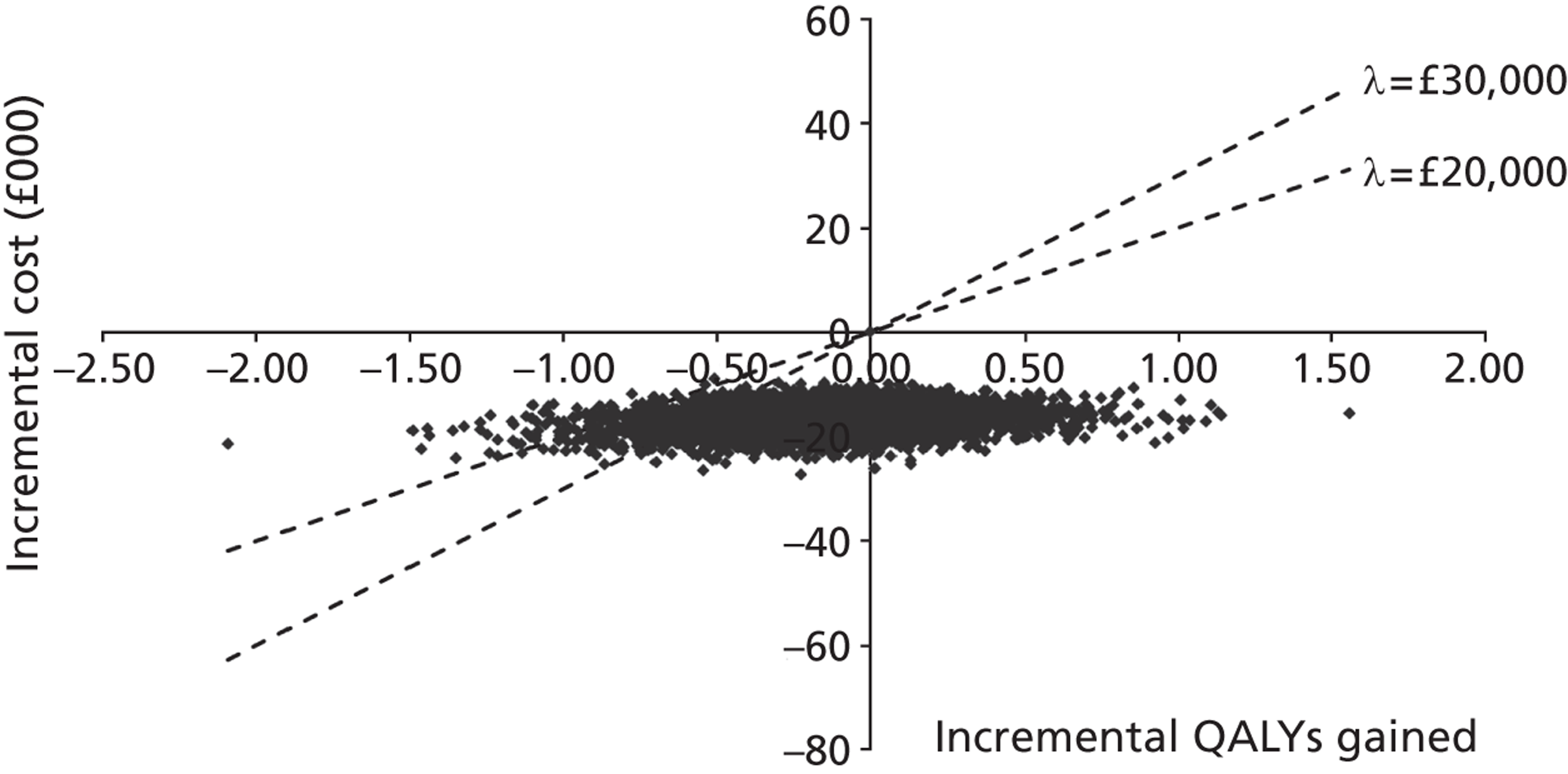

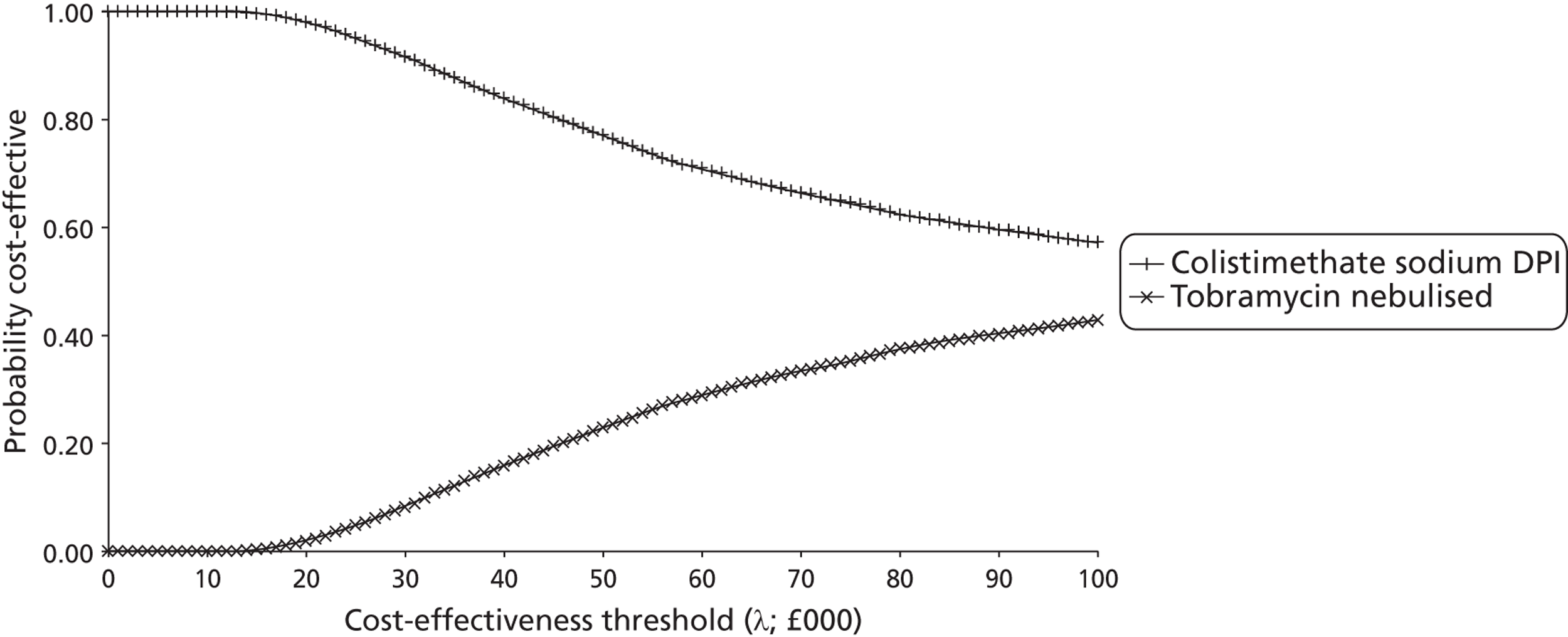

Notes

Article history

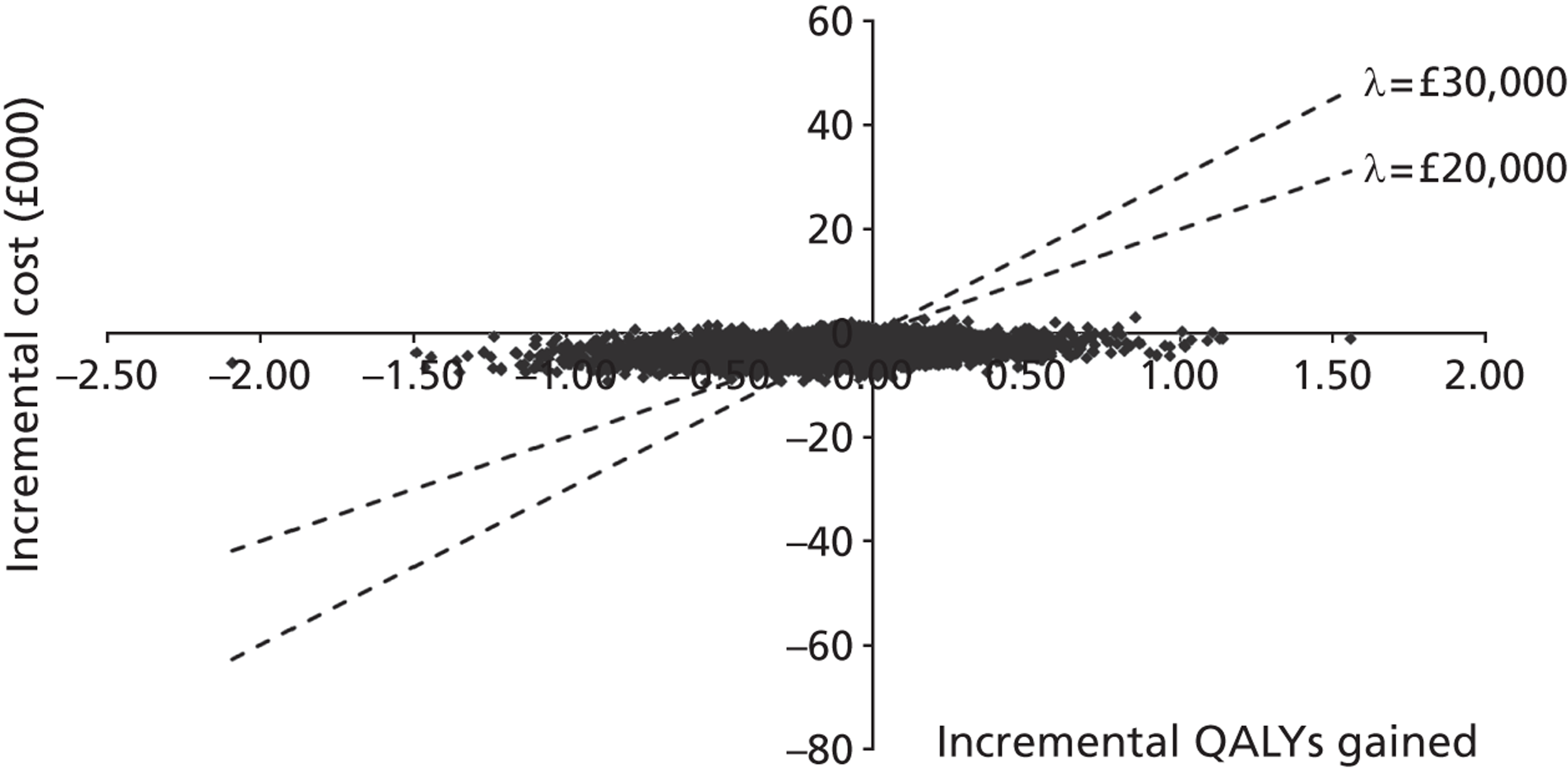

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 10/08/01. The protocol was agreed in January 2011. The assessment report began editorial review in April 2012 and was accepted for publication in November 2012. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of clinical advisors/peer reviewers

Dr Keith Brownlee attended a Novartis Pharmaceuticals Advisory board on future developments in cystic fibrosis (CF) in 2010, and received a fee and travel expenses from Forest Laboratories for a lecture given at the East Anglia Cystic Fibrosis Club in 2010. Dr Diana Bilton is the chairperson of the UK CF Registry Committee and is involved in assisting the design of registry surveillance of patients receiving Colobreathe. Dr Diana Bilton is also chief investigator on the Insmed trial of once-daily nebulised Arikace for CF and was chief investigator of a trial of aztreonam compared with tobramycin. Dr Diana Bilton is also chief investigator of a planned study on the effects of TOBI Podhaler on treatment burden, quality of life and adherence.

Note

This monograph is based on the Technology Assessment Report produced for NICE. The full report contained a considerable number of data that were deemed commercial-in-confidence and/or academic-in-confidence. The full report was used by the Appraisal Committee at NICE in its deliberations. The full report with each piece of commercial-in-confidence and/or academic-in-confidence data removed and replaced by the statement ‘commercial-in-confidence and/or academic-in-confidence information (or data) removed’ is available on the NICE website: www.nice.org.uk.

The present monograph presents as full a version of the report as is possible while retaining readability, but some sections, sentences, tables and figures have been removed. Readers should bear in mind that the discussion, conclusions and implications for practice and research are based on all the data considered in the original full NICE report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Tappenden et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Description of the health problem

Brief statement of the health problem

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an inherited disease that shortens life expectancy and greatly reduces the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of patients. CF is characterised by abnormal ion movement across transporting epithelia. This leads to the production of thick sticky mucus in the lungs, pancreas, liver, intestine and reproductive tract, and an increase in the salt content in sweat. People with CF have problems with digestion, which can affect growth and body mass index (BMI), and are prone to lung infections by a range of pathogens, including Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. This is thought to be because the thick mucus makes it difficult for the body to clear inhaled bacteria, and because people with CF have an increased airway inflammatory response to pathogens. 1 Although both digestive problems and lung infections contribute to morbidity and mortality, respiratory tract infections with P. aeruginosa have been shown to be a major risk factor contributing to mortality. 2

In the early stages of disease, management aims to identify and vigorously treat infection,3 and thereby limit structural changes that may predispose a patient to chronic infection with P. aeruginosa. If bacterial infection is not successfully prevented or treated, a chronic infection/colonisation can develop, whereby bacterial microenvironments, known as ‘biofilms’, form within the bronchial tree. Biofilms are difficult for immune cells and antibiotics to penetrate, and once established, are associated with clinical deterioration and ultimately increased mortality. 2 Treatment of chronic infection typically involves regular use of nebulised antibiotics, such as tobramycin [Bramitob® (Chiesi) or TOBI® (Novartis Pharmaceuticals)] and colistimethate sodium [Promixin® (Profile Pharma) or Colistin® (Forest Laboratories)], to suppress bacterial growth and prevent flare-ups (known as exacerbations), and to maintain lung function and quality of life. Treatment can be time-consuming for patients, with administration of nebulised antibiotics taking up to 1 hour per day during good health, and longer during periods of ill health. 1 Newer nebulisers, such as the eFlow® rapid nebuliser (PARI Medical, West Byfleet, Surrey, UK) or the I-neb™ (Philips Respironics, Murrysville, PA, USA) adaptive aerosol delivery (AAD) system, may allow for more rapid administration of treatment. Pulmonary exacerbations may have a substantial negative impact on a patient’s quality of life4 and are usually treated using intravenous (i.v.) antibiotics, either in hospital or at home, or in a combination of these settings. 5

Aetiology and pathology

Cystic fibrosis is an autosomal recessive disorder, for which both copies of the gene that codes for a protein called the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) contain a mutation. Over 1600 different mutations of the gene have been identified, causing different changes to the function of the protein, and hence different severities of disease in the individual. The most common mutation is the deletion of phenylalanine at codon 508. This deletion was present in an estimated 91.3% of the mutant alleles in the UK in 2010. 6

Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is a large (∼170-kDa) multidomain protein belonging to the adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-binding cassette family of membrane transporters. 7 It is located in the cell membrane of various cells in the body, including epithelial cells in the respiratory tract, pancreas, liver, intestine and reproductive tract, where it regulates fluid secretion. CFTR acts as an ion channel that utilises the energy released by the binding and hydrolysis of ATP to open. When open, chloride ions pass across the cell membrane by diffusion in the direction of their electrochemical gradient. 8 When functional, this promotes efflux of chloride ions from the cell into the extracellular fluid. Sodium ions and water follow by a paracellular route (between cells rather than through cells) and hence the volume of liquid on the epithelial surface is regulated. In CF, impaired CFTR function is most commonly thought to lead to a decrease in the surface liquid volume of epithelial cells (although there are theories that also consider reduced antibacterial properties of mucus and increased mucin secretion as putative mediators of the characteristics of CF). In the epithelia of the airways, these changes result in a decrease in mucociliary clearance in the respiratory tract, which is the body’s primary defence against invading pathogens. People with CF are more prone to respiratory infections as a result. In addition, people with CF have an excessive inflammatory response. The aetiology of this is unknown,9 but along with the damage caused by respiratory infections it leads to bronchiectasis and obstructive pulmonary disease, the primary causes of death among people with CF.

