Notes

Article history paragraph text

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/145/01. The contractual start date was in March 2011. The draft report began editorial review in November 2011 and was accepted for publication in June 2012. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Bond et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Description of the health problem

In 1988, the NHS introduced a national breast screening programme (NHSBSP) for women aged 50–64 years in response to recommendations by the Forrest Committee. 1 In 2001, the age range was extended to women aged 50–70 years, currently it is being expanded to women aged 47–73 years. In the UK, women are invited for routine screening by mammography every 3 years.

Rate of uptake

The most recent statistics from the Health and Social Care Information Centre show that in 2009–10 more than 2.24 million women in this age group in England were invited to take part in the programme, of whom 73.2% attended a screening clinic. 2 The rate of response varied according to the history of previous screening. Women who had previously attended routine screening were more likely to reattend (87.2%) than those who had received their first invitation (69.0%). 2 Of the 1,639,953 women (aged 50–70 years) who attended for routine breast screening in 2009–10 in England, 64,104 (3.9%) were recalled for further assessment. This included additional mammography, ultrasound, cytology, fine-needle aspiration (FNA), core biopsy and/or open biopsy of tissue. Another 1089 women (0.07%) were put on the early recall system and invited for further screening 6 or 12 months later. 2 Of the 64,104 women recalled, 12,525 (19.5%) were diagnosed with cancer through routine screening in England in 2009–10. Thus, 51,579 women of those recalled did not have breast cancer in 2009–10 (80.5% of those recalled and 3.1% of those screened). It is this group of women who are the subject of this systematic review.

Definition of false-positive mammogram

For the purposes of this study the definition of a false-positive mammogram is that given by the World Health Organization (WHO): ‘an abnormal mammogram (one requiring further assessment) in a woman ultimately found to have no evidence of cancer’. 3 This definition is rejected by some clinicians because having a positive screening mammogram is not a diagnosis of cancer in itself, but an indication that further assessment is needed. Nevertheless, for the purposes of this systematic review it is necessary to use the definition most commonly adopted in academic journals.

Incidence of breast cancer

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in the UK, with 48,034 new diagnoses in 2008. 4 It accounts for 31% of all cancers in women, with a one in nine lifetime risk. 4 The incidence of breast cancer in the separate countries within the UK can be seen in Table 1.

| England | Wales | Scotland | Northern Ireland | UK | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (n) | 39,681 | 2624 | 4232 | 1156 | 47,693 |

| Crude rate per 100,000 population | 151.8 | 171.4 | 158.6 | 127.9 | 152.6 |

| Age-standardised rate (European) per 100,000 population (95% CI) | 123.8 (122.6 to 125.0) | 128.4 (123.5 to 133.4) | 123.6 (119.8 to 127.3) | 116.6 (109.9 to 123.3) | 123.9 (122.8 to 125.0) |

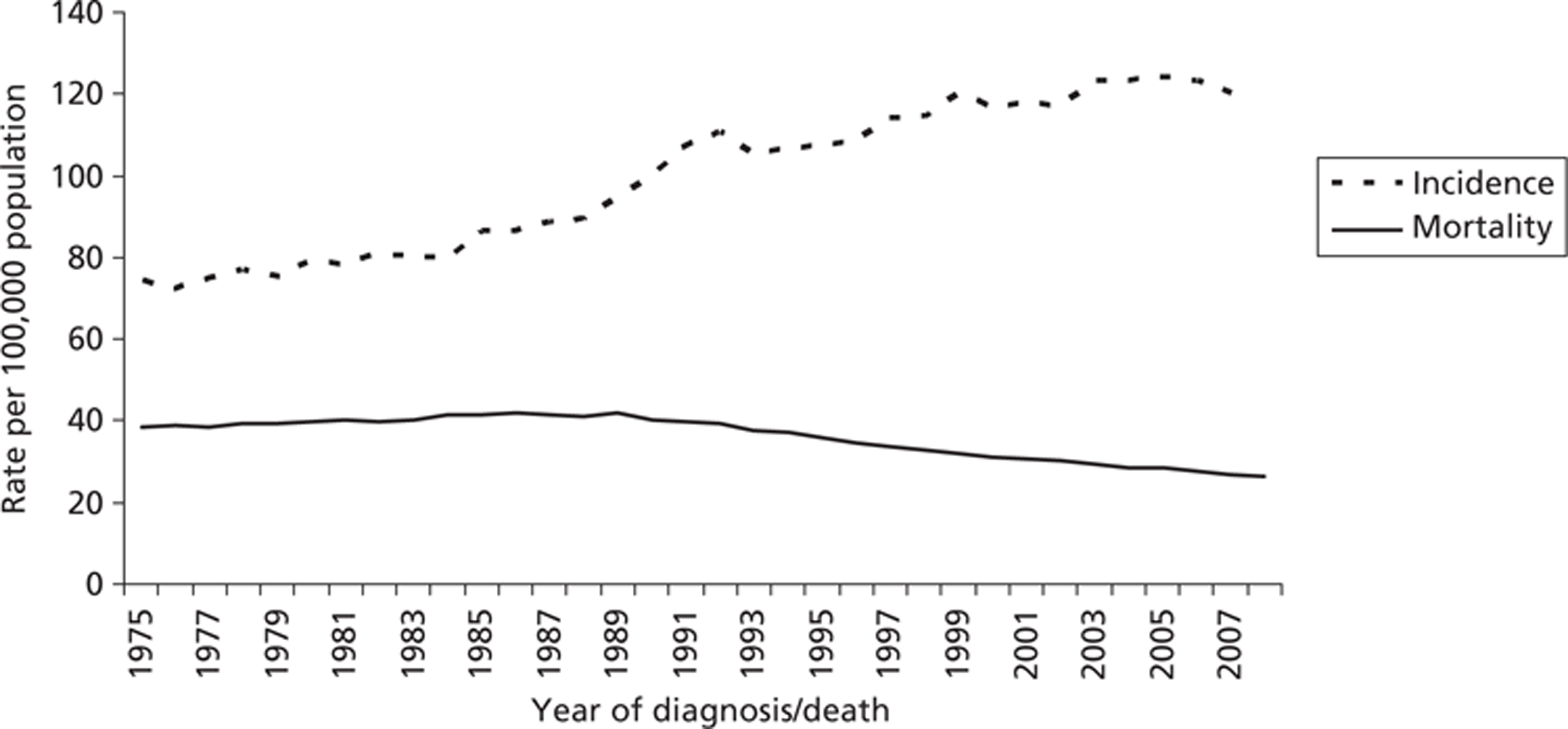

The number of cases of breast cancer in women has been steadily increasing in the UK over the last 30 years, with the annual incidence rising from 24,120 in 1978 to 47,693 in 2007. When the age of the women is standardised, the European age-standardised incidence rate increased by more than half (57%) over this time, from 77 per 100,000 in 1978 to 124 per 100,000 in 2008. 4 However, since the introduction of the national screening programme in 1988, the mortality rate has declined (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Age-standardised European incidence and mortality rates for breast cancer in women, UK, 1975–2008. 4

The rise in incidence has been greatest in women in higher socioeconomic groups. 5 It is thought that this may be linked to their greater use of hormone replacement therapy for menopausal symptoms6 and the trend for having babies later in life. 7

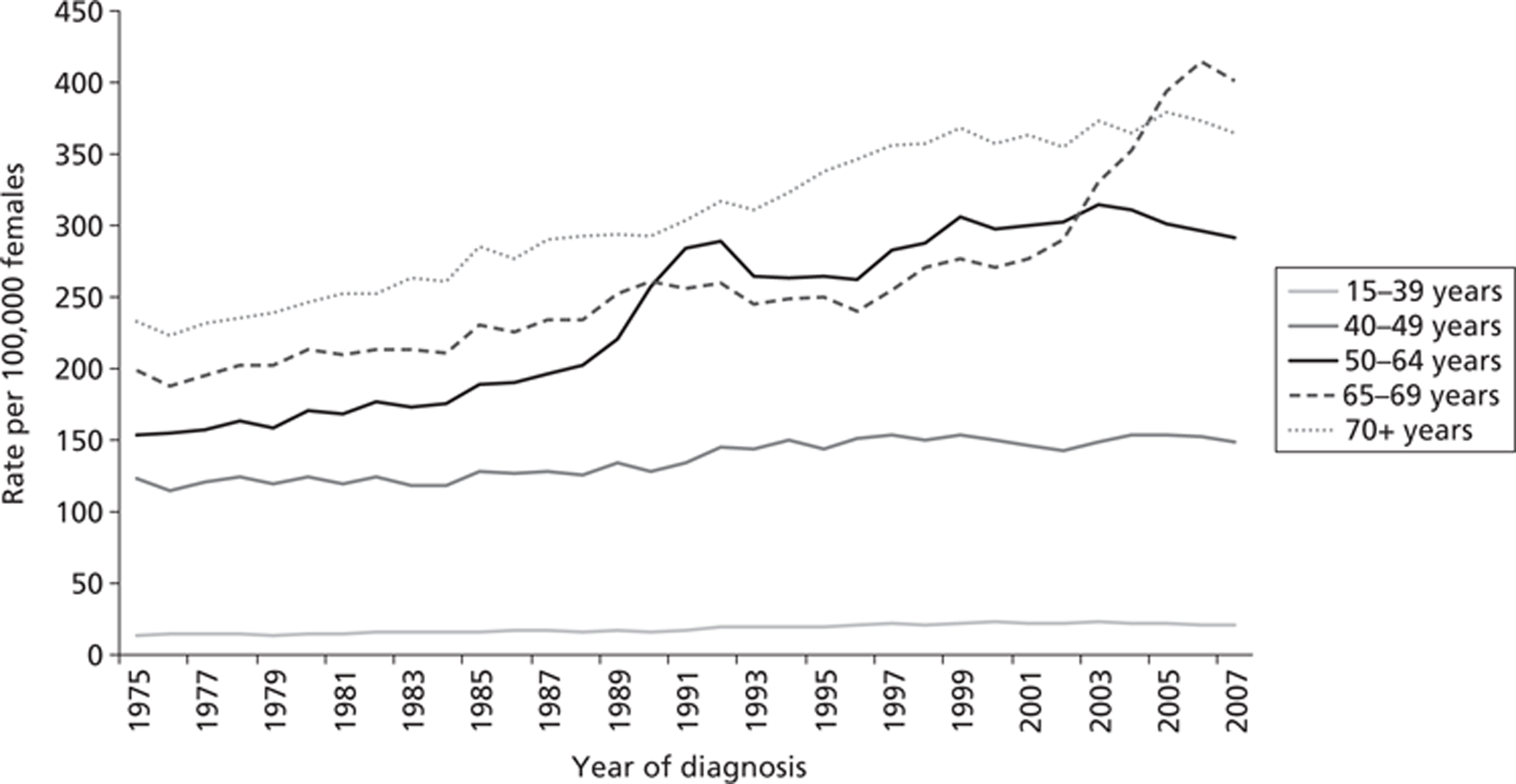

When the figures are broken down by age, the effects of the screening programme can be seen by the sharp increase in incidence over this time among women aged 50–64 years. 8–10 The screening programme will detect cancers that would not have been noted in the patient's lifetime (overdiagnosis) and will bring forward the date of identification of cancer, finding it at an earlier stage, thus producing lead-time bias (Figure 2).

