Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 98/04/99. The contractual start date was in April 2008. The draft report began editorial review in September 2012 and was accepted for publication in July 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

The ARTISTIC trial extension was funded by the NIHR HTA with co-funding from the NHS Cervical Screening Programme – the grant was paid to the authors’ institutions. HCK is chair of the Advisory Committee in Cervical Screening (ACCS). The views expressed in this report are those of the author(s) and in no way represent views of the ACCS or the Department of Health. MD uses ThinPrep® liquid-based cytology for other laboratory diagnostic work as clinical head of a cytology laboratory. AS received support for travel to meetings from Roche. All authors (except KC) have previously received funding from the HTA to complete the first two rounds of screening in the original ARTISTIC trial. KC is co-principal investigator of a new trial of primary HPV screening in Australia, for which the pilot study is partially supported by Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Pleasanton, CA, USA. Prior development of the model platform used for the economic evaluation was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council Australia (NHMRC project grants #1007518 and #440200), the Medical Services Advisory Committee Australia, the National Screening Unit in New Zealand, the NHS Cervical Screening Programme in England and Cancer Council, NSW, Australia. KC receives salary support from the NHMRC Australia (CDF1007994). None of the authors has any competing interest with GlaxoSmithKline, manufacturer of Cervarix™.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Kitchener et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

The ARTISTIC (A Randomised Trial In Screening To Improve Cytology) trial was a randomised comparison of human papillomavirus (HPV) testing in combination with liquid-based cytology (LBC) versus LBC alone in primary cervical screening. It was based on outcomes over two rounds of screening and which have been published recently in a Health Technology Assessment (HTA) monograph1 and other peer-reviewed publications,2–6 including analyses of clinical outcomes, psychosocial outcomes, health economics and other HPV typing and testing data.

The following summarises the principal findings of ARTISTIC based on the two screening rounds:

-

Detection of high-grade disease was not significantly increased by LBC combined with HPV testing compared with LBC alone, in either the first round of screening or both rounds combined. 1,2 Other trials of HPV testing, which showed that HPV testing was more sensitive than cytology, used conventional cytology and not LBC. 7–9

-

Prevalence of high-risk (HR) HPV infection [Hybrid Capture 2 (HC2) test] by age: 28% in women aged 25–29 years, falling to 6.5% in women aged 50–64 years. 1,3,4

-

Prevalence of type-specific HPV infection by cytology grade: HPV 16 and/or HPV 18 were detected in 10% of borderline, 22% of mild dyskaryosis and over 50% of moderate/severe dyskaryosis. 1,3

-

The use of HPV testing did not significantly increase psychosocial distress engendered by cervical screening. 5

-

Combined testing (LBC and HPV) was more expensive and, with an incremental cost-effectiveness of £38,771 per additional case of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) grade 3 or worse (3+) detected, could not be justified. The mean cost of primary LBC triaged with HPV testing, or primary HPV testing with cytology, was less than the routine NHS Cervical Screening Programme (NHSCSP) protocol of repeat cytology for low-grade abnormalities. 1

-

A HC2 HPV test result cut-off of relative light unit/mean control (RLU/Co) 2 is superior in terms of clinical utility than the manufacturer’s recommended cut-off of RLU/Co 1. 6

Those conclusions will inform future consideration of HPV testing as a primary screening test. ARTISTIC data have also been used in validating models for evaluating the cost-effectiveness of HPV vaccination, which will help inform any decision to implement a national programme. 10 One of the key attributes of HPV testing could be the potential to lengthen screening intervals as suggested by data from other studies. 11

We have extended the follow-up of the trial cohort to October 2009 (up to 8 years after entry) to provide data from a third round of screening. This would offer valuable insight into the predictive ability of HPV testing compared with LBC as negative baseline tests, and for women who tested cytology negative/HPV positive. In the event of considering HPV testing as an initial screen, it would be important to understand what length of protection could be obtained from a negative HPV test and, in the event of a HPV-positive/cytology-negative result, what degree of risk existed over what period of time, and whether or not the type of HPV was important.

With HPV vaccination having been established in the UK in 2008, it would be possible using genotyping data to estimate how much disease would be prevented over a 6-year period by the prevention of HPV infection by the vaccine. We have then undertaken cost-effectiveness analysis of HPV primary screening, triaged with cytology, compared with current screening based on cytology triaged with HPV testing.

Hypotheses

-

1. A negative HPV test at baseline would provide a greater duration of protection against CIN grade 2 or worse (2+) when compared with a negative cytology result, and would allow extended screening intervals.

-

Research questions:

-

– What are the round 3 and cumulative rates of CIN2+ and CIN3+ between the revealed and concealed arms of ARTISTIC after three screening rounds over 6 years?

-

– What is the cumulative incidence of CIN2+ over three screening rounds following negative screening cytology with that following negative baseline HPV?

-

– Could the screening interval be safely extended from 3 to 6 years (continued hypothesis)?

-

-

2. Genotyping HPV to identify certain HR types could be clinically useful in terms of rapid referral to colposcopy following reflex cytology.

-

Research question:

-

– What are the differential rates of disease associated with various HR genotypes?

-

-

3. Increasing the HC2 cut-off from 1RLU/Co to 2RLU/Co could maintain sensitivity and improve specificity of HPV testing.

-

Research question:

-

– What is the effect of HC2 cut-off on the proportion of women with CIN2+?

-

-

4. The impact of the national vaccination programme against HPV types 16/18 will lead to a major reduction in the incidence of CIN2.

-

Research question:

-

– What is the proportion of disease and cytological abnormalities associated with types 16/18?

-

-

5. Conversion from cytology-based screening to HPV-based screening would, through increased ability to predict future risk of CIN2+ and CIN3+, save life-years and by increasing the screening interval, save costs.

-

Research question:

-

– What is the cost-effectiveness of moving from cytology- to HPV-based cervical screening?

-

Aims

The two principal aims of the trial extension were:

-

to determine, over a 6-year period, the predictive significance of a positive or negative HPV test, and specific HPV types with respect to the development of CIN, and to compare this with cytology, in order to determine the impact of HPV testing on cervical screening recall intervals

-

based on the ARTISTIC data, to model cost-effectiveness of changing cervical screening nationally from cytology triaged by HPV testing to HPV testing triaged by cytology.

Other outcomes were:

-

the round 3 and cumulative incidence of CIN2+ and CIN3+ in the original randomised arms of the trial

-

CIN2+ rates in relation to HPV type-specific persistence

-

the predicted impact of prophylactic HPV 16/18 vaccination on cervical screening outcomes in the NHSCSP

-

the potential benefit of using a HC2 cut-off value of 2 rather than 1 RLU in maintaining sensitivity but increasing specificity of HPV testing.

Chapter 2 Methods

ARTISTIC study extension

Study design

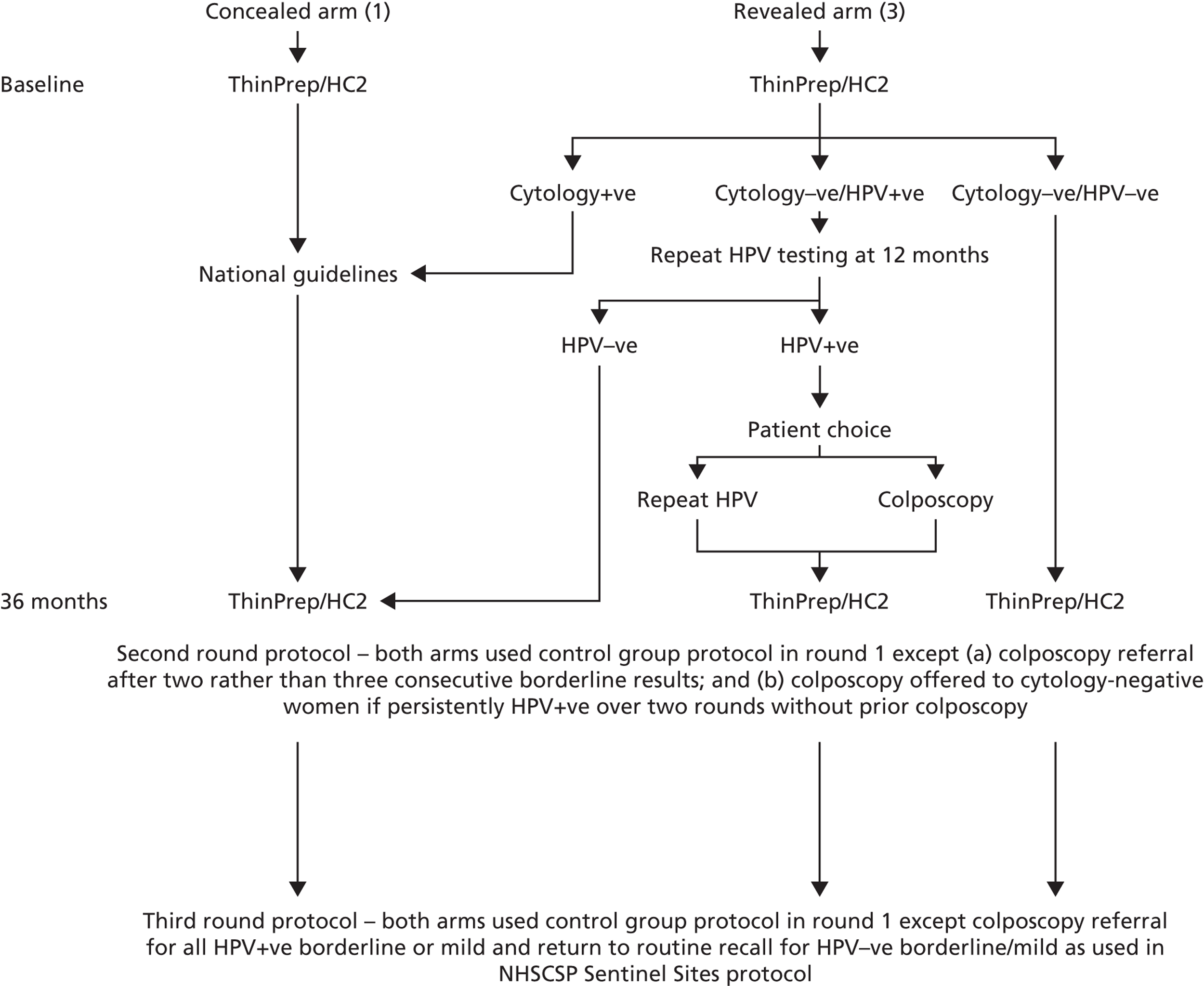

The original ARTISTIC study design has been previously described in detail. Briefly, 25,410 women aged 20–64 years undergoing routine cervical cytology screening in Greater Manchester between July 2001 and September 2003 underwent co-testing for HPV. They were randomised 3 : 1 to have the test either revealed and acted upon or concealed so as not to affect management. The intervention in the revealed arm was in those women who were cytology negative but HPV positive. Such women were invited back at 12 months and, if persistently HPV positive, were offered the choice between either colposcopy or a repeat HPV test at 24 months. If still positive at that time, all were offered colposcopy. In the event, two-thirds of those who chose selected colposcopy.

Women who had abnormal cytology at baseline were managed according to national guidance irrespective of HPV status. The hypothesis was that the addition of HPV testing would add sensitivity to detection of high-grade CIN in the first round and result in a reduction of high-grade CIN in round 2. The original primary outcome was therefore the incidence of detected high-grade CIN in round 2.

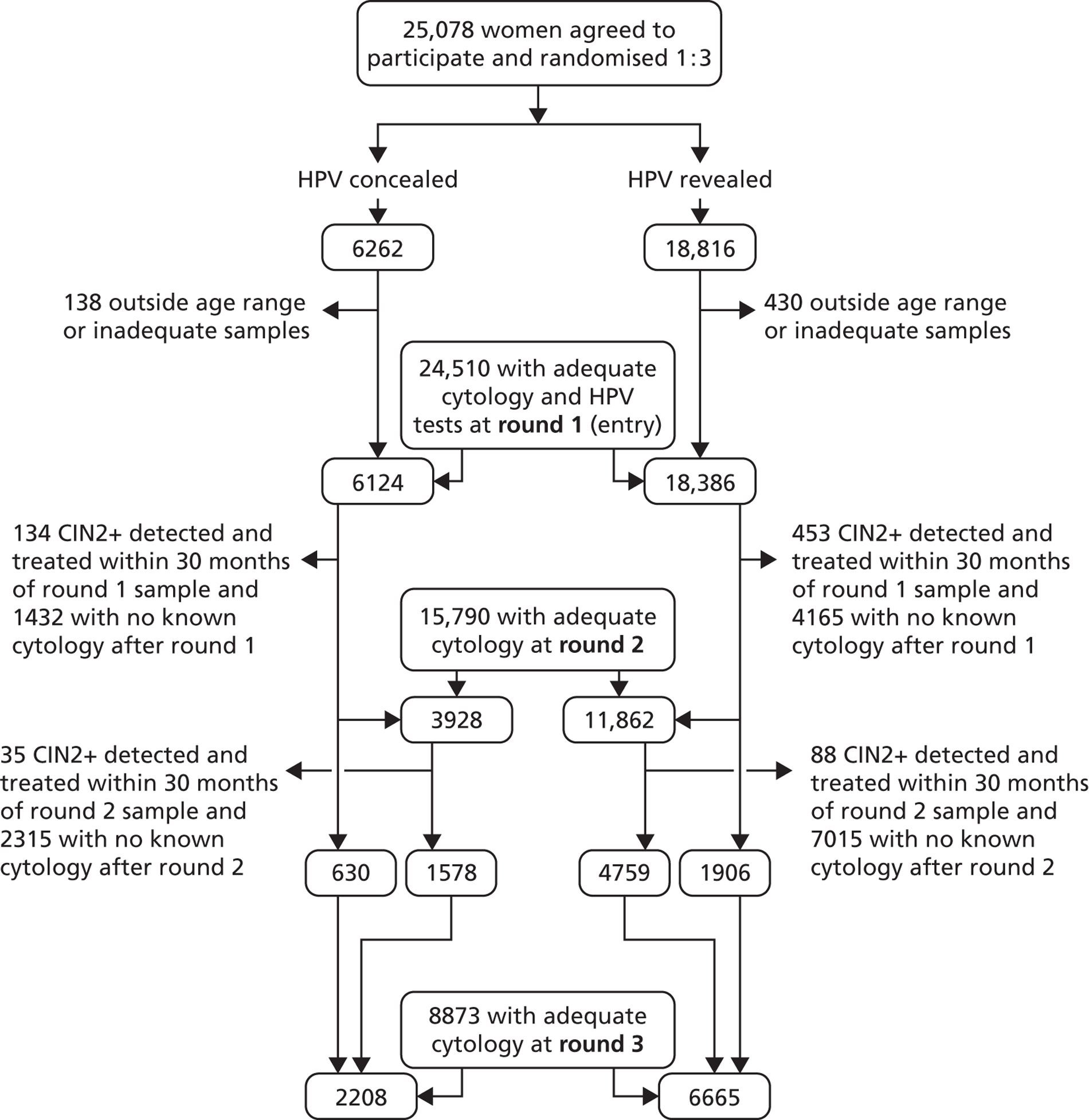

This extension of ARTISTIC involved extending follow-up of the study cohort through a third round of screening (Figure 1). All ARTISTIC women were invited to participate in a third round of screening 3 years following round 2. All women who participated in round 3 had LBC and HPV testing; however, for reasons explained below, a HPV-positive result only affected the management of those women with borderline changes or mild dyskaryosis who were then offered colposcopy, and this applied to both of the original arms. In all other respects routine clinical care applied.

FIGURE 1.

ARTISTIC protocol for rounds 1, 2 and 3.

As was the case throughout the ARTISTIC study, all colposcopy was performed by practitioners accredited in colposcopy through the British Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Equally, all cytology procedures were done according to NHSCSP Quality Assurance (QA) standards and HPV testing was performed in a Clinical Pathology Accreditation-approved laboratory.

Setting and ethics committee approval for the extension

The original protocol did not include continued HPV testing after the second screening round. The trial extension with a further (third) round of HPV testing in addition to cytology was initially approved by the North West Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (ref 00/8/30) on the basis that there were no significant changes to the management of women involved in the 6-year follow-up and that all participants were reconsented to the study. It was anticipated by the investigators that this would be difficult to achieve. The patient information leaflets are included in Appendix 5 and Appendix 6 and consent forms are included in Appendix 7.

General practitioner and family planning involvement

The original primary care practices and family planning clinics maintained their involvement in the trial extension. As all clinics had been participating since 2001, and LBC roll-out and update training across the region had been completed, it was deemed unnecessary to hold any information or training sessions. All practices involved were sent information about the trial extension and spare copies of the patient literature to keep in the clinic rooms.

Reconsenting procedures

All previously enrolled women were sent a letter to their last known address, detailing the aims and procedures of the trial extension. The appropriate patient information leaflet and consent form were also included. Women were given stamped addressed envelopes to return the consent form to the trial office. Women who did not wish to continue their participation in the trial were asked to return their consent forms blank with just their unique trial number included to allow identification. Women who withdrew from the extension did not receive any further correspondence from the trial office. Non-responders to the initial information were sent a repeat letter containing the same information to give them an additional opportunity to reconsent.

General practitioners (GPs) and family planning clinics were sent lists of all ARTISTIC women so that they were able to check whether or not the women were still participating when they attended for screening. A reimbursement of £5 was offered to sample-takers to reconsent women at the clinics who had failed to respond to the letters from the trial office. As some women had changed GPs since the first round of screening in the trial began, practices that were not originally part of the trial were sent additional information about the trial and its extension, if they had ARTISTIC women registered with them.

Protocol amendments

Throughout the course of the third round extension, two major protocol amendments were necessary:

-

An amendment was submitted to the ethics committee to seek approval for triaging all ARTISTIC women on the basis of reflex HPV testing for low-grade abnormalities in line with the NHSCSP Sentinel Sites protocol. This amendment was approved on the basis that to deny the women participating in the trial access to the triage would have provided them with inferior management than that received by other women attending for routine screening in the Greater Manchester area.

-

Within 9 months of the process of reconsenting for the third round extension of ARTISTIC, it became clear, as had been anticipated, that this was not viable. Fewer than one-quarter of women had returned consent forms, and not all of these women actually underwent screening. It was obvious that this would result in insufficient data to allow any useful conclusions to be drawn. A substantial amendment was submitted to the ethics committee, who agreed that under the circumstances it was in the public interest for approval to be given to the use of unconsented samples to be tested for HPV and recommended the following:

-

to obtain samples of residual material from routinely performed cytology (ARTISTIC participants)

-

to ensure that the HPV test result would not generate any non-routine clinical action

-

to ensure that data were anonymised by removing the use of the patient NHS number on the study database and instead use the unique study identifier to make it impossible for researchers to link HPV data to named individuals.

-

This amendment meant that colposcopy could not be offered to cytology-negative women who were HPV positive at the third screening round. Consequently, the positive and negative predictive values could be affected by the lack of colposcopy verification in cytology-negative/HPV-positive women. On the other hand, the triage of low-grade abnormalities would have resulted in rapid colposcopic verification of underlying CIN. The impact of the protocol amendments on the management of women in the trial is summarised in Table 1. Round 3 management was based on the post-amendments management recommendations.

| Pre-amendments | Post-amendments |

|---|---|

| Both arms | |

| High-grade cytology – colposcopy | High-grade cytology – colposcopy |

| Low-grade cytology | Low-grade cytology/HPV+ve – colposcopy |

| Mild dyskaryosis – colposcopy | |

| Borderline changes – repeat and refer if abnormal | |

| Negative cytology – colposcopy HPV+ve second and third round (revealed arm only) | Negative cytology – routine recall |

Impact of the NHS Cervical Screening Programme sentinel sites for human papillomavirus triage

On 1 March 2008, the Manchester Cytology Centre became one of six sentinel sites for HPV triage in England. The aim of the sentinel sites project was to evaluate the roll-out of HPV triage of low-grade cytological abnormalities. Women who tested HPV positive were referred to colposcopy, while those who were negative were returned to routine recall. This process expedited the referral to colposcopy for those who were at risk of an underlying abnormality, while women who were negative, and therefore at low risk, were spared repeat cytological testing.

In order to keep the management of the ARTISTIC women in line with local policies as required by the ethics committee, women in both revealed and concealed arms were entered into the triage protocol. 12 Women entered into the triage protocol received both a combined cytology/HPV result letter from the screening agencies as well as a results letter from the trial office. The changes in the HPV testing protocol were explained in the patient information leaflets. Women living in the Stockport area were also sent a leaflet explaining HPV triage, as this would not have been sent to them by their local screening agency.

The trial protocol originally meant that only the HPV result in women with negative cytology influenced management in the revealed arm and differentiated the effect of HPV testing between the two arms. The maintenance of the revealing and concealment of HPV results in round 3 was rendered impossible by the consequences of the ethics committee’s decision.

Clinical samples

All samples were collected as previously described. 1 Samples that were reported as showing low-grade abnormalities were HPV tested as part of the sentinel sites protocol. All HPV triage testing was carried out at the Manchester Virology laboratory alongside the ARTISTIC HPV testing. Samples were reported as positive and acted upon at the recommended cut-off of 1 RLU/Co. During the course of the ARTISTIC study, the following QA measures were followed: retesting of every 50th sample and participation in external QA schemes when they became available. External QA schemes included National External Quality Assessment Service (NEQAS), Quality Control for Molecular Diagnostics (QCMD) and samples sent from the Scottish HPV Reference laboratory.

Reading of cytology slides and samples

All samples were read and reported in line with current laboratory and NHSCSP guidelines as previously reported. 1 Samples were reported blind to both the allocation of the sample within the trial and the HPV test results, with the exception of slides showing low-grade abnormalities which were sent for HPV testing as part of the NHSCSP Sentinel Sites project.

Human papillomavirus testing

Hybrid Capture 2 cut-off values

Unless otherwise stated, HC2 results have been reported using a cut-off RLU/Co of 1 or greater. The alternative cut-off of 2 RLU/Co has been calculated for the purposes of comparison with a cut-off of RLU/Co of 1 or greater and these cut-offs have been clearly identified where relevant.

Changes to human papillomavirus genotyping protocol

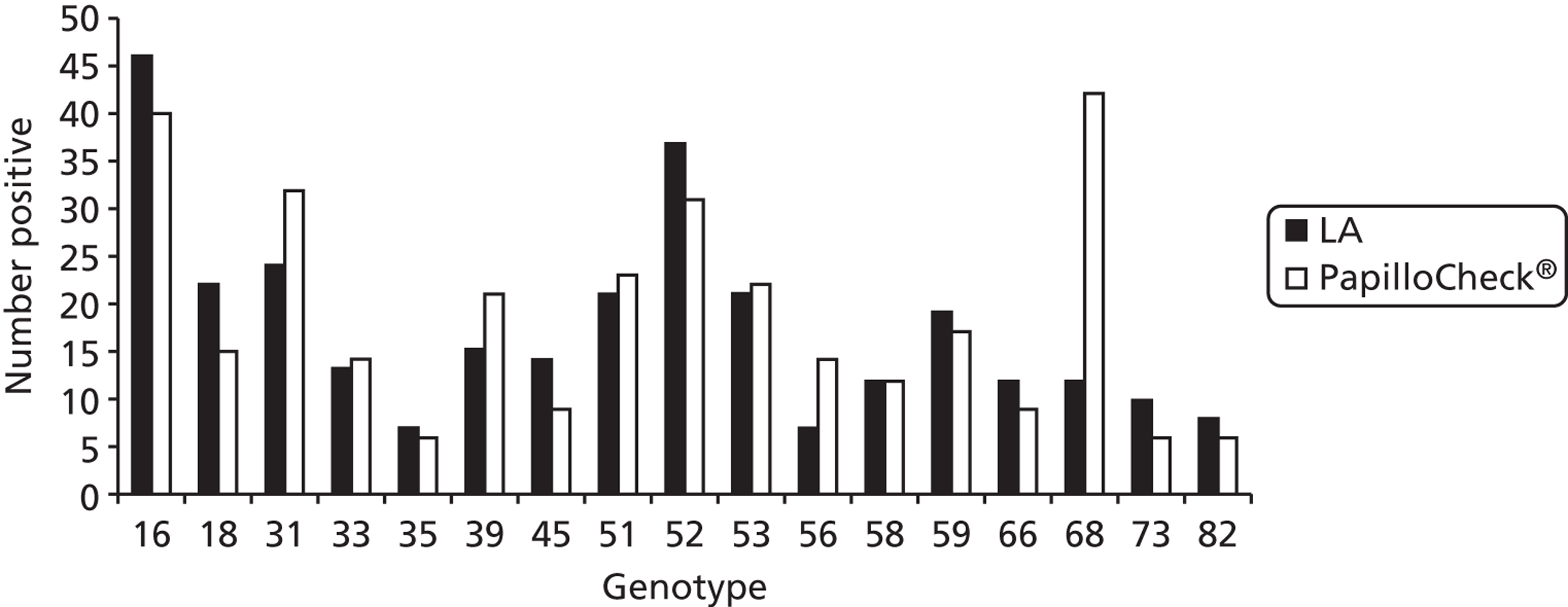

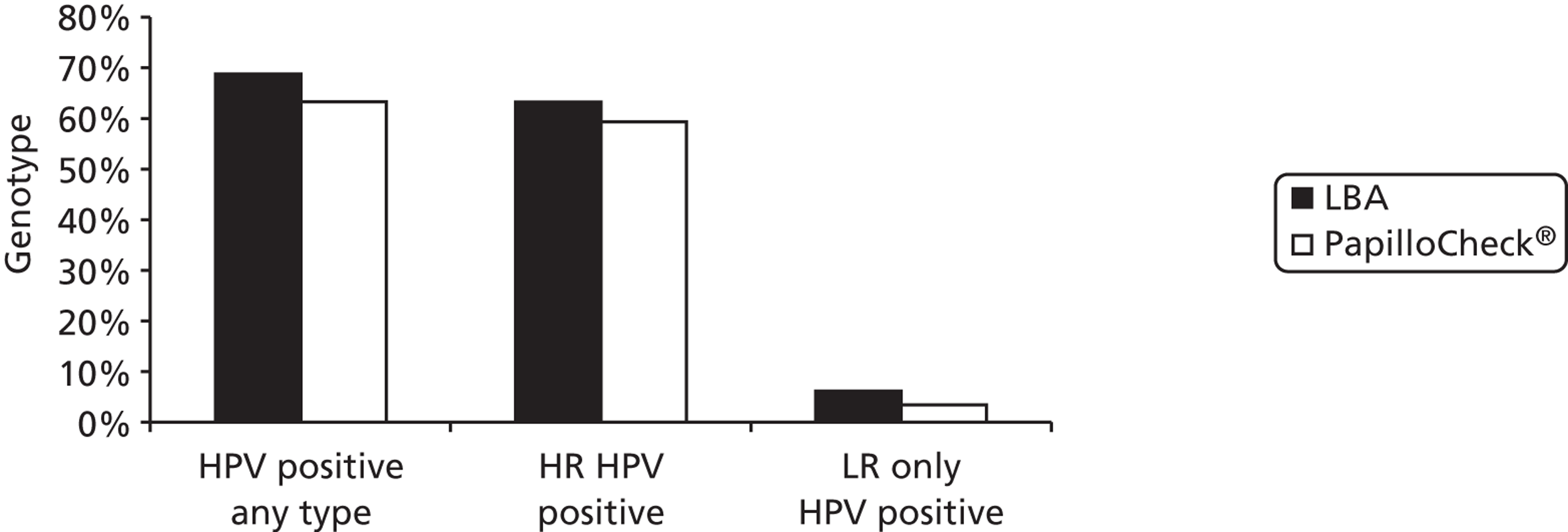

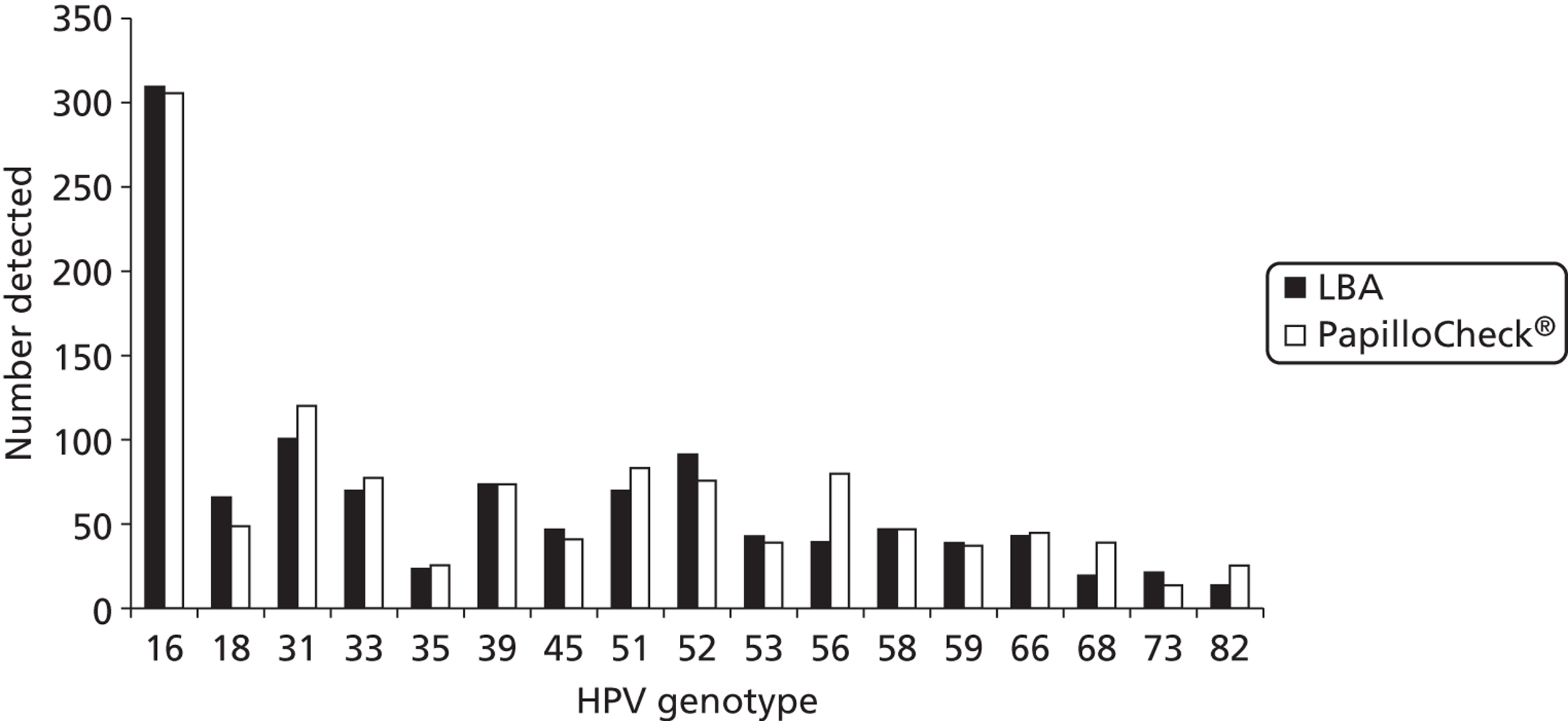

Three typing assays for HPV detection were considered during the study to genotype HC2-positive samples. All of the HC2-positive samples accrued during the original trial were genotyped using the prototype Roche Line Blot Assay® (LBA) as previously described. 1

In order to compare typing assays, two-thirds of HC2-positive round 1 archived samples were also tested by the Greiner Bio-One PapilloCheck® assay (Greiner Bio-One GmbH, Frickenhausen, Germany). In round 2, one-third of archived HC2-positive samples were tested by the Roche Linear Array® (LA) (Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Pleasanton, CA, USA). As a result of the prototype LBA being replaced with the commercially available LA assay during the extension period of this study, only 34% of HC2 positive samples in round 3 were actually tested by the LBA. The remainder were tested using PapilloCheck® only (23%), LA only (15%) or both PapilloCheck® and LA (28%). In order to present as many genotyping data as possible, typing results using the PapilloCheck® assay have been included. Any type detected by any of the assays used on a particular sample in all rounds were considered in the analysis.

Human papillomavirus genotyping by the Greiner Bio-One PapilloCheck® test

The PapilloCheck® HPV test is a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based assay designed to simultaneously detect and genotype 24 mucogenital HPV types including the 13 HR types targeted by the HC2 test (Qiagen, Gaithersberg, MD, USA). The PapilloCheck® test uses a consensus primer set targeting the E1 region of the HPV genome followed by HPV-type specific product detection using a micro-array hybridisation system.

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) extraction for the PapilloCheck® assay was carried out using the Nuclisens easyMAG automated extraction system (bioMérieux, Inc., Durham, NC, USA). Storage samples (4) were thawed and 50 µl was added to the appropriate well in the easyMAG carrier strip. Twenty-four samples were extracted at a time. The purified total nucleic acid was eluted in 100 µl of extraction buffer, which was transferred to a 2-ml vial for storage at −70 °C prior to amplification.

A 350-bp fragment within the E1 region of the HPV genome was amplified by PCR using a broad-spectrum consensus primer set. In addition, a fragment of the human ADAT1 gene was amplified and fluorescently labelled with Cy5 in the same reaction. This acted as an internal control to assess the quality of DNA. The amplified products were then hybridised to HPV type-specific oligonucleotide probes immobilised onto a DNA chip and were detected by the binding of a Cy5-dUTP labelled oligonucleotide. After hybridisation and subsequent washing, the PapilloCheck® DNA chip was scanned using the CheckScanner apparatus (Greiner Bio-One GmbH, Frickenhausen, Germany) at excitation wavelengths of 532 and 635 nm. Evaluation and analysis of the DNA chip was carried out using the CheckReport analysis software.

Human papillomavirus detection by the M2000 Abbott real-time high-risk human papillomavirus assay

During the course of the ARTISTIC trial the virology laboratory was invited to participate in the Abbott HPV early access evaluation programme. The Abbott test was performed on archived samples for which women had consented to further testing. None of the Abbott results were acted upon clinically.

The recently introduced highly automated Abbott real-time HR HPV assay is a PCR-based real-time assay designed to detect 14 HR HPV genotypes (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66 and 68). By the use of different dyes, the assay identified infection with types 16 and 18 singly while the 12 remaining types were detected as a group. Following extraction of DNA from the LBC sample using the Abbott M2000sp extraction robot (Abbott Molecular, Maidenhead, UK), any HR HPV DNA present in the sample was amplified and detected simultaneously using the Abbott M2000rt sequence detection system. The system also co-amplified and detected a portion of human DNA which acted as a sample integrity control.

A 400-µl aliquot of ThinPrep® Medium (Hologic, Inc., Bedford, MA, USA) was added to 100 µl of archived sample prior to DNA extraction using the M2000sp as per the Abbott protocol. Following DNA extraction, any HR HPV DNA was amplified and detected using the M2000rt system as per the recommended protocol.

Statistical analysis

Definitions

Women were eligible if they were aged 20–64 years when they provided a round 1 sample which was defined as the first cytologically adequate sample after randomisation at entry that gave a satisfactory HPV result. Many women attended their next routine screen earlier or later than the scheduled 3-year recall. Originally, ARTISTIC round 2 was defined as 30–48 months after entry. This resulted in CIN2+ lesions being excluded and, in the HTA ARTISTIC report,1 the broader definition of 26–54 months was also used. This latter definition, which was used in the Lancet Oncology manuscript,2 was employed in this current report. Alternative results are shown in Appendix 3 of this report defining round 2 as the first sample 30–48 months after the round 1 entry smear. The round 3 sample was defined as the first cytologically adequate sample at least 54 months after the round 1 smear, and at least 24 months after the round 2 smear (if there was one). Women were classified histologically at round 1, round 2 and round 3 on the basis of the highest grade of histology within 30 months of the round 1, round 2 or round 3 cytology. Women with CIN2 histology or worse (CIN2+) were excluded from subsequent rounds.

Women were followed for cytology until the end of June 2009 and for histology to October 2009. Follow-up was based on cytology and histology reports received by the laboratories in Manchester and Stockport. Cytology and histology taken outside these areas were not available.

Persistent infection at round 2 was defined as detection of one or more of the same HPV types also found at round 1. Persistent infection at round 3 was defined as detection of one or more of the same types also found at round 1 (any round 2 result was ignored for this analysis). Positive HPV results at round 2 or 3 were thus considered to be either ‘new’ or ‘persistent’. Additionally, these HPV positive results were split by HPV type present (according to the previously defined hierarchy and groupings) at round 2 or 3. CIN2+ and CIN3+ rates have been presented for new and persistent infections. HC2-positive results where no HR type was detected have been considered to be ‘new’ infections; hence, no exclusions were made in the analysis.

Data collection

Data were collected as described in the original HTA monograph. 1 For round 3, all patient identifiers, bar the unique trial identifying number, were removed from the database on the advice of the ethics committee.

Data analysis

Human papillomavirus prevalence, cytological abnormality and CIN2+ rates were tabulated by combinations of round, age at round, randomisation arm and HPV status at entry or at round. HPV status was split further by main HPV type identified: (1) HPV 16 or HPV 18, (2) HPV 31, HPV 33, HPV 45, HPV 52 and HPV 58 and (3) other HC2 positive, including HC2-positive samples where none of the 13 types was identified. The rationale behind these groupings was that 16/18 are the types targeted by the Cervarix™ vaccine (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, Rixensart, Belgium), which was used in the UK vaccination programme until September 2012, after which it was switched to Gardasil® (Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., Merck & Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA). The Cervarix™ vaccine has also been reported to exhibit a degree of cross-protection against types 31/33/45/52/58. According to published efficacy data, Cervarix achieved 98% efficacy against 16/18 related CIN2+, 68% efficacy against 31/33/45/52/58 related to CIN2+ and 70% against CIN2+ of any HR type in females who were HPV naive prior to vaccination. 13

Cumulative CIN2+ and CIN3+ rates were estimated as P = 1 – (1 – P1)(1 – P2)(1 – P3), where Pi denotes the proportion with disease (Di/Ni) in round i. Confidence intervals were calculated from Greenwood’s formula for the standard error: √(1 – P)2Σi{Di/[Ni(Ni – Di)]}14 (suffix numbers refer to screening round). Comparisons using two-sided Fisher’s exact test were also based on these binomial proportions. Between-round differences in rates of abnormal cytology and histology were estimated by unconditional logistic regression adjusted for age and HPV status at round, cytology (for comparing CIN2+ rates) and randomisation. All analyses were programmed in Stata 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Economic analysis