Expression of the CFTR gene in the body is widespread and symptoms are not confined to lung disease. Reproductive function in both males and females may be disrupted (although there is conflicting evidence in women). Exocrine tissues in the pancreas are also affected, where abnormal mucus can block and damage pancreatic ducts. This process starts in utero and causes a decrease in the secretion of digestive juices, which contain the enzymes, bicarbonate and water that are essential to digestion, which, in turn, leads to malabsorption of ingested food and malnutrition. Ultimately, damage to the pancreatic tissue can also lead to destruction of the pancreatic β cells in the islets of Langerhans. 10 These endocrine cells normally secrete insulin into the bloodstream, and their absence leads to diabetes mellitus. It is thought that this has a negative impact on lung disease, as lung function is affected by maintaining a normal body weight. This is also associated with a negative impact on survival. Insulin replacement therapy improves both lung function and body mass. 10

Children with CF are born without lung infection, but from the moment they are born they are exposed to pathogens and they become infected over time. Common infections include S. aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, P. aeruginosa and B. cepacia complex. P. aeruginosa is the most prevalent infection, with 37.5% of patients of all ages having a chronic infection in 2010. 6 Between the ages 20 and 49 years, between 55% and 65% patients have chronic P. aeruginosa infection. P. aeruginosa infection starts as an intermittent infection with non-mucoid variants of the bacterium. Studies suggest that this phenotype can be eradicated by antipseudomonal antibiotics,11,12 and current practice is to treat all incidents of infection energetically, with the aim of clearing the infection from the respiratory tract using oral or nebulised antibiotics (or both, depending on the UK centre). 3 However, over time, intermittent infections develop into colonisation. Chronic infection is associated with increased mortality and morbidity. 13 The environmental pressures imposed on the bacteria by the conditions within the CF lung are thought to drive the conversion of the non-mucoid phenotype to the mucoid phenotype, which secretes large quantities of alginate exopolysaccharide and forms biofilms. Biofilms are aggregates of cells set in an extracellular matrix composed largely of the alginate secreted by the mucoid phenotype. It is hypothesised that these slippery biofilms grow in microaerophilic or anaerobic environments created by the thick mucus that is characteristic of CF. Other factors present in CF lungs, such as actin, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and decreased bacteriocidal secretions, are also thought to contribute to the formation of the biofilms. 14 The biofilms are very resistant to antibiotic treatment,15 and once a chronic mucoid infection has been established then eradication is not possible. Acquisition of this phenotype is again associated with the worsening of symptoms16 and a considerably worse prognosis. 17

Once bacterial colonisation is established, patients experience a gradual deterioration in lung function as lung tissue is damaged by the infection, which ultimately results in atelectasis (diminished lung volume), severe bronchiectasis, respiratory failure and death. 1 Patients experience increasingly frequent respiratory exacerbations, which severely affect quality of life and are usually treated with i.v. antibiotics and may require admission to hospital. Episodes of haemoptysis and pneumothorax may also occur. Historically, there have been differences in the diagnostic criteria for determining an exacerbation. These events have usually been characterised by an acute worsening of symptoms, such as increased cough, increased expectoration, decreased tolerance to physical activity, loss of weight or appetite and a deterioration in respiratory function. A marked increase in airway bacterial load [in colony-forming units (CFUs)/ml] has been cited as a criterion that may indicate an exacerbation,18 but is subject to some contention. Although forced expiratory volume in first second percentage predicted (FEV1%) usually improves with treatment, Wagener et al. 19 demonstrated a progressive decrease in the best FEV1% recorded in the 180 days after the exacerbation compared with the best FEV1% recorded in the year prior to the exacerbation. The authors interpret this as being suggestive of an overall decline in FEV1% associated with each exacerbation. In 2011 the EuroCare CF Working Group published a proposed definition for exacerbations. 20

Patients in the end stages of lung disease may be assessed for lung or lung and heart transplant, and may be added to the transplant waiting list. Owing to the systemic nature of the disease, transplants for other organs (e.g. liver, kidney) may also be necessary. In the UK, in 2010, 169 patients were evaluated and 82 accepted on to the transplant list. 6 Kidney transplants are sometimes needed as a consequence of the toxicity of the high-dose aminoglycoside antibiotics that are used to treat exacerbations. Once a lung transplant has taken place, the risk of death for people with CF is the same as the risk of death for all lung transplants. However, not all patients are fortunate enough to find an appropriate donor in time, and only 27 patients within the UK CF Registry eventually received a bilateral lung or heart and lung transplant in the UK in 2010. 6

Prognosis

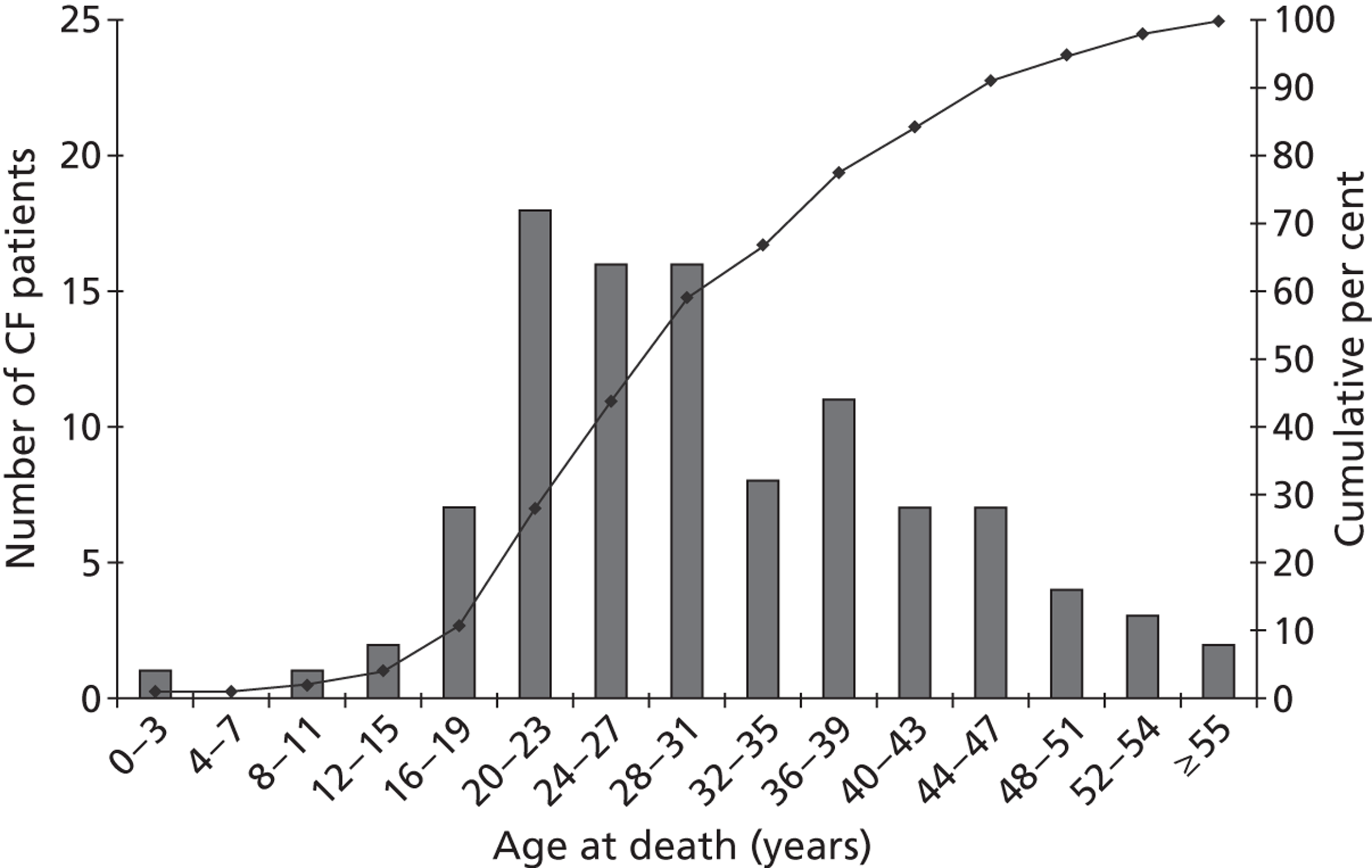

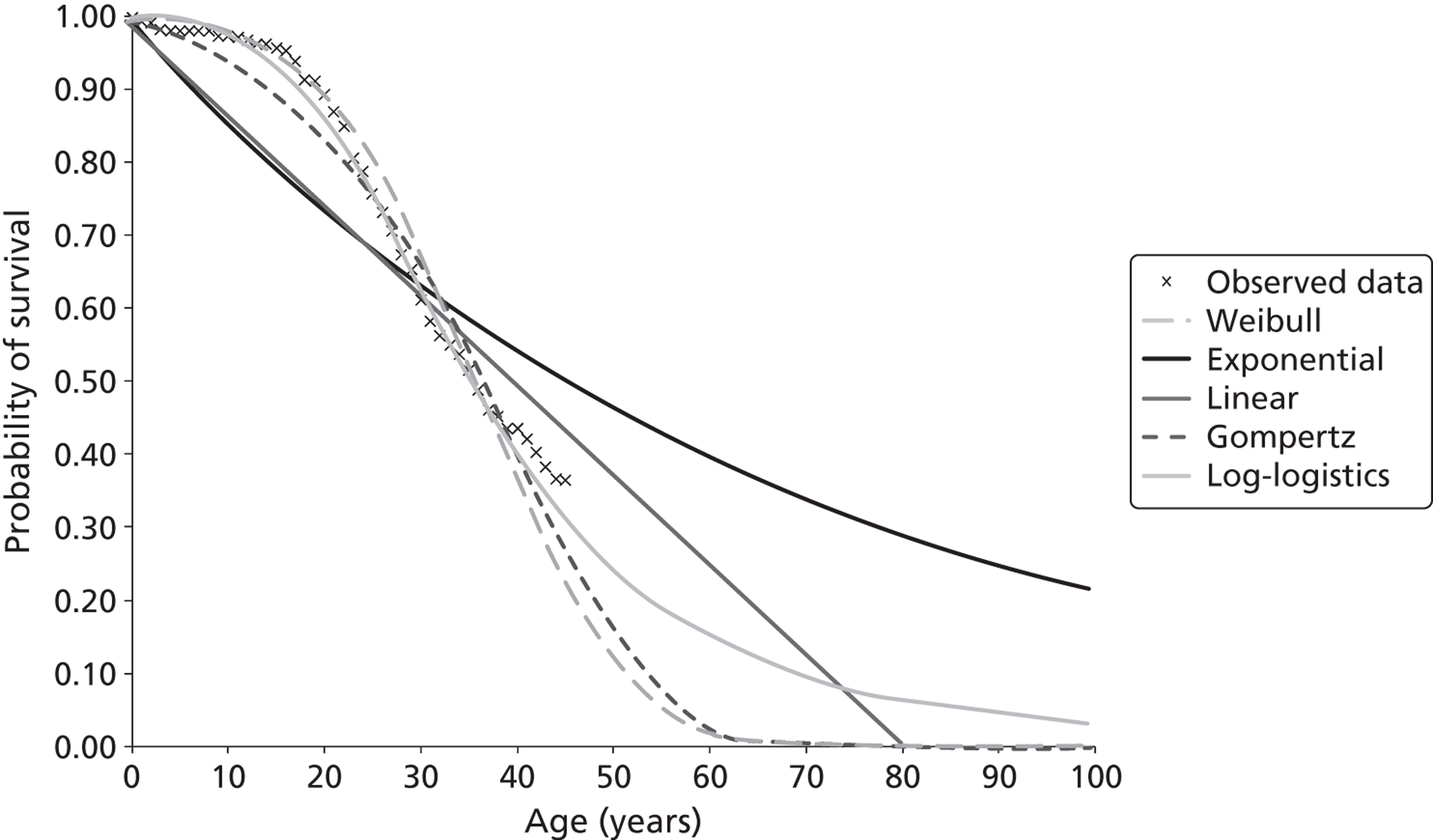

The impact of CF on survival is substantial. In 2010, 103 deaths were recorded in UK patients with CF, details of whom were held within the CF Registry; the median age at death was 29 years (minimum = 0 years; maximum = 61 years). 6 Figure 1 shows the age distribution of deaths in patients with CF, based on 2010 data.

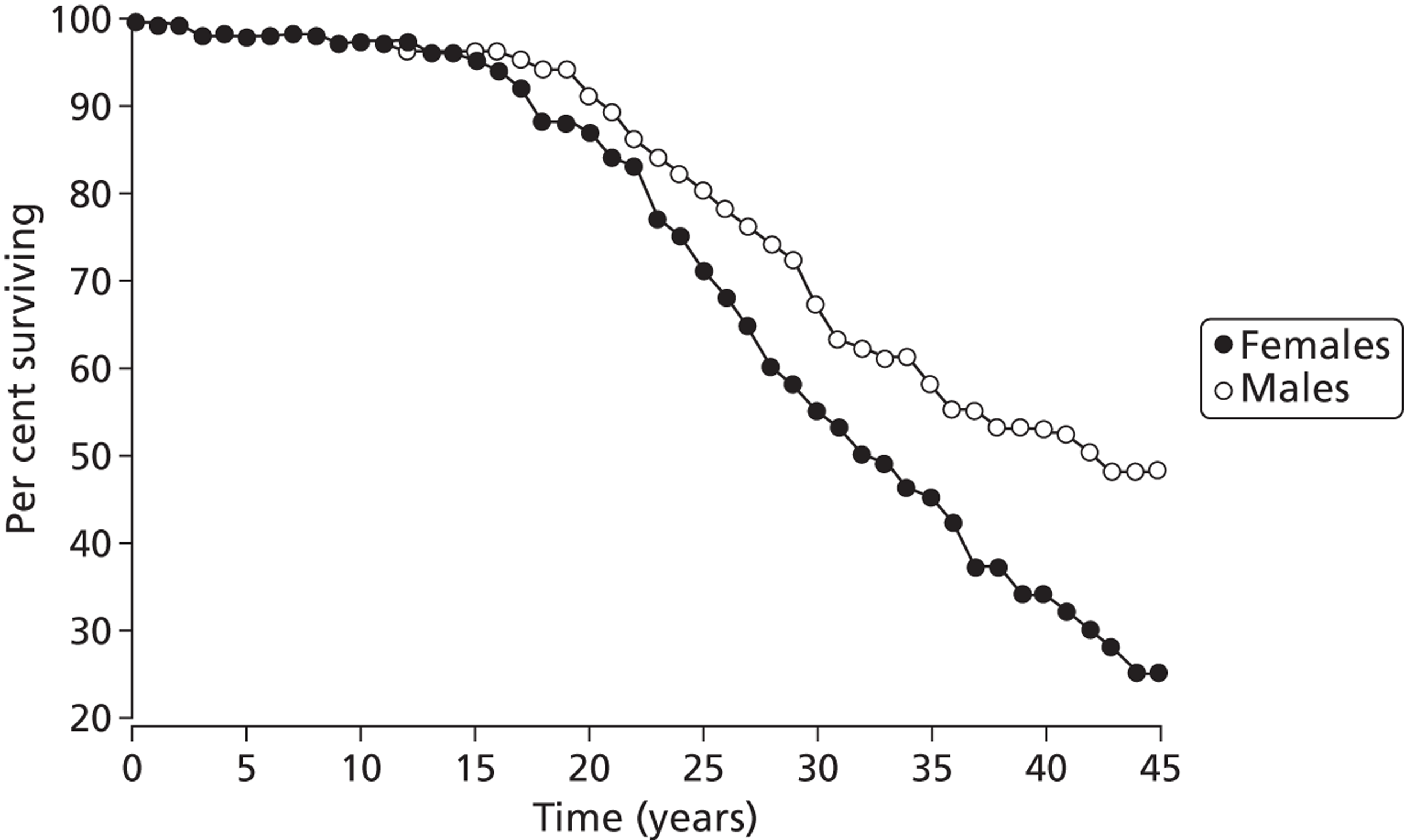

Although more people with the condition are living longer than in previous decades, only half of those patients living with CF are likely to live beyond their late thirties. Figure 2 shows recent estimates of survival for males and females with CF, based on a large UK-based cohort study. 22 Similar actuarial survival estimates are not currently available from the CF Registry.

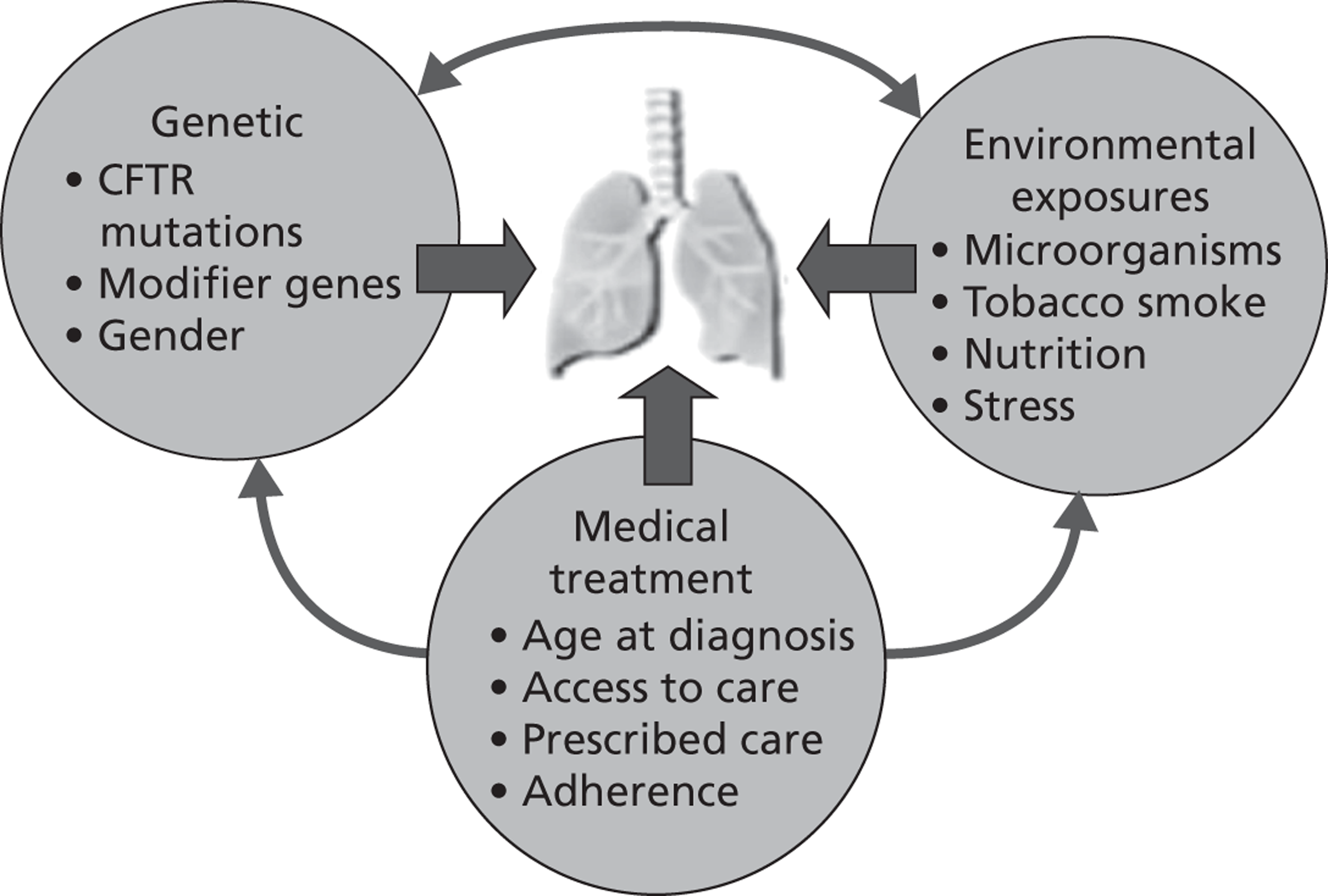

It has been suggested that a number of other factors, such as genetics, medical treatment and environmental exposures, may interdependently influence prognosis, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Epidemiology: incidence and prevalence

According to 2010 estimates from the Cystic Fibrosis Trust, over 9300 people in the UK have CF. Complete data on 7937 of these individuals are available from the CF Registry for 2010. The majority of CF cases are diagnosed by neonatal screening or during early infancy. Around 55.5% of those included in the registry are > 16 years of age and the incidence is spread evenly between males and females. For UK patients registered as having CF, approximately 82.2% are located in England, 3.9% in Wales, 4.7% in Scotland and 9.3% in Northern Ireland (Table 1).

