Notes

Article history

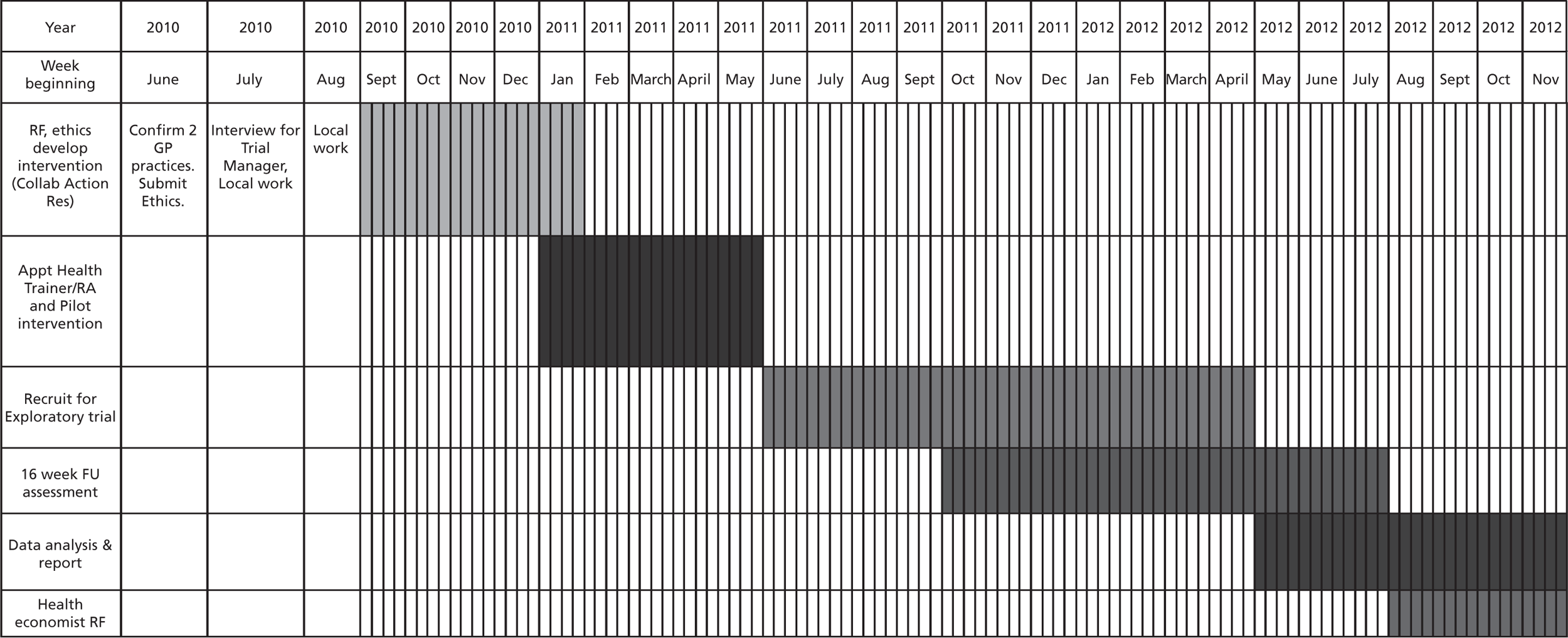

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 07/78/02. The contractual start date was in September 2010. The draft report began editorial review in December 2012 and was accepted for publication in April 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

PA has been a consultant and done research for manufacturers of smoking-cessation products. RW has undertaken research and consultancy for companies that develop and manufacture smoking-cessation medications. He is co-director of the National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training and a trustee of the stop-smoking charity, QUIT. He has a share of a patent on a novel nicotine delivery device. All other authors have declared no competing interests.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Taylor et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

During the course of this pilot trial a number of methodological issues arose and these were resolved. A specific section in the discussion chapter within the main report considers discrepancies in reported methods (e.g. inclusion/exclusion criteria, sample size, outcome measurement) between different sections such as the protocol (see Appendix 2), methods (see Chapter 2) and results (see Chapter 3). Sequentially the protocol and methods describe what we planned to do, and the results and discussion chapters describe what was achieved.

Scientific background

Current treatment/management options for smoking cessation and reduction, especially among disadvantaged smokers

Health service priorities for helping people to quit smoking focus on identifying a quit date with associated abrupt cessation, involving pharmacological and behavioural support. 1 After 1 year, only about 4% of those who attempt to quit without support succeed,2 whereas in the UK that figure is almost doubled (7%) with NHS support in primary care and almost quadrupled (15%) with the support of the NHS specialist Stop Smoking Service (SSS). 3 In recent years greater resources have been directed towards helping disadvantaged groups (e.g. unemployed people, low-skilled manual workers and people with mental health problems) to quit in an attempt to address growing health inequalities. 4 The rate of those attempting to quit is constant across social groups, but those from more disadvantaged backgrounds are less likely to succeed in remaining abstinent. 5 This results in a growing disparity in smoking prevalence rates between social groups and therefore in consequent health inequalities. For example, from 2007 to 2008, among those in social class grades C2–E smoking prevalence rates reduced by only 1.3% compared with 2.3% for grades AB–C1. 6

Good-quality evidence for the effectiveness of smoking-cessation interventions for disadvantaged groups is limited. 7 Further research is needed on how best to increase the reach of interventions to those who are less attracted to smoking-cessation services, and increase smoking-cessation success among such groups to reduce health inequalities. It is likely that a range of options may be needed to increase the reach of services and to reduce smoking prevalence, such as locating services in community settings with most need,4 developing roles for NHS outreach workers [e.g. health trainers (HTs)],8 and developing complex behaviour-change interventions that are specifically designed for disadvantaged groups. 9

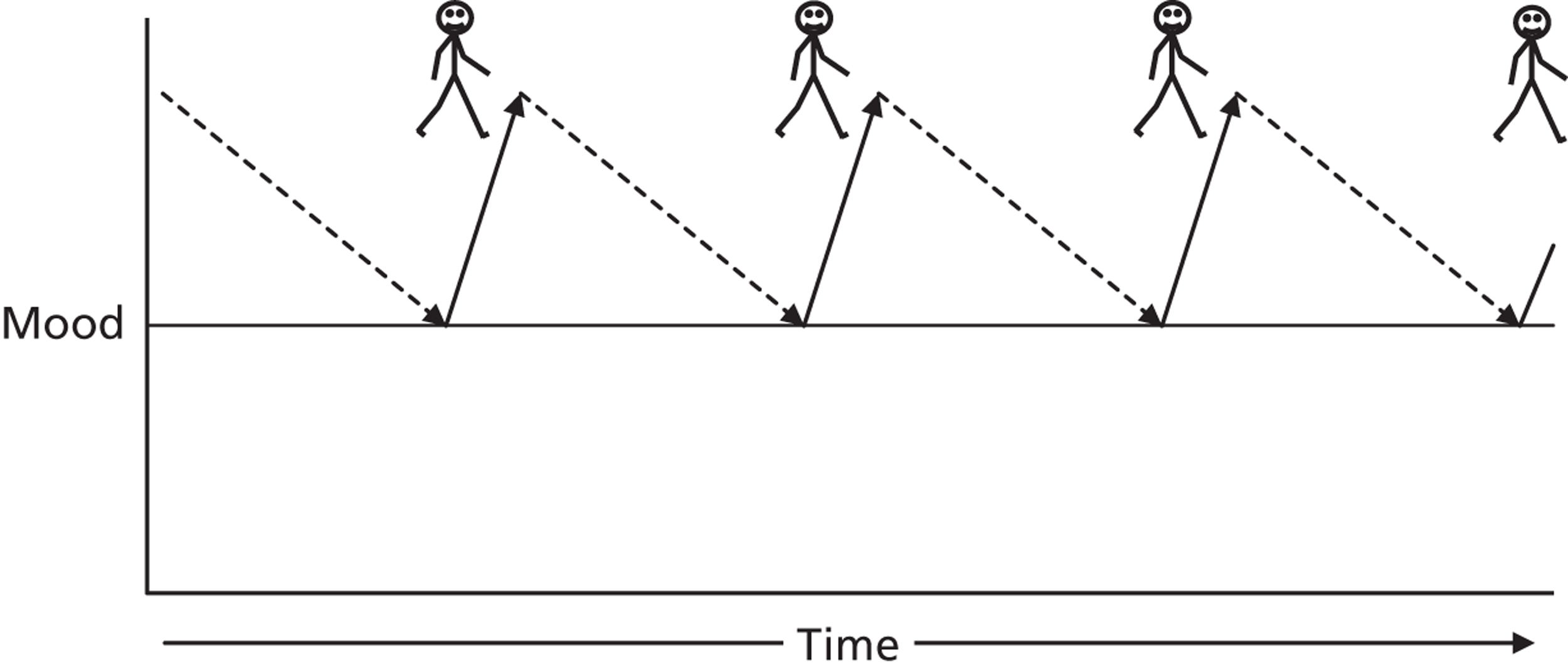

Abrupt cessation is the preferred treatment approach for quitting because, in theory, smokers who cut down prior to quitting may gain greater reward from each cigarette as they become fewer and farther between and hence find quitting more difficult. 1 Yet in the English Smoking Toolkit Study, 57% of current smokers reported that they were in the process of cutting down,6 with a variety of approaches being used. 10 While nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) is popular as an aid for smoking reduction, another study revealed that 31% of smokers believed that sustained use of NRT was ‘very’ or ‘quite’ harmful to health. 11 Furthermore, stop-smoking advisors and managers have expressed concern that combining NRT with smoking may have negative health consequences. 12 There is clearly a need for further research on supporting smoking reduction for those who do not wish to use NRT, among both those who do wish to quit and those who do not. Among those who do wish to quit, smoking reduction using pharmacotherapy and behavioural support appears to be equally as effective as abruptly quitting. 13

In a US survey, interest in reduction was highest among those who were less interested in quitting and among heavier smokers. 14 However, epidemiological studies suggest that cutting down is associated with an increased probability of trying to quit. Also, smokers who do not intend to quit in the next month, but do cut down (with NRT), are more likely to make a quit attempt and remain abstinent at follow-up. 15 Smoking reduction may increase the motivation to quit, which is highly predictive of quit attempts, and reduce smoking dependence, which is related to successful quitting. 16 Motivational advice (without NRT) can increase quit attempts lasting at least 24 hours and 7-day point prevalence abstinence at 6 months. 17 Behavioural support aims to increase confidence in smokers so that they can cope with cravings and withdrawal symptoms, reduce smoking, and ultimately remain abstinent. 18

Evidence for the effectiveness of exercise for smoking cessation and related outcomes

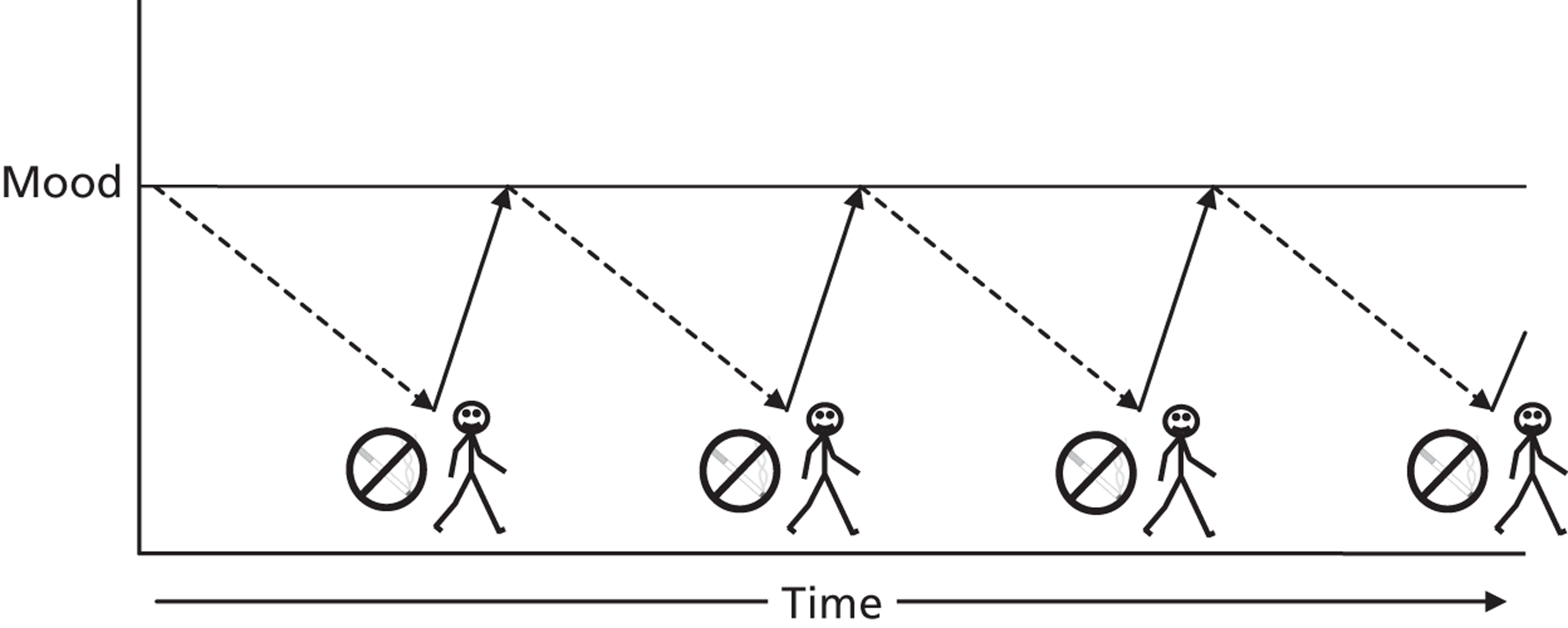

There is strong evidence that a single session of physical activity (PA) can reduce both cigarette cravings19 and withdrawal symptoms. 20 It can also delay smoking21,22 and decrease puff volume during temporary abstinence. 22,23 A review of exercise interventions (vs. usual care) as an aid for long-term smoking cessation24 identified 16 studies. However, most were methodologically limited, with seven involving fewer than 25 participants in each arm. Of the seven that were adequately powered, three supported significant increases in abstinence at the end of treatment, but only one supported increased abstinence rates at 12-month follow-up. Variation in study length, type (e.g. structured group-based exercise, and PA counselling) and content of the control condition complicated comparison of the studies in the review. The timing of the introduction of PA also varied across studies, with some studies promoting involvement in PA several weeks before a quit attempt. All these studies were among smokers who wished to quit, and none with those who wished only to cut down. Almost all studies focused on the use of prescriptive exercise sessions supervised by an exercise professional, with only a few promoting changes in daily lifestyle activity as a way to manage cigarette cravings and withdrawal symptoms. Coupled with epidemiological data suggesting that physically active smokers are more likely to attempt to quit,24 there is therefore scope to explore if PA could facilitate smoking reduction and cessation induction.

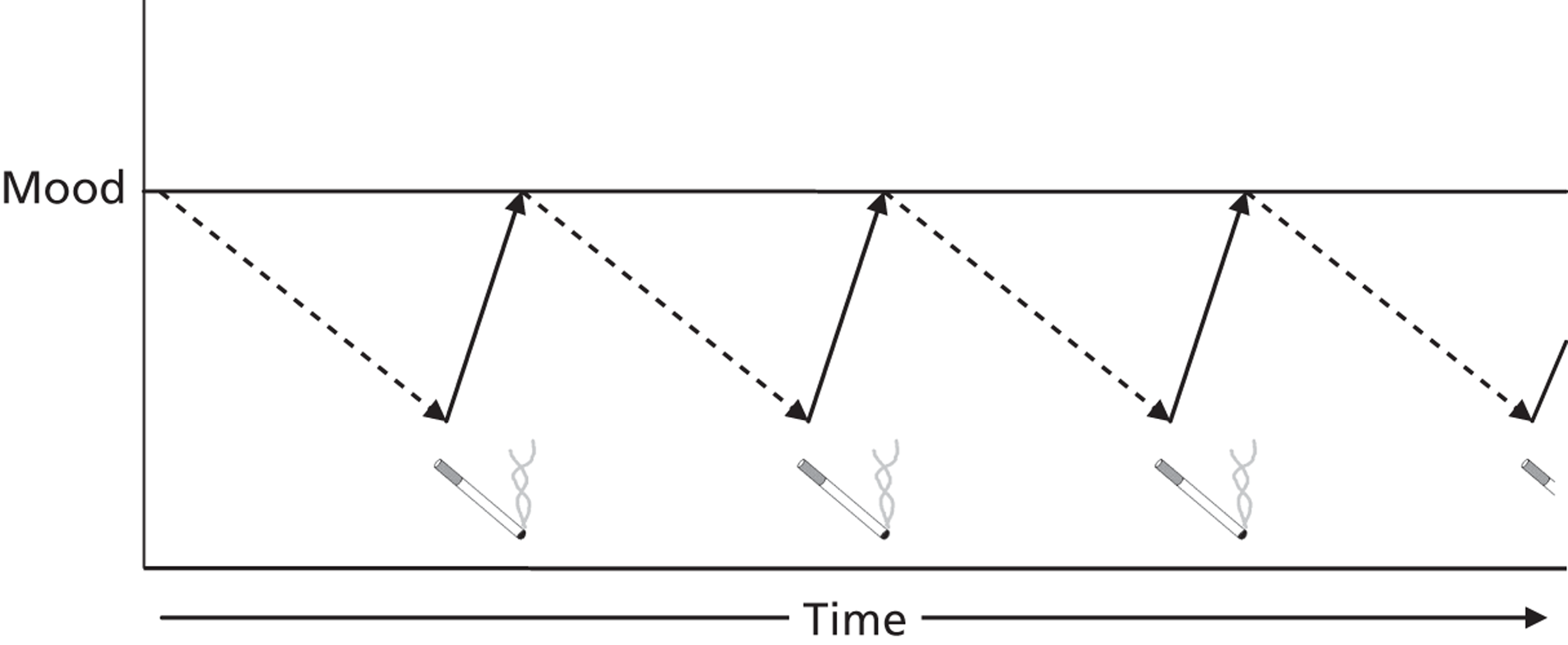

Possible mechanisms for how exercise might influence smoking

There are several ways in which an increase in PA may putatively facilitate smoking reduction and cessation induction. 25 In addition to smokers explicitly using short bouts of PA to cope with cravings and withdrawal symptoms (see above), it may also help to reduce the substantial weight gain associated with cessation. 26 On average, smokers experience almost 5 kg of weight gain, with 13% gaining over 10 kg, in the year after quitting. 26 In a limited number of studies, increasing PA has been shown to be a useful strategy to prevent weight gain among those quitting smoking,27 and its promotion is popular with smoking-cessation practitioners. 28 PA may be effective by both increasing energy expenditure and enhancing self-regulation of emotional food snacking associated with low mood. 29,30 Of relevance to the present study, systematic reviews and prospective cohort studies suggest that people of lower socioeconomic status and heavier smokers (among other characteristics) are at increased risk of weight gain. 31

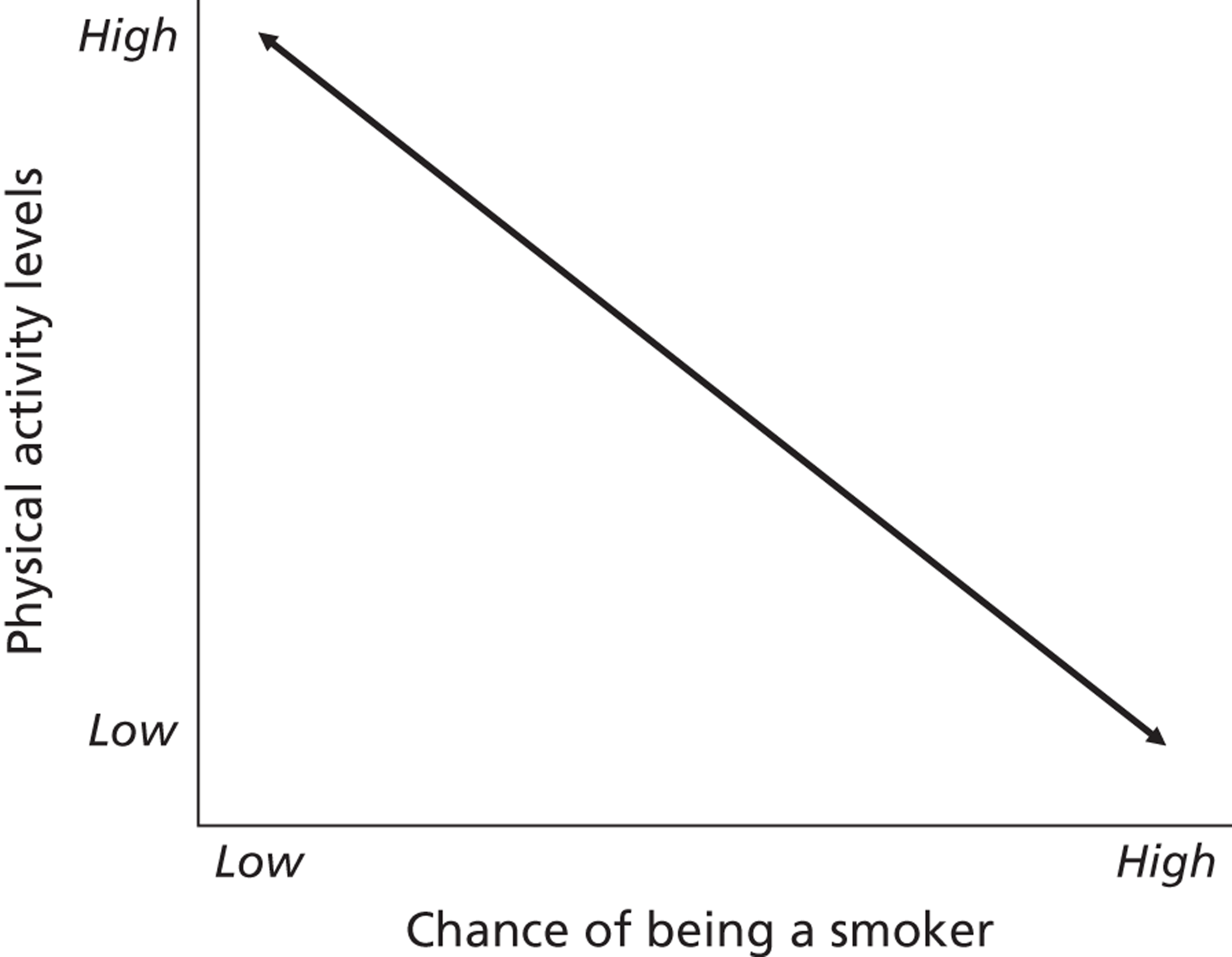

Smoking prevalence is greater among people with mental health problems, perhaps because nicotine may improve concentration and cognition, relieve stress, improve depressive affect and increase pleasurable sensations. 32 PA can reduce depression33 and anxiety34 and (speculatively) may replace the need to smoke. In laboratory studies, a single session of exercise appears to reduce attentional bias to smoking cues,35 and reduce activation in areas of the brain associated with reward seeking while viewing smoking-related images. 36 Finally, it may be reasonable to speculate that undertaking more PA may help or reinforce a shift from the identity of a smoker to that of an exerciser, with the potential for a reduced exposure to environments and cues associated with smoking. In a cross-sectional survey the negative association between PA and smoking was mediated by having a physically active identity. 37 Thus, by simply increasing PA there may be implicit positive effects on smoking habits.

