Notes

Article history paragraph text

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 10/11/01. The protocol was agreed in November 2010. The assessment report began editorial review in June 2011 and was accepted for publication in March 2012. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors'report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Note

This monograph is based on the Technology Assessment Report produced for NICE. The full report contained a considerable number of data that were deemed commercial-in-confidence. The full report was used by the Appraisal Committee at NICE in their deliberations. The full report with each piece of commercial-in-confidence removed and replaced by the statement ‘commercial-in-confidence information removed’ is available on the NICE website: www.nice.org.uk.

The present monograph presents as full a version of the report as is possible while retaining readability, but some sections, sentences, tables and figures have been removed. Readers should bear in mind that the discussion, conclusions and implications for practice and research are based on all the data considered in the original full NICE report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Hoyle et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Abstract

Background

Colorectal cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in the UK after breast and lung cancer. People with metastatic disease who are sufficiently fit are usually treated with active chemotherapy as first- or second-line therapy. Recently, targeted agents have become available including anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) agents, for example cetuximab and panitumumab, and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor agents, for example bevacizumab.

Objective

To investigate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of panitumumab monotherapy and cetuximab (mono- or combination chemotherapy) for Kirsten rat sarcoma (KRAS) wild-type (WT) patients, and bevacizumab in combination with non-oxaliplatin chemotherapy, for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer after first-line chemotherapy.

Data sources

The assessment comprises a systematic review of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness studies, a review and critique of manufacturer submissions and a de novo cohort-based economic analysis. For the assessment of effectiveness, a literature search was conducted in a range of electronic databases, including MEDLINE, EMBASE and The Cochrane Library, from 2005 to November 2010.

Review methods

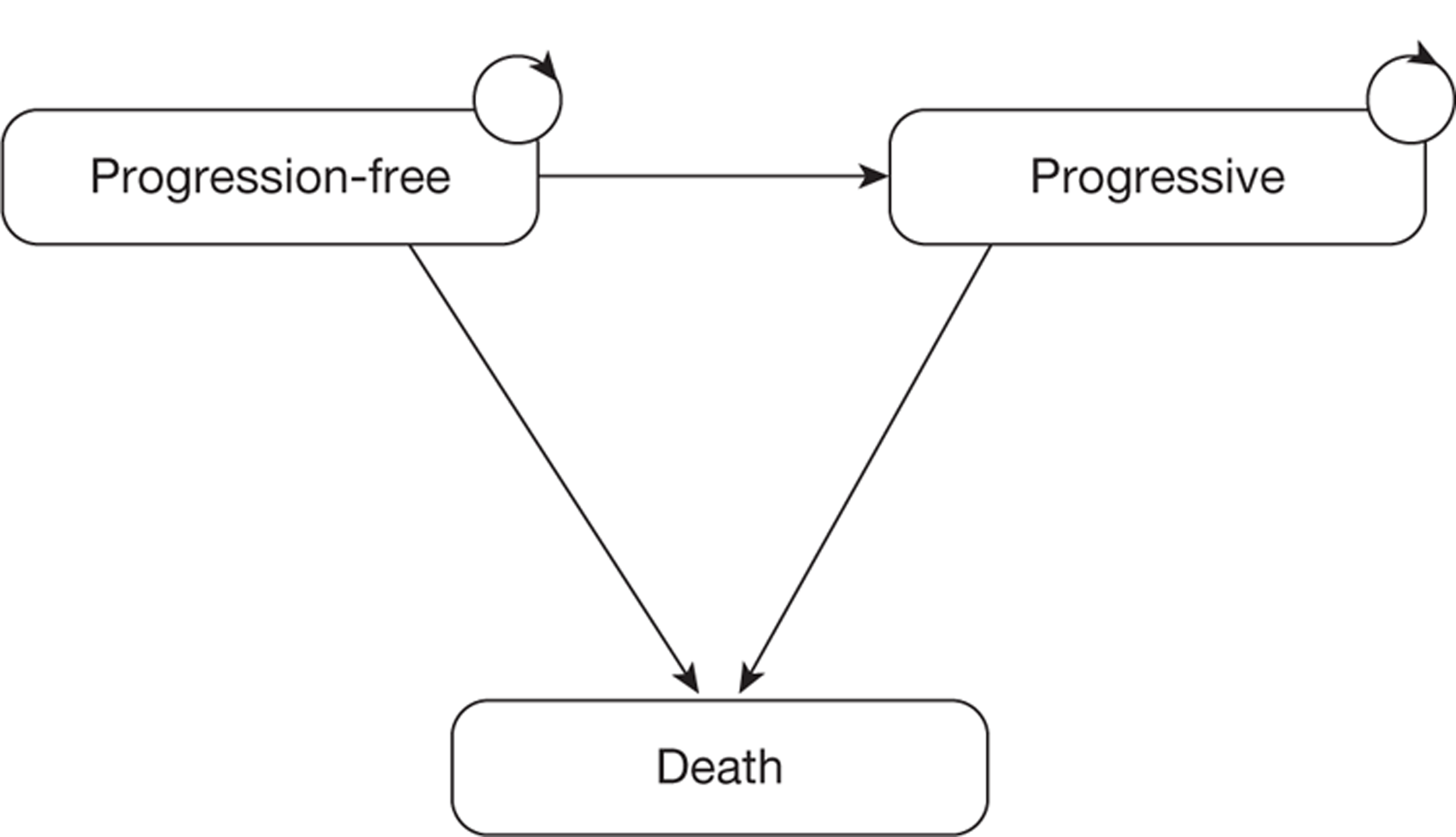

Studies were included if they were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or systematic reviews of RCTs of cetuximab, bevacizumab or panitumumab in participants with EGFR-expressing metastatic colorectal cancer with KRAS WT status that has progressed after first-line chemotherapy (for cetuximab and panitumumab) or participants with metastatic colorectal cancer that has progressed after first-line chemotherapy (bevacizumab). All steps in the review were performed by one reviewer and checked independently by a second. Synthesis was mainly narrative. An economic model was developed focusing on third-line and subsequent lines of treatment. Costs and benefits were discounted at 3.5% per annum. Probabilistic and univariate deterministic sensitivity analyses were performed.

