Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 06/11/01. The contractual start date was in July 2006. The draft report began editorial review in March 2008 and was accepted for publication in March 2012. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2012. This work was produced by Gillett et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to NETSCC. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2012 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) accounts for roughly 80–90% of all cases of diabetes. The prevalence of T2DM is rising both in the UK and worldwide as a result of an ageing population, an increasingly sedentary lifestyle across communities, and a rise in the prevalence of obesity. 1 Certain ethnic groups, foremost of which in the UK are South Asians, are at increased risk of developing T2DM. The disease is characterised by hyperglycaemia. It has a slow onset, with few or no symptoms initially, and is sometimes referred to, mistakenly, as ‘mild diabetes’. However, it can lead to complications such as angina, cardiac failure, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, visual loss and renal failure. The TARDIS-2 report published in 2000 estimated that T2DM costs the NHS approximately £2B per annum, with an additional £36M spent on related social services and private health care. This equates to an annual expenditure of roughly £1738 per patient with T2DM. 2

Prevalence of diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glucose in the UK

In 2009 there were estimated to be 2,213,138 people with diabetes in the adult population in England, a prevalence of 5.1%. 3

The Health Profile of England 2009 reports a prevalence of 5.6% of men and 4.2% of women with diabetes in England in 2008. 4 Diabetes was flagged as one of the ‘particular challenges’.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus was estimated to account for 92% of all (diagnosed and undiagnosed) diabetes. The Yorkshire & Humber Public Health Observatory (YHPHO) provides a very useful set of data on diabetes in England. Between 1994 and 2003 the incidence of diabetes doubled from 1.8 to 3.3 per 1000 (age standardised) and the diagnosed prevalence doubled. 5 However, recent data from the Association of Public Health Observatories (APHO) model6 suggest that 26% of men and 22% of women with diabetes are undiagnosed.

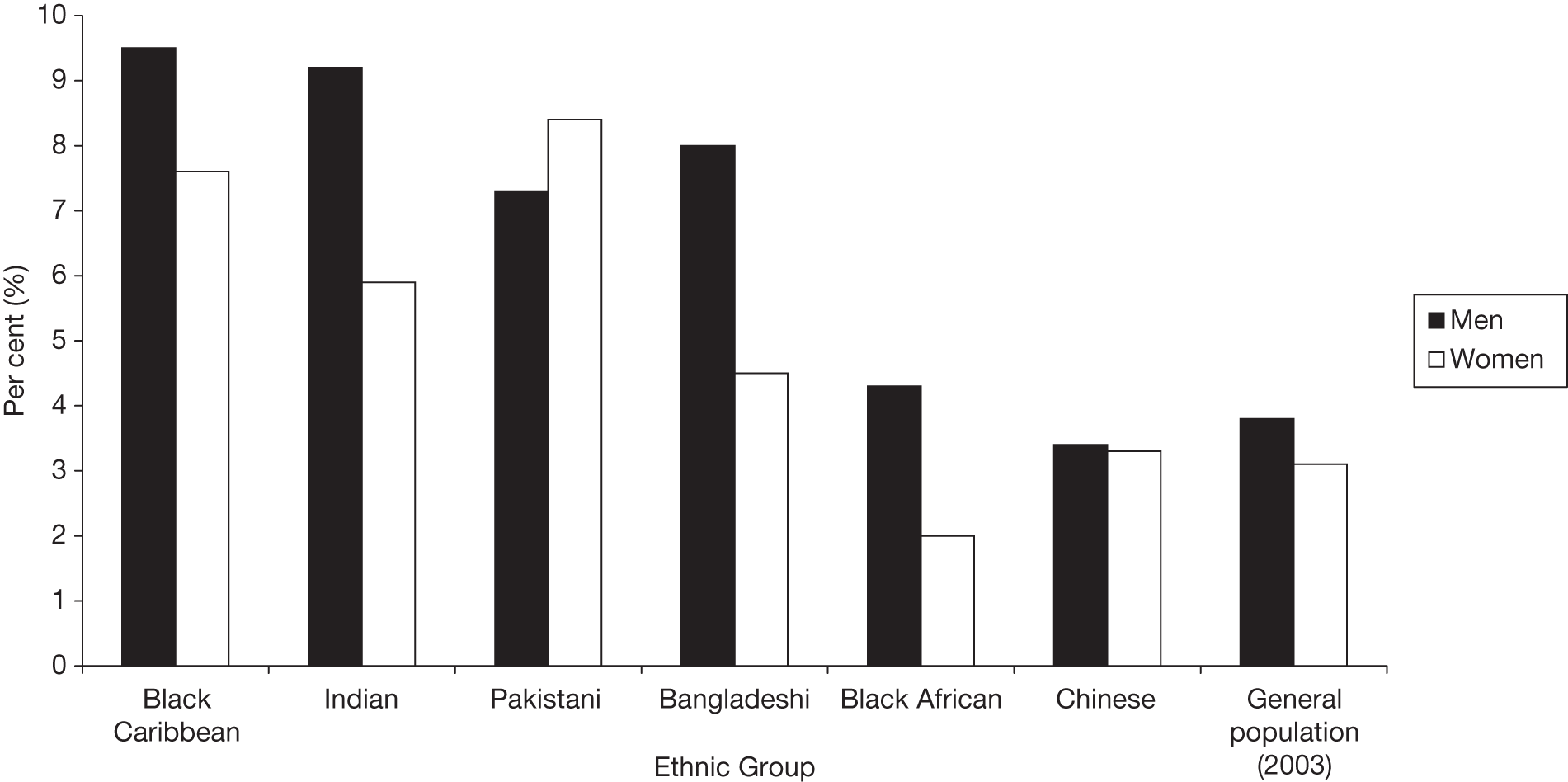

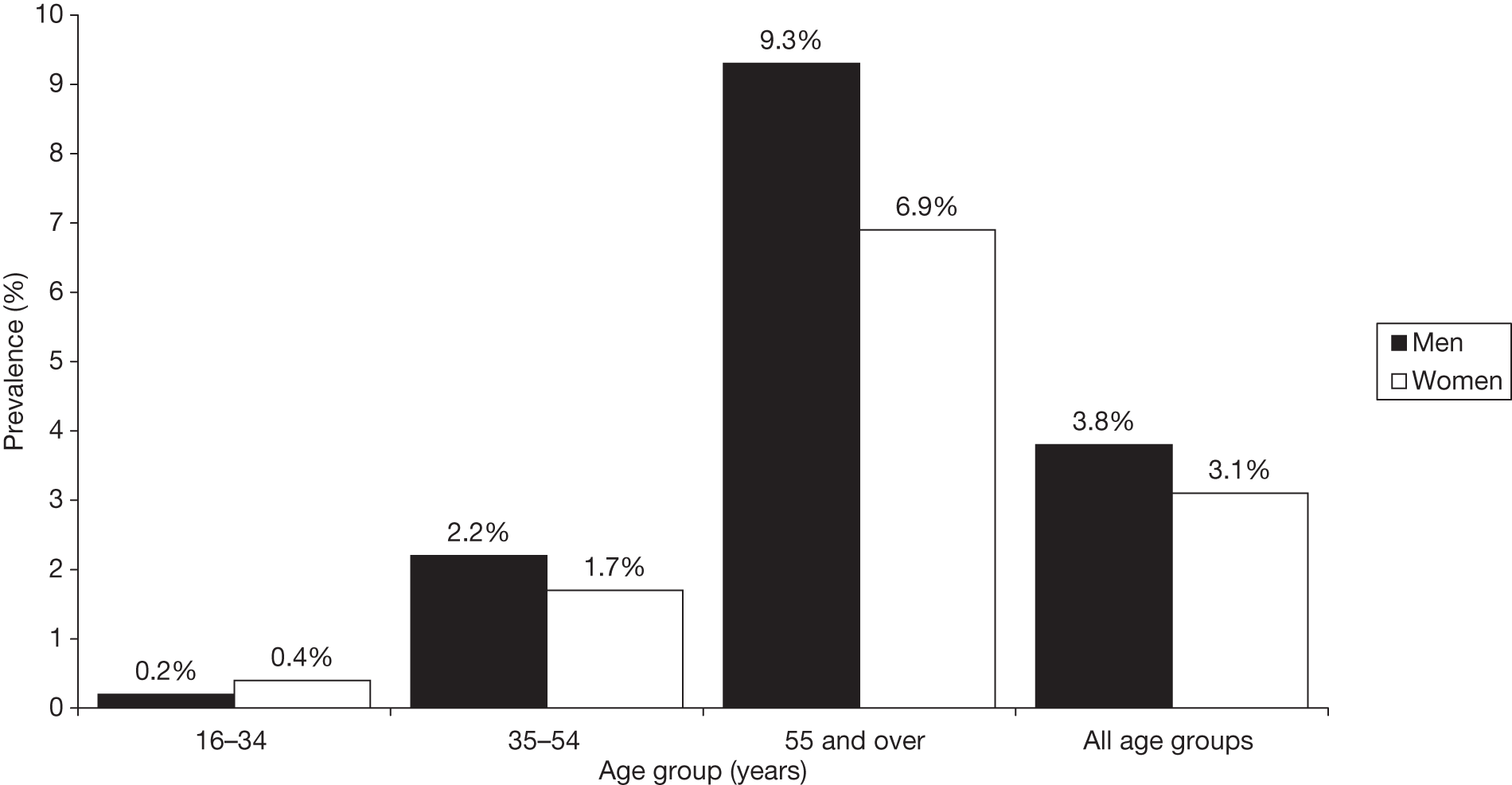

The prevalences of doctor-diagnosed T2DM in England in different age and ethnic groups were reported in the Health Survey for England 20047 and are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

FIGURE 1.

Prevalence of doctor-diagnosed T2DM between different ethnic groups in England. Note: figures for the general population were taken from the 2003 survey and represent all ethnic groups in England, which would be predominantly white. Copyright© 2011, re-used with the permission of The Health and Social Care Information Centre. All rights reserved.

FIGURE 2.

Prevalence of doctor-diagnosed T2DM by age group. Copyright© 2011, re-used with the permission of The Health and Social Care Information Centre. All rights reserved.

A study by Bagust et al. (2002)8 predicts that by 2036 there will be approximately 20% more cases of T2DM in the UK than in 2000, as a result of the population ageing and increased levels of obesity. 8

The consequences and costs of diabetes

Some key consequences are:

-

Life expectancy is reduced. The National Service Framework9 summarised this as being, on average, a loss of up to 10 years of life, but it will vary by age and by gender, with females losing more than males. 5

-

Atherosclerosis – arterial disease, which increases the risk of heart attacks, strokes and amputation. The increase is more marked in women. The relative risk (RR) for fatal coronary heart disease (CHD) is 50% higher in women with diabetes than it is in men. 10

-

Mortality rates from CHD are up to five times higher for people with diabetes, and the risk of stroke is three times higher. 9

-

Nephropathy – disease of the kidneys, which can lead to renal failure requiring dialysis or transplantation. Diabetes is a leading cause of renal failure, and the second commonest cause of lower-limb amputation.

-

Retinopathy – disease of the eye, which can lead to visual loss. Diabetes is the leading cause of blindness in people of working age. 9

-

Neuropathy – damage to the nerves, which cause a range of problems, including loss of sensation, neuropathic pain, muscle wasting, and altered blood flow.

-

Diabetes is estimated to account for 5% of all NHS expenditure and 9% of hospital costs. 5

-

The presence of diabetic complications increases the overall NHS spending per patient more than fivefold and increases by five the chance of a person needing hospital admission. 9 Based on TARDIS-2 data, a person in the UK with T2DM incurs average direct costs of > £2000 per year, accounting for 4.7% of all NHS expenditure. 2

-

One in 20 people with diabetes incurs social services costs, and for these people the average annual cost was £2450 in 1999. 9

Maintenance of blood glucose levels as close to normal as possible slows or prevents the onset and progression of eye, kidney and nerve diseases caused by diabetes. The evidence for the link between glucose control and arterial disease is less strong, but good control reduces the risk. 11–13

The development of type 2 diabetes mellitus

Glucose is the principal energy source for human cells and is derived from three sources: food, de novo synthesis in the body, and breakdown of glycogen (a stored form of glucose). Blood glucose levels are normally kept within a narrow band, with a maximum of 5.5 mmol/l. Insulin and glucagon, hormones secreted by the pancreas, regulate blood glucose levels. Insulin lowers the glucose concentration in the blood, and glucagon raises it, in order to maintain a constant concentration, despite activities such as eating and exercise.