At least 50 cross-sectional surveys have assessed the association between self-reported PA and smoking status,38 with most reporting a negative association. Physically active smokers are more likely than inactive smokers to have attempted cessation in the past year. 39 However, RCTs to assess the effects of a primary care intervention to promote PA have shown that increases in PA were not associated with concurrent reductions in smoking among the subsample of smokers in the study. 40,41 This evidence questions the idea that simply increasing PA will lead to a spontaneous change in smoking behaviour.

Promoting physical activity among disadvantaged groups

The relationship between PA and socioeconomic status among adults is type dependent. Disadvantaged groups undertake less leisure-time PA but undertake more activity associated with work and active transport (in part due to low rates of car ownership). 42,43 This relationship has implications for the effectiveness of interventions to generally increase PA. 44 Systematic reviews have found that interventions that use a set of established behaviour change techniques (especially self-regulation techniques) are more likely to produce increases in PA than those that do not. 45

The role of health trainers in supporting behaviour change among disadvantaged populations

In the UK, NHS HTs were introduced in the ‘Choosing Health’ White Paper,46 and were established to facilitate health behaviour change in disadvantaged communities. The role of a HT fits within a broader role family called ‘health-related lifestyle advisors’, which also includes lay or peer workers or volunteers. Their predominant function is to support health behaviour change in a way that is acceptable to target populations and provides appropriate support to increase motivation and engage in action planning to facilitate healthy lifestyles. HTs are trained to help smokers to develop the motivation to quit smoking (and adopt other health behaviours) and then typically refer their clients to SSS for support to quit abruptly. At the time of initiating this research, there was no synthesis of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of HTs or ‘health-related lifestyle advisors’. A recent review of 26 studies (across a wide range of targeted health behaviours, from promoting immunisation and breastfeeding to smoking cessation and PA) suggested that those working in such a role, in general, have little impact on healthy lifestyle. 47 Overall, there was little evidence for effectiveness that interventions could change smoking and PA among disadvantaged communities and the available studies lacked individuals, while methodological rigor and reporting was not always clear.

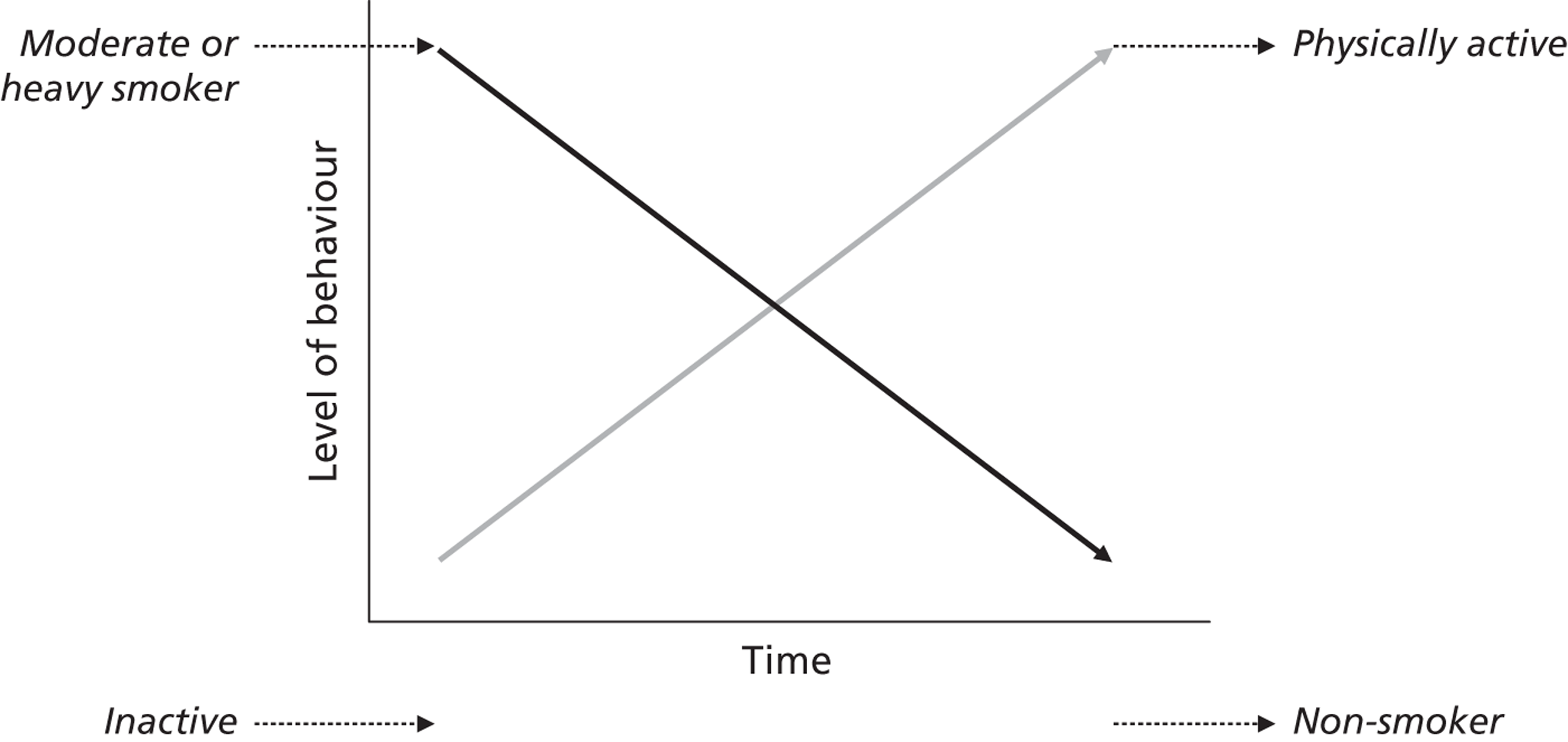

The challenge, therefore, is to design a PA promotion intervention that explicitly helps a smoker to build a connection between doing PA and smoking reduction among a disadvantaged population. Within the UK, such an integrated intervention was piloted among smokers who were attempting to quit with the help of smoking-cessation practitioners. 48 There are mixed views on whether multiple behaviour changes (e.g. increases in PA and dietary change) should be tackled simultaneously or sequentially when smokers quit. 1 Anecdotal evidence suggests that attempting to modify diet and PA while quitting is not detrimental to successfully quitting and can be facilitative. 28,49 However, an integrative approach has not been developed or evaluated for disadvantaged smokers who do not wish to quit abruptly, but do want to reduce smoking.

Aims and objectives

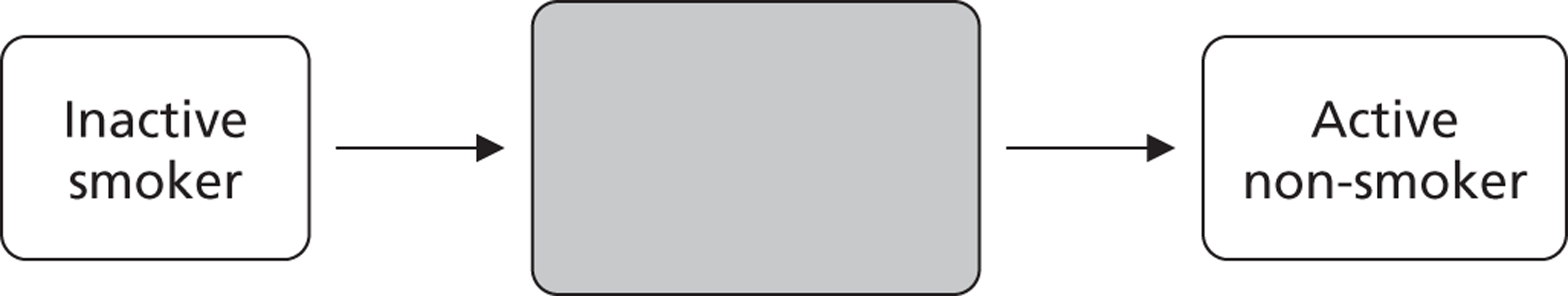

The aim of this pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT) was to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of a novel PA and smoking reduction counselling intervention for disadvantaged smokers who do not wish to quit in the immediate future but do want to reduce their smoking. The pilot study also seeks to inform the design of a full RCT of Exercise Assisted Reduction then Stop (EARS) among disadvantaged smokers.

The present research comprised the following to address those aims:

-

the development of a theoretically based PA intervention designed to increase PA levels in smokers, in a way that may complement and support smoking reduction and increase quit attempts and smoking cessation

-

the conduct of a pilot RCT in which the PA intervention (in addition to usual care) was compared with usual care alone

-

an examination of the feasibility and acceptability of the collection of secondary outcomes

-

estimation of the intervention effect on the primary outcome

-

an examination of the acceptability and feasibility of the intervention and its delivery

-

an examination of the acceptability and feasibility of the trial design and methods

-

an evaluation of the intervention fidelity from taped intervention sessions

-

identification of good practice within the intervention sessions to inform future training and delivery of the intervention

-

an evaluation of the cost of providing the PA intervention, and the conducting of exploratory modelling to assess the framework needed for future cost-effectiveness analyses alongside a full trial.

Development of the Exercise Assisted Reduction then Stop intervention

The aim was to develop a pragmatic intervention that could improve the reach of SSS to offer another option to reduce smoking for ‘hard to reach’ or disadvantaged smokers not ready to make an abrupt quit attempt.

Four steps were taken prior to initiating a pilot RCT, as follows:

-

individual and focus group discussions with smoking-cessation practitioners, researchers, public health consultants, community workers (including volunteers) and smokers to inform the EARS intervention structure and delivery

-

reviewing literature on using exercise as an aid to quitting, and consulting with academic experts on behaviour change for PA, smoking reduction and cessation, alone and in combination to inform the EARS intervention principles and theoretical basis

-

development of an EARS-specific training manual to build on the existing HT manual (www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_085779)

-

training EARS HTs, piloting the intervention with smokers who did not wish to quit in the immediate future and, in response to the reviewing of recorded intervention sessions and discussions with the HTs and smokers, adapting the intervention over a 4-month period prior to the pilot RCT for delivery in the targeted neighbourhoods of Devonport and Stonehouse (Plymouth, UK).

Exercise Assisted Reduction then Stop intervention structure and delivery

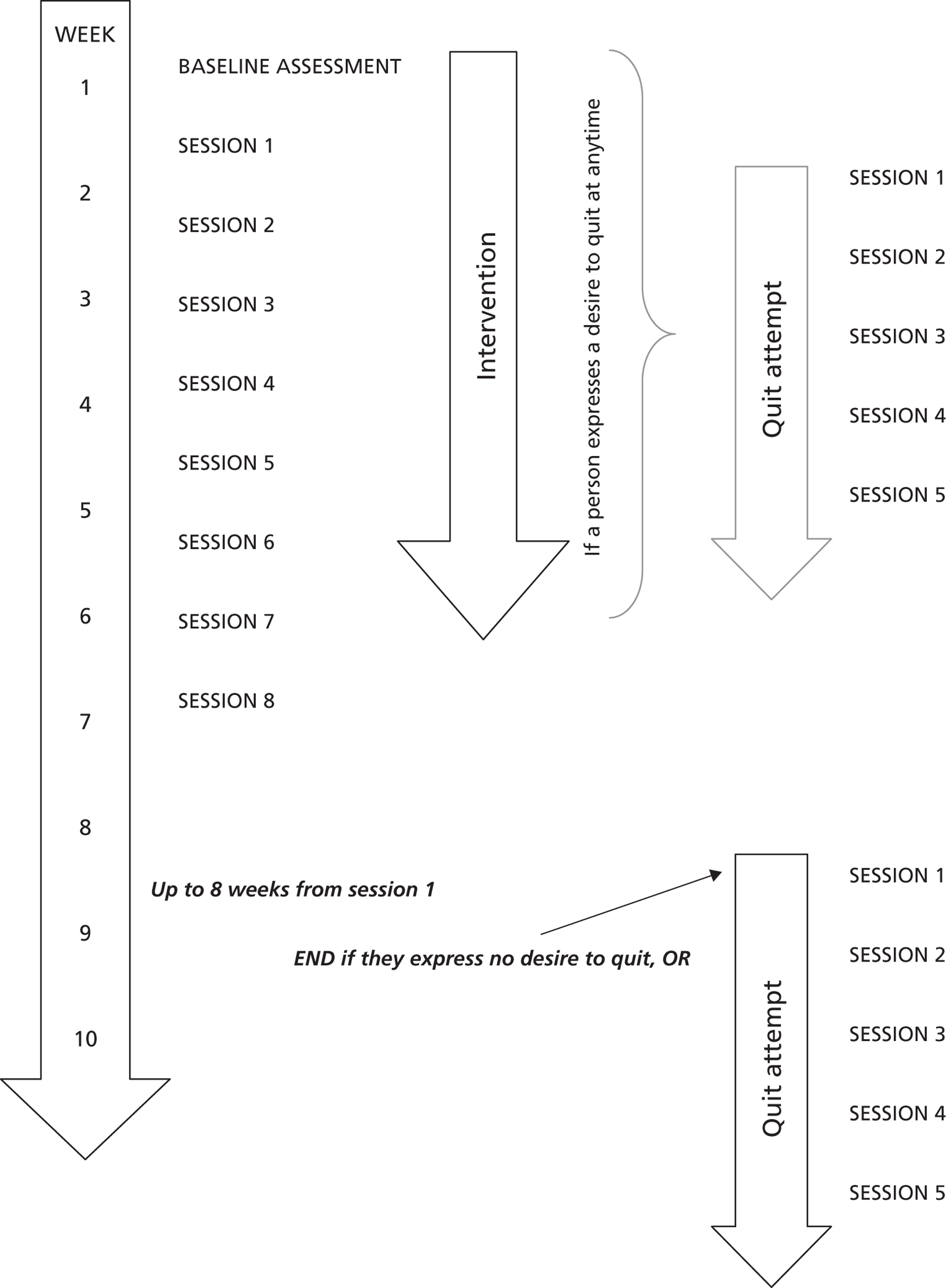

The EARS intervention was designed to involve up to 8 weeks of one-to-one support from a HT, in person or by telephone, after an initial face-to-face session. The HT provided no supervised PA sessions but offered subsidised access to PA opportunities (e.g. swimming, gym admission and transport subsidies to walking events), subject to individual preference. The focus was always on making any change in PA sustainable through motivational support.

Participants were given up to 8 weeks to cut down until they were ready to make a quit attempt. To count as abstinent a participant needed to have set a quit date within 12 weeks of randomisation to provide confirmation of a successful 4-week cessation by the final assessment at 16 weeks within the pilot RCT. Anyone who was ready to set a quit date was encouraged to attend and referred to the local SSS for support if they wished to get support. After quitting they were also offered weekly counselling to support ongoing PA from the HT for up to a further 6 weeks.

Exercise Assisted Reduction then Stop intervention principles and theoretical basis

The intervention was client centred in that smokers (who wanted to reduce but not quit in the immediate future) set the speed of reduction and their level of engagement in PA. The HT worked with the participant using client-centred motivational interviewing (MI) techniques50 throughout the intervention. The intervention was further informed by self-determination theory (SDT)51,52 which suggests that changing smoking behaviour will be facilitated by helping the smoker to fulfil three core human needs: a sense of competence or mastery, autonomy or control, and relatedness or companionship. Enhancing autonomy and competence motivations has been shown in prior research to increase abstinence rates and lead to greater cessation. 53 Links between54 MI and SDT have been made in the literature,55–57 suggesting that there may be good synergies in combining these two intervention approaches: both focus on helping the client to develop a sense of ownership of any change and empowerment. In addiction research, there is evidence that a client-centred counselling approach is effective for engaging with clients, building commitment to change,58 and increasing cognitive dissonance59 which can predict treatment outcomes. 60 There is some evidence that MI is effective in treating substance abuse61 and for smoking cessation,62 albeit from generally low-quality studies with questions about treatment fidelity. MI has also been shown to be an effective intervention for increasing PA. 63 The EARS intervention drew from principles of MI but also drew on SDT and other theories of behaviour change (as below).

In particular, MI does not focus on social influences on behaviour change, but SDT-founded interventions seek to help clients fulfil a need for a sense of relatedness. In the EARS intervention, techniques are described that were used to help participants to find social support for smoking reduction and increasing PA.

