Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/117/02. The contractual start date was in November 2010. The draft report began editorial review in June 2012 and was accepted for publication in November 2012. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Peter Bower has acted as a paid scientific consultant to the British Association of Counselling and Psychotherapy and Paul Stallard was a named co-applicant on two other research grants at the time this work was submitted: National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Grant 06/37/04 and National Institute for Health Research Public Health Grant 09/3000/03.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Bee et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background and objectives

Serious parental mental illness poses a significant challenge to quality of life (QoL) in a substantial number of infants, children and adolescents. Research suggests that the children of parents with serious mental illness (SMI) are at increased risk of a range of emotional, social, behavioural and educational difficulties that arise from a complex interplay of genetic, environmental and psychosocial factors. 1 A recent shift in UK policy has placed greater emphasis on the well-being of these children, with the shared recommendation that their needs should be better addressed by health- and social-care services. 2 In 2010, the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme prioritised an evidence synthesis of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of community-based interventions aimed at increasing or maintaining QoL in children and adolescents of parents with SMI. The results of this work are presented here.

The epidemiology of serious parental mental illness

A substantial proportion of children and adolescents experience SMI in family members. Many of these children remain invisible to services. A lack of recognition of the family circumstances of many service users,2 historically poor integration between adult and child mental health services3 and the inadequate identification of children caring for parents with mental illness4 have traditionally hampered the accurate quantification of point prevalence rates.

Conservative estimates suggest that, within the UK, approximately 175,000 children provide informal care for a parent or sibling,5 almost one-third (29%) of whom will care for a relative with a mental health difficulty. 6 However, such data pertain only to those children who are formally recognised as young carers and, as such, may substantially underestimate the true number of children affected by parental mental illness. Best estimates suggests that more than 4.2 million parents within the UK suffer from mental health problems. 7 Approximately half of all adult mental health service users will have children under the age of 18 years, and 1 in 10 will have a child under the age of 5 years. 8

The proportion of parents who experience SMI is less well defined. A recent systematic review has reported that at any one time in the UK, 9–10% of women and 5–6% of men will be parents with a mental health disorder, fewer than 0.5% of whom will be experiencing a psychotic disorder. 9 These data do not include adults with a personality disorder, for whom the UK prevalence rates are estimated at around 4%. 10 Other empirical work suggests that at least one-quarter of adults admitted to UK acute inpatient settings have dependent children and that between 50% and 66% of people with SMI will be living with children under the age of 18 years. 11

Current UK policy initiatives

Current guidance published by the Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE) recognises parents with mental health problems and their children as a high-risk group with multifaceted needs,2 which have historically been neglected by UK service provision. 12 Successive organisational evaluations acknowledge that parents with mental health problems are a group prone to exclusion from health- and social-care provision and in doing so emphasise that greater effort may be required to reach these vulnerable families. 2,13

In response, a recent and notable shift in UK health- and social-care policy has instigated new initiatives that place greater emphasis on the need to support parents in their parenting roles. 13,14 From a mental health perspective, national UK outcome strategies2,15–17 are explicit in targeting mental health across the lifespan and in steering services towards severing intergenerational cycles of mental health difficulties through the promotion of whole-family assessments and recovery plans. Similar advances are advocated by educational and social reform initiatives. These initiatives call for greater family-focused service provision, enhanced coordination between child and adult mental health services and increased intervention for troubled families. 6,14,18

The clinical and social consequences of serious parental mental illness

In any given population, SMI is likely to be associated with poorer mental and physical well-being, impaired functioning, lower economic productivity and marked decrements in an individual’s health-related QoL. 19–21 When parents experience SMI, this burden extends far beyond the individual concerned, with potential for multiple adverse outcomes in successive generations. 22

The burden that is placed on the children of parents with SMI is substantial. Evidence demonstrates that the children of mentally ill parents are at risk of poorer psychological and physical health23,24 increased behavioural and developmental difficulties,24–26 educational underachievement8,27 and lower competency than their peers. 26,28–30 These problems may be exacerbated if both parents suffer mental illness. 31

Children of parents with SMI may also experience greater exposure to parental substance misuse,1,32 domestic violence and child abuse. 1 A recent meta-analytic review has reported parental mental illness to be a key risk factor for child maltreatment,33 with parental depression, personality disorder and alcohol or substance misuse all implicated in the physical abuse and neglect of minors. In rare cases, parental mental health difficulties have also been associated with increased rates of all-cause and cause-specific mortality in children. 34 Large population studies have reported elevated risks for neonatal death, sudden infant death syndrome, accidental injury and child homicide. 34

The longer-term impact of serious parental mental illness has been demonstrated to extend into adulthood and includes a higher risk of social and occupational dysfunction,35,36 increased psychological and psychiatric morbidity,37 lower self-esteem and increased alcohol or substance misuse. 38–40

Potential mechanisms of effect

The mechanisms by which parental mental illness may impact on familial and child outcomes are multifarious, encompassing a broad range of temporal, genetic and psychosocial influences. 41 Nevertheless, the existing evidence is relatively consistent in suggesting that socioenvironmental factors, and particularly family context, may ultimately be more important in accounting for child outcomes than biological vulnerability. 42

Although not inevitable, the care-giving environments provided by parents with SMI have been associated with an increased risk of their children failing to meet developmental norms. 43 The cognitive and psychological impairments that accompany episodes of SMI can substantially affect a parent’s capacity to meet his or her child’s needs. 44 Adults with SMI have been reported to display less emotional availability, reduced parenting confidence and poorer quality stimulation for their children than their healthy counterparts. 26,45 The affective quality of parental–child interactions has in turn been associated with the socioemotional adjustment of children, including internalising and externalising behaviours, and the nature and quality of parent–child attachments. 46 Parenting resilience, especially that occurring early in life, is thus thought to play a key role in determining the developmental, psychosocial and clinical outcomes of children of parents with SMI. 47,48

Nonetheless, interrelationships between parental mental illness and child outcomes are complex and parents living with SMI are also likely to experience additional challenges to the provision of safe and stable family environments. 49 These challenges arise not only because of the difficulty of parenting while managing psychiatric symptoms, but also because of the threat of children being moved to out-of-home care. 50 Mothers with SMI are more likely to be involved with children’s social services and more likely to have children in care than mothers with more common mental health problems. 51 Parenting may be compromised by a need to overcome social isolation, social discrimination and other external stress factors which typically result in low social capital, poverty and health inequalities for mental health sufferers and their children. 52 Research suggests that families affected by parental mental illness are more likely to experience economic hardship, housing problems and relationship discord than families not affected by such illnesses. 42 A total of 140,000 families, approximately 2% of all UK families, are reported to suffer the combined effect of parental illness, low income, lower educational attainment and poor housing, and this group exists as one of the most vulnerable in society. 14,18

Ultimately, however, families are not homogeneous in social circumstance or demography and, thus, any intervention programmes developed for this population must also be capable of responding to a diversity of need. Key moderators of adverse outcomes in children include their age and developmental maturity at the onset of parental mental illness, the severity and duration of their parent’s symptoms, the strengths and resources of family members, their own resiliency and the degree of social exclusion or discrimination that they experience. 41,49 While impaired parenting during infancy may have a long-term impact on children’s social and cognitive development, for example, exposure to parental mental illness in later childhood may present a more immediate and self-acknowledged stressor, with a qualitatively very different effect. Recognition of this temporal influence highlights the importance of developing multiple evidence-based services capable of being delivered in a developmentally and age-appropriate manner.

