Notes

Article history paragraph text

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 03/38/01. The contractual start date was in July 2005. The draft report began editorial review in October 2011 and was accepted for publication in November 2011. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Lilford et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction to report

Background

Introduction

Liver disease represents a major source of morbidity and mortality in the UK. 1 Abnormal liver function tests (LFTs) have been shown to be predictive not only of liver disease mortality, but also of more general causes of mortality. 2 LFTs are a good example of inexpensive tests (modern auto-analysers process large batches of samples using inexpensive reagents) that are frequently ordered as a ‘test of exclusion’ in patients with non-specific symptoms, such as tiredness or upper abdominal discomfort. The tests are also non-specific in the sense that none of the four to eight analytes included in the LFT panel points directly to a specific diagnosis, and many are not even specific to the liver. A doctor may order a laboratory test because a patient has features of a particular disease; for example, the gradual onset of jaundice in a user of injectable substances points to hepatitis C. The prior risk of hepatitis in such a person would be high: many positives would be true-positives. In most cases, however, LFTs are ordered without such a traceable link between symptoms and a specific diagnosis, for example when patients have vague symptoms or as part of the monitoring of patients with chronic diseases. Such tests are often offered as a type of insurance policy, but the prior risk of disease is low and the predictive value of LFTs is, a priori, likely to be low also. LFTs are interpreted by reference to population norms, rather than explicit calculus of the relative benefits and harms of false-positive and false-negative diagnoses. Many patients have a positive test, but it is not clear what proportion of these are true-positives, especially when the test result is only mildly abnormal. Review of the literature (see Previous research) shows that there is little evidence from large cohorts of people with abnormal LFT results to guide clinical actions when LFT results are mildly abnormal. The issue of how, or even whether, to investigate abnormal LFTs under various scenarios is not settled.

It is clear that a very large number of tests are ordered and abnormal results are common. The laboratory at University Hospital Birmingham received 67,182 requests for LFTs in 2003, from 83 general practitioner (GP) practices representing 210 GPs. Of these, 9779 (15%) led to an abnormal result in the sense that at least of one of the analytes on the LFT panel exceeded the reference range. As LFTs are inexpensive and easy to organise as one of the standard ‘blood tests’ in the GP's repertoire, their use has become widespread without careful study of their meaning in a general practice setting. As the meaning of the various combinations of possible test results and clinical features is unclear, different practitioners respond in different ways to the same test profile – the eclectic nature of practitioners' responses to the same scenarios has been well documented. 3

Most abnormal LFT results are false-positives. Thus, large numbers of follow-on tests and much anxiety can ensue if a low threshold is used to define abnormality. On the other hand, there are arguments to adopt a low threshold for subsequent evaluation, as LFTs have the ability to detect diseases when they are most treatable, for example by reducing overload in patients with metal storage diseases or by administering antiviral agents in those with chronic viral hepatitis. Furthermore, theory-based interventions designed to modify behaviour that leads to liver damage, while clearly far from a panacea, nevertheless produces worthwhile benefits in that some people adopt healthy lifestyles when they perceive that their health is threatened and that engaging in the recommended behaviour will reduce this threat. 4–6

The incidence of many liver diseases is rising, for example with migration from places with high rates of chronic hepatotoxic viral infection, and as a result of alcohol and calorie excess. Comorbidity is becoming more common as alcohol misuse and calorie excess unmask other diseases of the liver, such as haemochromatosis.

Thus, three interacting factors create an urgent need to better understand the clinical epidemiology of abnormal LFTs:

-

frequent use of these tests

-

lack of clarity about the meaning of the results

-

increasing treatability and rising incidence of liver diseases.

A number of authors have produced diagnostic algorithms for the investigation of people with abnormal LFTs. 7–12 These provide sensible advice – for example stressing the importance of taking a careful family history or of responding to tests that suggest obstructive biliary disease – but they do not provide a clear probabilistic basis for their reasoning. In particular, there is no scientific rationale for the widespread advice to repeat an abnormal LFT before conducting further tests. Green and Flamm13 state in their 2002 review of 1400 papers: ‘Unfortunately … there are no long term prospective studies to define the natural history of liver disease in patients with abnormal liver chemistries tests.’ They call for a substantial prospective study of a well-documented population given a standardised diagnostic work-up in general practice and then followed up for a period of time. It was this gap in the literature that the Birmingham and Lambeth Liver Evaluation Testing Strategies (BALLETS) study was designed to rectify.

Previous research

There is considerable literature on the laboratory measurement of analytes. Dufour et al. 14,15 carried out a systematic review of this topic in 2000. This review contains much useful information on biological variability and how it is affected by sex, age, race, use of the oral contraceptive pill (and other medicines), pregnancy, exercise, delay in analysis and time of day. The study also reviews the patterns of abnormality of each analyte given different diseases. A further systematic review that distilled 14,000 references was commissioned by the American Gastroenterology Association Clinical Practice Committee in 2002. 13 Again, most of the references describe probabilities of test results given various diseases, rather than the probabilities of the various diseases given test results. For example, Bonacini 16 describes ‘test results in people with cirrhosis due to chronic hepatitis infection’. Only a small proportion of articles report likelihood of disease by test result. Studies in this category tend to be based on hospital patients with serious abnormalities, such as ‘notably raised aspartate aminotransferase’17 or ‘requiring liver biopsy’. 18–20 Angulo et al. 21 investigated a remarkable 733 patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) confirmed by liver biopsy to determine which features were associated with more serious disease, while Ekstedt et al. 22 followed up 129 patients with biopsy-confirmed NAFLD for a mean of 13 years and showed that the subgroup with ‘steatohepatitis’ had an increased risk of both cardiovascular and liver-related death compared with a reference population.

We updated the above review (Table 1) and selected studies that started with the LFT result and then followed the cohort, so as to provide the type of probability needed for decision-making. MEDLINE was interrogated, with limits placed on the overall search with respect to ‘humans’ and ‘publishing date post 1980’. Owing to the variety of nomenclature regarding LFTs a variety of search strings were used for this category. Search strings relating to abnormal LFT results included ‘liver function test’, ‘transaminases’, ‘alanine aminotransferases’, ‘aspartate aminotransferases’, ‘alkaline phosphatase’ and ‘gamma-glutamyltransferases’. The search was focused by using the limits of blood, analysis and metabolism. Despite the limits, these search strings retrieved over 35,000 references. The term ‘hepatitis’ was considered too narrow when attempting to find studies that followed up patients for a variety of diseases, so the more general term of ‘liver diseases’ was included, with limits of diagnosis, enzymology, epidemiology, mortality and virology, which retrieved around 8500 references. When these two search strategies were combined, 1448 papers were returned, the abstracts of which were read.

| LFT search strings (limited using the subheadings; blood, analysis and metabolism) | Hepatitis search strings |

|---|---|

| ‘liver function test’ | ‘liver diseases’ (diagnosis) |

| ‘transaminases’ | ‘liver diseases’ (epidemiology) |

| ‘alanine aminotransferases’ | ‘liver diseases’ (enzymology) |

| ‘aspartate aminotransferases’ | ‘liver diseases’ (virology) |

| ‘alkaline phosphatase’ | ‘liver diseases’ |

| ‘gamma-glutamyltransferases’ | |

| With limits added (‘humans’ and ‘publishing date post 1980’) | With limits added (‘humans’ and ‘publishing date post 1980’) |

| Papers returned = 35,070 | Papers returned = 8526 |

Eight studies were found that matched our requirement of following up patients who had experienced an abnormal LFT result. Two additional articles were selected from the references of relevant studies. As a result, to the best of our knowledge, there are only 10 studies for which a cohort of asymptomatic patients with abnormal LFTs was followed up (Table 2). However, one article was written in Korean (only the abstract was translated) and was excluded from our analysis.

| Author and country | Date | Type of study and population studied | Analytes used | No. of patients enrolled | No. of patients with abnormal LFT results (%) | Prevalence of viral hepatitis in patients with abnormal LFT results (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McLernon et al.,2 Scotland | 2009 | Record linkage; laboratory database of GP tests, hospital admissions and death certificates | Bilirubin, albumin, ALP, GGT, ALT, AST (transaminases sometimes combined). GP selected | 95,977 | 20,827 (21.7) | 2.2 | Mean follow-up of 3.7 years. Risk of underascertainment |

| Pendino et al.,27 Italy | 2005 | Prospective cohort study; general population | AST, ALT, GGT | 1645 | 319 (19.4) | 17.9 | High baseline rate of viral hepatitis: 5.6% |

| Kim et al.,23 Korea | 2004 | Record linkage: insurance data and death certificates | AST, ALT | 142,055 | 11,193 (7.9) | N/A | Outcome was liver disease mortality |

| Yano et al.,28 Japan | 2001 | Prospective cohort study; ‘healthy’ office workers | AST, ALT, GGT | 1973 | 358 (18.1) | 2.7 | Assumed that all liver cancer and cirrhosis was a result of viral hepatitis |

| Daniel et al.,18USA | 1999 | Prospective cohort study; primary-care population | ALT, AST raised 50% above normal on at least two occasions across a 6-month period | 1124 | 1124 (100) | N/A | Marker-negative patients only, so infected patients excluded from analysis |

| Mathiesen et al.,30 Sweden | 1999 | Prospective cohort study; primary-care population | AST, ALT raised for at least 6 months (ALP had to be normal) | 150 | 150 (100) | 15.3 | |

| Whitehead et al.,17 UK | 1999 | Prospective cohort study; primary-care population | AST markedly raised [10 times (> 400 U/l) above the ULN] | 137 | 137 (100) | 2.2 | |

| Bellentani et al.,26 Italy | 1994 | Prospective cohort; general population | AST, ALT, GGT | 6917 | 1473 (21.3) | 2.4 | |

| Hultcrantz et al.,29 Scandinavia | 1986 | Prospective cohort study; primary-care population | AST, ALT moderately raised for at least 6 months (ALP had to be below twice the ULN) | 149 | 149 (100) | 2.7 |

Two of the remaining nine English-language papers described record linkage studies. One such study was based on the Korean insurance database, which was linked with death certificates. 23 This study reported that increased alanine aminotransferase (ALT), even within the upper end of the normal range, was associated with eventual death from liver disease. A study carried out in Scotland linked general practice and hospital databases. 2,24 However, this was a retrospective study so a full liver screen was not conducted and follow-up was for a median of only 4 years, whereas many diseases, including chronic viral hepatitis, have much longer prodromal periods. 25

The other seven studies were prospective cohort studies, based on testing asymptomatic members of the general population. The famous Dionysos study,26 based on three analytes from the LFT panel, is included among these. In this study, an impressive 6917 citizens from two communities in northern Italy were screened. Although the authors tested for viral hepatitis all of those in whom the LFT result was abnormal (n = 1473), and among whom they found a prevalence rate of 2.4%, the main aim of their study was to determine the effect of alcohol and diet on LFTs. Testing for viral hepatitis was used as a method of excluding causes of liver damage other than their topic of interest, so in-depth analysis on how viral hepatitis affected the pattern of LFTs was not published. Another Italian study, by Pendino et al. ,27 screened 1645 inhabitants from a town in southern Italy, with both a LFT [ALT, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT)] and viral screen. 27 The prevalence of viral hepatitis is much higher in this region because of a significant immigrant population, and the authors performed a more extensive analysis of the impact of viral hepatitis on LFTs. Of the 319 (19.4%) individuals in whom LFT results were abnormal, nearly 18% were infected with viral hepatitis. However, the LFT failed to detect 34 (37%) of the 92 cases of viral hepatitis present in the community. Perhaps the most comprehensive prospective analysis looking at the effect of viral hepatitis on individual analytes was carried out on a population of Japanese office workers. 28 The study used data from compulsory health checks, which included an ALT/AST/GGT panel along with certain additional tests, including a viral screen, which were added for study purposes. The authors found that ALT was the most sensitive of the three analytes used, detecting nearly half of cases of viral hepatitis, while being abnormal in 14% of the cohort (278 abnormal results in 1973 participants). The remaining four prospectively designed studies were carried out in general practice and were therefore closer in population terms to the BALLETS cohort. However, three of these are restricted to patients with persistently abnormal LFT results over a 6-month period,18,29,30 and one of these did not include a test for viral hepatitis. The final prospective study, by Whitehead et al.,17 was small and based on only one analyte.

After this review of the literature we concluded that no study has fully investigated a cohort of patients in primary care with an abnormal LFT result (from the full LFT panel) and no obvious or known liver disease. BALLETS is thus the first study to test the validity of the various strategies that a GP could use to make a diagnosis in patients with abnormal LFTs. The BALLETS study was based on performing a full LFT panel of investigations to identify diseases such as chronic viral hepatitis and primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) that could otherwise be identified only by follow-up lasting many decades. The study was therefore designed to look into, and ‘concertina’, the future. Patients were also followed up over 2 years to detect systemic diseases attacking the liver (e.g. disseminated cancer), to follow the progress of people with excess alcohol consumption and/or ‘fatty liver’ on ultrasound and to ascertain the rates at which abnormal LFTs reverted to normal according to diagnostic category and type of analyte that was abnormal.

We also identified a relevant study by Kim et al. 31 This study prospectively followed a group of ‘healthy’ Korean factory workers, taking measurements of ALT, AST and GGT on at least two separate occasions. The full article was in Korean so we had access to the abstract only.

Structure of this report

The central idea behind the BALLETS study was to create a well-characterised cohort (as described above) and follow patients for 2 years. A database would thereby be created for statistical analysis. The generation and analysis of this database are referred to as the ‘main study’. The objectives of this study are detailed in Chapter 2, the methods are described in Chapter 3 and the results are presented in Chapter 4. The report also contains a series of substudies, the objectives of which are spelled out in Chapter 2. The methods and results of these substudies are then described in Chapter 5, which contains sections dealing with the psychological effects of a positive test (see Chapter 5 Psychology 1: effects of positive tests); a qualitative account concerning the effects of testing on behaviour (see Chapter 5 Psychology 2: effects of results on behaviour); a qualitative account of clinicians' motivations for testing (see Chapter 5 Sociology of testing: an exploration of the clinical and non-clinical motives behind the decision to order a liver function test); a decision analysis covering options following a positive LFT test result (see Chapter 6); and a study of markers for fibrosis in a subset of patients with ‘fatty liver’ from the Birmingham cohort (see Chapter 6). In Chapter 6 we discuss the implications of our study, integrating lessons from the main study and substudies. We approach this task by imagining that all of the scientific information regarding LFTs – including that from the BALLETS study – was available, but that LFTs had not yet come into widespread, routine use. We also make use of the different reasons for testing that emerge from the qualitative substudy of GP reasons for ordering LFTs. This perspective leads to proposals to use different testing strategies according to the different reasons for conducting laboratory investigations. Perhaps provocatively we argue that the idea of a one-size-fits-all panel is obsolete. The original protocol for the study is included as Appendix 1 (BALLETS study protocol).

Chapter 2 Objectives

Main study

The Health Technology Assessment (HTA) commissioning brief made it clear that the overall objective was to inform general practice decision-making. Thus, the main objective can be framed as follows: ‘How does the probability of disease vary by the pattern of abnormal LFTs and the clinical features of a patient?’. ‘Pattern’ of abnormal LFTs describes which analytes are abnormal (singly or in combination) and the degree (extent, magnitude) of the abnormality. In particular, we set out to ascertain the predictive value of the pattern of LFTs for the specific and often treatable viral, genetic or autoimmune liver diseases in Table 3.

| Disease | Prevalence (%) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic viral hepatitis C | 0.42 | Health Protection Agency website, cited 201132 |

| Chronic viral hepatitis B | 0.3 | Health Protection Agency website, cited 201133 |

| Metal storage disease – iron | 0.25 | Worwood 199834 |

| PBC | 0.024 | Metcalf et al. 199735 |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 0.001 | Autoimmune Hepatitis website, cited 200936 |

| Metal storage disease – copper | < 0.025 | Olivarez et al. 200137 |

| A1AT deficiency | < 0.025 | de Serres 200238 |

Secondary objectives of the main study were:

-

To follow up people who had neither one of the above serious and treatable liver diseases nor another serious disease (such as metastatic cancer) and to evaluate the extent to which abnormal LFTs progressed or remitted over a 2-year period.

-

To determine the proportions where ‘fatty liver’ progressed, improved or stayed the same and to investigate how clinical, behavioural and biochemical features correlated with progression, resolution or maintenance of the ultrasound finding. This study was not part of the original protocol but was prompted by the high incidence of fatty liver at entry to the study. Repeat ultrasound was funded under an extension to the original grant.

-

To investigate the issue of redundancy among LFT analytes by measuring what would be lost in terms of prognostic accuracy by dropping certain analytes from the full panel of LFT analytes. This is an important issue because the benefit of analytes that offer small marginal gains in detection rates may be outweighed by losses as a result of false-positives.

-

To shed light on the utility of undertaking LFTs in the first place by determining the prevalence of serious disease in the cohort as a whole.

Some of these figures may be underestimates of the incidence of the various pathological entities since we now know that many people may have subclinical disease with such long lead times that they do not present clinically during the person's lifetime. This applies in particular to haemochromatosis and PBC, a point to which we return.

Psychological substudy

Abnormal LFTs may have psychological consequences, and this is important given the high proportion of false-positive results that were anticipated. The original protocol thus included a psychological substudy based mainly around the measurement of (any) induced anxiety at various stages following disclosure of a positive result.

We became increasingly aware that knowledge of abnormal LFT results, and performance of some tests prompted by abnormal LFT results, might constitute an intervention in their own right, as news of these results might affect behaviour (see Sociological substudy, below). For example, a person with persistently abnormal LFT results and an ultrasound diagnosis of fatty liver may be influenced by these results to modify unhealthy behaviour (excessive calorie and/or alcohol intake). Conversely, a normal result may provide false reassurance. The follow-on study was thus adapted not only to observe any residual anxiety caused by testing, but also to collect data on (any) changes in eating and drinking habits. The additional data collection for this purpose at the 2-year follow-up point was funded by an extension to the HTA grant.

Sociological substudy

A (perhaps predictable) early finding from our study was that LFTs do not offer high diagnostic precision, and that the positive predictive value (PPV) (probability of disease given a positive test) is low. Moreover, the value of LFTs, as of any test, lies in its incremental diagnostic accuracy given what the doctor knows before the result is made available. For example, finding a raised ALT level in a patient with a known alcohol problem would not be a surprise. On the other hand, such a result may buttress the doctor's advice to reduce alcohol consumption. These considerations raise the question of why so many LFTs are ordered in the first place. If GPs (erroneously) thought that LFTs were highly predictive of serious treatable disease then we may expect the BALLETS results to reduce demand for LFTs. If, however, the low predictive value of these tests is not news to GPs then other approaches would be necessary to reduce test ordering (if this was perceived as desirable – see Decision analysis, below). We therefore carried out a further study, not included in the original protocol, to find out more about GPs' motivation for ordering LFTs. This substudy included a general review of the literature on GPs' test-ordering behaviour. The protocol for this study is described in this report.

