Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 06/304/229. The contractual start date was in December 2007. The draft report began editorial review in September 2011 and was accepted for publication in May 2012. The authors identified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2012. This work was produced by Woods et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to NETSCC. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2012 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Reminiscence interventions in dementia care

The development and evaluation of therapeutic interventions intended to benefit people with dementia and their family carers is the subject of much research interest at present. In view of the large and growing numbers of people with dementia, and the costs associated with meeting needs for care, there are clear advantages for health- and social-care services in supporting people with dementia in the community for longer but less intensively. However, there is consensus that this should not be at the cost of an additional burden on family carers. 1

Most attention has been given to pharmacological interventions, but there is increasing recognition that psychosocial interventions may have comparable value,2,3 and may be preferable in some contexts, for example where medication may be ineffective or have negative side-effects. 3,4 A number of systematic reviews of psychosocial interventions are now available,1,5,6 as well as a number of Cochrane reviews of specific approaches. 7,8

In the UK, reminiscence therapy appears to be the best-known therapeutic approach to working with people with dementia. For example, over half of care homes in Wales claimed to offer this approach to their residents according to a 2002 survey. 9 Reminiscence work with people with dementia has an extensive history,10,11 engendering enjoyable activities that promote communication and well-being. One factor in its popularity is that it works with early memories, which are often intact for people with dementia, thus drawing on the person’s preserved abilities rather than emphasising the person’s impairments. However, its popularity has not led to a corresponding body of evidence on its effects. The existing research literature was reviewed in our revised Cochrane review on reminiscence therapy for people with dementia. 12 Only four randomised controlled trials (RCTs) suitable for analysis were identified. Each examined different types of reminiscence work; all were small or of poor quality. The trials together identified significant improvements in cognition and mood 4–6 weeks after treatment and stress in caregivers who participated with the person with dementia in a reminiscence group. However, the review12 concluded that ‘in view of the limitations of the studies reviewed, there is an urgent need for more quality research in the field’. This dearth of evidence is reflected in the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) and Social Care Institute for Excellence guideline on the management and treatment of dementia,3 which found insufficient evidence to recommend that reminiscence should be routinely offered to people with dementia, although its potential impact on mood of the person with dementia was highlighted.

Since the publication of the Cochrane systematic review,12 six papers have been identified as reporting research looking at various aspects of reminiscence therapy for people with dementia. Two papers13,14 appear to be based on the same community-living sample, with the later paper14 providing a reanalysis broken down by type of dementia (Alzheimer’s vs vascular dementia). A third paper15 reports an institutional sample. Positive findings on cognition and mood are reported from the institutional study, while the effects on people with vascular dementia emerge as longer lasting than those on people with Alzheimer’s in the community sample, in relation to withdrawal and cognition. None of the papers involved family caregivers in the groups. A further three papers16–18 report studies using technology to support reminiscence in dementia, all in a care home context, and none directly involving family caregivers. Gudex and colleagues16 note that the main effects of integrating reminiscence therapy into daily care were on staff, while Hsieh and colleagues17 found that reminiscence group therapy had significant efficacy in the treatment of depressed mood and apathy in nursing home residents with mild to moderate stage dementia. Haslam and colleagues18 found that group skittles appeared to perform better than reminiscence in relation to well-being, while group reminiscence was associated with better cognitive performance. However, a number of methodological flaws mean that these results should be viewed with caution.

To take research forward, there is a need to specify clearly the exact nature of the reminiscence work undertaken and its aims. Typically, a group approach has been implemented with ‘memory triggers’ (photographs, recordings, artefacts, etc.) used to promote personal and shared memories. A relatively recent development has been to include family carers in reminiscence groups alongside their relatives with dementia. Descriptive evaluations suggest that this joint approach [described as ‘Remembering Yesterday, Caring Today’ (RYCT)19] may improve the relationship between carer and person with dementia, benefiting both. 20 As it is the breakdown of this caregiving relationship that increases the likelihood of the person with dementia being placed in an alternative care setting, such as a care home, this effect could have far-reaching implications for families, society and public spending. Our group have reported a very small pilot study evaluating this joint reminiscence approach (seven patient–carer pairs in the treatment group; four in the waiting-list control group), which showed some trends in improved quality of life for patients and reduced stress for caregivers. 21 In a larger trial platform, funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC), improvements in autobiographical memory and carer depression were associated with reminiscence groups containing 50 patient–carer pairs.

The justification for evaluating the joint reminiscence approach specifically comes from these promising pilot data and the great interest in this approach in the field of reminiscence work. 10 More generally, a recent meta-analysis1 on interventions with family carers of people with dementia suggested that joint approaches may be more effective in improving carer outcomes than approaches targeted only at the carer. The previous tradition in dementia care of providing interventions for people with dementia and their carers separately from each other is being questioned. For example, in many areas of the UK, Alzheimer Café sessions have been established with an agenda including education as well as social contact, attended by both people with dementia and their carers. 22 The emphasis has shifted from ‘person-centred care’ to ‘relationship-centred care’, with recognition of the central importance of the patient–carer relationship to the benefit of both. 22 Although a joint focus on people with dementia and their caregivers is not possible for all people with dementia, only 6% of people with dementia have no identifiable caregiver,23 and these individuals have an increased risk of entering care homes.

Economics of dementia and the role of family carers

In the UK, the number of people with dementia is estimated to be > 800,000, a figure expected to rise owing to an ageing population. 24 Health-care services will face a significant challenge in meeting the needs of an ageing population, and in the case of people with dementia there will also be a sizeable burden on informal caregivers since two-thirds of people with dementia live in private residences. This informal care by friends and family contributes £12B (55%) of the estimated £23B annual cost of dementia to the UK economy. The direct cost to the health service is £1B, and £9B is accounted for by institutional care costs. 24 Worldwide, the estimated cost of informal care is estimated to be US$251B. 25 Considering that the informal care sector is a vast resource, it is essential that when reviewing dementia care, whether in terms of interventions delivered by the NHS or social services or as fiscal measures, the effects on the caregiver are taken into account. From an NHS perspective, this is line with the NICE ‘reference case’ which reports that ‘the perspective on outcomes should be all direct health effects, whether for patients or, when relevant, other people (principally carers)’. 26

Aim and objectives

This report presents data gathered from a pragmatic RCT to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of RYCT joint reminiscence groups, for people with mild to moderate dementia and their family caregivers, compared with ‘usual care’. The objectives of the trial were as follows:

-

To compare the effectiveness (in ameliorating the quality of life of people with dementia and the stress on their carers) of joint reminiscence groups with participants and carers followed by reminiscence-based maintenance with that of ‘usual treatment’.

-

To compare the incremental cost-effectiveness (in ameliorating the quality of life of people with dementia and the stress on their carers) of joint reminiscence groups with participants and carers followed by reminiscence-based maintenance with that of ‘usual treatment’.

Chapter 2 Methods

Intervention

Overview

The practice of using joint reminiscence groups attended by people with dementia and their carers19 emphasises active as well as passive forms of reminiscence by both carers and the people with dementia. This approach is known as RYCT. 19 People with dementia and their family caregivers attended 12 two-hour weekly sessions, in a social setting rather than a clinical setting where possible. Community centres and museums were among the venues employed.

Each session focused on a different theme, including childhood, schooldays, working life, marriage, and holidays and journeys (Box 1). Couples were encouraged to contribute with materials brought from home. Each session blended work in large and small groups, and a range of activities including art, cooking, physical re-enactment of memories, singing and oral reminiscence. The inclusion of the person with dementia was paramount. In the joint reminiscence groups, facilitators and volunteers guided carers to allow the person with dementia to respond and to value their contribution. In certain sessions a separate activity was arranged for the carer members of the group in a separate room for part of the session. This allowed the carers to share experiences and ask questions that they might have found difficult in front of the person with dementia.

-

Introductions – names and places

-

Childhood and family life

-

Schooldays

-

Starting work

-

Going out and having fun

-

Courting and marriage

-

Homes, gardens and animals

-

Food and cooking

-

The next generation – babies and children

-

Holidays and journeys

-

Festivals and special days

-

Rounding up and evaluation

After the 12 weekly sessions, maintenance sessions were held monthly for 7 months, following a more flexible programme aimed at responding to interests of group members, as well as revisiting popular topics, continuing to follow the same principles. A session might focus on a particular decade (e.g. the 1950s) with appropriate music and video clips.

Two facilitators led each session. These facilitators came from a variety of professional backgrounds, and included occupational therapists, mental health nurses, clinical psychologists, arts workers and community support workers.

A maximum of 12 dyads (participant with dementia and carer) were invited to attend each series of groups.

The manual

The manual19 was developed during the trial platform and incorporates the experience of running the groups in that context. It provides detailed session-by-session outlines for each of the 12 weekly sessions, as well as an account of the underlying principles (Box 2) and background. It includes a number of exercises and template forms for use at various points in the sessions.

-

Value each person’s contribution

-

Make people welcome and appreciated

-

Use a rich array of memory triggers – stimulate all the senses

-

Use non-verbal communication

-

Give people plenty of time to respond

-

Use creative ways to explore memories

-

Use failure-free activities

-

Divide time: large group/small group/feedback small-to-large group

-

Make connections between people

-

Celebrate differences, achievements, individual stories, shared experience

Volunteers

The two trained facilitators in each group were supported by several trained volunteers. Volunteers covered a range of ages and came from the voluntary sector (e.g. Alzheimer’s Society and Age Concern), health professional trainees and former carers with an understanding of working with older people. The presence of volunteers meant that if, for any reason, carers were not able to attend all the group sessions, the person with dementia could still contribute to the group sessions. A number of volunteers took part in the training sessions and the groups to contribute to their own professional development.

Training of facilitators

The training programme for facilitators and volunteers is also set out in the RYCT manual. Training engenders skills in listening, interpreting behaviours, group dynamics, and enthusing carers and people with dementia. Two half-day training sessions took place before each group commenced. After each session there was time for facilitators and volunteers to prepare session notes, complete attendance forms and collate evaluation forms on how the session had gone. Further evaluation forms were collected from carers and people with dementia at the end of the first session and at the end of the 12-week programme. The originator of this intervention approach, Pam Schweitzer, conducted training sessions in each centre and was available for consultation throughout the project. A number of meetings were held at a central location, where the group facilitators could discuss the treatment groups with Pam Schweitzer and with facilitators from other centres, offering peer supervision.

Treatment fidelity

It had been planned originally to videotape a sample of group sessions and to rate these videotapes for adherence to the intervention manual, but reviewers advised a lighter touch approach. Accordingly, group facilitators were asked to ensure that an adherence checklist was completed at the end of each session, often by a volunteer who had been in a position to observe the session. The checklist was based on the application of the essential principles of RYCT as well as relating to specific aspects of each session.

Trial platform

The current study is based on a pilot study comparing these joint reminiscence groups with usual treatment as part of a trial platform funded by the MRC (2004–6), which also refined outcome measures and prepared a detailed treatment manual. The trial platform also included an additional condition where people with dementia attended reminiscence groups without their carers.