| Location | No. | No. of patients registered at paediatric clinics/centres | Percentage | No. of patients registered at adult clinics/centres | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK | 9336 | 4475 | 47.93 | 4861 | 52.07 |

| England | 7640 | 3627 | 47.47 | 4013 | 52.53 |

| Wales | 366 | 217 | 59.29 | 149 | 40.71 |

| Scotland | 883 | 407 | 46.09 | 476 | 53.91 |

| Northern Ireland | 447 | 224 | 50.11 | 223 | 49.89 |

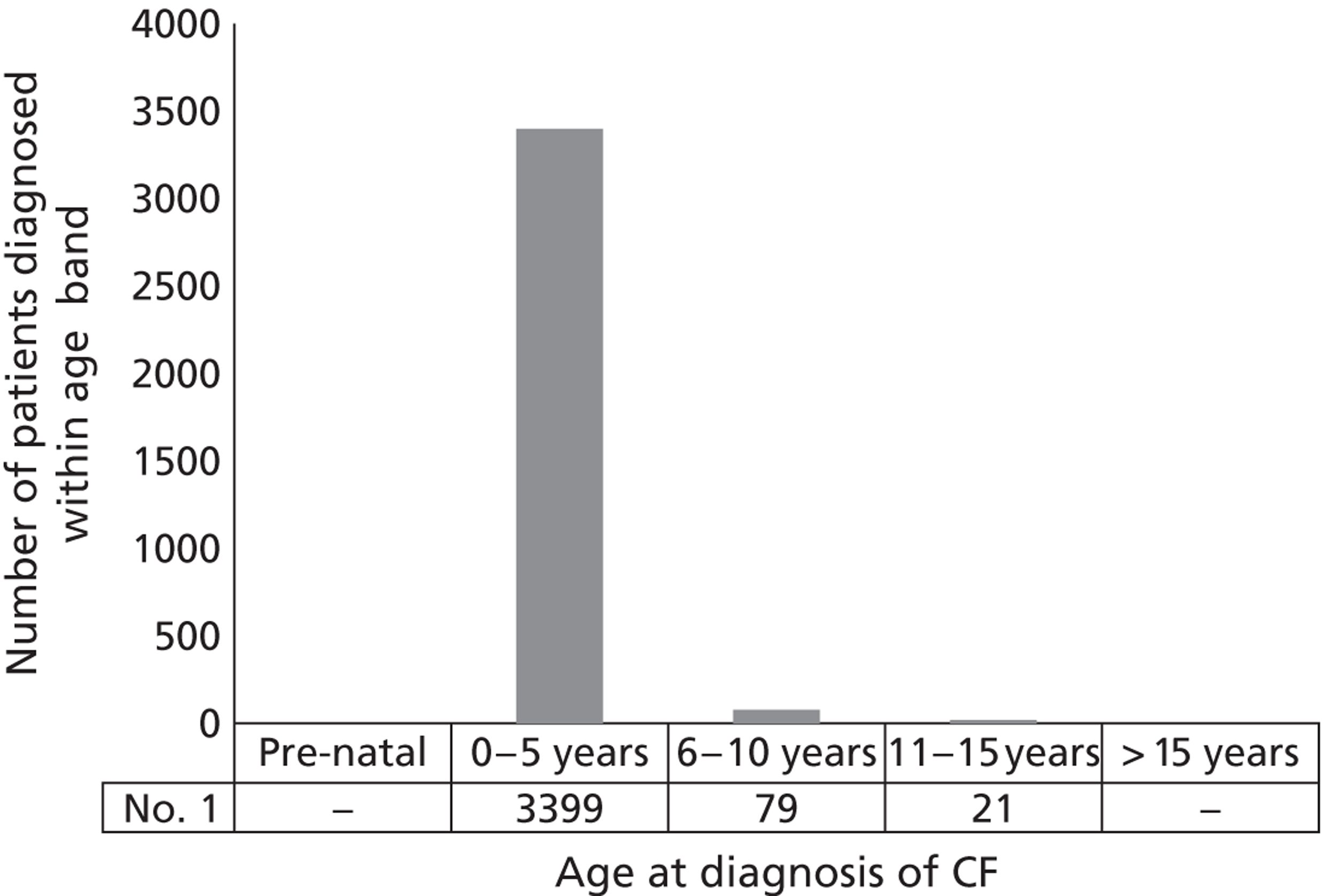

According to the Cystic Fibrosis Trust, approximately five babies are born with CF each week. During the period 2007–10, between 235 and 301 new cases of CF were registered each year. Around 1 in 25 people are thought to be carriers of the CF gene, although this incidence of disease estimate is limited to white people living predominantly in Europe and America. Incidence in other races is lower but CF is increasingly being reported. 1 Figure 4 shows the age distribution of those patients for whom data are available within the 2010 CF Registry report.

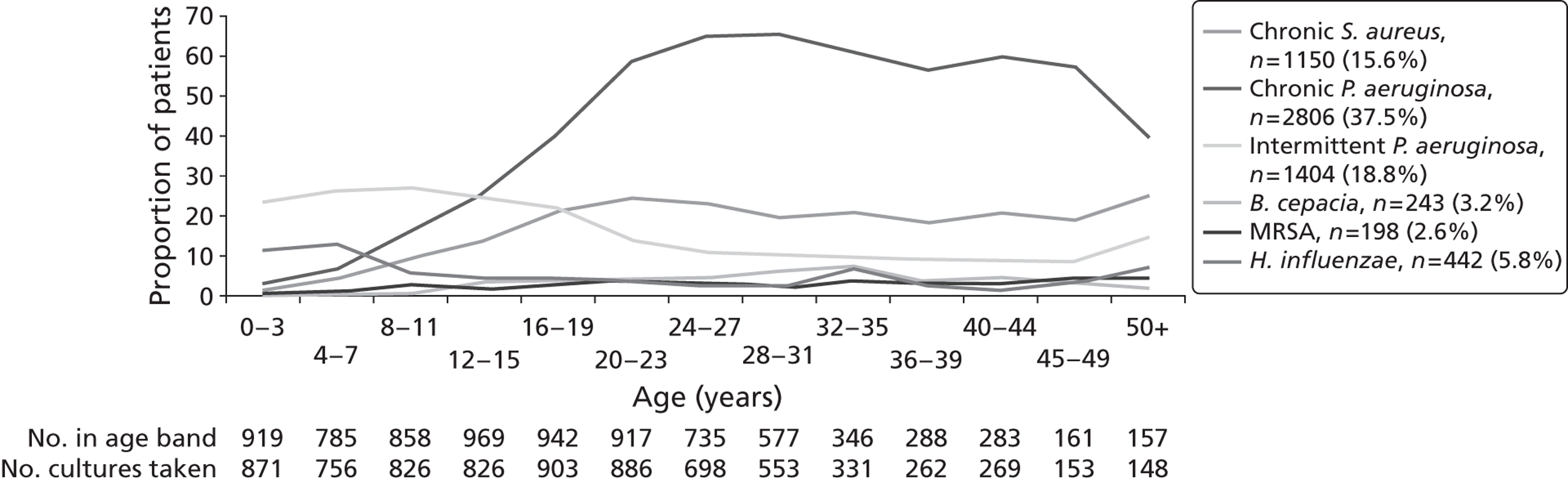

The prevalence of lung infection among the broader CF population is high. Around 37.5% of people living with CF are chronically infected with P. aeruginosa. Age-specific prevalence rates of Pseudomonas infection are shown in Figure 5. The prevalence of P. aeruginosa infection increases markedly with increasing age, up to around 25–30 years of age, with slightly lower rates in older age groups. These lower rates may be due to these patients having less severe mutations, which make them less likely to develop colonisation.

FIGURE 5.

Prevalence of CF lung infections by age group in 2010. 6 MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Impact of health problem

Cystic fibrosis has a significant impact on the survival and quality of life of patients. The disease also impacts on carers and requires a considerable commitment of health-care resources. In 2003, an analysis of data from 196 adult patients with CF attending the Manchester Cystic Fibrosis Unit reported that 113 (57.6%) patients were attending work or study; however, 1799 days were lost as a result of sickness. 5 More recently, based on an analysis of complete data records from patients aged > 16 years, the Cystic Fibrosis Trust reported that 69.7% of patients are in work or studying. Although 18.5% were reported to be unemployed, only 5.6% of patients classed themselves as ‘disabled’. 6 Patients require monitoring and treatment by the NHS for the duration of their lives. Additionally, two young lives a week are lost to CF, which represents a significant impact on the families of CF sufferers. As the UK’s most common life-threatening inherited disease, CF continues to present a considerable cost burden for the NHS.

Measuring disease in cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis can be broadly categorised into early stage, intermediate stage and end stage with complications. Patients with early-stage CF are characterised by the absence of infection with P. aeruginosa, or intermittent infection, which can usually be eradicated using antibiotics. Patients with intermediate-stage disease [forced expiratory volume in first second (FEV1)] ∼30–70% predicted are chronically infected with P. aeruginosa or other less common organisms, whereas patients with end-stage disease (FEV1 < 30% predicted) suffer from severe haemoptysis, pneumothorax and respiratory failure. 1 Patients have routine check-ups to monitor the status and stage of their disease. Measurements during these check-ups usually include assessment of bacterial infection and measurement of lung function, both of which contribute to treatment planning and prognosis. In some centres sputum tests are not performed routinely.

In the context of clinical trials, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) research guidelines for the development of new medicinal products for CF18 recommend additional disease measures to gauge the efficacy of interventions. These include measuring rates of microbial resistance, the number of acute exacerbations and the patient’s HRQoL. FEV1 is recommended as the primary end point for studies investigating CF treatments; however, a microbiological primary end point is also considered necessary for confirmatory trials. 18

Measuring microbiological indicators of infection

The presence of a microbial infection is ascertained using sputum colony density. This measurement is also recommended as a secondary end point for clinical trials assessing safety and/or efficacy of antipseudomonal antibiotics. 18

Sputum culture in patients with CF requires the collection of a sample of sputum, which is subsequently cultured and analysed in a clinical laboratory. 25 Sputum samples can either be obtained spontaneously (through expectoration) or induced by the use of throat swabs; nasopharyngeal aspiration (a small catheter through the nostril); or through inhalation of nebulised hypertonic saline to induce expectoration. In spontaneous expectoration the sample may be optimised by chest physiotherapy or by using bronchodilators and/or a recombinant human deoxyribonuclease (rhDNase) aerosol. 26 Clinical analysis of the sputum sample may be assayed for bacterial density, cell count and differential inflammatory markers before and after treatment with antibiotics. These measurements can be quantified in CFUs per gram of sputum and can be used to assess the clinical efficacy of antipseudomonal antibiotics. However, these measurements would not be routinely taken from patients with CF in clinical practice.

Chronic lung colonisation is defined by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) as the ‘presence of P. aeruginosa in the bronchial tree for at least 6 months, based on at least three positive cultures with at least one month between them without direct (inflammation, fever, etc.) or indirect (specific antibody response) signs of infection and tissue damage’. 27

Measuring rates of resistance

Microbial response can also include analyses of resistance through minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of isolates or breakpoint analysis. Clinical trials for antipseudomonal antibiotics often use the MIC50 (MIC required to inhibit the growth of 50% of organisms in culture). Sputum samples are analysed for evidence of resistance or susceptibility to the drug in question according to established MIC breakpoints. The British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (BSAC) publishes breakpoints, which are discriminatory antimicrobial concentrations used in the interpretation of results of susceptibility testing to define isolates as susceptible, intermediate or resistant. Published breakpoints vary from year to year. At the time of the trials, colistimethate breakpoints moved from resistant ≥ 8 mg/l and susceptible ≤ 4 mg/l to a single breakpoint of 4 mg/l. Tobramycin-resistant breakpoints moved from ≥ 8 mg/l to ≥ 4 mg/l, and in 2005 moved to a single breakpoint of 4 mg/l.

Although these breakpoints are well established, and assessment of microbial resistance is recommended in the EMA research guidelines18 and are required by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for the purpose of this assessment, the relevance of MIC susceptibility breakpoints to inhaled antibiotics is debated. There are two main reasons why the breakpoints may not be relevant:

-

Breakpoints are established primarily in relation to antibiotic concentrations achievable in the bloodstream. Because many antibiotics are toxic above a certain blood concentration, the therapeutic window is necessarily limited by this toxicity, and the breakpoints are correspondingly low. Antibiotics delivered by inhalation can reach far higher concentrations in the lung without causing the same toxic levels in the bloodstream, and the therapeutic window extends to a much higher concentration. Therefore, higher breakpoints may be more relevant in this context.

-

Breakpoints are established by culturing samples in vitro then testing the susceptibility of the organisms. Phenotype (characteristics of the organism in response to their environment) plays a significant part in resistance. Infection with P. aeruginosa in the CF lung often involves the formation of biofilms with the mucoid phenotype (which are more resistant to antibiotics) in response to the environment of the lung. Cultured organisms removed from the environment of the lung display a different phenotype, and therefore a different level of susceptibility to the antibiotic, making the relevance of the cultured organisms’ susceptibility questionable.

Although the phenotype may be different in vivo, and although higher concentrations can be achieved in the lung, an increase in the minimum inhibitory concentration required to inhibit the growth of 50% of organisms in culture (MIC50) may still be an indicator that more resistant genotypes are being selected for by the antibiotic, and may therefore still have some relevance in indicating increased resistance.

Finally, as at present this is the established measure for susceptibility, and it is required by the EMA and listed in the NICE scope, this outcome will be reported for consideration.

Measuring lung function

The widespread availability of spirometers and the availability of standardised methods for assessment28,29 make spirometry the preferred method of measurement of lung function. Spirometry can be reliably performed by children who are aged > 5/6 years, and provides a number of potentially useful measurements. FEV1 is defined as ‘the maximal volume of air exhaled in the first second of a forced expiration from a position of full inspiration, expressed in litres at body temperature (i.e. 37 °C), ambient pressure and saturated with water vapour (BTPS)’. 28 It is converted by use of an equation (e.g. Knudson et al. 30) to a percentage of the normal predicted value for a healthy person of the same age, sex and height to give the ‘FEV1% predicted’ or FEV1%. There are a number of such equations that can be used,30–34 which will affect the FEV1% calculated. There does not appear to be a consensus with respect to which equation should be considered most appropriate.

There are, however, some problems with FEV1 as a measure of the pulmonary health of people with CF. Primarily, FEV1 is a global assessment of lung function, and is largely insensitive to localised disease. Additionally, it is influenced by a number of other (sometimes transitory) factors, including respiratory muscle strength (which, in turn, is sensitive to nutritional status),35 acute exacerbations,36 respiratory viral infections37 and so on. FEV1, like other spirometry tests, relies on volitional motion, and is associated with some degree of error around the mean; one review reports error ranging from 2.2% to 4.7%. 38

There are other spirometry measurements and other technologies that are increasingly being used to assess lung function. Forced vital capacity (FVC) is defined as ‘the maximal volume of air exhaled with maximally forced effort from a maximal inspiration . . . expressed in litres (BTPS)’,28 and the mean forced expiratory flow during the middle half of the FVC is known as forced expiratory flow (at 25–27% of vital capacity; FEF25–75%). Decreases in FEF25–75% are thought to provide the earliest indications of obstructive pulmonary disease. 39 These obstructive changes later become evident in FEV1% readings and will eventually have an impact on FVC. Computerised tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also be used to assess lung disease. 40 CT is considered the gold standard; however, this exposes the patient to a significant dose of radiation and its use is therefore limited as life expectancy increases. 41 MRI is thought to have lower specificity for small airway disease, but may be comparable or even superior for imaging some other indicators of lung disease. 40

Although there may be a role for FEF25–75%, and CT and MRI may be useful in certain circumstances, FEV1% is currently the recommended primary end point for clinical trials,18 and, owing to the number of studies linking FEV1% (either absolute readings or slope of decline) to prognosis,2,42–46 is a key indicator of disease progression used to monitor patients’ health.

Measuring acute exacerbations

The EMA defines an exacerbation as the onset of an acute episode of clinical deterioration when the patient is in a stable state. The definition of clinical deterioration has recently been revisited by the EuroCare CF Working Group. 20 Clinical deterioration is defined by the EMA27 by the presence of at least three of the following new clinical findings:

-

increased cough

-

increased expectoration (volume and purulence)

-

decreased tolerance to effort or physical activity

-

loss of weight or loss of appetite

-

deterioration of respiratory function (FEV1, FVC), and

-

a marked increase in airway bacterial load (in CFU/ml) during routine monitoring.

There is a lack of clear recommendations for clinical trials with respect to the definition of acute exacerbations and how they should be measured. Frequently, the corresponding measurement for acute exacerbations is ‘mean time to first additional antipseudomonal antibiotic use’ as well as the duration of this reactive treatment and/or whether the rescue medication was i.v. or not. ‘Hospitalisations’ and ‘length of hospital stay’ are also used as measures under the acute exacerbation outcome. More recently there has been a general decrease in hospitalising patients for treatment23 and a trend towards more patients being treated at home. 47 Consequently, the use of ‘hospitalisation’ as a surrogate measure for acute exacerbation may be unreliable. The most robust data at present are likely to be the number of acute exacerbations and the duration of i.v. use, although these measures are also subject to a degree of random error.

There are currently, therefore, several methods of measuring outcomes for acute exacerbation. A clear recommendation regarding how to measure acute exacerbation has yet to be adopted. This judgement requires consensus on reporting the number of acute exacerbation events or the number of patients who experienced an acute exacerbation. Recommendations for measuring acute exacerbations in clinical trials should also consider that these outcomes could be measured as the percentage change from baseline or in terms of absolute event rates.

Measuring health-related quality of life

As CF is incurable, interventions often aim to improve both the quality and duration of a patient’s life. To date, four measures specific to CF have been developed48–51 to overcome a perceived lack of sensitivity of generic HRQoL measures, such as the EQ-5D and SF-6D (Short Form questionnaire-6 Dimensions), to aspects of the disease that are important to people with CF. The Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire (CFQ) was developed and validated by a French group,49 and exists in different formats for children and adults. A translated version validated in an American cohort52,53 is also available and in common use. This questionnaire is supported by the EMA research guidelines as an outcome measure,18 which should be recorded at least 3–6 months into therapy. These are not preference-based measures and do not allow the calculation of health utility scores. The use of generic health status measures, such as the EQ-5D, have been very limited in the measurement and valuation of different states of health for patients with CF (the available evidence is reviewed in Chapter 4).

Current service provision

Management of disease

The care of most patients in the UK is co-ordinated by a tertiary CF centre, with formal ‘shared care’ with local clinics. Further, primary care teams may also play a role in the surveillance and early treatment of infection, the provision of dietary and nutritional support, and the provision of social and psychological support for patients and their families. 1 A wide range of treatments may be required at various stages of the disease, including physiotherapy, pharmacological therapies, educational advice and surgical interventions for certain complications.

There are two main stages of P. aeruginosa lung infection, each of which requires a different approach to treatment. The first stage is characterised by intermittent growths of both mucoid and non-mucoid P. aeruginosa, and typically develops during infancy and childhood. This can be treated and sometimes eradicated with antibiotics to maintain respiratory function. Colonisation develops subsequently, and may be associated with mucoid change: it is a marker of reduced survival. Chronic infection cannot be eradicated by antibiotics as biofilm formation prevents antibiotics from working effectively. Acute exacerbations characterised by an acute decrease in respiratory function occur and become more frequent as the disease progresses. It is thought that acute exacerbations may contribute to a stepwise decrease in lung function, with FEV1% failing to return to pre-exacerbation baseline values. However, evidence to support this theory remains limited. At this stage, for most patients, continuous antibiotic use will be required.

