Notes

Article history

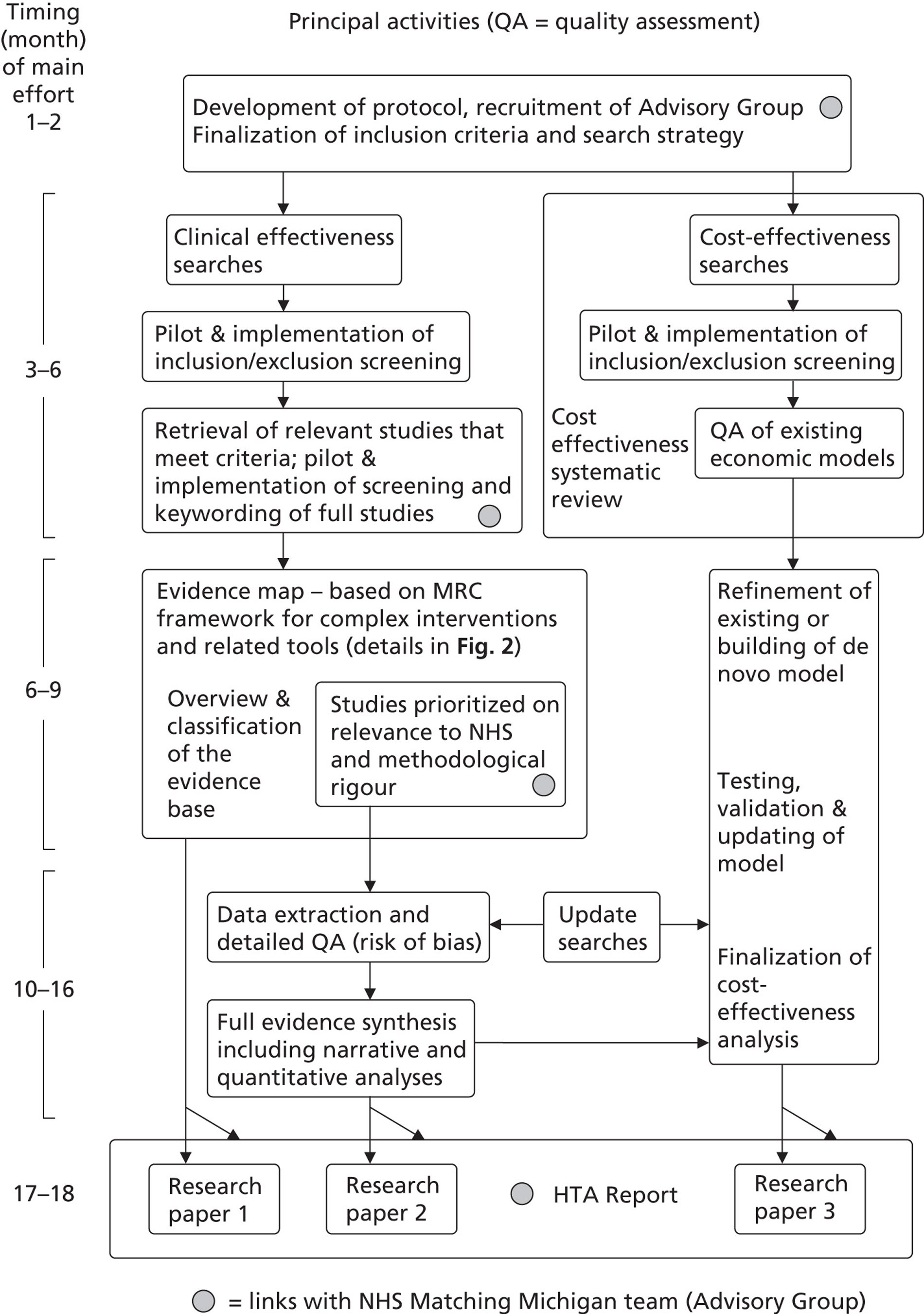

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/01/25. The contractual start date was in September 2010. The draft report began editorial review in July 2012 and was accepted for publication in November 2012. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors:

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Frampton et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

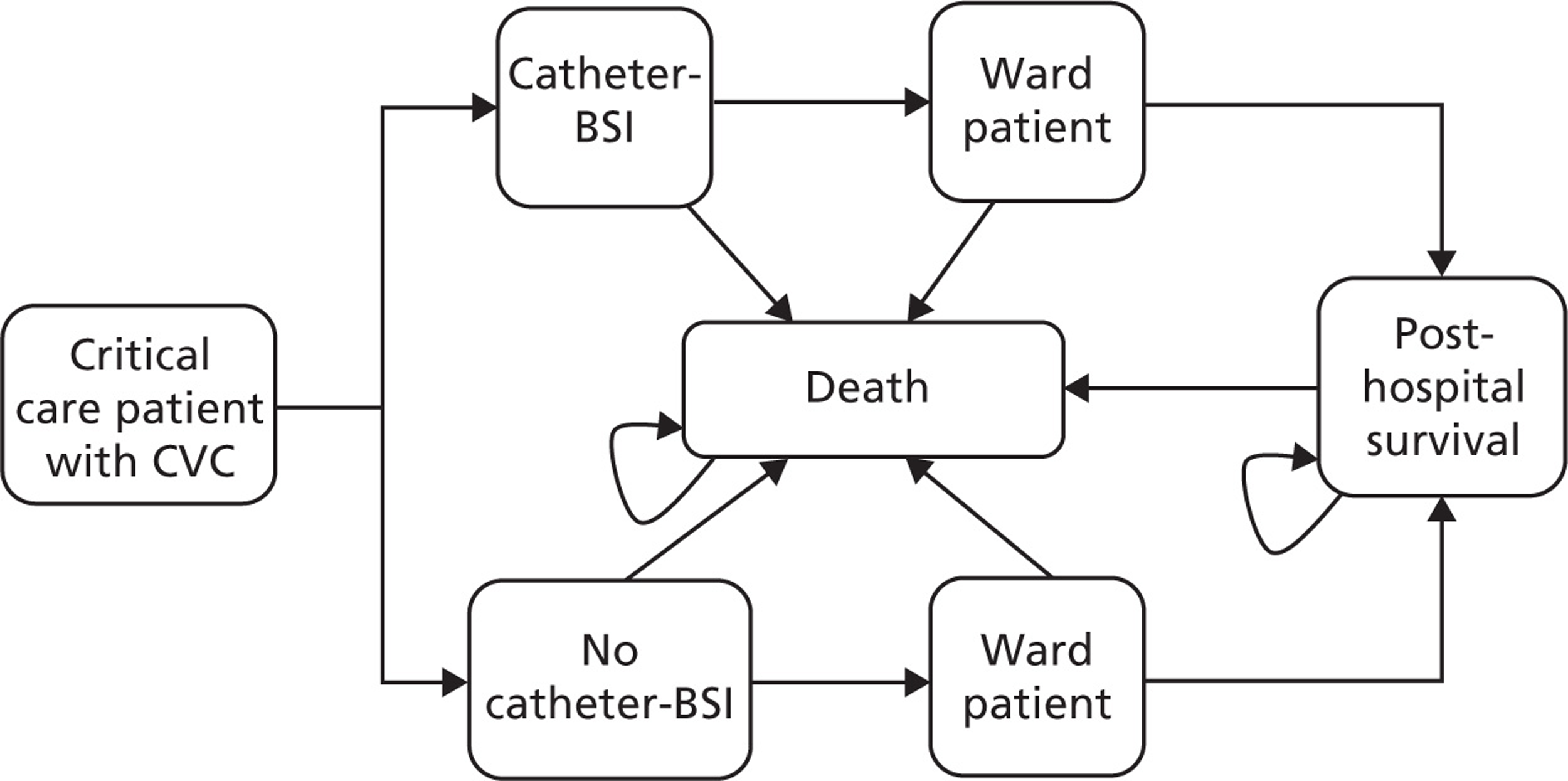

Chapter 1 Background

Intravascular catheters are used for the administration of medication, fluids, blood products and parenteral nutrition, as well as for patient monitoring,1 but they are an important cause of bloodstream infections (BSIs). 2–4 The most frequently used type of intravascular catheter is a central venous catheter (CVC), also referred to as a central line. A CVC is defined as an intravascular device that terminates in one of the great veins, or in or near to the right atrium, and includes peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs), haemodialysis catheters and parenteral nutrition catheters. Insertion sites for CVCs are usually the jugular, subclavian and femoral veins, although femoral insertion may be associated with higher risk of BSIs than insertions at other sites. 5 Intravascular catheters vary in the material from which they are made, the presence or absence of antimicrobial or anticoagulant coatings, the number of lumens present and whether they are tunnelled, and these variables may have an important bearing on the risk of BSI. 6

Four distinct pathways may be identified in the infection process of catheter-BSI. The two major pathways are the external and internal bacterial colonisation of the catheter surface, both eventually leading to catheter-tip colonisation, with the potential for subsequent bacteraemia. Additional pathways include microbial contamination of the infusate and direct mechanical introduction of pathogens into the bloodstream. 7 A wide variety of microorganisms may cause catheter-BSI, including, among others, Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis8 and enterococci. 9 Catheter-BSI result from inadequate hygiene and suboptimal catheter management procedures. These include inadequate hand hygiene by hospital staff; inadequate skin hygiene at the site of patients' catheter insertion; suboptimal location of catheters; and unnecessary placement of catheters. 6 Other risk factors are the patient's age and underlying disease,6 and the duration of catheterisation. 10

Bloodstream infections arising from the placement of vascular catheters (catheter-BSI) are a particular problem in critical care units owing to the high frequency of intravascular catheter placement and increased susceptibility to infections among critical care patients. 11 The latest (2011) point prevalence survey in England,12 showed that 64% of all patients with a BSI had a vascular access device in the 48 hours prior to onset of infection, and 59.3% of critical care patients received a CVC compared with 5.9% of other hospital patients. A 1-month audit in a hospital in England found that 65% of patients in the critical care unit required a CVC, whereas in surgical and renal wards the proportion ranged from 3.5% to 25%. 13

Prevalence of catheter-bloodstream infection

Prevalence of catheter-BSI is usually standardised to the number of CVC-days, and is typically expressed as the incidence density per 1000 CVC-days, although the definition of a device-day varies (multiple concurrent vascular catheters in the same patient are often not counted separately14). According to the 2011 point prevalence survey in England, intravascular catheter placement accounted for 29% of hospital-acquired BSI. 12 Unpublished data from presentations about the ‘Matching Michigan’ programme in England15–17 (described further below) reported an incidence density of catheter-BSI of 3.7 per 1000 CVC-days for a subset of 19 critical care units in northern England sampled in mid-2009. The most recent published incidence density data available for the UK are from the Intensive Care Unit Associated Infection (ICUAI) National Surveillance Programme (NSP), based on data from May 2009 until January 2010 for 19 critical care units in Scotland. The NSP reported a catheter-BSI incidence density of 0.7 per 1000 CVC-days. 18 A 2009 report of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) estimated prevalence of catheter-BSI to be 4.3 per 1000 CVC-days, based on aggregated data from 12 European countries, which included some data from England. 19

There is evidence that prevalence of BSI associated with vascular catheters has decreased as a result of national and local infection prevention programmes in several countries. For example, in the USA the Institute for Healthcare Improvement's ‘100,000 Lives’ Campaign (2005–6) and ‘5 Million Lives’ Campaign (2006–8) were among a number of programmes that recruited a large number of hospitals and promoted (among other objectives) strategies for the prevention of catheter-BSI. The most recent data available from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)20 show that a 58% decrease in the prevalence of catheter-BSI occurred from 2001 to 2009. The point prevalence surveys conducted in England indicate a decline in the overall prevalence of BSI in recent years but the data are difficult to interpret owing to changes that occurred in the sampling methodology. 12

Definitions and diagnosis of catheter-bloodstream infection

Various definitions and terms are used, and sometimes confused, in the literature to describe a BSI that has developed as a consequence of an indwelling intravascular catheter. Laboratory-confirmed bloodstream infections (LCBSIs) which are proven microbiologically to result from vascular catheter use are generally referred to as catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRBSIs). In the absence of microbiological testing and after ruling out other possible sources, BSIs that appear to be linked to vascular catheter use are referred to as catheter-associated bloodstream infections (CABSIs). The gold standard for diagnosis of CRBSI is isolation of the same microorganism from a peripheral blood culture as that obtained from the tip of the removed catheter. 21 As many patients suspected of having a BSI will not have their catheter removed, and quantitative blood cultures are not universally performed, alternative definitions to CRBSI that do not require catheter removal are often used (i.e. CABSI), and these overestimate the true incidence of CRBSI. The most widely cited definitions of CABSI and CRBSI are the surveillance definitions of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Nosocomial Infection Surveillance System (NNIS), which operated up to 2004, and the CDC National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) which replaced the NNIS in 2005. The latest CDC guidelines on defining and diagnosing CABSI and CRBSI, endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, were reported by Mermel and colleagues. 22 Recently, stringent definitions of CABSI and CRBSI, based on the CDC definitions, have been developed for use in the ‘Matching Michigan’ programme in England17 (see Table 1). As we describe below (see Current prevention of catheter-bloodstream infectionsin the NHS), Matching Michigan was a programme for prevention of catheter-BSI in critical care units in England that has direct relevance to NHS practice.

