Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 09/27/06. The contractual start date was in May 2010. The draft report began editorial review in June 2011 and was accepted for publication in November 2011. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2012. This work was produced by Thangaratinam et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2012 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Aim

The aim of this health technology assessment (HTA) project was to evaluate the effectiveness and harm of dietary and lifestyle interventions in pregnancy for reducing or preventing obesity and on obstetric, fetal and neonatal outcomes, through a systematic review of literature.

Background

Obesity in pregnancy

In total, 50% of women of childbearing age are either overweight [body mass index (BMI) 24.9–29.9 kg/m2] or obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), with 18% starting pregnancy as obese. 1 Currently, in the USA and Europe, 20–40% of women are found to gain more than the recommended weight during pregnancy,2 resulting in an increased risk of maternal and fetal complications. 3 More than half of women who die during pregnancy, childbirth or the puerperium are either obese or overweight. The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH) report identified maternal obesity as a growing overall threat to the childbearing population in the UK. 4 The maternal risks of obesity include maternal death or severe morbidity, cardiac disease, spontaneous first-trimester and recurrent miscarriage, pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes, thromboembolism, post-caesarean wound infection, infection from other causes such as urinary and respiratory infections, post-partum haemorrhage and low breastfeeding rates. 4,5 There is also an identified, although poorly studied, adverse psychological impact on obese pregnant women. The fetal risks include stillbirth and neonatal death, macrosomia, neonatal unit admission, preterm birth, congenital abnormalities and childhood obesity with associated long-term risks. 5,6

Excessive weight gain in pregnancy is associated with persistent retention of the weight beyond pregnancy in the mother. 7–10 Interpregnancy weight gain increases the risk of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes in subsequent pregnancies. 11 An increase in BMI of ≥ 3 units between pregnancies doubles the risk of pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes, stillbirth and large-for-gestational-age (LGA) birth in subsequent pregnancies. Maternal obesity is also a major risk factor for childhood obesity. The obesity rate is doubled in 2- and 4-year-old children born to obese mothers. Excess weight gain during pregnancy is predictive of offspring obesity, independent of other factors. 12 This link is primarily associated with the mother’s ability to breastfeed, poor dietary and exercise habits of the mother before and during pregnancy, the parenting practices of overweight and obese mothers and the exposure of the child to poor dietary behaviours and a sedentary lifestyle once they are born.

The joint Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) and Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries (CMACE, formerly CEMACH) guidelines13 and the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidance14 recommend that women with a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2 should have consultant care rather than midwifery-led care, which places a massive burden on maternity unit resources. Obese women spend an average of 4.83 more days in hospital, resulting in a fivefold increase in the cost of antenatal care. 15 The costs associated with newborns are also increased, as babies born to obese mothers have a 3.5-fold increased risk of admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). 4 Obesity now costs the NHS around £1B a year and the UK economy a further £2.3B of indirect costs. Reducing maternal and childhood obesity, through effective obesity treatment programmes, could result in significant advantages for the NHS and society.

The RCOG has identified weight management interventions targeting mothers as an important long-term challenge that needs research. 16 The antenatal period is an ideal time to provide dietary and physical activity interventions to manage weight. Pregnant women are highly motivated to make changes and they have opportunities for regular contact with health professionals. 17 Weight management in pregnancy plays a crucial role not only in reducing women’s future risk of obesity but also in reducing their children’s behavioural risk factors for obesity. Even a modest fall in BMI of > 1 unit (equivalent to 2.5 kg) between pregnancies reduces the risks of pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes and LGA birth. 11 There is a need to identify the optimal interventions that can be delivered in pregnancy and which are effective, acceptable and safe in improving the short- and long-term outcomes for the mother and the baby.

Existing guidelines and reviews

Current recommendations from NICE,14 RCOG18 and the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (ACOG)19 for the management of obesity include healthy diet and exercise in pregnancy with referral to a nutritionist if required. The target weights for weight gain in pregnancy are based on the recommendations provided by the Institute of Medicine (IOM),20 ACOG19 and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). 21 The recent NICE guidance has recommended a ‘life course approach’ by focusing on pregnancy and 1 year after childbirth as the crucial periods to target weight management interventions based on behavioural change and dietary and physical activity. 14

A recent review in this area found insufficient evidence to recommend specific dietary and/or physical activity interventions to moderate gestational weight gain in pregnant women. 22 The latest CMACE/RCOG guideline on the management of obese women in pregnancy provides recommendations on the antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care of this group of high-risk women;13 however, gestational weight gain and the role of dietary and lifestyle interventions in pregnancy were prespecified to be outside the scope of the guideline.

Systematic reviews help clinicians, patients and policy-makers make decisions by summarising evidence. The details of the existing reviews evaluating the effect of weight management interventions on maternal and fetal outcomes are provided in Appendix 1. Existing reviews of the effectiveness and adverse effects of weight management interventions in pregnancy show deficiencies in quality and evidence when assessed against a validated tool and reporting checklists: PRISMA23 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) and MOOSE (Meta analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology). 24 This is one of the main reasons for their limitations in the role of informing practice. An accurate and reliable summary of the evidence with clear and transparent reporting is needed to maximise their usefulness to clinicians, patients and policy-makers. 3

Objectives of the project

This HTA project was undertaken to meet the following objectives:

-

to determine, primarily, the effectiveness of dietary and lifestyle interventions in pregnant obese and normal-weight women for:

-

– maternal weight change

-

– fetal and neonatal weight

-

-

to determine, secondarily, the effectiveness of dietary and lifestyle interventions in pregnant obese and normal weight women for:

-

– obstetric and medical complications in pregnancy

-

– fetal and neonatal morbidity and mortality

-

-

to evaluate the potential short- and long-term adverse effects in mother and baby resulting from the type of intervention in pregnancy.

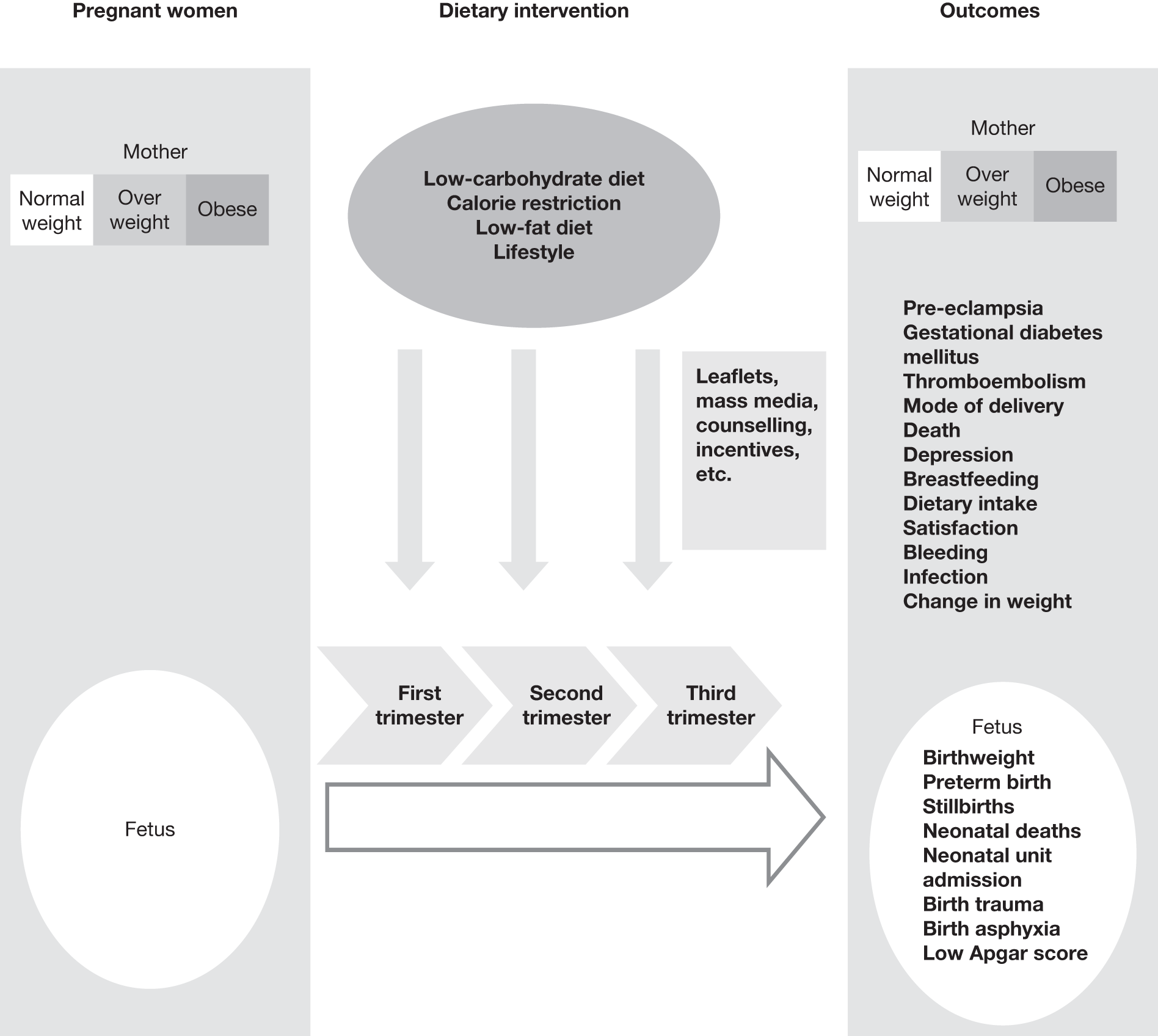

Figure 1 shows our proposed framework for the work undertaken.

FIGURE 1.

A framework to study the effectiveness of dietary and lifestyle interventions for maternal and fetal outcomes.

Chapter 2 Systematic review methods

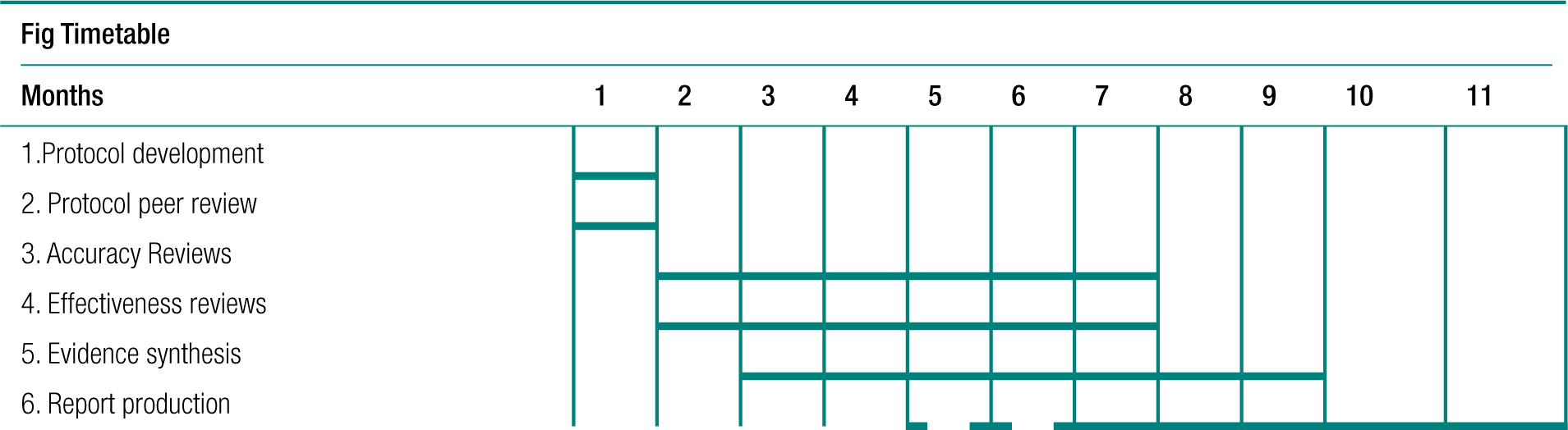

Protocol development

Systematic reviews of the effectiveness of and harm caused by interventions were carried out using methodology25–27 in line with the recommendations of the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination and the Cochrane Collaboration, including the Cochrane Adverse Methods Subgroup. 25–33 The systematic reviews of effectiveness and of adverse effects were carried out simultaneously .

The protocol for this review included the following: a detailed literature search to identify all relevant citations, prioritisation of outcomes relevant to clinical practice by Delphi survey, assessment of the risk of bias for the individual studies and evaluation of the strength of evidence for individual outcomes using GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) methodology.

Research question

The structured question addressed by the project is given in Table 1.

| Question components | Details |

|---|---|

| Population | Pregnant women who are obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) or overweight (BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2) and pregnant women of normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2) |

| Intervention | Dietary intervention, physical activity-based intervention and mixed approach (see Table 2) |

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome: weight-related outcomes Secondary outcomes: obstetric outcomes, fetal and neonatal morbidity and mortality (see Table 3) |

| Study design | Systematic review |

Methods for effectiveness review

Search strategy

A detailed search of the relevant published and unpublished literature was conducted by constructing a comprehensive search strategy for the effectiveness of dietary and lifestyle interventions in pregnancy. The following databases were searched: MEDLINE, EMBASE, BIOSIS, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS), Science Citation Index, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), HTA database and PsycINFO. In addition, information on studies in progress and unpublished research or research reported in the grey literature were sought by searching a range of relevant databases including Inside Conferences, Systems for Information in Grey Literature (SIGLE), Dissertation Abstracts and ClinicalTrials.gov. Internet searches were also carried out using specialist search gateways (such as OMNI: www.omni.ac.uk/), general search engines (such as Google: www.google.co.uk/) and meta-search engines (such as Copernic: www.copernic.com/). The aim was to identify all studies evaluating the effectiveness of interventions for weight management in pregnancy.

The search strategy was designed in a multistep process by combining search terms related to pregnancy and weight. The search was limited by including search filters for ‘human studies’ and ‘study type’ (randomised clinical trials and observational trials without case series and case studies). Existing search strategies or filters, such as the InterTASC Information Specialists’ Sub-Group Search Filter Resource, were used to develop the search strategy with some modifications as needed. No further limitations were applied. The detailed search strategy for effectiveness is provided in Appendix 2. MEDLINE and EMBASE were searched from inception to May 2010. Other databases were searched from inception to June 2010. The search was repeated and updated until March 2011. A comprehensive master database of articles was constructed using Reference Manager 12.0® software (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY, USA).

Inclusion criteria

The criteria for inclusion of studies in the effectiveness review are described in the following sections.

Population

Pregnant women expecting one or more than one baby (i.e. twins or triplets) were included. We included women who were of normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2) or obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). We excluded pregnant women who were underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2).

Setting

Any setting including primary care or secondary and tertiary units.

Interventions

We included any dietary, physical activity and behavioural change intervention that has the potential to influence weight change in pregnancy. Studies that evaluated interventions mainly based on dietary advice were classified in the dietary interventions group. Interventions primarily based on physical activities such as swimming, running and aerobic exercise were classified in the physical activity group. The mixed approach interventions group included studies that employed diet and physical activity components that may, or may not, be underpinned by behavioural theory. Table 2 lists the various interventions reviewed.

| Interventions and intervention delivery | Details |

|---|---|

| Dietary intervention | Energy and intake of total diet and specific food (e.g. low-carbohydrate diet, low-fat diet, high-fibre diet, low-protein diet, balanced diet, Atkins diet, Slimming World diet); dietary patterns, frequency of eating; and meal composition |

| Physical activity-based intervention | Walking, swimming, aerobic dancing, low-intensity resistance exercise, aqua aerobics and exercise regimes of various intensity |

| Mixed approach intervention | Intensive counselling regarding diet and physical activity in pregnancy and stepped-care advice. Behavioural change model (e.g. transtheoretical model, theory of planned behaviour, self-determination theory) predominantly underpinning the intervention |

| Intervention delivery |

One-to-one counselling, motivational talk, dietary consultation, group exercise, supermarket tours, cooking demonstration, parentcraft classes, walking group, benefits/incentives, slimming club and mass media (TV, radio, DVD, social websites, NHS websites) BMI chart, diet self-monitoring tools, self-weight check, postal questionnaires, IOM weight gain grid; Bassett obstetric chart |

Comparison

The control group consisted of women with no intervention or routine antenatal care. In women with obstetric or medical complications the care provided was appropriate to the condition (e.g. insulin in diabetic women).

Outcomes

The maternal and fetal outcomes included in the review are provided in Table 3.

| Outcomes | Components |

|---|---|

| Weight-related outcomes (primary) | |

| Maternal | Change in maternal weight (absolute gain or loss in weight; percentage of weight gained or reduced in comparison with pre-intervention weight), fat content measurement (BMI, skinfold thickness, ponderal index, fat-free mass) and fat distribution measures (waist-to-hip ratio, waist size) in pregnancy |

| Fetal | Birthweight related to gestational age and sex, fetal fat mass and ponderal index (weight/length3) |

| Obstetric and pregnancy-related outcomes | |

| Fetal and neonatal complications | Pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes mellitus, gestational hypertension, premature rupture of membranes, caesarean section, post-partum haemorrhage, sepsis, maternal death, preterm labour, abruption, complications of labour and delivery, instrumental delivery, perineal trauma, induction of labour, need for hospitalisation, day-care unit visits in pregnancy and the puerperium, use of intensive care in pregnancy or the puerperium, thromboembolism, stillbirth, perinatal and neonatal death, congenital abnormalities, prematurity, abnormal Apgar score, neonatal respiratory distress, shoulder dystocia, abnormal cord pH at birth, hypoxic–ischaemic encephalopathy, long-term neurological sequelae, need for NICU admission, mechanical ventilation and duration of hospital stay |

| Childhood and adult outcomes in offspring | Childhood obesity, adult obesity, diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, hypertension, stroke, depression and death |

| Other relevant outcomes | Maternal: cardiac arrest, stroke, psychiatric problems, depression, self-esteem, low back pain, and change in diet and exercise |

Study design

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the effectiveness of dietary and lifestyle weight management interventions in pregnancy for maternal and fetal outcomes. Non-randomised studies (NRSs) and observational studies (cohort and case–control) were included in the analysis only when the evidence from RCTs was insufficient. Studies that did not provide data to estimate effectiveness measures such as relative risk (RR) or mean difference (MD) were excluded.

Subgroups

The following subgroups were specified a priori and reported in the review:

-

intervention: dietary, physical activity and mixed approach interventions

-

BMI: obese only, obese and overweight and mixed-group populations

-

setting: studies in developed countries and developing countries

-

year of publication: studies published before 1990 and since 1990

-

diabetes in pregnancy

-

responders to the intervention with significant reduction in gestational weight gain.

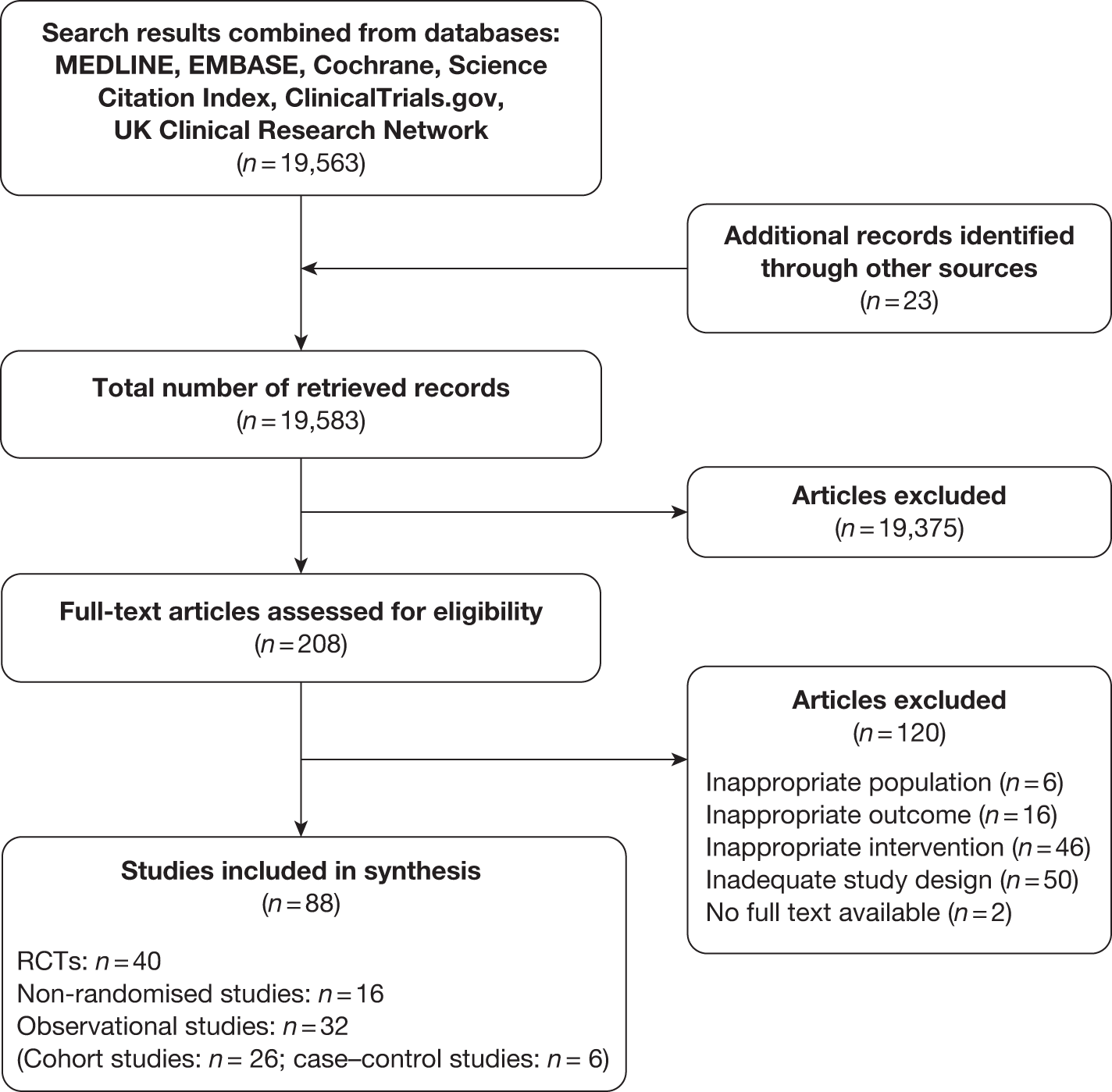

Study selection

Study selection was conducted in two stages: an initial screening of titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria to identify potentially relevant papers followed by screening of the full papers of the identified citations without language restrictions. Two reviewers independently assessed each citation (ER and SG) for inclusion in the review. Any differences in opinion were resolved by discussion and by involving a third reviewer. Further information was sought from the study authors if required. The process of study identification and selection is presented in Figure 2, consistent with the PRISMA guidelines.

Study quality assessment

The studies were classified by study design according to the NICE guidelines algorithm for classifying quantitative study designs. 34 Quality assessment was carried out separately for the different study designs (RCTs, NRSs and observational studies).