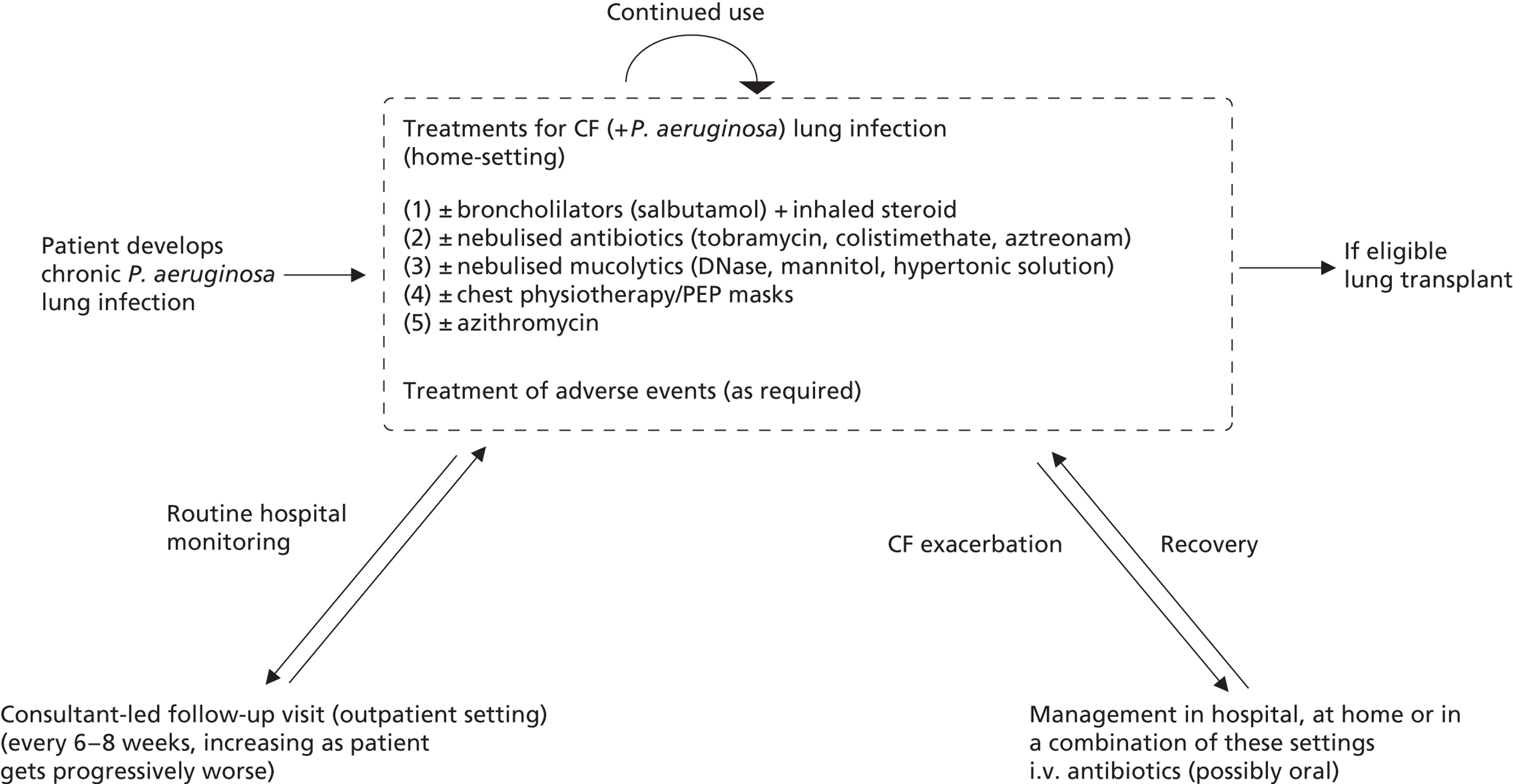

Current management pathways for patients with chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection

Figure 6 presents a general management pathway for patients with CF with chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection. This is intended to be representative of the UK Cystic Fibrosis Trust guidelines,3 which, in turn, reflect usual clinical practice in the majority of UK CF centres. There is likely to be some variation in practice across some of the smaller centres, and specific antibiotic choices may differ by centre according local bacterial sensitivities. Generally speaking, decisions concerning the use of particular treatments tend to be more related to severity than age, therefore treatment use is broadly similar across both paediatric and adult populations. 6

FIGURE 6.

Treatment pathway for patients with chronic P. aeruginosa. PEP, positive expiratory pressure.

Continuous drug treatments

Following chronic infection with P. aeruginosa, all patients will be offered ongoing nebulised antibiotic treatment, which takes place in the home setting. In a small proportion of patients (around 10–15%) with P. aeruginosa lung infection may not receive nebulised antibiotic therapy (Table 2). Current antibiotic treatment options include colistimethate sodium, tobramycin and, less commonly, aztreonam (Cayston®, Gilead Sciences). Colistimethate sodium is given every day. Tobramycin and aztreonam differ in that each 28-day treatment cycle is followed by a 28-day period that does not include the use of these drugs. The current guidelines from the Cystic Fibrosis Trust recommend initial treatment using Colistin; tobramycin is recommended if Colistin is not tolerated or if clinical progress is unsatisfactory. 3 In practice, some patients whose lung function fails to stabilise on monotherapy may receive 28 days of treatment using colistimethate sodium, followed by 28 days of treatment using tobramycin as an ongoing repeated sequence.

Concomitant therapies

A number of concomitant treatments may be used alongside nebulised antibiotics. A considerable proportion of patients with CF exhibit a degree of airway reversibility (asthma-like changes) and will be treated with bronchodilators (e.g. salbutamol) plus inhaled steroids (e.g. salmeterol xinafoate/fluticasone propionate). This is often administered as a combination inhaler, with up to 50% of patients with CF receiving inhalers for this reason. The inhaled drugs for P. aeruginosa infection result in bronchospasm (narrowing of the airways) in a proportion of patients. In these patients, a bronchodilator is given before the inhaled antibiotics with prophylactic intent. In addition, patients with chronic P. aeruginosa infection typically receive macrolides (most commonly azithromycin). These are given between three and seven times per week on an ongoing basis, and are used for their anti-inflammatory properties, with the intention of arresting the decline in lung function; however, there is conflicting evidence concerning their efficacy. 54–56 Patients may also receive mucolytic drugs [e.g. rhDNase, mannitol (Bronchitol®, Pharmaxis) or hypertonic saline], with the intention of reducing the viscosity, adherence and tenacity of the sputum, and to aid efficient clearance. 57 In addition, many CF centres would advocate some form of airway clearance using either traditional percussion/drainage via chest physiotherapy or using positive expiratory pressure (PEP) devices.

Follow-up

Patients are invited to attend routine follow-up to monitor progression of the disease and to inform decisions regarding treatment. For children, follow-up appointments are usually every 6–8 weeks. However, the frequency of follow-up visits typically increases as the disease progresses. Adults in Band 3 or 4 (see Appendix 1) may be supervised more closely. Band 5 patients may be in hospital more or less continuously.

Adverse events and the management of exacerbations

Adverse events (AEs) should be reported to the CF care team and may be an indication for stopping or modifying therapy. However, patients experiencing exacerbations will require further antibiotic treatment administered intravenously. Many centres now deliver i.v. antibiotics in part at home. Hospital admissions for the management of AEs are more common in adult centres where patients are likely to be more severely ill.

Lung transplantation

A small proportion of patients are eligible for lung transplantation. Most of these patients will no longer require inhaled antibiotics; however, antirejection therapies and treatments for other organs affected by CF will still be required.

Current usage

Table 2 shows current registry estimates of antibiotic use among patients with chronic P. aeruginosa infection. The data suggest that approximately 78.8% of individuals with chronic P. aeruginosa infection receive at least one antibiotic post transplant. The CF Registry states that around 90% of patients with chronic P. aeruginosa should be prescribed one or more of these treatments. 6

| Drug(s) | Overall | Percentage | < 16 years | Percentage | ≥ 16 years | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobramycin solution | 691 | 24.63 | 97 | 22.05 | 594 | 25.11 |

| Other aminoglycoside | 66 | 2.35 | 15 | 3.41 | 51 | 2.16 |

| Colistin | 1237 | 44.08 | 238 | 54.09 | 999 | 42.22 |

| Promixin | 726 | 25.87 | 119 | 27.05 | 607 | 25.66 |

| At least one of the above | 2212 | 78.83 | 383 | 87.05 | 1829 | 77.30 |

| Patients with chronic P. aeruginosa | 2806 | 100.00 | 440 | 100.00 | 2366 | 100.00 |

Recent UK-relevant cost estimates relating to the treatment of CF are limited. A recent UK cost of illness study, undertaken in the east of England, estimated the mean annual cost of treating 174 patients to be £1,040,087 (£5976 per patient). 58 Multiplying this estimate up to the current number of patients in the CF registry yields a crude annual cost of around £57M for patients with CF in England and Wales. However, the true cost to the NHS may be considerably higher (Diana Bilton, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Royal Brompton Hospital, 2012, personal communication).

Variations in services and uncertainties about best practice

It has been noted elsewhere that many aspects of current practice in the management of CF have evolved without being subjected to high-quality clinical trials. 1 This may be partly a result of the rarity of the disease and associated difficulties with recruitment to clinical trials, as well as variations between patients in terms of how the disease manifests and is treated. With respect to interventions for the management of lung infection, evidence relating to the long-term clinical and mortality benefits of treatments is rarely available.

There is currently no NICE guidance relating to the detection, diagnosis or management of patients with CF. A single technology appraisal of mannitol dry powder for inhalation (DPI) for the treatment of CF was completed in 2012. This appraisal did not specifically relate to the management of patients with P. aeruginosa lung infection.

Since 1 April 2011, the Department of Health has adopted a ‘Payment by Results’ (PbR) tariff for patients with CF. This will link ‘activity’ to funding received, whereby money will follow the patient through their hospital journey, paying for treatment and care (excluding drugs) received along the way. 25

Description of technologies under assessment

Summary of interventions and comparators

This assessment includes two interventions that are delivered as a DPI: colistimethate sodium DPI [Colobreathe® (plus Turbospin®), Forest Laboratories] and tobramycin DPI [TOBI® (plus Podhaler®), Novartis Pharmaceuticals]. The antibiotics colistimethate sodium and tobramycin also represent the relevant comparators for the assessment, albeit in nebulised form.

Colistimethate sodium (Colobreathe/Colomycin/Colistin) belongs to the polymyxin group and is a cyclic polypeptide antibiotic derived from Bacillus polymyxa, var. colistinus. Colistimethate sodium works by disrupting the structure of the bacterial cell membrane in a detergent-like way by changing its permeability, leading to bacterial death. It is also thought to act intracellularly to precipitate ribosomes and other cytoplasmic components. Colistimethate sodium is active against aerobic Gram-negative organisms, including P. aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumanii and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Forest Laboratories currently markets colistin sulphate (Colomycin) as a tablet or syrup, and colistimethate sodium as a powder for injection or nebulisation. Profile Pharma currently markets colistimethate sodium (Promixin) as a powder for i.v. injection or for inhalation specifically using an I-neb device. Colobreathe (which is also colistimethate sodium) is available as 125-mg hard capsules and is administered specifically using the Turbospin inhaler device. It is anticipated that both the treatment and the Turbospin device will be marketed and packaged together.

The summary of product characteristics (SmPC) (www.ema.europa.eu/) lists the following AEs for colistimethate sodium DPI: unpleasant taste (dysgeusia), cough, throat irritation, dyspnoea, dysphonia, coughing, bronchospasm, balance disorder, headache, tinnitus, haemoptysis, asthma, wheezing, chest discomfort, lower respiratory tract infection, productive cough, crackles – lung, vomiting, nausea, arthralgia, pyrexia, asthenia, fatigue, decreased forced expiratory volume, drug hypersensitivity, weight fluctuation, decreased appetite, ear congestion, chest pain, exacerbated dysphonia, pharyngolaryngeal pain, epistaxis, sputum purulent, abnormal chest sound, increased upper airway secretion, diarrhoea, toothache, salivary hypersecretion, flatulence, proteinuria and thirst. Sore throat or mouth (probably due to Candida albicans infection or hypersensitivity) has been reported for nebulised colistimethate sodium and the SmPC states that this may occur with Colobreathe also. AEs listed in the electronic Medicines Compendium (eMC) (www.medicines.org.uk/) for the nebulised form also include bronchospasm, cough, hypersensitivity reactions and skin rash/rashes.

Tobramycin belongs to the aminoglycoside group of antibiotics and is obtained from cultures of Streptomyces tenebrarius. It enters susceptible bacterial cells via a complex active transport mechanism and acts by binding irreversibly to the 30S ribosomal subunit. It is thought that this interferes with essential steps in protein synthesis and consequently affects the permeability of the cell membrane, although there is some suggestion that it may also act directly on the cell membrane. 59 Once the cell envelope becomes compromised, cell death follows. It also acts to induce misreading of the genetic code of the messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) template, resulting in incorporation of incorrect amino acids, which can result in cellular malfunction. Two tobramycin nebuliser solution (TNS) products are available: Novartis Pharmaceuticals currently markets TOBI® nebuliser solution, and Chiesi market Bramitob® nebuliser solution. TOBI DPI is available as 28-mg capsules and is administered specifically using the Podhaler device. Both the treatment and device are marketed and packaged together.

Adverse events listed by eMC (www.medicines.org.uk/) for tobramycin DPI include hearing loss, tinnitus, haemoptysis, epistaxis, dyspnoea, dysphonia, productive cough, cough, wheezing, rales, chest discomfort, nasal congestion, bronchospasm, oropharyngeal pain, vomiting, diarrhoea, throat irritation, nausea, dysgeusia, rash, musculoskeletal chest pain and pyrexia. Cough was the most frequent adverse reaction. With respect to nebulised tobramycin, AEs reported in controlled clinical trials include dysphonia and tinnitus. AEs reported in the post-marketing phase include laryngitis, oral candidiasis, fungal infection, lymphadenopathy, hypersensitivity, anorexia, headache, dizziness, aphonia, somnolence, tinnitus, hearing loss, ear disorder, ear pain, dysphonia, dyspnoea, cough, pharyngitis, bronchospasm, chest discomfort, lung disorder, productive cough, haemoptysis, epistaxis, rhinitis, asthma, hyperventilation, hypoxia, sinusitis, dysgeusia, nausea, mouth ulceration, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, rash, urticaria, pruritus, back pain, asthenia, pyrexia, chest pain, pain, malaise and pulmonary function test decreased.

Place in the treatment pathway

Both interventions are to be used for the ongoing treatment of chronic P. aeruginosa, as described above (see Current service provision). One of the principal anticipated benefits of the interventions is that they are quicker to use and are portable, which means that they can be self-administered by the patient as indicated, thereby avoiding time required for inhalation using a nebuliser. The DPIs may also result in savings in terms of the time associated with cleaning traditional nebulisers. It is hypothesised that these benefits may lead to improvements in compliance with treatment.

Identification of important subgroups

Specific subgroups have not been identified a priori within this appraisal. Consideration was given within this assessment to evidence relating to those groups of individuals for whom these therapies may be particularly clinically effective or cost-effective.

Current usage in the NHS

The use of TOBI in conjunction with the Podhaler device was granted full marketing authorisation by the EMA in 2011. TOBI Podhaler is indicated for the suppressive therapy of chronic pulmonary infection due to P. aeruginosa in adults and children with CF, aged ≥ 6 years. The Podhaler inhaler device bears an initial date of Conformité Europeénne (CE) marking of 28 July 2005. The Novartis Pharmaceuticals submission states that this date is noted on the European Commission (EC) Declaration of Conformity to the European Union (EU) Medical Device Directive 93/42/EEC as amended for this Class I device. 60

Colobreathe used in conjunction with the Turbospin device was granted full marketing authorisation by the EMA in February 2012. Colobreathe is indicated for the management of chronic pulmonary infections due to P. aeruginosa in patients with CF aged ≥ 6 years.

Anticipated costs associated with the intervention

Table 3 summarises the acquisition costs associated with the interventions and comparators, based on list prices from the British National Formulary (BNF). 61

| Generic name | Trade name | Manufacturer | Indication | Form of administration | Cost per unit | Cost per 28 days of treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colistimethate sodium | Promixin | Profile Pharma | Adult and child > 2 years, 1–2 MU b.i.d.; increased to 2 MU three times daily for subsequent respiratory isolates of P. aeruginosa | Powder for nebuliser solution | 1-MU vial = £4.60 | £257.60 (1 MU per dose b.i.d.) to £772.80 (2 MU per dose three times daily) |

| Colomycin | Forest Laboratories | Powder for injection or nebuliser solution | 1-MU vial = £1.68 2-MU vial = £3.09 |

£94.08 (1 MU per dose b.i.d.) to £259.66 (2 MU per dose three times daily) | ||

| Colobreathe + Turbospin | Forest Laboratories | 125 mg twice daily | DPI | Price not confirmed at the time of the assessment | ||

| Tobramycin | Bramitob | Chiesi | Adult and child > 6 years, 300 mg every 12 hours for 28 days, subsequent courses repeated after 28-day interval without TNS | Powder for nebuliser solution | 75 mg/ml, net price 56 × 4-ml (300-mg) unit = £1187.00 | £1187.00 |

| TOBI | Novartis Pharmaceuticals | Powder for nebuliser solution | 60 mg/ml, net price 56 × 5-ml (300-mg) unit = £1187.20 | £1187.20 | ||

| TOBI + Podhaler | Novartis Pharmaceuticals | Adult and child > 6 years, 112 mg every 12 hours for 28 days, subsequent courses repeated after 28-day interval without tobramycin inhalation powder | DPI | 224 × 28-mg capsules + five Podhalers = £1790.00 56 × 28-mg capsules + one Podhaler = £447.50 |

£1790.00 | |

| Aztreonam | Cayston | Gilead Sciences | Adult > 18 years, 75 mg three times daily (at least 4 hours apart) for 28 days; if additional courses required, a minimum of 28 days without aztreonam nebuliser solution recommended between courses | Powder for nebuliser solution | 84 × 75-mg vials (with solvent and nebuliser handset) = £2566.80 | £2566.80 |

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Overall aims and objectives of the assessment

This assessment addresses the question ‘what is the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of colistimethate sodium DPI and tobramycin DPI for the treatment of chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection in CF compared with current treatments?’