Mortality from breast cancer

The magnitude of the effect of mammography screening on breast cancer mortality is highly contested. Statistics for mortality from breast cancer in England are not available for 2009–10, but in 2008 a little over 10,000 women died from this disease, a rate of 26 per 100,000. 11 It can be shown that mortality from breast cancer began to decline in England at about the same time that the national breast screening programme was introduced, from about 40 per 100,000 to about 26 per 100,000 in 2008. 11 However, the exact effect that breast screening has had on breast cancer mortality is difficult to determine because it is hard to disaggregate the effects of improved treatments and other factors from the effects of screening.

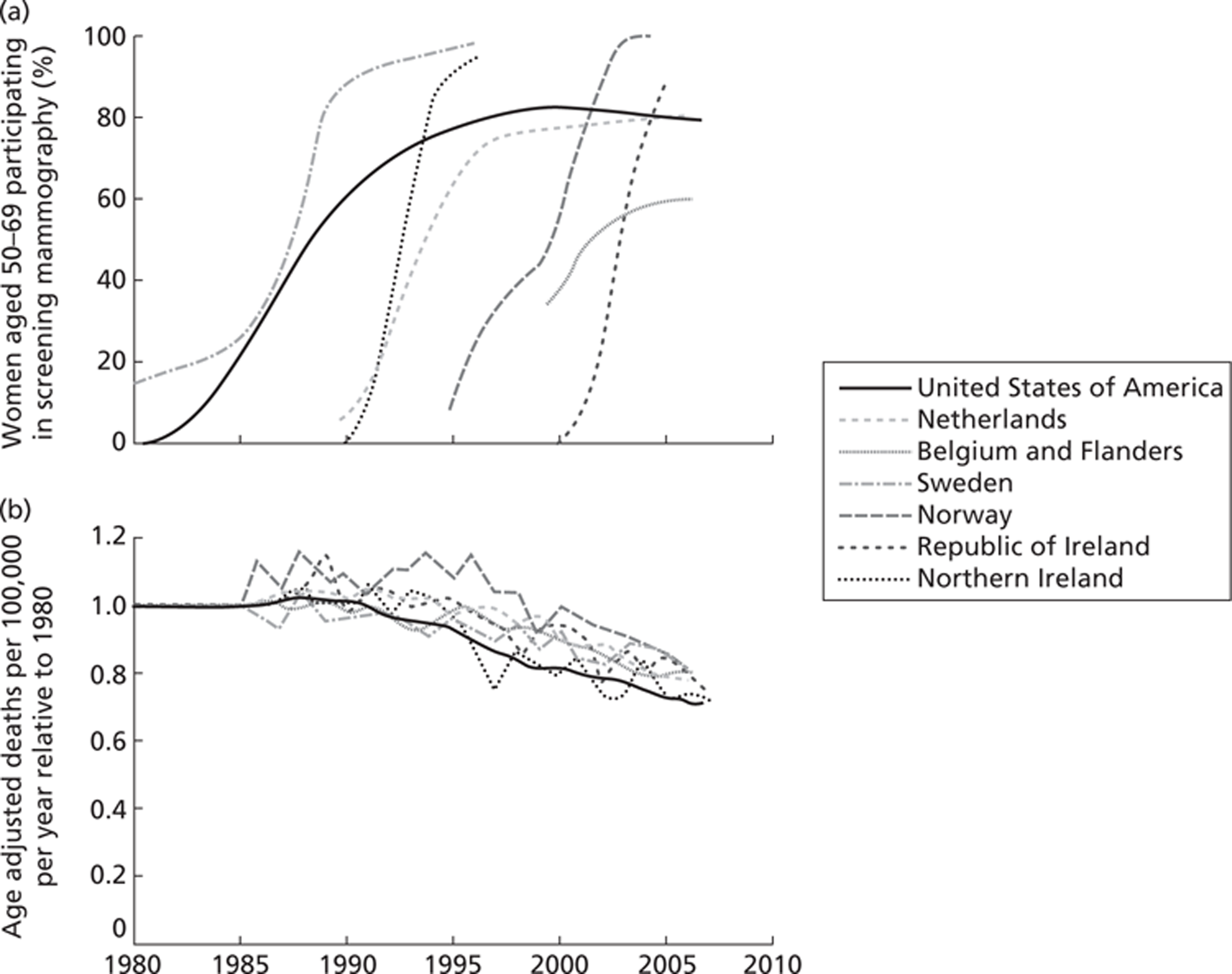

However, a recent retrospective trend analysis by Autier et al. 12 has attempted to do this. Autier et al. 12 compared breast cancer mortality trends in three pairs of neighbouring European countries using WHO data from 1989 to 2006. The pairs of countries had similar demographics, quality and availability of health care. They differed in when breast cancer screening was introduced, with one country introducing it in about 1990 and the other about 10–15 years later. Autier et al. 12 calculated changes in breast cancer mortality using linear regressions of age-adjusted death rates. They found that although there was a wide difference in timing of the introduction of breast cancer screening in the pairs of countries there was a striking similarity in the rate of reduction of breast cancer mortality from 1990. They concluded that this reduction in breast cancer mortality was unlikely to have been the result of mammography screening. Similar findings have been replicated by the US Preventative Services Task Force,13 who have revised their endorsement of routine screening for women aged < 50 years. 13 In a letter to the British Medical Journal (BMJ), Bleyer14 presented a graph comparing US data with data from Autier et al. 12 Bleyer14 concluded that improved treatment, rather than screening, is the main reason for the reduction in mortality.

This research by Autier et al. 12 has been criticised by de Koning15 for being based on geographical comparisons which are unreliable and for the use of standardised all-age mortality. Further criticisms are that Autier et al. 12 have not accounted for the delay in time from the introduction of screening to realising its benefits.

Furthermore, in a recent systematic review of breast screening randomised controlled trials (RCTs), Gotzsche and Nielsen16 (n = 600,000) estimated that breast screening led to a 15% reduction in breast cancer mortality, but, conversely, that there was also a 30% increase in overtreatment of women whose cancer would never become apparent in their lifetime. 16 They estimated that, over 10 years, one woman would be saved from death by breast cancer for every 2000 women invited for screening. Additionally, 10 healthy women who would have remained undiagnosed would have been treated unnecessarily for breast cancer. On top of this, for the same cohort, at least another 200 women would go through the possible distress of a false-positive outcome. 16

Of the eight eligible trials in the Gotzsche and Nielsen review16 (New York 1963,17–19 Malmo 197620–22 and Malmo II 1978,23 Two–County 1977,24–26 Edinburgh 1978,27–29 Canada 1980,30–33 Stockholm 1981,34–37 Goteborg 198238,39 and UK Age Trial 199140–44), one was excluded from meta-analysis because the randomisation was seriously flawed and the data held to be unreliable (Edinburgh 197828,29). Gotzsche and Nielsen16 found that only three of the remaining trials had adequate randomisation. Pooling the data from these trials revealed no statistically significant benefit from screening on breast cancer deaths after 7 years {relative risk (RR) 0.93 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.79 to 1.09]} or after 10 years (RR 0.90; 95% CI 0.79 to 1.02). When the data from these trials were combined with data from the other four suboptimally randomised trials, a statistically significant reduction in death from breast cancer was found after both 7 and 13 years [RR 0.81 (95% CI 0.72 to 0.90) and RR 0.81 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.87), respectively]. The pooled data from the adequately randomised trials similarly showed that there was no significant effect from breast screening on all-cause mortality after 7 years (RR 0.98; 95% CI 0.94 to 1.03) and after 13 years (RR 0.99; 95% CI 0.93 to 1.06). 16 Gotzsche and Nielsen16 did not present data on all-cause mortality from all the included trials because the estimates were unreliable.

FIGURE 3.

(a) Percentages of women taking part in mammography screening in each country. (b) Change in national breast cancer mortality rate relative to country's mean rate during 1980–5. Reproduced from Bleyer A. Breast cancer mortality is consistent with European data. BMJ 2011;343:d5630,14 with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

These results are controversial and a lively debate continues about the benefits and harms of breast cancer screening. Gotzsche and Nielsen's16 findings have been heavily criticised by Kopans et al. ,45,46 who claim that the reduction in breast cancer mortality due to screening is of the order of 20–25%. Others are also highly critical and have estimated the reduction in breast cancer due to screening to be as much as 30%. 47,48 Indeed, one modelling study estimated the reduction in mortality due to screening to be between 28% and 65%. 49 The best methods for arriving at an accurate estimate of mortality reduction are also contested. 50 It is beyond the scope of this systematic review to attempt to resolve these differences. However, currently (2011), Professor Sir Mike Richards is undertaking a review to evaluate the benefits and harms of the NHS breast cancer screening services.

Significance for patients

The negative psychological impact of false-positive screening results has been documented in the fields of prenatal and cervical cancer screening. 51,52 Their impact on the psychological well-being and behaviour of women who receive false-positive results from routine mammography has been less well researched and synthesised, particularly in the UK population.

