Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 09/67/01. The contractual start date was in June 2010. The draft report began editorial review in May 2011 and was accepted for publication in December 2011. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design.The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2012. This work was produced by Rodgers et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2012 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Description of health problem

The term ‘depression’ can refer to a range of mental health problems primarily characterised by persistent depressed mood and loss of interest in activities, among other associated emotional, cognitive, physical and behavioural symptoms. 1

Depression is the most common mental disorder in community settings, and a major cause of disability across the world. A World Health Organization cross-sectional survey revealed the global 1-year prevalence of a depressive episode to be 3.2%. 2 The prevalence is greater still in people with other medical conditions (e.g. 10–14% of patients receiving general hospital care). 3 Neuropsychiatric disorders account for one-third of all years lost to disability (YLDs), with unipolar major depressive disorder alone accounting for 11% of global YLDs. 3

The Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (PMS) of UK adults aged 16–74 years in 2000 reported a overall prevalence rate for depression of 26 per 1000 people, with slightly higher rates for women than for men. 4 This survey also suggested that having a depressive episode was associated with unemployment, belonging to social classes 4 and below, having no formal educational qualifications, living in local authority or housing association accommodation, moving three or more times in the last 2 years, and living in an urban environment. 4

Various theories for the causation of depression have derived from research on the impact of physical and endocrine processes,5 brain structure and function,6 and cognitive and emotional processes. 7 All of these factors are likely to influence an individual’s vulnerability to depression, alongside factors such as gender, genetic and family factors, adverse childhood experiences, personality factors and social circumstances. 8 In terms of depression, vulnerability factors (e.g. genetic factors) interact with social or physical triggers, such as stressful life events or physical illness, to result in a depressive episode. The stress–vulnerability model suggests that the probability of a mental health problem occurring is based on an interaction between a person’s vulnerability to developing that problem and that person’s exposure to particular stressors or risk factors for that problem. 9 However, some episodes of depression occur in the absence of a stressful event, and, conversely, many such events are not followed by a depressive disorder in those with vulnerabilities. 8

Even after successful treatment, the risk of relapse after remission is significant, and has been reported as 50% among patients having experienced one episode of major depression, and 70% and 90% after two and three episodes, respectively. 10 In many of these individuals this pattern becomes worse with subsequent repeated depressive episodes, with an increase in severity and frequency and a lack of responsiveness to treatments. 11,12 Research has shown that the long-term outcome for those individuals who experience multiple episodes has altered little in the last 20 years. 13 At least 10% of patients have persistent or chronic depression. 14

Current guidance from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) cites a review by the King’s Fund, which estimated that there were 1.24 million people with depression in England in 2006, and this was projected to rise to 1.45 million by 2026. Based on these figures, the total costs for depression in 2007 (including prescribed drugs, inpatient care, other NHS services, supported accommodation, social services and lost employment in terms of workplace absenteeism) were estimated to be £1.7B, with lost employment increasing this total to £7.5B. These figures were projected to be £3B and £12.2B, respectively, by 2026. 15

Diagnosis

Depression is typically diagnosed according to criteria set out in either the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fourth Edition (DSM-IV),1 or the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Edition (ICD-10). 16 DSM-IV was developed by the American Psychiatric Association, whereas the ICD-10 is the comparable European guide for diagnosis of mental disorders. Although similar, the two systems are not identical, having slightly differing thresholds for the number of symptoms required for a depressive episode (as termed in ICD-10; ‘major depressive episode’ in DSM-IV).

The 2010 NICE guideline8 on depression states that a diagnosis of a depression requires assessment of three linked but separate factors: (1) severity, (2) duration and (3) course. Diagnosis requires a minimum of 2 weeks’ duration of symptoms and including at least one key symptom (low mood, loss of interest or pleasure). Individual symptoms should be assessed for severity and impact on function and be present for most of every day. The following categories adapted from DSM-IV were outlined:

-

subthreshold depressive symptoms (fewer than five out of nine symptoms of depression)

-

mild depression (few, if any, symptoms in excess of the five required to make the diagnosis, and the symptoms result in only minor functional impairment)

-

moderate depression (symptoms or functional impairment are between ‘mild’ and ‘severe’)

-

severe depression (most symptoms, and the symptoms markedly interfere with functioning).

Treatment

The objective of treatment is to achieve remission or at least adequate control of depressive symptoms. For some, depression can become a gateway to a lifetime of disability and impairment, so it is important to develop interventions and services to not only reduce depressive symptoms and restore functioning, but also to enable people to self-manage their problems and prevent relapse and recurrence of episodes of major depression. This acknowledgement of the nature of recurrent depression and the high potential of recurrence has therefore led to a greater emphasis on long-term management approaches. 17

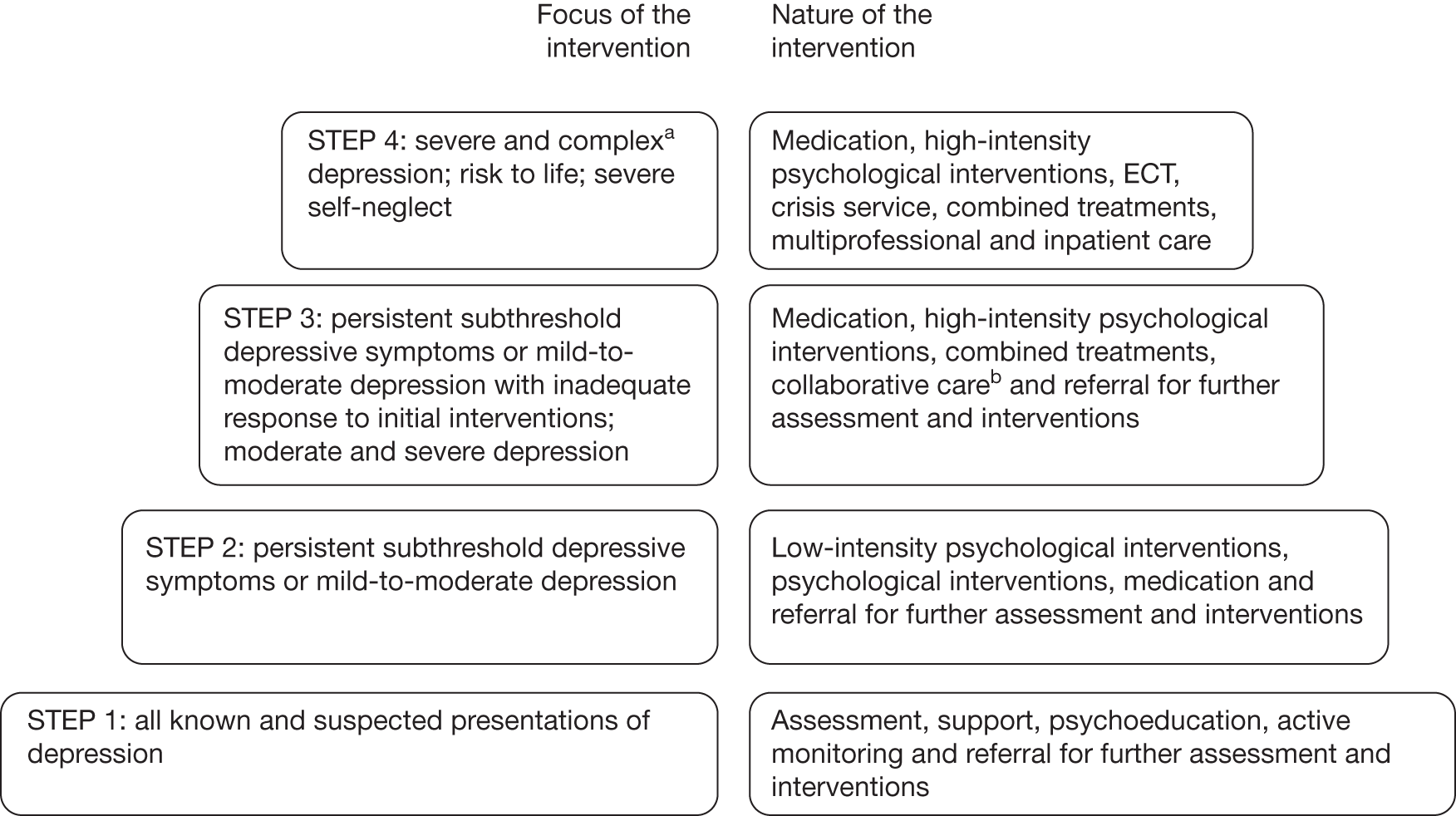

Many people are unwilling to seek help for depression and there is a failure to recognise depression, especially in primary care; of those patients diagnosed with depression, the majority will receive psychological, pharmacological or combined treatment in primary care. 8 Pharmacological treatments typically include antidepressant agents such as tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) or, more commonly, specific serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Other drugs used either alone or in combination with antidepressants include lithium salts and antipsychotics, although these are usually reserved for people with severe, psychotic or chronic depression, or as prophylactics. 8 Psychological treatments for depression reviewed in the most recent NICE depression guidelines include cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), behaviour therapy (BT), interpersonal therapy (IPT), problem-solving therapy (PST), counselling, short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy and couple-focused therapies. Owing to the different needs of individuals with depression, the NICE clinical guidelines advocate a ‘stepped-care’ treatment model (Figure 1), which aims to provide a framework to organise the provision of services supporting patients, carers and health-care professionals in identifying and accessing the most effective interventions. 8

FIGURE 1.

