Notes

Article history paragraph text

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/22/165. The contractual start date was in October 2010. The draft report began editorial review in July 2012 and was accepted for publication in November 2012. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Perel et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Each year, around 4 million people die worldwide from unintentional injury and violence, with tens of millions more left permanently disabled. Most of the victims are from low-income countries (LICs) and middle-income countries (MICs). 1 Although many of these deaths occur at the scene of the injury, it is estimated that 44% of deaths occur after hospital admission. 2

Severe bleeding accounts for about one-third of in-hospital trauma deaths and is an important contributory factor in other causes of death, in particular head injury and multiorgan failure. 3 Failure to initiate appropriate early management in bleeding trauma patients is a leading cause of preventable trauma death. 4 Triage criteria that allow the rapid identification of high-risk patients have the potential to reduce trauma mortality, and recent evidence that the early administration of tranexamic acid (TXA) substantially reduces mortality in bleeding trauma patients further emphasises the clinical importance of the timely identification of life-threatening bleeding. 5 However, any such early prediction would have to be based on variables that can be readily measured soon after injury.

Several clinical variables related to the physiological response to reduced intravascular volume predict the risk of death in bleeding trauma patients. These include blood pressure, capillary refill time, level of consciousness [Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score], heart rate (HR) and respiratory rate (RR). 6 Because all of these variables are of limited predictive value when considered in isolation, prognostic models that combine variables are required for better predictive accuracy. 7–9 An accurate and user-friendly prognostic model to predict mortality in bleeding trauma patients could assist doctors and paramedics in pre-hospital triage whether in civilian or battlefield settings; its use could shorten the time to diagnostic and life-saving procedures such as surgery and TXA. The Clinical Randomisation of an Antifibrinolytic in Significant Haemorrhage (CRASH-2) trial showed that a short course of TXA given to bleeding trauma patients within 3 hours of injury significantly reduces all-cause mortality with no apparent increase in the risk of thrombotic adverse events. As a result, TXA is being incorporated into trauma protocols around the world. These protocols generally focus on the care of the most severely injured. Patients with a high baseline risk of death have the most to gain from the use of life-saving treatments because the absolute benefits of an effective treatment tend to increase as the baseline risk increases, whereas adverse effects can be independent of baseline risk. On the other hand, there are more low-risk trauma patients than high-risk patients and it is possible that a large number of patients at low risk might contribute more deaths than a smaller number of patients at high risk.

We have previously published a prognostic model for traumatic brain injury patients which is accurate, user-friendly and clinically useful for supporting physicians' decision-making. 10,11

Existing prognostic models for bleeding trauma patients are limited. 12 Most were developed using data collected many decades ago and have methodological limitations. There is a need for models based on contemporary data because treatment practices have changed and the age of trauma patients has increased in high-income countries (HICs). Furthermore, although most trauma deaths occur in LICs and MICs, most prognostic models are based on data from HICs. 12

We aimed to develop a simple prognostic model which could be used at the point of care to estimate risk of death in patients with traumatic bleeding. In addition, we report further analysis of the CRASH-2 trial data to examine how TXA treatment effects vary according to the baseline risk of death in bleeding trauma patients. We then use data from a large hospital-based trauma audit to assess the extent to which current trauma protocols maximise the patient benefits of TXA treatment.

Chapter 2 Methods

Model development

For the development of the prognostic model, we involved potential users from three settings: pre-hospital, battlefield and emergency departments. We held separate meetings with paramedics, military doctors and emergency medicine consultants to identify variables and interactions that they considered important and convenient for their settings and to obtain information on how to present the prognostic model in a user-friendly format. In each of these meetings we conducted a semistructured interview following a prespecified questionnaire (see Appendix 1).

Sample

We included patients from the CRASH-2 trial. 13 The trial included 20,127 trauma patients with, or at risk of, significant bleeding, within 8 hours of injury, and was undertaken in 274 hospitals in 40 countries.

Outcome

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality. Patient outcomes were recorded as discharge, death in hospital or death 28 days after injury, whichever occurred first.

Predictors

Variables analysed as potential predictors were taken from the patient entry form completed prior to randomisation. Variables included in the CRASH-2 trial entry form can be divided into:

-

Patient demographic characteristics: age and sex.

-

Injury characteristics: type of injury and time from injury to randomisation.

-

Physiological variables: GCS score, systolic blood pressure (SBP), HR, RR and central capillary refill time.

Variable definitions

Age was recorded as a continuous variable measured in years. Type of injury had three categories: (1) penetrating, (2) blunt or (3) blunt and penetrating. However, it was analysed as penetrating, and blunt and penetrating. Time from injury was recorded as a continuous variable measured in hours. The five physiological variables were recorded according to usual clinical practice. For each of these variables, the value given on the entry form was the first measurement taken at hospital admission.

Multivariable analysis

We conducted complete-case analyses, as the number of missing data was very low in the CRASH-2 trial. All candidate predictors were included initially in the multivariable logistic regression. Analyses were adjusted for treatment by including treatment allocation as a covariate in the models. We also included a variable for economic region (i.e. LIC, MIC or HIC as defined by the World Bank). 14 We used logistic regression models with random intercepts by country. Continuous variables were initially analysed as linear terms. Departure from linearity was assessed graphically and by adding quadratic and cubic terms into the model. We also explored other variable transformations using fractional polynomial and splines; however, none of these provided a better fit to the data and they were discarded because they had a more difficult interpretation, and because splines require some arbitrary decisions about the number and placement of knots. Interactions by age and by type of injury were specifically explored. Time since injury was dichotomised into < 3 hours or > 3 hours, as the effect of this variable was reasonably well captured by using it as binary.

We conducted a backward stepwise approach. We first included all potential prognostic factors and interaction terms that were considered plausible by users. These interactions included all potential predictors with type of injury, time since injury and age. We then removed, one at a time, terms for which there was no strong evidence of an association, judged according to the p-values (< 0.05) from the Wald test. Each time, we calculated a log-likelihood ratio test to check that the term removed did not have a big impact in the model. Eventually, we reached a model where all terms were statistically significant. We used the R software environment (version 2.13.1, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Performance

The predictive ability of the prognostic model was assessed in terms of calibration and discrimination. Calibration indicates whether or not observed risks agree with predicted risks and was assessed graphically by plotting the observed outcomes compared with the predicted probabilities of the outcomes. Discrimination indicates whether or not low-risk patients can be separated from high-risk patients and was assessed using a concordance (C) statistic. 15 For the CRASH-2 trial data, the predictions were estimated by setting the random effect of country to 0.

Optimism in the performance was assessed by bootstrap resampling. We drew 200 samples with replacement from the original data, with the same size as the original derivation data. In each bootstrap sample we repeated the entire modelling process, including variable selection. We averaged the C-statistics of those 200 models in the bootstrap samples. We then estimated the average C-statistic when each of the 200 models was applied in the original sample. The difference between the two average C-statistics indicated the ‘optimism’ of the C-statistic in our prognostic model. 15

External validation

For the external validation we used the data from TARN. Membership of TARN is voluntary and includes 60% of hospitals receiving trauma patients in England and Wales and some hospitals in Europe. Data are collected on patients who arrive at hospital alive and meet any of the subsequent criteria: death from injury at any point during admission, stay in hospital for longer than 3 days, require intensive or high-dependency care or require interhospital transfer for specialist care.

Patients with isolated closed-limb injuries and patients of > 65 years old with isolated fractures of the neck of femur or pubic ramus were excluded. The physiological data available in TARN are identical to those in the CRASH-2 trial, in that for every patient the HR, SBP, GCS score, RR and capillary refill time on arrival are entered by the hospital data co-ordinators. For each patient the volume of blood loss is estimated. This is done by allocating an estimated percentage of total volume of blood lost to each injury code in the abbreviated injury scale dictionary by blinded, then consensus, agreement from two emergency physicians. This estimation is based on previous work on blood loss in specific injuries. 16

Adult patients (aged > 15 years at the time of injury) presenting between the years 2000 and 2008 to TARN-participating hospitals were selected. The definition used in the CRASH-2 trial of significant haemorrhage was not available; therefore, we selected only patients with an estimated blood loss of at least 20% who we considered would be clinically comparable with the CRASH-2 trial patients.

For the validation in the TARN data set we conducted multiple imputations to substitute the missing values of the predictors included in the prognostic model using the procedure of imputation by chained equations in Stata (release 11, 2009; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). For the imputation model the following variables were included: injury severity score, age, sex, outcome (alive/dead), intubation/ventilation (yes/no), transfer status, mechanism of injury, head injury (yes/no), treatment at neurocentre (yes/no) and pre-existing condition (yes/no). We applied the coefficients of the model developed in the CRASH-2 trial with the estimated UK intercept to the five imputed data sets of TARN, obtaining five predictions of mortality for each patient in TARN. We then averaged over these five predictions to calculate calibration and discrimination. 15

Simple prognostic model

For ease of use at point of care, we developed a simple prognostic model. For this model we included the strongest predictors with the same quadratic and cubic terms as used in the full model, adjusting for TXA. The prognostic model was presented as a chart that cross-tabulates these predictors, but each of them recoded in a number of categories. The categories were made considering clinical and statistical criteria. In each cell of the chart we estimated the risk for an individual with values of each predictor at the mid-point of the predictor's range for that cell. We then coloured the chart cells in four groups according to ranges in the probability of death: < 6%, 6–20%, 21–50% and > 50%. We decided these cut-offs based on the feedback from the potential simple prognostic model users and by looking at previous publications. 17,18

Evaluation of the effect of tranexamic acid according to baseline risk

For these analyses, we used the prognostic model to stratify the patients in the CRASH-2 trial who were treated within 3 hours of injury into four mortality risk strata (< 6%, 6–20%, 21–50% and > 50%). We then examined the effect of TXA on all-cause mortality, death due to bleeding and thrombotic events (fatal and non-fatal myocardial infarction, stroke, deep-vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism) within these strata. We prespecified that unless there was strong evidence against the null hypothesis of homogeneity of effects (i.e. p < 0.001), the overall OR would be considered the most reliable guide to the approximate relative risks in all risk strata. We examined the effect of TXA on arterial (myocardial infarction and stroke) and venous (deep-vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism) thrombotic events separately and combined.

We also used the prognostic model to estimate the number and cumulative proportion of deaths at different levels of baseline risk in UK trauma patients using TARN data. For each TARN patient we used the prognostic model described above to estimate the predicted risk of death and then estimated the proportion of premature deaths averted by applying the OR from the CRASH-2 trial to each of the risk strata. For these analyses we included only patients within 3 hours of injury. The discussion on what type of patients should receive TXA was further informed by a consultation meeting with accident and emergency (A&E) consultants with whom we discussed the results about the effect of TXA according to baseline risk.

The original protocol is included in Appendix 2.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study and the use of the CRASH-2 trial data was obtained from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK. TARN already has ethical approval (PIAG section 60; PIAG3-4(e)/2006) for research on the anonymised data that are stored securely on the University of Manchester server.

