Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/02/02. The contractual start date was in January 2011. The draft report began editorial review in February 2013 and was accepted for publication in May 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Mytton et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Commissioning brief

In autumn 2008 the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme published a research brief (reference 09/02) asking the question: are parenting interventions effective in the prevention of childhood injuries in children under 5 years? The brief specified that the technology, a parenting programme, should be developed by the researchers for delivery by a health professional to the families of children who had sustained a significant injury in the previous 12 months. The feasibility of testing the programme should be assessed against usual care, with a primary outcome being the number of injuries in the under-fives, together with a range of secondary measures including maternal and family outcomes (such as injury events in the siblings of the index child). The rationale for the research was the proposal that a range of positive outcomes of parenting interventions could also be effective in preventing unintentional injury in childhood, and that a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of a theoretically based intervention could test the causal pathway linking the intervention to the occurrence of childhood injury.

Outline of this report

This report describes our response to the commissioning brief. It documents how we developed and assessed the acceptability of a health promotion programme for the parents of young children that combined parenting support with injury prevention education. It also explores the feasibility of delivering and evaluating the programme through a cluster RCT.

In Chapter 1, we set the scene, describing the background to the issues, how we responded to the commissioning brief, the aims and objectives of the study, and the resulting component activities of the study. In Chapter 2 we summarise two systematic reviews: one of parenting interventions to prevent injuries and the second of the barriers and facilitators to parental engagement in parenting programmes. The findings of these reviews underpin the theoretical development of the parenting programme. Chapter 3 describes the development of the parenting programme, through collaboration with two voluntary sector organisations: Parenting UK (now known as Family Lives) and the Whoops! Child Safety Project. In Chapter 4 we describe the development of a tool to collect our primary outcome measure of parent-reported child injuries, and Chapter 5 describes a feasibility cluster RCT to assess the potential to evaluate the parenting programme in a main trial. Chapter 6 describes the parameters that would be necessary for a study of the cost-effectiveness of the parenting programme during a future trial. Following delivery of four courses of the parenting programme during the feasibility study, we evaluated the parenting programme from four perspectives and subsequently made changes to the intervention. These changes are described in Chapter 7. We draw our findings together in Chapter 8, where we discuss the strengths and weaknesses of our study, whether or not we have met our study objectives and the implications of our findings for a future trial. At the end of Chapters 2–7, learning points have been summarised and form the basis of the implications for a full trial detailed in Chapter 8. We report our conclusions in Chapter 9.

Background

Burden of disease from unintentional injury

Unintentional injury is a major cause of death and disability in children globally,1 and in the UK it is the leading cause of preventable death in children over the age of 1 year. In addition to those who die from injuries, many more suffer morbidity and possible long-term consequences. Half a million children aged 0–4 years attend UK hospitals every year because of a home injury, representing 78% of all injuries occurring to children in this age group. 2 The type and location of child injuries varies with age and developmental stage. Longitudinal cohort studies have shown that the majority of preschool injuries occur within the home, both in this country3,4 and in other high-income countries. 5 Injuries result from falls, hitting, being hit or crushed by objects, poisoning, and burns or scalds. 2

Risk factors for injury

A number of child, family and environmental factors are associated with increased risk of injury. Socioeconomic disadvantage is the risk factor most strongly associated with child mortality and morbidity. 6–12 Family structures such as single-parent families, step-families and large families, and factors that may relate to caregiver supervision such as very young parents, maternal life events, maternal depression and parental behaviours such as excessive use of alcohol, have all been associated with increased risk of child injury. 3,13–18 Male sex and difficult behaviour in childhood, particularly that relating to antisocial, aggressive or hyperactive behaviour, have been associated with increased incidence of unintentional injuries in the UK19,20 and in other high-income countries. 21

Parenting programmes

Parenting programmes are short-term interventions to promote changes in the behaviour of parents that support children. 22 They have been increasingly recognised as an intervention to improve the life chances of children owing to their effectiveness in reducing antisocial behaviour and conduct disorder, increasing educational attainment, and improving mental health and well-being outcomes in children and their parents. Consequently, they have become a core component of child and family policy in the UK. 23,24 Parenting programmes are usually delivered as face-to-face programmes, either individually or in groups. They have been developed on the basis of two main theoretical approaches, behavioural and relational, although some programmes combine elements of both. Behavioural approaches aim to develop parental understanding of the negative impact of attention to problem behaviour and lack of attention to positive behaviour, and to teach positive discipline practices including praise and time-out; relational programmes aim to improve interactions between parent and child, correcting inappropriate parental interpretations of child behaviour, increasing empathy and understanding of developmental phases.

Analyses of longitudinal studies have shown the influence of parents on child outcomes that are related to injury risk. Positive parenting behaviour and parent–child interaction, and a stimulating home environment have been associated with enhanced development by the age of 3 years25 and improved cognitive and behavioural outcomes in children by age 5 years26 or children who are well adjusted and developmentally competent. 27 The use of positive parenting practices, such as increased use of praise to encourage desirable behaviours, is associated with a reduction in injuries. 28 Supportive parent training can improve childcare practices for mothers with learning difficulties29 and enhanced carer supervision can reduce injury risk to children. 30,31 Parenting interventions have the potential to reduce poor maternal mental health and increase maternal self-efficacy,32,33 to improve maternal–child interactions,34 and to change child behaviour, especially behaviour that is challenging or could place the child at risk of injury. 32,35–37 Reductions in injury risk could also be mediated through information to enable parents to make realistic expectations of their child’s development and skills,38 enhanced parental knowledge of safety practices,39 improvement in the quality of the home environment,40 or through the use of home safety practices such as having a fitted and functioning smoke alarm, using stair gates or keeping sharp objects in a safe place. 41,42 Generic parenting support interventions delivered by health visitors, and which may or may not include a focus on injury prevention, have been shown to reduce injury rates in both prospective observational studies43 and RCTs. 44 Meta-analyses of RCTs measuring one-to-one parenting interventions that are delivered primarily through home visiting and primarily conducted with high-risk or disadvantaged families have demonstrated significantly lower risks of injury, as measured by parental self-report of either medically or non-medically attended injuries,45,46 but it is unclear if group-based programmes can achieve similar effects. Parental understanding of the relationship between injury risk and child behaviour and development is variable, and provision of educational anticipatory guidance has been recommended. 47

There is strong evidence that home safety education with the provision of safety equipment is effective in increasing a range of home safety practices. 42 The features of parenting interventions that are most effective are becoming clearer. A review of ‘what works?’ in parenting interventions has shown that interventions are more likely to be effective if they are delivered early in childhood, if intensity is proportional to need, if they include group activities where parents can benefit from the social aspect of working with peers, if they include formal programmes or manuals to maintain the consistency of the delivery of the intervention which should be delivered by trained staff, and if there is a focus on specific parenting skills and practical ‘take-home’ tips. 48 Parents value programmes that enable the acquisition of knowledge, skills and understanding, and facilitate acceptance and support from other parents. 49 The fear of being perceived as a bad parent may inhibit participation in programmes. Positive outcomes from programmes reduce feelings of guilt and social isolation, increase empathy with children, and give confidence to cope with challenging child behaviour. 50

Cost-effectiveness of parenting programmes

As well as being a health and well-being issue, child injury also has economic impacts. Scarce resources with competing uses in all health systems, and the need to decide between new, ‘efficacious’ primary prevention parenting programmes on the grounds of cost-effectiveness, have increased the significance of economic evaluation as a concept and methodology. 51,52 Recent guidance from the UK Medical Research Council for the development and evaluation of complex behavioural interventions suggests that efficacy and cost-effectiveness should be established before programmes are implemented at the population level. 53,54 However, the meaningful determination of these criteria is often problematic for complex interventions. It is therefore important to develop the conceptual and measurement process by which effectiveness and cost-effectiveness can be evaluated during a feasibility trial.

There are some studies to build upon. The cost-effectiveness of parenting programmes had not been widely studied55 at initiation of this study, but some evidence for modelling costs and longer-term savings56 and estimating the long-term return on investment57 has emerged during the time frame of this study. Previously, a systematic review of economic evaluations of child and adolescent mental health interventions demonstrated that most evaluations were small scale, had short time horizons for assessing outcomes and had limited reporting,58 a finding supported by a recent review of UK programmes to prevent child behaviour problems. 59 Some evidence of cost-effectiveness of parenting programmes has been published for group parenting programmes; a formal evaluation of one programme widely used in English Sure Start children’s centres demonstrated improved child behaviour outcomes for modest costs and considered the programme value for money. 60 This study has been used to produce a costing publication61 now widely used for this type of evaluation.

Aims of the study

The aims of this study were:

-

to develop a health professional-delivered programme for the parents of children aged 0–4 years that provides injury prevention education tailored to the stages of preschool child development, underpinned by the principles of parenting support

-

to assess the acceptability of the programme to parents and professionals

-

to assess the feasibility of delivering and evaluating the parenting programme through a cluster RCT, including the identification of appropriate parameters to determine cost-effectiveness in a future trial.

