Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 09/141/01. The protocol was agreed in September 2010. The assessment report began editorial review in April 2011 and was accepted for publication in December 2011. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2012. This work was produced by Papaioannou et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to NETSCC. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2012 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Description of health problem

Epidemiology

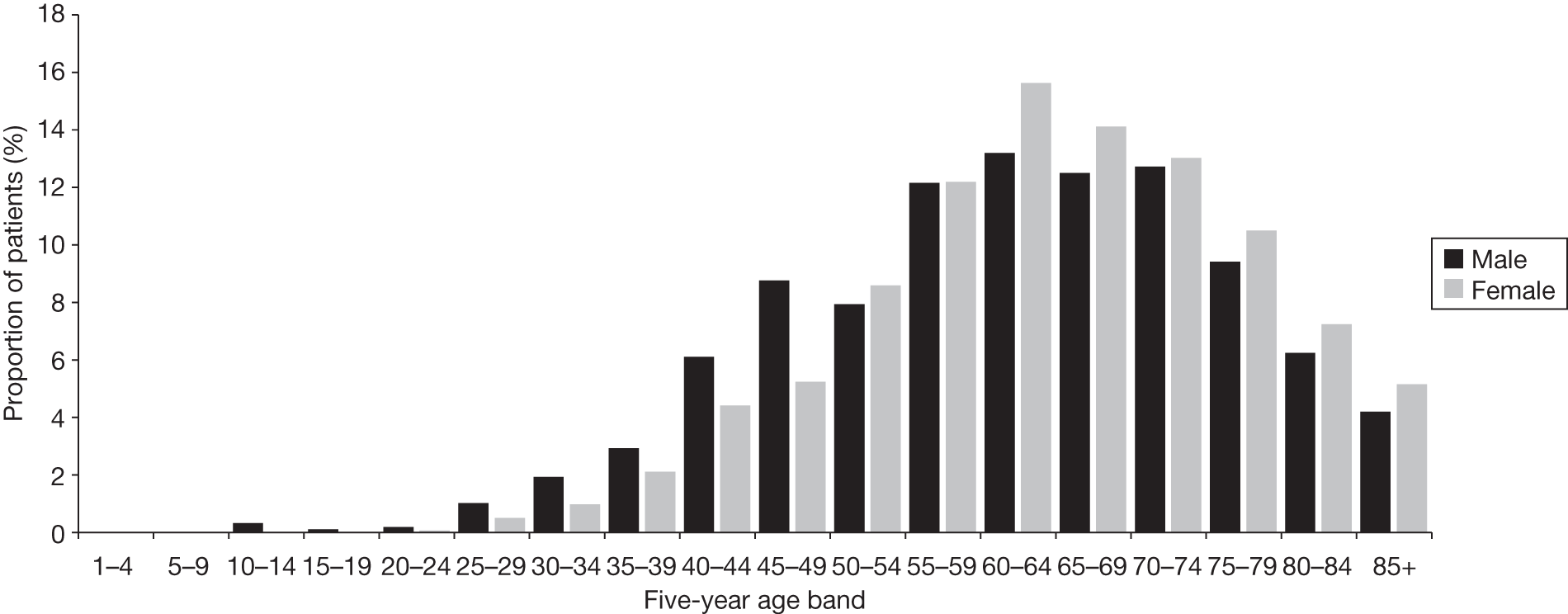

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHLs) account for approximately 4% of all cancers diagnosed in the UK,1 and are also the fifth most common cancer in the UK for both sexes combined (fifth in males and seventh in females). 2 In 2008, there were 10,319 new cases of NHL registered in England and Wales,3 and 3978 registered deaths in 2008. 4

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is a type of low-grade or indolent NHL, in which the cancer develops slowly, often without symptoms, for many years. FL is the second most common type of NHL within Western Europe and the USA,5 and is reported to account for between 20% and 30% of all NHLs. 6–9 The UK incidence of FL is approximately 3.4 per 100,000 persons (see Table 1), and around 70% of all cases are diagnosed in people aged > 60 years. 10 FL occurs equally in males and females. Most patients with FL present with advanced disease; approximately 50% of patients will present with bone marrow involvement (i.e. stage IV disease; see Staging, later in this chapter).

| NHL/FL incidence | England | Wales | England and Wales |

|---|---|---|---|

| All NHLs: no. of cases (2008) | 9676 | 643 | 10,319 |

| All NHLs: crude rate per 100,000 (2008) | 18.8 | 21.5 | 18.9 |

| FL: no. of cases (2008) | 1757 | 112 | 1869 |

| FL: crude incidence per 100,000 (2008) | 3.4 | 3.7 | 3.4 |

Over 70% of people with FL are still alive 5 years after the diagnosis,11 with the 10-year predicted survival rate for patients in England and Wales in 2007 reported as 50.8%. 2 In the last decade, longer median survival has been reported, with one centre reporting median overall survival (OS) of up to 18 years,12 and the percentage of survival at 20 years as high as 44%. 13 Some have attributed this to novel therapeutic strategies,14,15 including chemoimmunotherapy [i.e. chemotherapy and rituximab (MabThera®, Roche Products)] and radioimmunotherapy. Relevant data on incidence and prevalence are provided in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

| NHL/FL prevalence | 1-year prevalence | 5-year prevalence | 10-year prevalence | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| England | Wales | England and Wales | England | Wales | England and Wales | England | Wales | England and Wales | |

| NHL prevalence (2006) | 6330 | 498b | 6761 | 24,207 | 1516 | 25,723 | 38,227 | 2224 | 40,451 |

| Estimated FL prevalence (based on FLs as 20–30% of NHLs)6–9 | 1266–1899 | 105b | 1371c–2028 | 4841–7262 | 303–455 | 5145–7717 | 7645–11,468 | 445–667 | 8090–12,135 |

The incidence of NHL has been increasing in the UK; rates have increased by more than one-third since the late 1980s, resulting in the incidence in people aged > 75 years being three times higher in 2007 than in 1975. 18 Other countries (Western Europe, USA, Japan, Brazil, India and Singapore) have also noted increasing incidences of NHL. In westernised countries, the annual incidence of FL has increased from 2–3/100,000 during the 1950s to 5–7/100,000 recently (date not specified). 19

It is unclear why the incidences of lymphomas are increasing, although better diagnosis, improved cancer reporting, changes in classification, unknown environmental factors, an increasing elderly population and increases in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related lymphomas will contribute to the increase in incidence. However, these factors are estimated to account for about half of the increase in observed incidence. 20

Aetiology

The causes of NHL in general, including FL, are unclear. There are a number of well-established risk factors, such as infectious agents [e.g. human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)],21 immunosuppression (e.g. post organ transplantation),22 genetic susceptibility (e.g. ataxia–telangiectasia)23 and environmental factors (e.g. exposure to agrochemicals). 24 Rare immunodeficiency conditions such as hypogammaglobulinaemia, Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome and ataxia–telangiectasia have been associated with as much as a 25% increased risk of developing lymphoma;25 however, the primary causes of NHLs remain elusive.

Pathology

Background

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas are a diverse group of cancers characterised by abnormal growth of tissue in the lymphatic system. The lymphatic system comprises the tissues, organs and vessels that produce, store and deliver cells that fight infection – ‘lymphocytes’. There are two main classes of lymphocytes – T lymphocytes and B lymphocytes – with each having a key role in protecting the body from pathogenic microorganisms. ‘T cells’ are responsible both for cell-mediated immunity and for stimulating ‘B cells’, which, when activated, produce antibody that kills or neutralises antigens. NHL may be classified as a B- or T-cell NHL, depending on whether it is B or T lymphocytes that are proliferating at an abnormal rate. Approximately 85% of all NHLs are of B-cell origin and the remaining 15% of T-cell origin. 26

Follicular lymphoma is classified as a B-cell NHL. It is an indolent (slow-growing) cancer that affects B-cell lymphocytes (centrocytes and centroblasts). Patients with FL typically present with painless, swollen lymph nodes in the neck, armpit or groin. Systemic or ‘B’ symptoms are rare: these include fever, fatigue, night sweats and unexplained weight loss. 5,27 Less frequently, there may be no peripheral lymphadenopathy, or patients develop abdominal or back pain owing to intra-abdominal (often paraortic) lymph node enlargement. 5 Usually disease is disseminated and involves lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm (stage III) or possibly extralymphatic organs or tissues (stage IV). 6,28

Despite being treatable, FL is characterised by a relapsing–remitting clinical course over several years, with each successive response becoming more difficult to achieve and of shorter duration. 27 The course and prognosis of FL improved only marginally from 1960 to the early 1990s, with a reported median survival of 8–10 years. 29 However, in the last decade, longer median survival has been reported and has been attributed to novel therapeutic strategies, including chemoimmunotherapy (i.e. chemotherapy and rituximab) and radioimmunotherapy. 14,15

Patients with advanced stage III–IV lymphomas will eventually become resistant to chemotherapy and transform to high-grade or aggressive lymphomas, such as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). 29,30 Resistant disease or transformation into DLBCL is the usual cause of death for patients with FL. 27 The risk of transformation to aggressive lymphoma is thought to be constant over time;29 the annual risk of transformation has been estimated as 3% per year and the median survival after transformation has been reported as 1.7 years, although this figure comes from the pre-rituximab era. 31 It is not clear whether specific therapies can increase or decrease this risk. 32

Diagnosis and grading

The diagnosis of FL is confirmed by lymph node biopsy, which optimally requires review by an pathologist or haematopathologist (in the UK). 32

Staging

Once FL is identified, it is staged to find out how far the disease has spread. Staging tests determine which areas of the body are affected by FL, the number of lymph nodes affected, and whether or not other organs are affected such as the bone marrow or liver. The Ann Arbor system (see Appendix 2) is a clinical tool that was originally developed for Hodgkin’s disease, but is also used for FL to determine the stage of the lymphoma. It classifies four stages of disease that reflect both the number of sites of involvement and the presence of disease above or below the diaphragm. 34 Each stage of disease is divided into two subsets of patients according to the absence (A) or presence (B) of systemic symptoms. Fever without other cause, night sweats and weight loss of > 10% of body weight are considered to be systemic symptoms. The tests carried out for staging include blood tests, computerised tomography (CT) scan, bone marrow biopsy. Positron emission tomography (PET) scan may also be used, although is not routine in the UK. At most, 10–15% of FLs are detected at the early stage;35 thus the majority present with advanced-stage disease (Ann Arbor stage III–IV).

Grade

Follicular lymphoma is a low-grade or indolent B-cell disease and is diagnosed according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification. Grade is determined by histology (i.e. by inspecting cells under the microscope), which looks at the number and size of abnormal cells taken from lymph node biopsies. The disease maybe subdivided into grades 1/2 (combined in the latest version of the WHO classification), grade 3a or 3b. These subdivisions of grade 3 are based on the presence of increasing numbers of more aggressive cells termed centroblasts. Grade 3b is treated in the same manner as the common high-grade NHL, DLBCL. Grades 1/2 and 3a are managed as indolent forms. Each disease stage (Ann Arbor stages I–IV) can be assigned a grade (1–3a/b).

Systems of classification

Follicular lymphoma is classified according to its morphology, immune phenotype, genetics, and clinical features of neoplasms. Since the 1970s, various classification systems have been used to differentiate NHLs, which have developed alongside an increasing understanding of the different cellular components of the lymphatic system that the cancer process affects. 36 It is useful to be familiar with previous classification systems in order to interpret the older literature for lymphomas with now outdated names. The third edition of the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O) provides a guide for translation of previous classification systems into the present. 37

The earliest classification systems were based on the cellular morphology of neoplastic cells and their relationship to the lymphoid tissue architecture. The Rappaport Classification, which was used until the 70s, was devised before lymphoid cells were split into T and B cells. 38 In the early 1970s, the Kiel Classification system was proposed, which classified lymphomas according to their cellular morphology and their relationship to cells of the normal peripheral lymphoid system. 39 The Working Formulation devised by the National Cancer Institute in 1982 attempted to translate the recognised classification systems for NHL (it did not include Hodgkin’s lymphomas). The Working Formulation was a purely histological classification and divided lymphomas into four grades (low, intermediate, high and miscellaneous), related to prognosis, and included subdivisions based on the size and shape of affected cells. However, this classification system did not differentiate between T and B cells and is now obsolete.

With the development and application of immunophenotyping and cytogenetic and molecular genetic testing, the Revised European–American Lymphoma Classification (REAL) classification system was devised in the mid-1990s and incorporated immunophenotype and genetic criteria. The WHO classification system, based on the REAL classification, is the latest classification system and the most widely used and accepted. The WHO classification was updated in 2008 and groups lymphomas by cell type and defines phenotypic, molecular and cytogenetic characteristics. There are three large groups of neoplasms: (1) B cell, (2) T cell and (3) natural killer cell neoplasms. FLs are grouped under the B-cell type (ICD-O-3 codes: 9690/3, 9691/3, 9695/3 and 9698/3).

Prognosis

Follicular lymphoma is curable for only a few patients, mainly those with localised or early-stage disease (Ann Arbor stages I and II). 40 Most advanced-stage patients respond to initial drug therapy and their symptoms go into remission. However, despite novel therapies and recent improvements in therapy, advanced FL is not considered curable. Patients with advanced FL undergo multiple relapses with the duration of remissions shortening at each subsequent treatment at recurrence. 30,41

Prognostic factors

Prognostic factors in FL can be categorised as patient-related factors and disease-related factors. By analysing prognostic factors, indices have been developed to predict clinical outcomes such as progression-free survival (PFS) and OS. Two such indices are the International Prognostic Index (IPI) and the Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI).

Patient-related variables

The most important patient-related prognostic factors are performance status and age. 42 Performance status, is defined by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG)43 and ranges from 0 (fully active) to 4 (completely disabled); thus poorer performance status is associated with a poorer FL prognosis (see Appendix 3 for ECOG performance status in detail). However, only 10–15% of patients with FL present with a poor performance status at the time of diagnosis. 42

Age of > 60 years is a significant factor for prognosis. 44,45 The existence of comorbidities and alterations in immunity with age might limit the drugs that can be used. 46 In addition, alterations in pharmacokinetics and reduction in hepatic and renal function occurs with increasing age. This affects the absorption, distribution, activation, metabolism and clearance of drugs. 46 This impacts on the clinician’s ability to treat elderly patients effectively. Gender has also been shown to be an important prognostic factor; the male sex is associated with a poorer clinical outcome. 28

Disease-related factors

Histological features such as lower degree of follicularity (i.e. greater diffuse areas),47–50 absence of interfollicular fibrosis47 and high content of macrophages in biopsy samples51 are associated with poor prognosis; helper T-cell infiltrates have been associated with a survival benefit. 52,53 Genetic features such as oncogenes or tumour-suppressor genes, chromosomal gains or losses and gene expression profiles have been found to affect prognosis. 42

Factors relating to disease extent are important in predicting prognosis. Patients with limited stage disease (i.e. Ann Arbor stage I or II) are likely to have prolonged survival. 42 However, the majority of patients present with advanced disease (stage III or IV), thus the effect of other clinical parameters has been investigated. A larger number of extranodal sites involved,44,45,54,55 presence of B symptoms,44,54 the presence and greater extent of bone marrow involvement56 and the presence of hepatosplenomgaly30 have all been found to affect adversely prognosis. In addition, tumour burden has been identified as an important prognostic factor; however, it is inconsistently defined according to size of lymph node masses, number of extranodal sites involved, degree of splenomegaly or hepatomegaly and the presence of circulating lymphoma cells. 42

Biological markers such as elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) have been found to predict lower response rates and survival. 28,44,54 A normal haemoglobin level has been found to be a favourable factor for prognosis, whereas a haemoglobin level of < 12 mg/dl is a poor prognostic factor. 30

International Prognostic Index

The IPI was originally designed as a prognostic tool for aggressive NHL (DLBCL), and is based on the presenting features and the extent of disease. The IPI has been reported to discriminate between patients with FL with significantly different survival periods,57 and is now used as a predictive tool for survival in FL (Table 3).

| One point is assigned for each of the following risk factors | The sum of the points allotted correlates with the following risk groups |

|---|---|

|

Age > 60 years Ann Arbor stage III or IV disease Elevated serum LDH ECOG/Zubrod performance status of 2, 3 or 4 More than one extranodal site |

Low risk (zero to one point): 5-year survival of 73% Low-intermediate risk (two points): 5-year survival of 51% High-intermediate risk (three points): 5-year survival of 43% High risk (four to five points): 5-year survival of 26% |

Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI and FLIPI2)

In 2004, the FLIPI was developed specifically for patients with FL. Evaluations of demographic, clinical and biological characteristics from > 4000 patients with FL were used in univariate and multivariate analyses to develop the FLIPI. It provides clinicians and patients with a prognostic index based on five criteria (age > 60 years, Ann Arbor stage III or IV, number of nodal sites of involvement greater than four, elevated serum LDH, and haemoglobin level of < 12 g/dl). The FLIPI assesses OS, i.e. carrying a low (zero to one risk factors), intermediate (two risk factors) or high risk (three to five risk factors). 58 The FLIPI has been further refined to accommodate more recent developments in the collection of biological data and newer treatment modalities such as immunotherapy, resulting in FLIPI2. 59 For example, β2-microglobulin is an independent prognostic marker included in later versions of the FLIPI.

Significance in terms of ill-health (burden of disease)

The nature of NHL in general, and the relapsing–remitting course of FL in particular, suggests that both individually and at a population level it is responsible for a considerable amount of morbidity and mortality (see Epidemiology). In 2009, NHL accounted for 0.8% of all deaths and 2.9% of all cancer deaths in England and Wales (see Appendix 4 for data sources and numbers used), and is the ninth most common cause of cancer mortality in the UK. 2

Current service provision

Objectives of treatment and important health outcomes

Advanced FL is not curable. However, because of the age distribution and presence of comorbidities, patients may remain uncured from FL but may die from other causes unrelated to the disease. The aim of disease management is both to increase patient life expectancy and to increase patient health-related quality of life (HRQoL). First-line treatment aims to produce a maximum initial response by reducing tumour burden,60 to prolong the periods of PFS and OS, to increase the duration between episodes of disease recurrence and to minimise the symptoms associated with relapse and treatment side effects. 61

Therefore, the following outcomes are likely to be of potential importance:

-

absence of disease at given points in time following diagnosis

-

absence of symptoms

-

absence of side effects

-

duration of survival

-

– OS

-

– PFS

-

-

HRQoL

-

patient and carer satisfaction.

