Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 05/46/01. The contractual start date was in February 2007. The draft report began editorial review in October 2011 and was accepted for publication in March 2012. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design.The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2012. This work was produced by Pickard et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to NETSCC.

2012 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

In 2005, the UK government National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment (NIHR HTA) programme called for a randomised controlled trial (RCT) to give a definitive answer to the question ‘Is there a benefit to using antimicrobial-coated urethral catheters over catheters without antimicrobial coatings in adults requiring catheterisation expected to be of limited duration, and what are the costs?’ This report describes the research (the CATHETER trial) that was subsequently commissioned.

The CATHETER trial was a large pragmatic UK-based multicentre RCT. It aimed to establish whether or not the short-term use of either of two commercially available antimicrobial catheters – an antimicrobial-impregnated urethral catheter (nitrofurazone) or an antiseptic-coated urethral catheter (silver alloy) – in comparison with the use of a standard urethral catheter reduced the incidence of symptomatic catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) up to 6 weeks after catheter insertion, and whether or not these catheters are cost-effective in the context of the UK NHS.

Background

Urethral catheter design

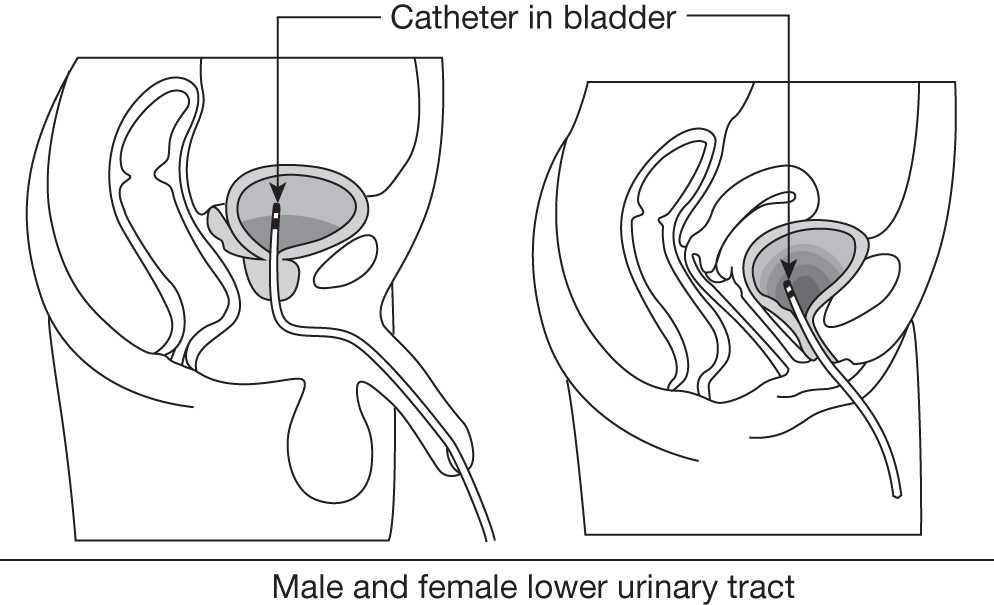

Tubes that can be inserted through the urethra to drain the urinary bladder have been used for centuries. The current standard single-use indwelling catheter design was developed by a urologist, Frederic Foley, in the mid-1930s and marketed by the American company CR Bard Inc. The catheter consists of a drainage channel, open both at the tip positioned in the bladder and at the other end outside the body, which can be connected to a drainage bag. 1 A second channel allows inflation, through a port with a non-return valve next to the drainage outlet, of a 10-ml retention balloon, which is positioned in the bladder and prevents the catheter coming out (Figure 1). The catheter is inserted into the urethra by a trained health professional, using an aseptic technique and lubricating anaesthetic gel, and is left indwelling for as long as is necessary; removal requires deflation of the balloon and simple withdrawal of the catheter. 2

FIGURE 1.

A urethral catheter positioned in the female and male bladder.

The calibre, length, number of channels and material of manufacture of the catheter can all be varied. 3 Natural extruded rubber (latex) continues to be used as the standard material of manufacture, although usually with an added internal and external water-resistant coating of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) to ensure that smoother surfaces are in contact with the urethral mucosa and urine. In 2011, these standard catheters in the UK NHS cost approximately £0.914 (US$1.48; €1.03) each. More recently, catheters made out of moulded plastics, such as silicone, have become available. These have the advantage of consistent smooth surfaces and hypoallergenicity but with higher costs of material and manufacture with a unit cost to the UK NHS in 2011 of £2.074 (US$3.41; €2.37).

Use of urethral catheters in hospitals

Urethral catheters are one of the most commonly applied medical devices, with an estimated 96 million used worldwide in 1999. 5 Within the UK, approximately 15–25% of the 14.5 million patients admitted to NHS hospitals each year will receive catheterisation at some stage during their stay. 6–9 The most common usage is for short term (which we have arbitrarily defined as up to and including 14 days) perioperative bladder drainage during and immediately after surgical or other interventional procedures. This patient group is the primary focus for our trial. 10 Other reasons for urethral catheterisation include prolonged unconsciousness or immobility, monitoring of urine output for management of fluid balance in critically ill patients, acute urinary retention and longer-term care of urinary incontinence. For patients undergoing interventions that require temporary catheterisation, the catheter is generally inserted just prior to starting the procedure and is removed when the patient is sufficiently recovered in terms of bladder function and mobility to safely re-establish normal micturition. The duration of catheterisation for these purposes is highly variable, with a recent study recording a mean [standard deviation (SD)/median] of 3.5 (4.8/2) days. 11 The type of catheter used depends on local purchasing policies and indication for use; for example, a recent audit in a large north-east England acute care hospital, which is likely to be typical of current NHS practice, showed that of the 15% of inpatients with an indwelling catheter, 50% were fitted with a silicone catheter and 36% a PTFE-coated latex catheter; in 14% the catheter type was unknown. 12

Definition of catheter-associated urinary tract infection

Normally, the urethral antimicrobial barrier is closed, preventing infection. The presence of an indwelling urinary catheter disrupts this barrier and allows colonisation of the urethra and subsequently the bladder with commensal and externally acquired organisms. These may result in bacteriuria, symptomatic urinary tract infection (UTI), and, rarely, bloodstream infection; these are collectively referred to as CAUTI. 13,14 For epidemiological and health protection purposes, CAUTI continues to be predominantly defined worldwide through consensus policy documents produced by the US government Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The CDC definition of symptomatic UTI associated with urethral catheterisation at the time of trial inception (2007)15 required the presence of appropriate symptoms together with either microbiological confirmation of significant bacteriuria or that a clinical diagnosis of UTI had been made and treatment instituted (Box 1).

Patient has an indwelling urethral catheter or has had one in the last 7 days before the urine culture

and

patient has at least one of the following signs or symptoms with no other recognised cause: fever (> 38°C), urgency, frequency, dysuria, or suprapubic tenderness

and

patient has a positive urine culture, that is, ≥ 105 microorganisms per cm3 of urine with no more than two species of microorganisms

Criterion 2Patient has an indwelling urethral catheter or has had one in the last 7 days before the urine culture

and

patient has at least two of the following signs or symptoms with no other recognised cause: fever (> 38 °C), urgency, frequency, dysuria or suprapubic tenderness

and

at least one of the following:

-

(a) positive dipstick for leucocyte esterase and/or nitrite

-

(b) pyuria (urine specimen with ≥ 10 WBC/mm3 or ≥ 3 WBC/high-power field of unspun urine)

-

(c) organisms seen on Gram stain of unspun urine

-

(d) at least two urine cultures with repeated isolation of the same uropathogen (Gram-negative bacteria or Staphylococcus saprophyticus) with ≥ 102 colonies/ml in non-voided specimens

-

(e) < 105 colonies/ml of a single uropathogen (Gram-negative bacteria or S. saprophyticus) in a patient being treated with an effective antimicrobial agent for a urinary tract infection

-

(f) physician diagnosis of a urinary tract infection

-

(g) physician institutes appropriate therapy for a urinary tract infection

WBC, white blood cell.

The CDC definitions were updated in 2009 while our trial was in progress. 16 The 2009 specification states that symptomatic infection can be deemed catheter-related only if an indwelling urinary catheter had been present within 48 hours of diagnosis. In addition, there must be evidence of concurrent symptoms and urinary abnormality – either pyuria or bacteriuria. Criteria 2f and 2g concerning physician diagnosis and treatment initiation have been removed in the updated 2009 version. This more restricted definition was designed for reporting of CAUTI from US hospitals as part of national surveillance of health-care-associated infections. It is less appropriate for our pragmatic trial design where we wished to additionally capture the community impact of CAUTI following discharge from hospital and avoid reliance on submission and microbiological analysis of urine specimens. For the primary outcome of the trial we therefore based definition of CAUTI on criterion 2g of the 2004 CDC definition. We do recognise, however, that other definitions of CAUTI have been used in previous trials. We therefore defined microbiologically proven antibiotic-treated UTI and the presence of bacteriuria irrespective of symptoms or treatment as tertiary outcomes.

The impact of catheter-associated urinary tract infection on hospital-based care

It is estimated that individuals with an indwelling catheter are faced with a daily risk of 5% of developing bacteriuria,6 with the proportion affected after 7 and 14 days of indwelling catheterisation being approximately 35% and 70%, respectively. It has been estimated that symptomatic UTI occurs in 20% of patients with bacteriuria,17,18 and while bloodstream infection occurs in < 1%,19,20 it is associated with a high (30%) mortality rate. An important possible consequence of development of CAUTI in an individual is the prolonging of hospital stay. Estimates of the average duration of this extra stay vary from 0.55 to 5 days. 21 CAUTI can also adversely affect health-related quality of life (QoL). 5,22 Both of these factors are important in health economic terms, as they impact on both QoL reduction and additional treatment costs, which, for the UK in 1995, were estimated to amount to a mean [95% confidence interval (CI)] of £1327 (£1140–1465) per episode, which extrapolates to a cost of £125M per annum to the NHS. 21 The presence of bacteriuria in hospital patients with an indwelling catheter is also a potential source of cross-infection, particularly in critical care units, with an estimated risk per episode of 15%. 23 In addition to CAUTI risk, short-term indwelling urethral catheters, although useful to avoid the need for voluntary bladder emptying, also contribute to postoperative discomfort, loss of dignity and delayed discharge from hospital.

The increasing realisation that hospital-acquired infections account for significant morbidity and mortality, together with associated financial and personal costs, led health-care providers to develop strategies to reduce the burden of these events. UTI, in general, is one of the two most common hospital-acquired infections, accounting for between 20% and 40% of cases. 24–26 Between 56% and 80% of these cases can be attributed to the use of indwelling urethral catheters. 20,26,27 CAUTI is therefore a major focus of these preventative strategies. The UK government Department of Health set up the Saving Lives initiative in 2007 and, subsequently, the High Impact Actions for Nursing and Midwifery initiative in 2009, which made reduction in CAUTI a key aim for the NHS through High Impact Action number 6. 28 This was based on guidelines for urethral catheter insertion and subsequent care developed from a systematic review of the evidence. 29

Pathogenesis of catheter-associated urinary tract infections

The development of bacteriuria associated with an indwelling catheter is thought to occur in stages. Microbes gain entry to the normally sterile upper urethra and bladder either by physical introduction during catheter insertion or by migration along the interface between the outer catheter surface and the urethral mucosa, or by upward migration through the internal catheter channel lumen following colonisation of the drainage system. 30 The disruption of the normal filling and emptying cycle of the bladder, and the position of the catheter drainage channel inlet above the catheter balloon resulting in a urine residue in the bladder, prevent physical removal of invading bacteria and so facilitate urinary colonisation. 31 Bacteria then adhere to the urinary tract epithelium or the catheter surface and excite an inflammatory reaction resulting in local and systemic symptoms. 32–34 Bacteria expressing more aggressive virulence factors can migrate further into the upper urinary tract or bloodstream, resulting in worsening sepsis. 35 As the duration of catheterisation increases, bacteria begin to attach to the catheter surfaces, where they multiply and produce polysaccharides, forming a biofilm. 36 Subsequently, mineral precipitation due to increased urinary pH causes catheter blockage and urinary stagnation, further facilitating bacterial growth. 37

Microbiology

Urinary tract infection associated with short-term catheterisation typically involves a single organism, in contrast with long-term catheterisation, where polymicrobial infection is frequent (Table 1). 38 Although a variety of microorganisms may be associated with CAUTI, enteric Gram-negative bacilli are the most frequently isolated. 40 Escherichia coli is the most frequently isolated single species, but other species such as Klebsiella spp., Proteus spp. and Enterobacter spp. are also commonly identified. Enterococci, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Candida spp. are also important causes of CAUTI, particularly in patients within critical care settings. 40 Staphylococci and other Gram-negative bacilli are isolated less frequently. 38

| Pathogen | % CAUTI |

|---|---|

| E. coli | 13 |

| Other Gram-negative bacilli, such as Proteus spp. | 26 |

| Enterococcus spp. and Streptococcus spp. | 26 |

| Candida spp. | 30 |

| Polymicrobial | 5 |

Risk factors for catheter-associated urinary tract infection

A number of patient characteristics are associated with increased risk of CAUTI, including female sex, older age, impaired immunity and illness severity. Care process factors include lack of antibiotic use, longer duration of catheterisation, insertion by poorly trained personnel, and deviation from catheter care protocols. 38

Measures and strategies aimed at reducing catheter-associated urinary tract infections

There are a number of existing recommendations that can reduce the risk of CAUTI (Box 2) and the evidence for each of these has been summarised in recent reviews. 29,38,41–44

-

Reduction in prevalence of catheterisation

-

Reduction in duration of catheterisation

-

Maintenance of closed drainage system

-

On insertion

-

Throughout duration of catheterisation

-

On removal

-

Closed drainage systems

-

Antimicrobial catheters

-

Sealed catheter and drainage systems

-

Catheter valves

A range of UK guideline and best practice documents have encouraged implementation of some of these measures into the NHS with performance monitoring of individual NHS organisations to ensure compliance. These can be broadly divided into eight distinct actions. 29,45–48

-

education of patients, their care-givers and health-care personnel, in terms of hand hygiene and steps in preventing spread of infection

-

assessing the need for catheterisation – to avoid or consider alternatives

-

selection of appropriate type of catheter for individual and clinical context

-

use of strict aseptic technique for catheter insertion

-

use of antibiotic prophylaxis in selected high-risk groups at insertion

-

use of a closed drainage system or catheter valve

-

maintenance of a sterile closed drainage system by obtaining urine specimens from the sampling port, positioning of drainage bag above floor level and below bladder level; frequent emptying of drainage bag to maintain urine flow and prevent reflux; daily washing of meatus

-

reduction in duration of catheterisation: regular review of need for catheterisation and aim for early removal of catheter.

Development of urethral catheters containing antimicrobials

The most researched technical innovation in catheter design over the past 10 years has been the introduction of antimicrobial coatings applied to catheter surfaces or impregnated into the catheter material. Several manufactures have marketed either antimicrobial-impregnated or silver-coated catheters as representing a technology to reduce CAUTI risk and it is this development that is the focus of this trial. 23

Silver

Silver has long been recognised as an antimicrobial agent with demonstrated activity against uropathogens through multiple mechanisms of action. 49 Silver exposure results in limited toxicity to mammalian cells50 and does not appear to induce microbial resistance. 51 Two silver-containing compounds have been used for urethral catheters: silver oxide and silver alloy. Silver oxide-coated catheters showed lack of clinical efficacy in early clinical studies and were superseded by silver alloy-coated urethral catheters, which showed more promise in reducing bacteriuria during catheterisation. 42 The current most widely used device is a hydrogel silver alloy-coated latex catheter marketed by CR Bard Inc., New Jersey, USA, with a 2007 UK NHS cost of £6.46. 52 This catheter has metallic silver in a gold and platinum coating, linked to a latex base on the external surface of the catheter and on the inner luminal surfaces. Silver ions are released into the periurethral space to exert antibacterial activity. The outer hydrogel layer gives the catheter its self-lubricating properties. 53

Antimicrobials

A potentially more direct method of inhibiting CAUTI is to coat or impregnate catheters with antimicrobials active against expected uropathogens. Two antimicrobial agents have been used in clinical studies. Initially, a minocycline/rifampicin mixture was used. 54 Despite promising preliminary results, this specific catheter was not pursued by the development company (Cook Urological). The second antimicrobial agent used for catheter impregnation was nitrofurazone, a topical nitrofuran related to nitrofurantoin, which has a spectrum of activity against many potential uropathogens. Nitrofurazone-impregnated urethral catheters are commercially available and marketed by Rochester Medical Corp in 2007 at a UK NHS cost of £5.29. 4 For this catheter design, nitrofurazone is impregnated into the external and internal luminal surfaces to give an effective concentration of 10.2 µg/mm3. The drug then elutes over time into the external surface–urethral mucosa and internal lumen–urinary boundaries. 55

Evidence for clinical and bacteriological effectiveness

Several systematic reviews have investigated the effectiveness of antimicrobial catheters in reducing CAUTI, including pooled data from up to 13,000 patients. The results of five systematic reviews23,42,56–58 suggest that silver alloy-coated catheters reduce the incidence of bacteriuria in hospitalised patients catheterised for < 2 weeks in comparison with standard catheters. The magnitude of relative risk reduction varied in each of the analyses due to different inclusion criteria, ranging from 16% (95% CI 6% to 47%; absolute risk reduction of 2.0%)58 to 46% (95% CI 33% to 57%; absolute risk reduction of 11.3%). 42 The pooled results for nitrofurazone-impregnated catheters showed a relative risk reduction of up to 48% (95% CI 32% to 66%; absolute risk reduction 8.6%);42 however, the benefit of this type of catheter appeared to be limited to the initial 7 days of catheterisation. It should be noted that these event rates and associated risk reductions apply to CAUTI diagnosis based solely on microbiological identification of bacteriuria without any patient-driven or clinician-defined contribution to the primary outcomes used. Overall, the methodological quality of these reviews was poor to moderate according to the AMSTAR quality assessment tool,59 with the exception of that by Schumm et al. ,42 which was methodologically more robust. [K Schumm (now K Gillies) and T Lam, authors of the updated Cochrane review, were both members of the trial steering and project management groups and are named authors of this monograph.]

In summary, these systematic reviews have concluded that silver alloy-coated and nitrofurazone-impregnated catheters do show promise for the reduction of CAUTI. The reviews did, however, highlight a number of uncertainties regarding the evidence base, in particular the clinical and health economic relevance of the outcome measures used.

Problems with current evidence

Clinical effectiveness

The majority of studies used the presence of bacteriuria on microbiological examination as the outcome measure for a diagnosis of CAUTI without specifying as to whether or not it was symptomatic and without linking to clinical decision to treat with antibiotics. 23,42,58 The lack of use of an outcome explicitly measuring patient benefit hampers interpretation of these data to guide change in practice. In addition, the majority of the individual trials were small and of poor to moderate methodological quality, with wide variations in study design, population studied, and outcome definitions, together with failure to account for confounding factors. 23,42 These aspects may account for the heterogeneity in effect size between individual studies and between meta-analyses. Given these uncertainties, the authors of systematic reviews and clinical practice guidelines emphasised the urgent need for well-designed, adequately powered RCTs using outcome measures of relevance to patients and health-care systems to determine the clinical effectiveness of antimicrobial-coated catheters. 42

Cost-effectiveness

For the background to our planned economic evaluation we performed a systematic literature search that identified 400 economic studies, of which six reports5,60–64 and two systematic reviews65,66 were deemed relevant, although only one was from the perspective of the UK NHS. 61 All reports concerned the comparison between silver alloy-coated and standard catheters, with no data on nitrofurazone-impregnated catheters. The design of the studies varied with two being model-based,5,61 two trial-based,60,62 and two surveillance-based studies. 63,64 These studies were summarised and critically evaluated (see Appendix 1).

A study using a decision model based on a simulated cohort of 1000 hospitalised patients from various specialties in the USA5 found that, based on an assumption that silver alloy-coated catheter use would result in a 47% relative reduction in CAUTI rate, there was a probability of 0.84 that cost savings would accrue with change in practice. A UK NHS-based study61 reported that if routine use of silver alloy-coated catheters was adopted, and assuming an additional cost of £9 per catheter, lower costs of extra hospital stay in medical patients, and a baseline risk for CAUTI of 7.3%, relative risk reductions in CAUTI of 14.6% in catheterised medical patients, and of 11.4% in catheterised surgical patients were required before cost savings could be made.

An economic analysis performed within a large cluster randomised trial involving 28,000 patients62 reported that use of silver alloy-coated catheters could lead to cost reduction of between 3.3% (US$14,456) and 35.5% (US$537,293) in annual institutional CAUTI costs, depending on whether low (US$840) or high (US$4693) estimates of the cost of an individual episode of CAUTI were used. A masked prospective study from a single institution calculated that the annual cost saving from the 41 episodes of CAUTI saved by routine use of silver alloy-coated catheters was US$98,021. 60 A study using surveillance data estimated that use of silver alloy-coated catheters resulted in a decrease in CAUTI incidence from 6.13/1000 catheter-days to 2.16/1000 catheter-days. 63 It was calculated that this would result in annual cost savings for the institution of either US$5811 or US$484,070, depending on whether low (US$700) or high (US$5682) estimates of the cost of an individual episode of CAUTI were used. Finally, estimates of annual, single institutional cost savings associated with routine use of silver alloy-coated catheters ranged from US$12,564 to US$142,315 based on mean (median) cost of a single episode of CAUTI of US$1214 (US$614). 64

The methodological quality of the studies varied and it is difficult to draw general conclusions from them. For example, in the model-based analyses, assumptions concerning baseline rate of CAUTI, the relative risk reduction associated with the intervention, and calculation of cost of CAUTI varied. Overall, these results do illustrate the high degree of uncertainty regarding the cost implications following introduction of antimicrobial catheters, and this predominantly reflects imprecision of the parameter estimates included in the specific models.

Need for a trial

The current frequency of indwelling urethral catheterisation in UK NHS acute hospitals suggests that more than 2 million people are at risk of CAUTI each year. The subsequent costs in terms of patient morbidity and extra care mean that CAUTI continues to be an important health-care problem. Current evidence from meta-analyses of predominantly small explanatory trials shows that antimicrobial catheters do reduce the risk of developing bacteriuria during periods of short-term urethral catheterisation. The logical next step is to demonstrate that this antimicrobial effect translates into clinical benefit for patients in terms of reducing the risk of symptomatic UTI requiring antibiotic treatment, and that it achieves this at an acceptable cost to the NHS. The current evidence base suggested that a pragmatic trial design was required which would be able to provide a definitive result generalisable across the population at risk. From a clinical effectiveness perspective, any trial would also need to measure discomfort and urinary symptom burden suffered by individuals within a specific health-care system, the UK NHS in this instance.

Trial objectives

The following questions were addressed: in hospitalised adults requiring short-term catheterisation what is the clinical benefit and cost-effectiveness of using antimicrobial-impregnated or antiseptic-coated urethral catheters over standard urethral catheters? Two pragmatic comparisons of equal importance were made:

-

antimicrobial-impregnated silicone catheter (nitrofurazone) compared with standard PTFE-coated latex catheter

-

antiseptic-coated hydrogel latex catheter (silver alloy) compared with standard PTFE-coated latex catheter.

The systematic review and meta-analysis of available randomised studies current at the time of inception of the trial suggested that the use of silver alloy catheters resulted in a 40% reduction in risk of catheter-associated symptomatic UTI against standard comparators [RR 0.60 (95% CI 0.50 to 0.73)]. 41 A previous epidemiological review estimated that for people catheterised for up to 10 days the absolute risk (95% CI) of developing bacteriuria was 26% (95% CI 23% to 29%) and of these, around a quarter (6.5% of the total) would develop a symptomatic infection. 67

These summarised data were used to generate the hypothesis to be tested by this trial: use of either silver alloy-coated or nitrofurazone-impregnated catheters reduces the incidence of CAUTI during short-term use by 40% relative to the standard catheter, with an absolute reduction of at least 2.8% (from 7.0% to 4.2%).