The stepped-care model. 8 a, Complex depression includes depression that shows an inadequate response to multiple treatments, is complicated by psychotic symptoms and/or is associated with significant psychiatric comorbidity or psychosocial factors. b, Only for depression in someone who also has a chronic physical health problem and associated functional impairment (see ‘Depression in adults with a chronic physical health problem: treatment and management’, NICE clinical guideline 918). ECT, electroconvulsive therapy.

Reproduced with permission from the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Depression. The NICE guideline on the treatment and management of depression in adults (updated edition). National clinical practice guideline 90. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2010.

Improving access to psychological therapies

The Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme was launched by the UK government in October 2007. The programme aimed to invest an additional £173M per annum from 2008 to 2011 in evidence-based psychological therapies for the treatment of depression or anxiety disorders recommended by NICE, and to promote a more person-centred approach to therapy. 18 Both ‘low-intensity’ (e.g. guided self-help, computerised CBT) and ‘high-intensity’ interventions (e.g. CBT, IPT, counselling) were considered within NICE’s proposed stepped-care model, within which low-intensity approaches would initially be considered for the treatment of mild-to-moderate depression. 8 Much of the IAPT investment is for the training of new psychological therapists to deliver such low-intensity interventions. 18 These ‘psychological well-being practitioners’ (PWPs; previously termed ‘low-intensity therapy workers’) typically provide high-volume, low-intensity cognitive behaviour-based interventions to patients with less severe depression and/or anxiety disorders.

A key argument initially put forward for increasing access to psychological services was the potential for a reduction in public costs (e.g. welfare benefits, medical costs) and increase in revenues (e.g. taxes from return to employment, increased productivity). 19,20 Although this argument was put forward on the basis of many people being unable to access appropriate mental health services, the notion of improving access to low-intensity interventions in order to prevent relapse of depression even among treated patients might also be considered an investment on similar grounds.

Low-intensity interventions for depression

In general, people with depression tend to prefer psychological and psychosocial interventions to pharmacological interventions. 21 However, high-intensity psychological and psychosocial therapies (e.g. CBT, problem-solving, counselling) that involve one-to-one therapy with a mental health professional over extended periods of time are resource intensive. Consequently, less intensive therapies and innovative delivery formats such as group-based work have been developed. Less resource-intensive therapies include a variety of psychological treatments in which there is no or only a low level of therapist involvement, including computer-delivered treatment and bibliotherapy among other intervention technologies. The 2010 NICE guideline8 on depression refers to such approaches as ‘low-intensity psychosocial interventions’ and provides clinical evidence on three main forms of low-intensity therapy:

-

Computerised cognitive behavioural therapy (CCBT) provides a structured programme of care based on the principles of standard therapist-delivered CBT, but is delivered via a CD-ROM/DVD or the internet. Where CCBT is delivered as a primary intervention with minimal therapist involvement, it is considered a low-intensity intervention.

-

Guided self-help involves the use of evidence-based self-help books or manuals aimed specifically at depression. Guided self-help is distinct from ‘pure’ self-help in that a health-care professional (or para-professional) facilitates the use of the material by introducing, monitoring and assessing the outcome of the intervention.

-

Physical activity programmes have been defined as any structured physical activity with a recommended frequency, intensity and duration when used for depression. This could be aerobic (e.g. running/jogging, dancing) or anaerobic (e.g. resistance training), and be supervised or unsupervised, and undertaken in a group or individually.

The NICE clinical practice guidelines recommend that CCBT, individual-guided self-help and structured group physical activity programmes be considered for people with persistent subthreshold depressive symptoms or mild-to-moderate depression. The recommended duration of CCBT and guided self-help is 9–12 weeks including follow-up. Group physical activity with practitioner support is recommended for three sessions per week over 10–14 weeks. 8

Although the NICE guidance covers low-intensity psychological interventions, it does not provide a clear definition of what constitutes ‘low-intensity’ treatment more broadly. However, recent good practice guidance produced by the IAPT programme states22 that ‘A low-intensity intervention … may use simple or “single strand” approaches that are less complex to undertake than formal psychotherapy; contact with people is generally briefer than in other forms of therapy and can be delivered by para-professionals or peer supporters using non-traditional methods such as telephone or the internet’. Low intensity, therefore, is defined on the basis of four characteristics: the complexity of the intervention, the duration of contact, the level of training and the mode of delivery. In IAPT, a particular emphasis is on interventions delivered by PWPs without formal health-care professional or CBT therapist qualifications. 23 Although the IAPT guidance states that there is no arbitrary session limit, evidence from the IAPT demonstration site showed that the mean number of low-intensity CBT-based interventions was around five per person, although there was considerable variability around this figure. 22

A similar definition of low intensity is offered by Bennett-Levy et al,24 who identified the ability of an intervention to offer high-volume access to treatment as the defining feature of a low-intensity intervention, which can be achieved through strategies such as reduced practitioner–patient contact and the use of practitioners who do not have formal professional or high-intensity therapy qualifications. They also pointed out that the definition of low intensity remains contested. For example, they chose to include mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) as a low-intensity treatment. This is a complex intervention that is typically delivered by a qualified mental health professional with specific expertise in its delivery but which limits patient contact time per therapist because it is delivered in a group format. They recognised that not everyone would agree with its inclusion.

Relapse and recurrence of depression

Given the high risk of repeated depressive episodes for some individuals with depression, it is important to aim not only to reduce depressive symptoms and restore functioning, but also to enable people to self-manage their problems and prevent relapse and recurrence of episodes of major depression.

Definitions

In an effort to standardise terms and facilitate communication, several conceptual definitions of improvement and subsequent return of depressive symptoms exist. 25–26 In terms of improvement, a distinction is made between response, remission and recovery. Response is defined as a clinically meaningful improvement in depressive symptoms that has continued for a sufficient length of time (3 consecutive weeks) to protect against misclassification owing to symptom variation or measurement error. 26 Response is typically operationalised as an improvement of ≥ 50% over pre-treatment scores. However, problems have been noted with this approach; for example, such a definition may be too stringent for patients with highly treatment-resistant depression. 26

Remission relies on a definition of an asymptomatic range, defined as the presence of no or very few symptoms. A person can be judged to be in the asymptomatic range only if neither of the two essential features of depression (sad mood and loss of interest or pleasure) is present and fewer than three of the additional core symptoms of depression are present. 26 Remission requires that the person remains in this range for at least 3 weeks, again to protect against factors such as natural symptom variation. After this point, remission status is still ascribed if the person’s symptoms fall above the asymptomatic range but fall short of meeting diagnostic criteria for a major depressive episode. Recovery is defined as an extended length of time in remission, which has been operationalised as at least 4 months. 26

The definitions of relapse and recurrence are linked to these definitions of improvement. Relapse occurs when a person in remission experiences a return to full symptoms of a major depressive episode. Relapse, therefore, occurs after achieving remission but before the recovery phase. Recurrence indicates the return to the full symptoms of depression after a person has achieved recovery status.

The definitions of relapse and recurrence are also linked to the differentiation of treatment phases. Acute-phase treatment is defined as treatment during an episode of depression, the aim of which is to achieve remission. Continuation-phase treatment occurs during the remission phase with the aim of continuing remission and ultimately achieving recovery. Maintenance treatment occurs during the recovery stage with the aim of maintaining this state.

Despite these definitions, there is still inconsistent use of the terminology within the literature, particularly in terms of the distinction made between relapse and recurrence. In the current project, ‘relapse and recurrence’ will be used as phrase throughout to refer to the return of full depressive symptoms. When the results of particular studies are described the terms used in that study are retained, even when their use is different to the definitions given above.