For the purposes of this report, we follow the definitions of CABSI, CRBSI and catheter-suspected BSIs, as defined in the Matching Michigan programme (Table 1), and these definitions are collectively referred to as catheter-BSI.

| Infection type | Definition |

|---|---|

| LCBSI | The patient has one or more recognised pathogens cultured from one blood culture If the microorganism is a common skin organism [i.e. diphtheroids (Corynebacterium spp.), Bacillus spp. (not B. anthracis), Propionibacterium spp., coagulase-negative staphylococci (excludes sensitive S. aureus), viridans-group streptococci, Aerococcus spp. or Micrococcus spp.], then . . . It must have been cultured from two or more blood cultures drawn on separate occasions, or from one blood culture in a patient in whom antimicrobial therapy has been started, and The patient has one of the following: fever of > 38 °C, chills or hypotension |

| CABSI | Criteria above must be met for LCBSI, and: The presence of one or more CVCs at the time of the blood culture, or up to 48 hours following removal of the CVC and: The signs and symptoms and positive laboratory results including the pathogen cultured from the blood are not primarily related to an infection at another site |

| CRBSI | Criteria above must be met for LCBSI, and: The presence of one or more CVCs at the time of the blood culture, or up to 48 hours following removal of the CVC, and One of the following: a positive semiquantitative (> 15 CFUs/catheter segment) or quantitative (> 103 CFU/ml or > 103 CFU/catheter segment) culture whereby the same organism (species and antibiogram) is isolated from blood sampled from the CVC or from the catheter tip, and peripheral blood; simultaneous quantitative blood cultures with a > 5 : 1 ratio of CVC vs. peripheral |

| Catheter-suspected BSI | Negative blood cultures in the presence of parenteral antimicrobials, and Clinical evidence of a systemic response to infection, and Clinical condition improves following removal of CVC, and No other likely source of infection |

Diagnosis of CRBSI is made in various ways, depending upon both local clinical practice and, for infection surveillance purposes, the definition of infection in use. The use of different definitions of infections can dramatically alter the reported infection rate unless they are aligned with clinical practice. For example, if clinical practice is not to send a CVC line tip to the laboratory for culture, or to draw only a single set of percutaneous cultures, then any definition requiring catheter-tip culture or more than one set of cultures will never be met, potentially giving an artificially low infection rate.

Impact of catheter-bloodstream infection on patients and health services

Catheter-BSI increase patients' discomfort and length of stay (LOS) in hospital23 and their risk of health complications and death. 24 Catheter-BSI can trigger a range of responses from systemic sepsis through to septic shock and multiple organ failure. Metastatic infection may lead to septic thrombosis, endocarditis and septic arthritis. 25 Further complications may include acute respiratory distress syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation and acute renal failure. 26

Robust data on mortality, quality of life (QoL) and long-term prognosis specifically related to catheter-BSI are not available for the UK. Recent estimates of the mortality rates of patients with catheter-BSI in critical care units in France, Germany and Italy ranged from 11% to 17.1%. 27 Estimates of the additional LOS per catheter-BSI episode in UK critical care units have ranged from 1.9 days27 to 11 days. 23 In 2006 the National Audit Office estimated the additional cost of a BSI to be £6209 per patient. 28 The most recent (2009) estimate of the financial impact for the NHS suggests that annual costs related to catheter-BSI in critical care units are £19.1–36.2M. 27

Educational interventions for preventing catheter-bloodstream infection

Educational interventions for preventing catheter-BSI have been trialled in critical care settings in many countries and vary considerably in their content and complexity. They range from the provision of simple fact sheets and posters29 to complex interventions comprising multiple behavioural components. 30 Educational approaches also include continuous quality improvement (CQI), which engages front-line staff in cycles of iterative problem solving, with decision-making based on real-time process measurements. 31 Interventions differ in the number and duration of education components, whether they are didactic or interactive, and whether infection surveillance feedback and performance feedback are also present. Interventions that contain several different elements which together aim to achieve a particular outcome are referred to as ‘multifaceted’, ‘multicomponent’ or ‘bundled’ interventions. 32 A care bundle is defined as a small set of practices that have been individually proven to improve patient outcomes and when implemented together are expected to result in better outcomes than when implemented individually. 33

Multifaceted educational interventions that have been developed for preventing catheter-BSI include the Michigan Keystone ICU project in the USA34 and the NHS ‘High Impact’ CVC care bundle. 28 These include, among others, specific components for ensuring appropriate staff behaviour for hand hygiene, patient skin hygiene, choice of catheter type and insertion site, and catheter ongoing care.

In general, educational interventions involve encounters between teachers and learners for one or more of the following purposes: to raise awareness; to enhance or improve knowledge; or to change behaviour. 35 Educational interventions for preventing catheter-BSI ideally should include behaviour modification components underpinned by relevant theory. 36

We defined educational interventions as those that contain any element of information provision intended to influence catheter-BSI outcomes (i.e. by changing health-care workers' behaviour). Included within this definition are checklists, and information feedback to health-care workers. We distinguish between infection surveillance feedback whereby staff are informed in real time of catheter-BSI incidence rates, and performance feedback whereby staff are informed of their compliance with evidence-based practices or progress with learning goals. According to our definition, educational interventions are not limited to purely educational practices but may also include non-educational activities, such as the provision of supplies. Such interventions may be described as providing ‘components beyond education’. 37

Current prevention of catheter-bloodstream infections in the NHS

Catheter-BSI are believed to be largely preventable following work in the UK that has successfully reduced the number of cases of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) BSI. It has been proposed that the majority of catheter-BSI could be prevented using evidence-based educational interventions to ensure that doctors and nurses are committed to a culture of safety and follow best practice to achieve this. 26,38

Evidence-based practices that are recommended for prevention of catheter-BSI include selection of an appropriate catheter type; avoidance of the femoral insertion site; antimicrobial cleansing of the insertion site; use of maximal sterile barrier precautions and aseptic technique (gloves, mask, hat, patient drapes) during catheter insertion; and use of a sterile semipermeable transparent dressing to allow observation of the insertion site. 6,39

To address the prevention of catheter-BSI, the NHS has developed ‘Saving Lives’ tools,40 which include ‘high-impact’ care bundles for CVCs and peripheral intravenous cannula. 28 The High Impact No. 1 CVC bundle consists of actions for preventing catheter-BSI in relation to CVC insertion (Table 2) and CVC ongoing care (Table 3). These bundles are based on ‘epic2’ guidelines,39 which stress the importance of education of hospital staff for successful implementation of infection control programmes. Similar guidelines produced by the US CDC also strongly emphasise the need for education and training in evidence-based practices for preventing catheter-BSI. 6 However, in both the epic2 guidelines39 and US guidelines6 there is a lack of evidence on the types of educational interventions that are most appropriate and effective, and the guidelines do not make any recommendations that specifically relate to critical care settings. Following a recommendation in the Darzi Report,41 during 2009–11 the UK National Patient Safety Agency implemented an initiative known as ‘Matching Michigan’38,42 to prevent catheter-BSI. Matching Michigan was based on a regional-scale intervention that had successfully reduced catheter-BSI incidence density in the Keystone ICU project, conducted in 103 critical care units in Michigan, USA. 34 However, the original study in the USA34 was not randomised and did not assess the importance of the education strategy in the effectiveness of the overall care bundle.

| Catheter type | Single lumen unless indicated otherwise Consider antimicrobial impregnated catheter if duration of 1–3 weeks and risk of CRBSI high |

| Insertion site | Subclavian or internal jugular |

| Skin preparation | Preferable use 2% chlorhexidine gluconate in 70% isopropyl alcohol and allow to dry If patient has a sensitivity use a single-patient-use povidone–iodine application |

| Personal protective equipment | Gloves are single-use items and should be removed and discarded immediately after the care activity Eye/face protection is indicated if there is a risk of splashing with blood or body fluids |

| Hand hygiene | Decontaminate hands before and after each patient contact Use correct hand hygiene procedure |

| Aseptic technique | Gown, gloves and drapes, as indicated, should be used for the insertion of invasive devices |

| Dressing | Use a sterile, transparent, semipermeable dressing to allow observation of insertion site |

| Safe disposal of sharps | Sharps container should be available at point of use and should not be overfilled; do not disassemble needle and syringe; do not pass sharps from hand to hand |

| Documentation | Date of insertion should be recorded in notes |

| Hand hygiene | Decontaminate hands before and after each patient contact Use correct hand hygiene procedure |

| Catheter site inspection | Regular observation for signs of infection, at least daily |

| Dressing | An intact, dry, adherent transparent dressing should be present |

| Catheter access | Use aseptic technique and swab ports or hub with 2% chlorhexidine gluconate in 70% isopropyl alcohol prior to accessing the line for administering fluids or injections |

| Administration set replacement | Following administration of blood, blood products – immediately Following total parenteral nutrition – after 24 hours (72 hours if no lipid) With other fluid sets – after 72 hours |

The Matching Michigan programme in England recruited 240 adult and 40 paediatric critical care units, with 97% of acute health trusts in England participating. Technical components of the Matching Michigan programme were a data collection system for infection surveillance; CVC insertion checklist; CVC trolley inventory; catheter-BSI fact sheet; and Department of Health High Impact bundles. 28 Matching Michigan also included non-technical strategies, which were to develop a culture of safety; facilitate learning from incidents; foster teamwork and collaborations; and develop executive and clinical partnerships. The Matching Michigan programme ran for 2 years and ended in 2011. Preliminary results of audits from individual participating trusts are starting to appear at conferences15–17 and in online presentations, but, to date, a detailed formal analysis of findings from Matching Michigan has not been published.

Evidence from existing reviews

A number of narrative reviews have suggested that educational interventions including care bundles may be effective at preventing catheter-BSI in various health-care settings,7,43–46 but no systematic reviews have specifically investigated the effectiveness of educational interventions for preventing catheter-BSI in critical care units. The most relevant systematic reviews in related areas have investigated interventions for preventing catheter-BSI (not limited to educational interventions or critical care);47 bundled behavioural interventions to control health care-associated infections (not limited to education, catheter-BSI or critical care);30 interventions for preventing catheter-BSI in critical care (not limited to education or behavioural interventions);48 educational interventions for preventing health care-associated infections (not limited to educational or behavioural interventions, catheter-BSI or critical care);37 and features of educational interventions that impact on competence in aseptic insertion technique and maintenance of CVCs by health-care workers (not limited to catheter-BSI or critical care). 49 Some of these systematic reviews included primary research studies relevant to the scope of our current evidence synthesis but the most recent of these reviews49 did not include any studies published after August 2008.

