summarise existing evidence concerning the cost-effectiveness of home-based, nurse-led health promotion in order to determine whether or not, and under what circumstances, and for whom, such a programme may represent good value for money for the NHS and associated sectors. A de novo health economic model was not developed as part of this review.

Identification of studies

A comprehensive systematic search of key health and medical databases was undertaken, as detailed in Chapter 3. Additional searching using Google Scholar was also undertaken to attempt to identify any relevant unpublished literature not identified by the systematic searches. The full economic search strategy is presented in Appendix 1.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review of economic analyses are detailed below.

Study inclusion/exclusion criteria for review of economic evaluations

Inclusion criteria

The following inclusion criteria (additional to those presented in Chapter 3) were applied:

-

Full comparative economic evaluations that present results in terms of both costs and health outcomes (cost-effectiveness analyses, cost–utility analyses, cost–benefit analyses and cost–consequence analyses). Cost minimisation studies were included, although, strictly speaking, these are not full economic evaluations.

-

Studies undertaken from the perspective of the UK NHS and PSS.

Exclusion criteria

The following types of studies were excluded:

-

studies that report only costs or outcomes

-

studies that evaluate interventions delivered in any other setting than the subjects’ home (e.g. institutional, residential or nursing home care)

-

studies in which a substantial proportion of patients were < 75 years of age

-

non-comparative studies

-

studies in which a substantive element of the intervention was not delivered by nurses

-

studies in which the intervention was not specifically related to health promotion

-

studies that were undertaken within a non-UK setting

-

studies referred to only in editorials, commentaries or letters were also excluded.

No exclusion criteria were applied with respect to the targeted nature of the intervention, i.e. the review does not discriminate between interventions that are intended to improve outcomes within the general older population whereby their capacity to benefit is assumed solely on the criterion of age, or those interventions that are applied on the basis of increased risk owing to a history of a specific medical condition (e.g. stroke, dementia, history of falls). Studies undertaken within a non-UK setting were excluded from the review; these were retained, however, to examine the availability of economic evidence within a non-UK setting.

Identification of relevant studies

All citations were imported into Reference Manager version 12 and duplicates were removed. UK-specific citations were identified; the abstracts of these were then sifted to identify any potentially relevant economic evaluation studies for inclusion in the review. In addition, the studies included in the review of clinical effectiveness (see Chapter 3) were also scrutinised to identify any potentially relevant economic studies missed by the economic searches. Full papers of potentially relevant studies were retrieved and scrutinised in greater detail by two reviewers (PT and AR). Subjective judgement on the part of the reviewers was required with respect to the application of certain inclusion criteria, in particular the age distribution of study subjects (the proportion of subjects ≥ 75 years and < 75 years, and the extent to which this is reported), the extent to which the intervention involves health promotion rather than care, and the extent of nurse involvement in the delivery of the intervention. Studies that included a slightly younger patient population were given additional consideration (substantial proportion subjects ≥ 70 years of age) if all of the other inclusion criteria were met. All sifting was undertaken by two reviewers (PT and AR) and disagreements were resolved through discussion among the research team.

Critical appraisal methods

Included studies were critically appraised using the checklist for economic evaluations reported by Drummond et al. 33

