Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 07/39/01. The contractual start date was in October 2007. The draft report began editorial review in July 2012 and was accepted for publication in March 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

This study had an initial start up grant of £3000 from the Newborn Appeal charity. Drs Roberts, Martin, Green, Walkinshaw and Bricker are occasionally paid monies for expert witness reports. Dr Walkinshaw and Professor Shaw are occasionally paid for invited lectures. Dr Walkinshaw has received payment from Ferring Pharmaceutical for invited lectures and meetings.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Roberts et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background and rationale

What are the risks of very early preterm prelabour rupture of membranes?

Preterm prelabour rupture of membranes (PPROM) is one of the major causes of perinatal mortality and morbidity because it causes preterm delivery in a third of cases in which it occurs. 1,2 Fetal survival is even more compromised when the amniotic membrane ruptures early in the second trimester.

There is a very high risk of delivery after very early PPROM. Moretti and Sibai3 reported a mean rupture to delivery interval of 13 days in pregnancies with PPROM between 16 and 26 weeks’ gestation, suggesting a high risk of delivery of previable fetuses and of infants at the extreme of viability. Forty-eight per cent of the pregnancies in their study delivered within 3 days of amniotic membrane rupture. The overall rate of preterm birth was 54%. Stillbirth after an infection, abruption or cord prolapse, prematurity and pulmonary hypoplasia are the major causes of perinatal mortality and morbidity in this group of babies.

The incidence of pulmonary hypoplasia in very early PPROM is reported to be as high as 62%. 4 Studies have suggested that oligohydramnios is the most important predictor of perinatal mortality in very early PPROM and that adequate residual amniotic fluid plays a critical role in determining the prevalence of pulmonary hypoplasia. 4–7 Oligohydramnios is also said to be associated with a higher risk of chorioamnionitis and neonatal infection. 5 Adequate amniotic fluid volumes, on the other hand, are said to be associated with better outcomes in pregnancies affected by very early PPROM. Locatelli et al. 8 found that pregnancies with a median residual amniotic fluid pocket persistently less than 2 cm were at highest risk of poor perinatal and long-term neurological outcome while pregnancies with a pocket greater than 2 cm had significantly better perinatal outcome (73–92% survival) and lower pulmonary hypoplasia rates. 8,9

What management options are available?

The management of cases with very early PPROM has changed over the years. Traditionally, termination of pregnancy was offered for these women because of the presumed risk of maternal sepsis and very poor fetal outcome. Expectant management (Exp) has, however, been shown to be relatively safe for mothers and results in the survival of a small proportion of infants.

Serial transabdominal amnioinfusion (AI) aiming to restore the amniotic fluid volume in pregnancies complicated by very early PPROM is an invasive procedure which has the potential to improve the perinatal outcome. 6 As discussed above, pregnancies with a median residual amniotic fluid pocket persistently less than 2 cm are at highest risk of poor perinatal and long-term neurological sequela. Those pregnancies that retain a pocket greater than 2 cm, either after AI or spontaneously, have significantly better perinatal outcome (73–92%) and lower pulmonary hypoplasia rates. 8 It has also been shown that women with persistent oligohydramnios after AI have a significantly shorter PPROM to delivery interval, lower neonatal survival (20%), higher rates of pulmonary hypoplasia (62%) and higher abnormal neurological outcomes (60%) than women in whom AI is successful (p < 0.01 for all cases). 7 AI is not, however, routinely used in the UK as it is an invasive procedure and its efficacy has not been evaluated fully in a well-conducted randomised controlled trial (RCT).

What is the evidence for management options in very early preterm prelabour rupture of membranes?

Most of the evidence on the management of very early PPROM is based on observational case–control or comparative studies. 3–11 The major risk of expectant is maternal infection leading to sepsis. High rates of postpartum morbidity10 and chorioamnionitis11 have been reported: 32% and 28%, respectively. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) guideline on PPROM12 does not give any specific guidance on the management of these pregnancies. It also does not support the practice of serial AI owing to lack of evidence.

To date, there have, to our knowledge, been no RCTs that have assessed the relative benefit of serial AI over expectant in pregnancies with PPROM between 16 and 26 weeks of pregnancy. Evidence from non-randomised cohorts is likely to be biased owing to selective reporting, and the comparisons are often based on historic cohorts and incomplete outcome data for a sample of pregnancies with PPROM not treated by AI. Long-term outcomes for surviving infants are rarely reported. Moreover, AI is an invasive intervention and, although, anecdotally, these studies suggest that it carries minimal risk to the mother and fetus,7 the evidence of harm is rarely systematically collected and reported.

Rationale for the trial

There is growing evidence to suggest that AI may have a role to play in improving the perinatal outcome in pregnancies with PPROM. A Cochrane review on AI for PPROM states: ‘These results are encouraging but are limited by the sparse data and unclear methodological robustness, therefore further evidence is required before AI for PPROM can be recommended for routine clinical practice’. 13 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) concluded, after review of existing literature, that more information from RCTs is required before AI can be considered routine therapy for very early PPROM.

Preterm birth represents a considerable burden to both patients and the NHS. The risk of neonatal death is high and surviving preterm babies are at risk of developing respiratory distress syndrome, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH), cerebral palsy, blindness and deafness, with huge impact on their families and society. The economic consequences of preterm birth are immense. A multilevel modelling of hospital service utilisation and cost profile of preterm birth using data from 117,212 children showed that the cumulative cost of hospital inpatient admissions averaged £17,819.94 for children born at less than 28 weeks’ gestation and £17,751.00 for children born at 28–31 weeks’ gestation. Evidence from observational studies suggests that most babies with very early PPROM are delivered before 31 weeks of pregnancy. If there was any chance that AI could improve outcomes for these babies, a well-designed trial would be required to determine that effect.

On the basis of this, we began a single-centre, investigator-led randomised trial in 2001. The trial was sponsored by the Liverpool Women’s NHS Foundation Trust and had North West Multiresearch Ethics Committee (MREC) approval. In response to the change in regulations for research trials in 2006, we applied to an open call for trial proposals by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme, which agreed to fund the long-term outcome phase of AI in preterm premature rupture of membranes (AMIPROM) pilot study – a pilot RCT on serial transabdominal AI versus expectant for very early PPROM – provided the trial was analysed as a pilot study and all outcomes were reported.

Specific objectives of the pilot study

-

To assess the feasibility of recruitment, the methods for conduct of the study and the retention through to long-term follow-up of participants in the study.

-

To perform an outcome assessment and to collect data to inform a larger, more definitive clinical trial if indicated.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

The AMIPROM was a multicentre, two-armed, non-blinded pilot RCT with equal randomisation. Randomisation was stratified for pregnancies with PPROM prior to, and after, 20+0 weeks’ gestation. Participants were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio to receive either:

-

expectant with weekly ultrasound assessments of the pregnancy, or

-

weekly AI if the deepest pool of amniotic fluid measured < 2 cm.

Approvals obtained

North West MREC approved the study in July 2002. Minor amendments to the protocol were made in October 2006. Substantial amendments were made in August 2007 and December 2008. The final protocol is in Appendix 1.

Clinical trial authorisations from the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency were sought but not required as saline/Hartmann’s solution used to perform AI is not a medicinal product. The trial was registered with International Standard RCT number (ISCTRN; ISRCTN no. 8192589).

Trial sites

There were four recruiting sites:

-

Liverpool Women’s NHS Foundation Trust (∼8000 deliveries per annum)

-

St. Mary’s Hospital, Manchester (∼5500 deliveries per annum)

-

Birmingham Women’s NHS Foundation Trust (∼7000 deliveries per annum)

-

Wirral University Teaching Hospital (∼3700 deliveries per annum).

Participants were recruited from Birmingham Women’s NHS Foundation Trust in 2008 following HTA programme funding approval.

Participant eligibility

The participants were women with PPROM between 16+0 and 24+0 weeks’ gestation.

Inclusion criteria

-

Singleton pregnancy.

-

Rupture of amniotic membranes between 16 weeks’ gestation and 24 weeks’ gestation.

-

Rupture of amniotic membranes confirmed by the presence of amniotic fluid in the posterior fornix on speculum examination and/or severe oligohydramnios on ultrasound examination.

Exclusion criteria

-

There was an obstetric indication for immediate delivery (i.e. fetal bradycardia, abruption, cord prolapse, advanced labour > 5 cm).

-

Multiple pregnancy.

-

Fetal abnormality.

Participants were also not recruited if they were unable to give informed consent.

Recruitment to the trial

The principal investigators (PIs) in the pilot received ‘good clinical practice’ training as well as training in all aspects of the trial, including participant recruitment, eligibility criteria, trial protocol, adverse event reporting procedures and trial documentation. Each study site received a trial pack prior to commencement of recruitment.

Participants were identified by health-care professionals at the study site or one of the hospitals that referred patients to the study site. An appointment for further assessment and confirmation of PPROM at the local fetal medicine unit (FMU) was arranged. Participants were given an information leaflet by the health-care professional who first saw them. Following discussion of the trial at the FMU and confirmation of very early PPROM, consent was obtained.

Women were randomised only if the pregnancy was still ongoing 10 days after rupture because of the high risk of miscarriage in the first week after PPROM. This protocol change was implemented in 2002 following discussion at an international meeting of fetal medicine specialists. 14

Participants were given a minimum of 24 hours, but more commonly longer, to read the information sheet and consider participation. Consent was obtained only after further discussion of the study with the fetal medicine teams in the study sites.

Randomisation

A computer-generated random sequence using a 1 : 1 ratio was used. Randomisation was stratified for pregnancies in which the amniotic membrane ruptured between 16+0 and 19+6 weeks’ gestation and those in which rupture occurred between 20+0 and 23+6 weeks’ gestation to minimise the risk of random imbalance in gestational age distribution between randomised groups. The randomisation sequence was generated in blocks of four. The sequence was generated by the Division of Statistics and Operational Research, University of Liverpool. Owing to the nature of the intervention (multiple needle insertions during pregnancy), neither clinicians nor participants were blinded to the treatment allocation. Assessors of long-term outcomes were not blinded to the intervention because, although it is a source of bias that the participants were aware of which arm they were allocated to, it would simply not have been possible to prevent them discussing this with the long-term outcome assessors post delivery.

Participants who consented to take part in the study were assigned their trial arm by ringing the telephone randomisation service administered by the Liverpool Women’s Hospital Research and Development Office. None of the investigators had access to the randomisation sequence or knew the randomised treatment to be allocated next.