Overweight and obesity are associated with the phenomenon known as insulin resistance, in which higher levels of insulin are required to have the same effects on its target cells. Initially, the beta cells in the pancreas produce more insulin, and the blood glucose level is maintained within the normal range. However, over time the beta cells cannot cope, some die and insulin production falls. By the time people develop T2DM, about half of the beta cell mass has been lost. 14 Insulin resistance is also associated with an increase in cardiovascular disease (CVD). 15

Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus

Global prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus

Based on current estimates, the global prevalence of T2DM will double from 171 million patients in 2000 to 334 million patients in 2025. The increase in the number of patients will be most pronounced in nations that are currently undergoing socioeconomic development, including increasing urbanisation. Global diabetes prevalence estimates from the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) suggest that the region with the highest prevalence of diabetes is North America at 7.9%, followed by Europe at 7.8%, and the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East at 7%. When absolute numbers of people with diabetes are considered, it is South East Asia and the West Pacific that are expected to experience the highest increases in prevalence over the coming years. 16

Risk factors for developing diabetes

Age, weight and ethnic group are the three factors that most affect prevalence of T2DM in the UK. The Health Survey for England 20047 reported that the prevalence of T2DM increases sharply with age (see Figure 2). In the general population (2003 data), the prevalence of T2DM in men and women increased from 0.2% and 0.4%, respectively, at age 16–34 years, to 2.2% and 1.7%, respectively, at age 35–54 years and to 9.3% and 6.9%, respectively, in those aged ≥ 55 years. The survey reported that in all but the youngest age groups, the prevalence of T2DM was higher in men than in women.

The risk of diabetes is much higher in people of South Asian ethnicity (i.e. from the Indian subcontinent: Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Nepal) (see Figure 1). We deal with their situation in greater detail later in Chapter 3.

Lifestyle factors are the main determinants of T2DM but there are strong familial influences:

-

In families in which no member has T2DM, the lifetime risk of developing it is approximately 10%.

-

If one parent is affected then the risk increases threefold (i.e. 30% lifetime risk).

-

If a sibling is affected then the risk increases fourfold (i.e. 40% lifetime risk).

-

If both parents are affected then the risk increases sevenfold (i.e. 70% chance).

-

If an identical twin is affected then the risk increases ninefold (i.e. 90% chance). 5

These risks are increased if the affected family member had early onset of T2DM. It is likely that the diabetes is preceded by impaired fasting glucose (IFG) and/or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), and that family history could provide opportunities for targeted screening.

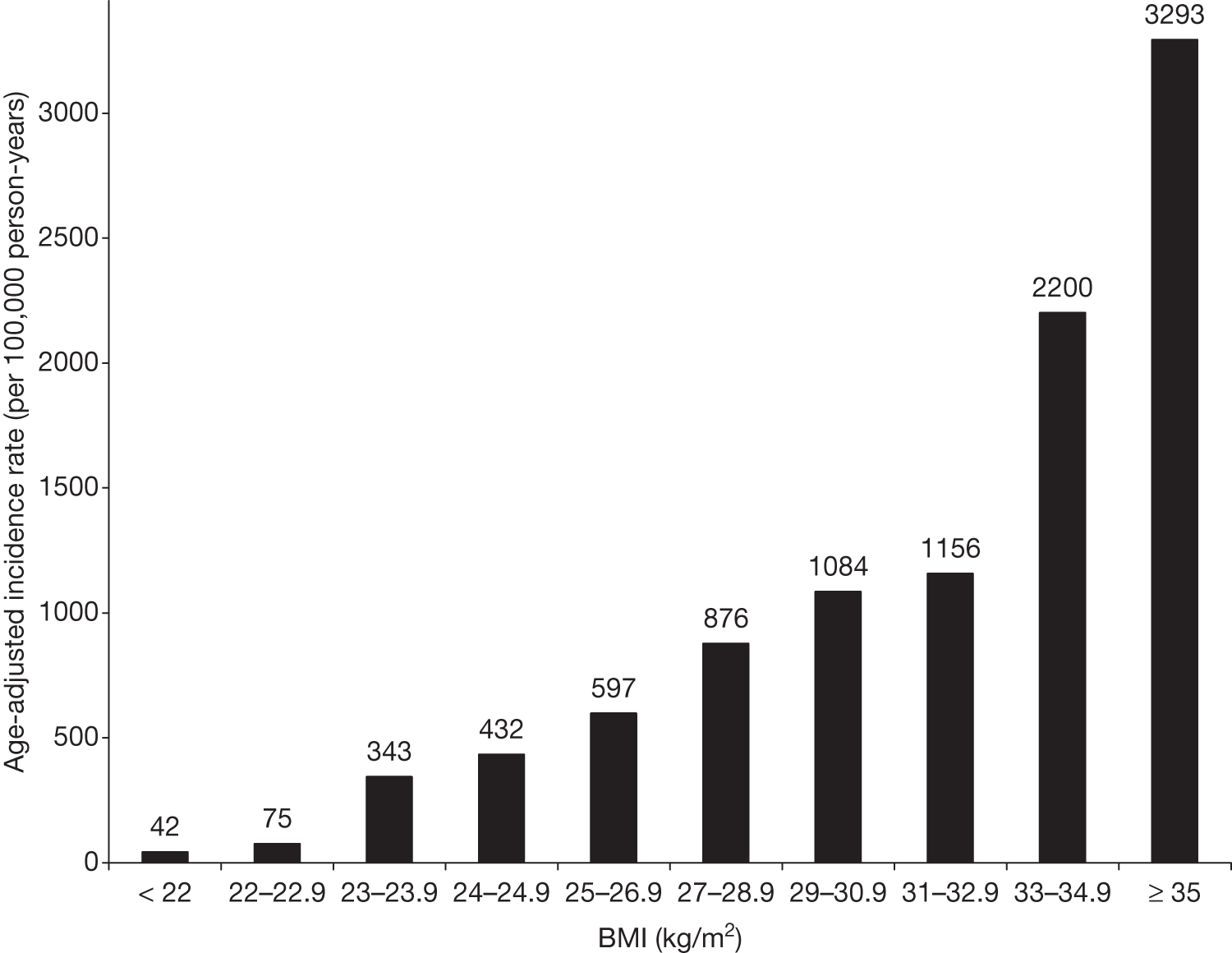

Obesity is a strong risk factor. It has been suggested that it is only obesity [body mass index (BMI of > 30 kg/m2)] that increases the risk and not overweight (BMI of > 26–29 kg/m2). Jarrett (1986),17 reviewing older studies, noted that there was little difference in the risk of diabetes at a range of BMIs of < 31 kg/m2. However, recent work shows the take-off to diabetes at lower BMIs18 [Figure 3, based on data in the study of Ford etal. (1997)18]. It may be that physical activity is less now than in previous decades. Jarrett (1986)17 was reviewing studies from the early 1980s.

FIGURE 3.

Age-adjusted incidence rates of diabetes as a function of baseline BMI in 30- to 55-year-olds (both sexes).

The National Audit Office suggests that 47% of T2DM cases in England can be attributed to obesity. 19 The risk of T2DM is almost 13 times greater in obese women than in women of normal weight. For men the risk is five times greater. 5

Physical activity reduces the risk of developing T2DM. Jeon et al. (2007),20 in a meta-analysis of cohort studies, found that the risk of T2DM was 30% lower in those undertaking regular moderate-intensity activity than in sedentary people. The reduction in risk associated with increased activity levels is independent of BMI. Sui et al. (2007),21 in a study of mortality in older American adults, found that fitness was a predictor of mortality, independent of adiposity; they also reported that when people were grouped into fitness quintiles (based on time tolerated on treadmills), the fittest quintile had a prevalence of diabetes of 12% compared with 25% in the least-fit quintile.

Physical activity is dealt with in greater detail later in Chapter 2.

The National Service Framework for Diabetes noted socioeconomic differences in the risks of developing T2DM. 9 Those in the most deprived fifth of the population are 1.5 times more likely than average to have diabetes at any given age.

Thomas et al. (2007)22 used data from the 1958 British birth cohort to provide an estimate of the national prevalence of diabetes risk in mid-life, using glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level of ≥ 5.5% as an indicator for possible subclinical alterations in glucose metabolism, which would detect those with IGT as well. The study consisted of 7799 participants born in England, Scotland and Wales and currently living in the UK.

The majority of the population (79.3%) had an HbA1c level of < 5.5%; 16.7% had an HbA1c level of 5.5–5.9%; 2.0% had an HbA1c level of 6.0–6.9%; and 0.6% had an HbA1c level of ≥ 7.0%. More men than women were found in the higher-HbA1c level categories and a highly significant inverse socioeconomic gradient was apparent for HbA1c levels of ≥ 5.5%. When looking at regional variation in HbA1c levels of ≥ 5.5%, it was found that the east of England had a significantly higher prevalence than the rest of the UK (24.3% vs 19.3%) and Scotland had the second highest prevalence (22%).

On the basis of these data, the authors suggest that a proportion of people are likely to have subclinical elevations in HbA1c level in their mid-40s, and this proportion is greater in some socioeconomic groups and geographical regions than in others. These individuals are likely to represent the population that has IGT, and at risk of developing T2DM.

Children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes mellitus

A recent alarming development is the emergence of T2DM and glucose intolerance in children and adolescents. 23 The year 1979 saw the first childhood cases of T2DM reported in Pima Indians; however, there are now worldwide reports of children with the disorder. This is thought to be associated with the growing problem of childhood obesity over the last 15 years. In particular, those ethnic groups at high risk of diabetes have reported a close association between the development of diabetes and childhood obesity. 24 Other contributing factors should also be considered, including genetic susceptibility as a result of variations in, for example, insulin sensitivity. In the UK, reports of children with T2DM have appeared only recently. 25 Compared with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), children with T2DM presented later (12.8 years vs 9.3 years) were usually female, overweight or obese (92% vs 28%) and a large proportion were from ethnic minority groups. In common with their adult counterparts, South Asian children have an increased risk of T2DM (RR = 13.7) compared with white UK children. It is therefore becoming apparent that preventative interventions may also need to be targeted at a younger age group than previously thought in order to prevent the progression to diabetes and heart disease at a later age.

Treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus

Treatments for T2DM aim to lower blood glucose and reduce the development of diabetes-associated secondary complications. 26 However, there is usually a progressive deterioration in blood glucose control in T2DM, necessitating changes in treatment with time. 27 People with T2DM are initially advised on lifestyle changes (weight loss, increased physical activity). If the lifestyle changes fail to control blood glucose, metformin (especially in overweight patients) or sulphonylureas (if metformin is contraindicated or not tolerated, or if the patient is not overweight) are considered. When monotherapy with these drugs no longer provides adequate glycaemic control, combination therapy is the next step (metformin plus sulphonylurea) but it may only be a matter of time before treatment must be intensified (e.g. insulin therapy or thiazolidinediones) to adequately control glucose levels. Other types of glucose-lowering drugs, such as the glucagon-like peptide analogues and the dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors, are now available.

A full review of the management of T2DM is not relevant here but can be found in the consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes,28 in the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) Clinical Guideline 8729 and the technology assessment report that underpinned the guideline. 30

For our purposes, the key points are that these treatments are far from perfect for controlling T2DM, and have side effects. Some, such as the sulphonylureas and insulins, cause weight gain, which can make glycaemic control more difficult. Others, such as the glitazones, can cause heart failure and fractures. Metformin may not be tolerated because of diarrhoea. Good control may not be achieved despite combination therapy, even with insulin, especially in overweight patients. 31–33 The problems with treatment of T2DM reinforce the need to prevent it as far as possible.