Methods

Three university centres participated in the trial (Bangor University, Bradford University and University College London). Across the centres, three joint groups and two reminiscence alone groups were run. Participating dyads were randomised to either the joint reminiscence condition or to an active control condition (reminiscence alone) or a passive control condition (treatment as usual), depending on the centre. In the Bradford centre, the Zelen randomisation method27 was trialled; participants initially agreed to complete the assessment procedures at each time point; if randomised to an active intervention, further informed consent was then sought.

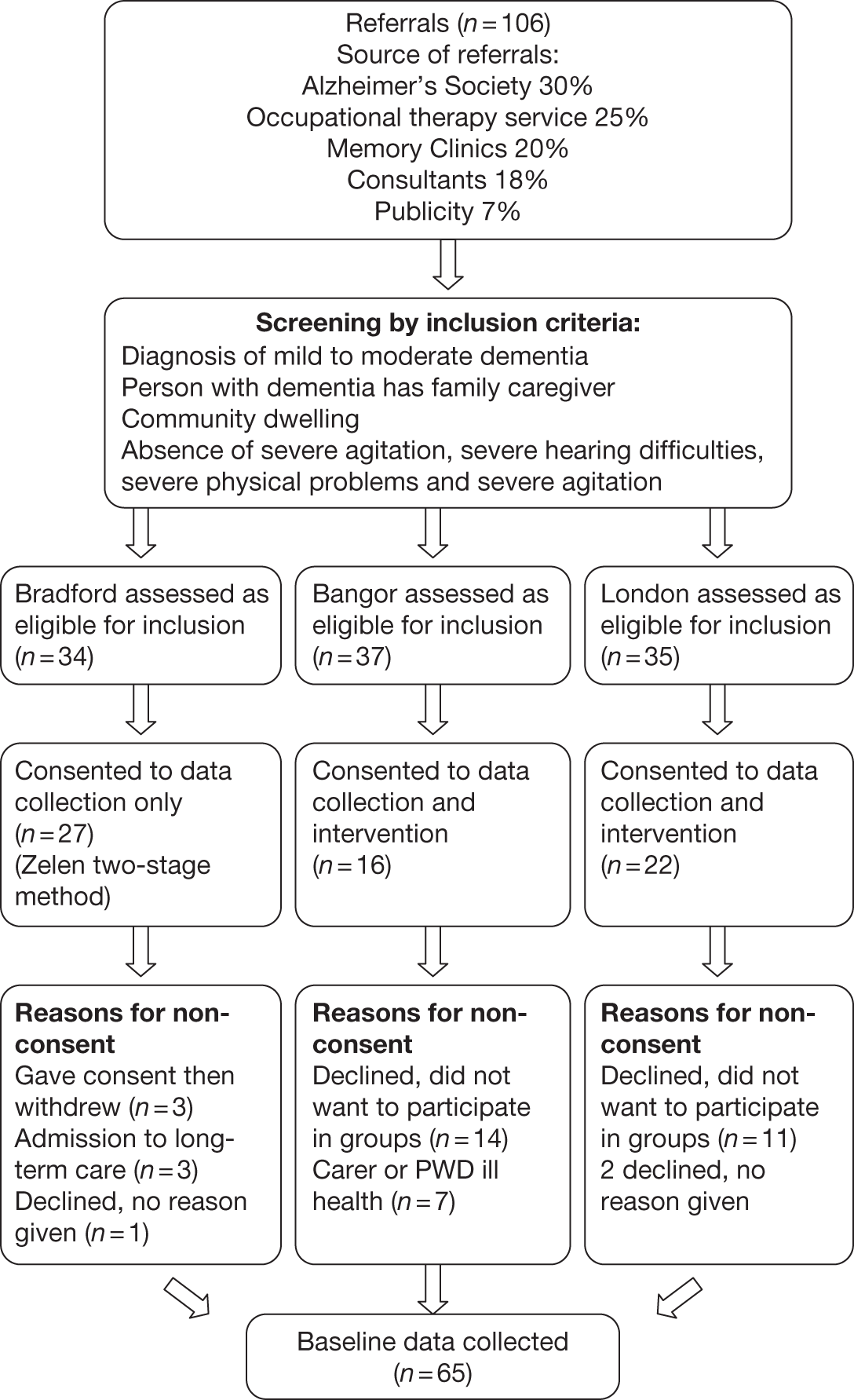

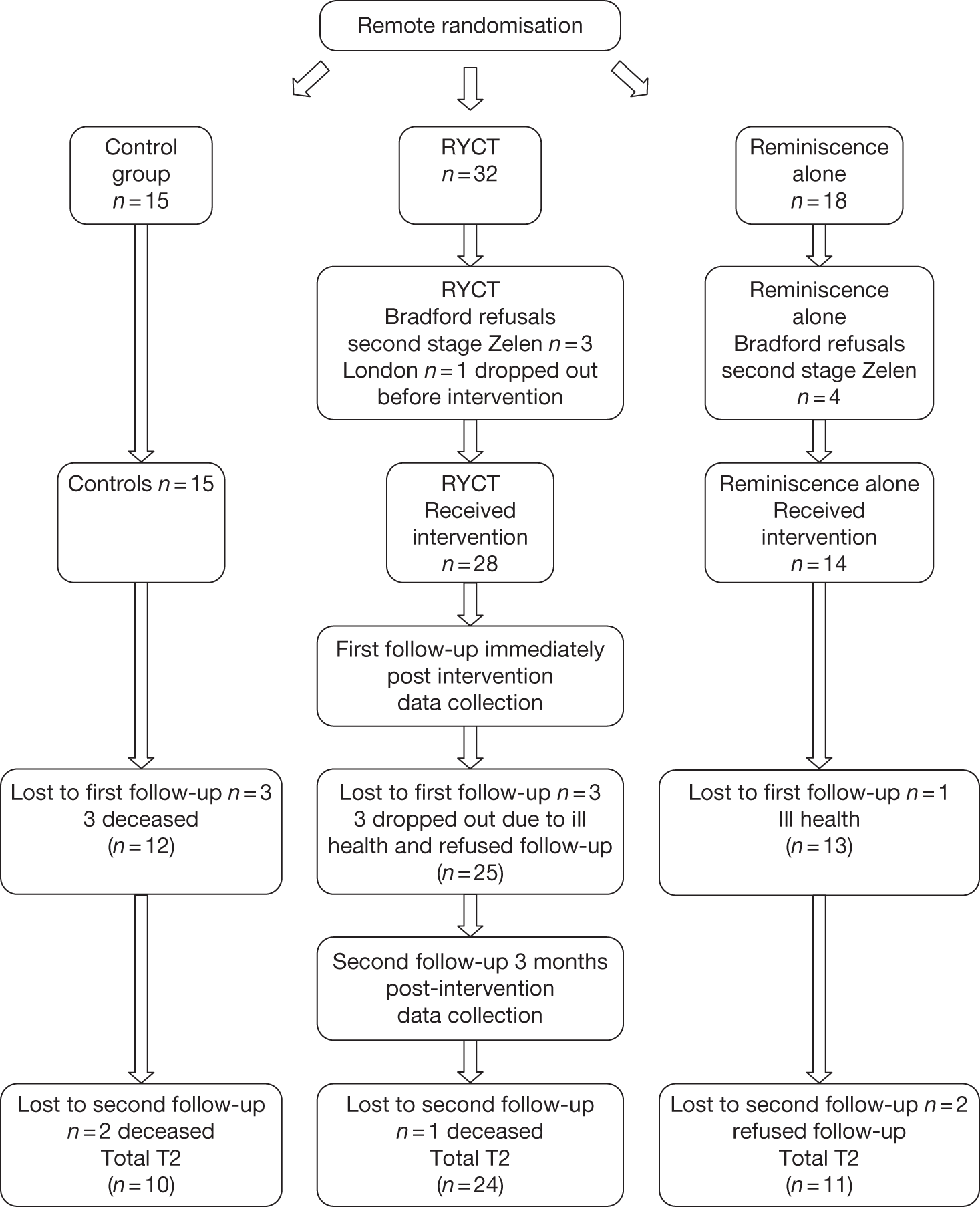

Participants were recruited from local NHS services, including Memory Clinics, and from voluntary agencies such as the Alzheimer’s Society. Inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of mild to moderate dementia and the absence of severe agitation and communication problems. All participants were required to have a family caregiver able and willing to attend reminiscence sessions with the person with dementia. Sixty-five participant dyads entered the trial and provided baseline data; 57 went on to receive the intervention to which they were randomised (seven of the eight lost at this point being stage 2 Zelen refusals). The post-treatment assessment was completed by 50 dyads; a 3-month follow-up assessment was completed by 45 dyads (10 treatment as usual, 24 joint reminiscence, 11 reminiscence alone). Most of the attrition at post-treatment and follow-up assessment was accounted for by death (six) and ill-health (four), with two withdrawals at the follow-up stage. A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram for the trial platform is provided in the trial protocol to be found in Appendix 10. The median age of the people with dementia was 78 years; that of the caregivers was 72 years. The average Mini-Mental State Examination28 score was 19.3 [standard deviation (SD) 5.0] (moderate dementia 12–20; mild dementia 21–26).

Primary outcome measures were quality of life in Alzheimer’s disease (QoL-AD),29 a quality-of-life measure completed with the person with dementia in a structured interview, which is also completed on a proxy basis by the caregiver; and Relatives’ Stress Scale (RSS),30 a self-report measure of the direct impact of caregiving. Secondary outcome measures included a measure of autobiographical memory (the type of personal memory over the lifespan that should be influenced by reminiscence work), adapted for the project to include more items and better coverage of the lifespan; measures of caregiver distress and depression [the General Health Questionnaire-28 item version (GHQ-28)31 and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15)];32 measures of the quality of relationship between the person with dementia and caregiver [quality of caregiver/patient relationship (QCPR)];33 and ratings of videotaped interactions between person with dementia and caregiver in two structured situations. 34

Results

All analyses reported were undertaken using analysis of covariance on post-treatment (or follow-up scores), with baseline scores as the covariate. For most of the measures in this small sample, differences between joint reminiscence and reminiscence alone were small. For the primary outcome measures, comparing either type of reminiscence with treatment as usual, the differences were not statistically significant; the effect sizes for QoL-AD, rated by the person with dementia, were small at post-treatment (0.17) and at 3 months’ follow-up (0.40); the initial rating for the caregiver rating of the quality of life for the person with dementia (a secondary outcome) was slightly higher (0.50), but the effect size at 3 months was similar (0.33). On the primary outcome for caregivers, the RSS, effect sizes were small to moderate (0.36 and 0.31).

