Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 09/14/02. The contractual start date was in March 2011. The draft report began editorial review in July 2011 and was accepted for publication in February 2012. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design.The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2012. This work was produced by Ramsay et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to NETSCC. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2012 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Description of the underlying health problem

The decision about which treatment is best for a man diagnosed with cancer of the prostate, a sex gland located at the base of the bladder in the pelvis, presents an abundance of different but inter-related aspects that have been the focus of a number of previous Health Technology Assessments (HTAs) worldwide. 1–3 The present review was tasked with determining whether, for the UK NHS, complete removal of the prostate (radical prostatectomy) is best achieved using laparoscopic (keyhole) surgery or robotic surgery.

To understand the need for the review it is first necessary to consider changes in the characteristics of men diagnosed with prostate cancer over the last 30 years (see Evolution of prostate cancer diagnosis) and the resultant evolution of the technique of radical prostatectomy during that time period (see Development of radical prostatectomy). The technologies to be considered will then be described (see Description of the interventions) followed by an outline of the current demand for their use in the NHS (see Current use in the UK NHS).

Evolution of prostate cancer diagnosis

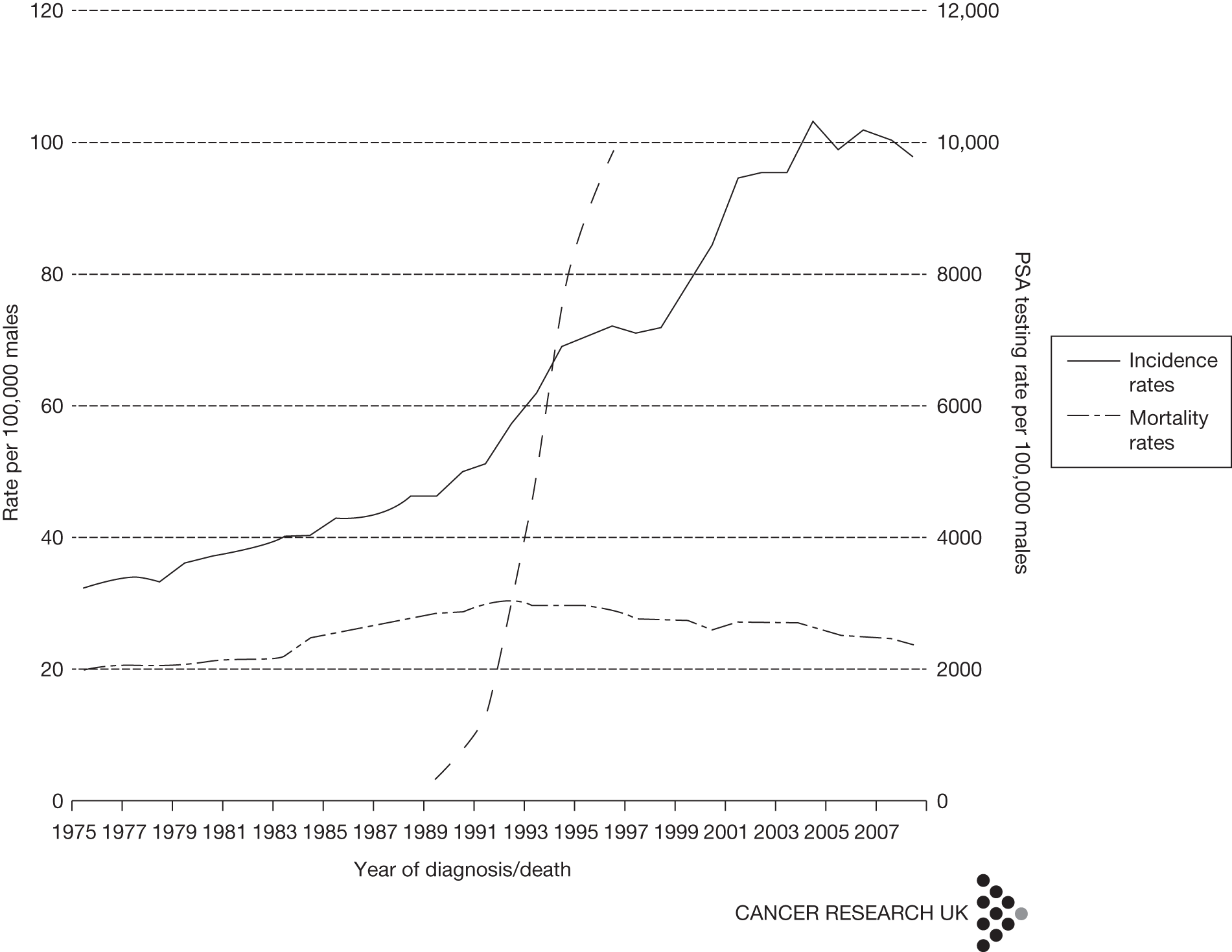

The discovery of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in 1979 as an organ-specific serum marker of prostate cancer, followed by its introduction as a commercially available laboratory test in 1986, transformed the way that prostate cancer was diagnosed and managed worldwide. 4 Before PSA testing, men were generally diagnosed with prostate cancer following an abnormal digital rectal examination, with worsening urinary symptoms or with symptoms of metastatic disease such as bone pain. This meant that approximately 70% had locally advanced or metastatic disease on presentation. 5 Although complete removal of the prostate (radical prostatectomy) was a treatment option for locally advanced disease, most men progressed to metastasis when only palliative treatment such as androgen ablation (castration) could be offered, resulting in 5-year survival rates of < 50%. 6 The advent of PSA testing allied to systematic biopsy of the prostate gland changed this situation dramatically. It was realised that men with a serum PSA raised above a threshold value, originally set at 4 ng/ml7 and more recently in the UK at age-specific values of between 3 and 5 ng/ml,8 were more likely to have prostate cancer, which, if present, was usually at a preclinical stage without symptoms and was not detectable on digital rectal examination. Autopsy studies had previously showed that small foci of prostate cancer were common in men older than 45 years and that this prevalence increased with age. It was therefore not surprising that widespread adoption of PSA testing resulted in a substantial increase in the number of men diagnosed with prostate cancer during the 1980s and 1990s9 (Figure 1). Areas of the world that adopted PSA testing have subsequently experienced falling mortality rates for prostate cancer, but whether this is due to more successful radical treatment or a mixture of length and lead-time bias remains uncertain. 11

FIGURE 1.

Change in rates of PSA testing and prostate cancer diagnosis in the UK. 10 Adapted with the permission of Cancer Research UK.

Development of radical prostatectomy

This sudden rise in incidence of localised prostate cancer inevitably led to an increased demand for curative treatments. The initial focus was on open radical prostatectomy, a surgical operation to completely remove the prostate together with its surrounding thin layers of connective tissue through a lower abdominal incision. 12 This procedure was historically associated with excessive blood loss, complete loss of erectile function and a high rate of urinary incontinence together with an appreciable mortality. 13 Rapid expansion of the number of predominantly asymptomatic men requiring treatment for PSA-detected cancer stimulated development of surgical techniques to reduce the morbidity and mortality of open radical prostatectomy while achieving long-term cancer cure. It was realised that routine use of specific manoeuvres to prevent blood loss together with precise identification and preservation of the nerves and blood vessels that supply the erectile tissue of the penis and urinary sphincter allowed the operation to be performed within an acceptable margin of safety without compromising cancer cure. 14,15 These techniques were further refined by many surgeon innovators, establishing the three main principles of radical prostatectomy termed the ‘trifecta’: to cure the cancer, to preserve continence and to preserve erectile function. Despite these developments, the outcome of open radical prostatectomy remains less than ideal, with 20% of men requiring a blood transfusion, 7% having long-term urinary incontinence and 40% suffering erectile dysfunction after surgery, although surgeons who perform larger numbers of cases tend to have better results. 16–18 The risk of these longer-term adverse effects is an important part of counselling for men having to face treatment choices for PSA-detected localised prostate cancer given that most will have normal urinary and sexual function before intervention. Surgeons and technology researchers have therefore continued to seek ways to reduce the functional disturbance of the procedure but maintain its disease-curing potential, leading to the development during the last decade of first laparoscopic prostatectomy,19 and subsequently robotic prostatectomy, to enhance the accuracy of surgical dissection and further reduce blood loss. 20 Although not the prime focus of this review, it must be noted that the technique of open prostatectomy also continues to evolve with the same aim of minimising harms. Large high-volume single-institution series, particularly from the USA, suggest that open prostatectomy remains an option for men considering surgery for localised prostate cancer. 21

Description of the interventions

Technical description

Laparoscopic prostatectomy

Experience in gall bladder and kidney surgery highlighted the advantages of a laparoscopic approach to intra-abdominal organ removal. Insufflation of the abdominal cavity and use of endoscopic lens and digital camera systems for image magnification greatly enhanced surgical view, aiding accurate dissection, and reduced bleeding. Technological development in instrument design and the use of differing energy sources for haemostasis added further potential benefits over open surgery. Appreciation of these advantages led to the first series of men undergoing laparoscopic radical prostatectomy being reported in 1997. 22

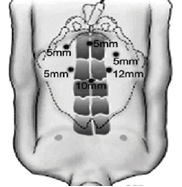

For standard laparoscopic radical prostatectomy the patient is anaesthetised and positioned supine on the operating table with legs abducted. Following skin cleansing and draping, the abdomen is punctured with a trocar at the umbilicus under vision using a Hassan technique and a pneumoperitoneum induced with CO2 gas, which is then maintained throughout the operation at a pressure of 10–12 mmHg. A telescopic camera is then inserted though the insufflation port (10 mm diameter) and a further three 5-mm ports and one 12-mm port are inserted in a specific configuration to allow ergonomic access to the pelvis without instrument clashes (Figure 2). The operating table is then adjusted with the patient in a 45° head-down position. The principal operating surgeon then proceeds with dissection of the prostate under televisual control using long narrow instruments such as a diathermy knife, scissors, graspers and needle holders passed through the ports while one or two assistant surgeons maintain the magnified view projected on two television screens by manipulating the telescopic camera and removing blood and fluid by suction. 23 Alternatively, the camera can be operated by a single active robotic manipulator arm that is controlled through voice commands from the operating surgeon. 24 Generally, blood loss is prevented by securing visible blood vessels with clips, diathermy and the use of other energy devices such as ultrasound. By considering preoperative findings and direct inspection of the prostate the surgeon will decide whether to preserve one or both neurovascular bundles attached to the posterolateral surface of the prostate that supply the urinary sphincter and penile erectile tissue. Once the prostate is dissected free it is placed in a retrieval bag within the abdomen and the continuity between the bladder and urethra restored by anastomosis using up to six interrupted sutures or by single continuous suture; a urinary catheter is then placed. One of the 12-mm ports is widened slightly to allow retrieval of the excised prostate, which is sent for pathological examination, haemostasis is then confirmed and the port sites closed with sutures. Anaesthesia is then reversed and the patient transferred to the recovery area for initial observation. The procedure typically takes 3.5–4 hours of operating theatre time. Increasing experience with the technique has demonstrated that it does result in reduced blood loss and earlier return to full activity compared with open prostatectomy, but any reduction in rates of erectile dysfunction and incontinence remains uncertain. 25,26

FIGURE 2.

Configuration of differently sized abdominal port sites through which instruments are introduced for laparoscopic prostatectomy. 23 Reproduced with permission from the International Brazilian Journal of Urology.

Robotic prostatectomy

A surgical robot can be defined as a powered device with artificial sensing that can be programmed or externally controlled by a surgeon to position and manipulate instruments to undertake surgical tasks. The key surgical benefits of robotic technology are to tirelessly make precise repetitive movements to move, locate and hold tools and to respond quickly to changes in commands. Robots are intended to assist rather than replace the surgeon, who retains control at all times. They can be broadly classified into three groups: passive, active and master–slave telemanipulators. 27,28 Early positive experience with passive devices, such as frames to accurately position instruments during brain surgery, and active devices programmed to respond to voice- or pedal-activated commands, such as extra ‘arms’ to position the endoscopic camera during standard laparoscopic surgery, led to the design of master–slave surgical manipulators. Here, the surgeon sits at a master console in the operating theatre separate from the patient and remotely controls arms that position and operate the camera and tools inserted into the patient through ports. The control mechanism can be through a joystick, pedals or, more appropriately for surgery, gloved handles that mimic the movements of the slave manipulator. The technology allows the scaling of motion whereby the relatively gross hand movements of the surgeon are translated to micromotions of the robotic arms. This is further enhanced by ‘wrists’ built into the instruments that allow six degrees of freedom of movement, which more closely approximates the range of movements possible by the human hand during open prostatectomy, rather than the more limited four degrees of freedom possible with standard laparoscopic instruments. An advanced camera lens system allows three-dimensional vision and 10–15 × magnification to be transmitted to the master console. Such master–slave telemanipulators were initially developed from previous US military designs by two commercial companies and used for coronary artery bypass surgery,29 but a subsequent commercial merger resulted in a single company, Intuitive Surgical Incorporated (Sunnyvale, CA, USA), which developed the da Vinci® system for wider clinical use. 30

The advantages of the multi-armed robotic telemanipulator system in terms of improved dexterity of operation of laparoscopic instruments by increasing articulation and scaling together with the three-dimensional magnified image all set in an ergonomic platform encouraged a number of centres, particularly in the USA, to apply this system to radical prostatectomy. It was also thought that the greater scope for telemedicine mentoring and the ability of the robot to scale surgeon movements and hence reduce unwanted movements such as tremor would widen the group of surgeons who could achieve competency at keyhole prostatectomy. 31,32

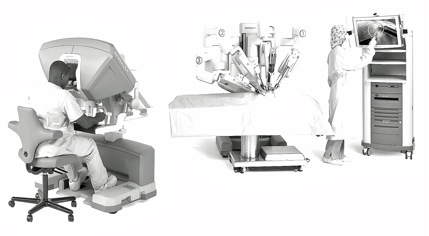

The initial preparation for robotic prostatectomy is identical to that for the standard laparoscopic procedure. The operating theatre is required to be of a minimum size to accommodate the extra equipment, although this is now standard for newer hospital facilities, including those within the UK NHS. Once the ports (generally six) are placed and the patient tilted in a 45° head-down position, the robot is then ‘docked’ to the patient, which generally takes 15–20 minutes. The docking requires the attachment of one robotic ‘slave’ arm to the telescopic camera while the other two (for the three-arm model) or three (for the four-arm model) are attached to the operating instruments that will be manipulated remotely by the lead surgeon. The arms are housed on a cart that is positioned adjacent to the patient. The assistant surgeon generally operates the suction device or retracting instruments through the remaining ports. The operating surgeon sits at a teleconsole within the operating theatre linked to the robot by cable, although more remote wireless locations are possible (Figure 3). 33 The console comprises a three-dimensional display monitor for the camera-fed operative view, ‘master’ arms linked to the ‘slave’ arms, which allow the surgeon to direct and operate the instruments, camera-positioning controls, foot pedals controlling diathermy for haemostasis and finally a central processing unit to regulate the system. Additional controls can adjust the display, the offset angle of the telescopic camera lens and the ratio of the scaling of surgeon’s movements to instrument movements. The procedure typically takes 3.5–4.5 hours of operating theatre time. Robotic prostatectomy also results in reduced blood loss and quicker return to full activity but again the hoped-for reduction in rates of incontinence and erectile dysfunction as a result of improved vision remains uncertain. 34 A deficiency of the robotic technique is the lack of transmission of the feel of the tissues from the remote instruments; reproduction of this haptic sense is a key aim of future development.

FIGURE 3.

da Vinci surgical robot system showing, from left to right, surgeon at remote console; three-armed (labelled 1–3) telemanipulator for docking to patient; and assistant adjusting room monitor. ©[2011] Intuitive Surgical, Inc. Reproduced with permission from ©2010 Intuitive Surgical, Inc.

It should be noted that the robotic technology within the da Vinci system continues to evolve and advancements tend to be added by Intuitive Surgical as options to the basic platform at extra cost. Currently, purchasers of the system can choose to have a fourth robotic arm, reducing the number of surgical assistants required, more advanced image transmission and an additional console to allow mentoring of surgeons under training (similar to dual controls for a motor car).

Current use in the UK NHS

Requirement for radical treatment of prostate cancer in the UK NHS

In the UK prostate cancer is generally detected by PSA testing of men complaining of lower urinary tract symptoms, although the numbers of asymptomatic men requesting a PSA test to assess their risk of having or developing prostate cancer is increasing, particularly among more affluent socioeconomic groups in the south of England. 35 For men with a serum PSA above a diagnostic threshold currently set in the UK at 3 ng/ml for men in their 50s, 4 ng/ml for those in their 60s and 5 ng/ml for those in their 70s, prostate biopsy is recommended. 8,36 Biopsy involves obtaining 10–12 cores of prostate tissue measuring 10 × 2 mm by transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)-guided needle biopsy as an outpatient procedure under local anaesthetic. This procedure is uncomfortable and is often associated with mild adverse effects such as bleeding and urinary tract infection (30–80%); more severe adverse effects such as systemic sepsis are uncommon (< 1%). 37

At present, approximately 25% of men with PSA levels above threshold will have cancer detected on biopsy,38 with 37,051 men being registered with the diagnosis in the UK during 2008. 11 Following diagnosis a treatment decision has to be made, which will involve consideration of the PSA level, the clinical stage of the cancer categorised on the tumour, node, metastasis (TNM) staging system,39 the aggressiveness of the cancer classified by grading the degree of disruption of the normal glandular architecture of the prostate seen on microscopic examination using the Gleason score40 and person factors such as life expectancy and treatment preference. 12,41,42 For men with apparent localised disease confined to the prostate gland (preoperative clinical classification of tumour stage cT1 and cT2, N0, M0), radical treatment by either surgery or radiation is an option, together with active surveillance programmes, with deferred treatment for men with a Gleason score ≤ 6. 43 Current evidence suggests that any benefit to the individual receiving radical treatment for prostate cancer takes at least 10 years to accrue and therefore these options are best used for men whose comorbidity and age suggests a life expectancy of > 10 years. 44 Finally, evidence is increasing that more aggressive cancers, categorised by a Gleason score of ≥ 8 out of 10 and a PSA of > 20 ng/ml, are likely to already have developed metastases and therefore such patients are considerably less likely to benefit from radical treatment alone. 45 The typical man who undergoes radical prostatectomy therefore is generally fit [American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade 0–2] and aged < 70 years and has tumour characteristics suggesting low or intermediate risk of disease progression according to the D’Amico risk classification system (Table 1). 46

| Group | PSA (ng/ml) | Gleason score (0–10)a | Clinical stagea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk | < 10 | and | ≤ 6 | and | cT1–cT2a |

| Intermediate risk | 10–20 | or | 7 | or | cT2b–cT2c |

| High risk | > 20 | or | 8–10 | or | cT3–cT4 |

Estimated demand for radical prostatectomy

Assuming that 45% of men diagnosed with prostate cancer in the UK are aged < 70 years11 and that the disease is localised to the prostate in 86% of cases,47 approximately 14,000 men would have the option of radical treatment each year. Health episode statistics recorded for NHS England48 show that approximately 4000 (28% of the estimated total) men underwent radical prostatectomy in the year 2009–10, this being a similar proportion to that seen for men diagnosed with cancer in the control arm of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer [946/3402 (28%)]. 49 [It is noted that there is a discrepancy between differing NHS datasets in the numbers of men coded as having a radical prostatectomy in NHS England in the financial year 2009–10: 4100 using the Office of Population Census and Surveys (OPCS) four-character procedure codes compared with 4703 using Healthcare Resource Group (HRG) codes.] The remaining men chose alterative treatment options such as implantation of radioactive seeds (brachytherapy, 15%), external beam radiotherapy (40%) or decided on an active surveillance protocol (17%). Demographic trends in terms of the increasing number of men at risk together with an anticipated continued rise in the use of PSA testing in the UK suggest that the demand for prostatectomy and other options to treat localised prostate cancer will increase over the next 10 years. Using the hypothetical scenario of increased ‘on demand’ use of PSA testing up to the rate currently practised in the USA would give an estimated figure of 7000 men per year,50 and this would rise further to an estimated 11,000 men per year with the hypothetical scenario of a national programme of PSA screening. 49,50

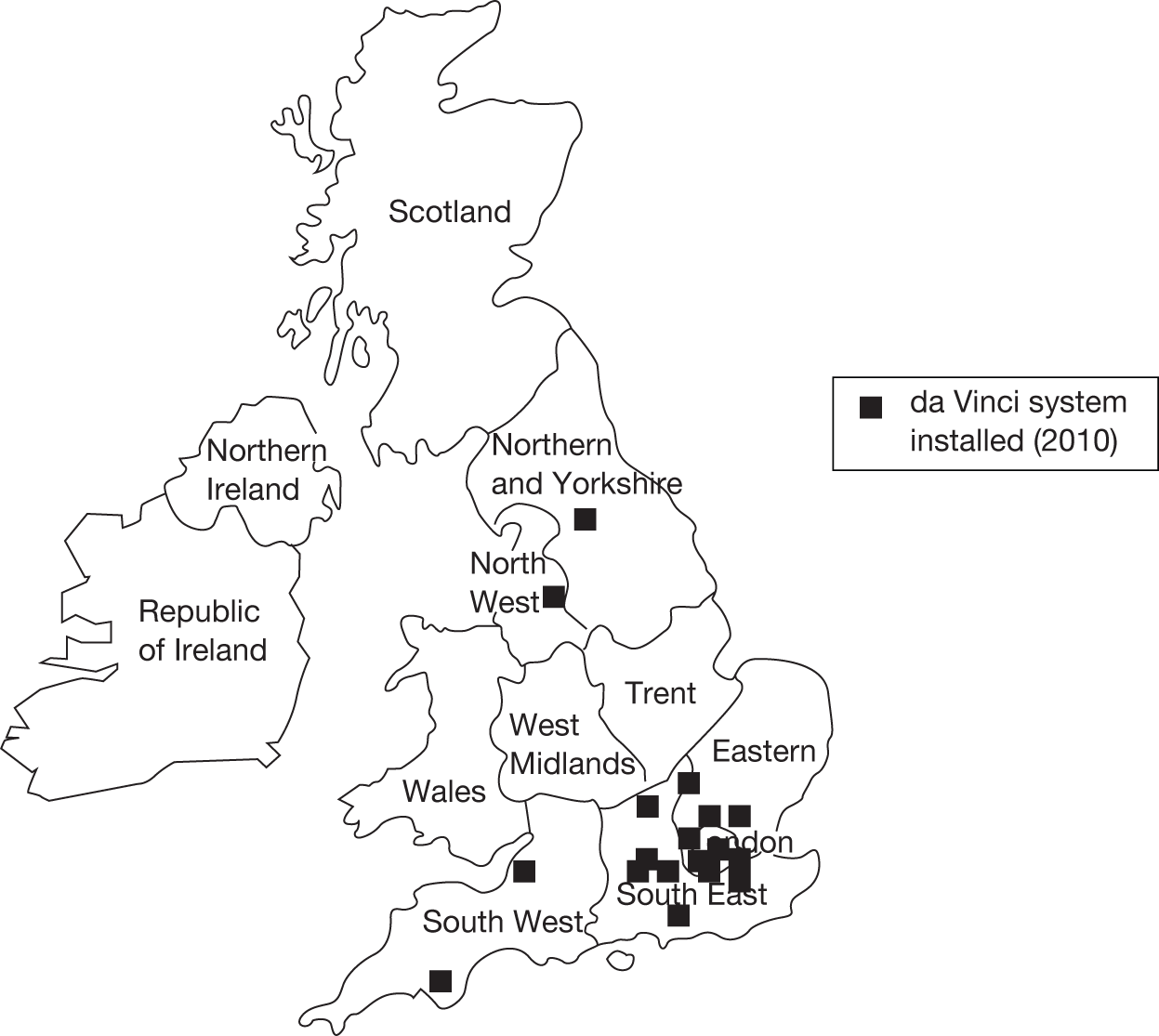

Current use of technologies in UK NHS

Under the NHS Cancer Plan pelvic cancer surgery, including radical prostatectomy, is concentrated within 60 UK cancer centres, of which approximately 20 perform at least some procedures laparoscopically [personal communication from expert panel members (D Neal, C Eden, R Kodelburg, N Soomro, A McNeil), 2010]. In 2010, 16 had access to a da Vinci robotic system, although most robotic systems in the UK were installed in 2009–10 and were not yet fully operational at the time of carrying out this review (Figure 4). 30,51 NHS England reference cost data recorded 1816 laparoscopic/robotic procedures in the year 2009–10, suggesting that these options were used for 46% of all radical prostatectomies. 52 Our own survey of cancer units known to be carrying out laparoscopic and robotic radical prostatectomies suggests a current 50 : 50 split between laparoscopic and robotic techniques, meaning that approximately 23% of radical prostatectomies carried out in the UK at present are performed using the robotic technique. Other areas of the world have experienced a greater uptake of robotic prostatectomy, for example in the USA it was estimated that 43% of all radical prostatectomies were performed using the robotic technique in the year 2006–7 and approximately 70% in 2008. 17,53,54

FIGURE 4.

