Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the National Coordinating Centre for Research Methodology (NCCRM), and was formally transferred to the HTA programme in April 2007 under the newly established NIHR Methodology Panel. The HTA programme project number is 06/92/06. The contractual start date was in September 2007. The draft report began editorial review in January 2011 and was accepted for publication in July 2011. The commissioning brief was devised by the NCCRM who specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2012. This work was produced by Freeth et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2012 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Part I Context and study design

The enigmatic concept of ‘safety culture’ ranks high on the list of safety concerns in the safety movement.

(Lilford, 2010, p. 1)1

Chapter 1 Introduction

Purpose and context

The purpose of the study was to compare measurements of organisational and safety cultures and the quality of care, employing two contrasting methods to measure culture. The list of detailed aims and objectives can be found in Aims and objectives.

Since the key document An organisation with a memory,2 patient safety and the means of promoting it have been high priorities in NHS policy. 3–5 The Department of Health set up the National Patient Safety Agency in 2001, and funded a Patient Safety Research Portfolio, beginning in 2001, with the final tranche of its 50 commissioned studies reporting during 2010. 1,6 In parallel, the Health Foundation commissioned the Patient Safety Initiative (2004–8). 7

Policy and academic work associated with patient safety draws on a large body of international research and practice development focused on patient safety that began in the early 1990s. Landmark reports8–10 showed that avoidable harm to patients was occurring frequently in health care. Understanding of patient safety quickly drew in ideas developed from studies of other safety-critical endeavours, for example aviation, offshore drilling, and nuclear power and chemical plants. 11–14 The World Health Organization is supporting patient safety research across the world. 15

An organisation with a memory2 recognises that organisational factors play a key role in patient safety. Research suggests that significant organisational influence is transmitted not only or mostly through particular processes or directives but through organisational culture:16 the term ‘safety culture’ has been used to denote those aspects of organisational culture that have particular relevance to the promotion of patient safety. 17 If a positive safety culture can contribute to safer care (or a negative safety culture can contribute to less safe care) we need to know how to recognise and promote positive safety cultures. Chapter 2 synthesises a selection of the literature concerning safety culture.

Our definitions of organisational and safety culture are as follows. Organisational culture is the collection of shared beliefs, values and norms of behaviour found in an organisation;18 safety culture is the subset of those values, beliefs and norms that relate to safety. 19 Climates are distinguished from cultures: organisational climate refers to the aggregate of individual perceptions, practices, policies, procedures and routines in an organisation, while safety climate refers to the aggregate of those perceptions as they relate to safety. 20 Climates are regarded as representing the surface manifestations of underlying cultures. 21

Evaluating and measuring organisational and safety cultures may allow organisations to identify areas for improving patient safety. Qualitative or quantitative assessments of culture may identify priorities for quality improvement interventions and act as a baseline for subsequent assessments. Questionnaires and other diagnostic frameworks for self-evaluation have been developed for this purpose and are widely used (see Chapter 2). In the UK, the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) and the ‘Patient Safety First!’ campaign promoted the use of safety climate questionnaires and safety culture diagnostic frameworks for ongoing quality improvement in a wide range of health care settings. 22,23 At the beginning of this study, the best-known and most extensively validated safety climate questionnaires were the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ),24 and the subset Teamwork and Safety Climate Survey:25 we used the latter in this study (see Chapter 3, Strand A: staff survey).

Safety climate questionnaires are inexpensive to administer and can be analysed quickly, so if they measure something that promotes high-quality care they are a valuable resource. However, questionnaire scores can be susceptible to ‘social desirability bias’26 or be invalidated by ‘cognitive dissonance’: the inability of staff to accept evidence that the service that they work in is less than safe. 27 Postal questionnaires, in particular, can elicit very low response rates or variable response rates depending upon the degree of interest recipients have in contributing their views on the topic of the questionnaire28 and, if there are systematic differences between responders and non-responders, non-response bias influences results. Response rates among health-care professionals appear to be falling29,30 and, since increased health-care delivery pressures and a rising number of requests to complete questionnaires or similar forms are thought to be probable causes, this trend looks set to continue.

In parallel with the development and promotion of questionnaires and other diagnostic frameworks, there has been investment in ethnographic studies focused on patient safety (see Chapter 2, Ethnographic methods, and Dixon-Woods31). Ethnographies focus on culture and illuminate microsocial interactions. They are thus well aligned with the concerns of the patient safety movement. However, ethnographies require participant observers to undertake lengthy immersion in the environment which is being studied, which makes them relatively expensive and slow to report. It is also difficult to conduct ethnographies on multiple sites. Consequently, interest in exploring whether less intensive observation can yield useful insights grew, alongside interest in whether any insights could be linked to the quality of care. Strategic observation combined with other data sources were used in clinical governance review and inspection,32 and highly structured observations have been used to measure the success of specific quality improvement interventions; for example, Catchpole and colleagues33 examined patient handover from surgery to intensive care. Our study required a quantifiable approach to evaluating culture ‘holistically’, using time-limited observations and yielding results that could be compared with survey-based assessments of climate and indicators of the quality of care. There were no well-established methods or prevalidated instruments for this task, so the iterative development of a suitable observation framework and scoring scheme formed a substantial part of the study. We used semistructured observation and brief key informant interviews, informed by an earlier ethnography conducted by three members of the study team. 34 The observation strand of this study will be described in Chapter 3, Strand B: observation-based holistic evaluation of safety culture.

At present, too little is known about how cultures and climates relate to the quality of care. Three studies16,35,36 found limited evidence to support or to challenge the hypothesis that organisational culture and health-care performance are linked: where found, links tend to be contingent and complex. However, Singer and colleagues37 suggested that aspects of safety climate and safety performance are related, while Silva and colleagues38 found organisational climate and safety climate to be inversely correlated with the incidence of accidents.

Bringing together these strands in patient safety research, this study sought to compare organisational and safety cultures as measured by questionnaire and observational tools, and markers of quality of care. Thus, data were collected from eight consultant-led delivery units (DUs) and eight emergency departments (EDs) in England. A DU is one of the specialised clinical areas provided within the continuum of care offered by maternity services. Local terms vary, but DU and delivery suite were the most common terms used at the research sites in this study. Occasionally, people referred to the labour ward. Some research sites preferred to refer to themselves as accident and emergency (A&E) departments, whereas others preferred ED. More recent literature and advice from practitioners suggested that the use of the term ED is growing and now outstrips the use of A&E, so ED will be used throughout this report.

The research sites were located in 6 out of 10 English strategic health authorities (see Table 3). There were three equally important strands of data collection (described in Chapter 3), named strands A, B and C for ease of later reference:

-

strand A, ‘staff survey’: a postal questionnaire for staff at each research site to elicit perceptions of organisational and safety climates, and identify some of the factors that may influence these perceptions

-

strand B, ‘observation-based holistic evaluation’: a profile of scores for organisational and team factors representing aspects of organisational and safety culture, derived from semistructured observations and brief key informant interviews

-

strand C, ‘audit’: audits of evidence-based markers of the quality of care for three purposively selected conditions commonly encountered in the research sites.

These data sets allowed examination of different ways of capturing facets of organisational and safety cultures and comparison of findings. In particular, comparisons aimed to establish whether clinical departments with high (or low) scores for the facets of culture captured in strand A also score highly (or poorly) for the facets of culture captured in strand B: in effect asking whether these two approaches to measuring culture would agree. In addition, the study afforded the opportunity to compare evaluations of culture from strands A and B with markers of the quality of care, which were collected in strand C. These comparisons will explore whether clinical departments with high (or low) scores for the facets of culture captured in strand A or strand B also score highly (or poorly) against the selected markers of the quality of care, again exploring whether there is agreement between different approaches to assessment.

Funding for this study

This study was designed in response to one of the final calls for research proposals from the Patient Safety Research Portfolio (see above) in January 2005. This commissioning round was halted as a result of a review and restructuring of Department of Health funding streams. Subsequently, a similar call was issued by the NHS R&D Methodology Programme in April 2006 (RM05/JH33; see Appendix 1). This study was funded to run from September 2007 to August 2010. Further restructuring of Department of Health research programmes led to this study being transferred to the MRC-NIHR portfolio and renumbered as 06/92/06. During the study, excessive delays occurred within research governance approvals processes at some research sites (see Chapter 4, Research governance). This was compounded by delays in identifying trust-based auditors for strand C and slower than anticipated progress with audits at most research sites (see Chapter 4, Engaging non-clinical auditors). Together, these factors necessitated the request and approval of a 3-month no-cost extension to the spending period for the study. The study was completed in November 2010.

Aims and objectives

The aims and objectives detailed at the beginning of the study are listed below. Following a convention in the field that will be discussed in Chapter 2, this report will use the term ‘climate’ rather than ‘culture’ when referring to assessments arising from questionnaires, for example in objective 2 below.

The aims of the study were:

-

to compare questionnaire and holistic assessments of organisational and safety culture

-

to compare assessments of organisational and safety culture with criterion-based assessment of the quality of care.

The tender specification (see Appendix 1) used the term ‘triangulate’, but several types of triangulation are defined in the research methods literature, and different forms of triangulation might be considered to apply to different parts of this study. The central purpose of the study was to compare different assessments of culture with each other and with markers of the quality of care, using quantified assessments. For clarity, compare is used in this report in preference to triangulate. The tender specification also used the term ‘holistic evaluation’, and this is reflected in the aims. The term ‘holistic evaluation’ is ambiguous and, for clarity, in this report we will reflect the dominant data collection method by substituting the term ‘observation-based assessment’. The tender specification used the term ‘generic’ where we will use organisational.

The objectives of the study were:

-

to work with staff in the participating trusts such that their organisational and professional knowledge was respected, the study was understood and supported within participating departments, and prompt feedback to participant departments allowed local development in advance of the study reporting to the wider health and research communities

-

to use questionnaires to obtain quantitative assessments of the organisational and safety climate at each site

-

to generate quantified holistic evaluations of organisational and safety culture for each site using observation

-

to obtain criterion-based measurements for the quality of care at each site

-

to compare levels of agreement between the questionnaire and holistic measurements of culture

-

to compare organisational culture with safety culture

-

to compare culture measurements and criterion-based measurements of the quality of care

-

to collect data such that, where sufficient respondents existed within a category to protect anonymity, data could be explored by stakeholder group (e.g. managers, midwives, nurses, doctors, allied health professionals, support staff) and level (e.g. management responsibility).