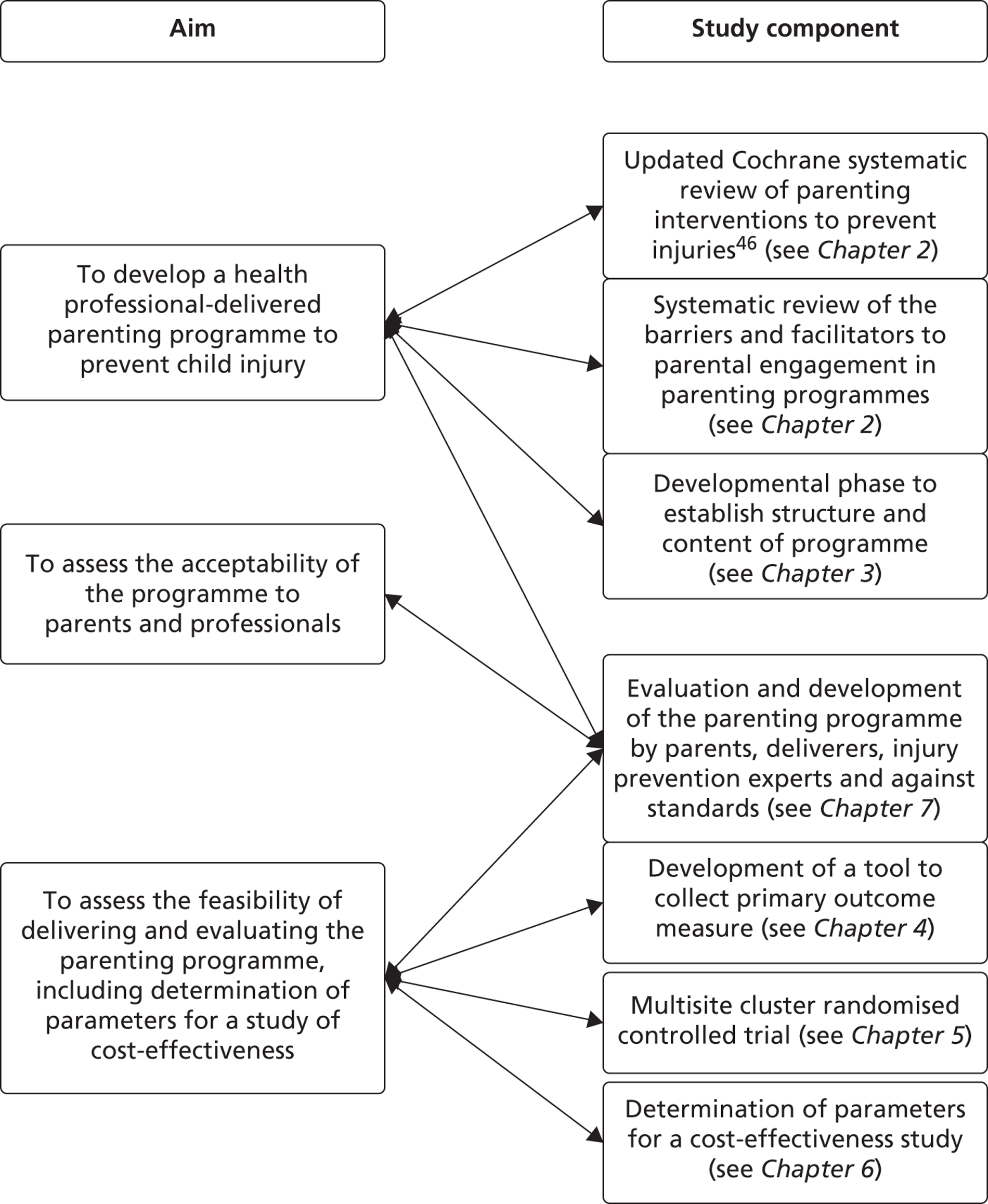

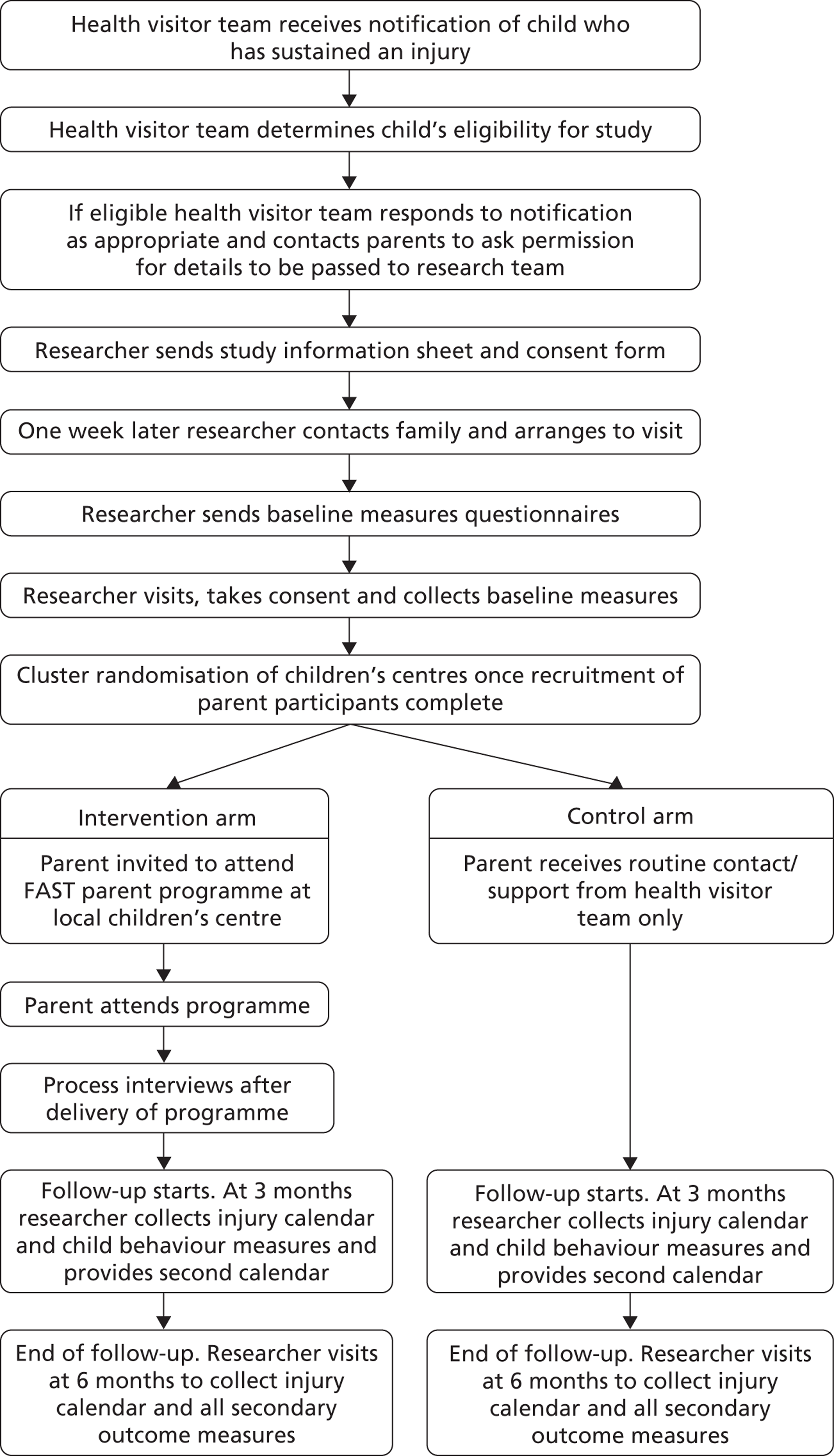

Component activities of the study, illustrates how the aims were addressed (see Figure 1). Specific objectives relating to the feasibility cluster RCT are detailed in Chapter 5.

How we responded to the brief

We decided to develop a programme in which parenting challenges and skills could be illustrated with injury risk and safety scenarios, providing the opportunity to concurrently deliver parenting skills development, effective communication, use of positive reinforcement, managing difficult behaviour, setting and maintaining appropriate boundaries, understanding how a child’s development influences their behaviour and injury risk, promoting self-assessment of home hazards and providing guidance on home safety practices and equipment. We chose to work with two voluntary sector organisations: Parenting UK, a parenting programme development organisation (now known as Family Lives), and the Whoops! Child Safety Project, which provides life-saving skills and first aid educational programmes for the public and professionals.

We interpreted a ‘significant’ injury (as specified in the commissioning brief) to be one where the parent sought medical attention following the injury event. The requirement to seek support can be considered a ‘teachable moment’ when parents may be receptive to information regarding injury risk in their children. 62 We were concerned from the outset that asking a parent to join a parenting programme after their child had sustained an injury could result in feelings of stigma, guilt or belief that they were perceived as an inadequate parent. In an attempt to destigmatise attendance to the programme, we chose to include a strong element of first aid and safety advice in our programme, as we knew that home safety education trials had successfully recruited parents of recently injured children63,64 and that parents are interested in learning first aid. 65

Support and information for the parents of young children in the UK is routinely provided in children’s centres; therefore, we decided to use the children’s centre as the setting to deliver our programme. As health visitors are the lead community health professional working with parents, they may be considered the most suitable to deliver the intervention. However, in recent years most areas have experienced a shortfall in the health visitor workforce. Consequently, many health visitors now work in teams, supervising other staff, including nursery or children’s nurses. Each children’s centre is linked to a health visiting team and most share a broadly similar catchment area. Therefore, we decided to identify pairs of health visitor teams and their associated children’s centre willing to participate in the study. The parenting programme would be delivered in the children’s centre, by the health visitor, cofacilitated by a member of her team.

The decision to deliver the parenting programme to groups of parents in children’s centre meant that there would be delays for some parents between recruitment and commencement of the group intervention. We anticipated that this, together with an intervention that was delivered over several weeks, could risk low retention rates.

Component activities of the study

The component activities of the study are mapped against the aims in Figure 1. The chapters relating to each of the component activities are specified to facilitate orientation through this report.

FIGURE 1.

Mapping of aims against the components of the study.

Parent advisory group

We wished to engage parents in all stages of the development and testing of the parenting programme, and so established a parent advisory group (PAG) at a children’s centre in Bristol that was not participating in the two arms of the feasibility trial. Parents who routinely attended the children’s centre were invited to participate in the advisory group. There were seven core members (all mothers) who attended most meetings, and two further mothers who attended once at the beginning. They were all approached by the community support manager and other community staff at the children’s centre and purposively sampled to include a range of socioeconomic backgrounds, education levels, experience of parent groups, number of children and involvement in activities at the children’s centre. The group was held in a small room at the children’s centre and crèche facilities were provided, if required. A community team staff member, who is also a local parent, attended the group as she knew some of the mothers and was a helpful facilitator.

The group met five times during the course of the study with an additional thank-you meeting just after the study had finished. Each meeting was facilitated by one or two of the researchers. Parents were asked to provide advice on the development of the intervention, identification of eligible families, recruitment and issues relevant for a future trial. Meetings with the PAG were timed, where possible, to allow feedback to the trial steering committee. Representatives of the group were invited to the trial steering committee, and attendance was supported by the researcher facilitator. When representatives of the group were unable to attend, comments from the group were fed back to the trial steering committee by the researcher facilitator.

Chapter 2 Development of a parenting intervention: theoretical phase

We conducted two evidence syntheses to underpin the development of the parenting intervention.

The first was an update of a systematic review published by Kendrick et al. 45 in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews in 2007. This review synthesised evidence of the effectiveness of parenting interventions for preventing unintentional injuries in children, and on the possession and use of safety equipment and parental safety practices. The review included nine RCTs in the primary meta-analysis indicating that intervention families had a statistically significantly lower risk of injury [relative risk (RR) 0.82, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.71 to 0.95], and that several studies reported greater use of home safety equipment and safety practices in intervention families. The authors noted that the majority of the interventions were multifaceted home-based interventions, and they were unable to determine if interventions delivered outside the home or delivered as group-based interventions were effective. An update of this systematic review was therefore required to identify if new evidence was available on these two issues specifically, in order to inform the development of the group-based, community-delivered parenting programme proposed.