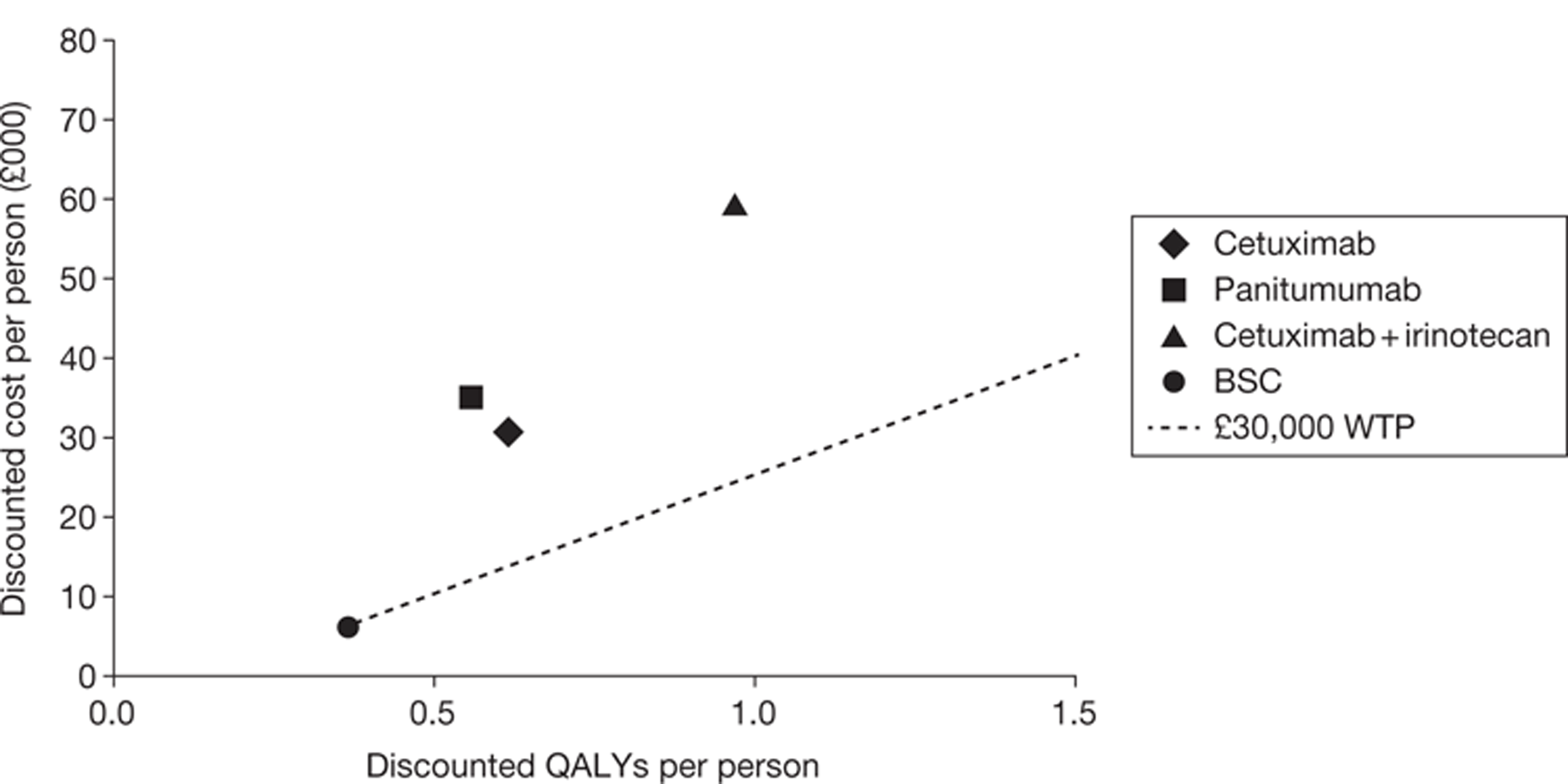

Results

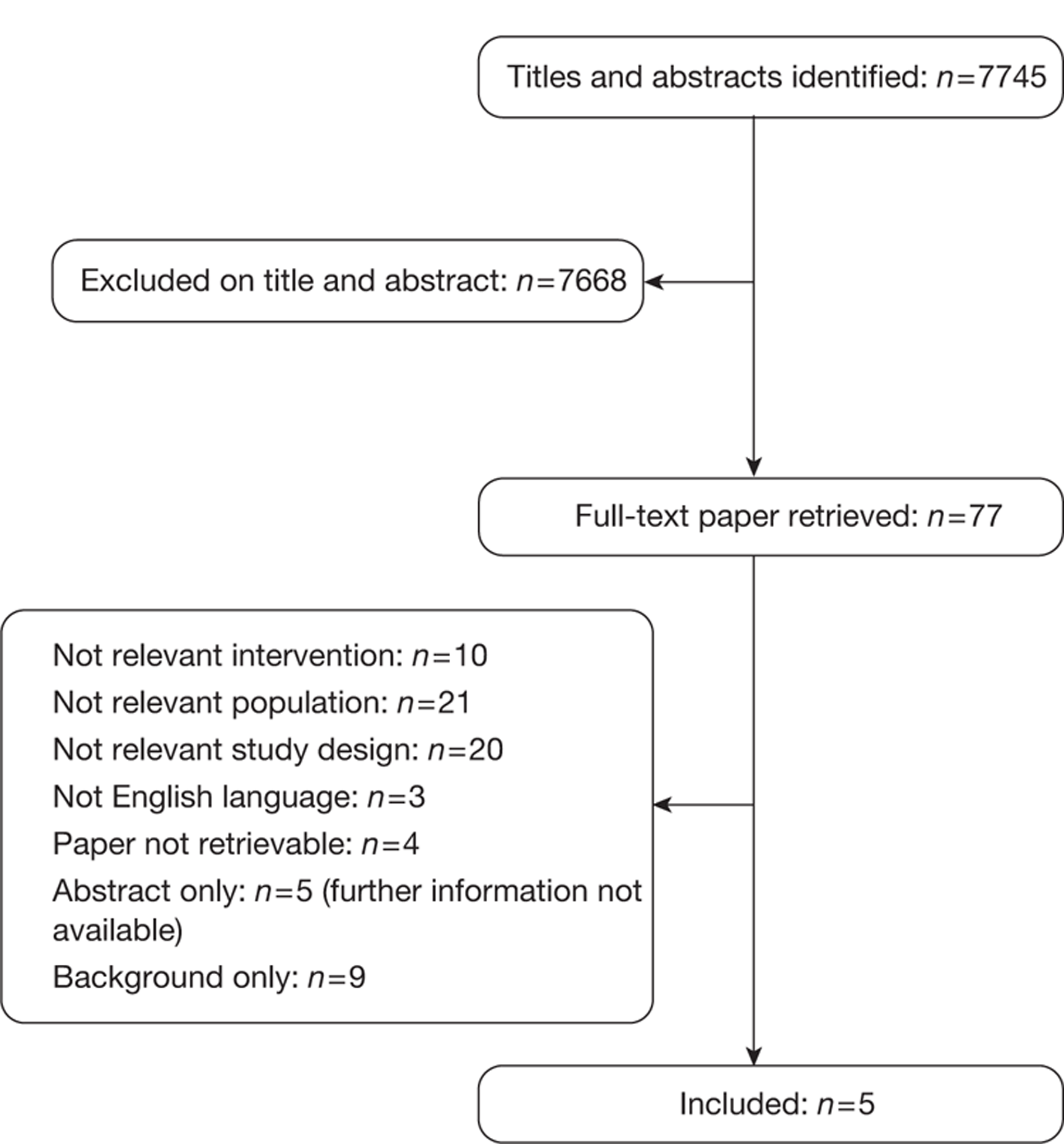

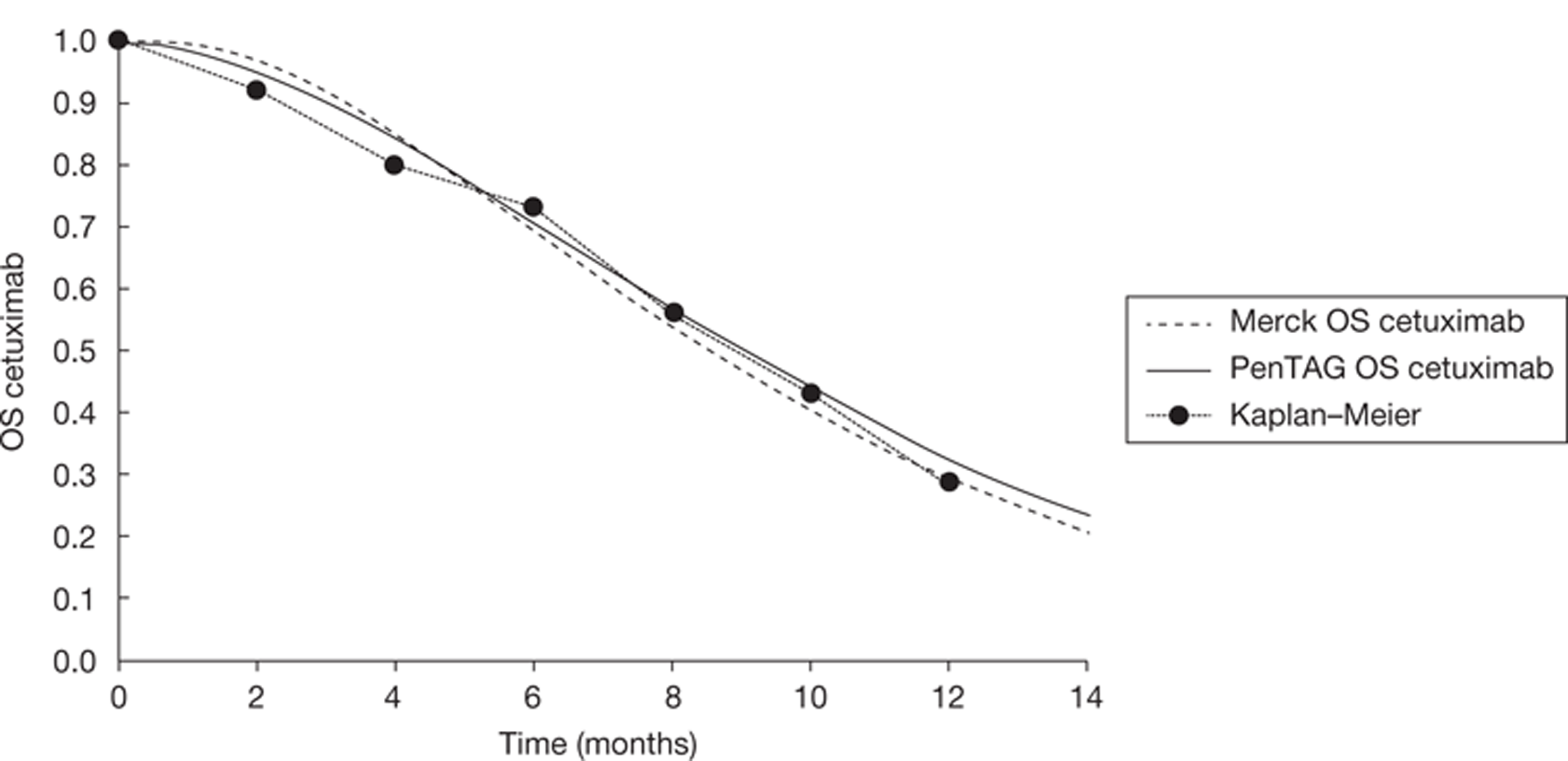

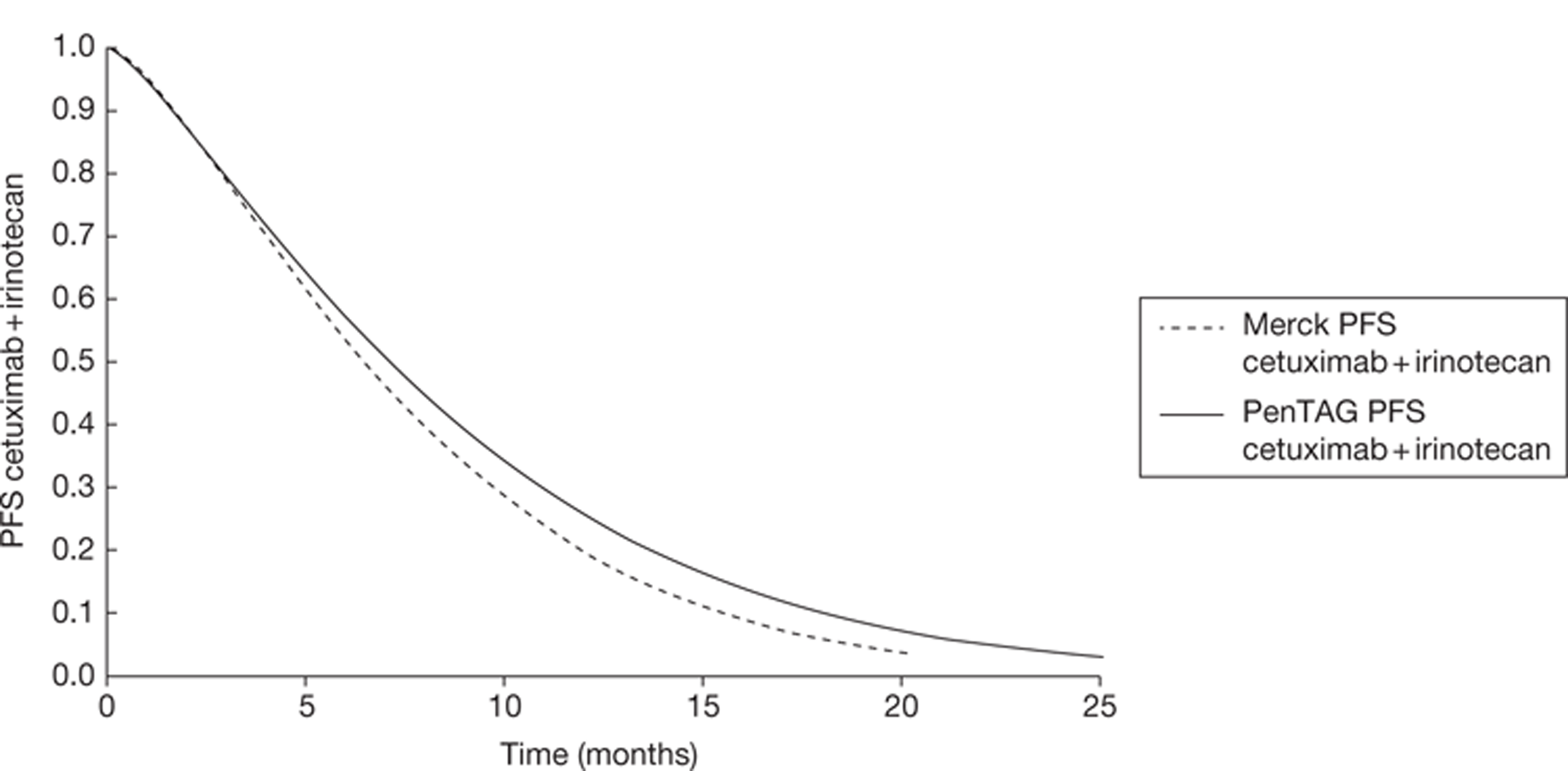

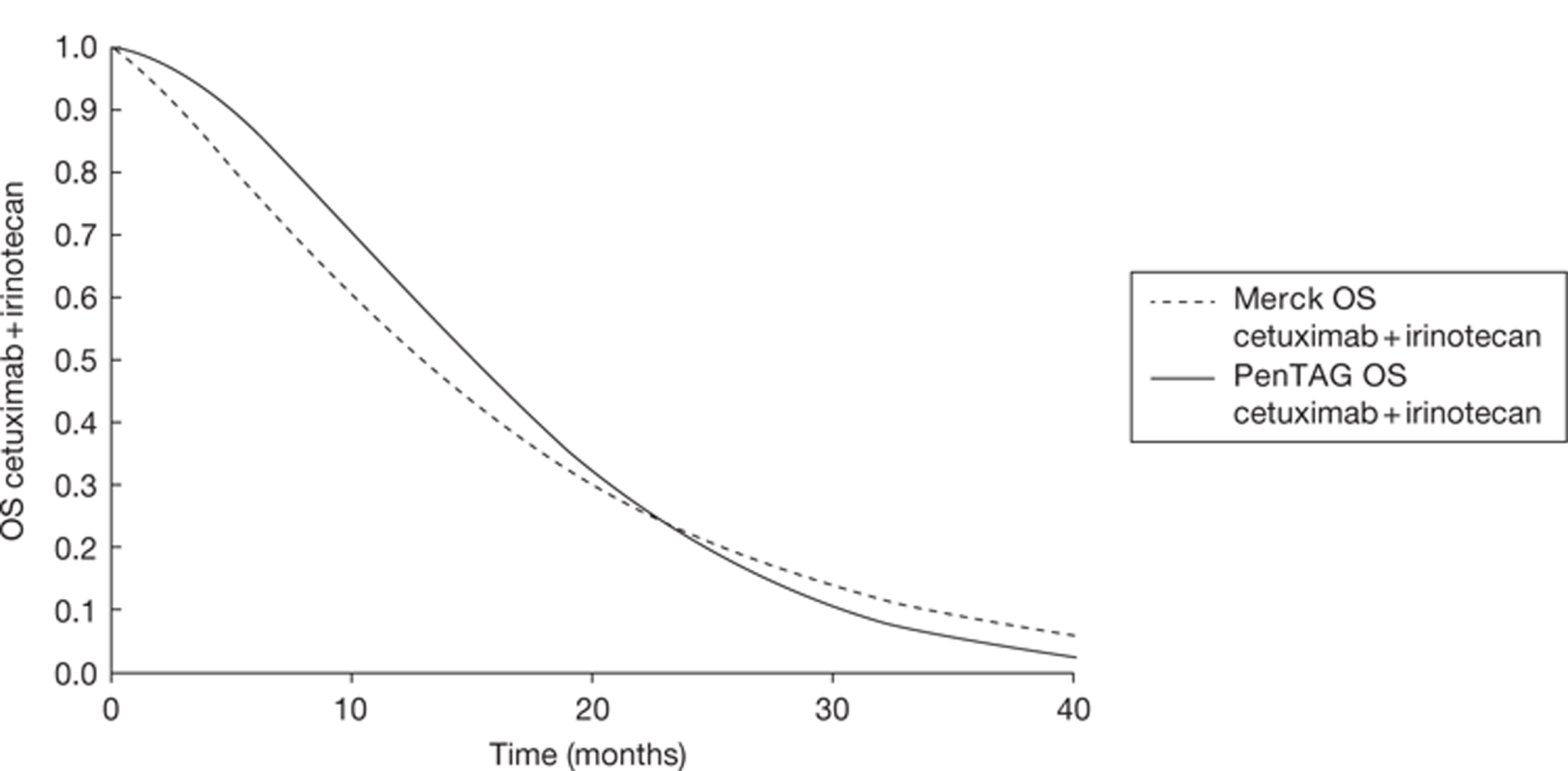

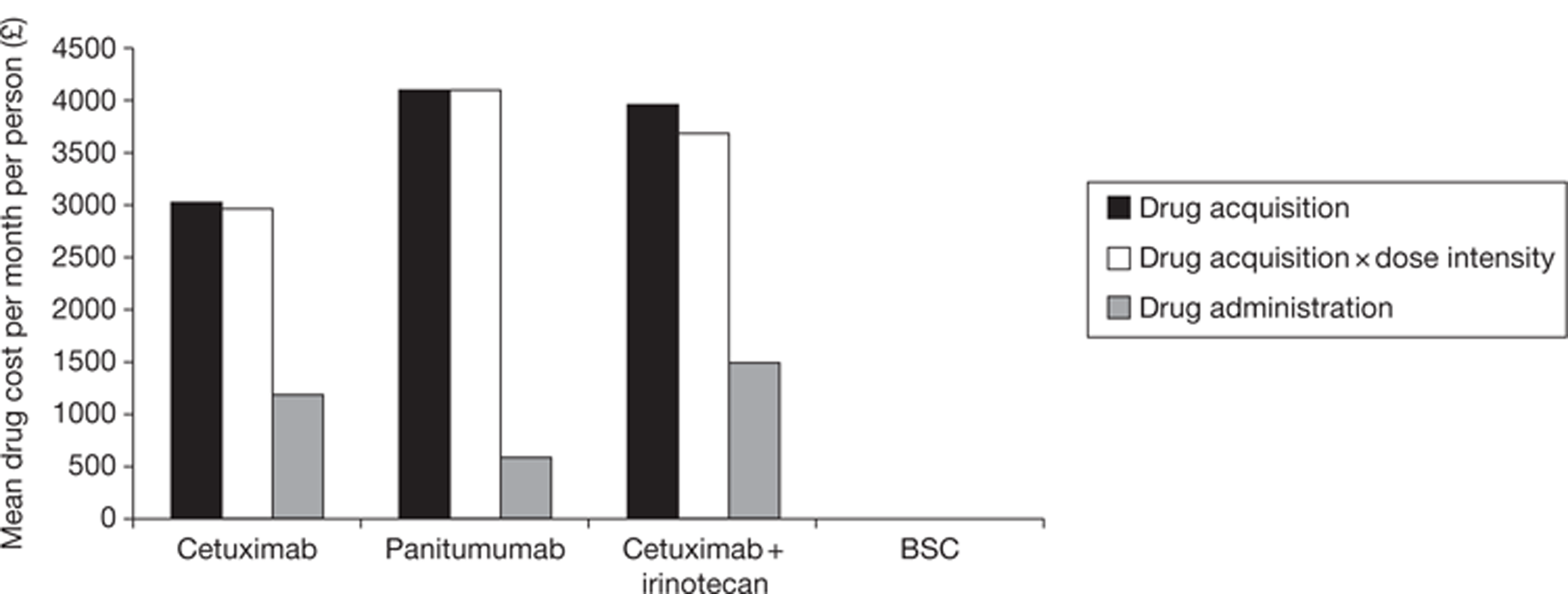

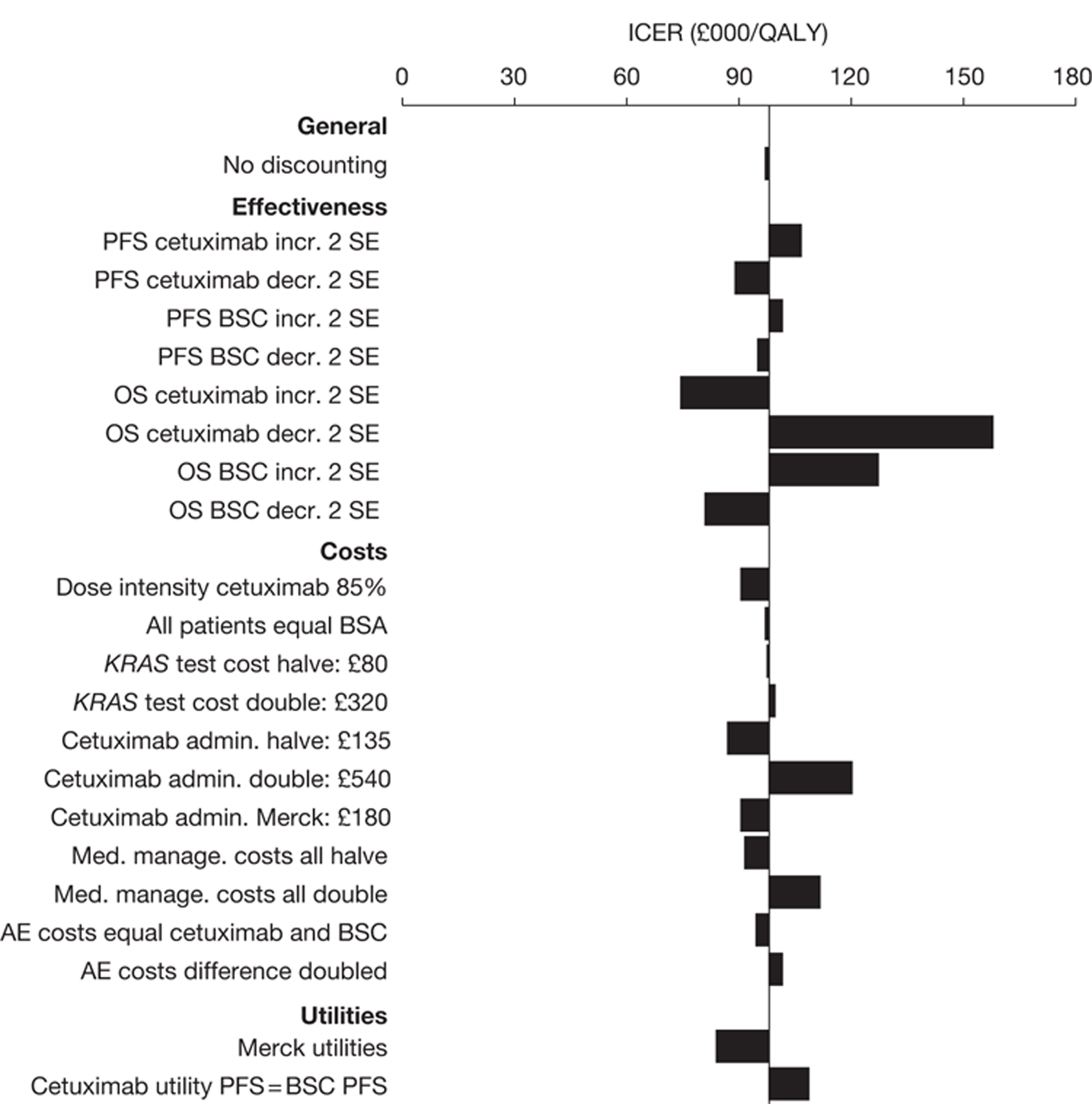

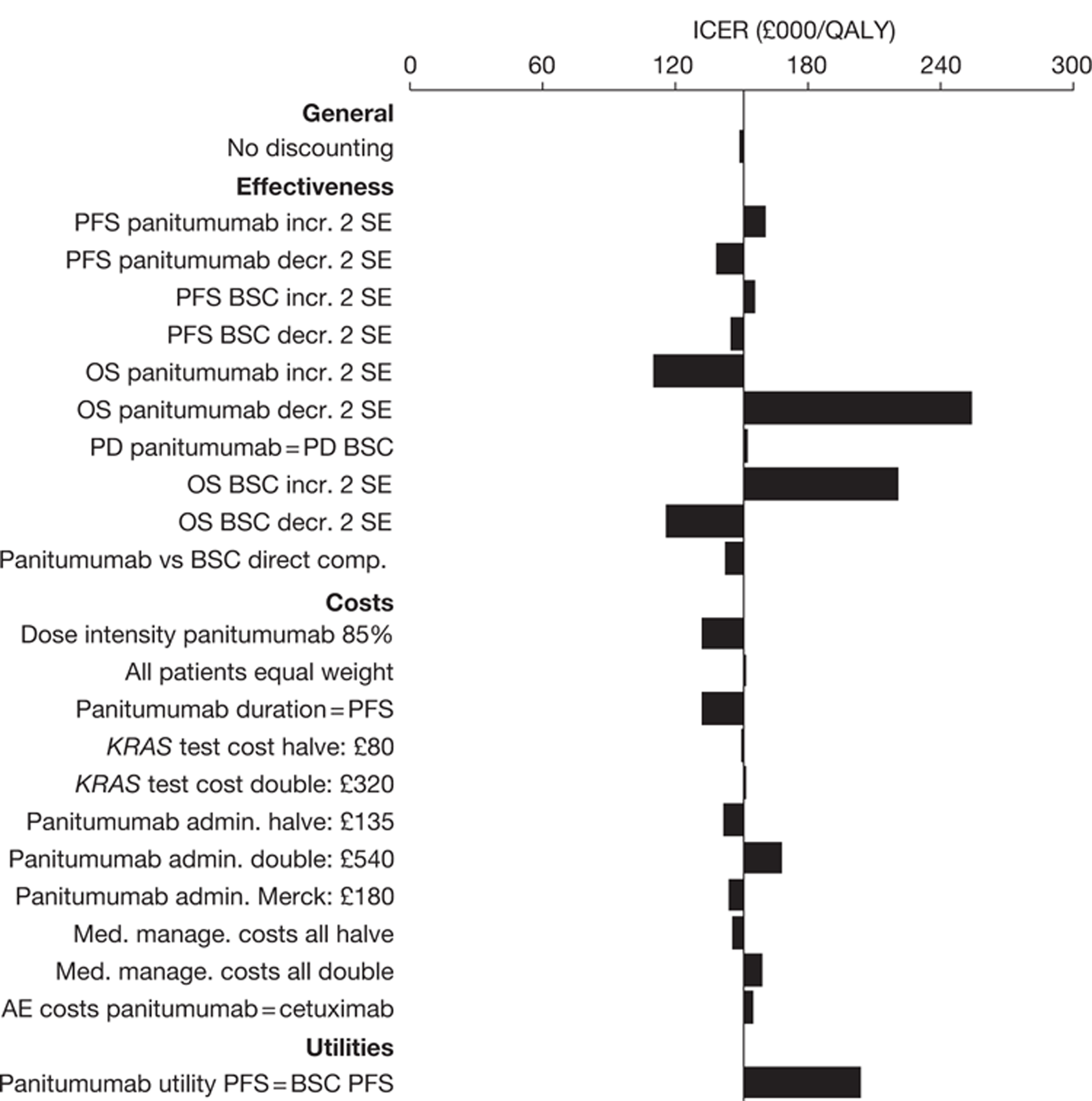

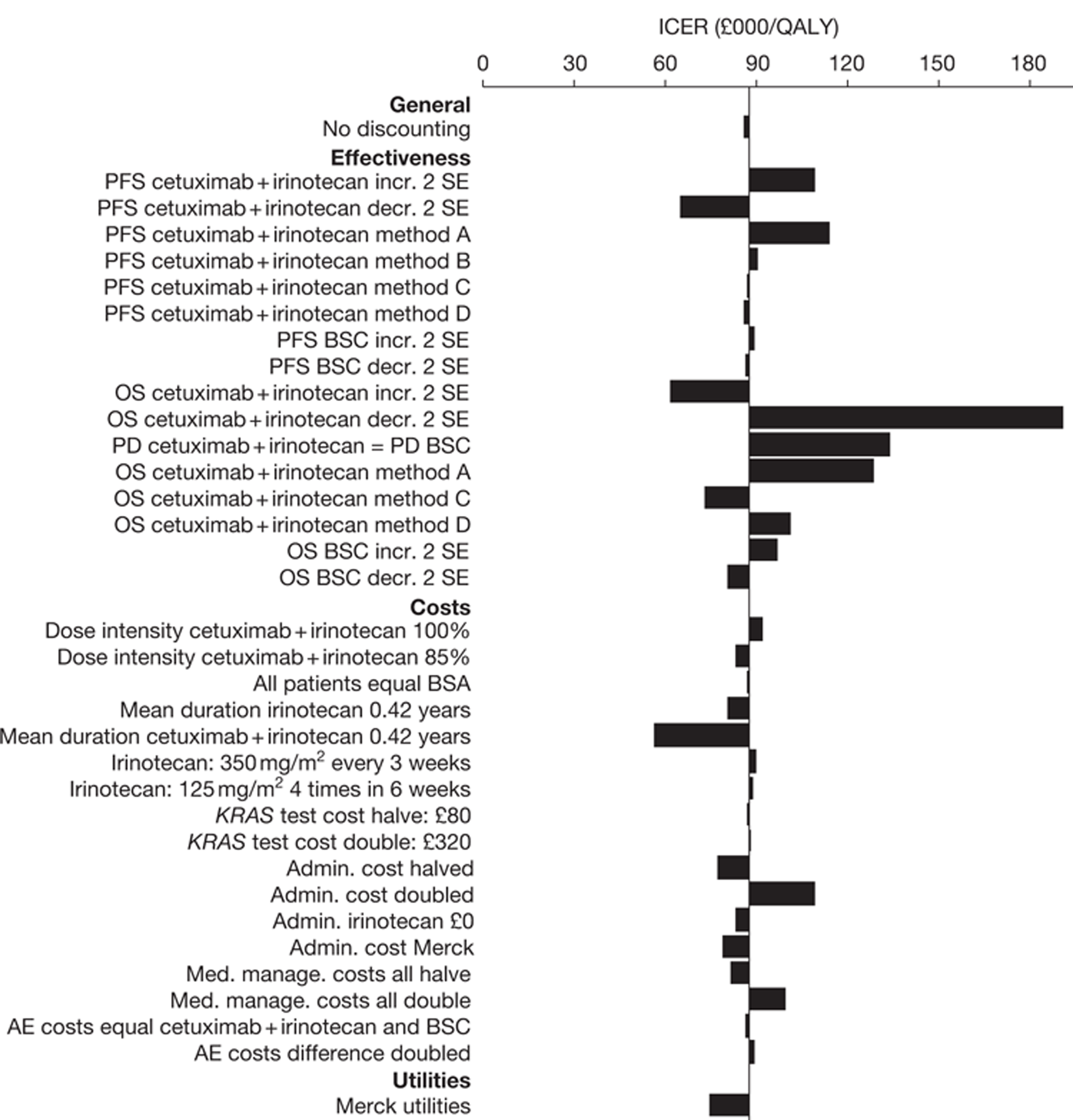

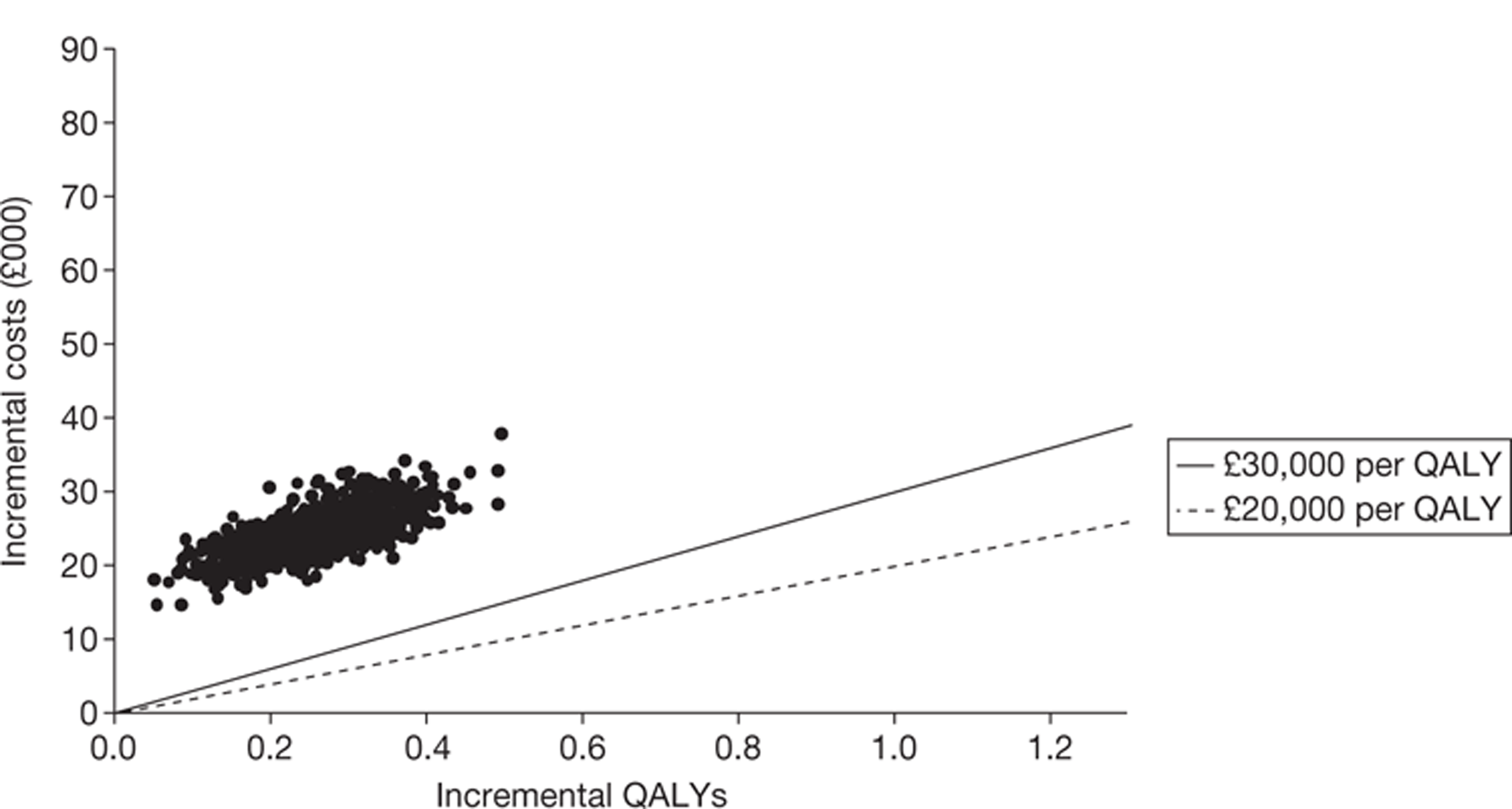

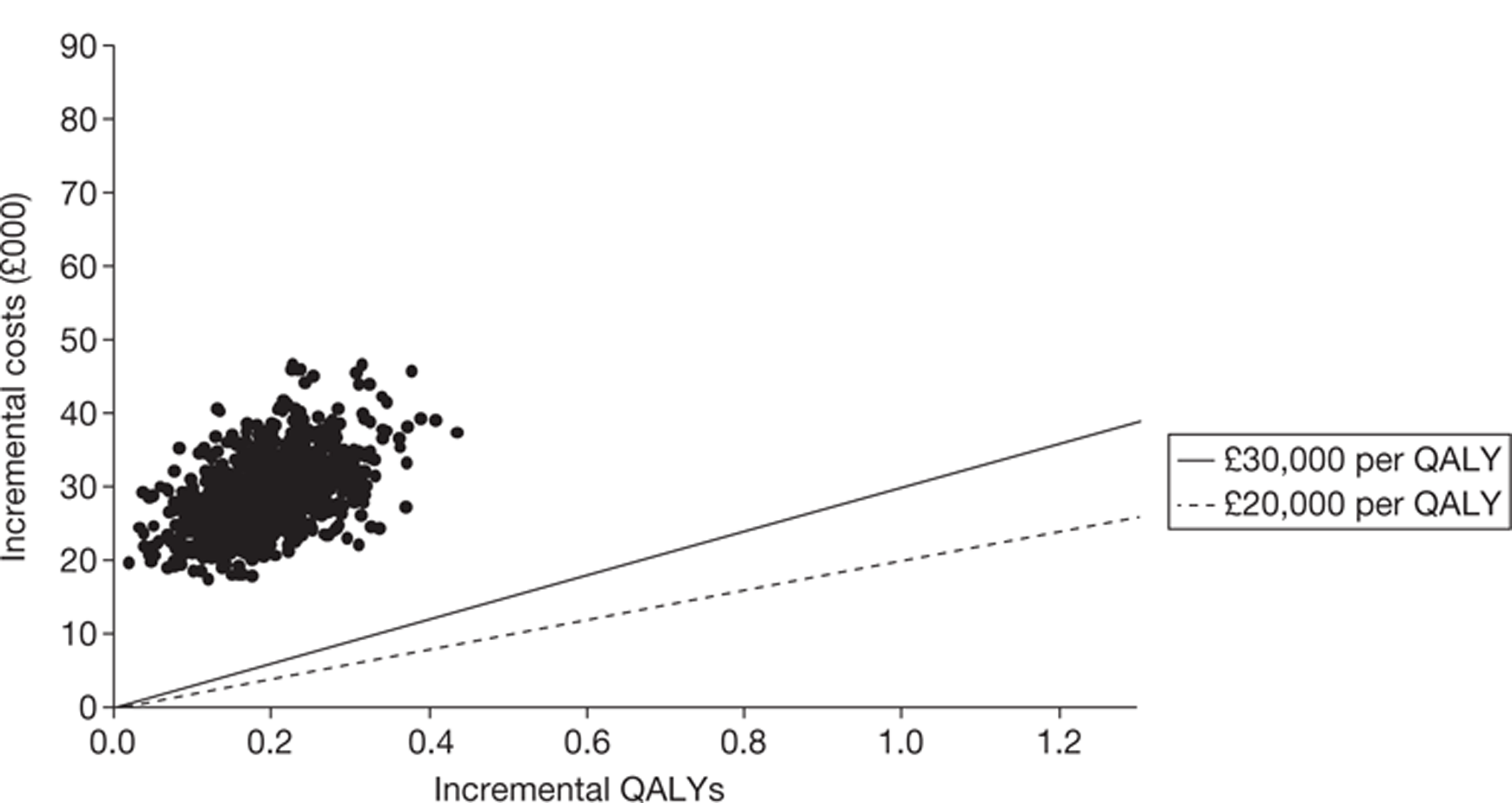

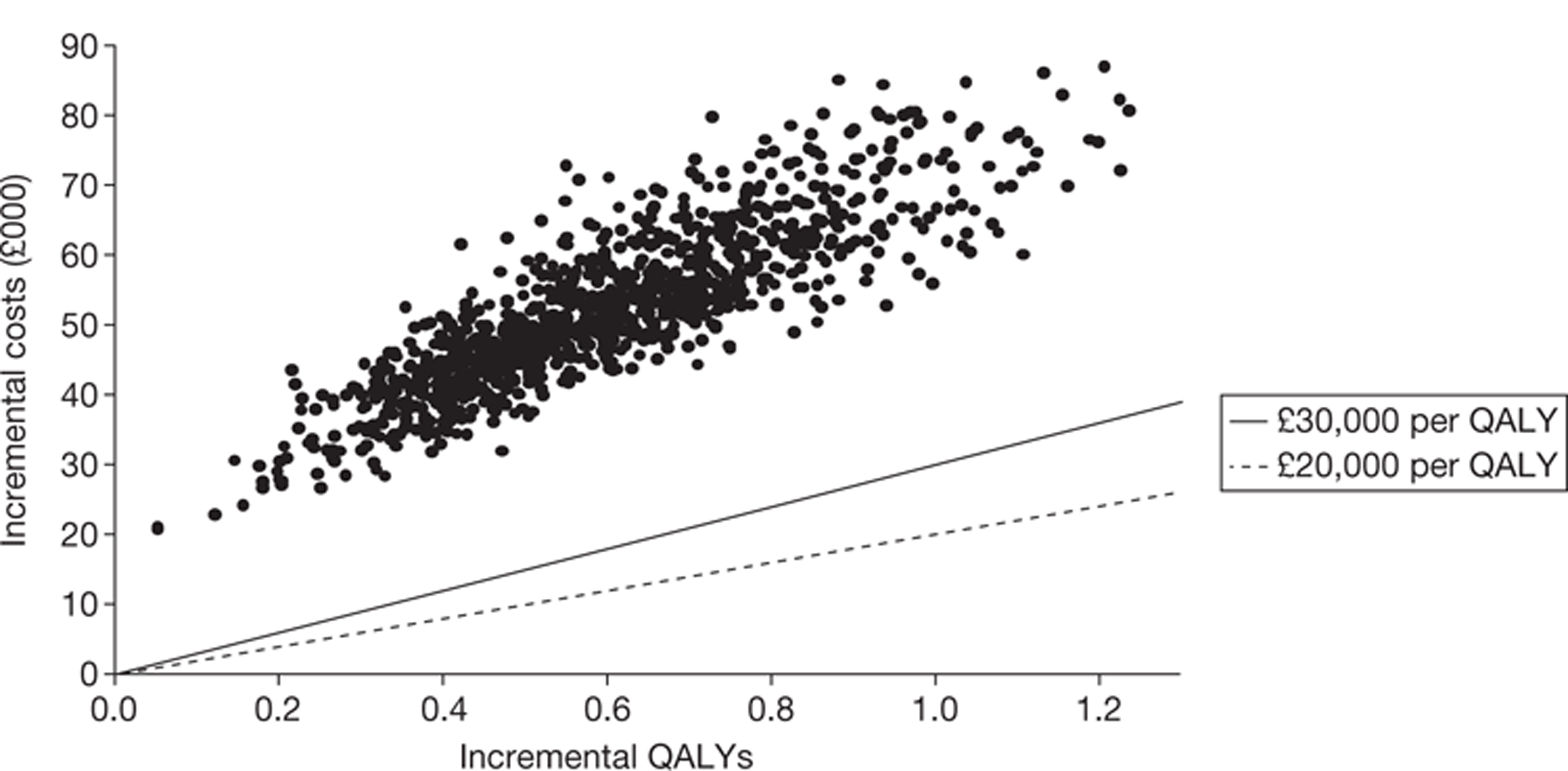

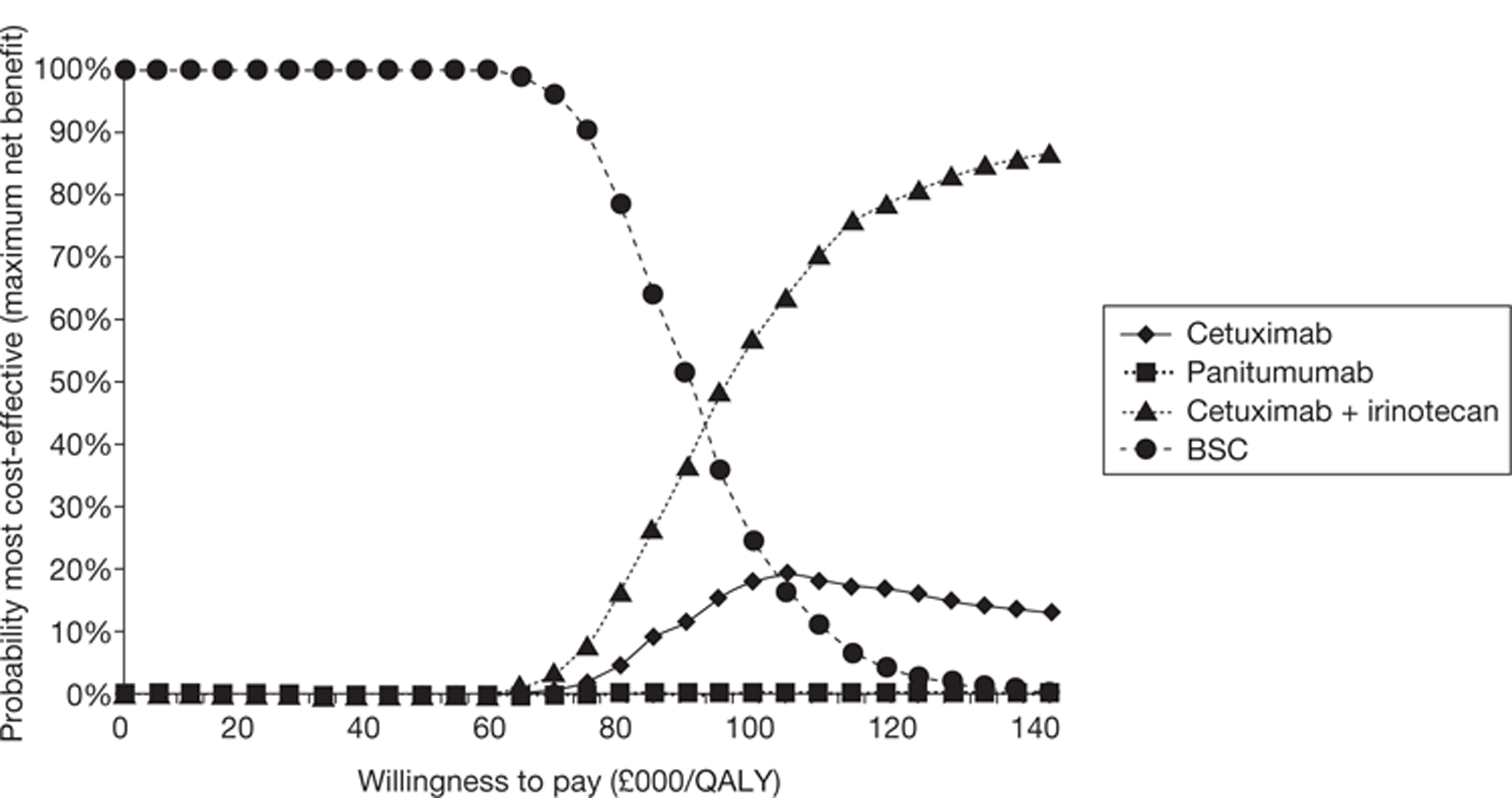

The searches identified 7745 titles and abstracts. Two clinical trials (reported in 12 papers) were included. No data were available for bevacizumab in combination with non-oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in previously treated patients. Neither of the included studies had KRAS status performed prospectively, but the studies did report retrospective analyses of the results for the KRAS WT subgroups. Third-line treatment with cetuximab plus best supportive care or panitumumab plus best supportive care appears to have statistically significant advantages over treatment with best supportive care alone in patients with KRAS WT status. For the economic evaluation, five studies met the inclusion criteria. The base-case incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for KRAS WT patients for cetuximab compared with best supportive care is £98,000 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY), for panitumumab compared with best supportive care is £150,000 per QALY and for cetuximab plus irinotecan compared with best supportive care is £88,000 per QALY. All ICERs are sensitive to treatment duration.

Limitations

In the specific populations of interest, there is a lack of evidence on bevacizumab, cetuximab and cetuximab plus irinotecan used second line and on bevacizumab and cetuximab plus irinotecan used third line. For cetuximab plus irinotecan treatment for KRAS WT people, there is no direct evidence on progression-free survival, overall survival and duration of treatment.

Conclusions

Although cetuximab and panitumumab appear to be clinically beneficial for KRAS WT patients compared with best supportive care, they are likely to represent poor value for money when judged by cost-effectiveness criteria currently used in the UK. It would be useful to conduct a RCT for patients with KRAS WT status receiving cetuximab plus irinotecan.

Funding

The National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme.

Chapter 1 Background

Description of health problem

Colorectal cancer is a malignant neoplasm arising from the lining of the large intestine (colon and rectum). Over 95% of colon and rectal cancers are adenocarcinomas, cancers that start in the cells that line the inside of the colon and rectum. Cancer cells eventually spread to nearby lymph nodes (local metastases) and subsequently to more remote lymph nodes and other organs in the body. The liver and the lungs are common metastatic sites of colorectal cancer.