Results of the cost-effectiveness review

Number and type of included studies

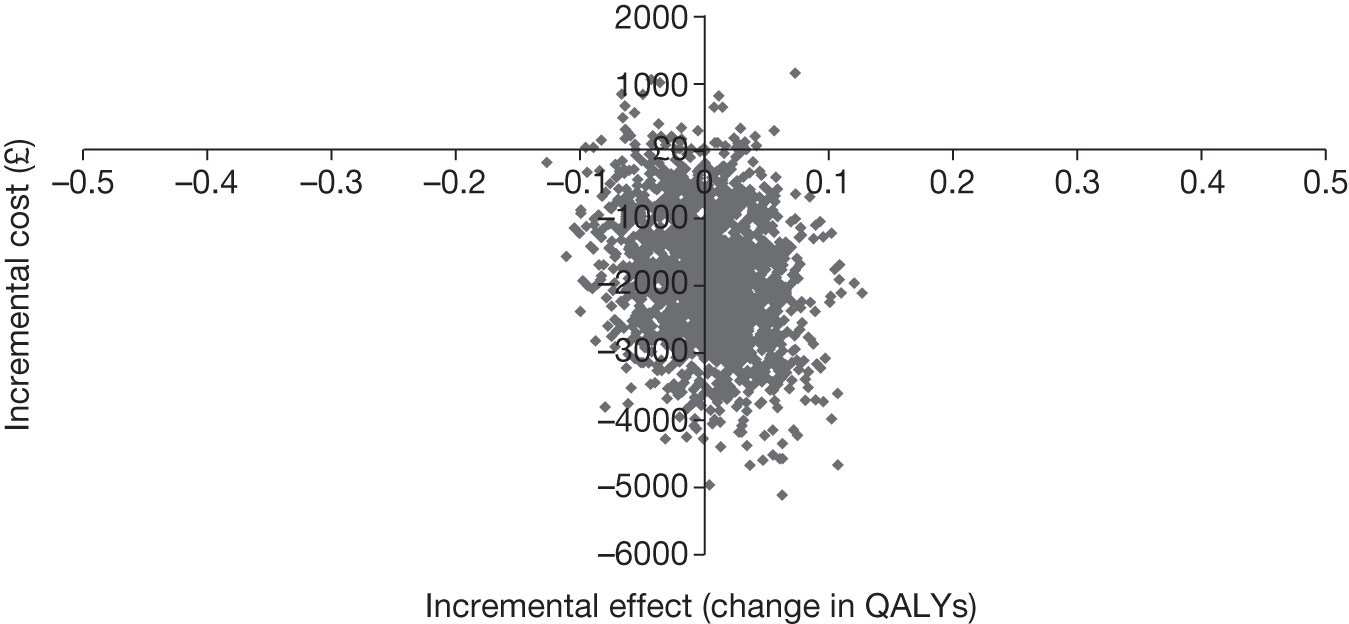

The systematic searches for economic evaluations identified 1988 potentially relevant citations, excluding duplicated records. Following an initial sift of abstracts and titles, full papers of 49 studies were retrieved for more detailed inspection. Forty-five of these studies failed to meet the inclusion criteria and were hence excluded from the review. The most common reasons for study exclusion were (1) the inclusion of younger age groups; (2) the absence of any substantive nursing element within the description of the intervention; (3) the absence of any form of health promotion in the definition of the intervention; or (4) the failure to undertake a comparative economic evaluation. In many instances, studies were excluded for more than one reason. In total, only three studies, reported across four papers, met the inclusion criteria for the review. Further hand-searching of included studies and web-based searching did not result in the retrieval of any additional relevant studies. An abridged PRISMA diagram is shown in Figure 5.

Table 8 presents a summary of the characteristics of the economic studies included in the review. Table 9 summarises the main resource components included within each study. Table 10 presents the results of the critical appraisal.

FIGURE 5.

PRISMA diagram for systematic review of cost-effectiveness.

| Study | Form of evaluation | Population | Intervention | Comparator | Primary economic outcome measure | Perspective | Time horizon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bakerly et al.34 | Case-matched cost minimisation analysis | COPD | Integrated care model including nurse-led education and advice (n = 130) | Usual care (n = 95) | Cost difference | NHS | 60 days |

| Hurwitz et al.,35 Jarman et al.22 | EEACT (presented as a cost–consequence analysis) | Parkinson’s disease | Parkinson’s disease nurse specialist service (n = 1041) (including counselling and education-based roles) | Usual care (n = 818) | EQ-5D, cost difference | Appears to be NHS and local authority | 2 years |

| Miller et al.36 | EEACT | Older patients on discharge from acute hospital inpatient stay | EDRS (n = 185) | Usual care (n = 185) | Incremental cost per QALY gained | NHS/PSS | 1 year |

| Resource groups/components | Bakerly et al.34 | Hurwitz et al.,35 Jarman et al.22 | Miller et al.36 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary care | |||

| Nurse home visits | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| GP/community care | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Occupational therapist home visit/home adaptations | ✓ | ? | ✗ |

| Ambulance transfers | ✓ | ✗ | |

| Pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments | |||

| Drugs/other therapies | × | ✓ | ✗ |

| Secondary care | |||

| Hospital outpatient visits | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| A&E department admissions | ✓ | ✓ | ? |

| Inpatient costs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Institutional/residential care | |||

| Institutional/residential/respite care | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Day care/home help | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Community and GP care | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Other | |||