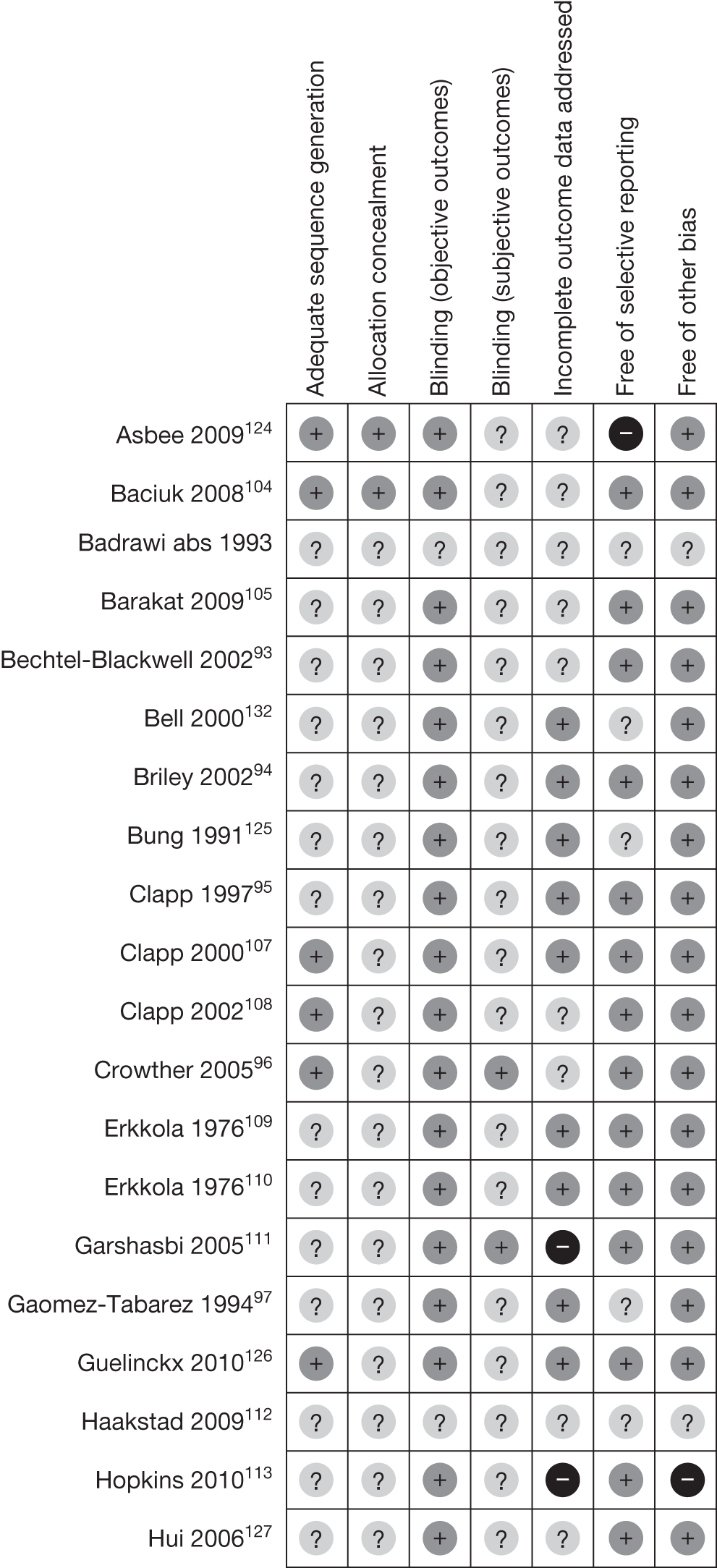

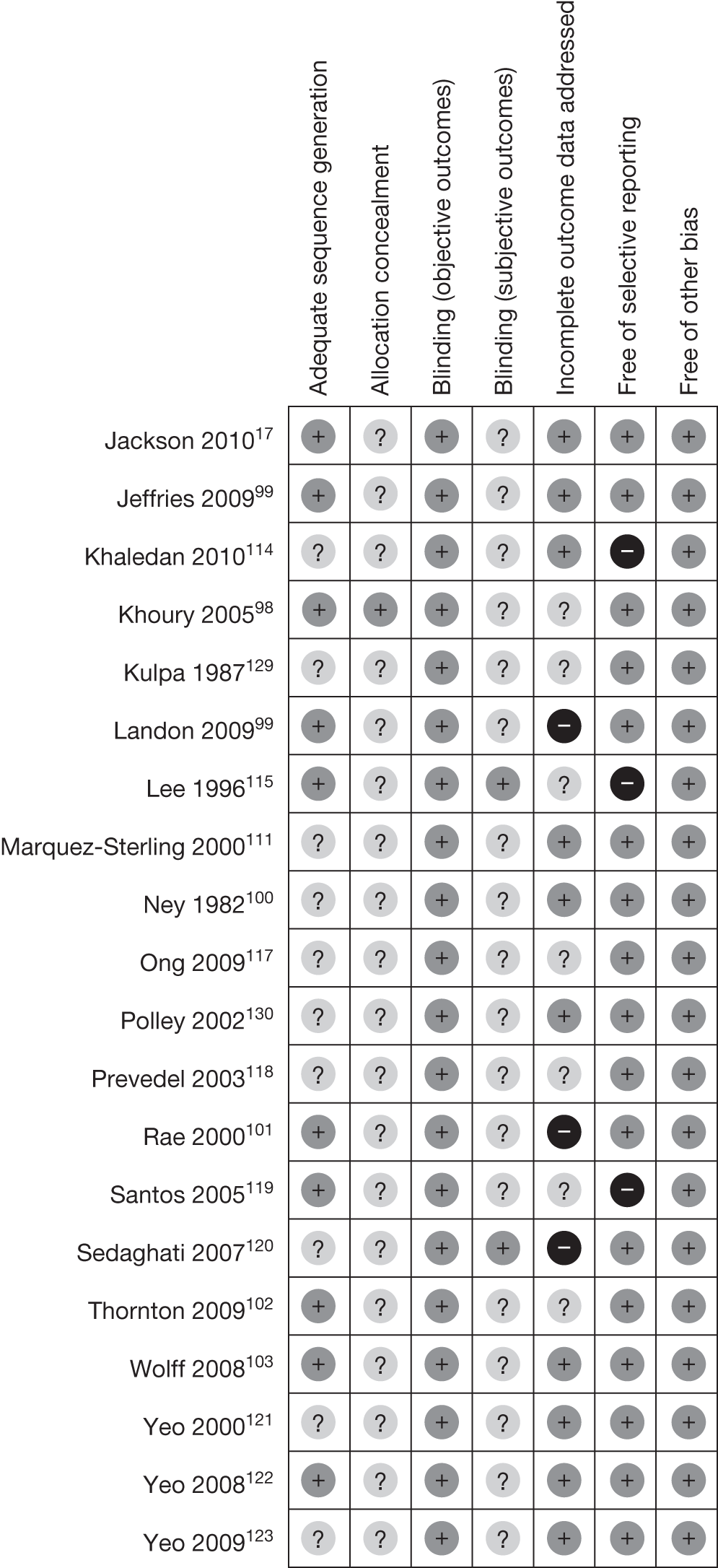

Randomised controlled trials

We assessed the risk of bias – selection bias, performance bias, measurement bias and attrition bias – in line with the recommendations made in the Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 35 Study quality was assessed in six domains: sequence generation, allocation sequence concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other potential sources of bias.

Sequence generation

An adequate sequence generation should describe the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether or not it should produce comparable groups. The use of a random component was considered to be adequate sequence generation. Systematic methods, such as alternation or assignment based on date of birth, case record number or date of presentation, were considered to be inadequate.

Allocation concealment

A study was categorised as being at low risk of bias for allocation concealment if it described the method used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to determine whether intervention allocations could have been foreseen in advance of, or during, enrolment.

The quality of allocation concealment was chosen using the following criteria:

-

adequate concealment of allocation, such as telephone randomisation, consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes

-

unclear whether adequate concealment of allocation

-

inadequate concealment of allocation such as random number tables, sealed envelopes that are not numbered or opaque.

Where the method of allocation concealment was unclear, whenever possible attempts were made to contact authors to provide further details.

Blinding

Adequate blinding described all measures used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. It should also provide any information relating to whether or not the intended blinding was effective. In assessing the risk of bias from blinding, we specifically assessed who was and who was not blinded. Furthermore, we also assessed separately the risk of bias for subjective and objective outcomes.

Incomplete outcome data

We evaluated the completeness of outcome data for each main outcome, including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We assessed whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers in each intervention group (compared with the total number of randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusions where reported and any reinclusions in the analyses.

A study was considered to be at low risk of bias for missing outcome data when we were confident that the participants included in the analysis were exactly those who were randomised into the trial. The risk of bias was considered to be unclear if the numbers randomised into each intervention group were not clearly reported. A study was labelled as having a high risk of bias for missing outcome data when there was a difference in the proportion of incomplete outcome data across groups and the availability of outcome data was determined by the participants’ true outcomes.

Selective outcome reporting

We compared the outcomes reported in the individual studies with the rest of the studies to assess the possibility of selective outcome reporting. The risk of this bias was assessed at the study level.

Other sources of bias

Any other important concerns about bias not addressed in the above domains were highlighted as other sources of bias. The proportions of studies with various risks of bias are shown in Appendix 4. The entries for each domain were marked as ‘Yes’, ‘No’ or ‘Unclear’ as appropriate.

Non-randomised studies

Quality assessment of NRSs was performed using a methodology checklist presented in Appendix 5. The Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) was used to assess the quality of the observational comparative studies with cohort and case–control designs. 25 The cohort studies were assessed for the following risks of bias:

-

selection of cohorts regarding the representativeness and selection of the exposed cohort, ascertainment of exposure and that the outcome of interest was not present at the start of study

-

comparability of the cohorts based on methods or analysis

-

assessment of outcome by evaluating the details of outcome assessment, adequacy of length of follow-up for the outcomes to appear and adequacy of follow-up of the cohorts.

The case–control studies were evaluated for the following risks of bias:

-

selection of cases and controls, assessing representativeness and adequate definition of the cases and adequate selection and definition of the controls

-

comparability of the cases and controls

-

ascertainment of exposure, method of ascertaining exposure of the cases and controls and rates of non-response in the groups.

The studies are allocated stars according to the rating. A study can be awarded a maximum of four stars for selection, two for comparability and three for ascertainment of exposure. 36

Data extraction

Study clinical characteristics and findings were extracted in duplicate by independent reviewers using predesigned and piloted data extraction forms. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus and/or arbitration involving a third reviewer. Missing information was obtained from investigators if it was crucial to the subsequent analysis. To avoid introducing bias, unpublished information was treated in the same way as published information. In addition to using multiple reviewers to ensure the reproducibility of the overview, sensitivity analyses around important or questionable judgements regarding the inclusion or exclusion of studies, the validity assessments and data extraction were performed. A copy of the data extraction form for the effectiveness review is provided in Appendix 18.

Data synthesis

We calculated pooled RRs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomous data. Continuous data were summarised as MD with standard deviation or median change in relation to the baseline. In the case of missing standard deviations, imputation techniques were used based on Cochrane recommendations. 35 Separate analyses were performed on randomised and non-randomised data. Non-randomised data were used for outcomes for which there were no RCTs or a very small number of poor-quality RCTs. The I2 statistic was used to assess statistical heterogeneity between trials. In the absence of significant heterogeneity, results were pooled using a fixed-effect model. If substantial heterogeneity was detected (I2 > 50%), possible causes were explored and subgroup analyses for the main outcomes performed. Subgroups defined a priori were BMI of the women, type of intervention, responders, publication year (before and after 1980), study quality and setting. Heterogeneity that was not explained by subgroup analyses was modelled using random-effects analysis where appropriate. For outcomes for which meta-analysis was not appropriate, the RCT and NRS results were presented, where possible, on a forest plot but without summary scores, allowing a visual presentation of the effects of each included trial. For observational studies, a narrative summary of the findings was given. Statistical analysis was performed when sufficient data were presented. RevMan, version 5.0, (The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used in the statistical analyses.

Methods for adverse effects review

The review of harm of interventions was undertaken based on recommended methods for systematic reviews, particularly those of observational studies and adverse events, including those of the Cochrane Adverse Effects Subgroup. 30,37–39

Search strategy

The scope of the review of adverse effects of any dietary intervention on pregnant women and their children was purposefully kept broad. This was to identify a variety of adverse effects that were previously not known or recognised. In addition to the search for relevant reviews and primary studies on the effectiveness of interventions, including those that were excluded from the analysis of benefit, we evaluated studies that specifically provided details of adverse effects resulting from the dietary and lifestyle interventions and weight loss in pregnancy. We designed a separate search strategy to identify studies on harm by including adverse effects text words and indexing terms in the databases previously described in the section on the effectiveness review. Existing search strategies or filters, such as the InterTASC Information Specialist Sub-Group Search Filter Resource, were used to develop the search strategy for this review, with some modifications if needed. The search was limited by including search filters for ‘adverse events’ , ‘human studies’ and ‘study type’ (exclusion of editorials and letters). The detailed search strategy for adverse effects can be found in Appendix 2. MEDLINE and EMBASE were searched from inception to June 2010. Other databases were searched from inception to July 2010. The search was updated until March 2011.

Inclusion criteria

The criteria for inclusion of studies in the adverse effects review are described in the following sections.

Population

Pregnant women expecting one or more than one baby (i.e. twins or triplets) were included. We included women who were of normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2) or obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). We excluded pregnant women who were underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2).

Setting

We included studies carried out in any setting including primary care or secondary and tertiary units.

Interventions

Any dietary and physical activity intervention or exposure that has the potential to cause harm to the mother or baby.

Outcomes

We included any clinically significant adverse outcomes in the mother and the child resulting from (1) a dietary intervention or (2) weight change in pregnancy. We also evaluated the most common adverse effects that led to pregnant women discontinuing an intervention.

Study design

Both comparative (RCTs, NRSs and observational studies) and non-comparative studies including case series and case reports were included. This encompassed any publication as an abstract or full text without any language restrictions.

Study selection and quality assessment

Criteria used to assess the quality of studies for the evaluation of adverse effects followed the same concepts as for assessing study quality for effectiveness: assessing risk of bias, inconsistency of results, indirectness of the evidence, imprecision and publication bias. For assessing the risk of bias in estimating adverse event rates associated with weight management interventions in pregnancy24 we took into account existing checklists for the evaluation of randomised and non-randomised studies,39,40 including study design and other features associated with outcome [e.g. small for gestational age (SGA), preterm delivery]. Quality assessment and presentation of results were carried out separately for RCTs, NRSs and observational studies with a control group and for observational studies without a control group (case series, case reports). Additionally, information on weight change per se in mother and baby were also extracted as these could be associated with adverse event rates or severity. The methodological quality of all eligible data sets (‘risk of bias’) was assessed to investigate internal validity (the extent to which the information is probably free of bias) using the following attributes:41

-

reporting of adverse maternal and fetal outcome definitions to reduce bias in ascertainment of denominator data in the series (any published definition reported vs no definition)

-

adequacy of data source to ascertain a capture of denominator data that is as complete as possible (use of multiple data sources, special surveys or clinical studies vs routine registration enrolment in weight loss programmes, in which adequate attribution of cause of harm has been shown to be questionable for maternal and fetal outcomes, leading to substantial under-reporting)

-

use of a robust approach to ascertain that the cause of harm is a representation of the underlying condition that is as true as possible (confidential enquiries, use of multiple sources of outcome vs no special efforts to confirm cause)

-

a sufficiently high proportion of cases with an attributable cause of harm established (< 5% unclassified).

Data extraction

Methods for study selection and data extraction for the adverse event review were similar to those for the effectiveness review. Study clinical characteristics and findings were extracted in duplicate by independent reviewers using a predesigned and piloted data extraction form (see Appendix 19). Any disagreements were resolved by consensus and/or arbitration involving a third reviewer. Missing information was obtained from investigators if it was crucial to subsequent analysis. To avoid introducing bias, unpublished information was treated in the same way as published information. In addition to using multiple reviewers to ensure the reproducibility of the overview, sensitivity analyses around important or questionable judgements regarding the inclusion or exclusion of studies, the validity assessments and data extraction were performed.

Data synthesis

The number of adverse events reported in pregnant women and children was obtained for each intervention to compute a percentage of the total number of women and children in whom the occurrence of a particular adverse event or confirmation of its absence was reported. 41 It is inappropriate to calculate adverse event rates from case studies; thus, a qualitative summary was undertaken. Quantitative adverse event rate calculations were restricted to series of women undergoing weight management interventions and weight change as identified from RCTs and observational studies, with and without controls (case series). The adverse events were quantified as RRs and 95% CIs. The point estimates of proportions and their 95% CIs are represented in forest plots to explore heterogeneity, and the possibility of the differences being due to chance was assessed statistically using Cochran’s Q test.

Grading of evidence

The quality of the evidence was assessed and reported separately for each outcome following the GRADE methodology. This is because even within one review the quality of the evidence can vary between the outcomes. We defined quality of evidence as ‘the extent of confidence that an estimate of effect is correct’. 42 The GRADE system classifies quality of evidence into one of four levels: high, moderate, low and very low (Table 4).

| High quality | Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect |

| Moderate quality | Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate |

| Low quality | Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate |

| Very-low quality | Any estimate of effect is very uncertain |

To assess the quality, we considered, first of all, the risk of bias (internal validity), that is, the extent to which the design, methods, execution and analysis were not controlled for bias in the assessment of effectiveness. 30 Furthermore, we explored the (in)consistency of results (heterogeneity), (in)directness of the evidence (with respect to the question under consideration, including surrogate parameters), (im)precision of the results and publication bias. We assigned all evidence a ‘high’ level of quality when it was based on RCTs. If any of the reasons below applied to the body of evidence, for each comparison–outcome pair the quality level was downgraded by one level (if the reason was classified as serious) or two levels (if the reason was classified as very serious):

-

Risk of bias may arise from limitations in the study design and implementation. We downgraded evidence quality if there was lack of allocation concealment (selection bias), lack of blinding (performance bias), incomplete accounting of patients and outcome events (attrition bias), and other limitations affecting outcome assessment (detection bias).

-

Inconsistency referred to heterogeneity in results, which could arise from differences in populations, interventions or outcomes. Widely differing estimates of the effects across studies suggests that there might be true differences in underlying effect. When heterogeneity existed, but investigators failed to identify a plausible explanation, the quality of evidence was downgraded by one or two levels, depending on the magnitude of the inconsistency in the results.

-

Indirectness referred to broader or more restricted assessment of the review question components including population, intervention, comparator and outcomes.

-

Imprecision of results referred to wide 95% CIs as a result of few participants or few events. We downgraded the quality of evidence because of imprecision if there was a non-significant result or wide CIs.

We tabulated these features and assigned an overall quality grade to the evidence for each comparison–outcome pair. The footnotes in each table (e.g. Table 10) provide an explanation as to how we downgraded evidence in light of various deficiencies (Table 5).

| Bias | No downgrading | Downgrading by one (possibly two) levels | Downgrading by two or three levels |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Selection bias | Studies with randomisation, allocation concealment, similarity of groups at baseline | RCTs with some deficiencies in randomisation e.g. lack of allocation concealment, or NRSs with either similarities at baseline or use of statistical methods to adjust for any baseline differences | Non-randomised, with obvious differences at baseline, and without analytical adjustment for these differences |

| 2. Performance bias | Differed only in intervention, which was adhered to without contamination; groups were similar for cointerventions or statistical adjustment was made for any differences | Confounding was possible, but some adjustment was made in the analysis | Intervention was not easily ascertained or groups were treated unequally other than for intervention or there was non-adherence, contamination or dissimilarities in groups and no adjustments made |

| 3. Measurement bias | Outcome measured equally in both groups, with adequate length of follow-up (i.e. at least 2 years after delivery); direct verification of outcome, with data to allow calculation of precision estimates | Inadequate length of follow-up or length not given | Inadequate reporting or verification of maternal mortality or differences in measurement in both groups |

| 4. Attrition bias | No systematic differences in withdrawals between groups and with appropriate imputation for missing values | Incomplete follow-up data, not intention-to-treat analysis or lacking reporting on attrition |

The secondary maternal and fetal outcomes critical to clinical care of the patient were prioritised by a two-round Delphi survey of clinicians. The Delphi panel of clinicians was chosen for their interest in the field. A structured list of these outcomes (Box 1) was sent to 20 clinicians along with a covering letter explaining the purpose of this survey. The questionnaire was sent by e-mail and anonymity was maintained between panellists. In the first round, the experts were asked to rank the outcomes for their importance on a 1–9 scale (1–3 not important; 4–6 important, but not critical; 7–9 critical). They were given the opportunity to add outcomes that were considered to be relevant but not included in the list. Summary statistics such as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) were generated for each outcome. The median was used to identify the location on the appropriateness scale and an IQR (i.e. a measure of dispersion generated by taking the difference between the 75th and the 25th percentiles) of ≤ 2 was predefined to indicate consensus. In the second round the experts were asked to reconsider their previous ratings in view of the panel score. The new median scores and IQRs were recalculated. The top 10 outcomes were identified for inclusion in the GRADE evidence profile in addition to the primary weight-related outcomes.

Gestational diabetes mellitus

Pre-eclampsia/pregnancy-induced hypertension

Post-partum haemorrhage

Prolonged labour

Preterm delivery

Induction of labour

Prelabour rupture of membranes

Caesarean section

Instrumental delivery

Perineal trauma

Puerperal pyrexia (≥ 38°C)

Miscarriage

Need for resuscitation at delivery

Antepartum haemorrhage

Thromboembolism

Admission to the high-dependency unit/intensive care unit

Anaemia

Back pain

Infections

Postnatal incontinence

Postnatal depression

Anxiety

Quality of life

Physical activity

Dietary behaviour

Body fat (%)

Breastfeeding

Threatened miscarriage

Failed instrumental delivery

Coronary artery disease

Non-infective respiratory distress

Fetal, neonatal and childhood outcomesSmall for gestational age

Large for gestational age

Skinfold thickness (mm)

Fetal fat mass (%)

Abdominal circumference

Head circumference

Ponderal index (g/cm3 × 100)

Neonate length/crown–heel length

Head-to-abdomen ratio

Birthweight-related outcomes such as BMI

Hypoglycaemia

Hyperbilirubinaemia

Intrauterine death

Respiratory distress syndrome

Admission to NICU

Shoulder dystocia

One or more perinatal complications

Birth trauma

Neural tube defect

Cleft lip or palate or both

Other congenital abnormalities

Abnormal Apgar score

Cardiotocographic abnormalities

Cord pH abnormal

Long-term neurological sequelae

Cord abnormalities

Long-term metabolic sequelae

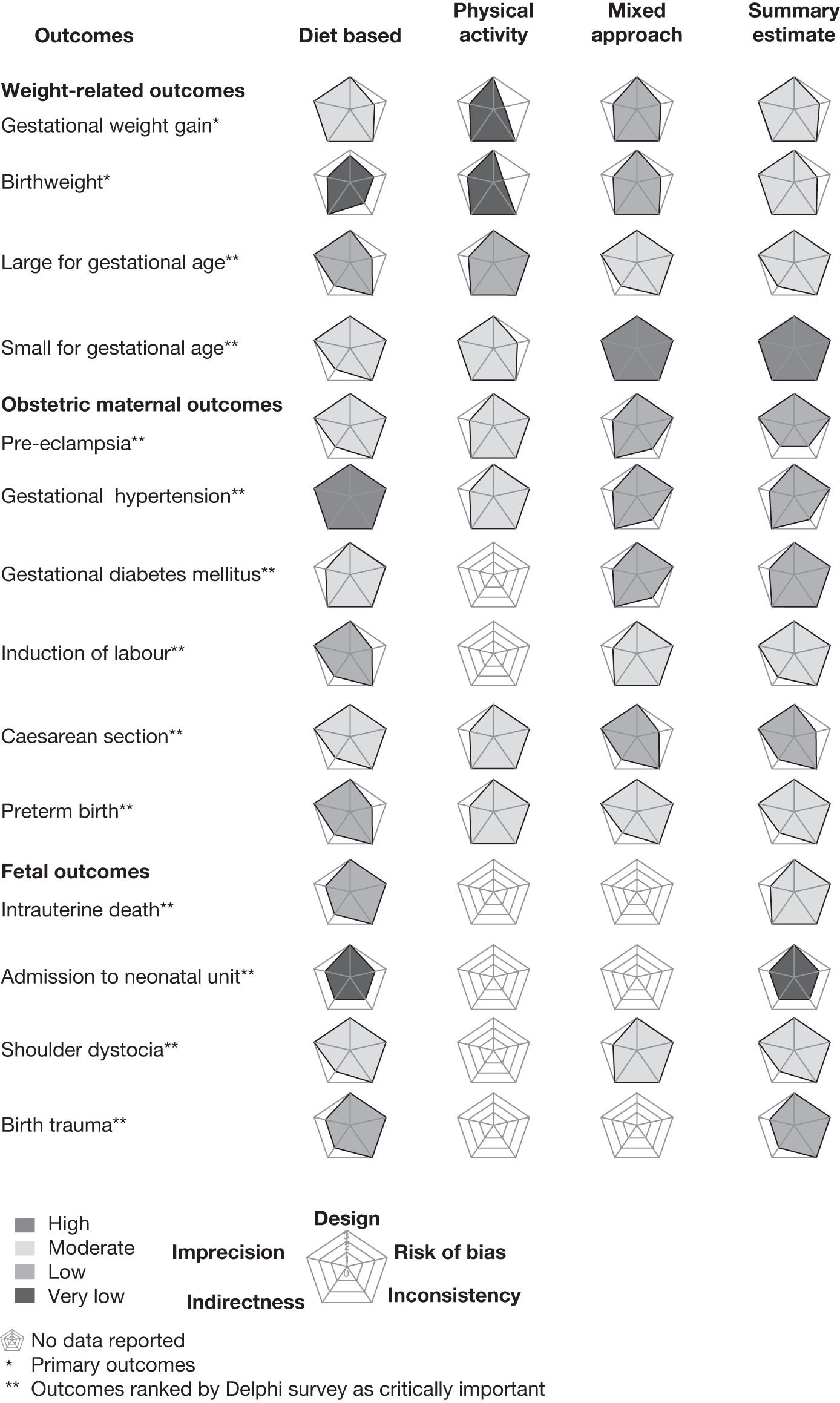

The strength of evidence for each outcome was assessed. The main maternal and fetal weight-related outcomes and those prioritised by the Delphi panel were assessed by GRADE methodology using GRADEpro software version 3.2.2 [GRADEpro (computer program), version 3.2 for Windows; Jan Brozek, Andrew Oxman and Holger Schürmann, 2008]. Two reviewers independently assessed the quality of each study; disagreements were resolved by consensus or arbitration involving a third reviewer. For each comparison–outcome pair we deployed a two-dimensional chart plotting five variables represented on equiangular spokes starting from the same point, each spoke representing one of the domains used in evidence grading. 43 These included study design, risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness and imprecision. The data length of a spoke was proportional to the magnitude of the quality, ranging from high to moderate to low to very low. A line connected the data values for each spoke generating a pentagon. Consistent use of the same position and angle of the spokes in all comparison–outcome pairs was used for easy visual interpretation in a multiplot format.

