Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 02/11/04. The contractual start date was in October 2004. The draft report began editorial review in January 2011 and was accepted for publication in May 2011. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

PT received funding from the pharmaceutical industry to deliver a lecture on stroke and from Boehringer Ingelheim to attend the 2010 European Stroke Conference. AV, LD, AH and PT receive expenses for attending meetings of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment panels. Several of the NHS Trusts participating in the study received funding from The Stroke Association towards their start up (year 1) excess treatment costs. During the study, GP and MW (retired 2005) were employed by charities representing people with stroke, Speakeasy and The Stroke Association. AY receives annual royalties from Authors’ Licensing and Collecting Society for academic publications.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2012. This work was produced by Bowen et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2012 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

In 2002 the UK’s National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme identified the need to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of speech and language (SL) therapy for aphasia and dysarthria following stroke, using therapy strategies likely to be effective yet feasible for routine NHS delivery and comparing these with an attention control (AC) involving patient contact but not specific therapy. This report describes the work commissioned to address these issues and to elicit the views of service users and carers.

Stroke

‘A stroke occurs when blood flow to part of the brain is interrupted causing damage to the brain tissue’. 1 The 2010 National Audit Office (NAO) report concluded that 110,000 people have a stroke each year in England alone, around 300,000 people are living with moderate to severe disabilities as a result and stroke care costs the NHS £3B per year.

Aphasia and dysarthria after stroke

Stroke can disrupt communication in different ways, through impaired motor speech production (dysarthria) or use of language (aphasia). Dysarthria is an output problem, resulting from impaired movements of the speech musculature including lips, tongue, palate, larynx and respiration. This limits intelligibility for the listener and may cause frustration and distress for the person with stroke. Aphasic problems can be receptive or expressive, affecting spoken, written or gestural forms of communication and are associated with emotional distress up to 6 months post stroke and beyond. 2–4 Restricted activity and social participation are common consequences of aphasia and dysarthria, as are psychological effects, vulnerability and adverse effects on families and informal caregivers. 5 Apraxia of speech also occurs6 but is outside the remit of this study.

Epidemiology of communication problems

Data on the frequency and recovery rates of dysarthria and aphasia vary between studies, depending on methodological factors such as sampling methods, timing of screening/assessment, method of assessment, expertise of the assessor and length of follow-up.

The prospective Lausanne Stroke Registry study7 of 1000 consecutive hospital admissions with first-ever stroke suggested that 46% had impaired communication (34% with aphasia) in the acute phase. A prospective, population-based study8 found that 30% of those with first-ever ischaemic stroke (FEIS) had aphasia and that the overall incidence rate attributable to FEIS from multiple overlapping sources of information was 43 per 100,000 inhabitants [95% confidence interval (CI) 33 to 52 per 100,000 inhabitants].

Despite some degree of spontaneous recovery, the prevalence of persisting speech and language difficulties (6 months post stroke) is 30–50 per 100,000 population. 9 The Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists (RCSLT) draws on Department of Health (DoH) data to conclude overall that around one-third of people are left with communication disability after stroke. 5

It is generally accepted that aphasia occurs more commonly than dysarthria, although they may co-occur. Research interest, both epidemiological and concerning effectiveness, has disproportionately focused on aphasia rather than dysarthria.

Speech and language therapy

Speech and language therapists in the NHS work with people with aphasia and dysarthria and their families in different settings across the stroke pathway, for example as part of a multidisciplinary team (MDT) on a specialist stroke unit, in outpatient clinics and in the community, although most provision is probably in the first few months after stroke. This system mostly works by referrals from MDT members. One of the most recent guidelines to summarise the specialist role of SL therapists is the 2010 Scottish guideline. 10 This outlines six key elements of the intervention for aphasia or dysarthria:

-

diagnosis

-

information (to patients, carers and health-care staff)

-

detailed assessment (to include impact on the individual and family and psychosocial situation and general well-being)

-

individualised care programme (including goal achievement and compensatory strategies)

-

access (to coping strategies, support groups, etc.)

-

facilitating referral.

Several authorities promote the main aim of rehabilitation as being about maximising the person’s ability to participate successfully in everyday communicative interactions. 5,11 Although the professional body is keen to stress that there is ‘no universally accepted treatment’ that can be applied to every person with aphasia, the reader is referred to the RCSLT’s detailed resource manual5 for commissioning and planning services for aphasia, which provides specific description of interventions for this client group, including how these address all three levels of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework: impairment, activity, participation. 12 The overall approach is summarised by RCSLT as use of multiple strategies to:

-

help the person to use remaining abilities

-

restore language abilities as much as possible by developing strategies

-

compensate for remaining problems

-

learn other methods of communication

-

coach others (family, health and social care staff) to learn effective communication skills to maximise the aphasic person’s competence.

Evidence for speech and language therapy for people with dysarthria

The Cochrane systematic review of SL therapy for dysarthria, published prior to the start of the ACT NoW (Assessing the effectiveness of Communication Therapy in the North West) study, was updated in 200513 following further literature searches. The authors initially identified 16 potential studies but subsequently excluded them all. Most (13) were not randomised controlled trials (RCTs), and nine of these were before-and-after group studies. The three RCTs were excluded because the intervention was not SL therapy14,15 or the participants had communication problems other than dysarthria and had a progressive condition. 16 This review highlighted a lack of RCTs of SL therapy for dysarthria after stroke or other non-progressive brain injury, and identified an urgent need for good-quality research in this area. 13

The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) 201010 guideline confirmed that there have been no further completed trials or systematic reviews since 2005. SIGN concluded that evidence for the effectiveness of SL therapy for dysarthria continues to be restricted to small group studies, single case studies or expert opinion, and that expert opinion is firmly in favour of the value of SL therapy intervention. They recommend referral to SL therapy but do not specify how early this should happen or at what intensity or duration.

The current National Clinical Guideline for Stroke17 observes that dysarthria has been poorly researched. They recommend (under certain circumstances) assessment, direct intervention and training communication partners. There is no dysarthria-specific intensity/duration recommendation beyond the generic rehabilitation recommendation of 45 minutes per day if needed and tolerated, and if the patient is willing.

Evidence for speech and language therapy for people with aphasia

Current clinical guidelines for the rehabilitation of aphasia post stroke10,17 and the SL therapist profession’s recent commissioning and planning manual5 are heavily influenced by two reviews. 18,19 The RCSLT draws attention to variations in the validity of the available reviews and distinguishes between the high quality of the Cochrane review11,18 and the serious methodological flaws of others. 19 These reviews reach opposing conclusions about effectiveness, unsurprising, perhaps, given their methodological differences.

Robey’s19 review of 55 group quasi-experiments including non-stroke populations (an update and expansion of his 21-study review20) generates 75 estimates of treatment effects. Most (60) are from the studies that made pre- and post-therapy comparisons, with the remaining 15 derived from non-randomised comparisons of treatment versus no treatment. Robey19 concludes that ‘on average, treatment for aphasic persons is effective’ and he argues, in this heavily cited paper, that further studies ‘to reinforce this general conclusion’ would waste resources.

However, Robey19 concludes that including RCTs (and homogeneous treatments) would reduce the number of effects to zero. This is supported by the findings from a systematic review by Greener et al. ,18 conducted using internationally accepted methods21 to exclude the sources of bias likely to have influenced Robey’s findings. 19 Greener et al. 18 considered the 12 existing RCTs of aphasia and concluded that because of their ‘poor or unassessable methodological quality’ they cannot be used to determine effectiveness.

The aphasia Cochrane review18 has recently been extensively modified and updated. 11 The revised protocol included a restructuring of the research questions, revision of the eligibility criteria and information on how to pool extracted data. It now comprises 30 RCTs, incorporating 10 of the original 12 included studies. This is a broad review with 41 subcomparisons, making it difficult to draw an overall conclusion. Some studies provided intervention in the acute phase post stroke, whereas others recruited people months and years later, with concerns raised by the review authors about the clinical relevance of this data set for a typical SL therapy clinical population.

The review’s summary of results covers three topics:

-

speech and language therapy versus no SL therapy

-

speech and language therapy versus social support and stimulation

-

one SL therapy approach versus another SL therapy approach.

A receptive language subtest was reported as favouring SL therapy. The review authors also observed a consistency in the direction of effect across most of the subcomparisons (85%), which favoured the provision of SL therapy. As a result, they concluded that there was ‘some indication’ of the effectiveness of SL therapy for people with aphasia following stroke. In the other two topics they concluded that SL therapy by a trained supervised volunteer was as effective as by a professional SL therapist, and that there was insufficient evidence to establish the effectiveness of one SL therapy approach over another.

In contrast to dysarthria, there is vibrant research activity into aphasia, much of which comes from the UK. This has mainly focused on theoretical development of the underlying impairment and differences in the range of aphasic presentations. The body of studies evaluating the effectiveness of therapy is growing but is mostly concentrated at the ‘theory/modelling’ stages (pre-clinical and phase I) of the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework for trials of complex interventions, consisting largely of single case experiments and case series. 22 Interventions that show promise in phase I studies are not typically taken forward into phase II and III trials. Although trials have been conducted (and systematically reviewed), they do not appear to have followed the progressive development suggested by the MRC framework. Even though methodological failings and insufficiently detailed therapy protocols within some RCTs have been rightly criticised, misunderstandings about RCTs per se (e.g. heterogeneity, efficacy vs effectiveness) are perpetuated, which presents barriers to building a robust evidence base. A prime example is the paper titled Ask a silly question: two decades of troublesome trials23 which, despite including several valid pro-RCT comments, tends to be wrongly interpreted as proof that RCTs are inappropriate for SL therapy.

Limitations of previous studies

There are no RCTs of specific SL therapy interventions for people with dysarthria after stroke nor of SL therapy service delivery for this client group. The limitations of previous research into SL therapy for aphasia after stroke include the following:

-

Observational studies and experimental single case designs or series contribute to the evidence base but cannot provide robust, reliable evidence of clinical effectiveness that generalises to the target clinical population.

-

Randomised controlled trials have not included an economic evaluation.

-

Randomised controlled trials have either not standardised the therapy, or the amount and content provided was not described in sufficient detail for replication or implementation into clinical services.

-

Randomised controlled trials have either not used or not reported methods to reduce bias (e.g. allocation concealment, blinding outcome assessors) as per the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) guidelines. 24

-

Randomised controlled trials have not included service user and carer opinions in the design and conduct of the study, for example to insure the inclusion of adequate patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) or aphasia-friendly (accessible) qualitative study methods.

-

Several RCTs have not included outcome measurement at the ICF activity and participation levels, focusing instead on impairment-level measures, which, on their own, do not provide a meaningful evaluation of whether an intervention is effective.

-

Some RCTs have not measured outcomes at a time point appropriate to determine whether there is a meaningful maintenance of any immediate post-therapy benefits, for example to at least 6 months.