Chapter 2 Trial design

The CATHETER trial was a RCT testing three types of short-term urinary catheters in a range of clinical settings in the UK.

Participants

Potential participants were identified according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria detailed below.

Inclusion criteria

Adults (≥ 16 years of age) requiring urethral catheterisation (which was expected to be required for a maximum of 14 days), from selected hospital wards with a high volume of short-term catheterisation.

Exclusion criteria

-

Patients for whom urinary catheterisation was expected to be longer-term (defined as > 14 days).

-

Patients who had urological intervention or instrumentation within the 7 days preceding recruitment (e.g. catheterisation, cystoscopy, prostatic biopsy and nephrostomy insertion).

-

Patients who required non-urethral catheterisation (e.g. suprapubic catheterisation).

-

Patients who had a known allergy to any of the following: latex, silver salts, hydrogel, silicone or nitrofurazone.

-

Any patient who had a microbiologically confirmed symptomatic UTI, at time of randomisation.

-

Patients who were unable to give informed consent or retrospective informed consent.

Participants were equally allocated to one of the three trial interventions using a web- or telephone-based system managed by the Centre for Healthcare Randomised Trials (CHaRT), University of Aberdeen. The inclusion criterion for participation of centres was a high volume of short-term catheterisations, principally as part of elective surgical activity. Twenty-four centres took part in the trial: Aberdeen Royal Infirmary; Royal Blackburn Hospital & Burnley General Hospital; Blackpool Victoria Hospital; Bristol Royal Infirmary; Edinburgh Royal Infirmary; Guy’s Hospital; Harrogate District Hospital; Hillingdon Hospital; Hinchingbrooke Hospital; Raigmore Hospital, Inverness; Liverpool Women’s Hospital; Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals (Newcastle General Hospital, Freeman Hospital, and Royal Victoria Infirmary); Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital; North Tyneside General Hospital; Nottingham City Hospital; Royal Preston Hospital; Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth; Southampton General Hospital; Sunderland Royal Hospital; Musgrove Park Hospital, Taunton; Torbay Hospital and Yeovil District Hospital. The trial recruited from a wide range of clinical settings including cardiovascular, obstetrics and gynaecology, orthopaedics and neurosurgery as detailed in Chapter 4.

Planned trial interventions

There were two experimental groups of equal importance:

-

nitrofurazone-impregnated silicone urethral catheter (N), sourced from Rochester Medical, UK (product reference number 95214)

-

silver alloy-coated latex hydrogel urethral catheter (S), sourced from CR Bard Ltd, UK (product reference number 236514UKS).

The control group was managed with a PTFE-coated latex urethral catheter (P), sourced from CR Bard Ltd, UK (product reference number 1254S14UK).

All catheters used in the trial had an external circumference of 14 mm, termed 14 French (Fr) or 14 Charrière (Ch), with equivalent luminal calibre, length, recommended balloon volume (10 ml), drainage ports and external connection fittings. The silver alloy-coated and control catheters were manufactured from latex, whereas the nitrofurazone catheters were made from silicone. The choice of a PTFE catheter as the ‘standard’ control was based on the results of an audit of short-term catheter use in all secondary care wards in Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals and Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, which confirmed that the PTFE-coated latex urethral catheter was the most commonly used in both hospitals (> 70%).

Proposed duration of intervention

The period of urethral catheterisation was expected to be between 1 and 14 days.

Comparisons

The outcomes were compared with:

-

nitrofurazone-impregnated catheters and standard PTFE catheters

-

silver alloy-coated catheters and standard PTFE catheters.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measure

Incidence of symptomatic UTI treated with antibiotics at any time up to 6 weeks post randomisation (number of participants with at least one occurrence). This was defined as any symptom reported up to 3 days after catheter removal, at 1 or 2 weeks post catheter removal, or at 6 weeks post randomisation combined with a prescription of antibiotics, at any of these times (see Table 4).

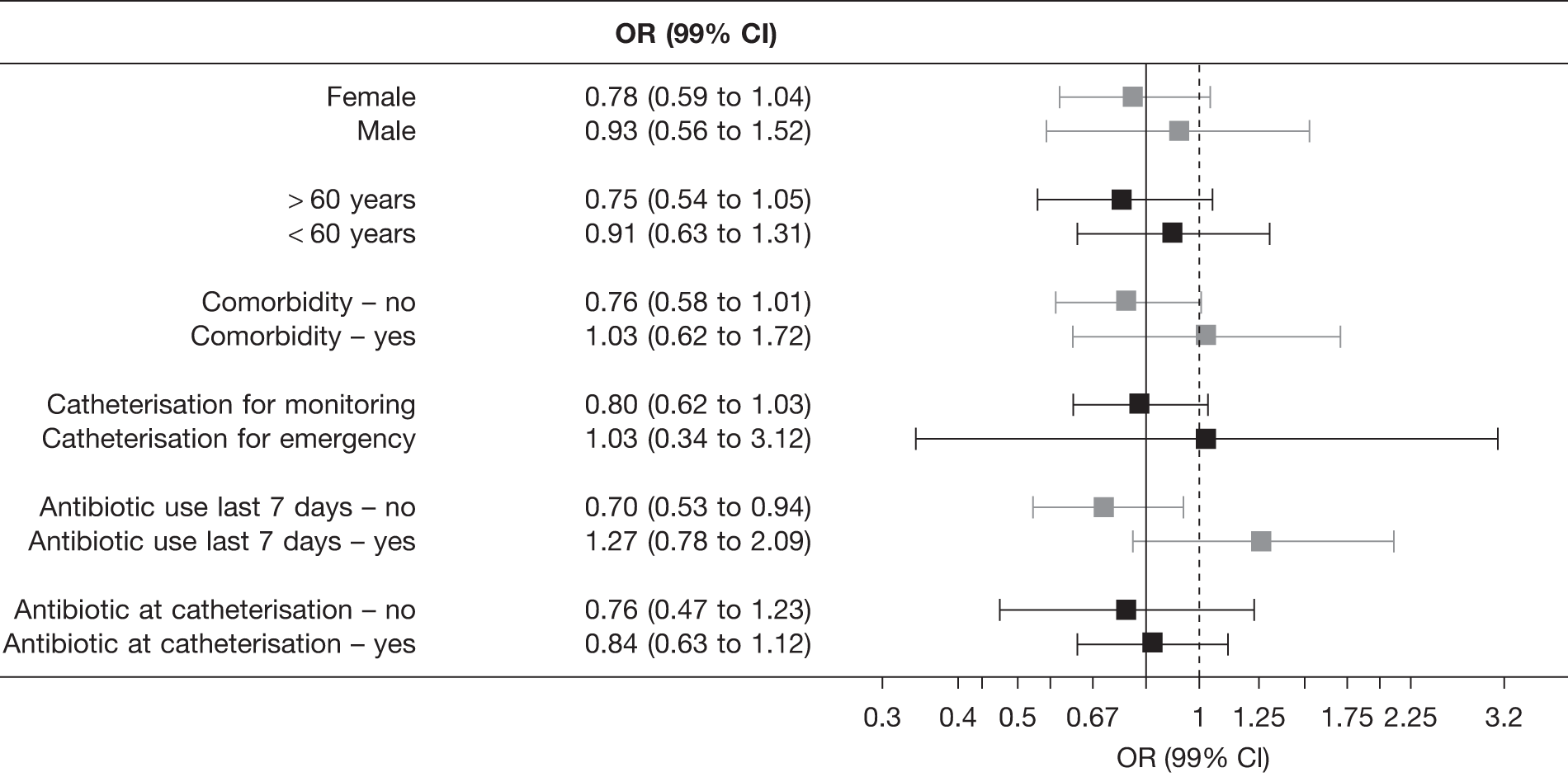

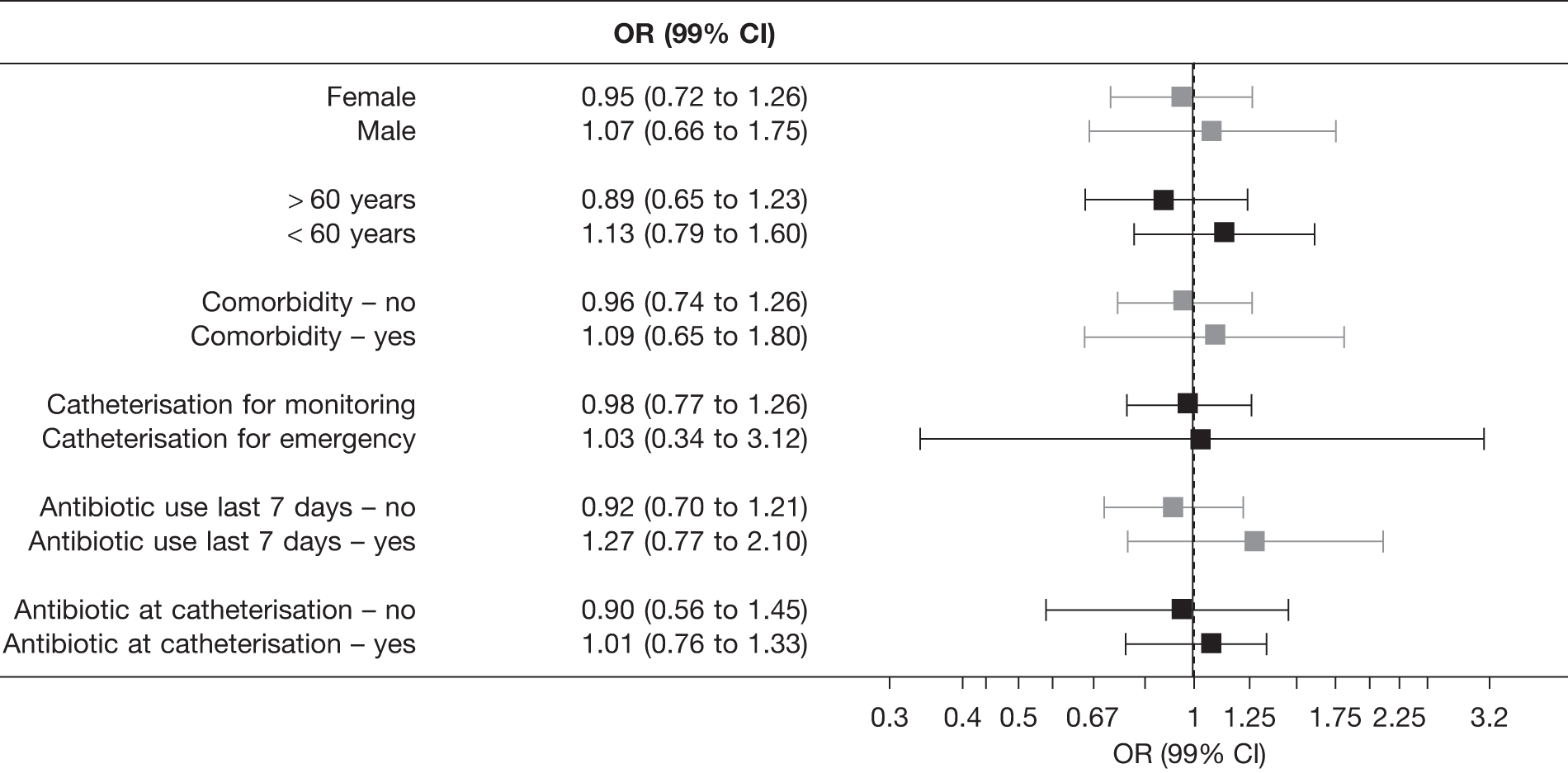

Subgroup analyses of the primary outcome examined possible interaction with participant age, sex, comorbidity, duration of catheterisation, indication for catheterisation and antibiotic use prior to trial enrolment.

Details of which data contributed to the primary outcome are shown later in this chapter (see Table 4), and Chapter 3 (see Important changes to methods after trial commencement) details how the attributes of the primary outcome were strengthened during the course of the trial.

Secondary outcome measures

Clinical

Microbiological confirmation of bacteriuria in addition to primary outcome: this was defined as those who fulfilled the criteria for the primary outcome and in addition had any microbiologically positive result where there were ≥ 104 colony-forming units (CFUs)/ml of no more than two different species of uropathogen. This was assessed by a protocol-mandated urine sample at 3 days after catheter removal.

Economic

-

Incremental cost per infection averted and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained.

-

QALYs estimated from European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) responses.

-

Cost to the NHS and patient of the different catheters.

Tertiary outcome measures

Individual analysis of the components of the definition of the primary and secondary outcomes is shown below.

Patient self-reported symptoms

-

Bacteriuria: any microbiologically positive result (≥ 104 CFU/ml of no more than two different species of uropathogen 3 days after catheter removal).

Other significant clinical events: septicaemia and mortality

-

Adverse effects of catheterisation apart from symptomatic UTI (e.g. urethral discomfort and pain on removal).

-

Antibiotic use following randomisation and indication.

Chapter 3 Methods

Ethics and regulatory approvals

The CATHETER trial and subsequent amendments were reviewed and given a favourable opinion by the North of Scotland Research Ethics Service, Grampian Research Ethics Committee 1 (reference 06/S0801/110) and local Research and Development Departments as appropriate prior to commencement. The trial was conducted according to the principles of Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and was registered and assigned an International Standard Randomised Clinical Trial Number (ISRCTN75198618). The CATHETER trial was not classed as a trial involving an Investigational Medicinal Product or Medical Device and therefore did not come under the EU Clinical Trials Directive.

Participants

Trial flow

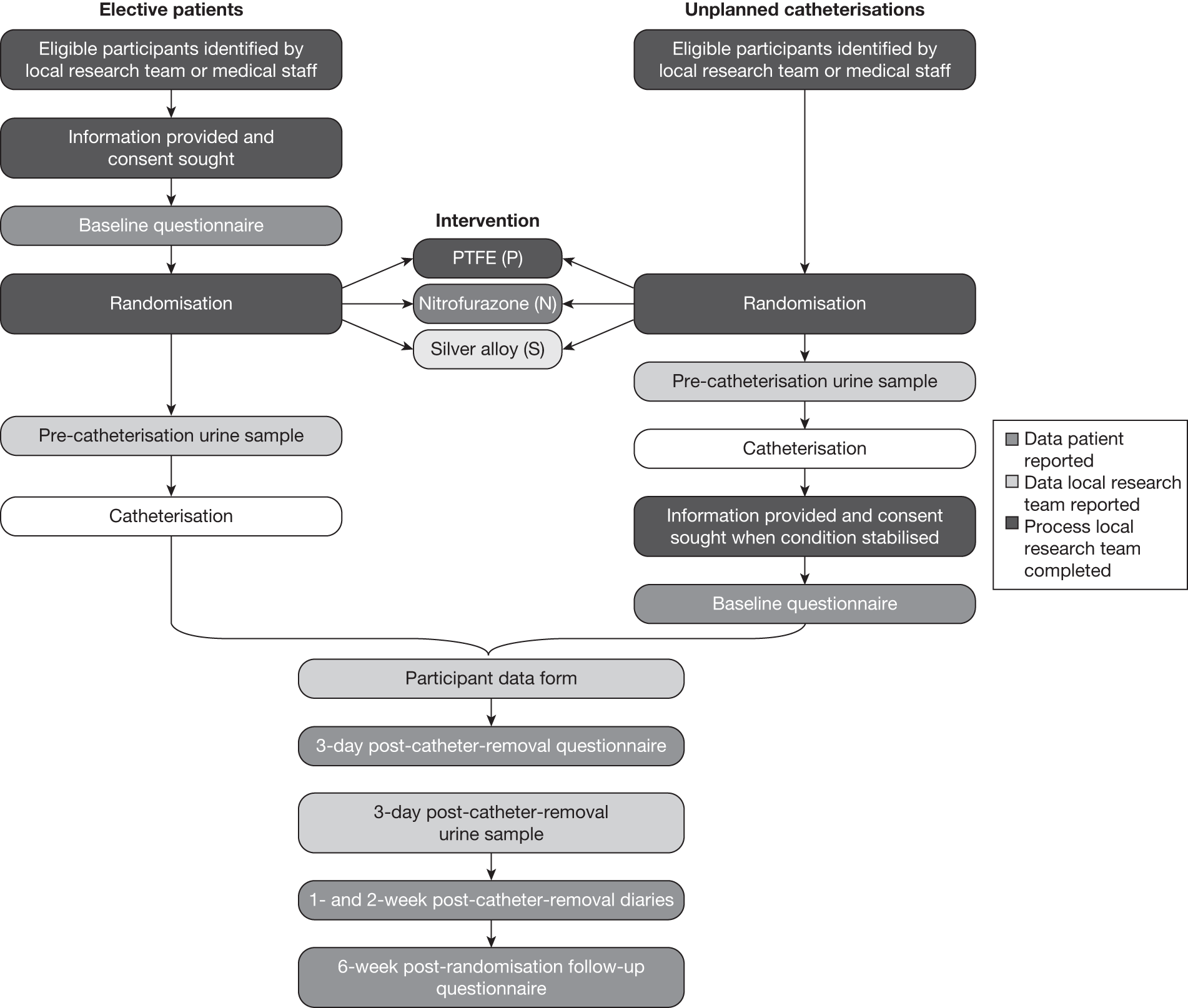

The trial process is detailed in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

The CATHETER trial recruitment processes and procedures.

Identification of patients

Patients were identified either by a member of the local research team or by ward staff. In order to publicise the trial to ward staff and patients, laminated recruitment posters were placed at prominent locations at each site as appropriate.

Recruitment process

Once a patient was identified as being eligible for the trial, he/she was approached by a member of the local research team and given the trial patient information sheet (see Appendix 2). Once the patient had been given time to consider and understand the implications and requirements of the trial, and was happy to take part, he/she was asked to sign the trial consent form (see Appendix 2).

The only exception to this was for patients in unplanned situations (e.g. non-elective admissions and catheterisations). The local research team was made aware of this and, once the patient’s condition had stabilised, he/she was provided with the patient information sheet and given an opportunity to consent retrospectively to take part in the trial; this methodology for recruitment was approved as part of our ethics submission. The decision to catheterise such patients was based solely on clinical need by the local clinical care team. As the antiseptic/antimicrobial-impregnated catheters have previously been reported to lessen the risk of infection compared with the usual standard catheter, the inclusion of these patients in the trial prior to informed consent did not pose a clinical risk, did not lessen their standard of care and was not thought to be otherwise disadvantageous to the participant. Patients who subsequently gave informed consent then completed the normal trial processes. Patients who declined to give informed consent retained the trial catheter as appropriate but no trial data were collected.

Randomisation and allocation to intervention

Eligible participants were randomly allocated 1 : 1 : 1 to one of the three interventions using a computer-generated system that was concealed and remote from the users. The local research team or ward staff performed randomisation using either the automated interactive voice recognition (IVR) telephone randomisation application or the CATHETER trial website (www.charttrials.abdn.ac.uk/catheter), both managed by CHaRT, University of Aberdeen. Both methods of randomisation were available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Compliance with the allocated intervention was recorded. No stratification or minimisation was used.

Blinding of trial interventions

The nitrofurazone catheter was easily identifiable because of its bright-yellow colour. To guard against bias in this respect, although the recruiter knew the allocated intervention, as far as was practicable participants and clinicians making decisions regarding the participant’s catheter care were not told. General practitioners (GPs) were also not informed by trial staff of the catheter type the participant received and therefore were unlikely to be influenced by knowledge of the catheter type. Urine samples taken at baseline and 3 days after catheterisation were analysed by staff at a local laboratory, who were blind to the intervention.

Interventions

The calibre of urinary catheters is measured as the external circumference in millimetres, Fr or Ch gauge, and they can be supplied in differing lengths to suit the male (38–46 cm) or female (24–28 cm) urethra. The uniform calibre and length of the three catheters tested in this trial was specified as 14 Fr and 40 cm, respectively. 68 This was chosen as 14 Fr is the standard calibre for short-term monitoring use. A longer urethral catheter does not cause problems when used in women, but it is not possible to use a shorter catheter in men. They were purchased direct from the manufacturers (CR Bard Ltd UK, Rochester Medical, UK) by the trial office at a unit price fixed in 2007 for the duration of the trial and distributed by the trial office in Aberdeen to the sites as needed. Each catheter had a detachable sticker attached to the outer packaging. This sticker displayed the ‘CATHETER’ logo and either ‘N’, ‘S’ or ‘P’ to denote catheter type (N = nitrofurazone, S = silver, P = PTFE). These stickers were then placed directly on to the participants’ consent forms to permit verification that they were given the catheter to which they were randomised.

Data collection

Questionnaires and diaries were designed to obtain information on symptomatic UTIs as well as other catheter-associated problems (e.g. urethral discomfort), QoL, and any health economic implications, such as costs to the participants and the NHS (see Appendix 3). Clinical data at baseline and throughout the participant’s hospital stay were collected by the local research team (see Appendix 4). An amended version of the UTI Symptom Assessment Questionnaire69 was used to assess UTI symptoms 3 days post catheterisation.

Following informed consent, the participants were asked to complete a baseline questionnaire before randomisation (for participants undergoing unplanned catheterisation, randomisation occurred before informed consent and the baseline questionnaire was then collected after consent was obtained). At baseline, a sterile mid-stream specimen of urine (MSSU) was collected and sent for microbiological analysis, in an accredited laboratory [Clinical Pathology Accreditation UK (CPA)] according to local diagnostic protocols, immediately prior to catheterisation (if one had not been sent within the preceding 48 hours). In situations where this was not possible, a specimen of urine was obtained during the process of catheter insertion, i.e. catheter specimen of urine (CSU) using standard aseptic techniques.

Three days post catheter removal, participant-reported outcome data were recorded by a questionnaire given to the participant by the local research team. When possible, these data were collected while the participant was hospitalised, but in situations where the participant was discharged before this time point, they were asked to complete this at home and return it to the trial office. An MSSU was collected for culture within or at 3 days of catheter removal (analysed in CPA-accredited laboratories according to local diagnostic protocols). For the purposes of the trial we defined a positive urine culture as the presence of at least 104 (CFUs)/ml.

If a clinical diagnosis of symptomatic UTI was made at any stage, including during the period of catheterisation, either a CSU or MSSU was obtained according to normal clinical practice.

Participants were asked to complete diaries at 1 and 2 weeks post catheter removal and at 6 weeks post randomisation. Table 2 describes the outcome data collected.

| Outcome data | Collected by | Baseline | Time post catheter removal | Time post randomisation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 days | 1 week | 2 week | 6 weeks | |||

| Urinary tract symptoms | Participant | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| EQ-5D | Participant | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Antibiotic use | Clinical | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Antibiotic use | Participant | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Antibiotic use | GP | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Use of health services | Participant | ✓ | ||||

Diaries and questionnaires completed prior to hospital discharge were collected by the local recruitment co-ordinator. On discharge, patients were supplied with a pack containing the relevant 1- and 2-week diaries and pre-paid addressed envelopes to return the diaries to the trial office. At 6 weeks post catheterisation, participants were sent the follow-up questionnaire from the trial office and asked to return it using the pre-paid addressed envelope provided. Where necessary, participants who did not return their diaries or questionnaires were telephoned either by the local research co-ordinator or a member of the trial office and asked to return their paperwork. If possible, primary outcome data were collected by phone at this point.

Where the period of catheterisation was longer than initially anticipated (i.e. the catheter was still in place after day 14), trial data were collected as if the catheter had been removed on day 14 (e.g. the 3-day post removal questionnaire was completed 17 days post catheterisation). The date of catheter removal was subsequently recorded. The rationale for this was that it would not be appropriate to exclude data from these participants but it also would not be justified to prolong follow-up for any participant beyond the planned 6 weeks after randomisation. Given the likely small numbers of participants affected, we chose to use the same documentation but we instructed local trial staff to aid participant completion, as the majority of patients affected were likely to remain in hospital during the extended period of catheterisation. This ensured that we captured any UTI event during the 6-week period and ensured effective use of limited resources.

