Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 09/87/01. The protocol was agreed in January 2010. The assessment report began editorial review in January 2011 and was accepted for publication in January 2011. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2012. This work was produced by Bond et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2012 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Aim of the review

The aim of this assessment is to review and update, as necessary, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidance to the NHS in England and Wales (issued November 2006, amended September 2007 and August 20091) on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and memantine for moderate-to-severe AD. 1

This previous guidance was primarily based on evidence presented to NICE in the assessment report by Loveman and colleagues2 in 2004. We will summarise the evidence presented in this previous report, and review and report new evidence from 2004 to the present.

Description of health problem

Pathology

Definitions

Dementia is usually a disease of later life and has been defined as:

A syndrome consisting of progressive impairment in memory and at least one other cognitive deficit (aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, or disturbance in executive function) in the absence of another explanatory central nervous system disorder, depression, or delirium.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)3

People with dementia may also show other symptoms, such as depression, psychosis, wandering and aggression.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia, and is additionally characterised by the presence of neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques in the cerebral cortex, observed at post-mortem.

Diagnosis

In the distant past, diagnosis of AD before death had been on the basis of excluding other causes. However, there are now agreed criteria that accurately predict up to 90% of AD cases (Box 1). Alternatively, diagnosis can be made from ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision4) and DSM-IV(Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition3).

Dementia established by clinical examination, documented by the MMSE or similar and confirmed by neuropsychological tests

Decline in memory and at least one non-memory intellectual function

Decline from previous level and continuing decline

Onset between 40 and 90 years of age

No disturbance in consciousnessAbsence of systemic disorders or other brain diseases that in, and of, themselves could account for the progressive deficits in memory and cognition

Definite AD

Clinical criteria of probable ADHistopathological evidence of AD at post-mortem or biopsy

Possible ADPatient has dementia syndrome with no other cause, but clinical variation from typical AD

Patient had second disorder that is sufficient to produce dementia, but not considered the cause of the dementia

Single gradually progressive cognitive deficit in absence of other causes

The diagnosis of dementia may happen many months after onset, as the development of symptoms is usually insidious. It may take some time for the individual to realise that significant memory, mood or ability changes are taking place. Other possible diagnoses, such as depression, delirium, vitamin B12 deficiency and hypothyroidism, have to be excluded first. Further testing is necessary to determine the particular cause of dementia. 5

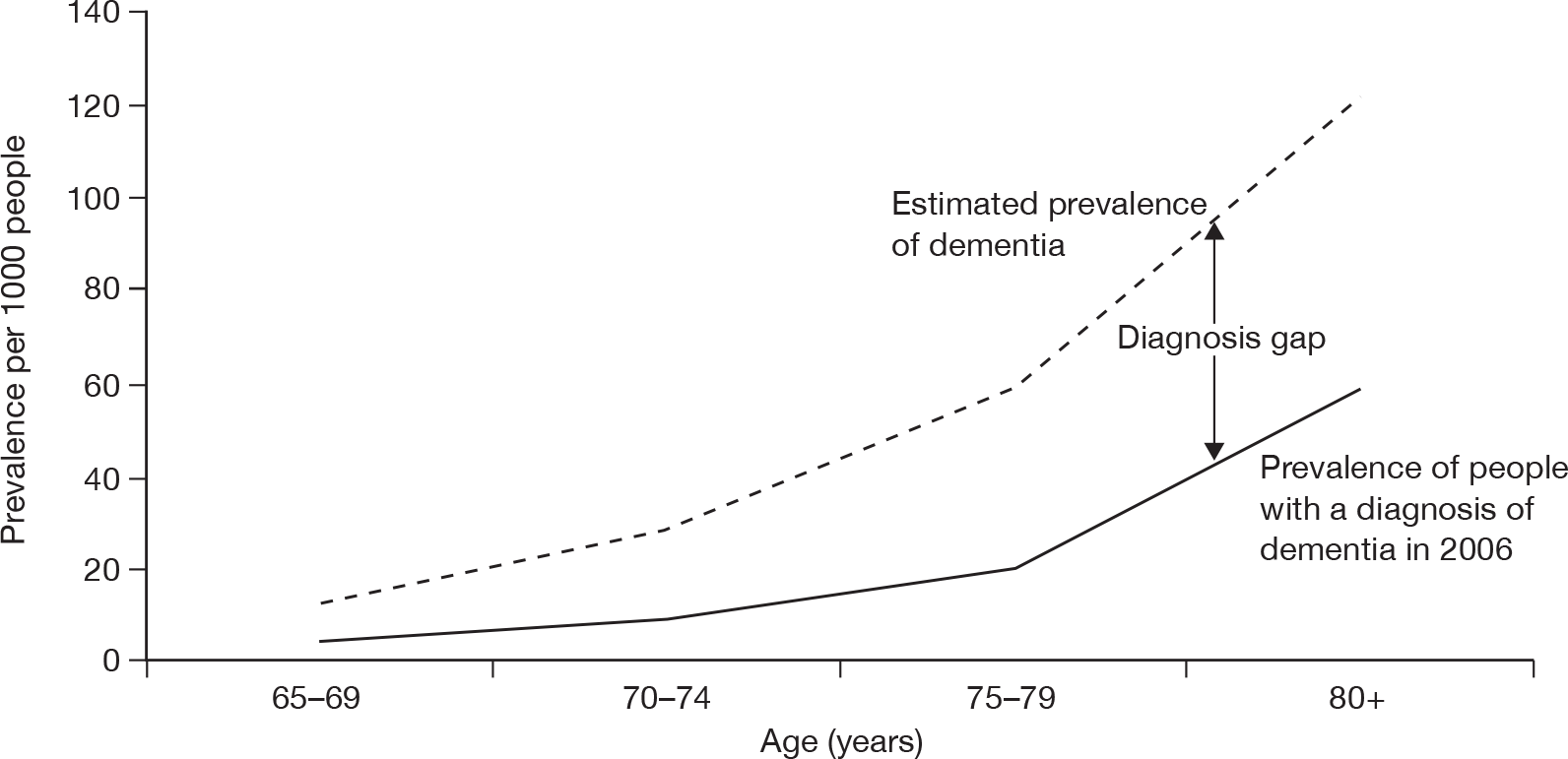

Examination by the National Audit Office (NAO) of data from primary care trusts (PCTs), the Dementia UK report8 and the Office for National Statistics (ONS) has indicated that, in England, more than 50% of people with dementia never receive a correct diagnosis. 9 See Figure 1 for 2006 estimates of the diagnosis gap.

FIGURE 1.

The gap between prevalence and diagnosis of dementia in England. Source: Knapp et al. 8 Dementia UK report to the Alzheimer’s Society, King’s College London and London School of Economics and Political Science (estimated actual average prevalence) and General Practice Research Database report to the NAO (reported prevalence based on diagnoses). The graph shows reported prevalence of dementia, based on levels of diagnosis within PCTs, for ages 65 years and upwards in 2006. The estimated actual average prevalence has been calculated using data from the 2007 Dementia UK report8 in conjunction with population estimates from the ONS. The latter does not take into consideration those aged 85 years and above, owing to restrictions on the data available, and as such forms a very prudent estimate of dementia in the > 65-year population.

Epidemiology

Alzheimer’s disease is predominantly a disease of later life, with some 5% of the UK population over 65 years affected. Early-onset AD can be found in younger people; this is a rare condition, accounting for only an estimated 2.2% of those with dementia. 8 Currently, there are estimated to be about 820,000 people in the UK with dementia (1.3% of the population); of these approximately 520,000 (62%) will have AD, of whom approximately 423,000 (83%) live in England and 26,000 (5%) live in Wales. 8,10 AD is more commonly found in women than men in the UK, with 67% of women with dementia having AD, but only 55% of men. 8 However, the association with gender is completely explained by the shorter life expectancy of men. 11

The incidence of dementia, therefore, increases with age. In England and Wales, among people aged 65–69 years, the incidence is estimated to be 7.4 per 1000 person-years [95% confidence interval (CI) 3.6 to16.1 per 1000 person-years]; this rises to 84.9 per 1000 person-years (95% CI 63.0 to 107.8 per 1000 person-years) at 85 years old and above. 12 These rates predict 180,000 new cases of dementia per year, and if 62% of these have AD (see above) then there are approximately 111,600 new cases of AD in England and Wales per year. The Medical Research Council’s Cognitive Function and Ageing Study (2006) found that in England and Wales increasing age was the greatest risk factor for dementia, with gender weakly associated. Having Parkinson’s disease increased the risk of dementia by three times [odds ratio 3.5 (95% CI 1.3 to 9.3)], but rating your own health as poor was a greater risk factor [odds ratio 3.9 (95% CI 2.2 to 6.9)]. Better education was a marginally protective factors [odds ratio 0.7 (95% CI 0.5 to 1.0)]. 11

Table 1 shows the combined numbers of diagnosed and undiagnosed cases of dementia in the UK in 2006 estimated by the Dementia 2010 study. 10

| Age group (years) | Gender | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||

| 30–59 | 19,840 | 11,381 | 31,221 |

| 60–64 | 25,034 | 7782 | 32,816 |

| 65–69 | 28,056 | 15,378 | 43,434 |

| 70–74 | 50,085 | 48,319 | 98,404 |

| 75–79 | 42,805 | 74,037 | 116,842 |

| 80–84 | 68,343 | 120,482 | 188,825 |

| 85–89 | 50,439 | 124,465 | 174,904 |

| 90–94 | 28,399 | 78,606 | 107,005 |

| 95–99 | 5008 | 23,424 | 28,432 |

| Total | 318,009 | 503,874 | 821,883 |

Aetiology

The cause of AD is uncertain. However, it is generally believed that the condition develops from multiple factors, with increasing age bringing the greatest risk. Up to 5% of cases are linked to genetic causes; medical history and lifestyle are also contributing factors. 12 At least three genes have been identified that are associated with the rare condition of early-onset AD. 14–16 A genetic link is also likely for those with a family history of late-onset AD, although a particular gene for this has not yet been identified. 5

There is evidence that it may be possible to prevent some incidence of AD; it is thought that due to the cerebrovascular contribution to brain pathology, managing cardiovascular risk factors (high cholesterol, high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes and being overweight) may delay or prevent the onset of AD. Other possibly preventative factors include regular exercise, a low-fat diet and a good social network. 17–19

Prognosis

There is currently no cure for AD. There is variation in the time it takes from diagnosis to death. The estimated median survival for AD from onset has been calculated as 7.1 years (95% CI 6.7 to 7.5 years) in the USA by Fitzpatrick and colleagues20 and is reported in Warrell and colleagues7 as about 10 years in the UK. Although, survival figures are varied and depend on whether or not they are from the time of reported onset or the time of actual diagnosis; in general, a diagnosis of AD halves life expectancy.

The contribution of AD to these survival figures is difficult to know, as people with AD frequently have comorbidities that will influence their longevity. The proportion of deaths estimated to be due to AD increases with age and varies with gender. At 65 years old, 1% of women and 2% of men are likely to die from dementia; at 85–89 years old, this rises to 23% of women and 18% of men. 8

Impact of health problem

Significance for patients

It can take several years of slow deterioration for the full effects of AD to be felt. 21 In the early stages there can be severe memory loss for recent events with associated repetitive questioning and loss of the ability to learn. 21,22 There may be a general deterioration in the ability to socialise, which can be difficult for both sufferer and carer to cope with. 23,24 As mild AD takes hold, normal activities of daily living, such as shopping or managing finances, become increasingly difficult as cognitive function deteriorates. 25 Communication also becomes a problem as vocabulary shrinks and fluency falters. 25,26 At this stage the sufferer may still be aware of their failing abilities, and the experience and known outcome of AD can frequently lead to associated depression.

Disease progression to moderate AD leads to further loss of cognitive abilities, including the ability to remember and/or understand words. Activities of daily living become increasingly affected as the ability to perform purposeful movements decreases, for example getting dressed or cooking. Commonly there are also neuropsychiatric symptoms such as anxiety, wandering, irritability, disinhibition and apathy. Visual and auditory hallucinations occur in about 30–59% of sufferers. 7 Managing these symptoms can be a very difficult burden for carers, who may well be elderly themselves. Indeed, the main predictors of full-time institutional care are caregiver exhaustion,27 the degree of patient dependence28 and the rate of disease progression. 29

In developed countries, sufferers of AD usually end their days in institutional care, as the last stages of AD bring complete dependence. This final stage is characterised by limitations such as inability to walk, manage personal care, mutism, inability to recognise familiar people and objects, and incontinence. There may also be seizures and involuntary twitching.

Significance for carers

Being the main carer for a person with AD can have an enormous impact on physical, psychological and social well-being. 30 From the early frustrations, prior to diagnosis, of living with others’ impaired cognitive function, through the devastating diagnosis, to the knowledge that the relation/friend is going to get progressively worse and die, the outlook for carers is bleak. Many carers are elderly spouses, perhaps with health concerns of their own or grown-up children who now have their own families to care for as well. 31 Carers may cope reasonably well with the early stages of the disease, but as the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) become more severe, full-time institutional care becomes increasingly likely. 5 For some carers this brings feelings of guilt and depression,32,33 possibly leading to the cognitive decline of the carers themselves. 34 Behavioural and psychological symptoms are common in AD and may be difficult to manage, causing distress to carers and patients alike. They have been shown to be better predictors of institutionalisation35 and carer distress36 than cognitive symptoms.

As AD progresses, increasing grief and feelings of loss may be experienced by carers. 37 Findings from the EUROCARE European study of co-resident spouse carers of dementia sufferers showed that co-resident carers carried a heavy burden and that mental distress was high. They concluded that issues of behavioural disturbance, negative social reactions, financial worries and younger spouse carers predicted greater distress. 38 However, there is evidence that enhanced counselling and support can relieve symptoms of depression in caregivers and delay admission to institutional care of people with AD. 39

Significance for the NHS and social services

With an increasingly elderly population, the burden of AD upon the NHS and social services is considerable. Of the estimated 520,000 people in the UK with AD,10 It is estimated that approximately 63.5% live at home and 36.5% are in residential care. 8 Unsurprisingly, the risk of moving into residential care increases with age and disease severity. The proportion of people with severe dementia increases from 6.3% among those between 65 and 69 years old to 23.5% among those aged 95 years or older. 8 Consequently, the proportion of people in the UK with dementia who live in residential care rises from 26.6% of those aged 65–74 years to 27.8% of those aged 75–84 years, 40.9% of those aged 85–89 years and 60.8% of those aged 90 years or older. 8

As the disease progresses, the balance of burden of care shifts from predominantly falling on the informal carers to the NHS and social services as patients are sustained with medication and support at home, until finally financial costs fall mostly on social services as patients move into institutional care, although a proportion of this cost may be borne by the carer or their family. Another proportion of people will qualify for the NHS Continuing Care programme, which will meet their care needs either in the community or in an institution. A longitudinal cohort study by Banerjee and colleagues40 has found that when a person with dementia lives with their main carer they are 20 times less likely, over the course of a year, to move into residential care than those who do not [odds ratio 0.05 (95% CI 0.01 to 0.42)]. They also found that the carer’s psychological quality of life (QoL) and the severity of behavioural problems shown by the patient were predictors of institutionalisation [odds ratios 1.10 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.19) and 1.08 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.15), respectively]. 40 However, in a similar study, de Vugt and colleagues41 found that it was the carer’s response to the behavioural symptoms (rather than the symptoms themselves) that predicted institutionalisation.

Measurement of disease

Details of individual measures used in the included trials can be found in Appendix 1.

A review of outcome measures used in clinical trials of drugs for AD by Wolfson and colleagues42 revealed a number of shortcomings in these measures. In particular, they found that several of the scales had weak psychometric properties, for example lack of responsiveness to change. Some studies had small sample sizes and others used inappropriate statistical analyses. 43

The progress and symptoms of AD can be measured through cognitive tests, behavioural measures, measures of functional ability/QoL and global rating scales.

A thorough assessment of cognitive ability would include measures of attention, processing speed, visuospatial function, praxis, language, executive function and abstraction. The most commonly used scales for this domain are the Mini Mental State Examination44 (MMSE) and the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale – Cognitive Subscale45 (ADAS-cog). Whereas the MMSE’s validity and reliability as a screening tool for AD have been established,44 it has problems with identifying change over time and scores are affected by people’s level of education. 46,47 Similarly, the ADAS-cog has been criticised for its insensitivity to change in cognitive ability at either end of the severity continuum. 48 It is concerning that the most commonly used instruments to measure change in cognitive function in drug trials for AD should be insensitive to change.

The measurement of behaviour change is important as it is these symptoms that many caregivers find most difficult to cope with, precipitating the transition into institutional care. 35,36 The most frequently used measure of behavioural change in AD trials is the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI). 49 This is a proxy-rated scale, usually completed by the main carer; its validity and reliability have been demonstrated by Cummings and colleagues. 49

There are two kinds of global rating scales for AD: those that measure the severity of illness at a point in time, for example the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) Scale50 and can, if used repeatedly, plot mental deterioration over time; the other sort of global instruments are change scales, such as the Clinician’s Interview-based Impression of Change – plus Caregiver Input (CIBIC-plus). 51 These measure broad changes in AD. However, their use may be biased towards cognitive abilities, as Claus and colleagues52 have found that clinicians may have a bias towards this aspect of AD, whereas carers place more emphasis on behavioural and psychological symptoms and functional ability. However, the use of CIBIC-plus may help to overcome this.

Measures of functional status in clinical trials are most commonly taken using the Activities of Daily Living (ADL) Scale53 or the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL). 54 Their reliability and validity has been described by McDowell and Newell. 55 However, this is not in the specific context of dementia.

Although the DEMQOL has been validated as a measure of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in people with dementia,56 in clinical trials the most frequently used measure is the patient-rated QoL scale. This is a seven-item patient-rated scale that measures feelings of well-being in the domains of relationships, eating, sleeping and social and leisure activities, on a 0–50 analogue scale. 57

Care for people with Alzheimer’s disease

The National Dementia Strategy for England58 says that everyone with suspected dementia should have access to ‘A rapid and competent specialist assessment; an accurate diagnosis sensitively communicated to the person with dementia and their carers; and treatment, care and support provided as needed following diagnosis’. The system needs to have the capacity to see all new cases of dementia in the area.

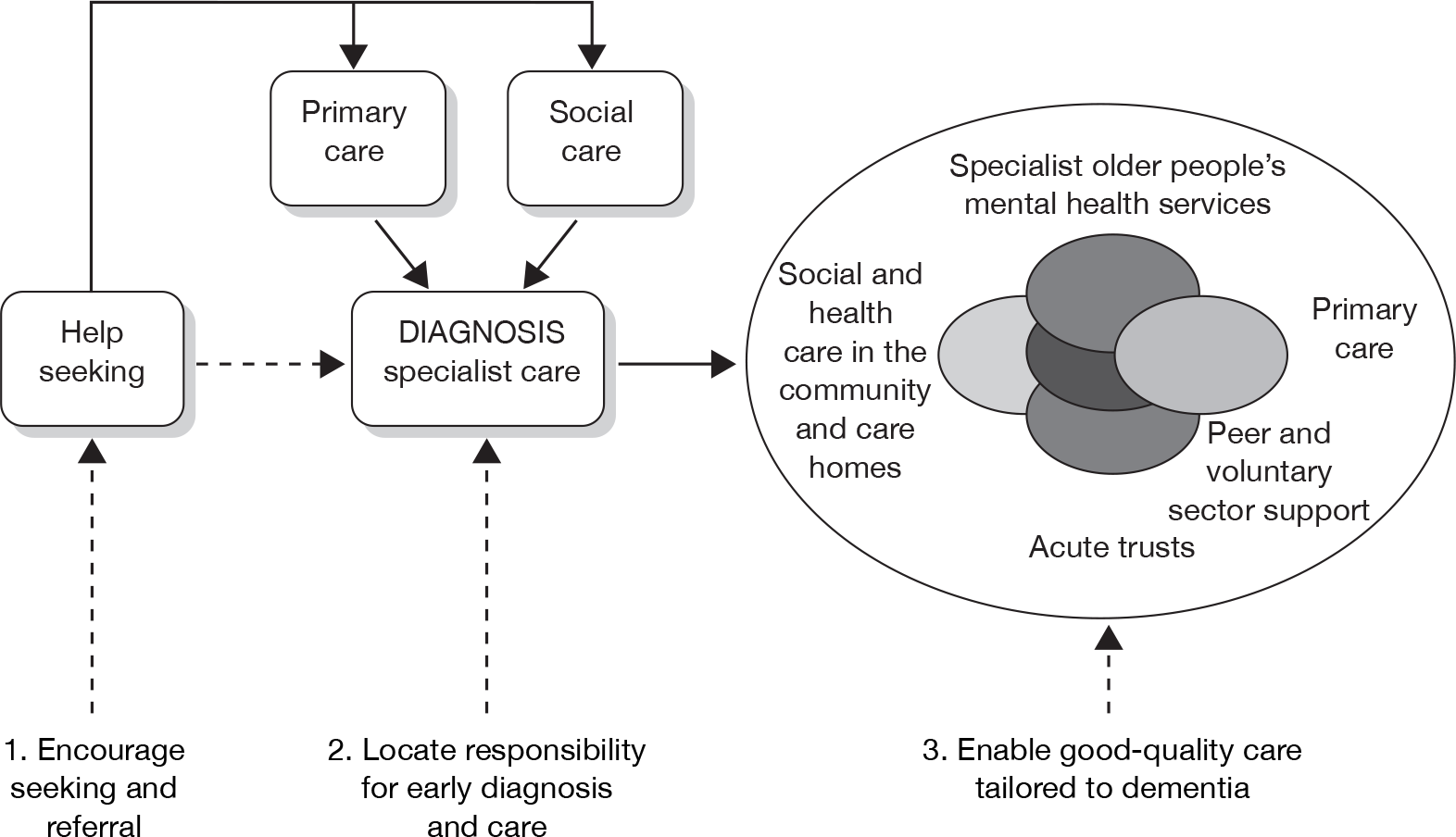

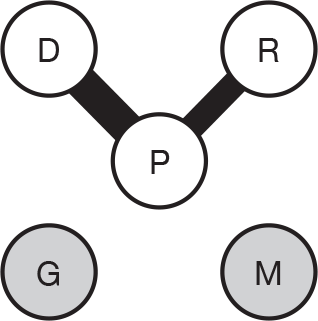

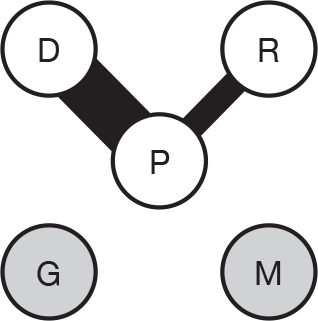

In order to achieve this goal the Department of Health has set out the following care pathway,58 as shown in Figure 2. A separate Dementia Action Plan has been developed for Wales.

FIGURE 2.

Care pathway summarising the three themes of the National Dementia Strategy and the commissioning challenges. Source: Department of Health 2009. 58

The provision of care for people with AD is complex, as it is shared between informal voluntary care, private care, social services and the NHS.

Informal care

Carers

An analysis of the General Household Survey (1998–9) data estimated that 53% of people over 65 years of age who could not live completely independently were supported by unpaid carers. 59 This estimate translates to approximately 4 million carers in England, most of working age. 60 Changing demographic patterns, with children living a considerable distance from their parents and more single people, may mean that this caring resource is reduced in the future. 61 Reports in the last decade have promoted support for carers: Support for Carers of Older People;60 Caring about Carers: A Strategy for Carers in Wales (Implementation Plan)62 and The NHS Plan. 63 However, many carers feel unsupported and isolated. 60 The burden of caring can affect the health and well-being of carers,64 possibly with high levels of depression,65 although another study found that over a 2-year period carers’ psychological well-being did not deteriorate. 66 Another effect of caring is the reduction of the capacity of the carer to earn a living. 67 The Medical Research Council’s Cognitive Function and Ageing Study (MRC CFAS) also found that 9% of carers of people with dementia had reduced their hours of work and one-fifth of carers who were younger than the statutory retirement age had given up work completely. 66

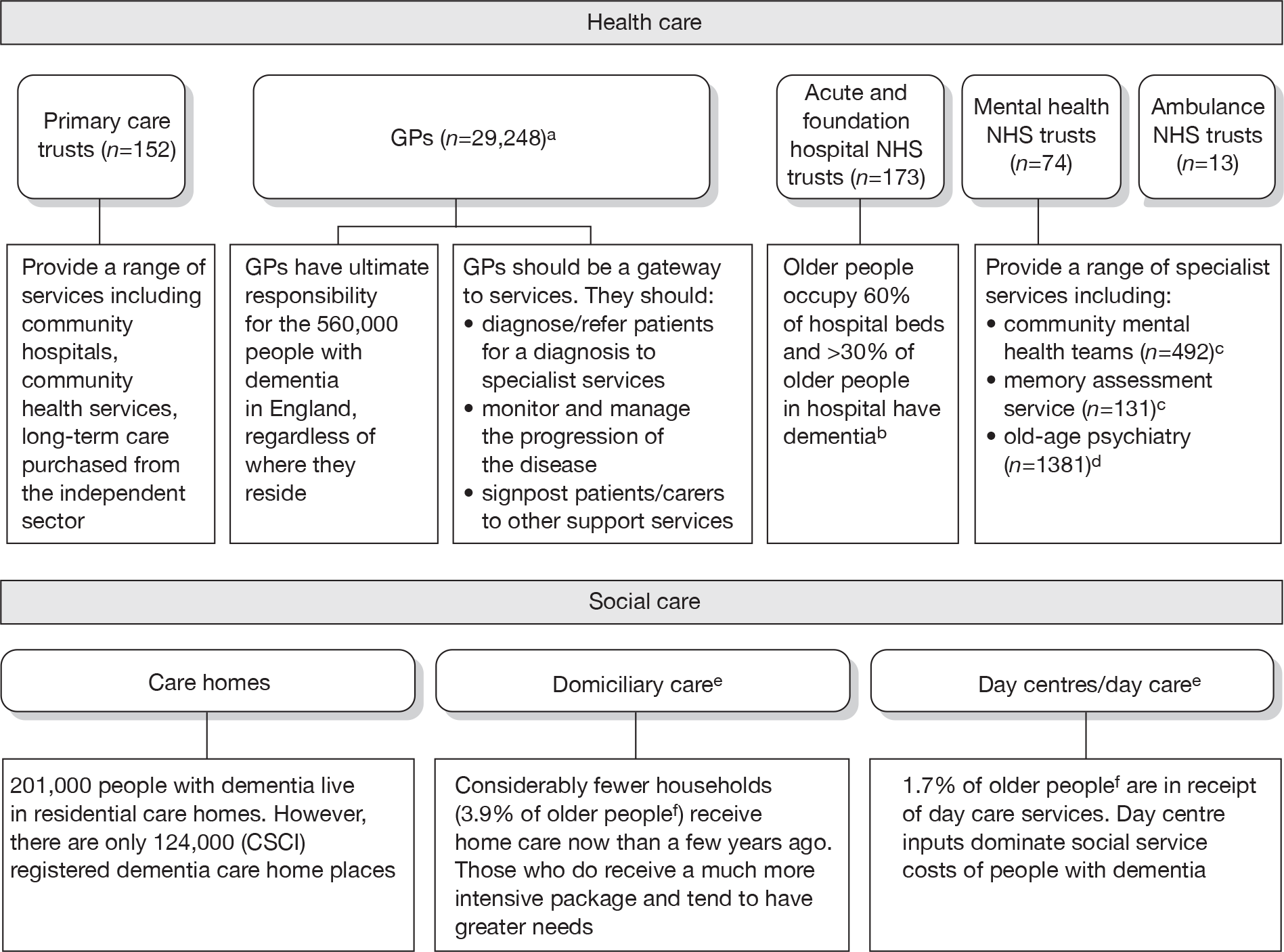

Formal care

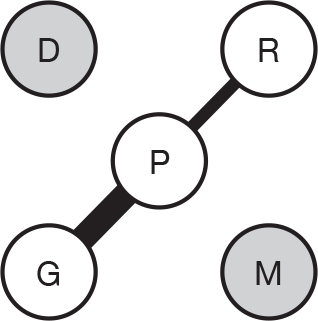

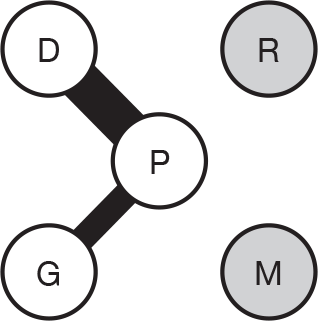

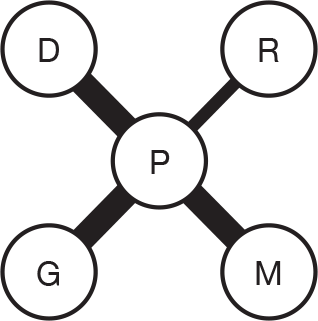

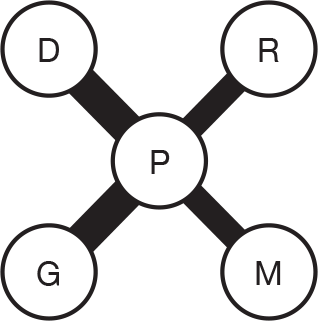

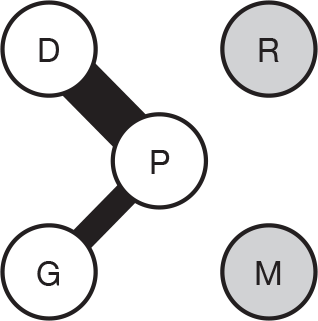

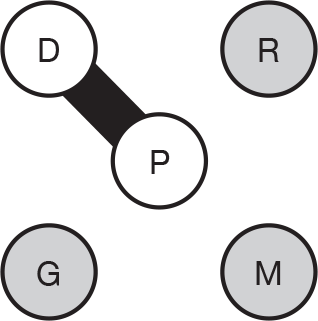

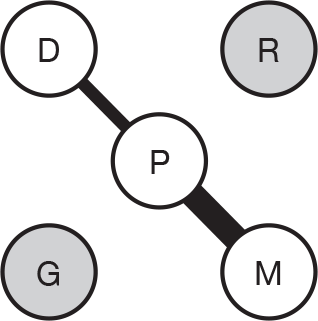

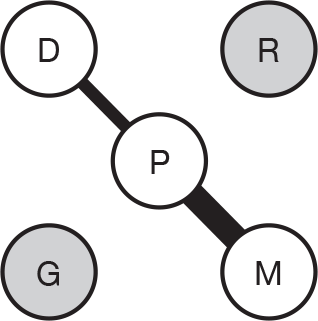

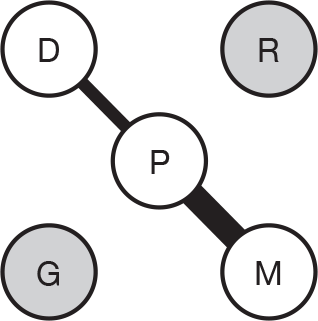

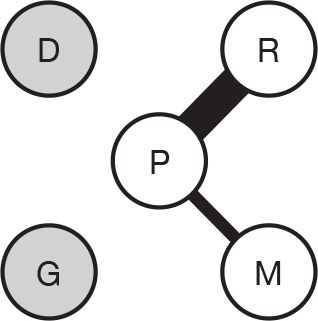

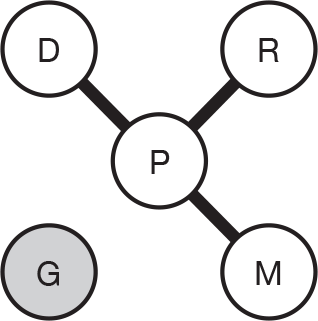

The formal care of people with AD falls mainly to the NHS and social services, although private and voluntary sector agencies are also involved. The NAO has produced a diagram to show the types of providers that are currently involved in dementia care (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Key public providers involved in the formal care of people with dementia. Source: NAO. 9 a, Royal College of General Practitioners;68 b, Royal College of Psychiatrists. 69 c, Barnes and Lombardo. 70 d, Membership Office. 71 e, Patients receiving domiciliary care may also be in receipt of day care and vice versa. f, Knapp et al. 8 Dementia UK report to the Alzheimer’s Society, King’s College London and London School of Economics and Political Science (older people are aged 65 years and over). The 2005 census data and Dementia UK both report that there are over 8 million older people in England.

In addition to informal care provided by unpaid carers, at any one time people with dementia will have, or need to, access to a range of health and social care services. For example, a person with dementia may receive services from the district nurse or community matron, see their GP, attend day care and be in receipt of domiciliary care. As the disease progresses, the needs of most people with dementia for domiciliary and other care and support will increase. Ultimately, a care home may become appropriate or the person with dementia may stay in their own home supported by various aspects of health and social care.

NHS services

The medical needs of people with AD span a wide range of specialties; as people with AD are usually elderly, comorbidities are common and their treatment is frequently complicated by the dementia. However, the main specialty involved is old age psychiatry, although, in the UK, a geriatrician may be responsible for diagnosis and treatment. The first contact a person with symptoms has is usually with primary care; a correct and early provisional diagnosis here is vital as this is the way into specialist care. 8

There are no nationally agreed criteria for referral; therefore, the burden of care falls differentially on primary and secondary care depending on location. The kinds of care provided can be grouped as either those for ‘serious mental illness’ or ‘early intervention’, depending on the severity of symptoms. The initial assessment of someone who may have AD is ideally conducted in their home, although many people with early stages of the disease are now seen in memory clinics. The home is a preferable setting to an outpatient department because it enables the assessor to see how the person functions in everyday situations. It also enables risk assessment of potential dangers in the home and is more likely to take place, as the possibly confused and forgetful person may lack understanding of their need to attend an assessment appointment.

Social services

Apart from cognitive and psychological decline, people with AD face a gradual loss of their ability to live independently. Initial support with everyday activities frequently comes from family and friends. However, where this is not available, and when the disease progresses, such support predominantly comes from social services, although private agencies may be involved.

There are no statistics about the total number of people with AD who are supported at home either by social services or the private sector. However, in England, there has been an increase in recent years, in the volume of home care bought by local authorities, a decrease in the numbers of people supported and an increase of support from private providers. 8 This means that fewer people are receiving help at home from social services than in the recent past, but those who do generally have greater needs and are receiving more comprehensive support. A consequence of this is that people are entering full-time residential care at later stages of AD. In Wales the picture is different, with a decrease in the amount spent on home care by local authorities. 8

In recent years the supply of residential care homes has been in decline in England and the balance of ownership has changed, with more homes now being in private hands. 8 Also the average size of a care home has increased to 34 beds and the quality of care provided continues to be variable; areas of concern include unstimulating environments and a low paid, poorly trained work force that has a high turnover, which undermines the building of relationships between staff and residents. 60 Standards have begun to rise as a result of regulation, according to the Audit Commission, but there is still a long way to go.