Vascular endothelial growth factor and epidermal growth factor receptor

Two key elements in the growth and dissemination of tumours are the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR); both pathways are closely related, sharing common downstream signalling pathways. 1 VEGF and EGFR play important roles in tumour growth and progression through the exertion of both indirect and direct effects on tumour cells. 1 Biological agents targeting the VEGF and EGFR pathways have shown clinical benefit in several human cancers, either alone or in combination with standard cytotoxic therapies. Inhibition of VEGF-related pathways is thought to contribute to the mechanism of action of agents targeting the EGFR. 2 Conversely, (over)activation of VEGF expression independent of EGFR signalling is thought to be one way that tumours become resistant to anti-EGFR therapy. 3 Specific ongoing point mutations in the EGFR gene are also thought to convey resistance to anti-EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. 4 The possibility that combined VEGF and EGFR pathway blockade could further enhance antitumour efficacy and help prevent resistance to therapy is currently being evaluated in clinical trials. 1

Kirsten rat sarcoma

Kirsten rat sarcoma (KRAS) is a gene that codes for a protein that plays an important role in the EGFR pathway, a complex signalling cascade that is involved in the development and progression of cancer.

The KRAS protein regulates other proteins, downstream in the EGFR signalling pathway, that are associated with tumour survival, angiogenesis, proliferation and metastasis. 5 Thereare different types of the KRAS gene found in tumours that either code for a ‘normal’, non-mutated KRAS protein known as KRAS wild type (WT), or an abnormal, mutated protein known as mutant KRAS. The KRAS ‘status’ (KRAS WT vs KRAS mutant) may be indicative of prognosis and predictive of response to certain drugs including those under consideration in this review. In tumours with KRAS WT status, the protein is only temporarily activated in response to certain stimuli such as EGFR signalling. This tight regulation warrants a close control of downstream effects. In tumours with the mutated version of the KRAS gene, the KRAS protein is permanently ‘turned on’ even without being activated by the upstream EGFR-mediated signalling. As a result the downstream effects that lead to tumour growth and spread continue unregulated.

The KRAS test is performed on a sample of tumour tissue that is sent to a laboratory for analysis of the KRAS mutation status – WT or mutant. The process helps to enable the most effective treatment to be selected for the individual patient. There are multiple methods for determining the KRAS mutation status of a tumour (Table 1);6 all appear to have adequate clinical sensitivity to detect patients unlikely to respond to cetuximab or panitumumab. The limitation of sequencing technologies is the requirement of > 5–10% mutant alleles for pyrosequencing and > 20% for Sanger sequencing, although newer approaches are being developed to increase the sensitivity of sequencing methods. 6