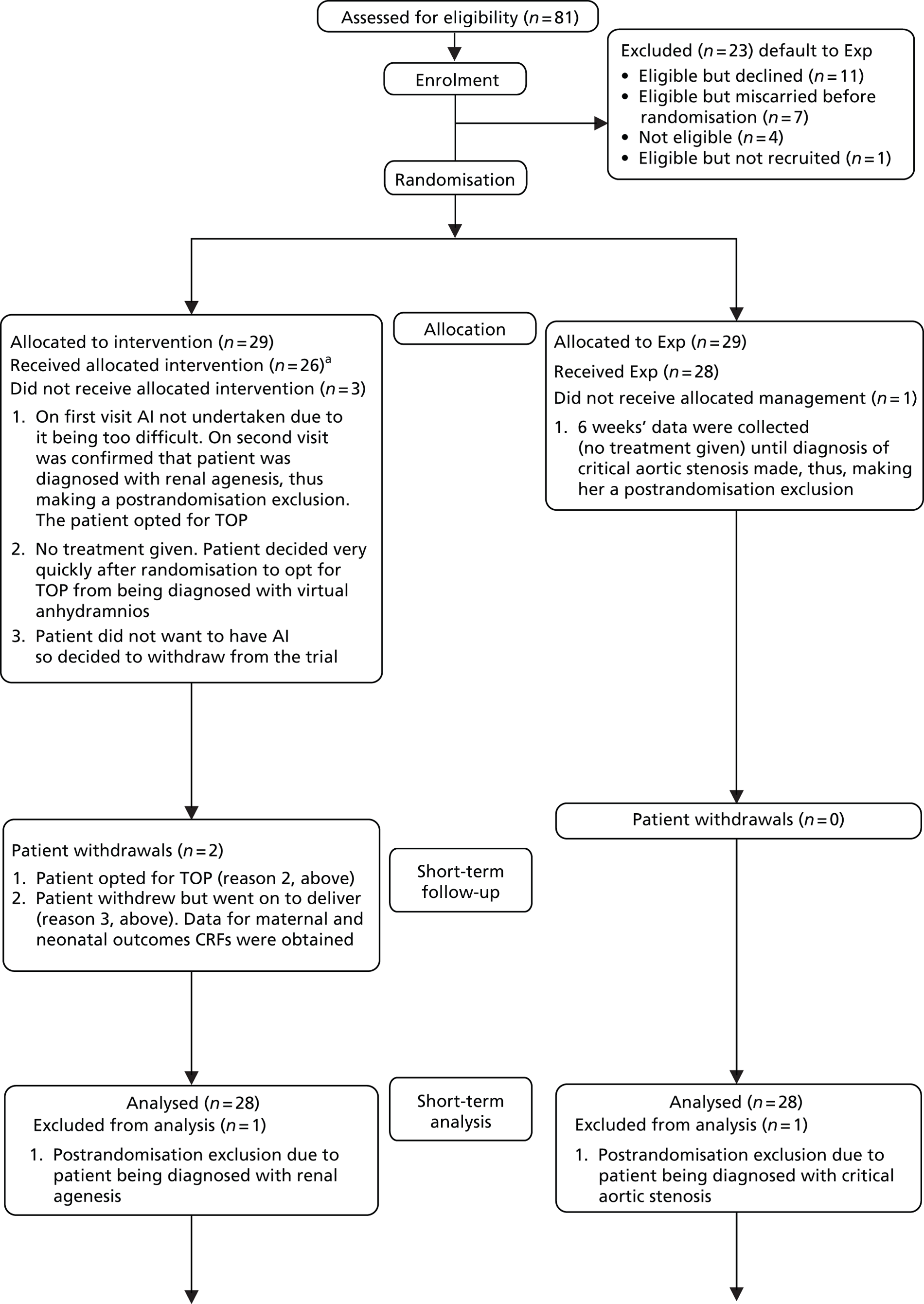

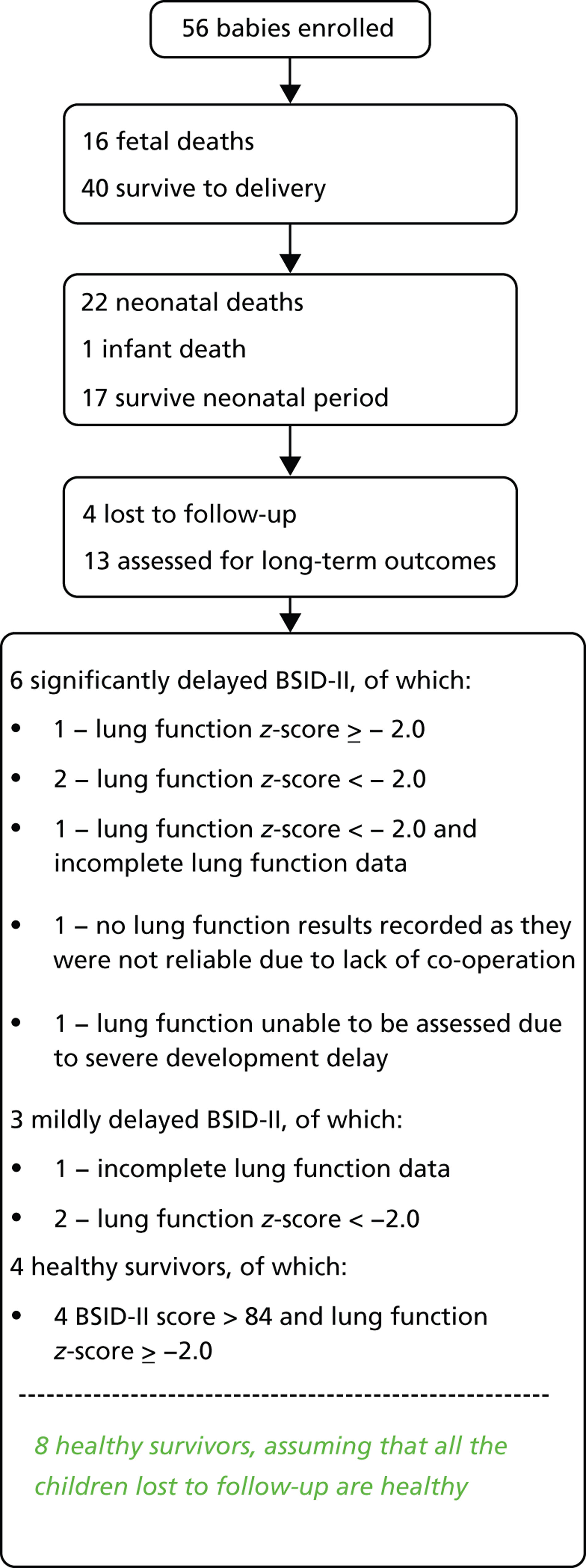

The flow of participants through the trial is presented in a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The CONSORT flow diagram. a, Four of the 26 women attended the study visits but had maintained a deepest pool of amniotic fluid > 2 cm throughout the duration of their participation so did not have any amnioinfusion fluid instilled at any time because they did not require it. They would have received amnioinfusion at a study visit had they required it. CGA, corrected gestational age; CRF, case report form; MDI, Mental Development Index; PDI, Psychomotor Development Index; TOP, termination of pregnancy.

Eligible women who declined participation

The FMUs were asked to keep a log of patients who were eligible but opted not to participate in the trial, to generate an idea of potentially eligible participants who declined the study or miscarried. This was collected on A4 sheets of plain paper and kept in the trial folder in the FMUs (see Chapter 3).

Sample size

An initial presumptive sample size of 62 participants was calculated based on an audit performed at the Liverpool Women’s NHS Foundation Trust. The audit revealed a composite adverse outcome of 75% in pregnancies with very early PPROM, in which there was a mortality rate of 65% and approximately 25% respiratory morbidity in the survivors (overall composite outcome approximately 75%). A reduction in composite outcome by 50% was chosen as the target difference because the nature of the intervention is such (i.e. invasive and repeated) that only a large difference would justify its introduction into routine practice. To reduce the composite outcome by 50%, at a 5% significance level with 80% power, 31 participants were required in each group. This included an allowance of 10% loss to follow-up. However, review by referees for the HTA programme in 2007 required that the study be treated as a pilot study. The NIHR suggested that smaller differences in substantive outcomes (rather than composite) are of interest and that a much larger ‘definitive’ study should be considered to determine effectiveness (or lack of it) with much greater precision. The assumptions used for initial sample size calculations are therefore only indicative and were treated as such by the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC). The final sample size in this study was the number of participants recruited at the end of the period defined by the timelines for the grant, i.e. the grant was funded for recruitment until April 2009.

Interventions

Both trial arms

Rupture of amniotic membranes was confirmed by presence of amniotic fluid in the posterior fornix on speculum examination and/or severe oligohydramnios on ultrasound examination. A high vaginal swab (HVS) was taken on admission and oral erythromycin commenced for 10 days.

Once rupture of the amniotic membranes had been confirmed, women were referred to the first available FMU assessment to exclude fetal abnormality, confirm rupture of amniotic membranes using ultrasonography and discuss the study. Women in both groups were assessed weekly by ultrasound and the following measurements recorded: deepest pool of amniotic fluid, thoracic circumference, lung length and abdominal circumference. Maternal haemoglobin level, white cell count (WCC), platelet count, HVS, C-reactive protein (CRP) and temperature were also recorded at each visit if they had been measured.

Antenatal corticosteroids were administered at 26+0 weeks’ gestation as a matter of routine prophylaxis. Earlier antenatal corticosteroids (between 23+0 and 25+6 weeks’ gestation) were given at the clinician’s discretion. Hospital admission for rest was recommended between 26+0 and 30+0 weeks’ gestation, but not mandatory.

Induction of labour at 37 completed weeks’ gestation was advised unless there was an obstetric indication for earlier delivery, or delivery by caesarean section (elective or emergency).

Expectant management arm

Women were seen weekly and ultrasonography used to obtain the following measurements: deepest pool of amniotic fluid, thoracic circumference, lung length and abdominal circumference. Maternal haemoglobin level, WCC, platelet count, HVS, CRP and temperature were also recorded at each visit if they had been measured. Corticosteroid administration and admission was in accordance with the process described for both arms.

Amnioinfusion arm

Women who were randomised to the intervention arm received AI received AI of saline/Hartmann’s solution only if the deepest pool of amniotic fluid at the weekly ultrasound assessment was < 2 cm. The protocol did not specify a maximum pool depth of < 2 cm for inclusion to the study as we were keen to capture all women with PPROM at these gestations in case they went on to develop a pool of < 2 cm. Between 2002 and 2006, a small number of randomised women in the AI arm never developed a deepest pool of < 2 cm and, therefore, never required AI. Recruiters were advised that, from then on, they should randomise only at the visit in which the deepest pool measured < 2 cm between 16+0 and 24+0 weeks’ gestation. This was not considered a formal protocol amendment but was recommended.

Amnioinfusion were performed only by fetal medicine specialists who had expertise in invasive procedures. The protocol for the method of AI is given in Appendix 2. All AI were performed under ultrasound guidance. All study sites were given a copy of the protocol for AI to ensure consistency of the procedure.

The full calculated volume of Hartmann’s solution or normal saline for the pregnancy (10 ml per week of gestation) was always infused. This ensured an adequate amount of fluid replacement to account for immediate leakage through the rupture. AI was ceased if the specialist had concerns about continuing the procedure. Possible reasons for this would have been uncertainty about being in the right space or if uterine contractions began. Antibiotics were not given specifically for the AI procedure. All participants were treated with oral erythromycin for 10 days after diagnosis of PPROM. Tocolysis was not required for AI and the procedures were performed as outpatient procedures. Participants were admitted following the procedure if it was felt necessary to do so by the specialist who performed the procedure. The post AI deepest pool of amniotic fluid was measured after the full calculated volume for gestation was amnioinfused. Participants were seen weekly and the AI repeated if the deepest pool of amniotic fluid remained at < 2 cm.

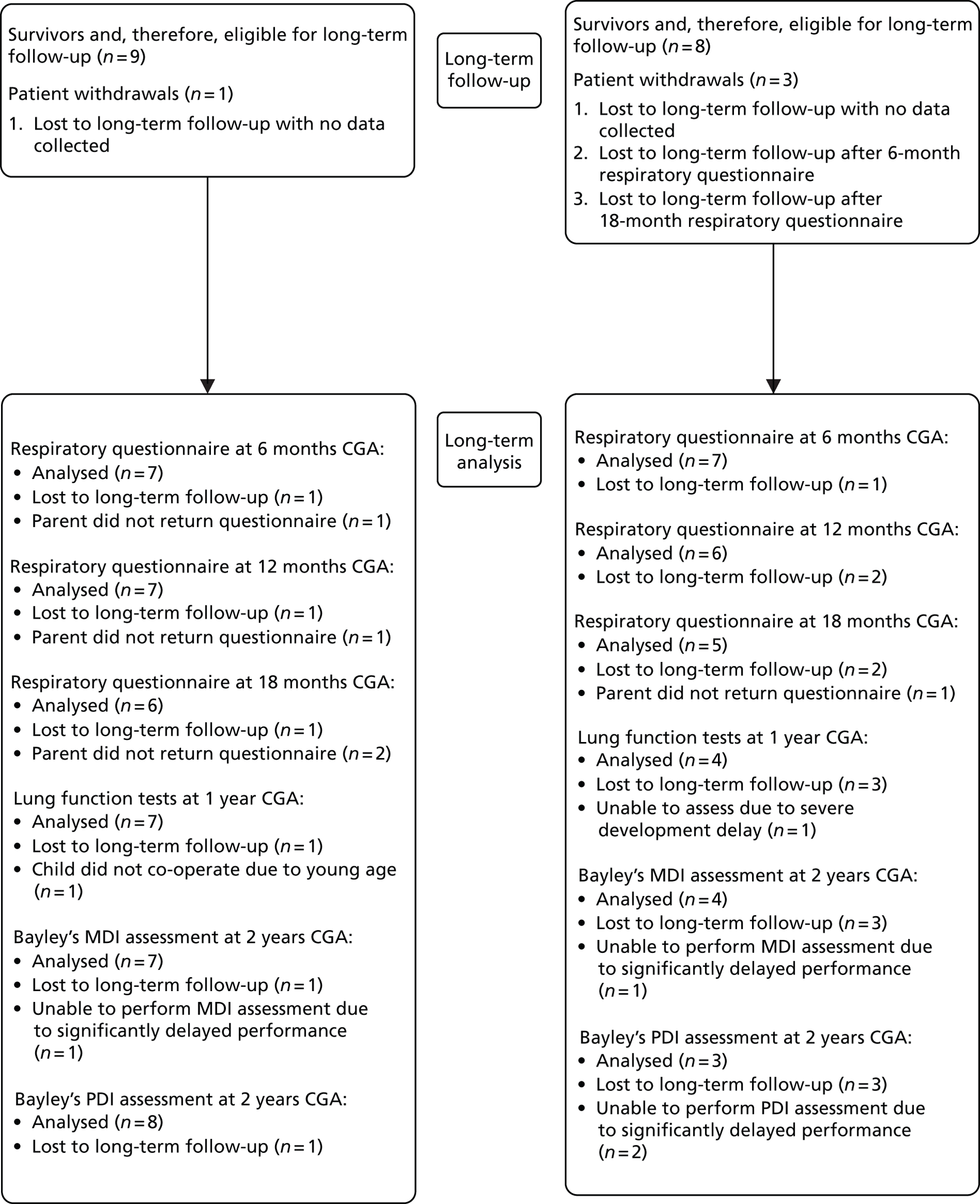

Participant follow-up

Figure 2 shows a summary of participant follow-up for the AMIPROM trial. Most participants were followed up in the FMUs, with a small proportion (four participants in Exp arm) followed up in their local units. This was mainly at the choice of the participant. Participants were sent paper respiratory questionnaires along with prepaid return envelopes by the trial co-ordinating centre at Liverpool Women’s NHS Foundation Trust. No incentives were given to increase the response rates to respiratory questionnaires. The Bayley’s assessments were performed in the homes of surviving children to increase response rate. The infant lung function tests were performed either at Leicester University Hospital or at Liverpool Women’s NHS Foundation Trust and participants were reimbursed for travel expenses to and from the Hospitals for the childhood follow-up part of the trial alone. Travel expenses were not reimbursed for weekly assessments at hospital or FMU as these were considered part of normal clinical care.

FIGURE 2.

Participant follow-up. TOP, termination of pregnancy.

Measurement of outcomes: short-term outcomes

Data were collected on five data sheets (see Appendix 1).

First visit post randomisation

Data sheet 1 was filled out by the specialist attending the participant on the day of randomisation. This was called the ‘first visit’ even though the participant may have attended the FMU previously for confirmation of the diagnosis and discussion about the study. Maternal parity, initial HVS, WCC, CRP and body temperature were recorded on data sheet 1, as well as whether the mother had a tender, irritable uterus or foul-smelling discharge. Other information recorded was the gestation at PPROM in weeks, the gestation at first AI in weeks, the deepest amniotic fluid pocket (before and after AI in the intervention arm), the thoracic circumference, lung length and abdominal circumference of the baby as measured using ultrasonography.

Subsequent visits

Measurements taken using ultrasonography of the baby’s thoracic circumference, the lung length, the abdominal circumference and the deepest amniotic fluid pocket (before and after AI in the AI arm) for subsequent visits were recorded on data sheet 2 by FMU staff.

Maternal outcomes

Maternal outcomes, including the result of maternal investigations, were recorded on data sheet 3. WCC and CRP measurements were performed weekly and HVS was performed at the discretion of the clinician attending the participant. HVS results were recorded whenever they were available and data sheet 3 was completed when the participant had delivered. Any missing data were reconciled by the chief investigator and trial administrator by contact with the PIs and examination of the hospital case notes.

The maternal and pregnancy outcomes recorded were antenatal corticosteroid prophylaxis, if the participant was given antibiotics, placental abruption, antepartum haemorrhage, chorioamnionitis, gestational age at delivery, mode of delivery, onset of labour, serious maternal sepsis requiring intensive therapy unit (ITU)/high-dependency unit (HDU) admission and maternal death.

Neonatal outcomes

Neonatal outcomes were recorded on data sheet 4. The neonatal outcomes recorded were gestational age at birth, birthweight, Apgar score at 5 minutes, cord blood gases, antepartum death, neonatal death, culture-positive sepsis, days on intermittent positive-pressure ventilation (IPPV), continuous positive airways pressure (CPAP) and high-frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV) (each analysed separately), pneumothorax requiring chest drain, discharge on home oxygen, O2 requirement at day 28, O2 requirement at week 36, necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) (including those who had surgery or were treated conservatively), treated seizures, treated retinopathy, IVH grade (0–3), periventricular leukomalacia (PVL), any shunting procedures and any fixed orthopaedic deformities.