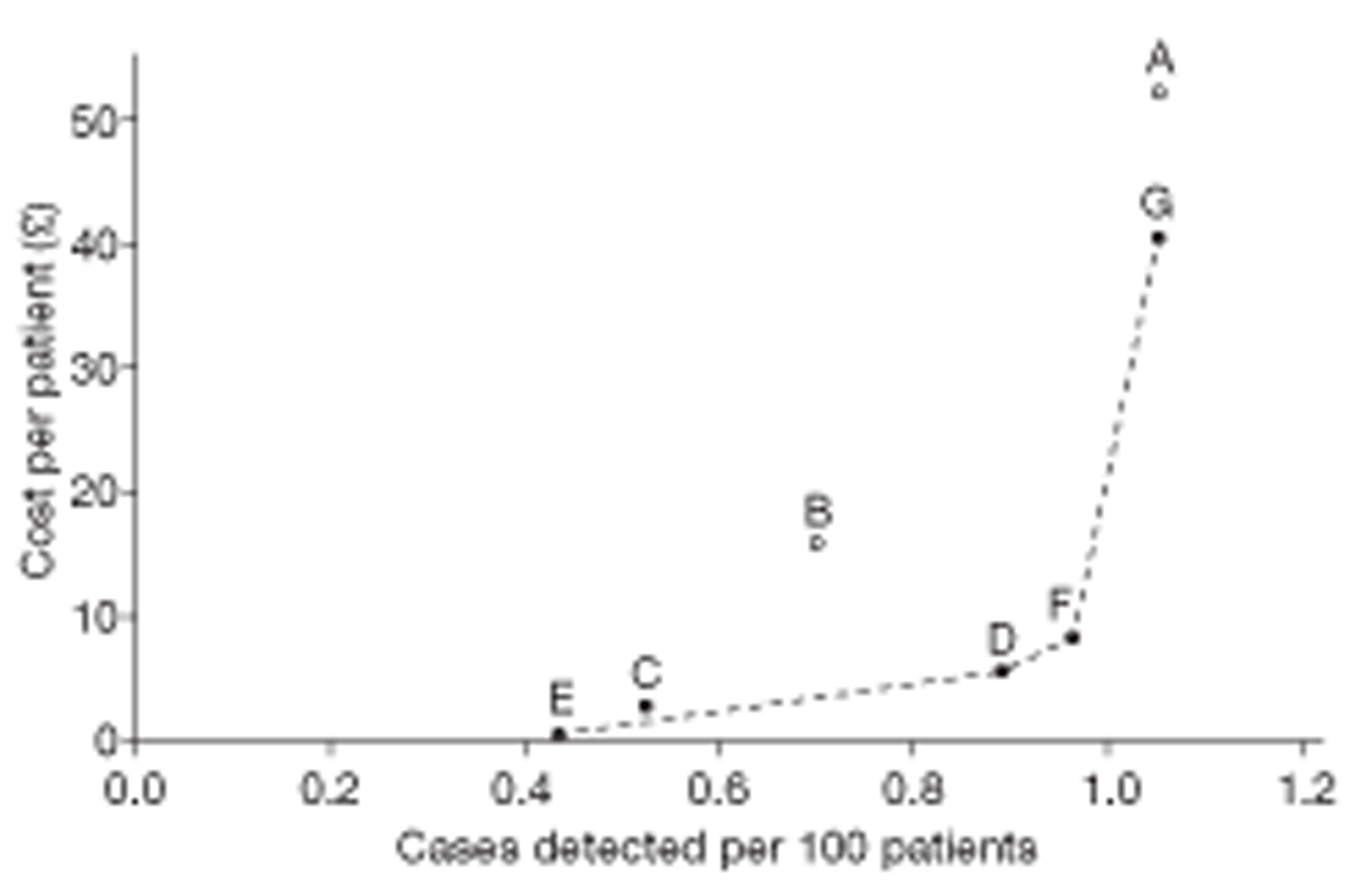

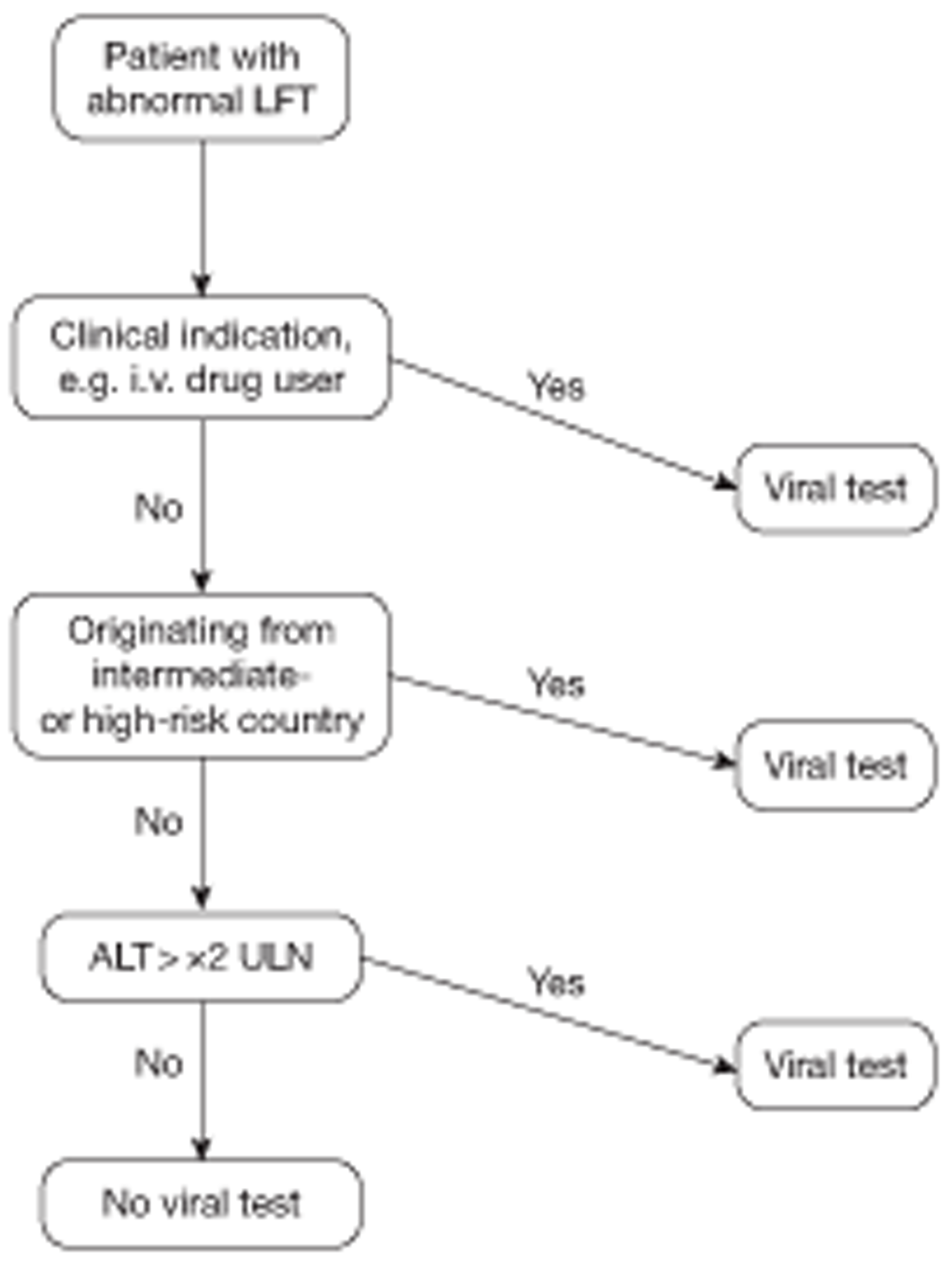

Decision analysis

As stated in Sociological substudy, above, it became clear from the literature (and emerging results in this study) that the predictive value of LFTs was rather low. This raises the question of what action (if any) a doctor should take when confronted by a mildly abnormal LFT result. Clearly, if there is an obvious clinical lead then this should be followed; for example, if a person has a history of intravenous drug use then a test for viral hepatitis is indicated. However, the majority of cases are more ambiguous. We therefore decided that it would be helpful to carry out a formal decision analysis to examine the losses and gains associated with various clinical opinions. Conducting a decision analysis for each potential disease and then consolidating them into one composite analysis would be well beyond the scope and resources of this project. We therefore selected one disease class – chronic viral hepatitis – as an exemplar on the basis that:

-

Unlike high alcohol intake and obesity, the clinician can diagnose the condition only by further testing.

-

The disease, if caught early, is highly treatable.

-

It is one of the most common of the specific liver diseases to present clinically.

We were aware of the previous decision analysis in the previous HTA report2 and our analysis includes a critique of this work.

Biochemistry of ongoing liver disease

It became clear at an early stage that the BALLETS study would generate a sizable cohort of people with fatty liver.

The extensive testing algorithm incorporated in the study did not include all necessary tests for the diagnosis of the enigmatic condition called ‘metabolic syndrome’. The literature suggests that a small percentage (5–10%) of people with fatty liver would progress to liver fibrosis, and the BALLETS study provides a platform for the study of novel blood tests that might predict such progression. We therefore performed an add-on study in which a fibrosis score was calculated. In addition, new hypotheses concerning the origin and prognosis of fatty liver may emerge over the next 4 years in this fast-moving field of enquiry. For these reasons, additional funding was sought and granted by the HTA programme to store frozen blood samples from consenting participants.

Chapter 3 Methods: main study

Selection of practices and patients

Practices were selected on the basis of geographic spread and their willingness to join the study. They had to be multiple-partner practices. We deliberately included inner city practices in order to ‘enrich’ the population to include a higher than average proportion of chronic viral hepatitis. Two city areas were selected: Birmingham and the Lambeth district of London. This was done so that the relationship between LFTs and this disease could be studied. The geographical location and demographic and ethnic features of the eight Birmingham practices and three Lambeth practices that we were able to recruit are described in Chapter 4 (see Nature of the population studied: Birmingham and Lambeth sites).

General practitioners from participating practices reviewed all abnormal LFT results arising in their practice to determine eligibility. Patients aged > 18 years were eligible if one or more analyte was abnormal, they did not have known liver disease, they were not deemed to require immediate referral to hospital and they were not pregnant. Seven out of the eight Birmingham practices sent samples to a single laboratory (University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust laboratories), whereas the remaining practice (Wand Medical Centre) sent samples to the laboratory of Russells Hall Hospital. All Lambeth practices used a single laboratory (Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust laboratory). The repertoire of analyses included, prompted by a request for LFTs from the participating practices, was extended over the study period from the usual five analytes in our laboratories to all eight listed in Table 4. The idea was to enable redundancy between tests to be detected and to help generalise to centres that included different analytes. The analytes were classified as normal or abnormal according to standard laboratory practice that is compliant with International Quality Control Standards. The classification was based on reference ranges specific to each of the (three) individual laboratories (see Table 4).

| Test | Reference range | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust | Russells Hall Hospital NHS Trust | Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust | |

| ALT | 1–41 U/l | 1–56 U/l | 1–45 U/l M, 1–28 U/l F |

| AST | 1–43 U/l | 1–45 U/l | 1–49 U/l |

| Bilirubin | 1–22 μmol/l | 1–22 μmol/l | 1–22 μmol/l |

| ALP | 1–320 U/l age < 40 years M | 1–120 U/l | 1–129 U/l |

| 1–330 U/l age ≥ 40 years M | |||

| 1–260 U/l age < 40 years F | |||

| 1–290 U/l age 40–49 years F | |||

| 1–330 U/l age ≥ 50 years F | |||

| GGT | 1–40 U/l F, 1–50 U/l M | 1–58 U/l | 1–65 U/l M, 1–38 U/l F |

| Albumin | 34–51 g/l | 35–47 g/l | 40–52 g/l |

| Globulin (derived) | 21–37 g/l | 21–37 g/l | 21–37 g/l |

| Total protein | 60–80 g/l | 65–83 g/l | 61–79 g/l |

Eligible patients were contacted to seek verbal consent to participate in the study. The method of contact varied from practice to practice so that it would be compatible with the normal procedures used in the practices. The bespoke protocols to inform patients of their results and the study process are described, for each practice, in Appendix 1 (section 10.2a–f). Once an eligible patient had been identified he or she was contacted and invited to attend the practice for a study session. The practice sent a Patient Information Sheet to all potential patients in advance of their attendance at the study session.

Testing strategy for patients in the Birmingham and Lambeth Liver Evaluation Testing Strategies study

Formal written consent was sought when the patient attended the study session. The following information was collected and recorded:

-

Clinical details (Table 5).

-

An alcohol use questionnaire was completed and the patient's weight, height, waist and hip size were measured (Table 6).

-

A single blood sample was obtained for detailed analysis. The LFT panel was repeated along with tests for specific (autoimmune, genetic and viral) diseases (Table 7).

-

An ultrasound scan (USS) of the liver was obtained using a portable ultrasound machine (TITAN® SonoSite) operated by experienced (10 years minimum) sonographers from the ultrasound department of the University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, Worcester Acute Hospitals NHS Trust or Guy's and St Thomas' Hospital NHS Trust. The sonographer completed a pro forma (see Appendix 1, section 10.7) that included a description of liver texture on a four-point scale, indicating normal, mild, moderate and severe echo density. Fatty liver on ultrasound was determined by comparison of brightness/echogenicity in the liver with the right kidney. The sonographer notified the named or on-call GP of any findings of a sinister nature so that they could be acted upon immediately. All scans were recorded on tape and 50 of these were selected at random from the first participating practice for scrutiny by a senior radiologist, as a form of quality control (see Quality control of ultrasound).

| 1. GP name and practice code | ||||

| 2. Patient study ID | ||||

| 3. Name and address | ||||

| 4. Date of birth | ||||

| 5. NHS no. | ||||

| 6. Gender | ||||

| 7. Current and recent medication | ||||

| 8. Reason for GP consultation/LFTs ordered? | ||||

| 9. Current/past Illnesses | ||||

| 10. Recent febrile Illness | ||||

| 11. Recent muscle damage | ||||

| 12. Substance abuse | Past □ | Current □ | Intravenous □ | Oral □ |

| 13. Recent travel history | Over last 6 months? | Where? | ||

| 14. Immunisation against HBV | ||||

| 15. Transfusion history | No □ | Yes □ | Date | |

| 16. Length of residence in the UK | ||||

| 17. Ethnic group | ||||

| 18. Preferred language | ||||

| 19. Country of birth | ||||

| Alcohol consumption (units per week over past 6 months?) | ||||||||

| a. How often do you drink? | Annually | Special occasions | Monthly | Fortnightly | ||||

| Weekly/daily | M | T | W | T | F | S | S | |

| b. What is the type or brand? | ||||||||

| c. What size of glass or can do you drink? | ||||||||

| d. Number of each type of drink consumed in a session? | ||||||||

| Measurements | ||||||||

| Height (cm) | ||||||||

| Weight (kg) | ||||||||

| Waist measurement (cm) | ||||||||

| Hip measurement (cm) | ||||||||

| Hepatitis B viral markers (HBV surface Ag) |

| HCV antibody (HCV Ab) |

| A1AT |

| Caeruloplasmin |

| Iron and transferring |

| SMA |

| AMAs |

The research team produced a consolidated report comprising the results of the index LFT and the first follow-up LFT, and all of the information described in Tables 5–7, along with the result of the ultrasound examination. The patient participant then attended the GP for a consultation informed by all of these data.

Note that the intention was for each patient to have three LFT panels performed as part of the BALLETS study:

-

the test that confirms eligibility: ‘the index test’

-

repeat test on agreeing to enter the study: ‘the first follow-up test’ (FU1)

-

test at 2-year follow-up: ‘the second follow-up test’ (FU2).

The GPs were provided with a set of guidelines to assist decision-making when one of the tests in Table 7 was abnormal or when an abnormality, such as fatty liver, was seen on the USS. The guidelines were produced by members of the study team (JN and RL) and approved by each practice. The guidelines are outlined in Appendix 1 (section 10.9). In addition, clinical members of the research team visited practices to provide proctorship on what to do about abnormal results. The results of follow-up tests were obtained from the laboratories by the research team. In some cases a follow-on test indicated according to the guideline was absent from the laboratory records. In these cases the chief investigator contacted the practice concerned to remind the GP to consider recommending the test to the patient. This issue of missing follow-on blood tests had not been foreseen by the research team and ethical permission was obtained to amend the protocol so that GPs could be contacted.

The 2-year follow-up visit

A second follow-up visit was offered to patients 2 years after the first follow-up visit . The electronic patient records at practices were scrutinised where possible and patients placed in four categories for the purpose of 2-year follow-up:

-

Deceased The cause and date of death were ascertained from notes or the practice database.

-

No longer registered with the practice The new practice was contacted and the GP asked to invite the patient to attend for a second follow-up LFT for submission to the original laboratory.

-

Patient under ongoing hospital care The diagnosis was obtained from study hepatologists in Birmingham or Lambeth.

-

Remaining patients The remainder were invited to attend the practice for the second follow-up LFT. The weight and body measurements and alcohol history were repeated at this visit. Extensions to the protocol were obtained from the funder to enable patients at Birmingham to undergo a repeat ultrasound examination and to be asked to consent for an aliquot of blood being preserved for cryogenic storage of cells and serum. These protocol amendments and patient documentation for this enhanced follow-up in Birmingham were approved by the ethics committee.