Management of disease

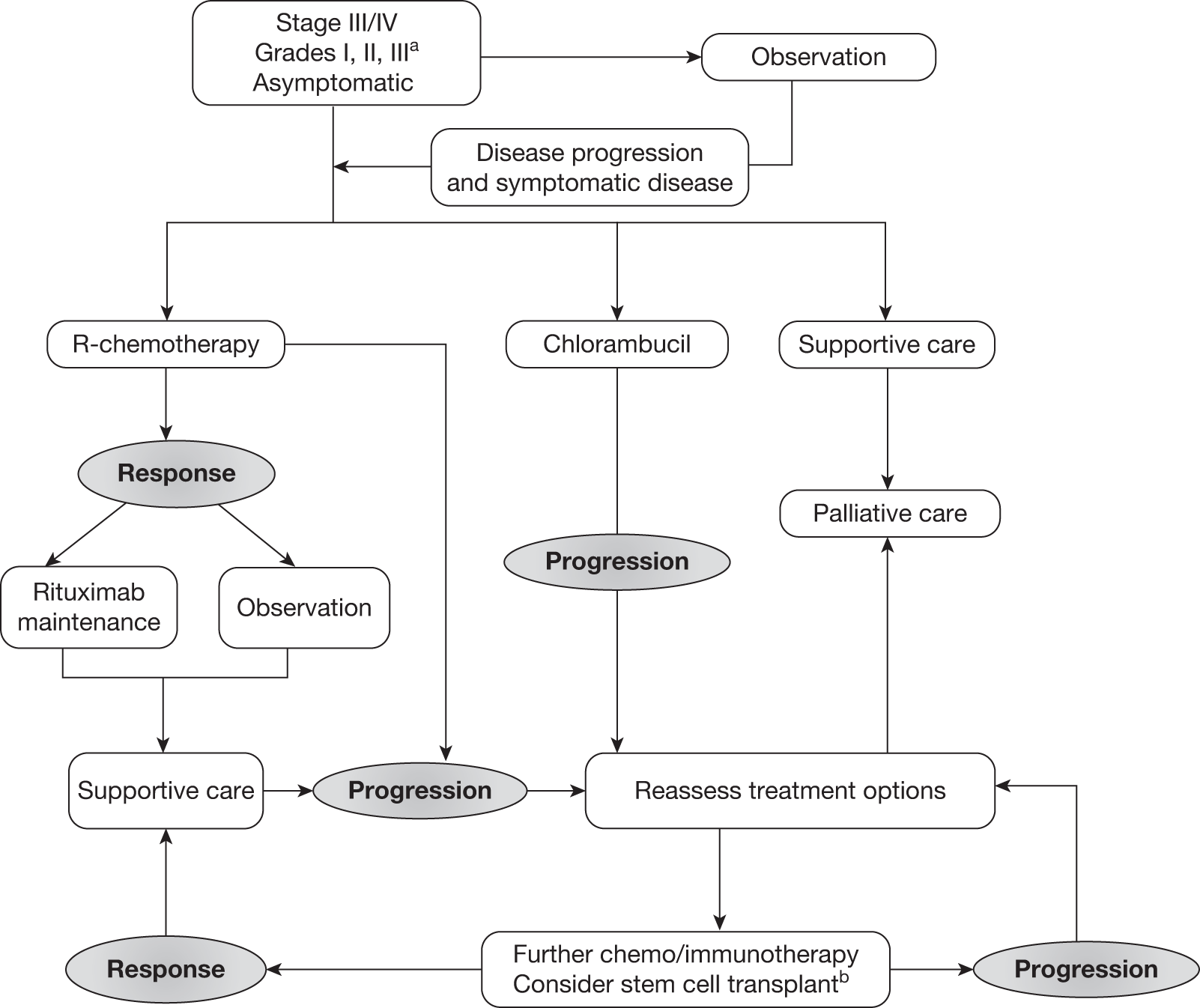

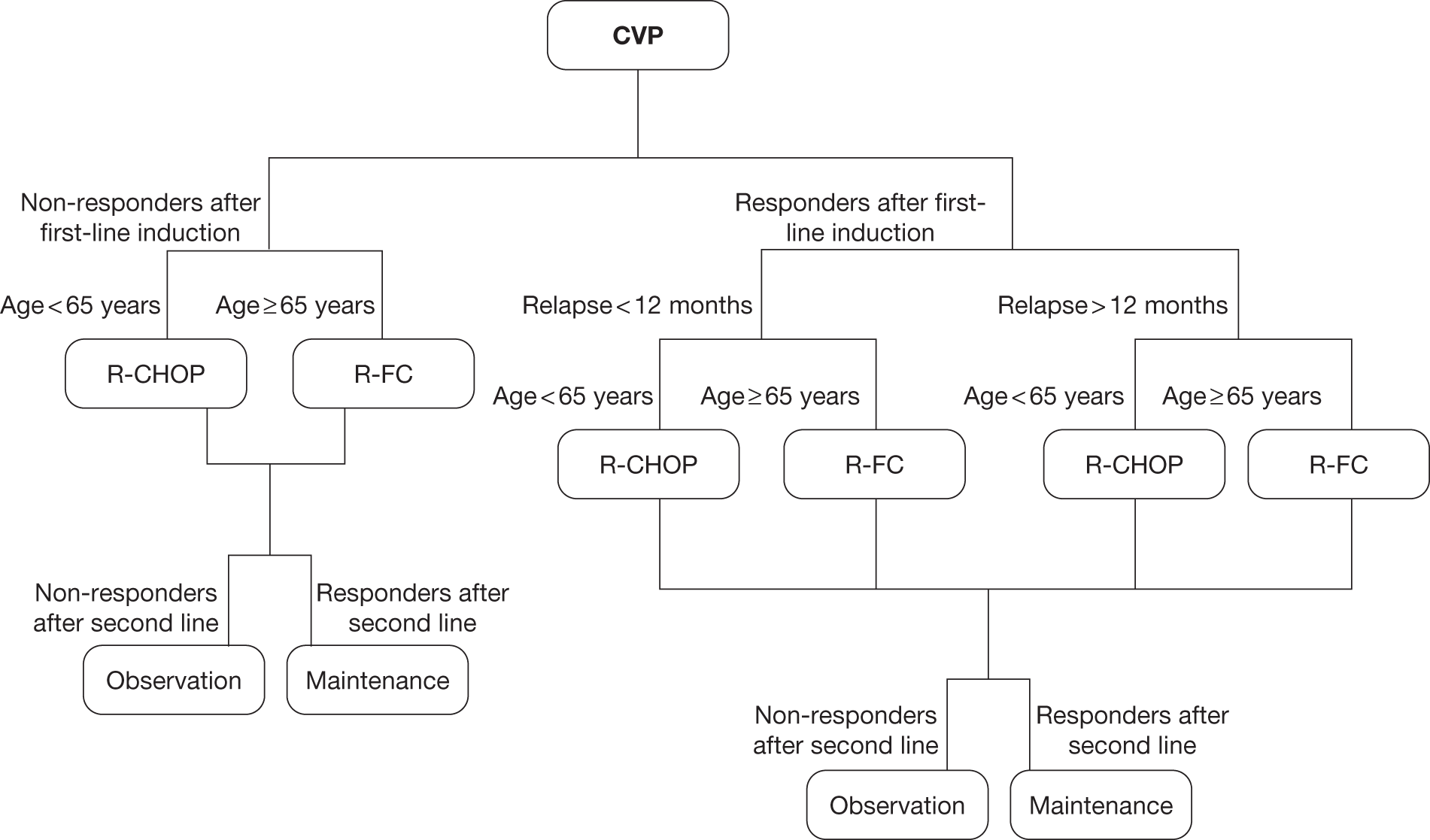

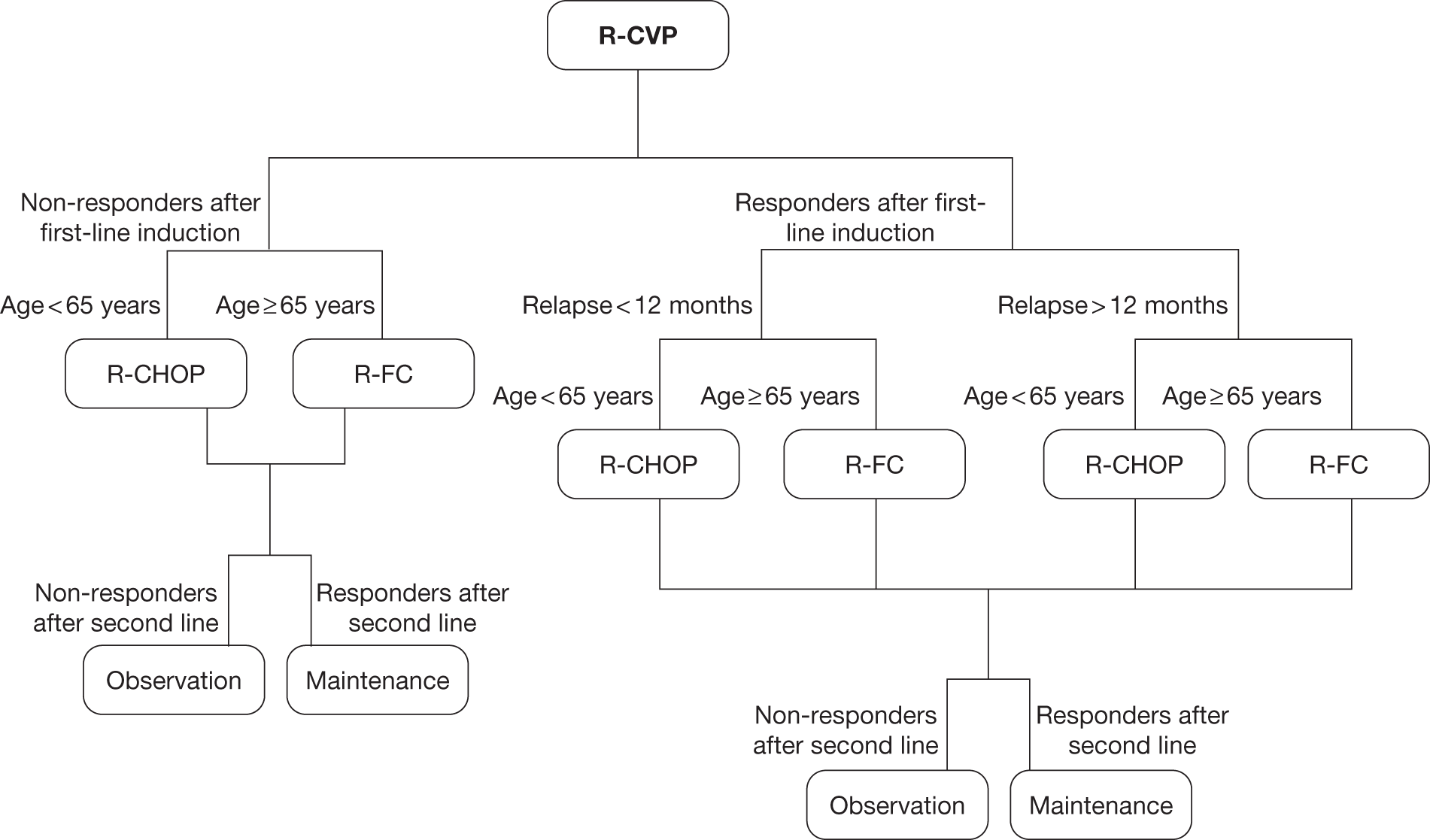

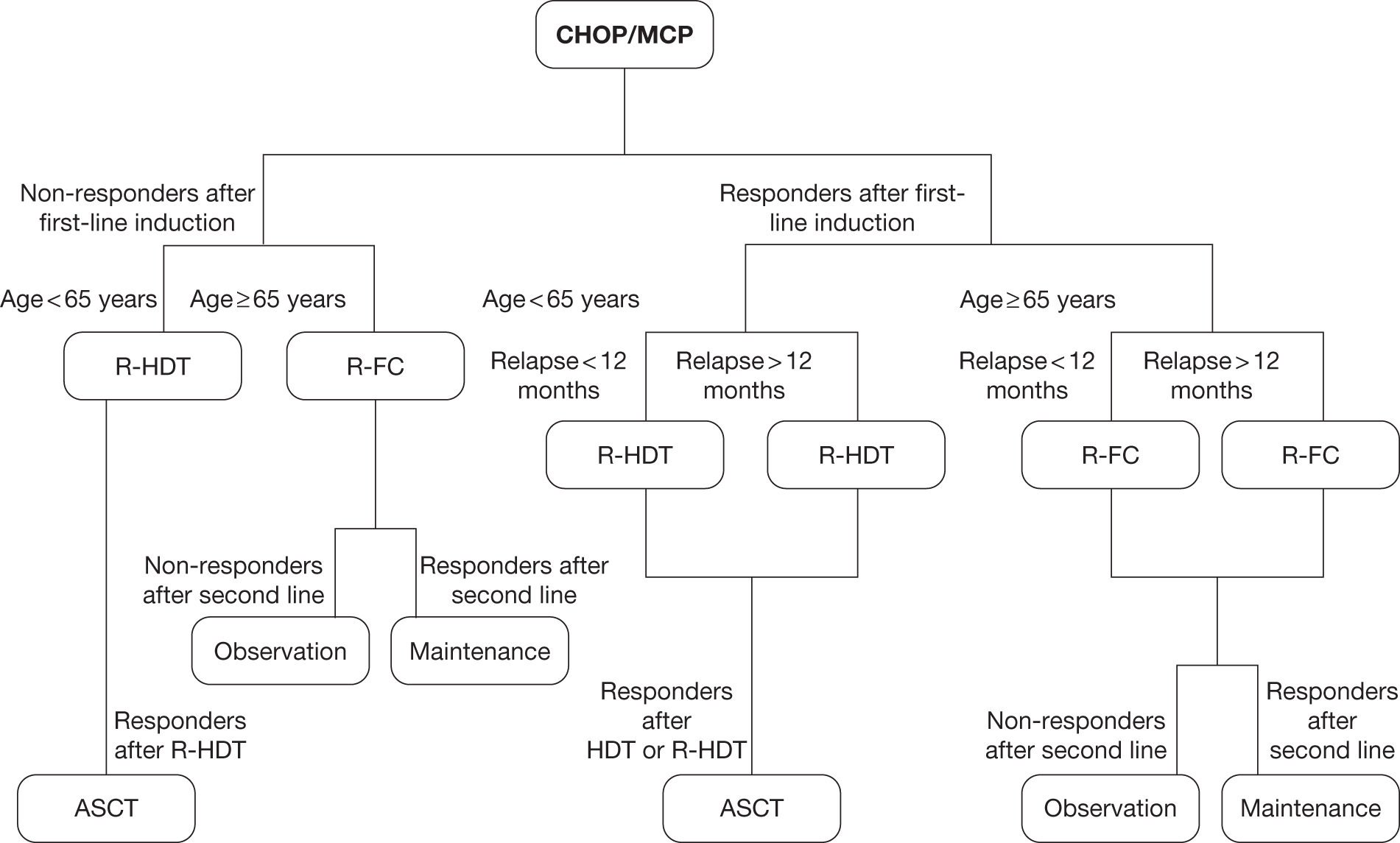

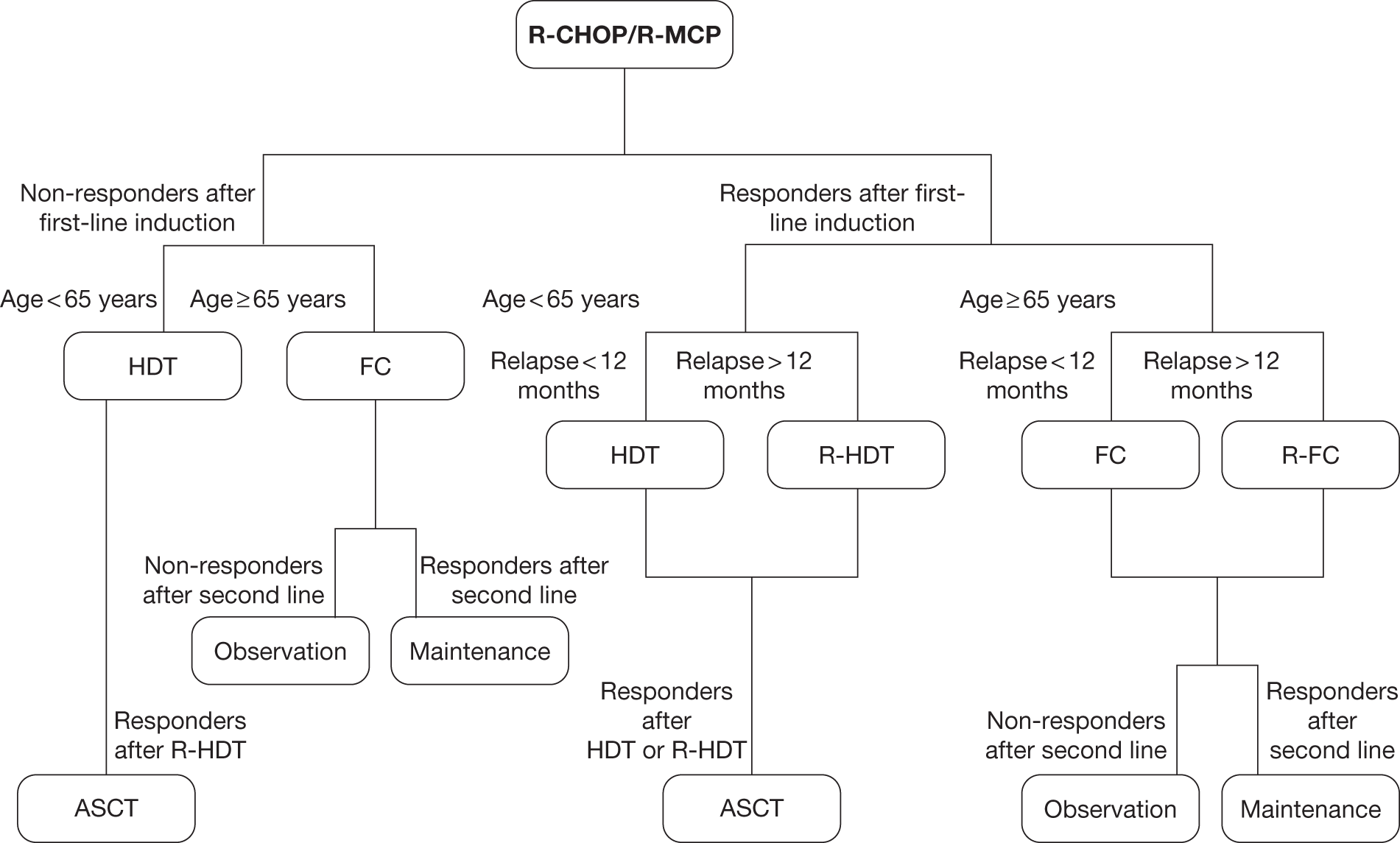

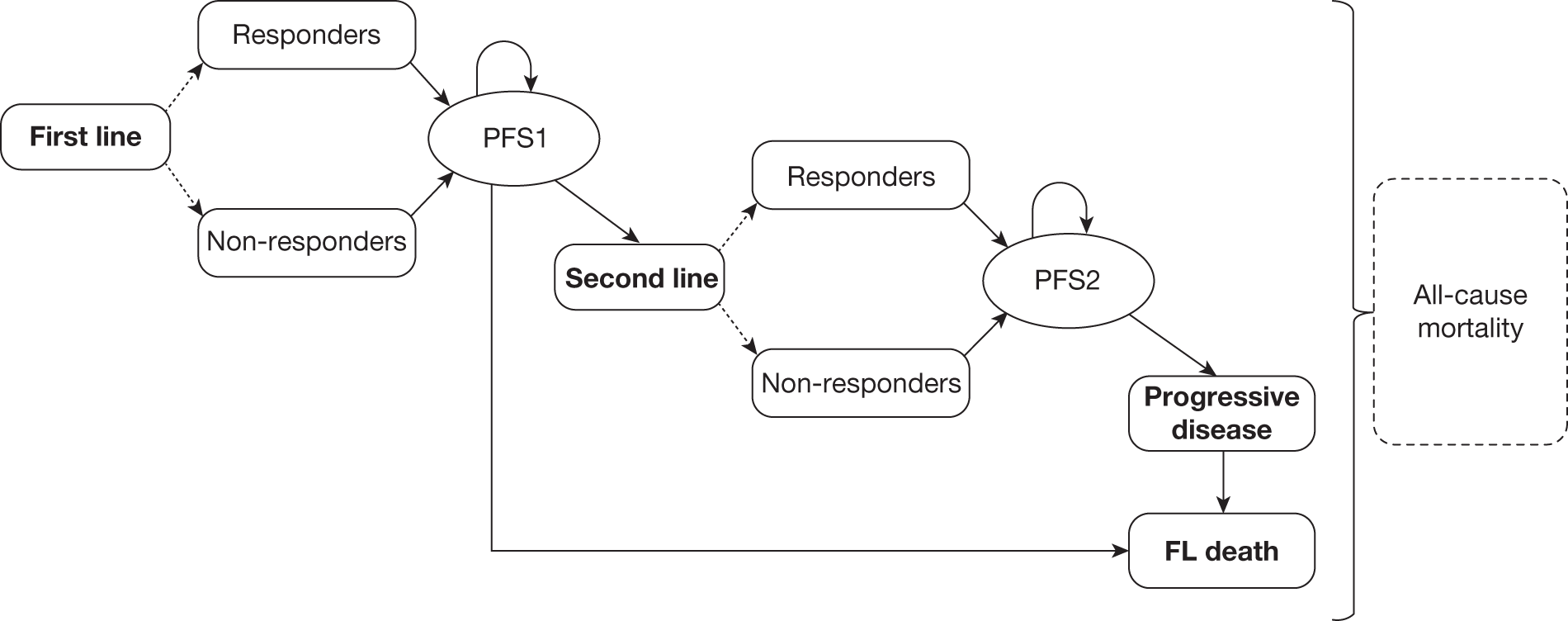

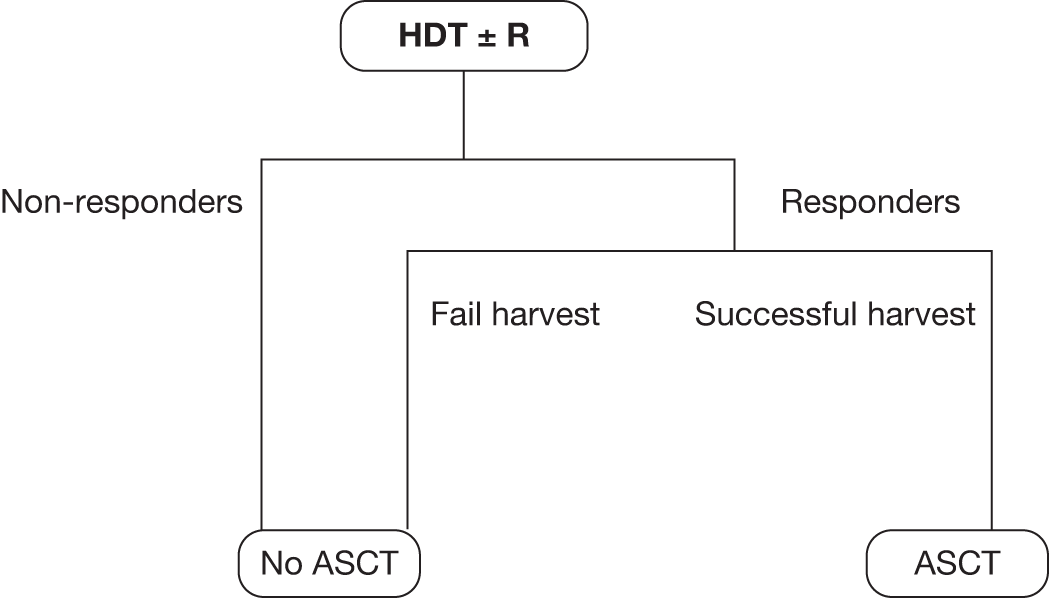

Grading, staging and symptoms determine treatment pathways. Figure 1 gives an overview of the treatment pathway for stage III/IV FL [adapted from the manufacturer’s submission (MS) for this appraisal]. 62 This pathway has been simplified and does not take into account the risk of transformation to DLBCL or the differences in treatment of disease that relapses early compared with later relapse. These are discussed later in this section.

FIGURE 1.

Treatment pathway for stage III/IV FL (adapted from MS). 62 a, Response can be complete or partial response. b, Note that patients who received chlorambucil in first-line treatment would not be eligible to receive stem cell transplant.

Asymptomatic patients

Most patients are asymptomatic on presentation (painless swelling of one or more lymph nodes) and a ‘watch and wait’ approach is usually adopted. Observational studies63,64 and three randomised controlled trials (RCTs)65–67 have shown that prognosis is not affected by immediate treatment compared with observation until symptomatic disease progression (bulky lymphadenopathy, bone marrow compromise, splenomegaly, etc.). Thus, treatment commences only when the disease becomes symptomatic.

First-line therapy: limited disease (Ann Arbor stages I–II)

Patients diagnosed in the early stages of the disease (stages I–II) usually respond well to radiotherapy and this is the treatment of choice, usually taking the form of extended or involved field form irradiation. This can result in long-term disease-free survival (DFS) and possible cure for between 45% and 80% of patients. 35

First-line therapy: advanced disease (Ann Arbor stages III–IV)

Chemoimmunotherapy [i.e. rituximab and chemotherapy (R-chemotherapy)] is the preferred treatment for first-line therapy in symptomatic advanced FL. The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) clinical practice guidelines recommend that when complete remission and long PFS are the aims of treatment, rituximab in combination with chemotherapy [such as cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin/adriamycin, vincristine and prednisolone (CHOP); cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisolone (CVP), fludarabine, cyclophosphamide (FC); fludarabine and mitoxantrone (FM) or bendamustine] should be used. 19 In 2006, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidance stated that rituximab in combination with CVP is indicated for the first-line treatment of symptomatic FL, in line with the licensed indication at the time the guidance was issued. 68 However, in 2008 the licence for rituximab was broadened so that it can be administered with other chemotherapies; there is no consensus, however, on the preferred chemotherapy option. 69 Antibody monotherapy or single-agent alkylating agents [e.g. chlorambucil (Leukeran®, Aspen)] can be considered an alternative in previously untreated patients with FL with particularly low-risk disease or those who are unsuitable for more intensive treatments. 19

Maintenance therapy (first line)

As disease recurrence is inevitable, ways of maintaining or improving the quality of the initial response to treatment are used, such as maintenance therapy. Maintenance treatment is a long-term approach that aims to delay relapse by stabilising the best response to initial therapy, eradicating any residual disease and maintaining remission after successful remission induction therapy. 70

The ESMO clinical practice guidelines acknowledge recent evidence that rituximab maintenance for 2 years can prolong PFS. 71 Guidance issued in June 2011 by NICE recommended rituximab maintenance therapy as an option for the treatment of people with follicular NHL lymphoma who have responded to first-line induction therapy with rituximab in combination with chemotherapy. Prior to this, the UK standard practice has been to closely observe patients during their first remission and retreat only when there is evidence of disease progression.

Aside from rituximab, other agents have been proposed for use as maintenance therapy, such as interferon-alpha (a biological therapy). However, a meta-analysis suggests a limited benefit of interferon-alpha maintenance therapy that has to be balanced against toxicity. 72 Clinical advice is not to use interferon-alpha as patients cannot tolerate the side effects.

Consolidation therapy is another type of treatment that has been proposed following successful induction of first-line remission. Consolidation therapy is delivered immediately after a response to induction therapy; however, it differs from maintenance therapy as it is a short course of treatment that aims to rapidly improve the response to induction therapy. 60 Radioimmunotherapy agents such as ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin®, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals) have been used in consolidation therapy; however, their benefit following a R-chemotherapy combination has not been established. 19

Treatment of relapsed disease

After every relapse, a biopsy should be undertaken to determine if transformation has occurred. 5,19 When transformation does occur, there is usually rapidly increasing lymph node enlargement, elevated LDH levels and development of systemic symptoms. Histological transformation can occur in 20–70% of patients, with the variability in reported incidence reflecting, to a large extent, local practice in terms of whether or not biopsies are performed at each recurrence. 5 Treatments for FL are not effective once transformation has occurred and patients are treated as for high-grade FL or DLBCL. Median survival following transformation has been reported as 18 months, although this figure comes from the pre-rituximab era. 5

When the disease has relapsed, treatment options are reassessed, with the selection of salvage treatment depending on the efficacy of prior regimens. 19 However, there may be some variations between clinical practice in the UK and the ESMO guidelines.

When there is early relapse following first-line R-chemotherapy treatment (< 6 months), the disease is considered as rituximab refractory in the ESMO guidelines, which state that rituximab is not indicated. However, clinical advice to the Assessment Group (AG) indicated that some clinicians may also consider which chemotherapeutic regimen was given in first-line treatment when choosing the second-line treatment. For example, if rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisolone (R-CVP) had been used in first-line induction therapy and early relapse occurred, rituximab, cyclophosphamide doxorubicin/adriamycin, vincristine and prednisolone (R-CHOP) may be selected for the second-line treatment, with the rationale being that it was the CVP-component rather than the rituximab that was responsible for the early relapse. If, however, R-CHOP had been used in first-line induction therapy, and relapse is early, this is indicative of a poor prognosis (based on clinical advice sought by the AG), making high-dose chemotherapy (with or without rituximab) and stem cell transplant (SCT) an appropriate second-line treatment.

The ESMO guidelines also state that in relapses of < 12 months, a non-cross-resistant scheme should be preferred with regard to the chemotherapy selected (i.e. two differing chemotherapeutic regimens such as fludarabine after CHOP for example). Rituximab monotherapy is also recommended as a treatment option by NICE for people with relapsed or refractory disease when all alternative treatment options have been exhausted. 73

The use of rituximab in retreatment of patients who have received rituximab at first-line treatment has been discussed previously in NICE technology appraisal (TA137), where evidence for clinical effectiveness of rituximab in second-line treatment of FL was from the EORTC 20981 trial,74,75 the population of which were rituximab-naive patients. However, although the Committee considered that ‘it was necessary to be cautious about the assumption that rituximab is as efficacious in patients who had already received it as in patients who are rituximab-naive’; clinical specialists present at the Committee stated that ‘the evidence indicated that follicular NHL could be retreated with rituximab with little or no loss of efficacy’. It was noted by the Committee that although this is as an area of uncertainty, this was biologically plausible given rituximab’s mechanism of action. 73 This is discussed in more detail, see Resistance to rituximab in patients previously exposed to rituximab treatment.

Second-line rituximab maintenance

Following response to second-line induction therapy (with or without rituximab), rituximab monotherapy may also given as second-line maintenance, as recommended by NICE. 73

Stem cell transplant

During the course of treatment, relapses become more frequent with shorter disease-free periods,69 and chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy are not able to induce a further stable remission period. SCT is a treatment option for patients with relapsed FL. However, the use of and position of SCT in the treatment pathway of FL has altered since the introduction of rituximab, and the ESMO guidelines state that its use needs to be re-evaluated in the rituximab era. 19 Clinical advice provided to the AG suggests its use has declined in the treatment of FL since the introduction of rituximab in first-line induction and maintenance, and second-line induction and maintenance. In second-line treatment, SCT appears to be reserved for patients with very aggressive disease and short remission periods following first-line induction therapy or patients who have undergone transformation to DLCBL. For patients who do not have aggressive disease and for whom a reasonable remission period has been achieved following first-line treatment, SCT is considered more frequently at the third-line treatment stage. At whichever point SCT is offered in the treatment pathway, it is usually only offered to younger patients (aged < 65 years), although clinical advice suggests that it may be offered to some fit patients up to the age of 70 years.

Relevant national guidelines

A summary of the relevant European Medicines Agency (EMA) licensing and NICE guidelines relating to the use of rituximab in the treatment of FL is presented in Table 4.

| Stage of disease | Treatment | Licensed by EMA | Recommendation by NICE | Conditions of NICE recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-line induction | R-CVP | ✓ | ✓ |

Previously untreated patients Symptomatic patients |

| First-line induction | R-chemotherapya | ✓ |

✗ Considered in this assessment report |

Not applicable |

| First-line maintenance | R-monotherapy | ✓ |

✗ Ongoing technology appraisal |

Being appraised: Only for responders to first-line induction therapy with rituximab in combination with chemotherapy |

| Second-line induction |

R-chemotherapya R-monotherapy |

✓ | ✓ | R-monotherapy only when all alternative treatment options have been exhausted (i.e. if there is resistance to or intolerance of chemotherapy) |

| Second-line maintenance | R-monotherapy | ✓ | ✓ | Only for responders to second-line induction therapy of rituximab or R-chemotherapy |

The ESMO has produced guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of newly diagnosed and relapsed FL19 as discussed above (see Management of disease). The British Committee for Standards in Haematology (BCSH) has produced guidelines on the diagnosis and reporting of NHLs76,77 from the BCSH website). A guideline on the investigation and management of follicular lymphoma is also available from the BCSH website. Archived guidance from the BCSH exists on the diagnosis and therapy for nodal NHL. 27

Variation in services and/or uncertainty about best practice

Although R-chemotherapy is the preferred treatment for first-line therapy in symptomatic advanced FL, there is no consensus on the preferred chemotherapy. 69 No direct trials have been undertaken that compare one R-chemotherapy regimen with another R-chemotherapy regimen; although there are four ongoing Phase III RCTs comparing one or more R-chemotherapy regimens against another R-chemotherapy78–81 (see Chapter 3, Results, for further details of ongoing trials). Siddhartha and Vijay82 conducted a meta-analysis to compare R-CHOP and R-CVP with respect to response rates (two separate analyses were provided for first-line treatment only and first-line plus relapsed treatment) and differences were noted in the quality of the responses achieved. A greater proportion of complete responses (CRs) were observed following R-CVP than R-CHOP. However, overall response rate (ORR) was better following the R-CHOP regimen [owing to more partial responses (PRs)]. It is difficult to know if there is a different effect in quality of response to R-CVP or R-CHOP; however, clinical advice to the AG noted that R-CHOP is more likely given to patients with bulky or more aggressive disease, who are more likely to achieve a PR than a CR.