On secondary outcome measures, people with dementia in the joint reminiscence group had significantly better autobiographical memory at post-treatment than those receiving treatment as usual (effect size 0.61; p = 0.007), but this was not maintained at follow-up. Caregivers involved in the joint reminiscence group reported less depression at post-treatment than those in the treatment as usual condition, a difference that was maintained at follow-up (effect size 0.57, p = 0.013, and effect size 0.42, p = 0.024, respectively). These findings were also clear when treatment as usual was compared with either type of reminiscence, with reminiscence work associated with better autobiographical memory at post-treatment, but not at follow-up, and the reminiscence conditions also associated with reduced caregiver depression and distress (on GHQ) at post-treatment and (on GDS and GHQ) at follow-up. Effect sizes for all these comparisons were in the range 0.48 to 0.6, except for autobiographical memory at follow-up, which was 0.13. The details of the comparisons between any form of reminiscence and treatment as usual are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

| Outcome measure | Baseline reminiscence | Baseline treatment as usual | Post-treatment reminiscence | Post-treatment treatment as usual | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QoL-AD (patient-rated) | 37.47 (5.46) | 35.50 (5.33) | 37.70 (5.22) | 34.83 (5.84) | 0.17 |

| RSS | 22.56 (13.77) | 20.50 (13.39) | 21.49 (12.77) | 24.33 (11.50) | 0.36 |

| GHQ-28 | 19.97 (9.94) | 21.82 (10.48) | 20.19 (10.66) | 27.64 (11.44) | 0.56 |

| GDS | 2.95 (3.45) | 3.09 (2.88) | 3.08 (3.22) | 5.09 (4.93) | 0.56 |

| AMI(E) | 69.01 (23.83) | 72.86 (27.96) | 67.58 (29.73) | 58.14 (30.54) | 0.54 |

| QoL-AD (carer-rated) | 30.82 (5.82) | 30.35 (4.71) | 30.99 (6.37) | 27.60 (4.97) | 0.50 |

| Outcome measure | Baseline reminiscence | Baseline treatment as usual | Follow-up reminiscence | Follow-up treatment as usual | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QoL-AD (patient-rated) | 37.08 (5.38) | 35.36 (5.57) | 35.49 (4.99) | 31.64 (11.79) | 0.40 |

| RSS | 20.11 (12.98) | 20.50 (13.39) | 22.78 (12.63) | 27.33 (13.85) | 0.31 |

| GHQ-28 | 18.97 (10.25) | 22.00 (10.01) | 21.14 (11.55) | 30.33 (13.24) | 0.62 |

| GDS | 2.46 (2.98) | 3.09 (2.88) | 3.41 (2.85) | 5.64 (4.70) | 0.48 |

| AMI(E) | 70.01 (23.30) | 72.86 (27.96) | 58.94 (28.96) | 58.59 (35.18) | 0.13 |

| QoL-AD (carer-rated) | 30.96 (5.56) | 29.59 (5.13) | 30.11 (6.50) | 26.82 (5.65) | 0.33 |

Implications of trial platform for the full trial

-

The Zelen method of randomisation led to several refusals to accept experimental interventions, thus weakening the effect of those interventions as Zelen analyses by ‘intention to treat’ (ITT); as there was no evidence that it otherwise assisted recruitment and retention in this field, it was not used in the current study.

-

Though the trial platform necessarily generated wide confidence intervals (CIs), the difference in effects between joint reminiscence and reminiscence alone appeared to be small, as one might have predicted a priori from the similar resources allocated to each. Indeed, reminiscence alone may have beneficial effects for caregivers also. This may be because of the brief respite afforded to the caregiver, or from the benefits they perceive the person with dementia is receiving.

-

Although it was considered that the further comparison of joint reminiscence and individual reminiscence would be of interest in providing a test of the additional effects of joint working and of relationship-centred care, the size and complexity of trial that would be required, given the probable small effect size for any difference between the two conditions, was judged not to be feasible. Accordingly, the current study focused on joint reminiscence groups.

-

Participants in the joint reminiscence groups requested monthly reunion meetings following the end of the 12 weekly sessions. They wished these to continue to have a reminiscence focus in addition to social contact. These maintenance sessions over the follow-up period have been incorporated into the current study.

Methods

Design

A pragmatic multicentre parallel group RCT of joint reminiscence and maintenance compared with usual treatment was carried out. Participants were randomised to the two groups using a restricted dynamic method of randomisation. The overall allocation ratio was 1 : 1, but this was restricted to ensure intervention groups were of a viable size. Data collection points were at baseline before randomisation, at 3 months immediately following completion of the weekly reminiscence sessions and at 10 months following completion of the seven monthly maintenance sessions of the therapy. The primary outcomes were assessed at all time points with the primary hypothesis examining these outcomes at the 10-month interval.

Ethics approval

A protocol was submitted for ethical scrutiny to the Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (MREC) for Wales (ref. no. 07/MRE09/58) in September 2007, with provisional approval being granted in October 2007. The issues identified by the committee as needing to be addressed were as follows:

-

Information sheets needed to be modified to make it clear that interviews and questionnaires could be completed over two sessions and that interviewees could take breaks if necessary.

-

Reference to section 32 of the Mental Capacity Act35 in the information sheets should be removed.

-

A protocol was required to deal with issues of neglect or ill treatment of people with dementia, especially in instances where the carer was the perpetrator.

After addressing these issues, final approval was granted in November 2007. Participating centres obtained approval from the appropriate Local Research Ethics Committee (LREC) and the relevant NHS Trust research and development (R&D) department.

Intervention and control conditions

Participants randomised to the intervention condition were invited to attend reminiscence group meetings as outlined above. Transport was arranged if required.

The control condition in this trial was designated as ‘treatment as usual’. The services and interventions available to people with dementia and family carers randomised to receive usual treatment varied between and within centres and over time. In principle, all the interventions offered to this group were also available to those in the active treatment groups as we were evaluating the additional effects of reminiscence work. The only exception to this was when reminiscence groups occurred at the same time as an alternative intervention. Our commitment to costing services and interventions received allowed us to monitor whether or not control groups were receiving alternative interventions in this way. Though changes and developments in the availability of medications for Alzheimer’s and other dementias should have affected both groups equally, this was also monitored through the service-use information collected.

Participants in the usual treatment group may have engaged in some form of reminiscence work during the 10 months of the study period. This is a popular approach in day-care centres, and reminiscence materials are widely available. However, it is unlikely that structured reminiscence work would have been offered in any of the centres, and even less likely that it would have been offered jointly to carers. It is this systematic group-based approach, rather than a general exhortation to reminisce to improve communication, that is the focus of this evaluation.

Study population

Eight centres in England and Wales were involved in the study: Bangor (covering north Wales), Bradford, Hull, London (north – covering the boroughs of Barking and Dagenham, Havering, Redbridge, Waltham Forest), London (south – covering the boroughs of Bexley, Bromley, Greenwich), Manchester (double centre – covering Bolton, Salford, Trafford) and Newport in south Wales (covering mainly Newport and Caerphilly). Researchers in six centres were based in the universities shown in Table 3, whereas those in Hull and Newport were based in NHS mental health services. Recruitment commenced in May 2008 and was completed in July 2010.

| REMCARE centre name | Organisations involved |

|---|---|

| Bangor | Bangor University |

| Conwy and Denbighshire NHS Trusta | |

| North East Wales NHS Trusta | |

| North West Wales NHS Trusta | |

| Bradford | University of Bradford |

| West Yorkshire Research and Development Consortiumb | |

| Hull | Humber Mental Health Teaching NHS Trustc |

| London (north) | University College London |

| North East London Mental Health NHS Trustd | |

| London (south) | University College London |

| Oxleas NHS Foundation Trust | |

| Manchester | University of Manchester |

| Greater Manchester West Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust | |

| Newport | Gwent Healthcare NHS Truste |

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion

All participants were people with dementia who at the time of the baseline assessment:

-

met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria for dementia of any type, including Alzheimer’s, vascular, Lewy body type and mixed

-

were in the mild to moderate stage of dementia (Clinical Dementia Rating)

-

could communicate and understand communication, shown by a score of 1 or 0 on the relevant items of the Clifton Assessment Procedures for the Elderly – Behaviour Rating Scale

-

could engage in group activity

-

were living in the community and had a relative or other caregiver who maintained regular contact, could act as informant, and was willing and able to participate in the intervention with the person with dementia.

Exclusion

Potential participants were excluded if they had any characteristic which could affect participation, for example:

-

major physical illness

-

uncorrected sensory impairment

-

disability or

-

high level of agitation.

Sample size

The original target sample size was 400 patients completing data collection for the trial after 10 months, comprising 200 in the intervention condition and 200 receiving treatment as usual. In the MRC trial platform intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) within randomised groups were negative (i.e. not significantly different from zero) for both the carer-specific GHQ and the carer-rated QoL-AD, but close to 0.1 for the QoL-AD rated by the person with dementia. Using a 5% significance level, comparison of 200 pairs completing reminiscence groups with 200 people with dementia receiving treatment as usual yields 80% power of detecting a standardised difference of 0.28 in the GHQ or the carer-rated QoL-AD. In contrast, because the patient-rated QoL-AD was estimated to suffer a ‘variance inflation factor’ of approximately 1.74 [namely 1 + 0.1 × (average completed group size of 8.4 – 1)], this yielded a power of 80% of detecting a standardised difference of 0.38. The trial platform, which had a sample size of 57 in three centres, suggested that these differences between 0.28 and 0.38 for the outcomes are plausible. In our judgement these differences also fall within the range of effects that are clinically important. Furthermore, because previous work had been exploratory, and therefore more heterogeneous than the current definitive trial, ICCs and SDs were expected to fall. To achieve a sample size of approximately 400, we allowed for 12% attrition between recruitment and the post-treatment assessment (estimated from our trial platform) and a further 18% over the following 7 months (estimated from a community study). 36 Hence, we set an initial sample size of 576, requiring 24 treatment groups initially comprising 12 dyads and another 288 randomised to usual treatment.

A review of the sample size calculation was completed in July 2009, as part of an extension application. This review revealed that as suspected the ICCs were lower than accommodated for within the original sample size calculation. The baseline data collected up to July 2009 showed that the ICCs for the patient-rated QoL-AD, using the difference method, was 0.0214. Given the smaller than anticipated group sizes in the study (estimated mean seven at 10-month follow-up) this led to a much reduced variance inflation factor (VIF) of VIF = 1 + 0.0214 × 6 = 1.1284. The revised recruitment target of 508 provided a potential sample size of 366 at 10-month follow-up, assuming 72% retention across the 10-month period. This provided 80% power to detect a standardised difference of 0.30 in the GHQ or carer-rated QoL-AD at the 5% significance level, and 80% power to detect a standardised difference of 0.31 in the patient-rated QoL-AD. The slight loss in power to detect a difference in the carer-rated measures is more than compensated for by the increased power to detect a difference on the patient-rated primary outcome measure.

Recruitment procedures

People with dementia and their family caregivers were recruited through mental health services for older people in each area [especially Memory Clinics, Community Mental Health Teams (CMHTs) for older people and associated professionals including psychiatrists, occupational therapists and Admiral Nurses®], associated day services and through relevant local voluntary sector agencies such as the Alzheimer’s Society. (Admiral Nurses are specialist mental health nurses, working primarily with carers of people with dementia. The service is available in a number of locations in England. ) The centres in Wales benefited from the support of Clinical Studies Officers accessed through the National Institute for Social Care and Health Research Clinical Research Centre (NISCHR-CRC). In Manchester and north London, support was given by the Dementias and Neurodegenerative Disease Research Network (DeNDRoN). In Hull, towards the end of the study, recruitment was extended to include certain general practitioner (GP) surgeries, as this was considered a potential additional source of participants.