Specifically, the objectives of the assessment are to:

-

assess the clinical effectiveness of colistimethate sodium DPI and tobramycin DPI for the treatment of chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection in terms of lung function, microbial response, respiratory symptoms and the frequency/severity of acute exacerbations

-

assess the AE profile associated with colistimethate sodium DPI and tobramycin DPI

-

estimate the incremental cost-effectiveness of colistimethate sodium DPI and tobramycin DPI compared with current standard treatments for the treatment of chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection.

This report contains reference to confidential information provided as part of the NICE appraisal process. This information has been removed from the report and the results, discussions and conclusions of the report do not include the confidential information. These sections are clearly marked in the report.

Decision problem

Interventions

Two interventions are included in this assessment:

-

colistimethate sodium DPI, used in conjunction with the Turbospin device

-

tobramycin DPI, used in conjunction with the TOBI Podhaler device.

Populations and subgroups

The population for the assessment includes people aged ≥ 6 years with CF and chronic P. aeruginosa pulmonary colonisation. Subgroups are considered according to the available evidence.

Relevant comparators

The interventions are compared against each other. Other relevant comparators include antibiotics used for nebulised inhalation, including colistimethate sodium for nebulised inhalation and tobramycin for nebulised inhalation. The availability of evidence of the effectiveness of other less commonly used nebulised antibiotics (e.g. aztreonam) with antipseudomonal activity is also considered within the assessment.

Outcomes

The following outcomes are considered within this assessment:

-

rate and extent of microbial response (e.g. sputum density of P. aeruginosa)

-

lung function measured in terms of FEV1%

-

respiratory symptoms

-

frequency and severity of acute exacerbations

-

HRQoL

-

AEs of treatment (including rate of resistance to antibiotic treatment)

-

cost-effectiveness measured in terms of the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained.

Chapter 3 Clinical effectiveness

This section presents the methods and results of a systematic review of clinical effectiveness of colistimethate sodium DPI and tobramycin DPI in comparison with currently used nebulised treatments.

Methods for reviewing clinical effectiveness

The protocol for this review is registered with PROSPERO (CRD42011001350) and is available from the NICE website (www.nice.org.uk/).

Identification of studies

A comprehensive search was undertaken to systematically identify literature relating to the clinical effectiveness of colistimethate sodium DPI and tobramycin DPI for the treatment of P. aeruginosa in CF. The search strategy comprised the following main elements:

-

searching of electronic databases

-

contact with experts in the field

-

hand-searching of bibliographies of retrieved papers.

The following electronic databases were searched from inception for published trials and systematic reviews:

-

MEDLINE: Ovid. 1950 to present

-

MEDLINE in-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations: Ovid. 1950 to present

-

EMBASE: Ovid. 1980 to present

-

The Cochrane Library: Wiley Online Library

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), 1996 to present

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE),1995 to present

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CCRT), 1995 to present

-

Cochrane Methodology Register, 1904 to present

-

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database , 1995 to present

-

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), 1995 to present

-

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL): EBSCOhost, 1982 to present

-

Web of Science Citation Index: Web of Knowledge, 1899 to present

-

Conference Proceedings Citation Index (CPCI): Web of Knowledge, 1990 to present

-

Bioscience Information Service (BIOSIS) Previews: Web of Knowledge, 1969 to present.

Additional searches were carried out for unpublished studies (e.g. ongoing, completed):

-

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)

-

Bandolier

-

Centre for Health Economics (CHE); University of York

-

ClinicalTrials.gov

-

Current Controlled Trials

-

The National Research Register Archive: NIHR, 2000–7

-

The metaRegister of Controlled Trials: Springer Science + Business Media, 2000 to present.

Manufacturers’ submissions received by NICE, as well as any relevant systematic reviews were also hand-searched in order to identify any further clinical trials.

The MEDLINE search strategy is presented in Appendix 2. The search strategy combined free-text and medical subject heading (MeSH) or thesaurus terms relating to CF with free-text and MeSH or thesaurus terms relating to P. aeruginosa, relevant antibiotics and classes of antibiotics, and the devices and comparator devices of interest. The search strategy was translated across all databases. No date or language restrictions were applied. Literature searches were conducted during February and March 2011. References were collected in a bibliographic management database and duplicates removed.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were based on the scope provided by NICE. 62 These are set out below.

Inclusion criteria

Studies were included if they satisfied the following criteria.

Interventions

Studies assessing the effectiveness of colistimethate sodium DPI (used in conjunction with the Turbospin device) or tobramycin DPI (used in conjunction with the TOBI Podhaler device) were included.

Population

Studies were selected to include only people aged ≥ 6 years with CF and chronic P. aeruginosa pulmonary infection. Children of < 6 years of age were excluded from the assessment, as they are subject to different treatment regimens, methods of assessment of lung function differ, and licensing has not been sought for this age group.

Comparators

Acceptable comparators were (1) the comparator intervention or (2) other antipseudomonal antibiotics for nebulised inhalation, including, as a minimum, colistimethate sodium for nebulised inhalation or tobramycin for nebulised inhalation.

Outcomes

Outcomes to be considered by the review were rate and extent of microbial response (e.g. sputum density of P. aeruginosa); lung function; respiratory symptoms; frequency and severity of acute exacerbations; HRQoL; and AEs of treatment (including rate of resistance to antibiotic treatment). Compliance was also considered as a post hoc addition to the outcomes set out in the NICE scope, as it became evident that this was of relevance to the claims made for the interventions by the manufacturers.

Study types

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were included in the assessment. Data from non-randomised studies were considered but were not included, as evidence was available from RCTs.

Systematic reviews were included if they provided additional data for RCTs meeting the inclusion criteria (i.e. unavailable from published trial reports). Other systematic reviews identified were not included but were checked for RCTs that met the inclusion criteria of this review.

Exclusion criteria

The following were excluded: studies based on animal models; preclinical and biological studies; non-RCTs; editorials, opinion pieces; reports published as meeting abstracts only where insufficient details were reported to allow inclusion; studies published only in languages other than English; studies with vasoactive drugs that were not within their licensed indications; studies in which the population was not restricted to CF, unless data for just this population was presented; and studies that did not present data for the included outcomes.

Based on the above inclusion/exclusion criteria, study selection was conducted by one reviewer (SH, CC or LU) and checked by a second reviewer (SH, CC or LU). In the first instance, titles and abstracts were examined for inclusion. The full manuscripts of citations judged to be potentially relevant were retrieved and further assessed for inclusion.

Scoping searches indicated that a head-to-head trial of the two interventions was unlikely to be available. In anticipation of this, studies that could potentially contribute to a network meta-analysis (NMA) were also identified on the basis of their abstract and title. Studies were considered potentially useful if they assessed the efficacy of nebulised antibiotics in the target population for the target condition, and reported relevant outcomes. Key study characteristics of the wider network of evidence were extracted by one reviewer. Based on these characteristics, the available network of evidence was constructed. Were viable networks possible, only studies that could contribute to this network would be included in the review. Were a network not possible, only studies providing direct comparisons with at least one intervention and at least one comparator listed in the inclusion criteria were included in the review.

Data extraction and critical appraisal strategy

Data were extracted without blinding either to authors or journal. Data were extracted by one reviewer using a standardised form and checked by a second reviewer. Where multiple publications of the same study were identified, quality assessment and data extraction were based on all relevant publications, and listed as a single study. The quality of included studies was assessed according to three sets of criteria. The purpose of quality assessment was to provide a narrative account of trial quality for the reader, and to inform subgroup analyses (where data allow). In order to assess the risk of bias, items listed in the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) report63 were used and were scored as ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘unclear’. To assess the clinical relevance and quality of the studies, items were generated from the EMA research recommendations. 18 Two trials were non-inferiority trials; a separate quality assessment form64 specific to this type of study was also used.

Data synthesis methods

The prespecified outcomes were tabulated and discussed within a descriptive synthesis. Where populations, interventions, outcome measures and available data were comparable and statistical synthesis was considered appropriate, classical meta-analysis or NMA was planned using Bayesian techniques, or Review Manager (RevMan) software version 5 (The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark; http://ims.cochrane.org/revman). If sufficient trials were available, sensitivity analysis was planned to examine whether the removal of poor-quality trials (in terms of risk of bias or compliance with research guidelines) influenced the results of the meta-analysis. Consideration was also given to subgroup analyses based on study characteristics.

Results

Quantity and quality of research available

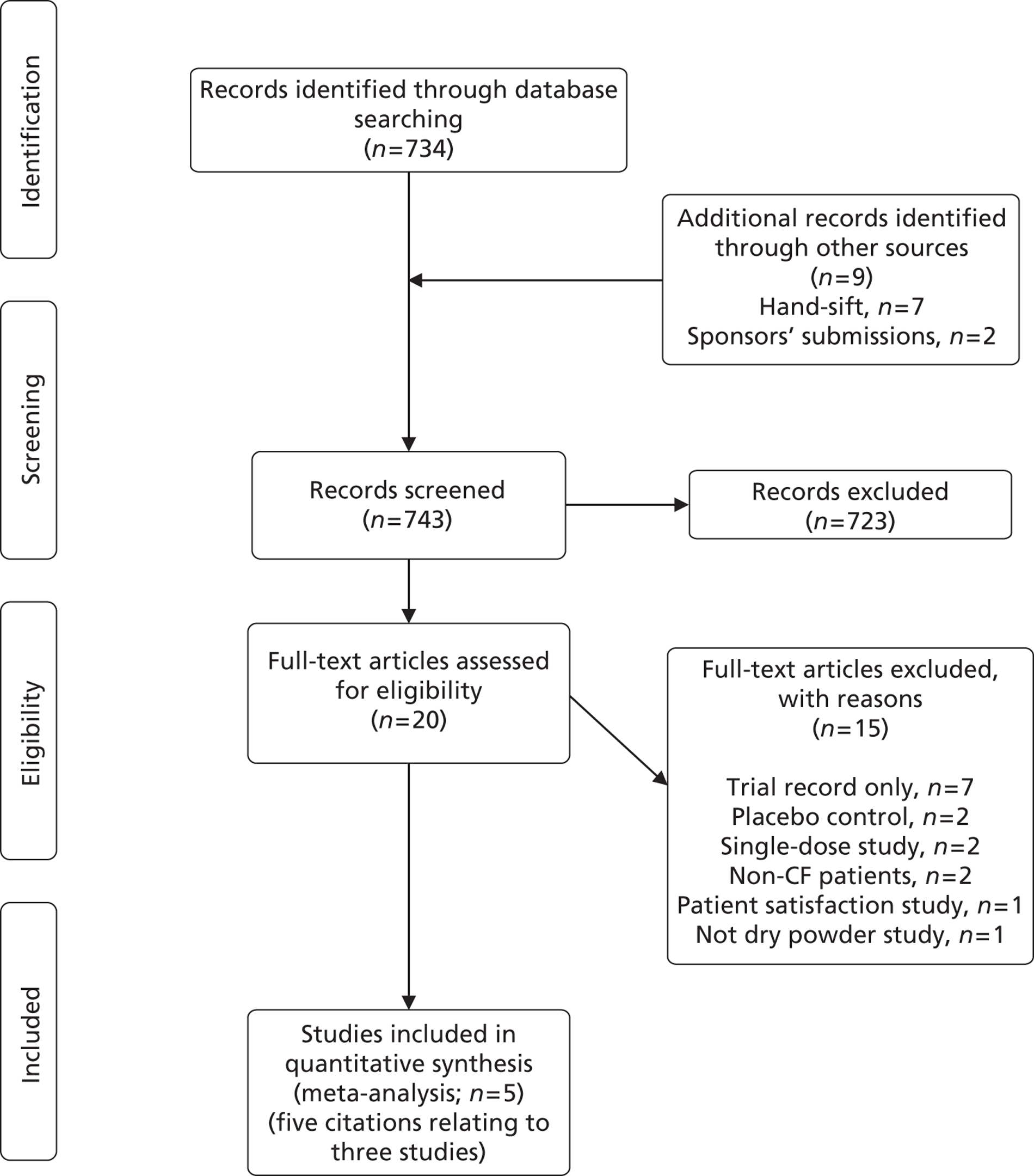

The search retrieved 743 potentially relevant citations (734 from searches of electronic databases, nine from secondary searches of relevant reviews, articles and sponsors submissions). Of these, 723 were excluded at the title and abstract stage, leaving 20 potentially includable citations.

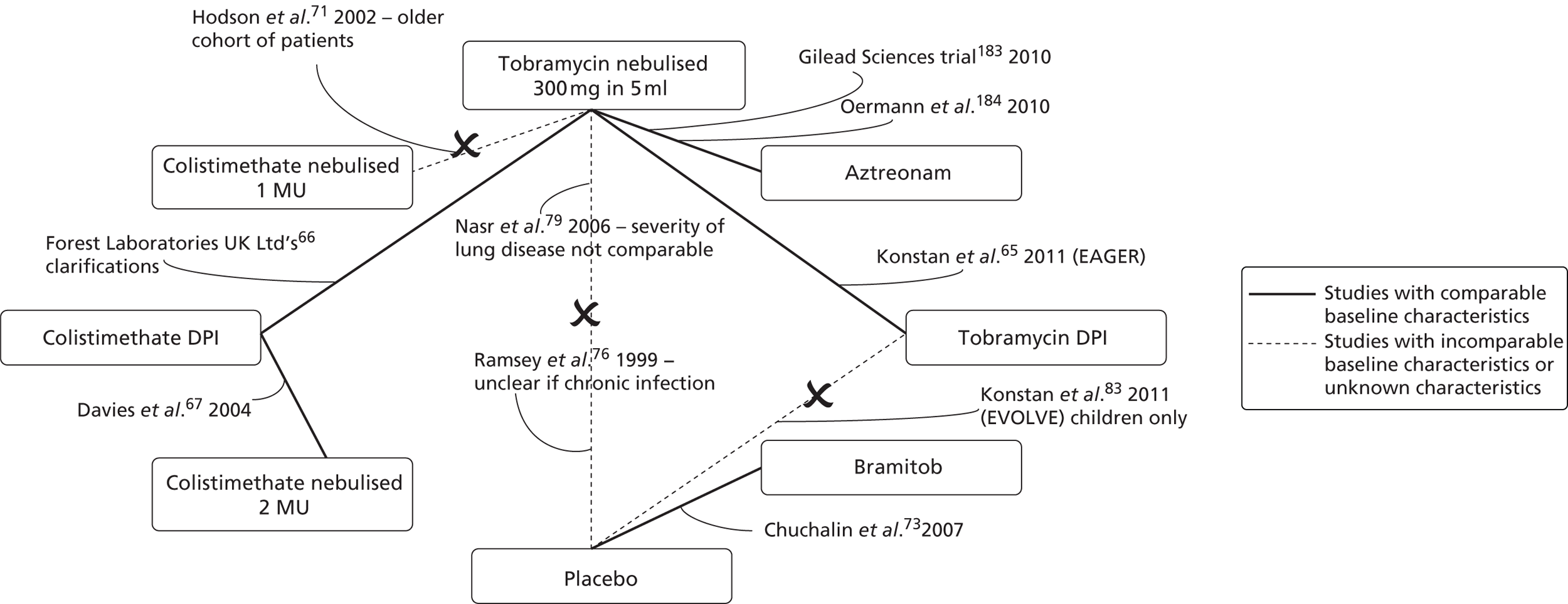

The full texts of the 20 articles were obtained for scrutiny. Fifteen did not meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded (see Appendix 3). Three studies60,65,66 comparing colistimethate sodium DPI or tobramycin DPI with a nebulised antibiotic were included in the review. One study was of tobramycin DPI in combination with the TOBI Podhaler,60,65 and two studies were of colistimethate sodium DPI in combination with the Turbospin device. 66 Information about the three trials included in the systematic review was available from five sources,60,65–68 as indicated in Figure 7. These comprise one published journal article,65 two conference abstracts67,68 and the two manufacturers’ submissions to NICE,60,66 with subsequent clarifications. It should be noted that data for the pivotal colistimethate sodium DPI trial, the COLO/DPI/02/06 trial,66 were available from the manufacturer’s submission,66 the clinical study report (CSR),69 the trial protocol70 and personal communication/clarifications only. None of this information was available in the public domain. The search process is summarised using a PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) diagram in Figure 7.

To assess the viability of a NMA, key study characteristic data were extracted from an additional 13 studies, from 16 citations. 65–67,71–83 Owing to clinical heterogeneity between the studies and incompleteness of the evidence network, a NMA was not performed (see Appendix 4).

Study characteristics

The included trials and the treatments assessed are summarised in Table 4. All studies were open-label, multicentre studies, two of which were multinational studies. 66 The EAGER (Establish A new Gold standard Efficacy and safety with tobramycin in cystic fibrosis) trial65 was a large trial (n = 533) that compared tobramycin DPI with nebulised tobramycin. The COLO/DPI/02/06 trial66 was slightly smaller (n = 380) and compared colistimethate sodium DPI with nebulised tobramycin. Both of these trials were powered to detect clinically relevant changes in FEV1%. The COLO/DPI/02/05 trial66 was much smaller (n = 16) and compared colistimethate sodium DPI with nebulised colistimethate sodium. The EAGER65 and COLO/DPI/02/0666 trials were both of 24 weeks’ duration, whereas COLO/DPI/02/0566 was a crossover trial, which reported outcome data at 4 weeks (before crossover) and 8 weeks (after crossover) only.

FIGURE 7.

Study inclusion (adapted from PRISMA).