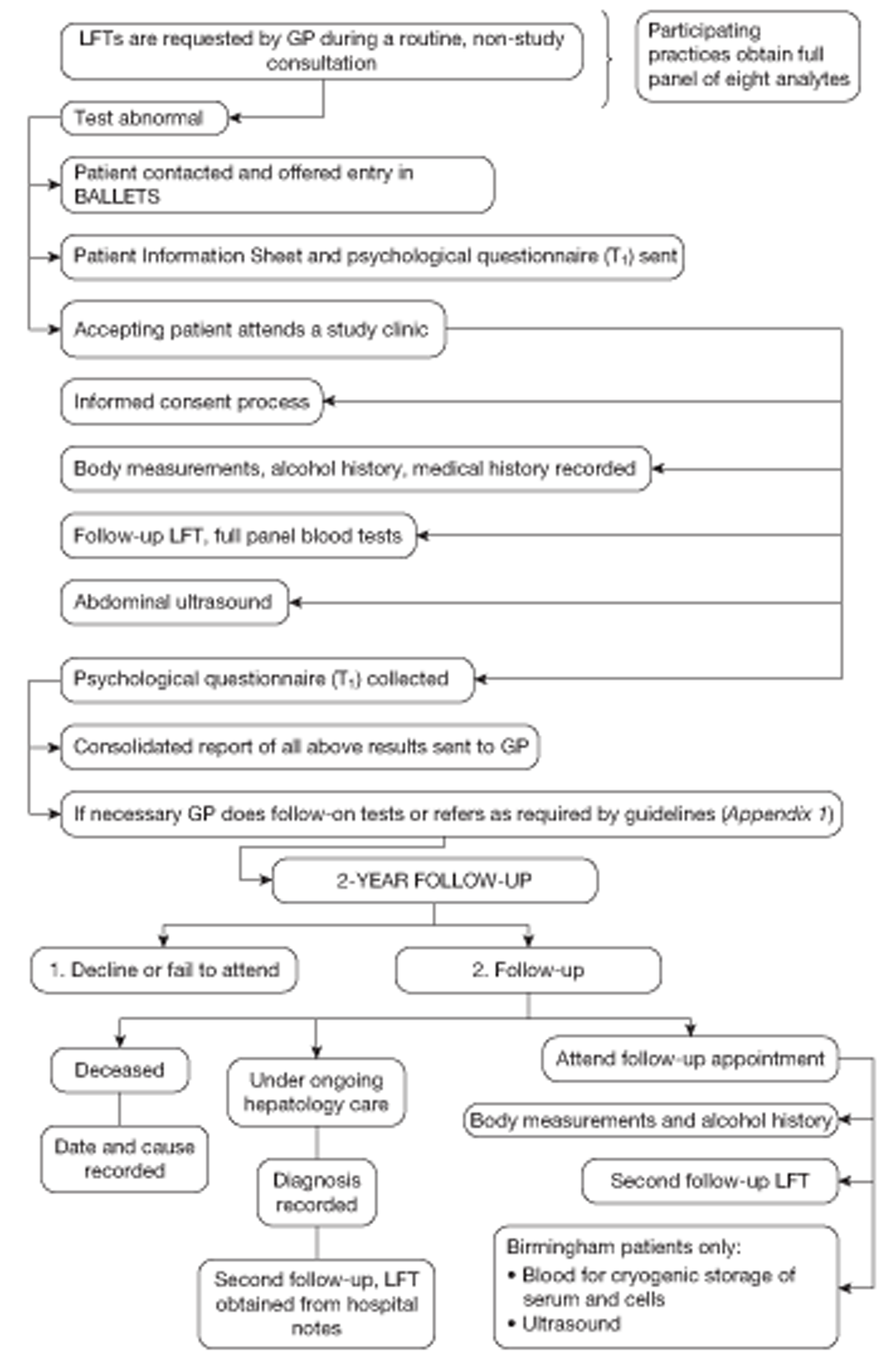

A summary of the full patient journey is illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Patient journey through the BALLETS study.

Laboratory methods

The biochemical measurements were carried out in the accredited (Clinical Pathology Accreditation UK) laboratories of University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust (Queen Elizabeth and Selly Oak Hospitals, Birmingham), of Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust (St Thomas' Hospital), and of Dudley Group of Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Russells Hall Hospital, Dudley). The measurements were performed on serum obtained from blood samples collected into Vacuette tubes (evacuated collection tubes) containing no anticoagulant (Greiner Bio-One GmbH, Kremsmuenster, Austria). Serum was obtained by centrifugation of the samples for 5 minutes at 1200 × g and measurements were performed on a Roche Modular Analytic system using specific reagents supplied by Roche Diagnostics (Roche Diagnostics Ltd, Burgess Hill, UK) in University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust (Queen Elizabeth and Selly Oak Hospitals Birmingham) and Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust (St Thomas' Hospital), and on Vitros 5.1 analysers using reagents supplied by Ortho Clinical Diagnostics (Ortho Clinical Diagnostics, Johnson & Johnson, High Wycombe, UK) in the Dudley Group of Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. ALT, albumin, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), AST, GGT, total bilirubin, total protein, caeruloplasmin and alpha-1 antitrypsin (A1AT) were assayed. Where A1AT concentrations were noted to be < 1.5 g/l, the sample was phenotyped by isoelectric focusing to help in diagnosis and monitoring. The phenotyping was performed on a Sebia Hydrasys instrument (Sebia UK River Court, Camberley, UK) with specific reagents and isoelectric focusing gels.

Integral pilot

Purpose of integral pilot

Rather than follow convention and collect a full data set before setting out on the analysis it was decided to analyse data from the first practice to complete recruitment – the Hall Green Practice in Birmingham. This practice completed its recruitment at a point in time when recruitment in other practices was nascent or yet to begin. Analysis of the integral pilot was carried out as soon as the FU1 data became available, i.e. the integral pilot does not include the FU2 results.

The purposes of this pilot were threefold:

-

to ‘test the system’ by detecting incomplete data and exploring systematic failures so that remedial action could be taken where necessary

-

to compare patients entered in the study with those who might have been eligible but who were not entered in the study

-

to conduct a quality control study on the accuracy of ultrasound findings by reviewing a sample of images stored on tape.

Missing data

One hundred and sixty-one patients were entered in the study in the pilot practice. Two patients did not attend for the ultrasound examination and have been excluded from the pilot analysis. The following analyses all relate to the remaining 158 cases. Their age and sex distributions are shown in Table 8.

| Age (years) | Male, n (%) | Female, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 44 | 24 (25.8) | 14 (21.5) | 38 (24.1) |

| 45–54 | 20 (21.5) | 9 (13.8) | 29 (18.4) |

| 55–64 | 20 (21.5) | 19 (29.2) | 39 (24.7) |

| ≥ 65 | 29 (31.2) | 23 (35.4) | 52 (32.9) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 54.7 (15.4) | 57.8 (15.0) | 56.0 (15.2) |

| Total | 93 (100.0) | 65 (100.0) | 158 (100.0) |

The index panel of LFT analytes was incomplete (i.e. not all of the eight results were available) for 26 out of the 158 patients and complete for 132 (84%) patients. The first follow-up panel of LFT analytes was not available in five cases and the panel was incomplete in 27 cases – thus complete data were available on the follow-up LFT panel for 126 out of the 158 (80%) patients. The full breakdown of the missing data is given in Table 9.

| No. of tests | Index test | FU1 test |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | 0 | 7 |

| 4 | 13 | 14 |

| 5 | 6 | 1 |

| 6 | 6 | 0 |

| 7 | 1 | 4 |

| 8 | 132 | 126 |

| Total | 158 | 158 |

The missing data did not follow any anticipated pattern (see Table 9). One might have expected that if those cases for which all eight analytes required for study purposes had not been included then the five default analytes for this particular laboratory would have been measured. This would have resulted in bimodal distribution, with high peaks at eight and five analytes. On further enquiry, it transpired that the clerks who receive the request forms and enter the requests on computer do so with variable fidelity (for study patients as for routine patients). A programme of staff training was therefore put in place to try to reduce this problem. However, we were advised that with large numbers and high turnover of clerical staff in the laboratory, some remaining laboratory omissions were inevitable.

Comparison of patients who were and were not ‘recruited’

Some eligible patients declined to participate, but we became aware that many more were not invited to participate by their GPs. Furthermore, some GPs recruited many more patients than others. One possible explanation was a tendency to select patients with the more severely abnormal results for entry in the study. This tendency could have been motivated by a desire to obtain all of the ancillary tests inherent in entry in the BALLETS study while reducing the need for further attendances and testing among those at lower perceived risk. This could lead to bias if, even among cases with equal severity of abnormality, GPs were somehow identifying patients with the worst prognosis for inclusion in the study. This could result in exaggerated estimates of the risks associated with abnormal LFTs.

In order to shed light on this issue, we collected baseline data from all (195) eligible but non-entered patients for two calendar months – May and June 2006 – and compared them with 53 participating patients for those months. This epoch was selected on the grounds that it corresponded to the period of highest recruitment.

The 195 non-entered patients constituted two subgroups: 129 patients had simply not been invited by the GP, despite fulfilling all objective criteria of entry to the study, while the remaining 66 had declined to take part (Table 10a). These subgroups are broken down by age and sex in Table 10b. The mean age of the invited patients, 58.6 years, is somewhat higher than the mean age of not-invited patients, 54.1 years (p = 0.028, two-sided t-test). There was no significant age difference between ‘consenters’ and ‘refusers’ within the invited group (p = 0.766). Thus, the 53 patients in the study tended to be older than those outside it. To put this in perspective, 68% (40/59) of eligible 65- to 74-year-olds were invited to join compared with 31% (22/72) of eligible patients under 45 years.

| Status | n | Mean (SD) age (years) |

|---|---|---|

| Consented | 53 | 58.2 (13.9) |

| Refused | 66 | 59.0 (16.5) |

| Total invited | 119 | 58.6 (15.3) |

| Not invited | 129 | 54.1 (17.2) |

| Total | 248 | 55.4 (17.3) |

| Category | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||

| ≤ 44 | 9 (17.0) | 13 (19.7) | 22 (18.5) | 40 (31.0) | 62 (25.0) |

| 45–54 | 10 (18.9) | 10 (15.2) | 20 (16.8) | 27 (20.9) | 47 (19.0) |

| 55–64 | 12 (22.6) | 13 (19.7) | 25 (21.0) | 26 (20.2) | 51 (20.6) |

| 65+ | 22 (41.5) | 30 (45.5) | 52 (43.7) | 36 (27.9) | 88 (35.5) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 33 (62.3) | 42 (63.6) | 75 (63.0) | 77 (59.7) | 152 (61.3) |

| Female | 20 (37.7) | 24 (36.4) | 44 (37.0) | 52 (40.3) | 96 (38.7) |

By contrast, the sex distribution was stable across all subgroups.

Abnormalities in the index LFTs for these 195 patients are analysed in Tables 11 and 12. The proportion of patients with abnormal GGT was higher (p = 0.011) among those invited to join the study (73.7%) than among those not invited (58.1%). However, there is no evidence of preferential invitation associated with abnormality on any other analyte, nor with the presence of more than one abnormality in the index panel (see Table 11). However, there was an (unexplained) tendency for invited patients with abnormal globulin to decline to participate (p = 0.002). Otherwise we found no evidence of recruitment bias.

| Analytes | Consented, n (%) | Refused, n (%) | Exact test | Total invited, n (%) | Not invited, n (%) | Exact testc | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 53 (100) | 66 (100) | 119 (100) | 129 (100) | 248 (100) | ||

| ALTd | 19 (38.0) | 18 (27.3) | 0.234 | 37 (31.9) | 33 (25.6) | 0.322 | 70 (28.6) |

| ASTd | 5 (10.2) | 3 (4.5) | 0.283 | 8 (7.0) | 15 (11.6) | 0.274 | 23 (9.4) |

| Bilirubind | 4 (8.2) | 1 (1.5) | 0.162 | 5 (4.3) | 10 (7.8) | 0.299 | 15 (6.1) |

| ALPd | 2 (3.9) | 7 (10.6) | 0.295 | 9 (7.7) | 16 (12.4) | 0.291 | 25 (10.2) |

| GGTd | 41 (78.9) | 46 (69.7) | 0.298 | 87 (73.7) | 75 (58.1) | 0.011 | 162 (65.6) |

| Albumind | 1 (1.9) | 3 (4.5) | 0.628 | 4 (3.4) | 3 (2.3) | 0.713 | 7 (2.8) |

| Globulind | 1 (2.0) | 14 (21.2) | 0.002 | 15 (12.9) | 23 (17.8) | 0.377 | 38 (15.5) |

| Total proteind | 5 (10.0) | 18 (27.3) | 0.033 | 23 (19.8) | 30 (23.3) | 0.538 | 53 (21.6) |

| More than one abnormal analytee | 17 (37.8) | 29 (43.9) | 0.560 | 46 (41.4) | 54 (41.9) | 1.000 | 100 (41.7) |

| Analyte | Consented | Refused | Total invited | Not invited | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Excess mean | Excess median | n | Excess mean | Excess median | n | Excess mean | Excess median | n | Excess mean | Excess median | |

| ALT | 19 | 1.37 | 1.29 | 18 | 1.46 | 1.32 | 37 | 1.42 | 1.32 | 33 | 1.55 | 1.32 |

| AST | 5 | 1.37 | 1.16 | 3 | 1.52 | 1.56 | 8 | 1.42 | 1.47 | 15 | 1.54 | 1.26 |

| Bilirubin | 4 | 1.90 | 1.86 | 1 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 5 | 1.74 | 1.55 | 10 | 1.34 | 1.20 |

| ALP | 2 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 7 | 1.49 | 1.17 | 9 | 1.43 | 1.17 | 16 | 1.85 | 1.24 |

| GGT | 41 | 1.79 | 1.30 | 46 | 2.16 | 1.54 | 87 | 1.99 | 1.42 | 75 | 2.15 | 1.42 |

| Albumin | 1 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 2 | 1.04 | 1.04 | 2 | 1.03 | 1.03 |

| Globulin | 1 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 14 | 1.15 | 1.14 | 15 | 1.14 | 1.14 | 20 | 1.08 | 1.05 |

| Total protein | 5 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 18 | 1.05 | 1.04 | 23 | 1.04 | 1.04 | 30 | 1.04 | 1.02 |

In the end, we were not able to exclude a degree of selection in patients entered. Some selection effects associated with age and GGT abnormality are suggested. Individual differences in how eligibility criteria are applied are inevitable in a large and busy practice and we cannot exclude a degree of bias owing to hidden confounders. If clinicians selected a group of patients with significantly higher prior risk, then it is possible that the study will somewhat overstate the association between mildly abnormal test results and the various disease end points. All we really know is that some apparently eligible patients were not invited by their GP to participate. This may be because of a purposive decision to exclude or because of some oversight. Such data are difficult to collect because doctors who are unwilling or too hard pressed to select patients for study entry are unlikely to go to the trouble of recording their reasons.

Quality control of ultrasound

In order to quality assure the liver imaging, the first (FU1) ultrasound images and paper reports of 50 randomly selected BALLETS patients were presented to the study radiologist, who was in complete agreement with the sonographer's findings in 34 out of the 50 cases. In the remaining 16 cases there was some ‘technical or relatively minor’ disagreement but ‘no serious clinical disagreement’ that might have altered clinical decision-making.

The process was repeated with 50 randomly selected FU2 ultrasound scans. The study radiologist agreed with the written report in 38 instances, and in the remaining 12 cases found that there was ‘technical or relatively minor’ disagreement, but, once again, no disagreement that would alter the clinical decision-making process.

Production of reference categories (categories of diagnostic groupings)

The analysis plan in the study protocol was to investigate the association between the index LFT panel and clinical outcome in order to address such questions as:

-

Which profiles of index test results suggest higher and lower risk of the presence of serious specific disease, and of the other reference standards?

-

What is the contribution of different test analytes? How does this vary by clinical features?

The idea here was that the information the GP would have at the time of the index test would constitute explanatory variables in an analysis of clinical outcome using polytomous regression methods to cope with multiple diagnostic categories. The BALLETS study would provide outcome data partly by repeating the LFT (at FU1 and FU2), but, more specifically, by doing exhaustive further testing to ‘concertina’ the future and reach a diagnosis.

This exercise required that each participant be assigned to an outcome (diagnostic) category. That is to say, we needed a reference standard. However, experience gained from our integral pilot suggests that this is tricky. The problem we encountered might be called ‘multiple and overlapping categories’. Briefly, when we came to analyse the data, we found that patients did not fall into a manageable number of discrete categories. For example, the category ‘fatty liver’ could be divided into ‘fatty liver alcohol excess’, ‘fatty liver overweight’, ‘fatty liver overweight and alcohol excess’ and ‘fatty liver and not overweight and no alcohol excess’. However, the job would still not be done – there could then be subcategories for each of the above according to whether the virology was positive or negative, for example. Then there would have to be categories for excess alcohol, overweight, viral diseases, immunological diseases and metal storage diseases – all with and without fatty liver. Our initial discussions with chemical pathologists, liver specialists and GPs suggested that consensus regarding a manageable number of mutually exclusive pathological diagnoses was unlikely to be obtainable. Indeed, even taking a liver biopsy would fall well short of resolving this issue.

It was therefore decided to ‘collapse’ the reference standards into a small number of broad ‘action groups’. These groups are based on the appropriate clinical response, rather than on the precise underlying (and often unknowable) pathophysiological entity.

The following groups were created:

-

Group 1 Specific category of viral, autoimmune or genetic aetiology from Table 13:

-

hepatocellular diseases: chronic viral hepatitis B and hepatitis C, haemochromatosis, autoimmune hepatitis, Wilson's disease, antitrypsin deficiency, cirrhosis (alcohol or fat induced)

-

diseases of the intrahepatic bile ducts: PBC, primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC).

-

-

Group 2 Serious liver or other pathology requiring referral. This would include metastatic cancer.

-

Group 3 Non-specific category. This is broken down into:

-

echo-bright (fatty) liver

-

not fatty liver.

-

| Reference group | Subgroups and sub-subgroups |

|---|---|

| Group 1 (serious viral, genetic or autoimmune disease) | Subgroup A, hepatocellular disease |

| Viral hepatitis B or C | |

| Haemochromatosis | |

| Wilson's disease | |

| Antitrypsin deficiency | |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | |

| Cirrhosis (alcohol or fat induced) | |

| Subgroup B | |

| PBC | |

| PSC | |

| Group 2 | Metastatic disease |

| Paget's disease of bone | |

| Infectious diseases, such as hepatitis A, glandular fever, leptospirosis | |

| Thyroid disease | |

| Group 3 (non-specific) | Echo-bright (fatty) liver on ultrasound |

| Alcohol excess | |

| Overweight | |

| Alcohol + overweight | |

| Neither alcohol nor overweight | |

| No fatty liver | |

| Gilbert syndrome | |

| Persistence of LFT abnormality at 2 years | |

| LFT abnormality resolved at 2 years |

The groups are hierarchical in the sense that a person would be assigned to the ‘top’ category when more than one category might apply. Thus, a person with ‘two hits’, such as haemochromatosis and ‘fatty liver’, would be assigned to group 1, not group 3.

The question could be asked as to why we did not include the diagnosis of alcoholic liver damage of a degree less extreme than cirrhosis. The answer is that, had we done so, alcohol use would serve two non-independent functions – as a clinical feature known in advance of testing (in many/most cases) and also as the outcome of testing. That is to say, the results would be subject to incorporation bias (where a variable serves both as an explanatory and as an outcome variable). Formally, the same could be said of alcoholic cirrhosis, but here the diagnosis rests in ultrasound and exclusion of other causes as well as alcohol history.

Statistical methods

This section gives an outline of the methods and approaches used. Fuller details of individual methodologies are presented as appropriate in the results sections.

