Notes

Article history

This issue of Health Technology Assessment contains a project originally commissioned by the MRC but managed by the Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Programme. The EME programme was created as part of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and the Medical Research Council (MRC) coordinated strategy for clinical trials. The EME programme is funded by the MRC and NIHR, with contributions from the CSO in Scotland and NISCHR in Wales and the HSC R&D, Public Health Agency in Northern Ireland. It is managed by the NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre (NETSCC) based at the University of Southampton

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Salisbury et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Structure of this report

This study was based on a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of PhysioDirect compared with usual care, incorporating an economic evaluation and nested qualitative research.

The report begins with a summary of the background to the problem of access to physiotherapy and a review of research on new approaches to improving access to physiotherapy and the use of telephone-based services in other relevant contexts. The first chapter concludes with a description of the research objectives.

The report then describes the methods and results from the RCT, followed by the methods and results from the economic analysis and then the methods and results from the qualitative research. Slightly unusually, the findings about the variables relating to the process of care are described before the results about the primary and secondary outcomes, because that makes it easier to interpret these outcomes.

The final chapter summarises and synthesises the findings from all three components of the study, providing interpretation in the light of previous studies. It also discusses the strengths and limitations of the research and its generalisability to the NHS and to other health-care systems. The conclusions are followed by recommendations for future research.

Background and objectives

Musculoskeletal problems and access to physiotherapy

Musculoskeletal (MSK) pain problems are one of the most common causes of disability. Over one-quarter of all patients registered in general practice will consult at least once for a MSK problem each year.1,2 Women consult with MSK problems more often than men, irrespective of age group.1–3 The high prevalence and persistent nature of many MSK problems makes MSK pain a major health problem.4 The most common types of chronic MSK pain are back pain and joint pain related to osteoarthritis,5 including knee pain and hand pain. For example, lifetime prevalence rates for low back pain as high as 84% have been reported.6

This high prevalence of MSK problems results in large direct and indirect health-care costs. 7 In 1998 alone, treatment for low back pain in the UK cost in the region of £10,668M,8 and recent reports suggest that these costs are likely to have risen by a further third in the last decade. 9 In the UK, low back pain is the fourth most common reason for consulting a general practitioner (GP) and is the most common MSK reason for consultation. Estimates suggest that between 6% and 9% of people registered with a GP consult annually with low back pain,10,11 which equates to approximately 5 million people each year in the UK. 8 In total, MSK pain accounts for around 15% of all GP consultations. 12 Most patients are managed with advice and analgesia, but many of these patients are also referred to physiotherapists, with 4.4 million new referrals to physiotherapy being made each year, of which 1.23 million are made by GPs. 13 The number of referrals to NHS physiotherapy increased by 37% in the 15 years between 1990 and 2005. 13 Guidelines for practice for common MSK conditions are increasingly recommending physical therapies, with recent guidelines for persistent low back pain recommending key treatments of exercise, manual therapy and acupuncture,9 and core treatments for the management of osteoarthritis of the knee including advice, education, exercise and weight loss. 14

Ensuring timely access to physiotherapy has long been an issue within the NHS, with waiting times of > 4 months in some areas. This is a problem for patients, because MSK conditions cause pain and disability, and for the economy, because these conditions are second only to mental health problems as a cause of days lost from work. In particular, back pain accounts for some 120 million days of certified absence from work each year and half of all patients with back pain who are off work for more than 6 months never return to employment. 8 Delayed access to physiotherapy is also a problem for the NHS because when patients are finally offered a physiotherapy appointment many fail to attend, and in other cases patients wait a long time for a physiotherapy consultation when it is unlikely that this will offer benefit, so it could be argued that much of the current physiotherapy resource is used inefficiently and ineffectively. While patients are waiting for physiotherapy they may repeatedly visit their GP and request medication, and the delay in access to physiotherapy may lead to unnecessary referrals to MSK interface services and outpatient orthopaedic specialists.

New service models: physiotherapy-led telephone assessment and advice services for musculoskeletal pain

In response to the problems described above, new service models have been developed that involve physiotherapy-led telephone assessment and advice as a way of managing patient demand and providing early access to physiotherapy advice. Physiotherapists in two areas of England, Huntingdon and Cheltenham, developed the concept and coined the term PhysioDirect at about the same time. The Huntingdon system was devised with the primary care lead for the primary care trust (PCT) and two local GP practices in 2001. By 2004, the whole of the population covered by Huntingdonshire PCT had access to the service, covering 155,000 people. A number of other PCTs have also since developed PhysioDirect services. Further details of the current service in Huntingdonshire are summarised in Box 1.

-

A computer program with templates containing dropdown boxes and free text designed for each region of the body records clinical data to assist the physiotherapist in making a diagnosis.

-

A section for advice about over-the-counter medication (if applicable), designed in conjunction with pharmacists.

-

The patient receives verbal and written advice on self-management, and is given a time frame for expected improvement and clear instructions to call back after a set period of time if their condition has not resolved as anticipated.

-

The GP receives a report on the outcome of the assessment.

-

The physiotherapist may also request a prescription or sickness certificate from the GP.

-

Clear pathways exist to move patients to tier II (or interface services) or on to secondary care.

Although there are several variations of PhysioDirect services, they all tend to involve patients being invited to telephone a physiotherapist for initial assessment and advice, following which many patients are posted information on self-management and exercise. Physiotherapists determine the priority of need, or ‘triage’, and provide rapid advice to the patient so that recommended self-management activities, such as postural improvements and exercise, can commence. Patients are advised to ring back if their condition does not improve and a time frame for the repeat call may be recommended. Some patients are invited for a face-to-face consultation if the initial telephone assessment establishes that this is necessary. Alternatively, they may be referred back to the GP or other health professional if that is appropriate. Within integrated services, patients may be referred to an interface service (where these exist) or on to secondary care following agreed local pathways. Thus PhysioDirect can form part of a streamlined patient management system that aims to ensure patient needs are met by the most appropriate clinician in a timely fashion. Some services are predominantly operated as call-back services, in which telephone assessments are pre-booked into physiotherapists’ diaries, and they make the call at a time of convenience for the patient. Additionally, patient assessments within PhysioDirect may be supported by computerised or paper-based templates.

Some services offer PhysioDirect in conjunction with self-referral to physiotherapy as a way of managing direct contacts from patients. Increasingly, the boundaries between telephone assessment and advice and self-referral services are blurring, given the impetus from recent Department of Health reports on MSK services,15 community services16 and the evidence about self-referral. 17,18

Summary of evidence about physiotherapy-led telephone assessment and advice services for musculoskeletal pain

The available evidence about physiotherapy-led telephone assessment and advice schemes for MSK pain, or PhysioDirect, was identified using searches on MEDLINE, EMBASE, The Cochrane Library, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), the Current Controlled Trials (CCT) database and the internet. These searches used terms and/or text words for ‘triage’, ‘PhysioDirect’, ‘telephone’ or ‘advice’ in combination with terms relating to physiotherapy [‘Physical Therapy Modalities’, ‘Exercise Therapy’, ‘Physical Therapy (Specialty)’, ‘physiotherapy.mp’]. We also specifically sought randomised trials of physiotherapy interventions using the Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy in combination with terms for physiotherapy. The search was originally conducted in August 2007 but the saved search in MEDLINE was conducted regularly throughout the research periods (2007–11) to identify any relevant new publications. A further comprehensive search to identify relevant literature since the protocol was written has been conducted in the following databases: NHS Evidence, Health Information Resources [Bandolier; UK Database of Uncertainties about the Effects of Treatments (DUETS); National Library of Guidelines, including National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidance, International Guidelines, Clinical Knowledge Summaries, NHS Evidence Specialist Collections (Musculoskeletal)]; TRIP database; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination [Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) and Health Technology Assessment (HTA)]; Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR); EMBASE; MEDLINE; Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro); Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED); Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL); OTseeker; ISRCTN (International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number) Register; Medical Research Centre: Clinical Trials Unit; UK Clinical Research Network Study Portfolio; NIH records on ClinicalTrials.gov; Nederlands Trial Register; German Clinical Trials Register; and the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry. Citation tracking was also used to locate relevant articles.

We did not identify any published randomised trial that directly addressed the effectiveness or cost-effectiveness of PhysioDirect or similar schemes. There was, however, literature pertaining to the effectiveness of physiotherapy interventions for MSK problems, and about the benefits of early treatment with physiotherapy for MSK problems, which is relevant to the argument in favour of developing new services to provide earlier access to a physiotherapist. In addition, there have been several local audits and evaluations of physiotherapy-led telephone assessment and advice services, as well as studies and trials of telephone care by other health professionals for other conditions, which are relevant to this trial.

Physiotherapy interventions for patients with musculoskeletal problems

The most common problems leading to physiotherapy referral relate to the back, shoulder, neck or knee. With regard to back pain, most studies have concluded that manual therapy provided by physiotherapists offers little benefit over simple advice for acute low back pain. 19,20 The UK Beam Trial included patients with pain of variable duration and suggested that manual therapy has a modest effect,21 and some studies have suggested that it is possible to identify subgroups of patients more likely to benefit from this type of treatment,22,23 but a recent review concludes that manual therapy is no more effective than other common therapeutic approaches. 24 Although systematic reviews about the effectiveness of manual therapy have reached inconsistent conclusions, in subacute and chronic back pain there is evidence for the effectiveness of physiotherapy interventions based on promoting exercise. 25–28 Importantly, recent trials have shown that a single session of advice from a physiotherapist is as effective as a course of routine physiotherapy for patients with mild to moderate back problems. 29,30 With regard to neck pain, there is evidence from two Cochrane reviews that combined exercise and manual therapy is effective. 31,32 For shoulder pain, a review found evidence of benefit from a range of physiotherapy interventions. Exercise advice appears to be of benefit in rotator cuff disease and manual therapy provided additional benefit in one trial. 33 Exercise has been shown to be effective for knee pain related to osteoarthritis, with recent trials showing the effectiveness of physiotherapy-led advice and exercise. 34–36

In summary, there is evidence that patients with MSK pain problems can benefit from interventions offered by physiotherapists, while for some patients it is more cost-effective to provide brief advice, and for others, treatments from physiotherapists have little to offer. Therefore, a service that provides assessment, triage and advice initially and reserves more intensive (and expensive) treatments for those who do not improve may be the most cost-effective strategy. This is analogous to the ‘stepped-care’ approach, which is increasingly advocated in a range of conditions, for example mental health, where there is a high level of demand and a need to target resources. 37 In the context of physiotherapy, this approach should reduce costs for patients and for the NHS, provide earlier advice for all patients and effective treatments more quickly for those who may benefit from them (by screening out those unlikely to benefit), and be more convenient and accessible for patients as a whole.

Earlier compared with delayed physiotherapy treatment

Providing prompt and convenient access to health care is one of the major aims of the policy drive to make the NHS more responsive to patients' needs, with fast access for health care being seen as a benefit in itself, irrespective of the effects in terms of clinical outcomes. However there is evidence from several studies that early physiotherapy intervention provides faster symptom relief, improves quality of life, reduces absenteeism, leads to a reduction in physician consultations, and is more cost-effective. 38–42 This approach is supported by the guidance from the Clinical Standards Advisory Group (CSAG) on the management of back pain. Following a review of evidence and expert advice, the CSAG advised that patients with new episodes of back pain should have prompt access to physical therapy, with the aim of reducing the risk of symptoms and disability becoming entrenched. 43 More recently, specific guidelines for the management of patients with back pain persisting for > 6 weeks recommend early referral to a range of physical therapies. 9

Telephone advice services in health care generally, and in physiotherapy

PhysioDirect is based on a practitioner supported by computerised templates to assess the patient in a structured way, and to offer tailored, personalised advice. This reflects a wider trend to explore the use of this type of new technology in health care, for example in NHS Direct. Research in relation to the use of similar telephone triage systems in clinical settings other than physiotherapy has shown that it is safe, clinically accurate, cost-effective, acceptable to patients, and reduces the workload of clinicians,44–47 although some health practitioners have some concerns in using telephone triage in patients presenting with acute health problems. 48

Within physiotherapy, local evaluations and small studies suggest that services based on telephone advice given by physiotherapists are likely to be popular with patients,49–51 although there is no evidence about costs or outcomes, or the important issue of safety. Audits in the pioneering physiotherapy services in Cheltenham and Huntingdonshire in England suggest that 40–60% of patients referred by GPs to physiotherapy can be managed by telephone alone without a face-to-face consultation, telephone consultations take approximately half as long as face-to-face consultations, waiting times for a face-to-face appointment have been reduced from 4 weeks to 10 days and did-not-attend (DNA) appointment rates have been reduced from 15% to 1%. Patients appear to be very satisfied with the service, with 80% rating it as good or excellent. 52

Diagnoses made by physiotherapists or MSK triage services have been shown to be comparable with diagnoses made in face-to-face assessments and are not influenced by experience of the therapist. 53–55 In addition, therapists from different allied health professions agree on the prioritisation of patient care using telephone assessment systems. 56 There are some suggestions, however, that management of patients with MSK conditions over the telephone compares less favourably when conducted by less experienced physiotherapists in comparison with more experienced colleagues. 53,57

Related new developments in access to physiotherapy services

The Department of Health has recently published a report of the evaluation of self-referral to physiotherapy pilot sites. 17 Although the evaluation was not based on a randomised trial, the report is broadly supportive of the concept of self-referral, as are other non-randomised evaluations. 18,58–60 A small number of studies evaluating self-referral to physiotherapy services highlight potential patient benefits of direct access. 61–63 Many physiotherapy service leads will consider using PhysioDirect telephone systems to help them manage self-referral, which increases the salience of our study.