Mapping interventions for families affected by serious parental mental illness

Developmental theorists conceptualise children and adolescents as active agents capable of both being influenced by, and exerting an influence upon, the social context in which they live. 53,54 Empirical research on parent–child interactions has also demonstrated a bidirectional relationship in which children and parents have been found to mutually influence each other’s behaviour. 55,56 QoL in children of parents with SMI thus attracts multiple influences and by implication multiple avenues of change.

A recent review of interventions for families affected by parental mental illness identifies a heterogeneous mix of interventions targeting children, parents and/or the parent–child dyad. 57 The format and content of these interventions varies. Direct interventions, by definition, establish the child as the major change agent and seek to improve child health or resiliency through either therapeutic or strength-based models of care. By virtue of their need for active child participation, these interventions typically target school-aged children or adolescents, with specific content and QoL outcomes dictated by the participants’ age, cognitive development and predominant life stressors. Examples from the literature include group-based psychoeducational programmes58,59 and psychotherapeutic techniques. 60,61

However, developmental immaturity often precludes direct intervention with infants under the age of 2 years. Therefore, in early childhood, parents will normally be considered the principal agent of change and interventions will aim to indirectly enhance child well-being through an improvement in parenting behaviour or enhanced parental health. Examples of these interventions include, but are not confined to, parenting education programmes,60,62,63 manualised parenting or behavioural skills programmes64,65 and parent-centred psychological therapies. Indirect interventions such as these may also be applied to the parents of older children.

In practice, direct and indirect interventions are not mutually exclusive and a limited number of hybrid interventions have also emerged. 66,67 These interventions seek to target both parents and children either simultaneously or separately and may be delivered to the families of both younger and older children.

Irrespective of their path of action, community-based interventions may be delivered to the individual, the individual family unit or operationalised within a wider group format intended to enhance interpersonal relationship building and peer support.

The economic benefits of intervention

The hidden nature of many children affected by parental mental illness and the historical disjuncture of adult and child services has made the true economic costs of these illnesses difficult to quantify. A rapid evidence assessment7 estimated in 2008 that for every pound invested in psychosocial interventions for young carers of parents with SMI, a conservative or ‘lower bound’ societal gain of almost seven times this amount may be achieved. This estimate takes into account the savings associated with supporting a young person’s caring activities alongside savings gained from reductions in the child truancy rate, teenage pregnancy rate and a reduced likelihood of a young person being taken into local authority care. Characteristically, the evidence on which this analysis was based was limited primarily to those in a recognised caring role and, as such, may not be representative of all children and adolescents of parents experiencing SMI. A separate, non-systematic synthesis of interventions for children of parents with SMI highlights a distinct paucity of published cost-effectiveness data, cost-effectiveness analyses and decision-modelling techniques. 52

The rationale for an evidence synthesis

As with any aspect of health delivery, the development of a clinically effective and cost-effective intervention programme for children of parents with SMI must be based upon the establishment of a secure evidence base. The measurement of children’s QoL has a central role in the evaluation of health-care interventions and in improving children’s experiences of health and social services. As yet, however, no comprehensive and rigorous review of the impact of community-based interventions on the QoL of children of parents with SMI exists. Previous reviews of parenting interventions and interventions aimed at the mother–child relationship have been published but these remain limited by a lack of systematic methodology, a neglect of grey literature and/or restrictions in the nature of the interventions, populations and outcomes studied. 68–70

In 2008, a SCIE-commissioned review57 evaluated the clinical effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving parenting skills and life outcomes for parents and families affected by mental illness. This study highlighted a lack of robust data resulting from a paucity of randomised controlled trials (RCTs), small sample sizes and a lack of consideration of attention control conditions. 57 However, the focus of this review was not directly orientated towards serious parental mental illness and it did not explicitly consider the effect of interventions on children’s and adolescents’ subjective QoL.

In 2012, a meta-analysis71 examined the clinical effectiveness of parent-based and parent–child dyadic interventions in enhancing the psychological well-being of children born to parents with mental illness. This study pooled data from 13 RCTs evaluating a range of cognitive, behavioural and psychoeducational approaches. Comparator conditions also varied and included treatment as usual, individual psychotherapy, and psychoeducational attention-control interventions. Pooling suggested that intervention had an overall positive effect on children’s internalising and externalising symptoms and significantly lowered the risk of children developing psychological disorders. The scope of this review extended to include children of parents with affective disorders and children of parents with alcohol dependence and substance misuse. The generalisability of its findings to children affected by SMI thus remains unclear.

To date, only two reviews32,52 have specifically focused on interventions for children of parents with SMI, only one of which adopts a systematic approach. 52 In 2006, Fraser et al. 52 conducted a systematic review of the literature and concluded that little evidence on the clinical effectiveness of interventions for children of parents with SMI could be found. Owing to a paucity of data, meta-analyses were not performed and no firm conclusions regarding the effectiveness of different intervention models could be made. Unfortunately, the authors of this synthesis did not fully report their review strategy and failed to specify a priori the criteria against which intervention and outcome eligibility judgements were made. Consequently, biases in the study findings cannot be ruled out.

Research aim and objectives

This review aimed to apply rigorous evidence synthesis techniques to provide a comprehensive and up to date summary of all available research evidence relating to the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of community-based interventions in maintaining or improving QoL in the children of parents with SMI. The objectives of this research were:

-

to provide a systematic and descriptive overview of all the evidence for community-based interventions for improving QoL in children and adolescents of parents with SMI, with specific reference to intervention format and content, participant characteristics, study validity and QoL outcomes measured

-

to examine the clinical effectiveness of community-based interventions in terms of their impact on a range of pre-determined outcomes, particularly those likely to be associated with QoL for children and adolescents of parents with SMI

-

to examine, when possible, potential associations between intervention effect and delivery including intervention format and content, prioritisation of child outcomes, child age group, parental mental health condition, family structure and residency

-

to explore all available data relating to the acceptability of community-based interventions intended to improve QoL for children and adolescents of parents with SMI, with specific reference to intervention uptake, adherence and patient satisfaction

-

to assess key factors influencing the acceptability of and barriers to the delivery and implementation of community-based interventions for improving QoL in children and adolescents of parents with SMI

-

to provide a systematic and descriptive overview of all the economic evidence for community-based interventions for improving QoL in children and adolescents of parents with SMI, with specific reference to intervention resources, cost burden, study validity, method of economic evaluation and economic outcomes measured

-

to examine the cost-effectiveness of community-based interventions in improving QoL for children and adolescents of parents with SMI using a decision-analytic model

-

to identify, from the perspective of the UK NHS and personal social services, research priorities and the potential value of future research into interventions for improved QoL in this population.

Chapter 2 Defining quality of life in the children of parents with serious mental illness

To ensure that the current synthesis delivered a comprehensive assessment of community-based interventions for improving or maintaining QoL in the children of parents with SMI, we first sought to define QoL in this population.

For ease of reading, the current chapter is divided into two parts. In the first we present a conceptual overview of QoL, the key similarities and differences between adult- and child-centred QoL concepts and current QoL models as applied to child populations. In the second, we consider the relevance of these models to the children of parents with SMI. A series of stakeholder consultation exercises were conducted as part of our review and the results of these are presented here. We conclude by presenting the outcome framework that was used to guide outcome extraction in this evidence synthesis.