Epidemiology of impaired glucose regulation

Definitions

Two conditions appear to precede T2DM. The first is IGT, in which fasting glucose is normal but there is post-prandial hyperglycaemia. The definition comes from the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). The second is IFG, when the fasting level is raised but the post-prandial level does not reach IGT levels. The normal FPG is currently defined as ≤ 5.5mmol/l.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines diabetes (Table 1) on the basis of a fasting plasma glucose (FPG) level of ≥ 7 mmol/l or a 2-hour level (in an OGTT) of ≥ 11.1 mmol/l. 34

| Category | Fasting | Two-hour OGTT |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | ≤ 6.0 | < 7.8 |

| IFG | 6.1–6.9 | < 7.8 |

| IGT | < 7.0 | 7.8–11.0 |

| Both IFG and IGT | 6.1–6.9 | 7.8–11.0 |

| Diabetes | ≥ 7.0 | ≥ 11.1 |

Impaired glucose tolerance is defined as an FPG level of < 7 mmol/l and a 2-hour level of 7.8–11.0 mmol/l.

Impaired fasting glucose is defined as the range of 6.1–6.9 mmol/l and a 2-hour level of < 7.8 mmol/l.

So those with IFG should exclude IGT, but this is not possible if the 2-hour level has not been measured, whereas those with IGT can have IFG as well.

These criteria differ from those of the ADA, which defined IFG as starting at 5.6 mmol/l. One effect is that a much greater proportion of people with IGT also have IFG. The Danish Inter-99 study35 found that using the WHO criteria, 25% of those with IGT have IFG compared with 60% using the ADA cut-off.

One problem with the WHO criteria is that there is a group of people with FPG levels of 5.6–6.0 mmol/l – above normal but lower than IFG. The ADA definition tidies up this anomaly. 36 There is reluctance in the WHO to do this. First, the prevalence of IFG would greatly increase. In the D.E.S.I.R. study of French men and women aged 30–64 years,37 the prevalence of IFG was 13% in men and 4% in women using the 6.1 mmol/l cut-off, but would rise to 40% and 16%, respectively, using the 5.6 mmol/l cut-off. Second, and more importantly, the risk of progression to diabetes is much higher in people with FPG levels of > 6.1 mmol/l (‘old IFG’) than in those with FPG levels of between 5.6 and 6.0 mmol/l (‘new IFG’).

Progression to type 2 diabetes mellitus from impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose

Impaired glucose tolerance and IFG have been called ‘pre-diabetes’ but the term is unsatisfactory because not all people with the two conditions go on to develop diabetes. The proportions of people who progress to diabetes vary among different studies in different populations (Table 2). 38 The 2005 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) report on the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of IGT and IFG concluded that with regard to prognosis of patients following evaluation of a number of trials that reported relevant outcomes:

| IFG status | Incidence of diabetes per 1000 person-years | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose level (mmol/l) | Age (years) | |||

| 30–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | ||

| Men | ||||

| Normal | < 5.6 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 1.1 |

| New IFG | 5.6–6.0 | 4.9 | 8.5 | 11.5 |

| Old IFG | 6.1–6.9 | 24.7 | 38.9 | 63.9 |

| Women | ||||

| Normal | < 5.6 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 0.7 |

| New IFG | 5.6–6.0 | 5.5 | 7.0 | 5.9 |

| Old IFG | 6.1–6.9 | 35.7 | 52.3 | 66.7 |

There is consistent evidence that IFG and IGT are both risk factors for the development of diabetes mellitus. The pooled RR for new DM is 6.02 [95% confidence interval (CI) 4.66 to 7.38] in people with IGT, 4.70 (95% CI 2.71 to 6.70) in people with IFG, and 12.21 (95% CI 4.32 to 20.10) in people with both disorders.

The D.E.S.I.R. study37,39 examined the risks of progression to diabetes from different baseline levels.

Progression from impaired fasting glucose to diabetes

The effect of different cut-points for IFG on diabetes incidence was examined in the Ely study40 from 1990–2000, a population-based longitudinal study. At baseline there were 1040 non-diabetic adults (defined by OGTT criteria) aged 40–69 years. Baseline glucose status was defined as normoglycaemia < 5.6 mmol/l, IFG-lower 5.6–6.0 mmol/l and IFG-original 6.1–6.9 mmol/l. The all-IFG group included fasting glucose values of 5.6–6.9 mmol/l. Median follow-up time was 10 years. The incidence rate was 7.3 (95% CI 5.7 to 9.4) per 1000 person-years of follow-up. The annual incidence of diabetes was 0.6%.

Forouhi et al. (2007)40 reported the progression rates in the Ely study by baseline FPG category as:

-

from normal glucose tolerance (NGT) (FPG < 5.6 mmol/l): 2.4 per 1000 person-years

-

for those in the 5.6–6.0mmol/l range (the ‘new IFG’ suggested by the ADA): 6.2 per 1000 person-years

-

for original IFG (6.1–6.9 mmol/l): 17.5 per 1000 person-years.

Cumulative incidence also increased by age at baseline:

-

40–49 years: 5.5 per 1000 person-years

-

50–59 years: 7.6 per 1000 person-years

-

60+ years: 9.5 per 1000 person-years.

However, rates by BMI were not reported. The three categories of baseline glucose tolerance had different BMIs: 24.8 kg/m2, 25.8 kg/m2 and 27.8 kg/m2, respectively.

Most people with IFG at baseline regressed to NGT – 83% of those with new IFG and 56% of those with original IFG. The rate of progression was lower in IFG than IGT. Those with both IFG and IGT had higher incidence.

In the Finnish MONICA study,41 the following risks of developing diabetes after 10 years’ follow-up were reported:

-

low NGT (FPG < 4.9 mmol/l): 2.4 per 1000 person-years

-

middle NGT (FPG 4.9–5.3 mmol/l): 2.5 per 1000 person-years

-

high NGT (FPG 5.4–6.0 mmol/l, equivalent to the ADA’s new IFG): 4.5 per 1000 person-years

-

IFG (FPG 6.1–6.9 mmol/l): 15.5 per 1000 person-years.

In the Danish arm of the ADDITION study,42 the progression rate (after 1 year of follow-up) from IFG (FBG 5.6–6.0 mmol/l) was 17.6 per 100 person-years. So there seems to be consistency among these three European studies of a low progression rate from isolated IFG to diabetes of about 17 per 1000 person-years, or about 2% a year.

In the USA, Nichols et al. (2007)43 compared rates of progression with diabetes in people with ‘old IFG’ (FPG 6.1–6.9 mmol/l) and ‘new IFG’ (FPG 5.5–6.0 mmol/l), although they called these ‘original IFG’ and ‘added IFG’. A total of 5.6% of original IFG subjects progressed to diabetes each year, compared with 1.3% of added IFG. During follow-up, ranging among subjects from 2 to 11 years, 8% of those with added IFG and 24% of those with original IFG became diabetic.

Progression from impaired glucose tolerance to diabetes

In the Finnish MONICA study,41 at 10 years of follow-up the progression rate from isolated IGT was 14.7 per 1000 person-years, but for those with both IGT and IFG, it was 50 per 1000 person-years. BMI for the IGT group was about 29 kg/m2 for both sexes, lower than in the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS) (see Chapter 4).

In the UK, the Ely study40 of 170 people with IGT reported that after 4.5 years, 10% progressed to diabetes, 33% remained with IGT and 56.5% regressed to NGT, and in Bedford44 only 16% of those with IGT developed diabetes after 10 years.

In the Danish arm of the ADDITION study,42 the progression rate from IGT to diabetes in the first year was 18.9 per 100 person-years. It was 12 per 100 person-years for isolated IGT and 28 per 100 person-years for those with IGT and IFG. Overall, 13% developed diabetes within 1 year. BMI was 29.5 kg/m2. 42

In a study by Little et al. (1994)45 in Pima Indians, 39% progressed from IGT to diabetes after a mean follow-up of 3.3 years, but the proportion developing diabetes was much higher in those with a raised baseline HbA1c level (13 out of 19; 68%) than in those with a normal baseline HbA1c level (13 out of 47; 28%). The upper limit of normal HbA1c level was taken to be 6%.

Edelstein et al. (1997)46 reviewed progression rates from six studies: Baltimore, Rancho Bernardo, San Antonio, Nauru, San Luis Valley and Pima Indians. IGT was defined as FPG of < 7.8 and 2-hour glucose levels of 7.8–11 mmol/l. The old fasting threshold of 7.8 was used for diagnosing diabetes. The overall progression rate to diabetes was 57 per 1000 person-years, but it varied considerably, from 36 per 1000 person-years in the Baltimore study to 87 per 1000 person-years among the Pima Indians. This variation reflected BMI of 26 kg/m2 in the Baltimore study and 33 kg/m2 among the Pima Indians. Predictors of progression included higher baseline fasting (> 6.1 mmol/l) and 2-hour glucose levels, waist circumference (WC), waist–hip ratio and obesity. Family history was not a predictor of progression.

Older studies often state that patients had IGT, and may not give details on proportions that also have IFG. The AHRQ Evidence Report38 reviewed a large number of studies (including some mentioned above, such as Pima Indians and Naurans) and summarised progression rates as follows:

-

isolated IGT: 1.8–34 per 100 person-years

-

isolated IFG: 1.6–23

-

both IGT and IFG: 10–15.

The D.E.S.I.R. study47 also found that progression was commoner in those with both IGT and IFG. That study also found that, among those with IFG, progression correlated strongly with HbA1c level, as did the report from Yoshinaga and Kosaka (1996),48 which found that the proportions of people with IGT progressing to diabetes ranged from 10% in those with HbA1c levels of < 6.4% to 23% in those with HbA1c levels of 6.4–6.7% and 53% in those with HbA1c levels of ≥ 6.8%.

So we have a wide range of progression rates from IGT to diabetes.

Among the studies, several factors increase the risk of progression: older age (although not consistently), IFG and higher baseline FPG, HbA1c level and BMI. Edelstein et al. (1997),46 in the pooled studies, found that every increase of 4 kg/m2 in BMI increased the risk of diabetes by 1.13. So an increase from overweight at BMI 26 kg/m2 to obese at BMI 30 kg/m2 would increase the prevalence of diabetes by 13%. The presence of IFG (defined then as FPG 6.1 to 7.7 mmol/l) increased the progression rate to 55% compared with 35% in those with FPG levels of between 5.6 and 6.0 mmol/l (calculated from figures in table 4 in Edelstein et al. ). 46

Supporting data on the impact of obesity on diabetes come from another source, the results after bariatric surgery. The Swedish Obesity Surgery Study49 reported that large amounts of weight loss were associated with resolution of diabetes. At 10 years, 7% of the surgical and 24% of the control groups had diabetes.

More recently, Dixon et al. (2008)50 from Australia reported that weight loss after gastric banding in people with T2DM led to almost 21% weight loss, with remission of diabetes in 73% of the banded group.

If impaired glucose regulation can be successfully treated and the risk of progression to diabetes prevented, it would also be of interest to know whether the increased cardiovascular risk in those with IGT and, to a lesser extent, IFG51 may also be improved by non-pharmacological intervention. Studies have reported that the prevalence of CVD,52,53 as well as CVD-related deaths and all-cause mortality,54,55 are higher in those with IGT than in those with NGT. Furthermore, an analysis of 6766 subjects from five Finnish cohorts reported that the incidence of CHD and CVD mortality in IGT was similar to that for newly diagnosed diabetes. Clearly, one of the goals of treating people with IGT would not only be to prevent progression to diabetes, but also to improve their cardiovascular risk profile. The 2005 AHRQ report38 on the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of IGT and IFG concluded that:

They [IGT and IFG] are also both risk factors for fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular outcomes; however, the evidence is less consistent for these outcomes. The pooled RR ranged from 1.48 to 1.66 for CVD mortality and all-cause mortality in people with IGT, and from 1.19 to 1.28 for nonfatal MI, nonfatal CVD, CVD mortality and all-cause mortality in people with IFG.