However, treatment/efficacy outcomes are not the only factors to consider when choosing chemotherapy. Clinical advice suggests that elderly patients or patients with comorbidities, particularly cardiac problems, are less likely to receive CHOP, as it is an anthracycline-based chemotherapy. In addition, where SCT is a potential future treatment, the chemotherapeutic agent selected must not interfere with the potential to harvest stem cells. Thus, in SCT candidates, fludarabine, a purine analogue therapy, is to be avoided as these can compromise the quality of the stem cell harvests.

The manufacturer sought clinical guidance from two clinicians whose responses also reflected the need for an individualised choice of chemotherapeutic agent in patients. 62 The clinicians also highlighted other important factors in treatment selection, including patient choice (e.g. acceptability of alopecia, which is higher after CHOP, and side effects tolerance) and the need to achieve a rapid response if a compression syndrome is present (e.g. deep-vein thrombosis, leg oedema).

Current usage in the NHS

Figures reported in the MS62 from an unpublished survey of UK haemato-oncologists (n = 50) suggest that approximately 92% of all eligible previously untreated stage III–IV patients with FL in the UK currently receive rituximab in combination with chemotherapy as standard treatment (these data were made available by the manufacturer to the AG). 62 The remaining 8% receive single-agent chlorambucil, FM, Bexxar (a radiolabelled monoclonal antibody) or alternative chemotherapy. Of the patients receiving a rituximab-containing regimen, approximately 67% are treated with R-CVP and a further 16% are treated with R-CHOP. The remainder receive rituximab combined with other chemotherapies, which includes R-chlorambucil (R-C), rituximab, fludarabine and cyclophosphamide (R-FC), rituximab, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and mitoxantrone (R-FCM) and R-fludarabine (R-F). 62 The AG requested access to the survey data from Roche and the results are presented in Table 5.

| Treatment | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| R-CVP | 80 | 67 |

| CVP | 1 | 1 |

| R-CHOP | 19 | 16 |

| Chlorambucil | 6 | 5 |

| R-C | 4 | 3 |

| R-FC | 5 | 4 |

| FM | 1 | 1 |

| R-FM | 1 | 1 |

| R-F | 1 | 1 |

| Bexxar | 1 | 1 |

| Alternative chemotherapy | 1 | 1 |

Clinical advice sought by the AG suggests that this seems a reasonable estimate, indicating that the great majority of patients receive R-chemotherapy. Chlorambucil as a single-agent chemotherapy regimen is reserved only for patients deemed too unfit or unwell for a R-chemotherapy regimen. The proportions of R-CHOP and R-CVP administered are difficult to quantify according to clinical advice; historically R-CVP has been the first choice chemotherapy arm; however, R-CHOP is the international standard. However, at present R-CHOP is not currently recommended by NICE, which is likely to affect its current uptake within the UK. Clinical advice suggests that the use of other chemotherapy regimens in combination with rituximab such as R-MCP (rituximab, mitoxantrone, chlorambucil and prednisolone), R-CNOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, mitoxantrone, vincristine and prednisolone), R-CHVP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, etoposide and prednisolone), R-FCM, R-FM, R-F and R-C is very infrequent within the NHS.

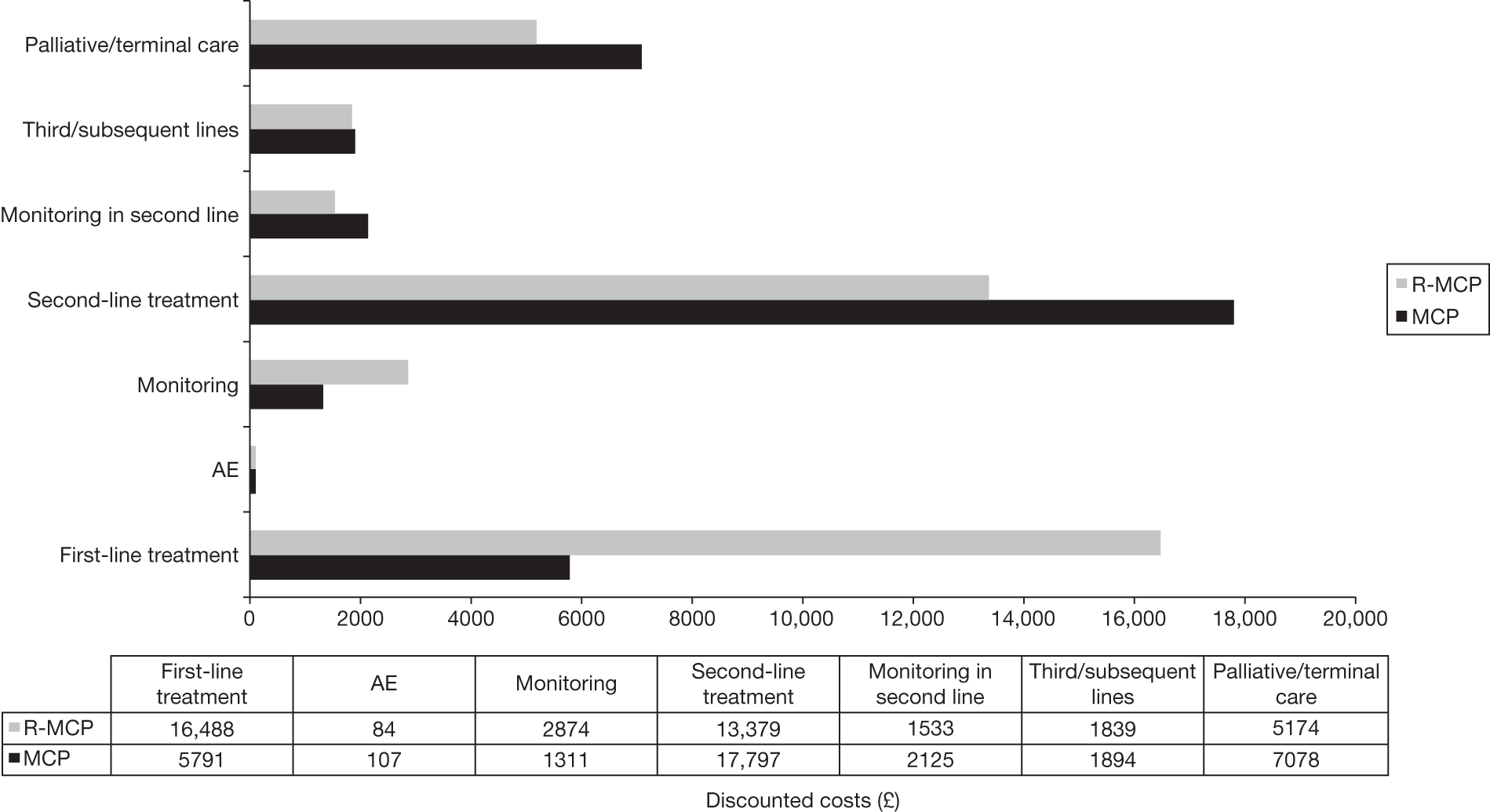

Current service cost

Because treatment of FL is part of general haematological or oncology services, the cost of caring for this group of patients is very difficult to derive from the routine financial information available for the NHS. However, consideration of the variety of treatments to which an individual might be exposed during the course of their illness suggests that the costs of caring for FL are likely to be considerable. In this, the support required from both primary and palliative care services in the terminal stages of the disease should not be underestimated.

Significance for the NHS

Rituximab with CVP is currently recommended by NICE for the first-line treatment of FL. 83 Thus, given the number of patients with FL, the introduction of rituximab with other chemotherapies would incur costs. However, neither new equipment nor intensive training would be required.

Description of technology under assessment

Identification of patients and important subgroups

Rituximab in combination with chemotherapy is considered as a possible option for the treatment of symptomatic stage III–IV FL.

Place in treatment pathway

This assessment report is concerned with the use of R-chemotherapy as first-line induction treatment. However, rituximab with or without chemotherapy is recommended by NICE at other points within the treatment pathway, and these impact on the cost-effectiveness of R-chemotherapy in first-line induction therapy (see Table 4 for NICE recommendations of rituximab).

Therapeutic classification

Rituximab is a genetically engineered ‘monoclonal antibody’ that has been designed to recognise an antigen/surface marker on B lymphocytes called CD20. Monoclonal antibodies are produced by fusing single antibody-forming cells (generated in laboratory mice) to tumour cells (grown in culture), producing large quantities of identical antibody molecules from a single, cloned antibody-producing cell, hence the name ‘monoclonal antibodies’. 36

The CD20 antigen/surface marker is present on the surface of B lymphocytes in > 90% of NHLs. 84 When rituximab attaches to the antigen, this causes cell death85 so that cancerous and normal B lymphocytes are destroyed. Although fully developed B lymphoma cells have CD20 on their surface, early B cells do not have the CD20 protein and are not killed.

Brand and generic name

Rituximab is the generic name; Roche’s brand name is MabThera (Genentech Inc.). Rituximab is also known as IDEC-C2B8 and Rituxan®. 86

Dosage form and route

Rituximab is sold as a concentrate for solution for intravenous infusion. A 10-ml single-use vial is available and contains 100 mg of rituximab (sold in packs × two vials). 85 A 50-ml single-use vial is also available (500 mg/50 ml).

Method of administration

Premedication with glucocorticoids should be considered if rituximab is not given in combination with glucocorticoid-containing chemotherapy. Premedication consisting of an antipyretic and an antihistaminic, for example paracetamol and diphenhydramine, should always be administered before each infusion of rituximab. 85

First infusion

The recommended initial rate for infusion is 50 mg/hour; after the first 30 minutes, it can be escalated in 50 mg/hour increments every 30 minutes, to a maximum of 400 mg/hour. 85

Subsequent infusions

Subsequent doses of rituximab can be infused at an initial rate of 100 mg/hour, and increased by 100 mg/hour increments at 30-minute intervals, to a maximum of 400 mg/hour. 84 The prepared rituximab solution should be administered as an intravenous infusion through a dedicated line. It should not be administered as an intravenous push or bolus. 85

Licensed indications

Rituximab is licensed for the treatment of previously untreated patients with stage III–IV FL in combination with chemotherapy. This current licence was issued in January 2008 and does not restrict the type of chemotherapy. The original licence agreement restricted use of rituximab in combination with CVP only and this is reflected in the existing NICE guidance. 83

Rituximab is also licensed for treatment of FL at other stages within the treatment pathway, other types of NHL, and has indications for treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) and rheumatoid arthritis. The indications for use in FL and NHL are included below for completeness:

-

Rituximab maintenance therapy is indicated for patients with FL who are responding to induction therapy with chemotherapy with or without rituximab.

-

Rituximab monotherapy is indicated for treatment of patients with stage III–IV FL who are chemoresistant or are in their second or subsequent relapse after chemotherapy.

-

Rituximab is indicated for the treatment of patients with CD20-positive DLBCL in combination with CHOP.

Contraindications

Rituximab is contraindicated for use in NHL in patients who have known hypersensitivity to the active substance or to any of the excipients or to murine proteins, in active severe infections or inpatients in a severely immunocompromised state. 85

Warnings

Infusion reactions

Infusion-related side effects (including cytokine release syndrome) are reported commonly with rituximab and predominantly occur during the first infusion and include symptoms such as fever and chills, nausea and vomiting, allergic reactions (such as rash, pruritus, angioedema, bronchospasm and dyspnoea), flushing and tumour pain. 86 Mild or moderate infusion-related reactions usually respond to a reduction in the rate of infusion, which can be increased on improvement of symptoms. Patients who develop severe reactions, especially severe dyspnoea, bronchospasm or hypoxia should have the infusion interrupted immediately. 85

Before each dose of rituximab, patients should be given an analgesic and an antihistamine to reduce these effects and consideration should be given to premedication with a corticosteroid. In all patients, the infusion should not be restarted until symptoms have resolved and laboratory values and chest radiographs appear normal. Patients who have experienced severe cytokine release syndrome should be closely monitored, as although they may show an improvement in symptoms, this may be followed by deterioration. Thus, such patients must be evaluated for evidence of tumour lysis syndrome and pulmonary infiltrations with chest radiography.

Fatalities following severe cytokine release syndrome (characterised by severe dyspnoea) and associated with features of tumour lysis syndrome have occurred 1–2 hours after infusion of rituximab. Patients with a high tumour burden and those with pulmonary insufficiency or infiltration are at increased risk and should be monitored very closely. 86

Anaphylactic and other hypersensitivity reactions have been reported following the intravenous administration of proteins to patients. Clinical manifestations of anaphylaxis may appear similar to clinical manifestations of the cytokine release syndrome. However, in contrast to cytokine release syndrome, true hypersensitivity reactions typically occurs within minutes after starting infusion. 85

Pregnancy and lactation

Rituximab should be avoided during pregnancy unless the potential benefit to the mother outweighs risk of B-lymphocyte depletion in the fetus. It is also contraindicated in women who are breastfeeding. Effective contraception is required during treatment and for 12 months after treatment. 86

Cardiovascular disease

Rituximab should be used with caution in patients who are receiving cardiotoxic chemotherapy or who have a history of cardiovascular disease because exacerbation of angina, arrhythmia and heart failure have been reported. Transient hypotension occurs frequently during infusion and antihypertensive drugs may need to be withheld for 12 hours before infusion. 86

Infections

Serious infections, including fatalities, can occur during therapy with rituximab. Physicians should exercise caution when considering the use of rituximab in patients with a history of recurring or chronic infections or with underlying conditions that may further predispose patients to serious infection. 86

Personnel involved

Treatment should be undertaken under close supervision of a specialist. 86 The delivery of rituximab requires no additional personnel to the administration of chemotherapy, namely a senior clinician (specialist registrar or above), a specialist nurse and a specialist pharmacist.

Setting

Outpatients would receive intravenous transfusion in the same chemotherapy suite as would be used for the administration of chemotherapy.

Equipment required

Full resuscitation equipment should be at hand. 86 The intervention would require no equipment outside of that normally associated with a chemotherapy suite. Some clinics advise that rituximab is infused while the patient is on a bed, rather than in a chair.

Length of treatment

Each service user would expect to receive one treatment on day one of each cycle, every 3 weeks, for up to eight cycles; in other words, eight intravenous days (4–6 hours each) at the chemotherapy suite, over the course of 24 weeks.

Follow-up required

The ESMO guidelines suggest follow-up treatment both during and after treatment. However, clinical advice to the AG suggests that follow-up differs in UK clinical practice, particularly with regard to the frequency of cross-sectional imaging, which is not undertaken routinely in the absence of clinical suspicion of progression.The BCSH guidelines87 on the investigation and management of follicular lymphoma specifically states that routine scans are not recommended.

During treatment, the ESMO guidelines state that ‘adequate radiological tests should be performed mid-term and after completion of chemotherapy’. Where an insufficient or no response is found, patients should be evaluated for early salvage regimens. The ESMO guidelines19 suggest the following as follow-up after treatment; however, it is noted that clinical advice does not agree with the frequency of imaging:

-

History and physical examination every 3 months for 2 years, every 4–6 months for a further 3 years, and subsequently twice a year with special attention to transformation and secondary malignancies including secondary leukaemia.

-

Blood count and routine chemistry every 6 months for 2 years, then only as needed for evaluation of suspicious symptoms.

-

Evaluation of thyroid function in patients with irradiation of the neck at 1, 2 and 5 years.

-

Minimal adequate radiological or ultrasound examinations every 6 months for 2 years and annually thereafter. (Note that this is not recommended by the clinical advice sought by the AG.)

Anticipated costs associated with intervention

The recommended dose of rituximab is 375 mg/m2; the net price for a 10-ml vial is £174.63 and for a 50-ml vial £873.15. 86

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Decision problem

Intervention

Rituximab is indicated for the treatment of previously untreated patients with stage III–IV FL in combination with chemotherapy at a recommended dose of 375 mg/m2 of body surface area (BSA) per cycle, for up to eight cycles. This assessment includes interventions where rituximab is given in combination with the following chemotherapy regimens:

-

CVP

-

CHOP

-

CNOP

-

CHVP

-

MCP

-

FCM (fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and mitoxantrone)

-

FM

-

bendamustine

-

fludarabine

-

chlorambucil.

When this appraisal started, bendamustine was not currently licensed as a first-line treatment with rituximab for first-line treatment of FL. However, as the anticipated date of licensing was not known and could occur within the time scales of the appraisal, bendamustine was included as a combination chemotherapy agent (with rituximab). At the time of writing, bendamustine remains unlicensed for use in this population for the first-line treatment indication.

Population including subgroups

The population comprised adults with symptomatic stage III–IV FL (a NHL) who have not received any previous treatment. Indolent FL is considered within this appraisal. Where data are presented for elderly patients with FL (aged ≥ 65 years), these will be examined as a subgroup.

Relevant comparators

Non-rituximab-containing chemotherapies are the relevant comparators, and for this assessment the following comparators are considered:

-

CVP

-

CHOP

-

CNOP

-

CHVP

-

MCP

-

FCM

-

FM

-

bendamustine

-

fludarabine

-

chlorambucil.

Outcomes

The outcomes considered in this appraisal mostly relate to clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness and include:

-

OS

-

PFS

-

response rates

-

duration of disease remission/response duration

-

adverse effects of treatment

-

HRQoL.

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

This assessment will address the question ‘What is the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of rituximab (in its licensed indication) with chemotherapy for the first-line treatment of symptomatic stage III–IV FL?’

The aim of this review is to systematically evaluate and appraise the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of rituximab (in its licensed indication) in combination with chemotherapy compared with non-rituximab-containing chemotherapy, for the first-line treatment of symptomatic stage III–IV FL. Note that owing to the scope specifying the intervention as rituximab given in combination with chemotherapy, interventions including rituximab in combination with other treatments, such as radioimmunotherapy or bone marrow/SCT, are not considered as an intervention for this appraisal.

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Methods for reviewing effectiveness

This systematic review was carried out according to the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. 88