Recruitment was in waves (3–5, depending on the centre), which offered the opportunity to focus on different geographical areas within the remit of each centre for each group. The project was briefly outlined to the potential participants by a member of the clinical team or Alzheimer’s Society worker, and permission for them to be contacted by a member of the research team was obtained. The research worker would then arrange to meet the potential participants and offer full details, respond to questions and, where the participants were willing to join the study, undertake the process of consent.

Informed consent

Participants were allowed to enter the study only after giving signed informed consent in accordance with the provisions of the Mental Capacity Act 2005. 35 For each couple participating in the trial, separate informed consent was sought from the person with dementia and their family caregiver. Participants with dementia were in the mild to moderate stages of dementia, and therefore could generally be expected to be competent to give informed consent for participation, provided that appropriate care was taken to explain the research and sufficient time allowed for them to reach a decision. In every case, participants with dementia were given at least 24 hours to consider the information provided. Wherever possible, the involvement of a family member, or other supporter, was sought.

It was made clear to both the person with dementia and the family caregiver that no disadvantage would accrue if they chose not to participate.

In seeking consent, current guidance from the British Psychological Society37 was followed on the evaluation of capacity. In this context, consent has to be regarded as a continuing process rather than a one-off decision, and willingness to continue participating was continually checked through discussion with the person with dementia during the assessments.

Where the participant’s level of impairment increased, so that he or she was no longer able to provide informed consent, the provisions of the Mental Capacity Act were followed, with the family caregiver as personal consultee. Where the person with dementia had him- or herself given informed consent initially, this provided a clear indication of the person’s likely perspective on continuing at later time points. The same procedure applied where the person with dementia appeared to lack capacity to consent initially but met the other criteria for the project. If at any point a person with dementia became distressed by the assessments, they were discontinued.

Ethical arrangements

There appear to be no documented harmful side effects from participating in reminiscence groups. Some past memories can be unhappy, and even traumatic, but with a skilled and trained facilitator participants will share only those aspects they feel comfortable with. Additional support on a one-to-one basis was given in the small number of cases where distressing memories surfaced.

Prospective participants were fully informed of the potential risks and benefits of the project. A reporting procedure was put in place to ensure that serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported to the chief investigator. On becoming aware of an adverse event involving a participant or carer, a member of the research team assessed whether or not it was ‘serious’. A SAE was defined in the trial as an untoward occurrence experienced by either a participant or carer which:

-

resulted in death

-

was life-threatening

-

required hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

was otherwise considered medically significant by the investigator

-

came within the scope of the Protection of Vulnerable Adults (POVA) protocol, which was in place to ensure that suspected cases of abuse or neglect were followed-up in an appropriate manner.

A reporting form was submitted to the chief investigator who assessed whether or not the SAE was:

-

related to the conduct of the trial

-

unexpected.

Serious adverse events that were judged to be related and unexpected were to be reported to MREC and the trial Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) within 15 days.

Randomisation

Randomisation was completed using a dynamic allocation method38 stratifying for spousal or non-spousal relationship of the dyad. Complete list randomisation for each wave of recruitment within each centre was completed. All participants for a wave were intended to be recruited before being randomised, although provision was made within the system to allow additional randomisations within a group to be performed. Although the overall allocation ratio was 1 : 1, it was stipulated that the RYCT groups needed at least eight participants to prove viable; the randomisation system was restricted in order to accommodate this. This restriction does mean that overall allocation to the intervention was higher than to the control, although within each wave this was constrained to within an acceptable level. The final overall allocation ratio was not sufficiently different from 1 : 1 to cause any issue for the analysis.

Allocation concealment

By undertaking a complete list randomisation for each wave at each centre, allocation knowledge of the next assignment would be irrelevant as all participants for a centre would be randomised together. Unblinded researchers were the only staff informed at each of the centres of the participant’s allocation.

Implementation

Researchers completed a randomisation request form detailing all participants to be randomised. This form was then emailed to the responsible trials unit [North Wales Organisation for Randomised Trials in Health (& Social Care)], the centralised randomisation centre, where allocation was performed. The allocations were filled out on the request form and returned to the nominated unblinded researcher in each centre.

Blinding

Owing to the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to blind the participants to the allocation that they received. Within each centre there was a nominated blinded researcher and an unblinded researcher. Both researchers were able to complete the baseline assessments with the participants and request the randomisation of participants. Once randomised, the unblinded researcher received the allocations and took the role of informing participants of their allocation and organising the joint reminiscence groups. The unblinded researcher in the majority of the centres was also the facilitator for the joint reminiscence group. The blinded researcher carried out all follow-up assessments. As part of the follow-up assessments, the researcher completed a perception sheet that indicated their prediction of which treatment arm a participant was in.

The analysts remained blind to the allocation for the main analysis. Analyses including the joint reminiscence groups attendance records were scheduled to be completed after the main analysis to ensure that blinding was kept intact for as long as possible.

Data-collection procedures

Primary and secondary measures were completed at baseline, 3 months after baseline (first follow-up) and 10 months after baseline (second follow-up and primary end point). Centres were instructed to conduct baseline assessments within a 2-month window prior to the first joint reminiscence group being held. The interviews for the first follow-up were conducted within 2 months of the completion of the weekly joint reminiscence group sessions, while the interviews for the second follow-up were scheduled within 2 months of the final monthly maintenance session.

Interviews were usually conducted in the family home, and though provision was made in the protocol for alternative venues to be used if required, this seldom happened in practice. The questionnaire measures were arranged in a number of booklets for ease of administration. In particular, self-reported health questionnaires for the carer and proxy measures completed by the carer with respect to the person with dementia were incorporated into booklets designed for self-completion. Where local resources allowed, two assessors would visit a couple, one interviewing the person with dementia while the other interviewed the carer in a separate room if possible. Assessors operating on their own were encouraged to ask the carer to complete their booklets in a separate room while the interview with the person with dementia took place. A second visit was sometimes made to complete assessments where an interviewee became tired, or where it was otherwise requested by participants or deemed appropriate by the assessor.

Measures

Primary outcome measures

-

Quality of life of the person with dementia, using the QoL-AD scale,29 which covers 13 domains of quality of life. This is reliable and valid for people with mild and moderate degrees of dementia when they take part in structured interviews with trained interviewers. 39,40 A higher score on the scale indicates a better quality of life.

-

Caregiver’s mental health, assessed using the 28-item, self-completed GHQ,31 which has been widely used in caregiver research. 41,42 We used the scoring system with 4-point Likert scales ranging from 0 to 3. The questionnaire includes indicators of anxiety, depression, insomnia, social dysfunction and somatic symptoms. We chose the GHQ over the RSS as the primary outcome because it is more general in scope and more widely used. A higher score on the scale indicates more distress for the carer.

Secondary outcome measures

-

Autobiographical memory, assessed using an extended version of the autobiographical memory interview [AMI(E)]. 43 The AMI(E) assesses the person with dementia’s recall of personal memories relating to both factual (semantic) information (e.g. names of schools or teachers) and specific incidents. In the trial platform, we validated an additional section covering the period from middle-age to retirement, to cover the lifespan of our participants. A higher score on the scale indicates a better memory recall function.

-

Quality of relationship, assessed by both person with dementia and carer using the QCPR. 33 Originally developed in Belgium, this scale comprises 14 items with five-point Likert scales designed to assess the warmth of the relationship and the absence of conflict and criticism. In the trial platform, the QCPR had good internal consistency for carers (α = 0.85) and for people with dementia (α = 0.80), and concurrent validity with other measures of relationship quality and carer stress. A higher score on the QCPR scale indicates a better perceived relationship. Two subscales provide separate measures of warmth and absence of conflict/criticism.

-

Depression and anxiety, using the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (CSDD)44 and the Rating Anxiety in Dementia (RAID)45 for the person with dementia; and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)46 for the carer. The CSDD is a 19-item scale, derived from interviews with the people with dementia and their carers in which the interviewer describes signs and symptoms to the interviewee. Where there is a discrepancy between carer’s and assessor’s ratings, the interviewer re-interviews the carer before making a final judgement. A higher score on the scale indicates more depressive symptoms. The RAID is an 18-item scale to rate anxiety in people with dementia based on structured interviews with them and their carers. A higher RAID score indicates more anxiety symptoms. The HADS is a well-validated 14-item, self-completed scale that measures both anxiety and depression, and is suitable for use with adults of all ages. Higher scores on the two HADS’ subscales denote the presence of more anxiety and depressive symptoms.

-

Stress specific to caregiving, using the RSS,30 which asks the caregiver to complete 15 five-point Likert items. A higher score overall on this scale indicates more stress specific to caregiving.

-

Quality of life of the person with dementia, rated by the caregiver using the proxy version of the QoL-AD,29 identical in structure and content to the version completed by the person with dementia. The proxy QoL-AD works on the same scale as the self-completed version, with a higher score indicating a better quality of life for the person with dementia, in this case as the carer perceives it.

-

General quality of life of both caregiver and person with dementia, using the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D). 47 The EQ-5D is a validated generic, health-related, preference-based measure comprising five domains: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain and discomfort, and anxiety and depression. Each domain has three levels (no problems, some problems and many problems). The EQ-5D scoring system defines 243 (35) possible health states with two additional states (dead and unconscious), where death has a value of 0 and best imaginable health has a value of 1. The questions are complemented by a visual analogue scale (VAS), with 0 representing worst imaginable health and 100 representing best imaginable health, on which respondents are asked to indicate their current health. Caregivers completed the measure from their own perspective and for the person with dementia; the measure was also completed with the person with dementia whenever possible.

-

Functional ability of the person with dementia, using the Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale,48 a 20-item scale completed by the carer. A higher score on this scale indicates less functional independence of the person with dementia.

-

Use of health care, social care and voluntary services. In a face-to-face interview, participants with dementia and their carers were each asked to recall, at baseline, 3 months and 10 months their contacts with health care, social care and voluntary services. This was done using an adapted Client Services Receipt Inventory (CSRI),49 used extensively in studies of mental health and dementia (e.g. Knapp and colleagues). 50

Data checking

Data for the project were collected in questionnaire packs completed by the researcher during an interview with the participants. All AMI(E) questionnaires were double scored at the centres before being sent for scanning to ensure consistency of scoring between individuals. This double scoring system was introduced and training was given at the first training day for researchers.

The completed questionnaire packs were then returned to the trials unit, the North Wales Organisation for Randomised Trials in Health (and Social Care). Each questionnaire book was scanned into Verity Teleform version 9.1 (Verity Inc., Sunnydale, CA), where the data underwent a verification and validation process before being exported to SPSS files. SPSS PASW version 18 (IBM Corporation, New York, NY) was used for all further data manipulations and analysis. A process of cleaning the SPSS files was undertaken. Variables were checked for out-of-range values and consistency. All corrections made to SPSS files were logged together with reasons for their change. A proportion of the questionnaire books were cross-checked with the SPSS data to allow identification of any issues with particular variables. Once issues had been identified then further in-depth cross-checking could take place. For example, the majority of the EQ-5D VASs required double checking, and all CSRIs required cross-checking with the hard copy owing to the amount of free-text contained in the form.