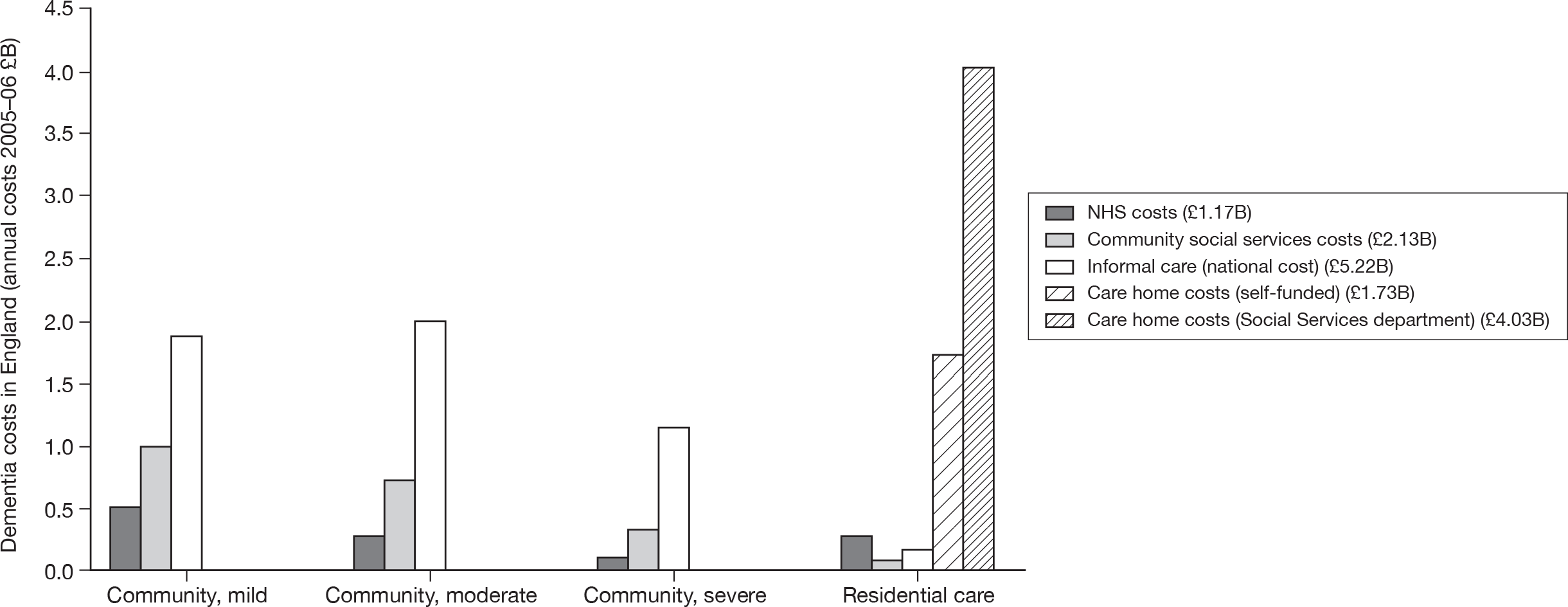

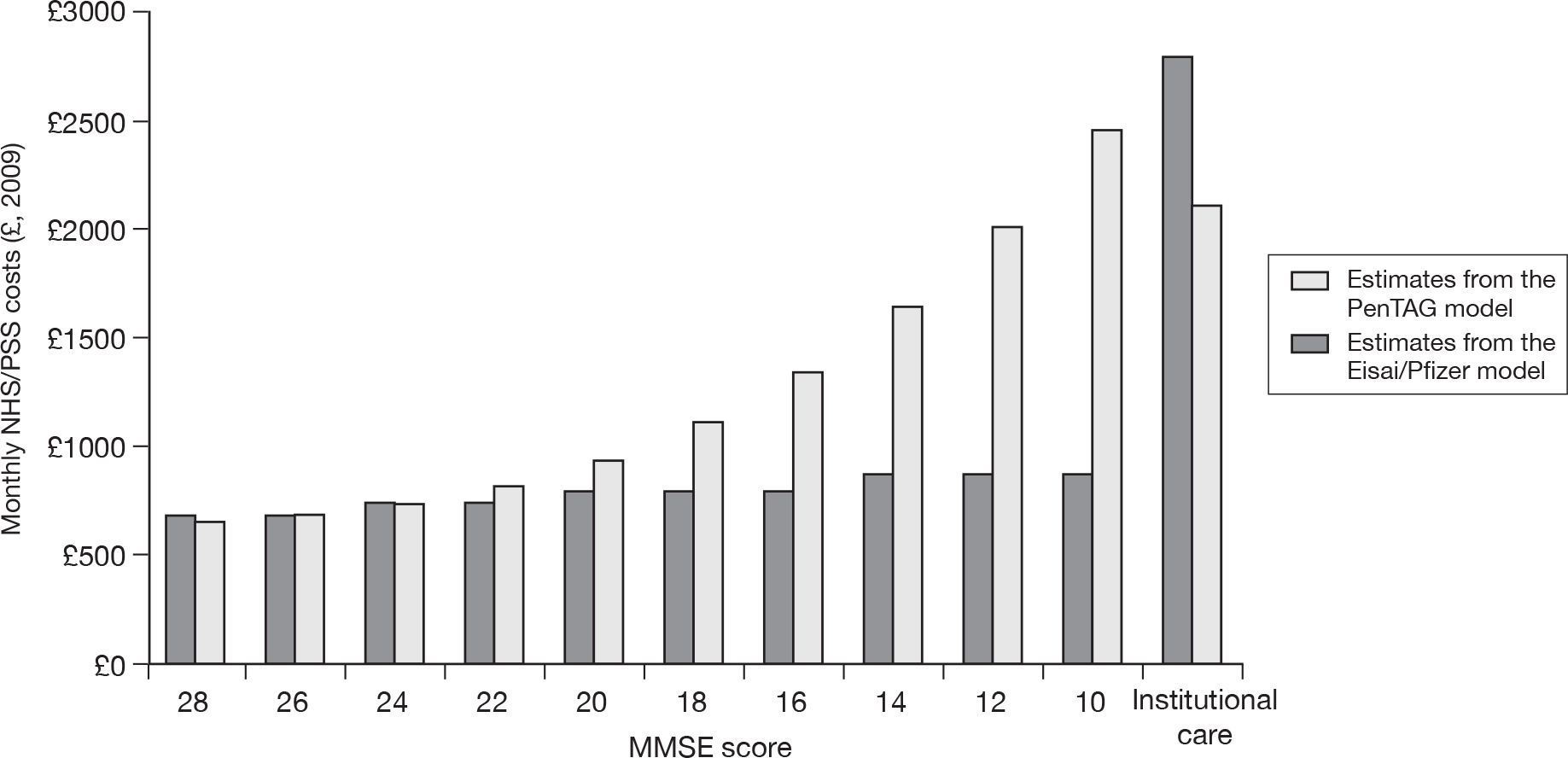

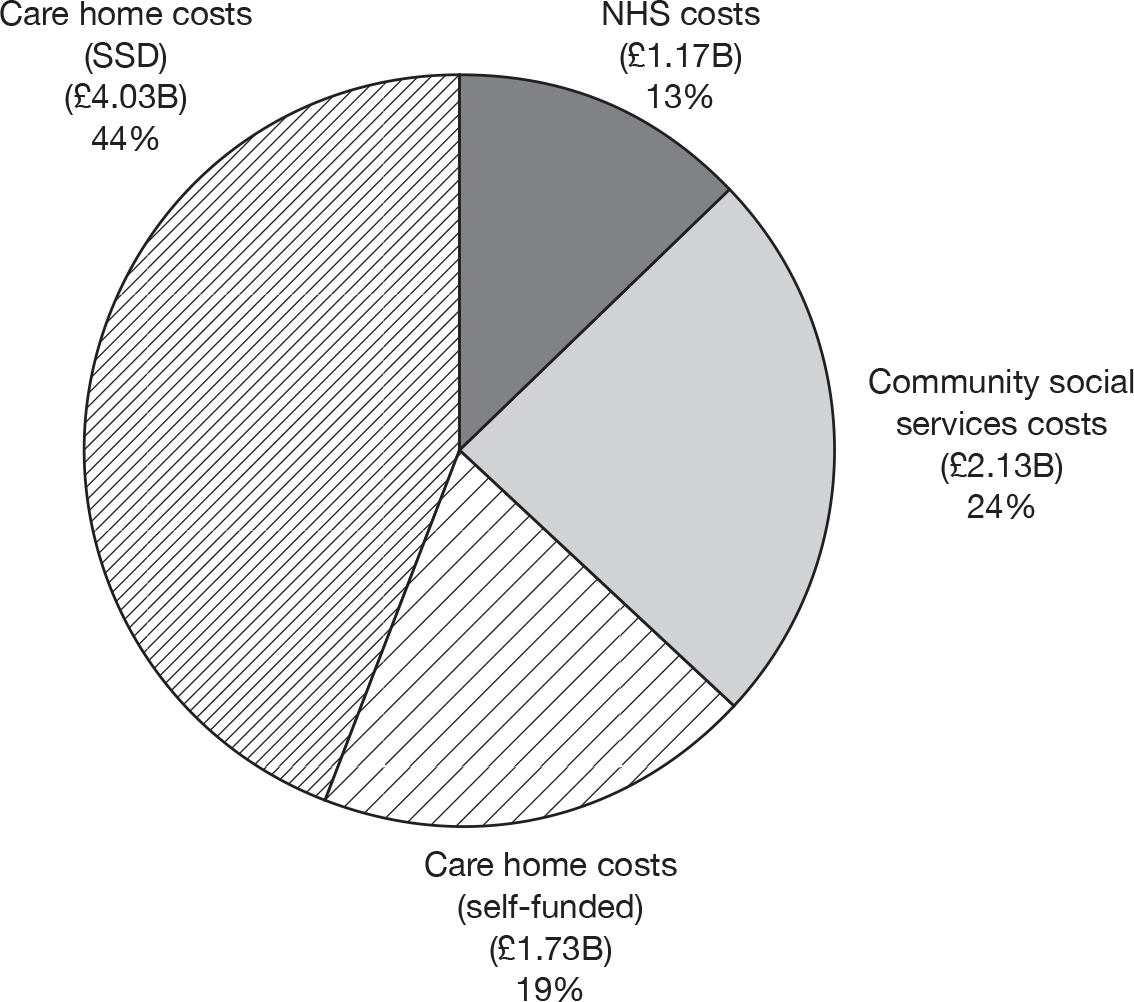

The cost of care: overview

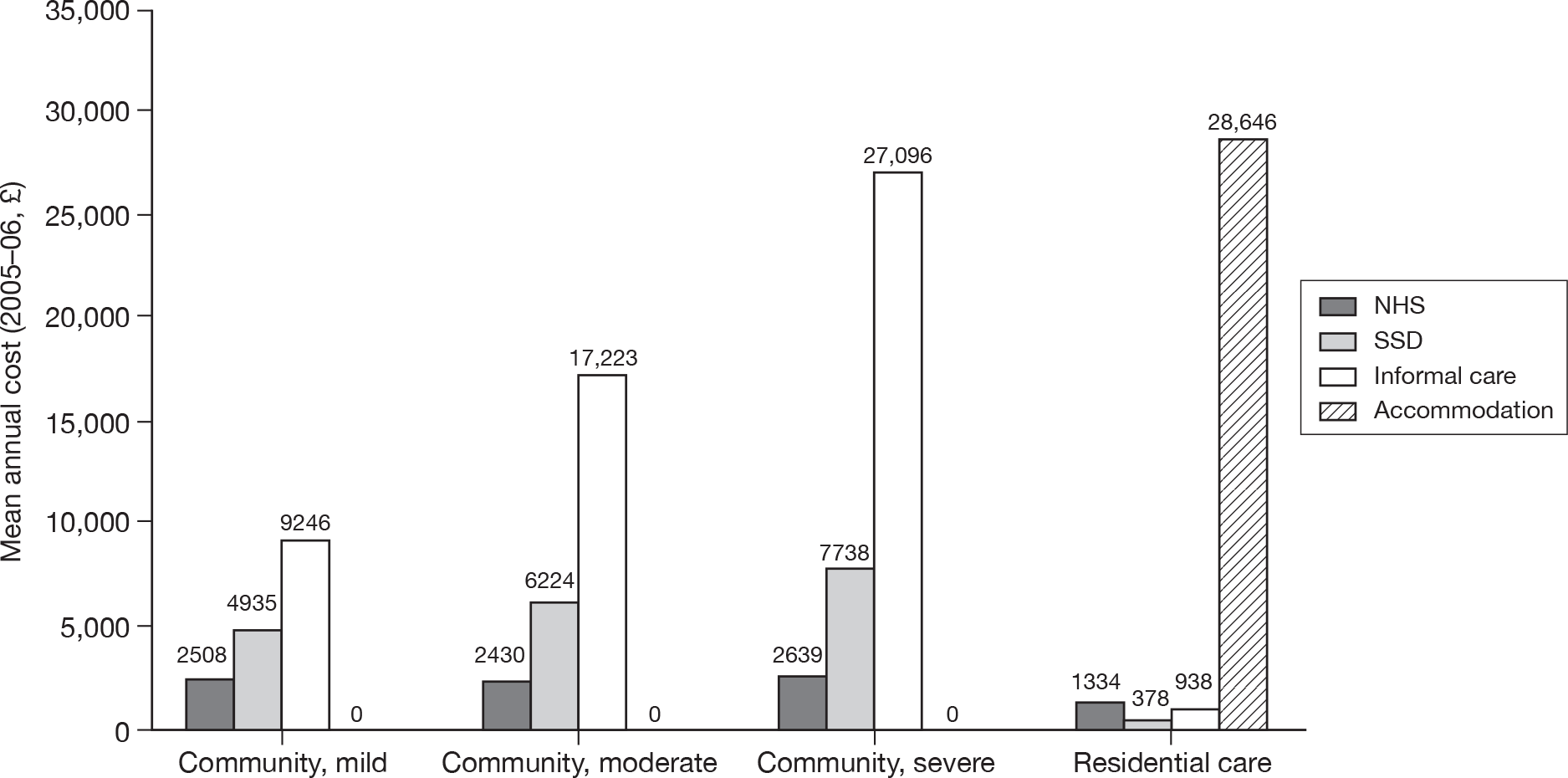

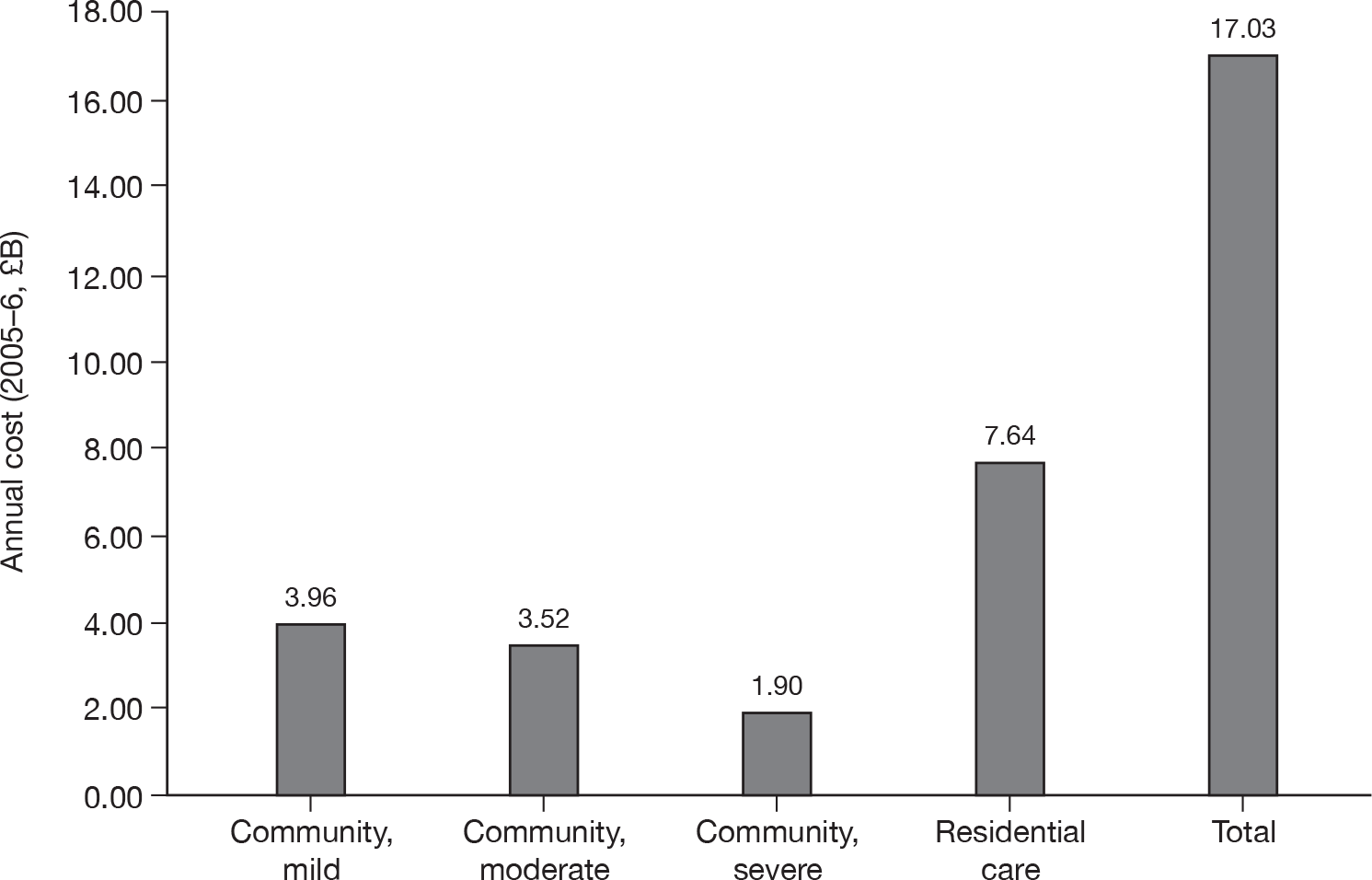

Around two-thirds of the care for people with AD comes informally from the community and it is the family who bares the greatest burden of cost. 9 The following diagram from the NAO report (Figure 4) shows how the cost of dementia was spread in England in 2005–6. [The categories of mild, moderate and severe dementia are based on the schedule named the Cambridge Mental Disorders of the Elderly Examination (CAMDEX). 72]

FIGURE 4.

Dementia costs in England 2005–6 by severity and place of residence. Source: NAO. 9 Dementia UK report to the Alzheimer’s Society, King’s College London, and London School of Economics and Political Science. Informal care is costed using (1) the hourly cost of a home care worker for specific tasks and (2) the minimum wage for time spent on general tasks and supervisory activities. The estimated service cost of late-onset dementia is over £14B per annum. Most of this is accounted for by supported accommodation (i.e. care home) costs and informal care (i.e. notional) costs. Some £6.87B is borne by people with dementia and their families.

It has been estimated in the recent Dementia 2010 report that these costs have risen to an annual cost to the UK economy of £23B per year (2007–8) (this compares with £12B per year for cancer and £8B per year for heart disease). The majority of this £12.4B cost fell on unpaid carers (55%); social services funded 40% (£9B) of the cost and the NHS funded 5% (£1.2B). 10

Presuming that 62% of people with dementia have AD (see Epidemiology), this translates to an annual cost to the UK economy of AD of over £14B per year. For each person with AD this gives an estimated annual cost of £27,647 – more than cancer (£6000), stroke (£5000) and heart disease patients (£3500) put together. 10 A full description of the costs of care for people with AD can be found in Chapter 7 (see Cost of health and social care received by Alzheimer’s disease patients).

Variation in services

The Dementia UK report8 indicated that there is a wide variation in the prescribing of anti-dementia medication in England and Wales. 8 Information specific to AD was not available, but it may be reasonable to suggest that the picture would be similar. The data were collected by IMS, a medical information consultancy, between October 2005 and September 2006 from 50% of the pharmacies in England and Wales, and represent 90% of all UK prescribing. This information is a reflection of national commissioning practice and shows, by PCT, the likelihood of being prescribed medication for dementia. The number of prescriptions per person with dementia in primary care varied from 12.0 prescriptions per year in Knowsley to 0.4 in West Berkshire. Most PCTs (75%) prescribed between 1.0 and 4.0 prescriptions per year. 8 The reason for this variation in provision is unclear.

National guidelines, guidance and reports

The following national guidelines, guidance and reports are related to this technology appraisal (TA).

-

Dementia 2010: The economic burden of dementia and associated research funding in the United Kingdom. 10

-

Living well with dementia: a national dementia strategy (2009). 58

-

NICE TA No. 111 entitled Donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine (review) and memantine for the treatment of AD (amended August 2009). 1

-

Dementia UK: the full report (2007). 8

-

Dementia: The NICE-SCIE Guideline on Supporting People with Dementia and their Carers in Health and Social Care (2007). 5

-

Improving services and support for people with dementia (2007). 9

-

Everybody’s Business – Integrated mental health services for older adults: a service development guide (2005). 73

-

Forget-me-not 2002: mental health services for older people – the Audit Commission. 74

-

National Service Framework for Older People (2001). 75

-

Forget-me-not: mental health services for older people – the Audit Commission (2002). 76

Description of technology under assessment

Summary of interventions

Three licensed acetylcholinesterase inhibitors

This technology assessment report (TAR) will consider four pharmaceutical interventions. Three have marketing authorisations in the UK for the treatment of adults with mild-to-moderately severe AD (measured by the MMSE score 26–10). These are donepezil (Aricept®, manufactured by Eisai Ltd), rivastigmine (Exelon®, manufactured by Novartis) and galantamine (Reminyl®, manufactured by Shire Pharma). They are acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs), which work by restricting the cholinesterase enzyme from breaking down acetylcholine, thus increasing the concentration and duration of acetylcholine at sites of neurotransmission.

Donepezil hydrochloride

Donepezil hydrochloride (Aricept®) is manufactured by Eisai Ltd and co-marketed with Pfizer Ltd. It was the first drug to be licensed in the UK specifically for AD. Donepezil is a reversible, specific AChEI. Donepezil is easily absorbed by the body and can be taken once a day, initially at 5 mg and then, after 4 weeks’ use, titrated up to 10 mg per day if necessary. Possible side effects associated with donepezil include, bradycardia (particularly in people with sick sinus syndrome or other supraventricular cardiac conduction conditions), seizures, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, muscle cramp, urinary incontinence, fatigue, insomnia and dizziness.

Rivastigmine tartrate

Rivastigmine tartrate (Exelon®) made by Novartis pharmaceuticals, is a selective inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase and also butrylcholinesterase, another enzyme. Owing to its short half-life (1.5 hours) it has to be taken twice a day. Doses start at 3 mg per day and increase gradually to between 6 and 12 mg per day. It can be taken orally or by a transdermal patch, with doses of either 4.6 or 9.5 mg/24 hours. Care should be used with people with renal disease, mild or moderate liver disease, sick sinus syndrome, conduction abnormalities, gastric or duodenal ulcers and a history of asthma or obstructive pulmonary disease. The main possible side effects found are nausea and vomiting, usually in the dose escalation phase.

Galantamine

Galantamine (Reminyl®) is manufactured by the Shire Pharmaceuticals Group. Galantamine was originally made from snowdrop and narcissus bulbs, but is now synthetically produced. It is a reversible inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase, with a half-life of about 7 hours, indicating that it should be taken twice a day at the recommended dose of 16–24 mg each time. An alternative version (Reminyl XL) is taken once a day at doses of 8, 16 or 24 mg. The side effects from galantamine are similar to those of the other AChEIs and are mainly gastrointestinal – abdominal pain, diarrhoea, nausea and vomiting – although bradycardia and dizziness have been reported.

Memantine hydrochloride

The fourth drug, memantine hydrochloride (Ebixa®), manufactured by Lundbeck, has a UK marketing authorisation for the treatment of people with moderate-to-severe AD (measured by the MMSE, score of ≤ 20). It is a voltage-dependent, moderate-affinity, uncompetitive N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist that blocks the effects of pathologically elevated tonic levels of glutamate which may lead to neuronal dysfunction. Memantine is taken orally twice a day. The starting dose is 10 mg/day and this can be increased to a maximum daily dose of 20 mg/day. Caution should be used when prescribing memantine for people with renal failure or epilepsy; it is also contraindicated for people with severe renal impairment. Side effects may include dizziness, confusion, headache and incontinence.

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Decision problem

The inclusion criteria for this assessment are as follows.

Population

The population for this assessment is adults with AD. However, as in the assessment that informed TA No. 111 (TA111),1 where trials have included participants with mixed dementias, these trials will be included where the dominant dementia is AD. Papers will be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Intervention

The intervention to be included is dependent on the severity of AD, measured by the MMSE criteria:

-

Mild AD (MMSE 21–26) – donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine.

-

Moderate AD (MMSE 10–20) – donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine and memantine.

-

Severe AD (MMSE < 10) – memantine.

Comparators

The comparators are again dependent on the severity of the AD:

-

Mild AD (MMSE 21–26) – placebo or best supportive care (BSC). (Best supportive care includes social support and assistance with day-to-day activities. These include information and education; carer support groups; community dementia teams; home nursing and personal care; community services, such as Meals on Wheels; befriending services; day centres, respite and care homes.)

-

Moderate AD (MMSE 10–20) – donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, memantine, placebo or BSC.

-

Severe AD (MMSE < 10) – placebo or BSC.

Outcomes

The outcomes of interest include measures of:

-

severity of disease and response to treatment

-

behavioural symptoms

-

mortality

-

ability to remain independent

-

likelihood of admission to residential/nursing care

-

HRQoL of patients and carers (where data permit, analysis will be carried out separately for patients alone, and for patients and carers combined)

-

adverse effects of treatment

-

cost-effectiveness and costs (review of economic studies).

Key issues

All medicines will be considered according only to their UK marketing authorisation.

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

The purpose of this assessment was to review and update as necessary guidance to the NHS in England and Wales on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine and memantine, within their UK licensed indications, for the treatment of AD, which was issued in November 2006, and amended in September 2001 and August 2009.

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

The purpose of the systematic review of clinical effectiveness is to record the studies found by Loveman and colleagues2 in 2004 and to update their findings with the results of subsequent trials.

This chapter has been arranged as follows:

-

methods for reviewing effectiveness

-

results of the systematic review

-

manufacturers’ reviews of clinical effectiveness

-

results – pair-wise comparisons

-

donepezil versus placebo

-

galantamine versus placebo

-

rivastigmine versus placebo

-

memantine versus placebo

-

-

head-to-head comparisons

-

combination therapy

-

results – multiple treatment comparisons

-

cognitive

-

functional

-

behavioural

-

global

-

-

summary of clinical effectiveness.

Methods for reviewing effectiveness

The clinical effectiveness of donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine and memantine for AD was assessed by a systematic review of research evidence. The review was undertaken following the principles published by the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD). 77 The study protocol can be viewed on the NICE website: www.nice.org.uk.

Identification of studies

Electronic databases were searched for systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and ongoing research in November 2009 and updated in March 2010; this updated search revealed no includable new studies. Appendix 2 shows the databases searched and the strategies in full. These included The Cochrane Library (2009 Issue 4, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials), MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, EMBASE, PsycINFO, EconLit, ISI Web of Science Databases – Science Citation Index, Conference Proceedings Citation Index, and BIOSIS, and the CRD databases – NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), Health Technology Assessment, and Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects databases. Where possible, a controlled trials and human filter was added. As this is an update of a previous review the searches were run in the time frame 2004 to current. The meta-register of controlled trials and ‘clinicaltrials.gov’ were searched for ongoing trials. Bibliographies of included studies were searched for further relevant studies. The reference lists of the industry submissions were also scrutinised for additional studies. Owing to resource limitations the search was restricted to English-language papers only. All references were managed using Reference Manager (Professional Edition, version 11; Thomson ISI ResearchSoft, Thomson Reuters, New York, NY, USA) and Microsoft Access 2003 software (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

Relevant studies were identified in two stages. Titles and abstracts returned by the search strategy were examined independently by two researchers (GR and MB) and screened for possible inclusion. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Full texts of the identified studies were obtained. Two researchers (GR and MB) examined these independently for inclusion or exclusion, and disagreements were again resolved by discussion. A third reviewer was available to resolve disagreements, but this was not necessary.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Study design

Inclusion criteria

For the review of clinical effectiveness, only systematic reviews of RCTs and RCTs were considered. The review protocol made provision for broadening the search criteria to include some observational evidence if insufficient systematic reviews or RCTs were identified; however, this proved unnecessary in view of the reasonable yield of evidence of a preferred design (see below).

Systematic reviews were used as a source for finding further RCTs and to compare with our systematic review. For the purpose of this review, a systematic review77–79 was defined as a review that has:

-

a focused research question

-

explicit search criteria that are available to review, either in the document or on application

-

explicit inclusion/exclusion criteria, defining the population(s), intervention(s), comparator(s) and outcome(s) of interest

-

a critical appraisal of included studies, including consideration of internal and external validity of the research

-

a synthesis of the included evidence, whether narrative or quantitative.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if they did not match the inclusion criteria, and in particular:

-

non-randomised studies [except for adverse events (AEs)]

-

animal models

-

preclinical and biological studies

-

narrative reviews, editorials, opinions

-

non-English-language papers

-

reports published as meeting abstracts only, where insufficient methodological details were reported to allow critical appraisal of study quality.

Population

Studies were included if they reported a population comprising adults with AD. Following the 2004 review, trials that included participants with mixed dementia were included if the predominant dementia was AD.

Participants in included trials were required to meet the definitions of disease severity specified in the technologies’ UK marketing authorisations (MMSE 26–10 for donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine; MMSE 20–0 for memantine).

The exact inclusion criterion adopted for MMSE scores was defined as an approximation of the principle that at least 80% of a study’s participants should be within the specified range. This approach relied on the assumption that reported baseline MMSE scores were normally distributed. On this basis, studies were included if the predefined thresholds were not exceeded by the reported mean baseline MMSE score ± 0.8416 standard deviation (SD), where 0.8416 is the inverse of the standard normal distribution corresponding to a probability of 0.8.

Interventions and comparators

Studies were included if the technologies they assessed fulfilled the following criteria:

-

Interventions The four technologies under review were considered within their UK marketing authorisations:

-

– mild-to-moderately severe AD (measured by the MMSE 26–10) – donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine

-

– moderate-to-severe AD (measured by the MMSE 20–0) – memantine.

-

-

Comparators For people with mild AD the comparators of interest were placebo and/or BSC (i.e. treatment without AChEIs and without memantine). For people with moderate AD the comparators were donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, memantine and placebo and/or BSC (i.e. treatment without AChEIs). For people with severe AD the comparator was treatment without memantine.

Outcomes

Studies were included if they reported data on one or more of the following outcomes:

-

measures of severity and response to treatment

-

behavioural symptoms

-

mortality

-

ability to remain independent

-

likelihood of admission to residential/nursing care

-

HRQoL of patients and carers

-

adverse events of treatment.

Data extraction strategy

Data were extracted by GR into forms in bespoke software and checked by MB. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. The items extracted can be found in the data extraction forms of included studies which are available in Appendix 3.

Critical appraisal strategy

Assessments of study quality were performed according to the instrument developed for the 2004 review (which was based on criteria recommended by the NHS CRD77). The instrument is summarised below; for full details, see Appendix 5 of the 2004 review. 2 Results were tabulated and the relevant aspects described in the data extraction forms.

Internal validity

The instrument sought to assess the following considerations:

-

Was the assignment to the treatment groups really random?

-

Was the treatment allocation concealed?

-

Were the groups similar at baseline in terms of prognostic factors?

-

Were the eligibility criteria specified?

-

Were outcome assessors blinded to the treatment allocation?

-

Was the care provider blinded?

-

Was the patient blinded?

-

Were point estimates and a measure of variability presented for the primary outcome measure?

-

Did the analyses include an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis?

-

Were withdrawals and dropouts completely described?

In addition, methodological notes were made for each included study, including the reviewer’s observations on sample size and power calculations, participant attrition, methods of data analysis, and conflicts of interest.

External validity

External validity was judged according to the ability of a reader to consider the applicability of findings to a patient group and service setting. Study findings can only be generalisable if they describe a cohort that is representative of the affected population at large. Studies that appeared representative of the UK AD population with regard to these considerations were judged to be externally valid.

Methods of quantitative synthesis

Where data permitted, the results of individual trials were pooled using the methods described in the following section.