The EARS intervention was also informed by social cognitive theory64 and control theory,65 in that it sought to promote self-regulation by helping clients to build confidence over time to reduce smoking and increase PA. The self-regulation processes we specifically targeted were action planning, self-monitoring, review of progress, problem solving and review of goals – together these represent a process of experiential learning. Uniquely, this intervention also sought to help participants to use PA to self-regulate smoking by identifying situations where it may be possible to reduce withdrawal symptoms and desire to smoke, enhance positive mood, and break the link between environment and smoking behaviours. A range of behaviour change techniques was matched to the above theoretical processes of change (Table 1) and these were all included in the EARS training programme.

| Intervention process/objective | Intervention strategy | Behaviour change techniques (see Table 2 for description) | Theoretical domains |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active participant involvement | Use MI principles and communication skills. Exhibit empathy using Open questions, Affirmation, Reflections, Summaries (OARS) | RC1, RC2, RC4, RC7, RC8, RC9, RC10 | Knowledge; skills; identity (e.g. social identity); capability beliefs; beliefs about consequences; reinforcement; intentions; goals; memory or attention; context/resources; social influences; emotion; behavioural regulation |

| Develop rapport, building trust, and shared respect and empower the participant to be the primary agent of change | Individual tailoring of techniques and responses to the individual participant’s existing knowledge, skills, needs or preferences | RD1, RD2 | |

| Explore initial beliefs about cutting down (importance and confidence, triggers for smoking) | Use OARS (as above) to explore current and past smoking behaviour, the pros and cons of cutting down. 0–10 questions to explore importance and confidence. Use OARS to develop discrepancies (e.g. by exploring possible futures) | RI1, RI2, BM3, BM9 | Knowledge; capability beliefs; beliefs about consequences; intentions; context/resources; social influences; emotion |

| Build/enhance motivation and confidence for cutting down | Identify strengths and barriers (e.g. by exploring past experiences of success and failure or asking ‘what might stop you?’). Identify possible solutions to barriers | RC6, RI3, RI4, A2, BM2, BS2 | |

| Desire to quit may also be discussed | Exchange information on pros and cons of cutting down and barrier-solutions using the elicit–provide–elicit (Ask–Tell–Discuss) technique | RC2, A2, BM2, BS2 | |

| Explore initial beliefs about PA and using it as an aid to cutting down (importance and confidence, barriers to PA) | Use OARS (as above) to explore pros and cons. Decisional balance tool, 0–10 questions to explore importance and confidence about introducing additional physical activities. Use OARS to develop discrepancies | C37 | Knowledge; capability beliefs; beliefs about consequences; intentions; context/resources; social influences; emotion |

| Identify strengths and barriers (e.g. by exploring past experiences of success and failure or asking ‘what might stop you?’). Identify possible solutions to barriers | C18, C37 | ||

| Build/enhance motivation and confidence for PA | Exchange information on pros and cons of PA and on barriers/solutions using the elicit–provide–elicit (Ask–Tell–Discuss) technique | C8, C31, C37 | |

| Set goals and discuss strategies to reduce smoking | Set SMART goals with smoker to reduce smoking. Discuss/offer a choice of specific strategies | BS3, BS4, BS6, BS7, BS8, BS9 | Intentions; goals; behavioural regulation |

| Negotiate strategy and rate of smoking reduction (over following 1 and 4 weeks) | C12, C23 | ||

| Encourage self-monitoring of daily smoking | BS6 | ||

| Set goals and discuss strategies for PA | Set SMART goals with smoker to increase PA/introduce new physical activities. Discuss preferences and smoker to choose activities. Signpost to relevant PA/exercise opportunities | C5, C7, C9, C23, C26, C24 | Intentions; goals; behavioural regulation; context/resources |

| Encourage self-monitoring of daily or weekly physical activity (e.g. using a pedometer) | C16 | ||

| Review and reflect on efforts to cut down smoking to build confidence gradually and perceptions of control and ability to self-regulate | Smoker and HT review progress with smoking reduction. Any successes are reflected on and reinforced | RC7, RC8, BM3, BS5 | Skills; identity (e.g. social identity); capability beliefs; beliefs about consequences; memory or attention; context/resources; social influences; emotion; behavioural regulation |

| Smoker and HT discuss any setbacks (reframing to normalise them, identifying social, environmental or other barriers and exploring ways to overcome them) | A2, RI4, RC6, BS1, BM5, BS8 | ||

| Set new targets (perhaps to quit) | BS3, BS4, BS5, BS6, BS7, BS9 | ||

| Reflection on/reinforcement of the smoker’s skills in avoiding or managing relapse | BM2, BM3 | ||

| Reassessment/checking of motivation/perceived benefits of reducing smoking and also of making an attempt to quit | BM2, BM9 | ||

| Review and reflect on efforts to increase PA to build confidence gradually and perceptions of control and ability to self-regulate | Smoker and HT review and reflect on successes in increasing PA/introducing new physical activities | C11 | Skills; identity (e.g. social identity); capability beliefs; beliefs about consequences; memory or attention; context/resources; social influences; emotion; behavioural regulation |

| Smoker and HT discuss any setbacks (reframing to normalise them, identifying social, environmental or other barriers and exploring ways to overcome them) | C8, C28, C29, C35 | ||

| Set new targets for PA | C10, C6, C7, C16 | ||

| Reassessment/checking of motivation/perceived benefits of physical activity in relation to smoking reduction, but also discussing other personal benefits | C37, C15 | ||

| Integration of concepts: building an association between PA and smoking reduction | The HT introduces PA as a healthy behaviour and aid to cutting down and quitting. A clear rationale is presented for how PA might be relevant to reducing smoking (as a distraction, as a way to reduce withdrawal symptoms such as stress or cravings) | RD1, RC2, RC8, R6 | Beliefs about consequences; emotion |

| The HT and smoker agree to experiment with using PA. The smoker reflects on use of PA and relates it to smoking urges and/or to number of cigarettes smoked | C6, C11 | ||

| Engage social support to facilitate behaviour change (both for reducing smoking and for physical activity) | Exploring the possible role of social influences as potential barriers to change and as potential facilitators of change is encouraged during the motivation, action-planning and review stages above | A2 | Social influences; emotion |

| Social support is conceptualised as being either informational (e.g. helping to make plans) practical (e.g. providing transport), or emotional (e.g. encouraging) | C29 | ||

| Identify and reinforce any identity shifts towards being a more ‘healthy person’ or ‘healthy living’. This represents a generalisation of the specific desire to stop smoking or to be more active into a more general self-concept of being someone who is healthy | Recognise and reinforce any identity change talk using reflective listening techniques | RC2, RC7, RC8, C30 NB: Explicitly encouraging/reinforcing positive changes in social identity is not currently a recognised BCT |

Identity (e.g. social identity); emotion |

| Referral to NHS Stop Smoking Services if needed | Ask if ready to quit and refer to NHS SSS if desired | RC2, RD1 | Context/resources |

Finally, EARS also drew from research on stage-matched interventions66,67 to help focus the use of specific behavioural change techniques at the appropriate time. Following an assessment of readiness to change and perceived importance of and confidence about cutting down, intervention techniques were used, as needed, to shift participants from pre-contemplation, contemplation and planning stages to action and maintenance, in terms of smoking reduction and quitting, and increasing PA as a way to facilitate changes in smoking behaviour.

Behavioural targets and support for action planning

The study inclusion/exclusion criteria meant that we could assume that smokers were ready to cut down but not quit in the next month. Given the addictive nature of smoking behaviour, part of the challenge of reducing smoking was deciding what to do and specifically how to do it. Having a clear and consciously regulated plan was considered to be helpful in disrupting habitual, automated patterns of smoking behaviour, and for extinguishing cigarette cravings associated with conditioned cues and environments. 68,69 Initial pilot work, prior to the trial, highlighted that no two smokers had identical personal situations or smoking and PA experiences, and that any intervention would require flexibility and tailoring to an individual’s needs.

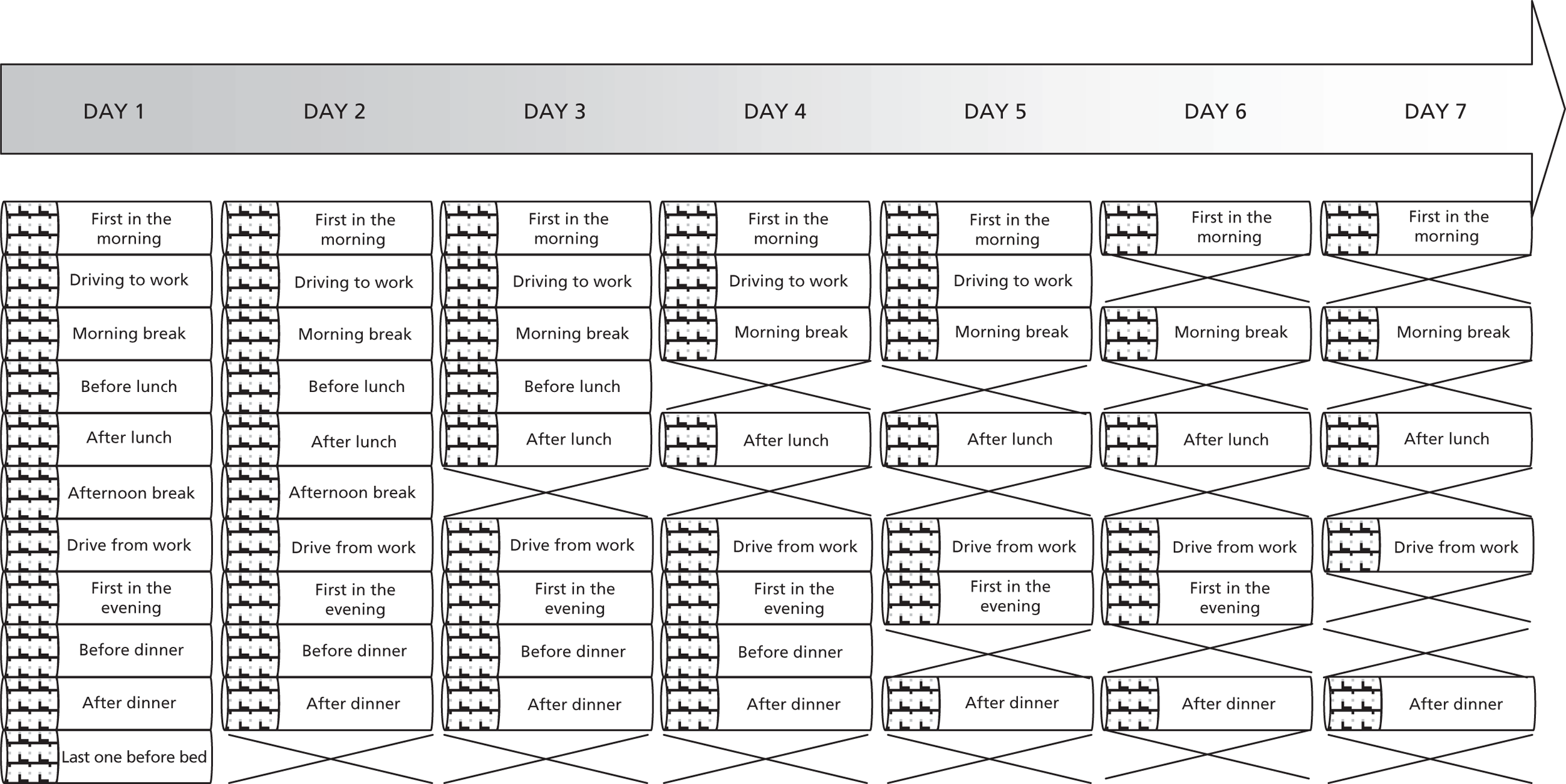

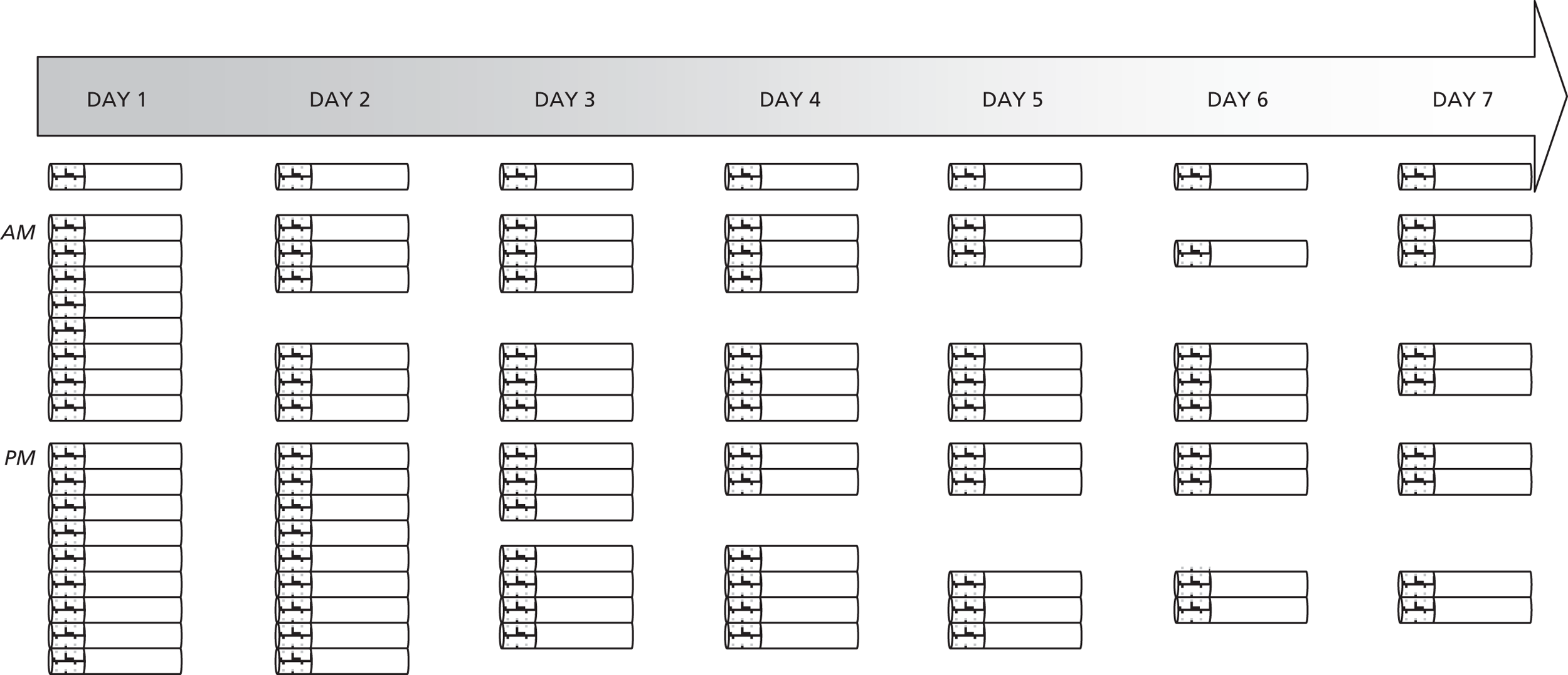

We therefore created a set of materials to help participants to think about and discuss different possible strategies for cutting down (see Appendix 1). Participants were encouraged to set an initial smoking reduction goal of 50% during the first 4 weeks, using one of four different reduction strategies70 as follows:

-

Hierarchical reduction: this involves identifying the easiest to the hardest cigarettes to give up during the course of a typical day, and then systematically giving up either the easiest or hardest cigarettes over time until a goal is reached.

-

Smoke-free periods: this involves identifying blocks of time through the day where the participant will not smoke, progressively increasing the length of these periods over time.

-

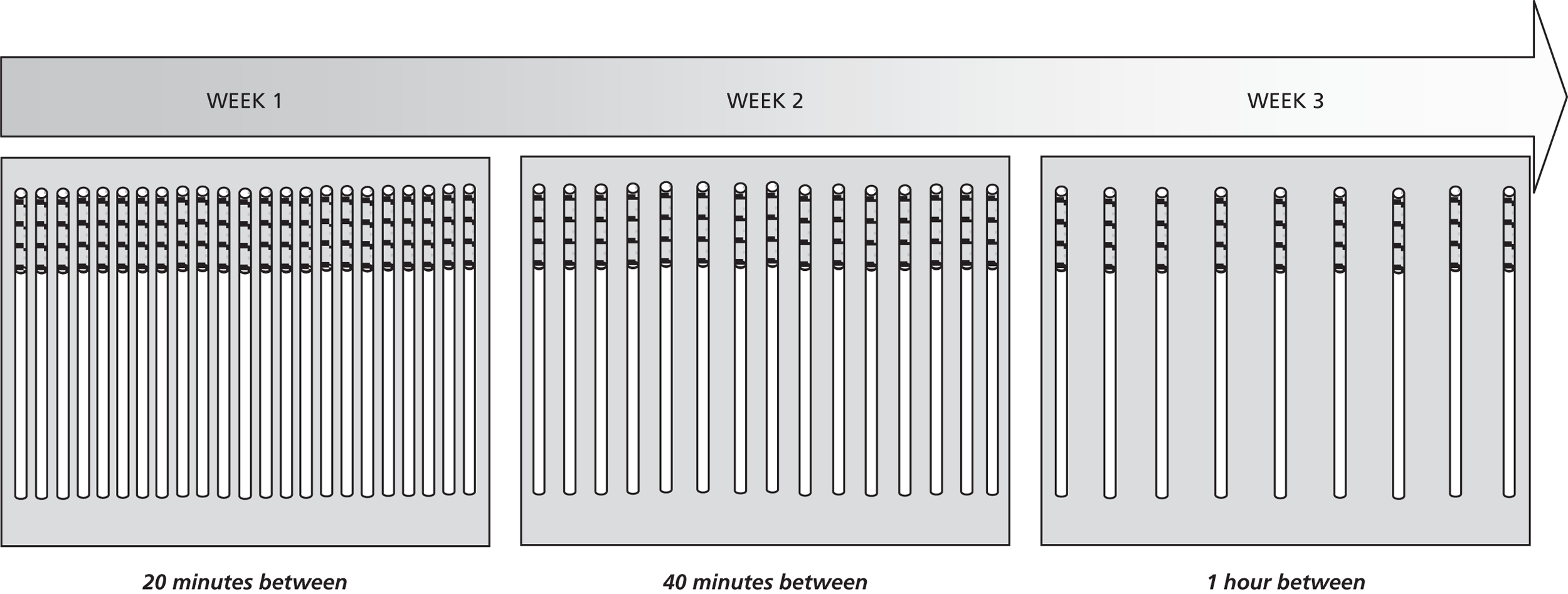

Scheduled reduction: this involves spacing cigarettes evenly through the day (e.g. smoking every 30 minutes) and progressively increasing the time between each cigarette.

-

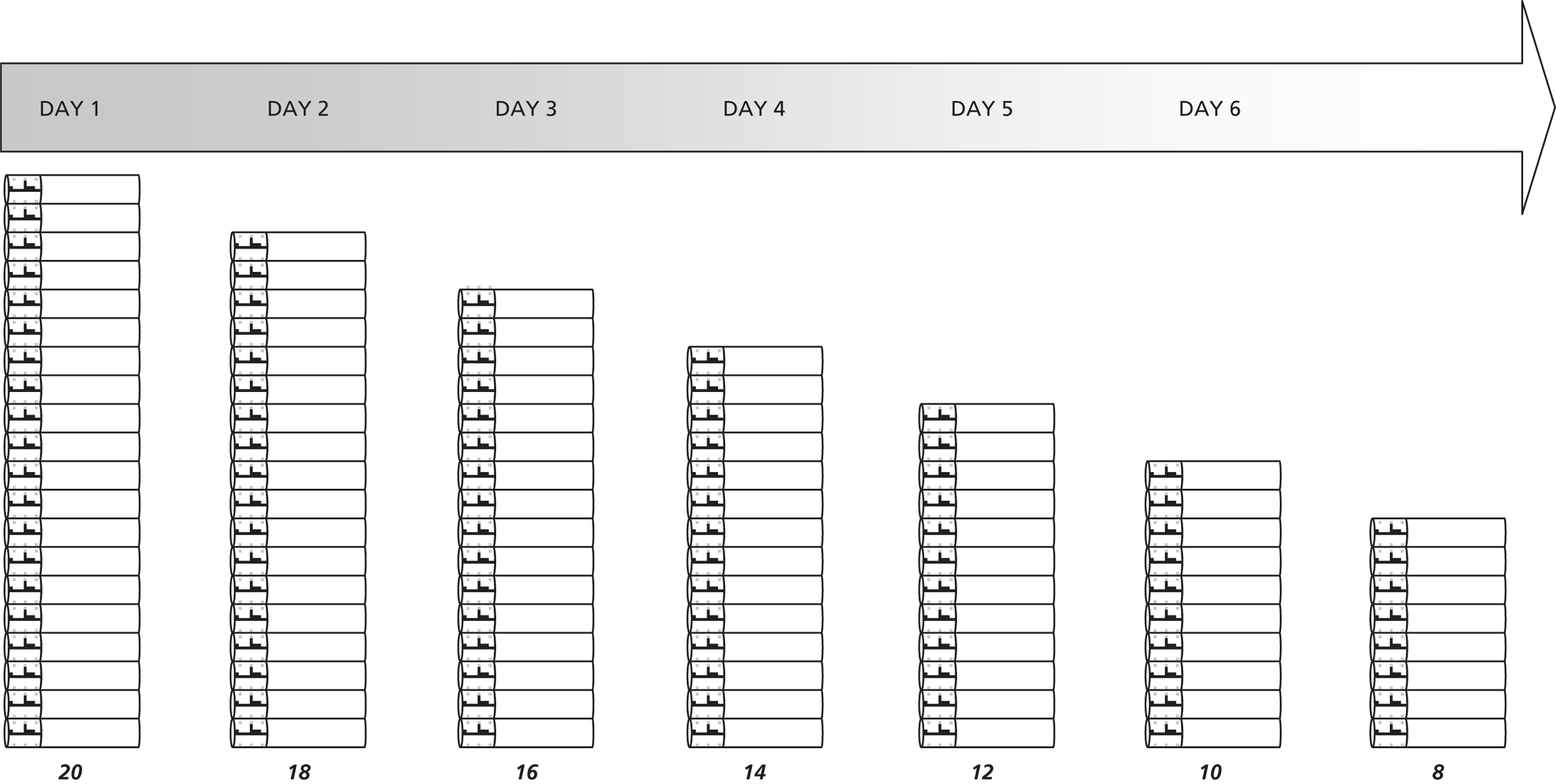

Planned reduction: this involves setting a target of a maximum number of cigarettes to smoke per day, and progressively decreasing this number over time.

The strategy chosen was not fixed but was used by participants in an exploratory way to discover which was most suitable. HTs recorded any reduction plans and used these to review and update further goals in subsequent sessions with participants as a way of encouraging self-monitoring and self-regulation. For each strategy, the aims were to build participants’ confidence to reduce smoking, to allow choice in how they achieved this and to encourage participants to seek support from others as appropriate.

Increasing physical activity

In the initial session HTs initiated a dialogue about how PA may influence smoking and may help any reduction. This was expected to include reduction of cravings, stress reduction and using PA as a distraction. Pilot work suggested that it was easier for the HT to focus on smoking reduction initially, and then introduce and develop goals for PA as a facilitating behaviour, though this was open for negotiation with the participant. As we did not exclude people who were already physically active, we expected participants to vary greatly in the amount of PA they were already doing and hence the intervention needed to be responsive to this variation.