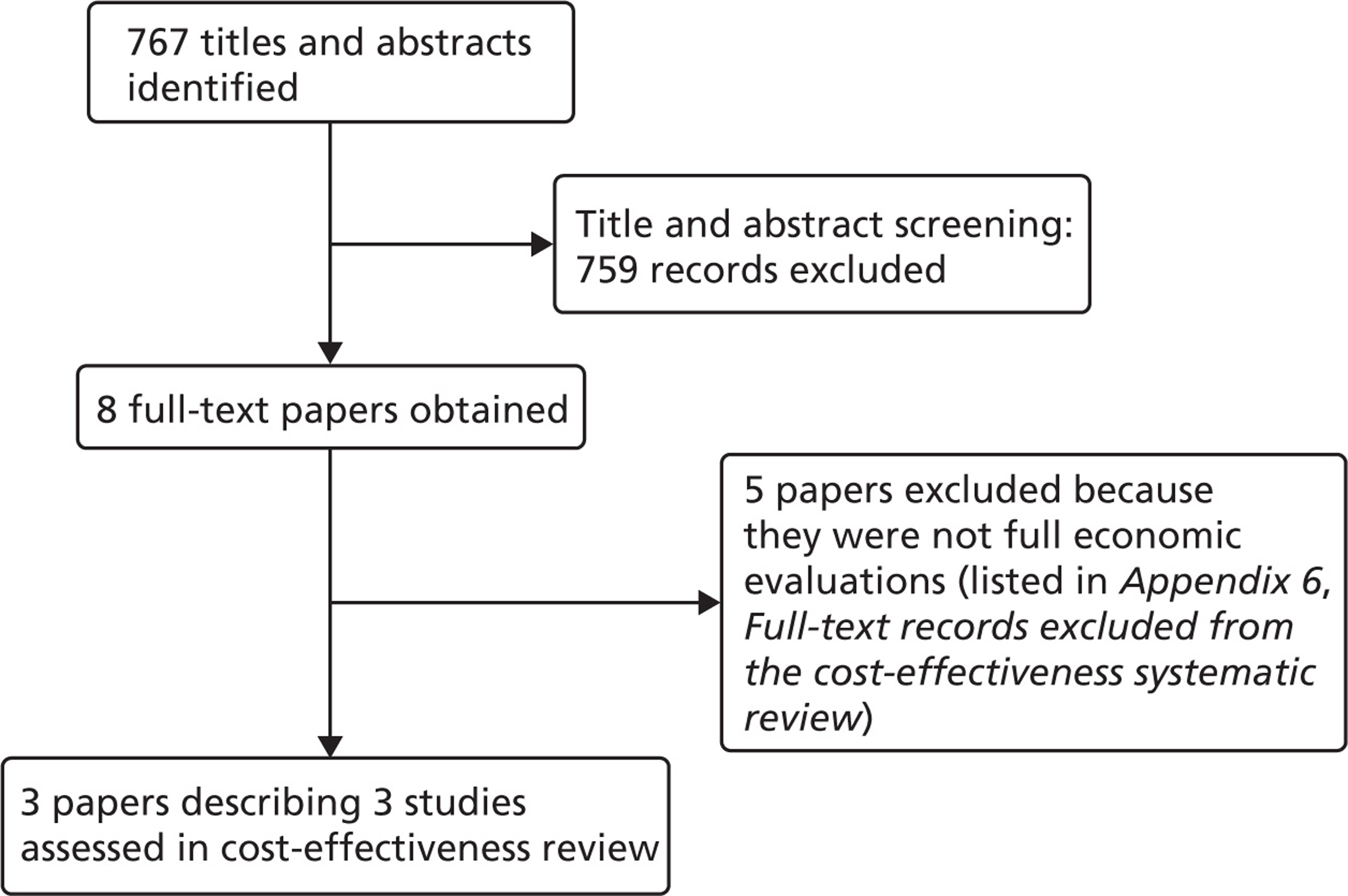

None of the systematic reviews referred to above included economic analyses. Most of the available information on the economic impact of catheter-BSI in critical care is from work conducted in the USA. 50,51 A recent brief narrative review of epidemiological studies27 provides an insight into the economic burden of catheter-BSI in critical care in European countries including the UK but, owing to a shortage of information on costs, its findings are based on numerous assumptions and uncertainties.

Objectives

The overall aim of this evidence synthesis is to provide a rigorous evaluation of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of educational interventions that are relevant to the NHS for preventing catheter-BSI in critical care units in England. The types of intervention that could be relevant appear diverse, but the quantity, quality and relevance of the primary clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness studies are unclear. To address these uncertainties the current project has the following specific objectives:

-

To create an evidence map summarising all potentially relevant primary research studies. This is necessary as a first step to clarify the quantity, quality and potential relevance to NHS policy and practice of the existing primary research studies.

-

To conduct a systematic review of a subset of studies in the evidence map considered most relevant to inform NHS policy and practice for prevention of catheter-BSI in critical care.

-

To conduct a systematic review of cost-effectiveness studies. This is necessary to clarify the quality and relevance of any existing studies of the cost-effectiveness of interventions for preventing catheter-BSI and may help to inform the structure of a decision-analytic economic model.

-

To develop a decision-analytic model to determine and compare cost-effectiveness of relevant groups of interventions and settings. This would utilise data on clinical effectiveness from Objective 2 and, if appropriate, relevant methodology and model parameters identified from Objective 3.

-

Based on the information provided from Objectives 1–4, to identify future research needs and consider the implications of implementing educational interventions for preventing catheter-BSI that are relevant to service users in the NHS.

Chapter 2 Methods for the mapping exercise and systematic review of clinical effectiveness

The a priori methods for systematically reviewing the evidence of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness are described in the research protocol (see Appendix 1). The protocol was sent to our expert Advisory Group (AG) for comment. Minor amendments were made as appropriate, but none of the comments we received identified specific problems with the methods of the review. Methods outlined in our protocol are briefly summarised below.

Search strategy

A sensitive search strategy was developed and refined by an experienced information scientist (see Appendix 2).

Searches for clinical effectiveness literature were undertaken from inception of databases to January/February 2011. No trial or study filter and no language restrictions were included in the search strategy.

The strategies were applied during February 2011 to the following databases:

-

MEDLINE (Ovid; searched 1948 to 19 January 2011)

-

Ovid MEDLINE(R) In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (searched to 1 February 2011)

-

EMBASE (Ovid; searched to 25 January 2011)

-

BIOSIS (searched 1969 to 2011)

-

Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) (searched on 1 February 2011)

-

CINAHL EBSCOhost (searched on 2 February 2011)

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CCRCT) (searched on 2 January 2011)

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) (searched on 2 January 2011)

-

Cochrane Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (searched on 3 February 2011)

-

Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) (searched from 1966)

-

Web of Science databases (searched to 1 February 2011):

-

Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE) (searched from 1970)

-

Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) (searched from 1970)

-

Arts & Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI) (searched from 1975)

-

Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science (CPCI-S) (searched from 1990)

-

Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Social Science & Humanities (CPCI-SSH) (searched from 1990).

-

In addition, we hand-searched reference lists of the papers retrieved and relevant systematic reviews for potential additional studies. Experts on the project AG were also asked to identify additional published and unpublished references. All search results were downloaded into a Reference Manager database version 12.0.3 (Thomson ResearchSoft, San Francisco, CA, USA). Searches were rerun using the same search strategies in March 2012 to identify any new primary research published during March 2011 to March 2012, which might impact on the findings of the report.

Inclusion criteria for descriptive mapping (stage 1)

The purpose of the mapping exercise was to facilitate a description of the evidence base so that a subset of policy-relevant studies from the map could be identified and subjected to a detailed systematic review. The following inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied to the references identified by the above search strategy to select studies eligible for inclusion in the evidence map:

-

Population Patients in critical care with any type of vascular catheter (including CVCs, arterial catheters, cannula). Critical care was defined as any critical or intensive care unit (ICU), including high-dependency units but excluded general or specialist (e.g. cardiac, neurological, surgical) non-critical units. Patients with urinary or other non-vascular catheters were only included if vascular catheters were also present. Studies solely on patients with urinary or other non-vascular catheters were excluded.

-

Design Interventional studies based on primary research.

-

Intervention(s) Educational interventions with an objective to reduce or prevent catheter-BSI. An educational intervention was defined as any intervention that aimed to prevent catheter-BSI and (1) included at least an element of factual information provision related to that aim; (2) was described by the authors as educational; or (3) was described by the authors as behavioural. Checklists were eligible as an educational tool. Interventions that did not target catheter-BSI (e.g. interventions for hand hygiene alone or for infection surveillance) were excluded; provision of factual information was also excluded if it was unrelated to prevention of catheter-BSI.

-

Outcomes Primary outcomes were BSIs, mortality or LOS associated with, related to, or suspected to result from intravascular catheter use. BSIs unrelated to vascular catheter use were excluded, as were non-vascular infections (e.g. urinary tract, organ space or skin). The following secondary outcomes were not used for study selection but were to be extracted from studies at the data collection stage if at least one primary outcome was reported: staff reaction to education; attitudes; knowledge; skills; compliance with interventions; and process evaluations (quantitative or qualitative descriptions of intervention processes, facilitators or barriers).

Study selection for descriptive mapping

Titles and abstracts of records identified by the bibliographic searches conducted in January/February 2011 were assessed independently by two reviewers for potential eligibility, using a pilot tested selection worksheet containing the above selection criteria (see Appendix 3). Any disagreements between the reviewers were resolved through discussion and in some cases with recourse to a third reviewer. Full-text papers were obtained for all titles and abstracts that met the selection criteria or were unclear. The full-text papers were then assessed independently by two reviewers using the same study selection worksheet. Any further disagreements between the reviewers were resolved through discussion and in some cases recourse to a third reviewer. Papers published in languages other than English were each assessed by at least one native or competent speaker of the publication language together with a member of the systematic review team.

In addition to the selection of primary research studies described above, any potentially relevant systematic reviews identified during title and abstract screening were obtained as full-text versions for detailed inspection.

Owing to lack of time, any new studies identified from the updated searches in March 2012 were not formally included in the evidence synthesis but their potential implications for interpretation of the evidence synthesis findings are considered in the discussion (see Chapter 7).

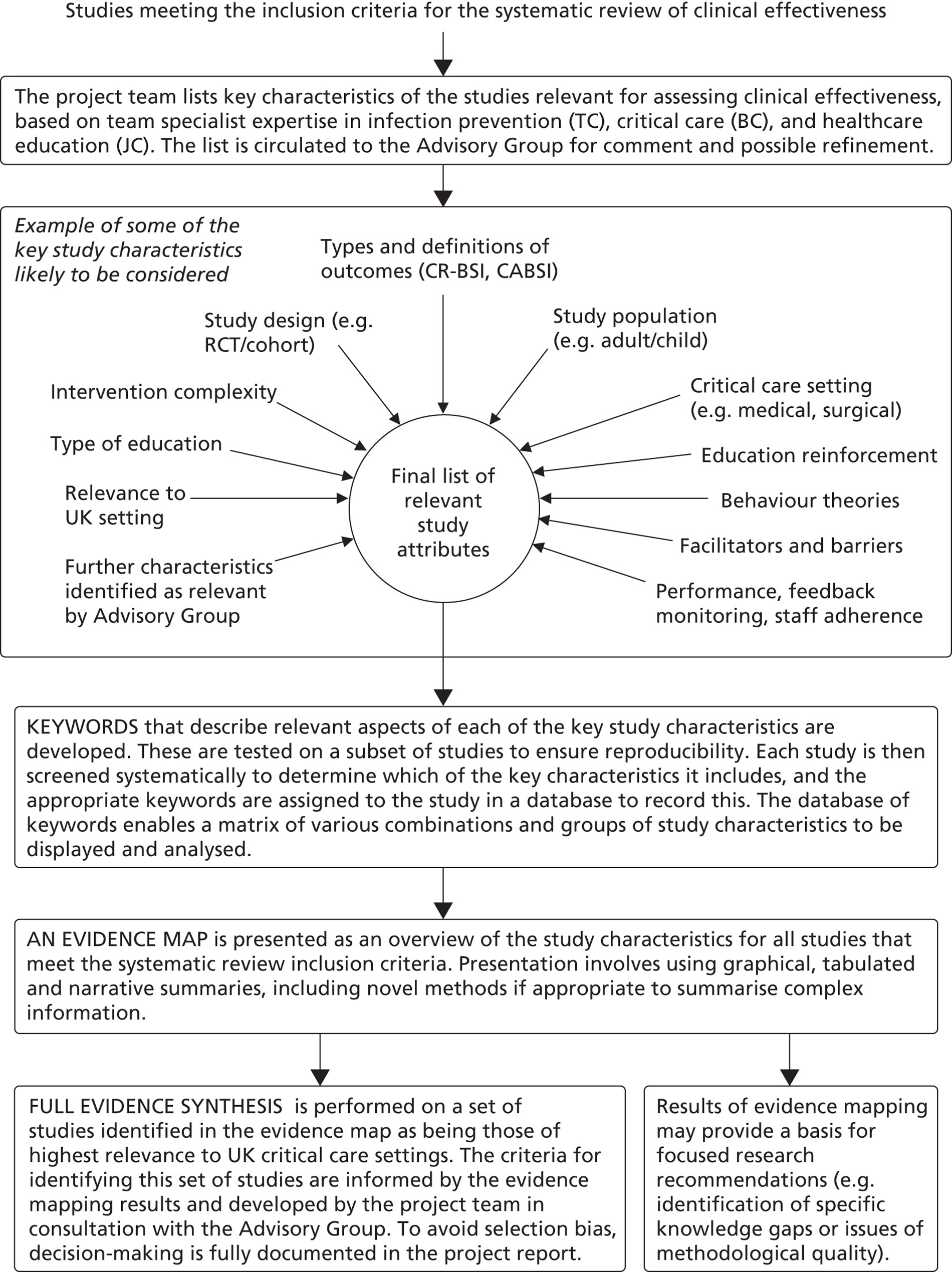

The process of descriptive mapping

As mentioned above, the purpose of the mapping exercise was to facilitate a description of the evidence base so that a subset of policy-relevant studies from the map could be identified and subjected to a detailed systematic review. This approach has been found to be useful in previously published systematic reviews. 52–54

Studies that met the selection criteria reported above were coded on the basis of their key characteristics using a classification instrument developed by the project team. The classification instrument (see Appendix 4) consisted of a standard list of keywords for capturing information on critical care specialties, vascular devices used, types of intervention used, study designs, outcomes and the educational strategies and topics covered. The classification instrument was provided in an Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) worksheet, together with instructions on how to interpret and apply the keywords, and was piloted by each member of the project team on three studies. Some amendments were made to both the keywords and the instructions to establish good inter-reviewer reliability within the team. Once finalised, the instrument was applied to the included studies by one or two reviewers depending on the publication language. Studies published in English were classified by one reviewer. Studies published in a language other than English were classified jointly by two reviewers, at least one of whom was a competent speaker of the publication language. A random sample of 40% of all the completed classifications was then checked independently by a further reviewer to ensure good inter-reviewer reliability.