The second evidence synthesis was conducted to explore the evidence explaining why parents do, or do not, engage and complete parenting programmes. Researchers have previously sought to identify the barriers and facilitators to parental engagement in such programmes but these have largely been taken from the perspective of providers, policy-makers or academics. 66,67 Studies have explored why parents believe that programmes may be helpful,50 but not parents’ beliefs on barriers and facilitators to engagement. A systematic review of the qualitative literature exploring the barriers and facilitators to parental engagement in parenting programmes was conducted to ensure that facilitators were utilised where possible and barriers were minimised in the proposed programme.

Systematic review 1: parenting interventions for the prevention of unintentional injuries in childhood

The full version of this Cochrane review can be found in The Cochrane Library (www.thecochranelibrary.com). 68 A summary of the findings from this review is reported below.

Objectives

The primary objective of the review was to update the evidence on the effectiveness of parenting programmes in preventing unintentional injury in childhood. The secondary objective was to evaluate the effectiveness of parenting programmes at increasing possession and use of home safety equipment and parental safety practices.

Methods

Studies for inclusion

We included RCTs, non-RCTs and controlled before-and-after (CBA) studies, which evaluated parenting interventions administered to parents of children aged 18 years and under. Included studies reported the primary outcome of self-reported or medically attended unintentional injury or injury of unspecified intent, or the secondary outcomes of possession and use of safety equipment or safety practices. This included the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME) scale, which contains one subscale measuring organisation of the environment in relation to child development and safety. 69 Parenting interventions were defined as those with a specified protocol, manual or curriculum aimed at changing knowledge, attitudes or skills covering a range of parenting topics.

Search methods for identification of studies

A search strategy was devised for use in MEDLINE and adapted as necessary for other databases. We searched a range of bibliographic databases from the date of inception to January 2011, including Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), MEDLINE (Ovid SP), EMBASE (Ovid SP), PsycINFO, Social Science Citation Index, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL; EBSCOhost), ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE), Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) and ISI Web of Science: Social Sciences Citation Index. We also searched international and national websites including the Children’s Safety Network, the International Society for Child and Adolescent Injury Prevention, the Child Accident Prevention Trust, the Injury Control Resource Information Network, the National Injury Surveillance Unit, the Injury Prevention Web, SafetyLit, Barnardo’s Policy and Research Unit, National Children’s Bureau and Children in Wales. We hand-searched abstracts from the World Conferences on Injury Prevention and Control and the table of contents for the journal Injury Prevention from first publication to January 2011. There were no restrictions by language or publication status.

Selection of studies

A two-stage screening process was undertaken. Two reviewers independently scanned titles and abstracts of articles to identify articles to retrieve in full. The full articles were retrieved for those papers retained at this stage, which were independently assessed by two reviewers. At each stage where there was disagreement between reviewers, a decision was made by a third reviewer. Data extraction was undertaken independently by pairs of reviewers. We extracted data on study design, design of intervention, sociodemographic characteristics of participants and outcome data. If key data were not available in the published reports, we contacted study authors to obtain missing information.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Critical appraisal of included studies was undertaken independently by two reviewers who assessed for risk of bias, including selection, performance, detection, attrition and reporting bias. Assessment was also made of the extent to which studies conformed to an intention-to-treat analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Pooled RRs and 95% CIs were used for binary outcome measures and mean differences and 95% CIs for continuous outcome measures. The primary analysis included RCTs reporting injury rates and used random-effect models. We adjusted for clustering where necessary for cluster allocated studies. Statistical tests of homogeneity were undertaken using chi-squared tests and the I-squared statistic. Publication bias was assessed for the primary analysis using a funnel plot and Egger’s test. Sensitivity analyses were undertaken including only RCTs considered at low risk of selection, detection or attrition bias. For secondary analyses, where there were insufficient clinically homogenous studies to combine in a meta-analysis, their results were combined in a narrative review.