Rationale for a randomised trial of PhysioDirect for patients with musculoskeletal problems

PhysioDirect services have been established in a number of areas, notably in Huntingdonshire and Cheltenham in England. These have been commended by the Commission for Health Improvement and the NHS Working in Partnership Programme as examples of good practice and have won awards for innovation. Several other areas have established, or considered, similar services. The NHS White Paper ‘Our Health, Our Care, Our Say’16 highlighted the need to test new models of physiotherapy to overcome current deficiencies. Without a high-quality randomised trial testing the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of PhysioDirect, it is unclear whether or not such services should be more widely implemented.

This study is a RCT of PhysioDirect, an approach to improving access to physiotherapy services based on initial telephone assessment and written advice sent by post, followed by face-to-face care only when appropriate. This type of service is being introduced in different parts of the UK, but there is currently no evidence about the effectiveness or cost-effectiveness of PhysioDirect compared with usual care (based on a waiting list and eventual face-to-face care).

Summary of rationale for PhysioDirect

In summary, the rationale for PhysioDirect is to:

-

Provide equivalent outcomes for patients compared with usual care based on a waiting list for face-to-face treatment.

-

Provide faster access to advice, which would result in more rapid improvement in symptoms and may allow patients to return more quickly to work and usual activities.

-

Provide equivalent outcomes at lower cost, meaning that the PhysioDirect service is more cost-effective from an NHS perspective. The lower cost of PhysioDirect would be achieved by better tailoring the use of physiotherapy time in relation to need and capacity to benefit, using telephone consultations which were presumed to be less costly than face-to-face consultations, and by better use of resources through lower DNA rates.

-

Increase patient satisfaction because of easier access to advice from a physiotherapist.

Research objectives

-

To assess whether or not PhysioDirect is equally as effective as the usual models of physiotherapy based on patients going on to a waiting list and eventually receiving face-to-face care.

-

To investigate the cost-effectiveness of PhysioDirect compared with usual care.

-

To explore the experiences and views of patients, physiotherapists and their managers.

-

To investigate the health outcomes and experiences of different groups of patients (those in different age groups and with different types of problems) when referred to PhysioDirect rather than usual care.

Chapter 2 Randomised controlled trial: methods

Study design

The study is a pragmatic RCT, with participants randomised individually to one of two parallel groups, incorporating economic evaluation and nested qualitative research. The comparison is between patients randomised either to be offered a service based on initial telephone assessment and advice from PhysioDirect, followed by face-to-face treatment when necessary, or to be offered usual care consisting of allocation of patients to a waiting list for face-to-face care.

The study was designed to assess equivalence between the two treatment groups in the primary clinical outcome. If equivalence in clinical outcomes is established, differences in the costs of providing care and in the secondary outcomes (particularly waiting times for treatment, time lost from work and usual activities, patient satisfaction, patient preference) become particularly important and relevant to future provision of services.

The equivalence design was chosen over a conventional superiority design because there was no hypothetical justification to suggest that the PhysioDirect service would produce better clinical outcomes than usual care by the main follow-up time point of 6 months. However, because it was anticipated that patients randomised to PhysioDirect would receive advice more quickly than those randomised to usual care it was conceivable that they would achieve improved outcomes at the first time point of 6 weeks, but this was a secondary outcome. Furthermore, although we wanted to test a hypothesis of equivalence in the primary outcome we also wanted to test for difference in some of the secondary outcomes. For these reasons the study was designed as an equivalence study rather than a non-inferiority study, as the former would require a larger sample size and would provide power to establish differences in the secondary outcomes.

It is arguable that the most important outcome for this study would be improved cost-effectiveness – for example, the PhysioDirect service might be slightly less effective but substantially less costly and therefore might be cost-effective. However, the different sources of uncertainty in cost-effectiveness analyses make it very difficult to design a study with cost-effectiveness as the primary outcome and in particular to estimate the appropriate sample size for such a study. Furthermore, the interpretation of findings that a service is less effective and less costly than usual care is contentious. 64

Setting

PhysioDirect services were newly established for the purposes of the trial in four areas of England. Each physiotherapy service provided care for patients from a defined group of general practices within one of the following PCTs: Bristol, Somerset, Stoke-on-Trent, and Central and Eastern Cheshire. The total population covered across all four PCTs was approximately 625,000 people.

Patients from 94 general practices participated in this study. Participating GP practices were typical of NHS general practices in England, representing a broad mix of practice sizes, the smallest serving a population of 2121 and the largest 28,599 people. These practices covered a wide range of types of area, including inner-city, suburban, market towns and rural areas. Although detailed information about the population of each participating practice was not collected, between them the practices provide care for patients of all age groups. The areas differed in terms of their ethnic mix, but none had a high proportion of patients from non-white ethnic backgrounds. Although 12% of the population of Bristol is from black and minority ethnic (BME) groups, the BME population in the city is concentrated in particular inner-city wards. By contrast, only 1.2% of the population of Somerset is from BME groups. About 5% of the population of Stoke is from BME groups (predominantly Pakistani and Bangladeshi). About 3% of the Cheshire population is from a range of different minority ethnic communities.

Between them, in 2008 the existing physiotherapy services in these PCTs received approximately 18,300 referrals from primary care professionals in the general practices participating in the trial. This equates to 29.3 referrals per 1000 patients per annum, which is slightly higher than the rate of 24.4 reported in the most recent available figures for England. 13 However, these national data were last reported in 2004–5 and it was noted then that referral rates were rising by about 4% per annum. 13

The physiotherapy services that participated in the trial were typical of NHS primary care-based physiotherapy in the UK. NHS physiotherapists in the UK accept referrals from primary and secondary care physicians, other health-care practitioners (such as nurse practitioners and allied health professionals) and, in some cases, offer direct access or self-referral pathways to physiotherapy. Treatment is delivered following a clinical assessment of the patient by the physiotherapist, and common interventions for MSK conditions include advice and education, specific and general exercise, manual therapy and pain-relieving modalities, such as electrotherapy and acupuncture.

Participants

The inclusion criteria were deliberately as broad as possible in order to maximise generalisability and to reflect the ‘real-world’ operation of PhysioDirect services. Inclusion criteria were adults (aged ≥ 18 years) who were referred by GPs or other members of the primary health care team or who referred themselves (self referred) for physiotherapy for a MSK problem.

Exclusion criteria were children (< 18 years); patients referred to physiotherapy by a hospital consultant, emergency department or primary/secondary care interface service; those needing domiciliary physiotherapy; those needing postoperative physiotherapy; those needing physiotherapy for non-MSK problems; very urgent referrals; those who did not confirm that they wanted physiotherapy; second or subsequent referrals for physiotherapy for an individual during the trial period; people unable to communicate by telephone in English; and those with hearing difficulties who may have had difficulty communicating by telephone.

It was necessary to exclude participants who had problems that were so urgent that it was not safe to delay assessment for the length of time it would take to gain consent to the trial. Frequently, referrals were designated as urgent by the referring clinician. It was important not to exclude most of these referrals, as one of the potential advantages of a PhysioDirect service is that it allows an early telephone assessment by a physiotherapist to prioritise those who need urgent care. Therefore, all referrals to each participating service were screened by a senior physiotherapist on receipt (see below) and only those which were deemed very urgent were excluded from the study (regardless of whether or not the referring clinician had marked the referral as urgent). The excluded patients were contacted and offered physiotherapy in the usual way for urgent cases.

Recruitment of participants

General practitioners or health-care professionals in the relevant practices referred patients to physiotherapy in the usual way, although patients could refer themselves in some areas of Stoke, as that service already had developed a self-referral pathway for patients for some GP practices. Referrals to each physiotherapy service were screened by a senior physiotherapist within one working day of receipt to confirm that the patient appeared to be eligible for the study. These potentially eligible patients were sent information about the trial by post from participating physiotherapy centres, along with a consent form and a baseline questionnaire.

The consent form asked potential participants to choose from one of three options: to consent to participation in the trial; to state that they wanted physiotherapy but did not want to participate in the trial; or to state that they no longer wanted physiotherapy.

Those who agreed to participate were randomised into the trial; those who declined participation but wanted physiotherapy were put on the waiting list for usual care; and those who did not want physiotherapy were discharged. All referrals were logged in order of when the referral form was originally received, so the process of gaining consent did not affect the patient's position on the waiting list for face-to-face physiotherapy if they ultimately received usual care.

If people did not reply to the information letter, they were sent a reminder mailing after 2 weeks to encourage them to respond. The reminder informed them that if they did not respond in any way within 2 weeks of the date the reminder letter was sent then they would be discharged and taken off the physiotherapy waiting list. This is standard practice, in that most physiotherapy services and many hospital outpatient services send patients a ‘partial booking’ letter inviting them to respond to request an appointment, and patients who do not respond are discharged and removed from the waiting list.

Randomisation

Patients who gave consent to participate and had completed the baseline questionnaire were randomised in a 2 : 1 ratio to PhysioDirect or usual care. This allocation ratio was chosen to ensure that sufficient patients were randomised to PhysioDirect to make this new service viable, given that all non-consenting and excluded patients continued to receive usual care, as well as those randomised to usual care. Randomisation was undertaken using web or telephone access to a secure remote automated allocation system maintained by the UK Clinical Research Collaboration (UKCRC)-registered Bristol Randomised Trials Collaboration. Allocation was made at the level of the individual, stratifying by physiotherapy site and minimising by sex, patient age group, and site of the presenting MSK complaint. Allocation was therefore fully concealed. Periodic checks were made during the study of the allocation ratios according to the minimisation factors, to ensure that the randomisation schedule was performing as intended.

Following randomisation, patients were sent a letter either inviting them to contact PhysioDirect and explaining how to do so (intervention arm), or explaining that they were on a waiting list for a face-to-face physiotherapy appointment and would be contacted by the service when the next appointment became available (control arm).

The number of patients excluded from or not participating in the trial for different reasons was recorded. The age, sex and postcode of all patients were also recorded in anonymised form, to make it possible to compare participating and non-participating populations.

Description of intervention and control arms

Intervention: ‘PhysioDirect’

The intervention is defined as the patient being offered treatment within the PhysioDirect treatment pathway. PhysioDirect is the provision of an easily accessible telephone assessment and advice service from an experienced physiotherapist, supported by a computerised assessment algorithm. Following the telephone assessment, patients are usually given exercise advice and then invited to telephone back to report progress. They can then be invited for a face-to-face appointment if necessary, or this can be offered following the initial assessment if appropriate.

The rationale for PhysioDirect is that all patients will have access to earlier assessment and advice about their problem from a physiotherapist. Furthermore, those patients most likely to benefit from face-to-face physiotherapy should be able to receive it more quickly (by filtering out the patients who do not need face-to-face care), hopefully leading to a faster clinical improvement and a quicker return to work and/or usual activities.

The term ‘PhysioDirect’ is used variably by different services in the UK, but the model used in this trial was modelled closely on the system developed by the Huntingdonshire PCT in 2001. This service was runner-up in the 2003 Health and Social Care Awards. Currently, 350,000 people in Cambridgeshire are served by this PhysioDirect system. The established nature of the service, the structured format of the system and the experience of the Huntingdon physiotherapy staff both in using and training other physiotherapists to use this system all made the system particularly suitable for use in the PhysioDirect trial.

Setting up the service

In order to establish a PhysioDirect service, each participating site needed to train sufficient physiotherapists to provide telephone assessments using the assessment software and to provide a suitable office. Apart from the training and set-up costs, no extra physiotherapist resources were used within the study – the time of the existing staff was reallocated within existing resources.

Training the physiotherapists

All physiotherapists operating the PhysioDirect telephone services undertook a structured training programme led by the physiotherapy service in Huntingdon which involved attending a 2-day course of teaching, demonstrations and observation of live calls. Each PCT trained about eight physiotherapists in order to provide sufficient capacity across the week (with some contingency in case of absence) and without any one physiotherapist having to spend more than half of their time working on the PhysioDirect service.

The PhysioDirect software (see below) was installed at each of the PCTs in the PhysioDirect trial prior to the trial physiotherapists attending the Huntingdon training so that following the training session the physiotherapists could practise and hone their skills. The Huntingdon PhysioDirect trainers were available by telephone throughout this period to provide advice if problems were encountered.

A visit to each participating PCT was undertaken by a PhysioDirect trainer approximately 2 weeks after completion of the training programme. The trainer observed calls and facilitated a problem-solving session. The trainer then listened to individual calls and, using a structured format, assessed each physiotherapist's competency to utilise the system safely and effectively. If physiotherapists did not reach the required competency at the first site visit a further visit to recheck competency was carried out approximately 6 weeks after the initial training. The competency check consisted of the trainer assessing 53 aspects of the telephone assessment process and completing a checklist indicating whether or not each aspect was performed to a satisfactory level. Each section was evaluated on a yes/no basis, with overall comments about performance, issues to be addressed and an agreed action plan if required. All physiotherapists had to be certified as competent to undertake PhysioDirect before they assessed patients in the trial.