The data sheet was completed when the baby was discharged home or after death. Any missing data were reconciled by the chief investigator and trial administrator by contact with the PIs and examination of the hospital case notes.

The data pack was returned to the trial co-ordination centre after the baby was discharged home or after death.

Measurement of outcomes: long-term outcomes

Respiratory questionnaires

Participants with surviving babies were sent a prepaid postal validated respiratory questionnaire at 6, 12 and 18 months after the birth of their baby. 15 These were sent out by the trial coordination centre at Liverpool Women’s NHS Foundation Trust and returned directly to the co-ordinating centre.

The respiratory questionnaire was designed to examine the frequency of mild respiratory symptoms such as wheezing in infants and preschool children. An abnormal score is described as one which falls within the confidence interval (CI) of children with asthma as defined by Powell et al. 15 We defined children with long-term mild respiratory symptoms as those at the 18-month questionnaire stage whose scores in any domain fell outside the 95% CI for asthma (Table 1).

| Score | 95% CI for children with a diagnosis of asthma |

|---|---|

| Daytime symptoms score | 21.7 to 43.5 |

| Night-time symptoms score | 6.4 to 10.8 |

| Impact on family score | 7.0 to 11.0 |

| Impact on child score | 5.5 to 9.2 |

Lung function tests

The protocol specified that surviving children had infant lung function tests performed when they were approaching 12 months’ gestational age. Lung function tests can be performed under sedation at this age. From the age of about 3 or 4 years, children can begin to do perform the blowing tests that older children can. Between these ages it is more difficult to perform these tests, for compliance reasons and, where possible, surviving children were invited to have the infant tests performed at Leicester Royal Infirmary. Where this was not possible, the simple blowing tests were performed at Liverpool Women’s NHS Foundation Trust.

The tests of lung function were chosen to detect small lung size. The most direct way of doing this is by whole-body plethysmography, which enables us to determine functional residual capacity (FRC). This test requires that the subject is enclosed within a Perspex chamber (that for older children or adults resembles a telephone kiosk) and breathes through an apparatus that measures the amount of air being breathed in or out. As the chest moves in and out, it causes small (but measurable) pressure changes in the Perspex chamber. Then, for a very short period of time, a shutter is transiently closed in the apparatus, so that the subject makes breathing efforts against this obstruction. This does not disturb the subject and, in the case of infant testing, does not last long enough to cause the sleeping infant to rouse. By measuring the pressure generated at the mouth when the shutter is closed, and relating this to the pressure changes in the chamber, it is possible to work out the size of the lungs. An alternative and indirect index of lung size is forced vital capacity (FVC), which is simply a measure of how much air can be breathed out between full inspiration to complete exhalation. The other measurements [forced expired volume in 1 second (FEV1) and maximum flow at FRC (VmaxFRC)] relate to airway function and give information relating to the dimensions and patency of the airways. Each measure of lung function was repeated at least three times to ensure reproducibility. For each test, predicted scores and z-values were calculated. A z-value < −2.00 is considered abnormal in any of the lung functions tested.

Neurological assessment

Developmental delay at 2 years corrected gestational age was assessed using the Bayley’s Scales of Infant Development-II (BSID-II). BSID-II is a standard series of measurements used primarily to assess the motor and cognitive development of infants and toddlers aged 0–3 years. This measure consists of a series of developmental play tasks. It takes between 45 and 60 minutes to administer, and raw scores of successfully completed items are converted to scale scores and to composite scores between 50 and 150 (mean score 100). These scores are used to determine the child’s performance compared with norms taken from typically developing children of their age (in months), e.g. going up the stairs unaided at 24 months.

The two scores reported in this trial are the Mental Development Index (MDI) and the Psychomotor Developmental Index (PDI). Their classifications are as follows:

-

A score of 50–69 suggests significantly delayed performance.

-

A score of 70–84 suggests mildly delayed performance.

-

A score of 85–114 is within normal limits.

-

A score of 115–150 suggests accelerated performance.

We defined major neurodevelopmental delay in any child as an MDI < 70 or a PDI < 70 or both MDI/PDI < 70. Mildly delayed performance was defined as a score of between 70 and 84 in any domain. 16

Neurodevelopmental assessments of the surviving children were performed in their own homes by a trained health professional. The protocol specified that the tests were to be performed at 24 months of age, corrected for prematurity. No monetary or other incentives were used to increase participation in the long-term outcome phase of the pilot. Participants were reimbursed their expenses for travelling to either Leicester or Liverpool for the infant lung function tests.

Trial completion

Recruitment and the final sample size was time limited as the study was funded until April 2009. The last woman was recruited to the study in April 2009. The last baby was assessed for long-term outcomes in July 2011.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by the Clinical Trials Research Centre, University of Liverpool. This pilot trial consists of both short-term outcomes of neonatal morbidity/mortality for the baby and maternal morbidities for the mother at birth and also various long-term developmental outcomes for the children assessed at 2 and 3 years corrected gestational age (CGA). The approach was first to write the short-term outcomes statistical analysis plan (SAP) (see Appendix 3) prior to completion of recruitment, then to perform the analyses once all the short-term outcome data had been received and then to present the results to the DMC. All outcomes were analysed using the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle. In the introduction of short-term outcomes SAP it stated that the DMC would give their recommendations to the Trial Steering Committee and they would decide whether to allow publication of the short-term outcome results. The short-term outcome results were presented to the DMC on 15 November 2011. The DMC agreed to unblinding of the short-term data to the trial team at this meeting so they could begin to write up the publication, but the publication should include the short-term and long-term outcome results. The DMC also requested that a per-protocol analysis be carried out on the short-term outcome data defined as mothers that had at least one AI or attended at least one hospital visit (Exp arm). The long-term outcomes SAP (see Appendix 4) was then written incorporating details of the per-protocol analysis that the DMC had requested. The statistical team made the decision not to do a per-protocol analysis for the long-term outcomes because so few participants were followed up as a result of all of the antenatal and neonatal deaths. Again, all outcomes were analysed using the ITT principle.

The statistical methods used are shown in Appendices 3 and 4. All of the statistical analyses for the trial results were carried out using SAS v.9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Missing data

Sensitivity analyses were performed to explore the effects of missing data on the long-term outcomes. These mostly considered the neonatal deaths and imputed on a worst-case scenario basis. Where other imputations were considered, these are described alongside the analyses.

Adverse events

All neonatal deaths were reported as adverse events on the Liverpool Women’s NHS Foundation Trust serious adverse event (SAE) reporting form (see Appendix 5). Suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions and all SAEs were reported to the PI or the Research and Development Department of the Liverpool Women’s NHS Foundation Trust.

Economic analysis

As this is a pilot study, no economic or cost-effectiveness analysis has been performed. It is envisaged that this will be performed if a larger, definitive trial is funded.

Chapter 3 Results (short-term outcomes)

Trial recruitment

Recruitment began in September 2002 and ceased in April 2009. Centres were chosen for their ability to perform AI if required. There were initially five study sites proposed – Liverpool Women’s NHS Foundation Trust (chief investigator site and trial sponsor), St. Mary’s Hospital, Wirral University Teaching Hospital, Warrington Hospital and Queen Mother’s Glasgow. Owing to local research governance and funding issues, Queen Mother’s Glasgow was unable to formalise local ethics and recruit; therefore, it ceased to be a study site in 2006. Warrington Hospital preferred to refer to the tertiary referral unit rather than run the study locally and ceased to be a study site by 2006. Participants were recruited from Birmingham Women’s NHS Foundation Trust in 2008 following HTA programme funding approval.

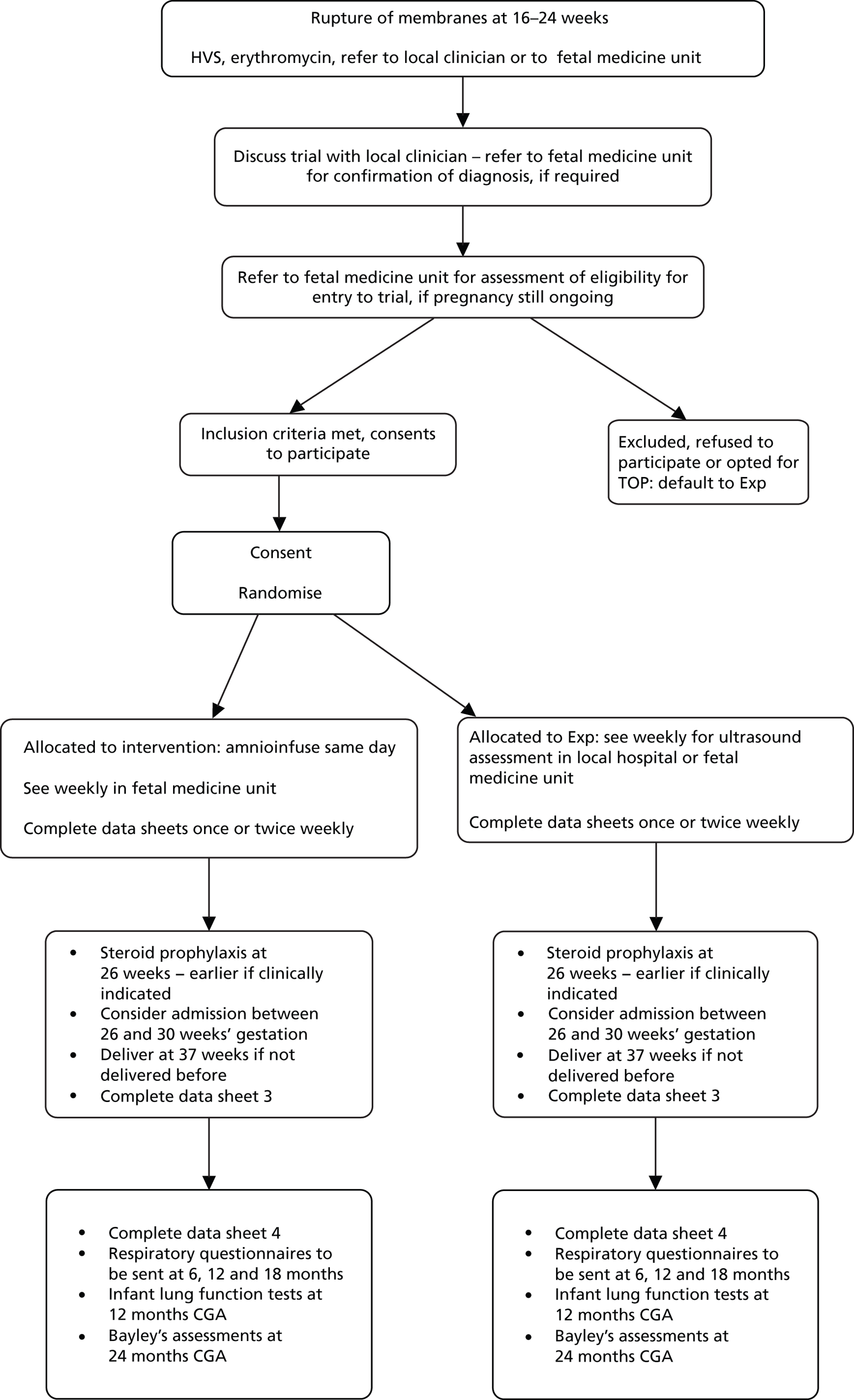

Two sites were recruiting participants and submitting data by 2005 (Liverpool Women’s NHS Foundation Trust and St. Mary’s Hospital) and the other two were recruiting participants and submitting data by 2008 (Wirral University Teaching Hospital and Birmingham Women’s NHS Foundation Trust). The number of patients recruited per annum is shown in Table 2. The recruitment rate by each site is shown in Figure 3.

| Number randomised per annum by treatment arm | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp arm | 0 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 2 |

| AI arm | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 0 |

| Overall | 1 | 3 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 14 | 12 | 2 |

FIGURE 3.

The number of patients randomised per centre, per annum.

In total, 81 women were screened as potential participants and 77 were eligible. The reasons why eligible participants did not enter the study are shown in Table 3 and Figure 1. Eleven women declined to participate in the study, seven miscarried in the 10 days after PPROM while considering the study and one decided too late (after 24 weeks) that she wanted to participate. This woman was not recruited, as she no longer met the criteria for inclusion to the study, i.e. between 16+0 and 24+0 weeks’ gestation.

| Reason for non-participation | Number of participants | Outcome of pregnancy |

|---|---|---|

| Eligible but declined | 11 | Termination of pregnancy (4) Miscarriage (2) Live birth with chronic lung disease (1) Neonatal death (3) No outcome data (1) |

| Eligible but miscarried before randomisation | 7 | Miscarriage (7) |

| Eligible but had exceeded 24 weeks’ gestation by the time decided to participate; too late to be randomised | 1 | Live birth (1) |

Baseline participant characteristics

Twenty-nine women were randomised to each group but one from each group was excluded post randomisation due to termination for fetal abnormality (renal agenesis in the AI arm and critical aortic stenosis in the Exp arm), leaving 28 in each arm for ITT analysis (see Figure 1).