Results

Description of studies

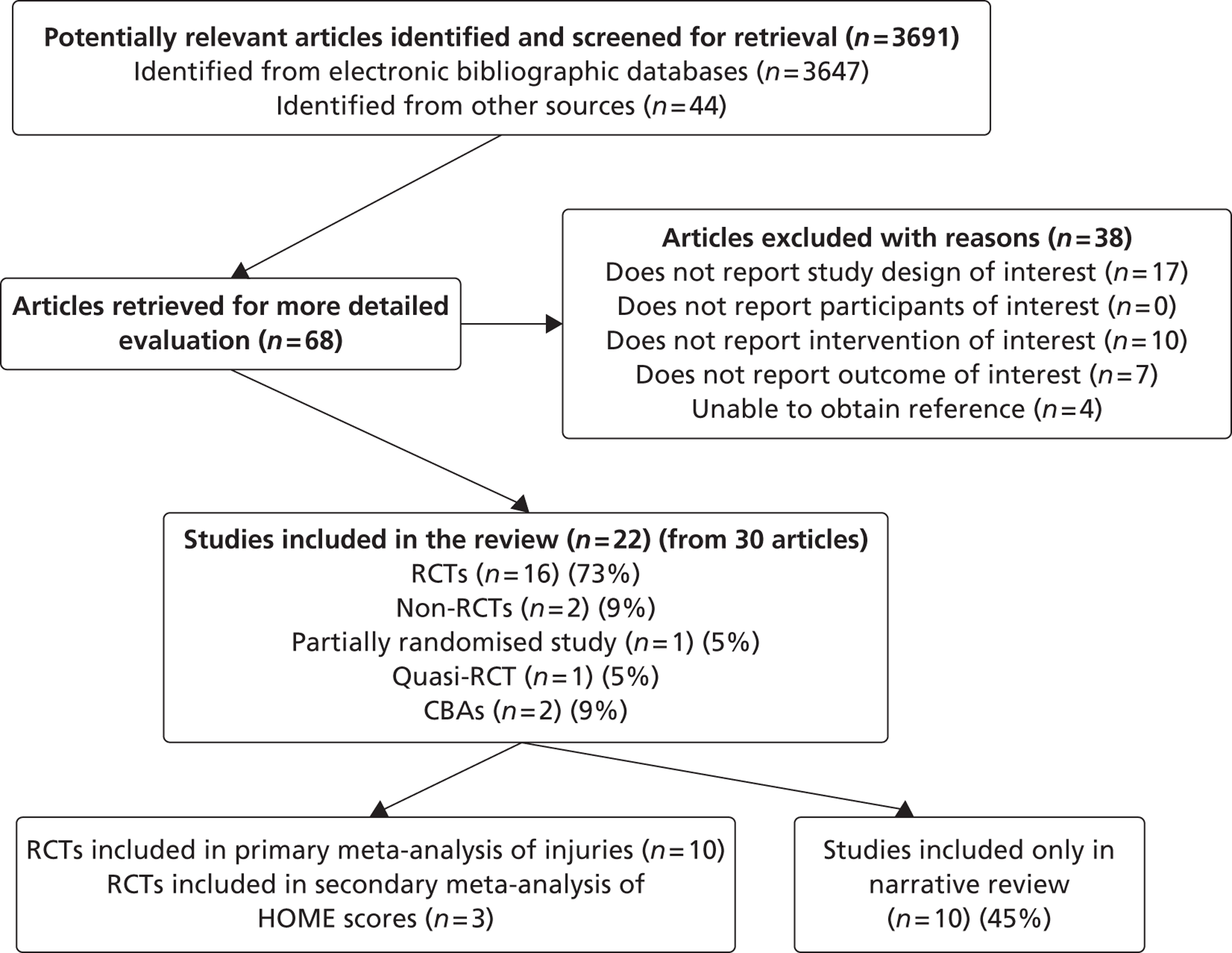

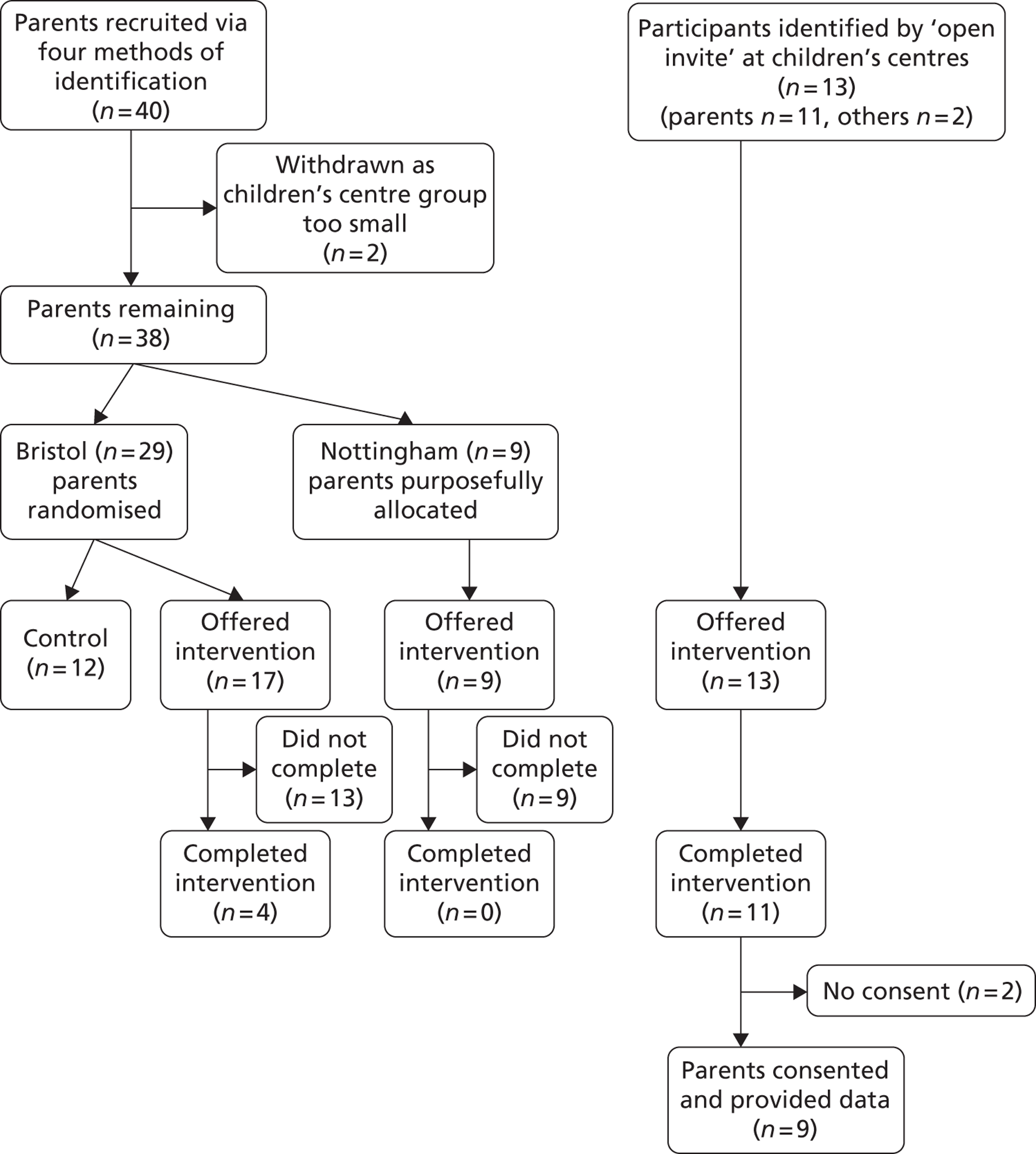

Twenty-two studies70–90 from 30 articles were included in the review (Figure 2 and see Appendix 1). Some authors reported results from the same study at different follow-up time points in separate papers and several authors reported results from the same study in more than one paper. Sixteen70–72,74,76–78,80,82–85,87,89,90 (73%) included studies were RCTs, two73,81 (9%) were non-RCTs, one86 (5%) was a partially randomised study with two randomised intervention arms and one non-randomised control arm, two75,88 (9%) were CBA studies and one79 (5%) was a quasi-RCT. Four studies73,75,81,88 used clustered allocation. Thirteen studies72–74,78–80,82,84,85,88–90 (59%) were from the USA, three from Australia70,83,87 (14%), two each from Canada76,86 (9%) and England71,75 (9%), and one each from Ireland81 (5%) and New Zealand77 (5%). Fifteen of the studies70–72,74,75,77–79,81,83–85,90 recruited socioeconomically disadvantaged participants. Two studies76,87 recruited participants with a learning disability, and three studies81,88 recruited consecutive newborns from a range of paediatric practices.

FIGURE 2.

Quorum flow chart detailing process of study selection for the review.

Seventeen studies70–75,77–81,83–86,89,90 evaluated multifaceted home visiting programmes aimed at improving a range of child, and often maternal, health outcomes. Three82,88 evaluated paediatric practice-based multifaceted interventions, aimed at improving a range of child health outcomes, all of which included some home visits. Two studies76,87 provided solely educational interventions in the home. None of the studies had injury prevention as a primary focus. All studies provided the intervention to individual parents. Four studies83,88,90 provided opportunities for peer support from other parents, one89 provided informal support from family and friends, and five studies78,80,82,85,90 provided parenting education to groups of parents which as a consequence would also provide opportunities for peer support.

Of 16 studies70,72–75,77–81,84–86,88,89 (73%) reporting medically attended or self-reported injury, two73,75 reported insufficient data to be included in the meta-analyses. Seven studies73,75,76,82,88,89 reported a range of safety outcomes such as use of socket covers and stair gates. Two studies87,89 reported home hazards using different tools, and one study82 reported scores from a home safety index. Ten studies70–72,74,83–86,89,90 measured the quality of the home environment using the HOME inventory. 69 One study73 measured the quality of the home environment using the Massachusetts Home Safety Questionnaire.

Risk of bias in included studies

In terms of selection bias, 1070,72,74,77,81,83–85,87,88 (63%) of the 16 RCTs had a low risk owing to adequate random sequence generation, and seven70,71,74,81,83,84,88 (44%) due to adequate allocation concealment. While 1571,72,74,76–78,80,81,83,85,87–90 (94%) of the 16 RCTs were judged to be at high risk of performance bias, only five77,78,80,81,83 (31%) were judged to be at high risk of detection bias. Six83,85,87–90 (38%) of the 16 RCTs had a high risk of attrition bias, and five78,83–85,89,90 (31%) were judged as being at high risk of selective reporting bias.

Effects of interventions

Medically attended or self-reported injury

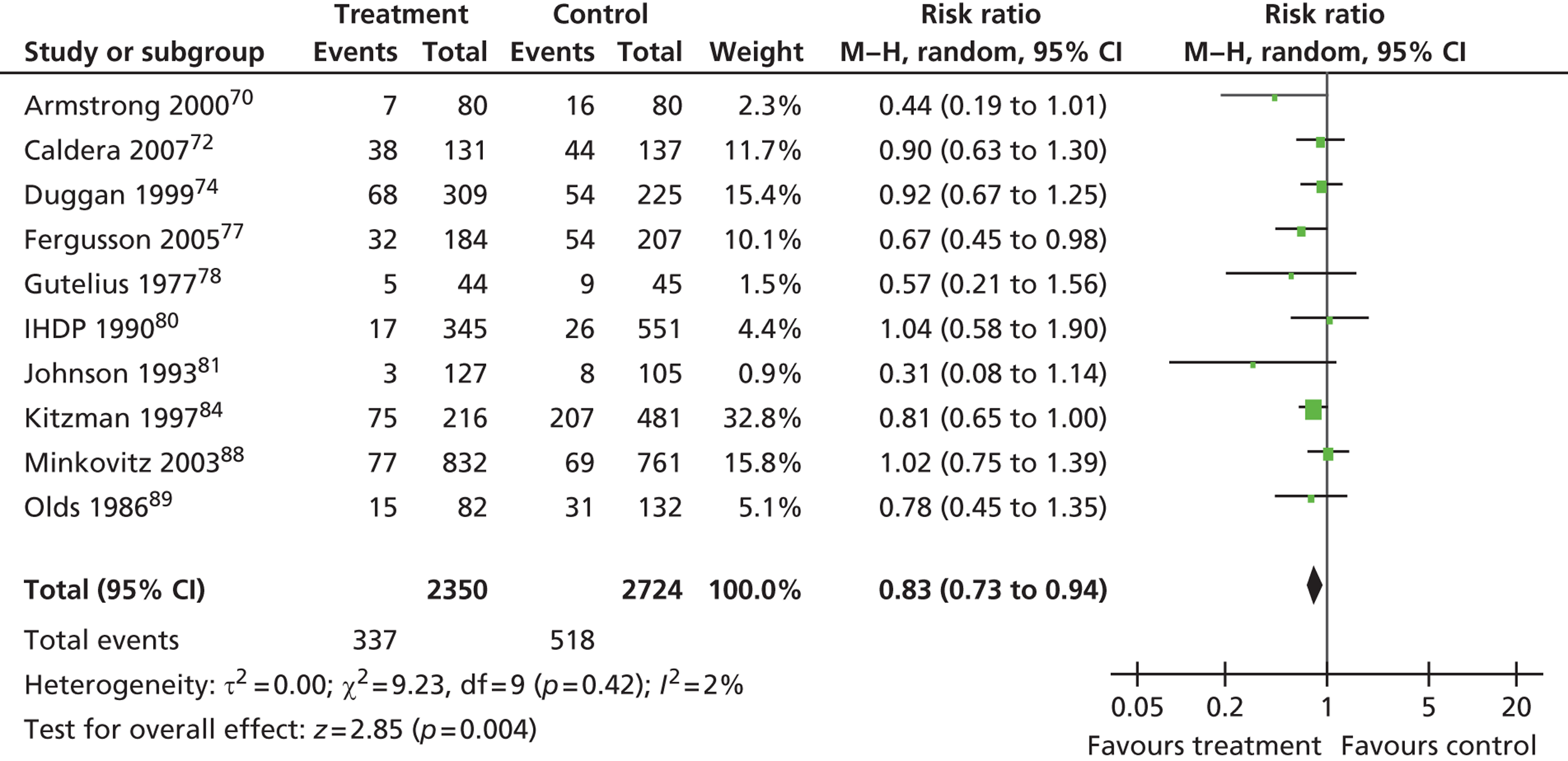

Sixteen studies70,72–75,77–81,84–86,88,89 reported medically attended or self-reported injury; 10 of these70,72,74,77,78,80,81,84,88,89 reported results from RCTs and were included in the primary analysis which showed that intervention arm families had a statistically significant lower risk of injury than control arm families (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.94) (Figure 3). There did not appear to be any evidence of publication bias among the 10 RCTs in the primary analysis {Egger’s test regression coefficient = –0.65 [standard error (SE) 0.49], p = 0.22}. Sensitivity analyses were undertaken for the primary analysis including only RCTs at low risk of various sources of bias. The findings were robust to including only those studies at low risk of detection and attrition bias but the effect size became statistically non-significant when analyses were restricted to studies at low risk of selection bias in terms of inadequate allocation concealment.

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot of medically attended or self-reported injury data – RCTs only. M–H, Mantel–Haenszel.

Home safety outcomes

Studies reported home safety practices and hazards using a variety of methods and scales. Data on total HOME scores at 12 months from three RCTs were included in a meta-analysis. The results showed that there was a non-statistically significant difference in pooled average total HOME scores between intervention and control arm families [mean difference 0.57, 95% CI –0.59 to 1.72; χ2 = 0.41, 2 degrees of freedom (df), p = 0.82; I2 = 0%], with intervention arm families scoring higher. Armstrong et al. 70 reported organisation of the home environment subscale scores and found a statistically significant difference favouring the intervention arm {mean score intervention arm 5.70 [standard deviation (SD) 0.77] vs. mean score control arm 5.11 (SD 1.16), p < 0.05}. Of the six studies72,83,84,86,89,90 not included in the meta-analysis owing to insufficient data but which reported total HOME scores or organisation of the environment subscale scores, two84,86 found statistically significant differences favouring intervention arm families, and four studies72,83,89,90 found no statistically significant difference between treatment arms, with one study83 finding statistically significant differences only among distressed mothers.