Variables and data

Demographic and lifestyle information – including body mass index (BMI) and alcohol consumption in units per week – was coded using categorical variables. Six categories each were used for age and alcohol consumption and four for BMI. The details may be read from Table 14.

| Characteristic | All subjects (n = 1290) | Subjects with 2-year follow-up LFTs (n = 790) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 724 | 56.12 | 453 | 57.34 |

| Female | 566 | 43.88 | 337 | 42.66 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤ 34 | 106 | 8.22 | 33 | 4.18 |

| 35–44 | 165 | 12.79 | 91 | 11.52 |

| 45–54 | 240 | 18.60 | 149 | 18.86 |

| 55–64 | 325 | 25.19 | 243 | 30.76 |

| 65–74 | 273 | 21.16 | 187 | 23.67 |

| 75+ | 181 | 14.03 | 87 | 11.01 |

| Ethnic group | ||||

| White | 1056 | 81.86 | 663 | 83.92 |

| Asian | 89 | 6.90 | 56 | 7.09 |

| Black | 66 | 5.12 | 33 | 4.18 |

| Other | 40 | 3.10 | 18 | 2.28 |

| Not known | 39 | 3.02 | 20 | 2.53 |

| BMI (kg/m2)a | ||||

| < 20 | 49 | 3.80 | 13 | 1.65 |

| 20–24.99 | 250 | 19.38 | 149 | 18.86 |

| 25–29.99 | 454 | 35.19 | 248 | 31.39 |

| 30+ | 498 | 38.60 | 294 | 37.22 |

| Not known | 39 | 3.02 | 86 | 10.89 |

| Alcohol consumption (units per week)a | ||||

| 0 | 547 | 42.40 | 282 | 35.70 |

| 1–14 | 352 | 27.79 | 251 | 31.77 |

| 15–29 | 153 | 11.86 | 90 | 11.39 |

| 30–49 | 122 | 9.46 | 53 | 6.71 |

| 50–99 | 84 | 6.51 | 39 | 4.94 |

| 100+ | 24 | 1.86 | 4 | 0.51 |

| Not known | 8 | 0.62 | 71 | 8.99 |

Concentrations of analytes in the LFT panels were recorded (see Table 4 for units) by the three individual laboratories. Laboratory-specific reference ranges, incorporating adjustments for age and sex (see Table 4), were used to categorise values as normal or abnormal. Thus, each LFT result was available in two forms: as a continuous variable (measured concentration) and as a dichotomous variable (normal/abnormal).

Liver fat on ultrasound was recorded on a four-point ordinal scale (normal, mild, moderate and severe). The condition ‘fatty liver on ultrasound’ was identified with the categories normal, mild and severe, and analysed as a binary variable.

Summaries of categorical variables (with percentages) are presented in tabular form. Summaries of analyte concentrations were expressed in terms of medians and quartiles.

Analysis of liver function test data

Abnormality

The presence of an abnormal analyte in the index panel was a criterion of entry to the study. Redundancy in the test panel was investigated by identifying subsets of analytes (i.e. subpanels) which would have recruited the highest proportions of study patients.

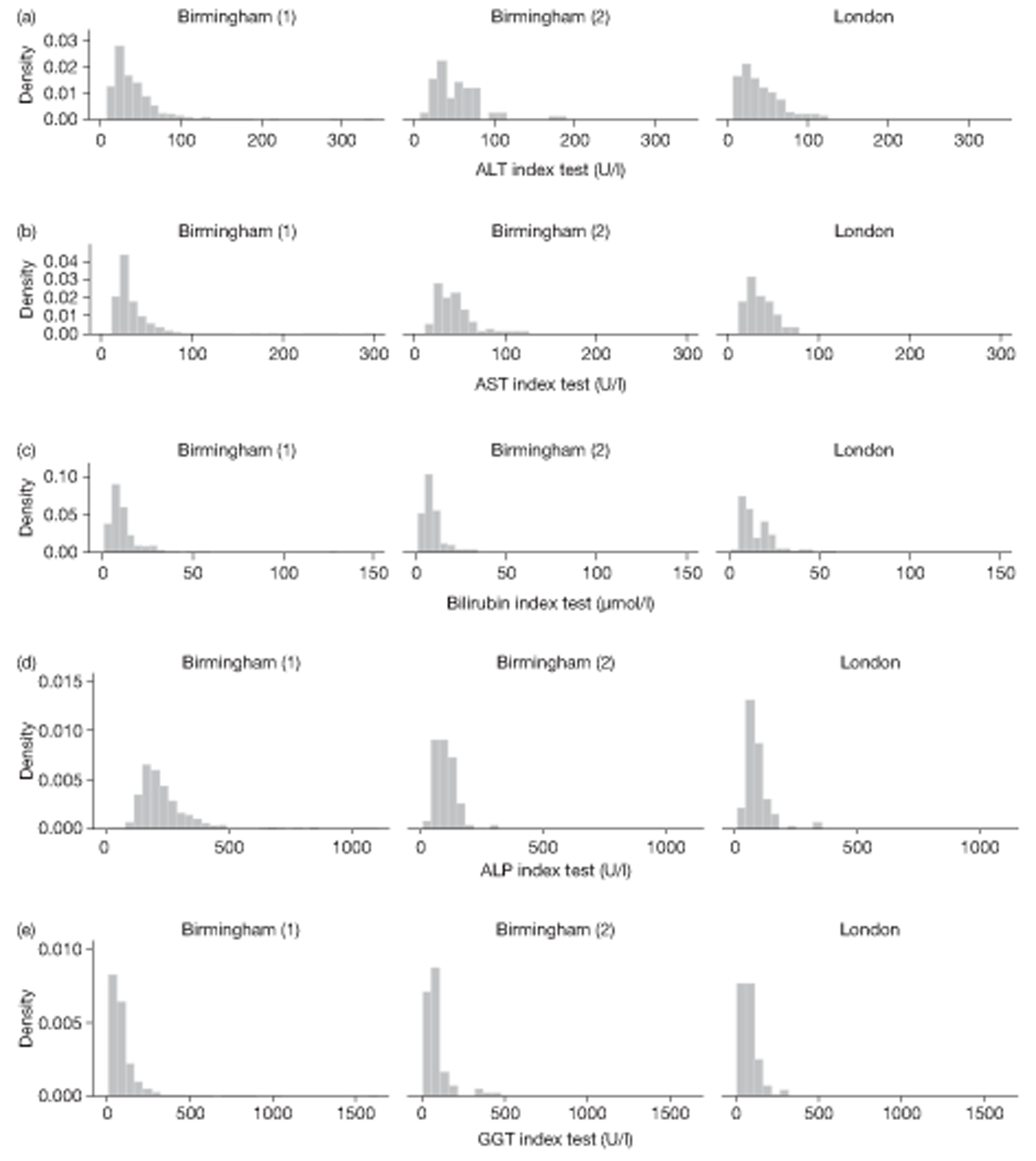

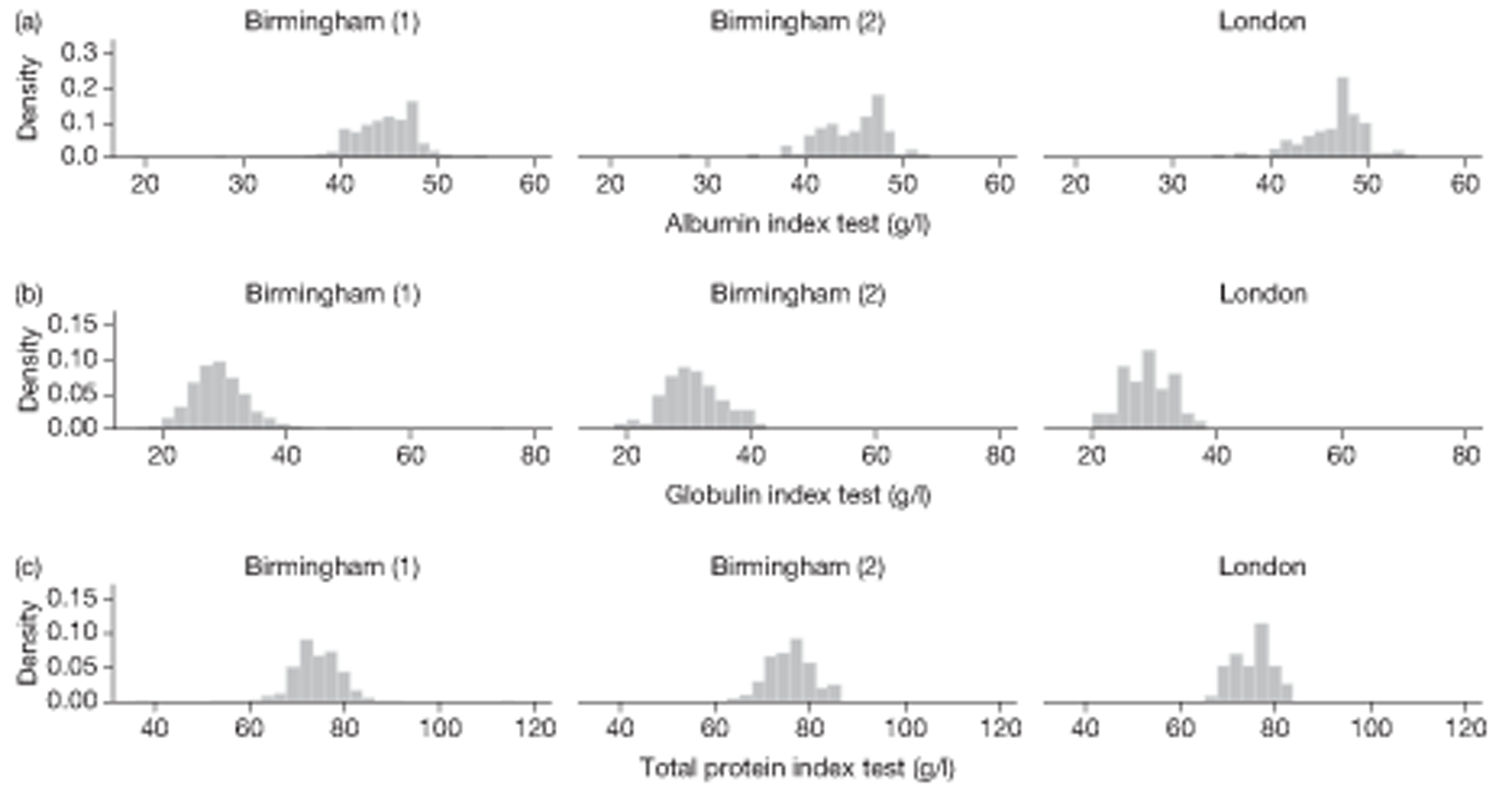

Analyte concentrations

Many of the analytes exhibited positive distributional skewness. Regression analyses of concentrations were conducted on log-transformed data. Differences in the distribution of results between laboratories were examined using quantile–quantile (Q–Q) plots and modelled using multiplicative factors (additive on the log-scale).

Pearson correlation analyses (using logged data standardised within laboratories) were carried out for different analytes in the same panel, and for individual analytes over time.

For each patient in the study, data were available from (up to) three LFT panels, recorded at different times. This gives an opportunity to analyse the development of patient readings over time as well as to relate results to demographic and diagnostic information. However, abnormality on the first panel is a criterion of entry to the study. It was anticipated that this feature would manifest itself in a ‘regression to the mean’ effect over the course of the study. Such selection effects could compromise the interpretation of any statistical analysis of the measured concentrations. The FU1 panels are the most complete panels in terms of missing data (certainly more complete than the FU2 data) and somewhat less biased by selection effects than the index panels, as they were not used as a criterion of entry to the study.

A time-series modelling approach was used to partition the variation in analyte concentrations between transient (short-term) components and persistent (long-term) components. The latter may be more relevant for the diagnosis of serious conditions. For this analysis, selection bias was handled by conditioning on the index LFTs. The variance explained by the persistent component in the model was compared with that from an analysis based on intrapatient correlations. Full details of the modelling methodology are found in Appendix 2 (BALLETS study analysis) along with the results.

Stepwise regression procedures were used to model the impact of demographic and lifestyle factors on LFT results from the FU1 panel. The explanatory models obtained were used in subsequent analyses.

Diagnostic category and liver function test results

The relationship between diagnostic category and LFT results was investigated in two ways: (1) by adding diagnostic category to the explanatory models already derived and (2) by means of a multiple discriminant analysis. The discriminant analysis was carried out using a set patient-level variables and (logged) analyte concentrations that had been identified from a series of preliminary logistics regression analyses. The preliminary analyses involved separate stepwise logistic regressions designed to find significant predictors of individual disease categories. These predictors were then used in a multiple logistic discriminant (polytomous logistic regression) analysis between the separate diagnostic categories. The performance of the discriminant to distinguish between liver disease and a non-specific diagnosis was assessed using the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve.

The stepwise element in the discriminant analysis described here was restricted to patients with a complete panel of LFTs at FU1. The diagnostic groups for serious liver disease were very small compared with the non-specific group, and further depleted in the complete case analysis. In order to make full use of the LFT data that were available from diseased patients, the analysis was repeated using a multiple imputation technique. Further details may be found in Chapter 4 (see Analysis of imputed data).

Fatty liver

Stepwise logistic regression was used to explore the relationship between fatty liver at FU1 and patient characteristics, including (logged) LFT results, BMI and alcohol consumption. In this analysis, linear and quadratic components for age and alcohol consumption were substituted for the categorical variable for ease of interpretation. These components relate to the ordered categories themselves rather than the raw data. Persistence of fatty liver from FU1 to FU2 was investigated by stepwise logistic regression, including fatty liver at FU1 as a predictor for fatty liver at FU2. The consequences for liver fat of a change in BMI within an individual subject were investigated by means of two ordinal regression analyses: (1) liver fat category at FU2 on liver fat category at FU1 with percentage change in BMI as a covariate and (2) numerical difference in liver fat category between FU1 and FU2 on percentage change in BMI. Change in alcohol units (on a square root scale) was incorporated as a covariate in these analyses.

Sample size

A main objective of the study was to investigate the connection between LFTs and serious liver disease. However, there were several diseases under consideration, and no single primary question on which to power the study [see Production of reference categories (categories of diagnostic groupings)]. In the original protocol, logistic regression methods were proposed to explicate the relationship between diagnostic group and analyte concentrations. Sample size calculations for such problems often focus on ‘events per variable’ rules, which, in this study, suggest that 5 to 10 positive diagnoses would be needed for each predictor variable. Here there are seven independent LFTs (given that total protein is the aggregate of two other analytes), suggesting that between 35 and 70 positive cases would be needed for an unadjusted analysis. The study was designed for 1500 patients, which gives a satisfactory number of events (60) assuming a prevalence of a positive diagnosis of 4%. In practice, 44 cases of serious liver disease were found. If serious liver disease is considered as a composite outcome, the events per variable approach suggests that a reliable analysis is possible, at least for the five non-protein analytes in the LFT panel together with a small number of covariates.

The ‘events per variable’ approach focuses purely on technical aspects of logistic regression estimates. In the original protocol, we also considered a novel alternative criterion based on the ability of a logistic discriminant to identify high-risk cases (i.e. patients with risk of disease higher than an acceptable threshold level). For this purpose a baseline level of acceptable risk was taken to be 2% of the average population prevalence. According to this approach, 1500 patients would be sufficient to estimate a logistic discriminant function with a 90% chance of flagging up any patient whose true risk was twice the acceptable baseline level. These calculations posited an average prevalence of 4% – close to that actually observed in the sample. In retrospect, it seems that the degree to which the risk is predictable from the LFT results was underestimated in the original calculations, suggesting that the true performance of the discriminant would exceed expectations. However, there does not seem to be any direct way to verify this, as the true risk profile remains an unknown function of LFT results. In any event, this approach is concerned only with case finding and attaches no penalty to false-positives.

The other principal statistical analysis is concerned with the incidence of fatty liver. For this the event rates are much higher than for serious liver disease, and the sample numbers required for a meaningful analysis are correspondingly less stringent.

Summary of changes to the protocol

The study protocol can be found in Appendix 1.

Changes to protocol by section

-

Section 2.5.6 The patient's perspective. Altered to describe the contents of psychology questionnaires.

-

Section 3.2.1 Practices. Additional practices were recruited in order to improve and maintain recruitment to the study.

-

Section 3.3.2 Formal enrolment in subsequent testing protocol: defining of the patient population and seeking consent. Changes to this section reflect alterations to the clinical process at each practice. The original clinical protocol was adapted to routine clinical practice.

-

Section 3.3.4 Collection of patient information. Altered to indicate that psychology questionnaires would not be translated into languages other than English.

-

Section 3.3.6 Long term follow-up. The 2-year follow-up phase in Birmingham was more complex than originally planned, including repeat USS, alcohol questionnaire and measurements. This section was altered to reflect changes to the process.

-

Section 3.5.1 Broad aim. Altered to address the possibility of selection bias, which could occur when suitable patients declined to take part or when suitable patients were not selected by their GP to take part (see section 3.5).

-

Section 3.7.1 Psychological pilot study. This pilot study was implemented to inform the development of psychological questionnaires for use in the main study. The study process was updated to indicate changes to measures and time points used for data collection.

-

Section 5.1 Substudy: Cryogenic storage and later testing Approval was obtained to collect and store an anonymised blood sample from consenting Birmingham patients attending their 2-year (FU2) clinic appointment.

-

Section 5.2 Substudy: A qualitative investigation into liver function test ordering behaviour of general practitioners involved in the BALLETS study. A substudy designed to examine the non-clinical motives behind a GP's decision to order an LFT.

-

Section 5.3 Substudy: Follow-up of abnormal test results. In the course of the study some patients tested positive for some specific liver diseases, but many were not followed up according to the agreed algorithm for referral or further testing. Letters were prepared by the study hepatologist and chief investigator suggesting appropriate follow-up of individual study patients testing positive for particular diseases.

-

Section 5.4 Substudy: Qualitative investigation exploring anecdotal and preliminary evidence that events associated with participation in the BALLETS study were motivational to patients with and without fatty liver. A random selection of study patients were interviewed, in response to anecdotal accounts from patients at 2-year follow-up clinics that they had implemented lifestyle changes following their first BALLETS clinic appointment.

Ethics committee approval for changes to the protocol

The main research ethics committee, St Thomas' Hospital Research Ethics Committee, gave favourable ethical opinion to the BALLETS study in April 2005.

During the recruitment and follow-up phases of the study, the St Thomas' Hospital Research Ethics Committee Modifications Subcommittee approved 10 substantial amendment applications for alterations to the study protocol and documentation. Detailed summaries of each amendment are provided in the appendices to the main report (Appendix 3, BALLETS study: summary of ethics and substantial amendment approval). All amendments were also approved by South Birmingham and Lambeth local research ethics/research and development committees.

Approval was sought for the recruitment of new study practices in Birmingham, and corresponding patient documentation, for two qualitative substudies, as described in Chapter 5 (see Psychology 1: effects of positive tests and Psychology 2: effects of results on behaviour), and for a more intensive 2-year follow-up phase for Birmingham patients, which included an additional USS and the cryogenic storage and later testing of cells and serum. In addition, approval was obtained for the study team to remind GPs by letter, of the need to follow up patients who tested positive for some specific liver diseases.

Chapter 4 Results: main study

This section begins with a brief description of the practices from which the participants were drawn and the demographics of the patients in the study (see Nature of the population studied: Birmingham and Lambeth sites and Patients and practice characteristics, below). Numerical summaries of the clinical data are also presented (see Summary of clinical data), namely LFT panels, diagnostic categories and ultrasound features. Some observations on the timing and completeness of panels are included here, together with a brief discussion of selection effects.

Analysis of the LFT panels themselves (see Analysis of the liver function test panels) is presented in two parts: (1) the inter-relationships between unadjusted LFT results and the utility of laboratory reference ranges for assessing abnormality (see Analysis of unadjusted liver function test results) and (2) variation in the concentrations of individual analytes, investigated using regression models to adjust for patient characteristics (see Impact of patient characteristics on liver function test results). The contribution of diagnostic grouping and fatty liver status to these models is also considered (see Impact of diagnostic surgery and Impact of fatty liver, respectively).