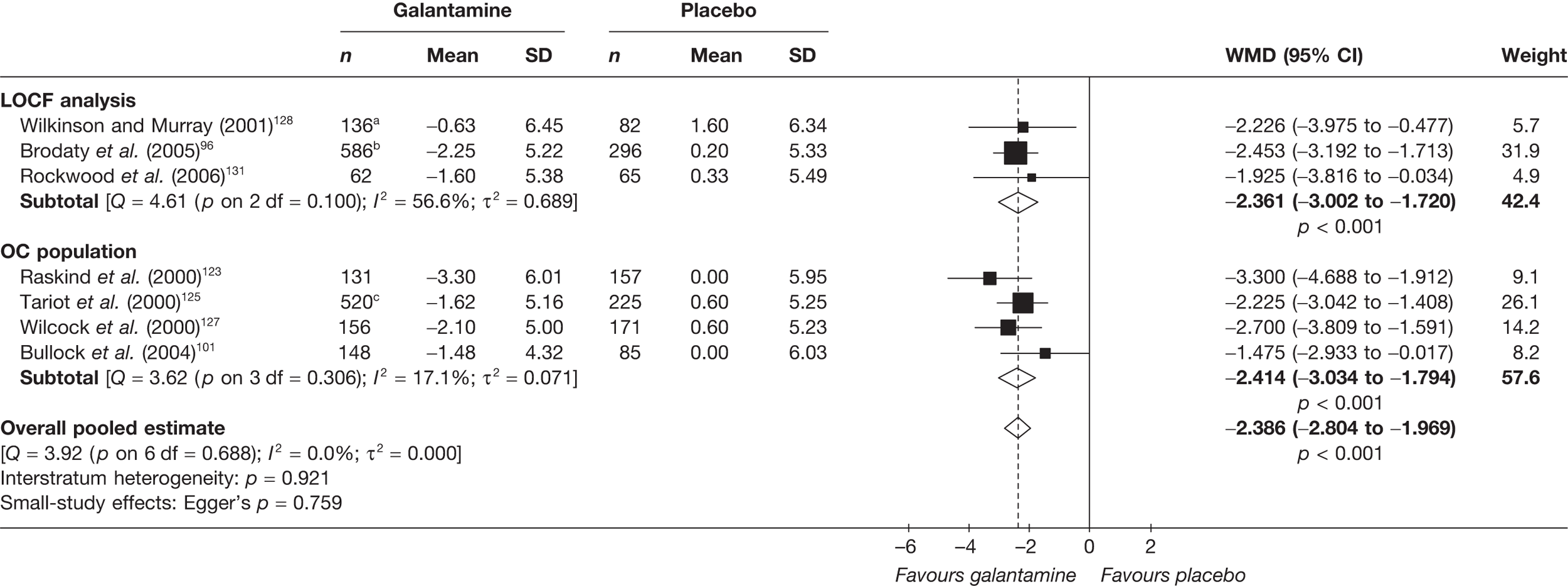

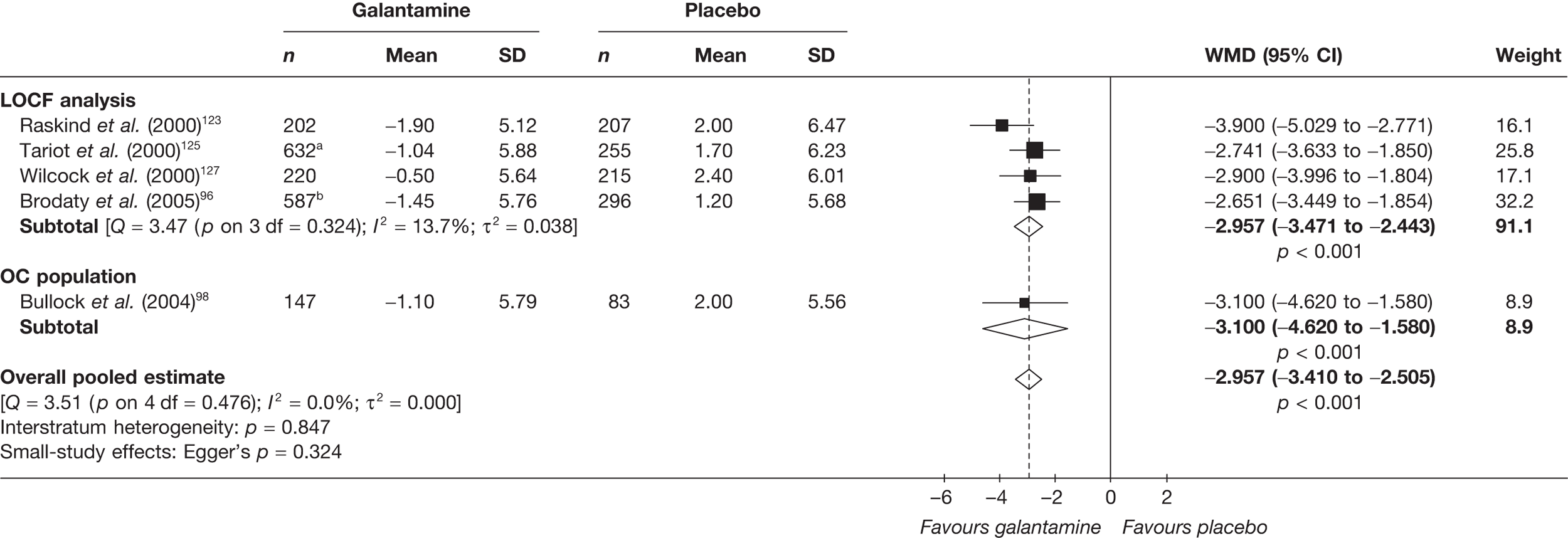

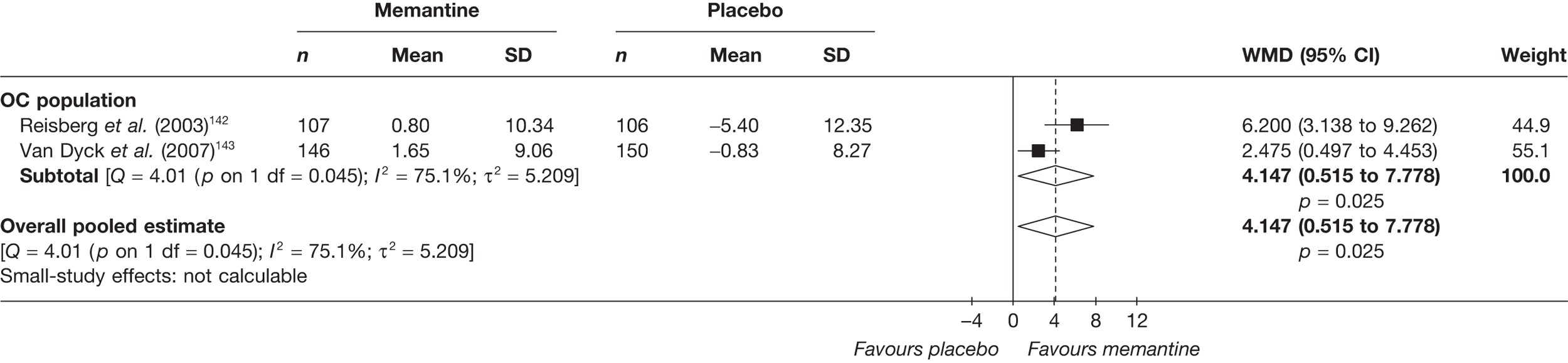

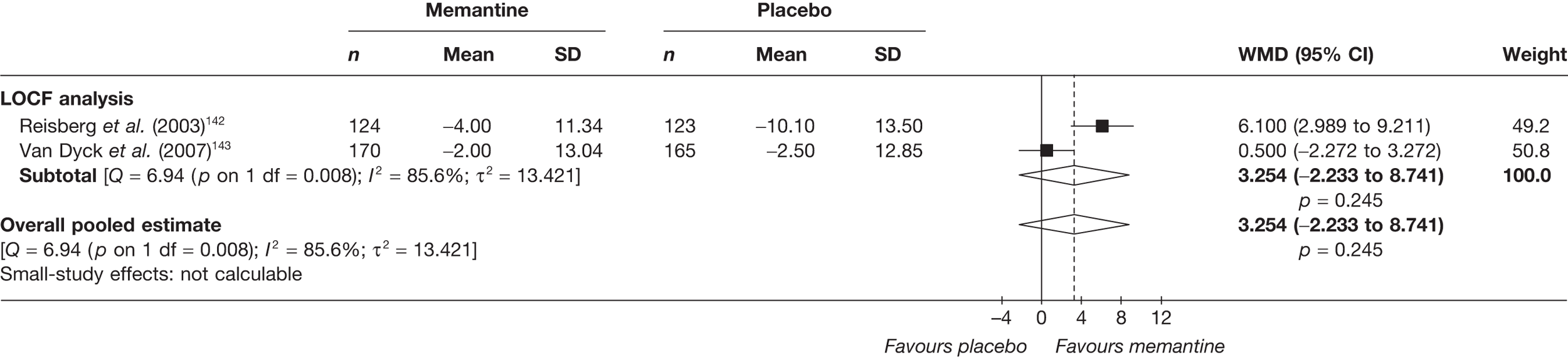

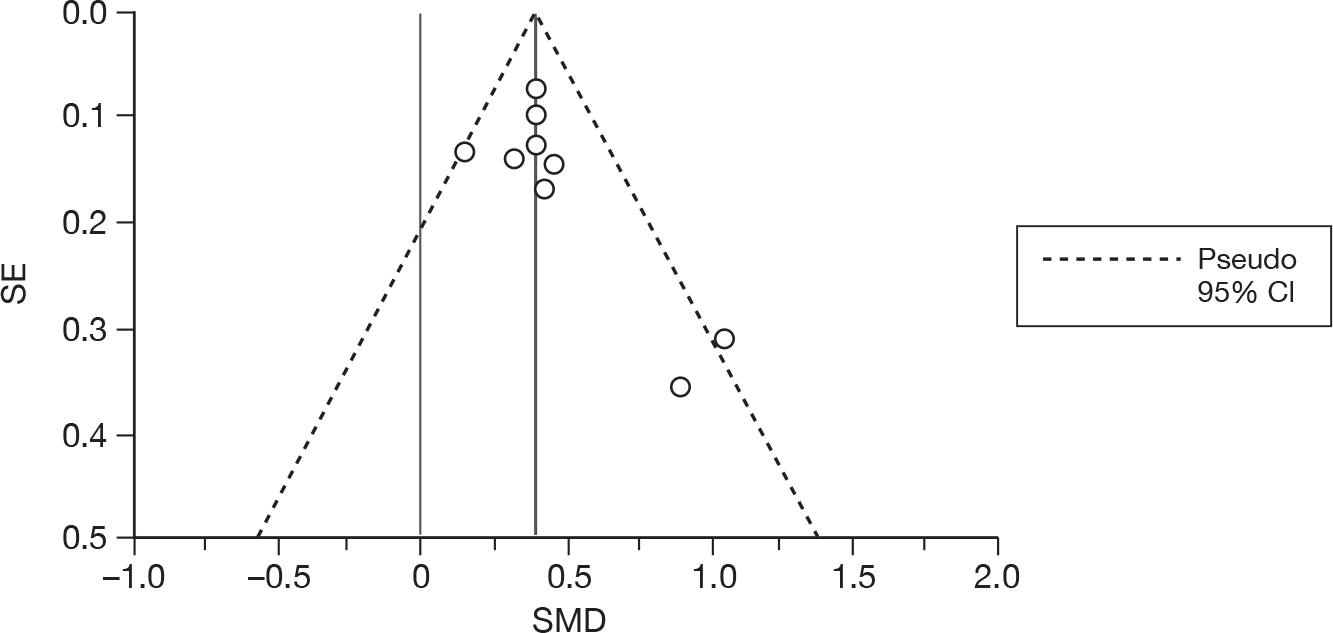

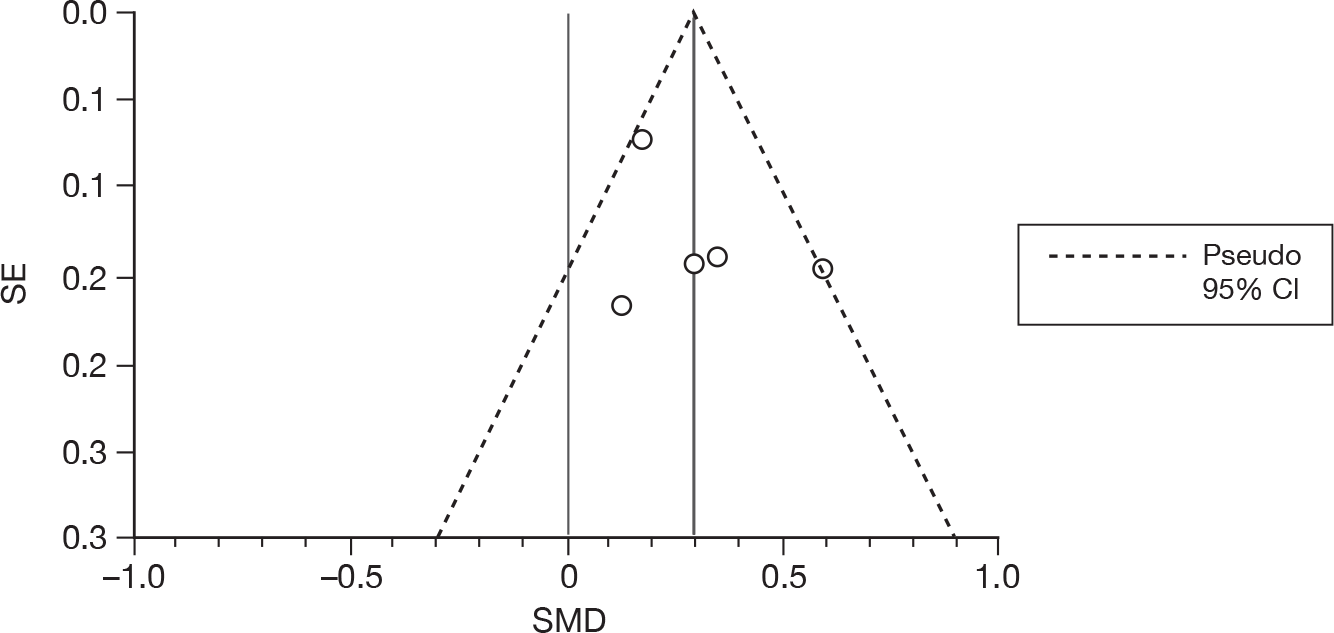

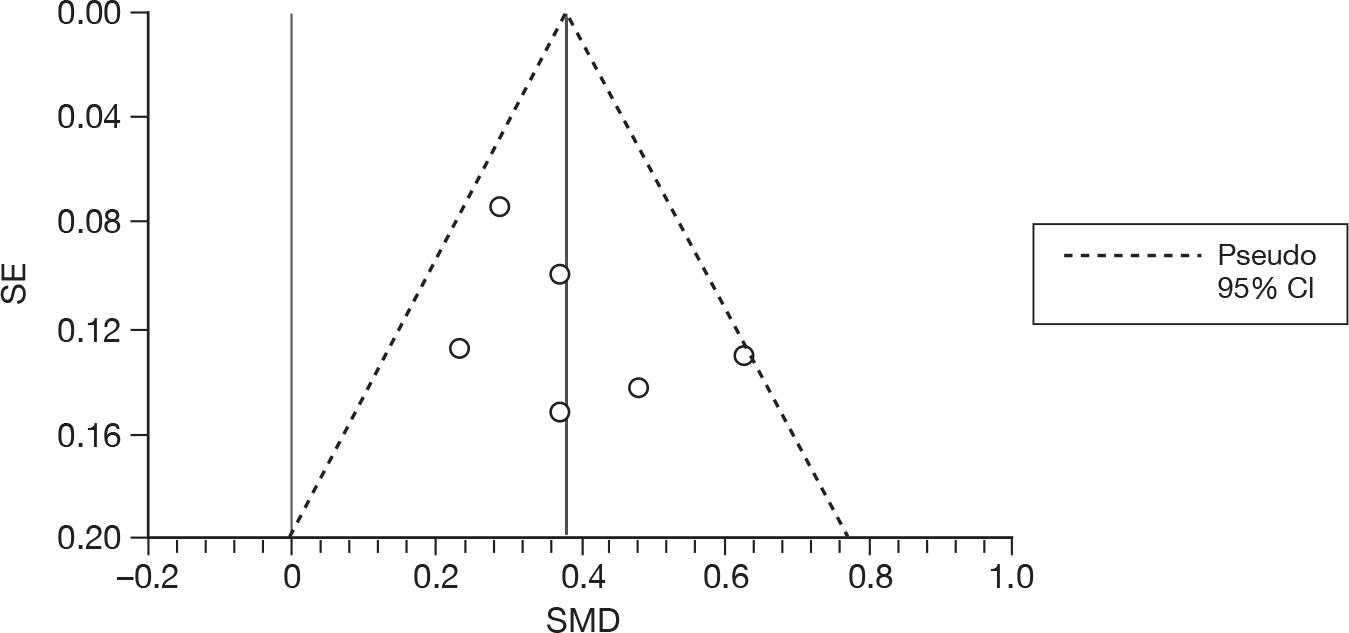

Pair-wise meta-analysis

We used random-effects meta-analyses (DerSimonian and Laird model80) only, regardless of any statistical evidence of interstudy homogeneity. Heterogeneity was explored by visualisation of results and, in statistical terms, both Cochran’s Q-test (compared with a chi-squared distribution)81 and the I2-statistic. 82,83 Small-study effects (including publication bias) were visualised using funnel plots and quantified using Egger’s test84 (see Appendix 4). Analyses were conducted using bespoke software, written in Microsoft Visual basic for Applications (version 6) and applied in both Microsoft Access 2003 and Microsoft Excel 2003 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Stata 10.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used to generate forest plots (‘metan’ command) and to assess small-study effects (‘metabias’ command).

Where more than one arm of a contributing trial was relevant to any analysis, data were pooled to form a single meta-arm as the unit of analysis, as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (section 16.5.4). 85 For the continuous outcome measures reported in this review, the mean for the combined arm is estimated as the weighted mean from the multiple separate arms (where the numbers in each arm provide the weights), and the SD for the combined arm is calculated according to the usual formula:

where i indexes a total of k arms being combined, ni is the number of participants in each arm, and si is the SD for that arm.

All meta-analyses were stratified according to the measurement population. Where multiple-measurement populations were reported in an individual study, we used the highest ranking according to a prespecified hierarchy:

-

true ITT

-

last observation carried forward (LOCF)

-

observed cases (OCs) only.

The issue of how to deal with missing data point from dropouts in ITT analysis of dementia patients is a contentious one. Owing to the natural course of this degenerative disease, the assumption of LOCF that disease progression stops at the last data point clearly does not reflect reality. Similarly, to use OCs only (i.e. not estimating any data points after dropout) may give misleading results. A better solution may be to apply the rate of decline found in the control group to all dropouts. 86

We performed separate analyses for different periods of follow-up. The two lengths of follow-up for which data were generally available were approximately 3 months (12–16 weeks of treatment) and approximately 6 months (21–28 weeks) (figures showing these results are in the body of the text).

Where different dosages of drugs were found in various studies, we meta-analysed comparable groups separately (figures for commonly used doses in the UK are in the body of the text). We also performed a single analysis in which all dosages were combined (figures from these analyses are in Appendix 5). For continuous outcomes measured over a longitudinal period of follow-up, it is possible for investigators to report outcomes in two ways: the mean of each participant’s observed change from a measured baseline score (mean change from baseline) or absolute measurements at the relevant juncture (absolute value). If randomisation is adequate, the difference between these values should be the same (i.e. the mean of the differences will be the same as the difference in the means). However, the dispersion of each measure may vary. It is stated in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (section 9.4.5.2) that ‘[t]here is no statistical reason why studies with change-from-baseline outcomes should not be combined in a meta-analysis with studies with final measurement outcomes’. 85 However, exploratory analyses showed that the inclusion of both types of data led to large differences in the results of meta-analyses, although this may be because the studies that only report final measurement data tend to be of a lower methodological standard (and, therefore, may also be more susceptible to biases that would distort reported treatment effect). As a result, we were not prepared to pool the two types of measurement, and all of our meta-analyses rely on studies reporting mean change from baseline only.

Pooling of multiple outcome measures

In addition to pair-wise meta-analyses of treatment effect pooled on each outcome’s natural scale [weighted mean difference (WMD)], we combined outcomes in a series of broad domains – cognitive, functional, behavioural and global – to investigate the overall characteristics of reported effectiveness evidence in each area (see figures in the body of the text and data sets used in the meta-analysis of pooled multiple outcome measures in Appendix 6).

In order to combine studies using different outcome measures within each domain, effect sizes were expressed as a standardised mean difference (SMD). The SMD expresses the size of the treatment effect in each trial relative to the variability observed in that trial. Accordingly, for a given trial i,

where m1i and m2i represent the reported means in active treatment and control cohorts, respectively, and si is the pooled SD across both groups, estimated as

where n1i, n2i and Ni represent the sample sizes of treated, control and combined cohorts, respectively, and the reported SDs of measurements in treated and control groups are SD1i and SD2i. In order to pool SMDs, it is necessary to derive the standard error (SE), which is estimated as follows:

The method assumes that the differences in SDs between studies reflect differences in measurement scales and not real differences in variability among study populations.

Where studies reported more than one outcome contributing to the same domain, a weighted average of all SMDs was calculated, using the precision of the estimates as the weighting factor (this could be seen as a submeta-analysis, adopting a fixed-effects model with inverse variance weighting). So that such studies were not given spurious weight, the sample size for each outcome measure was divided by the total number of outcomes.

This approach has the advantage of enabling a broader evidence base to be combined, but it has the disadvantage of requiring estimates to be pooled on a scale that has no direct clinical meaning. Accordingly, we used these analyses solely to explore the characteristics of the evidence base, and not to draw direct conclusions about the magnitude of relative effectiveness of the comparators. In particular, we used the analyses as a basis for metaregression (see below), and for assessing small-study effects.