Seven studies73,75,76,81,88,89 reported a range of specific safety practices or use of items of safety equipment, such as use of electric sockets covers and stair gates, but each study measured different practices. Of the seven studies, five75,76,81,88,73 found effects favouring intervention arm families. Two studies87,89 reported measures of home hazards. Olds et al. 89 reported statistically significantly fewer observed hazards in the homes of intervention arm families than control arm families. Llewellyn et al. 87 found that intervention parents identified statistically significantly more dangers within the home and implemented a statistically significantly greater number of precautions to reduce the risk of injury than control arm parents. Three studies used composite home safety measures other than the HOME scale: two used the Home Safety Index82,91 and one used the Massachusetts Home Safety Questionnaire. 73 Families in the intervention arms of these three studies scored statistically significantly higher on safe practices and safer homes than the control group families.

Discussion

We found that parenting interventions, most commonly provided on a one-to-one basis in the home as part of multifaceted interventions to improve a range of child (and often maternal health) outcomes during the first 2 years of a child’s life, were effective in reducing self-reported or medically attended injury among young children. The finding was consistent across studies with little evidence of statistical heterogeneity between effect sizes and was robust to most aspects of study quality and study design. There was evidence that parenting interventions can have a positive effect on the use of home safety equipment and practices.

The strengths of the review include a comprehensive search strategy that included searching grey literature and hand-searching conference abstracts. The analysis adjusted for cluster allocated studies where necessary and a range of sensitivity analyses were undertaken to test assumptions regarding the potential for bias, uncertainty as to the extent to which the intervention was based on a protocol, manual or curriculum, follow-up period and injury type. The findings were robust to these assumptions. Limitations relate mainly to the generalisability of the findings, particularly the study populations which mainly comprised families considered to be ‘at risk’ of adverse child health outcomes. All studies provided the intervention to individual parents, and while several also included some parents’ groups, the findings may not be generalisable to group-based parenting interventions. Similarly, most studies provided the intervention mainly within the home, and so the findings may not be generalisable to parenting interventions provided outside the home.

Most studies used parental reports of injuries which may be subject to biased reporting, particularly as blinding participants to treatment arm allocation is not possible with interventions such as these. The quality of studies was variable, with either half or more of the RCTs included in the meta-analysis being susceptible to bias in terms of allocation concealment and/or outcome assessment. However, despite this, sensitivity analyses demonstrated little impact of excluding studies without blinded outcome assessment on the results. Only two studies included in the meta-analysis reported high attrition rates.

While our review suggests that parenting interventions are likely to improve home safety, there are other plausible explanations for why parenting interventions may reduce childhood injuries. All studies included in the primary and secondary meta-analyses were aimed at improving a range of child (and often maternal) health outcomes. Seven of these studies reported statistically significant improvements in child behaviour, four reported less punitive discipline practices among intervention group parents, six reported increased or improved mother–child interaction and two reported improvements in maternal psychological well-being. It is therefore possible that the reduction in childhood injuries may be mediated through improvements in child behaviour, more effective supervision or discipline practices or more positive interactions between mother and child, all of which may be associated with improved maternal psychological well-being.

Implications for this study

This systematic review supports the evidence that parenting interventions reduce parent-reported and medically attended child injuries and increase home safety practices and behaviour. The findings are stronger with regard to injury reduction than to home safety practices, suggesting that the mechanism may be a generic change in parenting. The review did not identify any group-based, community-delivered programmes such as that proposed for this study.

Learning points

-

Parenting interventions that include home-based, one-to-one, multifaceted components can reduce parent-reported and medically attended child injuries, and appear to improve home safety measures.

-

The mechanisms through which parenting programmes may reduce child injury are unclear but may include generic change in parenting.

-

There is no current evidence from RCTs of the effectiveness of solely group-based, community-delivered parenting programmes to reduce child injury.

Systematic review 2: barriers and facilitators to parental engagement in parenting programmes

To inform the development of the intervention we sought to identify the features of parenting programmes that enabled parents to join, and remain engaged with, programmes. Published evidence on this topic has largely been derived from surveys of those delivering or developing programmes. 48,66,67 We therefore conducted a systematic review of qualitative literature to identify studies where participants had provided evidence, for example through interview or focus groups, on the barriers and facilitators to their participation, and compared their perceptions with those delivering or researching programmes. We focused on evidence emerging from manualised group-based programmes that were more likely to be relevant to the proposed intervention.

The systematic review has been published online ahead of print in the journal Health Education and Behavior93 and the abstract is reproduced below, followed by a report of the implications of the findings for this study. Our search strategy identified 16,513 citations, from which we identified 26 for inclusion in the final review by using text-mining technology.

Abstract from manuscript accepted for publication

Parenting programmes have the potential to improve the health and well-being of parents and children. A challenge for providers is to recruit and retain parents in programmes. Studies researching engagement with programmes have largely focused on providers’, policy makers’ or researchers’ reflections of their experience of parents’ participation. We conducted a systematic review of qualitative studies where parents had been asked why they did or did not choose to commence, or complete programmes, and compared these perceptions with those of researchers and those delivering programmes. We used data-mining techniques to identify relevant studies and summarised findings using framework synthesis methods. Six facilitator and five barrier themes were identified as important influences on participation, with a total of 33 subthemes. Participants focused on the opportunity to learn new skills, working with trusted people, in a setting that was convenient in time and place. Researchers and deliverers focused on tailoring the programme to individuals and on the training of staff. Participants and researchers/deliverers therefore differ in their opinions of the most important features of programmes that act as facilitators and barriers to engagement and retention. Programme developers need to seek the views of both participants and deliverers when evaluating programmes.

Implications for this study

The review identified key features of programmes that enabled or hindered parental engagement and retention. Participants appeared to prioritise different issues compared with those delivering, or researching, programmes. However, on exploration, some of these issues were not entirely unrelated. For example, parents emphasised the need for trust in the person delivering the programme, while deliverer training appeared to emphasise the ability to deliver the manualised content of the programme rather than the ability to facilitate a group, including issues such as group cohesion. We have summarised the implications for the development of the parenting programme in this study in the learning points below.

Learning points

The key learning points from this review that are relevant to this study are detailed below.

-

Participants were interested in joining and completing parenting programmes if they believed that in doing so they would have the opportunity to learn new and specific skills, either for their own personal development or because they believed their skills would support their children.

-

The relationship between the participant, the deliverer and the other group members was very important. Participants needed to feel safe both with the deliverer and within the group. A known or trusted deliverer of the programme was helpful, but the deliverer needed to have the skills to present the programme in a non-judgemental, empathic and supportive manner. Participants needed to be able to relate to the other members of the group.

-

Practical issues such as the location, frequency and timing of the programme influenced parental engagement. Programmes needed to fit around existing commitments. Incentives such as childcare, travel expenses and refreshments were important.

-

Those delivering the programmes emphasised the need to be able to respond to the needs of the group, i.e. to be able to tailor the programme where necessary. This is in potential conflict with the production of manualised programmes that support fidelity of intervention delivery. Deliverer training needs to include group facilitation skills in addition to the ability to deliver the programme materials.

-

The potential difference in issues raised by participants and those delivering programmes indicate that both perspectives should be explored when evaluating programmes.