Part 1: conceptualising quality of life

Quality of life is a complex concept and no widely accepted standard definition exists. Ultimately, interpretations will vary according to the priorities of different stakeholder groups. At a societal level, objective QoL indicators such as a community’s standard of living may be used to facilitate the distribution of public resources to the areas of greatest need. At a health policy level, standardised indicators such as quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) are used to establish clinical and cost-effective services. At the individual level, QoL becomes much more synonymous with personal well-being.

Individual QoL constructs encompass both objective and subjective perspectives. 72 While objective perspectives focus on observable phenomena (e.g. a person’s physical health symptoms), subjective perspectives reflect people’s internal evaluations of their circumstances. Each type of measurement has its own strengths and weaknesses. Ultimately, objective measures may facilitate comparisons against population norms yet have relatively poor predictive validity for self-assessed QoL. Subjective measures are thus more generally accepted to reflect QoL constructs, despite being more easily influenced by respondent bias or adaptation to chronic life stressors. 73

Challenges to quality-of-life measurements

The inherent subjectivity of QoL belies some unique challenges to its measurement. At its most basic level, QoL can be conceptualised as comprising two key components: a cognitive component, typically expressed in terms of life satisfaction, and an affective component, typically expressed in terms of psychological health. 74 Different operational definitions, however, give rise to different assessment approaches. Distinction can be drawn between one-dimensional measures that quantify satisfaction with a single aspect of life and multidimensional models that consider satisfaction across a broader range of life domains. One-dimensional models often fail to reflect the full scope and complexity of QoL judgements and, as a consequence, lack sensitivity to change. Multidimensional models are therefore generally preferred. 73

The nature and number of life domains assessed by multidimensional QoL models are not fixed phenomena. Nevertheless, most generic models remain consistent in delineating five core life domains. These domains relate to (1) physical health, (2) emotional health, (3) material well-being, (4) environmental well-being and (5) social function. In addition, models that adopt a psychological or needs-based approach may also separately emphasise a unique contribution from self-actualisation and achievement. 75 These constructs overlap theoretically and empirically with measures of self-esteem and coping76–78 and in doing so introduce concepts of autonomy into subjective QoL assessments.

However, in certain contexts, narrower definitions may be applied, as is the case in health-related quality of life (HRQoL). HRQoL remains distinct from health status and is a particularly valuable tool in the assessment of behavioural and psychological interventions. HRQoL prioritises those domains that fall under the influence of health-care systems, policy makers and providers. 79 The World Health Organization’s (WHO) definition of health80 has been highly influential in determining the scope of these domains and focuses most attention towards the perceived quality of people’s physical, mental and social function. HRQoL thus remains distinct from broader QoL models in which material and environmental domains will typically be included. Greater emphasis is often placed on HRQoL in evaluative health research and health economic evaluations, for which the need to make resource allocation decisions between competing interventions for a disease, or between different categories of disease, has led to a policy preference for a common unit of outcome. 81–83 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), for example, requires outcomes to be measured in terms of QALYs, for which quality is determined using the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) measure of HRQoL. 84 The EQ-5D is a generic, preference-based measure of HRQoL measured on five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression), each rated on three levels (no problems, some problems, severe problems). Respondents are classified into one of 243 health states, each associated with a score that can be used to calculate QALYs. 85

Conceptualising children’s quality of life

Health-related QoL is an important outcome for both adult and child populations. However, compared with the exponential attention being directed towards adult QoL constructs, child-centred models remain in a relatively early stage of development. 74

UK policy perspectives on children’s quality of life

Several UK policy initiatives offer perspectives on children’s QoL. These policies include the Every Child Matters (ECM) agenda in England and Wales,86 the Children’s and Young People’s Strategy in Northern Ireland87 and the ‘Getting it Right for Every Child’ approach in Scotland. 17 Five broad QoL domains are shared between these initiatives and are termed within the ECM’s agenda as: (1) child health, (2) safety, (3) economic well-being, (4) enjoyment and achievement and (5) positive societal contribution. By placing equal emphasis on each of these domains, policy models uphold notions of children’s QoL as a multidimensional construct underpinned by various aspects of esteem, well-being and socialisation. However, a potential weakness to such models is their inevitable bias towards societal perspectives and thus to outcomes more readily quantified through objective means.

Research perspectives on children’s quality of life

Research instruments arguably offer a more direct approach to assessing children’s subjective QoL, although a systematic review in 2004 has highlighted marked inconsistency in the scope of children’s HRQoL measures. 88 While published scales remain relatively consistent in integrating physical, psychological and behavioural influences, the specific factors or items that make up these domains vary. 88 Early assessments of children’s HRQoL were developed purely from a biomedical perspective and, as such, remain largely disease specific. 76 Generic measures have developed from 1995 onwards with greater generalisability across clinical and non-clinical populations. 73,89

A review of generic child-centred measures reveals a wide array of factors that have previously contributed to assessments of children’s health-related QoL. 76 These include, but are not limited to, aspects of children’s physical appearance, peer relationships, recreational opportunities, family experience, cognitive functioning, academic performance, perceived autonomy and future life prospects. Consensus suggests that, at a minimum, peer relationships, family functioning and social interaction should be included in children and adolescents’ QoL models. 89 These factors display the greatest degree of coherence across published scales and underpin instruments developed from both child consultation and from expert opinion. 74

Challenges in measuring children’s quality of life

From a methodological perspective, notable challenges exist in the measurement of children’s HRQoL. 89 The WHO90 is clear in defining QoL as:

An individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live, and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns.

This definition implies that QoL should, whenever possible, be measured directly from a person’s own perspective. Nevertheless, considerable debate surrounds the issue of children’s self-reported HRQoL. Best-estimates suggest that children can only reliably report concrete aspects of health, such as pain or medication use, from the age of approximately 5 years. 91–93 More complex, psychologically orientated constructs, such as the emotional impact of illness, may necessitate proxy measurement. The validity of these proxy measures is not well established. Limited evidence suggests that parental reports may be more accurate than those of health professionals,94 but empirical investigations of the level of agreement between parent and child appraisals yields mixed results. 89 Ultimately, greater agreement may be observed for ratings of children’s physical well-being than for assessments of emotional or social function. Further difficulties arise in establishing the levels of agreement between two parents,73,95 the potential for bias within parental ratings89 and the potential differences in the life priorities of parents and children. 96

Differences in life circumstances, intellectual development and peer group norms have all been implicated in influencing the manner in which children’s subjective QoL judgements are made. 89 Disparities in cognitive understanding, for example both between adults and children and between children of different ages, may manifest in very different appraisals of family experience. Likewise, differences in social maturity and autonomy may also influence the relative weighting that different children afford this domain. For the most part, however, family functioning is accepted as an extremely important influence on children’s psychosocial development and a central component in children’s QoL assessments. Empirical evidence has demonstrated associations between children’s familial experiences and their social cognitions, behaviours and relationships in external settings. 97–99 The inter-relationships between these variables challenge a clear distinction between children’s QoL outcomes and influences, and in doing so support the derivation of conceptual QoL models for use in specific populations.

Part 2: conceptualising quality of life in the children of parents with serious mental illness

A UK review of the cost-effectiveness of interventions for young carers has suggested that standard definitions of QoL may not fully capture the experiences of children with mentally ill parents. 7 Children living with serious parental mental illness are reported to encounter specific stressors related to disrupted life routines, family, academic and social dysfunction, poor mental health literacy and ineffectual coping. 100 Any consideration of QoL in this population group must thus also explicitly consider the scope and nature of the challenges encountered by this group.