Data analysis

Missing data

There were two types of missing data within this data set: missing items within a measure and missing measures at a particular time point.

For items missing within a measure, the rules for completing missing data for the relevant measure were applied. The missing data rules implemented for each measure are considered part of the validated tool and were therefore used as designed in line with the original validation. This rule affected two measures used in this study: QoL-AD and the HADS. For QoL-AD, up to two missing items are replaced with the mean score of the remaining items. For the HADS, a single missing item from a subscale may be replaced by the mean of the remaining six items.

Once the measure rules had been implemented, missing time point data were considered. For baseline, a linear regression model was applied, taking into account age, gender, spousal care, centre, wave and other baseline measurement scores. This gave a complete baseline data set. For the follow-up time points, a linear regression was again used, this time within a measure. The linear regression model was fitted for each of the outcome measures separately, taking into account age, gender, spousal care, centre, wave, treatment group allocation and all previous time point scores. For follow-up 1 (FU1), baseline scores were used in the model, whereas for follow-up 2 (FU2), baseline and FU1 scores were used in the model. The imputations for the follow-up time points were carried out as a multiple imputation providing five replicate data sets for assessment.

Baseline characteristics

As recommended, no formal tests were carried out for significant differences of baseline characteristics between the treatment arms. 51 Data were tabulated for the whole sample, intervention and control groups for both demographic and clinical variables.

Interim analyses

No interim analyses had been scheduled for the data. During the course of the trial, no additional analyses were identified or requested by the DMEC.

Primary effectiveness analyses

A linear-mixed model analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to analyse the quantitative repeated measures. For each quantitative response the baseline value was used as a covariate. The treatment group was a fixed factor. The different centres were random factors. The participants within a centre were also random factors.

The usual ‘wide data’ format is where each row represents a participant and each column represents a measurement made on that participant. The data file was transformed to the ‘long’ format where there are two rows for each participant, one for the measurements made at 3 months and one for the measurements made at 10 months. A column was created to indicate at which time point the measurements were made. Time was included in the model as a fixed factor, together with the interaction between treatment group and time. The advantage of this method of analysis is that all participants are included and all observations that are collected are included in the analysis.

The above analysis gives consistent unbiased estimates of the treatment effect provided the data are missing completely at random. This was assessed by seeing if any variables, for example treatment, centre, baseline values, gender, age, and so on, predicted whether or not an observation was missing using a logistic regression. Any predictors identified were included as covariates in the linear-mixed model ANCOVA, allowing the missing completely at random conclusion to be drawn.

-

Model 1: Is QoL-AD affected by treatment and time, taking into account covariates of age, gender, baseline score, centre and spousal care?

-

Model 2: Is the GHQ affected by treatment and time, taking into account covariates of age, gender, baseline score, centre and spousal care?

Secondary effectiveness analyses

The initial secondary models replace the 10-month outcome with the 3-month outcome.

-

Model 3: All models repeated for the secondary outcomes.

-

Model 4: Treatment adherence incorporated into the models.

Additional analyses

Additional analyses looked at the stipulated subscales of the GHQ, AMI(E) and the QCPR.

Economic analyses

Perspective

A public sector perspective was adopted spanning the NHS (dementia services, primary and secondary care) and local government (social services).

Micro-costing of reminiscence group therapy and maintenance

Micro-costing is a necessary part of economic evaluation. It allows a bottom-up construction of the costs of setting up and delivering a new programme by recording the types and quantities of resource input including, in the case of REMCARE, staff time, materials, room rental, recruitment and supervision of staff. Unit costs, tariffs or prices are then assigned for a particular currency and year. Within a country, results from micro-costing can be transferred between different settings and situations transparently. 52,53

Patterns of health care, social care and voluntary sector service use and associated costs by participants with dementia and their carers

In a face-to-face interview, participants with dementia and their carers were each asked to recall, at baseline, 3 months and 10 months, their contacts with health care, social care and voluntary services. This was done using an adapted CSRI. 49 We developed the CSRI by looking at instruments used in previous dementia studies and through consultation with the principal investigator on the REMCARE trial. As part of the CSRI asking about services use, interviewers asked participants with dementia and their carers about the drugs they had been prescribed and were taking. We were particularly interested in drugs prescribed for dementia, anxiety and to aid sleep.

Valuing resource use

The costs of resource use were estimated using national unit costs obtained from the Department of Health54 and Curtis. 55 Drug prices were obtained from the British National Formulary. 56 Unit cost data are listed in Appendix 1.

Imputation

The imputed values derived for the effectiveness analysis (as described in Missing data) were used, where appropriate, in the health economics analyses (i.e. for missing GHQ, QoL-AD, EQ-5D data). Missing costs were not imputed; only cases with full cost data were used.

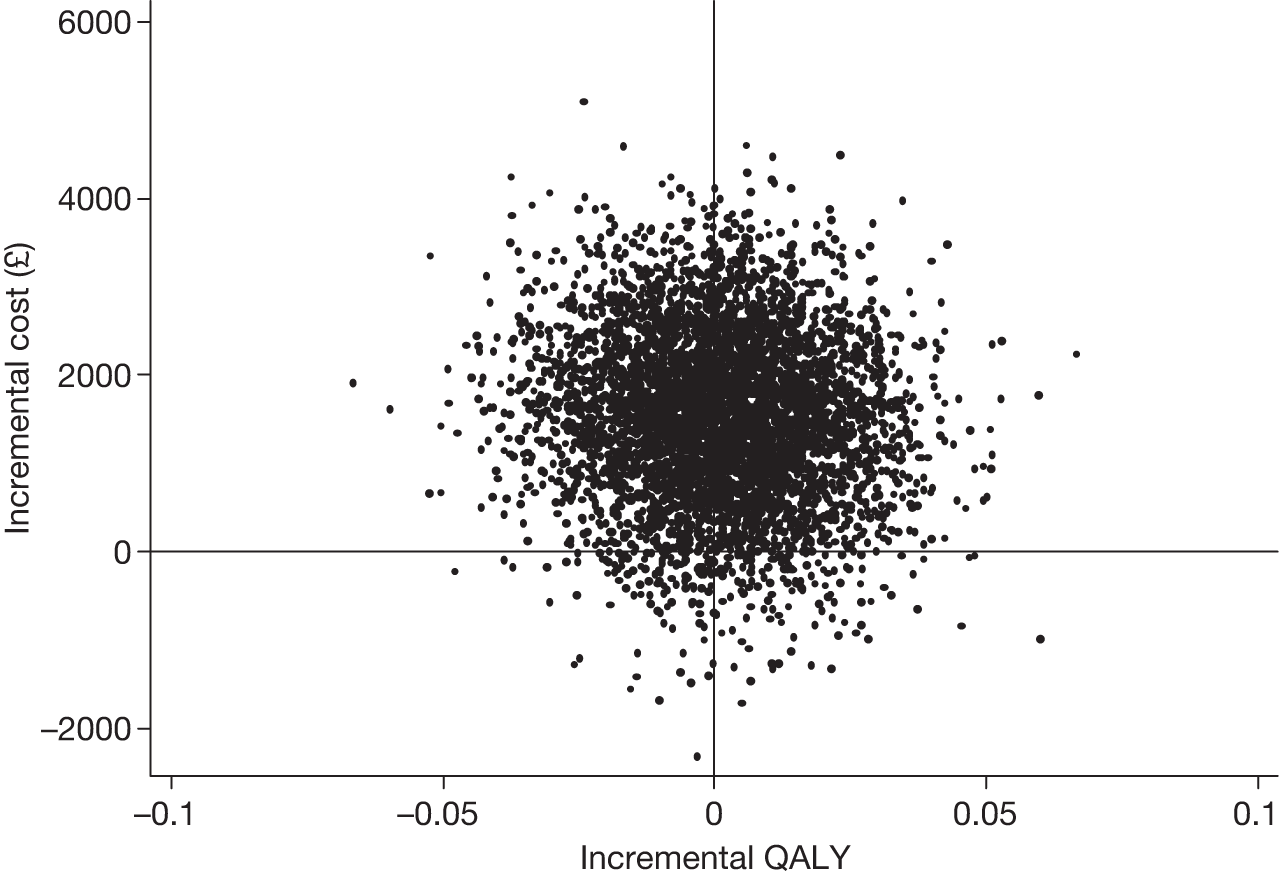

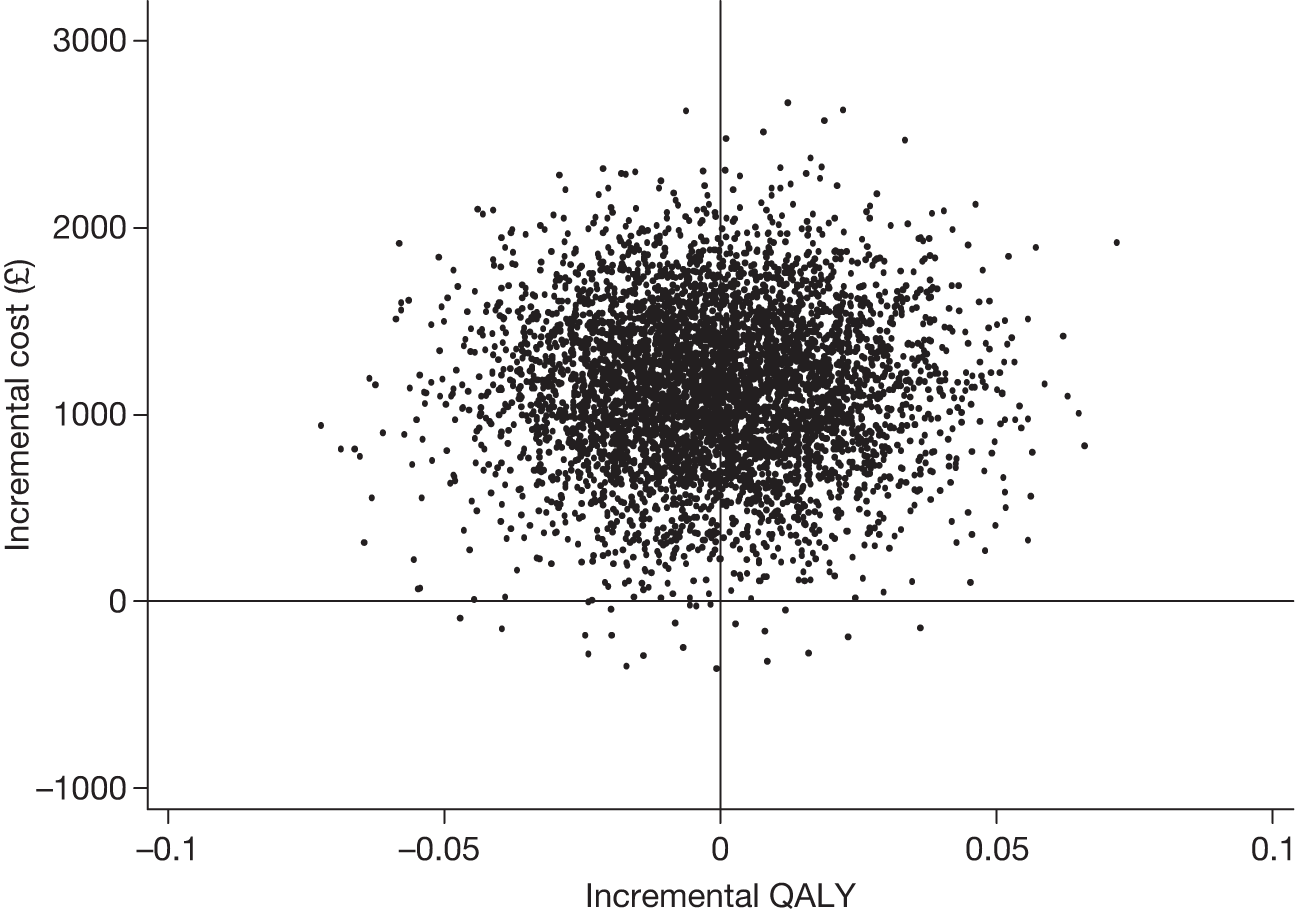

Cost-effectiveness analysis

Effectiveness was evaluated in terms of the primary clinical outcomes: the disease-specific quality-of-life measure QoL-AD for participants with dementia and the GHQ for carers at the primary end point. Non-parametric bootstrapping (5000 replications) was used to address the uncertainty associated with point estimates of costs and outcomes.