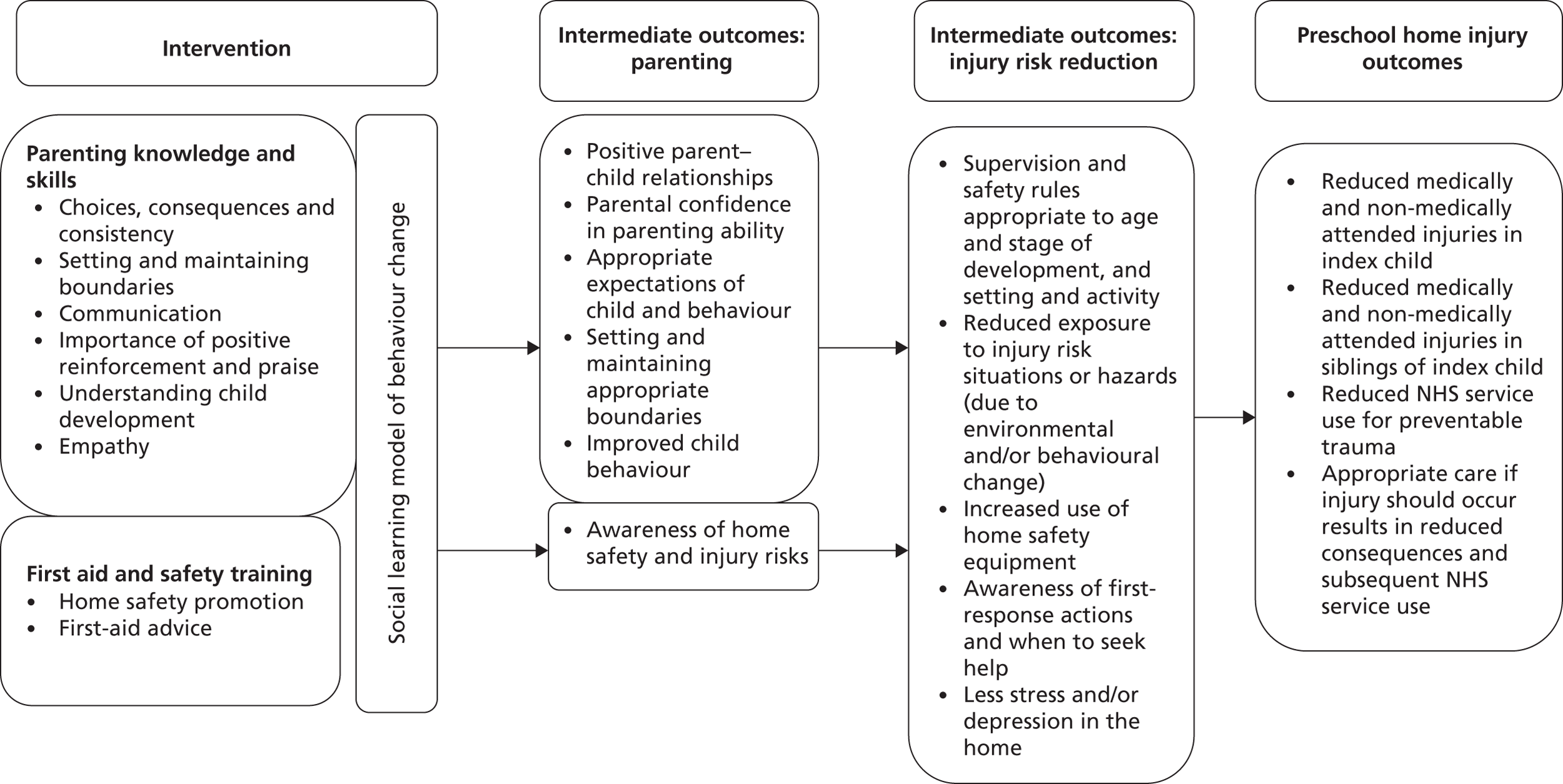

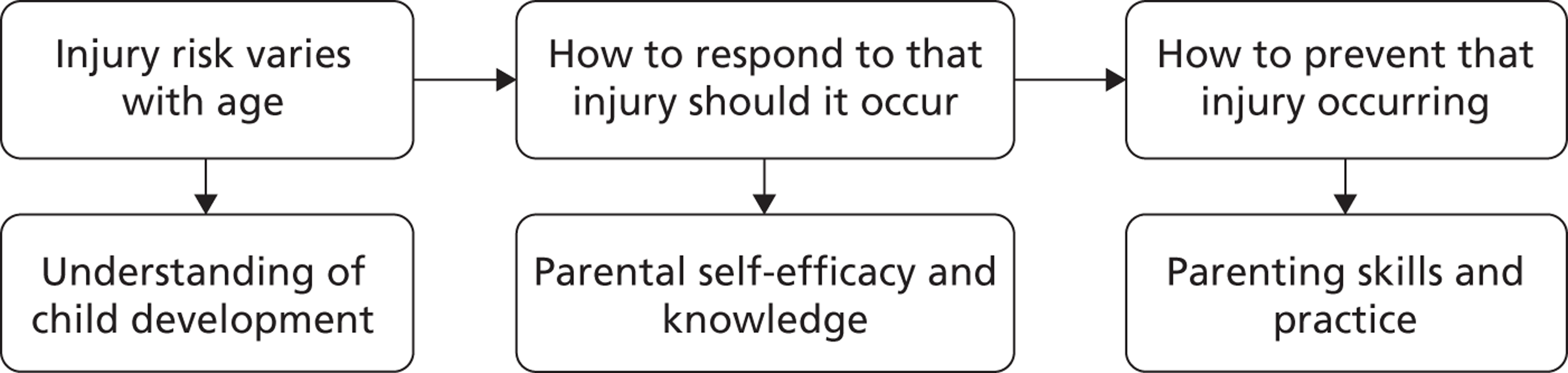

Theoretical model

We have developed a theoretical model through which positive outcomes from a parenting programme could lead to reductions in home injuries in preschool children (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Theoretical model for the impact of a parenting programme on preschool home injuries.

Effective parenting programmes have the potential to result in a range of outcomes that relate to how parents and children interact:

-

positive parent–child relationships and enhanced communication

-

parental confidence in parenting ability

-

appropriate expectations of child and behaviour

-

setting and maintaining appropriate boundaries

-

improved child behaviour.

We propose that a parenting programme that combines parenting skills and knowledge with first aid advice and home safety promotion has the potential to improve parental awareness of injury risks at different ages and stages. That in turn may lead to reduced home injuries in preschool children through a number of intermediate outcomes that reduce injury risk:

-

parental supervision and safety rules that are appropriate to the child’s age and stage of development, as well as the setting and activity

-

use of age-/developmental stage-appropriate safety rules

-

reduced exposure to home hazards as a result of environmental change (e.g. locked medicines cupboard, or removing or repairing tripping hazards)

-

increased use of home safety equipment

-

behavioural change that increases safe practices (e.g. handling hot beverages, storing medicines out of reach or not leaving child on a raised surface/alone in the bath)

-

reduction in stress, depression or anxiety in the home.

Should an injury occur, the consequences of that event may be reduced by:

-

parental awareness of immediate paediatric first aid actions

-

parental awareness of when to seek medical advice/when to treat injuries at home.

Reduced injury risk has the potential to result in fewer injury events taking place and fewer injuries sustained. It could be hypothesised that an effective parenting programme that incorporates a focus on injury prevention could result in fewer preschool home injuries presenting to emergency departments and other community NHS providers (e.g. NHS walk-in centres, or general practice). The reduction in injury risk may not eliminate injuries but may reduce the severity of the injury sustained. In these circumstances, a relative increase in the proportion of injuries that are minor or managed at home with first aid may be observed. Furthermore, if the parenting programme was successful in increasing parents’ knowledge of injuries and when to seek attention, this could result in increased health service use. For example, knowing that a bang to the head could lead to a potentially serious injury may encourage attendance at the emergency department. Providing information on when to seek help or advice will be required to encourage appropriate use of health-care services.

In Chapter 5 we have explored the feasibility of testing this model through a cluster RCT. A future trial would be required to determine if it is possible to reject the null hypothesis of no difference in injury outcomes for parents receiving or not receiving the parenting programme.

Chapter 3 Development of a parenting intervention: developmental phase

Objective

To develop a parenting programme to prevent recurrent unintentional home injuries in preschool children, together with the resources required to test the feasibility of evaluating the intervention.

Methods

Commissioning of Parenting UK to develop the programme

Parenting UK was commissioned to develop a group-based parenting programme. The commissioning brief specified that the programme should include:

-

parenting skills that have the potential to prevent injuries including, but not limited to:

-

relationship building

-

setting and maintaining boundaries

-

behaviour management

-

appropriate levels of supervision for the age and development of the child

-

-

first aid response to common injury scenarios occurring to children under the age of 5 years in the home, including but not limited to:

-

falls

-

burns and scalds

-

ingestions and poisonings

-

foreign bodies and choking

-

unconsciousness/recovery position

-

life-saving skills/cardiopulmonary resuscitation

-

cuts and wounds

-

broken bones

-

-

safety practices and equipment that, when used in an age-appropriate and/or development-appropriate way, can prevent injuries from occurring.

In addition, Parenting UK was requested to provide the materials, equipment and documentation to support the delivery of the programme during the testing of the intervention. This included the development of a programme manual for those delivering the programme to use as a reference aid. Six sets of materials were required to be produced for subsequent testing in a feasibility study.

Governance of the programme development

A programme development subgroup (PDS) was convened to oversee the development of the programme. Membership included three co-applicants: the chief investigator (JM), an academic with expertise in evaluating parenting programmes (S-SB) and a practising health visitor (BP), together with the Director of the Whoops! Child Safety Project, which provides first aid training for parents. This team communicated with the chief executive of Parenting UK and the manager employed by Parenting UK to carry out the development work. Communication between the manager and the PDS was by e-mail and teleconferences held every 3 weeks between February 2011 and July 2011. The emerging findings of the two systematic reviews conducted during the theoretical phase of this study were passed to the staff at Parenting UK to help inform development of the programme.

The Parenting UK manager was asked to keep a log to record the decisions and rationale for choices made during the development of the programme, to provide an interim report after 3 months, and to provide a final report. The manager from Parenting UK made a presentation to the research team at the end of 6 months (July 2011) to describe the course that had been produced, and seek final sign-off prior to production of the materials.

User involvement

The PAG was consulted prior to Parenting UK commencing work on the programme. During the PAG’s second meeting we asked the mothers what they had liked and disliked about any parent support courses that they had attended and what had been good or not so good about any first aid training or courses that they had attended. We then discussed the possible content and format of a course on first aid and home safety including resources and things they could do at home. They made some very helpful suggestions, which were passed onto the staff at Parenting UK.

At the next meeting of the PAG some of the resources developed by Parenting UK for use in the course were discussed. The outline of the course was described and members discussed some of the proposed activities. They were very positive about the content and resources, and this was fed back to the staff at Parenting UK.

Results

An 8-week programme, designed to be delivered in an acceptable, participant-friendly, incrementally progressive style, was produced and is summarised in Table 1, and described in more detail in Appendix 2. The content of each session, designed to be delivered over 90 minutes, was acknowledged to be challenging, particularly for a less skilled/experienced trainer. While acknowledging that some parenting programmes include sessions of 2 hours’ duration, the length of the sessions was chosen to be 90 minutes as a result of concerns that a longer session may reduce the likelihood of parents engaging with the programme owing to the perception of it being an onerous commitment. Each week started with a reflection on the previous week’s content and exploration of the application of knowledge or skills at home since the group last met. Each week ended with an opportunity to discuss and clarify details discussed that week together with suggestions of activities parents might wish to try at home.

| Week | Content |

|---|---|

| 1 |

Introduction to the course

|

| Discussion about the challenges parents face in keeping their children safe | |

| 2 |

Child development and injury risk. Illustrate with head

injury scenarios and advice

|

| Discussion of how home hazards link to injury and development | |

| 3 |

Communication between parents and children. Illustrate

with choking risk scenarios and advice

|

| Responding when your child is choking, preventing choking | |

| 4 |

Managing attention-seeking behaviour, using praise.

Illustrate with burn and scald scenarios

|

| Providing appropriate supervision for your child | |

| 5 |

Setting and maintaining boundaries. Illustrate with

ingestion and poisoning scenarios and advice

|

| Keeping children safe from poisons and ingestions/first response | |

| 6 |

Appropriate expectations of children. Illustrate with safe

play scenarios

|

| Safe toys and games at different ages | |

| 7 |

Attachment/how we react when upset or angry. Illustrate

with unconscious child scenarios

|

| What to do if your child were unconscious/recovery position and resuscitation | |

| 8 |

Drawing the course together

|

| Wrap up/thanks for participation/certificates of attendance |

The programme and trainer manual were developed through an iterative process informed through written comments on each draft version and three weekly teleconference discussions with the PDS. Some materials were identified from other programmes and resources and, where included, written permission was provided. The artwork was directly commissioned by Parenting UK for this programme. The decision log is summarised in Appendix 3.

The following outputs were delivered:

-

Twelve A4 trainer manuals – white polyvinyl chloride (PVC) ring binders, with a 4 × D-ring mechanism, clear pockets on the front cover and spine for colour inserts, and the contents divided into three sections: (1) general introduction to the programme and advice on running groups, (2) the contents of each of the 8 weeks of the programme, broken down into timed components and activities and (3) resources and materials used in each session.

-

Fifty A5 parent handbooks – white PVC ring binders with a 4 × D-ring mechanism and clear pockets on the front cover and spine for colour inserts – for the participants to store handouts provided during the weekly course sessions together with any notes that they chose to make.

-

Four sets of laminated pictures/tools for the delivery teams to use during session delivery.

-

Two resource kits (one for each study centre) were provided by the Whoops! Child Safety Project. Kits contained two burns dolls, doll for demonstration of resuscitation and choking response, choking tube, heat change colour mug, fire safety DVD, leaflets and an A3 poster tube with laminated drawings.