Hypotheses

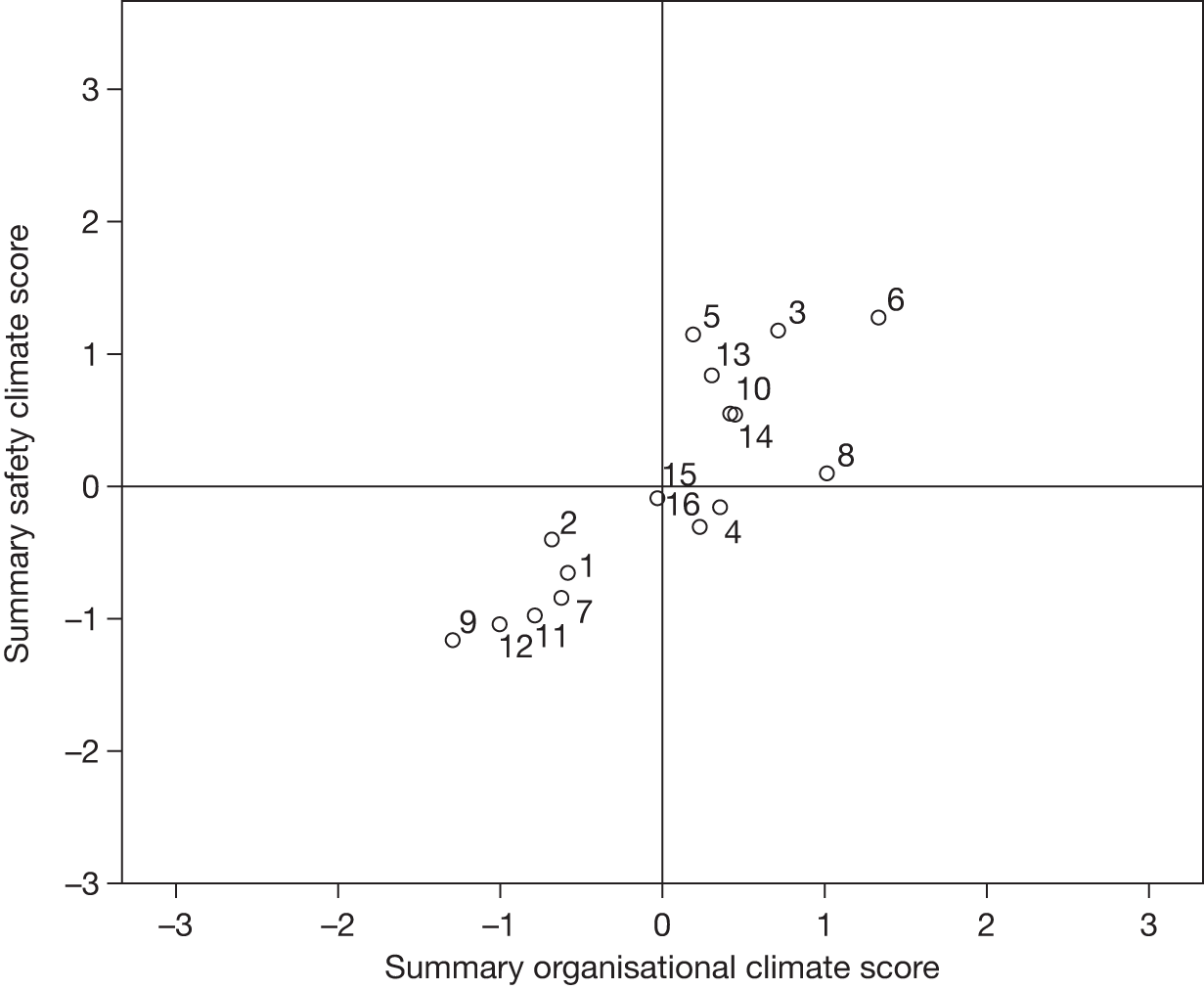

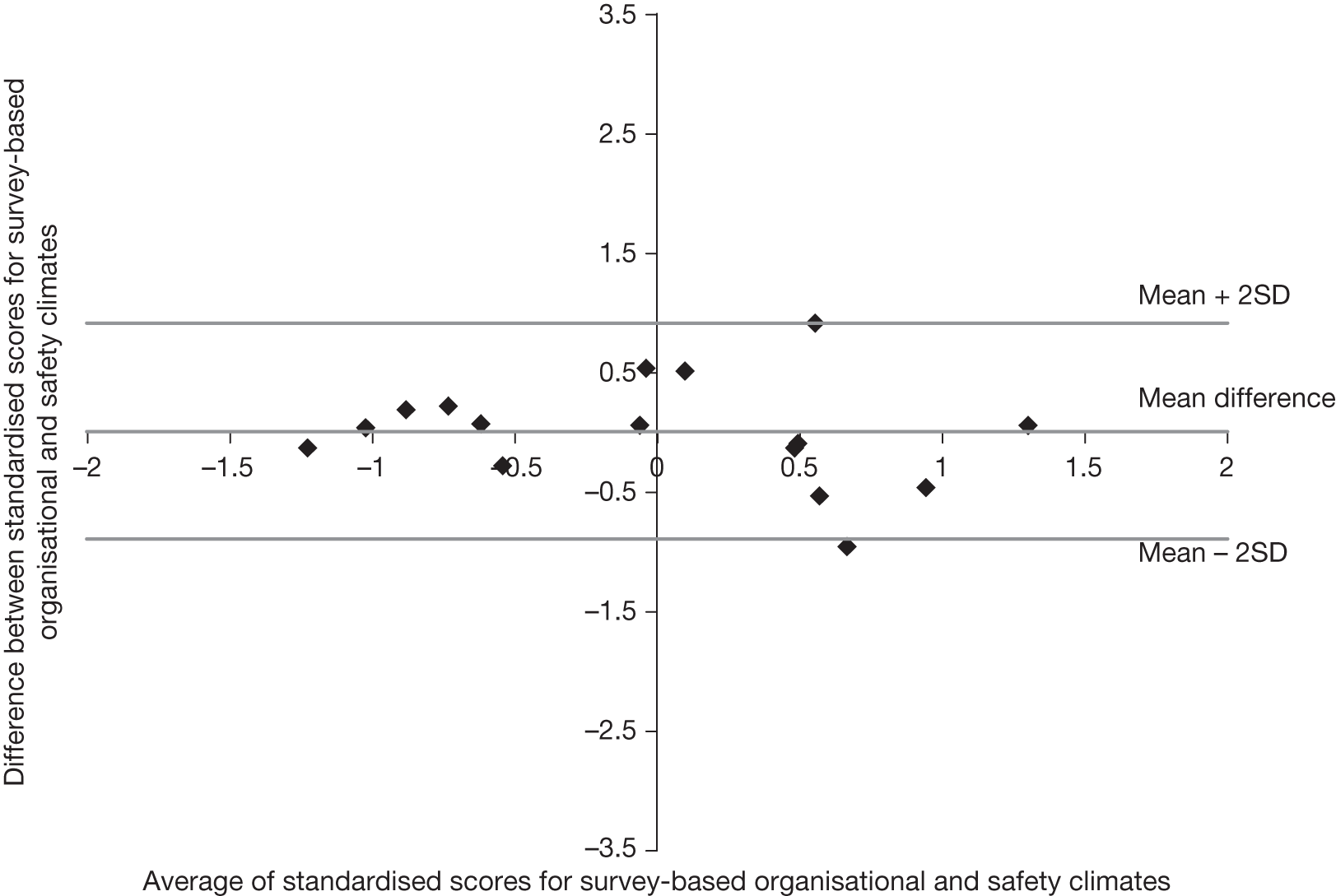

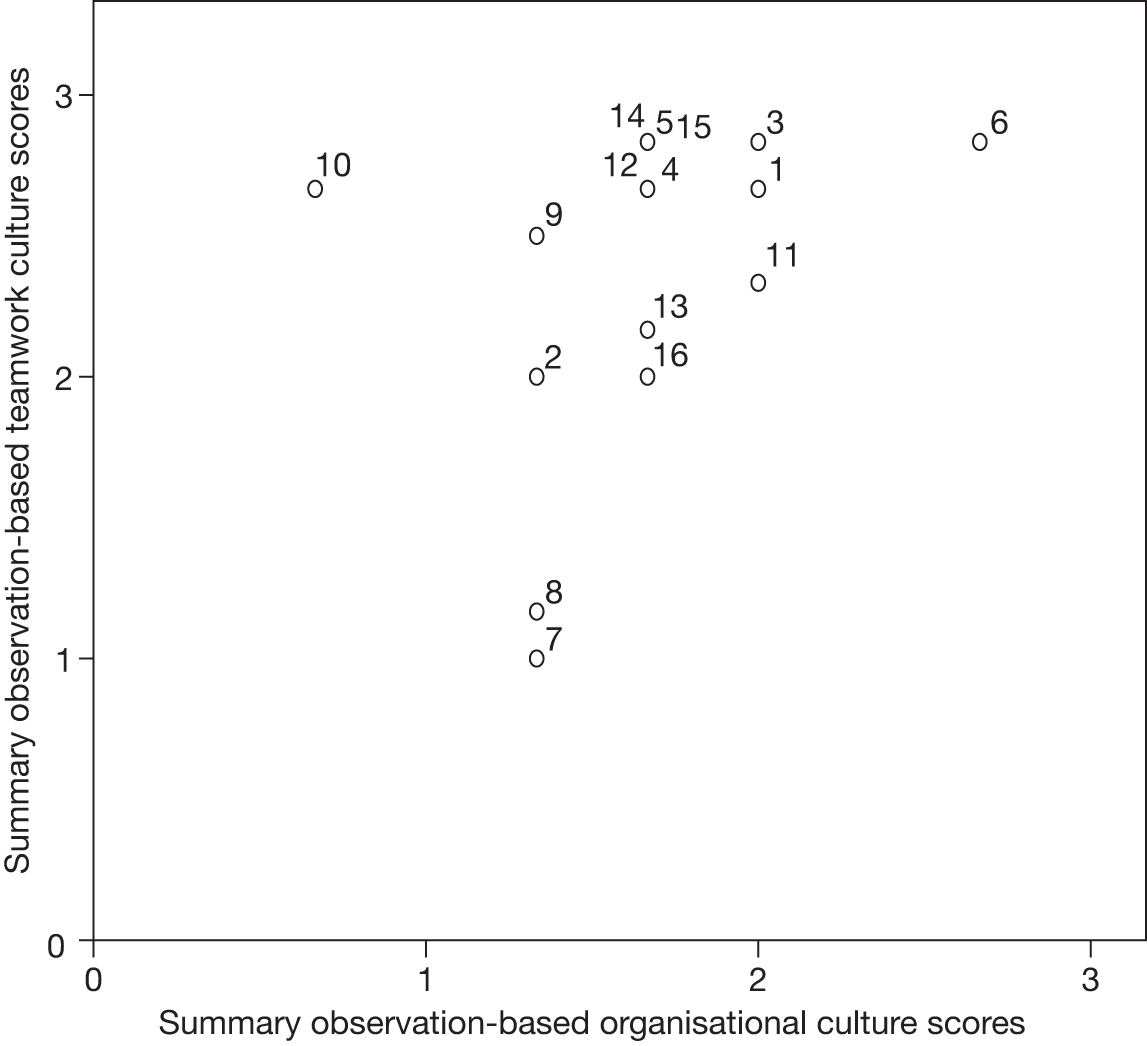

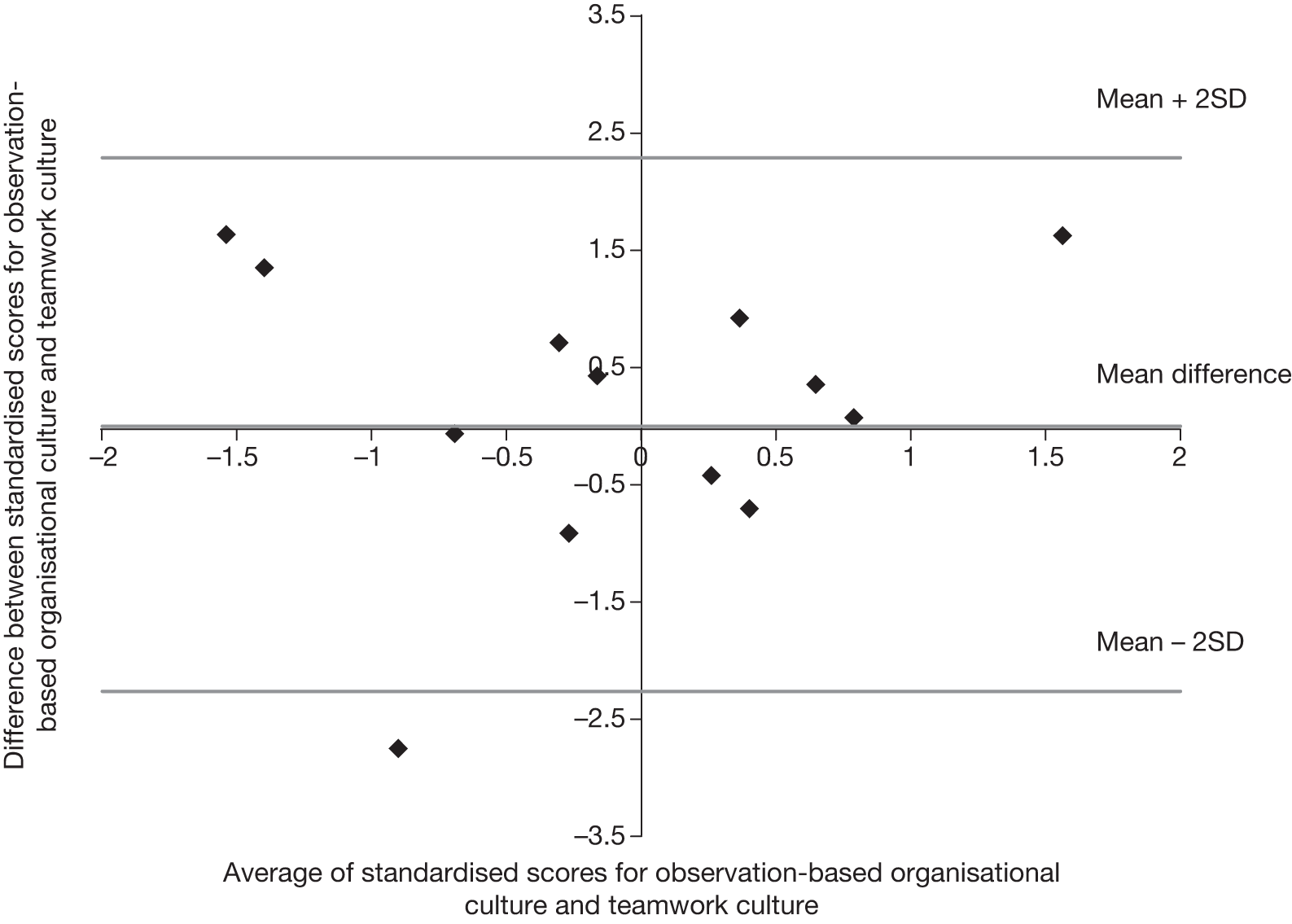

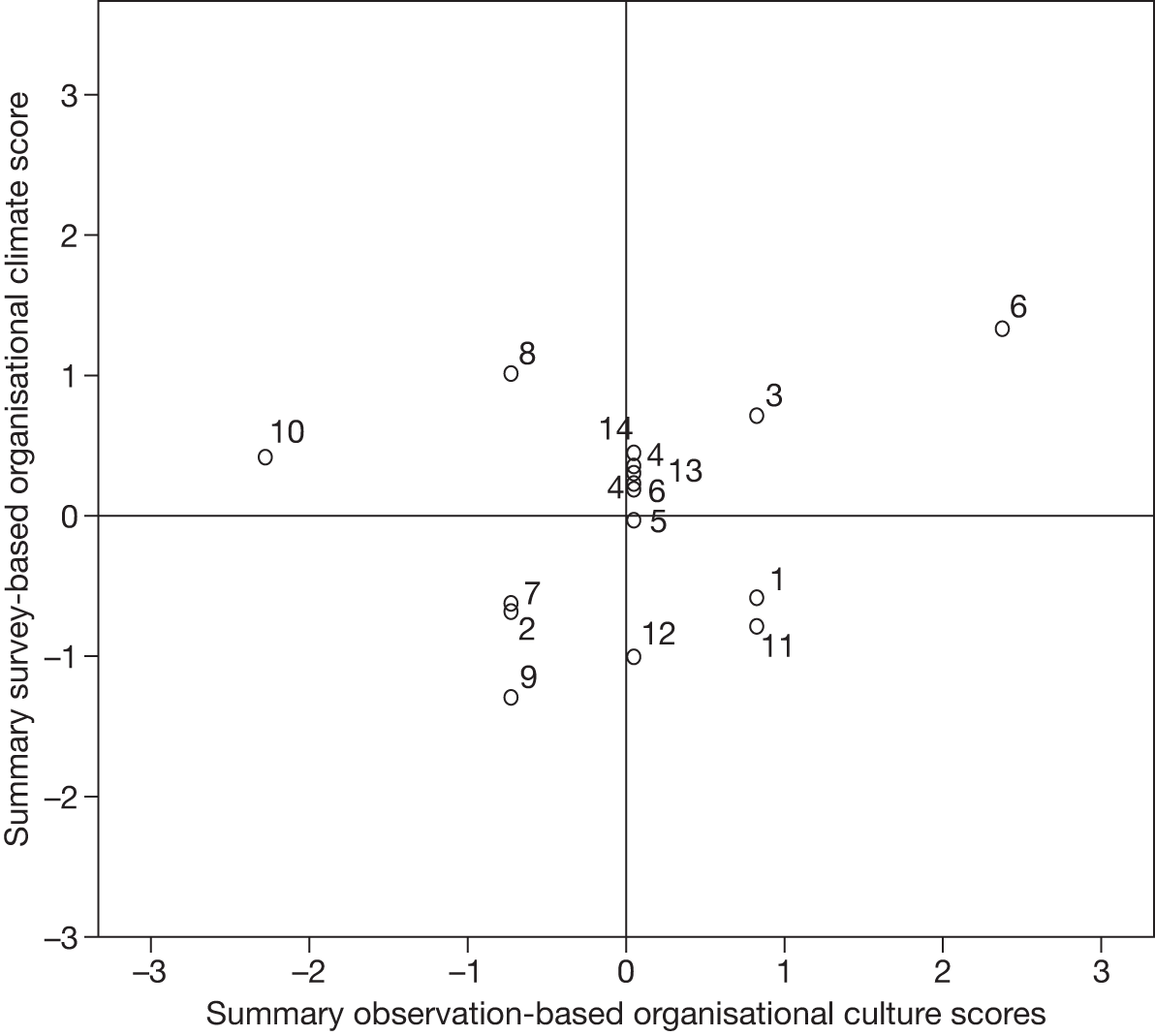

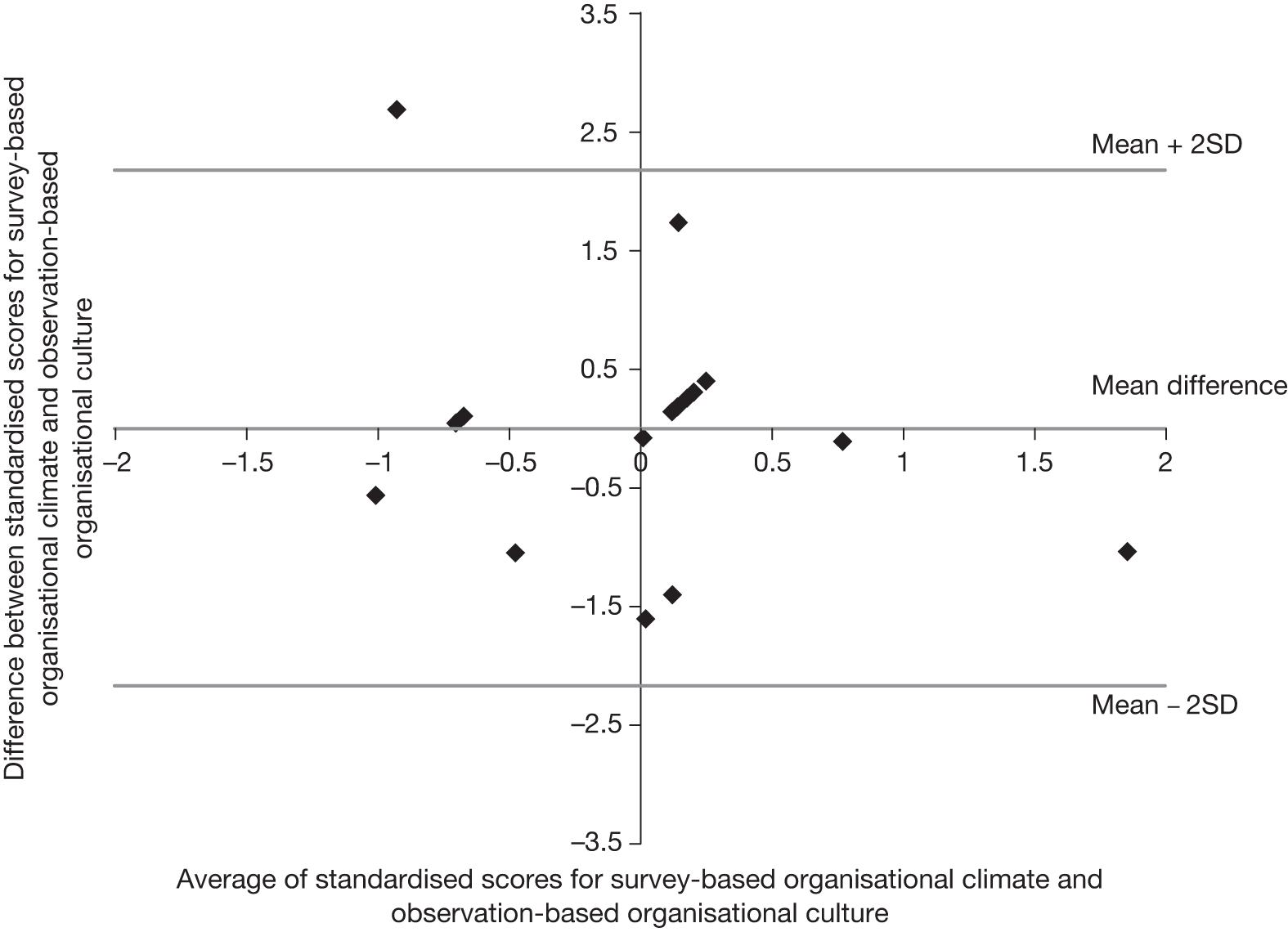

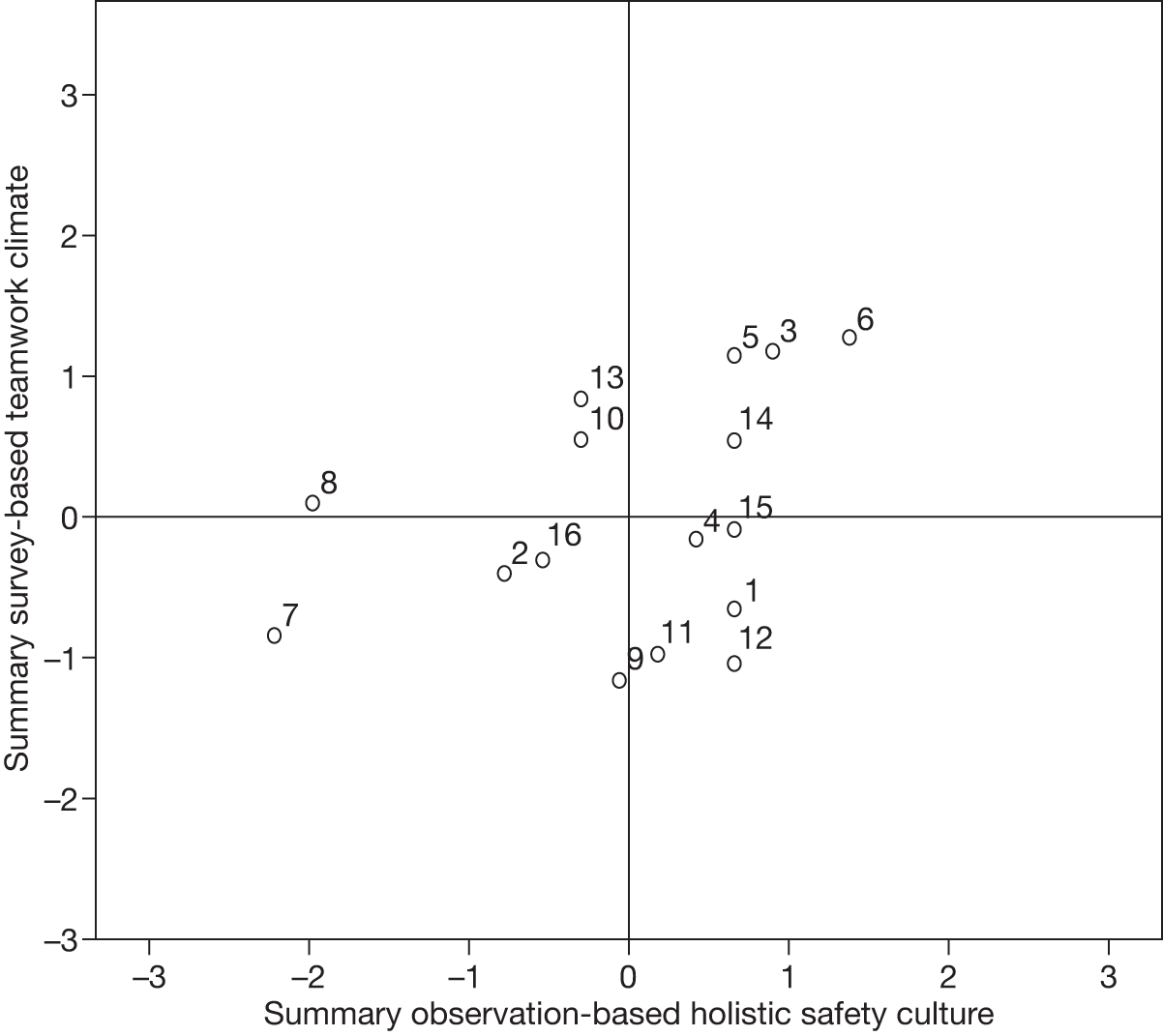

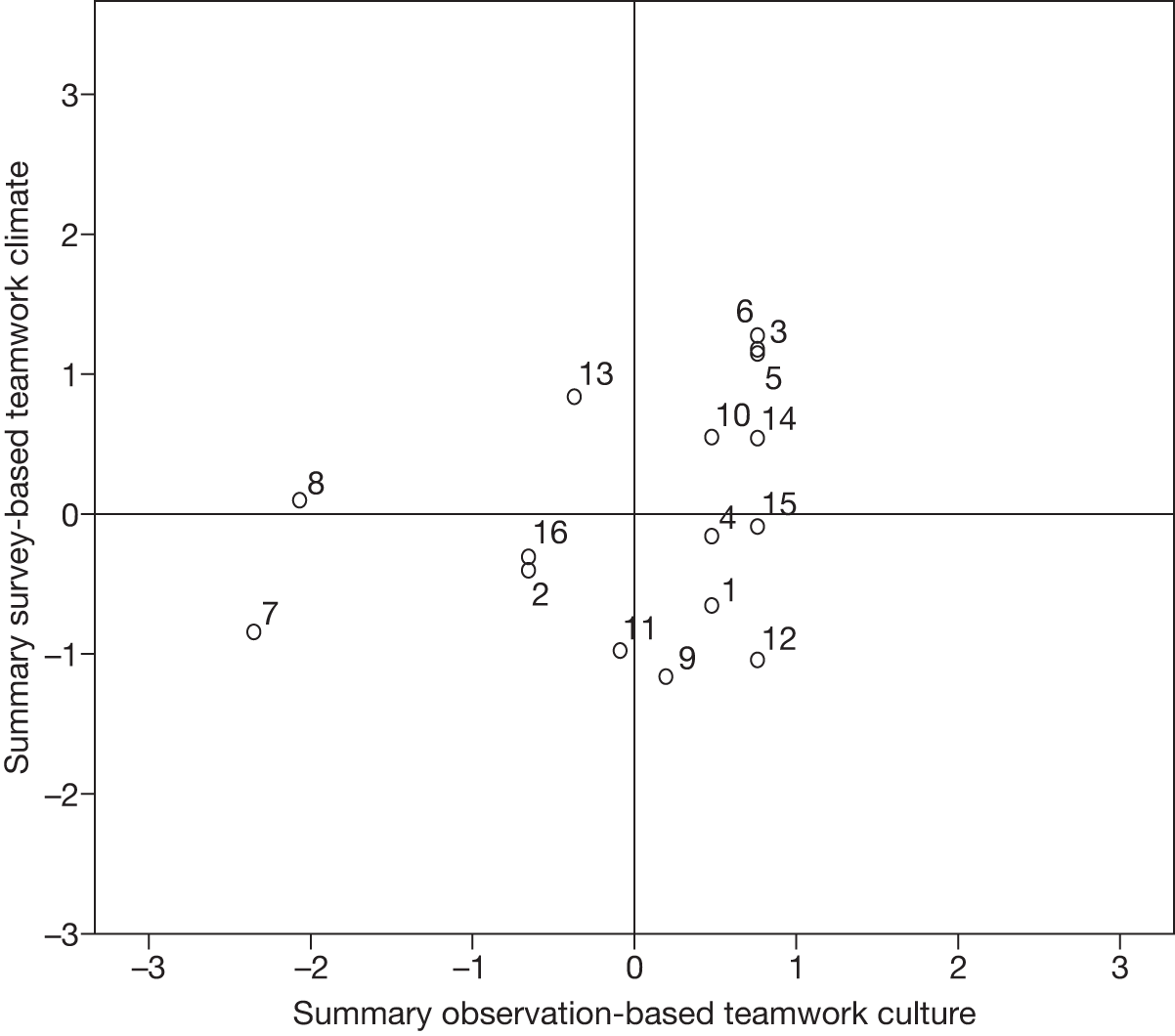

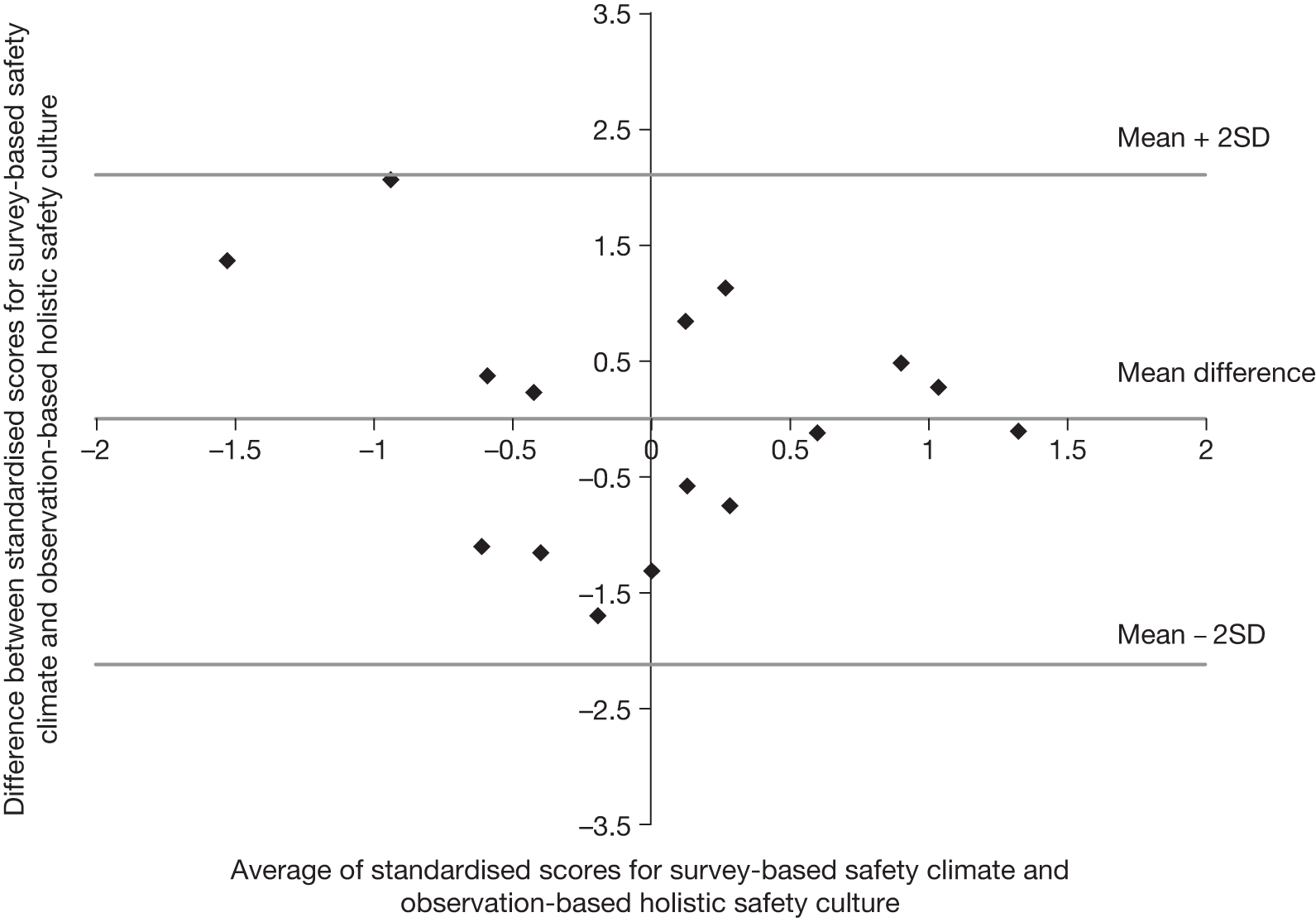

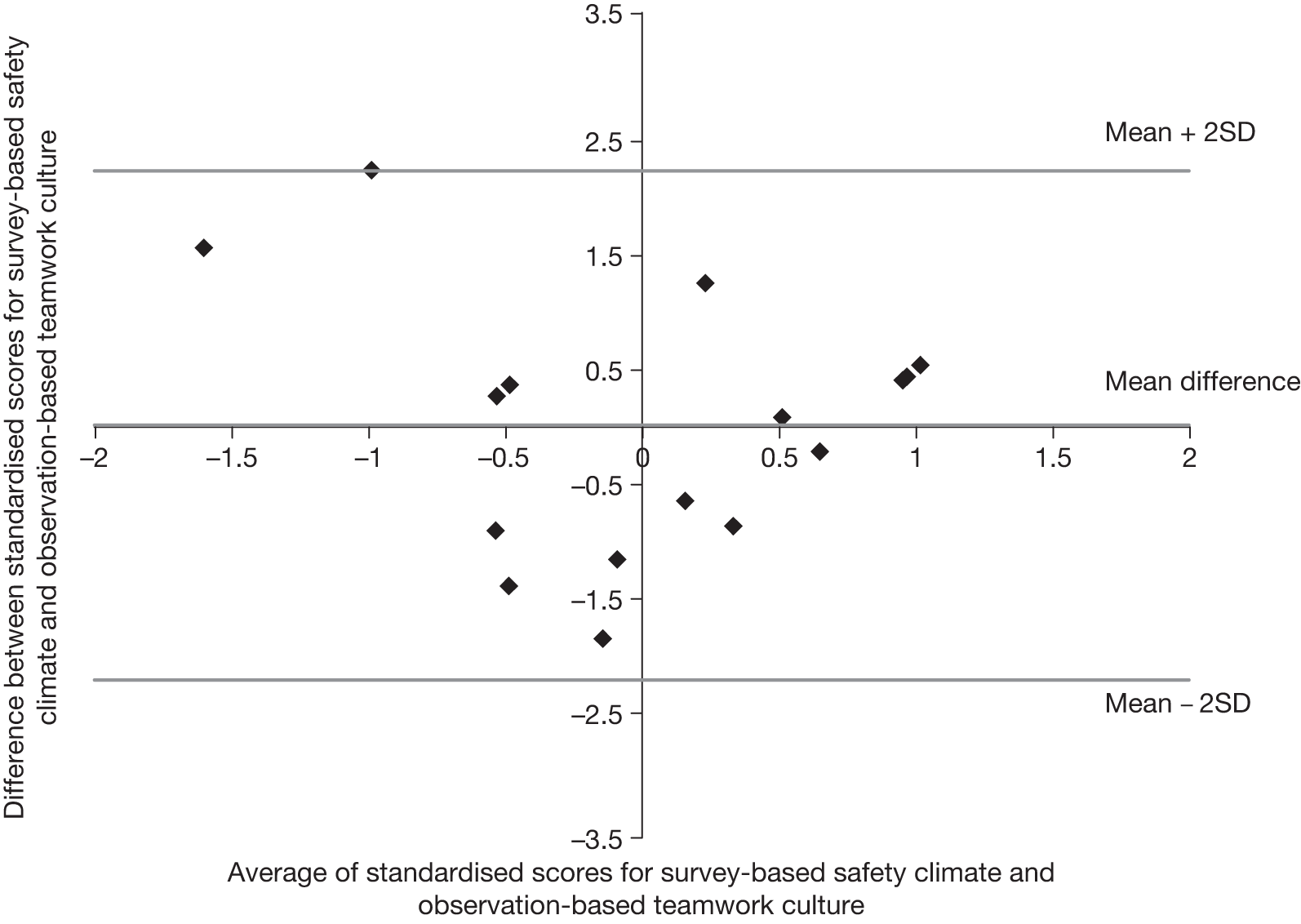

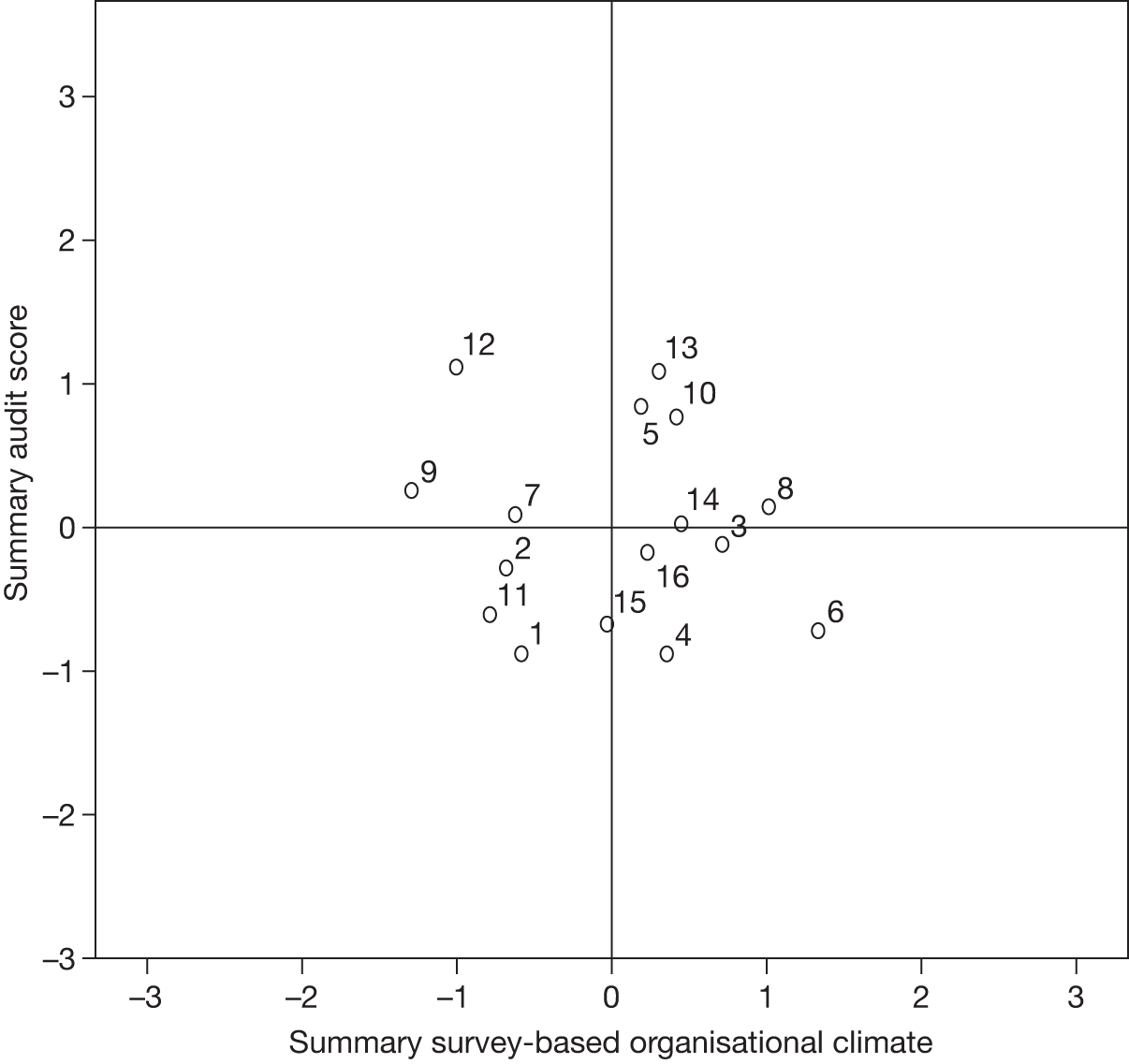

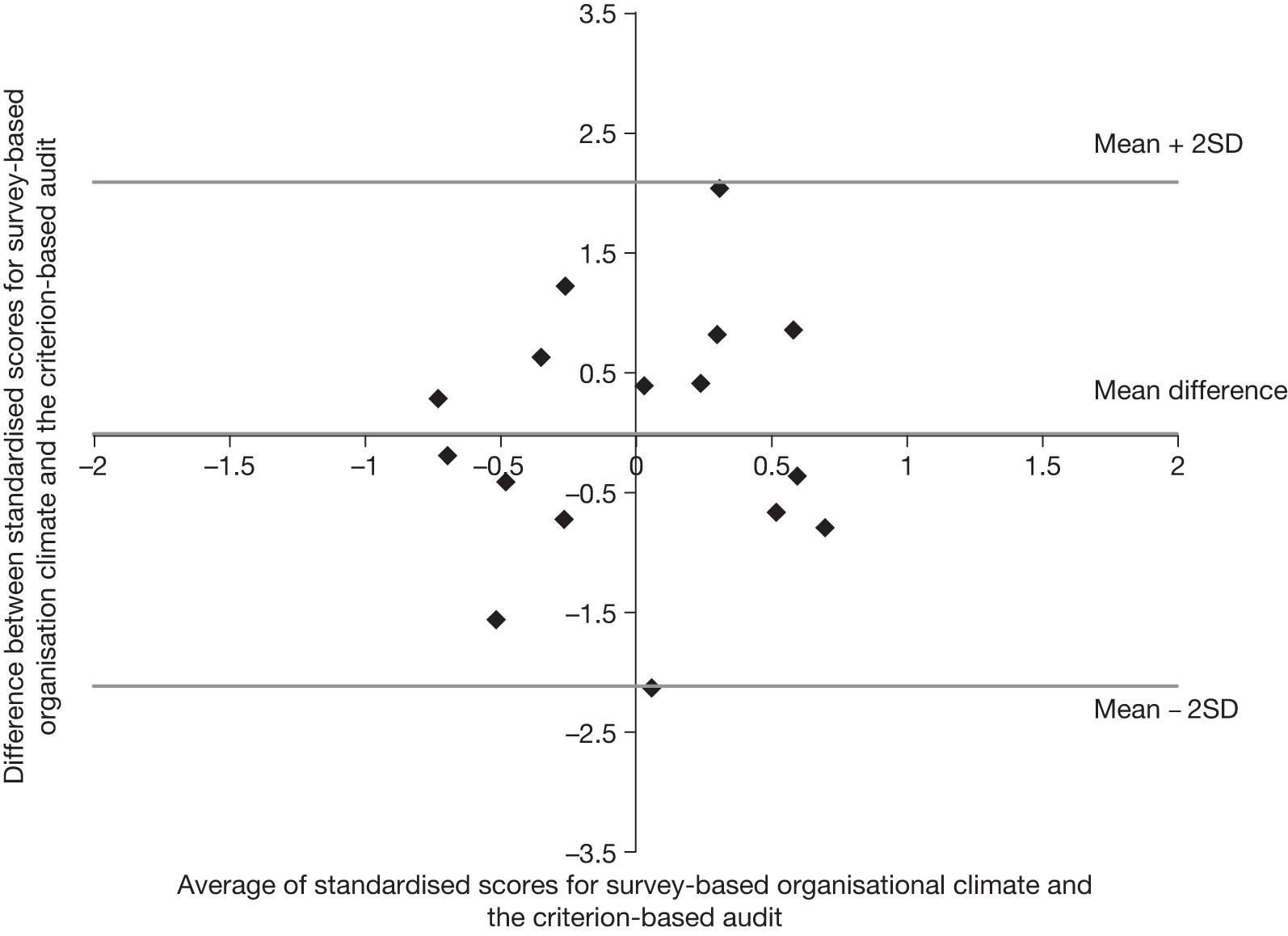

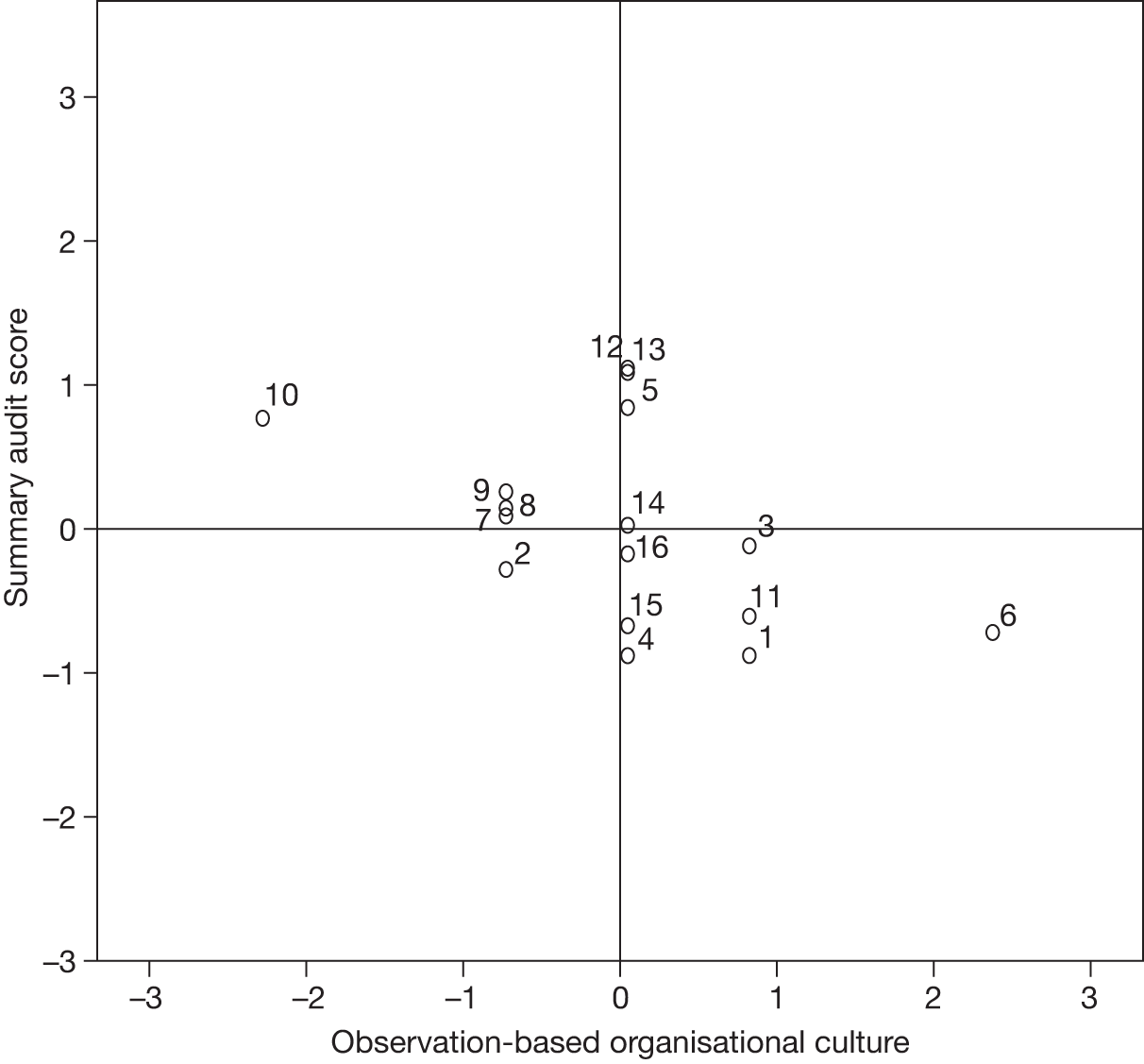

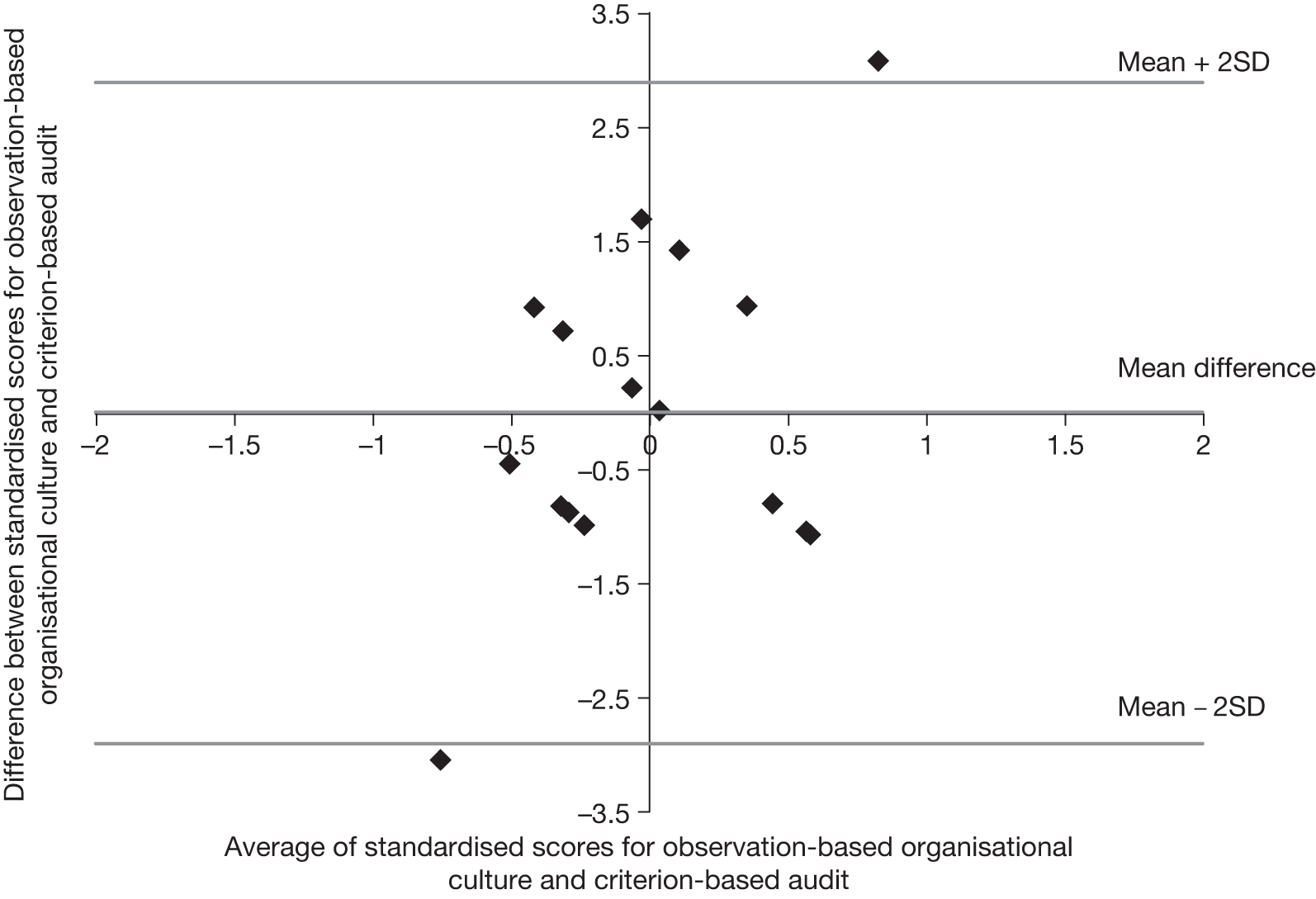

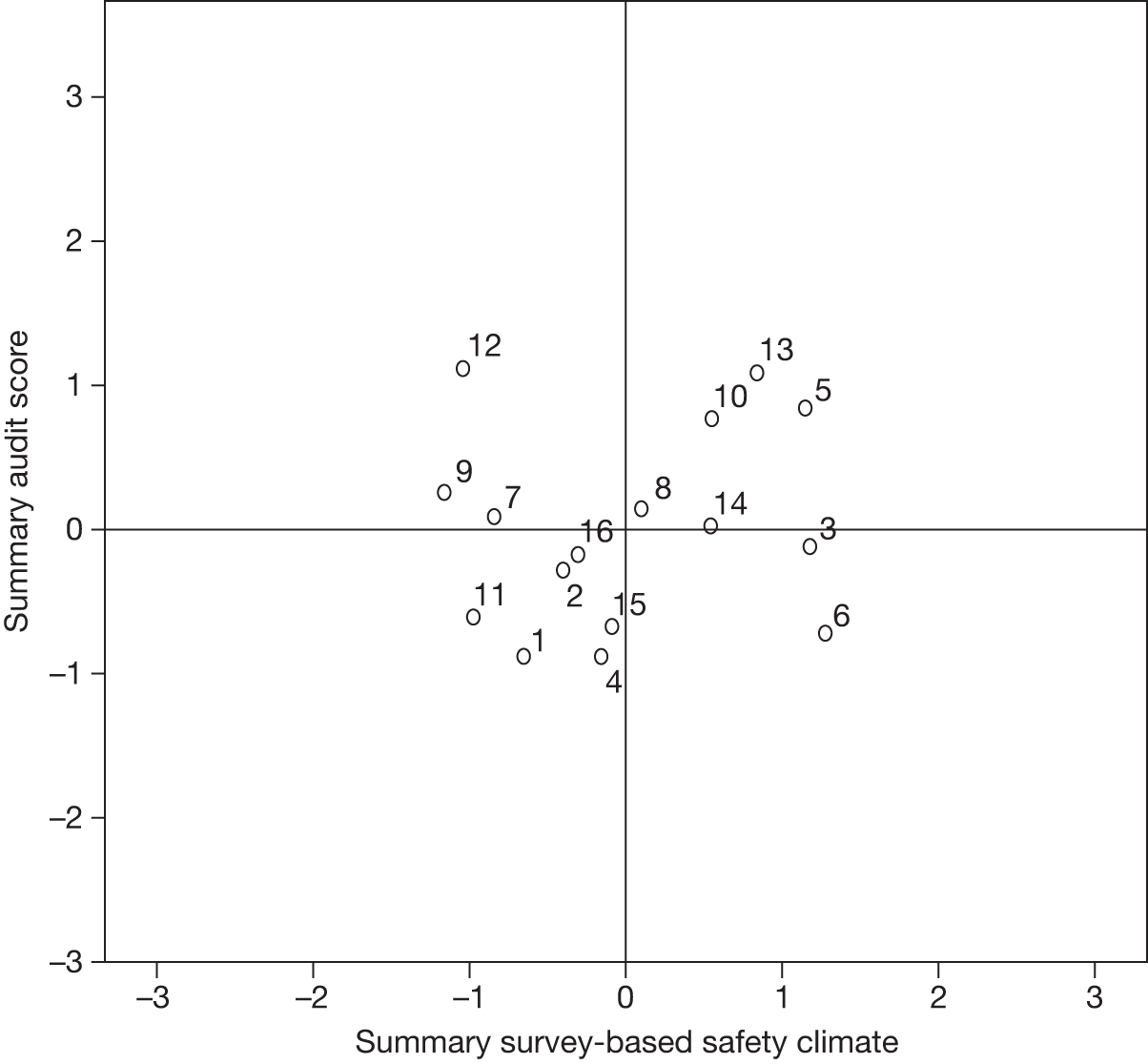

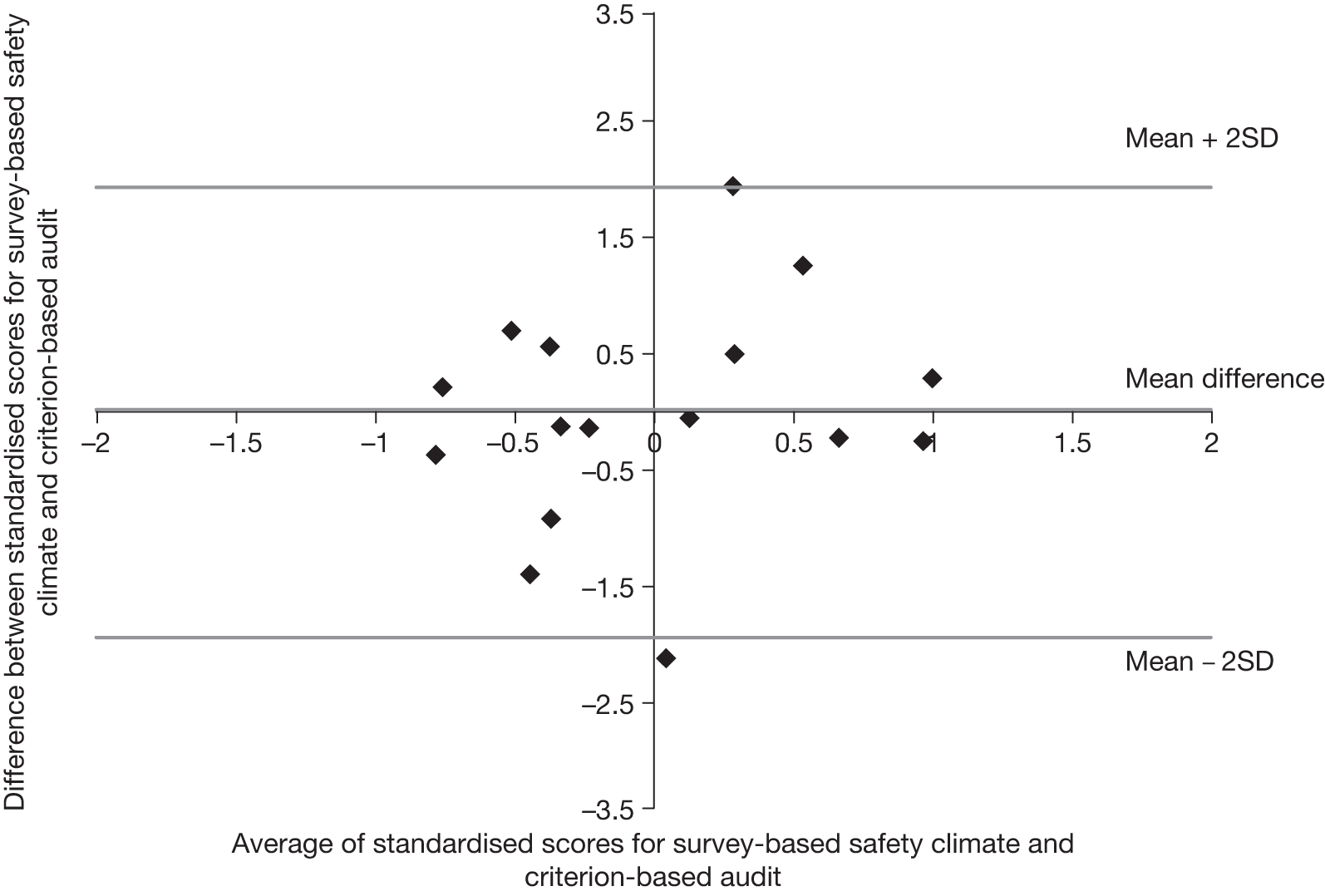