Interventions to reduce depressive relapse or recurrence

Pharmacological interventions

Although the preventative effects of antidepressant medication do not extend beyond the end of treatment,27 there is evidence that their continued use after an acute treatment phase can reduce the risk of relapse. A systematic review identified 31 randomised controlled trials (RCTs: total n = 44,210) that compared continued treatment with a range of antidepressants (predominantly TCAs and SSRIs) against placebo in people who had responded to treatment with antidepressants during an acute phase. 28 Continued treatment ranged from under 6 months to 36 months, with most studies having approximately 12 months of follow-up. Relapse rates were 41% in the placebo group and 19% for those continuing active medication [pooled odds ratio for relapse = 0.30, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.22 to 0.38]. The different classes of antidepressant performed comparably and there appeared to be no substantial differences in the proportional risk reduction according to length of initial treatment or continued treatment. The majority of the studies were conducted in secondary care settings, so caution is needed in generalising these results to primary care settings, in which the risk of relapse may be lower. 28

High-intensity psychological interventions

Unlike pharmacological interventions, psychological treatment during an acute phase does have relapse-preventative effects that continue beyond the end of treatment. A meta-analysis of the effect of CBT on reducing relapse and recurrence in depression identified seven trials that compared relapse rates after acute-phase treatment with CBT or antidepressant medication in which no continuation phase was offered for either treatment. CBT significantly reduced relapse compared with medication. 29 Over a mean of 68 weeks’ follow-up, relapse–recurrence rates were 39% for CBT and 61% for medication. 29

Meta-analyses of behavioural activation, an intervention that shares some similarities with CBT, suggest no significant differences between acute-phase behavioural activation and CBT in terms of depressive symptoms at follow-up. 30–32 For example, one meta-analysis found effect sizes that were small and non-significant at a range of follow-up time points (1–3, 4–6, 7–12 and 13–24 months),32 although for the longest phase of follow-up findings relied on a small number of studies. 33–34 Evidence for the effects of other psychological treatments relative to CBT is small, but there are indications of no significant differences between acute-phase CBT and other treatments, such as IPT, in terms of relapse rates. 35

Although there is evidence that psychological interventions have preventative effects that continue after the end of treatment, it is of note that subsequent rates of relapse remain high; for example, one review reports a 1-year relapse–recurrence rate of 29% and 2-year rate of 54% for those who had responded to acute-phase CBT. 29 Acute-phase psychological treatment, although it reduces relapse relative to acute-phase antidepressant medication, may also be insufficient for the reduction of relapse risk. In recognition of this, a number of continuation-phase psychological interventions have been developed.

Vittengl et al. 29 identified four trials that compared continuation- or maintenance-phase CBT with a non-active control treatment. In these studies, continuation treatment significantly reduced relapse–recurrence relative to control. Over a mean of 41 weeks of follow-up, relapse–recurrence rates were 12% in the CBT, whereas in the control arms the rates were 38%. Vittengl et al. 29 also compared the preventative effects of continuation-phase CBT with those of other active treatments. This comparison identified five studies. Although there were no significant differences, there was a trend towards significance favouring CBT (p < 0.06). Over a mean of 27 weeks, relapse–recurrence rates were 10% for CBT and 22% for the other active treatments. 29

A small number of studies have also compared continuation and maintenance IPT with non-active control subjects and active treatments. One study randomised currently remitted patients with recurrent depression to one of five arms: (1) IPT alone; (2) IPT and antidepressant medication (imipramine) at acute dosage; (3) IPT with a drug placebo; (4) antidepressant medication (imipramine) at acute dosage with medication clinical visits; and (5) drug placebo with medication clinical visits. Survival analysis suggested that the addition of IPT to antidepressant did not lower recurrence rates compared with antidepressant treatment alone. IPT without active medication had a prophylactic effect between antidepressant medication and placebo. 36 A study by the same research group in adults aged > 60 years found that the combination of maintenance antidepressant medication (nortriptyline) and IPT showed a trend towards significance relative to antidepressant treatment alone in reducing recurrence. 37

Low-intensity psychological interventions

Although the effectiveness of low-intensity interventions has been extensively evaluated to treat primary symptoms of psychological difficulties,38–40 there has been substantially less research examining the use of these interventions as a relapse prevention strategy.

As discussed earlier, the definition of a low-intensity psychological intervention is not agreed on, which can make it difficult to distinguish low-intensity interventions from high-intensity interventions. The Vittengl et al. 29 meta-analysis, for instance, combined studies that would clearly be classified as high intensity with those that under some definitions could be classified as low intensity, such as MBCT. 29 We were unable to identify any previous reviews that focused exclusively on low-intensity interventions, however defined. This is the aim of the current review.

Chapter 2 Definition of decision problem

Decision problem

The decision problem concerns the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of low-intensity psychological interventions to prevent relapse or recurrence in patients who have received and responded to treatment for depression.

As discussed above, the terms relapse and recurrence are not consistently used in the literature. Therefore, we have considered both relapse and recurrence; we will refer to relapse or recurrence in our discussions unless a clear distinction has been made between the terms, but when reporting the findings of identified studies we will use the terminology as defined by individual study authors.

There is a lack of a clear, generally agreed on definition of low-intensity psychological interventions. We chose to emphasise the characteristic of the practitioner delivering the treatment as the main defining feature because of the current policy and practice context in the UK. Low-intensity psychological interventions are predominantly used in IAPT services, and in these services they are delivered by PWPs, who do not have formal health-care professional or CBT therapist qualifications.

However, in recognition that the definition of low intensity remains unclear, we also considered a broader definition of brief interventions typically delivered by clinical psychologists, CBT therapists, and other qualified mental health professionals involving limited patient contact time (delivered in a group setting or involving brief individual encounters). An inclusion threshold of 6 hours of contact per patient was used to select these intervention studies. We did not distinguish between the types of group intervention, although there is a very wide range; some interventions, such as psychoeducational groups and large community-based interventions, are low intensity, whereas others are high intensity and require high-level group therapy skills. For group interventions, the total contact time of the mental health professional(s) was divided by the number of patients in the group to create an average duration per patient. Although of less direct relevance to the decision problem, these interventions may be of interest to decision-makers concerned with improving access to psychological therapies, and so the literature in this area is briefly described and classified in a scoping review. Thus, the review was conducted in two parts as described below.

Overall aims and objectives

The main aims of this project are to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of low-intensity psychological or psychosocial interventions to prevent relapse or recurrence in patients with depression.

As the broader definition of ‘low-intensity’ psychological intervention is somewhat contested, and the resources of the review were limited, the review was conducted in two parts:

-

A systematic review of all evaluations of ‘low-intensity’ interventions that were delivered by para-professionals, peer supporters or PWPs as defined by the IAPT programme. Such evaluations were not restricted by length of treatment or number of sessions.

-

A scoping review of all relevant evaluations of interventions involving qualified mental health professionals (e.g. psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, CBT therapists) involving < 6 hours of contact per patient.

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

The review of the evidence for clinical effectiveness was undertaken systematically following the general principles recommended in the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD)’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care41 and the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement. 42

Methods for reviewing clinical effectiveness

Search strategy

Literature searches were developed to systematically identify studies on the effectiveness of low-intensity psychological interventions to prevent relapse or recurrence after depression. The base search strategy was constructed using MEDLINE and then adapted for other resources searched. The search strategy included the following components:

-

depression terms, and

-

relapse terms, and

-

low-intensity psychological intervention-related terms.

The searches were restricted to studies published after 1950. No language restrictions or study design filters were applied.

Search terms were identified by scanning key papers identified at the beginning of the project, through discussion with the review team and clinical experts, and the use of database thesauri.

Sources of information were identified by an information specialist with input from the project team. The following databases were searched during September 2010:

-

MEDLINE (via OvidSP)

-

MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (via OvidSP)

-

PsycINFO (via OvidSP)

-

EMBASE (via OvidSP)

-

The Cochrane Library (via Wiley)

-

– CDSR (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews)

-

– DARE (Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects)

-

– CENTRAL (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials)

-

– HTA (Health Technology Assessment Database)

-

-

Science Citation Index (via ISI Web of Knowledge)

-

Social Science Citation Index (via ISI Web of Knowledge)

-

BIOSIS Previews (via ISI Web of Knowledge and Dialog).

In addition, a range of resources were searched or browsed to identify guidelines on the treatment of depression. The bibliographies of relevant reviews and guidelines and included studies were checked for further potentially relevant studies.

Records were managed within an EndNote library, version X3 (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA). After de-duplication, 9112 records in total were identified.