Collection of information to describe urinary tract infections

The primary outcome was derived using information collected from the sources at the time points described in Table 3 and was determined using the algorithm described in Appendix 5.

| 1. | During catheterisation | Ward-based diagnosis from symptoms and observations (supported by microbiology where appropriate) and clinician-directed use of antibiotics for UTI. Data recorded by local research team |

| 2. | Three days post catheter removal | Ward-based diagnosis from symptoms and observations and clinician directed use of antibiotics for UTI. Urine specimen for microbiological confirmation of bacteriuria |

| Data recorded by local research team and participant | ||

| 3. | One and two weeks post catheter removal | Participant diary collected data on symptoms, clinician contact and antibiotic usage for UTI. Where antibiotic use was documented this was confirmed as being for UTI by the participant’s GP |

| 4. | Six weeks post randomisation | Symptoms, clinician contact, antibiotic usage for UTI and hospital readmissions were reported by the participants. Where antibiotic use was documented this was confirmed as being for UTI by the participant’s GP |

Participants met the definition of the primary outcome if they fulfilled the criteria described in Table 4. This is expanded in Appendix 5.

| Outcome measurement | Method of collection |

|---|---|

| Received antibiotics for UTI during catheterisation with associated symptoms | Recorded from clinical records |

| Participants given an antibiotic for a symptomatic UTI | Recorded at 3 days post catheterisation from clinical records and participant report |

| Participant-reported symptomatic UTI at 1 or 2 weeks post catheter removal or 6 weeks post randomisation with GP confirmation of antibiotic prescription for UTI | Recorded up to 6 weeks post randomisation from participant diaries and questionnaires and GP records |

General practitioner confirmation of antibiotic prescription

Where participants reported antibiotic use at 1, 2 or 6 weeks or failed to return any trial paperwork at these time points, confirmation of these details, or a request for this information, was sent to the participant’s GP. This included a brief letter explaining the need for this information and a table for the GP to complete asking whether or not the participant had presented to them with a UTI during the period of their participation in the trial, and if so whether or not they had given the participant a prescription for antibiotics for UTI (see Appendix 4).

Change of status/withdrawal

The status of some participants changed during the trial for a number of reasons. These included post-randomisation exclusions; participants deciding they no longer wished to be a part of the trial; and decisions by medical staff that it was not appropriate for the participant to remain in the trial.

Participants were free to decline further follow-up from the trial at any point without giving a reason. Participants could also be withdrawn for medical reasons. In such cases, primary outcome data were still collected if the participant consented to the use of their relevant hospital and general practice records.

In addition, some patients were classed as post-randomisation exclusions for one of the following reasons:

-

patients who were randomised but received a suprapubic catheter

-

patients who were randomised but did not have any catheter inserted

-

emergency patients who were randomised but subsequently declined to participate in the trial.

The justification for excluding participants who did not receive a urethral catheter from the analysis was that they did not fulfil intention-to-treat criteria, as the ultimate decision-maker, the responsible clinician in the operating suite, determined that an alternative urine drainage option was preferred.

Data management

Data collected at site were input into the electronic CATHETER database through the trial web portal (www.charttrials.abdn.ac.uk/catheter) by the local research team; those received by the trial office were entered by the trial office staff.

At the end of the trial, a random 10% sample of all of the trial data were re-entered by the trial office to verify correct data input. Any discrepancies between originally entered data and re-entered data were reviewed and checked against the original paper copy by an individual who was not involved in entering either data set. Incorrectly entered data were corrected at the time of checking. An initial data entry error rate of > 5% would have triggered a requirement to re-enter the entire data set from that questionnaire. This was not found to be necessary.

Trial oversight committees

A Trial Steering Committee (TSC), consisting of an independent chairperson, two further independent members and the grant holders, provided oversight of the trial. The TSC met six times over the course of the trial (at least annually).

The independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) met early in the trial and agreed its terms of reference and other procedures. They then met six times over the course of the trial (at least annually). The DMC reported any recommendations to the chairperson of the TSC.

Important changes to methods after trial commencement

Primary outcome

In response to recommendations from the DMC in June 2008, the TSC reviewed the method of recording the definition of the primary outcome to ensure that the trial was reliably capturing all events that determined catheter-associated symptomatic UTI. Over the course of the third and fourth meetings (dates 8 June 2009 and 23 November 2009) the DMC commented on a higher than anticipated proportion of trial participants with a positive primary outcome. Further investigation showed that this was due to high levels of urinary tract symptoms reported by the trial participants at 3 days, perhaps due to irritation from the recently removed urethral catheter, together with uncertainty regarding the purpose of prescribed antibiotics. As a result, at this time point (3 days post catheter removal) description and recording of the events needed to qualify as symptomatic UTI were strengthened in the case report form to explicitly include a record of appropriate antibiotic treatment for patient reported symptomatic UTI. Although it was felt that this had been implicit in the original wording, an amendment was made stating this to clearly qualify which events define the primary outcome.

Sample size calculation

The original sample size calculation for the trial was revised upwards. Given that the primary outcome for the trial was patient-reported symptomatic UTI supported by antibiotic treatment rather than bacteriuria or microbiology confirmed UTI, it became evident during the trial that the actual incidence of symptomatic UTIs without the requirement for microbiologically proven bacteriuria was greater than originally anticipated. This prompted a reassessment of the initial sample size calculation. Both the original and revised calculations are outlined below.

Original proposed size of the trial

Based on the Cochrane review and other data,5,41,67 the anticipated incidence of UTI in the standard control group was 7.0% and a reasonable estimate of the effect of the intervention catheters would reduce this to 4.2% [absolute risk reduction 2.8%, relative risk (RR) 0.60, odds ratio (OR) 0.58]. We estimated that based on a stricter alpha error rate of 0.025 (to correct for the two principal comparisons) and 90% power, 1750 participants were required for each arm of the trial. We inflated this to adjust for an anticipated 8.0% post-randomisation exclusion rate resulting in 1900 per arm, or 5700 total randomised.

Revised sample size calculation

Ongoing monitoring of the overall rate of the primary outcome in the trial indicated that the original estimate of the incidence of symptomatic UTI supported by antibiotic treatment was an underestimate and consequently this was revised upwards from 7% to 11% in the PTFE control group. The effect size was revised in light of this to reduce the primary outcome to 7.7% in the primary catheter groups (absolute risk reduction 3.3%, RR 0.7, OR 0.67). Recalculating the sample size based on these new parameters resulted in approximately 2000 required for each arm of the trial. Furthermore, the empirical rate of post-randomisation exclusion was also higher than originally estimated and therefore the final number required was inflated to compensate for an estimated 15% post-randomisation exclusion rate, resulting in a total required sample size of approximately 7035.

Recruitment from specific clinical areas

As described in the trial protocol, we originally intended to have a wider recruitment area encompassing patients admitted to hospital for both elective and emergency reasons, including those admitted to or transferred to critical care areas who required unplanned catheterisation. Early in the trial it was established that recruitment and pre-consent randomisation of participants undergoing unplanned catheterisation was resource intensive in terms of NHS clinical and research staff activity, and that there was a high rate of subsequent refusal of consent, which raised ethical concerns. In discussion with the trial management committees, it was decided to concentrate our finite resources on recruitment of patients admitted for elective interventions associated with planned urethral catheterisation. To ensure generalisability we proceeded to establish a large number of sites including all of the relevant clinical specialties.

Statistical methods/trial analysis

All analyses were carried out using SAS software version 9.2 for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), unless otherwise stated. The principal comparisons within the trial were between those allocated to (1) the nitrofurazone and PTFE catheters and (2) silver alloy and PTFE catheters. All UTI outcomes were also summarised as the absolute risk difference expressed as a percentage. The primary and secondary outcomes were analysed using generalised linear models. All estimates are presented with 97.5% CIs (to reflect the stricter level of alpha due to multiple comparisons used in sample size calculations). Estimates from marginal models (unadjusted) and conditional models are presented adjusted for:

-

age (< 60 years, ≥ 60 years)

-

sex

-

comorbidity (pre-existing urological disease, diabetes, immune suppression)

-

indication for catheterisation (incontinence, urinary retention and monitoring purpose)

-

antibiotic use prior to enrolment.

All outcomes related to UTI were based on the intention-to-treat principle, with all included participants analysed as randomised, regardless of the catheter received. All participants were assumed to have not had a UTI unless indicated otherwise (see algorithm for primary outcome).

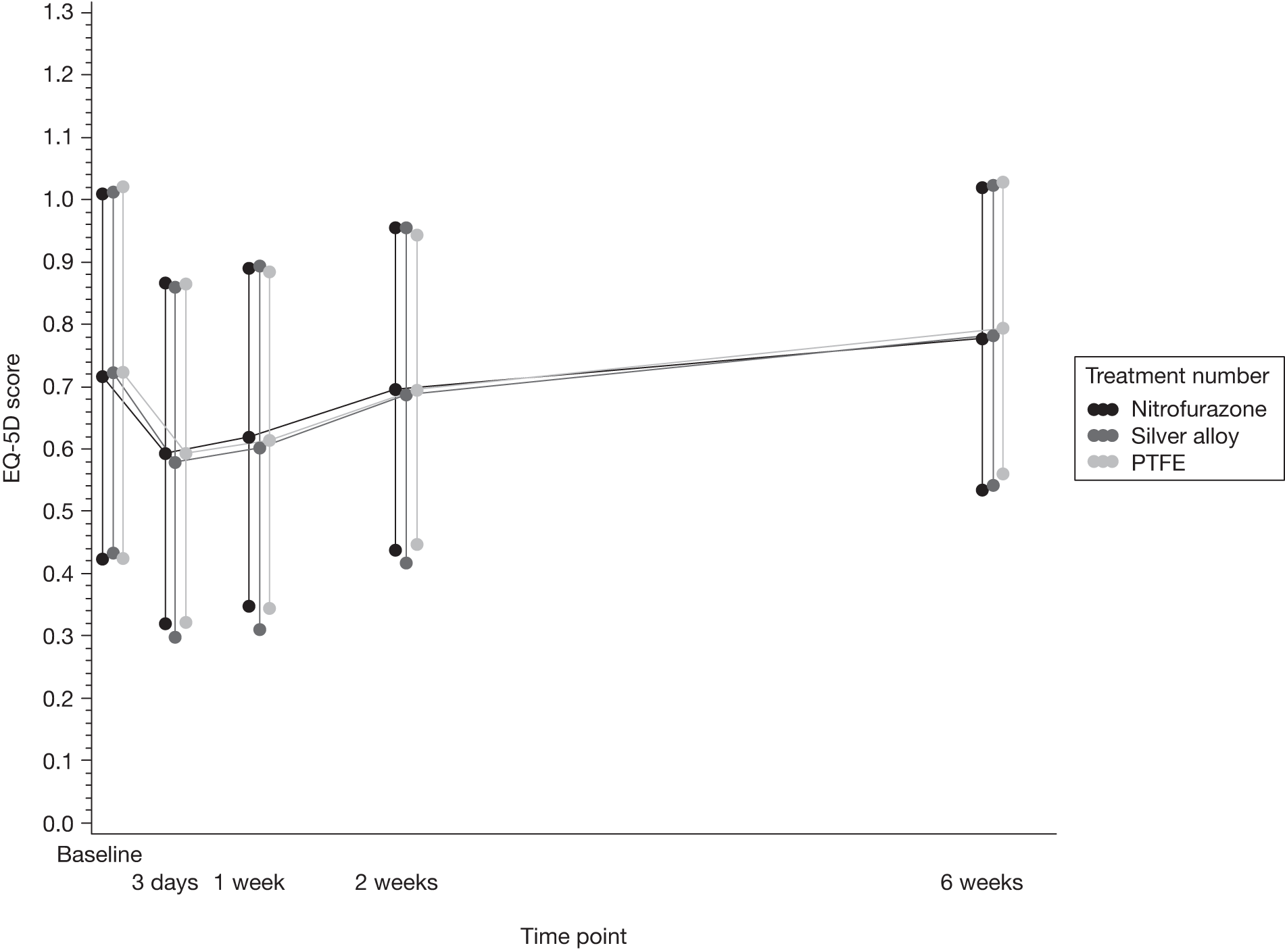

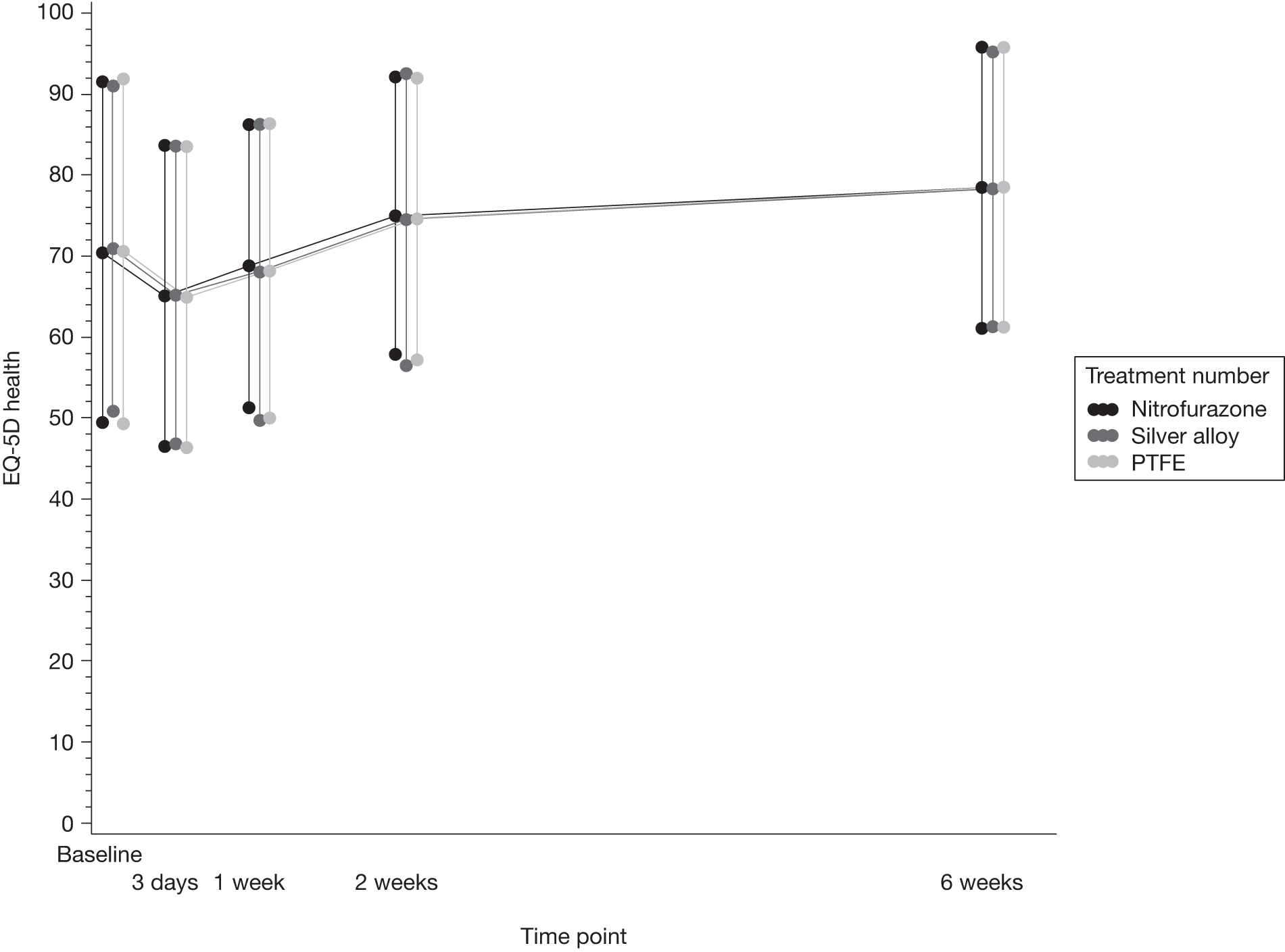

Quality-of-life data were analysed in a repeated measures framework using SAS PROC MIXED. An AR(1) autoregressive correlation structure was used. QoL data are presented as means and SDs at each time point, and presented in a graph for ease of comparison over time. Analysis was by complete case intention to treat; sensitivity to missing data was explored using PROC MI under the missing-at-random assumption.

All outcomes related to symptoms and catheter-associated discomfort were analysed using ordered logit models (also called proportional odds or ordered logistic regression) that were suitable for ordinal outcome data implemented in Stata 11.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Results are presented as ORs (and 97.5% CIs). To aid interpretation the difference in predicted probabilities (and 97.5% CIs) of being in a particular category between intervention and control catheters are also presented. 70 Analysis was complete case intention-to-treat and a sensitivity analysis using multiple imputations (under the assumption of missing at random) was carried out for each of these outcomes.

Timing and frequency of analyses

The data monitoring committee considered confidential interim inspection of the data on five occasions. At the first meeting, the DMC recommended refining the definition of algorithm used to define the primary outcome; this was due to a higher than anticipated rate of UTI (for further details, see Chapter 3, Important changes to methods after trial commencement).

Planned secondary subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses

Subgroup analyses of the primary outcome examined possible effect modification of the following:

-

age (< 60 years, ≥ 60 years)

-

sex

-

comorbidity (pre-existing urological disease, diabetes, immune suppression)

-

indication for catheterisation (incontinence, urine retention and monitoring purpose)

-

antibiotic use prior to randomisation

-

duration of catheterisation.

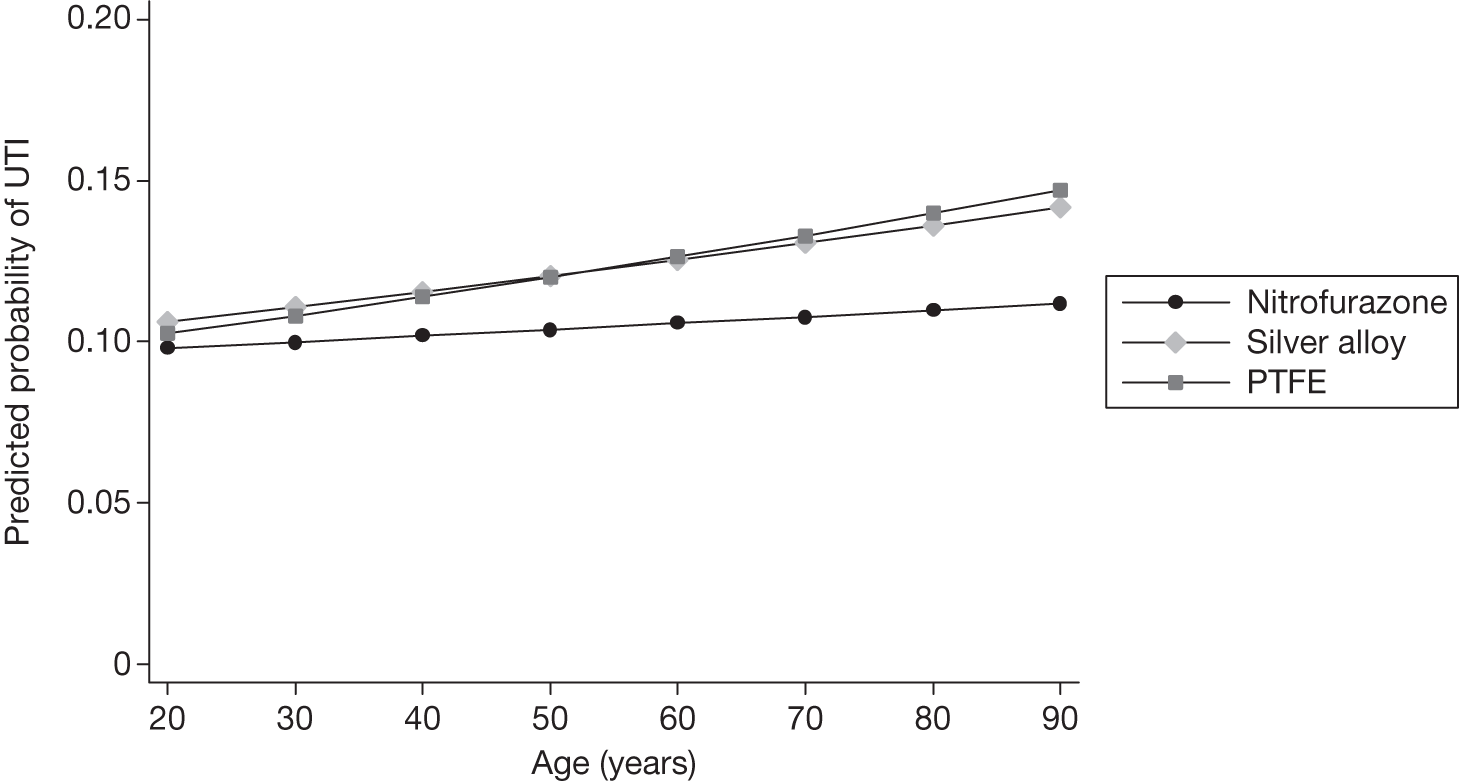

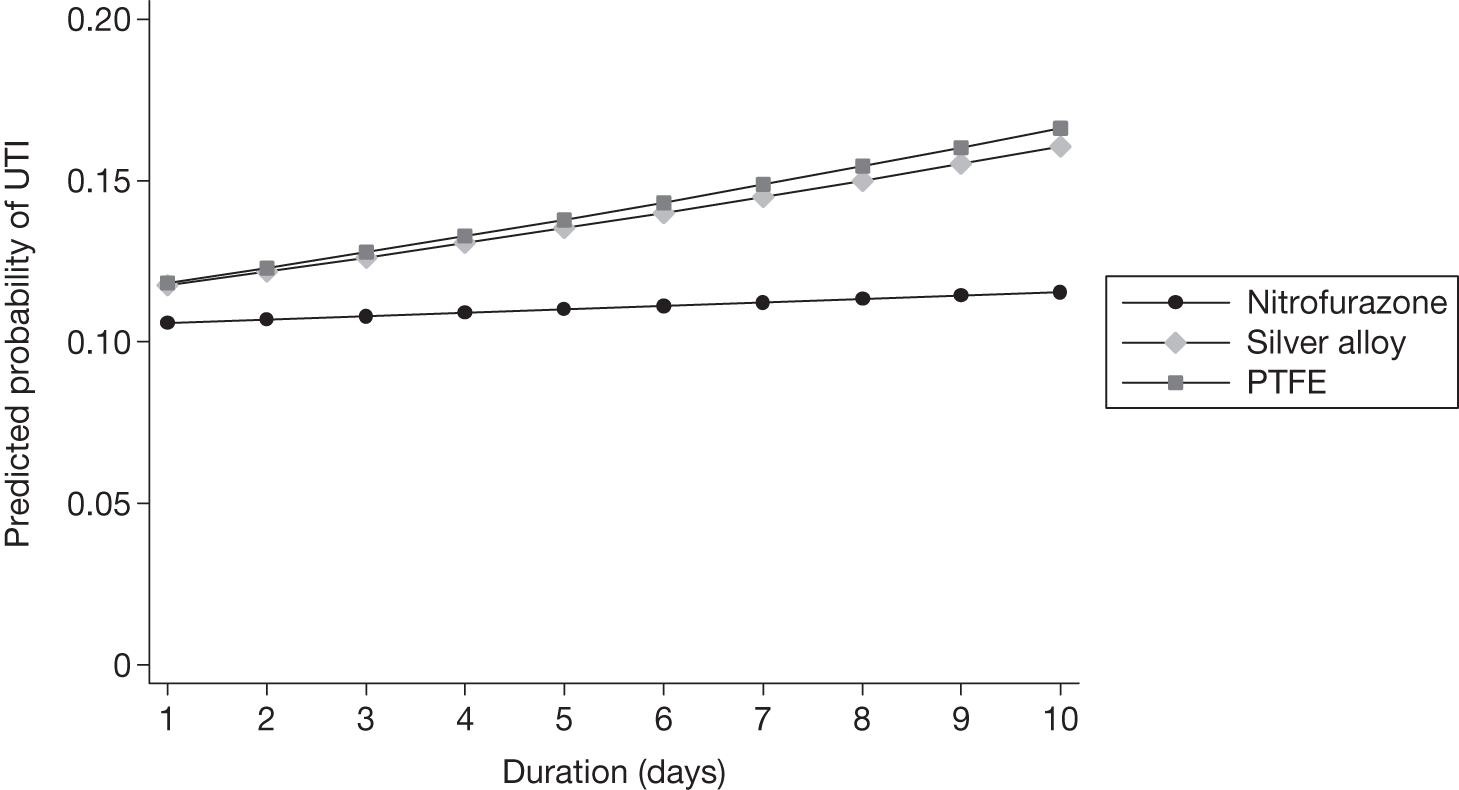

Modification of the treatment effect was explored using tests for interaction (all at stricter levels of significance; p < 0.01), and results are presented as forest plots with 99% CIs to reflect the exploratory nature of these analyses. Two further post hoc effect modification sensitivity analyses were carried out treating (1) age and (2) duration of catheterisation as continuous variable interactions with treatment allocation to explore any potential differential effects across catheters. All subgroup and treatment effect modification analyses were analysed using the same generalised linear modelling framework as the main analyses. A further sensitivity analysis was carried out to assess any potential impact of centre on the precision of estimates of treatment effects by including a random effect for centre in the model for the primary outcome.