The section Liver-related disease contains a detailed clinical description of the categories of liver disease in the sample. Diagnostic value of liver function tests builds on the regression models (see Impact of patient characteristics on liver function test results) to investigate the diagnostic potential of the LFT panel, taking account of individual patient characteristics. The approach is based on stepwise procedures to find the analytes with the greatest discriminatory potential and uses imputation methods to cope with missing values in sparsely populated diagnostic categories.

Fatty liver is investigated in Fatty liver on ultrasound. The risk of fatty liver is modelled using logistic regression techniques. Relationships between fatty liver and lifestyle variables over the course of the study are investigated.

Nature of the population: Birmingham and Lambeth sites

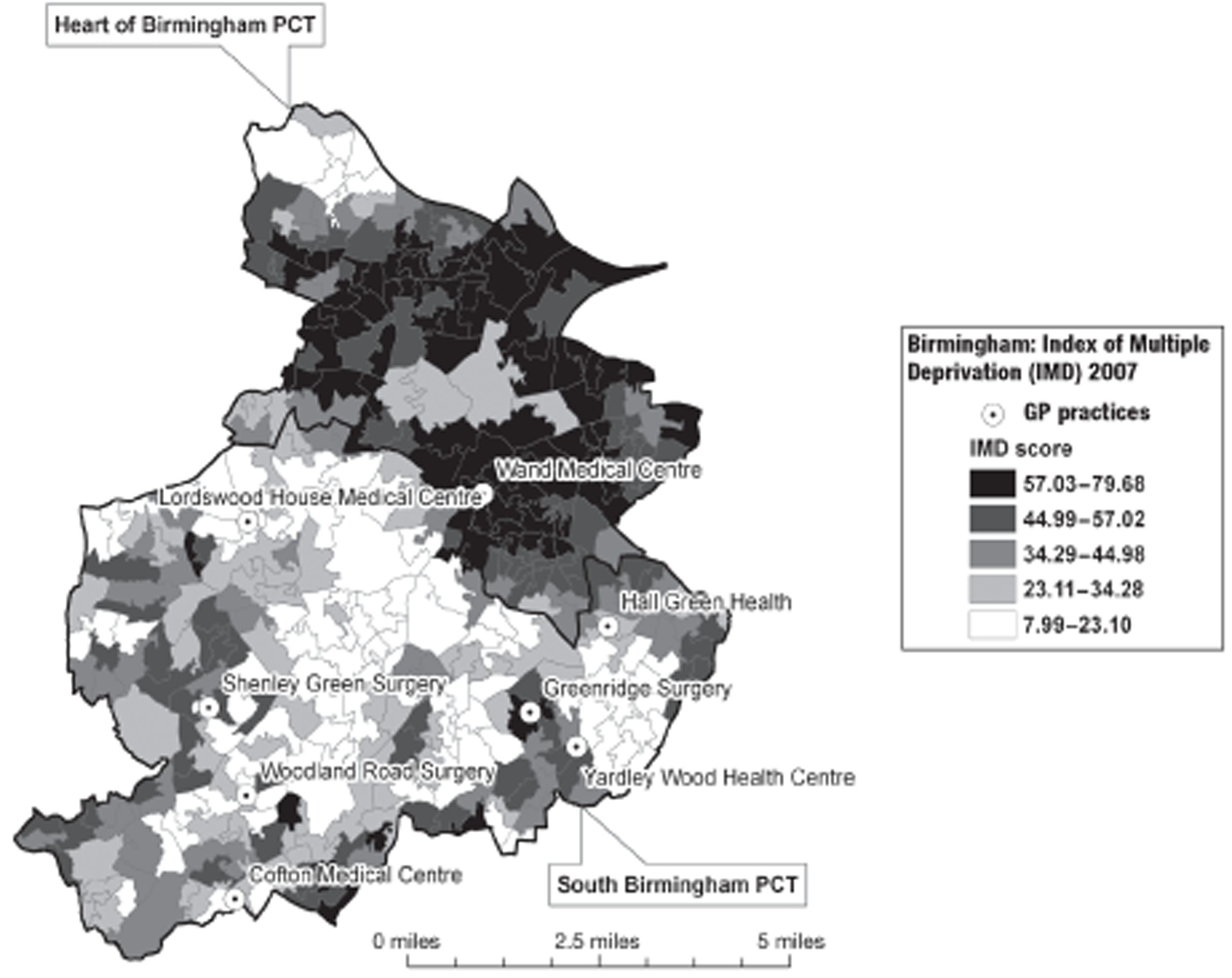

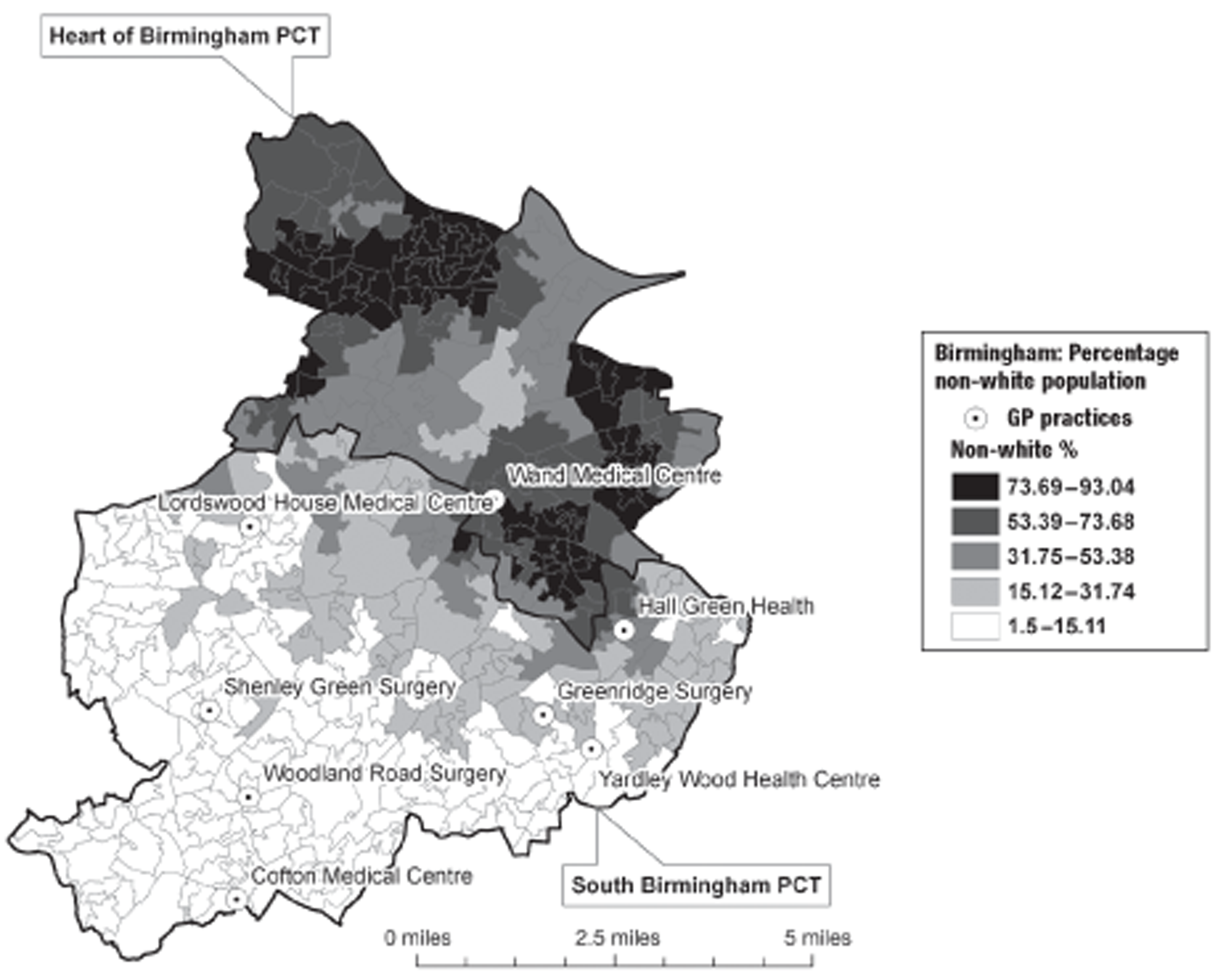

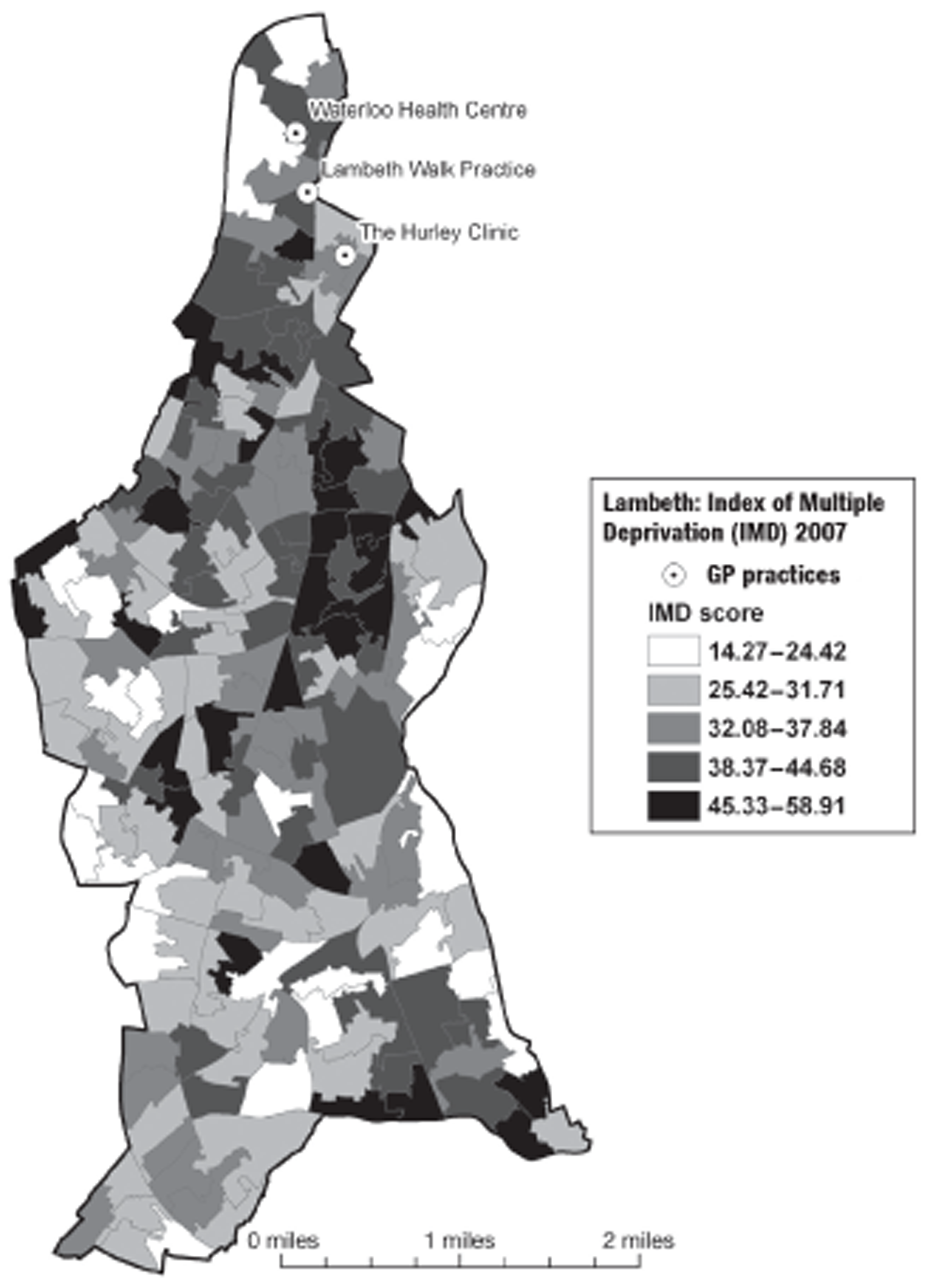

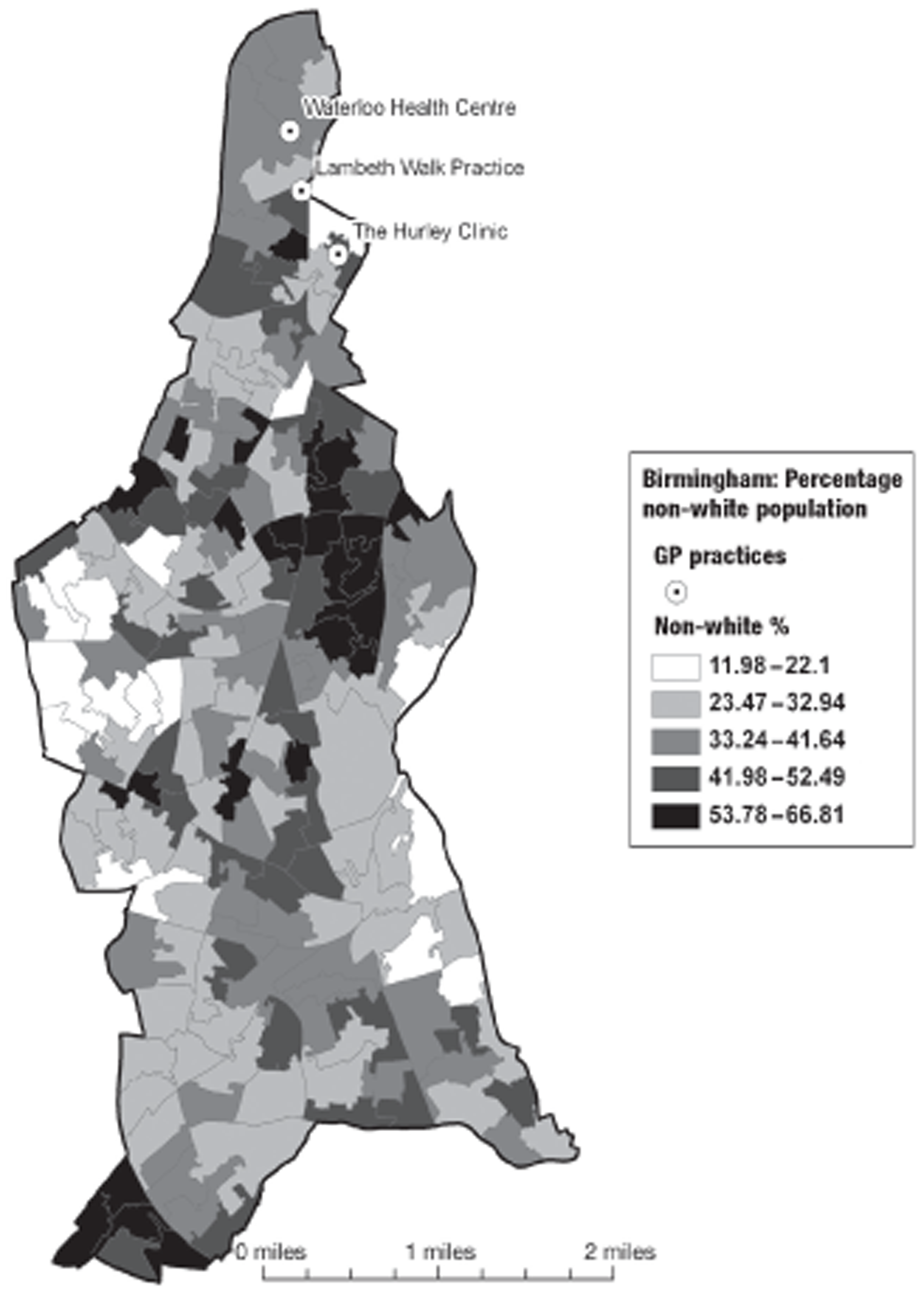

In Birmingham, 1197 participants were recruited from eight practices. The location of the practices within the Birmingham conurbation and the socioeconomic and ethnic group characteristics of the surrounding areas are shown in Figures 2 and 3. In Lambeth, 147 participants were recruited from three practices. The location of the practices within the Lambeth conurbation and the socioeconomic and ethnic group characteristics of the surrounding areas are shown in Figures 4 and 5.

FIGURE 2.

Location of participating practices in relation to socioeconomic group (Townsend Deprivation score quintile by lower-level super output area). PCT, primary care trust. Adapted from 2001 Census, Output Area Boundaries. 39 ©Crown Copyright 2003. Census output is Crown Copyright and is reproduced with the permission of the Controller of HMSO and the Queen's Printer for Scotland.

FIGURE 3.

2001 Census location of participating practices in relation to ethnic mix (proportion of black and ethnic minority population by lower-level super output area). PCT, primary care trust. Adapted from 2001 Census, Output Area Boundaries. 39 ©Crown Copyright 2003. Census output is Crown Copyright and is reproduced with the permission of the Controller of HMSO and the Queen's Printer for Scotland.

FIGURE 4.

Location of participating Lambeth practices in relation to socioeconomic group (English Indices of Deprivation 2004). Adapted from 2001 Census, Output Area Boundaries. 39 ©Crown Copyright 2003. Census output is Crown Copyright and is reproduced with the permission of the Controller of HMSO and the Queen's Printer for Scotland.

FIGURE 5.

Location of participating Lambeth practices in relation to ethnic mix (proportion of black and ethnic minority population). Adapted from 2001 Census, Output Area Boundaries. 39 ©Crown Copyright 2003. Census output is Crown Copyright and is reproduced with the permission of the Controller of HMSO and the Queen's Printer for Scotland.