The initial aims and objectives were linked to six hypotheses to be tested following collection of primary data. The hypotheses were framed to examine whether different approaches to evaluating culture were correlated (had a linear relationship) and agreed (had the same value when measured on the same scale). For this study strong correlation was defined at the outset as 0.7 and moderately strong correlation as 0.4 (see Chapter 3, Comparison of data sites: threshold correlation, power calculations and clustering); agreement was evaluated from inspection of Bland–Altman plots (see Chapter 3, Testing the study hypotheses: correlation and agreement).

Comparing questionnaire assessments with holistic (observation-based) assessments:

-

H1a There will be a strong correlation and good agreement between questionnaire-based and observation-based evaluations of organisational culture.

-

H1b There will be a strong correlation and good agreement between questionnaire-based and observation-based evaluations of safety culture.

Testing the relationship between organisational and safety climate/culture:

-

H2a There will be a strong correlation and good agreement between questionnaire-based evaluations of organisational and safety climates (for a discussion of the convention regarding the terms ‘culture’ and ‘climate’ see Chapter 2, Safety culture and climate).

-

H2b There will be a strong correlation and good agreement between holistic evaluations of organisational and safety cultures.

Comparing culture assessments with the quality of care:

-

H3a There will be a moderately strong correlation and reasonably good agreement between criterion-based measurements of the quality of care and both (1) questionnaire-based and (2) holistic evaluations of organisational climate/culture.

-

H3b There will be strong correlations and good agreement between criterion-based measurements of the quality of care and both (1) questionnaire-based and (2) holistic observation-based evaluations of safety culture.