Inclusion criteria for the systematic review (stage 2)

Once all of the studies had been classified, analysis was performed to construct the descriptive map (for results of the map, see Chapter 3).

The results of the descriptive map were presented to the AG in September 2011 for discussion. The group assisted us in prioritising a subset of studies for systematic review that most closely resemble current UK practice, and which are most likely to address current policy and practice needs for preventing catheter-BSI in critical care. Suggestions for systematic review study selection criteria were provided by seven members of the AG and 11 members of the project team, and these were discussed at a face-to-face meeting of the project team in October 2011.

Numerous potential selection criteria for the systematic review were discussed. These included limiting the systematic review to particular study designs; geographical regions; types of catheter; population age groups; types of educational approaches; or levels of study quality. A detailed description of the issues discussed is available from the authors upon request.

Based on the discussion, the inclusion criteria for the systematic review were set as follows:

-

Population Adults (i.e. excluding neonatal and paediatric critical care units)

-

Design Clearly reported as prospective

-

Outcomes Studies had to provide a definition of catheter-BSI (including any definitions given in the publication or accompanying supplementary material or hyperlinks).

Study selection for the systematic review

Once the criteria for the systematic review had been set, all of the studies classified in the map were rechecked by one reviewer to ensure that the keywords regarding the population, design and outcomes were accurate. Studies from the map which met the three inclusion criteria reported above for population, design and outcomes were then entered into the full systematic review.

Data extraction in the systematic review

A data extraction and quality assessment form was devised for the systematic review based on a standard template used by the project team for other systematic reviews. The template was adapted to take into account the reporting standards recommended by the TREND Statement for reporting non-randomised studies of behavioural interventions;55 a Best Evidence in Medical Education (BEME) Guide for systematically reviewing educational interventions;56 and the ORION Statement for reporting intervention studies of nosocomial infections. 57 The form was piloted on a subset of the studies to ensure good inter-reviewer reliability. Data from each study included in the systematic review were then extracted by one reviewer and were checked by a second reviewer. Any disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus or if necessary by arbitration by a third reviewer. The completed data extraction forms can be seen in Appendix 5.

Quality assessment

Using criteria specified a priori, we assessed two aspects of the quality of the included studies: (1) risk of bias, which identifies methodological deficiencies in studies that could lead to systematic errors in outcomes and (2) the reporting of the methods used to collect data, which was identified by the project AG as an important aspect of study quality that should be assessed.

Risk of bias

The concept of risk of bias indicates whether study outcomes are likely to be valid and, hence, whether they may be trusted in the data synthesis. 58 Project scoping searches indicated that before-and-after studies were likely to be the most frequent research approach used for evaluating the effectiveness of educational interventions for preventing catheter-BSI. Our quality assessment criteria therefore focused on before-and-after studies, with additional criteria provided for assessing the quality of randomised controlled trials (RCTs), where appropriate. Risk of bias criteria have been established by the Cochrane Collaboration for RCTs58 and could, in principle, be adapted or developed for assessing some aspects of bias in non-randomised studies. 59 Before-and-after studies without a concurrent control group may be particularly at risk of performance bias, as investigators may be unable to isolate effects of their intended changes in health-care practice (e.g. implementation of an intervention) from other changes that could influence patient outcomes (e.g. intrahospital, regional or national changes in health-care practices or policies). Before-and-after studies may also be at risk of selection bias if the population characteristics of the intervention and comparator (baseline) groups differ systematically, and attrition bias if availability of data differs between the intervention and comparator groups.

Specific criteria for assessing risk of bias have not been published for before-and-after studies. We developed assessment criteria for risk of selection bias, performance bias and attrition bias (Table 4), based on the general format of the Cochrane risk of bias tool, in which risk of bias is judged either as low, high or unclear. 58 Judgements of ‘unclear’ risk of bias were made if insufficient information was reported to assess a given risk of bias criterion. The risk of bias criteria were agreed by the review team and then applied independently by two reviewers to the studies included in the systematic review. The criteria were revised in light of disagreements between the reviewers' judgements. The final risk of bias criteria (see Table 4) are intended to assist interpretation of the current data synthesis [see Chapter 4, Synthesis of effectiveness (primary outcomes)] and may not be applicable outside this current systematic review. It should be recognised that assessment of risk of bias is an imperfect science, as subjectivity of interpretation and inter-reviewer disagreements occur even with the well-established Cochrane risk of bias criteria for RCTs. 60

| Type of bias | Criteria for judgement of ‘low’ | Criteria for judgement of ‘high’ |

|---|---|---|

| Selection bias risk: systematic differences between groups | Characteristics of the patient groups were similar in the baseline and intervention periods, or any differences would be unlikely to influence risk of catheter-BSI | Characteristics of the patient groups differed between the baseline and intervention periods to an extent that could influence risk of catheter-BSI |

| Performance bias risk: effects of other concurrent intervention(s) | Outcomes are interpretable in relation to a specified intervention | Outcomes could be explained by more than one intervention |

| Performance bias risk: other concurrent staff or policy changes | Baseline and intervention periods were similar in staff numbers and expertise; patient management policies (at hospital or critical care unit levels); and critical care unit infrastructure (e.g. bed numbers) | There were notable differences between the baseline and intervention periods in staff numbers or expertise; in patient management policies; and/or critical care unit infrastructure |

| Performance bias risk: outcome assessment not blinded | Staff involved in blood sampling and culturing were unaware they were in a research study | Staff involved in blood sampling and culturing were aware they were in a research study |

| Performance bias risk: outcome definition or measurement differences between groups | Methods for taking blood for cultures and/or criteria for diagnosing catheter-BSI did not differ between baseline and intervention periods | Methods for taking blood for cultures and/or criteria for diagnosing catheter-BSI were different in baseline and intervention periods |

| Attrition bias risk: imbalances between groups in missing data | Patient population clearly described and the numbers of patients who provided primary outcome data agree with the described population for baseline and intervention periods | Availability of primary outcome data differed between baseline and intervention periods; and/or reasons for missing data related to intervention effectiveness |

For RCTs, we applied the risk of bias criteria listed in Table 4 to before-and-after comparisons within each study arm so as to enable comparisons with the non-randomised studies; and we also assessed risks of selection bias according to the adequacy of randomisation and allocation concealment, according to the standard Cochrane risk of bias criteria for RCTs. 58

In addition to the risks of selection, performance and attrition bias reported above which we assessed using the criteria specified a priori (see Table 4), any other possible sources of bias noted by the reviewers in the primary studies were recorded at the data collection stage, in a free text field of the data extraction form.

Reporting of data collection in the primary studies

We recorded whether the methods of data collection were reported for clinical outcomes, infection surveillance and staff performance. Judgements were agreed by two reviewers and were recorded as yes, no, partly or unclear, together with an explanatory statement, in the data extraction form for each study. If data collection processes were reported, we also recorded whether they were shown to be validated and reliable.

Data synthesis

Studies were synthesised narratively following a structured approach similar to one proposed by Rodgers and colleagues. 61 In addition to the narrative synthesis, we explored the possibility of calculating pooled-effect estimates across independent studies in meta-analysis, taking into consideration methodological similarities and differences between the studies.

The primary review outcome was incidence density of catheter-BSI, expressed as the number of catheter-BSI per 1000 catheter-days. Effects were expressed as incidence density risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), for comparisons between intervention and baseline periods in the before-and-after studies. If a RR and CI were not reported for a primary study, we calculated these from catheter-BSI incidence data and the corresponding number of catheter-days, using the method of Kirkwood and Sterne. 62 In cases when catheter-BSI incidence and catheter-days were not reported, we sought these data from the study investigators. All secondary review outcomes (including compliance and process evaluations) were synthesised narratively. For all steps of the data synthesis, calculations and narrative syntheses were conducted by one reviewer and were then checked by a second reviewer.

Chapter 3 Results of the mapping exercise

Results of the literature search

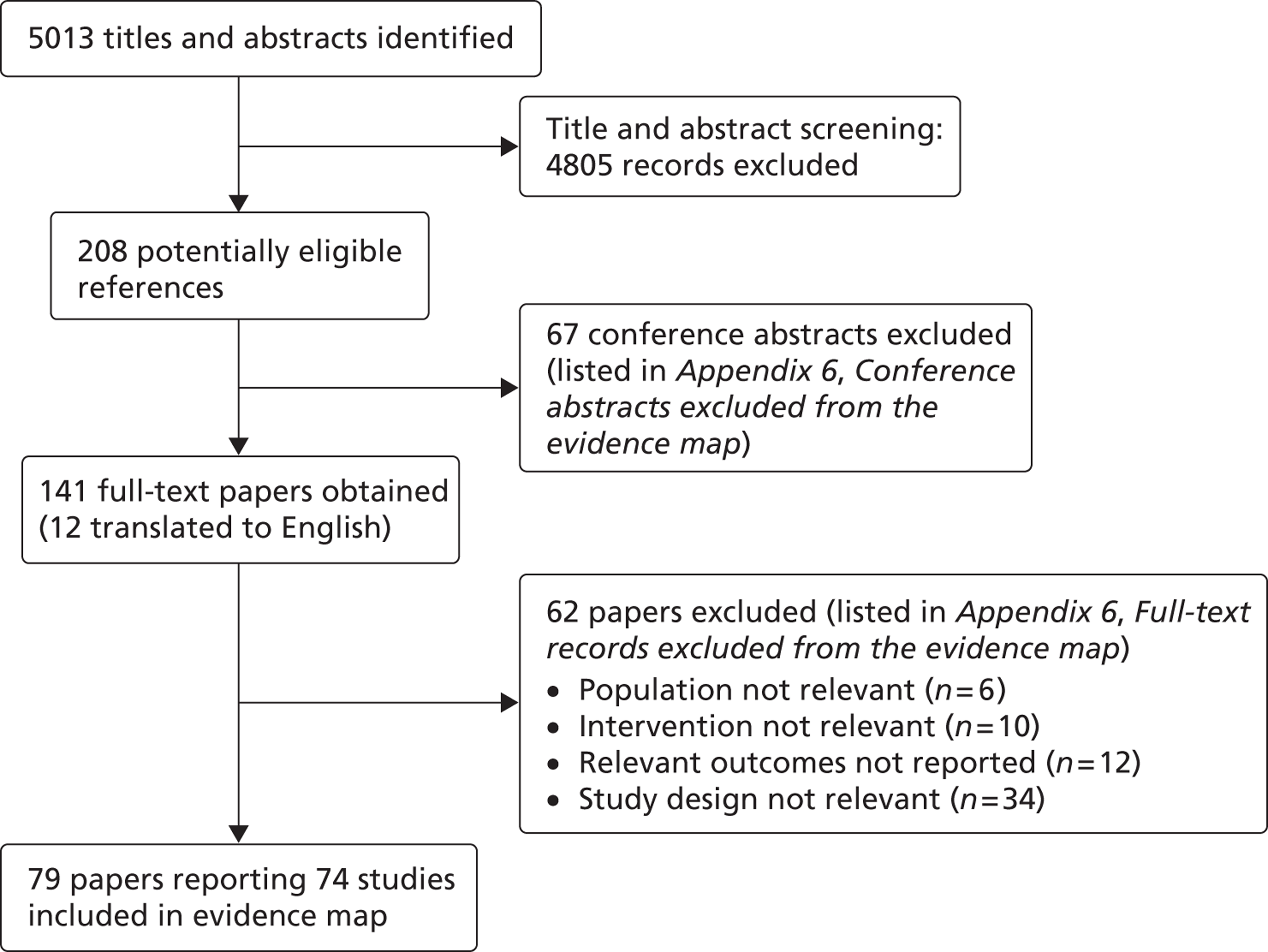

The process for identifying relevant references and selecting studies for the evidence map is shown in Figure 1. After excluding duplicates, we identified a total of 5013 potentially relevant references. Of these, we excluded 4805 references, as their titles and/or abstracts clearly did not meet the selection criteria. Reviewer agreement at the title and abstract screening step was 99% [Cohen's kappa (κ) = 0.90]. Sixty-seven of the records not initially excluded were conference abstracts. These were found to provide too little information to contribute to the keyword mapping exercise and were subsequently excluded. We retrieved the full-text publications for the remaining 141 records for inspection. These included 12 non-English-language publications, which we translated from Spanish,63–69 French,70–72 German73 and Swedish. 74 Following this selection process, 79 of the full-text records describing 74 primary research studies were included in the evidence map. 34,50,51,64,65,68–70,75–146

FIGURE 1.