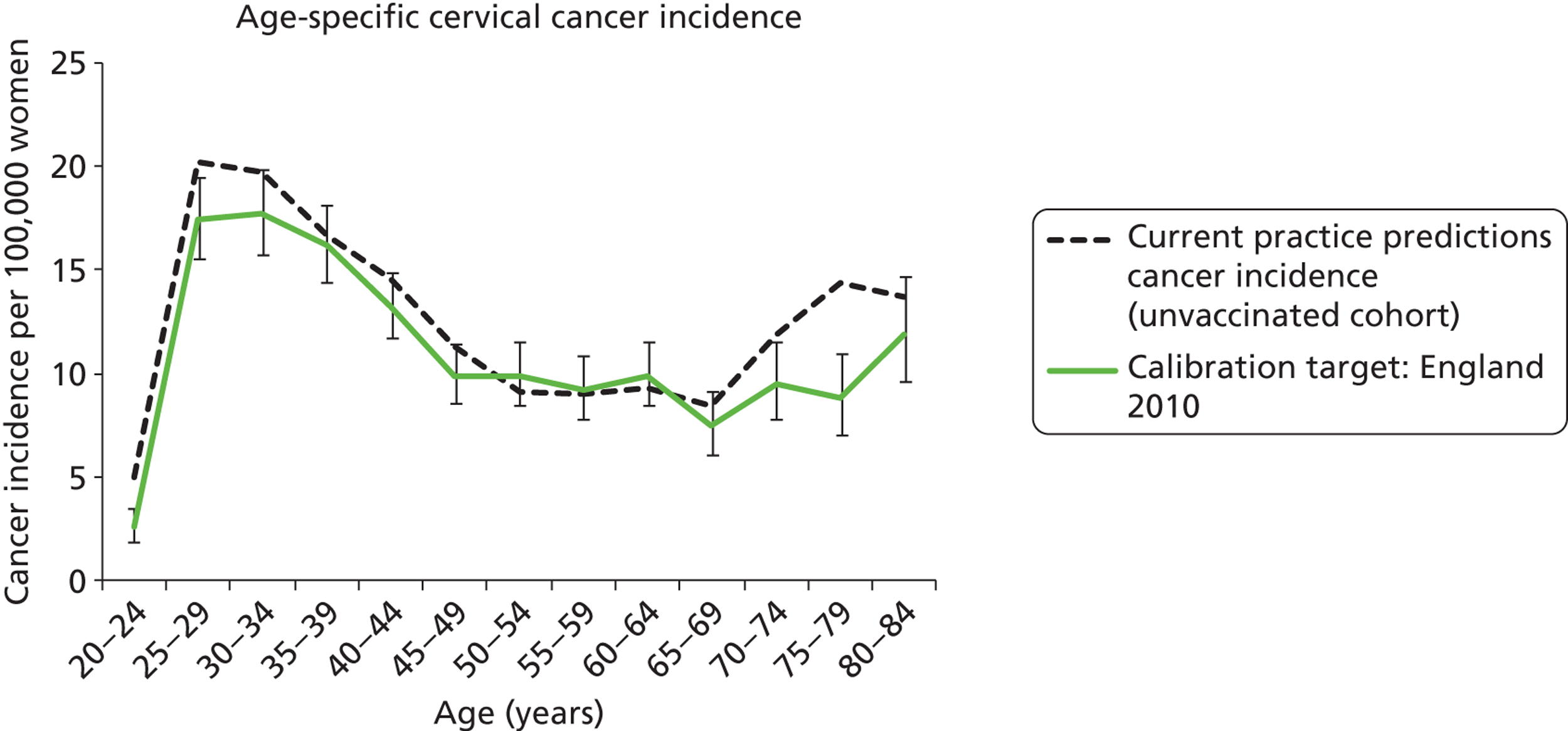

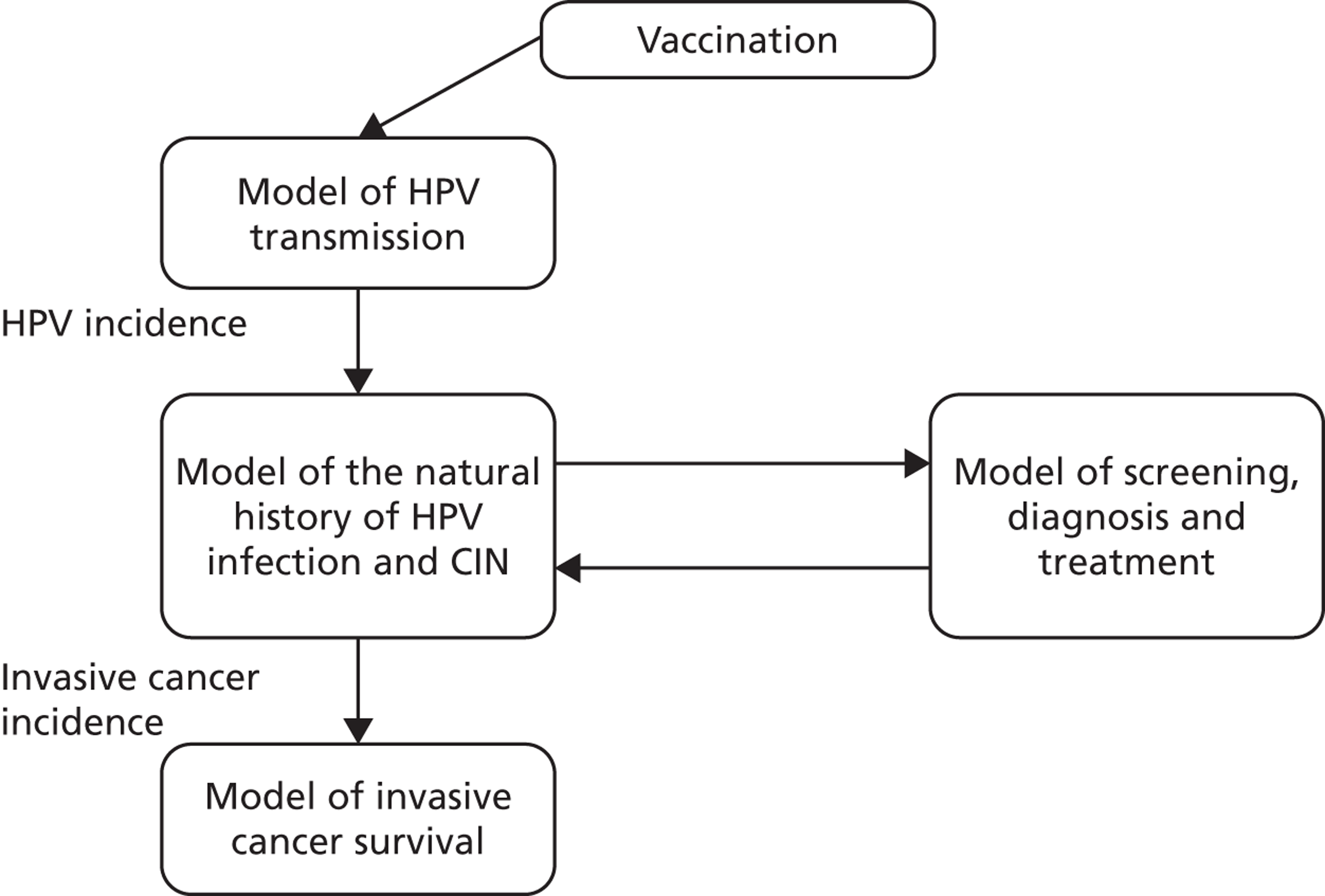

Overview of model platform used for the evaluation

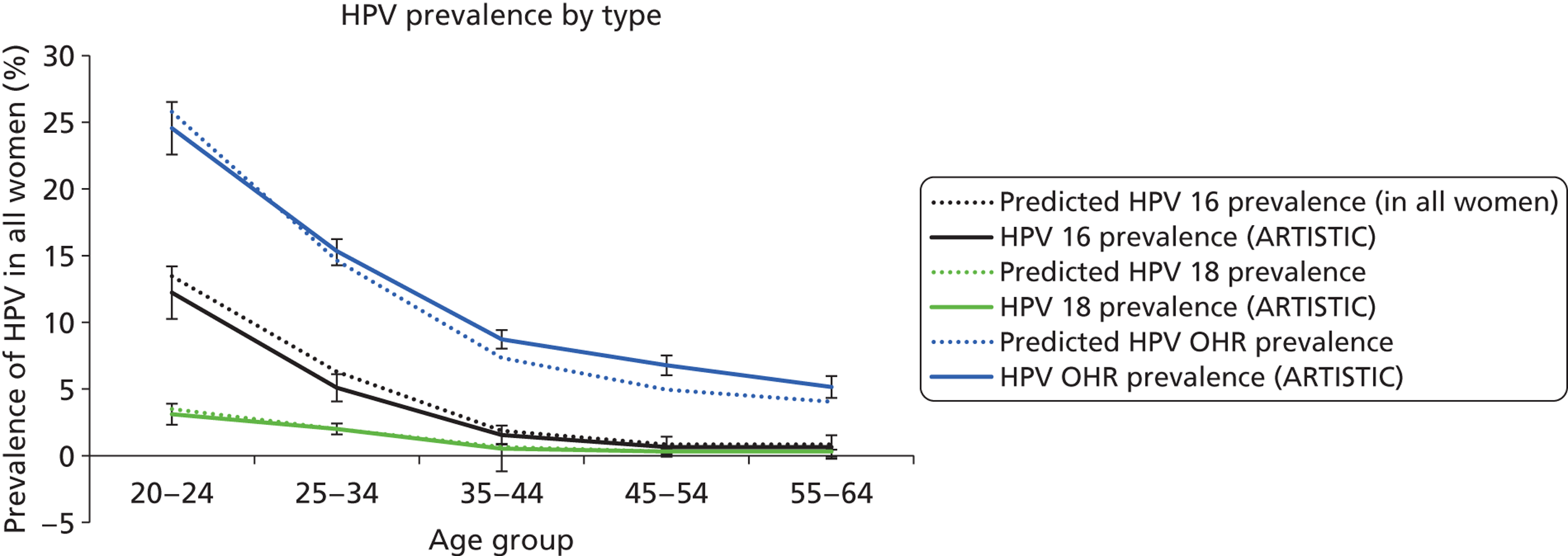

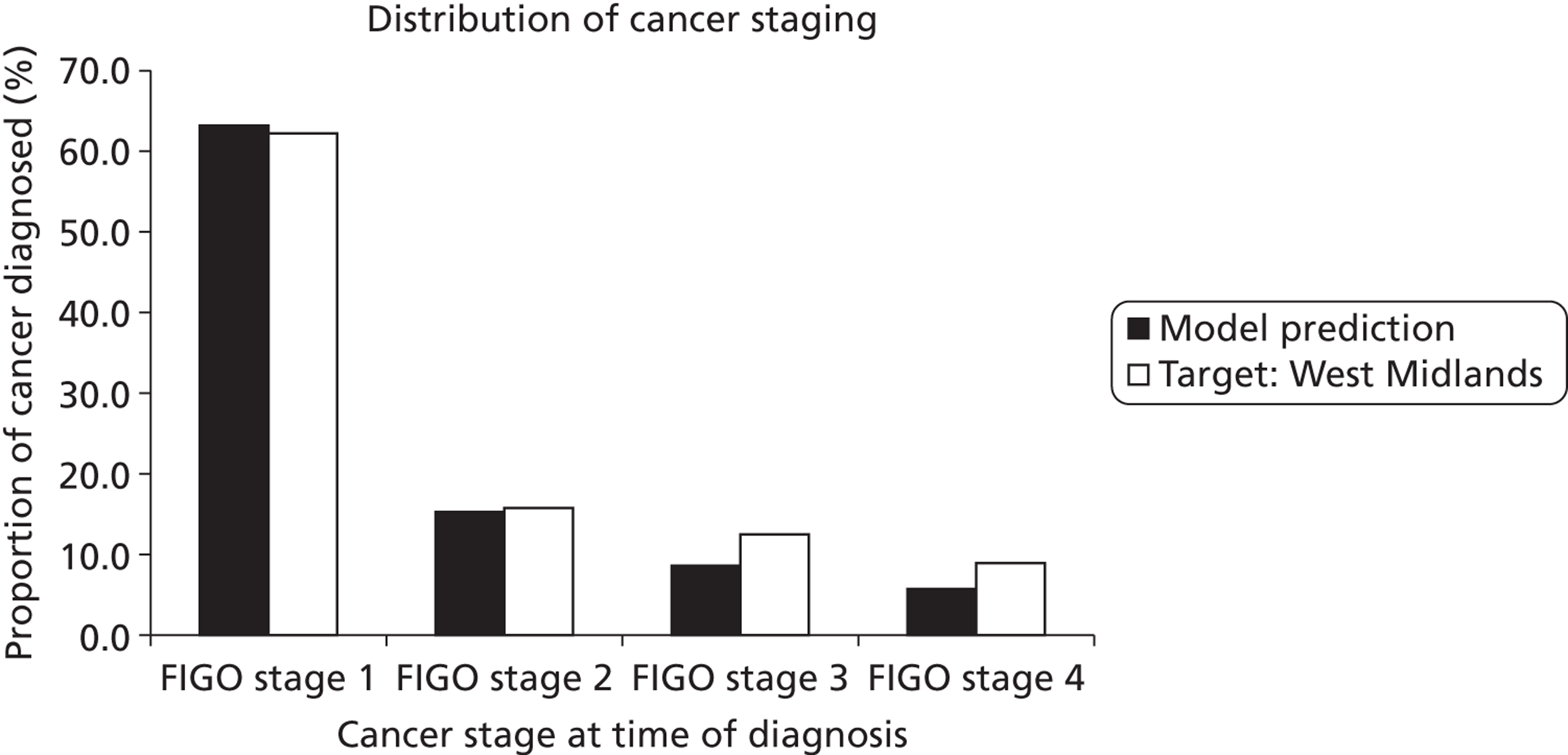

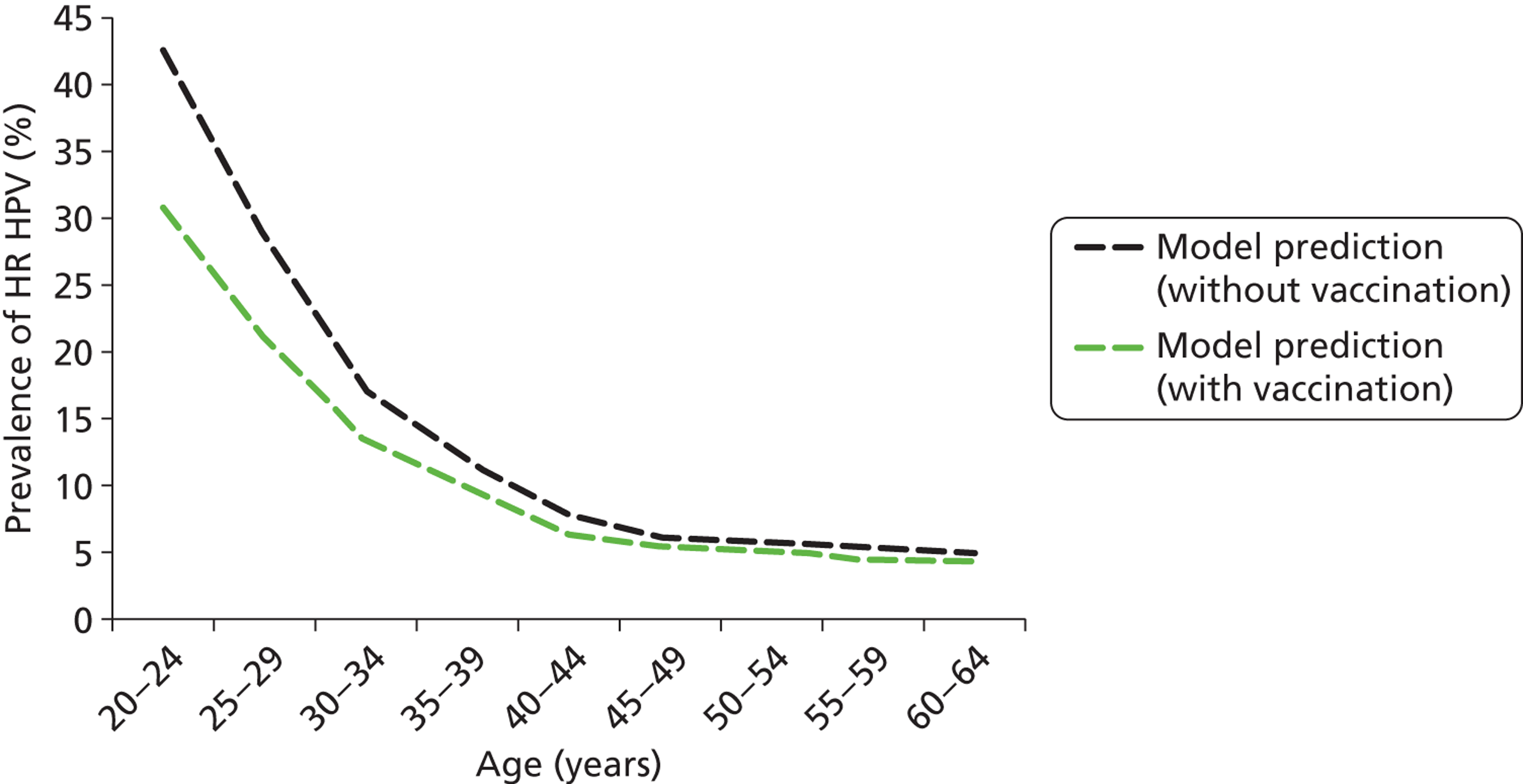

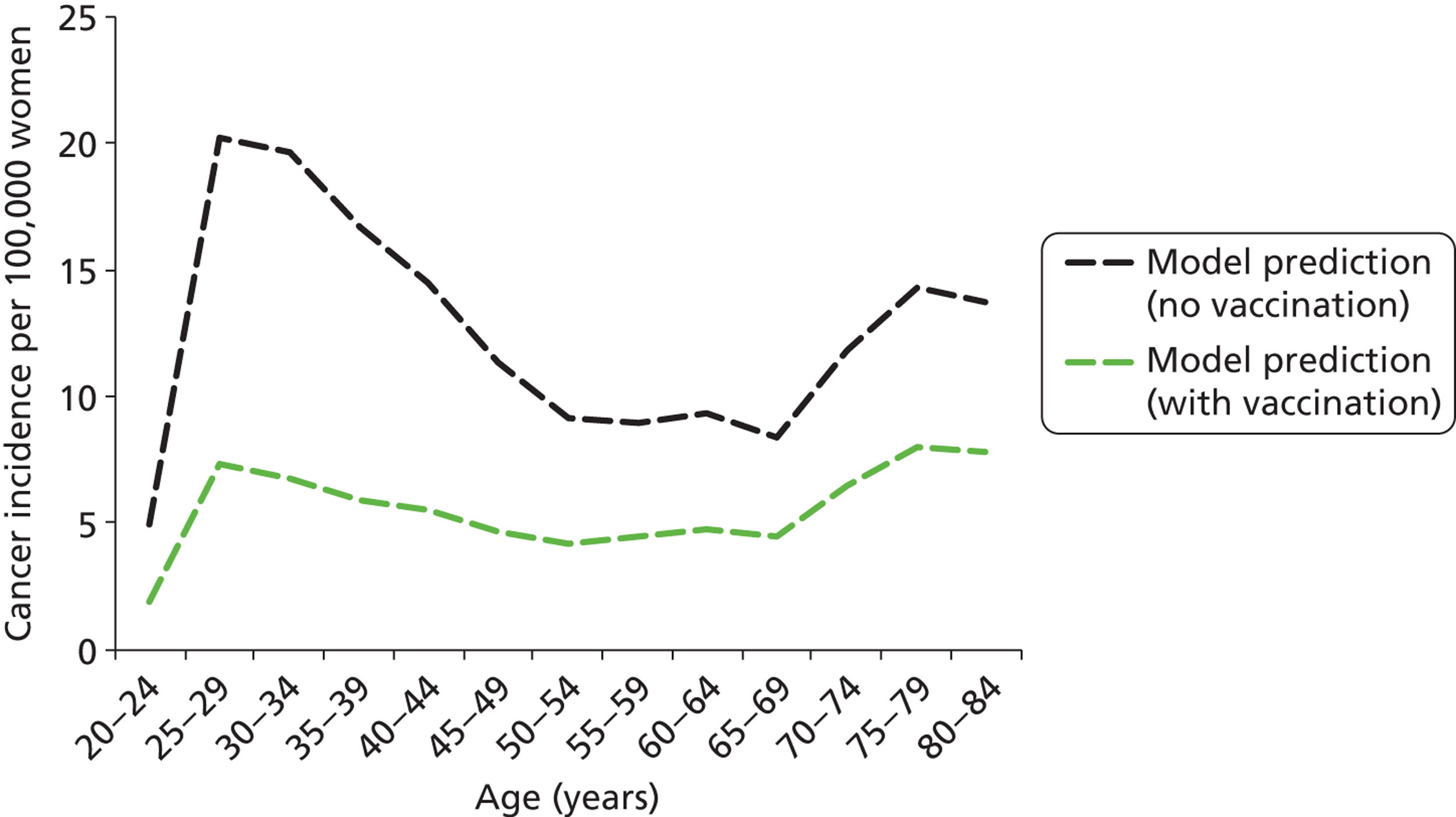

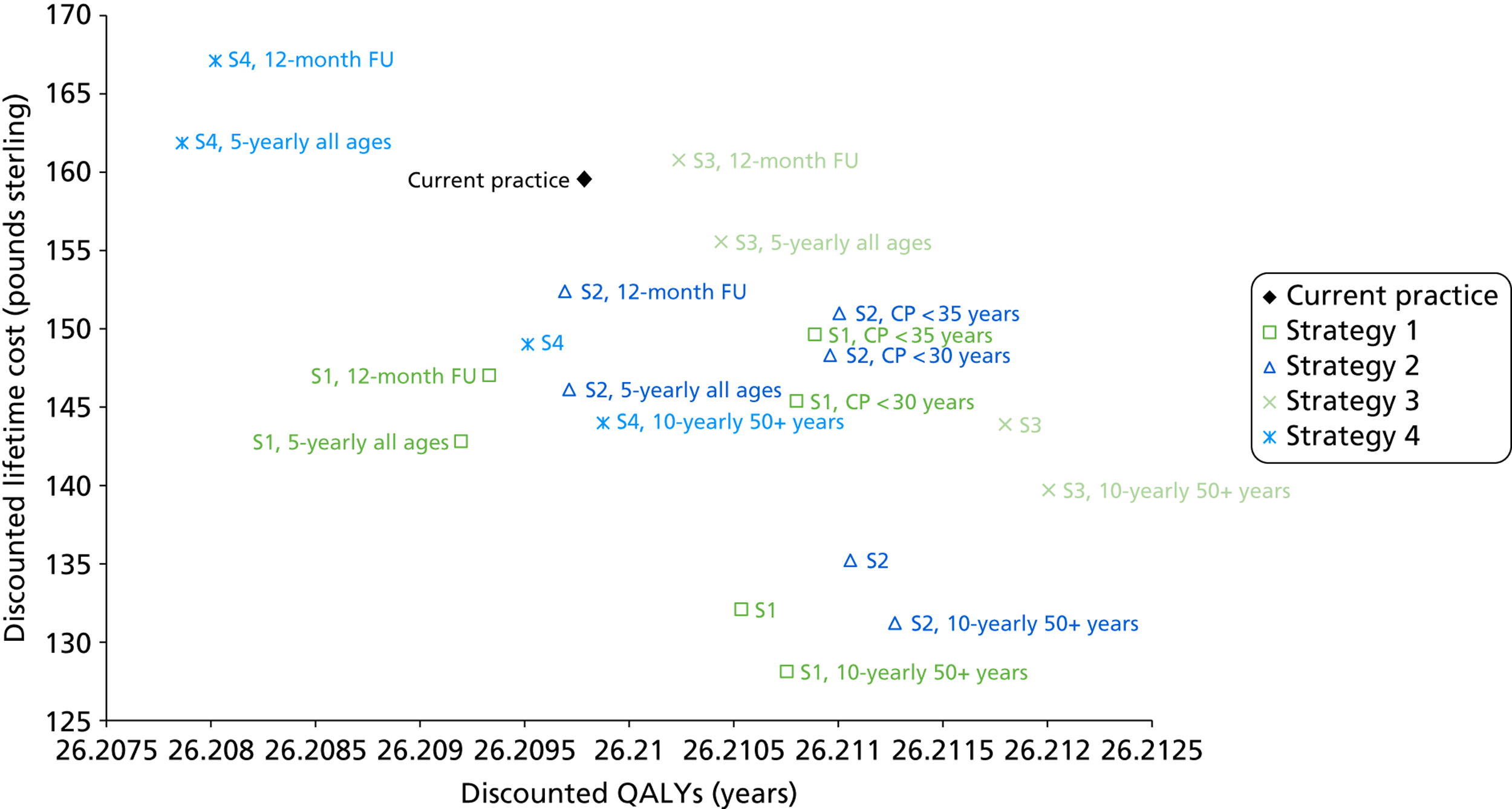

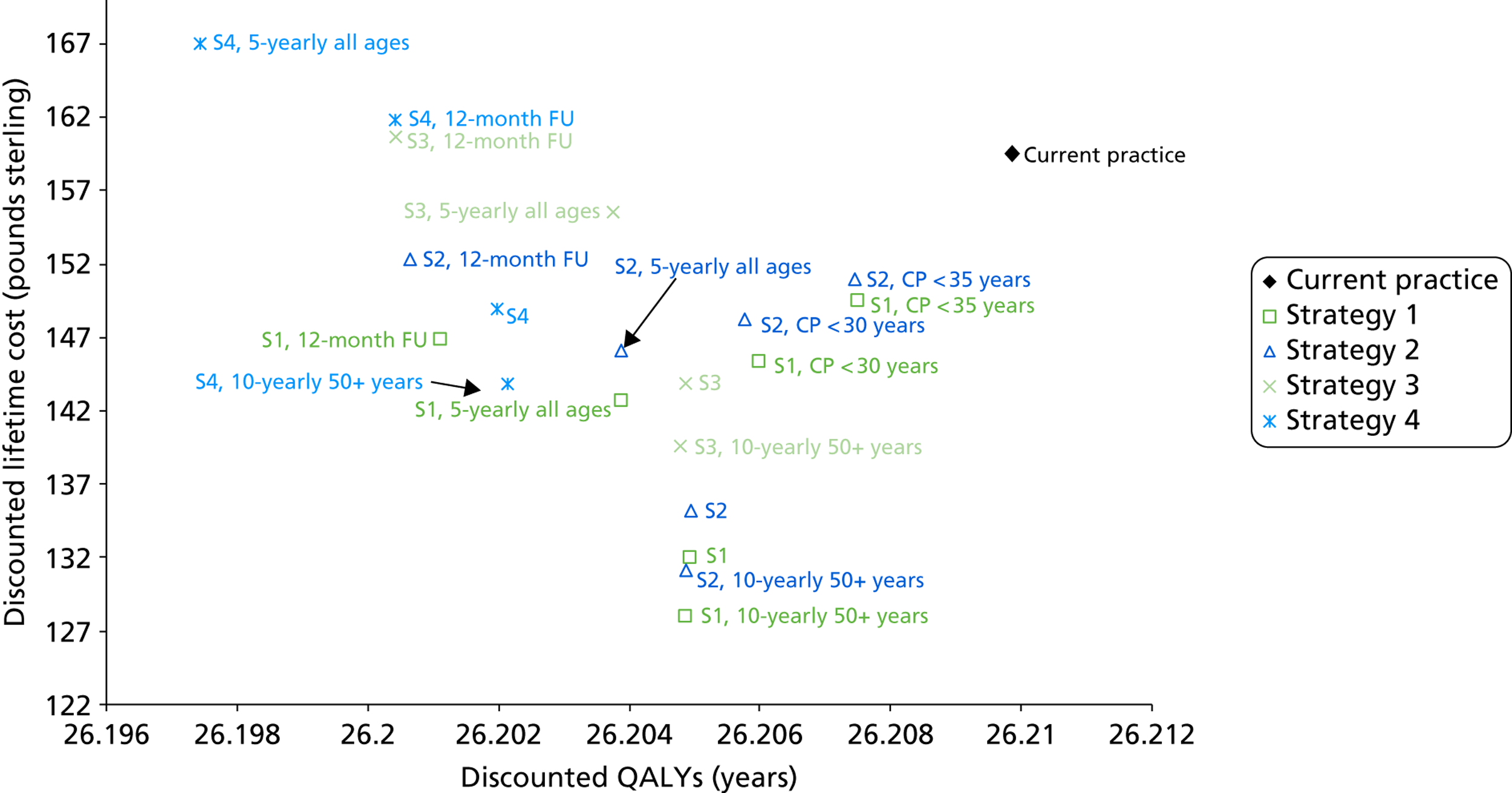

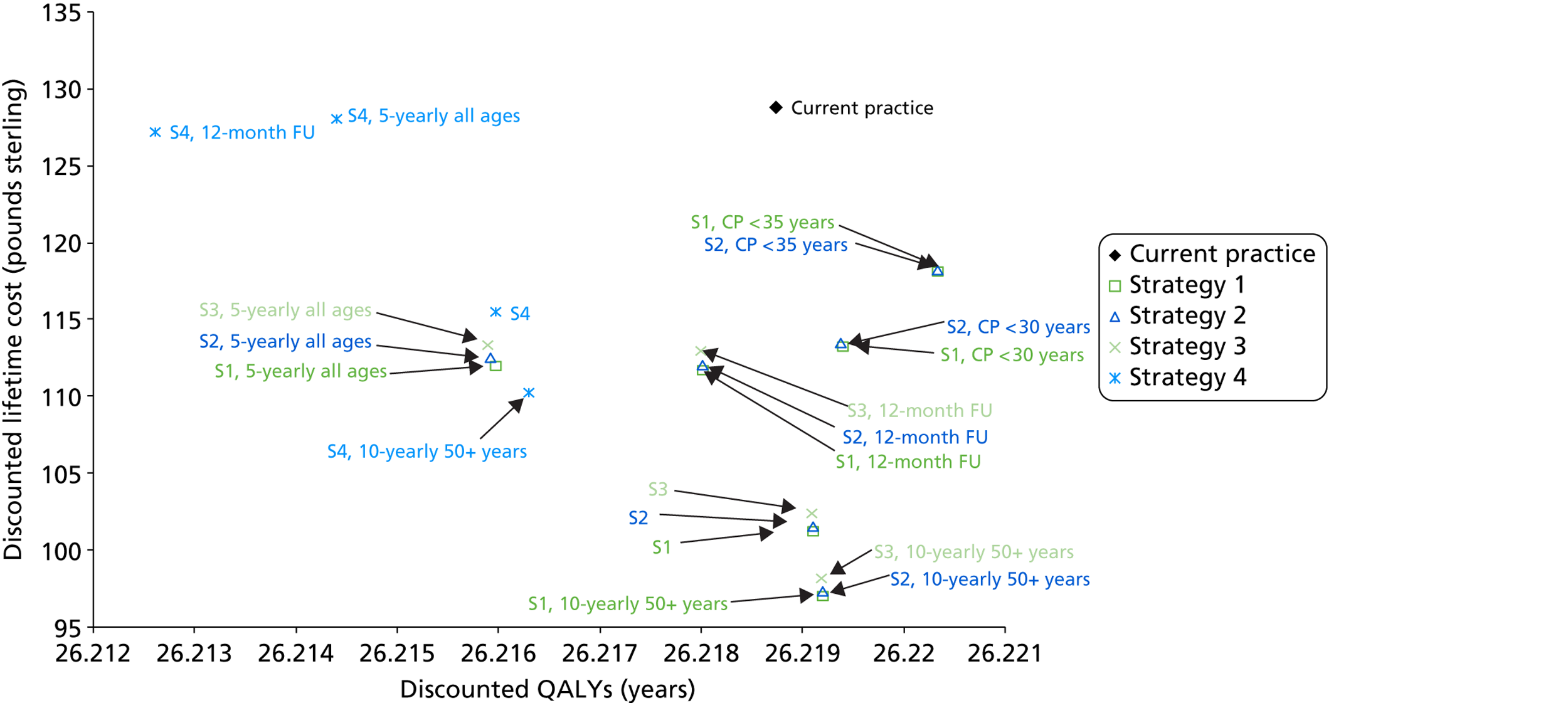

An existing model platform was adapted for the economic analysis, and the components of this platform are summarised in Figure 2. This model platform has been previously used to evaluate changes to the cervical screening interval in Australia and the UK,15,16 the role of alternative technologies for screening in Australia, New Zealand and England,17–19 the role of HPV triage testing for women with low-grade cytology in Australia and New Zealand,20 and the cost-effectiveness of alternative screening strategies, combined screening and vaccination approaches in China. 21,22 The model platform has three main components:

-

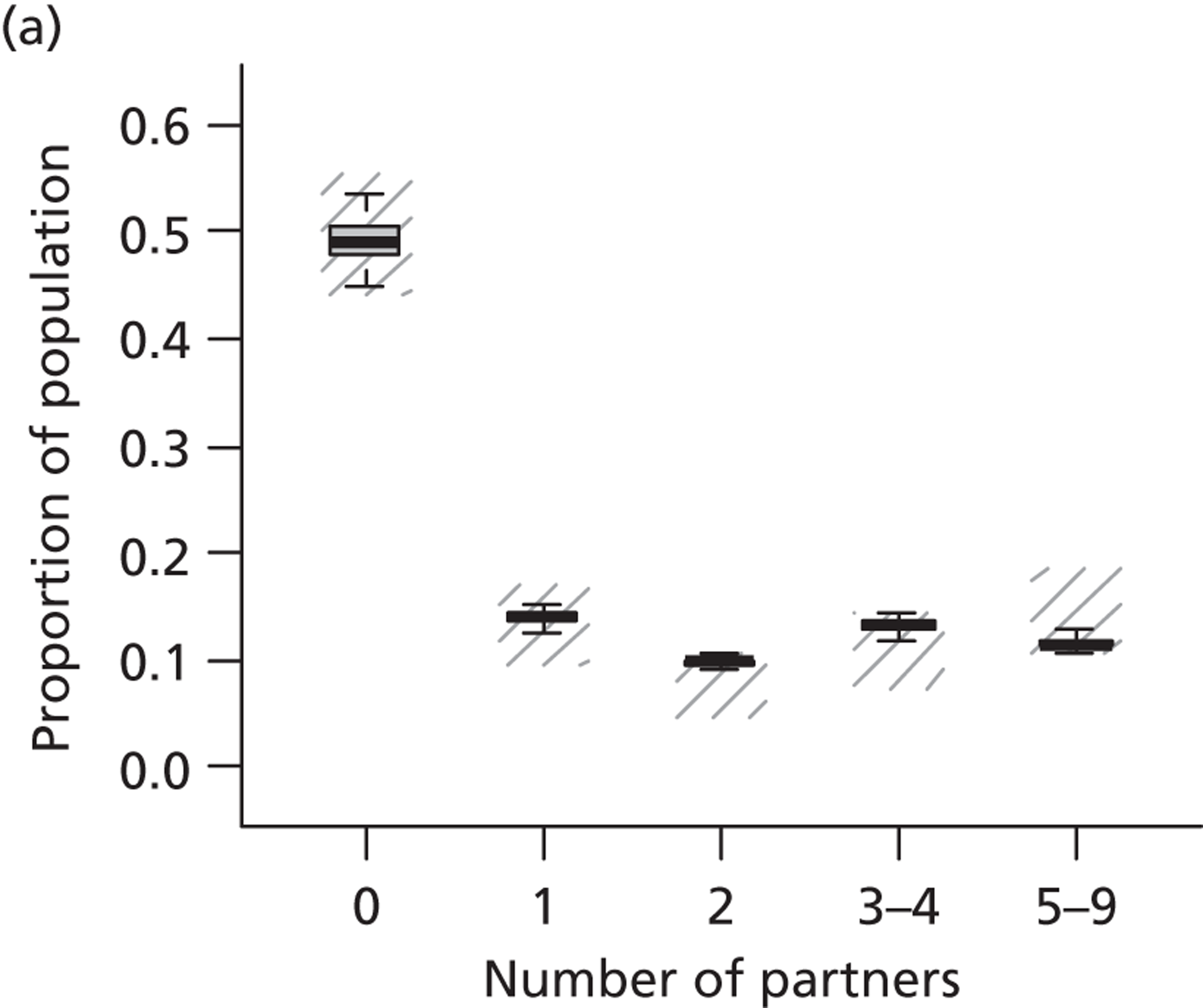

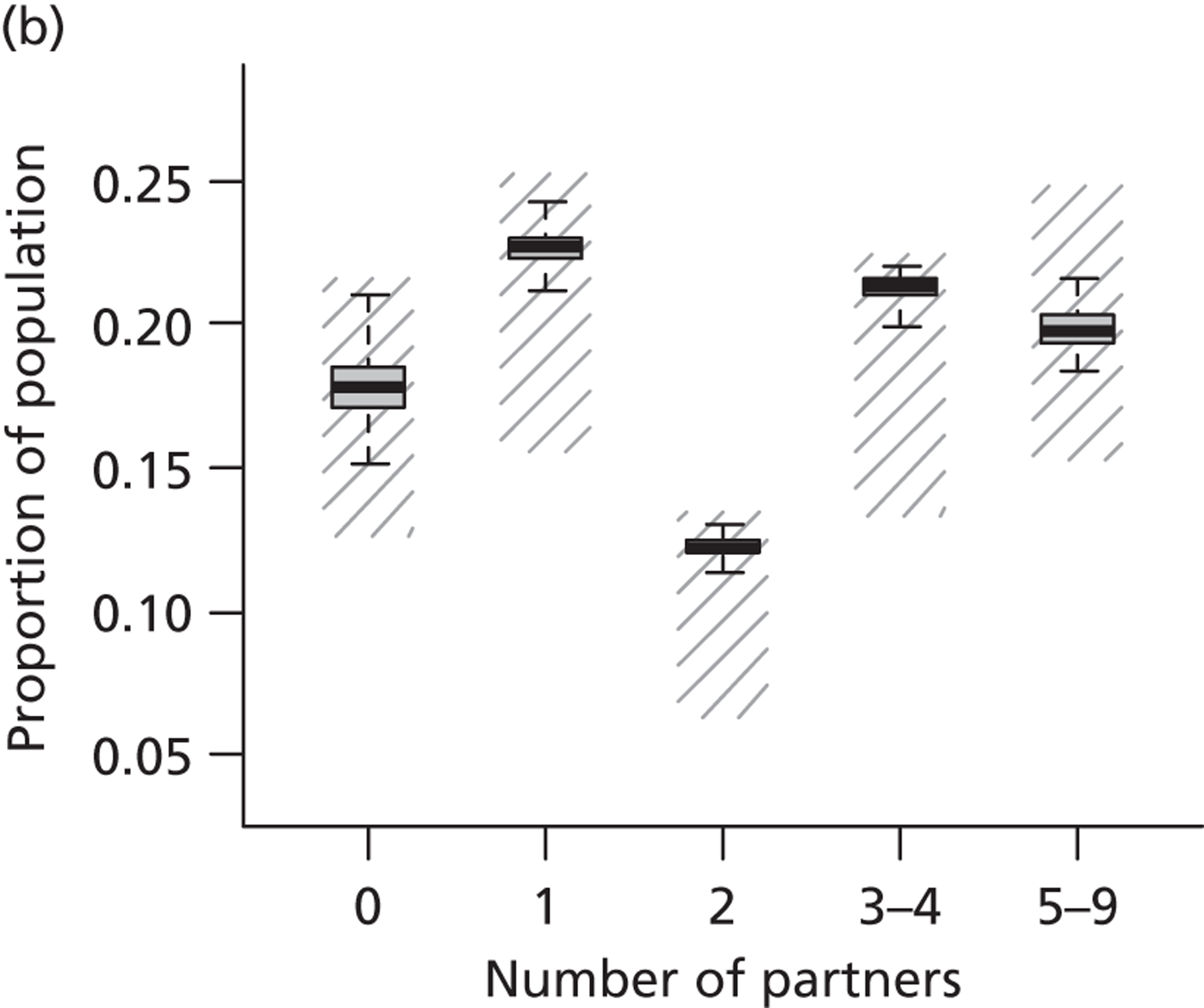

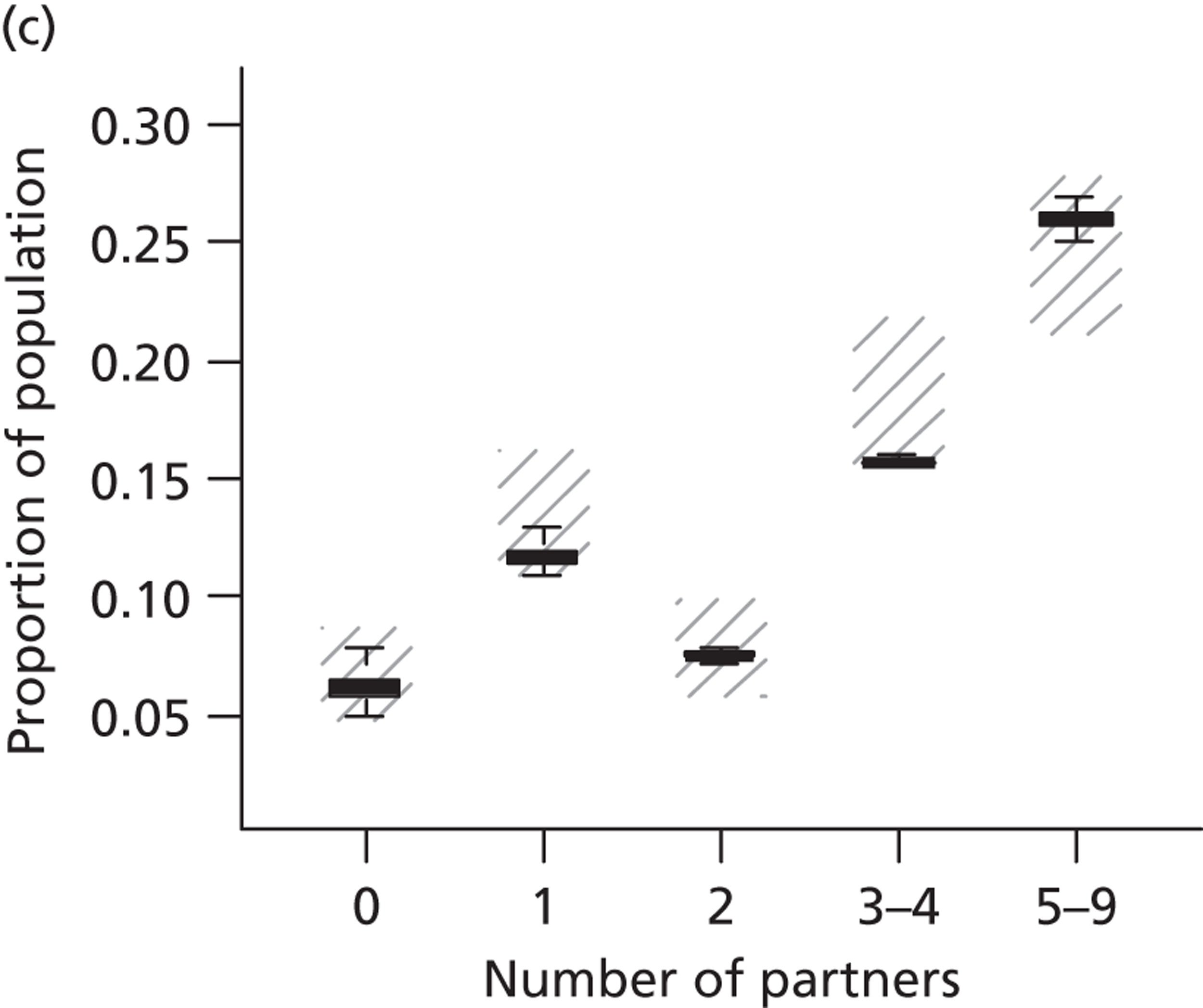

A dynamic model of sexual behaviour and HPV transmission (and vaccination as appropriate) in England. This incorporates other data from local sexual behaviour surveys,23 and information on vaccination catch-up and coverage rates in England. 24

-

A multitype Markov cohort model of the natural history of CIN and invasive cervical cancer (referred to as the ‘natural history model’). The natural history model takes into account differing clearance and progression rates associated with HPV 16 and HPV 18, compared with other oncogenic types. The model also explicitly simulates post-treatment recurrence in women previously treated for high-grade lesions.

-

A cohort and multicohort model of screening, diagnosis, treatment and post-treatment management.

FIGURE 2.

Schematic diagram of model platform.