Office facilities

Each site required a quiet office with at least two computers with installed software, and a telephone system with headsets for the physiotherapists, a fax machine and an answering machine. Ideally (but not necessarily), the receptionist would work close by in an adjacent office.

The PhysioDirect software

Shortly after its inception, the Huntingdon PhysioDirect system was translated into a computer-based system to assist the safe, efficient and effective delivery of the telephone assessment and advice service. The challenge during the development of the computerised system was to maintain sufficient structure to guide an effective and efficient assessment by prompting physiotherapists to cover all key aspects of the patient assessment, while being flexible enough to be responsive to presentations of individual patients and taking account of the lack of visual clues provided by a patient during a face-to-face consultation. The system had to be as simple as possible as physiotherapists undertaking telephone assessment are required to perform a number of skills simultaneously, including asking questions, visualising the patient and their presentation, analysing the patient's responses, formulating the next question and typing responses into the system. The solution was to include mandatory fields with dropdown menus and tick boxes for key aspects of the assessment, with text boxes provided to allow the physiotherapists to record responses to supplementary questions eliciting further information or clarification from the patient.

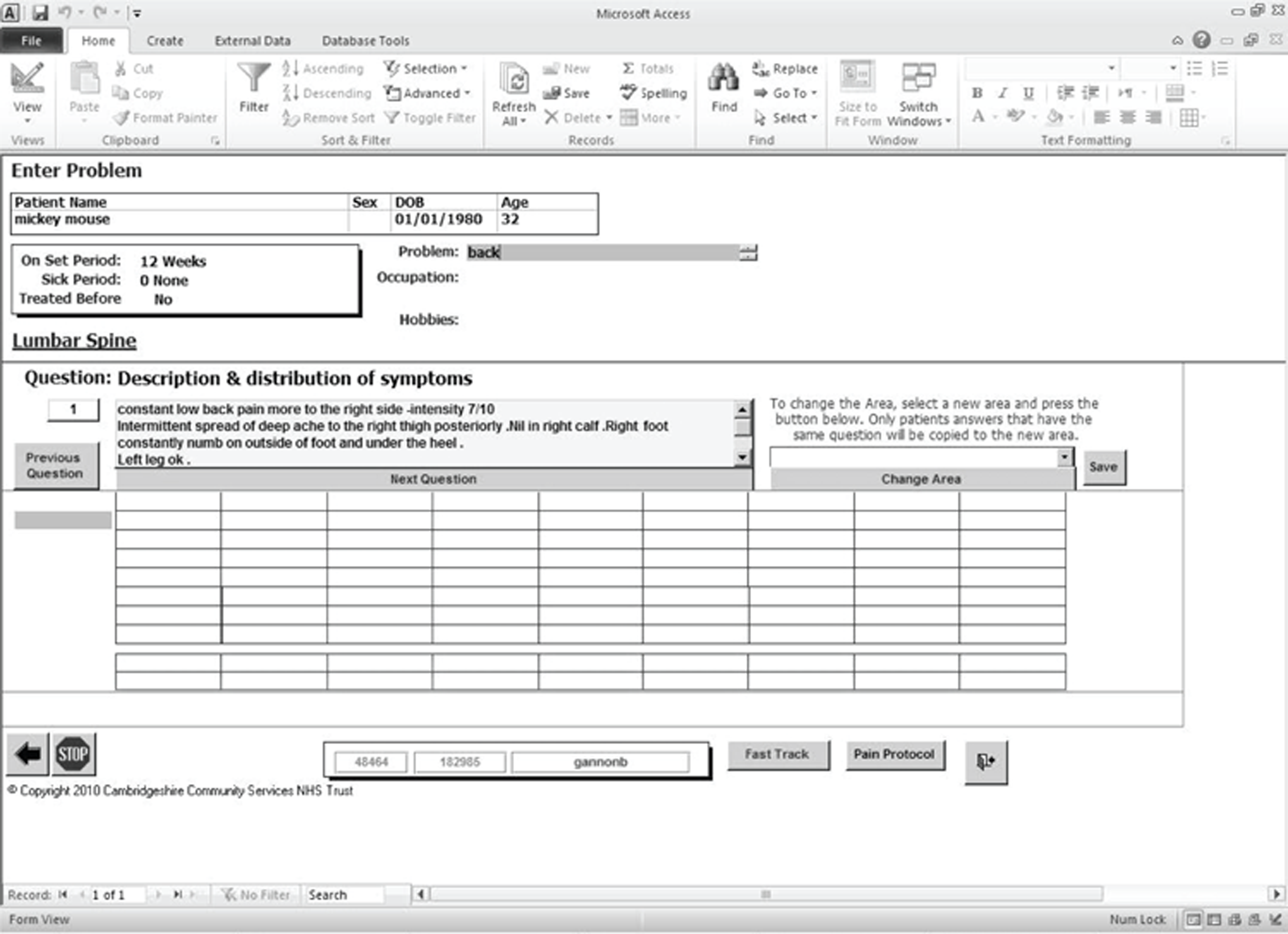

The software is a based on a program developed using Microsoft Access 2003 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), which first allows the patient's demographic details to be checked, then brief details regarding the patient's occupation, hobbies/activities and main problem for which they have been referred. When using the software the physiotherapist selects an appropriate assessment framework, depending on the area of the body affected. This ensures any relevant ‘special questions’ are asked that relate to that area. For example, if the patient is complaining of low back pain, questions regarding symptoms suggestive of cauda equina compression are included by the computer software in the assessment algorithm. This assessment, prompted by the software, includes the investigation and recording of the patient's presenting, medical and drug history, details of aggravating, easing and diurnal patterns and assists the physiotherapist in reaching a clinical diagnosis. An example screen from the system is shown overleaf.

Further information about the PhysioDirect software used in this trial can be obtained from Mrs Jill Gamlin, Physiotherapy Department, Hinchingbrooke Hospital, Hinchingbrooke Park, Huntingdon PE29 6NT, UK (e-mail: jill.gamlin@nhs.net).

Standardisation of PhysioDirect across the sites

All four physiotherapy services participating in this trial set up a PhysioDirect service following the same model of organisation and using the same assessment software as developed in Huntingdonshire (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Example screen shot from PhysioDirect assessment software. Reproduced with permission from Cambridgeshire Community Services NHS Trust.

As far as possible, the PhysioDirect service was implemented in the same way in each of the four sites. The physiotherapists received the same training and were accredited in the same way, they used the same PhysioDirect software, and they used the same suite of advice and exercise leaflets. Furthermore, all recruitment and other research procedures were standardised in all sites. In this way, a high degree of consistency in how the intervention was delivered in each local service was ensured.

After the physiotherapists had been trained and assessed as competent to assess and advise patients via PhysioDirect, each physiotherapy site carried out a run-in period of at least 1 month to ensure smooth running of the service before patients to be included in the main trial were recruited. During this run-in period, all trial procedures of recruitment and randomisation were followed, making it possible to fully pilot the research procedures in parallel with the physiotherapy services gaining experience of the new way of working. Follow-up data collection for most outcome measures was also undertaken, although with less intensive use of reminders than in the subsequent main trial because of resource limitations.

Staffing the service

Based on advice from Huntingdon, it was decided that only experienced physiotherapists would be involved in providing the PhysioDirect telephone advice. Each service therefore trained several of their more senior staff who were on Agenda for Change Band 6 or above to conduct the PhysioDirect sessions. Details of the training and experience of these physiotherapists were collected at the training sessions. These are described in Table 1.

| Characteristic | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (n = 32) | ||

| Male | 7 | 22 |

| Female | 25 | 78 |

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 12 | (8) |

| Seniority: Agenda for Change band (n = 31) | ||

| 6 | 13 | 42 |

| 7 | 17 | 55 |

| 8 | 1 | 3 |

| Any previous specific postgraduate training in telephone assessment or advice services? (n = 31) | ||

| Yes | 4 | 13 |

| No | 27 | 87 |

| Previous experience of using PhysioDirect or other telephone assessment system to advise patients? (n = 31) | ||

| Yes | 11 | 35 |

| No | 20 | 65 |

Because (in the context of a trial) only a minority of patients were randomised to PhysioDirect, the number of patients did not justify having a physiotherapist available to answer the telephone at all times in the week. Each site was asked to provide telephone sessions spread across a range of days of the week and at different times of day, to allow patients some choice about when to telephone. These opening times were included in the letter inviting patients to telephone the service. If patients telephoned at other times, an answerphone message asked them to telephone again when the service was open.

Process of the encounter

As soon as possible after consent to participate in the trial was received, patients were sent a letter inviting them to telephone an experienced physiotherapist for initial assessment and advice and explaining the times during which the PhysioDirect service was available each week. When a patient called the service, if a physiotherapist was not engaged in a call, they would be the first person the patient spoke to and the assessment would start immediately. If the staff were all engaged with other calls then the first person they would speak to would be a receptionist. The receptionist would take the patient's details and place them on a ‘call-back’ list along with information regarding when would be most convenient for this to happen. The physiotherapists would either field any calls arriving if they were free, or consult the call-back list for available patients.

The physiotherapist responding to the telephone call followed the computer-assisted assessment system to assess the patient and record the findings.

Process of care following the encounter

There were several possible outcomes following the initial telephone call:

-

In some cases, at the end of the call the physiotherapist posted a relevant advice leaflet about self-management and exercises to the patient, inviting them to telephone back to report progress after about 2–4 weeks, if appropriate. If the patient telephoned back they could be given further advice or be booked for a face-to-face consultation if necessary.

-

In some cases, the initial telephone call established that face-to-face assessment and/or care was needed, in which case this was arranged either by putting the patient on the PhysioDirect waiting list for face-to-face care or by arranging an urgent appointment if necessary.

-

In other cases, the initial assessment established that physiotherapy was unlikely to be effective and the patient was given appropriate advice or referred to another service, and discharged from physiotherapy.

-

In a few cases the initial assessment revealed that urgent medical intervention was required and these patients were sent to accident and emergency (A&E) with an accompanying fax detailing the need for attendance. If the medical intervention was not considered ‘an emergency’ then patients were asked to attend their GP, for example to obtain a radiograph.

The assessment process allocates patients to one of five categories. These categories and the subsequent management pathways are summarised in Table 2.

| Patient category | Management pathway |

|---|---|

Specific MSK problem and the assessment indicate that the patient can be given a sound explanation of the MSK problem:

|

Patient is given clear verbal explanation and advice. Information sent in the post to facilitate self-management

|

| The presenting problem is MSK but there are indications of serious pathology present | Specific pathway followed for presentation, e.g. cauda equina |

| Specific MSK condition but face-to-face assessment is required, for example neurological status assessment for patients with radiculopathy | Patient booked into clinic for face-to-face appointment for further examination and assessment |

| Not possible to make a sound diagnosis with telephone assessment | Patient booked for face-to-face appointment to clarify the diagnosis and commence appropriate management |

| The primary presenting problem is not MSK | Patient referred back to GP |

Providing PhysioDirect in the context of a randomised controlled trial

Separate waiting lists were held for patients randomised to PhysioDirect and to usual care, so that any impact of the PhysioDirect pathway on how long people waited for a face-to-face appointment could be detected. For the same reason, we sought to allocate physiotherapist time in proportion to the number of people who were randomised to the PhysioDirect arm of the trial. Based on experience in the pilot study it was possible to estimate the proportion of patients referred for physiotherapy who would be eligible for the trial and the proportion of those who would consent to take part. Using these data, and also taking into account that one in three of the eligible, consenting patients would be randomised to usual care, it was possible to estimate that approximately 20% of all patients would be allocated to PhysioDirect rather than usual care. Each site was therefore asked to allocate 20% of their total physiotherapist staff resources to patients allocated to the PhysioDirect arm of the trial, and within this proportion to allocate about half the time to telephone sessions and the remainder to face-to-face care for people in the PhysioDirect arm.

Patients randomised to the PhysioDirect arm could state at any time that they did not want to discuss their problem on the telephone but instead wanted to wait for a face-to-face appointment. This was allowed within the PhysioDirect pathway and did not mean that the patient needed to withdraw from the trial. It is important to note that the PhysioDirect ‘intervention’ was based on offering patients an initial telephone assessment with a physiotherapist, with face-to-face care available if necessary. The ‘intervention’ is not the telephone call, and a face-to-face consultation should not be equated with ‘usual care’. The PhysioDirect intervention is the care pathway, which can encompass both telephone advice and face-to-face care.

Control: usual care

The control arm is defined as the patient being offered treatment within the usual MSK physiotherapy care pathway.

Usual care involved patients being referred to a physiotherapist by a GP or other member of the primary health care team. In some areas in Stoke, PCT patients could also refer themselves directly. As is usual physiotherapy practice, patients were put on to a waiting list for an initial face-to-face physiotherapy assessment and then, if appropriate, had a series of follow-up treatment appointments. The waiting time differed considerably in the four participating physiotherapy services, at different sites providing physiotherapy within each service, and at different times of year. This reflects usual care in physiotherapy services more widely.