Chapter 3 Results

General characteristics

Tables 1 and 2 show the characteristics of the patients in the CRASH-2 trial and TARN data sets respectively.

| Characteristics | All patients (n = 20,127) | Alive (n = 17,051) | Dead (n = 3076) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Missing (%) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |

| Age (years) | < 1 | 30 (24–43) | 30 (23–42) | 35 (25–48) |

| SBP (mmHg) | < 1 | 91 (80–110) | 100 (84–110) | 84 (70–100) |

| HR (beats per minute) | < 1 | 105 (90–120) | 104 (90–120) | 111 (96–126) |

| RR (breaths per minute) | < 1 | 22 (20–26) | 22 (20–26) | 24 (20–30) |

| GCS score (total) | < 1 | 15 (11–15) | 15 (13–15) | 8 (4–14) |

| Capillary refill time (seconds) | 3 | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | 4 (3–5) |

| HIS | 0 | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–4) |

| PIN | 0 | 6522 (32%) | 5813 (34%) | 709 (23%) |

| Characteristics | All patients (n = 14,220) | Alive (n = 12,455) | Dead (n = 1765) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Missing (%) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |

| Age (years) | 0 | 39 (25–57) | 38 (25–55) | 43 (27–70) |

| SBP (mmHg) | 16 | 129 (110–145) | 130 (112–145) | 111 (88–140) |

| HR (beats per minute) | 16 | 88 (75–105) | 87 (75–102) | 103 (80–126) |

| RR (breaths per minute) | 29 | 19 (16–24) | 18 (16–23) | 22 (17–30) |

| GCS score (total) | 21 | 15 (15–15) | 15 (15–15) | 12 (3–15) |

| Capillary refill time (seconds) | 84 | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) |

| HIS | 64 | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–1) |

| PIN | 0 | 1993 (14.0%) | 1785 (14.3%) | 208 (11.8%) |

In the CRASH-2 trial, the majority of patients were male and the median age was 30 years. Patients who died were on average older, had lower SBP, higher HR and lower GCS score. There were few missing data for all of the variables. There were 3076 deaths (15%) among the 20,127 CRASH-2 trial patients, and 1765 deaths (12%) in the 14,220 TARN patients. In comparison, the patients from TARN were older (median age 39 years), they had fewer penetrating injuries and they had a higher SBP.

Relationship between predictors and overall mortality

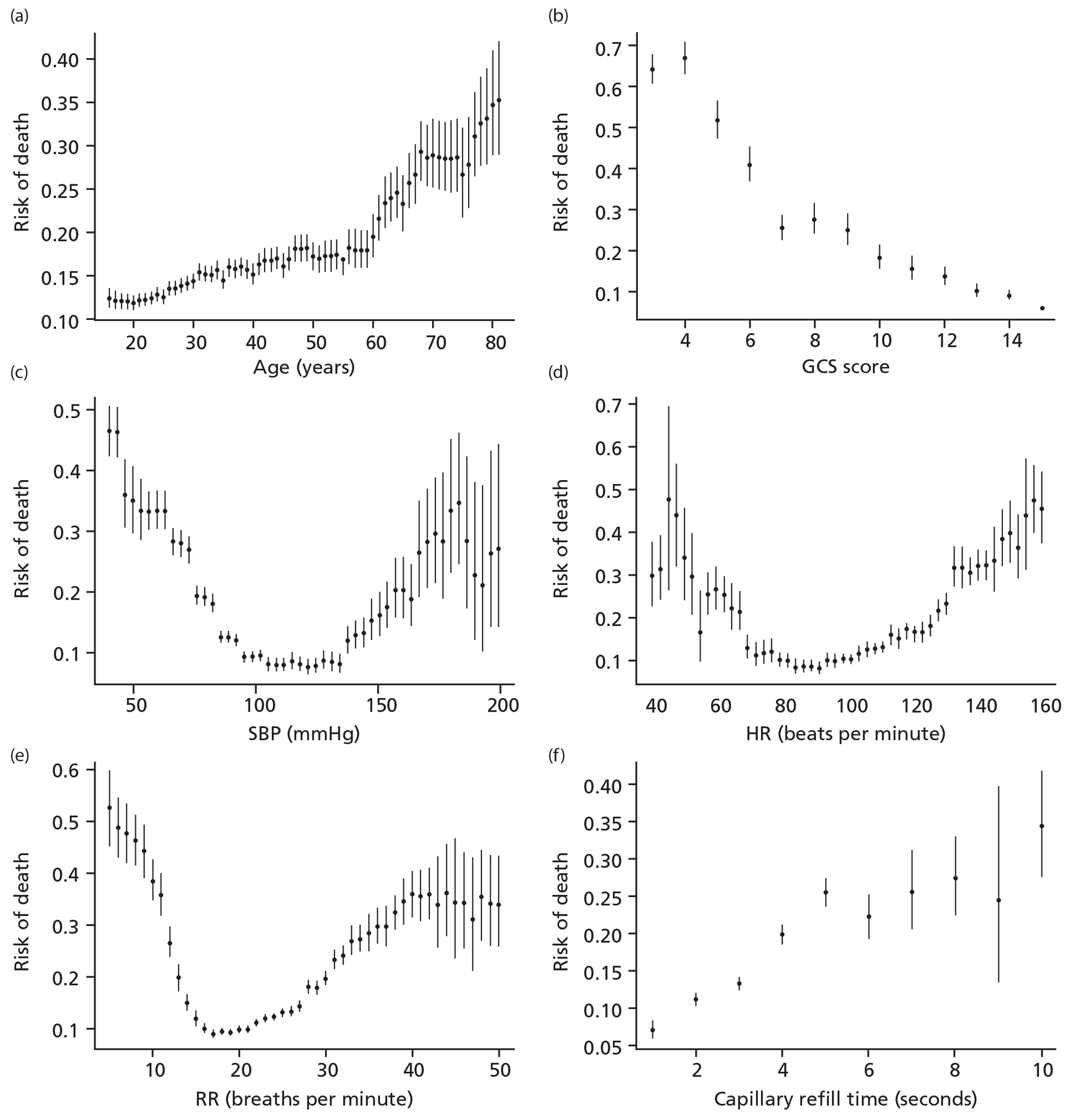

Age showed a positive and increasing association with risk of death. SBP, HR and RR showed a U-shape relationship, and GCS score showed a negative association with risk of death (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Association between continuous predictors and death among CRASH-2 trial patients. The error bars represent the 95% CI of that observed unadjusted risk in that level of the biomarkers.

Table 3 shows that in the CRASH-2 trial, age of patient was positively associated with mortality for each of the described causes of death, with the highest relative increase for vascular occlusive death.

| Age (years) (n) | Causes of death (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bleeding | Vascular occlusion | Multiorgan failure | Head injury | Other causes | Any cause of death | |

| < 25 (5615) | 4.6 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 4.4 | 1.1 | 11.8 |

| 25–44 (9874) | 5.3 | 0.3 | 2.1 | 5.9 | 1.2 | 14.8 |

| 45–59 (3188) | 5.6 | 0.6 | 2.8 | 6.9 | 1.6 | 17.4 |

| ≥ 60 (1449) | 7.2 | 1.3 | 4.3 | 11.9 | 2.6 | 27.3 |

Prognostic model

We included quadratic or cubic transformations in the prediction model to accommodate the departures from linearity. In the multivariable analysis, GCS score, SBP and age were the three strongest predictors. HR, RR and hours since injury (HSI) were associated with mortality and also included in the final model. All of these variables were considered important by users. Patients in LICs and MICs were more likely to die than patients in HICs. Although capillary refill time was weakly associated with mortality, it was not included in the prognostic model because in situations with poor visibility, such as on the battlefield, it is difficult to measure. In addition, capillary refill time was missing in > 80% of the TARN patients. There was some evidence for statistical interaction between GCS score and type of injury. Low GCS scores were associated with worse prognosis for blunt injuries (Table 4).

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | p-value | Deviance | df |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.012 (0.006 to 0.023) | |||

| MICs | 2.14 (1.03 to 4.44) | 0.0405 | 18 | 2 |

| LICs | 3.59 (1.30 to 9.89) | 0.0134 | ||

| TXA before 3 hours | 0.81 (0.72 to 0.90) | 0.0002 | 13 | 2 |

| TXA after 3 hours | 1.02 (0.87 to 1.20) | 0.8158 | ||

| > 3 HIS | 0.75 (0.65 to 0.87) | 0.0001 | 13 | 2 |

| Age (linear component) | 1.37 (1.16 to 1.62) | 0.0002 | 223 | 3 |

| Age2 | 0.91 (0.84 to 0.99) | 0.0228 | ||

| Age3 | 1.02 (1.01 to 1.03) | 0.0015 | ||

| SBP (linear component) | 0.90 (0.87 to 0.93) | < 0.0001 | 292 | 3 |

| SBP2 | 1.03 (1.02 to 1.03) | < 0.0001 | ||

| SBP3 | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | 0.0008 | ||

| RR (linear component) | 0.74 (0.59 to 0.92) | 0.0069 | 171 | 3 |

| RR2 | 1.48 (1.24 to 1.77) | < 0.0001 | ||

| RR3 | 0.93 (0.90 to 0.97) | 0.0004 | ||

| HR (linear component) | 0.97 (0.92 to 1.02) | 0.1915 | 24 | 2 |

| HR2 | 1.02 (1.01 to 1.02) | < 0.0001 | ||

| GCS score (linear component) | 0.84 (0.80 to 0.88) | < 0.0001 | 1993 | 4 |

| GCS score2 | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.01) | < 0.0001 | ||