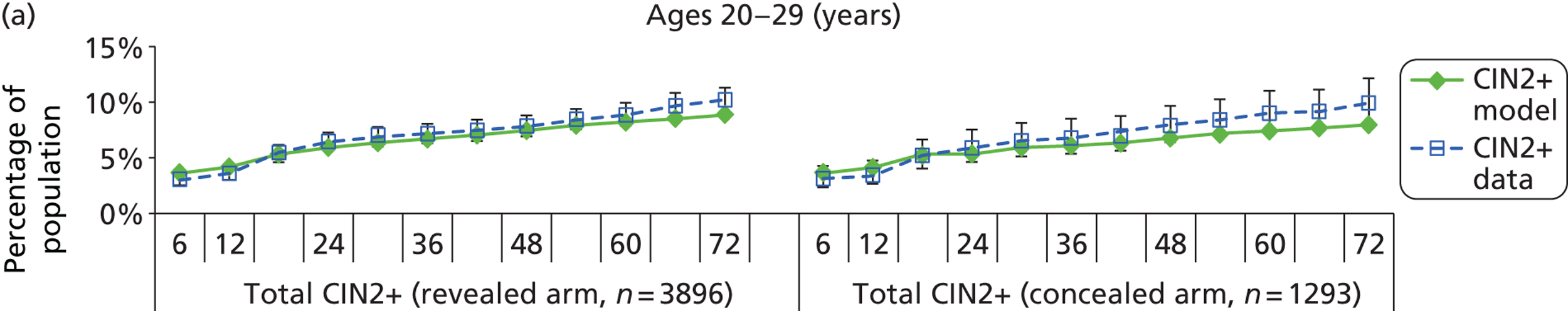

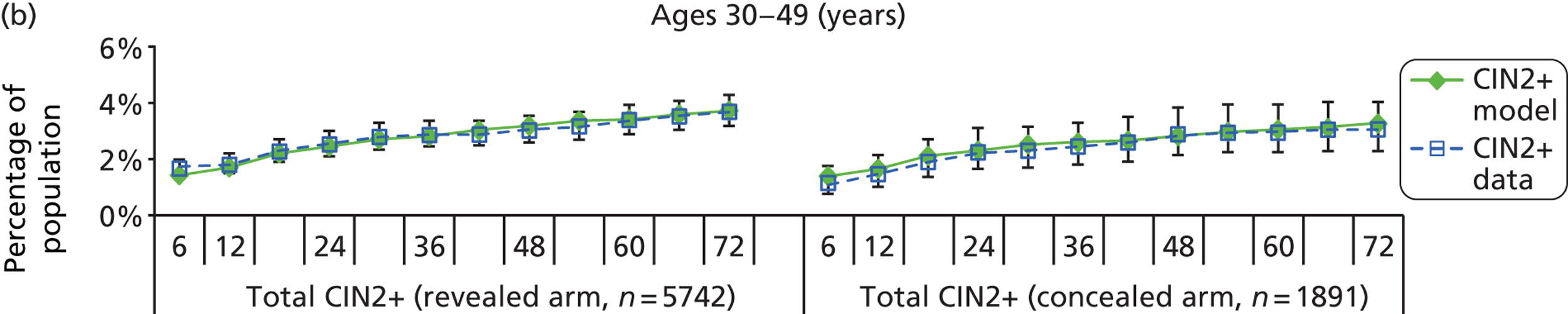

Methods for model validation against ARTISTIC data

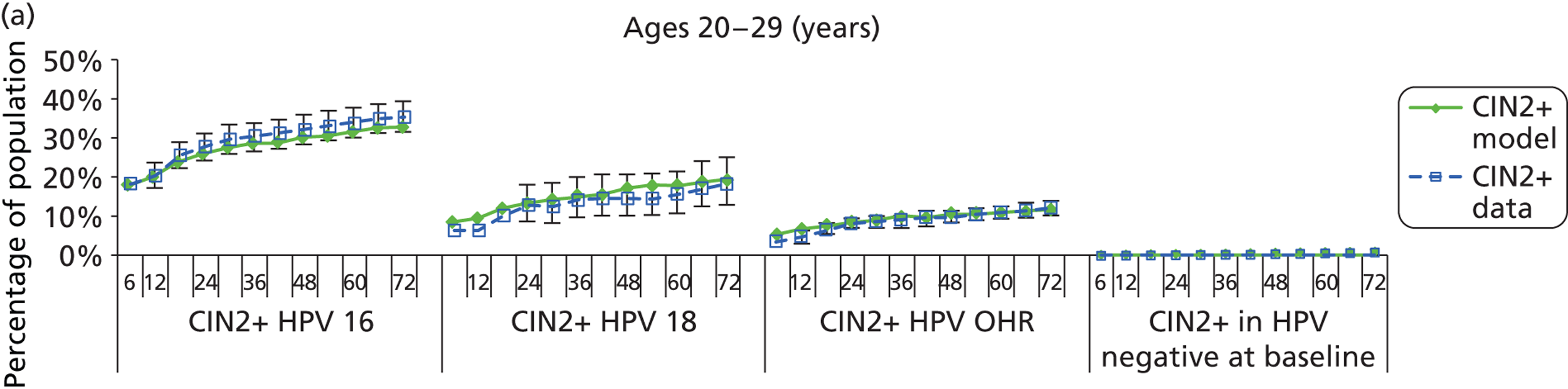

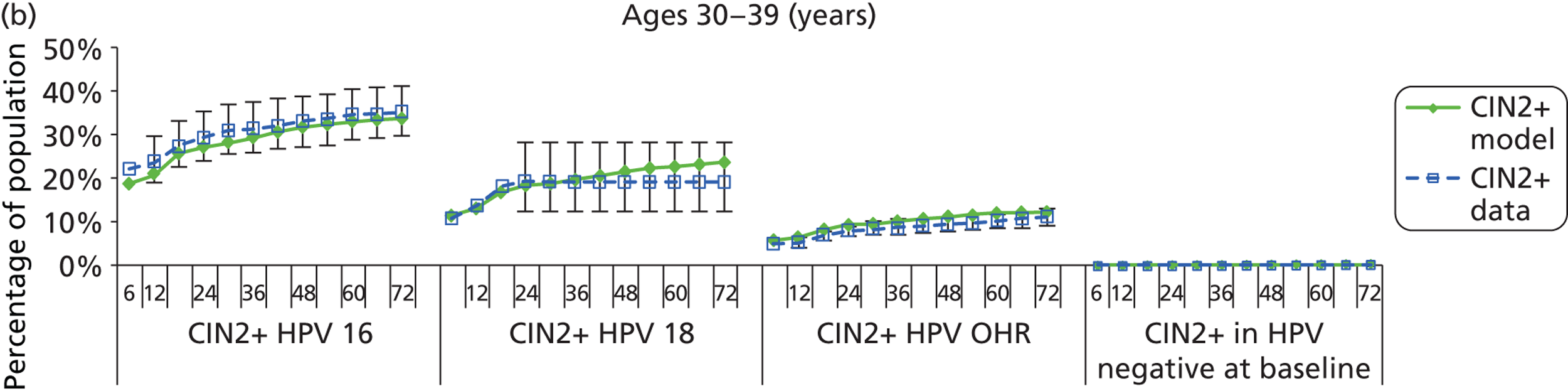

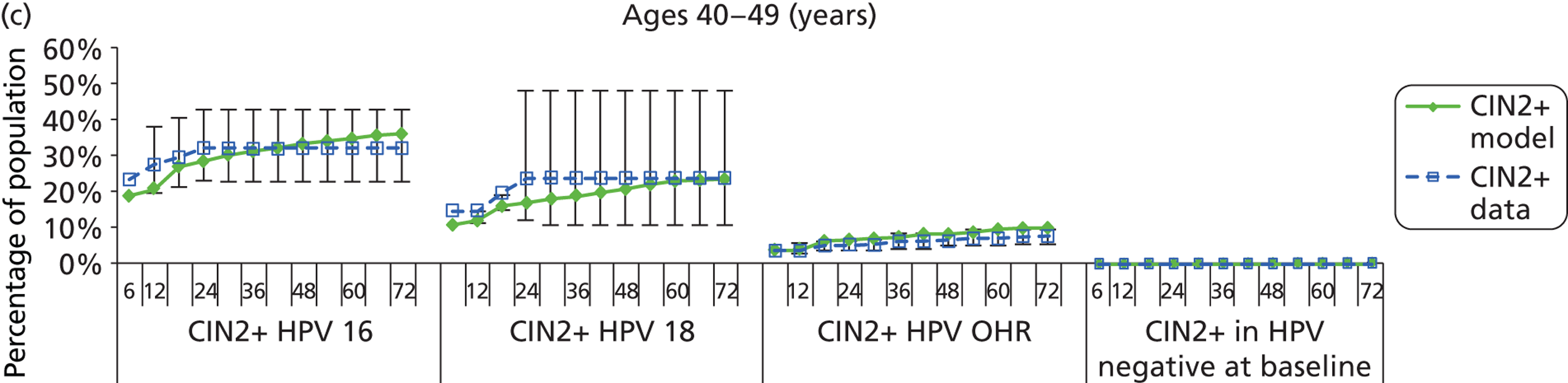

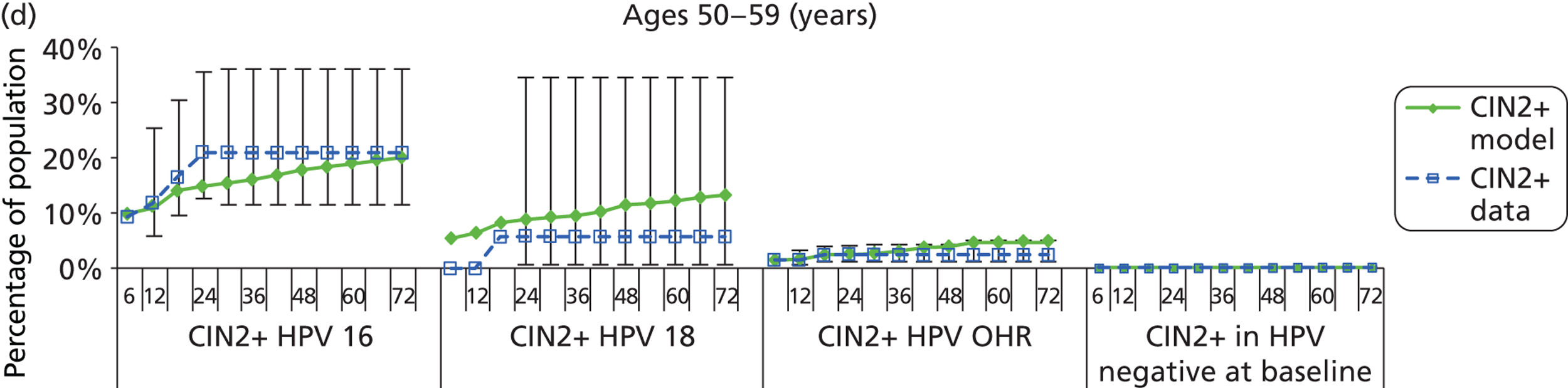

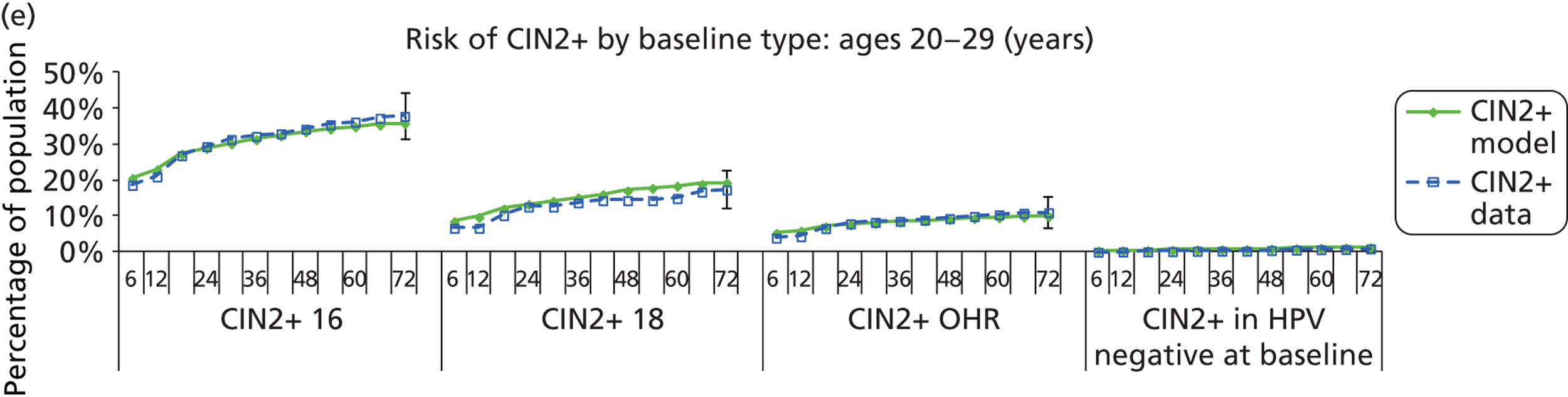

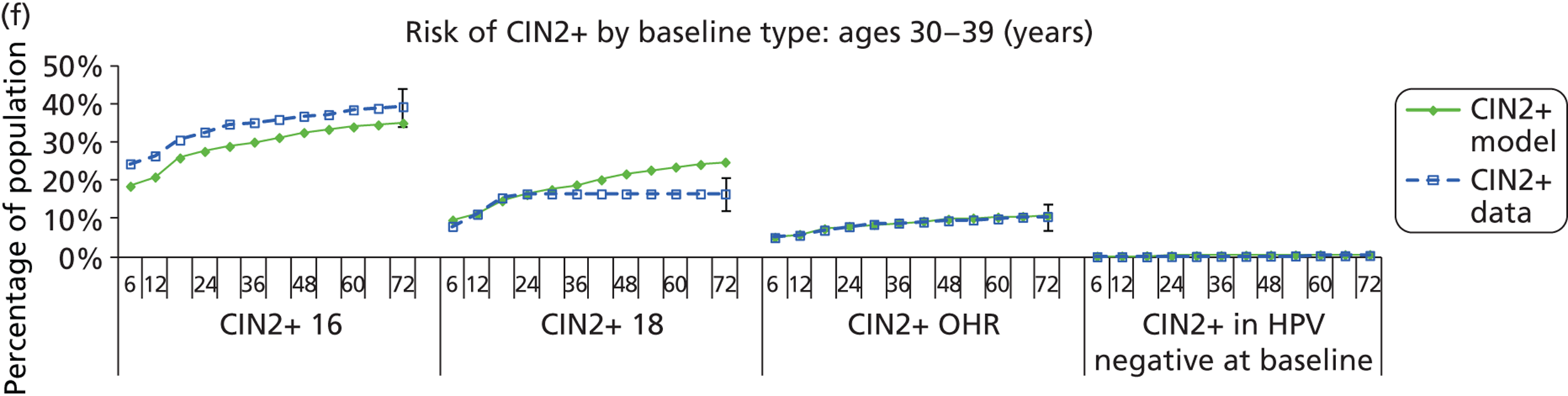

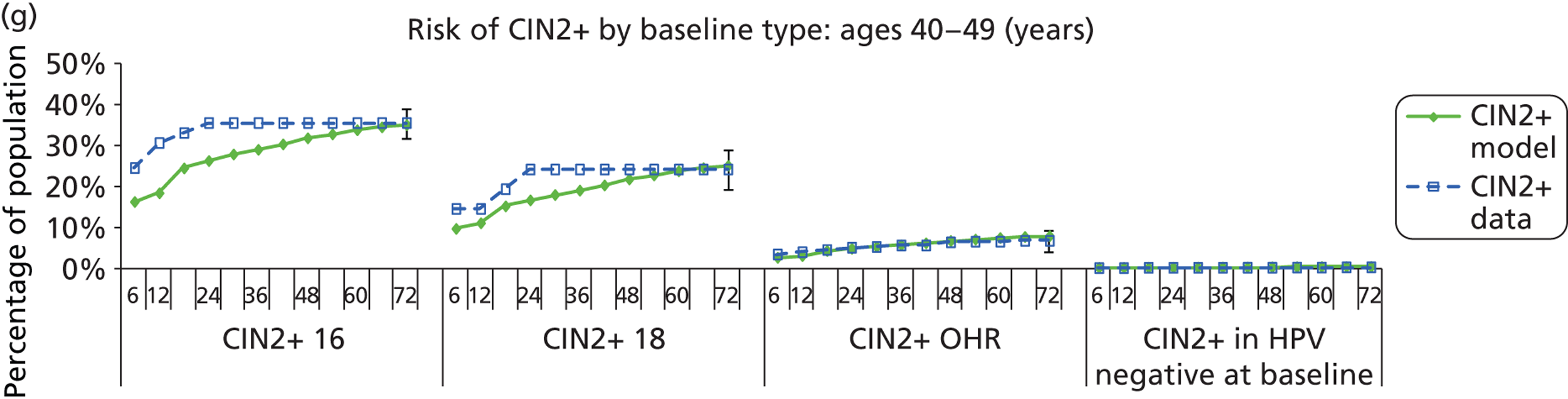

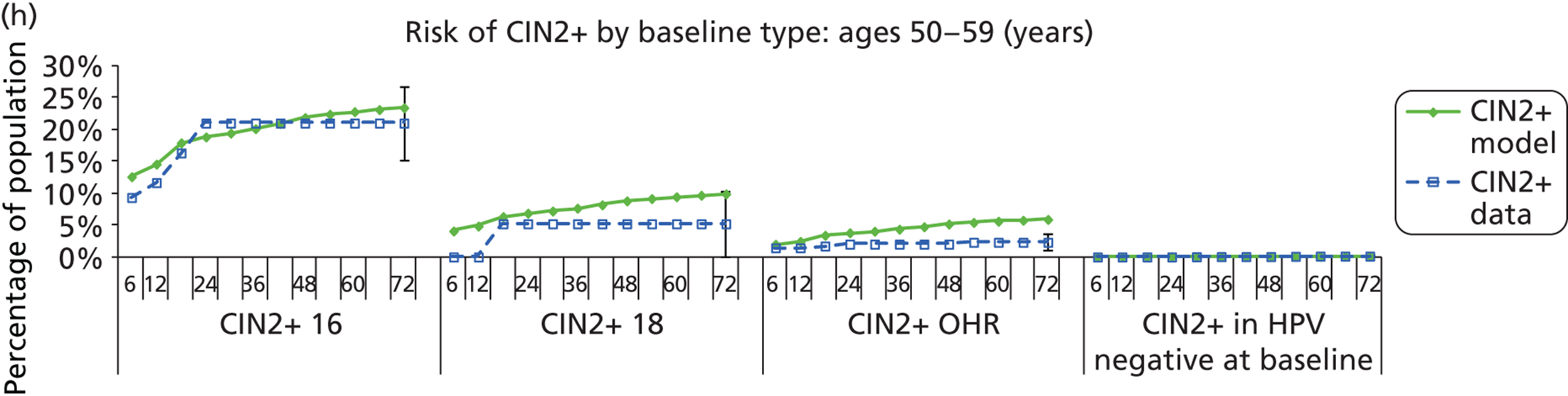

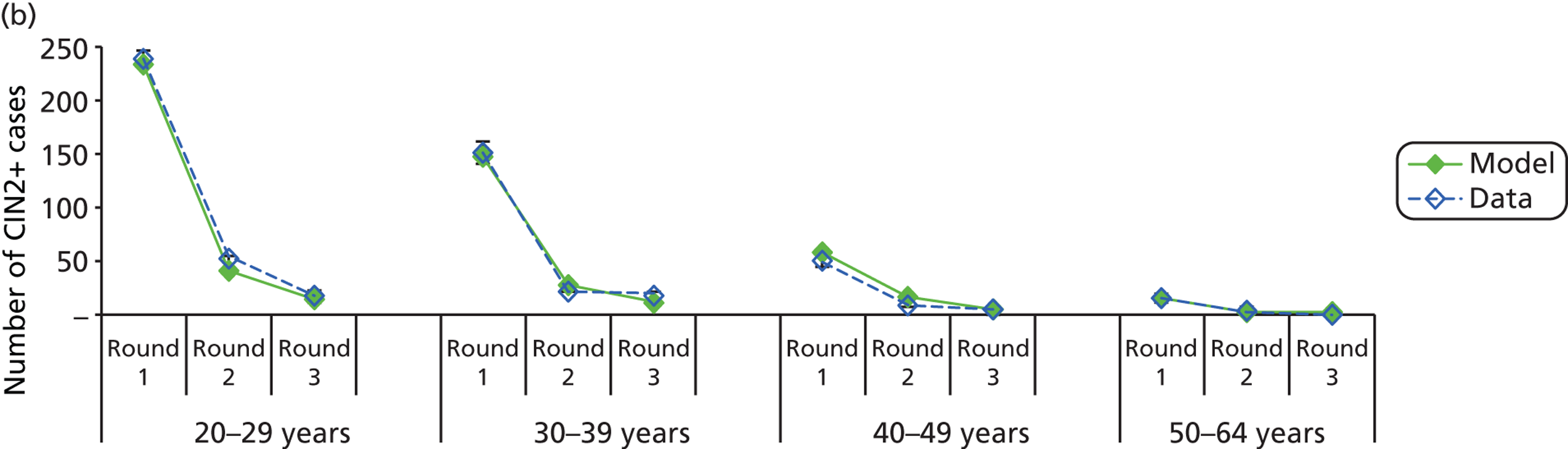

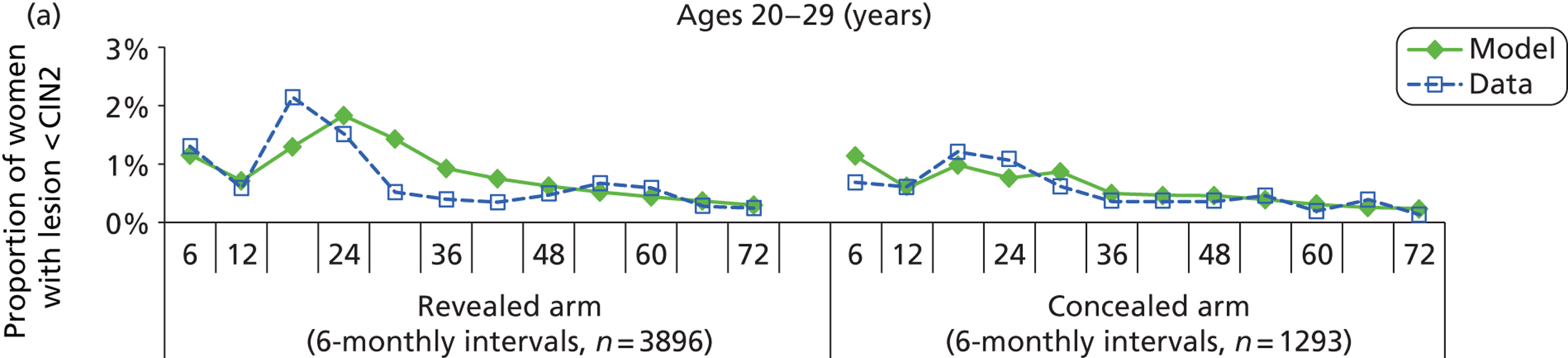

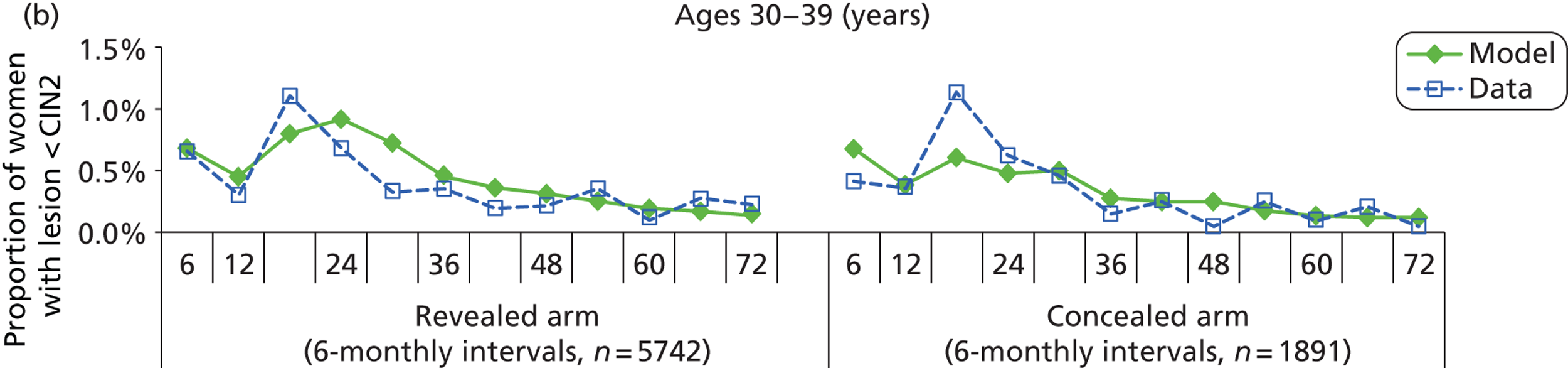

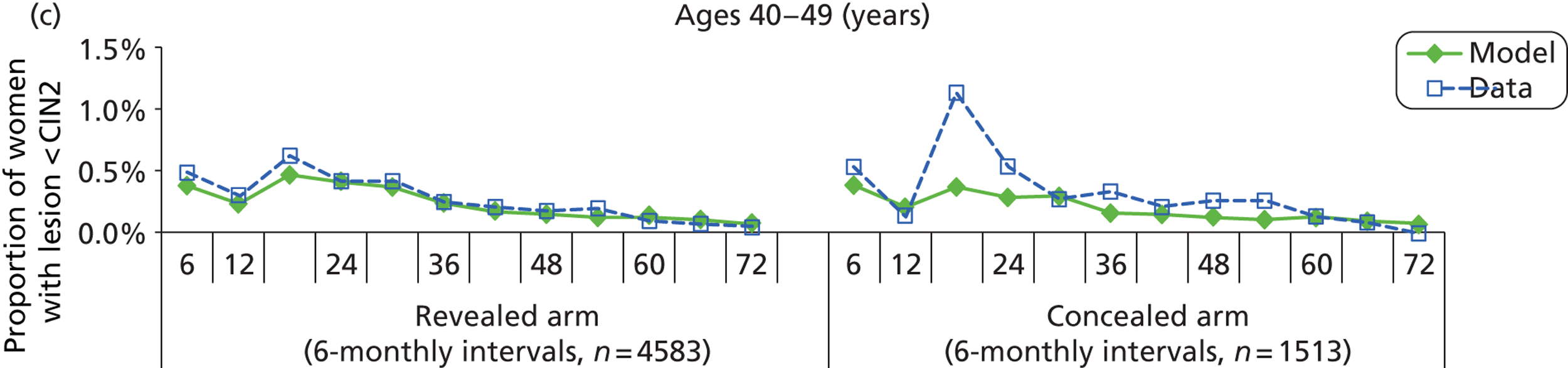

Reanalysis of ARTISTIC was used to support validation of the existing model platform. The steps involved in ARTISTIC validation can be summarised as follows:

-

Set up and simulate a ‘virtual’ cohort based on the age distribution and screening behaviour of the ARTISTIC trial cohort.

-

Run a multicohort simulation (i.e. a subsimulation for each age group in the cohort) to predict the number of screen-detected low- and high-grade cervical abnormalities that would be observed in each age group and overall, over the duration of trial follow-up.

-

Validate the predictions obtained from the model with the data from the ARTISTIC trial.

The model platform used for the main evaluation has three main components. These three components consider:

-

HPV transmission and vaccination

-

the natural history of cervical CIN and cancer in HPV-infected women; and

-

cervical screening.

The methods by which the model components two and three above were adapted for modelling the ARTISTIC cohort are described below.

Human papillomavirus transmission and dynamic modelling

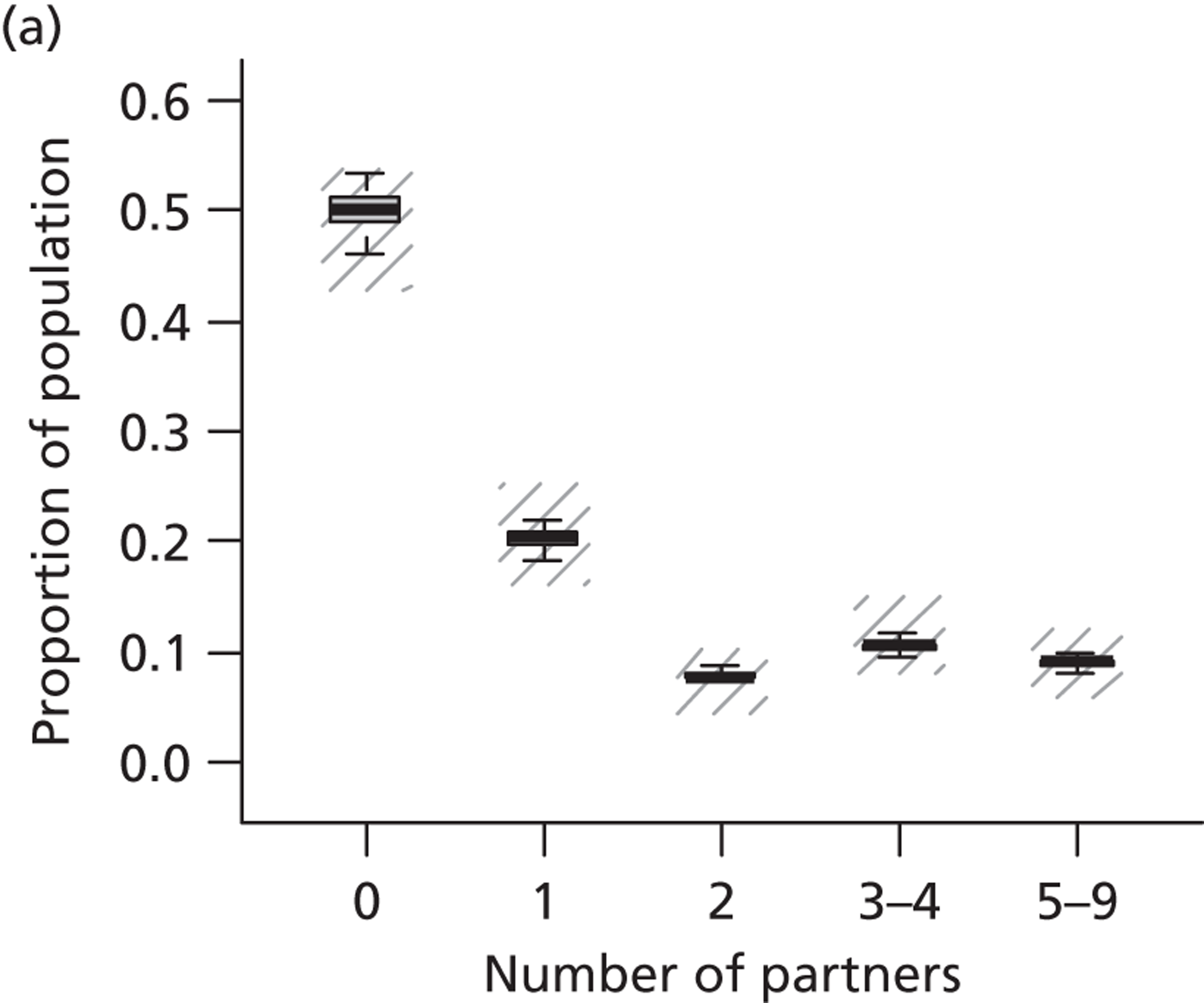

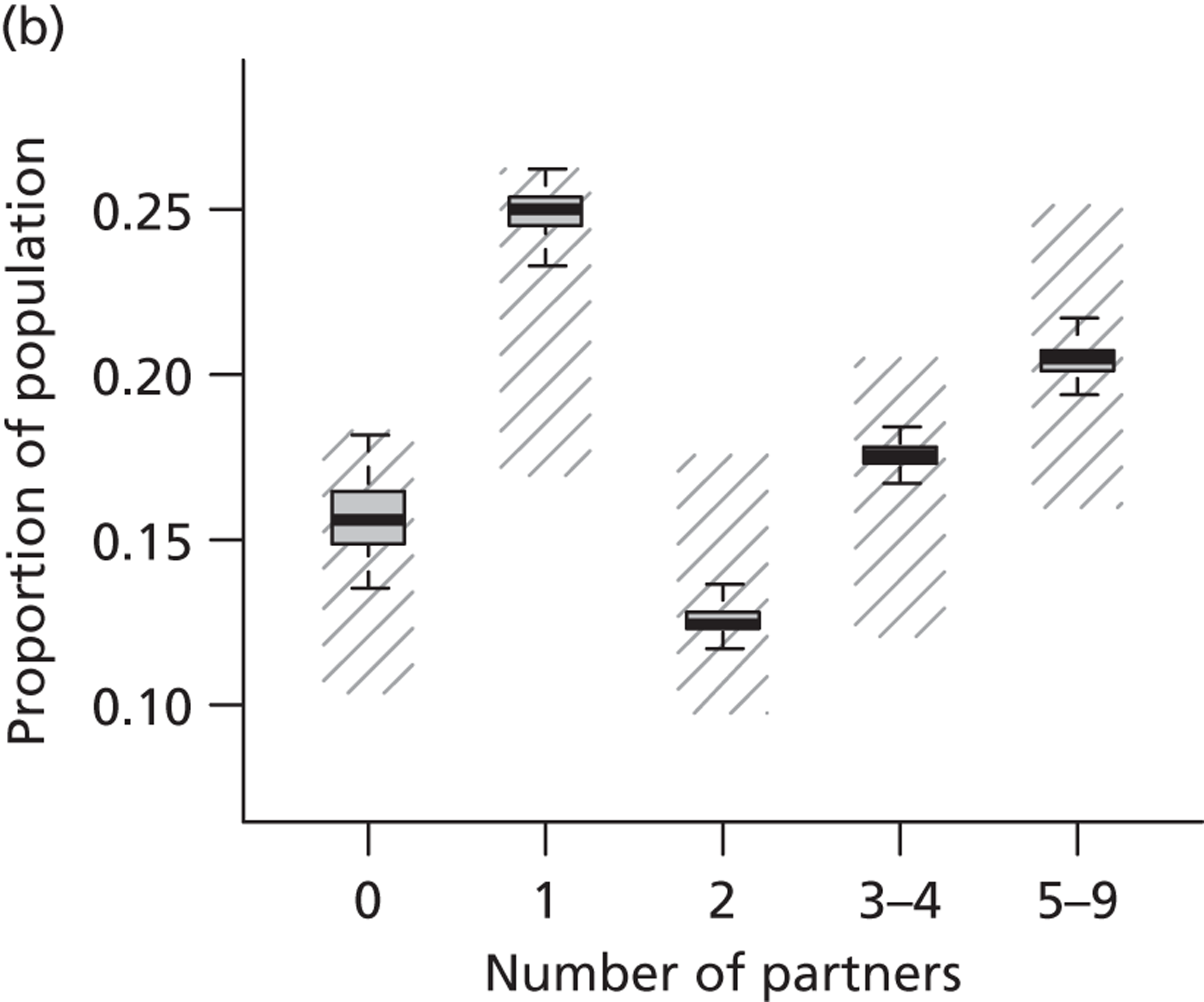

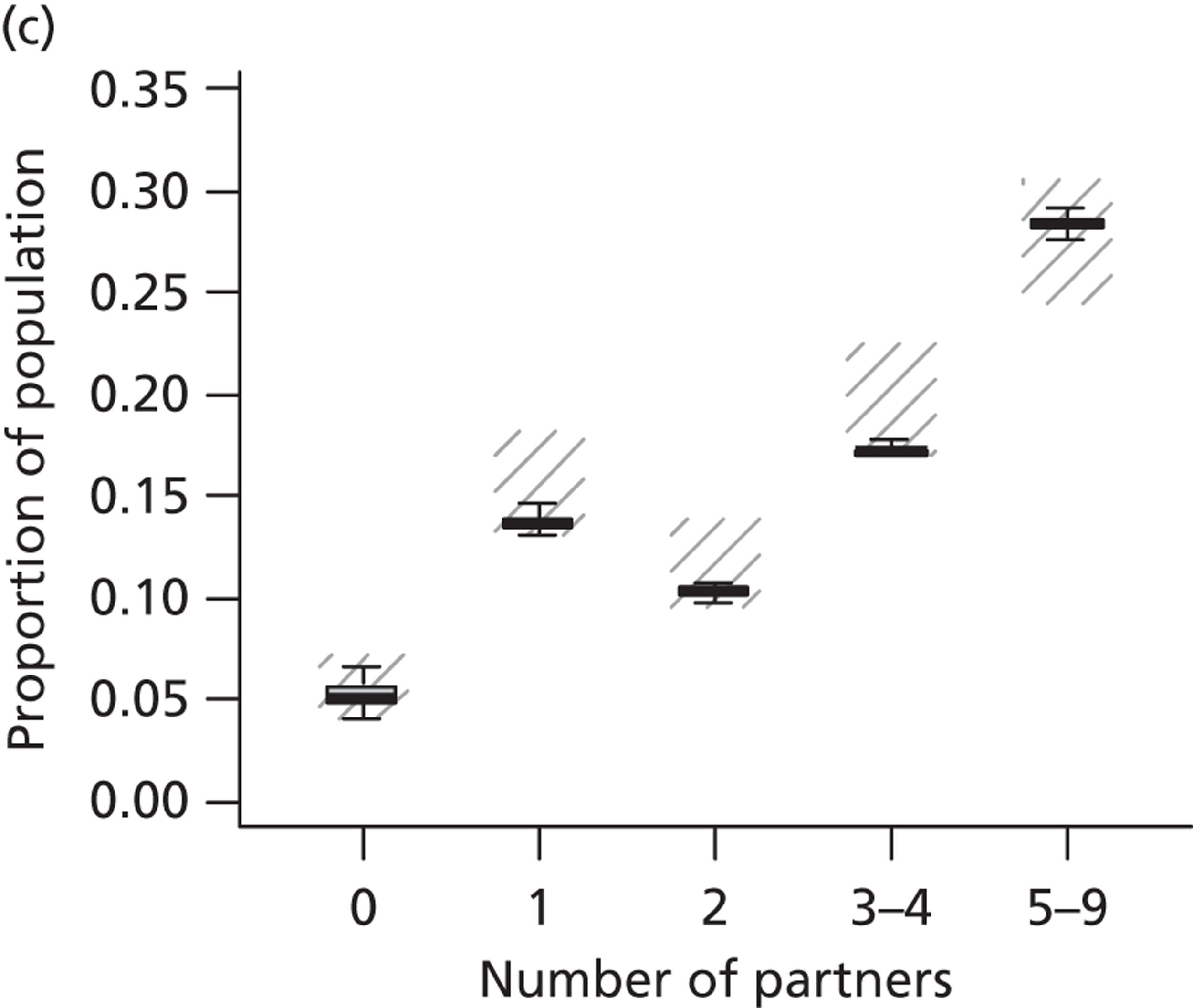

Age-specific pre-vaccination HPV incidence was obtained from a dynamic model of HPV transmission. As the model is a dynamic transmission model, the effects of herd immunity are taken into account. Data on sexual behaviour from the UK’s National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles II (NATSAL II)25 (data collected between 2000 and 2001) were incorporated into the model. (See Appendix 16 on sexual behaviour data for the population model for more details on the simulation of sexual behaviour in England.)

Model of the natural history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer

The model assumes that once a woman becomes infected with HPV, the virus can be cleared, or can persist and eventually cause CIN or cancer of the cervix. Six different health states in which a woman can exist were considered: well (or uninfected with HPV); HPV; CIN1 (persistent HPV infection); CIN2; CIN3; and cancer. The cancer state was further divided into stages to reflect International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) clinical stage at diagnosis and for each stage, diagnosed and undiagnosed cancer. Women who are diagnosed with invasive cervical cancer have an increased, stage-specific rate of death. Women who have survived cervical cancer for over 5 years are considered cancer survivors in the model, and their rate of survival is assumed to be the same as that of the normal population. Women who had HPV, CIN1, CIN2 or CIN3 were further categorised into three pathways associated with HPV 16, 18 or other HR types. The initial prevalence of each HPV type for each CIN state and for each age group was weighted to be consistent with the type-specific prevalence observed at enrolment in the ARTISTIC trial.

The natural history aspect of the model captures the rates at which women in different health states can progress to a more advanced stage (e.g. CIN2 to CIN3), remain in the same health state (e.g. remain in the CIN2 state), or regress (e.g. CIN2 to CIN1). This was captured in a HPV-type-specific matrix of progression, regression and stasis rates between HR HPV infection, CIN1, CIN2, CIN3 and invasive cervical cancer. The model captured the higher rates of disease progression and lower rates of regression in women infected with HPV 16 and 18 compared with other HR HPV types.

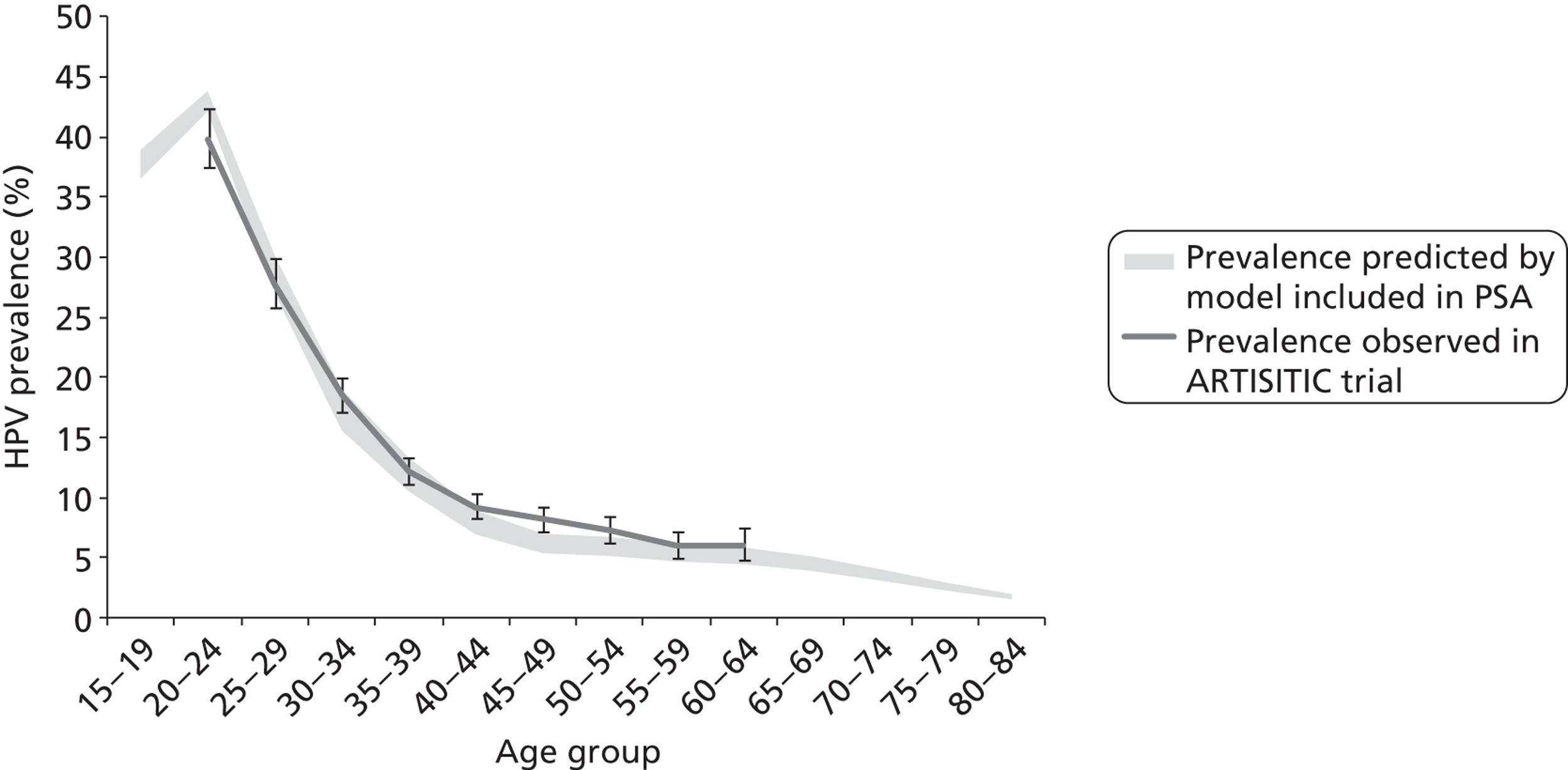

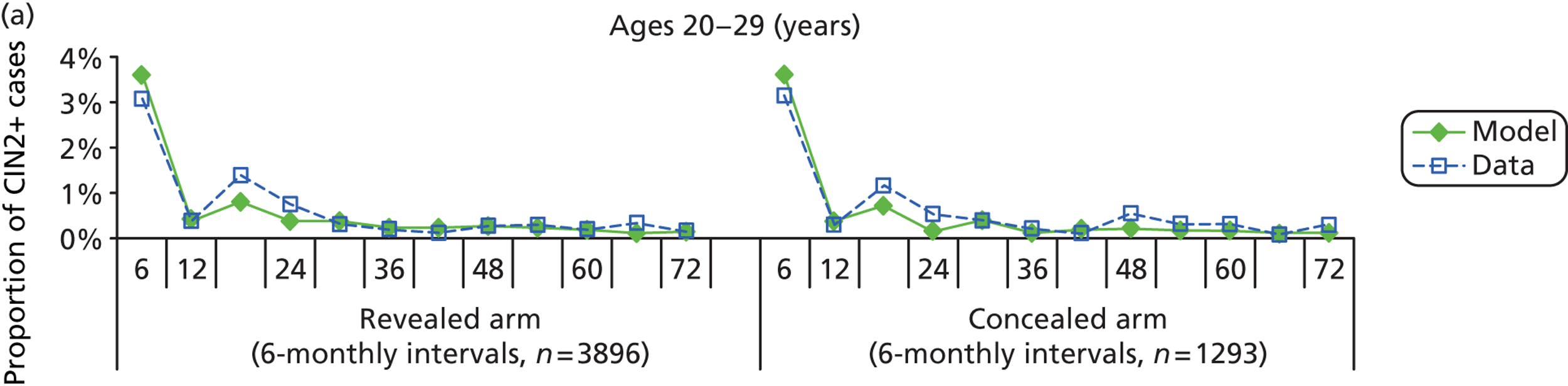

The rates of progression, regression and stasis between the different health states have been calibrated and validated previously. However, the ARTISTIC data were used to further validate the natural history model.

Modelling screening

The natural history aspect of the model dealt with modelling the actual underlying health state distribution of women in the population. However, the ARTISTIC trial reported histology results from women who attended screening and were referred for colposcopy and biopsy. Thus, in order to compare the natural history model results with ARTISTIC results, screening behaviour as observed in the trial was simulated. Management of the two different screening arms of the trial were simulated, and the ARTISTIC data were used to determine the rates of non-attendance, early rescreening and late rescreening.

We then compared model predictions for histology detected CIN cases with observed data from the trial.

Fitting test characteristics for cytology and the underlying health state in the ARTISTIC cohort

In order to simulate the ARTISTIC cohort, the actual underlying health states of women entering the trial were estimated. To do this, we also needed to estimate the test characteristics of LBC and HPV testing in the ARTISTIC trial.

The test characteristics for LBC describe the probability of receiving any test result for each possible health state. For each underlying health state (of which there were six: well, HPV, CIN1, CIN2, CIN3 and cancer), there were five possible LBC test results (given an adequate test result): negative, borderline, mild, moderate and severe. The probabilities of receiving each test result for each possible health state form a table called the ‘test probability matrix’, or TPM. The TPM gives complete information on test characteristics and the test parameters for sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value (PPV). Negative predictive value can be secondarily derived for thresholds at any health state [such as high-grade lesions (CIN2+) or all CIN lesions] and for any testing threshold (such as borderline or mild dyskaryosis for cytology).