The AusDiab (Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle Study),56 a large national population based cohort, investigated the relationship between different categories of abnormal glucose metabolism and the risk of all-cause and CVD mortality. The glucose tolerance status was determined in 10,428 participants after a median follow-up of 5.2 years. Compared with those with NGT, the adjusted all-cause mortality hazard ratios (HRs) were 1.6 (95% CI 1.0 to 2.4) for those with IFG and 1.5 for those with IGT (95% CI 1.1 to 2.0). For those with known diabetes mellitus, the HR was 2.3 (95% CI 1.6 to 3.2).

When CVD mortality was measured it was found that the HRs were 2.5 (95% CI 1.2 to 5.1) for those with IFG and 2.6 (95% CI 1.4 to 4.7) for those with known diabetes mellitus. However, the risk for those with IGT was not increased.

The authors concluded that there is a strong association between abnormal glucose metabolism and mortality, and suggested that this condition contributes to a large number of CVD deaths in the general population. Hence, in addition to people with known diabetes mellitus, those with milder forms of abnormal glucose metabolism need to be targeted in order to prevent premature mortality, particularly CVD death.

UK prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glucose

A number of factors influence the prevalence of IGT. As with T2DM, increasing age, obesity levels and ethnicity are risk factors for the development of IGT. As discussed previously, the use of different diagnostic criteria means prevalence rates may not be standardised across studies. 57 Two studies in London58,59 reported prevalences of IGT in over-40-year-olds of 3% and 4.1%, respectively, whereas a study conducted in a slightly older age group of 59- to 70-year-olds in Hertfordshire reported a dramatically increased prevalence of 18%. 60 The UK prevalence of IFG was reported as being approximately 17% in men and women aged > 60 years from a sample of over 7000. 61

In terms of variation among ethnic groups, a study in Coventry62 has reported higher prevalence of IGT in Asians than in the Caucasian population; they reported prevalences of 11.2% and 8.9% in Asian men and women, respectively, compared with 2.8% and 4.3% in Caucasian men and women.

Global prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glucose

The Diabetes Atlas, 2nd edition, 2002, compiled by the IDF, collated global regional estimates of prevalence of IGT in the 20- to 79-year age group using data from 212 countries and territories. 16 In 2003, the South East Asian region had the highest prevalence rate of IGT (13.2%), compared with 10.2% in Europe, 7.3% in both Africa and South/Central America, 7.0% in North America, 6.8% in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East and 5.7% in the Western Pacific region. These figures relate to single, broad age categories and did not divide prevalence according to age group and sex. This publication predicts that by 2025 an additional 7 million people in Europe will have IGT.

Studies in other developed countries, such as Australia, support the observation that the rate of IGT varies among studies. Dunstan et al. (2002)63 reported 9% and 12% in men and women, respectively; however, this was much higher than the 3.4% seen in two (smaller) previous Australian studies (Busselton and Victoria, in 1981 and 1992, respectively). 64,65 In the USA, 15.4% of a cross-section sample of adults aged 40–74 years (tested from 1988 to 1994) had IGT. The potential effect of migration on prevalence of IGT may be illustrated by the results from studies on the Chinese population both in the UK and in China. In a population of 375 Chinese people in Newcastle aged between 25 and 64 years, the prevalence of IGT was 8.0% (4.0% to 12.0%) in men and 16.1% (11.0% to 21.2%) in women66 compared with a large study of 92,187 people in the Da Qing province of China,67 which reported prevalence of 0.9% in both sexes. This shows that prevalence rates in source populations may not always be relevant to migrants to the UK.

The prevalence of IFG is not as widely reported as IGT. Dunstan et al. (2002)63 reported that the prevalence of IFG in Australia was 8% in men and 3.4% in women. In the USA, 33.8% of a cross-section sample of adults aged 40–74 years had IFG; however, more recent estimates from 1999 to 2002 indicate that, among US adults aged ≥ 20 years, 26% had IFG, which was similar to the prevalence in 1988–94 (25%). In India, both IFG (8.7%) and IGT (8.1%) show high prevalence with an overlap in one-third.

Quality of life

Compared with the normal population, people with T2DM have increased morbidity and mortality, resulting in reduced quality of life (QoL). 27 The QoL may be reduced even before diabetes is diagnosed, i.e. in those with IGT. The relationship between impaired glucose metabolism and QoL was examined in Ausdiab,68 a population-based study of 11,247 people of whom 610 had IFG and 1264 had IGT. Compared with those with NGT, those with IGT had significantly adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for the physical functioning [1.44 (1.14 to 1.81)] and social functioning [1.46 (1.20 to 1.77)] dimensions on the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36). In particular, difficulties were reported in performing tasks such as walking, climbing stairs and bending. In contrast, those with IFG showed no evidence of reduced QoL.

Impairments in QoL in patients with IGT or diabetes relate to specific symptoms including psychological distress and well-being, vitality, sleep disturbance, cognitive activities and sexual functioning. 69 A systematic search of the literature up to December 199770 yielded 58 studies examining QoL and T2DM. QoL as measured by SF-36 appeared to be unrelated to glycaemia control or to improvements or deterioration in glycaemic control within individuals; however, scales that measured feelings of distress associated with symptoms and functioning demonstrated responsiveness to changes in glycaemic control.

Current service provision for impaired glucose regulation

In the UK, specific guidelines for non-pharmacological interventions aimed at those with IGT or IFG do not exist; however, lifestyle advice (physical activity and diet) is the mainstay of current care pathways following diagnosis of impaired glucose regulation. Regular monitoring is recommended to assess whether the person’s glucose tolerance is progressing towards a diagnosis of diabetes or regressing towards normal. Not all trusts in England and Wales have specific protocols for management of impaired glucose regulation, partly because people with impaired glucose regulation are detected not through national screening programmes but opportunistically during investigation for other conditions, such as heart disease, or by practice-based screening or case-finding programmes.

A report by the Scottish Public Health Network71 also noted an absence of organised screening for diabetes.

In Chapter 6 we examine the use of data from the General Practice Research Database (GPRD) to indicate current management of intermediate hyperglycaemia.

There have been discussions in the UK National Screening Committee (NSC) and Department of Health (DH) about screening for T2DM. In its early stages, T2DM can display no symptoms but can be causing damage to small and large blood vessels. As reported in a previous technology assessment report,72 if there is screening for diabetes, we would expect, depending on method used and cut-offs chosen, to detect as many, or more, people with IGT and/or IFG, as with diabetes. If there are effective interventions to reduce diabetes, there would be a stronger case for applying them in IGT and IFG compared with the general population. Furthermore, intervention is more likely to be cost-effective than in lower-risk groups.

The conclusions from the NSC and DH discussions are summarised on the NSC website:73

General population screening should not be offered. Whole population screening has been assessed against the UK NSC criteria and does not meet a number of the criteria.

The UK National Screening Committee has identified the need for a Vascular Risk Management Programme, however, which includes diabetes.

The policy on screening for diabetes will be reviewed in 2012.

An integrated approach to cardiovascular risk reduction is advocated, and the health departments in the four nations will devise their own solutions.

Chapter 2 Modifiable risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus

Obesity

Obesity is the main risk factor for T2DM,74 but the mechanisms for this association are poorly understood. Manson and Spelsberg (1994)75 reviewed the current epidemiological evidence for potentially modifiable determinants ofT2DM, including obesity, body fat distribution, physical activity, and dietary factors. Achievable reductions in the risk of T2DM were estimated to be 50–75% by reducing obesity and 30–50% by increasing physical activity. Inconsistent results have been observed between specific dietary factors, including saturated fat, sugar and fibre intake.

We know that a number of risk factors are associated with development of T2DM. Being overweight or obese greatly increases the risk. Colditz et al. (1990)76 followed a cohort of 113,861 women aged between 30 and 55 years and reported a positive correlation between BMI and risk of T2DM; over 90% of cases of T2DM could be attributed to BMIs of ≥ 22 kg/m2, with the risk rising progressively with increasing BMI. (Note that the threshold BMI is below that which is defined as overweight.) Meisinger et al. (2006)77 reported that both overall and abdominal obesity were also strongly related to increased risk of T2DM in a German population of 6012 men and women aged between 35 and 74 years, with the highest risk reported in those participants with a high BMI in combination with a high WC and high waist–hip ratio. Hence, a large number of cases of T2DM may theoretically be preventable. In the UK, the prevalence of obesity and overweight are rising. Zaninotto et al. (2007),78 in an obesity forecast for the DH, reported that nearly one-third of men in England will be obese by 2010, with figures increasing from 4.3 million in 2003 to 6.7 million in 2010. The number of overweight men was forecast to increase slightly, from 8.4 million in 2003 to 8.6 million in 2010. Compared with males, a smaller proportional increase in number of obese females was expected, 4.8 million in 2003 to 6.0 million in 2010, with the number of overweight females expected to decrease slightly from 6.7 million in 2003 to 2.5 million in 2010.

A later study by Colditz et al. (1995)79 examined the relation between adult weight change and the risk of diabetes among middle-aged women. The participants were from the US Nurses Study: 114,281 female registered nurses aged 30–55 years followed from 1976 to 1990.

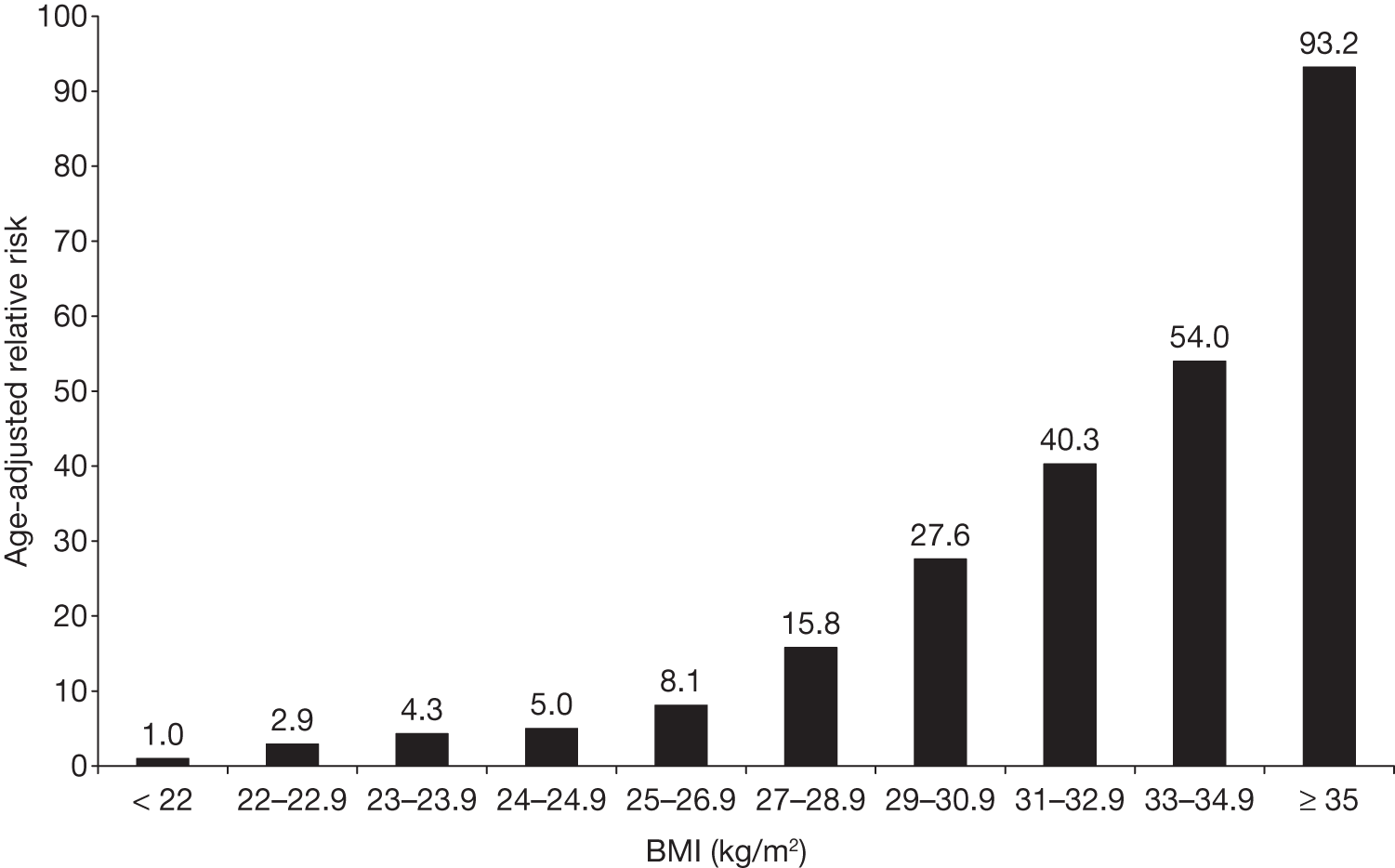

After adjustment for age, BMI was the dominant predictor of risk for diabetes mellitus. The risk increased with greater BMI, and even women with average weight (BMI 24.0 kg/m2) had an elevated risk compared with those with BMIs of < 22 kg/m2 (Figure 4). 79

FIGURE 4.