Study design

Using questionnaire- and observation-based methods, the study assessed organisational and safety climates/cultures in the DU and ED of eight hospitals (i.e. 16 research sites). Quality of care was assessed from retrospective audits of patients’ notes focused on three commonly occurring conditions for each type of clinical setting (DU and ED). These data sets permitted the comparisons required by the study objectives. The details of data collection and analysis can be found in Chapter 3 and the research protocol in Appendix 2.

Hospitals were purposively selected and researched sequentially, each hospital receiving feedback at the end of its data collection period. Sixteen independent research sites were needed to yield 90% power to test the hypotheses listed in the previous section, at the 1% level (see Chapter 3, Comparison of data sites: threshold correlation, power calculations and clustering).

Delivery units and emergency departments are high-stakes clinical settings, which were identified as priorities in a number of policy initiatives, such as the Reforming Emergency Care programme,39,40 the National Service Framework for maternity services,41 the NPSA Women’s Services programme of work42,43 and NPSA oversight of the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal and Perinatal Deaths. In each service, frontline staff must possess an extensive range of technical and non-technical skills and knowledge, applying these correctly and flexibly in a manner that supports choice. Effective interprofessional teamwork is essential, alongside effective collaboration with other parts of the hospital and community services for health and social care.

These clinical environments were expected to provide good opportunities for observing a range of safety-related processes and issues, including the management of triage; handovers within teams and between the multiple teams that attend these areas according to need; high turnover of patients/clients within each 24-hour period; high footfall through the department (including the multidisciplinary team and relatives); high variability in patient dependency, requiring ongoing skill mix management; patient/client transfer (within the hospital, to other hospitals and to community services); referral (to primary and secondary care and other agencies); responding to staff shortages or suboptimal skill mix; and, of course, the clinical issues that arise throughout the hospital (e.g. medications safety, infection control and adherence to evidence-based guidelines).

Arguably, our chosen units are untypical of hospital services in general. Hall and colleagues44 argue that EDs are likely to be the most unsafe of all hospital departments, with one-third of patient visits including a ‘non-ideal care event’, although these are usually not associated with harm. Woloshynowych and colleagues45 (p. 9) list the unique features of EDs, and some are also true of DUs, particularly the lack of scope for staff to manage demand. Unmanaged demand may require care teams to be particularly skilled at negotiating flexibly in order to respond appropriately and promptly to high demand. Conversely, one could argue that team cohesion is less likely in such settings, because there is less opportunity than elsewhere for staff meetings and discussion, or team-building. However, this study was designed not to measure the safety culture of a range of hospitals, but to compare contrasting approaches to making such assessments. These busy, high-risk clinical settings provided opportunities to assess culture and compare culture assessments to markers of the quality of care.

No claim is made that the empirical results reflect hospital-wide cultures or quality. However, we would argue that the research processes used in this study are feasible across a very wide range of clinical settings, which was part of our intent in selecting DUs and EDs. A high proportion of patient safety studies are focused on work practices and the environment in operating theatres and other highly bounded situations. Although well-developed approaches to observing well-bounded settings or activities are likely to transfer readily to other well-bounded health-care settings (e.g. intensive care, pharmacies) or bounded activities (e.g. drug rounds and team meetings), they are less well suited to less bounded health-care settings and activities, that is, the majority of hospital work and many aspects of community-based services. The semistructured approach to observation-based evaluation of culture developed during this study would be feasible in both bounded and unbounded contexts, although it needs further refinement and testing in a wider range of contexts.

Wears and colleagues46 identified ‘the distributed nature of A&E clinical work’ (p. 698) as a particular challenge for observational research in emergency care. Work in maternity units is also highly distributed across patients, specialised spaces and different professional teams as well as individual service providers. Conducting this study in DUs and EDs was ambitious and challenging, but an important springboard for shifting attention and the development of research methods towards approaches more suitable for less bounded environments and activities, and for environments that are characterised by distributed work.

Multisite research ethics approval was gained from Oxfordshire Research Ethics Committee C (REC reference: 07/H0606/87). This was a straightforward process with committee discussion, minor clarifications and the final approval occurring within a few weeks. Research governance approvals were obtained from each participating trust (eight; see Table 3). This was an extremely lengthy and time-consuming process that, at times, threatened the successful completion of the study (see Chapter 4, Research governance).

The next chapter reviews a selection of literature focused on safety culture and its measurement. Chapter 3 describes data collection and analysis for each strand of the study. There are five results chapters in Part II of the report: Chapter 4 describes process results that arose as the study progressed; Chapter 5 describes the results from strand A, the staff survey, and tests hypothesis H2a (Hypotheses); Chapter 6 presents the results from strand B, the observation-based assessment of culture, and tests hypothesis H2b; Chapter 7 describes the results from strand C, the retrospective audit of evidence-based markers of the quality of care; and, finally, Chapter 8 compares the results from strands A–C, thus testing hypotheses H1a and b and H3a and b. Part III of the report contains a discussion of the findings and the conclusions of the study.

Chapter 2 Safety and organisational cultures and climates

Introduction

Over the past 40 years, technological catastrophes including Three Mile Island, Chernobyl and the Challenger accidents have created growing interest in concepts of safety47,48 and led to the emergence of safety culture as ‘an explanation for accidents’ and ‘a recipe for improvement in complex sociotechnical systems’49 (p. 341). Within health care, improving patient safety has become an important aspect of quality improvement. International reports detail that between 2.9% and 16.6% of patients admitted to a hospital suffer some form of unintentional harm. 50–52 Many of these adverse events may be avoidable. Patient safety improvement programmes have called for cultural change to be tackled alongside structural reorganisation and systems reform in order to bring about a culture in which excellence can flourish. 53

Nature of the problem

Concerns regarding patient safety within health care point to a number of key factors that make a clinical service less safe: pressure on resources, unwillingness to admit fallibility and difficulties in reporting concerns across professional boundaries and organisational hierarchies. 10,54,55 Taking a lead from other safety-critical environments such as aviation, causes of adverse incidents are perceived to go beyond individual clinical failures, extending to systemic factors such as inadequate training and poor communication, equipment design, management systems and work processes. 10,56,57 Together such factors create not only behaviour patterns, but also organisational cultures, i.e. shared beliefs, norms and values that underpin and reinforce behaviours. 19,55,58,59

Measuring culture

Underpinning these understandings of safety culture are those approaches that regard culture as something an organisation is, i.e. that which is elusive, emergent and indeterminate. 49 Contrasting views suggest culture is something an organisation has, i.e. aspects that can be isolated, described and manipulated. 60 These distinctions lead to different assumptions regarding how much an organisation’s culture is controllable. Within safety scholarship, both approaches acknowledge the value of describing and evaluating cultural characteristics. However, viewing culture as something an organisation has is more likely to sustain an interest in measuring culture (or at least facets of culture), as this can support the diagnosis of excellence and problems, and both guide and monitor change efforts. Research on NHS reforms embodies this view,18 as does the burgeoning activity around developing measurement instruments (see Structured questionnaire research instruments). Davies and colleagues18 caution against going ‘too far down this road’, suggesting (p. 112) a view of organisational culture as:

an emergent property of that organisation’s constituent parts – that is, the culture may emerge somewhat unpredictably from the organisation’s constituents (making it not necessarily controllable), but nonetheless characteristics of that culture may be described and assessed in terms of their functionality vis-à-vis the organisation’s goals.

The tender specification (see Appendix 1) placed the requirements for this study firmly in a view of culture as something an organisation has, stating:

There is increasing interest in the idea that one way of improving healthcare performance factors such as quality, efficiency and patient safety could be through influencing professional and organizational culture … In order to test the validity of culture as a marker for quality/safety, it is necessary to have access to reliable measurements of both quality and culture.

This study focused on comparing different approaches to evaluating culture with each other and with criterion-based assessment of the quality of care. Nevertheless, our underlying conception of culture is close to that of Davies and colleagues18 (see above).

Because culture is a fusion of values, attitudes, perceptions, competencies and behaviour, it is difficult to measure, although many attempts have been made in health-care organisations. 61 A commonly used method is the survey, using questionnaires that elicit individual perceptions of the organisational and safety culture, which are then aggregated to indicate group perceptions. A more invasive alternative is temporary immersion in the work environment: either prolonged engagement as in traditional ethnography62 or shorter strategic immersion, such as clinical governance review and inspection32 and highly focused assessments of the efficacy of quality improvement interventions. 33 There is a need to compare these methods, which this study begins to address.

Organisational and safety cultures: concepts and definitions

Safety culture is often framed as a dimension or subset of organisational culture. Although there is little agreement on a precise definition of organisational culture, numerous components or attributes can be said to contribute to an organisation’s character and norms: dress, language, behaviour, beliefs, values, assumptions, symbols of status and authority, myths, ceremonies and rituals, and modes of deference and subversion. 63 As a subset of organisational culture, safety culture comprises these attributes as they relate to patient safety. Facets of a positive safety culture include:

-

norms and rules for handling hazards, attitudes towards safety; reflexivity on safety practice64

-

positive attitudes to safety behaviours and role modelling of such behaviours to peers and juniors65

-

recognition of the inevitability of error and proactively seeking to identify latent threats55,66

-

non-punitive reporting systems, analysis of errors and near-misses, feedback to frontline staff, sharing learning3,57,67

-

openness, fairness and accountability at all organisational levels68

-

maintenance of situational awareness among team members34,74,75

-

non-hierarchical teams in which roles are flexible76,77 and staff at all levels feel empowered78 and

-

attention to staff development,67,79 with consequent reduction in staff stress and burnout. 80,81

Wide variation in the framing of organisational and safety cultures and climates makes it inevitable that there will be little agreement on how they should be observed or measured. The most common method is self-evaluation by staff. Self-evaluations need to be structured, and one useful framework is the Manchester Patient Safety Framework (MaPSaF),82,83 which has been adapted for a range of clinical settings. 84 More commonly a structured questionnaire is used. The next section provides examples of the wide range of structured questionnaire assessment tools. In research studies the main alternative to structured self-evaluations by staff is observation and in Ethnographic methods we will provide examples of observation-based studies that have drawn from the ethnographic tradition. In Strategic immersion in the environment we summarise a different approach to observation-based assessments of health care, which we have termed strategic immersion.

Structured questionnaire research instruments

Structured questionnaire research instruments typically adopt a typological or a dimensional approach, but vary in terms of their theoretical or conceptual underpinnings, their scope and their depth. 63 Several organisational climate and culture measures have been applied in health-care settings, for example:

-

Harrison’s85 Organizational Ideology Questionnaire assesses the ‘ideology’ of the organisation and its relationship to the interests of its members and to the external environment. The tool has been used in the UK to examine of the effect of NHS reforms and the monitoring of culture over time. 86

-

The Competing Values Framework (CVF)87–89 (originated and is better known outside health care) uses a typology of four dominant culture types based on core values that characterise an organisation, arranged on two axes: internal–external focus and flexibility/individuality–stability/control. It has a strong theoretical basis and has been used in UK health care. 16,90

-

The Organizational Culture Inventory91 assesses 12 sets of normative beliefs related to 12 different cultural styles; these reduce to three general types of culture: constructive, passive–defensive and aggressive–defensive. The tool has been widely used including in health care92,93 but is too lengthy to be completed by busy clinical staff.

-

The Quality Improvement Implementation Survey94 (QIIS) uses four culture concepts associated with the CVF and adds an extra dimension (‘rewards’).

As interest in health care and health services research in the 1990s and early 2000s shifted towards patient safety, attention turned towards developing measures of those aspects of organisational culture and climate that related to safety. In the USA, several high-profile safety climate and culture measures were developed and validated for use in audit and research in health-care settings. Pronovost and Sexton95 provided a useful review and guidance. Well-developed research instruments include:

-

multiple versions of the SAQ, including the Teamwork and Safety Climate Survey25,96 and the Institute for Health Care Improvement Safety Climate Survey,24,96,97 all of which were developed and extensively tested by the University of Texas Center of Excellence for Patient Safety Research and Practice

-

Nieva and Sorra’s Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture for the United States Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)55,98–100

-

the Patient Safety Climate in Healthcare Organizations questionnaire (PSCHOQ) (Stanford University with the Palo Alto Veterans’ Affairs Health Care System), also funded by AHRQ under its Systems Related Best Practices initiative,20 and based on several existing surveys including the Operating Room Management Attitudes Questionnaire,101 an earlier iteration of the SAQ; the PSCHOQ has been extensively used37,59,102–106

-

Gershon and colleagues’107 Hospital Safety Climate Questionnaire which, in contrast with the more generic tools above, focuses on universal precautions for blood-borne pathogens; Turnberg and Daniell108 adapted it for use in respiratory care.

Each of these instruments takes a dimensional approach to evaluating safety culture by aggregating individuals’ levels of agreement with statements on Likert scales. The dimensions of safety culture that are explored include teamwork climate, safety climate, job satisfaction, stress recognition, perceptions of management, working conditions, absence of barriers to safe working practices, minimal conflict and good communication among staff, safety-related feedback, and many more.

In the UK, there are three notable strands of development of instruments drawing together organisational and safety climate:

-

The MaPSaF is based on Westrum’s theory of organisational safety (reprised in Westrum, 2004109). It is a typological tool initially developed for use in primary care trusts (PCTs) to assess safety culture maturity. It is intended primarily for team-based reflection and development82 and has been tailored for use in acute, ambulance and mental health settings. 84

-

The NPSA sponsored the development of organisational and safety culture instruments for use across the NHS. 110 Aston University has developed the TCAM (Team Climate Assessment Measure). 111 The dimensions addressed include task reflexivity, team stability, leadership, participative trust and safety, open exchange and interprofessional exchange.