Outcome assessment

Outcomes were assessed at baseline, and at 6 weeks and 6 months after randomisation.

The primary outcome was clinical outcome at 6 months, assessed using the Physical Component Score (PCS) measure from the Short Form questionnaire-36 items, version 2 (SF-36v2) questionnaire. 65 The SF-36v2 PCS is a well-recognised generic measure of health status. It was particularly suitable for this trial because, unlike disease-specific measures, it is applicable to the wide range of MSK problems referred to physiotherapy.

Although there could be a concern that generic measures may be less responsive than disease-specific measures, the physical functioning and bodily pain scales of the SF-36 (which contribute most of the variation in the PCS summary measure) compare reasonably well with disease-specific measures in patients with MSK problems. 66–70

Several further measures of clinical outcome were also used. The first was the Measure Yourself Medical Outcomes Profile (MYMOP)71 questionnaire (version 2), which is a patient-generated measure. It allowed patients to specify up to two symptoms and one functional limitation for which they had been referred to physiotherapy, then follow-up questionnaires assessed change in those specific symptoms/limitations. This individualised and validated measure has also been used to assess patients with a wide range of problems. 71 The MYMOP was included as, by focusing on the patient's main problem, it might be more sensitive to change than the PCS. The MYMOP was designated an important secondary outcome.

Second, a single question was included as a global measure of individual rating of overall change, based on a seven-point Likert scale from ‘very much worse’ to ‘very much better’.

Third, we created a composite measure of response to treatment using the approach recommended by the Outcomes Measures in Rheumatology Clinical Trials – Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OMERACT-OARSI) initiative. 72 This combined measures of physical function (the SF-36 physical function scale), pain (SF-36v2 bodily pain scale) and overall perception of the main problem (question 1 from the MYMOP questionnaire).

Other secondary outcomes were:

-

costs (described in more detail later)

-

quality of life [measured using the EQ-5D measure73 (European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions; EuroQol health utility measure)]

-

the individual scales and the mental component summary measure from the SF-36

-

waiting times for treatment, based on data collected from routine physiotherapy records

-

time lost from work and usual activities, based on patient questionnaires

-

satisfaction with care provided (development of the measure is described in Appendix 2)

-

preference for physiotherapy or usual care if they needed physiotherapy in future, based on a single question in the patient questionnaire.

Process evaluation

Measures of the process of care were particularly important in this study. Data about the services provided included:

-

the number, type and duration of consultations with physiotherapists

-

time to first physiotherapy assessment (telephone or face to face) and to first face-to-face appointment, where applicable

-

rates of non-attended appointments with physiotherapists

-

the clinical grade or banding under Agenda for Change of all physiotherapists who provided care, and further details of the qualifications of the 32 physiotherapists who provided telephone advice in the PhysioDirect arm, as previously described.

In addition, it was important to collect data about the use of other health services in relation to the referral problem, particularly consultations in general practice, referrals to hospital outpatient services, hospital admissions, use of private physiotherapy and other private sector treatments. These are relevant to the economic evaluation but also to a full understanding of the impact of the different models of physiotherapy service on other health-care providers.

A system was established to collect, record and investigate details of any suspected adverse events (AEs) encountered by the trial participants.

Collection of data

Baseline data about patient characteristics, and the nature of the problem for which patients were referred to physiotherapy, were collected from the referral forms at each participating physiotherapy centre.

Outcome and process data were collected from questionnaires administered to patients at baseline, 6 weeks and 6 months after randomisation, from electronic data downloaded from the PhysioDirect software, from routine records of consultations collected by each physiotherapy service, and from general practice records.

The baseline patient questionnaire collected data about patient characteristics and about the outcome measures. Data about outcomes at follow-up were collected from similar questionnaires sent by post at 6 weeks and 6 months after randomisation. Non-responding patients were sent a first reminder questionnaire by post after 2 weeks, and a second after a further 2 weeks, if needed. If patients did not respond to this second reminder within 2 weeks, attempts were made for up to a further 2 weeks to collect outcome data by telephone. In this situation, priority was given to obtaining data about the primary outcome (the SF-36v2 PCS). Similarly, if patients did complete postal questionnaires but key questions were omitted then telephone contact was attempted in order to collect missing question items that were necessary to calculate the primary outcome.

Some ‘screening’ questions were included to identify patients who had accessed rarely used but potentially expensive resources (e.g. hospital admissions) because of the problem for which they were referred for physiotherapy. Patients who responded positively to these questions were then telephoned to obtain more detailed information.

Data about telephone consultations with the PhysioDirect service were collected by download from the assessment software used in this service. Data about face-to-face consultations were obtained from routine records maintained by each physiotherapy service. Data about primary care consultations were obtained from general practice notes, extracted by research staff. Details of consultations with NHS walk-in centres, emergency departments, hospital outpatient appointments and admissions were obtained from the patient questionnaire, as were details of non-NHS consultations.

Details of the physiotherapists participating in the PhysioDirect service were obtained from questionnaires administered before these physiotherapists undertook training to use the PhysioDirect software. Details of the grades of the other physiotherapists providing face-to-face consultations were obtained from the managers of each service.

Table 3 lists the various outcome measures, the timing of data collection and the source of the data.

| Measure | Timing | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Patient identifers, type of problem, age and sex | Pre-consent | Referral letter. Recorded (anonymised) in research database |

| Demographic details | Baseline | Baseline patient questionnaire, data from research database |

| SF-36v2 | Baseline, 6 weeks, 6 months | Patient questionnaires |

| MYMOP | Baseline, 6 weeks, 6 months | Patient questionnaires |

| EQ-5D | Baseline, 6 weeks, 6 months | Patient questionnaires |

| Overall rating of change | 6 weeks, 6 months | Patient questionnaires |

| Time lost from work and usual activities | Baseline, 6 weeks, 6 months | Patient questionnaires |

| Satisfaction with care provided | 6 weeks, 6 months | Patient questionnaire |

| Preference for PhysioDirect or usual care | Baseline, 6 months | Patient questionnaires |

| Waiting time for first assessment by a physiotherapist | Collected at end of study | Physiotherapy service records, from date of randomisation (and also from date the referral was originally received) to date of first telephone or face-to-face consultation |

| Patient and companion costs | 6 weeks, 6 months | Patient questionnaires |

| Cost of lost production associated with time off work and usual activities | 6 weeks, 6 months | Estimated from information in patient questionnaires |

| Costs of providing physiotherapy | Set up costs: collected during the PhysioDirect service set-up phase and once the service was operating | Set-up: data from PCTs about resources involved in setting up the PhysioDirect service; treatment: physiotherapy records, data collected within the trial about lengths of consultations, staff use of time, staff grades, etc. |

| Treatment over 6 months: collected at end of study | ||

| Costs in general practice (consultations, treatments, investigations) | Collected at end of study, from randomisation to 6 months' follow-up | Patient GP records – consultations costed using Netten and Curtis and NHS reference costs for other costs |

| Costs of prescriptions | Collected at end of study, from randomisation to 6 months' follow-up | Patient GP records, costed using the BNF |

| NHS secondary care costs (outpatients, inpatients, admissions) | 6 weeks, 6 months | Patient questionnaires for resource use, costed using NHS tariffs |

| Process evaluation: number, type and duration of consultations with physiotherapists; non-attended appointments with physiotherapists | Collected at end of study, from randomisation to 6 months' follow-up | Physiotherapy records |

| Qualifications and experience of physiotherapists | Collected at the beginning of the study | Online questionnaire completed by physiotherapists |

| Suspected adverse events and adverse events | Collected throughout study from randomisation to 6 months' follow-up | To be notified by patients, physiotherapy services, general practices or any other sources |

Data entry

All questionnaire data were entered into a bespoke database in Microsoft Access v2000. A 1-in-10 sample of each questionnaire type was independently checked to assess the accuracy of data entry. Of 58,615 fields checked, there were just 73 errors (0.125% error rate).

Blinding

In pragmatic trials of this type, as in the real world, it is not possible to blind participants or physiotherapists, whether they are in the intervention or control arm of the trial.

Most of the outcome data were obtained from patient questionnaires, which were therefore not blind to treatment allocation. However, all data entry from these questionnaires was conducted blind to allocation. The collection of data about PhysioDirect calls was by electronic download. The collection of data about face-to-face physiotherapy consultations from administrative records and from general practice records was conducted by research staff not involved in providing the intervention, as far as possible blind to allocation, although in some cases (7%; 160/2228) this was not possible because the allocation was recorded in the records.

Sample size and power

This study was powered to establish clinical equivalence using the PCS scale from the SF-36. At the time of planning the study, previous studies in a range of populations and conditions had suggested that a minimum clinically important difference on the SF-36v2 PCS was about 4 points [0.4 standard deviation (SD)],74–77 although the latest version of the SF-36v2 manual now suggests that ‘a minimum important difference of 2–3 points is reasonable’. 78

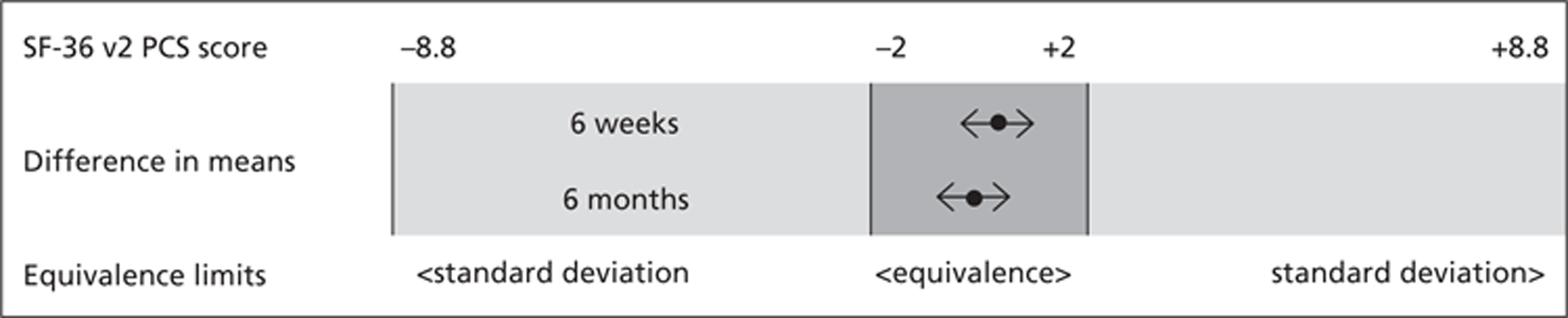

In this study, a difference of no greater than 2 points was conservatively specified as demonstrating equivalence. This is equivalent to an effect size of 0.2 SDs, which is considered a small effect size. 77 Sample sizes for analysis of 976 and 488 in the PhysioDirect and usual-care groups, respectively, would yield 95% power to reject a null hypothesis of non-equivalence (i.e. the difference in means, μPhysioDirect − μusual care, is not less than 0.2 SDs) with an overall two-sided alpha of 0.05 alpha if the observed difference in means is zero. The same sample size would yield 80% power to reject the null of non-equivalence if the observed difference between the groups is 0.046 SDs rather than zero.

The target sample size for patients completing the final 6-month follow-up questionnaire was 1000 patients in the PhysioDirect arm and 500 patients in the usual-care arm. Assuming 20% non-collection of the primary outcomes, it was necessary to recruit 1250 and 625 patients in the PhysioDirect and usual-care arms, respectively, or 1875 patients in total.

Statistical methods

The main hypotheses were that care via the PhysioDirect service would be clinically equivalent to usual care and more cost-effective at 6 months after randomisation.

Primary analysis

Analysis and presentation of data were conducted in accordance with CONSORT guidelines (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials), including the extensions relating to non-pharmacological trials, non-inferiority and equivalence trials and pragmatic trials. 79–83 The primary analysis employed multivariable regression to investigate between-group differences in SF-36 PCS score at 6 months' follow-up. The primary analysis was conducted on an intention-to-treat basis, with due emphasis placed on the confidence interval (CI) for the between-arm comparison when inferring equivalence (or otherwise) of the two groups. It was determined a priori that clinical equivalence between the arms would only be concluded if the 95% CI for the primary outcome lay wholly inside the range −2 to +2 points on the PCS. Analyses were adjusted for stratification variables (physiotherapy site), minimisation variables (age, sex, main referral problem) and baseline outcome variable scores.

Because the intervention is being offered either the ‘PhysioDirect’ or ‘usual care’ treatment pathway, all patients were analysed within their randomised groups and there is no difference between an ‘intention-to-treat’ and an ‘on-treatment’ analysis.

Secondary analysis

Sensitivity analysis

-

Repeating the primary analysis adjusting also for any variables exhibiting marked imbalance at baseline to check that this did not influence the findings.

-

Investigating the effect of missing primary outcome data using multiple imputation methods.

-

Investigating clustering of outcomes by (a) practice and (b) physiotherapy service.

Secondary outcomes

-

Assessing equivalence in clinical outcome using the MYMOP score at 6 months.