The initial aim was to increase motivation and confidence to increase PA and to build beliefs in the reinforcing value of PA to aid smoking reduction. Later in the sessions, PA facilitation focused mainly on encouraging the selection of options that were likely to be sustainable and accessible for the individual participant. The focus was on moderate lifestyle activity (including walking, active transport or activities with few barriers to engagement) and activities that were enjoyable to the participant. The HT had a number of options to help participants increase PA, including a free low-cost MP3 player preloaded with a 10-minute spoken isometric exercise instruction track;71 a free rubber exercise band for home use; a free pedometer (self-monitoring with pedometers has been shown to increase PA);72 and free, or subsidised, access to local leisure and exercise facilities (e.g. for swimming or gym use). Participants were encouraged to self-monitor the number of daily steps they achieved and set goals (both important behaviour change techniques73), identify their use of PA in managing smoking cravings (or providing a distraction) and elicit any other positive associations that they recognised. The focus was not only on increasing the volume of PA and using this as an aid to reduce smoking, but also on helping participants to build a more generalised sense of competence, control and companionship through the activities they engaged in.

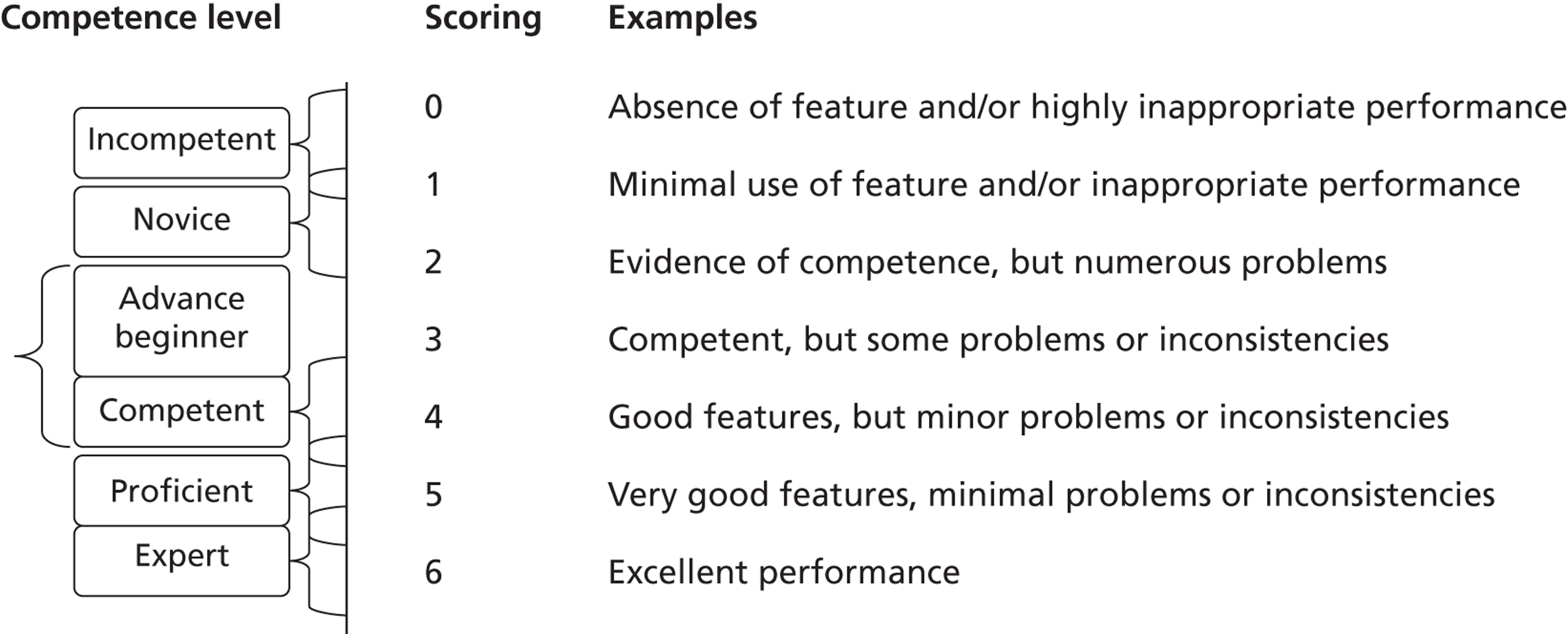

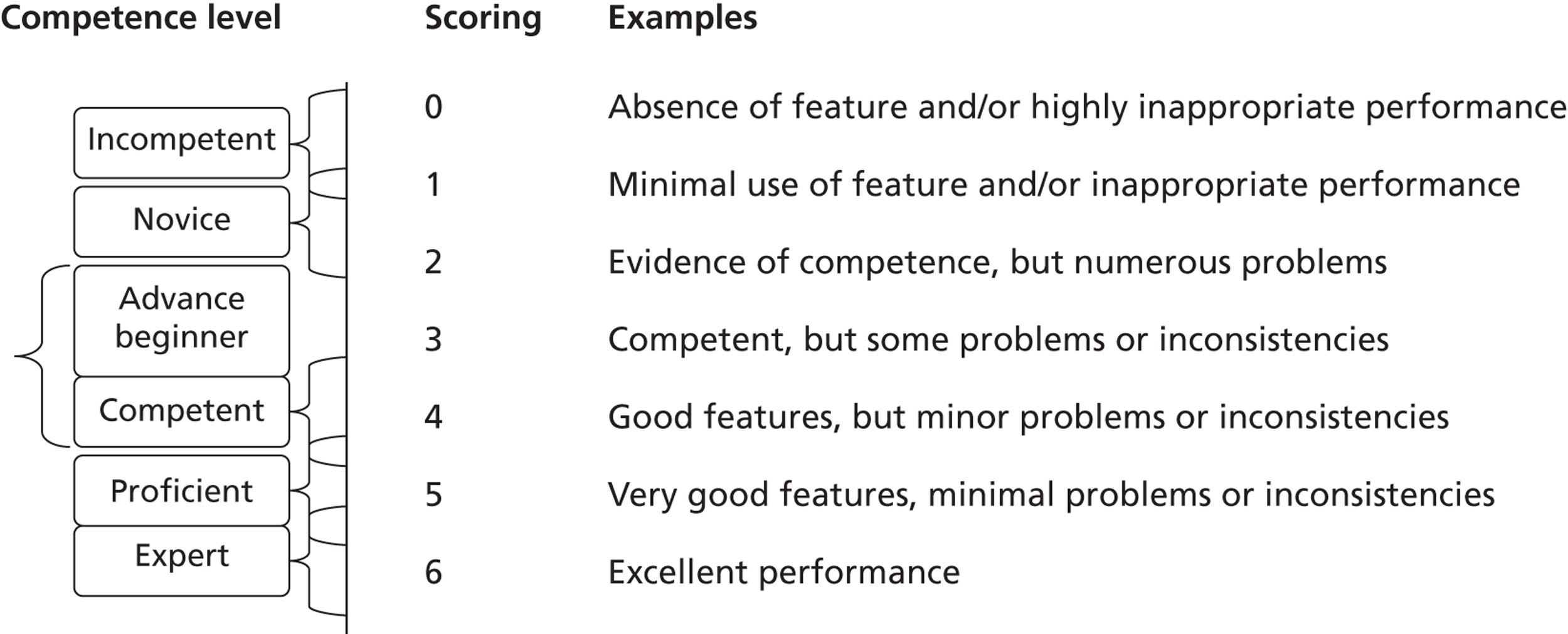

Training the health trainers

Health trainers were initially trained, using an intervention manual, in PA counselling (see Appendix 1) to achieve the above aims. Table 2 shows a list of behaviour change techniques (BCTs)74,75 that the HTs were trained to use and are linked to the main theoretical constructs (see Table 1) that underpinned the intervention.

| Behaviour addressed | BCT (modified for the EARS protocol of delivery) |

|---|---|

| aSmoking reduction74 | BM2 (boost motivation and self-efficacy) |

| BM3 (offer feedback on current behaviour) | |

| BM5 (offer normative information about others’ behaviour and experiences) | |

| BM9 (elicit reasons for wanting and not wanting to stop smoking or cut down) | |

| BM11 (measure CO) | |

| BS1 (facilitate barrier identification and problem solving) | |

| BS2 (facilitate relapse prevention and coping) | |

| BS3 (facilitate action planning/develop treatment plan) | |

| BS4 (facilitate goal setting) | |

| BS5 (prompt review of goals) | |

| BS6 (prompt self-recording) | |

| BS7 (offer to provide support with techniques for changing behaviour) | |

| BS8 (prompt thoughts on environmental restructuring) | |

| BS9 (help set graded tasks) | |

| A2 (advise on/facilitate use of social support) | |

| RD1 (tailor interventions appropriately) | |

| RD2 (emphasise choice) | |

| RI1 (assess current and past smoking behaviour) | |

| RI2 (assess current readiness and ability to quit cut down) | |

| RI3 (assess past history of quit attempts) | |

| RI4 (assess withdrawal symptoms) | |

| RC1 (build general rapport) | |

| RC2 (elicit and answer questions) | |

| RC4 (explain expectations regarding treatment programme) | |

| RC6 (provide information where appropriate on withdrawal symptoms) | |

| RC7 (use reflective listening) | |

| RC8 (elicit client views) | |

| RC9 (summarise information/confirm client decisions) | |

| RC10 (provide reassurance) | |

| bPA75 | C5 (goal setting – behaviour) |

| C6 (goal setting – to achieve possible benefits from increasing PA) | |

| C7 (action planning) | |

| C8 (barrier identification/problem solving) | |

| C9 (set graded tasks) | |

| C10 (prompt review of behavioural goals) | |

| C11 (prompt review of achievement of benefits from PA) | |

| C12 (prompt rewards contingent on progress) | |

| C15 (prompting generalisation of a target behaviour) | |

| C16 (prompt self-monitoring of behaviour) | |

| C18 (prompting focus on past success) | |

| C23 (teach to use prompts/cues) | |

| C24 (environmental restructuring) | |

| C26 (prompt practice) | |

| C28 (facilitate social comparison) | |

| C29 (plan social support) | |

| C30 (prompt identification as role model) | |

| C31 (prompt anticipated regret from not changing current behaviour) | |

| C35 (relapse prevention/coping planning) | |

| C37 (motivational interviewing) |

Intervention developmental phase with stakeholders and test participants

Context familiarisation and initial research activity

Previous research48 had helped to build a positive working relationship with the Plymouth NHS SSS. From the very beginning of the research and intervention development phase, meetings were held with those offering support for smoking cessation within the SSS and public health teams. Further afield the research team met with HTs and with those responsible for training and their management in the south-west. We focused questions on how HTs identified and engaged with clients to promote PA and smoking cessation. Plymouth itself did not employ HTs but similar outreach work was undertaken by public health specialists. One stop smoking advisor who we consulted with, based in the deprived area of Devonport, had gained extensive experience in trying to recruit smokers into a SSS. Devonport itself had received over £50M via the Devonport Regeneration Community Partnership, over a 10-year period, to support a broad range of environmental-, social- and health-related initiatives. We interviewed a wide range of formal and informal community leaders about how the local community engaged in lifestyle change support initiatives, such as employees in local leisure services and representatives of Voice of Devonport and the Pembroke St. Housing Association.

The aim of the information gathering was to develop a strong understanding of how the communities of Devonport and adjoining Stonehouse may respond to our planned intervention to facilitate changes in smoking and PA. We also developed an initial compendium of PA opportunities in the local community and further afield. All this was done over several months prior to the employment of HTs, and continued with their input throughout the training and intervention delivery. Each HT also worked in other part-time employment in and around Devonport and Stonehouse, and they were encouraged to work as a team, sharing information on opportunities for PA and community recruitment. The employment of three part-time HTs (2 × 0.5 and 1 × 0.4), with one common afternoon for weekly meetings and supervision, provided opportunities for team building, sharing good practice, and supervision.

Training

The training manual and programme for initial training are shown in Appendix 1 and Appendix 5a. We began by covering generic material in the Department of Health Training Manual for HTs, which provided a framework for the role and for developing core competencies for supporting behaviour change. The training then progressed to developing an understanding of the options available to aid smoking cessation with NHS support, and behaviour change for smoking reduction and increasing PA (in its broadest sense). The manual was largely completed prior to the beginning of training but did become more refined during and after the training. The version shown in the appendices would require further adaptation based on the findings from the pilot trial, ahead of a larger trial.

Towards the end of the training, and leading into the start of recruitment for the pilot trial, we opportunistically identified six test participants (through local contacts) who did not wish to quit smoking in the immediate future. They were able to help us resolve issues such as how best to describe the study and intervention to potential participants, how to adapt the intervention to individual differences and needs, how to maintain a client-centred approach and encourage goal setting, how to sequence multiple behaviour change, how to conduct assessments and how to stay in touch with participants. The experiences of working with six test participants are shown in Table 3. In total, they attended 35 sessions consisting of face-to-face and telephone contacts. Most sessions were digitally recorded, eight sessions directly observed, and most were discussed with the three HTs, by AHT, TT and CGVS, with field notes recorded throughout. The sessions informed the learning process and intervention development, and increasingly, leading up to the start of the actual pilot trial, increased uniform practice across the HTs.

| Issues | Participants | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Initial smoking behaviour | History: failed quitter. 20–25 cigarettes daily | Smokes c. 20 a day (mainly at home). Smokes when bored and more at weekends with friends | 20–30 cigarettes daily. Has given up for 3 years in the past. Smokes when bored and more at weekends | 25–30 cigarettes daily. Would not have got involved if we were ‘preaching about stopping’ | c. 40 roll-ups daily. History of serious drug abuse | 12–15 cigarettes daily. Smokes a lot more when out socialising with friends |

| Initial PA levels | No transport so walks a lot. A few back problems, which means they can be sedentary for extended periods | Not a ‘gym person’, but does a bit of (enjoyable) walking to break day up. Asthmatic and back trouble. c. 7500 steps per day | Walks a lot at work (12–17,000 steps per day). Weekend is a time to relax/be sedentary (4000–5000 steps). Does not enjoy gyms. Desires to be as active as wife | Steps range from 7000–16,000 daily. Busy home life with young children and a dog | Walks to most places – has no transport. Has health concerns. Heavily asthmatic | Walks dog daily, about 1 mile. Pedometer steps between 6000 and 20,000. Is lightly involved in youth football coaching |

| Smoking behaviour change processes and outcome for smokers | Processes: hierarchical reduction moved into planned reduction. Enlisted friend. Saved money in jar. Smokes less of each cigarette. New job with youths changed smoking habits | Processes: initial self-monitoring of smoking, and motives/pleasure. Goal to halve smoking. Tried smoking every hour and extending the time between cigarettes by roughly 15 minutes each week. Changed to loose tobacco to reduce smoking. ‘Come this far, can go further’ (self-efficacy) | Processes: goal to delay morning cigarettes. Attempted to increase times between cigarettes (scheduled reduction) without much success. Switched to five cigars a day instead of cigarettes. Health concerns a motive. ‘I do not know why I do it, it’s a disgusting habit.’ Very important to reduce but low confidence | Processes: initial smoking diary – shocked by number smoked. Goal to reduce two a day in week 1, by distraction. Treated reduction as an experiment, with PA. Planned to avoid cues to smoking such as waiting for children to finish school | Processes: planned reduction by pre-rolling fixed number of daily cigarettes, smoke-free periods at work, and support from boss. Goal to avoid social cues to smoking. Self-monitoring with smoking diary | Processes: motivated by health and money (saved in jar). Supported by girlfriend and father. Used hierarchical reduction to cut out the ‘easier’ cigarettes, with the intention to develop strategies for cutting out the ‘harder’ cigarettes |

| Outcomes: stopped smoking in the morning (easy!). Down to eight a day during week and up to 15 a day at weekends | Outcomes: reduced to 10 per day. Stopped chain smoking in mornings | Outcomes: only limited reduction. Failed to identify why it is easier on some days | Outcomes: reduced to 10 a day. Explicitly aware of own patterns of smoking and cues to smoking | Outcomes: reduced to c.20 roll-ups a day on average. Still prone to smoke more when out drinking/socialising | Outcomes: reduced to c. seven a day on average. Well placed to progress further, but lost contact | |

| PA behaviour change processes and outcome for smokers | Processes: looked for walking group (to enlist support). Uses pedometer for self-monitoring. Enlisted a friend to walk with as well as cut down with. Feels ‘healthier’ | Processes: set goals and self-monitored daily steps (> 8000 per day) – useful. Enlisted family to walk with. Aware of reduced smoking when on long walks. Explicit use of walking to lower cravings | Processes: goal to start swimming classes and work on allotment more often with wife (enlist support). Self-monitored PA with pedometer (sometimes). Linked more pedometer steps to less smoking | Processes: goals to walk more. Then thinking about jogging with friend (enlist support). ‘Walking more gave a sense of achievement, more energy, less breathless, skin better, fewer chest infections, and thought about smoking less’. Treated link between PA and smoking as experiment | Processes: already very active so hard to increase. Conscious effort made to walk at a brisker pace and take longer routes. Thought of using a gym, but no plans emerged (low importance/confidence) | Processes: goal to do minimum – 10,000–15,000 daily steps (including cricket and football coaching twice a week). Chose longer routes to walk places. Explicitly used PA to reduce smoking – by distraction |

| Outcomes: used cross-trainer at home and walked regularly | Outcomes: chest not so tight. Increased PA (walking) | Outcomes: failed to get to swimming classes. Completing more work on the allotment at weekends to break up sedentary time | Outcomes: achieved > 16,000 steps most days. Weight loss through extra PA | Outcomes: continued to walk a lot, possibly increasing, but difficult to know due to loss of contact | Outcomes: ‘just feel better mentally’. Maintained higher average number of steps and additional activities | |

| Challenges for individuals and for HTs to engage | Struggled with plans and goals by 3rd/4th week due to unsettled personal circumstances (new active job, daughter at home) and chaotic lifestyle. Low confidence from previous failed attempts to quit. Seven sessions held | Low confidence to cope with social cues to smoking. Boredom a real challenge due to unemployment. Reduction becoming progressively harder. Seven sessions held | Strong social cues to smoke. Active work undermined ‘selling’ activity to reduce smoking. Scheduled reduction did not fit work. Little commitment to goals. Weight-gain concerns. Five sessions held | Close family member diagnosed with cancer: presented high levels of stress and complicated adherence to sessions. Became increasingly difficult to keep in contact with. Six sessions held | Smokes a lot when binge drinking – up to 20 pints a night. Hard to avoid others smoking. Became very difficult to keep in touch due to unpredictable lifestyle. Completed six sessions in person (no telephone!) | Keeping in contact became difficult quite early on. Unknown reasons for loss of contact. Four sessions held |

The HTs gained encouragement and confidence from these experiences, which complemented their own working practice in their other part-time roles as a cardiac nurse, drug and alcohol service practitioner and trainer, and occupational health promotion practitioner.