| PIN | 0.91 (0.77 to 1.07) | 0.2414 | 41 | 3 |

| PIN × GCS score | 0.92 (0.84 to 1.01) | 0.0930 | 37 | 2 |

| PIN × GCS score2 | 0.99 (0.98 to 0.99) | 0.0012 | ||

| Total | 3126 | 21 |

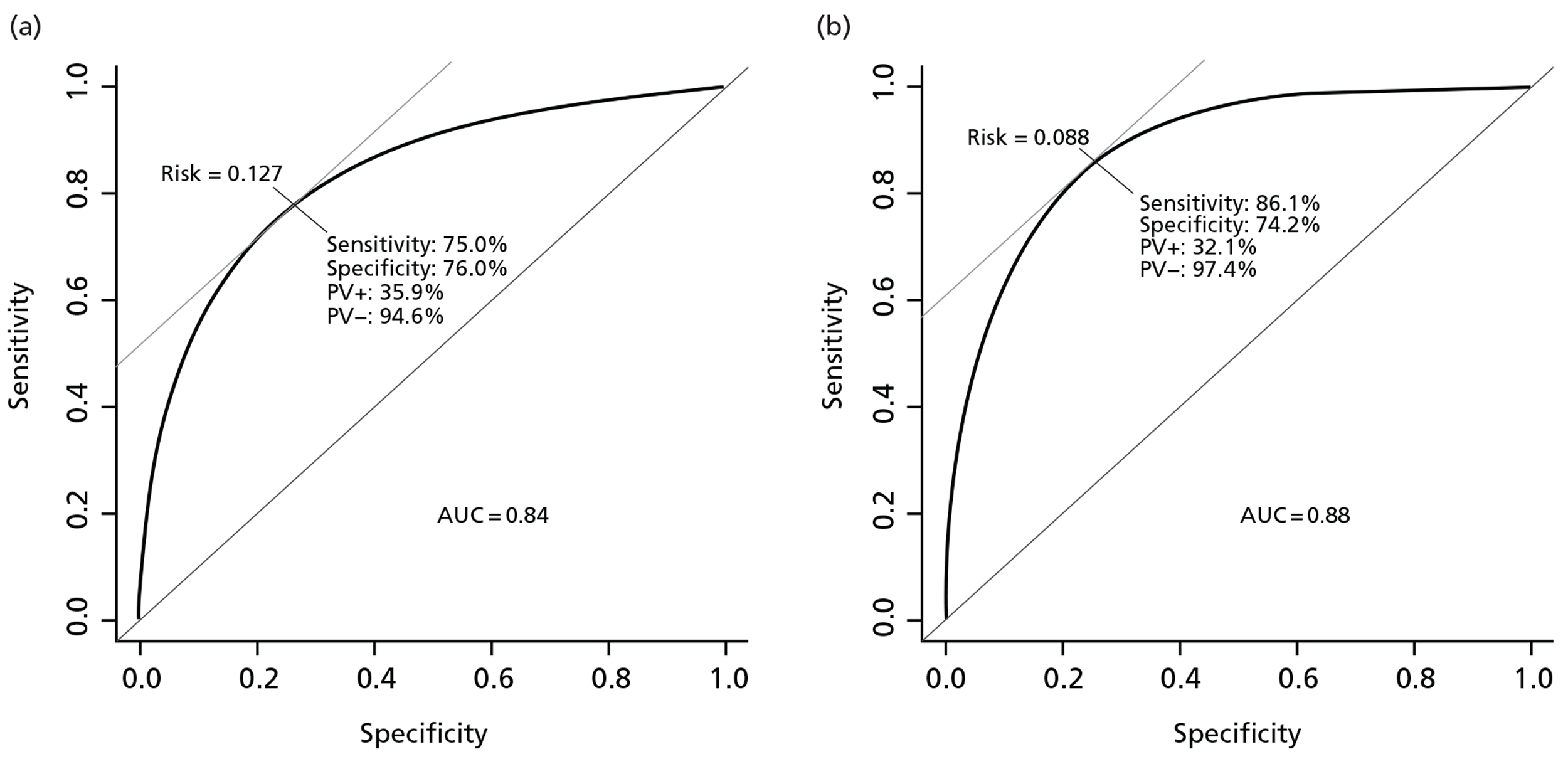

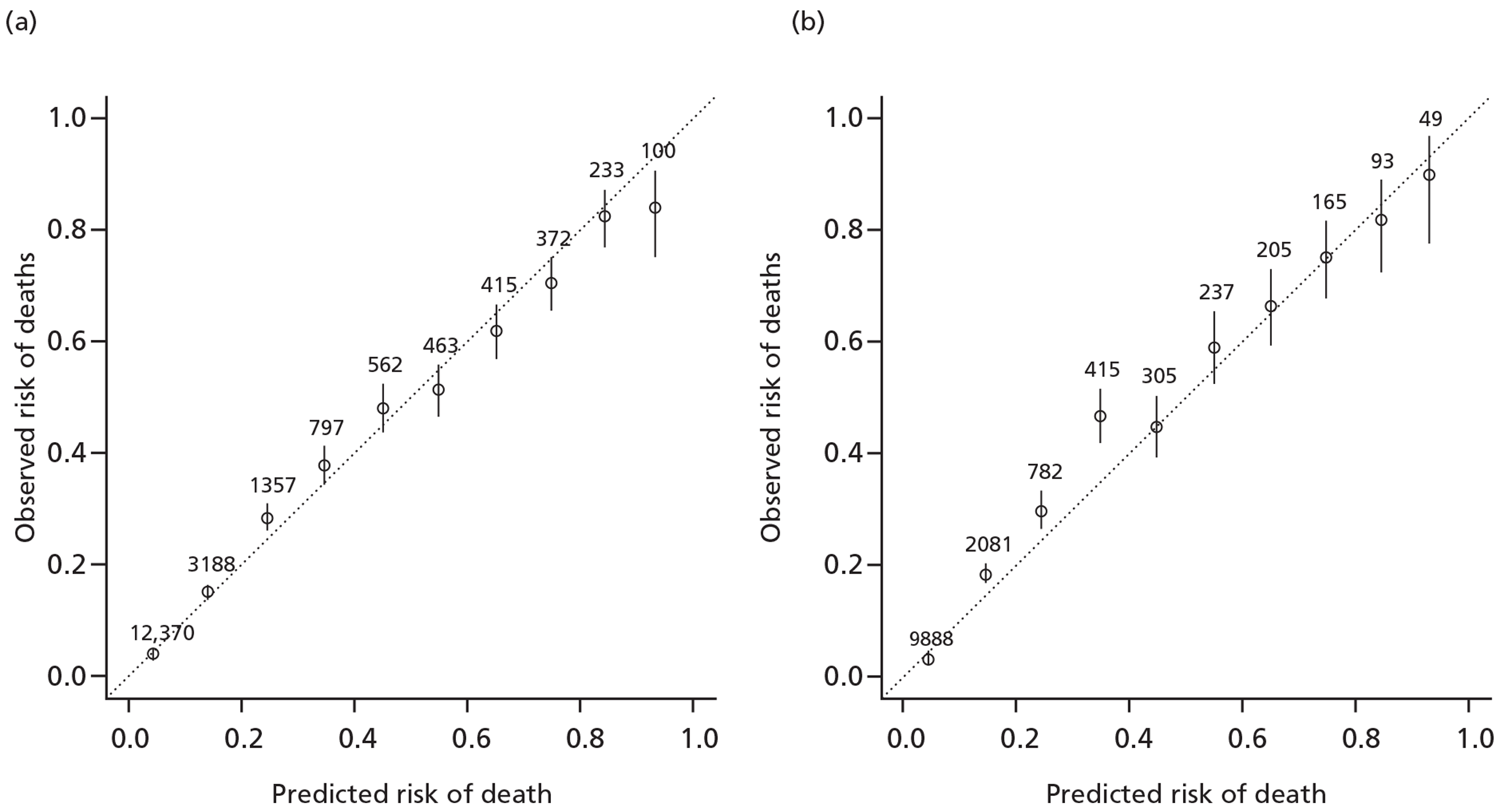

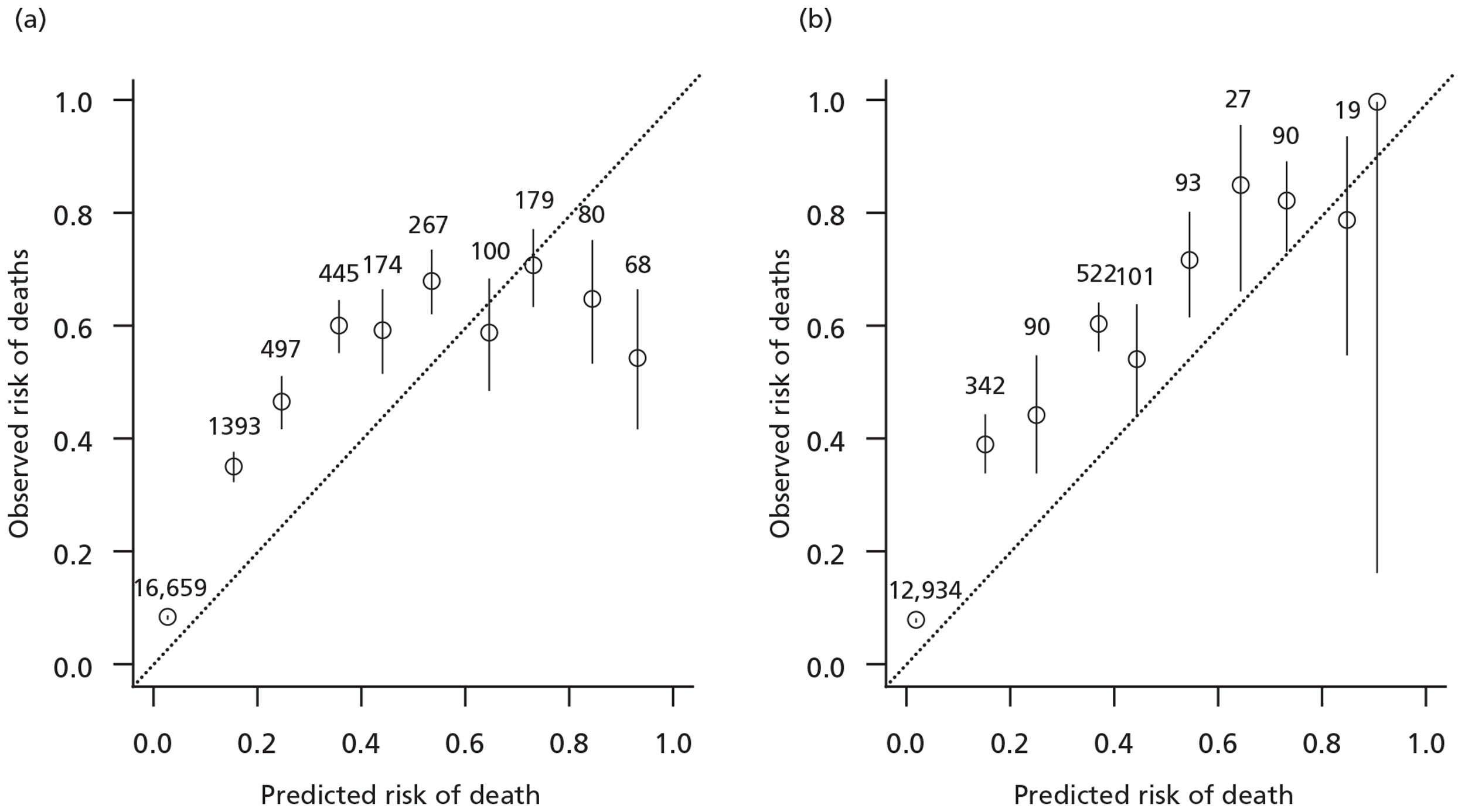

Validation

The model showed a good internal validity, with a C-statistic of 0.84 (Figure 2) and good calibration except in very high-risk patients for whom the model over-predicted risk (Figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

Internal and external discrimination displayed by the receiving operating characteristic. AUC, area under the curve; PV, predictive value. (a) CRASH-2 trial data (internal discrimination); (b) TARN data (external discrimination). Curves showing point where the addition of sensitivity and specificity is maximum and corresponding cut-points of risk.

FIGURE 3.

Goodness of fit and external calibration of the prognostic model by levels of predicted risk. (a) CRASH-2 trial data (goodness of fit); (b) TARN data (external validation).

Internal validation using bootstrapping showed a minimal decrease of the C-statistic from 0.836 to 0.835. This indicates that there is very low over-optimism in the model development.