The full search strategies and results for each database can be found in Appendix 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Two reviewers independently examined titles and abstracts for relevance; all potentially relevant papers meeting the inclusion criteria were ordered. All full papers were then independently screened by two reviewers, with disagreements resolved by consensus.

Population

Studies of participants who have received treatment for depression were included. Studies establishing a diagnosis using a gold-standard structured interview for DSM or ICD criteria, such as the Structure Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID)43 were included, as were studies defining depression on the basis of a score above a cut-off point on a recognised psychometric measure or on the basis of unaided clinical diagnosis. The decision problem is concerned with the prevention of relapse or recurrence in patients who have received and responded to treatment. Consequently, studies of patients who were treated for an acute episode and then subsequently measured for relapse or recurrence were excluded; studies where patients had ‘recovered’ from their acute episode (responding to treatment or asymptomatic) and the aim was to prevent subsequent relapse or recurrence were included. Studies of participants with bipolar disorder were excluded, as were studies of children.

Interventions

For part A (systematic review of efficacy), all evaluations of ‘low-intensity’ interventions as defined by the IAPT programme22,23 were considered relevant. Specifically, this incorporated any unsupported psychological/psychosocial interventions or any supported interventions that did not involve highly qualified mental health professionals. ‘Highly qualified professionals’ includes clinicians, who, in most instances, will have a core professional qualification (e.g. psychiatrist, clinical psychologist, mental health nurse) and have received formal, specialist training in the delivery of complex psychological interventions (e.g. 16+ session CBT, psychodynamic psychotherapy, systematic therapy, etc.).

Any interventions involving support from para-professionals, peer supporters, PWPs, physical trainers, case managers (as in collaborative care models) or no personal support at all (e.g. entirely computerised interventions) were included. ‘Para-professionals’ includes people who do not have a core professional qualification and do not have specialist training in complex psychological interventions, although may have some training in less complex interventions. Inclusion was not restricted by length of treatment, number of sessions or mode of delivery.

For part B (scoping review), all relevant evaluations of interventions involving qualified mental health professionals (e.g. clinician, CBT therapist) were included if they involved < 6 hours of contact per patient. For group treatment, contact estimates per patient were calculated by dividing treatment duration by the mean number of patients per group (with adjustments as necessary if there is > 1 therapist). Where the amount of contact time was unclear, study authors were contacted to obtain additional details. If authors could not be contacted or did not respond, clinical experts (ML, DM) were consulted as to whether or not the intervention was likely to be brief (i.e. < 6 hours per patient).

High-intensity psychological interventions requiring ongoing interaction with a mental health professional (e.g. CBT, behavioural activation, problem-solving therapy and couples therapy) were excluded. Studies evaluating interventions for the acute phase of treatment of an acute episode of depression were also excluded.

Studies evaluating pharmacotherapy alone [including TCAs, SSRIs, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), anxiolytic medication, mood stabilisers and others] were excluded from the review of clinical effectiveness, as were studies of alternative and complementary treatment methods.

Comparators

Study inclusion was not restricted by type of comparator treatment and could include no treatment (including waiting list control), placebo, psychological or pharmacological interventions.

Outcomes

Studies reporting outcomes related to relapse or recurrence (e.g. relapse rate, time to relapse, and severity of relapse episode) after initial treatment success were included. Other relevant outcomes such as social function and quality-of-life (QoL) measures were recorded where reported.

Study designs

Randomised, quasi-randomised and non-randomised studies with concurrent control patients were considered for inclusion. Animal models, preclinical and biological studies, reviews, editorials and opinions were excluded.

Translations of non-English-language papers and additional details of studies published only as meeting abstracts were obtained where time and budget constraints allowed.

Data extraction strategy

Data were extracted independently by one reviewer using a standardised data extraction form and checked by another. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion, with involvement of a third reviewer when necessary. Authors were contacted for any missing data or for clarification where necessary. Data from multiple publications of the same study were extracted as a single study. Extraction included data on patient characteristics, interventions, comparators, study design and outcomes.

Critical appraisal strategy

The quality appraisal checklist for quantitative intervention studies described in NICE’s guide to methods for developing guidance in public health was obtained for assessing the internal and external validity of studies included in the systematic review of low-intensity interventions (part A). 44 For the scoping review of brief therapy interventions (part B), formal critical appraisal of the included studies was not planned or conducted, with the exception of one study,45 in which the necessity of health professionals to deliver the intervention was unclear (see Assessment of effectiveness, Part B: brief therapy interventions for the prevention of relapse of depression, below).

Methods of data synthesis

Given the limited number of included studies and their clinical and methodological heterogeneity, a meta-analysis was not appropriate. Therefore, extracted data have been tabulated and discussed in a narrative synthesis.

Results of review of clinical effectiveness

Quantity and quality of research available

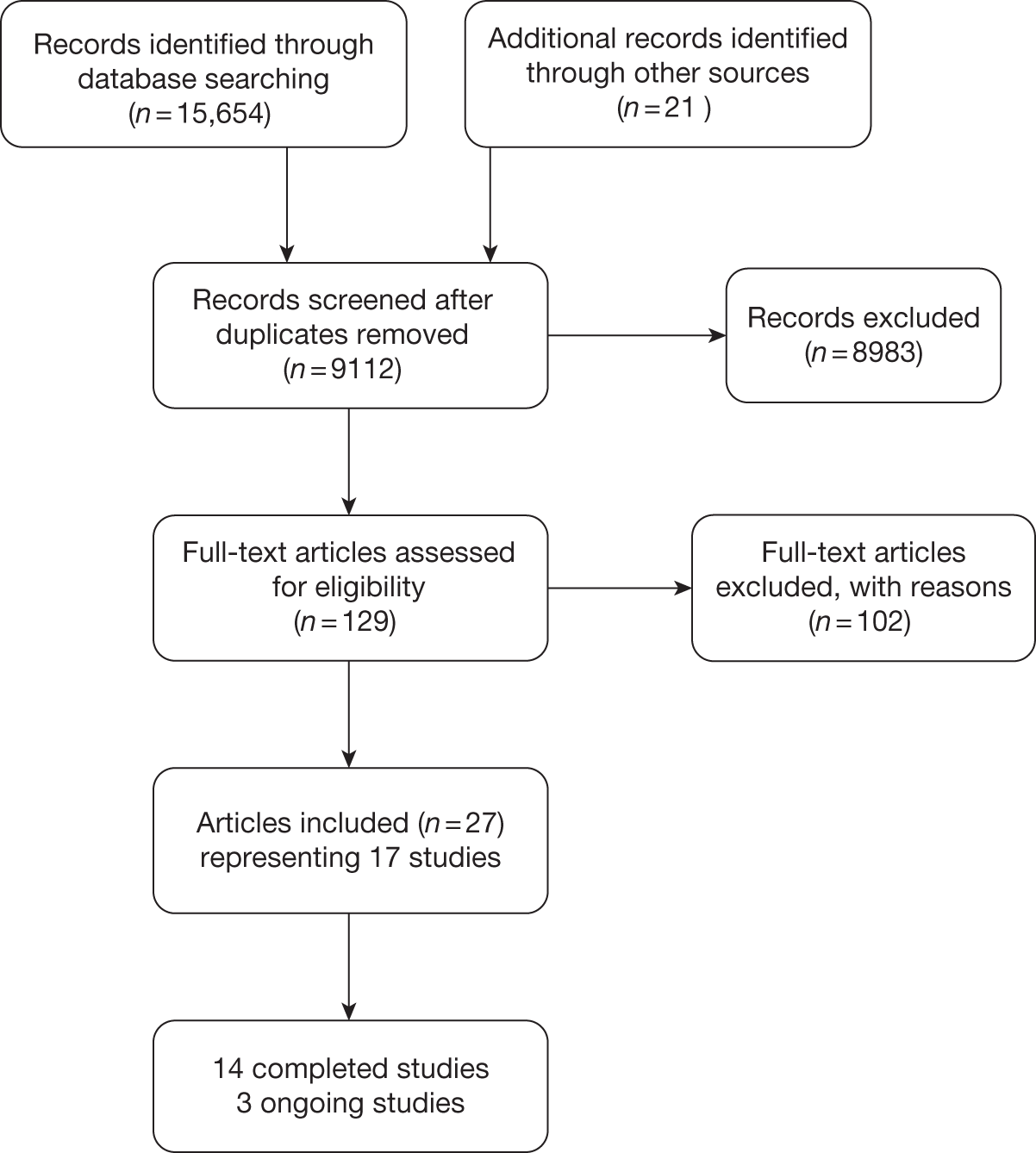

A total of 9112 unique records were identified from the searches and 129 articles were ordered for assessment. Figure 2 shows the flow of records through the review process, and the numbers included and excluded at each stage. Details of studies excluded at the full publication stage are presented in Appendix 2 (excluded studies).