| Method | Sensitivity of mutant alleles (%) | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sanger sequencing | 20 |

|

|

| Pyrosequencing | 5–10 |

|

|

| Allele-specific real-time PCR | 1 |

|

|

| Post-PCR fluorescent melting curve analysis with specific probes | 5–10 |

|

|

| PCR clamping method | 1 |

|

|

In colorectal cancer, up to 65% of patients are KRAS WT status; the remaining 35% are KRAS mutant. 7

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Colorectal cancer is a common form of malignancy in developed countries but occurs much less frequently in the developing world. It is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in the UK, with around 39,991 new cases registered in the UK in 2008 (32,644 cases registered in England and Wales). 8 The number of cases of colorectal cancer and the incidence rates in England and Wales are shown in Table 2.

| England | Wales | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Cases | 18,040 | 1311 |

| Crude rate per 100,000 | 71.2 | 89.8 | |

| ASR per 100,000 population (95% CI) | 57.0 (56.2 to 57.8) | 64.4 (60.9 to 67.9) | |

| Women | Cases | 14,604 | 89.8 |

| Crude rate per 100,000 | 55.9 | 64.6 | |

| ASR per 100,000 population (95% CI) | 36.9 (36.3 to 37.5) | 39.3 (36.9 to 41.8) | |

| Total | Cases | 32,644 | 2300 |

| Crude rate per 100,000 | 63.4 | 76.9 | |

| ASR per 100,000 population (95% CI) | 46.1 (45.6 to 46.6) | 50.7 (48.6 to 52.8) |

Data for colorectal cancer patients diagnosed in England in 2000–4 did show a deprivation gradient for male patients with incidence rates 11% higher in the most deprived groups than in the affluent groups. 8

The occurrence of colorectal cancer is strongly related to age, with 86% of cases arising in people aged 60+ years. 8 Until age 50, men and women have similar rates for colorectal cancer, but in later life the incidence rate for men is higher. In numerical terms there are more cases of colorectal cancer in men among almost all age groups up to the age of 84, after which cases of colorectal cancer in women are in the majority, even though their rates are lower, as women make up a larger proportion of the elderly population. 8 Overall, the male-to-female ratio is 11 : 10. 8 The lifetime risk of being diagnosed with colorectal cancer in the UK is estimated to be 1 in 16 for men and 1 in 20 for women. 8

Pathology

Colorectal cancer includes malignant growths from the mucosa of the colon and rectum. Cancer cells eventually spread to nearby lymph nodes (local metastases) and subsequently to more remote lymph nodes and other organs in the body. The liver and the lungs are common metastatic sites of colorectal cancer.