The baseline characteristics are summarised by treatment arm in Table 4.

| Baseline characteristics | AI (participants randomised n = 28) | Exp (participants randomised n = 28) | Total (participants randomised n = 56) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parity, n | (n = 26)a | (n = 28) | (n = 54) |

| 0 | 16 | 11 | 27 |

| 1 | 4 | 11 | 15 |

| 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| HVS, n (%) | (n = 25)a [25 separate types]b | (n = 24)a [27 separate types]b | (n = 49)a [52 separate types]b |

| Bacterial vaginosis | 1 (4.0) | 2 (7.4) | 3 (5.8) |

| Coliform | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (1.9) |

| Enterococcus | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (1.9) |

| B Streptococcus | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (1.9) |

| Mixed anaerobes | 1 (4.0) | 1 (3.7) | 2 (3.8) |

| None | 1 (4.0) | 1 (3.7) | 2 (3.8) |

| Normal flora | 20 (80.0) | 16 (59.3) | 36 (69.1) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) |

| Streptococcus | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.4) | 2 (3.8) |

| Yeast | 1 (4.0) | 2 (7.4) | 3 (5.8) |

| WCC (109/l) | (n = 26)a | (n = 26)a | (n = 52) |

| Mean (SD) | 10.74 (± 2.71) | 11.51 (± 2.28) | 11.13 (± 2.51) |

| Range | 5.8–18.6 | 7.1–17.6 | 5.8–18.6 |

| CRP (mg/l) | (n = 25)a | (n = 25)a | (n = 50)a |

| Median (IQR) | 5 (5–6) | 7 (5–16) | 6 (5–10) |

| Range | 2–22 | 3–44 | 2–44 |

| Temperature (°C) | (n = 23)a | (n = 19)a | (n = 42)a |

| Mean (SD) | 36.80 (± 0.34) | 36.93 (± 0.22) | 36.86 (± 0.29) |

| Range | 36.0–37.2 | 36.4–37.3 | 36.0–37.3 |

| Tender, irritable uterus, n (%) | (n = 26)a | (n = 28)a | (n = 54)a |

| Yes | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) |

| Foul-smelling discharge, n (%) | (n = 26)a | (n = 28)a | (n = 54)a |

| Yes | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Weeks’ gestation at PPROM | (n = 24)c | (n = 28) | (n = 52) |

| Mean (SD) | 19.21 (± 2.00) | 19.22 (± 2.21) | 19.22 (± 2.10) |

| Range | 16.0–22.6 | 15.1–23.3 | 15.1–23.3 |

| Weeks’ gestation at randomisation | (n = 28) | (n = 28) | (n = 56) |

| Mean (SD) | 21.36 (± 1.75) | 21.14 (± 2.00) | 21.25 (± 1.87) |

| Range | 17.7–25.4 | 7.4–24.7 | 17.4–25.4 |

| Maternal age at randomisation (years) | (n = 28) | (n = 28) | (n = 56) |

| Mean (SD) | 27.46 (± 5.88) | 28.30 (± 6.45) | 27.88 (± 6.13) |

| Range | 17.0–39.3 | 17.7–42.8 | 17.0–42.8 |

| Vaginal bleeding, n (%) | (n = 28) | (n = 28) | (n = 56) |

| Yes | 7 (25.0) | 11 (39.3) | 18 (32.1) |

| Thoracic circumference (mm) | (n = 23) | (n = 22) | (n = 45) |

| Mean (SD) | 146.84 (± 26.30) | 135.47 (± 25.88) | 141.28 (± 26.43) |

| Range | 105.0–238.2 | 89.5–202.2 | 89.5–238.2 |

| Abdominal circumference (mm) | (n = 24) | (n = 26) | (n = 50) |

| Mean (SD) | 166.43 (± 28.21) | 162.44 (± 24.11) | 164.35 (± 25.96) |

| Range | 105.0–218.0 | 117.8–198.0 | 105.0–218.0 |

| Lung length (mm) | (n = 21) | (n = 23) | (n = 44) |

| Mean (SD) | 23.34 (± 6.31) | 23.86 (± 5.30) | 23.61 (± 5.74) |

| Range | 15.0–45.0 | 12.0–34.6 | 12.0–45.0 |

Both arms are well balanced for possible confounders. There was no apparent difference in the mean WCC, temperature, weeks gestation at rupture of the amniotic membrane, weeks gestation at randomisation or maternal age at randomisation between arms. There was no apparent difference in the median CRP between the arms.

Antenatal course

The antenatal management of all participants in the trial followed the same pathway from diagnosis until randomisation to the trial. All women had a HVS taken and were given 250 mg oral erythromycin four times a day for 10 days following confirmation of rupture of amniotic membrane. As a result, the most commonly used antibiotic in the antenatal period was erythromycin.

Participants attended for their first fetal medicine assessment at the earliest convenient time, but were randomised to the study at least 10 days after the amniotic membrane ruptured. This criterion was adopted following discussions at an international fetal medicine meeting. 14 The international consensus at the time was that the risk of miscarriage in the first week after rupture was too high. In our cohort, seven of the 81 women (8.6%) miscarried before they could be randomised to the study (see Table 3).

Of the 29 women allocated to AI, 22 received the intervention, one had a termination of pregnancy, one declined AI after randomisation and four maintained a deepest pool level of approximately 2 cm throughout. No woman in the Exp arm received AI. One baby in each arm was found to have a fetal abnormality with an impact on neonatal survival (Figure 1).

Women were seen weekly for an ultrasonography assessment irrespective of the arm they were randomised to. The median number of antenatal visits prior to delivery was 5 (range 0–15) in the AI arm and 4.5 (range 1–14) in the Exp arm (Table 5). The median number of AI performed was 3 (range 0–12; Table 6).

| Number of visits | AI | Exp |

|---|---|---|

| n Median [Q1, Q3] Range |

(n = 28) 5 [2.5, 8.5] 0–15 |

(n = 28) 4.5 [2.0, 8.5] 1–14 |

| 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 1 | 2 | 5 |

| 2 | 3 | 5 |

| 3 | 2 | 3 |

| 4 | 3 | 1 |

| 5 | 4 | 2 |

| 6 | 1 | 4 |

| 7 | 3 | 0 |

| 8 | 1 | 1 |

| 9 | 3 | 2 |

| 10 | 0 | 2 |

| 11 | 2 | 2 |

| 12 | 1 | 0 |

| 13 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | 0 | 1 |

| 15 | 1 | 0 |

| Number of AI | AI | Exp |

|---|---|---|

| n Median [Q1, Q3] Range |

(n = 28) 3 [1, 4] 0 to 12 |

(n = 28) 0 |

| 0 | 6a | 0 |

| 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 2 | 5 | 0 |

| 3 | 4 | 0 |

| 4 | 5 | 0 |

| 5 | 3 | 0 |

| 6 | 1 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 1 | 0 |

| 11 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 1 | 0 |

Table 7 shows that the volume of Hartmann’s solution infused (10 ml per week of gestation) was sufficient to produce an average amniotic fluid pocket difference of 2.66 cm, which is considered adequate to improve the risk of pulmonary hypoplasia. Three women had amniotic fluid pocket sizes of < 2 cm after AI because of amniotic fluid leakage as the procedure was taking place. For two of these women, AI improved the deepest pool from 0 to 1.9 cm and 1.0 cm, respectively. In one woman, there was no change in the deepest pool of amniotic fluid after AI.

| Women with at least one AI (n = 22) | n (%) |

| Fluid instilled on at least one occasion (n = 26a) | |

| Yes | 22 (84.62%) |

| Amniotic fluid pocket difference [after minus before (cm)] for those patients that had fluid instilled at visit (n = 78b) | |

| No. of visits | |

| Mean (SD) | 2.66 (1.33) |

| Range | 0.0–7.0 |

| Amniotic fluid pocket size at visit for patients with no fluid instilled (n = 65) | |

| No. of visits | |

| Mean (SD) | 2.73 (0.73) |

| Range | 1.2c–4.6 |

Not all participants in the AI arm required AI at every visit as it was performed only if the deepest pool of amniotic fluid was < 2 cm. Sixteen women had no fluid instilled on at least one visit and, for those visits in which no AI was performed, the mean pool depth was 2.73 cm.

The risks to the mother in the antenatal period are mainly of abruption, bleeding or infection. There was no difference in the arms for any of these outcomes (Tables 8 and 9).

| Maternal morbidity outcome in the antenatal period | AI (n = 28a) | Exp (n = 28) | RR (95% CI) (n = 56a) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abruption of the placenta | (n = 27) | (n = 28) | – |

| n (%) | 4 (14.8) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | 9.32 (0.53 to 165.26) |

| Antepartum haemorrhage | (n = 27) | (n = 28) | – |

| n (%) | 8 (29.6) | 7 (25.0) | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | 1.19 (0.50 to 2.82) |

| Chorioamnionitis | (n = 27) | (n = 28) | – |

| n (%) | 4 (14.8) | 7 (25.0) | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | 0.59 (0.20 to 1.80) |

| Required antibiotics antenatally | (n = 27) | (n = 28) | – |

| n (%) | 22 (81.5) | 22 (78.6) | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | 1.04 (0.80 to 1.35) |

| Number of doses of steroids, n (%) | (n = 27) | (n = 28) | – |

| 0 | 8 (29.6) | 13 (46.4) | – |

| 1 | 3 (11.1) | 3 (10.7) | – |

| 2 | 15 (55.6) | 11 (39.3) | – |

| 3 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| 4 | 1b (3.7) | 1b (3.6) | – |

| Chi-squared test for trend p-value | – | – | 0.25c |

| Maternal morbidity outcome | AI (n = 22a) | Exp (n = 25b) | RR (95% CI) (n = 47) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abruption of the placenta | (n = 22) | (n = 25) | – |

| n (%) | 3 (13.6) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | 7.91 (0.43 to 145.20) |

| Antepartum haemorrhage | (n = 22) | (n = 25) | – |

| n (%) | 7 (31.8) | 5 (20.0) | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | 1.59 (0.59 to 4.30) |

| Chorioamnionitis | (n = 22) | (n = 25) | – |

| n (%) | 4 (18.2) | 6 (24.0) | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | 0.76 (0.25 to 2.34) |

| Required antibiotics antenatally | (n = 22) | (n = 25) | – |

| n (%) | 18 (81.8) | 20 (80.0) | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | 1.02 (0.77 to 1.35) |

| Number of doses of steroids, n (%) | (n = 22) | (n = 25) | |

| 0 | 8 (36.4) | 11 (44.0) | – |

| 1 | 3 (13.6) | 2 (8.0) | – |

| 2 | 11 (50.0) | 11 (44.0) | – |

| 3 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| 4 | 0 (0.0) | 1c (4.0) | – |

| Chi-squared test for trend p-value | – | – | 0.96d |

The protocol required a single course (two doses) of antenatal corticosteroids to be given at 26+0 weeks’ gestation, or earlier if clinicians felt it was indicated. It is not routine practice to give an additional rescue course of steroids. One woman in the Exp arm was given a first course of corticosteroids before 26+0 weeks and a rescue course later in pregnancy (see Table 9). Those who did not receive any antenatal corticosteroids were women who delivered prior to achieving 26+0 weeks’ gestation.

Labour and delivery

Women in the AI arm went into spontaneous preterm labour at a median gestation of 28.45 weeks ± 4.44 standard deviation (SD) and those in the Exp arm at 29.82 weeks 4.33 SD (Table 10). The default mode of delivery was vaginal unless there was a clinical indication to deliver by caesarean section. The pregnancy outcomes are shown in Tables 11 and 12. Of 39 pregnancies aiming for vaginal delivery at the onset of labour, 34 delivered vaginally. There were more caesarean sections in the AI arm than in the Exp arm, but this difference was not statistically significant.

| Neonatal morbidity outcome | AI | Exp | Mean difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fetal deaths omitted (n = 23) | Fetal deaths omitted (n = 17) | Fetal deaths omitted (n = 40) | |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | (n = 23) | (n = 17) | – |

| Mean (SD) | 28.45 (4.44) | 29.82 (4.33) | – |

| Range | 19.4–37.6 | 24.9–38.1 | – |

| Mean difference (SD) | – | – | −1.36 (4.40) |

| 95% CI | – | – | −4.21 to 1.48 |

| Birthweight (kg) | (n = 23) | (n = 17) | – |

| Mean (SD) | 1.18 (0.62) | 1.46 (0.67) | – |

| Range | 0.2–3.0 | 0.7–3.1 | – |

| Mean difference (SD) | – | – | −0.28 (0.64) |

| 95% CI | – | – | −0.69 to 0.14 |

| Apgar score at 1 minute | (n = 21) | (n = 16) | – |

| Mean (SD) | 4.38 (2.78) | 5.25 (2.74) | – |

| Range | 1–10 | 0–9 | – |

| Mean difference (SD) | – | – | −0.87 (2.77) |

| 95% CI | – | – | −2.73 to 0.99 |

| Apgar score at 5 minutes | (n = 21) | (n = 16) | – |

| Mean (SD) | 6.86 (2.78) | 7.00 (2.31) | – |

| Range | 1–10 | 2–10 | – |

| Mean difference (SD) | – | – | −0.14 (2.59) |

| 95% CI | – | – | −1.89 to 1.60 |

| Cord pH | (n = 15) | (n = 8) | – |

| Mean (SD) | 7.26 (0.15) | 7.10 (0.46) | – |

| Range | 6.8–7.4 | 6.0–7.4 | – |

| Mean difference (SD) | – | – | 0.16 (0.29) |

| 95% CI | – | – | −0.10 to 0.43 |

| Base excess | (n = 12) | (n = 5) | – |

| Mean (SD) | 1.78 (8.42) | −1.18 (6.28) | – |

| Range | −8.5 to 18.8 | −9.3–6.8 | – |

| Mean difference (SD) | – | – | 2.96 (7.91) |

| 95% CI | – | – | −6.01 to 11.94 |

| Lactate | (n = 0) | (n = 1) | – |

| Mean (SD) | – | 4.8 | – |

| Range | – | – | – |

| Mean difference (SD) | – | – | – |

| 95% CI | – | – | – |

| Sex, n male (%) | (n = 26) | (n = 25) | – |

| ITT | 17 (65.4) | 15 (60.0) | – |

| Sex, n male (%) | (n = 21) | (n = 24) | – |

| Per protocol | 14 (66.7) | 15 (62.5) | – |

| Pregnancy outcome | AI (n = 28a) | Exp (n = 28) | Chi-squared test p-value (n = 56a) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset of labour, n (%) | (n = 28) | (n = 28) | – |

| Induced | 4 (14.2) | 5 (17.9) | – |

| Spontaneous | 12 (42.9) | 18 (64.2) | – |

| Caesarean section | 12 (42.9) | 5 (17.9) | – |

| Chi-squared test p-value | – | – | 0.12b |

| Mode of delivery, n (%) | (n = 28) | (n = 28) | – |

| Normal | 12 (42.9) | 20 (71.4) | – |

| Instrumental | 1 (3.5) | 1 (3.6) | – |

| Emergency LSCS | 12 (42.9) | 7 (25.0) | – |

| Elective LSCS | 3 (10.7) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Chi-squared test p-value | – | – | 0.10b |

| Reason for delivery of fetus | (n = 27) | (n = 27) | – |

| APH | 2 (7.4) | 1 (3.7) | – |

| APH/abnormal cardiotocography | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Placental abruption | 3 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Cord prolapse | 2 (7.4) | 2 (7.4) | – |

| Elective LSCS | 1 (3.7) | 1 (3.7) | – |

| Emergency caesarean section | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.4) | – |

| Fetal death in utero | 1 (3.7) | 2 (7.4) | – |

| Fetal distress | 1 (3.7) | 1 (3.7) | – |

| Induction of labour | 2 (7.4) | 1 (3.7) | – |

| Spontaneous labour | 14 (51.9) | 11 (40.8) | – |

| Spontaneous miscarriage | 0 (0.0) | 6 (22.2) | – |

| Pregnancy outcome | AI (n = 22a) | Exp (n = 25b) | Chi-squared test p-value (n = 47) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset of labour, n (%) | (n = 22) | (n = 25) | – |

| Induced | 3 (13.6) | 4 (16.0) | – |

| Spontaneous | 9 (40.9) | 16 (64.0) | – |

| N/A (caesarean section) | 10 (45.5) | 5 (20.0) | – |

| Chi-squared test p-value | – | – | 0.17b |

| Mode of delivery, n (%) | (n = 22) | (n = 25) | – |

| Normal | 12 (54.5) | 18 (72.0) | – |

| Instrumental | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Emergency LSCS | 9 (40.9) | 7 (28.0) | – |

| Elective LSCS | 1 (4.6) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Chi-squared test p-value | – | – | 0.32c |

| Reason for delivery of fetus, n (%) | (n = 22) | (n = 25) | – |

| APH | 2 (9.0) | 1 (4.0) | – |

| APH/abnormal cardiotocography | 1 (4.6) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Abruption | 3 (13.6) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Cord prolapse | 2 (9.0) | 2 (8.0) | – |

| Elective LSCS | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.0) | – |

| Emergency caesarean section | 0 (0.0) | 2 (8.0) | – |

| Fetal death in utero | 1 (4.6) | 2 (8.0) | – |

| Fetal distress | 1 (4.6) | 1 (4.0) | – |

| Induction of labour | 1 (4.6) | 1 (4.0) | – |

| Spontaneous labour | 11 (50.0) | 10 (40.0) | – |

| Spontaneous miscarriage | 0 (0.0) | 5 (20.0) | – |

Perinatal outcomes

Fourteen out of 81 women who could potentially have been recruited to the study had a miscarriage, giving an overall miscarriage rate of 17% (see Tables 3, 11 and 12 and Figure 1).