-

A ‘train the trainer’ package, designed as a 2-day course for delivery teams and described in detail in Appendix 4.

Support for those delivering the programme

The manager from Parenting UK made a number of recommendations regarding support for those delivering the programme. It was acknowledged that support to all the deliverers in a group face-to-face environment would enable shared learning and avoided duplication of information exchange. However, it was recognised that the courses were unlikely to be delivered concurrently across the study centres, resulting in deliverers having different support needs at different times. In addition, not all of the course deliverers would be available at the same time. Therefore, the manager at Parenting UK offered to be available to provide weekly telephone and e-mail support as required for those delivering the four courses planned during the feasibility study. The option of video conference contact was considered but rejected owing to the limited electronic access available to course deliverers in their usual work locations.

Discussion

The process of developing the 8-week programme, working with two voluntary sector organisations – Parenting UK to develop the programme, and the Whoops! Child Safety Project to advise on the first aid and safety content of the programme – proved to be a very constructive and positive experience for the organisations and researchers involved. The process of combining elements of parenting programmes with information on injury risk and injury prevention was acknowledged by all parties as challenging, but considered worthy of the effort on account of the perceived benefits of a programme with the potential to reduce unintentional injuries in the home for preschool children.

The programme was developed to provide a ‘spiral curriculum’ of parenting skills and knowledge, where issues were revisited several times during successive weeks of the course. This process encourages the participants to try the new skills themselves when at home, and then receive support and opportunities for discussion when the subject was revisited. The parenting skills and knowledge were introduced using injury risk and injury outcome scenarios to illustrate how parenting skills can help to keep children safe.

The challenge of intervention fidelity is well known among those developing and evaluating parenting programmes. The small-scale nature of the feasibility study of the programme meant that quite personalised support could be made available to those delivering the courses in the two study centres. It was acknowledged early on that any future trial or subsequent roll-out of the programme would need a different process to ensure fidelity of delivery and support for course facilitators. Recommendations made by Parenting UK are included in Chapter 8 (see Implications for a main trial).

Learning points

-

Voluntary sector organisations working with the participant group were informed and valued partners in the intervention development process.

-

The involvement of the voluntary sector organisations in the production of the 8-week parenting programme, informed by recommendations made by the PAG and a parents’ forum facilitated by Parenting UK resulted in an intervention more likely to meet the needs of the participant group than if developed from a theoretical perspective alone.

Chapter 4 Development of tool to collect primary outcome measure

Objective

The objective of this component was to develop a tool for parents to report unintentional home injuries occurring to their preschool children. This tool would be used during the study to test the feasibility of evaluating the parenting programme through a cluster randomised controlled design.

Elements required to be captured by the tool

The tool needed to capture the following features of each injury event:

-

the date of the event (to confirm occurrence was within the follow-up period)

-

the location of the injury event (to confirm that it was an injury occurring within the home, garden, drive or yard)

-

the type of injury sustained (e.g. cut, fracture, head injury, etc.)

-

the action that was taken [e.g. first aid, telephoned general practitioner (GP), took child to hospital, etc., to determine medically attended from non-medically attended injuries, and to enable the collection of data for any subsequent cost-effectiveness analysis]

-

whether the injury was sustained by the index child or by any preschool siblings in the household.

Development process

The follow-up period during which the tool would be tested was for 6 months. It was decided early on that a calendar-style record might be acceptable to parents. To develop the injury measure we planned to take designs to the PAG for discussion and feedback.

The initial two versions of the injury calendar were prepared on landscape A4 paper using a ‘month-to-a-view’ design with a box for each day of the month, in which the parent could indicate that an injury had been sustained. On the first version, the calendar filled one side, and space for adding detail about the injury event was made available on the reverse. On the second version, the calendar section was smaller, allowing details about the first two injury events that month to be included on the front and details of further injury events on the reverse. We anticipated that a parent might wish to stick the calendar on the door of the fridge, a kitchen cupboard or notice board for convenience. A series of tick boxes enabled the parent to record the location of the injury event, the type of injury and the action taken for up to six injury events that month. Tick boxes were used in an attempt to reduce the time taken to complete the record. The tool would have required six such pages, one for each month of the follow-up period. The PAG members did not like the initial designs, expressing concern about the appearance (too big for a fridge door) and the clarity of the instructions, and they were concerned that it would take too much time to complete. They felt that a 6-month collection period was lengthy and suggested they might give up completing it, or forget about it after a few weeks. The group discussed the value of incentives to continue and support their completion. Following this discussion, the study team agreed to redesign the tool based on the PAG’s feedback, and bring a revised tool back to them.

A new version of the diary was designed working with a graphic designer at the University of the West of England, Bristol. A month-to-a-view calendar design was retained but this time developed as a tall slimline calendar (A3 size, split lengthways, and spiral bound along the top short edge, suitable for hanging on the wall). A line for each day of the month provided space to record details of any injury events occurring on that day. The front page of the calendar was designed to provide instructions on how to complete the calendar, including a definition of ‘an injury’, and space to record the child’s name. For each month in the calendar, the first line was filled in with an example of how it could be completed. The unique identification number for each participant in the study could be recorded in the footer of each page. The text was reviewed to improve understanding and use language in common use; for example, ‘head injury’ was changed to ‘bang on the head’. This second design was presented to the PAG and was received very positively. They suggested having space to write additional comments on the reverse of each month, so that they would have space to explain what happened if they wished to.

Further minor amendments were made to the calendar, including adding space on the reverse of each month as recommended, and addition of a ‘don’t know’ option when recording the location of the injury. The final version of the tool is shown in Appendix 5.

Use of the injury calendar

The calendar was used for the feasibility study to collect parent-reported injuries in the preschool children of participants. The methodology and results (completion rates and data captured) are described in Chapter 5.

Discussion

The PAG was central to the development of the injury measure. They informed the appearance, content and utility of the design. Although the number of data items requested for each injury event was small, there was a risk of poor completion if either the format was too complicated or the instructions were not understandable. The familiarity of the slim spiral-bound calendar design was welcomed by the parents. The positive feedback from the second version of the tool increased our confidence that parents recruited to the feasibility study might complete the tool.

Originally we planned to call our primary outcome measure an injury diary. In July 2011 we decided to change the name from an injury diary to an injury calendar. A common understanding of a diary is that a certain amount of writing would be required and use of the word ‘calendar’ was felt helpful to promote the understanding that only brief notations were required. It was important to make the language used on the calendar easy to understand. While the early designs had tried to avoid medical terminology, comments from the PAG identified additional text suitable for amendment and made suggestions for ease of completion. The PAG suggested the option of text reminders for parents to encourage the completion and return of calendars.

The use of a professional graphic designer improved the appeal and familiarity of the calendar, which appeared to be particularly important in the acceptability of the final design when presented to the PAG. The designer was able to advise on the format to improve the likelihood that completion would be perceived as straightforward.

Learning points

-

The acceptability of a new parent-reported injury outcome measure was improved by the use of a graphic designer who recommended changes to simplify the information recording process and to increase the familiarity of the design.

-

The PAG provided feedback on designs, which increased the likelihood that the recording of potentially sensitive information would be completed.

Chapter 5 Feasibility study

Aim and objective

The aim of the feasibility study was to assess the ability to deliver and evaluate the parenting programme through a cluster RCT.

The objectives were:

-

to assess the recruitment and retention of parents

-

to assess compliance with delivery of the intervention

-

to determine the training, equipment and facilities needed for the delivery of the programme

-

to assess the collection of primary and secondary outcome measures

-

to clarify ‘normal care’

-

to assess the resource utilisation and costing data that would need to be collected in a main trial

-

to produce estimates of effect sizes to inform sample size estimation for a future trial.

The methods and results for objectives (a)–(e) and (g) are reported in this chapter. Objective (f) is reported in Chapter 6.

The protocol for this feasibility study has been published in the journal Injury Prevention. 94 The original study protocol (version 1) approved by NHS Ethics is presented in Appendix 6. The final protocol after amendments (version 4) is presented in Appendix 7.

Methods

Trial design, funding and approval

The feasibility study was a multicentre, cluster randomised, unblinded trial comparing the First-aid Advice and Safety Training (FAST) parent programme against usual care. The two study centres were Bristol and Nottingham.

The trial was funded by the NIHR HTA programme (reference number 09/02/02) and commenced in January 2011. It was approved by the South West Level 3 Research Ethics Committee (reference number 10/H0106/78) and was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Register (reference number 03605270).

Participants

Children’s centres

Inclusion criteria

In accordance with the original study protocol, children’s centres in both study centres were ranked according to the number of children aged 0–4 years who had attended the local children’s emergency department with an injury in the previous 12 months, and had a postcode that would have entitled them to access that children’s centre. Children’s centres with the highest rankings in each city (i.e. the centres with the largest numbers of young children attending with injuries) were invited to join the study until sufficient numbers of children’s centres had been recruited.

Exclusion criteria

Children’s centres were excluded from participating if they were already involved in other injury prevention research.

Parents

Inclusion criteria

Parents and carers (hereafter referred to as parents) were eligible for recruitment if they:

-

had a child under 5 years of age who sustained an unintentional physical injury in the home (or within the boundary of the home and garden/yard) for which they sought medical attention from a health professional at a NHS emergency department, minor injuries unit, or walk-in centre during the recruitment period or in the previous 12 months

-

were living at an address within the geographical catchment area of a children’s centre participating in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Parents were not eligible to join the study if:

-

they were unable to understand written and spoken English

-

the child suffered an injury suspected or confirmed to be intentional. Should an injury originally considered to be unintentional be later discovered to have been intentional then routine referral processes for safeguarding would be activated. The parent would not be asked to withdraw from the programme, but data for that child would not be included in the analysis.

If a parent already recruited to the study sought medical attention for an injury in a preschool sibling of the index child they would not be invited to join the study again.

Recruitment of children’s centres and health visitor teams

Recruitment of children’s centres and health visitor teams began in March 2011 and ended in January 2012. While it was feasible to rank children’s centres on the basis of rate of attendances of preschool children with injuries, it quickly became apparent that the factor most likely to influence the ability of a children’s centre to participate in the study was the engagement of the linked health visitor team. Each children’s centre is linked to a named health visitor team. The degree to which the children’s centre and the health visitor team are linked varies significantly from being based in a shared building and working closely together, to being linked in name only and working independently.