Identification of studies

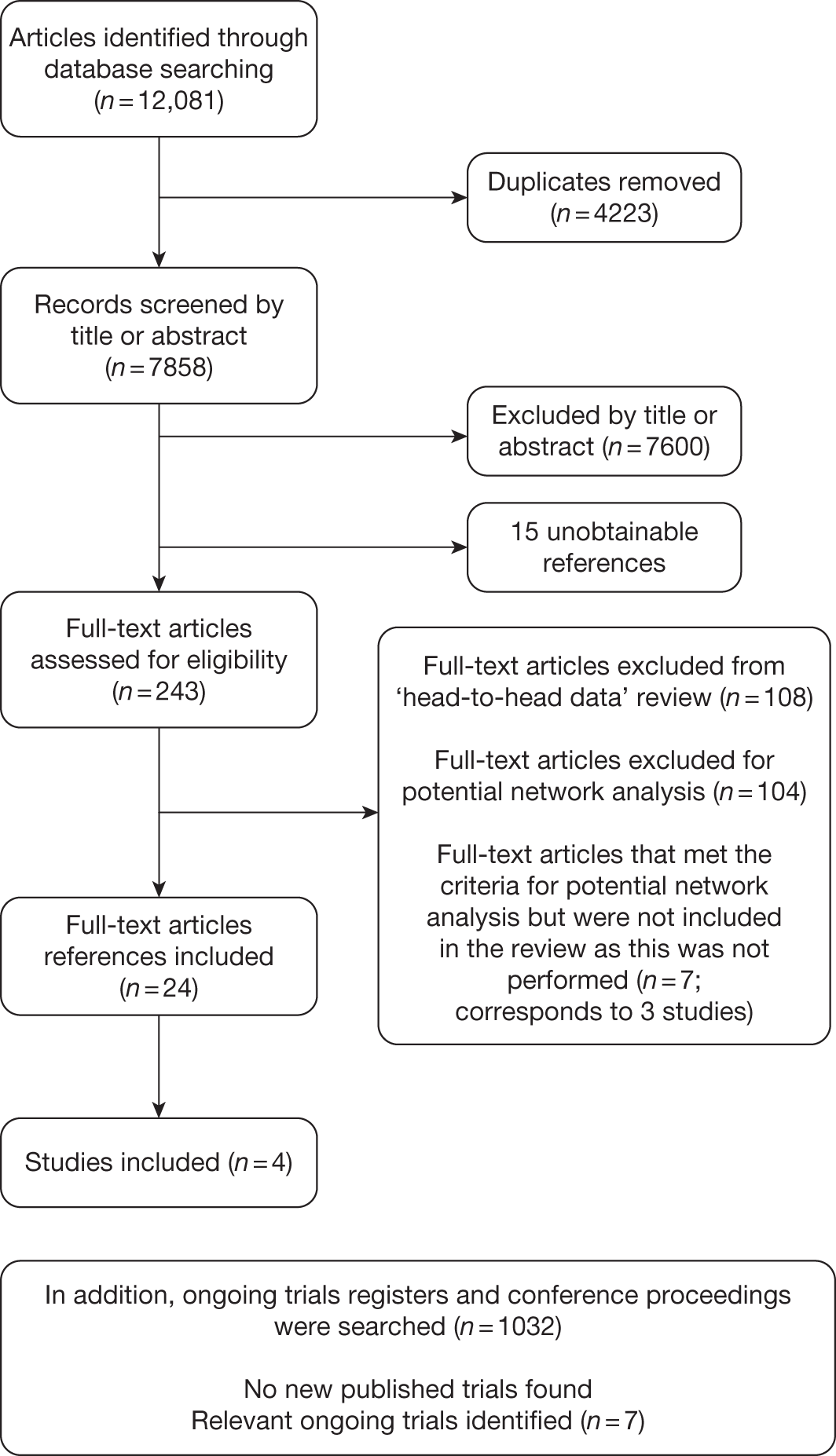

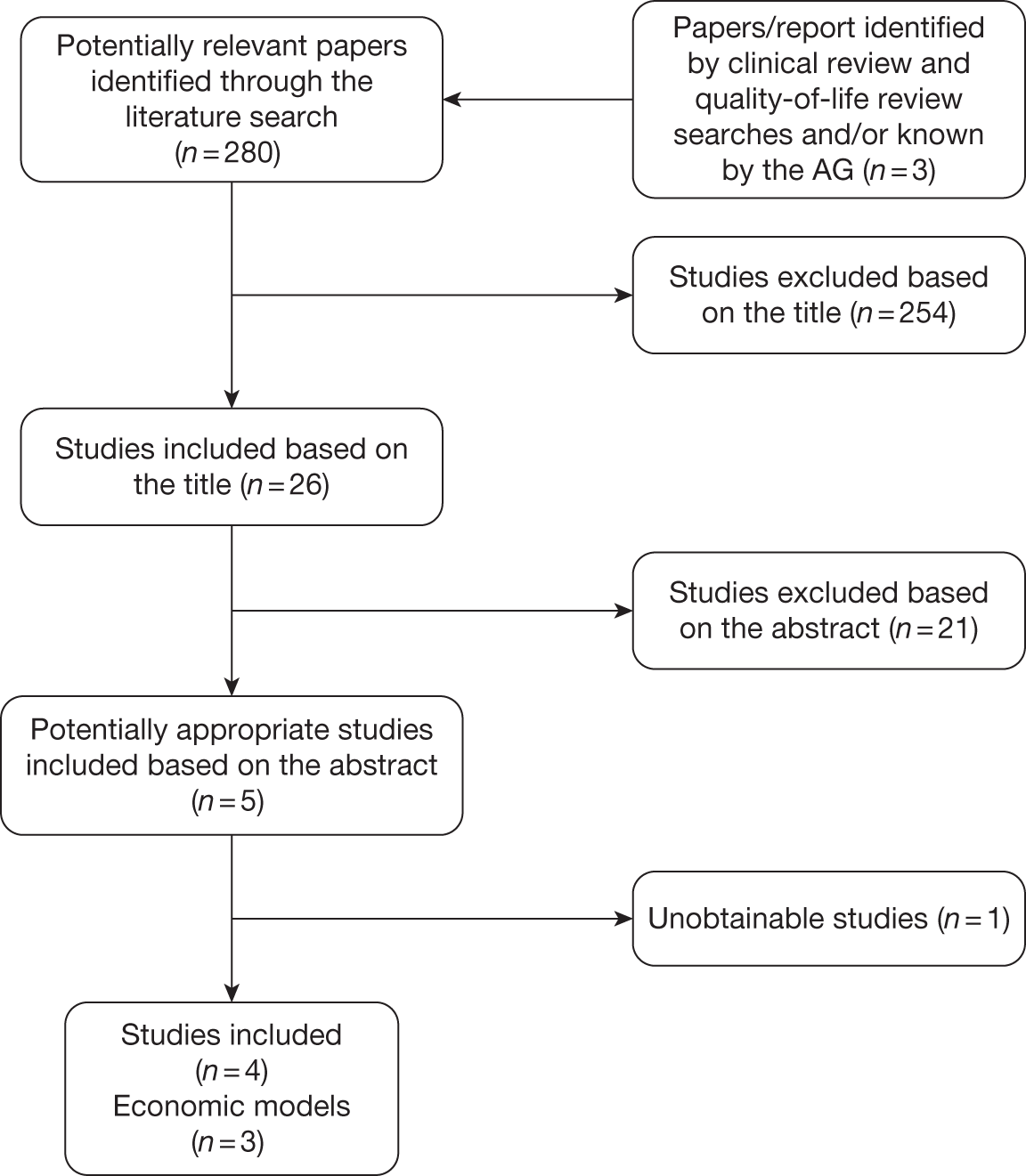

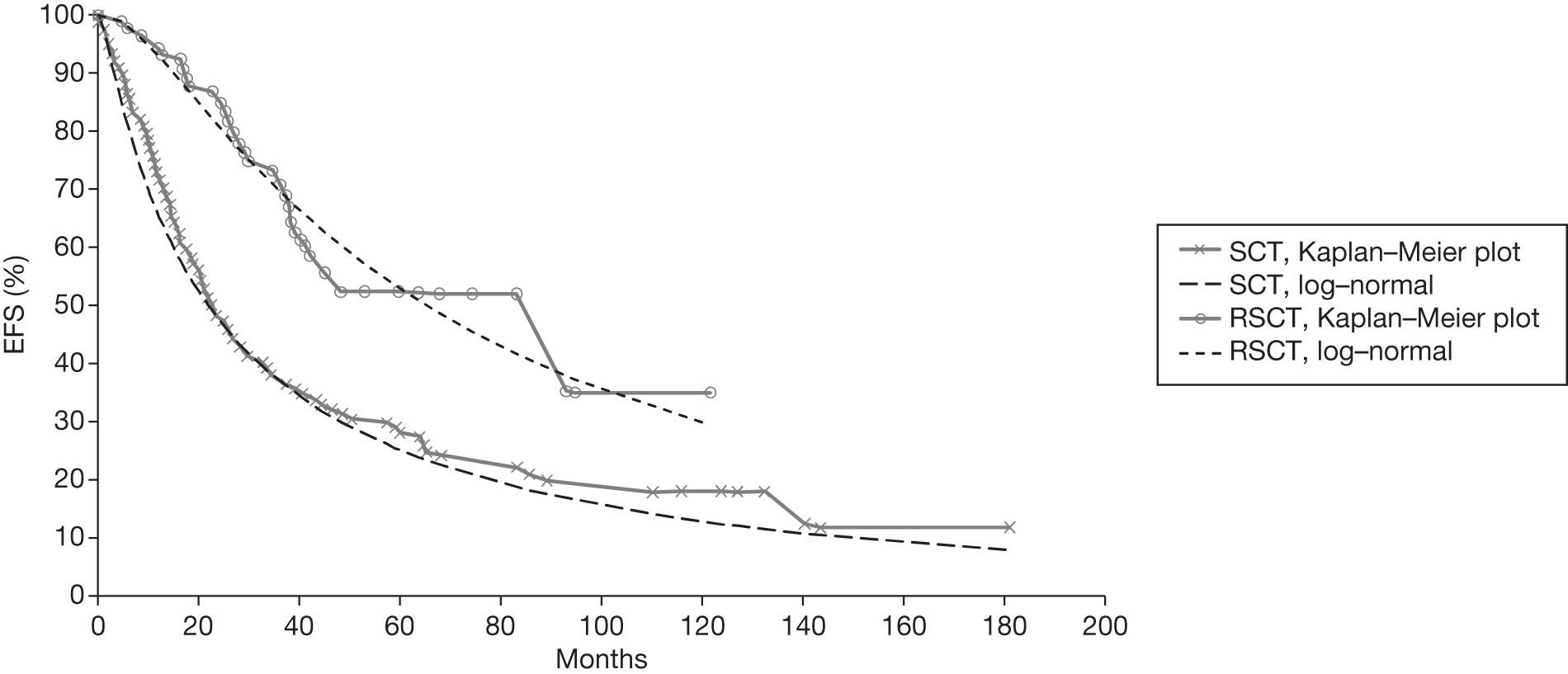

The PRISMA flow diagram shown in Figure 2 provides a summary of the study identification process.

FIGURE 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses-adapted flow diagram.

Search strategy

The search aimed to systematically identify all literature relating to the clinical effectiveness of (1) the intervention: rituximab in combination with chemotherapy or (2) the comparators, i.e. chemotherapy alone for the treatment of FL. The searches were conducted in September and October 2010.

Sources searched

Eleven electronic databases were searched from inception: MEDLINE including MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (Ovid); CINAHL; EMBASE; The Cochrane Library including the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) and Health Technology Assessment (HTA) databases; Science Citation Index (SCI); and BIOSIS.

Ongoing research was searched using clinical trials databases and registers including NIHR Clinical Research Network Portfolio; National Research Register (NRR) archive 2000–7; Current Controlled Trials (CCT) and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Relevant conference proceedings were searched, including the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), European Society of Clinical Oncology (ESCO), American Society of Hematology (ASH), the British Society for Haematology (BSH) and the European Hematology Association (EHA).

In addition, the reference list of relevant articles and the MS62 was handsearched. The review team also contacted experts in the field and scrutinised the bibliographies of retrieved papers to identify relevant evidence.

Search terms

A combination of free text and thesaurus terms were used. ‘Intervention’ terms (e.g. rituximab, MabThera, Rituxan) or chemotherapy terms (CHOP, CVP, etc.) were combined with ‘population’ search terms (e.g. lymphoma, non-Hodgkin’s). Copies of the search strategies used in MEDLINE are included in Appendix 5 (these were adapted for use in other databases).

Search restrictions

Searches were not restricted by language or publication date. Where possible, a filter was applied in order to limit search results to systematic reviews/meta-analyses, economic/cost evaluations, quality-of-life studies or RCTs. Examples of the RCT filter, cost-effectiveness filter and quality-of-life filter are provided in Appendix 5.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Study design

According to the accepted hierarchy of evidence, RCTs were included for the clinical effectiveness review, as they provide the most authoritative form of evidence. In the event of insufficient data being available from RCTs, it was planned that observational studies or clinical trials would be considered; however, this was not required in this review.

Intervention(s)

Rituximab in combination with any of the following chemotherapy regimens: CVP, CHOP, CNOP, CHVP, MCP, FCM, FM, bendamustine, fludarabine or chlorambucil.

Comparator(s)

The comparator was chemotherapy without rituximab, which for this review was considered to be one of the following: CVP, CHOP, CNOP, CHVP, MCP, FCM, FM, bendamustine, fludarabine or chlorambucil.

Potential for a network meta-analysis

The literature search was undertaken to allow identification of trials involving either an intervention or comparator defined in the decision problem, as it was anticipated that the work may require a network meta-analysis to be undertaken to determine efficacy. It was planned to populate such an analysis with all identified trials involving either an intervention or a comparator. Although it is noted that the network meta-analysis could potentially be strengthened by the inclusion of RCTs involving two pharmaceuticals that were neither interventions nor comparators (provided there were RCTs comparing these pharmaceuticals with an intervention or a comparator), literature searches for all RCTs from these pharmaceuticals were not conducted, as they are likely to have little impact on the results of interest and would have significant resource implications. In addition, where the evidence allowed, interventions were planned to be compared with each other.

Population

The population comprised adults with symptomatic stage III–IV FL who had not received any previous treatment.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest for this appraisal in relation to clinical effectiveness was OS. Secondary outcomes were PFS, response rates (CR, PR and ORR), duration of disease remission/response duration, and adverse/toxic effects of treatment.

Overall survival was defined and calculated as the time from randomisation to the date of death by any cause. PFS was defined and calculated as the time from randomisation to disease progression or death. Response rate was defined in the terms laid down by Cheson et al. 87 (see Appendix 6). ORR combined CRs and PRs. Unconfirmed complete responses (CRus) were considered as PRs so that the CR and PR rates were comparable between studies. However, it is noted this may result in an underestimation of CR, as clinical advice suggests that CRus are more likely to follow a similar clinical course to CRs. Duration of disease remission/response duration was taken as the time from response achieved (CR or PR) to disease progression or death. Adverse events (AEs) were defined as any adverse change from the patient’s baseline condition, including intercurrent illness that occurred during the course of the clinical trial after the start of treatment, whether or not considered related to trial treatment. HRQoL was also considered as a secondary outcome.

Exclusion criteria

Reviews of primary studies were not included in the analysis, but were retained for discussion and identification of additional trials. Studies that were considered methodologically unsound were excluded from the review as well as the following publication types: non-randomised studies; animal models; preclinical and biological studies; narrative reviews, editorials, opinions; non-English-language papers and reports in which insufficient methodological details are reported to allow critical appraisal of study quality. In addition, although not stated in the protocol, studies that included populations other than those described above or studies that included NHL populations but did not provide outcome data separately for patients with FL who were excluded.

Study selection

Studies were selected for inclusion through a two-stage process according to the above inclusion/exclusion criteria. Titles and abstracts were examined for inclusion by one reviewer. Screening was checked by a second reviewer on 10% of citations. The kappa coefficient (range 0–1) calculated to measure inter-rater reliability was good, approaching ‘very good’ at 0.79. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers when necessary, and did not require involvement of a third reviewer. Full manuscripts of selected citations were retrieved and assessed by one reviewer against the inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Data extraction strategy

Data were extracted by one reviewer using a standardised data extraction form and checked by a second reviewer. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion and did not require input from a third reviewer. Where multiple publications of the same study were identified, data were extracted and reported as a single study.

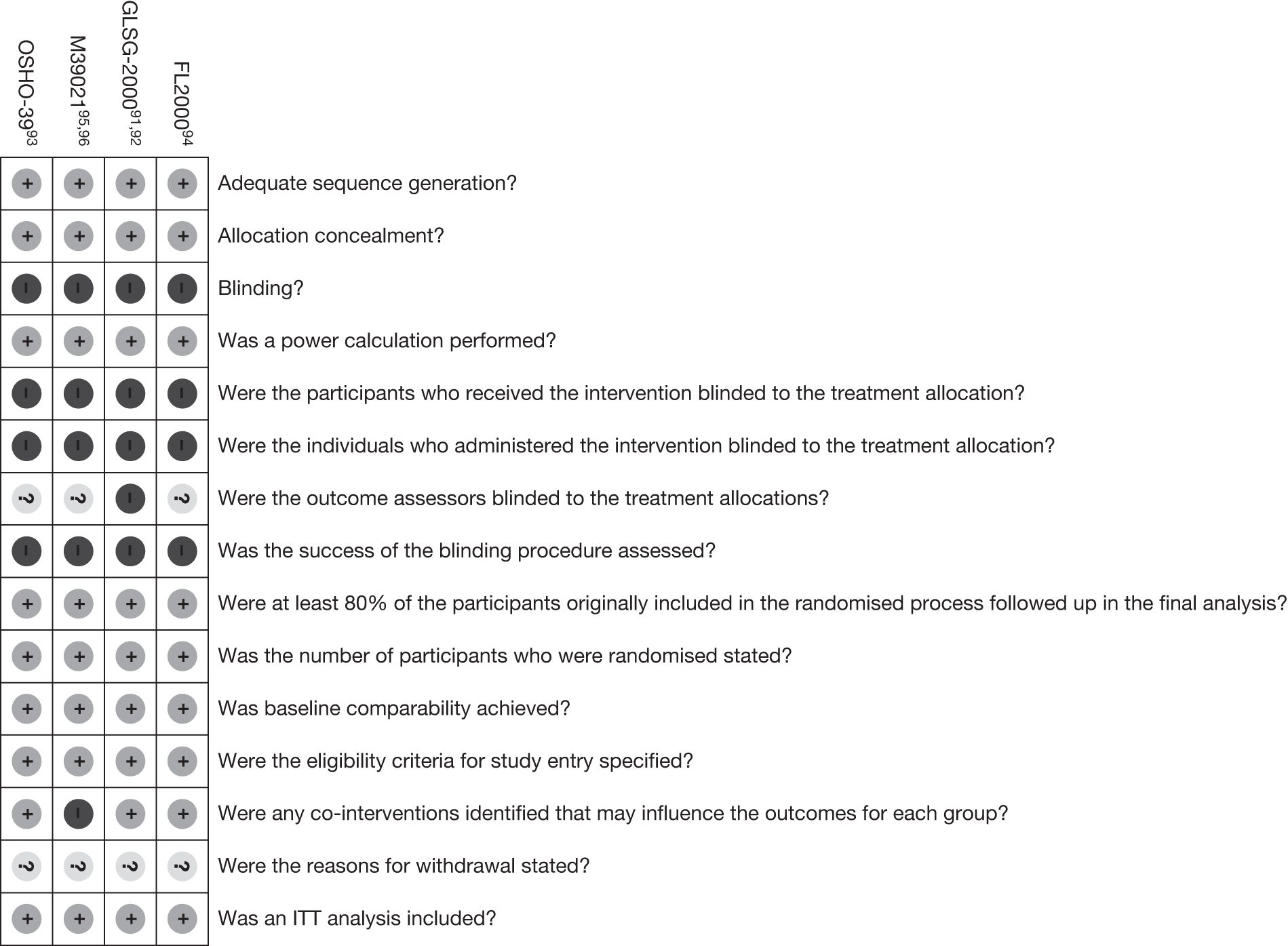

Critical appraisal strategy

The methodological quality of each included study was assessed by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer, according to criteria based on those proposed by the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) for RCTs. 90

The following factors were considered: method of randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding of patients, outcome assessors and data analysts, numbers of participants randomised, baseline comparability between groups, specification of eligibility criteria, whether or not intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis was performed, completeness of follow-up and whether or not study power calculations were performed and reported.

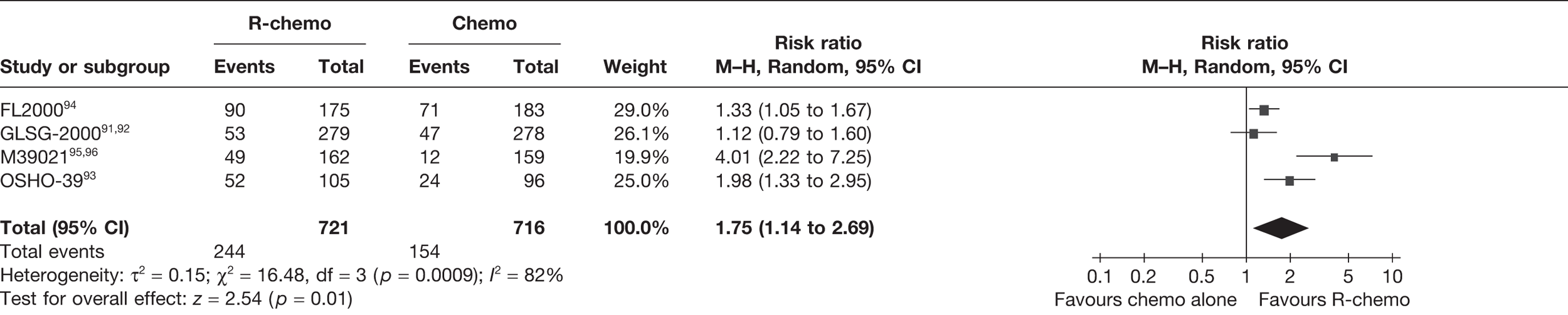

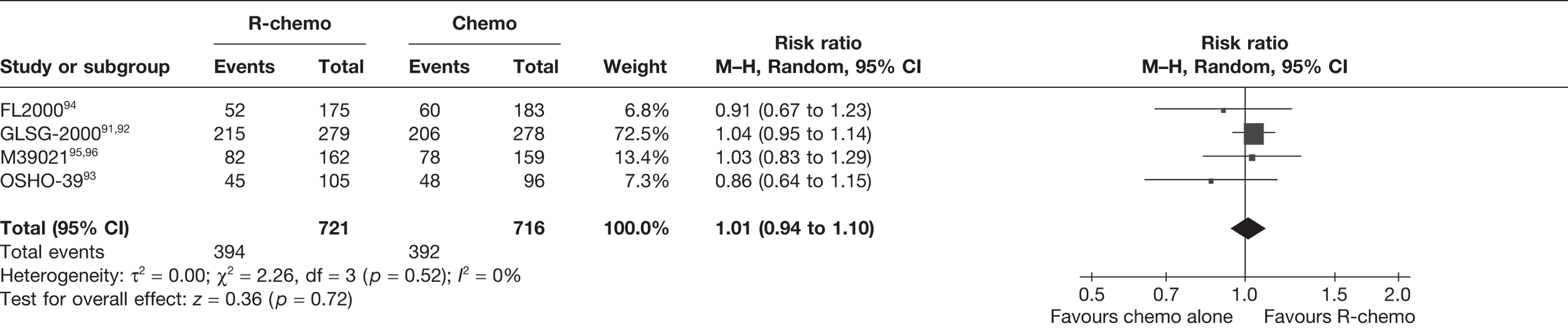

Methods of data synthesis

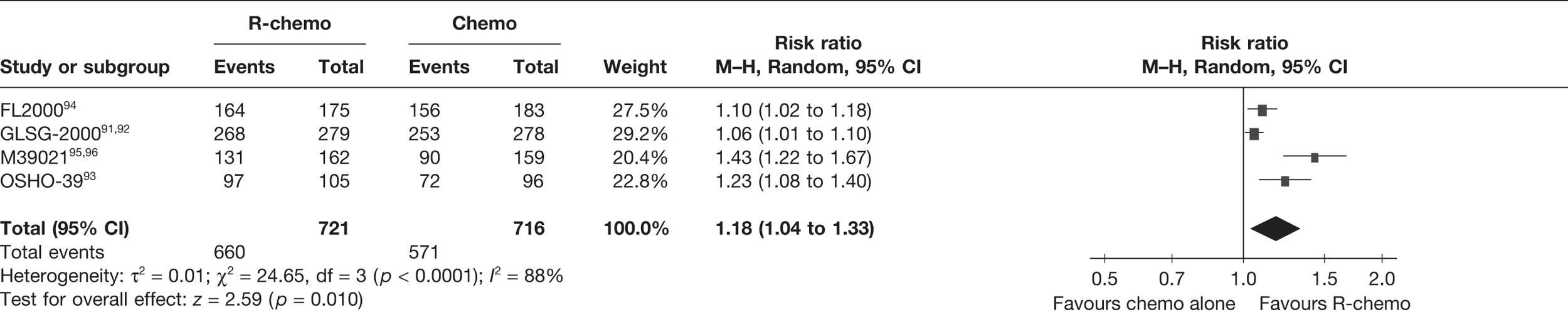

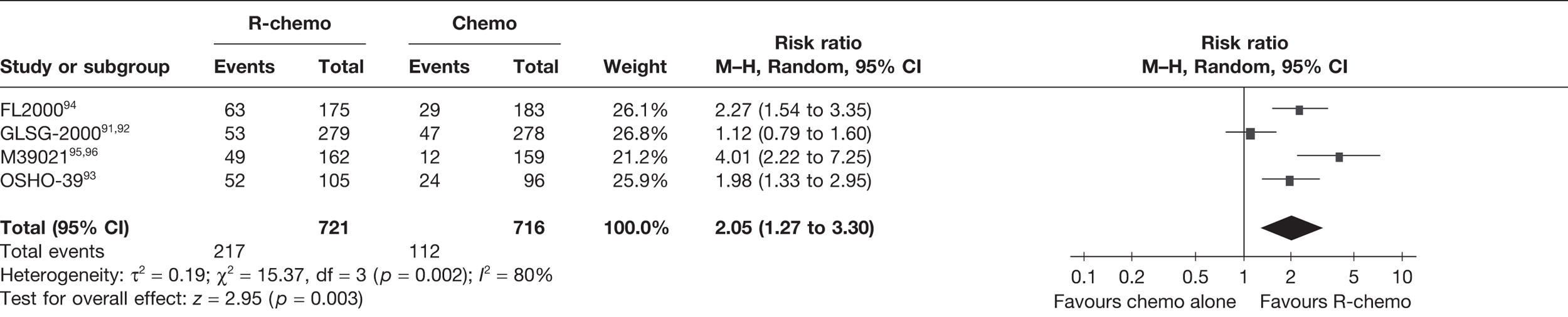

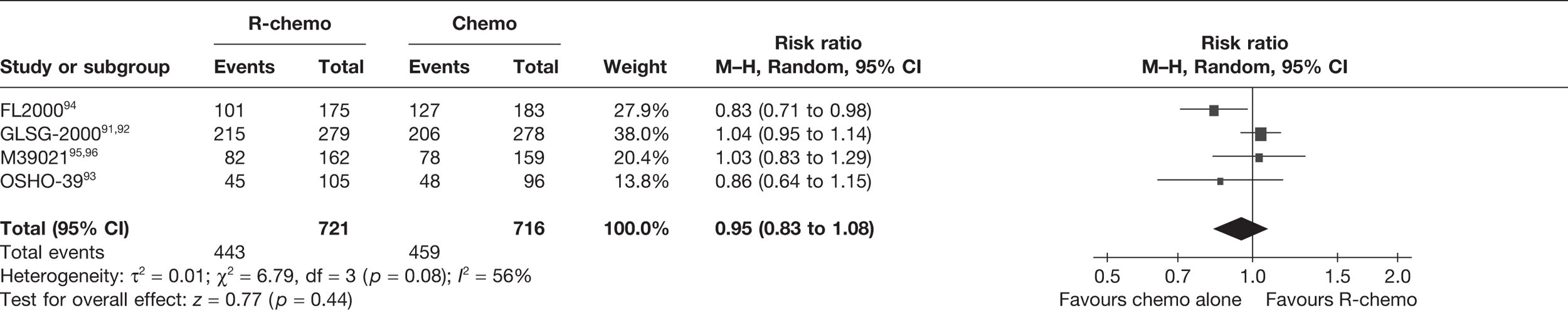

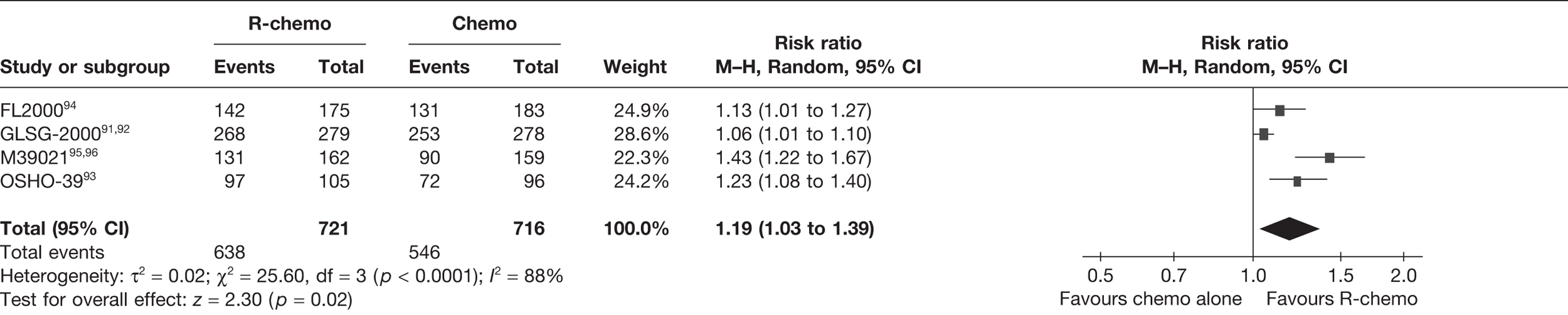

Data were tabulated and discussed in a narrative review. Exploratory meta-analyses were performed to estimate a summary measure of the effect of response rates (ORR, CR and PR) based on ITT analyses. CRus were considered as PRs in the meta-analyses so that the CR and PR rates were comparable between studies. However, it is noted this may result in an underestimation of CR, as clinical advice suggests that CRus are more likely to follow a similar clinical course to CRs. Heterogeneity in these analyses was explored through consideration of the study populations, methods and interventions, by visualisation of results and, in statistical terms, by the chi-squared test for homogeneity and the I2-statistic. Meta-analysis was carried out using random-effects models, using the Cochrane Collaboration Review Manager© (RevMan) software, version 5.0 (The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark).