UK sites with an installed da Vinci robotic surgical system in 2010.

Current costs for the UK NHS

NHS reference costs for England for the financial year 2009–10 published by the UK government’s Department of Health show an average tariff for open radical prostatectomy (HRG code LB21Z) of £4614 with 2897 procedures claimed by NHS hospitals giving a total annual cost of £1,336,758. For laparoscopic and robotic prostatectomy (HRG code LB22Z), the average tariff was £5257, with 1816 procedures claimed, giving a total annual cost of £9,546,712. (It is noted that there is a discrepancy between differing NHS datasets in the numbers of men coded as having a radical prostatectomy in NHS England in the financial year 2009–10: 4100 using OPCS four-character procedure codes compared with 4703 using HRG codes.) These data suggest a grand total tariff-based cost to the English NHS of £10,883,470 for the year 2009–10. Both an increase in the number of radical prostatectomies required and an increase in the proportion of procedures carried out using a laparoscopic or robotic technique would substantially increase the cost to the NHS. For example, a scenario of increased use of PSA testing leading to a demand for 7000 procedures per year that were all carried out laparoscopically or robotically would increase the tariff-based cost by 240% to £36,799,000.

Summary

Policy-makers within the UK NHS are therefore faced with the need to plan service provision for the increasing number of men diagnosed with localised prostate cancer who decide on radical prostatectomy as their preferred treatment option. A keyhole technique of radical prostatectomy either by standard laparoscopy or with the aid of robotic technology does appear to offer advantages in terms of reduced morbidity over the traditional open surgical approach. Advocates of the robotic system claim greater precision in dissection and more rapid gaining of surgeon competence for the procedure but this comes at a substantially greater equipment cost. This review has therefore been designed to help inform decisions regarding the commissioning and use of robotic surgery for men with localised prostate cancer in the NHS.

Aim of the review

This study aimed to determine the relative clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of robotic prostatectomy compared with laparoscopic prostatectomy in the treatment of localised prostate cancer within the UK NHS (the full study protocol is available at www.hta.ac.uk/2169). The specific objectives of the study were to:

-

describe clinical care pathways for laparoscopic and robotic prostatectomy in a UK context

-

determine the relative clinical effectiveness and safety of each procedure

-

determine the influence of the learning curve on estimates of effectiveness and safety

-

perform a systematic review of existing economic evaluations of each procedure

-

determine which procedure is most likely to be cost-effective for implementation in the NHS

-

identify future research needs.

Chapter 2 Description of the care pathway

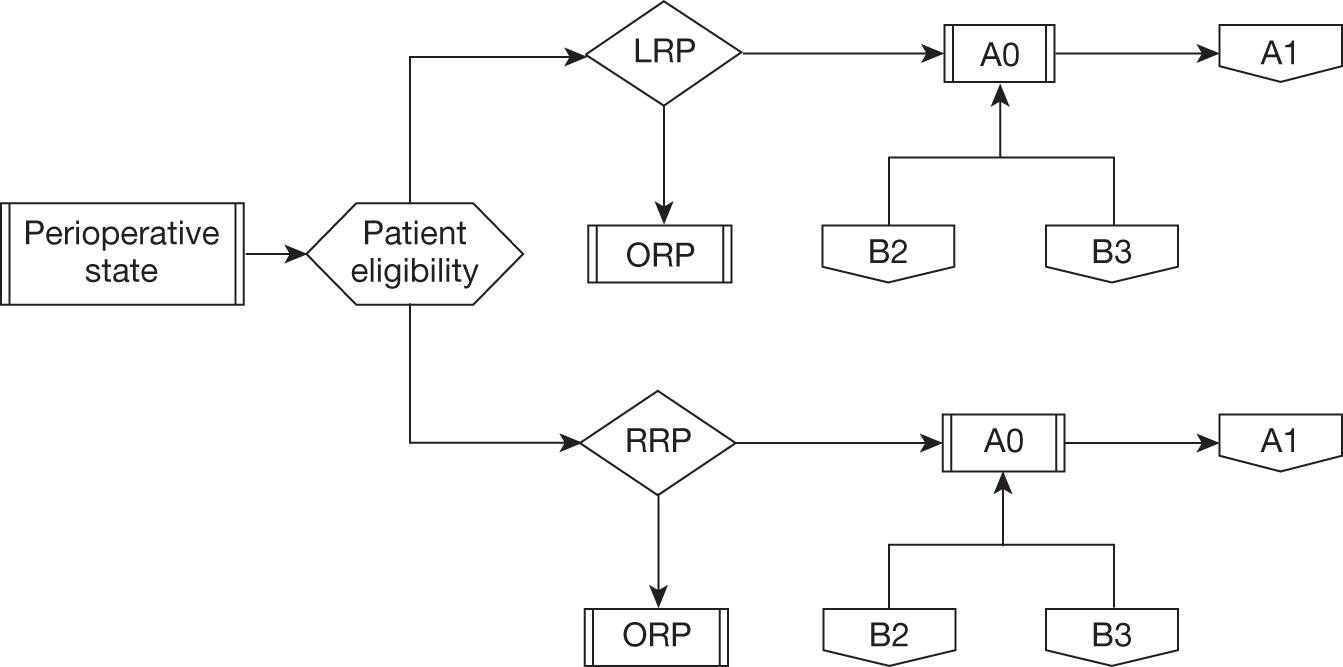

Introduction

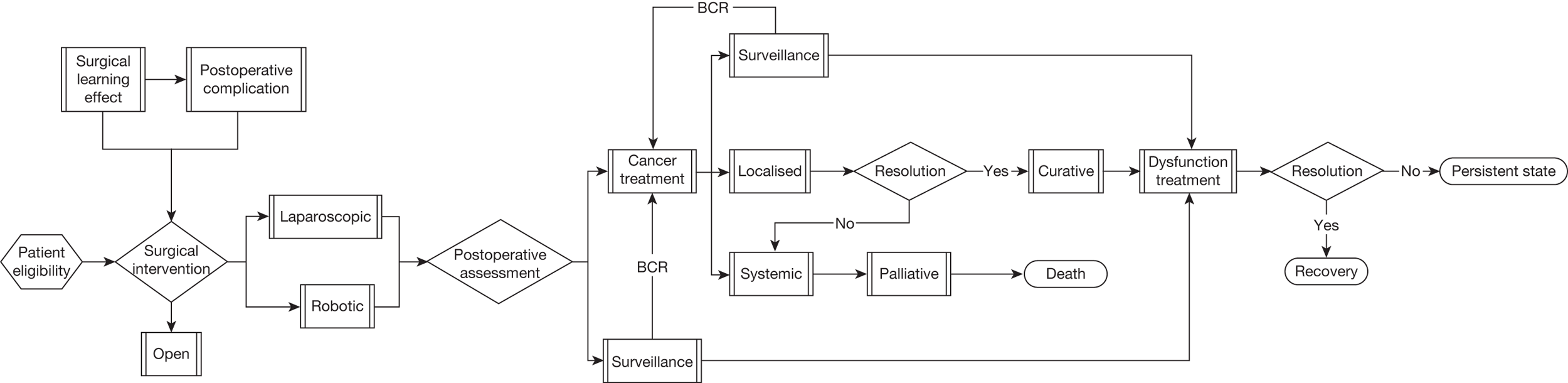

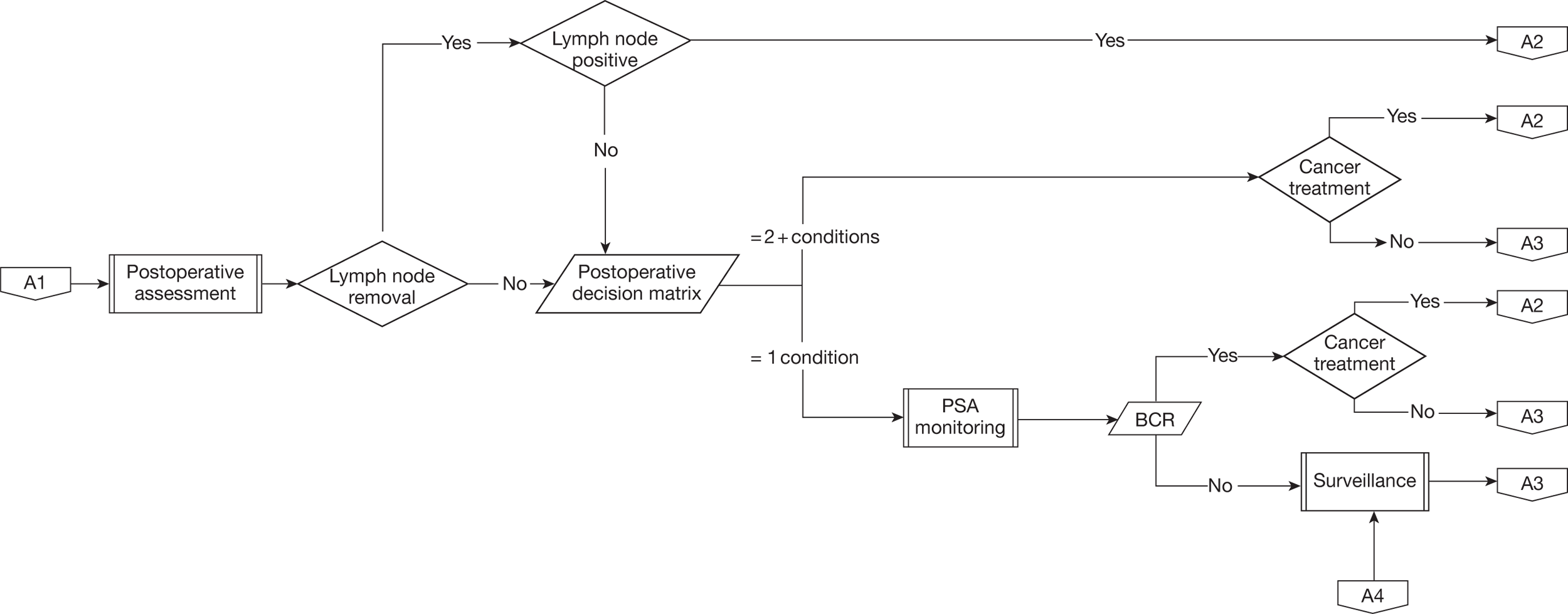

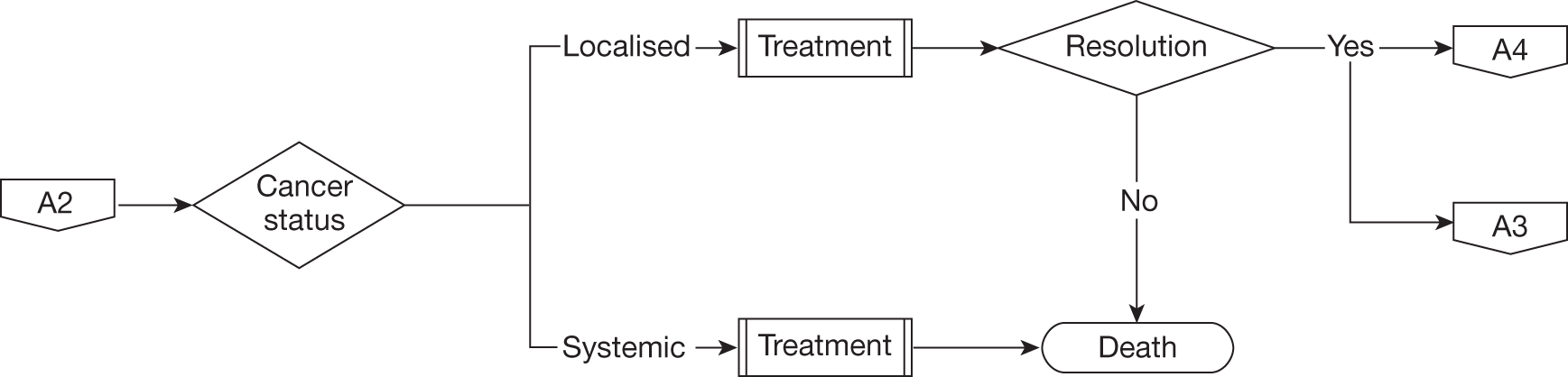

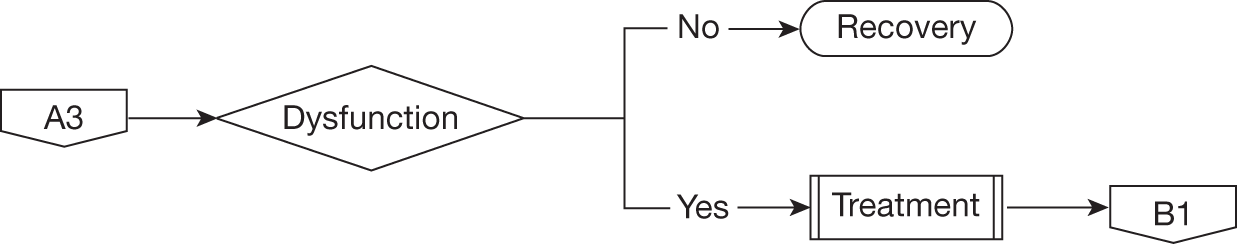

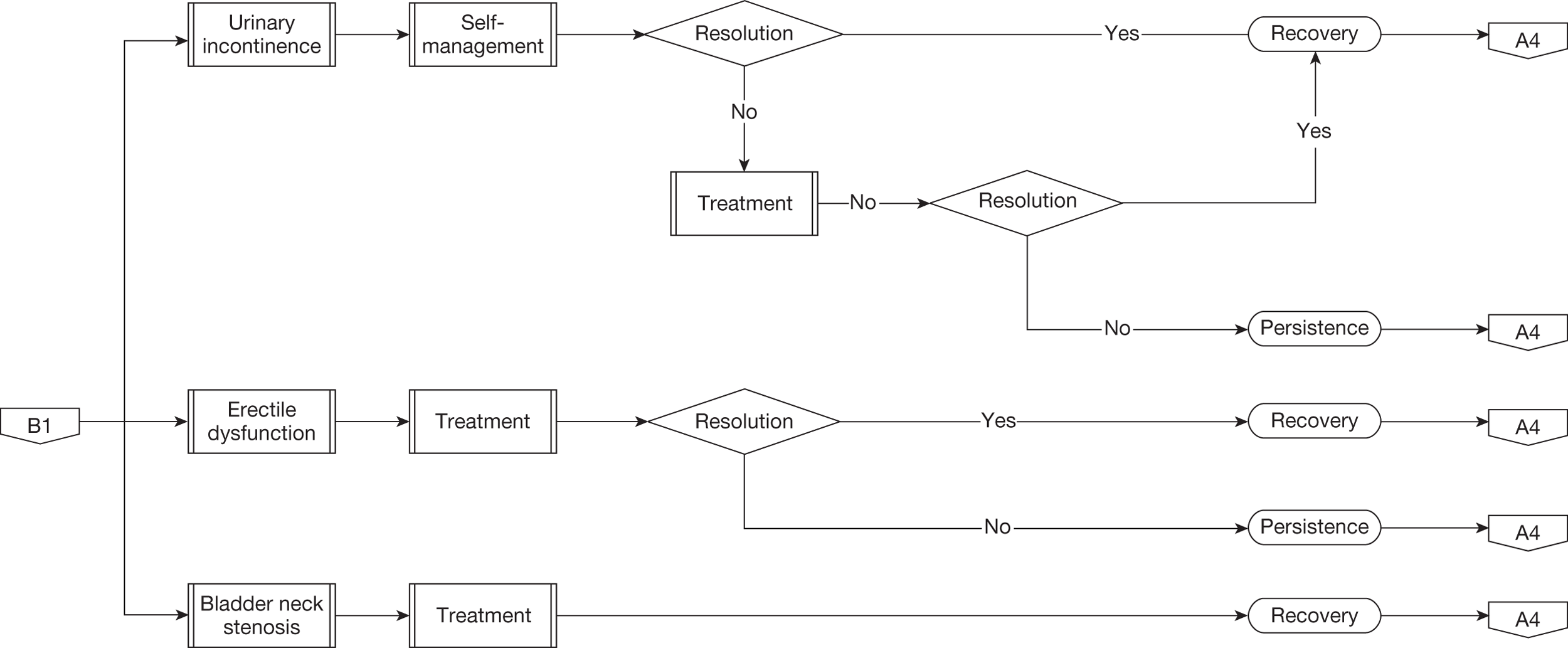

The described care pathway (Figure 5) was constructed using available evidence and consensus building through two meetings of the expert panel convened for this review. Although it is primarily constructed to plan the systematic assembly of evidence and design the mathematical model that will estimate effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, the pathway is consistent with previously published clinical pathways of care. 43,45,51,55,56 This chapter will describe each component of the pathway.

FIGURE 5.

Summary flow chart showing complete care pathway used to frame the systematic review questions and the health economic model. BCR, biochemical (PSA) recurrence.

Preoperative characteristics of men undergoing radical prostatectomy

Patient characteristics

The population of patients considered for this review are men with localised prostate cancer undergoing radical prostatectomy at designated pelvic cancer surgical treatment centres within the UK NHS. The patient variables that define this population include age and comorbidity that together determine an estimated life expectancy of at least 10 years. The great majority of such men are able to undergo radical prostatectomy by either standard laparoscopic or robotic techniques; the few exceptions suited only to the open approach are those with poor respiratory reserve, morbid obesity or previous extensive pelvic surgery.

Disease factors are focused on the estimated risk of developing recurrent disease from metastases not identified at preoperative assessment or because of failure to completely remove localised disease. The approximate magnitude of this risk for an individual man diagnosed with prostate cancer can be calculated using a nomogram developed from linear regression models, the most commonly used version being hosted by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Institute in web-based form. 57 These models use the preoperative disease factors of age, PSA, clinical tumour stage, Gleason grade and number of needle biopsy cores positive for cancer.

Preoperative level of prostate-specific antigen

The preoperative serum PSA level is an independent statistically significant predictor of future recurrence but on its own is limited in reliability and predictive value. For prognostic purposes the value is defined in groupings corresponding to low (< 10 ng/ml), intermediate (10–20 ng/ml) and high (> 20 ng/ml) risk of disease progression.

Staging of prostate cancer

The stage of an individual’s cancer is categorised according to the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) 2009 classification (Table 2). 39 Preoperatively this is determined by clinical assessment using digital rectal examination and imaging with the allocated tumour stage (T) given the prefix ‘c’, for example cT1. Following prostatectomy, pathological examination of the prostate and, in some cases, adjacent lymph nodes may result in a change in the staging as more accurate information concerning the size of the tumour and whether it has breached the external surface of the prostate will be available. To indicate this more accurate evaluation, the T stage assigned following pathological examination of the whole prostate is given the prefix ‘p’, for example pT2a. Rarely, no tumour will be found on pathological examination of the prostate following radical prostatectomy for biopsy-proven cancer; this is designated pT0.

| Stage | Substage | Description |

|---|---|---|

| T0 | No evidence of cancer found on complete pathological examination of the prostate | |

| T1 | Clinically unapparent tumour, not detected by digital rectal examination nor visible by imaging | |

| T1a | Incidental histological finding; ≤ 5% of tissue resected during TURP | |

| T1b | Incidental histological finding; > 5% of tissue resected during TURP | |

| T1c | Tumour identified by needle biopsy | |

| T2 | Confined within the prostate | |

| T2a | Tumour involves half of the lobe or less | |

| T2b | Tumour involves more than half of one lobe but not both lobes | |

| T2c | Tumour involves both lobes | |

| T3 | Tumour extends through the prostate capsule but has not spread to other organs | |

| T3a | Extracapsular extension (unilateral or bilateral) including bladder necka | |

| T3b | Tumour invades seminal vesicle(s) | |

| T4 | Tumour is fixed or invades adjacent structures other than seminal vesicles | |

| T4a | Tumour invades external sphincter and/or rectum | |

| T4b | Tumour invades levator muscles and/or is fixed to pelvic wall |

Gleason grading

The qualitative low-magnification microscopic histological description of prostate cancer first suggested by Gleason58 remains an essential aspect of prognostic categorisation although there have been substantial modifications over the subsequent years. 40 The classification grades individual areas of prostate cancer according to the degree of disruption of normal glandular architecture, with grade 1 indicating minimal disruption, grade 5 complete loss of normal glandular arrangement and grades 2, 3 and 4 intermediate between these two extremes. Standard practice consists of identifying the first and second most prevalent patterns within a set of biopsy cores, which give the primary and secondary Gleason grades (each rated 1–5). These are then added together to give the overall Gleason sum score (2–10). Recent consensus tends to limit the use of grades 1 and 2 and therefore scores generally range between 6 and 10. 59 Any tertiary higher disease areas are also reported irrespective of their extent. Higher individual grade and total sum score indicate more aggressive disease with the primary grade being more predictive. For example, an individual whose tumour is categorised as Gleason score 4 + 3 = 7 will tend to have a worse prognosis than an individual with a Gleason score of 3 + 4 = 7. 60 Recent consensus mandates that pathological reporting of prostate cancer using the Gleason grading system should include the most prevalent pattern (primary grade), the second most prevalent pattern (secondary grade) and the presence of any areas that are assigned a higher grade than that assigned to either the primary or secondary patterns (tertiary grade). For needle biopsies the Gleason score is obtained by summing the higher of the secondary or tertiary grades. For radical prostatectomy specimens the Gleason score is obtained by summing the primary and secondary grades, any higher-grade tertiary pattern being stated separately if it occupies < 5% of the tumour.