A brief examination of observational studies, looking at the psychological consequences of false-positive mammograms, showed conflicting results. Some studies indicate that, while women show increased distress between receiving the information about the need for a follow-up appointment and receiving the all-clear, in the longer term their anxieties about breast cancer and mammography are not increased. 53–55 Other studies report that there are long-term adverse psychological consequences to receiving a false-positive mammogram. 56,57 The outcomes of studies looking at whether or not having false-positive results affects future attendance at breast screening appointments are similarly conflicting. 58–61

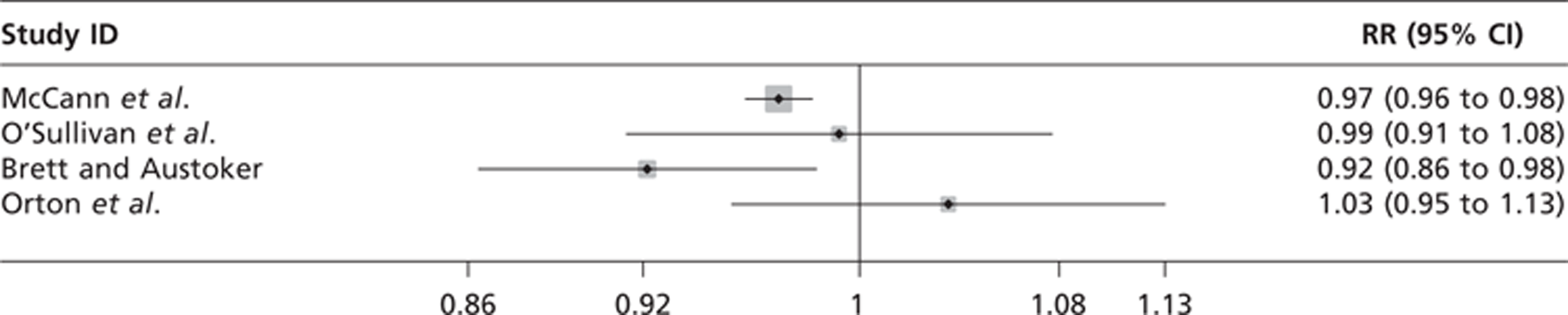

A quantitative systematic review in 2007 by Brewer et al. 62 found that the impact of a false-positive mammogram on subsequent screening attendance varied with nationality, although the reasons for this were unclear. They also reported a varying impact on long-term psychological distress, anxiety and depression, and on other behaviours such as frequency of breast self-examination. However, their review did not report the reasons for this variation in response. Furthermore, Brewer et al. 's review62 found no statistically sound studies that investigated if anxiety over a false-positive mammogram directly affects whether or not women return for routine screening or increase breast self-examination. There was little evidence about the effects on quality of life or trust of health-care services and no evidence about whether or not women who felt anxious after a false-positive screening result replaced routine screening attendance with breast self-examination.

However, the significance of receiving a false-positive mammogram result may go beyond distress and other effects on behaviour. McCann et al. 61 conducted a retrospective cohort study of 140,387 women, aged 49–63 years, attending NHSBSP routine screening clinics. They found that, among those women who were recalled for assessment which showed that they did not have cancer, the risk of interval cancer was increased more than threefold [rate per 1000 women screened, 9.6 (95% CI 6.8 to 12.4) compared with 3.0 (95% CI 2.7 to 3.4); odds ratio (OR) 3.19 (95% CI 2.34 to 4.35)] and these women were more than twice as likely to have cancer detected at their next routine screen in 3 years' time [rate per 1000, 8.4 (95% CI 5.8 to 10.9) vs 3.9 (95% CI 3.5 to 4.3); OR 2.15 (95% CI 1.55 to 2.98)]. This, of course, brings into question whether these women had false-positive or true-positive screening mammograms or whether or not something else explains these phenomena. It is beyond the scope of this systematic review to investigate this further.

Current related guidance

The following guidelines relate to this systematic review.

2011

NHS Breast Screening Programme 59: Quality Assurance Guidelines for Breast Cancer Screening Radiology. 63 These guidelines aim to raise radiology standards in breast cancer screening and relate to the transition to full-field digital mammography and the extension of the invitation to screening to women aged 47–73 years in England. They include minimising the numbers of women who are recalled and, therefore, the numbers of false-positives.

2010

NHS Breast Screening Programme 49: Clinical Guidelines for Breast Cancer Screening Assessment. 64 These guidelines set out minimum standards for breast cancer screening assessment. The guidelines state that this should be done using mammography or ultrasound, with clinical examination and image-guided biopsy if necessary. Women who are not diagnosed with cancer should receive written confirmation of the outcome.

2009

NHS Breast Screening Programme: Quality Assurance Guidelines for Surgeons in Breast Cancer Screening. 65 Among other guidelines for surgeons in breast cancer screening, these guidelines set out waiting-time targets for non-operative biopsy results to be given in < 1 week and for the time between the decision to refer for surgical assessment and the surgery taking place to be ≤ 1 week. They also aim to minimise the numbers of benign diagnostic open surgical biopsies to ≤ 15 per 10,000, prevalent screen and quantity of tissue taken to ≤ 20 g.

Current service provision

The UK NHSBSP is extending its service to invite women aged 47–73 years to attend for screening by mammography every 3 years. The purpose is to detect breast cancer in the general population. Contact details of eligible women are obtained through lists of registered patients by general practitioner (GP) surgery.

Mammography involves having an X-ray taken of the breasts. In the UK, two views are taken: craniocaudal (head-to-foot) and mediolateral oblique (angled side view). The mammogram is then read by two radiologists. Methods of resolving differences in opinion vary from unit to unit, but most commonly arbitration is used and a third radiologist will review the mammogram. If it is found to be normal, then the woman is put on routine recall and will receive another screening invitation in 3 years' time. There may be technical problems with the quality of the film, in which case the woman will be recalled to have the technically inadequate views repeated. Alternatively, the mammogram may show a suspicious area and the woman will be recalled for further assessment. It takes a maximum of 2 weeks from having a mammogram until a letter with the normal results is received. If further assessment is needed, the appointment for this must be within 3 weeks of the initial mammogram.

The further assessment may include another mammogram, ultrasound or core biopsy with or without FNA. FNA employs a 21-gauge needle to remove cells which are then cytologically assessed; biopsy requires a larger 14-gauge needle, which allows histologists to see the architectural context within which cells are placed and so allows more accurate diagnosis. In the UK, the lesions found are graded on a system of increasing severity: B1 is normal, B2 is benign, B3 is suspicious but probably benign, B4 is suspicious and probably cancer and B5 is cancer. B5 is further subdivided into (a) non-invasive disease, most commonly ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), a non-invasive, obligate precursor to invasive breast cancer, but a lesion which may not develop into invasive cancer in the lifetime of the woman, which is situated in the milk ducts; and (b) invasive cancer. It is not possible yet to assess which cases of DCIS will progress to invasive cancer and which will not do so in the lifetime of any given woman. It is likely that many such lesions would not affect the woman's lifespan. Furthermore, some lesions that are invasive may not progress to cause morbidity in the life of the individual woman. There is a debate over the amount of overdiagnosis, as this is described, that occurs.

If cancer is found, then the woman will be transferred from screening services to an oncology department. Treatment will normally be received within the NHS 62-day target from initial screening. It is usual to offer treatment for invasive cancer and non-invasive cancer as well as for many indeterminate lesions (B3 and B4).

Throughout the screening and assessment process women should have access to a clinical nurse specialist (CNS) or breast care nurse, whose role is to educate, inform and support her in a manner which is sensitive and timely and recognises her need for safety, comfort and dignity. 66 Women who are recalled are told in their letter that a breast care nurse will be available to talk to at the clinic or before the clinic by telephone if they have any concerns. Screening clinics, which may be some way from a hospital, do not routinely have breast care nurses on site. However, the invitation letter for screening will often mention the availability of a breast care nurse by telephone to allay any concerns.

Research questions

The aim of this research was to conduct a systematic review to identify the psychological impact on women of false-positive screening mammograms and any evidence for the effectiveness of interventions designed to reduce this impact. This is necessary because there is uncertainty about the nature and magnitude of their psychological impact on women, including what the predictors are of negative psychological outcomes that may affect attendance at future mammography screening. There is also a need to identify whether or not these effects differ in women from different backgrounds. This research is important because of the large number of false-positive results that come from routine mammography screening (see above).

The questions that this systematic review will address are:

-

What evidence is there for medium or long-term adverse psychological consequences from false-positive screening mammograms (≥ 1 month after assessment)?

-

Do the types of psychological consequences differ between different groups of women?

-

-

What evidence is there of interventions that reduce adverse psychological consequences?

Measurement of psychological consequences

A number of different measures of psychological morbidity are used in the primary research studies included in this systematic review. A brief summary of their characteristics is given below.

Disease specific

Psychological Consequences Questionnaire

The Psychological Consequences Questionnaire (PCQ)67 is a reliable and validated questionnaire that was developed specifically to measure the psychological consequences of mammography screening. It comprises two subscales, one consisting of 12 statements relating to possible negative consequences of mammography screening (i.e. how often in the past week the woman has experienced loss of sleep, change of appetite, feeling depressed, being scared, feeling tense, feeling under strain, being secretive, being irritable, withdrawing socially, having difficulty in doing ordinary activities at home and work or feeling worried about the future). The second subscale relates to potential benefits from screening and has 10 items covering feeling reassured, being able to cope better with everyday life, feeling less anxious about breast cancer, feeling more hopeful and a greater sense of well-being. The statements are scored on a four-point Likert scale ranging from not at all, rarely, some of the time to quite a lot of the time, with a range of 0–36 for the negative subscale and 0–30 for the positive subscale.

Cancer Worries Scale-Revised

The Cancer Worries Scale-Revised (CWS-R)68 is a six-item questionnaire that assesses the frequency of worries about developing cancer and how these worries affect daily mood and activities. It has been shown to be reliable and valid in at-risk populations. 68–70 The items are scored on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all or rarely) to 4 (almost all of the time).

Generic

Brief COPE

This is a shortened version of the COPE scale, which was developed to assess people's coping responses to stressful situations. The brief COPE71 has been used in breast cancer patients, although the work has not been published, and in hurricane survivors. The brief version has 28 items measuring a range of coping strategies (e.g. self-distraction, active coping, denial, substance use, emotional support, instrumental support, disengagement, venting, positive reframing, planning, humour, acceptance, religion and self-blame).