Chapter 3 Effectiveness of the interventions

Study selection

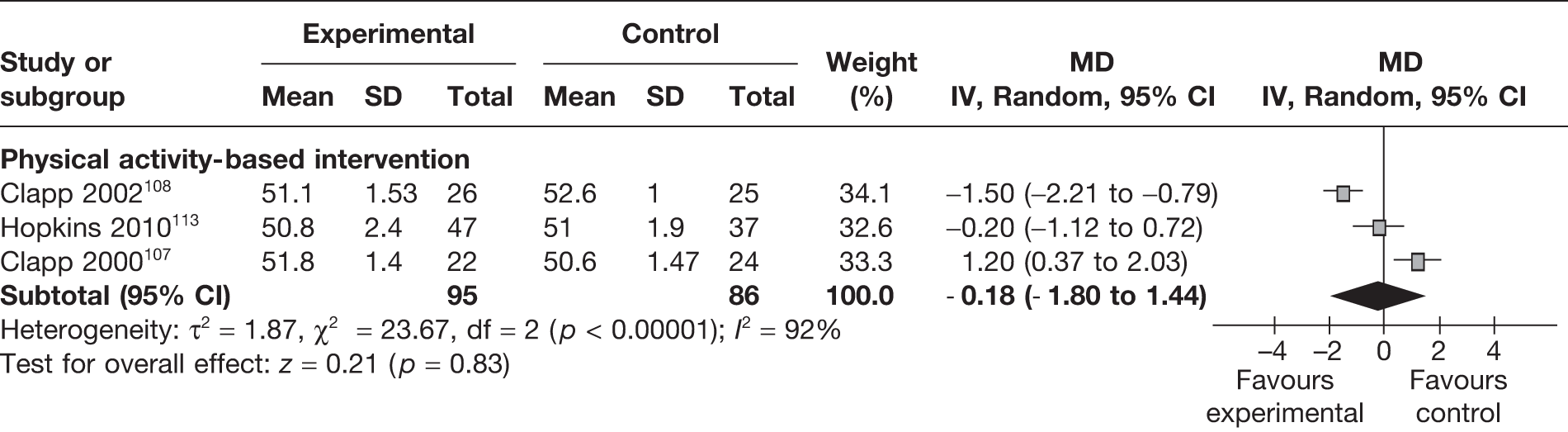

At the final update on 31 March 2011, 19,563 potentially relevant citations were identified from the major electronic databases to evaluate the effectiveness of weight management interventions in pregnancy for maternal and fetal outcomes. A further 23 studies were identified from the reference lists of the identified studies. In total, 88 articles were included in the review. Figure 2 shows the flow diagram of study identification, selection and exclusion.

FIGURE 2.

Flow chart of study identification and selection in the effectiveness review.

A total of 56 experimental studies (40 randomised and 16 non-randomised controlled studies;44–59 involving 8842 women) and 32 observational studies (26 cohort60–85 and six case–control studies;86–91 involving 173,297 women) evaluated the effectiveness of dietary, physical activity and other lifestyle interventions in pregnancy for maternal and fetal outcomes. The 40 RCTs included 12 trials on dietary interventions,92–103 20 on physical activity104–123 and eight on mixed approach124–130 in pregnancy for the prevention or reduction of obesity. Appendix 3 provides details of the included RCTs.

Quality of included studies

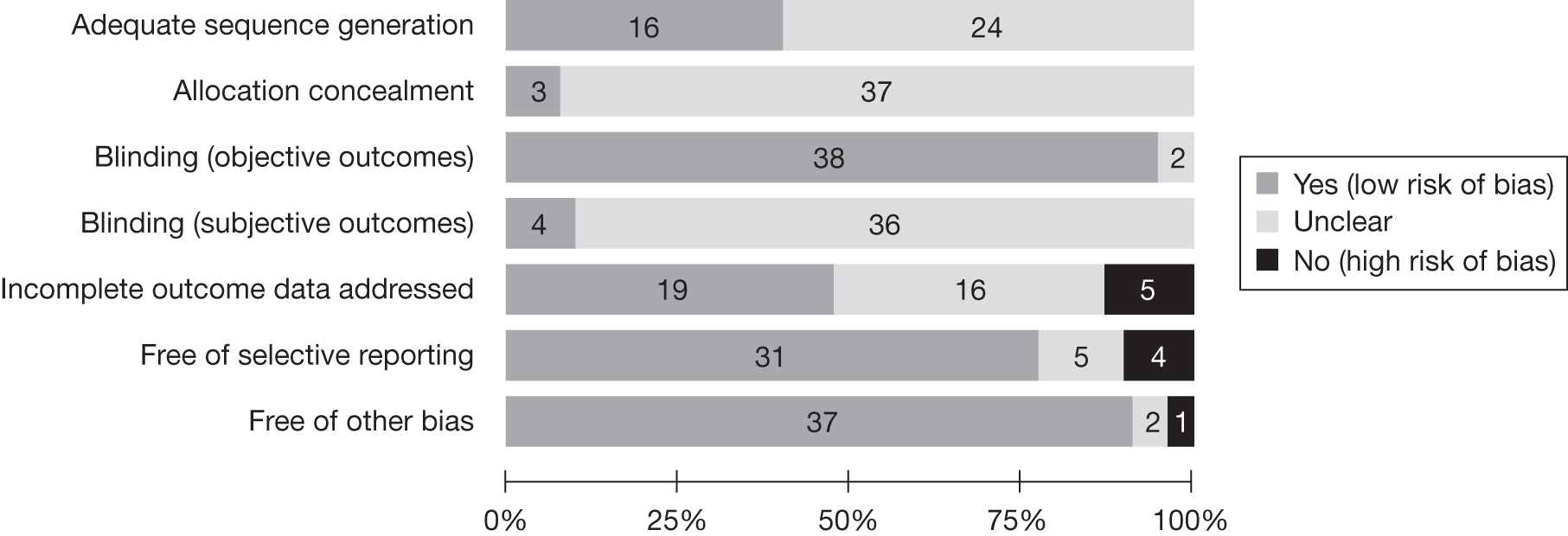

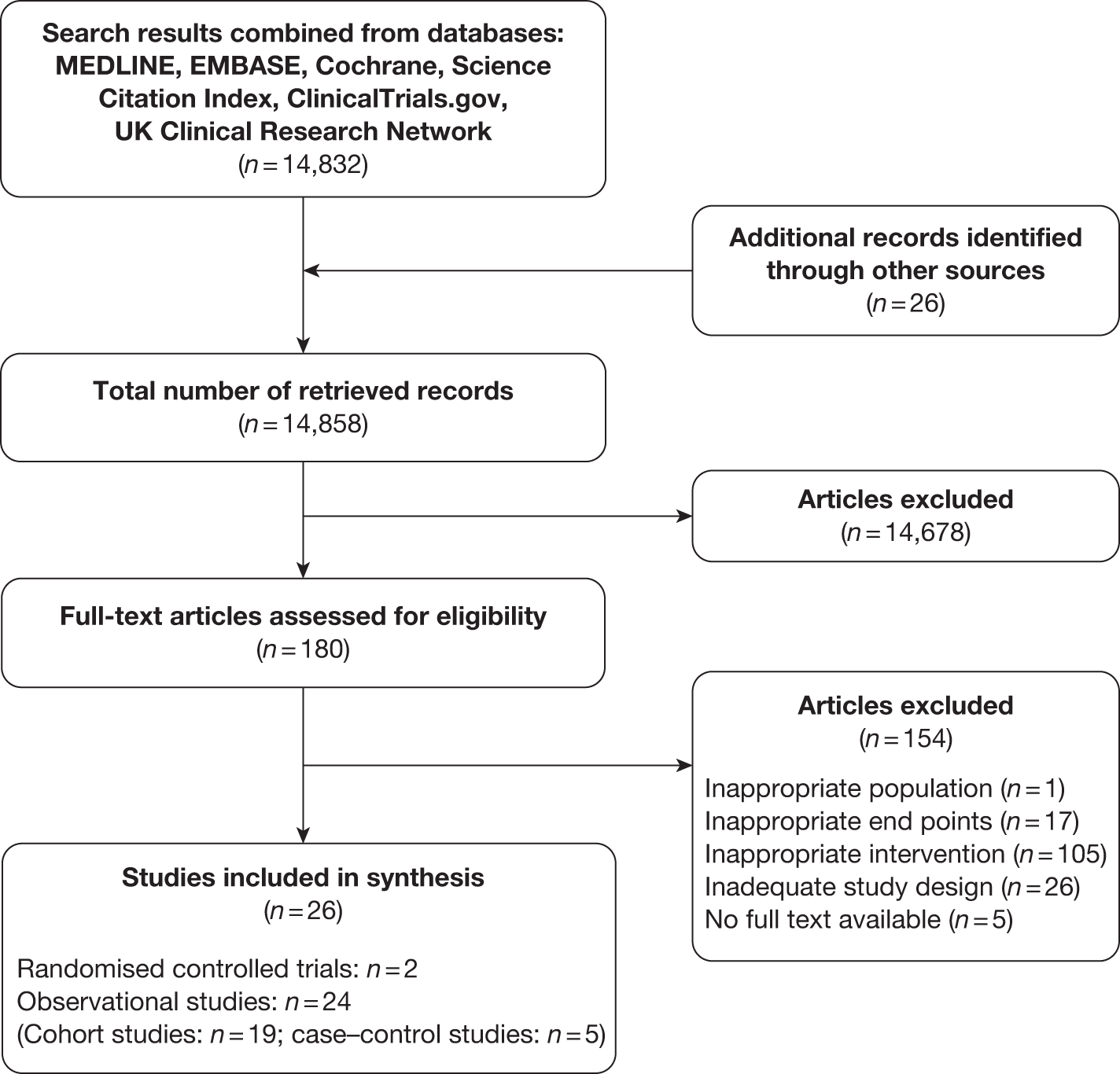

Randomised controlled trials

Figure 3 demonstrates the risk of bias of the included RCTs in the seven domains. Two-thirds of studies scored a low risk of bias for selective reporting of outcomes and blinding for objective outcomes. Although there was no obvious evidence of a high risk of bias for sequence generation, allocation concealment and blinding for subjective outcomes, a large proportion of the studies were unclear in their reporting in these domains. Appendix 4 provides a detailed quality assessment of the individual RCTs.

FIGURE 3.

Quality assessment of the included RCTs.

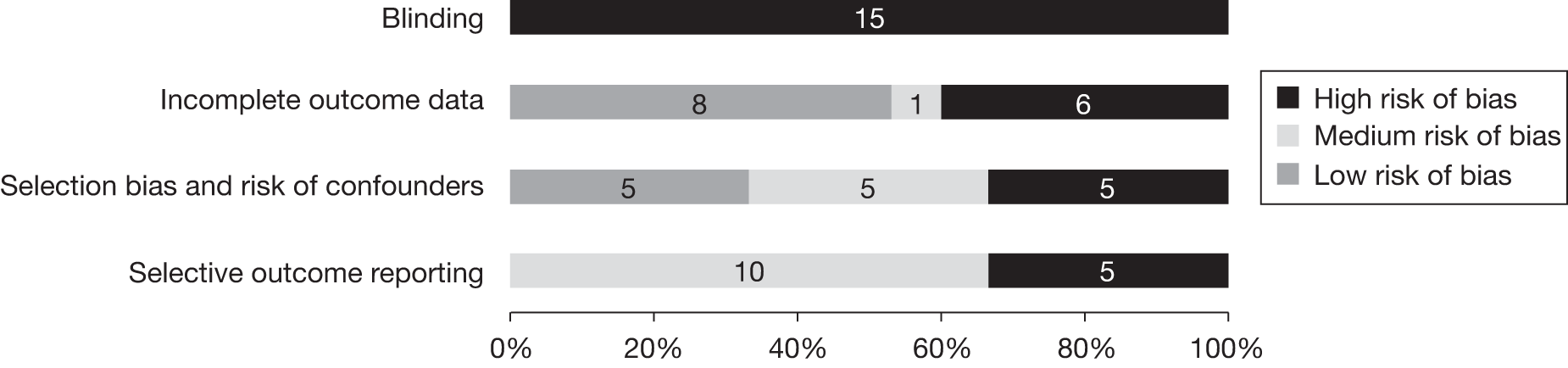

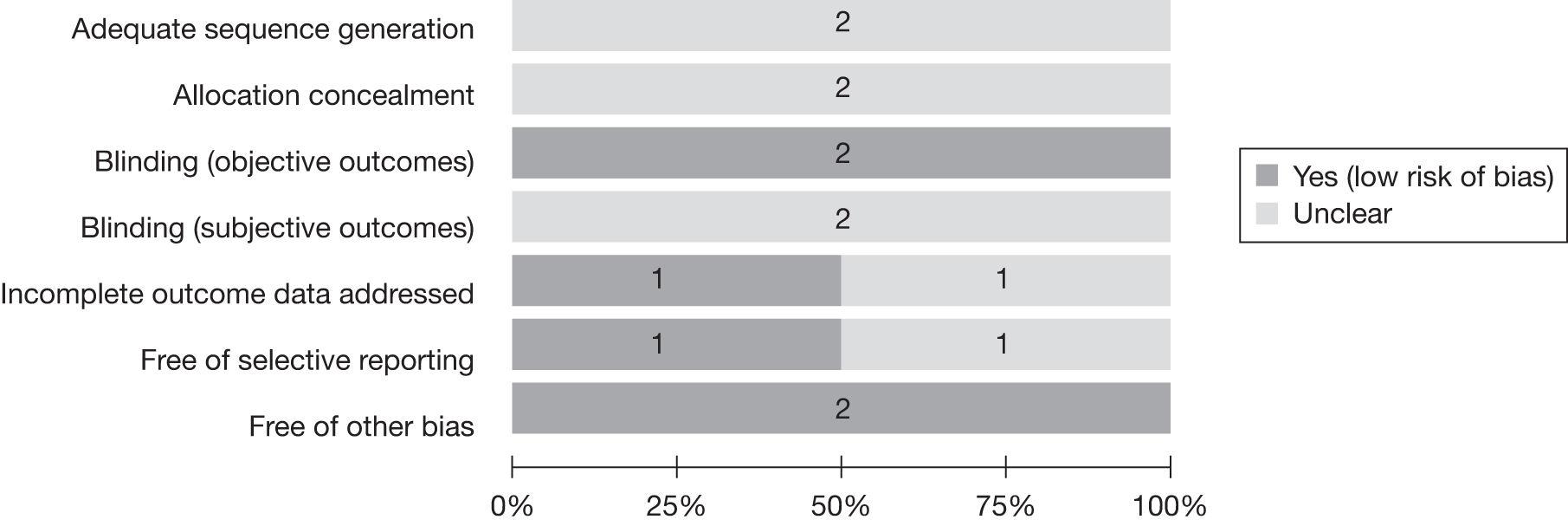

Non-randomised studies and observational studies

The internal validity of NRSs has been assessed in line with the NICE checklist. 34 Figure 4 presents the quality of the included NRSs. Further details of the individual study quality for non-randomised and observational studies are provided in Appendices 5 and 6. The observational studies were evaluated using the NOS and could score a maximum of nine stars, with four stars for selection, two for comparison and three for outcome assessment. In total, 7/26 (26.9%) cohort studies had a low risk of bias and scored seven or more stars, 18/26 (69.2%) had a medium risk of bias and scored between four and six stars and one study (3.8%) had a high risk of bias (see Appendix 6). All six case–control studies had a medium risk of bias.

FIGURE 4.

Quality assessment of the included NRSs.

Effect of the interventions on weight-related outcomes

Maternal weight-related outcomes

Maternal weight gain in pregnancy

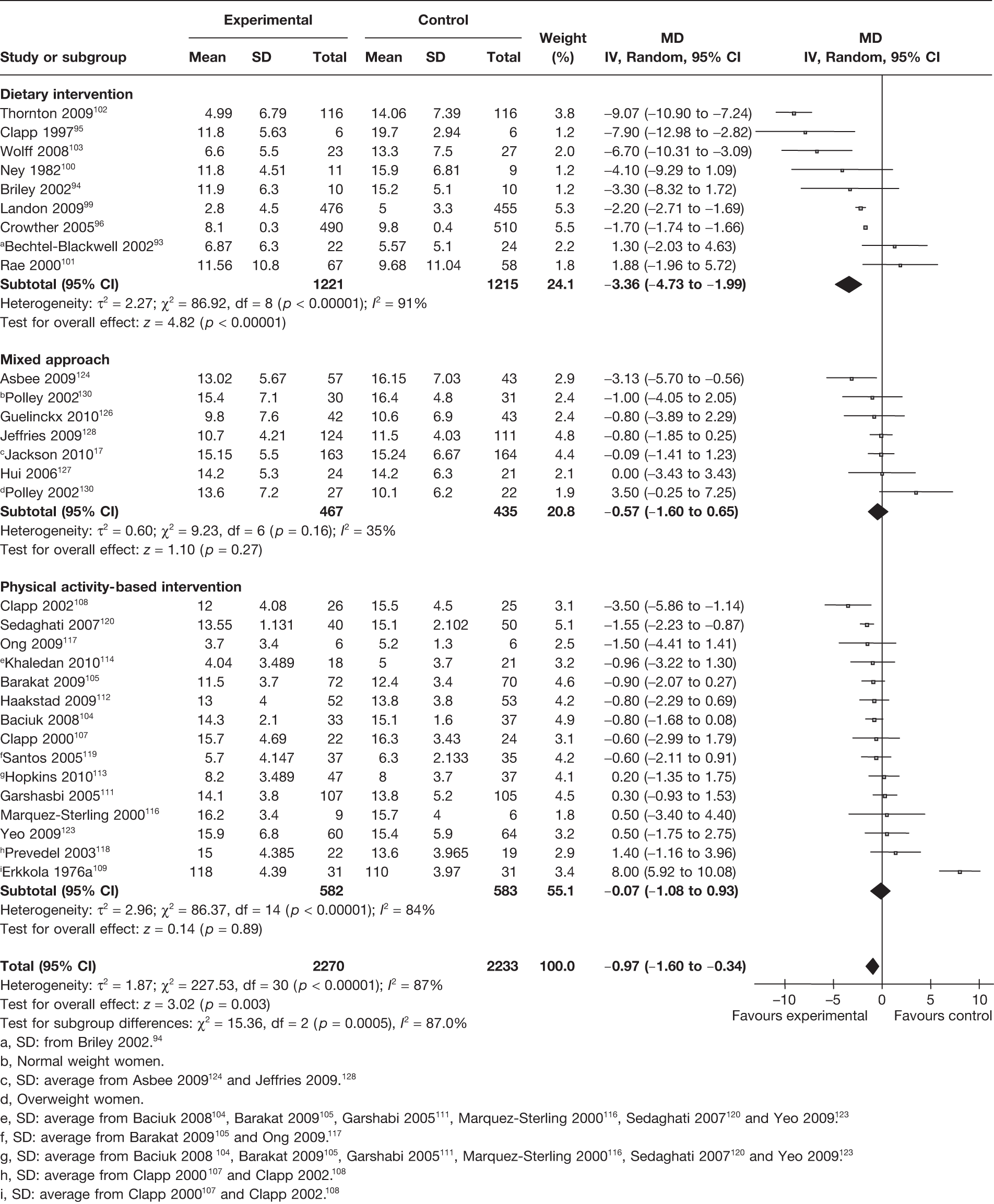

A total of 30 RCTs17,93–96,99–105,107–109,111–114,116–120,123,124,126–128,130 including 4503 women evaluated the effect of interventions on maternal weight gain in pregnancy. This included nine93–96,99–103 trials on dietary interventions, six17,124,126–128,130 on mixed approach and 15104,105,107–109,111–114,116–120,123 on physical activity interventions. There was a significant decrease in weight gain in pregnancy with interventions of 0.97 kg (95% CI –1.60 kg to –0.34 kg; p = 0.003; I2 = 87%). The largest reduction in weight gain was observed in the dietary intervention studies, with a MD of –3.36 kg (95% CI –4.73 kg to –1.99 kg; p < 0.00001; I2 = 91%), followed by mixed approach, with a MD of –0.57 kg (95% CI –1.60 kg to 0.65 kg; p = 0.27; I2 = 35%). The studies were heterogeneous with an I2 of 87%. There was a statistically significant difference between the intervention groups (p = 0.0005) (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Effect of weight management interventions on maternal weight gain in pregnancy. SD, standard deviation. a, SD: from Briley 2002. 94 b, Normal weight women. c, SD: average from Asbee 2009124 and Jeffries 2009. 128 d, Overweight women. e, SD: average from Baciuk 2008104, Barakat 2009105, Garshabi 2005111, Marquez-Sterling 2000116, Sedaghati 2007120 and Yeo 2009. 123 f, SD: average from Barakat 2009105 and Ong 2009. 117 g, SD: average from Baciuk 2008104, Barakat 2009105, Garshabi 2005111, Marquez-Sterling 2000116, Sedaghati 2007120 and Yeo 2009. 123 h, SD: average from Clapp 2000107 and Clapp 2002. 108 i, SD: average from Clapp 2000107 and Clapp 2002. 108