| Social security benefits | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Question | Bakerly et al.34 | Hurwitz et al.,35 Jarman et al.22 | Miller et al.36 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Was a well-defined question posed in an answerable form? | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was a comprehensive description of the competing alternative given? | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was there evidence that the programme’s effectiveness had been established? | Questionable | Not in terms of QALYs | Not in terms of QALYs |

| Were all the important and relevant cost and consequences for each alternative identified? | Yes for costs | Yes for costs | Yes |

| No outcomes included | No outcomes included | ||

| Were costs and consequences measured accurately in appropriate physical units? | Yes for costs | Yes for costs | Yes for costs |

| No outcomes included | No outcomes included | Unclear how/if QALYs were measured at baseline | |

| Were costs and consequences valued credibly? | Yes for costs | Yes for costs | Yes |

| No outcomes included | No outcomes included | ||

| Were costs and consequences adjusted for differential timing? | No | No | No |

| Was an incremental analysis of costs and consequences of alternatives performed? | Yes for costs | Yes for costs | Not for expected ICER |

| No outcomes included | No outcomes included | ||

| Was allowance made for uncertainty in the estimates of costs and consequences? | No | No | Yes |

| Did the presentation and discussion of results include all issues of concern to users? | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Critical assessment of included studies

This section presents a critical appraisal of the three included studies22,34–36 in the systematic review.

Bakerly et al.

The study reported by Bakerly et al. 34 presents the methods and results of a cost minimisation analysis based on the results of a non-randomised prospective study of an early discharge and integrated care protocol for patients admitted to hospital with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This study was not included in the review of clinical effectiveness (see Chapter 3) owing to its non-randomised design. Although the authors purport to have adopted a NHS perspective, PSS costs were also included within the analysis. Costs were valued at year 2007 prices.

The population within the intervention group included 130 out of 546 patients who were admitted to hospital with acute exacerbations of COPD and who consented to the integrated care intervention during the period August 2003 to August 2004. The comparator group for the economic analysis comprised 95 out of 662 patients who were admitted to hospital with acute exacerbations of COPD between August 2002 and August 2003, and who stayed in hospital for the full duration of his or her treatment. Members of the control population were selected to match members of the intervention population in terms of age, gender and postcode.

The average age of patients who were allocated to the intervention group was 70 years [standard deviation (SD) = 8 years] and the average age of patients within the retrospective comparator group was 68 years (SD = 11 years). The intervention assessed within this study was an early discharge and integrated care protocol in which patients discharged from hospital early were visited at home by specialist respiratory nurses until they were totally discharged. The Acute COPD Assessment Service (ACAS) was able to provide short-term nebulisers and oxygen to patients. The ACAS team was staffed by three full-time specialist respiratory nurses and a middle-grade physician, who dedicated 40% of his time to the programme. During the last visit, patients and their carers were educated regarding COPD and its causes, how to prevent ill health as a result of the disease and how to manage suspected COPD exacerbations, and were given advice on exercise, healthy living and smoking cessation. In addition, patients were also given a written self-management plan (in conjunction with their GPs), and were given steroids and antibiotics to initiate at home when required. Patients were assessed in clinic 60 days after the index episode and a comprehensive management plan was agreed with the patient and communicated to their GP. Patients who were deemed unfit for early discharge were followed up daily in the hospital by programme nurses until they were well enough to be discharged with or without integrated care support. The comparator group received inpatient hospital care until the patients were considered well enough for discharge.

The objective of the study was to determine any cost savings that could be achieved by the introduction of an early discharge and integrated care protocol. Within the analysis, outcomes for the ACAS programme were assumed to be equivalent between the intervention and control groups. Although the authors did refer to a previous systematic review reported by Ram et al. 37 as evidence that the intervention was safe, the study did not involve the prospective collection or analysis of evidence regarding health-related quality of life (HRQoL), survival or other intermediate clinical outcomes.

Resource use was measured for patients receiving the early discharge and integrated care protocol and for patients within the retrospective control group. Resource components included the original hospital admission and length of stay, emergency ambulance transfers, and accident and emergency visits prior to their original hospital admission. Additional resource-use components recorded within the intervention group included visits by specialist respiratory nurses, emergency home visits, contact with various health-care professionals, accident and emergency visits following discharge, hospital readmissions, and outpatient clinic visits. Unit costs used to value resource use were obtained from appropriate reference sources, including NHS Reference Costs 2007/0838 and Curtis et al. 39

The authors did not report the results of any sensitivity analysis to examine the impact of costing assumptions on the likely cost savings of the protocol. The use of discounting was not reported; although this may be considered appropriate given the short time horizon for resource measurement (60 days), the potential resource and cost differences beyond this time point remain subject to considerable uncertainty.