General Health Questionnaire

The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) was designed as a screening tool for psychiatric illness in the context of general practice or general medical outpatients (i.e. non-psychiatric settings). 72 The GHQ covers the four domains of depression, anxiety, objectively observable behaviour and hypochondrias with 60 items. This instrument looks at recent experience and elicits responses on a four-point Likert scale using the statements less than usual, no more than usual, rather more than usual and much more than usual. A number of shorter versions have been developed: GHQ-12, GHQ-20, GHQ-28 and GHQ-30. 73 Items are scored 0–3 to give a total score or can be scored dichotomously with a particular threshold deemed to indicate that the respondent is ‘a case’.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was developed to screen for psychiatric disorders in general hospital settings, excluding psychiatric wards. 74 It has two subscales, anxiety and depression, which are measured with 14 items using a four-point Likert scale (0–3). The items are totalled to give an overall score for anxiety or depression. Respondents with a score of 8–10 are considered to be ‘doubtful cases’ and ≥ 11 are considered to be ‘cases’.

Life Orientation Test-Revised

The Life Orientation Test75 is a validated measure of dispositional optimism. It has 10 items that are responded to on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (I strongly disagree) to 4 (I strongly agree).

State–Trait Anxiety Inventory

The State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) measures anxiety in adults as both a current state and an enduring trait. 76 It consists of a 20-item scale of how the respondent feels in general and a 20-item scale of how they feel now. Each item is scored on a four-point scale that ranges from ‘not at all’ to ‘very much so’. Higher scores are related to higher anxiety.

Chapter 2 Methods

The systematic review was carried out following the principles published by the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD). 77 The study protocol can be found in Appendix 1.

Methods for reviewing studies

Identification of studies and search strategy

The search strategy comprised the following main elements:

-

searching of electronic bibliographic databases

-

internet searches

-

scrutiny of references of included studies

-

contacting experts in the field.

The following electronic databases were searched in December 2010 for studies which met the inclusion criteria: MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, EMBASE, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC), Cochrane Central Register for Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, CRD Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, CRD Health Technology Assessment (HTA), Cochrane Methodology, Web of Science, Science Citation Index, Social Sciences Citation Index, Conference Proceedings Citation Index-Science, Conference Proceeding Citation Index-Social Science and Humanities, PsycINFO, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Sociological Abstracts, the International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS) and the British Library's Electronic Table of Contents. Ongoing trials were searched for at: UK Clinical Research Network (UKCRN), ControlledTrials.com, ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), UK Database of Uncertainties about the Effects of Treatments (DUETs), a filter was applied to capture qualitative research as well as quantitative designs. Further searches for qualitative and grey literature were run in January 2011 on the following databases: MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, EMBASE Classic and EMBASE, British Nursing Index and Archive, Social Policy and Practice, CINAHL plus, The Cochrane Library, HMIC, PsycINFO, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, Web of Science, CRD and IBSS. All searches were run from inception to 25 January 2011. Bibliographies of included studies were searched for further relevant studies. References were managed using Reference Manager version 11 (Thomson ResearchSoft, San Francisco, CA, USA) and EPPI-Reviewer 4 (Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre, University of London, London, UK).

Initial searches were carried out between 8 October 2010 and 25 January 2011. Update searches were carried out on 26 October 2011 and 23 March 2012.

Refer to Appendix 2 for the search strategy for MEDLINE.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for the systematic review are summarised in Table 2.

| Question(s) | Criteria | Specification | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 and 2 | Population | Women who had received a positive result from routine mammography screening in the UK and had been invited for further assessment which showed that they did not have breast cancer | Where data permitted we looked at subgroups (including socioeconomic status and ethnic group) |

| 2 | Intervention | Those interventions delivered to individuals to address the adverse psychological and behavioural consequences of a false-positive mammogram result | These were individual interventions not group ones |

| 1 | Comparator | Women who had received a negative (normal) result from routine mammography screening in the UK | |

| 2 | Comparator | An absence of an individual intervention in the same population | |

| 1 and 2 | Outcomes | Psychological and behavioural outcomes and those from qualitative studies | Including subsequent attendance at routine mammography screening and quality of life |

| 1 and 2 | Setting | UK | Secondary care |

| 1 and 2 | Study design | Systematic reviews, randomised, non-randomised, observational and qualitative studies | We did not consider individual case studies |

| 1 and 2 | Length of follow-up | At least 1 month from the ‘all-clear’ | Measured over the medium- to long-term (i.e. not the immediate response to receiving a false-positive result) |

| 1 and 2 | Language | English language only | Non-English-language papers were included in the searches and screened, so that the number of potentially includable foreign-language papers is known |

Exclusion criteria

The following types of studies were excluded: narrative reviews, editorials, opinion pieces, non-English-language papers, individual case studies and studies only reported as posters or by abstract where there is insufficient information to assess the quality of the study.

Study selection

Based on the above inclusion/exclusion criteria, papers were selected for review from the titles and abstracts generated by the search strategy. This was done independently by two reviewers (MB, TP); discrepancies were resolved by discussion, with the involvement of a third reviewer if necessary. Retrieved papers were again reviewed and selected against the inclusion criteria by the same independent process.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from included studies by one reviewer using standardised data extraction forms and checked by another reviewer. Authors of studies were contacted to provide missing information, as necessary. Data were gathered on the design, participants, methods, outcomes, baseline characteristics and results of the studies. The data extraction forms can be found in Appendix 3.

Critical appraisal – assessing risk of bias

Studies were assessed for internal and external validity according to criteria suggested by the updated NHS CRD Report No. 4, according to study type. 77,78 The quality of systematic reviews was evaluated using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. 79 Individual RCTs were appraised with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement80 and individual observational studies with Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines. 81 There were insufficient studies in each domain to produce a meaningful assessment of publication bias with a funnel plot.

Internal validity

Consideration of internal validity addresses how well potential sources of bias and confounding are acknowledged and accounted for. Bias can be characterised as potentially undermining an experimental study in four ways: through selection bias, so that the participants in each group are dissimilar; performance bias, where the treatment of the different groups varies apart from the intervention; detection bias, which can occur if the study assessors are aware of which groups participants are in; and attrition bias, where all participants are not fully accounted for or violations of the study protocol have occurred. In particular, checks of study internal validity should address the following: whether or not there is sufficient description of the inclusion criteria, outcomes, study design, setting and the intervention to ascertain that study groups were similar in all respects and were treated in similar ways except for the intervention; if a justification for the sample size is given; if appropriate data analysis techniques were used; if dropouts and withdrawals are accounted for; if the technique used to account for missing data is described and adequate; and if assessors were blind to the group status of participants.

Another threat to validity can come from confounding. This is where an unknown agent is acting independently on the outcome being measured and the matter under investigation, so that an association appears to be occurring between the outcome measure and the matter of interest, but which is an artefact of the independent relationships.

External validity

External validity was judged according to the ability of a reader to consider the applicability of findings to a patient group and service setting. Study findings can only be generalisable if they describe a cohort that is representative of the affected population at large. Studies that appeared representative of the UK breast cancer screening population with regard to these considerations were judged to be externally valid.

Methods for analysis and synthesis

Analysis

Analysis was carried out using StatSEv12 software (TX, USA). The principal summary measure was RR with 95% CIs.

Synthesis

All study designs had a narrative synthesis. Additionally:

Randomised controlled trials and controlled trials There was only one RCT and no controlled trials.

Observational studies Observational studies had possible sources of heterogeneity carefully considered before any meta-analysis was attempted to avoid potentially spurious relationships being found. Heterogeneity was explored through assessment of the studies' populations, methods and interventions. The heterogeneity of the data did not permit meta-analysis.

Chapter 3 Results

Quantity of research available

Number and type of studies included

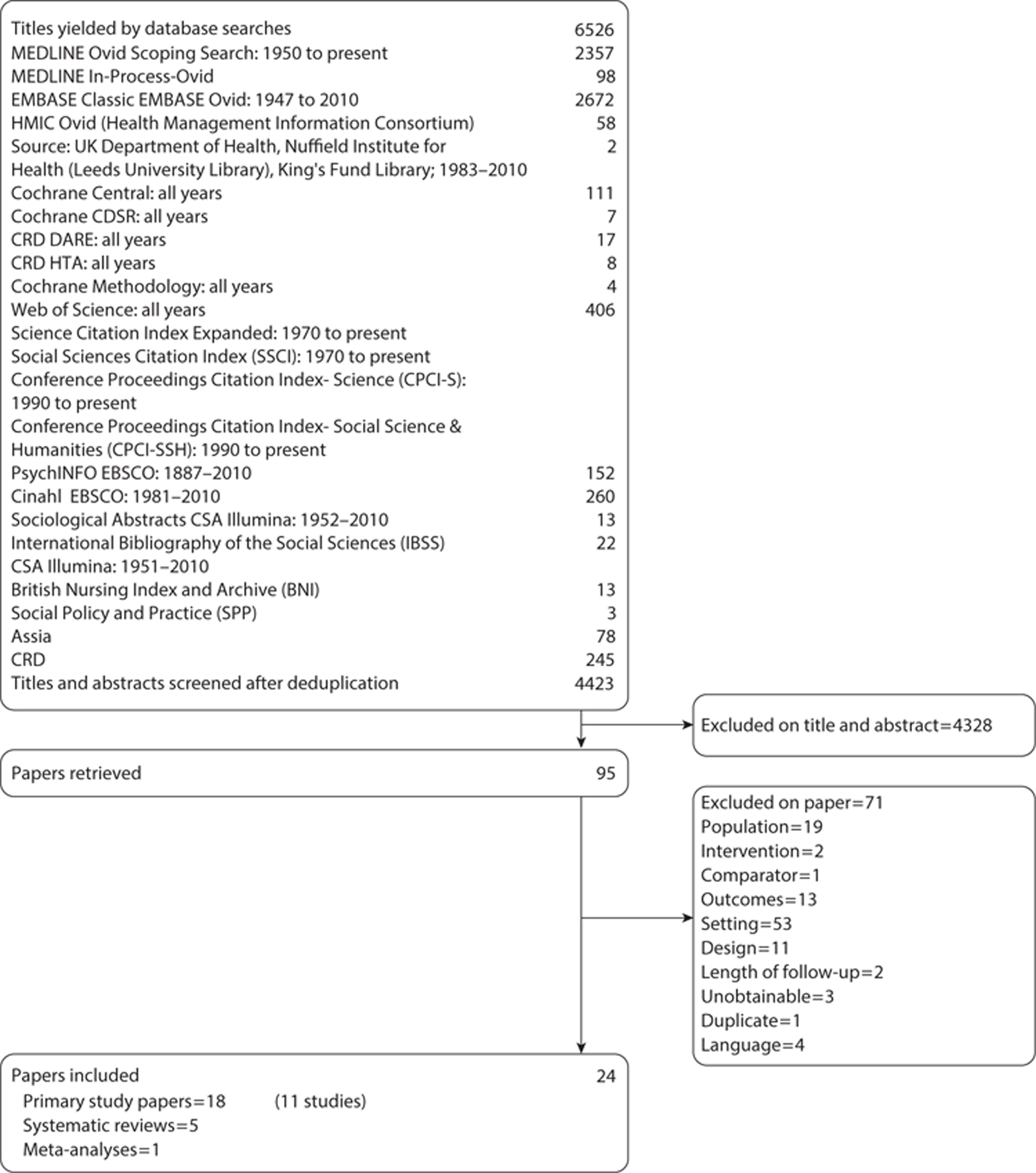

Electronic database searches were conducted between 8 October 2010 and 25 January 2011. The initial searches found 883 titles and abstracts after deduplication. When these were screened, 67 papers were requested for further review and two PhD theses were unobtainable. Of the 65 papers that were available, 20 were found to meet the study inclusion criteria. Four of these were systematic reviews, one was a meta-analysis and 15 were research papers; although a qualitative search filter was used, none of the papers had qualitative designs.