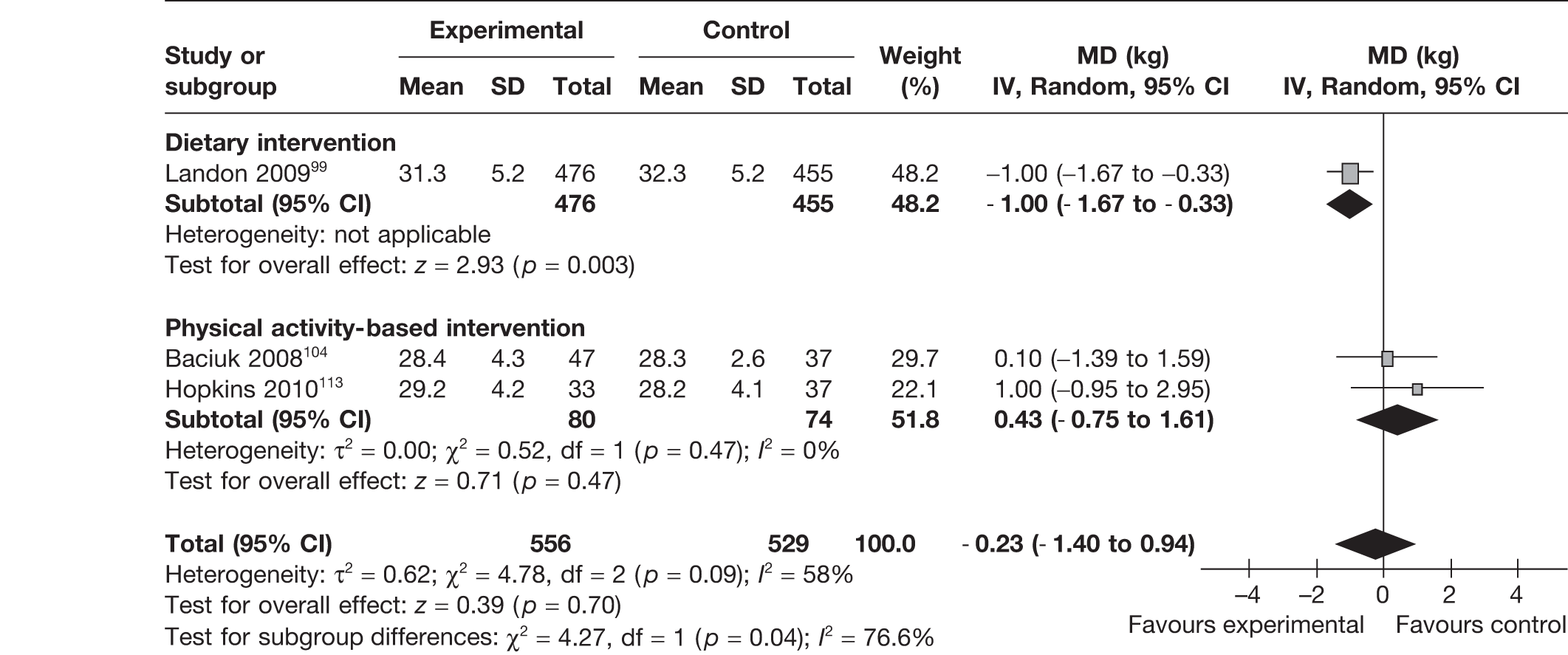

Maternal body mass index at delivery

Three RCTs99,104,113 reported on the effect of interventions on the mother’s BMI at delivery. There was a significant reduction in BMI with dietary intervention, with a MD of –1.00 kg/m2 (95% CI –1.67 kg/m2 to –0.33 kg/m2; p = 0.003). This effect was not observed with interventions based on physical activity. The overall pooled estimate showed a MD of –0.23 kg/m2 (95% CI –1.4 kg/m2 to 0.94 kg/m2; p = 0.70) with a heterogeneity of I2 = 58%. There was a significant difference between the subgroups (p = 0.04) (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Effect of weight management interventions on maternal BMI at delivery. SD, standard deviation.

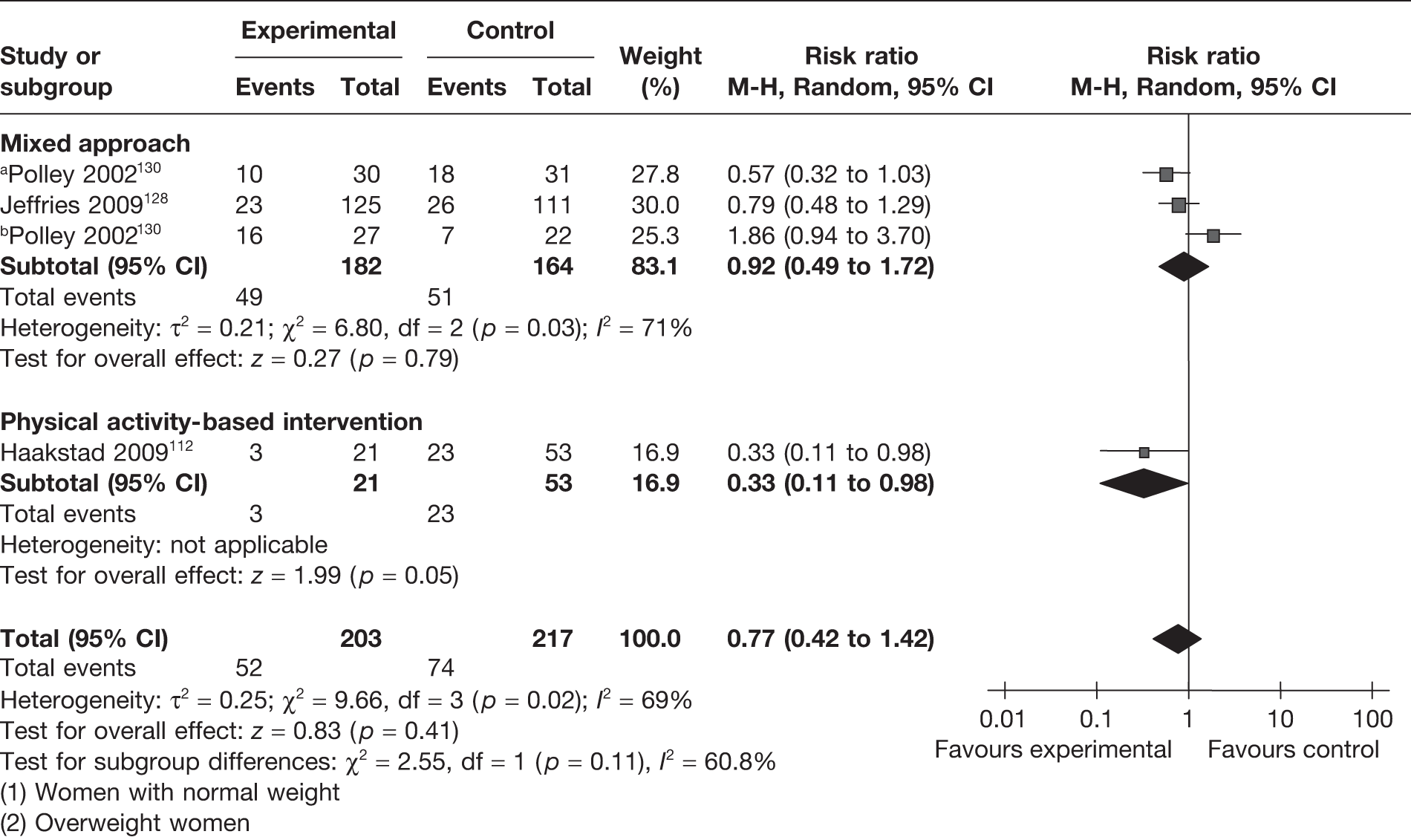

Exceeding the Institute of Medicine’s recommendations on weight gain in pregnancy

The IOM guidelines131 recommend the optimum weight gain in pregnancy for American women based on their BMI. The recommended gestational weight gain is 11.5–16.0 kg in women with normal BMI (BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2), 7.0–11.5 kg in overweight women (BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2) and 5.0–9.0 kg in obese women (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). Two RCTs128,130 reported a reduction in the number of women exceeding IOM recommendations with a dietary and physical activity intervention, which was not statistically significant (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

Effect of weight management interventions on IOM recommendations. a, Women with normal weight. b, Overweight women.

Fetal and neonatal weight-related outcomes

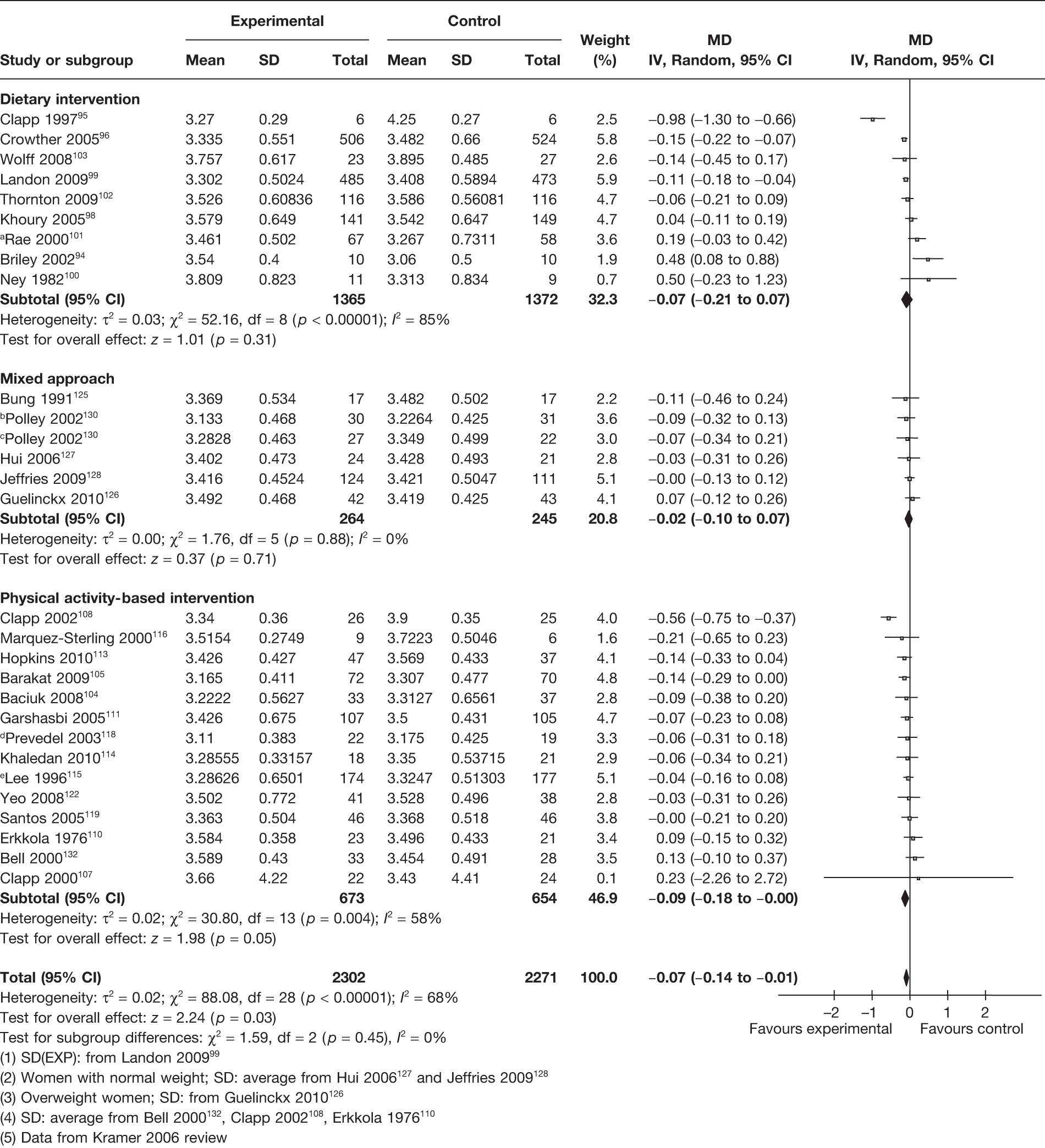

Birthweight

A total of 28 RCTs (4573 newborns) evaluated the effect of the interventions on the birthweight of the newborn. This included nine RCTs on dietary interventions,94–96,98–103 five on a mixed approach intervention125–128,130 and 14 on physical activity-based interventions. 104,105,107,108,110,113–116,118,119,122,132 Overall, there was a small, but statistically significant, reduction in the mean birthweight of 0.07 kg (95% CI –0.14 kg to –0.01 kg; p = 0.03). There was heterogeneity observed among the groups (I2 = 68%), with no large birthweight reduction in the three intervention subgroups (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8.

Effect of weight management interventions on birthweight. SD, standard deviation. a, SD(EXP): from Landon 2009. 99 b, Women with normal weight; SD: average from Hui 2006167 and Jeffries 2009. 128 c, Overweight women; SD: from Guelinckx 2010. 126 d, SD: average from Bell 2000132, Clapp 2002108, Erkkola 1976. 110 e, Data from Kramer 2006 review.

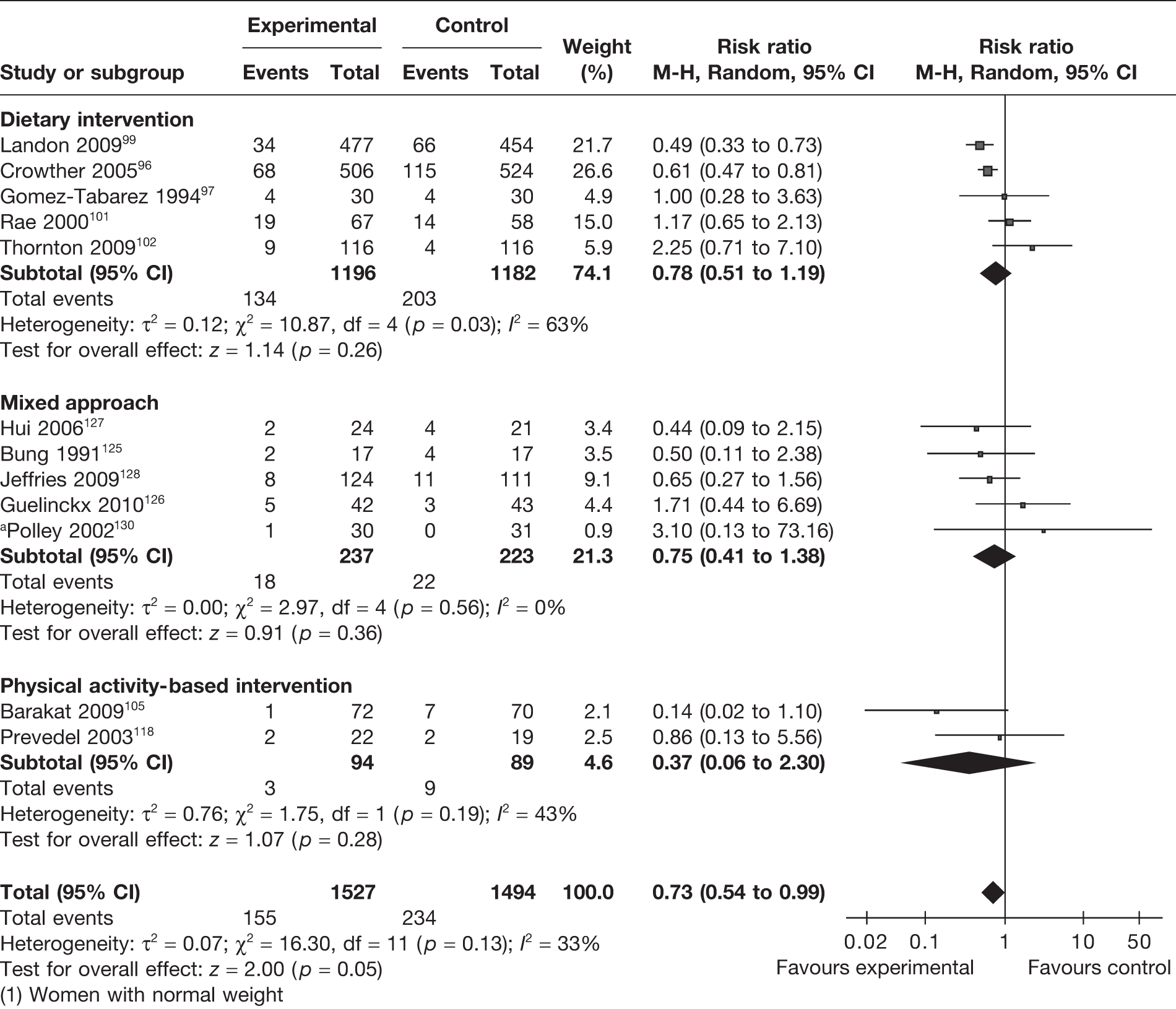

Large for gestational age at birth

We defined LGA infants as those above the 90th centile or with a birthweight > 4 kg. Twelve RCTs96,97,99,101,102,105,118,125–128,130 evaluated this outcome in 3021 newborns. There was a 27% reduction (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.99; p = 0.05) in the risk of having a LGA newborn. The results were not heterogeneous, with an I2 of 33% (p = 0.13). This reduction in the incidence of LGA infants was observed with all interventions in pregnancy (Figure 9). Five RCTs reported the effects of the interventions on obese and overweight women. There was no significant difference in the incidence of LGA infants between the experimental and control groups of obese and overweight women (RR 1.32, 95% CI 0.55 to 3.16; p = 0.54; I2 = 78%).

FIGURE 9.

Effect of weight management interventions on the incidence of LGA infants. a, Women with normal weight.

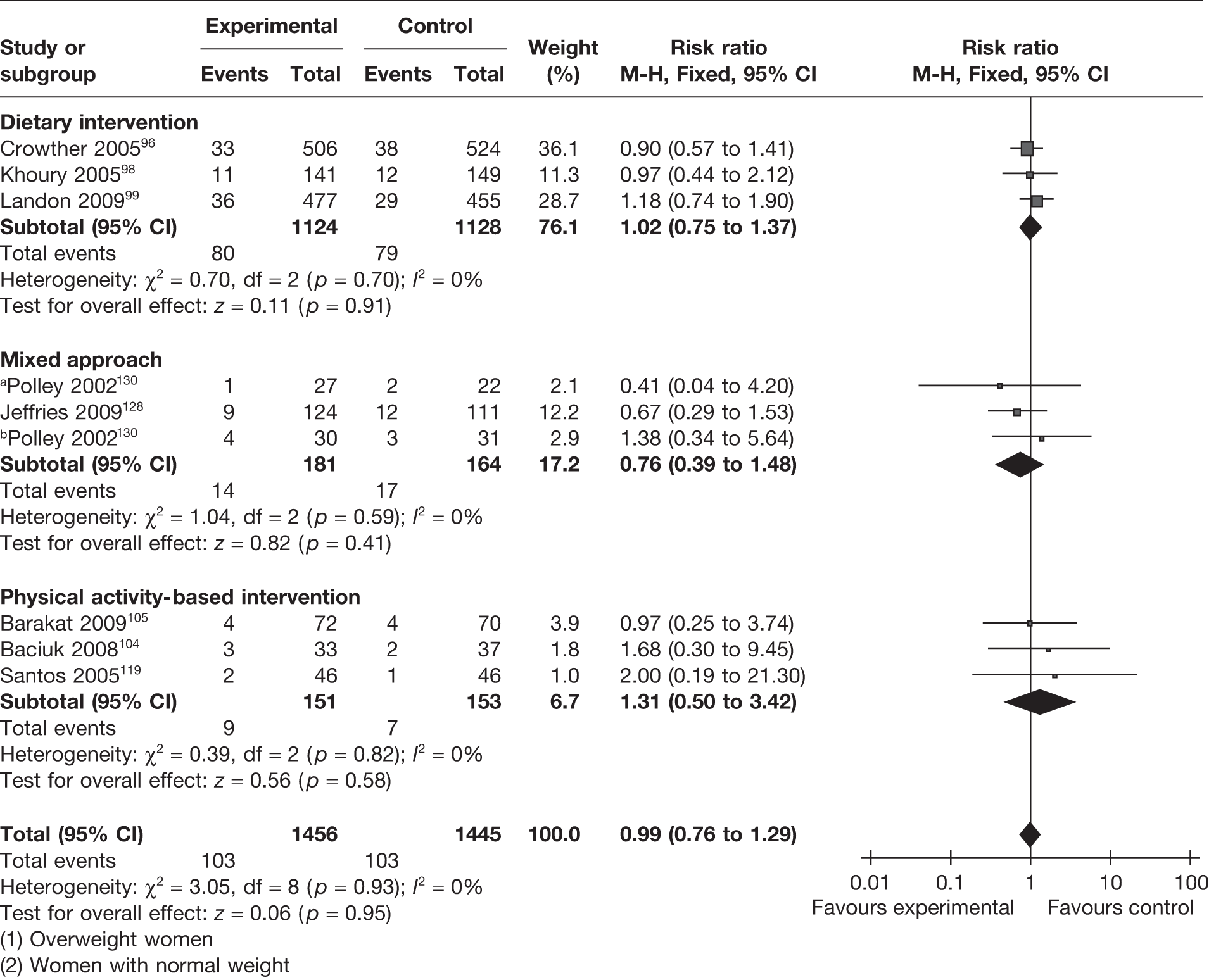

Small for gestational age at birth

Small-for-gestational-age newborns were defined as those with a birthweight below the 10th centile or < 2.5 kg. This outcome served the dual purpose of assessment of the beneficial effect of the intervention and assessment of any adverse effect of the intervention on fetal weight. Eight RCTs96,98,99,104,105,119,128,130 (2901 newborns) evaluated the effectiveness of the weight management interventions for this outcome. The summary estimate of the RCTs showed no difference in the incidence of SGA infants with a RR of 0.99 (95% CI 0.76 to 1.29). The studies were homogeneous. The effect was consistently observed with all three interventions (Figure 10).

FIGURE 10.

Effect of weight management interventions on the incidence of SGA infants. a, Overweight women. b, Women with normal weight.

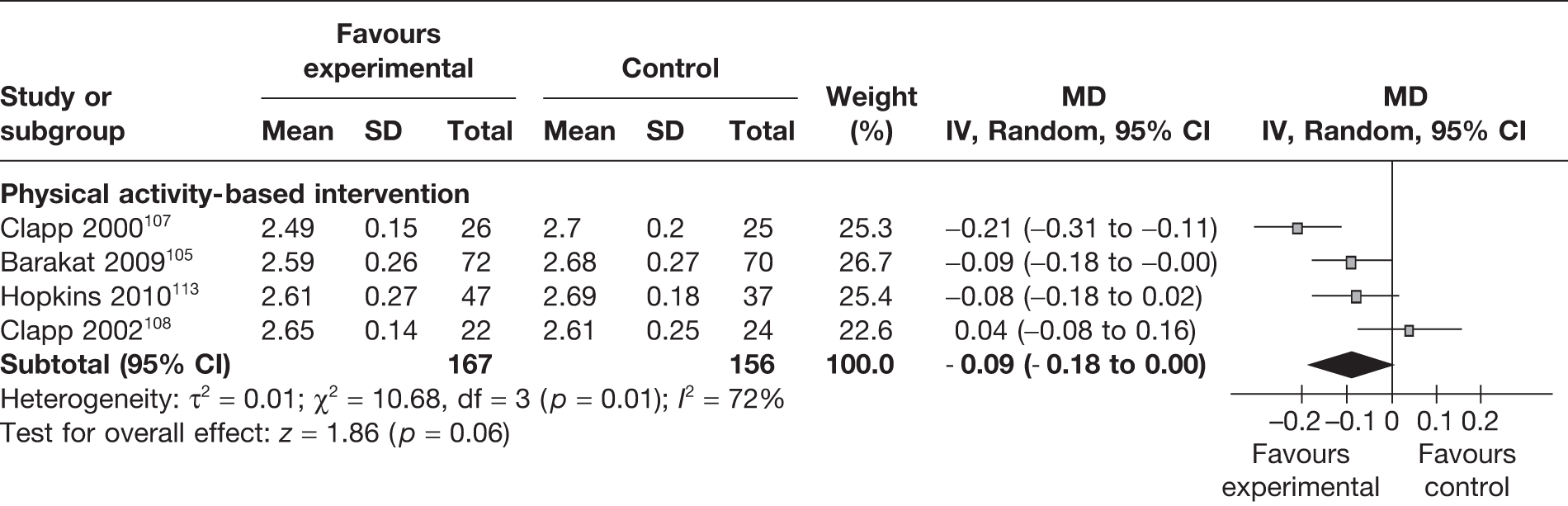

Ponderal index

The ponderal index for newborns assesses the relationship between the weight of the newborn and its length (kg/m3). Four RCTs105,107,108,113 (333 newborns) evaluated the effect of the weight management interventions on the ponderal index. The summary estimate of the trials showed no significant difference in ponderal index of the newborns between the intervention and the control groups, with a MD of –0.09 kg/m3 (95% CI –0.18 to 0.00 kg/m3, I2 = 72%) (Figure 11).