Attained BMI and RR for T2DM in US women aged 30–55 years in 1976 and followed for 14 years.

Women of average weight (BMI 24–24.9 kg/m2) had a RR of 5.0 (95% CI 3.6 to 6.6) for T2DM, compared with those with BMIs of < 22 kg/m2. Women with a BMI of ≥ 31.0 kg/m2 had an age-adjusted RR of ≥ 40.0.

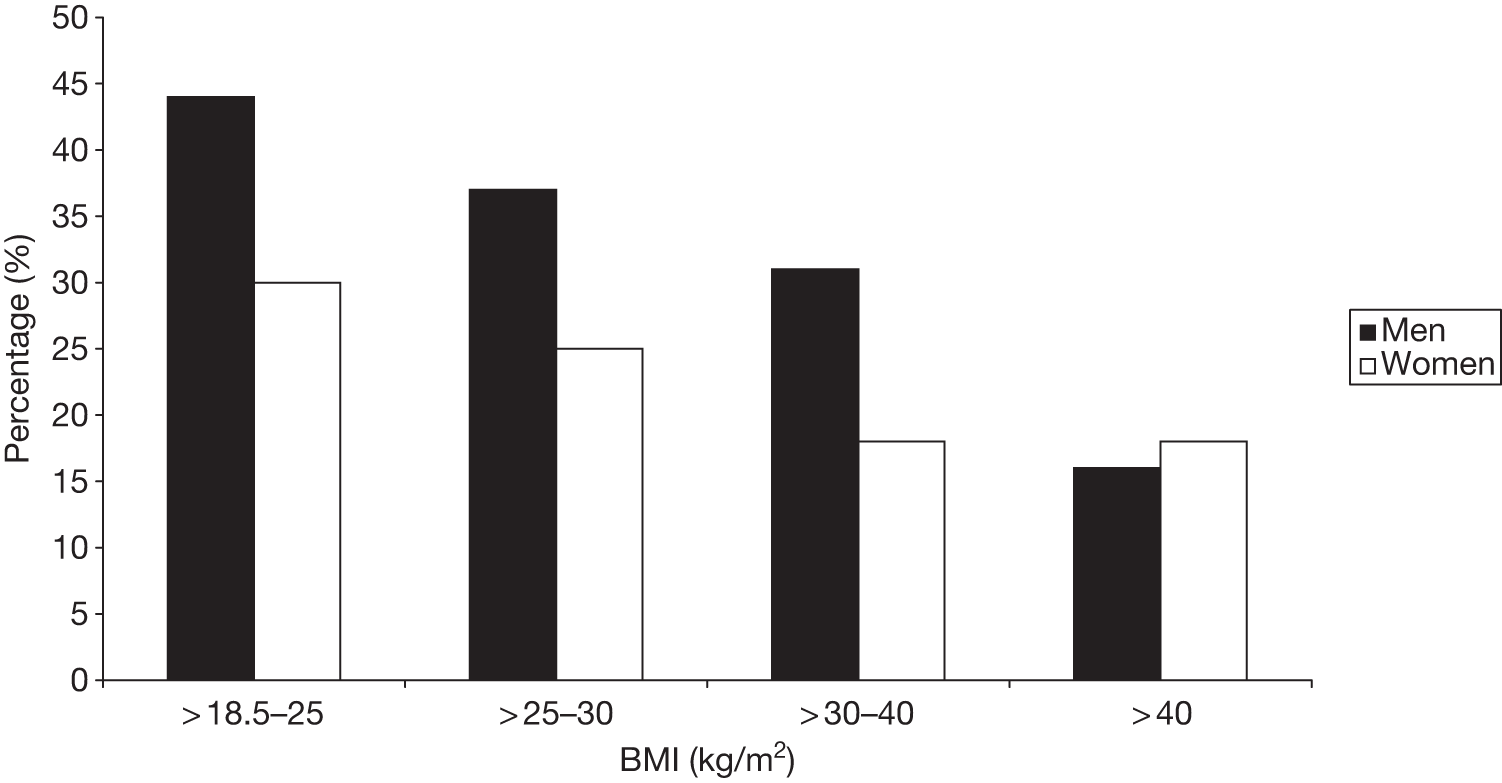

Hart et al. (2007),80 from the Renfrew/Paisley study, investigated the relationship between BMI in middle age with development of diabetes mellitus using data from two large prospective studies with around 30 years of follow-up. The participants were 6927 men and 8227 women from the general population study and 3993 men from the collaborative occupational study. Participants were aged 45–64 years and did not have reported diabetes mellitus at the beginning of the study.

Compared with the normal-weight group, the age-adjusted ORs for incident diabetes in the Renfrew/Paisley men were 2.73 (95% CI 2.05 to 3.64) in the overweight and 7.26 (95% CI 5.26 to 10.04) in the obese. The comparable figures for Renfrew/Paisley women were 2.54 (95% CI 1.95 to 3.31) and 5.82 (95% CI 4.41 to 7.68) and for collaborative men were 3.28 (95% CI 2.26 to 4.77) and 9.96 (95% CI 6.29 to 15.77). When the normal, overweight and obese groups were further subdivided, age-adjusted ORs increased as BMI increased. Compared with the lower half of the normal-weight group (BMI 18.5 kg/m2 to < 22.5 kg/m2), even the higher normal-weight group (BMI 22.5 kg/m2 to < 25.0 kg/m2) had between two and three times the risk of developing diabetes.

Assuming a causal relation, the authors estimated that around 60% of cases of diabetes mellitus could be attributed to being above normal weight in these populations.

Similar findings were reported from a large cross-sectional Canadian study by Jiang et al. (2008),81 who reported that in people aged 20–64 years (with an excellent 85% response rate in a national survey) the ORs for diabetes, compared with those with BMIs of < 25 kg/m2, was 2.1 for BMI 25–29 kg/m2 and 4.3 for BMIs of > 30 kg/m2 in men, and 2.6 and 7.7 for the same bands in women. They concluded that > 40% of diabetes in men and > 50% in women could be avoided by keeping to normal weight. The authors note that these proportions are smaller than in some other studies, possibly because of inclusion of people with T1DM, and because of self-reporting biases.

Central adiposity may carry particular risks, even in people with a normal BMI but a large waist. 82 WC, an indicator of central adiposity, is a predictor of risk for developing T2DM. 83

Does ethnicity affect the association between obesity and diabetes?

Diaz et al. (2007)84 used cross-sectional data for eight ethnic groups from the 2003–4 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and the 2003–4 Health Survey for England to examine the relationships of BMI, WC and waist–height ratio (WHR) with diabetes risk and across different ethnic groups.

The presence of diabetes was ascertained in 11,624 adults ≥ 20 years old, self-reported as US white, US black, Mexican American, English white, English black, Bangladeshi, Pakistani, Indian or Chinese. Diabetes was defined as self-report of doctor diagnosis or HbA1c level of > 6.1%.The crude prevalence of total diabetes for individuals of < 40 years old did not differ between the ethnic groups, but for individuals ≥ 40 years old there were significant (p < 0.01) differences.

The percentage of individuals with normal BMIs (< 25 kg/m2) who had diabetes was lowest (3.4%) in English white people. Higher prevalences were seen in other ethnic groups (5.0–10.9%). Mexican Americans (10.9%) and Bangladeshis (10.8%) have the highest prevalence of total diabetes, followed by Indians (8.7%) and Pakistanis (8.0%). Receiver operating characteristic curves for the association of total diabetes with BMI, WC and WHR for adults ≥ 40 years old showed that overall, for both genders, WHR and WC have larger areas under the curve than BMI, reflecting a statistically significantly (p < 0.05) higher discriminating ability for these two measures than for BMI. When stratifying by ethnic group it was generally found that WC and WHR generally have larger areas under the curve than BMI. However, there were differences between ethnic groups and between genders. WC and WHR were both significantly better predictors of future diabetes for both men and women in US white people and in women in US black people. In English white people, WHR in men and both WC and WHR were significantly better than BMI. WC and WCR showed no significant difference to BMI in either gender in Bangladeshis and Chinese.

Therefore, it appears that the association of diabetes and BMI may differ among ethnic groups, and different thresholds may be necessary. Adding other anthropomorphic measures, such as WC, may improve risk assessment. An important finding was that diabetes was found in many individuals who were classed as being of normal weight by BMI.

Qualitative aspects of diet

In terms of diet, a high fat intake, rich in saturated fatty acid, and a low intake of dietary fibre, wholegrain cereals and low-glycaemic carbohydrates have been shown to increase the risk of T2DM. 85

The ADA nutritional recommendations86 are shown in Box 1. The letters after each recommendation indicate the level of evidence, with ‘(A)’ the highest and ‘(E)’ the lowest.

-

Among individuals at high risk for developing T2DM, structured programmes that emphasise lifestyle changes that include moderate weight loss (7% body weight) and regular dietary strategies (such as reduced intake of fat) to reduce calories can reduce the risk for developing diabetes and are therefore recommended. (A)

-

Individuals at high risk for T2DM should be encouraged to achieve the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) recommendation for dietary fibre (14 g fibre/1000 kilocalories) and foods containing whole grains (one-half of grain intake). (B)

-

There is not sufficient, consistent information to conclude that low-glycaemic load diets reduce the risk for diabetes. Nevertheless, low-glycaemic index foods that are rich in fibre and other important nutrients are to be encouraged. (E)

-

Observational studies report that moderate alcohol intake may reduce the risk for diabetes, but the data do not support recommending alcohol consumption to individuals at risk of diabetes. (B)

-

Although there are insufficient data at present to warrant any specific recommendations for prevention of T2DM in youth, it is reasonable to apply approaches demonstrated to be effective in adults, as long as nutritional needs for normal growth and development are maintained. (E)

In the technical report that underpinned the ADA recommendations, Franz et al. (2002)87 also considered qualitative aspects of diet. It had been suggested that dietary fat might have an effect independent of calorie intake, perhaps via insulin resistance, but Franz et al. (2002)87 concluded that the main effect was through energy balance, and that if there were any specific metabolic effects of dietary fat then these were minor.

Franz et al. (2002)87 also noted that recent studies have suggested that diets with increased intake of whole grains and fibre may reduce the risk of T2DM, although, again, this might be via an effect on total calorie intake.