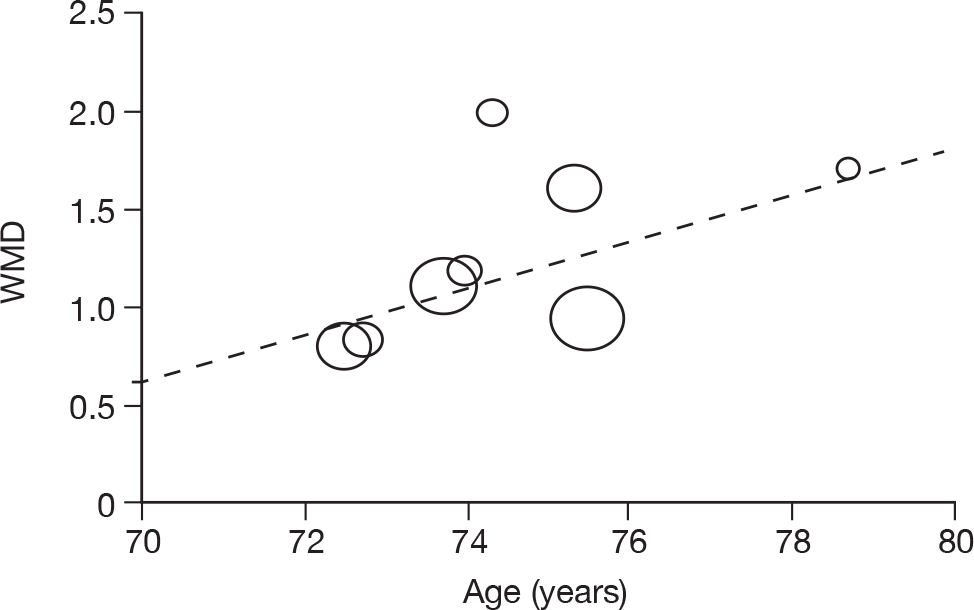

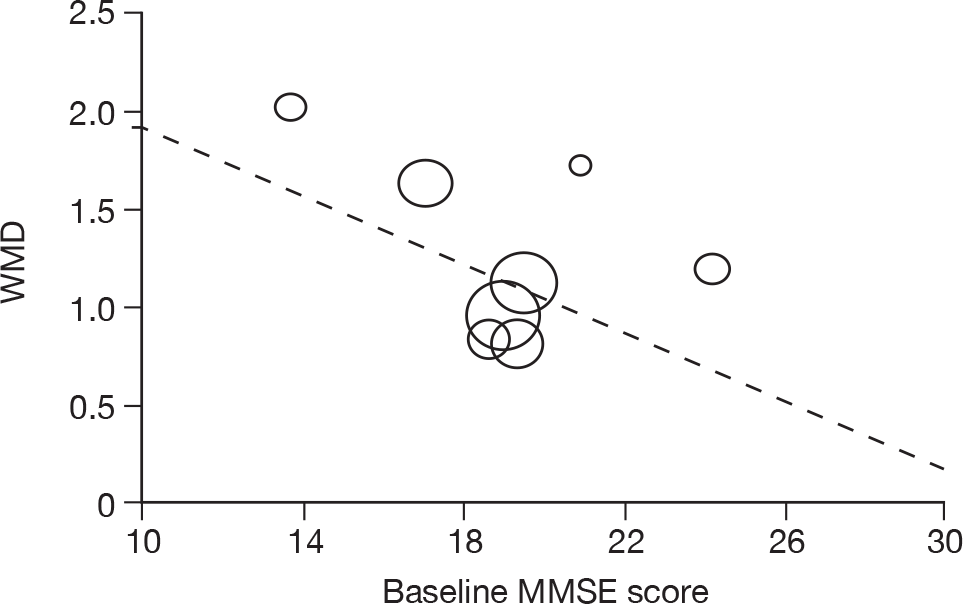

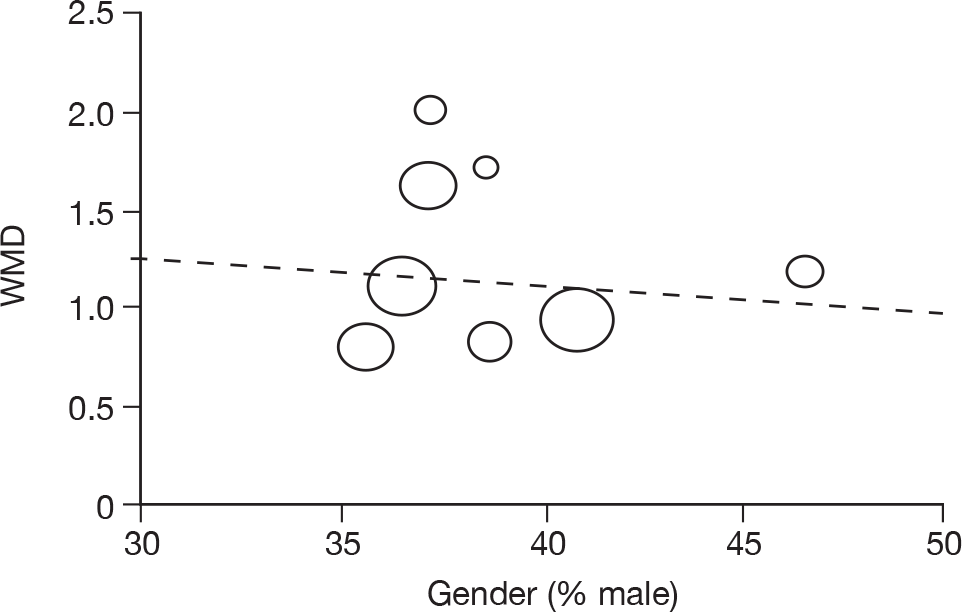

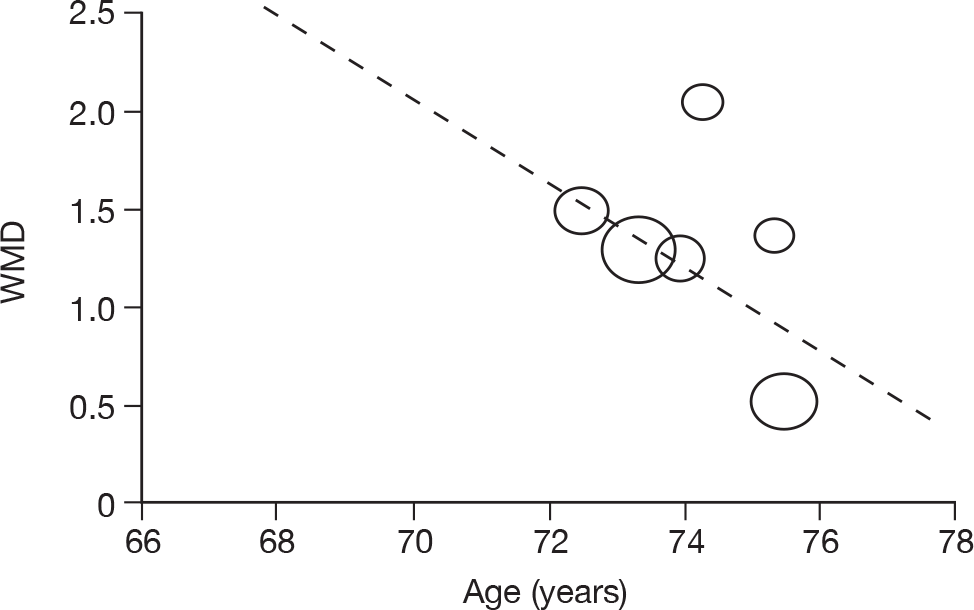

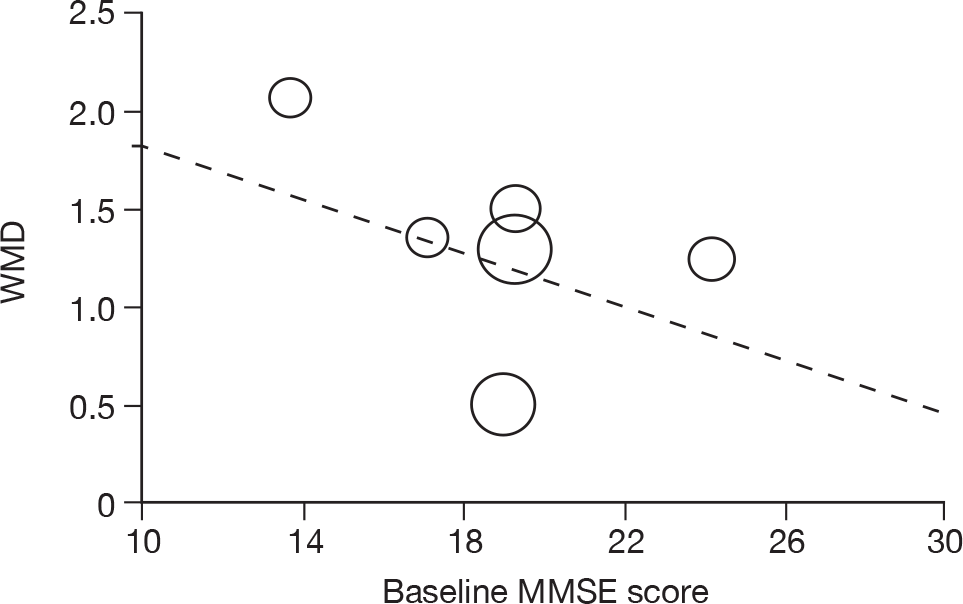

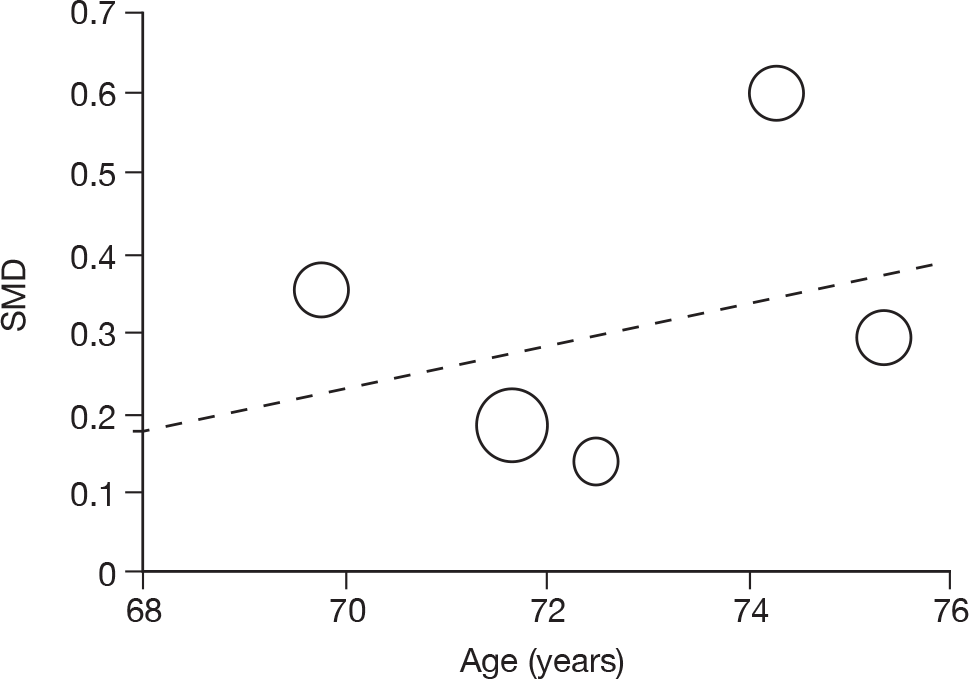

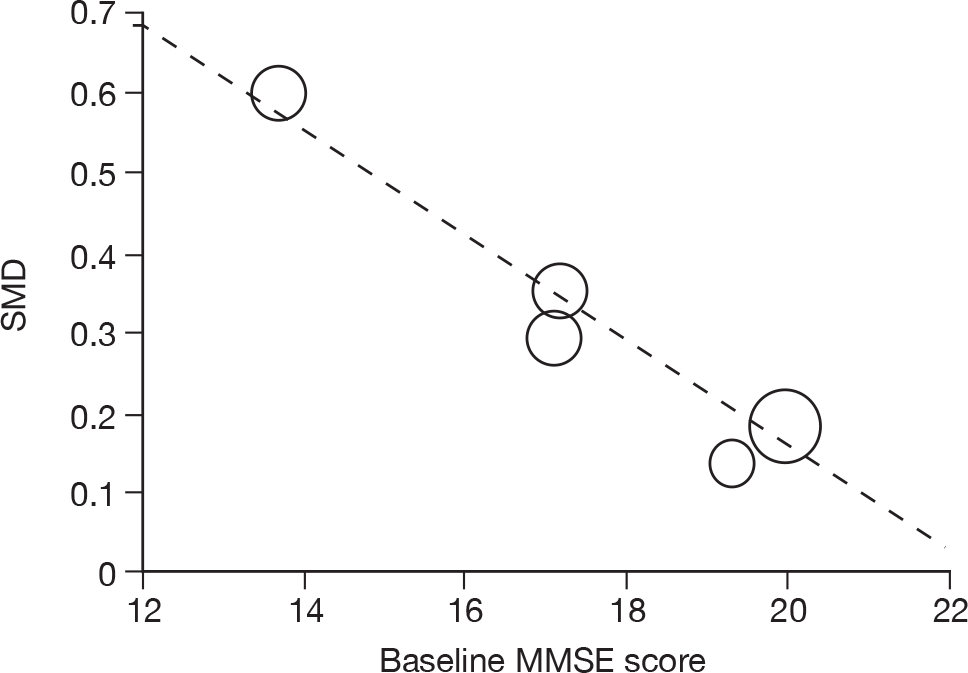

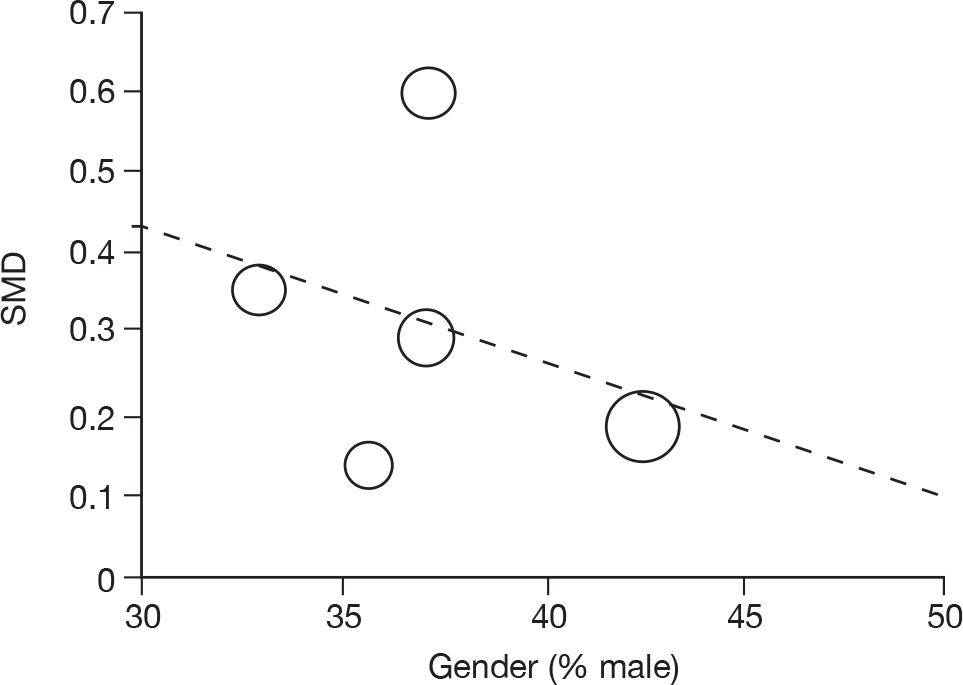

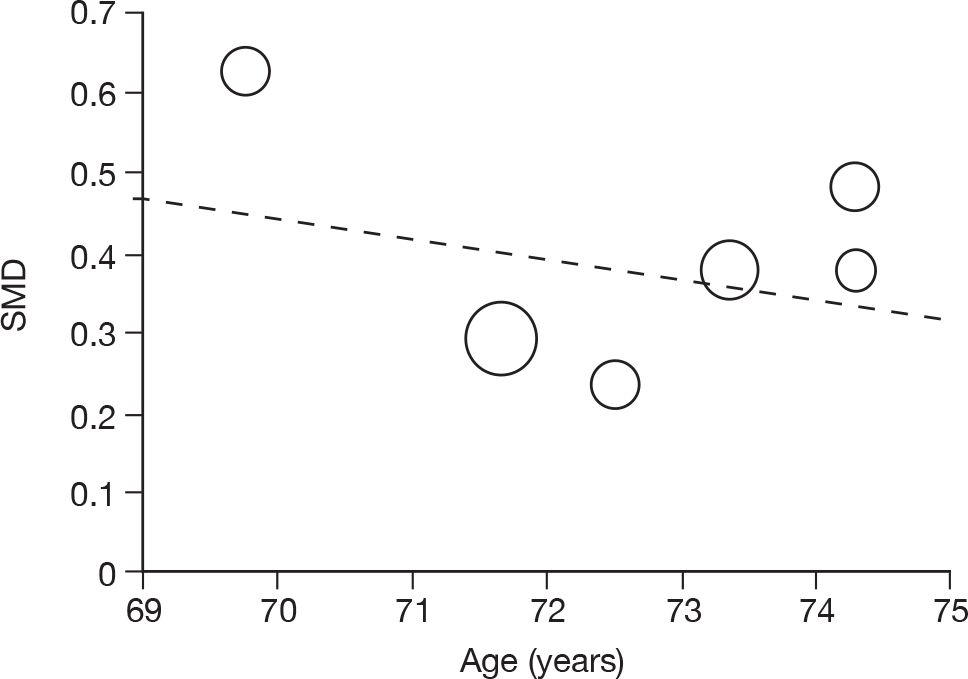

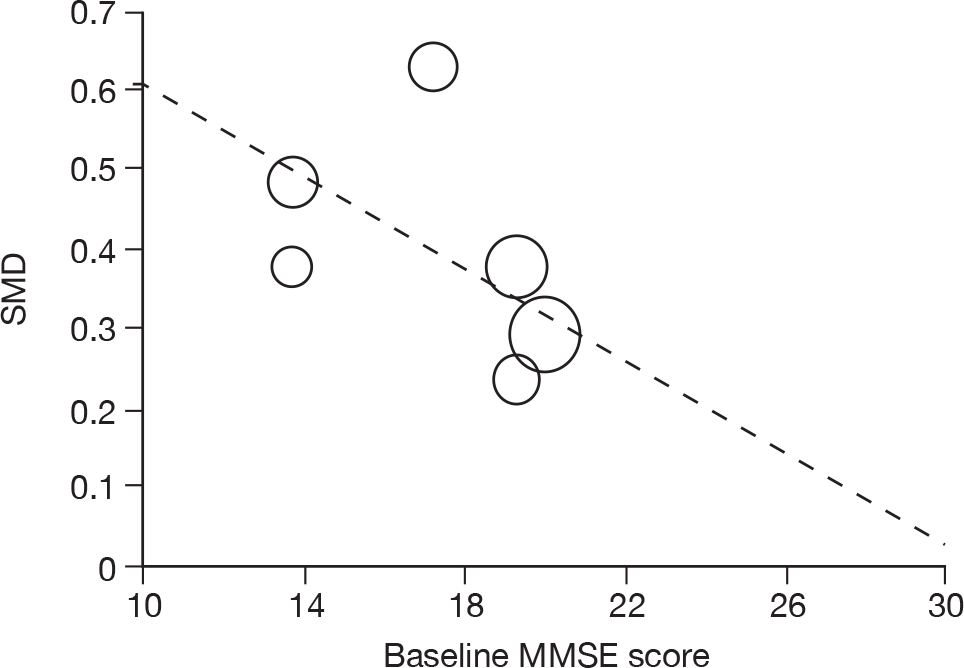

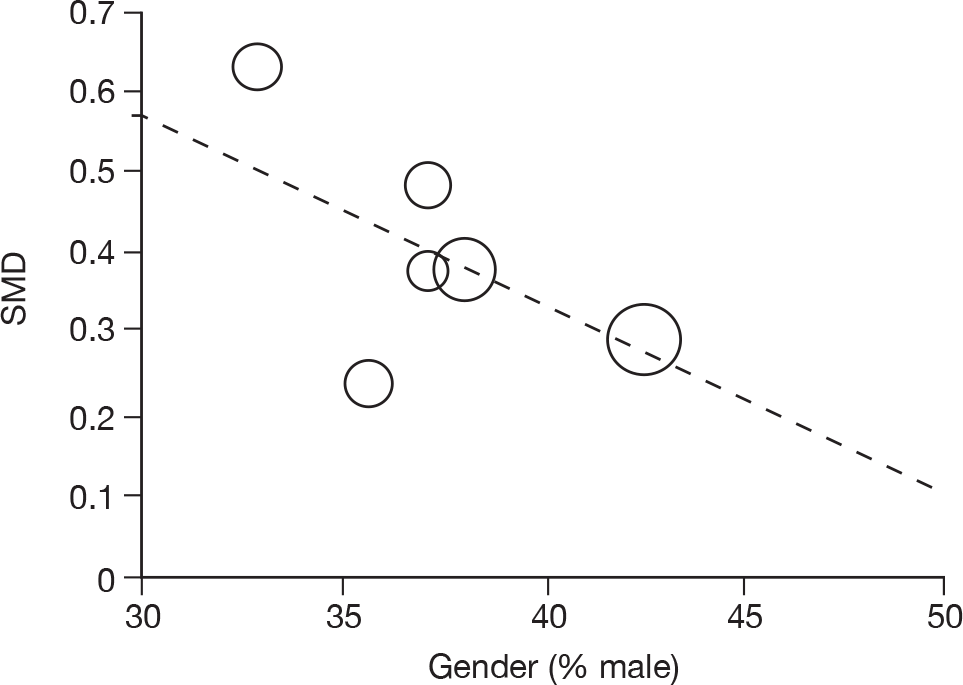

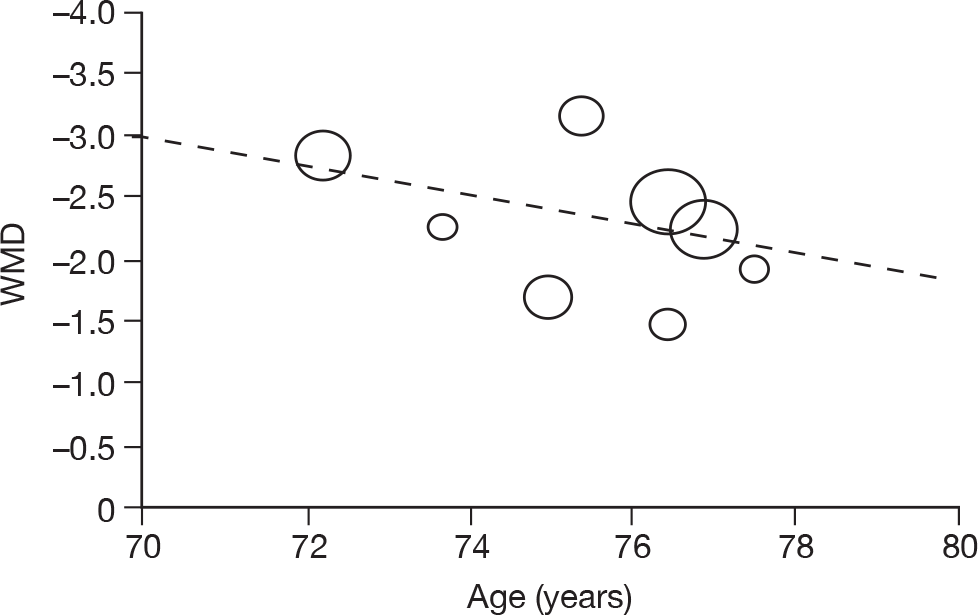

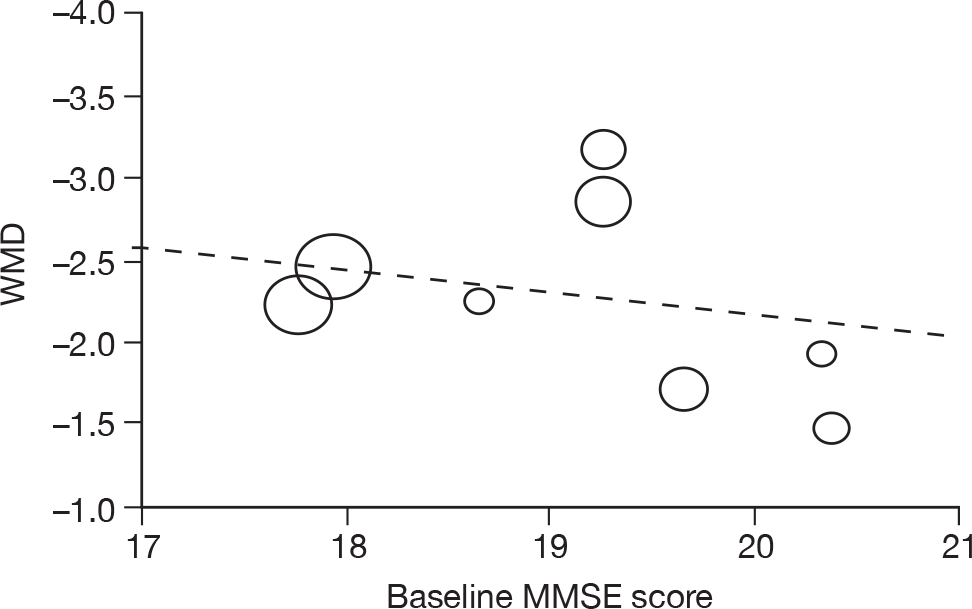

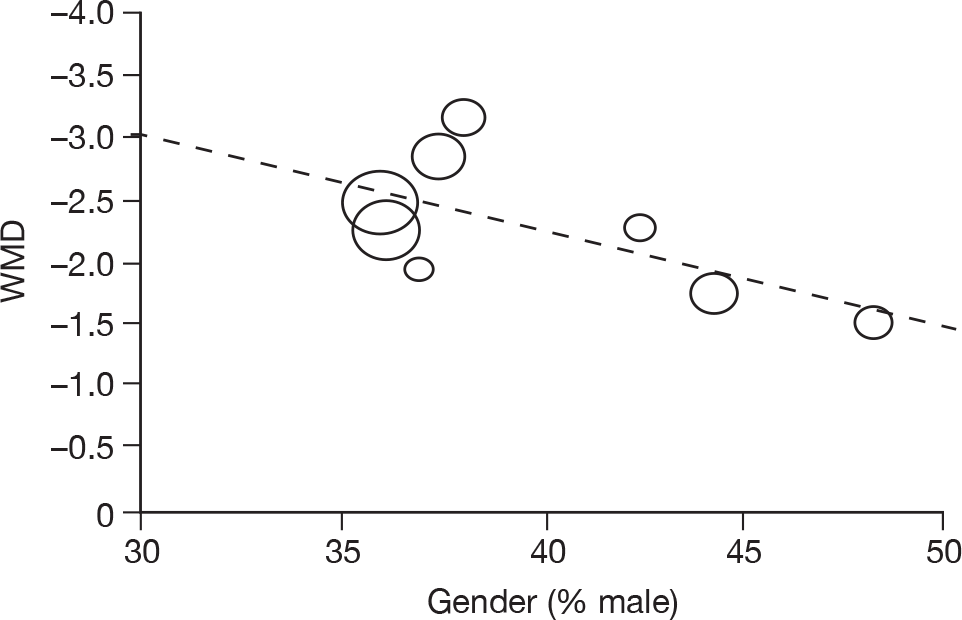

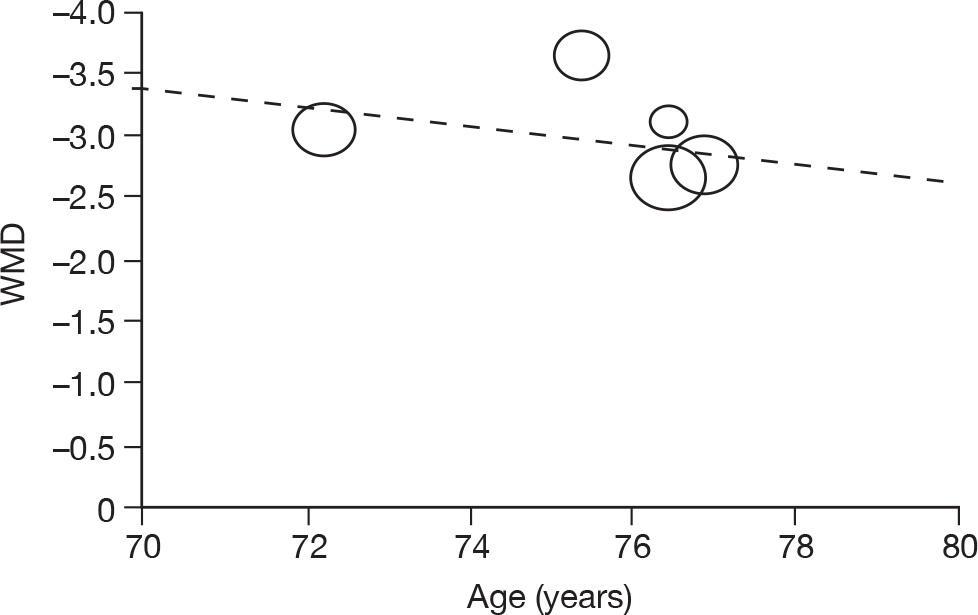

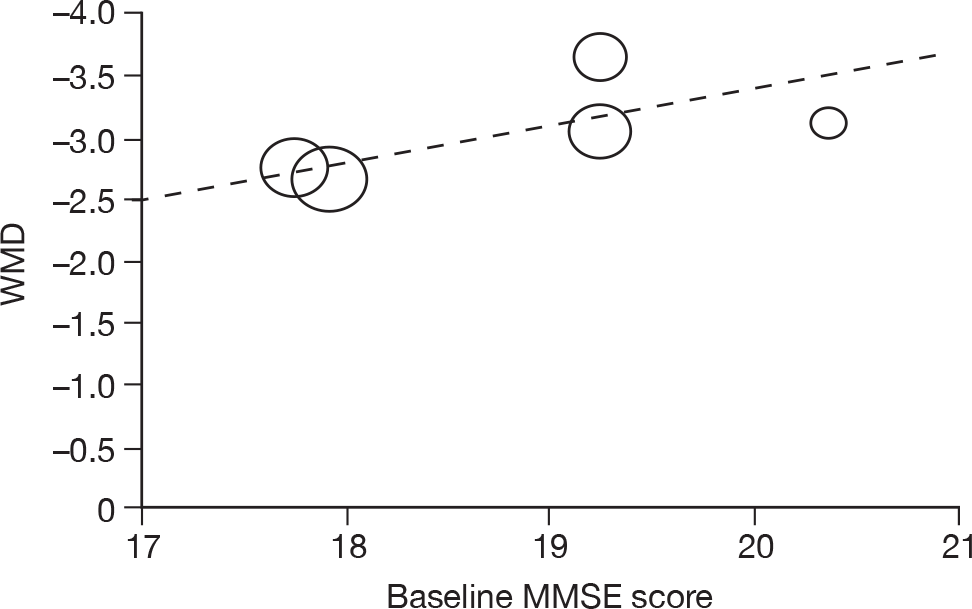

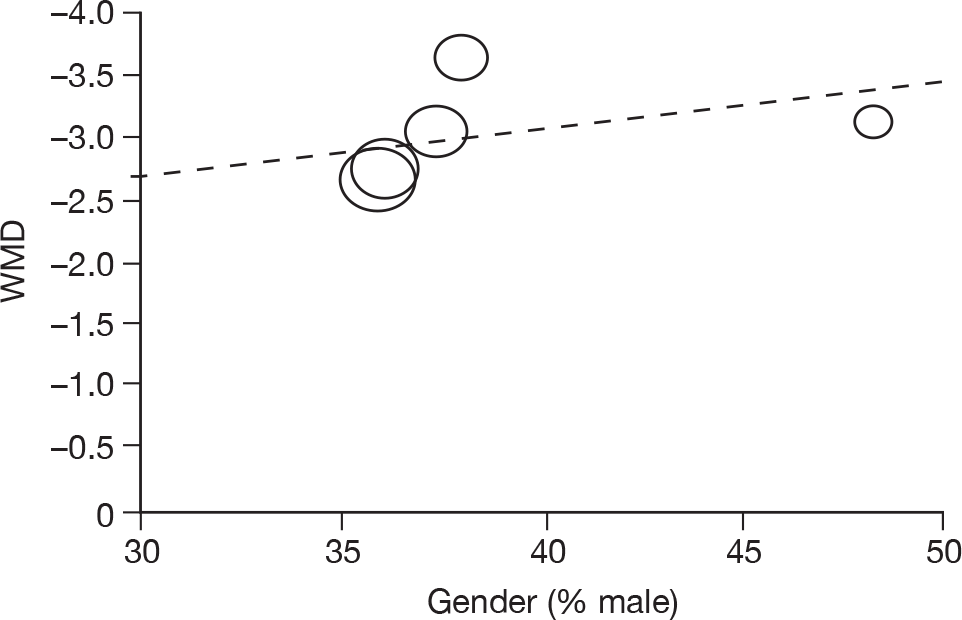

Metaregression

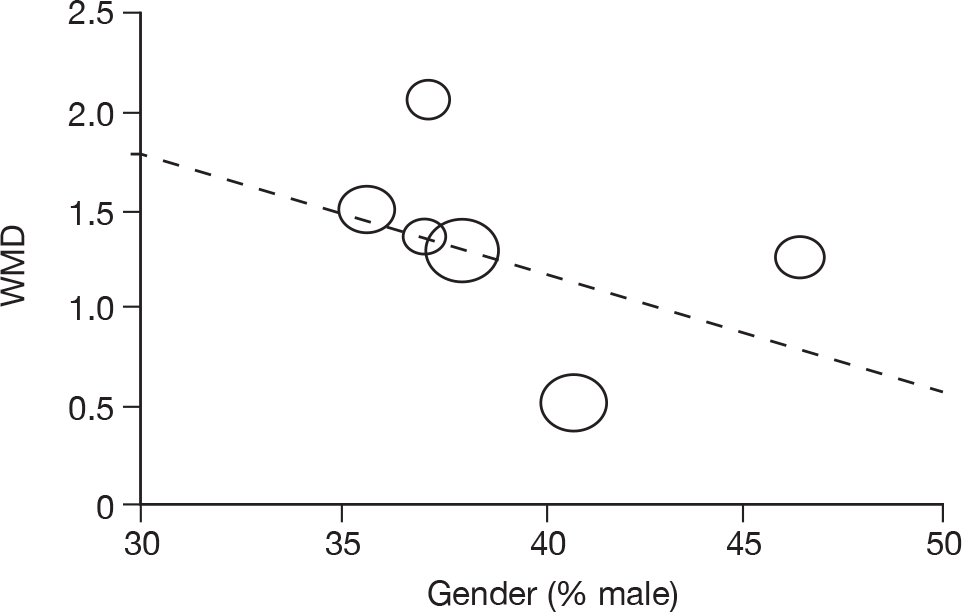

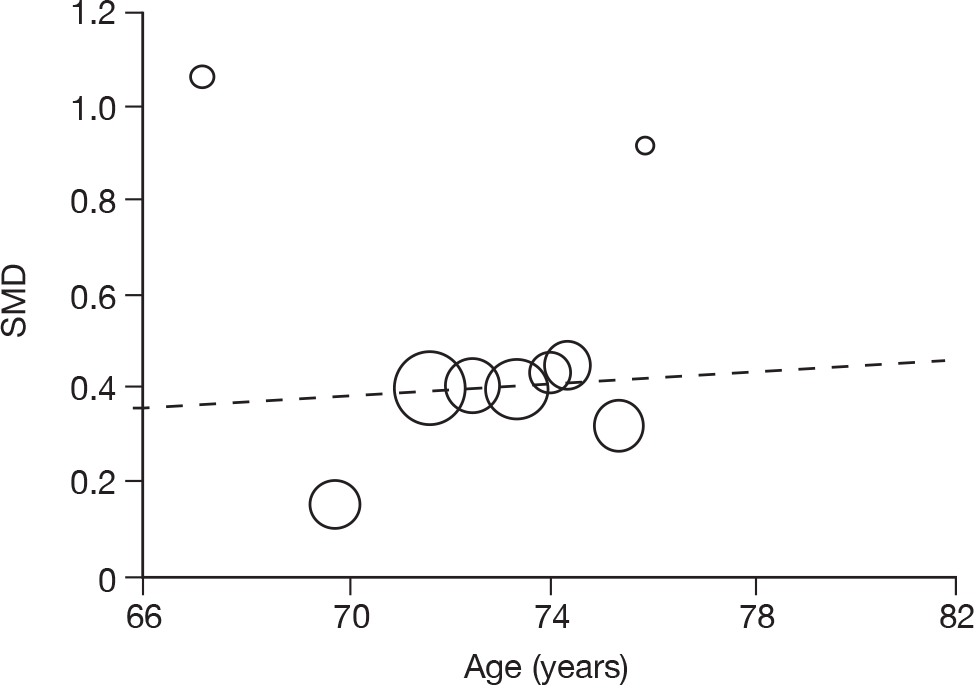

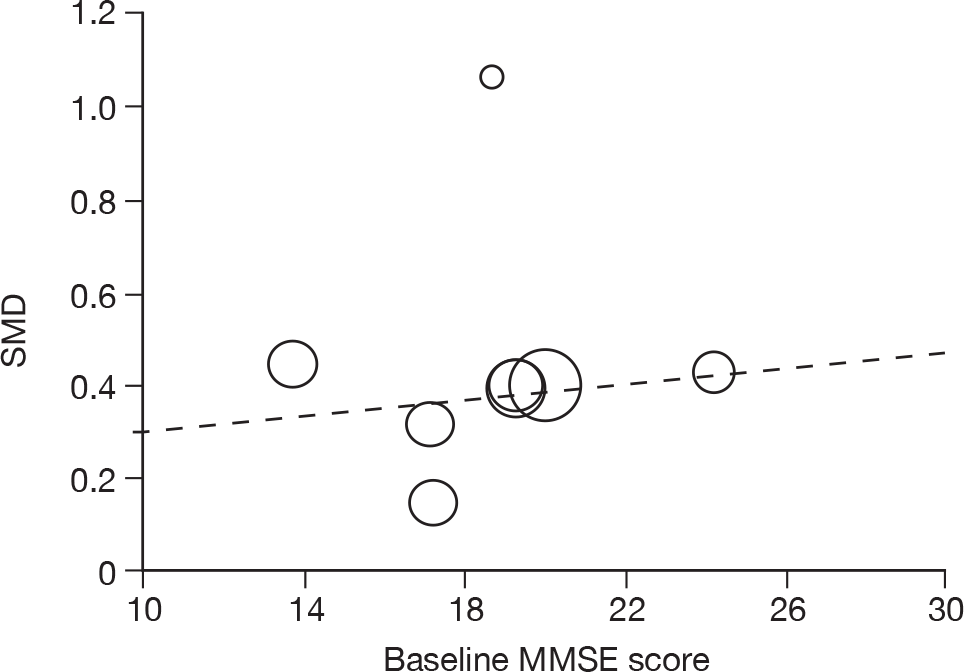

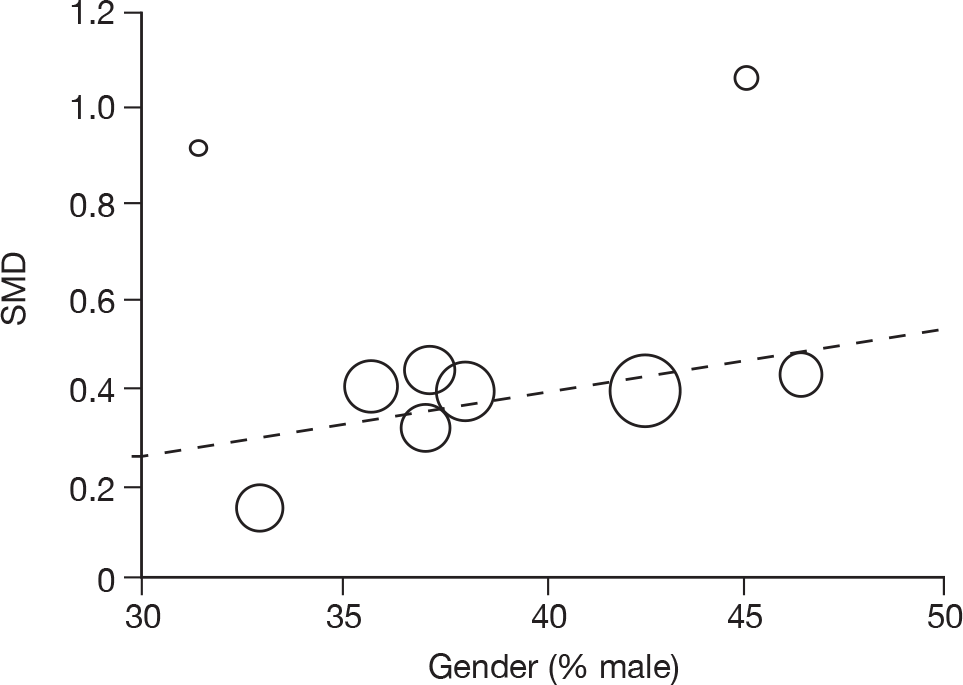

Where there was sufficient evidence (at least five individual data points in a meta-analysis), study-level regression (‘metaregression’) was used to explore the statistical heterogeneity across studies. Three prespecified covariates were explored: population gender, population gender, and baseline disease severity (as measured by MMSE). Because of inconsistencies in the evidence base, it was not possible to undertake multivariate analyses, so regressions were conducted solely on a univariate basis. Metaregression was undertaken in Stata 10.1 (‘metareg’ command), using the restricted maximum likelihood estimator, as recommended. 87,88 These figures are in Appendix 7.

Mixed-treatment comparison: indirect comparison

In addition to pair-wise meta-analyses, where sufficient data were available, we synthesised information on all technologies and their comparators simultaneously, in a mixed-treatment comparison (MTC) using Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling. 89–92 The analyses were performed using WinBUGS 1.4.1 (MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge UK) (model code is reproduced in Appendix 8).

Vague prior distributions were used in the analyses (Normal[0, 0.000001] for mean difference between treatments; Uniform[0,2] for SD of random-effects distribution). Point estimates and 95% credible intervals were calculated from 100,000 simulated draws from the posterior distribution after a burn-in of 10,000 iterations.

Outputs are presented in terms of treatment effect compared with a common baseline. In each case in the presented analyses, the available evidence networks included at least one placebo arm; therefore, the baseline treatment is always placebo. This is helpful, as it enables all MTC outputs to be interpreted on a common level. In addition to treatment effect relative to placebo, the posterior probability that each treatment is most effective is presented, simply calculated as the proportion of MCMC trials in which the given treatment had the highest (or lowest, for negative scales) estimated treatment of all comparators.

This approach assumes ‘exchangeability’ of treatment effect across all included trials, such that the observed treatment effect for any comparison could have been expected to arise if it had been measured in the populations reported in all other included trials. Exchangeability was judged through examination of the trial populations and comparability of outcomes in the common treatment group facilitating the comparison. Figures representing these analyses are in the body of the text.

As for pair-wise syntheses, we generated separate MTCs for different periods of follow-up (12–16 weeks and 21–28 weeks). We also generated separate analyses according to measurement population: LOCF only; ITT plus LOCF; OC only; and all measurement populations combined (see Appendix 9). Where multiple measurement populations were reported in an individual study and more than one was pertinent to one of these analyses, we used the highest ranking according to the hierarchy given above. Multiple relevant arms within a single study were pooled according to the methods detailed above (see Pair-wise meta-analysis), before being entered into the MTC.