Process for selecting studies in the evidence map

Characteristics of the studies

Geographical locations

Of the 74 primary research studies reporting educational interventions for preventing catheter-BSI which we included in the evidence map, most (65%) have been conducted in North America. Seven studies have been conducted in Spain (10%),64,65,68,69,121,122,127 five in Brazil (7%),108,109,112,118,132 two each in Argentina,129,130 France,70,117 Switzerland,94,144 and the UK,110,128 and one each in Australia,83 Belgium,111 Canada,119 Italy,120 South Korea142 and Mexico. 103 The UK studies were conducted in Northern Ireland128 and Scotland110 in paediatric and adult critical care units, respectively. No multinational studies were identified.

Spatial and temporal scales

Most (58) studies (78%) were conducted in single hospitals, with 40 of the studies (54%) conducted in single critical care units. Of the included studies, 11 were conducted in 10 or more critical care units. 34,68,82,83,85,91,107,115,133,140,141 The largest study conducted was the Michigan Keystone ICU project,34 which included 103 critical care units in 67 hospitals in Michigan, USA.

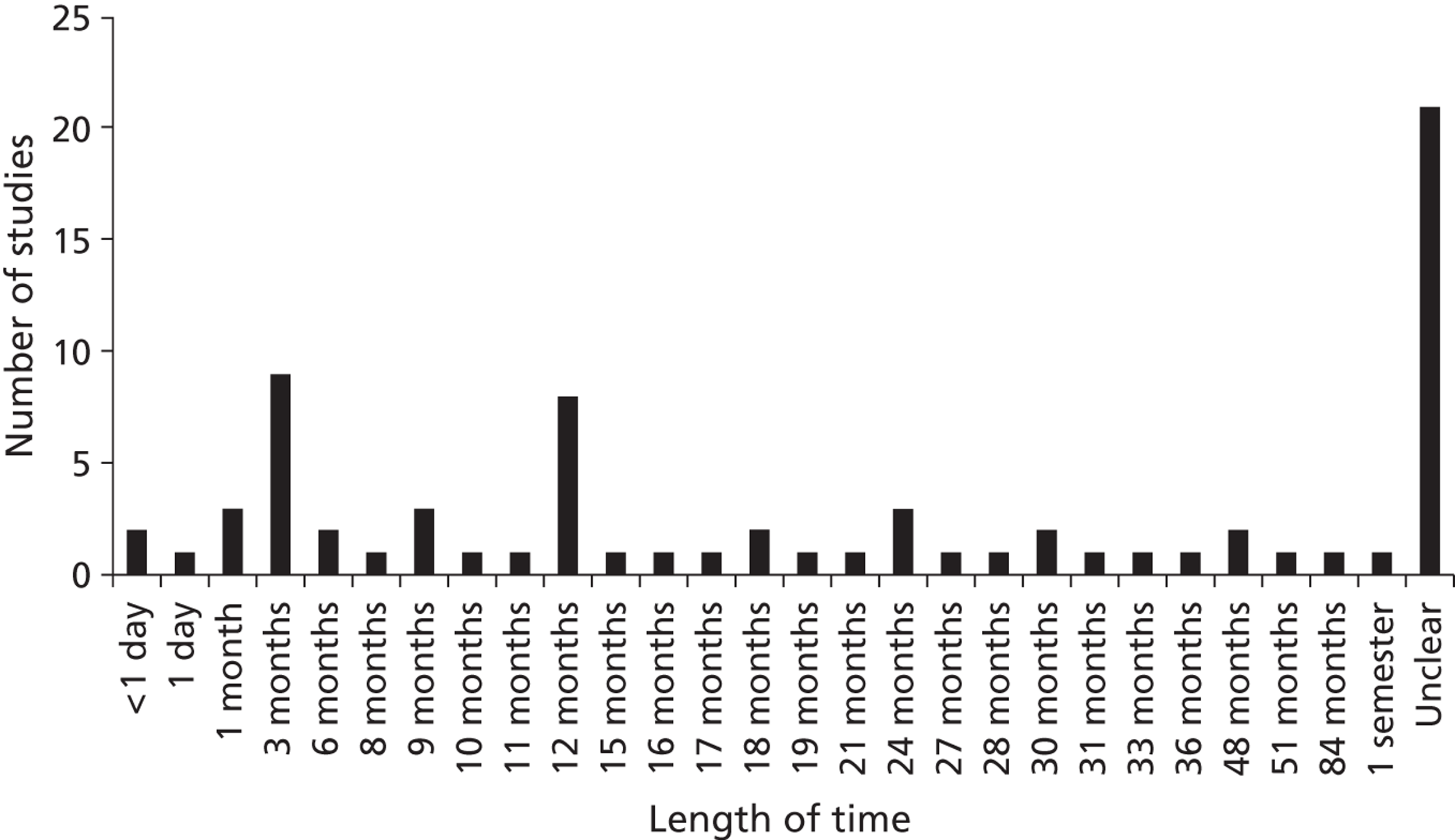

The duration of interventions ranged from < 1 day to 7 years. In approximately one-quarter of the studies the intervention duration was unclear owing to inadequate or ambiguous reporting (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Duration of interventions

Study designs

The designs of the interventional studies are summarised in Table 5, based on a classification system proposed by the Cochrane Collaboration. 58,59 The order of study designs in Table 5 reflects a hierarchy of the reliability of evidence, with risk of bias likely to be lower in well-conducted RCTs than in cohort studies.

| Study design (Cochrane classification59) | No. (rounded %) of studies (n = 74) |

|---|---|

| Before-and-after study – prospective | 48 (65) |

| Design unclear | 9 (12) |

| Before-and-after study – historically controlled | 8 (11) |

| Controlled trial (including RCT, quasi-RCT, non-randomised) | 3 (4) |

| Interrupted time series (controlled or uncontrolled) | 2 (3) |

| Before-and-after study – unclear whether prospective | 4 (5) |

The most frequently used study design, in 48 studies (65%), was a prospective before-and-after study (see Table 5). Eight studies81,96,111,116,134,137,141,142 were historically controlled before-and-after studies. Three studies68,136,145 were controlled trials but only two of these were randomised. 136,145 Speroff and colleagues136 conducted a cluster RCT in the USA, in which 60 hospitals were randomised to either a virtual collaborative quality improvement (QI) programme or a toolkit-based approach for preventing catheter-BSI. Khouli and colleagues145 conducted a RCT in the USA in which medical residents were randomised in a simulation laboratory to simulation-based plus video training for CVC insertion or video training alone. Palomar-Martinez and colleagues68 conducted a study in Spain in which 17 critical care units received either an intervention based on the Michigan Keystone ICU project or served as controls. Two studies used an interrupted time series approach. 88,115 In the remaining 13 of the 74 studies (18%) the design was judged unclear, either because it was unclear whether pre-intervention groups were selected prospectively or retrospectively (four studies100,106,120,121), or because too little information about the study methods was reported to classify the design (nine studies78,80,82,90,101,102,105,113,125).

Critical care specialties

The majority of studies were in adult medical, surgical and cardiac critical care units (Table 6). The specialties were not described consistently in the studies and in some cases were unclear. Numbers in Table 6 do not sum to 74, as some studies covered multiple specialties.

| Specialty as described by the study authors | No. of studies |

|---|---|

| Medical | 20 |

| Medical–surgical | 18 |

| Surgical | 18 |

| Cardiac/coronary | 17 |

| Neonatal | 11 |

| Paediatric | 8 |

| Neurological/neurosurgical | 9 |

| Trauma | 6 |

| General or mixed | 4 |

| Burn | 1 |

| Other | 6 |

| Not reported or unclear | 7 |

Intravascular devices

The studies in general provided very little information about the vascular devices used. Sixty-nine studies (93%) referred to central lines or CVCs. Five studies65,94,105,117,131 stated that they included arterial catheters as well as CVCs, and one study51 specifically excluded arterial catheters. Many of the studies did not report the insertion site (64% of the studies), lumen material (95%), whether antimicrobial-impregnated catheters were used (74%) or the number of lumens used (91%) (Table 7). Comparisons between studies are problematic, as unreported differences in vascular devices could contribute to interstudy differences in catheter-BSI incidence rates. Only three studies83,90,131 reported catheter-BSI data separately for different types of vascular catheter.

| Device characteristics | No. (rounded %) of studies (n = 74) |

|---|---|

| Insertion site | |

| Fully reported | 15 (20) |

| Partly reported | 12 (16) |

| Not reported | 47 (64) |

| Lumen material | |

| Fully reported | 4 (5) |

| Partly reported | 0 (0) |

| Not reported | 70 (95) |

| Lumen coating/impregnation | |

| Fully reported | 13 (18) |

| Partly reported | 6 (8) |

| Not reported | 55 (74) |

| Lumen number | |

| Fully reported | 3 (4) |

| Partly reported | 4 (5) |

| Not reported | 67 (91) |

Description and definition of catheter-bloodstream infection

In 36 of the 74 studies (49%) the authors described BSIs as catheter-associated (CABSI) and in 31 of the studies (42%) the authors described BSIs as catheter-related (CRBSI). Three studies70,104,117,125 described BSIs in other ways and the remaining three studies80,86,118 provided no description for the infection data they presented. Twenty-eight of the 74 studies (38%) provided a definition of catheter-BSI within their report and 56 studies (76%) cited a reference to a definition. Most of the studies defined catheter-BSI according to criteria of the US CDC NNIS, which operated up to 2004, or the CDC NHSN, which replaced the NNIS in 2005. Although the CDC definitions have changed through time, studies continued to cite old versions. For example, at least seven studies published since 2005 referred to infection definitions published in 1988.

Aims of the studies

Most (57) of the 74 studies (77%) stated that their aim was specifically to prevent catheter-BSI in critical care. The remaining studies mostly aimed to prevent catheter-BSI together with ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP),82,102,128,136 together with VAP and urinary tract infections (UTIs),86,104,114,117,130,137 or together with VAP and sepsis prevention. 91,101 Five studies89,93,94,118,120 each included prevention of catheter-BSI as part of a more general aim (Table 8).

| Aim | No. (rounded %) of studies (n = 74) |

|---|---|

| Specifically to prevent catheter-BSI | 57 (77) |

| Other aims | |

| Prevention of catheter-BSI and VAP | 4 (5) |

| Prevention of catheter-BSI and VAP and UTI | 6 (8) |

| Prevention of catheter-BSI and VAP and sepsis | 2 (3) |

| Prevention of MRSA, catheter-BSI, VAP and UTI | 1 (1) |

| Prevention of VAP, pressure ulcer, UTI, VAP, deep vein thrombosis | 1 (1) |

| Prevention of ICU-acquired infections including catheter-BSI | 1 (1) |

| Prevention of nosocomial infections including catheter-BSI | 1 (1) |

| Identification of risk factors for catheter-BSI | 1 (1) |

Types of educational intervention

Of the 74 studies, 25 (34%) provided information on development or testing of their interventions but only three77,102,119 (4%) reported that their interventions were based on educational theory.