The overall perinatal survival in both arms was 17 out of 56 (30.4%) and the overall perinatal mortality was 39 out of 56 (69.6%) (Tables 13 and 14). Four antepartum deaths were secondary to cord prolapse, two in each arm. Neonatal deaths were attributable to extreme prematurity and/or small lungs and not oxygenating despite maximum ventilation. Further details about the perinatal deaths can be seen in Serious adverse events. All SAEs had a severity of ‘death’.

| Outcome | AI (n = 28a) | Exp (n = 28) | RR (95% CI) (n = 56a) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fetal death, n | 5 | 11 | 0.4545 (0.1815 to 1.1386) |

| Neonatal and fetal death, n | 19 | 19 | 1.0000 (0.6973 to 1.4341) |

| Infant, neonatal and fetal death, n | 19 | 20 | 0.9500 (0.6720 to 1.3430) |

| Outcome | AI (n = 22a) | Exp (n = 25b) | RR (95% CI) (n = 47) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fetal death, n | 4 | 9 | 0.5051 (0.1805 to 1.4133) |

| Neonatal and fetal death, n | 17 | 16 | 1.2074 (0.8330 to 1.7501) |

| Infant, neonatal and fetal death, n | 17 | 17 | 1.1364 (0.7995 to 1.6153) |

There was no significant difference in mean gestational age at delivery between the AI and Exp arms (28.45 weeks vs. 29.82 weeks; mean difference −1.36, 95% CI −4.21 to 1.48) or Apgar score at 5 minutes (6.86 vs. 7.00; mean difference SD −0.14, 95% CI −1.89 to 1.60). Birthweight in the Exp arm was, however, slightly higher (1.18 kg vs. 1.46 kg; mean difference SD −0.28, 95% CI −0.69 to 0.14) and cord pH was noted to be higher in the AI arm (7.26 vs. 7.10; mean difference SD 0.16, 95% CI −0.10 to 0.43) (see Table 10).

After removing fetal deaths, there were 23 patients in the AI arm and 17 in the Exp arm. Any neonatal morbidity outcome results with numbers lower than this are a result of missing patient data.

There was no difference between the arms in the overall risk of any serious neonatal morbidity by ITT [23/28 vs. 25/28; relative risk (RR) 0.92, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.14] (Tables 15 and 16), or in any morbidity at birth or some time after birth (Tables 17 and 18).

| Outcome | AI (n = 28) | Exp (n = 28) | RR (n = 56b) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Death or serious neonatal morbidity, n (%) | (n = 28) | (n = 28) | – |

| Yes | 23 (82.1) | 25 (89.3) | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | 0.9200 (0.7419 to 1.1408) |

| Outcome | AI (n = 22b) | Exp (n = 25c) | RR (n = 47) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Death or serious neonatal morbidity, n (%) | (n = 22) | (n = 25) | – |

| Yes | 20 (90.9) | 22 (88.0) | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | 1.0331 (0.8492 to 1.2567) |

| Neonatal morbidity outcome | AI | Exp | RR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients with data (n = 28a,b) | Fetal deaths omitted (n = 24a) | All patients with data (n = 28c) | Fetal deaths omitted (n = 17) | All patients with data (n = 56a) | Fetal deaths omitted (n = 41a) | |

| Culture-positive sepsis, n (%) | (n = 27) | (n = 23) | (n = 28) | (n = 17) | – | – |

| Yes | 5 (18.5) | 5 (21.7) | 7 (25.0) | 7 (41.2) | – | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | – | – | 0.74 (0.27 to 2.05) | 0.53 (0.20 to 1.38) |

| Pneumothorax, n (%) | (n = 27) | (n = 23) | (n = 28) | (n = 17) | – | – |

| Yes | 3 (11.1) | 3 (13.0) | 3 (10.7) | 3 (17.7) | – | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | – | – | 1.04 (0.23 to 4.70) | 0.74 (0.17 to 3.22) |

| NEC (operated), n (%) | (n = 27) | (n = 23) | (n = 28) | (n = 17) | – | – |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | – | – | N/A as no events in either arm | N/A as no events in either arm |

| NEC (treated conservatively), n (%) | (n = 27) | (n = 23) | (n = 28) | (n = 17) | – | – |

| Yes | 2 (7.4) | 2 (8.7) | 1 (3.6) | 1 (5.9) | – | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | – | – | 2.07 (0.20 to 21.56) | 1.48 (0.15 to 15.00) |

| Treated seizures, n (%) | (n = 27) | (n = 23) | (n = 28) | (n = 17) | – | – |

| Yes | 1 (3.7) | 1 (4.4) | 1 (3.6) | 1 (5.9) | – | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | – | – | 1.04 (0.07 to 15.76) | 0.74 (0.05 to 11.00) |

| Treated retinopathy, n (%) | (n = 27) | (n = 23) | (n = 28) | (n = 17) | – | – |

| Yes | 1 (3.7) | 1 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | – | – | 3.11 (0.13 to 73.11) | 2.25 (0.10 to 52.07) |

| PVL, n (%) | (n = 27) | (n = 23) | (n = 28) | (n = 17) | – | – |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.6) | 1 (5.9) | – | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | – | – | 0.35 (0.01 to 8.12) | 0.25 (0.01 to 5.79) |

| Shunt, n (%) | (n = 27) | (n = 23) | (n = 28) | (n = 17) | – | – |

| Yes | 1 (3.7) | 1 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | – | – | 3.11 (0.13 to 73.11) | 2.25 (0.10 to 52.07) |

| Home O2,d n (%) | (n = 27) | (n = 9) | (n = 28) | (n = 9) | – | – |

| Yes | 2 (7.4) | 2 (22.2) | 3 (10.7) | 3 (33.3) | – | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | – | – | 0.69 (0.13 to 3.82) | 0.67 (0.14 to 3.09) |

| O2 requirement at day 28,d n (%) | (n = 27) | (n = 9) | (n = 28) | (n = 9) | – | – |

| Yes | 3 (11.1) | 3 (33.3) | 4 (14.3) | 3 (33.3) | – | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | – | – | 0.78 (0.19 to 3.16) | 1.00 (0.27 to 3.69) |

| Neonatal morbidity outcome | AI | Exp | RR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients with data (n = 22a) | Fetal deaths omitted (n = 18) | All patients with data (n = 25b) | Fetal deaths omitted (n = 16) | All patients with data (n = 47) | Fetal deaths omitted (n = 34) | |

| Culture-positive sepsis, n (%) | (n = 22) | (n = 18) | (n = 25) | (n = 16) | – | – |

| Yes | 4 (18.2) | 4 (22.2) | 7 (28.0) | 7 (43.8) | – | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | – | – | 0.65 (0.22 to 1.92) | 0.51 (0.18 to 1.42) |

| Pneumothorax, n (%) | (n = 22) | (n = 18) | (n = 25) | (n = 16) | – | – |

| Yes | 3 (13.6) | 3 (16.7) | 2 (8.0) | 2 (12.5) | – | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | – | – | 1.70 (0.31 to 9.28) | 1.33 (0.25 to 7.00) |

| NEC (operated), n (%) | (n = 22) | (n = 18) | (n = 25) | (n = 16) | – | – |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | – | – | N/A as no events in either arm | N/A as no events in either arm |

| NEC (treated conservatively), n (%) | (n = 22) | (n = 18) | (n = 25) | (n = 16) | – | – |

| Yes | 2 (9.1) | 2 (11.1) | 1 (4.0) | 1 (6.3) | – | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | – | – | 2.27 (0.22 to 23.38) | 1.78 (0.18 to 17.80) |

| Treated seizures, n (%) | (n = 22) | (n = 18) | (n = 25) | (n = 16) | – | – |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.0) | 1 (6.3) | – | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | – | – | 0.38 (0.02 to 8.80) | 0.30 (0.01 to 6.84) |

| Treated retinopathy, n (%) | (n = 22) | (n = 18) | (n = 25) | (n = 16) | – | – |

| Yes | 1 (4.6) | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | – | – | 3.39 (0.15 to 79.22) | 2.68 (0.12 to 61.58) |

| PVL, n (%) | (n = 22) | (n = 18) | (n = 25) | (n = 16) | – | – |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.0) | 1 (6.3) | – | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | – | – | 0.38 (0.02 to 8.80) | 0.30 (0.01 to 6.84) |

| Shunt, n (%) | (n = 22) | (n = 18) | (n = 25) | (n = 16) | – | – |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | – | – | N/A as no events in either arm | N/A as no events in either arm |

| Home O2,c n (%) | (n = 22) | (n = 5) | (n = 25) | (n = 9) | – | – |

| Yes | 2 (9.1) | 2 (40.0) | 3 (12.0) | 3 (33.3) | – | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | – | – | 0.76 (0.14 to 4.13) | 1.20 (0.29 to 4.95) |

| O2 requirement at day 28,c n (%) | (n = 22) | (n = 5) | (n = 25) | (n = 9) | – | – |

| Yes | 3 (13.6) | 3 (60.0) | 4 (16.0) | 3 (33.3) | – | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | – | – | 0.85 (0.21 to 3.40) | 1.80 (0.19 to 1.93) |

The data presented in Tables 15 and 16 are indicative of the overall morbidity and death in the cohort. Although outcomes such as culture-positive sepsis, pneumothorax, O2 requirement at day 28, NEC, seizures, retinopathy, PVL, shunt and IVH 3 or 4 have been described in the analysis of the short-term outcomes, the sequelae of these morbidities are assessed in terms of their impact on long-term outcomes, i.e. blindness, long-term respiratory morbidity as assessed by infant lung function tests and neurodevelopmental delay as assessed by BSID-II (see Chapter 4).

There was no difference between arms in O2 requirement at day 28 (Tables 17 and 18).

The incidence of IVH grades 2 and 3 (two from the AI arm vs. four from the Exp arm) and postural orthopaedic deformities (one from the AI arm vs. two from the Exp arm) were similar in both arms. The numbers are too small to conclude any significant differences. This would require a larger study. There were no incidences of fixed orthopaedic deformities (Tables 19 and 20). The number of days a patient spent on ventilation and the number of days that a patient required O2 are shown in Tables 21 and 22, respectively.

| Neonatal morbidity outcome | AI (n = 28) | Exp (n = 28) | Chi-squared test p-value (n = 56) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IVH grade, n (%) | (n = 27) | (n = 28) | – |

| No IVH | 25 (92.6) | 24 (85.7) | – |

| Grade 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Grade 2 | 1 (3.7) | 1 (3.6) | – |

| Grade 3 | 1 (3.7) | 3 (10.7) | – |

| Chi-squared test for trend p-value | – | – | 0.34a |

| Orthopaedic deformities, n (%) | (n = 27) | (n = 28) | – |

| None | 26 (96.3) | 26 (92.9) | – |

| Fixed | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Postural | 1b (3.7) | 2c (7.1) | – |

| Chi-squared test p-value | – | – | 0.57a |

| Neonatal morbidity outcome | AI (n = 22a) | Exp (n = 25b) | Chi-squared test p-value (n = 47) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IVH grade, n (%) | (n = 22) | (n = 25) | – |

| No IVH | 21 (95.5) | 21 (84.0) | – |

| Grade 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Grade 2 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.0) | – |

| Grade 3 | 1 (4.5) | 3 (12.0) | – |

| Chi-squared test for trend p-value | – | – | 0.12a |

| Orthopaedic deformities, n (%) | (n = 22) | (n = 25) | – |

| None | 21 (95.5) | 23 (92.0) | – |

| Fixed | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Postural | 1 (4.5) | 2 (8.0) | – |

| Chi-squared test p-value | – | – | 0.63c |

| Analysis | AI | Exp |

|---|---|---|

| Fetal deaths excluded, neonatal deaths with maximum observed value in trial imputed (n = 23) | Fetal deaths excluded, neonatal deaths with maximum observed value in trial imputed (n = 17) | |

| Number of neonatal deaths | 14 | 8 |

| Days IPPV, n (%) | (n = 23) | (n = 17) |

| Yes | 10 (43.5) | 10 (58.8) |

| Median (IQR) | 69 (3–69) | 5 (2–69) |

| Range | 0–69 | 0–69 |

| Days CPAP, n (%) | (n = 23) | (n = 17) |

| Yes | 7 (30.4) | 5 (29.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 35 (2–35) | 23 (1–35) |

| Range | 0–35 | 0–35 |

| Days HFOV, n (%) | (n = 23) | (n = 17) |

| Yes | 3 (13.0) | 2 (11.8) |

| Median (IQR) | 4 (0–4) | 2 (0–4) |

| Range | 0–4 | 0–4 |

| Outcome | AI | Exp |

|---|---|---|

| Fetal deaths excluded, neonatal deaths with maximum observed value in trial imputed (n = 23) | Fetal deaths excluded, neonatal deaths with maximum observed value in trial imputed (n = 17) | |

| Number of neonatal deaths | 14 | 8 |

| Days on O2, n (%) | (n = 23) | (n = 15a) |

| Median (IQR) | 28 (24–28) | 28 (5–28) |

| Range | 0–28 | 0–28 |

Postnatal maternal outcomes

Coamoxiclav, cephalosporins and metronidazole were most commonly used postnatally. One woman in the Exp arm had serious maternal sepsis requiring admission to ITU/HDU (Tables 23 and 24). There were no maternal deaths.