Further, more sensitive, qualitative searches were then conducted to see if they led to admissible studies. These searches yielded 2350 titles and abstracts after deduplication; when these had been screened 14 papers were requested. The review of these papers led to the inclusion of three primary research papers and one more systematic review. One of these papers was a summary of a nested qualitative study from an included study; this had been published only as a conference poster. Contact with the author revealed that this study had not been published in full. No published qualitative studies were found.

In order to be certain that the search strategy was picking up all includable papers, a highly sensitive further scoping search of breast cancer (and breast cancer terms) and qualitative research [as a medical subject heading (MeSH)/EMTREE/controlled syntax term] or qualitative methods (free-text terms) and qualitative terms (free text) were used. This was followed by a further scoping search of the breast cancer terms with the qualitative cluster of terms. These searches produced an enormous number of titles and abstracts (n = 189,580). A sample of these was screened (n = 258) and no further includable studies were found.

A search for grey literature produced 13 titles after deduplication. One paper was retrieved but was subsequently excluded. Breast cancer charity websites were also searched; however, no includable papers were found.

After consultation with the information specialist (CC) it was decided to do a forwards chase of citations (n = 48) and a backwards chase of references (n = 50) from one of the included systematic reviews, by Brett et al. ,82 to see if this was a more productive strategy for finding includable papers. This led to the retrieval of another eight papers, none of which were included. However, it was concluded that screening bibliographies and chasing citations of retrieved papers, together with contacting experts and authors, was more likely to produce includable studies than pursuing highly specific but extremely insensitive searches. This strategy is supported by Greenhalgh and Peacock,83 who found only 30% of includable studies through searches from protocol inclusion criteria. This approach produced no further includable papers.

Update searches were carried out on 26 October 2011 and 23 March 2012; no new includable studies were found. The search strategy is available in Appendix 2 and the updated search strategy is available from the authors.

In total, 24 papers were included (18 primary studies, five systematic reviews and one meta-analysis). The list of included papers was sent to experts in the field to confirm that there were no more relevant published papers; it was accepted that saturation had been obtained. A list of ongoing studies can be found in Appendix 4.

No studies were found that were either about or that had subgroups of women from different ethnic, socioeconomic or other groups. One study was found of women who had a false-positive mammogram and had a family history of breast cancer (FHBC).

A flow chart of the selection process can be found in Figure 4. A list of papers excluded at the paper review stage with reasons for their exclusion is available in Appendix 5.

FIGURE 4.

Flow chart of published evidence included in this systematic review.

Quality of studies – study characteristics and risk of bias

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses

The searches identified five systematic reviews and one meta-analysis that partly or wholly addressed the research questions of this systematic review. It was decided to evaluate the quality of all these studies against PRISMA criteria which, although not designed as a quality assessment tool, can be used for the critical appraisal of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. 79Table 3 provides a summary of the inclusion criteria of these studies.

Overall, the quality of methods and reporting in these systematic reviews is not high. This is despite them being conducted in the post-QUORUM (quality of reporting of meta-analyses) and, in some cases, post-PRISMA era. The exception to this is the review published by the UK HTA programme. 84 The features most commonly missing are information about access to the study protocol, presentation or access to the full electronic searches and, more worryingly, consideration of the risk of bias both within and across studies. It seems that most authors were happy to accept the results of their included studies de facto, despite being largely observational with many opportunities for bias and confounding to affect the results. A summary of the quality of the included systematic review can be found in Table 4.

| Author, year and reference | Title (no. of included studies) | Participants | Intervention | Comparator | Outcomes | Design | Exclusion criteria | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salz et al. 201085 | Meta-analysis of the effect of false-positive mammograms on generic and disease-specific psychosocial outcomes (17) | Women aged ≥ 40 years who had been invited to mammography screening | Screening with mammography | No comparator | Measures of well-being and behaviour | Observational studies | Mammography prompted by symptoms, hypothetical studies | This study is linked to the systematic review by Brewer et al. 200762 |

| False-positive vs normal results | BDI, CES-D, CWS-R, GHQ, HADS, HSCL, IAS, IES, K6, PCQ, RPCS, STAI, ad hoc | |||||||

| Hafslund and Nortvedt 200986 | Mammography screening from the perspective of quality of life: a review of the literature (17) | Women aged 40–74 years who had been invited to mammography screening | Screening with mammography | No comparator | Quality of life | Observational studies | Women with an increased risk of breast cancer, a diagnosis of cancer, aged ≥ 74 years or < 40 years, or the intervention was focused on anxiety. Non-English-language papers | Narrative synthesis |

| False-positive vs normal results | BCAI, BDI, GHQ, HADS, HQ, PCQ, SCL-90, STAI, TTO, | |||||||

| Brewer et al. 200762 | Systematic review: the long-term effects of false-positive mammograms (23) | Women aged ≥ 40 years who had been invited to mammography screening | Screening with mammography | No comparator | Return for routine screening | Observational studies | Mammography prompted by symptoms, hypothetical studies. Non-English-language papers | Includes a meta-analysis of the effects of false-positives on returning for routine screening |

| False-positive vs normal results | Measures of behaviour, well-being and beliefs | |||||||

| BDI, CES-D, GHQ, HADS, HSCL, IAS, IES, K6, PCQ, SCL-90, STAI, ad hoc | ||||||||

| Measured ≥ 1 month after assessment | ||||||||

| Armstrong et al. 200787 | Clinical guidelines. Screening mammography in women aged 40–49 years: a systematic review for the American College of Physicians (22) | Women aged 40–49 years who had been invited to mammography screening. The subgroup of false-positive women included those ≥ 50 years old | Screening with mammography | No comparator | Measures of behaviour and well-being | Observational studies | Case series | The false-positive studies were a subgroup of a more general review of screening mammography |

| False-positive vs normal results | FCS, GHQ, HADS, HSCL, IES, PCQ, STAI, ad hoc | Narrative synthesis | ||||||

| Brett et al. 200582 | The psychological impact of mammographic screening. A systematic review (52) | Women who had been invited to mammography screening | Screening with mammography | No comparator | Measures of behaviour and well-being | Observational studies | True-positive as a result of screening or symptomatic at the time of screening. Studies where the focus was on the impact of an intervention on anxiety. Non-English-language papers | Narrative synthesis |

| False-positive vs normal results | BDI, HADS, HSCL, GHQ, PCQ, POMS, STAI, ad hoc | |||||||

| Bankhead et al. 200384 | The impact of screening on future health-promoting behaviours and health beliefs. A systematic review (28) | Women who had been invited to mammography screening | Screening with mammography | No comparator | Health-promoting behaviours, attitudes and beliefs that result from breast screening | All study designs | Non-English-language papers and papers focusing on anxiety, pain or discomfort unless these affected health-promoting behaviour. Interventions to improve uptake of screening | The false-positive mammography studies were a subset of a more general review of screening that included breast, cervical and cholesterol screening |

| False-positive vs normal results | Ad hoc | Narrative synthesis |

| Section/topic | Item | Checklist item | Salz et al. 201085 | Hafslund and Nortvedt 200986 | Brewer et al. 200762 | Armstrong et al. 200787 | Brett et al. 200582 | Bankhead et al. 200384 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | ||||||||

| Title | 1 | identify the report as a systematic review, meta-analysis or both | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Abstract | ||||||||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary including, as applicable, background, objectives, data sources, study eligibility criteria, participants, interventions, study appraisal and synthesis methods, results, limitations, conclusions and implications of key findings, systematic review registration number | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Introduction | ||||||||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of questions being addressed with reference to participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes and study design | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Methods | ||||||||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate if a review protocol exists, if and where it can be accessed and if available, provide registration information including registration number | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify study characteristics and report characteristics used as criteria for eligibility, giving rationale | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Information sources | 7 | Describe all information sources in the search and date last searched | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Search | 8 | Present full electronic search strategy for at least one database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated | ∼a | ∼a | ∼a | ∼a | ∼a | ✓ |

| Study selection | 9 | State the process for selecting studies | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Data collection process | 10 | Describe method of data extraction from reports and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data are sort and any assumptions and simplifications made | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Risk of bias in individual studies | 12 | Describe methods used for assessing risk of bias of individual studies and how this information is to be used in any data synthesis | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Summary measures | 13 | State the principal summary measures | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Synthesis of results | 14 | Describe the methods of handling data and combining results of studies, if done, including measure of consistency for each meta-analysis | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✗ | – | – |

| Risk of bias across studies | 15 | Specify any assessment of risk of bias that may affect the cumulative evidence | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Additional analyses | 16 | Describe methods of additional analyses, if done, indicating which were pre-specified | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Results | ||||||||

| Study selection | 17 | Give numbers of studies screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally from a flow diagram | ✗ | ∼a | ✓ | ✗ | ∼c | ∼d |

| Study characteristics | 18 | For each study, present characteristics for which data were extracted and provide the citations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Risk of bias within studies | 19 | Present data on risk of bias of each study and, if available, any outcome-level assessments | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ∼b |

| Results of individual studies | 20 | For all outcomes considered, present for each study (a) simple summary data for each intervention group and (b) effect estimates and CIs, ideally with a forest plot | ✗ | ∼c | ∼d | ∼f | ✓ | ✓ |

| Synthesis of results | 21 | Present results of each meta-analysis done, including CIs and measure of consistency | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – |

| Risk of bias across studies | 22 | Present results of any assessment of risk of bias across studies | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Additional analysis | 23 | Give results of additional analyses, if done | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Discussion | ||||||||

| Summary of evidence | 24 | Summarise the main findings including the strength of evidence for each main outcome: consider their relevance for key groups | ∼e | ∼hh | ∼h | ∼f | ✓ | ✓ |

| Limitations | 25 | Discuss limitation at study and outcome level and at review level | ∼g | ∼h | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Conclusions | 26 | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence, and implication for future research | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Funding | ||||||||

| Funding | 27 | Describe sources of funding for the systematic review and other support and role of funders for the systematic review | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

The most recent study is a meta-analysis of the detection of the psychological impact of false-positive screening mammograms by generic and disease-specific psychosocial measures by Salz et al. 85 This is a secondary analysis of their previous systematic review data, published in 2007. 62 The authors were interested in comparing the difference in sensitivity of generic and disease-specific outcome measures to detect the degree of well-being experienced by women who had received a false-positive screening mammogram. Their searches found 17 observational studies of women aged ≥ 40 years that compared psychological outcomes between women who had had a false-positive mammogram with those whose screening results had been normal.