A Gibbs sampler was used to simulate the posterior distribution of the health state and LBC test probability parameters using the cytology and HPV data observed at baseline in ARTISTIC. 26 Multiple chains were run and the mixing of the different sequences was monitored. The sampler was stopped when the potential scale reduction was near one for all the estimated parameters. The LBC TPM determined from this sampling procedure was further modified to match histology outputs from the ARTISTIC trial (see Appendix 9 for more information on the Gibbs sampling and fitting procedure).

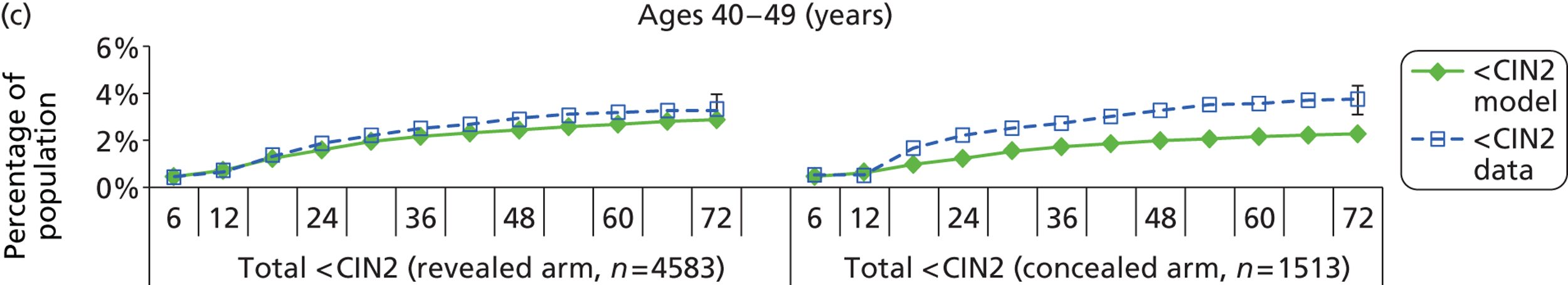

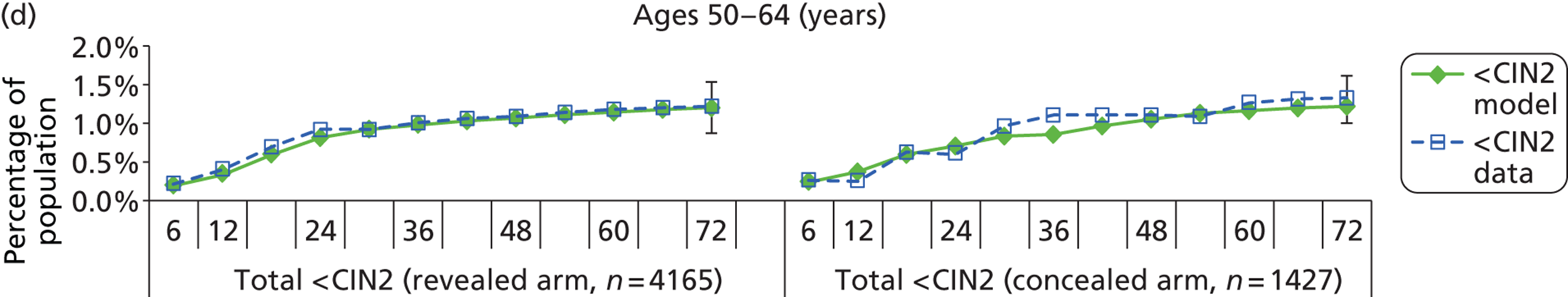

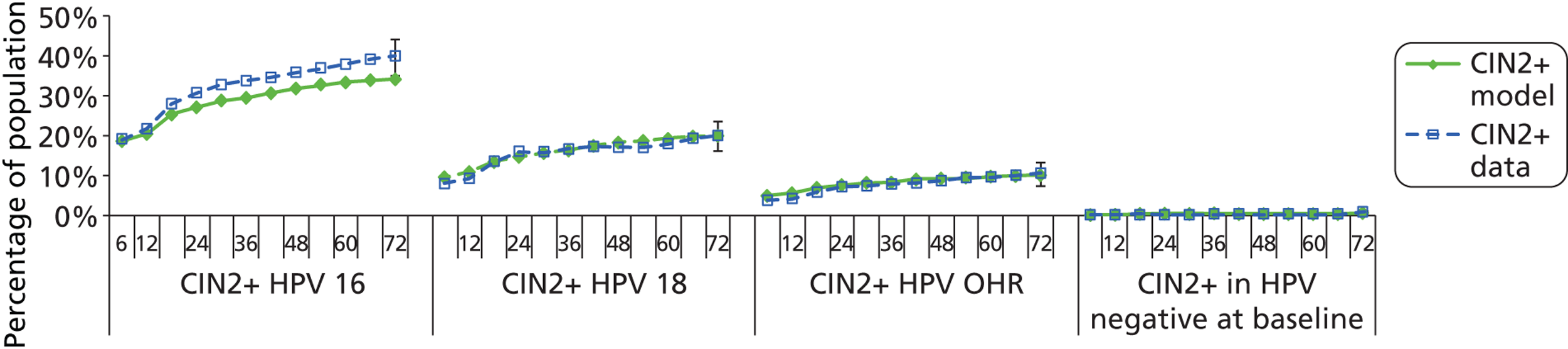

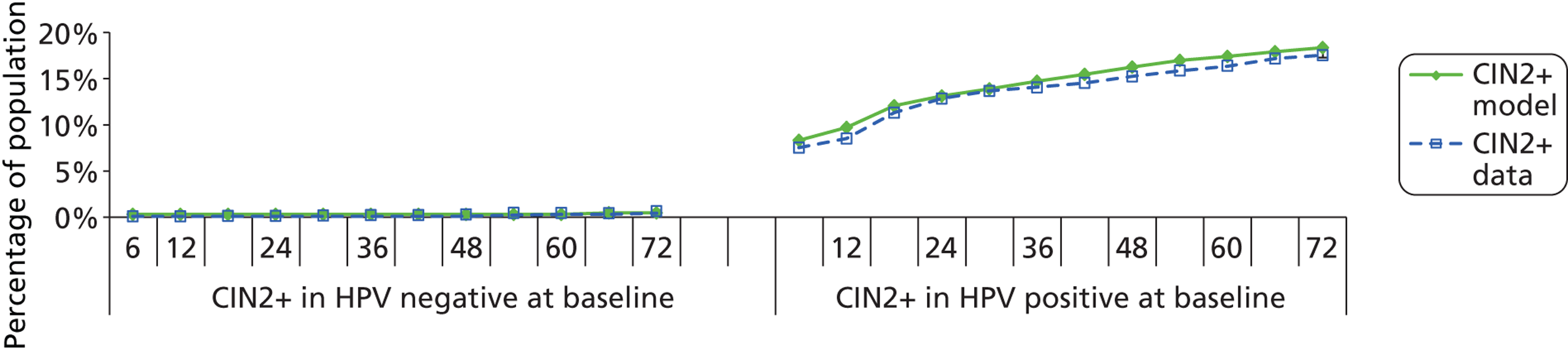

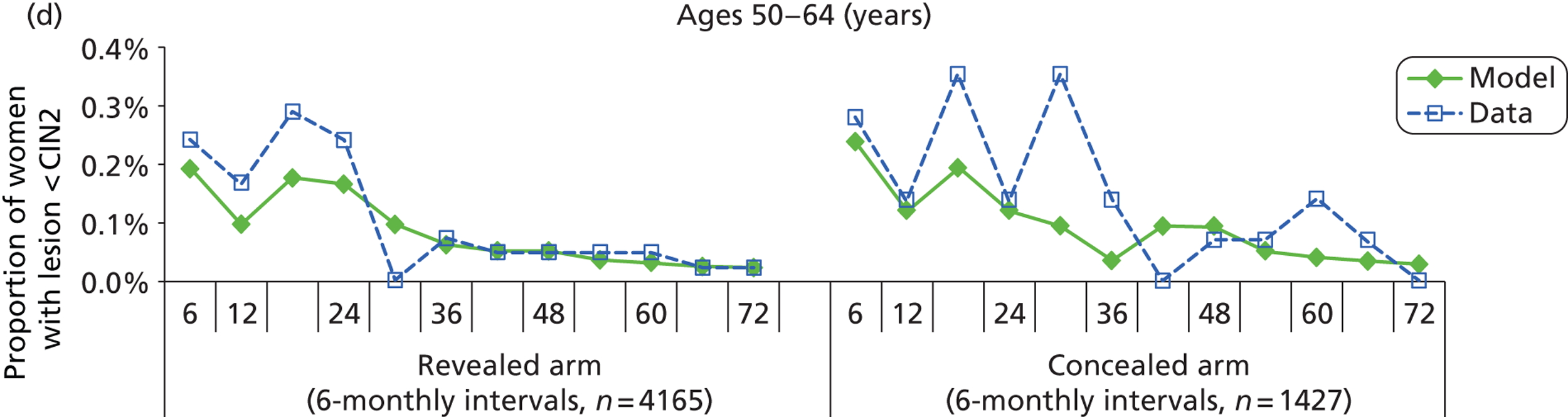

Construction of the virtual ARTISTIC cohort and validation of model outcomes to ARTISTIC data

The procedure for simulating the ARTISTIC cohort can be summarised in the following steps:

-

A ‘virtual’ ARTISTIC cohort was configured to represent the trial population as at ARTISTIC enrolment. The enrolled virtual cohort represented the actual ARTISTIC cohort in terms of age profile and HPV test positive (type-specific) rates at baseline. We assumed that all women attended their baseline screen at the same time, and so screening events are synchronised (as opposed to simulating the actual date of attendance, in line with the way such trial and cohort data are routinely reported). All women had a baseline cytology and HPV test, with follow-up management dependent upon their trial arm, baseline test results and compliance with guidelines as observed in the ARTISTIC trial. The actual rates of colposcopy referral, delays in colposcopy attendance and screening attendance rates that occurred throughout ARTISTIC were captured in the model.

-

Each woman’s true underlying health state was updated at 6-monthly intervals throughout the simulation according to the parameters from the natural history model and the HPV transmission model. The number of women attending routine screening, follow-up screening or colposcopy was also updated at 6-monthly intervals.

-

For the modelled cohort, for woman with histologically detected CIN2+, any subsequent screening visits were censored, and this group were removed from the simulation. If the histology result was less than CIN2 (‘< CIN2’: CIN1 or histological manifestations of HPV effect), women remained in the simulation.

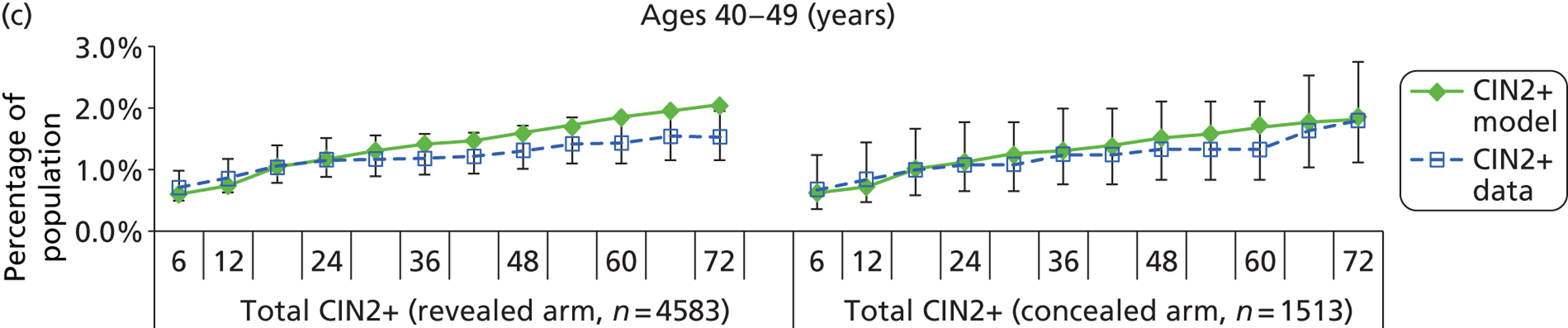

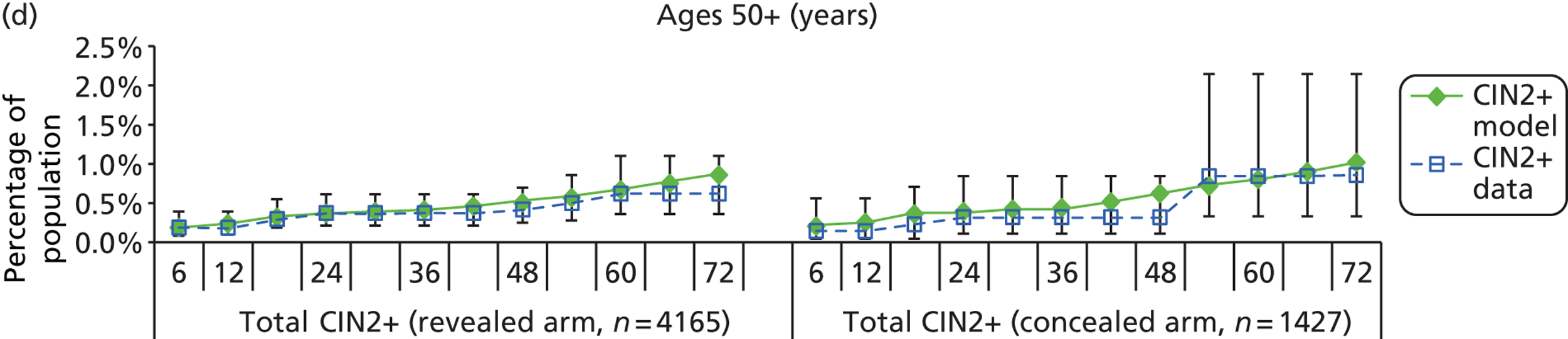

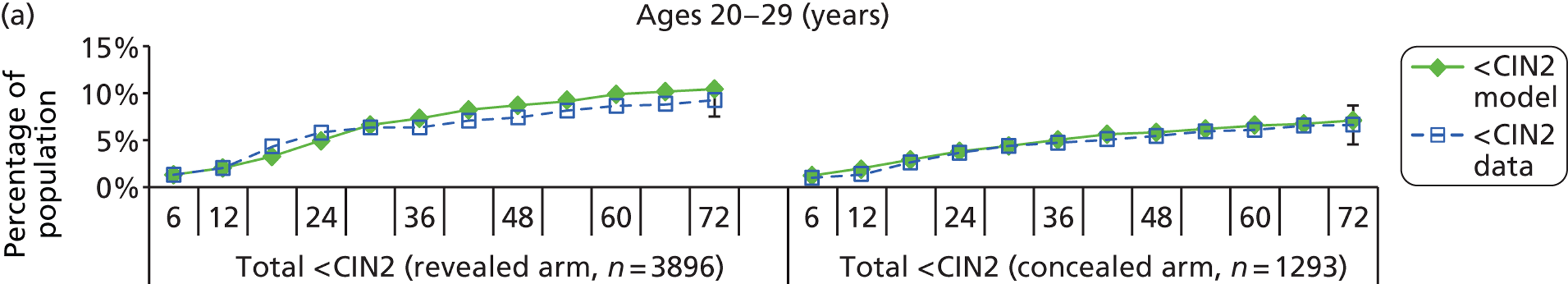

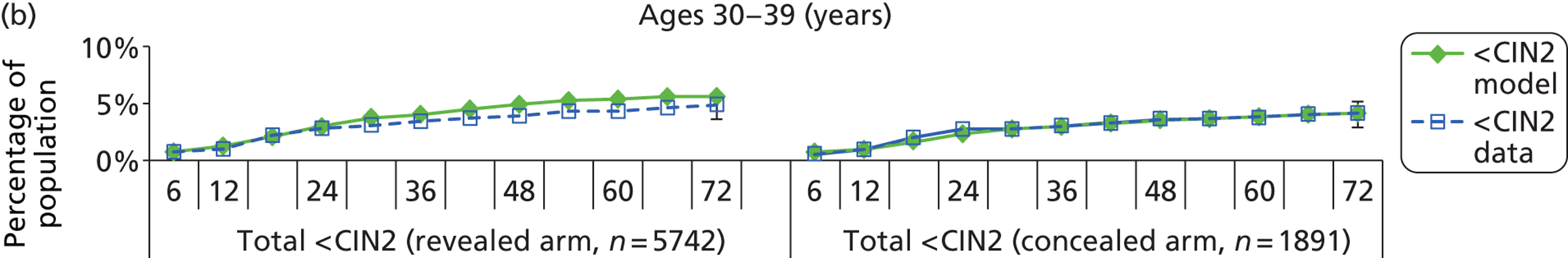

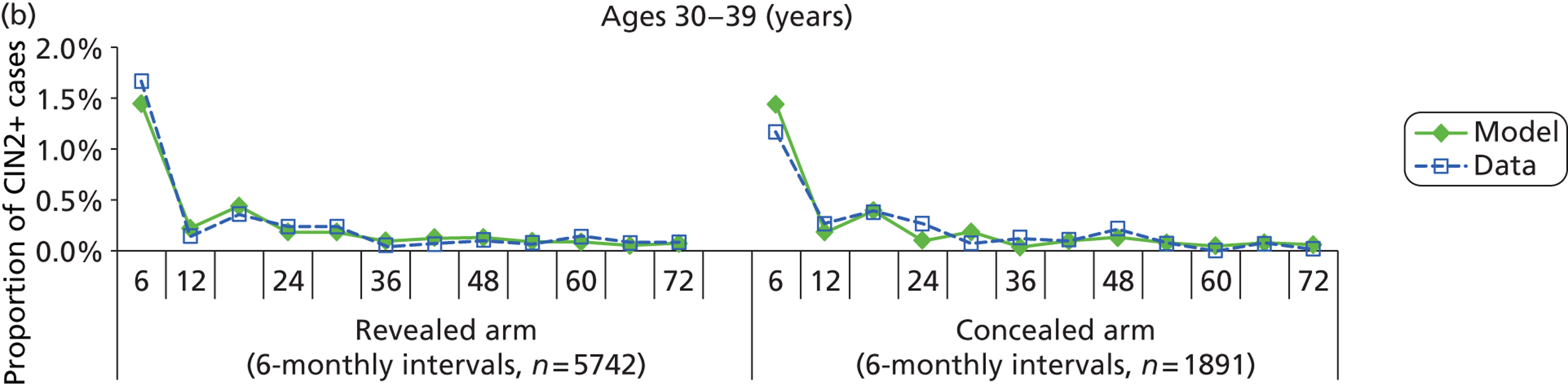

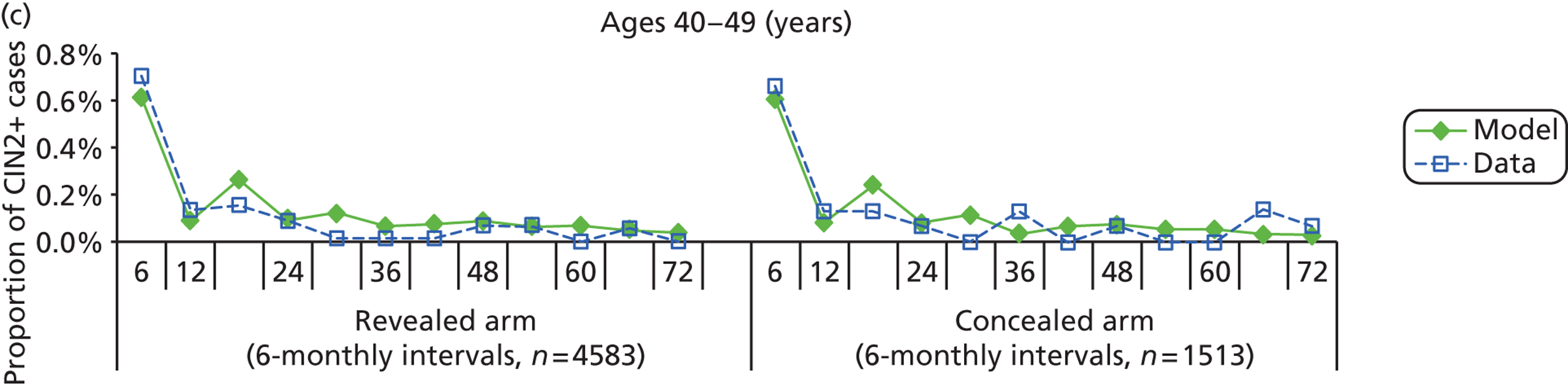

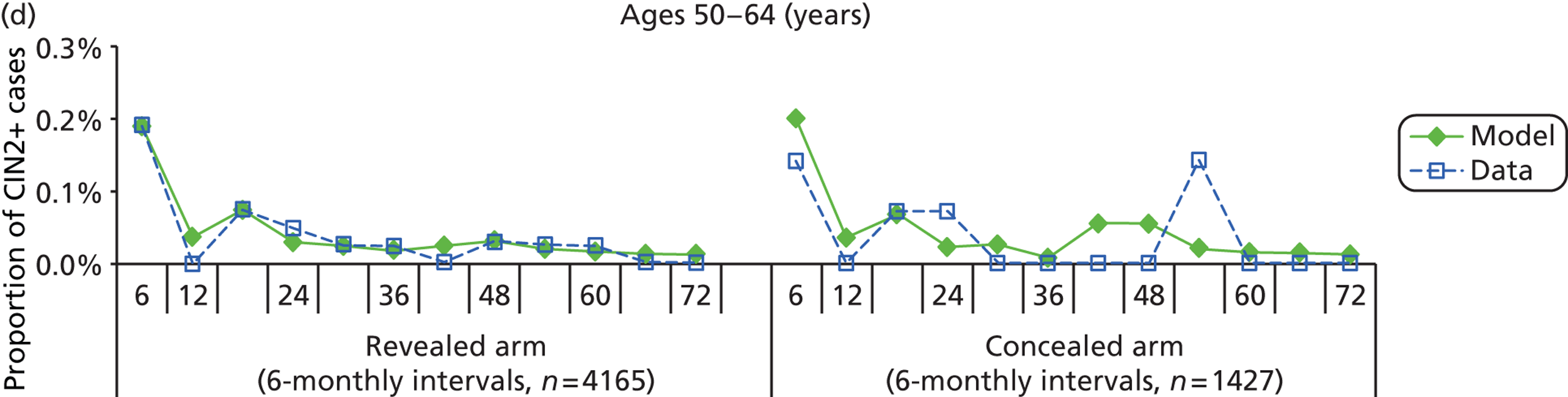

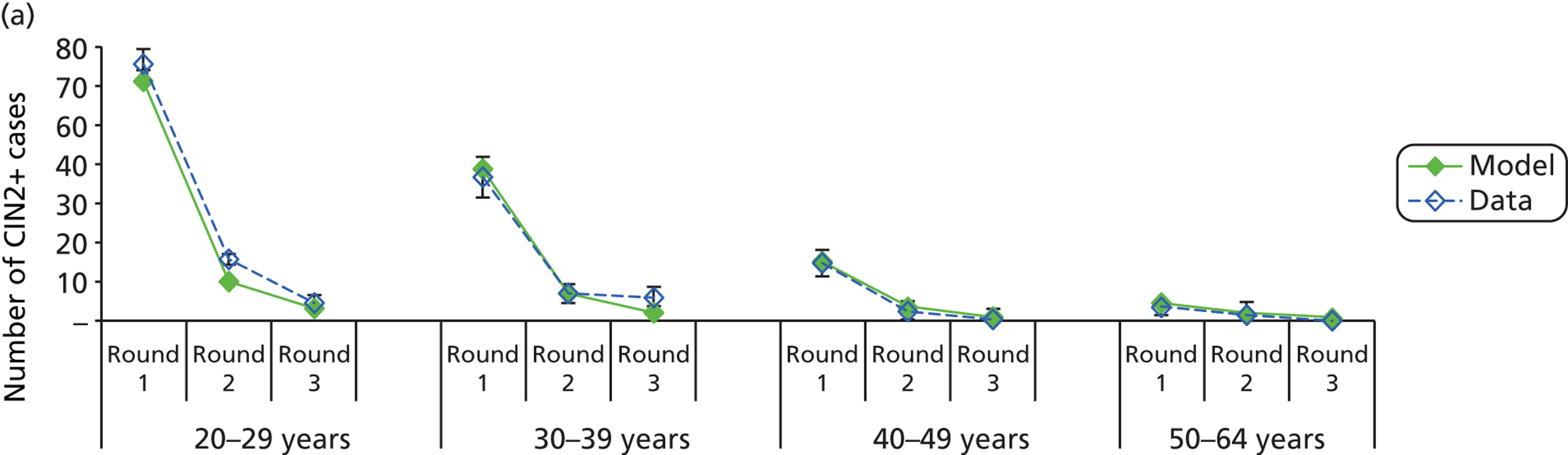

The simulation predicted the number of histology-detected CIN cases at 6-monthly intervals, and these model predictions were compared with the data from the ARTISTIC trial at 6-monthly intervals. As the natural history simulated in the model captured disease progression and regression at various rates, the actual underlying health states of women throughout the trial changes over time. Thus, the model outputs at later times in the trial give an indication of how well the natural history model captured the rates of disease progression, regression and stasis (after taking into account the ‘overlay’ of screening, i.e. the influence of screening behaviour and test characteristics on the observed outcomes in the trial).