Economics methods

Introduction

Two types of economic analyses were planned. The first was a ‘within-trial’, economic evaluation undertaken using data collected as part of the trial, and the second was based on a modelling exercise aiming to address the uncertainty (background noise) introduced by the heterogeneity in terms of underlying illness and type of operative procedure undergone by trial participants. The question addressed by both economic evaluations was: what is the cost-effectiveness of antimicrobial-impregnated (nitrofurazone) or antiseptic-coated (silver alloy) catheter versus standard PTFE-coated catheter? The methods and analysis for both the within-trial analysis and the modelling analysis are described below. The perspective of study was that of the UK’s NHS.

Within-trial analysis

Measurement of resource utilisation

The use of health services was recorded prospectively for each participant. Resource utilisation data were collected using the questionnaires at baseline, 3 days after catheter removal, 1 week and 2 weeks after catheter removal, and at 6 weeks post randomisation. As noted earlier the questionnaires were targeted at identifying symptomatic antibiotic-treated UTI as well as other catheter-associated problems (e.g. urethral discomfort), QoL, and any health economic implications such as costs to the NHS. The areas of resource considered are outlined in Table 5 and are grouped into four broad areas:

-

intervention resource use

-

other secondary care resource use

-

primary care resource use

-

resource use incurred by the patient.

| Area of resource use | Source | Reported outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention | ||

| Antimicrobial impregnated (nitrofurazone) | CRF | No. used |

| Antiseptic coated (silver alloy) | CRF | No. used |

| PTFE | CRF | No. used |

| Days in hospital (by level of care) | ||

| Medical ward | CRF | No. of days |

| Urology | CRF | No. of days |

| Cardiothoracic | CRF | No. of days |

| General surgery | CRF | No. of days |

| Obstetrics and gynaecology | CRF | No. of days |

| Ear, nose and throat | CRF | No. of days |

| Orthopaedics | CRF | No. of days |

| Vascular | CRF | No. of days |

| Gastroenterology | CRF | No. of days |

| Other costs | ||

| Antibiotics prescribed after discharge | PQ | No. and type |

| Outpatient visits | PQ | No. |

| Practice nurse home and surgery visits | PQ | No. |

| Practice doctor home and surgery visits | PQ | No. |

| Other health-care professional visits | PQ | No. and type |

The number and type of catheter used were collected from the case report form. Use of secondary care services following the period of catheterisation was collected using the 6-week participant follow-up questionnaire. This recorded information on outpatient visits and readmissions to hospital for a UTI during the 6-week period after randomisation. The use of primary care services including contacts with primary care practitioners (e.g. GPs and practice nurses) and prescription medications were collected using the health-care utilisation questionnaires administered at 1 and 2 weeks after catheter removal and at 6 weeks after randomisation.

Derivation of costs

Unit costs were based on study-specific estimates and data from standard sources. A summary of unit costs is presented in Table 6. Unit costs for the interventions were obtained from the manufacturers of the products through personal communication or from published price lists. The unit cost per day in hospital for each level of care was obtained from Information Services Division (ISD) of NHS Scotland. 71 This source does not give a cost per inpatient-day for all hospital services but rather presents data as a total cost per average case for each clinical specialty along with an average length of stay. We used these data to calculate ‘cost per day’ for each level of care. The total cost per case for each specialty provided by ISD includes both theatre costs and allocated costs (representing the costs of running the hospital). The former were omitted from our analyses, as we were not concerned with the costs of surgery undergone by trial participants (apart from the catheter unit cost) and we omitted the infrastructure costs, as they represent a fixed cost that will not vary with length of stay. The unit cost per case with these two elements removed was divided by the trial estimate of average length of stay for each specialty to give a cost per day. For example, the total gross cost per case in urology given by ISD was £2019 and the direct theatre cost per case was £479 (22%). We estimated the unit cost per stay by taking the theatre cost per case away from the unit cost per stay and then removing the allocated costs. This figure was then divided by the trial estimate of average length of stay for this specialty (3.3 days) to give the trial estimate of cost per day of £321 for participants treated under this specialty group.

| Area of resource use | Unit cost (£ sterling) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention | ||

| Antimicrobial impregnated (nitrofurazone) | 5.29 | Personal communication with manufacturer (cost includes VAT). This was the price to the NHS of the catheter at trial commencement (2007) |

| Antiseptic impregnated (silver alloy) | 6.46 | Personal communication with manufacturer (cost includes VAT). This was the price to the NHS of the catheter at trial commencement (2007) |

| PTFE | 0.86 | This was the price to the NHS of the catheter at trial commencement (2007) |

| Cost per day in hospital (by level of care) | ||

| Medical ward | 265 | Based on specialty group costs, inpatients in medical ward (excluding long stay) (ISD) |

| Neurology | 498 | Based on specialty group costs, inpatients in neurology department (excluding long stay) (ISD) |

| Urology | 321 | Based on specialty group costs, inpatients in urology department (excluding long stay) (ISD) |

| Cardiothoracic department | 530 | Based on specialty group costs, inpatients in cardiothoracic department (excluding long stay) (ISD) |

| General surgery | 331 | Based on specialty group costs, inpatients in general surgery department (excluding long stay) (ISD) |

| Obstetrics and gynaecology | 337 | Based on specialty group costs, inpatients in obstetrics and gynaecology department (excluding long stay) (ISD) |

| ENT | 492 | Based on specialty group costs, inpatients in ENT department (excluding long stay) (ISD) |

| Orthopaedics department | 321 | Based on specialty group costs, inpatients in orthopaedics department (excluding long stay) (ISD) |

| Vascular | 305 | Based on specialty group costs, inpatients in vascular department (excluding long stay) (ISD) |

| Gastroenterology | 341 | Based on specialty group costs, inpatients in gastroenterology department (excluding long stay) (ISD) |

| Other costs | ||

| Antibiotics | 5.41 | Cost of antibiotic based on the average cost of UTI prescriptions in Scotland (ISD) |

| Outpatient visit | 94 | Based on the total average total direct cost per attendance of all specialties outpatient consultant-led clinics (ISD) |

| Practice nurse visit | 10 | Based on cost per consultation (PSSRU) |

| GP visit | 36 | Based on per surgery consultation lasting average of 11.7 minutes (PSSRU) |

| Personal costs incurred by participants for visits to other health-care professionals | Various | As provided by the participants |

Total patient NHS costs were derived by combining information on resource use with information on the unit costs of those resources. For each area of resource use, estimates of resource utilisation were combined with unit costs to derive total costs for each item of resource use for each patient. Averages were then calculated to give estimates for each item of resource use. The patient-level costs for each item of resource were summed to produce a total cost for each patient and allow an estimate of average total cost per patient to be calculated.

Effectiveness outcomes for cost-effectiveness analysis

Effectiveness was measured in terms of number of catheter-associated symptomatic UTIs treated with antibiotics up to 6 weeks after randomisation (trial primary outcome) and QALYs at 6 weeks.

Quality-adjusted life-years were derived using data from participant completion of the EQ-5D, a generic health status measurement tool, at baseline, 3 days after catheter removal, 1 and 2 weeks after catheter removal and at 6 weeks post randomisation as part of the main study questionnaires. The EQ-5D measure divides health status into five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression). Each of these dimensions can have three levels, giving 243 possible health states. 72 These responses were converted into health–state utilities using UK population tariffs. 73 The utility scores were used to estimate the mean QALY score for each of the three trial groups. The estimation of QALYs took into account the death of any study participants with allocation of a utility score of zero from date of death to the date of 6 weeks after randomisation for participants who died during their involvement in the trial. QALYs were estimated using linear extrapolation between the QALY scores at baseline and all available EQ-5D data.

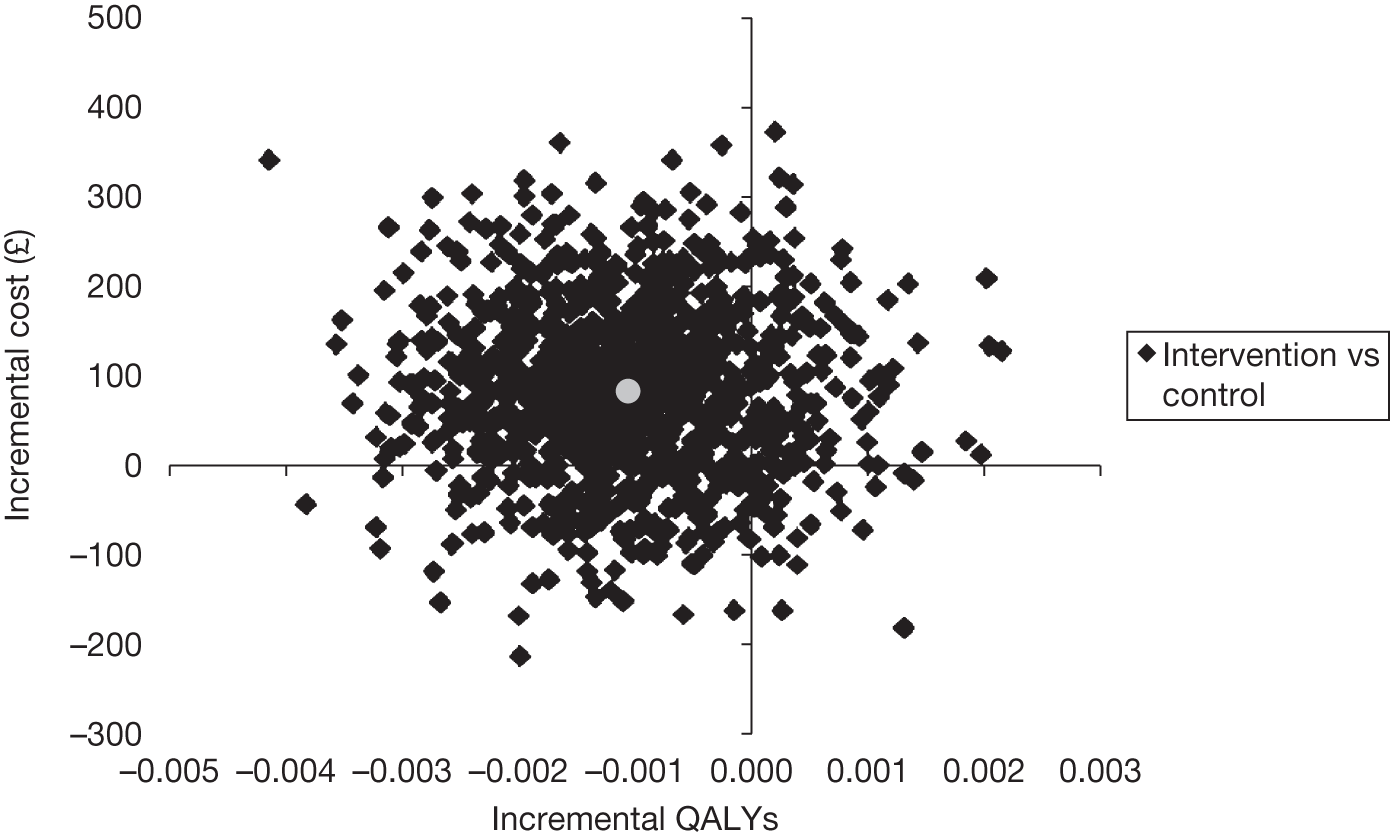

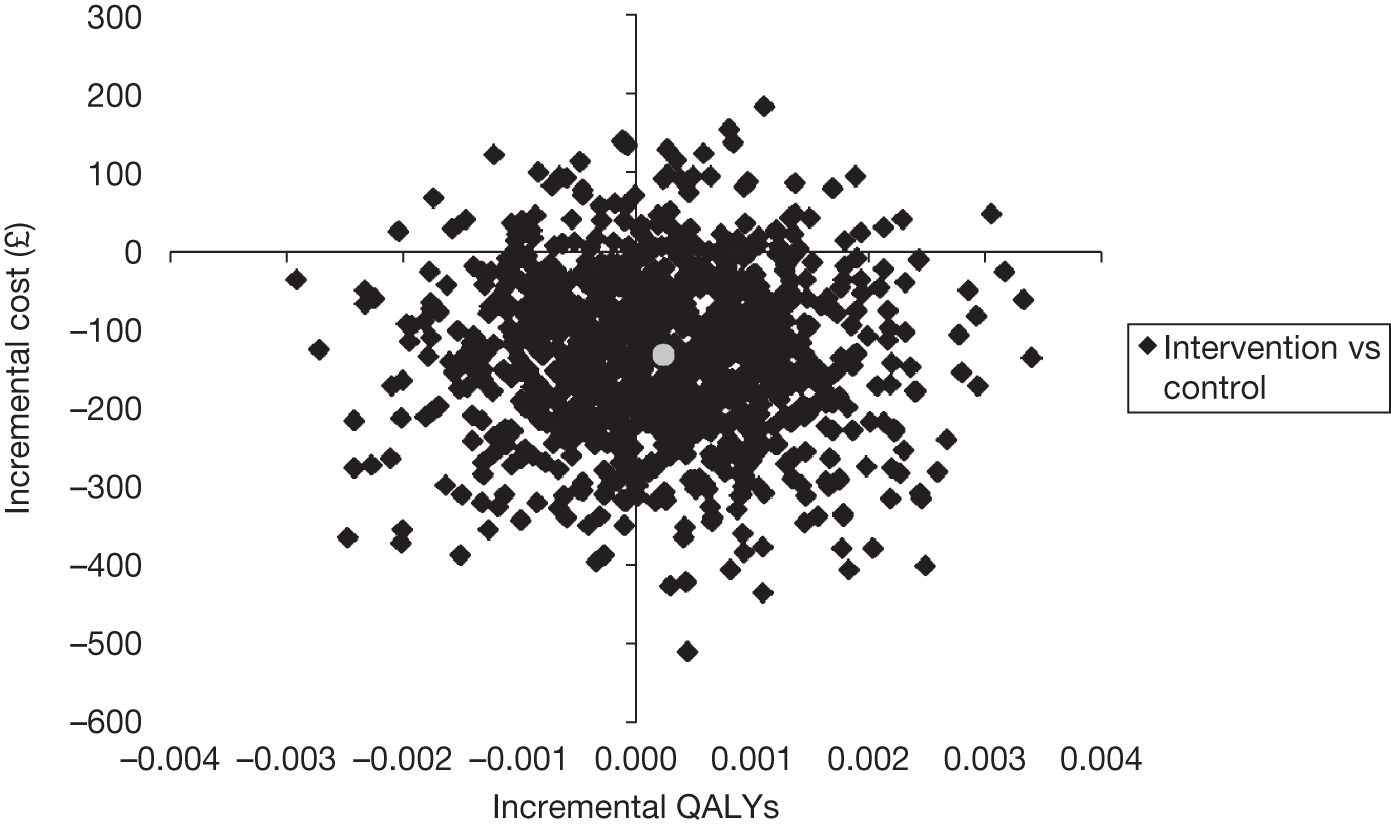

Incremental cost per infection avoided and quality-adjusted life-year gained

Average costs per patient for each intervention were calculated and the described comparisons were made. Similarly, the average number of QALYs were calculated for each intervention and compared with the control. Data collected on costs and effects of the interventions were combined to obtain an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). This was performed by dividing the mean difference in costs by the difference in effect between the interventions and control group. This provides the incremental cost per infection avoided or incremental cost per additional QALY gained for the new interventions relative to standard practice, i.e. ΔC/ΔE = ICER (where C = cumulative costs at 6 weeks and E = cumulative effects over 6 weeks).