-

Examining clinical outcome at 6 weeks using the SF-36 PCS.

-

Comparison of the proportion of patients who ‘respond to treatment’ in each arm, in line with the OMERACT-OARSI recommendations,72 using the SF-36 physical function and bodily pain scales and the main problem score from the MYMOP.

-

Analyses of the other secondary outcomes using similar approaches as described for the primary outcome.

-

Investigation of process measures such as physiotherapy consultation rates, waiting times, physiotherapy DNA rates and consultation rates with other health-care services in the NHS and private sectors.

-

Repeated measures analysis using an interaction term for time to investigate any divergent/convergent pattern in the SF-36 PCS over 6 weeks' and 6 months' follow-up.

Subgroup analyses

Appropriate interaction terms were entered into the primary regression analysis for SF-36 in order to conduct pre-specified subgroup analyses according to site of presenting MSK problem, patient age group, socioeconomic status and PCT physiotherapy service. As the trial was powered to detect overall equivalence between the groups rather than interactions of this kind, these analyses were essentially exploratory and would need to be interpreted with due caution.

Economic analysis and qualitative research

The methods for the economic analysis and for the qualitative research are described in detail in subsequent chapters, after the main quantitative results from the trial.

Investigation of adverse events and serious adverse events

General practitioners from participating practices and physiotherapists treating trial patients were asked to report any death, hospitalisation, significant disability or incapacity, life-threatening circumstance or other medically significant occurrence that he/she considered may be potentially related to physiotherapy, or to the trial procedures, to the Chief Investigator within 5 days of occurrence. The Chief Investigator would investigate these using a predetermined set of criteria and report any related and unexpected serious adverse events (SAEs) to the Main Research Ethics Committee, within 15 days of becoming aware of the event, using the SAE report form for non-CTIMPs (Clinical Trial of an Investigational Medicinal Product) taken from the National Research Ethics Service website. A log would be kept of all AEs or SAEs reported to the Chief Investigator; his/her assessment of the intensity, causality, expectedness and seriousness of the AE; the reasons for those decisions; and (when appropriate) the dates on which the SAE was reported to the main Research Ethics Committee, Sponsor, and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee.

Ethics and research governance approval

Multisite research ethics approval was obtained from Southmead Research Ethics Committee, Reference 08/H0102/95. All necessary research governance approvals were also obtained for each physiotherapy site.

Trial registration

Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN55666618.

UK Clinical Research Network (UKCRN) 4778.

The trial protocol has been published. 84

Summary of changes to the project protocol

The following changes were made to the original protocol after it was funded. The first five changes were all made before the trial started, the sixth was included a priori in the trial analysis plan, and the seventh was made during recruitment. All were approved by the Trial Steering Committee.

-

Patients who were referred by a primary care health professional or self-referred to physiotherapy were also included, rather than only those referred by a GP.

-

Needing physiotherapy for non-MSK problems was added as an exclusion criterion.

-

Sex was included as a minimisation factor in the randomisation procedure.

-

Analysis of health status in order to calculate quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) was based on the EQ-5D measure rather than the Short Form questionnaire-6 Dimensions (SF-6D) measure derived from the SF-36v2.

-

The primary outcome was originally described as the clinical outcome assessed using two measures: the SF-36v2 PCS and the MYMOP. However, after discussion with the TSC it was agreed that having two primary outcomes could lead to problems in interpretation of findings. Therefore, the SF-36v2 (as the better established measure) was designated as the primary outcome and the MYMOP as an important secondary outcome. Wording was changed to clarify that the equivalence limit for the PCS was based on 2 points rather than 0.2 SDs.

-

The recruitment rate was defined as the percentage of patients consenting to participate from those responding to the initial letter to confirm that they did want physiotherapy. Patients who did not respond to the initial invitation or reminder letters from the physiotherapy service, despite reminders, were taken off the physiotherapy waiting lists and were defined as not eligible for the study.

-

Because of lower than anticipated follow-up rates at 6 months in patients recruited in the run-in phase it was agreed to continue inviting patients to the main trial until 2000 had given consent to participate, recognising that the final total recruited would be about 2143 patients because of the lag between invitation and consent. This sample size would provide the target sample size of 1500 patients completing questionnaires at 6 months, even if only 70% were followed up successfully.

Chapter 3 Randomised controlled trial: results

Generalisability

Patients were recruited between July 2009 and December 2009, and followed up until June 2010.

We considered several patient characteristics in order to evaluate the generalisability of this study: sex, age, deprivation (as measured in quintiles based on postcode), PCT and body region of MSK problem.

We compared the characteristics of patients in two groups: (a) those who were ineligible for the study on the basis of their referral letter (Table 4) or because they did not confirm that they wanted physiotherapy and (b) those who were eligible.

| Reason | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| < 18 years | 180 (13) |

| Hearing problems | 27 (2) |

| Non-English language | 27 (2) |

| Non-MSK problem | 166 (12) |

| Needs domiciliary physiotherapy | 197 (14) |

| Very urgent | 376 (26) |

| Postoperative | 105 (7) |

| In trial already | 178 (13) |

| Problem unsuitable for telephone consult | 135 (9) |

| Problem unsuitable for physiotherapy | 12 (1) |

| Patient unsuitable for telephone consult | 41 (3) |

| Other (reason stated) | 9 (1) |

| Other (reason not stated) | 89 (6) |

Among the eligible patients, we also compared those who did or did not consent to participate and were randomised to participate in the trial.

Obvious differences between those patients who were or were not eligible, reflecting the eligibility criteria, were observed for the site of MSK problem for which patients were referred to physiotherapy. A higher proportion of patients in Bristol and a lower proportion in Somerset were deemed eligible. More women were referred than men, and slightly fewer men were eligible. Patients who were eligible were slightly older than those whose who were ineligible (Table 5).

| Patient characteristics | Wanted physiotherapy and eligible: n = 6870 (100%) | Randomisation: n = 4523 (65.84%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No: n = 2347 (34.16%) | Yes:a n = 4523 (65.84%) | Test | Not randomised: n = 2267 (50.12%) | Randomised:a n = 2256 (49.88%) | Test | |

| Sex (%) | ||||||

| Female | 56.97 | 59.74 | x12 = 4.90, p = 0.03 | 59.91 | 59.44 | x12 = 0.10, p = 0.75 |

| Male | 43.03 | 40.26 | 40.09 | 40.56 | ||

| Median age (years) (IQR) | 46.0 (31.0 to 62.0) | 50.1 (37.3 to 63.0) | Rank-sum, z = −6.79, p < 0.001 | 52.00 (38.0 to 65.0) | 48.30 (36.5 to 61.3) | Rank-sum, z = 5.64, p < 0.001 |

| Deprivation quintile (5 = most deprived) (%) | ||||||

| 1 | 8.76 | 10.24 | x42 = 14.43, p = 0.01 | 10.31 | 10.32 | x42 = 7.16, p = 0.13 |

| 2 | 19.72 | 20.06 | 20.13 | 20.04 | ||

| 3 | 25.51 | 27.00 | 25.84 | 28.37 | ||

| 4 | 22.04 | 22.53 | 22.17 | 22.58 | ||

| 5 | 23.96 | 20.18 | 21.55 | 18.70 | ||

| PCT (%) | ||||||

| Bristol | 26.5 | 31.70 | x32 = 42.16, p < 0.001 | 30.14 | 21.55 | x32 = 5.29, p = 0.15 |

| Somerset | 29.19 | 23.17 | 23.79 | 33.29 | ||

| Cheshire | 21.39 | 23.86 | 24.39 | 23.36 | ||

| Stoke | 22.92 | 21.27 | 21.68 | 20.57 | ||

| Site of problem for which referred (%) | ||||||

| Cervica | 8.73 | 12.74 | x82 = 582.08, p < 0.001 | 13.06 | 12.15 | x72 = 3.78, p = 0.80 |

| Thoracic | 1.67 | 2.17 | 2.14 | 2.17 | ||

| Lumbar | 25.49 | 27.8 | 28.25 | 27.41 | ||

| Upper limb | 19.03 | 23.38 | 23.37 | 23.37 | ||

| Lower limb | 26.56 | 29.09 | 28.34 | 29.93 | ||

| Widespread pain | 0.68 | 0.58 | 0.47 | 0.67 | ||

| Multiple MSK | 4.32 | 3.76 | 3.90 | 3.64 | ||

| Other MSK | 6.46 | 0.49 | 0.47 | 0.67 | ||

| Non MSK | 7.06 | 0.00 | NA | NA | ||

Considering the eligible patients, those patients who were randomised were slightly younger, on average, than those who were not. Apart from this, there were few differences between those who were randomised and those who were not (Table 5).

Patients from the least deprived areas (quintile 1) were under-represented in this study in comparison with the national population. Patients who were from the most deprived areas were slightly less likely to be eligible or to consent to participate in the study and be randomised.

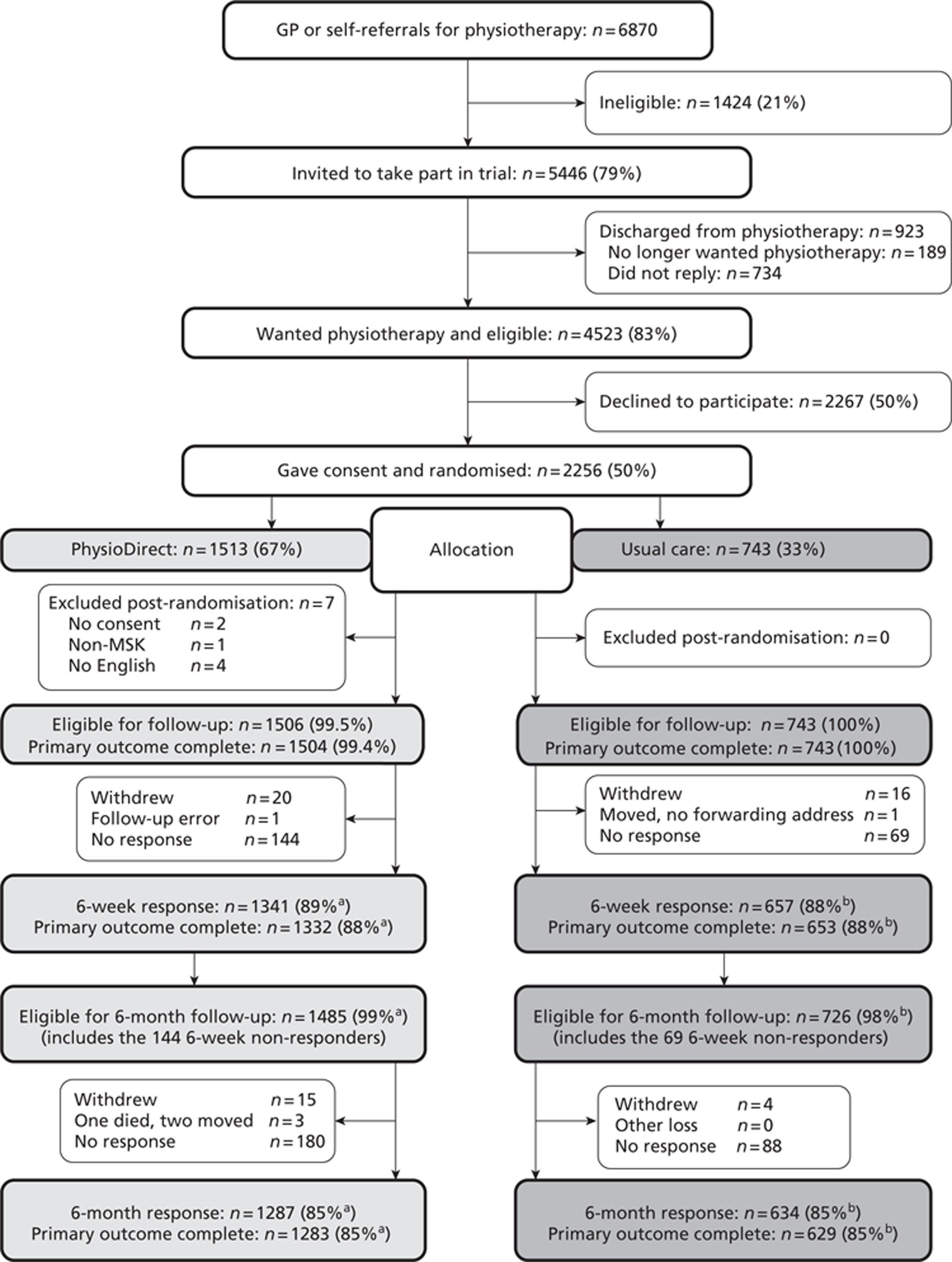

The recruitment rate, defined as the percentage of patients consenting to participate from those who were eligible (responding to the invitation letter confirming that they did want physiotherapy), was 2256/4523 or 50% (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram: flow of participants through the trial, a. Per cent is expressed as n/1506 × 100. b, Per cent is expressed as n/743 × 100.