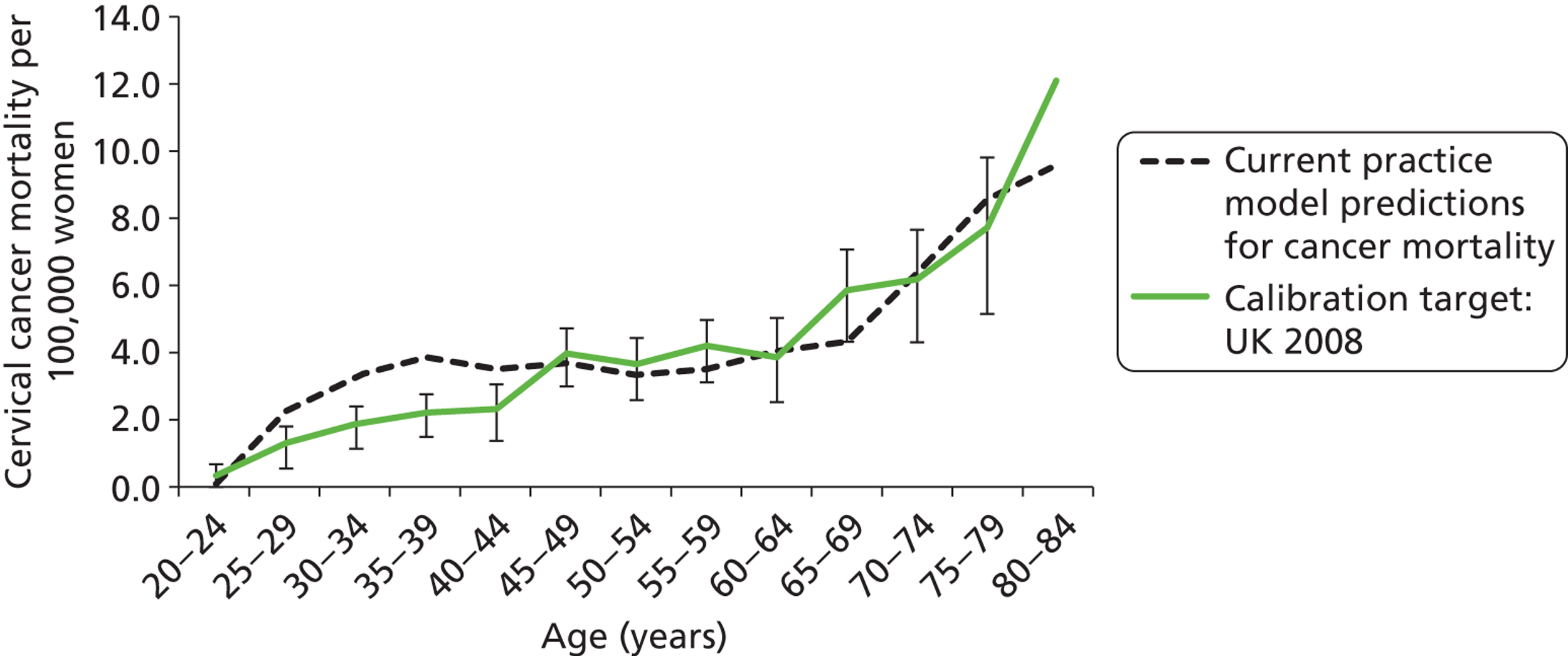

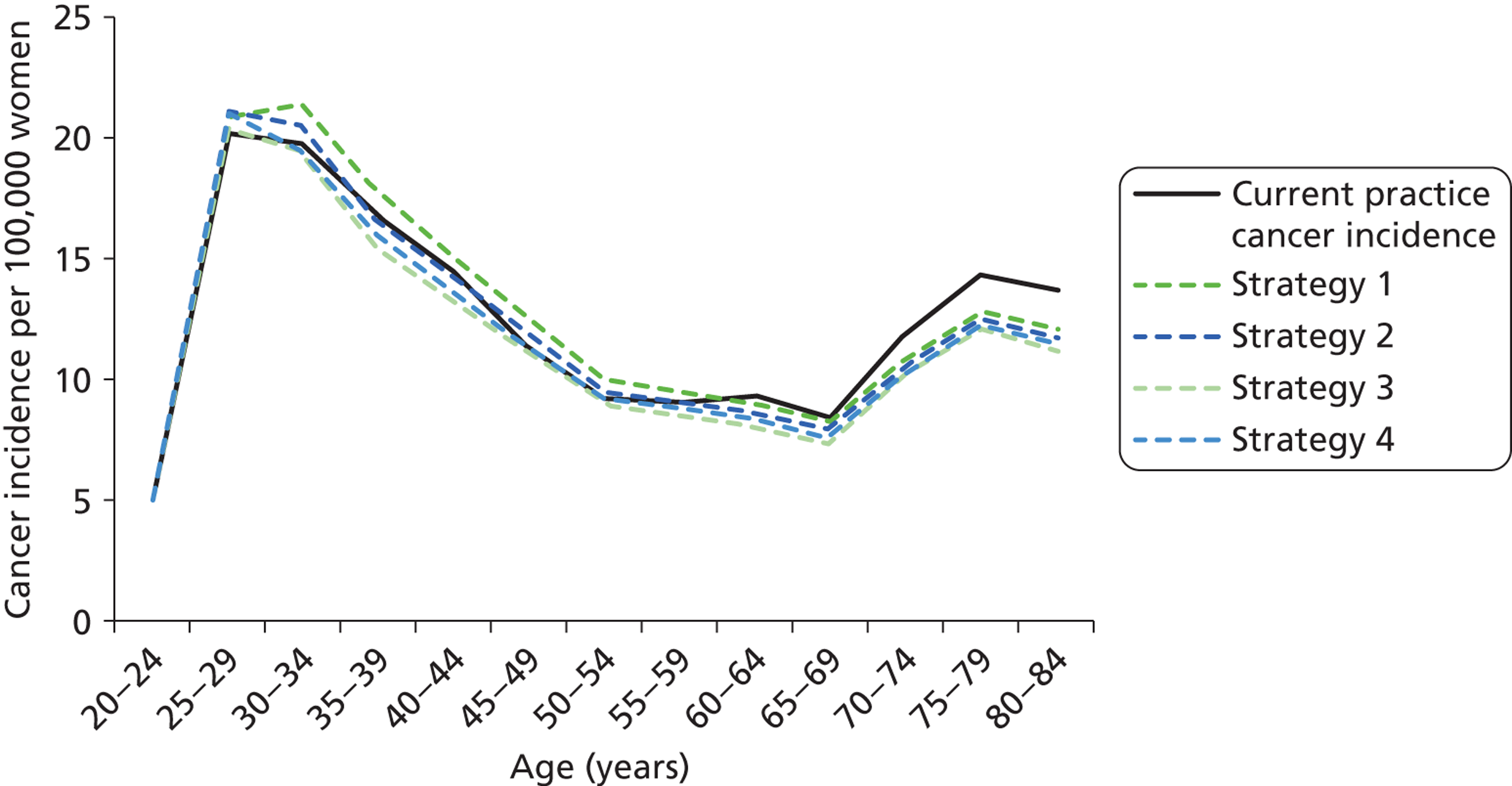

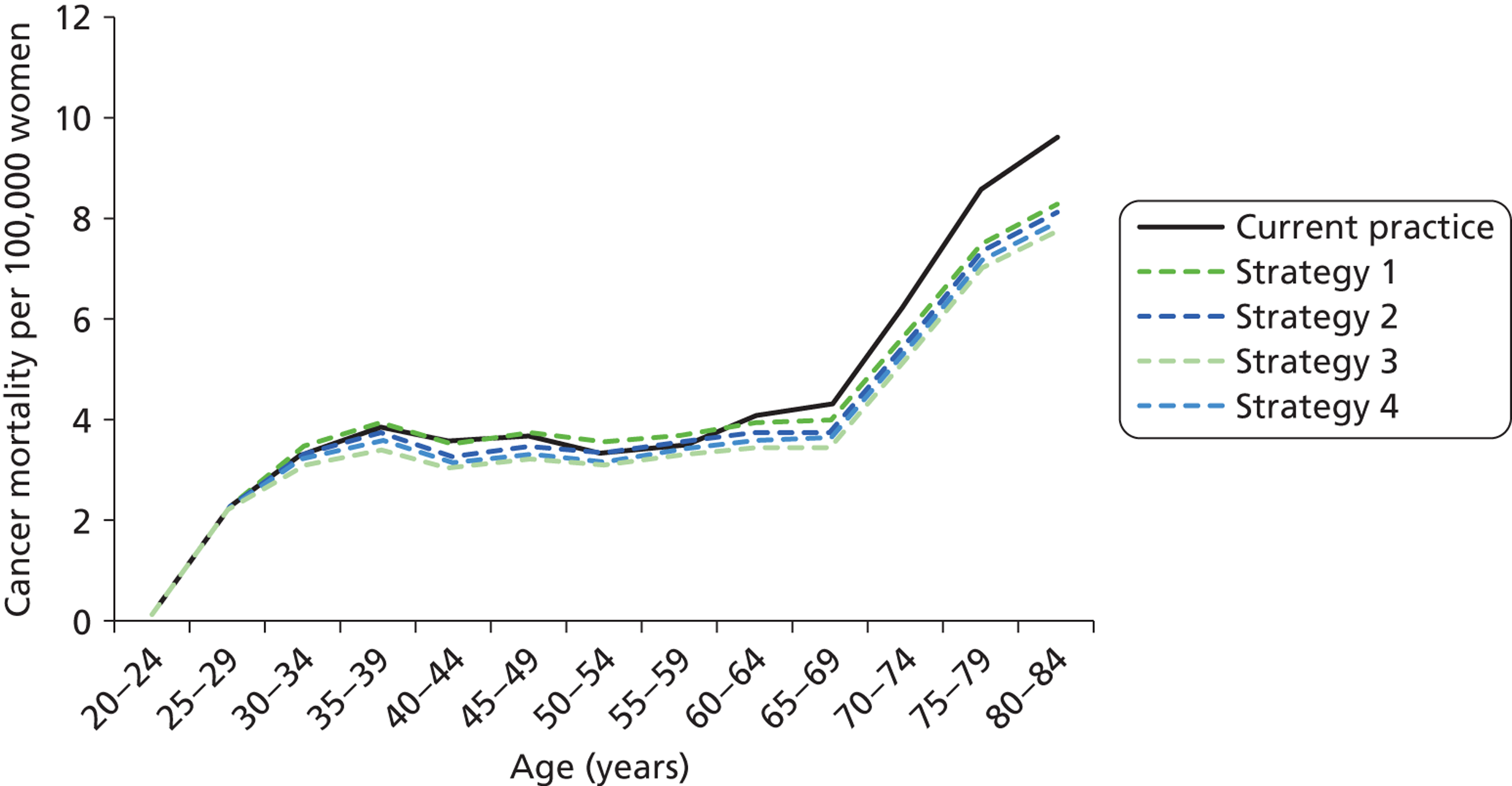

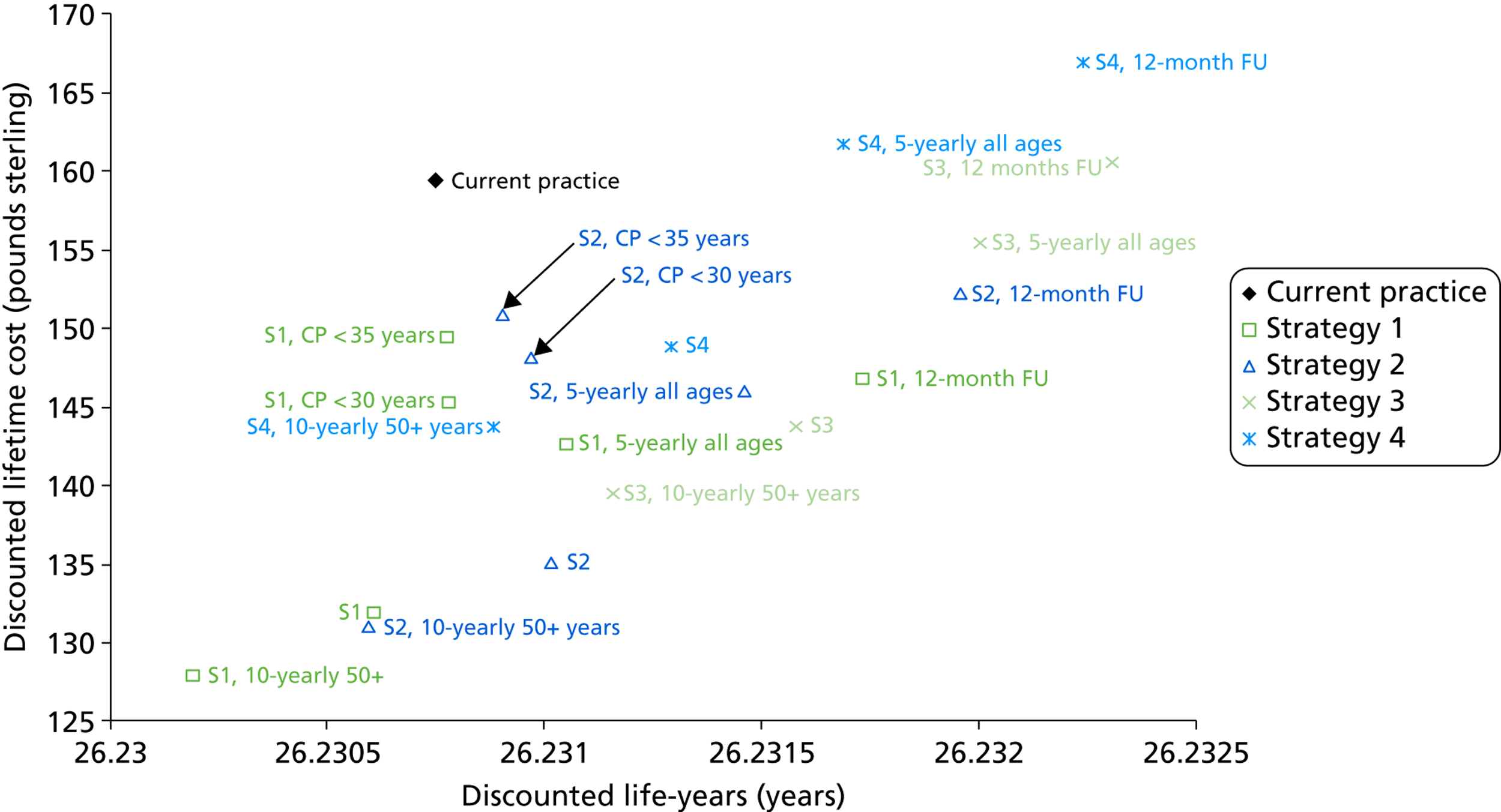

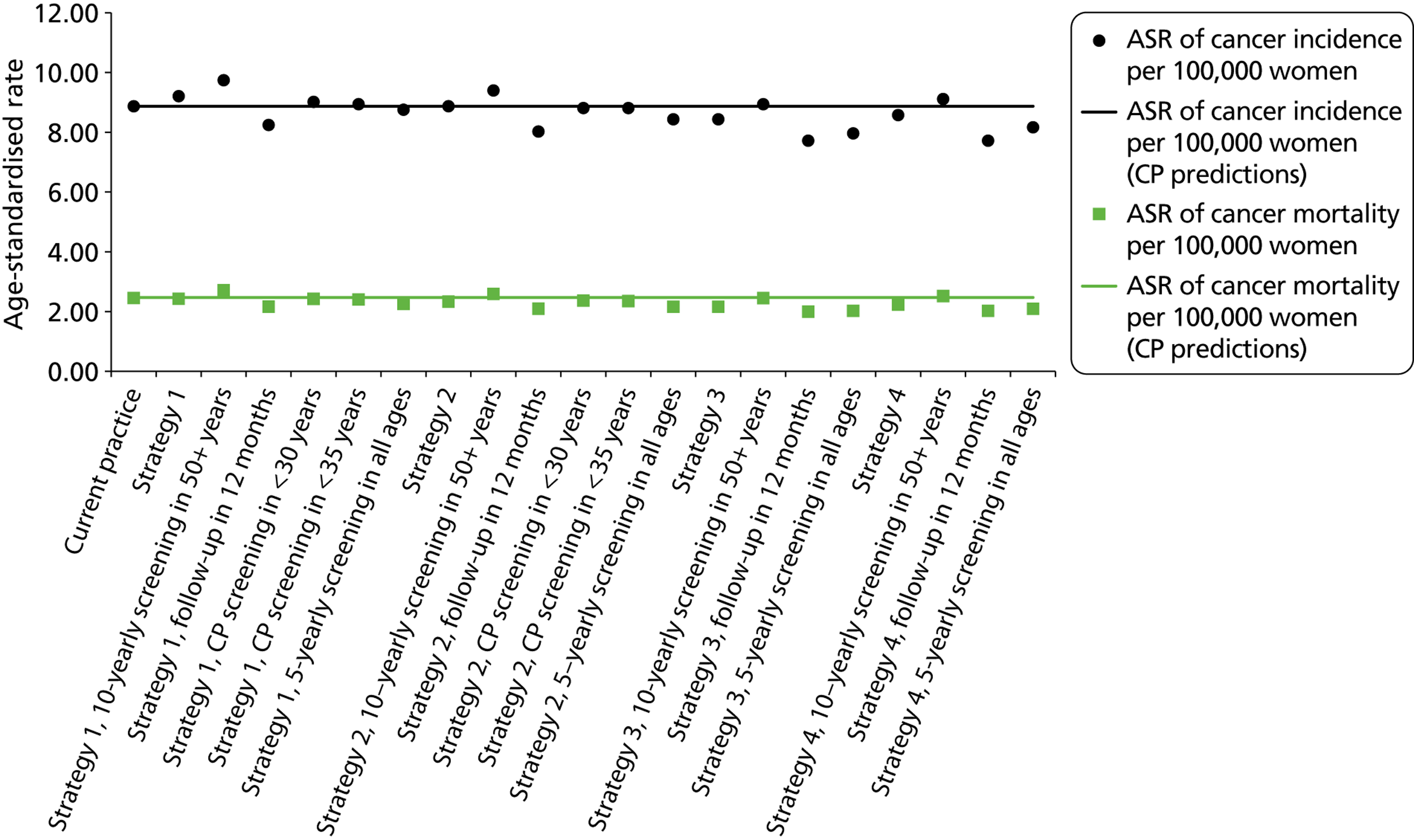

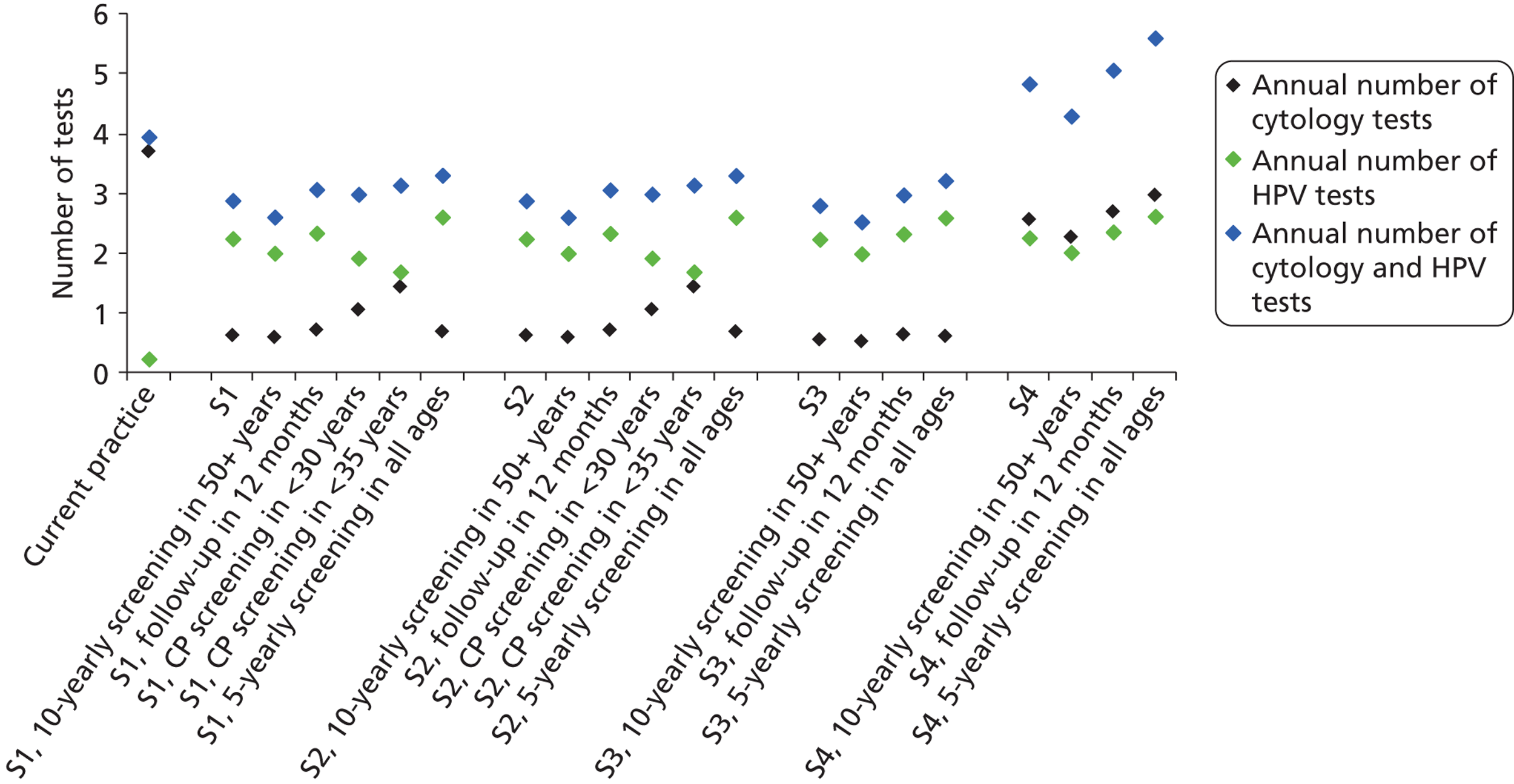

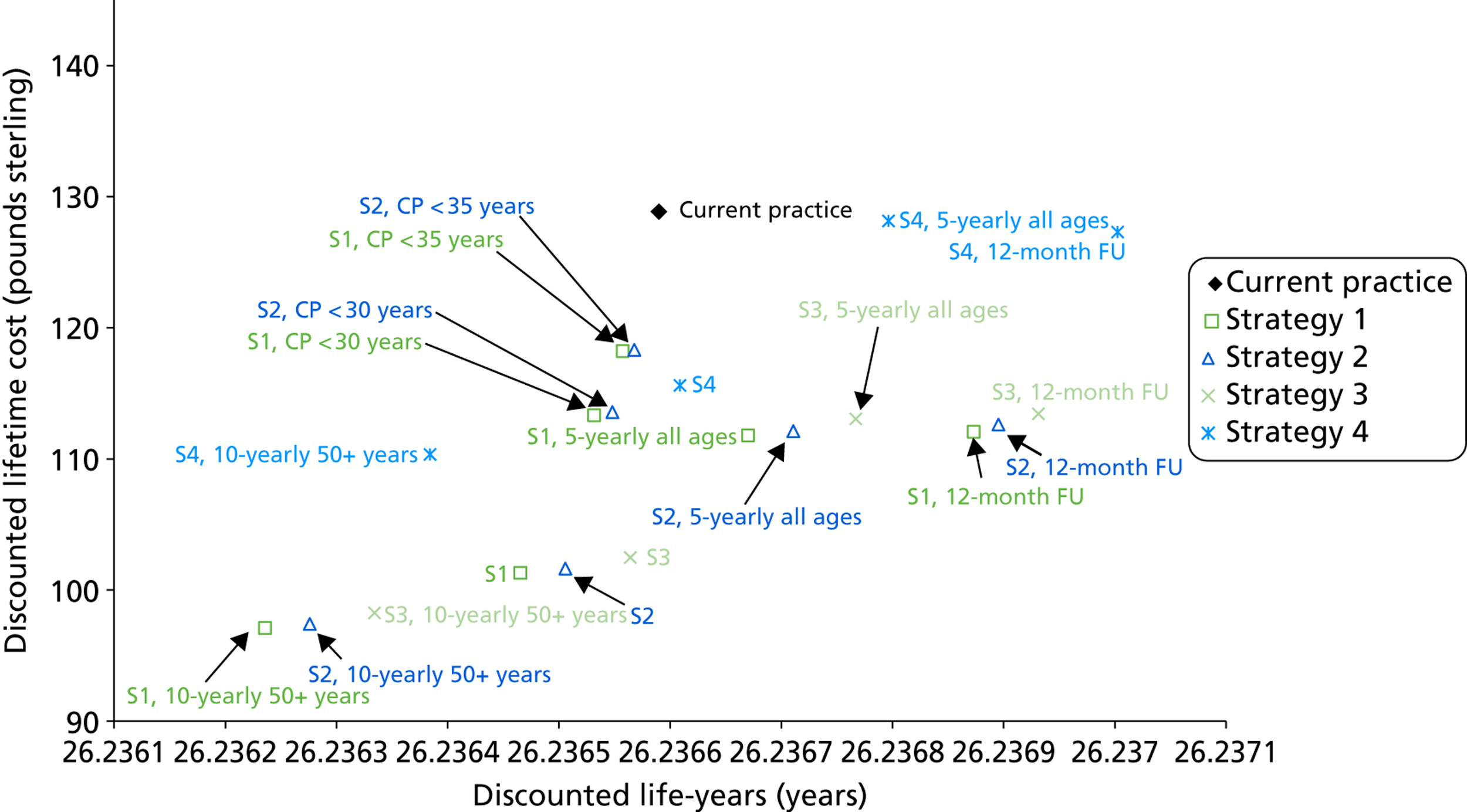

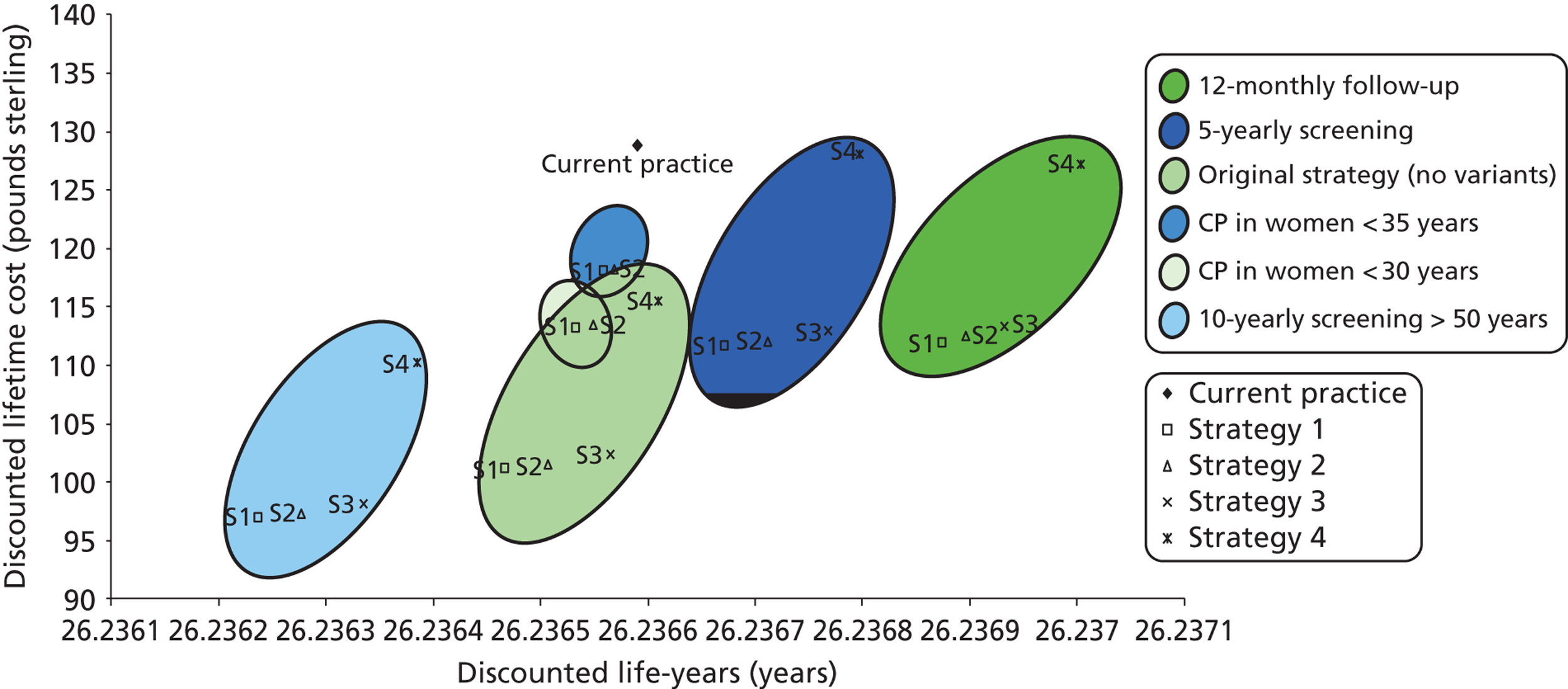

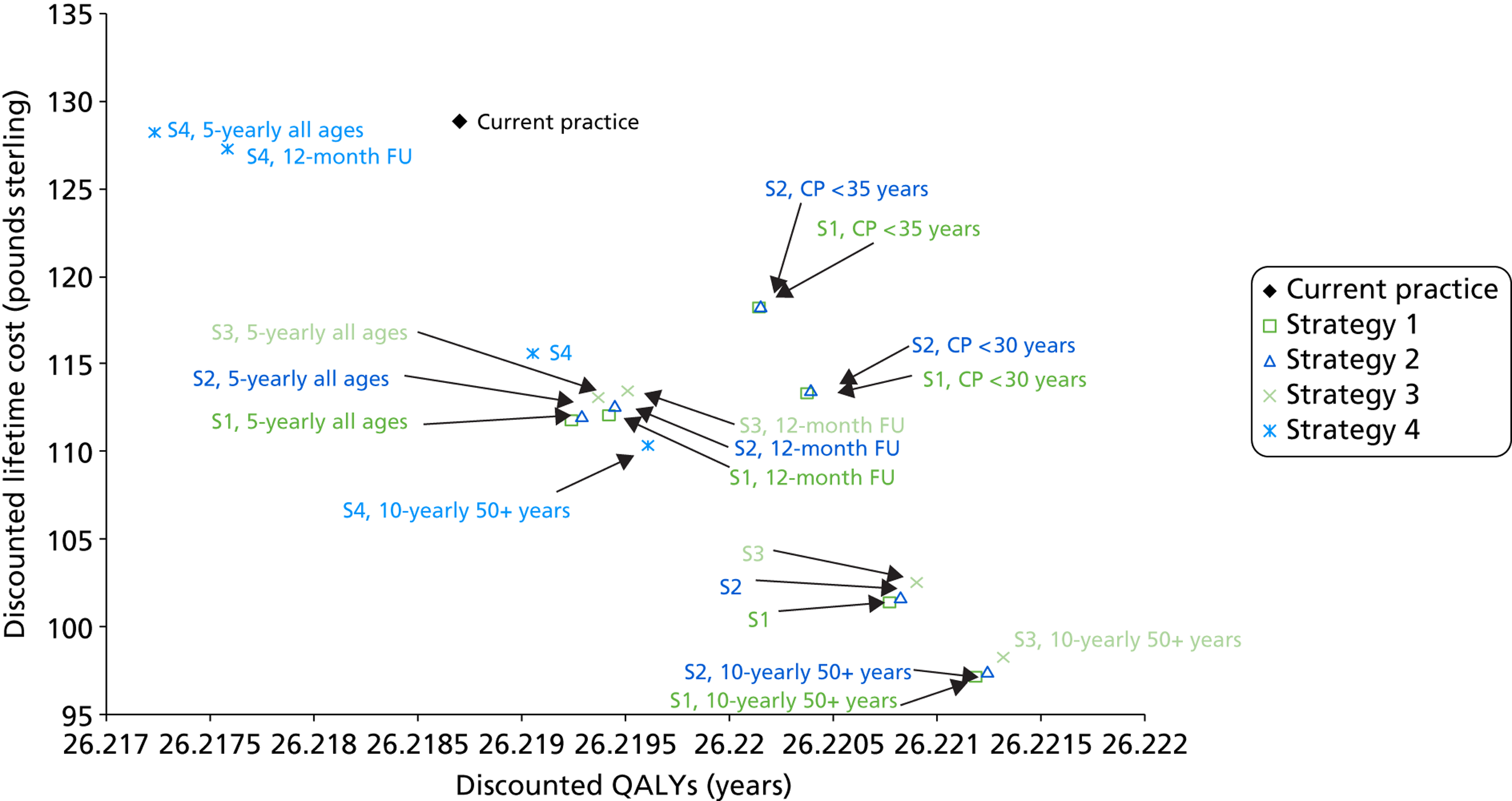

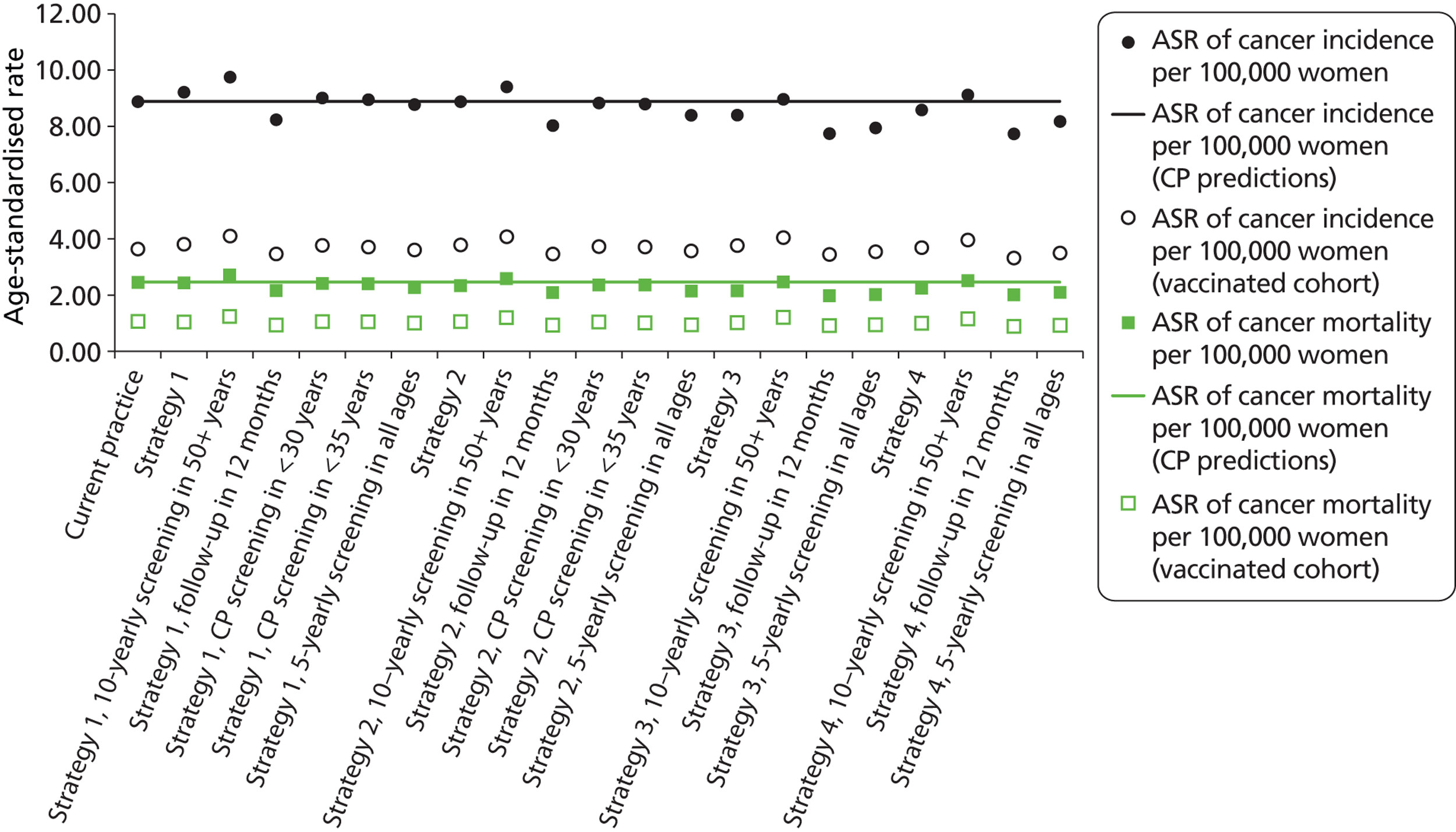

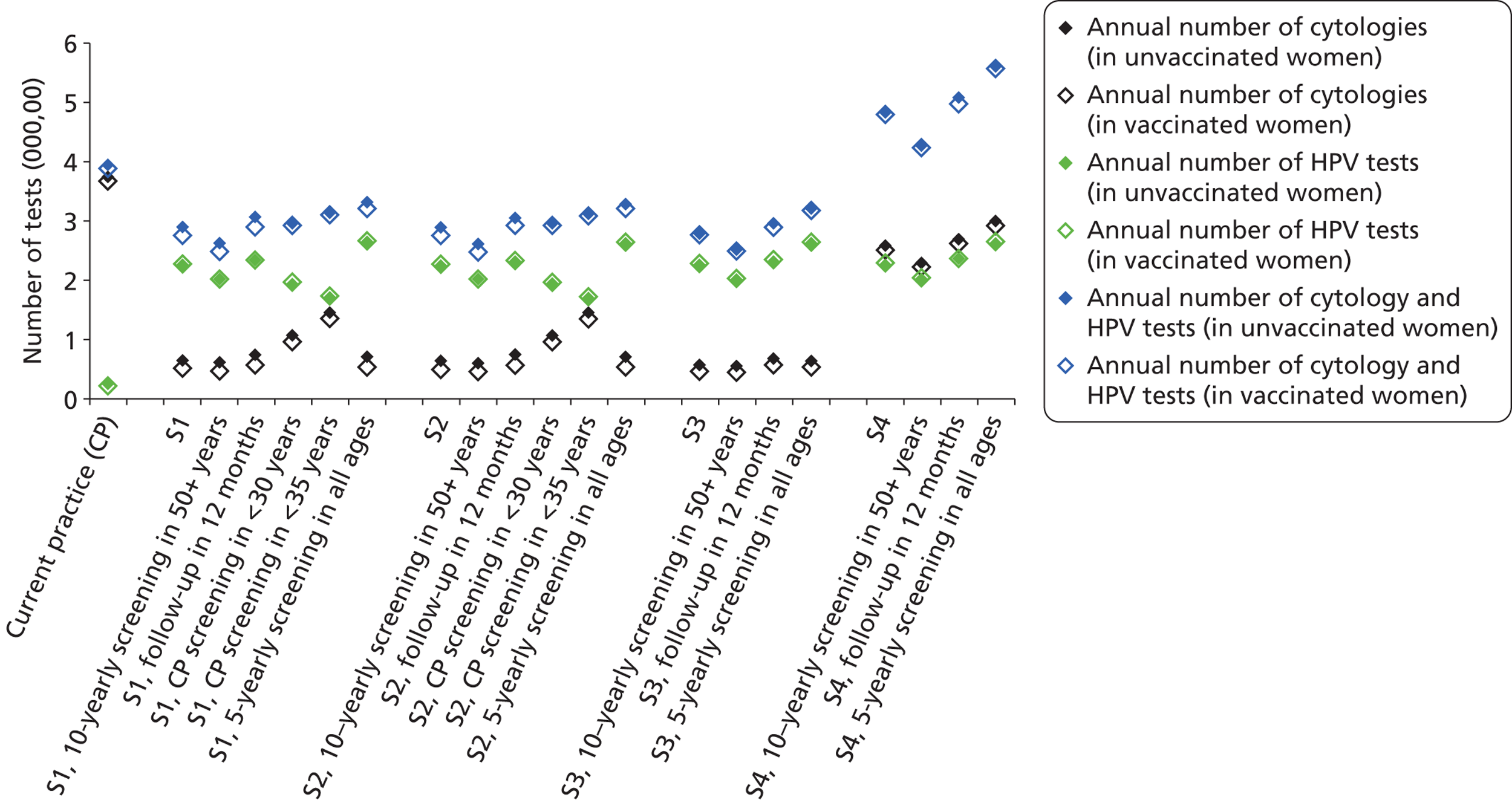

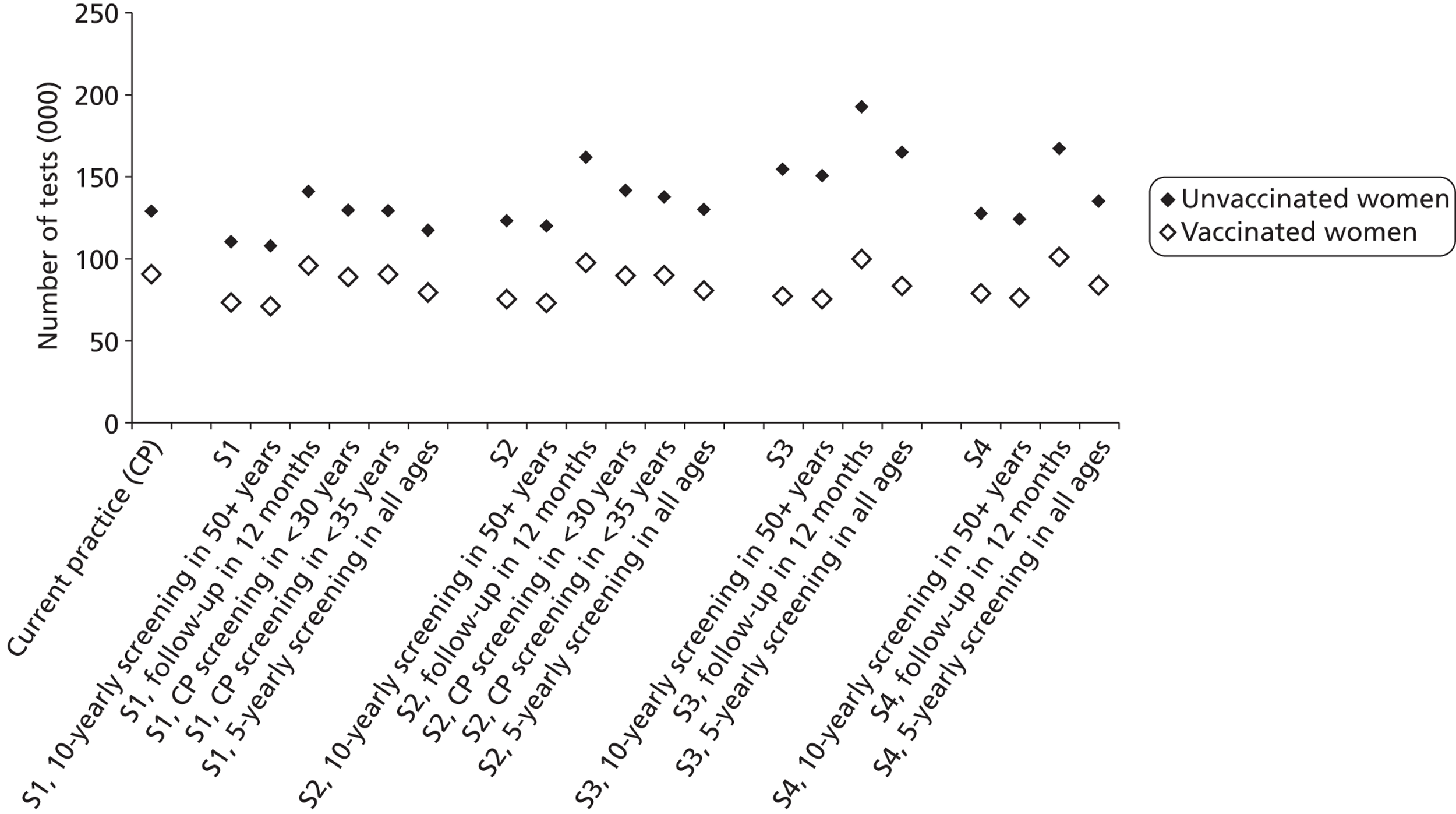

Methods for the evaluation of primary human papillomavirus screening in England

The validated natural history model of CIN and invasive cervical cancer was then used to evaluate health outcomes under different screening strategies on a population basis for England. The cost-effectiveness of various HPV primary screening strategies were evaluated against a comparator of current screening practice, and cross-sectional outcomes, including estimated rates and case numbers of cervical cancer cases and deaths, detected high-grade abnormalities, colposcopies and numbers of screening tests, were predicted after incorporating information on the population age structure. Data from local sexual behaviour surveys, screening compliance information, and information on vaccination catch-up and coverage rates were also incorporated into the England-wide model.

A health-services perspective was used for the collection of costs. The economic evaluation also took a health-services perspective, taking into account the health-services costs associated with population-based screening, management, diagnosis, follow-up, and CIN and cancer treatment. A discount rate of 3.5% was used for costs and effects (the 3.5% discount rate for both costs and effects is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence based on the recommendations of the UK Treasury, 2008 guide). 27

Primary human papillomavirus screening strategies considered in the evaluation

A number of potential future primary HPV screening strategies were simulated. These are described and detailed diagrammatically in the following pages. Many of the strategies chosen were thought to represent possible candidates for effective, and cost-effective, strategies in England. Other, more exploratory, strategies (as noted) were included for comparative purposes.

Comparator strategy (current screening practice)

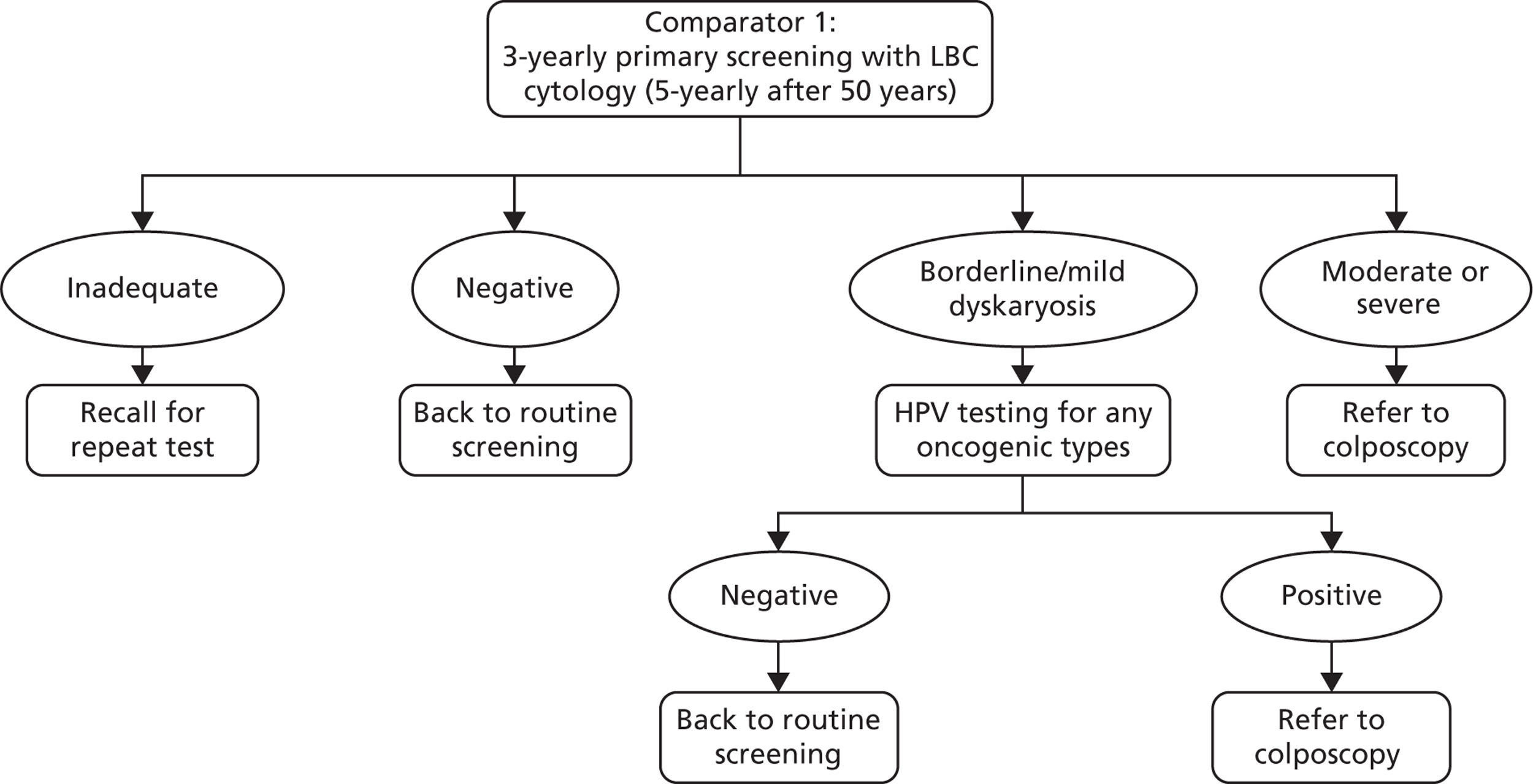

The comparator for the evaluation is current screening practice, with and without the effects of HPV vaccination, and is depicted in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Comparator strategy (current screening practice).

The comparator strategy involves cytology-based screening with LBC and HPV triage testing of low-grade abnormalities (borderline changes and mild dyskaryosis). The recommended screening interval is 3 years for women aged 25–49 years and 5 years for women aged 50–64 years.

Primary human papillomavirus screening strategies

We assumed that strategies two and three are carried out using a HPV test that has the ability to separately output information on HPV 16 and 18, that is to say a ‘partial genotyping’ test [note that one technology also provides information on type 45 but for the purposes of this analysis we did not model differential management based on detection of type 45, assuming that, even if this output was available, women with type 45 were managed as for women with other oncogenic types (not 16/18)].

‘Real-world’ screening compliance was assumed. Screening attendance was informed by a previous analysis performed for the UK,19 and updated to reflect the most recent data on the age-specific percentage of eligible women who attended at least once in a 5-year period in England (2009–10). This analysis allowed the model to take into account non-attendance, early rescreening, late rescreening, and screening in ages outside the target age range for screening. Attendance rates for colposcopy and post treatment were based on those used in a prior model of HPV test-of-cure in England. 28

For all strategies, colposcopy management was assumed to be as detailed later (see Figure 8). Post-treatment management was assumed to use HPV as a test-of-cure as per the protocol used in the NHS Sentinel Sites evaluation. 12

The following primary HPV screening strategies were considered.

Basic strategies

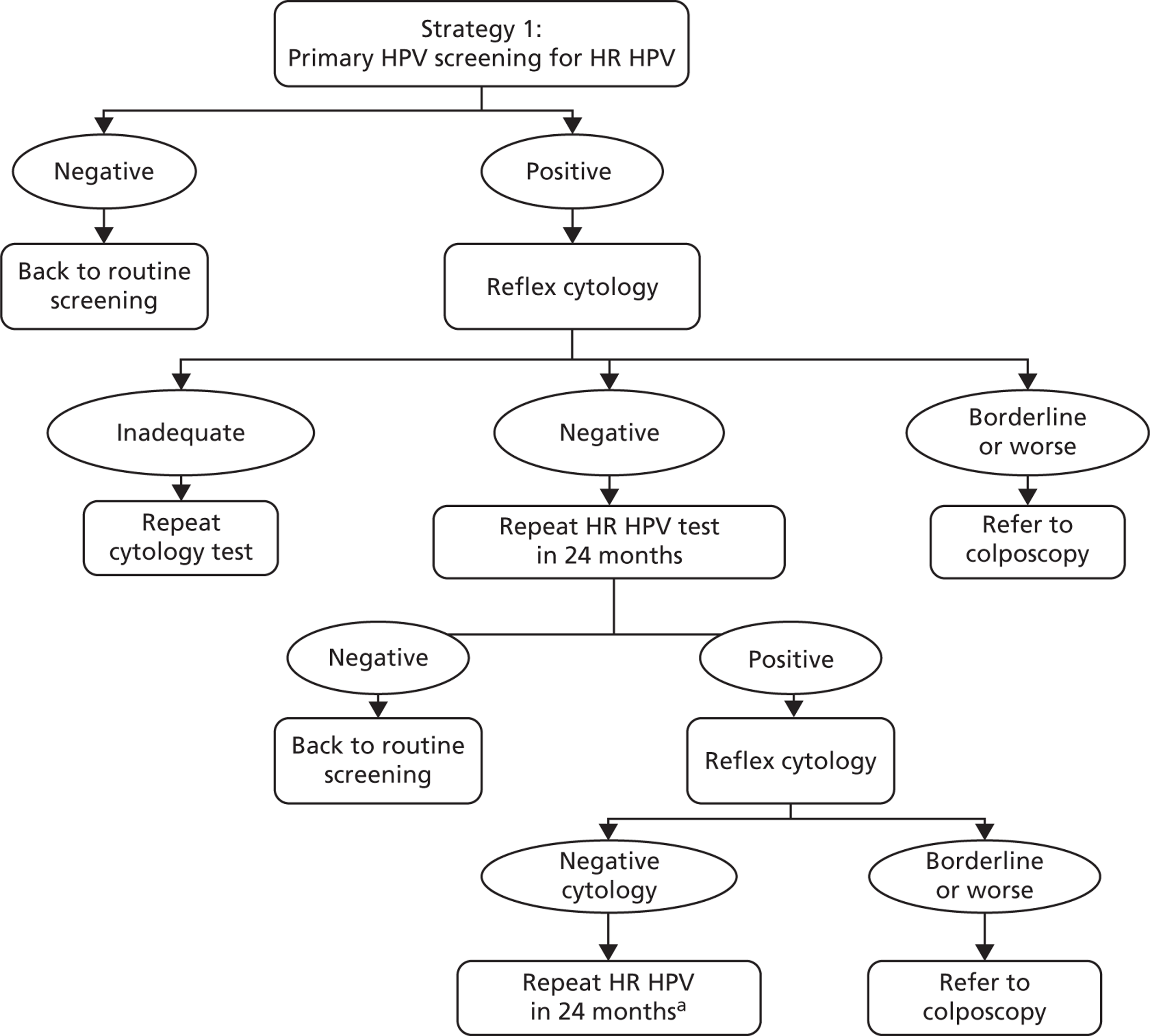

Strategy 1 (Figure 4)

The strategy can be summarised as follows: women positive for any oncogenic infection receive reflex cytology triage testing. Cytology-positive women (borderline dyskaryosis or worse) are referred to colposcopy. Cytology-negative women are sent for repeat HPV testing with cytology triage in 24 months, and any women who are HPV positive and borderline dyskaryosis or worse are referred to colposcopy at that point. HPV-positive, triage-negative women are sent for a repeat HPV testing in another 24 months, and HPV-positive women at that point are referred to colposcopy. HPV-negative women are returned to routine screening at each stage.

FIGURE 4.

Screening and follow-up management of primary HPV screening for strategy 1. a, At the second 24-month follow-up, women negative for HPV are returned to routine screening and HPV-positive women are referred to colposcopy.

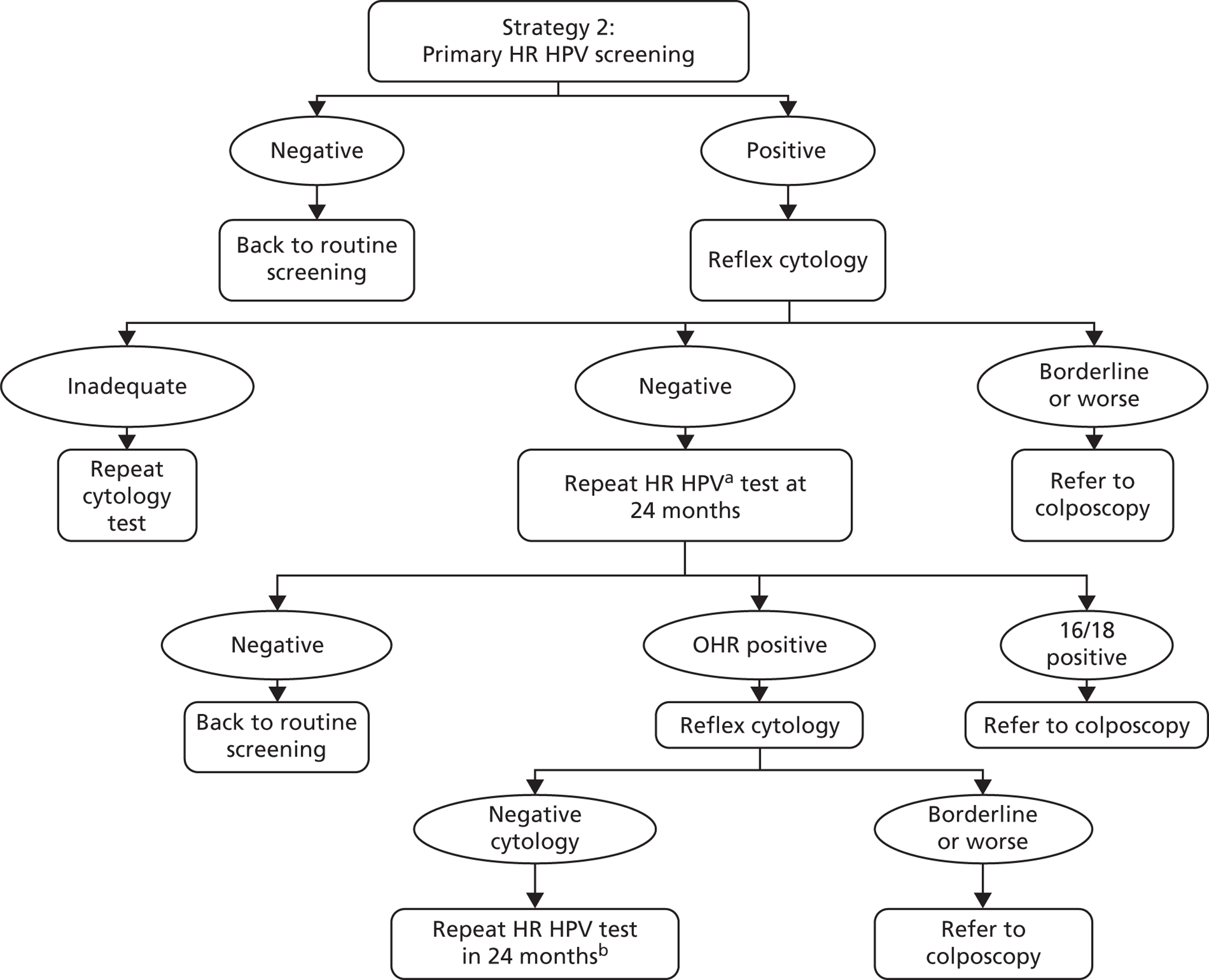

Strategy 2 (Figure 5)

The strategy can be summarised as follows: women with any oncogenic HPV-positive infection have reflex cytology triage. Cytology-positive women (borderline dyskaryosis or worse) are referred to colposcopy. HPV-positive, cytology-negative women have repeat HPV and reflex cytology in 24 months with partial genotyping and any HPV 16/18 positive or borderline dyskaryosis or worse are referred to colposcopy at that point. Cytology-negative women and/or women negative for HPV 16/18 are sent for a repeat HPV test in another 24 months, with any HPV-positive women referred to colposcopy at that point. HPV-negative women are returned to routine screening.

FIGURE 5.

Screening and follow-up management of primary HPV screening for strategy 2. a, Using a HPV test that has HPV 16/18 partial genotyping. b, At the second 24-month follow-up, any oncogenic HPV positive is referred to colposcopy. HPV negatives return to routine screening. OHR, other high risk.

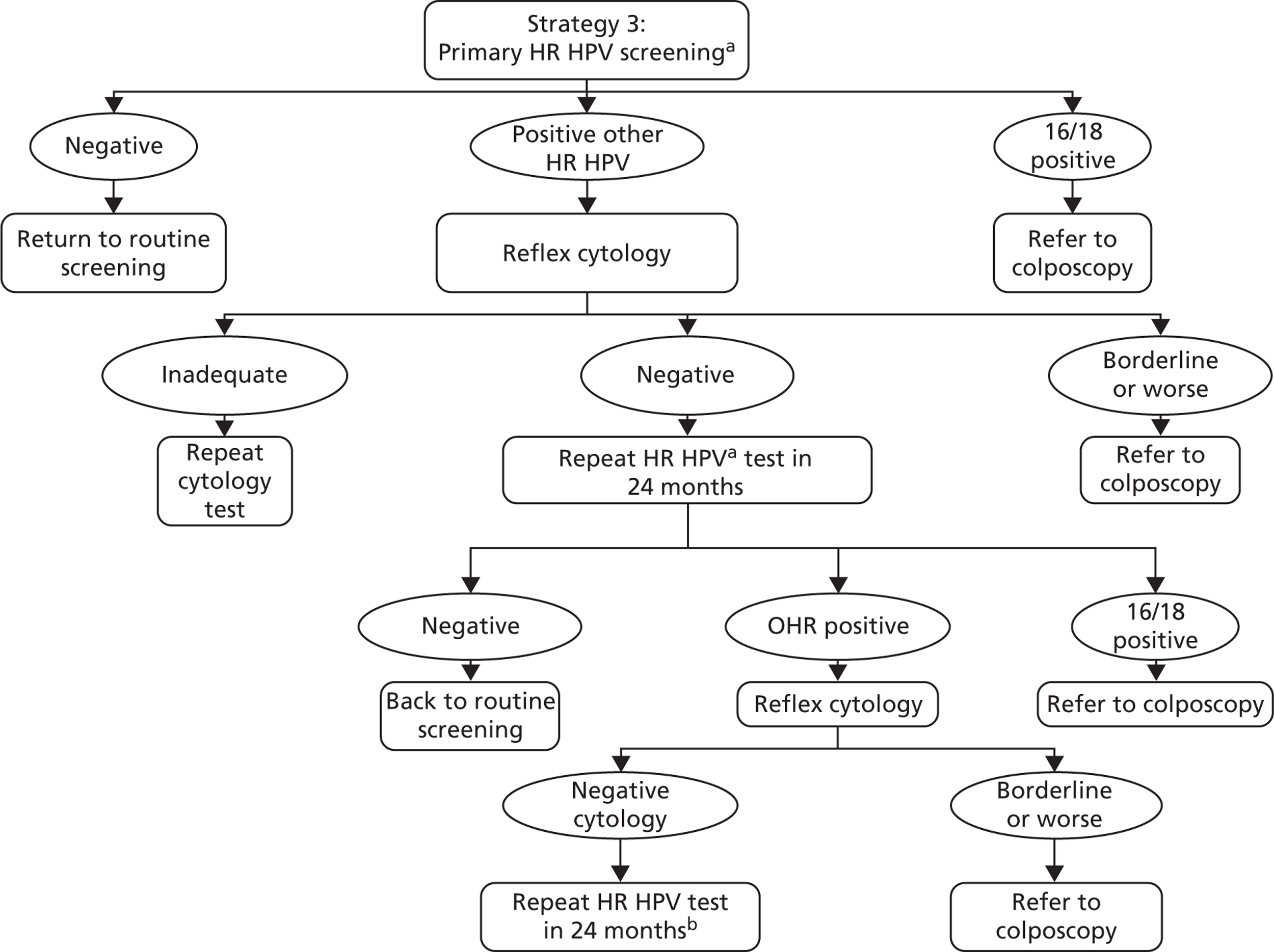

Strategy 3 (exploratory) (Figure 6)

The strategy can be summarised as follows: a primary screening test with partial genotyping is used and women with HPV 16/18 are referred directly to colposcopy. Cytology triage is performed on other oncogenic HPV-positive women, with those cytology-positive (borderline dyskaryosis or worse) referred to colposcopy. Other oncogenic HPV-positive women who are cytology negative are then followed up as in strategy 2.