During the period between preparation of the original protocol and commencement of the study, organisational change combined with worsening health visitor capacity issues had resulted in:

-

change of the employer of health visitors in both study centres; neither of the new employers had been involved in initial discussions about the study prior to funding

-

new management structures within health visiting services in both cities in response to workforce capacity difficulties. Previously, health visitors were relatively autonomous professionals. The new structures placed managers as gatekeepers to health visitor teams, and required permission from the manager prior to engagement with the teams themselves. The identification and engagement of managers was difficult and slow in both centres.

In addition, another nationally funded injury prevention study based in children’s centres in both Bristol and Nottingham reduced the number of eligible children’s centres for this study.

The intended model of identification of paired children’s centres and health visitor teams was found not to capture the complex and variable ways in which children’s centres and their health visitor teams worked across the two study centres. In both cities, even though each children’s centre had a theoretical catchment area, parents attended the children’s centre that most appropriately met their needs rather than the one that was closest to them. In addition, children’s centres would not refuse a parent attending simply because they did not live locally. Children’s centres were found to have markedly variable facilities, with some not having the capacity to host both a programme and a crèche concurrently.

The identification of four pairs of linked children’s centres and health visitor teams in each centre was therefore achieved through a process of negotiation and an attempt to achieve a reasonable geographical distribution of participating children’s centres across each city.

Recruitment of parent participants

In our original protocol we anticipated identifying eligible parents through health visitor teams over 4 months. As a result of slower identification than anticipated, recruitment took place over 12 months (between May 2011 and April 2012) and during this period we added alternative strategies to identify the optimal methods for a future trial. Three further methods of identifying eligible families were assessed: emergency department identification using telephone contact, emergency department identification using postal contact, and identification via children’s centres (Table 2). At any one site several strategies ran concurrently. For three of the strategies (health visitor identification, emergency department identification via telephone contact, and children’s centre identification), the names and contact details of parents interested in finding out more about the study were passed to the research team who confirmed eligibility, provided further information and answered questions, and took consent. For the remaining strategy (emergency department identification via postal contact), potentially eligible participants contacted the researchers directly, who then confirmed eligibility and took consent.

| Study centre | Identification through health visitor teams | Identification via emergency department using telephone contact | Identification via emergency department using postal contact | Identification through children’s centres |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bristol | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Nottingham | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Identification of participants via health visitor teams

Recruitment via health visitor teams was the method specified in our original proposal and was used between May 2011 and March 2012. Health visitor teams are routinely faxed details of children who have sustained an injury and attended an emergency department, minor injuries unit or walk-in centre within their catchment area of responsibility. Upon receipt of a notification of attendance, a member of the health visiting team contacted the family to advise them that their local children’s centre was participating in a study to follow up preschool children who had an injury and that some children’s centres were providing a course for parents that included first aid advice and home safety information. To reduce the risk of stigmatisation, parents were not advised that the course was a parenting programme at this initial contact. Parents were asked if their details could be passed to the research team who would tell them more about the study. To facilitate the task, health visitor teams were provided with a guide to eligible families, a template to record eligible families and outcomes of contacts, a suggested script to guide the telephone discussion with families, and a parent information sheet. Health visitor teams were able to claim service support costs to cover the time taken for this additional work.

To reduce the workload for health visitors, we proposed that the health visitor clerk could undertake the task of contacting families. In practice, clerks did not feel confident to telephone parents and the task was undertaken by either a health visitor or a nurse in her team. We suggested that eligible families could be identified both prospectively and retrospectively (where a child had sustained an injury within the previous 12 months). The contact details of parents agreeing to have their contact details passed to the research team were sent to the research office via fax.

Identification of parent participants via emergency departments using telephone contact

This approach was used in the emergency department of the children’s hospital in Bristol. Ethical approval for the additional recruitment strategy was obtained in September 2011. Parents were not approached at the time of their presentation to the emergency department, but afterwards, by telephone. A research nurse and an administrator contacted the parents of children under the age of 5 years who had presented to the emergency department with an apparently unintentional injury where the hospital record suggested that the injury may have been sustained in the home or garden. The nurse advised the parent that there was a local study that aimed to support parents of young children to help keep them safe from injuries at home, and that parents who joined the study may be able to take part in a first aid advice and safety course. The parent was asked if their contact details could be passed to the research team who would contact them with more information.

Eligible parents were identified prospectively between October 2011 and March 2012, and retrospectively via a review of electronic attendance records between July 2011 and September 2011. To facilitate the task, the research nurse and administrator were provided with inclusion and exclusion criteria, a template to record eligible families and outcomes of telephone contacts, a suggested script to guide the telephone discussion with families, and a parent information sheet. The contact details of parents agreeing to have their information passed to the research team were sent to the research office via fax. The number of parents approached but declining to have their details passed to the research team was noted, together with the reason for refusal where provided.

Identification of parent participants via emergency departments using postal contact

This approach was used in the emergency department of the children’s hospital in Nottingham. Ethical approval for the additional recruitment strategy was obtained in September 2011. An emergency department research nurse performed a retrospective search of attendance records to identify potential eligible families with a general practice address that mapped to the catchment areas of children’s centres participating in the study. In November 2011, letters were sent to children who were identified as having attended the emergency department in the previous 6 months for treatment of an unintentional injury. Information sent to the parents included an introductory letter from the emergency department consultant, a parent information booklet, a reply slip and a freepost envelope. A reminder letter was sent out 2 weeks later to any parents who had not responded to the first letter. As a result of a low response rate, the time period of retrospective emergency department attendance was extended to from 6 months to 13 months (i.e. by a further 7 months). All potentially eligible parents identified in this second period were sent letters in January 2012.

Identification of parent participants via children’s centres

This approach was used in both study centres, Bristol and Nottingham, between December 2011 and April 2012. Approval from the ethics committee of the University of the West of England was obtained in November 2011. Following advice both from health visitors and from children’s centre staff, we established a fourth strategy to identify eligible families. In each of the four children’s centres in both Bristol and Nottingham members of the research team attended parent groups (such as ‘stay and play’ or ‘parent and toddler’ groups) to talk to parents about the study, hand out A5-sized flyers and answer questions. In addition, children’s centre staff were briefed on the study and encouraged to discuss the study with parents, hand out flyers and offer to ask the research team to contact the parent if they were interested. We provided the children’s centres with A3-sized posters and A5-sized flyers that contained information including the criterion of having a preschool child who had sustained a medically attended injury (see Appendix 8).

Parents who expressed an interest in the study could take home parent information sheets, consent forms and a stamped addressed envelope, or could complete them with the researcher at the children’s centre at that time if they wished. If consent was given at the children’s centre, parents could choose to complete the baseline questionnaires at the same time or take them home along with a stamped addressed envelope.

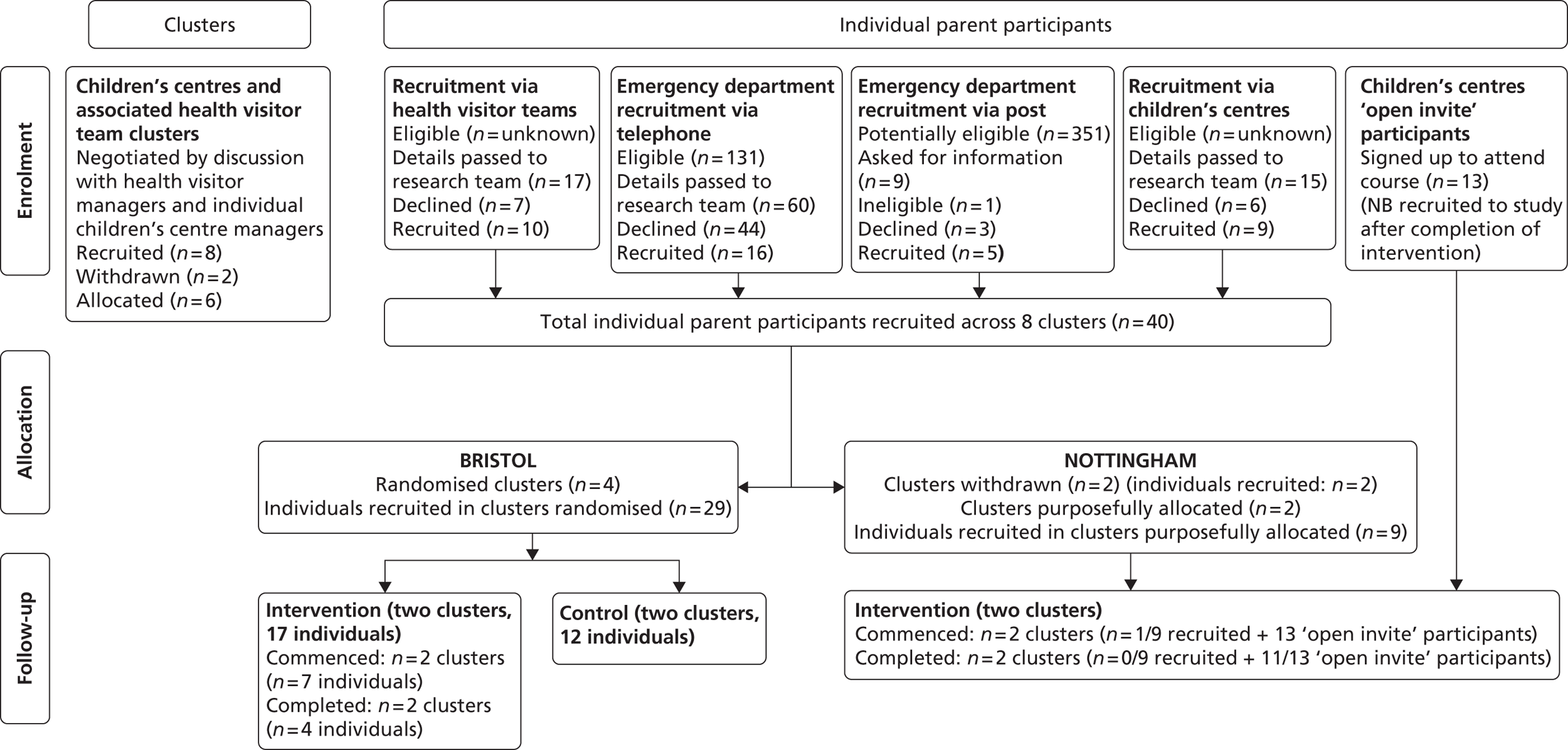

Randomisation and allocation