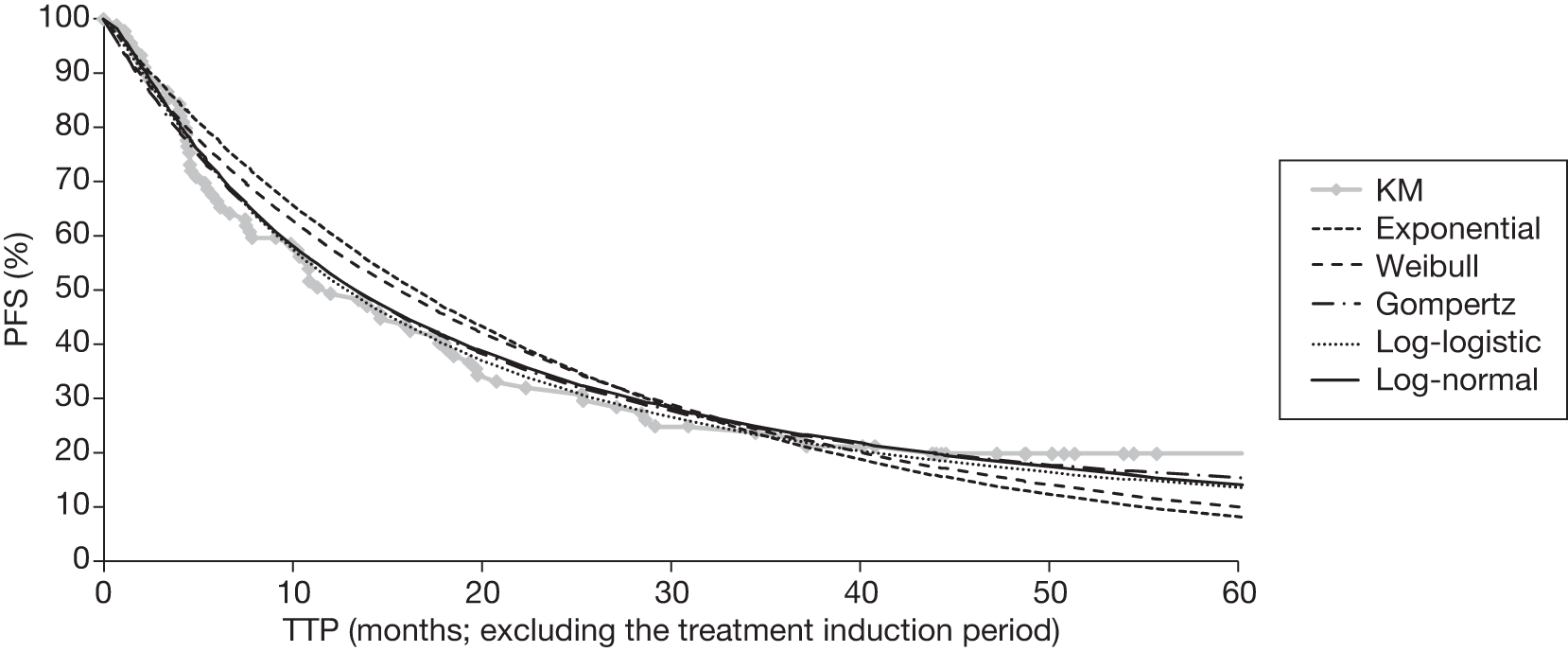

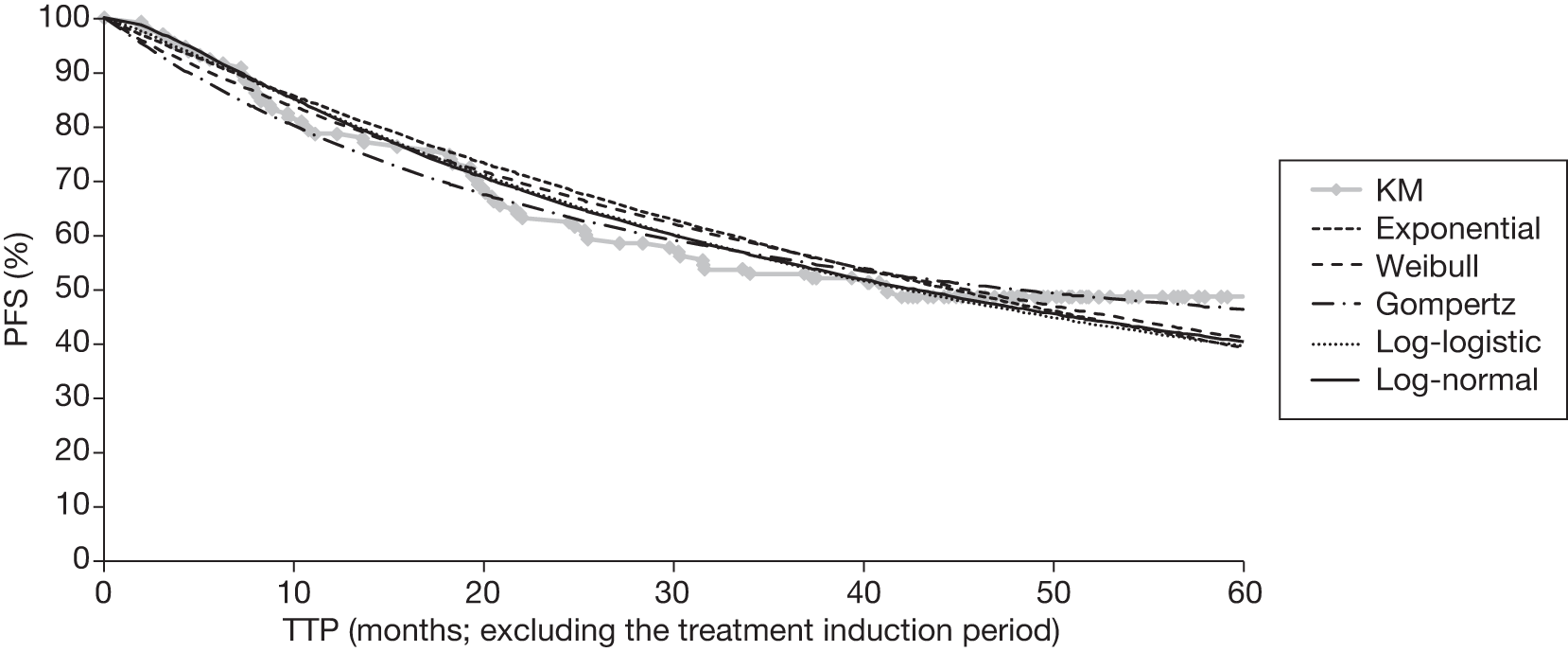

Meta-analysis was not performed for the outcome of PFS as only one study was identified measuring this outcome. Meta-analysis was not performed for the outcome of OS because of problems with the data in three of the trials. The population in two studies were given subsequent treatment as part of the study intervention. The German Low Grade Lymphoma Study-2000 (GLSG-2000) trial91,92 randomised responders who were aged < 60 years old to receive either interferon maintenance or dose-escalation chemotherapy and SCT; responders aged > 60 years old were given interferon maintenance therapy. Responders in the trial93 East German Society of Haematology and Oncology (OSHO-39; R-MCP vs MCP) were all given interferon maintenance therapy. Thus, the subsequent maintenance therapy confounds the OS data. The population in the (follicular lymphoma-2000 FL2000) trial94 included 10% patients with stage II FL and included the biological therapy interferon as part of the 6-month induction treatment phase and as a consolidation treatment for a further 12 months.

Other time-to-event data were presented in the included studies such as event-free survival (EFS), DFS, time to progression (TTP). No meta-analyses were performed on these additional time-to-event outcomes owing to inconsistencies in the way the outcomes were defined. These issues are discussed in more detail below (see Results, below). A network meta-analysis was not carried out. The reasons for this are discussed below (see Quantity and quality of research available).

Results

Quantity and quality of research available

Number of studies identified

The search retrieved 7858 unique citations relating to clinical effectiveness (4223 duplicates were removed). Of these, 7600 articles were excluded at title/abstract stage, 243 articles were examined at full-text level, and 15 articles were unobtainable from the interlibrary loans service (see Appendix 7). In addition, 1032 articles were examined from ongoing trials registers and conference proceedings.

Number and type of studies included

Four RCTs were included: M39021 trial by Marcus et al. ,95,96 GLSG-2000 by Hiddemann et al. ,91,92 OSHO-39 trial by Herold et al. 93 and the FL2000 trial by Salles et al. 94 Overall, 24 published reports were identified which related to the four included studies, and these are listed in Appendix 8. The principal source/sources for each study are listed in Table 6.

Number and type of studies excluded

In total, 212 citations were excluded from the full text selection (see Appendix 9). Studies that could potentially have provided head-to-head data for the interventions and comparators accounted for 108 excluded articles; 44 were excluded because they were not RCTs, i.e. case reports, literature reviews, commentaries and single-arm interventions; 29 studies were excluded because the interventions used were not relevant; 13 studies were excluded because the patient group was clinically heterogeneous and data for patients with FL were not reported separately; nine studies were excluded because patients did not have FL (e.g. Hodgkin’s disease or NHL unspecified) or had aggressive disease; six studies did not provide first-line treatment; five non-English-language studies were excluded; two were study protocols; and one did not provide relevant outcome data.

One hundred and four citations that were potential candidates to inform a network meta-analysis were excluded. Fifty-four were excluded because the participants did not have FL (e.g. NHL not specified) or the disease was not indolent; 21 were excluded because the population was heterogeneous and data relating to FL were not reported separately; 15 were excluded because the interventions were not relevant; eight were excluded because they were not RCTs; four were excluded because they were non-English-language reports; one was excluded as outcome data were not relevant; and one study was not included as it did not report on first-line treatment.

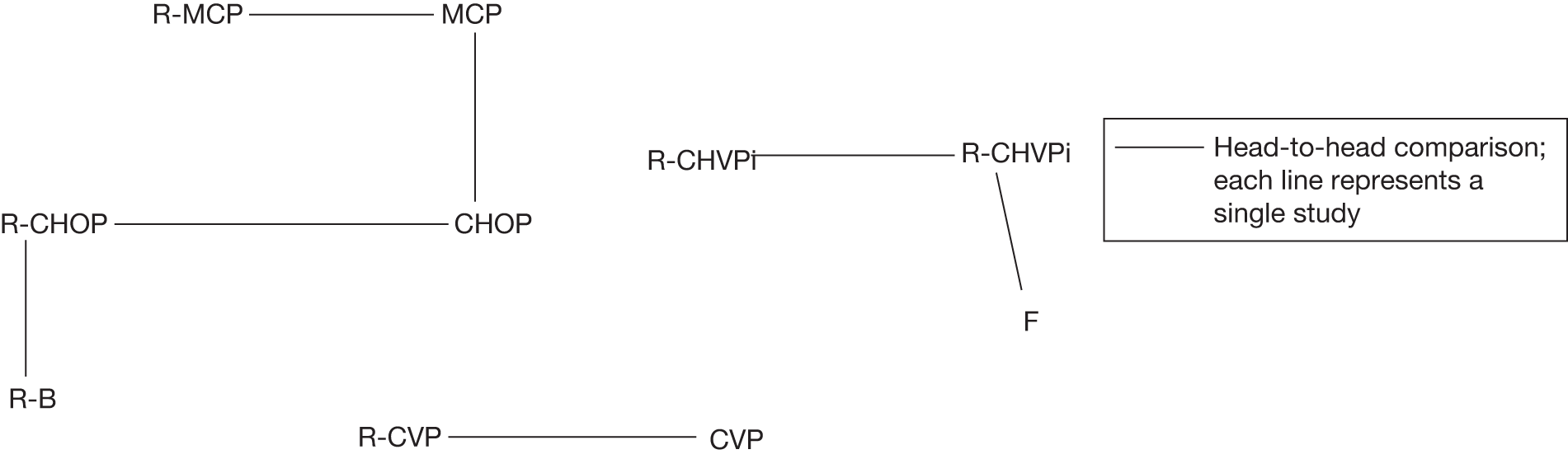

Studies identified for a potential network meta-analysis

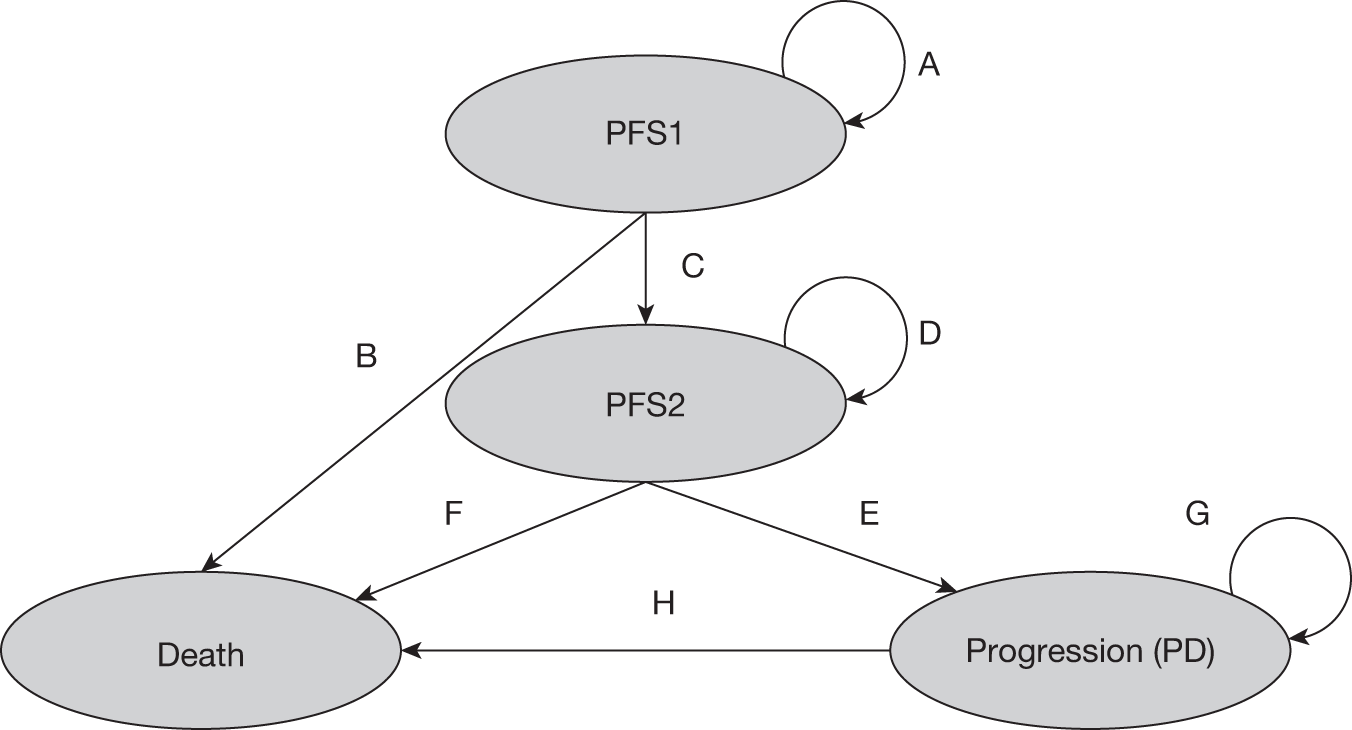

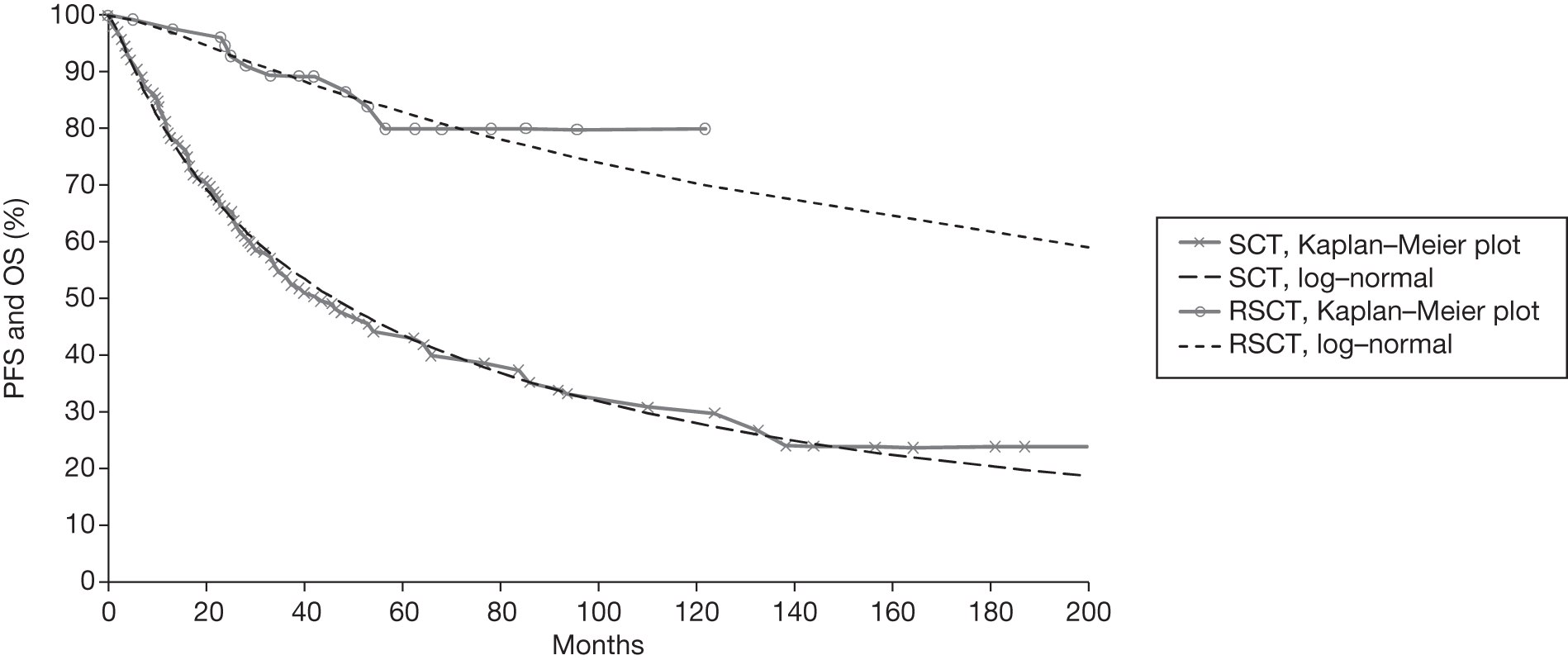

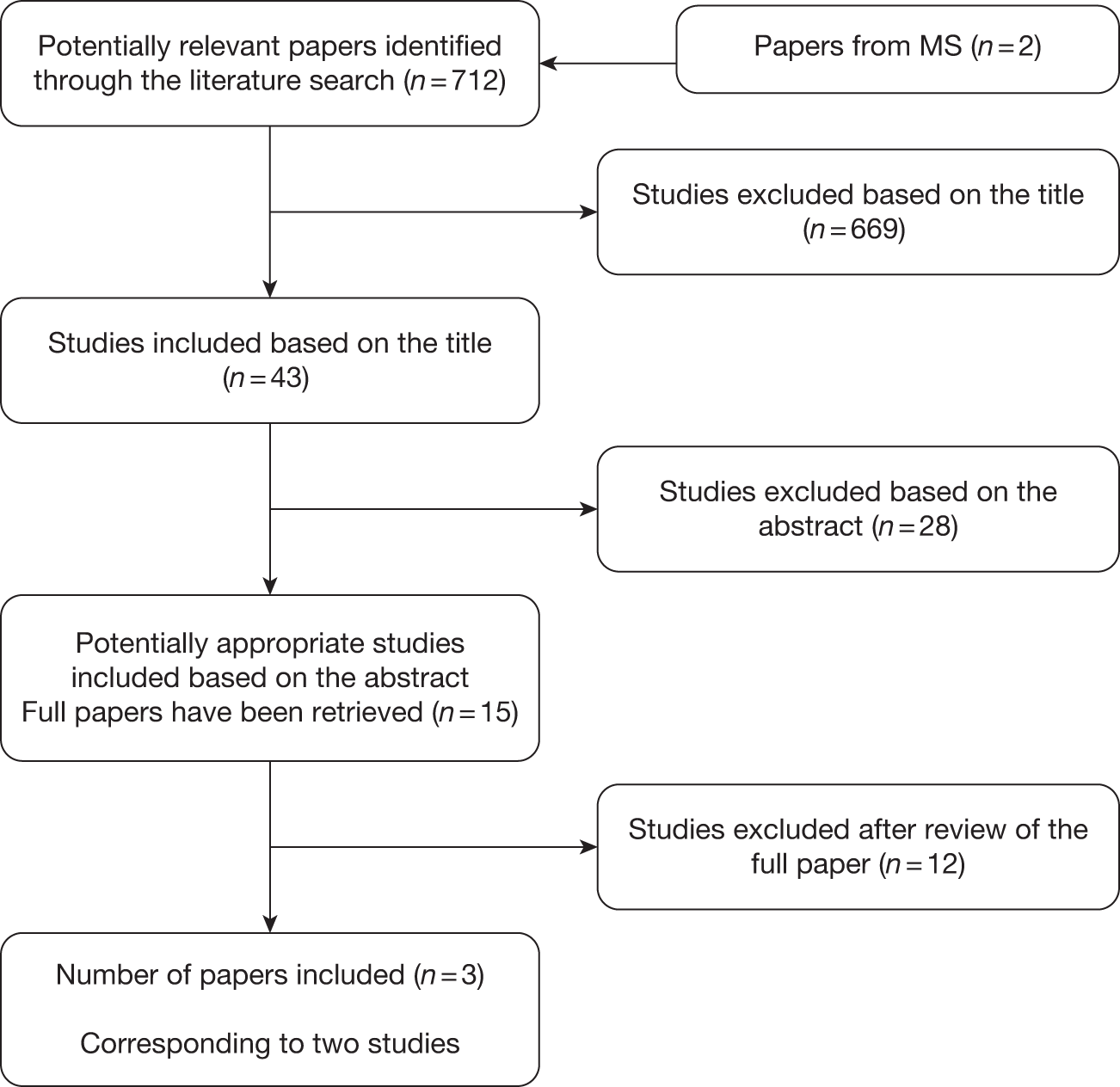

Three additional studies (corresponding to seven references – see Appendix 10 for list) met the criteria for providing evidence within a network meta-analysis, i.e. the population included FL (with analysis for FL presented separately), the therapy being investigated was either a relevant intervention or comparator (as stated in the decision problem – see Chapter 2) and appropriate outcomes were reported (as stated in the decision problem – see Chapter 2) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Network of evidence. F, fludarabine; R-B, rituximab and bendamustine; R-CHVP, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, etoposide, prednisolone and interferon-alpha.

Incorporating these three studies into a network of evidence would facilitate the comparison of interventions when a direct head-to-head trial was not available (as depicted in Figure 3). However, the network meta-analysis was not undertaken, as it was not deemed appropriate given that treatment efficacy is not the only factor in terms of choice of chemotherapy selection (see Chapter 1 for discussion of other factors). Additionally, head-to-head data were available to inform a comparison between a chemotherapy regimen and that regimen with the addition of rituximab. It is noted that NICE has a strong preference for evidence from head-to-head RCTs that directly compare the technology with the appropriate comparator in the relevant patient groups as stated in the NICE methods guide (p. 15). 97

Ongoing trials

Seven ongoing studies were identified (Table 7). 70,77–80,98,99 Four studies are investigating one R-chemotherapy against another R-chemotherapy; one study is closed [a randomised phase III study of the STiL (Study Group Indolent Lymphomas)] with study follow-up complete and initial results reported as a conference abstract;78 one study is ongoing but not recruiting (ML17638)98 and two studies are ongoing and still recruiting [Purine-Alkylator Combination In Follicular lymphoma Immuno-Chemotherapy for Older patients (PACIFICO80) and Polish Lymphoma Research Group 479 (PLRG4)]. The study population in the PACIFICO trial81 is patients with FL aged > 60 years or aged < 60 years but with an anthracycline-based therapy contraindicated. Two ongoing studies are investigating the use of rituximab in maintenance following first-line induction therapy; one study is closed with follow-up completed [Primary Rituximab and Maintenance (PRIMA) study71], whereas the other study (ML17638)98 is ongoing but not recruiting. One study99 is investigating one chemotherapy compared with another chemotherapy regimen [British Lymphoma Investigation Group (BNLI) MCD vs FMD].

| Study characteristics | Study | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRIMA study71 | STiL trial (Rummel et al.78) | BNLI MCD vs FMD99 | R-CVP vs R-CHOP vs R-FM79 | ML1763899 | PACIFICO81 | PLRG480 | |

| Study identifier | UKCRN ID 2249 | ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT00991211 | UKCRN ID 908 | ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT00774826 | ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT01144364 | UKCRN ID 6898 | ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT00801281 |

| Participants | FL | FL and MCL | FL | FL (including stage II) | FL | FL | FL |

| n = 1200 | n = 549 | n = 400 | n = 431 | Target sample size 100–500 | n = 680 | n = 250 | |

| Age: > 18 years | Age: ≥ 18 years | Age: 18–70 years | Age: 18–75 years | Age: 60–75 years | Age: ≥ 60 years, or < 60 years but anthracycline-based therapy contraindicated | Age: ≥ 18 years | |

| Treatment | After induction of response with rituximab and chemotherapy:

|

|

|

|

After brief induction with chemotherapy (FMD) plus rituximab:

|

|

|

| Status | Closed: follow-up complete | Closed: follow-up complete | Closed: follow-up complete | Ongoing treatment phase: not recruiting | Ongoing treatment phase: not recruiting | Ongoing treatment phase: recruiting | Ongoing treatment phase: recruiting |

Summary of trials

Four multicentre, open-label trials were included, which randomised between 322 and 630 participants. The GLSG-200091,92 and OSHO-39 trials93 were undertaken in Germany; the M39021 trial95,96 was undertaken in centres across 11 countries including the UK, and FL2000 trial94 was undertaken in centres within France and Belgium. Three trials compared a R-chemotherapy regimen with a chemotherapy-alone regimen; the FL2000 trial compared a R-chemotherapy biological regimen with a chemotherapy biological regimen alone. The median follow-up ranged from 47 to 60 months (Table 8).

| Trial | Study type, country | Numbers randomised | Intervention | Comparator | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M3902195,96 |

Multicentre, open-label RCT 47 centres in Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, France, Israel, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland and the UK |

n = 322a Stage III–IV FL |

R-CVP (n = 162) | CVP (n = 159) | Median 53 months (no range reported) |

| GLSG-200091,92 |

Multicentre, open-label RCT 200 institutions in Germany |

n = 630b Stage III–IV FL |

R-CHOP (n = 279) | CHOP (n = 278) | Median 56 months (no range reported) |

| OSHO-3993 |

Multicentre, open-label RCT 34 centres in Germany |

n = 376 (including MCL) n = 201/376 were FL Stage III–IV FL |

R-MCP (n = 105) | MCP (n = 96) | Median 47 months (49 months for R-MCP and 42 months for MCP) (no range reported) |

| FL200094 |

Multicentre, open-label RCT 54 centres in France and Belgium |

n = 360c Stage II–IV |

R-CHVPi (n = 175) | CHVPi (n = 183) | Median 60 months (range 0.2–6.4 years) |

Population

Baseline demographic data are provided in Table 9. The target population were advanced-stage patients with FL who were symptomatic and requiring treatment (detailed eligibility criteria for each study are presented in the data extraction tables in Appendix 11). The M3902195,96 and GLSG-2000 trials91,92 recruited patients with stage III–IV FL, whereas the FL2000 trial94 recruited patients with stage II-IV FL. The OSHO-39 trial93 included CD20-positive patients with indolent NHL, which included lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma or mantle cell lymphoma (MCL); however, the primary analysis population was defined as the population of patients with FL. The OSHO-3993 and GLSG-200092 trials limited to grade 1 or 2 FL (WHO classification); the M39021 trial95,96 included grade 1–3 FL; and the FL2000 trial94 included grades 1, 2 and 3a FL.