Stakeholder consultation

In order to explore the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of community-based interventions in enhancing the QoL of children of parents with SMI, we first sought to develop a conceptual model of HRQoL in this population. It was established a priori that the primary outcomes for this review would comprise validated generic or population-specific QoL measures, including measures of life satisfaction and/or child-centred psychological health. Potential secondary outcomes pertaining to second-order QoL domains were identified from national policy agendas and child-centred, HRQoL models. Stakeholder consultation ultimately provided the mechanism by which to ensure that these secondary indicators remained cognisant of the potentially unique contexts in which the children of parents with SMI may live.

We acknowledged from the outset that the range of stakeholders consulted for this exercise was likely to hold a range of different views. Meaningful stakeholder engagement depends upon active efforts to identify and reflect the different perspectives of participant groups. Within the current review, three separate consultation exercises were undertaken. The first involved a mix of clinical academics (with backgrounds in mental health, child psychiatry and clinical psychology) in conjunction with professionals recruited from health- and social-care services, voluntary user-led organisations and national children’s trusts. The second and third consultations were undertaken with individuals with potentially lower influence yet higher stakes, in this case parents and the children of parents with SMI.

Stakeholder consultation took place early in the study to assist the research team in developing an outcome framework for evidence synthesis. Stakeholders also contributed to literature searching (see Chapter 3) and came together in a final meeting to assist in framing the presentation of our synthesis results.

Stakeholder participants

A favourable ethical review was obtained from the host institution’s Research Ethics Committee and the research panels of national voluntary user organisations as appropriate.

In total, 19 individuals participated in stakeholder consultation. Ethical requirements aimed at protecting participant anonymity demanded that each of the three stakeholder groups should be recruited from a different geographical area or via a distinct recruitment pathway. The first group comprised eight representatives recruited from clinical and academic settings or through direct correspondence with national user-led organisations, child-orientated charities and service initiatives. Organisational representation was present for Barnardo’s, Young Minds, the National Children’s Bureau, the National Society for the Protection and Care of Children (NSPCC) and the Fairbridge Trust. The second stakeholder group comprised five parents (four mothers and one father) who were independently recruited via advertisements placed on the website, e-mail bulletins and Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) feeds of a large national mental health user and carer organisation (Rethink Mental Illness). Each parent had at least one child under the age of 18 years and suffered from a severe and enduring mental health difficulty, in this case personality disorder (n = 1), bipolar disorder (n = 2) and major depressive disorder (MDD) (n = 2). The final group consisted of six young people with current lived experience of parental mental illness. These children were recruited via a young carers’ service in the south-west of England and ranged in age from 13 to 18 years. Primary parental mental health diagnoses comprised bipolar disorder (n = 2), MDD (n = 2), schizophrenia (n = 1) and borderline personality disorder (n = 1). Owing to ethical and pragmatic constraints, the views of younger children could not be collected. Whenever possible, the interviewer sought to explore potential age-related variation in children’s life priorities.

Consultation methods

Stakeholders participated in focus groups or individual interviews according to availability and personal preference. In all cases, discussion centred around the participants’ general perceptions of QoL, their awareness of different QoL models, the perceived validity of these models to the children of parents with SMI and the key QoL domains that should be included in our evidence synthesis.

The data underwent an inductive thematic analysis for the purposes of informing a population-specific QoL model. All focus groups and interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data were analysed by author PBe using Microsoft Word 2007 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Individual themes emerging from each stakeholder group were identified and combined into a smaller number of metathemes, each representing a key QoL subdomain. These subdomains were subsequently mapped against current QoL models used in policy and academic research to identify key similarities and differences in scope.

Consultation findings

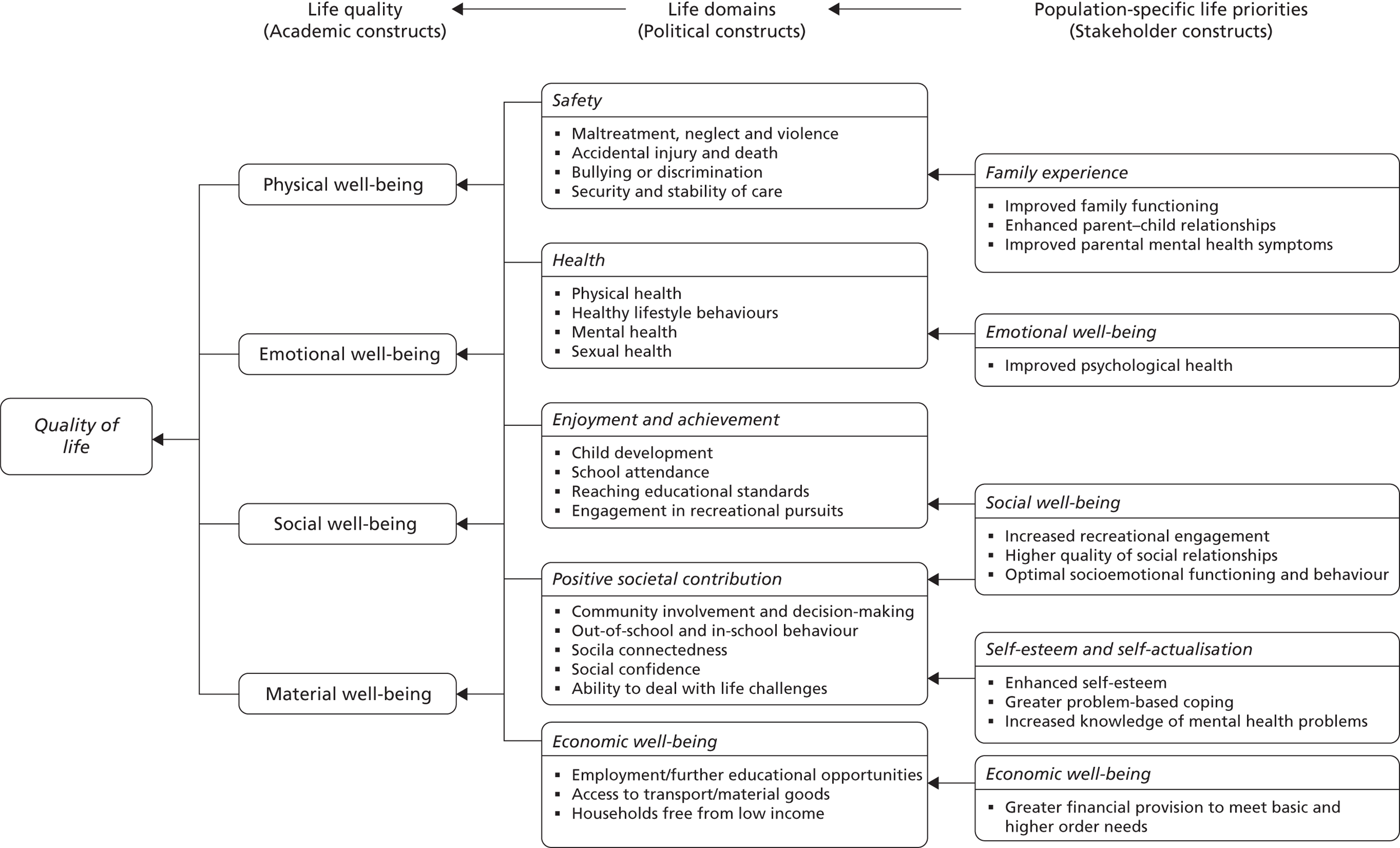

Each stakeholder consultation exercise was inevitably influenced by the different perspectives and priorities of its participant group. Nonetheless, substantial overlap in QoL concepts emerged. Fifty-nine themes were initially identified from the data and grouped into 11 key metathemes (see Appendix 1). Mapping each metatheme against existing QoL concepts revealed a multidimensional model that endorsed to a greater or lesser degree the core domains of existing models (Figure 1). In total, five different domains were identified:

-

children’s emotional well-being

-

children’s social well-being

-

children’s economic well-being

-

children’s family contexts and experiences

-

children’s self-esteem and self-actualisation.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual QoL map for children of parents with mental illness. Reproduced from Bee P, Berzins K, Calam R, Pryjmachuk S, Abel K. Defining quality of life in the children of parents with severe mental illness: a preliminary stakeholder-led model. PLOS ONE 2013;8:e73739. © 2013 Bee et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

These five domains are discussed in further detail below.