For the external validation we used the same variables as included in the derivation model except HSI, as this variable had a very large number of patients with missing data. Discrimination was good (C-statistic 0.88) and calibration satisfactory (see Figures 2 and 3).

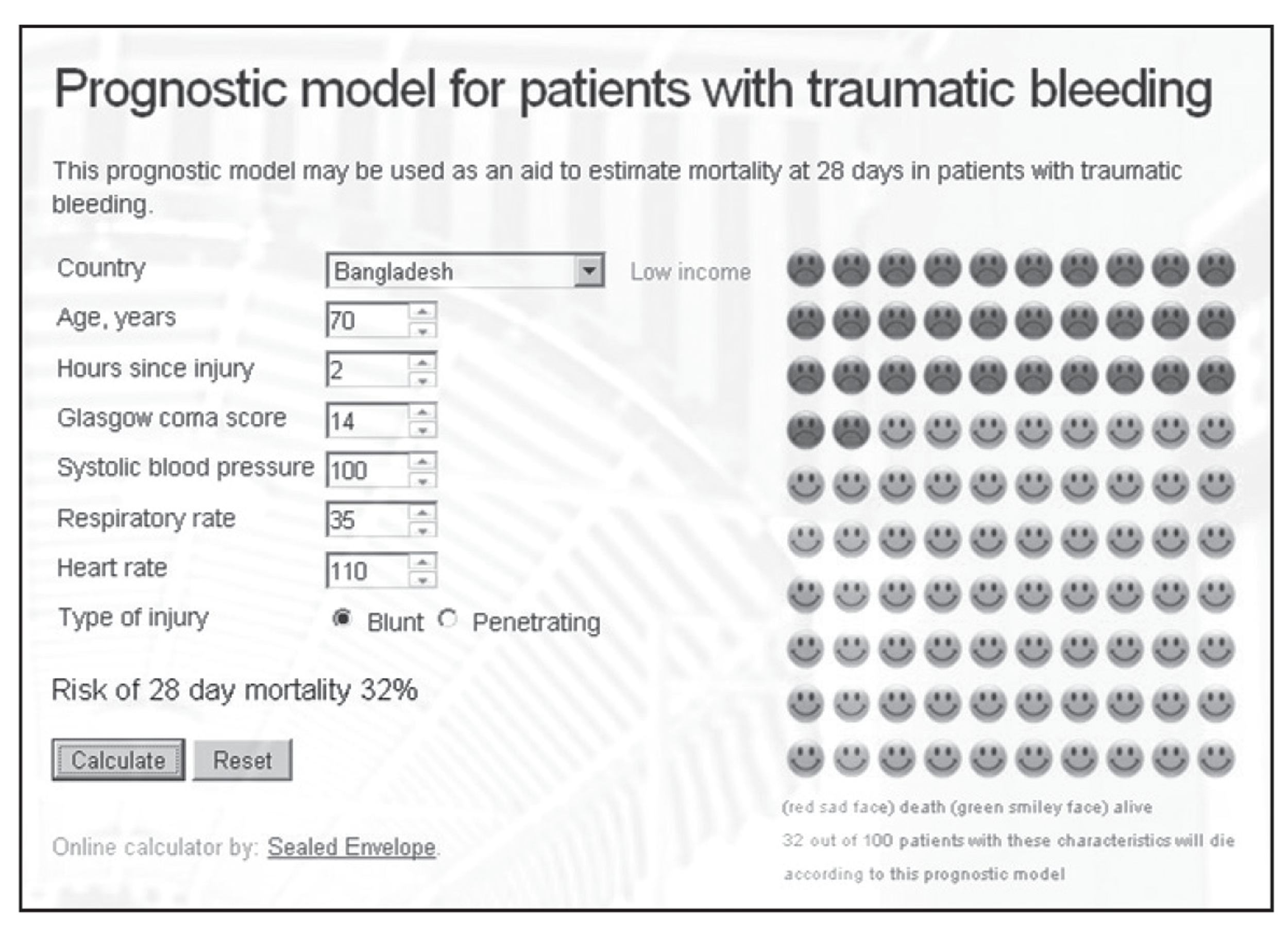

Model presentation

The prognostic model is available online (www.crash2.lshtm.ac.uk), so risk of death can be obtained for individual patients. By entering the values of the predictors, the expected risk of death at 28 days is displayed. For example, a 70-year-old patient from a LIC, with a GCS score of 14, SBP of 100 mmHg, HR of 110 beats per minute and a RR of 35 breaths per minute, has a 32% probability of death at 28 days (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Snapshot of the web-based prognostic model.

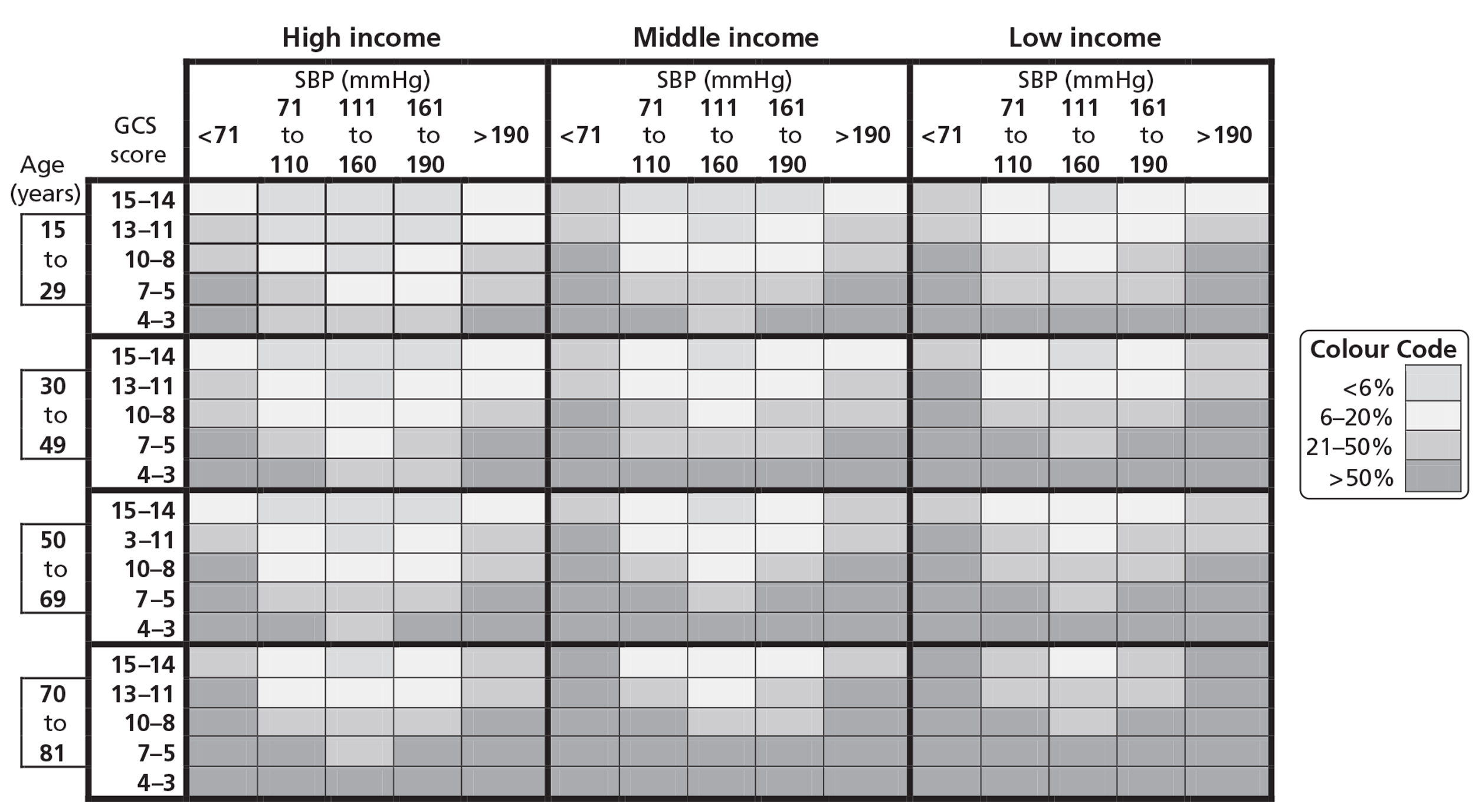

Users also highlighted the importance of a simple prognostic model that could be used at the bedside. The simple prognostic model included the three strongest prognostic variables (GCS score, SBP and age). We developed different prognostic models for patients within 3 hours of injury in LICs, MICs and HICs, and presented them as charts (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Chart to predict death in trauma bleeding patients.

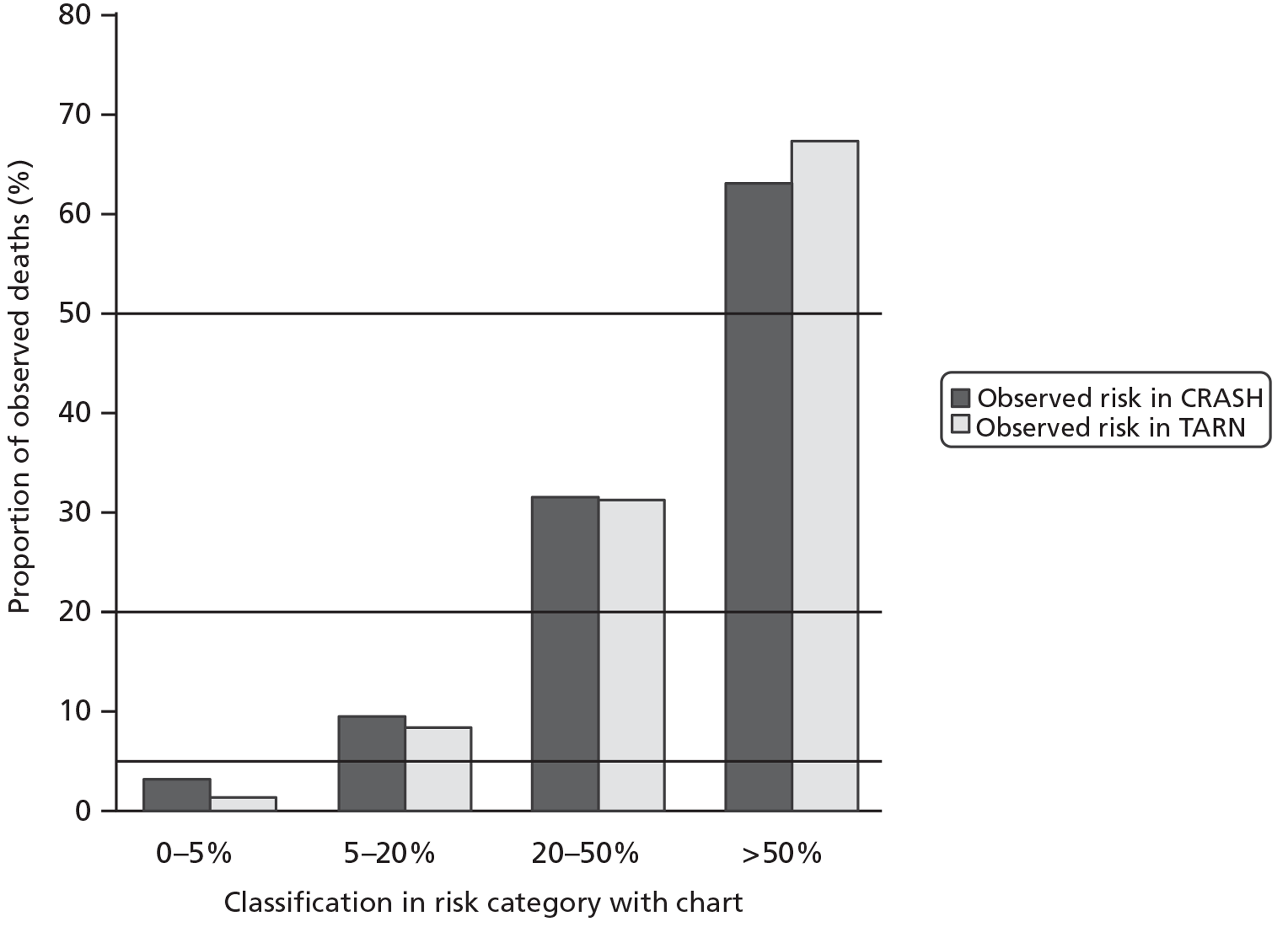

These simple charts also showed good internal and external calibration (Figure 6). The area under the curve (AUC) for the simpler model was 0.82 for CRASH-2 trial data and 0.86 for TARN data.