FIGURE 6.

Screening and follow-up management of primary HPV screening for strategy 3. a, Using a HPV test that has HPV 16/18 partial genotyping. b, At the second 24-month follow-up, any oncogenic HPV positive is referred to colposcopy. HPV negatives return to routine screening. OHR, other high risk.

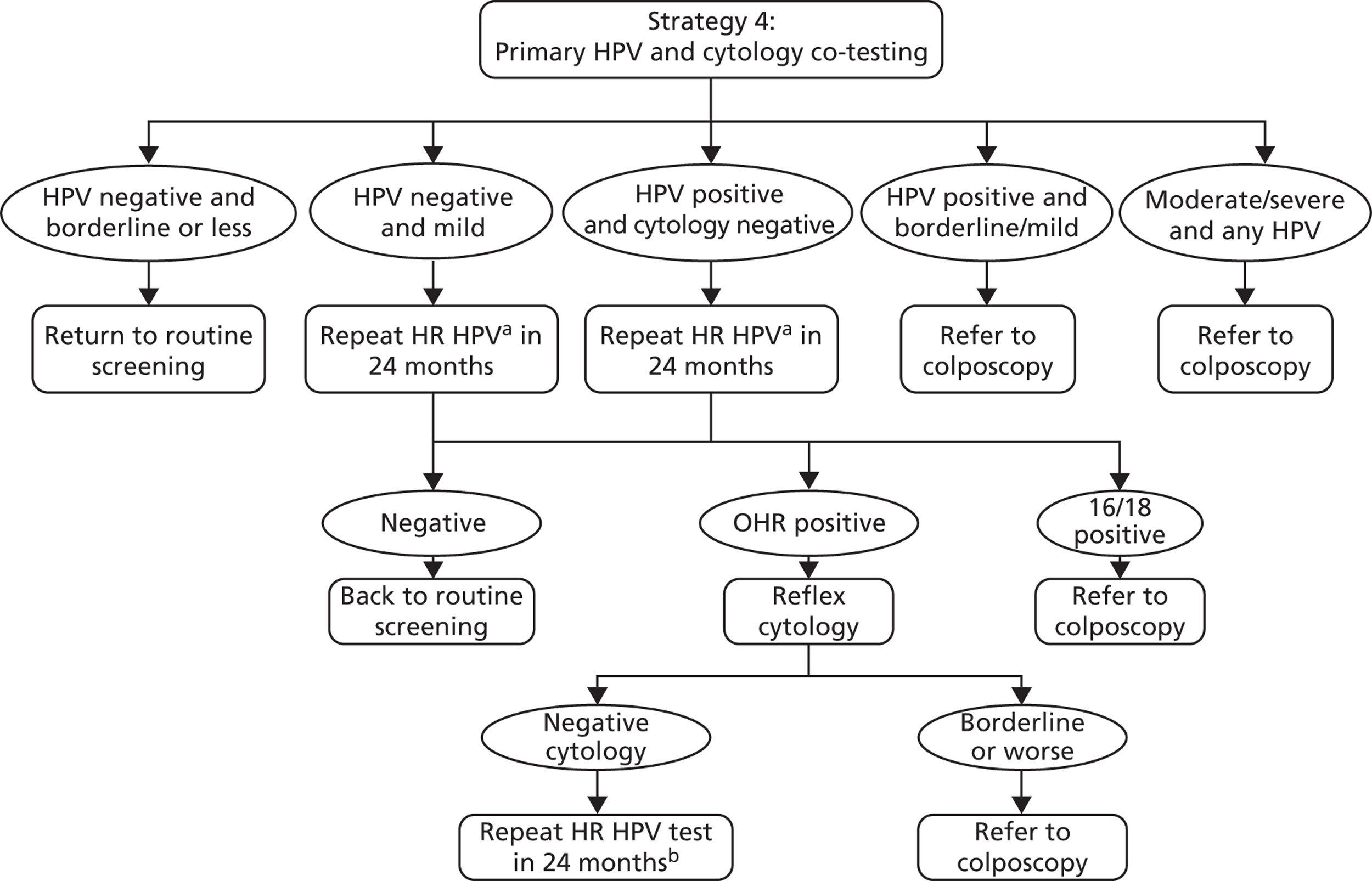

Strategy 4 (exploratory) (Figure 7)

This ‘co-testing’ exploratory strategy can be summarised as follows: women receive HPV and cytology co-testing. Women with moderate or severe dyskaryosis are referred to colposcopy. Women who are HPV positive with a cytology result of borderline or mild dyskaryosis are also referred to colposcopy. Women who are HPV positive with a normal cytology result have repeat testing in 24 months, and are thereafter managed as in strategy 2. Women who are HPV negative with a cytology result of mild dyskaryosis also have repeat testing in 24 months, and are thereafter managed as in strategy 2. Women who are HPV negative with a cytology result of borderline dyskaryosis or normal are returned to routine screening.

FIGURE 7.

Screening and follow-up management of primary HPV screening for strategy 4. a, Using a HPV test that has HPV 16/18 partial genotyping. b, At the second 24-month follow-up, any oncogenic HPV positive is referred to colposcopy and HPV negatives return to routine screening. OHR, other high risk.

Strategy variations

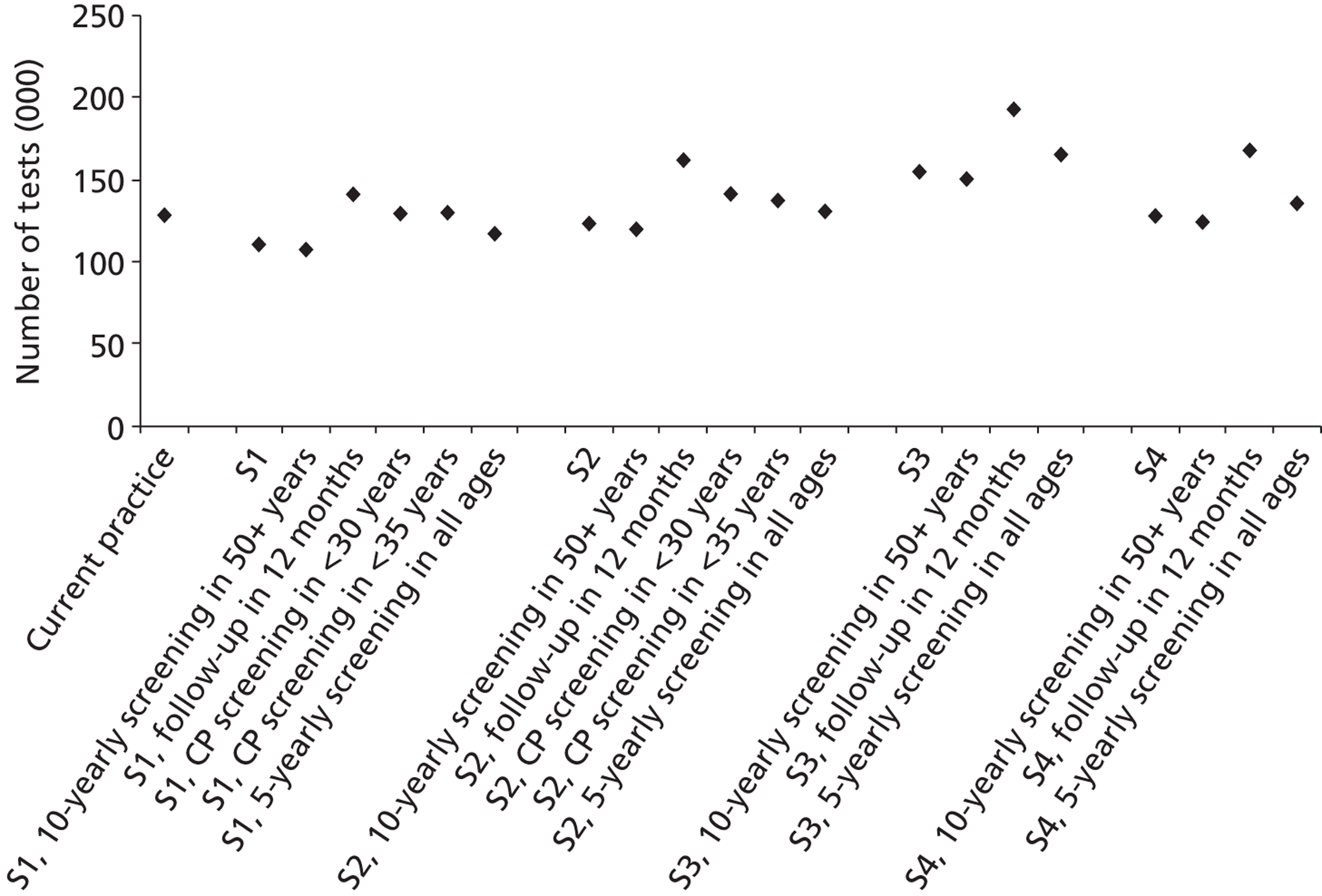

Screening interval

We considered three different screening interval scenarios for each strategy:

-

a 6-yearly screening interval for women aged 25–64 years (used in basic strategies)

-

a 6-yearly screening interval in women aged 25–49 years and a 10-yearly interval in women aged 50–64 years

-

a 5-yearly screening interval for women aged 25–64 years.

Combined primary cytology and primary human papillomavirus strategies (exploratory analysis)

For each of strategies 1 and 2, we also modelled the following combined screening options where cytology was retained as the primary screening test for younger women and then primary HPV screening was used in older women, assuming that:

-

cytology screening according to current recommendations was performed in women 25–29 years, with primary HPV screening in women > 30 years

-

cytology screening according to current recommendations was performed in women 25–34 years, with primary HPV screening in women > 35 years.

For these strategies, we assumed that a woman would ‘switch’ primary screening tests at the first screen attendance after the ‘switching’ age (which may be several years later in the case of underscreened women). We assumed that women who had been screened prior to the ‘switch’, and who were in follow-up management at the time of the switch, completed that cycle of management until discharged back to routine screening. However, it should be noted that detailed recommendations for how underscreened women and women under follow-up management should be handled after the ‘switch’ would require review, and the nature of such recommendations would have the potential to change these findings. Therefore, these strategies should be considered exploratory.

Follow-up of human papillomavirus-positive/cytology-negative women

Each strategy was modelled under alternate assumptions about follow-up for HPV-positive women who were not referred immediately to colposcopy (e.g. because the triage cytology test was negative):

-

Women were assumed to be followed up at 24 months (used in basic strategies).

-

Women were assumed to be followed up at 12 months.

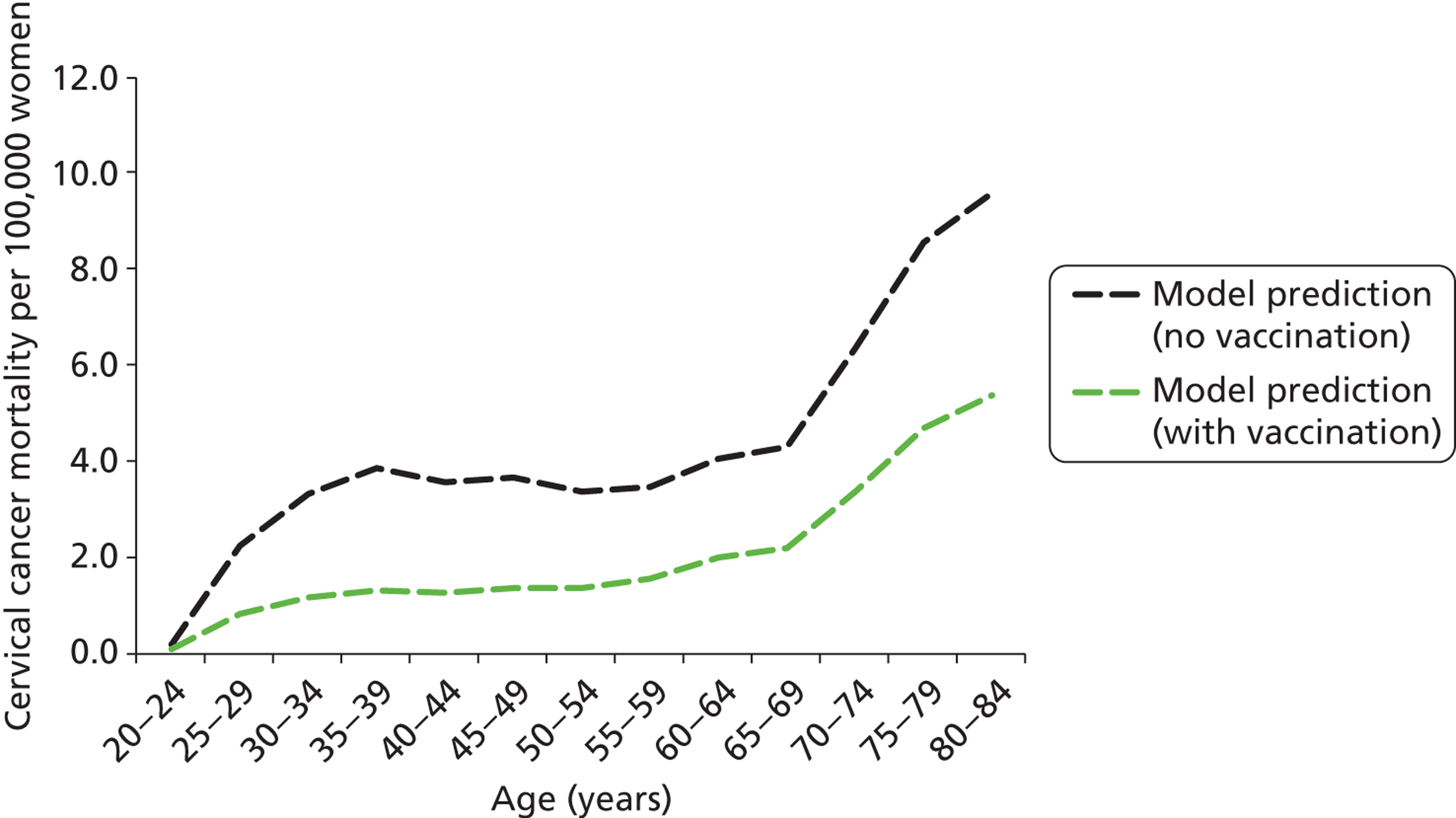

Modelling human papillomavirus vaccination

Each strategy was modelled under alternate assumptions about vaccination status:

-

Women were assumed to be unvaccinated.

-

Women were assumed to be part of a cohort who were offered vaccination as pre-adolescents (12–13 years). The effects of the national HPV vaccination programme were modelled (2010–11 coverage rates24). The vaccination catch-up programme (with appropriate coverage rates obtained from Sheridan and White24) was also simulated, as this would have some effect on the cohorts offered routine vaccination via the effects of herd immunity.

Each cost and effectiveness calculation was performed for the primary HPV screening strategy, compared with current practice, in both vaccinated and unvaccinated cohorts. The effect of vaccination on the incidence of the vaccine-included types was modelled using the dynamic transmission model (which took into account the effects of prior exposure to HPV on vaccine effectiveness and also herd immunity); these differences in HPV incidence were then input to the CIN natural history model and this difference thus impacted the rate of development of HPV 16- and 18-associated CIN and cervical cancer in the model.

We assumed that the HPV 16/18 vaccine was 100% effective in preventing future HPV 16 and HPV 18 infections in HPV-naive women at the time they were vaccinated and who completed all three doses of the vaccine course. This protection was assumed to be life-long. We made these assumptions so that the most generous estimate of vaccine effectiveness can be taken into account when considering new options for cervical screening, when compared with unvaccinated scenarios. No protection was conferred in the model in women with a prevalent infection at the time of vaccination, or who are immune (due to a naturally acquired previous infection) from infection at the time of vaccination. The model assumed that the vaccine conferred no therapeutic effect in women with a prevalent HPV infection, or with pre-existing CIN. In this case, the risk of viral clearance, progression, or regression from CIN in the model remains the same as that in an unvaccinated woman. It was also assumed that an incomplete vaccine course offered no protection; however, the possibility of higher ‘effective’ vaccine coverage in England due to effective two-dose or one-dose vaccination was examined in sensitivity analyses (see Appendix 17).

We did not consider the effects of cross-protection against non-vaccine HPV types, nor, as we were carrying out a cost-effectiveness evaluation of cervical screening (as opposed to vaccination), did we consider the effects of vaccination on anogenital warts. Thus, the results of our analysis are applicable to situations where either bivalent or quadrivalent vaccines have been used.

The screening evaluations in vaccinated women involved a modelled cohort of women born in 1998 who were offered vaccination as 12-year-olds in 2010. Herd immunity effects on the modelled cohort from vaccination delivered to both older birth cohorts (born 1990–7; included in the catch-up programme) and younger birth cohorts (1999 or later) were fully taken into account by the dynamic transmission model. Thus, the effects of the catch-up cohort were included in our analysis through the herd immunity effects they provided to the cohort we investigated for screening. The overall clinical effectiveness of the vaccine administered to the catch-up cohorts was expected to be lower because some of these women will have had prior exposure to HPV; however, for HPV-naive women in the catch-up cohorts, the vaccine is assumed to be clinically effective, and these effects were taken into account in the dynamic transmission model. The outcomes for catch-up cohorts are, therefore, expected to be intermediate to those predicted and presented here for HPV-naive vaccinated cohorts and unvaccinated cohorts.

In the model, we used a hierarchical approach to lesion type-assignment when fitting the model to observed data (fitting HPV 16-positive first, then HPV 18-positive, then other oncogenic types). Because of the potential for multiple infections, this method may result in underestimation in the model of the prevalence of other oncogenic-type infections. However, in our model, women who are vaccinated against HPV types 16 and 18 are available to contract other HR HPV types, partially reducing the effects of this modelling assumption in vaccinated populations.

Diagnosis and treatment procedures

The diagnosis and treatment procedures simulated in the model are detailed in Figures 8–10.

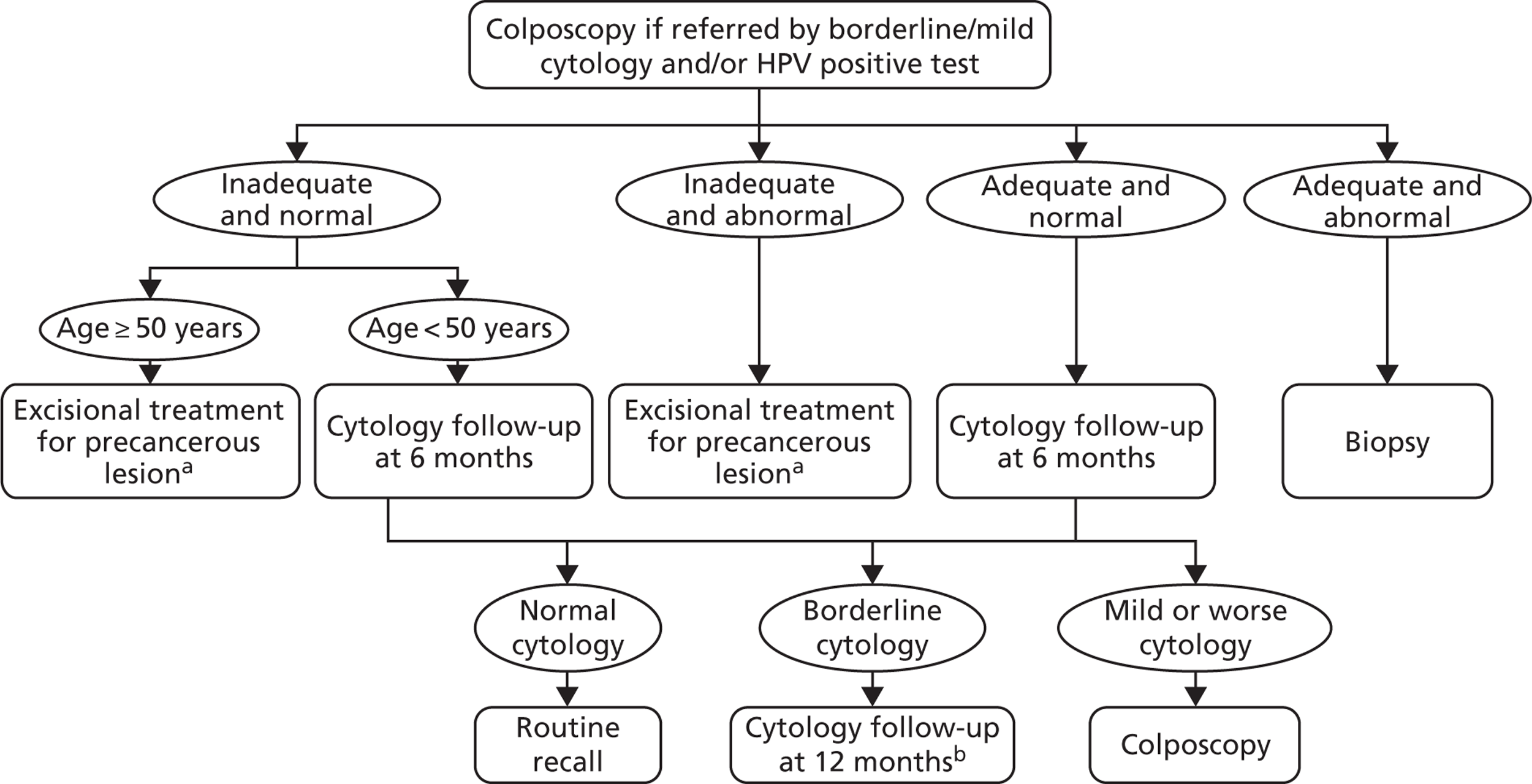

FIGURE 8.

Colposcopy management for women referred with borderline/mild cytology and/or a HPV positive test. a, Women diagnosed with invasive cancer undergo cancer treatment. Women treated for CIN undergo HPV and cytology testing 6 months post treatment. If both cytology and HPV negative, women are returned to routine screening. Women with abnormal cytology or positive HPV result are referred to colposcopy and are subsequently followed up under current practice post-treatment management. b, At the 12-month follow-up, any abnormal cytology result is referred to colposcopy. Women with normal cytology are referred to routine screening.

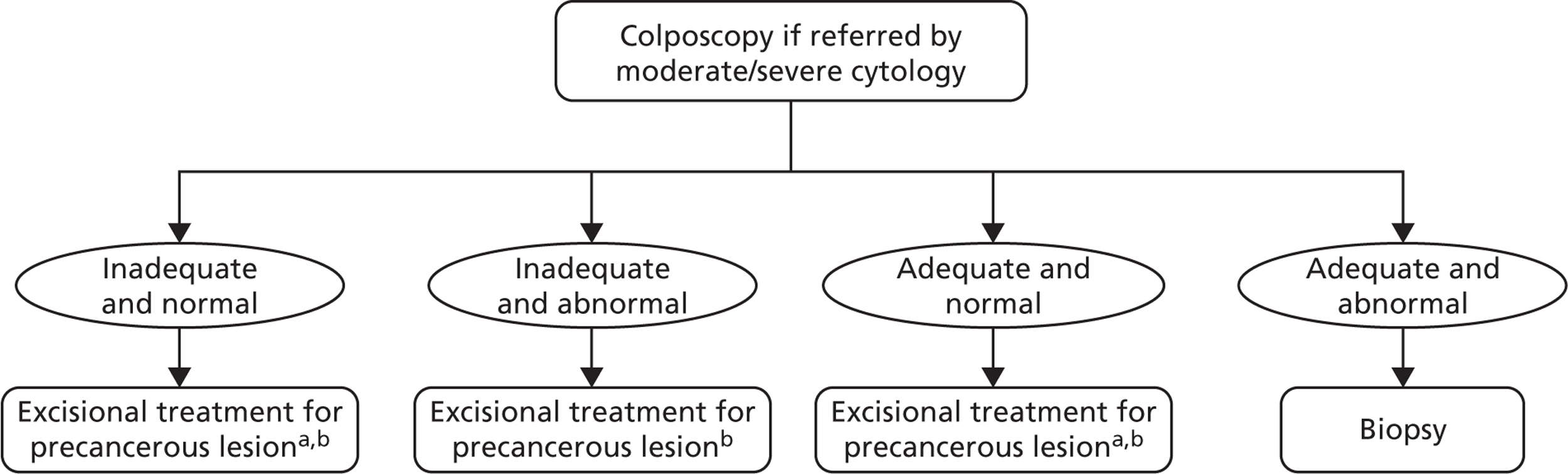

FIGURE 9.

Colposcopy management for women referred with moderate/severe cytology. a, Immediate in women over 50 years; delay 12 months in women younger than 50 years. b, Women diagnosed with invasive cancer undergo cancer treatment. Women treated for CIN undergo HPV and cytology testing 6 months post treatment. If both cytology and HPV negative, women are returned to routine screening. Women with abnormal cytology or positive HPV result are referred to colposcopy and are subsequently followed up under current practice post-treatment management.

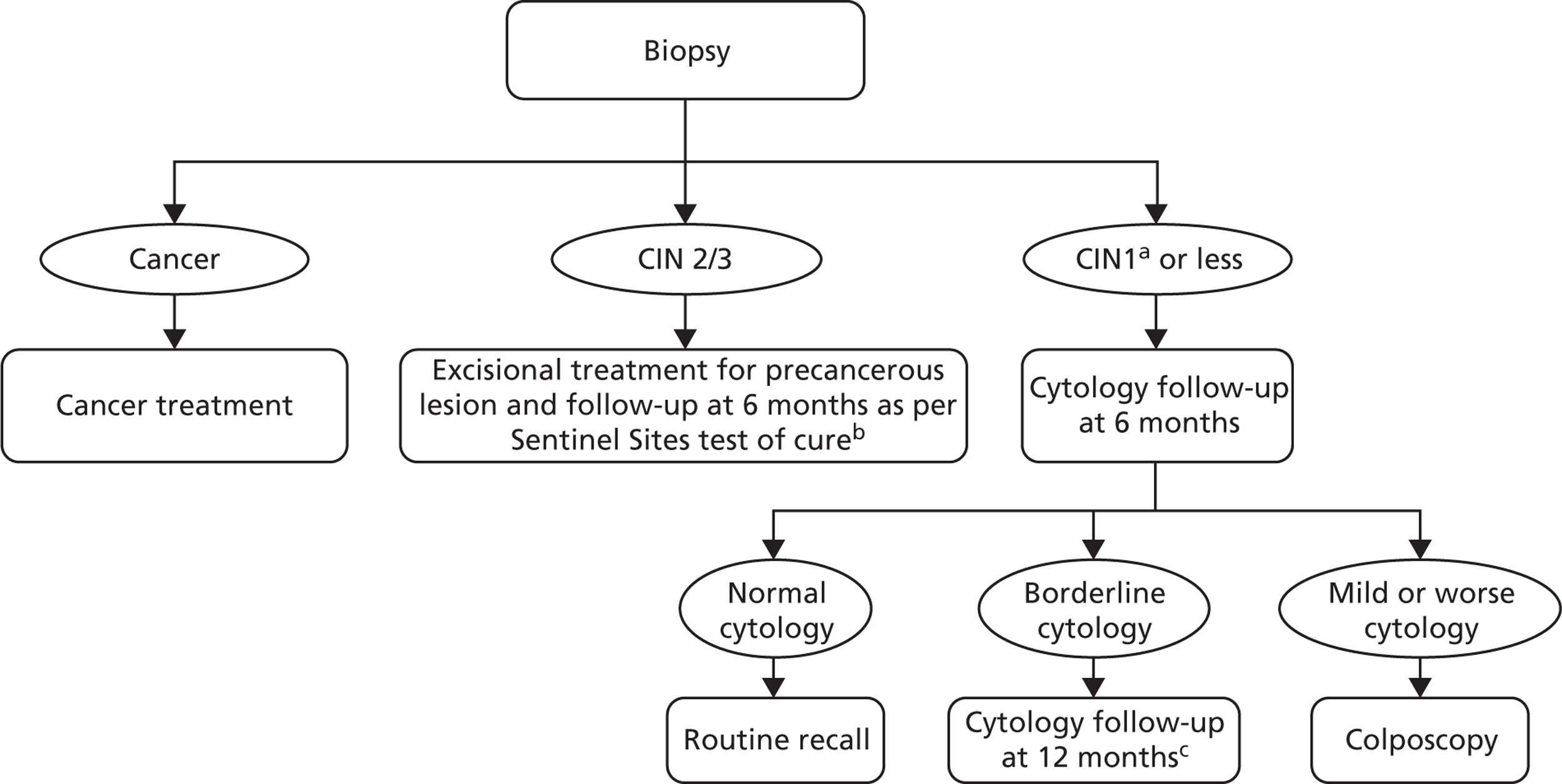

FIGURE 10.

Management for women undergoing biopsy. a, A small proportion of CIN1 are assumed to be treated along with CIN2+. b, Women undergo HPV and cytology testing 6 months post treatment. If both cytology and HPV negative, women are returned to routine screening. Women with abnormal cytology or positive HPV result are referred to colposcopy and are subsequently followed up under current practice post-treatment management. c, At the 12-month follow-up, any abnormal cytology result is referred to colposcopy. Normal cytology is referred to routine screening.

Data sources

Screening and diagnostic test characteristics

Liquid-based cytology

With regard to the sensitivity of LBC, in the base case it was assumed that test positivity rates for CIN2+ were equivalent to those from a multicentre screening study conducted in UK (the HART study). 29 ARTISTIC cytology test characteristics were not assumed for the national evaluation [although they were used for the validation exercise reported in Chapter 3 of this report (see Economic analysis validation results)] because ARTISTIC did not recruit nationally, and it is possible that cytology in the baseline round of ARTISTIC was influenced by the retraining associated with the recent introduction of LBC to the NHSCSP at the time of the trial commencement. 2

Although HART was conducted a number of years prior to ARTISTIC, and did not involve LBC, it did recruit across a wider range of centres and thus is more likely to be representative of the performance of cytology across England. The use of HART data to represent LBC test accuracy was considered to be appropriate because the sensitivity of LBC and conventional cytology for detection of CIN2+ have been shown in meta-analysis to be close to equivalent,30 and the inadequate smear rate for LBC (which is known to be lower than the rate for conventional cytology in England) was specifically modelled using other data sources. In the current analysis, the inadequate rate of LBC was assumed to be 3% in the analysis base case. 19

The test positivity rates derived from HART data for cytology for CIN2+ and CIN3+ were 76.7% and 75.9%, respectively, at a borderline dyskaryosis smear threshold; and 70.1% at both CIN2+ and CIN3+, at a mild dyskaryosis smear test threshold. With regard to the specificity of LBC, the positivity rate for CIN1 was assumed to be 37.6% at a borderline dyskaryosis smear threshold and 28.0% at a mild dyskaryosis smear threshold. Alternative sets of test characteristics for LBC, encompassing the test characteristics derived for ARTISTIC, were investigated in the sensitivity analysis (see Appendix 11 for more details).

Human papillomavirus testing

The HPV test positivity rate used in the base-case analysis and its range for sensitivity analysis was informed by a previous meta-analysis of international literature,31 and also findings from the ATHENA trial32 and the HART study. 29 The accuracy of HPV testing was based on extensive data in the literature on HC2 testing, which were used in ARTISTIC and HART. The use of these test characteristics does not necessarily assume that the specific platform was used, but assumes that HC2 or alternative platforms with close-to-equivalent performance were used. For some strategies, the use of new automated test platforms with partial genotyping for HPV 16/18 was assumed (sometimes referred to as ‘genotyping’ here).

With regard to the sensitivity of HPV test, in the base case it was assumed that the test positivity rates for CIN2 and CIN3 were 95.5% and 95.7%, respectively. With regard to specificity, the test positivity rate for CIN1 was assumed to be 84.2% (see Appendix 11 for more details).

The base-case assumptions assumed that the HPV test threshold was such that the test performance was equivalent to HC2 at a 2 pg/ml threshold. However, the sensitivity analysis encompassed the possibility that a test with performance equivalent to that of HC2 with a threshold of 1 pg/ml performance was used.

Colposcopy

The test characteristics and unsatisfactory rate of colposcopy were based on those used in previous modelling work performed in the UK and Australian context. 12,18,20 The test positivity rate for colposcopy was assumed in the base case for CIN1 and CIN2+ to be 79.2% and 90.8%, respectively. Colposcopy was assumed to be capable of detecting abnormalities of the cervix in all women with undiagnosed cervical cancer at the time of examination (see Appendix 11 for more details).

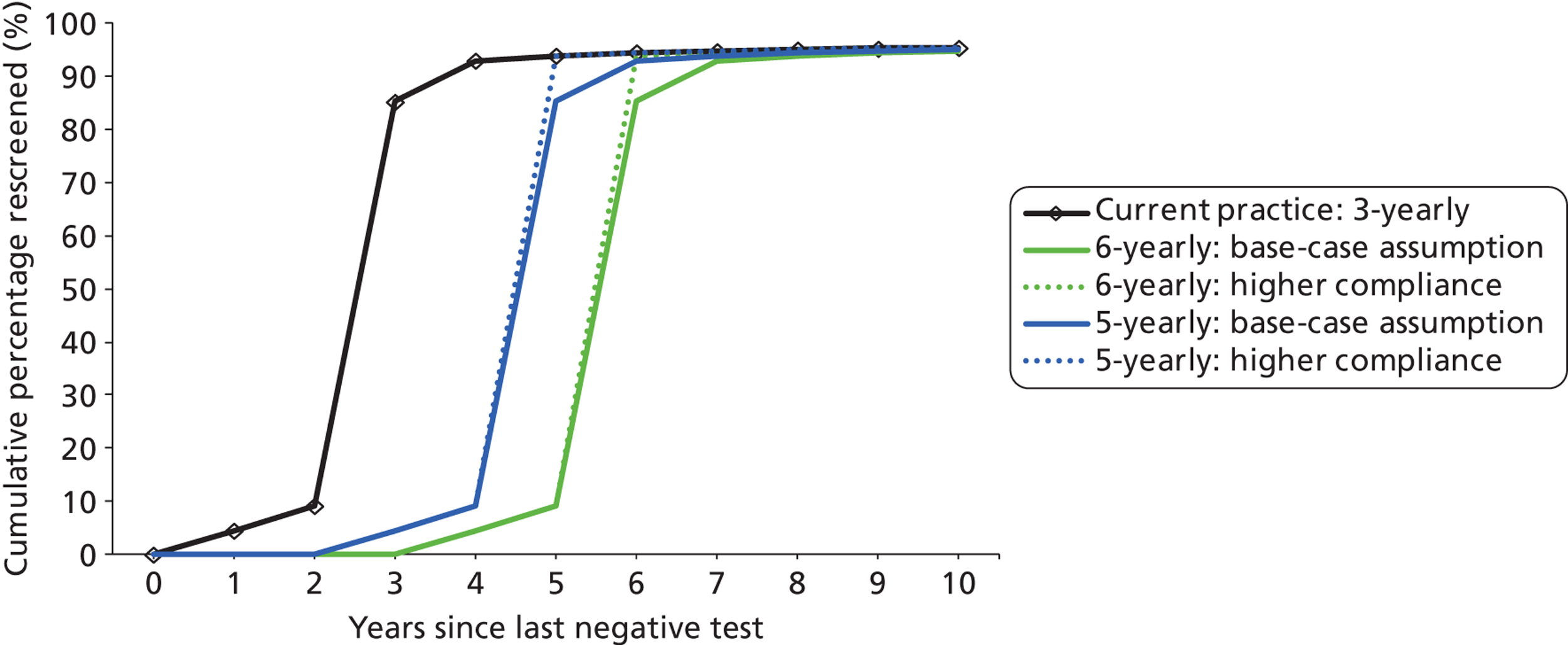

Compliance with screening and management recommendations

For strategies that simulate current practice, we used registry data from Oxfordshire to estimate the cumulative rescreened proportion at various times after a negative smear for women who appeared on the register. 33 We used age-specific data on the percentage of eligible women who attended at least once in a 5-year period in England (2007–8)12,34 to adjust these data and derive age- and interval-specific probabilities of women attending for routine screening. This allows the model to take into account non-attendance, early rescreening, late rescreening, and screening in ages outside the target age range for screening.

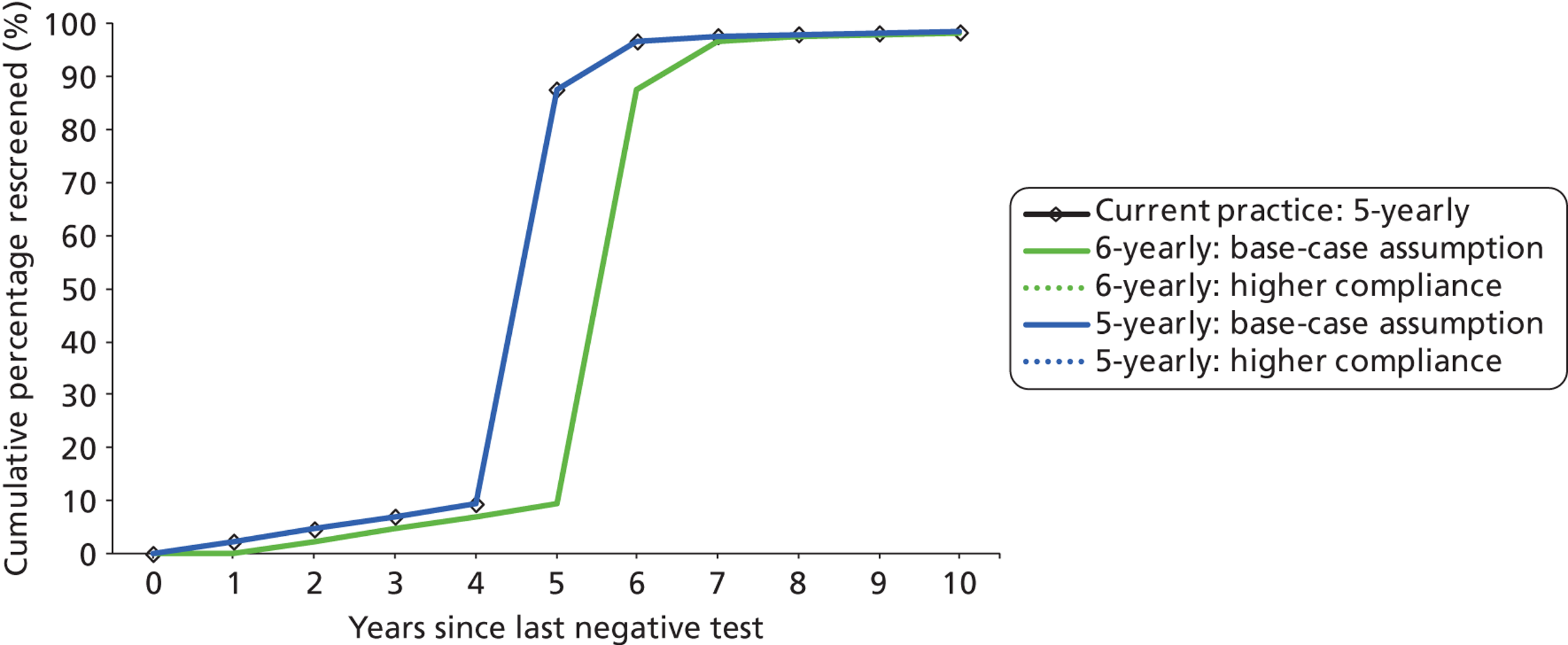

For the primary HPV screening strategies involving a recommended 6-yearly interval, the proportion of women rescreened at the sixth year after the last negative test was assumed to be the same as the observed proportion for current practice after the third year following a negative cytology test, or fifth year in women older than 50 years.

Compliance with follow-up recommendations for HPV-positive, cytology-triage-negative women was assumed to be 80% by the recommended follow-up interval (either 24 or 12 months) in the base case. This is higher than the compliance rate observed in the ARTISTIC trial, although ARTISTIC was not nationally representative. Currently, women are either referred for colposcopy (if they have a cytology result of borderline or mild dyskaryosis and a positive HPV test, or if they have moderate or severe dyskaryosis) or referred back to routine screening after their primary screening test. Therefore, there is no directly analogous situation for the NHSCSP from which we can take up-to-date data on compliance for the future scenario in which HPV-positive, triage-negative women are referred for follow-up. However, the NHS Sentinel Site experience has shown that compliance with colposcopy referral in women with a cytology low-grade result who were HPV positive was 90.2% (with a range of 81.4–96.2% depending on the region). Although this relates to colposcopy referral rather than to follow-up compliance, the Sentinel Site experience is more representative nationally than ARTISTIC. The use of two alternate recommended follow-up intervals in this group effectively also assessed the sensitivity of the findings to compliance assumptions (as our modelled simulation of 80% compliance to follow-up at a recommended 24 months is analogous to a situation where the recommended follow-up was 12 months with poor compliance to that interval and in which late attendance between 12 and 24 months occurred in the remaining women).

Compliance to referral for colposcopy and compliance for follow-up at intervals of either 6 months or 12 months in the new strategies were assumed to remain the same as current practice (see Appendix 12 for more details).