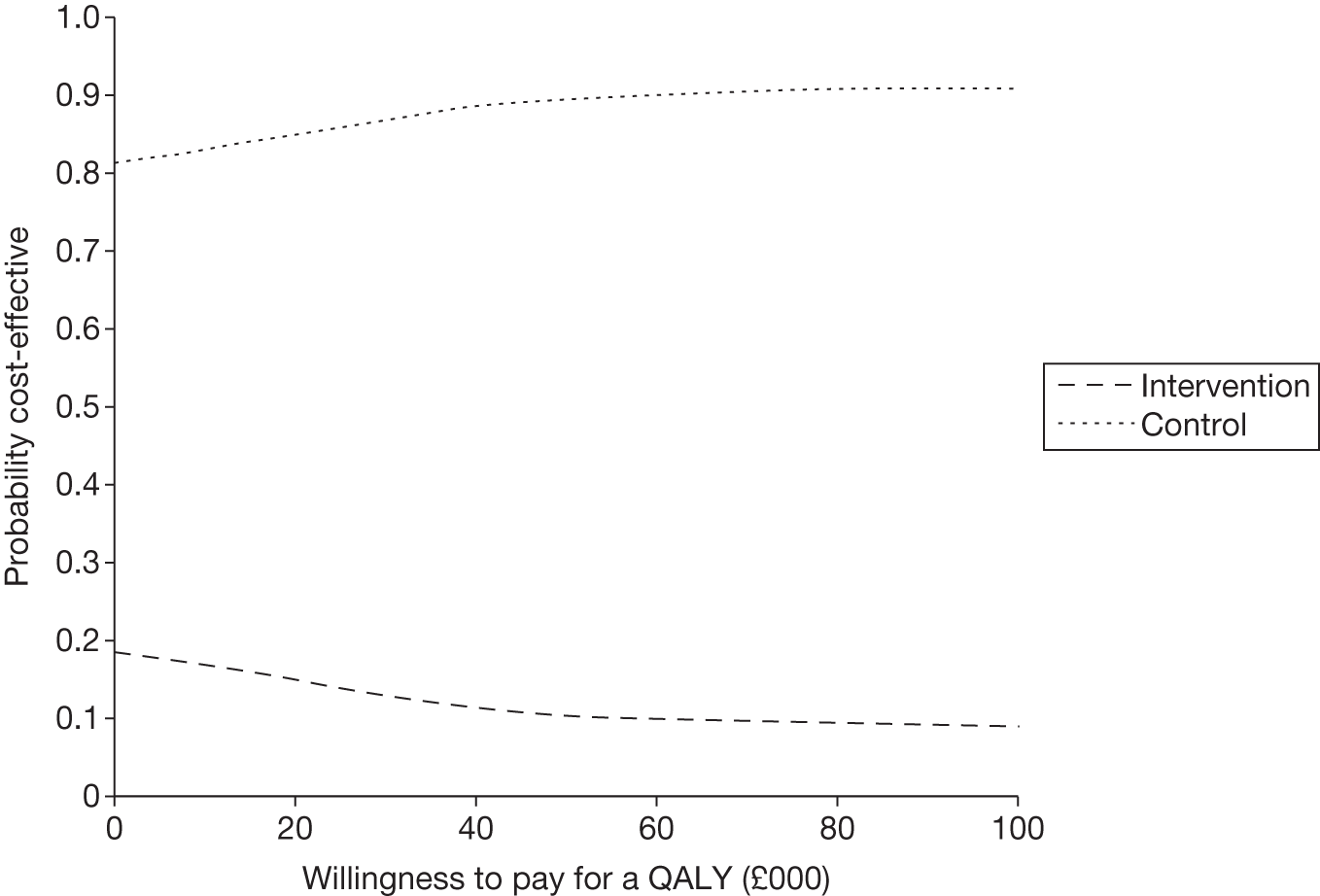

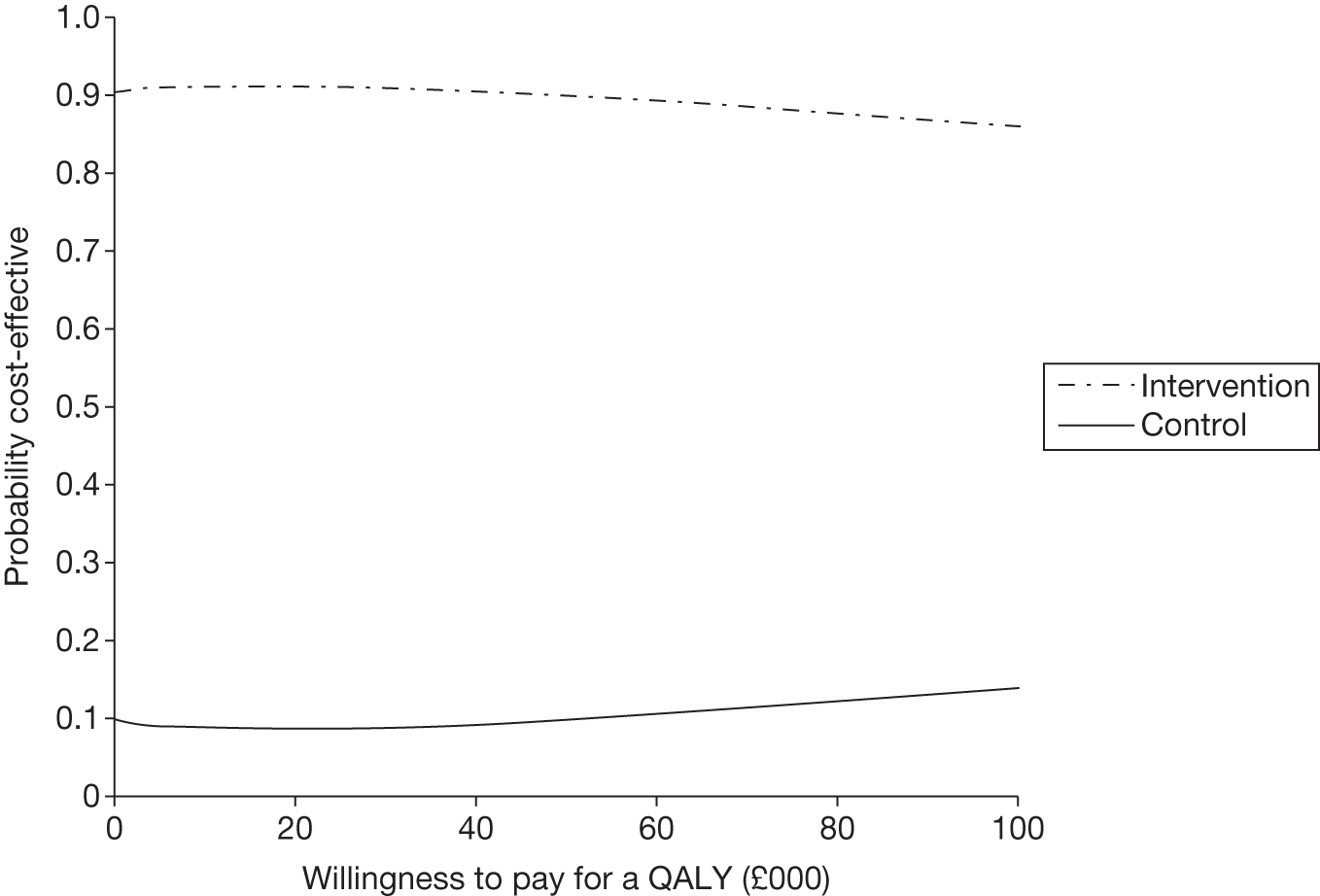

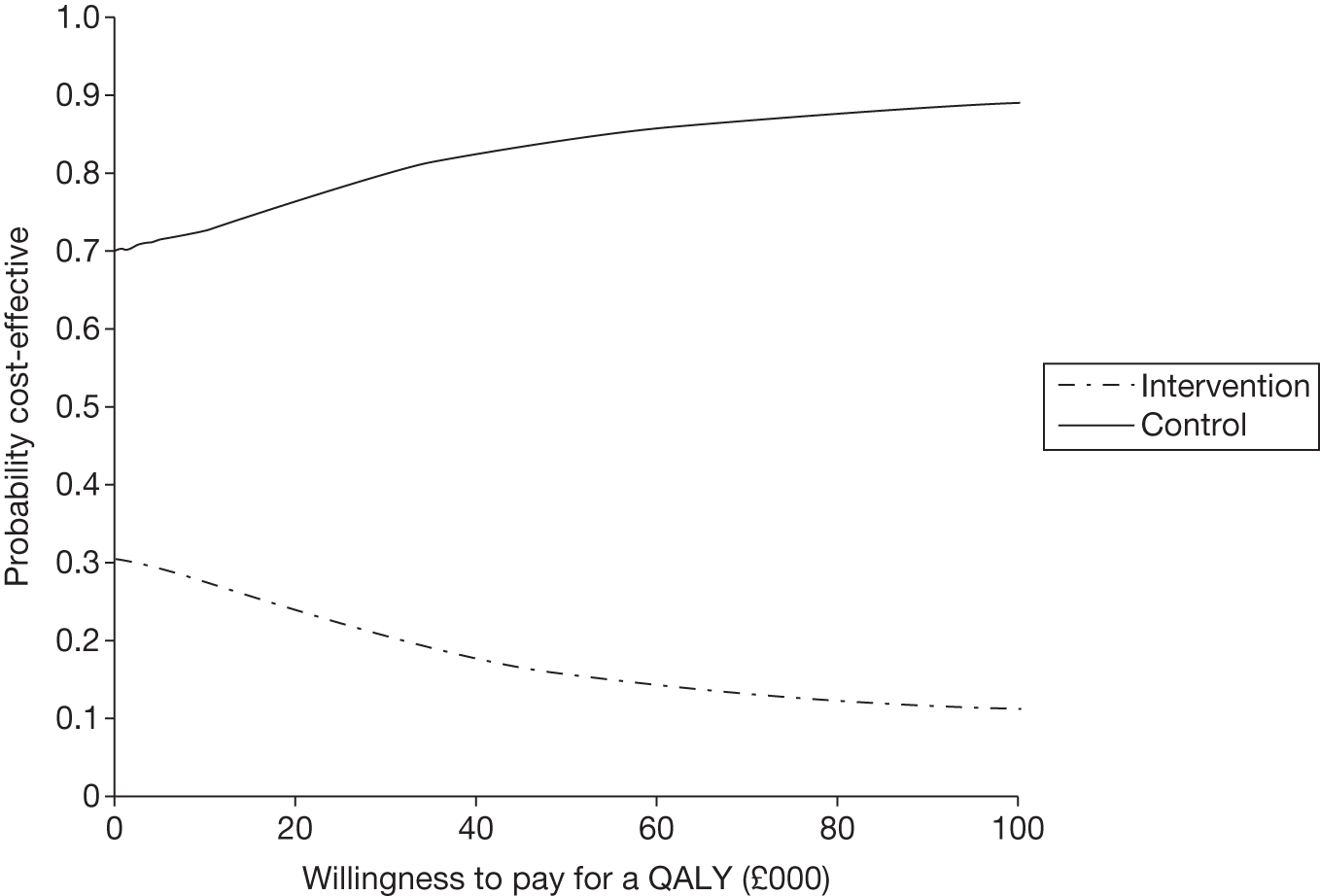

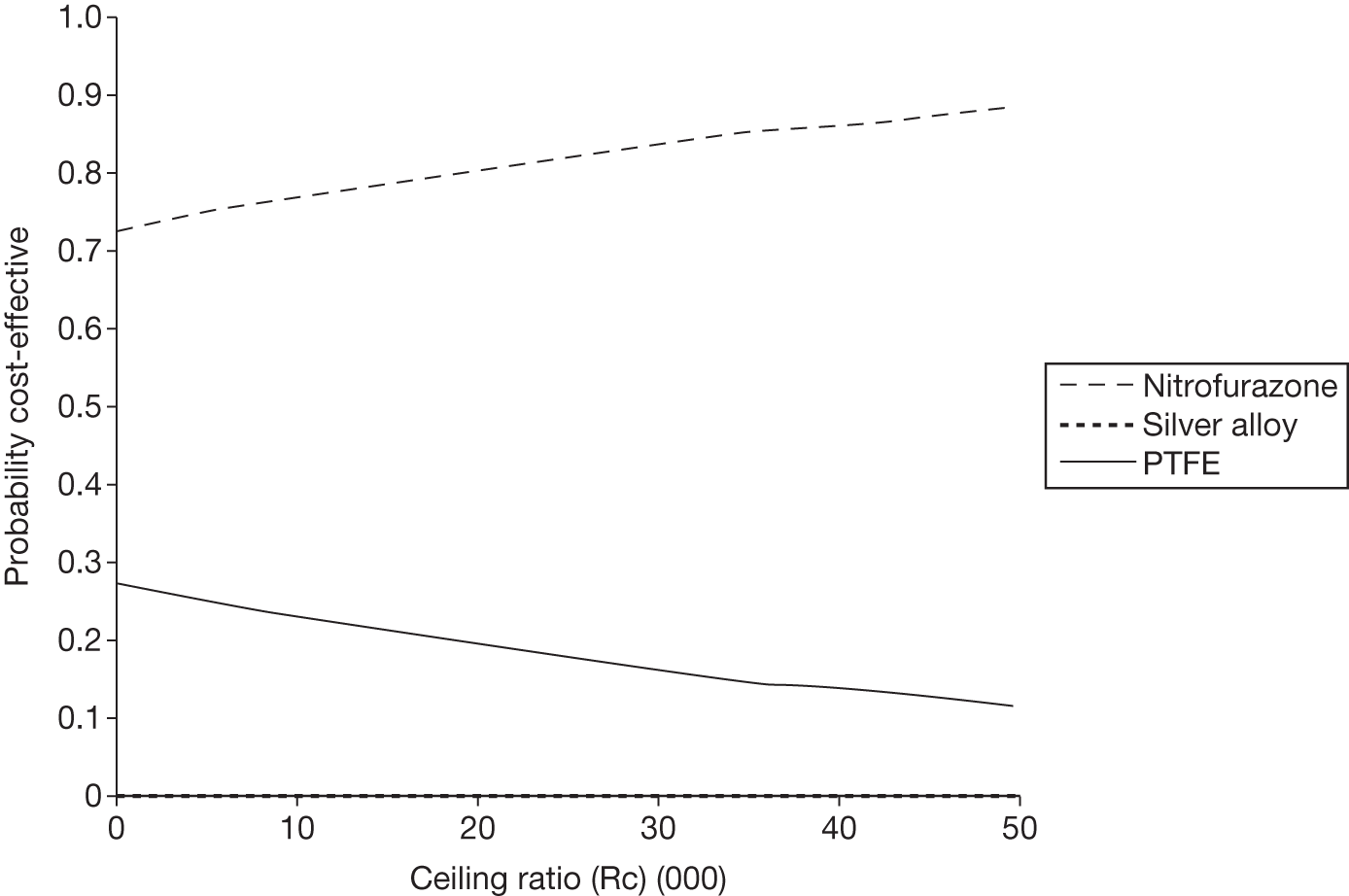

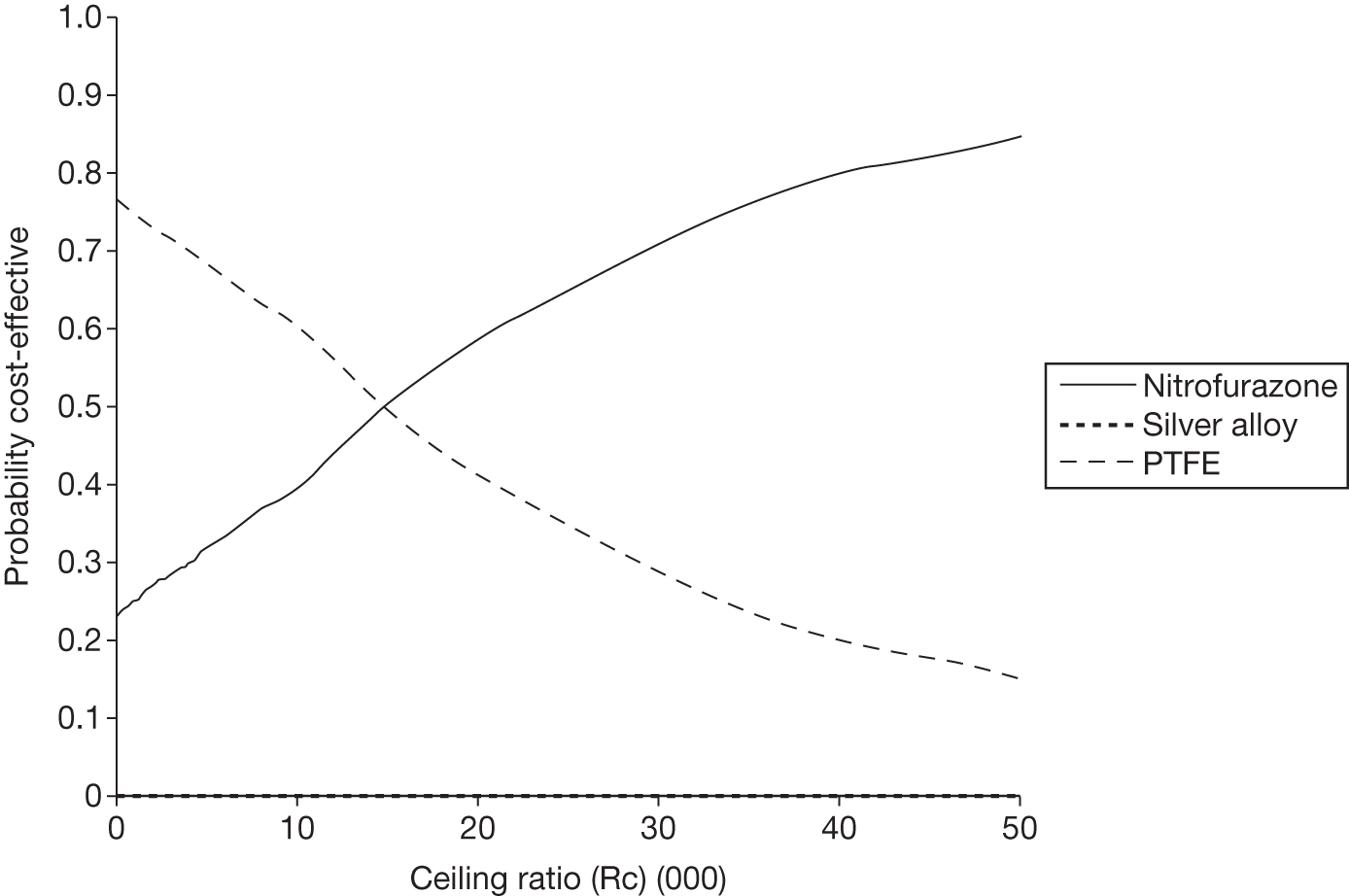

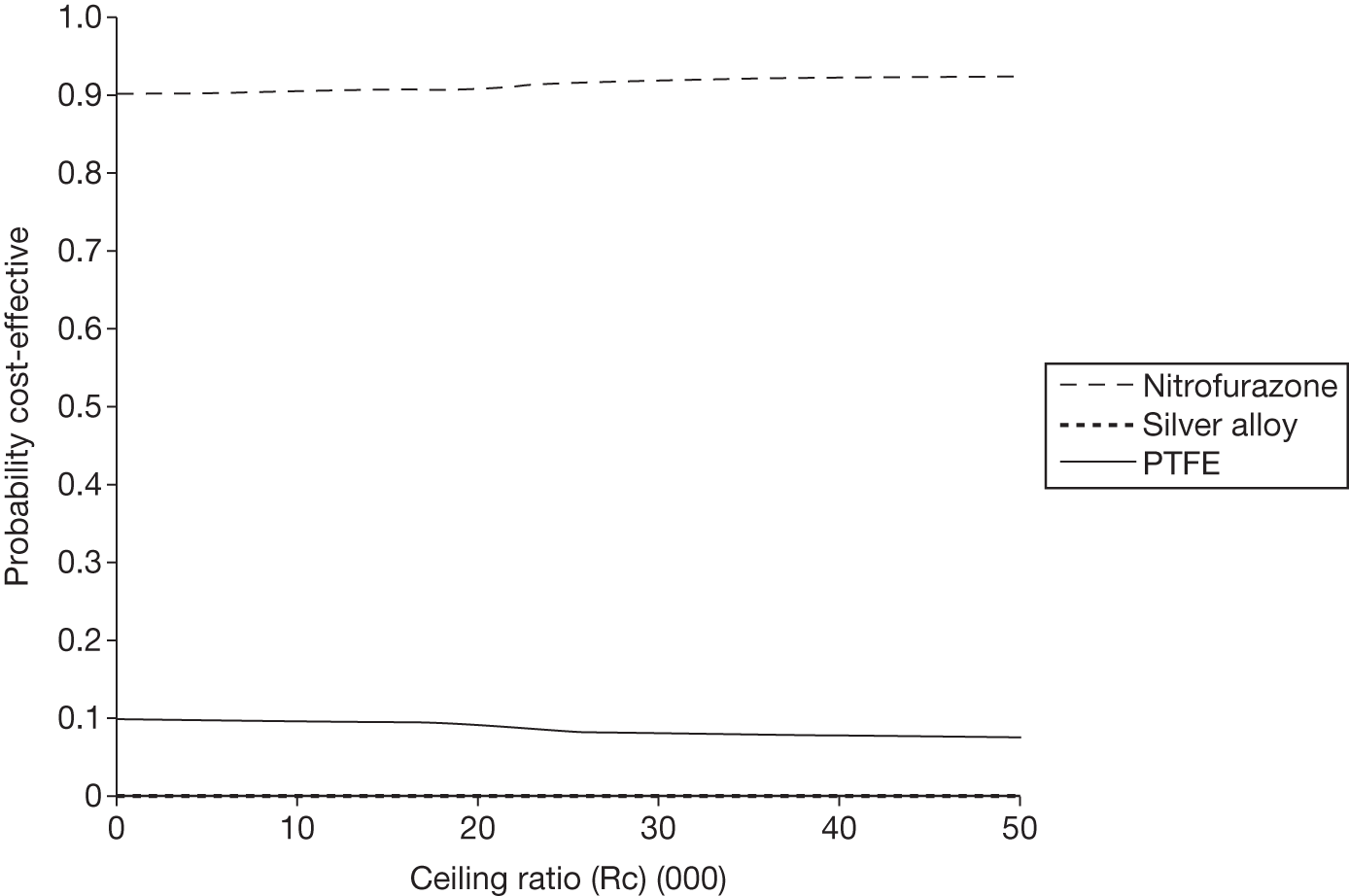

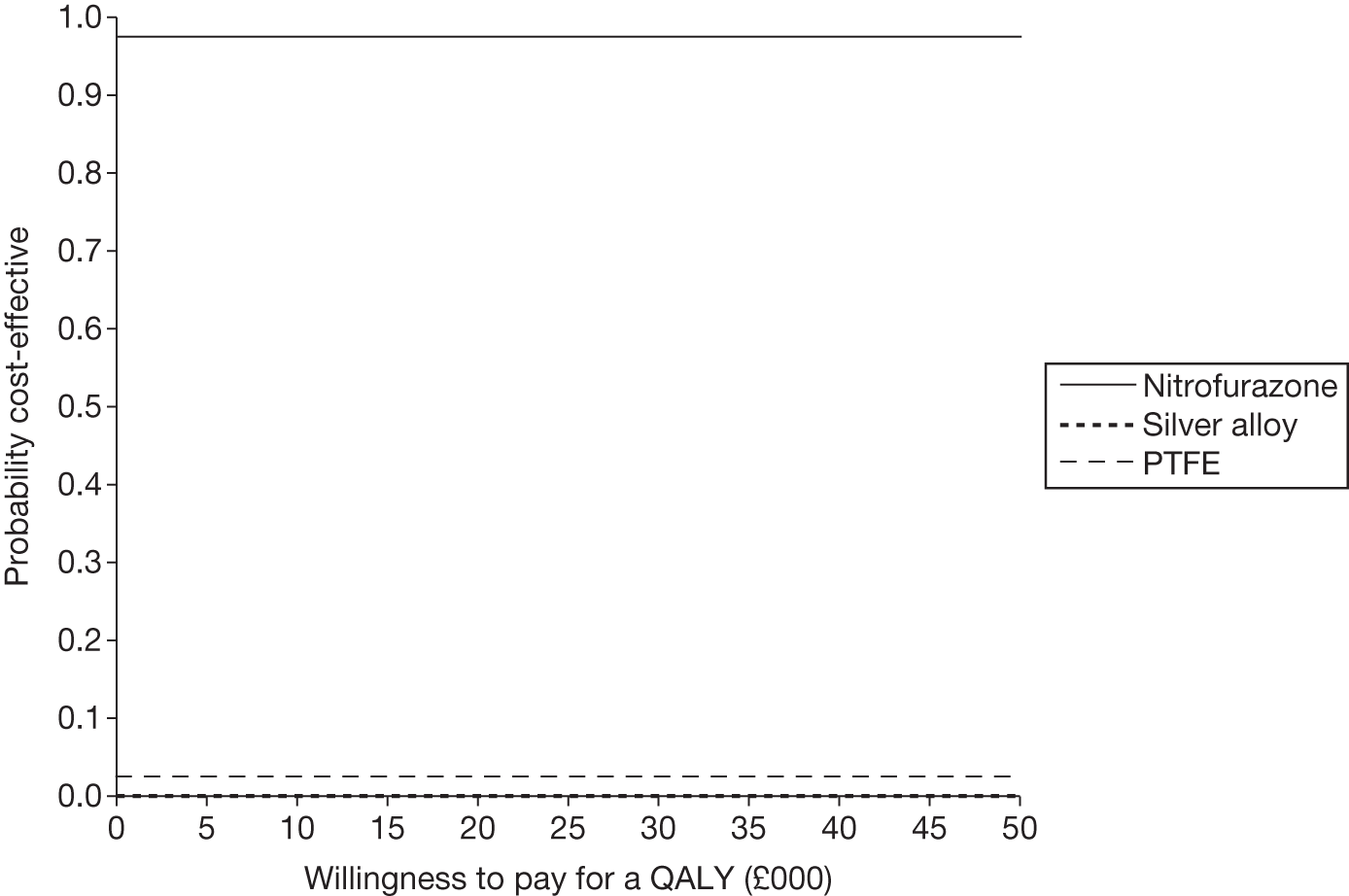

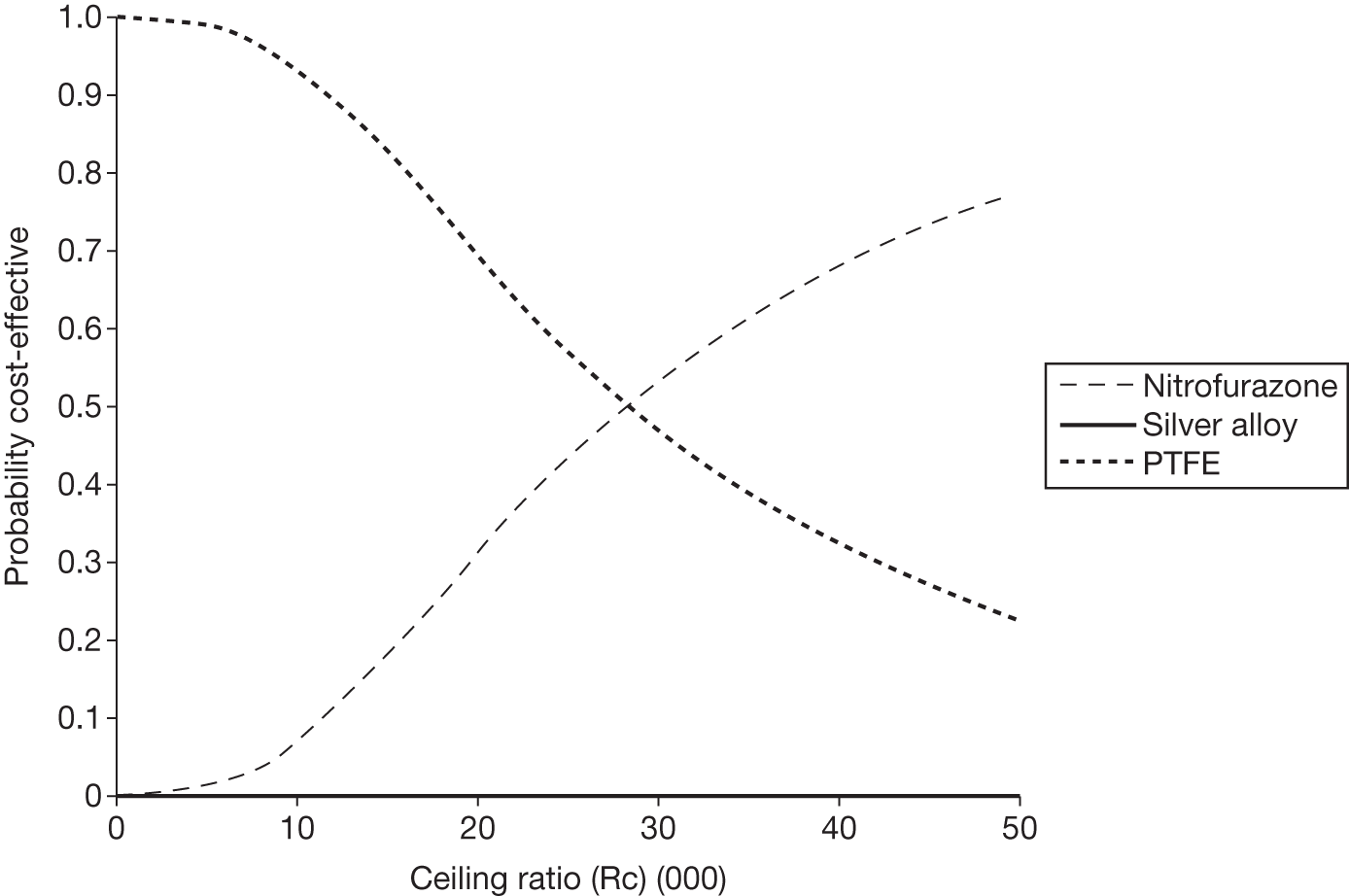

Measures of variance for these costs, infections and QALYs were derived using bootstrapping. 74 From the results of the bootstrapping, cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) were created. CEACs are used to represent whether or not the two novel interventions are cost-effective at various threshold values for society’s willingness to pay for an infection avoided or additional QALY. CEACs present results when the analysis follows a net benefit approach. This approach utilises a straightforward rearrangement of the cost-effectiveness decision rule used when calculating ICERs (see below) to create the net monetary benefit (NMB). The NMB of the interventions in question is as shown below:

where λ represents the decision-maker’s willingness to pay for an infection avoided or for a QALY gained. If the above expression holds true, the intervention is considered cost-effective. As society’s willingness to pay is unknown, the NMB will be calculated for a number of possible λ values, including the threshold value of £20,000–30,000 for a QALY that is often adopted by policy-makers within the NHS. 75 The estimates of NMB at various threshold values for society’s willingness to pay for a unit of outcome are used to produce graphical and tabular representations of the CEAC.

Data analysis

As trial data were collected over a 6-week period no discounting was carried out. The number of missing data for variables used in the cost analysis was low, and data that were missing were therefore considered to be missing completely at random.