FIGURE 11.

Effect of weight management interventions on ponderal index. SD, standard deviation.

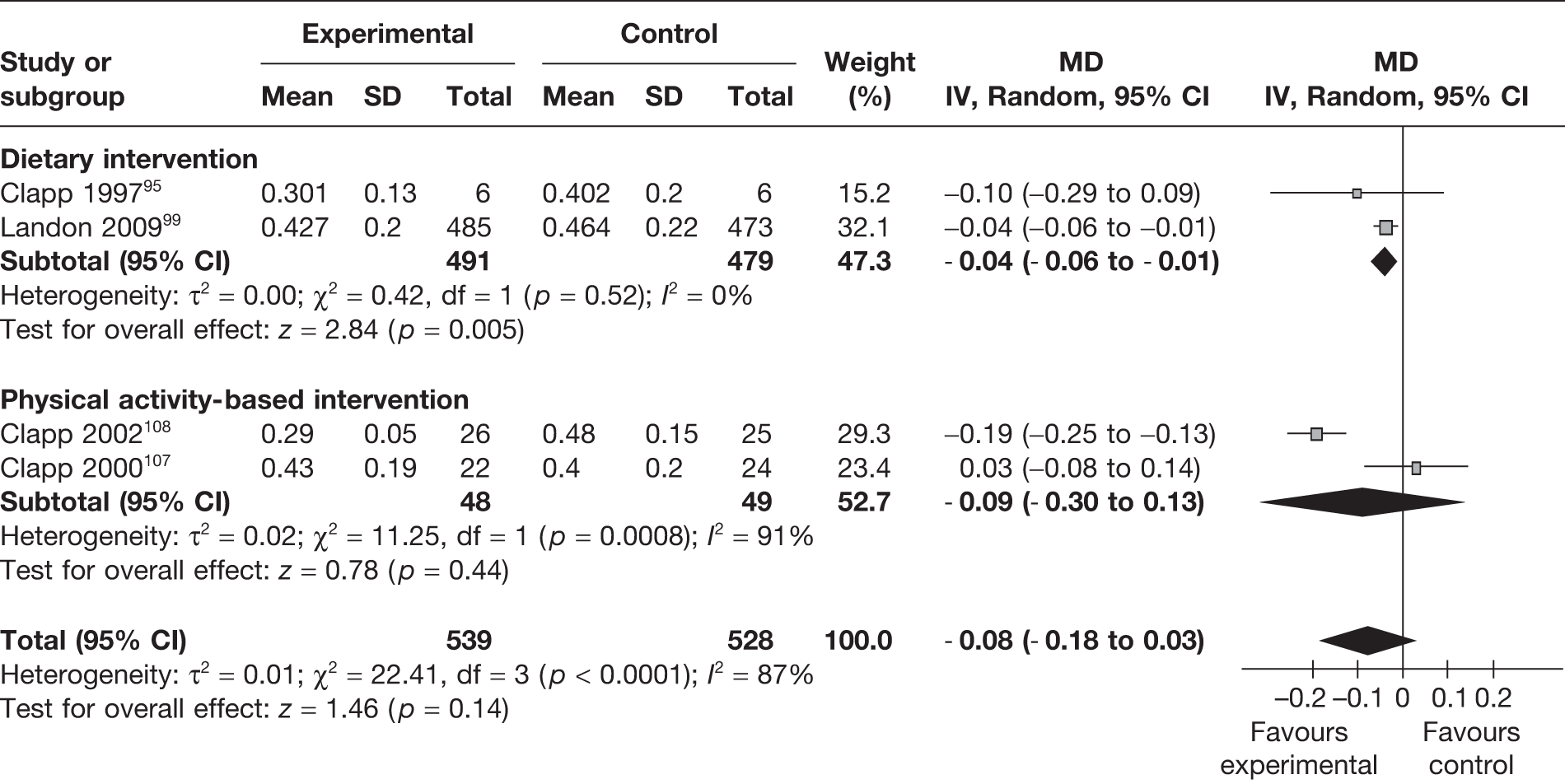

Fetal fat mass

Fetal fat mass in kilograms was reported in four trials. 95,99,107,108 Dietary interventions resulted in a significant reduction in fetal fat mass in the intervention group, with a MD of –0.04 kg (95% CI –0.06 kg to –0.01 kg; p = 0.005; I2 = 0%) (Figure 12).

FIGURE 12.

Effect of weight management interventions on fetal fat mass. SD, standard deviation.

Effect of the interventions on obstetric maternal outcomes

Gestational diabetes mellitus

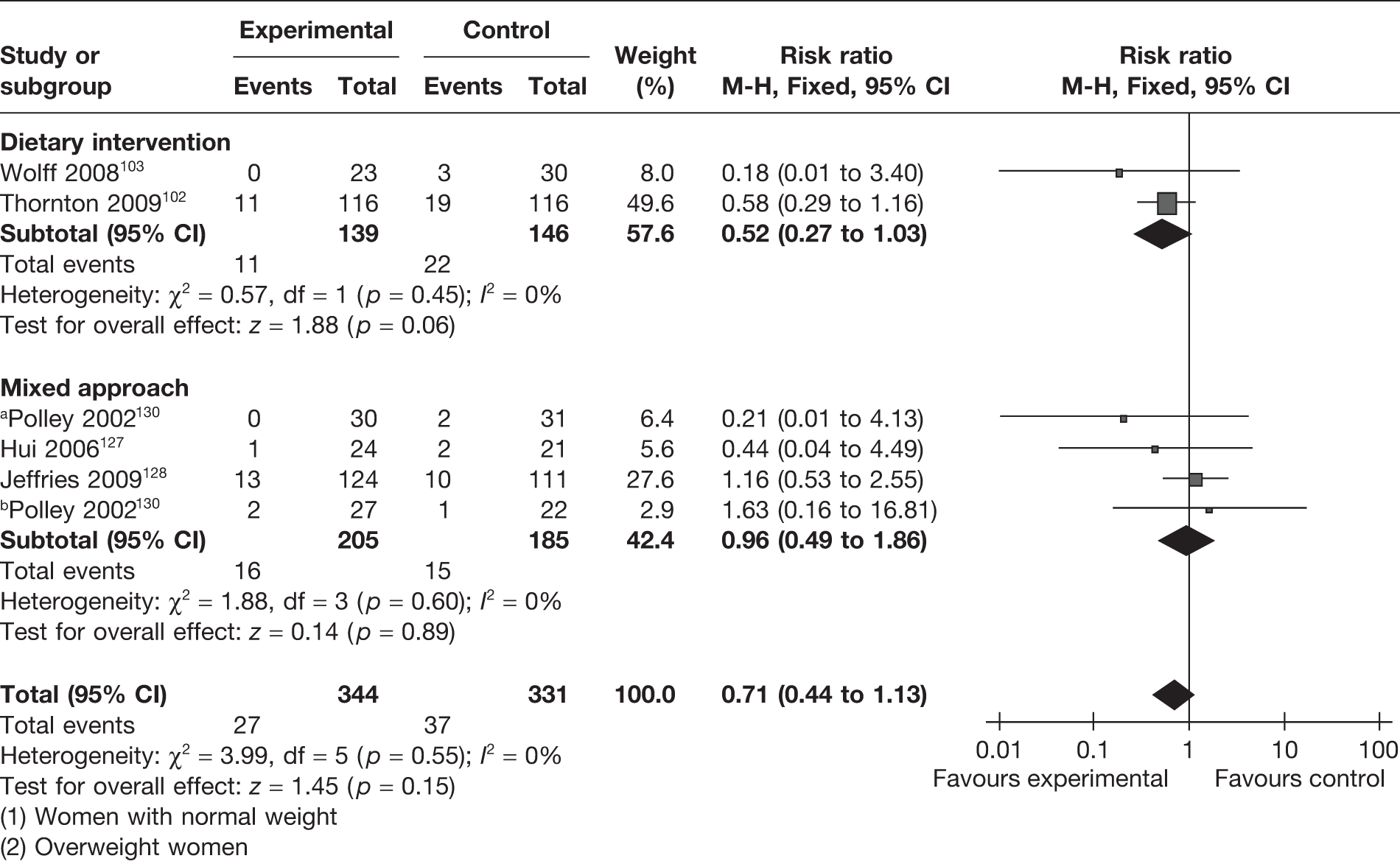

Five RCTs (involving 675 women) reported on the effect of weight management interventions on gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). Three studies included only obese or overweight pregnant women for the evaluation of a dietary intervention (two RCTs102,103) and a mixed approach-based intervention (one RCT130). There was an overall reduction in the incidence of GDM of 29% (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.13; p = 0.15), which was not statistically significant (Figure 13). Weight management interventions in obese and overweight women showed a reduction of 42% (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.09; p = 0.09). The findings were homogeneous (I2 =0) across studies and did not reach statistical significance.

FIGURE 13.

Effect of weight management interventions on GDM. a, Women with normal weight. b, Overweight women.

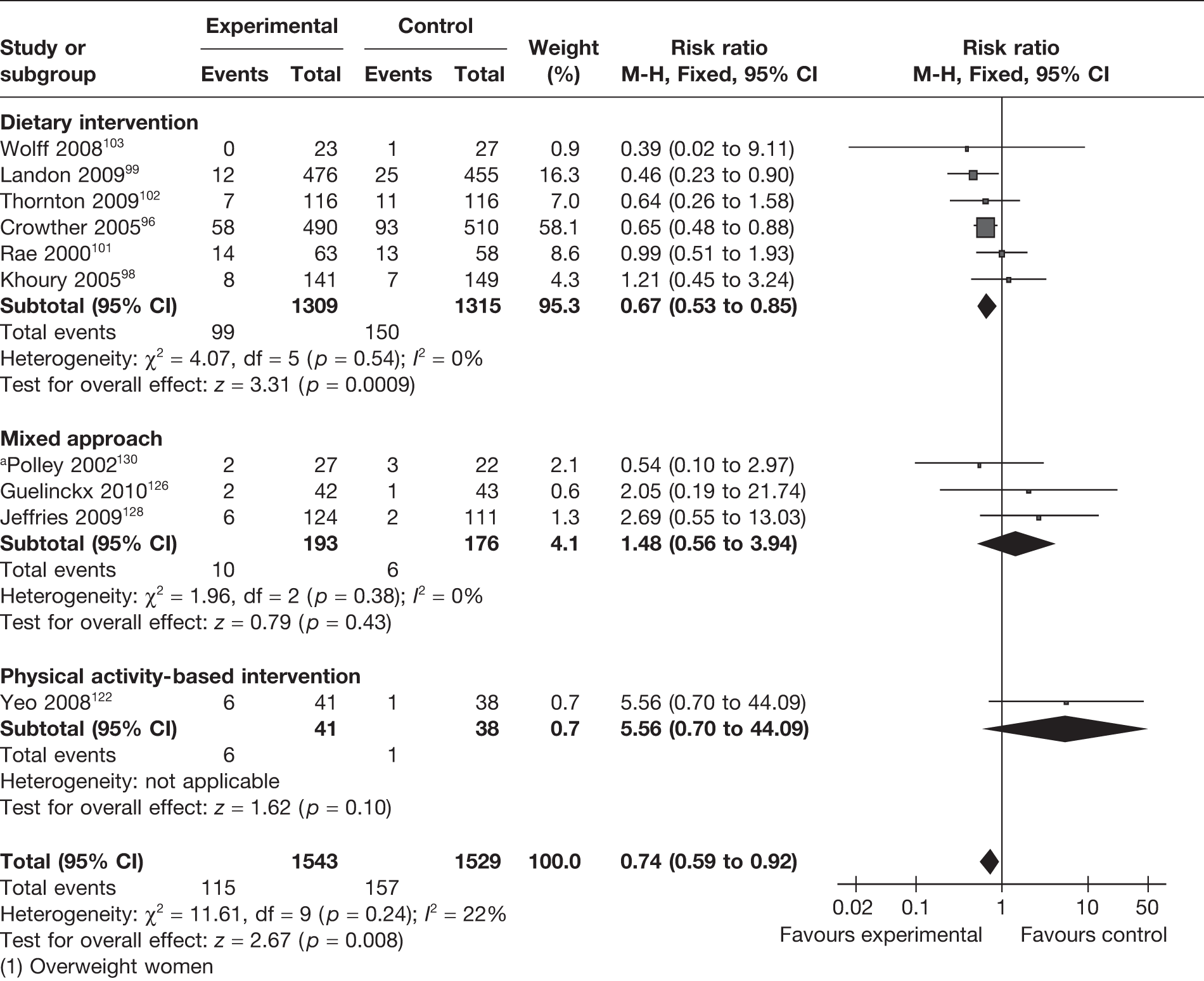

Pre-eclampsia

Ten studies96,98,99,101–103,122,126,128,130 (involving 3072 women) reported the effect of weight management interventions on the incidence of pre-eclampsia. There was an overall statistically significant reduction in pre-eclampsia of 26% (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.92; p = 0.008; I2 = 22%). The largest reduction in pre-eclampsia (33%) was observed with dietary intervention (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.85; p = 0.0009) with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0). A similar effect was not observed with physical activity-based intervention or a mixed approach (Figure 14). Six studies included only obese and overweight women and showed a significant reduction in pre-eclampsia with the interventions (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.97; p = 0.04; I2 = 0).

FIGURE 14.

Effect of weight management interventions on the incidence of pre-eclampsia. a, Overweight women.

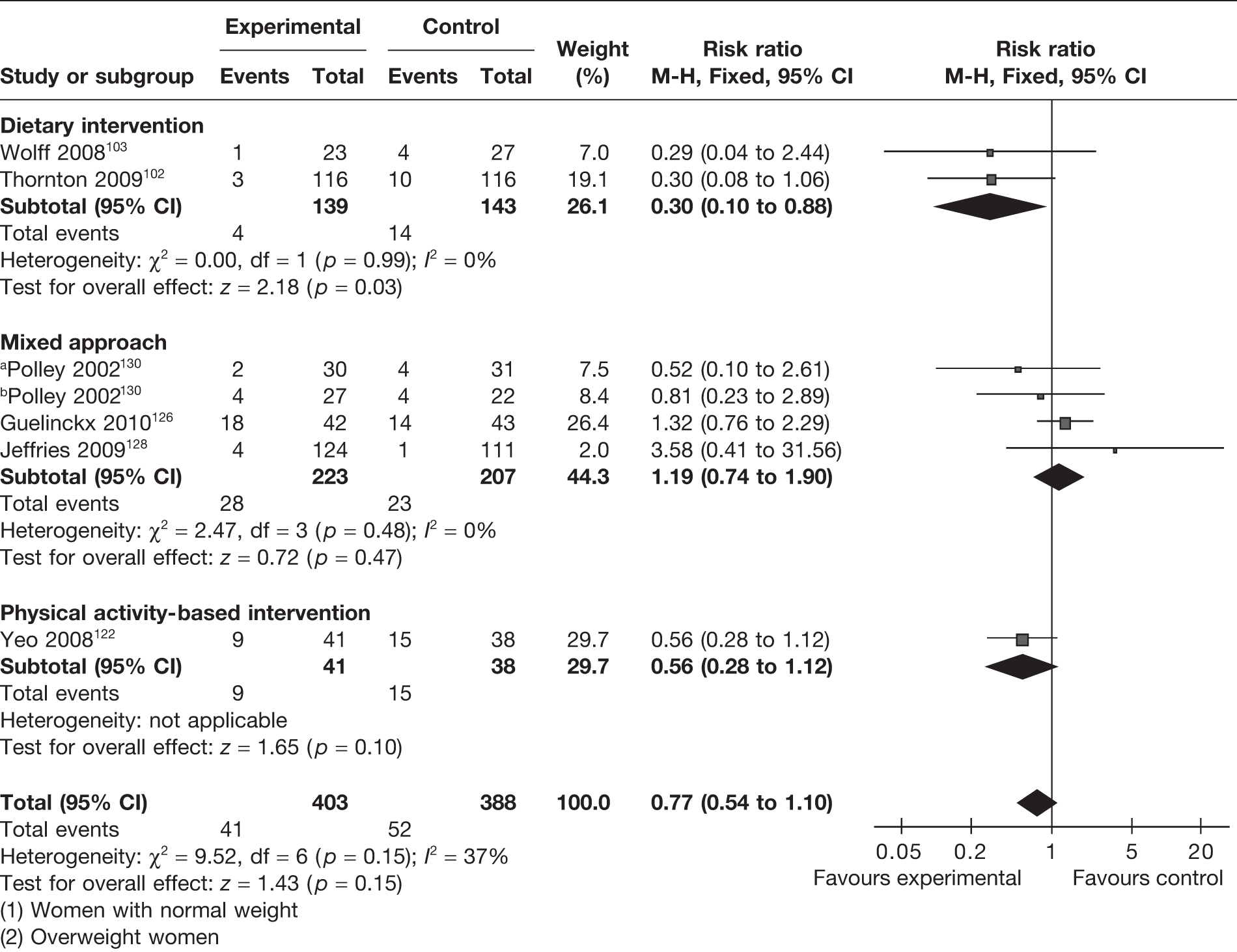

Gestational hypertension

Gestational hypertension was evaluated as an outcome in six RCTs. 102,103,122,126,128,130 There was a reduction in gestational hypertension with interventions, which was not statistically significant (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.1; I2 = 37%) (Figure 15). Dietary intervention (two RCTs)102,103 in pregnancy showed the greatest benefit by reducing gestational hypertension by 70% (RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.88; p = 0.03), with homogeneity between the studies (I2 = 0). Both of the studies on dietary intervention were undertaken in obese and overweight women. The four studies on obese and overweight women102,103,126,130 showed a reduction in gestational hypertension incidence that was not significant (RR 0.70, 95% 0.30 to 1.16; p = 0.4).

FIGURE 15.

Effect of weight management interventions on the incidence of gestational hypertension. a, Women with normal weight. b, Overweight women.

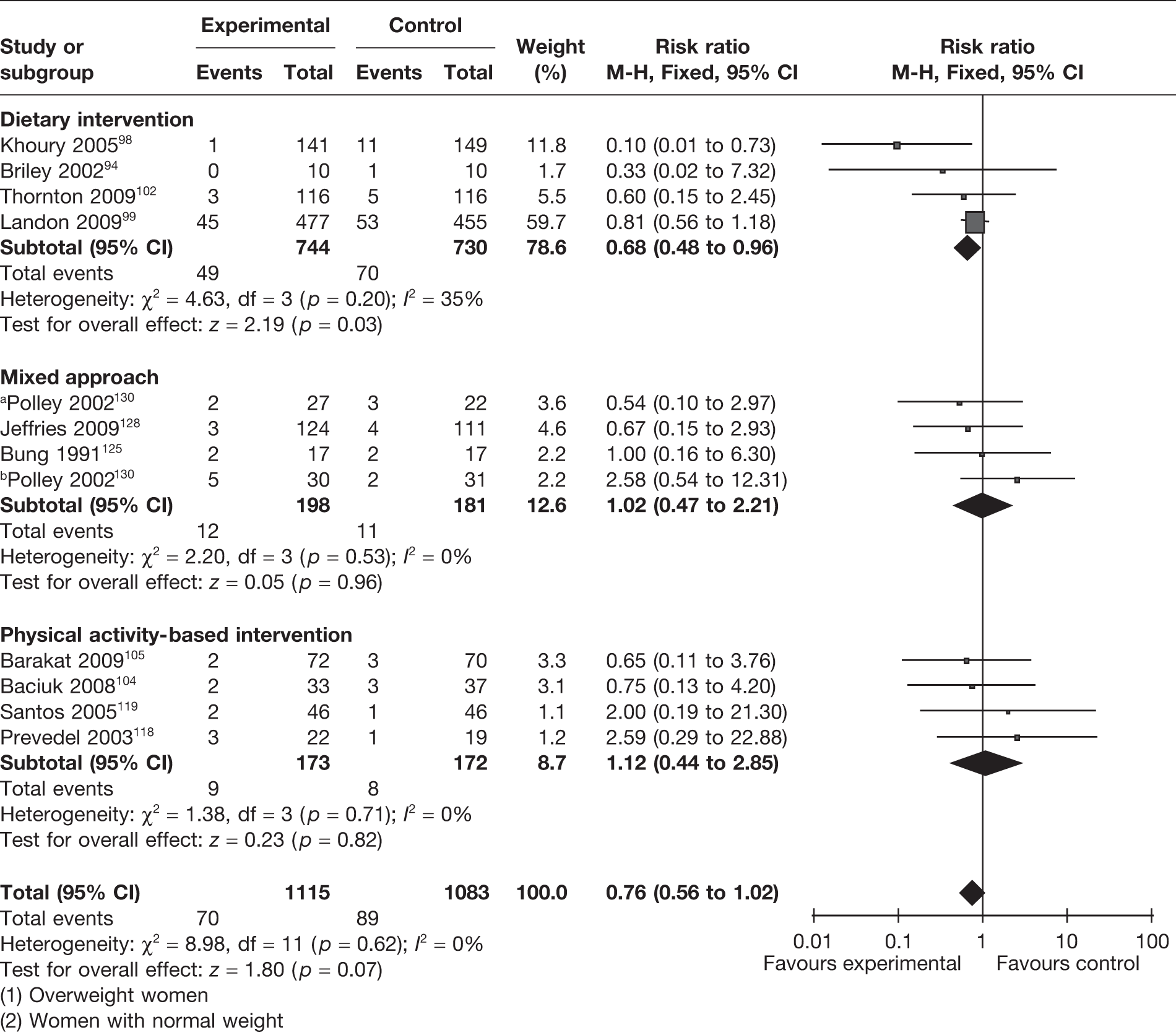

Preterm delivery

Eleven RCTs (involving 2198 women)94,98,99,102,104,105,118,119,125,128,130 evaluated the effectiveness of weight management interventions in pregnancy on preterm delivery before 37 weeks of gestation. There was no overall difference in the rates of preterm births between the two groups, with a RR of 0.76 (95% CI 0.56 to 1.02) (Figure 16). The studies were homogeneous (I2 = 0%). The four RCTs94,98,99,102 that evaluated a dietary intervention (n = 1474) showed a significant reduction in preterm births of 32% (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.48 to 0.96; p = 0.03; I2 = 35%). Four RCTs99,102,119,130 (involving 1305 women) including obese and overweight women showed a reduction in preterm births that was not statistically significant (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.13; p = 0.21, I2 = 0%).

FIGURE 16.

Effect of weight management interventions on preterm delivery before 37 weeks of gestation. a, Overweight women. b, Women with normal weight.