Interventions and comparators

Intervention and comparator dosing complied with current UK licensing (www.medicines.org.uk/EMC/medicine/). In the two trials of colistimethate sodium DPI (COLO/DPI/02/0666 and COLO/DPI/02/0566), patients took colistimethate sodium DPI treatment every day throughout the study. In both the EAGER trial65 and the COLO/DPI/02/06 trial,66 the dosing pattern for nebulised tobramycin was cycles of 28 days on treatment, followed by 28 days off treatment, for three cycles. Within the EAGER trial,65 the same treatment approach was used for tobramycin DPI. This administration cycle is standard practice for tobramycin,61 with the aim of preventing antibiotic resistance.

| Study name and sources of information | Source of funding | Study design | Dates study undertaken | Study location | Intervention | Comparator | Duration of trial | Treatment schedule |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAGER trial Konstan et al. 2011;65 TBM100C2302 manufacturer’s submission;60 manufacturer’s clarifications |

Novartis Pharmaceuticals | RCT, open label (n = 533) |

February 2006 to March 2009 | 127 centres in 15 countries (including North America, Europe, Australia, Israel and Latin America) | Tobramycin DPI T-326 Inhaler 112 mg b.i.d. |

Tobramycin inhalation solution PARI LC Plus jet nebuliser 300 mg/5 ml b.i.d. |

24 weeks | Intervention and comparator: 28 days on treatment followed by 28 days off treatment |

| COLO/DPI/02/06 manufacturer’s submission;66 manufacturer’s clarifications |

Forest Laboratories | RCT, open label (n = 380) |

NR (last patient visit 14 August 2007) | 66 centres in EU countries, Russia and the Ukraine | Colistimethate sodium DPI Turbospin device 125 mg b.i.d. |

Tobramycin inhalation solution PARI LC Plus jet nebuliser 300 mg/5 ml b.i.d. |

24 weeks | Intervention: continuous treatment Comparator: 28 days on treatment followed by 28 days off treatment |

| COLO/DPI/02/05 Davies et al. 2004;67 manufacturer’s submission;66 manufacturer’s clarifications |

Forest Laboratories | RCT, open label with crossover (n = 16) |

NR | Three centres in the UK | Colistimethate sodium DPI Turbospin device 125 mg b.i.d. |

Colistimethate sodium solution Device: NR 2 MU b.i.d. |

8 weeks | Intervention and comparator: continuous treatment |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarised and compared in Table 5. Criteria seem largely compatible between the two major trials (EAGER65 and COLO/DPI/02/06),66 although criteria for COLO/DPI/02/0666 were complicated. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are not reported in full here.

The EAGER65 trial and COLO/DPI/02/06 trial66 selected patients with ‘confirmed’ or ‘documented’ CF, who were clinically stable, and aged ≥ 6 years, whereas the COLO/DPI/02/05 trial66 selected patients who were ≥ 8 years. Patients in the EAGER65 trial and COLO/DPI/02/06 trial66 had to have an FEV1% value of ≥ 25%, up to 75%, whereas in the COLO/DPI/02/05 trial66,67 no upper limit for FEV1% was set. Patients in all trials continued with usual CF treatments (except other routine antipseudomonal treatments). Patients in all three trials had a chronic P. aeruginosa infection. The criteria used to define a chronic infection did not meet with EMA recommendations18 in any trial, as all called for only two positive cultures in the last 6 months, rather than three. In the case of the COLO/DPI/02/06 trial,66 three positive cultures were required in the last 6 months, but patients could also qualify with only two in the last 2 months. As such, it is unclear whether or not the trials have truly selected chronically infected patients, and how comparable the degree of infection is between the two trials.

The COLO/DPI/02/06 trial66 had a run-in period whereby participants were required to have received 16 weeks (two cycles) of nebulised tobramycin prior to beginning the trial. Tobramycin has been documented to peak rapidly in efficacy in the first cycle of treatment with the effect not being sustained over time. 76 Therefore, the run-in phase was intended to eliminate this short-term change in FEV1% predicted. In addition, this run-in phase was intended to exclude any patients who could not tolerate tobramycin. In comparison, the EAGER trial65 had a washout period of any systemic or inhaled antipseudomonal antibiotics for 28 days prior to randomisation, which ensured that patients already on tobramycin complied with the standard dosing schedule of 28 days on treatment followed by 28 days off treatment. The difference between these two criteria may result in slightly different populations.

| Study | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| All trials | Adequate contraceptive methods for female participants Written informed consent from patient or patient’s guardian Documented diagnosis of CF from a specialist CF unit (genotype and/or positive sweat tests) Current CF condition had to be clinically stable Chronic P. aeruginosa infection |

Pregnant or breastfeeding patients Inability to comply with any of the study procedures or the study regimen (including inability to use study devices, i.e. during dry powder inhaler and nebuliser training) Use of an elective course of i.v. antibiotic therapy or investigational drug within 28 days of screen Acute respiratory exacerbation within 28 days prior to first day of trial medication administration Patients who were colonised with B. cepacia |

| EAGER65 | Aged ≥ 6 years old FEV1 > 25% to < 75% predicted, based on Knudson equations. Patients with chronic P. aeruginosa infection (sputum or throat cultures positive for P. aeruginosa within 6 months of screening and at baseline) |

Use of systemic or inhaled antipseudomonal antibiotics or other drugs that can affect FEV1% within 28 days prior to study drug administration Haemoptysis of > 60 ml within 30 days prior to study Hypersensitivity to aminoglycosides or inhaled antibiotics Serum creatinine ≥ 2 mg/dl, blood urea nitrogen ≥ 40 mg/dl, or an abnormal urinalysis defined as ≥ 2 + proteinuria Clinically relevant history of hearing loss or chronic tinnitus |

| COLO/DPI/02/0666 | Aged ≥ 6 years old FEV1 > 25 to < 75% predicted, based on Knudson equations Run-in inclusion criteria (patients to receive a minimum of two nebulised tobramycin on/off cycles immediately prior to randomisation) Non-smokers or a past smoker who had not smoked within the past 12 months Patients who, on first day of trial medication administration (Visit 1), had ≥ 28 days but ≤ 35 days off tobramycin Patients with chronic P. aeruginosa infection (two or more sputum or throat cultures positive for P. aeruginosa within 6 months of screening) |

|

| COLO/DPI/02/0566 | Aged ≥ 8 years old FEV1 > 25% prediction, based on Knudson equation Non-smokers or a past smoker who had not smoked within the past 12 months prior to the date of entry |

Known sensitivity to colistimethate sodium or salbutamol Existence of any prestudy medical conditions which, in investigator’s judgement, warranted exclusion from the study Inability to communicate/co-operate with investigator due to language problems, poor mental development or impaired cerebral function Laboratory parameters falling outside the expected normal ranges for CF (investigator decision) Patients who, on first day of trial treatment, had < 28 days off tobramycin Patients who had experienced < 72 hours washout from other antipseudomonal agents Patients who were complicated by ABPA Patients who were awaiting heart–lung or lung transplantation |

Patient characteristics

The baseline characteristics of patients in the three trials are presented in Table 6. The patients in the COLO/DPI/02/06 trial66 had a lower mean age than those in the EAGER trial. 65 Mean age was not reported for trial COLO/DPI/02/05. 66 As age and FEV1% status are thought to have an inverse correlation, it might be expected that the patients in the COLO/DPI/02/06 trial66 were earlier in their stage of chronic Pseudomonas infection than those in the EAGER trial. 65 However, the baseline FEV1% predicted values are similar between these two trials, with the FEV1% predicted in COLO/DPI/02/0666 being slightly lower. This may be due to inclusion criteria for chronic infection not being defined according to EMA recommendations. 18 For all trials, this may result in the recruitment of patients with intermittent infections, who may respond differently to treatment than chronically infected patients. It is also probable that some patients recruited to the COLO/DPI/02/06 trial66 may be slightly less well than the EAGER trial65 participants, as criteria were more stringent in this population. In both trials, the lack of consistency and conformity with the EMA guidelines18 may affect generalisability, with the trial populations not being entirely made up of the chronically infected patient population as defined by the EMA and European and French consensus conference. 27

In line with the potentially slightly poorer health (based on FEV1% values) of the COLO/DPI/02/0666 trial patients, the BMI was also, on average, lower than in the EAGER trial. 65 However, it should be noted that these differences have not been subjected to statistical scrutiny and may not be significant. The clinical relevance of differences of this size are also uncertain.

Concomitant medication use could not be compared between trials as few data were provided (after a request for clarification from the Assessment Group) for the EAGER trial. 65 Many allowed medications (e.g. macrolides and bronchodilators) that could affect FEV1% measurements, and their impact on the trial results are unknown, and may be different between studies.

In terms of prior antipseudomonal use, patients in the COLO/DPI/02/06 trial66 had all used nebulised tobramycin immediately before the trial, whereas only around 25% of patients in the EAGER trial65 had used nebulised tobramycin immediately before the trial [with an additional 55% (approximately) having used it within 3 months prior to the trial]. As such, patients in the COLO/DPI/02/0666 trial may have been more tolerant of tobramycin in terms of AEs, and will have experienced the initial peak in tobramycin FEV1% results within the first 4 weeks of the run-in period, rather than during the trial itself. Conversely, the EAGER trial65 had a proportion of patients who were not tobramycin tolerant having never used tobramycin, and a proportion who had not used tobramycin immediately prior to the 28-day washout period. Some or all of these patients may have experienced an initial peak in efficacy (see Table 6) during the trial, and may be more likely to experience AEs associated with tobramycin than patients in the COLO/DPI/02/0666 trial.

Given that age, BMI, concomitant medications, prior exposure to antipseudomonal antibiotics and FEV1% all have prognostic value in CF, it is difficult to determine whether or not these cohorts are comparable in terms of overall health and propensity to benefit from antipseudomonal treatments.

| Study | Age: mean (SD) | Gender: male/total (%) | BMI (kg/m2): mean (SD) | FEV1% predicted mean | Concomitant and previous treatment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Comparator | Intervention | Comparator | Intervention | Comparator | Intervention | Comparator | Intervention | Comparator | |

| EAGER trial65 | 26 (11.4) < 13 years, 9.1%; ≥ 13 years, 90.9% |

25 (10.2) < 13 years, 8.6%; ≥ 13 years, 91.4% |

171/308 (55.5) | 115/209 (55.0) | 20.7 (4.0) | 20.4 (3.5) | 53 (SD 14.2, SE 0.81) | 53 (SD 15.9, SE 1.11) | Chronic macrolide use n = 187 (60.7%) CiC information has been removed Use of antipseudomonal antibiotics prior to first dose (n, %):

|

Chronic macrolide use n = 125 (59.8%) CiC information has been removed Use of antipseudomonal antibiotics prior to first dose (n, %):

|

| ≥ 25 < 50: 41.6 | ≥ 25 < 50: 42.6 | |||||||||

| ≥ 50 ≤ 80:a 58.4 | ≥ 50 ≤ 80:a 57.4 | |||||||||

| COLO/DPI/02/0666 | Mean (SD): 21.3 (9.72) years | Mean (SD): 20.9 (9.30) years | 103/183 (56.3%) | 101/190 (53.2%) | Mean (SD): 18.67 (3.396) | Mean (SD): 18.46 (3.584) | 51.76 (SE 1.02) | 50.82 (SE 0.99) | Any medication (93.4%) Mucolytics (74.3%) Selective β2-adrenoreceptor agonists (76.5%) Macrolides (49.7%) Azithromycin 85 (46.4%) Dornase alpha 94 (51.4%) Glucocorticoids 66/183 (36.1%) Anticholinergics 34/183 (18.6%) |

Any medication (94.2%) Mucolytics (79.1%) Selective β2-adrenoreceptor agonists (71.2%) Macrolides (51.3%) Azithromycin 97 (50.8%) Dornase alpha 105 (55.0%) Glucocorticoids 67/191 (35.1%) Anticholinergics 39/191 (20.4%) |

| COLO/DPI/02/0566 | ≥ 8 to < 13 years; 37.5% ≥ 13 years 62.5% | NR | NR | Overall for participants, mean (SD): 19.99 (4.011) | 75.92 (SE 11.86) | 79.51 (SE 7.707) | Concomitant: NR Patients were permitted to continue with pre-existing non-antipseudomonal CF medications Bronchodilators: refrained from use 4 hours prior to pulmonary function test; salbutamol administered as rescue medication for bronchoconstriction after either intervention or comparator administration Previous: all were on nebulised colistimethate sodium |

|||

Study withdrawals

Table 7 shows the number of participants in each arm of each trial and the numbers of participants who withdrew throughout the study. Both trials saw a relatively high dropout rate, and this was higher in the intervention arm of both major trials. 65,66 In both key trials, there appear to be data missing and unaccounted for in some analyses, with more patients missing than are listed as withdrawals in the intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses for EAGER trial65 [commercial-in-confidence (CiC) information has been removed] (see Table 7). The implications of these missing data points are unknown.

Table 8 describes the reasons for withdrawals. In both trials, more patients withdrew owing to AEs than for any other single reason, with withdrawal of consent/patient request the second most common reason. In the EAGER trial,65 AEs accounted for proportionately more withdrawals in the tobramycin DPI arm than in the nebulised tobramycin arm. Similarly, more patients withdrew consent for the trial in the DPI arm. In the COLO/DPI/02/06 trial,66 the same pattern was seen, with more patients withdrawing from the colistimethate sodium DPI arm than from the nebulised tobramycin arm owing to AEs, although withdrawals owing to patient request were lower in the DPI arm. In this trial, the difference between arms appears larger than in the EAGER trial,65 although the absolute number of withdrawals is smaller in COLO/DPI/02/06. 66 Differences between the two trials in dropout numbers may be attributable to differences between patients’ tolerance to nebulised tobramycin at baseline; patients who tolerated nebulised tobramycin poorly were likely to have been excluded before randomisation in COLO/DPI/02/06. 66 The Forest Laboratories submission to NICE66 reports 16 screening failures but it is unclear if these patients failed during the run-in period because of lack of tolerance for tobramycin. However, if this was the case, it could account for at least some of the difference in withdrawals between arms, and between the two main studies.