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses similar to those described in Statistical methods/trial analysis examined possible modification of the cost-effectiveness results by the following characteristics:

-

age (< 60 years, ≥ 60 years)

-

sex

-

comorbidity (pre-existing urological disease, diabetes, immunosuppression)

-

duration of catheterisation (< 4 days, ≥ 4 days)

-

indication for catheterisation (incontinence, urine retention and monitoring purpose)

-

use of antibiotics in the last 7 days

-

use of antibiotics at catheterisation.

Effect modification was explored using tests for interaction (all at stricter levels of significance; p < 0.01), and results are cost differences with 99% CIs to reflect the exploratory nature of these analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was performed to gauge the impact of varying key assumptions and/or parameter values in the base-case analysis.

-

Sensitivity analysis around cost per day of hospital treatment. This analysis explored the impact of using an alternative source of unit cost data for the cost per day in hospital. Sensitivity analysis was performed using unit costs from other published sources, for example NHS reference costs. 76

-

The base-case analysis was conducted using data that were adjusted for the characteristics mentioned above for the subgroup analyses. To indicate the importance of adjusting for these baseline factors a further analysis has been conducted using cost data that were not adjusted for any potential imbalance at baseline.

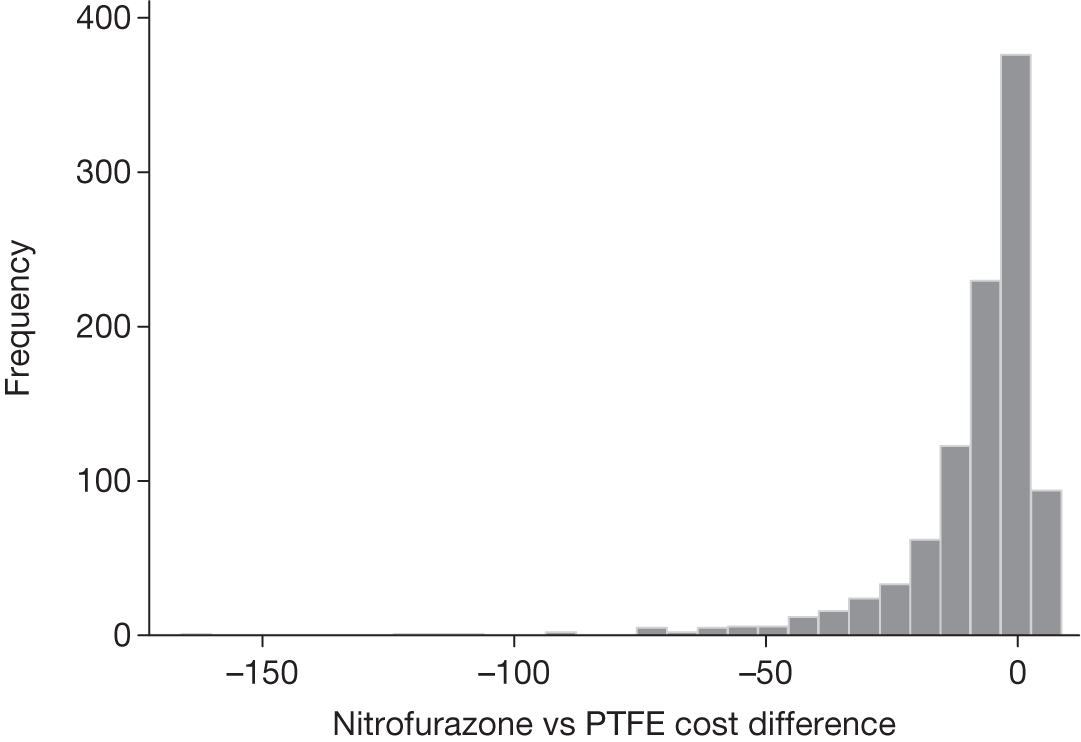

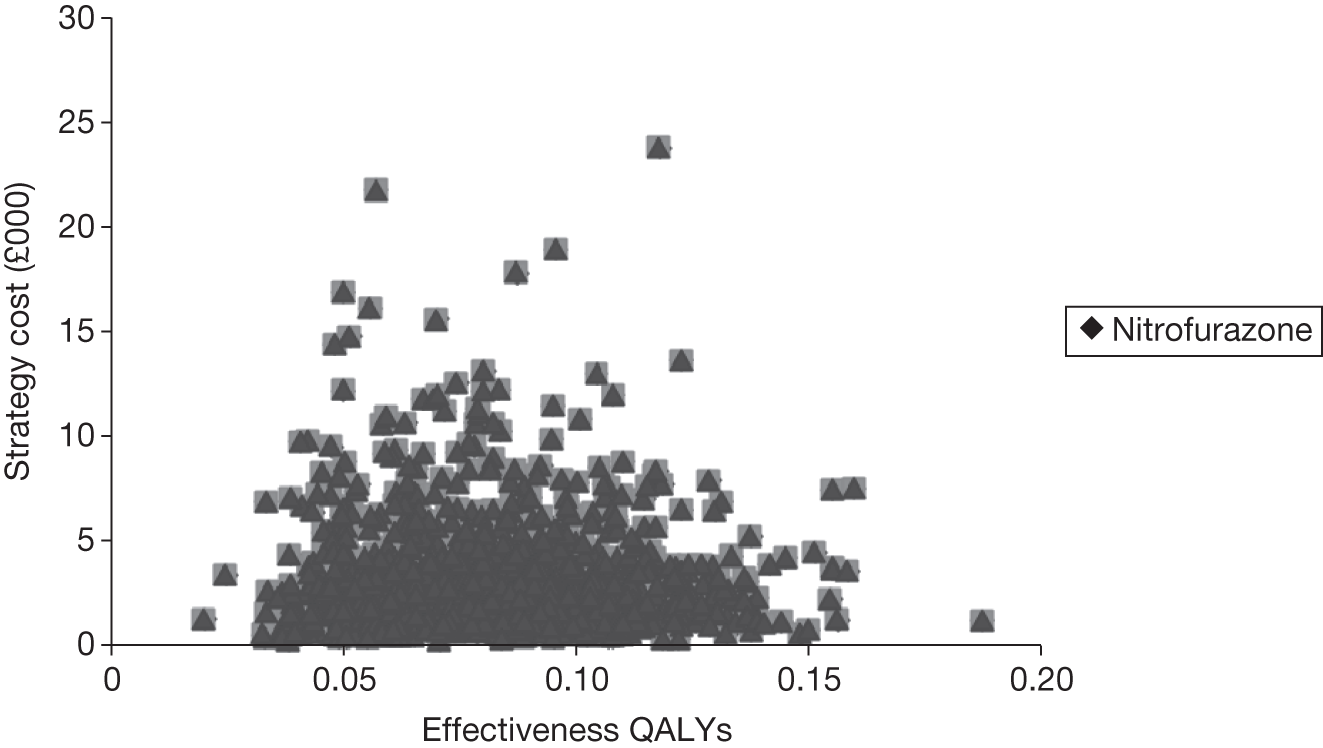

Model-based analysis

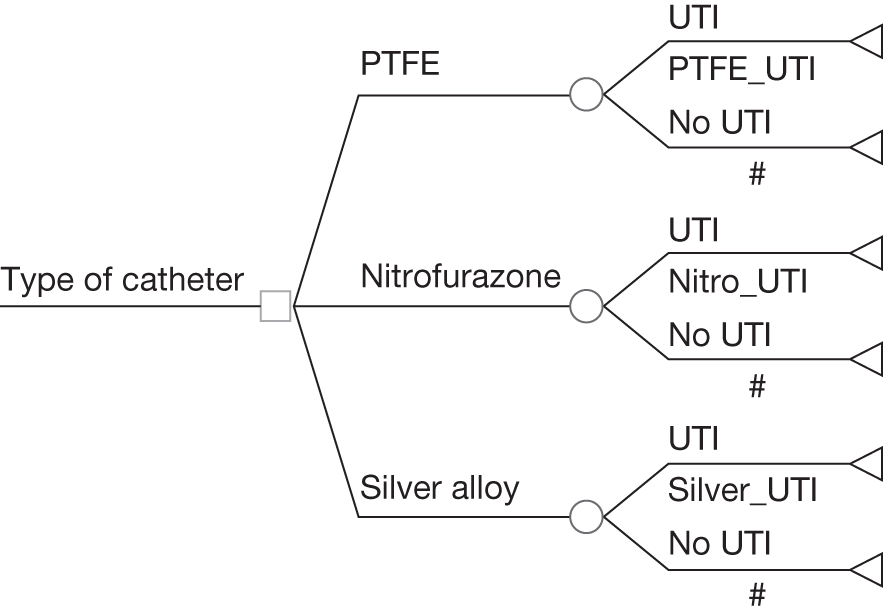

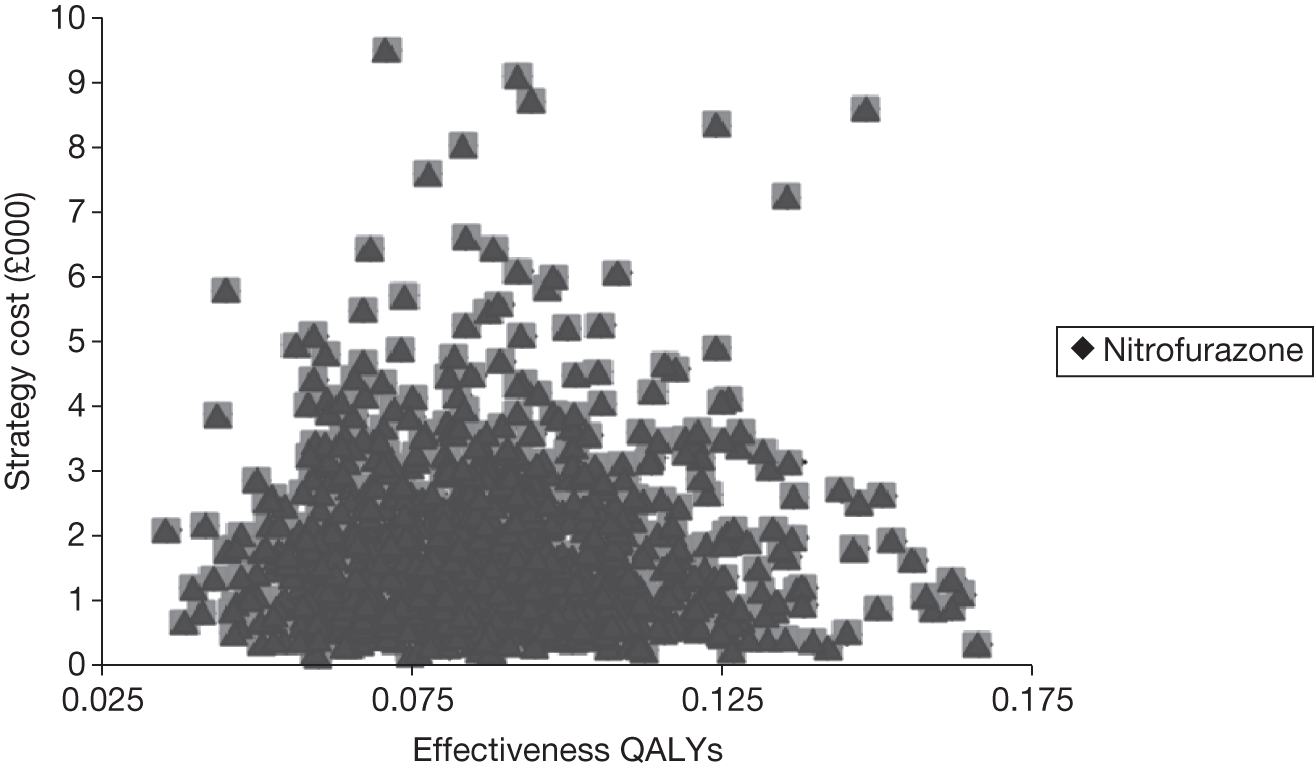

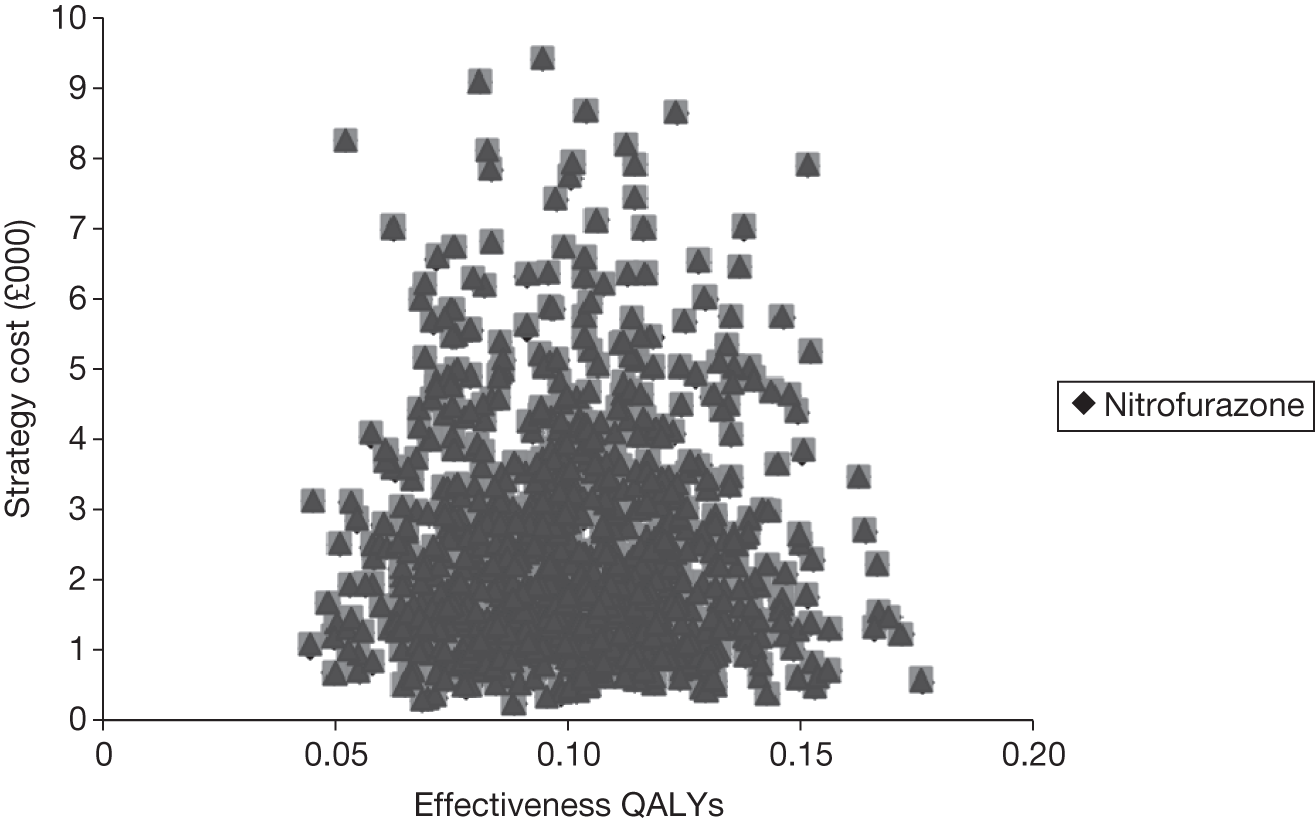

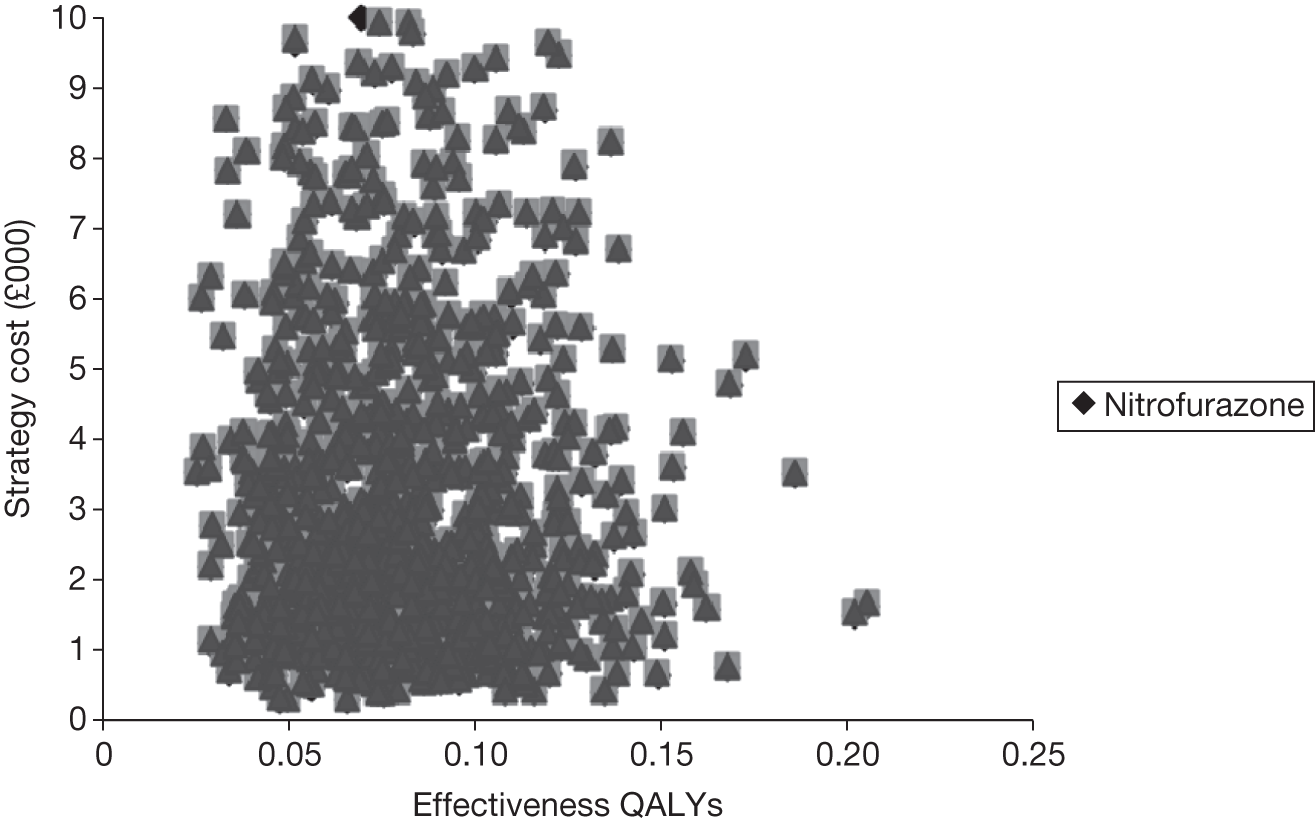

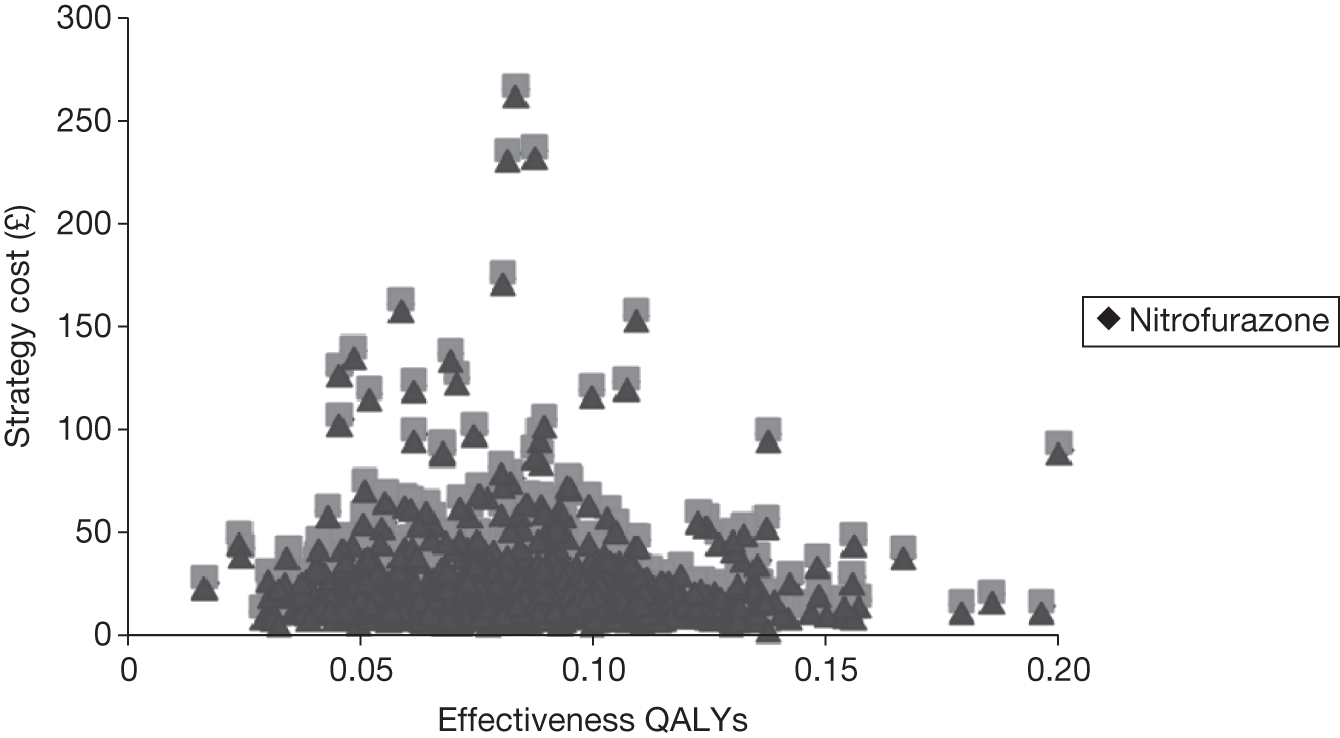

A decision-analytic model was developed to compare the different catheters in terms of the loss of QoL (based on the responses to the EQ-5D collected as part of the trial) and change in cost caused by a symptomatic catheter-associated UTI (Figure 3). In this modelling exercise, a comparison was drawn between the three different types of catheter (as shown in Figure 3). The trial-based analysis was expected to be characterised by considerable variation between patients in terms of both costs and QALYs. This was because, as noted above, participants within the trial were being treated for a variety of different conditions and the effect of these underlying conditions may have obscured or distorted the effect of the different catheters. Therefore, a modelling exercise was conducted which made the assumption that differences between the randomised arms are solely the result of differences in the risk of infections occurring.

FIGURE 3.

Simple decision tree.

Model-based analysis was performed from the perspective of the UK NHS. In this analysis it was assumed that the only difference in QoL was caused only by a symptomatic UTI and that the type of catheter did not affect QoL except by changing the risk of a symptomatic UTI occurring. Parameters used in the model included the costs of participants’ care, QALYs and the probability of having a symptomatic UTI. The costs and QALYs data required were derived from the within-trial analysis and were estimated based on whether or not a participant had a symptomatic UTI.

Regression methods were used to estimate the QALYs for those with and without a symptomatic UTI. A similar approach was used to estimate costs associated with developing a symptomatic UTI compared with costs for those without an infection. The parameters required for the model were the risk of infection, the utilities associated with participants experiencing or not experiencing an infection, and management costs. Data to inform the model were derived from the within-trial analysis.

Data collected on costs and effects of the interventions were combined to obtain an ICER. This was performed by calculating the mean difference in costs between each intervention group and control, and dividing by the difference in effect between each intervention group and control. This generated the cost per QALY gained for the new interventions relative to standard practice, i.e. ΔC/ΔE = incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (where C = cumulative costs at 6 weeks and E = cumulative effects over the same period). Measures of variance for these outcomes were estimated by bootstrapping estimates of costs and QALYs, and incremental cost per participant with UTI and per QALY. Incremental cost-effectiveness data are presented in terms of CEACs.