Baseline comparability of randomised groups

No marked difference was observed between patients randomised to the two arms of the trial in terms of demographic, stratification/minimisation or outcome variables at baseline (Table 6). At baseline, 59% of participants in the trial were female, 96% were white, the majority were in employment, and patients from the least deprived areas were under-represented. Almost everyone had access to a telephone and the vast majority had access to a car (Table 7).

| Patient baseline characteristics | Randomised patients: n = 2249a (100%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Usual care: n = 743 (33.04%) | PhysioDirect: n = 1506 (66.96%) | |

| Sexb (%) | ||

| Female | 58.95 | 59.56 |

| Male | 41.05 | 40.44 |

| Median ageb (years) (IQR) | 48.18 (36.01 to 61.93) | 48.27 (36.72 to 61.01) |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||

| White | 95.79 | 96.71 |

| Black | 1.09 | 0.87 |

| Asian | 1.63 | 1.01 |

| Dual/mixed | 0.95 | 0.74 |

| Chinese | 0.14 | 0.13 |

| Other | 0.41 | 0.54 |

| Deprivation quintile (5 = most deprived) (%) | ||

| 1 | 9.92 | 10.57 |

| 2 | 20.95 | 19.61 |

| 3 | 29.33 | 27.96 |

| 4 | 21.79 | 22.88 |

| 5 | 18.02 | 18.98 |

| Employment status (%) | ||

| Employed | 57.05 | 62.08 |

| Unemployed | 6.16 | 4.70 |

| Student | 2.60 | 2.55 |

| Ill/disabled | 7.11 | 5.57 |

| Retired | 22.02 | 20.40 |

| Not working/other | 5.06 | 4.70 |

| Profession (%) | ||

| Administrative | 16.91 | 13.54 |

| Technical | 10.73 | 11.72 |

| Elementary | 8.78 | 10.21 |

| Manager | 10.57 | 9.34 |

| Personal services | 7.32 | 9.34 |

| Operatives | 5.53 | 5.62 |

| Professional | 17.56 | 17.97 |

| Customer services | 11.22 | 11.24 |

| Skilled trade | 11.38 | 11.01 |

| Patient baseline characteristics | Randomised patients: n = 2249a (100%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Usual care: n = 743 (33.04%) | PhysioDirect: n = 1506 (66.96%) | |

| Site of MSK problemb (%) | ||

| Cervical | 11.99 | 12.28 |

| Thoracic | 1.75 | 2.32 |

| Lumbar | 27.36 | 27.36 |

| Upper limb | 23.45 | 23.31 |

| Lower limb | 30.32 | 29.88 |

| Widespread pain | 0.94 | 0.53 |

| Multiple MSK | 3.64 | 3.65 |

| Other MSK | 0.54 | 0.66 |

| PCTb (%) | ||

| Bristol | 33.78 | 33.13 |

| Somerset | 22.21 | 23.11 |

| Cheshire | 23.42 | 23.44 |

| Stoke | 20.59 | 20.32 |

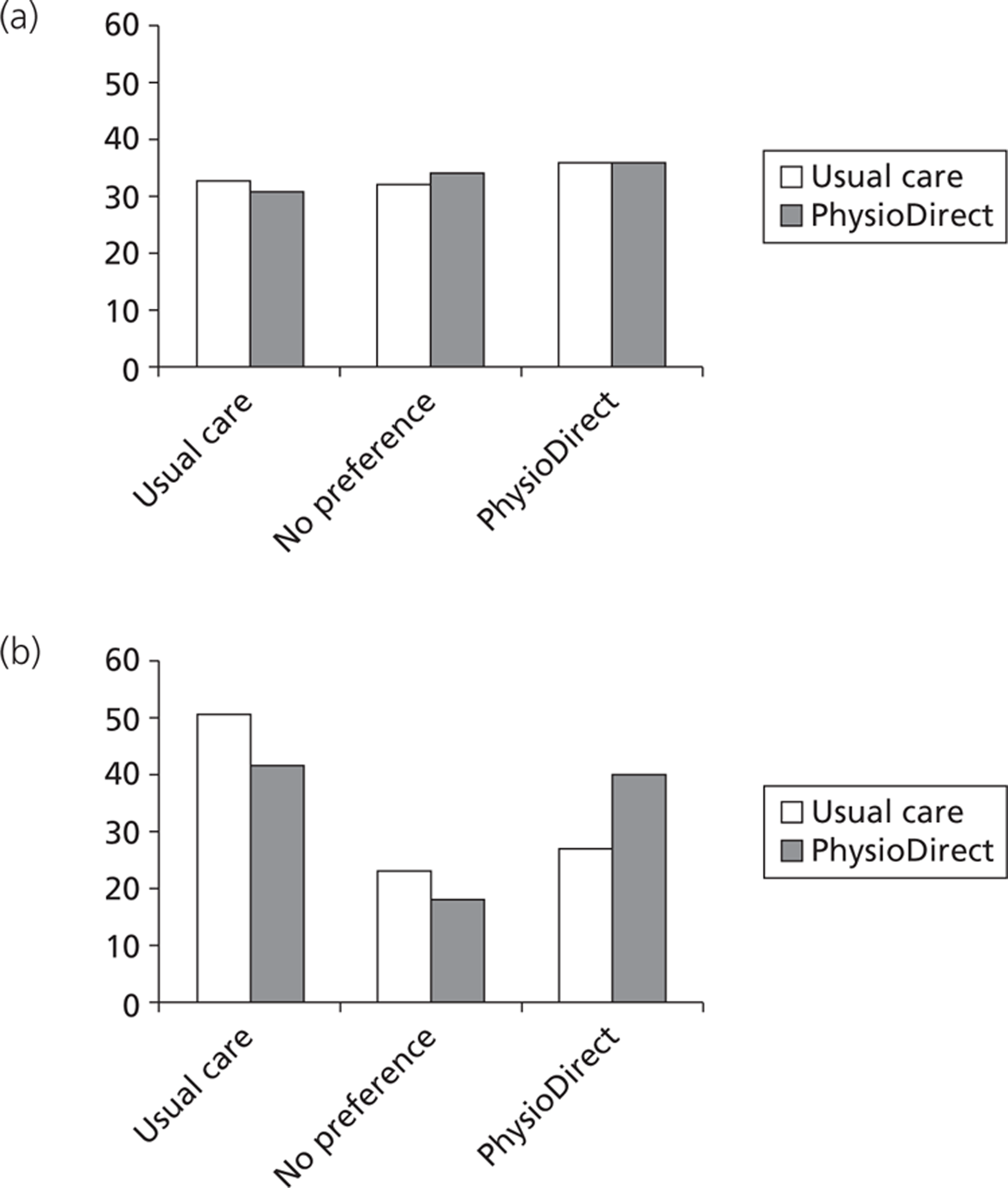

| Physiotherapy preference (%) | ||

| Usual care | 32.97 | 30.71 |

| PhysioDirect | 35.29 | 35.57 |

| No preference | 31.74 | 33.72 |

| Median time off work (days) (IQR) | 0 (0-5) | 0 (0-5) |

| English, native speaker (%) | ||

| No | 2.88 | 3.64 |

| Yes | 97.12 | 96.36 |

| Telephone (%) | ||

| No | 0.54 | 0.93 |

| Yes | 99.46 | 99.07 |

| Car (%) | ||

| No | 17.12 | 16.72 |

| Yes | 82.88 | 83.28 |

The most common reasons for referral were lower limb problems (including hip and knee problems), lumbar problems and upper limb problems (including shoulder). Participants from each of the PCTs were reasonably well represented, with Bristol contributing the highest proportion. People were fairly evenly split in their preference for future care between usual care, PhysioDirect and having no preference (see Table 7). There were no important differences in outcome measures assessed at baseline (Table 8).

| Patient outcome measures at baseline | Randomised patients: n = 2249a (100%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Usual care: n = 743 (33.04%) | PhysioDirect: n = 1506 (66.96%) | |

| SF-36v2 PCS | ||

| Mean (SD) | 37.72 (8.63) | 36.81 (8.88) |

| Median (IQR) | 37.59 (31.39 to 43.93) | 36.95 (30.44 to 43.16) |

| SF-36v2 MCS | ||

| Mean (SD) | 45.66 (13.29) | 46.07 (12.65) |

| Median (IQR) | 47.86 (36.24 to 56.55) | 48.46 (36.51 to 56.52) |

| MYMOP | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.80 (0.99) | 3.84 (0.99) |

| Median (IQR) | 3.75 (3.25 to 4.50) | 4.00 (3.25 to 4.50) |

| EQ-5D | ||

| Mean (SD) | 0.56 (0.29) | 0.53 (0.30) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.69 (0.43 to 0.76) | 0.69 (0.23 to 0.76) |