This meta-analysis has some weaknesses. There is no indication that any consideration of the risk of bias or confounding within or across studies was made, although the inclusion criteria and methods for study selection are clearly stated.

Additionally, Salz et al. 85 do not account for the number of studies screened or provide a flow chart or details of the results of the individual studies they have included. In the results section, rather than present forest plots for each analysis, they present a table of pooled effect sizes for the different criteria of outcome (e.g. distress or depression). In the discussion, although they summarise their main findings, no comment was made on the strength of the findings or their limitations at study level.

This meta-analysis was preceded by Hafslund and Nortvedt,86 who conducted a systematic review, published in 2009, that looked at the impact on quality of life of mammography screening in women aged ≥ 40 years, comparing those who received a false-positive result with those whose result was normal. Psychological measures were taken in the short to medium term. The authors found 17 observational studies, which were given a narrative synthesis.

Overall, this is a poor-quality systematic review. Although methods for assessing the risk of bias in individual studies are described, insufficient information is given about the data collection process and the kind of data to be collected. The results section gives an estimation of the risk of bias within studies but the results of individual studies are inadequately presented, with little summary data. There is no assessment of the risk of bias across studies. Although the review's findings are summarised in the discussion, this is without relation to the strength of the evidence under review.

The systematic review by Brewer et al. 62 is of reasonable quality. Brewer et al. 62 were interested in the long-term effects of false-positive screening mammograms on women's attendance at their next routine breast screening clinic. They were also interested in the impact on psychological outcomes, which they measured at least 1 month after the assessment. They found 23 observational studies that met their inclusion criteria.

The rationale and methods for conducting the study are well reported, with the notable exception of those for evaluating the risk of bias in individual studies, although methods for countering the cumulative effects of bias and assessing publication bias are given. Not surprisingly, the results section does not report the risk of bias within studies and the reporting of individual studies' results for psychological outcomes is inadequate as only a vote-counting approach is taken. However, individual, summary and pooled data for reattendance at routine screening are presented. The discussion provides a good summary of the evidence and incorporates a consideration of the limitations of the review and its components, although the strength of the evidence is not reflected on.

In the same year (2007), Armstrong et al. 87 published a systematic review with the aim of assessing the evidence of risks and benefits of screening mammography for women aged 40–49 years, but included a subgroup of women aged up to 71 years who had received false-positive results. This older population was compared with those with a normal screening outcome. They found 22 observational studies about false-positive mammograms.

Unfortunately, this is a poor-quality systematic review. The methods used are inadequately described with no mention of the outcomes included, methods of data synthesis or any assessment of the risk of bias across studies. The authors used a crude measure of study quality that is solely based on design, which does not consider risk of bias or confounding within studies. Furthermore, there is no indication that they have thought how bias might affect the validity of their results. The study results are particularly poorly reported; there is no account of the results of the study screening process, no results of assessment of risk of bias, inadequately described results of individual studies and a narrative synthesis almost devoid of quantified outcomes. The very brief discussion does not consider the review's limitations at any level or offer an interpretation of the results with reference to other reviews.

A systematic review by Brett et al. 82 was of better quality, although still lacking many of the markers of a good-quality systematic review. The authors aimed to assess the negative psychological impact of mammography screening and how long this lasted; this included the impact on women given the all-clear after screening as well as those with false-positive results. They found 52 observational studies that met their inclusion criteria.

The abstract and introduction are clear. However, the methods section is confusing to read as it contains paragraphs that should be in the introduction and results sections. The process of study selection is described, but there is no flow chart showing the progress of screening. Furthermore, the risk of bias affecting the results of individual studies or across studies is not considered in the methods or results sections. The findings of individual studies are given a comprehensive narrative summary. Recognition is given in the discussion to the shortcomings of some of the instruments used and that bias and confounding could have influenced the results. However, how this might relate to individual studies or the overall conclusions is not discussed.

The final systematic review that has been included is a good-quality HTA programme publication by Bankhead et al. 84 This is a broad-ranging systematic review looking at the impact of several types of screening, including mammography, on health behaviours and beliefs. Bankhead et al. 84 found 28 observational studies that looked at women with false-positive mammography results.

The introduction and methods are clear and comprehensive and consideration is given to the risk of bias in individual studies. However, the risk of bias across studies is not mentioned. The results section, together with the tables in the appendices, gives a full account of the findings by outcome and study, although, again, the possible effects of risk of bias across studies are not reported. The discussion section gives a clear and thorough summary of the findings and the limitations of the study with suggestions for further research.