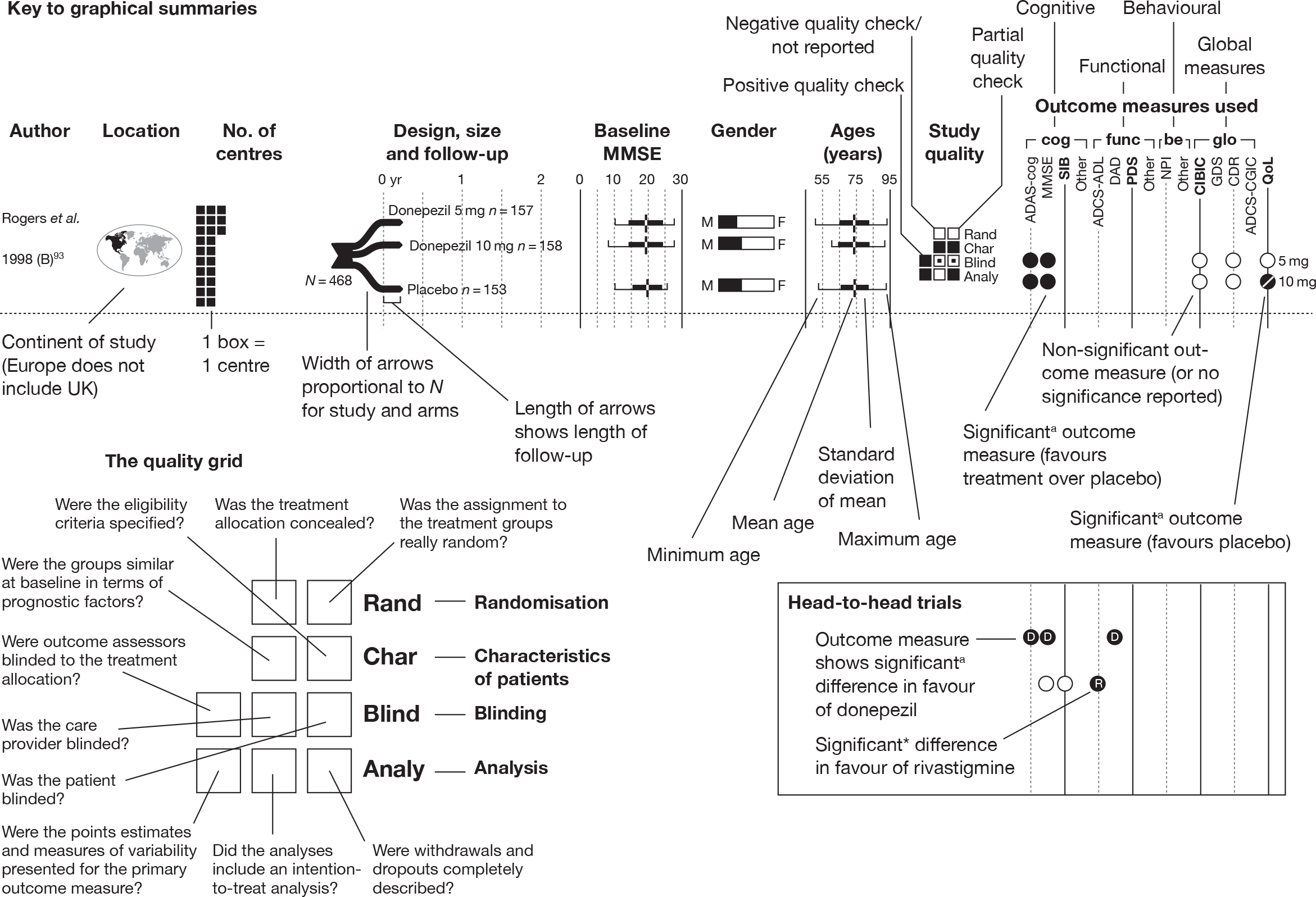

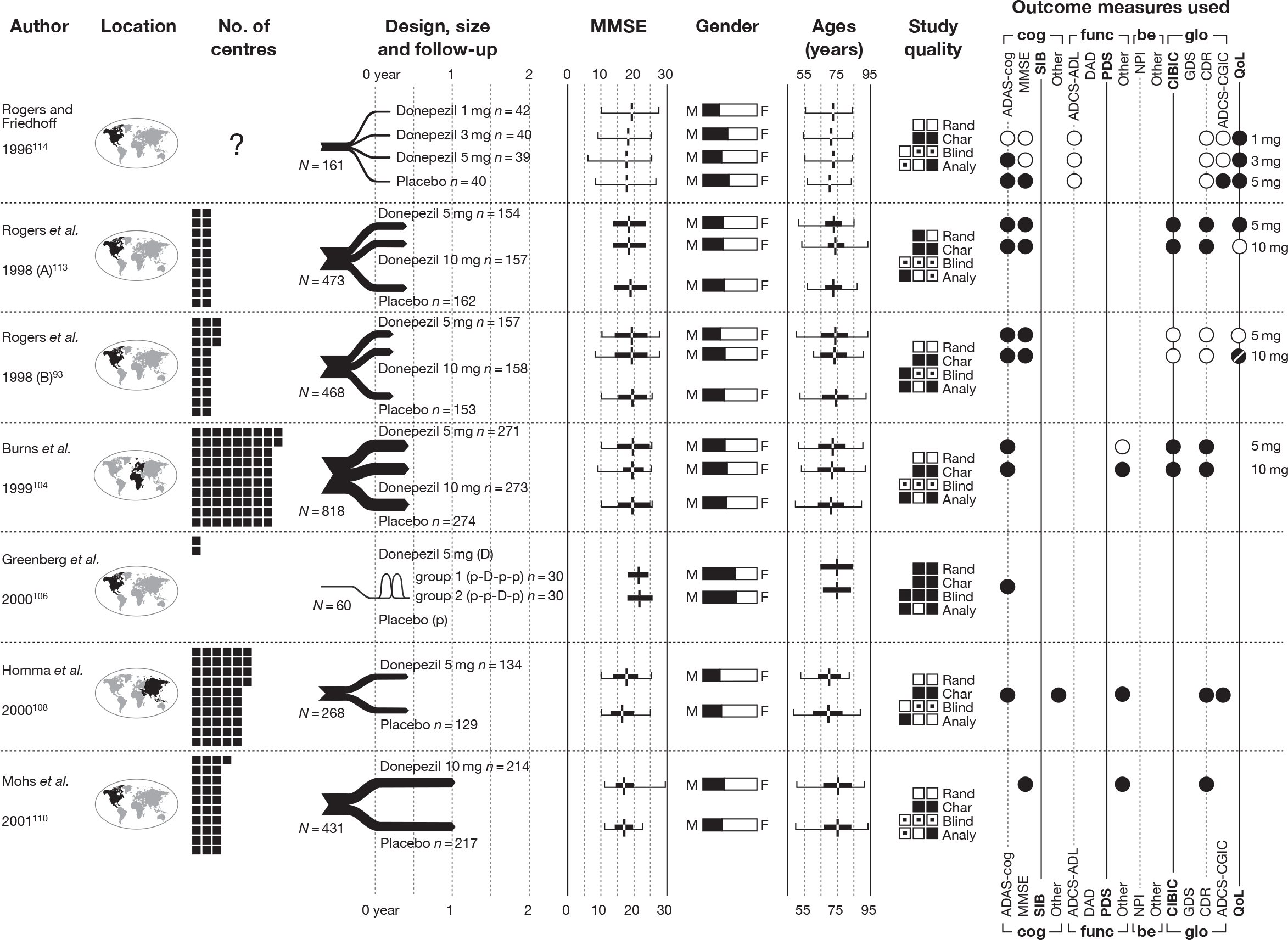

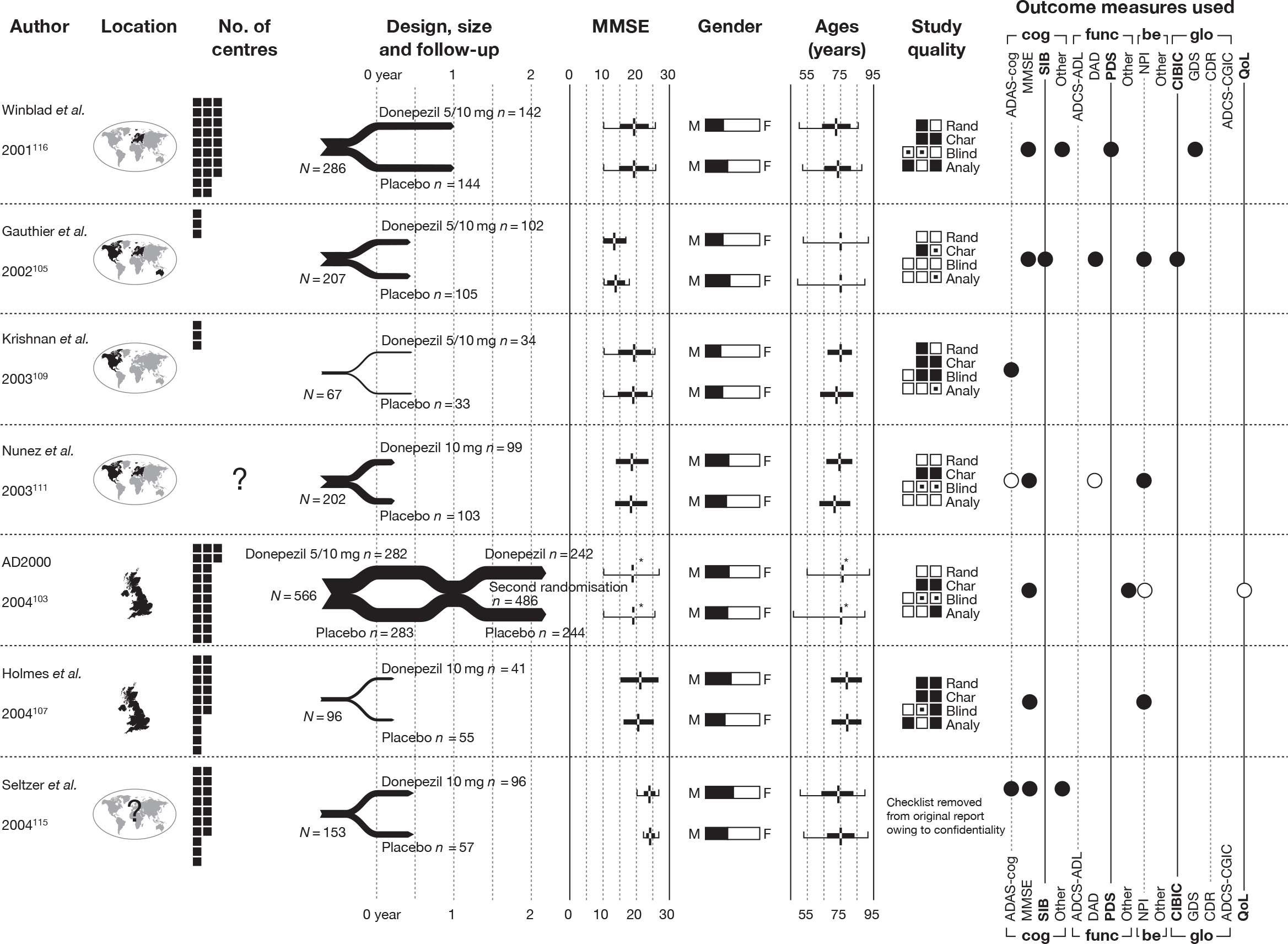

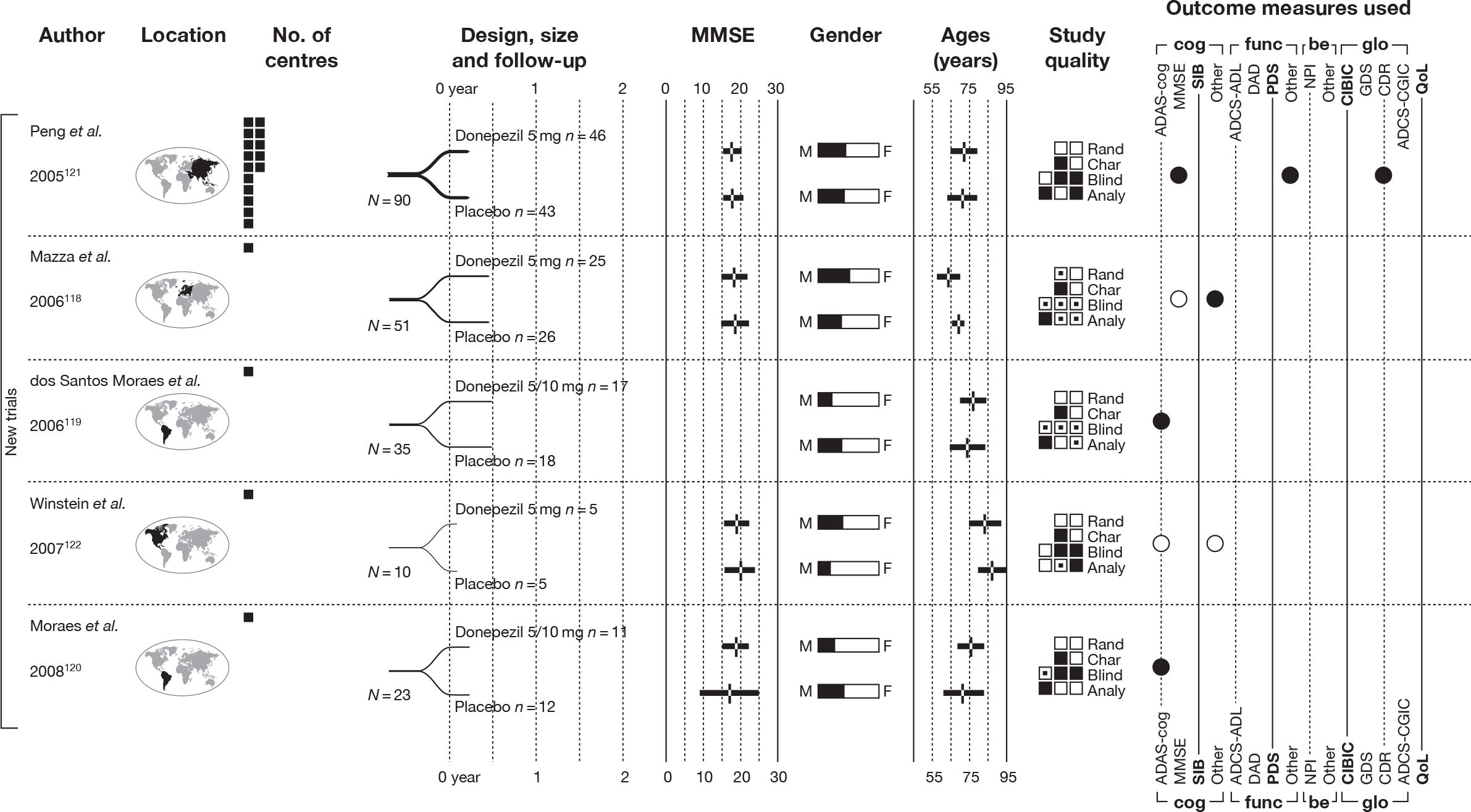

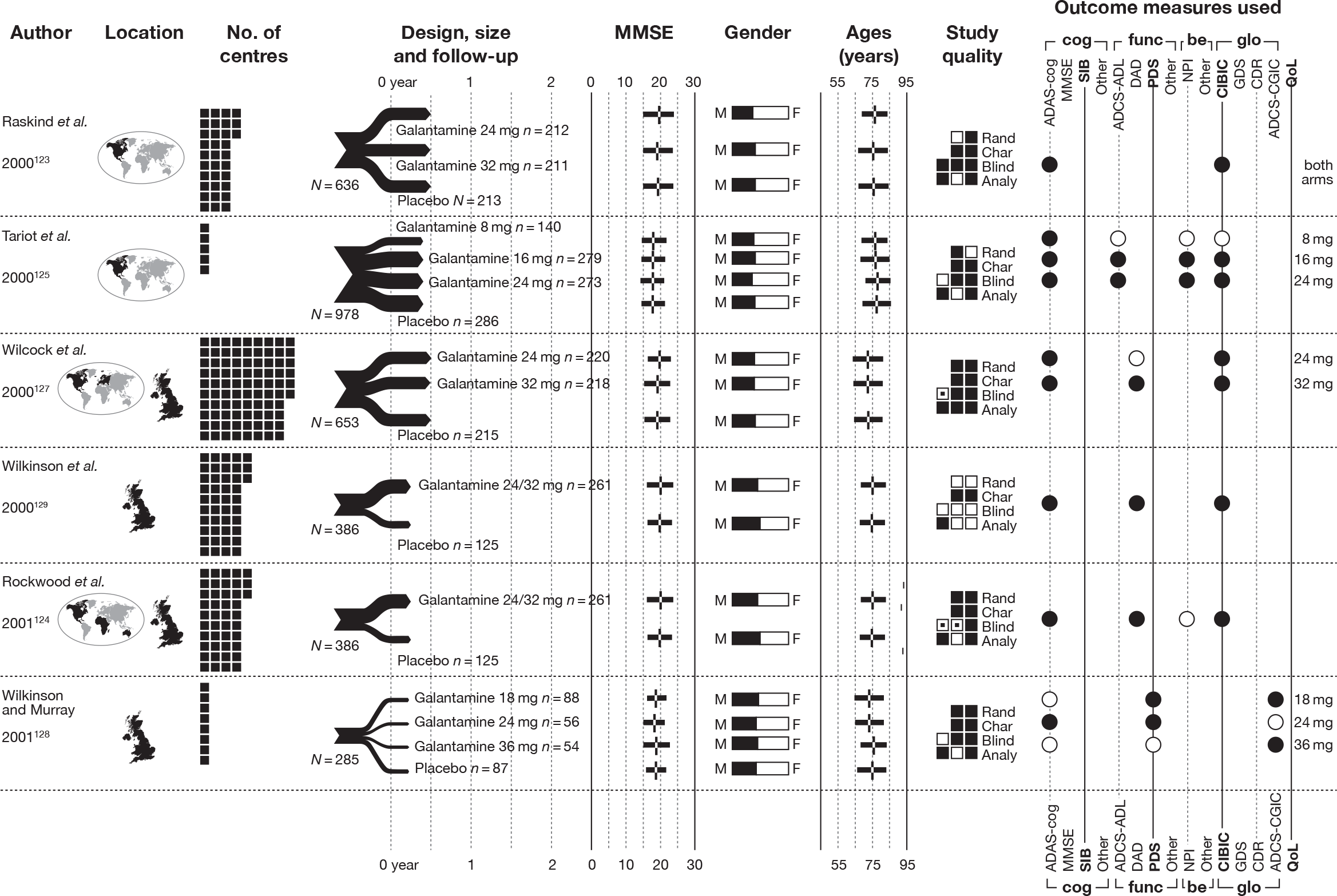

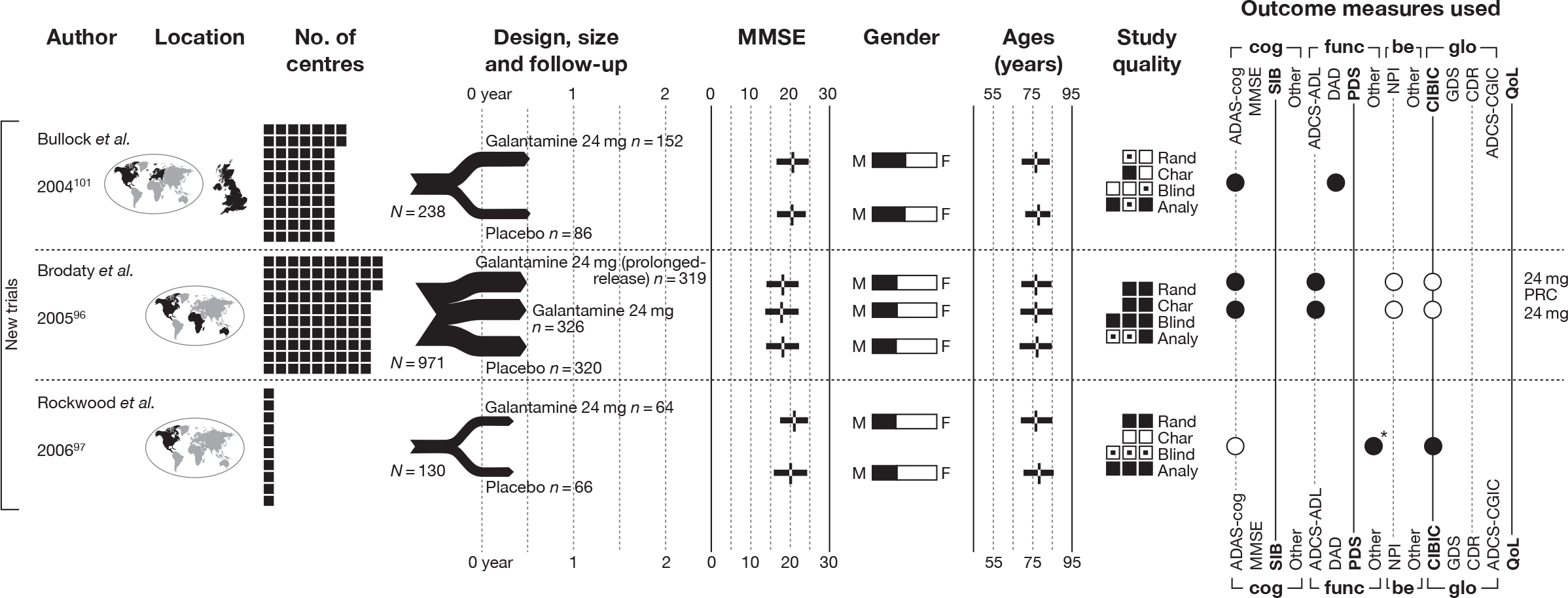

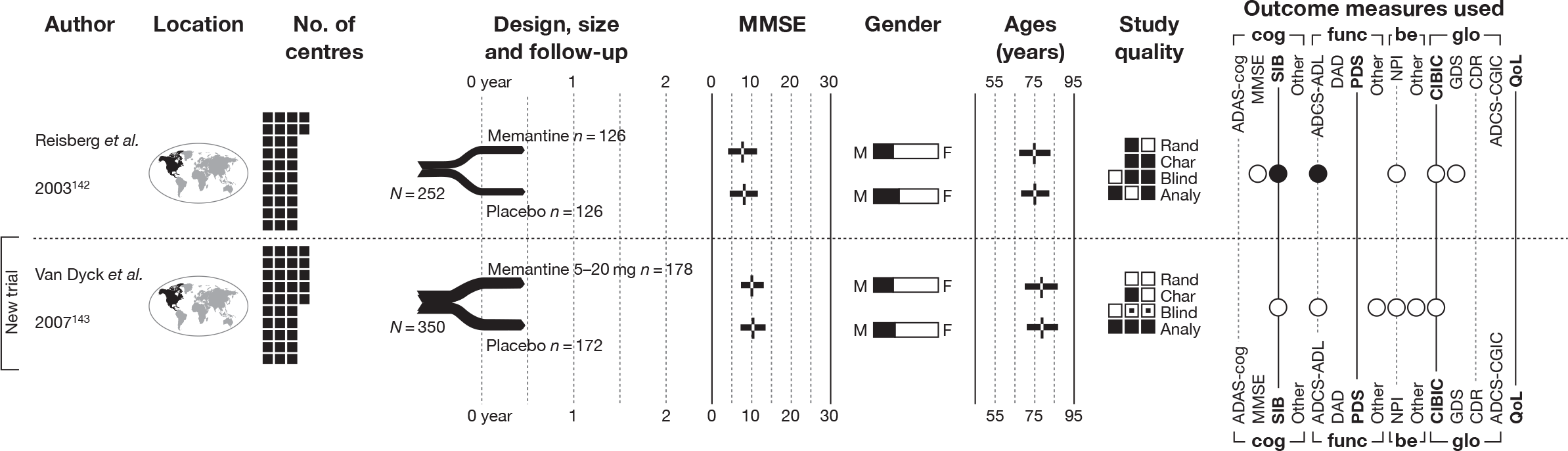

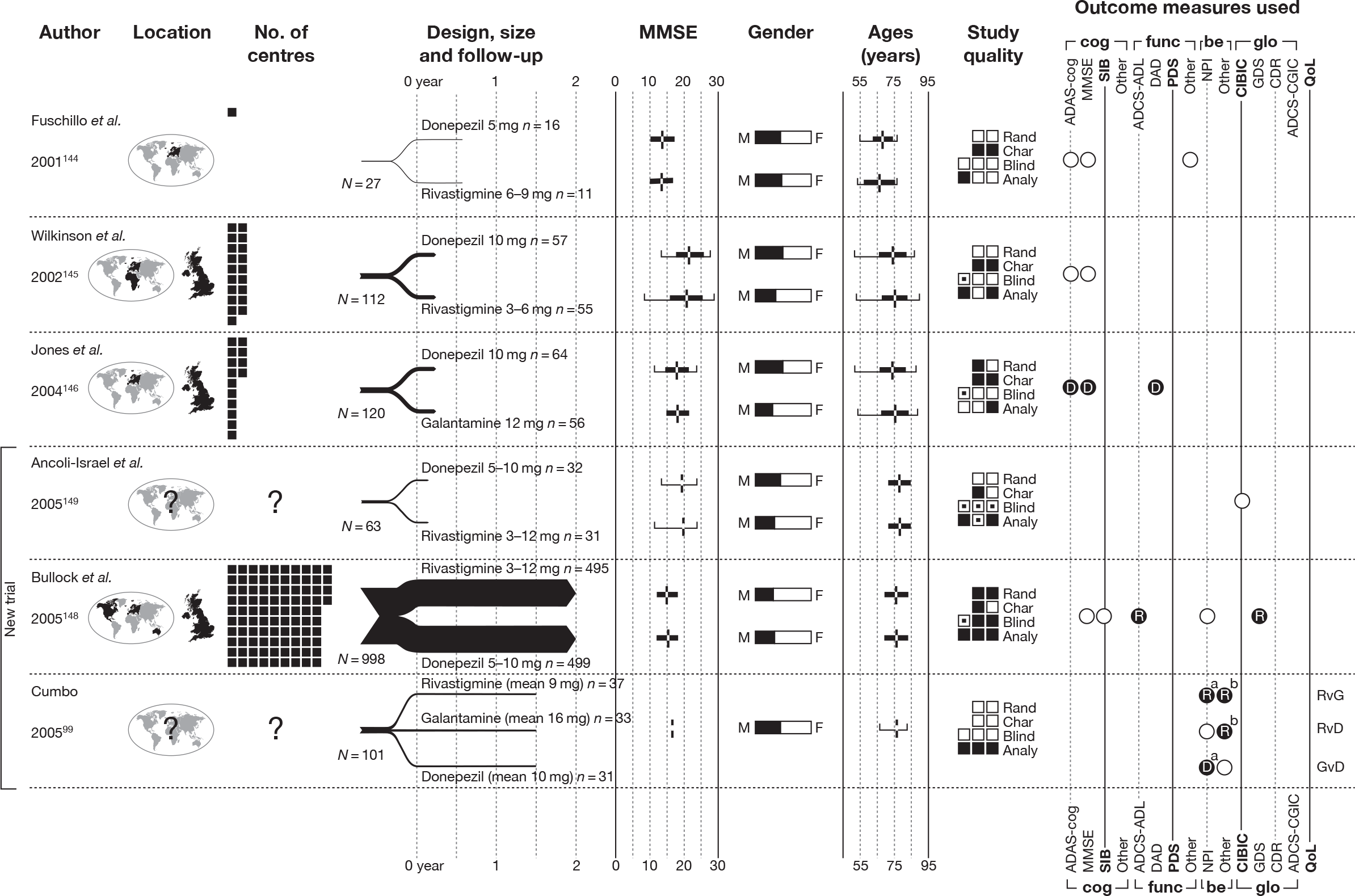

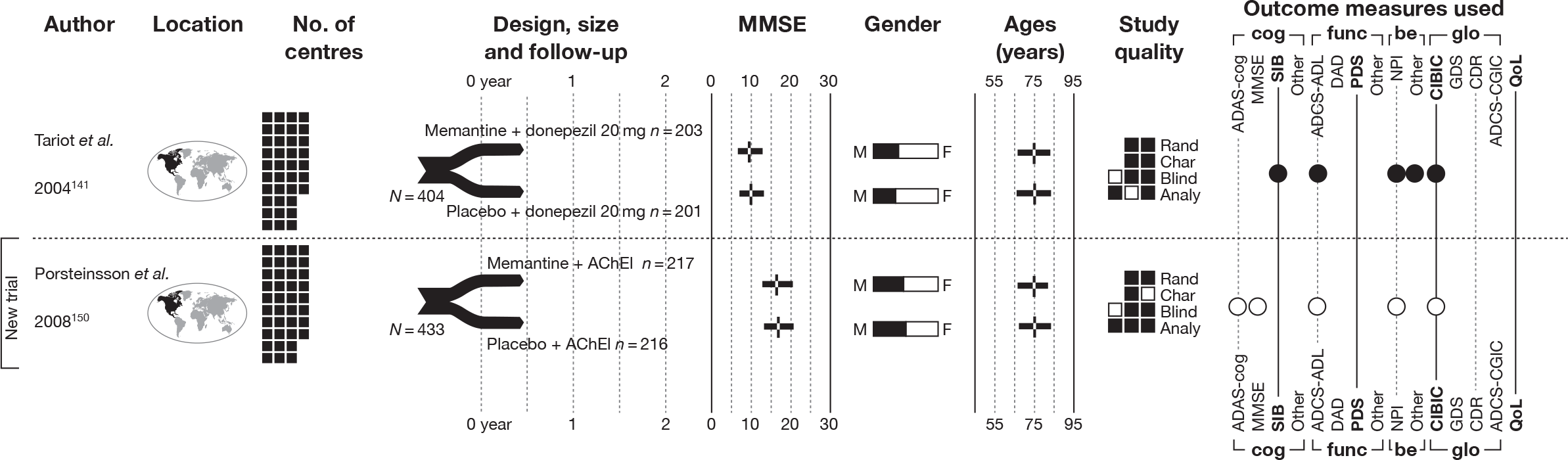

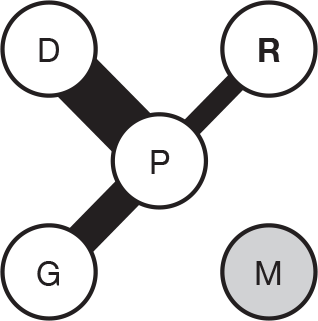

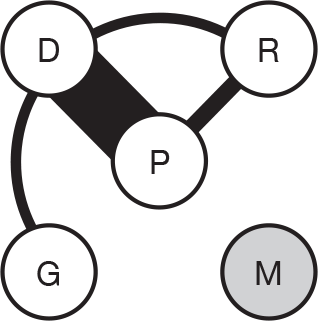

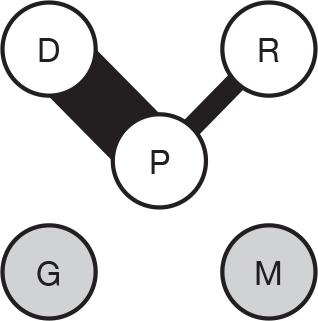

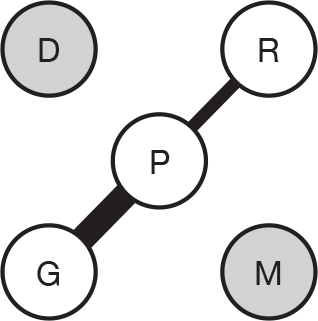

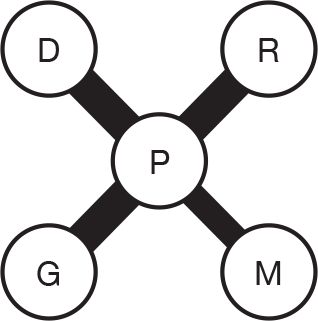

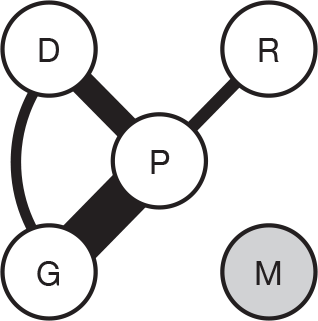

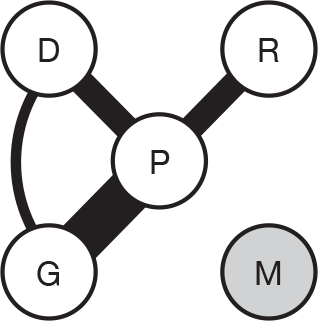

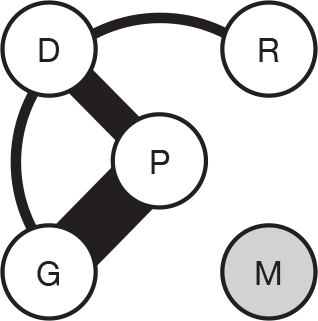

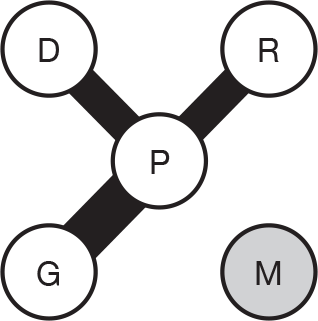

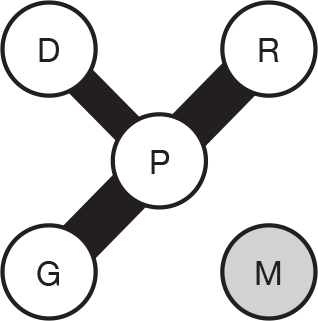

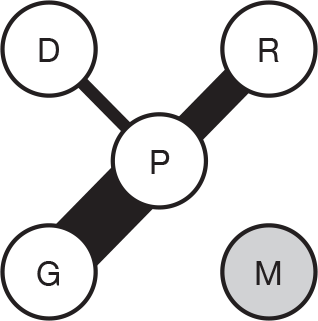

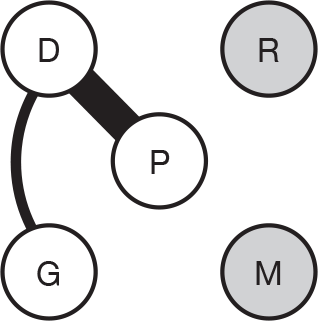

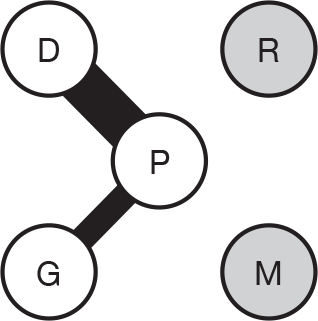

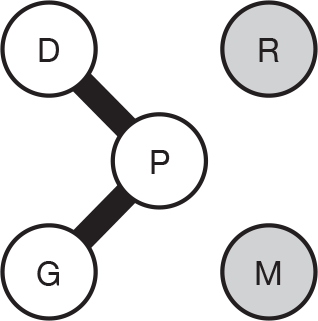

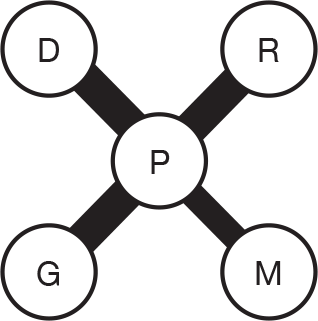

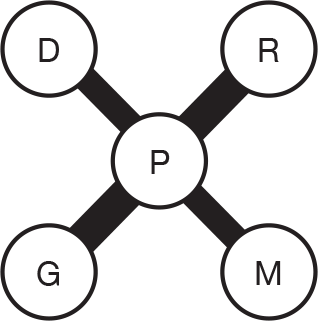

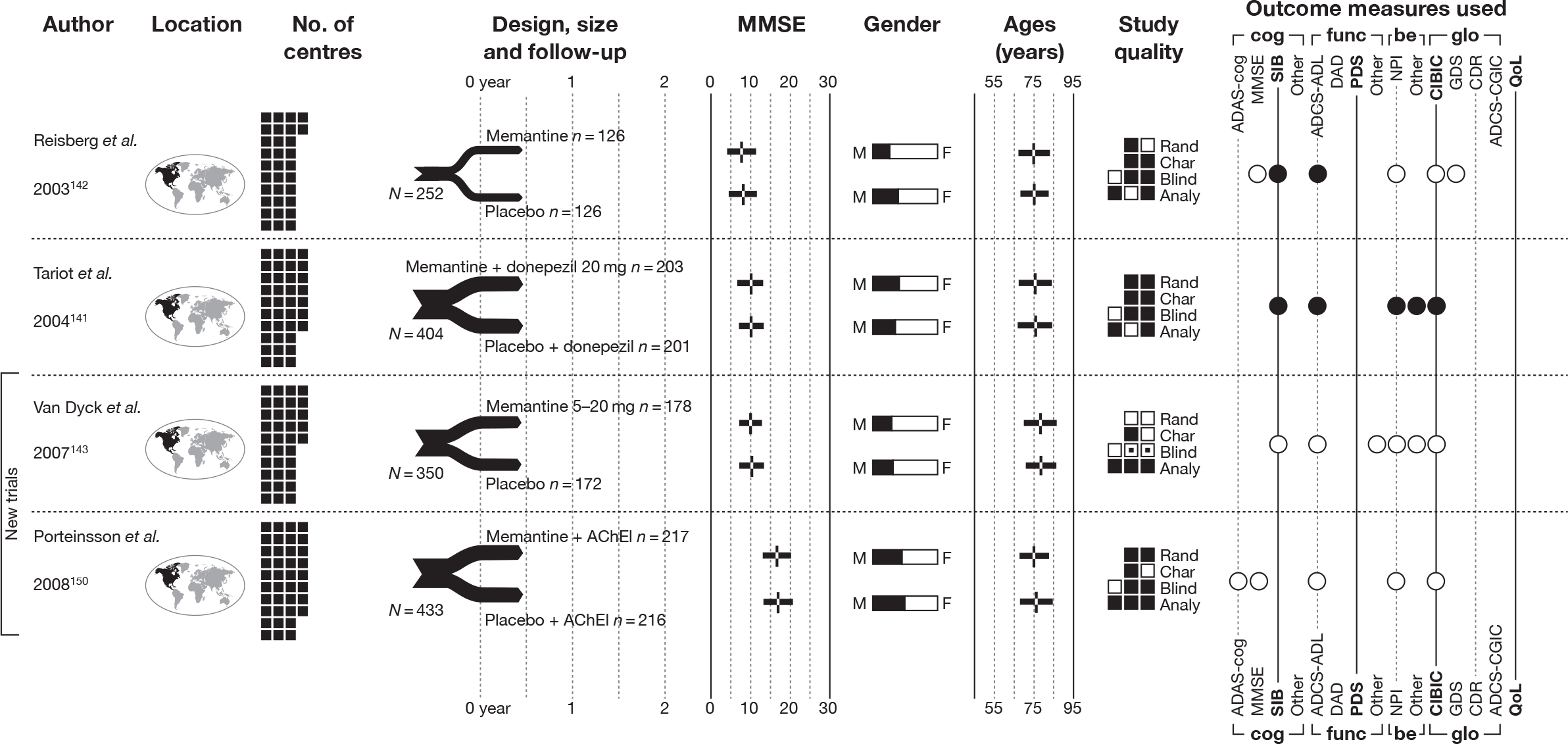

Graphical representation of summary trial information

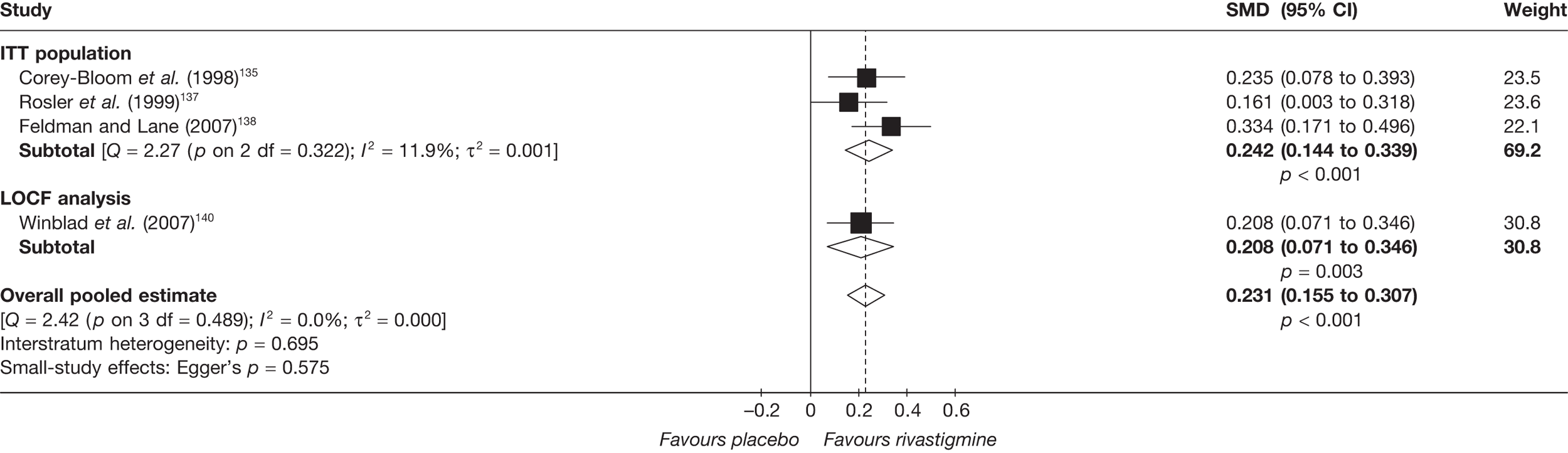

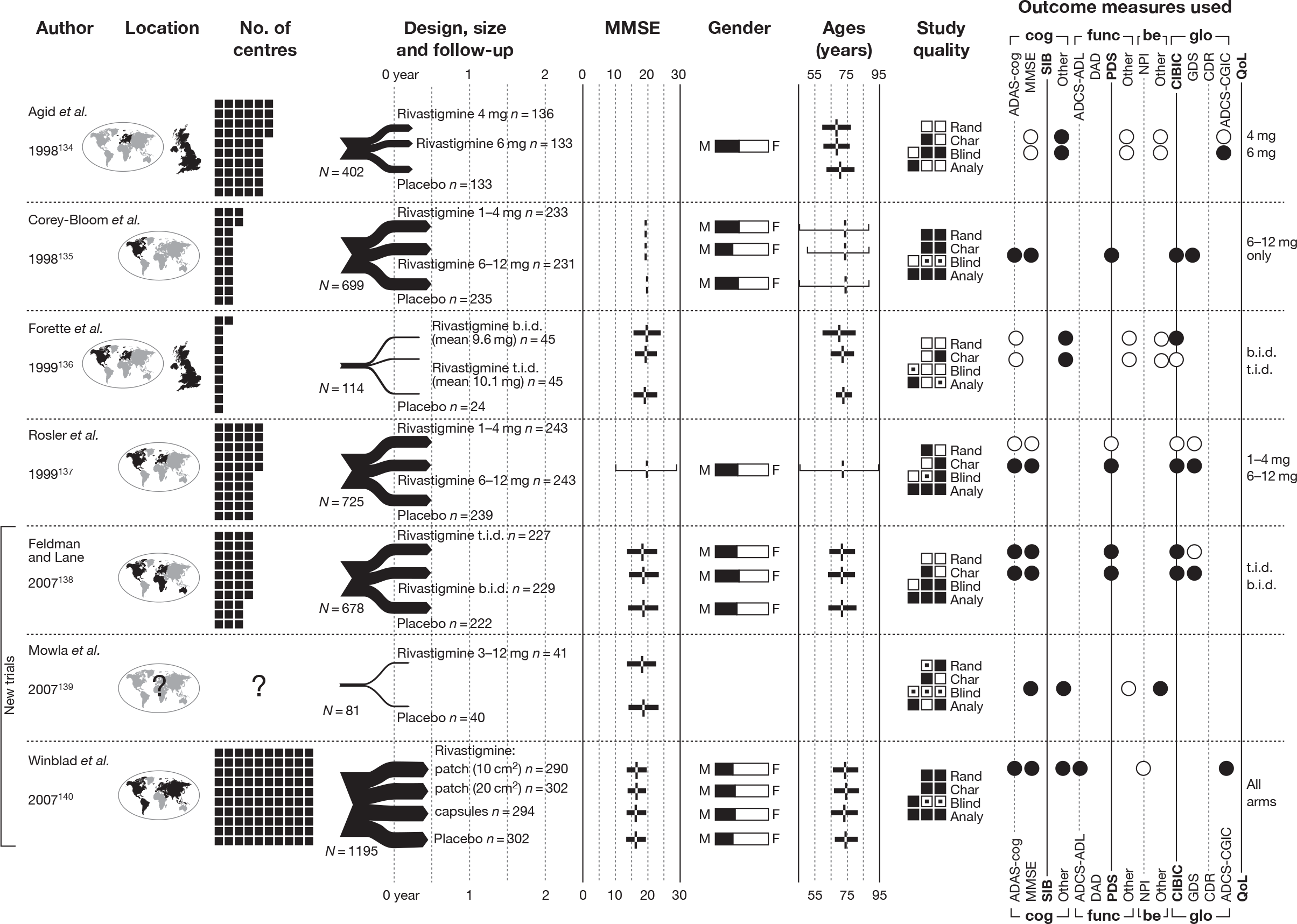

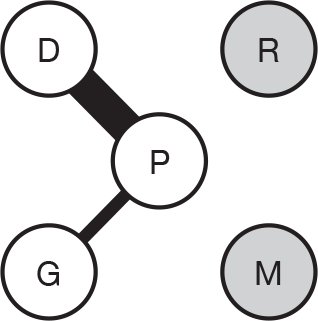

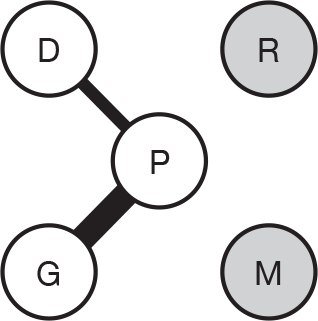

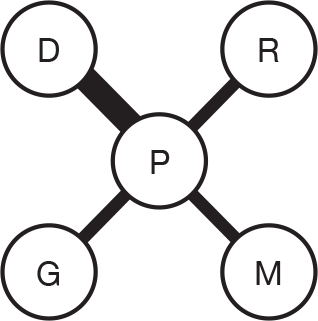

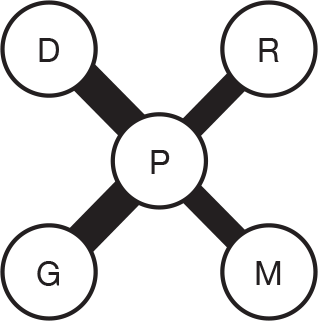

We present a novel approach to summarising the complex information relating to each trial at the end of each comparison section. These figures graphically represent the location, size, MMSE score at baseline, gender, age, study quality and results in a format that allows quick comparison between trials. A key to understanding the graphics is presented below in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5.

Key to graphical summaries. aSignificance displayed if mean change scores reported show significance of p < 0.05. In the case of multiple analyses, ITT is favoured over LOCF, which is, in turn, favoured over OC analyses. ADCS-CGIC, Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study–Clinical Global Impression of Change; be, behavioural; cog, cognitive; DAD, Disability Assessment for Dementia Scale; GDS, Global Deterioration Scale; F, female; func, functional; glo, global; M, male; PDS, Progressive Deterioration Scale.

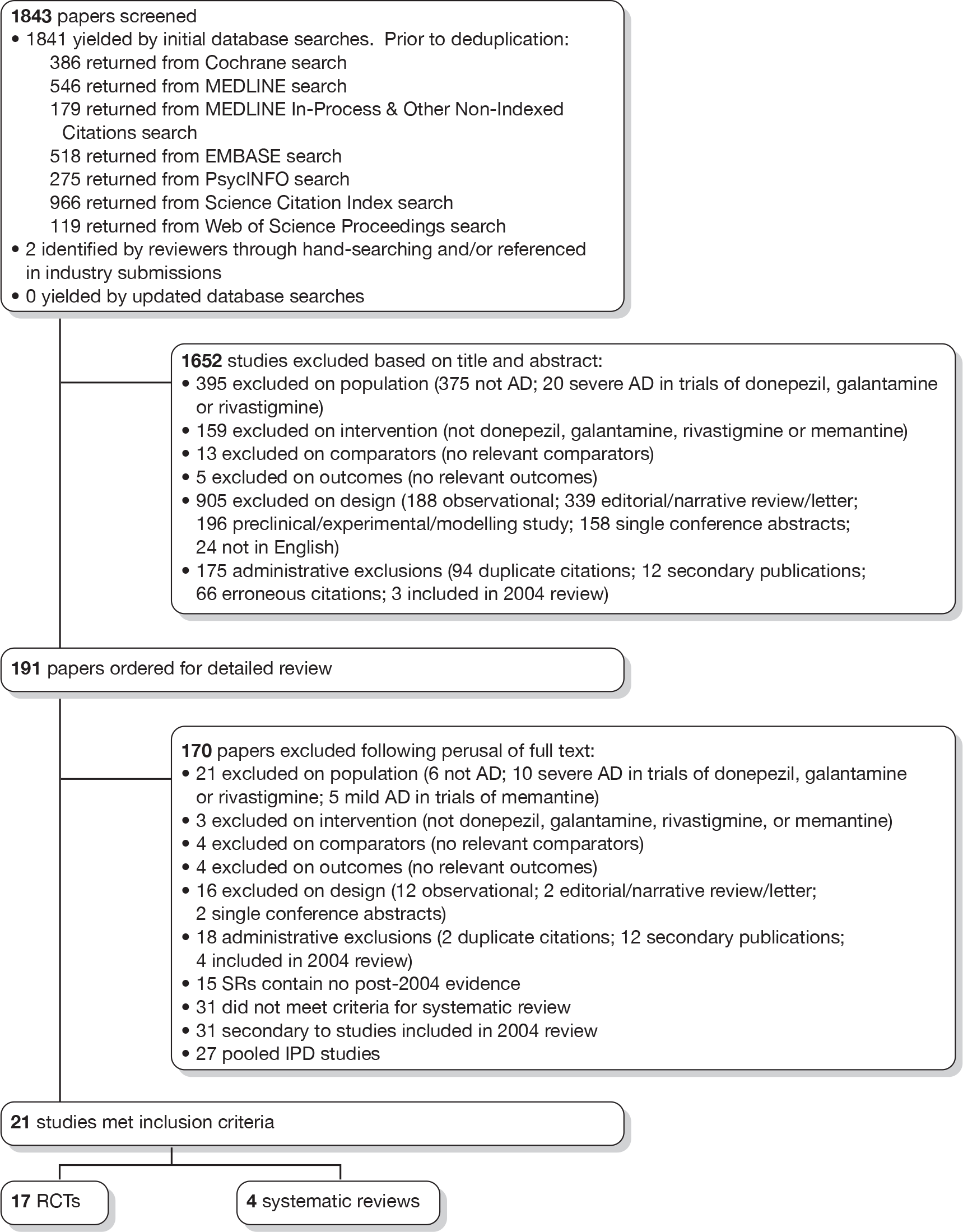

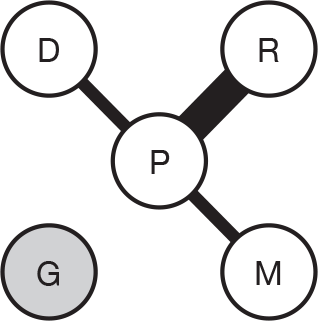

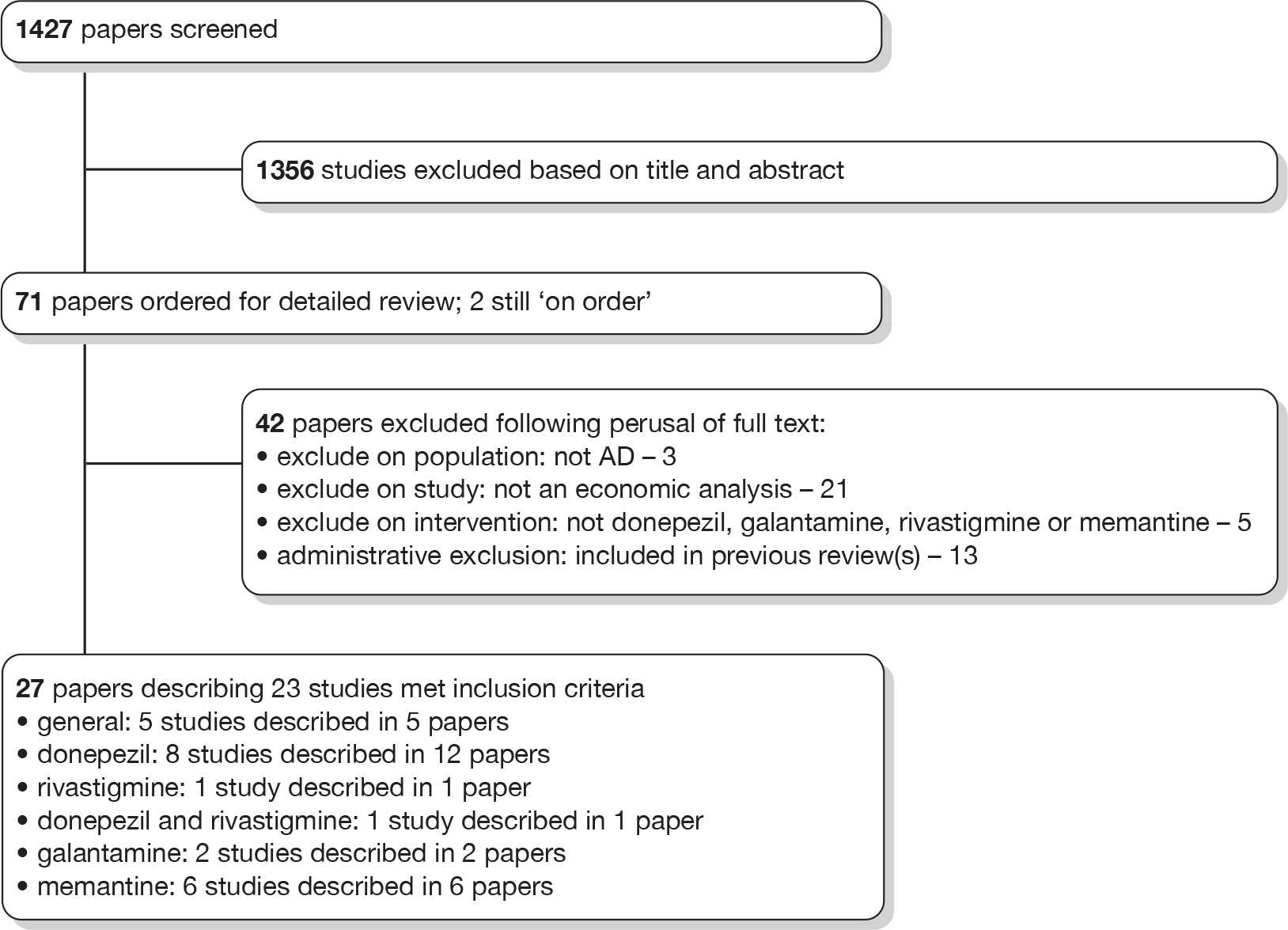

Results of the systematic review: identification of evidence

From screening the titles and abstracts of the 1843 references identified by our searches and additional sources, we retrieved 191 papers for detailed consideration, of which 21 were judged to meet the inclusion criteria for the review. The process is illustrated in detail in Figure 6. In assessing the titles and abstracts, agreement between the two reviewers was moderately good (κ = 0.642). At the full-text stage, agreement was moderate (κ = 0.538). At both stages, initial disagreements were easily resolved by consensus.