Riccardi et al. (2008)88 also reviewed the evidence on low-glycaemic-index foods in a narrative review, and concluded that there had been no intervention studies to assess the value of low-glycaemic-index, high-fibre foods in preventing progression from IGT to diabetes. 88 They did note that some prevention studies included an increase in such foods as part of the intervention package. They also noted that studies of low- glycaemic-index foods suggested benefit in people who already have diabetes.

Carter et al. (2010),89 in a high-quality review of fruit and vegetable intake and incidence of T2DM, found only six studies that were suitable for inclusion. 89 There was considerable heterogeneity and, in meta-analyses of five studies, neither fruit nor vegetables reduced the risk of diabetes. In a further meta-analysis of four of the studies, consumption of green leafy vegetables did appear to reduce the risk, with an OR of 0.86 (0.77 to 0.96) for highest compared with lowest intakes. However, what was meant by green leafy vegetables varied among studies.

Hays et al. (2008),90 as part of a wider review of prevention and treatment of diabetes, provide a useful account of the evidence for 50 food supplements or food types, ranging from alcohol to xanthan gum. 90 They note that, for most, there are insufficient data, with evidence of possible effects in 13 food supplements or food types.

Physical activity

Evidence suggests that people with a physically active lifestyle are less likely to develop insulin resistance, impaired glucose regulation or T2DM. 91,92 Furthermore, physical exercise may prevent progression to T2DM in those with IGT, and reduce the risk of complications in those already diagnosed with T2DM. 93 Potential determinants of exercise-associated prevention of T2DM are the location, frequency, intensity, duration and type (aerobic, resistance or combined) of exercise programme, age of person, dropout rate and the likely adherence to a particular exercise programme.

Description of the ‘FITT principle’:

-

Frequency The frequency refers to the number of times (usually measured per week) that a person exercises.

-

Intensity The intensity refers to the amount of effort required during exercise. Although the metabolic response is influenced by many factors (e.g. nutrition, age, type of exercise and physical condition), work intensity and duration are the most important. 94

-

Time The time refers to how long is spent exercising.

-

Type Exercise is commonly categorised as aerobic or resistance. Aerobic exercise involves the muscular and cardiorespiratory systems (e.g. brisk walking, cycling, swimming, jogging). Resistance exercise involves using muscular strength to move a weight or work against a resistive load (e.g. free weights or weight machines).

Frequency

Evidence suggests that exercise needs to be taken regularly for preventative effect. 95 The effect on insulin sensitivity of a single bout of aerobic exercise lasts between 24 and 72 hours, depending on the duration and intensity. 96 As the duration of increased insulin sensitivity is generally not more than 72 hours, the ADA recommends no more than two consecutive days without aerobic exercise. 94

In men there is a clear dose–response relationship between total energy expenditure in physical activity and the prevention of T2DM. Burchfiel et al. (1995)97 reported that the findings of the Honolulu Heart Program, in a large cohort of over 6800 Japanese American men, indicated a lower risk of diabetes in men who were taking the most exercise. Similarly, in the Physicians’ Health Study, the age-adjusted RR for diabetes gradually fell from 0.77 (CI 0.55 to 1.07) in men who exercised only once a week, when compared with men who did not exercise at all, to 0.58 (CI 0.40 to 0.84) in men who exercised five or more times per week (p = 0.0002 test for trend). 98

The evidence on the frequency of exercise in relation to the risk of diabetes in women is less clear. The Nurses’ Health Study found that regular exercise (at least once a week) was associated with a reduced incidence of T2DM (RR = 0.67, 95% CI 0.6 to 0.75, p < 0.001) but it found no clear trend according to frequency of exercise. 99 Compared with sedentary women (nurses who did not exercise weekly), RRs of T2DM are 0.74 (95% CI 0.6 to 0.91) for those who exercised once a week, 0.55 (95% CI 0.44 to 0.68) for those who exercised twice a week, 0.73 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.90) for those who exercised three times a week, and 0.63 (95% CI 0.53 to 0.75) for those who exercised four or more times a week. 99 In the Nurses’ Health Study, exercise was defined as ‘vigorous’ exercise, i.e. whether participants engaged in ‘any regular activity similar to brisk walking, jogging, bicycling, etc., long enough to work up a sweat’.

Intensity

A Cochrane review100 identified evidence for improvements in glycaemic control over a range of exercise intensities. Analyses conducted using the data from the Nurses’ Health Study cohort found that after controlling for intensity of exercise the RRs of T2DM were 0.67 (95% CI 0.55 to 0.81) for < 1 hour/week and 0.56 (95% CI 0.46 to 0.69) for ≥ 1 hour/week (the test for trend being significant at p < 0.001). 101 In a 14-year cohort of almost 6000 American men, it was found that for every 2.1-megajoule (MJ) (500 calories) increment in weekly energy expenditure, there was a 6% decrease in diabetes risk. 91 The age-adjusted risk of diabetes in American men who played vigorous sport was lower than in men who played moderate sport only. In this study, the age-adjusted risk of diabetes gradually fell from 1.00, 0.90, 0.69 to 0.65, as the levels of sports activity (self-reported at baseline) increased from no sports, moderate sports (energy expenditure 5 kcal/minute), vigorous sports (10 kcal/minute) to a combination of moderate and vigorous sports (p = 0.02 for trend).

Although the majority of evidence suggests that the most vigorous activity is protective, some evidence suggests little additional benefit in exceeding moderate-intensity activity. 95

Moderate- and high-intensity exercise may confer comparable benefits. 102 The Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study reported that increased participation in non-vigorous as well as overall and vigorous physical activity was associated with increased insulin sensitivity. 103 Improvements in insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance are seen in sedentary individuals who incorporate moderate levels of activity into their lifestyle but the change appears to occur far more slowly and less dramatically compared with higher-intensity activity. 104

In a 10-year cohort study Finnish women who engaged in vigorous activity [a metabolic equivalent of task (MET) value of ≥ 6] less than once a week were found to have a greater age-adjusted risk of diabetes of 2.23 (95% CI 0.95 to 5.23; p = 0.043) than women who engaged in vigorous activity at least once a week. 105 A similar trend was found for men, although the association was weak (age-adjusted RR = 1.63, 95% CI 0.92 to 2.88; p = 0.082). However, the association between intensity of activity and subsequent incidence of diabetes was no longer statistically significant for both genders after adjusting for total amount of activity (total energy expenditure).

In a prospective study of 7577 British men, the risk of diabetes decreases progressively as the intensity of physical activity increased from light to moderate, but the risk was not decreased any further in men who regularly performed vigorous activity. 106 Similar results were reported from a more recent prospective study of 7142 British men. 107 The study reported the age-adjusted risk of developing diabetes was lower in men who engaged in moderate physical activity (RR = 0.53) than in those who engaged in light (RR = 0.66) physical activity. However, no further reduction in risk was seen in men who engaged in moderately vigorous activity (RR = 0.53).

Jeon et al. (2007)20 carried out a systematic review of moderately intense physical activity and the risk of diabetes. ‘Moderately intense’ was defined as requiring a MET task score of 3.0–6.0 but not as high as vigorous (defined as requiring more than six times resting metabolic rate), and studies that involved mixtures of moderate and vigorous were excluded. Using MEDLINE, EMBASE and checking reference lists of retrieved studies, they identified 10 cohort studies involving 310,221 participants, of whom 9367 developed diabetes.

The risk of diabetes was reduced by 31% by moderate physical activity (RR = 0.69; 95% CI 0.58 to 0.83) compared with being sedentary. However, adjusting for BMI reduced the reduction to 17% (RR = 0.83; 95% CI 0.76 to 0.90).

One concern in debates about the prevention of diabetes has been to distinguish between exercise (e.g. an activity taken in addition to activities of daily living) and physical activity (with a broader meaning including all forms of activity). Taking exercise may incur time and financial costs, whereas increasing physical activity could be done as part of daily living, such as simply walking more. Another concern is whether those who take fixed periods of exercise may do less at other times.

Five of the studies in the review by Jeon et al. (2007)20 examined the role of walking, usually defined as at least 2.5 hours a week of brisk walking [e.g. walking at 5.6 km/hour (3.5 miles/hour) on a flat surface requiring 3.8 MET]. 20

Those who walked regularly had a 30% reduction in diabetes (RR = 0.70; 95% CI 0.58 to 0.84), though, again, adjusting for BMI reduced the reduction to 17% (RR = 0.83; 95% CI 0.75 to 0.91). However, this implies that moderate-intensity physical activity can reduce progression to diabetes even in those who do not lose weight. Compared with the minimal amount of walking in the reference category, the highest category was at least 10 MET hours/week, which is equivalent to ∼2.5 hours/week of brisk walking.

Time

The review by Bassuk and Manson (2005)108 identified evidence that shows physical activity sessions lasting as little as 10 minutes can improve the metabolic and cardiovascular risk profile of otherwise sedentary individuals. 102 The US Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) reported a 58% decrease in the development of diabetes in high-risk individuals who exercised for a minimum of 150 minutes per week (approximately 20 minutes per day).

The same total amount of exercise taken in several instalments appeared to be more effective in a small study by Eriksen et al. (2007). 109 Eighteen patients with T2DM were randomised to either three 10-minute sessions or one 30-minute session daily, of home-based cycle training, for 5 weeks. Both groups got fitter, but the 3 × 10-minute group had lower fasting and post-load glucose levels. The authors speculate that more energy is expended in short bursts.

Type

It is evident that alternative forms of physical activity that produce similar metabolic improvements to aerobic exercise may also be beneficial in the management of T2DM. The review by Eves and Plotnikoff (2006)110 identified evidence to suggest that resistance training may be effective in improving glycaemic control. They reported that results of three randomised controlled trials (RCTs) showed the effectiveness of resistance exercise to improve insulin sensitivity was comparable with that reported for aerobic exercise. These three RCTs compared resistance training with control (either flexibility exercise or no exercise), but the review suggests that the reported effect was comparable with that reported for aerobic exercise in other studies. There is also some evidence that the duration of effect of resistance training on insulin sensitivity is somewhat longer, perhaps as some of its effects are mediated by increases in muscle mass. 111 One RCT randomised 43 individuals with T2DM to either resistance or aerobic training for 4 months. 112 The authors reported that HbA1c level was significantly reduced with resistance training (from 8.3% ± 1.7% to 7.1% ± 0.2%; p < 0.001), but not with aerobic training (from 7.7% ± 0.3% to 7.4% ± 0.3%; p > 0.05). Fasting blood glucose and insulin resistance were also reduced and lipid profile improved with resistance but not aerobic training.

Although both aerobic and resistance exercise increase glucose disposal, resistance exercise tends to increase muscle mass and therefore glucose storage space. 94 The review by Eves and Plotnikoff (2006)110 found that increases in skeletal muscle mass are related to decreases in HbA1c level. 110 This supports the hypothesis that resistance training improves glycaemic control by augmenting the skeletal muscle storage of glucose. In one of the studies cited in the Eves and Plotnikoff review (2006),110 Castaneda et al. (2002)113 reported that resistance training significantly improved glycaemic control, increased fat-free mass and reduced abdominal adiposity, whereas body weight, and total, arm and leg fat mass did not change between intervention and control groups. The review also found ‘no significant relationship between the improvements in insulin sensitivity and the losses in either visceral or subcutaneous fat’ with regard to resistance training. Improvements to functional status and body composition often occur more rapidly with resistance compared with aerobic training, and therefore might be more immediately rewarding. ‘As there is substantial evidence that supports both aerobic and resistance training, it is possible that a combination of both may be the optimal intervention’. 110

A recent meta-analysis of 27 studies to examine the effects of different modes of exercise training on measures of glucose control concluded that all forms of exercise training (aerobic, resistance and combined) produce reductions in HbA1c levels (reductions 0.8% ± 0.3%), a measure of glucose control, with combined training generally being more effective than aerobic or resistance training alone. 114 (Note: These reductions are as great as seen with many glucose-lowering drugs. 30) The authors emphasise that the effects of exercise are similar to those of dietary and drug interventions and the combined effects might be moderate or large. Furthermore, evidence also suggested small beneficial effects on related risk factors for complications of diabetes and those with more severe disease were found to benefit most.