| Maternal morbidity outcome | AI (n = 28a) | Exp (n = 28) | RR (n = 56a) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Required antibiotics postnatally | (n = 27) | (n = 28) | – |

| n (%), yes | 6 (22.2) | 8 (28.6) | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | 0.78 (0.31 to 1.95) |

| Serious maternal sepsis requiring ITU/HDU admission | |||

| ITT | (n = 27) | (n = 28) | – |

| n (%), yes | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.6) | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | 0.35 (0.01 to 8.12) |

| Maternal death | 0/28 | 0/28 | N/A |

| Maternal morbidity outcome | AI (n = 22a) | Exp (n = 25b) | RR (n = 47) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Required antibiotics postnatally, n (%) | (n = 22) | (n = 25) | – |

| Yes | 5 (22.7) | 6 (24.0) | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | 0.95 (0.33 to 2.68) |

| Serious maternal sepsis requiring ITU/HDU admission, n (%) | (n = 22) | (n = 25) | – |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.0) | – |

| RR (95% CI) | – | – | 0.38 (0.02 to 8.80) |

| Maternal death | 0/22 | 0/25 | N/A |

Serious adverse events

All SAEs had a severity of ‘death’ (Tables 25 and 26).

| Event | Description | AI (n) | Exp (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antepartum death | Antepartum death – no additional information | 1 | 1 |

| Cord prolapse | 2 | 1 | |

| Cord prolapse, stillbirth | 0 | 1 | |

| Miscarriage | 0 | 5 | |

| Spontaneous miscarriage | 0 | 2 | |

| Stillbirth | 1 | 1 | |

| Termination of pregnancy | 1 | 0 | |

| Total | 5 | 11 | |

| Neonatal death | Cord prolapse, emergency caesarean section | 0 | 1 |

| Extreme prematurity, pulmonary hypoplasia, placental abruption | 1 | 0 | |

| Fetal abnormalities undiagnosed prior to birth | 1 | 0 | |

| Neonatal death – no additional information | 5 | 1 | |

| Preterm birth and extreme prematurity | 3 | 4 | |

| Preterm birth and extreme prematurity, pulmonary hypoplasia | 2 | 1 | |

| Pulmonary hypoplasia | 1 | 0 | |

| Pulmonary hypoplasia, pulmonary stenosis and small right ventricle | 0 | 1 | |

| Pulmonary hypoplasia, renal agenesis | 1 | 0 | |

| Total | 14 | 8 | |

| Infant death | Chronic lung disease | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 0 | 1 | |

| Total SAEs | 19 | 20 | |

| Event | Description | AI (n) | Exp (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antepartum death | Antepartum death – no additional information | 1 | 1 |

| Cord prolapse | 2 | 1 | |

| Cord prolapse, stillbirth | 0 | 0 | |

| Miscarriage | 0 | 4 | |

| Spontaneous miscarriage | 0 | 2 | |

| Stillbirth | 1 | 1 | |

| Termination of pregnancy | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 4 | 9 | |

| Neonatal death | Cord prolapse, emergency caesarean section | 0 | 1 |

| Extreme prematurity, pulmonary hypoplasia, placental abruption | 1 | 0 | |

| Fetal abnormalities undiagnosed prior to birth | 1 | 0 | |

| Neonatal death – no additional information | 4 | 1 | |

| Preterm birth and extreme prematurity | 3 | 3 | |

| Preterm birth and extreme prematurity, pulmonary hypoplasia | 2 | 1 | |

| Pulmonary hypoplasia | 1 | 0 | |

| Pulmonary hypoplasia, pulmonary stenosis and small right ventricle | 0 | 1 | |

| Pulmonary hypoplasia, renal agenesis | 1 | 0 | |

| Total | 13 | 7 | |

| Infant death | Chronic lung disease | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 0 | 1 | |

| Total SAEs | 17 | 17 | |

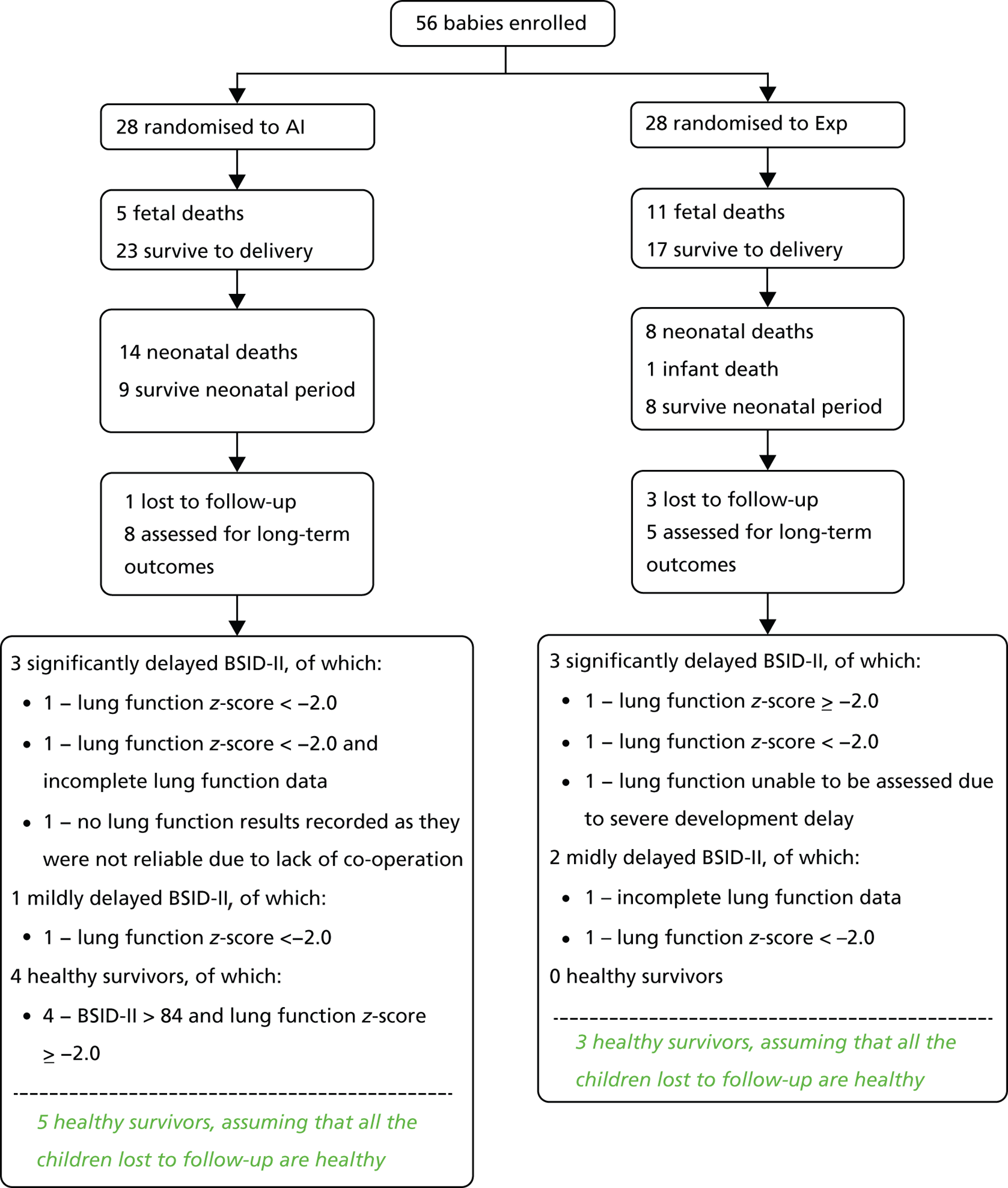

Chapter 4 Results (long-term outcomes)

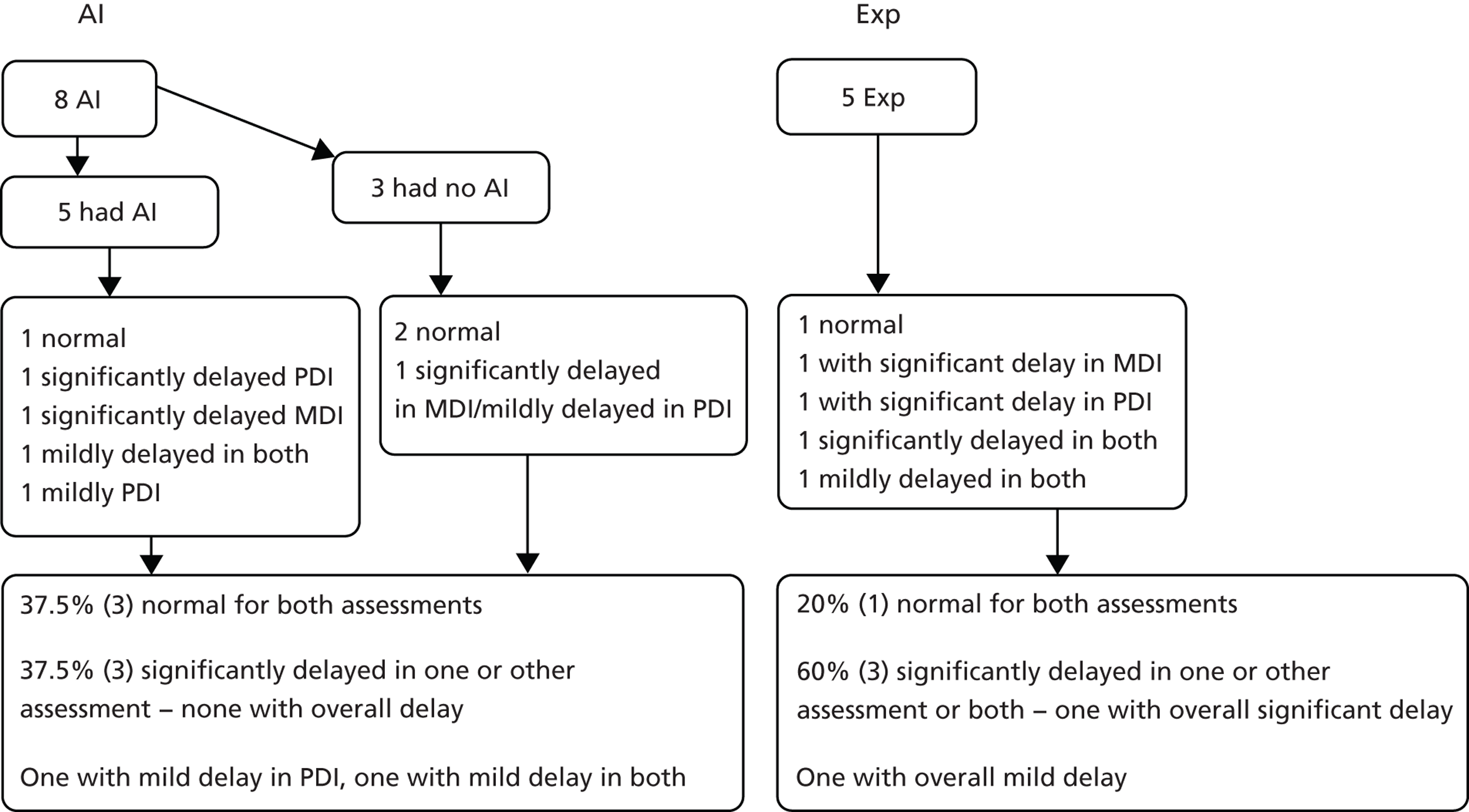

There were nine survivors in the AI arm and eight in the Exp arm. The numbers are too small to make meaningful comparisons. This is, however, the first time that long-term follow-up of respiratory and neurodevelopmental outcomes has been performed in survivors of very early prelabour rupture of the amniotic membranes.