Children’s emotional well-being

Children’s emotional well-being was endorsed by one broad metatheme related to children’s mental health. This metatheme was advocated by all three stakeholder groups. Both professionals and children focused heavily on children’s propensity to feel anxious or depressed about their parent’s mental health condition and highlighted the possibility of clinically significant symptoms of depression developing in children of parents with SMI.

I don’t know really it just . . . kind of affected me slightly mentally, having to deal with that, having to deal with what she’s like. Like, past like attempts of her trying to take too many pills, like, and sort of how to keep her calm. It’s hard. The doctor’s said I’m depressed.

Child stakeholder, 15 years old, mother with bipolar disorder

Parents expressed concern that their illness had led to mental health problems in their children, with genetic transmission, behavioural mimicking and increased psychosocial stress all being postulated as possible causes.

My son says, ‘I can accept it mum’, but, but, what also happens is, they adopt a different persona, it rubs off on him to a certain degree, and he becomes irritated as well.

Parent stakeholder, mother with depression

Children’s social well-being

Children’s social well-being was endorsed by three metathemes relating to: (1) children’s socioemotional functioning and behaviour, (2) social relationship quality and (3) recreational activity engagement. Children described feeling different to their peers and placed much emphasis on their need to access ‘normal’ recreational or social activities. Out-of-home activities were perceived by both parents and children to offer both respite from specific family stressors and more innate opportunities for general social and physical development.

Social, creative, miscellaneous type things, so my good day would be doing anything like that, playing the piano, going out with my friends, helping other people out, that would be part of my day.

Child stakeholder, 17 years old, mother with psychosis

Adequate social support delivered within the context of a high-quality social relationship was identified by all three stakeholder groups as a key aspect of children’s QoL and an important factor in enhancing children’s resilience to parental SMI. However, caring responsibilities and/or financial hardship were often found to prohibit opportunities for social networking and leisure pursuits. Parents described additional difficulties in fostering and nurturing their children’s independence and expressed concern that their own symptoms and behaviours had led to social withdrawal and behavioural dysfunction in their children.

If I’m punching the wall, say, or I scream or just get so angry, she curls over . . . she’s just not there, not there emotionally I mean.

Parent stakeholder, mother with bipolar disorder

Children’s economic well-being

Economic well-being was endorsed by one metatheme (economic resources) that encompassed a range of different yet inter-related needs. All three stakeholder groups upheld financial stability and economic resources as a central factor in determining children’s QoL, with multiple benefits emanating from a family’s capacity to meet children’s needs. Financial security was deemed vital both for the purposes of meeting basic family needs (e.g. food provision) and higher order needs including children’s engagement in recreational and social activity. Economic instability was identified by children as a key source of stigma and a frequent barrier to social integration with their peers.

And mum she just says that, ‘I don’t have any money at all,’ and so we literally have no food in our house, so I don’t really eat. My mum doesn’t have a fridge freezer, so we don’t have the normal things, things that everyone else would have . . .

Child stakeholder, 14 years old, mother with psychosis

Children’s family contexts and experiences

Children’s family contexts were endorsed by three metathemes. These metathemes related to: (1) parental mental health symptoms, (2) family functioning and conflict and (3) quality of the interaction occurring between children and their parents. Alleviating parental mental health symptoms was the main priority of all of the children we consulted. Across all three stakeholder groups, participants described a level of unpredictability in parents’ behaviour that impacted heavily on children’s own sense of security and emotional well-being. Both professional and child stakeholders described episodes of parental ill-health in which parenting may become more difficult and children’s needs may be less likely to be met.

She may not be able to depend on her mum as much as she used to and she’ll have to, kind of, grow up a bit more. When her mum’s ill, a lot really, sometimes she may have to put her mum in front of her, of what she wants and needs

Professional stakeholder

Psychiatric symptoms have been shown to account for most of the variance in the community functioning of mothers with mental illness101 and it is acknowledged that specific symptoms of SMI, such as delusional thoughts, may be focused on the child. 1 It is also accepted that children may experience intermittent or permanent separation from their parents as the result of a volitional or enforced hospital admission. Stakeholder discussions, however, also extended to encompass more routine aspects of domestic function. Adequate family functioning was consistently emphasised as a key contributor to children’s sense of belonging and a core factor influencing their QoL judgements. Children in particular described the enjoyment they derived from spending ‘ordinary’ time within their families and from engaging in warm and positive interactions with their parents.

My mum being happy, yes, seeing my mum have a smile on her face. Doing things together, even if it is going out, like walking down to the chip shop to go and get some chips, that would make me happy . . .

Child stakeholder, 13 years old, mother with personality disorder

Children’s esteem and self-actualisation

The final domain, children’s esteem and self-actualisation, was endorsed by three metathemes relating to: (1) children’s self-esteem, (2) children’s problem-based coping and (3) children’s levels of mental health literacy. Children described an inherent desire for greater autonomy both within their own lives and within the context of their parent’s care. Parents focused primarily on the need for children to develop their self-esteem while professionals emphasised the value of fostering children’s confidence, optimism and resiliency to parental mental illness.

It’s about accepting . . . not accepting it in a sort of negative way but appreciating just how well they’re doing to be coping with it, building up their own confidence about how much they can do.

Professional stakeholder

Studies specifically focusing on young carers report these children to have multiple responsibilities, including looking after other members of the family, mediating family conflict and seeking out help for the ‘looked-after’ person. 102 Such observations provide one explanation for why effective coping strategies, and particularly those based on problem-focused approaches, were endorsed by our stakeholders as a key mechanism through which children may be empowered to maintain their long-term emotional health. Low mental health literacy and poor understanding of parent’s symptoms and behaviours significantly reduced children’s abilities to cope with their parent’s mental illness, to the extent that greater communication between children, parents and health-care providers was advocated by all of our stakeholder participants.

I would like to know what to do, like for him, and how I can help, and to understand, understand what’s going on . . . because it’s just like really hard sometimes to know what to do.

Child stakeholder, 14 years, father with severe depression

Reflections on stakeholder perspectives

The contested nature of QoL suggests that greater emphasis should be placed on determining the relevance of generic QoL models to the children of parents with SMI. The current study drew on stakeholder perspectives to inform a conceptual model of QoL model in this population. A total of five key domains and 11 subdomains (metathemes) were identified from this consultation, all of which could be mapped to one or more components of existing QoL models.

Our stakeholder consultation identified some particular priorities specific to the children of parents with SMI. These included the alleviation of parental mental health symptoms, a pressing need for problem-based coping skills and increased mental health literacy. Similar requirements have been reported by other user consultation exercises1,57 and empirical work. 100 Population-specific QoL measures that take account of these issues may ultimately be more sensitive to changes and more effective at detecting treatment effects.