The pathology of the tumour is usually determined by analysis of tissue taken from a biopsy or surgery. Colorectal cancer stage can be described using the modified Dukes'staging system (based on postoperative findings – a pathological staging based on resection of the tumour and measuring the depth of invasion through the mucosa and bowel wall) or the more precise TNM staging system, which is based on the depth of tumour invasion (T), nodal involvement (N) and metastatic spread (M) assessed preoperatively by radiological examination (Table 3). 9

| Staging group | TNM staging and sites involved | Modified Dukes' stage |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 0 | Carcinoma in situ (Tis, N0, M0) | |

| Stage I | No nodal involvement, no distant metastases | A |

| Tumour invades submucosa (T1, N0, M0) | ||

| Tumour invades muscularis propria (T2, N0, M0) | ||

| Stage II | No nodal involvement, no distant metastases | B |

| Tumour invades muscularis propria into pericolorectal tissues (T3, N0, M0) | ||

| Tumour penetrates surface of visceral peritoneum or directly invades or is adherent to other organs or structures (T4a/b, N0, M0) | ||

| Stage III | Nodal involvement, no distant metastases (any T, any N, M0) | C |

| Stage IV | Distant metastases (any T, any N, M1a/M1b) | D |

Knowing the stage of colon cancer is important for several reasons, including helping the physician to define an appropriate treatment plan and in predicting prognosis. In the UK, approximately 11% of patients are diagnosed at TNM stage I, 32% at stage II, 26% at stage III (lymph node involvement) and 30% at stage IV (metastatic disease). It is estimated that around 30% of patients present with metastatic disease and a further 20% may eventually develop metastatic disease. 10 Metastatic disease often develops first in the liver but metastases may also occur at other sites, including the lungs. 10

Prognosis

The treatment, prognosis and survival rate depend on the stage of disease at diagnosis.

The 5-year relative survival rates for both men and women with colorectal cancer have doubled between the early 1970s and the mid-2000s. 11 Five-year survival rates for men with colorectal cancer rose from 25% in the early 1970s to 51% in the mid-2000s and from 27% to 55% for men with colon cancer. 11 These improvements are a result of earlier diagnosis and better treatment but there is still much scope for further progress. 11 Ten-year survival rates are only a little lower than those at 5 years indicating that most patients who survive for 5 years are cured from this disease. 11

Patients who are diagnosed at an early stage have a much better prognosis than those who present with more extensive disease. 11 Over 93% of patients diagnosed with stage A on the modified Dukes'classification system (the earliest stage of the disease) survived for 5 years compared with < 7% of patients with advanced disease (stage D) (Table 4). 11

| Modified Dukes' stage at diagnosis | Percentage of cases | 5-year relative survival (%)a |

|---|---|---|

| A | 9 | 93 |

| B | 24 | 77 |

| C | 24 | 48 |

| D | 9 | 7 |

| Unknown | 34 | 35 |

Treatment of colorectal cancer may be curative or palliative depending on the location of the tumour and the degree to which the tumour has penetrated the bowel and spread to other organs in the body. Treatment options differ considerably for colon and rectal tumours. Recurrence of colorectal cancer may be local or metastatic; however, local recurrence is less commonly reported in patients with colon cancer. Treatments of metastatic recurrence of colorectal cancer are typically palliative; however, hepatic resection and pulmonary resection may offer a chance of cure in a small proportion of patients. The mainstay of treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer involves chemotherapy; cytotoxic agents include 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), capecitabine, oxaliplatin, irinotecan, tegafur with uracil, and mitomycin. Again, these may be given according to a variety of regimens across different lines of therapy.

Impact of the health problem

Significance for patients in terms of ill-health (burden of disease)

Colorectal cancer is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality. When treating patients with metastatic colorectal cancer, the main aims of treatment are to relieve symptoms and to improve health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and survival. 12 In 2008 there were 14,233 deaths from colorectal cancer in England and Wales. The majority of deaths occurred in older people: around 80% in people aged 65+ years and almost 40% in those aged 80+ years (Table 5). 12

| England | Wales | |

|---|---|---|

| Deaths | ||

| Men | 7178 | 499 |

| Women | 6138 | 418 |

| Total | 13,316 | 917 |

| Crude rate per 100,000 population | ||

| Men | 28.4 | 34.1 |

| Women | 23.5 | 27.3 |

| Total | 25.9 | 30.6 |

| ASR (European) per 100,000 population (95% CI) | ||

| Men | 21.8 (21.3 to 22.3) | 23.6 (21.5 to 25.6) |

| Women | 13.6 (13.3 to 14.0) | 14.6 (13.2 to 16.0) |

| Total | 17.3 (17.0 to 17.6) | 18.6 (17.4 to 19.8) |

Quality of life

Assessment of HRQoL has become an important feature of cancer trials, enabling evaluation of treatment effectiveness from the perspective of the person with the condition and facilitating improved clinical decision-making.

There are several general HRQoL instruments for people with cancer that can be used to assess quality of life (QoL) both in research studies and in clinical practice, for example the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Colorectal Cancer Symptom Index (NCCN FCSI) and the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire C30 (QLQ-C30).

Significance for the NHS

Current service provision

National guidelines

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has issued the following guidance:

-

Technology appraisal (TA) No. 93 – Irinotecan, oxaliplatin and raltitrexed for the treatment of advanced colorectal cancer: review of technology appraisal No. 3314

-

TA61– Guidance on the use of capecitabine and tegafur with uracil for metastatic colorectal cancer15

-

TA118 – Bevacizumab and cetuximab for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer16

-

TA176 – Cetuximab for the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer17

-

TA105 – Laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer: review of NICE technology appraisal No. 11718

-

TA212 – Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin and either fluorouracil plus folinic acid or capecitabine for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer19

-

Guidance for Commissioning Cancer Services: Improving Outcomes in Colorectal Cancers: Research Evidence for the Manual Update 13

-

Clinical Guideline 131– Colorectal cancer: The diagnosis and management of colorectal cancer20

In addition, the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland (ACPGBI) has published guidelines for the management of colorectal cancer. 21

Current management

The treatment and prognosis for colorectal cancer depend on the stage of the cancer. For early cancer, treatment may consist of surgery alone. 10 Surgery to remove the primary tumour is the principal first-line treatment for approximately 80% of patients, after which about 40% will remain disease free in the long term. 20 In 20–30% of cases the disease is too far advanced at initial presentation for any attempt at curative intervention; many of these patients die within a few months. 20

The most frequent site of metastases is the liver. In as many as 50% of patients with advanced disease the liver may be the only site of spread, and for these patients surgical resection may be the only chance of a cure. 10,20 Reported 5-year survival rates for resection of liver metastases range from 16% to 48%, which is considerably better than those for systemic chemotherapy. 10

Individuals with metastatic disease who are sufficiently fit (normally those with World Health Organization performance status ≤ 2) are usually treated with active chemotherapy as first- or second-line therapy. 20 The backbone to treatment across all lines of therapy is composed of fluoropyrimidine, irinotecan or oxaliplatin. More recently, targeted agents have become available, including anti-EGFR agents, for example cetuximab and panitumumab, and anti-VEGF agents, for example bevacizumab (see National guidelines).

Based on a literature review and elicitation of expert opinion, Shabaruddin and colleagues22 identified predominant treatment pathways within NHS colorectal cancer specialties as first-line treatment with oxaliplatin-based regimens, second-line treatment with irinotecan-based regimens and third-line treatment with mitomycin-based regimens. Current evidence indicates that the use of 5-FU, oxaliplatin and irinotecan at any sequence within a patient's care pathway has survival advantages. 23

A treatment algorithm for colorectal cancer in England and Wales developed by Tappenden and colleagues10 (TA11816) estimates that up to 85% of patients with advanced metastatic colorectal cancer not amenable to resection receive active first-line therapy. Of these, approximately 50% go on to receive second-line therapy with 5% of those estimated to go on to receive third-line therapy. This treatment algorithm showed that roughly 300 patients receive a third-line chemotherapy in England and Wales. However, there is a paucity of data based on modern clinical oncology practice documenting the proportions of patients on the various pathways of disease once metastatic colorectal cancer has occurred, and this is often estimated via expert advisory groups.

First-line treatment

First-line active chemotherapy options include oxaliplatin plus infusional 5-FU/folinic acid (FA) (FOLFOX) and irinotecan plus infusional 5-FU/FA (FOLFIRI) (TA93). 14 Additionally, TA93 did not recommend raltitrexed for those with advanced colorectal cancer unless they were taking part in a clinical trial. Oral analogues of 5-FU (capecitabine and tegafur with uracil) may also be used instead of infusional 5-FU (TA61). 15

Cetuximab in combination with FOLFOX or in combination with FOLFIRI is also recommended by NICE as an option for the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer when the metastatic disease is confined to the liver and the aim of treatment is to render the metastases resectable (TA176). 17

In 2009 NICE did not recommend bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin and either 5-FU/FA or capecitabine for those with metastatic colorectal cancer. 16

Second-line treatment

For those patients first receiving FOLFOX, irinotecan may be a second-line treatment option, whereas for patients first receiving FOLFIRI, oxaliplatin may be a second-line treatment option (TA93). 14 Patients receiving 5-FU/FA or an oral analogue as first-line treatment may be offered FOLFOX or FOLFIRI as second-line and subsequent therapies.

Technology appraisal No. 118 did not recommend cetuximab in combination with irinotecan for the treatment of those with metastatic colorectal cancer previously treated with irinotecan. 16

Third-line treatment

In the third-line setting the majority of patients will receive best supportive care.

Description of technologies under assessment

Bevacizumab (Avastin®, Roche)

Bevacizumab is a recombinant humanised monoclonal antibody that acts as an angiogenesis inhibitor. It targets the biological activity of human VEGF, which stimulates new blood vessel formation in the tumour. 24 Depriving tumours of VEGF has several effects that are relevant to the therapeutic use of bevacizumab. These include preventing the development of new tumour blood vessels, causing the regression of existing vasculature and normalising the function of the remaining tumour blood vessels resulting in enhanced delivery of concomitantly administered cytotoxic drugs. 25

Bevacizumab is licensed in combination with 5-fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy and is indicated for treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. 24 The original European Medicines Agency (EMA) marketing authorisation for bevacizumab in metastatic colorectal cancer restricted it to use in the first-line setting in combination with 5-FU-based chemotherapy with or without irinotecan, based on the Phase III trial data then available. The EMA granted a broader marketing authorisation in 2010 licensing bevacizumab in combination with fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy for treatment of patients with metastatic cancer of the colon and rectum. The extension to the marketing authorisation followed publication of further studies showing that bevacizumab added to combinations of 5-FU or capecitabine in the first- or second-line setting also improved treatment outcomes. 26,27

Bevacizumab is contraindicated in patients who are pregnant or who have hypersensitivity to products derived from Chinese hamster ovary cell cultures or other recombinant human or humanised antibodies. Special warnings and precautions for use include gastrointestinal perforations, wound healing complications, hypertension, proteinuria, arterial thromboembolism, haemorrhage and congestive heart failure/cardiomyopathy. 24

The most common adverse events with bevacizumab (incidence > 10% and at least twice the control arm rate) are epistaxis, headache, hypertension, rhinitis, proteinuria, taste alteration, dry skin, rectal haemorrhage, lacrimation disorder and exfoliative dermatitis.

Bevacizumab must be administered under the supervision of a clinician experienced in the use of antineoplastic medicinal products. 24 It is administered over 90 minutes as an intravenous infusion at a dose of 5 mg/kg body weight once every 14 days, and is recommended until there is underlying disease progression. 24

Cetuximab (Erbitux®, Merck Serono Pharmaceuticals)

Cetuximab is a recombinant monoclonal antibody that blocks the human EGFR. EGFR is found on the surface of some cells and plays a role in regulating cell growth. Cetuximab is believed to interfere with the growth of cancer cells by binding to EGFR so that the normal epidermal growth factors cannot bind and stimulate the cells to grow.

Cetuximab, used in combination with irinotecan, is indicated for the treatment of EGFR-expressing KRAS WT metastatic colorectal cancer either in combination with chemotherapy or as a single agent in patients who have failed oxaliplatin- and irinotecan-based therapy and who are intolerant to irinotecan. 28 The Summary of Product Characteristics recommends that cetuximab must be administered under the supervision of a physician experienced in the use of antineoplastic medicinal products. Close monitoring is required during the infusion and for at least 1 hour after the end of the infusion in a setting with resuscitation equipment and other agents necessary to treat anaphylaxis. Patients requiring treatment should be monitored for longer. 28

Special warnings and precautions for use include hypersensitivity reactions, dyspnoea and skin reactions. Only patients with adequate renal and hepatic function have been investigated to date (serum creatinine ≤ 1.5-fold, transaminases ≤ 5-fold and bilirubin ≤ 1.5-fold the upper limit of normal). 28 Cetuximab has not been studied in patients presenting with one or more of the following laboratory parameters:28

-

haemoglobin < 9 g/dl

-

leucocyte count < 3000/mm3

-

absolute neutrophil count < 1500/mm3

-

platelet count < 100,000/mm3.

The most common adverse events with cetuximab (incidence ≥ 25%) are cutaneous adverse reactions (including rash pruritus and nail changes), headache, diarrhoea and infection.

The recommended initial dose, either as monotherapy or in combination with irinotecan, is 400 mg/m2 administered as a 120-minute intravenous infusion (maximum infusion rate 10 mg/ minute). The recommended subsequent weekly dose, either as monotherapy or in combination with irinotecan, is 250 mg/m2 infused over 60 minutes (maximum infusion rate 10 mg/minute) until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

There is limited experience in the use of cetuximab in combination with radiation therapy in colorectal cancer. 28

Panitumumab (Vectibix®, Amgen)

Panitumumab is a recombinant monoclonal antibody that targets the EGFR receptor, thereby inhibiting the growth of EGFR-expressing tumours. Panitumumab is licensed as monotherapy for treating patients with EGFR-expressing metastatic colorectal cancer with KRAS WT status after failure of previous chemotherapy regimens containing fluoropyrimidine, irinotecan and oxaliplatin.

Panitumumab treatment should be supervised by a physician experienced in the use of anticancer therapy. 29 The recommended dose of panitumumab is 6 mg/kg of body weight given once every 2 weeks. 29 Before infusion, panitumumab should be diluted in 0.9% sodium chloride injection to a final concentration not to exceed 10 mg/ml. 29

Panitumumab is contraindicated in patients with a history of severe or life-threatening hypersensitivity reactions to the active substance or to any of the excipients. 29 The most common adverse events (incidence ≥ 20%) are skin toxicities (i.e. erythema, dermatitis acneiform, pruritus, exfoliation, rash and fissures), paronychia, hypomagnesaemia, fatigue, abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhoea and constipation.

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Decision problem

The purpose of this report is to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cetuximab (mono- or combination chemotherapy), bevacizumab (combination with non-oxaliplatin chemotherapy) and panitumumab (monotherapy) for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer after first-line chemotherapy. 30

Population including subgroups

The population for this assessment is adults with metastatic colorectal cancer who have failed first-line chemotherapy. This is further restricted to patients with EGFR-expressing metastatic colorectal cancer with KRAS WT status for cetuximab and panitumumab in line with the marketing authorisations for these treatments.