The most frequently addressed clinical practices were hand hygiene (49 studies), catheter insertion site preparation (typically providing guidance on the use of chlorhexidine or povidone–iodine) (45 studies), use of full barrier precautions (43 studies), and catheter insertion site selection (typically discouraging use of the femoral site) (36 studies). The studies were variable in the extent to which they reported the clinical practices addressed by their interventions, and it was not always clear which clinical practices were included in education. For example, of the 49 studies with interventions that targeted hand hygiene behaviour, only 37 studies mentioned explicitly that intervention included education about hand hygiene (Table 9).

| Clinical practice | Included in intervention | Specified as target of education |

|---|---|---|

| Hand hygiene | 49 | 37 |

| Catheter insertion site preparation, management, and/or ongoing care | 45 | 29 |

| Barrier precautions – full | 43 | 28 |

| Catheter insertion site selection (e.g. avoidance of femoral site) | 36 | 24 |

| Checklist (principally about catheter insertion) | 35 | 5 |

| Dressing care (hygiene, removal, replacement) | 33 | 23 |

| Catheter need review (e.g. daily inspection; removal of unnecessary catheters) | 30 | 17 |

| Barrier precautions – specific (e.g. drapes, gloves, gown) | 27 | 20 |

| Unspecified aseptic or sterile technique | 22 | 19 |

| Catheter device ongoing management (e.g. flushing; hub care, including ‘scrub the hub’) | 20 | 19 |

| Dressing selection (e.g. antimicrobial biopatch) | 19 | 13 |

| Infection prevention and/or control (including evidence-based practice; guidelines) | 15 | 15 |

| Central line cart use | 15 | 1 |

| Catheter (re)placement procedure (e.g. use of ultrasound or radiography; avoidance of guidewires) | 10 | 8 |

| Epidemiology of BSIs | 8 | 8 |

| Catheter type selection (e.g. lumen number, chemical impregnation) | 5 | 4 |

| Documentation and auditing of processes | 5 | 3 |

| Team approach to catheter care | 5 | 4 |

| Administration of intravenous medication or infusate | 4 | 4 |

| Blood draw and/or culture technique | 4 | 4 |

| Measurement and/or definition of infection | 4 | 4 |

| Catheter-BSI risk factors | 2 | 2 |

| Responsibilities of health-care workers | 1 | 1 |

| Complications of vascular catheter insertion | 1 | 1 |

| Isolation and contact precautions | 1 | 1 |

| Educational topic(s) not reported or unclear (only a very general or vague description was provided) | 16 | 16 |

Twenty-two studies (30%) reported interventions that were purely educational and 52 studies (70%) reported that their interventions contained components beyond education (e.g. provision of antiseptic, or a catheter supplies cart).

The educational forum types (approaches to education delivery) are summarised in Table 10. Studies often gave rather general descriptions of educational approaches in which specific details were not reported. For this reason, the numbers of studies that used particular educational forum types may have been underestimated.

| Education forum | No. of studies |

|---|---|

| Checklist | 35 |

| Lecture(s), course(s) or workshop(s) | 29 (+ one unclear)a |

| Printed material (leaflet, pamphlet, magazine, book, course documents) | 27 |

| Discussion group(s) | 20 |

| Poster | 18 |

| Audiovisual (video or slide show) | 12 |

| Fact sheet | 11 |

| Electronic teaching materials (multimedia resources on CD, DVD, computer, internet) | 12 |

| Champion/opinion leader (= group based) | 11 (+ one unclear) |

| Practical demonstration of catheter technique or related activity | 10 |

| Face-to-face meetings | 9 |

| Self-study | 8 |

| Skills practice | 8 (+ one unclear) |

| Goal sheet | 7 |

| Virtual learning (computer-mediated instruction) | 6 |

| Supervision | 6 |

| Conference calls | 5 |

| Reminders | 4 |

| Simulation | 3 |

| Mentoring, shadowing or coaching | 3 |

| Information label | 2 |

| One or more component(s) of the educational forum unclear | 16 |

| Education materials not reported or unclear | 34 |

Thirty-one studies (42%) reported infection surveillance feedback and 36 studies (49%) reported performance feedback, but in nine studies79,80,85,115,118,119,125,128,142 it was unclear whether feedback approaches were used. In several studies, feedback approaches that were described as being part of an intervention also appear to have been used during the pre-intervention period. 50,87,136,138,139

Characteristics of the educational approaches are summarised in Table 11 and also may have been underestimated owing to incomplete reporting by the study authors. Active learning approaches that reinforced education delivery by repeated information provision, testing and assessment and/or feedback approaches were reported in 49 of the 74 studies (66%), but in 18 studies (24%) it was unclear whether active or passive (non-reinforced) educational approaches were used. It is difficult to draw firm conclusions about the use of didactic and interactive educational approaches because often teaching sessions were described too superficially for us to be sure of their approach. At least 31 of the studies (42%) used an interactive approach to learning which encourages self-discovery of information. Of the 74 studies, 21 studies (28%) made it clear that their educational sessions were mandatory, 46 studies (62%) conducted at least some of the training in-service, and group-based education appears to have been more frequently used than individual training (see Table 11).

| Education characteristics | No. (rounded %) of studies (n = 74) |

|---|---|

| Mode of learning | |

| Passive | 7 (9) |

| Active | 25 (34) |

| Both passive and active | 24 (32) |

| Unclear | 18 (24) |

| Mode of information presentation | |

| Didactic | 7 (9) |

| Interactive | 15 (20) |

| Both didactic and interactive | 16 (22) |

| Unclear | 36 (49) |

| Participation in educational sessions | |

| Mandatory | 21 (28) |

| Voluntary | 4 (5) |

| Unclear | 49 (66) |

| Location of education/training | |

| In service | 46 (62) |

| External, residential | 0 (0) |

| External, non-residential | 4 (5) |

| Unclear | 24 (32) |

| Contact type | |

| Individual based | 10 (14) |

| Group based | 38 (51) |

| Both individual and group based | 13 (18) |

| Unclear | 13 (18) |

Knowledge of the providers and recipients of the education (Table 12) and the intensity (concentration) of education (Table 13) is important for determining the resources that would be required if the intervention were to be replicated in another setting. Only 27 of the studies (36%) provided full information on who delivered the education, whereas 47 of the studies (64%) fully reported the intended recipients. In 42 of the studies (57%) it was unclear how many educational sessions were used and in 54 (73%) it was unclear how much time the educational sessions occupied.

| Category | No. (rounded %) of studies (n = 74) |

|---|---|

| Education providers | |

| Fully reported | 27 (36) |

| Partly reported | 12 (16) |

| Unclear | 35 (47) |

| Education recipients | |

| Fully reported | 47 (64) |

| Partly reported | 10 (14) |

| Unclear | 17 (23) |

| Educational sessions | No. (rounded %) of studies (n = 74) |

|---|---|

| Frequency | |

| Fully reported | 12 (16) |

| Partly reported | 20 (27) |

| Unclear | 42 (57) |

| Duration | |

| Fully reported | 6 (8) |

| Partly reported | 14 (19) |

| Unclear | 54 (73) |

| Both frequency and duration fully reported | 6 (8) |

| Frequency and duration both unclear | 33 (45) |

Concurrent changes in clinical practice, policy or infrastructure in addition to the intended intervention for preventing catheter-BSI were evident in 17 studies (23%). These included changes in the use of antimicrobial catheters, mechanical ventilation and/or UTI prevention bundles, hand hygiene programmes, staffing or critical care bed number. Where such changes occurred it would be difficult to isolate the effects of the intended intervention for prevention of catheter-BSI. Only 7 of the 74 studies (9%) explicitly stated that other concurrent interventions or changes in patient care did not occur during a study. 70,77,85,86,121,122,145

Mapping exercise: summary of results

Seventy-four studies were identified that have investigated the effectiveness of educational interventions for preventing catheter-BSI in critical care. The majority of research has involved uncontrolled before-and-after studies conducted in the USA, predominantly local-scale studies in single critical care units but also some regional-scale studies with up to 103 critical care units. Very limited information is available for the UK. Approximately half of the studies described catheter-BSI as CABSI and the other half as CRBSI, with few other descriptions reported. The most commonly targeted clinical practices were hand hygiene, preparation of the insertion site and the use of maximal sterile barrier precautions, with a wide variety of educational approaches used to address these. Interventions containing components beyond education were reported approximately twice as frequently as interventions consisting of education alone. Few studies reported the intensity of education they provided, which makes it difficult to determine resource requirements.

The evidence map highlights that secondary synthesis of educational interventions for preventing catheter-BSI is a complex area requiring appraisal of educational/behavioural strategies, complex interventions and non-randomised studies.

As mentioned earlier in Chapter 2 (see The process of descriptive mapping), the results of the mapping exercise were discussed with the project's AG to identify studies relevant to NHS practice and policy for prevention of catheter-BSI. Various different inclusion criteria for the systematic review were discussed, based on the findings of the map. These discussions led to the identification of the following inclusion criteria for the systematic review:

-

Population Adults (i.e. excluding neonatal and paediatric critical care units).

-

Design Clearly reported as prospective.

-

Outcomes Studies had to provide a definition of catheter-BSI (including any definitions given in the publication or accompanying supplementary material or hyperlinks).

Chapter 4 Results of the systematic review of clinical effectiveness

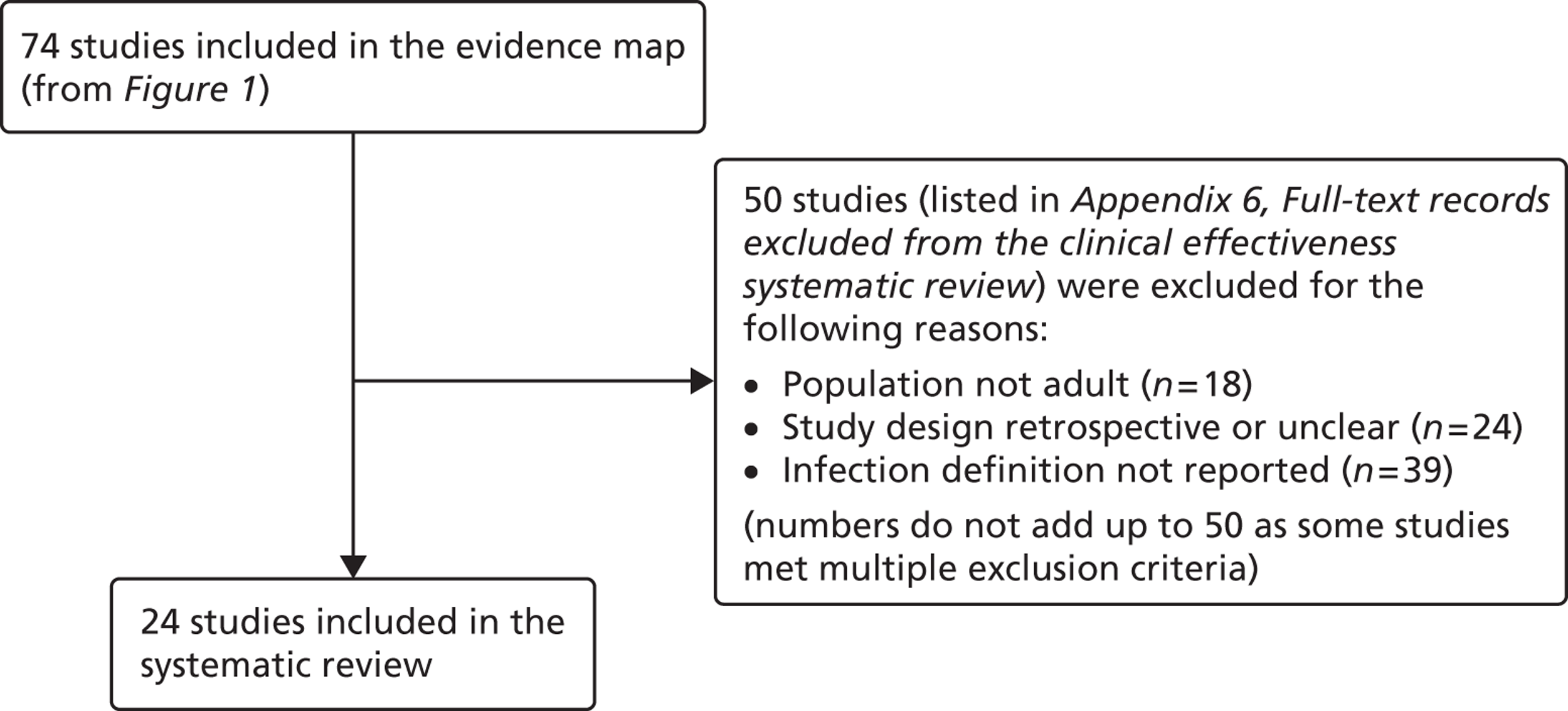

The inclusion criteria for the systematic review were chosen through discussion with the project's AG, to prioritise studies that were likely to be of most relevance to current NHS policy and practice for preventing catheter-BSI in critical care units in England. The agreed inclusion criteria specified that studies should have assessed interventions in adult critical care units; used and clearly reported a prospective study design; and provided a definition of catheter-BSI. Twenty-four34,50,51,68,83,87,93,94,97,98,103,108–110,117,122,126,129,130,135,136,138,139,144 of the 74 studies included in the evidence map met these criteria and were included in the systematic review (Figure 3). Below, we describe the key characteristics of these 24 studies, before going on to consider their methodological quality and the effectiveness of their educational interventions for the prevention of catheter-BSI.