Secondary cost–utility analysis

A cost–utility analysis (CUA) was conducted using EQ-5D47 completed by participants with mild to moderate dementia to calculate quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) for these participants (1) assuming full compliance (i.e. all those allocated to the intervention group attended the joint reminiscence and maintenance sessions) and (2) using a compliance threshold (i.e. attending a minimum number of joint reminiscence and maintenance sessions). Subsequent analyses are planned that will use EQ-5D data collected from carers relating to their own health, and carer proxy measures that relate to the participant with dementia.

Triangulation substudy to compare self-report of service use by participants with dementia with their general practitioner records

A small substudy (n = 36) was undertaken to compare the self-report service use by participants with dementia with their GP records. Cases were selected randomly from those participants with dementia who had completed all three sets of assessments, with the aim of having an equal number from the intervention and control groups. Although three centres (Bangor, Hull and London) were initially selected from which to draw the sample, it subsequently proved not possible to collect data in London. This was mainly due to the difficulty of engaging the selected GP practices to assist with the study, as well as logistical issues in arranging visits to collect data. Consequently, it was decided that efforts to collect these data would be focused on the Bangor and Hull centres.

Data were collected for service utilisation relating to primary care, secondary care, as well as medication (dementia and other), for a period of 13 months (corresponding to baseline recall of 3 months plus the 10-month trial period). The substudy aimed to identify any systematic differences between contacts reported by study participants and GP records of frequency of GP visits, practice nurse visits, community psychiatric nurse (CPN) visits, psychiatrist appointments and hospital use. Weighted kappa was used to measure the level of agreement. 57

A comparison of European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions scores of trial participants with UK norms

The EQ-5D is a commonly used generic health-related quality-of-life measure supported by NICE (2008),26 used in economic evaluation of health-care interventions in the UK and internationally. The EQ-5D measure is described in detail in the Measures, (f) section above. A recent review of EQ-5D in dementia studies showed that it could be used in studies of people with mild to moderate dementia. 58 We wanted to compare the scores of participants with dementia and carers in the REMCARE trial with UK population norms,59 based on a survey of a representative sample of 3395 men and women aged ≥ 18 years, living in the UK.

Summary of changes to protocol

Approval was sought and obtained from MREC for 10 substantial amendments to the protocol during the trial. One of these was related to the production of a leaflet to assist with recruitment. Four were related to two bolt-on studies (not reported as part of the trial) undertaken by the centres in London and Bangor (one in each). The remaining five were connected to participant recruitment covering additional sites (Hull, London, Manchester), increased numbers (Bangor, London) and the inclusion of primary care trusts in Hull to facilitate recruitment through GP surgeries.

Chapter 3 Results

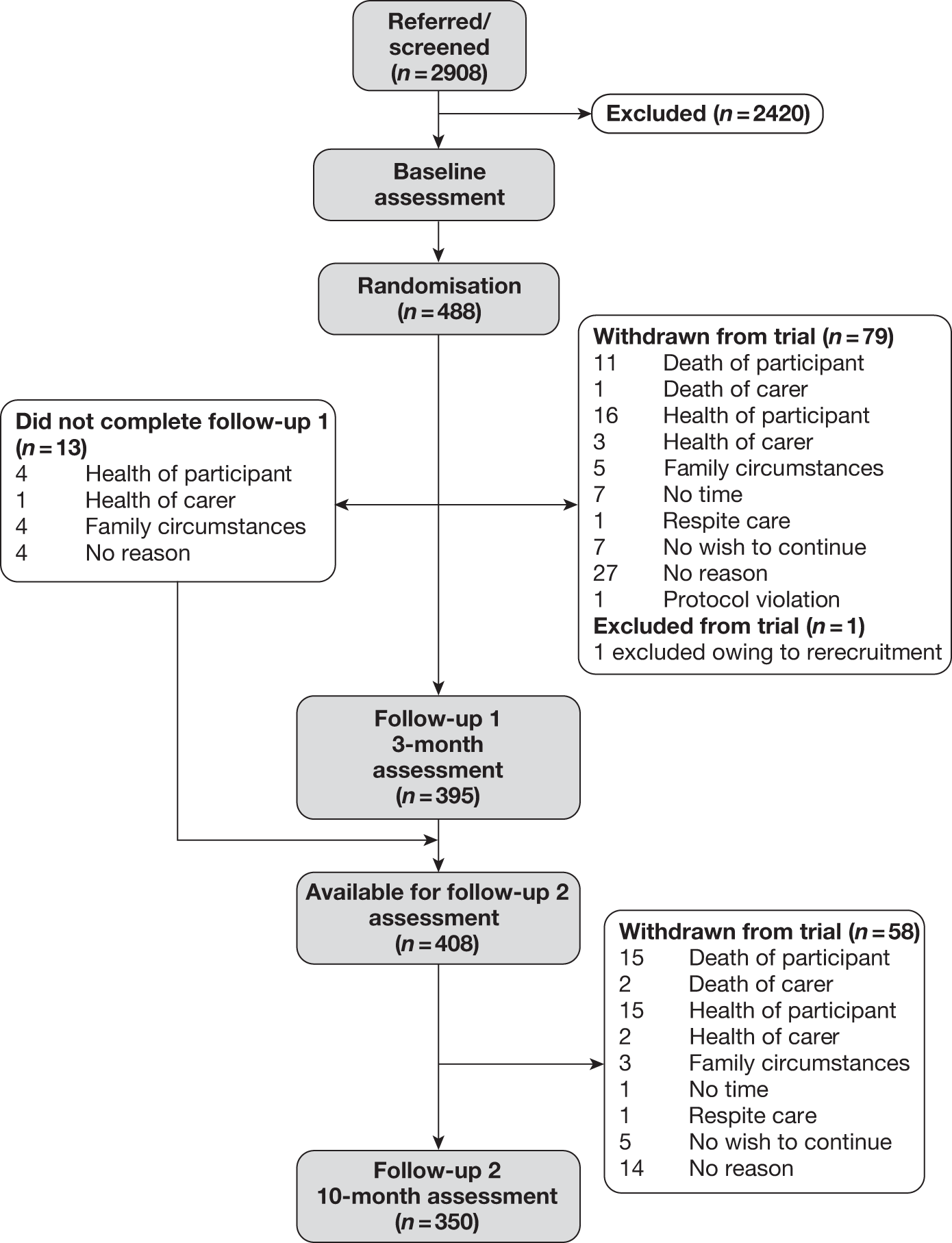

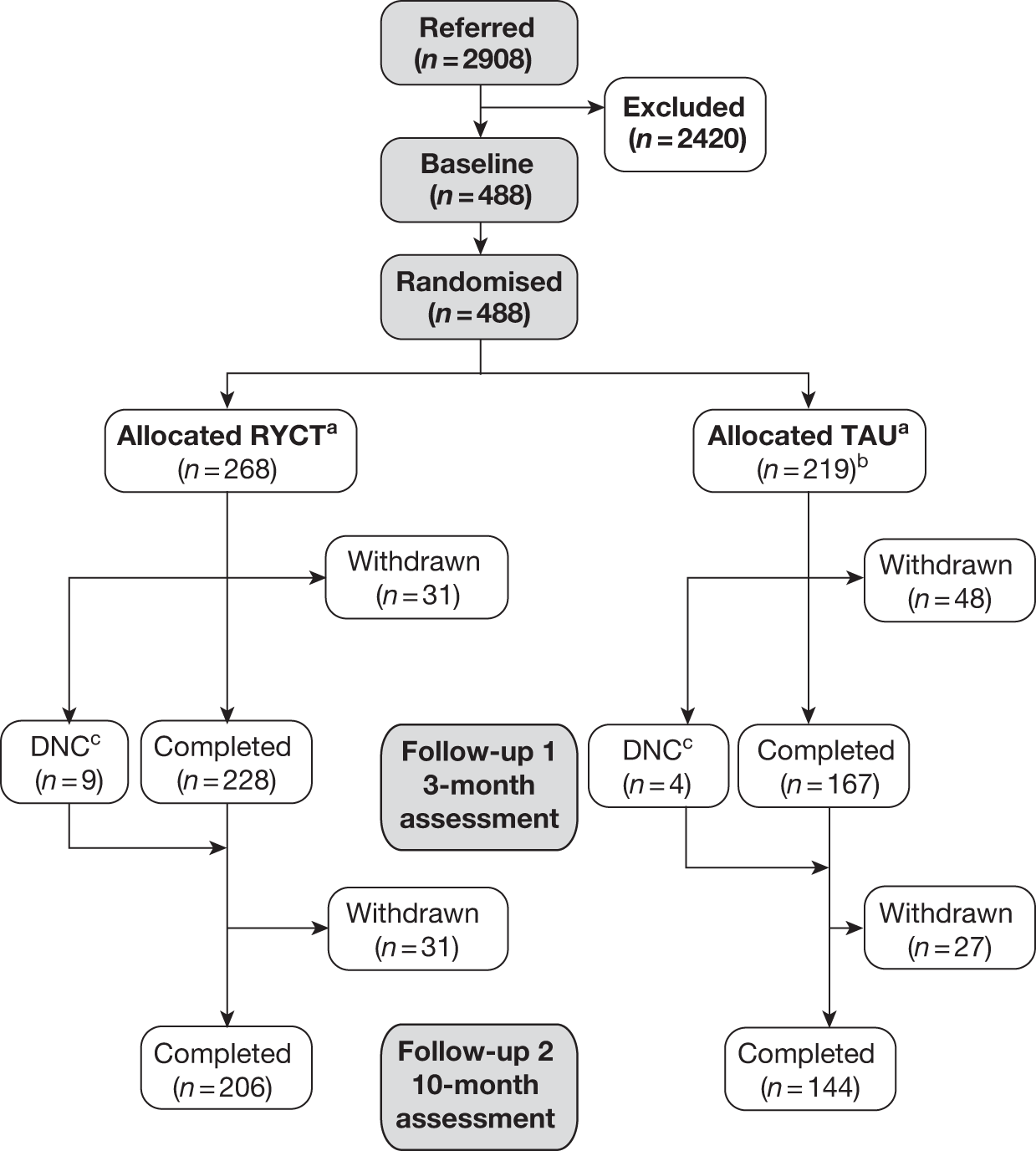

Figure 1a and b presents the details of the flow of participants through the trial. In total, 2908 people were considered for inclusion in the study. From these, 488 were ultimately randomised, although the final sample size was 487 (as one participant who was inadvertently recruited again to a later wave was excluded). The commonest reason for loss between referral or screening and randomisation was potential participants not wishing to participate in the research. The exclusion and clinical criteria accounted for around 15% of the losses and as such indicated no barrier to recruitment (Table 4).