The results of the analysis reported by Bakerly et al. 34 are summarised in Table 11.

| Treatment group | Mean cost per patient (£) | 95% CI (£) |

|---|---|---|

| Early intervention and discharge (intervention) | 1653 | 1521 to 1802 |

| Inpatient care (control) | 2256 | 2126 to 2407 |

| Cost difference | 603 | – |

The results of the economic analysis suggest that the early discharge and integrated care protocol for patients admitted to hospital with acute exacerbations of COPD may generate substantial cost savings compared with usual inpatient care. However, it should be noted that the study design adopted by Bakerly et al. 34 used a non-randomised design without any form of blinded allocation to the groups under assessment. In particular, although the prospective intervention and historical control groups were selected for inclusion in the study using a case-matching approach, subjects were matched only on the basis of age, gender and postcode. Prognostic factors and other baseline characteristics were not included as part of this process. Consequently, the study may be at risk of selection bias.

Hurwitz et al./Jarman et al.

The study reported by Hurwitz et al. 35 and Jarman et al. 22 presents the methods and results of an economic analysis of a RCT of community-based nursing for patients with Parkinson’s disease. The authors describe the economic analysis as a cost minimisation analysis and report primary economic outcomes in terms of the cost difference between the intervention and control arms of the trial. However, the study would be more accurately described as a cost–consequence analysis, as disease-specific clinical outcomes and HRQoL outcomes are also reported within both papers. 22,35 The perspective adopted for the analysis was not clearly reported in either paper; however, the types of resource components included within the analysis include those that would typically fall on the NHS (although some local authority costs were also included such as institutional and respite care). Costs were valued at year 1996 prices.

Within the RCT, patients were randomly assigned either to a community-based nursing intervention (n = 1041) or standard care (n = 818). The study population consisted of patients identified as suffering from Parkinson’s disease by 438 general practices in nine randomly selected health authorities in England. The intervention was delivered by nurses who had no previous experience of nursing patients with Parkinson’s disease in the community. However, some of the nurses did have experience of nursing patients with Parkinson’s disease in a hospital setting. All of the nurses attended a course on meeting the needs of people with Parkinson’s disease and their carers. The clinical position of the nurses during the trial was not clinically autonomous; rather they worked in an advisory role to GPs and consultants. The nurses counselled and educated patients and carers about Parkinson’s disease, monitored the clinical well-being of patients and their response to treatment at least twice a year, and reported the results back to GPs or consultants as appropriate. The nurses also investigated options for respite or day hospital care, visited patients in hospital and liaised with hospital staff on discharge, assessed social security benefit entitlement, and, where appropriate, liaised with members of local multidisciplinary primary care teams regarding ongoing assessment and therapy. The nurses also provided drug information to patients under the auspices of GPs and consultants. Although the nurses were not empowered to change patient medication, they could make suggestions to GPs about altering a patient’s dose regimen. The comparator intervention was defined as standard care; however, patients allocated to the control arm were offered a single assessment by a Parkinson’s disease nurse specialist at the end of the 2-year intervention period. Further details of this trial are included in Chapter 3 of this report.

A number of primary and secondary clinical and health-related quality-of-life outcomes were measured. The primary outcomes include the results from the stand-up test and the dot-in-square test, the proportion of patients sustaining fracture and HRQoL as measured using the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire. Patient well-being was also measured using the PDQ-39 (Parkinson’s disease-specific measure of health status questionnaire) and a self-perceived global health question asking patients to rate their change in general health over the previous year on a scale from 0 (much better) to 4 (much worse). Outcomes assessments were undertaken during interviews between patients and non-professional interviewers employed by the National Centre for Social Research. Interviewers had received prior training. Other secondary outcomes included the median dose of l-dopa in each group, the proportion of patients on l-dopa controlled-release medication, the proportion of patients on a combination of pharmaceuticals, the proportion of patients referred to ancillary therapy, and the proportion of patients referred to a Parkinson’s disease specialist. Again, these secondary outcomes were measured during interviews. Patient mortality for each group was obtained from the NHS Central Registry.