Notably, our stakeholder consultants failed to endorse three key QoL influences currently upheld by national child-centred policy initiatives. These components comprised children’s safety (defined in terms of child neglect, maltreatment or violence), children’s development and children’s physical and sexual health. Ultimately, the omission of these influences may reflect a bias towards healthy participants recruited from non-clinical settings. Alternatively, it may be that these factors do not sit well within children’s subjective QoL models. Self-perceived HRQoL remains somewhat distinct from physical health status and caution should always be taken when interpreting these outcomes as proxy indicators of children’s QoL.

Derivation of an outcome framework for evidence synthesis

For the purposes of this review, primary outcomes were established a priori to include validated measures of children’s QoL or mental health symptoms. In addition, 10 of the 11 subdomains that were identified by stakeholder consultation were retained as secondary outcome variables for our evidence synthesis. These individual subdomains can, at best, only be taken as proxy indicators of a multidimensional QoL construct.

Young people’s economic well-being, while pertinent to more generic QoL agendas, was judged to fall outside the auspices of HRQoL and was therefore omitted from our final outcome framework. Additionally, owing to their centrality within current UK child-orientated QoL models, outcomes related to children’s physical health, safety and cognitive development were also retained. The relative importance that stakeholders attributed to different secondary outcomes was considered during the data synthesis stage. The final framework guiding our evidence synthesis thus remained cognisant of a variety of research, policy and stakeholder perspectives. It was endorsed in its entirety by the advisory panel guiding this evidence synthesis and is delineated by source in Table 1.

| Review outcomes | Specified a priori | Conceptually supported | Politically supported | Stakeholder validated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | ||||

| Validated measures of QoL/HRQoL | ✓ | |||

| Child-centred mental health symptoms | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Secondary | ||||

| Children’s physical well-being | ||||

| Children’s physical health | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Children’s safety, maltreatment and neglect | ✓ | |||

| Children’s social well-being | ||||

| Children’s social function and behaviour | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Quality of children’s social relationships | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Children’s recreational engagement | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Children’s family contexts and experiences | ||||

| Parental mental health symptoms | ✓ | |||

| Family function and conflict | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Quality of parent–child interactions | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Children’s esteem and self-actualisation | ||||

| Children’s cognitive development | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Children’s problem-focused coping | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Children’s mental health literacy | ✓ | |||

| Children’s self-esteem | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

Chapter 3 Review methods

We synthesised the available research literature regarding community-based interventions for children of parents with SMI. Our search was kept deliberately broad and targeted a range of study designs relevant to the aims set out in Chapter 1. The outcome extraction was guided by the QoL framework developed in Chapter 2. At all phases of the review, we adhered to guidelines outlined by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD)103 and the Cochrane Collaboration. 82 One large search was undertaken across all phases of the review, with specific adaptations when necessary to reflect the different research objectives and research designs required to achieve them. A copy of the review protocol is provided in Appendix 2.

Search methods

Search term generation

Search terms relating to the key concepts of the review were identified by scanning the background literature, browsing the MEDLINE medical subject heading (MeSH) thesaurus and via discussion between the research team and an information officer from the Cochrane Collaboration Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Review Group (CCDAN). The electronic search strategy was modified and refined several times before implementation. All searches took place between November 2010 and January 2011 (see Appendix 3 for the specific dates of individual searches) with an updating search being performed in May 2012. All databases were searched from inception. No language or design restrictions were applied.

In order to ensure comprehensive coverage of the evidence base, search terms were kept deliberately broad. It was acknowledged that children’s QoL outcomes had the potential to be both imprecise and poorly indexed and thus terms related to outcomes were not used to limit the search. Search terms were instead confined to population characteristics and broad intervention terms (e.g. program$, intervention$ or service$). Search terms relating to specific intervention or therapy models were not named in the search to avoid imposing unnecessary restrictions on the evidence that was retrieved. Full details of the search strategies and search terms used are reported in Appendix 3.

Search strategy

Changes to the search protocol

All searches were conducted as specified in the original review protocol with the exception of two electronic databases that were not searched as part of the final review (Social Work Abstracts and CommunityWise). These omissions were enforced owing to prolonged difficulties in obtaining access subscriptions. Reviews of the social-care literature are frequently limited by a distinct lack of empirical data, reflecting a preference for descriptive or theoretical study. 57 Coverage of the existing social-care evidence base was ensured through searches of two databases maintained by the SCIE. The potential impact of this protocol change was therefore judged to be minimal.

Searches of two further databases for economic evidence were not undertaken owing to lack of access subscriptions [The American Economic Association’s electronic bibliography (EconLit) and the Health Economic Evaluations Database (HEED)]. However, coverage of economic studies was ensured through searches of the NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), the Paediatric Economic Database Evaluation (PEDE) database and the IDEAS database of economics and finance research, as well as via the searches undertaken to identify clinical effectiveness data.

Implementation of search strategies

In accordance with the review protocol, search strategies included electronic database searches, journal hand searches, reference list searches, targeted author searches, grey literature searches (including material generated by user-led organisations), research register searches, forward citation searching and stakeholder enquiry.

Electronic databases

To identify evidence relevant to the research question, electronic searches were undertaken on the following health, allied health and education databases:

-

MEDLINE (accessed via Ovid; www.ovid.com/)

-

CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) (accessed via Ovid; www.ovid.com/)

-

PsycINFO (accessed via Ovid; www.ovid.com/)

-

EMBASE (accessed via Ovid; www.ovid.com/)

-

CENTRAL (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) (accessed via The Cochrane Library; www.thecochranelibrary.com/)

-

CDSR (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews) and DARE (Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects) (accessed via The Cochrane Library; www.thecochranelibrary.com/)

-

ISI Web of Science including SSCI (Social Science Citation Index), AHCI (Arts and Humanities Citation Index) and SCIEXPANDED (Science Citation Index Expanded) (accessed via Web of Knowledge; www.wos.mimas.ac.uk/)

-

HSRProj (Health Services Research Projects in Progress) (accessed via www.nlm.nih.gov/hsrproj/)

-

HMIC (Health Management Information Consortium) (accessed via Ovid; www.ovid.com/)

-

ASSIA (Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts) (accessed via ProQuest; www.proquest.com)

-

Sciverse SCOPUS (accessed via www.scopus.com)

-

IBSS (International Bibliography of the Social Sciences) (accessed via ProQuest; www.proquest.com)

-

Social Services Abstracts (accessed via ProQuest; www.proquest.com)

-

Social Care Online (accessed via www.scie-socialcareonline.org.uk/)

-

ChildData (accessed via Athens; www.childdata.org.uk/)

-

ERIC (Education Resources Information Centre), AUEI (Australian Education Institute) and BRIE (British Education Institute) (accessed via ProQuest; www.proquest.com)

-

Dissertation Abstracts (accessed via Ovid; www.ovid.com/)

-

NCJRS (National Criminal Justice Reference Service) and Abstracts (accessed via ProQuest, www.proquest.com)

-

The publicly available parental mental health database created by SCIE in partnership with the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI) (accessed via www.eppi.ioe.ac.uk/webdatabases/).

In addition, the following databases were searched for economic studies:

-

NHS EED (accessed via CRD; www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/crddatabases.htm)

-

PEDE (accessed via http://pede.ccb.sickkids.ca/pede/index.jsp)

-

IDEAS database of economic and finance research (accessed via http://ideas.repec.org/).