Respiratory questionnaires

Respiratory questionnaires were sent out three times in the period of long-term outcome analysis: at 6 months, 12 months and 18 months. Table 27 shows the questionnaire status at each of the time points.

| Questionnaire status | Questionnaire time point | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months | 12 months | 18 months | ||||

| AI survivors (n = 9) | Exp survivors (n =8) | AI survivors (n = 9) | Exp survivors (n = 8) | AI survivors (n = 9) | Exp survivors (n = 8) | |

| Questionnaires returned (and analysed) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| Lost to follow-up | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Parent did not return questionnaire | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

The respiratory questionnaire scores at each time point are summarised in Table 28 and the outcomes of the latest returned questionnaires are shown in Table 29. At 18 months, two children in the Exp arm and two children in the AI arm had scores within the CIs for asthma defined by Powell et al. 15 Additionally, three children in the Exp arm (patient numbers 22, 28, 31) and three patients in the AI arm (patient numbers 8, 11, 16) did not have outcome data available at 18 months.

| Domain | Questionnaire time point | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months | 12 months | 18 months | |||||||

| AI | Exp | Difference in medians (95% CI) | AI | Exp | Difference in medians (95% CI) | AI | Exp | Difference in medians (95% CI) | |

| Overall total | |||||||||

| Complete case | |||||||||

| n = 7 | n = 7 | n = 7 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 5 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 16 (14–32) | 13.5 (7–35) | 2 (−31 to 24) | 18 (3–28) | 15.5 (6–29) | 1.5 (−26 to 23) | 10.5 (4–40) | 13 (4–42) | 0 (−44 to 40) |

| Range | 4–59 | 0–63 | 0–50 | 0–62 | 0–60 | ||||

| Sensitivity analysis, neonatal | |||||||||

| n = 21 | n = 15 | n = 21 | n = 14 | n = 20 | n = 13 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 84 (32–84) | 0 (0 to 6) | 84 (28–84) | 84 (16–84) | 0 (0 to 34) | 84 (51–84) | 84 (42–84) | 0 (0 to 20) | |

| Range | 4–84 | 0–84 | 0–84 | 0–84 | 0–84 | ||||

| Daytime symptoms | |||||||||

| Complete case | |||||||||

| n = 7c | n = 6a | n = 7 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 5 | ||||

| 10 (9–20) | 10 (5–18) | 1 (−17 to 15) | 14 (1–20) | 6 (3–22) | −0.5 (−17 to 17) | 6.5 (2–17) | 6 (4–21) | −3 (−29 to 17) | |

| 3–37 | 5–54 | 0–35 | 0–31 | 0–35 | 0–40 | ||||

| Sensitivity analysis, neonatal | |||||||||

| n = 21 | n = 14 | n = 21 | n = 14 | n = 20 | n = 13 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 54 (20–54) | 54 (11–54) | 0 (0 to 4) | 54 (20–54) | 54 (8–54) | 0 (0–20) | 54 (26–54) | 54 (21–54) | 0 (0–11) |

| Rangea | 3–54 | 5–54 | 0–54 | 0–54 | 0–54 | 0–54 | |||

| Night-time symptoms | |||||||||

| Complete case | |||||||||

| n = 7 | n = 7 | n = 7 | n = 6a | n = 6 | n = 5 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 2 (0–6) | 4 (1–10) | −2 (−10 to 1) | 2 (1–4) | 3 (0–5) | 0 (−4 to 4) | 4 (2–5) | 6 (0–7) | −0.5 (−6 to 5) |

| Range | 0–7 | 1–13 | 0–12 | 0–7 | 0–11 | 0–9 | |||

| Sensitivity analysis neonatal | |||||||||

| n = 21 | n = 15 | n = 21 | n = 14 | n = 20 | n = 13 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 13 (6–13) | 13 (4–13) | 0 (0 to 1) | 13 (4–13) | 13 (5–13) | 0 (0 to 6) | 13 (8–13) | 13 (7–13) | |

| Range | 0–13 | 1–13 | 0–13 | 0–13 | 0–13 | 0–13 | 0 (0 to 4) | ||

| Effect on the child | |||||||||

| Complete case | |||||||||

| n = 7 | n = 7 | n = 7 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 5 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 2 (0–3) | 0 (0–6) | 0 (−4 to 3) | 1 (0–3) | 2 (0–3) | 0 (−3 to 3) | 0 (0–8)b | 1 (0–5) | 0 (−5 to 8) |

| Range | 0–8 | 0–6 | 0–8 | 0–5 | 0–8 | 0–5 | |||

| Sensitivity analysis, neonatal | |||||||||

| n = 21 | n = 15 | n = 21 | n = 14 | n = 20 | n = 13 | ||||

| 8 (3–8) | 8 (0–8) | 0 (0 to 2) | 8 (3–8) | 8 (3–8) | 0 (0 to 3) | 8 (8–8) | 8 (5–8) | 0 (0 to 3) | |

| 0–8 | 0–8 | 0–8 | 0–8 | 0–8 | 0–8 | ||||

| Effect on the family | |||||||||

| Complete case | |||||||||

| n = 7 | n = 7 | n = 7 | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 5 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 2 (0–8) | 2 (0–6) | 0 (−5 to 5) | 1 (0–8) | 2.5 (1–3) | −0.5 (−3 to 7) | 0 (0–8)b | 0 (0–6) | 0 (−9 to 8) |

| Range | 0–10 | 0–11 | 0–11 | 0–9 | 0–10 | 0–9 | |||

| Sensitivity analysis, neonatal | |||||||||

| n = 21 | n = 15 | n = 21 | n = 14 | n = 20 | n = 13 | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 11 (8–11) | 11 (2–11) | 0 (0 to 2) | 11 (8–11) | 11 (3–11) | 0 (0 to 2) | 11 (9–11) | 11 (6–11) | 0 (0 to 2) |

| Range | 0–11 | 0–11 | 0–11 | 0–11 | 0–11 | 0–11 | |||

| Study arm | Patient number | Latest questionnaire available | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI | 8 | 12 months | No indication of asthma |

| 10 | 18 months | Asthma | |

| 11 | No questionnaires returned | Missing data | |

| 16 | Lost to follow-up | Missing data | |

| 20 | 18 months | No indication of asthma | |

| 30 | 18 months | No indication of asthma | |

| 35 | 18 months | No indication of asthma | |

| 45 | 18 months | No indication of asthma | |

| 55 | 18 months | Asthma | |

| Exp | 5 | 18 months | No indication of asthma |

| 22 | 12 months | Asthma | |

| 25 | 18 months | Asthma | |

| 28 | 6 months | Asthma | |

| 31 | Lost to follow-up | Missing data | |

| 33 | 18 months | No indication of asthma | |

| 44 | 18 months | No indication of asthma | |

| 58 | 18 months | Asthma |

Complete-case analysis is defined as analysis of only those domain scores and overall scores that have no missing data owing to there being no validated methods available to handle missing data in this respiratory questionnaire.

-

Best case is sensitivity analysis assigning missing questions a score of 0.

-

Worst case is sensitivity analysis assigning missing questions a score of 4.

There was only one patient with missing answers to the questions in one of the sections in the ‘daytime symptoms’ domain so the best- and worst-case sensitivity analyses are only needed for ‘daytime symptoms’ and ‘overall total’ scores (Table 30).

| Domain | 6 months | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| AI | Exp | Difference in medians (95% CI) | |

| Overall total | |||

| Complete case | |||

| n = 7 | n = 6a | ||

| Median (IQR) | 16 (14–32) | 13.5 (7–35) | 2 (−31 to 24) |

| Range | 4–59 | 6–84 | |

| Best case (missing answers = 0) | |||

| n = 7 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 14 (7–41) | 1 (−27 to 18) | |

| Range | 6–84 | ||

| Worst case (missing answers = 4) | |||

| n = 7 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 14 (7–65) | 0 (−50 to 18) | |

| Range | 6–84 | ||

| Daytime symptoms | |||

| Complete case | |||

| n = 7 | n = 6a | ||

| Median (IQR) | 10 (9–20) | 10 (5–18) | 1 (−17 to 15) |

| Range | 3–37 | 5–54 | |

| Best case (missing answers = 0) | |||

| n = 7 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 11 (5–19) | 0 (−15 to 11) | |

| Range | 5–54 | ||

| Worst case (missing answers = 4) | |||

| n = 7 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 11 (5–43) | −1 (−33 to 10) | |

| Range | 5–54 | ||

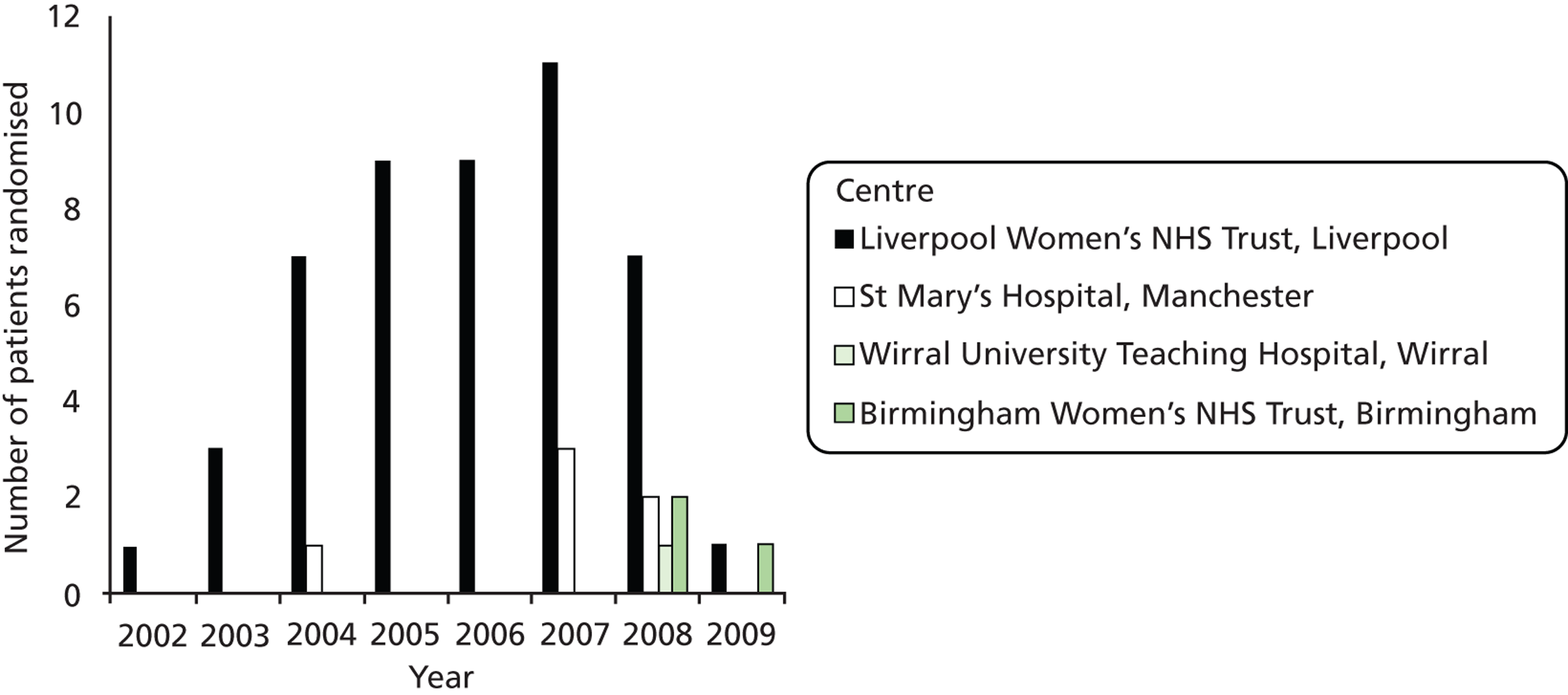

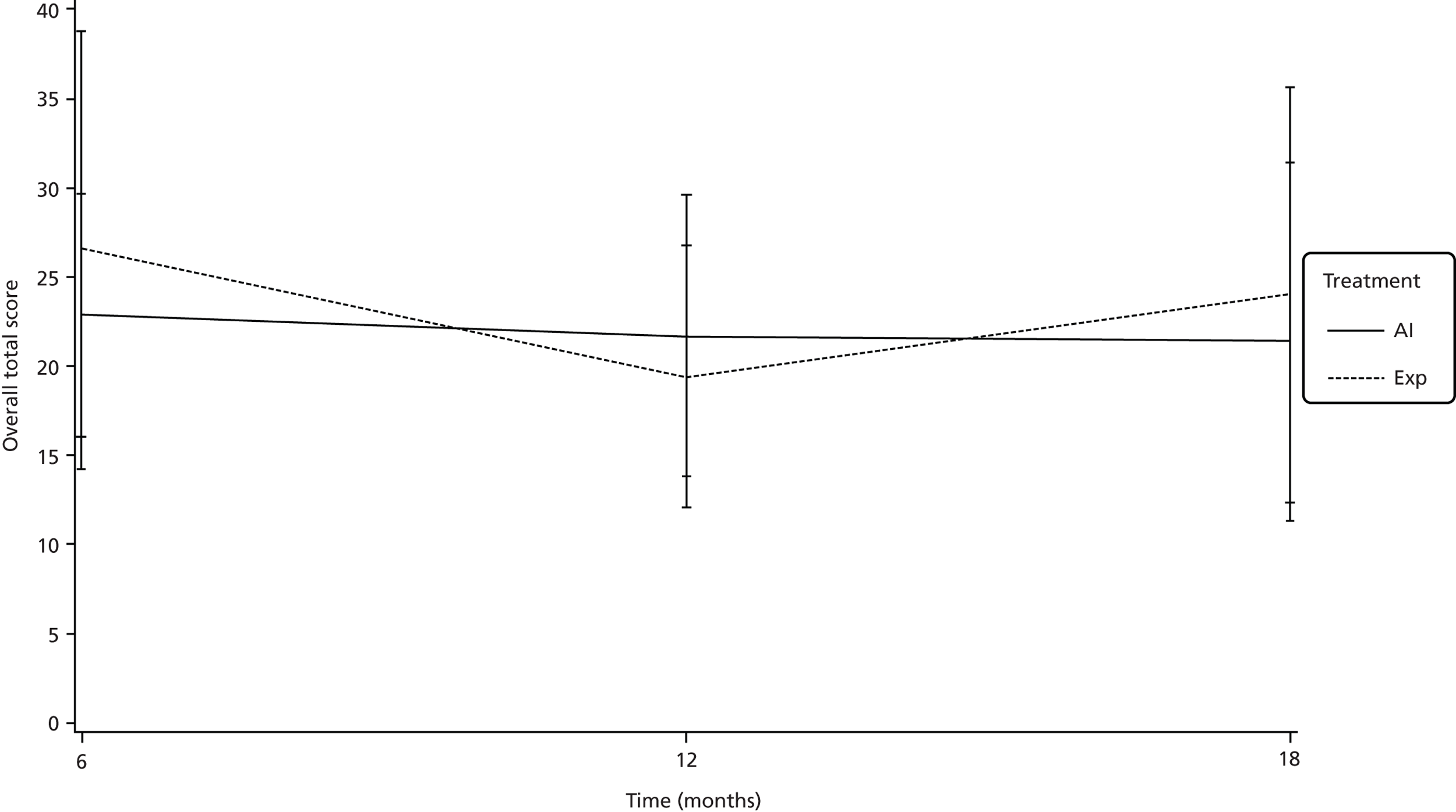

The mean profile plots for overall total score of the respiratory questionnaires is shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Mean profile plots for overall total score of the respiratory questionnaire.