FIGURE 6.

Identification of published evidence for review. IPD, individual patient data; SR, systematic review.

The submissions from Eisai/Pfizer and Lundbeck contained a number of published and unpublished items that we have excluded from our review because they did not meet our inclusion criteria. A list of these items, with reasons for their exclusion, can be found in Appendix 10. A list of ongoing trials can be found in Appendix 11.

Results: systematic reviews

Our searches found four systematic reviews that met our inclusion criteria. These were critically appraised using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement checklist, which describes 27 items that a report of a systematic review or meta-analysis should contain. 78 A summary table of whether or not these quality indicators were present in these systematic reviews can be found in Appendix 12. The references of each systematic review were checked to see if they held any includable additional trials, no further includable studies were found. A brief summary of each systematic review can be seen below.

Summary of included systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Donepezil

No systematic reviews of donepezil were found that matched our inclusion criteria.

Galantamine

No systematic reviews of galantamine were found that matched our inclusion criteria.

Rivastigmine

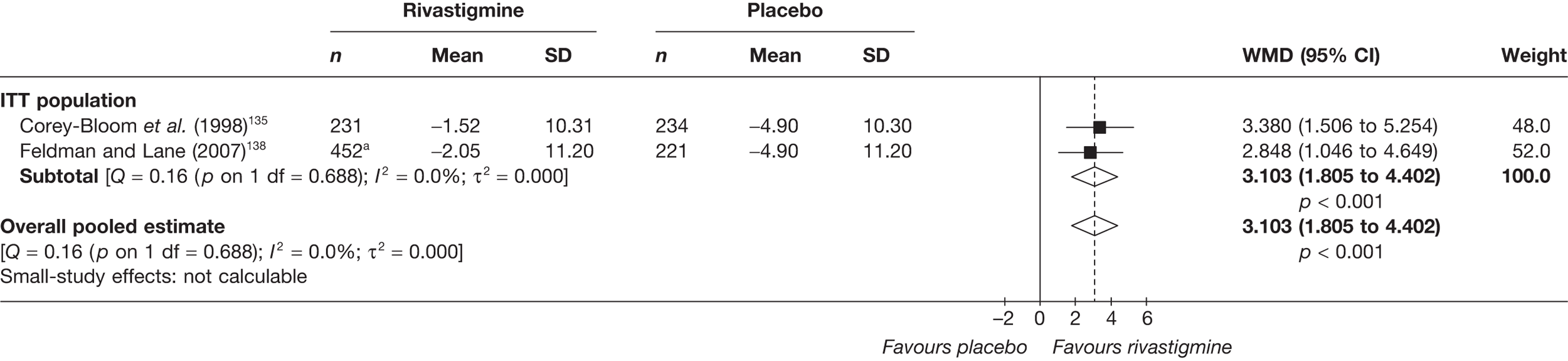

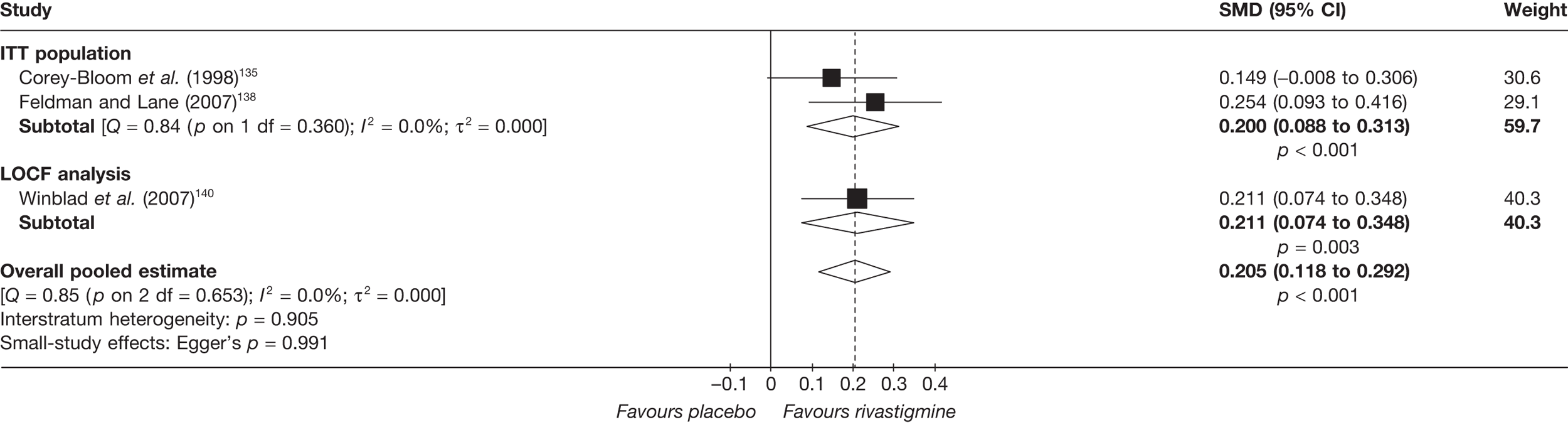

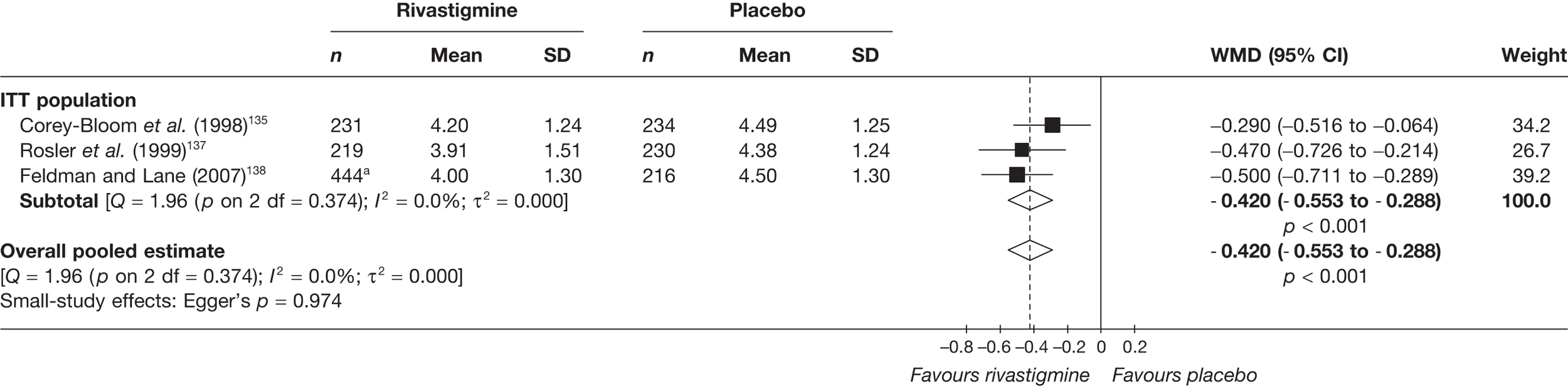

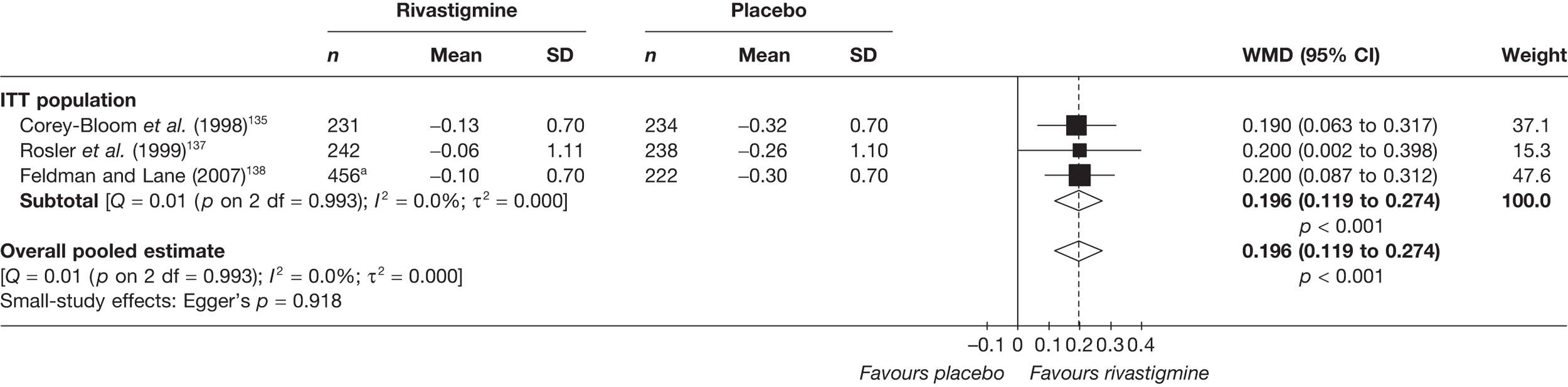

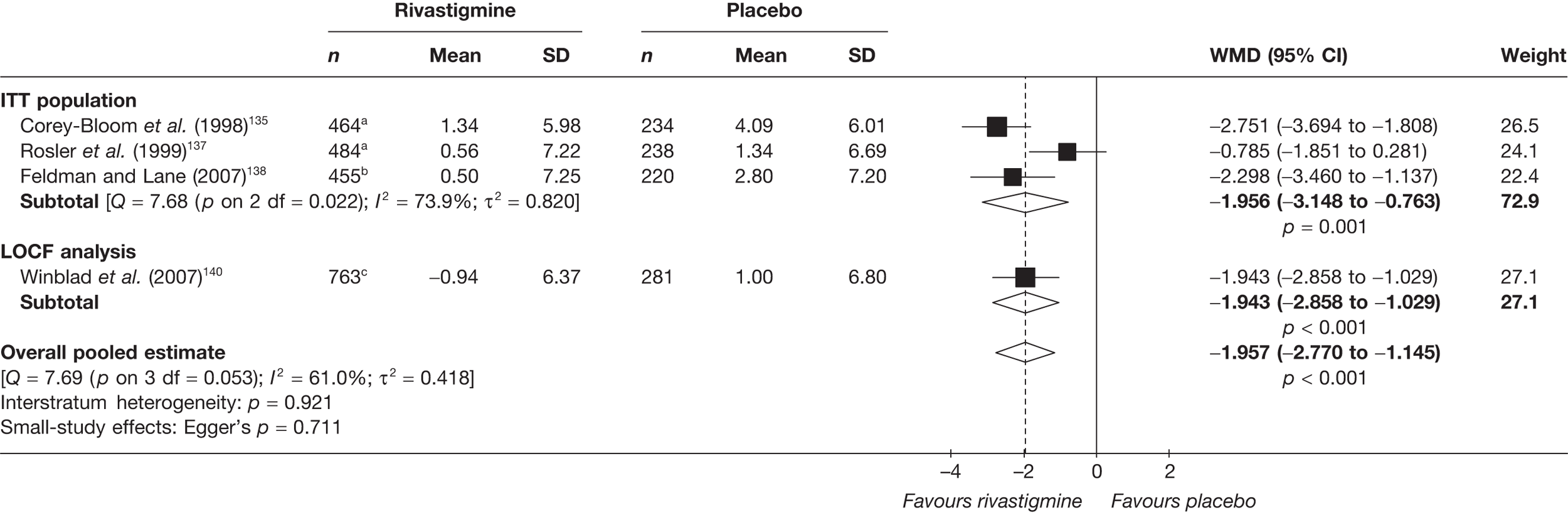

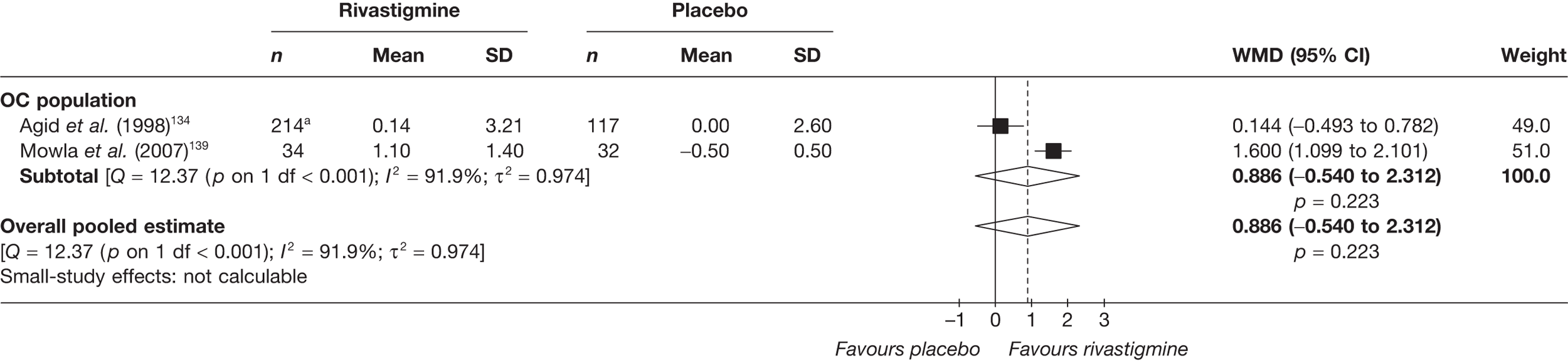

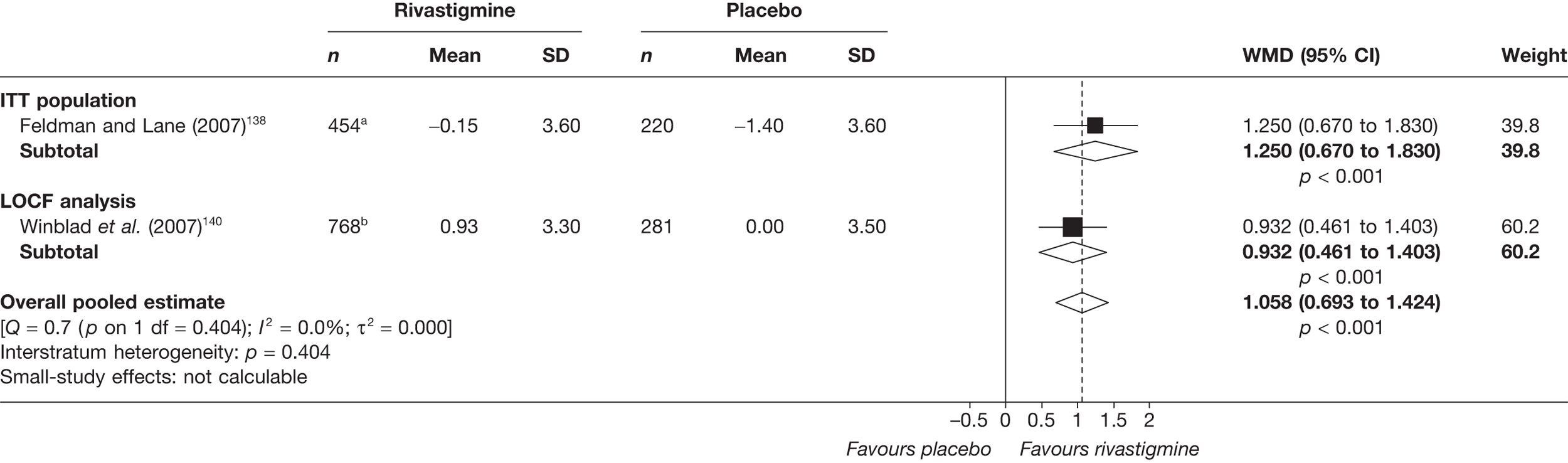

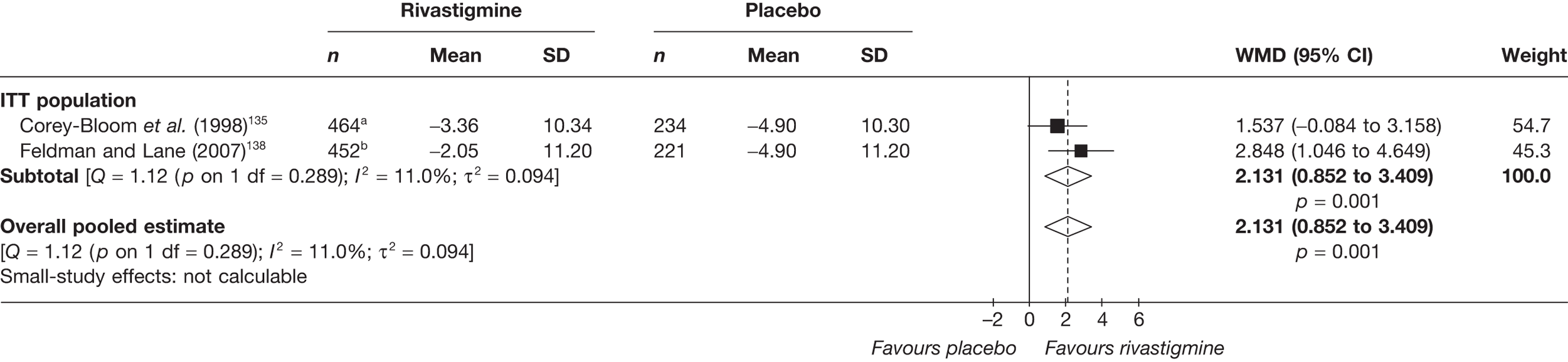

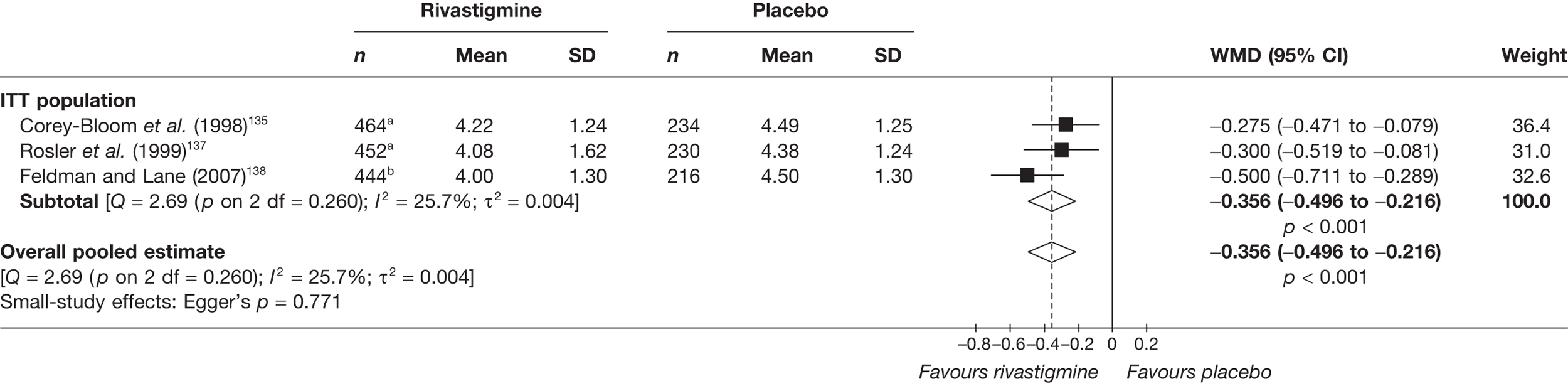

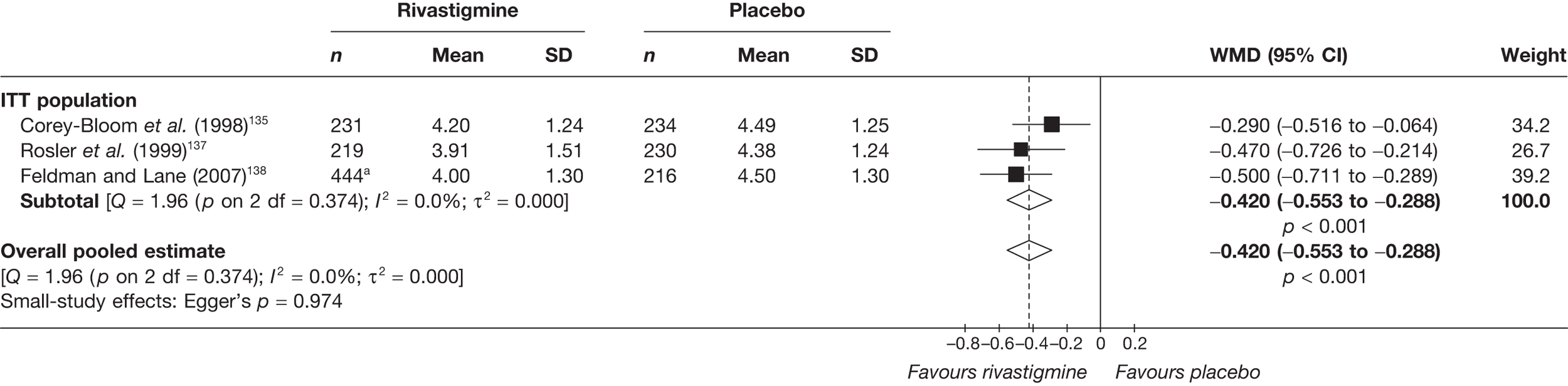

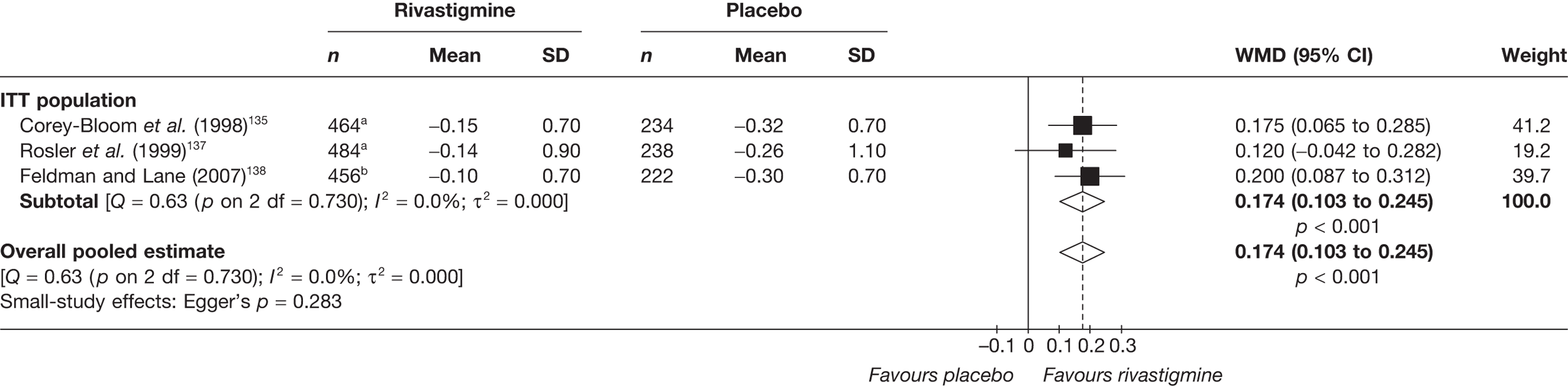

Birks and colleagues94 conducted a Cochrane review of rivastigmine compared with placebo for people with mild-to-moderate AD. They found nine trials with a total of 4775 participants. The review found that the use of rivastigmine (6–12 mg daily) was associated with a two-point improvement on the ADAS-cog compared with placebo [ITT WMD –1.99 (95% CI –2.49 to –1.50)] and a 2.2-point improvement on the Progressive Deterioration Scale (PDS) for ADL [ITT WMD –2.15 (95% CI –3.16 to –1.13)] at 26 weeks. The authors concluded that rivastigmine gave benefit to people with mild-to-moderate AD when compared with placebo. The review also considered delivery of the drug by transdermal patch. It found that the lower dose patch (9.6 mg/day) was associated with fewer side effects than the capsules or the higher dose patch (17.4 mg/day), and produced similar efficacy. The main AEs were gastrointestinal (nausea and vomiting), usually occurring during the titration phase.