FIGURE 3.

Process for selecting studies for inclusion in the systematic review

Characteristics of the included studies

The current systematic review focuses on studies of adult critical care units, with prospective designs, and which provided definitions of catheter-BSI, but in other respects the characteristics of the included studies are broadly representative of those included in the evidence map (Table 14). Half of the studies were conducted in the USA, and the majority used single-cohort before-and-after designs. One of the two UK studies in the evidence map was excluded from the systematic review because it was conducted in neonatal critical care units,128 and one of the two RCTs in the evidence map was excluded from the systematic review because it did not provide a definition of catheter-BSI. 145 The systematic review includes studies conducted at different spatial and temporal scales, and involving different types of education, either focusing on education alone, or including additional intervention strategies beyond education (see Table 14). Further details of the study characteristics are presented below.

| Study characteristic | No. (rounded %) of studies included in the evidence map (n = 74) | No. (rounded %) of studies included in the systematic review (n = 24) |

|---|---|---|

| Conducted in the USA | 48 (65) | 12 (50) |

| Conducted in the UK | 2 (3) | 1 (4) |

| Prospective before-and-after study | 40 (54) | 20 (83) |

| RCT | 2 (3) | 1 (4) |

| Design unclear | 13 (18) | 0 |

| Education alone | 22 (30) | 14 (58) |

| Components beyond education | 52 (70) | 10 (42) |

| Short term (≤ 12 months) | 32 (43) | 13 (54) |

| Long term (> 12 months) | 21 (28) | 11 (46) |

| Duration unclear | 21 (28) | 0 |

Study designs

The 24 studies included in the systematic review had the following designs. Most (20) were prospective before-and-after studies and these involved either single critical care units,50,51,87,93,94,97,108,110,138 multiple critical care units for which results were pooled across the units,34,83,98,126,129,130,135,139 or multiple critical care units for which results were presented separately for each unit. 103,109,122,144 One RCT136 was based on clusters, with hospitals randomised to interventions, but implementation was at the level of the critical care unit, comparing ‘Virtual Collaborative’ and ‘Toolkit’ CQI programmes in 60 critical care units. One non-randomised study68 compared a CQI intervention and control (no intervention) in 17 critical care units. The remaining two studies83,117 were single-cohort CQI programmes without a true baseline period in which data from early in the intervention period served as the baseline (Table 15).

| Study (publication year) | Country (no.: specialty of critical care units) [duration of intervention]. Intervention summary | Study design |

|---|---|---|

| Burrell;83 CEC146 (2010, 2011) | Australia (37: not reported; included paediatric units at two hospitals) [18 months]. CQI programme based on principles of the Michigan Keystone ICU intervention,34 including a ‘clinician bundle’ (hand hygiene, barrier precautions and sterile technique) and a patient bundle (skin preparation, patient draping and imaging catheter positioning during insertion) with performance feedback and infectionsurveillance feedback; aimed at ICU staff (staff grades not specified) | Single cohort without true baseline period |

| Coopersmith (2002)50 | USA (1: surgical/burn/trauma) [6 months]. Multimodal education on CVC care and unspecified topics including in-services, posters and fact sheets, self-study and performance feedback; aimed at critical care nurses and also non-critical care staff | Prospective before-and-after study |

| Coopersmith (2004)87 | USA (1: surgical) [15 months]. Multimodal education including lectures, self-study, practical demonstration, in-services, pictures of CVC maintenance, with broad topic coverage; aimed at nurses | Prospective before-and-after study |

| DuBose (2008)93 | USA (1: trauma) [3 months]. Daily quality rounds checklist with 2 out of 16 checklist items relevant to CRBSI prevention; aimed at ICU fellows, residents and medical students | Prospective before-and-after study |

| Eggimann (2000),94 (2005)95 | Switzerland (1: medical) [up to 6 years]. Education based on 30-minute slideshows, bedside in-services and practical demonstration; aimed at all critical care staff (physicians, nurses and nursing assistants) | Prospective before-and-after study |

| Galpern (2008)97 | USA (3: medical and surgical (mixed across three locations), one cardiac) [19 months]. Central line bundle including discussion sessions about CVC access and care, checklist, infection surveillance feedback, performance feedback and catheter cart; aimed at all ICU staff (physicians and nurses) | Prospective before-and-after study |

| Guerin (2010)98 | USA (2: medical, surgical) [1 year]. Post-insertion central line care bundle including 4-hour hands-on practical sessions on CVC access and care followed by competence evaluation; included performance feedback and provision of an intravenous therapy team; aimed at all critical care unit nursing staff | Prospective before-and-after study |

| Higuera (2005)103 | Mexico (2: medical surgical, neurosurgical) [9 months]. Process control intervention including 1-hour classes and provision of CDC infection control guidelines, with performance feedback and the provision of alcohol hand rub; aimed at ICU nurses, ancillary staff and physicians | Prospective before-and-after study |

| Lobo (2005)108 | Brazil (2: medical) [8 months + 12 months’ follow-up]. Multimodal education with infection surveillance feedback, including posters and fact sheets with emphasis on hand hygiene; aimed at all critical care staff | Prospective before-and-after study |

| Lobo (2010)109 | Brazil (2: medical) [9 months]. Two educational interventions with performance feedback and infection surveillance feedback: ICU A – monthly lectures and monthly questionnaire, ICU B – single lecture, unspecified duration; aimed at all critical care staff | Prospective before-and-after study |

| Longmate (2011)110 | Scotland (1: medical surgical) [up to 36 months]. CQI programme (including VAP prevention) incorporating checklist, infection surveillance feedback and performance feedback; aimed at critical care nurses and trainee doctors | Prospective before-and-after study |

| Misset (2004)117 | France (1: medical surgical) [unclear, ≈ 5–6 years]. CQI programme (including VAP and UTI prevention) based on infection surveillance feedback; aimed at all ICU staff (nurses and residents) | Single cohort without true baseline period |

| Palomar Martinez (2010)68 | Spain (17: not reported) [3 months]. Pilot study evaluating the feasibility of national implementation of a CQI intervention based on the Michigan Keystone ICU intervention34 | Non-randomised controlled trial, historical baseline |

| Perez Parra (2010)122 | Spain (3: medical, general post surgery, cardiac post surgery) [15–20 minutes + 9 months’ follow-up]. Short (15-minute) lecture on approaches for CVC care and maintenance; aimed at all critical care staff, with post-test 6 months after intervention | Prospective before-and-after study |

| Pronovost (2006),34 (2008),124 (2010)123 | USA (103: including medical, cardiac surgical, neurological surgical, cardiac medical, trauma and one paediatric) [up to 3 years]. CQI programme (Michigan Keystone ICU project) using a checklist, presentations and meetings, fact sheet, infection surveillance feedback and catheter supplies cart; aimed at ‘ICU colleagues’ (unspecified) | Prospective before-and-after study; some ICUs without true baseline period |

| Render (2006)126 | USA (8: medical) [unclear; data reported for 1 year]. Continuous QI programme based on work/learning/reporting cycles, including performance feedback and infection surveillance feedback; aimed at ICU nurses and physicians | Prospective before-and-after study |

| Rosenthal (2003)129 | Argentina (4: cardiac, medical-surgical) [8–10 months]. Unspecified education and performance feedback; aimed at health-care workers (unspecified). The education period (1–2 months) was followed by a performance feedback period (7–8 months) | Prospective before-and-after study |

| Rosenthal (2005)130 | Argentina (2: cardiac, medical surgical) [17 months]. Daily 1-hour educational classes and discussion groups for 1 week, followed by performance feedback during the remainder of the intervention period to enhance hand hygiene compliance; aimed at health-care workers (nurses, physicians and ancillary staff) | Prospective before-and-after study |

| Sherertz (2000)135 | USA (7: general medical and surgical + 1 step down unit) [3 days in each of 2 years]. Hands-on 1-day course on infection control practices and procedures including simulation and performance feedback; aimed at third year medical students and physicians completing their first postgraduate year. Course run on 3 days in June 1996 and 3 days in June 1997, with follow-up to December 1997 | Prospective before-and-after study |

| Speroff (2011)136 | USA (60: not reported, but included two paediatric per arm) [18 months]. Hospitals randomised to Virtual Collaborative and Toolkit CQI approaches (including VAP prevention), with access to interactive web seminars for both groups. Virtual collaborative: monthly educational and troubleshooting conference calls, individual coaching and electronic mailing list (designed to stimulate interaction among teams). Toolkit: based on evidence based guidelines, fact sheets, review of QI and teamwork methods, educational on-line tutorials and standardised data collection/charting tools. Included performance feedback | RCT |

| Wall (2005)138 | USA (1: medical) [2 years]. CQI programme involving real time feedback of infection rates and compliance with insertion practice, based on use of checklist, supervision of insertions, and web-based tutorial with competence assessment; aimed at ICU house staff (proceduralists) and nursing staff (as observers of procedures) | Prospective before-and-after study |

| Warren (2003)139 | USA (2: medical, surgical) [3 months + 10 months’ follow-up]. Multimodal education including lectures, self-study, bedside teaching, in-services, staff meetings, posters and fact sheets and performance feedback, with broad topic coverage; aimed at nurses and physicians | Prospective before-and-after study |

| Warren (2004)51 | USA (1: medical) [1 month + 23 months’ follow-up]. Multimodal education including lectures, self-study, bedside teaching, discussion groups, posters and fact sheets and performance feedback, with broad topic coverage; aimed at nurses and physicians | Prospective before-and-after study |

| Zingg (2009)144 | Switzerland (5: medical, trauma, cardiovascular, general surgery) [5 months]. Multimodal education including interactive training modules and video demonstrations focusing on hand hygiene and vascular catheter care; aimed at nurses and physicians | Prospective before-and-after study |

Populations

Characteristics of the critical care patient populations were generally reported superficially. Only 10 out of the 24 studies (42%)50,87,93,103,109,110,129,136,139,144 reported the age and/or sex of their patient population (Table 16). The youngest patients reported were on average in their early 40s, in the studies by DuBose and colleagues93 and Higuera and colleagues. 103 The oldest critical care population group reported was in the study by Rosenthal and colleagues,129 in which the mean age was close to 72 years. Where reported, the studies included mixed-sex populations, with the proportion of men ranging from 46% to 79%. Only one study mentioned the patients' ethnicity, stating that 94% of the population was Caucasian. 139 Comorbidities were reported inconsistently, with some studies providing considerable detail and others providing no information (see data extractions in Appendix 5). In most studies the population characteristics either did not differ between the intervention and comparator groups or were not reported. Where differences between groups were evident we considered the risk of bias (reported below).

| Study | Age (years) (mean unless stated) | Sex (% male) |

|---|---|---|

| Coopersmith (2002)50 | Not reported | Baseline 59.8; intervention 55.3 |

| Coopersmith (2004)87 | Baseline 54.5; intervention 57.4 | Baseline 49.4; intervention 56.9 |

| DuBose (2008)93 | Baseline 41.1; intervention range 40.3–41.6 | Baseline 73.0; intervention range 67.0–78.9 |

| Higuera (2005)103 | Baseline 44.32; intervention 45.91 | Baseline 45.5; intervention 48.2 |

| Lobo (2010)109 | ICU A: baseline 54; intervention 53 | ICU A: baseline 62; intervention 43 |

| ICU B: baseline 55; intervention 51 | ICU B: baseline 49; intervention 50 | |

| Longmate (2011)110 | Not reported | Baseline 56.1; intervention range 55.5–56.2 |

| Rosenthal (2003)129 | Baseline 71.98; intervention 71.91 | Baseline 48.8; intervention 53.6 |

| Speroff (2011)136 | Not reported | Baseline: virtual collaborative group 50.3; toolkit group 49.7 |

| Warren (2003)139 | Overall study period 67 | Overall study period: 52 |

| Zingg (2009)144 | Median: baseline 62; intervention 61 | Baseline 64; intervention 67 |

The critical care specialties most frequently reported were medical, surgical and cardiac. Three of the regional-scale studies33,83,136 were not conducted entirely in adult critical care units but we judged the studies to have met the population inclusion criterion for the systematic review because the proportion of non-adult critical units was small. Burrell and colleagues83 included two paediatric critical care units (95% were adult units), Pronovost and colleagues35 included one paediatric unit (99% were adult units) and Speroff and colleagues136 included two paediatric units in each study arm (93% were adult units). Palomar Martinez and colleagues68 appeared to focus on adult critical care but did not state this explicitly (the study authors were contacted but had not clarified this at the time of writing).