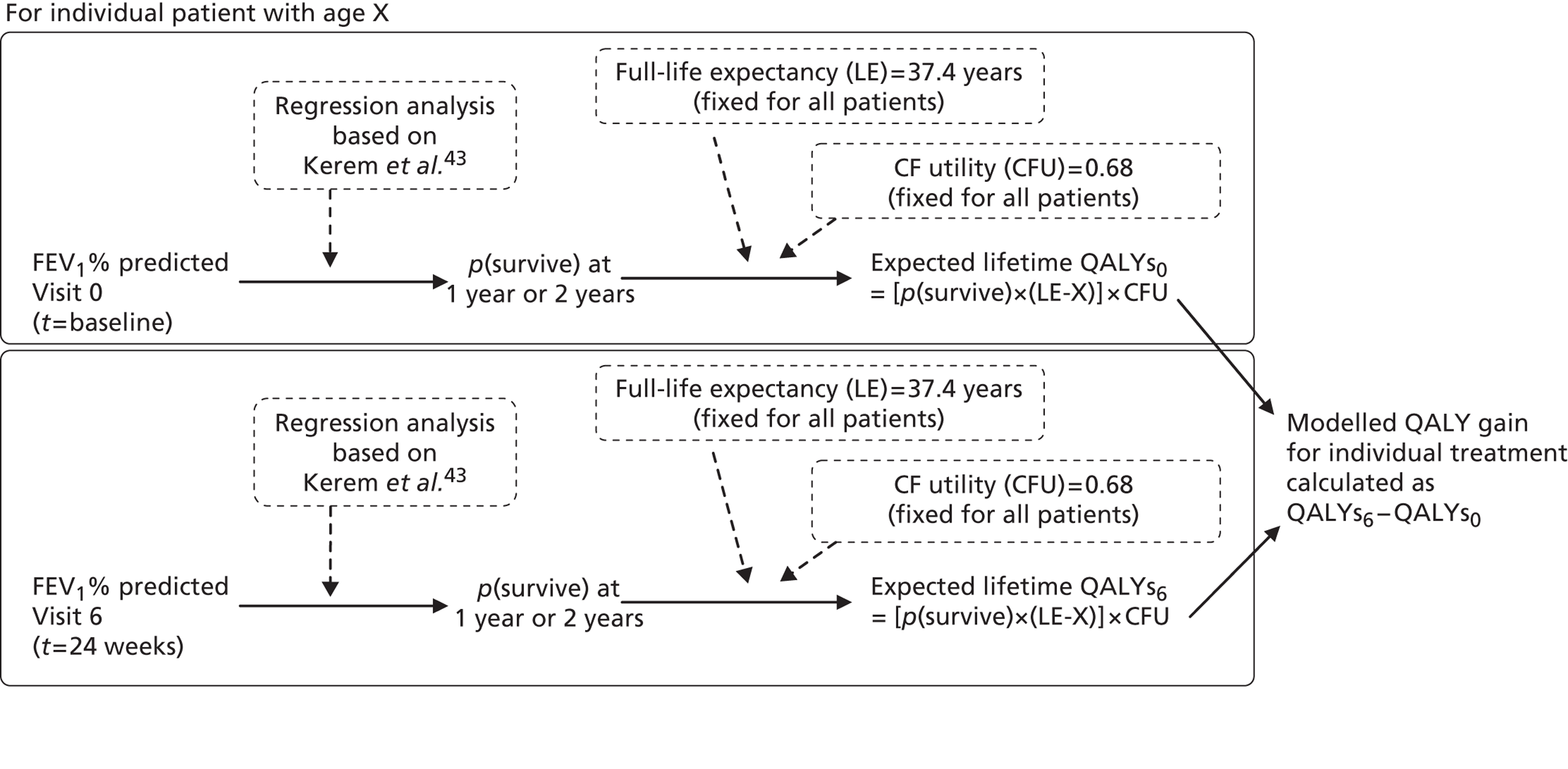

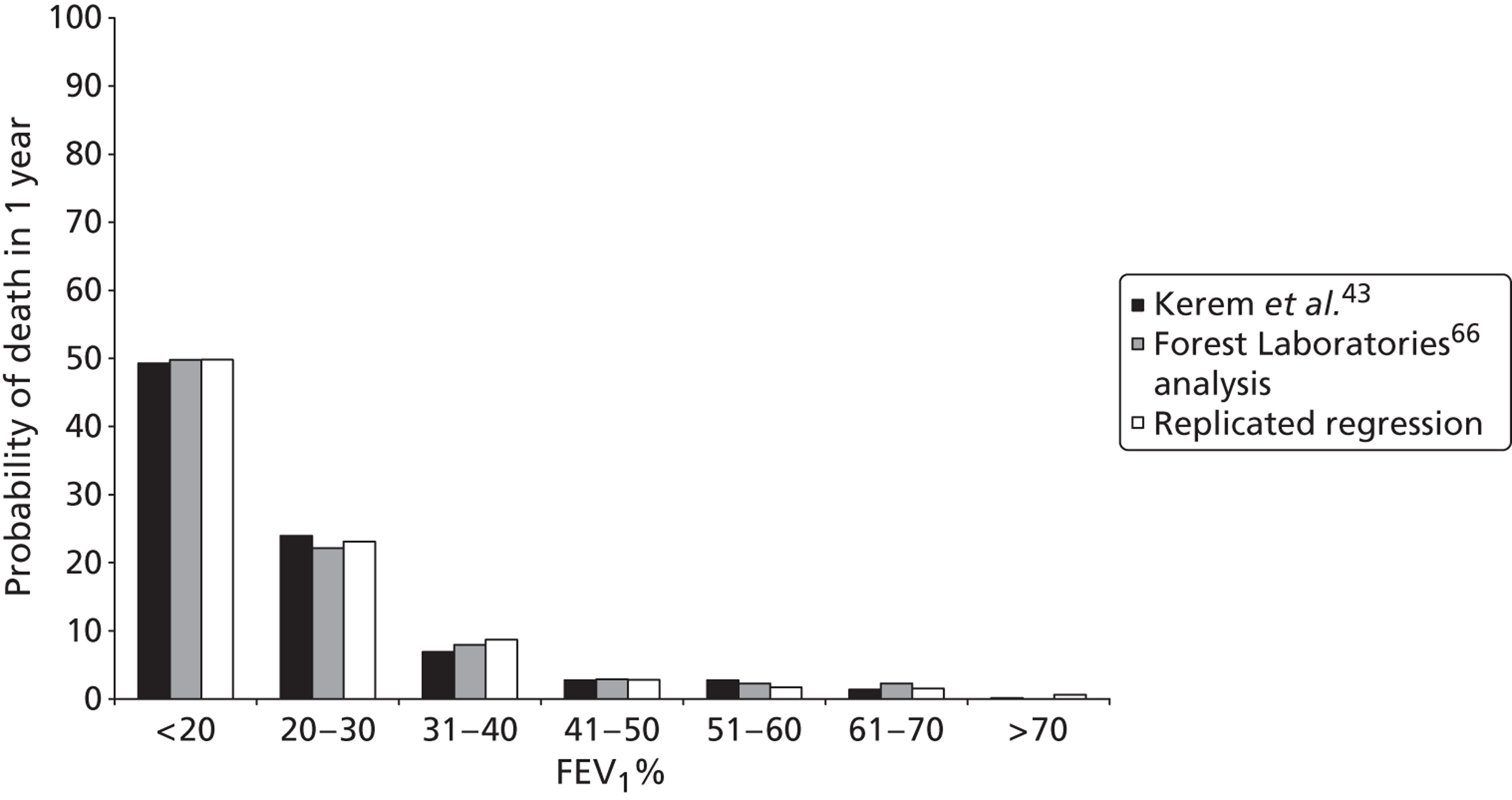

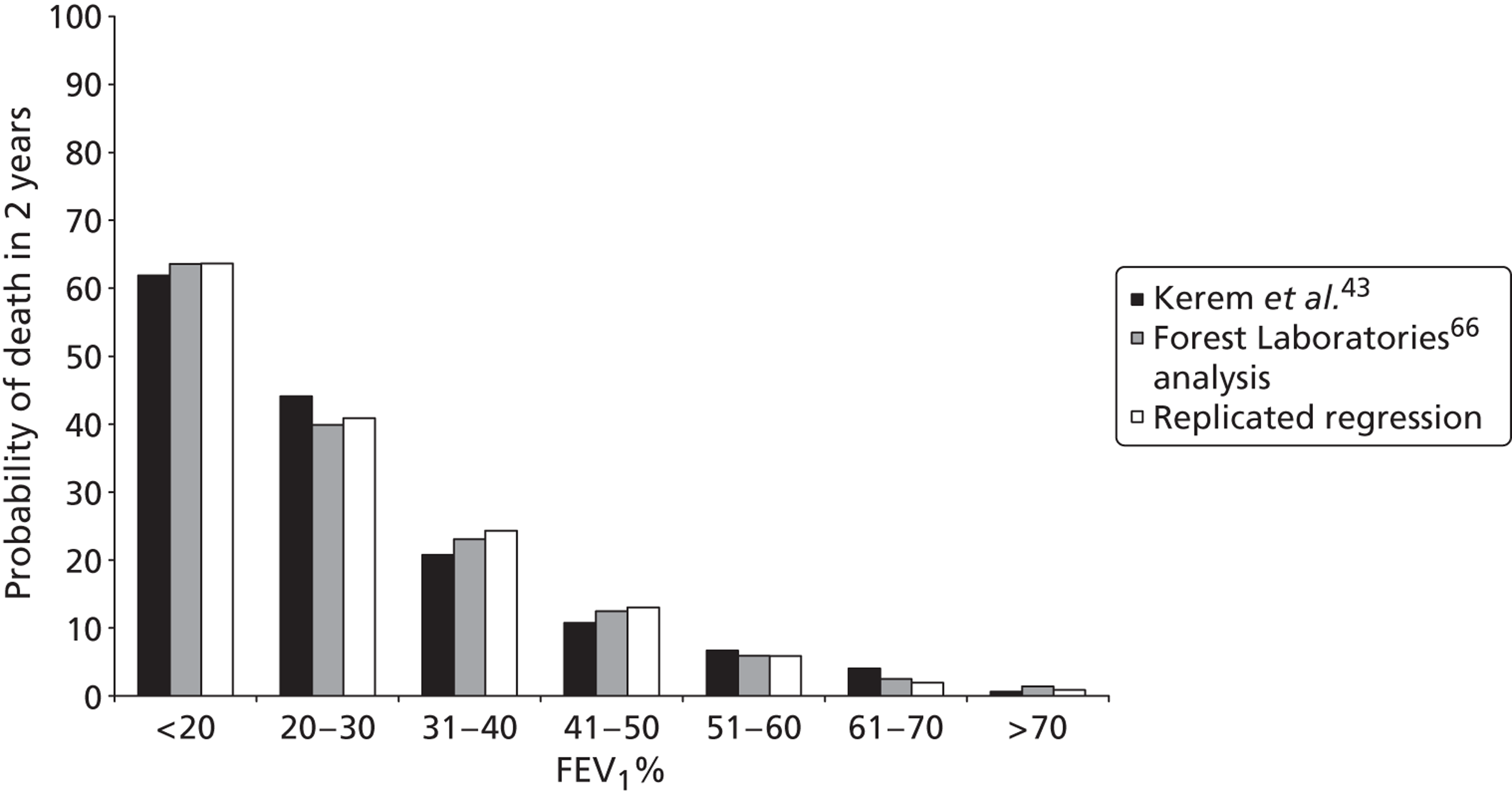

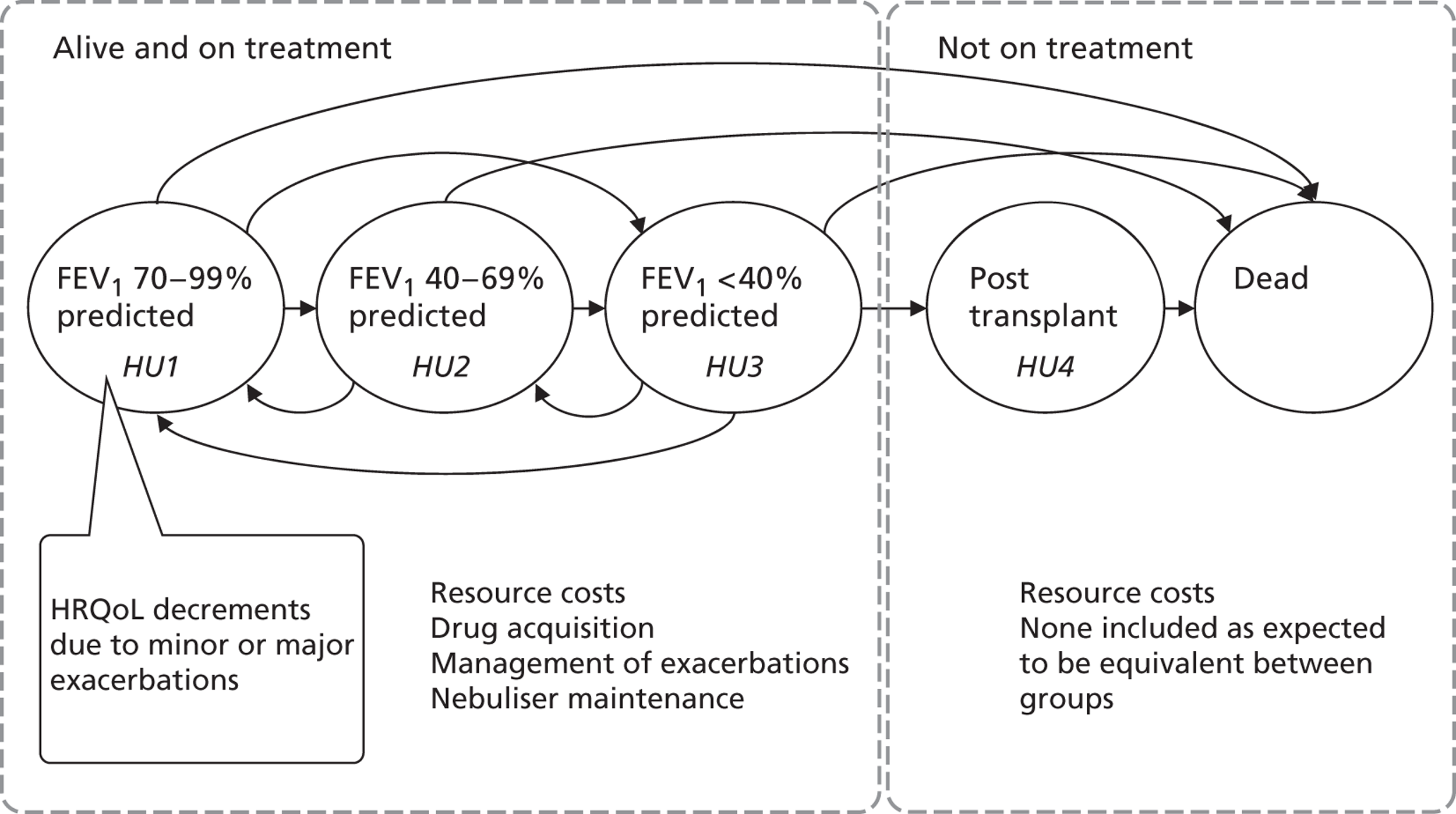

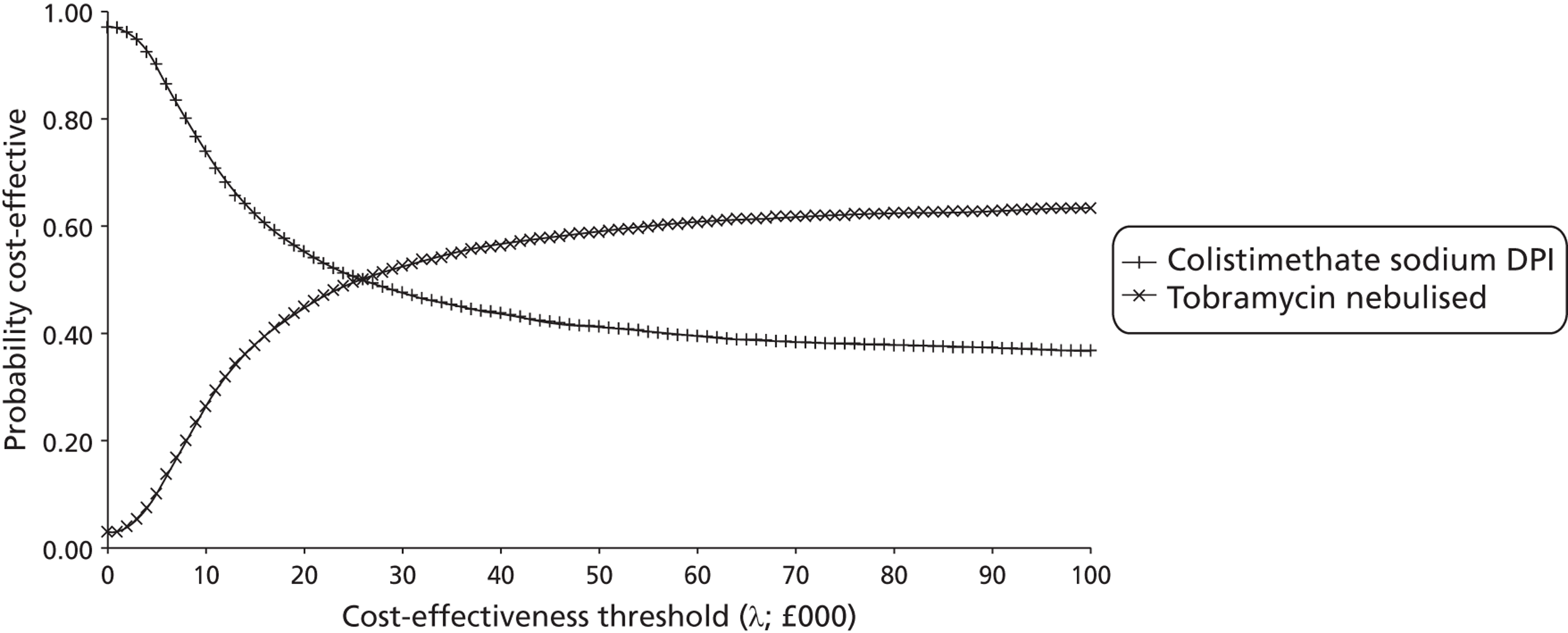

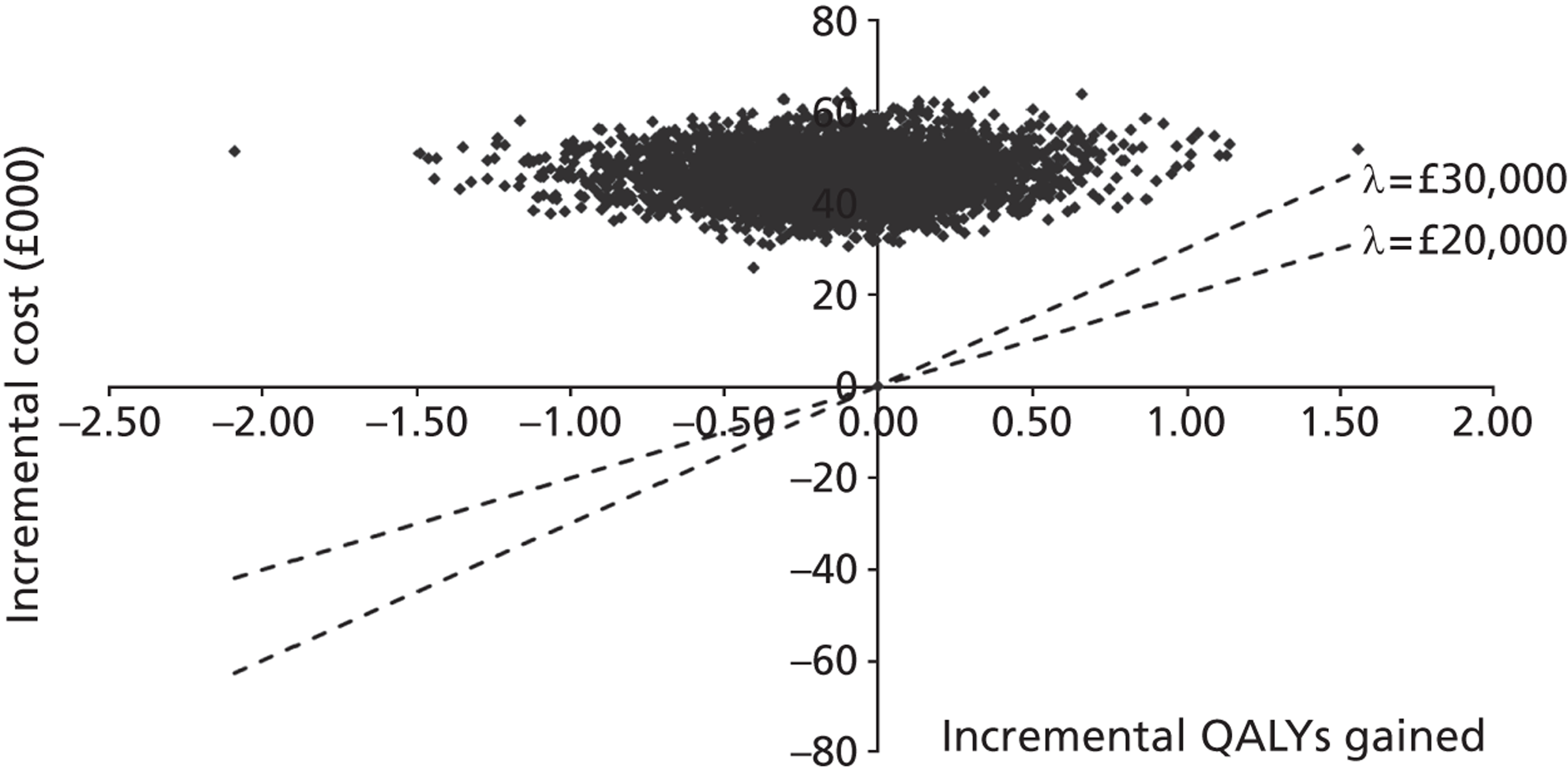

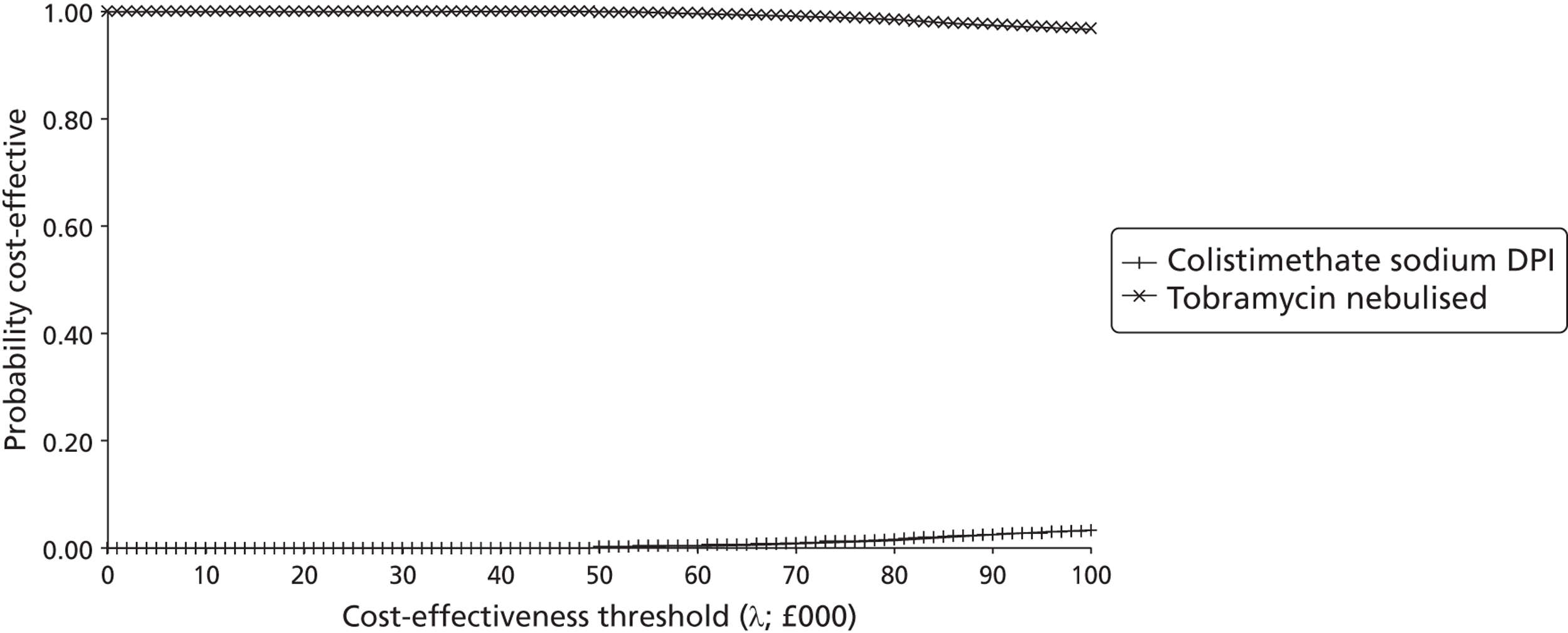

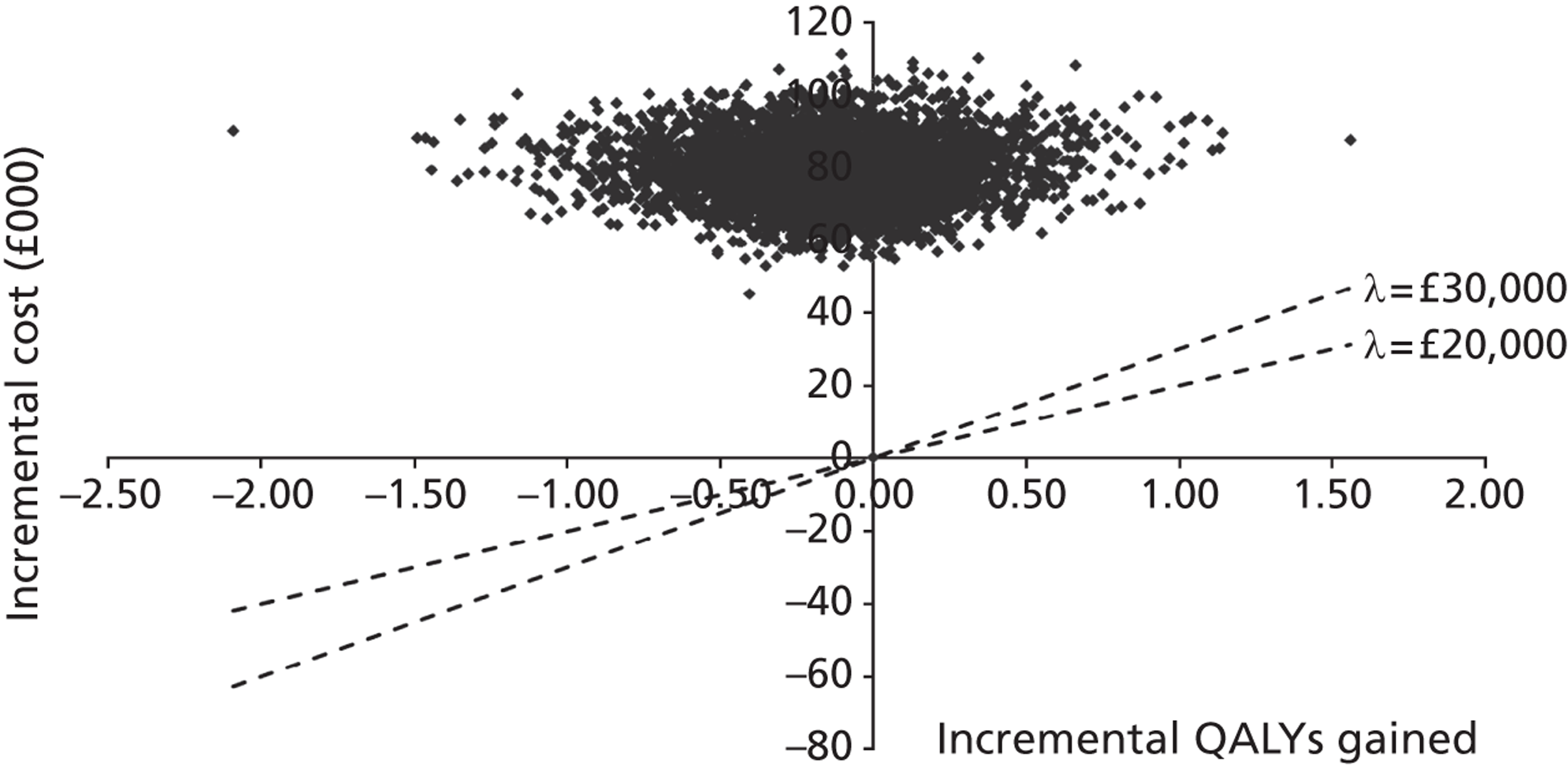