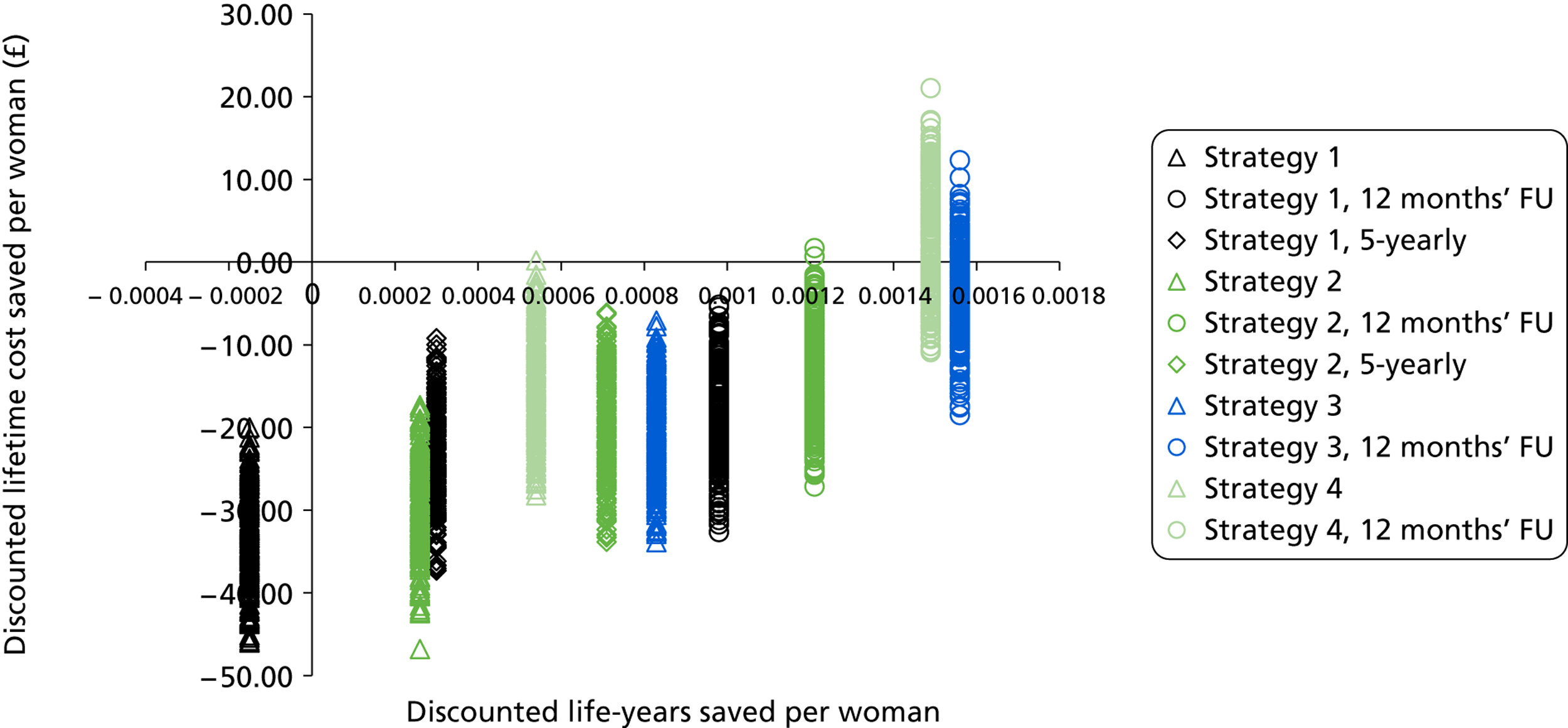

Cost and utilities (quality-adjusted life-year weights)

The costs of HPV testing both for general HR types and specifically for genotypes 16/18 were obtained from the manufacturers of four HPV tests: the Abbott® RealTime High Risk HPV test (Abbott Molecular, Maidenhead, UK), the Cobas 4800 HPV test (Roche®), Cervista® HPV HR and Cervista® HPV 16/18 Cervista™ HPV (Hologic®) and the Digene HC HR HPV DNA test and the HPV Genotyping PS test, which can test for HPV 16, 18 and also HPV 45 if required (Qiagen, Gaithersberg, MD, USA). The average cost across the manufacturer-supplied prices was used as the baseline estimate for the unit cost of HPV testing. In the base case, we assumed partial genotyping would be obtained at no extra cost (based on the emergence of systems that provide this information as standard) but the effects of this assumption were assessed in sensitivity analysis.

The cost of LBC was based on reanalysis of the cost data from the MAVARIC study19 and the costs of diagnosis and treatment for CIN and cancer were based on the findings of Martin-Hirsch et al. 35 and Sherlaw-Johnson et al. 36 All costs for the final model inputs were adjusted using the Hospital and Community Health Service (HCHS) pay and price index to the year 201037 (see Appendix 13 for details on the costs used in the model). Probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) was performed to access the robustness of the results to the input costs.

For this evaluation the primary outcome for effectiveness was considered to be life-years saved, because there is a paucity of data to inform the choice of quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) weights (health-state utilities) for HPV testing when it is used as a primary screening test, and for the subsequent referral and management processes. However, as a supplementary analysis and as a secondary outcome of the evaluation, two sets of QALY weights were used to examine the potential impact of considering QALYs, and to assess the sensitivity of the findings to the particular choice of QALY weights. These were as follows.

Quality-adjusted life-year weights set 1

The first set of weights used for the current analysis was from a study recently conducted specifically to assess health-state utilities relevant to primary HPV screening and subsequent triage testing and management. This study was conducted in metropolitan Sydney, NSW, Australia, and measured QALY weights via a two-stage standard gamble. 38 The QALY weights for patients diagnosed with invasive cervical cancer were obtained from published studies. 39,40 Based on the study findings, this set of weights assigned some disutility to the experience of being screened, even if the test result was negative.

Quality-adjusted life-year weight set 2

Previously published weights were used,40,41 although these were not obtained in the context of health-state preference assessment specifically for primary HPV testing. This set of weights did not assign any disutility to the experience of being screened per se.

Details of QALY weight assumptions used in the model are provided in Appendix 14. The impact of the choice of QALY weights was assessed via comparison of the findings using the two different sets of weights.

Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage rates

The screening evaluations in vaccinated women involved a modelled cohort of women born in 1998 and offered vaccination as 12-year-olds in 2010. In the base case it was assumed that the HPV vaccination coverage rate was as reported in 2010–11 by the Department of Health (84.2% three-dose coverage rate in routinely vaccinated 12- to 13-year-old girls). 42 As vaccination is an ongoing activity and it is possible that this level of coverage is not constant over time, and as emerging data on two-dose efficacy suggest the possibility of relatively high effectiveness for two doses (meaning that the ‘effective’ coverage in England may be higher than the reported three-dose coverage), lower and higher coverage rates for vaccination were investigated in sensitivity analysis (see Appendix 15 for details of the age-specific vaccination coverage used in the model).

Demographic data and cancer survival

The rate of death from causes other than cervical cancer was calculated by subtracting the rate of cervical cancer death43 from all-cause mortality rate. 44 The rate of benign hysterectomy was obtained from a published study conducted in England and Wales. 45 The invasive cancer survival rates used in the model were based on the previous work. 19