Cancer extent

There is some evidence that the tumour extent on needle core biopsy estimated by measuring the number of cores positive for cancer, the percentage of needle core tissue affected by cancer and the length in millimetres of the core segments with cancer present is also an independent prognostic factor predictive of future disease progression. 61 Similarly, the total volume of cancer identified by pathological examination of the whole prostate after radical prostatectomy has been assessed as a possible predictive factor for recurrence but was found not to be independently significant on multivariate analysis. 62 These pathological measures of cancer extent have not been included in our care pathway given the current uncertainty of the evidence base.

Summary

Variables collected preoperatively for men undergoing radical prostatectomy including age, tumour stage, Gleason score and tumour volume can predict the risk of disease progression at some time after surgery, with stage and Gleason sum score being most useful. It is therefore important that studies comparing treatments, such as this review, include an assessment of whether or not the patient groups undergoing each procedure are balanced for these variables.

Perioperative care

Introduction

For the purposes of this review it is assumed that the procedures being considered will be carried out in hospitals that have the necessary resources in terms of staff, facilities and NHS cancer plan approval to carry out either laparoscopic prostatectomy or robotic prostatectomy on a routine basis. This will comprise operating theatre and recovery facilities including critical care and standard urology wards, the required clinical and technical expertise including surgeons, anaesthetists, theatre nursing team, pathologists and technicians, and continued care including outpatient review, repeat imaging and facilities for further treatment for adverse events or cancer progression. The procedures have been described in Chapter 1. 30,63 For the safe conduct of both procedures it is important that all members of the operating theatre team have had specific training in the performance of the procedures, this being particularly crucial from a technical point of view for the robotic procedure.

Surgeon learning curve

Both laparoscopic and robotic prostatectomy are currently being implemented in the UK NHS, requiring the training of surgeons to perform the procedures. The performance of repeated tasks tends to improve with experience and this improvement is characteristically rapid at first and then slower as a steady state expert level is reached, leading to the use of the term ‘learning curve’ to describe the process. Learning of surgical procedures can be additionally influenced by the previous experience of the surgeon or surgical team, case-mix selection, use of multiple outcomes defining ‘success’ and continued development of the technology. 64 The learning curve effect is often crudely quantified by the number of procedures required to reach competence or the reducing time taken to perform the procedure; in open prostatectomy, for example, experience-related changes in performance may continue even after 250 procedures. 18 As use of laparoscopic prostatectomy increased it was realised that the procedure was difficult to master, requiring a high number of training procedures to achieve competence, and that the skills required did not translate directly from those used in open surgery. 65 This is a particular problem in countries such as the UK, where few centres undertake more than 50 cases per year, the suggested volume required for training and maintenance of competency. 66 Findings from individual case series suggest that robotic prostatectomy reduces the number of cases required for competence, enabling the surgeon to reach an expert level quicker, and that previous experience of laparoscopic prostatectomy is not essential. 67 In addition, it is possible that some surgeons who are unable to master the laparoscopic technique can take advantage of the greater movement control offered by the robotic system to become competent in robotic prostatectomy. Any evaluation of effectiveness and safety of the prostatectomy procedures must therefore balance the relative effects of the learning curves.

Pelvic lymphadenectomy

Men whose disease is characterised preoperatively as intermediate or high risk (see Table 1) may be advised to undergo pelvic lymphadenectomy as part of their laparoscopic or robotic radical prostatectomy in order to detect occult lymph node metastases. The lymphadenectomy is performed as the first part of the radical prostatectomy procedure using a standard dissection template and the package of lymph nodes is removed separately from the prostate for subsequent pathological examination. The prostatectomy would be aborted only if there was gross visible lymph node enlargement, which, given preoperative imaging, is a very rare circumstance. For the purposes of this evaluation we chose, in consultation with the expert panel, to assume that all men with intermediate- or high-risk disease undergoing laparoscopic or robotic prostatectomy would also have a pelvic lymphadenectomy. This is in line with current guidance but we do acknowledge the controversy in this area. 45

Hospital stay

Men are generally admitted to hospital either on the day of surgery or the evening before. A rectal enema is administered to clear the lower bowel. Just before surgery prophylactic antibiotics are given according to local policy and venous thrombosis/embolism prophylaxis also commenced. After surgery the patient is routinely nursed on a standard ward in the UK although specific comorbidities or intraoperative complications may require a period in a critical care area. In the UK, men are typically discharged home after 3 days with an indwelling catheter although this can be reduced by managed care programmes. They then return to the ward after a further 7–14 days according to local protocol as a day patient for urinary catheter removal and voiding check.

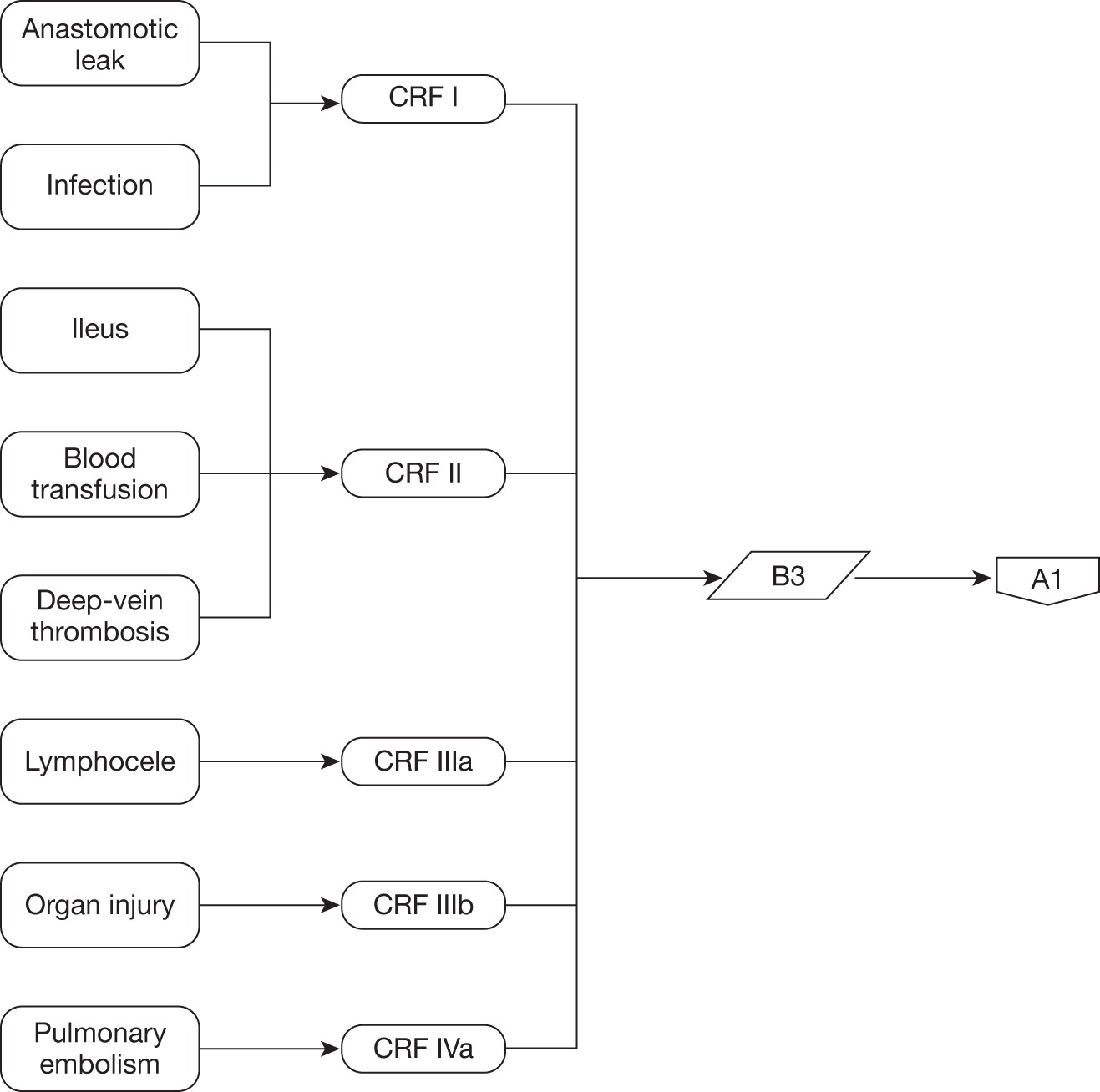

Perioperative adverse events

General

Although men undergoing this surgery generally do not have concurrent comorbidity that is a persistent threat to their health a proportion will be expected to suffer adverse events associated with major surgery and prolonged anaesthesia such as cardiac ischaemia, pulmonary embolism and prolonged loss of bowel function (ileus). In addition, specific complications include urinary and bloodstream infection, inadvertent injury to adjacent organs, particularly rectal perforation, excessive blood loss requiring transfusion and prolonged urinary or lymphatic leakage from abdominal drains. The adverse effect of these complications in terms of their severity and requirement for additional interventions and hospital stay can be summarised according to the Clavien–Dindo system (Table 3). 68,69

| Grade | Definition | Exclusions |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 0 | No deviation from planned postoperative course considering procedure and pre-existing comorbidity | |

| Grade I | Any deviation from the normal postoperative course without the need for specific pharmacological treatment or surgical, endoscopic and radiological interventions | |

| Grade II | Requiring pharmacological treatment with drugs other than those allowed for grade I complications. Includes blood transfusions and total parenteral nutrition | Treatments listed under grade I |

| Grade IIIa | Requiring surgical, endoscopic or radiological intervention not under general anaesthesia | |

| Grade IIIb | Requiring surgical, endoscopic or radiological intervention under general anaesthesia | |

| Grade IVa | Life-threatening complication affecting single organ system requiring IC/ICU management | TIA |

| Grade IVb | Life-threatening complication affecting more than one organ system requiring IC/ICU management | TIA |

| Grade V | Death of a patient |

Bladder neck contracture

An additional specific short-term complication is fibrosis and contracture of the sutured join between the top of the urethra and bladder outlet, the vesico-urethral anastomosis, termed bladder neck contracture or bladder neck stenosis. This will become noticeable after removal of the draining catheter with the narrowing of the urine channel, resulting in voiding problems reported by the patient over the next 3–6 weeks according to the severity of contracture. It is treated by endoscopic incision of the narrowed area, which requires an additional short hospital stay and a 7-day period of catheterisation. For most men the problem is cured by a single incision although for some this may need to be repeated once or twice. 70

Pathological examination of the prostate

Careful and thorough microscopic examination of the removed prostate by an experienced pathologist is required to determine the true extent of the disease and to identify whether or not the surgery may have been unable to remove all of the contained cancer (positive margin), whether or not the cancer has spread outside the prostate (extraprostatic extension) and, if lymphadenectomy has been performed, the presence of lymph node metastatic disease. In addition, a more comprehensive assessment of the Gleason patterns within the cancer is possible. 71 This examination will recategorise the disease according to stage and, if appropriate, lymph node status (pT and pN) and postoperative Gleason sum score, which will allow more accurate estimation of prognosis according to available post-radical prostatectomy prognostic nomograms57 and inform whether early additional (adjuvant) treatment should be advised. The crucial nature of this examination has led to regular international plenary meetings of expert pathologists who have made consensus recommendations guiding best practice for specimen collection, processing, examination and analysis in order to promote consistency in pathologist reporting of radical prostatectomy specimens. 59,72

Surveillance following radical prostatectomy

Follow-up schedule

Men who have undergone radical prostatectomy are generally seen by the operating team as outpatients 6 weeks after their surgery and then 3-monthly for the first year and 6-monthly for the next 4 years. At each follow-up consultation serum PSA is checked for evidence of tumour recurrence and a qualitative assessment made for continence and desired sexual function. If further assessment or treatment is required for any of these aspects then the pathway of care will be changed accordingly (see Figure 5).

Detection of persistent or recurrent disease

The risk of disease recurrence is higher if one or more of the following disease factors are present: preoperative PSA > 20 ng/ml, pathological Gleason score > 7, pathological extraprostatic disease (pT3/pT4), pathological positive margin or positive lymph nodes (pN1/pN2). If positive lymph nodes are found or the likelihood of disease persistence or recurrence is otherwise deemed to be very high then immediate adjunctive treatment may be offered. For the majority of men, however, PSA surveillance is started according to a standard schedule, for example that defined in the preceding paragraph. Following removal of the prostate, serum PSA (half-life 2.2 days) levels will rapidly fall to an undetectable level, defined as values less than the sensitivity of the assay. Generally, ultrasensitive PSA assays are used for men following radical prostatectomy giving postoperative values of < 0.01 ng/ml. Definitions of the threshold of PSA rise that signifies cancer recurrence vary but generally the finding of two successive PSA readings > 0.2 ng/ml is used, this being denoted biochemical recurrence. 73,74 Once biochemical recurrence occurs a decision will be made with the patient whether to continue surveillance or commence adjuvant treatment. This decision will be informed by tests such as magnetic resonance imaging and radionuclide bone scanning designed to demonstrate the site of recurrence as being in the prostatic bed (localised) or as lymph node or bony metastases (systemic).

Adjuvant treatment

For purely localised recurrence radical radiotherapy is recommended as defined in the RADICALS trial protocol. 75 The treatment consists of delivery of up to 66 Gy of radiation divided into daily doses over 4–6 weeks. It is uncertain whether or not the addition of short-term androgen deprivation is beneficial for presumed localised disease, a research question that RADICALS is designed to address. For men with likely systemic recurrence, long-term, typically life-long, androgen deprivation therapy (medical castration) most commonly achieved with a luteinising hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist is recommended. This consists of 3-monthly subdermal injections of a depot preparation of the chosen drug. Alternatively, some men may choose surgical castration, removing both testicles (bilateral orchiectomy). The use of long-term androgen deprivation therapy or bilateral orchiectomy for metastatic disease is thought to be palliative because at some point the disease will lose androgen dependency (castrate-resistant prostate cancer). The duration from start of therapy to escape from androgen control, signified by a further substantial rise in PSA values, varies according to the aggressiveness and extent of disease, with a median time of approximately 12 months. Side effects of androgen deprivation therapy include hormonal changes leading to hot flushes, gynaecomastia and altered fat distribution together with osteoporosis. Men with castrate-resistant prostate cancer have a median survival of approximately 18 months and further treatment is usually palliative with symptom control and use of corticosteroid drugs to improve well-being. The chemotherapeutic agent docetaxel does have some activity, extending survival by 3 months on average, but is suited only to men with good performance status. 76

Urinary incontinence

Recovery of continence following radical prostatectomy can take up to 12 months although most men will regain continence by 6 months. In general, therefore, men suffering urinary incontinence will be advised to use containment devices such as absorbent pads or penile sheath drainage for the initial 12 months. If bothersome leakage persists beyond this time then the main treatment options will be surgical implantation of an artificial urinary sphincter (AUS) or continued use of containment devices. For the purposes of this evaluation we used the individual definition of urinary incontinence given in each study without attempting to separate out differing definitions or categorisation of severity. A recently reported randomised controlled trial (RCT) of pelvic floor muscle therapy following radical prostatectomy demonstrated that the rate of urinary incontinence beyond 12 months using patient-reported measures and data collection independent of the clinical team was higher than that given by most of the studies used in our meta-analysis. 77

Erectile dysfunction

For men who were sexually active before surgery, approximately 40% will experience worsening of their sexual function and in particular difficulty initiating and sustaining penile erection sufficient for desired sexual activity. This is particularly dependent on preservation of one or both neurovascular bundles at the time of radical prostatectomy. Similar to urinary incontinence full recovery can take up to 12–18 months following surgery. For men with persistent and bothersome erectile dysfunction, treatment options will include drug treatment taken on an as-required basis, a vacuum constriction device or penile implant surgery. Most men will first trial an oral phosphodiesterase type V inhibitor, with a suggested prescribing frequency of one treatment per week according to NHS guidance. The next option will be alprostadil (Carerject®, Pfizer) given as an intraurethral pellet or an intracavernosal injection with suggested NHS prescribing frequency again of one treatment per week. For men who achieve satisfactory restoration of sexual activity with these drugs their use will continue long term. If drug treatments are unsuccessful men may trial a vacuum constriction device or consider surgical implantation of a penile prosthesis. The proportion of men pursuing these last two options is small as most will accept their loss of sexual function in the longer term. In addition, it should be noted that, although this outcome is an important aspect determining treatment selection for many men with localised prostate cancer, the definition of any deterioration is not standardised and collection of data concerning sexual function before and after surgery is generally poor. Most studies do not separately categorise those men who were sexually active before surgery and who underwent deliberate nerve-sparing surgery with the aim of preserving sexual function.

Chapter 3 Methods of the systematic review of clinical effectiveness

Methods

Comprehensive electronic searches were conducted to identify reports of published studies. Highly sensitive search strategies were designed including appropriate subject headings and text word terms, interventions under consideration and specific study designs. There was no language restriction but searches were restricted to years from 1995 onwards, reflecting the time of introduction of the techniques. MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, EMBASE, BIOSIS, Science Citation Index and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) were searched for primary studies while the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) and the HTA database were searched for reports of evidence syntheses. Reference lists of all included studies were scanned to identify additional potentially relevant reports. The expert panel provided details of any additional potentially relevant reports.

Conference abstracts from meetings of the European, American and British Urological Associations were searched. Ongoing studies were identified through searching Current Controlled Trials, ClinicalTrials.gov, the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools Expenditures and Results (RePORTER). Websites of manufacturers, professional organisations, regulatory bodies and the HTA were checked to identify unpublished reports. Full details of the search strategies used are detailed in Appendix 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Types of study

Evidence was considered from RCTs, non-randomised comparative studies and, for estimates of learning curve effects only, case series. For estimating learning curve effects robotic or laparoscopic arms of comparative studies were treated as separate case series. Conference abstracts and non-English-language reports were included only if they were of comparative studies.

Types of participants

The types of participants considered were men with clinically localised prostate cancer (cT1 or cT2), defined as cancer confined to the prostate gland and considered curable by radical removal of the prostate. Studies were included if ≥ 90% of the included men fulfilled this definition.

Types of interventions and comparators

Robotic radical prostatectomy was considered as the intervention and laparoscopic radical prostatectomy as the comparator. Open radical prostatectomy was also considered in studies comparing open radical prostatectomy with robotic radical prostatectomy and/or laparoscopic radical prostatectomy so that such studies could be included in a mixed-treatment comparison model (see Data analysis) assessing the relative effectiveness of robotic and laparoscopic radical prostatectomy.

Types of outcome measures

The following types of outcome measures were considered:

-

complications and adverse events including blood transfusion, anastomotic leak, bladder neck contracture, wound infection, organ injury, ileus, deep-vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

-

cancer related:

-

– rate of positive margin in resected specimen

-

– biochemical (PSA) recurrence

-

– need for further cancer treatment

-

– disease-free survival, defined as absence of clinically detectable disease

-

– survival

-

– mortality

-

-

functional:

-

– recovery of sexual (penile erection) function, quantified where possible by validated scores such as the International Index of Erectile Function-5 (IIEF-5)

-

– urinary continence, defined as use of one thin pad or less per day and/or as assessed on a validated symptom score

-

-

patient driven

-

– pain, quantified on a validated pain score, and analgesic requirements

-

– productivity (time to return to full activity)

-

– generic and disease-specific quality of life, measured through validated scores

-

-

descriptors of care

-

– equipment failure

-

– conversion to open procedure

-

– operative time

-

– duration of catheterisation

-

– hospital stay

-

–learning curve.

-

Exclusion criteria

The following types of report were excluded:

-

studies of men with metastatic disease

-

case series of open radical prostatectomy.

Data extraction strategy

Three reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts of all identified items. Full-text copies of all potentially relevant reports were obtained and independently assessed by two reviewers to determine whether or not they met the inclusion criteria. Three reviewers extracted details of study design, methods, participants, interventions and outcomes onto a data extraction form (see Appendix 3). Each reviewer’s data extraction was independently checked by a second reviewer for errors or inconsistencies. Any disagreements were resolved through consensus or arbitration by a third party. For studies reporting adverse events, two surgeons categorised each complication using the Clavien–Dindo classification of surgical complications68 (see Table 3) with a third surgeon acting as arbiter in cases of disagreement about classification.