In summary, valuable lessons were learnt during this pre-pilot developmental phase. The general aims and application of theory to practice were confirmed as appropriate, with some fine tuning of implementation of the intervention and methods for conducting assessments with test participants. With input from AHT, CGVS and TT, and drawing on the past experiences of the three HTs, the training provided an opportunity for team building and common achievement of the core aims of the pilot study.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Study design

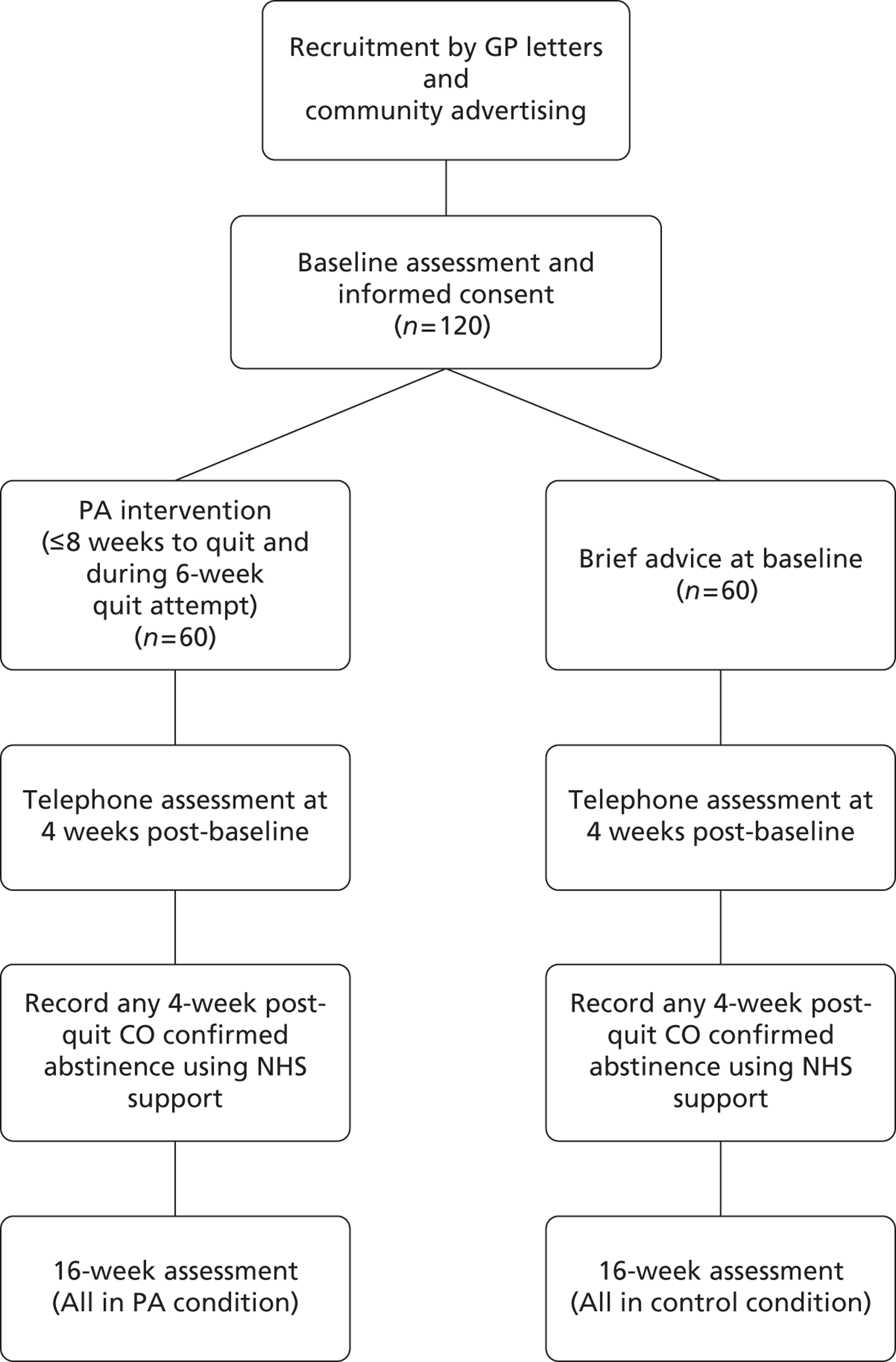

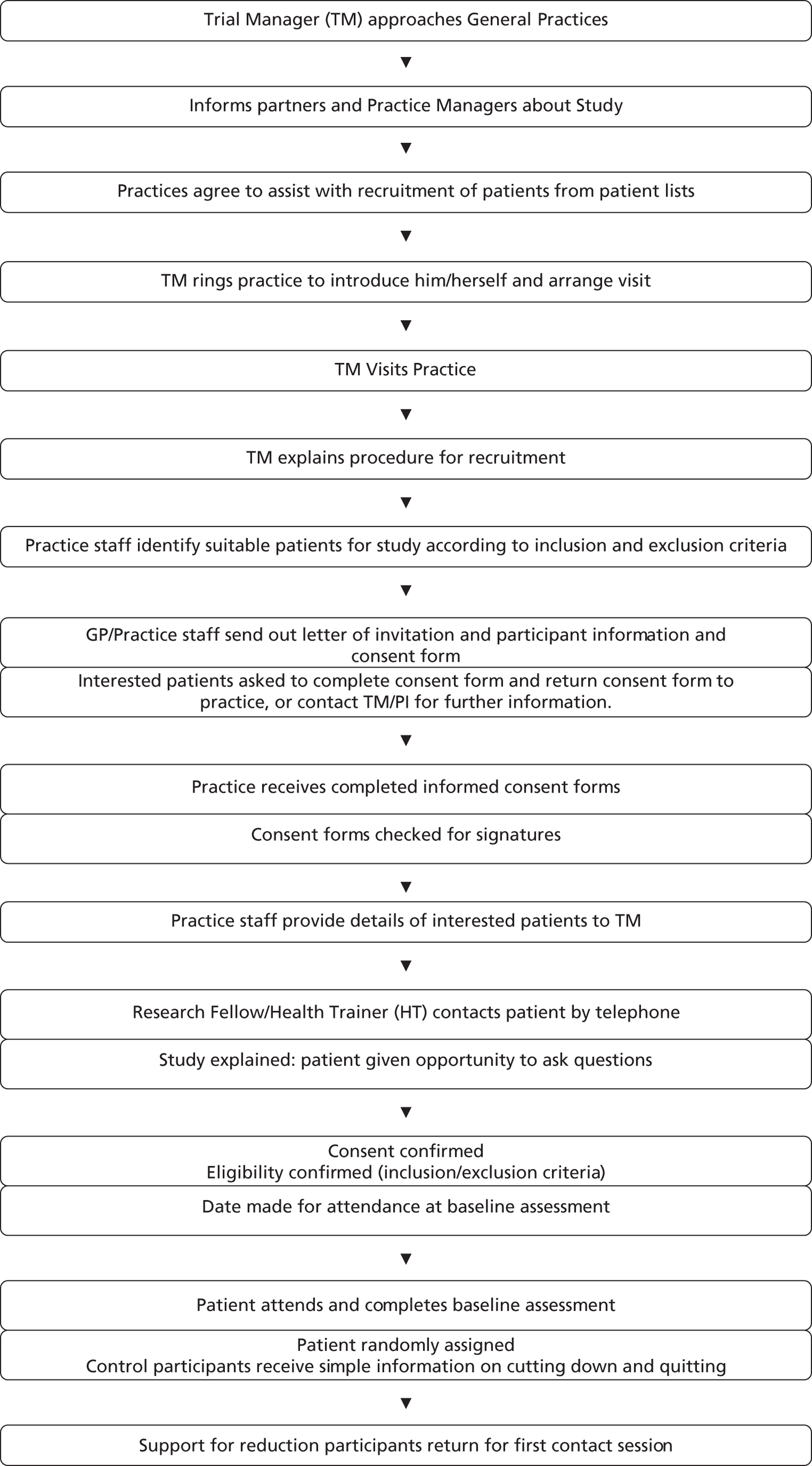

The EARS smoking study was a pragmatic, pilot, two-arm RCT into which disadvantaged smokers were recruited by three distinct approaches: (1) through primary care via general practitioner (GP) invitation letter with reminder telephone calls; (2) through NHS SSS invitation letter (aimed at those who have previously failed to quit) with reminder telephone calls; or (3) through a variety of other community-based approaches without a personalised invitation letter. The study compared the effect of individual PA and smoking counselling with brief advice (on SSS support to quit) among disadvantaged smokers not wishing to quit in the next month (see Appendix 1). Those who expressed a desire to quit post randomisation were referred to the SSS if they wished, and continued in the study with PA support if they were in the intervention arm. Following baseline, follow-up assessments were conducted at 4, 8 and 16 weeks in both groups. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the NHS National Research Ethics Service Committee South West, in the UK.

Eligibility criteria

Participants were eligible to enter the study if they were over 18 years old, smoked at least 10 cigarettes per day (and had done so for at least 2 years), did not want to quit in the next month, were able to engage in moderate-intensity PA (walk without stopping for at least 15 minutes), were registered with a GP, and did not wish to use NRT to reduce smoking. The study focus was on initially reducing smoking, not on quitting, and so those who expressed an immediate desire to quit were referred directly to the SSS without entering the study. Those wishing to use NRT were excluded to avoid any confounding of the effects of PA on their smoking behaviour. We excluded those with severe mental health problems and ongoing substance misuse due the potential difficulties of engaging them in the intervention given the large uncertainties and complexities of its delivery, and the fact that they may have put the safety of the research team at risk. Given the exploratory nature of the study, participants were required to be able to converse in English.

Sample size

Given the lack of research involving behavioural smoking reduction interventions, the effect of our intervention was uncertain. While the sample size of the study was primarily chosen to undertake the feasibility objectives of the study, we also sought to obtain an estimate of the intervention impact (relative to control). 76 Using data from a recent meta-analysis of trials of smoking cessation15 we undertook a scenario analysis in order to examine the precision of the effect size estimation based on different pilot trial sample sizes and plausible effect sizes (Table 4). A sample size target of 120 (60 per group) was initially selected for this pilot.

| Control quit ratea | Sample sizeb (control–intervention ratio) | Effect size; relative risk | Precision of effect size estimate (95% CI)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5% | 60 (1 : 1); 60 (1 : 1) | 2.00; 4.00 | 0.19 to 20.89; 0.47 to 33.72 |

| 5% | 120 (1 : 1); 120 (1 : 1) | 2.00; 4.00 | 0.52 to 7.63; 1.18 to 13.46 |

| 5% | 160 (1 : 1); 160 (1 : 1) | 2.00; 4.00 | 0.63 to 6.38; 1.28 to 11.41 |

Recruitment

Recruitment for the study was over a 12-month period between May 2011 and May 2012. We planned to recruit 50% of participants through primary care via GP invitation letters from three identified GP surgeries (on the basis that this has been shown to be a successful approach77) in two very socially deprived wards in Plymouth (Indices of Multiple Deprivation 2010 values = 52–59.9, placing them in within the 3% ‘most deprived’ in England). GP practice lists were searched based on cursory inclusion/exclusion criteria [including smoking status, incidents of physical health conditions (especially in the previous 12 months) that may contraindicate moderate-intensity PA and current serious mental illness or drug dependence] (see Appendix 3). A list of potential participants was generated and invitation letters sent with a postal reminder 1 week later. To ensure that nobody was discriminated against on the grounds of illiteracy, telephone calls were made to non-responders to check that they had received and understood the invitation. If there was no reply on the first call a message was left to enquire if the invitation had been received and to leave a contact number for further information. Up to four more calls were made but no further messages were left, to avoid harassment. Interested participants were screened for eligibility (see inclusion/exclusion criteria) by telephone before being invited to attend a baseline assessment.

The aim in the pilot RCT was to recruit participants of whom at least 75% were in social class C2–E (www.nrs.co.uk/lifestyle.html), 30% were single parents and 20% had a mental health problem. This operational definition of disadvantaged was based on the high prevalence of smoking among these subpopulations. 5

We planned to recruit the other 50% of participants by a variety of community-based approaches to maximise the chances of reaching disadvantaged smokers. One approach involved sending invitation letters (with a postal reminder 1 week later) to those on the database of the Plymouth SSS who had failed to successfully quit with the service within the past 2 years. Other planned community recruitment approaches included media engagement, attendance and networking with local community centre groups including housing trusts and parent and toddler groups, distribution and display of flyers, cascading information through workplaces, and opportunistic recruitment of people with a mental health problem [through the local Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) service]. Interested participants contacted the research team directly (in person or by telephone) or indirectly by returning contact details with a request for further information. Following screening to determine eligibility, a time for attending a baseline session was arranged.

As an incentive for completing data collection at baseline, and at weeks 8 and 16, participants were offered a small financial incentive on each occasion for returning an accelerometer after wearing it for a 7-day period. Initially this was £10 for each occasion, but was increased to £30 later in the study to investigate whether or not this improved data collection and the likelihood of participants returning the device.

Randomisation and concealment

Following screening and baseline data collection, the researcher phoned the trial manager who then allocated smokers using a password-protected web-based randomisation system set up and managed by the UKCRC accredited Peninsula Clinical Trials Unit (PenCTU). Randomisation was 1 : 1 and minimised (in order to ensure balance between the two arms) by age (30 years and under/over 30), sex, HT (one of three), and smoking dependence (high = smokes first cigarette within 30 minutes of waking; low = smokes first cigarette later). To maintain concealment, the minimisation algorithm retained a stochastic element. On occasion when two potential participants were closely acquainted, at random, only one of the pair was selected for inclusion in the study to avoid contamination. If the individual was randomised to the intervention arm then both were permitted to attend sessions together but only the individual randomised provided data.

Data collection

Baseline data collection

At baseline the following data were collected: participant demographic information (i.e. age, sex, marital status, cohabiting with other smokers, parental status, employment status, age of leaving full-time education, ethnicity, weight and height), smoking history (age started smoking, longest period of cessation in last year, attempts at cutting down, cessation aids used in past year, use of SSS) (Table 5). A more detailed schedule and content of assessments is shown in the study protocol (see Appendix 2).

| Variable | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive | Physical activity | Confidence for undertaking PA |

| SOC to use PA to control smoking | ||

| Smoking | Confidence for and importance of quitting | |

| Behavioural | Physical activity | Accelerometer data |

| 7-day PA recall | ||

| Smoking | Self-reported cigarettesa | |

| Expired CO | ||

| Number of quit attempts made | ||

| Cessation aids used | ||

| Alcohol consumption | Alcohol consumption | |

| Emotional/affective | Withdrawal symptoms | MPSS |

| Strength of desire to smoke | Self-reported cravings and strength of urge to smoke | |

| Quality of life | EQ-5D | |

| Nicotine dependence | FTND | |

| Subjective stress | PSS | |

| Smoking satisfaction | mCEQ | |

| Weight | ||

Given that baseline and follow-up assessments were conducted by a researcher who also provided the intervention, it was not possible to blind outcome assessment. This decision was made to provide a more seamless interaction with participants who had no prior experience of engaging in a research study and with whom it may have been particularly challenging to remain in contact. One of the aims of the process evaluation was to examine whether or not this was indeed important for participants.

Feasibility outcomes

The following feasibility outcomes were identified: participant recruitment rate (the proportion of those invited, via different methods, who agreed to take part), follow-up and outcome data collection rates, flow of smokers through the trial from each location [e.g. numbers of smokers recruited, number ineligible (with reasons), number declined, numbers failing to continue with data collection]; number of those deciding to quit who chose to use a SSS; number who chose to quit who could be tracked on a weekly basis [and hence inform the number with 4 weeks’ expired air carbon monoxide (CO) confirmed abstinence], and demographic characteristics of the sample relative to a disadvantaged definition.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is expired air CO-confirmed abstinence [< 10 parts per million (p.p.m.)] using a Micro+ Smokerlizer (Bedfont Scientific Ltd, Maidstone, Kent, UK) using standardised procedures, with a self-reported time since last cigarette, at 4 weeks post quit. The outcome is binary, that is to say abstinent or not abstinent (those lost to follow-up are assumed to be still smoking78). Participants with an expired air CO reading ≥ 10 p.p.m. and those whose self-report data did not confirm their quit status were assumed to have started smoking again. The EARS intervention aimed to reduce smoking with the hope that a quit attempt and successful quitting might follow.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes included the number of participants reducing their self-reported smoking levels by at least 50% along with several other cognitive, behavioural and emotional outcomes outlined in Table 5.

Cognitive variables

Participants were asked at baseline, 8 weeks and 16 weeks how confident they were in their ability to (1) do at least 30 minutes of moderate-intensity PA on most days of the week over the next 6 months and (2) walk continuously for 15 minutes at a brisk pace, using a 7-point response scale from ‘not at all confident’ (1) to ‘extremely’ (7). Stage of readiness to use PA to control smoking was assessed by participants ticking one from five options as follows: (1) I do not use physical activity as a way of controlling my cigarette smoking and I do not intend to start; (2) I do not use physical activity as a way of controlling my cigarettes smoking but I’m thinking of starting; (3) I use physical activity once in a while as a way of controlling my cigarette smoking, but not regularly; (4) I use physical activity regularly as a way of controlling my cigarette smoking, but only started within the past 6 months; (5) I use physical activity regularly as a way of controlling my cigarette smoking and have been doing so for longer than 6 months. Responses reflected being in the pre-contemplation, contemplation, planning, action, or maintenance stage, respectively. All the above questions have been previously used. 67

To assess beliefs about quitting smoking the following questions were asked using a 7-point response scale from ‘not at all’ (1) to ‘extremely’ (7): How important is it for you to stop smoking permanently and completely in the next six months?; how confident are you that you can stop smoking permanently and completely in the next six months?; an important person in your life thinks you should quit smoking; how confident are you that over the next week (except at baseline when we referred to ‘over the next 4 weeks’) you will smoke only half the number of cigarettes you smoked at the time of entry into the study?

Behavioural measures

Physical activity data were collected using a tri-axial GT3X accelerometer (Actigraph, Pensacola, FL, USA). Data were recorded using a 1-second epoch, over a 7-day period. Self-reported PA was collected using the 7-day PA recall questionnaire. 79 Minutes of moderate to vigorous PA (MVPA) and average nightly sleep were recorded, and minutes of light activity were derived. Minutes of MVPA and energy expenditure were calculated. Smoking status was recorded by the question (1) How many cigarettes, cigars, or pipes, have you usually smoked each day over the past week (recorded in numbers smoked or grams/ounces of loose tobacco)? Those who reported no smoking in the past week (with expired air CO confirmation of < 10 p.p.m.) at 16 weeks were defined as not smoking at that point and we used this to report 16-week point prevalence abstinence. Alcohol consumption was assessed to monitor changes in another lifestyle behaviour often associated with smoking, using two questions taken from the World Health Organization’s (WHO) validated AUDIT alcohol screening tool:80 (1) How often do you have a drink containing alcohol? (0, ≤ 1 per month; 2–4 times per month; 2–3 times per week; ≥ 4 times per week); (2) How many drinks containing alcohol do you have on a typical day when you are drinking? (1–2; 3–4; 5–6; 7–9; ≥ 10); and the addition of the third question: how many drinks containing alcohol have you had in the past week? (1–2; 3–4; 5–6; 7–9; ≥ 10).

Emotional/affective measures

Strength of urge to smoke and time spent with those urges over the past week were assessed using two items (1–6 point response scale)81 and withdrawal symptoms assessed using an adapted 9-item Mood and Physical Symptoms Scale (MPSS). 82 Quality of life is assessed using the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D). 83 Smoking dependence was assessed using the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND). 84,85 Subjective stress was assessed using the 4-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS),86 to monitor any changes associated with smoking reduction or increasing PA. Satisfaction from smoking was assessed using the 10-item modified Cigarette Evaluation Questionnaire (mCEQ),87 as we expected that the pleasure derived from smoking may reduce with increased PA participation.

All questionnaire data were scanned and manually checked using Teleform Scanning software (Cardiff Software, Digital Vision, Highland Park, IL, USA). A second researcher double-checked 10% of the entered data against the raw data and if more than a 1% error was found, all questionnaire data would have been manually rechecked. The data were stored on a secure institutional server.

Statistical analysis

We report the flow of participants through this study according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines for non-pharmaceutical interventions. 88 Given that this was a pilot study, the primary approach to data analysis is descriptive (i.e. proportions, means and standard deviations, or median and interquartile ranges) for primary and secondary outcomes at baseline and follow-up for each of the two groups reported. However, to inform the power of a future definitive trial we also calculated an estimate of the intervention (vs. control) effect size [relative risk (RR)] and its precision [95% confidence interval (CI)] for the primary outcome (i.e. continuous expired air CO-confirmed abstinence at 4 weeks post quit), and other dichotomous smoking-related outcomes (e.g. point prevalence abstinence and proportion reducing by at least 50% at 16 weeks). Participants lost to follow-up were assumed to still be smoking the same amount as at baseline.

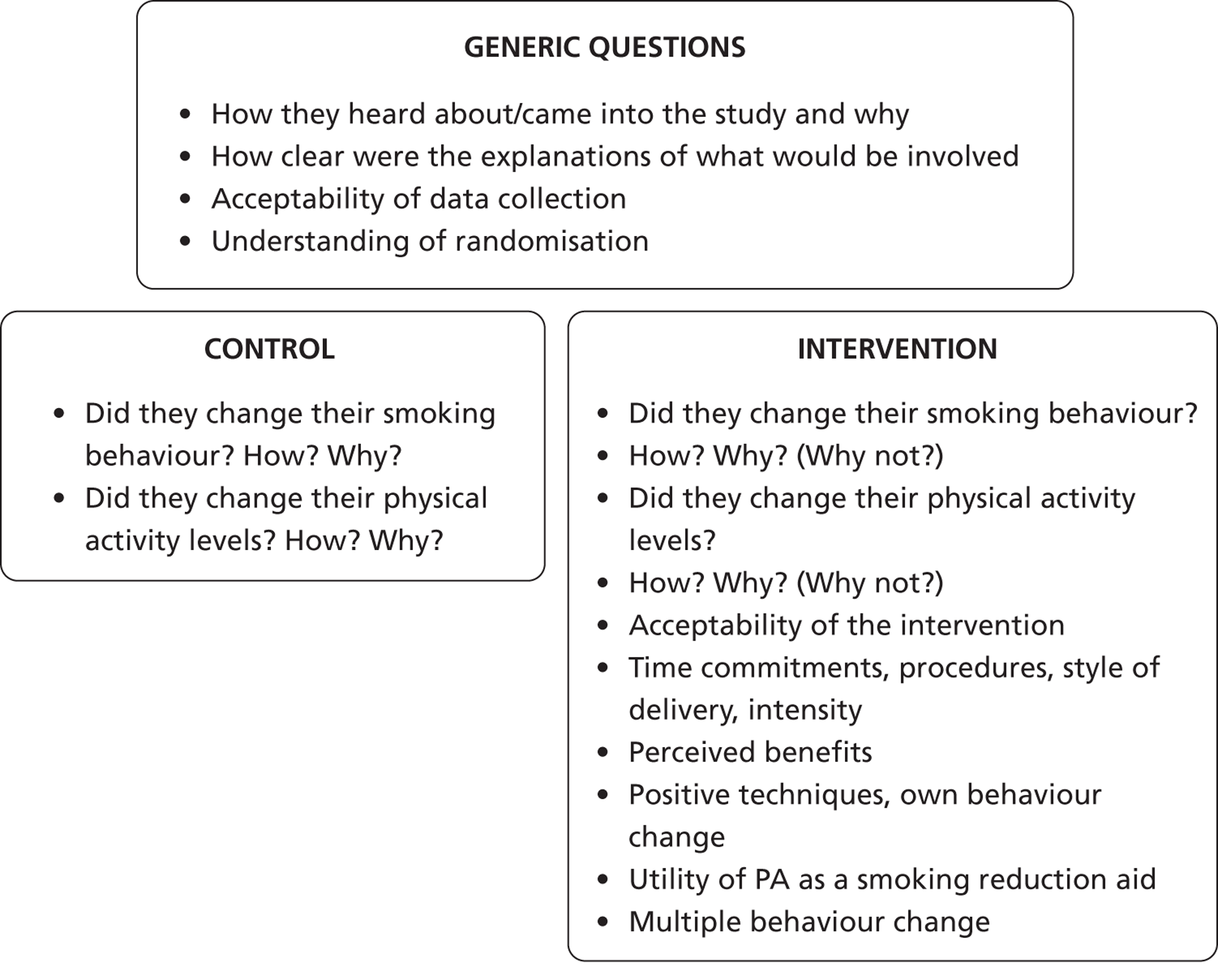

Qualitative data collection and analysis

The methods, procedures, data analysis and findings are reported in Chapter 5.