FIGURE 6.

Internal and external calibration of the simple chart.

Effect of tranexamic acid according to baseline risk

Table 5 shows the characteristics of CRASH-2 trial patients who were treated within 3 hours of injury according to baseline risk. Patients with higher baseline risk of death were older, had lower SBP and GCS scores, higher HRs and RRs, and were more likely to have blunt trauma than patients with a lower risk. Most patients (97%) were from MICs and this frequency distribution was similar for all of the risk strata.

| Characteristics | Risk strata | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 6% | 6–20% | 21–50% | > 50% | |

| Total number of patients, n (%) | 4840 (36) | 5395 (41) | 1848 (14) | 1190 (9) |

| Male, n (%) | 4111 (85) | 4457 (83) | 1533 (83) | 1002 (84) |

| Age (years), mean (IQR) | 27 (22–36) | 32 (25–44) | 35 (25–48) | 35 (25–49) |

| Blunt injury, n (%) | 2761 (57) | 3186 (59) | 1316 (71) | 980 (82) |

| SBP (mmHg), mean (IQR) | 100 (90–120) | 90 (80–110) | 80 (70–100) | 80 (60–90) |

| HR (beats per minute), mean (IQR) | 100 (90–112) | 106 (92–120) | 110 (97–124) | 118 (98–130) |

| RR (breath per minute), mean (IQR) | 20 (18–24) | 24 (20–28) | 24 (20–30) | 24 (16–30) |

| GCS score (total), mean (IQR) | 15 (15–15) | 15 (13–15) | 10 (7–13) | 4 (3–6) |

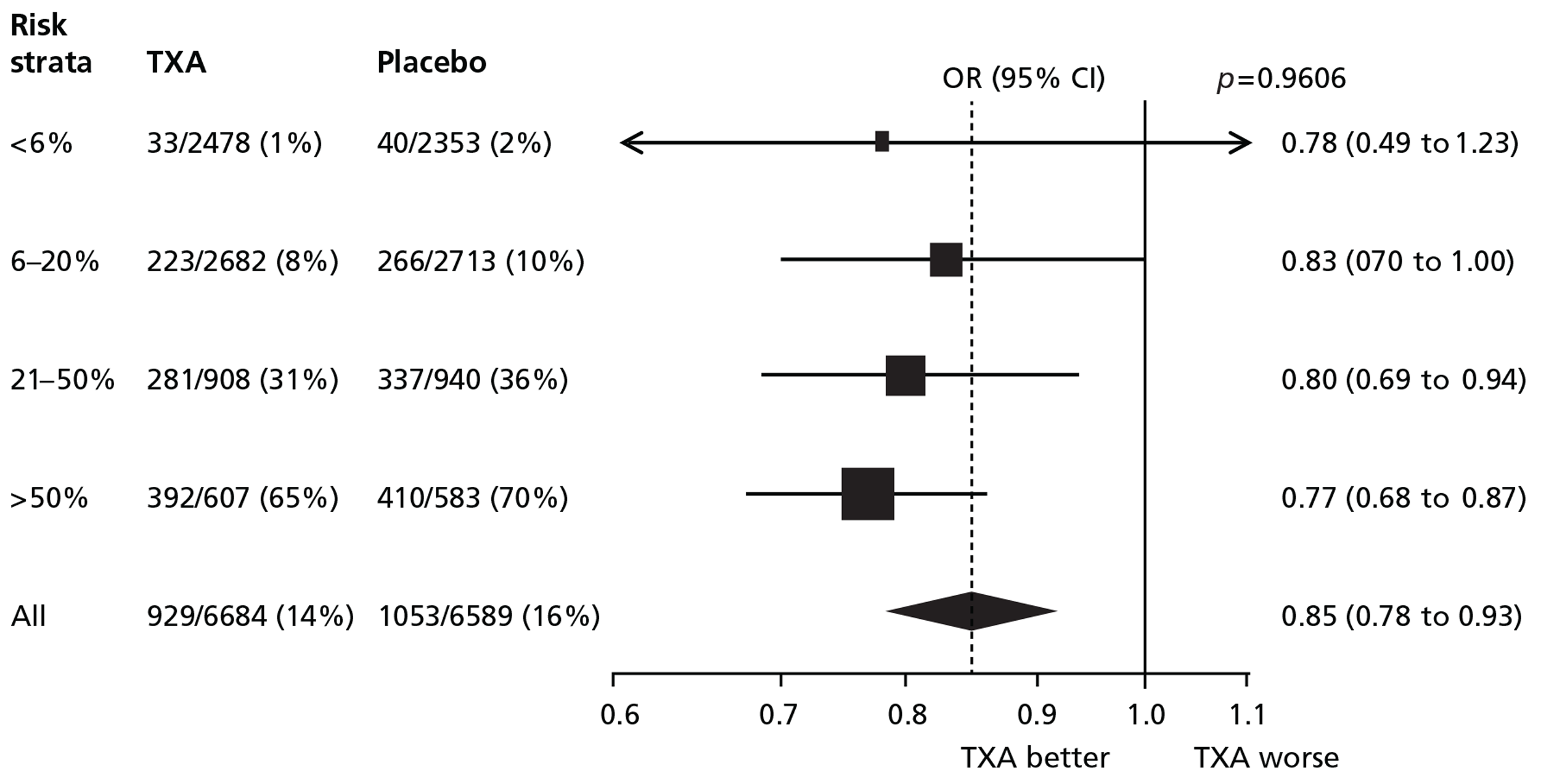

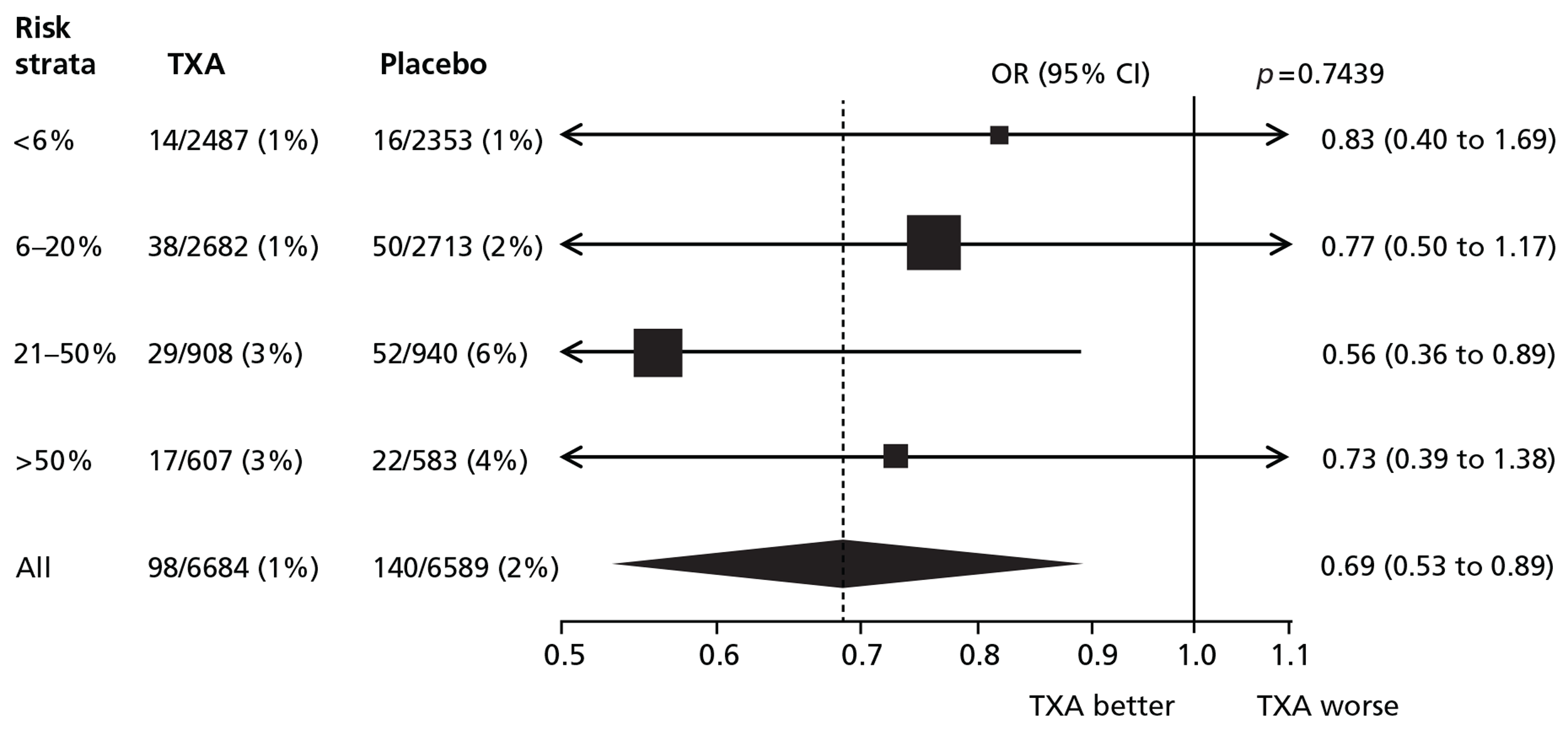

Figure 7 shows the effect of TXA on all-cause mortality by baseline risk. TXA reduced all-cause mortality in each stratum of baseline risk. There was no evidence of heterogeneity in the effect of TXA on all-cause mortality (p-value for interaction = 0.96).

FIGURE 7.

Death from all causes.