Sensitivity analysis

Parameter uncertainty was integrated by the incorporation of probability distributions into the model and using the Monte Carlo simulation. Other forms of uncertainty, such as that associated with cost estimates detailed in the within-trial analysis, were addressed by using the cost results of different samples from the study population, such as those who had an EQ-5D score of ‘1’ (full health) at 3 days and those participants treated on the obstetrics and gynaecology ward who were hypothesised to have experienced a homogeneous pathway of care. Other analyses considered the impact of basing costs and QALYs on whether or not a participant had experienced a symptomatic UTI at 3 days after catheter removal together with the impact of excluding inpatient costs.

Chapter 4 Participant baseline characteristics

Trial recruitment

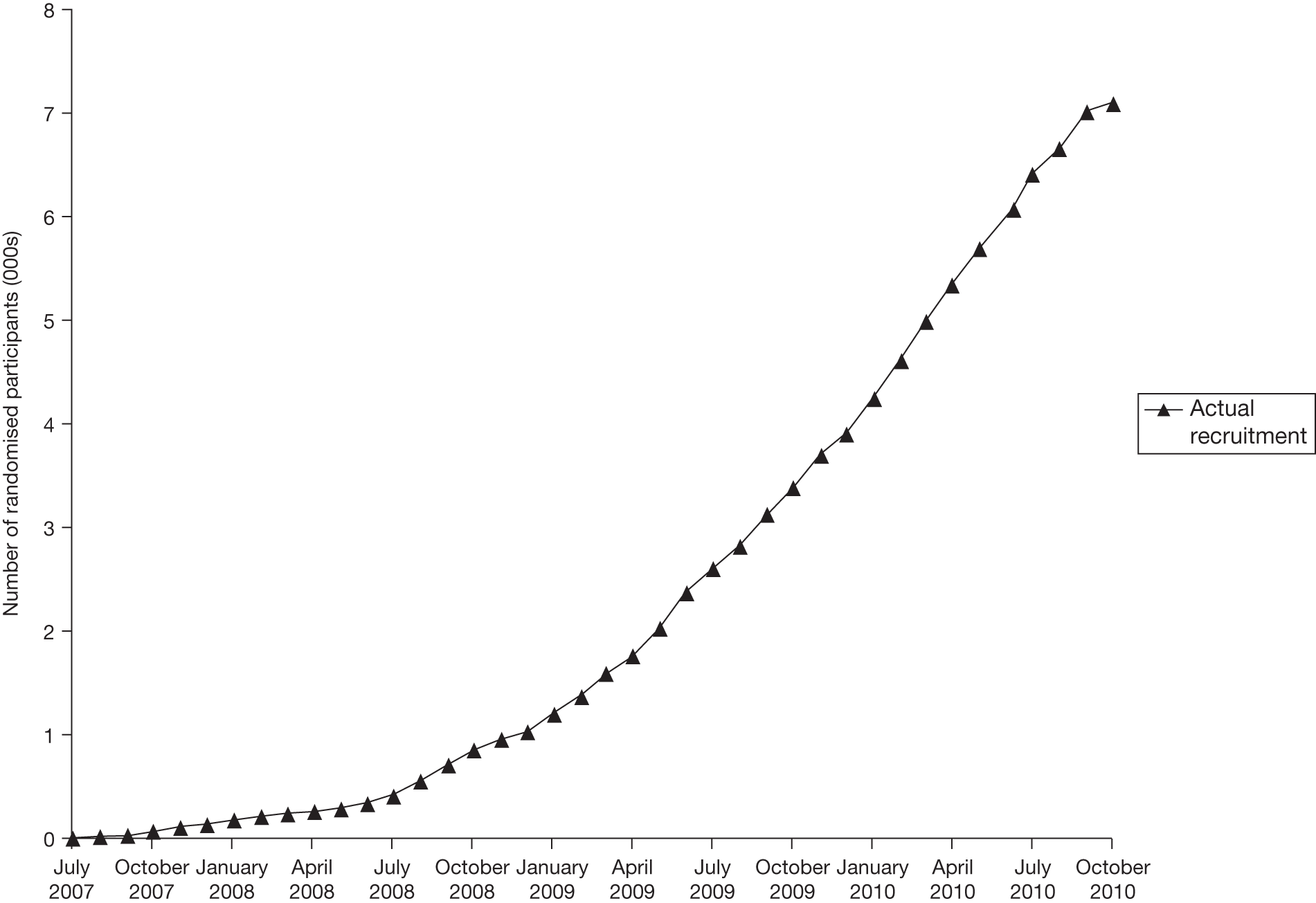

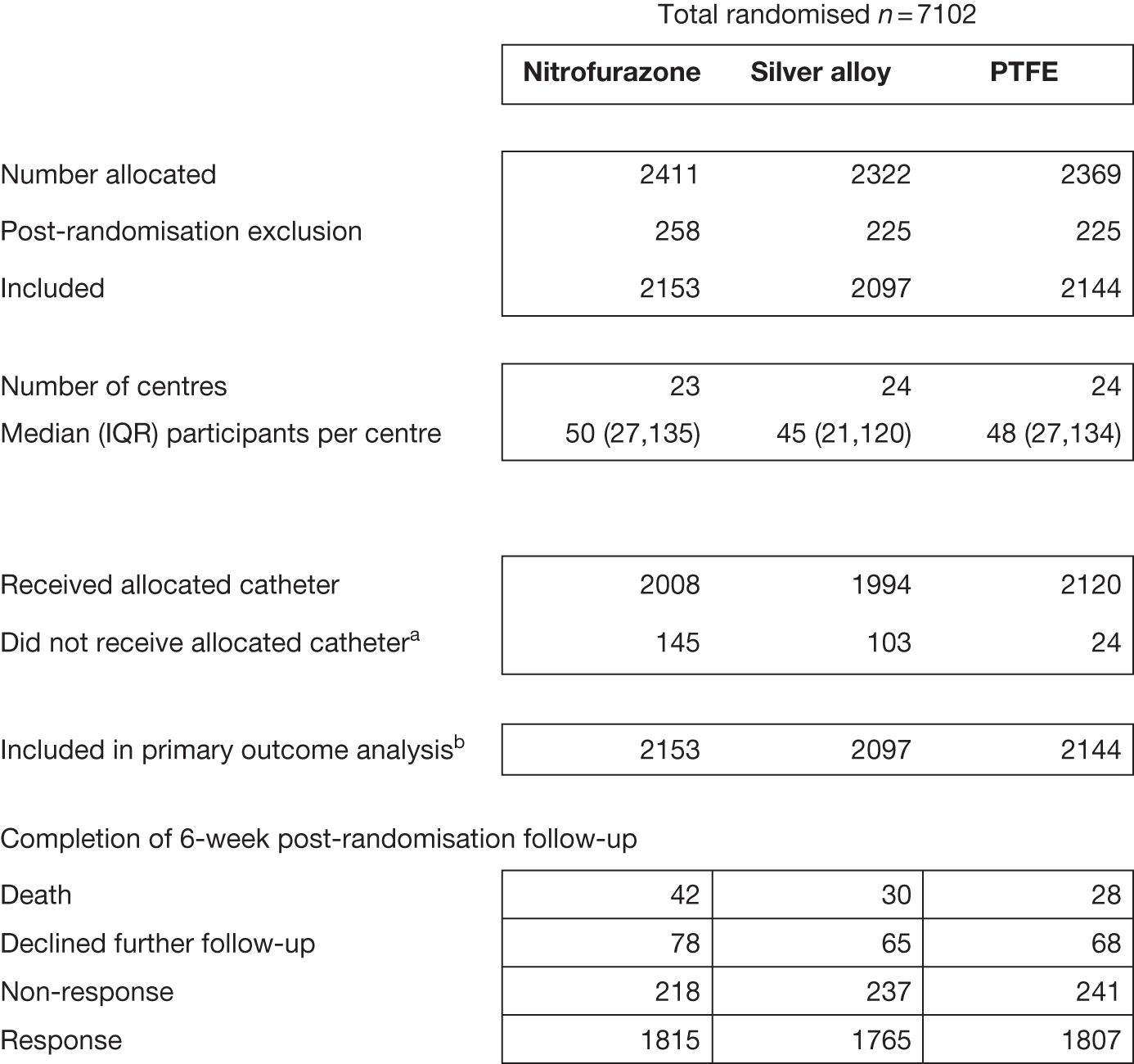

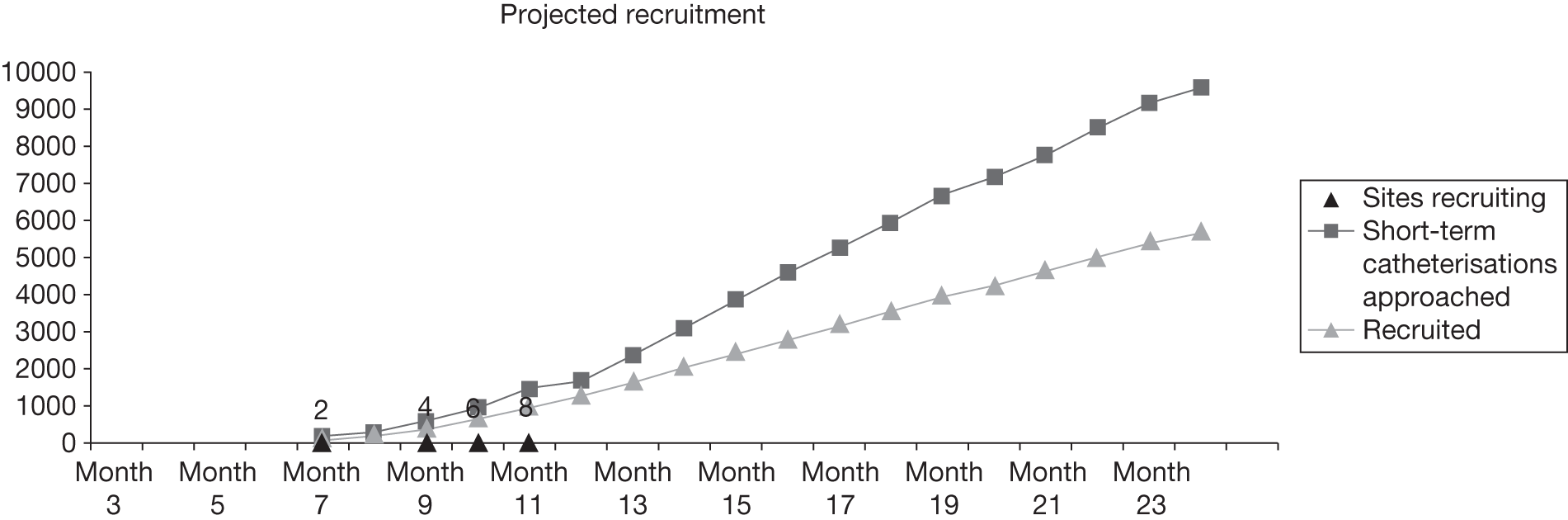

In total, 7102 patients anticipated to require short-term catheterisation as part of their standard care were randomised from 24 hospitals over 40 months between July 2007 and October 2010. Figure 4 shows total recruitment from all sites over time and Table 7 shows the numbers recruited at each site and the number of months over which that site recruited.

| Site | Ward specialties recruited | No. randomised | Percentage of total recruitment (7102) | Months recruiting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aberdeen Royal Infirmary | Cardiothoracic, general surgery, vascular, obstetrics and gynaecology | 1421 | 20.0 | 40 |

| Royal Blackburn Hospital & Burnley General Hospital | Obstetrics and gynaecology | 109 | 1.5 | 7 |

| Blackpool Victoria Hospital | Cardiothoracic, obstetrics and gynaecology | 203 | 2.9 | 16 |

| Bristol Royal Infirmary | Cardiothoracic, general surgery | 6 | 0.1 | 5 |

| Edinburgh Royal Infirmary | Obstetrics and gynaecology | 114 | 1.6 | 25 |

| Guy’s Hospital, London | Renal transplant | 234 | 3.3 | 17 |

| Harrogate District Hospital | Obstetrics and gynaecology | 4 | 0.1 | 5 |

| Hillingdon Hospital | General surgery, obstetrics and gynaecology | 201 | 2.8 | 29 |

| Hinchingbrooke Hospital | Orthopaedics | 64 | 0.9 | 10 |

| Raigmore Hospital, Inverness | Orthopaedics, general surgery | 971 | 13.7 | 34 |

| Liverpool Women’s Hospital | Obstetrics and gynaecology | 149 | 2.1 | 8 |

| Newcastle General Hospital | Neurosurgery, general surgery | 869 | 12.2 | 29 |

| Freeman Hospital, Newcastle | Cardiothoracic | 486 | 6.8 | 17 |

| Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle | Obstetrics and gynaecology | 312 | 4.4 | 10 |

| Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital | Orthopaedics, obstetrics and gynaecology | 42 | 0.6 | 8 |

| North Tyneside General Hospital | General surgery, urology, obstetrics and gynaecology, medical ward, orthopaedics | 619 | 8.7 | 20 |

| Nottingham City Hospital | Orthopaedics, obstetrics and gynaecology | 158 | 2.2 | 12 |

| Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth | Obstetrics and gynaecology | 151 | 2.1 | 7 |

| Royal Preston Hospital | Obstetrics and gynaecology | 109 | 1.5 | 16 |

| Southampton General Hospital | Cardiothoracic | 575 | 8.1 | 26 |

| Sunderland Royal Hospital | Obstetrics and gynaecology | 64 | 0.9 | 24 |

| Musgrove Park Hospital, Taunton | General surgery, orthopaedics | 33 | 0.5 | 14 |

| Torbay Hospital | General surgery, medical ward | 90 | 1.3 | 9 |

| Yeovil District Hospital | General surgery, obstetrics and gynaecology | 118 | 1.7 | 11 |

| Total | 7102 | 100 | 399 | |

FIGURE 4.

The CATHETER trial: recruitment over time.