-

The Healthcare Commission (subsequently Care Quality Commission) National Staff survey was derived from a model developed by Aston University that links work context (including organisational climate) to the management of people, psychological consequences for staff, staff behaviour and experiences, and errors and near-misses that ultimately affect patient care. 112

Elsewhere in Europe, Silva and colleagues38 developed an organisational and safety climate inventory, based on the CVF,87 while, during the course of this study, the development of other instruments has begun. 113–117

Ethnographic methods

Because culture is a fusion of values, attitudes, perceptions, competencies and behaviours, it is very difficult to measure. However, evaluations of culture can be obtained from temporary immersion in the environment: either prolonged engagement, as in traditional ethnography,62 or shorter strategic immersion, as employed in clinical governance review and inspection. 32 Ethnographies provide rich, multilevel understandings of researched environments, but they are time-consuming, and comparison of multiple environments is difficult. A wide range of safety culture studies have adopted the ethnographic approach. 34,45,118–125

Strategic immersion in the environment

A major advantage of direct observation, in contrast with the questionnaire response, is that it enables researchers to see what people do and say rather than just what they say they do. 126 It can uncover how complex jobs are routinised together with ‘the tacit skills, the decision rules, the complexities and the discretion’ utilised in routine and marginal work (Smith,127 p. 221). Although traditional ethnography requires lengthy immersion in the researched environment by participant observers, accomplishing high-quality observational research during relatively brief periods of immersion is potentially achievable providing researchers restrict their studies to a topic or ‘lens’ through which to view the group they are studying. Willis128 (p. 557) refers to ‘focused (limited gaze) ethnography’ and ‘rapid (quick time) ethnography’, where speed is a virtue and a necessity. Strategic immersion represents a more structured approach to observation and supplementary data collection, to provide defined coverage at reasonable expense and to permit comparison between different organisations. For example, studies of nursing care have used checklists of features of good practice to structure strategic immersion,129–131 whereas observations to develop or evaluate quality improvement interventions are structured by the focus of the intervention itself. 33,118

Strategic immersion is unsuitable for settings or issues for which there is inadequate earlier work to define a framework for observation. However, previous work in the field of organisational and safety culture renders evaluation through strategic immersion possible in this study. In particular, the observation strand of this study benefited from an earlier 3-year ethnographic study in delivery units, which three of the study team completed,34 and which linked experience of setting ethnographic observations alongside highly structured observations. 132

During strategic immersion to observe health-care teams at work there is limited or no observer participation in the observed environment, as the limited time period does not allow the observer time to negotiate an active role in the team being observed. The method may therefore be described as primarily that of ‘passive participation’. 133 However, passive observers may ask brief questions for instruction and clarification, although in health-care settings this may not always be possible when staff are busy. The scope for immersion may be limited by the difficulties associated with the qualifications required to enter into many of the roles of medical work. Smith127 (p. 227) argues that diversity of observational approaches results not from ‘methodological sloppiness’, but from ‘real constraints governing the conditions under which researchers can and cannot conduct qualitative field research’.

Hammersley134 (p. 26), discussing observation, argues ‘there are always multiple, non-contradictory, true accounts possible of any scene and we need to know the basis for particular selections’. Actions of individuals are observable, but the meaning attached to the physical actions is divorced from the actions themselves. Researchers may apply their own meanings to these actions, which may be different to the meanings of the actors. 135 The degree of inference and, therefore, potential for error is likely to be greater when observing some features of health-care practice than others.

Safety culture and climate

Whereas culture is generally taken to indicate the collection of values, beliefs and assumptions that guide behaviours19 and that are shared by group members,35 climate refers to the aggregate of individual perceptions of practices, policies, procedures and routines about safety in an organisation. 14,136 Being more concerned with health-care practitioners’ conscious perceptions and attitudes, safety climate is thus easier to measure than more deep-seated and less overt beliefs and values,20 and it is often argued that staff surveys capture ‘safety climate’ rather than ‘safety culture’. 25 In this study we have treated the staff survey (see Chapter 3, Strand A: staff survey) as reflecting some important aspects of safety climate (aggregated espoused attitudes and values, aggregate perceptions of situated work practices) and observation-based evaluations (see Chapter 3, Strand B: observation-based holistic evaluation of safety culture) as reflecting some important aspects of safety culture (situated practices and artefacts supporting the enactment of shared norms and meanings).

The theoretical distinction between culture and climate is not always upheld in practice: the meanings of each are contested137,138 and confused. For example, some authors use the terms interchangeably58,139 while one review of safety climate measures140 includes four measures that use the term ‘culture’. In this report, we follow Sexton and colleagues25 by acknowledging the terminological confusion while using safety climate (measured by questionnaire) to designate the surface indications of an underlying safety culture.

Selecting organisational levels for research into safety culture and climate

Although the literature typically refers to organisational culture, there is nevertheless substantial evidence that, at any rate in relation to safety culture, the department or ward may be as important. Mohr and Batalden141 argue the need to examine patient safety at the level of the ‘clinical microsystem’ (a small organised group of staff caring for a defined population of patients). Zohar and Luria142 found meaningful variations in safety climate scores within as well as between organisations, and Smits and colleagues143 found that responses to a patient safety survey clustered more strongly at unit than at hospital level. Huang and colleagues137 found that perceptions of safety culture varied even across similar units within the same hospital (in this case, intensive care units), and Gaba and colleagues139 commenting on that study emphasised that research needs to be carried out at both clinical unit and organisational levels. However, unit-level research brings its own problems: the boundaries of the unit are porous when units are ‘highly coupled’, so that decisions in one constrain choices in another (e.g. ED cannot move a fracture patient until an orthopaedic ward is willing to admit). 144

In this study, for example, our staff survey was designed to distinguish between the wider organisational climate and the climate in the immediate clinical department by, on the one hand, asking questions about trust-level communication, error wisdom and support for continuing professional development (CPD) and, on the other hand, asking questions about respondents’ individual role contexts, line management and teamwork and safety climates in the immediate clinical department (further details in Chapter 3). However, some staff perceptions may arise from a fusion of organisational-level and department-level factors; many health-care professionals work in more than one team or department, and departments are closely coupled to other departments and services. We will return to this discussion in Chapter 4, Close-coupling of departments and services.

Quality: case note review

The use of clinical process measures to monitor the quality of health care has many advantages,145 although the concept of quality itself is multidimensional and contested. Case note review (comparing recorded activity with evidence-based standards of care) is often used in quality research, for example to detect adverse events146 or to assess compliance with predetermined evidence-based standards. 147–149

The methodology of case record review has considerable strengths. It has been noted to provide a more complete indication of the incidence of adverse events or critical incidents than reporting systems. 150 Case review forms provide a standardised method of recording and data collection which is robust when used on a random sample of case records. 150 The epidemiological data obtained are potentially useful for comparative studies, although any comparisons need to take account of variations in methodology, particularly with the definition and inclusion criteria.

Criterion-based review has been proposed as an effective alternative to semistructured holistic review methods that rely on professional judgement to determine standards of care and quality, which have been associated with concerns about inter-rater reliability,151 consistency,152 hindsight bias153 and reviewer idiosyncrasy. 154 Clinical audit in the UK has adopted criterion-based review to identify substantial variations in organisation and clinical care between hospitals. 155 However, adoption of the criterion-based approach may fail to identify the nuances of health-care variation. 156 Lilford et al. 157 note that, although certain clear-cut violations, such as failure to check a patient’s blood potassium level when indicated, can be detected from case note review, other factors, such as the quality of communication with patients or surgical skill, remain largely in the tacit domain. Hospitals also tend to vary considerably in adherence to quality standards. 158 A particular hospital may not, for example, do well in getting patients with hip fractures to surgery within 24 hours, but it may have high adherence to drug therapy after a heart attack. 157 Process-based monitoring is subject to potential bias as the opportunity for error varies by case mix:159 sicker patients need more care, which gives greater opportunity for errors of commission and omission. 160

Case note audit is underpinned by ‘the assumption that good quality recording reflects good quality care’161 (p. 134) or, at any rate, that good-quality recording is an important and tangible aspect of good quality care. Zegers and colleagues162 distinguished between poor-quality information within case notes, which was linked to an increase in adverse events, and missing information, which underestimated adverse events. Case note audit is a challenging method,163 as well as being limited: only a proportion of the whole narrative of care is recorded,164 and the unmeasured and unaudited may constitute an important aspect of care quality. 165,166 It is wholly dependent on the accuracy, completeness and legibility of patient records. Incomplete records do not necessarily provide evidence that an event did not occur. 149 Hindsight bias is an additional challenge. 157 Documentation provides only a ‘partial’ representation of events. Studies have demonstrated considerable discrepancy between ‘objective’ assessment of adverse events reported by patients and ‘objective’ accounts constructed via retrospective auditing of patient records. This can partly be explained by differences in professional and patient perceptions of errors, but may also be due to incomplete documentation in medical records. 167,168

Criterion-based review focuses on adherence to or violation of agreed evidence- or logic-based standards, suggesting that what is written is a direct measure of performance. Although the record can be seen as a form of ‘organisational memory’,169 it is not a neutral repository of information. It mediates medical work and there is selectivity in what ends up in the record. 170 What is written represents the production of hierarchical relations and socialisation processes that constitute medical work. 170 Scientific evidence is not clear, accepted and bounded. 171 The evidence base for particular health-care technologies and practices is often contested and continually redefined to fit the local context. 172 Documentation provides a reconstruction of events and may be subject to normative expectations to comply with evidence-based standards that may not be reflected by the reality of practice.

In this study, a retrospective review of case notes was used to evaluate recorded compliance with a spectrum of evidence-based markers of the quality of care. The methods used are described in Chapter 3, whereas challenges arising during the audit process are discussed in Chapter 4, Strand C: criterion-based audit of clinical notes.

Comparing measurements of culture and evaluations of the quality of care

The various methods of measuring safety climate and culture outlined above have not been systematically compared, a gap that this study goes some way to filling. Attempts have been made to investigate the link between organisational culture and the quality of health care, although reviews16,35–36 have found that the evidence available is sometimes contradictory and suggested links are contingent and complex. However, there is some evidence of a link between safety climate/culture and health-care performance, although it is not known whether a causal relationship exists, and the direction of any causality would need to be established. 37,38,173

Conclusion

Aspects of culture such as poor communication and a climate that discourages speaking up to ask questions or alert others to potential problems have been linked to accidents, suboptimal processes and outcomes and avoidable harm in a wide range of contexts, including health care. Logically, this has spurred interest in assessing and, where necessary, improving certain aspects of culture with the aim of preventing avoidable harm and using resources (human, physical and financial) as productively as possible. However, culture is difficult to measure because it is a fusion of values, attitudes, perceptions, competencies and behaviour. Nevertheless, a range of questionnaires and frameworks have been developed to evaluate aspects of culture at different levels within organisations and ethnographies have provided complementary insights. Less immersive observation-based studies have also captured targeted facets of culture or the quality of care in the observed health-care environment.

In parallel, there has been greater attention to monitoring the quality of care to identify areas of success and areas for improvement. Monitoring usually focuses on key markers which are important for safety, the patient experience or for good management of limited resources. Few studies have compared quantitative or qualitative evaluations of culture with assessments of the safety and quality of care. The evidence to date is equivocal. This study provides an additional set of comparisons for the slowly growing evidence base and, further, examines the processes and challenges of obtaining estimates of culture or climate and the quality of care.

No prior studies were found which compared quantitative and qualitative assessments of culture. Although some would argue ‘Why would one wish to compare apples with pears?’, this study was charged with responsibility for examining agreement between very different approaches to assessing culture. Quantitative data about facets of organisational and safety climates were collected using a questionnaire distributed to staff in 16 clinical departments. Semistructured observations were made by researchers who made multiple visits to these departments. To enable the required comparisons, the observations had to be banded, i.e. made quantitative. The process is described in Chapter 3.

Chapter 3 Methods for data collection and analysis

Comparison of data sets: threshold correlation, power calculations and clustering

Silva and colleagues38 obtained a strong correlation (r = 0.72) between organisational and safety climate, and showed organisational climate and safety climate to be inversely correlated with the incidence of accidents (–0.955 ≤ ρ ≤ –0.865). Setting a similar threshold correlation level for this study is reasonable. It acknowledges that not only can these measures be highly correlated but indeed they should be if safety climate measures are meaningful. In the power calculations for this study the threshold correlation was set at 0.7. For independent research sites, 80% power at 5% significance requires 12 pairs of measurements174 and 90% power at 1% significance requires 16 pairs of measurements.

Sixteen research sites were recruited to this study but, for efficiency, the study was carried out in DUs and EDs at eight NHS hospitals in England so a degree of clustering was present at the organisational level, although these clinical departments have virtually no interaction at team level. When the study began there was no prior work from which intracluster correlation coefficients (ICCs) could be estimated to allow for clustering in the power calculations. However, multilevel modelling has been used to allow for clustering in the data (see Multilevel modelling).

Selecting the sample of research sites

The reasons for selecting DUs and EDs were outlined in Chapter 1, Rational for focusing on delivery units and emergency departments. For efficiency, the study was restricted to hospitals that have both types of clinical provision. Hospitals in England were purposively selected using a number of criteria:

-

Geographical spread. The research sites were situated in 6 out of the 10 strategic health authorities in England (East Midlands, East of England, London, South West, West Midlands, and Yorkshire and Humberside).

-

Type of NHS trust. The selected research sites included general hospitals and major tertiary centres; single-site and split-site provision; and foundation and non-foundation trusts.

-

Size of NHS trust and participating departments. This was indicated by the approximate trust income and patient throughput statistics for the relevant clinical areas. The hospital reporting year 2008–9 was selected for the comparisons shown in Chapter 4 (see Table 3). This was the midpoint of the study. Patient and birth statistics for England allowed us calculate the boundaries for quartiles and place each study site in the relevant quartile: Q1 (smallest 25% of departments), Q2, Q3 or Q4.

We also sought to include variation in relation to the populations served by the hospitals (rural and urban; ethnic diversity; mobility; indices of social deprivation; complexity of case mix; and the ease of recruiting and retaining a well-qualified workforce). The sample of research sites is described in Chapter 4, Recruiting research sites.

Strand A: staff survey

This strand relates to objective 2: to use questionnaires to obtain quantitative assessments of the organisational and safety climate at each site.

Developing the organisational and safety climate questionnaire

We wished to use prevalidated questions and scales within the organisational and safety climate questionnaire for staff because the aims of the study (see Chapter 1, Aims and objectives) centred on comparing different approaches to evaluating culture rather than developing and validating new research instruments. A review was conducted at the beginning of the study (2007) to establish the availability and psychometric properties of organisational climate and safety climate data collection instruments. The instruments identified were examined more closely by reading the associated websites and manuals. We also discussed (in person or by e-mail) the development, reliability and availability of a range of climate instruments with people engaged in their initial or continuing development. A small number of climate instruments developed in languages other than English were considered, but translation and revalidation were not feasible within our study funding and timetable.

The final selection of instruments from which to draw questions to evaluate organisational climate and safety climates used the following criteria:

-

availability of material describing the development and testing of the instrument, scores from psychometric testing and benchmarking data

-

stability and reliability

-

extensive prior use in England and

-

cost (no fees were levied for use of the scales and questions selected for this research study).

The staff survey questionnaire (see Appendix 3) was developed by combining groups of questions from the NHS national staff survey175 and the Teamwork and Safety Climate Survey. 25 We received permission to use questions from the NHS national staff survey in any month except October. This was to minimise any possible confusion with the annual NHS staff survey, which is distributed each October. The data collection timetable for this study was adjusted to satisfy this restriction.