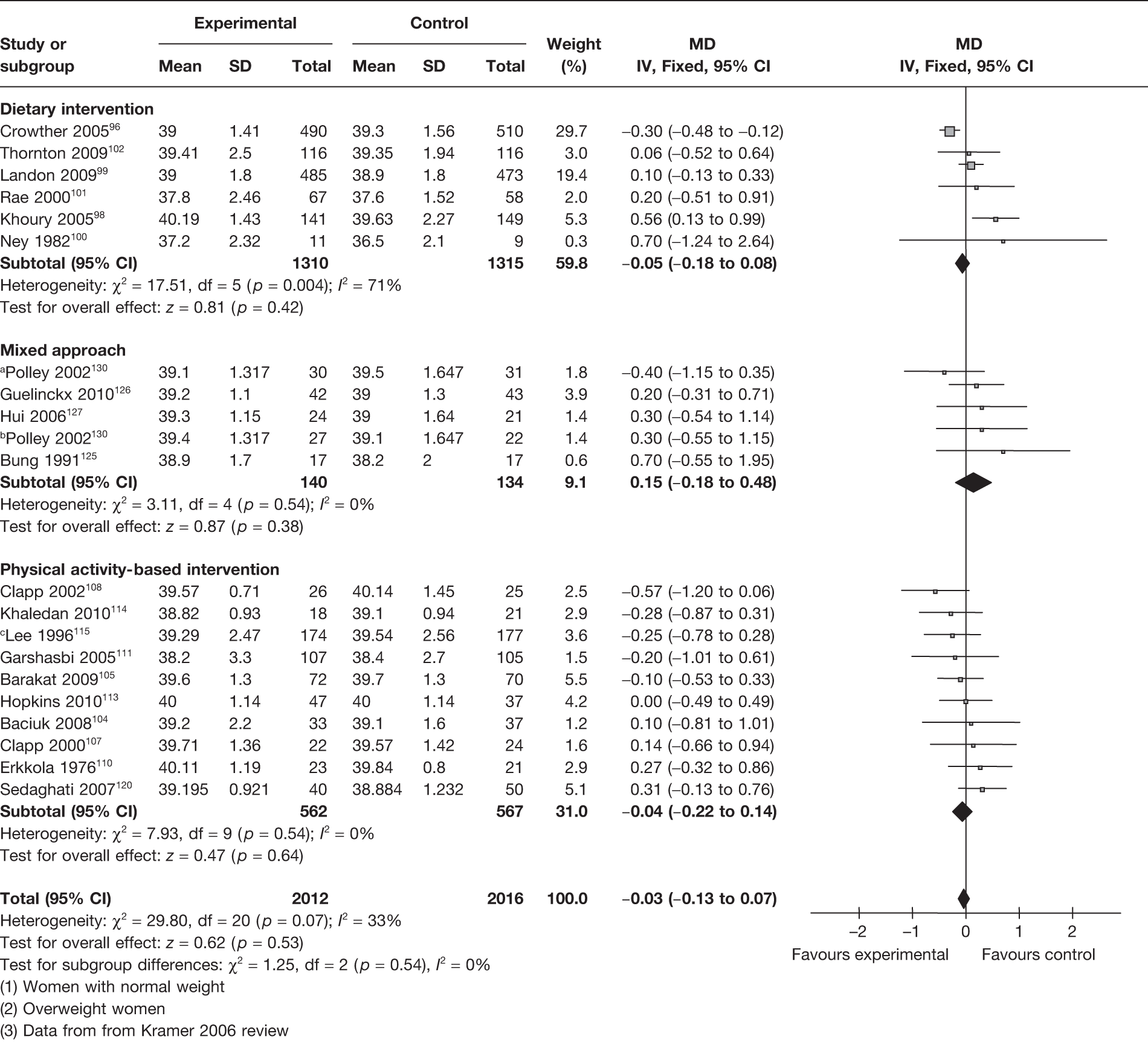

Gestational age at delivery

A total of 20 RCTs96,98–105,107,108,110,111,113–116,120,125–127 (4028 women) evaluated the effect of the interventions on the gestational age at delivery. There were no significant differences in the gestational age at delivery between the intervention and control groups, with a MD of 0.03 weeks (95% CI –0.13 weeks to 0.07 weeks; I2 = 33%) (Figure 17). There was low heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 33%). Dietary intervention (six RCTs, involving 2625 women) resulted in a MD in the gestational age at delivery of 0.05 weeks (95% CI –0.18 weeks to 0.08 weeks; p = 0.42; I2 = 71%).

FIGURE 17.

Effect of weight management interventions on gestational age at delivery. SD, standard deviation. a, Women with normal weight. b, Overweight women. c, Data from Kramer 2006 review.

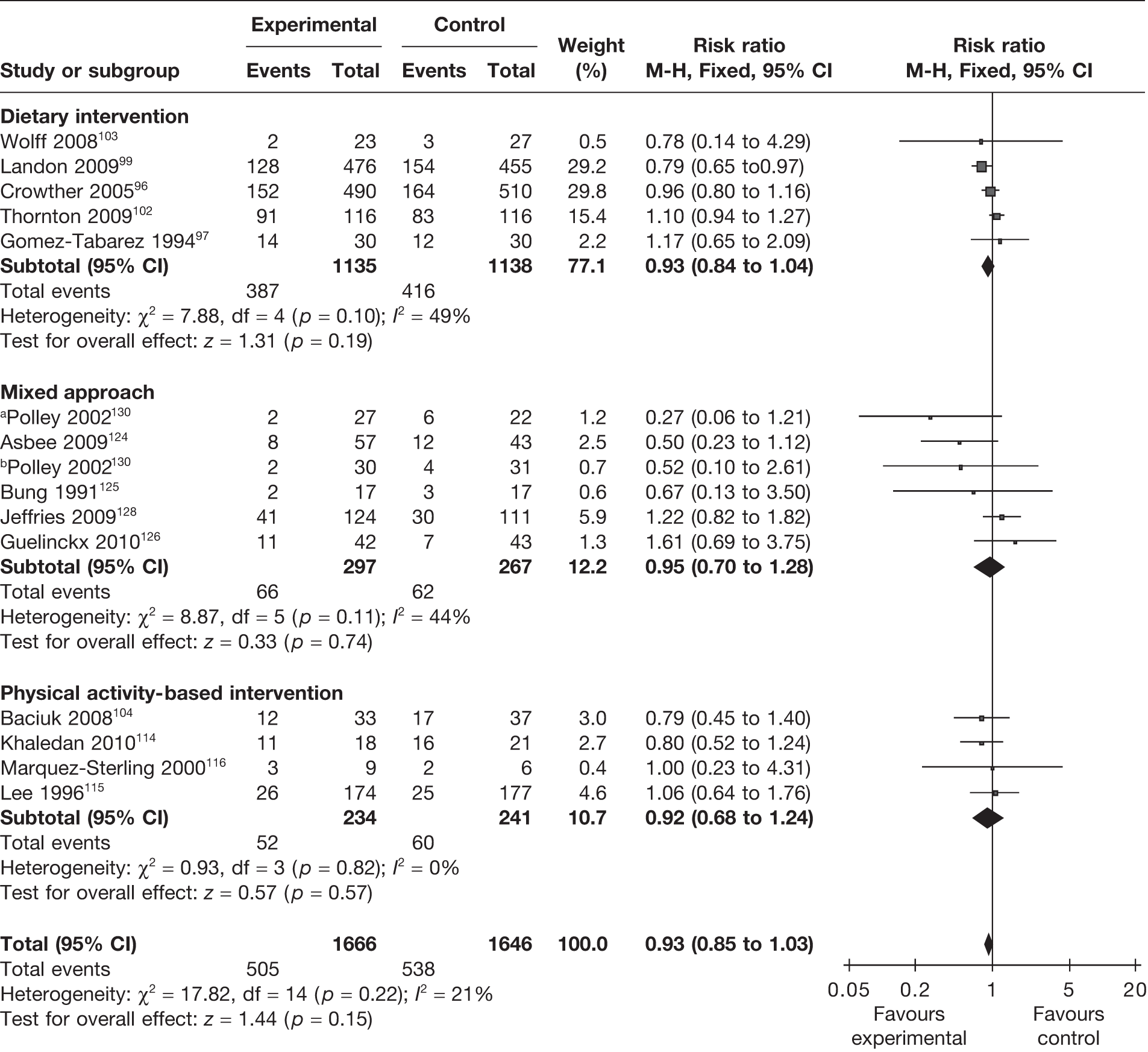

Mode of delivery

The rate of caesarean section was evaluated as an outcome in 14 RCTs96,97,99,102–104,114–116,124–126,128,130 involving 3312 women. This included five trials96,97,99,102,103 on dietary interventions, four104,114–116 on physical activity-based interventions and five124–126,128,130 on a mixed approach. There were no differences between the experimental and the control groups with any intervention. The summary estimate for caesarean section was a RR of 0.93 (95% CI 0.85 to 1.03; p = 0.15) (Figure 18). There was no significant heterogeneity between the groups (p = 0.22, I2 = 21%). A total of 6 of the 14 RCTs involved obese and overweight women and showed no change in the rate of caesarean section (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.28; I2 = 61%).

FIGURE 18.

Effect of weight management interventions on rate of caesarean section. a, Overweight women. b, Women with normal weight.

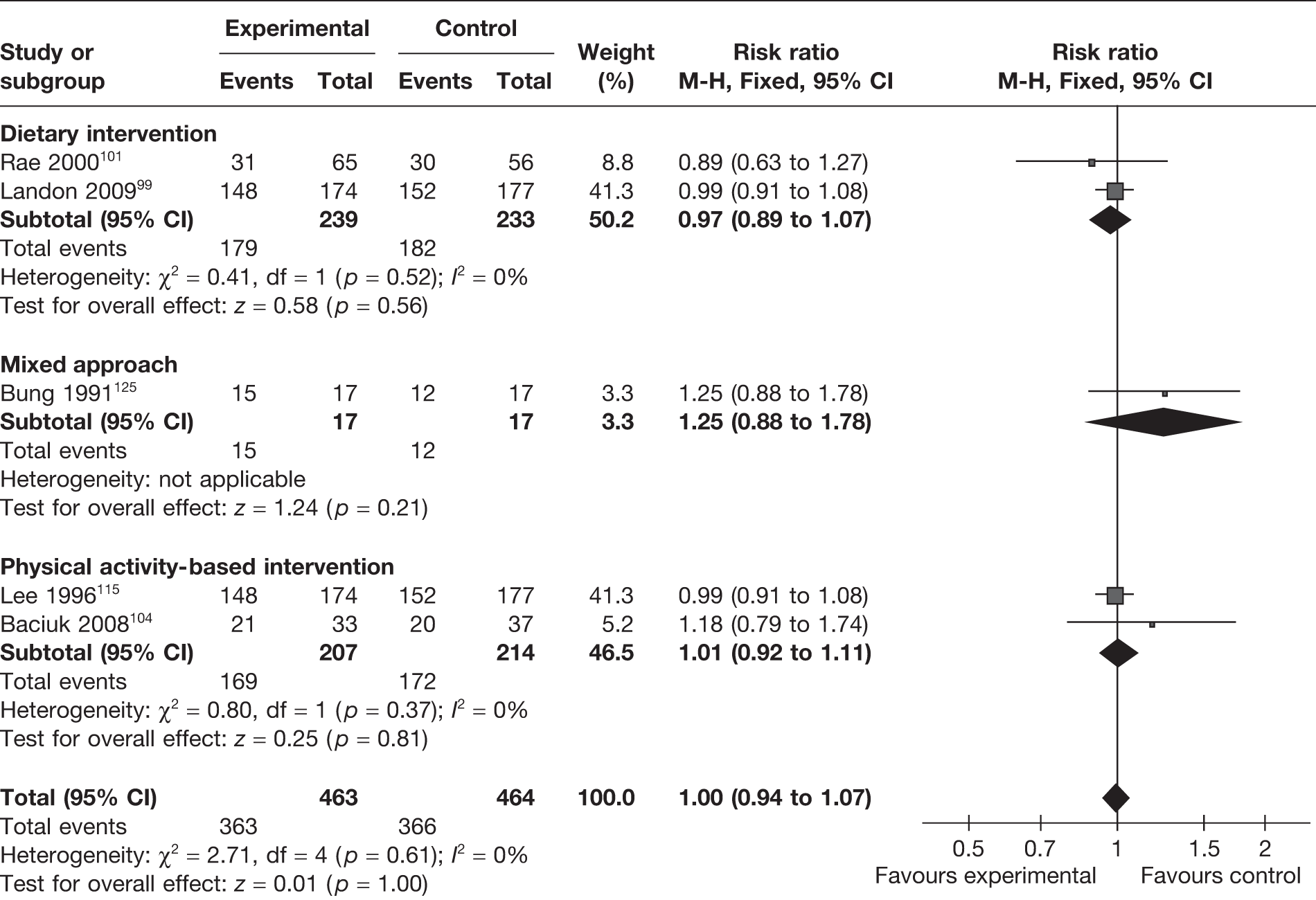

The rate of vaginal delivery was evaluated in five RCTs. 99,101,104,115,125 There was no difference in the rate of vaginal delivery with any intervention. The pooled estimate showed a RR of 1.00 (95% CI 0.94 to 1.07; p = 1). The studies were homogeneous (Figure 19). The effect of dietary intervention on vaginal delivery in obese and overweight mothers was studied in two RCTs. 99,101 The rate of vaginal delivery did not change with the intervention, with a RR of 0.97 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.07; I2 = 0).

FIGURE 19.

Effect of weight management interventions on rate of vaginal delivery.

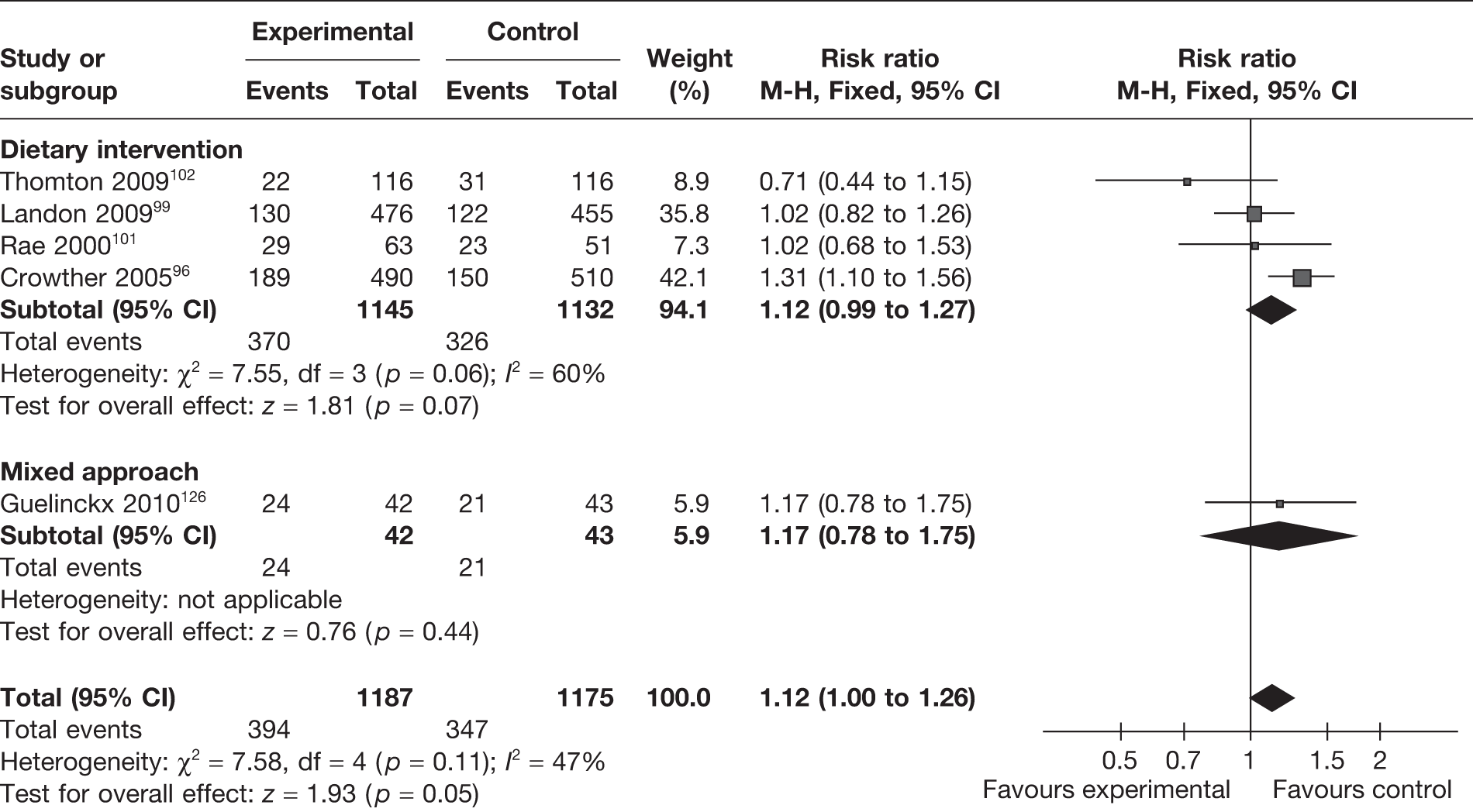

Induction of labour

The effect of weight management interventions in pregnancy on induction of labour was studied in five RCTs (involving 2362 women). 96,99,101,102,126 There was a slight increase in induction of labour in the intervention arm that was not significantly different from that of the control arm (RR 1.12, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.26; p = 0.05; I2 = 47%) (Figure 20). Obese and overweight women only were included in four RCTs99,101,102,126 (involving 1362 women); in these studies there was no difference in the rate of induction of labour between the intervention and control groups (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.16; I2 = 0%).

FIGURE 20.

Effect of weight management interventions on induction of labour.

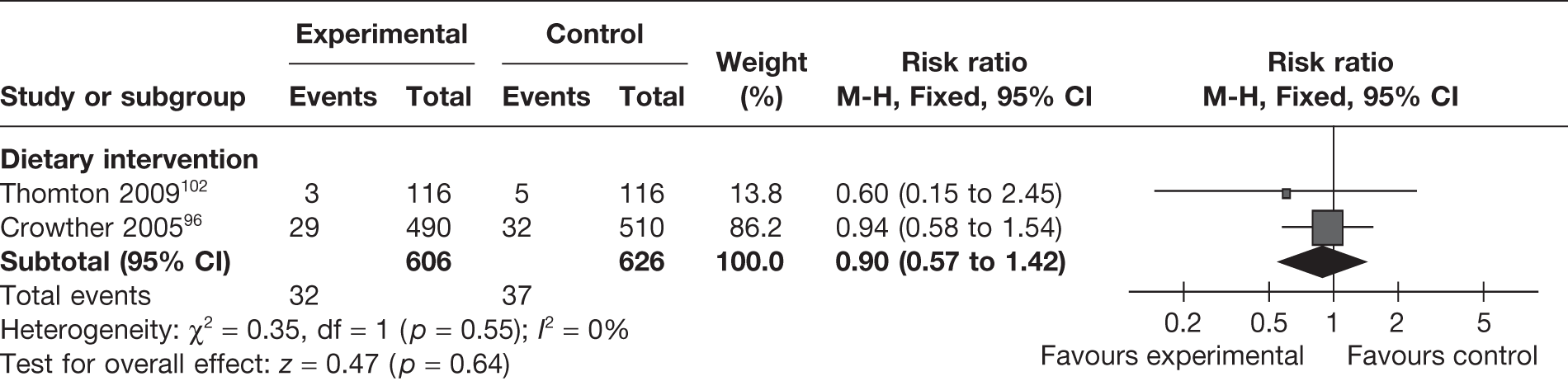

Post-partum haemorrhage

Two RCTs96,102 (n = 1232) compared the rates of post-partum haemorrhage between the weight management intervention group and the control group. The pooled estimate of the studies did not show any significant differences between the groups (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.42; I2 = 0%) (Figure 21).

FIGURE 21.

Effect of weight management interventions on post-partum haemorrhage.

Two observational case–control studies77,78 studied the effect of physical activity-based interventions on post-partum haemorrhage and found no difference between the intervention and control groups.

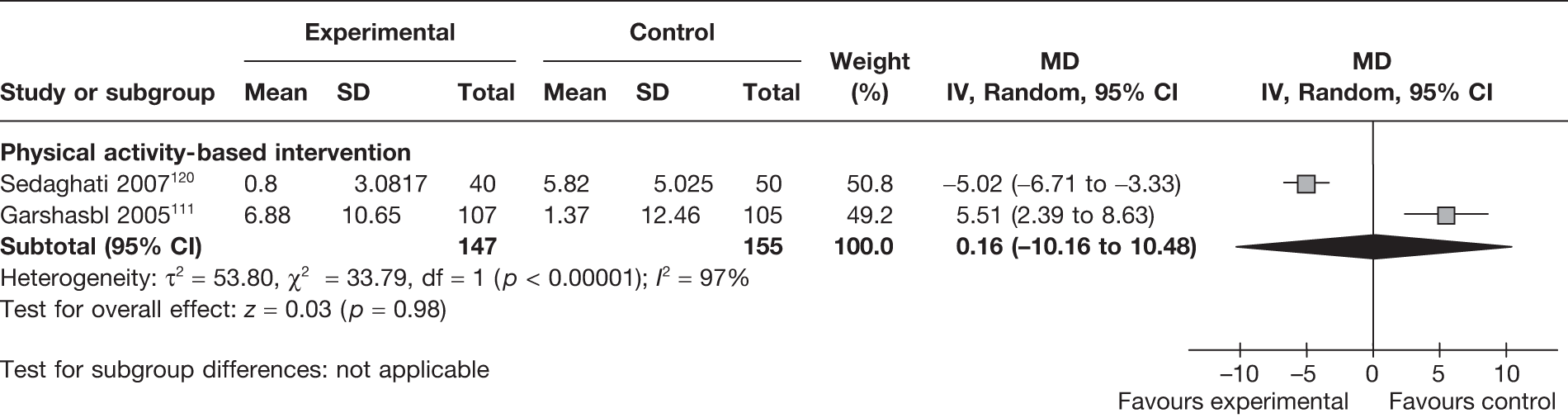

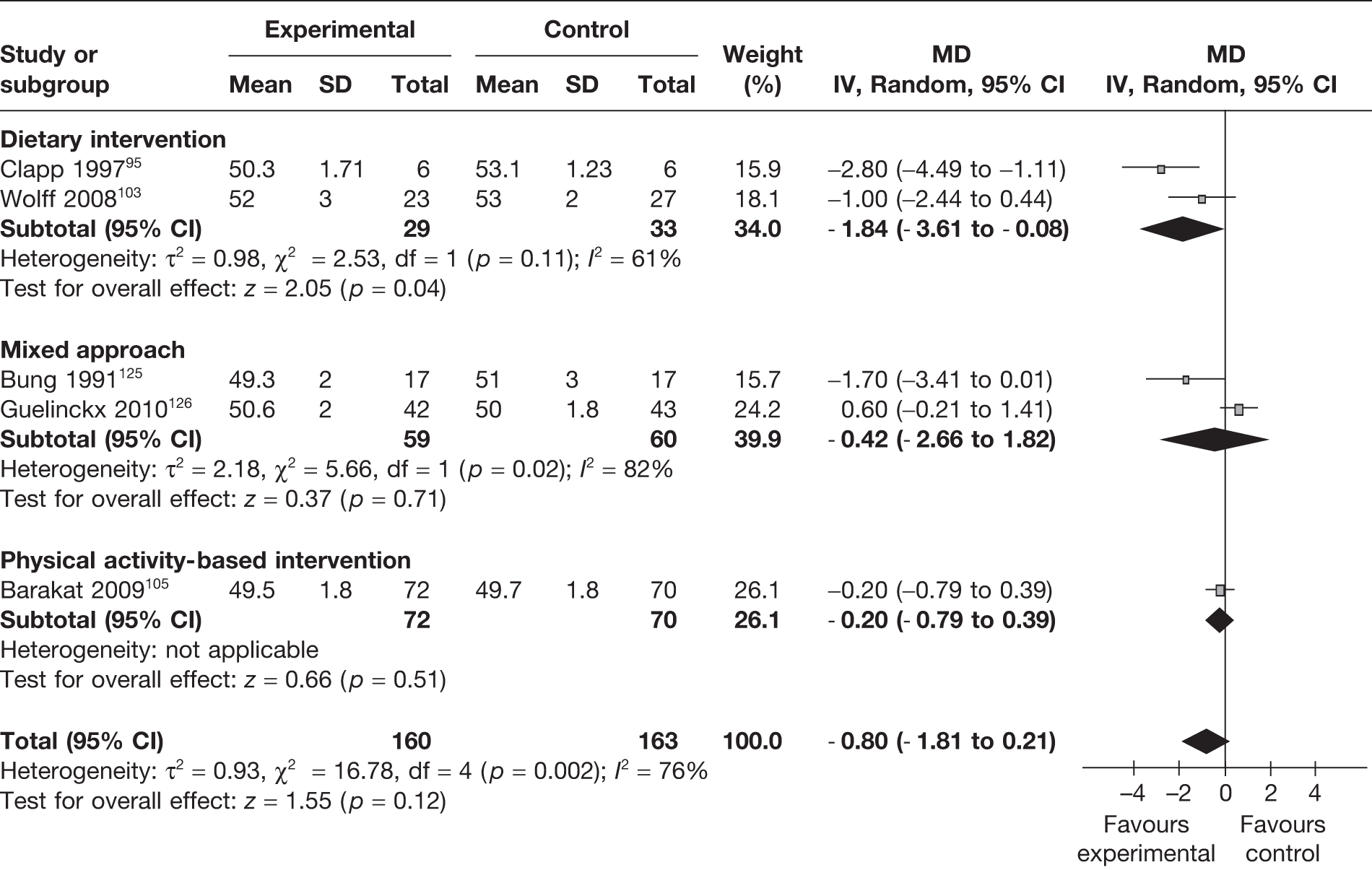

Low back pain

Low back pain was reported as an outcome in two RCTs111,126 (involving 302 women) evaluating physical activity-based interventions. The severity of low back pain was increased in one study111 and decreased in the other study. 120 The pooled estimate did not show any differences in back pain between the two groups (MD 0.16, 95% CI –10.16 to 10.48; I2 = 97%) (Figure 22).