FIGURE 2.

Study selection process for clinical effectiveness.

Part A: low-intensity interventions for the prevention of relapse of depression

No studies met the main part A inclusion criteria for ‘low-intensity’ interventions that were delivered by para-professionals, peer supporters or PWPs as defined by the IAPT programme, without any restriction on length of treatment.

Part B: brief therapy interventions for the prevention of relapse of depression

Seventeen studies, reported in 27 publications, met the part B inclusion criteria for brief therapy interventions delivered by mental health professionals involving < 6 hours of contact per patient. 45–71 Fourteen of the studies were completed and published;45–68 three are ongoing. 69–71

Table 1 provides details of the related publications for each of the included studies. In the following sections, reference will be made to the primary study only; the other linked publications provided additional information or results that are included in the data extraction tables (see Appendix 3).

| Primary publication | Linked publications |

|---|---|

| Completed studies | |

| Bockting 200546 | Bockting 2004,47 2006,48 2008,49 200950 |

| Bondolfi 201051 | None |

| Fava 199852 | Fava 200452 |

| Godfrin 201054 | None |

| Hepburn 200955 | None |

| Howell 200856 | None |

| Katon 200145 | Lin 2003,57 Ludman 2003,59 Ludman 2000,58 Simon 200260 |

| Kuhner 199661 | Kuhner 199462 |

| Kuyken 200863 | None |

| Ma 200464 | None |

| Rohde 200865 | None |

| Takanashi 200266 | None |

| Teasdale 200067 | None |

| Wilkinson 200968 | None |

| Ongoing studies | |

| Kuyken 201069 | None |

| Watkins 201070 | None |

| Williams 201071 | None |

Completed studies

Of the 14 completed studies,45–68 12 were parallel-group RCTs;45,46,51,52,54–56,63–65,67,68 the remaining two studies61,66 were non-randomised with concurrent control patients. Eight of the RCTs recruited participants from multiple centres,45,46,51,56,63,65,68,72 one of which used cluster randomisation. 56

Assessment of effectiveness

Part A: low-intensity interventions for the prevention of relapse of depression

No studies evaluating ‘low-intensity’ interventions that could be delivered by para-professionals, peer supporters, or PWPs as defined by the IAPT programme were identified.

Part B: brief therapy interventions for the prevention of relapse of depression

The following section provides a classification and description of studies identified which were identified as meeting the ‘part B’ inclusion criteria (i.e. they evaluated brief therapy interventions in which participants had up to 6 hours’ contact with mental health professionals, such as clinicians or CBT therapists). As these studies fall outside the primary focus of this review, they are briefly described in an overview below, with key study characteristics presented in Appendix 3. In one study (Katon et al. 45), the intervention could potentially be delivered by PWPs or equivalent practitioners, although in the retrieved evaluations it was delivered by mental health professionals. Given the potential relevance of this study to our part A question, it is discussed in greater detail below, and has been assessed for internal and external validity (see Appendix 4).

Completed studies

Ten of the completed studies evaluated interventions delivered in a group setting. 46,51,54,55,61,63,64,66–68 Of these, six specifically evaluated some form of MBCT. 51,54,55,63,64,67 Three MBCT studies were based on an identical protocol that involved eight weekly sessions of 2 hours’ duration, in which up to 12 participants met with experienced cognitive therapists to receive a programme based on the principles of CBT and mindfulness-based stress reduction. 51,64,67 Participants in this programme attended two further meetings during the subsequent 52 weeks of follow-up. Other MBCT programmes were of a similar duration (typically 2 hours to 2 hours and 45 minutes, weekly for 8 weeks), although with larger groups of up to 15 or 17 participants. 54,55,63 Three studies46,66,68 evaluated brief group CBT of a similar intensity to the MBCT interventions, but without any explicit mindfulness content. The one remaining group-based intervention was a brief 12-week ‘Coping with Depression’ (CWD) course, which was based on a multimodal psychoeducational approach, delivered by clinical psychologists and psychiatrists. 61

Four studies evaluated brief therapy interventions delivered by mental health professionals to participants on an individual basis. 45,52,56,65 One such intervention51 provided individuals with a brief CBT-based intervention (30 minutes every other week for 20 weeks) alongside ongoing pharmacotherapy. A second intervention56 incorporated a multimodal skills-based approach, providing support materials and general practitioner (GP) training to allow tailoring of evidence-based psychosocial strategies to individual patients in Australian primary care (‘Keeping The Blues Away’); this is a small pilot study for which it may be that the intervention could potentially be delivered by PWPs or equivalent but it is unclear from the detail provided what level of training is required. One study65 evaluated the effects of ‘continuation CBT’ (around 6 hours per patient) following initial CBT treatment in adolescents with depression. Another study45 evaluated a ‘multifaceted relapse prevention programme’ for patients who were at high risk of relapse, which is described in more detail below.

Eight of the 14 studies formally established the occurrence of relapse or recurrence using gold standard criteria, specifically Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Third Edition-Revised (DSM-III-R) or DSM-IV criteria. 45,46,51,54,61,63,64,67 Of these, seven explicitly stated that they established this outcome using SCID. 45,46,51,54,63,64,67 Elsewhere, relapse was established using other criteria [Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC)]52 or a variety of self-report and clinician-administered symptom scales [Beck Depression Inventory (BDI),55,66 Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS),68 Clinical Global Impression Improvement scale (CGI-I),65 Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS)56].

The results of this diverse group of interventions in terms of preventing relapse or recurrence of depression are mixed. Even among MBCT studies following the same protocol, findings were inconsistent: two studies64,67 reported a statistically significant benefit for MBCT over treatment as usual (TAU) in patients with three or more previous episodes of depression at 14 months, but a third trial restricting inclusion to this subgroup of patients reported no overall difference in relapse between treatment groups over the same period. 51 Other studies reported results that clearly favoured MBCT over TAU54 were of borderline significance63 or showed no difference between groups. 55 One study68 suggested no significant benefit of brief CBT over TAU for preventing relapse, whereas another suggested any such benefit was restricted to participants with at least five previous depressive episodes. 46 One observational study did not report relapse rates and found no significant difference in scores 1 year after the intervention. 66 One study reported a statistically significant benefit of a multimodal psychoeducational approach over no intervention in terms of relapse prevention over 6 months, although this small observational study had several methodological limitations. 61

The study evaluating a brief CBT-based intervention (alongside ongoing pharmacotherapy51) reported a statistically significant impact on relapse after 2 years, an effect that remained at 6 years’ follow-up. Relapse rates were similar for the ‘Keeping The Blues Away’ programme and usual care in Australian primary care. 56 The study of ‘continuation CBT’ in adolescents reported significant benefits of the intervention alone over both antidepressant medication treatment and combined continuation CBT/medication. 65

Katon et al.

Five articles reported the findings of just one study (Katon et al. ). 45,57–60 Although the practitioners in this study were predominantly mental health professionals, and therefore did not strictly meet our part A inclusion criteria, it was unclear whether or not delivery by a mental health professional was mandatory for the implementation of the intervention. Therefore, this study was critically appraised and is summarised in further detail below.

This study was a RCT that evaluated the effectiveness of a ‘multifaceted relapse prevention programme’ in a US primary care setting (see Appendix 3). 45 This programme was provided to adult patients who had recovered from depression but who were at high risk of relapse and were encouraged to continue with antidepressant medication. The relapse prevention programme included aspects of patient education/self-help (patients were provided with a book and videotape developed by the trial investigators) alongside ongoing support from ‘depression specialists’. Each participant was scheduled two face-to-face sessions with a depression specialist (an initial 90-minute session and a 60-minute follow-up session), which were followed by three ‘telephone visits’ scheduled at 1, 4 and 8.5 months after the second face-to-face session. In addition, participants received ‘personalised mailings’ (at 2, 6, 10 and 12 months), containing a graph of participant BDI score over time and checklists on symptoms and medication adherence. The depression specialist alerted the primary care physician if the participant appeared to be symptomatic or had discontinued medication, based on data from participant feedback or from a monthly review of automated pharmacy data on antidepressant refills. Each depression specialist met with a supervising psychiatrist for 15–30 minutes each week to review cases and adjust treatment recommendations.