Hand searching

Nine psychiatry, psychology and child health journals were identified as being likely to contain relevant research evidence. These journals were hand-searched for the publication period 2010–11 and selected articles examined to establish relevance to this review. The journals that were searched comprised the American Journal of Psychiatry, the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, Archives of General Psychiatry, Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, the British Journal of Psychiatry, the Journal of Clinical Psychology, Schizophrenia Bulletin and Psychological Medicine.

Reference lists

Additional studies were sought by examining the reference lists from the text of retrieved and eligible reports. Bibliographies of relevant retrieved reviews were also inspected to ensure that all potentially relevant studies had been identified. For studies that were published as abstracts, or when there was insufficient information to assess eligibility, full texts were obtained.

Targeted author searches and unpublished research

Brief targeted author searches were conducted following the identification of key researchers in the field. A list of key researchers was initially identified by the review team and subsequently augmented following abstract screening. Key researchers were contacted via email with a list of inclusion criteria for the review and a request for information regarding any studies that they felt may be relevant. A total of eight authors from the UK, the USA and Australia were contacted for further information and four authors responded providing further information. No studies were cited that had not already been retrieved by other means.

Ongoing research

The metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT) (accessed via Current Controlled Trials; http://controlled-trials.com/) was examined for information on current or recent trials in the relevant area. Search terms for this register comprised ‘parent’, ‘mother’, ‘father’, ‘child’, ‘family’ and ‘mental health’. All references located by this method were cross-referenced with studies identified via other pathways to ensure comprehensive coverage. For trials that were identified but no publications existed, research teams were contacted directly to enquire about potentially eligible data. Nine teams were contacted for further information and seven authors responded providing further information.

Forward citation searching

Forward citation searching was undertaken for all trials eligible for inclusion in the review. This process was undertaken using the Web of Science (WoS) Institute of Scientific Information (ISI) citation database. Each study was entered separately and all citations to the paper since publication were identified. Titles and, when available, abstracts of the papers citing the eligible trials were downloaded and screened for eligibility according to the same criteria used for the primary searches (see below).

Theses

The Dissertations Abstracts International database was searched through PsycINFO using the comprehensive search strategy developed for the other electronic databases searches. Theses and dissertations were also identified through reference and bibliography lists.

Grey literature and material generated by user-led or voluntary sector enquiry

Grey literature, including conference abstracts, proceedings, policy documents and material generated by user-led enquiry, was identified via electronic databases, internet search engines and websites for relevant government departments and charities. These included, but were not limited to, the British National Bibliography for Report Literature, Google Scholar, Mental Health Foundation, Barnardo’s, Carers UK, ChildLine, Children’s Society, Depression Alliance, Mind, Anxiety UK, NSPCC, Princess Royal Trust for Carers, SANE, The Site, Turning Point and Young Minds. An exhaustive list of websites searched is provided in Appendix 3.

Stakeholder consultation

Requests for additional publications and potential references were lodged with the external advisory panel and with stakeholders during consultation exercises. A brief summary of the review was also posted on the website of the host institution with an email contact link through which people could submit additional references.

Study screening and selection

Eligibility criteria

All records retrieved from the searches were imported into a bibliographic referencing software program [Reference Manager 11.0 (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY, USA)] and duplicate references identified and removed. Two reviewers (JG, MC) independently screened titles and abstracts for eligibility using prespecified inclusion criteria (described below). Additional economic abstracts located through NHS EED, PEDE or IDEAS were independently screened for eligibility by two reviewers (SB and MC) using the same prespecified inclusion criteria.

When both reviewers agreed on exclusions, the reasons for exclusion were recorded. When both reviewers agreed on inclusion, or when there was ambiguity or disagreement, full text articles were retrieved. Two reviewers then independently assessed the full text of these articles against the predetermined inclusion criteria. Any remaining disagreements were resolved by consensus or discussion with a third party, if necessary. Our protocol originally specified that we would obtain a measure of inter-rater reliability regarding study eligibility judgements; however, given the stringent procedures that were put in place to resolve ambiguous cases, the meaningful contribution of this statistic remained unclear. Inter-rater reliability was therefore not calculated in this instance.

Study inclusion criteria

Studies were initially assessed for inclusion across all phases of the review according to a standard set of eligibility criteria summarised in Boxes 1 and 2, and described in full below. Additional inclusion and exclusion criteria were set for specific phases of the review and these are presented in the relevant chapters, when appropriate.

Child: Any individual aged 0 to < 18 years.

Parent: An umbrella term covering mothers, fathers, adoptive parents, legal guardians, foster parents or other adult assuming a primary care-giving role for a dependent child.

SMI: An umbrella term covering schizophrenia, psychosis, borderline personality disorder and personality disorder.

Severe affective mood disorders: An umbrella term comprising severe unipolar depression, severe postnatal depression and/or puerperal psychosis.

Community-based intervention: Any non-residential, psychological or psychosocial intervention involving professionals or paraprofessionals for the purposes of changing parents’ and/or children’s knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, emotions, skills or health behaviours.

QoL: A multidimensional construct arising from children’s mental and physical health, social well-being, family experiences, self-esteem and self-actualisation.

-

Population: Children aged 0 to < 18 years or their parents, one or more parents with SMI with or without substance misuse/other mental health comorbidity, > 50% sample participants experiencing parental SMI.

-

Intervention: Any health, social-care or educational intervention aimed at the young person, parent or family unit. Individual or group interventions delivered alone or in combination with pharmacology.

-

Comparator: Any active or inactive treatment, in which inactive treatment is defined as a waiting list delayed treatment or usual care management control.

-

Outcomes (clinical effectiveness/cost-effectiveness): Validated generic or population-specific measures of QoL such as children’s mental health, physical well-being, social well-being, family functioning and self-esteem or -actualisation.

-

Outcomes (acceptability): Intervention uptake, adherence or participant satisfaction.

-

Design (clinical effectiveness/cost-effectiveness): Priority given to randomised and quasi-RCTs or controlled observational studies (e.g. case–control studies). Uncontrolled studies retained and summarised.

-

Design (acceptability): Quantitative/qualitative data collected as either a stand-alone or mixed method study.

-

At-risk populations.

-

A population with < 50% or an unclear proportion of participants experiencing parental SMI.

-

Inpatient interventions, e.g. assisted accommodation, mother and baby residential units.

-

Pharmacological/physiological interventions without a psychological/social component.

-

Interventions aimed at health-care professionals.

-

Case studies, opinion papers, descriptive studies and editorials.

-

Non-English-language publications.

Participants

Study participants were children or adolescents aged 0 to < 18 years, or the parents of these children. For the purposes of our review, parents were defined as mothers, fathers, adoptive parents, legal guardians, foster parents or any other adults assuming a primary caring role for a dependent child, whether resident or non-resident. To be eligible for inclusion in the review, one or more parents had to have a serious mental health condition as defined by a current or lifetime clinical diagnosis or a comparable symptom profile. In accordance with the user perspective,104 serious mental health conditions were defined to include schizophrenia, psychosis, borderline personality disorder and personality disorder, with or without substance misuse or other mental health comorbidity. Severe affective mood disorders including severe unipolar depression, severe postnatal depression and puerperal psychosis were also included. Separate syntheses were conducted for parental SMI and severe parental depression. The method and rationale by which severe depression was defined in this review is described further in Chapter 5. Studies were eligible for inclusion in the review if the majority of participants (> 50%) in the sample fulfilled our criteria for SMI. Populations in which only a minority (< 50%), or an indeterminable proportion, of participants had SMI were excluded from the review. At-risk populations with no current or prior diagnoses were also excluded.