Justification for the current study

Communication problems affect the lives of a considerable proportion of those who survive a stroke. They can persist for years, resulting in lifelong activity-level restrictions and decreased opportunity for social participation. Service user surveys repeatedly find high levels of dissatisfaction with current service level provision. 25 National audits highlight low levels of provision of SL therapy, although these figures perhaps attract less attention than they should, given concerns about the even worse provision of clinical psychology. 26 In 2010 the NAO found that the actual staffing levels [0.4 whole-time equivalent (WTE) per 10 beds] of SL therapists on stroke units in April 2009 were about half of that expected by the 2007 DoH strategy staffing assumptions (0.8 WTE), and were far lower than occupational therapy and physiotherapy 2009 levels (1.1 and 1.3 WTE, respectively) and that swallowing therapy may have taken precedence over communication therapy.

Although many stakeholders consider that the amount of SL therapy currently provided within the NHS is less than desirable, it is nevertheless an intervention that is routinely commissioned within the NHS, in hospital and community services. Given the cost to the public purse, and in the wider context of improvements to stroke service provision, an examination of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of SL therapy for aphasia and dysarthria is justified and indeed essential. The ACT NoW study was designed to evaluate the effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and service users’ views of an early, well-resourced intervention by SL therapists for people with aphasia or dysarthria admitted to hospital with stroke.

Structure of the Health Technology Assessment monograph

The ACT NoW study consisted of two stages, each containing several study types. Chapter 2 summarises the aims, methods and findings of the component parts of stage 1, the feasibility study. Stage 2, the main study, consisted of a RCT (Chapters 3 and 4), economic evaluation (Chapters 5 and 6) and qualitative study (Chapter 7). The design and delivery of the SL therapy data and that from the control arm are described in Chapters 2–4. The studies are combined into an overall discussion and conclusion in Chapters 8 and 9, respectively. The appendices contain detailed additional information.

Chapter 2 Feasibility study

The ACT NoW study consisted of two stages. This chapter summarises stage 1, the feasibility study and its components. The feasibility study was only a means to an end, and was reported on in detail to the funder as it progressed, and so will be reported in brief here. At the time of writing this monograph, four papers have been published27–30 and others are in preparation for submission in 2012. [Young A, Gomersall T, Bowen A. Trial participants’ experiences of early, enhanced speech and language therapy after stroke compared with employed visitor support: a qualitative study nested within a RCT. Clin Rehabil 2012;in press; Bowen A, Hesketh A, Patchick E, Young A, Davies L, Vail A, et al. Does early, enhanced speech and language therapy for people with aphasia or dysarthria after stroke add more benefit than providing support alone? The ACT NoW randomised controlled trial (Assessing Communication Therapy in the North West). BMJ 2012;submitted.] The reader is referred to these for detailed descriptions of our development of novel outcome measures27,28 and our validation of a novel use of an existing outcome measure. 29,30

Aims and objectives of the feasibility study

The overall aim of the feasibility study was to develop the methods and materials needed for each part of the subsequent main study (the RCT, economic evaluation and qualitative study), to pilot these and determine whether a main study would be feasible.

There were eight specific objectives. These were to:

-

define the patient population of interest and develop a pragmatic screening procedure

-

describe the intervention in a written manual, so it could be replicated and generalised

-

test the feasibility of recruiting and training volunteers, to provide the AC

-

develop a method of maximising recruitment, given difficulties recruiting to previous RCTs in this area

-

select, and if necessary develop, outcome measures for the main RCT, based on user/carer preferences and adequate for statistical comparisons

-

develop qualitative methods for the main study, to engage service users and carers in driving the research process, and to elicit their views of NHS services

-

develop cost data collection methods, tailored for these specific clinical conditions and services

-

test the feasibility of recruiting and retaining participants in a RCT (implementing the methods and materials developed in objective 4) and quantify the patient population.

Perceived challenges

At the outset we perceived many challenges to the successful running of the study (of the RCT in particular), such as whether ethics and research governance approval would be granted (given the initial plan to deliver the AC through volunteers) and whether the essential involvement of NHS SL therapists could be obtained.

These challenges were overcome and helped plan the timetable for the main study. The feasibility study received research ethics approval (04/MRE03/30 ‘The ACT NoW pilot study’) and research governance approval (including, eventually, honorary contracts for the volunteers) for a pilot RCT, health economics and qualitative study to recruit people with stroke admitted to four NHS acute stroke services and follow them through into the community 6 months later. This work began in October 2004. These approvals were amended to include a larger outcomes validation study that completed data collection in August 2006 and has since been published. 27–30

Research partnerships

NHS speech and language therapists and service users

We formed two key partnerships. The first was with the NHS SL therapists who would design and implement the screening and intervention approaches. The SL therapist group’s role and achievements were essential for achieving objectives 1 and 2 (see Aims and objectives of the feasibility study) and are described below (see Partnership with NHS SL therapists: screening and intervention).

Research user group

The second partnership was with stroke service users and their carers, who named themselves ‘the RUG’ (research user group). The RUG’s role began during the feasibility study and continued through to its support in the dissemination of the main study. A detailed paper has been prepared for publication, describing the methods used to work in partnership with service users to maximise recruitment to the RCT. A second paper is in preparation, cowritten with the RUG members, and focuses on the impact on them of their long-term involvement in this research study. In addition, we produced a paper in January 2007 at the request of the Stroke Research Network entitled ‘ACT NoW: involving service users in research’. This was a detailed guide for researchers intending to work collaboratively with service users with stroke, includes materials used in the ACT NoW study and is downloadable from www.uksrn.ac.uk (under PCPI, links).

In summary the RUG’s main tasks were to:

-

advise on the interview panel for the selection of research staff

-

train research staff in how to facilitate successful communication with research participants with aphasia

-

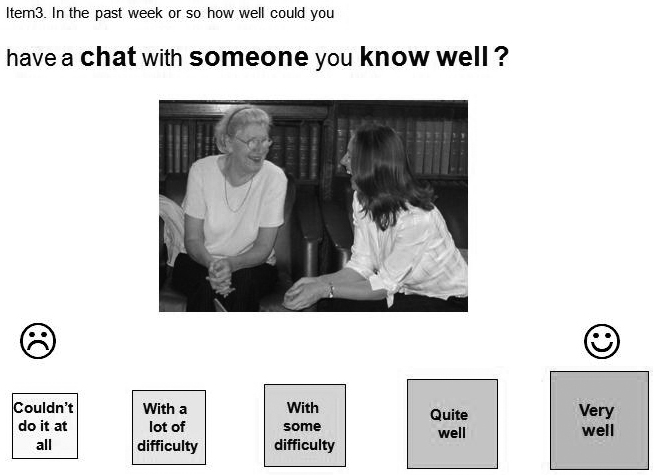

develop accessible, aphasia-friendly information and consent materials in a variety of media (objective 4: Figure 1 and Chapter 3)

-

advise on the content and accessibility of the outcome measures including a newly developed and validated patient-centred outcome measure [objective 5; see COAST (Communication Outcomes After Stroke scale), etc., below, under Outcomes validation study]

-

advise on the choice of accessible qualitative study interview questions (objective 6; see below and Chapter 7).

FIGURE 1.

Information and consent materials developed in collaboration with the RUG. Readers can view and download the written recruitment materials from www.psych-sci.manchester.ac.uk/actnow/patients/needtoknow/

All of these tasks were achieved through a model of facilitated regular meetings at a convenient location in a meeting hall in the community. During the feasibility stage, eight service users with aphasia and/or dysarthria and two carers collaborated with researchers. There were a few early changes to membership, which otherwise remained remarkably steady throughout the subsequent 4 years of the main study.

Outcomes validation study

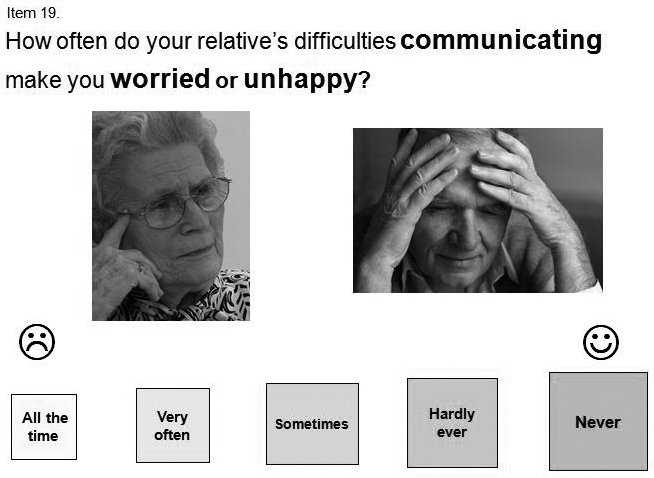

Following a comprehensive consideration of 10 possible outcome measures and decision that none were suitable in their current form, a 20-item, patient-centred COAST was developed and validated with a sample of 102 people following a stroke and 68 carers (objective 5). 28 The RUG worked with the project leads AL and AH to provide input on the content (items) and the presentation (aphasia-friendly visual aids and layout). The COAST measures participants’ perception of their communication effectiveness and the impact this has on their quality of life (Figure 2). A parallel version, the Carer COAST (Communication Outcomes After Stroke scale, carer version), was validated to provide the carers’ perspective on the patients’ communication effectiveness and its effect on the carers’ own related quality of life. 27 The COAST and Carer COAST were included as secondary outcome measures in the main RCT (these and other resources developed are available at www.psych-sci.manchester.ac.uk/actnow/outputs/resources/).

FIGURE 2.

Items from the COAST (left) and Carer COAST (right). Images for the example from the Carer COAST are reproduced with permission from http://en.fotolia.com/ (©Fotolia).

A clinically feasible procedure for collecting a video-recorded, semistructured conversation sample between the service user and an unfamiliar conversation partner was developed. Such a conversation sample provided data for the main RCT’s primary outcome measure. We tested its rating by expert SL therapists, using the existing Therapy Outcome Measure activity subscale (TOM). The agreement between service user, carer and therapist perspectives on the person’s functional communication has also been explored. 30 As we discuss in one of our papers,29 ‘Our findings support the use of the TOM by an unfamiliar observer to rate a short conversation as part of outcome measurement. The use of independent expert SL therapists to provide TOM activity-level ratings on structured conversation samples with an unfamiliar partner reduced the variability known to affect judgements of conversation, and was shown to have promise as a clinically feasible, socially relevant and reliable measure (p. 971)’.

Findings

The outcomes validation study resulted in the successful production of novel, patient-centred outcome measures, with demonstrated reliability, indicative evidence on convergent validity and practical to use in research, and a standardised method of collecting blinded professional ratings, suitable for making valid and reliable statistical comparisons in the RCT.

Partnership with NHS speech and language therapists: screening and intervention

A working party of NHS SL therapists and university-based researchers was established to develop a pragmatic screening procedure (objective 1) and define the intervention (objective 2) so that both could be standardised across the four sites participating in the pilot RCT. The latter is described below (see Intervention).

All admissions with stroke to the four sites participating in the feasibility study’s pilot RCT were screened. This was considered necessary as therapists were initially concerned that potential participants, especially those people with milder or more subtle language problems, would be missed if solely dependent on referrals to SL therapy from other NHS staff. A multistep screening method was used:

-

A therapy assistant (TA) reviewed the medical notes of everyone admitted with stroke to identify those with a possible communication problem and to search for documentation of any of the study’s exclusion criteria, for example some people had died or were receiving end-of-life care, whereas others lived out of the area covered by the NHS SL therapy service or were not fluent in English.