The focus of the relapse prevention intervention appeared to be largely on maintaining adherence to antidepressant medication. Meetings between patients and intervention ‘depression specialists’ integrated cognitive–behavioural and motivational interviewing approaches and provided information on the prevalence, course and efficacious treatment of depression. The depression specialist explained why each patient was at high risk of relapse, while acknowledging the individual’s attitudes, beliefs and treatment choices. Depression specialists and patients discussed evidence illustrating the efficacy of pharmacotherapy for preventing relapse and recurrence, the perceived risks and benefits of long-term pharmacotherapy, approaches to manage specific medication side-effects and concerns of the patient. In addition, the depression specialist attempted to improve self-efficacy for preventing relapse and recurrence of depression through self-management behaviours such as monitoring depressive symptoms and scheduling pleasant activities.

In this trial, three different depression specialists were provided for 194 patients receiving the relapse prevention intervention programme. One depression specialist was a psychologist, one was a nurse practitioner with a master’s degree in psychosocial nursing and the third was a social worker. Each of these had received a 60-page training manual and attended two half-day training sessions with a psychiatrist, a psychologist and a primary care physician before the start of the trial.

A total of 191 participants in the comparison group received ‘usual care’, which typically consisted of prescription for antidepressant medication (as in the intervention group), plus between two and four visits with a family physician over the first 6 months of treatment, with the option to refer to health maintenance organisation (HMO)-provided mental health services.

Relapse/recurrence was defined as either a current episode of depression according to the SCID (at 3, 6, 9 or 12 months) or incidence of an episode within each 3-month period according to the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation. 73 Other outcomes included depressive symptoms [measured by the 20-item Hopkins Symptom Checklist (SCL-20)], medication adherence, and number of primary care visits for reasons other than depression.

The authors reported significantly greater adherence to antidepressant medication in the relapse prevention intervention group than the usual-care group (adjusted odds ratio 1.91, 95% CI 1.37 to 2.65; p < 0.001). Depressive symptoms (as measured by the SCL-20) improved in both groups over time, with a small but significant greater reduction for the intervention group (p = 0.04). However, the rates of relapse/recurrence for the intervention and usual-care groups (35% vs 34.6%) are almost identical, suggesting that the intervention did not prevent relapse relative to usual care over 12 months’ follow-up. The authors suggested that a more intensive programme might be needed to reduce relapse rates.

The internal and external validity of this study were assessed using the quality appraisal checklist for quantitative intervention studies described in NICE’s guide to methods for developing guidance in public health (see Appendix 4). 44 This appeared to be a reasonably well-conducted RCT, although with some important limitations. Given the nature of the interventions, blinding of participants and clinicians was not possible, although the authors did not state whether or not the outcome assessors were blinded to allocation (which may have led to bias). Other concerns raised by the assessment were the lack of a power calculation and the methods use to adjust findings to account for missing data. However, given other strengths of the study, the reported lack of benefit for the relapse-prevention programme is unlikely to be due to a type II error (i.e. a ‘false-negative’ finding), but is likely to be a reasonably valid finding for the studied population. However, as with any such study comparing an intervention against ‘usual care’, it is difficult to separate benefits of the treatment programme per se from benefits of the attendant increase in support, engagement and monitoring that the intervention involves. In terms of external validity, the study population was drawn from four primary care clinics of one HMO in western Washington, USA. Participants were predominantly female, white, college educated and in paid employment. The findings of this study may not therefore be directly generalisable to more socially or ethnically diverse populations or to a UK primary care setting.

Ongoing studies

Three of the identified studies are ongoing RCTs. 69–71 Two of these studies are evaluating MBCT approaches,69,71 one alongside cognitive psychoeducation without any mindfulness content. 71 The third trial is evaluating the impact of cognitive training self-help in addition to TAU. 70 The available details of these studies are presented in Appendix 3.

Chapter 4 Assessment of cost-effectiveness evidence

Methods for reviewing cost-effectiveness

The purpose of this review was to examine the existing cost-effectiveness literature on low-intensity psychological interventions for the secondary prevention of relapse after depression in detail, with the aim of identifying important structural assumptions, highlighting key areas of uncertainty and outlining the potential issues of generalising the results of the existing body of work. This review was used to identify the central issues associated with adapting existing work to address the specific research question posed and, if the evidence allowed, to assist in the development of a de novo economic model drawing on the issues identified in the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness review.

Search strategy

The literature search strategy for the identification of cost-effectiveness studies was developed from the base search strategy usedfor the clinical effectiveness searches (see Chapter 3, Search strategy). Economic terms were added to the strategy to limit retrieval to economic studies. The additional economic terms were from the search strategy used for identifying studies for the NHS Economic Evaluations Database (NHS EED).

The following databases were searched in October 2011:

-

MEDLINE (via OvidSP)

-

EMBASE (via OvidSP)

-

EconLit (via OvidSP)

-

The Cochrane Library (via Wiley)

-

– CENTRAL (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials)

-

– NHS EED

-

-

IDEAS [via Research Papers in Economics (RePEc)].

After de-duplication in EndNote X3, 466 records were identified. The full search strategies and results for each database can be found in Appendix 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Two reviewers independently examined titles and abstracts for relevance; all potentially relevant papers meeting the inclusion criteria were ordered. All full papers were then independently screened by two reviewers, with disagreements resolved by consensus.

In addition to the criteria used to screen for the clinical papers (see Chapter 3, Data extraction strategy) a set of cost-effectiveness criteria were also applied to screen for the papers on cost-effectiveness. Only full economic evaluations that compared two or more treatment options and considered both costs and consequences (including cost-effectiveness, cost–utility and cost–benefit analyses) were included in the review of economic literature. Economic evaluations conducted alongside trials, modelling studies and analyses of administrative databases were all considered for inclusion. As with the clinical review, the review of cost-effectiveness evidence was also conducted in two parts: A and B (see Chapter 2, Overall aims and objectives).

Critical appraisal strategy

The quality of the cost-effectiveness studies was assessed according to a checklist updated from that developed by Drummond and Jefferson. 74 This information is summarised within the text of the report, alongside a detailed critique of included studies and the relevance to the NHS.

Methods of data synthesis

Drawing on the findings from the systematic reviews of both clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, the intention was to develop a de novo economic model to assess the cost-effectiveness of low-intensity interventions to prevent relapse in patients with depression, and to further use this economic model to estimate the expected value of perfect information (EVPI) in order to help determine future research priorities in this area. However, given the lack of any studies meeting the main part A inclusion criteria in either the clinical effectiveness or cost-effectiveness review, the development of a de novo model was not considered feasible. Instead, through our review of the existing literature we have highlighted key issues that we think should be addressed as part of any future modelling work in this area.