All of the patients in the study were interviewed to estimate NHS resources used. Resource components included institutional, respite, hospital and day care, community and general practitioner care, social security benefits, home aids, adaptations and pharmaceuticals. Unit cost estimates were obtained from appropriate reference sources including the Monthly Index of Medical Specialities (MIMS)40 and Netten et al. 41 The authors calculated that, including administrative costs and car hire, the intervention would cost approximately £200 per patient per year.

The authors did not report the results of any sensitivity analysis. Although the authors used non-parametric bootstrapping to check the assumptions of their mean estimates, a comprehensive analysis of decision uncertainty was not reported. Even though the intervention period was 2 years, there is no evidence that discounting of future costs was undertaken. The headline economic results for the study are summarised in Table 12. Although the economic study design adopted here is reported to be that of a cost minimisation analysis, EQ-5D scores were actually reported to be non-significantly lower in the intervention arm (mean EQ-5D difference = –0.02). On the basis of the total direct NHS costs for each group in those completing the study, and absolute EQ-5D differences between the groups, the nurse-led intervention appears to be dominated by standard care (less effective and more expensive). However, this is subject to considerable uncertainty.

| Treatment group | Cost (£) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| EQ-5D utility | Year 1 | Year 2 | |

| Nurse group | 4055 | 5860 | 0.37 |

| Control group | 3480 | 5630 | 0.39 |

| Difference | 575 | 230 | –0.02 |

Miller et al.

Miller et al. 36 present the methods and results of an economic evaluation conducted alongside a RCT to estimate the cost-effectiveness of an early discharge and rehabilitation service for older patients admitted to hospital. The analysis adopted a NHS and PSS perspective. The formal price year was unspecified within the paper; however, it appears from the cost sources used that costs were valued at year 2000 prices.

Within the RCT, patients were randomly assigned to one of two groups: (1) an early discharge and rehabilitation service (n = 185) or (2) standard social services home care and outpatient rehabilitation (n = 185). The study population consisted of patients who had been admitted to hospital for acute care; the most frequent reasons for admission were fracture (28%), neurological conditions including stroke (26%) and cardiorespiratory illness (14%). The median age of patients was 80 years, although the trial was open to any patient aged ≥ 65 years who was medically ready for discharge, had rehabilitation needs that could be met at home and did not need 24-hour care. Of the patients recruited to the trial, 246 were female (67%) and 247 lived alone (67%). The median hospital length of stay was 13.5 days. The intervention comprised a home care and rehabilitation service that was delivered by a team of nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists and rehabilitation assistants during up to four visits per day for up to 4 weeks. Patients who were allocated to the comparator arm received standard care, which included social services home care and rehabilitation delivered through an outpatient department.

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions HRQoL estimates were elicited at 12-month follow-up using postal questionnaires. Sixty-six patients died before follow-up and were assigned a zero score. The remaining 32 patients withdrew consent or declined follow up. EQ-5D estimates were obtained for 272 patients of the recruited who were still alive at 12 months. Importantly, the authors do not report whether or not EQ-5D assessments were undertaken at baseline; hence, the methods used to estimate incremental QALYs between the groups are not entirely clear. This may affect the credibility of the results of the economic analysis.

Resource costs were measured for all participants in both the intervention arm and the control arm; these included the costs of the intervention, the costs of the acute hospital stay following randomisation, the costs of any readmissions to hospital or outpatient visits, and the costs of any nursing home admissions or any contact with GPs, community health services or social services within the 12-month follow-up period. Total resource use for each patient was estimated using data collected from service providers over the follow-up period. The cost of the intervention was based on recorded client contact time with members of the early discharge rehabilitation service. Hospital inpatient admissions were costed according to the length of stay and clinical specialty. Outpatient attendances were also costed according to clinical specialty. The cost of contact with GPs was based on the recorded number of face-to-face and telephone consultations. The cost of contact with community health service professionals was based on recorded contact time. Unit costs were obtained from standard references sources including the NHS Reference Costs 2000/0142 and Netten et al. 43 The cost of nursing and residential home admission was based on duration of stay multiplied by the average cost obtained from Netten et al. 43 The cost of referrals to social services professionals was based on the assumption of 1 hour of contact time per visit, with the hourly rate being obtained from Netten et al. 43 The costs of local authority funded social services were based on recorded contact time.