Patients and practice characteristics

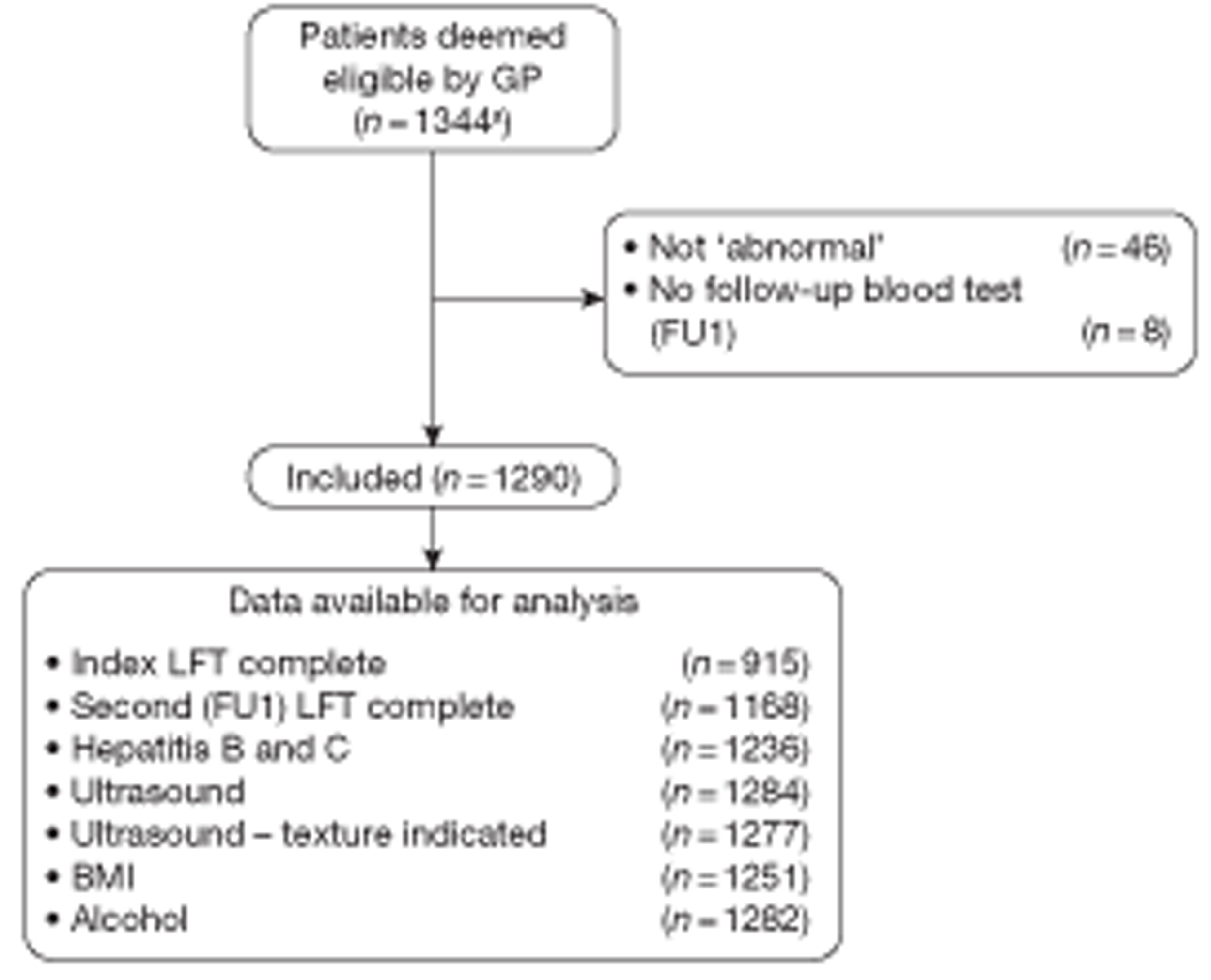

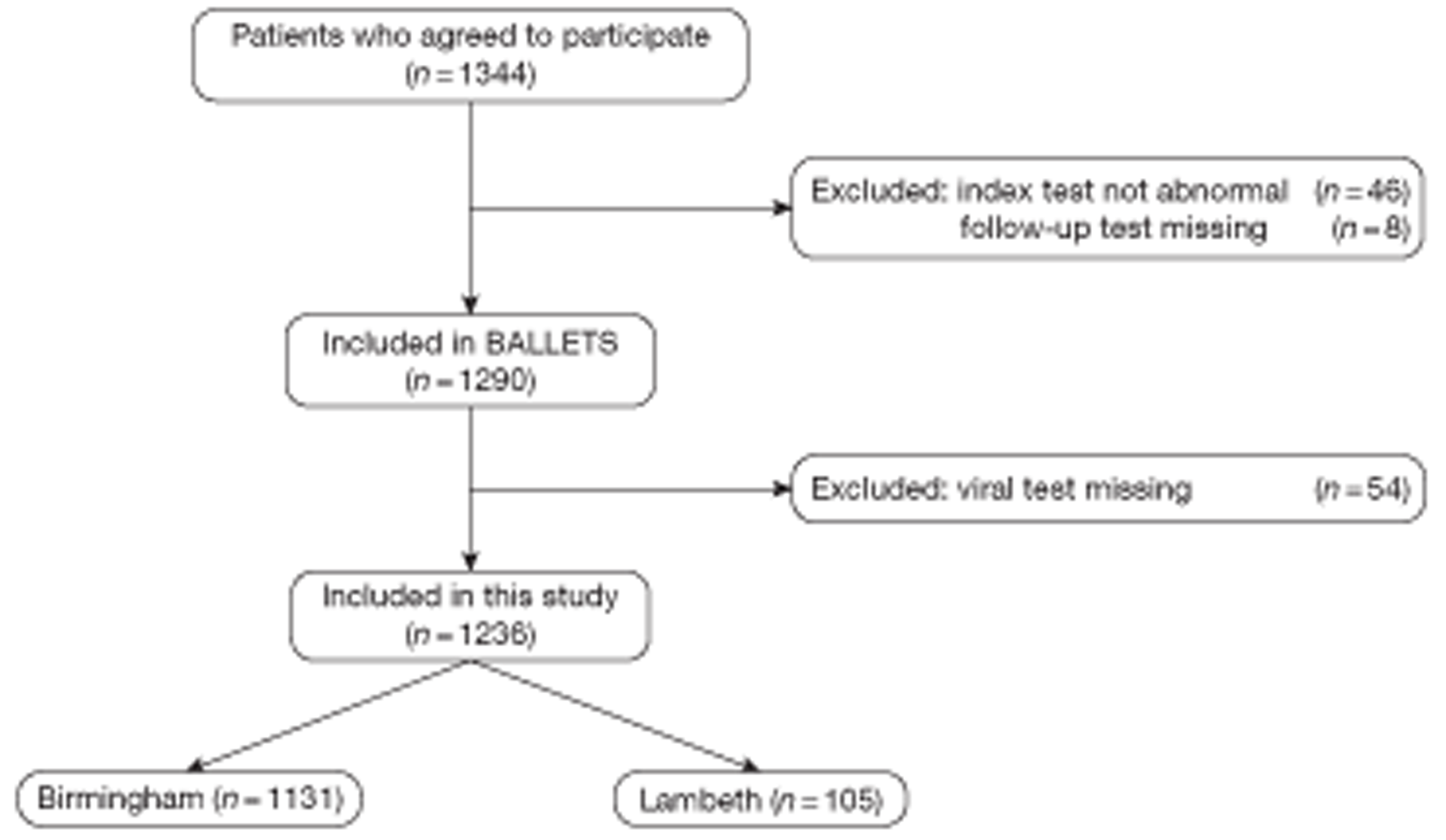

Forty-six patients of the total 1344 patients were excluded because none of the original LFTs was, in fact, abnormal. Eight patients were excluded because the second blood test result was completely missing such that neither the FU1 LFT nor any of the tests for specific diseases was available (Figure 6). The analyses use data from the remaining 1290 patients, whose individual characteristics are summarised in Table 14. This includes basic demographic information (recorded at FU1), together with BMI measurements (taken at FU1 and again at FU2) and results from the alcohol questionnaire (administered at FU1 and FU2). Results are given for all subjects (at FU1) and for the subsample who contributed to the FU2 LFT data. The reasons for ordering the index LFTs are summarised in Table 15.

FIGURE 6.

Flow diagram showing exclusions and data completeness. a, For an analysis of information on patients with abnormal LFTs but not recruited to the study, see Chapter 3, Comparison of patients who were and were not ‘recruited’.

| Reasons for LFT ordering | Total |

|---|---|

| Investigations | |

| Abdominal symptoms or signsa | 70 |

| General symptoms or signs | 318 |

| Suspected alcohol abuse | 18 |

| Reviews | |

| CVD | 53 |

| Cholesterol | 57 |

| Hypertension | 151 |

| Diabetes | 220 |

| Medication | 95 |

| Other | 308 |

| Total | 1290 |

Eleven general practices contributed to the study and their participation is summarised in Table 16. The first eight practices in the table are situated in Birmingham, and the remaining three in London.

| Practice | All subjects (n = 1290) | Subjects with 2-year follow-up LFTs (n = 790) | Processing laboratory | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Hall Green | 161 | 12.48 | 117 | 14.81 | a |

| Lordswood | 213 | 16.51 | 134 | 16.96 | a |

| Greenridge | 195 | 15.12 | 103 | 13.04 | a |

| Yardley Wood | 144 | 11.16 | 100 | 12.66 | a |

| Woodland Road | 149 | 11.55 | 97 | 12.28 | a |

| Cofton | 126 | 9.77 | 76 | 9.62 | a |

| Shenley Green | 75 | 5.81 | 42 | 5.32 | a |

| Wand | 89 | 6.90 | 58 | 7.34 | b |

| Lambeth Walk | 71 | 5.50 | 31 | 3.92 | c |

| Waterloo Health | 48 | 3.72 | 26 | 3.29 | c |

| The Hurley Clinic | 19 | 1.47 | 6 | 0.76 | c |

| Total | 1290 | 790 | |||

Summary of clinical data

Diagnostic categories

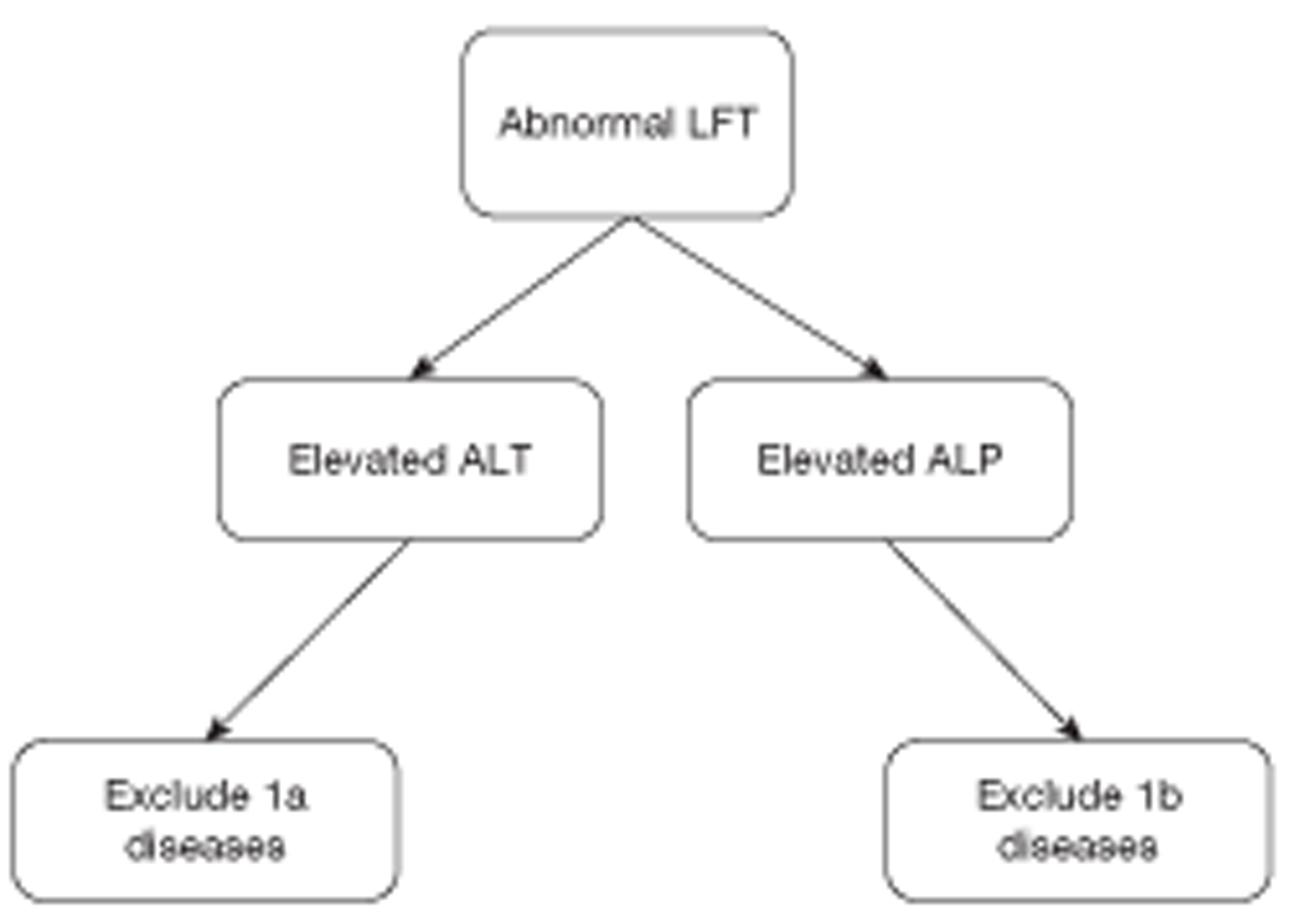

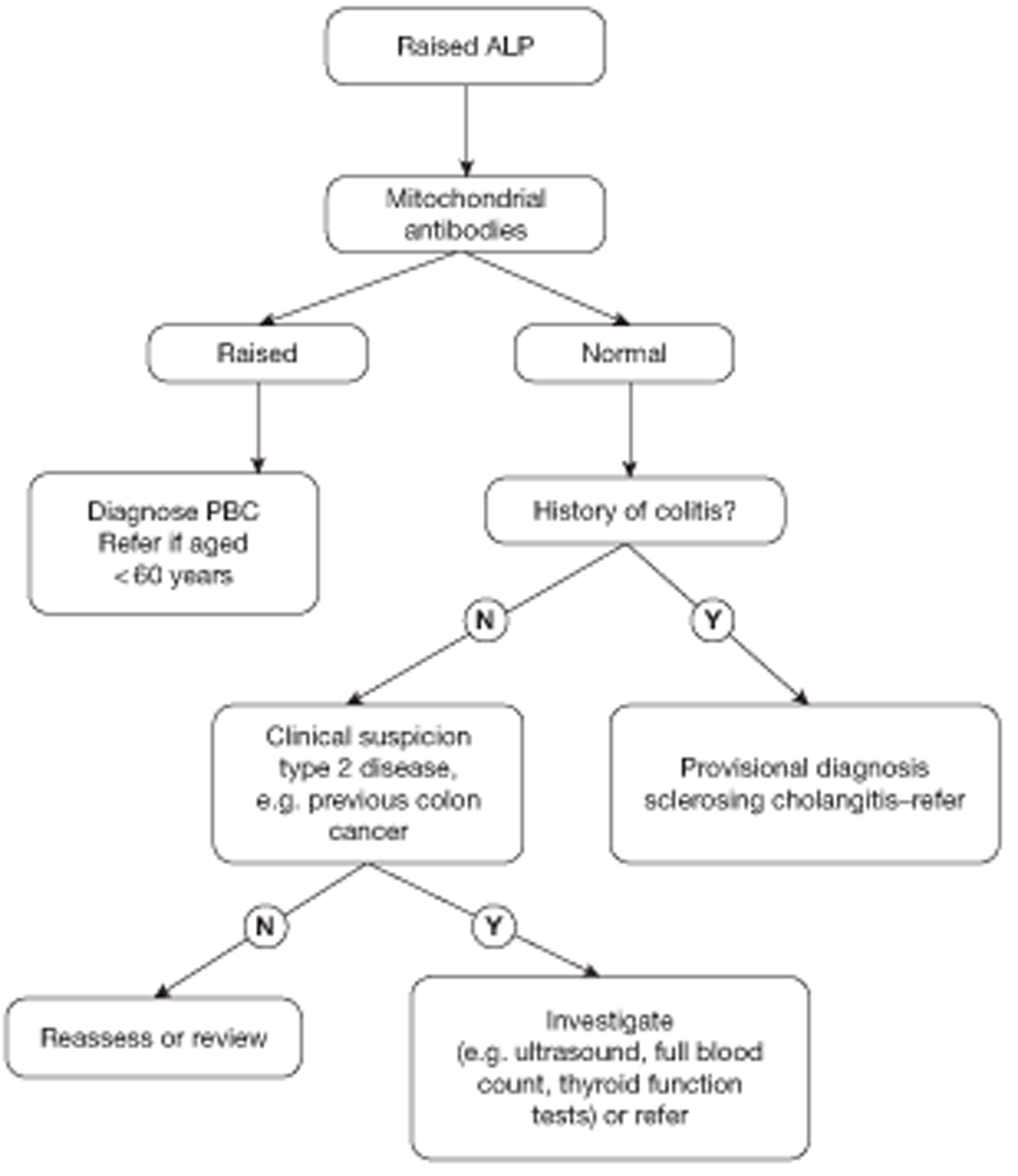

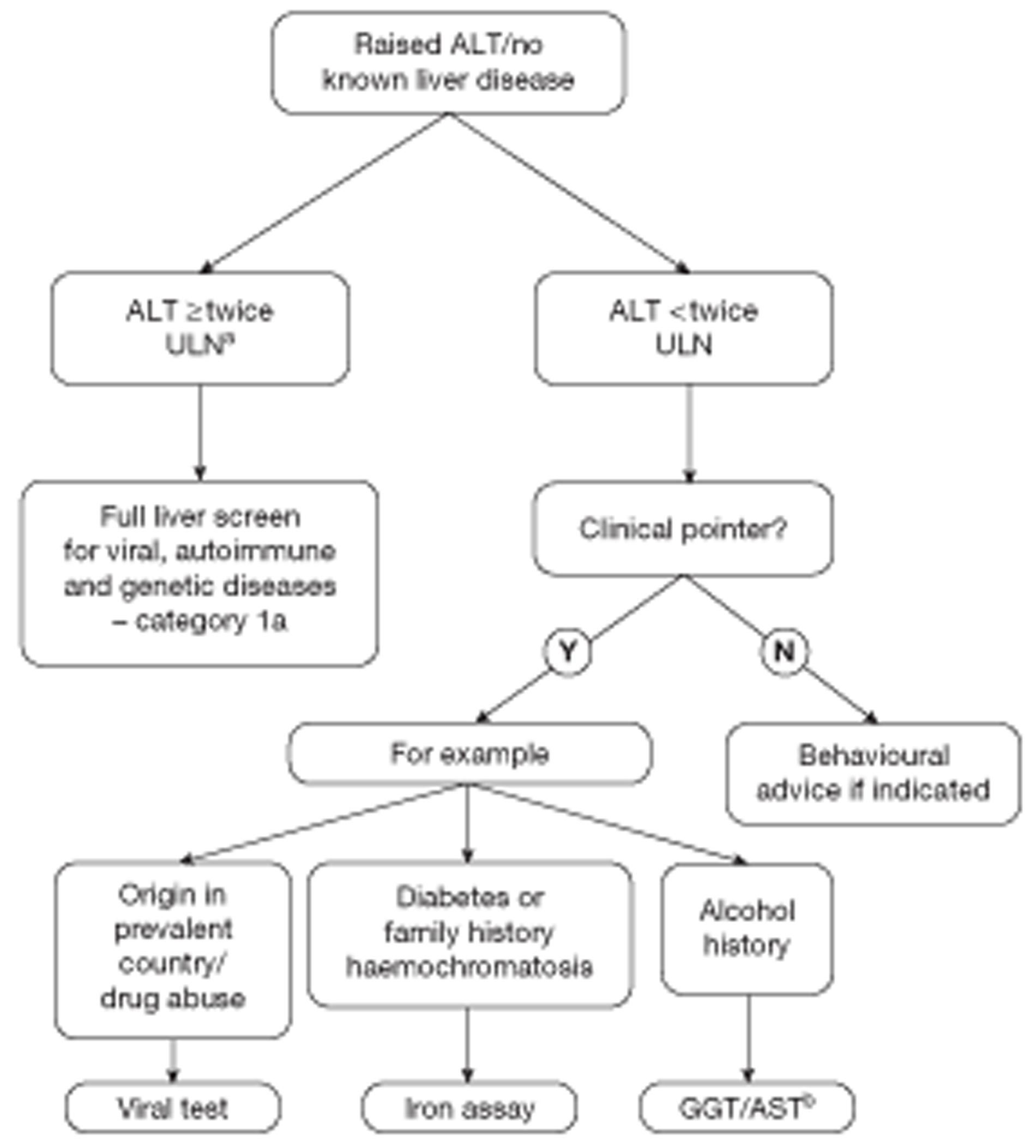

Patients were categorised into three broad diagnostic groups, described more fully in Chapter 3 (Methods: main study). Categories 1 and 2 are the two broad ‘serious liver disease’ categories, which may be further subdivided into: category 1a (hepatitis B and C + other hepatocellular diseases). Category 1b (hepatic bile duct disease) and category 2 [other diseases (such as metastatic cancer)] affecting the liver. The remaining cases (category 3) are rather non-specific.