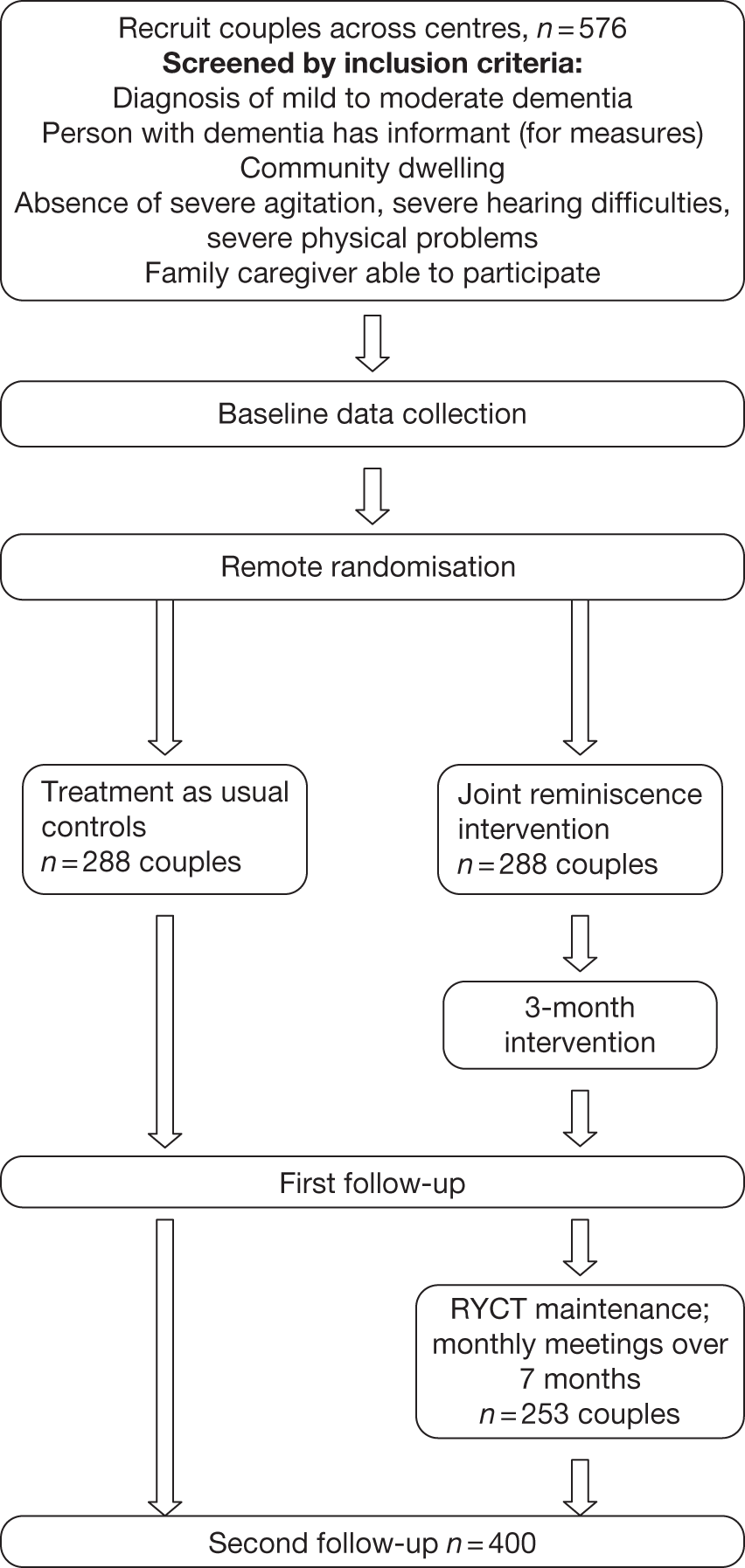

FIGURE 1a.

Participant flow throughout the trial.

FIGURE 1b.

Participant flow through the trial indicating treatment allocation. a, Constrained randomisation to ensure viable RYCT groups against TAU (treatment as usual); b, one dyad removed owing to rerecruitment; c, the participants did not complete (DNC) FU1 assessment.

| Reason | Total (%) |

|---|---|

| Total referred or screened | 2908 |

| Unable to find Memory Clinic record | 115 (5) |

| Could not make contact by telephone | 393 (16) |

| Does not wish to take part | 863 (36) |

| Does not meet clinical criteria | 108 (4) |

| No suitable carer | 69 (3) |

| Now in residential care | 95 (4) |

| Already participating in similar study | 14 (< 1) |

| Exclusion criteria apply | 91 (4) |

| Unable to attend on day that joint reminiscence groups are being held | 113 (5) |

| Other | |

| Family situation at the time | 41 (2) |

| Carer or participant died | 96 (4) |

| Health issues for participant or carer | 168 (7) |

| Participant unaware of dementia diagnosis | 5 (< 1) |

| Not available | 209 (9) |

| Does not like groups – reference to dislike of intervention | 17 (< 1) |

| Unknown | 23 (1) |

| Total lost between referral/screening and randomisation | 2420 |

| Total number randomised | 488 |

| Conversion rate | 17% |

Table 5 indicates that the majority of referrals, 73%, to the project came from Memory Clinics in the various centres.

| Source | Total (%) |

|---|---|

| Memory Clinic | 2112 (73) |

| CMHT | 406 (14) |

| Alzheimer’s Society | 90 (3) |

| Psychology/psychiatry referral | 77 (3) |

| Day centres/well-being cafe | 60 (2) |

| Admiral Nurse/Memory Clinic nurse | 60 (2) |

| No information | 50 (2) |

| Other | 33 (1) |

| Age Concern | 21 (1) |

| Total | 2908 |

Randomised allocation

The 488 dyads gave informed consent and were randomised after baseline assessment between June 2008 and July 2010. A total of 268 dyads were randomised to the joint reminiscence groups and 220 were randomised to the control group. There was a differential rate of conversion between the centres [χ2 = 109.1, degrees of freedom (df) = 6; p < 0.001], presumably reflecting differences in referral and screening practices (Table 6). For example, the London centres relied more on screening of case records to identify potentially suitable participants. As mentioned above, one dyad was excluded at this point because of the same dyad being rerecruited a second time into the trial. This reduced the total sample size to 487 overall.

| Centre | Total referrals | Total randomisations (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Bangor | 375 | 71 (19) |

| Bradford | 116 | 50 (43) |

| Hull | 129 | 66 (51) |

| London (north) | 848 | 96 (11) |

| London (south) | 1000 | 91 (9) |

| Manchester | 195 | 88 (45) |

| Newport | 245 | 26 (11) |

| Total | 2908 | 488 |

Follow-up retention rates

Retention rates at 3-month time point

Between randomisation and FU1 there were 92 losses (Table 7). Seventy-nine of these were complete withdrawals from the trial, which includes 12 deaths. Thirteen of the dyads were not available to complete FU1 assessment but were available to complete the final follow-up assessment. There were differential retention rates between the centres at first follow-up (χ2 = 30.7; df = 6; p < 0.001).

| Centre | Baseline | Completed 3-month FU1 (retention rate) (%) | Completed 10-month FU2 (retention rate) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bangor | 71 | 64 (90) | 59 (83) |

| Bradford | 50 | 46 (92) | 42 (84) |

| Hull | 66 | 53 (80) | 53 (80) |

| London (north) | 96 | 73 (76) | 62 (65) |

| London (south) | 90 | 62 (69) | 50 (56) |

| Manchester | 88 | 78 (87) | 68 (77) |

| Newport | 26 | 19 (73) | 16 (62) |

| Total | 487 | 395 (81) | 350 (72) |

Retention rates at 10-month time point

At final follow-up (see Table 7) a further 58 dyads withdrew from the study, which includes a further 17 deaths. This gave a total of 137 complete withdrawals from the trial (including 29 deaths), which equates to a retention rate of approximately 72%, which was the predicted retention rate used in the updated sample size calculations. There were differential retention rates between the centres at FU2 (χ26 = 37.9; p < 0.001). In terms of withdrawals from the study (i.e. excluding deaths), the attrition rate was 22%.

Retention rates by allocated group

Table 7 indicates that during the course of the trial there were a total of 137 withdrawals. There were 62 (23%) withdrawals from the intervention group and 75 (34%) withdrawals from the control group. A comparison of baseline characteristics of those who dropped out did not indicate any significant differences between those in the intervention group and those in the control group. Baseline characteristics considered were age of participant with dementia [joint reminiscence 78.37 (7.41), control 78.36 (5.83); F1,135 = 0; p = 0.99], age of carer [joint reminiscence 70.47 (11.95), control 70.26 (11.68); F1,134 = 0.01; p = 0.92], gender of participant with dementia [joint reminiscence 30/32, control 39/36 (female/male); χ21 = 0.18; p = 0.67] and gender of carer [joint reminiscence 41/21, control 48/25 (female/male); χ21 = 0.002; p = 0.96). The baseline values for the two primary outcomes were also tested with no significant difference found, QoL-AD [joint reminiscence 36.42 (5.84), control 36.47 (5.40); F1,129 = 0.002; p = 0.96] and GHQ-28 [joint reminiscence 23.33 (10.43), control 24.65 (11.76); F1,123 = 0.43; p = 0.51]. Assessing the difference between the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR)60 scores for the two groups did lead to an almost significant difference between the withdrawals from each group (joint reminiscence 3/33/26, control 5/53/17 for CDR scores 0.5/1/2, respectively; χ21 = 5.85; p = 0.054) with the dropouts from the control group having a lower level of severity.