Loss to follow-up

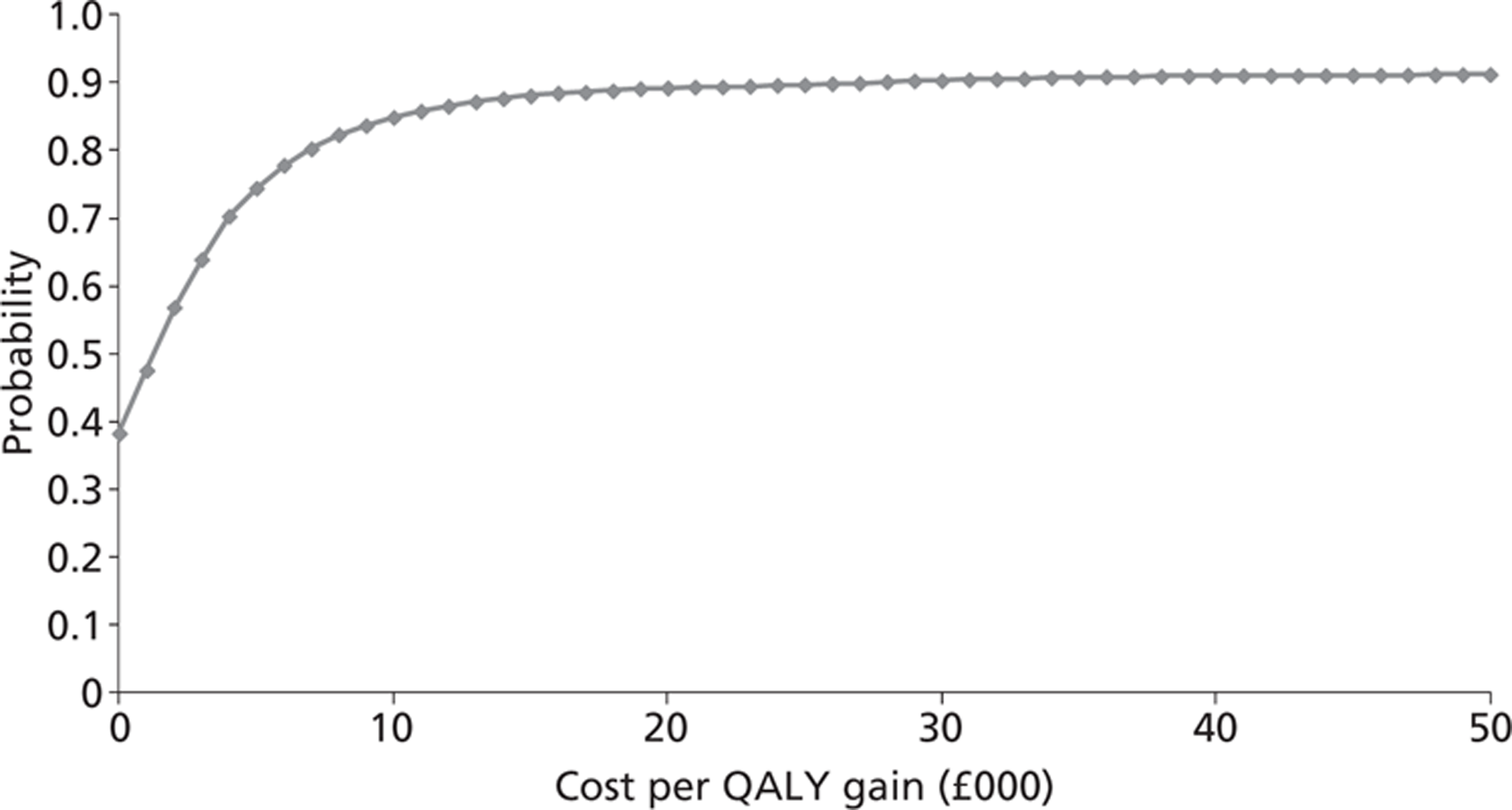

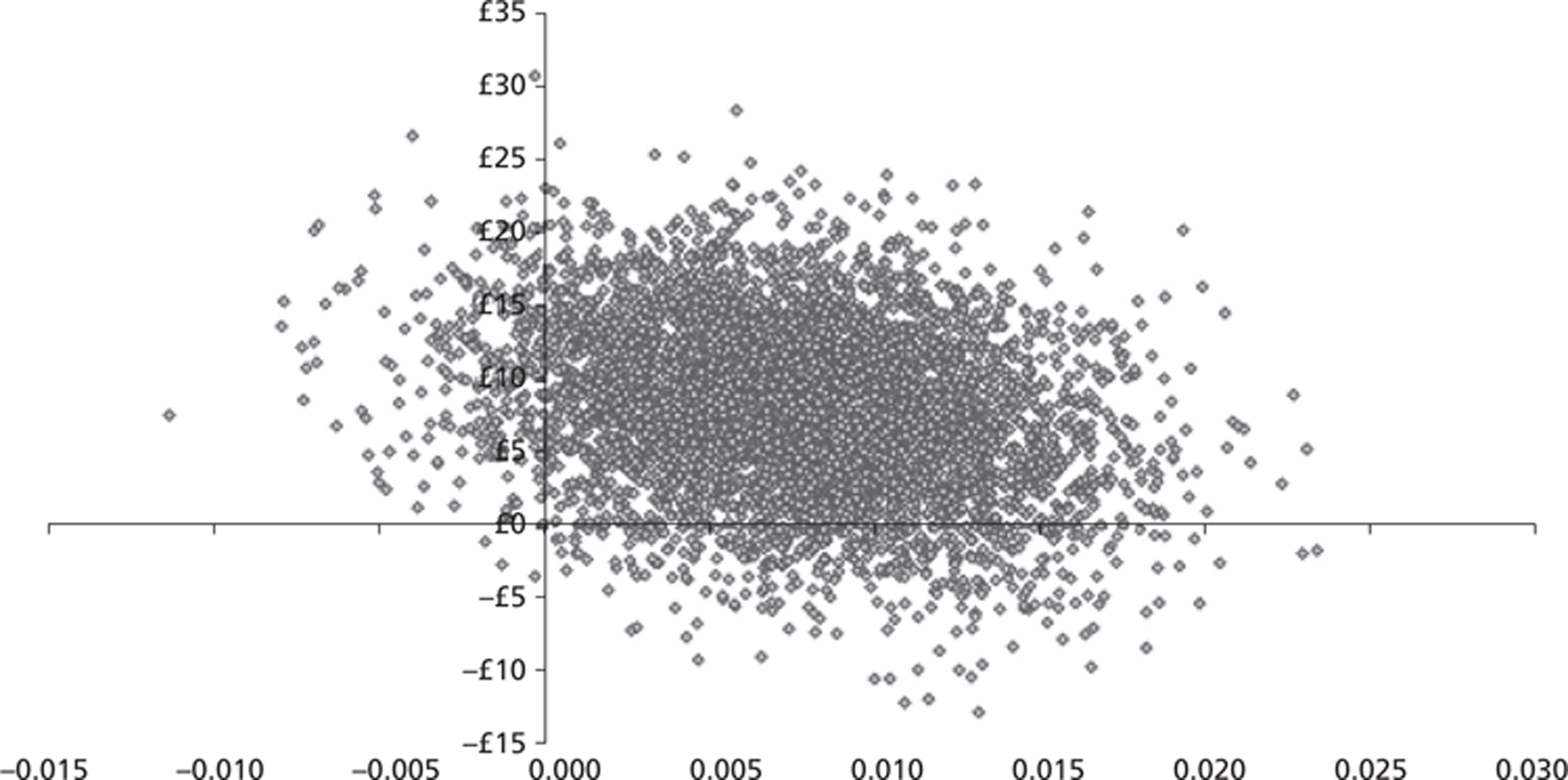

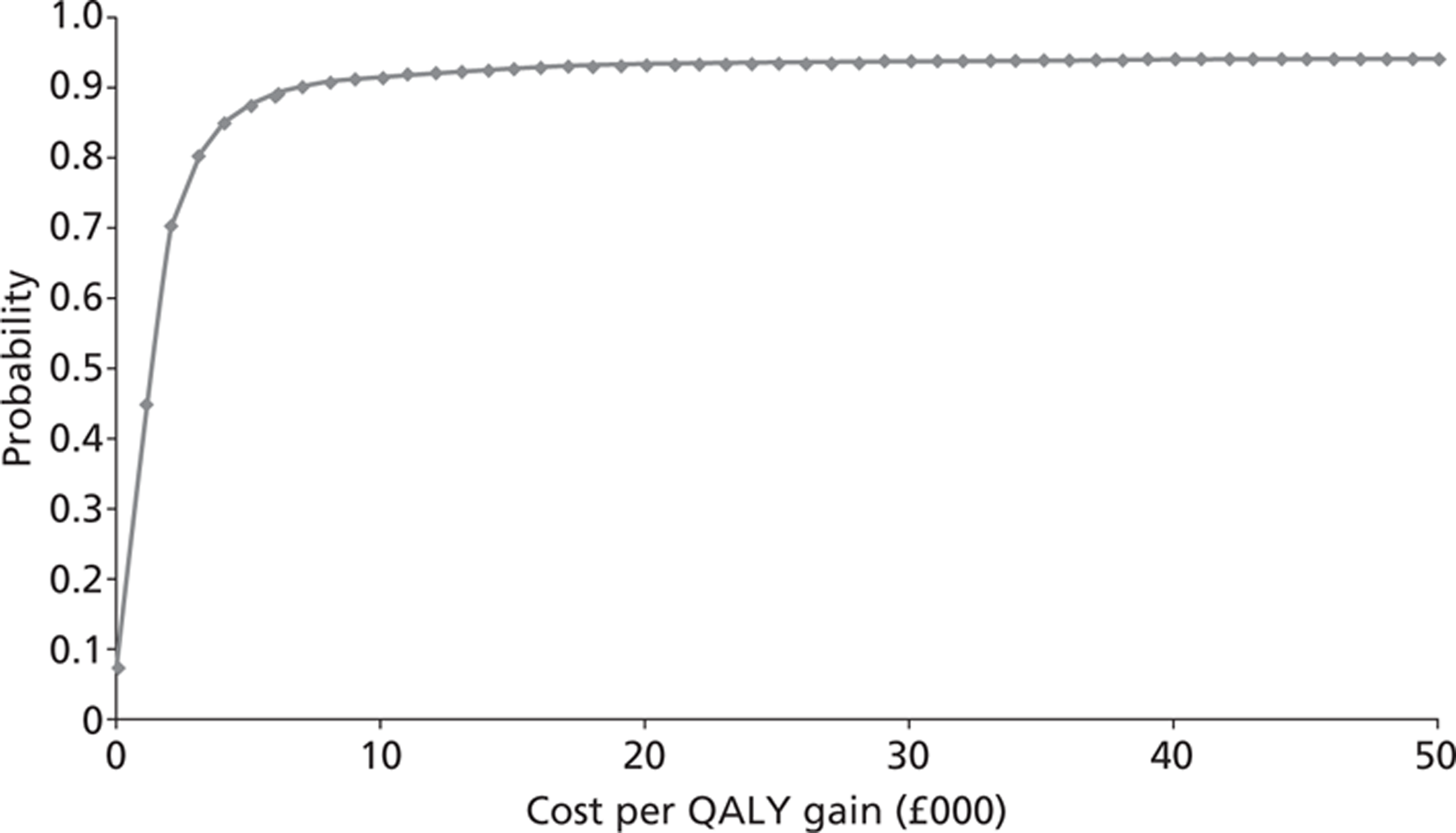

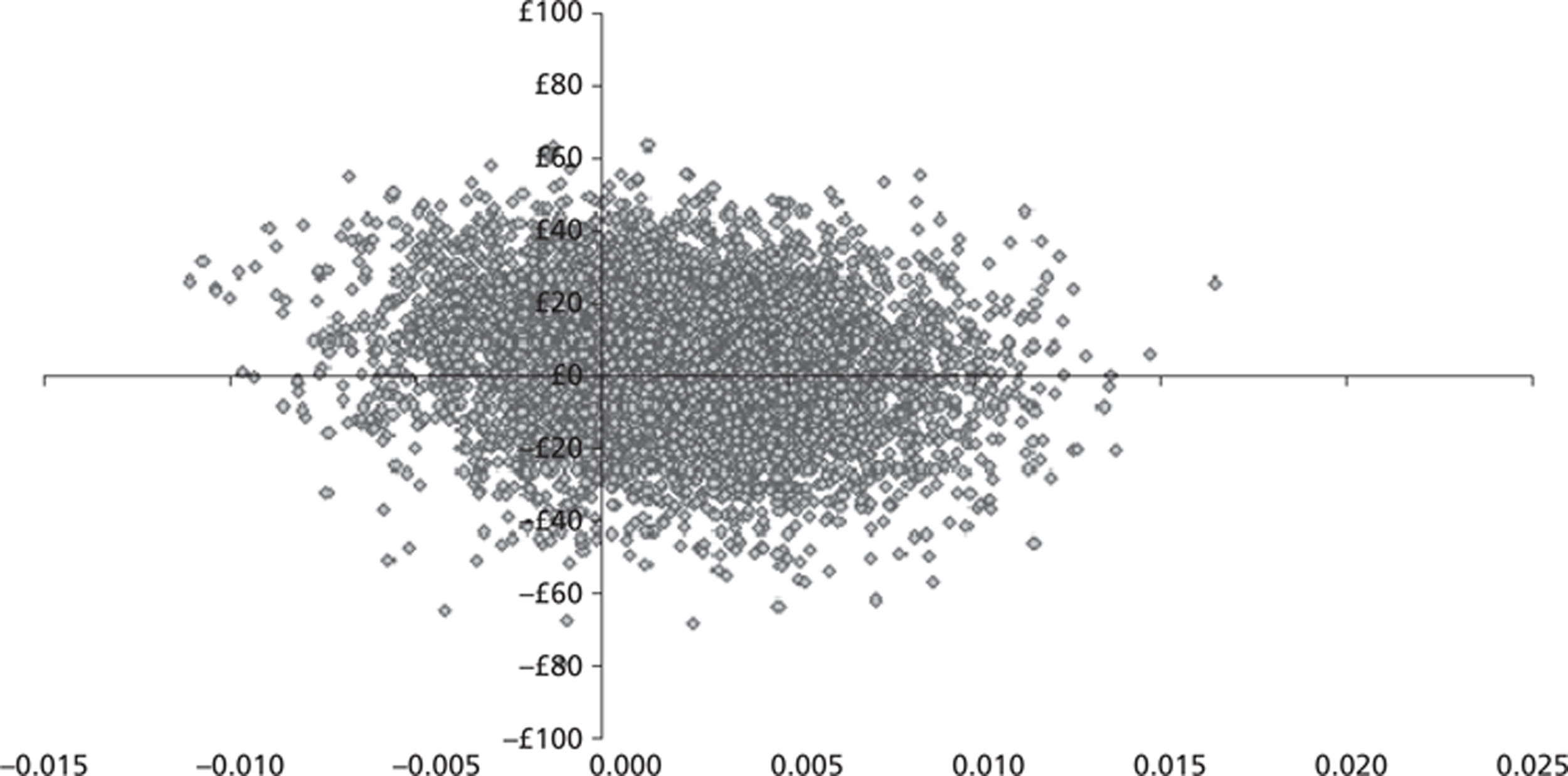

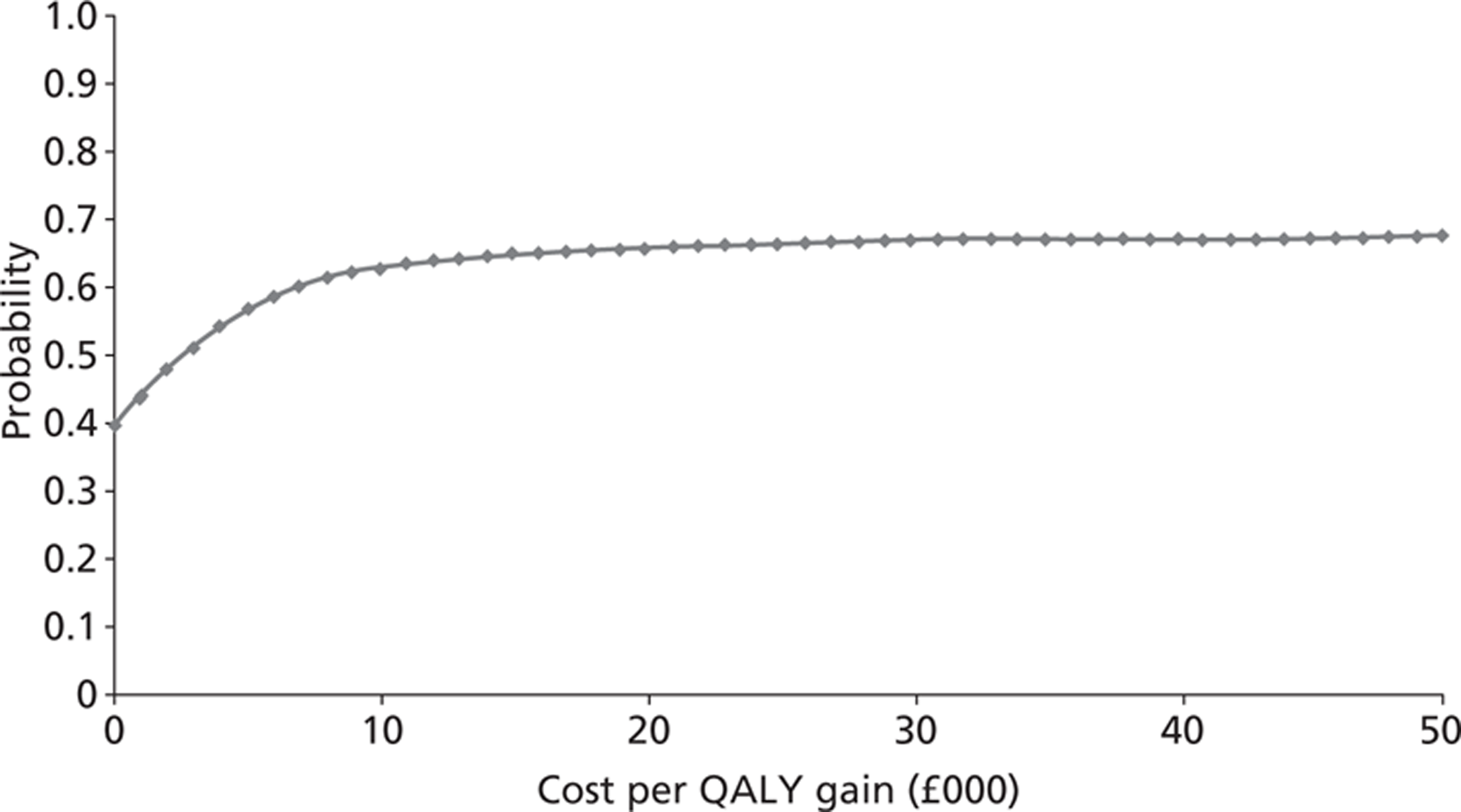

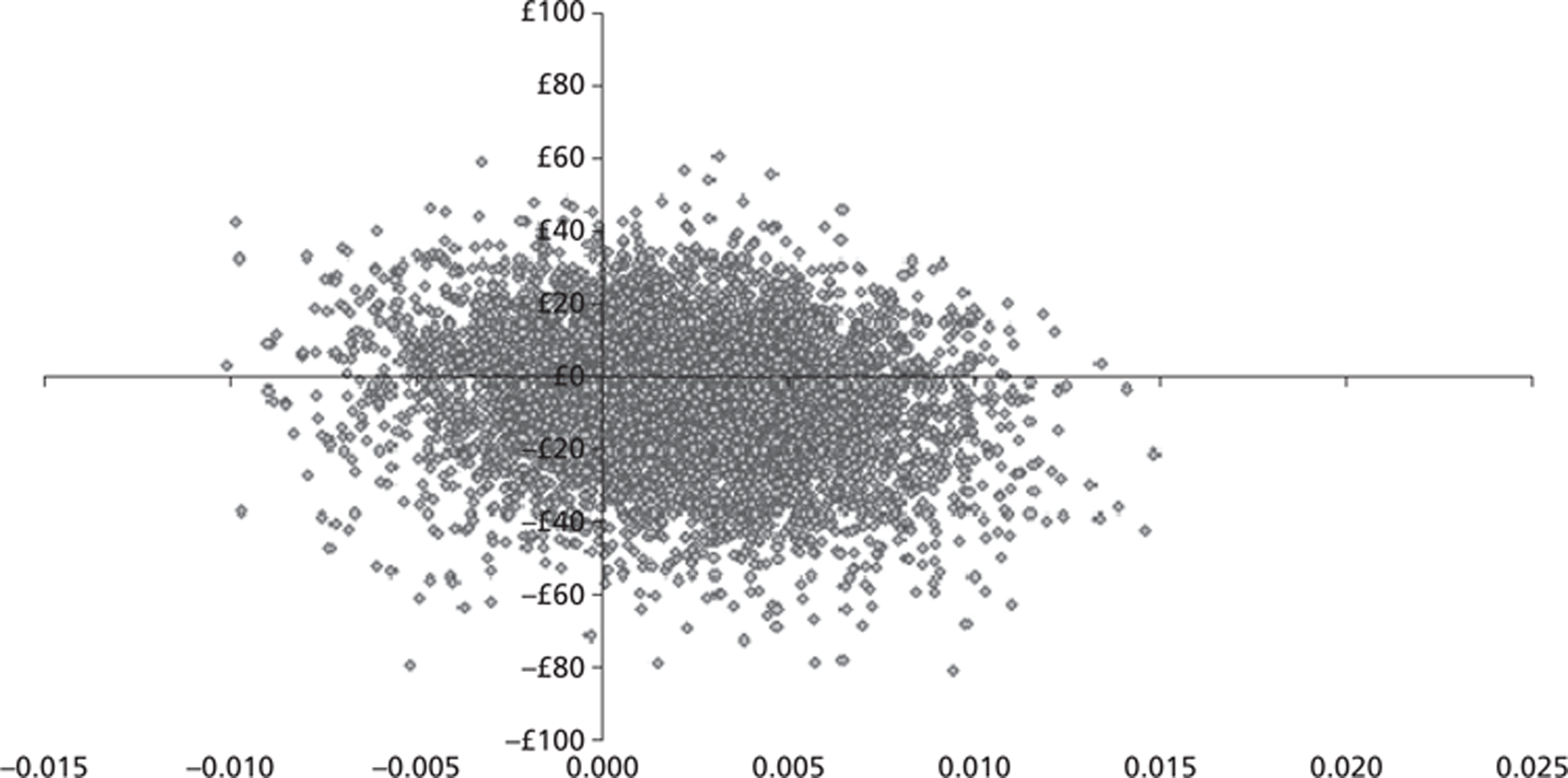

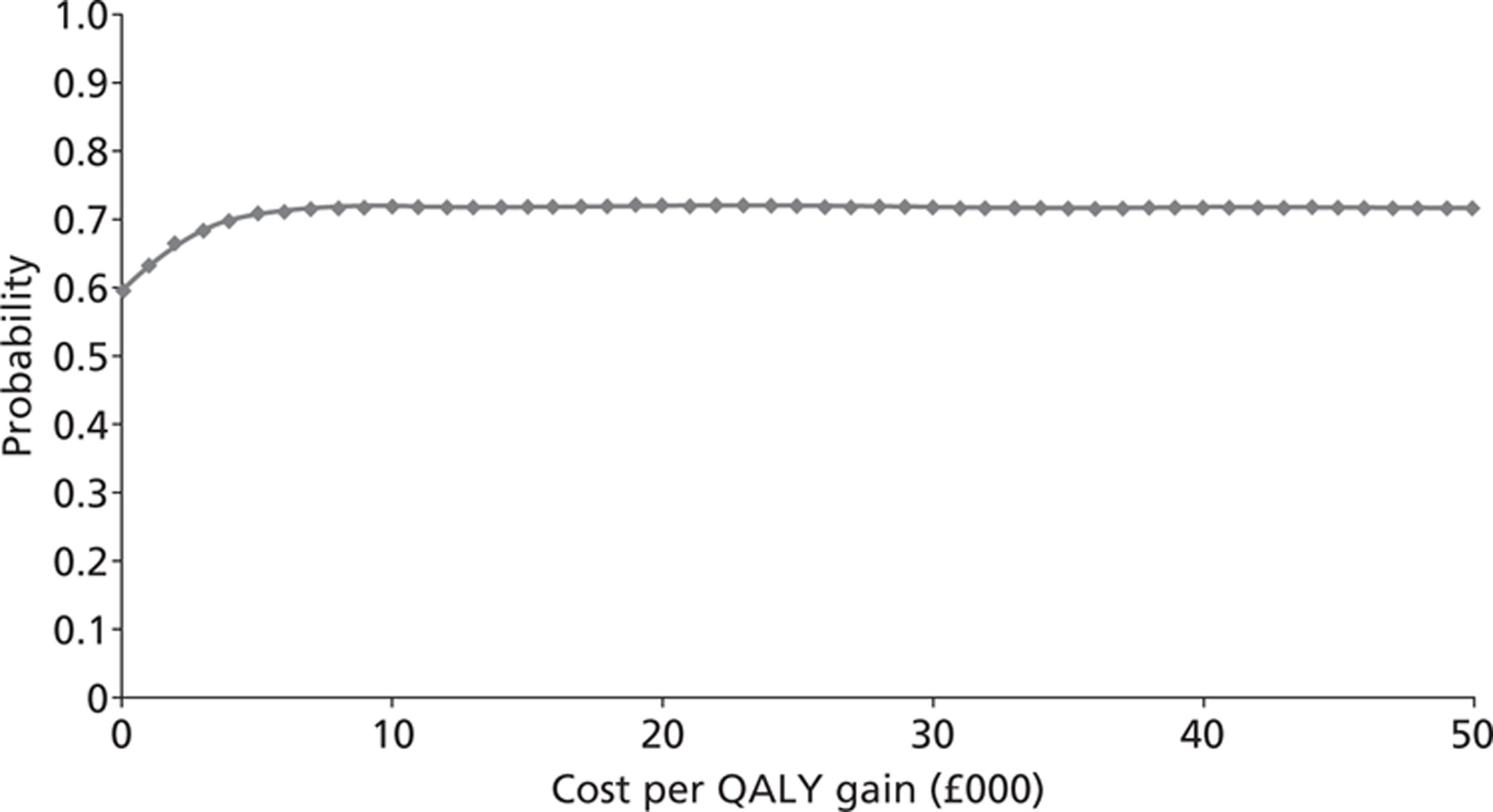

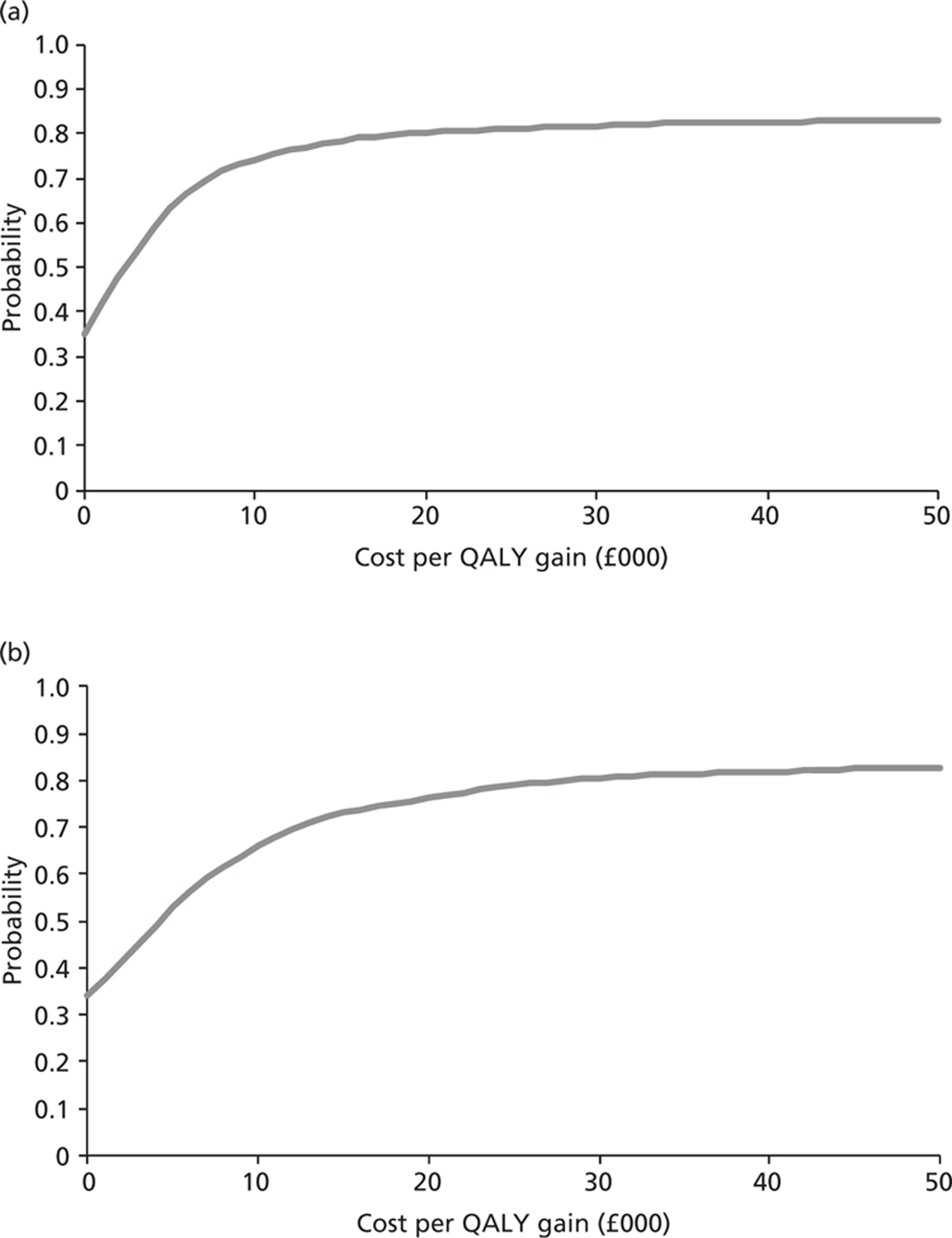

Primary outcome data were collected for 88% (1985/2249) of patients at the 6 weeks' follow-up time point and 85% (1912/2249) of patients at the primary outcome time point of 6 months, with no difference between trial arms. Details of the relationship between loss to follow-up and patient characteristics are given in Appendix 1.