Ultrasound features

Sonography reports for the liver were obtained at FU1 for 1277 patients and at FU2 for 658 out of 1152 patients from Birmingham practices. Second ultrasound examinations were not performed in Lambeth (see Chapter 3, The 2-year follow-up visit). A four-point ordinal scale (normal, mild, moderate and severe) was used to describe liver fat on each occasion (see Chapter 3, Testing strategy for patients in the BALLETS study), with results summarised in Table 17.

| First follow-up | Second follow-up | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Not known | DNAa | Total | |

| Normal | 324 | 44 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 413 | 793 |

| Mild | 62 | 61 | 28 | 0 | 1 | 111 | 263 |

| Moderate | 23 | 37 | 36 | 6 | 1 | 74 | 177 |

| Severe | 4 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 26 | 44 |

| Not known | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 8 |

| DNA | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| Total | 415 | 147 | 83 | 9 | 4 | 632 | 1290 |

The subsequent version of the table (Table 18) shows the persistence of the ultrasound diagnosis of fatty liver between the two epochs.

| Initial sonography | Two-year sonography | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (%) | Abnormal (%) | Total (%) | |

| Normal | 324 (85.49) | 55 (14.51) | 379 (100.00) |

| Abnormal | 89 (32.84) | 182 (67.16) | 271 (100.00) |

| Total | 413 (63.54) | 237 (36.46) | 650 (100.00) |

Liver function test panels

Timing and completeness of panels

The LFT panel was extended from the usual five analytes to eight analytes for study purposes – that is to say the intention was to report on eight analytes on each occasion – the index result that triggered entry in the study and the FU1 and FU2 tests used as part of the comprehensive testing strategy. The number of analytes actually reported on each occasion is shown in Table 19. Complete reporting (all eight analytes) occurred for 915 (70.9%) on index testing, and 1168 (90.5%) at FU1 and 642 (81.3%) at FU2. A complete panel was recorded on the first two occasions (index and FU1) for 844 (65.4%) participants. Compared with the integral pilot data (see Chapter 3, Laboratory methods), completion improved for the follow-up visit but deteriorated for the index visit. A bimodal pattern of testing can be observed, with modes at eight analytes (as required for study purposes) and five analytes (the default situation) (see Chapter 3, Missing data).

| No. of tests | Index | FU1 | FU2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 (0.0) | 15 (1.2) | – |