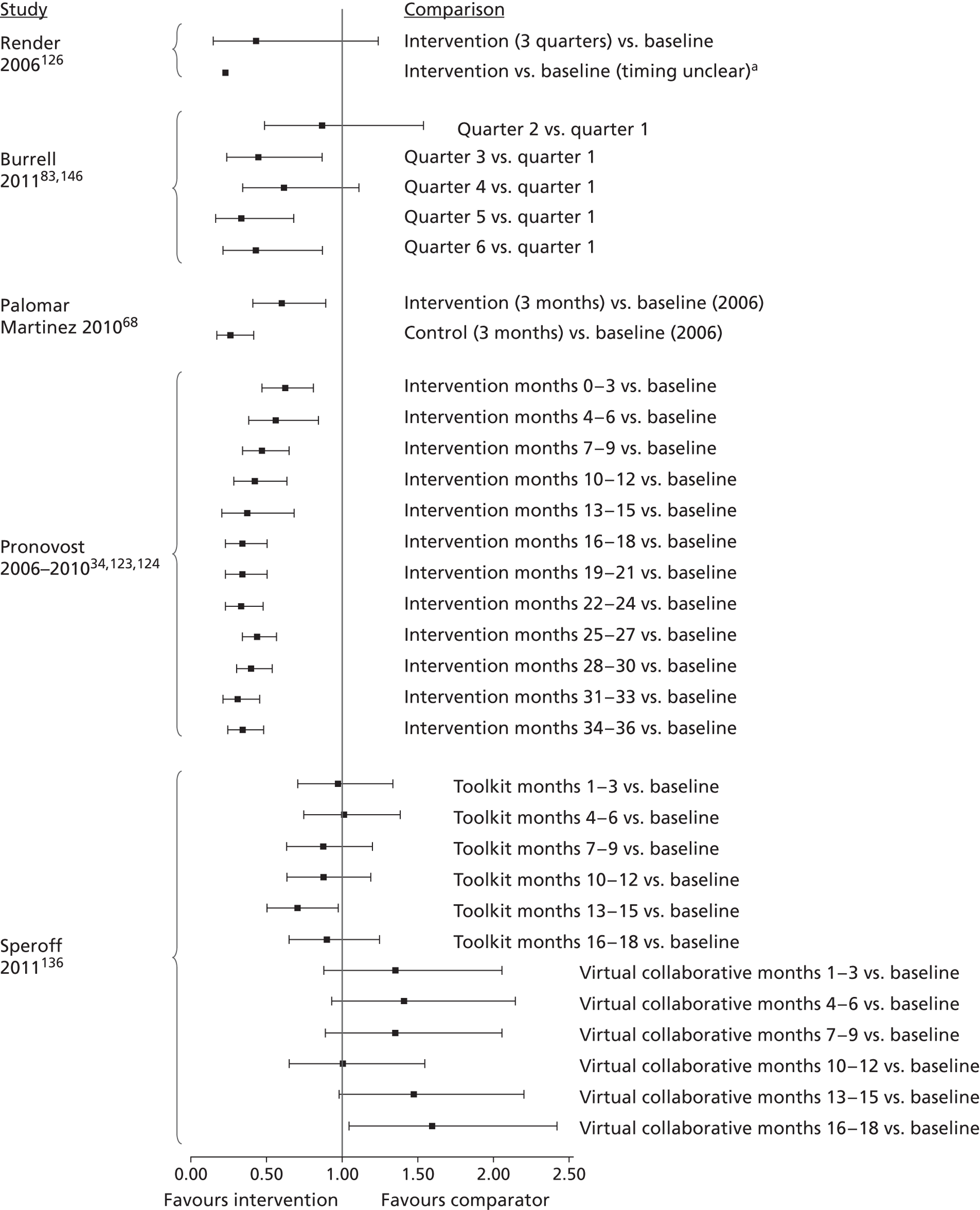

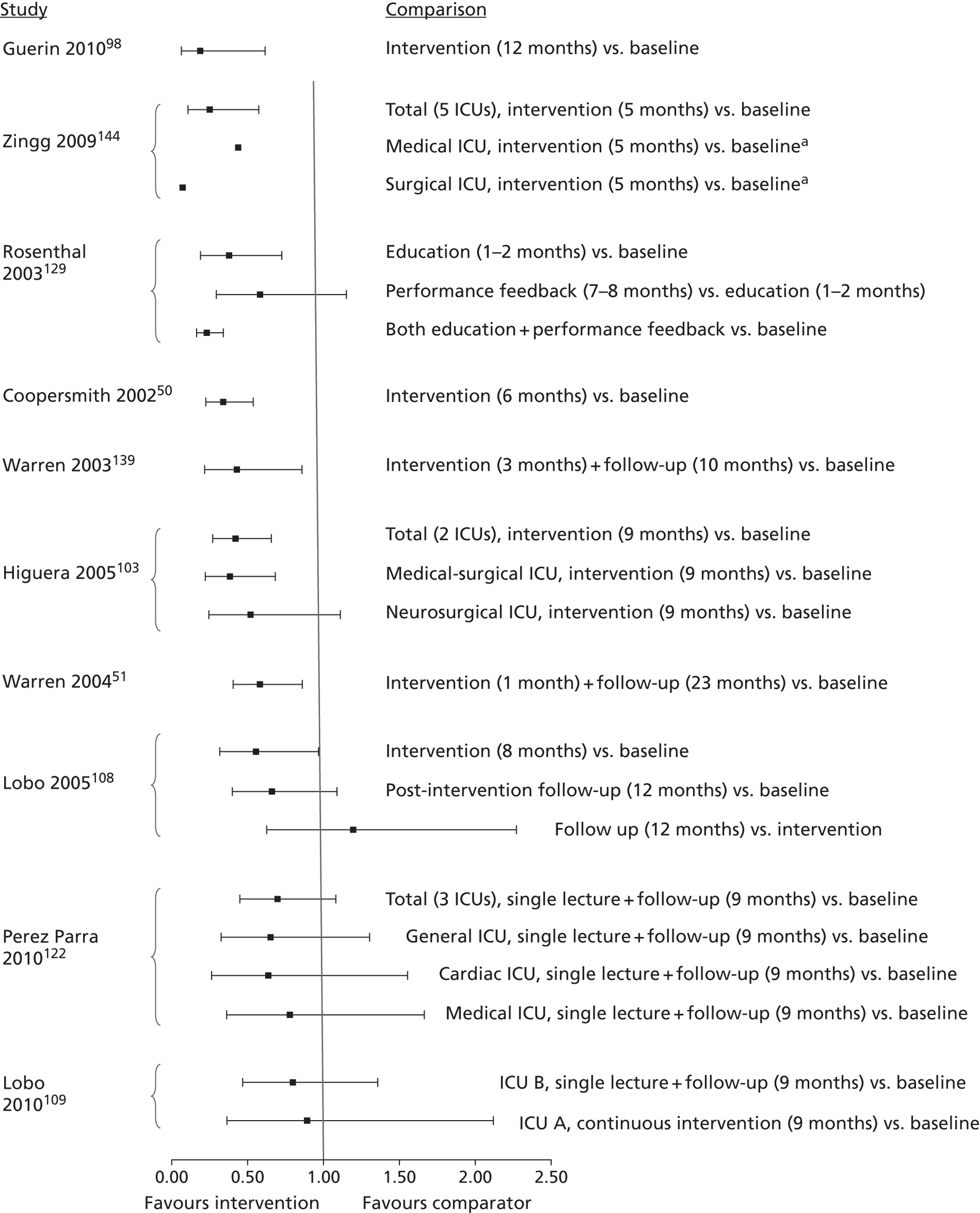

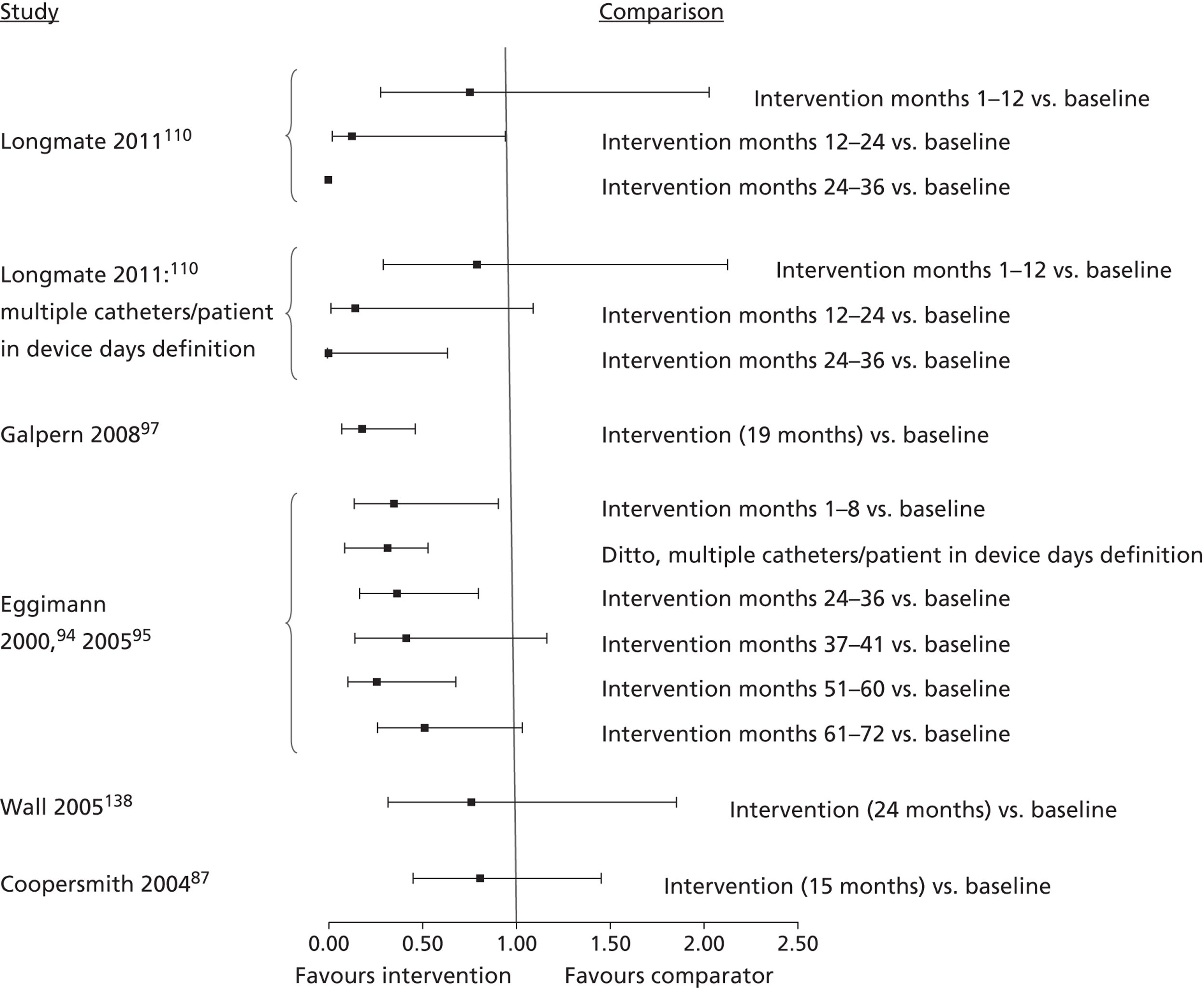

Vascular devices