All cholinesterase inhibitors

The German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of all of the cholinesterase inhibitors included in this report for people with mild-to-moderate AD. 95 They included RCTs up to June 2006 in their systematic review, and found 27 studies with a total of 9883 participants. Only four of these trials met our inclusion criteria. 96–99 The IQWiG concluded that all the AChEIs provided benefit in improving or maintaining cognitive function and ADLs, and that galantamine alleviated psychological symptoms. However, none of the studies provided evidence of improvement in QoL. A summary table of these results can be found in Appendix 13.

Memantine

A systematic review of memantine for dementia was carried out by Raina and colleagues. 100 Their inclusion criteria were broader than ours and included all major types of dementia, patients with mild-to-moderate disease severity and all drugs for treating dementia. Of the 59 studies they included, only two met our inclusion criteria for trials. 96,101 The data syntheses from this systematic review are not relevant to this TAR and will not be discussed.

All included drugs

Hansen and colleagues102 conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of functional outcomes from the use of donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine and memantine for people with mild-to-moderate AD. They included 13 RCTs, 12 of which were included in the previous TAR (No. 111). The new study, which is included in this review, is Brodaty and colleagues. 93 Overall, they found a small effect size (d = 0.1–0.4) favouring drug treatment. A metaregression showed that this effect was not affected by disease severity, age, gender and drug dose. AEs were most commonly gastrointestinal.

Manufacturers’ reviews of clinical effectiveness

Three reviews were presented summarising evidence on the effectiveness of donepezil, galantamine and memantine by the manufacturers of each of the drugs. Although not part of the Peninsula Technology Assessment Group (PenTAG)’s systematic review they are presented here for convenience and because their findings are compared with our own review. Each submission is briefly discussed in the sections below.

Donepezil

Eisai and Pfizer submitted a systematic review as part of their joint submission on donepezil. It included both RCTs and targeted non-RCT/observational studies. Concerning the effect of donepezil relative to placebo the reported results of effect on cognition, function, behaviour and global impact were consistent with the results of the PenTAG review. There was, however, limited information on any summary estimates of effect in the manufacturer submission. Challenges to the validity of the AD2000 trial103 were re-emphasised.

Published meta-analyses were used to explore whether or not the effect of donepezil varied depending on the severity of AD, particularly the effectiveness in patients with mild AD. These suggested that a beneficial effect of donepezil relative to placebo on cognition, global impact and behaviour was present for patients with mild AD. The summary estimates quoted for mild AD were broadly similar to the overall summary estimates calculated in the PenTAG systematic review.

Results from non-RCT and observational data were presented to support the following additional aspects of the effectiveness of donepezil:

-

duration of effectiveness extending beyond 6 months up to at least 3 years

-

worsening of symptoms following withdrawal of treatment

-

emergence of benefit after initial absence of changes suggesting response

-

impact on carers, particularly caregiver stress and carer time

-

trends towards reductions in antipsychotic medication use

-

reductions in mortality.

Galantamine

Shire Pharmaceuticals presented a summary of all available RCTs (not just those from 2004 onwards) comparing galantamine with placebo, but did not indicate how the review had been conducted. They emphasised the importance of newer dosing regimens and highlighted deficiencies in the previous systematic review by the Southampton Health Technology Assessment Centre (SHTAC), particularly concerning failure to include a study directly comparing galantamine with donepezil.

The pooled summary estimates presented for the effect of galantamine on cognition, behaviour and function were consistent with the summary estimates in the PenTAG systematic review. The Shire Pharmaceuticals submission provided additional analyses, indicating an increase in effect with increasing severity of disease. Similar analyses could not be done in the PenTAG systematic review because of the requirement for individual patient data (IPD).

Memantine

Lundbeck presented a meta-analysis of pivotal trials as part of its submission. Although some details on the methods of analysis were provided, there was no information on how the pivotal trials were ascertained. The inclusion criteria were given and in essence the included studies were double-blind RCTs comparing memantine with placebo measuring cognition, disability, global health state and behaviour at 3 or 6 months. The need for IPD was further stipulated to allow subgroup analysis. There were six included studies in the main analysis covering all periods, not just 2004 onwards. The reasons why some studies were included in the Lundbeck analysis but not included in the PenTAG meta-analysis are documented in Appendix 10. Briefly, these were that Lundbeck’s pooling methods relied on the availability of IPD to which PenTAG did not have access, and Lundbeck were prepared to pool data from trials of memantine plus AChEIs versus AChEIs alone with data from trials of memantine monotherapy versus placebo to produce a single estimate of memantine effect. PenTAG were not comfortable with the assumptions necessary to justify such a single analysis. Notwithstanding this, the direction and size of effect of memantine relative to placebo on cognition, disability, global health state and behaviour are consistent between the Lundbeck and PenTAG analyses. In this, account needs to be taken of the fact that the results in the Lundbeck submission are presented as SMDs, whereas those in the PenTAG analysis were WMDs. Approximate interconversion is achieved by multiplying or dividing by the pooled SD. The 95% CIs are narrower in the Lundbeck analysis because of the greater number of included studies. The submission identified no evidence that the effectiveness varied by severity of AD, by past use of AChEIs or by concurrent use AChEIs. These analyses could not be repeated in the PenTAG systematic review because they depend on IPD.

Lundbeck also examined whether or not there was evidence of a difference in effectiveness depending on the presence of agitation/aggression and/or psychotic symptoms (APS), defined by the baseline NPI score being ≥ 3 (as opposed to the definition of > 0 used in the last the submission for the last NICE guidance). The results suggested that there is greater effectiveness in patients with APS but, again, these analyses could not be repeated in the PenTAG systematic review because they depend on IPD.

Unavailable evidence

Subgroup analyses

The study protocol specified that if evidence allowed subgroups based on disease severity, response to treatment, behavioural disturbance and comorbidities should be considered. However, none of the included trials reported any of these subgroup analyses. Therefore, we are unable to comment on them.

Outcomes

None of the included trials reported mortality or institutionalisation outcomes, or reported on outcomes beyond 28 weeks.

Results: pair-wise comparisons

Donepezil versus placebo

Identified evidence

The 2004 review2 identified 14 RCTs investigating the effectiveness of donepezil compared with placebo. 93,103–116

Notes:

-

The Nunez and colleagues trial111,112 was reviewed in poster form in 2003; a full publication, authored by Johannsen and colleagues,112 is now available, from which we have extracted data; however, for consistency with the 2004 review, we continue to refer to this RCT as ‘Nunez and colleagues’.

-

The Seltzer and colleagues trial115 was reviewed on a commercial-in-confidence (CiC) basis using information supplied by the manufacturer in 2004 – a full publication, authored by Seltzer and colleagues. 115

-

Winblad and colleagues,116 with additional information contained in the trial of Wimo and colleagues. 117

Our searches identified an additional five RCTs. 118–122 A summary of their design characteristics can be found in Table 2 and the interventions, comparators and baseline characteristics of the participants in Table 3. Critical appraisal of these small studies showed that none was of good quality; neither study was reporting adequate randomisation nor allocation concealment. A summary of the markers of internal validity is presented in Table 4.

| Study details | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Methodological notes | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mazza et al. (2006) 118 Design: Parallel double-blind RCT Country: Italy? No. of centres: 1 No. randomised: 76 Maximum follow-up: 24 MMSE range included: 13–25 Funding: Not reported |

AD (DSM-IV criteria) Brief Cognitive Rating scale mean score 3–5 Hachinski Ischaemic Score < 4 Adequate level of premorbid intelligence (IG > 80, global assessment) |

Dementia of other aetiology Severe organic diseases (tumours, severe infectious diseases, brain trauma, epilepsy, cerebrovascular malformations, alcohol or drug abuse) Pseudodementia or a history of schizophrenic or affective psychoses (Geriatric Depression Scale, 15-item version, total score < 9) Vasoactive drugs, nootropics and long-term treatment with other drugs were proscribed during the study, with the exception of low doses of benzodiazepines and neuroleptic drugs in the treatment of behavioural disturbances |

Sample attrition/dropout: 60 of 76 randomised patients completed the study (a further 41 were excluded during the run-in period). Reasons for dropout were not reported Randomisation and allocation: Randomisation computer generated (whether or not unreadable before allocation is not stated). Appearance of pills and placebo not reported Power calculation: Not reported |

Therapy common to all participants: Single-blind placebo 4-week run-in period (in order to exclude placebo responders) Study funding: Not reported Other conflicts: Not reported |

|

dos Santos Moraes et al. (2006) 119 Design: Parallel double-blind RCT Country: Brazil No. of centres: 1 No. randomised: 35 Maximum follow-up: 26 MMSE range included: Not reported Funding: FAPESP, AFIP |

Probable AD (ADRDA criteria) CDR (Brazilian version) 1–2 (mild to moderate) |

Other causes of dementia Other current severe medical or psychiatric disease Evidence of moderate to severe sleep disorders, based on medical, sleep, and psychiatric interviews Apnoea–hypoapnoea index > 10/hour and periodic leg movement index > 5/hour at baseline polysomnographic recording Psychoactive drugs in the month prior to entering the study |

Sample attrition/dropout: Eight patients left the study owing to technical difficulties in polysomnography recordings Randomisation and allocation: Randomisation process not reported. Individual responsible for the random allocation of patients to the trial arms was blind to the treatment code (how blinding was attained is not reported). Appearance of donepezil and placebo tablets is not described Power calculation: Data from 10 patients were initially analysed for sample size estimation (procedure not reported). Based on this analysis, a sample size of 15 subjects in each group was calculated to set out a difference of eight percentage points in REM sleep percentage (significance level of 1% and power of 95%). To assess the interaction term in the ANOVA model, 27 people were required in each group (sample size not attained) – power of 80% was possible with the sample size analysed |

Therapy common to all participants: Two nights of polysomnographic recording (for purposes of habituation) Study funding: FAPESP, AFIP Other conflicts: Authors state no financial conflicts of interest No financial support from industry for study |

|

Moraes et al. (2008) 120 Design: Parallel double-blind RCT Country: Brazil No. of centres: 1 No. randomised: 23 Maximum follow-up: 12 MMSE range included: 6–27 Funding: FAPESP, AFIP |

AD (ADRDA criteria) Rating of 1–2 (mild to moderate) on Brazilian version of CDR |

Rating of ≥ 3 on Brazilian version of CDR Other causes of dementia Other current severe medical or psychiatric disease Psychoactive drugs in the month prior to entering the study |

Sample attrition/dropout: Not reported Randomisation and allocation: Randomisation performed using computer-generated random number list (0–1) with uniform distribution, with patients consecutively allocated to the two treatment groups (≤ 0.5 to group A, > 0.5 to group B). Donepezil and placebo pills were ‘packed in the same fashion’, but precise appearance of pills not reported Power calculation: Not reported |

Therapy common to all participants: Two nights of polysomnographic recording (for purposes of habituation) Study funding: FAPESP, AFIP Other conflicts: Authors state no conflicts of interest to disclose |

|

Peng et al. (2005) 121 Design: Parallel double-blind RCT Country: China No. of centres: 15 hospitals in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou No. randomised: 90 Maximum follow-up: 12 MMSE range included: 10–24 Funding: Not reported |

AD (NINCDS-ADRDA and DSM-IVR criteria) ≥ 55 years old In female patients, menopause ≥ 2 years Sufficient vision and hearing to complete assessments |

Other disease that may lead to dementia Severe heart or kidney dysfunction, active peptic ulcer or active epilepsy Allergy to cholinergic drugs |

Sample attrition/dropout: 89 of 90 completed the study. n = 1 dropped out due to AE (dizziness) Randomisation and allocation: Randomisation procedure not described. Placebo described as having the same colour, shape, flavour and size as donepezil Power calculation: Not reported |

Therapy common to all participants: None Study funding: Not reported Other conflicts: Not reported |

|

Winstein et al. (2007) 122 Design: Parallel double-blind RCT Country: USA No. of centres: 1 No. randomised: 10 Maximum follow-up: 4 MMSE range included: 11–26 |

Probable AD diagnosis (criteria not reported) Independent in ambulation Alert Able to follow simple instructions |

Delirium Familial tremor Parkinson’s disease Stroke Peripheral neuropathy Dementia due to other than probable AD Use of any concurrent pharmaceutical treatment for cognitive dysfunction |

Sample attrition/dropout: 10 of 10 completed study Randomisation and allocation: Randomisation procedure not described. Placebo described as identical in appearance to donepezil Power calculation: Not reported |

Therapy common to all participants: None Study funding: University of Southern California Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centre, Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centres of California, and Pfizer, Inc. Other conflicts: None reported |

| Study | Arm | Dose (mg/day) | Dosage details | N | Age, years (SD) | Gender, n male (%) | Race, n white (%) | Weight, kg (SD) | Education, years (SD) | Duration of dementia, months (SD) | ADAS-cog, score (SD) | MMSE, score (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dos Santos Moraes et al. (2006)119 | Donepezil | 5–10 | Starting daily dose of 5 mg for the first month, increased to 10 mg/day in the second month | 17 | 77.4 (6.60) | 4 (23.5) | 4.40 (3.60) | 35.6 (13.7) | ||||

| Placebo | – | Single daily dose | 18 | 74.5 (9.80) | 7 (38.9) | 6.00 (5.20) | 39.0 (18.5) | |||||

| Mazza et al. (2006)118 | Donepezil | 5 | 5 mg daily | 25 | 64.5 (6.00) | 13 (52.0) | 18.6 (3.47) | |||||

| Placebo | – | Not reported | 26 | 69.8 (3.00) | 10 (38.5) | 18.8 (3.63) | ||||||

| Moraes et al. (2008)120 | Donepezil | 5–10 | Single dose of 5 mg (administered at bedtime) in the first month, increased to single dose of 10 mg in second month | 11 | 76.8 (6.20) | 3 (27.3) | 34.5 (15.8) | 19.0 (3.60) | ||||

| Placebo | – | Single dose administered at bedtime | 12 | 72.6 (11.0) | 5 (41.7) | 29.3 (17.3) | 17.2 (7.80) | |||||

| Peng et al. (2005)121 | Donepezil | 5 | Same dose administered throughout duration of study | 46 | 72.6 (6.80) | 21 (45.7) | 17.8 (2.30) | |||||

| Placebo | – | – | 43 | 71.8 (8.20) | 19 (44.2) | 18.2 (2.70) | ||||||

| Winstein et al. (2007)122 | Donepezil | 5 | One tablet taken nightly | 5 | 84.2 (8.67) | 2 (40.0) | 24.0 (3.08) | 19.2 (3.35) | ||||

| Placebo | 5 | 88.0 (7.62) | 1 (20.0) | 26.0 (11.6) | 20.2 (4.09) |

| Study | Was the assignment to the treatment groups really random? | Was the treatment allocation concealed? | Were the groups similar at baseline in terms of prognostic factors? | Were the eligibility criteria specified? | Were outcome assessors blinded to the treatment allocation? | Was the care provider blinded? | Was the patient blinded? | Were the point estimates and measure of variability presented for the primary outcome measure? | Did the analyses include an ITT analysis? | Were withdrawals and dropouts completely described? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mazza et al. (2006)118 | Partial | Inadequate | Reported – yes | Inadequate | Partial | Partial | Partial | Adequate | Partial | Partial |

| dos Santos Moraes et al. (2006)119 | Unknown | Inadequate | Reported – yes | Inadequate | Partial | Partial | Partial | Adequate | Unknown | Partial |

| Moraes et al. (2008)120 | Inadequate | Inadequate | Reported – yes | Unknown | Partial | Adequate | Adequate | Adequate | Unknown | Inadequate |

| Peng et al. (2005)121 | Unknown | Unknown | Reported – yes | Unknown | Unknown | Adequate | Adequate | Adequate | Inadequate | Adequate |

| Winstein et al. (2007)122 | Unknown | Unknown | Reported – yes | Inadequate | Unknown | Adequate | Adequate | Inadequate | Partial | Adequate |