Sigal et al. (2007)115 carried out a RCT in 251 people with T2DM, aged 39–70 years, with four arms:

-

aerobic training

-

resistance training

-

both the above

-

a sedentary control group.

Exercise was carried out three times weekly for 22 weeks, in community facilities. The primary outcome was HbA1c level at 6 months. Other outcomes included plasma lipids and blood pressure. HbA1c level was reduced in the aerobic group by 0.51% (p = 0.007), in the resistance group by 0.38% (p = 0.038) and in the combined group by 0.9% compared with the control subjects. The bigger reductions in the combined group of 0.46% compared with aerobics alone, and 0.59% compared with resistance alone, were also statistically significant (p = 0.014 and 0.001, respectively). This may simply reflect the greater amount of exercise in the combined group. No significant differences were seen in blood pressure and lipids at 6 months.

Some of the conflicting results above may be related to baseline risk. Gill and Cooper (2008)116 carried out a systematic review of both observational studies and prevention trials. In brief, they noted that the marked reduction in diabetes incidence was attenuated once adjusted for BMI but that even after such adjustment physical activity reduced the risk by 20–30%. They also examined the evidence for thresholds, finding that there was uncertainty about whether there was a minimum level to achieve benefit, especially in women, but also that there appeared to be a level above which additional activity conferred no additional benefit. However, perhaps the most useful aspect of their review was the examination of the benefit according to baseline risk. Thus, in lean individuals with very low risk of diabetes, physical activity made little difference, whereas in people at high risk (high BMI, family history), physical activity was clearly beneficial, although especially so if combined with weight loss. They suggest a BMI threshold of 27 kg/m2 (23 kg/m2 in those of Asian descent) for prescribing higher levels of physical activity than the current health guidelines recommend (150 minutes of moderate activity or 60–90 minutes of vigorous activity per week).

Adherence

It is often those who would benefit the most from aerobic exercise that have the greatest difficulty performing it. Adherence with an exercise programme is important for successful outcomes. However, there are considerable problems of adherence with formal exercise programmes. 117 Around 50% of participants commonly drop out of supervised exercise programmes, and as many as 90% of participants drop out after 1 year. 118 Even though the importance of exercise is stressed more to diabetic people than non-diabetic individuals, diabetic individuals are no more likely to exercise than non-diabetic individuals. 117 Those more likely to adhere to exercise programmes appear to be elderly individuals, females, self-referred patients and patients participating in programmes along with a spouse. 117 The type of exercise programme also affects adherence, as described below.

Adherence and frequency

Lack of time is a common barrier to carrying out exercise and maintaining activity levels. As expected, King et al. (1995)119 found better adherence to a programme of exercise on 3–4 days per week compared with 5–7 days per week. However, a study by Perri et al. (2002)120 randomised 379 sedentary, non-diabetic, men and women to walk 30 minutes per day at a frequency of 3–4 or 5–7 days per week and an intensity of 45–55% or 65–75% of the maximum heart rate. The results showed that a prescription of higher frequency walking resulted in a greater amount of exercise (92 minutes per week) compared with moderate frequency (60 minutes per week) over a 6-month period. Similar levels of adherence were observed for exercise prescribed at a moderate (61%) and higher frequency (63%).

Adherence and intensity

A meta-analysis of 127 intervention studies found better adherence to lower-intensity activities than higher-intensity activities. 121 The effect size was found to be far greater for physical activities carried out at a low intensity (r = 0.94; 95% CI 0.91 to 0.97) than with higher intensities (r = 0.24; 95% CI 0.06 to 0.41). Results from a multiple linear regression analysis also showed that interventions emphasising physical activity of low intensity showed better adherence than those using higher-intensity activities.

The greater risk of injury occurrence in high-intensity activity might have a strong negative influence on adherence to high-intensity physical activity compared with lower-intensity activity. In some cases, the higher self-reported injuries during higher-intensity activity may represent ‘excuses’ for not completing an activity that involved maximal effort. 120

Perri et al. (2002)120 found that a prescription for walking at moderate intensity produced both better adherence to the exercise prescription (66% vs 58%) and a greater amount of exercise completed (85 minutes vs 72 minutes per week) compared with a prescription for walking at a higher intensity. McGinnis (2002)122 stressed the importance of incorporating physical activity into one’s lifestyle as it then has the potential to be maintained for years. A 3-year RCT of walking, with a 10-year follow-up, concluded that moderate-intensity activities such as walking are much more likely to be maintained over the years by people of many different ethnic and economic groups than high-intensity sport. 123

Motivating people to exercise is usually a challenge. The Cochrane review by Thomas et al. (2006)100 found that a gradual increase in exercise, starting from low-intensity and increasing to moderate-intensity exercise, performed regularly, may be a more successful approach to incorporate exercise into daily lives on a long-term basis than introducing more intense levels of exercise from the outset, which will be difficult to maintain in the longer term.

Adherence and time

Many people find it easier to conduct fewer longer exercise sessions than five or more weekly sessions. 94 The recommendations from the US Surgeon General’s report state that most people should accumulate > 30 minutes of moderate-intensity activity on most, ideally all, days of the week. 124

A study by Jakicic et al. (1995)125 reported that exercising in multiple short bouts (i.e. 10 minutes) improved adherence compared with single longer daily bouts of exercise.

Adherence and type

The Cochrane review by Thomas et al. (2006)100 reported that varying the type of exercise and having a choice of exercise activity may be an important factor in ensuring adherence with exercise programmes after the intervention period. The easier the exercise is to maintain, the more likely it is that people will do it. As Avenell et al. (2006)126 suggest, the message should be to ‘reduce inactivity’ rather than ‘do more exercise’. The Cochrane review concluded that dedicated exercise regimes should be prescribed in addition to lifestyle-based incidental types of activities for everyday life, such as cycling rather than using the car, using stairs instead of a lift and carrying groceries instead of pushing them in a trolley. 100

The success of exercise programmes is also highly dependent on adherence to a particular regimen. 120,127,128 For example, Perri et al. (2002)120 assessed 379 sedentary adults who were randomly assigned to walk 30 minutes per day at a frequency of either 3–4 or 5–7 days per week, at an intensity of either 45–55% or 65–75% of maximum heart rate reserve. 120 The study reported that prescribing a higher frequency increased the accumulation of exercise without a decline in adherence, whereas prescribing a higher intensity decreased adherence and resulted in the completion of less exercise. Similarly, Sallis et al. (1986)127 reported that, compared with vigorous exercise, rates of exercise adoption were higher and 1-year dropout rates lower for moderate activities.

Supportive evidence was also reported by Dishman and Buckworth (1996),121 who found that, compared with moderate- or high-intensity activities, greater increases in physical activity were seen for low-intensity activities. Surveys also indicate a preference for those activities that can be performed as an individual rather than in more structured settings. 129

In conclusion, easily adoptable exercise regimens of moderate intensity are therefore probably more likely to be successful that those that are of high intensity.

One issue is whether improvement in physical fitness can improve health even if no weight loss occurs. The effects on mortality were examined in the US Nurses’ Health Study by Hu et al. (2004). 130 They defined ‘lean’ as a BMI of < 25 kg/m2 and ‘obese’ as a BMI of ≥ 3 kg/m2, and ‘active’ as spending 3.5 or more hours on exercise each week. Taking lean active women as the reference case, with RR of 1.0, gave the following RRs;

-

lean and active: RR = 1

-

lean but inactive: RR = 1.55

-

obese and active: RR = 1.9

-

obese and inactive: RR = 2.4.

At all levels of BMI, physical activity was beneficial but it could not fully offset the higher risks imposed by obesity.

Summary

Physical activity protects against the development of diabetes. This applies to all forms of exercise. The benefit increases with frequency. However, the evidence on intensity is less clear and there may be an upper threshold above which increased intensity confers no extra benefit in terms of incidence of diabetes.

Adherence is important, and there may be trade-offs between amount and type, and adherence. Greater net benefits may come from a modestly effective form of activity with good compliance, compared with a more vigorous form of exercise with poorer compliance.

Current recommendations

The ADA made the following recommendations on physical activity for prevention of T2DM in June 2006:131

-

In people with IGT, a programme of weight control is recommended, including at least 150 minutes/week of moderate to vigorous physical activity and a healthy diet with modest energy restriction (level of evidence A).

-

To improve glycaemic control, assist with weight maintenance and reduce risk of CVD, at least 150 minutes/week of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity (40–60% of VO2max max or 50–70% of maximum heart rate) and/or at least 90 minutes/week of vigorous aerobic exercise (> 60% of VO2max or > 70% of maximum heart rate). Physical activity should be distributed over at least 3 days/week and with no more than two consecutive days without physical activity (A).

-

Performing ≥ 4 hours/week of moderate to vigorous aerobic and/or resistance exercise or physical activity is associated with greater CVD risk reduction than lower volumes of activity. (B)

-

For long-term maintenance of major weight loss (> 13.6 kg/30 lb), larger volumes of exercise or (7 hours/week of moderate or vigorous aerobic physical activity may be helpful). (B)

-

In the absence of contraindications, people with T2DM should be encouraged to perform resistance exercise three times a week, targeting all major muscle groups, progressing to three sets of 8–10 repetitions at a weight that cannot be lifted more than 8–10 times. (A)

Physical activity and exercise patterns

It may be useful to distinguish between physical activity, which includes both activity as part of daily life (e.g. walking or cycling to work, occupational activity) and exercise, from the sorts of exercise that require participation in sports or other activities which are not part of everyday life (e.g. hillwalking, going to gyms).

If we try to categorise physical activity patterns over a lifetime, we would need quite a complicated classification, including:

-

always active – active at school and continuing throughout life, albeit with different sports at different ages

-

never active after school, and possibly not even at school

-

active in younger ages, but stopping – girls probably earlier than boys; boys may go on to play sports, such as football or rugby, into their late 20s or longer

-

active in younger age groups then stopping because of work or family commitments, but then starting again for social reasons or after retirement

-

as for (4) but starting again for health reasons

-

mixed stops and starts.

For our purposes, we could think a slow progress towards IGT over many years, with groups (2) and (3) being the most at risk.

Given that the average age at diagnosis of IGT may be in the fifties, we may be identifying a group of people who are not only inactive and overweight, but also have been so for decades. The implication of that is that unhealthy habits may be hard to change. It may be unrealistic to expect them to take up exercise, and the main thrust may have to be to try to encourage an increase in physical activity, such as walking.

This raises two issues. The first is about efficacy compared with effectiveness, with efficacy referring to results in trials (volunteers, perhaps high level of input) and effectiveness referring to results in real life. The second is whether modest increases in physical activity, such as walking, are sufficient to reduce diabetes. Is there a threshold level which must be exceeded to get an effect, or is there a continuum in which all activity has some effect? It may be that strenuous exercise is better metabolically, but modest will achieve greater uptake. A review by the Health Development Agency concluded that132 ‘Interventions that promote moderate-intensity physical activity, particularly walking, and are not facility dependent, are also associated with longer-term changes in behaviour.’

Di Loreto et al. (2003)133 addressed the issues of real-life applicability and achieving adherence in a randomised trial of a carefully designed intervention to promote physical activity in unselected people with T2DM. Having noted the benefits of exercise in diabetes, they go on to comment that133 ‘many physicians do not spend time making an effort to convince type 2 diabetic subjects to exercise, probably because older adults comply poorly with their recommendations.’

They then designed an intervention that was based on a number of factors, including motivation, self-efficacy, family support, removing impediments, enjoyment, and checking on understanding of benefits. They took care not to suggest radical increase in exercise, but used a staged approach so that people were not discouraged. Nevertheless, these small steps achieved, over time, a considerable increase in physical activity. Patients might start with only a 20-minute walk daily but would increase this at weekly intervals. From a baseline activity level of about one MET hour/week, the intervention group increased to 27 METs. The control group were given standard advice, including on exercise, but increased to only four METs/week. The target level of over 10 METs hours/week was achieved by 69% of the intervention group and 18% of the control group. One weakness in the report is that the method of randomisation was not given. Another is that results were given at 24 months, when it appeared that the intervention was continuing. It would be interesting to know if the increase continued after it was stopped.