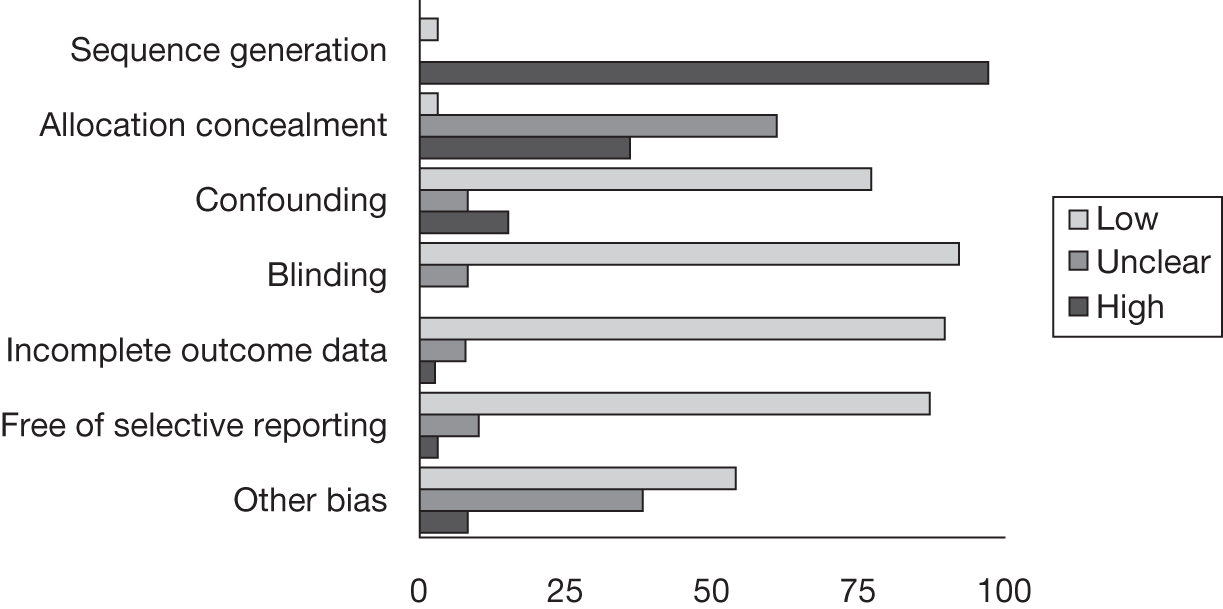

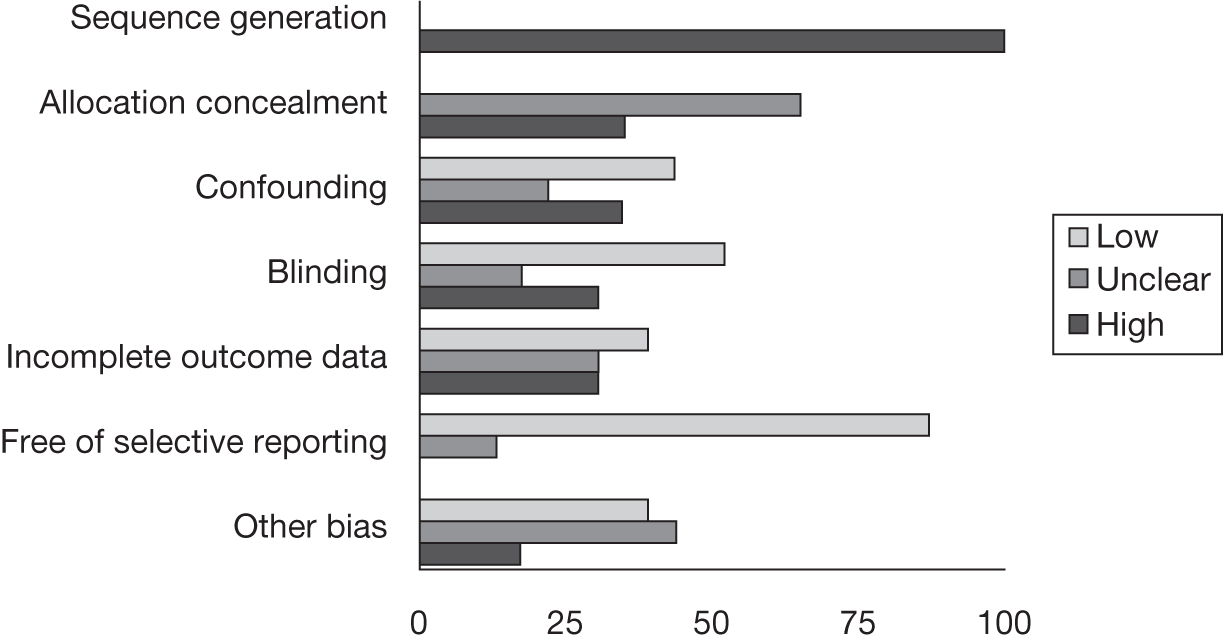

Quality assessment strategy

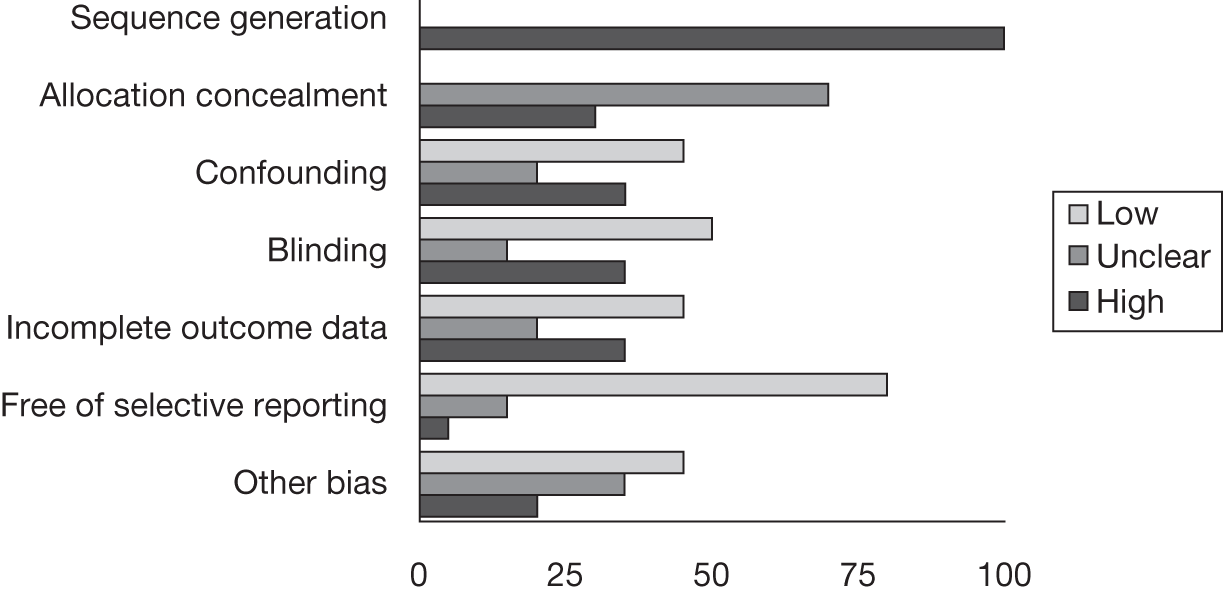

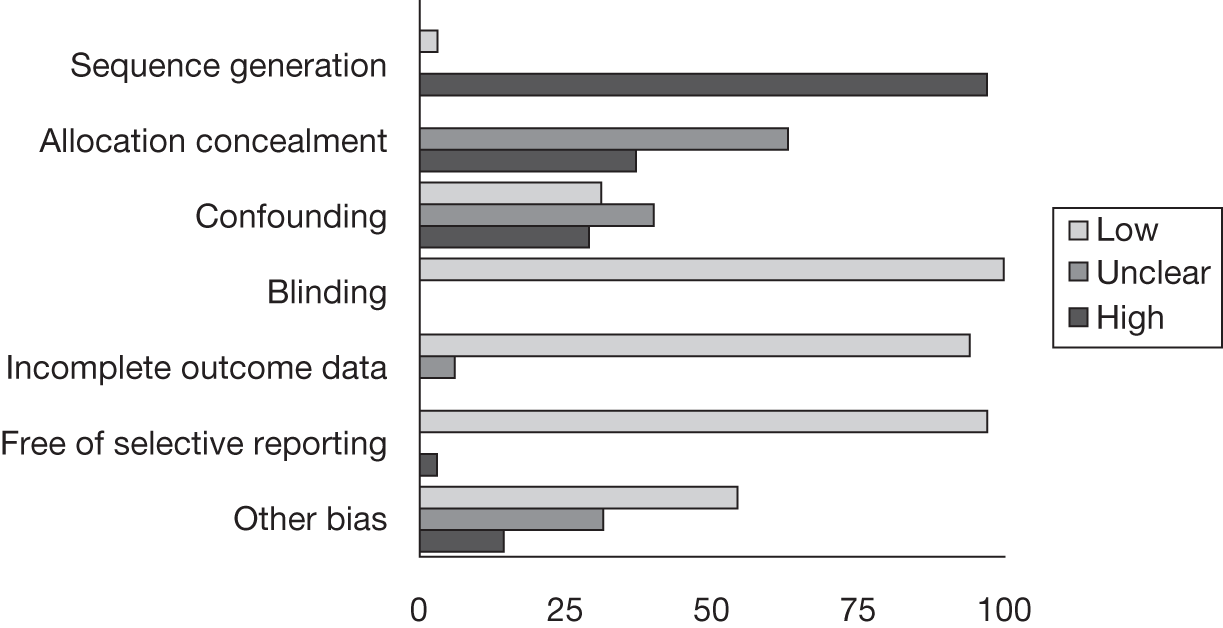

Risk of bias

A modified version of the Cochrane risk of bias tool78 was adapted to include potential topic-specific confounders, which were identified through discussions with members of our project advisory group and our knowledge of existing literature. The topic-specific confounders related to specific outcomes are shown in the modified risk of bias tool (see Appendix 4). Three sets of two reviewers independently assessed the risk of bias of included full-text studies, with the exception of non-English publications and conference abstracts. Any differences in assessment or issues of uncertainty were resolved by discussion and consensus between the reviewers. The risk of bias assessment was summarised at the study level using judgements incorporating individual outcomes as well as study-level risk of bias domains. Individual outcomes were categorised as high risk of bias, low risk of bias or unclear risk of bias. The categories were weighted to reflect higher disagreement between the two clear categories of low and high risk with lower weighting for disagreement between either high- or low-risk and unclear judgements. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus or arbitration by a third party. The kappa statistic was used to assess inter-rater agreement between assessors of the risk of bias in each study, with 0–0.2 as slight agreement, 0.21–0.4 as fair agreement, 0.41–0.6 as moderate agreement, 0.61–0.8 as substantial agreement and 0.81–1 as perfect agreement. 79 If there was a sufficient number of low risk of bias studies, a meta-analysis would be performed restricted to only these studies (see Data analysis).

Determination of surgical margin status

Various protocols are described for the standardisation of processing and reporting of radical prostatectomy specimens, to identify pathological factors that could accurately predict patient outcome. 59,80–82 Variations in the protocols employed may potentially affect the determination of surgical margin status. Details of the methods described for the handling, processing and reporting of radical prostatectomy specimens were tabulated and summarised (see Table 7). The categories for the tabulations were derived from the findings of a recent international consensus conference on handling and staging of radical prostatectomy specimens, which convened following a web-based survey of members of the International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) with the intention to promote consistency in pathological reporting and the collection of appropriate prognostic information. 83,84 If there was a sufficient number of studies, a meta-analysis would be performed restricted to only the studies that reported all criteria (see Data analysis).

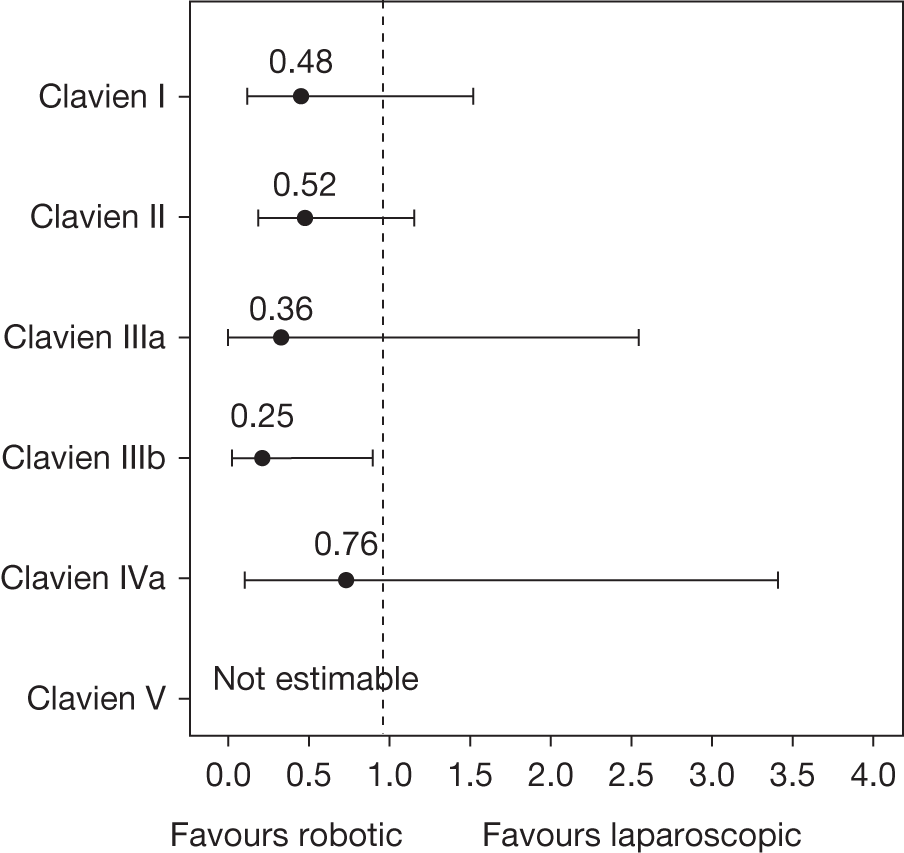

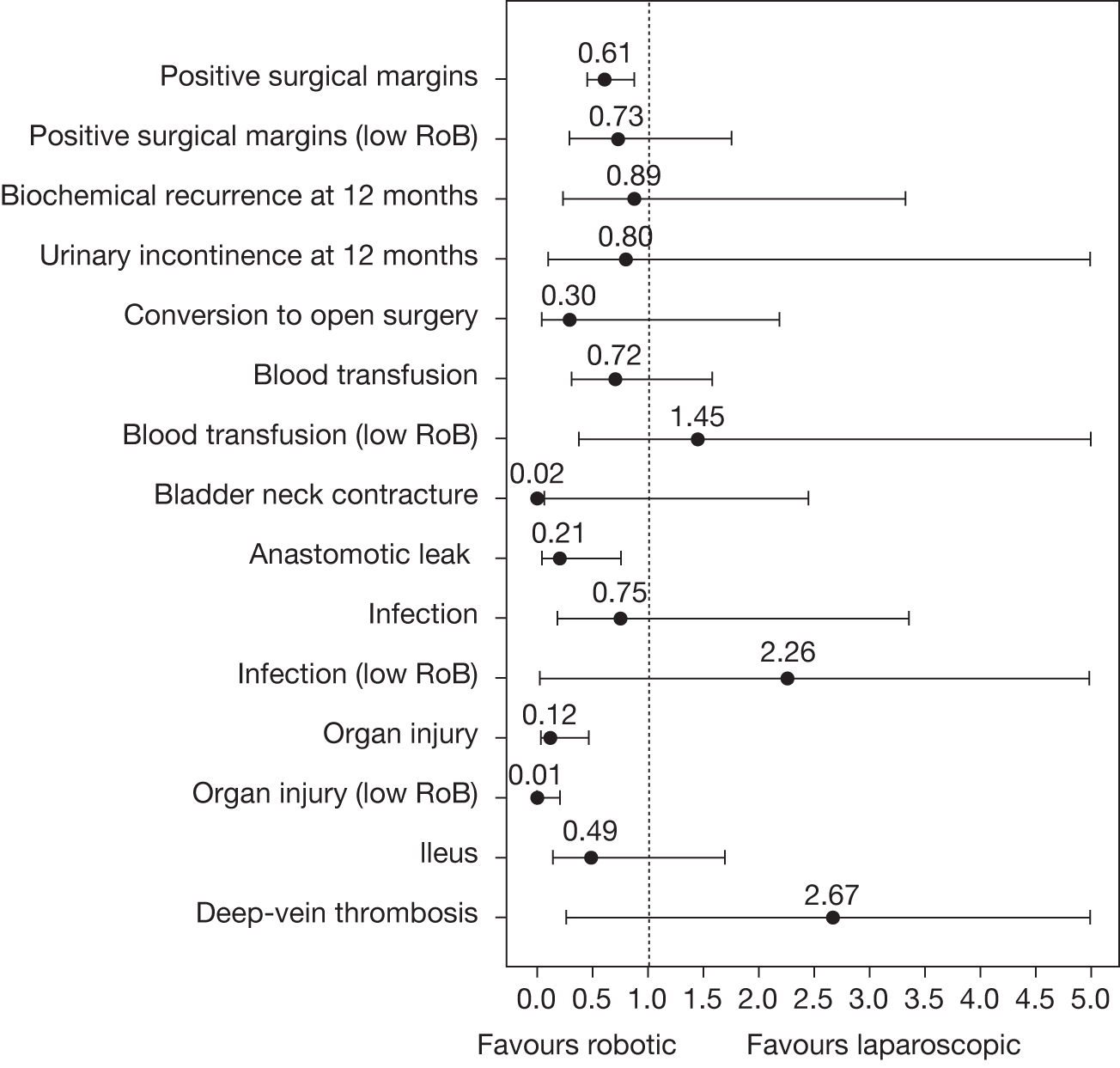

Data analysis

Data from each study were tabulated and summarised for each procedure in a form appropriate for the mixed-treatment comparison model. The lack of RCT evidence precluded undertaking a standard two-group meta-analysis; therefore, an indirect comparison (cross design) approach allowing inclusion of non-randomised comparative data was adopted85 within a mixed-treatment comparison framework. The models implemented were based on mixed-treatment comparison models developed by Lu and Ades. 86 The main parameters in the models for dichotomous outcomes are the logarithm of the odds ratios (log-ORs) of each procedure compared with the reference procedure open surgery. A random-effects model was adopted that incorporated an adjustment for the correlation between arms in studies that compared all three procedures. The model parameters were estimated within Bayesian methodology with the use of WinBUGS software version 1.4.3 (MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK).

For continuous data for duration of operation, a similar model was constructed using means and standard errors instead of log-ORs and standard errors. This was carried out only in studies that compared robotic with laparoscopic procedures directly. Some assumptions were made because of the inconsistent reporting of duration of operation. If a median was reported but no mean the median was used as a substitute for the mean. Furthermore, if the standard deviation (SD) was not reported, imputation was conducted using the method proposed by Marinho and colleagues. 87 In this method, a linear regression of log (standard deviation) on log (mean) for all studies that reported a mean and standard deviation is first undertaken. The resultant predictive formula is then used to impute standard deviations for studies missing this value given the reported mean. This was conducted for each radical prostatectomy procedure separately.

Odds ratios (ORs) and associated 95% central credible intervals (CrIs) were estimated between laparoscopic surgery (the base case) and robotic surgery; if the OR is > 1 the calculated odds of a particular event are higher for robotic surgery than for laparoscopic radical prostatectomy, whereas if the OR is < 1 the calculated odds of a particular event are higher for laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. The CrI will show the degree of uncertainty around these calculated values. The statistical probability of the OR being different from 1, and hence the probability that robotic radical prostatectomy was better or worse than laparoscopic radical prostatectomy for specific outcomes, was calculated (this is sometimes called the ‘Bayesian p-value’ and is the proportion of the samples in the simulation in which the OR was < 1). In this report we have assumed that a probability equal to 0.95 is ‘statistically significant’. Finally, an individual estimate of the probability of the event occurring for each type of radical prostatectomy was calculated. These estimates were calculated from the model by using a prior distribution for the probability of an event when using the reference treatment (which was open radical prostatectomy) and combining that with the OR between each type of surgery and open surgery. The prior distribution for the event rate for open surgery was estimated using the data for open surgery in the included studies only and by applying a normal distribution to the log-OR of the probability of each outcome, with its mean and variance being estimated from a standard Bayesian random-effects model.

When there were a sufficient number of studies, the heterogeneity of effects was explored by repeating the analyses including only data from studies assessed at low risk of bias. In addition, for surgical margins, if there was a sufficient number of studies, the heterogeneity of effects was explored by repeating the analysis including only data from studies that reported all key pathological data (see Quality assessment strategy).

Vague prior distributions were used on the necessary parameters: the log-ORs of intervention procedures compared with open surgery, the individual study event rates and the random-effects standard deviation. For most outcomes a burn-in period of 20,000 iterations was adequate to achieve convergence and a further 100,000 samples were taken for each outcome.