| Demographics | M3902195,96 | GLSG-200091,92 | OSHO-3993 | FL200094 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-CVP (n = 162) | CVP (n = 159) | R-CHOP (n = 279) | CHOP (n = 278) | R-MCP (n = 105) | MCP (n = 96) | R-CHVPi (n = 175) | CHVPi (n = 183) | |

| Age and gender | ||||||||

| Median age in years (range) | 52 | 53 | 57 (27–90) | 57 (21–81) | 60 (33–78) | 57 (31–75) | 61 (25–75) | |

| Aged > 60 years: no. (%) | 41 (25) | 44 (28) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 89 (51) | 96 (52) |

| Male: no. (%) | 88 (54) | 85 (53) | 120 (43) | 146 (53) | 53 (50) | 36 (37) | 96 (55) | 82 (45) |

| Female: no. (%) | 74 (46) | 74 (47) | 159 (57) | 132 (47) | 52 (50) | 60 (63) | 79 (45) | 101 (55) |

| Ann Arbor stage, no. (%) | ||||||||

| II | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23 (13) | 18 (10) |

| III | 45 (28) | 45 (28) | NR | NR | 30 (29) | 22 (23) | 152 (87) | 165 (90) |

| IV | 114 (70) | 112 (70) | 194 (70) | 191 (69) | 75 (71) | 74 (77) | ||

| Not evaluable/missing | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | NR | NR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Performance status (ECOG), no. (%) | ||||||||

| 0 | 93 (57) | 90 (57) | 97 (35) | 88 (32) | 68 (65) | 54 (56) | 164 (94) | 167 (91) |

| 1 | 65 (40) | 60 (38) | 155 (56) | 167 (60) | 29 (28) | 36 (38) | ||

| > 1 | 4 (2) | 8 (5) | 18 (6) | 19 (7) | 7 (7) | 6 (6) | 11 (6) | 16 (9) |

| Not evaluable/missing | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 9 (3) | 4 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| IPI, no. (%) | ||||||||

| 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| 1 | 72 (44) | 69 (43) | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| 2 | 57 (35) | 57 (36) | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| 3 | 19 (12) | 21 (13) | NR | NR | 60 (34) | 71 (39) | ||

| 4 | 2 (1) | 3 (2) | NR | NR | ||||

| Not evaluable/missing | 11 (7) | 8 (5) | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| FLIPI, no. (%) | ||||||||

| Low (0–1) | 80 (49) | 75 (47) | 39 (14) | 31 (11) | 8 (8) | 6 (6) | 28 (16) | 37 (20) |

| Intermediate (2) | 114 (41) | 119 (43) | 38 (36) | 37 (39) | 63 (36) | 59 (32) | ||

| High (3–5) | 71 (44) | 75 (47) | 123 (44) | 123 (44) | 59 (56) | 53 (55) | 79 (45) | 83 (45) |

| Not evaluable/missing | 11 (7) | 9 (6) | 3 (1) | 5 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (3) | 4 (2) |

| Other factors, no. (%) | ||||||||

| B symptoms presence | 65 (40) | 51 (32) | 108 (39) | 113 (41) | ≥ 46 (44) | ≥ 34 (35) | 38 (22) | 52 (28) |

| Bone marrow involvement | 103 (64) | 102 (64) | 180 (65) | 179 (64) | 73 (70) | 71 (74) | 108 (62) | 121 (66) |

| More than extranodal site | 28 (17) | 27 (17) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 60 (34) | 73 (40) |

| Elevated LDHb | 39 (26) | 39 (26) | 73 (26) | 66 (24) | 31 (30) | 30 (31) | 64 (37) | 66 (36) |

| β2-Microglobulin > 3 mg/lc | 146 (99) | 141 (100) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 62 (35) | 56 (31) |

| Haemoglobin < 12 g/dl | NR | NR | 54 (19) | 56 (20) | NR | NR | 37 (21) | 30 (16) |

The median age of patients randomised across the trials ranged from 52 to 61 years. Two trials presented the percentage of participants aged over 60 years: 26% in the M39021 trial95,96 and 52% in FL2000 trial. 94 The majority of patients had stage IV FL (69–77% in the three studies that reported these data). Most participants had an ECOG performance status of 0–1, ranging from 91% to 97%. Bone marrow involvement was present in 62–74% of patients, and 22–44% presented with one or more B symptoms (defined as fever, weight loss or night sweating). Elevated LDH levels (a marker of aggressive disease) were recorded in 26–37% of patients.

Within the individual studies, the treatment groups were well balanced with respect to demographic and disease characteristics, with the exception of gender in OSHO-39 trial92 (more males in the R-MCP group; no p-value reported) and the GLSG-2000 trial (higher proportion of males in the CHOP arm; p = 0.027). The populations were reasonably similar when compared across the four studies, although there were some differences, including younger median age (52–53 years) in the M39021 trial,95,96 and larger proportion of patients aged > 60 years and inclusion of stage II participants in the FL2000 trial. 93 The study populations included were generally reflective of the general FL population, with the exception of age – the median age of participants in the trials being younger than seen in clinical practice (70% are aged > 60 years when diagnosed). 10 The younger median age of trial participants meant that ECOG performance status was better than that seen in clinical practice. In addition, the M3902195,96 and OSHO-3993 trials excluded patients with an ECOG performance status of > 2.

Interventions and comparators

The interventions in each of the four studies were a R-chemotherapy combination; each trial used a different chemotherapy agent. The comparator within each trial was the chemotherapy regimen minus rituximab. These are described in Table 10. Two studies provided subsequent treatment following response to first-line treatment. The OSHO-39 trial93 planned to provide all responders with interferon-alpha maintenance [3 × million international units (MIU)/week] until disease progression. The GLSG-2000 trial92,93 randomised responding patients who were aged < 60 years to a high-dose chemotherapy regimen followed by autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) or interferon-alpha maintenance treatment (3 × 5 MIU/week until disease progression of intolerable AEs). Patients aged ≥ 60 years received interferon-alpha maintenance.

| Author/study | Treatment regimens | Cycles | Response assessment | Amendment to dose or cycles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M3902195,96 |

CVP: 750 mg/m2 cyclophosphamide i.v. on day 1; 1.4 mg/m2 of vincristine, up to a maximal dose of 2 mg i.v. on day 1; and 40 mg/m2 of prednisone per day p.o. on days 1–5 Rituximab: 375 mg/m2 infusion on day 1 |

Every 21 days for a maximum of eight cycles | Assessed after cycle 4 and at the end of treatment | Insufficient therapeutic response, i.e. disease progression or stable disease after cycle 4 were withdrawn from study treatment. Those achieving at least a PR continued to eight cycles |

| GLSG-200091,92 |

CHOP: 750 mg/m2 cyclophosphamide; 50 mg/m2 doxorubicin, 1.4 mg/m2 vincristine: all given i.v. on day 1. Prednisolone given 100 mg/m2 daily on days 1–5 p.o. Rituximab: 375 mg/m2 infusion on the day before the respective CHOP course |

Every 21 days for a total of six to eight cycles | Assessed every two cycles and 4 weeks after completion of last course |

Patients, in either study arm, with disease progression at any time during the study were taken off the study Patients achieving CR after four cycles were treated with a total of six cycles; all other patients received eight cycles |

| OSHO-3993 |

MCP: 8 mg/m2 mitoxantrone i.v. on days 1 and 2; 3 × 3 mg/m2 chlorambucil and 25 mg/m2 prednisolone p.o. on days 1–5 Rituximab: 375 mg/m2 i.v. infusion on day 1 (8 mg/m2 mitoxantrone i.v. on days 3 and 4; 3 × 3 mg/m2 chlorambucil and 25mg/m2 prednisolone p.o. on days 3–7) |

Every 28 days for a maximum of eight cycles | After completion of induction treatment, patients were observed every 8 weeks during the first year, at 3-month intervals during the second year, and then every 6 months from the third year onwards |

Patients with disease progression after two cycles of therapy or who had not reached a PR or CR after six cycles of therapy were prematurely withdrawn from study CR or a PR after six cycles of treatment received a further two cycles of treatment |