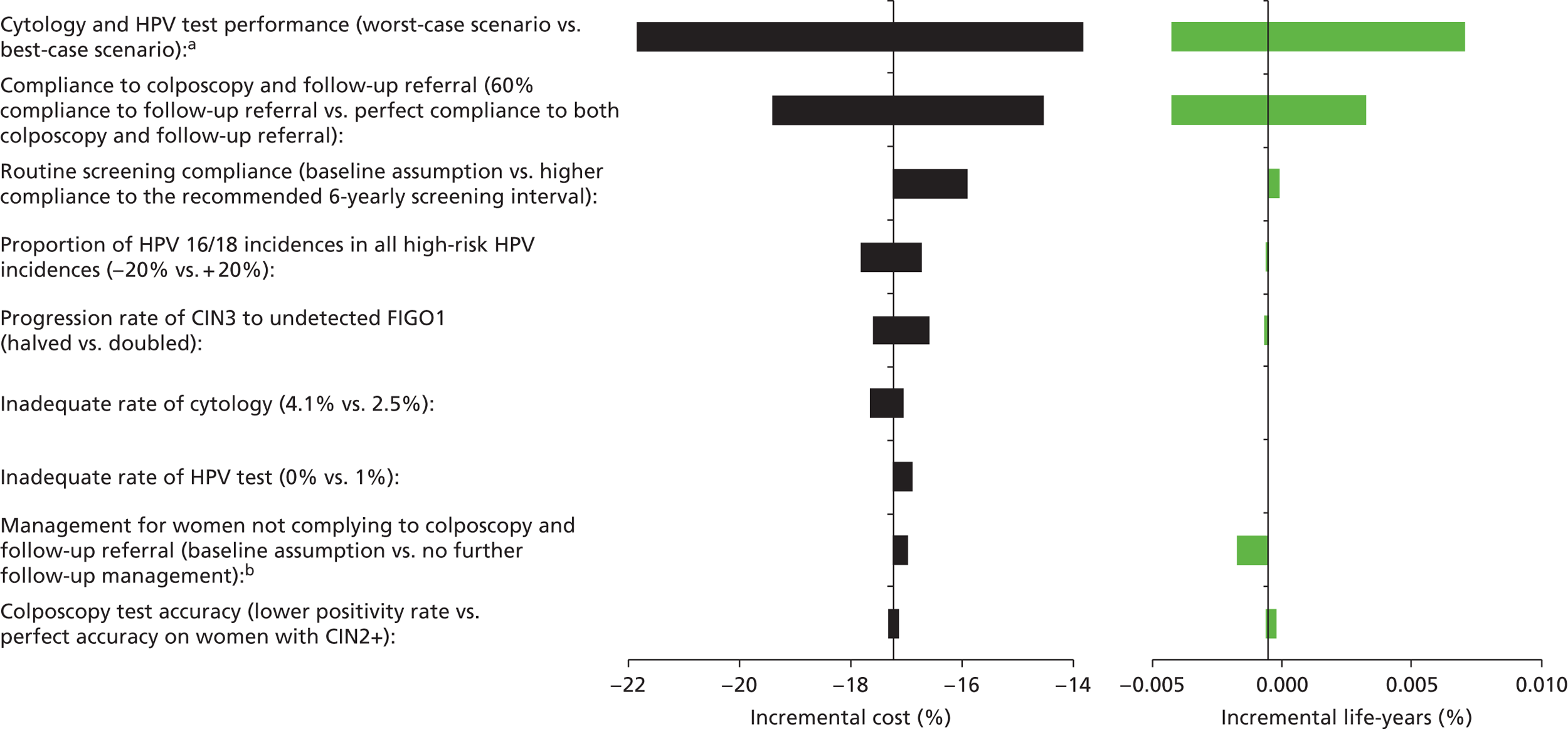

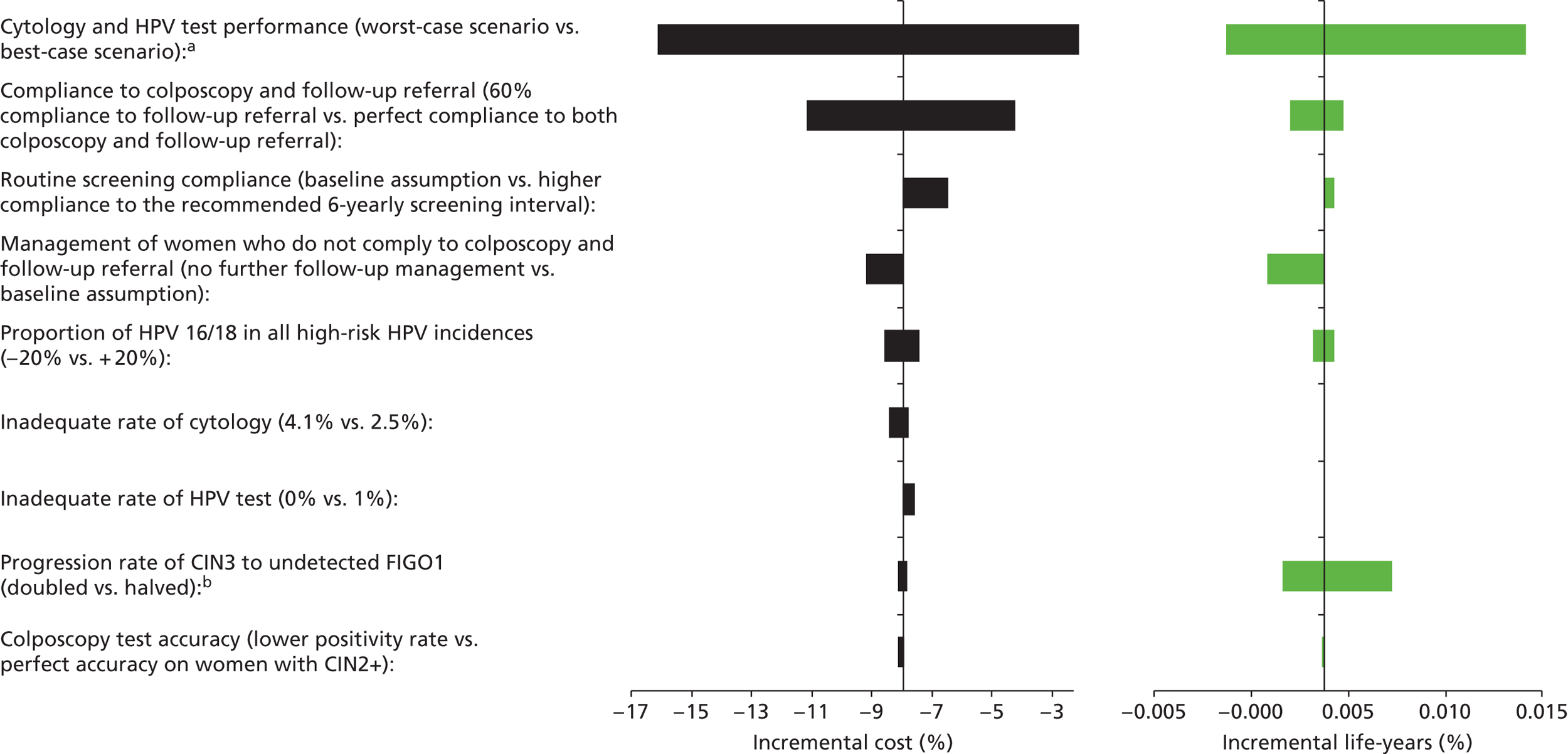

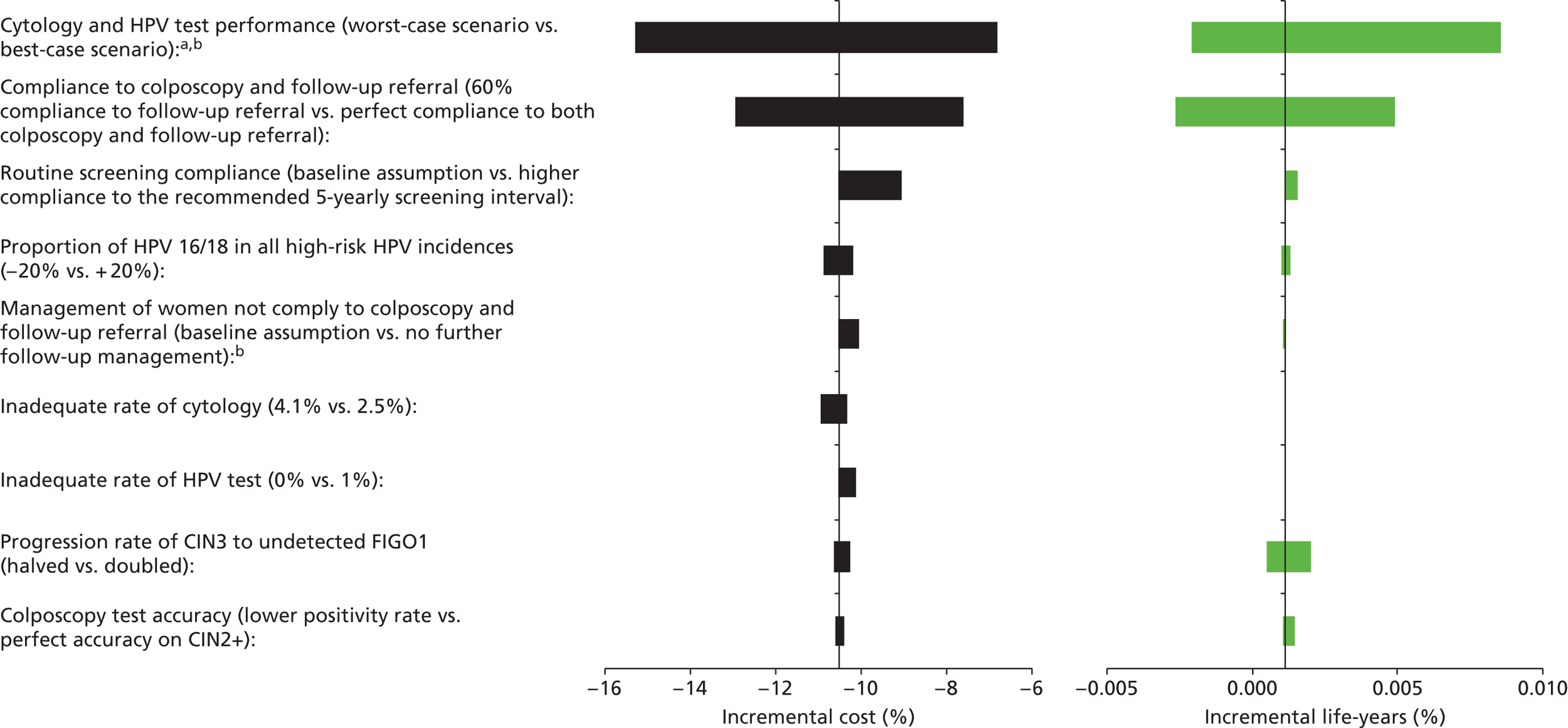

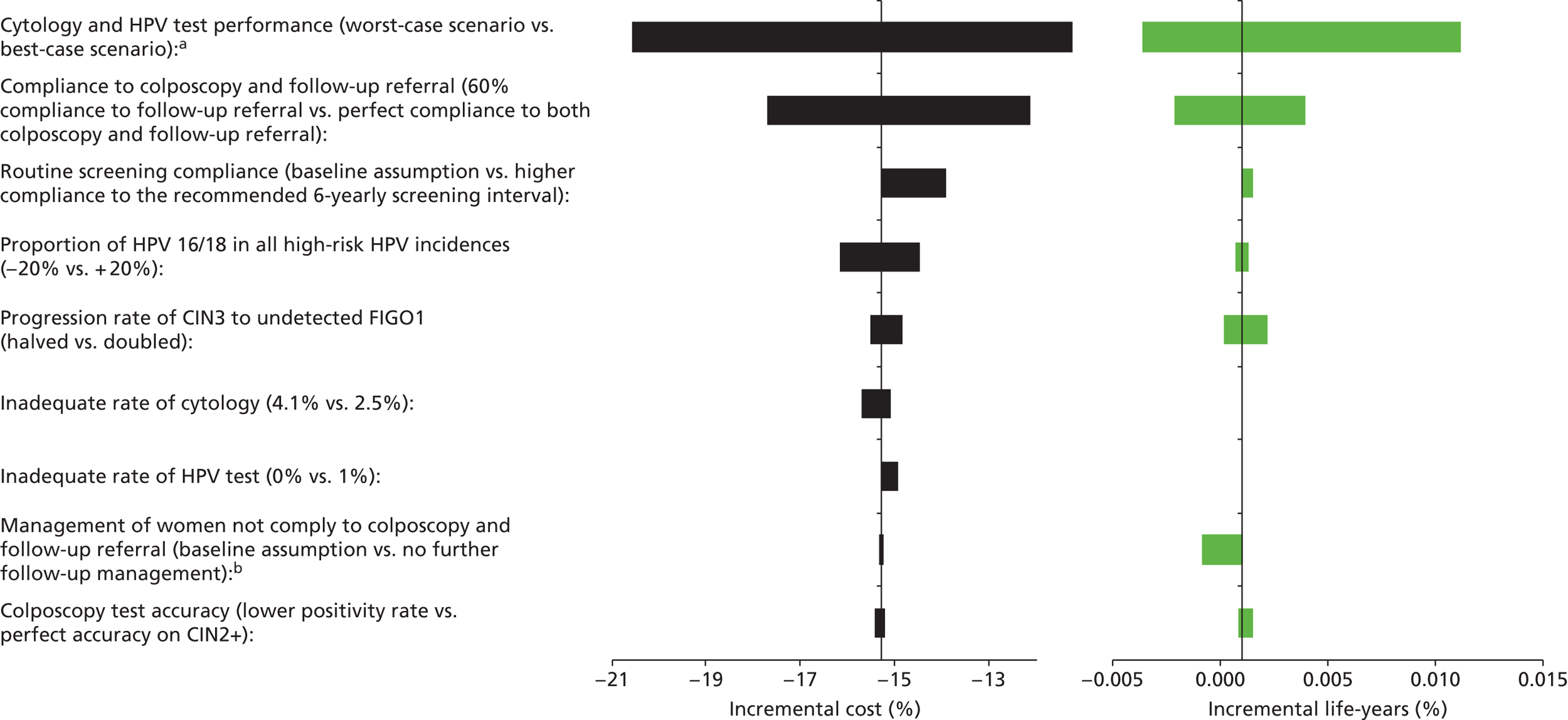

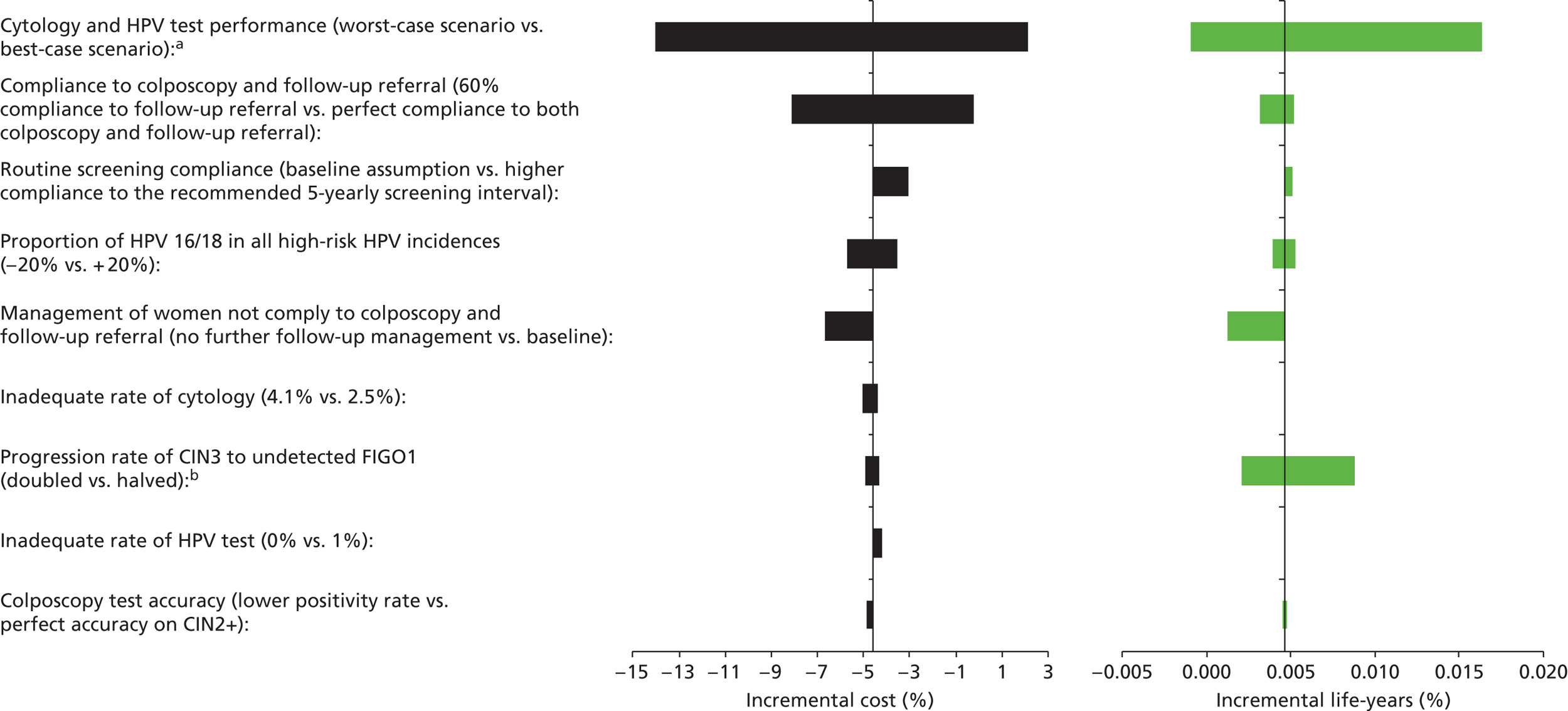

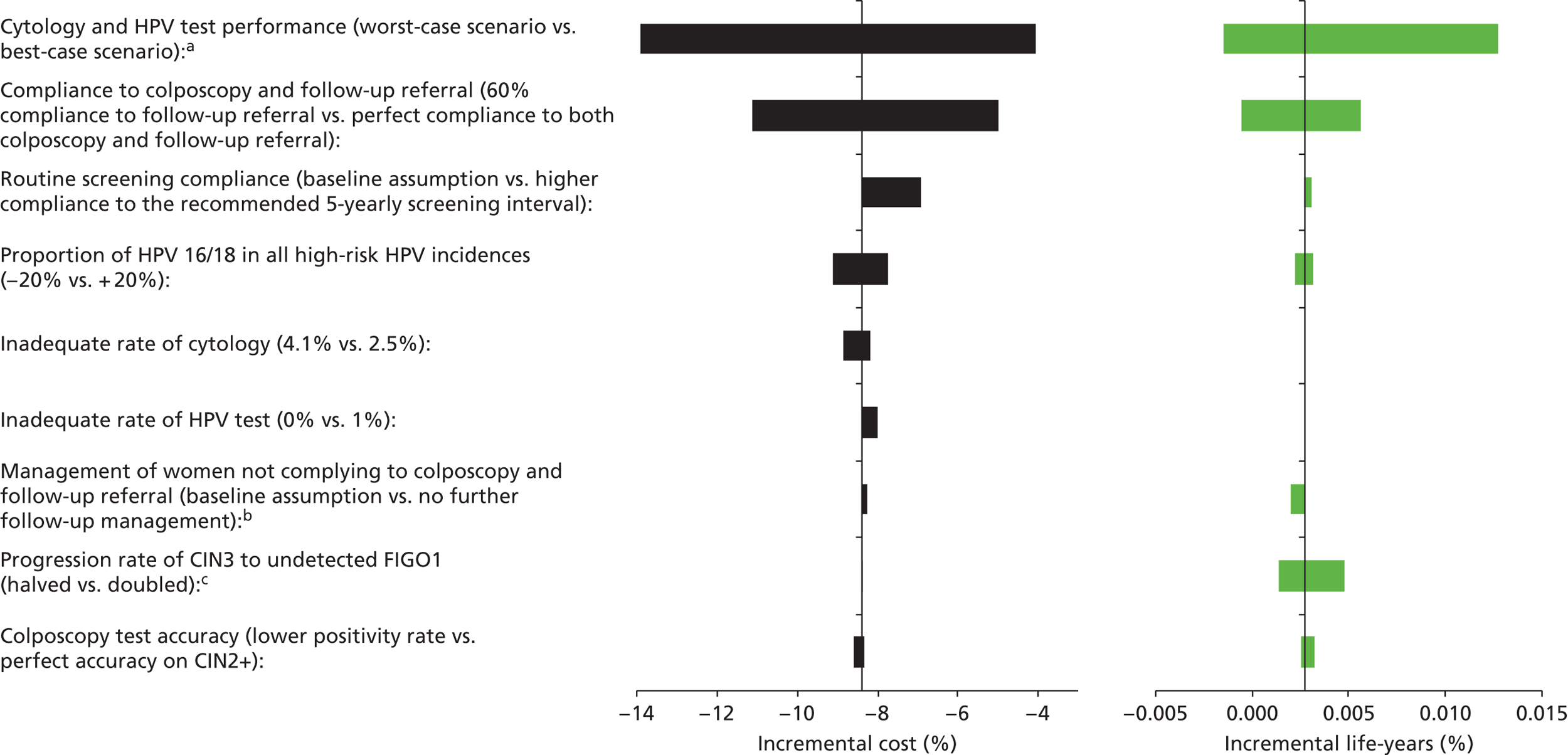

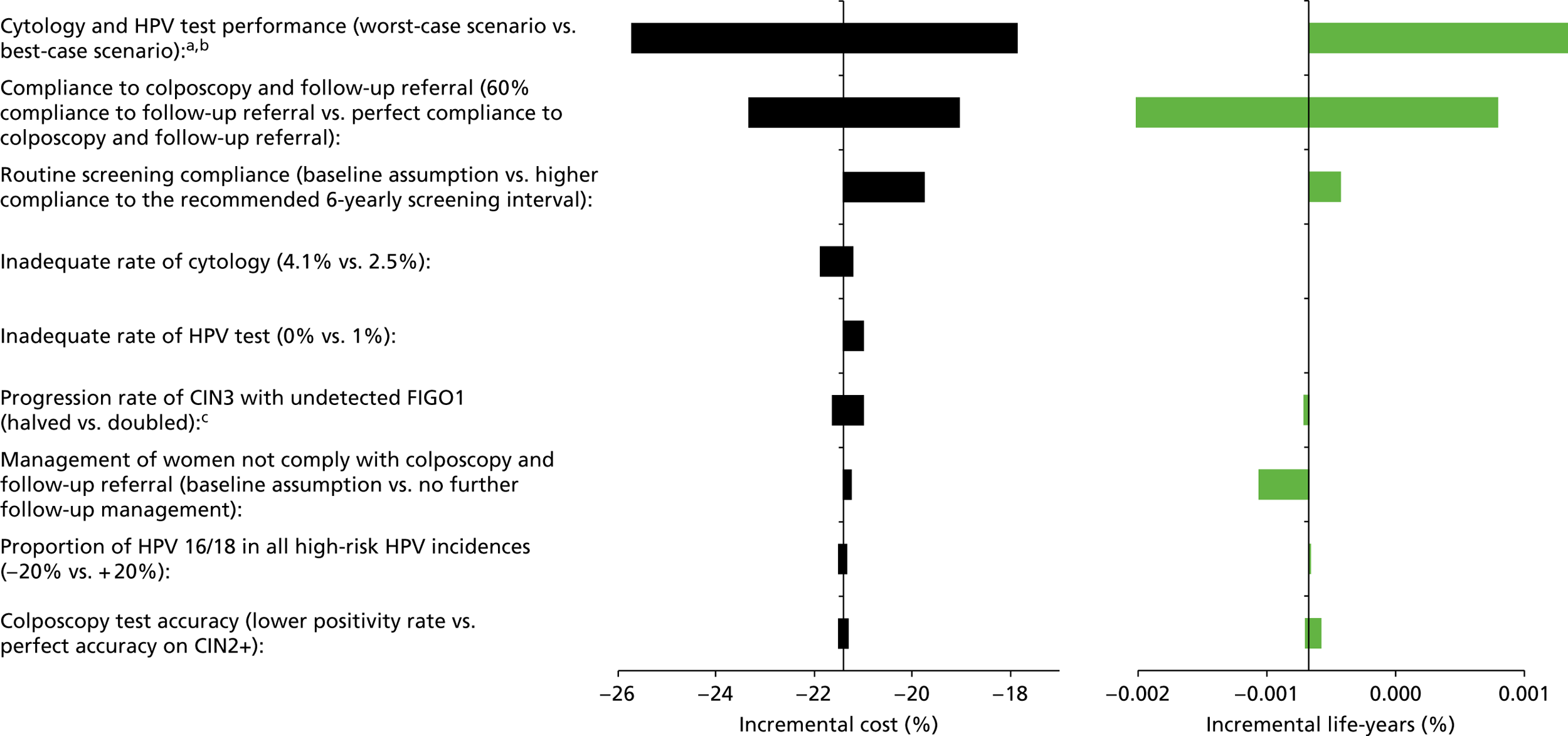

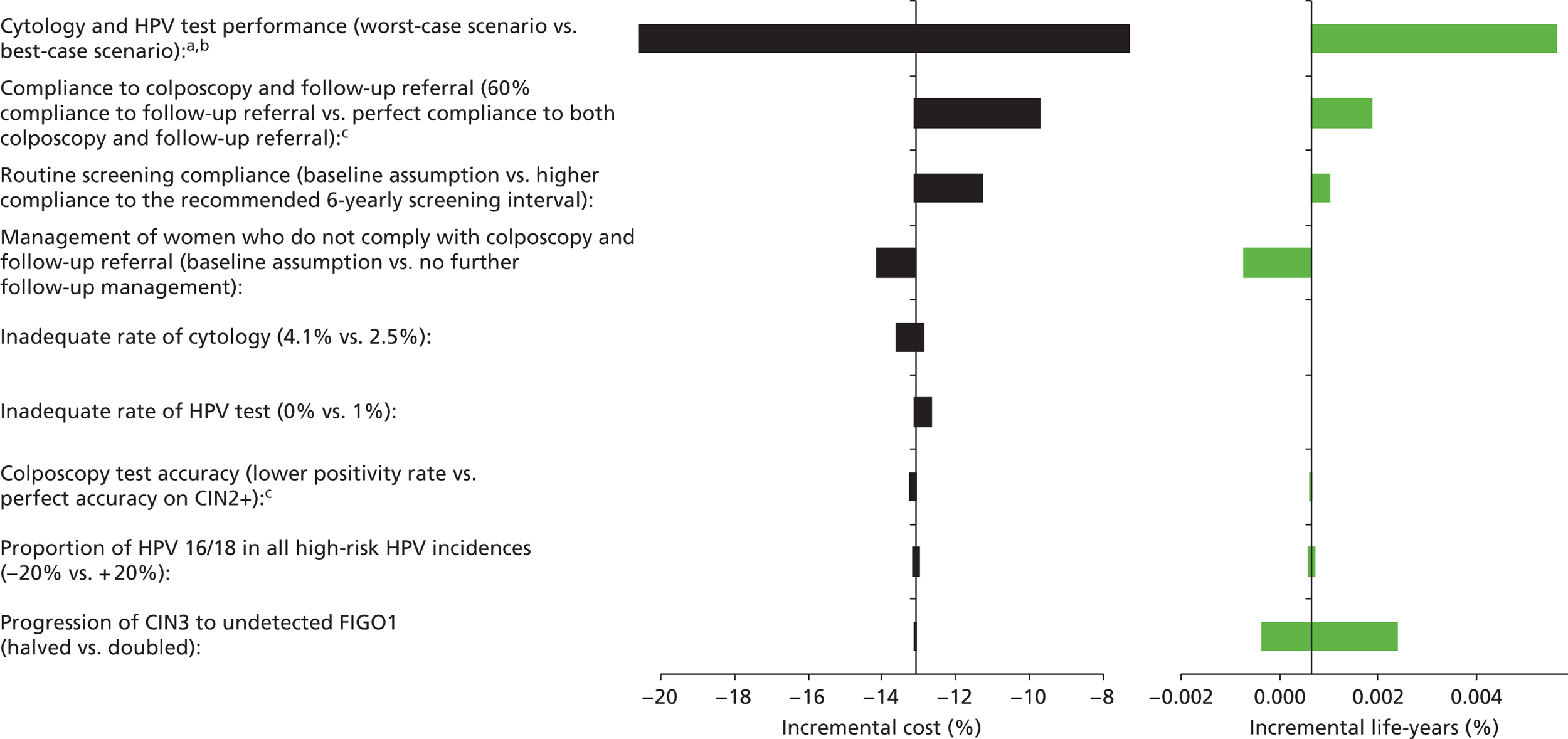

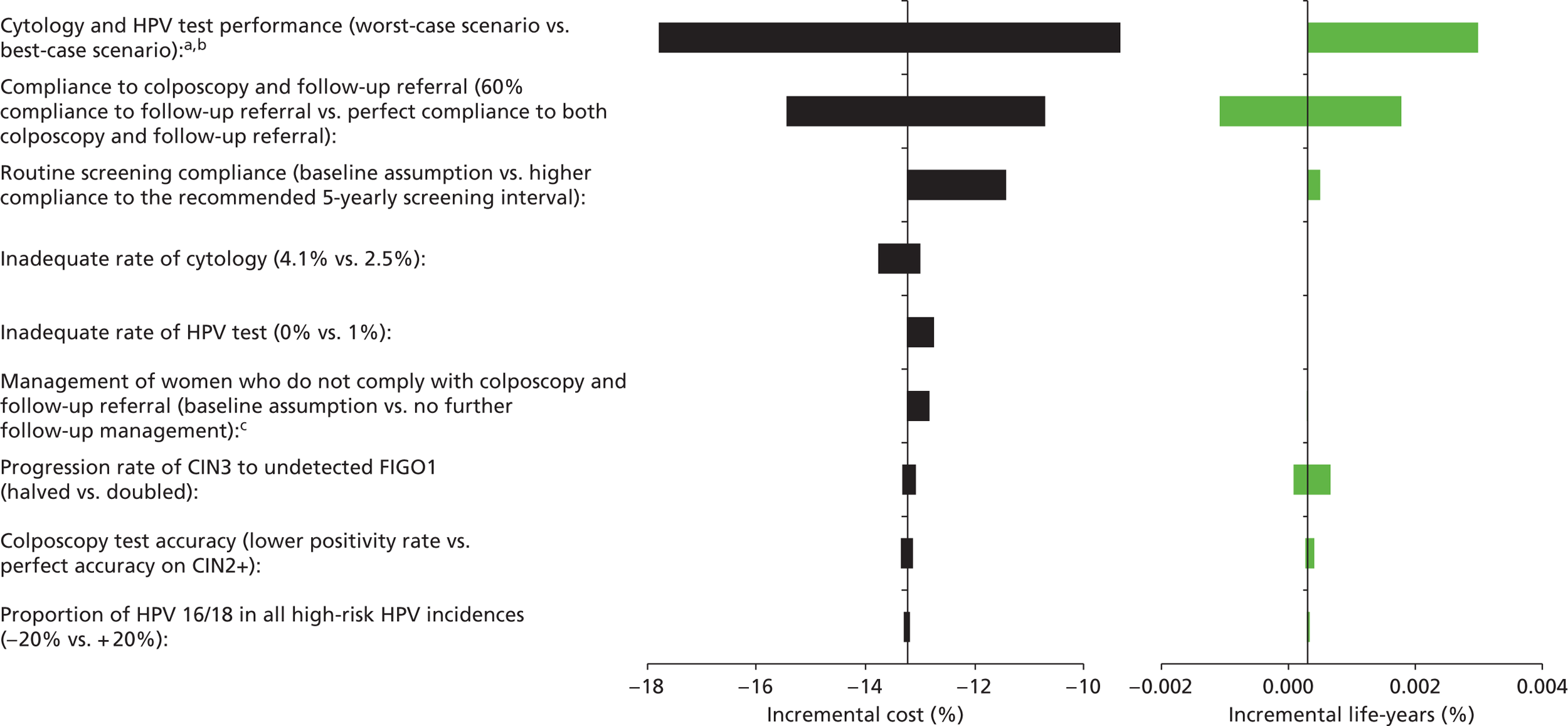

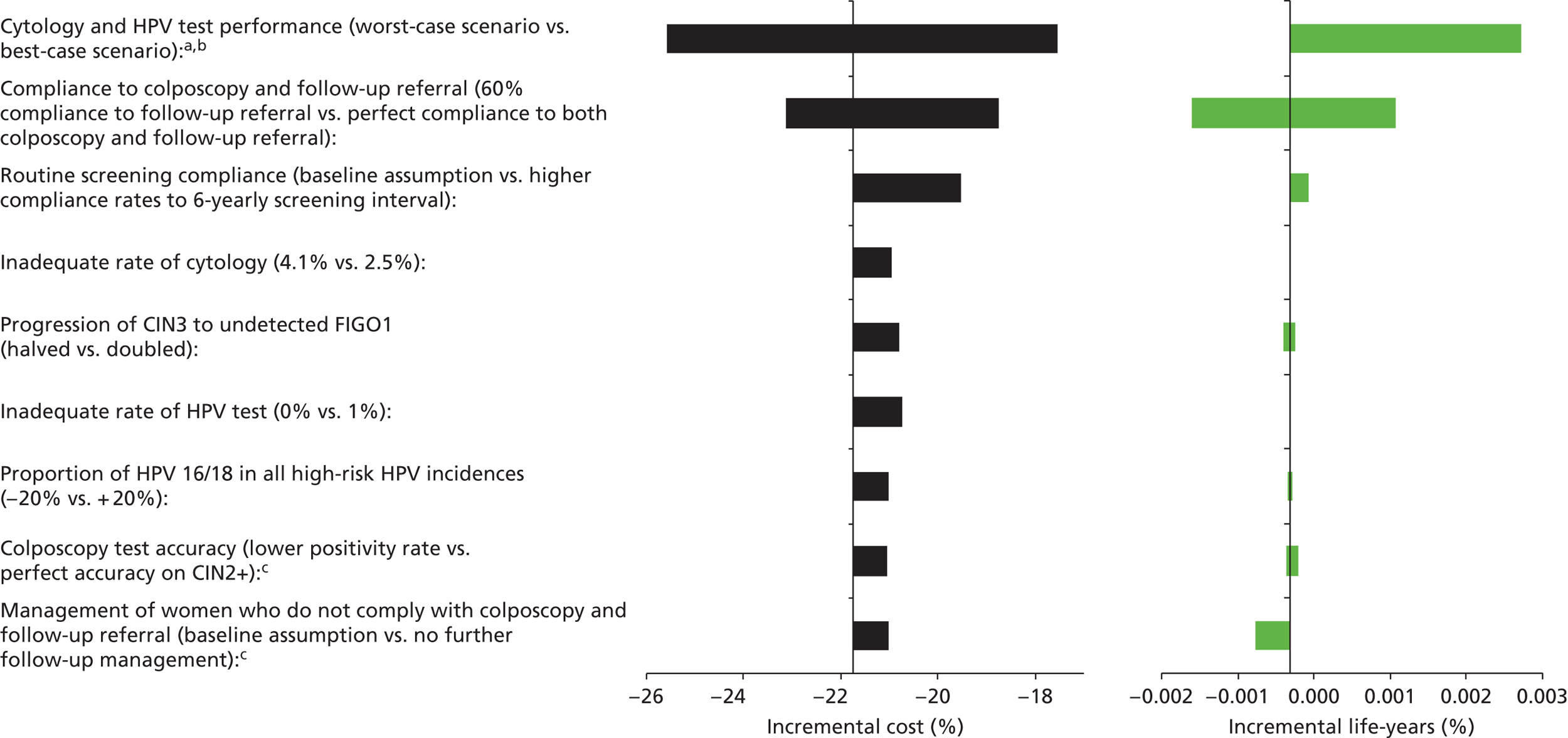

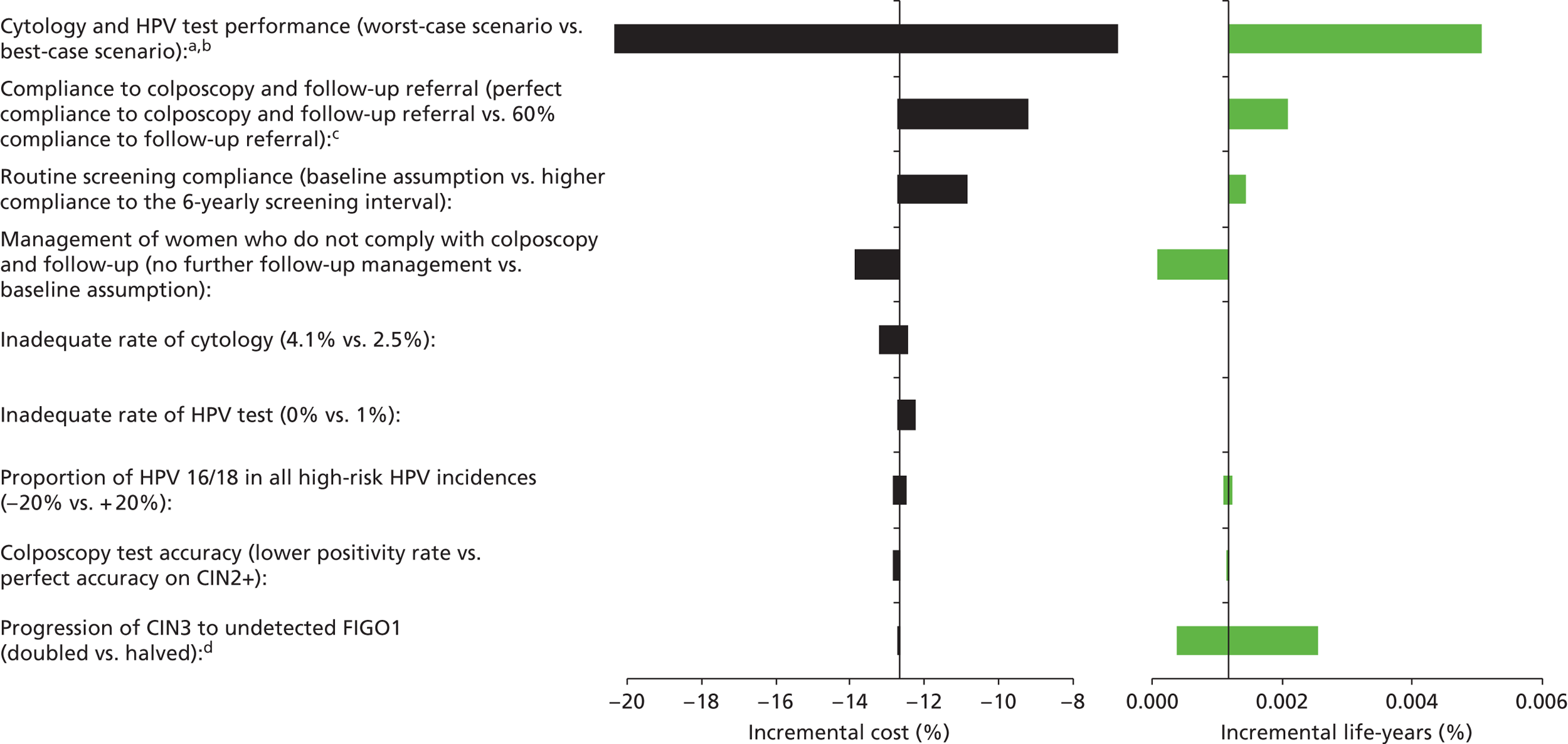

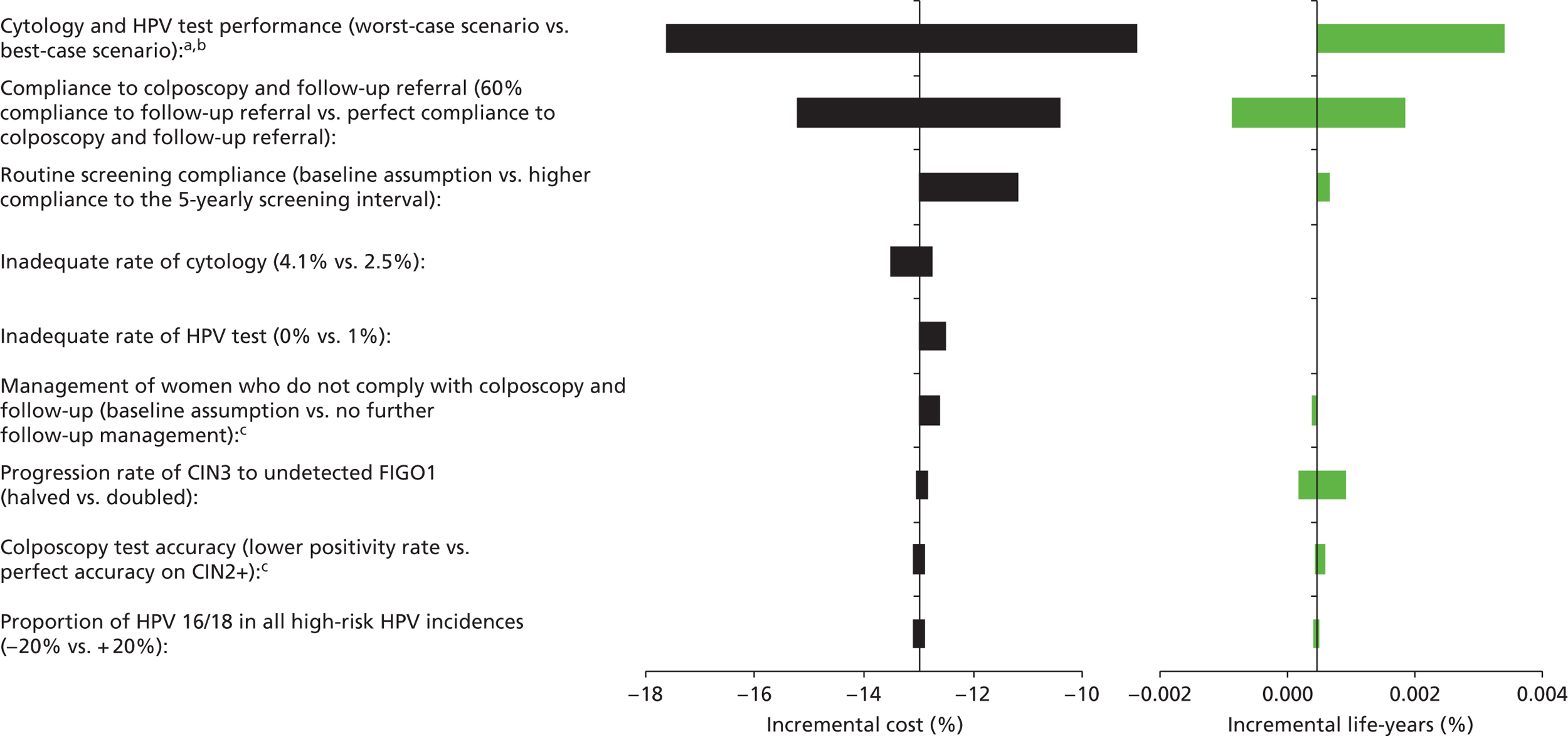

Sensitivity analysis

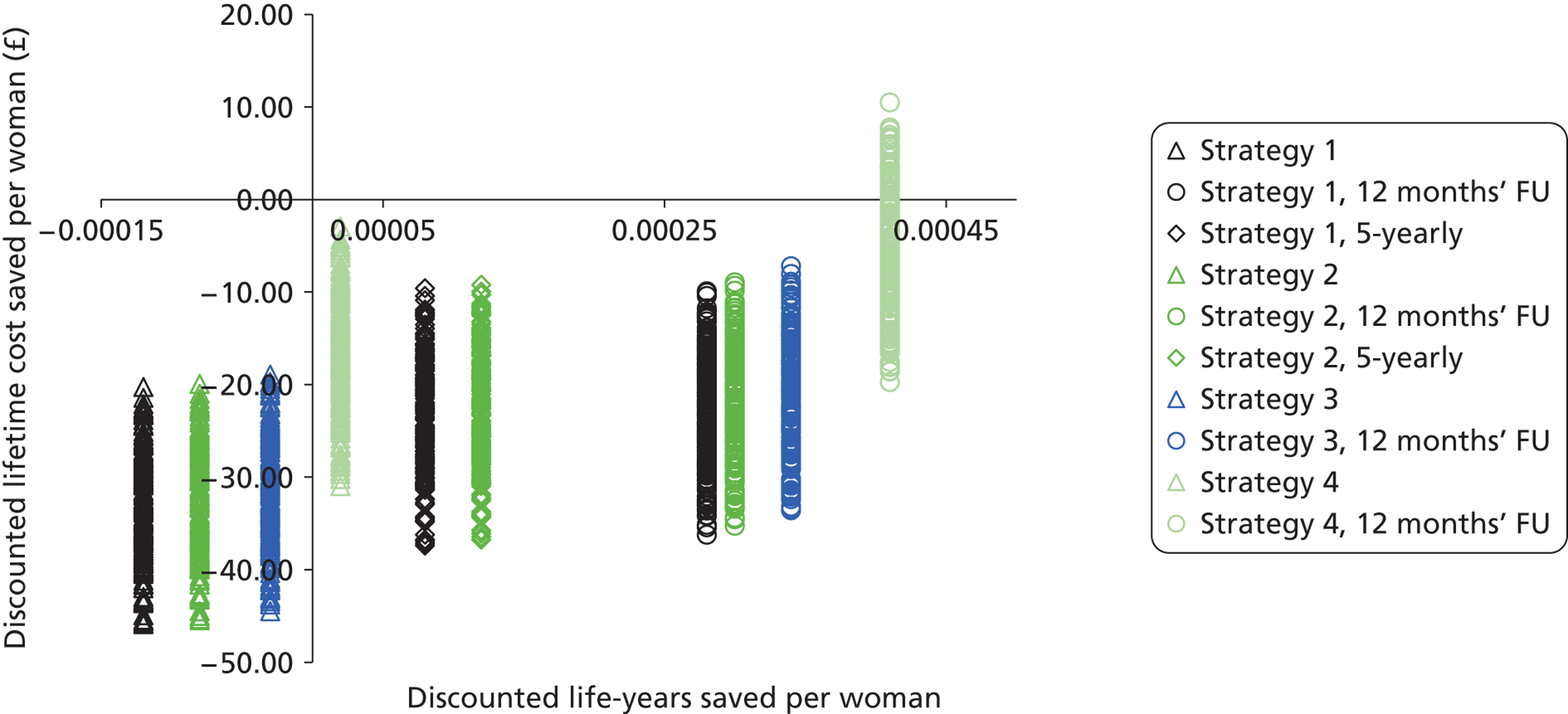

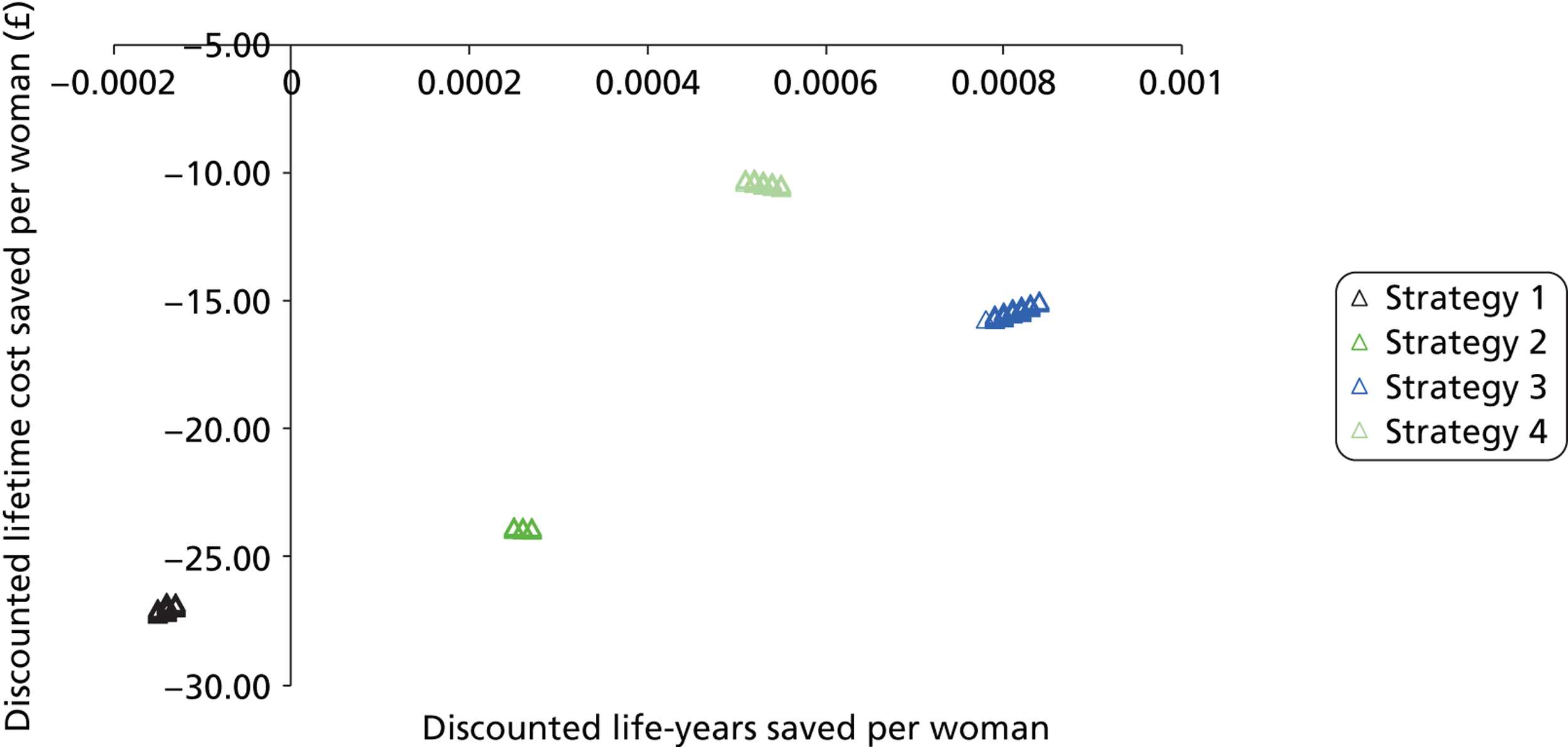

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses were performed separately for cost assumptions for selected strategies. Strategies for which full PSAs were performed included all basic strategies and the strategy variants associated with the most favourable outcomes.

One-way sensitivity analyses were also performed to determine how sensitive the outcomes were to various model assumptions. The following assumptions were varied over a feasible range of possible values:

-

screening attendance rate

-

compliance to colposcopy referral

-

test characteristics for HPV testing

-

test characteristics of LBC (accuracy and inadequate rate)

-

test accuracy of colposcopy

-

assumptions regarding CIN progression and regression

-

the proportion of new oncogenic HPV infections attributable to HPV 16/18

-

vaccination coverage.

Chapter 3 Results

ARTISTIC STUDY EXTENSION

Follow-up characteristics and compliance through the three rounds of screening

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram (Figure 11) shows that, of the 24,510 women who entered the trial, 15,790 (64.4%) were screened in round 2 and 8873 (36.2%) were screened in round 3 between January 2006 and June 2009, including 6337 who had also been screened in round 2.

FIGURE 11.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram.

The numbers of women screened, median duration of follow-up and lesions detected in rounds 2 and 3 are shown in Table 2, according to the definitions of rounds 2 and 3 used in this report (definition 1: round 2, 26–54 months; round 3, > 54 months after entry and > 24 months after round 2), and the original definition of round 2 used in the initial ARTISTIC HTA report1 (definition 2: round 2, 30–48 months; round 3, > 48 months after entry and > 24 months after round 2). Whichever definition is used, the numbers of lesions detected in rounds 2 and 3 combined are similar, but definition 1 increases the number of lesions in round 2.

| Round (R) and grades of CIN detected | Definition 1 (this report): R2, 26–54 months after entry; R3, > 54 months after entry and > 24 months after R2 | Definition 2 (previous report): R2, 30–48 months after entry; R3, > 48 months after entry and > 24 months after R2 |

|---|---|---|

| R2 | ||

| n | 15,790 | 14,336 |

| Follow-up (months) | 26–54 (median 36.6) | 30–48 (median 36.6) |

| CIN2 | 70 | 57 |

| CIN3+ | 53 | 45 |

| CIN2+ | 123 | 102 |

| R3 | ||

| n | 8873 | 9781 |

| Follow-up (months) | 54.1–95.3 (median 72.7) | 48.1–95.3 (median 71.8) |

| CIN2 | 35 | 43 |

| CIN3+ | 31 | 39 |

| CIN2+ | 66 | 82 |

| R2 + R3 | ||

| CIN3+ | 84 | 84 |

| CIN2+ | 189 | 184 |

| Excluded CIN2+ by this definition onlya | One CIN3 | Five CIN2, one CIN3 |

Table 3 shows the characteristics at entry of women attending at round 2, rounds 2 and 3, and round 3 but not round 2. Attendance was unrelated to allocated arm, and the apparently lower round 2 attendance rates in women who were HPV-positive or had moderate+ cytology at entry are due to the exclusion of round 1 CIN2+ cases in round 2. Their round 2 attendance rates when these are ignored are 76.1% (102 out of 134) for moderate+ cytology and 63.5% (2070 out of 3262) for HPV positive.

| Characteristics at entry | Round 1, n (%) | Round 2, n (%) | Round 3 and round 2, n (%) | Round 3, no round 2, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arm | ||||

| Revealed | 6124 (100) | 3928 (64.1) | 1578 (25.8) | 630 (10.3) |

| Concealed | 18,386 (100) | 11,862 (64.5) | 4759 (25.9) | 1906 (10.4) |

| HPV status | ||||

| Negative | 20,697 (100) | 13,720 (66.3) | 5382 (26.0) | 2170 (10.5) |

| Positive | 3813 (100) | 2070 (54.3) | 955 (25.0) | 366 (9.6) |

| Cytology | ||||

| Normal | 21,380 (100) | 13,930 (65.2) | 5450 (25.5) | 2349 (11.0) |

| Mild/borderline | 2667 (100) | 1758 (65.9) | 816 (30.6) | 176 (6.6) |

| Moderate+ | 463 (100) | 102 (22.0) | 71 (15.3) | 11 (2.4) |

| Age at entry (years) | ||||

| 20–24 | 2600 (100) | 1292 (49.7) | 656 (25.2) | 350 (13.5) |

| 25–29 | 2589 (100) | 1349 (52.1) | 729 (28.2) | 342 (13.2) |

| 30–39 | 7633 (100) | 4858 (63.6) | 2698 (35.3) | 893 (11.7) |

| 40–49 | 6096 (100) | 4311 (70.7) | 1890 (31.0) | 557 (9.1) |

| 50–64 | 5592 (100) | 3980 (71.2) | 364 (6.5) | 394 (7.0) |

| All women | 24,510 (100) | 15,790 (64.4) | 6337 (25.9) | 2536 (10.3) |

Cumulative follow-up (Kaplan–Meier analysis of time to next cytology or HPV test) up to 8 years after entry in women with normal cytology at entry was identical in the randomised arms: 79.7% [95% confidence interval (CI) 77.3% to 82.0%] concealed and 79.7% (95% CI 79.0% to 80.5%) revealed. Cytology outside the study area could not be ascertained reliably, so these long-term rates probably underestimate the proportion with any subsequent cytology.

The cumulative follow-up to next cytology or HPV test within 24 months in women who were HPV positive and cytologically normal at each screening round indicates the proportion of women complying with allocated recall. This proportion was 62.4% by 24 months after round 1 and 58.3% by 24 months after round 2 in the revealed arm.

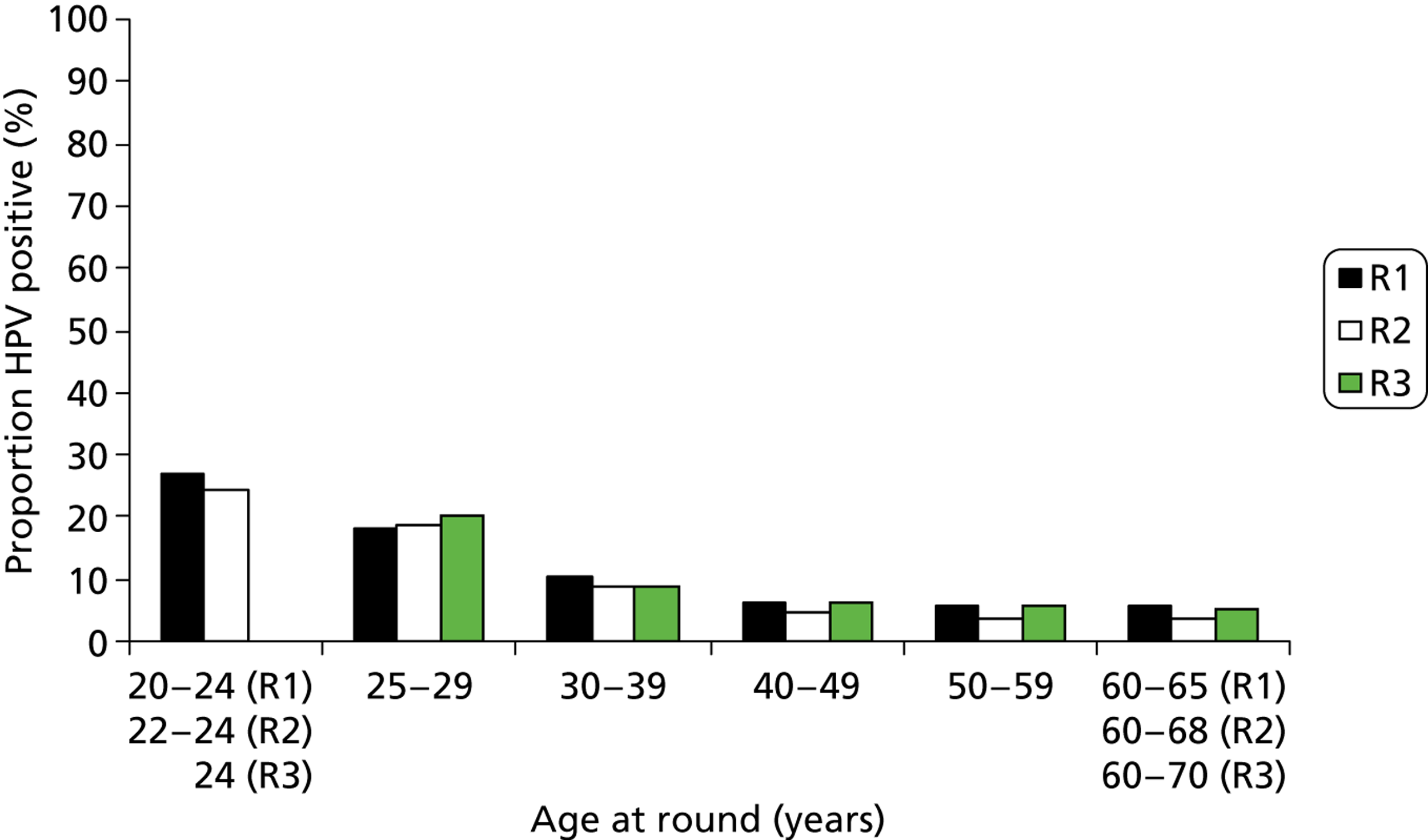

Relationship between age, cytology and human papillomavirus by round of screening

The HPV prevalence by round and age at that round is shown in Table 4, using a RLU/Co of 1. The advancing age of the cohort meant that in round 3 there were HPV data for a small number of women aged 65 years and older. It is interesting to note that the HPV prevalence according to age did not change a great deal between rounds, except that between rounds 1 and 2 there was a fall among women aged over 40 years, and between rounds 2 and 3 there was a rise of similar magnitude. In the previous ARTISTIC HTA report,1 the high population of ‘false positive’ HR results in older women was noted, but this should not change between rounds in similarly aged quinquennia.

| Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV+/total (%) | HPV+/totala (%) | HPV+/totala (%) | ||

| Age at round (years) | ||||

| 20–24 | 1036/2600 (39.85) | 139/418 (33.25) | 4/14 (28.57) | |

| 25–29 | 717/2589 (27.69) | 246/972 (25.31) | 198/754 (26.26) | |

| 30–39 | 1161/7633 (15.21) | 433/3567 (12.14) | 314/2504 (12.54) | |

| 40–49 | 533/6096 (8.74) | 248/4428 (5.60) | 263/3330 (7.90) | |

| 50–59 | 290/4351 (6.67) | 143/3319 (4.31) | 93/1462 (6.36) | |

| 60–64 | 76/1240 (6.13) | 47/1112 (4.23) | 13/287 (4.53) | |

| 65–70 | N/A (N/A) | 12/416 (2.88) | 6/77 (7.79) | |

| Total | 3813/24,510 (15.56) | 1268/14,232 (8.91) | 891/8428 (10.57) | |

In women aged between 25 and 64 years, the HPV rate did fall from 12.7% in round 1 to 8.3% in round 2 and increased to 10.6% in round 3. This fall is probably explained by treatment of CIN which cleared infection, and also the natural clearing of infection within the ageing cohort. The reason for the small increase in round 3 is unclear but may be due to newly acquired infection in women over 40, among whom the increased rate has occurred. It could be due in part to the higher false-positive rate with HC2 in older women as reported in the original ARTISTIC HTA report. 1 We have looked at the possibility that those attending in round 3 selected, for some reason, women with a higher HPV prevalence in round 1, but this was not the case. The age-standardised HPV prevalence at round 1 for those women who attended in rounds 1, 2 and 3, and rounds 1 and 3 only, were 10.9% and 9.1%, respectively, compared with 10.6% for the entire cohort at round 1.

Whether or not round 3 women were screened in round 2 is shown in Table 5. Twenty-nine per cent of round 3 women had not been screened in round 2, a figure which was similar between the arms. A higher proportion of moderate+ cytology was seen in women who did not attend for an intermediate round of screening (0.9% vs. 0.4%).

| Characteristics at round 3 | With round 2, n (%) | Without round 2, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Arm | ||

| Revealed | 4759 (75.1) | 1906 (75.2) |

| Concealed | 1578 (24.9) | 630 (24.8) |

| HPV status | ||

| –ve | 5403 (89.5) | 2134 (89.3) |

| +ve | 635 (10.5) | 256 (10.7) |

| Not done | 299 | 146 |

| Cytology | ||

| Normal | 6056 (95.6) | 2405 (94.8) |

| Mild/borderline | 255 (4.0) | 107 (4.2) |

| Moderate+ | 26 (0.4) | 24 (0.9) |

| Age at round 3 (years) | ||

| 24–29 | 478 (7.6) | 318 (12.5) |

| 30–39 | 1835 (29.0) | 804 (31.7) |

| 40–49 | 2751 (43.4) | 757 (29.9) |

| 50–59 | 1072 (16.9) | 464 (18.3) |

| 60–64 | 155 (2.4) | 154 (6.1) |

| ≥ 65 | 44 (0.7) | 39 (1.5) |

| All women | 6337 (100) | 2536 (100) |

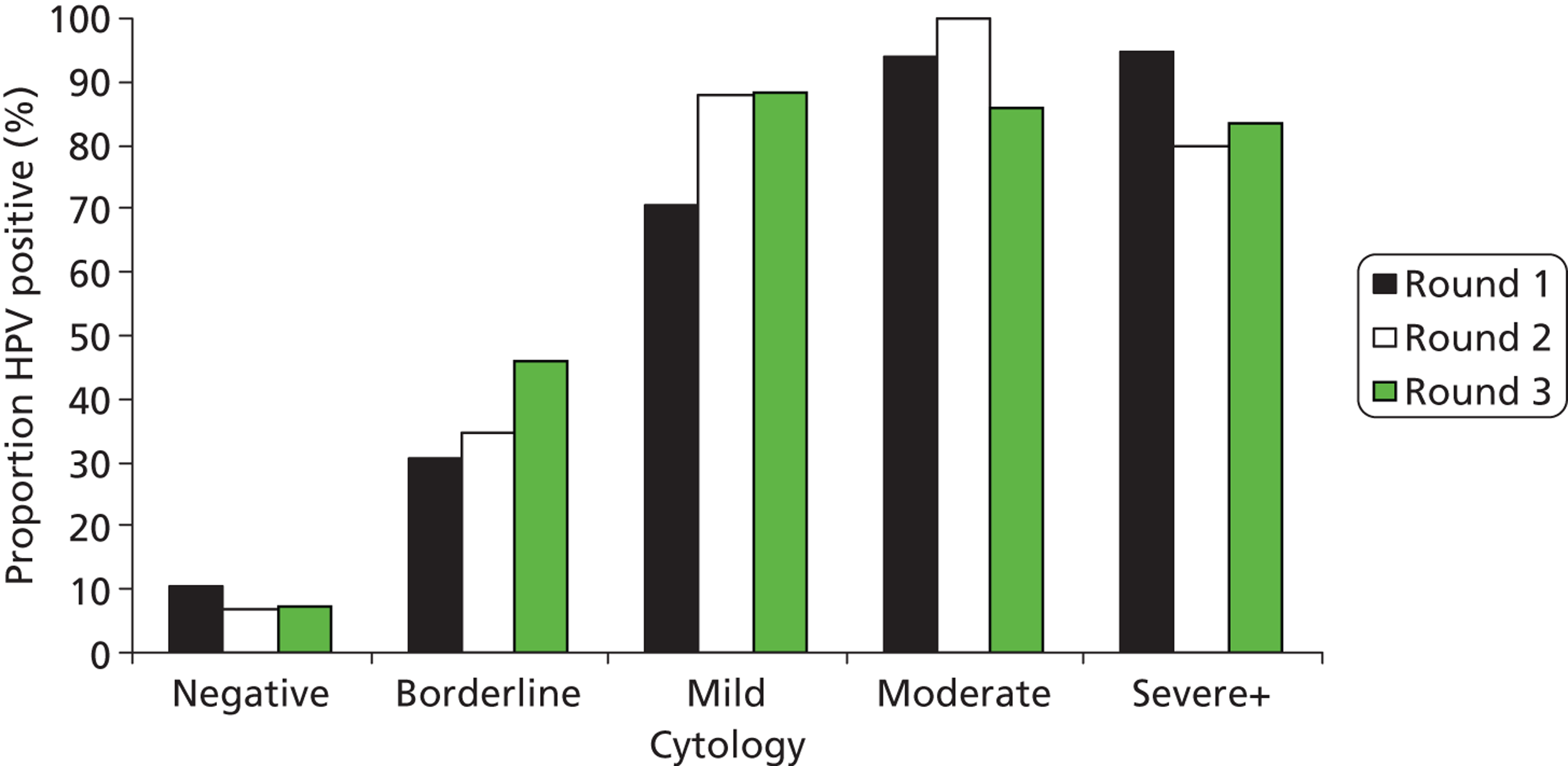

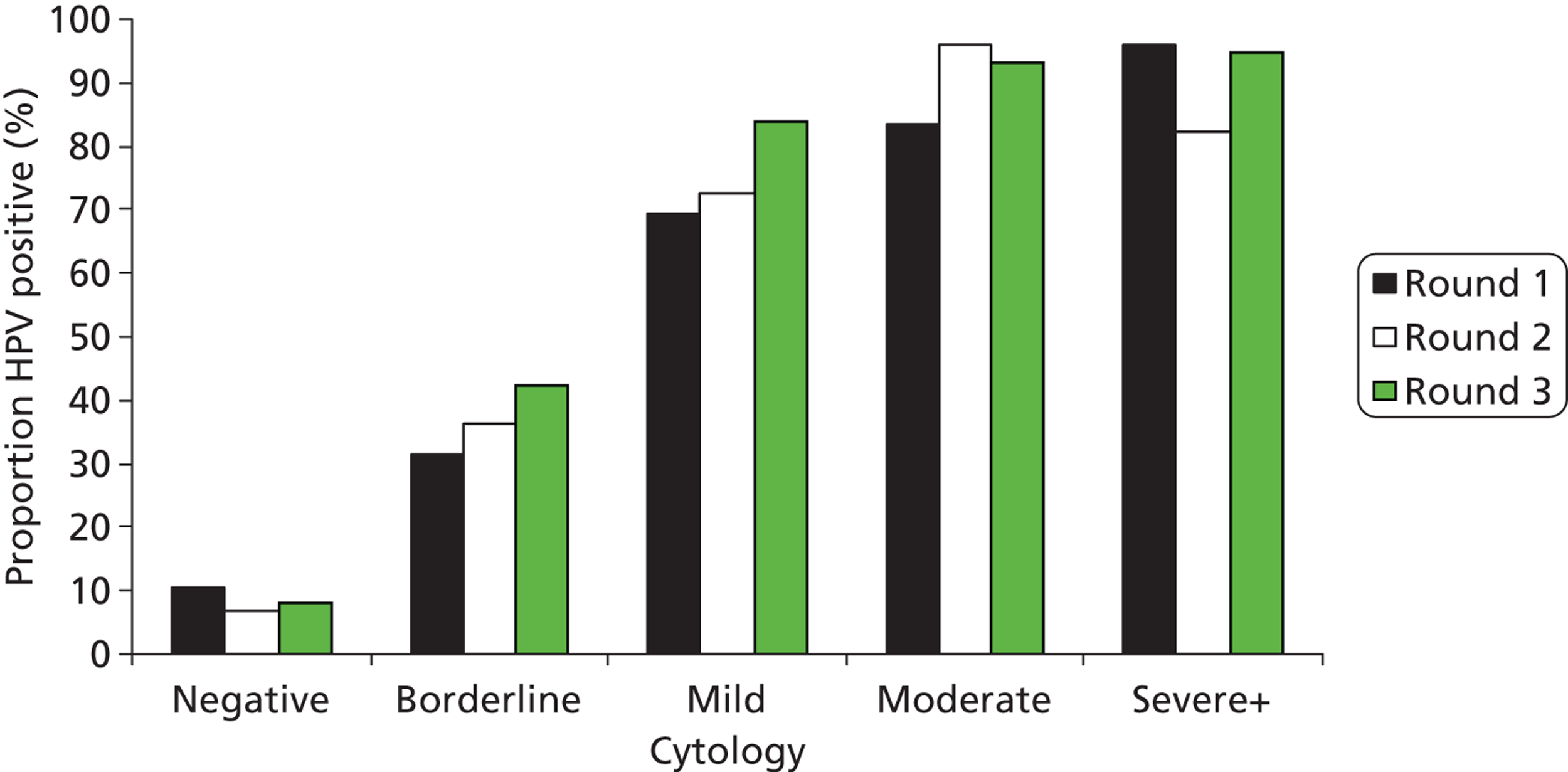

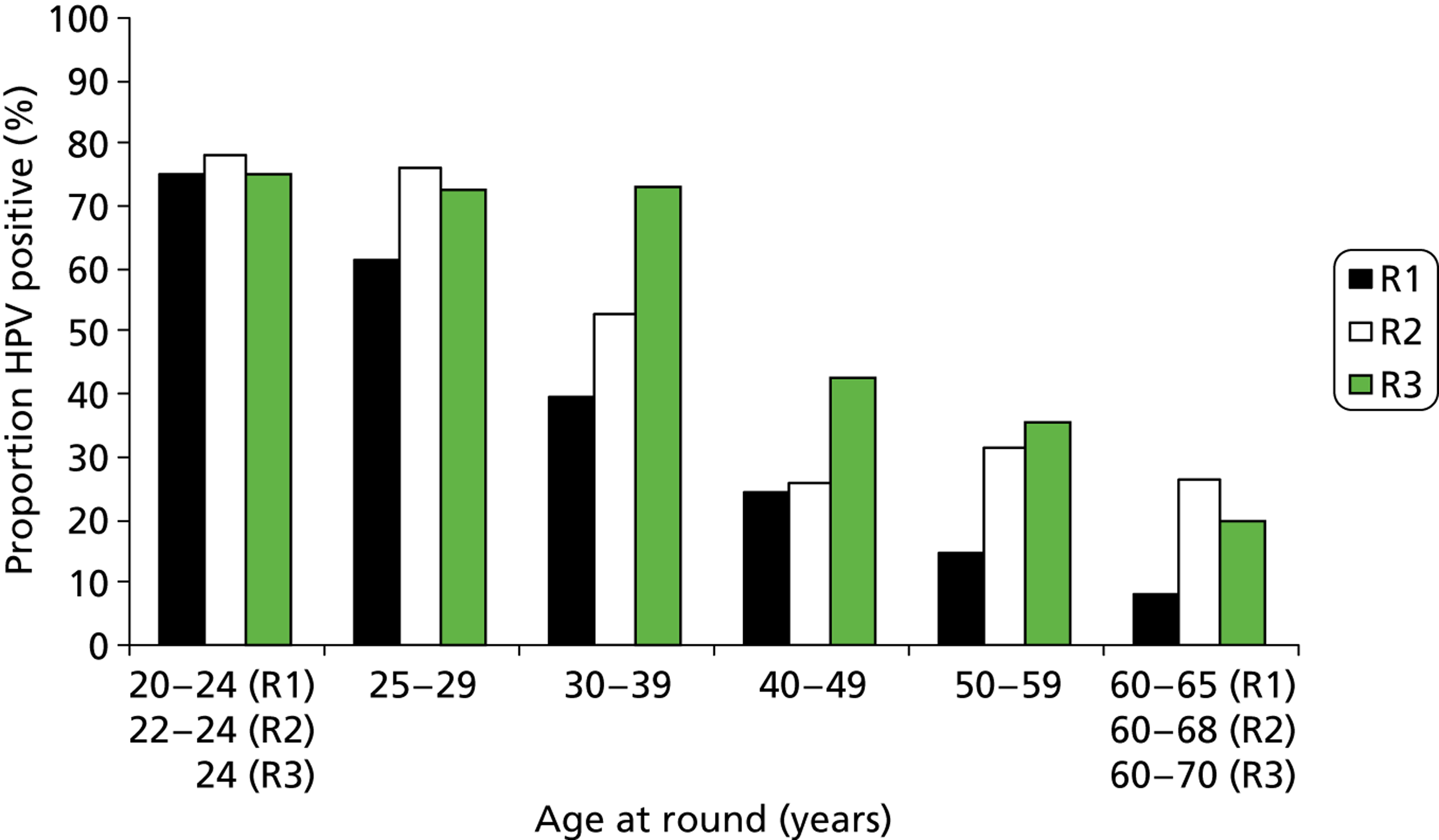

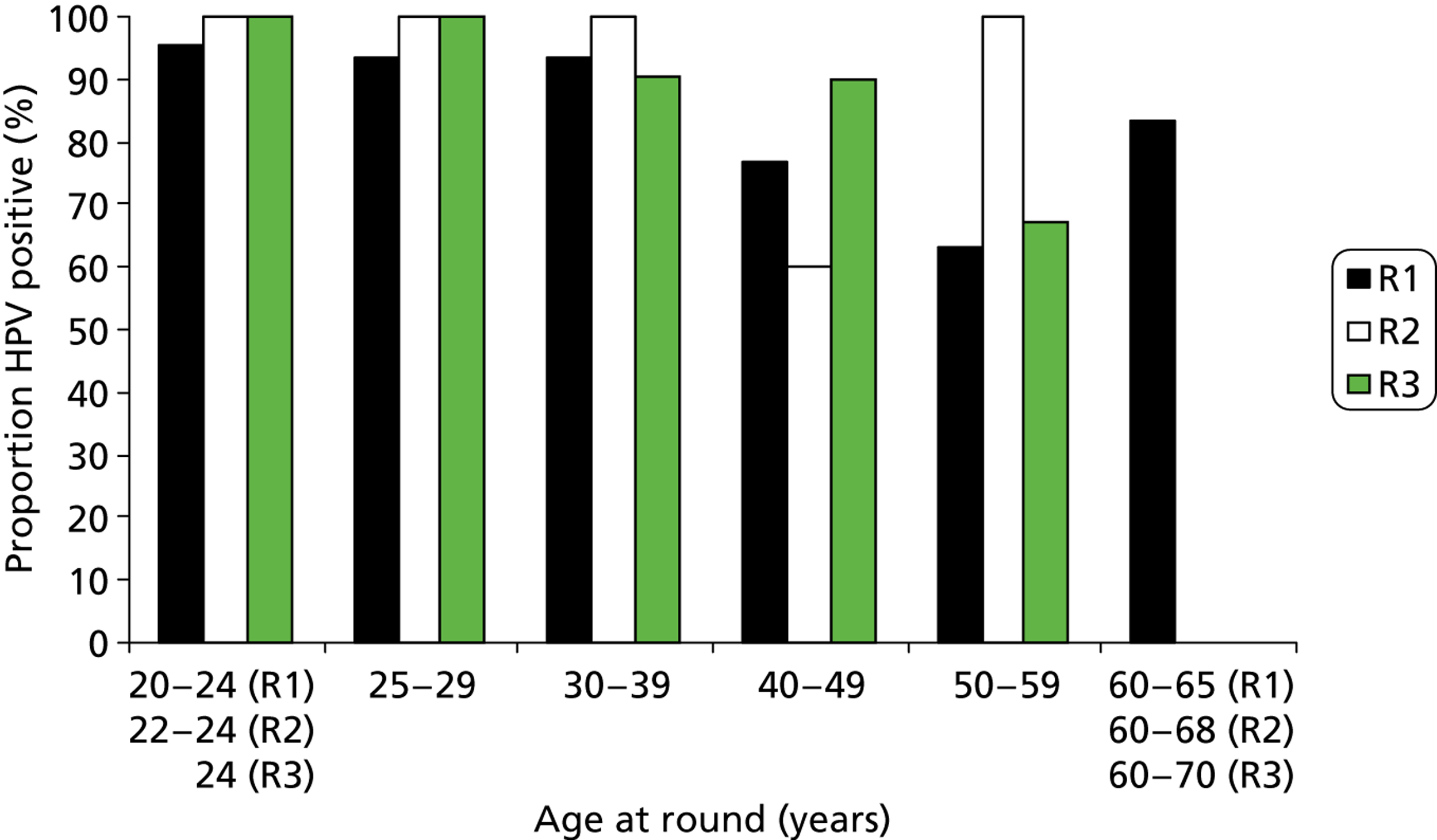

The proportion with abnormal cytology was 12.8%, 5.0% and 4.6% in rounds 1, 2 and 3, respectively (Table 6). Figures 12 and 13 show the proportion of HPV positive results by cytology grade in each of the arms and Table 6 shows the cytology results in rounds 1, 2 and 3, respectively. The proportions of women who were HPV positive remained broadly similar in the two arms of the trial and within each grade of abnormality.

| Cytology | Round 1, n (%) | Round 2, n (%) | Round 3, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revealed | Concealed | Revealed | Concealed | Revealed | Concealed | |

| Negative | 16,042 (87.3) | 5338 (87.2) | 11,282 (95.1) | 3715 (94.6) | 6355 (95.4) | 2106 (95.4) |

| Borderline | 1343 (7.3) | 446 (7.3) | 350 (3.0) | 138 (3.5) | 150 (2.3) | 51 (2.3) |

| Mild | 643 (3.5) | 235 (3.8) | 183 (1.5) | 59 (1.5) | 115 (1.7) | 37 (1.7) |

| Moderate | 204 (1.1) | 67 (1.1) | 28 (0.2) | 11 (0.3) | 16 (0.2) | 8 (0.4) |

| Severe+ | 154 (0.8) | 38 (0.6) | 19 (0.2) | 5 (0.1) | 20 (0.3) | 6 (0.3) |

| Total | 18,386 | 6124 | 11,862 | 3928 | 6665 | 2208 |

FIGURE 12.

Proportion of HPV-positive results by cytology grade and round in the concealed arm.

FIGURE 13.

Proportion of HPV-positive results by cytology grade and round in the revealed arm.

Relationship between human papillomavirus, cytology and age over three rounds

Figure 14 depicts the comparable proportion of women who tested cytology negative and HPV positive according to their age at that round, and the proportions of low-grade and high-grade cytology, according to age at round 1, 2 and 3, are shown in Figures 15 and 16, respectively. The numbers of abnormalities in round 3 are small due to the effect of previous screening and the reduced proportion of the original cohort being screened. The number of women under age 25 years fell as the cohort became older, with almost none by round 3. By contrast, the number of women aged over 64 years increased.

FIGURE 14.

Proportion of normal cytology with a positive HPV result according to age at round. R, round.

FIGURE 15.

Proportion of borderline/mild cytology with a positive HPV result according to age at round. R, round.

FIGURE 16.

Proportion of moderate+ cytology with a positive HPV result according to age at round. R, round.

As has been found elsewhere, the proportion of HPV-positive women overall fell rapidly with age. This is most obvious in women with normal cytology, where HPV prevalence decreased from around 25% in those under 25 years to around 5% in those over 50 years; this remained relatively unchanged over the rounds. There was also a marked fall in the HPV positivity rate by age among women with abnormal cytology in round 1. In rounds 2 and 3, the proportion of women with cytological abnormalities was much lower and the data by age became sparse.

The numerical data (see Tables 62–71 in Appendix 8) allow an indication of primary screening with HPV triaged with cytology to be shown over repeated rounds of screening. The round 1 data are broadly representative of what would happen in routine population-based screening, and rounds 2 and 3 reflect the impact of the detection of disease in the first (prevalent) round.