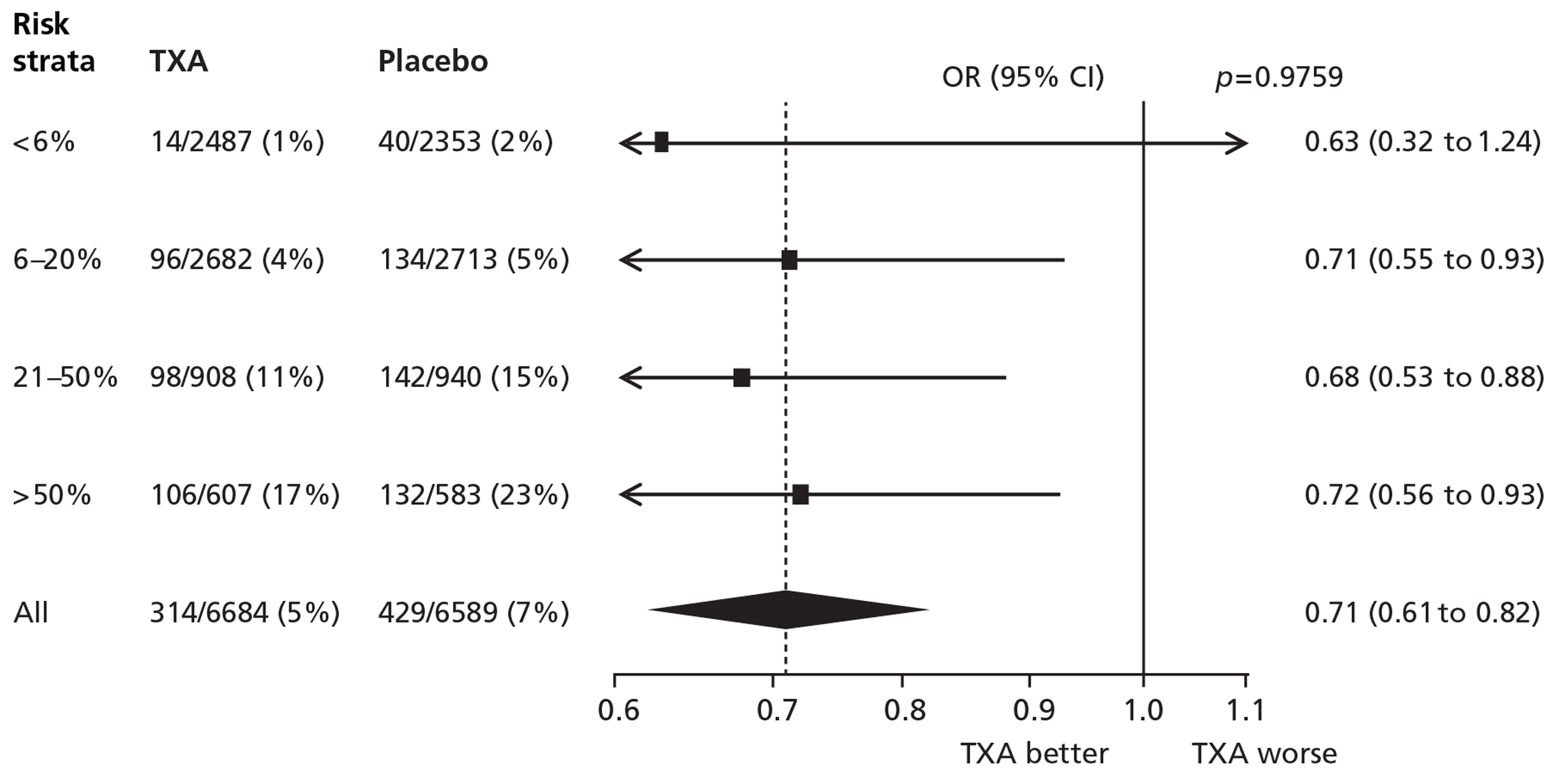

Figures 8 and 9 show the effects of TXA on death due to bleeding, and on fatal and non-fatal thrombotic events by baseline risk of death.

FIGURE 8.

Death due to bleeding.

FIGURE 9.

Fatal and non-fatal thrombotic events.

There was no evidence of heterogeneity in the effect of TXA on death due to bleeding (p = 0.98) or on thrombotic events (p = 0.74). There was a reduction in non-bleeding deaths that was not statistically significant (OR = 0.97; 95% CI 0.86 to 1.09), with no evidence of heterogeneity according to baseline risk (p = 0.99).

Table 6 shows the effect of TXA on fatal and non-fatal thrombotic events in patients treated within 3 hours of injury. There was a significant reduction in the risk of fatal and non-fatal thrombotic events with TXA (OR = 0.69; 95% CI 0.53 to 0.89; p = 0.005).

| Thrombotic eventsa | TXA (N = 6684), n (%) | Placebo (N = 6589), n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any event | 98 (1.5) | 140 (2.1) | 0.69 (0.53 to 0.89) | 0.005 |

| Any arterial event | 47 (0.7) | 80 (1.2) | 0.58 (0.40 to 0.83) | 0.003 |

| Myocardial infarction | 23 (0.3) | 46 (0.7) | 0.49 (0.30 to 0.81) | 0.005 |

| Stroke | 28 (0.4) | 40 (0.6) | 0.69 (0.43 to 1.11) | 0.128 |

| Any venous event | 60 (0.9) | 71 (1.1) | 0.83 (0.59 to 1.17) | 0.295 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 42 (0.6) | 47 (0.7) | 0.88 (0.58 to 1.33) | 0.548 |

| Deep-vein thrombosis | 25 (0.4) | 28 (0.4) | 0.88 (0.52 to 1.50) | 0.641 |

There was a statistically significant reduction in arterial thrombotic events with TXA (OR = 0.58; 95% CI 0.40 to 0.83; p = 0.003). There was no evidence of heterogeneity in the effect of TXA on arterial thrombotic events (p = 0.91). There was a reduction in the risk of venous thrombotic events with TXA that was not statistically significant (OR = 0.83; 95% CI 0.59 to 1.17; p = 0.295). There was no evidence of heterogeneity in the effect of TXA on venous thrombotic events by baseline risk (p = 0.85).