Interventions

Eligible interventions comprised any community-based (i.e. non-residential) psychological or psychosocial intervention that involved professionals or paraprofessionals and parents or children, for the purposes of changing knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, emotions, skills or behaviours concerning health and well-being. This included any health, social-care or educational intervention aimed at the young person, their parent or their family unit. Interventions that targeted children in the community were eligible for inclusion irrespective of their parents’ inpatient or outpatient status. Interventions in which both children and parents were required to be inpatients (e.g. mother and baby residential units, assisted accommodation) were excluded from the review.

Both individual and group interventions were included, whether delivered alone or in combination with pharmacological treatment. Prevention and treatment studies were both eligible for inclusion. Prevention studies were defined as those that recruited prospective parents with SMI in pregnancy and delivered all, or part, of the intervention in advance of parenthood. These studies were only eligible for inclusion if parents had a pre-existing and clinically diagnosed SMI, and eligible QoL outcomes were assessed in the postpartum period. Treatment studies both recruited parents and delivered their interventions post birth and up to 18 years of age.

Comparators

Comparisons of two or more active interventions or of an active treatment with a ‘no treatment’ comparator were included. The ‘no treatment’ category was defined to include waiting list controls, delayed treatment and usual care management. A previous review57 has reported difficulties in defining what may constitute standard care in this relatively disparate group and, therefore, no specific criteria were placed on this comparison. Restricting evidence to studies that adopt a strict ‘no treatment’ comparator raises the potential for bias due to possible placebo effects, i.e. the effect of a particular intervention cannot be differentiated from the non-specific effects of researcher or clinical attention. Marked differences in comparators were taken into account during data summary and analyses. Trials comparing pharmacological or physiological interventions without a psychological or social component were excluded from the review, as were trials assessing interventions aimed at health-care professionals.

Outcomes

Rigorous evidence syntheses demand the a priori selection of a manageable number of conceptually relevant outcomes. In the absence of a standard definition of QoL, we adopted a comprehensive and inclusive approach to the outcome framework guiding this review.

It was established a priori that our primary outcomes would comprise validated generic [e.g. Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36)] or population-specific measures of QoL [e.g. Paediatric QoL Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (PQ-LES-Q), KIDSCREEN-52]. Child-centred mental health symptoms were also specified a priori as a primary outcome.

Secondary outcomes comprised additional QoL indicators identified from conceptual models, empirical literature and UK policy. Stakeholder consultation provided the mechanism by which these generic QoL indicators were adapted to better reflect the specific goals and concerns of children whose parents experience SMI. The findings of this consultation have already been reported in Chapter 2. For the purposes of our evidence synthesis secondary outcomes comprised:

-

Children’s physical well-being, specifically children’s physical health, safety, maltreatment and neglect.

-

Children’s social well-being, specifically children’s socioemotional function and behaviour, social relationship quality and recreational engagement.

-

Children’s family experiences, specifically parental mental health symptoms, family function and the quality of parent–child interactions.

-

Children’s self-esteem and self-actualisation, specifically children’s cognitive development, problem-focused coping, mental health literacy and self-esteem.

Data on secondary outcomes were included however defined. For the purposes of synthesising evidence relating to intervention acceptability, additional outcomes comprised intervention uptake, adherence and participant satisfaction. Trials that reported no relevant parental or child outcomes were excluded from the review.

Study design

In synthesising evidence of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, priority was given to those designs in which a comparator or control group was present, i.e. RCTs, quasi-RCTs and controlled observational studies (e.g. case–control studies).

Discriminating between quasi-randomised and non-randomised studies is a difficult process, not least because there remains a lack of consensus over which types of studies are most relevant for systematic reviews. For the purposes of assessing clinical effectiveness, we used the Cochrane checklist for non-randomised studies82 and only included those studies that used randomised or quasi-randomised allocation methods potentially capable of creating similar groups, i.e. random-sequence generation, sequential assignment or matched pairs allocation. Differences in the risk of bias associated with these different methods were taken into account during data analysis. We excluded studies that reported non-randomised allocation methods founded on mechanisms highly likely to lead to important differences between groups, i.e. allocation by patient preference, treatment outcomes, service availability or time. Lower levels of evidence (i.e. non-randomised trials and uncontrolled studies) were retained and summarised either for the purposes of future research priority setting or to provide data that may be suitable for inclusion in an economic model (i.e. we included partial economic studies in the review to assess whether they contained resource use or cost data that may help populate an economic model).

Acceptability was assessed via quantitative and qualitative designs conducted either as stand-alone studies (i.e. a quantitative survey or qualitative investigation) or as part of a larger mixed-methods approach (e.g. a nested acceptability study).

Studies undertaken in any country were eligible for inclusion across all phases of the review and no restrictions were placed on date of publication. Case studies, opinion papers, descriptive studies, editorials and non-English-language publications were excluded.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction procedures

Data extraction and validity assessment of all studies included in our clinical effectiveness and acceptability syntheses was performed by one reviewer (KB) and independently verified by a second (SP). Study outcomes were extracted separately (by PBo) and independently verified (by PBe). Discrepancies were resolved by referral to the original studies and, if necessary, via arbitration from a third reviewer.

The data extraction process was guided by a prespecified data extraction sheet that detailed the study author, year of publication, study design and key features of the study sample, setting, and intervention and comparator conditions. When there were multiple publications for the same study, data were extracted from the most recent and complete publication. For cases in which the duplicate publications reported additional relevant data, these data were also extracted.

Data extraction from economic studies was performed by one reviewer (MC) and independently verified by a second (SB). Data extraction used a prespecified data extraction sheet designed for the purpose of this study. This included study author, year of publication, study design, setting, population, interventions, method of economic evaluation, economic perspective, costs and outcomes reported and quality criteria.

Methodological quality

Studies were assessed for methodological quality across all phases of the review. Evidence of clinical effectiveness was assessed for quality at the study level using the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for RCTs82 or the Cochrane guidance for non-randomised designs. 82 Economic studies were assessed using a standard critical appraisal checklist for economic evaluations. 81

Qualitative studies eligible for inclusion in our acceptability synthesis were assessed for quality using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool for qualitative research105 and the principles of good practice for conducting social research with children. 106 Although all eligible studies were assessed for quality, no study was excluded on the basis of this quality appraisal. The relative impact of methodological flaws was summarised narratively or explored via a sensitivity analysis, when data allowed.

Methods of data synthesis

Across all phases of the review included studies were synthesised according to (1) the nature of the parents’ mental health disorder and (2) the level of evidence that was presented.

Classification by parental disorder

In the absence of an internationally agreed standard for SMI, irregularities in its scope and classification invariably exist. Nonetheless, both national user organisations104 and policy documents107 are consistent in the core components of their operational definitions. These definitions share common elements of diagnosis, disability, duration, safety and informal and formal care. According to these criteria, SMI is identifiable in people who (1) display florid symptoms and/or suffer from severe and enduring mental health difficulties, (2) experience occasional risk to their own safety or that of others, (3) undergo recurrent crises that lead to multiple hospital admissions and/or interventions and (4) suffer substantial disability or place significant burden on informal carers as a result. From a diagnostic perspective, such illnesses typically comprise non-organic psychoses (including schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders), personality disorders and severe affective mood disorders, with or without concurrent substance misuse. Severe affective mood disorders can in turn be strictly defined to include bipolar disorder and puerperal psychosis.