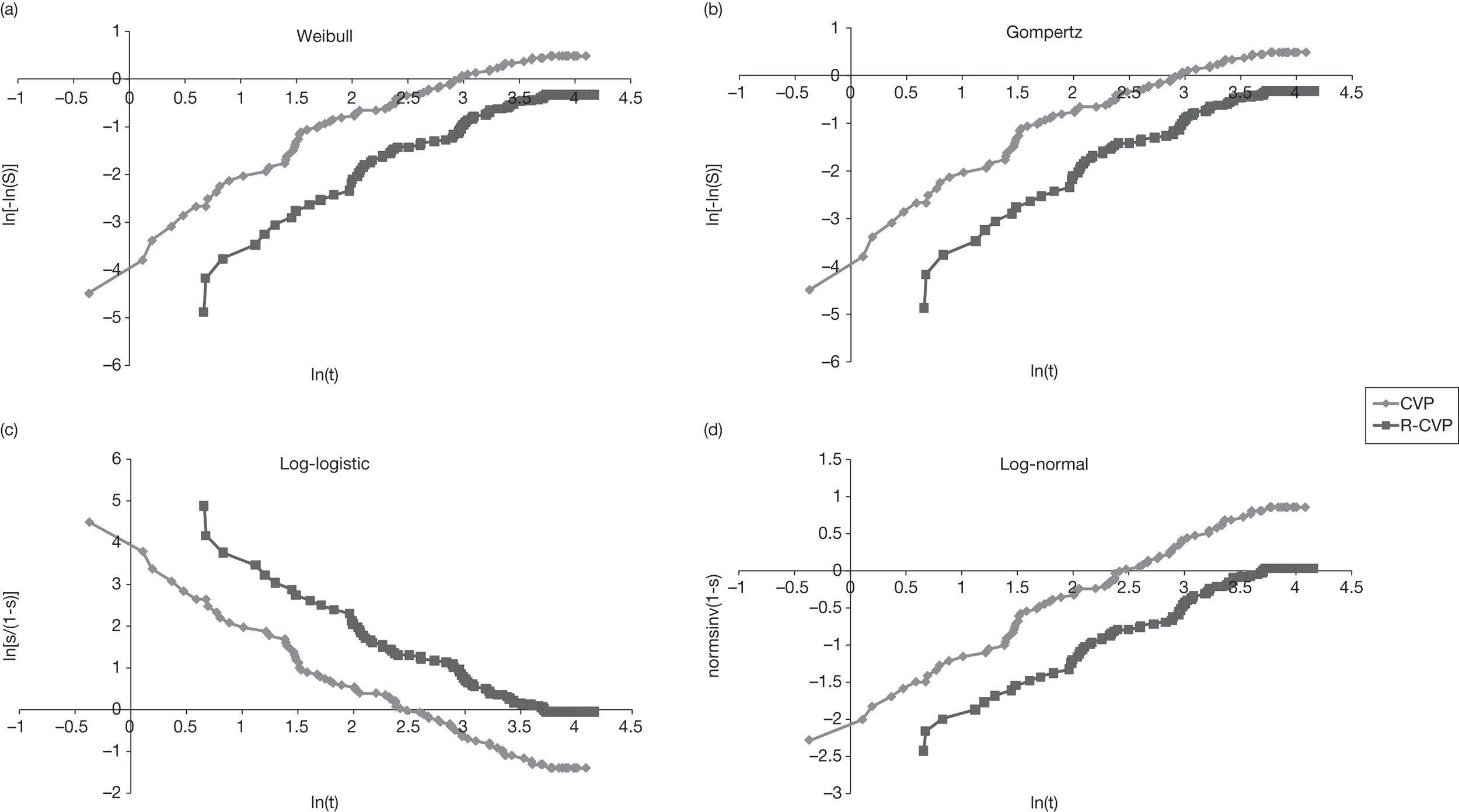

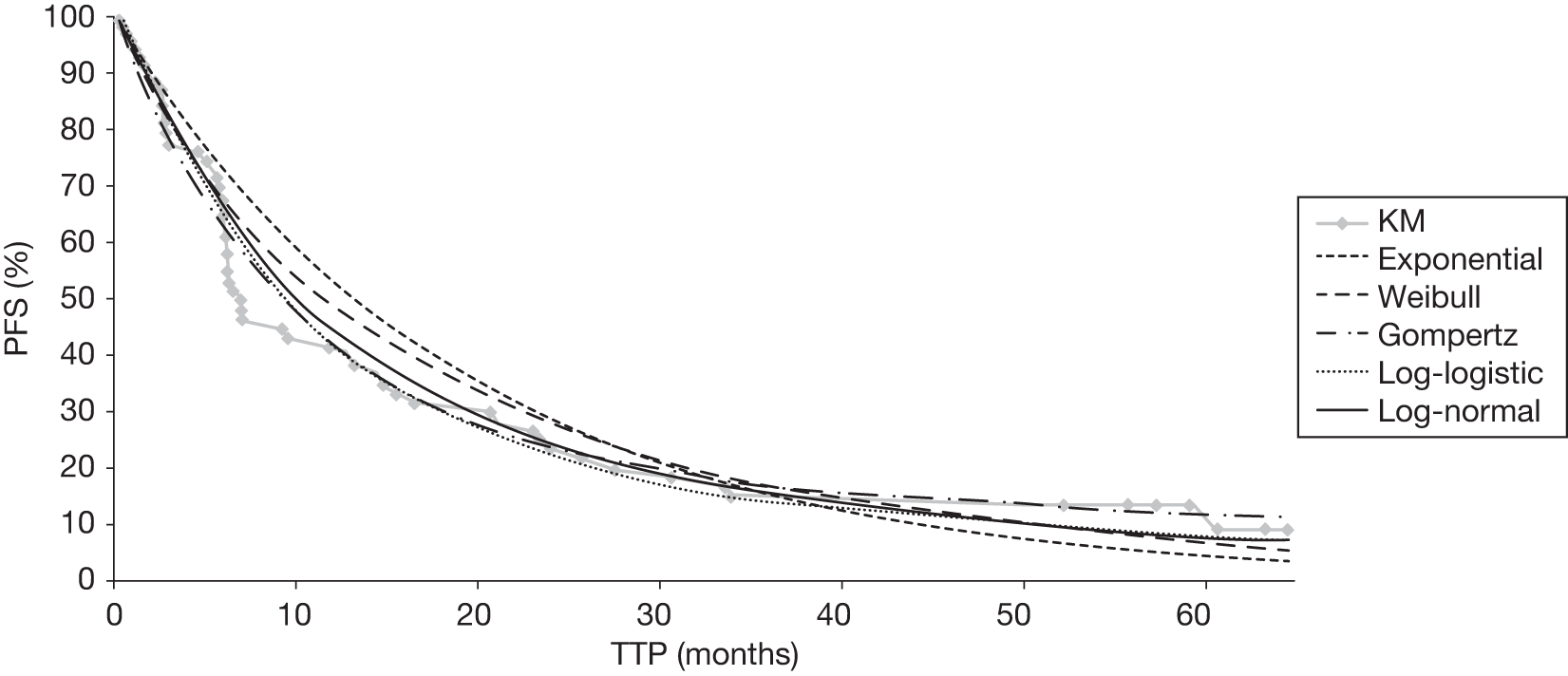

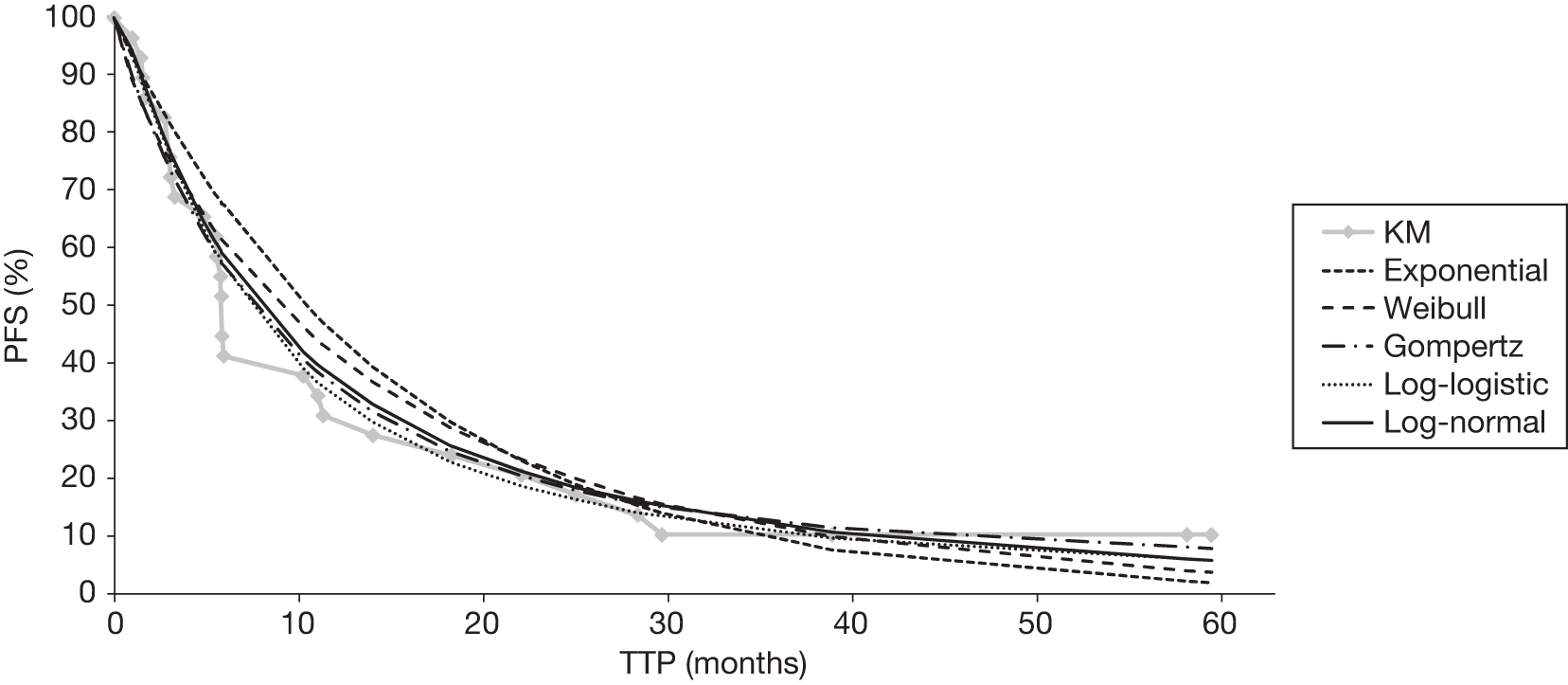

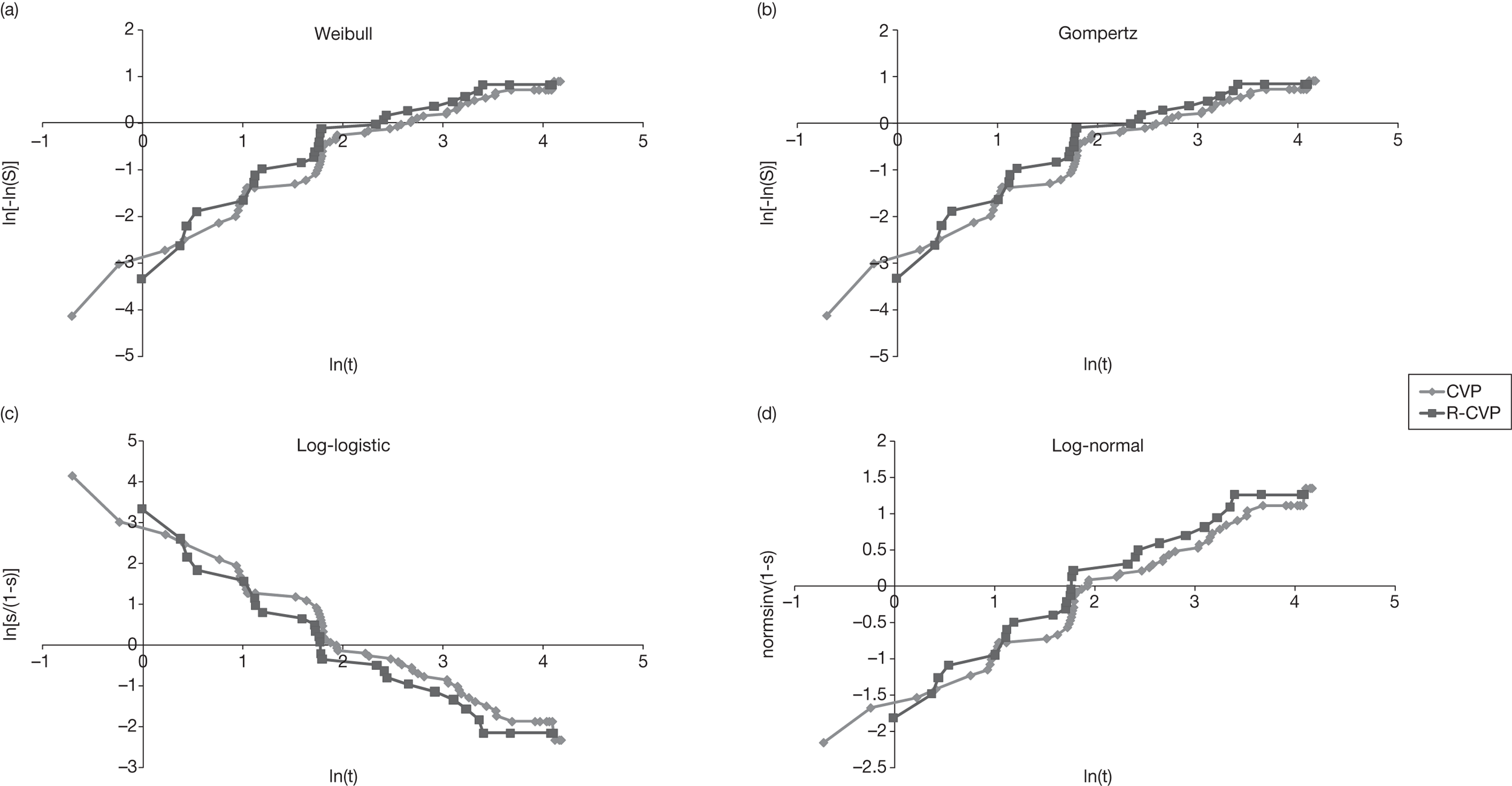

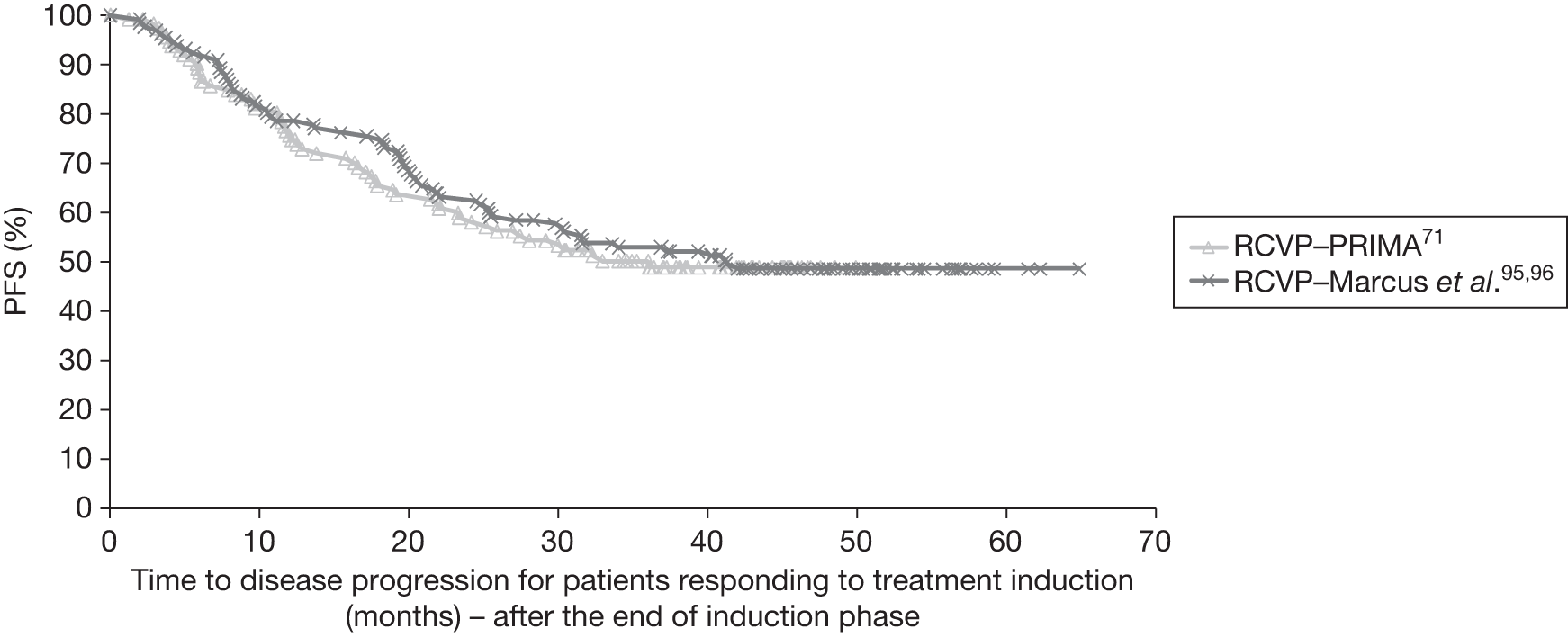

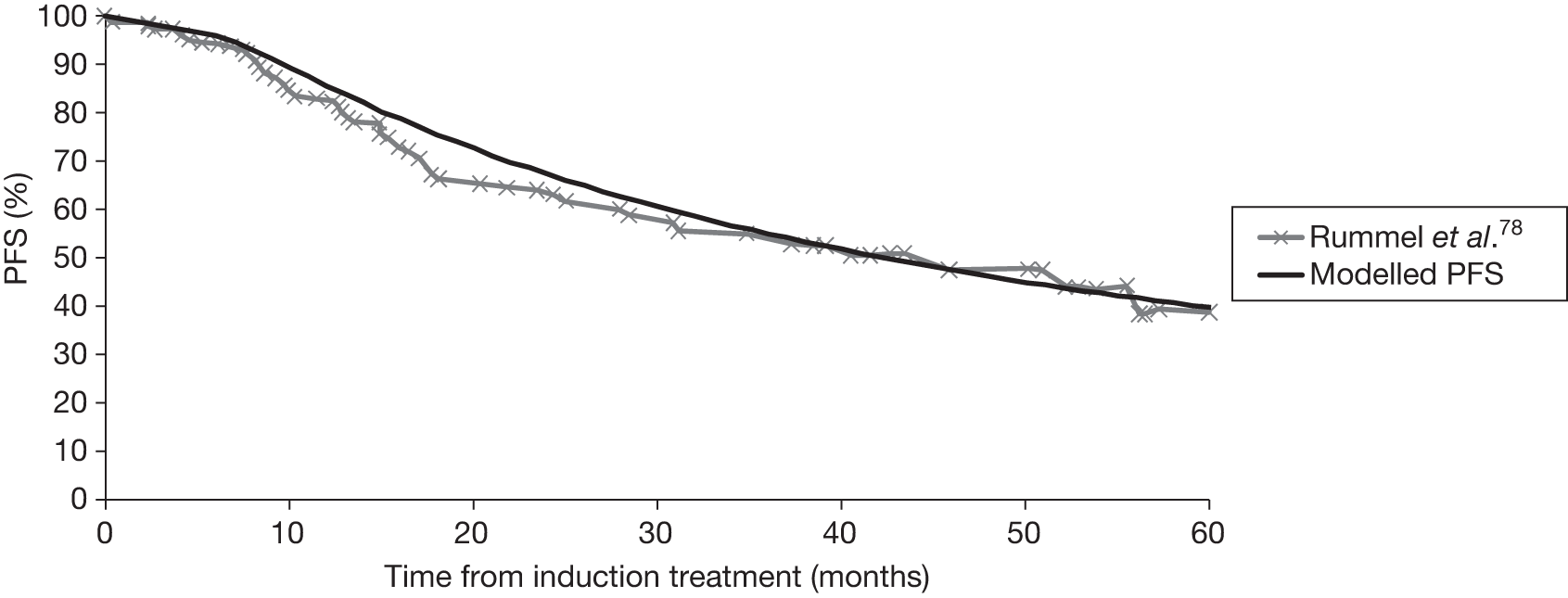

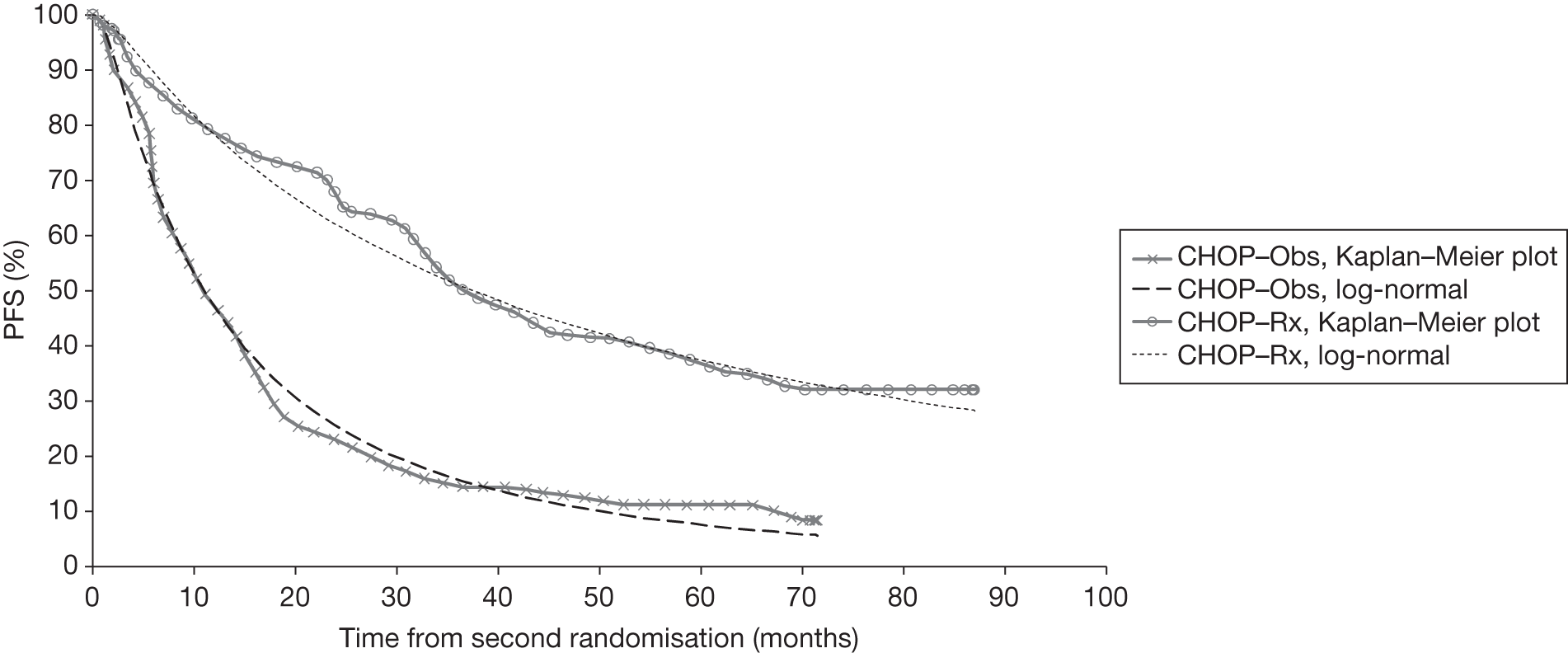

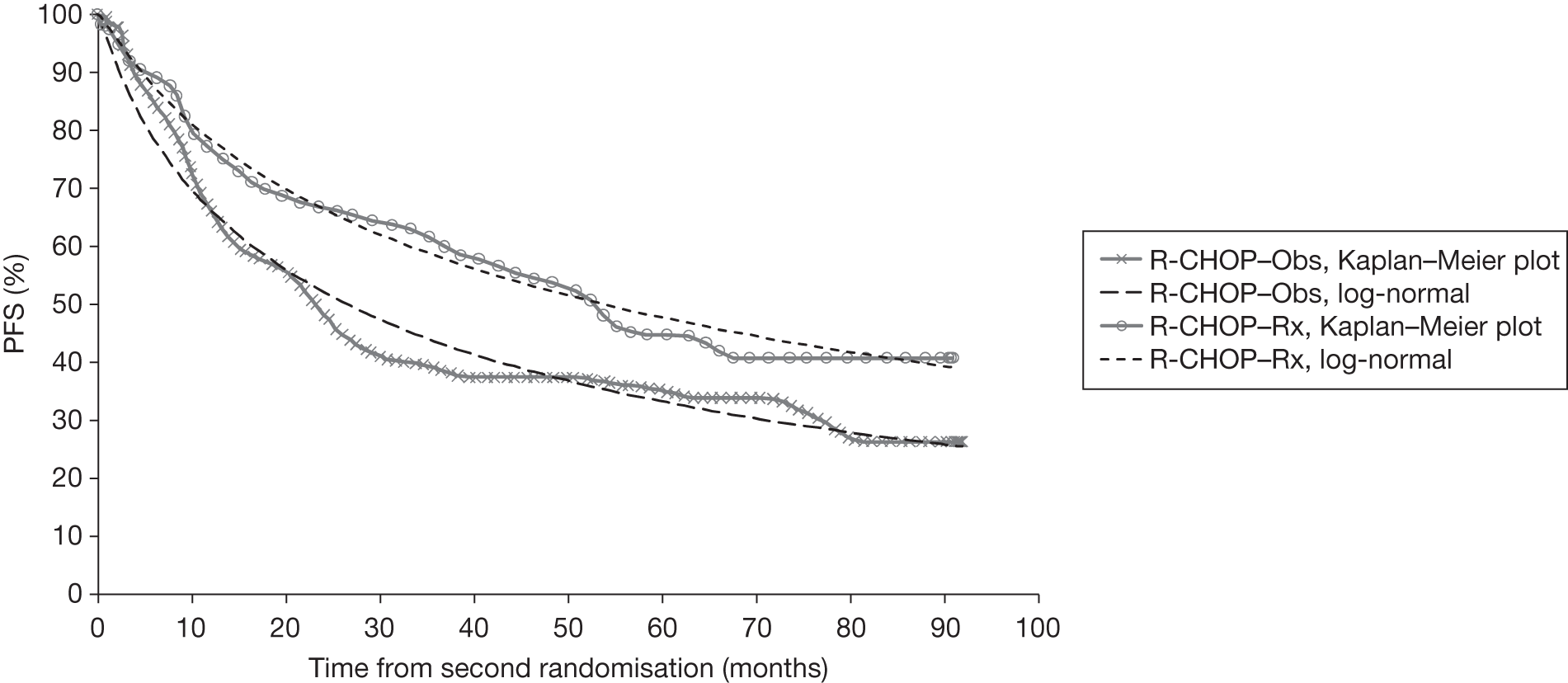

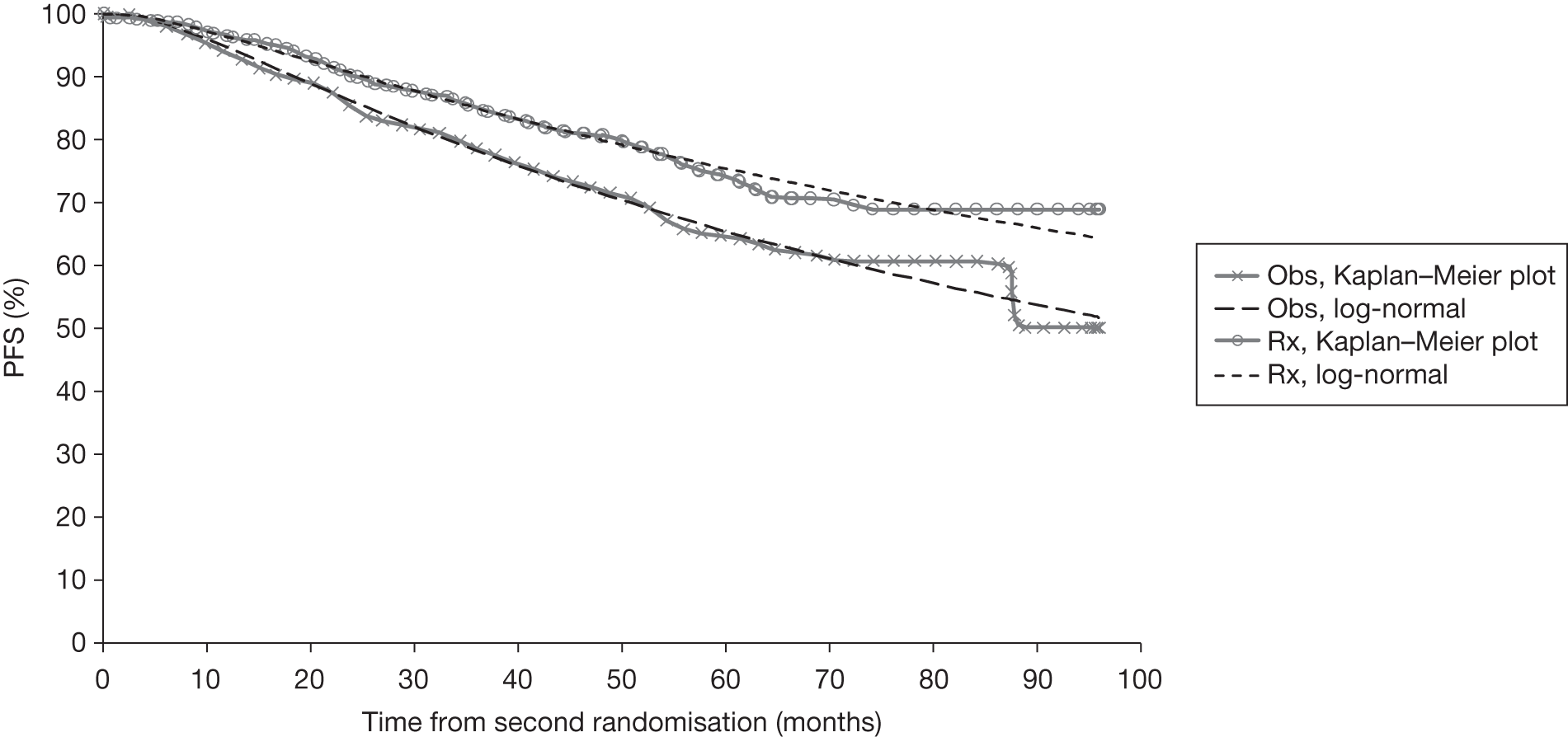

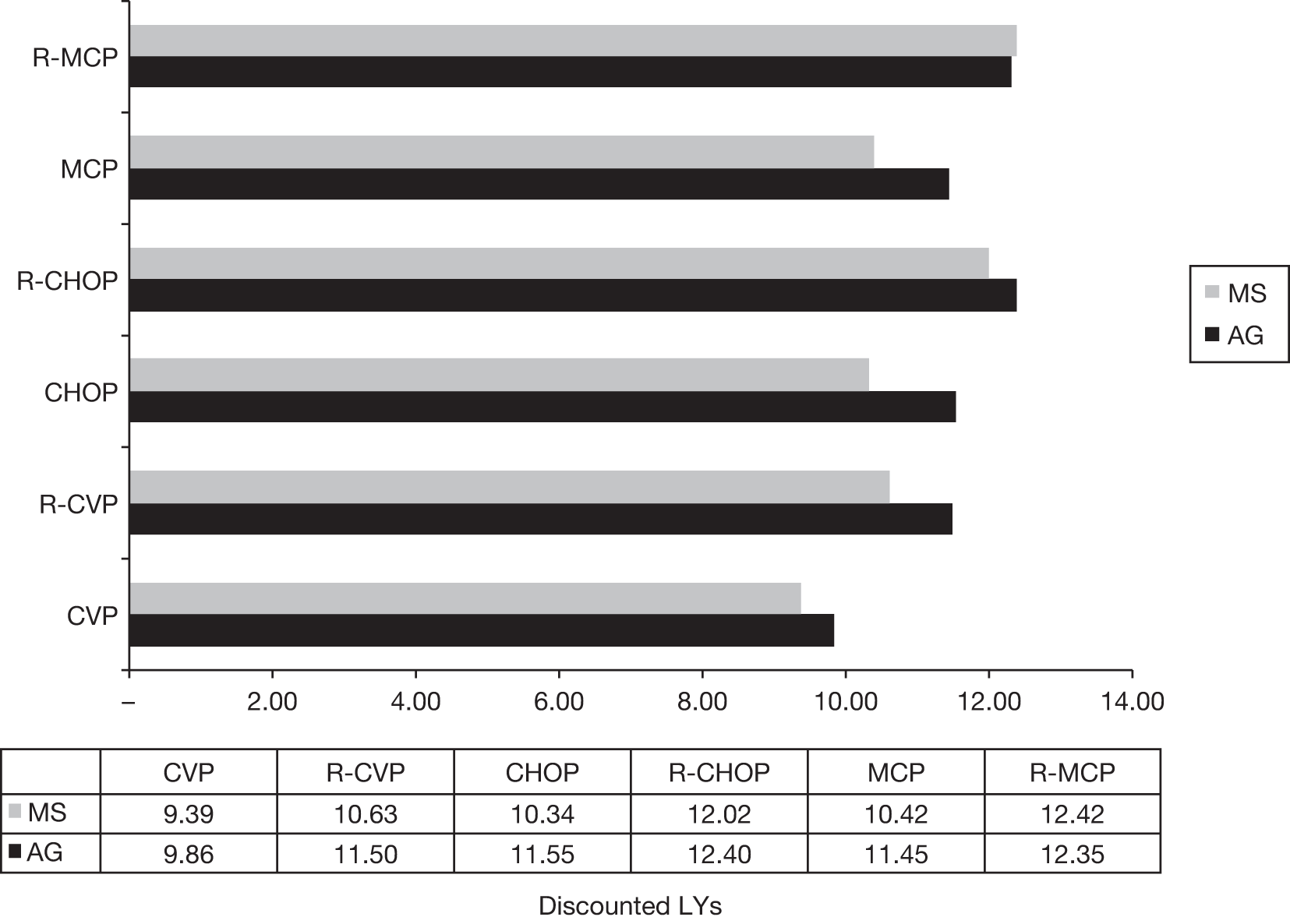