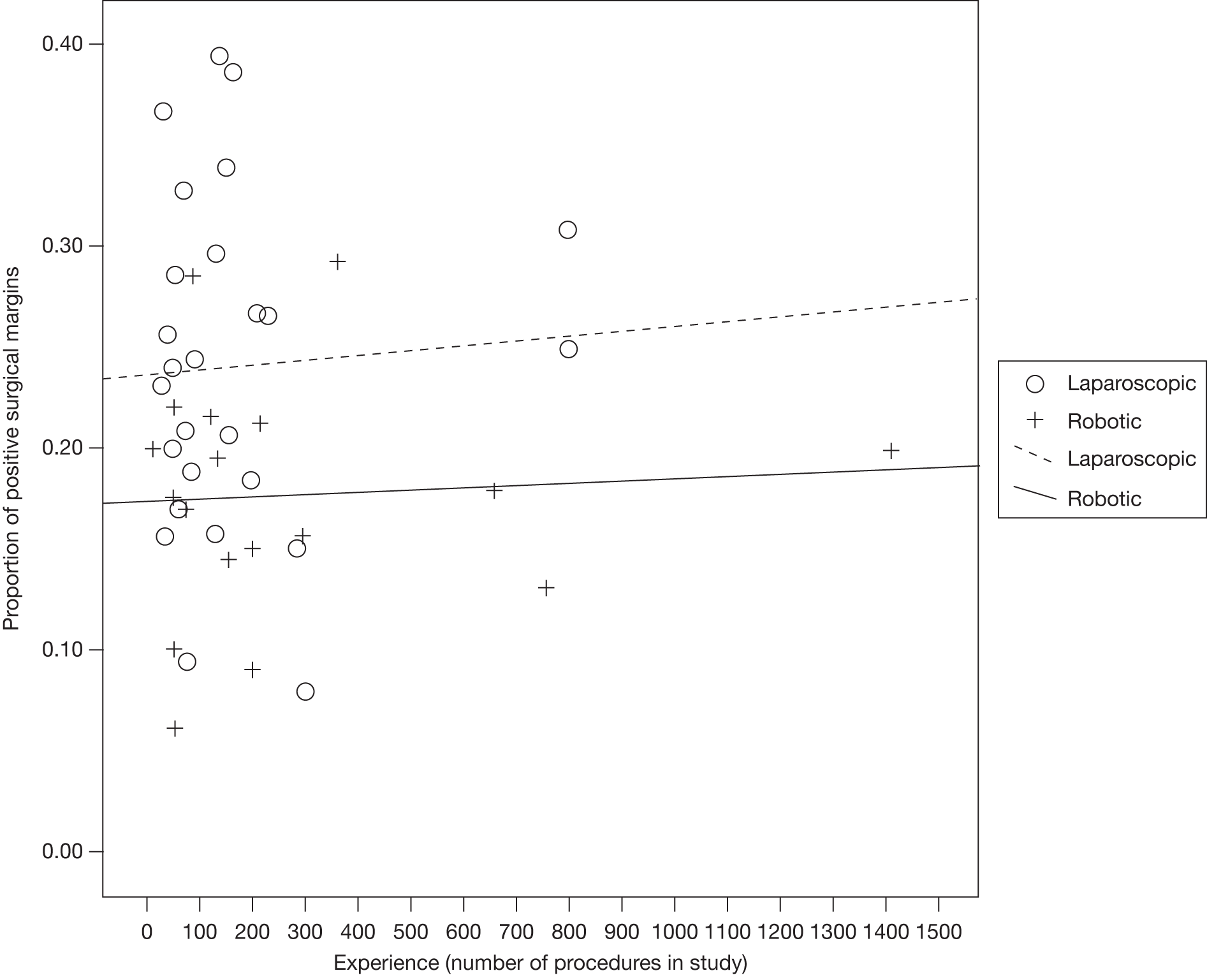

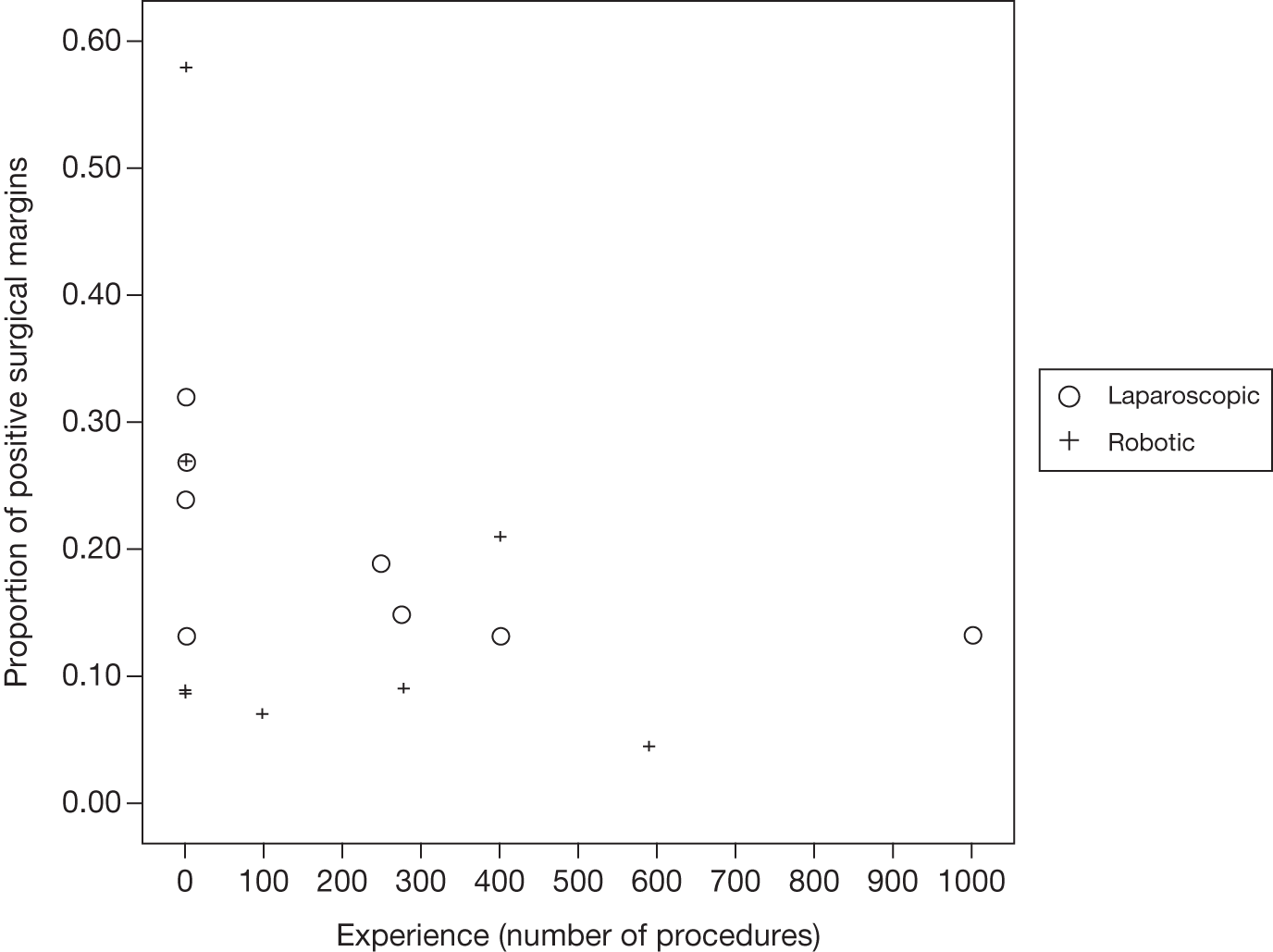

Assessment of learning curves

The approach developed by members of our project team to estimate the learning effects on key outcomes was used. 88 In this approach, the expertise of the participating surgeons or centres described in each included study was first categorised according to previous experience (number of previous radical prostatectomies undertaken using open, laparoscopic or robotic techniques) and according to occurrence of the key outcomes of positive surgical margin rate. Positive margin rate was then plotted against previous experience to describe learning curve effects in the included studies. Data on the three key features of learning (starting level, rate of learning and expert level) were extracted where possible and a random-effects meta-analysis performed to estimate the pooled effect of the key features together with an appropriate measure of uncertainty [95% confidence interval (CI)].

The robustness of the above approach was assessed by extending the inclusion criteria to include case series of laparoscopic and robotic radical prostatectomy that included > 200 men. Positive surgical margin rates for the first and last cases were abstracted from each included case series (together with any other parameters used in the studies to assess learning). A test for a logarithmic shape of learning was undertaken using a linear least-squares regression (using the natural logarithm of procedure number as the independent variable and the natural logarithm of the positive surgical margin rate as the dependent variable). A dummy variable for robotic compared with laparoscopic case series was included in the analysis to test for any difference in rate of learning between the two radical procedures and the associated 95% CI was calculated.

Chapter 4 Clinical effectiveness of robotic compared with laparoscopic techniques

Quantity and quality of evidence

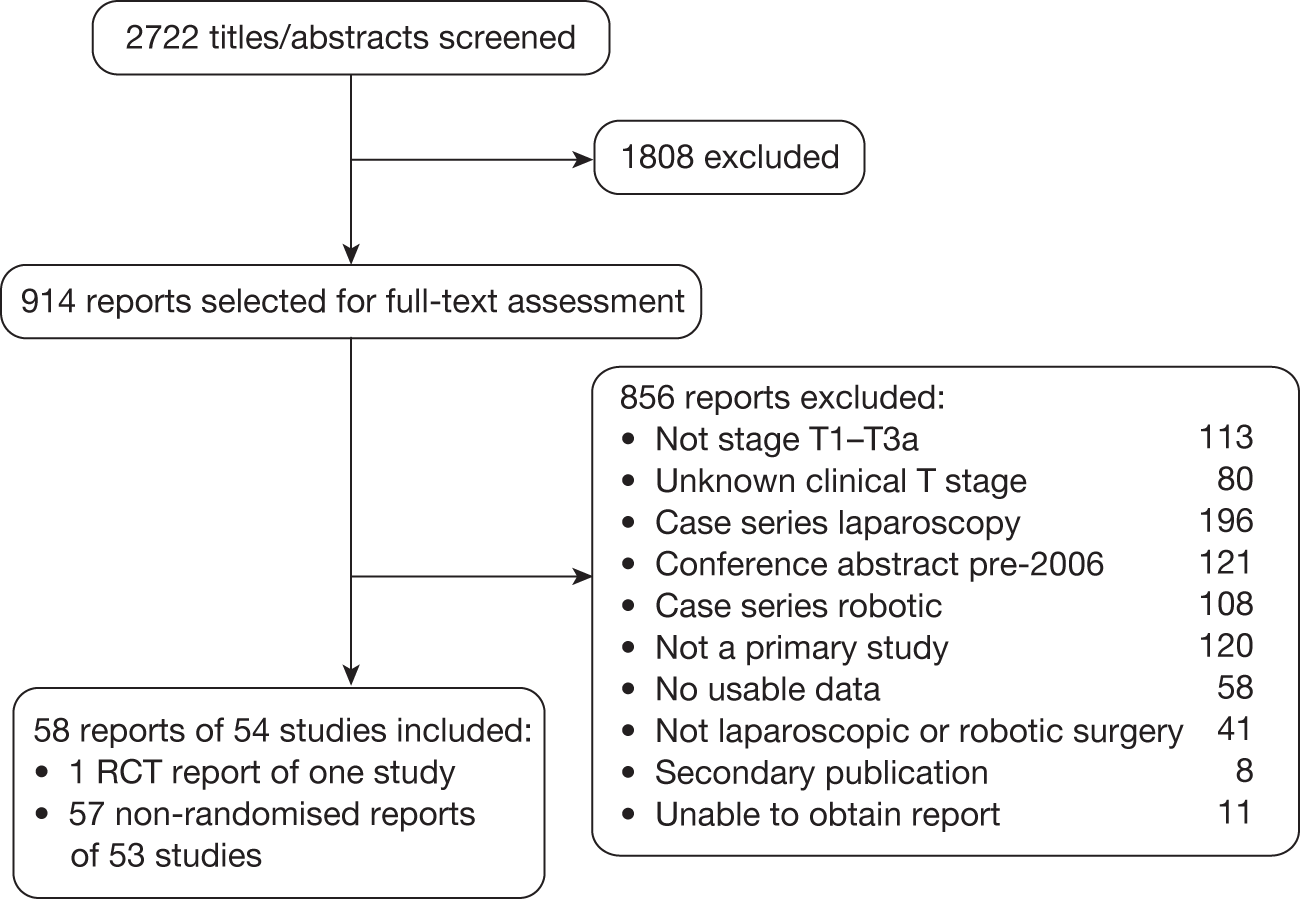

Number of studies identified

The searches identified 2722 potentially relevant titles and abstracts (Figure 6), from which 914 reports were selected for full-text eligibility screening. Of these, 58 reports (54 studies) were included and 856 reports were excluded with reasons for exclusion detailed in Figure 6. We attempted to obtain further details for 69 of the 80 (86%) reports that were excluded because of lack of clear information on the number of patients for each baseline clinical stage and which had contact details available. Nineteen replies were obtained. Only one of these 19 reports89 was subsequently deemed eligible for inclusion, but confirmation of this was received too late for it to be included in the review. Appendices 5 and 6 give the bibliographic details of the included and excluded studies respectively.

FIGURE 6.

Flow chart of the number of potentially relevant reports of identified studies and the numbers subsequently included and excluded from the clinical effectiveness review.

Number and type of included studies

The searches identified one RCT of laparoscopic versus open radical prostatectomy90 and 57 non-randomised comparative reports of 53 studies from 40 different clinical institutions: eight robotic versus laparoscopic prostatectomy;91–98 four robotic versus laparoscopic versus open prostatectomy [three primary,99–101 one secondary102 (earlier report of the same study but containing unique data)]; 18 robotic versus open prostatectomy (16 primary,103–118 two secondary119,120) and 27 laparoscopic versus open prostatectomy (26 primary,121–146 and one secondary147). There were three conference abstracts: two comparing robotic versus laparoscopic prostatectomy94,97 and one comparing robotic versus laparoscopic versus open prostatectomy. 102 Four studies were considered to include potential patient overlap: the study conducted by Menon and colleagues95 was a comparison of 40 laparoscopic and 40 robotic prostatectomies performed between 23 October 2000 and 22 October 2001; Tewari and colleagues116 report an extension of this work but compared 100 open and 200 robot operations between October 1999 and December 2002. As these studies included different comparators, they were treated as separate studies but the potential for overlap of robotic prostatectomy patients was noted. Similarly, Joseph and colleagues94 report a comparison including 800 laparoscopic cases from the Henri Mondor hospital, France, and 745 robotic cases from the University of Rochester, USA, between 2002 and 2006. An earlier publication93 analysed the last 50 cases from a series of 70 laparoscopic and 200 robotic cases from the University of Rochester (dates not given). The studies were treated as separate. Similar affiliated institution details of first authors were noted for seven studies: those by Anastasiadis122 and Salomon,140 Ficarra106 and Fracalanza,107 and Greco,129 Jurczok131 and Fornara. 127 These studies report overlapping treatment dates and similar procedures but it is unclear whether or not they include patient overlap as details of the institutions where the men were treated are not clearly given within the reported text. Similarly, we noted similar author institution details for another seven studies: those by Malcolm,110 Ball99 and Soderdahl,142 Trabulsi98 and Brown,125 and Loeb109 and Wagner146 although these involved different comparison groups and were treated as separate studies.

The 57 non-randomised comparative reports (of 53 studies) included 28 prospective and 17 retrospective reports. Three studies92,112,114 included a mixture of prospective and retrospective data and eight96,97,100,119,123,132,134,138 did not report the method of data collection. The method of data collection was uncertain in the study by Kim and colleagues132 because of a limited translation of the full-text version. Table 4 provides further details of the number and type of included studies.

| Comparison | Study report | Data collection | Number of reports |

|---|---|---|---|

| Robotic vs laparoscopic | RCT | 0 | |

| Non-randomised comparative | Prospective | 2 | |

| Retrospective | 3 | ||

| Both | 1 | ||

| Not reported | 2 | ||

| Total | 8 | ||

| Robotic vs laparoscopic vs open | RCT | 0 | |

| Non-randomised comparative | Prospective | 1 | |

| Retrospective | 1 | ||

| Not reported | 2 | ||

| Total | 4 | ||

| Robotic vs open | RCT | 0 | |

| Non-randomised comparative | Prospective | 8 | |

| Retrospective | 6 | ||

| Both | 2 | ||

| Not reported | 2 | ||

| Total | 18 | ||

| Laparoscopic vs open | RCT | Prospective | 1 |

| Non-randomised comparative | Prospective | 15 | |

| Retrospective | 7 | ||

| Unclear | 1 | ||

| Not reported | 4 | ||

| Total | 28 |

The RCT conducted by Guazzoni and colleagues90 comparing laparoscopic with open prostatectomy was set in Italy. Half of the included non-randomised studies were conducted in the USA (28/57, 49%). The remaining studies were conducted in France,91,94–96,101,122,140 Italy,106,107,114,123,129,134 Germany,127,131,137 Japan,135,136,144 Canada;121,130 there was one study from each of Australia,105 Austria,139 Brazil,141 Chile,133 Croatia,143 Republic of Korea,132 Spain,138 Sweden104 and Taiwan, Province of China. 113 Of the non-randomised comparative studies comparing robotic with laparoscopic radical prostatectomy, three primary full-text studies92,93,98 and one conference abstract97 were set in the USA, one conference abstract was set in both the USA and France94 and three studies were set in France. 91,95,96 Of the non-randomised comparative studies comparing robotic, laparoscopic and open radical prostatectomy, two primary studies99,100 and one secondary report102 were set in the USA and one study was set in France. 101 Of the non-randomised comparative studies comparing robotic and open radical prostatectomy, 10 primary studies103,108–112,115–118 and two secondary reports119,120 were set in the USA, one study was set in Australia,105 three primary studies106,107,114 were set in Italy, one study was set in Sweden104 and one was set in Taiwan, Province of China. 113 Of the non-randomised comparative studies comparing laparoscopic and open radical prostatectomy, seven primary studies124–126,128,142,145,146 and one secondary report147 were set in the USA, three primary studies127,131,137 were set in Germany, three primary studies135,136,144 were set in Japan, three primary studies123,129,134 were set in Italy, two primary studies122,140 were set in France and one study each was set in Austria,139 Brazil,141 Canada,121 Chile,133 Croatia,143 Republic of Korea132 and Spain. 138

The four full-text publications that required translation paired with their original language were Fornara and Zacharias127 (German), Kim132 (Korean), Soric143 (Croatian) and Raventos Busquets and colleagues138 (Spanish).

Characteristics of patients

The 58 reports included 21,126 men at enrolment. Excluding secondary reports and following exclusions because of ineligibility or participant dropout, the final study analyses included 19,064 men, of whom 6768 underwent robotic radical prostatectomy, 4952 underwent laparoscopic radical prostatectomy and 7344 underwent open radical prostatectomy. The demographic and disease characteristics of these included men are summarised in Table 5.

| Variable | Robotic | Laparoscopic | Open |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 6768 | 4952 | 7344 |

| Age (years), median | 60.7 | 61.9 | 63 |

| Interquartile range (years) | 59.8–62 | 60.0–63.65 | 60.5–64.8 |

| Clinical stage, n (%) | |||

| cT1 | 4380 (64.7) | 3257 (65.8) | 3956 (53.9) |

| cT2 | 1743 (25.8) | 1312 (26.5) | 2194 (29.9) |

| cT3 | 58 (0.9) | 26 (0.5) | 148 (2.0) |

| cT4 | 1 (0.01) | 8 (0.2) | 0 (0) |

| Missing/unknowna | 586 (8.7) | 349 (7.0) | 1046 (14.2) |

| Preoperative Gleason score, n (%) | |||

| ≤ 6 | 2179 (32.2) | 989 (20.0) | 2389 (32.5) |

| 7 | 949 (14.0) | 429 (8.7) | 1574 (21.4) |

| 8–10 | 198 (2.9) | 54 (1.1) | 333 (4.5) |

| Missing/unknowna | 3442 (50.9) | 3480 (70.3) | 3048 (41.5) |

| Preoperative PSA (ng/ml), median | 6.3 | 7.2 | 7.9 |

| Interquartile range (ng/ml) | 5.4–7.1 | 6.3–8.6 | 6.0–9.3 |

| Postoperative whole prostate radical prostatectomy Gleason score, n (%) | |||

| ≤ 6 | 1200 (17.7) | 485 (9.8) | 1666 (22.7) |

| 7 | 1110 (16.4) | 415 (8.4) | 1634 (22.2) |

| 8–10 | 161 (2.4) | 49 (1.0) | 379 (5.2) |

| Missing/unknowna | 4297 (63.5) | 4003 (80.8) | 3665 (49.9) |

| Pathological tumour stage, n (%) | |||

| pT0 | 7 (0.1) | 6 (0.1) | 22 (0.3) |

| pT1 | 0 (0) | 29 (0.6) | 25 (0.3) |

| pT2 | 2060 (30.4) | 2373 (47.9) | 4246 (57.8) |

| pT3 | 571 (8.4) | 669 (13.5) | 1368 (18.6) |

| pT3/4b | 23 (0.3) | 45 (0.9) | 76 (1.0) |

| pT4 | 7 (0.1) | 17 (0.3) | 33 (0.4) |

| Missing/unknowna | 4203 (62.1) | 1710 (34.5) | 1574 (21.4) |

All studies reported age with a median (interquartile range) of 62 (60–64) years and a total range of 35–84 years.

Baseline clinical tumour staging data were reported for all studies except that conducted by Bolenz and colleagues;100 however, clinical staging data for this study were available from an earlier report in abstract form. 102 Eight reports107,111,120,126,139,141,143,147 did not report specific baseline clinical stage, simply reporting their inclusion criterion as ‘≤ cT1–T2’, and one109 did not report clinical stage by procedure. The baseline clinical tumour staging was similar between the laparoscopic and robotic radical prostatectomy patients with 68% and 69%, respectively, categorised as T1.

Less than half of the included reports (23/58, 40%)91,98,99,101,103,105–108,110,115,117–121,125,128,135,136,142,145,146 gave detailed biopsy Gleason scores for men undergoing prostatectomy in the format we required: numbers of men categorised as Gleason score ≤ 6, 7 or ≥ 8. Seven studies90,95,97,111,126,139,141 and one secondary report147 did not report biopsy Gleason grades or score. Over one-third of the included reports (21/58, 36%) reported either mean93–95,113,122–124,129,130,132,139,140,143,144 or median104,114,127,131,133,134,137 scores. The remaining reports presented details using different scoring formats90,92,102,138,141 or did not present separately by procedure. 100 Two-thirds of men undergoing both laparoscopic and robotic radical prostatectomy had a Gleason score ≤ 6.

Fifty reports90,91,93–101,103–109,112–119,122–125,127–146 gave preoperative PSA values, with the majority (38/50, 76%) reporting mean PSA for each group of men. Nine studies106–108,131,134,141,142,144,145 reported median group PSA values, whereas two studies135,136 reported mean and median PSA and one study119 reported PSA range only. Combining the median and mean PSA values across all of the studies demonstrated slightly lower levels of preoperative PSA in the robotic than in the laparoscopic procedures: 6.3 ng/ml and 7.2 ng/ml respectively. Three studies92,121,126 reported the number of men in each group falling into varying ranges of PSA values but as the ranges were inconsistent we were unable to include these data in the summary.

The postoperative Gleason sum score following pathological examination of the prostate was similar between the robotic and laparoscopic patients with 50% of the men in both groups with combinable Gleason information having a Gleason score ≤ 6. Pathological staging assigned following consideration of the operative finding during surgery and pathological examination of the removed prostate was similar between the robotic and laparoscopic patients with 78% of the men with combinable staging information in both groups categorised as pT2. There was a trend towards worse disease characteristics in men undergoing open prostatectomy with 55% having a post-prostatectomy Gleason score > 6 and 30% categorised as pT2 or higher.

Twenty-nine primary reports90–93,96,99,100,106,108,110–113,118,122,123,125,126,128,129,132,135–137,139,142,144–146 and two secondary reports102,119 reported the use of nerve-sparing techniques.

Overview of types of outcomes reported

The numbers and types of included studies reporting our main considered outcomes are summarised below.

Efficacy

Thirty-nine studies (67%)90,94–98,101,103,105–109,112–116,118,122,123,125–127,129–134,137–141,143–146 reported data on the rate of positive surgical margins in the excised prostate specimen.