-

Those who may have communication problems and appeared eligible progressed to the second screening stage, at which they were seen by an SL therapist who used the Frenchay Aphasia Screening Test (FAST)31 and TOM32 to confirm the presence/absence and persistence of communication problems, provide a differential diagnosis (of aphasia, dysarthria or aphasia and dysarthria), determine the severity of the communication problem at the level of impairment and restricted activity (disability), and rule out all exclusion criteria. Dysarthria was diagnosed by a TOM rating of the FAST’s picture description task.

-

Anyone referred to SL therapy automatically progressed to the second screening stage (i.e. without note review by an assistant).

-

Those who appeared eligible but were not yet able to engage in stage 2 were rescreened by assistants during the following 2 weeks to avoid excluding people who needed a bit more time before they were ready to participate.

-

Those with no documented communication problems in their notes (and no obvious exclusion criteria) were also seen by the SL therapist to identify people with subtle communication problems who were not identified in the standard clerking or referral procedures. Up to four specific methods were used: a brief conversation with the therapist, the Graded Naming Test,33 rapid lip and tongue movements [diadochokinetic rates (DDK)] and a graded oral spelling test. 34 Those failing any of the four were screened as described above (see step 2).

The numbers admitted and screened are considered below (see Findings from the pilot randomised controlled trial). In brief, 103 of the 265 admissions were initially considered as eligible for participation. Following SL therapists’ screening, 34 of the 66 who continued to have communication problems were considered eligible. The other 32 were excluded for a variety of reasons, as several of the exclusion criteria were not apparent at note screening, for example pre-existing dementia or learning difficulties, severe cognitive deficits or other medical problems rendering the SL therapy intervention unsuitable.

The study found that although the screening procedure was feasible the additional elements (conversation, DDK rates, naming and spelling) did not identify any further eligible patients. Therefore, the feasibility study concluded that only those referred to SL therapy or with communication problems documented in their notes needed to be screened by SL therapists in the main RCT. (Apraxia of speech was outside the remit of this study. If present in the participants it was not treated as a unitary disorder and was assessed only as part of the speech or language disorder.)

Intervention

During the feasibility study the NHS SL therapists and academic colleagues worked together across a series of intensive week-long workshops to agree and describe an intervention suitable for piloting in a RCT (objective 2). The methods used were to review the literature, including the grey literature around clinical guidelines, and to reach a consensus on what was considered to be best practice for the early treatment of aphasia and dysarthria. This included both the specific components of interventions and service delivery issues. This can be described as a set of best practice guidelines and a compendium of resources. The therapists also established an agreed coding system to record the type and amount of therapy received by each participant. As well as providing these quantitative measures, the participating therapists attended bimonthly aphasia meetings at the University of Manchester (which are open to all aphasia therapists in the area), at which each site presented one case to illustrate to other therapists how they had implemented the guidelines. The feasibility study allowed the therapists to try out the intervention and recording methods, highlight any practical difficulties and make changes prior to the main RCT.

Six key components were identified ranging from assessment (summarised in Appendix 16) and direct one-to-one intervention with patients through to the SL therapist’s role within the MDT and the SL therapists’ support for informal carers. These are listed briefly in Table 1.

| 1. Assessment | Initial and ongoing, standardised, functional, case history, goal setting |

| 2. Information provision | Communication problem, strategies/equipment to assist communication, intervention plan, therapist opinion of progress, available information resources and support networks |

| 3. Provision of communication materials | Communication book for recording activities; an AAC device if required |

| 4. Carer contact | Discussion and information giving, observation and participation in therapy, conversation partner training, preparation for the end of the research intervention |

| 5. Indirect contact | Written descriptions of needs, abilities and strengths, discussions with clinical teams, MDT goal planning |

| 6. Direct contact | Therapy to improve language skills at all levels of the World Health Organization ICF model:12 impairment (improving language skills), activity (compensatory strategies), participation (developing confidence, accessible information) |

Key features

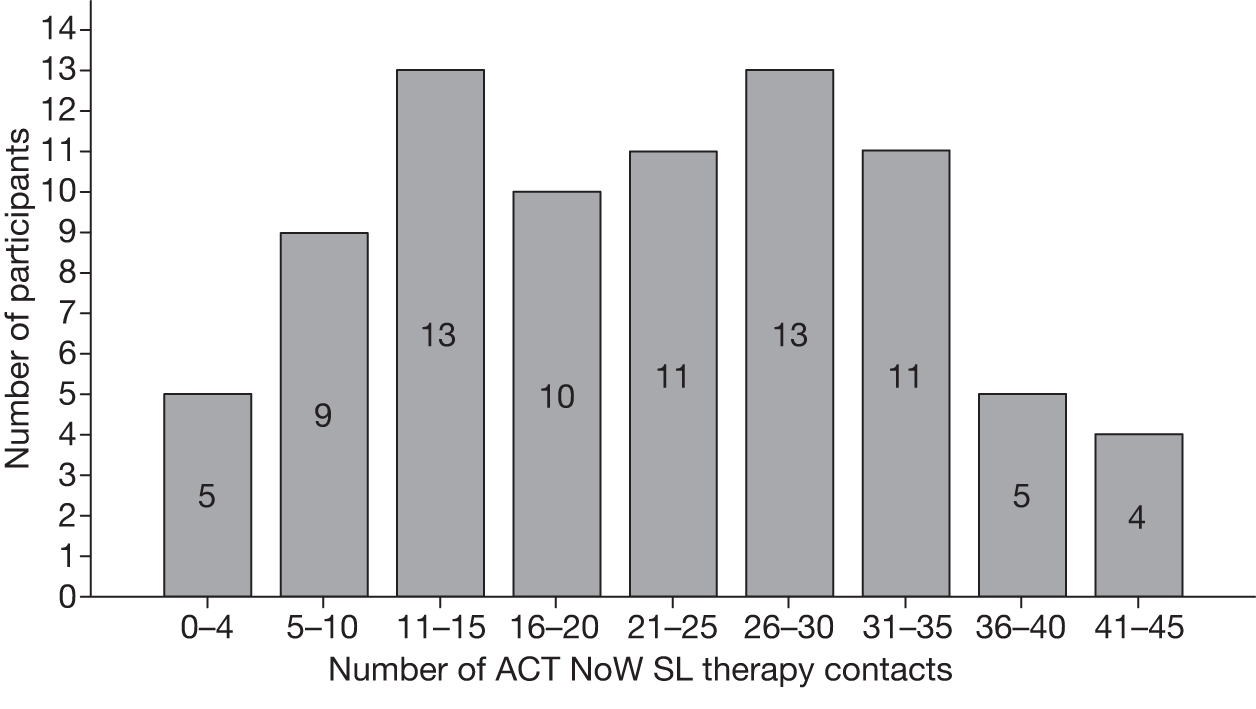

The intervention was designed for those admitted to hospital with stroke and timed to begin during the acute phase of the stroke pathway. As such, it was specifically designed to evaluate early intervention, a period when most therapy is currently provided aimed at channelling recovery and adjustment to disability. However, it was to be practical for NHS delivery and one aspect of this meant that the intervention start date was flexible, depending on what was most appropriate for each individual, as determined by the SL therapist’s clinical judgement. Intensity and duration were to be available up to three times a week, for up to 3 months but flexibly and not of a one-size-fits-all prescribed dose. Intensity and duration varied both between and within participants, as determined by the SL therapist’s clinical judgement and agreement with the patient about what was appropriate. Another important feature of the intervention was that it was to be capable of being provided in whatever setting the patient was in, for example to provide continuity into the community for those discharged from inpatient care.

Findings

Seventeen of the 34 participants eligible for the pilot RCT consented (or provided proxy consent from an informal carer) to take part. Nine of these were randomised to the intervention arm, of whom five had aphasia and dysarthria, two had aphasia only and two had dysarthria only. The full range of severity (mild to severe) on the TOM scores was represented in this small group.

The intervention data recorded suggested that information giving, carer contact, indirect contact (MDT) and direct contact (face to face) with a SL therapist were common to all participants. The most popular therapy types were impairment, functional and conversation based. Counselling and support for both participant and carers was also a common feature. Five participants required therapy for the full 3 months. Of the other four, one died and the other three all had mild TOM scores.

Some intervention techniques were not tested in the feasibility study owing to the small numbers of participants and the rolling admission into the study over 3 months, for example group work with participants or carers, high-technology alternative or augmentative communication (AAC) devices.

The best practice guidelines were modified as the feasibility study progressed. A key change was the increase in the maximum duration from 3 to 4 months, based on a consensus among therapists that more time was likely to be needed by some participants. At the end of the feasibility study a summary of the revised intervention for evaluation in the main RCT was produced (see Appendix 1) along with a detailed 103-page manual and compendium of resources (available on request). Two descriptive case studies were written to illustrate the range of activities and the time course for these over the intervention period (available on request).

Attention control

The feasibility study aimed to develop an AC and test the feasibility of delivering this through the use of volunteers (objective 3). The intention was to provide participants allocated to the AC arm with an equivalent amount of contact time (attention) as those in the intervention arm (up to three times a week, for up to 3 months) but without providing SL therapy. The AC acted as a comparator to determine if between-group differences were truly due to the early communication input provided by SL therapists as opposed to the potential psychosocial benefits of regular, frequent one-to-one contact.

Attention control was to be delivered by a volunteer rather than an SL therapist because of the likelihood of contamination between arms if both were provided by the latter. It was also clear that therapists would not feel comfortable providing the AC, nor would they have sufficient resource to see both groups as early and as frequently as might be necessary.

Volunteer recruitment and training

Seventy-four people responded to advertisements for volunteers for the feasibility study using posters and leaflets in sports, health and jobs centres, shops, university and college campuses across the north-west of England. Volunteering agencies were also used, and university students were targeted at fairs and by e-mail. Volunteers had to be ≥ 18 years and have no prior experience or specific training in stroke rehabilitation. Informal information sessions were delivered across the four pilot RCT sites, aimed at providing potential volunteers with more detailed information about the research. Fifty-one people completed the next step, a 2-day training session, and 26 of these became operational volunteers in the pilot RCT. The training programme was a modified version bought in from a voluntary sector organisation.

A volunteer coordinator was used. The coordinator managed the administration around research governance requirements of using volunteers within a clinical research study [e.g. applications for enhanced disclosures from the Criminal Records Bureau (CRB) and securing honorary NHS contracts for volunteers to visit research participants in hospital and later in the stroke pathway in the participants’ homes]. The coordinator also monitored the quality and quantity of each contact between volunteer and participant by accompanying volunteers on initial visits and reviewing the volunteers’ data collection sheets.

Findings

The feasibility study proved invaluable in highlighting limitations with the use of volunteers to provide AC to acute stroke patients in the feasibility study:

-

It was difficult to recruit and retain the type of volunteer considered best suited to this clinical research study. Twenty of the 26 operational volunteers were students. Five others were professionals and one person was retired. All but two of the 26 were aged 18–29 years. The large time commitment placed on volunteers (visiting up to three times a week, up to 3 months) was the main reason for dropout or failure to deliver all the required visits.