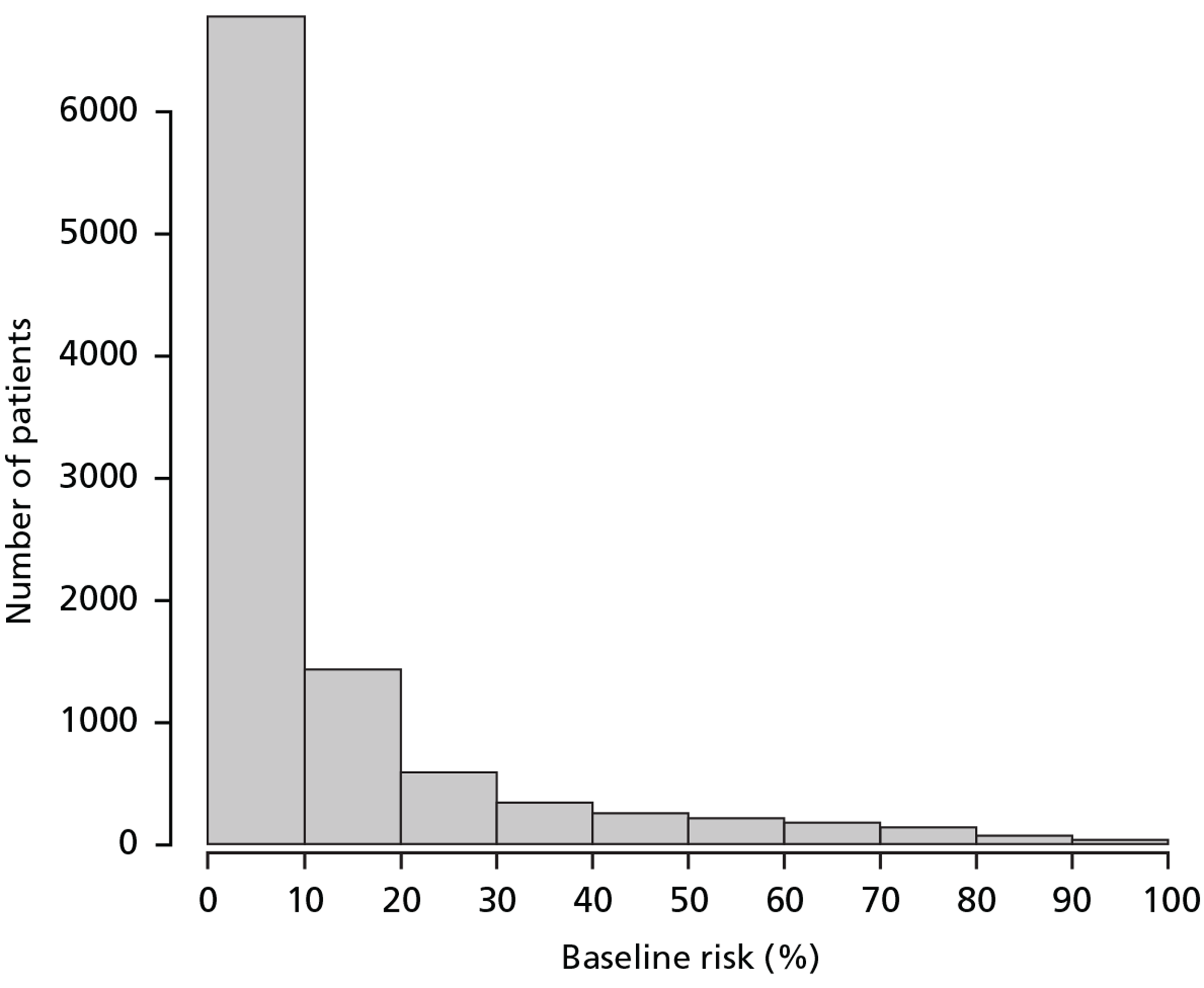

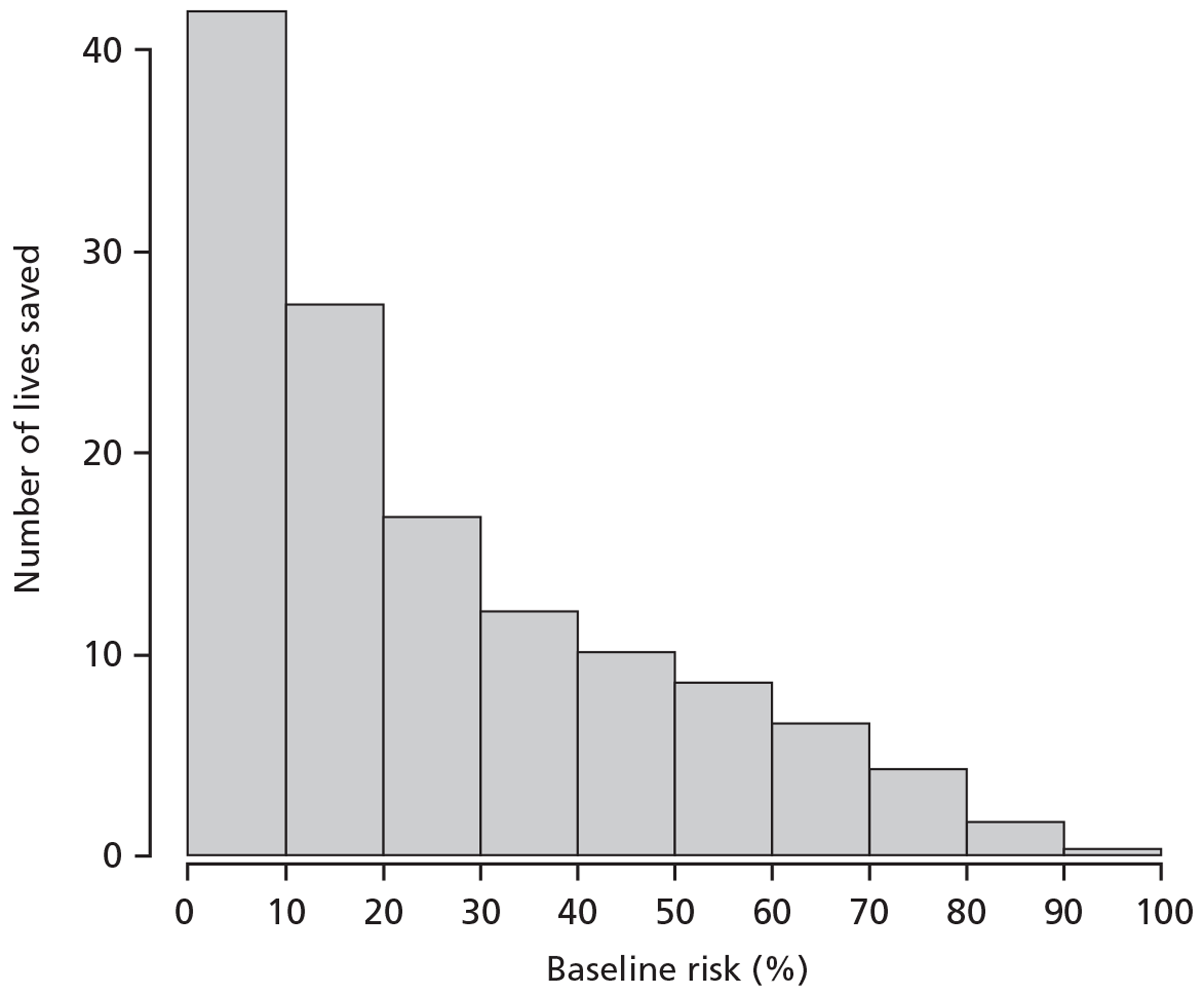

Estimation of lives saved if tranexamic acid given to different risk strata

Assuming that the effect of TXA is the same in all risk strata (constant OR), the percentage of premature deaths that could be averted in TARN by administering TXA within 3 hours of injury in each risk stratum (< 6%, 6–20%, 21–50% and > 50%) is 17%, 36%, 30% and 17% respectively. Figure 10 shows the distribution of patients according to baseline risk in TARN, and Figure 11 shows the absolute number of deaths that could potentially be averted through the use of TXA in patients in the UK TARN by baseline risk of death.

FIGURE 10.

Trauma Audit and Research Network: distribution of patients by baseline risk.

FIGURE 11.

Trauma Audit and Research Network: distribution of lives saved if TXA was given to everyone (with constant OR −0.85).

Chapter 4 Discussion

Main findings

We have developed and validated a prognostic model for trauma patients with clinical parameters that are easy to measure. The model is available as a web calculator and can be used at the point of care in its simplified form. Separate models are available for patients from LICs, MICs and HICs. This simple prognostic model could inform doctors about the risk of death and guide them in the early assessment and management of trauma patients.

The ORs for all-cause mortality and death due to bleeding with TXA do not appear to vary by baseline risk. TXA reduced the odds of death due to bleeding by approximately 30% in each of the risk strata. TXA also appeared to reduce the odds of thrombotic events by 30%. Once again, this reduction does not appear to vary by baseline risk. Taken together, these data suggest that TXA can be administered safely to a wide spectrum of trauma patients and that its use should not be restricted to the most severely injured. However, although we did not find evidence of heterogeneity for the effect of TXA according to baseline risk, in the lowest-risk group the precision of the estimated effect is low.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths. Our models were based on a prospective cohort of bleeding trauma patients, with standardised collection of data on prognostic factors, very few missing data and low loss to follow-up. Unlike previous prognostic models, we explored more complex relationships between continuous predictors and mortality, and captured non–linear relationships. All of these factors provide reassurance about the internal validity of our models. The large sample size in relation to the number of prognostic variables is also an important strength. As most previous models were derived from single-centre studies in HICs, we developed separate models for LICs, MICs and HICs. Unlike most previous models, we conducted an external validation in a large cohort of trauma patients. This confirmed the discriminatory ability of the model in patients from HICs and showed good calibration. Another methodological strength was our use of imputation to address missing data, which has rarely been done in previous model validation studies. To the best of our knowledge this is the only prognostic model for this population that is available in a web-based calculator and a simplified chart that can be used at point of care. Importantly, we obtained advice from the potential users of the model throughout its development.

There are also some limitations. The data from which the models were developed come from a clinical trial and this could therefore limit external validity. For example, patients were recruited within 8 hours of injury, and we cannot estimate the accuracy of the models for patients evaluated beyond this time. Nevertheless, the CRASH-2 trial was a pragmatic trial that did not require any additional tests and, therefore, included a diversity of real-life patients. In addition, the relationship between predictors and outcome could be different in patients included in a clinical trial and in routine practice. The TARN data included a larger proportion of patients with blunt injuries than in the CRASH-2 trial; however, that the model's performance was very good in a trauma registry population provides reassurance that any potential bias (if present) was small. Another limitation was that for the validation we used a cohort of trauma patients that were not equally defined and we included them using an estimation of the blood loss. In any case, this weakness would have underestimated the accuracy of the model. Other potentially important variables such as pre-existing medical conditions, previous medications and laboratory measurement were not collected in the CRASH-2 trial and, therefore, were not available for inclusion into the model. However, these are variables that are usually unavailable in the acute care trauma setting in which the model is intended to be used. The prognostic model predicts overall death rather than death due to bleeding, as death due bleeding was not available in the TARN data set. However, it is expected that bleeding contributes to the other main causes of death in trauma patients. In addition, some deaths classified as non-bleeding could in fact be due to bleeding.

Regarding the effect of TXA according to baseline risk, it is important to note that the data examined here are a subset of the entire CRASH-2 trial. As most trauma protocols restrict TXA use to patients within 3 hours after injury, we restricted our analyses to these patients. Given that our results are based on a subgroup analysis, they should be interpreted cautiously. On the other hand, there was also a reduction in the risk of fatal and non-fatal myocardial infarction (relative risk = 0.64; 95% CI 0.42 to 0.97; p = 0.035) in the main trial analysis of patients treated up to 8 hours from injury, and there were fewer thrombotic events in TXA-treated patients. Although there may be grounds for scepticism about the reduction in arterial thrombotic events with TXA, the data provide reassurance that there is no increased risk.

The absence of evidence of an interaction between the effect of TXA and baseline risk could be due to a lack of statistical power for the interaction tests; however, graphically it seems unlikely that the findings are due to lack of power and they suggest that the effect of TXA is not influenced by baseline risk. We used a multivariable approach that has been shown to improve the power of subgroup analysis in comparison with individual predictor subgroup analyses. 19 Simulation studies have shown that the power to detect an interaction is increased from 23% to 83% when a multivariable approach is used. Nevertheless, the absence of evidence of interaction should not be taken as evidence of absence of an interaction.

That we analysed data from a randomised controlled trial using a prognostic model derived from the same trial might be considered a weakness. On the other hand, the prognostic model we used has good external calibration and discrimination, and there are few models available that can be reliably applied to the trauma population included in the CRASH-2 trial. The revised trauma score, one of the most widely used scores, was developed many years ago, has several methodological limitations, and showed poor calibration in the CRASH-2 trial and TARN data sets (Figure 12). 20

FIGURE 12.

Calibration of the revised trauma score in CRASH-2 trial and TARN data. (a) CRASH-2 trial data (prediction with revised trauma score); (b) TARN data (prediction with revised trauma score).

Establishing cause of death in trauma patients can be difficult and any inaccuracy might have affected our estimate of the effect of TXA on fatal thrombotic events. There may also have been inaccuracy in the diagnosis of non-fatal events. The diagnosis of myocardial infarction is particularly challenging in trauma patients, many of whom are anaesthetised or sedated. Elevations in creatine kinase-MB isoenzyme are hard to interpret because of muscle injury and we did not collect data on troponin. However, diagnostic inaccuracy tends to obscure treatment effects and would not readily explain the observed reduction in thrombotic events with TXA.

Implications of the study

Many trauma protocols use blood pressure as the main criterion for determining which patients should receive urgent intervention. However, according to our model, a 75-year-old patient with blunt trauma and a SBP of 110 mmHg, HR of 80 beats per minute, RR of 15 breaths per minute and a GCS score of 15 has a similar risk of death as a 45-year-old patient with exactly the same parameters but with a SBP of 60 mmHg. These findings have important practical implications. According to many trauma protocols, only the younger patient would receive urgent interventions such as TXA, whereas the older patient would be denied this life-saving intervention. The effect of age is particularly important bearing in mind that in HICs the average age of trauma patients is increasing. Data from TARN show that one-quarter of trauma deaths in England and Wales occur in patients > 70 years. The effect of age is likely to reflect the increased incidence of co-existing diseases, in particular cardiovascular diseases. Elderly patients are more likely to have coronary heart disease and the decrease in oxygen supply associated with traumatic bleeding can increase the risk of myocardial ischaemia. 21 Another potential explanation for the increased risk of vascular occlusive death is related to the inflammation process trigger after trauma. It is known that after trauma there is a potent inflammatory response that involves increased serum levels of interleukin 1 (IL-1), IL-2, tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), IL-6, IL-12 and interferon-gamma. 22 In patients with traumatic bleeding there is activation of plasmin which plays a key role in the fibrinolytic response in the early hours after injury. Plasmin also has pro-inflammatory effects through the activation of cytokines, monocytes, neutrophils, platelets and endothelial cells. 23 It has been suggested that vascular risk rises in short time periods of inflammatory responses to exposures such as infections or major surgery. 24 It is possible that some of the observed prognostic role of age in trauma patients is due to the acute trauma inflammatory response, which might trigger acute vascular events, particularly in those older patients who have a more widespread atherosclerotic condition. Furthermore, the prognostic role of age could be explained partially by a self-fulfilling prophecy phenomenon, as age has been shown to be positively associated with do-not-resuscitate orders. 25

We found that trauma patients in LICs and MICs were at higher risk of death than patients from HICs. It is important to emphasise that the income classification refers to the country and not to individual patients. Some of the effect of income classification might be the consequence of the differences on health-care settings. Other studies have shown similar results, but to our knowledge this is the first one to include a large number of LICs and MICs. 26 Although we did not have enough information to explore the causes of these differences, it is likely that the rapid increase in the number of trauma patients and the lack of resources in poorer countries are among the most important reasons. Scaling up cost-effective interventions in these settings could save hundreds of thousands of lives every year.