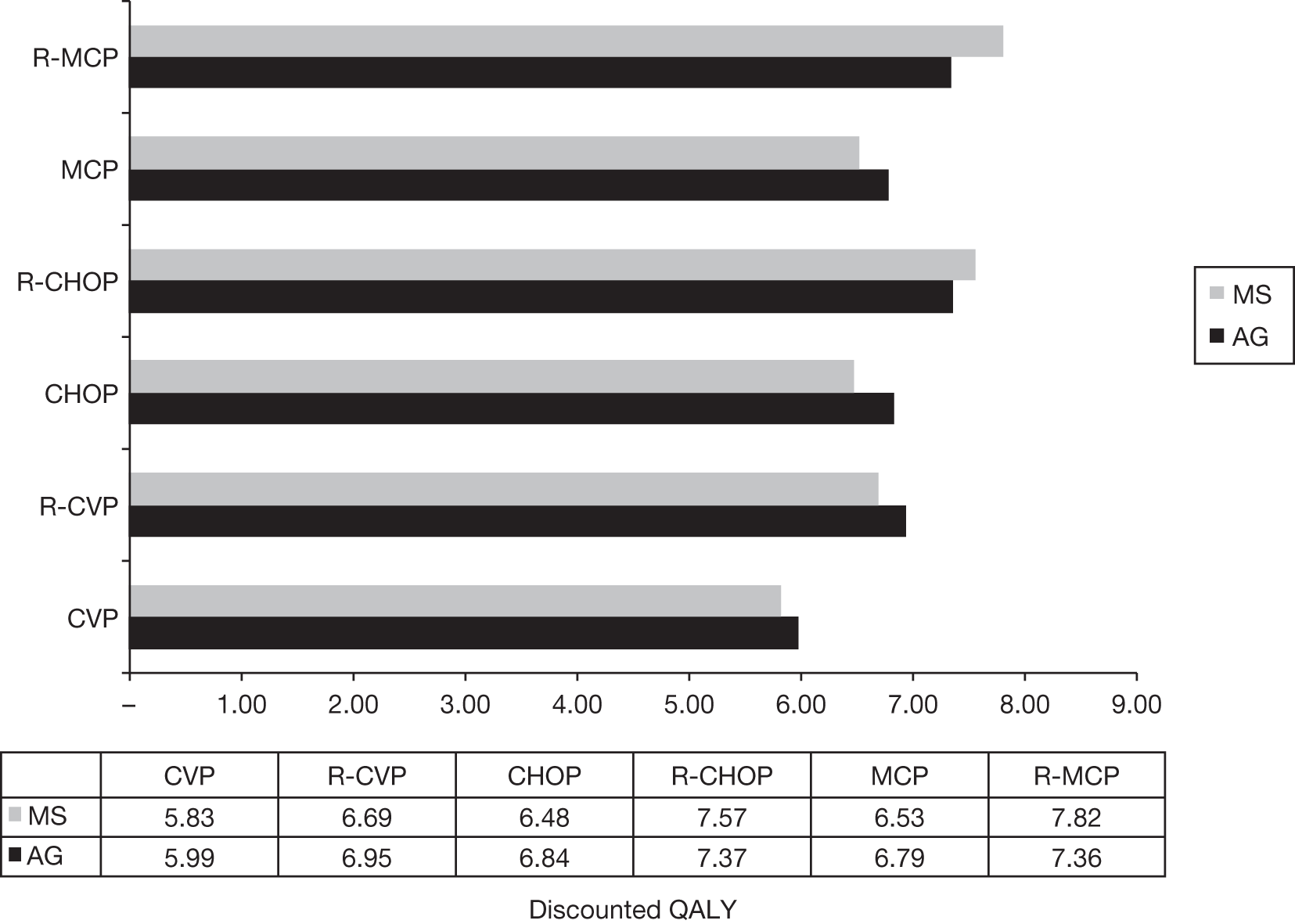

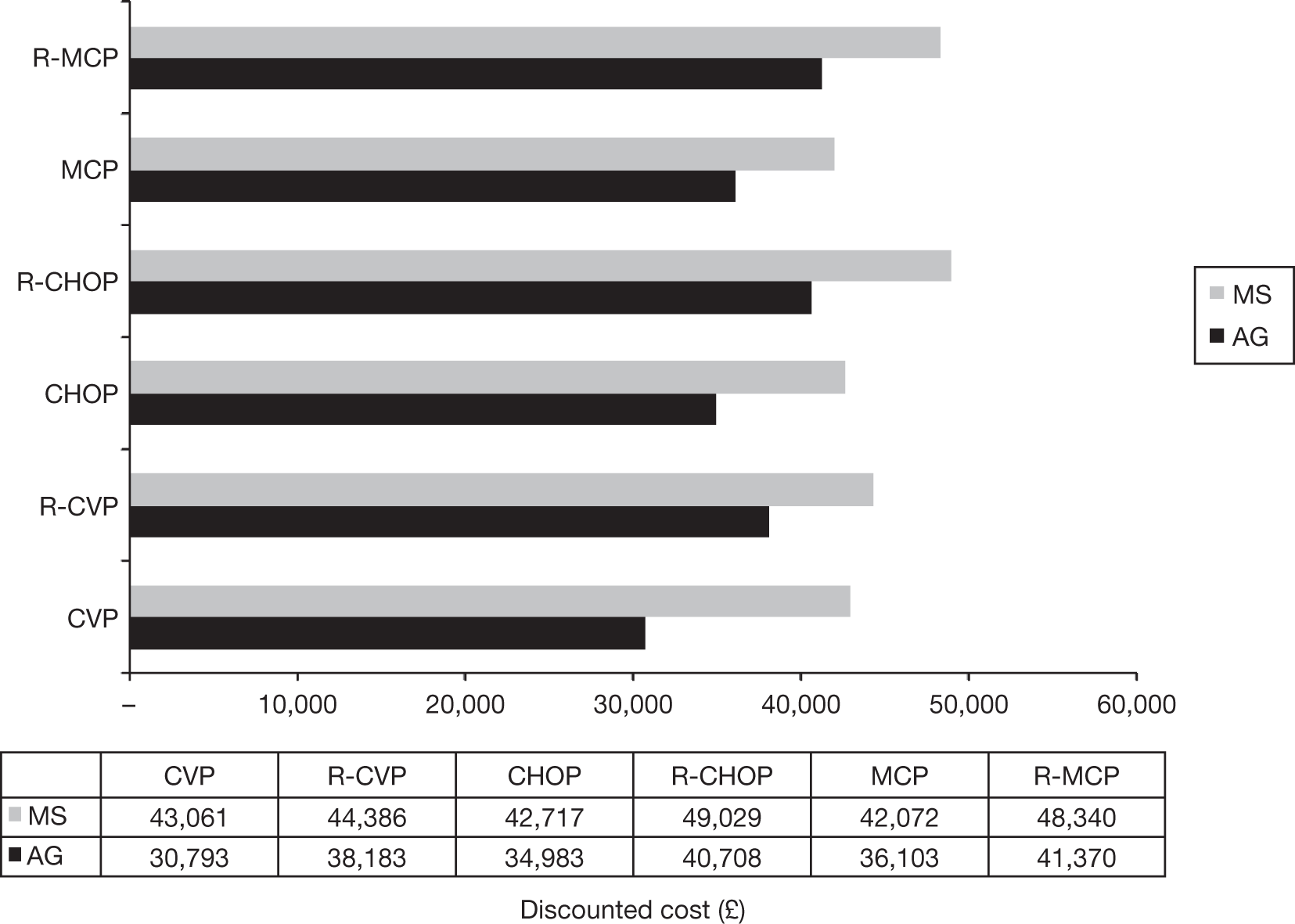

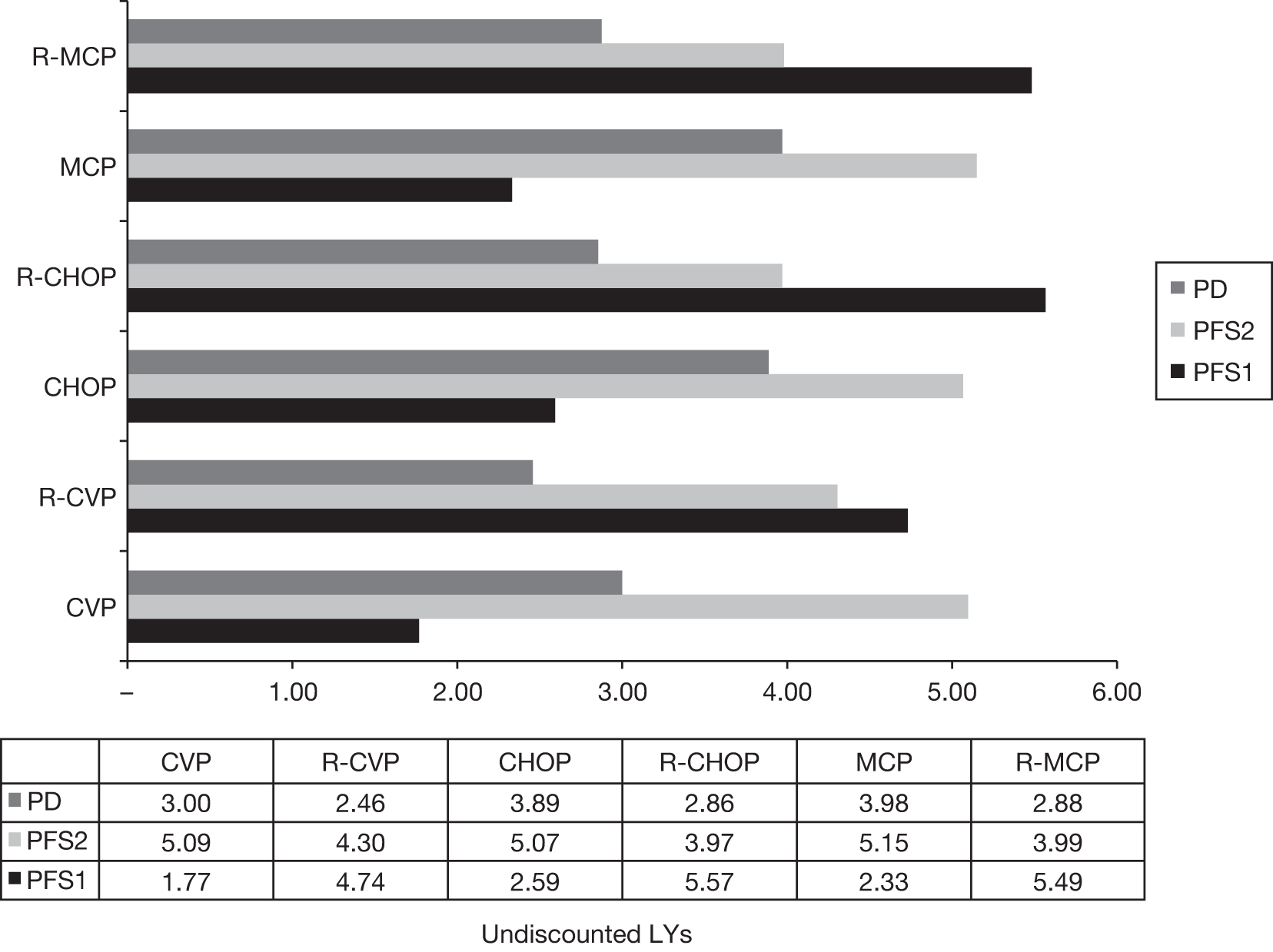

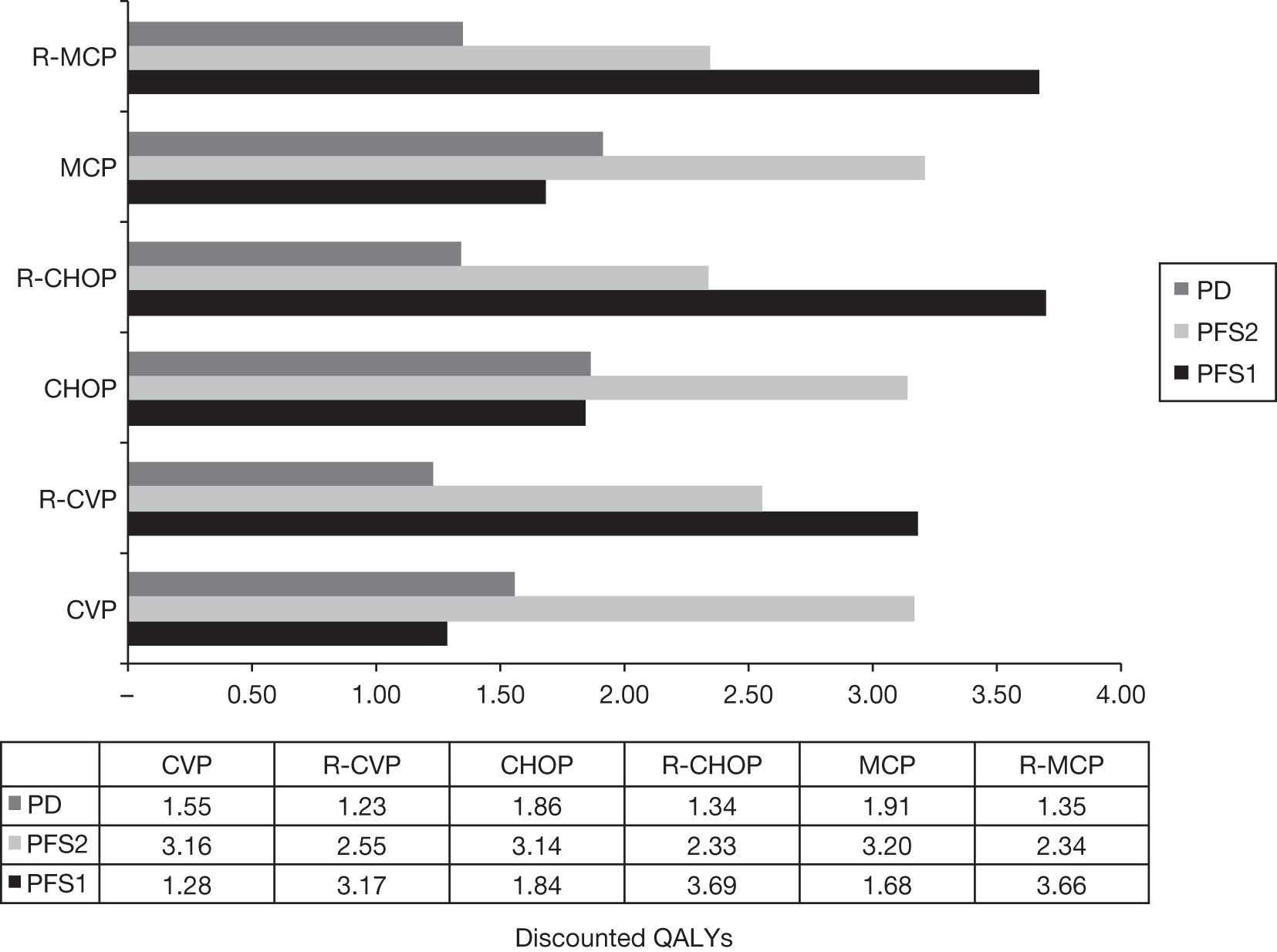

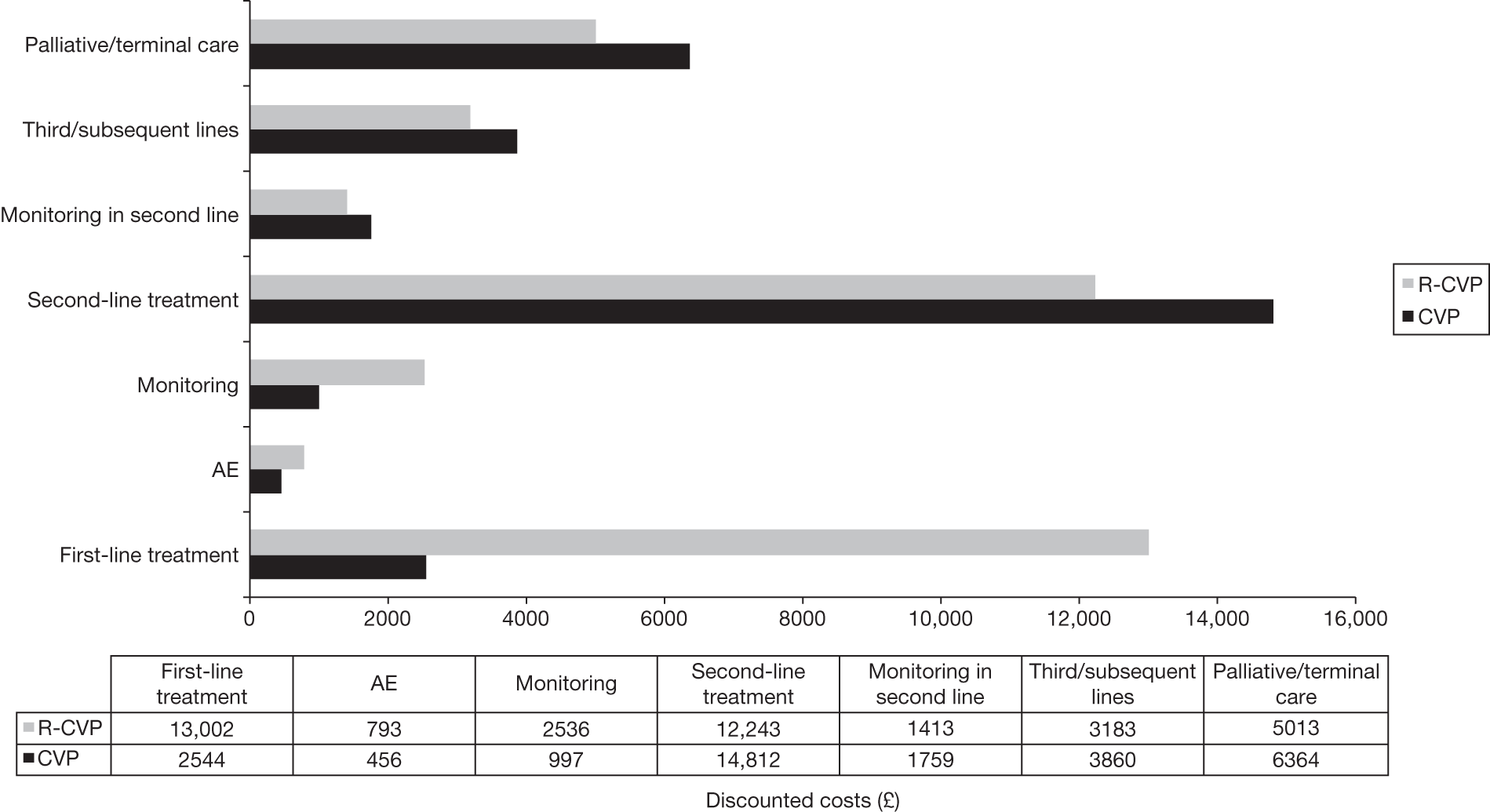

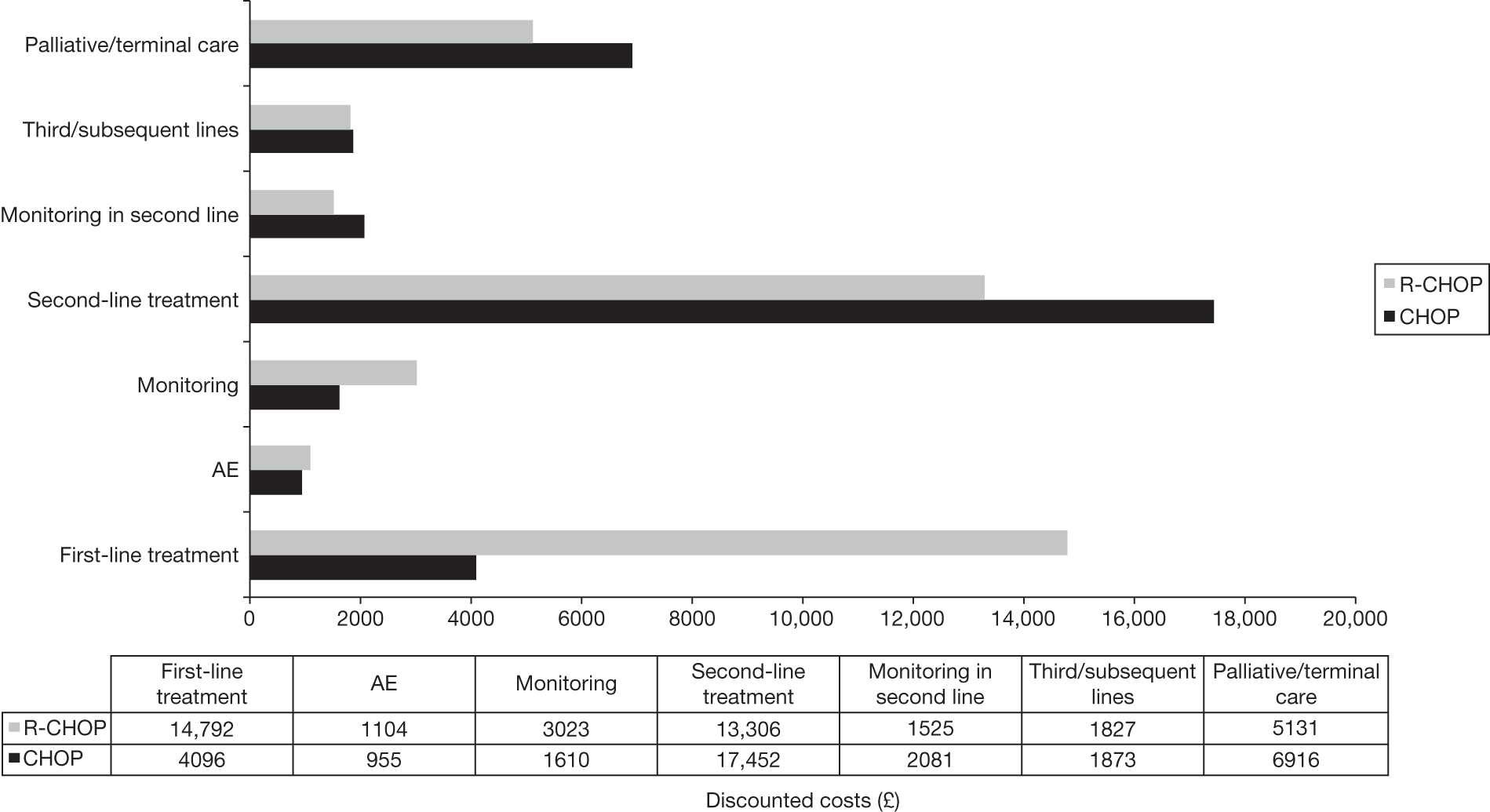

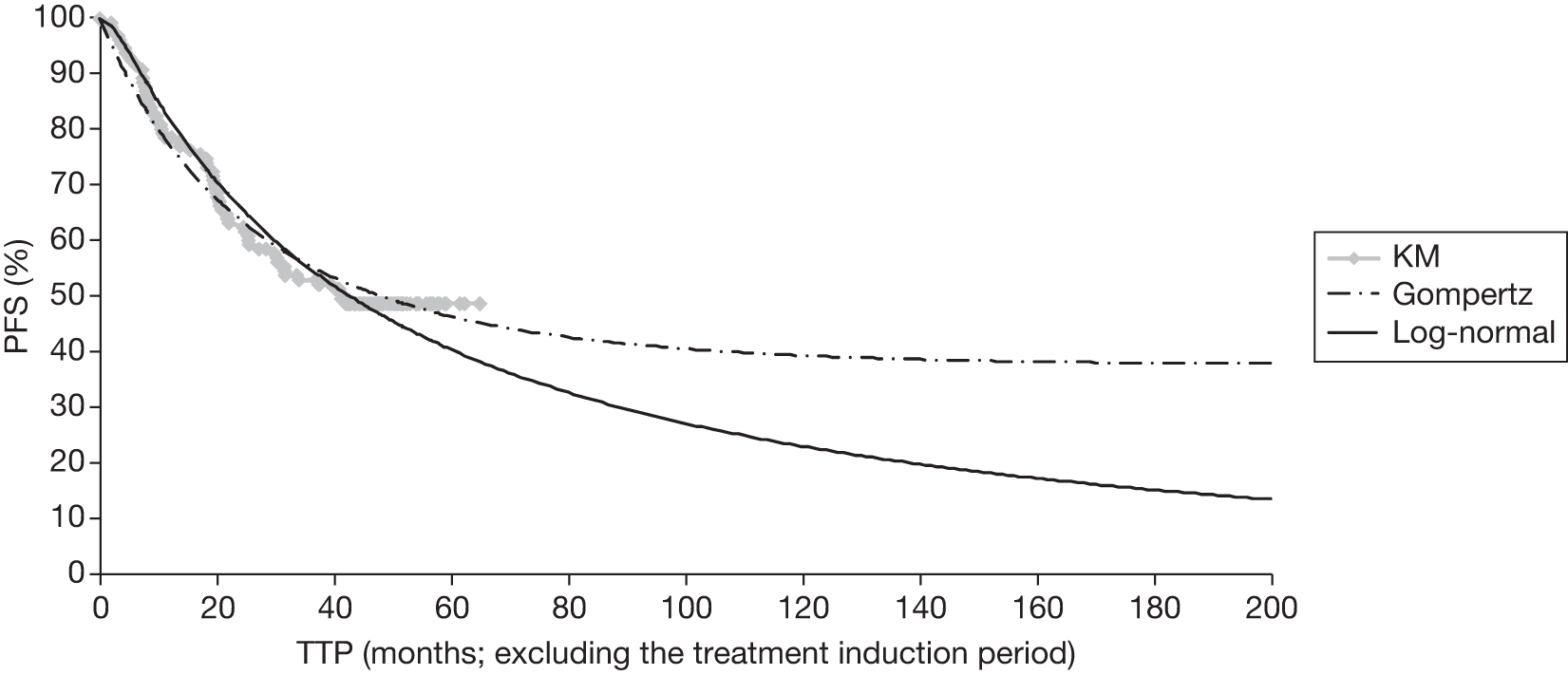

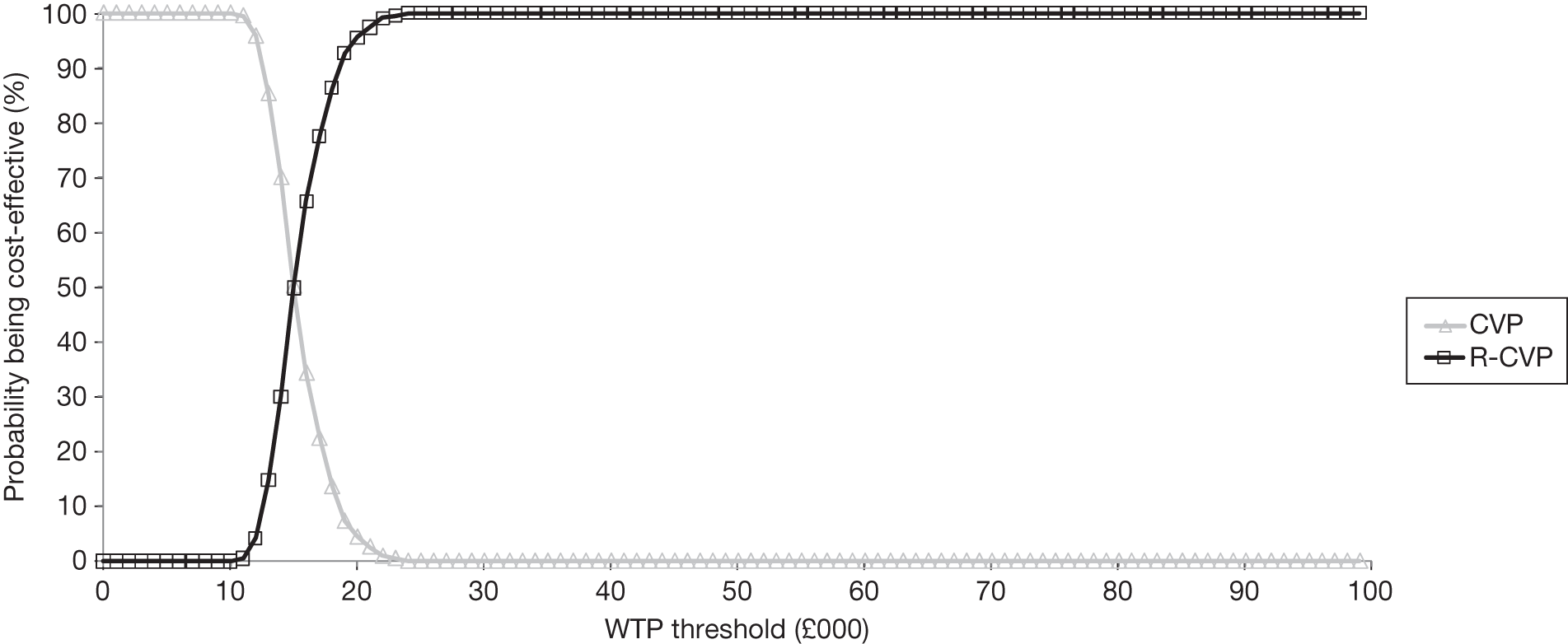

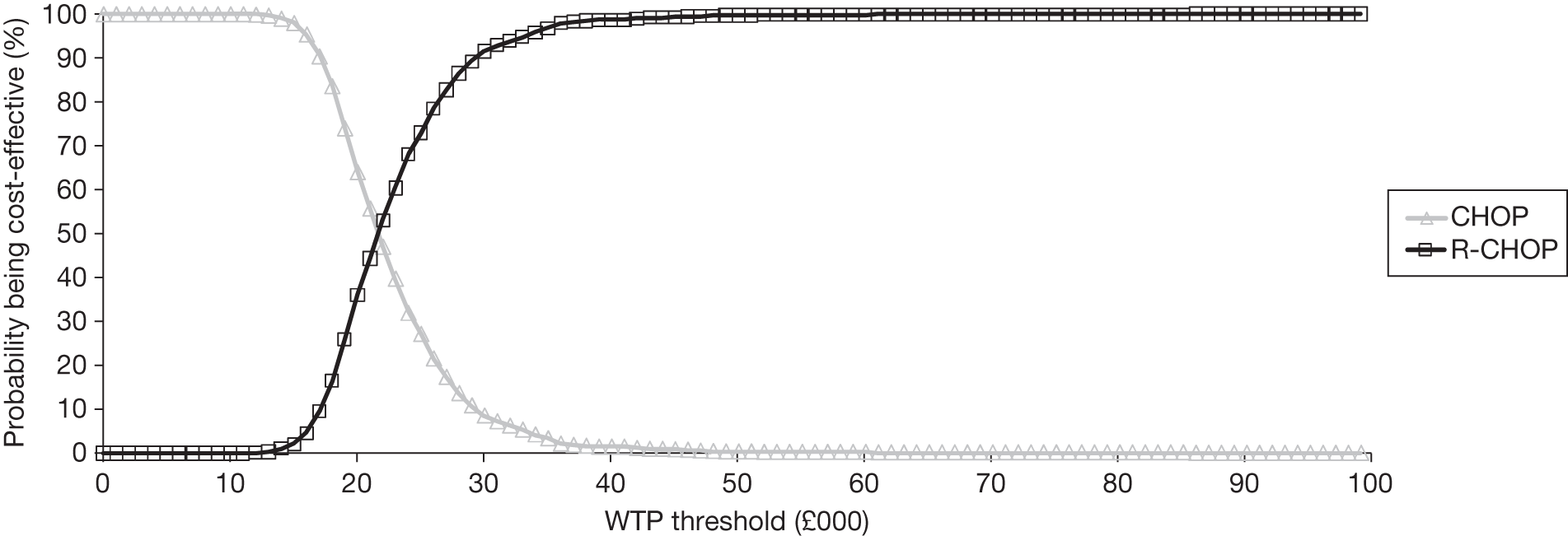

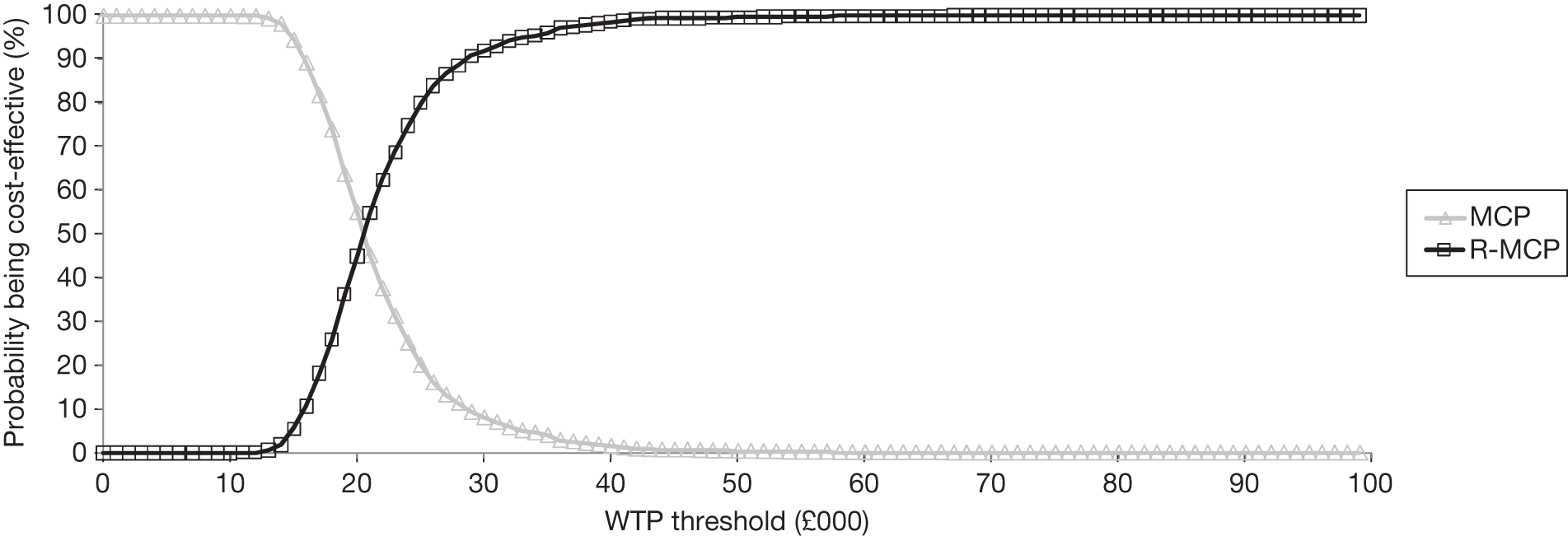

| FL200094 |