| 1 | 3 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) |

| 2 | 6 (0.5) | 3 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) |

| 3 | 6 (0.5) | 23 (1.8) | 26 (3.3) |

| 4 | 103 (8.0) | 16 (1.2) | 42 (5.3) |

| 5 | 134 (10.4) | 21 (1.6) | 29 (3.7) |

| 6 | 99 (7.7) | 17 (1.3) | 25 (3.2) |

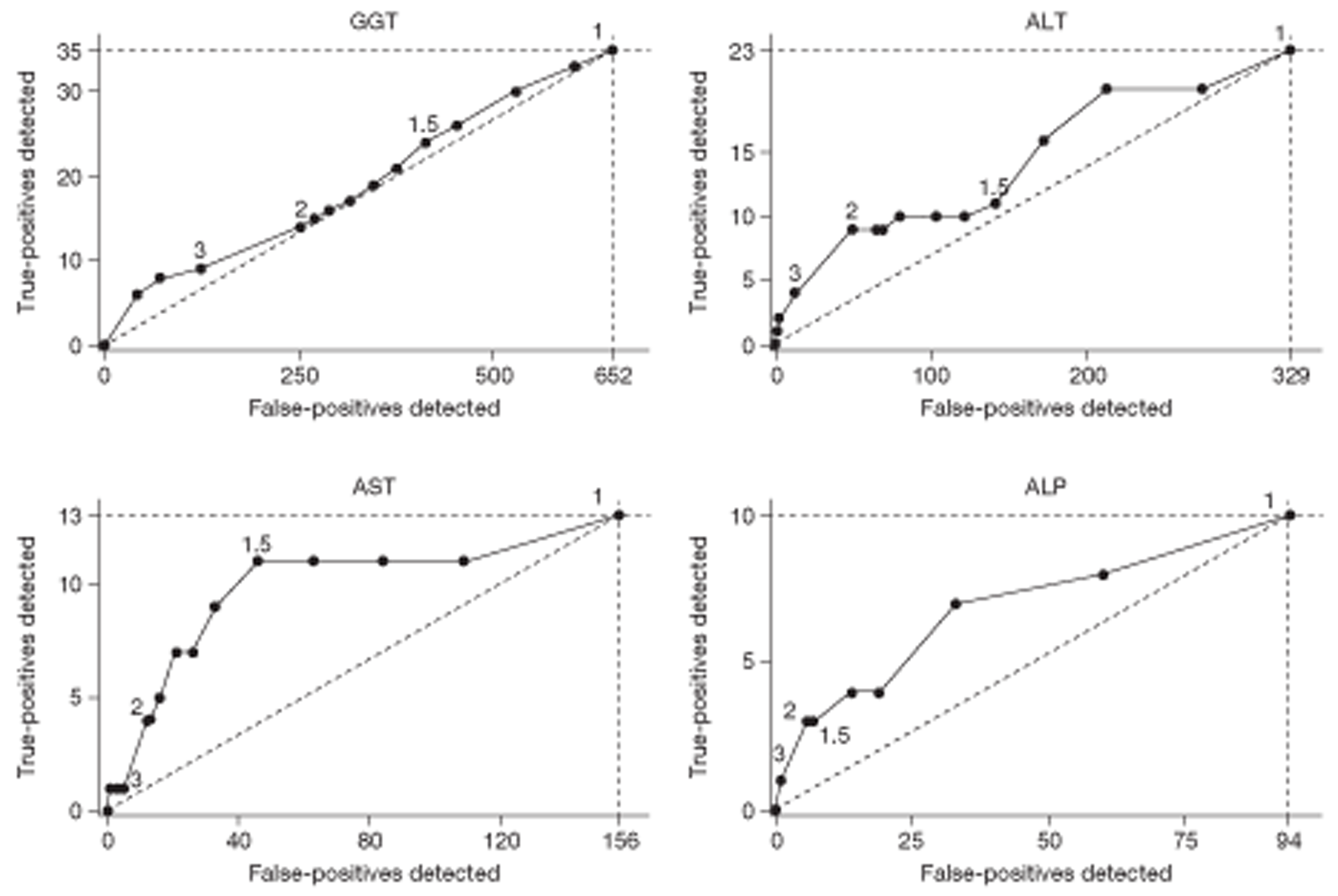

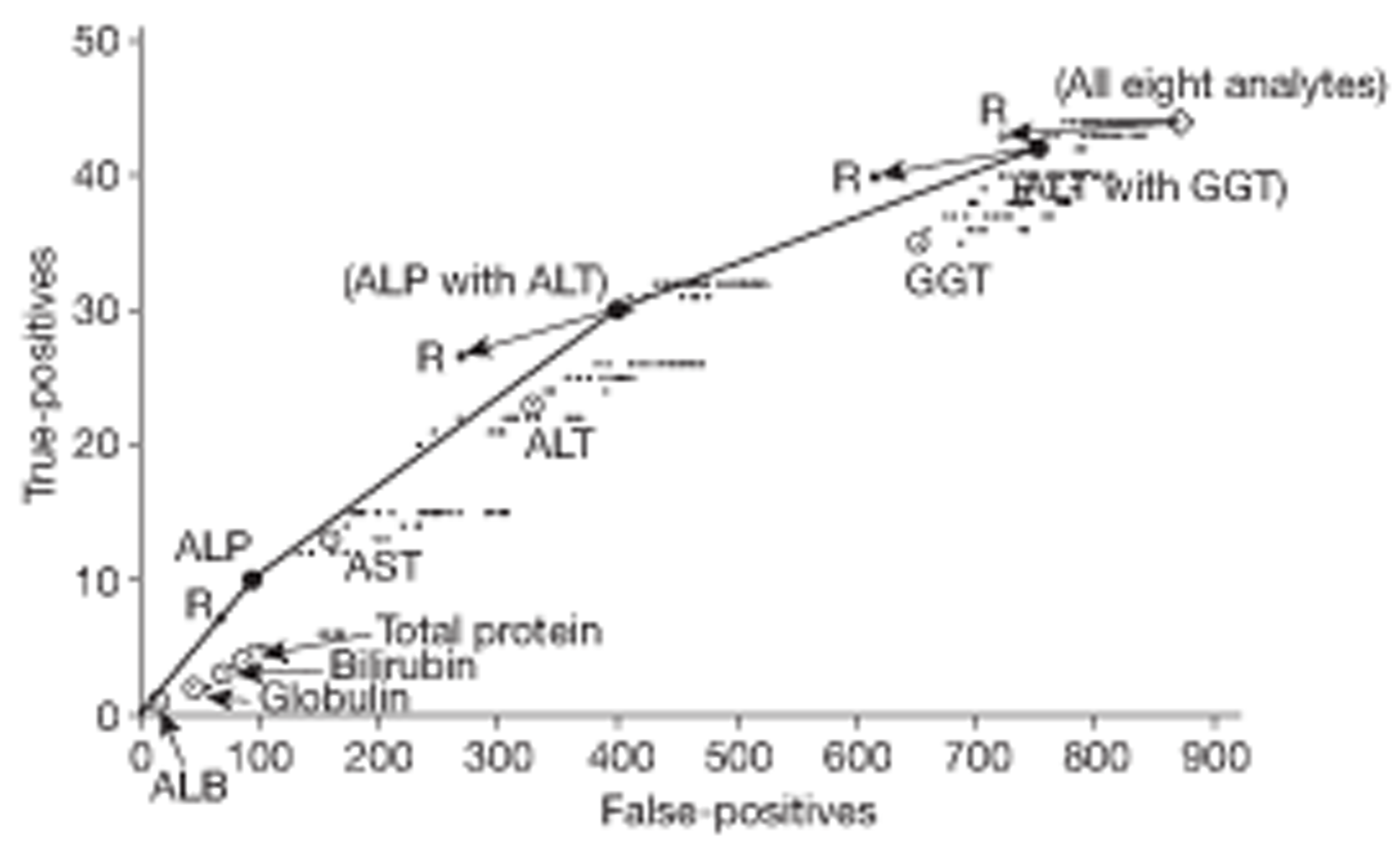

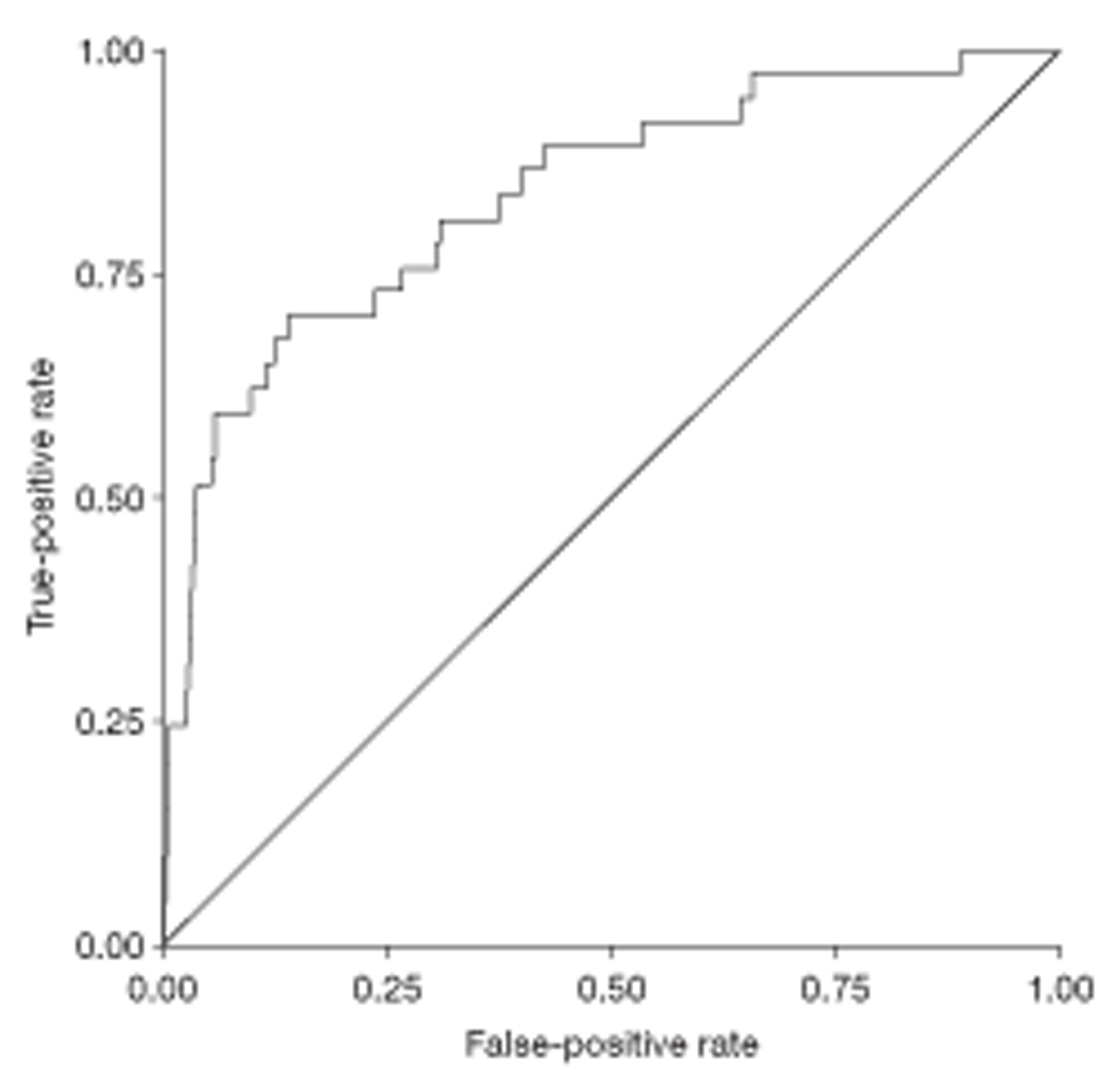

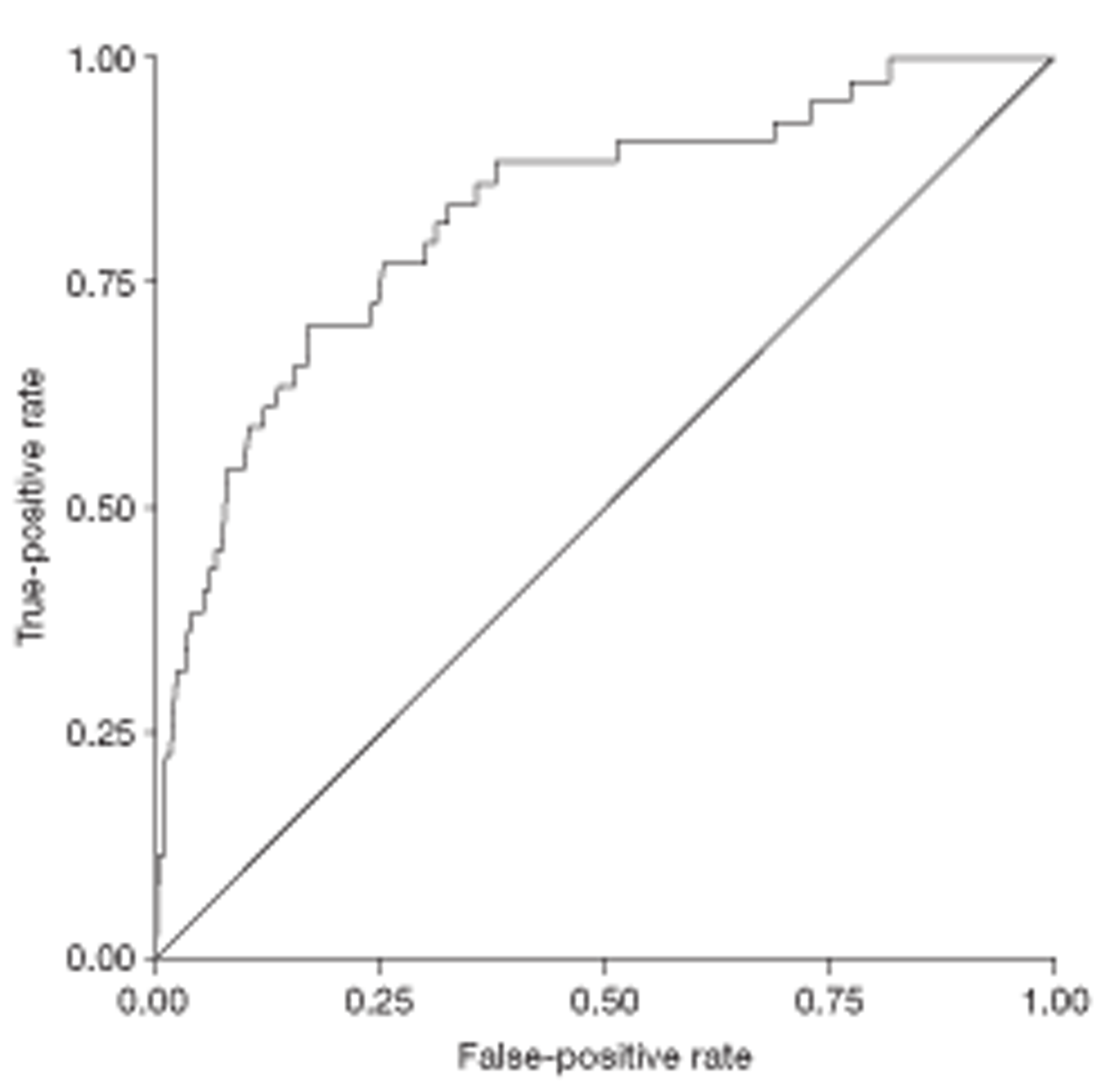

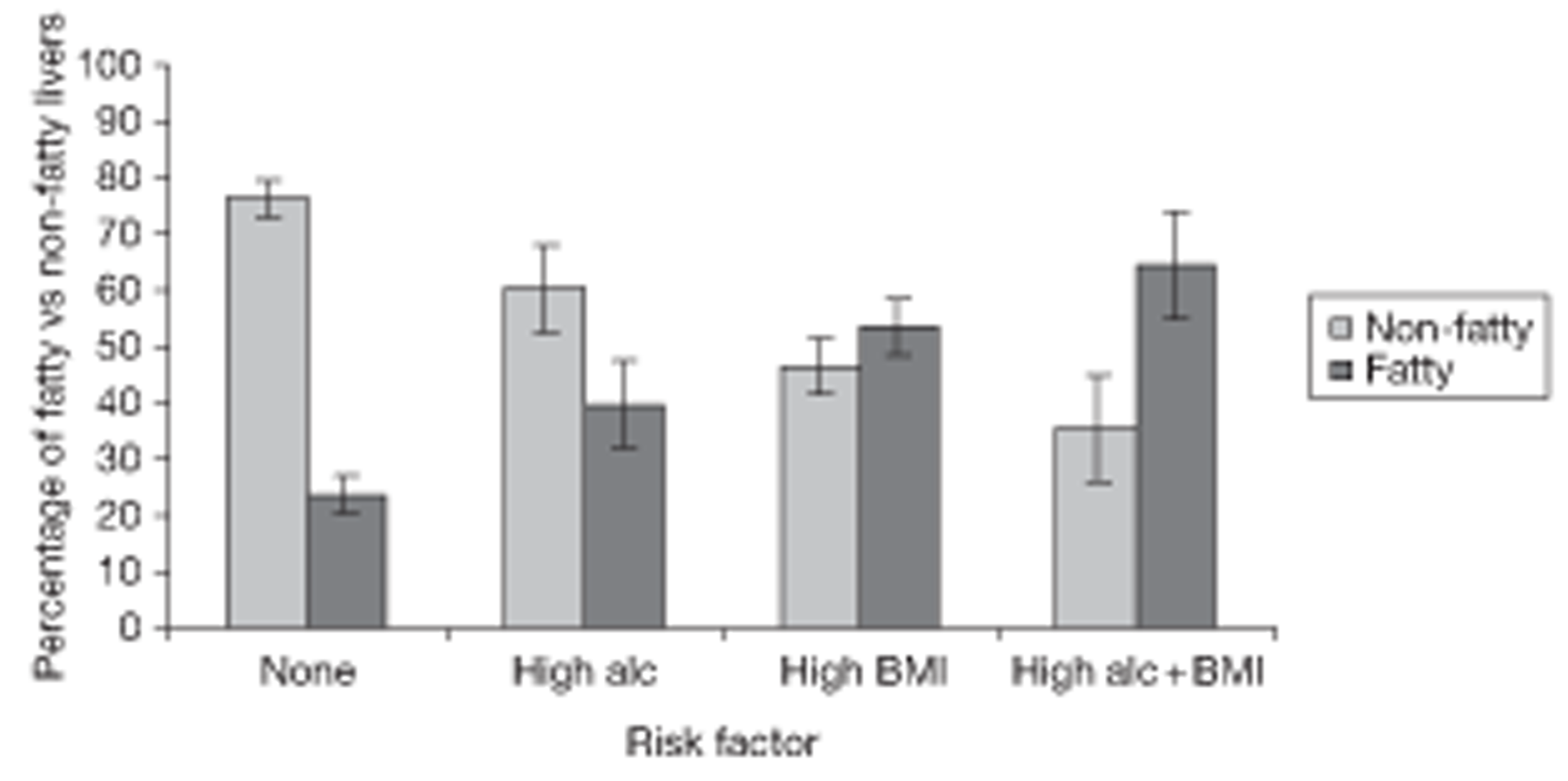

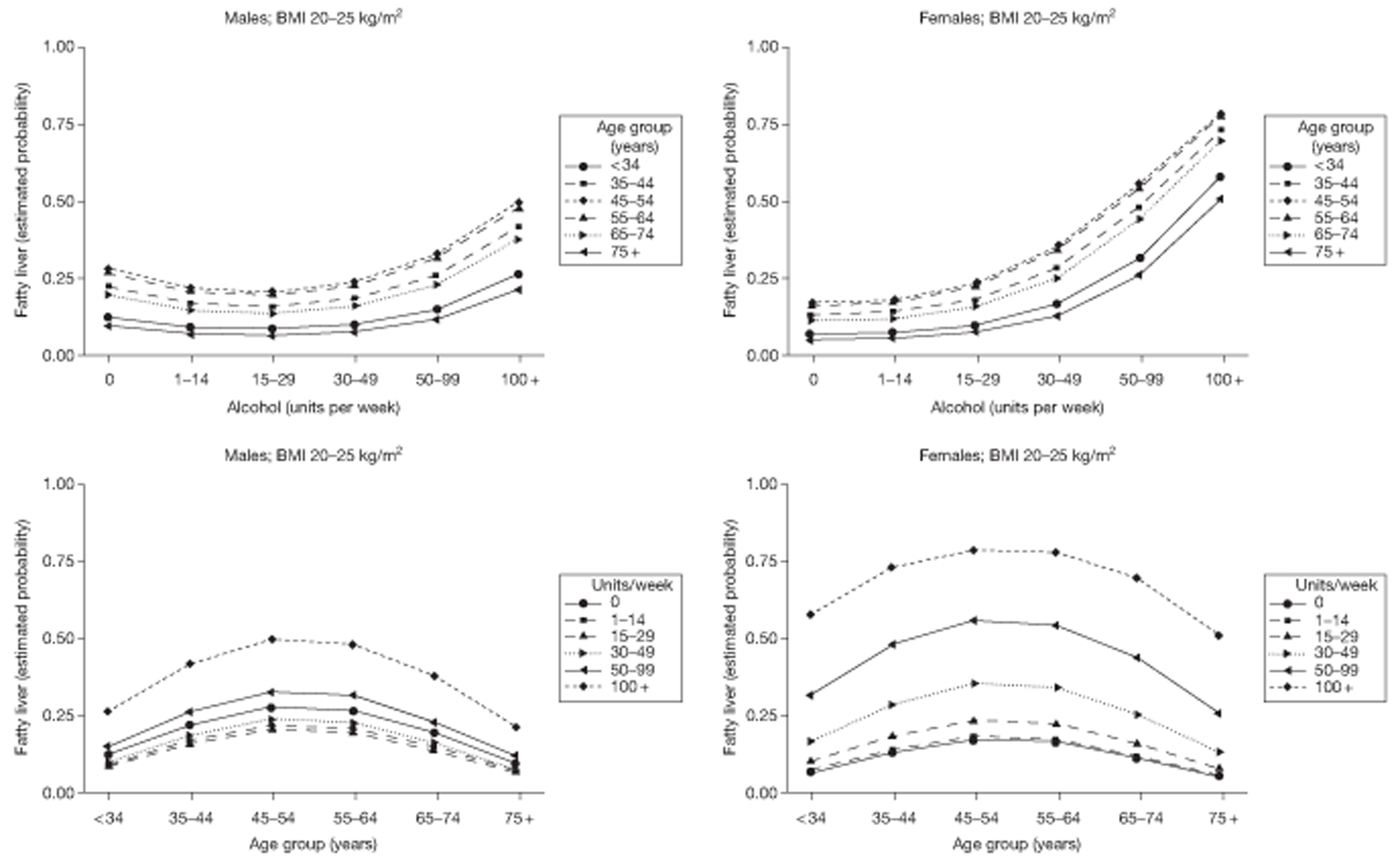

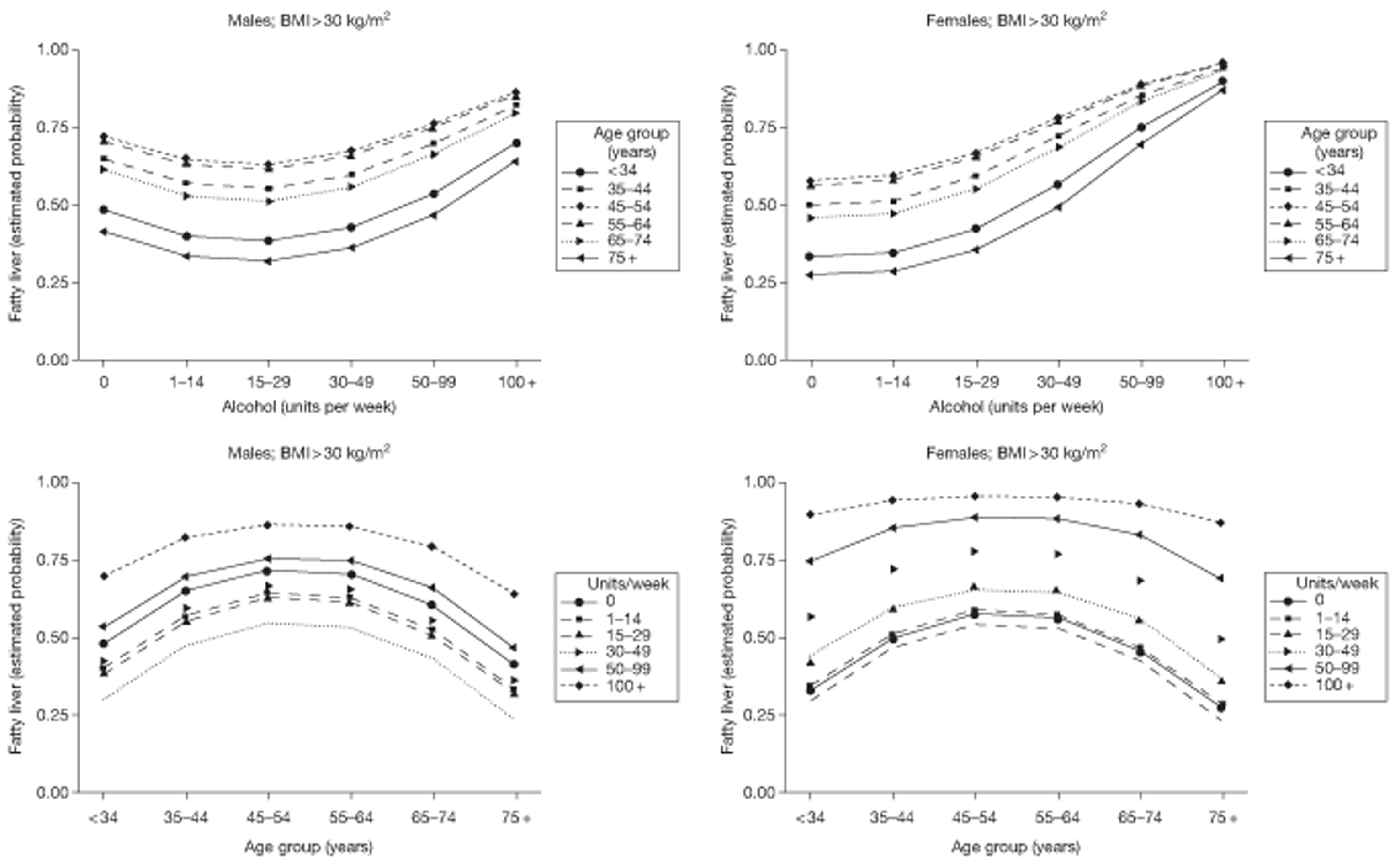

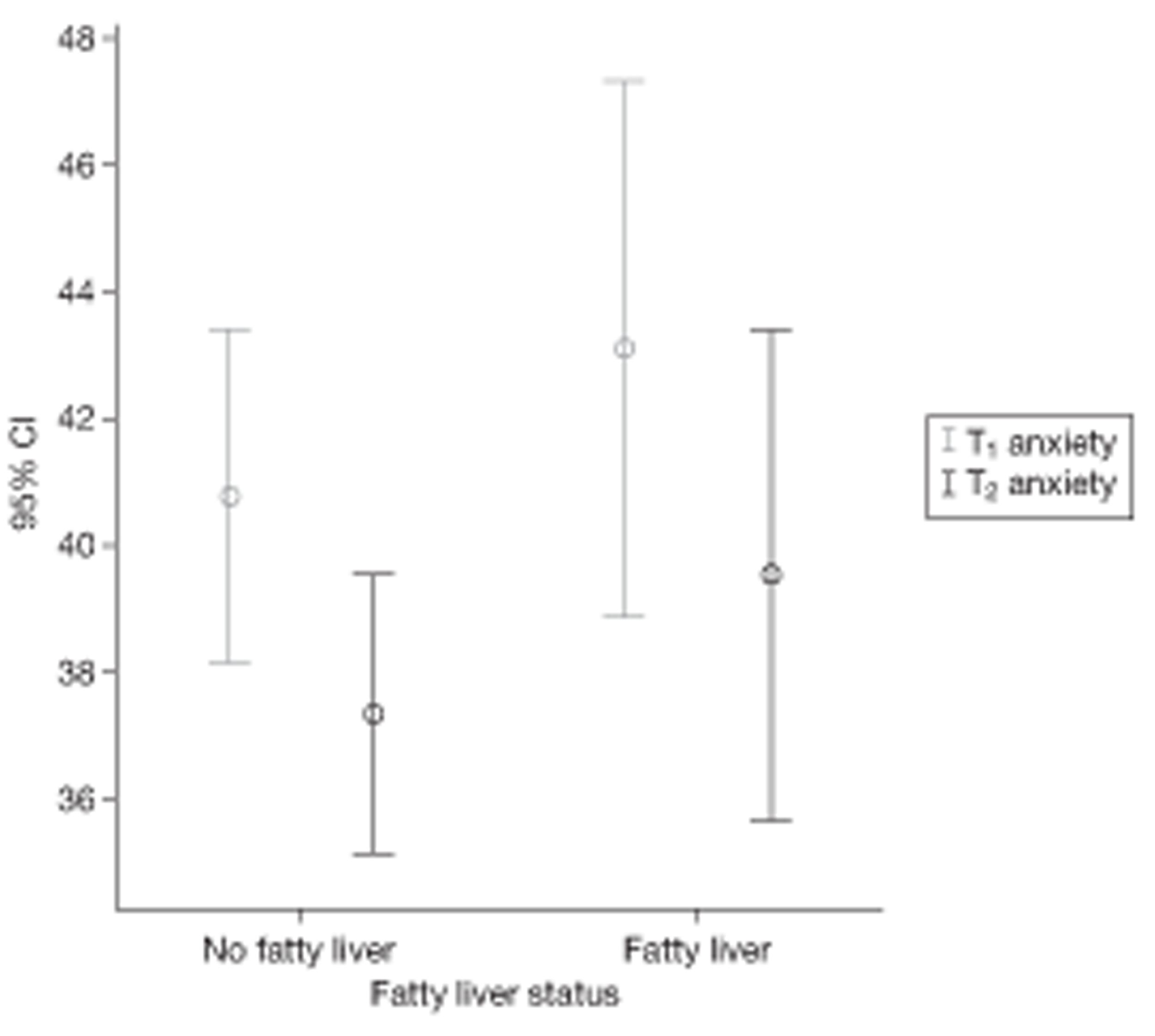

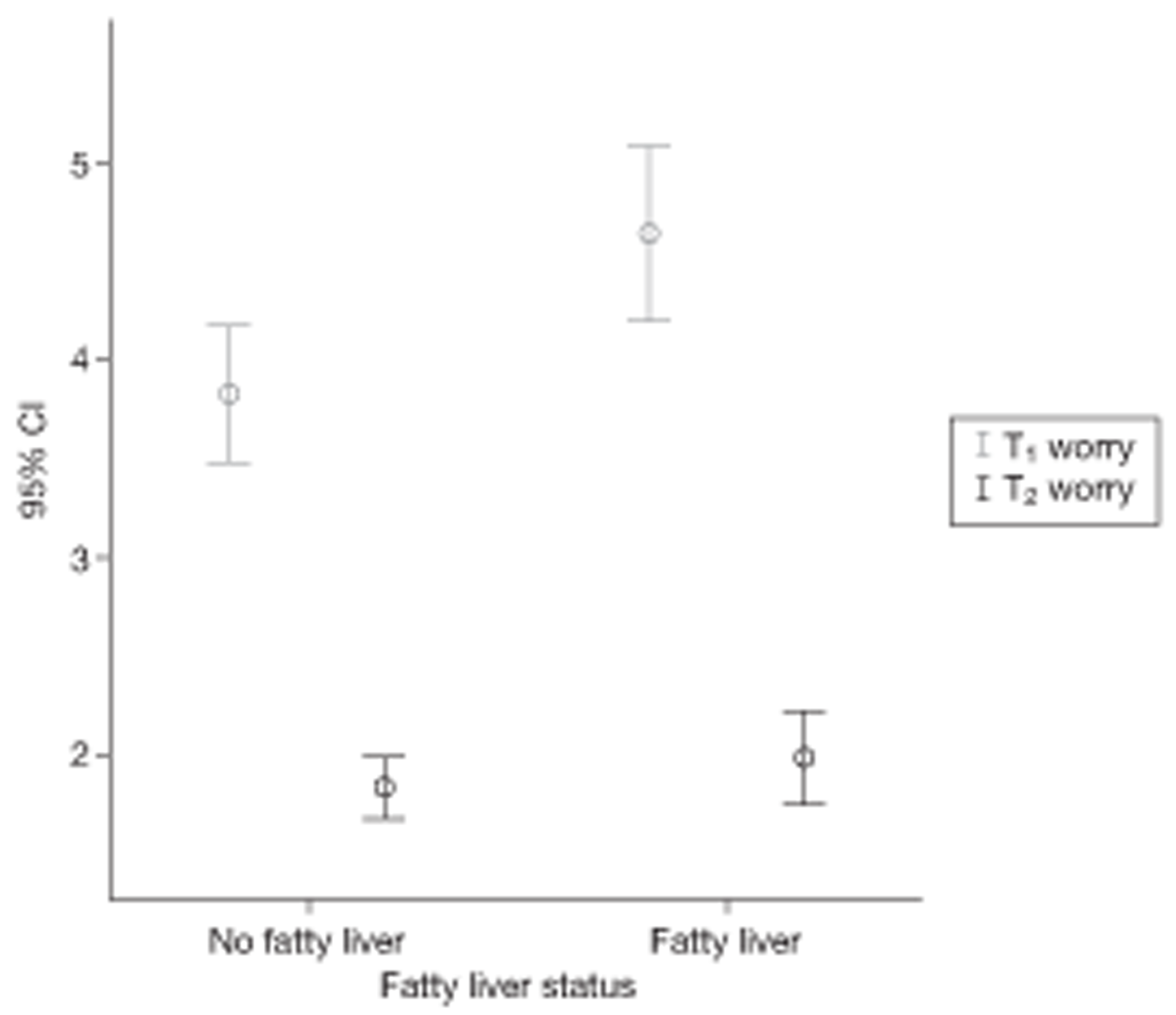

| 7 | 24 (1.9) | 24 (1.9) | 24 (3.0) |