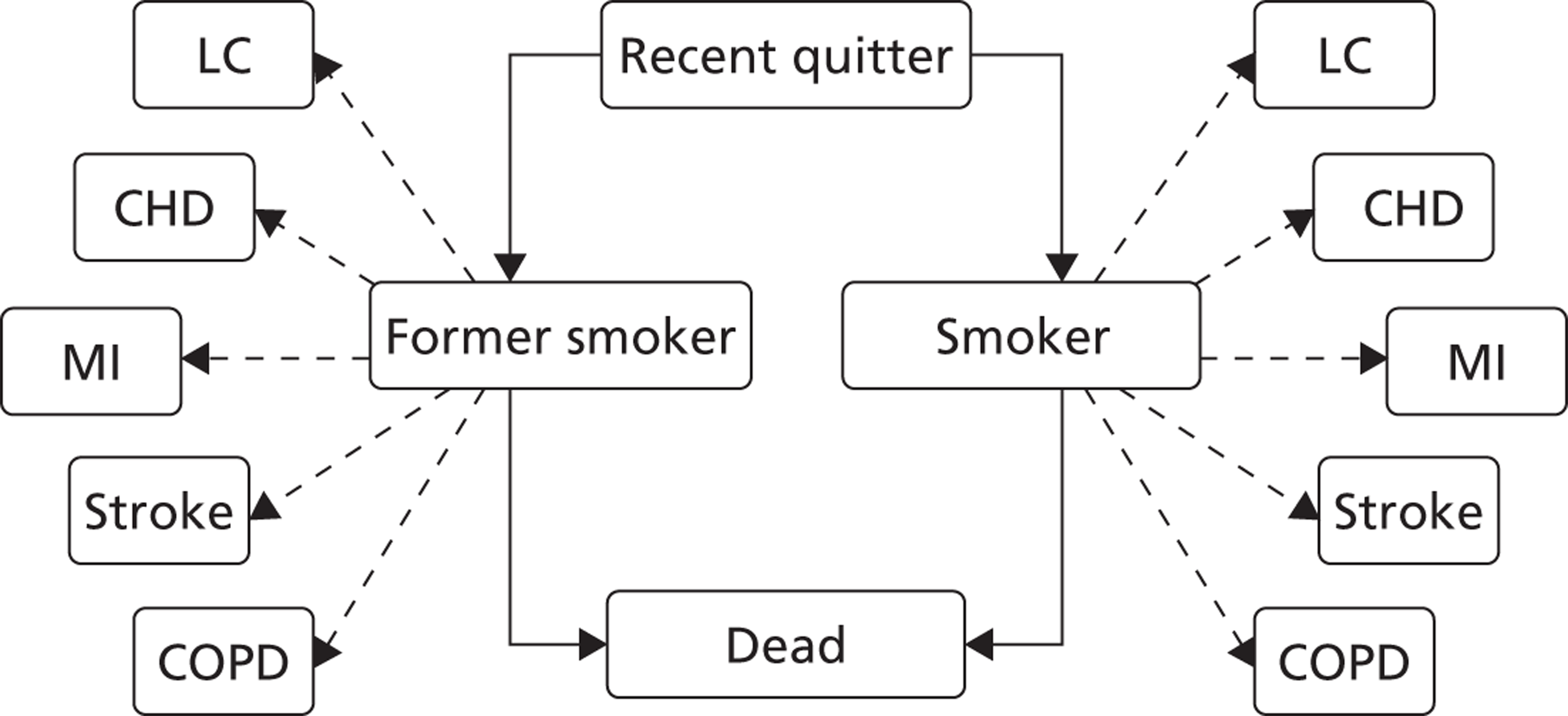

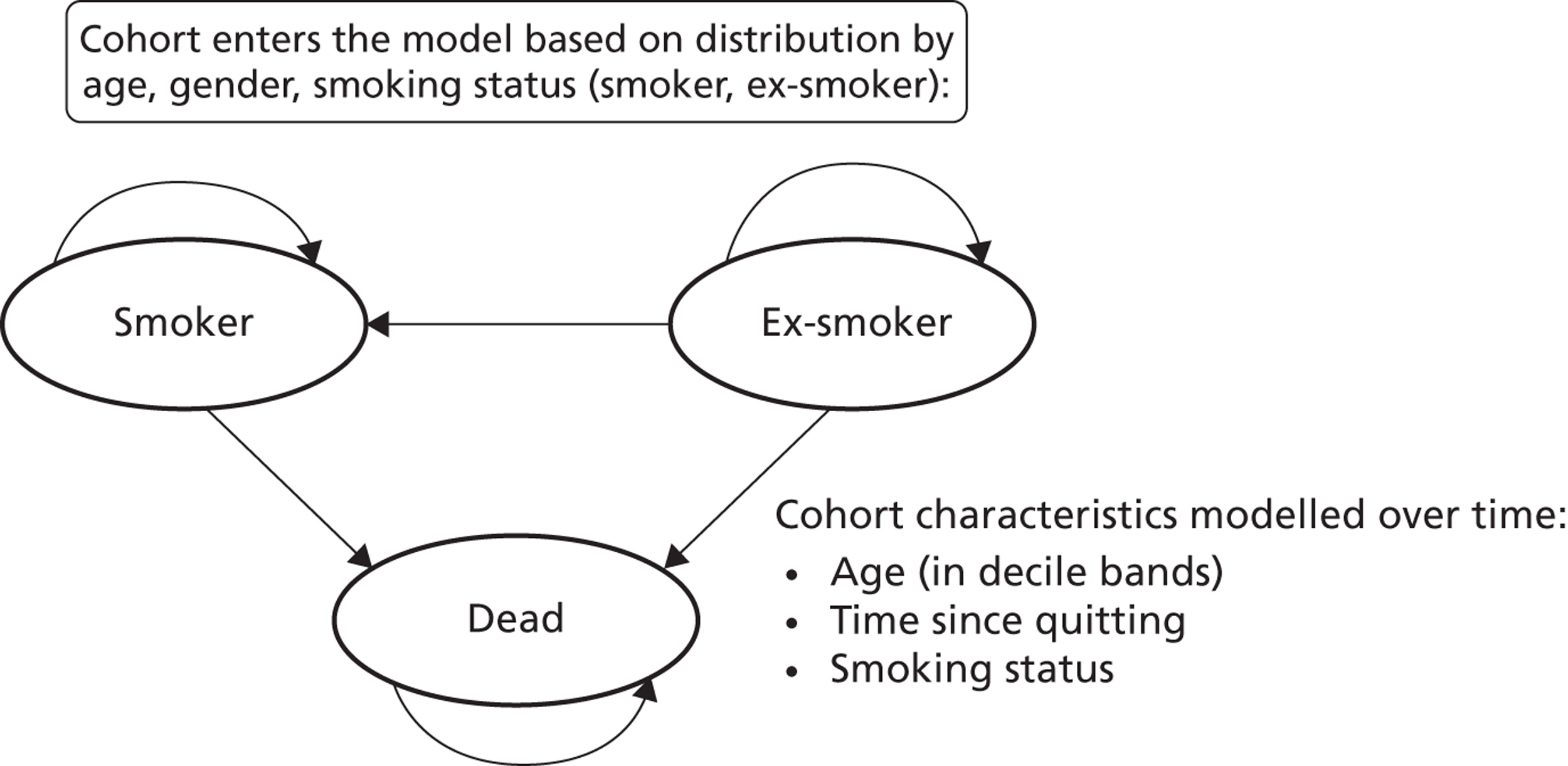

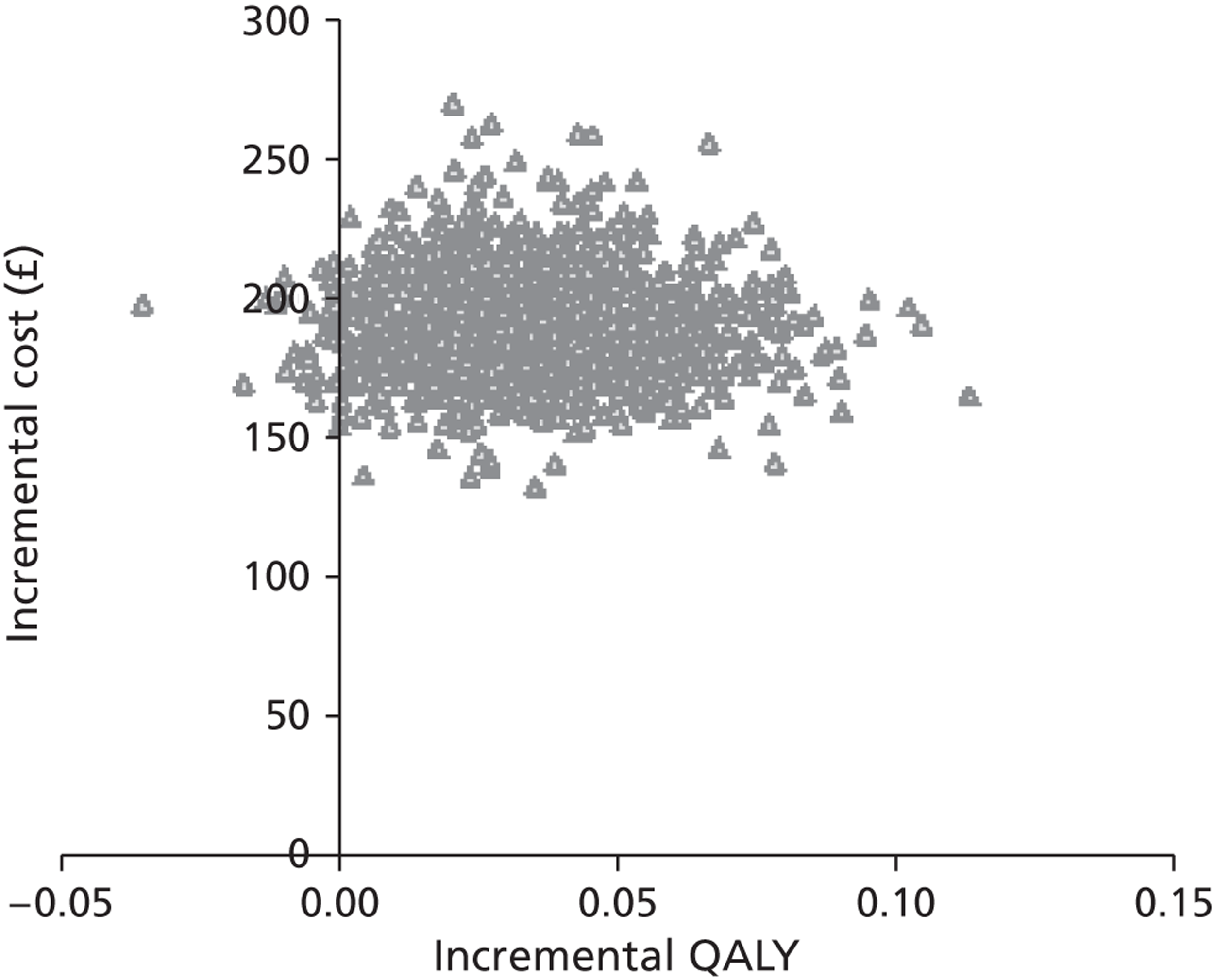

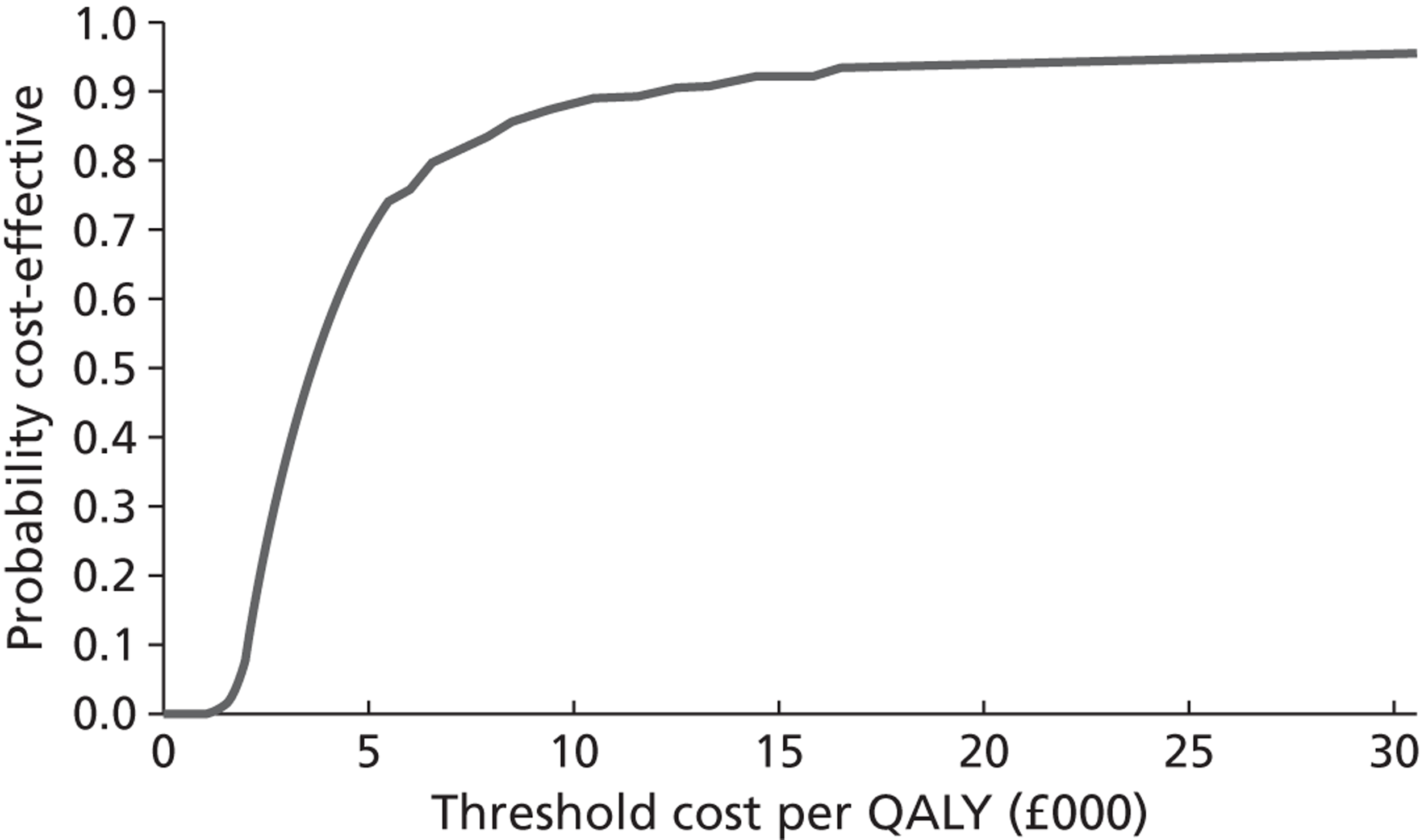

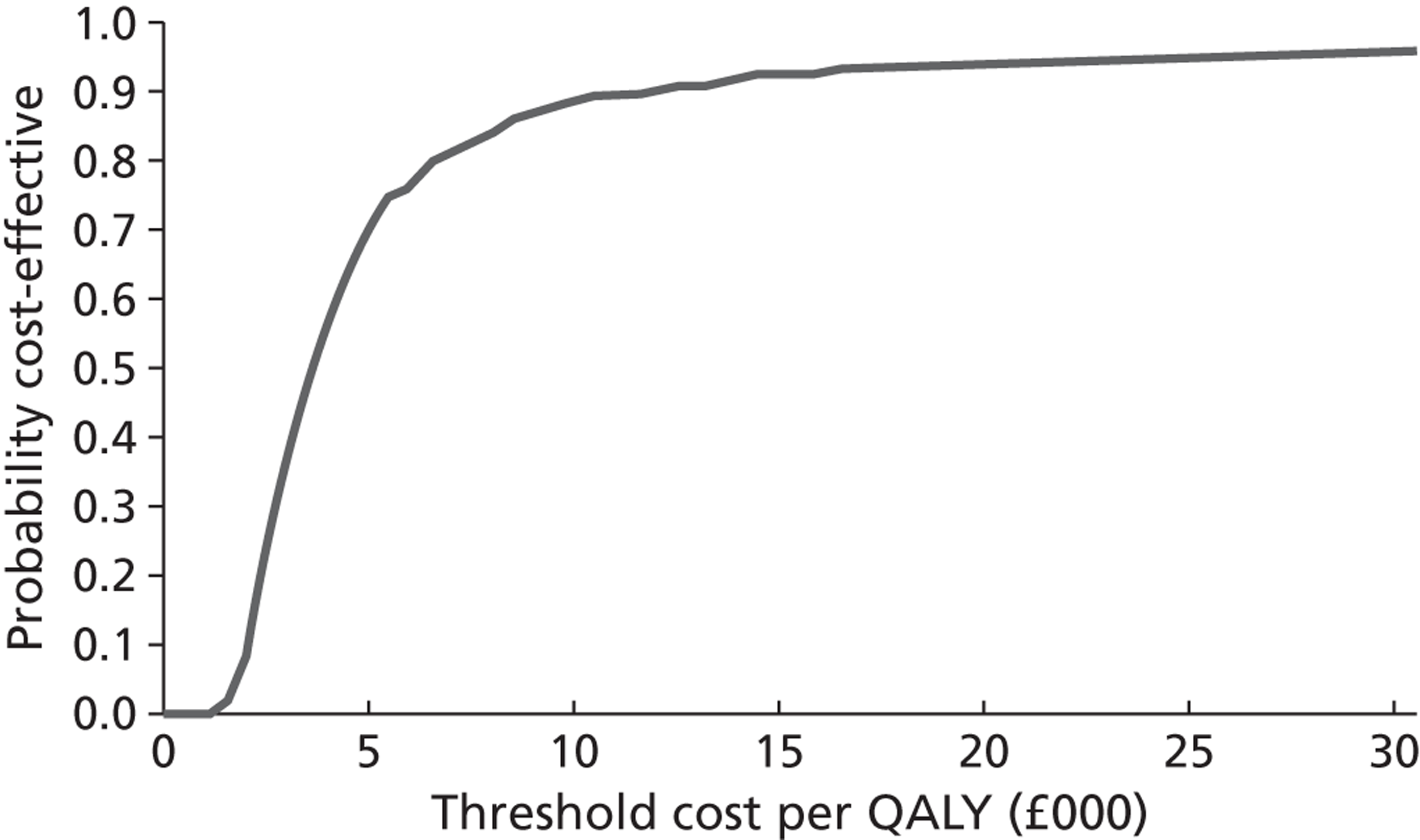

Cost-effectiveness data collection, analysis and modelling

Within-trial data collection was used to estimate resource use associated with the delivery of the EARS intervention. Items of resource use were combined with published unit cost data to estimate the cost of the EARS intervention, per participant. Evidence review, on modelling methods used to assess cost-effectiveness of smoking-cessation interventions, informed the development of a framework for cost-effectiveness analyses. We present the initial stages of development of a decision-analytic model to compare EARS with brief advice over the longer term. Exploratory cost-effectiveness analyses are undertaken, using assumptions on inputs for effectiveness of EARS. The methods, procedures, data analysis and findings are reported in Chapter 6.