Results of review of cost-effectiveness

Quantity and quality of research available

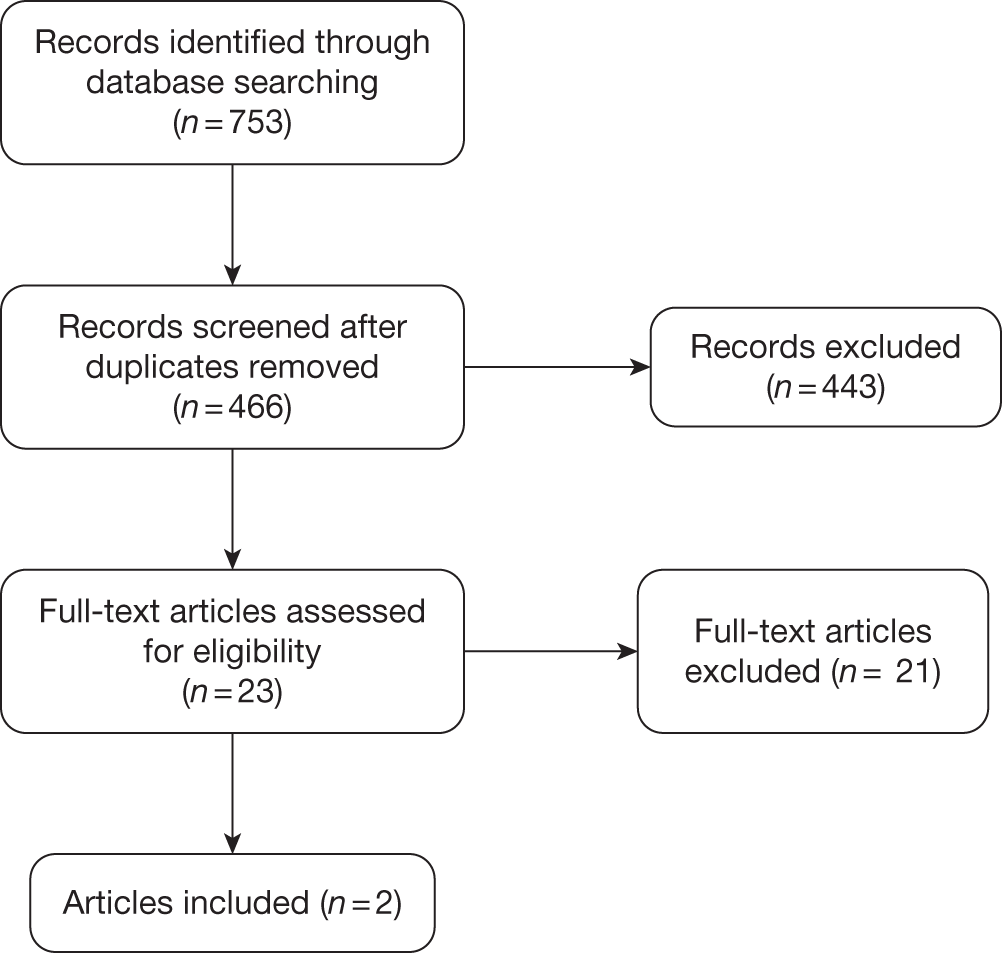

A total of 466 unique records were identified from the searches and 23 articles were ordered for assessment. Figure 3 shows the flow of records through the review process and the numbers included and excluded at each stage.

FIGURE 3.

Study selection process for cost-effectiveness.

Part A: low-intensity interventions for the prevention of relapse of depression

No papers met the main part A inclusion criteria for ‘low-intensity’ interventions that were delivered by para-professionals, peer supporters or PWPs as defined by the IAPT programme, without any restriction on length of treatment.

Part B: brief therapy interventions for the prevention of relapse of depression

Two papers met the part B inclusion criteria for brief therapy interventions delivered by mental health professionals involving < 6 hours of contact per patient. One of these papers, by Simon et al. ,75 is the economic evaluation based on the Katon et al. 45 study discussed in detail in Chapter 3 (see Assessment of effectiveness). The other paper, by Kuyken et al. ,63 is a cost-effectiveness analysis of a trial of MBCT in a UK primary care setting.

Assessment of cost-effectiveness

The following sections provide a detailed critique of the cost-effectiveness evidence from the included studies and an assessment of the quality and relevance of the data from the perspective of the NHS. A quality assessment checklist is provided in Appendix 5.

Part A: low-intensity interventions for the prevention of relapse of depression

No studies evaluating ‘low-intensity’ interventions that could be delivered by para-professionals, peer supporters or PWPs, as defined by the IAPT programme, were identified.

Part B: brief therapy interventions for the prevention of relapse of depression

Two papers were identified as potentially meeting the ‘part B’ inclusion criteria (i.e. they evaluated brief therapy interventions in which participants had up to 6 hours of contact with mental health professionals, such as clinicians or CBT therapists). These two papers are critically appraised and are summarised in further detail below.

Review of Simon et al.

This study is an economic evaluation based on the Katon et al. 45 study discussed in the clinical review (see Chapter 3, Assessment of effectiveness, above, and Appendix 3). The study is a trial-based evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of a multifaceted low-intensity relapse prevention programme (patient education, two visits with a depression specialist, telephone monitoring and follow-up) in addition to usual care (antidepressant medication and visits to a physician) compared with usual care alone for the prevention of relapse in patients with either long-term depression or a history of recent depression. The economic evaluation had a 12-month time horizon and was conducted from a strict health insurer perspective. Costs were expressed in 1997–8 US dollars (USDs). No discounting was applied to either costs or effects, given the short time horizon used. The primary outcome measure was the incremental cost per depression-free day, with a secondary outcome of the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY).

Effectiveness was measured by means of a SCL-20 score assessed at baseline, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months. Days with SCL depression scores of ≤ 0.5 were considered depression free. Days with SCL depression scores of ≥ 2.0 were considered fully symptomatic. Days with intermediate severity scores were assigned a value between depression free and fully symptomatic by linear interpolation, between the two cut-off points (0.5 and 2.0 on the SCL-20). Depression severity data from the consecutive outcome assessments were used to estimate depression severity for each day during the intervals between assessments, again using linear interpolation. Using this approach, the number of depression-free days was calculated as the sum of the depression-free proportion of each day in the study period. This was achieved by computing the area under the interpolated line joining the five measured points. The mean number of depression-free days during the 12-month period was 253.2 (95% CI 241.7 to 264.7 depression-free days) in the relapse prevention group and 239.4 (95% CI 227.3 to 251.4 depression-free days) in the usual-care group. After adjusting for patient age, sex, baseline SCL depression score and chronic disease score, the incremental number of depression-free days in the relapse prevention group was calculated as 13.9 (95% CI –1.5 to 29.3 depression-free days); this difference was not statistically significant at the 5% significance level. CIs for depression-free days were estimated by bootstrap resampling with 1000 draws using bias correction. The difference in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) between fully symptomatic depression and fully recovered was reported as being between 0.2 [derived from intermediate health status measures, such as the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D76)] and 0.4 (derived from direct assessment methods, such as the standard gamble or time trade-off techniques77). These values were used in conjunction with the incremental cost per depression-free day to calculate incremental costs per QALY.

The resource use and costs evaluated included the direct costs of the intervention itself, as well as other health service utilisation directly related to depression treatment over the 12-month period. Health plan computerised data were used to identify all of the health services provided or paid for by the HMO during the 12 months after randomisation. These costs were split across the 15 different components captured by the HMO’s accounting system. The costs of intervention visits were estimated based on costs of similar services provided by the HMO. Costs of other intervention services were estimated using actual input costs. Estimated direct costs of the intervention programme were $256 (95% CI $249 to $264). The costs of antidepressant prescriptions were approximately $100 higher for the participants in the relapse prevention programme than for those receiving usual care, but these were offset by the costs of the other speciality mental health care, which were approximately $100 lower for those on the relapse prevention programme. Adjusted mean total costs were estimated to be $273 (95% CI $102 to $418) higher in the relapse prevention programme than the usual-care arm (details of the adjustments made were not provided). CIs around these cost values were estimated by bootstrap resampling with 1000 draws using bias correction.

The cost per additional depression-free day was reported as $24 (95% CI –$59 to $496). This was used to estimate the cost per QALY gained as $21,650 per QALY using an increment of 0.4 as the difference in HRQoL of depression-free year over a fully symptomatic year and as $43,800 per QALY using a QALY increment of 0.2. No attempt at characterising the uncertainty around these estimates of incremental costs per QALY was reported. The cost-effectiveness analysis was based on a 12-month time horizon over which the intervention appeared to be marginally more costly and marginally (although not statistically significantly at the 5% significance level) more effective than usual care.

The quality assessment highlighted several important issues that potentially limit the generalisability of the findings from this study to UK clinical practice. Key issues influencing the internal and external validity of these findings are discussed below, together with a more general discussion of the potential difficulties of generalising from the results of this study to inform UK practice.

The cost-effectiveness analysis did not directly address relapse prevention as suggested by the title; rather it assessed differences in levels of depressive symptoms between the two treatment options. Linear interpolation was used extensively in the calculation of the intermediate outcome measure, number of depression-free days, with the result being based on the five assessments. The point assessments themselves were calculated by interpolating SCL scores; this assumed a linear relationship between SCL scores and the proportion of the day that can be classed as depression free. Limited sensitivity analysis was reported to have been conducted on the conversion rates between SCL scores and depression-free days, but the results of this analysis were not reported. The analysis used complete case analysis rather than intention to treat (ITT) and missing data were not balanced across trial arms. The results indicated that the dropout rate was lower in the intervention arm than in the control arm, suggesting possible bias. Uncertainty around the cost per depression-free day was reported as a CI. This is potentially misleading and ambiguous, especially as in this case negative values were reported, which can reflect a treatment either being dominated (it is more costly and less effective than its comparator) or dominating (it is less costly and more effective than its comparator). 77 No substantial attempt was made in the study to quantify the HRQoL differences between the treatments. Furthermore, no formal method was used to derive the QALY calculations or assess the uncertainty around them.

The cost-effectiveness analysis was conducted in the USA and costs were measured from a strict health insurer perspective, omitting any out-of-service costs not covered by the patient’s health plan. Unit costs and resource-usage levels were reported for only a subset of the total costs. We updated these estimates to current UK values by converting the 1997–8 USD results to UK prices using purchasing power parity (PPP) exchange rates for that year and then inflating the costs to 2009–10 UK prices using health-care-specific inflation indices. 78–79 This gives a cost per depression-free day of £24 (95% CI –£59 to £493) and cost per QALY estimates of £21,511 and £43,519 based on the two HRQoL impacts of depression from the paper (0.4 and 0.2, respectively). However, there are significant differences in the way the US and UK health-care systems are structured, resulting in different models of care, as well as widely differing health-care costs. 80 In addition, the dated nature of the cost data and the various limitations noted previously makes generalising the results to the UK difficult.