Thirteen studies (22%)95,101,103,108,109,112,113,115,116,123,133,137,140 reported the rate of biochemical recurrence, but the time points at which this was censored, the definition of biochemical recurrence and the threshold values of PSA used varied between studies.

The need for and outcome of further treatment for prostate cancer recurrence was reported by one study. Dahl and colleagues126 reported information on the numbers of men requiring further cancer treatment consisting of salvage external beam radiation therapy, androgen deprivation therapy or both for cohorts of men undergoing laparoscopic or open prostatectomy.

Eight studies90,111,116,130,135–137,139 reported quality-of-life data using validated measures.

Safety

The majority of reports (45/58, 78%) included data on perioperative adverse events.

Thirteen primary reports93,94,99,103,109,110,130,135,136,141,142,144,145 and one secondary report147 did not report perioperative safety outcomes.

Four studies104,105,126,140 reported deaths within 30 days postoperatively because of surgical complications.

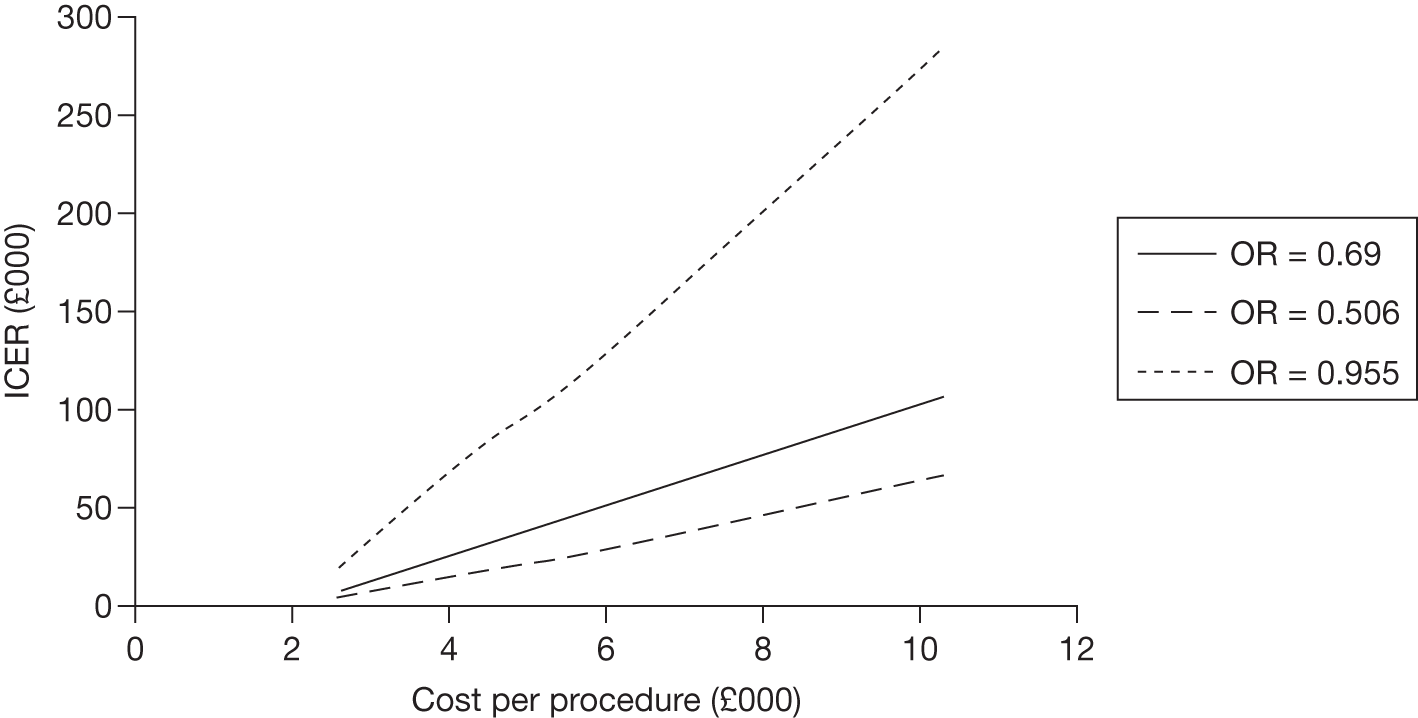

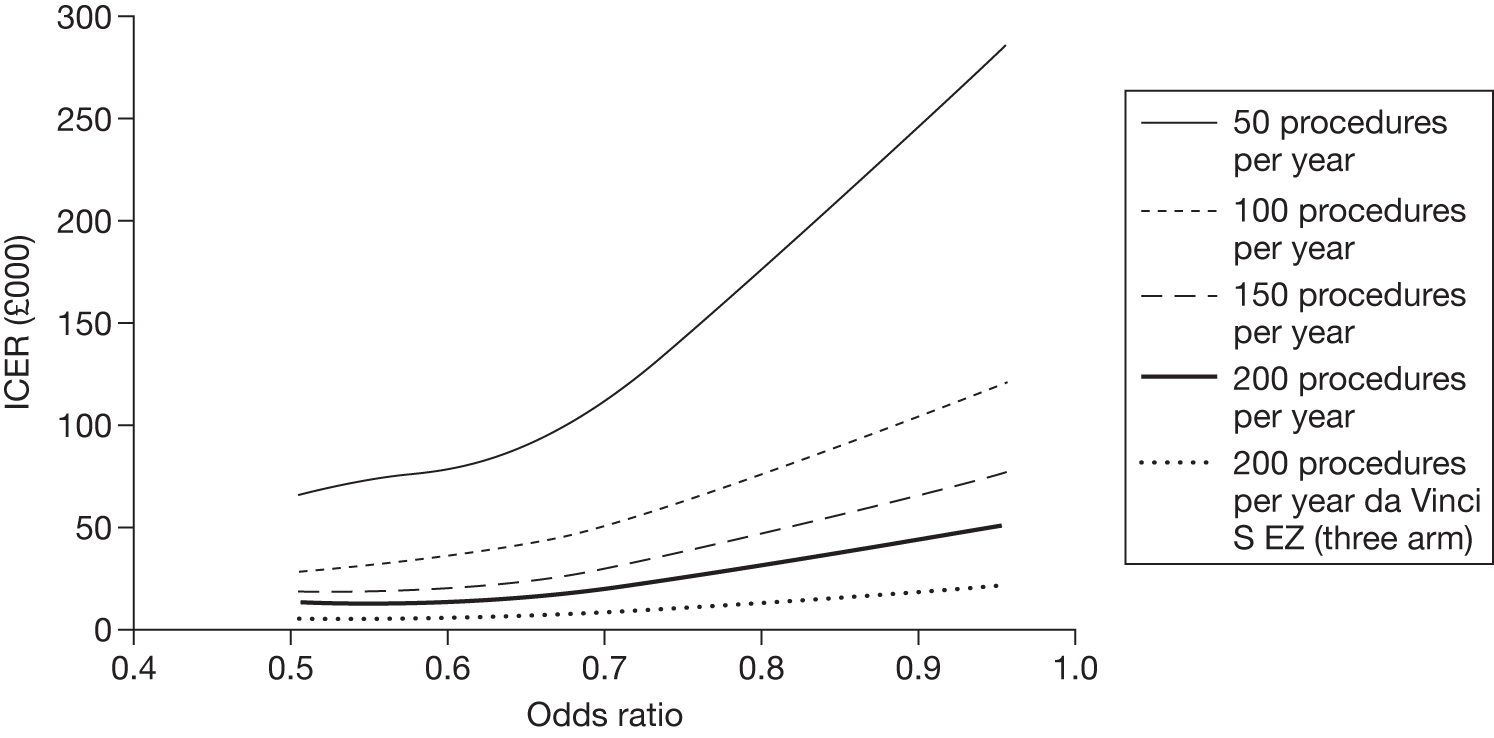

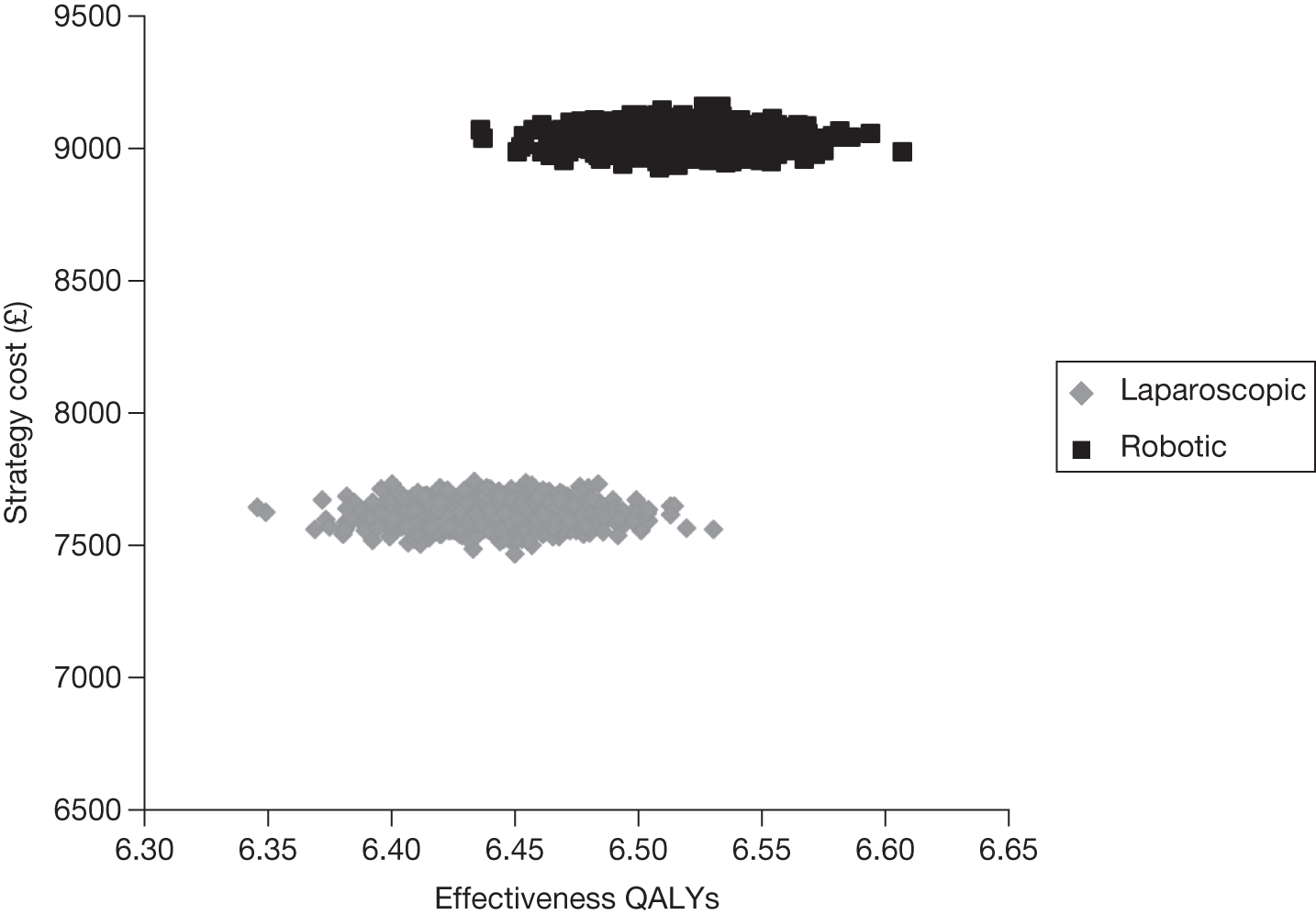

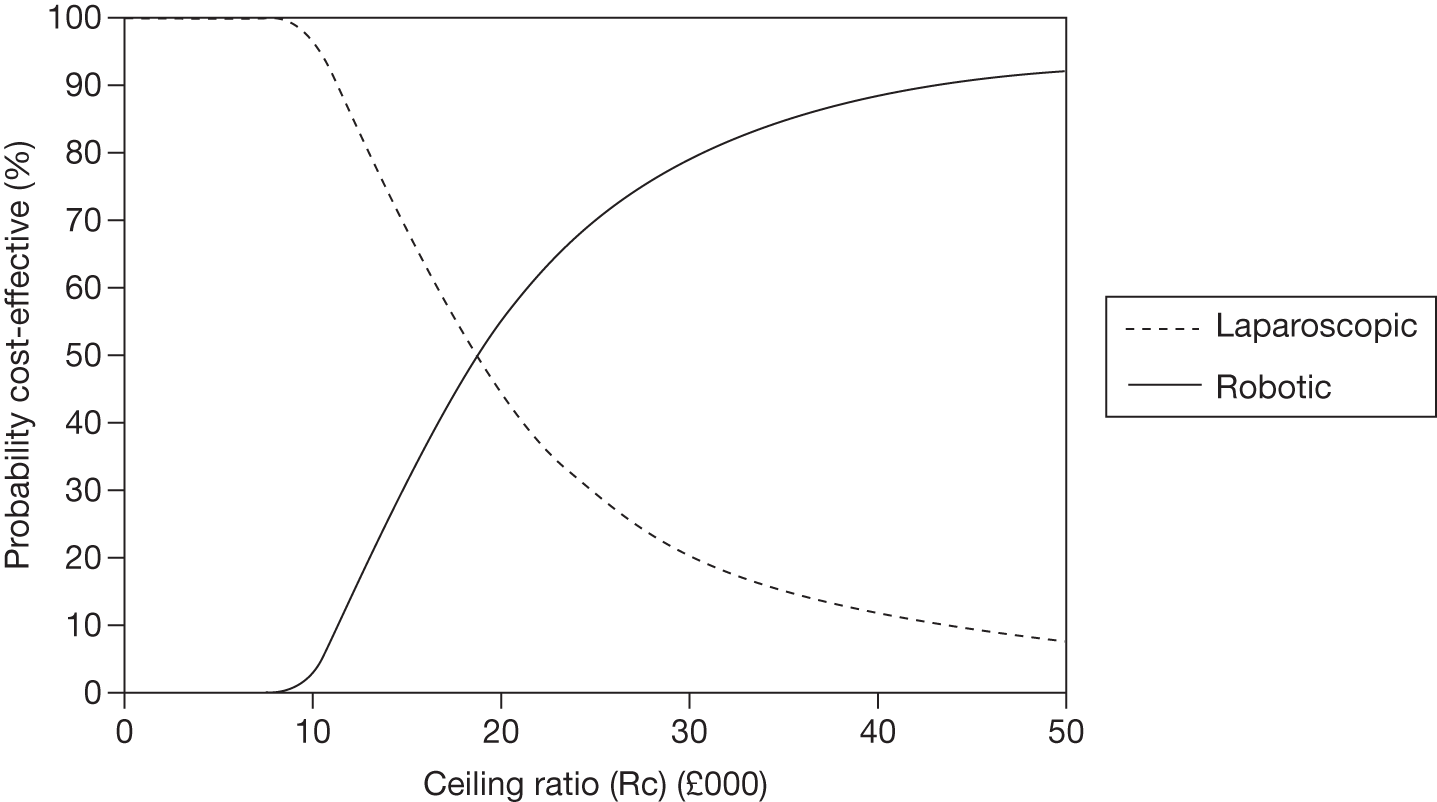