Interventions

This technology assessment report will consider three pharmaceutical interventions:

-

bevacizumab in combination with non-oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy

-

cetuximab monotherapy and in combination with chemotherapy

-

panitumumab monotherapy.

Each should be being used in accordance with the marketing authorisation and in the populations indicated in Population including subgroups.

Relevant comparators

Any clinically relevant alternative treatment for the population in question, but particularly including:

-

irinotecan- or oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy regimens (in the case of second-line treatment)

-

best supportive care (in the case of third-line or later treatment) consisting of pain control, antiemetics, appetite stimulants (steroids) and, in some cases, radiotherapy

-

one of the other interventions under consideration.

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Methods for reviewing effectiveness

The clinical effectiveness of bevacizumab, cetuximab and panitumumab for metastatic colorectal cancer was assessed by a systematic review of research evidence. The review was undertaken following the principles published by the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD). 31

Identification of studies

Electronic databases were searched using terms related to the population and the interventions only, without recourse to methodological or outcome filters. The sensitivity here allowed for the multiple requirements of the review.

Appendix 1 shows the search strategies undertaken databases searched; these included MEDLINE, EMBASE (both via Ovid), The Cochrane Library, Web of Science (ISI) (including Conference Proceedings Citation Index) and EconLit (EBSCOhost). ClinicalTrials.gov, Current Controlled Trials, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) website and the EMA website were also searched. The search initially used as its basis a previous multiple technology assessment (MTA) by Tappenden and colleagues10 to construct the population aspect of the search. Searches were not limited by language but were limited by date (2005–17 November 2010), as stated in the protocol (see Appendix 2).

Included studies and industry submissions were analysed to ensure the saturation of relevant studies.

All references were exported into EndNote X4 (Thomson Reuters CA, USA) for conversion to RIS format before being uploaded into EPPI Reviewer (version 4, EPPI-Centre, Institute of Education, London, UK) where manual deduplication was performed.

Relevant studies were then identified in two stages. Titles and abstracts returned by the search strategy were examined independently by two researchers (LC and TJH) and screened for possible inclusion. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Full texts of the identified studies were obtained. Two researchers (LC and TJH) examined these independently for inclusion or exclusion, and disagreements were again resolved by discussion.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Study design

Inclusion criteria

For the review of clinical effectiveness, only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews of RCTs were considered. The review protocol made provision for broadening the search criteria to include some observational evidence if insufficient systematic reviews or RCTs were identified.

Systematic reviews were used as a source for finding further RCTs and to compare with our systematic review. For the purpose of this review, a systematic review was defined as one that has:

-

a focused research question

-

explicit search criteria that are available to review, either in the document or on application

-

explicit inclusion/exclusion criteria, defining the population(s), intervention(s), comparator(s) and outcome(s) of interest

-

a critical appraisal of included studies, including consideration of the internal and external validity of the research

-

a synthesis of the included evidence, whether narrative or quantitative.

The preliminary screening of titles and abstracts did not discriminate according to KRAS status, to ensure that trials were not excluded in error. However, during the full-text screening process it became apparent that no clinical trials existed with prospective analysis of KRAS status. Because this relatively recent understanding of KRAS WT status and intervention efficacy is key to this review, trials that retrospectively analysed outcomes according to this subgroup were included.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if they did not match the inclusion criteria and in particular were:

-

non-randomised studies (except for adverse events)

-

animal models

-

preclinical and biological studies

-

narrative reviews, editorials, opinions

-

non-English-language papers

-

reports published as meeting abstracts only, in which insufficient methodological details were reported to allow critical appraisal of study quality.

Population

Randomised controlled trials were included for panitumumab and cetuximab if they reported clinical outcomes for an adult population with EGFR-expressing metastatic colorectal cancer with KRAS status assessed that has progressed after first-line chemotherapy. The justification for including only studies in which the population had their KRAS status assessed revolves around recent evidence indicating that anti-EGFR-targeted antibodies, such as cetuximab and panitumumab, are effective only in patients with KRAS WT as opposed to KRAS mutant oncogenes. 32

For bevacizumab, studies were included if the population with metastatic colorectal cancer had progressed after first-line chemotherapy. No stipulation for EGFR expression or KRAS status was required as this has been shown to have no influence on bevacizumab activity. 33

Interventions and comparators

Studies were included if the technologies they assessed fulfilled the following criteria:

-

after first-line therapy with cetuximab as monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy

-

after first-line therapy with bevacizumab in combination with non-oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy

-

after first-line therapy with panitumumab as monotherapy.

Alternative treatments for the population in question (clinically relevant comparators) were:

-

irinotecan- or oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy regimens

-

one of the interventions under consideration

-

best supportive care.

We have also considered the validity of indirect comparisons between interventions when appropriate.

Outcomes

Studies were included if they reported data on one or more of the following outcomes:

-

overall survival

-

progression-free survival

-

tumour response rate

-

adverse effects of treatment

-

HRQoL

-

liver resection rates.

Data extraction strategy

Data were extracted by one reviewer (TJH) using a standardised data extraction form in Microsoft Access 2007 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and checked by a second reviewer (LC). Disagreements were resolved by discussion, with involvement of a third reviewer if necessary. Data extraction forms for each included study can be found in Appendix 3.

Critical appraisal strategy

The methodological quality of the studies was assessed according to criteria specified by the CRD. 31 Quality was assessed by one reviewer and judgements were checked by a second. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion, with involvement of a third reviewer as necessary. The instrument is summarised below. Results were tabulated and the relevant aspects described in the data extraction forms.

Internal validity

The instrument sought to assess the following:

-

Was the assignment to the treatment groups really random?

-

Was the treatment allocation concealed?

-

Were the groups similar at baseline in terms of prognostic factors?

-

Were the eligibility criteria specified?

-

Were outcome assessors blinded to the treatment allocation?

-

Was the care provider blinded?

-

Was the patient blinded?

-

Were point estimates and a measure of variability presented for the primary outcome measure?

-

Did the analyses include an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis?

-

Were withdrawals and dropouts completely described?

In addition, methodological notes were made for each included study, with the reviewer's observations on sample size and power calculations, participant attrition, methods of data analysis, and conflicts of interest.

External validity

External validity was judged according to the ability of a reader to consider the applicability of findings to a patient group and service setting. Study findings can be generalisable only if they provide enough information to consider whether or not a cohort is representative of the affected population at large. Therefore, studies that appeared to be typical of the UK metastatic colorectal cancer population with regard to these considerations were judged to be externally valid.

Methods of data synthesis

Details of the extracted data and quality assessment for each individual study are presented in structured tables and as a narrative description. Any possible effects of study quality on the effectiveness data are discussed. Survival data (overall survival and progression-free survival) are presented as hazard ratios where available.

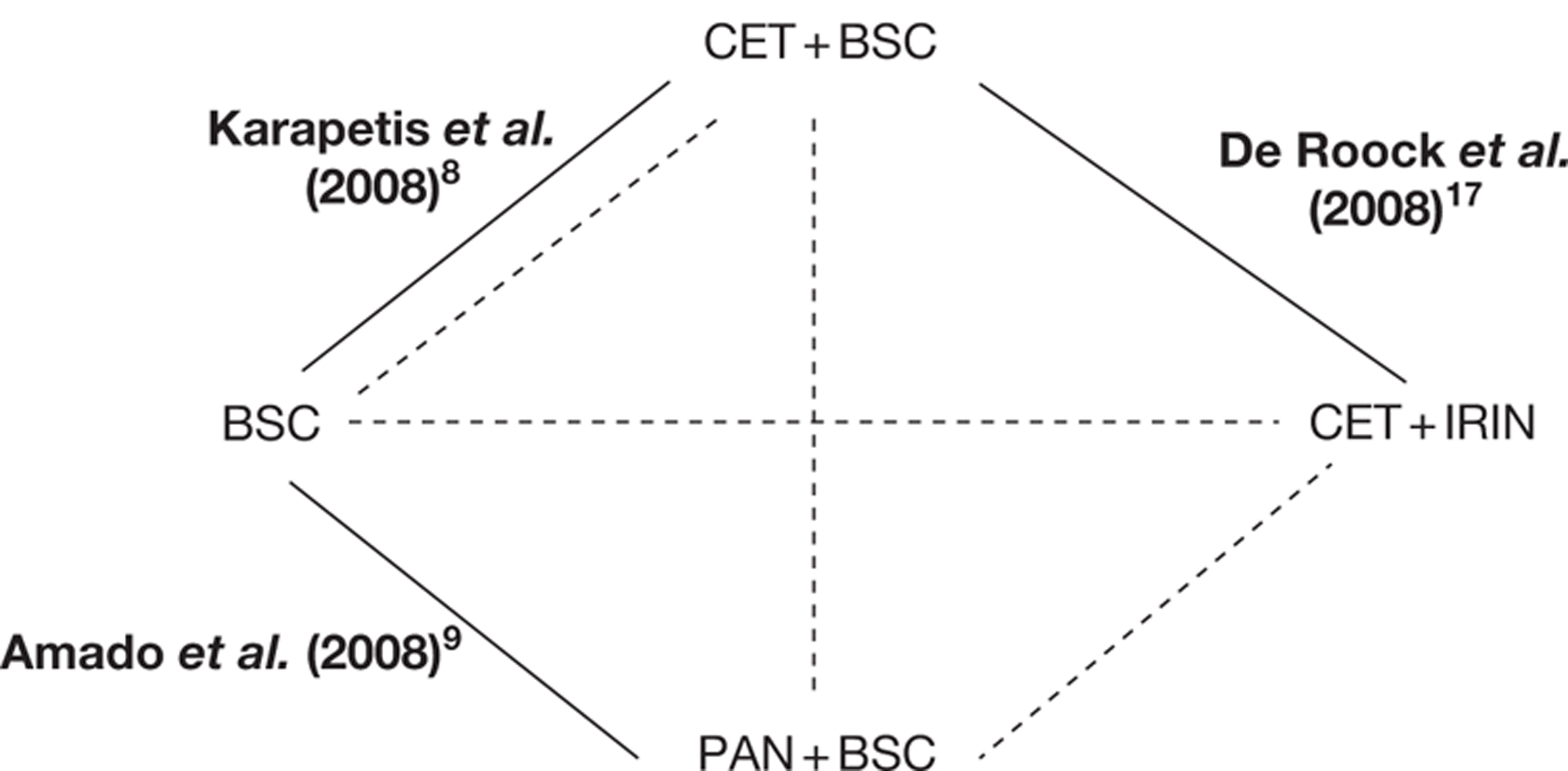

When data on head-to-head comparisons between interventions were not available, we performed adjusted indirect comparisons using an adaption of the method described by Bucher and colleagues. 34 This method aims to overcome the potential problems of a simple direct comparison (i.e. comparison of simple arms of different trials), in which the benefit of randomisation is lost leaving the data subject to the biases associated with observational studies. The method is valid only when the characteristics of patients are similar between the different studies being compared. Further details of the methods used can be found in Appendix 4.

Use of manufacturers'submissions to the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence

A description of the search strategy employed in each of the manufacturers'submissions and a comment on whether or not it was appropriate is detailed in Appendix 5. All of the clinical effectiveness data included in the manufacturers'submissions were assessed. When these met the inclusion criteria and had not already been identified from published sources, they were included in the systematic review of clinical effectiveness. However, it became apparent that the manufacturers'submissions were dependent on evidence that did not include KRAS status and would not fulfil the inclusion criteria for this part of the report. Therefore, to maintain consistency, the papers reported in the manufacturers'submissions are briefly critiqued here, with a more detailed discussion in Chapter 5.

Interpreting the results from the clinical trials

Effectiveness

Most of the clinical trials in which the efficacy of these interventions has been evaluated report results in terms of hazard ratios – the ratio of hazard rates in two groups, such as a treatment group and a control group. The hazard rate describes the number of events per unit time per number of people exposed (i.e. the slope of the survival curve, or the instantaneous rate of events in the group). A hazard ratio of ≥ 1 indicates that the event of interest is happening faster in the treatment group, whereas a hazard ratio of ≤ 1 indicates that the event of interest is happening more slowly in the treatment group. A hazard ratio of 1 suggests that there is no difference between the groups.

Adverse drug effects

The National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria (NCI-CTC) (Table 6) are frequently used by trials to report drug toxicities. 35 For each adverse event, grades are assigned using a scale from 0 to 5. Grade 0 is defined as absence of an adverse event or within normal limits for values. Grade 5 is defined as death associated with an adverse event.

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | No adverse event or within normal limits |

| 1 | Mild adverse event |

| 2 | Moderate adverse event |

| 3 | Severe or medically significant adverse event but not immediately life-threatening |

| 4 | Life-threatening or disabling adverse event |

| 5 | Death related to an adverse event |

Results of the clinical effectiveness review

The results of the assessment of clinical effectiveness are presented as follows:

-

An overview of the quantity and quality of available evidence together with a table summarising all included trials (see Table 7) and a summary table of key quality indicators (see Table 9).

-

A critical review of the available evidence for each of the stated research questions (see Study characteristics), covering:

-

the quantity and quality of available evidence

-

a summary table of the study characteristics

-

a summary table of the baseline population characteristics

-

comparison of the baseline populations in the included trials

-

study results presented in narrative and tabular form

-

comparison of the results in terms of effectiveness and safety.