Primary research

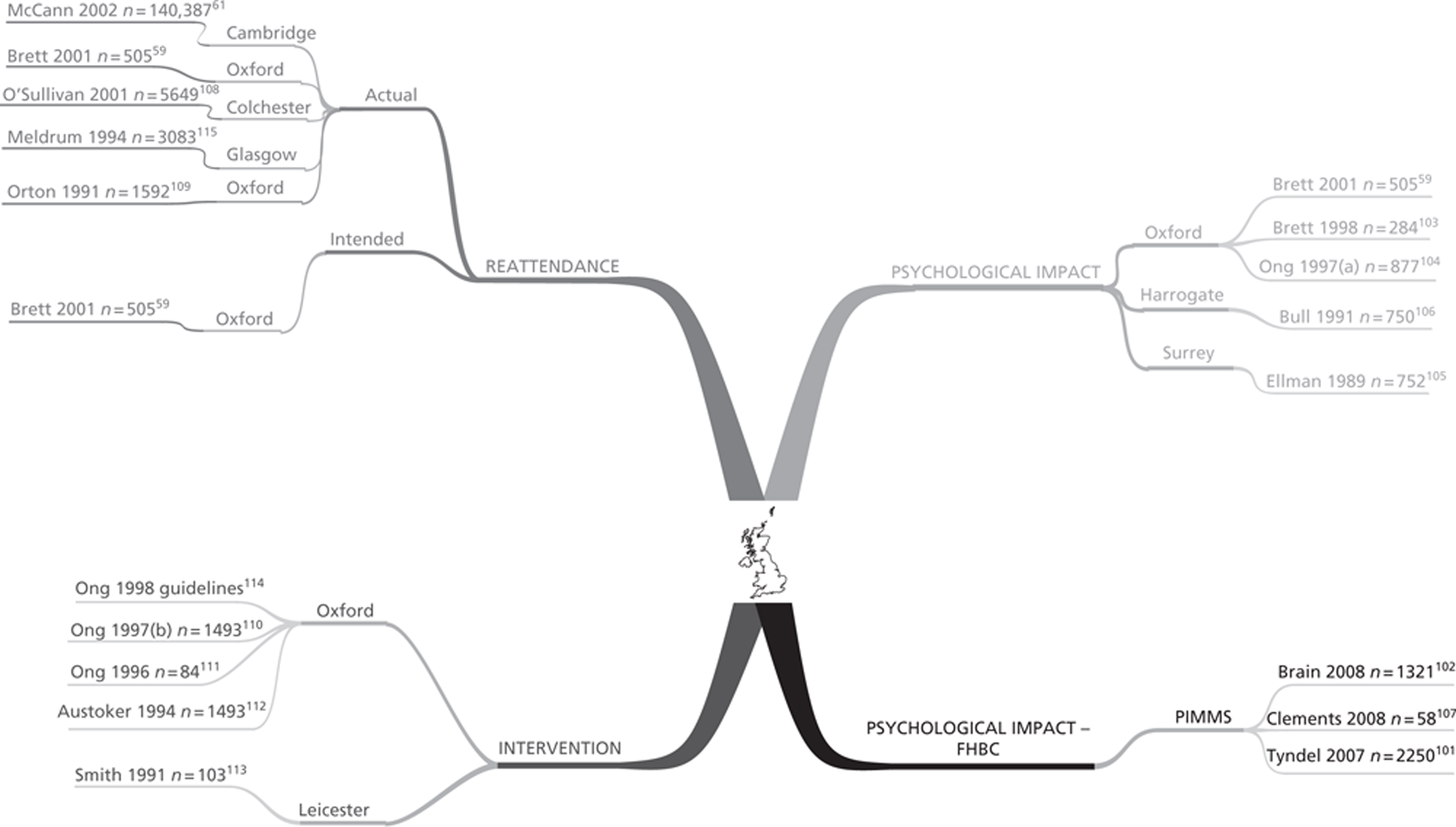

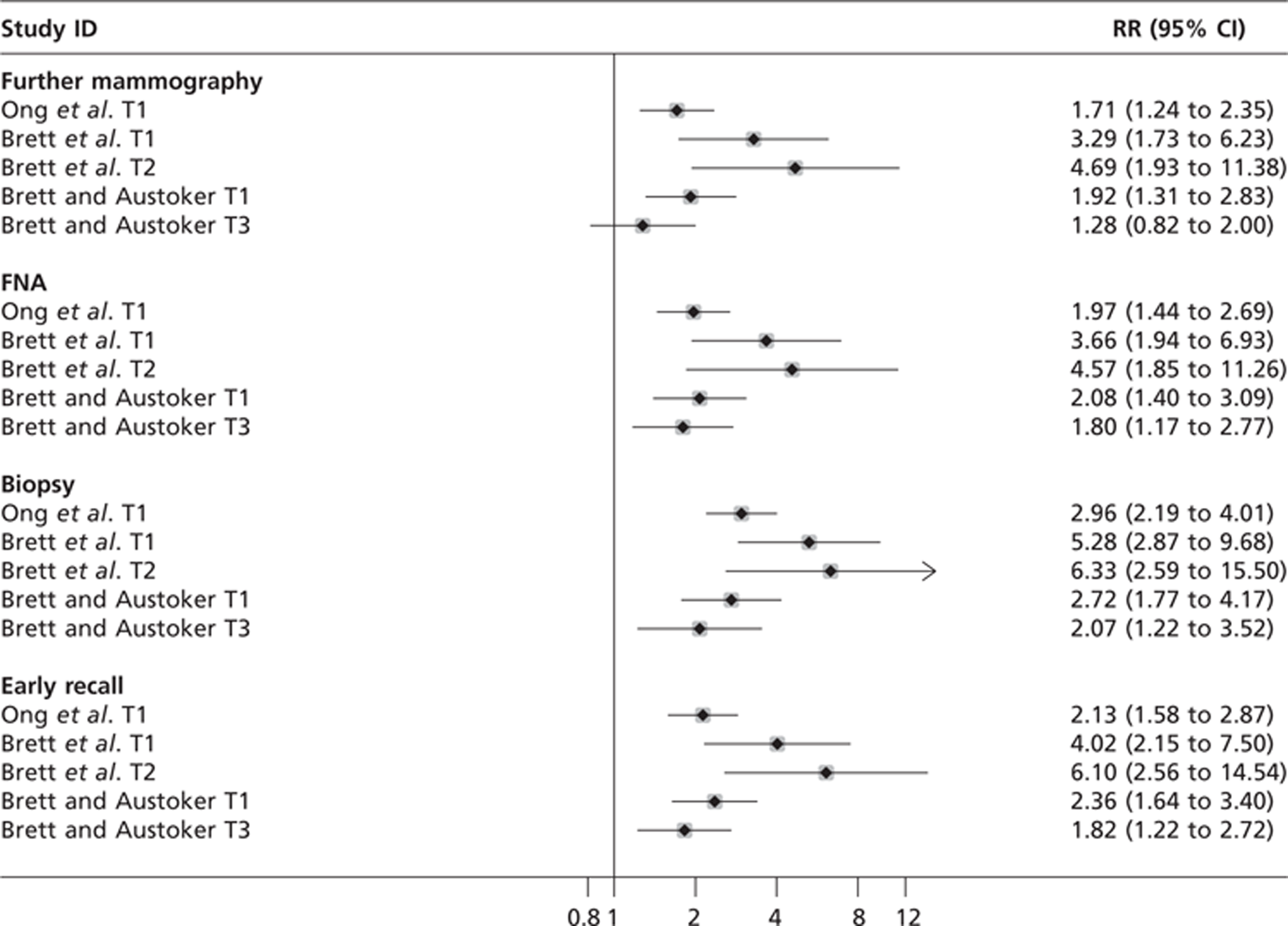

The searches returned 11 primary research studies (18 papers) that met the inclusion criteria (including being conducted in the UK). Four of the studies were prospective cohorts,59,101–106 one of these studies107 included a nested interview study but this was only published as a conference poster, four were retrospective cohorts,55,61,108,109 two had a cross-sectional design,110–113 one of these studies114 produced national guidelines that contained research findings and one was a RCT115 of an intervention to improve reattendance.

Four studies looked at the psychological impact of false-positive mammograms in the normal-risk population. 55,59,103–106 One study looked at the impact of having a false-positive screening mammogram among a population of women with a FHBC. 101,102,107 Five studies looked at the impact on returning for routine mammography screening59,61,103,108,109,115 and two studies investigated the impact of written information on distress or reattendance. 110–114

In some of the studies, groups of women were included with characteristics outside the scope of this systematic review; in these cases only data from the study population included in this review are extracted and reported.

Although worded slightly differently, the definition of woman with a false-positive mammogram is consistent in all of the included studies and agrees with the definition used in this systematic review (i.e. a woman who is recalled for assessment of any kind on the basis of a routine screening mammogram who is not then diagnosed with breast cancer).

This section first of all gives an overview of the relationship of the studies to each other according to their domain of interest (Figure 5). Some papers report outcomes in more than one domain and are therefore shown accordingly in Figure 5. After this, the characteristics and quality of the studies are discussed according to their domain. This is followed by a summary table of the characteristics of each paper (Table 5). Finally, a summary in Table 6 gives an overview of the quality of the observational studies. More detailed information about all the primary studies can be found in the data extraction forms in Appendix 3. A summary description of the measures used in the included primary research can be found in Chapter 1, Measurement of psychological consequences.

FIGURE 5.

Mind map showing the relationship of included studies to their domain of interest.

| Study, author, year (funding) | Design | n | Participants | Intervention group | Control group | Outcomes | Length of follow-up | Exclusion criteria | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological impact | |||||||||

| Brett and Austoker 200159 (Cancer Research Campaign) | Prospective cohort, multicentre | 505 | Women invited for routine screening by mammography, already participating in the study at 5 months | Routine screening by mammography with a false-positive result (n = 375) | Routine screening by mammography with a normal result (n = 130) | PCQ, intention to reattend and actual reattendance satisfaction with service ad hoc questionnaire | 3 years (35 months) after assessment | Aged > 65 years, symptomatic referral, in another study, developed cancer | |

| Psychological impact | |||||||||

| Brett et al. 1998103 (Cancer Research Campaign) | Prospective cohort, multicentre | 284 | Women invited for routine screening by mammography, already participating in the study at 1 month | Routine screening by mammography with a false-positive result (n = 163) | Routine screening by mammography with a normal result (n = 52) | PCQ, intention to reattend, ad hoc questionnaire | 5 months after assessment | Aged > 65 years, symptomatic referral, in another study, developed cancer | 69 (24%) women chose not to return the questionnaire |

| Psychological impact | |||||||||

| Ong et al. 1997104 (Cancer Research Campaign, NHSBSP) | Prospective cohort, multicentre | 877 | Women invited for routine screening by mammography who were recalled for assessment | Women placed on early recall (< 3 years) (n = 182) | Women placed on routine recall after mammography (n = 173), further mammography assessment (n = 166), FNA (n = 109) or biopsy (n = 31) | PCQ | NA | Not reported | This study was primarily about the effects of early recall on women who had been called back for assessment after their mammogram, measures taken 1 month after assessment |

| Psychological impact | |||||||||

| Bull and Campbell 1991106 (Yorkshire Regional Health Authority) | Prospective cohort | 750 | Women invited for routine screening by mammography who were recalled for assessment | Routine screening by mammography with a false-positive result (n = 308) | Routine screening by mammography with a normal result (n = 420) | Ad hoc questionnaire including frequency of breast self-examination, HADS | 6 weeks after the ‘all-clear’ | Not reported | It is not known if the women had previously had cancer or were in a high-risk group |

| Psychological impact | |||||||||

| Ellman et al. 1989105 (DHSS Research Management Division) | Prospective cohort | 752 | Women invited for routine mammography screening and those recalled for further assessment and those with symptoms being further investigated | Routine screening by mammography with a false-positive result (n = 271) | Routine screening by mammography with a normal result (n = 295), symptomatic women who did not have cancer (n = 134), symptomatic or recalled screened women who did have cancer (n = 38), history of breast cancer with or without symptoms (n = 14) | GHQ-28, ad hoc questionnaire | 3 months after clinic attendance | Not reported | Participants also received clinical examination. Only those groups meeting the inclusion criteria will be considered in this systematic review |

| Psychological impact | |||||||||

| Psychological impact with a FHBC | |||||||||

| Brain et al. 2008102 (Cancer Research UK) | Prospective cohort | 1321 | Women aged 35–49 years invited for routine annual screening by mammography with a FHBC | Routine annual screening by mammography with a false-positive result (n = 112) | Routine annual screening by mammography with a normal result (n = 1174) | Questionnaire including: CWS-R, cognitive appraisal, COPE, perceived risk of breast cancer, dispositional optimism | 6 months, measures taken at 1 month before screening and 1 and 6 months after the ‘all-clear’ | Previous history of breast cancer or family history of ovarian cancer | This study aimed to find predictive variables of cancer-specific distress |

| Psychological impact | |||||||||

| Clements et al. 2008107 (Cancer Research UK) | In-depth interviews | 58 | Women aged 35–49 years invited for routine annual screening by mammography with a FHBC | Routine annual screening by mammography with a false-positive result (n = 22) | Routine annual screening by mammography with a normal result (n = 36) | Reactions of women to false-positive recall and value placed on the screening programme | NA | Previous history of breast cancer or family history of ovarian cancer | It is not known if the women had previously had cancer or were in a high risk group |

| Psychological impact | |||||||||

| Tyndel et al. 2007101 (Cancer Research UK) | Prospective cohort | 2321 | Women aged 35–49 years invited for routine annual screening by mammography with a FHBC | Routine annual screening by mammography with a false-positive result (n = 166) | Routine annual screening by mammography with a normal result (n = 2084) | CWS-R, PCQ | 6 months, measures taken at 1 month before screening and 1 and 6 months after the ‘all-clear’ | Previous history of breast cancer or family history of ovarian cancer | |

| Psychological impact | |||||||||

| Impact on reattendance | |||||||||

| McCann et al. 200261 (NHS Executive Eastern Region) | Retrospective cohort | 140,387 | Women aged 49–63 years invited for routine breast screening by mammography | Routine screening by mammography with a false-positive result (n = 4792) | Routine screening by mammography with a normal result (n = 108,617) | Subsequent attendance at routine screening after a false-positive result and rate of interval cancer – from records | 3 years | Women who were older than 63 years at follow-up | |

| Reattendance and interval cancer | |||||||||

| O'Sullivan et al. 2001108 (Cancer Research Campaign) | Retrospective cohort | 5649 | Women invited for mammography screening for the second or subsequent time | Routine screening by mammography with a false-positive result (n = 248) | Routine screening by mammography with a normal result (n = 5401) | Subsequent attendance at routine screening after a false-positive result – from records | Unclear, probably from 1989 to 1997 | Women invited for the first time and women who had been previously invited but had never attended | Effects of a false-positive result on reattendance for those on early recall and routine recall |