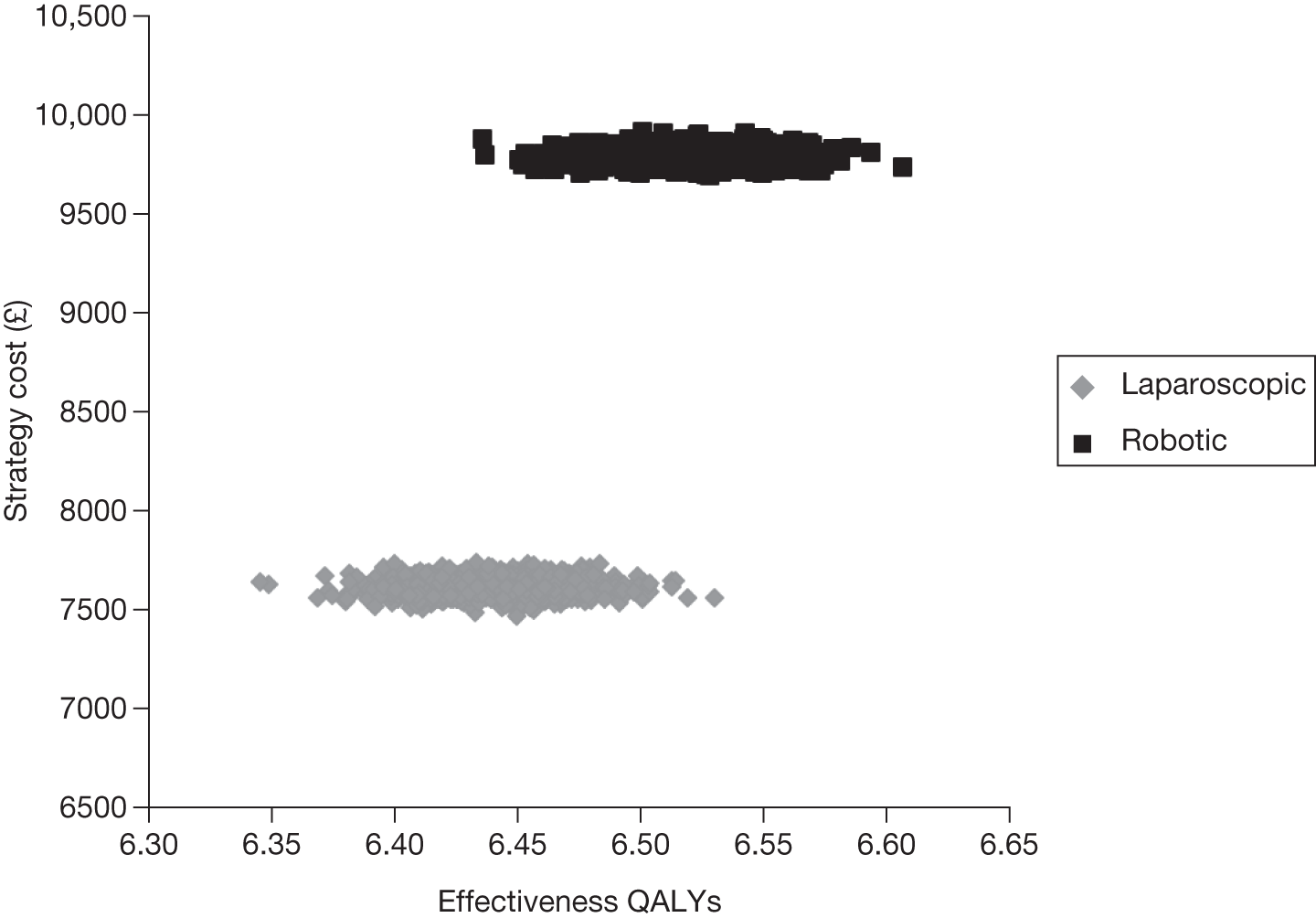

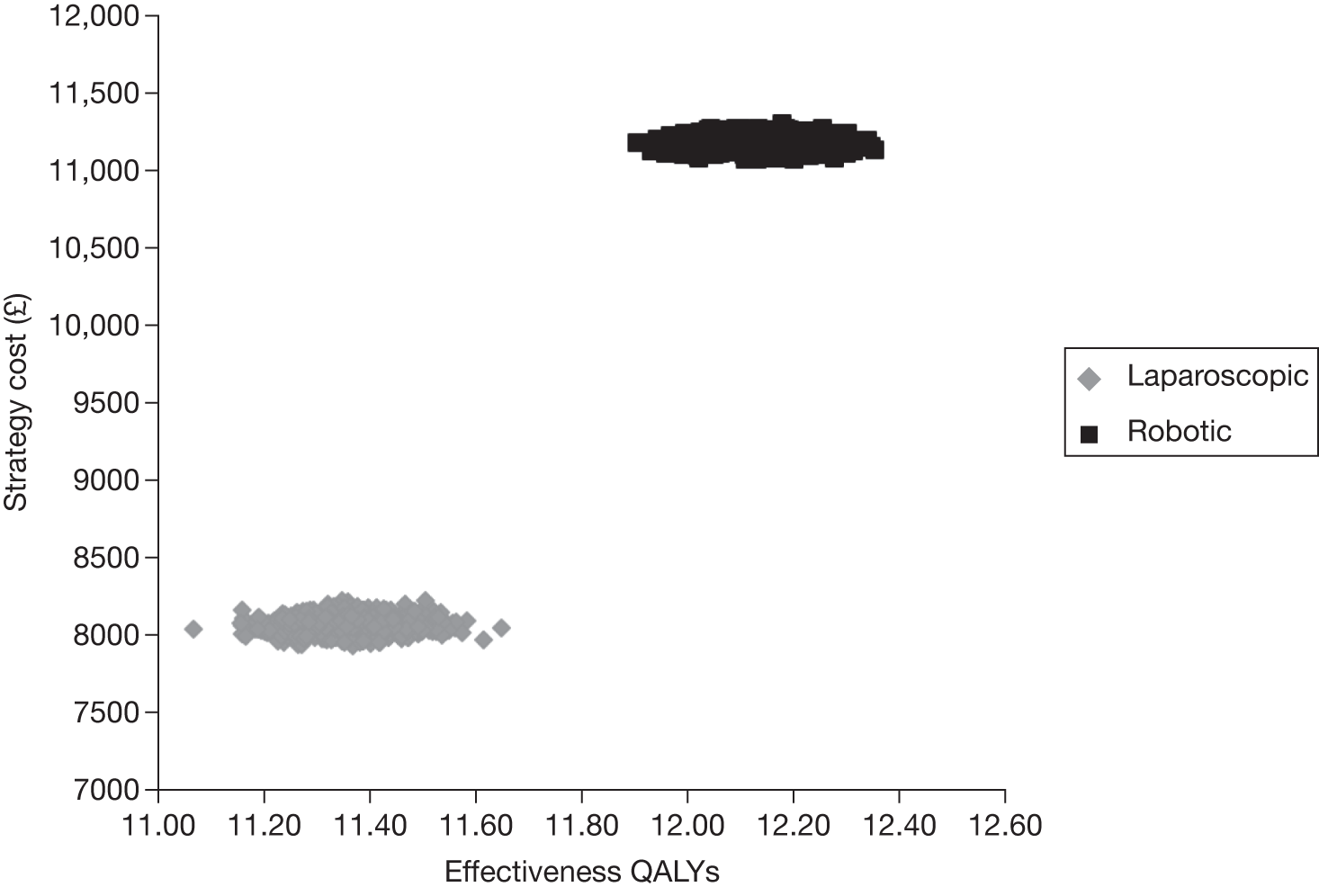

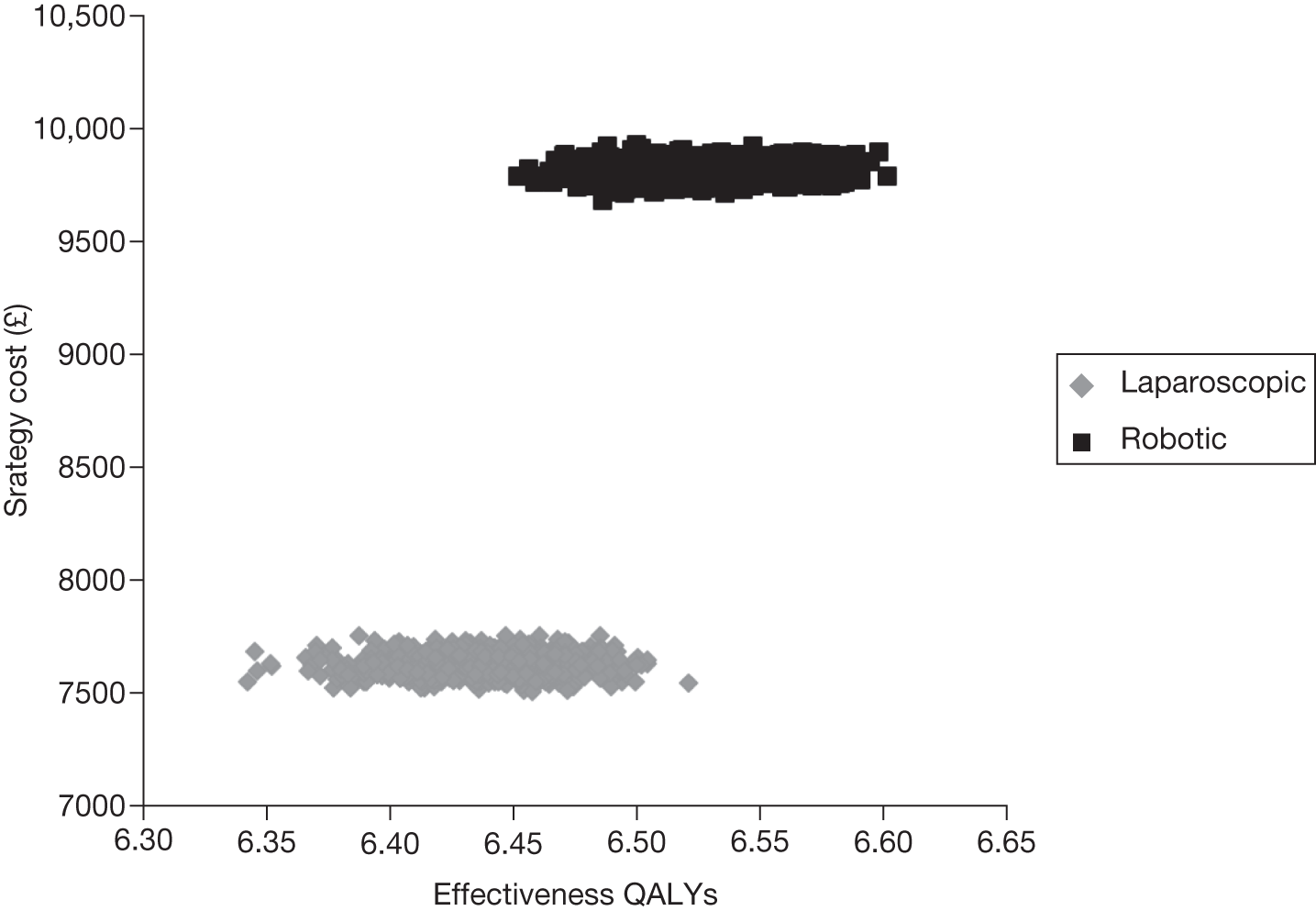

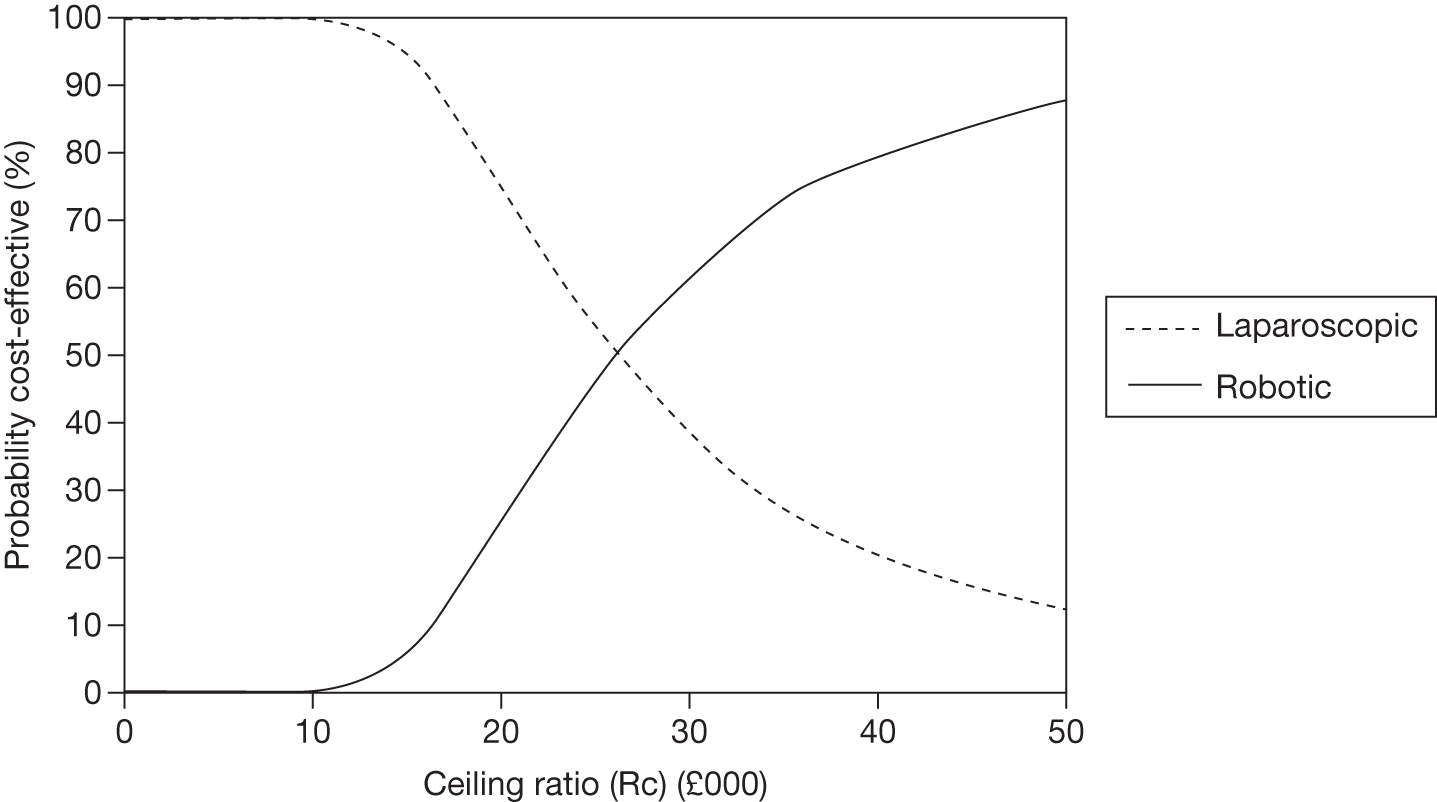

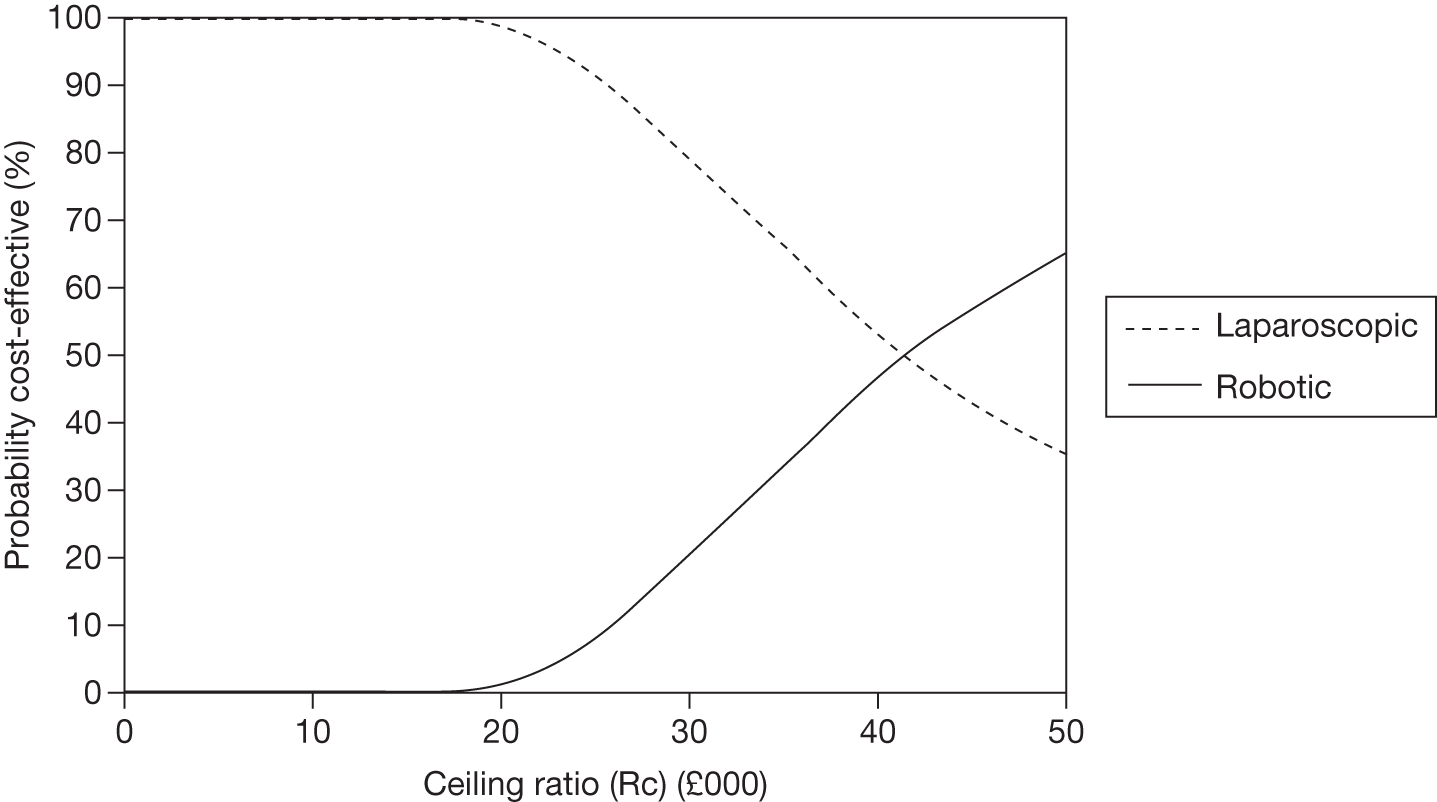

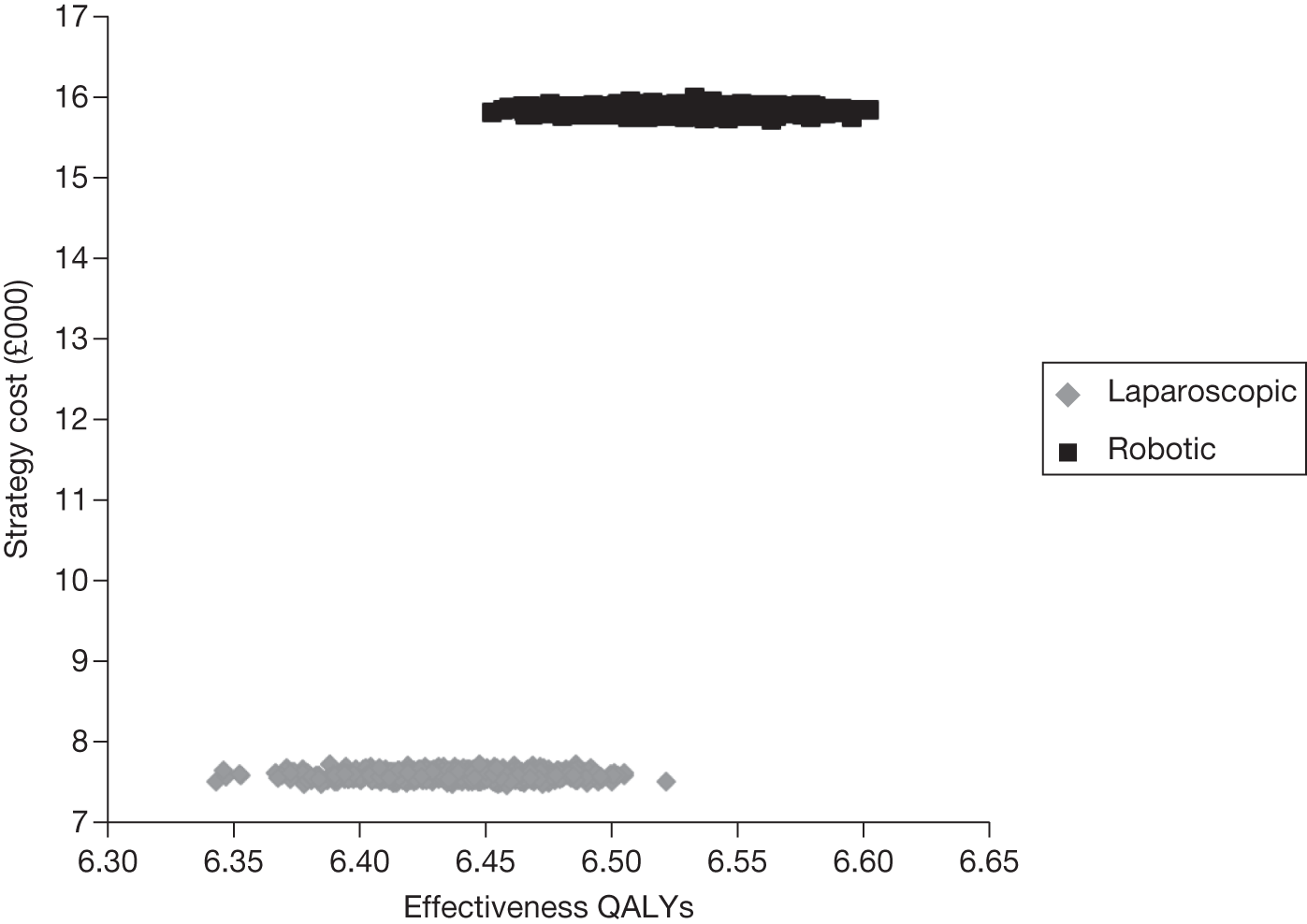

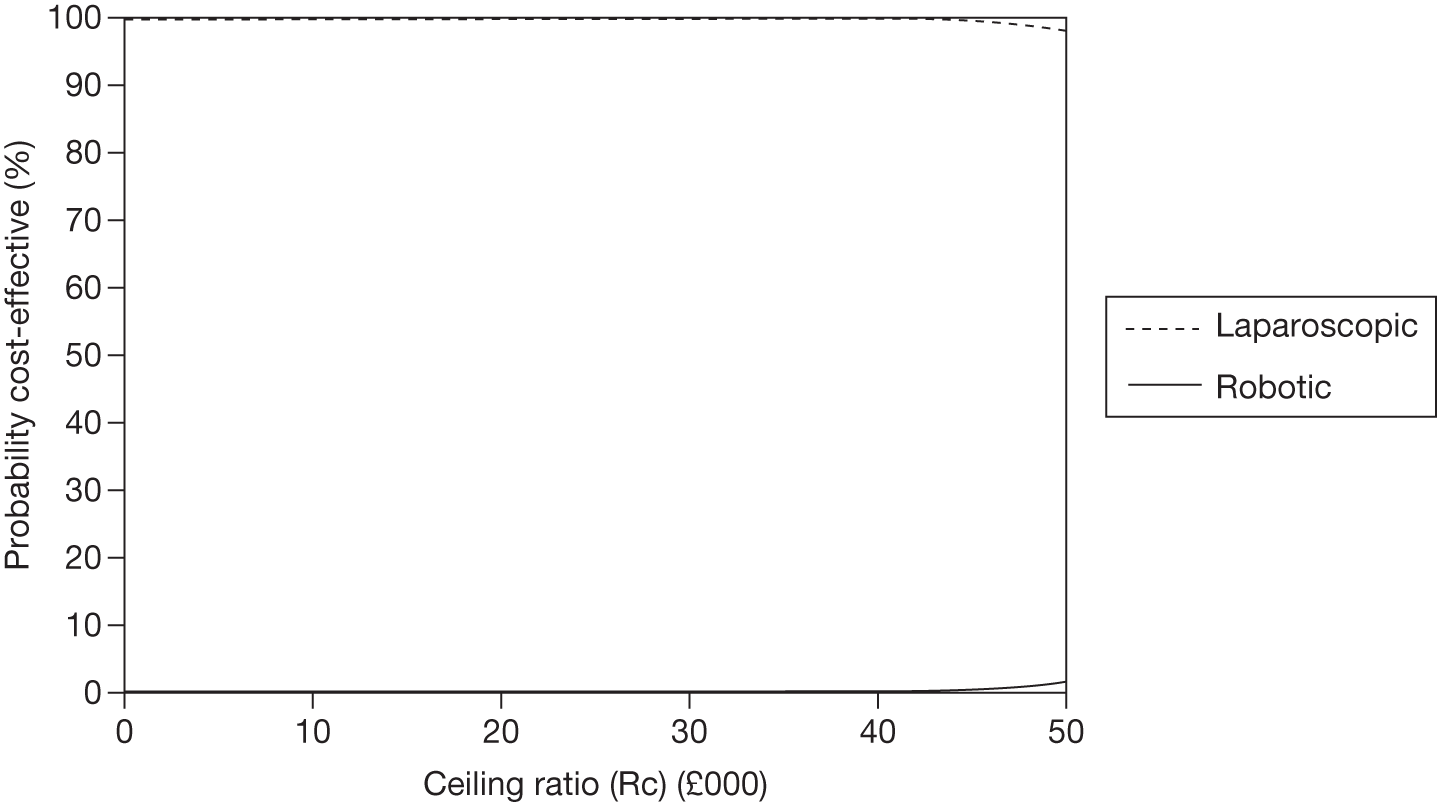

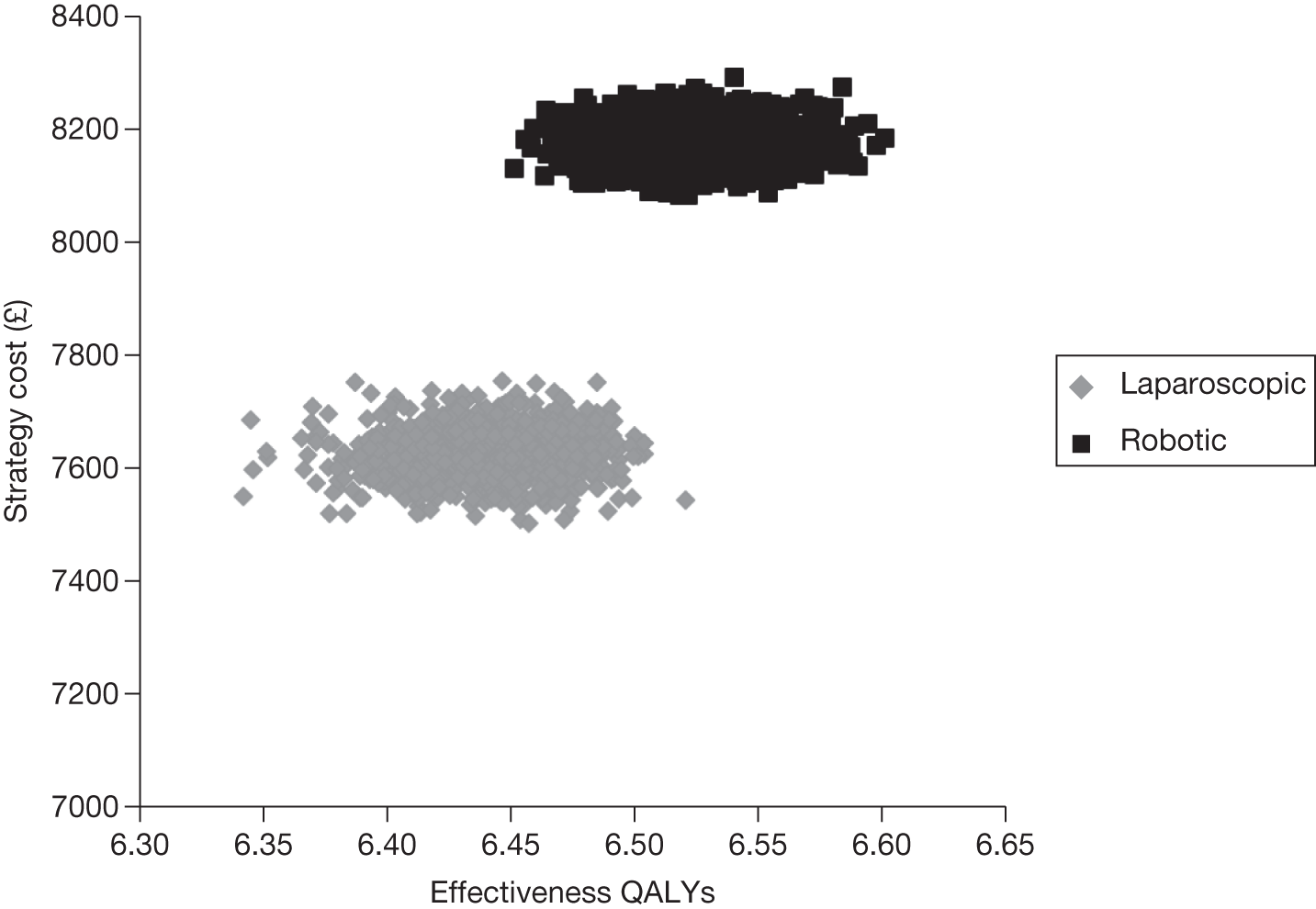

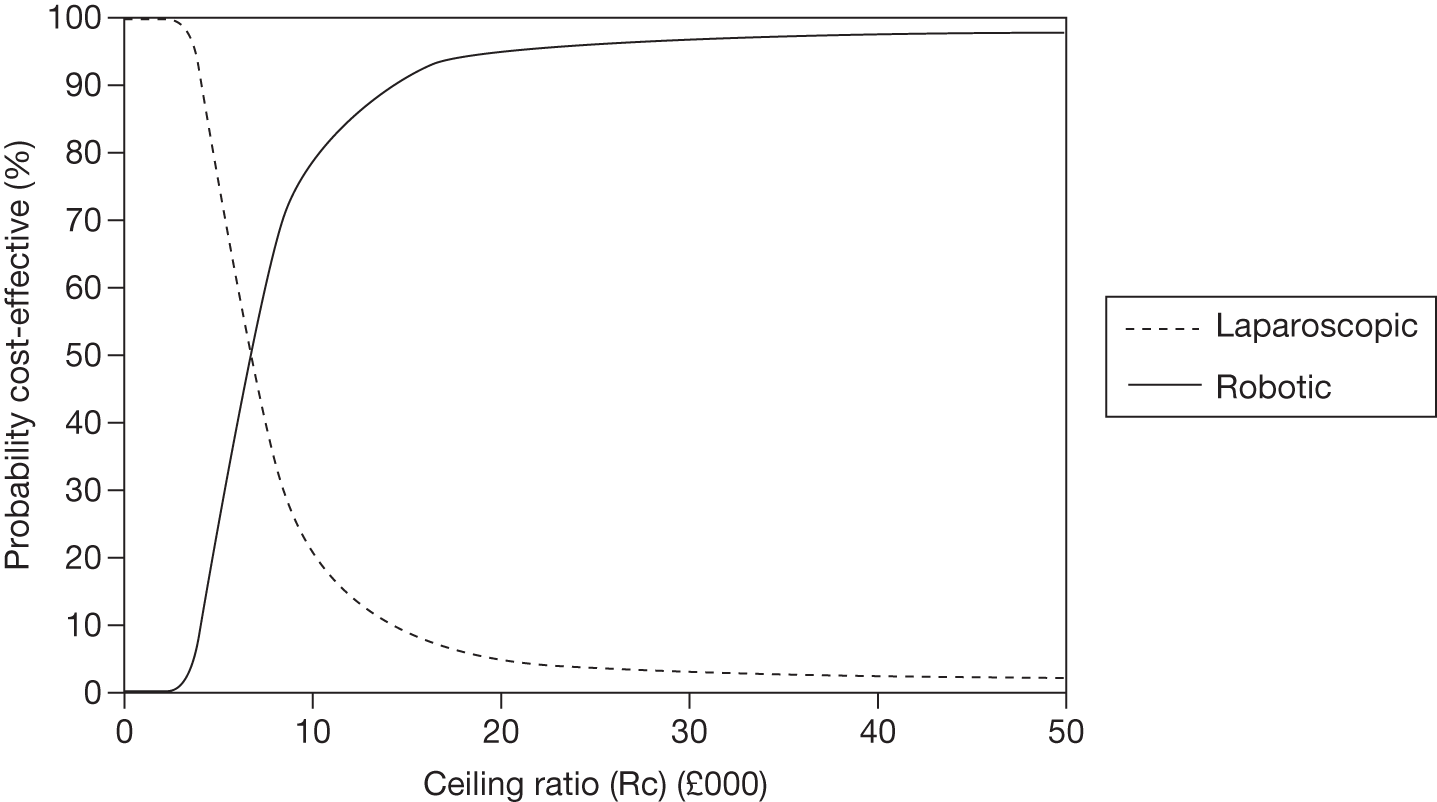

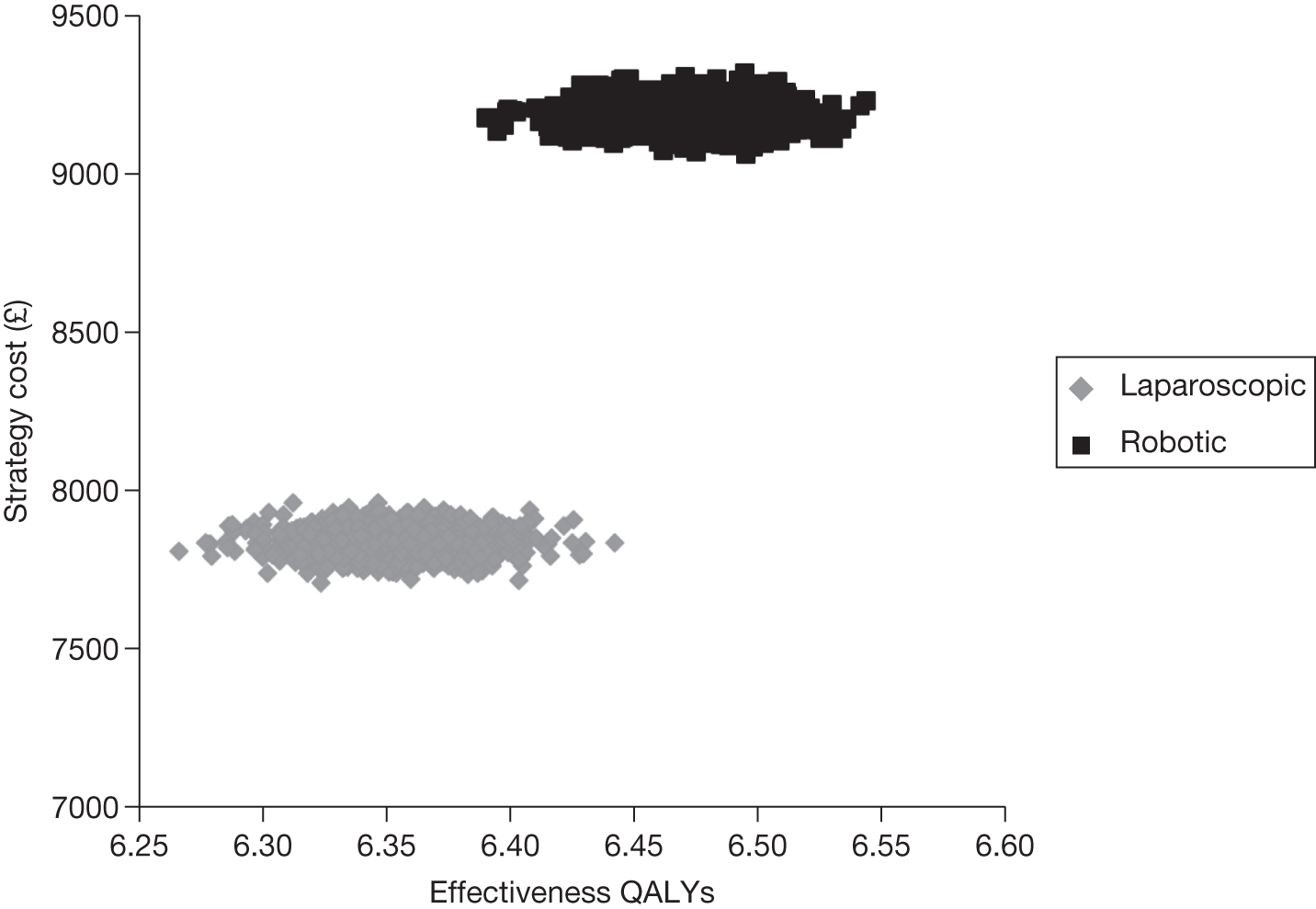

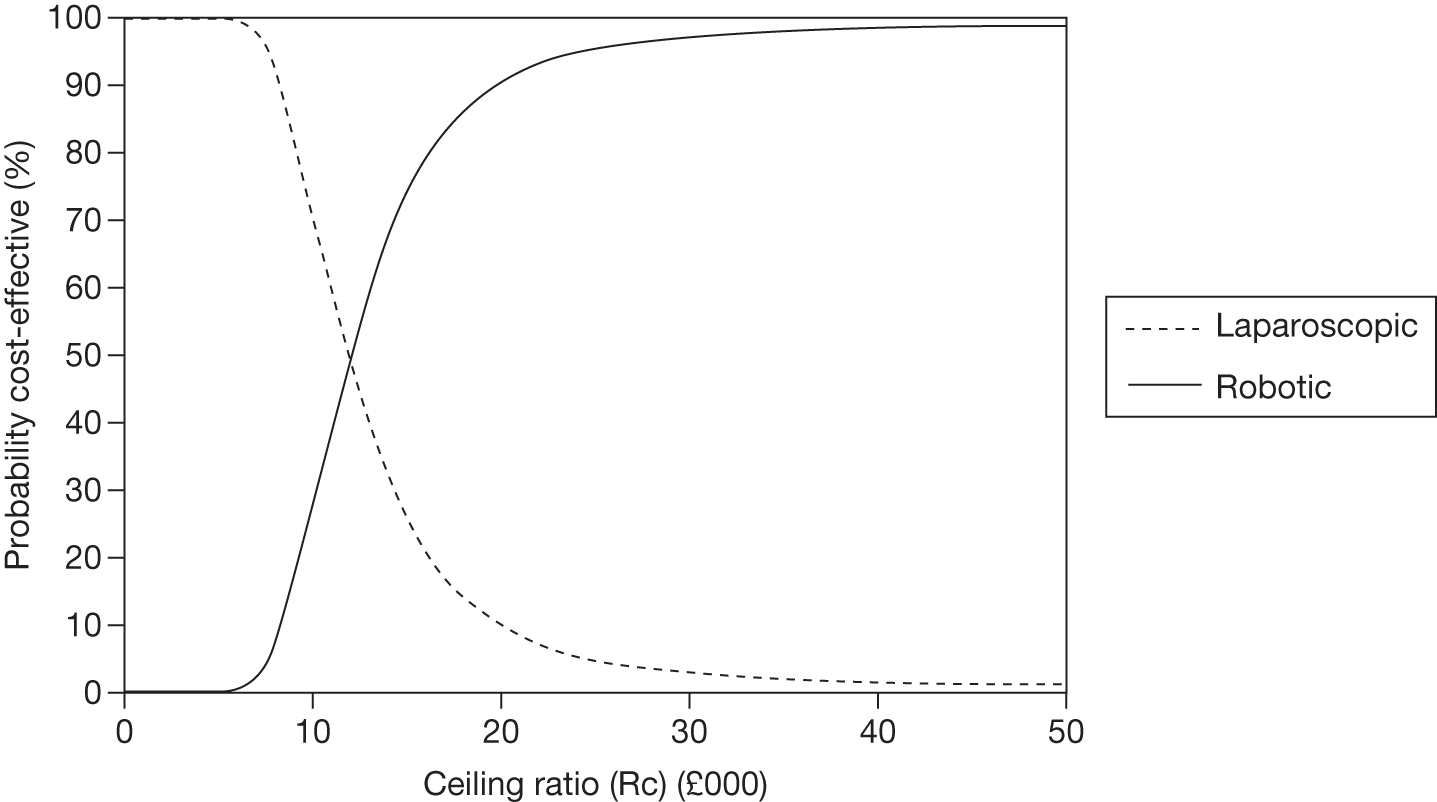

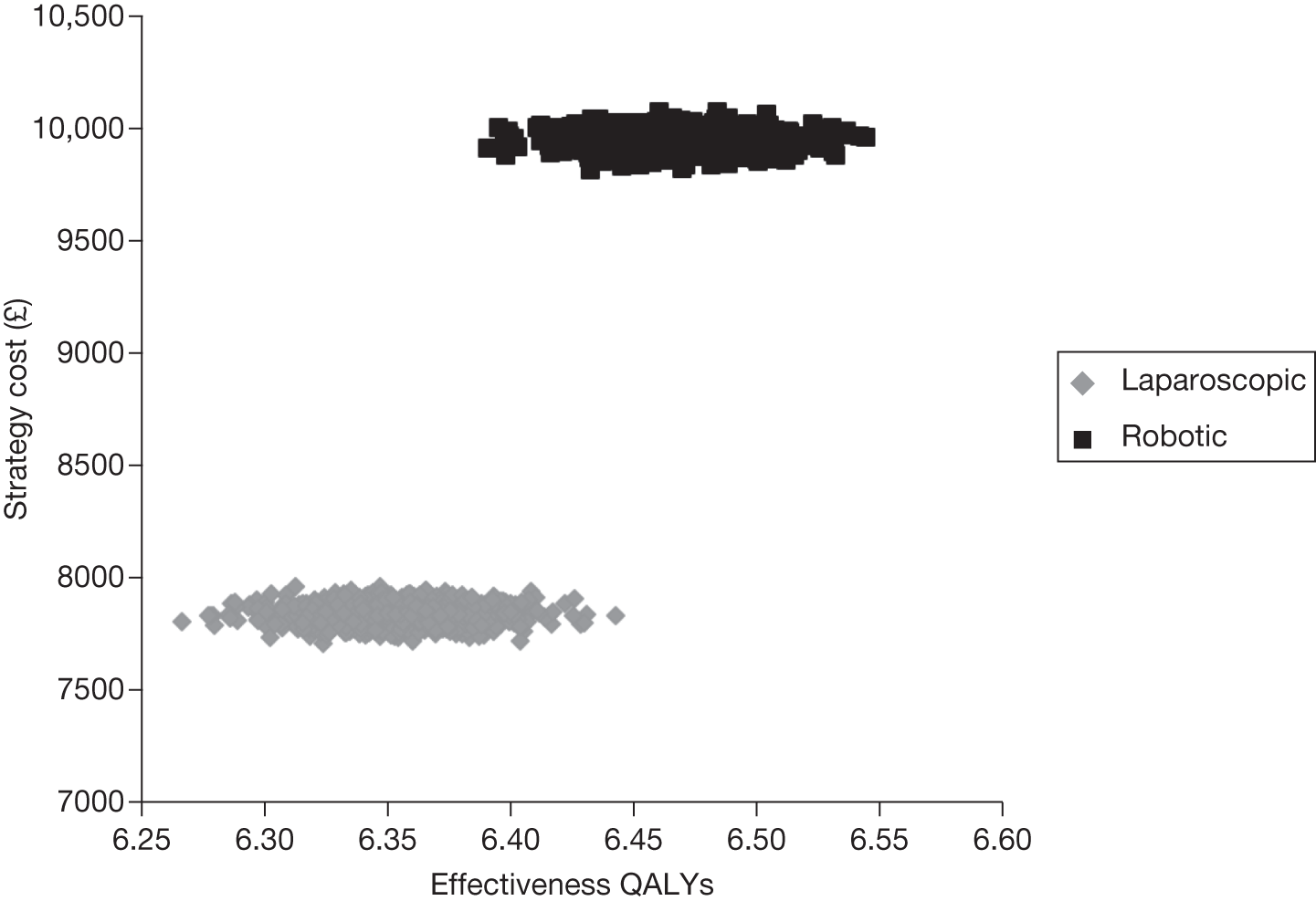

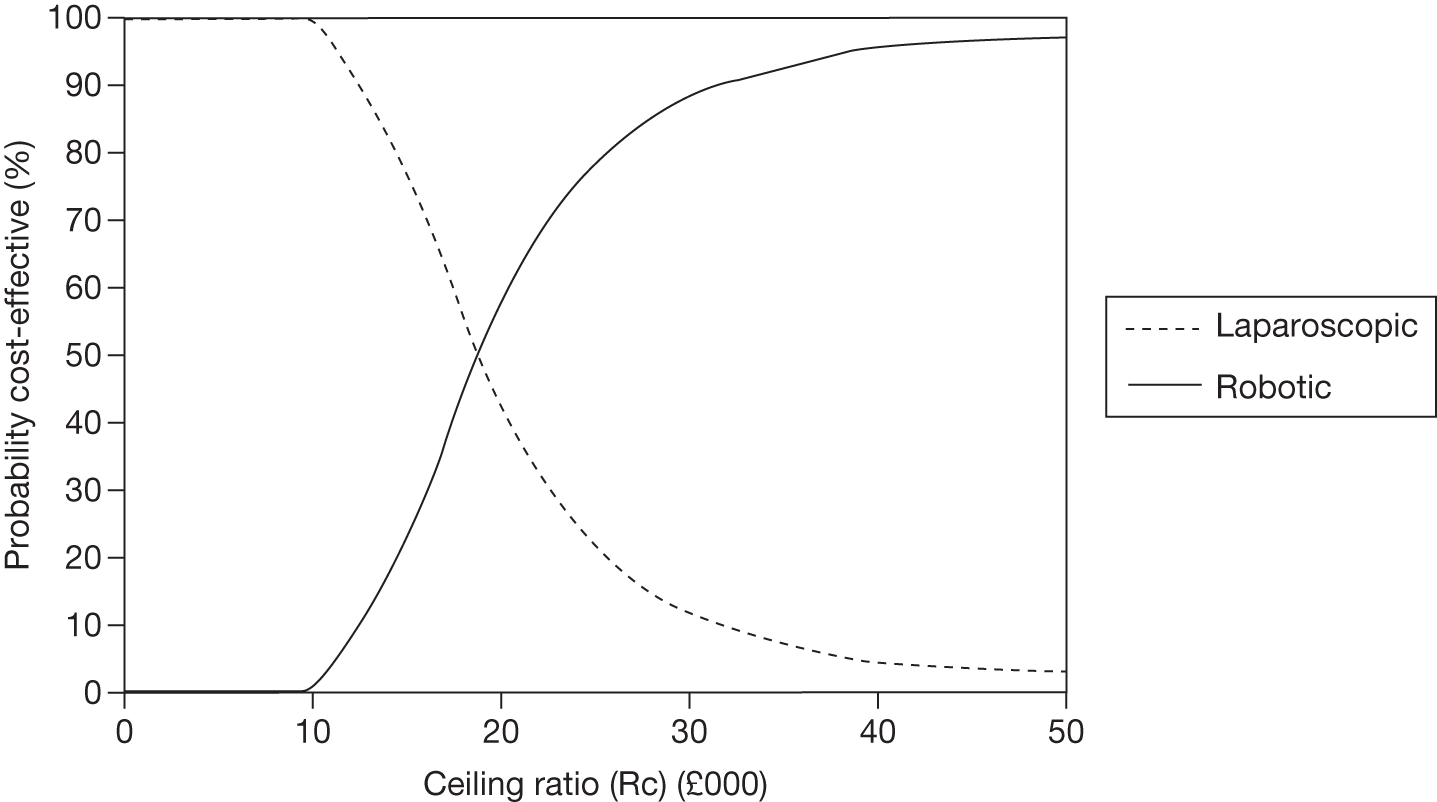

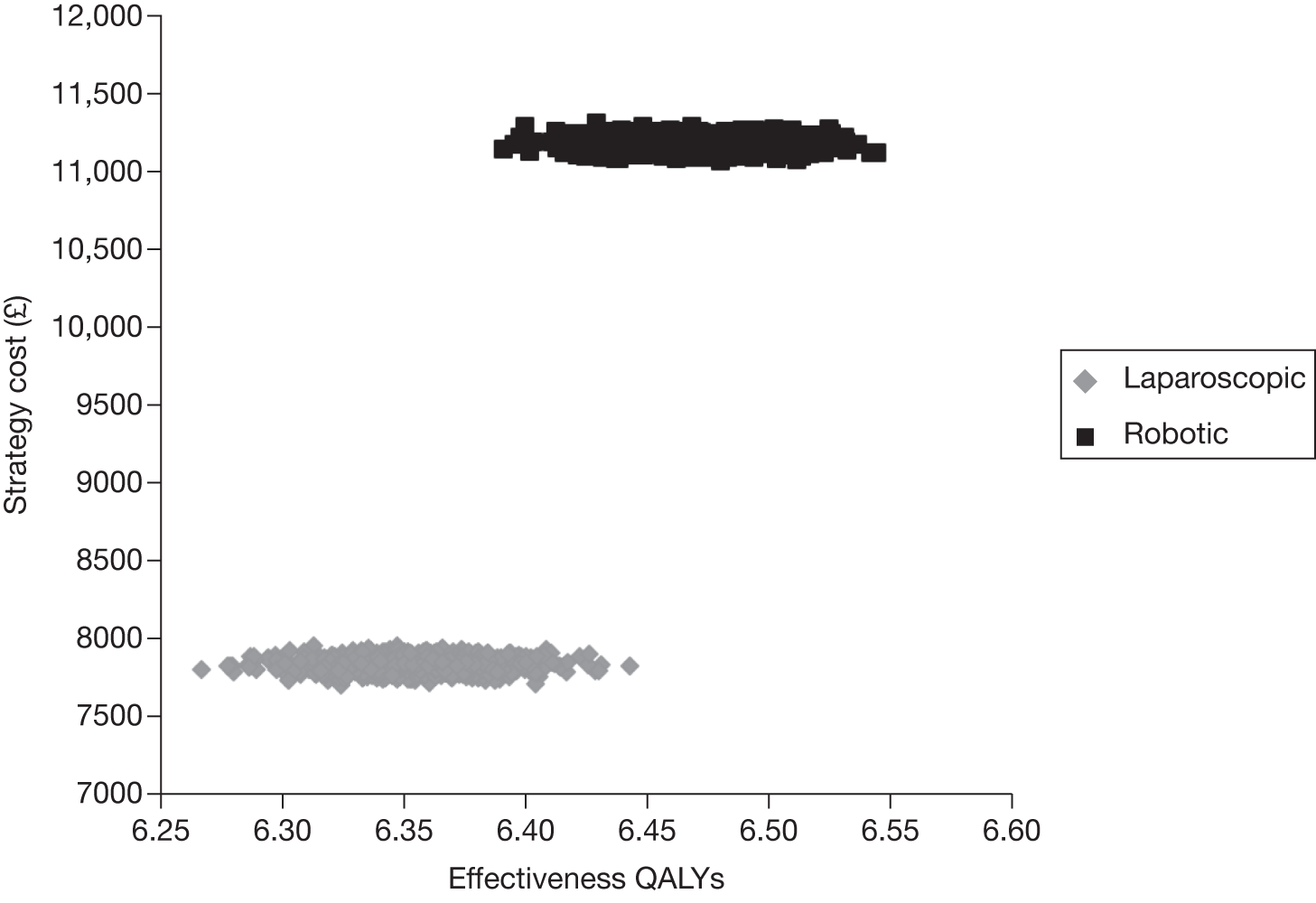

Postoperative incontinence and sexual dysfunction