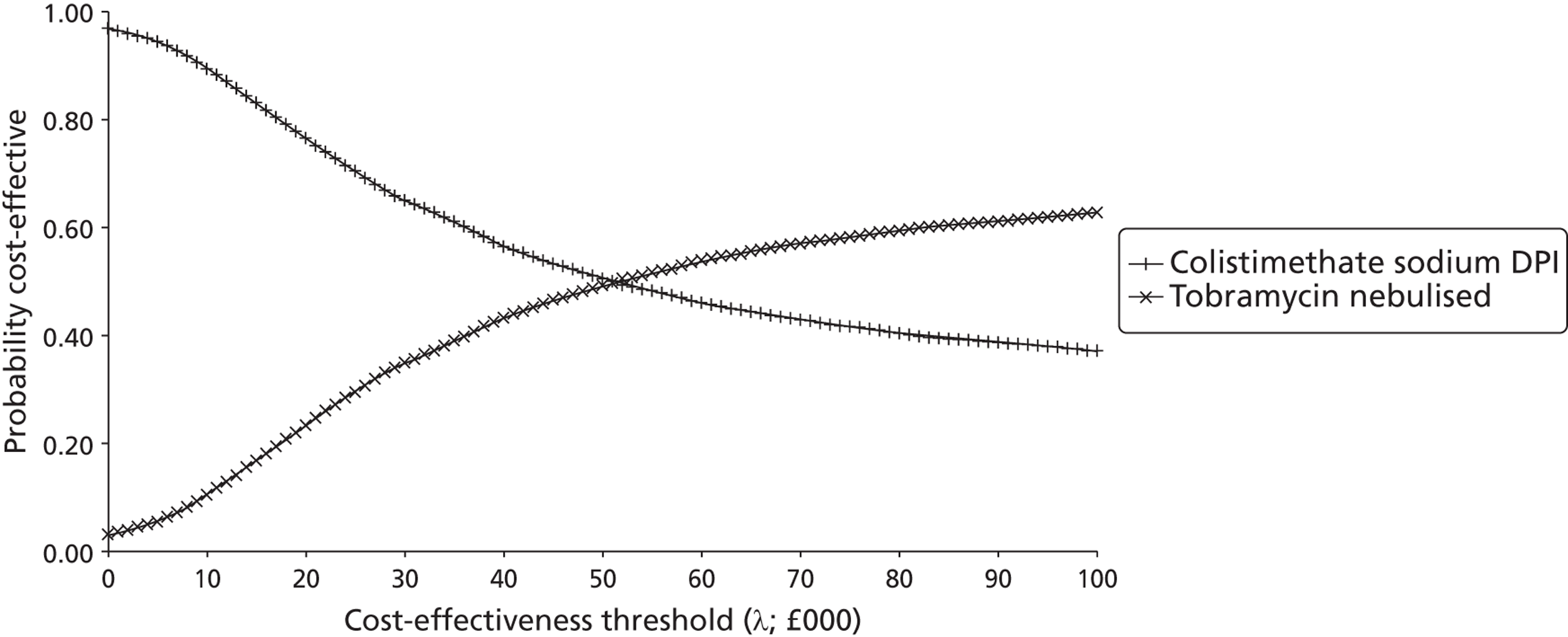

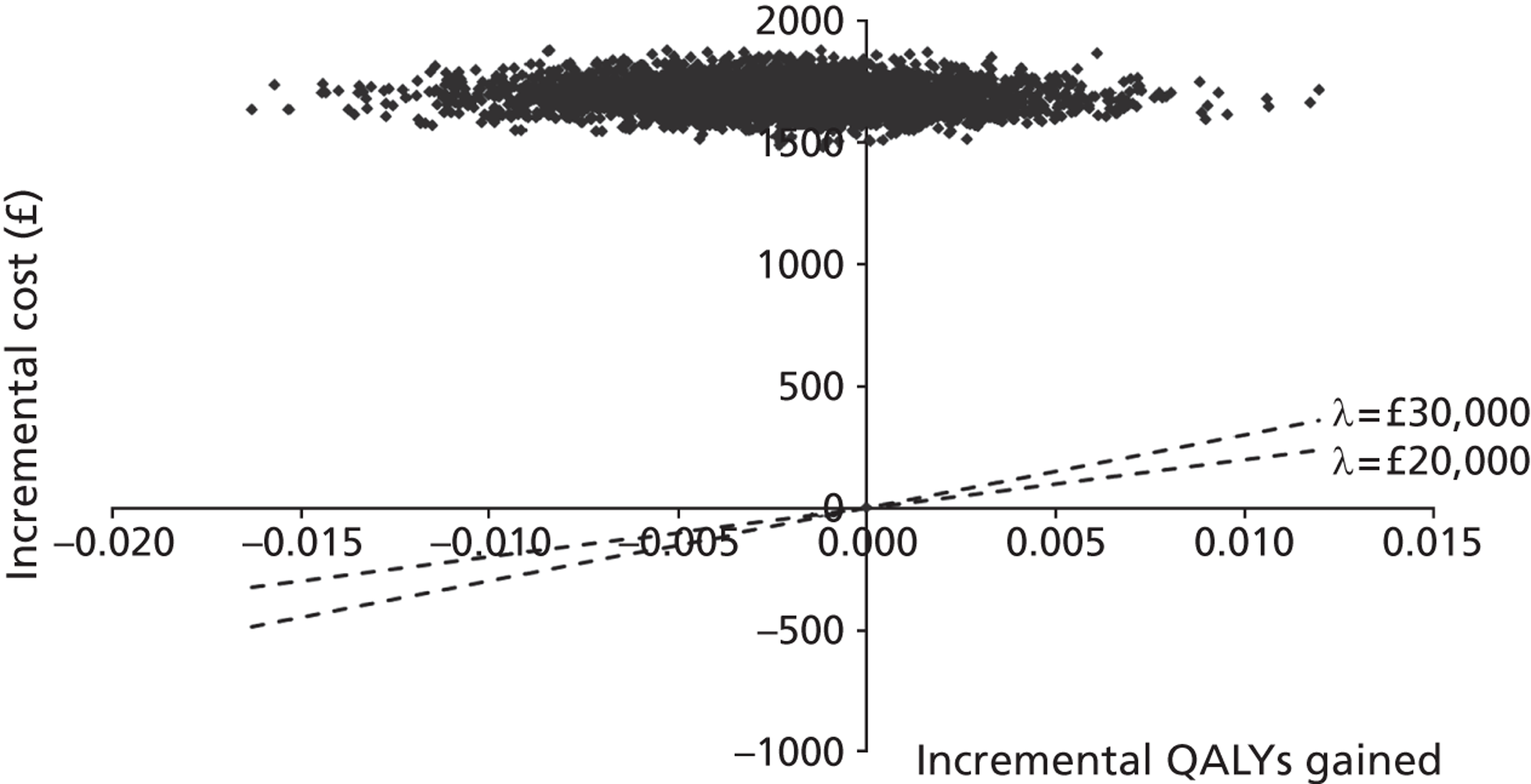

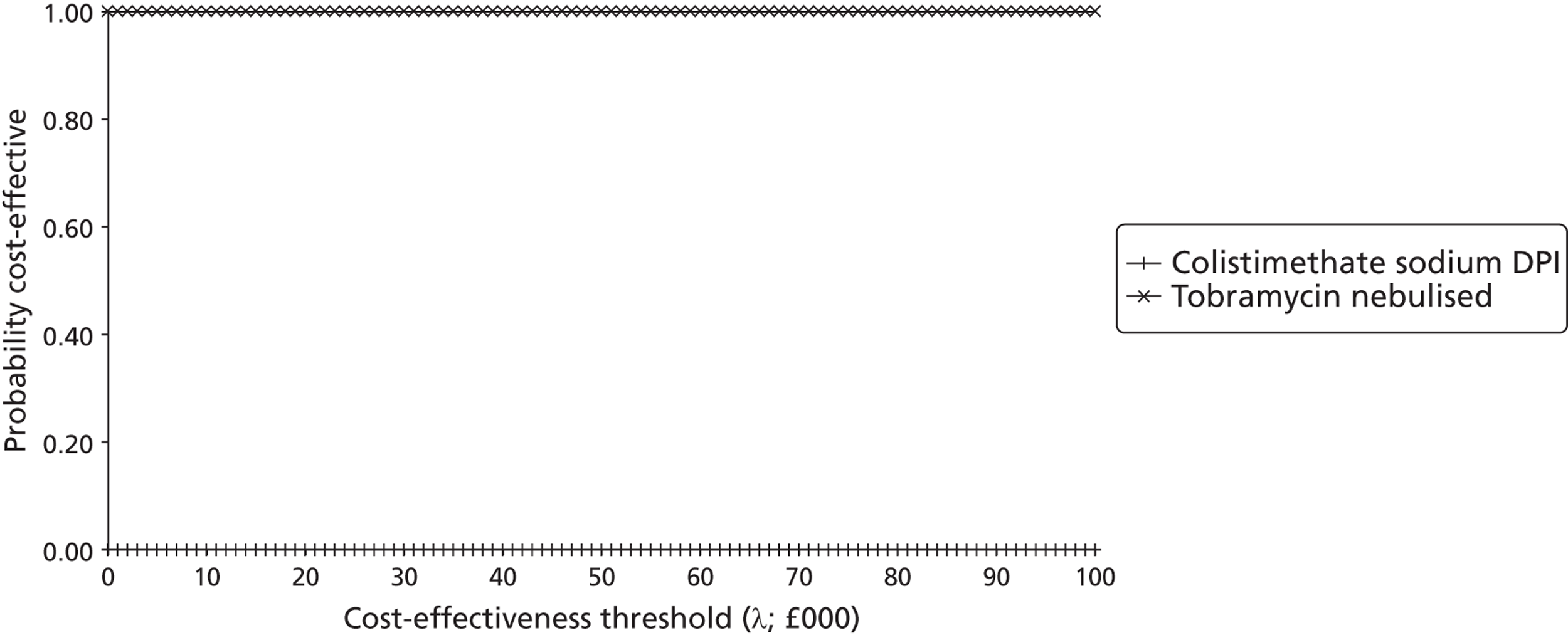

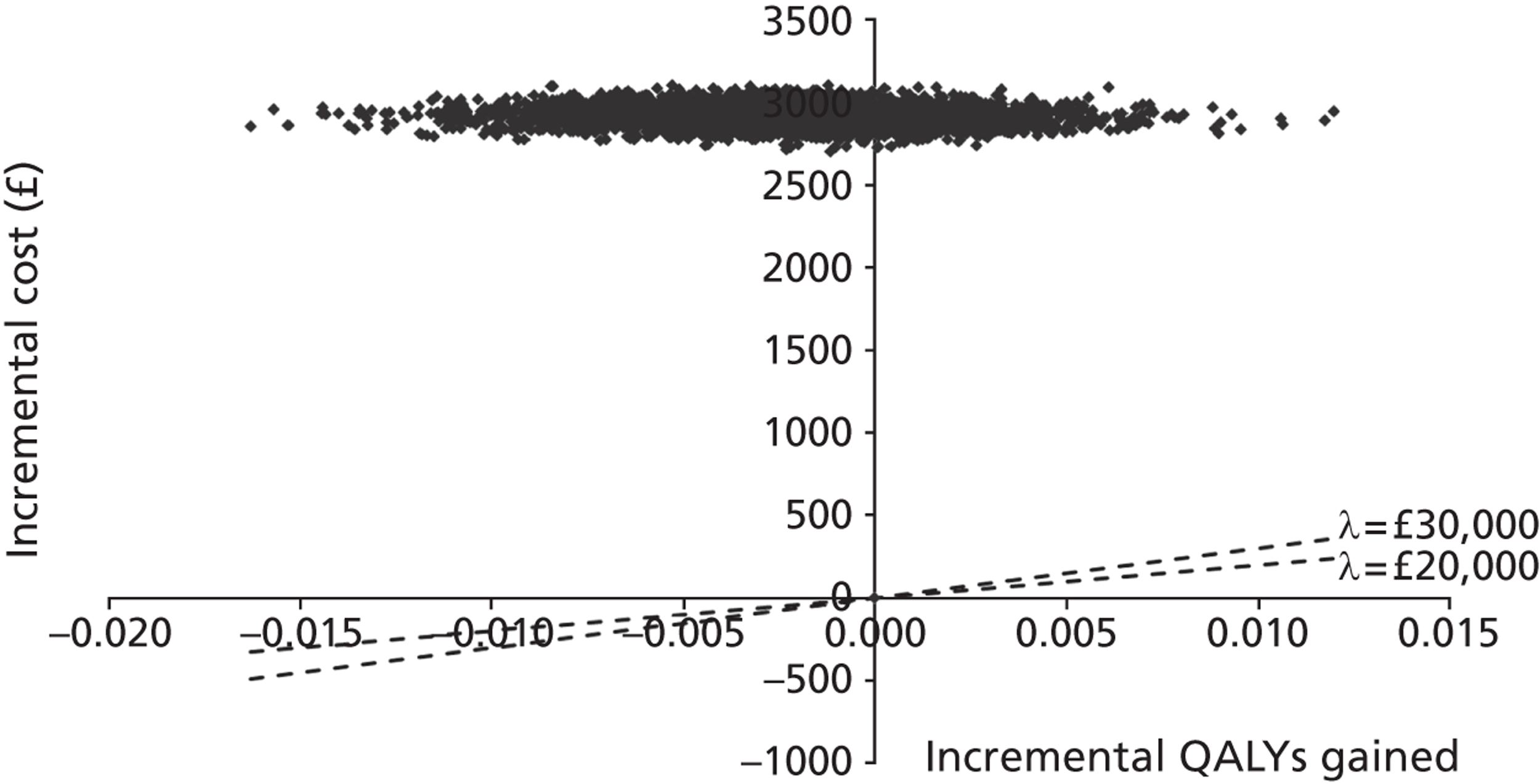

| Study | No. randomised | No. who withdrew before medication (%) | No. in ITT analysis: n (%) | No. who withdrew after medication or lost to follow-up:a n (%) | No. in PP analysis | |||