| Reattendance | |||||||||

| Brett and Austoker 200159 (Cancer Research Campaign) | As above in Psychological impact | ||||||||

| Brett et al. 1998103 (Cancer Research Campaign) | As above in Psychological impact | ||||||||

| Meldrum et al. 1994115 (Scottish Offce Home and Health Department) | RCT nested telephone interview study | 3083 | All women invited for second round routine mammography screening (aged 50–65 years) | Tailored invitation with a false-positive result (n = 115) and with a normal result (n = 800) | Standard invitation with a false-positive result (n = 112) and with a normal result (n = 791) | Subsequent attendance at routine screening and effect of a tailored invitation on subgroups | Not reported | Women with breast cancer and those whose screening history was not available | Trial comparing the effect of a tailored invitation on second-round screening attendance with a standard invitation |

| Orton etal. 1991109 (funding not reported) | Retrospective cohort | 1582 | Women, aged 45–64 years, invited to attend for second-round screening by mammography | Routine screening by mammography with a false-positive result (n = 50) | Routine screening by mammography with a normal result (n = 1532) | Reattendance, acceptability of screening | NA | Not reported | Data are not available for the acceptability of screening for false-positive participants |

| Reattendance | |||||||||

| Interventions to reduce the impact of false-positive mammograms | |||||||||

| Ong et al. 1998114 (Cancer Research Campaign, NHSBSP) | Guidelines and summary evidence from cross section, multicentre | NA | Women invited for routine screening by mammography who were recalled for assessment | NA | NA | Ad hoc questionnaire and criteria for evaluating breast screening information material developed by Austoker and Ong 1994112 | NA | Women recalled due to poor quality X-rays | National guidelines about information given prior to recall for further assessment based on the findings of Ong et al. 1997,104 1996111 and Austoker and Ong 1994112 |

| Information intervention | |||||||||

| Ong and Austoker 1997110 (Cancer Research Campaign, NHSBSP) | Cross section, multicentre | 1493 | Women invited for routine screening by mammography who were recalled for assessment | n = 1493 | NA | Ad hoc questionnaire | NA | Women recalled due to poor quality X-rays | Evaluation of women’s experiences at the assessment clinic and their information needs there and afterwards. Discourse analysis of open questions |

| Information intervention | |||||||||

| Ong et al. 1996111 (Cancer Research Campaign, NHSBSP) | Cross section, multicentre | 84 | UK breast screening assessment centres | Evaluation of information given in the initial letter/leaflet and prior to recall for further assessment | NA | Criteria for evaluating breast screening information material developed by Austoker and Ong 1994112 | NA | NA | |

| Information intervention | |||||||||

| Austoker and Ong 1994112 (Cancer Research Campaign, NHSBSP) | Cross section, multicentre | 1493 | Women invited for routine screening by mammography who were recalled for assessment | n = 1493 | NA | Ad hoc questionnaire | NA | Women recalled due to poor quality X-rays | Evaluation of information given prior to recall for further assessment from eight UK breast screening centres |

| Information intervention | |||||||||

| Smith et al. 1991113 (funding not reported) | Cross section | 103 | Women attending assessment clinic following recall after routine mammography screening | False-positive (N = 91) | NA | Ad hoc questionnaire | NA | Not reported | Survey of different versions of an invitation to return for further assessment. The responses from both groups of women are aggregated |

| Survey | Other outcome (N = 12) | ||||||||

The UK research in the field of false-positive mammography screening has been dominated by the University of Oxford Primary Care Education Research Group (OPCERG) who first published a series of papers from 1997 about the information needs of women recalled for further assessment following a screening mammogram. This work then developed to investigate the psychological impact of false-positive mammograms on the general population of screened women and how this affected their reattendance at their next routine screening, and latterly looked at the psychological impact of receiving a false-positive mammogram on women who have a FHBC. Other research groups in England and Scotland have also studied these four aspects and in many cases preceded the Oxford research.

Psychological impact

The papers from the OPCERG study in this domain span 5 years, with measures being taken at 1 month (T1), 5 months (T2) and 35 months (T3) from the last screening appointment. This study is a multicentre prospective cohort at 13 NHSBSP clinics in England and Scotland. The papers follow the same cohort of women over this time but the methods used appear to vary at different time points and it is not always clear on what basis the women included in the study have been selected or how the main outcome measure, the PCQ, has been used. The study includes women with normal mammograms as the control group and compares them with women with false-positive outcomes according to the process used in their further assessment (another mammogram, FNA or biopsy) or if they had been placed on early recall of 6 or 12 months following further assessment.

The first publication by OPCERG, by Ong et al. 104 (n = 877), reported primarily on the adverse psychological consequences of being placed on early recall (6 or 12 months recall rather than 3 years) at T1. These effects were measured using the PCQ negative scale which has 12 items on a four-point Likert scale (scored 0–3). 67 Participants were considered to be ‘cases’ if they responded positively to at least one item.

The study by Ong et al. 104 is a moderately good-quality study that used appropriate methods to address its aims. The authors reported almost all the key criteria specified by the STROBE statement. 81 However, they omitted to provide demographic data for all participants, not just those on early recall, which makes it difficult to interpret the results. They also failed to fully discuss the limitations of their study and its generalisability to other situations.

Following on from the study by Ong et al. ,104 Brett et al. 103 (n = 284) recruited from the same pool of women to find out what difference, if any, a further 4 months had on how these women were feeling after their false-positive mammogram. This was also 1 month before those on early recall were due for another screening mammogram. In this prospective cohort study, the previous studies' results (Ong et al. 104) were used as the baseline measures for comparison with the same subgroups. This study only included 12 centres, as one centre did not put any women on early recall.

Although this was a fairly good-quality study,103 it did not quite meet the same standards of reporting as the previous one. 104 Omissions include not considering potential sources of bias, giving an explanation of how missing data were handled and not providing demographic information.

The latest publication from OPCERG on the population at normal risk of breast cancer is by Brett and Austoker59 (n = 505). This study follows the same cohort of women as Brett et al. 103 in 13 NHSBSP clinics in England and Scotland. They took measures of adverse psychological consequences with the PCQ at 35 months after participants' last assessment (i.e. 1 month before their next routine screening mammogram was due). Brett and Austoker59 deemed that a total score ≥ 12 (range 0–36) on the PCQ showed negative psychological consequences and so it is only the percentage of scores ≥ 12 that are reported. It is not clear why they have chosen this total score as the cut-off point for showing psychological harm. The original validation paper by Cockburn et al. 67 does not have this cut-off but indicates that the bottom quartile of scores represent no dysfunction, the second quartile mild psychological disturbance, the third quartile moderate disturbance and the top quartile marked disturbance.

Brett and Austoker59 also used an ad hoc questionnaire to measure satisfaction with the breast screening service and assess factors that may influence women's level of anxiety. They also asked women about their intention to attend their next routine mammography screening. This last outcome was compared with their actual attendance.

Again, this is a generally well-described study but with similar omissions as before: no explanation of how missing data were dealt with or consideration of the role bias may have played in the results. However, they do provide some demographic information about the participants (marital status, home ownership and educational level).

Prior to the work by the Oxford team, Sutton et al. 55 (n = 1021) conducted a retrospective cohort study that was primarily interested in the levels of anxiety experienced by women attending routine mammography screening who had normal outcomes. However, they also looked at anxiety levels in women who had false-positive results. Nine months after the pre-screening baseline, they asked these women and others with normal results to retrospectively reflect on how anxious they had felt at six stages of the screening process: (1) receiving the invitation; (2) waiting at the clinic for the mammogram; (3) at the clinic after the mammogram; (4) waiting for the results; (5) after reading the results letter; and (6) now. These measures were taken on a three-point ad hoc scale, ranging from not anxious (1), a bit anxious (2) to very anxious (3). The retrospective results are only reported numerically at stages 3–5, therefore these data have been extracted. The data at other time points are reported in graphical form only and so could not be reliably extracted.

| STROBE statement – checklist of items that should be included in reports of observational studies | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item no. | Recommendation | Brett and Austoker 200159 | Brett et al. 1998103 | Ong et al. 1997104 | Sutton et al. 199555 | Bull and Campbell 1991106 | Ellman et al. 1989105 | Brain et al. 2008107 | Tyndel et al. 2007101 | McCann et al. 200261 | O'Sullivan 2001108 | Orton et al. 1991109 | Ong and Austoker 1997110 | Ong et al. 1996111 | Austoker and Ong 1994112 | Smith et al. 1991113 | |

| Title and abstract | |||||||||||||||||

| 1 | (a) Indicate the study's design with a commonly used term in the title or the abstract | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | |

| (b) Provide in the abstract an informative and balanced summary of what was done and what was found | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ||

| Introduction | |||||||||||||||||

| Background/rationale | 2 | Explain the scientific background and rationale for the investigation being reported | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Objectives | 3 | State specific objectives, including any pre-specified hypotheses | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Methods | |||||||||||||||||

| Study design | 4 | Present key elements of study design early in the paper | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Setting | 5 | Describe the setting, locations, and relevant dates, including periods of recruitment, exposure, follow-up and data collection | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | P | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | P | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Participants | 6 | (a) Cohort study – give the eligibility criteria, and the sources and methods of selection of participants. Describe methods of follow-up | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Case–control study – give the eligibility criteria and the sources and methods of case ascertainment and control selection. Give the rationale for the choice of cases and controls | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Cross-sectional study – give the eligibility criteria and the sources and methods of selection of participants | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| (b) Cohort study – for matched studies, give matching criteria and number of exposed and unexposed | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | P | ||

| Case–control study – for matched studies, give matching criteria and the number of controls per case | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ✓ | ||

| Variables | 7 | Clearly define all outcomes, exposures, predictors, potential confounders and effect modifiers. Give diagnostic criteria, if applicable | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | P | P | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | P |

| Data sources/measurement | 8 | For each variable of interest, give sources of data and details of methods of assessment (measurement). Describe comparability of assessment methods if there is more than one group | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | P | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Bias | 9 | Describe any efforts to address potential sources of bias | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Study size | 10 | Explain how the study size was arrived at | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | NA | NA | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Quantitative variables | 11 | Explain how quantitative variables were handled in the analyses. If applicable, describe which groupings were chosen and why | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Statistical methods | 12 | (a) Describe all statistical methods, including those used to control for confounding | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| (b) Describe any methods used to examine subgroups and interactions | NA | NA | ✓ | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ✗ | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||