-

The training package was difficult to adapt for research purposes and, with hindsight, did not prepare the volunteers adequately for the difficult task of visiting the eight people with aphasia or dysarthria who had been allocated to the AC in the pilot RCT. Data collection forms did not adequately record the content of each visit, essential to ensure that volunteers were providing only attention (e.g. conversation, companionship) rather than offering communication strategies.

-

A lack of clarity in research governance guidelines at the time on how to register non-employed volunteers operating with a clinical research study meant that there were long delays that jeopardised research deadlines (e.g. NHS honorary contracts were difficult to obtain) and in fact reduced the pilot RCT recruitment phase to 12 weeks.

-

Volunteers were unable to offer the flexibility of time and travel essential to cover all sites and fit in with participants’ requirements. These restrictions on their availability meant that the employed coordinator had to conduct 42% of the 86 AC visits. Furthermore, the average number of sessions for participants allocated to the pilot RCT’s AC arm was 1.1 per week compared with 1.8 per week for those allocated to SL therapy.

In conclusion, use of an AC group with this clinical population was feasible but several difficulties needed to be overcome for the main study. Participants did agree to the concept of randomisation and 86 visits were successfully carried out with the eight people randomised. As described below, see Findings from the pilot qualitative study, AC participants reported their experiences positively. However, the feasibility study showed that the use of volunteers would be, counterintuitively, too costly and time-consuming for delivering AC in the main RCT. This model also risked failing in its main objective – to offer equivalent amounts of attention to both arms. This finding led to extensive redesign of the AC arm by employing paid part-time visitors, designing a new training and monitoring package and employing an experienced person to monitor the visitors for the duration of the main RCT. A summary of the main study’s AC is provided in Appendix 2 and a paper is in preparation for publication comparing AC in the feasibility and main study.

Pilot studies

This chapter has so far presented examples of materials and methods developed in collaboration with the RUG, for example accessible, aphasia-friendly, information and consent materials to maximise recruitment (objective 4, also described below) and RCT outcome measures, based on user/carer preferences and adequate for statistical comparisons (objective 5). We have also described the pragmatic screening procedure and defined intervention (objectives 1 and 2) that were developed by NHS SL therapists. To test the feasibility of recruiting and retaining participants in a RCT and to quantitate the patient population (objective 8) we tested these materials/methods with pilot studies. The RUG also contributed through a series of facilitated and communication supported group discussions to the development of qualitative methods to elicit communication-impaired RCT participants’ views of the intervention and control arms (objective 6). The final set of materials and methods developed during the feasibility study were the service use data collection forms for the economic evaluation, tailored for these specific clinical conditions and services (objective 7).

Findings from the pilot randomised controlled trial

The intention of the pilot RCT was not to compare outcomes but to determine the feasibility of conducting the main Phase III trial. We decided, for practical reasons, to recruit from four sites (both large urban hospitals and smaller more rural hospitals) for 4 months. This was reduced to 3 months because of delays obtaining the necessary approvals for volunteers and resulted in 17 participants who were allocated to a maximum of 3 months’ intervention or AC and were followed up at 6 months. This provided data to estimate the recruitment rate for the main RCT.

As discussed above, 265 people with stroke were admitted to hospital. All were screened to ensure that subtle communication problems would not be missed if depending on referrals alone. One hundred and three people had possible communication problems at note screening. This was reduced to 34 people following the SL therapists’ face-to-face screen, usually because mild communication problems had resolved or other exclusion criteria, not obvious from the early medical notes, were identified at interview. Exclusion criteria could be identified at various steps in the initially complicated screening process, making it difficult to obtain definitive rates for specific eligibility criteria. Once one exclusion criterion was identified the screening ended and so the actual incidence of each individual criterion was not known. Changes to data coding and simplification of the screening process itself were introduced by the therapists for the main study on the basis of lessons learned.

Ten of the eligible 34 refused any information but the recruitment materials were well received by the 24 who expressed an interest in receiving them, and resulted in a consent/proxy consent rate of 17/24. The procedure, which was developed with service user input from the RUG, was for a researcher to meet the potential participant to present the information in a manner most suited to the particular needs of that patient. Three versions of the information booklet were produced and used:

-

standard information (17)

-

aphasia friendly (5)

-

simplified/pictorial (2).

Audio and audio-visual formats (see Figure 1) were offered on three occasions in place of or to supplement the paper versions. Different levels of consent materials were also used. Five people were recruited by witnessed consent and one by proxy consent.

Attrition and breach of protocol were low and outcome assessments progressed without difficulty. One person died in the control arm and one refused their allocation to AC to obtain NHS SL therapy but agreed to take part in outcome measures. One person in the intervention arm breached protocol after the 3-month maximum had been reached, in order to obtain extra NHS SL therapy before the 6-month outcome assessment.

Fifteen of the 24 provided with information about the study had aphasia and some (8) had both aphasia and dysarthria. Of the seven who refused consent, three had dysarthria alone.

Findings from the pilot economic evaluation

Data collection tools and methods were developed by the ACT NoW team, based on available literature and knowledge of the services used by people following stroke. Two forms were produced for measuring resource use. A ‘Use of Hospital Services’ form was completed by research assistants (RAs), largely through hand-searching medical records retrospectively at the 6-month outcome assessment. This focused on use of hospital-based services. A ‘Support from Others’ form was completed by, and from the perspective of, the main informal carer at the 6-month assessment and also included use of primary- and community-based services. Both forms were tested and modified within the pilot RCT. The final forms developed for the main RCT are described in Chapters 5 and 6. The process of the pilot study and the data collected, combined with discussion with the study team, indicated that it was not feasible to collect reliable and consistent information from carers about the time they spent providing care and support to the study participant. Accordingly, these data were not collected in the main trial. This meant that the perspective of the economic study was changed from a societal viewpoint to that of the NHS, providers/funders of non-hospital care facilities and of patients and families. These actors are expected to incur the key costs and benefits of services for SL therapy for communication difficulties due to aphasia/dysarthria following stroke.

Findings from the pilot qualitative study

Four participants were sampled for qualitative analysis, two from each arm of the pilot RCT, purposively chosen to ensure interview materials were piloted across the range of severity of communication difficulties following stroke. The qualitative interview had three distinct parts to:

-

elicit participants’ perception of what had occurred during their intervention or control sessions

-

discuss what they had found ‘good’ and ‘difficult’

-

explore respondents’ views on how the sessions had impacted upon their life, either through improvements in their communication or through any other factors salient to the respondent.

Interviews were transcribed and coded thematically. The interviews worked well and revealed interesting insights. All four respondents valued their experience with either the volunteer or the SL therapist, and felt that their communicative abilities had improved, including gaining support from the volunteer/therapist and the amiable characteristics of the volunteer/therapists, which contributed to the respondents’ overall experience.

Conclusion of the feasibility study

The feasibility study, which began in 2004, had eight specific objectives, all of which were achieved by the end of 2006:

-

define the patient population and develop a pragmatic screening procedure

-

define the intervention, so that it can be replicated and generalised

-

test the feasibility of recruiting and training volunteers to provide the AC

-

develop a method of maximising recruitment, given known difficulties recruiting to previous RCTs

-

select RCT outcome measures and develop and validate a patient-centred measure of communication difficulties (COAST and Carer COAST) and a standardised method of collecting blinded professional ratings

-

develop qualitative methods for the main study, to engage service users and carers in driving the research process, and to elicit their views of NHS services

-

develop service use data collection forms for the health economic evaluation, tailored for these specific clinical conditions and services

-

test the feasibility of recruiting and retaining participants in a RCT, and quantitate the patient population.

The following chapters describe the methods and results used in the main RCT (Chapters 3 and 4), stated preference survey and economic evaluation (Chapters 5 and 6) and qualitative study (Chapter 7). Data on the actual intervention and AC provided to the main RCT participants, and issues around concordance, are described within Chapter 4.

Chapter 3 Randomised controlled trial methods

This chapter describes the design and conduct of the RCT. This was used to meet the study’s primary objective and the first three secondary objectives below. The remaining objectives, relating to the health economics components and the embedded qualitative study, are listed here to give an overall picture of the ACT NoW study but are then not addressed until Chapters 5–7.

Methods

Study design

The ACT NoW study was a pragmatic, multicentre, parallel-group RCT comparing clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness for two groups allocated in a 1 : 1 ratio. An embedded qualitative study was used to explore users’ and carers’ views on the process and effects of therapy and of AC. (A PDF of the protocol, version 4, dated 1 December 2008, is available on the NIHR HTA site at ‘www.hta.ac.uk/project/1390.asp#outputs’ and in Appendix 3.)

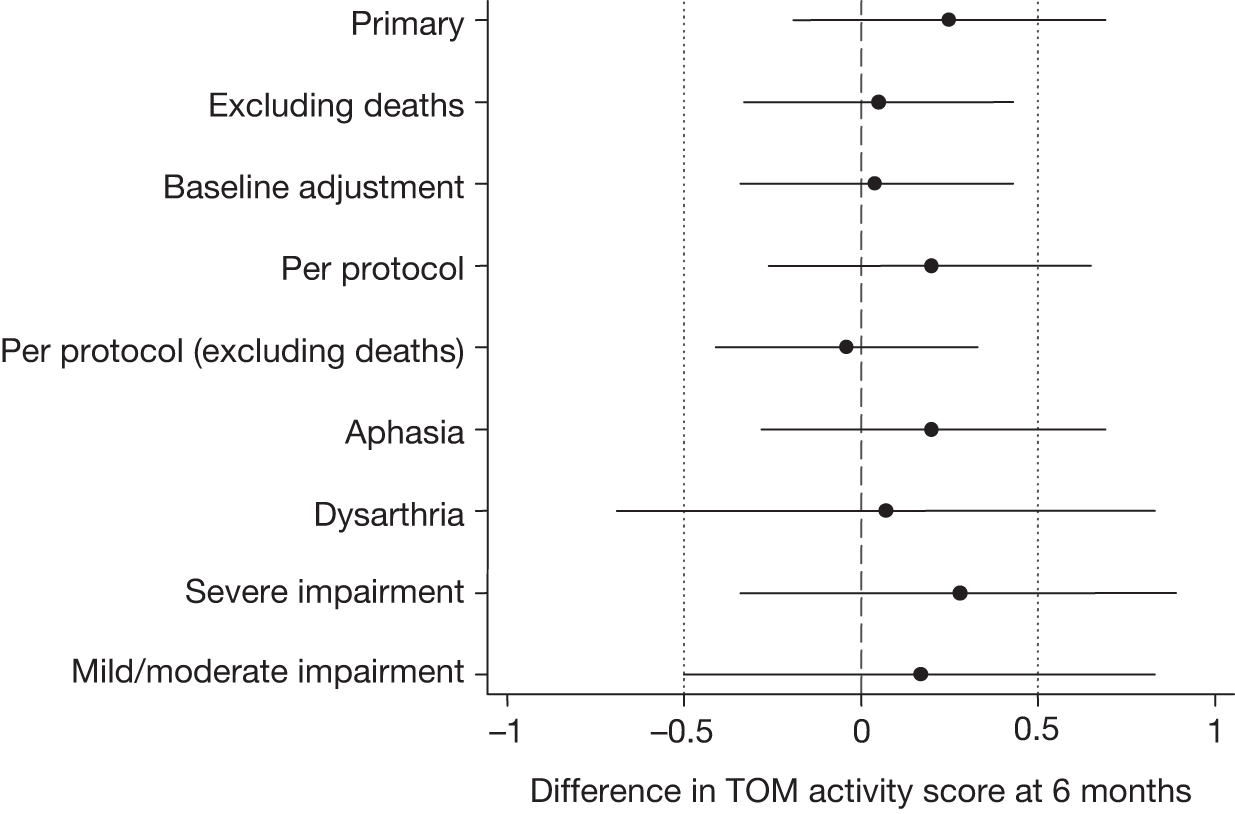

Primary objective

To evaluate the clinical effectiveness of an early well-resourced SL therapy intervention for people with aphasia or dysarthria after stroke when delivered by NHS therapists, compared with AC, as measured by blinded experts’ TOM ratings of videos of service users’ functional communication after 6 months.