Maintenance of ‘blind’ follow-up assessments

Perception sheets were completed for 389 (out of 395) FU1 interviews. Table 8 indicates that where researchers were able to make a judgement as to which condition the person had been allocated to, they were indeed more likely to be correct than incorrect in the direction of their prediction. However, they were certain of their judgement in only one-quarter of instances, and in the majority of instances were not able to correctly judge group allocation. It is interesting to note that in seven cases the researcher felt he or she definitely knew which allocated group the participant was in but this turned out to be incorrect.

| Researcher perception | Actual treatment group allocation | Total (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Joint reminiscence (%) | Control (%) | ||

| ‘Definite’ judgement – incorrect | 4 (2) | 3 (2) | 7 (2) |

| ‘More likely’ judgement – incorrect | 35 (15) | 12 (7) | 47 (12) |

| Equally in control or joint reminiscence group | 97 (43) | 73 (45) | 170 (44) |

| ‘More likely’ judgement – correct | 25 (11) | 51 (31) | 76 (20) |

| ‘Definite’ judgement – correct | 65 (29) | 24 (15) | 89 (23) |

| Total | 226 | 163 | 389 |

Perception sheets were completed for 346 (out of 350) FU2 interviews. Table 9 shows that researchers were again more likely to be correct than incorrect when they felt able to make a judgement, but again they were only able to make a definite judgement in one-quarter of instances. At this time point, in five cases the researcher believed that he or she definitely knew which allocated group the participant was in but this turned out to be incorrect. Given the discrepancy between correct and incorrect judgements there is clearly likely to have been some degree of unblinding occurring at the two follow-up assessment points, but the proportion of correct definite judgements remains low, at around 25%, reflecting the considerable remaining uncertainty.

| Researcher perception | Actual treatment group allocation | Total (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Joint reminiscence (%) | Control (%) | ||

| ‘Definite’ judgement – incorrect | 4 (2) | 1 (< 1) | 5 (1) |

| ‘More likely’ judgement – incorrect | 37 (18) | 4 (3) | 41 (12) |

| Equally in control or joint reminiscence group | 74 (36) | 51 (36) | 125 (36) |

| ‘More likely’ judgement – correct | 25 (12) | 63 (44) | 88 (25) |

| ‘Definite’ judgement – correct | 64 (32) | 23 (16) | 87 (25) |

| Total | 204 | 142 | 346 |

Analysis

Baseline characteristics of randomised dyads

Demographic information

Demographic information has been split into two main tables, one describing the demographics of the person with dementia (Table 10) and one for the carer data (Table 11). For the whole sample there is a high proportion of white married people who own their own homes.

| Characteristic | Total (%) | Joint reminiscence (%) | Control (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female person with dementia | 242/487 (50) | 127/268 (47) | 115/219 (53) |

| Ethnicity: white | 447/469 (95) | 254/259 (98) | 193/210 (92) |

| Marital status: married | 337/468 (72) | 187/258 (72) | 151/210 (72) |

| Owner-occupied accommodation | 410/485 (85) | 218/268 (81) | 192/217 (88) |

| Characteristic | Total (%) | Joint reminiscence (%) | Control (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female carer | 325/485 (67) | 188/268 (70) | 137/217 (63) |

| Ethnicity: white | 448/467 (96) | 254/259 (98) | 194/208 (93) |

| Marital status: married | 394/466 (85) | 222/256 (87) | 172/210 (82) |

| Carer accommodation owner-occupieda | 71/84 (85) | 43/51 (84) | 28/33 (85) |

Table 12 indicates the means, SDs and range of ages of the participants. The age of carers ranged from 23 to 91 years, and of people with dementia from 54 to 95 years. Within the sample there were 345 spousal dyads recruited and 142 non-spousal dyads. The 142 non-spousal dyads were made up of son/daughter (96), son/daughter-in-law (5), brother/sister (7), other relative (4), friend (15), partner (11), foster carer (1), carer (1), spouse–separated (1) and missing (1 randomised as other).

| Participant type | Total | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | SD | Range | |||||||

| Person with dementia | 487 | 77.53 | 7.3 | 54–95 | ||||||

| Carer | 486a | 69.65 | 11.6 | 23–91 | ||||||

| Carer spousal | 345 | 73.95 | 7.8 | 44–91 | ||||||

| Carer non-spousal | 141 | 58.94 | 12.6 | 23–91 | ||||||

| Joint reminiscence | Control | |||||||||

| n | Mean | SD | Range | n | Mean | SD | Range | |||

| Person with dementia | 268 | 77.72 | 7.4 | 56–93 | 219 | 77.30 | 7.18 | 54–95 | ||

| Carer | 268 | 69.55 | 11.7 | 30–90 | 218 | 69.66 | 11.6 | 23–91 | ||

| Carer spousal | 189 | 74.26 | 7.6 | 45–89 | 156 | 73.58 | 8.1 | 44–91 | ||

| Carer non-spousal | 79 | 58.28 | 12.0 | 30–90 | 62 | 59.79 | 13.2 | 23–91 | ||

Of the 236 female–male dyads (Table 13), 218 were spousal relationships and of the 151 male–female dyads 127 were spousal relationships. Of the nine male–male dyads, eight of these were a child–parent relationship whereas the final dyad was noted as being a partner relationship. There was a majority of female-carer led dyads in both spousal and non-spousal stratifications.

| Gender of participant | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | ||

| Gender of carer | |||

| Female | 89 | 236 | 325 |

| Male | 151 | 9 | 160 |

| Total | 240 | 245 | 485 |

Details of dementia diagnosis subtype were not collected initially. This information proved difficult to ascertain in a number of the centres, and was ultimately obtained for 38% of the sample. In a fifth of these cases the subtype of dementia was not known (Table 14). The great majority of the 147 participants where a subtype was reported were thought to have Alzheimer’s disease alone (72%), or in combination with vascular dementia (11%).

| Diagnosis | Total (%) | Joint reminiscence (%) | Control (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s | 106/183 (58) | 58/105 (55) | 48/78 (62) |

| Vascular | 23/183 (13) | 15/105 (14) | 8/78 (10) |

| Lewy body | 1/183 (< 1) | 0/105 | 1/78 (1) |

| Mixed Alzheimer’s and vascular | 17/183 (9) | 11/105 (10) | 6/78 (8) |

| Not known | 36/183 (20) | 21/105 (20) | 15/78 (19) |

Table 15 indicates that the proxy ratings of depression for the participants with dementia reached the threshold for probable major depression in 24% of cases (CSDD score > 10), whereas the proxy ratings for anxiety reached clinically significant levels of anxiety in 31% of cases (RAID score ≥ 11).

| Mood measure | Thresholds | Total (%) | Joint reminiscence (%) | Control (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSDD – person with dementia | < 6 Absence of depressive symptoms | 190/395 (48) | 101/215 (47) | 89/180 (49) |

| > 10 Probable major depression | 85/395 (22) | 48/215 (22) | 37/180 (21) | |

| > 18 Definite major depression | 11/395 (3) | 4/215 (2) | 7/180 (4) | |

| RAID – person with dementia | ≥ 11 Significant clinical anxiety | 130/425 (31) | 67/234 (29) | 63/191 (33) |

| HADS (depression) – carer | ≥ 8 Mild disturbance | 60/483 (12) | 28/266 (11) | 32/217 (15) |

| ≥ 11 Moderate disturbance | 24/483 (5) | 14/266 (5) | 10/217 (5) | |

| ≥ 15 Severe disturbance | 4/483 (1) | 4/266 (2) | 0/217 (0) | |

| HADS (anxiety) – carer | ≥ 8 Mild disturbance | 92/483 (19) | 53/266 (20) | 39/217 (18) |

| ≥ 11 Moderate disturbance | 72/483 (15) | 42/266 (16) | 30/217 (14) | |

| ≥ 15 Severe disturbance | 16/483 (3) | 10/266 (4) | 6/217 (3) |

For carers’ own symptoms, self-reporting of clinically relevant levels of depressive symptoms were at 18% (HADS depression subscale ≥ 8). Self-reported levels of anxiety were almost double this at 37% (HADS anxiety subscale ≥ 8). From the baseline data the RSS appears to be significantly correlated with many of the other carer measures. Pearson’s biserial correlation with: proxy QoL-AD –0.609; QCPR –0.618; HADS depression subscale 0.636; HADS anxiety subscale 0.632; and GHQ-28: 0.615. This indicates that the higher the reported stress levels of the carer the higher the depression, anxiety and GHQ-28 scores, whereas the carer’s perception of the person with dementia’s quality of life is lower as is their perception of their quality of relationship. Other strongly correlated measures are HADS subscales with GHQ-28: 0.741 (anxiety) and 0.664 (depression). RAID and CSDD is correlated at 0.721. The two subscales of the AMI are also strongly correlated at 0.608. Baseline correlations are given in Appendix 5.

Primary analysis of outcomes

The mean values for the two treatment groups at each of the three time points are given in Table 16. The primary ITT analysis did not demonstrate any evidence of a difference between the two treatment groups at any time point. The primary model fitted was an ANCOVA using 10-month outcome as the dependent variable, baseline score on the outcome measure and the age of the person with dementia as covariates, treatment allocation, gender of the person with dementia, spousal (spouse/other) as fixed factors and location and wave as random factors, with the interaction between location and allocation also being taken into account. Carer age and gender were also added for carer and proxy outcomes.

| Outcome measure | Baseline | 3 months | 10 months | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joint reminiscence | Control | Joint reminiscence | Control | Joint reminiscence | Control | |

| Participant with dementia | ||||||

| QoL-AD | 37.48 (5.32) | 36.96 (5.35) | 36.91 (5.61) | 36.97 (5.88) | 36.63 (5.63) | 35.96 (5.28) |

| AMIF | 56.07 (23.00) | 54.28 (24.20) | 54.31 (25.28) | 48.95 (24.76) | 50.53 (25.81) | 46.95 (25.55) |

| AMIM | 12.46 (6.93) | 12.94 (7.79) | 11.72 (7.61) | 11.20 (7.63) | 11.33 (8.21) | 10.61 (8.04) |

| EQ-5D VAS | 71.85 (20.33) | 70.72 (19.79) | 72.64 (18.40) | 71.82 (19.73) | 73.02 (18.32) | 72.42 (18.32) |

| EQ-5D utility | 0.75 (0.25) | 0.76 (0.26) | 0.77 (0.23) | 0.78 (0.24) | 0.77 (0.24) | 0.79 (0.23) |

| QCPR | 57.83 (6.42) | 57.45 (6.10) | 57.89 (6.52) | 57.37 (6.71) | 57.64 (6.25) | 57.08 (6.72) |

| QCPR warmth | 34.39 (3.58) | 34.46 (3.51) | 34.29 (4.10) | 34.29 (3.80) | 34.06 (3.65) | 33.57 (3.89) |

| QCPR negative | 23.37 (3.67) | 22.91 (3.76) | 23.63 (3.64) | 23.04 (3.78) | 23.47 (3.50) | 23.41 (3.58) |

| Carer | ||||||

| GHQ-28 | 22.75 (11.71) | 23.06 (12.00) | 22.67 (11.80) | 22.90 (10.37) | 24.34 (13.07) | 22.79 (12.50) |

| GHQ-28 somatic | 5.68 (3.81) | 6.03 (4.33) | 5.73 (3.96) | 6.13 (3.79) | 6.47 (4.45) | 6.27 (4.47) |

| GHQ-28 anxiety | 7.19 (4.74) | 7.26 (4.63) | 7.20 (4.53) | 6.80 (4.15) | 7.77 (4.61) | 6.70 (4.63) |