Table 31 shows descriptive statistics regarding asthma diagnosis, medications for asthma, and hospital and general practitioner visits for chest symptoms. Numbers were too small to perform meaningful statistical analyses.

| Domain | Questionnaire time point | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months | 12 months | 18 months | ||||

| AI (n = 7) | Exp (n = 7) | AI (n = 7) | Exp (n = 6) | AI (n = 6) | Exp (n = 5) | |

| Inhalers taken as treatment for chest symptoms,a n (%) | 2/7 (28.6) | 3/7 (42.9) | 3/7 (42.9) | 3/6 (50.0) | 2/6 (33.3) | 2/5 (40.0) |

| Medicines taken as treatment for chest symptoms,b n (%) | 4/7 (57.1) | 3/7 (42.9) | 2/7 (28.6) | 1/6 (16.7) | 2/6 (33.3) | 2/5 (40.0) |

| Child had visited or had a visit from a general practitioner for chest problems, n (%) | 5/7 (71.4) | 3/7 (50.0) | 5/7 (71.4) | 2/6 (33.3) | 3/6 (50.0) | 2/5 (40.0) |

| Child had attended hospital clinics for chest problems, n (%) | 2/7 (28.6) | 0/7 (0.0) | 1/7 (13.3) | 3/6 (50.0) | 2/6 (33.3) | 1/5 (20.0) |

| Has child been diagnosed with asthma by a doctor, n (%) | 1/7 (14.3) | 1/7 (14.3) | 1/7 (14.3) | 0/6 (0.0) | 1/6 (16.7) | 0/5 (0.0) |

Lung function tests

The purpose of the lung function tests was primarily to determine whether there was evidence of small lungs in either patient arm. The individual lung function test results are shown in Table 32. Data presented in Table 32 are for means of at least three recorded values, unless otherwise indicated.

| Study number | Treatment | Reason tests not performed | Age at tests (years) | Age category | FRCP (l) | FRCP predicted (l) | FRCP z-value | FVC (l) | FVC predicted (l) | FVC z-value | FEV1 (l) | FEV1 predicted (l) | FEV1 z-value | Vmax FRC (ml/s) | Vmax FRC predicted (ml/s) | Vmax FRC z-value | Comment on test | Comment on result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | AI | – | 3.50 | Preschool | 0.88 | – | – | 0.98 | 0.83 | 1.08 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.16 | – | – | – | Plethysmography done with child sitting on mother’s knee. All measurements somewhat variable, as expected in a young child, but child did very well | Spirometry indicates normal forced expiratory volumes and the shape of the flow-volume curve was normal |

| 10 | AI | – | 3.08 | Preschool | 1.07 | – | – | 0.85 | 0.73 | 0.95 | 0.76 | 0.71 | 0.41 | – | – | – | Child did very well | Flow-volume loop showed no evidence of gross abnormality |

| 11 | AI | – | 2.89 | Preschool | 0.83a | – | – | 0.34 | 0.61 | −2.58 | – | – | – | – | – | – | Child did well for his age. FRCp is based on a single value so should be viewed with extreme caution | Predicted values are scarce for small preschool children so measured values should be interpreted with caution |

| 16 | AI | Lost to long-term follow-up | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| 20 | AI | – | 4.18 | Preschool | – | – | 0.89 | 1.00 | −0.69 | 0.84 | 0.96 | –0.80 | Excellent co-operation | Normal spirometry | ||||

| 30 | AI | – | 1.42 | Infant | 0.25 | 0.26 | −0.18 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 117.00 | 315.00 | −2.31 | Very good. Settled well. No problems | Resting lung volume is normal but maximum expiratory flow is somewhat reduced |

| 35 | AI | – | 1.06 | Infant | 0.18 | 0.27 | −1.16 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 64.00 | 253.00 | −2.63 | Straightforward, no problems. Child noted to be a little snuffly, either was just starting a cold or was teething | |

| 45 | AI | – | 2.26 | Preschool | – | – | 0.68 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.67 | 0.60 | 0.68 | Did well for his age | Normal spirometry | ||||

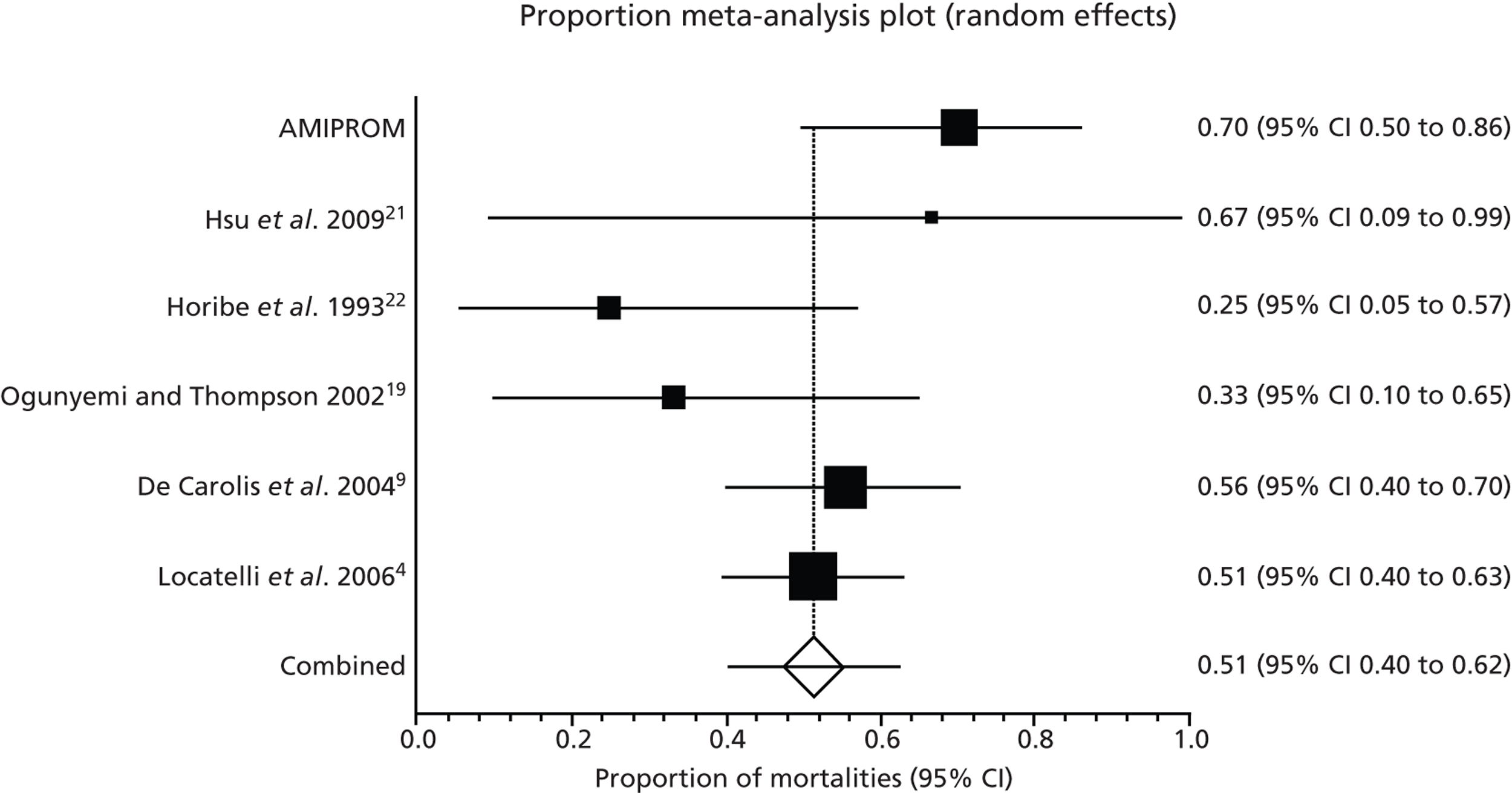

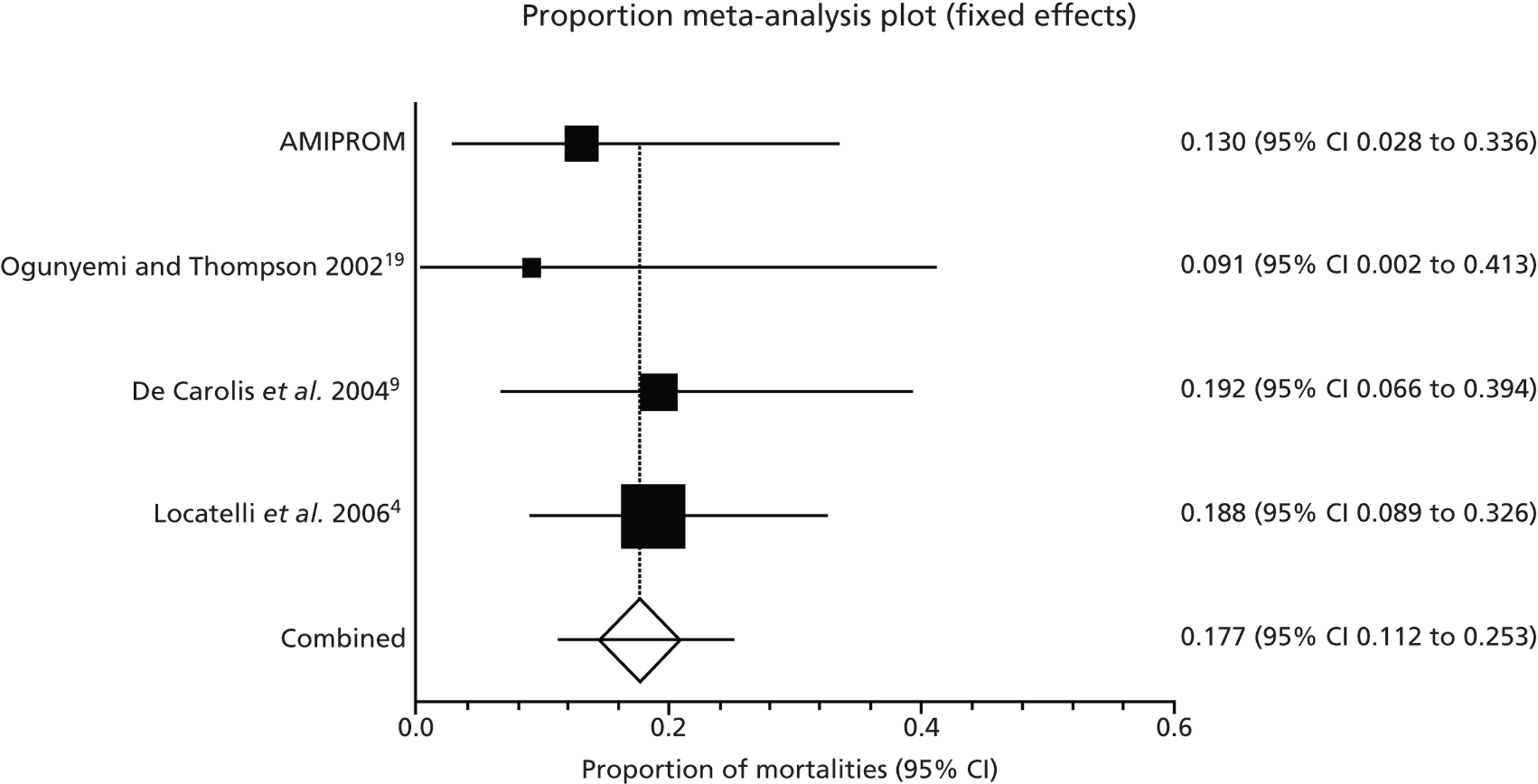

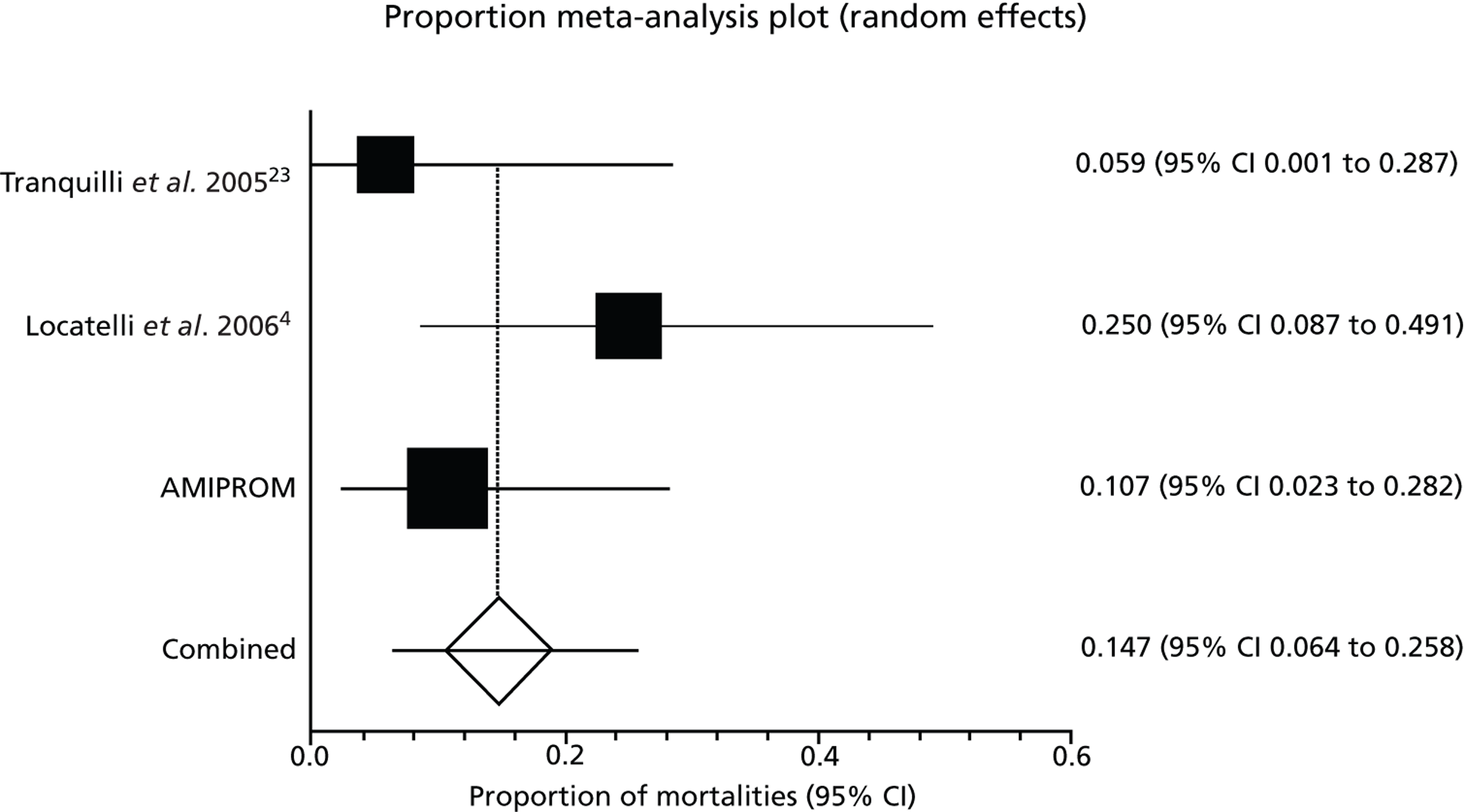

| 55 | AI | – | 2.44 | Preschool | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Not really old enough to have the co-operation for spirometry | Co-operation not good enough for results to be reliable. Cautious report sent to medical staff caring for him | |