FIGURE 22.

Effect of weight management interventions on low back pain in pregnancy. SD, standard deviation.

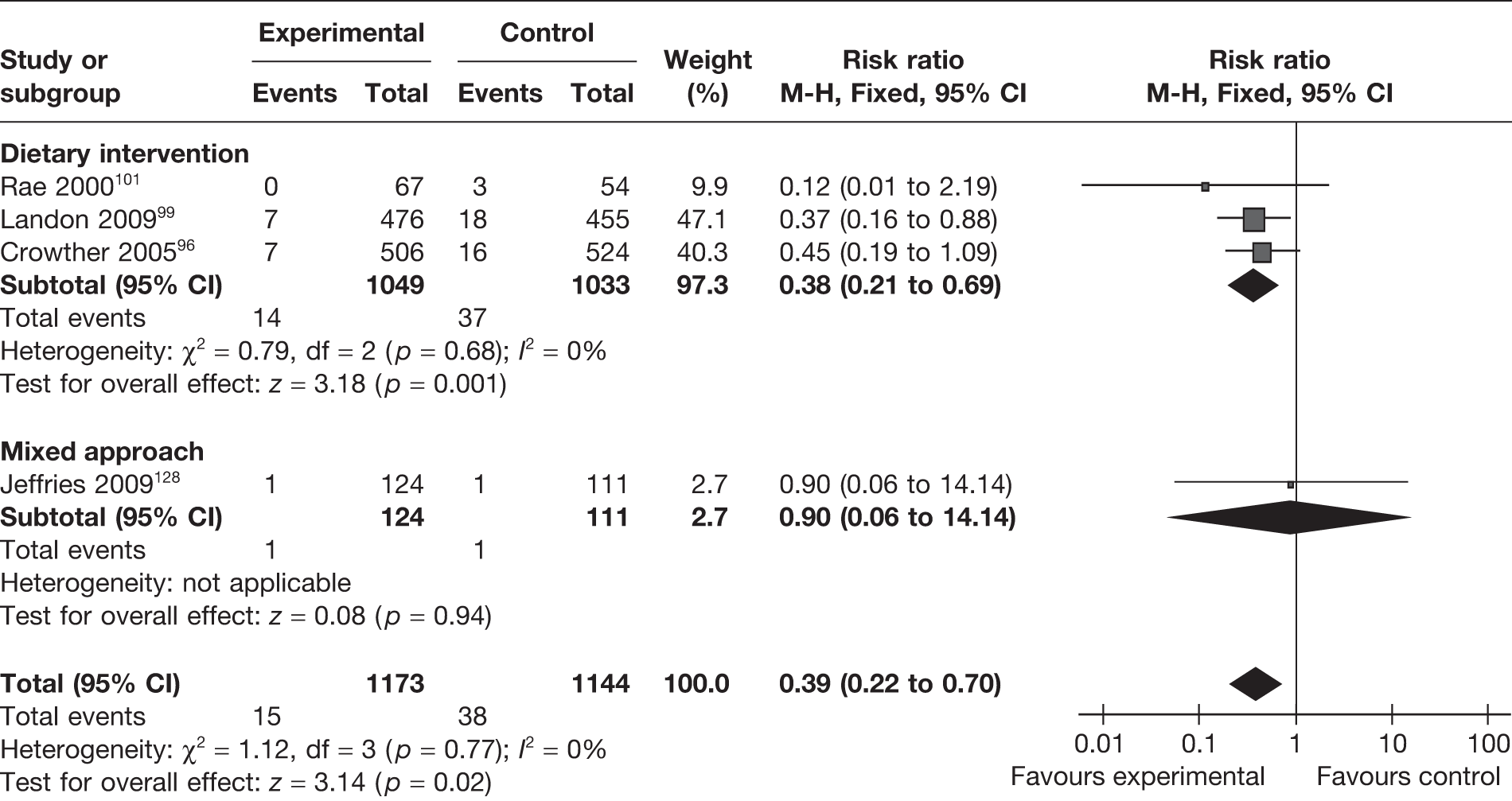

Effect of the interventions on fetal and neonatal morbidity and mortality

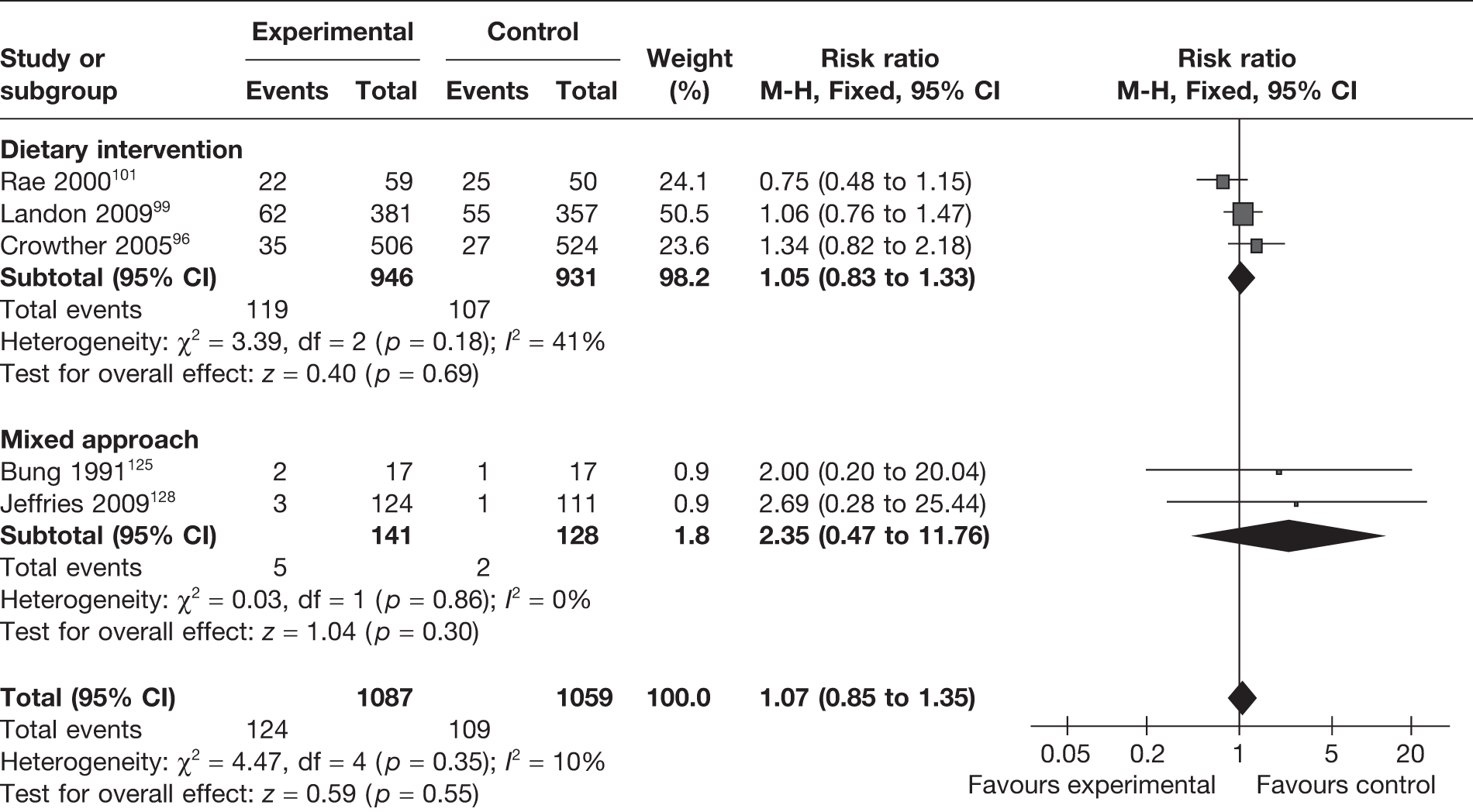

Shoulder dystocia

Four RCTs96,99,101,128 (2317 newborns) evaluated the effect of interventions (three dietary96,99,101 and one mixed128 approach) on the incidence of shoulder dystocia. Overall, there was a 61% reduction in the incidence of shoulder dystocia (RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.70; p = 0.02). The studies were homogeneous (I2 = 0%). The largest proportion of women in the analysis were in the dietary intervention group, which showed a similar effect (Figure 23). This beneficial effect was increased in the population of obese and overweight women (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.74; p = 0.008).

FIGURE 23.

Effect of weight management interventions on shoulder dystocia.

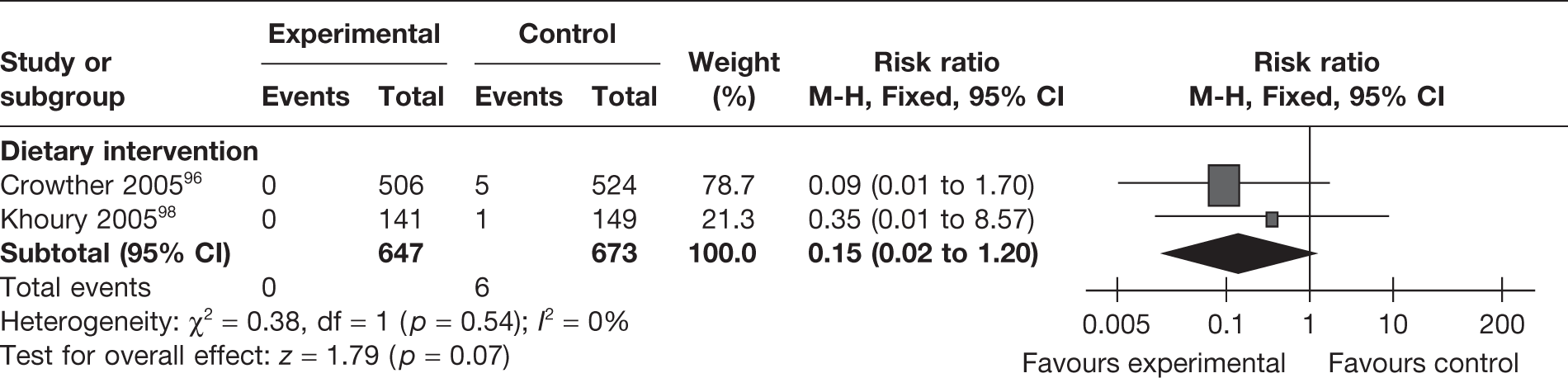

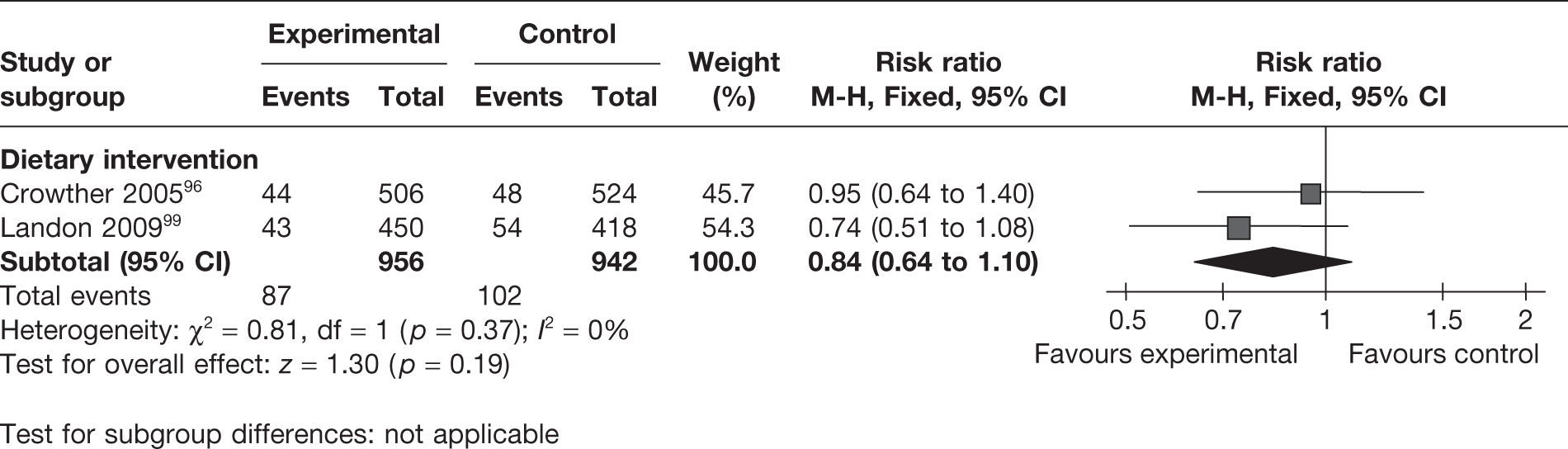

Intrauterine death

Two RCTs96,98 (involving 1320 women) evaluated the effect of dietary intervention on stillbirths. There was a reduction in the incidence of intrauterine death, which was not statistically significant (RR 0.15, 95% CI 0.02 to 1.20; p = 0.07; I2 = 0%) (Figure 24).

FIGURE 24.

Effect of weight management interventions on intrauterine death.

One observational cohort study by Perichart et al. 82 evaluated the effect of a dietary intervention compared with no intervention on intrauterine death. There were no significant differences between the groups. This effect was consistent for women with type 2 diabetes [unadjusted odds ratio (OR) 0.96, 95% CI 0.12 to 1.09] or GDM (unadjusted OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.06 to 16.57).

Respiratory distress syndrome

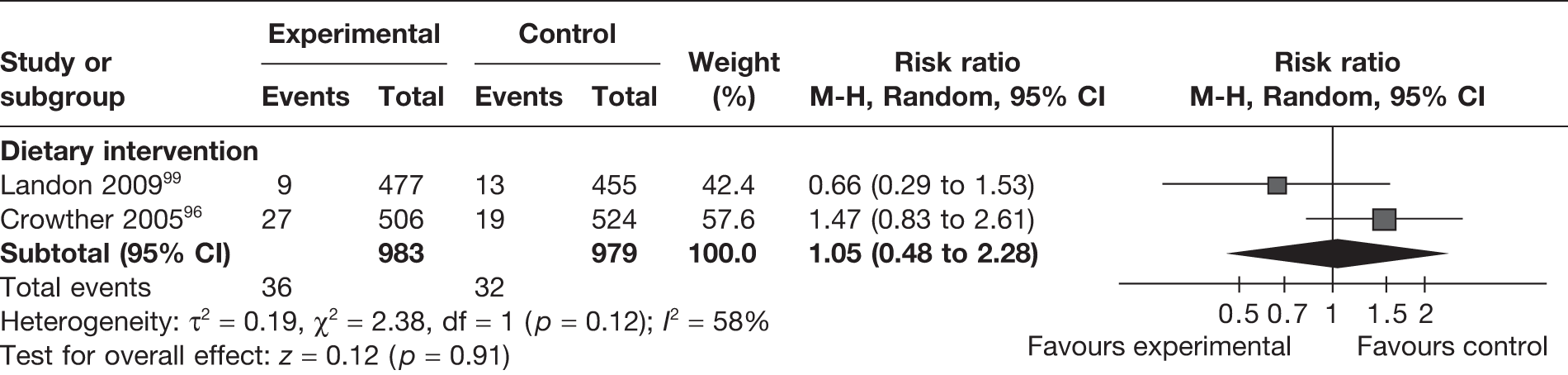

Two RCTs96,99 (involving 1962 women) evaluated respiratory distress syndrome with the newborn in mothers undergoing a weight management intervention in pregnancy. The two studies were on dietary interventions and the pooled estimate did not show a difference between the intervention and control groups (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.48 to 2.28; I2 = 58%) (Figure 25).

FIGURE 25.

Effect of weight management interventions on respiratory distress syndrome.

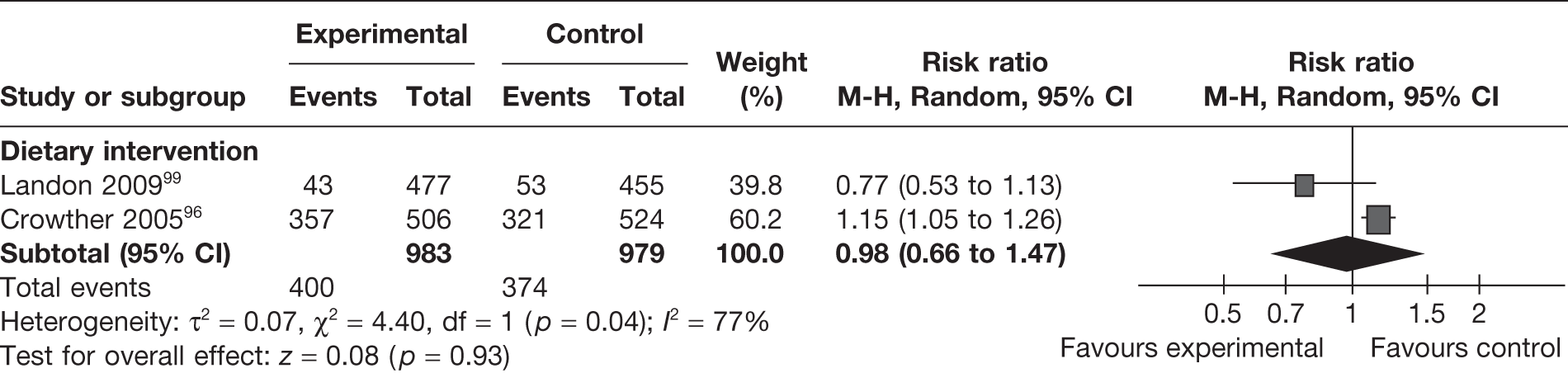

Admission to the neonatal intensive care unit

Admission to NICU was reported as an outcome in two RCTs96,99 (involving 1962 women) evaluating dietary interventions. The studies were heterogeneous (I2 = 77%) and the pooled estimate did not show any difference between the groups (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.47) (Figure 26). One observational study82 evaluating a dietary intervention in pregnancy reported on NICU admission in two groups: women with type 2 diabetes and those with GDM. The reported unadjusted OR was significant only in the case of women with type 2 diabetes (OR 0.21, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.51).

FIGURE 26.

Effect of weight management interventions on admission to NICU.

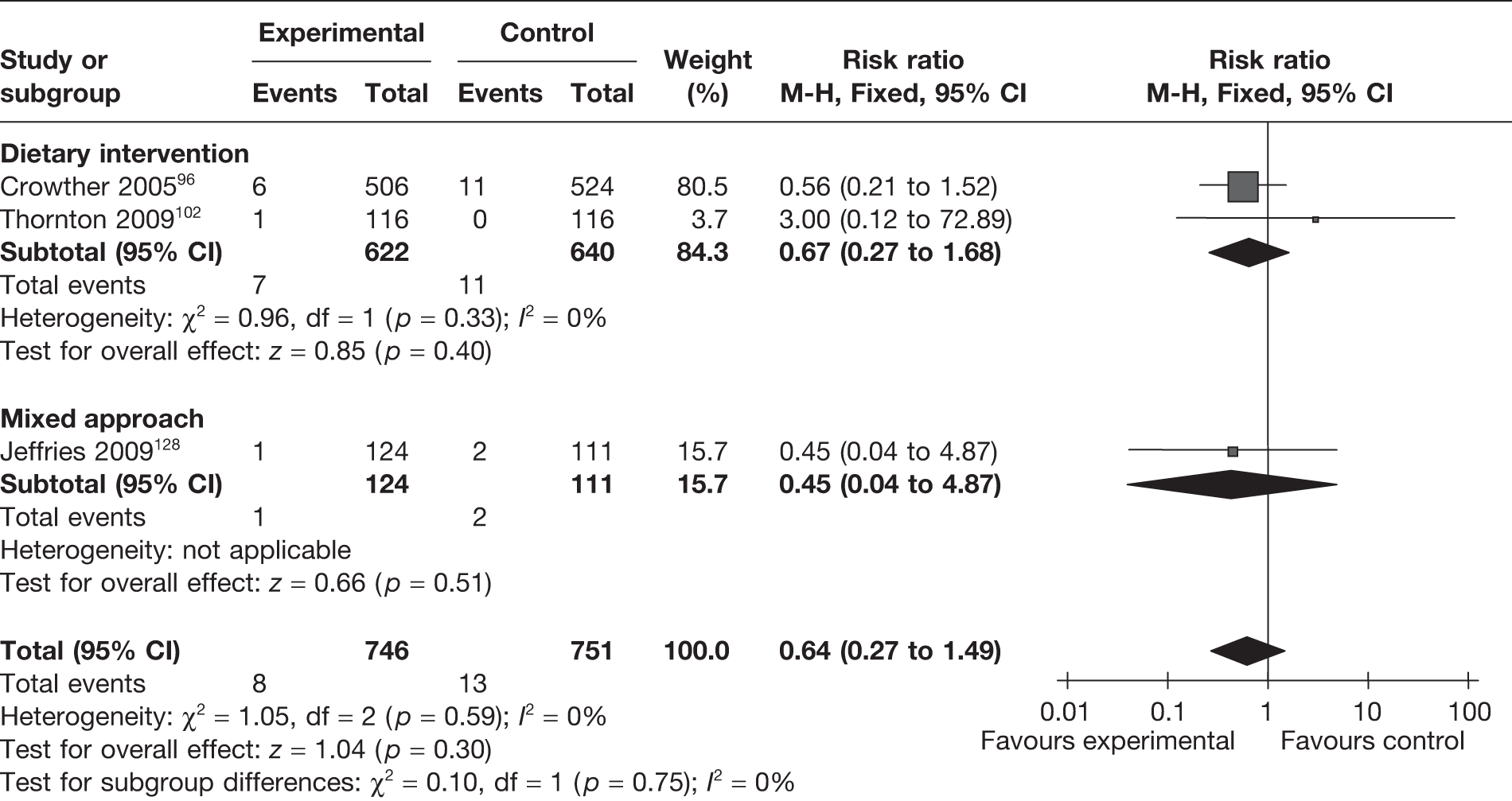

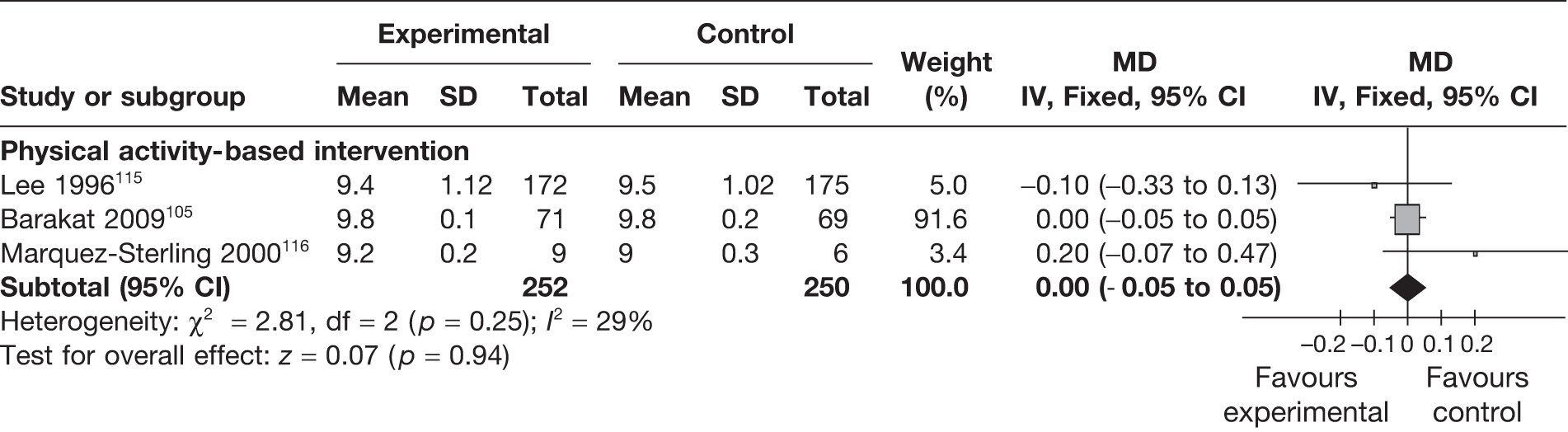

Apgar scores

Apgar scores were evaluated as an outcome in six RCTs96,102,105,115,116,128 studying the effect of weight management interventions in pregnancy. Three studies96,102,128 reported scores of < 7 at 5 minutes and three studies105,115,116 provided the scores at 5 minutes for comparison. There were no differences in the abnormal scores (< 7 at 5 minutes) (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.49; p = 0.3, I2 = 0%; Figure 27) or in the mean scores (MD 0.0, 95% CI –0.05 to 0.05; p = 0.94; Figure 28) between the two groups.