Chapter 3 Trial results: quantitative results

This chapter reports on:

-

participant recruitment

-

participant characteristics for the total sample and across treatment arms

-

study attrition and associated factors

-

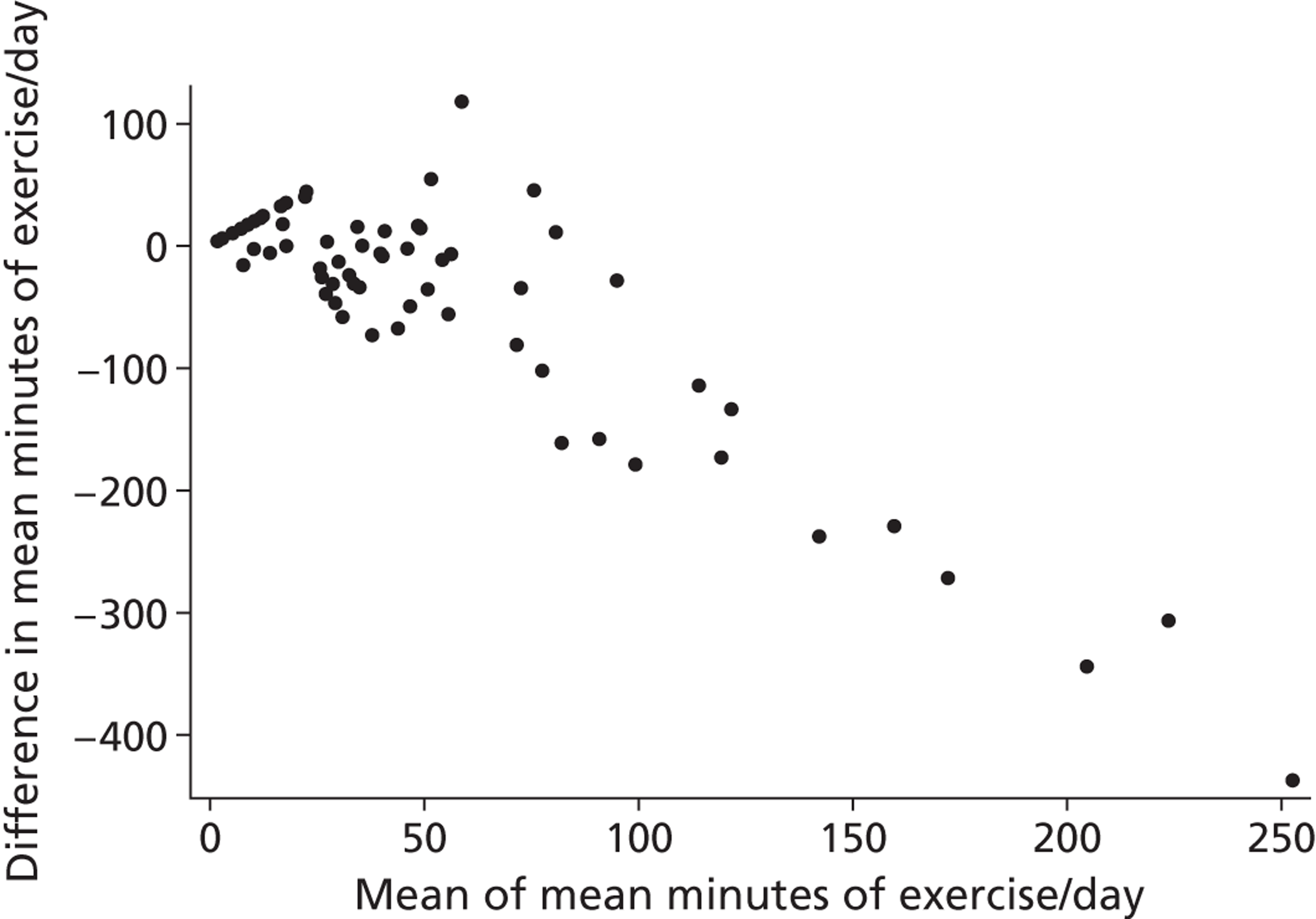

bias in self-reported PA

-

changes in outcomes over time, by treatment arm

-

intervention adherence and its association with outcomes.

Participant recruitment

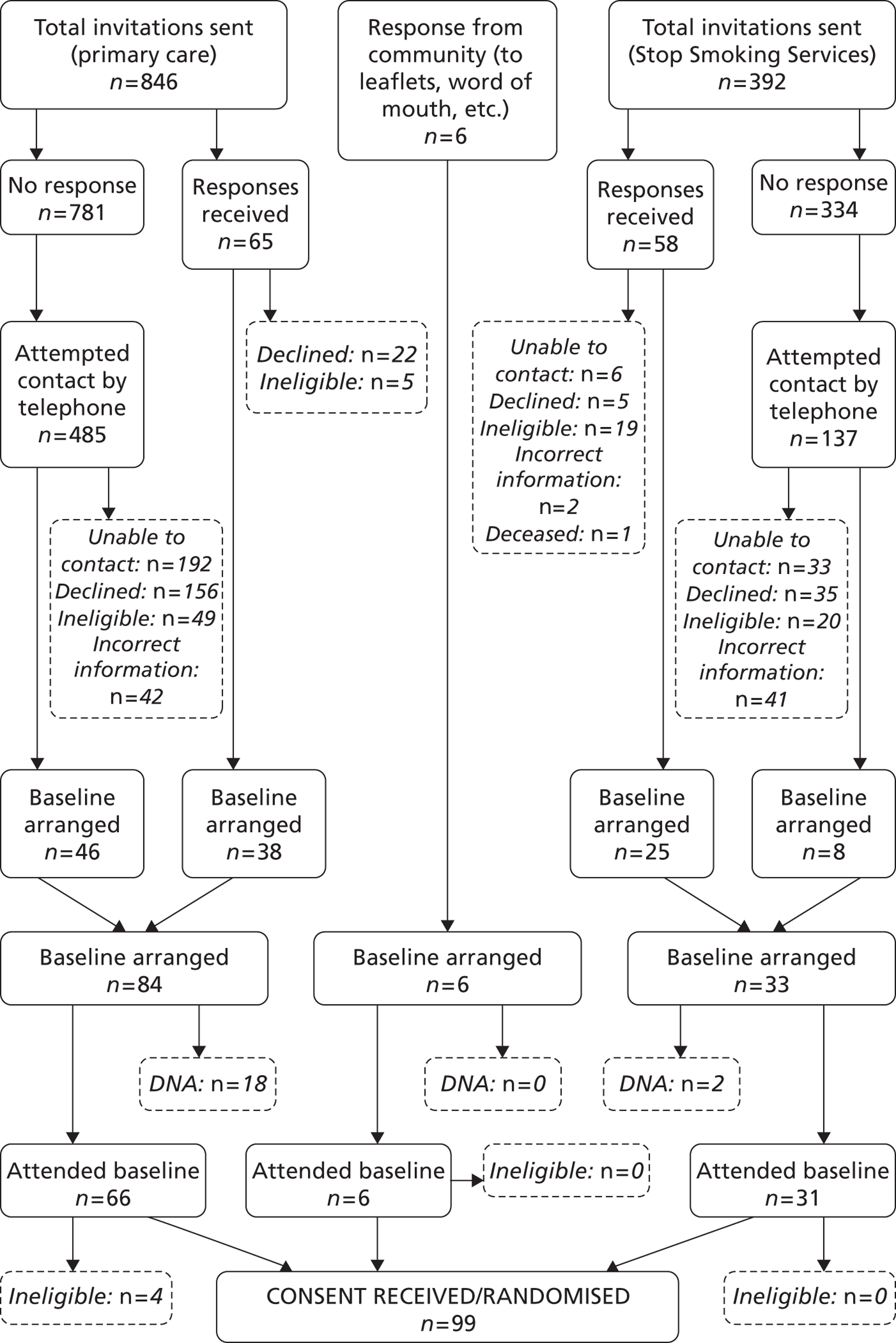

The flow of participants from invitation letter via GP surgery and SSS, and via other community approaches, is shown in the CONSORT diagrams (Figure 1, up to randomisation, and Figure 2, after randomisation).

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials chart showing recruitment approaches, and participant flow, up to randomisation. DNA, did not attend.

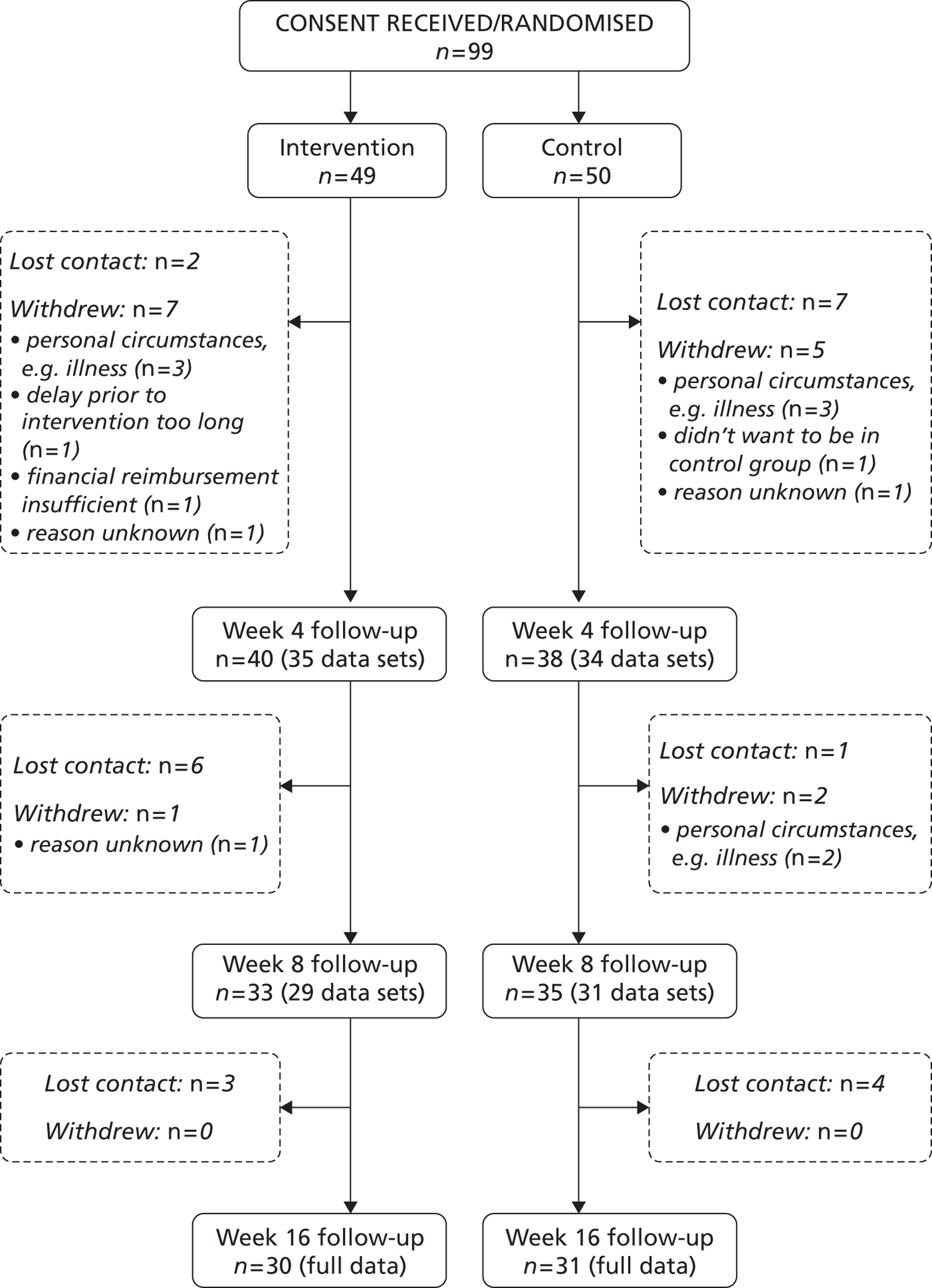

FIGURE 2.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials chart showing recruitment approaches, and participant flow, after randomisation. DNA, did not attend.

Process of recruitment

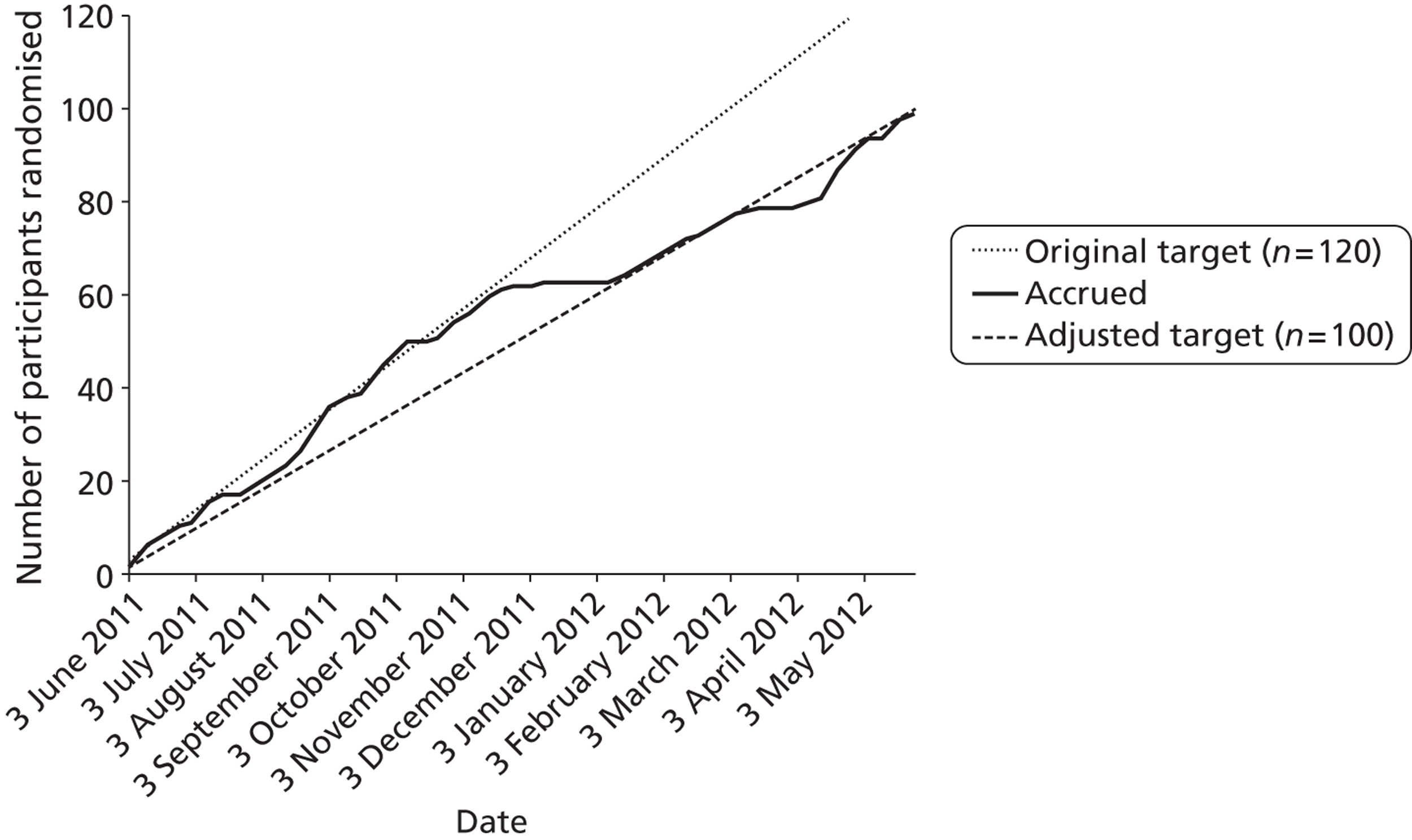

We began by focusing recruitment on mailed invitations from GP practices and the SSS. This was done to ensure that the research team initially gained confidence in the trial methods and intervention delivery, including the invitation and recruitment rate. Mailed invitations were done in batches of about 100 from each GP practice, or the SSS, to reduce the burden on associated GP practice screening and administration time, and to establish a steady flow of willing participants into the study. The aim was to recruit 60 participants from GP mailed invitations: 30 from SSS-mailed invitations and 30 from other community approaches. As Figure 3 shows, we remained on target during the first 6 months for recruiting the planned 120 participants. By this time we had exhausted the patient database of eligible smokers in one GP surgery and began recruiting from another surgery. Recruitment slowed prior to the Christmas period, and the new surgery also wanted to screen all participants before mailing an invitation rather than waiting to screen any willing participants who had responded to the invitation. This required additional time between identifying potential participants and mailing invitations. At this time we also allocated one HT/researcher to other community recruitment activity, which we anticipated would have greater uncertainty with recruitment rates. We revised our recruitment target, as shown in Figure 3, to 100 participants at this point.

FIGURE 3.

Participant recruitment accrual graph over the duration of the study.

Overall, there was a higher percentage of smokers contacted through the SSS who were ineligible to enter the study, likely due to the extra level of screening that took place through GP practice recruitment. The reasons for ineligibility were similar across recruitment methods and are shown in Table 6. The most common reason for ineligibility was due to the individual having already quit smoking, suggesting out-of-date records in both GP practices and the SSS.

| Reasons | Primary care | SSS |

|---|---|---|

| Health/physical (%) | 15.8 | 20.5 |

| Already quit (%) | 57.9 | 53.8 |

| Smokes < 10 cigarettes per day (%) | 10.5 | 10.4 |

| Close friend or relative of somebody already in the trial (%) | 0.0 | 5.1 |

| Currently using NRT (%) | 5.3 | 5.1 |

| Under 18 years old (%) | 0.0 | 5.1 |

| Wants to quit immediately (%) | 10.5 | 0.0 |

Different amounts of effort were involved in following up participants invited by letter from the three GP surgeries and the SSS. The maximum effort involved telephoning, on up to five occasions, all smokers who had not responded to an initial invitation letter and postal reminder. If there was no response a message was left with contact details for the study on the first call, but not on subsequent calls to avoid harassment. The percentage of the total sample recruited, by recruitment method, is shown in Table 7.

| Recruitment method | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Primary care | 62 (62.6) |

| Letter only | 31 (31.3) |

| Letter plus reminder telephone calls | 31 (31.3) |

| SSS | 31 (31.3) |

| Letter only | 24 (24.2) |

| Letter plus reminder telephone calls | 7 (7.1) |

| Community (without invitation letter) | 6 (6.1) |

Recruitment by letter and reminder telephone calls (from GP or SSS)

In terms of response rates, we were able to substantially increase the proportion of people invited by letter who were randomised, from about 7% to 11%, by making up to five reminder telephone calls. A lack of availability of staff prevented us from making reminder telephone calls to all those initially invited, particularly to those invited from the SSS. The associated researcher time to recruit one participant ranged from approximately 20 minutes for those who responded directly to the letter invitation up to approximately 150 minutes for completing reminder telephone calls to those who did not initially respond to the letter invitation.

Community recruitment without invitation letter

A variety of approaches were attempted to recruit participants other than by letter as summarised in Table 8. Our efforts focused on workplaces with a high proportion of manual and unskilled workers, educational sites (in an effort to recruit single parents), local media, opportunistic referral through the IAPT to target people with depression and anxiety, and a wide range of other community sites and organisations in Devonport and Stonehouse. We estimate that at least 46 hours of dedicated time by the HTs/researchers resulted in the six participants recruited via these approaches.

| Recruitment sites | Recruitment activity |

|---|---|

| Workplace site | |

| Local adult education and training provider | Flyers and packs in the refectory. Contact at the centre distributed packs |

| Post office MDEC | Information cascaded through managers to all employees in team briefings |

| Educational site | |

| Local primary school | Article in parent newsletter |

| Mother/toddler groups; several local children’s centres | Mother/toddler groups visited through Sure Start. Posters and packs left, packs given out during groups |

| Community site/organisation | |

| Job centre (Devonport) | 100 packs given out over several periods in a week |

| Local community hub cafe | Local health promotion sessions and food bank session attended |

| Local community co-operative organisation | Flyers and posters given out for the Guildhall and workers based there |

| YMCA (community-run gym) | Posters on display. Fitness manager promoted study to users of the Stonehouse gym. HTs attended a children’s session; one pack given out. |

| Local gym | Gym instructors gave out flyers and packs |

| Local social club | Central contact gave out several packs and reply sheets |

| Public health | Posters and packs given to the local health club in Devonport |

| Three local housing associations | 180 flyers distributed through mailboxes in housing association residences in Plymouth; flyers distributed and attendance at residents’ meetings. Posters, flyers and packs left at site for visitors |

| Neighbourhood managers (city council) | HT met with managers in Devonport and Stonehouse. Information distributed |

| Local community learning centre | Information and flyers displayed. HT attended information sessions |

| Other | |

| Local library | Flyers and posters on display. |

| Heart Radio/Plymouth Sound/Radio Devon/newspaper | Radio chat about the study and news advert in paper |

| Word of mouth | First 60 trial participants asked to invite friends/acquaintances to join study |

| Individual contacts (e.g. Church of England minister, local day support facility member, publican) | Posters displayed by contacts |

| IAPT Service, Plymouth | Met and encouraged psychological well-being practitioners. Left flyers to be distributed. Encouraged by e-mail |

Participant characteristics across recruitment methods

Table 9 shows the demographic characteristics of those recruited by GP and SSS invitation letter and via other community approaches without an invitation letter. Given the small number of participants recruited via other community approaches, any comparison with approaches involving an invitation letter are meaningless. Comparisons of the characteristics of participants recruited by invitation letter from the GP versus the SSS appear to show little difference.