Potential biological mechanisms

The effect of TXA in arterial events was unexpected. Treatments to reduce haemorrhage often increase thrombosis risk and the use of anticoagulants tends to increase the risk of bleeding. However, TXA reduces the risk of haemorrhage death and appears to also reduce the risk of arterial thrombotic events. What mechanisms might account for this? Trauma marks the onset of a period of greatly increased myocardial oxygen demand as pain and hypovolaemia lead to a rapidly increased HR. At the same time, blood loss results in hypotension and anaemia, which reduces myocardial oxygen delivery. The imbalance between increased oxygen demand and reduced supply may be sufficient to cause myocardial infarction, particularly in patients with pre-existing coronary artery stenosis. Cohort studies have shown that even a modest reduction in haemoglobin is a strong risk factor for death in patients with stable angina. In this respect, the pathophysiology of myocardial ischaemia in trauma patients may be similar to stress-induced myocardial infarction in perioperative patients (type 2 perioperative myocardial infarction). 27 By reducing traumatic blood loss and anaemia, an early short course of TXA could reduce myocardial oxygen demand and increase oxygen supply.

Tranexamic acid might also play a role in the prevention of acute coronary thrombosis following trauma. 28 Traumatic injury triggers an acute inflammatory state with increases in TNF-α, IL-1 and IL-6. These inflammatory mediators have been implicated in coronary plaque fissuring and acute coronary thrombosis. TXA reduces bleeding through the inhibition of plasmin, the enzyme responsible for fibrinolysis. However, plasmin also has a wide spectrum of pro-inflammatory effects, raising the possibility that the observed reduction in the risk of arterial thrombotic events in trauma patients treated with TXA may be mediated via an anti-inflammatory effect. 29

Implications for clinical practice

The result that the effect of TXA does not vary by baseline risk has important implications for the care of trauma patients. First, it suggests that TXA can be used safely in all trauma patients with or at risk of significant bleeding, as per the inclusion criteria used in the CRASH-2 trial, and not just in those with massive haemorrhage. Second, the observed reduction in the risk of arterial events with TXA suggests that the absolute benefits from TXA administration are likely to be greatest in older trauma patients, who at any given level of injury severity have a higher baseline risk of haemorrhage death and thrombotic events. Clinical concern about an increased risk of ischaemic cardiac events may be a reason to give rather than to withhold TXA. It is worth noting that trials of TXA in cardiac surgery patients, a group at high risk of cardiac events, provide no evidence of any increased risk with TXA. 30 We acknowledge that estimating the risk of significant bleeding is a challenging ongoing process that uses not only physiological variables but also other variables such as laboratory measurements and response to treatments. Physicians will use all of this information and their clinical judgement when deciding whether or not to use TXA. However, in situations of uncertainty physicians can use the prognostic model to support the decision-making process and should certainly consider administering TXA to patients with a risk of death > 5%.

Future research

The relationship between age and mortality needs further exploration; a better understanding of the mechanism underlying the association between age and increasing mortality could lead to effective interventions to improve the outcome in this vulnerable population.

As we were able to validate the model only in patients from high-income regions, future studies should also explore its performance in LIC and MIC settings.

Finally, future research should evaluate whether or not the use of this prognostic model in clinical practice has an impact on the management and outcomes of trauma patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the CRASH-2 trial collaborators and the TARN Executive for making their data available. The authors want to acknowledge the ambulance crew, military personnel and emergency doctors who gave feedback at the different stages of the prognostic model development and validation. The authors also want to acknowledge the A&E consultants who attended the consultation meeting to discuss the effect of TXA according to baseline risk and Maria Ramos who helped to edit this report.

Contribution of authors

Pablo Perel (Senior Lecturer), Haleema Shakur (Senior Lecturer) and Ian Roberts (Professor) designed the study.

David Prieto-Merino (Lecturer) analysed the data.

All authors contributed to writing the paper.

Disclaimer

This report presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the HTA programme or the Department of Health.

References

- Krug EG, Sharma GK, Lozano R. The global burden of injuries. Am J Public Health 2000;90:523-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.90.4.523.

- Ker K, Kiriya J, Perel P, Edwards P, Shakur H, Roberts I. Avoidable mortality from giving tranexamic acid to bleeding trauma patients: an estimation based on WHO mortality data, a systematic literature review and data from the CRASH-2 trial. BMC Emerg Med 2012;12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-227X-12-3.

- Kauvar DS, Lefering R, Wade CE. Impact of hemorrhage on trauma outcome: an overview of epidemiology, clinical presentations, and therapeutic considerations. J Trauma 2006;60:S3-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.ta.0000199961.02677.19.

- Tien HC, Spencer F, Tremblay LN, Rizoli SB, Brenneman FD. Preventable deaths from hemorrhage at a level I Canadian trauma center. J Trauma 2007;62:142-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.ta.0000251558.38388.47.

- The CRASH-2 Collaborators . The importance of early treatment with tranexamic acid in bleeding trauma patients: an exploratory analysis of the CRASH-2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011;377:1096-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60278-X.

- Dutton RP. Current concepts in hemorrhagic shock. Anesthesiol Clin 2007;25:23-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.atc.2006.11.007.

- Geeraedts LM, Kaasjager HA, van Vugt AB, Frolke JP. Exsanguination in trauma: a review of diagnostics and treatment options. Injury 2009;40:11-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2008.10.007.

- Parks JK, Elliott AC, Gentilello LM, Shafi S. Systemic hypotension is a late marker of shock after trauma: a validation study of Advanced Trauma Life Support principles in a large national sample. Am J Surg 2006;192:727-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.08.034.

- Siegel JH, Rivkind AI, Dalal S, Goodarzi S. Early physiologic predictors of injury severity and death in blunt multiple trauma. Arch Surg 1990;125:498-50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.1990.01410160084019.

- Perel P, Arango M, Clayton T, Edwards P, Komolafe E, Poccock S, et al. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: practical prognostic models based on large cohort of international patients. BMJ 2008;336:425-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39461.643438.25.

- Honeybul S, Ho KM, Lind CR, Corcoran T, Gillett GR. The retrospective application of a prediction model to patients who have had a decompressive craniectomy for trauma. J Neurotrauma 2009;26:2179-83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/neu.2009.0989.

- Rehn M, Perel P, Blackhall K, Lossius HM. Prognostic models for the early care of trauma patients: a systematic review. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2011;19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1757-7241-19-17.

- CRASH-2 Collaborators . Effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events, and blood transfusion in trauma patients with significant haemorrhage (CRASH-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2010;376:23-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60835-5.

- World development indicators. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2011.

- Steyerberg EW. Clinical prediction models. New York, NY: Springer; 2009.

- Guly HR, Bouamra O, Hatton M, Dark P, Coats T, Driscoll P, et al. Vital signs and estimated blood loss in patients with major trauma: testing the validity of the ATLS classification of hypovolaemic shock. Resuscitation 2011;82:556-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.01.013.

- Kondo Y, Abe T, Kohshi K, Tokuda Y, Cook EF, Kukita I. Revised trauma scoring system to predict in-hospital mortality in the emergency department: Glasgow Coma Scale, age and systolic blood pressure score. Crit Care 2011;15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/cc10348.

- Sartorius D, Le Manach Y, David JS, Rancurel E, Smail N, Thicoïpé M, et al. Mechanism, Glasgow coma scale, age, and arterial pressure (MGAP): a new simple prehospital triage score to predict mortality in trauma patients. Crit Care Med 2010;38:831-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cc4a67.

- Hayward RA, Kent DM, Vijan S, Hofer TP. Multivariable risk prediction can greatly enhance the statistical power of clinical trial subgroup analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol 2006;6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-6-18.

- Champion HR, Sacco WJ, Copes WS, Gann DS, Gennarelli TA, Flanagan ME. A revision of the Trauma Score. J Trauma 1989;29:623-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005373-198905000-00017.

- Wardle TD. Co-morbid factors in trauma patients. Br Med Bull 1999;55:744-56. http://dx.doi.org/10.1258/0007142991902754.

- Lenz A, Franklin G, Cheadle WG. Systemic inflammation after trauma. Injury 2007;38:1336-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2007.10.003.

- Levy JH. Antifibrinolytic therapy: new data and new concepts. Lancet 2010;376:3-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60939-7.

- Smeeth L, Hingorani A. Short-term vascular risk: time to take notice?. Nat Rev Cardiol 2010;7:409-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2010.64.

- Nathens AB, Rivara FP, Wang J, Mackensie EJ, Jurkovivh G. Variations in the rate of do not resuscitate orders after major trauma and the impact of intensive care unit environment. J Trauma 2008;64:81-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e31815dd4d7.

- Mock CN, Jurkovich GJ, nii-Amon-Kotei D, Arreola-Risa C, Maier RV. Trauma mortality patterns in three nations at different economic levels: implications for global trauma system development. J Trauma 1998;44:804-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005373-199805000-00011.

- Shah AD, Nicholas O, Timmis AD, Feder G, Abrams KR, Chen R, et al. Threshold haemoglobin levels and the prognosis of stable coronary disease: two new cohorts and a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2011;8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000439.

- Godier A, Roberts I, Hunt B. Tranexamic acid: less bleeding and less thrombosis. Crit Care 2012;16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/cc11374.

- Jimenez JJ, Iribarren JL, Lorente L, Rodrigue JM, Hernandez D, Nassar I, et al. Tranexamic acid attenuates inflammatory response in cardiopulmonary bypass surgery through blockade of fibrinolysis: a case control study followed by a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Crit Care 2007;11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/cc6173.

- Ker K, Edwards P, Perel P, Shakur H, Roberts I. Effect of tranexamic acid on surgical bleeding: systematic review and cumulative meta-analysis. BMJ 2012;344. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e3054.

Appendix 1 Semistructured interviews

Appendix 2 Project submitted to Health Technology Assessment programme

Project submitted to Health Technology Assessment programme (PDF download)

List of abbreviations

- A&E

- accident and emergency

- AUC

- area under curve

- CI

- confidence interval

- CRASH-2

- Clinical Randomisation of an Antifibrinolytic in Significant Haemorrhage trial

- GCS

- Glasgow Coma Scale

- HIC

- high-income country

- HR

- heart rate

- HSI

- hours since injury

- IL

- interleukin

- IQR

- interquartile range

- LIC

- low-income country

- MIC

- middle-income country

- OR

- odds ratio

- RR

- respiratory rate

- SBP

- systolic blood pressure

- TARN

- Trauma Audit and Research Network

- TNF-α

- tumour necrosis factor alpha

- TXA

- tranexamic acid

All abbreviations that have been used in this report are listed here unless the abbreviation is well known (e.g. NHS), or it has been used only once, or it is a non-standard abbreviation used only in figures/tables/appendices, in which case the abbreviation is defined in the figure legend or in the notes at the end of the table.