Secondary objectives

Six months after entry to the study, to:

-

evaluate the clinical effectiveness of SL therapy compared with AC, as measured by service users’ self-reported functional communication and quality of life

-

evaluate the clinical effectiveness of SL therapy compared with AC, as measured by carers’ perceptions of service users’ functional communication

-

evaluate the clinical effectiveness of SL therapy compared with AC, as measured by carers’ own well-being and quality of life

-

evaluate the relative resource use, costs and cost-effectiveness of SL therapy compared with AC, including a societal perspective of valuations

-

elicit users’ and carers’ views on the process and outcomes of therapy compared with the views of those who received the AC

-

construct a ‘service user’s checklist’ of indicators of satisfaction and quality, which can inform and monitor the future implementation of the evaluated technology.

Summary of design of randomised controlled trial

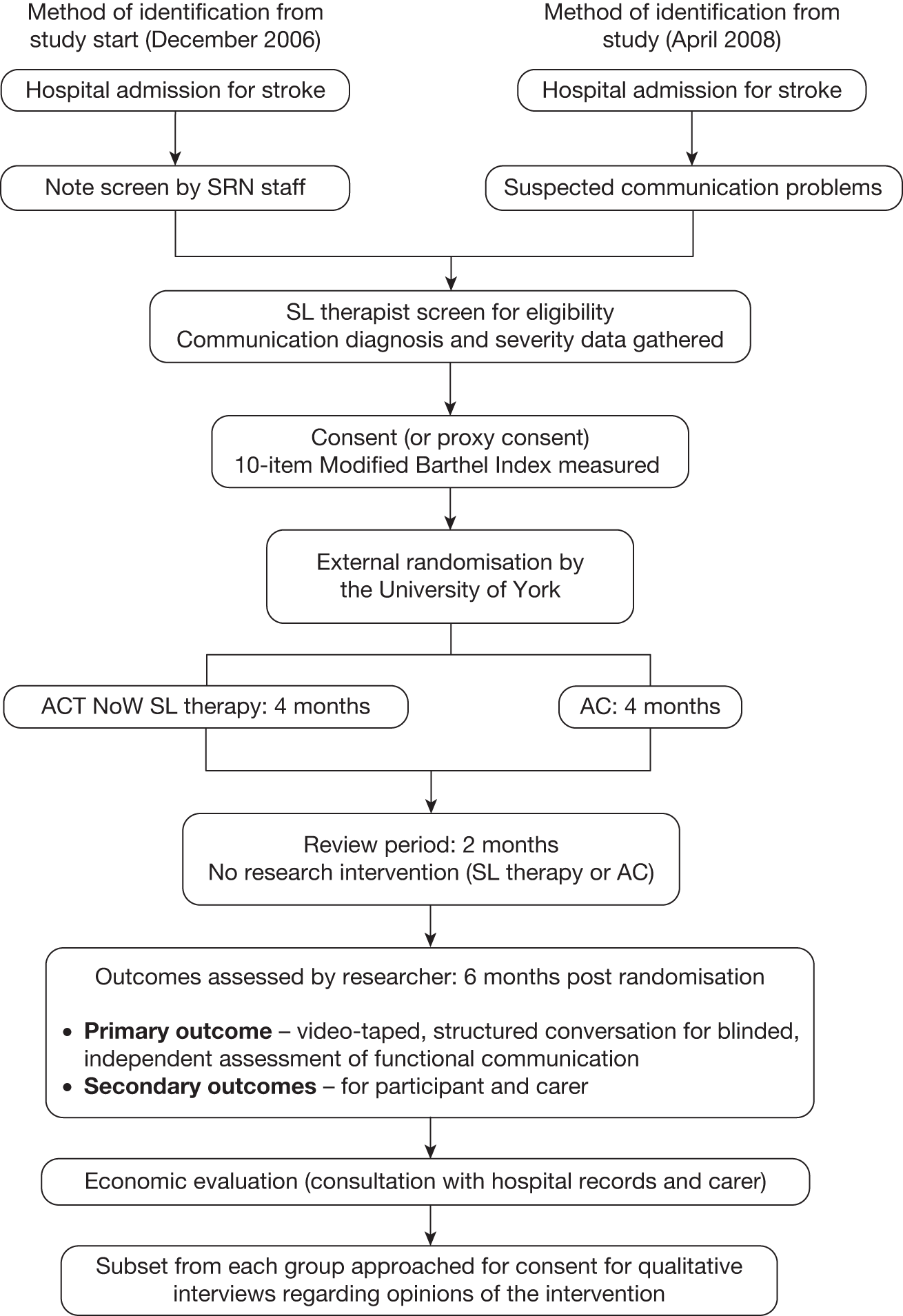

Figure 3 summarises the study method.

FIGURE 3.

Study method flow chart. SRN, Stroke Research Network.

Adults admitted to hospital with stroke and communication problems were screened as soon as possible by SL therapists to determine eligibility. (As described in Chapter 2, the screening method was revised until it was, from April 2008, reduced to SL therapist screening of only those with suspected communication problems.) Participants had to be able to engage in and likely to benefit from SL therapy (as assessed by SL therapists themselves). Participants who consented to join the trial were externally randomised (see Randomisation) to either SL therapy or AC with concealment of allocation in a 1 : 1 ratio. Randomisation was stratified by:

-

severity of communication impairment assessed on the TOM for the worse of aphasia and dysarthria (two levels: 0 to 2, 2.5 to 5)

-

recruiting site.

During the intervention phase, participants were seen up to three times per week for a maximum of 4 months. After 4 months, support was stopped for a ‘review’ period of 2 months. At the end of this period (6 months post randomisation) outcomes were assessed and service use data collated. Participants and carers from each arm of the trial were sampled after outcome assessment and approached for consent to take part in qualitative interviews (see Chapter 7).

Setting and locations

The study was coordinated by the University of Manchester and involved multiple sites across the north-west of England. Eight sites began the study but during the course of the recruitment period four other sites were set up to boost patient recruitment.

Participants were always identified initially after an inpatient hospital stay but were often discharged from inpatient care after the first few weeks when the trial intervention continued in other settings, for example outpatients, domiciliary visits.

The sites involved in the study were:

-

Bolton patients admitted to Royal Bolton Infirmary

-

Burnley patients admitted to Burnley General Hospital. Part-way through the study, stroke services at Burnley were reorganised and patients were then identified after admission to Royal Blackburn hospital. Participants were sometimes transferred to Pendle Community Hospital for pre-discharge rehabilitation

-

Central Manchester patients admitted to Manchester Royal Infirmary

-

North Manchester patients admitted to North Manchester General Hospital

-

Salford patients admitted to Salford Royal (Hope Hospital)

-

Trafford patients admitted to Trafford General Hospital

-

Warrington patients admitted to Warrington General Hospital

-

Wigan patients admitted to Royal Albert Edward Infirmary and often transferred to Leigh Infirmary for pre-discharge stroke rehabilitation.

The above sites were involved in ACT NoW from the start of the study in December 2006 until the end (last patients identified January 2010 and completed outcome assessments in July 2010). The four additional sites were:

-

Blackpool patients admitted to Royal Victoria Hospital; joined the study in July 2008 and recruited participants for 1 year until July 2009, after which they were unable to continue due to clinical staffing problems

-

Crewe patients admitted to Leighton Hospital; joined the study in April 2009 and remained recruiting until the end of the study

-

Lancaster patients admitted to Royal Lancaster Infirmary but could be discharged to a range of secondary care hospitals including Westmorelands and Kendall; joined the study in April 2009 and remained recruiting until the end of the study

-

Stoke patients admitted to University Hospital of North Staffordshire and North Staffordshire Royal Infirmary with a number of secondary care facilities, including Haywood Hospital; joined the study in September 2009, with only 4 months to recruit patients.

Inclusion criteria

Adults with a stroke who were admitted to hospital were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria:

-

communication impaired due to aphasia or dysarthria

-

considered, by the SL therapist, able to engage in therapy

-

considered, by the SL therapist, likely to benefit from communication therapy

-

informed consent or proxy consent provided by carers.

Exclusion criteria

Screening, as described below, was used to identify the following exclusion criteria:

-

subarachnoid haemorrhage

-

dementia

-

pre-existing learning disabilities likely to prevent benefits from therapy

-

unable to communicate in the English language (provision of bilingual SL therapists was considered to be beyond the scope of this study)

-

other serious concomitant medical conditions (such as newly diagnosed terminal disease)

-

the patient being unable to complete eligibility screening, even after three attempts over a 2-week period

-

family or carer objections

-

(rare) cases when a SL therapist was asked to contribute to an urgent assessment of a person’s mental capacity to consent to an NHS treatment, before the therapist had time to complete screening to determine eligibility for the trial.

Screening and baseline assessment

A standardised procedure for communication screen was used across all sites. This determined eligibility and baseline assessment information for stratification and was always completed by an SL therapist.