| Baseline characteristic | Primary care (N = 62) | SSS (N = 31) | Community (N = 6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 28 (45.2) | 13 (41.9) | 2 (33.3) |

| Female | 34 (54.8) | 18 (58.1) | 4 (66.7) |

| Age (years), mean (SD); median (IQR) | 45.9 (11.4); 47.1 (38.0 to 55.0) | 47.1 (11.7); 48.9 (38.3 to 56.9) | 50.8 (8.6); 49.6 (44.3 to 58.2) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White British | 58 (93.6) | 31 (100) | 6 (100) |

| Other | 4 (6.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Cohabiting status, n (%) | |||

| Cohabiting | 35 (56.5) | 12 (38.7) | 3 (50.0) |

| Not cohabiting | 27 (43.6) | 19 (61.3) | 3 (50.0) |

| Children under 16 years, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 16 (25.8) | 9 (29.0) | 3 (50.0) |

| No | 46 (74.2) | 22 (71.0) | 3 (50.0) |

| Single parent,a n (%) | |||

| Yes | 2 (3.2) | 2 (6.5) | 2 (33.3) |

| Employment status, n (%) | |||

| Employed | 37 (59.7) | 13 (41.9) | 4 (66.7) |

| Not employed | 25 (40.3) | 18 (58.1) | 2 (33.3) |

| Job status, n (%) | |||

| A to C1 | 5 (8.1) | 2 (6.5) | 2 (33.3) |

| C2 to E | 32 (51.6) | 11 (35.5) | 2 (33.3) |

| Unemployed | 25 (40.3) | 18 (58.1) | 2 (33.3) |

| Age (years) on leaving education, mean (SD); median (IQR) | 16.3 (2.1); 16.0 (15.0 to 16.3) | 16.2 (1.6); 16 (15 to 16) | 16.0 (1.3); 15.5 (15.0 to 17.3) |

| Age (years) on starting smoking, mean (SD); median (IQR) | 14.5 (3.6); 14.0 (13.0 to 16.0) | 14.6 (3.1); 15.0 (12.0 to 16.0) | 16.8 (3.0); 17.0 (13.8 to 20.0) |

| Does partner or other cohabitant smoke, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 20 (32.3) | 10 (32.3) | 1 (16.7) |

| No | 20 (32.3) | 5 (16.1) | 2 (33.3) |

| Not applicable | 22 (35.5) | 16 (51.6) | 3 (50.0) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD), n; median (IQR) | 27.6 (6.5), 62; 26.5 (22.2 to 31.3) | 28.9 (6.6), 30; 27.7 (22.5 to 35.0) | 29.9 (4.1), 6; 30.2 (26.5 to 33.3) |

| Indicated mental health problem,b n (%) | |||

| Yes | 24 (38.7) | 16 (51.6) | 1 (16.7) |

| No | 38 (61.3) | 15 (48.4) | 5 (83.3) |

| Duration of smoking (years), mean (SD); median (IQR) | 31.5 (12.2); 33.1 (22.2 to 40.0) | 32.5 (13.0); 36.4 (23.3 to 43.1) | 34.0 (8.9); 34.1 (29.9 to 42.2) |

| Previous use of SSS, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 17 (27.4) | 22 (71.0) | 2 (33.3) |

| No | 45 (72.6) | 9 (29.0) | 4 (66.6) |

| Satisfaction with previous use of SSS (if used) (scale 1–11); mean (SD), n | 7.3 (3.28), 17 | 8.9 (2.3), 21 | 10.5 (0.7), 2 |

| Did the participant make a quit attempt lasting 24 hours or more in the past year, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 17 (27.4) | 18 (58.1) | 2 (33.3) |

| No | 45 (72.6) | 13 (47.9) | 4 (66.6) |

| Did the participant cut down before previous cessation,c n (%) | |||

| Yes | 1 (5.9) | 4 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| No | 16 (94.1) | 14 (77.8) | 2 (100.0) |

| Total n | 17 | 18 | 2 |

| Used cessation aids as part of a quit attempt in previous 12 months,d n (%) | |||

| Yes | 11 (64.7) | 17 (94.4) | 1 (50.0) |

| No | 6 (35.3) | 1 (5.6) | 1 (50.0) |

| Total n | 17 | 18 | 2 |

| Used cessation aids not as part of a quit attempt in previous 12 months, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 8 (17.8) | 10 (26.3) | 3 (75.0) |

| No | 37 (82.2) | 3 (73.7) | 1 (25.0) |

| Total n | 45 | 13 | 4 |

We also compared the characteristics of those recruited after an immediate response to the invitation letter with those recruited in response to a subsequent reminder letter and reminder telephone call as shown in Table 10. The numbers were fairly small for some categories of response but there appeared to be little difference between contact methods, suggesting that making the additional effort to recruit participants does not necessarily increase the reach of the intervention to more disadvantaged participants or increase generalisability.

| Baseline characteristic | Contact methode | |

|---|---|---|

| Letter (N = 55) | Letter and reminder telephone call (N = 38) | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 25 (45.5) | 16 (42.1) |

| Female | 30 (54.6) | 22 (57.9) |

| Age (years), mean (SD); median (IQR) | 47.3 (11.7); 48.9 (38.0 to 55.5) | 44.9 (11.0); 46.0 (38.1 to 53.6) |

| Age (years), n (%) | ||

| 30 and under | 6 (10.9) | 7 (18.4) |

| 31 and over | 49 (89.1) | 31 (81.6) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White British | 53 (96.4) | 36 (94.7) |

| Other | 2 (3.6) | 2 (5.3) |

| Cohabiting, n (%) | 27 (49.1) | 20 (52.6) |

| Children under 16, n (%) | 15 (27.3) | 10 (26.3) |

| Single parent,a n (%) | 2 (3.6) | 2 (5.3) |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||

| Employed | 29 (52.7) | 21 (55.3) |

| Not employed | 26 (47.3) | 17 (44.7) |

| Job status, n (%) | ||

| A to C1 | 5 (9.1) | 2 (5.6) |

| C2 to E | 24 (43.6) | 19 (50.0) |

| Unemployed | 26 (47.3) | 17 (44.7) |

| Age (years) on leaving education, mean (SD); median (IQR) | 16.2 (1.8); 16.0 (15.0 to 16.0) | 16.4 (2.1); 16.0 (15.0 to 16.3) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD), n; median (IQR) | 28.0 (6.0), 54; 27.3 (22.5 to 33.0) | 28.1 (7.3), 38; 26.4 (22.2 to 31.3) |

| Indicated mental health problem,b n (%) | ||

| Yes | 22 (40.0) | 18 (47.4) |

| No | 33 (60) | 20 (52.6) |

| Age (years) on starting smoking, mean (SD); median (IQR) | 14.9 (3.5); 14 (13 to 16) | 14.1 (3.3) 14 (12 to 16) |

| Does partner or other cohabitant smoke, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 20 (36.4) | 10 (26.4) |

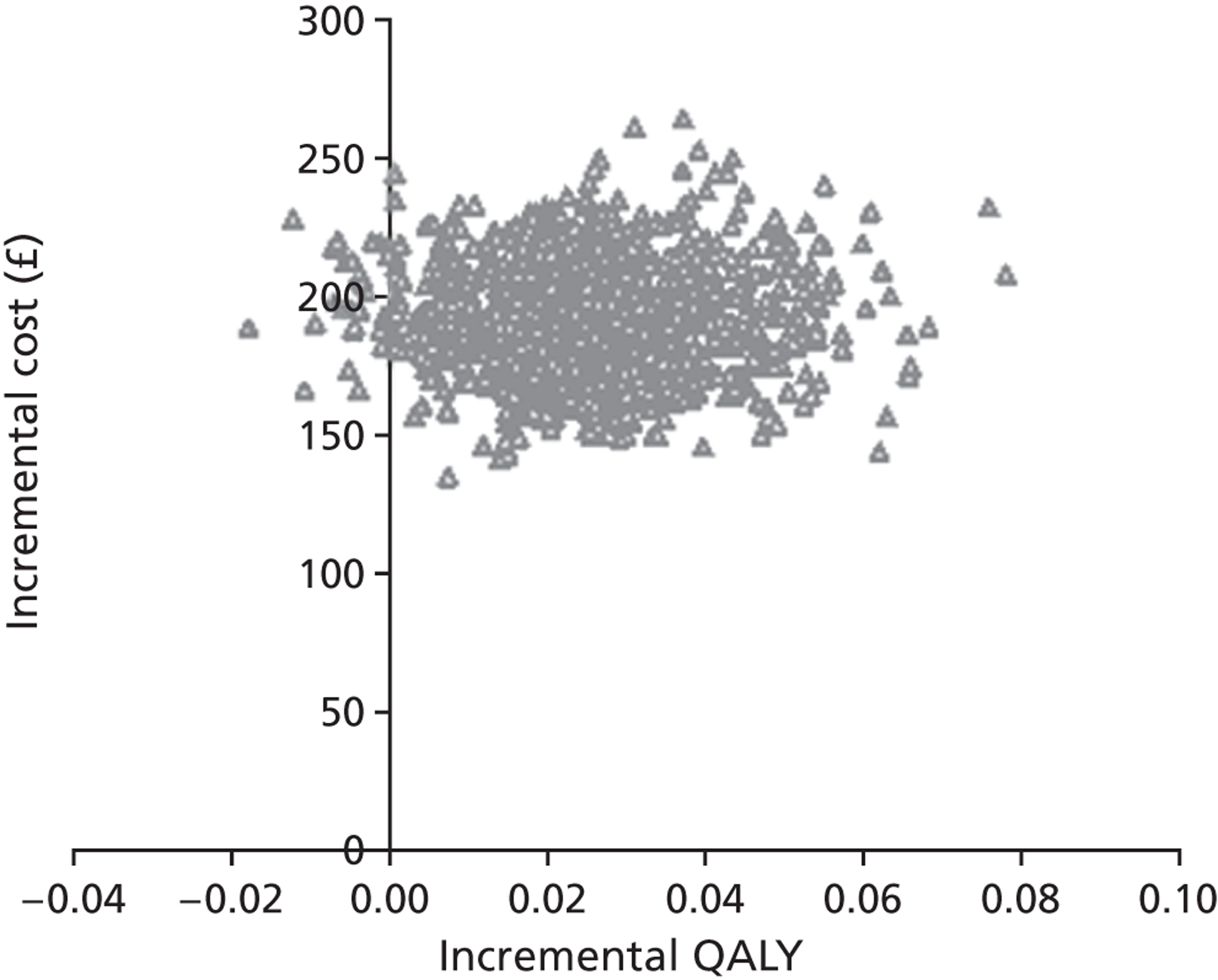

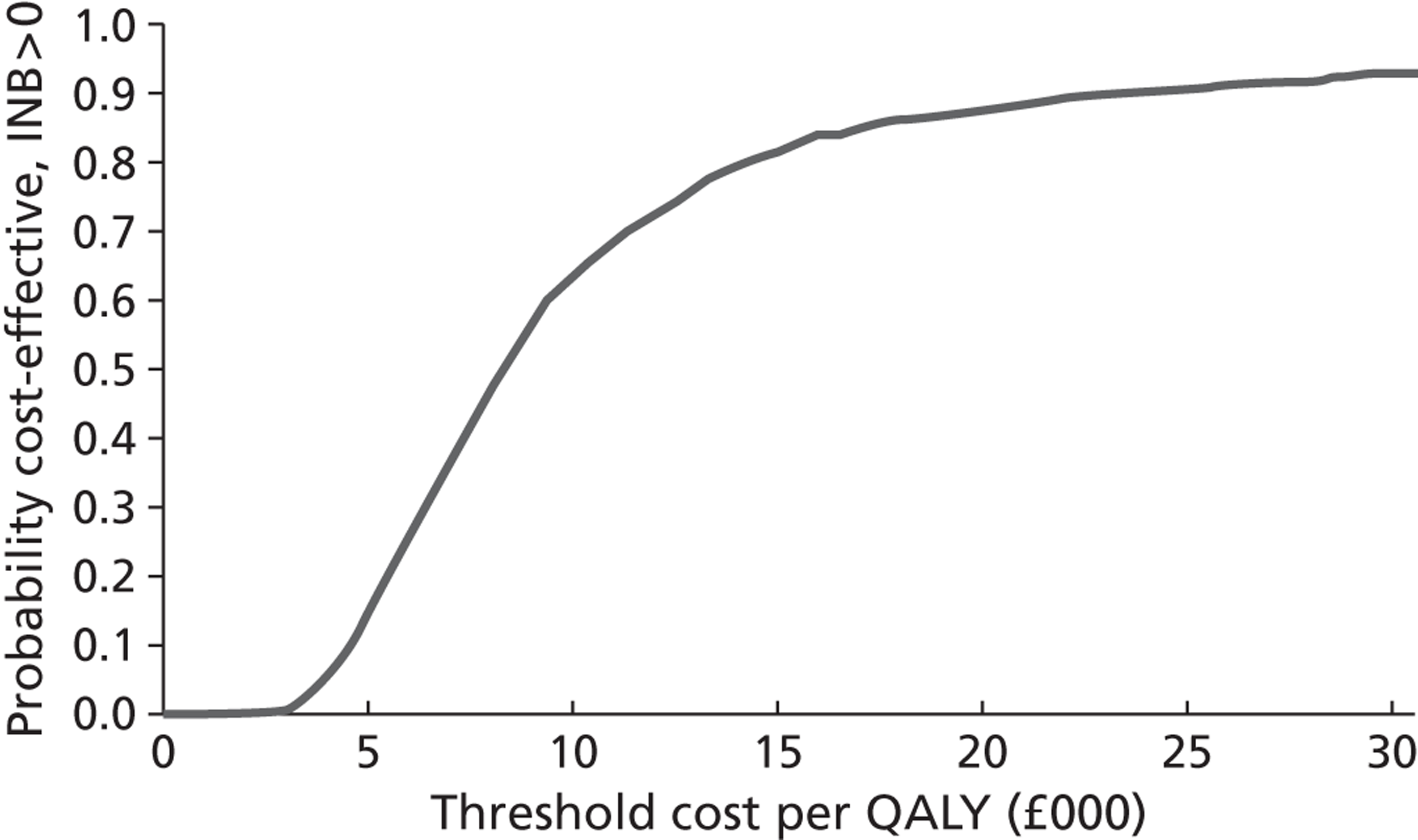

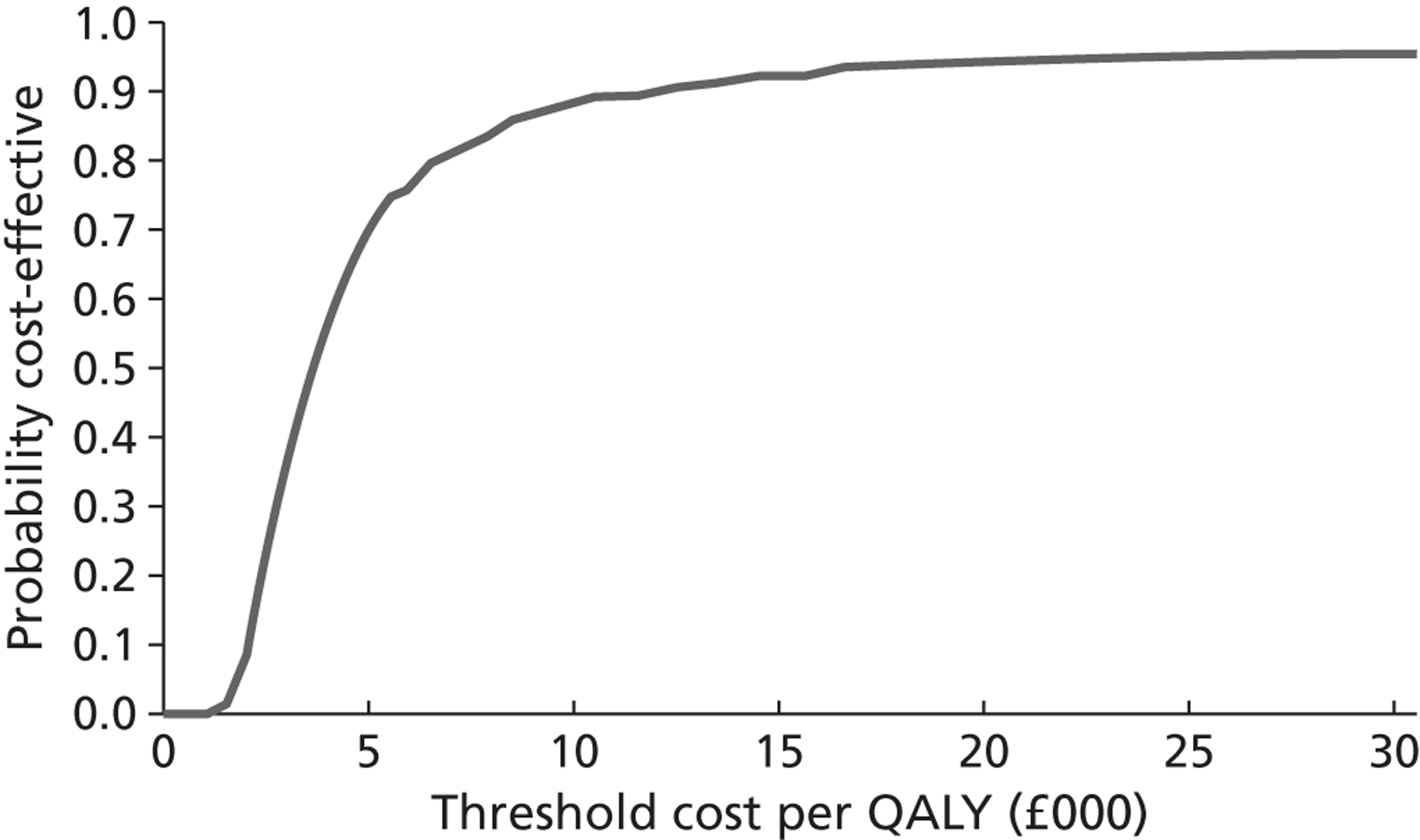

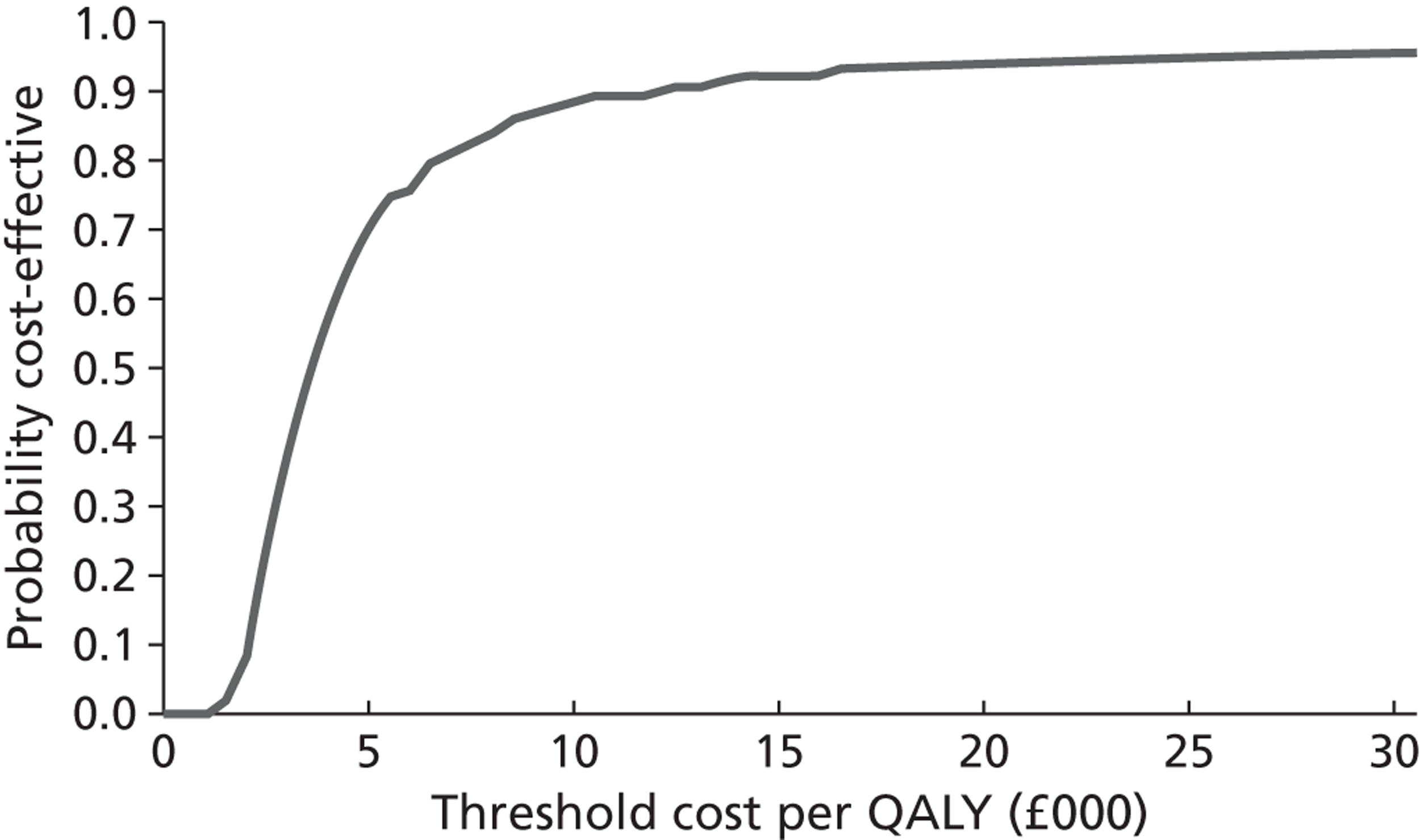

| No | 11 (20.0) | 14 (36.8) |