The study questionnaire contained four sections of questions from the NHS national staff survey which were intended to capture facets of organisational climate, namely:

-

Q6 a six-item scale evaluating perceptions of the organisation, which in subsequent analyses we have termed ‘organisation’

-

Q7 two questions about whistle-blowing

-

Q8 a question about reporting errors, near-misses and incidents

-

Q9 a seven-item scale concerning organisational responses to errors, near-misses and incidents, which we have termed ‘error wisdom’ in subsequent analyses.

At research sites 1 and 2, the staff survey contained additional questions relating to other aspects of organisational culture, but response rates from these sites that were lower than we had hoped for prompted shortening of the questionnaire (see Sampling, delivery and maximising returns).

A further five sections of the questionnaire were intended to capture perceptions of safety climate and team factors or local work environment factors that are thought to be related to safety climate (see Chapter 2), namely:

-

Q2a–c a three-item scale, which we have labelled ‘overload’

-

Q2d a five-point Likert-scale item called ‘Relationships at work are strained’

-

Q3 a five-item scale evaluating supportive behaviours from the respondent’s immediate manager, which in subsequent analyses we have termed ‘line management’

-

Q4 one question each concerning working closely with other team members and meeting regularly to discuss effectiveness and improvement

-

Q10 teamwork climate scale (six items)

-

Q11 safety climate scale (seven items).

Questions 2–9 were reproduced from the NHS national staff survey,175 whereas questions 10 and 11 were Teamwork Climate and Safety Climate scales. 25 A minimal change to question 10 was required to reflect professional titles in study sites: in the questionnaires distributed to DU staff the word ‘nurse’ was replaced with ‘midwife’.

One question (Q5, Appendix 3) asked about trust-provided or trust-supported training, learning or development during the past year. This was included because CPD of individuals and teams is argued to be important for developing and maintaining positive organisational and safety cultures67 and to maintain job satisfaction and motivation. 81 Information on common forms of CPD was elicited in the form of closed questions (see Table 9) and space provided for additional responses. The listed categories of CPD overlapped, but all were included because previous research has shown that people find it surprisingly hard to call to mind examples of workplace or work-related learning. 176 Providing a variety of prompts, including the most popular approaches to CPD, was intended to help respondents recall CPD and to encourage them to recognise learning within a wide variety of activities.

Demographic and role-related questions were also included to permit analysis of whether these factors mediated responses to the organisational climate and safety climate questions and to address objective 8 (see Chapter 1, Aims and objectives). This study used response categories from the NHS national staff survey to maximise opportunities for comparison between the study results and trust-wide or national results from the same survey questions.

Piloting with clinicians associated with the university where most members of the study team were based established the usability and face validity of the questionnaire for clinicians from different professions working in DUs or EDs, and that it took < 30 minutes to complete.

Sampling, delivery and maximising returns

Clinical leads at the research sites were asked to identify staff who should be invited to complete the staff survey. Thus, midwives, nurses, doctors, support workers, administrators and managers (and, where appropriate, allied health professionals) were invited to participate in the survey, the exact selection being determined by team leaders’ definitions of team membership. However, clinical leads were asked to exclude certain groups whom we felt they would have insufficient consistent experience of the culture of the particular clinical area: students and members of staff who had joined the department < 4 weeks before the survey was distributed, and in particular Foundation Programme doctors (doctors in training in their first 2 years after graduation from medical school). Comparison of the national rotation schedules for these junior doctors and the data collection timetable for the sequentially researched study sites revealed that these junior doctors would be eligible for inclusion at some sites but not at others due to very recent rotations: we therefore asked that they be excluded from staff lists at all sites. It is a moot point whether these exclusions were necessary and advisable, as newcomers may evaluate the culture of their work environment very quickly and may be better able than more established members of clinical teams to identify safety concerns. Further research into the differing perspectives of newcomers and established members of staff may be useful.

Seeking a locally defined definition of the ED or DU team was part of the commitment stated in objective 1 to work with staff in participating trusts, respecting their organisational and professional knowledge. The definition of the departmental team was thus conceptually coherent for senior clinicians at each research site but differed between research sites. We accept that our design in this respect is vulnerable to the criticism that data between sites were not directly comparable. However, health-care teams do vary between departments and hospitals, according to local need, resources and preferences; so strict comparability between staff survey samples from multiple research sites would be an unrealistic ideal for any study. In this study it was deemed more important to examine how team compositions and perceptions of the team varied. For example, some sites had dedicated allied health professionals, administrative and clerical staff, porters and cleaners, and one (an ED at two geographically separated locations) had dedicated ambulance staff; others had few or none of these. The use of agency and/or locum staff for long periods (months or even years) varied substantially between sites: these may be key team members but do not appear on trust staff lists. We would suggest that the variability we have documented is a feature of all multisite studies of teams, but rarely made explicit.

Hand delivery and collection of questionnaires at 16 research sites was not feasible for research fellows, and preliminary work with research sites established that local clerical or clinical staff would not be able to undertake this work, so a postal survey was conducted. Questionnaires were sent to all designated members of staff along with a covering letter and a project information sheet. A stamped, addressed envelope was provided for the return of the questionnaire. One reminder was sent to non-respondents after 2 weeks. A unique identifier, which could be removed by respondents if desired, was placed on each questionnaire to prevent unnecessary reminders. The key to the identifiers was stored separately from the returned questionnaires and destroyed when no longer required. Each distribution of the questionnaire required minor updating to reflect the specific clinical area, contact details for queries and requested return dates. The data collection timetable of sequentially researched sites involved a risk of late returns from one site being allocated to the next site. To avoid this, we alternated the named contact for questionnaire responses at the first 10 sites. This strategy was insufficient at research sites 11–16, where data collection overlapped to compensate for earlier delays in the data collection timetable. For these sites different coloured paper was used for the questionnaires to prevent misallocation of responses.

Because most staff surveyed were nurses or midwives, we anticipated that the response rate would be no higher than 50–55%,30 even with the inclusion of elements that are known to support better response rates in the general population: sending from a university address, including a stamped return envelope, sending a reminder and offering an incentive for returning the questionnaire177 (entry into a prize draw with the opportunity to win one of 10 gift vouchers for a popular high-street store to the value £10). Salience is an important factor influencing response rates from health-care practitioners and the general population. 29,177 Patient safety was expected to be a salient issue in DUs and EDs, since this study coincided with a peak of safety-focused policy and practice development initiatives. However, it is possible that, particularly by the time of data collection at the later research sites, staff may have begun to be jaded by multiple waves of safety-focused activity. Response rates were lower than hoped for at the first two research sites (20% and 27%; see Table 5), and two steps were taken with a view to improving response rates. First, the questionnaire was shortened,177 largely by omitting questions about matters with a less immediate relationship to patient safety culture than those that remained (e.g. work–life balance; physical attacks on staff). In the final version in Appendix 3, 52 separate responses are requested, whereas the original questionnaire requested 107 separate responses. Secondly, changes were made to the use of the prize draw as an incentive for staff to complete and return the questionnaire promptly. Initially, the draw (for 10 gift vouchers) was made after 2 weeks but, to encourage responses to the reminder letters, a draw for four of the prizes was held 2 weeks after the second mailing at site 3 onwards. The unique identifiers were used to trace prize winners.

Response rates were variable and remained lower than hoped for, although similar to comparable studies. 100,178 A final attempt to increase response rates was trialled for research sites 11–14. This will be discussed in Chapter 4, Examining influences on response rates.

Analysis

Cleaning the data file and gaining an overview of results

Staff survey questionnaire data were coded within a SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) v. 17.0 data file, which was cleaned by exploring each variable using a variety of descriptive statistics and single variable analyses. This process allowed the researchers to become very familiar with the survey data and gain an intuitive sense of patterns within it. Because response rates varied widely between research sites (Table 5), site-specific response rates were added to the data file to make this fluctuating level available for subsequent analyses.

Missing data

Each analysis in Chapter 5 included all cases for which responses to the questions under analysis were present. Percentages have been calculated after removing cases with missing data from the denominator. Sections within Chapter 5 indicate the number of missing cases for the analyses in that section.

Testing for normality

Throughout the data set continuous variables were examined for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, comparison of the mean and median and inspection of histograms and P–P plots (probability–probability plots, which are used to check how well two distributions agree).

Descriptive statistics and correlations

The descriptive statistics and correlations reported in Chapter 5 were calculated using SPSS v. 17.0. Exact p-values were calculated using an online Statistical Toolbox. 179 We found no definitive reference for the interpretation of correlation coefficients but consulted a panel of statisticians with experience of health services research. In this report correlation coefficients will be interpreted as follows:

-

< 0.1, negligible

-

0.1 to < 0.4, low

-

0.4 to < 0.7, moderate

-

0.7 and above, high.

Calculating scores on prevalidated scales

In line with instructions in the associated manuals, mean scores were calculated for the items that formed prevalidated scales. Where required, scores from negatively worded items (questions 2a–c, 9c, 10b and 11g) were reversed before calculating the mean scores. All scores contributing to the overload scale were reversed to achieve consistency across all scales such that high scores represent positive outcomes.

Multilevel modelling

As the 16 research sites were clustered within eight hospitals, multilevel modelling supported by MLwiN 2.9 software (Centre for Multilevel Modelling, Bristol, UK) was used to analyse the survey data. First, influences on site-specific response rates were investigated by fitting a two-level model (hospital and research site) and adding the three site-level characteristics that were known in this study: the type of service (ED or DU), the size of the hospital department represented by the quartile recorded (see Table 3) and the number of people to whom questionnaires were sent (this was centred on the mean number of questionnaires distributed to ease interpretation of the parameter estimate) to indicate how inclusively the definition of team was drawn. An alternative indicator of inclusiveness could have been the number of professional groups included in the local definition of team. These characteristics were included in the model as fixed functions. The results can be found in Chapter 4, Examining influences on response rates.

Secondly, influences on scores for each of the prevalidated scales reported in Chapter 5, Organisational climate and Safety climate and team factors, were investigated using a three-level multilevel model of individual responses nested within research sites nested within hospitals. Site-level and individual-level demographic and role-related variables were added one by one to investigate whether any had a significant coefficient and provided a better-fitting model, as indicated by the reduction in the value of ‘–2*log-likelihood’ with degrees of freedom (df) equal to the number of new parameters entering the model. 180 This included variables such as service (ED or DU), survey response rate, number of questionnaires distributed, gender, age, ethnicity, profession, hours worked, CPD profile over the past 12 months, years worked for the trust and whether the current role includes managing staff.

Combining indicators of organisational climate

To facilitate the study’s central aim of comparing different approaches to evaluating safety culture (see Chapter 1, Aims and objectives), it was necessary to create a summary survey-based measure of organisational climate to set alongside summary measures from Chapter 6 (observations) and Chapter 7 (audit) in the comparisons made in Chapter 8. A weighted average was used: the responses to the well-established organisation and error wisdom scales (see Appendix 3, Q6 and Q9) were weighted equally (one-third), whereas the individual questions (Q7 and Q8) were weighted one-ninth each to form the other third of the summary organisational climate score. To avoid the weighted average being distorted by combining values from different normal distributions, before averaging each component was scaled to fit the standard normal distribution [z-scores, centred on mean 0 and with standard deviation (SD) 1]. Before this, the responses to the questions 7 and 8 had to be converted from categorical variables (yes, no, don’t know) to continuous variables. The conversion was made by calculating the proportion of respondents at each site answering ‘yes’ to each question (see table in Appendix 4). The three newly created variables were inspected and found to be normally distributed, paving the way for conversion to a common scale and the calculation of a weighted average.

Combining indicators of safety climate

To facilitate the comparison among strands A–C, a summary score for safety climate was created. This combined questionnaire elements relating to the immediate work context that are thought to contribute to the local safety culture (see Chapter 2). As described in Developing the organisational and safety climate questionnaire, the questions included were prevalidated scales from the NHS annual staff survey,175 which we termed ‘overload’ and ‘line management’; three individual questions from the same source (questions 2d, 4a and b; see Appendix 3); and Sexton and colleagues’ teamwork and safety climate scales. 25 Mirroring the procedure described above, the four well-established scales were weighted equally (one-fifth each) and the individual questions were accorded less weight (collectively constituting one-fifth). As noted in Chapter 5, Safety climate and team factors, 90% responded positively to question 4a, ‘Do you have to work closely with other team members to achieve the team’s objectives?’, rendering this question less able to differentiate between sites than the other two stand-alone questions, 2d and 4b. Question 4a was, therefore, allocated half of the weight of questions 2d and 4b. Thus the indicators were combined as shown in equation 1 so that, as required, the weights total 1. As with the calculation of the summary survey-based organisational climate score, before combining each element of the survey-based safety climate score was scaled to fit the standard normal distribution and so z-scores are shown in the equation and subsequent results.

Strand B: observation-based holistic evaluation of safety culture

This strand relates to objective 3 (see Chapter 1, Aims and objectives): to generate quantified holistic evaluations of organisational and safety culture for each site using observation. There was no well-established method or prevalidated instrument available for this strand. The closest fitting well-developed approach was MaPSaF,84 but pilot work with this framework convinced us that it would not be suitable for this study and, furthermore, to use it in this study would require an inappropriate subversion of its intended usage as a developmental tool based on self-assessment and reflexivity. A specifically tailored approach had to be developed as part of this study.

The holistic evaluations were derived from strategic immersion, primarily direct observation of staff at work and their working environment, supplemented by brief conversations with key informants. This method was derived from previous work by team members in delivery units,34,132 and its application to EDs was piloted at a local hospital not included in the study.

Use of the word ‘holistic’ derives from its use in the commissioning brief (see Appendix 1): because our method was primarily observational, we generally use that term instead in the text, though we continue to use the term ‘holistic’ when referring directly to the study’s objectives, so as to preserve the structure of the report in line with the commissioners’ specification and the research protocol.

Data collection

Six 1-day visits were undertaken at each hospital by at least two observers, which allowed sustained non-participant observation to see how staff behaved over a number of hours, and sampled sufficient time points to gauge the range of work and activity levels. In recognition of fluctuating workloads and staffing levels, the visits were distributed throughout the week. Data were, therefore, collected at all periods of the day excluding midnight to 6 am, and on all days except Sunday.

Researchers recorded their observations in hand-written field notes. These were made during observation periods, then reviewed and annotated within 24 hours. Field notes contained a minimum of identifying information, for example labelling participants in any documented interactions by their profession and level or role rather than by name or initials. No identifiable patient information was recorded, although patients were anonymously included in notes if their interactions with staff were of relevance. See Developing an observation prompt list for description of developing prompts to guide data collection.