-

-

A summary of evidence for clinical effectiveness used in the manufacturers'submissions. This is included to address the trials used by the manufacturers, none of which meet the inclusion criteria for this systematic review (see Study characteristics).

| Study | Year | Study type | n | Intervention | Comparator | Supplementary publications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CET + BSC vs BSC after first-line therapy | ||||||

| Jonker et al.37 | 2007 | R, O, C, BR, Phase III, international, multicentre | 572 | CET + BSC | BSC | 8, 13, 49–51 |

| PAN + BSC vs BSC after first-line therapy | ||||||

| Van Cutsem et al.7 | 2007 | R, O, C, BR, Phase III, international, multicentre | 463 | PAN + BSC | BSC | 9, 11, 52, 54 |

| PAN after first-line therapy – supplement to main trial (above) | ||||||

| Van Cutsem et al.38 | 2008 | ES, O, single-arm supplement | 176 | PAN | NA | – |

Quantity and quality of research available

Number of studies identified

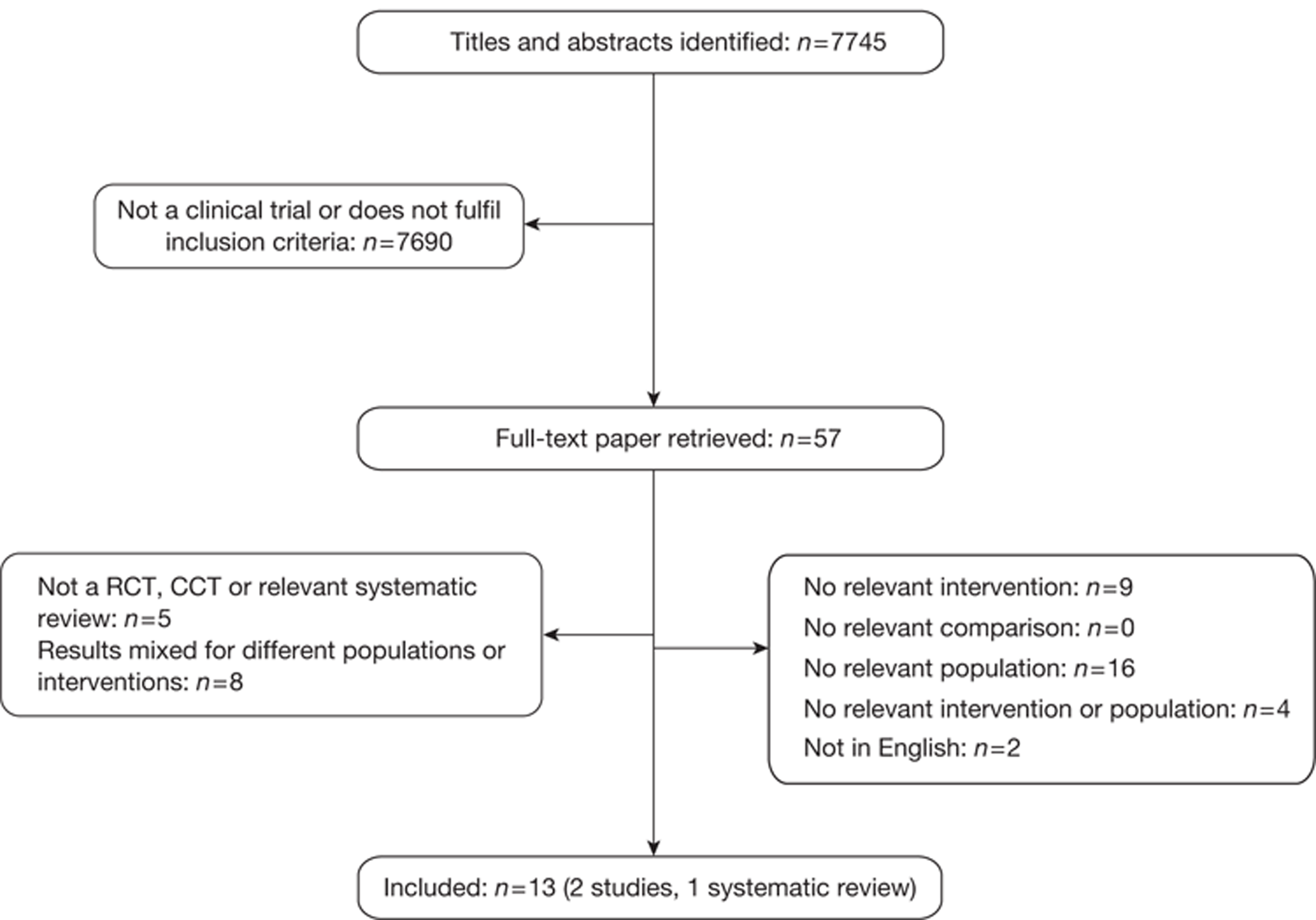

The electronic searches retrieved a total of 7745 titles and abstracts. No additional papers were found by searching the bibliographies of included studies. A total of 7690 papers were excluded based on screening the title and abstract. The full text of the remaining 55 papers was requested for more in-depth screening, resulting in a total of 13 papers being included in the review. The process of study selection is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Summary of study selection.

Number of studies excluded

Papers were excluded for at least one of the following reasons: duplicate publication, narrative review, uncontrolled study (when evidence from controlled trials was available for the research question) and publication (systematic reviews and individual studies) not considering the relevant interventions, population, comparisons or outcomes. The bibliographic details of studies retrieved as full papers and subsequently excluded, along with the reasons for their exclusion, are detailed in Appendix 6.

Number and description of included studies

Two main clinical trials and one single-arm extension reported in 12 papers were included in the review for cetuximab plus best supportive care and panitumumab plus best supportive care. One systematic review was also included. 36 Both trials had retrospective KRAS status determination after the study had been completed. All included clinical effectiveness studies are detailed in Table 7. It should be noted that no studies used in the earlier NICE report10 that reviewed bevacizumab and cetuximab for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer met the inclusion criteria in this instance, as the included trials for bevacizumab were first line and KRAS status was not established for cetuximab.

We were unable to identify any suitable data on the clinical effectiveness of bevacizumab with non-oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy; however, a clinical trial is currently under way comparing bevacizumab with FOLFIRI against panitumumab with FOLFIRI after first-line treatment (Appendix 7). 39 No data have yet been published.

Study characteristics

Bevacizumab

There is currently no clinical evidence for the effectiveness of bevacizumab with non-oxaliplatin therapy after first-line treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer, although the EMA has granted marketing authorisation for its use in this clinical setting (see Description of technologies under assessment, Bevacizumab). However, Roche reports three trials that it considers relevant to the consideration of bevacizumab for first-line use in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer, which were not included in the review. These are the ‘966 Study’ by Saltz and colleagues40 on oxaliplatin-combined therapy, the study by Hurwitz and colleagues on irinotecan-combined therapy26 and the study by Kabbinavar and colleagues27 on 5-FU/FA combined therapy. For second-line combined treatment, Roche refers to the ‘E3200 Study’ by Giantonio and colleagues41 on bevacizumab with oxaliplatin therapy. Further details can be found in Chapter 5; however, the outcomes will be briefly discussed in this chapter for consistency.

Cetuximab plus best supportive care compared with best supportive care

Jonker and colleagues37 report the results of the CO.17 trial, an open-label RCT in which 572 patients across Canada and Australia with advanced colorectal cancer expressing EGFR were randomised to receive either cetuximab plus best supportive care or best supportive care alone. Note that this primary paper does not analyse results according to KRAS status. The trial has been reported in one publication37 and four supplementary papers,42–45 one of which addresses the retrospective analysis of tissue samples for KRAS mutations with the others looking at cost-effectiveness, QoL and subgroup analysis.

The aim of the study was to demonstrate the effectiveness of cetuximab for survival and QoL in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. To that end, the primary end point was overall survival, defined as time from randomisation until death from any cause. Secondary outcomes investigated were progression-free survival, QoL and response rates. Objective tumour response was evaluated using the modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST)46 and QoL was assessed using the EORTC QLQ-C30.

To be eligible for entry into the trial participants had to have advanced colorectal cancer expressing EGFR that was detectable by immunohistochemical methods in a central reference laboratory. The participants must have experienced tumour progression, unacceptable adverse events or contraindications to treatment with fluoropyrimidine, irinotecan or oxaliplatin.

Randomisation was performed centrally in a 1 : 1 ratio to cetuximab plus best supportive care or best supportive care alone, with participants stratified according to Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (0 or 1 vs 2) and centre. Patients in the treatment arm received intravenously administered cetuximab over 120 minutes with an initial dose of 400 mg/m2 of body surface area, followed by a weekly maintenance infusion of 250 mg/m2 over 60 minutes. An antihistamine was given 30–60 minutes before each dose of cetuximab. Treatment was continued until death in the absence of unacceptable adverse events, tumour progression, worsening symptoms of the cancer or request by the patient.

The median duration of follow-up was reported as 14.6 months, although no range is given and it is not clear if this is for both arms. The median duration of cetuximab treatment was only 8.1 weeks (range 1–60 weeks), largely because of disease progression. The median dose intensity after the initial dose was 247 mg/m2/week and the relative dose intensity, that is, the ratio of the dose administered to the planned dose, was ≥ 90% in 75% of patients.

The first supplementary paper by Karapetis and colleagues47 considers the association between KRAS status and clinical benefit from cetuximab. The rationale for this investigation revolved around evidence suggesting that KRAS mutation rendered EGFR inhibitors, in this case cetuximab, ineffective. 36,48 The retrospective analysis was performed on 394 tumour samples obtained from the 572 participants of the CO.17 trial, with KRAS status then correlated with overall survival, progression-free survival and QoL.

The examination of tissue samples was performed by blinded assessors, with all statistical analysis performed in accordance with a protocol written before the assessment of KRAS status was performed. 47 The primary and secondary outcomes were consistent with those of the main trial report. 37

Au and colleagues44 focused on HRQoL in patients participating in the CO.17 trial to assess the influence of KRAS status in predicting benefit of cetuximab. The primary HRQoL analyses were defined prospectively as a comparison of the change of scores on the EORTC QLQ-C30 from baseline to 8 and 16 weeks for the physical function and global health status scales. Secondary HRQoL analyses included comparisons of the proportions of patients with worsened physical function and global health status at 8 and 16 weeks. A 10-unit change in score was predefined as clinically important.

The paper by Asmis and colleagues43 considered the relationships between comorbidity, age and performance status as predictors of outcome. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was used to measure comorbidity, with the score determined by two physician reviewers. Variables of participant age and CCI score were dichotomised: age < 65 years compared with ≥ 65 years and CCI score 0 compared with ≥ 1, with higher scores indicating greater comorbidity. Univariate analysis was also performed for the association between age group and baseline characteristics.

Finally, the study by Mittmann and colleagues42 evaluated the cost-effectiveness of cetuximab with some preference-based health utility values, using the Health Utility Index (HUI) Mark 3 (HUI3).

In addition to the CO.17 trial, Merck Serono provided details of the BOND trial49 through De Roock and colleagues. 48 This is a retrospective analysis of cetuximab plus best supportive care compared with cetuximab plus irinotecan according to KRAS status. Data are used from the following four trials: BOND,49 EVEREST,50 SALVAGE51 and BABEL. Because De Roock and colleagues are not reporting a trial, or a systematic review, this study is not formally included in this review of clinical effectiveness. However, the de novo model relies heavily on this evidence; therefore, relevant information will be included throughout this chapter. Further details with a more substantial critique may be found in Chapter 5.

Panitumumab plus best supportive care compared with best supportive care

Van Cutsem and colleagues7 present the results of an open-label, Phase III, international (Western Europe, Central Europe, Eastern Europe, Canada, Australia, New Zealand) multicentre RCT in which 463 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer were randomised to receive either panitumumab and best supportive care or best supportive care alone. The trial has been reported in one main publication7 and four supplementary publications,32,38,52,53 which are summarised in Table 8.

Eligibility criteria included pathological diagnosis of metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma and radiological documentation of disease progression during treatment or within 6 months following the last administration of fluoropyrimidine, irinotecan and oxaliplatin.

| Study | Description | Median (range) follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|

| Van Cutsem et al.7 | Main trial of PAN + BSC vs BSC | 8.8 (3.8–19) |

| Siena et al. 53 | Analysis of association of progression-free survival with colorectal cancer symptoms, HRQoL and overall survival | 18 (13–28.3) |

| Van Cutsem et al. 38 | Crossover extension study | 15.3 (4.5–25.8) |

| Amado et al. 32 | Retrospective KRAS analysis of main trial | 14.1 (for 36 patients remaining at time of analysis) |

| Peeters et al. 52 | Analysis of association of skin toxicity severity with efficacy of PAN | 18 (13–28.3) |

The aim of the study was to evaluate the effect of panitumumab monotherapy in patients with chemorefactory metastatic colorectal cancer. The primary outcome was progression-free survival assessed by blinded central radiology. Secondary outcomes were best objective response, overall survival, time to response and duration of response.

The study was designed to have 90% power for a two-sided 1% significance level test given a hazard ratio of 0.67 (panitumumab relative to best supportive care).

Patients were randomly assigned in the ratio 1 : 1 to receive panitumumab plus best supportive care or best supportive care alone; however, details of the randomisation procedure are not given. Random assignment was stratified by ECOG performance status (0 or 1 vs 2) and region (Western Europe vs Central and Eastern Europe vs the rest of the world). Patients allocated to the intervention arm received panitumumab via a 60-minute intravenous infusion of 6 mg/kg once every 2 weeks until progression or unacceptable toxicity developed.

All patients were followed for survival every 3 months for up to 2 years after randomisation; however, median follow-up reported in this paper was approximately 35 weeks (range 15–76 weeks) in the panitumumab arm.

In the best supportive care group, 176 (76%) patients received panitumumab in a crossover protocol, which is reported in a supplementary paper. 38 The median time to crossover was 7 weeks (range 6.6–7.3 weeks) and the median follow-up after crossover was 61 weeks (range 18–103 weeks). The median duration of treatment and dose intensity were not reported.

Siena and colleagues53 examine the association of progression-free survival with colorectal cancer symptoms, HRQoL and overall survival for the panitumumab trial. Patient-reported outcomes were measured using the NCCN FCSI for colorectal cancer symptoms and HRQoL was measured using the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) Health Index Scale, the EQ-5D visual analogue scale (VAS) and the EORTC QLQ-C30 global health status/QoL scale. In this paper median follow-up time for survival (enrolment to data cut-off for analysis) for all patients was reported as 72 weeks (range 52–113 weeks).

The efficacy and safety findings for panitumumab from the extension study of the main trial, that is, the crossover from best supportive care to panitumumab, are presented by Van Cutsem and colleagues;7,38 hence, this was a multicentre, open-label, single-arm trial. To be eligible, participants must have documented disease progression and were required to have completed the last assessment on the Phase III study not more than 3 months before enrolment in the extension study. During the interim participants could not have received systemic chemotherapy, radiotherapy, investigational agents or antitumour therapies.

Patients were followed for survival approximately every 3 months for up to 2 years from the randomisation date into the Phase III study. 7 The primary end point was safety and, although not prespecified in the protocol, progression-free survival, objective response rate, time to and duration of response, duration of stable disease and survival were explored.

The sample size was limited to the patients enrolled in the best supportive care arm of the Phase III study who met the eligibility criteria. Assuming a true event rate of 1%, the probability of at least one patient experiencing a given adverse event was 87% for a sample size of 200. Median follow-up time was reported as 61 weeks (range 18–103 weeks).

Amado and colleagues32 reported on a retrospective study assessing the predictive role of KRAS status in the main panitumumab trial. Of the 463 patients originally enrolled, 427 were included in the KRAS analysis, although the assessable sample size was 380 because of unavailable or poor-quality samples. The primary objective was to determine whether or not the effect of panitumumab plus best supportive care on progression-free survival differed between patients with KRAS mutant status and those with KRAS WT status. Secondary outcomes included whether or not panitumumab improved progression-free survival, overall survival and response rate in the KRAS WT group compared with the best supportive care group.

Estimating a 60% KRAS WT status prevalence, power was calculated at more than 99% if the hazard ratio was 1.0 in the KRAS mutant group and at 87% if the hazard ratio was 0.80 in the KRAS mutant group, assuming an overall hazard ratio of 0.54 among all patients.

The final supplementary paper by Peeters and colleagues52 uses data from the main trial to investigate the association of skin toxicity severity and patient-reported skin toxicity with progression-free survival, overall survival, disease-related symptoms and HRQoL. Associations by KRAS status were also evaluated.

Assessment of study quality

A summary of the quality assessment of studies included in this review is shown in Table 9; study characteristics are summarised in the narrative below and in Appendix 3.

| Jonker et al.37 | Van Cutsem et al.7 | Van Cutsem et al.38 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study design | RCT | RCT | Single arm/crossover |

| Is a power calculation provided? | Yes | Yes | N/A |

| Is the sample size adequate? | Yes | Yes | N/A |

| Was ethical approval obtained? | ? | Yes | Yes |

| Were the study eligibility criteria specified? | Yes | Yes | N/A |

| Were the eligibility criteria appropriate? | Yes | Yes | N/A |

| Were patients recruited prospectively? | Yes | Yes | N/A |

| Was assignment to the treatment groups really random? | Yes | ? | N/A |

| Was the treatment allocation concealed? | No | No | No |

| Were adequate baseline details presented? | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were the participants representative of the population in question? | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were the groups similar at baseline? | Yes | Yes | N/A |

| Were baseline differences adequately adjusted for in the analysis? | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Were the outcome assessors blind? | ? | Yes | N/A |

| Was the care provider blind? | No | No | N/A |

| Are the outcome measures relevant to the research question? | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Is compliance with treatment adequate? | Yes | ? | ? |

| Are withdrawals/dropouts adequately described? | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Are all patients accounted for? | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Is the number randomised reported? | Yes | Yes | N/A |

| Are protocol violations specified? | No | No | No |

| Are data analyses appropriate? | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Is analysis conducted on an ITT basis? | Yes | Yes | N/A |

| Are missing data appropriately accounted for? | Partial | No | Yes |

| Were any subgroup analyses justified? | Yes | Yes | No |

| Are the conclusions supported by the results? | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Cetuximab plus best supportive care compared with best supportive care

The CO.17 trial reported by Jonker and colleagues37 is a good-quality, open-label, randomised Phase III trial. The evaluation of the trial in relation to study quality is shown in Table 9.