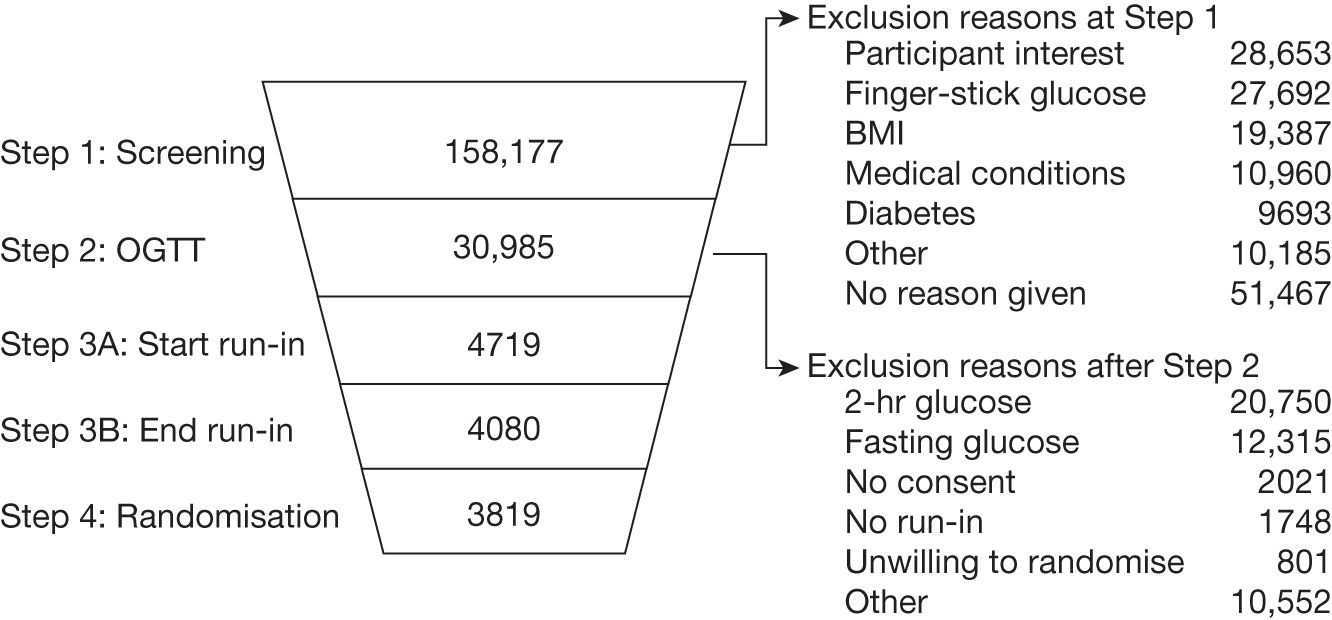

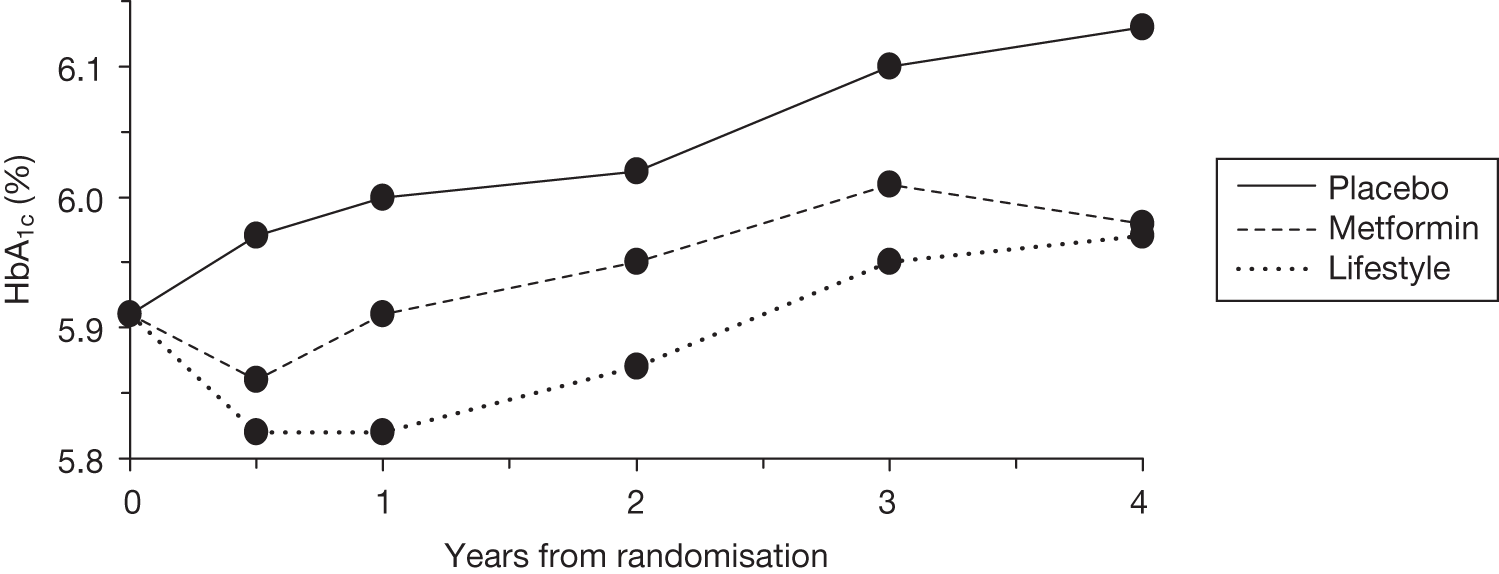

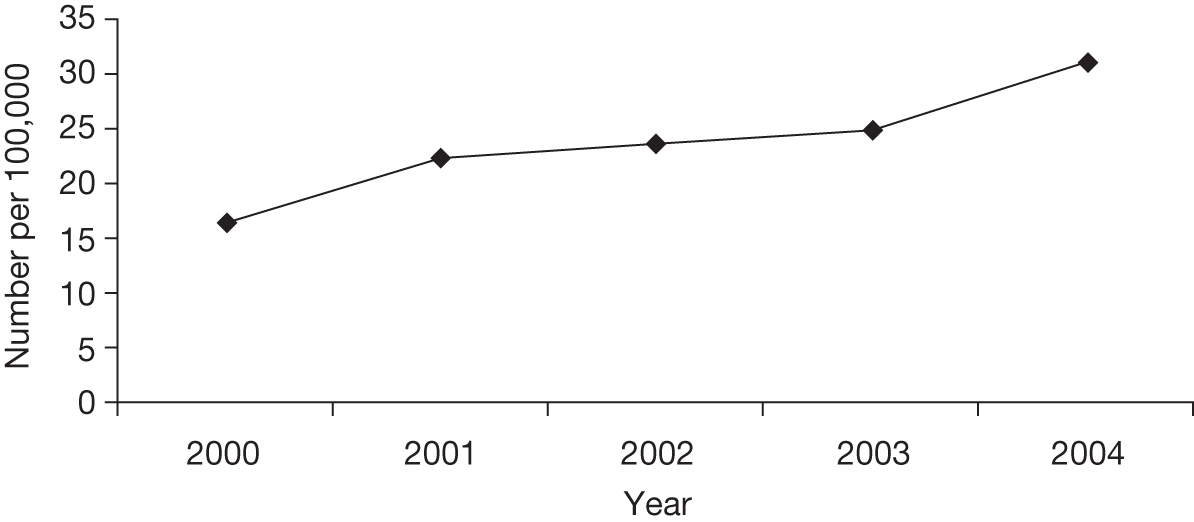

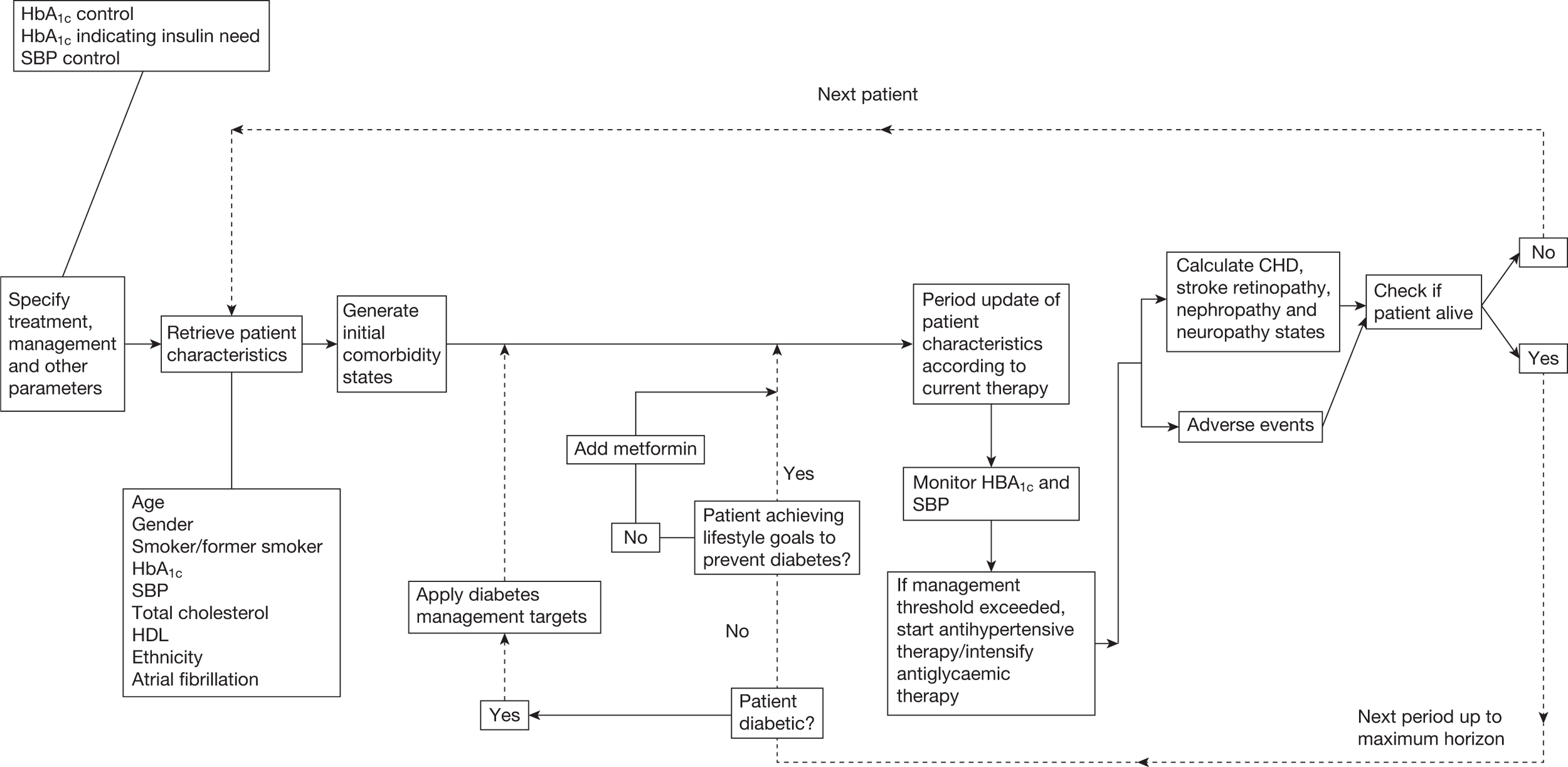

The authors attribute success partly to their own enthusiasm for exercise – the counselling was given by physically active physicians. They also emphasise the importance of not deterring people: ‘This step-by-step approach intentionally avoided goals that the patient was unable to imagine attaining’.