FIGURE 27.

Effect of weight management interventions on abnormal Apgar scores (< 7 at 5 minutes).

FIGURE 28.

Effect of weight management interventions on Apgar scores at 5 minutes. SD, standard deviation.

Infant hypoglycaemia

Hypoglycaemia in the first few days after birth is defined as blood glucose < 40 mg/dl. In preterm infants, repeated blood glucose levels of < 50 mg/dl may be associated with neurodevelopmental delay. Five RCTs96,99,101,125,128 reported the rate of hypoglycaemia among the children of studied mothers. Neither a comprehensive approach nor dietary interventions had any significant influence on hypoglycaemia rate (Figure 29).

FIGURE 29.

Effect of weight management interventions on infant hypoglycaemia.

Infant hyperbilirubinaemia

Two RCTs96,99 evaluated the effect of dietary interventions on the rates of hyperbilirubinaemia in 1898 newborns. The studies were homogeneous. There was a trend towards a reduction in hyperbilirubinaemia with the interventions, which was not significant (Figure 30).

FIGURE 30.

Effect of weight management interventions on infant hyperbilirubinaemia.

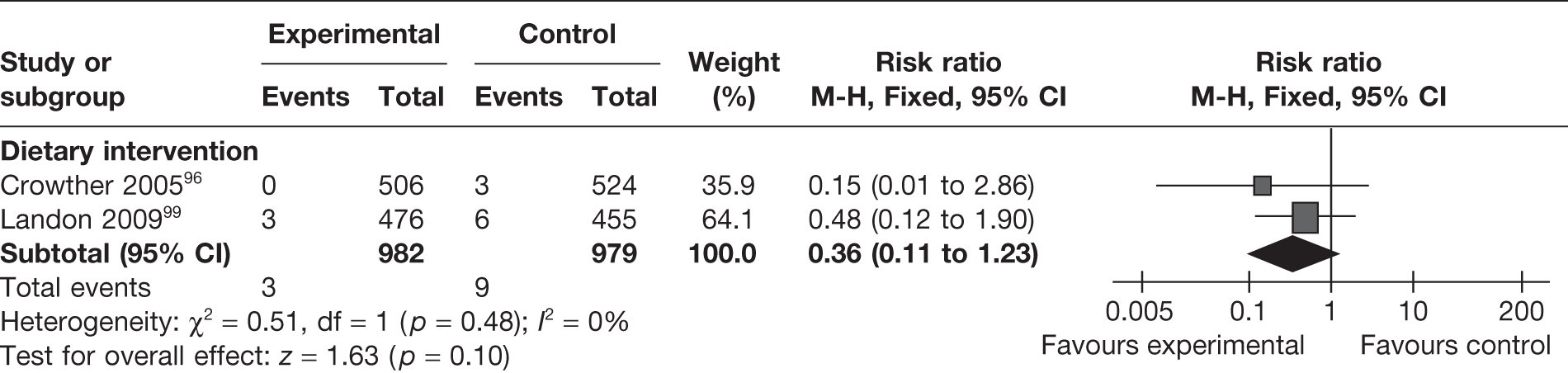

Birth trauma

Two RCTs96,99 evaluated the effect of dietary interventions on the risk of birth trauma. The studies showed a reduction in the risk of birth trauma (RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.11 to 1.23; I2 = 0%), which was not statistically significant (Figure 31).

FIGURE 31.

Effect of weight management interventions on birth trauma.

Effect of interventions on neonatal anthropometric measurements at birth

Child’s birth length

Five RCTs95,103,105,125,126 (323 newborns) evaluated the birth length of the newborn. The birth length of the newborn was reduced with the interventions, but the difference was not statistically significant (Figure 32).

FIGURE 32.

Effect of weight management interventions on birth length. SD, standard deviation.

Abdominal circumference of the newborn

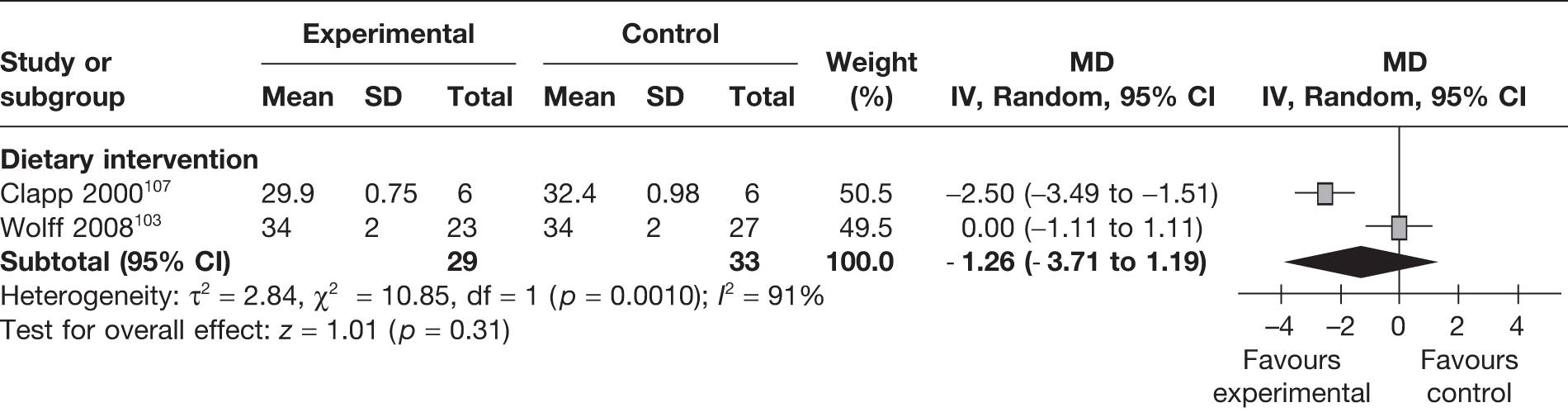

Two RCTs103,107 evaluated the effect of dietary weight management interventions on abdominal circumference in 62 newborns. The studies were heterogeneous and overall there was no significant change in the intervention group in comparison with the control group (MD –1.26 cm, 95% CI –3.71 cm to 1.19 cm; p = 0.31; I2 = 91%) (Figure 33).

FIGURE 33.

Effect of weight management interventions on abdominal circumference. SD, standard deviation.

Crown–heel length

Three RCTs107,108,113 evaluated the effect of physical activity based weight management interventions on crown–heel length in 181 newborns. The studies were heterogeneous and overall there was no significant change in the intervention group in comparison with the control group (MD –0.18 cm, 95% CI –1.80 cm to 1.44 cm; p = 0.83; I2 = 92%) (Figure 34).

FIGURE 34.

Effect of weight management interventions on crown–heel length. SD, standard deviation.

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses on the basis of period of publication, country of study (developed vs developing), GDM status and risk of bias from allocation concealment showed no differences in the summary estimates of gestational weight gain, birthweight and incidence of LGA and SGA infants. The type of intervention resulted in significant differences (p = 0.003) between the groups for weight gain in pregnancy, with the maximum reduction in gestational weight gain seen in the dietary intervention group (MD –3.36 kg, 95% CI –4.73 kg to –1.99 kg). Women with diabetes in pregnancy showed a significant reduction in the incidence of pre-eclampsia with weight management interventions (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.84) compared with women without diabetes (RR 1.16, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.93), and the difference in the summary estimates between the groups was statistically significant (p = 0.04). There was a significant reduction in pre-eclampsia in the responders – women with significantly reduced gestational weight gain with intervention (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.79) – compared with the group with no significant change in weight (RR 1.33, 95% CI 0.84 to 2.11) (p = 0.004). There was a significant difference between the responders (MD –0.29 kg, 95% CI –0.46 kg to –0.12 kg) and non-responders (MD –0.02 kg, 95% CI –0.06 kg to –0.03 kg) for birthweight (p = 0.002). Subgroup analysis of the summary estimates of birthweight and incidence of LGA and SGA infants did not show a statistically significant difference according to the type of intervention (Table 6).

| Subgroup | Gestational weight gain (kg) | Pre-eclampsia | Birthweight (kg) | LGA infants | SGA infants | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | MD (95% CI) | p-value for interaction | No. of studies | RR (95% CI | p-value for interaction | No. of studies | MD (95% CI) | p-value for interaction | No. of studies | RR (95% CI) | p-value for interaction | No. of studies | RR (95% CI | p-value for interaction | |

| Publication year | |||||||||||||||

| After 1990 | 28 | –1.22 (–1.77 to –0.66) | 0.57 | – | – | – | 26 | –0.08 (–0.15 to –0.02) | 0.11 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Before 1990 | 2 | 2.19 (–9.66 to 14.04) | – | – | 2 | 0.14 (–0.13 to 0.41) | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Country status | |||||||||||||||

| Developed countries | 24 | –1.09 (–1.92 to –0.27) | 0.42 | – | – | – | 23 | –0.08 (–0.15 to 0.00) | 0.77 | 10 | 0.72 (0.51 to 1.03) | 0.63 | 6 | 0.97 (0.74 to 1.27) | 0.40 |

| Developing countries | 6 | –0.64 (–1.39 to 0.12) | – | – | 5 | –0.06 (–0.16 to 0.04) | 2 | 0.95 (0.33 to 2.75) | 2 | 1.79 (0.44 to 7.23) | |||||

| Intervention type | |||||||||||||||

| Diet | 9 | –3.36 (–4.73 to –1.99) | 0.003 | 6 | 0.67 (0.53 to 0.85) | 0.05 | 9 | –0.07 (–0.21 to 0.07) | 0.45 | 5 | 0.78 (0.51 to 1.19) | 0.73 | 3 | 1.02 (0.75 to 1.37) | 0.61 |

| Mixed | 6 | –0.36 (–1.40 to 0.68) | 1 | 5.56 (0.70 to 44.09) | 14 | –0.02 (–0.10 to 0.07) | 5 | 0.75 (0.41 to 1.38) | 2 | 0.76 (0.39 to 1.48) | |||||

| Physical activity | 15 | –0.07 (–1.08 to 0.93) | 3 | 1.48 (0.56 to 3.94) | 5 | –0.09 (–0.18 to 0.00) | 2 | 0.37 (0.06 to 2.30) | 3 | 1.31 (0.50 to 3.42) | |||||

| Diabetic status | |||||||||||||||

| Women with diabetes | 5 | –1.84 (–2.36 to –1.32) | 0.09 | 3 | 0.65 (0.50 to 0.84) | 0.04 | 5 | –0.06 (–0.17 to 0.05) | 0.75 | 4 | 0.65 (0.46 to 0.92) | 0.30 | 2 | 1.03 (0.74 to 1.42) | 0.73 |

| Normal women | 25 | –0.86 (–1.85 to 0.13) | 7 | 1.16 (0.70 to 1.93) | 23 | –0.08 (–0.16 to 0.00) | 8 | 0.91 (0.53 to 1.59) | 6 | 0.93 (0.59 to 1.46) | |||||

| Risk of bias – allocation concealment | |||||||||||||||

| High risk | 27 | –0.81 (–1.60 to –0.01) | 0.18 | 8 | 0.77 (0.60 to 0.98) | 0.48 | 25 | –0.08 (–0.15 to 0.00) | 0.85 | 11 | 0.82 (0.57 to 1.16) | 0.06 | 5 | 0.88 (0.62 to 1.26) | 0.33 |

| Low risk | 3 | –1.79 (–2.98 to –0.60) | 2 | 0.62 (0.36 to 1.06) | 3 | –0.06 (–0.16 to 0.03) | 1 | 0.49 (0.33 to 0.73) | 3 | 1.15 (0.77 to 1.70) | |||||

| Maternal weight change with intervention | |||||||||||||||

| Significantly reduced gestational weight gain | 4 | 0.61 (0.47 to 0.79) | 0.004 | 6 | –0.29 (–0.46 to –0.12) | 0.002 | 3 | 0.67 (0.41 to 1.07) | 0.36 | 2 | 1.03 (0.74 to 1.42) | 0.73 | |||

| No significant change in gestational weight gain | 6 | 1.33 (0.84 to 2.11) | 22 | –0.02 (–0.06 to –0.03) | 9 | 0.88 (0.60 to 1.30) | 7 | 0.93 (0.59 to 1.46) | |||||||

Sensitivity analysis that excluded studies on women with diabetes in pregnancy consistently showed a overall reduction in gestational weight gain with interventions (MD –0.88 kg, 95% CI –1.85 kg to 0.09 kg; p = 0.001), including diet (MD –5.18 kg, 95% CI –9.44 kg to –0.91 kg; p < 0.00001) and physical activity (MD –0.07 kg, 95% CI –1.08 kg to 0.93 kg; p < 0.00001). The reduction in birthweight with intervention persisted (MD –0.08 kg, 95% CI –0.16 kg to 0.0 kg; p = 0.04) with no differences in the incidence of SGA and LGA infants or shoulder dystocia between the groups. The estimates of other studies for the effect of diet on the incidence of gestational hypertension, preterm birth, vaginal delivery, caesarean section and SGA infants were similar after excluding studies on women with diabetes. There was a trend towards a reduction in the incidence of pre-eclampsia with diet in these studies.

Summary

This review on the effectiveness of weight management interventions has identified a large number of RCTs, especially for the primary weight-related outcomes in the mother and the fetus. Two-thirds of the included studies showed a low risk of bias for addressing incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and blinding for objective outcomes. Fewer than one-sixth of the studies showed a high risk of bias for addressing incomplete outcome data and selective reporting. The commonly reported outcomes were maternal weight gain in pregnancy and birthweight of the newborn.

Weight management interventions in pregnancy resulted in a statistically significant reduction in weight-related outcomes such as maternal weight gain in pregnancy, and birthweight of the newborn. However, there were no differences between the intervention and control groups for incidence of SGA fetuses. Although we did not observe a beneficial effect of reduction in growth restriction in the babies with intervention, it was a reassuring finding because there have been concerns over fetal weight reduction with weight management interventions.

There was a significant decrease in the rates of key obstetric outcomes such as pre-eclampsia and shoulder dystocia in the analysis of outcomes for all interventions. It is likely that this reduction in shoulder dystocia will be of greatest benefit in women with GDM or pre-existing diabetes. There was a trend towards a reduction in the rates of obstetric complications such as GDM, gestational hypertension and preterm birth before 37 weeks with weight management interventions.

Of the three interventions, dietary intervention showed the most beneficial effect by significantly reducing rates of obstetric complications such as gestational hypertension, preterm births, pre-eclampsia and shoulder dystocia. The significant reduction in the rate of preterm births with dietary interventions is likely to be reflected in the finding of increased gestational age with dietary interventions. For fetal outcomes the evidence was limited to dietary interventions only and showed a trend towards a reduction in rates of intrauterine deaths, birth trauma and hyperbilirubinaemia.

The dietary components of the interventions evaluated a balanced diet of carbohydrates, fat and protein, moderate energy and caloric restriction based on individual requirements, low-fat and -cholesterol diets and the use of a food diary for monitoring. The physical activity-based interventions included weight-bearing sessions, walking for 30 minutes a day and low-intensity resistance training. The mixed approach group included dietary and physical activity interventions with associated in-depth behavioural risk assessments and tailored counselling.

The main strengths of the effectiveness review were the peer-reviewed protocol, the comprehensive search strategy without any language restrictions and the use of randomised data to draw inferences. Non-randomised data were included only when there was a paucity of evidence. This review has identified the largest body of evidence on this topic, for both weight-related outcomes and clinically relevant obstetric and fetal outcomes. Dietary interventions in pregnancy have consistently shown a beneficial effect on weight-related, obstetric and fetal and neonatal outcomes compared with other interventions. The review findings are limited by the lack of detail about the components of the intervention in some of the included studies, gestational age at which the intervention was commenced, its frequency and the method of delivery. Furthermore, there are very few studies for important clinical outcomes such as intrauterine death, maternal admission to the high-dependency unit (HDU) and neonatal admissions to NICU. There are no data available to assess the long-term effects of these outcomes on the mother and the fetus.

[Note: The results of this systematic review for effectiveness of weight management interventions in pregnancy includes only studies published before March 2011. The findings with the updated search (until January 2012) can be accessed at BMJ 2012;344:e2088 doi10.1136/bmj.e2088.]

Chapter 4 Adverse effects of interventions

Study selection

From a systematic search of the literature to identify the maternal and fetal adverse effects of weight management interventions in pregnancy, 14,832 potentially relevant records were obtained (up to 31 March 2011). A search of the reference lists of the relevant articles led to the identification of 26 further citations. After reviewing the abstracts, the full texts of 180 papers were obtained for detailed assessment. After exclusion of 154 publications, 26 papers were included in the review. Figure 35 provides details of the process of study selection.

FIGURE 35.

Flow chart of study identification and selection for the evaluation of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.

Of the included studies, two were RCTs (involving 277 women)129,132 and 24 were observational studies (19 cohort studies and five case–control studies, involving 468,581 women). 63,64,67,68,70,73–77,80,85,89,133–143 The studies evaluated the effect of dietary, physical activity and other lifestyle interventions in pregnancy on maternal and fetal outcomes. Appendices 7 and 10 provide details of the included RCTs and observational studies, respectively, that assessed the adverse effects of outcomes.

Quality of the included studies

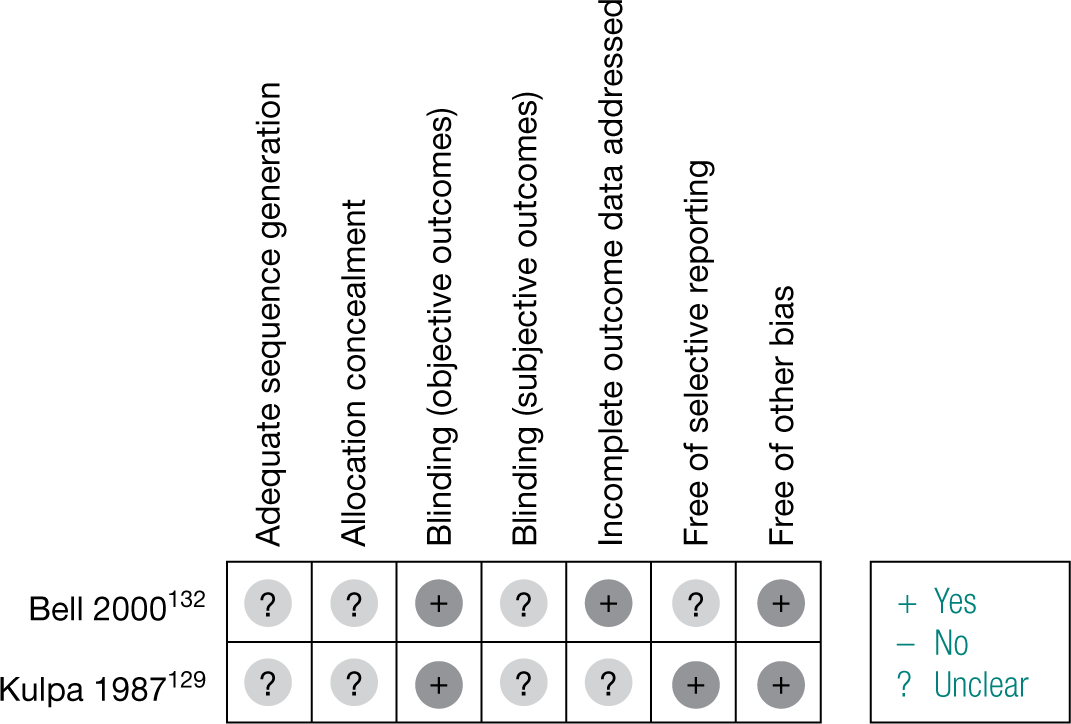

Randomised controlled trials

The quality of the two included RCTs129,132 is shown in Figure 36. The details regarding sequence generation, allocation concealment and blinding for subjective outcomes were unclear in both studies. A detailed quality assessment of the included RCTs is provided in Appendix 8.

FIGURE 36.

Quality of the included RCTs for the adverse effects review.

Observational studies

The 24 observational studies included 19 cohort studies and five case–control studies. 63,64,67,68,70,73–77,80,85,89,133–143 The quality assessment of the cohort and case–control studies is summarised in Appendix 9. The studies, evaluated using NOS, could score a maximum of nine stars, with four stars for selection, two for comparison and three for outcome assessment. In total, 3/19 (15.8%) cohort studies had a low risk of bias and scored seven or more stars; 16/19 (84.2%) had a medium risk of bias and scored between four and six stars.

Results

The adverse outcomes included in the review were defined as those that occurred unintentionally with potential harm to the mother or baby. We also included those outcomes that may have been the direct result of the intervention itself, for example risk of preterm delivery due to strenuous physical exercise.

Randomised clinical trials