The cost-effectiveness analysis had a short-term time horizon looking at cost-effectiveness over a 12-month period in a group of patients with a high risk of relapse. The main outcome measure was the number of depression-free days, a measure not directly related to relapse. The effectiveness results were highly uncertain, and it was not clear from the results that the intervention was either clinically effective or cost-effective compared with usual care. The evaluation did not attempt to measure the HRQoL scores of the different depression states observed; instead it informally assigns a QALY value to the value of depression-free days. Uncertainty around the cost-effectiveness estimates was not adequately addressed and where sensitivity analyses had been conducted the results of these were not presented. The evaluation was conducted from a health insurer’s perspective in a US primary care setting and did not detail the breakdown of the costs incurred. The combination of the issues identified made it difficult to generalise these results to a NHS setting.

Review of Kuyken et al.

This trial based cost-effectiveness analysis compared MBCT with maintenance antidepressant medication (m-ADM) in depressive relapse prevention for patients with recurrent depression. The evaluation took a societal perspective and had a 15-month time horizon. No discounting was applied to either costs or effects. The primary outcome of the cost-effectiveness analysis was the incremental cost per relapse prevented with a secondary outcome of the incremental cost per depression-free day. The analysis was based on a RCT conducted within a primary care setting in England. Patients were followed up at 3-month intervals over the 15-month time horizon of the evaluation. Patients in the MBCT arm of the trial took part in 8-weekly (2-hour) MBCT group sessions and were supported in tapering and discontinuing their antidepressant medication (ADM).

Clinical effectiveness was measured in terms of time to relapse/recurrence using the depression module of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV to assess retrospectively the 3-month period between assessments. Relapse/recurrence was defined as an episode meeting the DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder. Cox regression was used to compare the relative reduction in hazard of relapse/recurrence of MBCT compared with m-ADM. The results indicated that there was borderline evidence of MBCT having a greater hazard reduction effect: ITT analysis gave a hazard ratio of 0.63 (95% CI 0.39 to 1.04).

A societal perspective was taken in measuring costs and resource usage. All hospital (inpatient, outpatient, emergency department), community health, social services and productivity losses resulting from time off work owing to illness were accounted for. Economic data were collected at baseline and then in 3-month intervals up to 15-months post randomisation using the Adult Service Use Schedule (AD-SUS), an instrument also used in other studies of adult mental health populations. All unit costs were for the financial year 2005–6 and no discounting was applied. National UK unit costs were applied where appropriate and productivity losses were calculated using the human capital approach. 80 Costs were converted to 2006 international dollars (Int$) using World Bank PPP indices. The mean per-person cost for MBCT over the 15 months was higher than that for m-ADM by Int$427 (95% CI –Int$853 to Int$1705), but this difference in costs was not statistically significant.

Cost-effectiveness estimates of Int$962 per relapse/recurrence prevented and Int$50 per depression-free day were reported. Uncertainty around the cost-effectiveness of the intervention, based on willingness to pay per relapse prevented, was characterised in the form of a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC).

The quality assessment highlighted important issues that potentially limit the generalisability of the findings from this study to UK clinical practice. Key issues influencing the internal and external validity of these findings are discussed below, together with a more general discussion of the potential difficulties of generalising from the results of this study to inform UK practice.

The cost-effectiveness analysis did not detail the data and methods used to calculate the estimates of the two cost-effectiveness outcome measures reported. Details of the data and methods used to characterise the uncertainty around these estimates were also omitted. Given the lack of detail it was difficult to assess how appropriate these cost-effectiveness estimates were.

The cost-effectiveness analysis did not attempt to measure utility. Cost-effectiveness estimates were instead reported using the measures of incremental cost per relapse prevented, and incremental cost per depression-free day. The use of disease-specific measures for cost-effectiveness made it difficult to generalise the results and compare them with other health-care interventions. We updated these estimates to current UK values by converting the 2005–6 USD results to UK prices using PPP exchange rates for that year and then inflating the costs to 2009–10 UK prices using health-care-specific inflation indices. 78–79 This gives a cost of £680 per relapse/recurrence prevented and £35 per depression-free day. The societal perspective taken for the analysis is also not in keeping with standard UK practice, which recommends limiting the perspective to the NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) only. 81

It is unclear whether or not MBCT was more cost-effective than m-ADM in terms of preventing depression relapse. Similarly, all the results presented were highly uncertain. Methods and data used in conducting the analysis were not reported, making it difficult to judge the appropriateness of the results. The evaluation was conducted in the UK and measures all of the relevant costs from a societal perspective; however, its use of disease-specific measures in reporting cost-effectiveness made it difficult to generalise the results.

Chapter 5 Discussion

Statement of principal findings

Clinical effectiveness

Although there is a substantial volume of literature on the effectiveness of low-intensity,38,82,83 high-intensity84–86 and mixed-intensity31,87,88 psychological treatments for the initial treatment of depression, this review has shown that there is currently very little intervention research specifically focused on the effectiveness of low-intensity interventions for relapse prevention.

No studies met the main review inclusion criteria (part A); a total of 17 completed and ongoing studies evaluating brief (≤ 6 hours of contact per patient) high-intensity therapy interventions (e.g. therapist-delivered continuation CBT, group MBCT) were identified and described (part B). These studies were clinically and methodologically diverse, and reported differing degrees of efficacy for the evaluated interventions. Of these, one study45 was felt to be of particular potential relevance to the main focus of the project, if the intervention could be delivered by PWP or equivalent practitioners. This was a RCT that evaluated a collaborative care-type programme which was specifically aimed at prevention of depressive relapse in high-risk patients in a US primary care setting. This study, which involved providing patients with face-to-face, telephone and postal contact with trained ‘depression specialists’, reported no difference between patients receiving the intervention and those receiving usual care in terms of relapse of depression over 12 months.

Cost-effectiveness

In the review of cost-effectiveness evidence, no studies met the main review inclusion criteria (part A); two studies that met the criteria for brief interventions (part B) were identified. 63,75 One of these was an economic evaluation of the same study identified as being potentially relevant to the main focus of the project in the clinical effectiveness review. This study demonstrated that the low-intensity intervention evaluated (providing patients with face-to-face, telephone and postal contact with trained ‘depression specialists’ in addition to usual care) may be a cost-effective use of NHS resources when compared with usual care. 75 However, the reported incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) when converted into sterling and inflated to 2010 prices of £21,511 per QALY to £43,519 per QALY ranged from borderline cost-effective to not cost-effective under accepted thresholds for cost-effectiveness. 81 It was also unclear how valid these estimates were for the NHS. The other study (regarding the use of MBCT to prevent relapse) was inconclusive; furthermore, its use of disease-specific measures in reporting cost-effectiveness made it difficult to generalise the results. 63

Strengths and limitations

Clinical effectiveness

This is currently the only systematic review of the literature on the effectiveness of low-intensity interventions for the prevention of relapse or recurrence of depression. This review involved a comprehensive search for relevant evidence; over 9000 records identified from searches of electronic databases, online resources, clinical guidelines and other sources were independently screened by two or more reviewers, with primary study authors contacted where necessary.

The effectiveness of high-intensity interventions for the prevention of relapse or recurrence in depression have been reviewed elsewhere. 29,89 However, given the dearth of evidence on the effectiveness of low-intensity interventions, this review also incorporated a scoping exercise covering evaluations of brief high-intensity therapies for the prevention of relapse or recurrence typically delivered by clinical psychologists, CBT therapists, and other qualified mental health professionals. Inclusion was restricted to interventions involving limited patient contact time (delivered in a group setting or involving very brief individual encounters), as these approaches may be of interest to decision-makers who are concerned with improving access to psychological therapies and/or maximising available resources. Although any definition of ‘brief’ is likely to be somewhat arbitrary, an inclusion threshold of 6 hours of contact per patient was used to select these brief high-intensity intervention studies. The majority of studies excluded on this basis evaluated clearly resource-intensive interventions, although occasionally studies with similar treatment protocols to those included in the scoping review had to be excluded on the basis of having only slightly more than 6 hours of contact per patient (e.g. Fava et al. 90,91). A full list of excluded studies with reasons for exclusion is available in Appendix 2.

Cost-effectiveness