The baseline communication screen consisted of two sections:

-

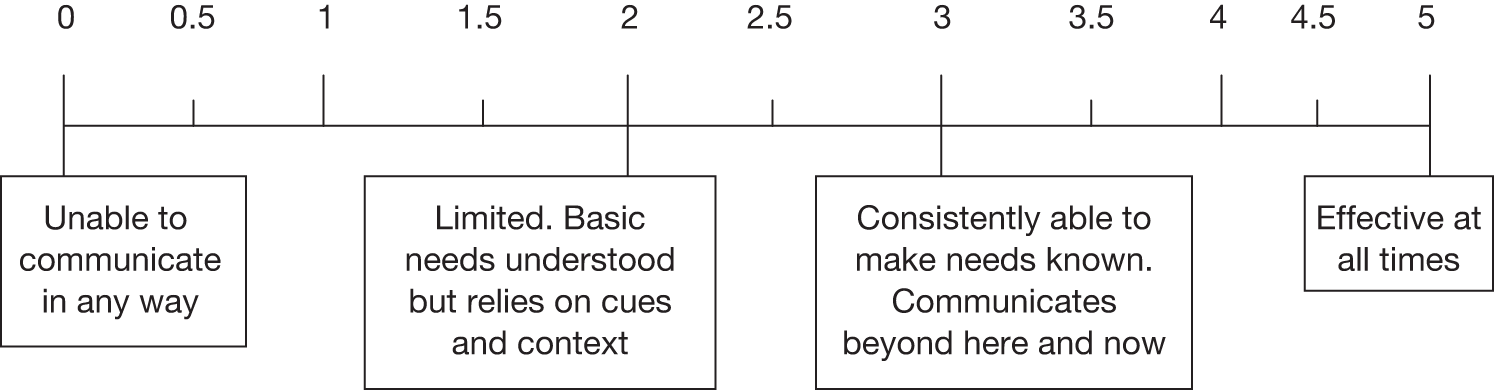

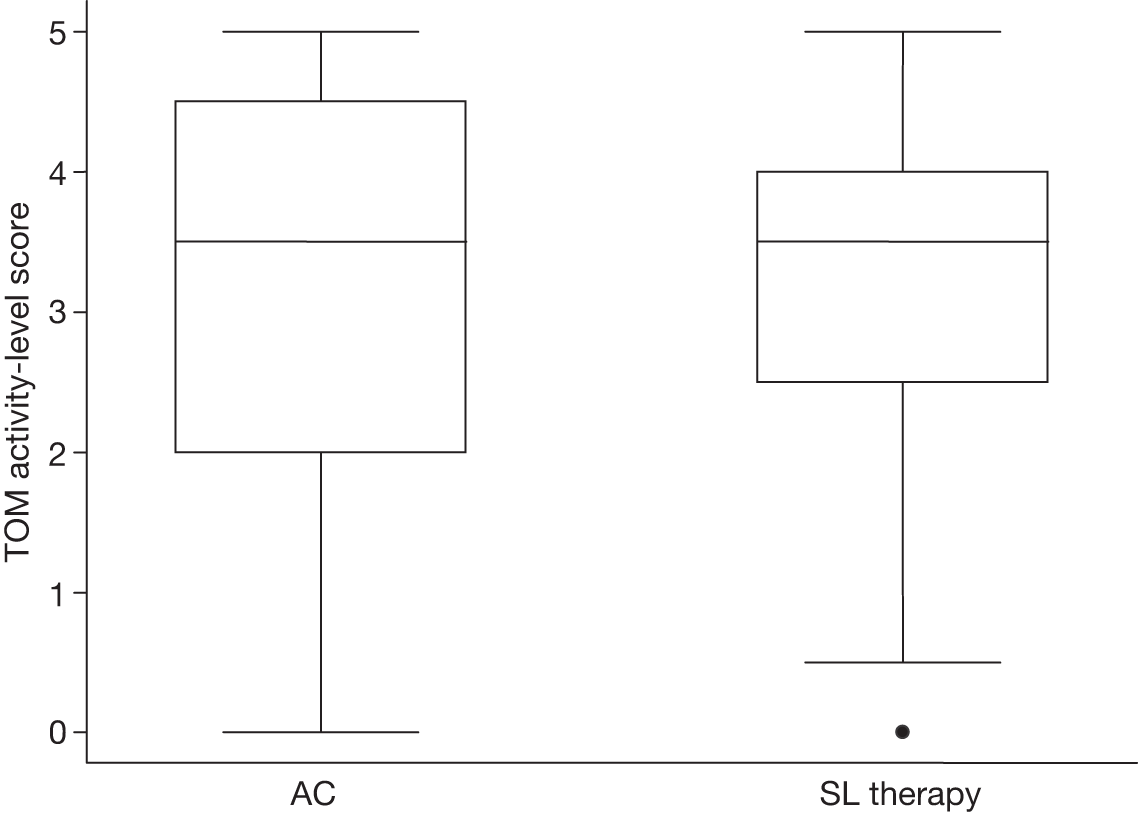

Language screen All patients were assessed using the FAST. The FAST provides health-care professionals working with patients who might have aphasia with a quick and simple method to identify the presence of a language deficit. It takes approximately 3–10 minutes to administer and has four subscales – comprehension, verbal expression, reading and writing – and is scored out of a total of 30 points. The verbal expression subscale involves a picture description that is also used as a speech sample to rate the severity of the language difficulties. If patients had severe difficulties and were unable to cope with the FAST then they were assessed informally using a selection of 10 object pictures or everyday objects, for example simple word to picture matching tasks. All patients were then rated on the impairment subscale of the aphasia TOM rating scale. This is an 11-point scale (0–5, with half points in between) that allows patients to be rated from ‘0’ (unable to communicate in any way) to ‘5’ (effective communication at all times).

-

Dysarthria screen The speech sample gained from the FAST and during conversation also led to a severity rating on the impairment subscale of the dysarthria TOM rating scale.

After these two screens, participants were also given a score on the aphasia/dysarthria activity subscale of the TOM and diagnosed for presence or absence of dysphagia (swallowing problems). (Apraxia of speech was outside the remit of this study. If apraxia of speech was present in the participants it was not treated as a unitary disorder and assessed only as part of the speech or language disorder.)

Prior to randomisation, the SL therapist provided all participants with an accessible leaflet about their diagnosis. Stickers were placed in the medical notes, meaning that the members of the MDT were aware that the patient had been diagnosed with aphasia or dysarthria. SL therapists did not provide support for communication to the patient, family or MDT until after they had had been informed about the study and, if consent was gained, until they had been randomised to the therapy arm.

Prior to randomisation, RAs also rated the patient on the 10-item Modified Barthel Index (BI)35 with the help of the hospital MDT. The BI gives a score out of 20 and indicates severity of overall disability (beyond communication) by rating the patient across 10 activities of daily living (ADLs), such as continence, personal care, feeding mobility and dressing.

Recruitment process

Once NHS SL therapists determined eligibility they telephoned the RAs, who met potential participants within the next day or two to provide information on the study and take consent. Participants were given a minimum of 24 hours between receiving first information about the study and joining the trial. This was to ensure that sufficient time for consideration and questions had been given and that participants had the opportunity to discuss joining the trial with family without a RA being present.

The use of aphasia-friendly information and consent materials (see Figure 1) ensured that RAs could provide an accessible and flexible approach to giving information to communication-impaired participants. Information materials were available in three versions: standard, aphasia-friendly and simplified/pictorial versions. All versions were in booklet format, printed on coloured A5 card and spiral bound to facilitate easy handling by patients with hemiplegia. Each of the written information materials had an associated audiotape that could be left with patients (as well as a personal tape player). These read out the information on each page to participants who had trouble reading. There was also a DVD/video of the standard-level information materials available, designed to be useful for families to take home and watch.

Consent materials were available in standard format (one-page consent form) or aphasia-friendly versions (with one statement per page, picture/icon support for the concept, broken down to facilitate understanding and large, easy-to-tick agreements).

If, because of their communication difficulties, the potential participant could not provide informed consent at that time, proxy consent could be requested from a carer/relative or Independent Mental Capacity Advocate/Consultee. Where proxy consent was gained, RAs later gave regular opportunities for participants to directly provide or withdraw their consent.

Randomisation

Once patients had consented to join the trial, their details were passed to the coordinating centre at the University of Manchester.

Randomisation was by an external, independent, web-based randomisation service from the York Trials Unit (University of York) to ensure concealment of allocation. Randomisation was stratified by severity of communication impairment assessed on the TOM for the worse of aphasia and dysarthria (two levels: 0 to 2, 2.5 to 5) and recruiting site. It was intended to stratify randomisation by a third factor, diagnosis (three levels: aphasia only, dysarthria only, both). During data checks after study completion it became clear that this had not occurred. Diagnosis and impairment were assessed by SL therapists at initial screening. Participants were randomised using a 1 : 1 allocation ratio and block sizes of two, four and six with differing combinations depending on the site. Variable block sizes were used to reduce the likelihood of selection bias through predictable allocation sequences. North Manchester, Trafford and Wigan all used strings generated using block sizes of two and four. All the other sites used blocks of four and six. No sites were aware of their block sizes.

Sites were able to temporarily suspend recruitment if staffing levels dipped below a point at which they would be able to take participants into the SL therapy arm, for example because of difficulty providing maternity leave cover. However, to prevent suspension from biasing selection it was permitted only if staffing problems were anticipated to last at least 3 months. This cut-off was necessary as staffing problems were a frequent occurrence and affected most, if not all, sites. Services had difficulty arguing for replacement posts because of the NHS research funding regulation that ‘excess treatment costs’ must be funded by normal commissioning36 and because the 80% of costs recoverable through a DoH central subvention was recoverable only retrospectively per person recruited to the SL therapy arm.

Intervention and control conditions

Participants were randomly allocated to the SL therapy intervention or an AC delivered by part-time employed visitors. See Chapter 2 for the development of these and Appendices 1 and 2 for summaries of content including minimum standards set for the intervention arm. The following sections describe the processes used to monitor delivery of both arms ensuring fidelity to the manuals.

Were minimum standards met, as set out in the therapy manual?

The SL therapy coordinator monitored and supported the SL therapists involved in the study. The aim of the monitoring process was to check that therapists were adhering to the therapy process described in the therapy manual and meeting the minimum standards for therapy provision described. Monitoring of therapy involved direct monitoring and bimonthly meetings at which the SL therapists presented to their peers details of a participant with whom they were working.

The SL therapy coordinator regularly visited all of the sites that were delivering therapy during the study to carry out 48 sessions of direct monitoring. During a monitoring visit, the following format was used: audit of case notes to check that the process of assessment (see Appendices 1 and 16) had been completed and goals for therapy had been clearly stated. As described in the minimum standards, this meant that impairments and functional limitations had been considered and therapy goals were based on sound theoretical rationale and the needs expressed by the participant. There would always be a discussion with the therapist about the rationale, and this also gave the therapists an opportunity to ask questions or for advice about therapy plans. In addition, checks were made to ensure that information had been given to participants about their difficulties, and that all were considered for AAC where appropriate. In addition, monitoring and support also took place by telephone and via e-mail, ensuring that therapists had someone who was more or less ‘on call’ to help with issues/queries as they arose.

There were a total of 22 therapy support meetings; at each meeting two sites presented a case study describing the therapy delivered to a participant in some detail, which was followed by peer discussion to promote consistency across sites.

Throughout the study, the therapists completed therapy record sheets that used codes to record interventions with participants in the study. Once completed, these were sent to the therapy monitor, and used as an additional check to ensure treatment fidelity. The monitor and peer group confirmed that standards were met during the trial. Therapy delivery at one site raised concern. This was closely monitored and extra support provided until the monitor was satisfied that the intervention was being provided as intended.

Visitor monitoring

Appointment of an AC monitor to provide appropriate training, close monitoring and supervision of the visitors was a major element of change and learning from the feasibility study. The primary purpose of this post was to ensure protocol adherence in guaranteeing that activities did not involve any form of communication strategy.

The monitor carried out the following duties and responsibilities:

-

prepared all training materials for visitors

-

selected and trained all visitors prior to visiting and ad hoc training as and when required when new visitors were appointed

-

ensured that visitors adhered to all relevant policies and procedures and to all health-and-safety-related guidelines

-

ensured that every visitor was monitored at least once at each of the three stages of the AC (rapport-building, core sessions and winding-down sessions)

-

ensured that monitoring visits covered both hospital and community sessions

-

highlighted any potential problems and/or training issues with the trial manager

-

planned and chaired bimonthly supervision/information sessions for all visitors

-

recruited replacement visitors, together with the trial manager, at the end of 1-year contracts (necessary to avoid a build-up of strategies for dealing with people with aphasia and dysarthria).