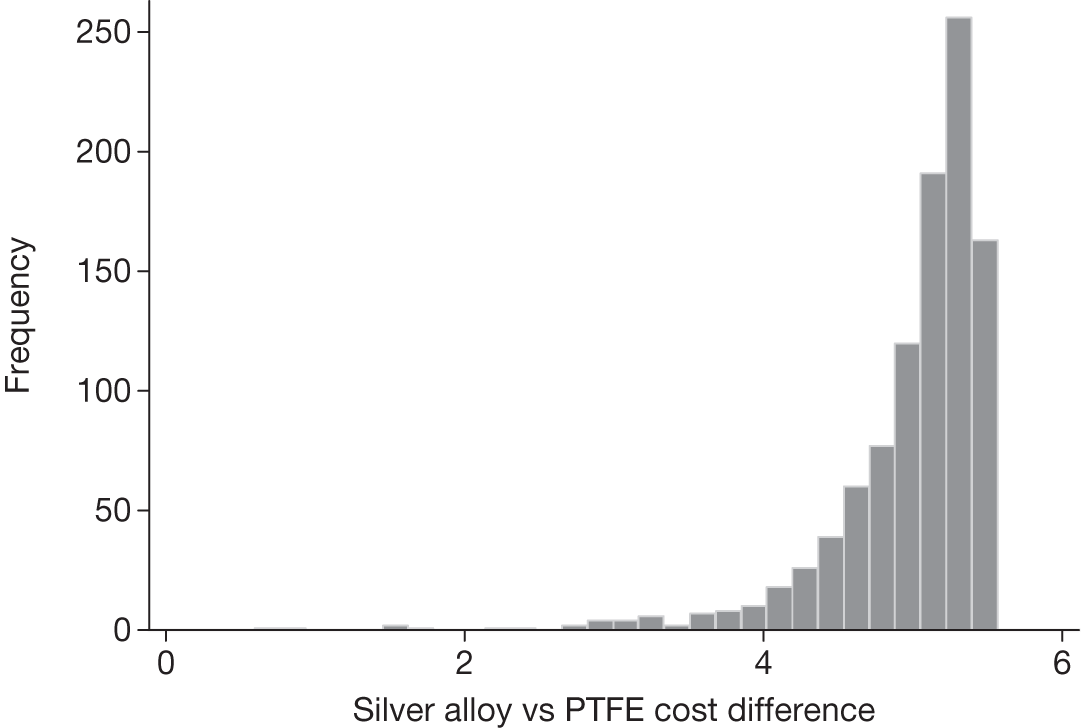

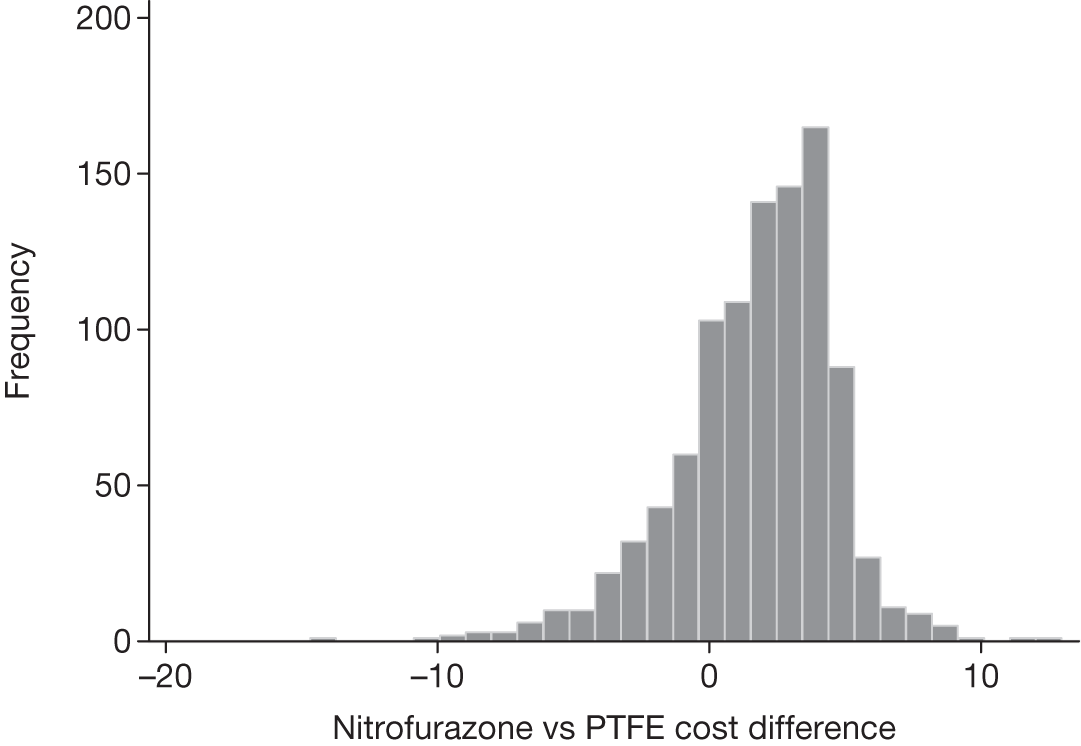

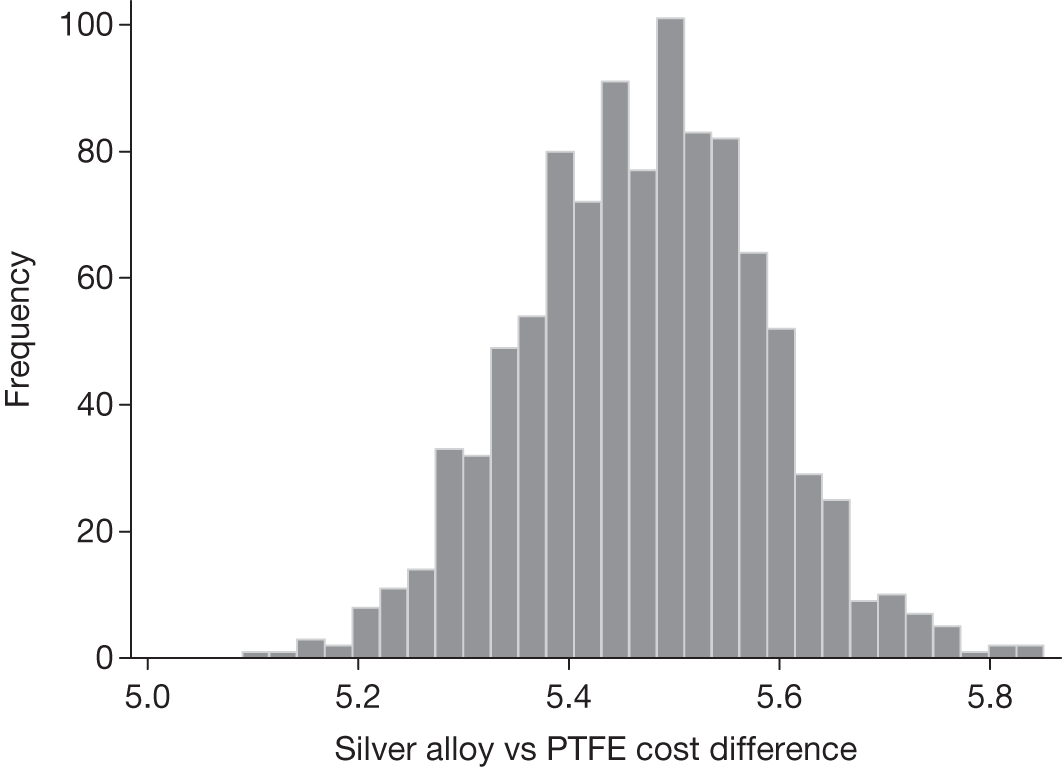

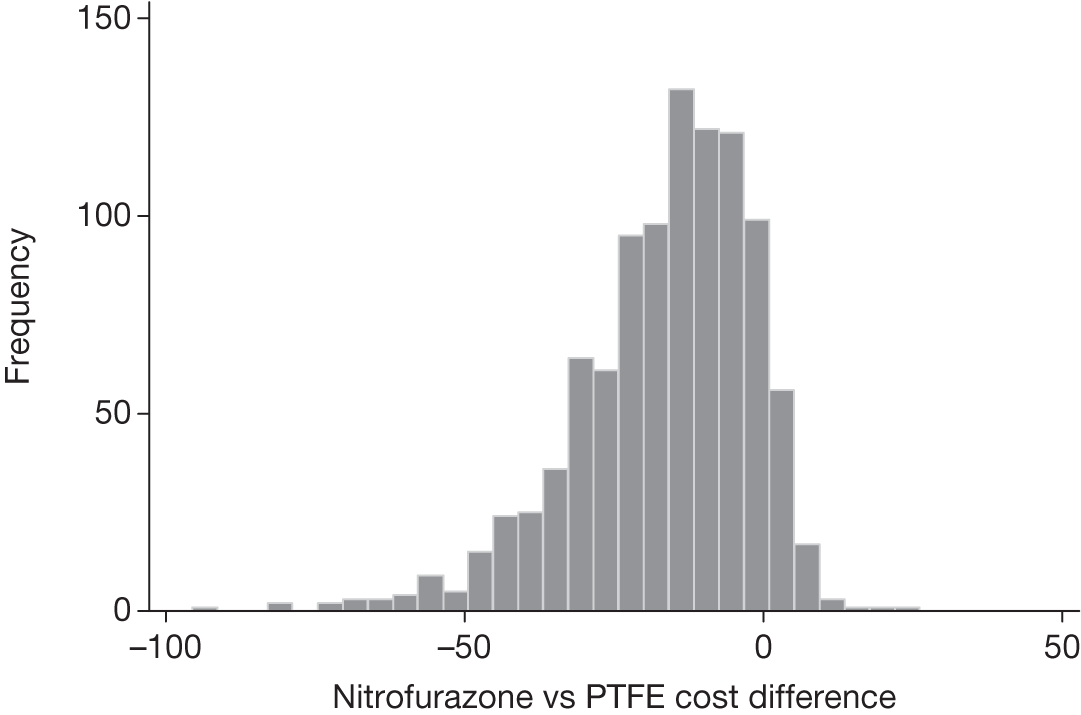

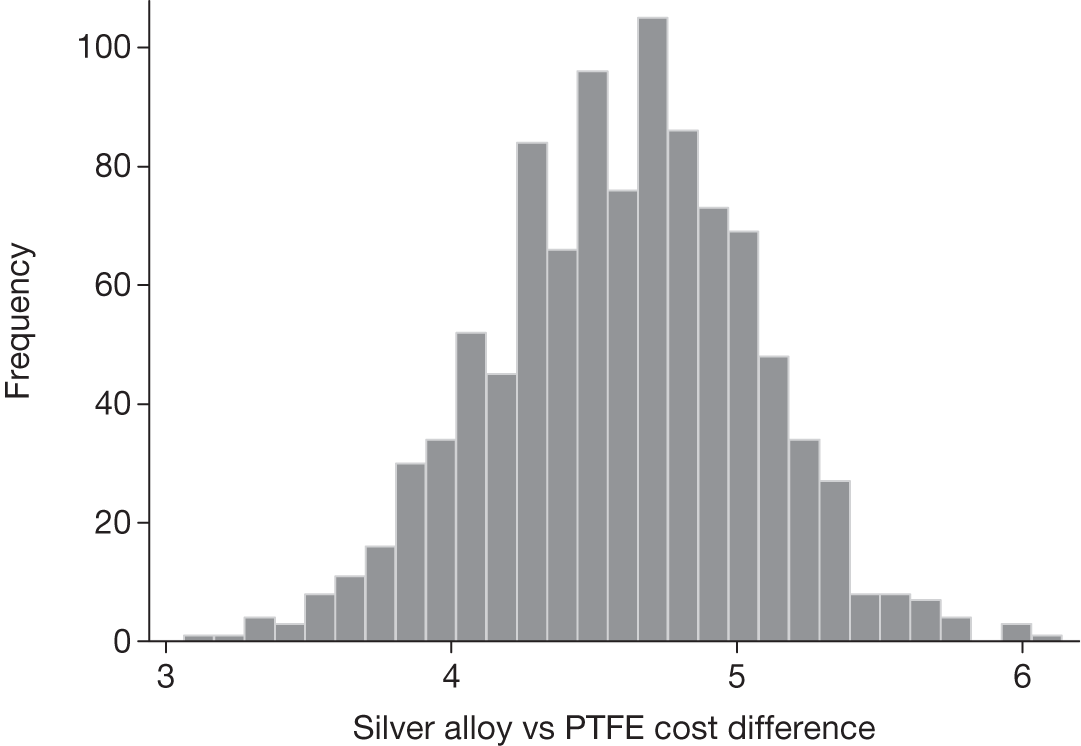

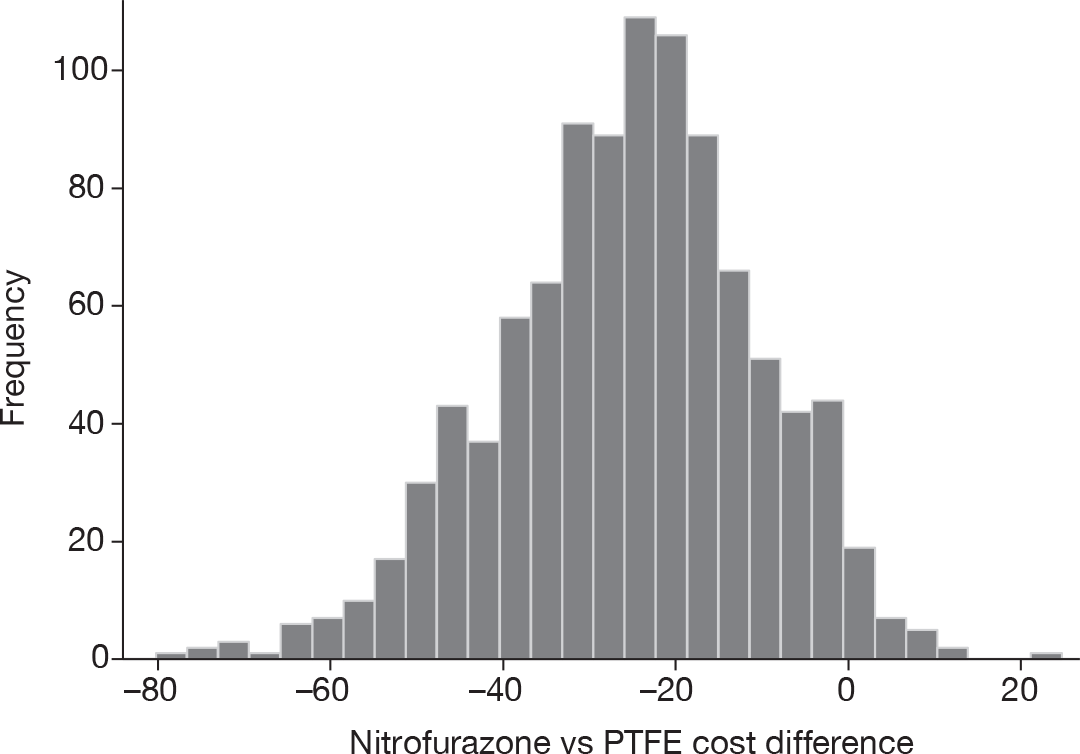

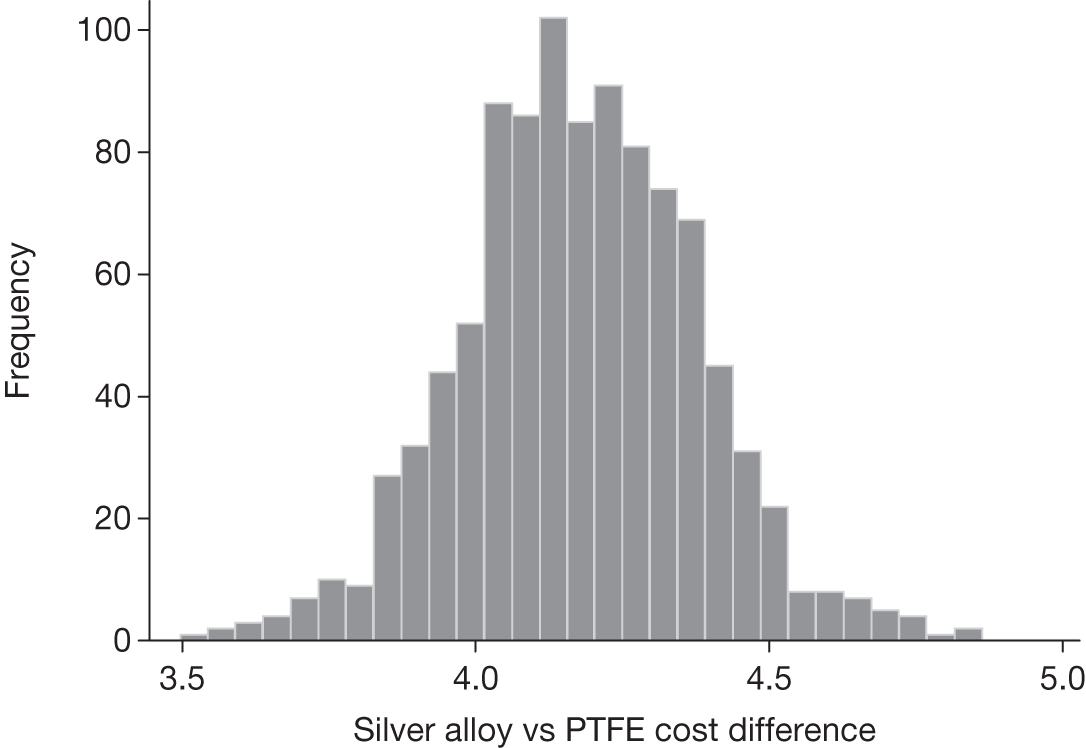

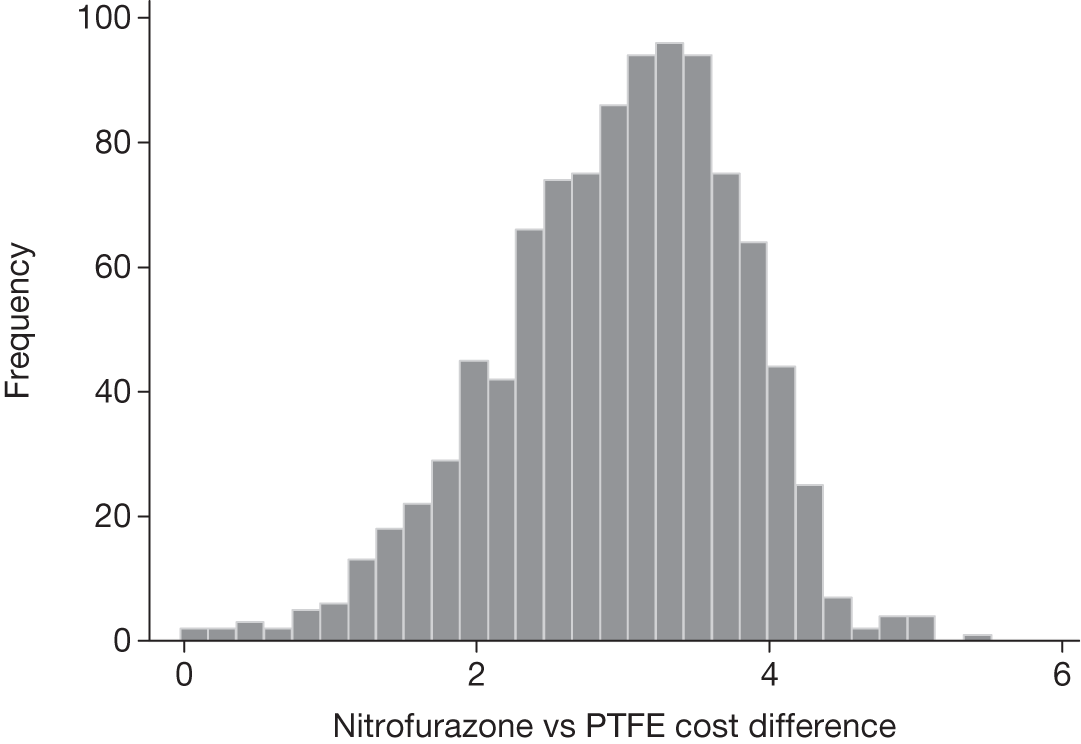

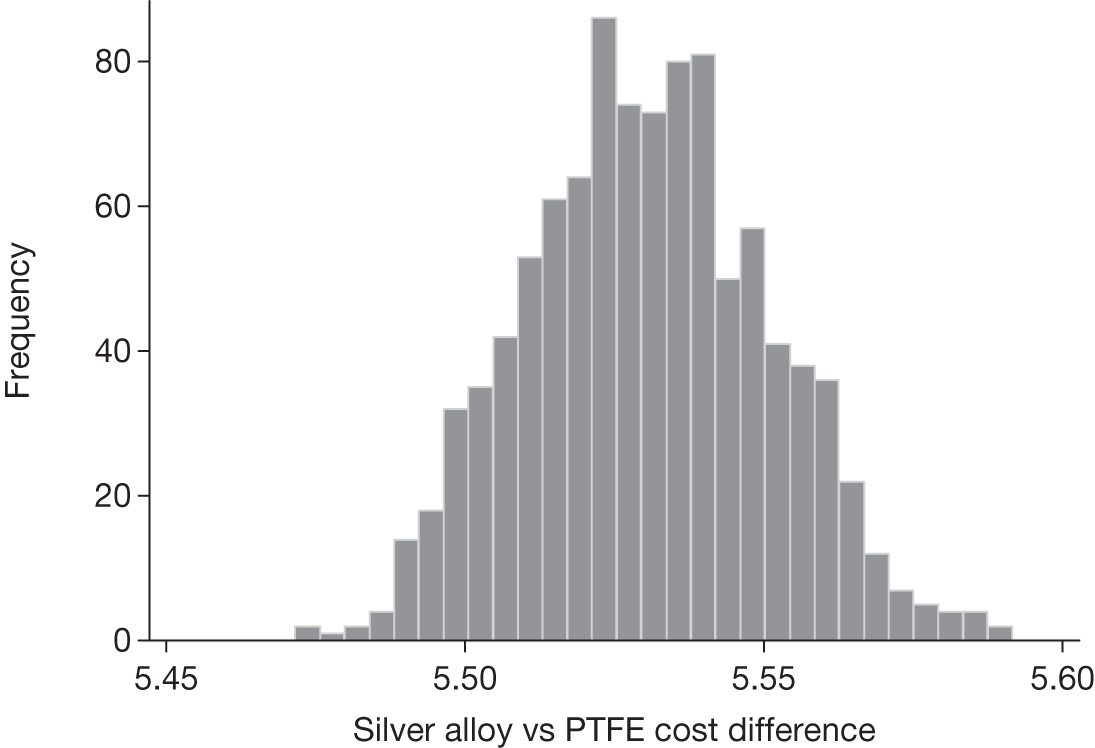

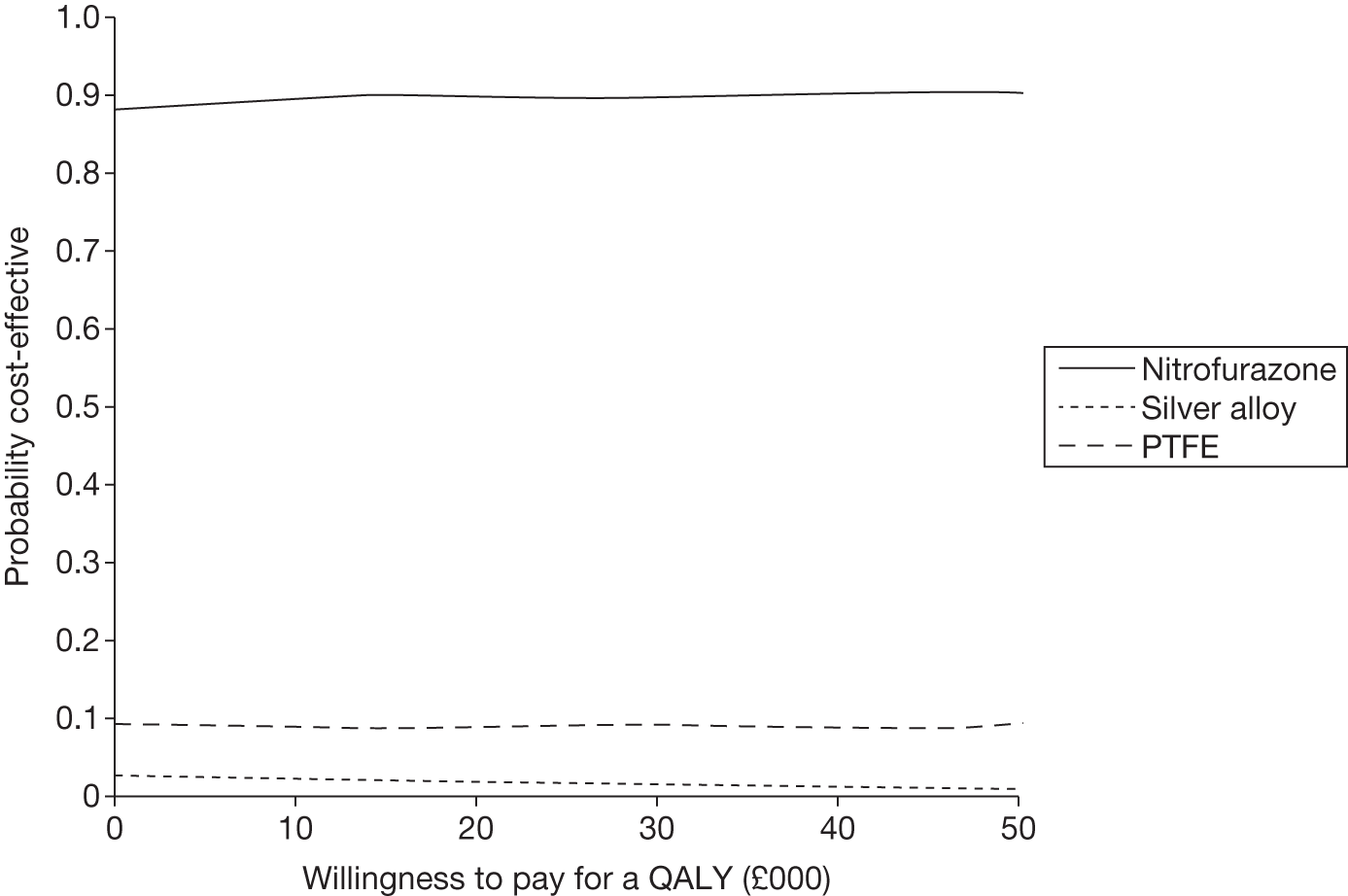

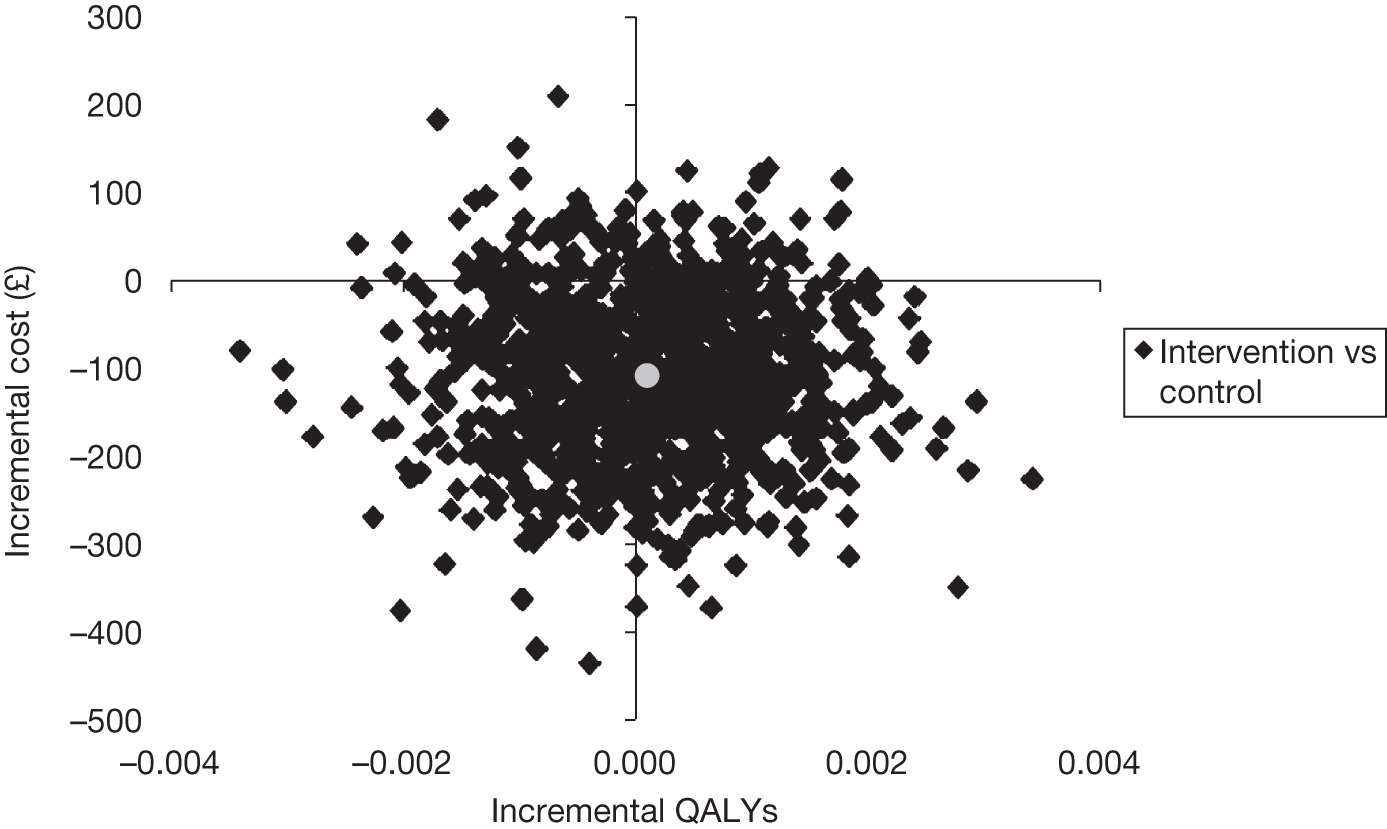

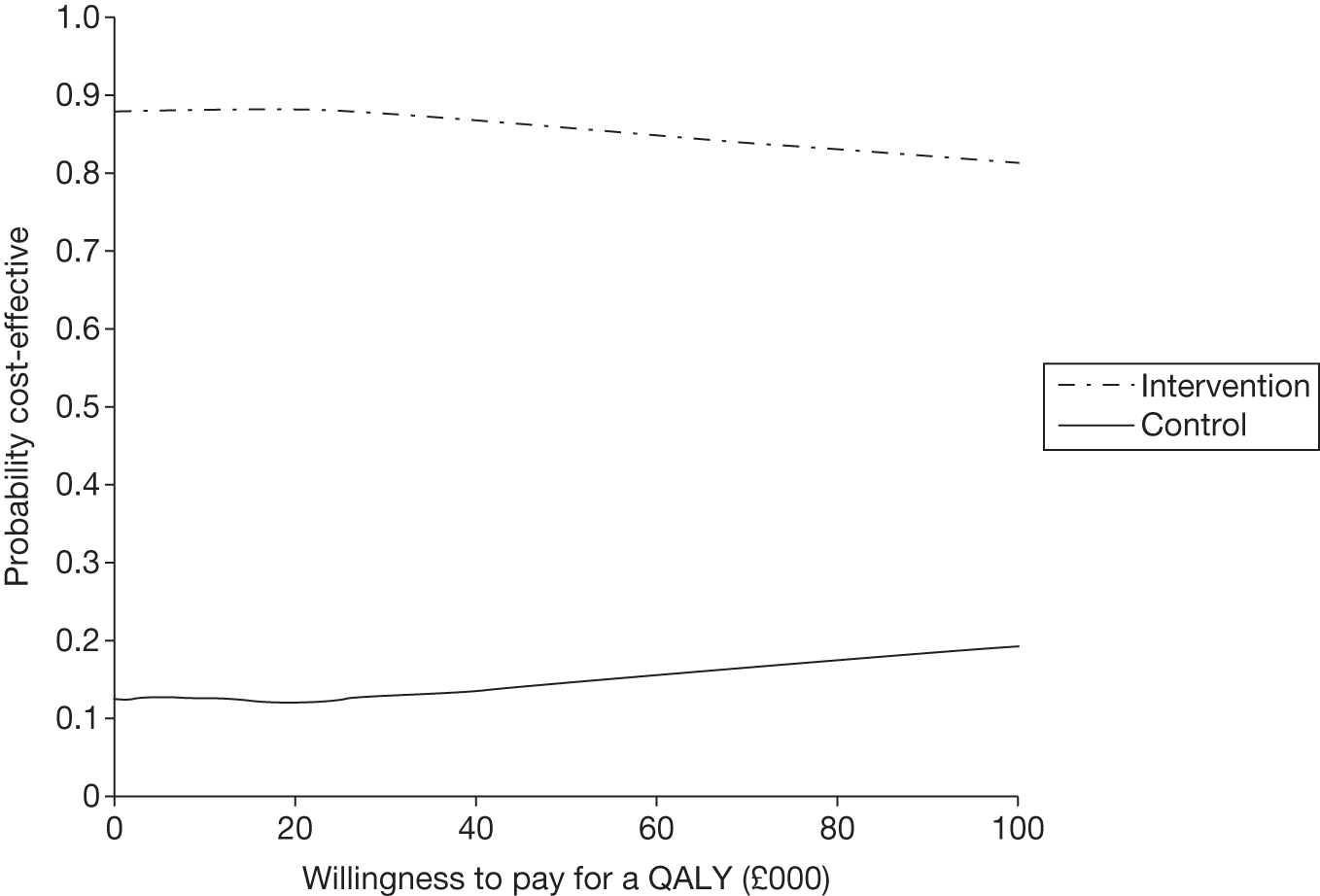

Patient flow