Randomisation methods and withdrawal were adequately reported. As previously mentioned, dose intensity was also noted to be adequate at 90%. However, blinding of assessors was not reported. A reason for the open-label nature of the study was also not given, although this may be due to the anticipated skin toxicity of anti-EGFR agents. The assessment of tissue samples for KRAS status was confirmed as performed in a blinded manner. 47

The De Roock study,48 not formally included in this review but cited by Merck Serono for clinical effectiveness, analyses KRAS status from several cetuximab-based studies. The data reveal several key issues:

-

of the relatively small sample size (n7 = 113), a total of 67 patients had KRAS WT status: 40% of the patients (n = 27) from the BOND trial,49 42% (n = 28) from the EVEREST trial,50 15% (n = 10) from SALVAGE51 and 3% (n = 2) from BABEL

-

in the BOND trial, 50% of patients from the cetuximab plus best supportive care arm received irinotecan after disease progression, indicating potential crossover and subsequent underestimation of overall survival in those treated with cetuximab plus irinotecan49

-

the EVEREST trial is described as a RCT comparing cetuximab plus irinotecan, escalating doses of cetuximab plus irinotecan and cetuximab plus best supportive care; however, it is unclear why only data from cetuximab plus irinotecan patients are included in De Roock and colleagues48,50,54,55

-

the SALVAGE study is a non-comparative study of patients receiving cetuximab plus best supportive care only who have received at least two previous lines of therapy51

-

the BABEL study appears to be investigating the effect of tetracycline to alleviate a rash in cetuximab therapy, although further details on this study have been difficult to identify

-

patients were included on the basis of availability of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumour tissue; however, there are no details on what this percentage was for each of the four studies contributing patient data.

As such, there are concerns regarding the disease progression and effectiveness estimates calculated using De Roock and colleagues. 48 The estimates are likely to be subject to high levels of bias and confounding, although it is unclear what impact this will have.

Panitumumab plus best supportive care compared with best supportive care

The trial by Van Cutsem and colleagues7 is a large, good-quality, open-label, international, multicentre, randomised Phase III study. The lack of participant and clinician/investigator blinding due to expected skin toxicity is discussed; however, to mitigate this, tumour assessments were performed by blinded central review. Unfortunately, it is unclear whether or not randomisation was performed centrally. Further details of the quality assessment can be found in Table 9.

Population baseline characteristics

For the main trial37 the demographic characteristics and disease status were well matched (Table 10). The baseline characteristics were re-examined by Karapetis and colleagues47 according to KRAS status, which is also included in Table 10. Of the original 572 samples, 394 were available for analysis. Fifty-eight per cent were revealed to be WT, with 51% assigned to cetuximab plus best supportive care and 49% to best supportive care. The relative proportions of each characteristic remained similar between arms.

| Jonker et al.37 | Karapetis et al.17 | Van Cutsem et al.7 | Amado et al.32 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CET | BSC | CET | BSC | PAN | ||||||||

| CET | BSC | Mutant | WT | PAN | BSC | Mutant | WT | BSC mutant | BSC WT | |||

| n a | 287 | 285 | 81 | 83 | 117 | 113 | 231 | 232 | 84 | 124 | 100 | 119 |

| Diagnosis | Advanced CRC expressing EGFR | Chemorefractory mCRC | ||||||||||

| Age (years), median (range) | 63 (29–88) | 64 (29–86) | 62 (37–88) | 64 (29–86) | 62 (27–82) | 63 (27–83) | 62 (27–79) | 63 (29–82) | 62 (27–83) | 63 (32–81) | ||

| Male, n (%) | 186 (65) | 182 (64) | 101 (62) | 156 (68) | 146 (63) | 148 (64) | 47 (56) | 83 (67) | 64 (64) | 76 (64) | ||

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 72 (25) | 64 (23) | 34 (21) | 56 (24) | 107 (46) | 80 (34) | 43 (51) | 53 (43) | 37 (37) | 40 (34) | ||

| 1 | 148 (52) | 154 (54) | 94 (57) | 127 (55) | 94 (41) | 115 (50) | 28 (33) | 56 (45) | 47 (47) | 62 (52) | ||

| 2 | 67 (23) | 67 (24) | 26 (22) | 47 (20) | 29 (13) | 35 (15) | 13 (15)b | 15 (12)b | 16 (16)b | 17 (14)b | ||

| 3 | – | – | – | – | 1 (0) | 2 (1) | – | – | – | – | ||

| Site, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Colon only | 171 (60) | 161 (57) | 108 (66) | 137 (60) | 153 (66) | 157 (68) | 53 (63) | 86 (69) | 65 (65) | 82 (69) | ||

| Rectum only | 63 (22) | 70 (25) | 32 (20) | 50 (22) | 78 (34) | 75 (32) | 31 (37) | 38 (31) | 35 (35) | 37 (31) | ||

| Colon and rectum | 53 (19) | 54 (19) | 24 (15) | 43 (19) | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Previous adjuvant chemotherapy, n (%) | 108 (38) | 99 (35) | 50 (31) | 77 (34) | 86 (37) | 78 (34) | 27 (32) | 50 (40) | 40 (40) | 32 (27) | ||

| No. of regimens, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| 1 or 2 | 50 (17) | 54 (19) | 27 (17) | 46 (20) | 230 (100) | 232 (100) | 54 (64) | 79 (64) | 74 (74) | 63 (53) | ||

| 3 | 109 (38) | 108 (38) | 69 (42) | 86 (37) | 84 (36) | 88 (38) | 23 (27) | 41 (33) | 24 (24) | 49 (41) | ||

| 4 | 87 (30) | 72 (25) | 46 (28) | 63 (27) | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| ≥ 5 | 41 (14) | 51 (18) | 22 (13) | 35 (15) | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| TSI | 287 (100) | 285 (100) | 164 (100) | 230 (100) | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Irinotecan | 277 (97) | 273 (96) | 161 (98) | 219 (95) | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Oxaliplatin | 281 (98) | 278 (98) | 163 (99) | 222 (97) | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Site of metastatic disease, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Liver | 230 (80) | 233 (82) | 129 (79) | 189 (82) | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Lung | 188 (66) | 180 (63) | 98 (60) | 144 (63) | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Lymph nodes | 130 (45) | 117 (41) | 64 (39) | 103 (45) | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Peritoneal cavity (ascites) | 45 (16) | 41 (14) | 23 (14) | 38 (17) | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| No. of sites of metastatic disease, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 40 (14) | 53 (19) | 27 (17) | 40 (17) | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| 2 | 84 (29) | 69 (24) | 45 (27) | 63 (27) | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| 3 | 84 (29) | 89 (31) | 42 (26) | 75 (33) | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| ≥ 4 | 79 (28) | 74 (26) | 50 (31) | 52 (23) | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

At baseline, the two groups were well matched in the original trial. 7 A slight difference was noted with disease status, with the best supportive care arm having 34% of participants with an ECOG performance status of 0 and 50% with an ECOG performance status of 1, and the treatment arm having 46% of participants with an ECOG performance status of 0 and 41% with an ECOG performance status of 1 (see Table 10). The supplementary study32 ascertained KRAS status in 92% of the original participants, showing the distribution of KRAS WT and KRAS mutant status between arms and ECOG performance status to be broadly similar.

Participants in the two main trials of cetuximab plus best supportive care compared with best supportive care were similar in terms of age, gender distribution and site of primary cancer. 45 However, as is usually the case with cancer trials, the study populations were significantly younger than the general population presenting with colorectal cancer, with the peak in number of cases in the UK, for example, between 70 and 79 years for men and 75–85+ years for women as opposed to a median of 62–64 years shown in Table 10.

Reporting of disease status in the panitumumab trial was limited to only ECOG performance status rather than providing details of primary or metastatic sites. A higher proportion of participants was noted to have an ECOG performance status of 0 in the treatment arm than in the best supportive care arm (46% vs 25%), which equates to ‘fully active, able to carry on all pre-disease performance without restriction’; therefore, this suggests a fitter population in the intervention arm.

Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Overall survival (Table 11)

There is currently no clinical evidence for the effectiveness of bevacizumab with non-oxaliplatin therapy after first-line treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer. However, the trials reported by Roche, which are not included in this review, will be briefly mentioned here.

| Study | Interventiona | n | Median OS (months) | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jonker et al.37 | All: CET + BSC | 287 | 6.1 | 0.77 | 0.64 to 0.92 | 0.005 |

| All: BSC | 285 | 4.6 | ||||

| Karapetis et al.47 | WT: CET + BSC | 117 | 9.5 | 0.55b | 0.41 to 0.74 | < 0.001 |

| WT: BSC | 113 | 4.8 | – | – | – | |

| Van Cutsem et al.7 | All: PAN + BSC | 231 | NR | 1.00 | 0.82 to 1.22 | 0.81 |

| All: BSC | 232 | NR | – | – | – | |

| Amado et al.32 | WT: PAN + BSC | 124 | 8.1 | 0.99 | 0.75 to 1.29 | NR |

| WT: BSC | 119 | 7.6 | – | – | – |

Saltz and colleagues40 conducted a RCT for first-line bevacizumab combined with oxaliplatin in 1401 patients, 75% of whom had not previously received chemotherapy. Treatment arms were capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (XELOX) plus bevacizumab, XELOX plus placebo, 5-FU, FA and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX-4) plus bevacizumab or FOLFOX-4 plus placebo. The hazard ratio for overall survival for bevacizumab compared with placebo was not statistically significant (hazard ratio 0.89, 97.5% CI 0.76 to 1.03, p = 0.077), with a median overall survival of 21.3 months for bevacizumab and 19.9 months in the placebo arm.

Hurwitz and colleagues26 randomised 813 people to receive either irinotecan, bolus fluorouracil and leucovorin (IFL) plus bevacizumab or IFL alone for first-line treatment (28% of IFL patients and 24% of IFL plus bevacizumab patients had received previous adjuvant chemotherapy). ITT analyses showed that median survival was 20.3 months for those treated with IFL plus bevacizumab and 15.6 months for those receiving IFL alone (hazard ratio 0.6, p< 0.001).

Kabbinavar and colleagues27 randomised 209 patients to receive fluorouracil and leucovorin (FU/LV) plus bevacizumab or FU/LV only. Twenty-one per cent of the FU/LV plus bevacizumab patients and 19% of the FU/LV patients had prior adjuvant chemotherapy. The primary end point of overall survival produced a non-statistically significant hazard ratio of 0.76 (95% CI 0.56 to 1.10) for FU/LV plus bevacizumab compared with FU/LV, with a median overall survival of 16.6 months in the FU/LV plus bevacizumab arm and 12.9 months in the FU/LV arm. The authors argue that the large number of patients receiving postprogression treatment could partly explain the lack of statistical significance in the primary end point of overall survival. A similar percentage of patients from both treatment arms received irinotecan, oxaliplatin or both post progression (39% of the FU/LV plus bevacizumab patients and 46% of the FU/LV patients).

Giantonio and colleagues41 report a RCT with 820 patients previously treated with a fluoropyrimidine and irinotecan randomised to one of three arms: FOLFOX-4 plus bevacizumab, FOLFOX-4 or bevacizumab alone. Median overall survival was greater in the FOLFOX-4 plus bevacizumab arm: 12.9 months compared with 10.8 months for FOLFOX-4 and 10.2 months for bevacizumab alone. The hazard ratio for overall survival associated with FOLFOX-4 plus bevacizumab compared with FOLFOX-4 was 0.75 (p = 0.01).

Overall survival, defined as the time between date of randomisation and death from any cause, was the primary end point in the CO.17 trial. 37 The analysis was performed on an ITT basis, with the final analysis conducted after at least 445 patients were known to have died.

The median overall survival was 6.1 months in the cetuximab group and 4.6 months in the best supportive care group, with a hazard ratio of 0.77 (95% CI 0.64 to 0.92, p = 0.005). Seven percent of patients receiving best supportive care were administered cetuximab after crossover; however, this would be unlikely to bias the results against treatment. 37

No significant differences were seen for the benefit of cetuximab on the basis of ECOG performance status at baseline, age or sex in subgroup analysis. However, unplanned analysis indicated that grade of rash in patients receiving cetuximab was correlated with overall survival, with median survival of 2.6 months in patients with no rash, 4.8 months in patients with grade 1 rash and 8.4 months is patients with grade 2 rash (p < 0.001). 37

For patients with KRAS mutant status, analysis by Karapetis and colleagues47 showed a median overall survival of 4.5 months for cetuximab and 4.6 months for best supportive care, with a hazard ratio of 0.98 (95% CI 0.70 to 1.37, p = 0.89). Among patients with WT status, the median overall survival was 9.5 months in the cetuximab group compared with 4.8 months in the best supportive care group, with an hazard ratio of 0.55 (95% CI 0.41 to 0.74, p < 0.001). Subsequent to adjustment for potential prognostic factors, which are reported to be as specified in the protocol but are not described in the paper, the hazard ratio increases to 0.62 (95% CI 0.44 to 0.87, p = 0.006); however, these results remain favourable towards cetuximab plus best supportive care.

Panitumumab plus best supportive care compared with best supportive care

At the time of analysis, the study had achieved the event rate required for 90% power. 7 Overall survival was calculated from the day of random assignment until death, censoring patients at the last day known to be alive. Median overall survival values were not given; however, it was reported that no significant difference was found between arms (hazard ratio of 1.00, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.22, p = 0.81). The authors cite confounding because of the rapid crossover of 76% of patients from the best supportive care arm to receive active treatment for the lack of significant difference between arms, 32, which would bias the results against treatment.

Exploratory analysis of skin toxicity demonstrated a longer overall survival in patients with a skin toxicity of grade 2–4 than in those with a skin toxicity of grade 1, resulting in an hazard ratio of 0.59 (95% CI 0.42 to 0.85).

The retrospective investigation of panitumumab efficacy and KRAS status revealed no statistically significant overall survival difference between treatment arms in either of the KRAS groups. 32 The hazard ratios for overall survival were 1.02 (95% CI 0.75 to 1.39) and 0.99 (95% CI 0.75 to 1.29) for the KRAS mutant and WT groups, respectively, which is in contrast to the analysis for skin toxicity, which apparently favours overall survival and only occurs in WT patients. 52

Median overall survival is also unclear. Patients with KRAS WT status treated with panitumumab show a median survival of 8.1 months compared with 7.6 months for those treated with best supportive care; and patients with KRAS mutant status treated with panitumumab show a median overall survival of 4.9 months compared with 4.4 months for those treated with best supportive care. 32

Progression-free survival (Table 12)

Roche mentions a number of papers that did not fulfil the inclusion criteria for this review, but their results will be briefly summarised here for completeness. Further details can be found in Chapter 5.

| Study | Interventiona | n | Median PFS (months) | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|