In the main this was a good framework, but it required some flexibility to enable the AC monitor to support and supervise lay visitors in an appropriate way, and to ensure that the highest level of adherence to research protocols was achieved.

Briefing programme

An initial 2-day briefing programme was delivered by the AC monitor, as described in the Visitors Manual, which prepared visitors for delivering appropriate social attention to AC participants.

More time than expected was required during the briefing programme for the visitors to fully comprehend and accept the strict protocols about not employing any form of communication strategy. As lay visitors, it really challenged their inherent instincts, as all thought that as a visitor they would be ‘helping’ people with their communication problems. Adjusting the programme and adding further experiential exercises helped, in part, to address this concern. It was only in practice that this was fully understood and only then that visitors found their own different strategies, with support, to avoid their natural instincts.

Feedback from visitors provided us with a clear message that the training was hard and emotionally challenging, but essential to do the job. And, had they not had such thorough preparation for the role, some would have dropped out, as they felt it took a great deal of courage and confidence to engage with someone with complex communication difficulties while complying with the AC protocols in consciously avoiding any form of communication strategy. Training and support throughout proved essential for their high performance.

Team meetings

Visitors were recruited in groups and team meetings were held every month for the first 3 months of a visitor’s contract then every 2 months for the remaining term. The meetings gave the chance to share experiences and common problems, discuss ideas for activities and gave the AC monitor the opportunity to informally monitor practices. It proved to be very important for the visitors, who all worked from a home base and did not have the benefit of peer support on a daily basis, although the AC monitor and trial manager were always available by telephone.

Monitoring and supervision

The early visits proved stressful for most visitors as every patient presented differently and visitors were testing out coping strategies they had only practised through role play. In the early weeks, one-to-one supervision was well utilised – with some visitors needing to talk on the telephone at length to the AC monitor after each visit. This was time-consuming for the monitor, but proved to be time well spent as this support system provided knowledge, advice and emotional underpinning, which helped to build visitors’ confidence fairly quickly.

Through close and prompt scrutiny of the weekly log forms, which reported the content, timings and any problems, the AC monitor was able to rectify activities, or anything that seemed inappropriate or needed clarification immediately, by telephone or by e-mail.

Outcome assessments

All outcomes were assessed at 6 months post randomisation. RAs visited patients and carers in their own homes or wherever they were living at that time point.

For the primary outcome, a semistructured conversation between the participant and a relatively unfamiliar communication partner (study RA) was videotaped (see Chapter 2). RAs were not SL therapists but all had gained experience of interacting with people with communication difficulties post stroke and had been specifically trained in communication-supportive techniques. Supportive techniques used a range of linguistic, paralinguistic and augmentative ramps to communication but RAs did not take specific communication aids with them. Only pens and paper were used, with participants encouraged to utilise any communication aids with which they had been provided as part of the research.

A framework script for the conversation was developed, which involved several starter and follow-up questions, to be used as necessary. Starter questions were open ended. The follow-up questions were more specific or offered more conceptual or linguistic support in order to facilitate a response. The same standard question was used to open (‘Can you tell me about your family and friends?’). If a natural conversation flowed from this initial starter there would be no necessity to return to the script. Further starter questions were brought in if conversation dried up on a particular topic and follow-up questions were used to enable responses within each topic as necessary. The aim was 10 minutes of interaction, although if all questions had been used, or at the RA’s discretion (e.g. if a participant became distressed), the conversation could be ended earlier.

The videotape of the conversation was stored and tapes were then sent in batches to an independent expert SL therapist, blinded to treatment allocation and not involved in treating study participants, who rated functional communication on the communication activity scale of the TOM (aphasia and dysarthria assessments share the same activity scale). Overall, three raters were trained in the use of this scale and the reliability of their ratings was confirmed by a quality monitoring check. We previously confirmed the reliability of using the TOM in this way in a published study involving 12 therapist raters and 102 videotaped conversations involving unfamiliar conversation partners. 29 The semistructured conversation script along with TOM rating sheet used is shown in Appendix 4. 29 The TOM activity scale ranges from 0 to 5 and includes half-points, resulting in a 11-point scale. The higher the score, the better the outcome (level of communication activity).

Secondary outcomes were as follows:

-

Participants’ perception of their functional communication and quality of life was assessed using the COAST. 28 As described in Chapter 2, its content, accompanying illustrations and layout were informed by items from the Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life Scale (SAQOL)37 and input from the RUG and NHS therapists to facilitate its use with patients with communication difficulties. It covers both understanding and expression in a range of communication situations and functional activities, including five items measuring quality of life. The overall score is converted to a percentage (but see Statistical analysis), with higher scores indicating better outcome. (See Figure 2 for visual presentations of items and Appendix 5 for the wording of the 20 items.)

-

Carers’ perception of the participants’ functional communication was measured using the first 15 questions on the Carer COAST. 27 An example of carer adaptation is that ‘… how well could you read …’ is changed to ‘… how well could your relative/friend read …’. The overall score is converted to a percentage, with higher scores indicating better outcome.

-

Carer ‘well-being’ was measured using the Carers of Older People in Europe (COPE) Index. This is a validated 15-item self-completed measure comprising three subscales: negative impact (a high score on this subscale is a poor outcome as it indicates stress), positive impact and quality of support (high scores on both of these subscales are a good outcome as they indicate satisfaction from carer role and that the carer feels supported). Carers’ own quality of life was also assessed with the relevant five questions from the Carer COAST. As for the parallel COAST, the overall score is converted to a percentage, with higher scores indicating better outcome.

-

Adverse events – second subsequent stroke: events leading to increased hospital stay or readmission to hospital, and death.

-

Participants also completed a European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D). This is a validated, widely used short measure of health status. The resulting score will be somewhere between ‘1’ (the person is in full health) and ‘0’ (the person has died). It is also possible for scores to be < 0, representing states that are considered by some to be worse than death. Service use data were also collected by RAs. These data were used in the economic evaluation and are described in Chapter 6.

Blinding

It would have been impossible to blind participants and those delivering intervention to the allocation group. Attempts were made to ensure that RAs who collected data on outcome assessments were blinded to the randomisation group. Certain precautions were taken within the study team (such as password-protected data related to allocation) and participants were asked not to mention group allocation at outcomes in a letter and by RAs on arrival. However, it was anticipated that RAs could become unblinded (e.g. by reference to name of therapist or visitor, or by seeing communication aids in use and knowing these would not have been provided to the control group). The primary outcome was based on the videotaped structured conversation, which was assessed by expert SL therapists who did not know the patients and were blinded as to allocation.

Safety evaluation

Both trial interventions were non-medicinal with no anticipated serious adverse reactions. It was hypothesised that SL therapy could have an impact on adverse events in the sense that improving communication could ensure better adherence to other therapy and secondary prevention activities. Therefore, serious adverse events (SAEs) that would be anticipated in a large group of stroke patients were recorded:

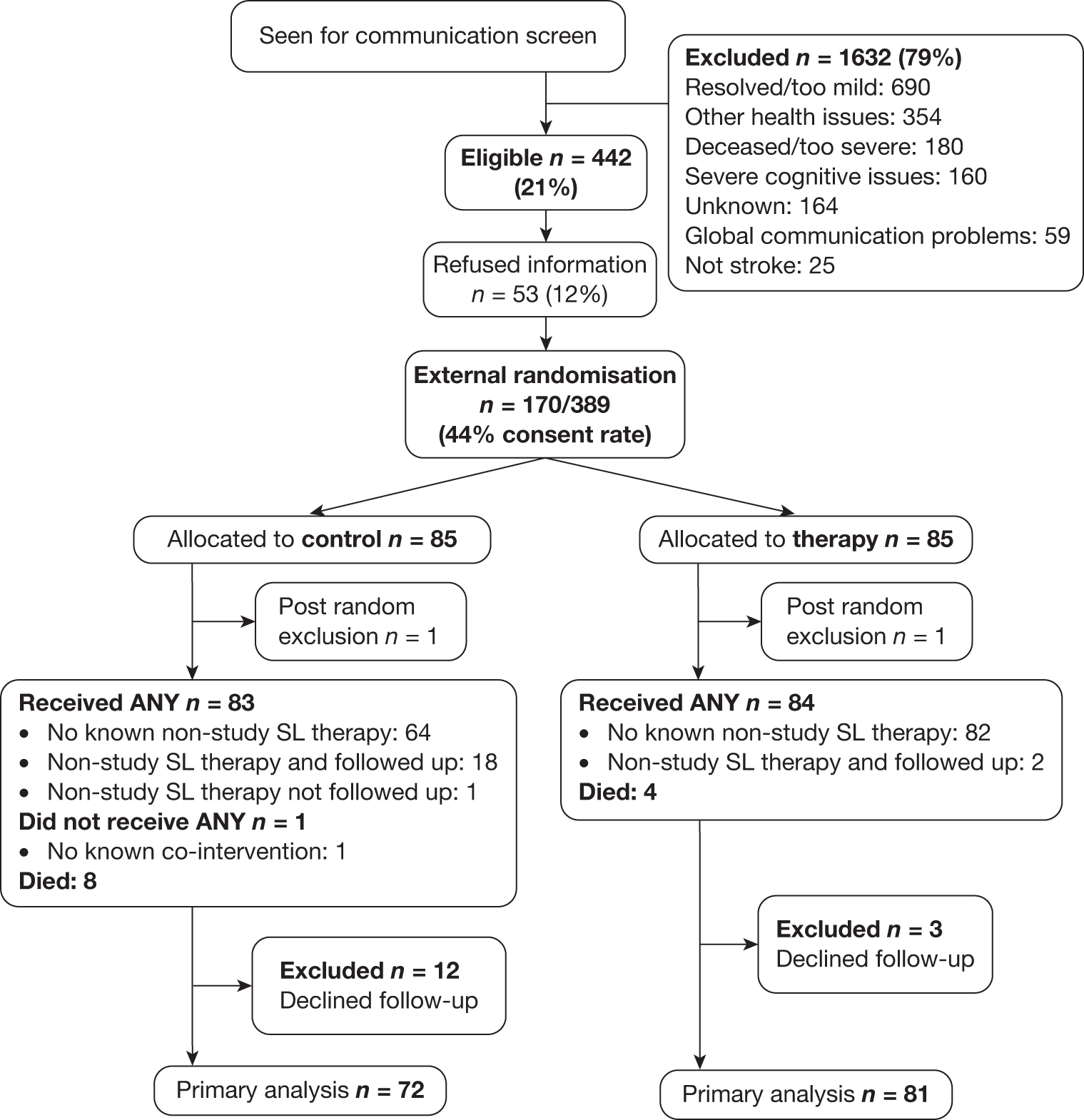

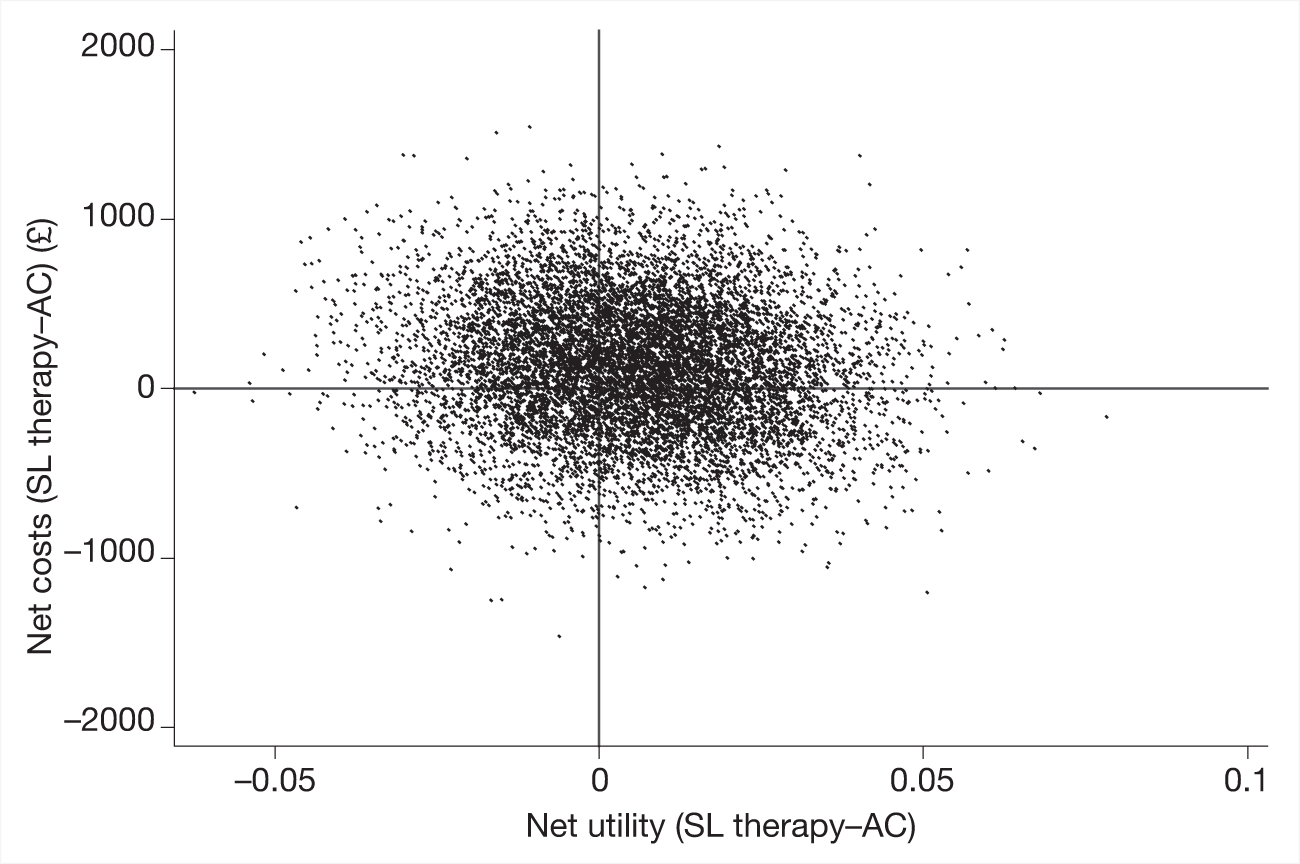

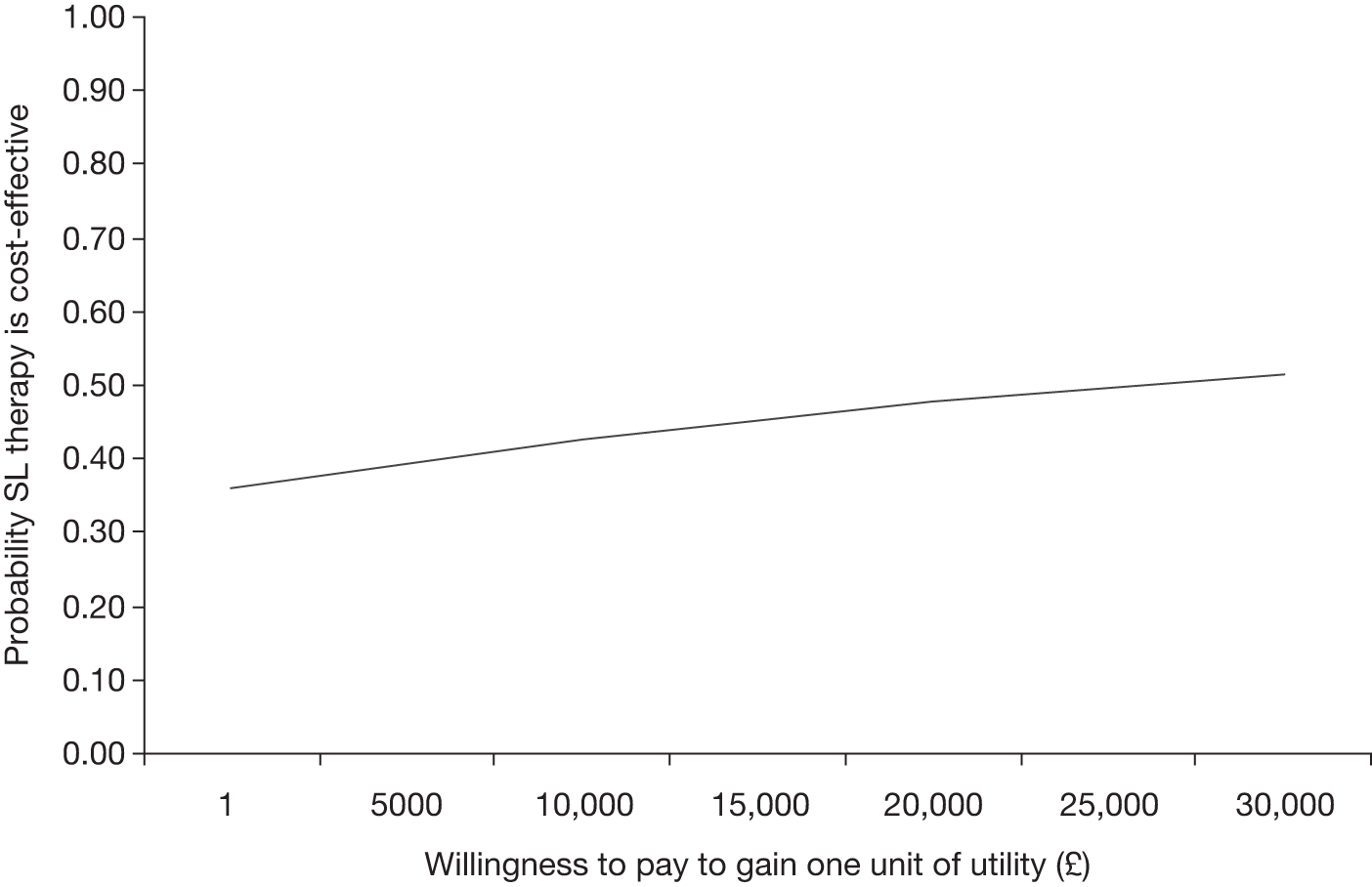

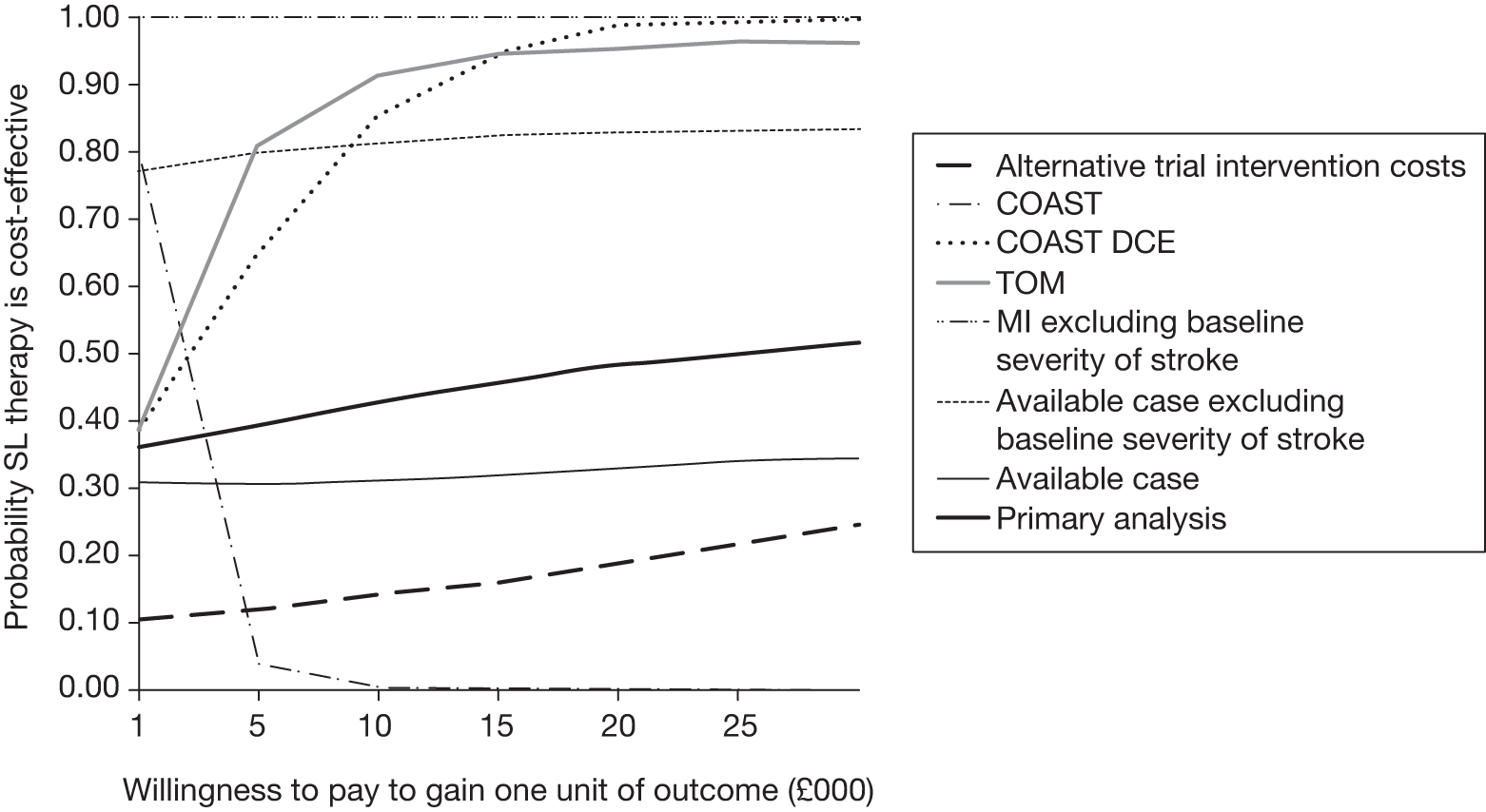

-