Evidence of clinical effectiveness

Cognition

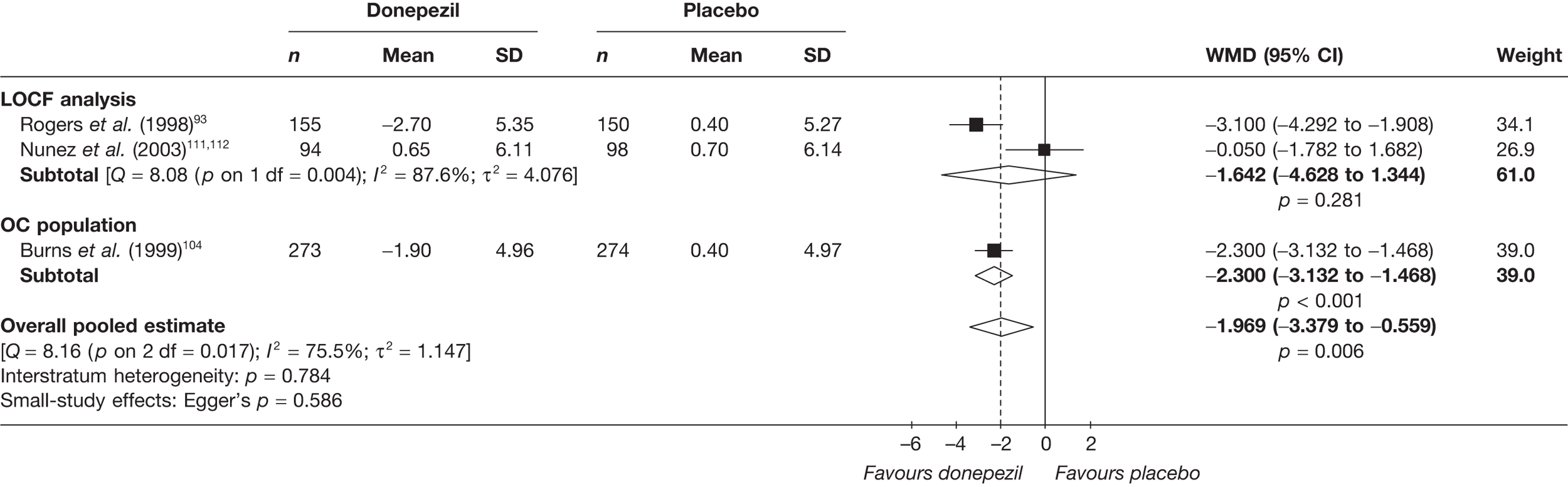

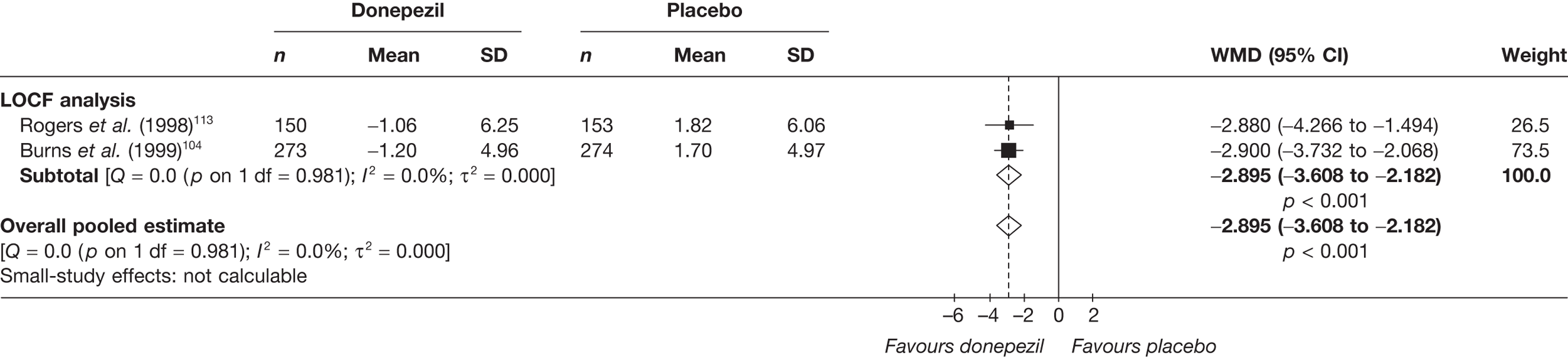

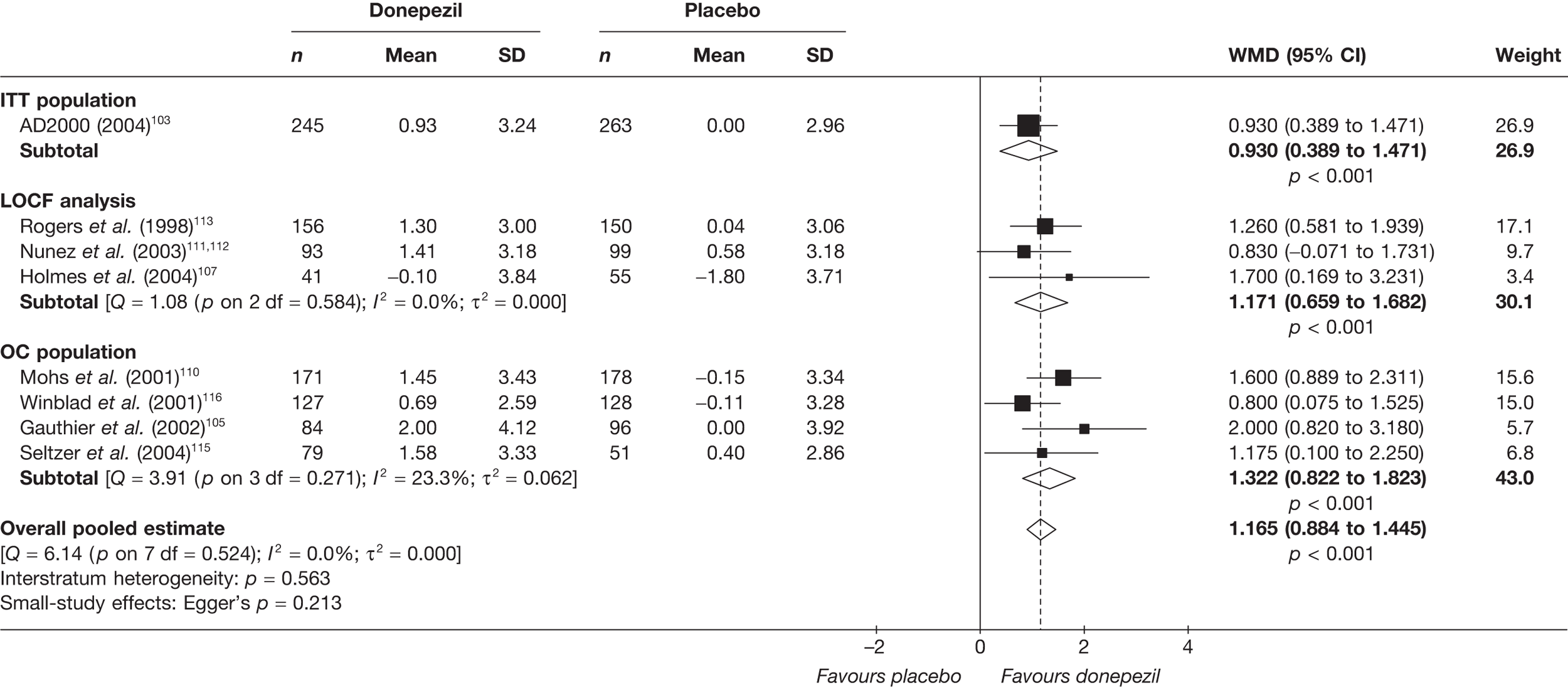

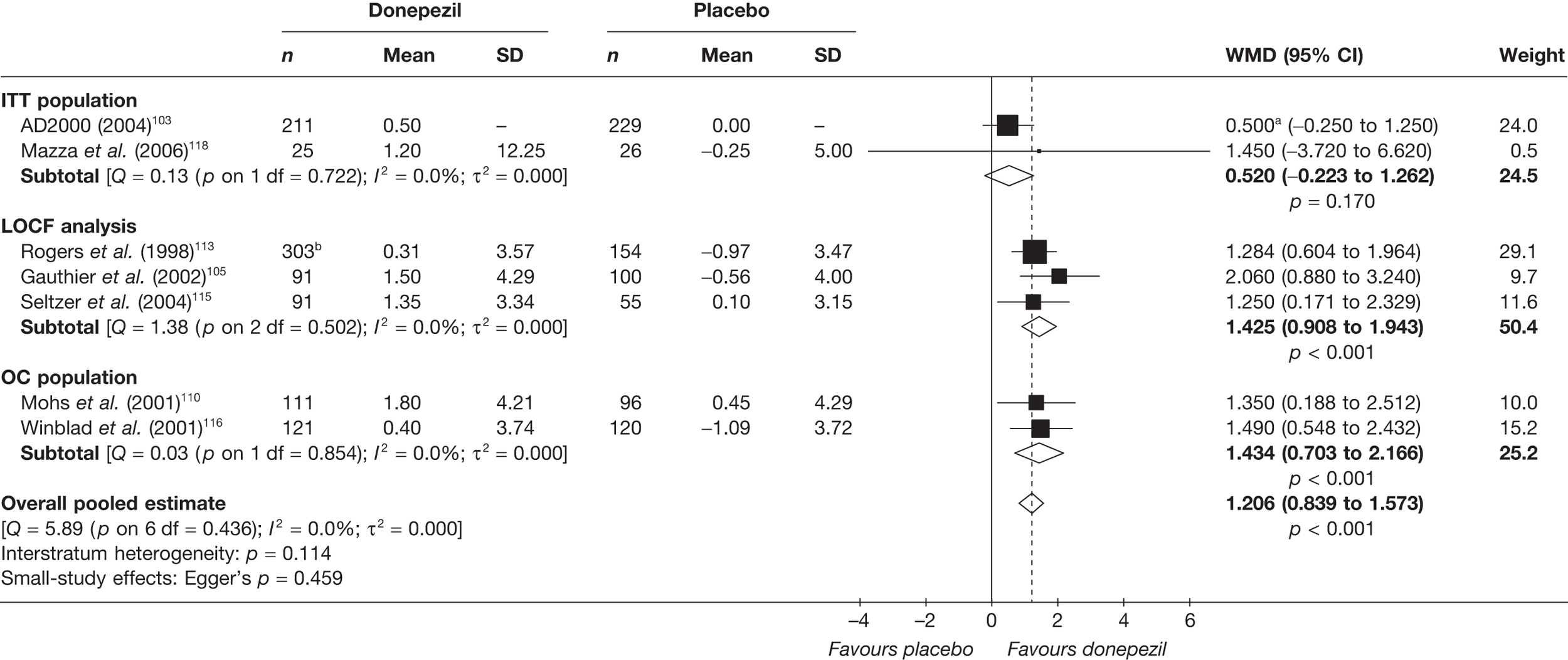

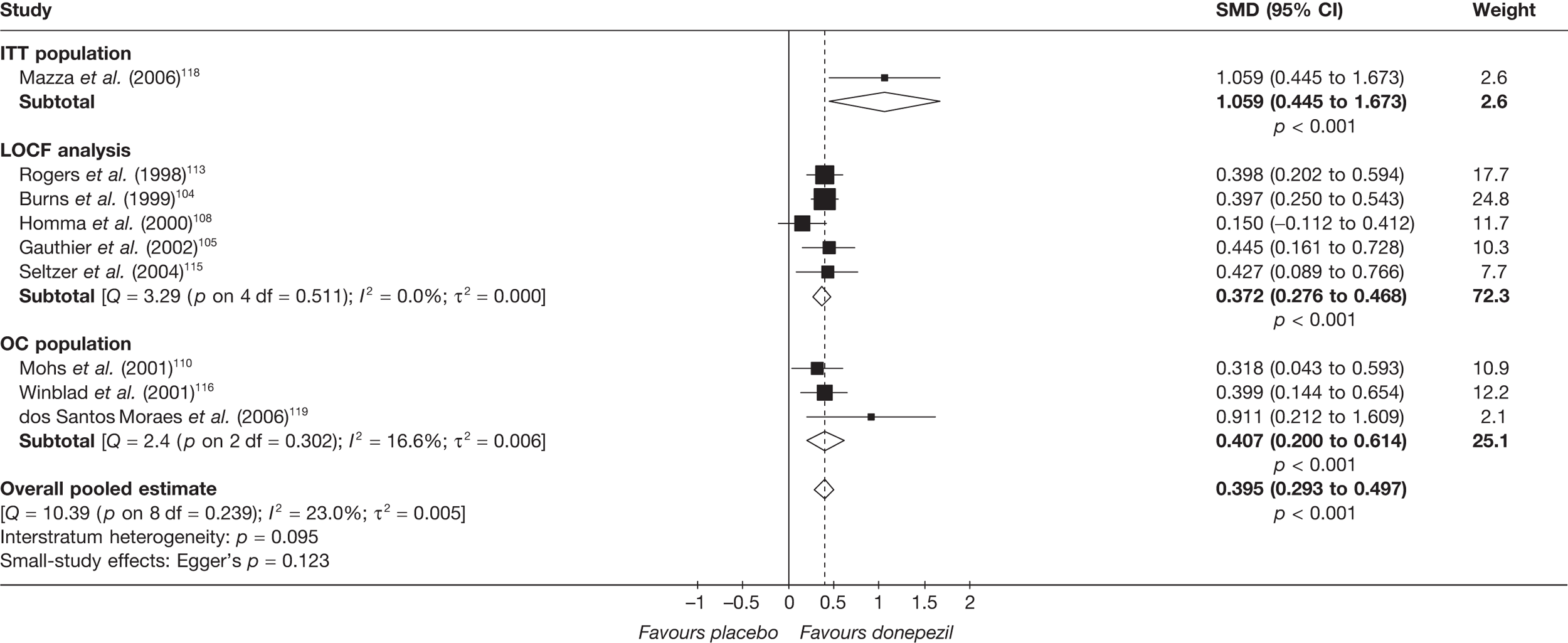

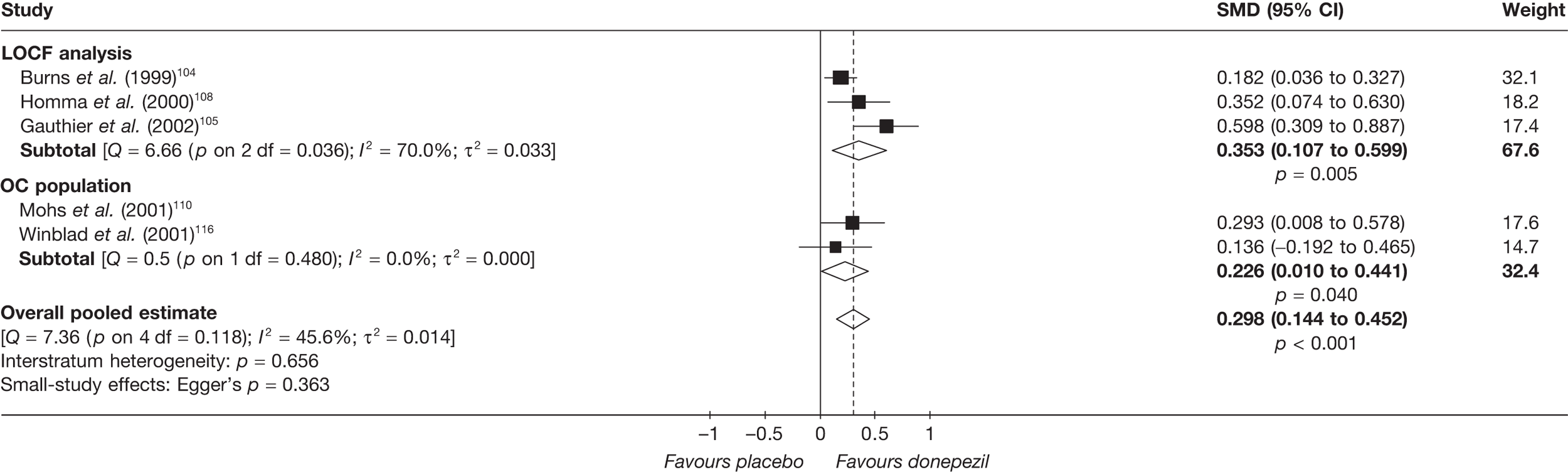

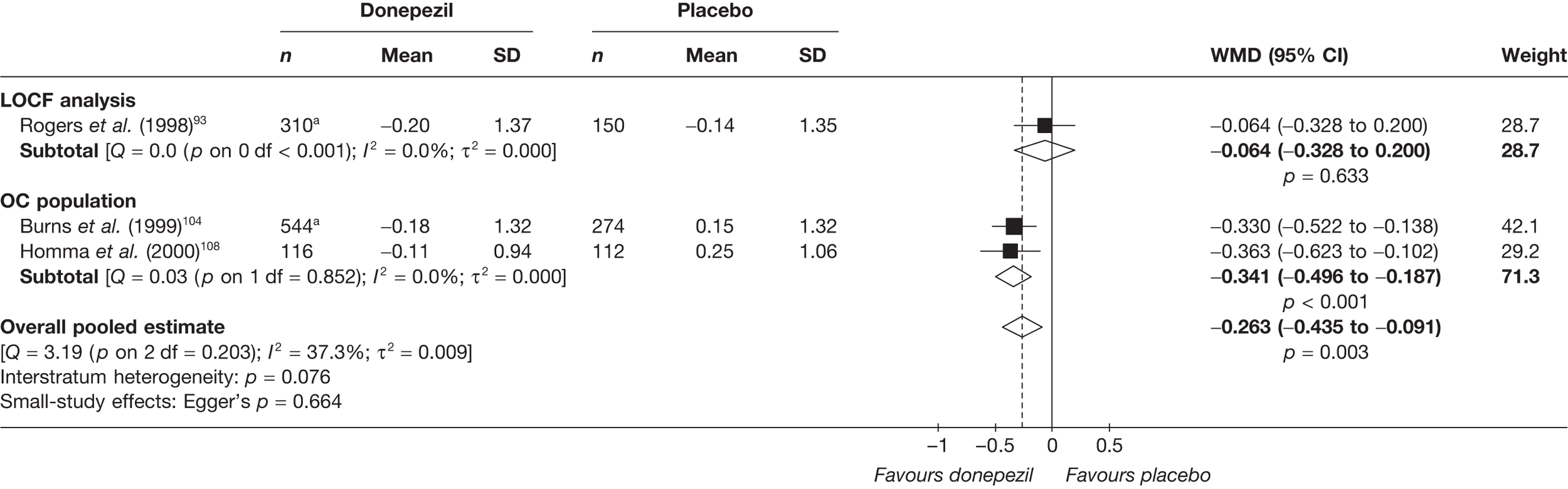

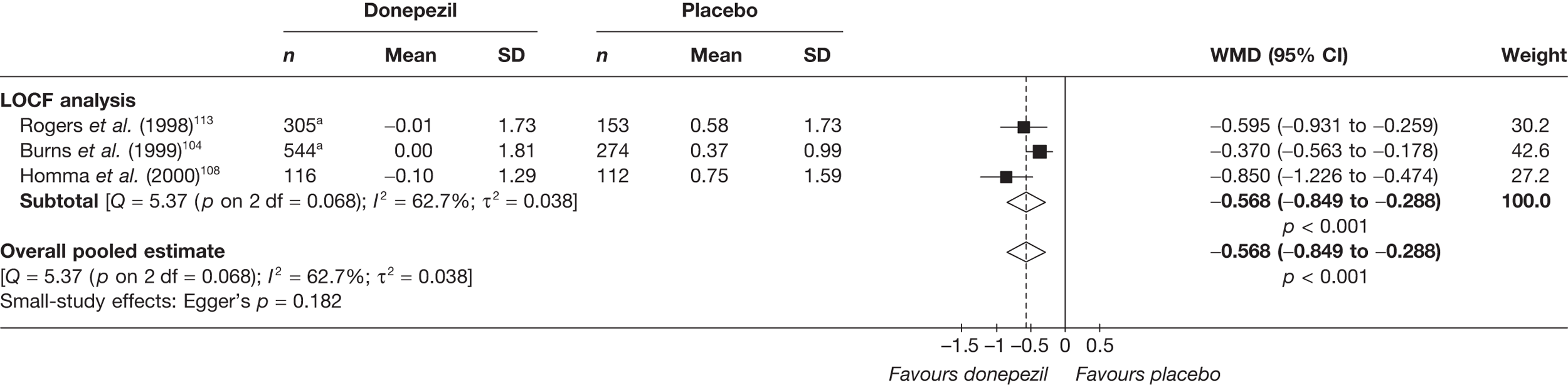

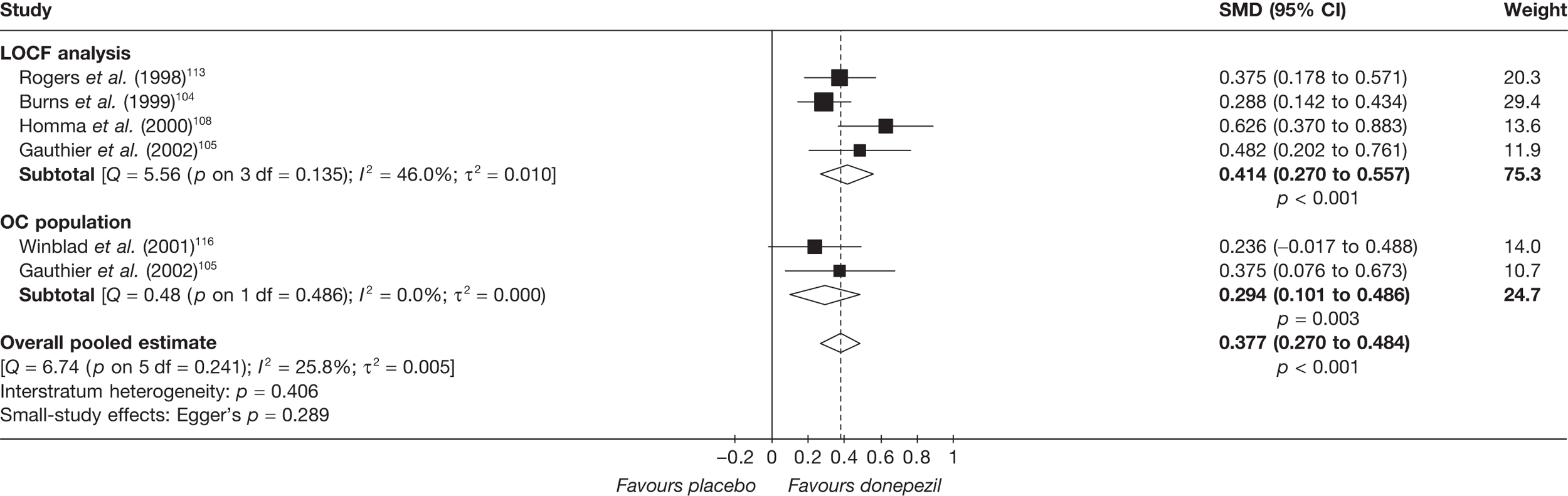

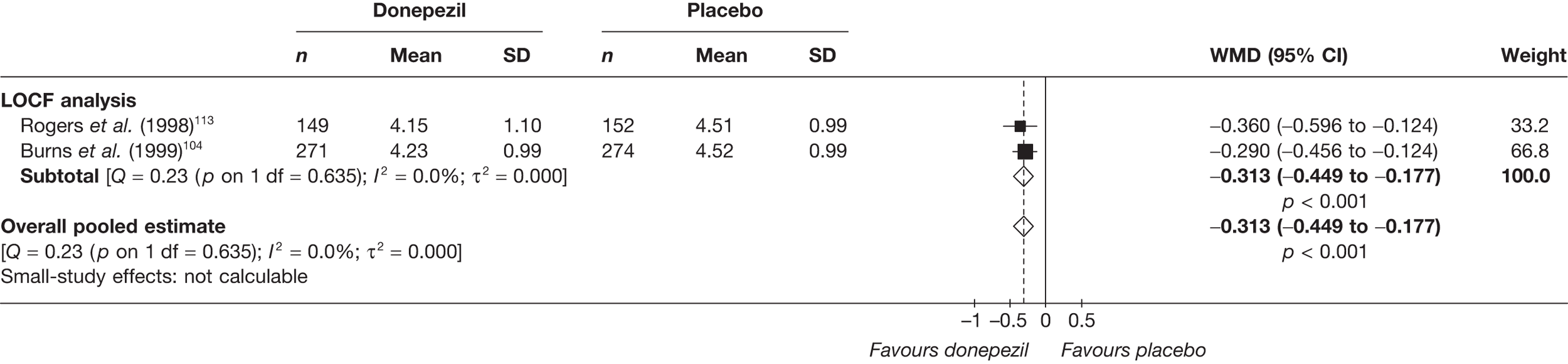

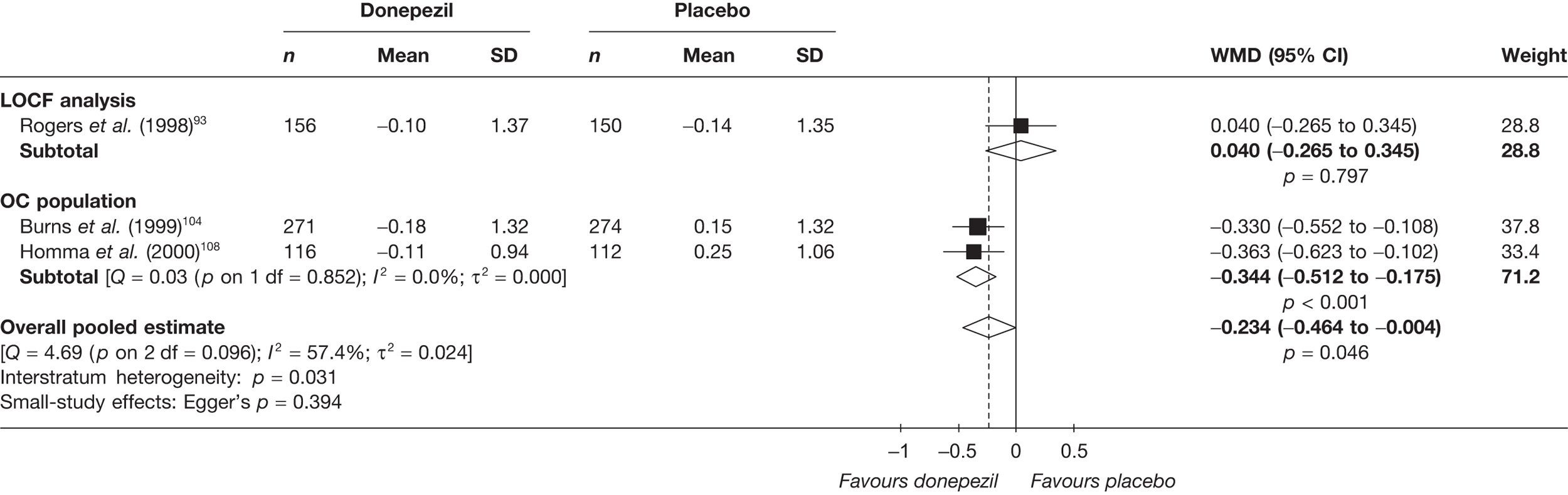

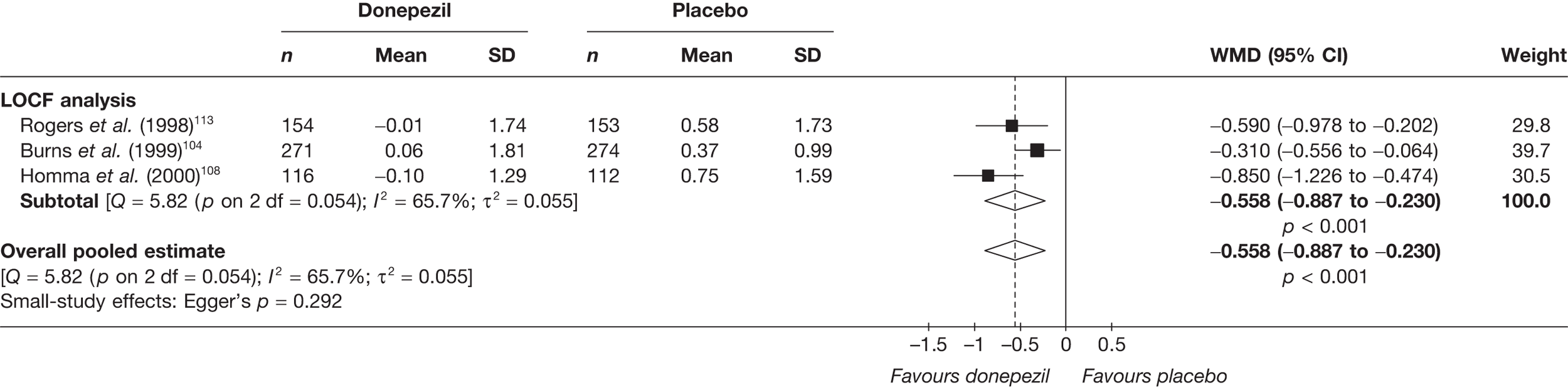

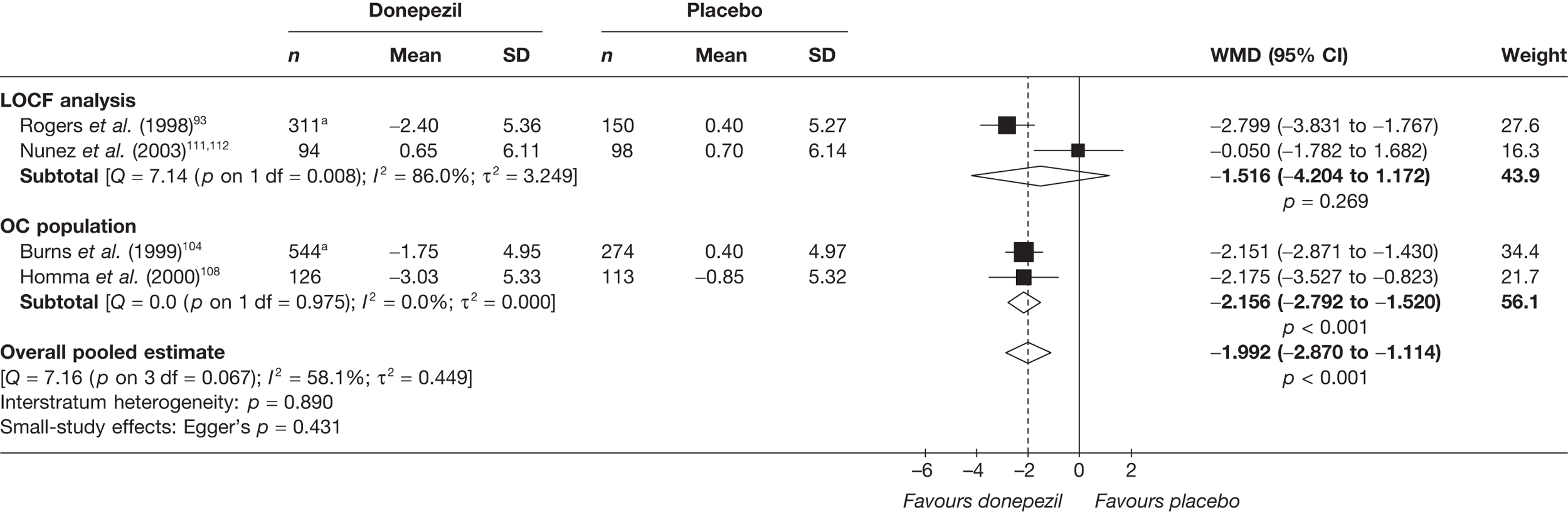

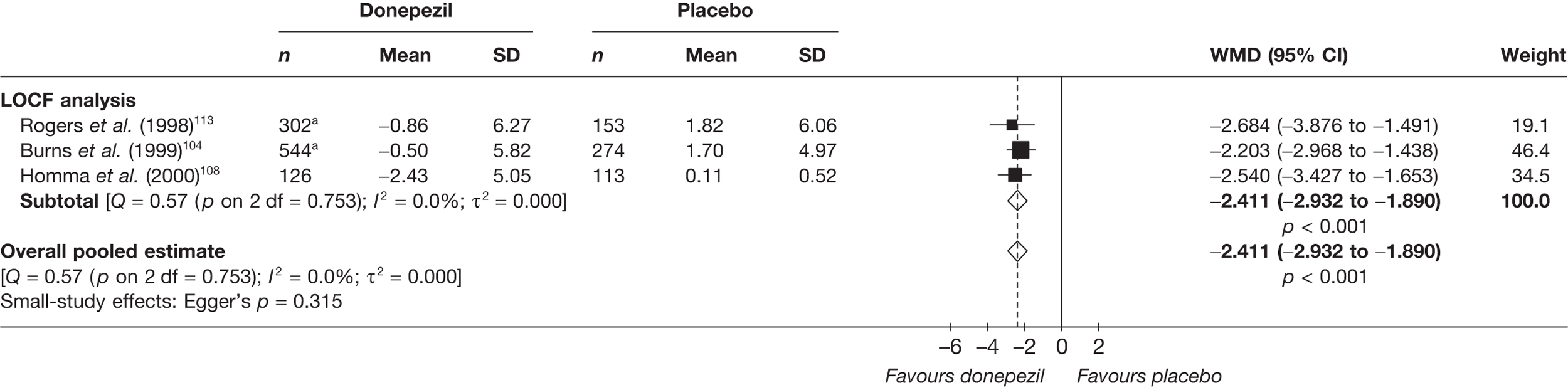

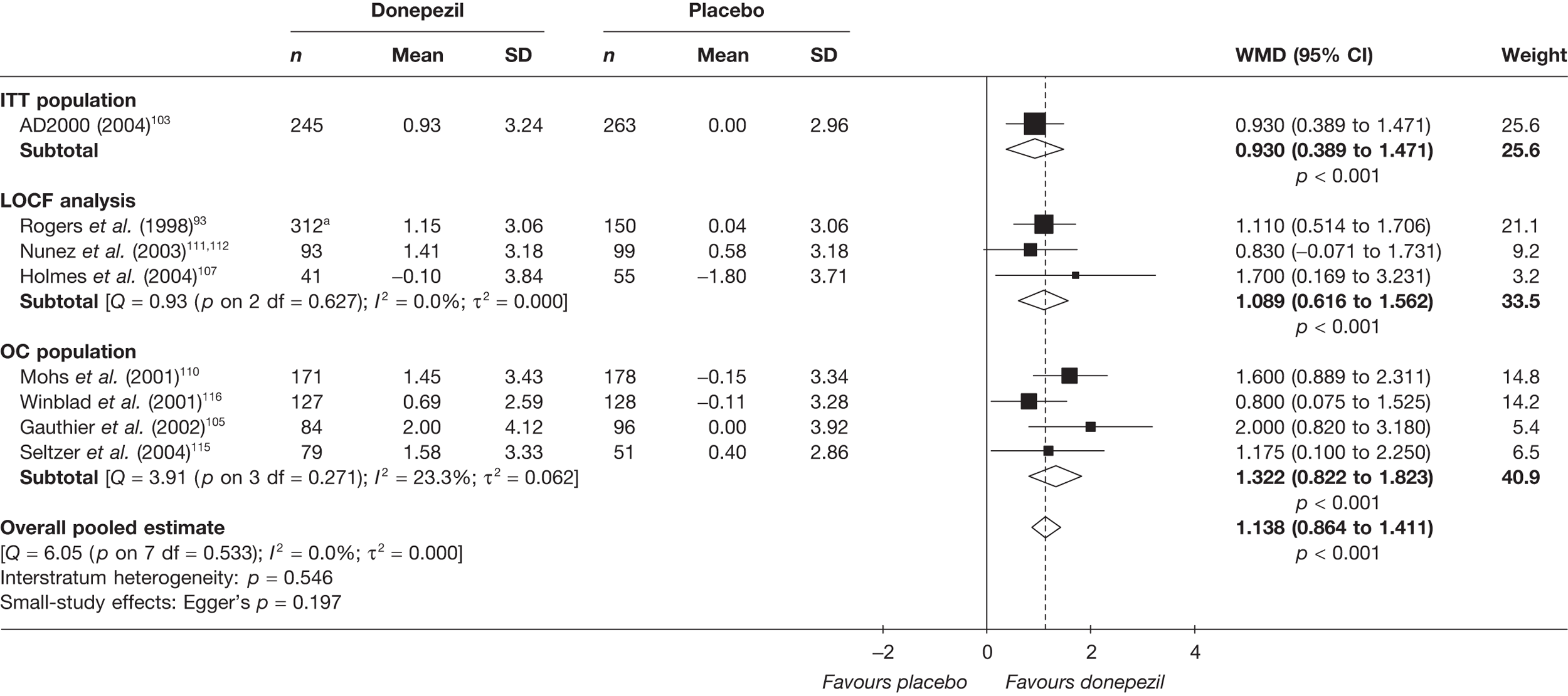

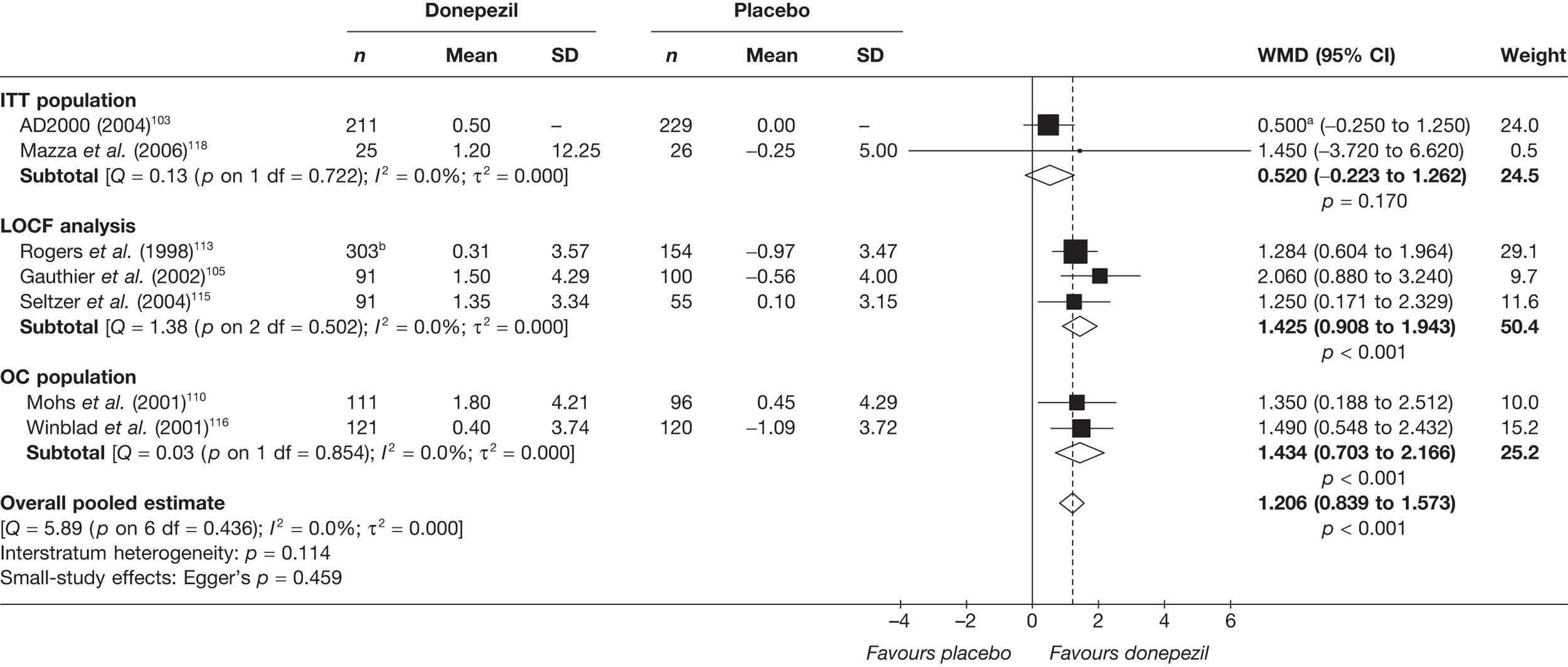

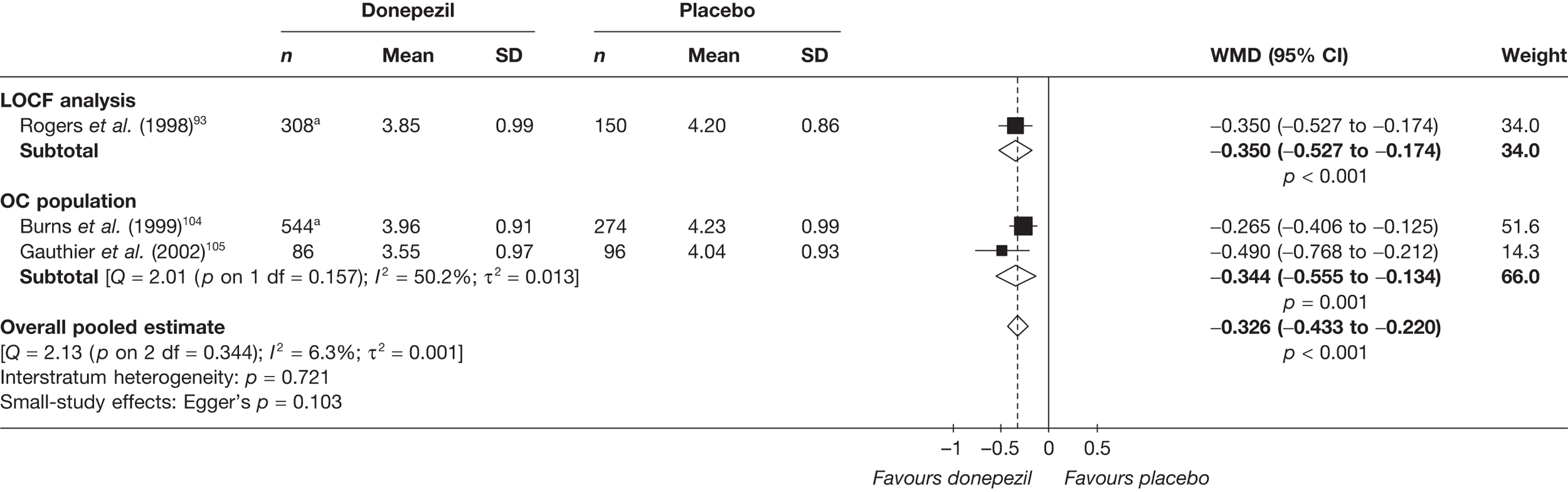

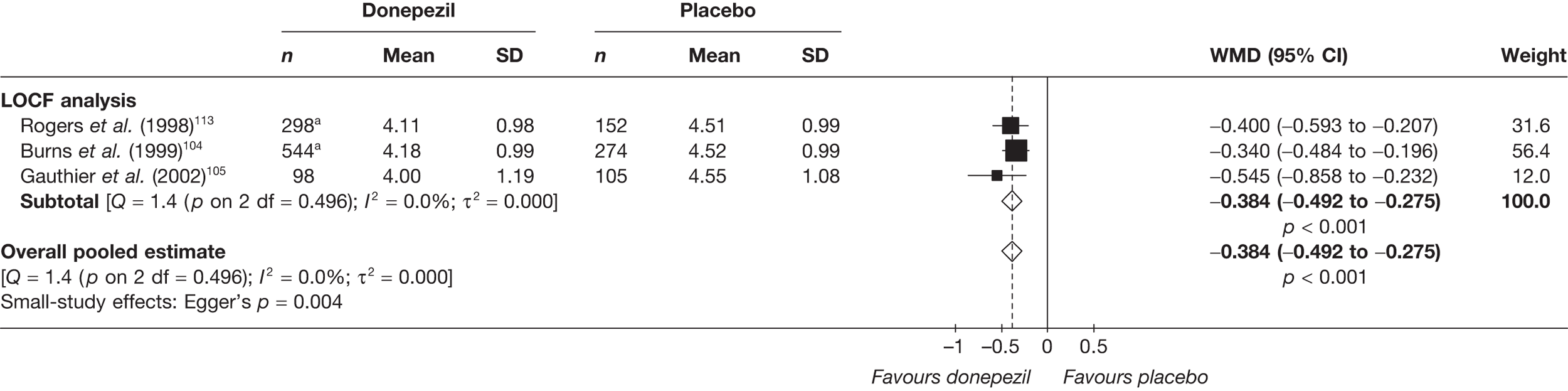

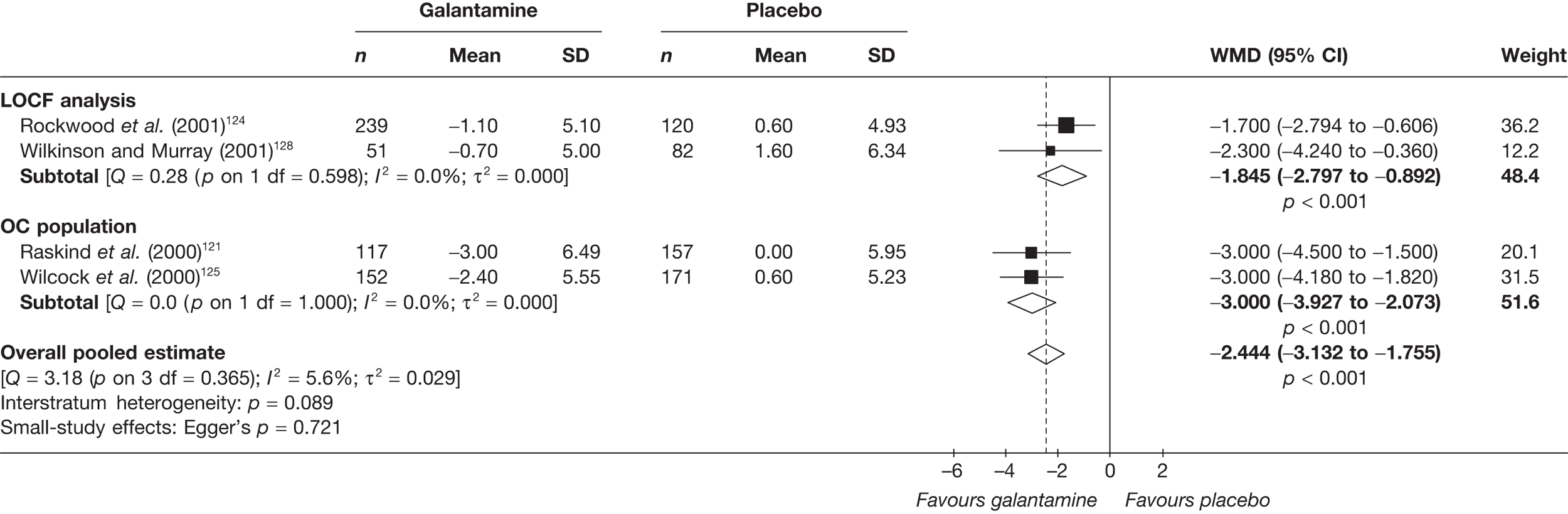

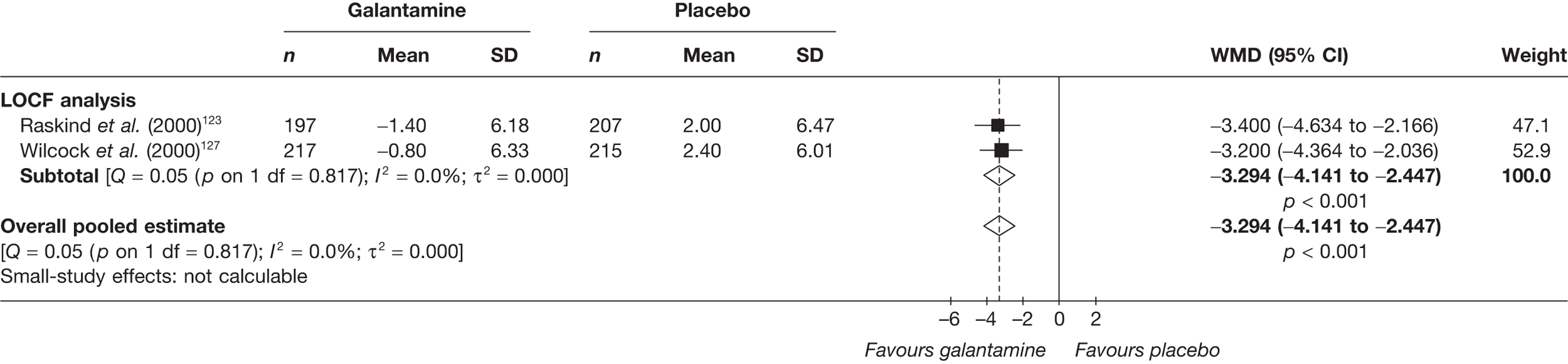

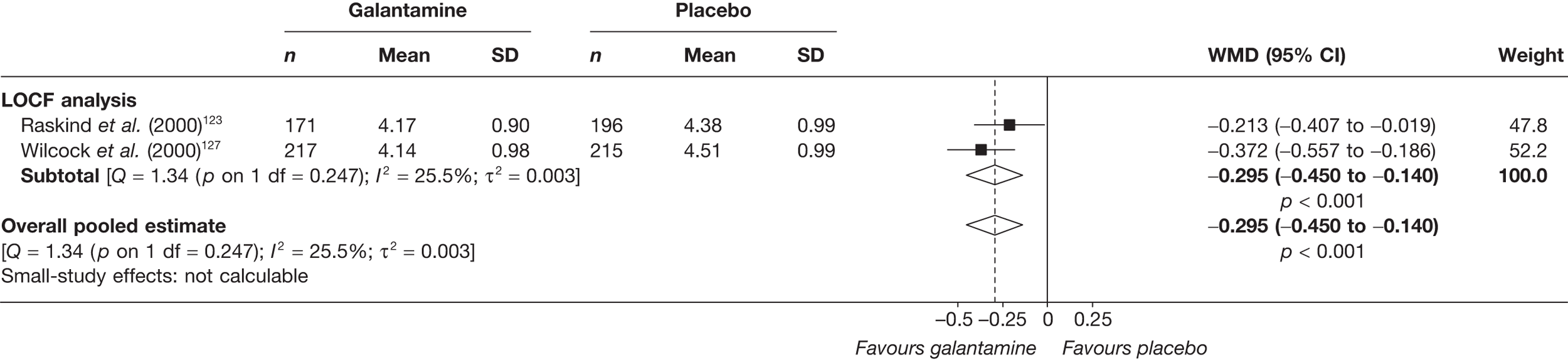

In 2004, Loveman and colleagues2 summarised the evidence they found for donepezil versus placebo for cognitive outcomes as follows: