Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/01/13. The contractual start date was in October 2010. The draft report began editorial review in April 2012 and was accepted for publication in April 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Jill Francis has a number of research projects funded by research councils and charities, and funds for travel for dissemination purposes are included in some research grants. Geoff Bellingan has received SuDDICU grant funding from University of Aberdeen for investigator travel to research meetings. He is the principal investigator in a HTA-funded trial of enteral vs. parental nutrition in intensive care units, and has spoken on the SuDDICU study at other related meetings, for example Scottish Intensive Care Society, and received travel support to attend these meetings. Martin Eccles’s institution received money for his efforts on this study. Peter Wilson received support for travel to meetings for the study from Aberdeen University. He has received payment for his work as a member of the Drug Safety Monitoring Board, Infection Control Services, for medico-legal work, and for Henry Smith professional lectures.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Francis et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Each year in the UK, 140,000 patients are admitted to intensive care and, of these, almost 60,000 will die within a year of admission. 1 Hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) are a major clinical problem for modern health services. Critically ill patients requiring intensive care unit (ICU) care are extremely susceptible to HAIs and these infections are associated with high additional mortality, prolonged hospital stays and large health-care resource utilisation. Between 20% and 50% of ICU patients suffer from such infections. Reducing the incidence and mortality from HAIs is currently the focus of many intensive care quality improvement programmes and government initiatives in the UK and worldwide. 2,3

One intervention that has gained much attention in reducing HAIs is selective decontamination of the digestive tract (SDD). SDD involves the application of topical non-absorbable antibiotics to the oropharynx and stomach and a short course of intravenous (i.v.) antibiotics. 4 The evidence base relating to SDD is reasonably strong, with the recent Cochrane review reporting a benefit in terms of reducing pneumonia rates. 4 A recent large cluster randomised study from the Netherlands enrolling an impressive 5939 patients demonstrated a 3.5% reduction in adjusted mortality with SDD, although the conclusion remains controversial and the authors concede that ‘since our study was performed in Dutch ICUs with a low prevalence of antibiotic resistance, our findings may not be applicable to settings with a markedly different bacterial ecology or different practices for preventing ventilator-associated pneumonia’. 5

In the Cochrane review, clinical heterogeneity is a problem potentially resulting from combining studies using both topical [which, when used on their own in the absence of systemic (i.v.) antibiotics, is called selective oral decontamination (SOD)] and topical plus systemic antimicrobials in the same analyses. Included studies suffered from several methodological flaws including lack of blinding, lack of data on compliance with intervention, mixing of studies of diverse patient groups, only including subgroups or no description of studies included. 4 The Cochrane review demonstrated that SDD was associated with reduction in pneumonia [odds ratio (OR) 0.32; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.26 to 0.38] and death (OR 0.75; 95% CI 0.65 to 0.87). 4 Since the Cochrane review, additional primary research has been published, which also showed a mortality benefit (OR 0.63; 95% CI 0.46 to 0.87). 5,6 However, a degree of controversy exists, with Hurley et al. 7 challenging that, across these studies, the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) at baseline was significantly lower in the ventilated control groups than in the SDD groups, which could falsely give the impression of benefit. 8 Nonetheless, if the documented mortality benefit could be realised in UK practice, then it could prevent as many as 2000–3000 avoidable deaths per annum.

Despite this evidence base, the UK ICU community has not widely adopted this intervention, with only 10–15 ICUs out of 240 reporting that they undertake SDD. 9,10 Existing practice surveys and our preliminary investigations as to why this strategy has not been fully adopted suggest three possibilities:9,10

-

Provision of prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics to critically ill patients may be counterintuitive to the principles of antibiotic stewardship whereby clinicians are encouraged to use antibiotics in a rational and sparing way to prevent the development of multiresistant organisms. 11–14

-

The current evidence base is inadequate in two ways. 9,10 First, there is a perception that the magnitude of the reported mortality benefit is not biologically plausible for such an intervention. Second, there is concern about the external validity and generalisability of the evidence. Most of the existing SDD trials have been conducted in countries where infections due to multiresistant Gram-positive organisms are uncommon and the incidence of multiresistant organisms, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), is low. Patterns of Gram-negative resistance are also different between the UK and the Netherlands, the country with the greatest evidence base for SDD. Hence, clinicians who take an evidence-based stance may come to radically different conclusions about SDD because they may doubt the validity or the applicability of the evidence that suggests clinical benefit.

-

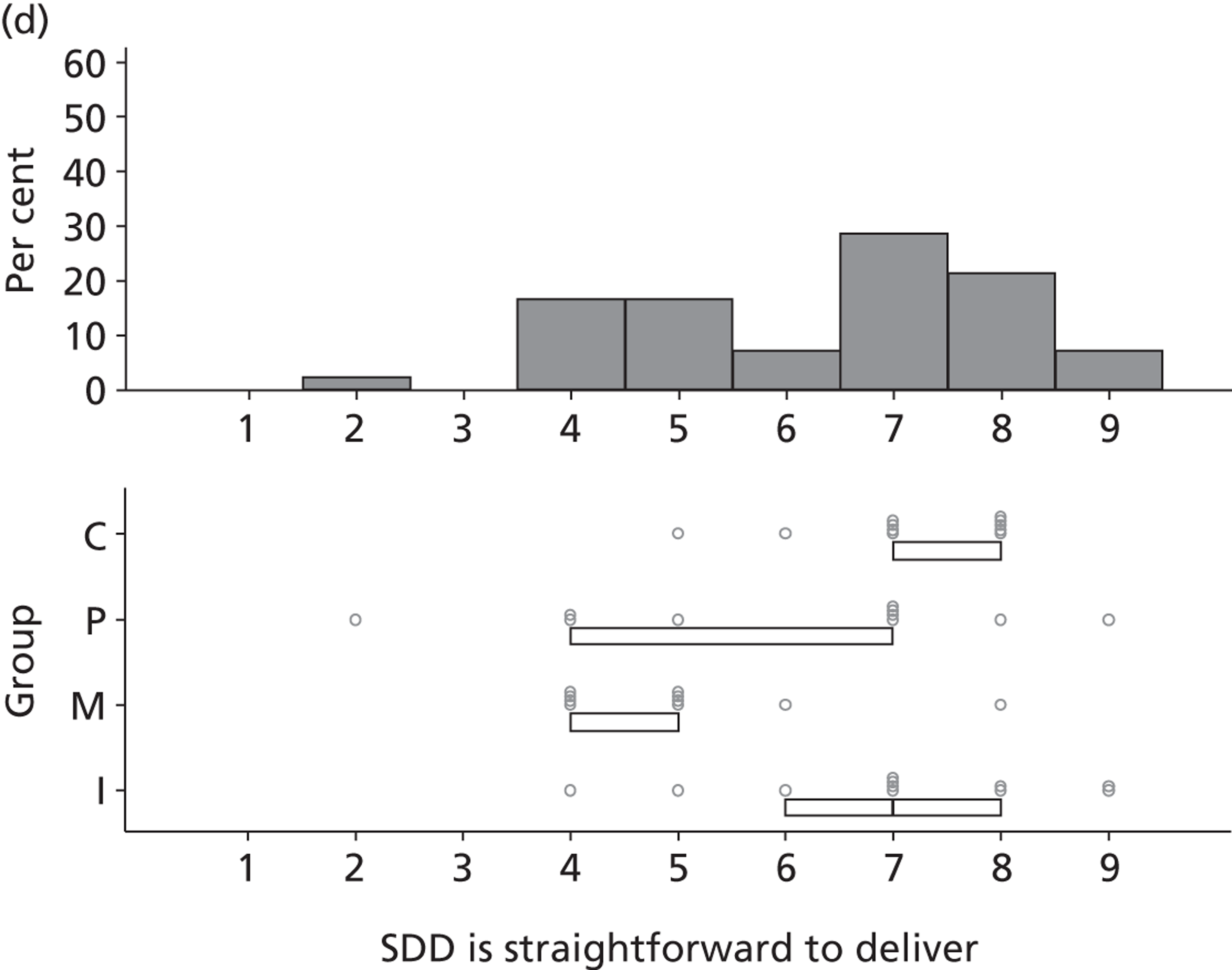

It is a common perception that implementation is difficult in practice as SDD is time-consuming and difficult to administer, although this may be a secondary point compared with the reasons outlined above. 10

However, these simple surveys fail to fully dissect the complex issues related to SDD use in the UK or internationally.

Many clinicians argue that existing evidence should be replicated in health-care systems in which infections due to multiresistant organisms are common and the incidence of multiresistant organisms such as MRSA and Clostridium difficile is comparatively high, such as in the UK. Furthermore, they argue that no existing study has included parallel high-quality infection surveillance programmes to study the long-term effects of SDD on the microbial ecology of the ICU. This may be the single most important weakness of the current evidence base and has brought about appropriate caution with the use of SDD. There is also the potential that clinicians believe that with the widespread use of chlorhexidine, especially for ventilated patients, coupled with the broad adoption of care bundles aimed at preventing VAP, there now may be no need for SDD. Existing data on the ecological impact of SDD are indeed limited, with some studies suggesting an increase in the incidence of Gram-positive organisms such as S. aureus and others failing to show such effects. 5,15–17 In addition, it is possible that SDD is so counterintuitive to existing views on antibiotic use that clinicians will not change their practice regardless of the evidence base or that one clinician group may prevent others in favour of the intervention from implementing it. For example, Silvestri et al. argue that ‘the longstanding disagreement amongst opinion leaders, with the predominance of detractors on those who advocate SDD, is an important factor contributing to the confusion’. 18 Other writers have called for immediate implementation of SDD into routine practice. For example, Zandstra et al. argue that ‘withholding SDD is now ethically questionable given the vast body of evidence on the technique reducing severe infections and mortality, requiring less antibiotic use, and providing less resistance’. 19

In summary, despite the limited surveys undertaken to date, little systematic evidence is available about clinicians’ beliefs regarding the existing evidence base, perceived benefits and risks of SDD in clinical practice, factors that influence current practice and the likely barriers to implementation. In addition, it is unclear whether or not further high-level evidence of clinical effectiveness and ecological impact of SDD from within the UK is required before implementation would become acceptable and what sort of study would be feasible and acceptable to clinicians and triallists.

The multimethod exploratory study reported here attempted to address these issues. It investigated the perspectives of a wide range of stakeholders in multiple settings, using a mixed-methods approach that combined observational, interview and questionnaire data analysed both qualitatively and quantitatively. To facilitate a robust approach informed by previous research and focused on the views and actions of health-care professionals, we used the theoretical domains framework (TDF) of health professional behaviour change to inform our programme of research. 20 It has a good fit with the kinds of issues that health-care providers consider when making clinical decisions and has been used in > 20 studies of health-care professional behaviour. 21 This framework enables systematic identification of a wide range of potential barriers to changing clinical practice. The TDF is elaborated and exemplified in Chapter 3. The results of this research programme thus reflect a comprehensive, theoretically robust and multifaceted evidence base to inform a decision about the kind of research that is needed to address the SDD issue.

A recent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) pilot study on patient safety made a strong research recommendation that SDD be subject to study including investigation of barriers to implementation. 22 The current clinical focus on HAIs, the move to making HAIs a key target of patient safety initiatives, the political prioritisation of HAIs and increased interest in this subject from research funding bodies indicated that this research was timely. The study [known as the selective decontamination of the digestive tract in intensive care units (SuDDICU) study] was also formally adopted and financially supported by the Intensive Care Foundation as one of its new UK National research studies. This highlights the importance of this question to the UK ICU community.

The variable uptake in SDD is also apparent in other countries outside of the UK, for example in Canada, Australia and New Zealand, where no ICUs currently deliver SDD. Reflecting the international importance of the topic, partner teams in Canada and in Australia and New Zealand also acquired funding to undertake parallel investigations (using the SuDDICU protocol) into the reasons for low uptake in these countries. These partner projects were each designed to stand independently (and were funded independently), but add to the generalisability of the UK study findings.

Research objectives and research questions

The overall aim of the SuDDICU study was to identify the perceived risks, benefits and barriers to the use of SDD in UK ICUs to inform recommendations for further research.

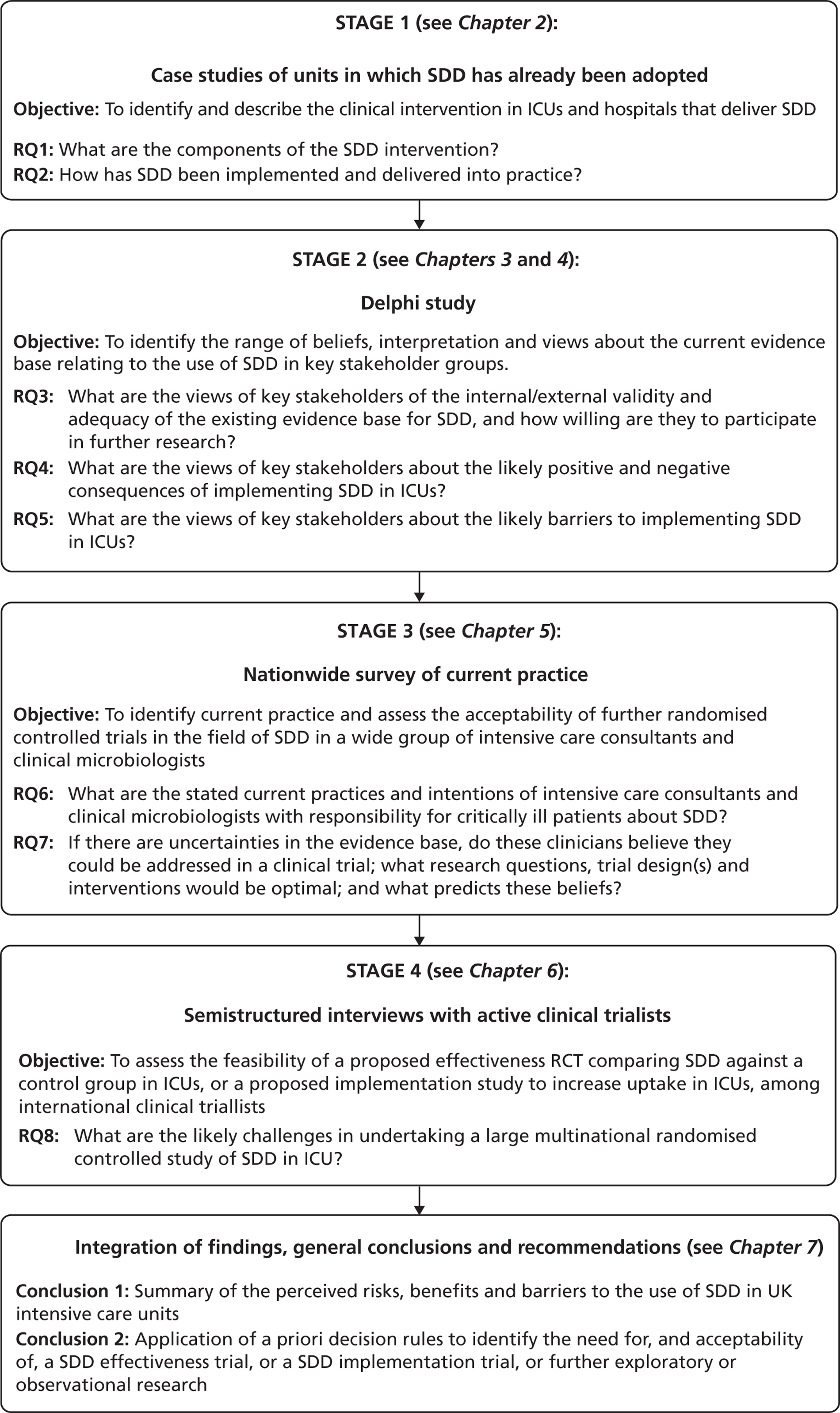

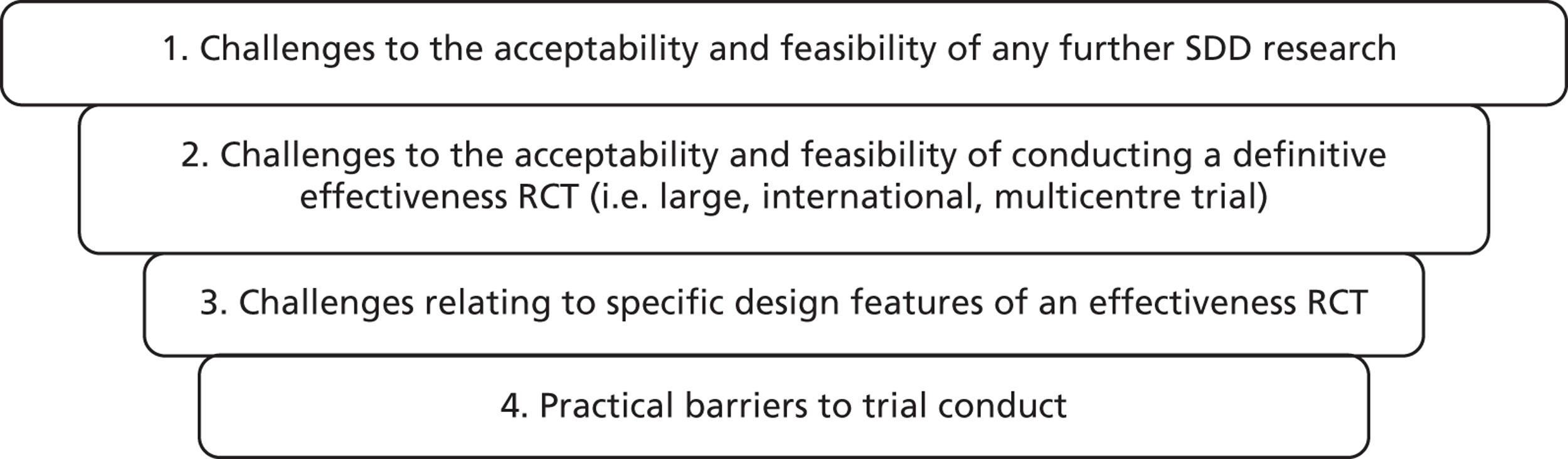

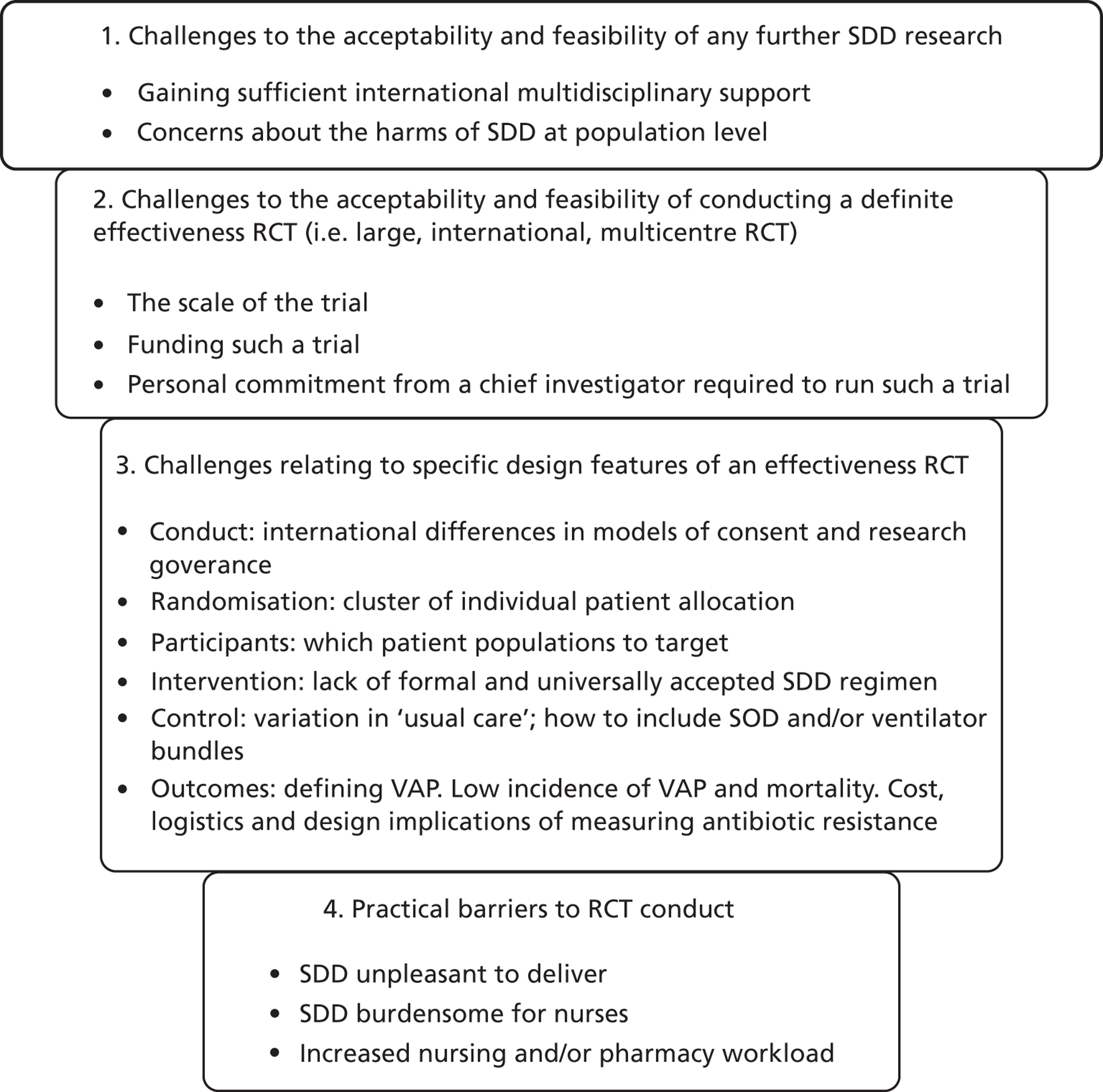

The investigation involved four inter-related stages (expanded further in Chapters 2–6) and culminated in an assessment of the need for – and acceptability of – an effectiveness trial, an implementation trial or further exploratory observational research. Figure 1 provides a linear representation of the four-stage study design and the associated objectives and research questions. It was our intention that the evidence from this investigation would then form the basis on which to design a trial or other study and to specify the intervention to be evaluated or, for an implementation trial, to develop the intervention to be evaluated.

FIGURE 1.

Design of exploratory study showing links to research questions. RQ, research question.

Reflecting the different stages of the research (as outlined in Figure 1), the results of the case studies are presented in Chapter 2, the results of the Delphi study are presented in Chapters 3 and 4, the results of the national survey are presented in Chapter 5 and the triallist interview data are presented in Chapter 6. In Chapter 7, the implications of the study as a whole are discussed, together with a summary of the implications for practice and for future research.

Chapter 2 Case studies to identify and precisely describe the clinical intervention in units and hospitals that deliver selective decontamination of the digestive tract

Background

Some of the uncertainty around the evidence relating to SDD may be associated with changes in the way SDD is specified in trial literature over time. A recent systematic Cochrane review noted that trials used different SDD protocols and investigators use different definitions for SDD. 4 Furthermore, some critics have proposed that SDD is difficult to deliver in practice. 10 Hence, before commencing a study to investigate clinicians’ views of SDD, it was important to be clear about its current specification and delivery in the UK practice setting. To this end, an observational study was conducted in two ICUs delivering SDD, to identify the similarities and differences in terms of the clinical and behavioural components (i.e. delivery features) of this intervention. Such specification would have implications for future research, but a more immediate objective was to ensure that all stages of this study were investigating SDD, based on an explicit and consistent definition. Thus, this study sought to address the following research questions:

Research question 1: What are the components of the SDD intervention?

Research question 2: How has SDD been implemented and delivered into practice?

At a more general level, health-care interventions are typically complex23 and involve two broad interacting categories of components: (1) clinical components, i.e. the clinical materials or equipment of the intervention and related features and (2) behavioural components, i.e. the actual behaviours required to deliver the intervention in practice. Health-care interventions are often specified clinically without explicitly addressing behavioural components. 24,25 Thus, interventions may be implemented differently across sites, potentially leading to variable effectiveness and resultant consequences for patient outcomes. The need to fully specify health-care interventions has been widely recognised, together with the need to report interventions in such a way as they could be directly replicated by others. 26

As described in Chapter 1, SDD is a complex intervention that has been shown to reduce HAI rates and mortality in critically ill patients. 4,5,27 SDD involves the application of antibiotics and antifungals to the mouth, throat and stomach combined with a short course of i.v. antibiotics. 28 Despite considerable evidence supporting the benefit of SDD,4,5,27 adoption internationally is low. 9,10 Among proposed reasons for this lack of adoption are controversies surrounding prophylactic use of antibiotics and associated risk of antibiotic resistance,29,30 and purported difficulty of SDD implementation and delivery. 31

In addition to the variation in the clinical components of SDD described in trials and used in clinical practice, behavioural components of SDD have not been systematically outlined in the empirical literature. A fully specified protocol describing both clinical and behavioural components of SDD implementation and delivery does not exist but could facilitate both widespread adoption and future implementation trials. Hence, this study sought to characterise the clinical and behavioural components of SDD as implemented in clinical practice.

Methods

Case study methodology32 was used in two UK ICUs routinely delivering SDD, with the ‘case’ (unit of analysis) consisting of an ICU. Data were collected from three sources: direct observation of SDD delivery at the bedside, face-to-face semistructured interviews with clinicians responsible for implementing and/or delivering SDD, and systematic assessment of written documentation (e.g. SDD protocols, training documents). The use of multiple data sources in case study research is considered to be one of its methodological strengths. 32 The chosen data sources were consistent with those commonly used in case studies and enabled triangulation for exploring the features of SDD delivery and implementation in context. 32

Sample

All UK ICUs delivering SDD, identified from a recent national SDD survey9 or known by the study investigators to deliver SDD, were deemed eligible for inclusion (15 ICUs). Two ICUs were purposively selected to represent different lengths of time since SDD adoption (one had adopted SDD < 5 years earlier and the other had adopted SDD > 5 years earlier) and different geographical locations (i.e. geographically dispersed ICUs to ensure different organisational profiles). Clinicians from different professions (i.e. intensive care consultants, clinical microbiologists, specialist clinical pharmacists and ICU nurses) have responsibility for the implementation and/or delivery of SDD. In each of the case study ICUs, all clinicians with potential involvement in the implementation and/or delivery of SDD were eligible for interview. From these, we recruited a purposive sample of clinicians from different professions. 33 Not all eligible clinicians were interviewed owing to lack of availability or time. Purposive sampling was appropriate for this small-scale exploratory qualitative study and the sample was not intended to be statistically representative. 33

Data collection

Direct observation offers the opportunity to record and analyse clinical behaviours and interactions as they occur in ‘real world’ contexts. 34 The use of direct observation as a data source allowed the process of SDD delivery to be ‘seen’ through the eyes of the researcher. Observations were conducted using an investigator-designed form to record all behaviours relating to ‘real time’ delivery of SDD. Additionally, the context (i.e. the physical environment where behaviours were performed), timing of procedures and physical presence of clinicians at time of delivery were recorded (see Appendix 1).

Semi-structured face-to-face clinician interviews were conducted in the study hospitals using a topic guide with prespecified prompts to ensure consistent coverage of key issues including behaviours relating to SDD implementation and SDD delivery as well as barriers and facilitators of described behaviours1 (see Appendix 1).

Finally, all written documentation relating to SDD implementation and delivery (e.g. SDD protocols, training documents) was provided by the participating ICUs for systematic analysis. This documentary information provided an unobtrusive and verifiable data source, which augmented and corroborated information from interviews and observations. The presence of relevant documents was established during the interviews. After the interviews, these documents were obtained.

Procedure

Data collection commenced with observation of SDD delivery performed by various ICU nurses to different patients at the bedside. A single researcher (SUD) visited the ICUs for 2 (case study 1) or 3 days (case study 2). Observation opportunities were identified by senior ICU nurses (i.e. they informed the researcher when and to whom SDD would be delivered). The number of patients eligible for, and receiving, SDD varied from day to day; therefore, it was not possible to prespecify the number of direct observations of SDD delivery that would occur during SUD’s visit. Semi-structured interviews were conducted in parallel with observations. Observed nurses were included in the interview sample to gain an in-depth understanding of observed behaviours. With participants’ permission, interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim and anonymised. All observations and interviews were conducted by SUD. Written documentation from each ICU was examined (by SUD) following completion of all observations and interviews, in order to minimise researcher bias during these stages.

The written documentation was examined to identify clinical and behavioural components of SDD delivery. Clinical components were defined as the pharmaceutical regimens forming part of SDD including drug, dose, route, frequency and duration. Behavioural components were defined as any actions that were/would be directly observable. We recorded the behaviours involved in delivering clinical components and those not related specifically to drug administration.

Data management and analysis

Data from the three sources were analysed within case to describe the clinical and behavioural SDD components, and synthesised across case to identify emergent themes describing SDD implementation and delivery in context. The analytical process was guided by the study aims, which included identification of SDD clinical and behavioural components and exploration of SDD implementation and delivery.

The three data sources were analysed separately within ICUs and in reverse order to data collection. First, we systematically examined written documentation and extracted clinical and behavioural components of SDD delivery. Second, we performed content analysis35 of interview transcripts to identify additional behaviours involved in SDD delivery (i.e. those not specified in the documents). Third, direct observations provided contextual ‘real time’ data32 and identified new and corroborative evidence on SDD clinical and behavioural components (i.e. data triangulation from multiple sources). 32

To identify features of SDD implementation and delivery across ICUs, a thematic analysis of the interview data was conducted using a framework approach. 36 This approach involves five stages: (1) familiarisation with the raw data, (2) identification of emergent themes associated with SDD implementation and delivery (i.e. relating to the behaviours and clinician groups involved), (3) systematic coding/indexing of all data relevant to each theme within each transcript, (4) creating charts (Microsoft Word tables) that contain the coded data for each theme and distilled summaries of views and experiences, and (5) interpretation of the data (e.g. identifying associations between themes and providing explanations for the findings). 36 A single researcher (SUD) conducted the thematic analysis, a second researcher (EMD) independently coded randomly selected portions of the data set to identify clinical and behavioural components and three researchers (MEP, JJF, LR) provided critical comments on analyses drafts.

This study was classified as service evaluation by the Research Ethics Committee (10/MRE00/32) and, therefore, was deemed by them not to require ethical approval. All participants who were observed and interviewed were aware of the study purpose and provided verbal consent prior to data collection.

Results

Case 1 implemented SDD 3.5 years prior to this study in response to increased HAI rates. Collected data comprised four observations, eight interviews [intensive care consultants (n = 3), nurses (n = 3), clinical microbiologists (n = 1) and pharmacists (n = 1)] and three SDD documents (protocol, prescription chart, training slides). Case 2 implemented SDD as part of a clinical effectiveness trial 26 years prior to this study. Interview data identified that the rationale for continued use of SDD was its perceived effectiveness. Collected data comprised three observations, eight interviews [intensive care consultants (n = 3), nurses (n = 3) and pharmacists (n = 2)] and one document (protocol).

Selective decontamination of the digestive tract clinical and behavioural components

Protocols documenting the specific clinical behaviours required for drug preparation and administration in the two ICUs are detailed in Table 1, demonstrating the degree of clinical complexity and also the variation encountered in clinical aspects of SDD. The documents identified in the interviews and subsequently analysed listed nine different medications and a total of 13 different preparations as part of SDD in the two case studies (see Table 1). Several behaviours directly relevant for drug administration were identified in examined documentation.

| Drugs | Dose | Route | Frequency | Behaviours (what) | Directions (how) | Frequency/duration (when) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case study 1 | ||||||

| Cefuroxime | 1.5 g (six doses) over 3–5 minutes | i.v. | 8-hourly | Prepare drug, administer drug | Dilute 1.5 g in 15 ml of water for injection. Administer intravenously over 3–5 minutes | Immediately after obtaining all admission surveillance and diagnostic microbiological samples and then at 8-hourly intervals |

| Ciprofloxacin (if allergic to cefuroxime) | 400 mg (four doses) over 60 minutes | i.v. | 12-hourly | Prepare drug, administer drug | Administer 400 mg intravenously over 60 minutes | Immediately after obtaining all admission surveillance and diagnostic microbiological samples and then at 12-hourly intervals |

| Nystatin | 100,000 units/ml | Oral and gastric tube | 8-hourly | Prepare drug, administer drug | Administer 5 ml topically to mouth and 5 ml via gastric tube. Use a new 30-ml bottle every 24 hours. If the tube in the stomach is draining freely into a drainage bag, flush tube with 20 ml sterile water and clamp for 30 minutes after administration of antibiotics/antifungals | Three times daily after oral hygiene regimen |

| Vancomycin | 500 mg | Oral and gastric tube | 6-hourlya | Prepare drug, administer drug | Reconstitute a 500-mg vial with 10 ml water for injections and administer 250 mg into the mouth and 250 mg via gastric tube | Four times daily after oral hygiene regimen |

| Colistin sulphate | 250,000 units/ml | Oral and gastric tube | 6-hourlya | Prepare drug, administer drug | Reconstitute a vial (licensed for injection) of 1,000,000 units with 0.9% sodium chloride (NaCl). Dilute the reconstituted vial to a total of 40 ml with NaCl 0.9%. This solution may be kept at the bed space for 24 hours. Administer 5 ml (125,000 units) of this solution into the mouth and 5 ml via gastric tube | Four times daily after oral hygiene regimen |

| Tobramycin | 80 mg | Oral and gastric tube | 6-hourlya | Prepare drug, administer drug | Dilute one ampoule of 80 mg (licensed for injection) in 10 ml NaCl 0.9%. Give 5 ml (40 mg) into mouth and 5 ml (40 mg) by gastric tube | Four times daily after oral hygiene regimen |

| Chlorhexidine gluconate; 4% liquid soap | 15 ml | Topical | 12-hourly | Administer body wash | Use 15 ml for body wash with water | Twice daily |

| Chlorhexidine gluconate; 0.2% mouthwash | 10 ml | Topical | 6-hourlya | Administer mouthwash | Not to be swallowed. Apply with pink sponge stick to teeth, gums, tongue and lining of the mouth as part of thorough mouth care | Twice daily before each application of topical antibiotics |

| Case study 2 | ||||||

| Cefotaxime | 1 g | i.v. | 8-hourly | Prepare drug, administer drug | Administer 1 g intravenously | Within 4 hours of admission. Administer first does prior to

intubation and other invasive ITU procedures Three times daily only for first 4 days of ITU admission |

| Tobramycin, colistin sulphate, amphotericin B, prepared by pharmacy manufacturing unit | 2% w/w of each constituent | Topical | 6-hourlya | Administer gel to oropharynx | Apply gel to palate and buccal surfaces | Within 4 hours of admission. Four times daily for duration of ITU admission until discharge |

| Tobramycin 27 mg/ml liquidb | 80 mg | Nasogastric tube | 6-hourlya | Administer solution/suspension | Deliver solution/suspension via nasogastric tube | Four times daily for duration of ITU admission |

| Colistimethate sodium (colistin) 50 mg/ml liquidb | 100 mg | Nasogastric tube | 6-hourlya | Administer solution/suspension | Deliver solution/suspension via nasogastric tube | Four times daily for duration of ITU admission |

| Amphotericin B 100 mg/ml liquidb | 500 mg | Nasogastric tube | 6-hourlya | Administer solution/suspension | Deliver solution/suspension via nasogastric tube | Four times daily for duration of ITU admission |

Aside from clinical and behavioural components directly relevant to SDD delivery, documents from both cases revealed several additional delivery behaviours performed by multiple clinicians in various clinical and environmental contexts (Table 2). To complement understanding of behavioural components that are important in SDD, but not specifically mentioned in the examined documentation, Table 3 outlines additional delivery behaviours identified through interviews and observations. Behaviours outlined in Tables 2 and 3 were performed by various clinician groups (e.g. nurses, physicians, pharmacists) in a variety of clinical and environmental contexts (e.g. bedside, ICU nursing stations, pharmacy).

| Behaviour | Professional group | Context | CS1 | CS2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clarifying SDD regimen (in ambiguous cases) | Nurse, intensivist, pharmacist, clinical microbiologist | ICU and bedside | ✓ | ✓ |

| Authorise SDD delivery | Intensivist, pharmacist | ICU (admission) and bedside | ✓ | |

| Prompt SDD authorisation | Nurse | ICU (admission) and bedside | ✓ | |

| Judging SDD delivery in unclear cases | Intensivist | ICU (admission) and bedside | ✓ | |

| Documenting SDD delivery | Nurse | ICU and bedside | ✓ | |

| Discarding of antibiotics (when out of date) | Nurse | Bedside | ✓ | |

| Storing reusable antibiotics | Nurse | ICU and bedside | ✓ | |

| Labelling leftover antibiotics/antifungals | Nurse | ICU and bedside | ✓ | |

| Check SDD is continued and operating | Intensivist, pharmacist | ICU, bedside | ✓ |

| Behavioural | Professional group | Context | CS1 | CS2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Check patient eligibility for SDD | Intensivist, pharmacist | ICU (admission) and bedside | ✓a | ✓a |

| Review and optimise SDD delivery | Intensivist, pharmacist, clinical microbiologist | ICU, bedside | ✓a | ✓a |

| Attend ward rounds (at which SDD is discussed) | Intensivist, pharmacist, clinical microbiologist | ICU, bedside | ✓a | ✓a |

| Dispose of SDD waste | Nurse | Bedside | ✓a,b | ✓b |

| Order SDD drugs from pharmacy | Nurse | ICU | ✓a | ✓a |

| Reassure patient/patient visitors before/during SDD administration | Nurse | Bedside | ✓b | ✓a,b |

| Reposition patient for SDD administration | Nurse | Bedside | ✓b | ✓b |

| Decision to discontinue SDD drugs | Intensivist, pharmacist | ICU and bedside | ✓a | ✓a |

| Print SDD documentation | Ward clerk | ICU | ✓a | |

| Monitor for SDD drug reactions | Intensivist, pharmacist | Bedside | ✓a | |

| Check stock and supply SDD drugs | Pharmacy technician | ICU | ✓a | |

| Order SDD drugs from suppliers | Pharmacy technician | ICU | ✓a | |

| Describe SDD during shift communication | Nurse | ICU and bedside | ✓a | |

| Handling contraindications | Nurse | Bedside | ✓b | |

| Collecting SDD drugs | Nurse | ICU and bedside | ✓a,b | |

| Preparation of antibiotics | Pharmacist | Production unit2 | ✓a | |

| Order raw materials | Pharmacist | Analytic lab2 | ✓a | |

| Check of antibiotic quality | Pharmacist | Quality Assurance Department2 | ✓a | |

| Liaise with pharmacy production unit | Pharmacist | ICU | ✓a | |

| Check naso/orogastric aspirate | Nurse | Bedside | ✓a,b |

Participant interviews provided most data relating to behavioural components, 49 components were identified through interviews, 22 through documentation and 12 through observations. Each data source gave rise to unique behaviours not mentioned in other sources (28, seven and four unique behavioural components for interviews, documentation and observations, respectively), confirming the added value of analysing multiple information sources. The number of unique behavioural components was 29 (case study 1) and nine (case study 2). Twenty-six behavioural components were common across ICUs, being identified in at least one data source for each case.

Selective decontamination of the digestive tract implementation and delivery

Based on our analysis, SDD implementation and delivery was conceptualised as a complex procedure consisting of four overlapping processes, each involving specific behaviours: adoption, operationalisation, provision and surveillance. Adoption concerned the decision to introduce SDD; operationalisation referred to the processes required to introduce SDD into clinical practice; SDD provision included actions involved in delivery of the clinical components; and surveillance, mentioned in both case studies, provided the foundation for adoption, operationalisation and provision by checking that SDD was effective in preventing infection.

Adoption and operationalisation

For adoption, we identified that actions often occurred at the organisational and team level involving organisational and group processes as well as individual action. As the implementation process moved from adoption to operationalisation, more behaviours emerged that were performed by individual staff (see Tables 2 and 3). Although operationalisation was complete following SDD introduction, elements of operationalisation continued owing to clinician staff turnover (e.g. although SDD was a standard procedure within the ICUs, the low national baseline adoption meant that additional training for clinicians new to these ICUs and SDD delivery was required).

Provision of selective decontamination of the digestive tract

Three themes emerged from the interviews on SDD provision: complexity/difficulty, protocol adaptation in practice, and facilitators and barriers.

Complexity/difficulty

Reflecting the theme of complexity, one intensive care consultant and several nurses reported that SDD provision represented additional and time-consuming work that made it unpopular with staff. When examining the sequencing and flow of actions, we identified evidence of complexity – multiple clinicians were involved in managing various behaviours within multiple clinical and environmental contexts using a range of materials delivered in specific sequences in a continuing flow of action (see Box 1 for quotations: P, participant). However, most nurses and doctors refuted the idea that SDD was complex and time-consuming, stating that providing SDD was effortless (Box 1). Low complexity/difficulty of SDD for these staff was supported by observational data indicating that administration of clinical components took no longer than 5 minutes, often less, and was performed in a swift sequence of actions. However, it is important to note that these were highly practised actions and may require considerable skill development to achieve this high level of expertise.

Supporting difficulty of providing SDD:

. . . there is extra work, four times a

day . . .

P1

. . . it’s relatively unpopular with

most of the nursing staff [. . .] because they

see it as excess workload.

P10

. . . delivery [. . .] can be

difficult.

P5

It only takes five/ten minutes, although that is another

five/ten minutes added on to the other five/ten minutes for

everything else that you have to do.

P7

Not supporting difficulty of providing SDD:

. . . it’s a part of your routine

already so I don’t find it difficult, it’s just

finding ways of how to do it, I mean it’s not too

difficult.

P6

[SDD provision] is really straightforward.

P7

. . . very simple [. . .], a

fairly straight forward thing to do.

P3

. . . the main message to take across is that

it’s, it works well. It is very easy to do.

P13

I don’t find it difficult.

P14

It is not that hard. It is really

straightforward.

P15

Supporting complexity of providing SDD:

[Overall, SDD delivery] involves a large amount of

co-operation between the microbiologists, the nursing staff and

the medical staff to [. . .] maintain an

appropriate antibiotic policy; it also involves

[. . .] quite a lot of monitoring of what is

involved with the patients [. . .] so that we

can manage the infections appropriately [. . .]

it involves applying some paste and some nasogastric SDD, but

these are relatively minor parts of the whole. It is a system of

which that is part.

P11

Protocol adaptation in practice

Protocol adaptation in SDD delivery was noted in observational and interview data. Preparation of antibiotics/antifungals varied, suggesting some deviation from recommended practice. Further adaptation was evident in the provision of SDD oral components such as different ways of applying oral drug components and timing with other nursing interventions such as oral hygiene. Authorising SDD involved multiple staff and deviation from recommended practice was noted. Although documentation indicated that patients should be routinely commenced on SDD, this did not always occur, owing to more pressing clinical concerns. As a result, multiple layers of control to ensure protocol adherence were described (Box 2).

. . . although it says the dose is 500 mg I

have been taught, in order to better manage my time, that I use

[a] 1 g bottle instead and instead of reconstituting it with 10

ml I reconstitute it with 20 ml.

P5

‘I have different ways [. . .] because

there are a lot of antibiotics’ and he/she did

not ‘know if it’s a good thing to mix all 4

antibiotics in one go and put them orally in one go

also’ and that

‘. . . others might do it

differently’.

P14

. . . it sometimes slips off the main agenda

of the patient’s day . . .

P8

I would ensure that all the relevant people get

SDD.

P17

I just make sure it is being put on.

P11

. . . if they haven’t prescribed it,

I’ll ask them to prescribe.

P14

Facilitators and barriers

Facilitators and barriers to SDD delivery were evident across both cases (Box 3). One facilitating factor frequently reported was dovetailing of SDD with other established and routine procedures. Thus, intensive care consultants might include SDD delivery behaviours as part of the admission process, nurses might include SDD as part of oral hygiene or other activities and clinical microbiologists and pharmacists dovetailed SDD actions within ward rounds. Dovetailing was evident in multiple interviews and in documentary data on SDD provision for oral hygiene. Although barriers were commonly reported during interviews in response to specific prompts, these were often referred to as minor inconveniences, rather than significant obstacles to SDD delivery (see Box 3).

-

Policies and protocols, e.g. ‘We have an admission policy, so [patients] come in and we have a set of investigations and [. . .] they’ll get SDD and [. . .] that’s just part of the admission’ [P10].

-

Patient state, e.g. ‘patient is deeply sedated, it’s easier’ [P1].

-

Perceived effectiveness, e.g. ‘the fact that you have a very few incidents of pneumonia’ [P17].

-

Colleague support, e.g. ‘if you’re working side by side with a nurse, that nurse will help you’ [P5].

-

Dovetailing, e.g. ‘you just tag it on with your aspirating stomachs’ [P15].

-

Workload, e.g. ‘When it’s a really busy day then it gets a lot to do’ [P5].

-

Patient state, e.g. ‘if they’re intubated and they’re just maybe biting’ [P6].

-

Side effects, e.g. ‘patients tend to get more diarrhoea when they are [on] SDD’ [P1].

-

Staff changes, e.g. ‘losing a senior microbiologist was a stress, he was very supportive’ [P10].

-

Cost, e.g. ‘The main challenges are the cost. The drugs themselves cost a lot of money’ [P10].

-

Materials, e.g. ‘there’s been a few supply problems over the last couple of years. Sometimes [. . .] there can be national shortages which can be a bit of a problem’ [P16].

Infection surveillance

A fourth theme emerged from the documentary analysis. Surveillance was specified in the SDD protocol in one of the case study sites, but not in the other, in which it was part of the wider regimen to combat HAIs. Despite these differences, surveillance was integral to the provision of SDD and included the performance of multiple behaviours of various clinicians in several clinical and environmental contexts.

Discussion

In line with frameworks for intervention development23 and description,26 this study has specified (for the first time) the full clinical and behavioural components of SDD and has described how they impact on SDD implementation and delivery. There are several advantages of specifying an intervention behaviourally alongside clinical specifications. First, it demonstrates procedural complexity and the situations in which complexity may be experienced. This information has direct relevance to clinicians and hospital decision-makers considering implementation of particular health-care interventions. It also can inform the scale and content of implementation strategies to facilitate diffusion and adoption within specific contexts. 37 Second, behavioural specification identifies potential areas where behavioural variation in practice may occur and, thus, allows prior specification of acceptable limits of protocol adaptation. Third, it may identify training needs to facilitate adherence to an expected standard. Fourth, behaviour specification facilitates precision in protocols and training materials by describing who should do what and when and where this should occur.

Answers to research questions

We found variation in SDD clinical components, in terms of the drug regimen, mode of drug delivery and specification of components (i.e. surveillance) between the two study sites. This may be appropriate to make the intervention simple and feasible to deliver within a local context. Various behaviours related directly to drug provision as well as other aspects of the SDD intervention (e.g. authorisation of SDD delivery) were performed by multiple clinicians in differing contexts. In terms of clinical components, topical antibiotics/antifungals and i.v. antibiotics were identified as SDD components in documents, but surveillance, general hygiene and general infection control regimen were not. Such inconsistency is also identified in the literature. 18 Both ICUs administered i.v. as well as topical/oral components. Overall, SDD implementation and delivery comprised the interrelated phases of SDD adoption, operationalisation, provision and surveillance.

Additional behaviours to those specified in documentation were identified and these behaviours are essential for SDD delivery. SDD involved a range of health-care professionals performing various behaviours in differing contexts. These findings emerged in the interview and observational evidence but were not always clearly specified in the documentation. Ensuring that these additional behaviours are specified in protocols, guidelines and the academic literature should lead to improvements in implementation, delivery and reproducibility of SDD. 24,25

Various behaviours were identified for SDD implementation, many at the organisational and team levels and others at the individual level. Several features of operationalisation involved an ongoing process (e.g. nurse training for SDD provision) as a result of staff turnover. SDD could thus be construed as a simple and easy intervention from the individual behavioural perspective that becomes increasingly complex when focusing on the flow of actions required at an organisational level for its delivery in practice. Consequently, some of the barriers and facilitators to SDD provision tended to centre on the environmental context and resource issues, rather than specific attitudinal (e.g. beliefs about SDD effectiveness) or skills barriers.

Strengths and limitations

The current study is the first to systematically identify and specify a full range of SDD components throughout the steps of SDD implementation and delivery. A limitation is the potential lack of generalisability owing to the use of two cases only. Additional clinical and behavioural components, as well as alternative methods of SDD implementation and delivery, may be evident if investigating SDD practice in a larger number of ICUs. However, the study was exploratory in nature with the goal of providing information-rich case studies that facilitate in-depth understanding of SDD in practice rather than a comprehensive picture of SDD across all UK ICUs. We recruited one microbiologist only, limiting the perspective from this profession. Finally, clinicians in ICUs that did not deliver SDD may have different views about barriers to SDD implementation. This was investigated in subsequent stages of the study.

Conclusion

This study was the first to provide a formal specification of the full clinical and behavioural components of SDD. We described a wide range of behaviours involved in delivering SDD, several of which were not included in local SDD protocols. Significant protocol adaptations resulting from these behaviours were observed across sites, suggesting the need for routine behavioural specification in SDD delivery protocols. Such specification would greatly facilitate the subsequent detection of acceptable variations and those that may lead to significant differences in patient outcomes.

Key messages from the case studies are reported in Box 4. The findings of this study phase informed the next stages of the current study in the following way. At the start of interviews or questionnaires that sought clinicians’ views about SDD, we first defined the clinical components of the intervention. For brevity, we did not specify the behavioural components; however, such specifications would be an important aspect of future trial design.

-

Delivering selective decontamination of the digestive tract included more than the provision of clinical components and involved multiple behaviours performed by multiple clinical team members.

-

Not all behaviours relevant for SDD provision were specified in SDD documentation.

-

SDD implementation included the interrelated phases of deciding whether or not to implement SDD (adoption phase) and deciding how to implement SDD (operationalisation phase), with both phases involving organisation-, team- and individual-level behaviours.

-

There was some complexity in the interplay and flow of the clinical and behavioural components of SDD, involving multiple staff. However, provision of SDD was simple from the perspective of individual staff and delivery was regarded as straightforward.

-

Infection surveillance provided the foundation for SDD implementation and delivery, but may not be seen as part of the SDD regimen itself.

Chapter 3 Delphi study to identify stakeholder views about selective decontamination of the digestive tract: round 1 interviews

Background

The second stage in the study was an in-depth investigation, using Delphi methods, of the views of key stakeholders most likely to have decisional authority with respect to local SDD policy (i.e. those people most likely to be involved in the decision to adopt SDD). This stage of the study was conducted in collaboration with a multinational research team, with parallel studies being conducted in Canada, Australia and New Zealand [funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Intensive Care Foundation (Australia) and the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists Foundation].

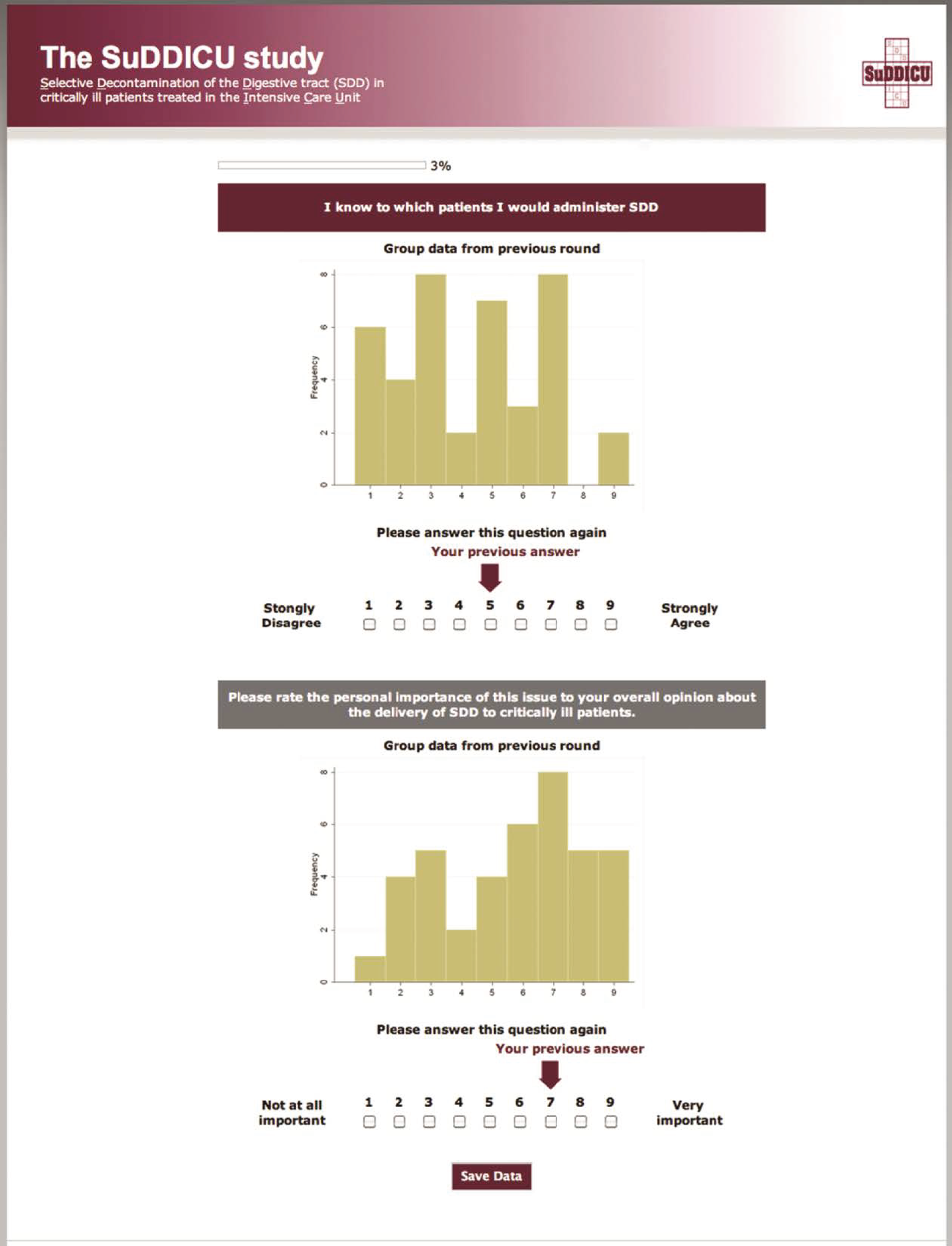

The Delphi approach uses a structured, iterative process including anonymised feedback, in a series of sequential questionnaires or ‘rounds’. The Delphi approach has been widely applied in health-care research. 38–40 Although the approach was originally designed to achieve expert consensus,41 it has developed into a method that can also assess levels of agreement (or disagreement) within an expert group. 42,43 The objective of assessing consensus rather than achieving consensus was the goal of this study phase and influenced a number of the design features.

The Delphi study was thus designed to generate iterative evidence about consensus and stability of views about SDD and addressed the following research questions:

Research question 3: What are the views of key stakeholders of the internal/external validity and adequacy of the existing evidence base for SDD and how willing are they to participate in further research?

Research question 4:. What are the views of key stakeholders about the likely positive and negative consequences of implementing SDD in ICUs and what is the relative importance of these beliefs in influencing overall views about SDD?

Research question 5: What are the views of key stakeholders about the likely barriers to implementing SDD in ICUs?

The Delphi study comprised an initial exploratory round involving interviews (reported in this chapter), followed by two iterations (reported in Chapter 4) using items generated from interview data. Hence, the first Delphi round was used to generate round 2 items that represented the full range of views raised, so that all could then be considered by participants in later rounds. 1

Methods

The round 1 interviews were based on a topic guide (further details below) that was arranged in three sections:

-

Asking about, and establishing, a definition of SDD (based on findings from the case studies).

-

Asking about the likely consequences of delivering SDD and potential barriers to implementation. This section was based on the TDF (see Table 4). 20

-

Asking about participants’ willingness to participate in further research.

The TDF was developed to facilitate coverage of a full range of potential opinions about, and barriers to, the use of health-care procedures. 21 It was developed from 33 theories of individual and organisational behaviour to assist researchers to identify constructs likely to influence health professionals’ behaviour. 20 The framework proposes that determinants of health professionals’ behaviour cluster into 12 domains. Each domain includes constructs from a number of behavioural theories that are potentially overlapping. One domain of particular relevance to this study is labelled Beliefs about consequences, as it relates directly to research question 4. Table 4 presents the labels and descriptions of the 12 TDF domains. These descriptions were used to guide the data analysis.

| Domain label | Description |

|---|---|

| Behavioural regulation |

|

| Beliefs about capabilities |

|

| Beliefs about consequences |

|

| Emotion |

|

| Environmental context/resources |

|

| Knowledge |

|

| Memory, attention and decision processes |

|

| Motivation and goals |

|

| Nature of the behaviours |

|

| Professional role and identity |

|

| Skills |

|

| Social influences |

|

Sample

A Delphi process gauges views from a panel of experts. 44 Ideally, potential Delphi participants would thus be experts in delivering SDD, or experts in terms of their knowledge of the SDD evidence base. Because of the low SDD uptake in UK ICUs at the time of this study, restricting the study sample to those with direct experience of SDD delivery or with a special interest in SDD research could systematically bias findings in favour of SDD adoption and delivery. Therefore, we decided to define ‘expertise’ more broadly to include the four stakeholder groups likely to exert decisional authority with regard to an ICU’s SDD policy or to how such a policy would be implemented in practice. Hence, the participants for the Delphi study were intensive care consultants, ICU pharmacists, clinical microbiologists with ICU responsibility and an ICU leaders group (including medical leads, nurse managers and educators working in NHS hospitals throughout the UK).

There is a broad range of estimates of suitable sizes for a Delphi panel, but smaller sizes (such as 10 for each stakeholder group) have been deemed appropriate where panel members have similar training. 45 Our minimum target sample size was thus set at 40 (10 in each stakeholder group). We also sought participant representation from across the four UK home nations.

Three clinical members of the research team (GB, APRW, RS) compiled lists of their clinician group and ranked them according to predetermined diversity factors (location, ICU size, current SDD practice and academic affiliation). A list of ICU nurse managers/educators was compiled by three members of the research team (GB, BHC, MEP) and ranked for the above diversity factors. Study invitations were issued to individuals according to rankings and in order of approvals made by the research and development (R&D) offices of each participating hospital trust. Sample diversity was tracked during recruitment. Additional participants from stakeholder lists (those working in NHS Trusts for which we had R&D approval) were specifically targeted to maximise variation. To preserve a minimum sample size of 10 in each stakeholder group by Delphi round 3, we oversampled by one to three participants in each of the four groups.

Data collection

At the start of each interview, to establish a shared understanding of SDD components, participants were first asked what they understood ‘selective decontamination of the digestive tract’ to mean. Irrespective of their initial definition of SDD, participants were, for the remainder of the interview, asked to consider SDD as application of antibiotics comprising all the following: (1) oral administration, to the mouth and throat, (2) gastric application via a nasogastric tube or similar and (3) a short course of i.v. antibiotics. We then asked whether or not SDD was delivered in the participant’s ICU. Responses to this second question determined which of two topic guides was used for the remainder of the interview (‘ICU currently delivering SDD’ or ‘ICU not currently delivering SDD’). Both topic guides are presented in Appendix 2 and included questions about:

-

factors that might influence adoption of SDD, such as participants’ views about the likely positive and negative consequences of SDD and their knowledge of the evidence base

-

participants’ views on the need for further research to settle questions around harms/benefits of SDD, what type of research [an effectiveness study or an implementation study (i.e. a study to evaluate strategies to increase uptake of SDD)] would be most informative and whether or not further effectiveness research on SDD was ethical

-

whether participants would be willing to participate in an effectiveness study to evaluate SDD and/or an implementation study to assess strategies that aim to increase uptake.

Procedure

Potential participants from stakeholder groups were invited to take part by an investigator-signed e-mail invitation (GB, APRW or RS). Expressions of interest were followed up with a short telephone call or e-mail from the study co-ordinator to further describe the study, answer any questions and, if the participant agreed to take part, arrange a convenient time for a 30-minute telephone interview. After 1 week, non-responders were sent a reminder e-mail signed by the appropriate clinician researcher. No further contact with non-responders was attempted. Recruitment continued until target sample sizes were achieved for each stakeholder group.

At the start of each telephone interview, participants were reminded that the aim of the study was to identify their personal views and opinions on SDD (there were no right or wrong answers). Consent to audio record the interview was requested and received from all participants.

Data management and analysis

Recordings were transcribed verbatim, checked for accuracy and anonymised. The objective of the analysis was to develop questionnaire items for the second round of the Delphi study, the quantitative questionnaire round. Analysis of the transcripts proceeded through a number of stages. First, ‘specific beliefs’ were identified within the transcripts. A specific belief was defined as a statement for which the content may indicate a perceived influence on SDD adoption or delivery. Specific beliefs that expressed the same theme or were polar opposites of the same theme were grouped together and were considered as repeats of the same belief. Summary statements representing these beliefs were devised, and these became the basis of the round 2 questionnaire items. This analysis was performed using an iterative and parallel process with the SuDDICU Canada team (who had adopted an identical topic guide and sampling strategy). All summary statements identified in the analysis were discussed by an international working group of study investigators to identify appropriate wording for representing the beliefs in round 2 of the Delphi study. When it was justifiable from the interview data, identical wording of questionnaire items was agreed across nations. When specific beliefs emerged only in the UK study, these were included in the UK version of the round 2 materials.

The next stage in the analysis involved allocation of the specific beliefs to the prespecified TDF domains. This was carried out independently by two researchers (JJF and one research assistant) using the TDF as an analytic framework and content analysis methods previously employed by the research team in the context of intensive care. 46 When there was disagreement between coders, these were discussed with a third researcher (MEP). Agreement was achieved for 42 of the 46 UK items; the remaining four items, for which discrepancy in domain allocation persisted, were discussed with an expert group of 16 researchers who were familiar with the TDF (the Aberdeen Health Psychology Group) and the majority view was taken for domain allocation.

To address research question 4 we examined the Beliefs about Consequences domain in detail. A preliminary assessment was made of the perceived importance of each specific belief in this domain. In round 1, assessment of importance was based on evidence from cognitive psychology, which identifies that the ‘cognitive accessibility’ of a belief (i.e. the readiness with which it comes to mind) is an indicator of its importance to an individual. 47 In ‘social cognitive’ models of planned action,48,49 importance is assessed at the group level by identifying the ‘modal salience’ of the belief, i.e. how many times the same belief is elicited across the whole sample of study participants, relative to other beliefs. Hence, the frequency with which a belief was elicited in the interviews was taken as an indicator of its relative importance. It was recognised that this procedure is based on a range of assumptions and so this early indicator of importance was later compared with data from rounds 2 and 3 (reported in Chapter 4), in which participants were asked to report their ratings of the importance of each belief. Importance was also examined quantitatively in the national survey (see Chapter 5) so that these three methods for assessing the relative importance of consequences could be compared. This was done to ensure that robust evidence could be used to identify the most important outcome measures to include in a possible effectiveness trial of SDD.

Using similar assumptions, the importance of each theoretical domain was assessed, in round 1, by identifying the level of elaboration provided by participants in their responses to the interview questions. The relative importance of the domains would identify key barriers to implementation, which would provide an evidence base for the design of an intervention to increase uptake in a possible implementation trial of SDD. For each domain, we identified how many utterances were coded, how many specific beliefs were generated across the sample and the content of those beliefs. For example, if the belief was essentially that the issue was not important or not a problem, this content was taken into account.

The project was coordinated by the Health Services Research Unit, University of Aberdeen. Ethics approval for Delphi study was granted by NHS North of Scotland Ethics Service (10/S0801/69).

The project was subject to extreme delays and difficulties in obtaining research governance approvals for sites in England, Northern Ireland and Wales. These delays negatively impacted upon recruitment and hence may have compromised our attempt to sample for diversity. Despite repeated attempts to contact trusts, 15 NHS trusts had failed to issue a decision on research governance by the time data collection closed (6 months after submitting the documentation). Further details can be found in Appendix 3.

Results

Participant characteristics

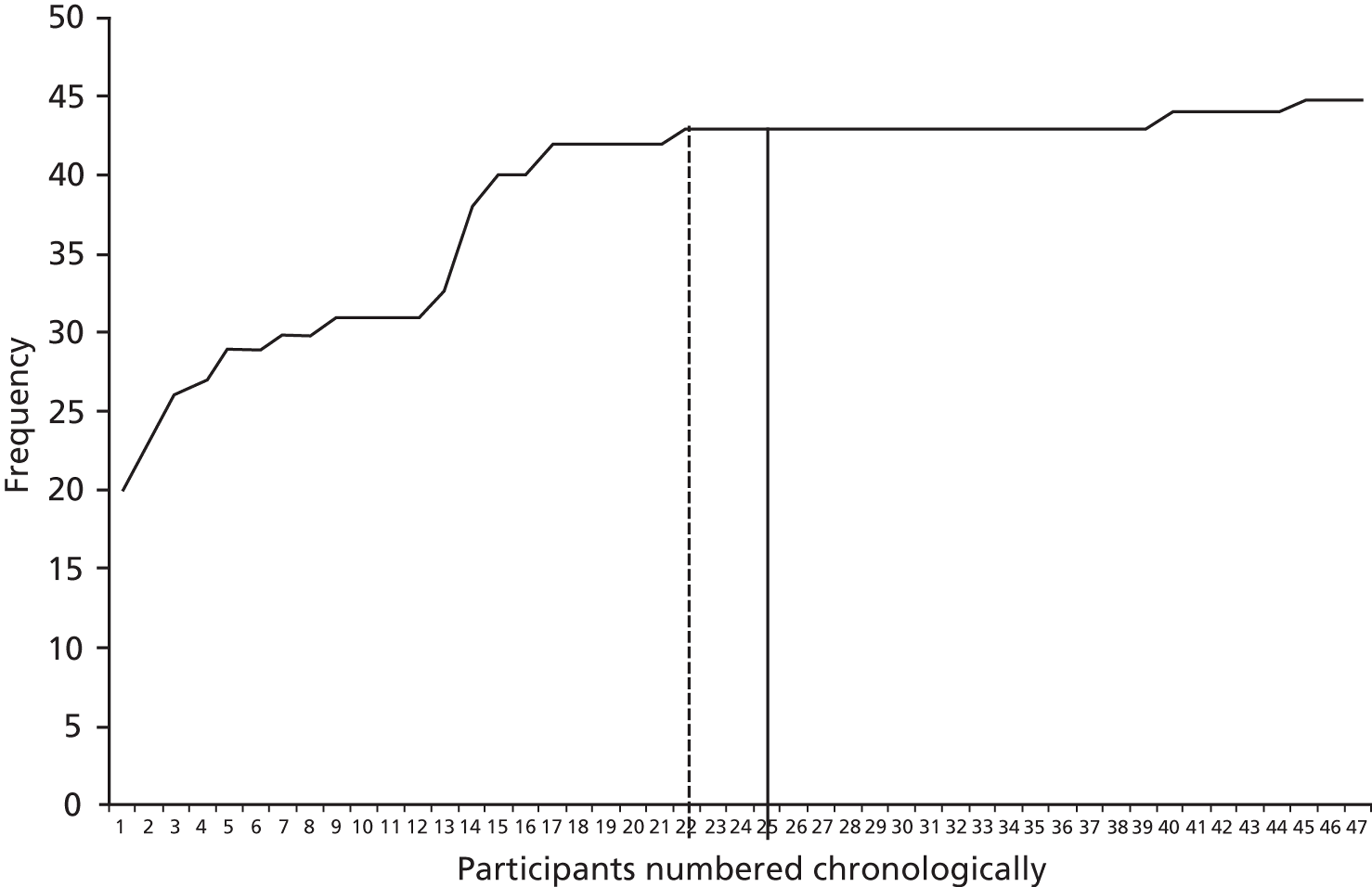

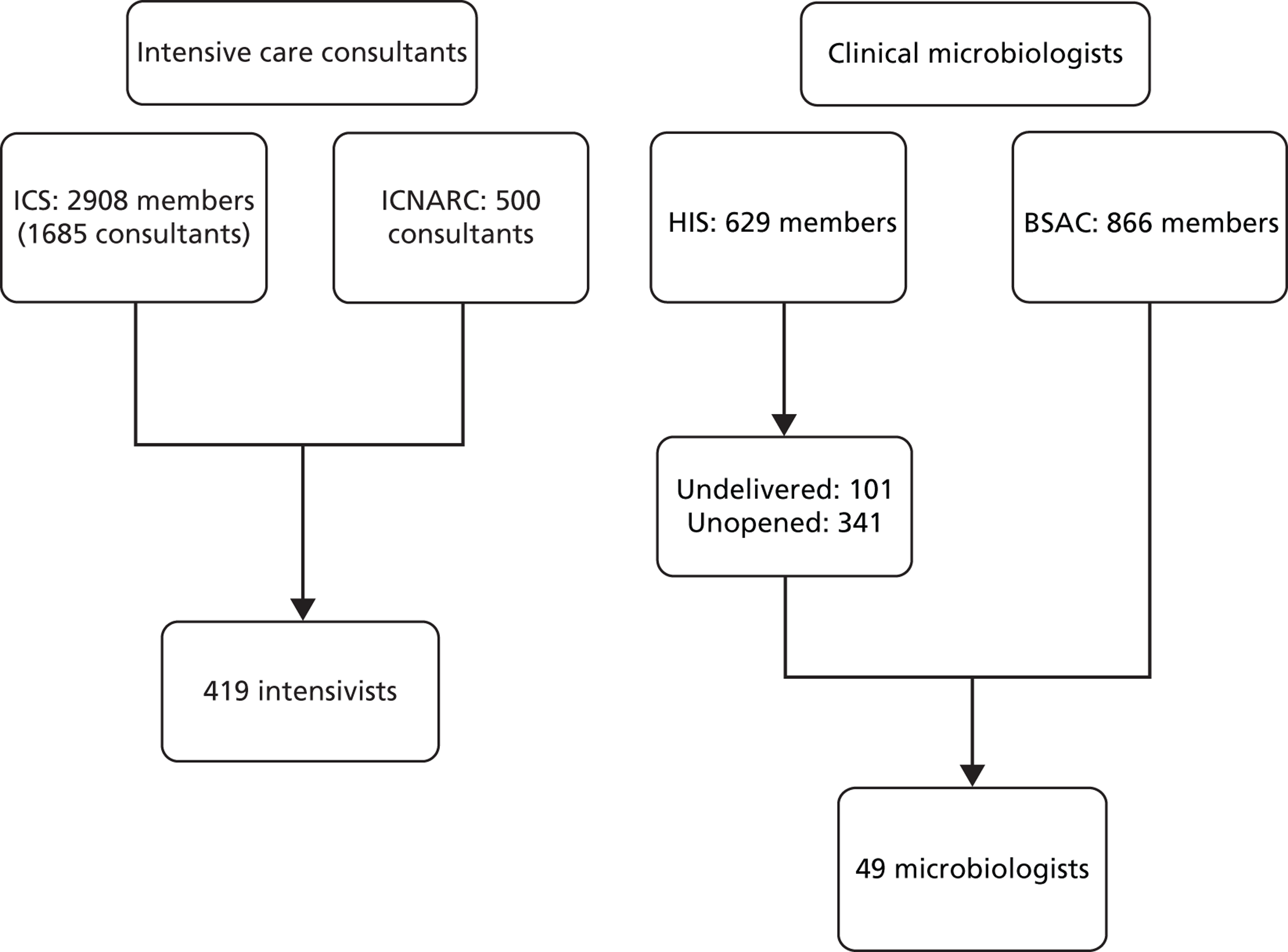

Ninety-four health professionals were invited to take part. Eight participants were excluded as not meeting eligibility criteria (had left the hospital or their profession) and three e-mails were returned undelivered. Forty-seven participants consented to participate and were interviewed (57% consent rate). Consent rates were highest among pharmacists (92%) and lowest among clinical microbiologists (39%), shown in Table 5.

| Stakeholder group | Invitations | Participants | Consent rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICU physicians | 20 | 12 | 60% |

| ICU pharmacists | 12 | 11 | 92% |

| Medical microbiologists | 28 | 11 | 39% |

| ICU clinical leads/ICU nurse managers/educatorsa | 23 | 13 | 57% |

| Total | 83 | 47 | 57% |

The mean age of the 47 participants was 45.7 years and 31 (66%) were male. Participants were working in 25 different hospitals with ICU bed numbers ranging from 8 to 75. Five participants worked in ICUs that currently delivered SDD, another five had personal experience of SDD from previous positions and the remainder had no direct experience with SDD. Participants had a mean of 18.2 [standard deviation (SD) 7.2] years of ICU experience. Participants were recruited from all four home nations (30 participants from England, 12 from Scotland, two from Wales and one from Northern Ireland).

Importance analysis at the level of theoretical domains

Table 6 provides details of the number of times participants made comments that were coded into each theoretical domain and a brief description of the content of each domain, in so far as it indicates the perceived importance of the domain.

| Domains (ranked in terms of frequency in column 2) | Number of utterancesa (from 47 interviews) | Brief description of content | Number of items generated for round 2 (specific beliefs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beliefs about consequences | 470 | Highly elaborated by participants and discussed as being an important influence on the adoption of SDD | 18 |

| Memory, attention and decision processes | 154 | Decision-making processes relevant to adoption of SDD were discussed as an important influence | 3 |

| Knowledge | 154 | Participants reported variable knowledge of the evidence base for SDD and observed that this would need to be addressed before SDD could be adopted | 3 |

| Motivation and goals | 122 | A lack of motivation to adopt SDD was highlighted by participants as being an important barrier to adoption | 6 |

| Environmental context and resources | 90 | Discrepancies between the clinical contexts in which evidence has been gathered and participants’ own clinical contexts were reported to be an important influence on relevance of the evidence to the UK | 4 |

| Skills | 52 | Skill was discussed by participants but was not judged to be an important barrier to adopting SDD. Participants reported that ICU staff already have the skills necessary for delivering SDD | 1 |

| Nature of the behaviours | 31 | Complexity of, or experience with, SDD delivery behaviours were not judged to be an important barrier to adopting SDD | 3 |

| Beliefs about capabilities | 18 | Participants reported feeling confident in their ability to influence SDD adoption when this was in line with their professional responsibilities. This domain was, therefore, not considered an important barrier to adoption of SDD | 1 |

| Professional role and identity | 13 | Participants discussed the importance of professional obligations to reduce the use of antibiotics and how such directives impacted upon opinions about SDD adoption | 3 |

| Behavioural regulation | 15 | This domain was elaborated by participants but was mostly discussed in terms of recommended strategies for the hypothetical situation of adopting SDD | 3 |

| Social influences | 6 | Participants discussed the influence of other people, such as the perceived majority position among ICUs in the UK with respect to SDD adoption | 2 |

| Emotion | 1 | One person discussed emotion in the sense that it is difficult to have a dispassionate discussion with colleagues about SDD adoption | 0 |

As shown in Table 6, most utterances were coded under the Beliefs about consequences domain and these utterances were coded into 18 specific beliefs. However, not all domains showed a direct relationship between the level of elaboration in interviews and the number of specific beliefs that were identified. For example, although Memory, attention and decision processes was the second most elaborated domain, the participants’ responses could be distilled into three specific beliefs relating to the decision-making processes required for SDD adoption (see Table 9). Furthermore, Motivation and goals produced the second highest number of specific beliefs but, in terms of the number of utterances, was elaborated less than the Memory, attention and decision processes or Knowledge domains.

The following sections provide further detail about the specific beliefs that emerged in each of the theoretical domains.

Beliefs about consequences

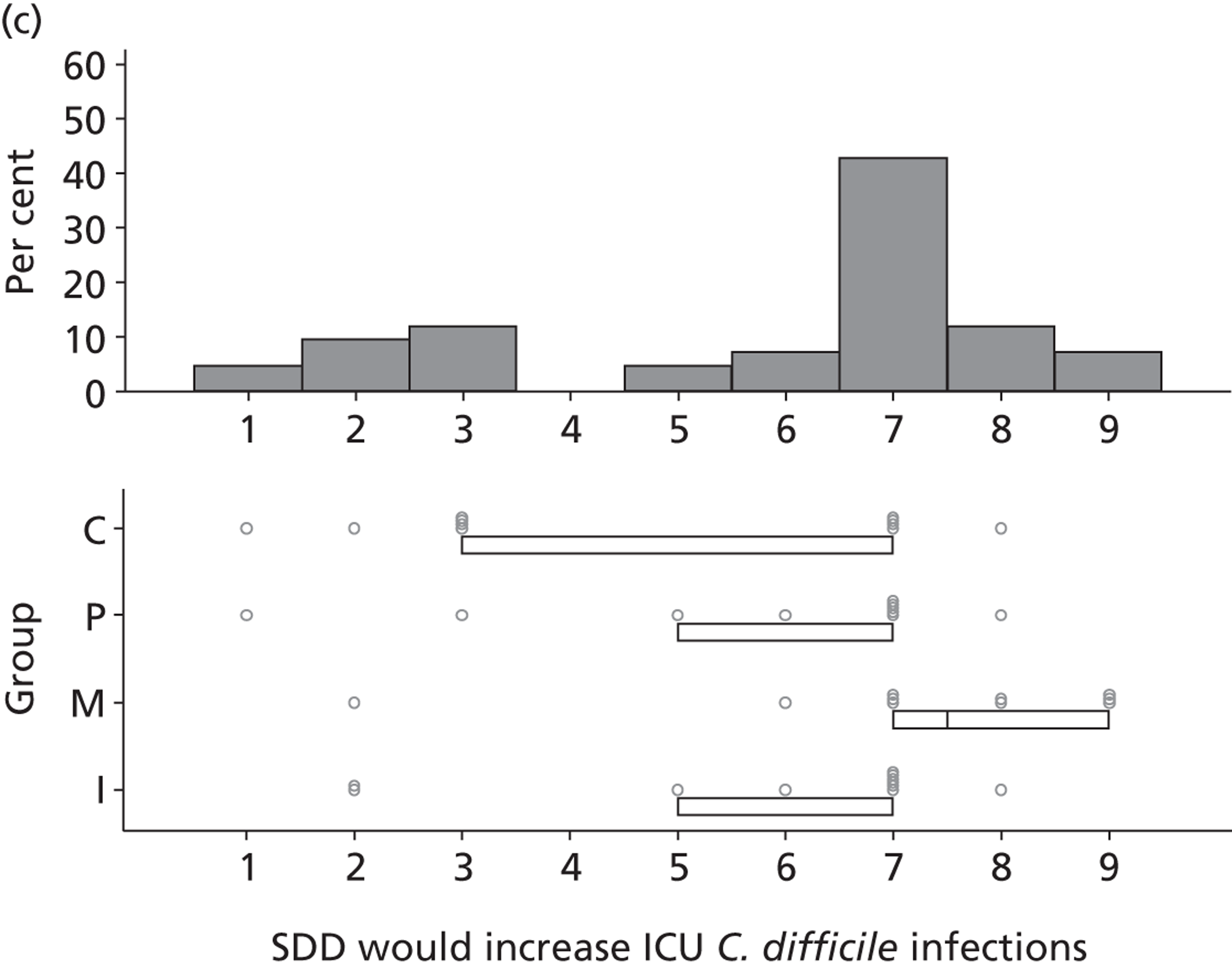

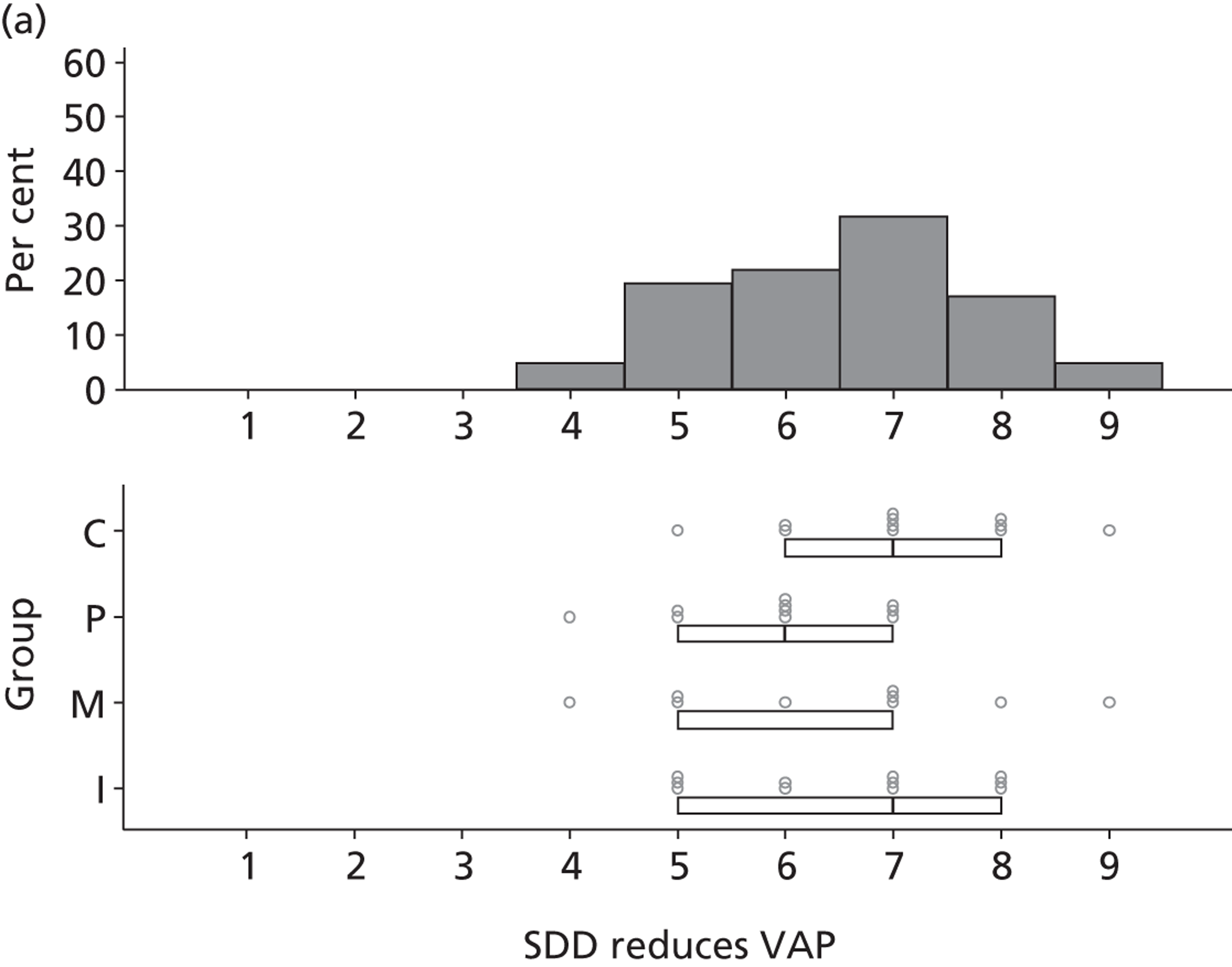

Participants discussed 18 Beliefs about the consequences of SDD, both positive and negative, and noted that SDD could produce positive benefits such as reduced morbidity, rates of HAIs including VAP and ICU length of stay. The most frequently mentioned concern about the negative consequences of SDD adoption was the potential for increased antibiotic resistance. Participants also discussed their concerns about the potential for increased rates of C. difficile infections.

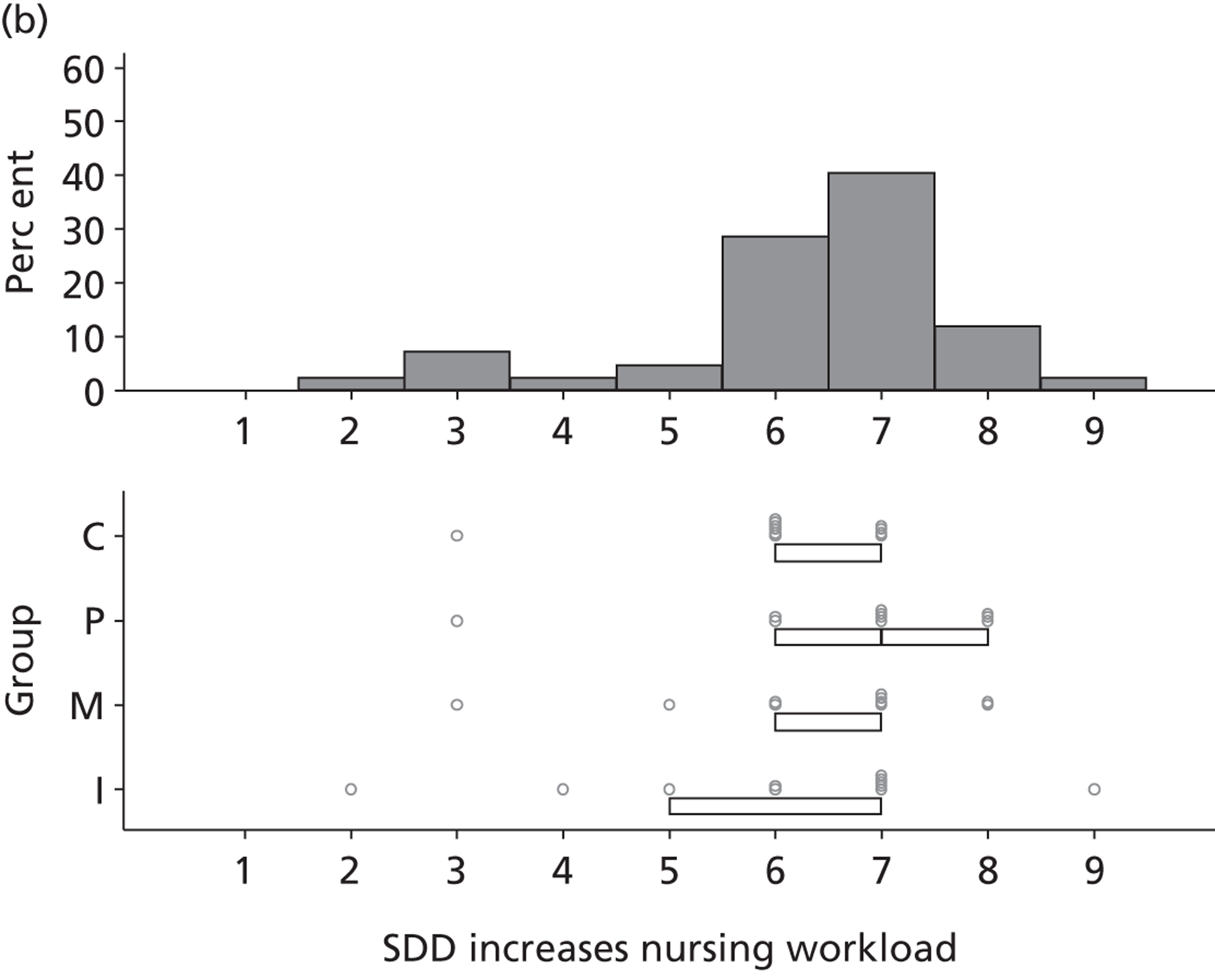

Non-nurse participants expressed concern that SDD delivery would increase nursing workload, specifically relating to administration of SDD components, taking cultures for microbiology and dealing with patient side-effects related to SDD such as diarrhoea. However, nurse participants raised none of these concerns. The only nurse to mention the impact of SDD delivery on nursing workload reported that it was not a barrier to implementation.

People who are wittering on about increased nursing time . . ., you cannot really use that as a great reason not to do something.

P41

Participants also stressed the importance of weighing risks and benefits associated with SDD. Specifically, they questioned whether the potential reductions in mortality and VAP were enough to balance the potential risk of increased antibiotic resistance and associated consequences. We noted considerable variation in viewpoints in this domain.

Financial consequences also were discussed both as potential cost-savings (due to reducing VAP and length of stay) but also the potential for increased costs in terms of SDD drugs and additional human resources required to deliver them.

Memory, attention and decision processes

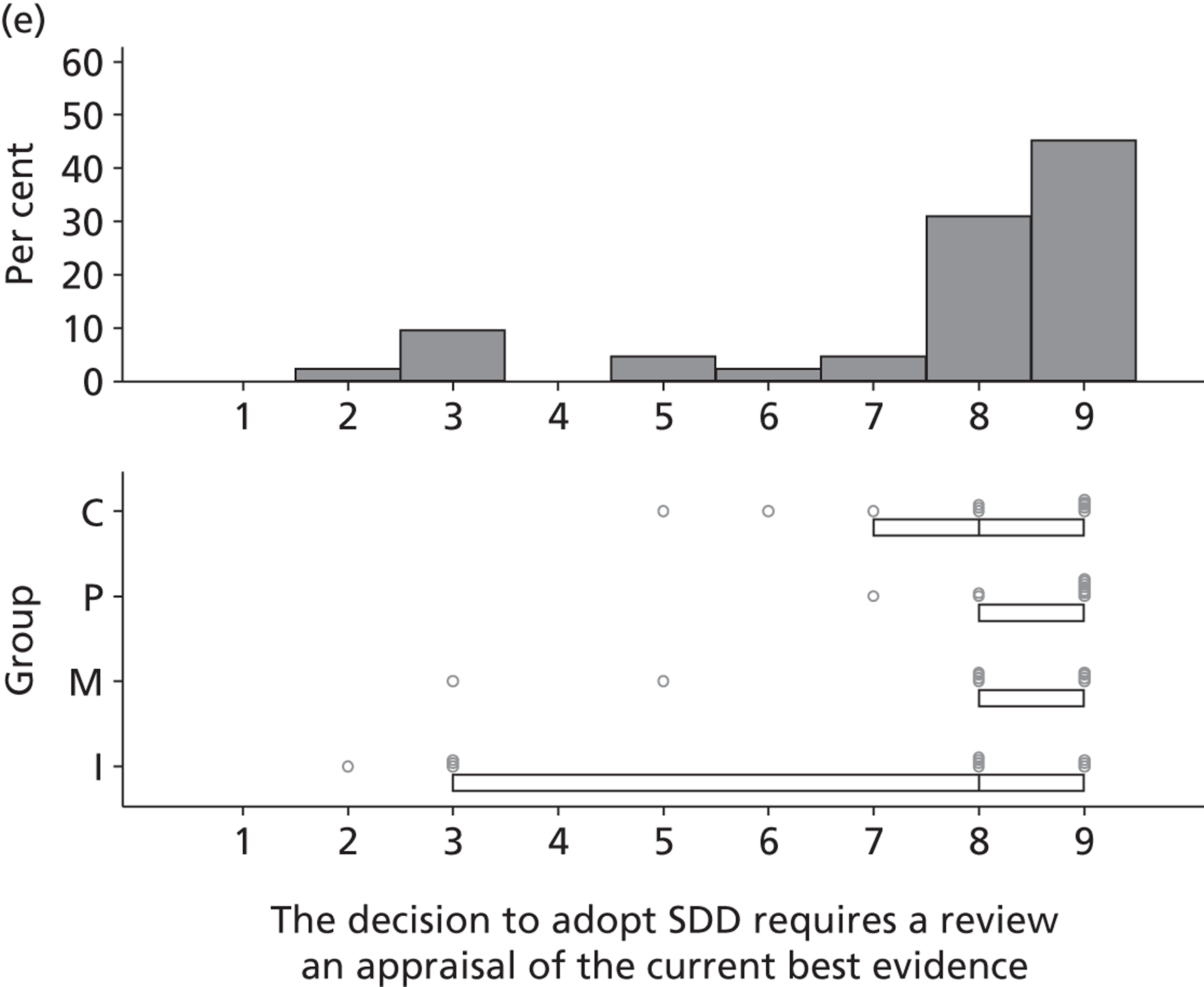

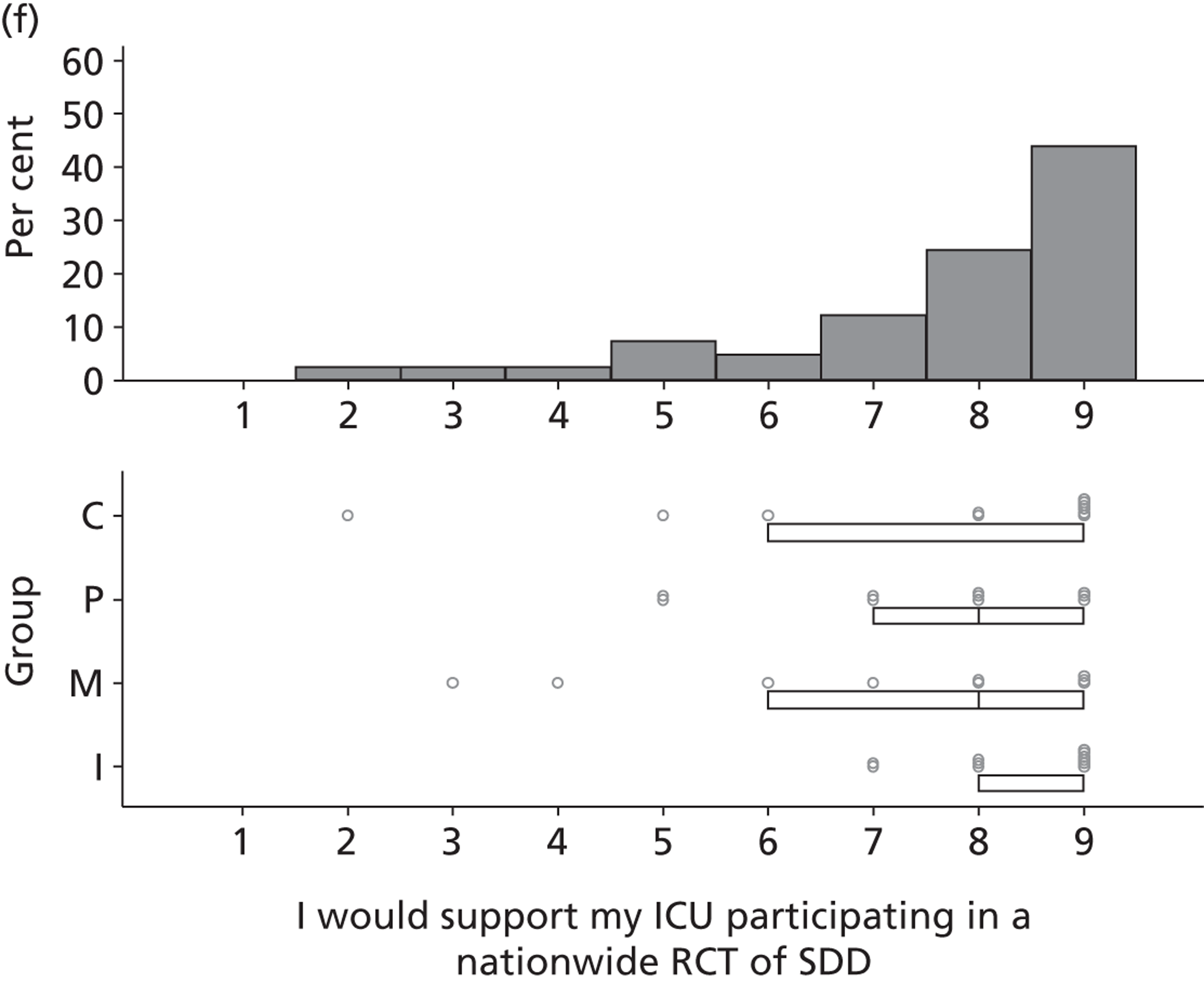

Three beliefs relating to decision-making processes were identified that would be required prior to adoption of SDD: the need to review and appraise current evidence (n = 35), the need for consensus among colleagues (n = 32) and the role of senior ICU doctors (consultant level) as key decision-makers (n = 13).

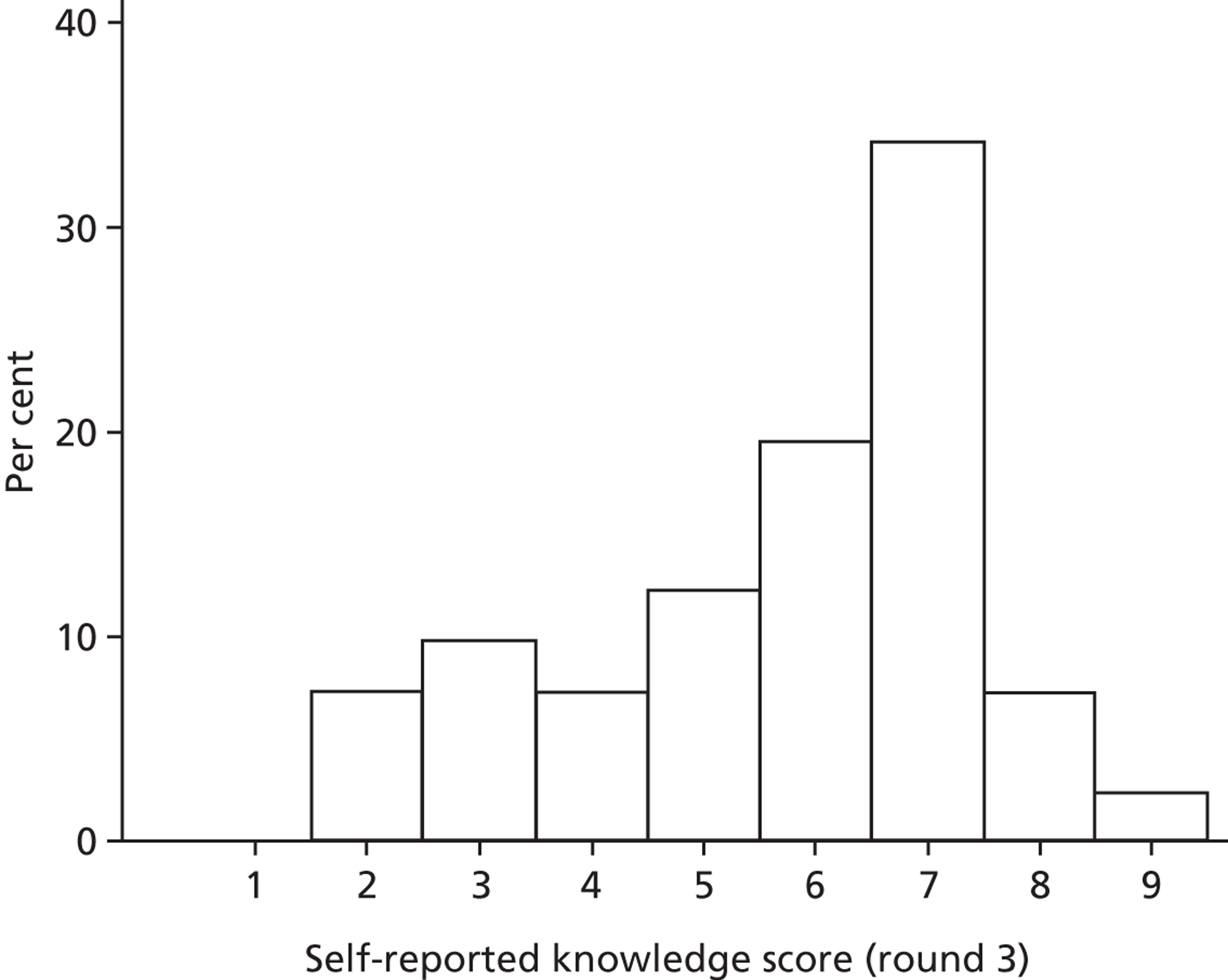

Knowledge

Participants varied in their self-assessed levels of knowledge about SDD components and in their views of their own and others’ knowledge of the evidence base. Importantly (but not surprisingly), knowledge of the evidence base was linked by some to their rating of the importance of SDD:

I have never quite got round to looking at it and I have to be honest that . . . when I got the original email to say . . . there’s going to be a questionnaire on this, I thought . . . this is something I have been meaning to look into for a while so . . . having looked at the evidence now, it is very important.

P05

Some participants were very knowledgeable:

There have been some very, very good trials recently . . . I think there is certainly plenty of evidence there that some of us should be looking at and I think the big problem is . . . not everybody has fully appraised the papers.

P05

Other participants identified a limited knowledge of existing evidence, which was potentially an important factor in interpreting the study findings. Knowledge data are reported in Chapters 4 and 5.

Motivation and goals

Six beliefs were coded into this domain. These beliefs included the perception that SDD was not currently a ‘front-and-centre issue’ and, therefore, not a topic of discussion in their units or among colleagues. Two intensive care consultants and one microbiologist reported that VAP was already adequately addressed by other interventions and, therefore, there was no motivation to pursue other options to reduce HAIs such as SDD. Other clinical priorities were reported to be more important, such as the adequate implementation of existing VAP bundle procedures.

The main reason is that we are on a very steep improvement curve for our intensive care unit, in terms of trying to improve the outcome of our patients and just haven’t got to SDD yet. We haven’t reached the level of sophistication by which we can look at interventions like SDD. We are still working on simpler things like sedation holding and breathing trials, you know, much simpler things and I think SDD will be on our list, I think we just haven’t got to it yet.

P19

Finally, four participants (two with previous experience of delivering SDD and two with no experience) reported that SDD was considered ‘old news’ and no longer a relevant clinical topic.

Environmental context and resources

Potential barriers to SDD were discussed by participants with respect to the domain Environmental context and resources. Previous trials, conducted outside the UK, were perceived to have limited generalisability to the UK ICU context owing to different patient characteristics, ICU ecology or microbial flora and standards of care.

It would be very helpful . . . if there is good research from the UK, because we use antibiotics differently, our ecology is different, our patients tend to be slightly different to other European ITUs [intensive therapy units].

P25

Professional role and identity

Three beliefs were identified within the Professional role and identity domain. Specifically, three participants reported that SDD conflicted with their professional obligations, most notably in reducing the administration of prophylactic antibiotics.

It is kind of bred into us, hammered into us publicly that we should limit and target the use of antibiotics as much as is possible.

P44

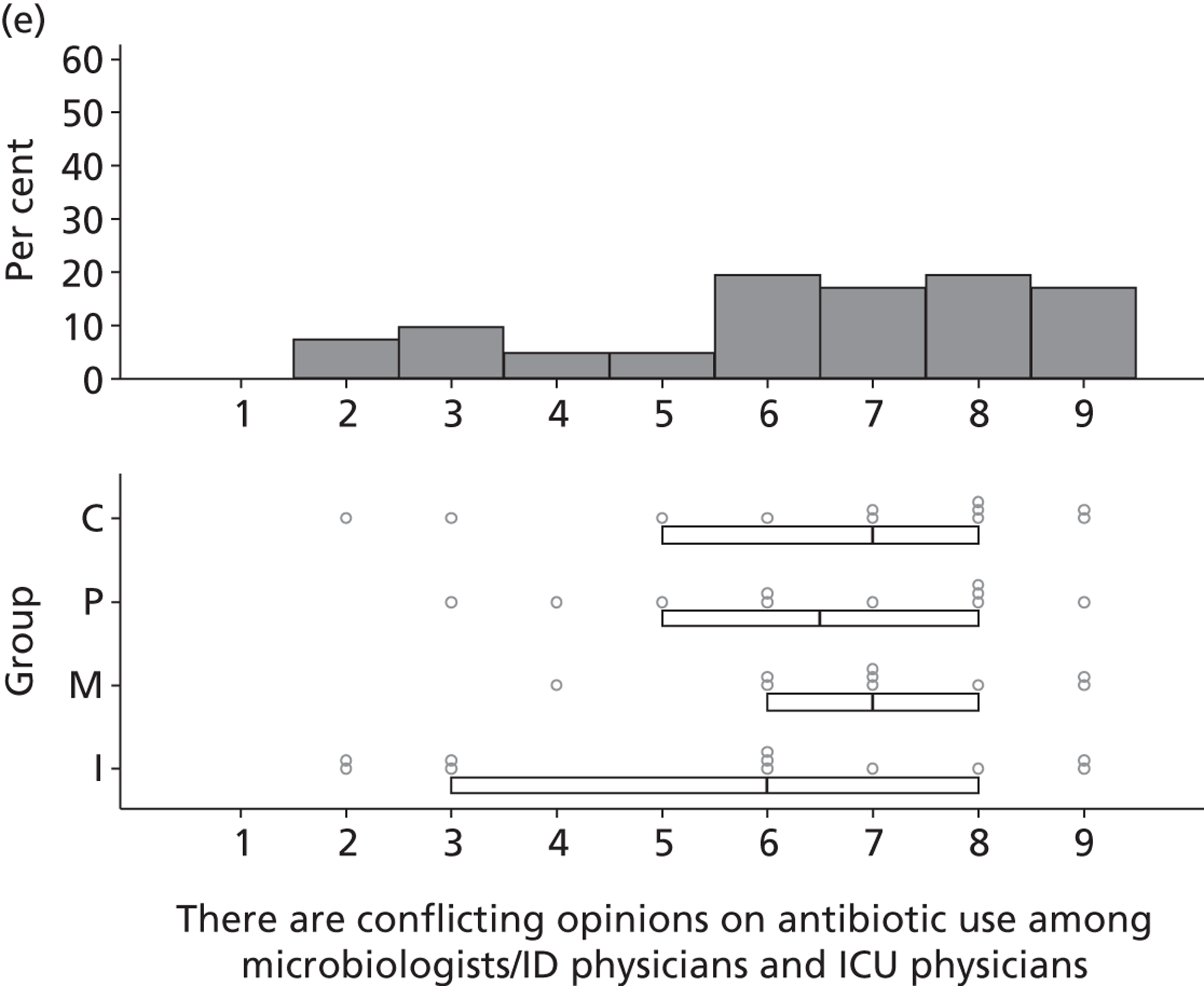

Participants reported that there were conflicting opinions among clinical microbiologists and intensive care consultants (on antibiotic delivery used within SDD) that could influence SDD adoption.

Behavioural regulation

Three beliefs coded into the Behavioural regulation domain were mentioned by five participants. They discussed the influence of national guidelines and regulatory requirements on local policy with respect to SDD adoption. There was a perception that endorsement of SDD from an authoritative body (e.g. mandate by NICE) would lead to the adoption of SDD into a unit’s routine clinical practice.

. . . if, certain NICE or a group like that . . . came forward and said this is an absolute . . . necessity for treatment in the ICU then I think it would happen in our unit.

P15

Social influences

Two beliefs were coded within the domain Social influence. Participants suggested that adoption would require a clinical champion or SDD expert to put SDD on the agenda, educate others and drive SDD forward. Two participants (a clinical lead and a microbiologist) also reported that their practice was influenced by the practice of other ICUs; more specifically, they felt reassured that their position on not delivering SDD was in line with the position of other ICUs.

Well I guess as the years go by and the lack of pressure to institute it, in other words, you know, lack of a persuasive argument that what we are doing leaves us as an outlier, then it becomes less important.

P31

Emotion

Finally, the domain Emotion was discussed by one participant, who described the emotion associated with colleagues’ certainty about the SDD issue:

. . . it is very difficult to have a dispassionate discussion with people about it [SDD]. They have already made up their minds.

P45

In the context of intensive care, three domains were similar conceptually, and all were viewed as not being barriers to adoption. These domains were Skills, Nature of the behaviour and Beliefs about capabilities. Skills was discussed by 34 participants, and the vast majority (n = 31) felt that delivering SDD was within the existing competencies of ICU nurses and, therefore, skills were not a barrier to SDD adoption.

I don’t think in the ICU there would be any reason to say that the nursing staff shouldn’t be able to give the drugs because they are doing that already.

P39

All participants (n = 47) made comments coded under the domain Nature of the behaviour, with most participants reporting that delivering SDD would not be a dramatic shift from current practice. This domain was not considered to be a barrier to SDD adoption and included in round 2.

I don’t think it would be that difficult [in comparison to what already doing].

P14

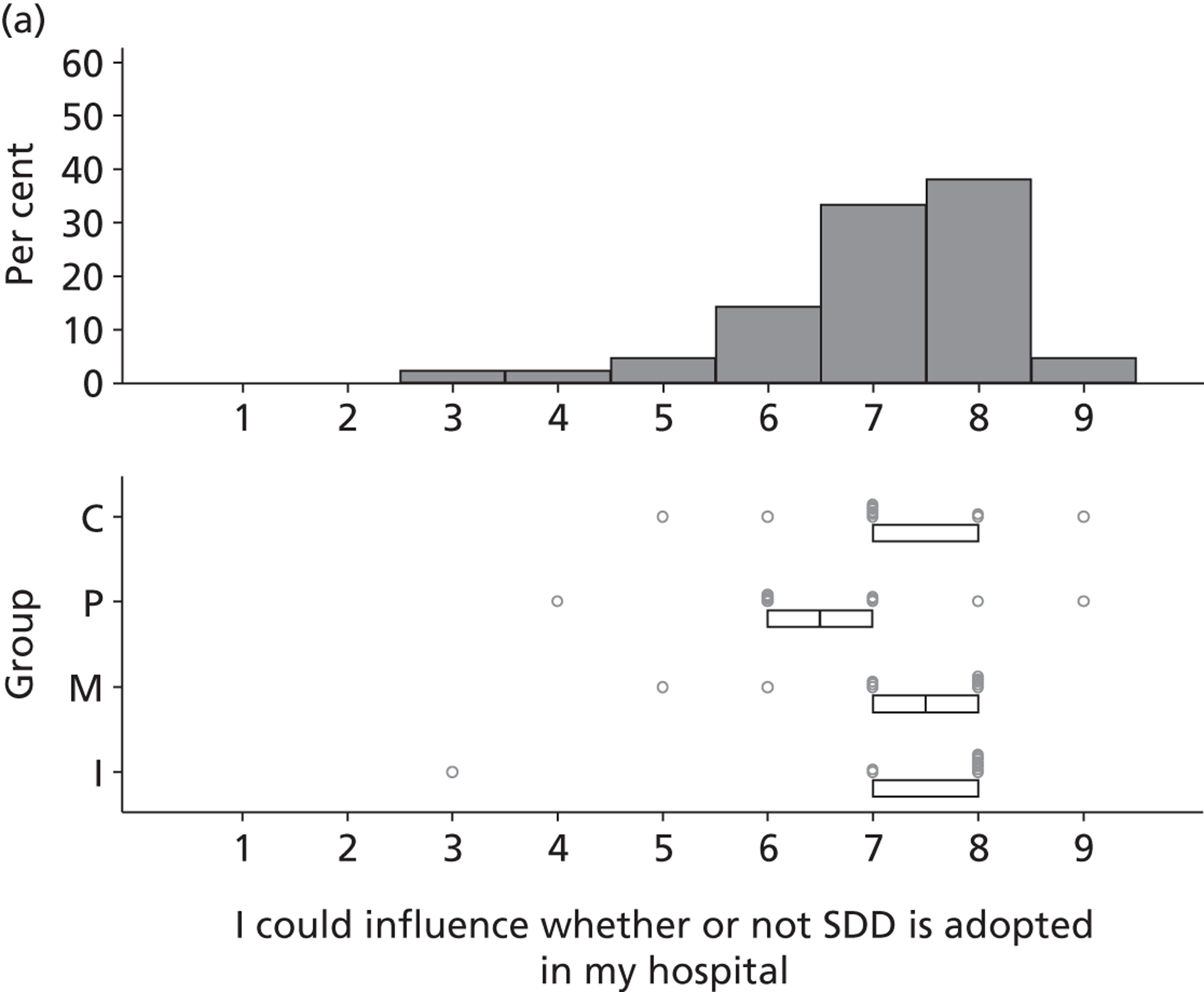

Participants’ Beliefs about capabilities (to influence adoption) were not considered to be a barrier to SDD adoption. Those key professionals who were responsible for instigating changes in policy (medical leads, intensivists and clinical microbiologists) reported that they felt they could influence the decision on whether or not to adopt SDD.

I would say that if I personally made it my crusade to do it [adopt SDD], we would do it.

P19

Nurses and pharmacists were less certain of their ability to influence SDD adoption, but most noted that they could suggest changes in policy to colleagues.

I can definitely suggest changes and I would have to get agreement with the consultants before we could institute a major change, but I could certainly discuss instituting major changes.

P24

In summary, when the theoretical domains were used as a framework for analysis, it was possible to identify beliefs about the likely positive and negatives consequences on SDD and other factors that are likely to be barriers to SDD adoption. Nine of the 12 domains were potentially important in this context; Beliefs about consequences, Memory, attention and decision processes, Knowledge, Motivation and goals, Environmental context and resources, Professional role and identity, Behavioural regulation, Social influence and Emotion.

Participants were also asked their views on the existing SDD evidence base and about potential future research directions. For discussion of data relating to these topics, see Views about the existing evidence base.

Views about the existing evidence base

There was considerable variation in participants’ reported views of the existing evidence base for SDD. Six participants reported that the evidence base for SDD was sufficient and three specifically stated that further effectiveness research would not be helpful in determining the next steps for SDD.

I think they have done enough research on it to show it is a good thing . . . the research has been done and it’s time to implement it.

P05

In contrast, 26 participants were not convinced by the existing evidence.

[Would further research settle some of the issues surrounding SDD?] I think so. I mean the problem with ITU is that we know that whatever is published one day, in about 6 months time or a year, there could be something different that will contradict it. But it [the research] has to be pretty definitive before, you know, we rush into anything.

P27

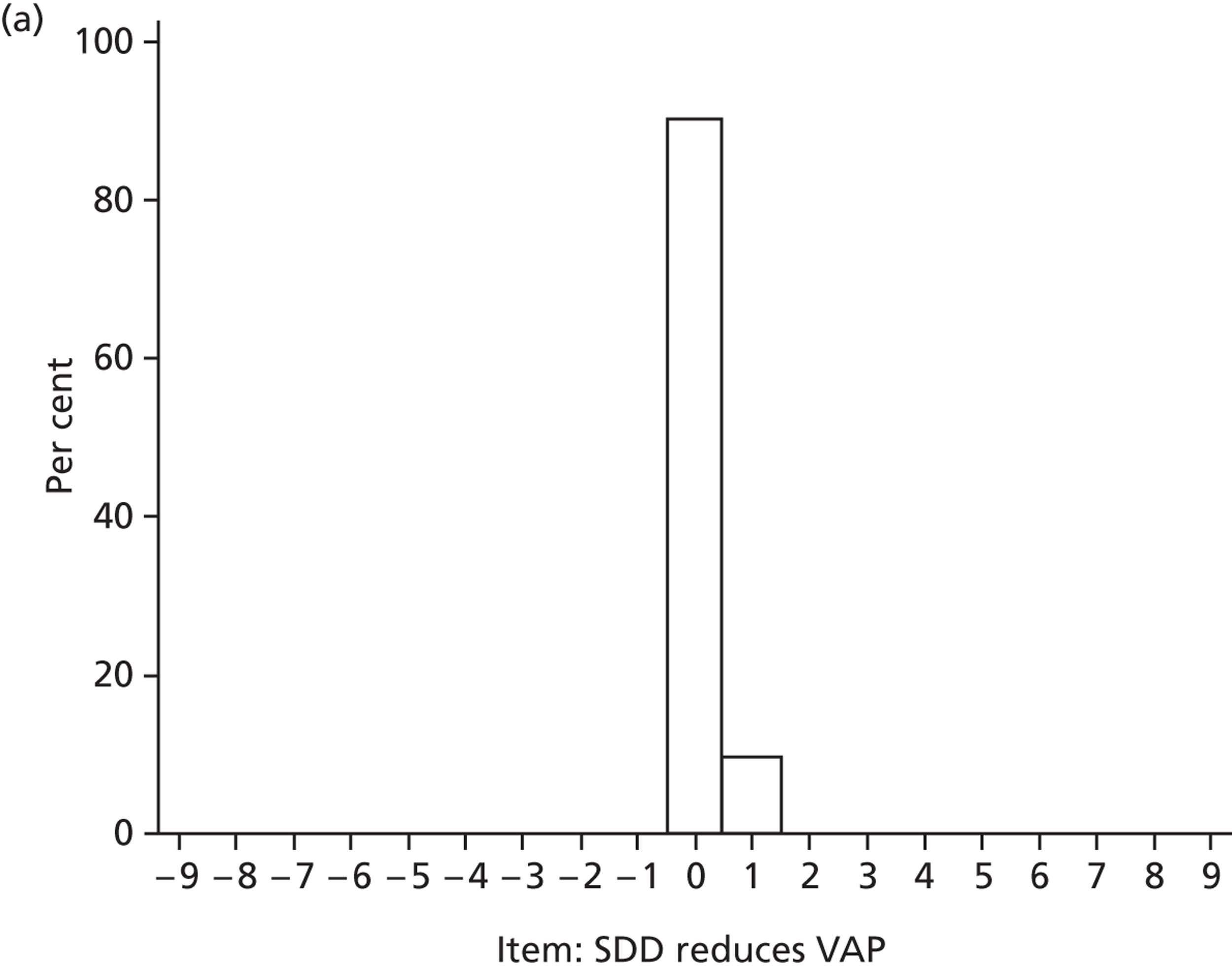

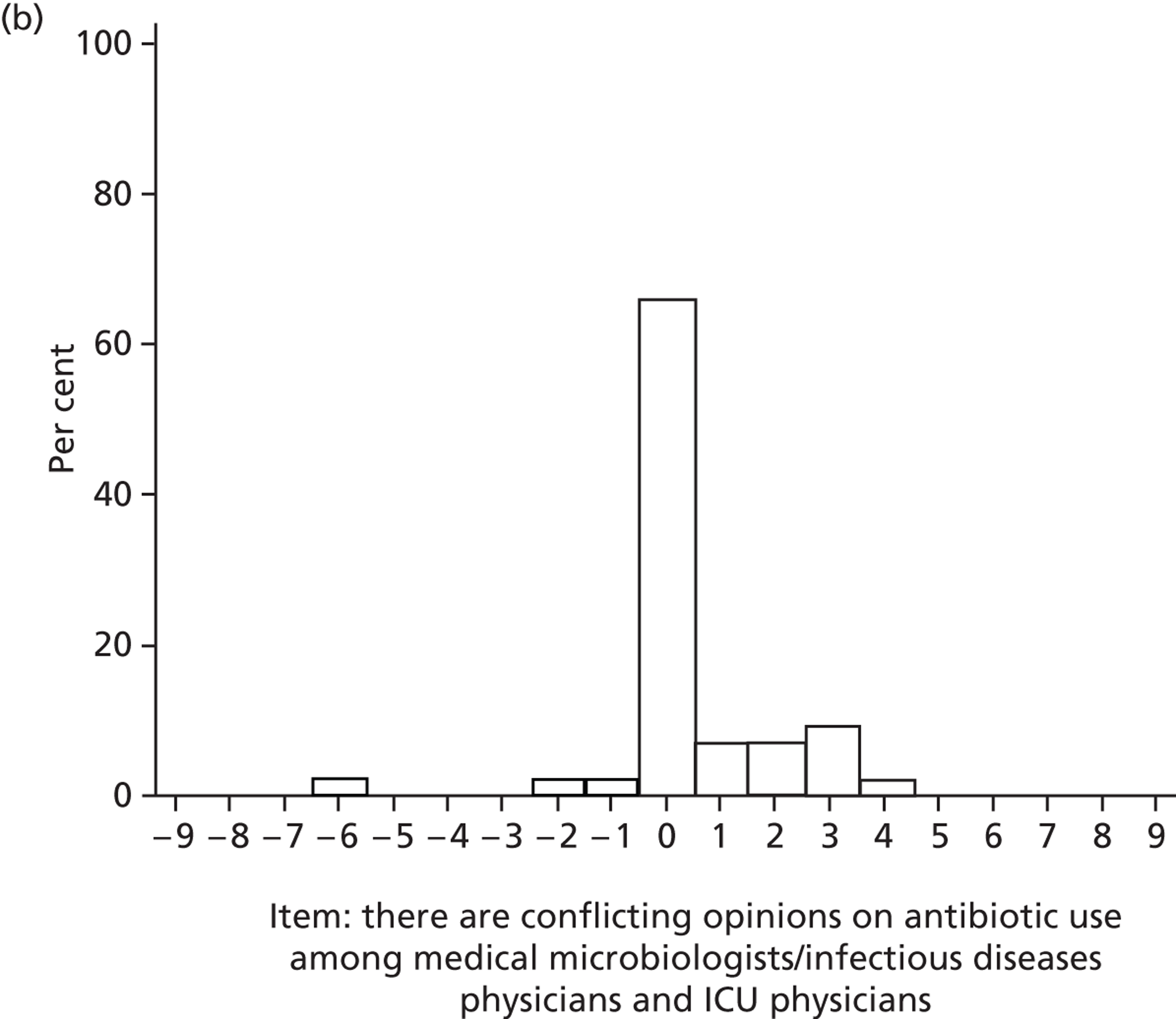

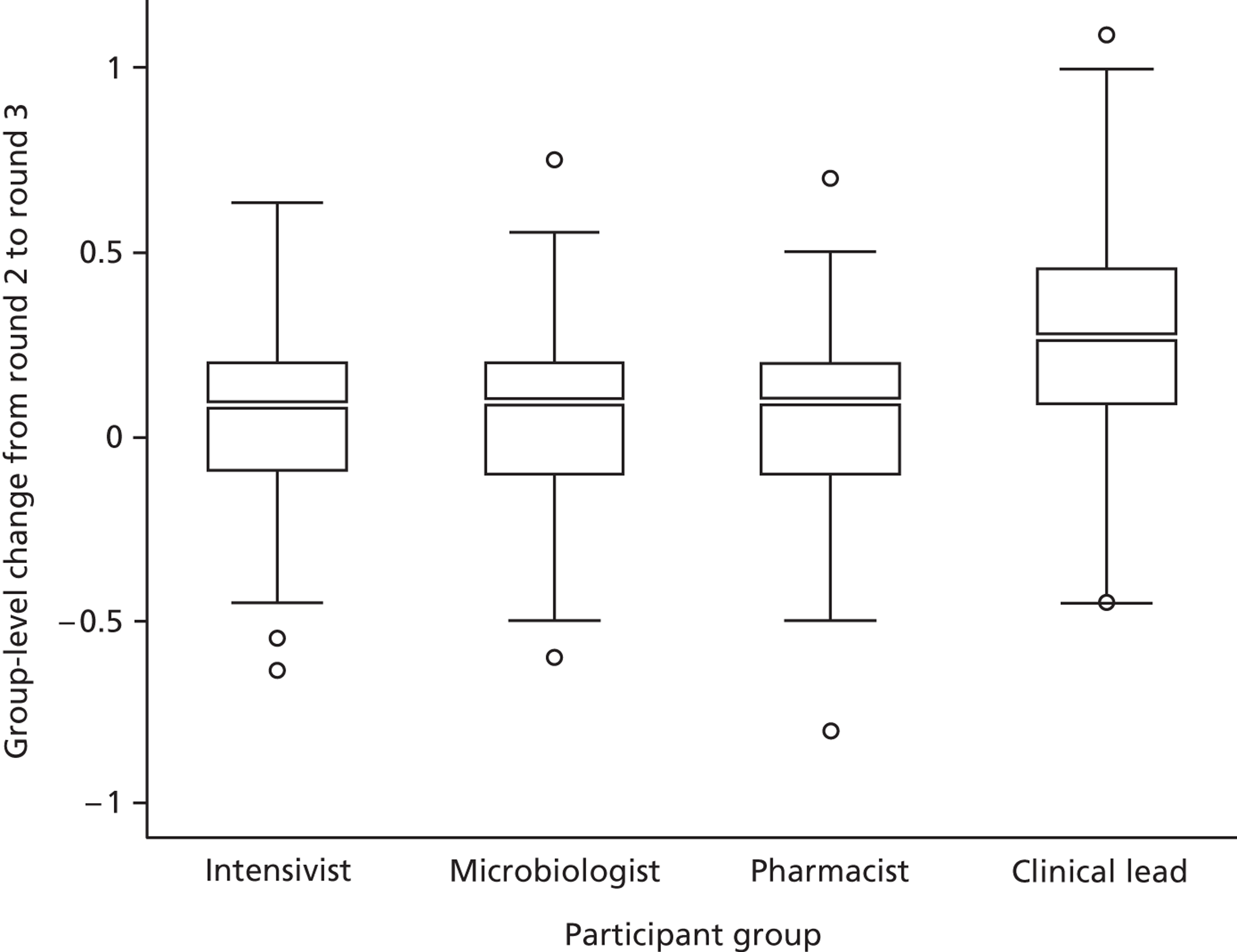

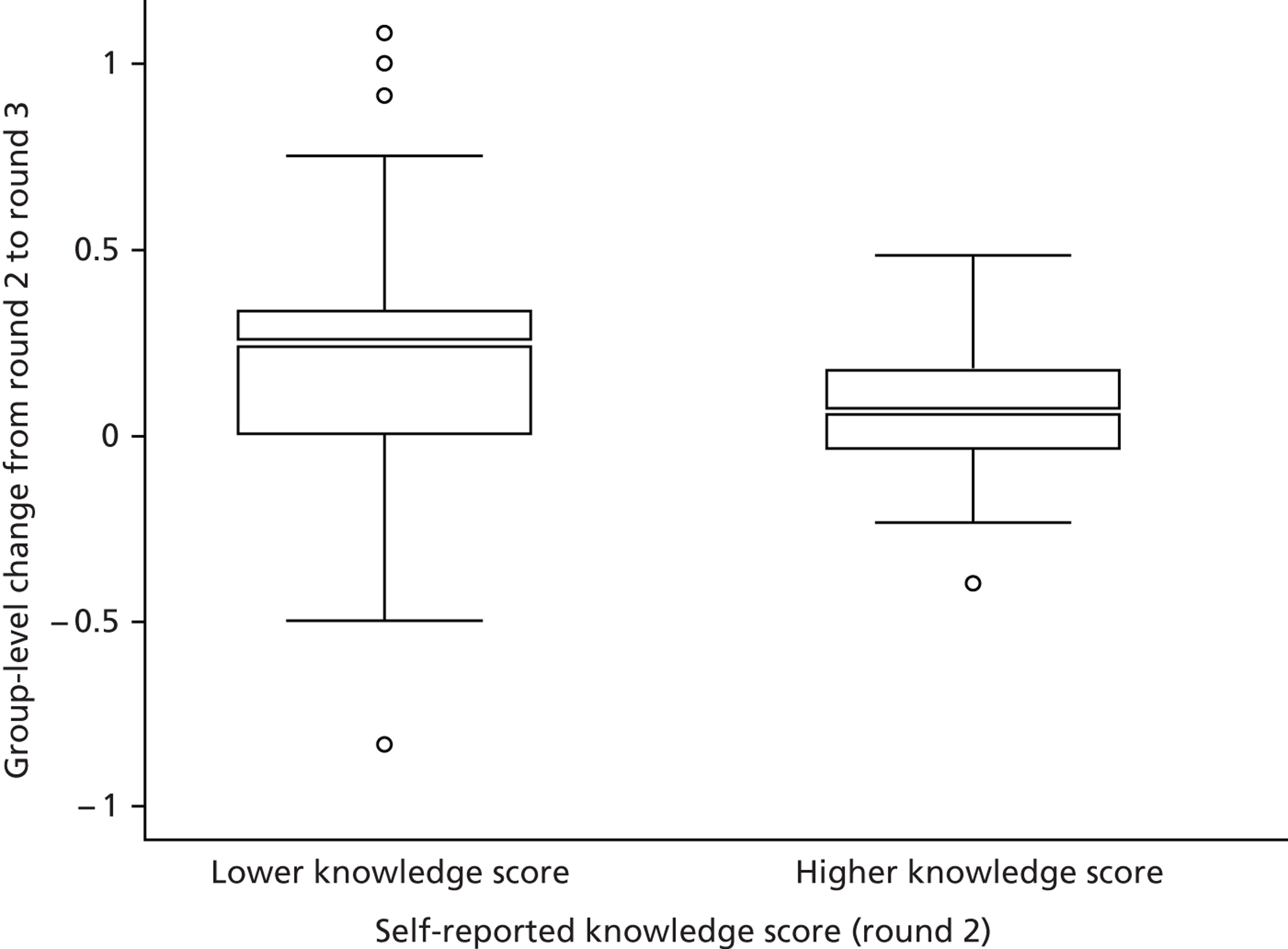

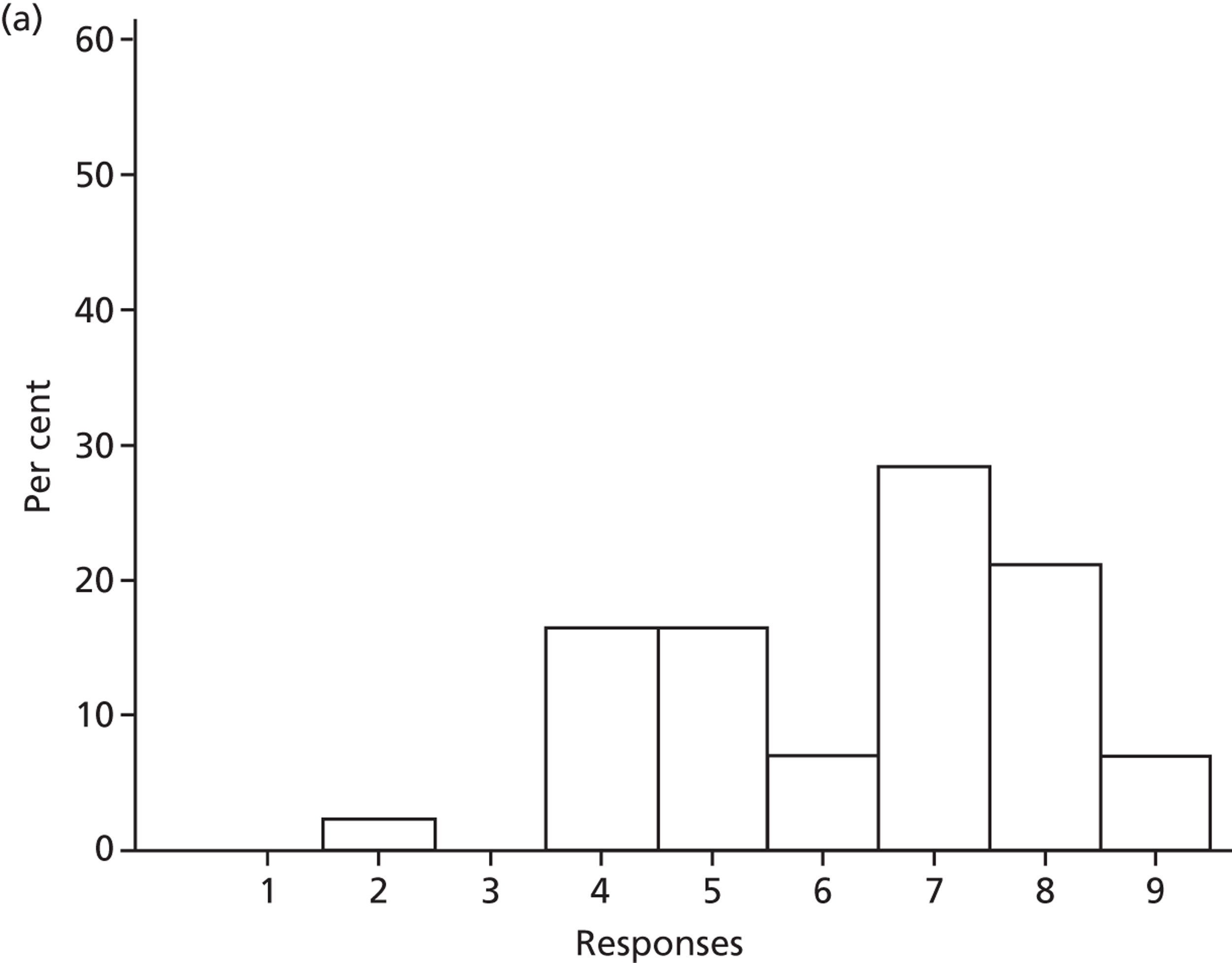

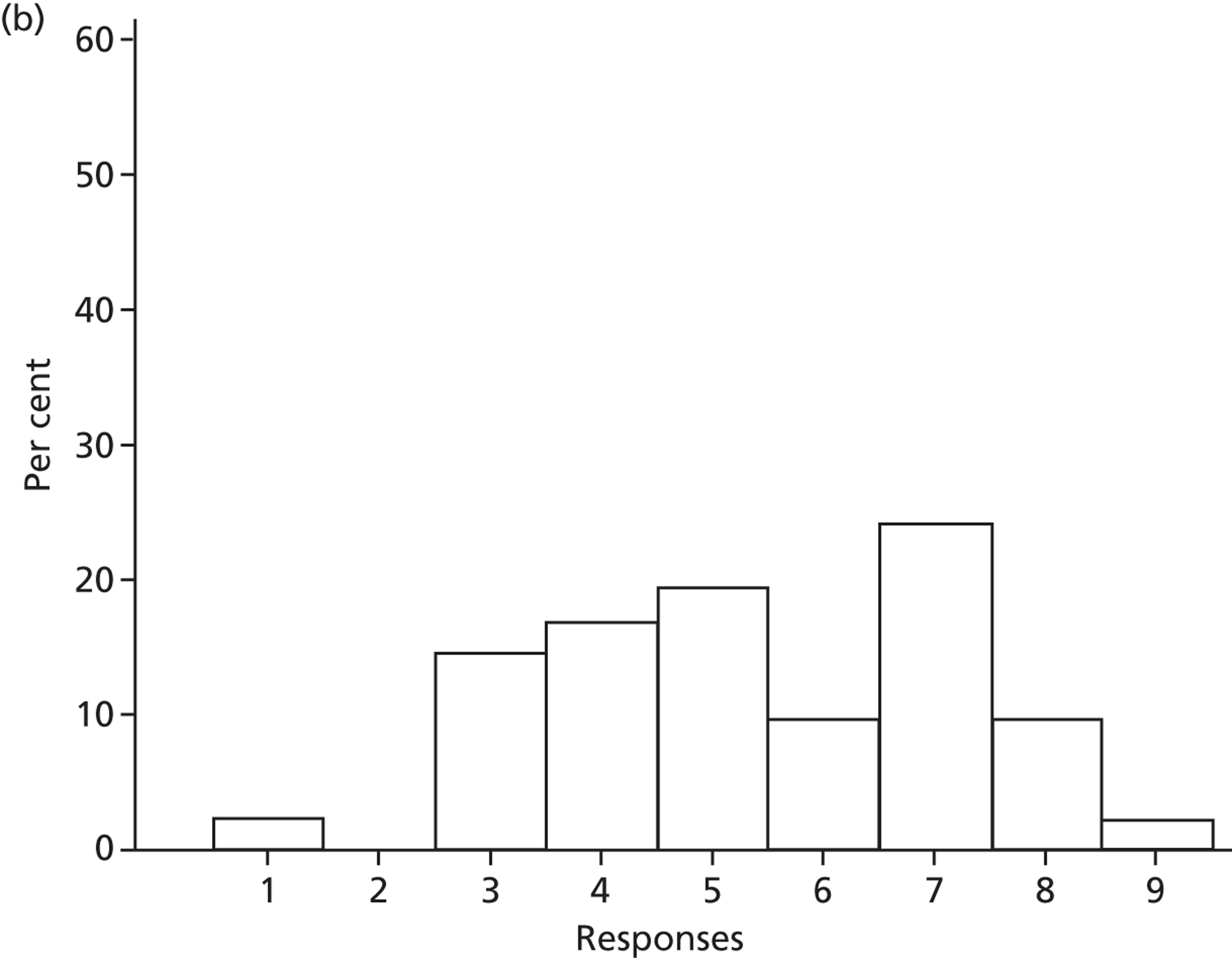

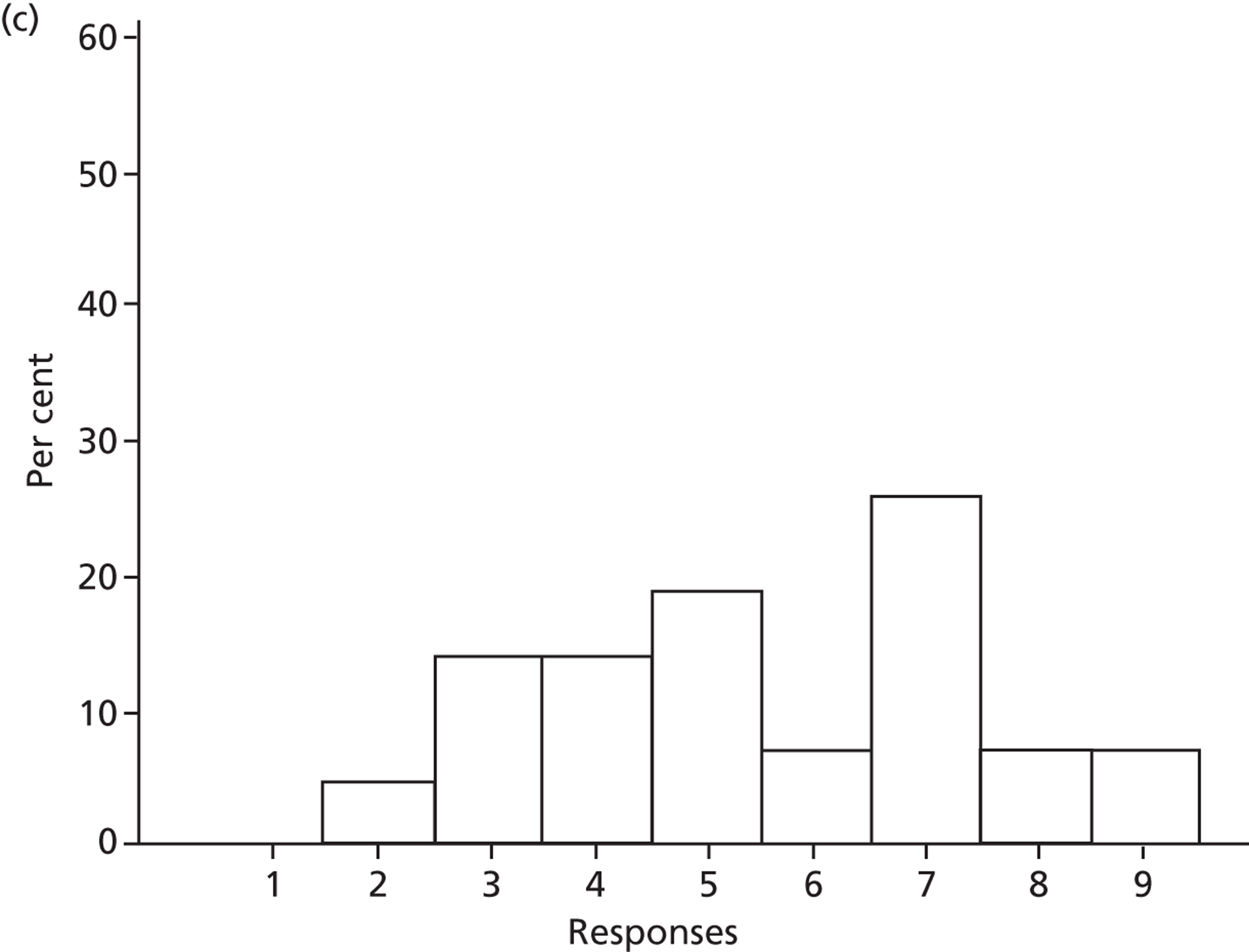

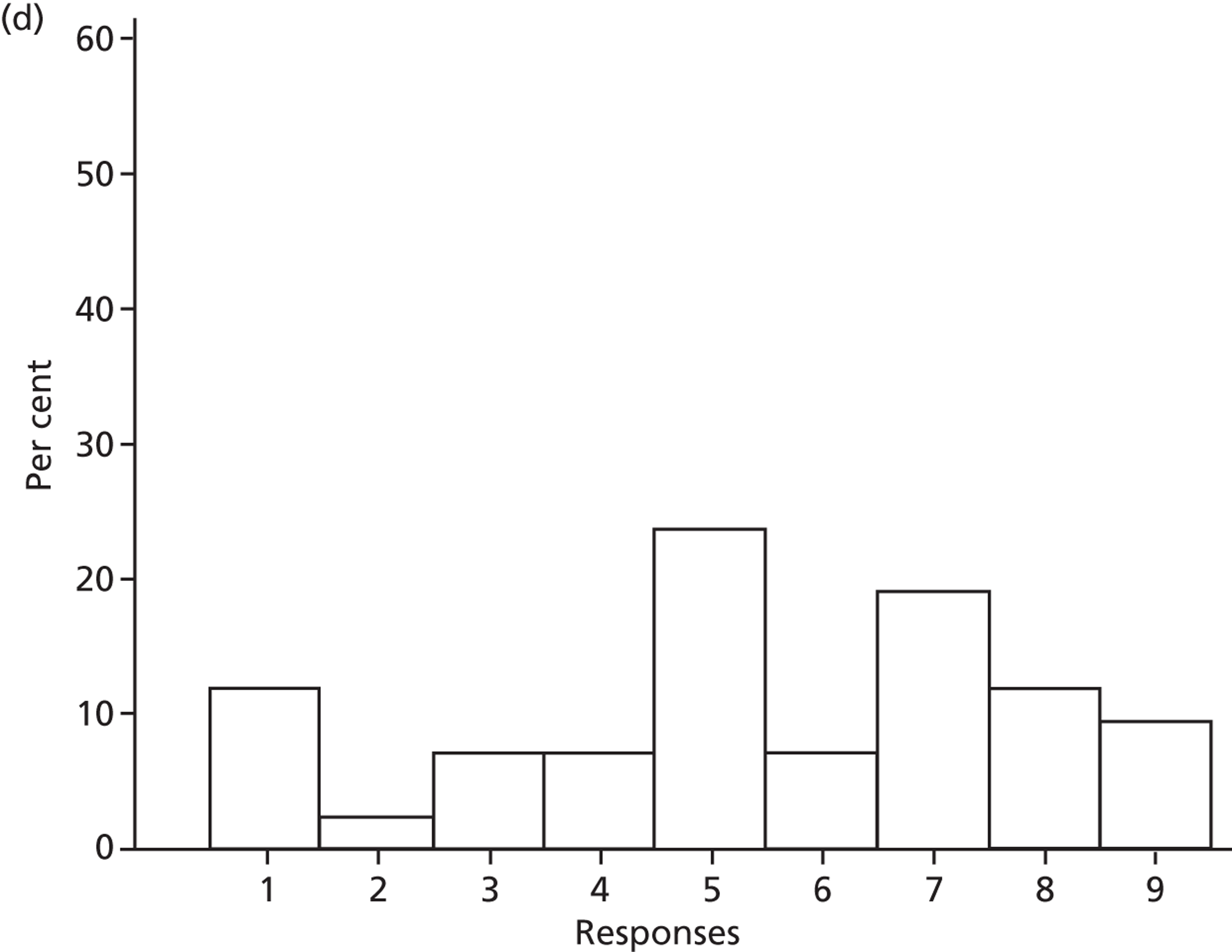

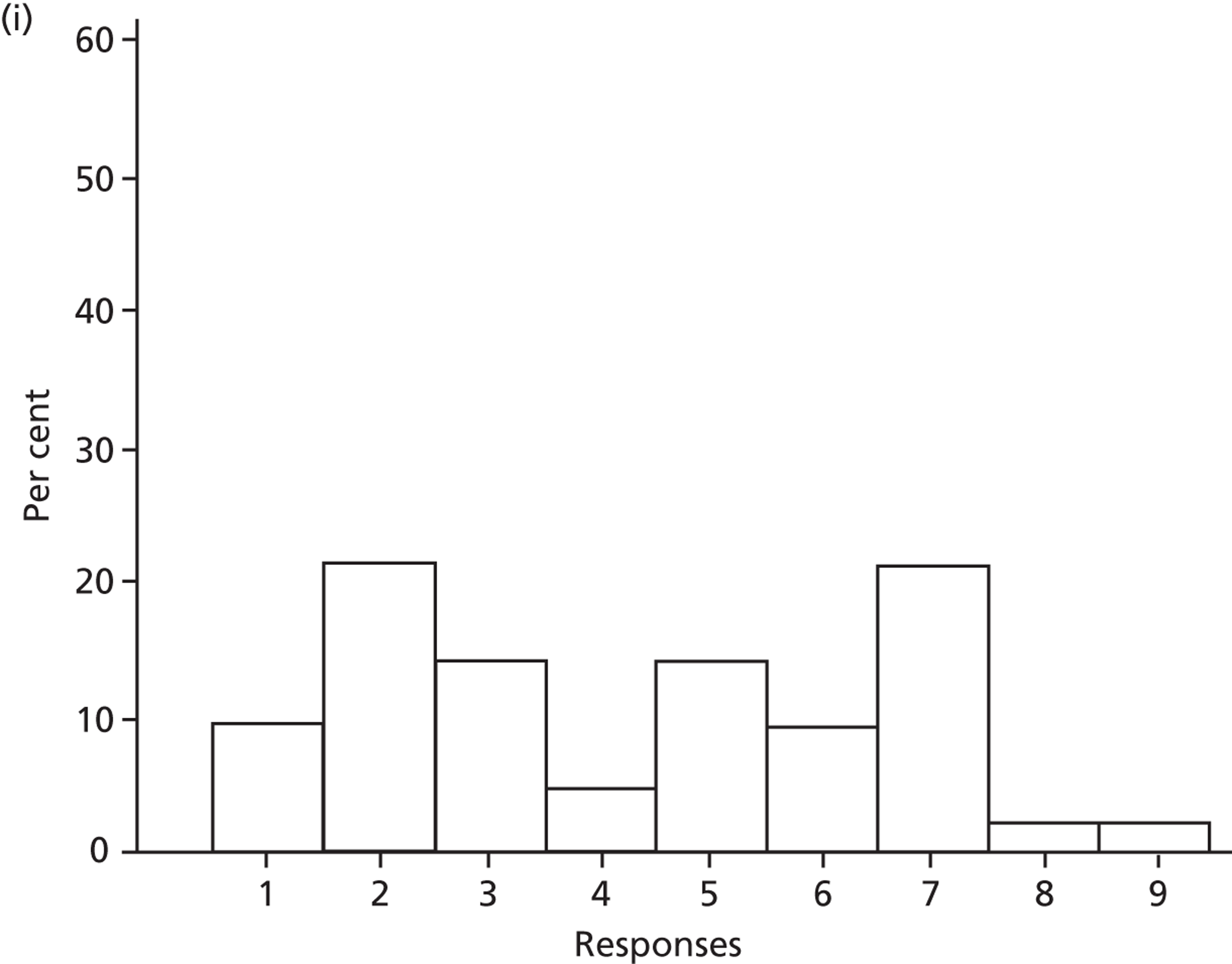

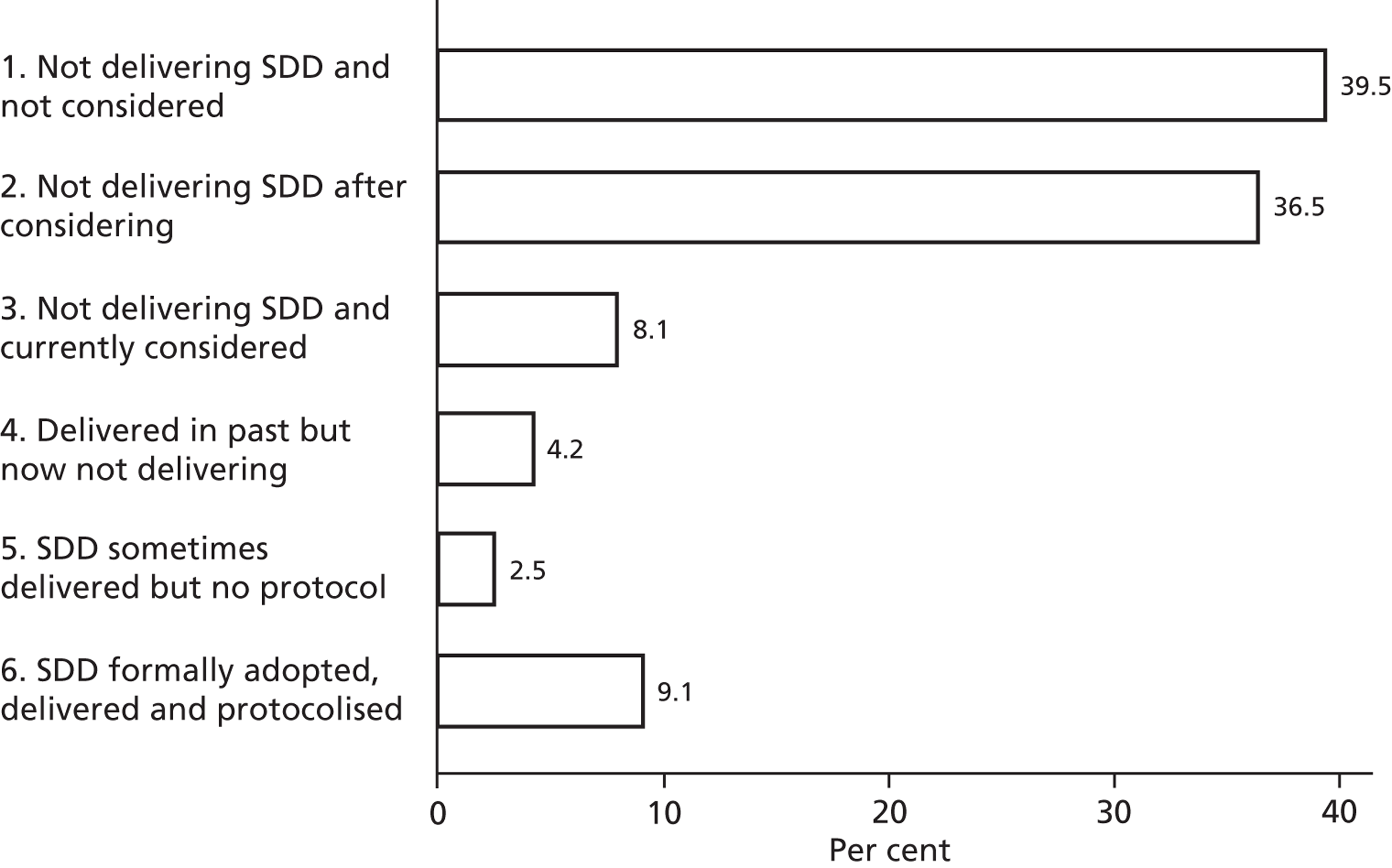

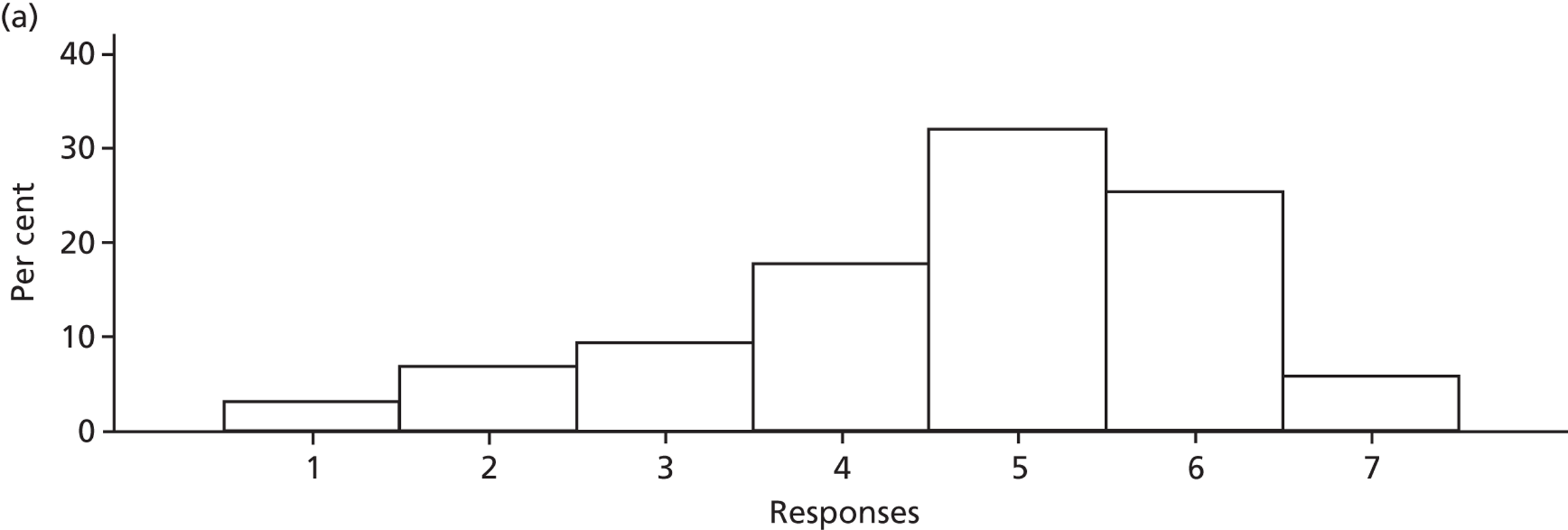

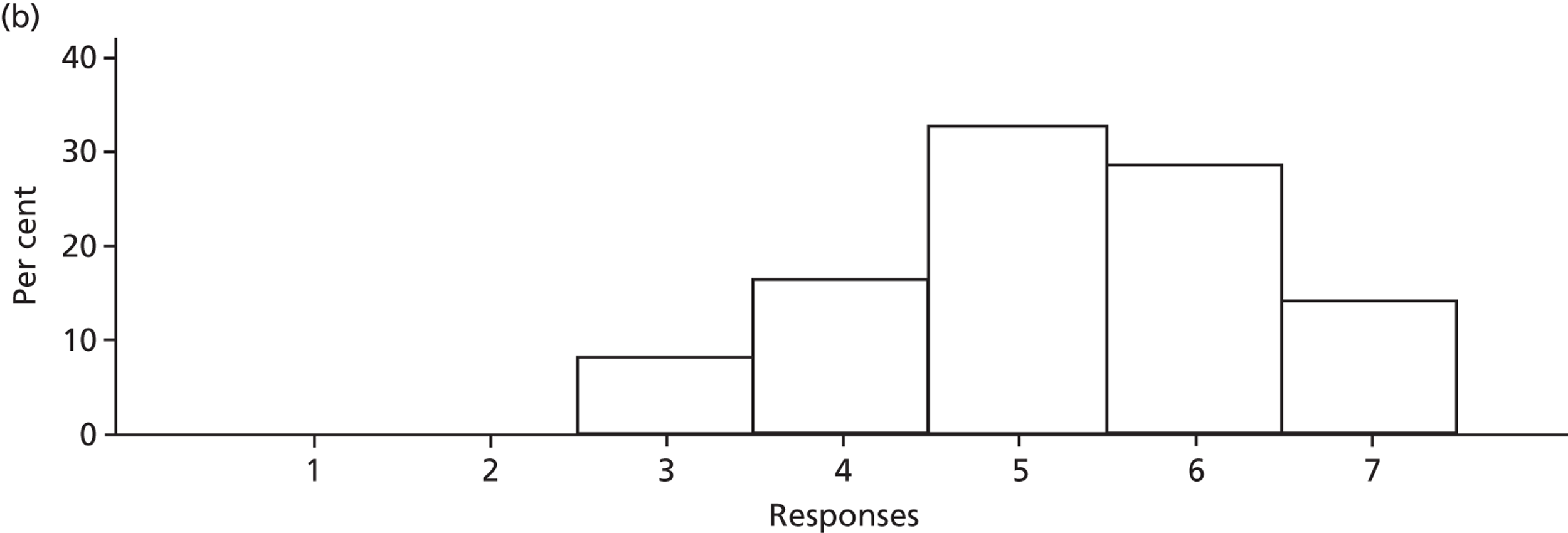

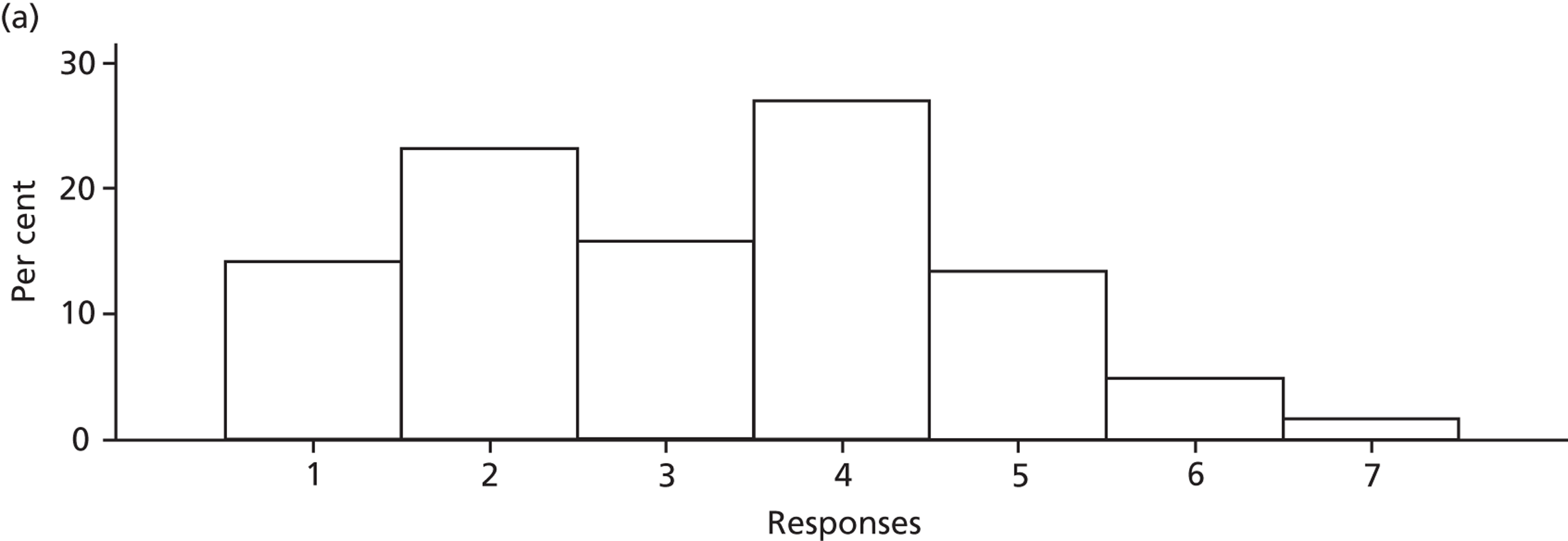

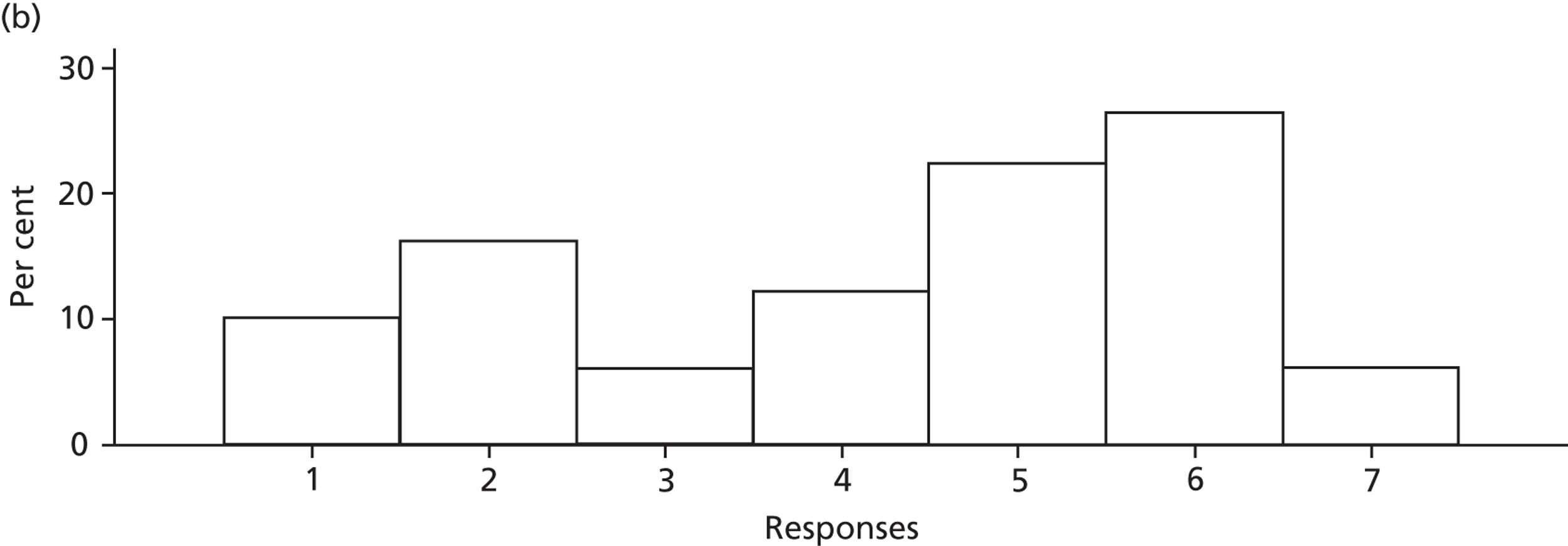

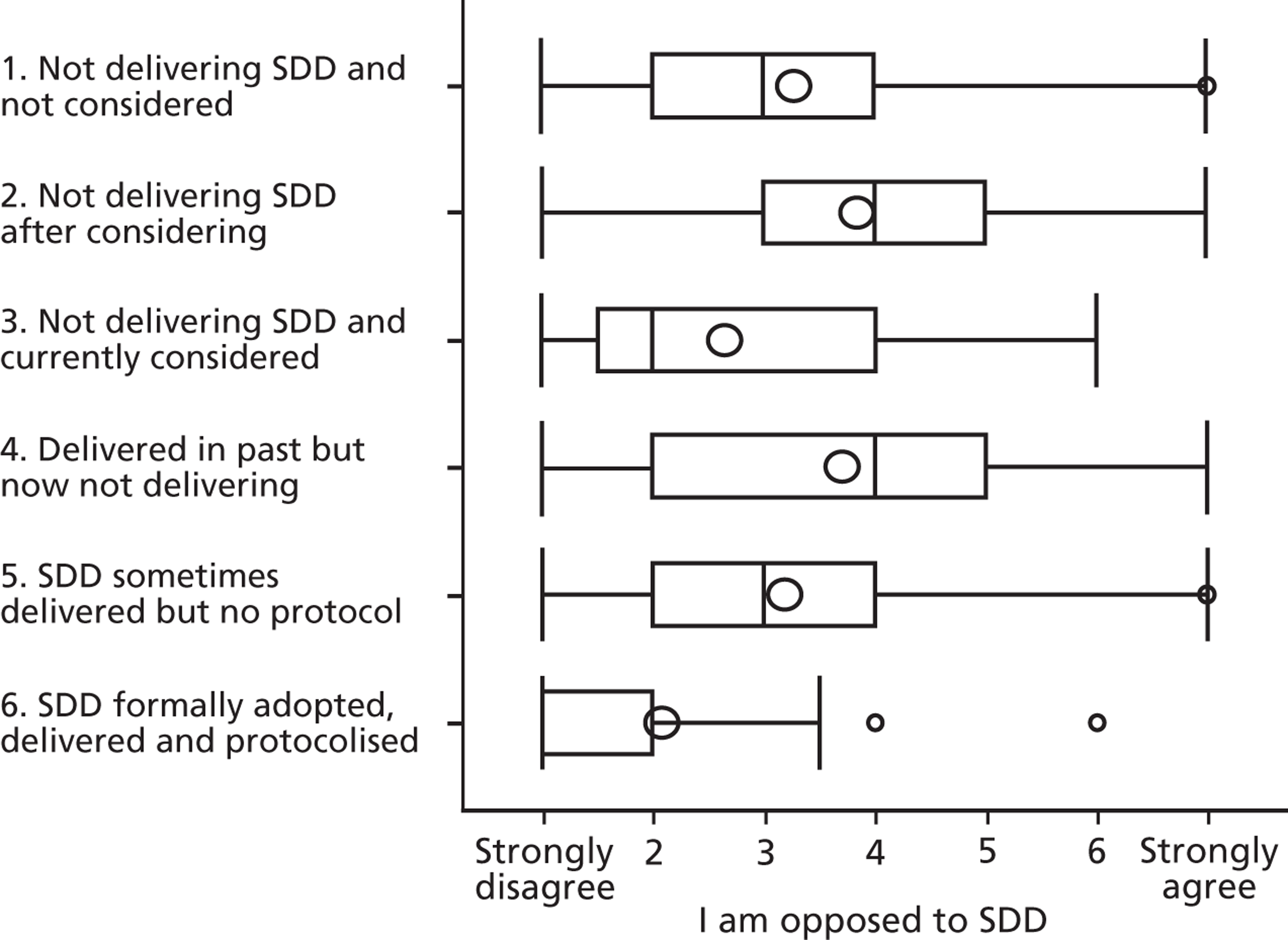

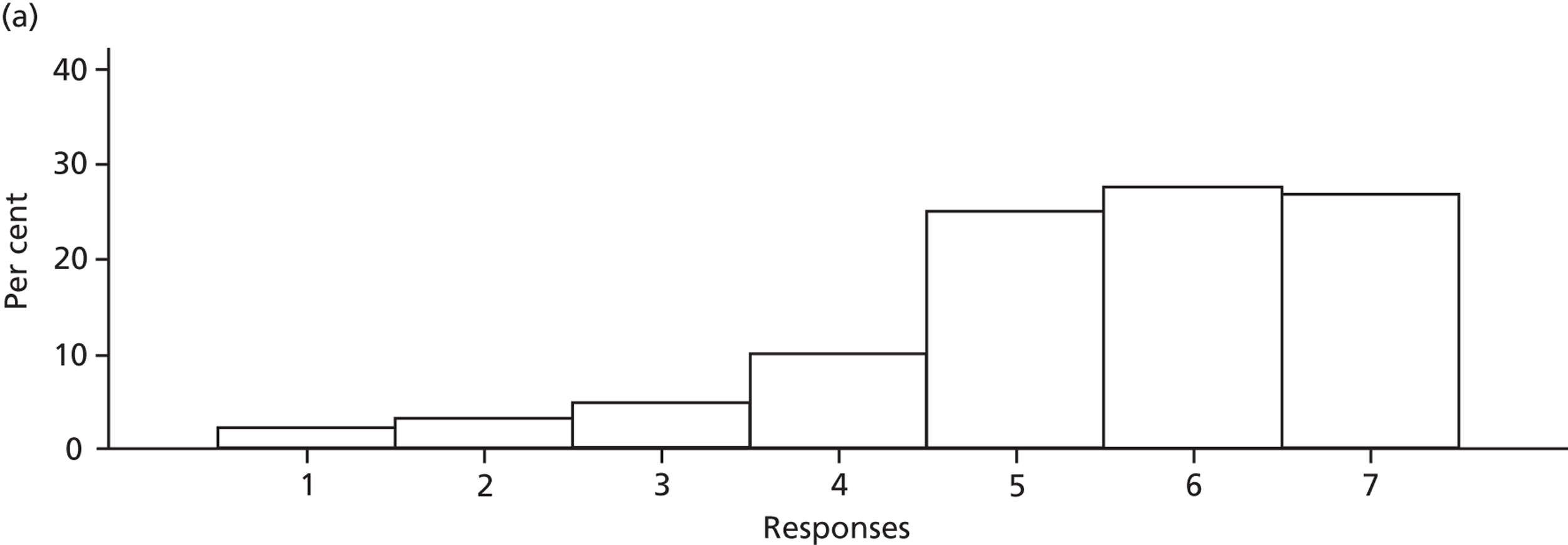

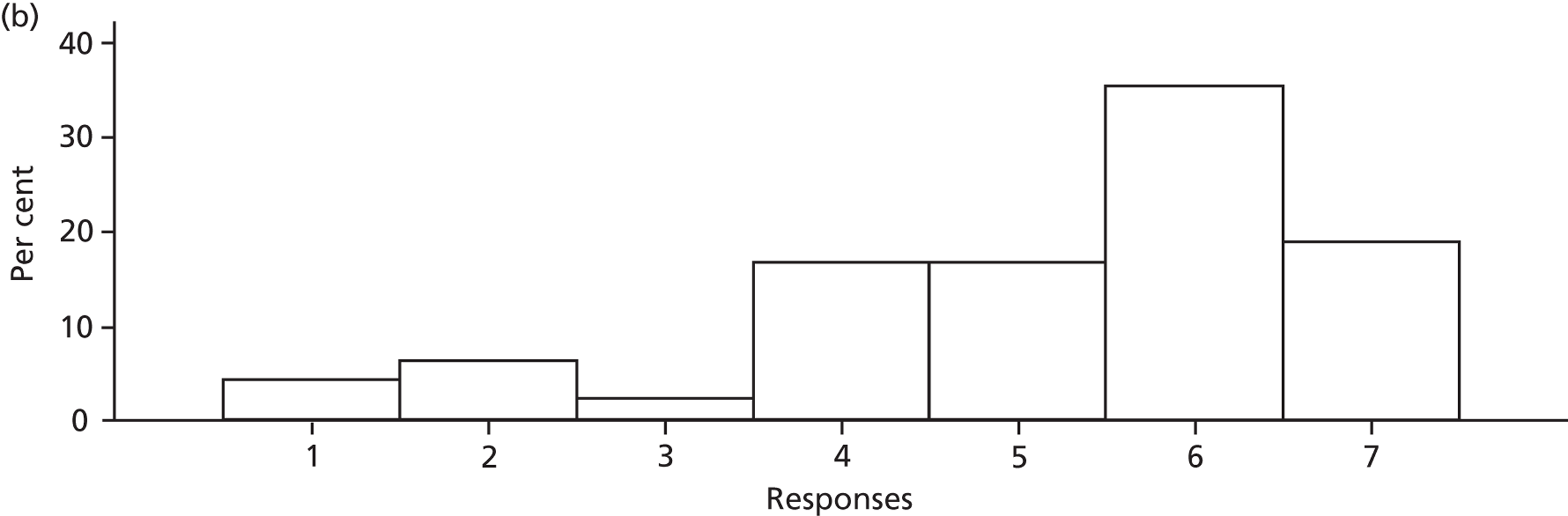

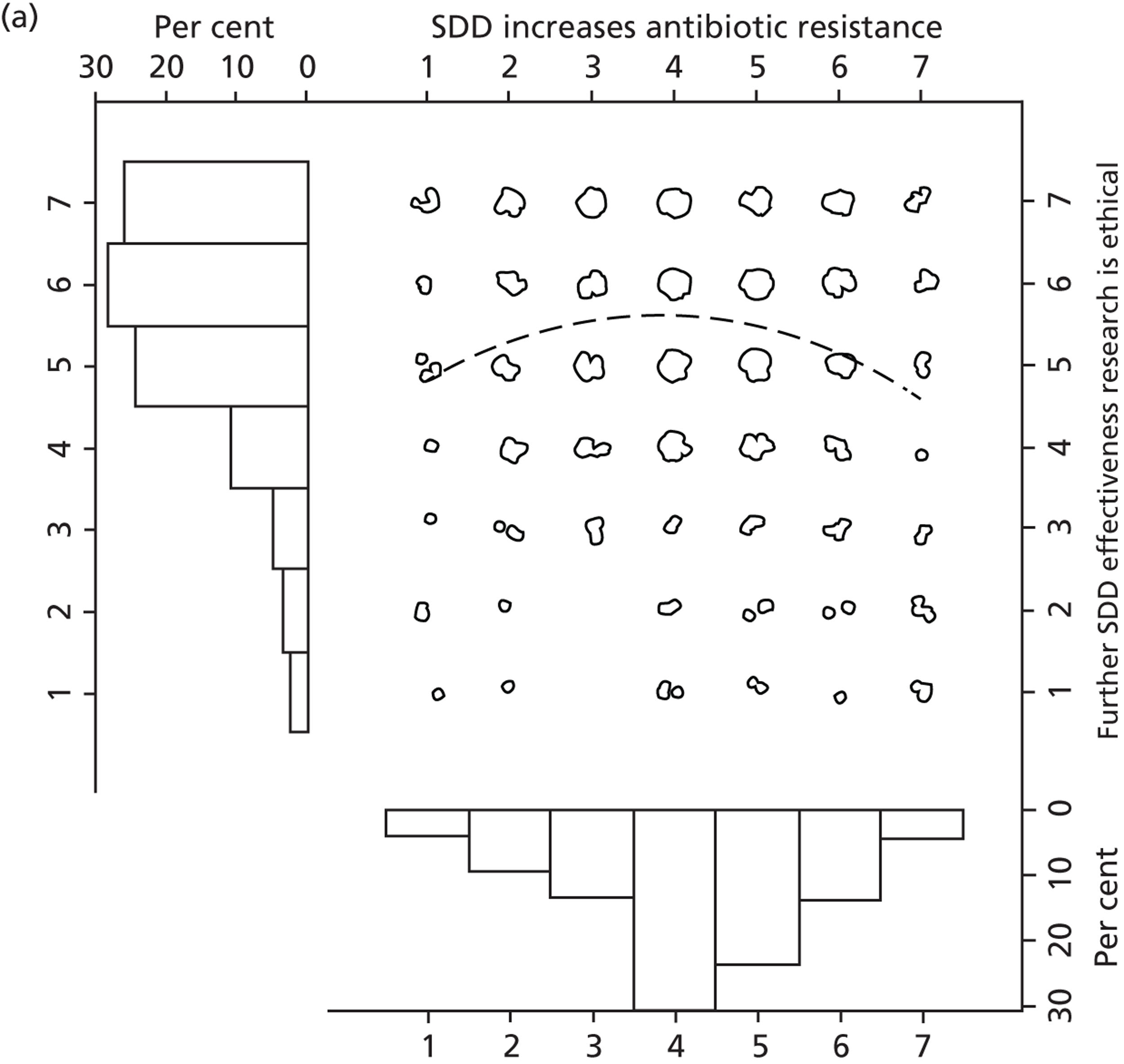

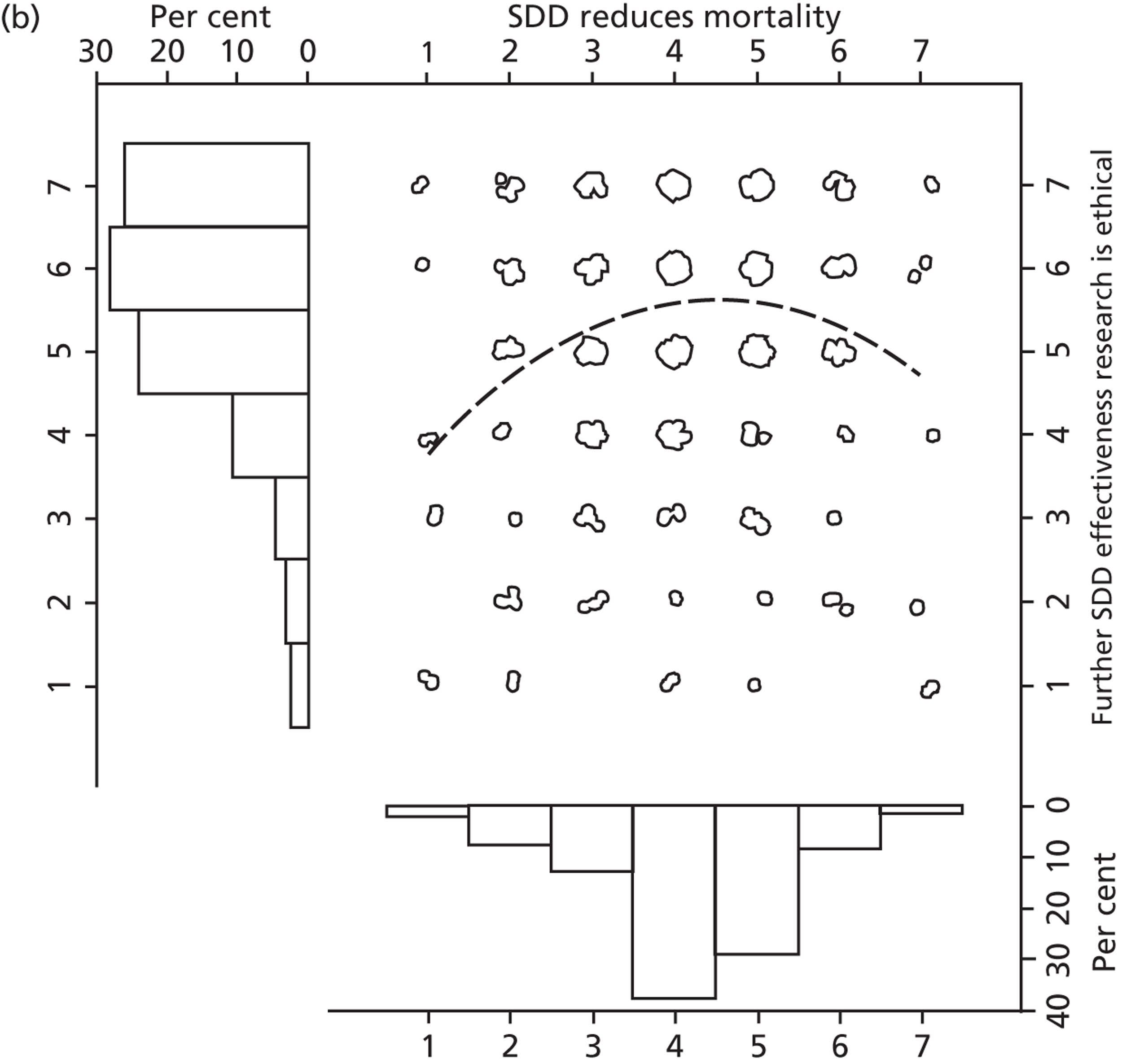

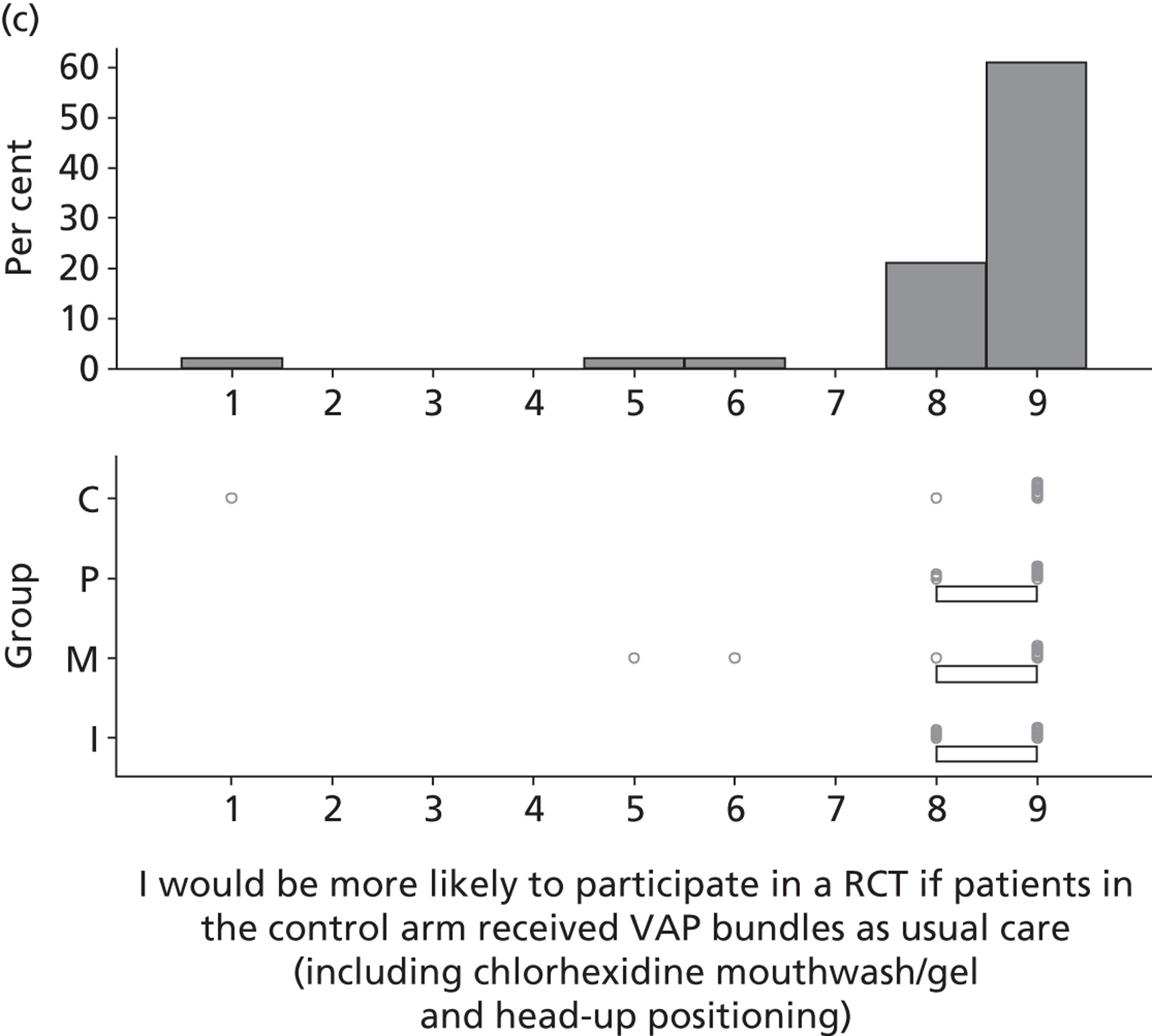

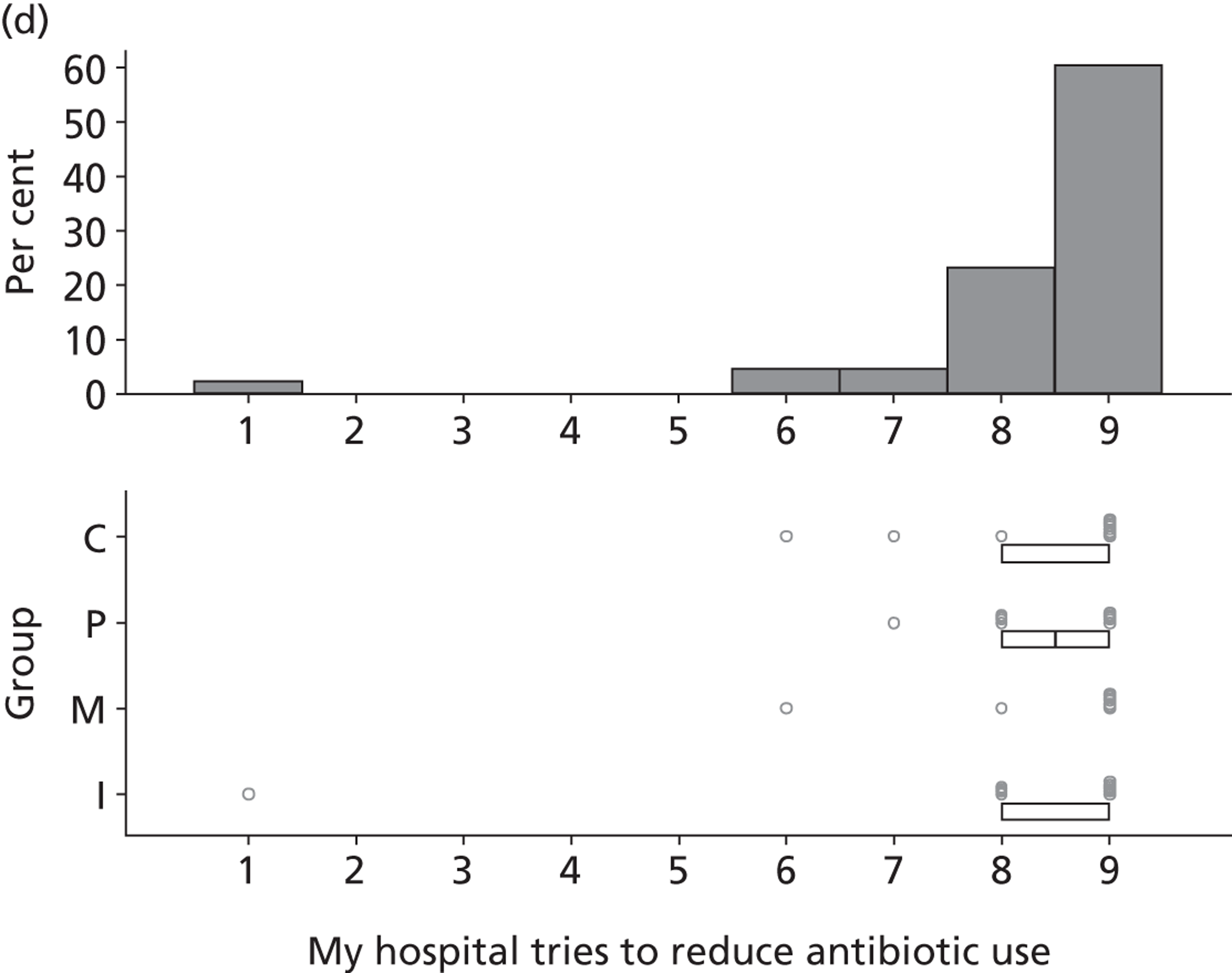

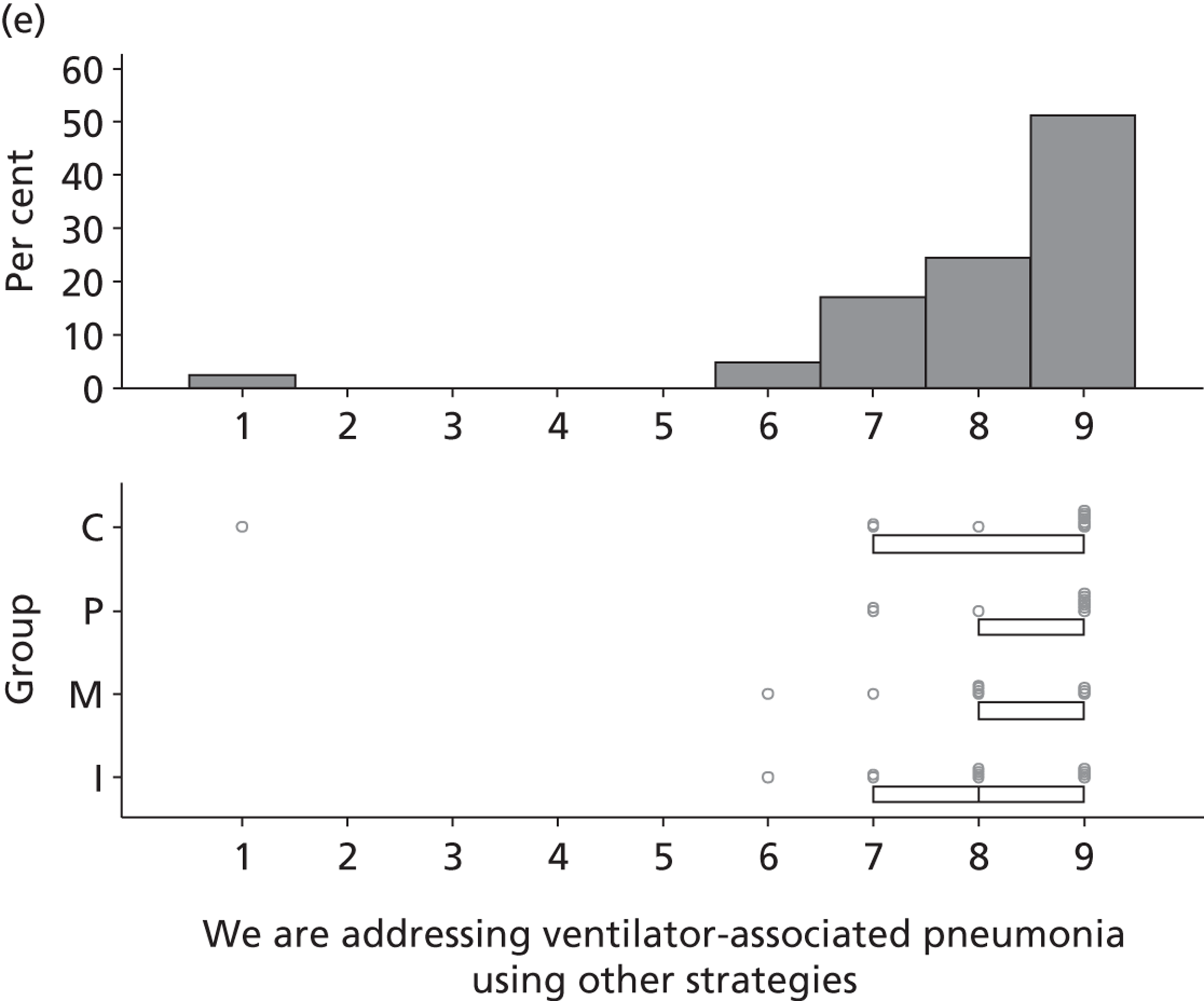

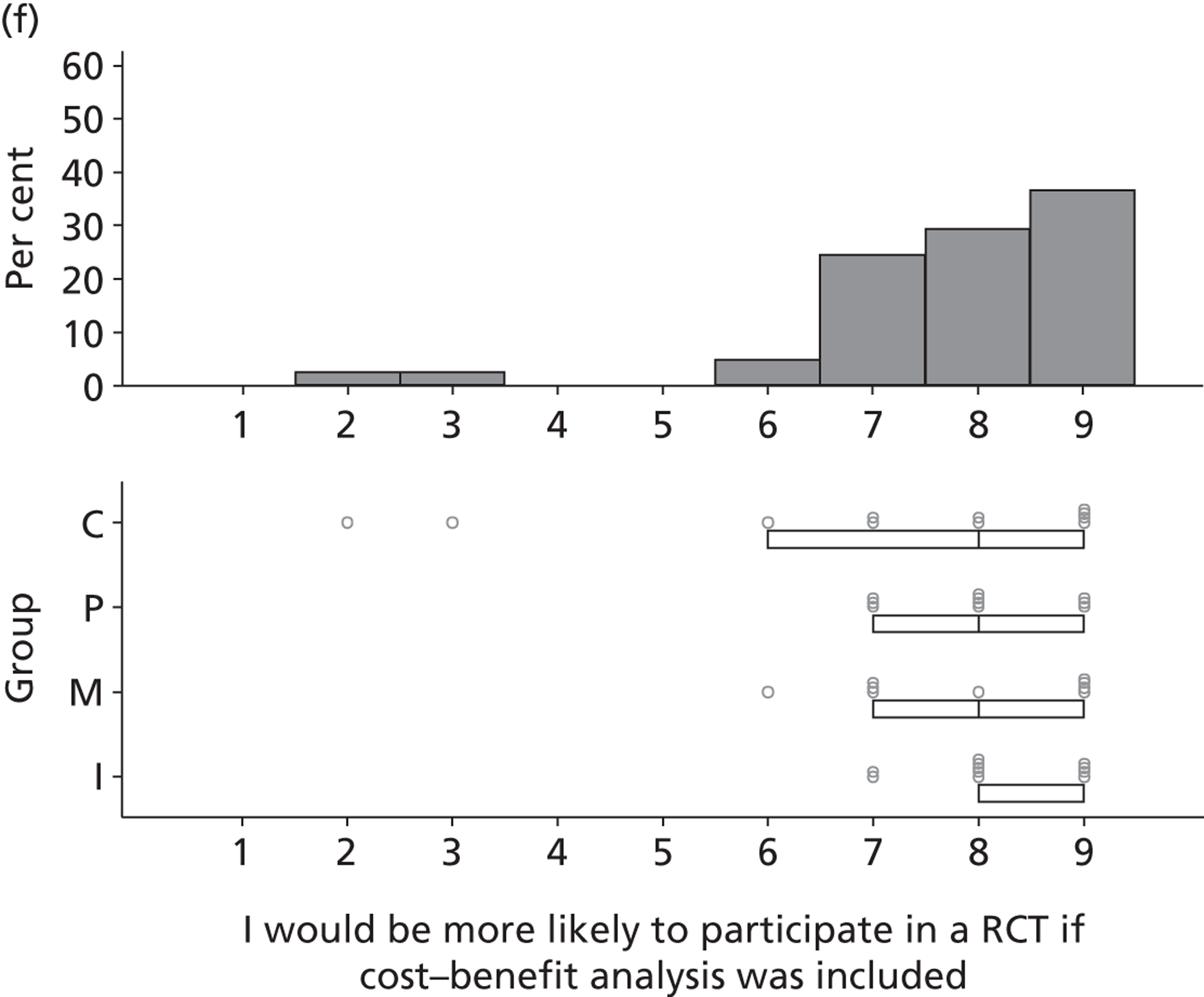

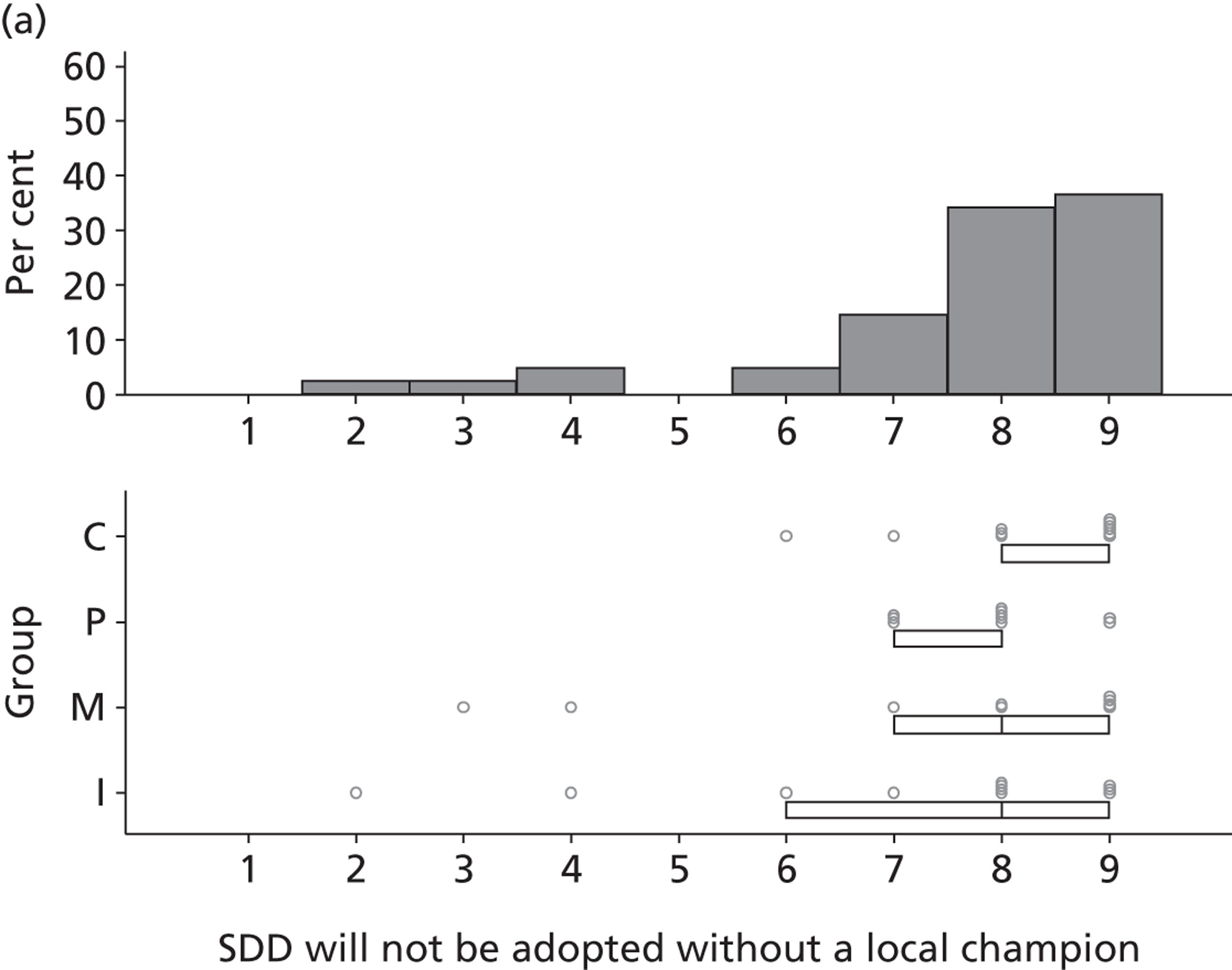

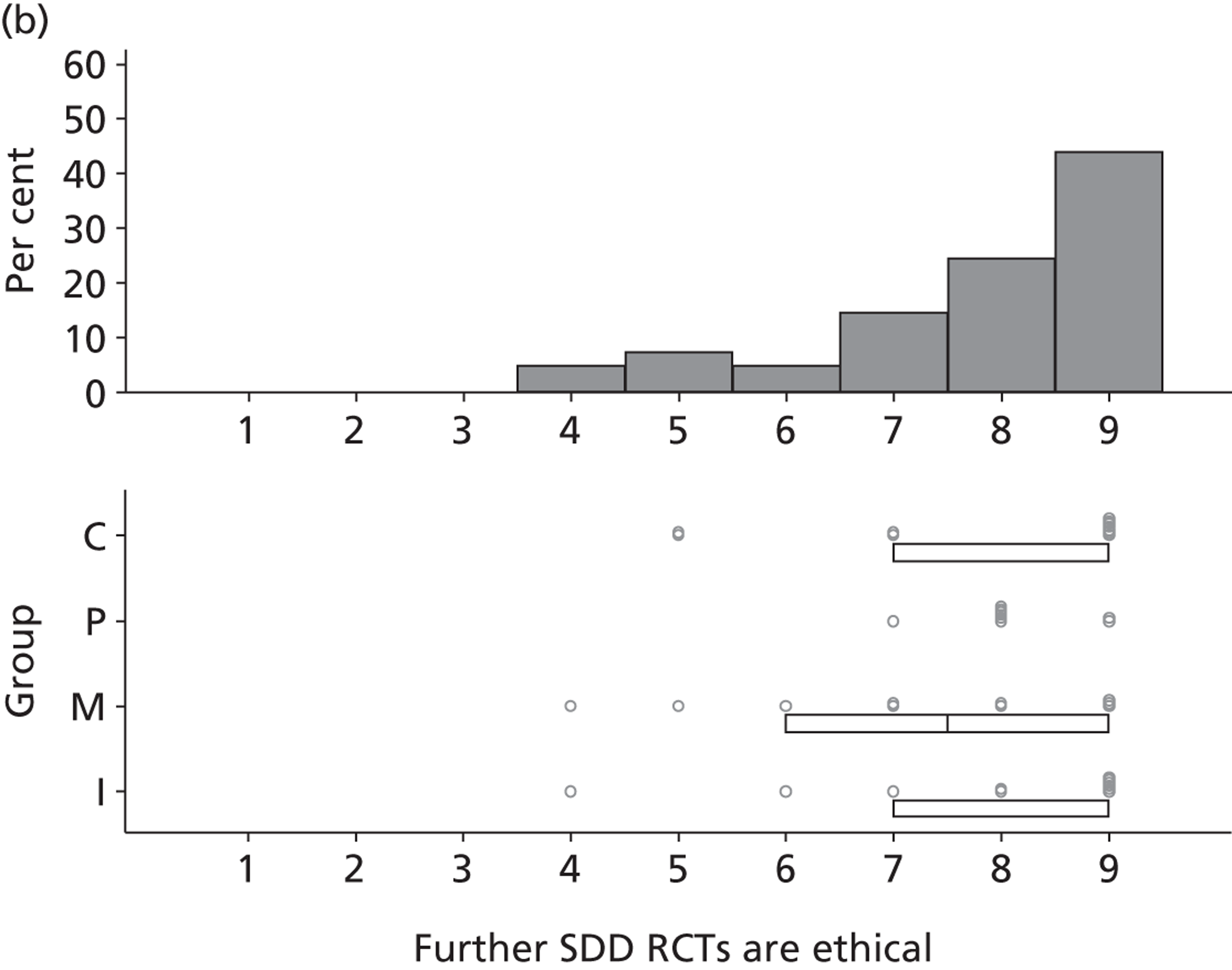

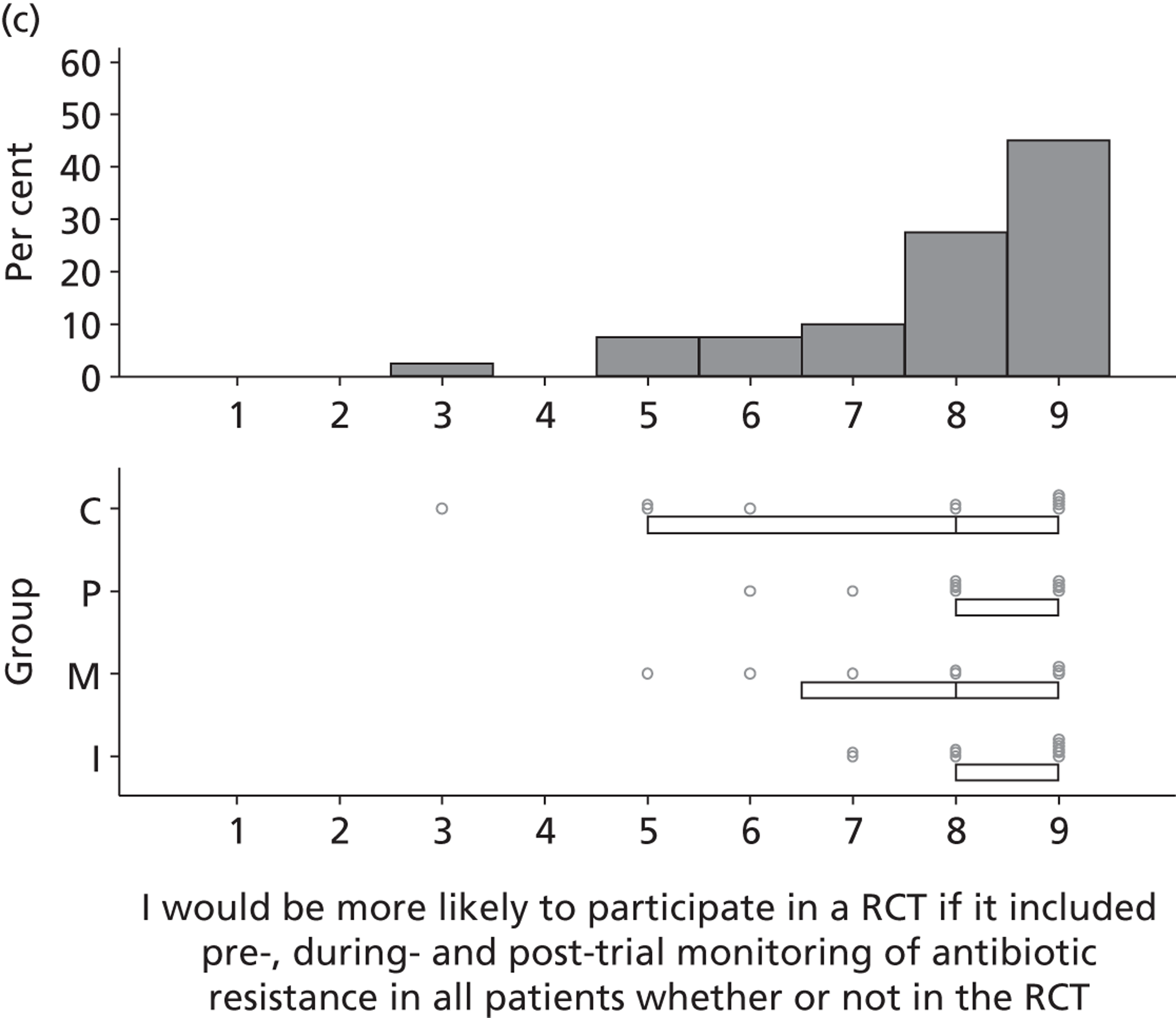

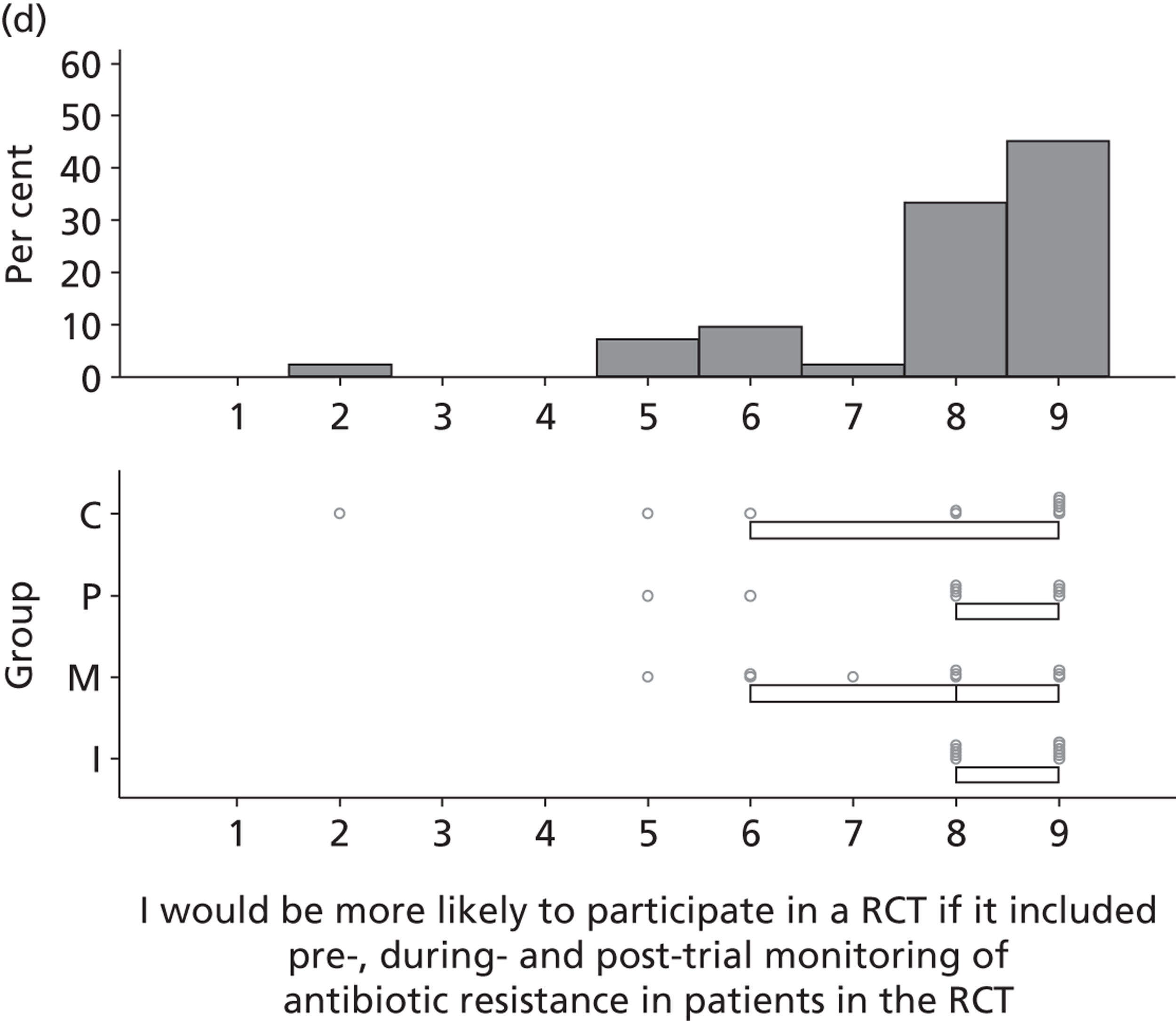

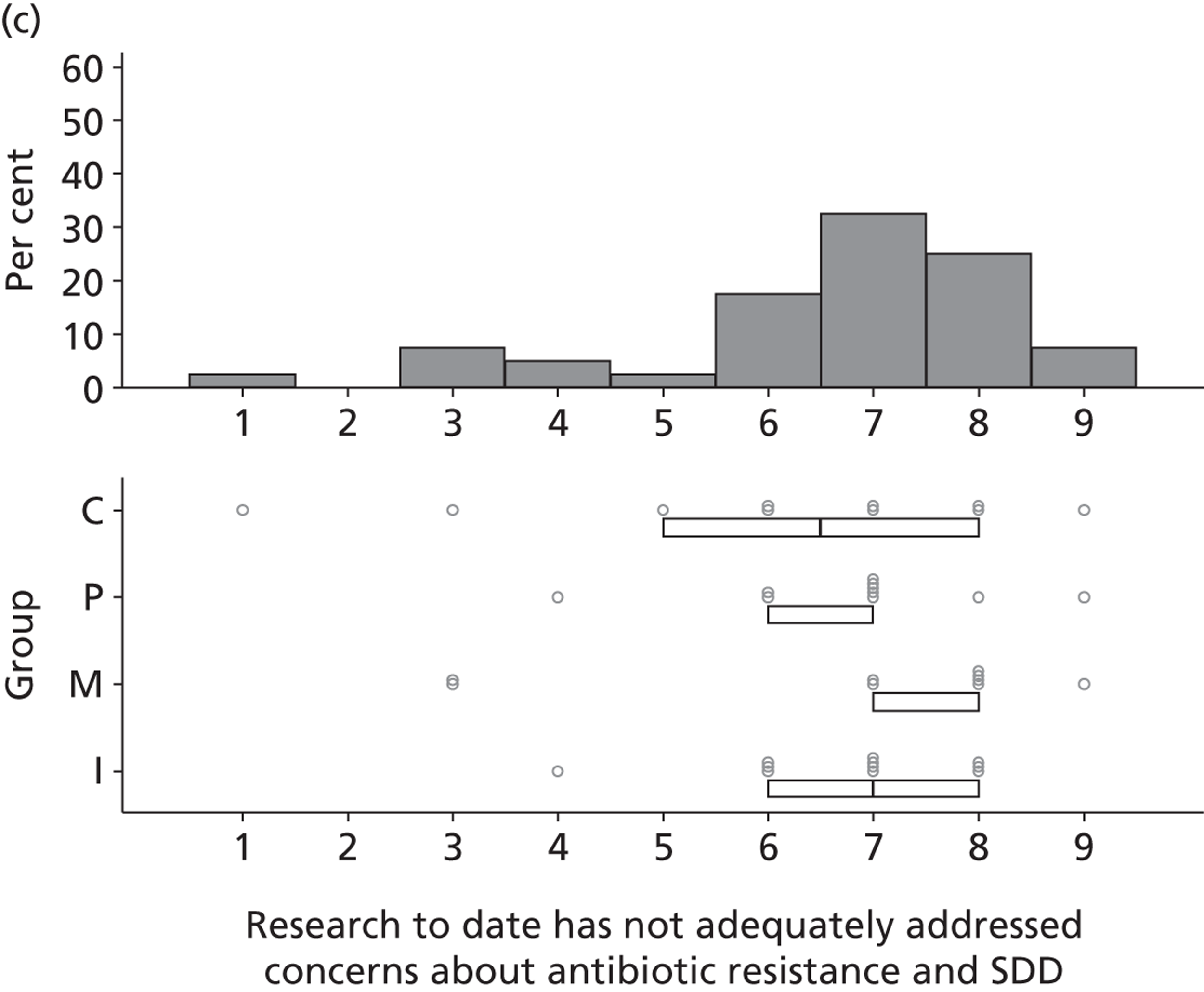

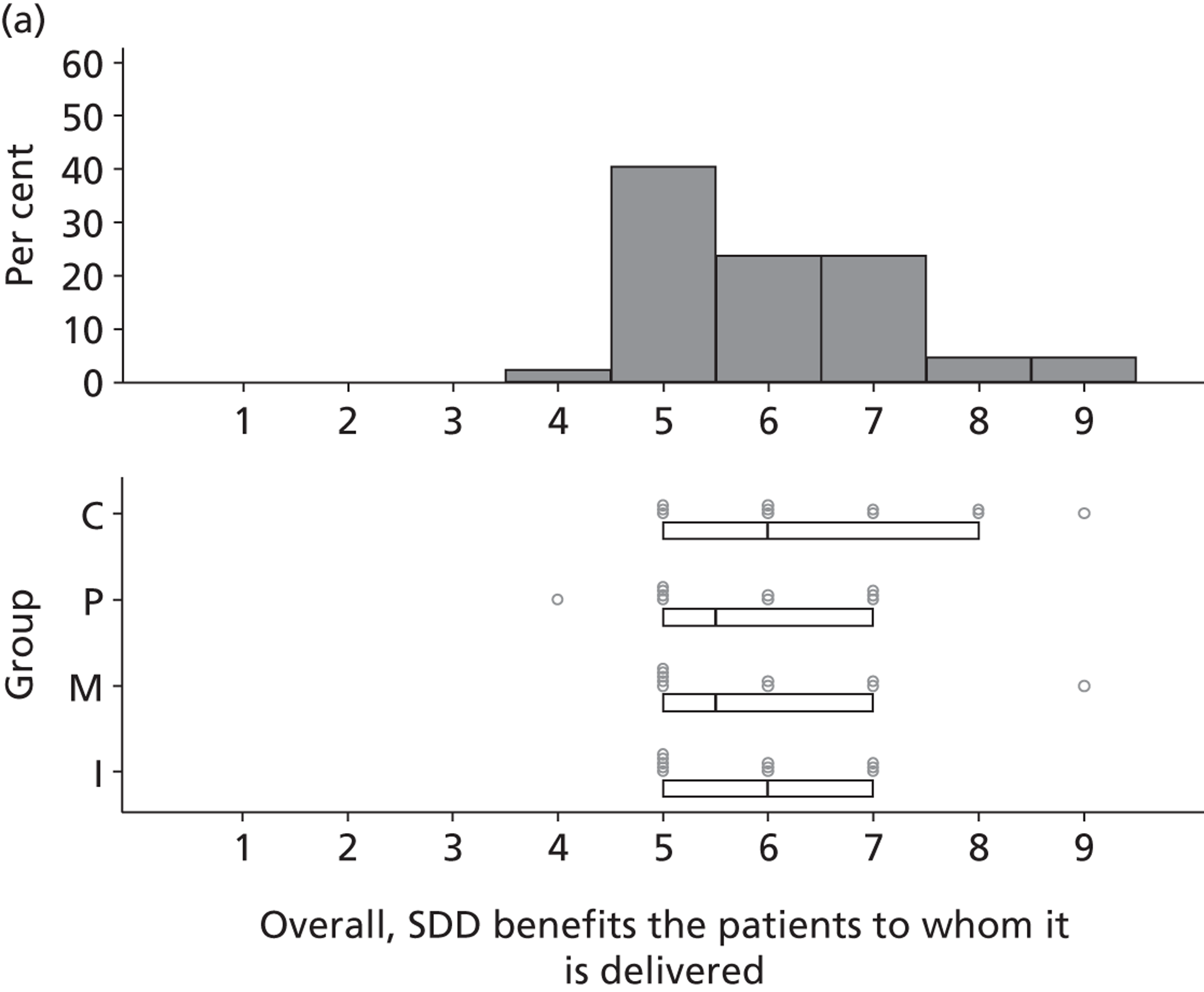

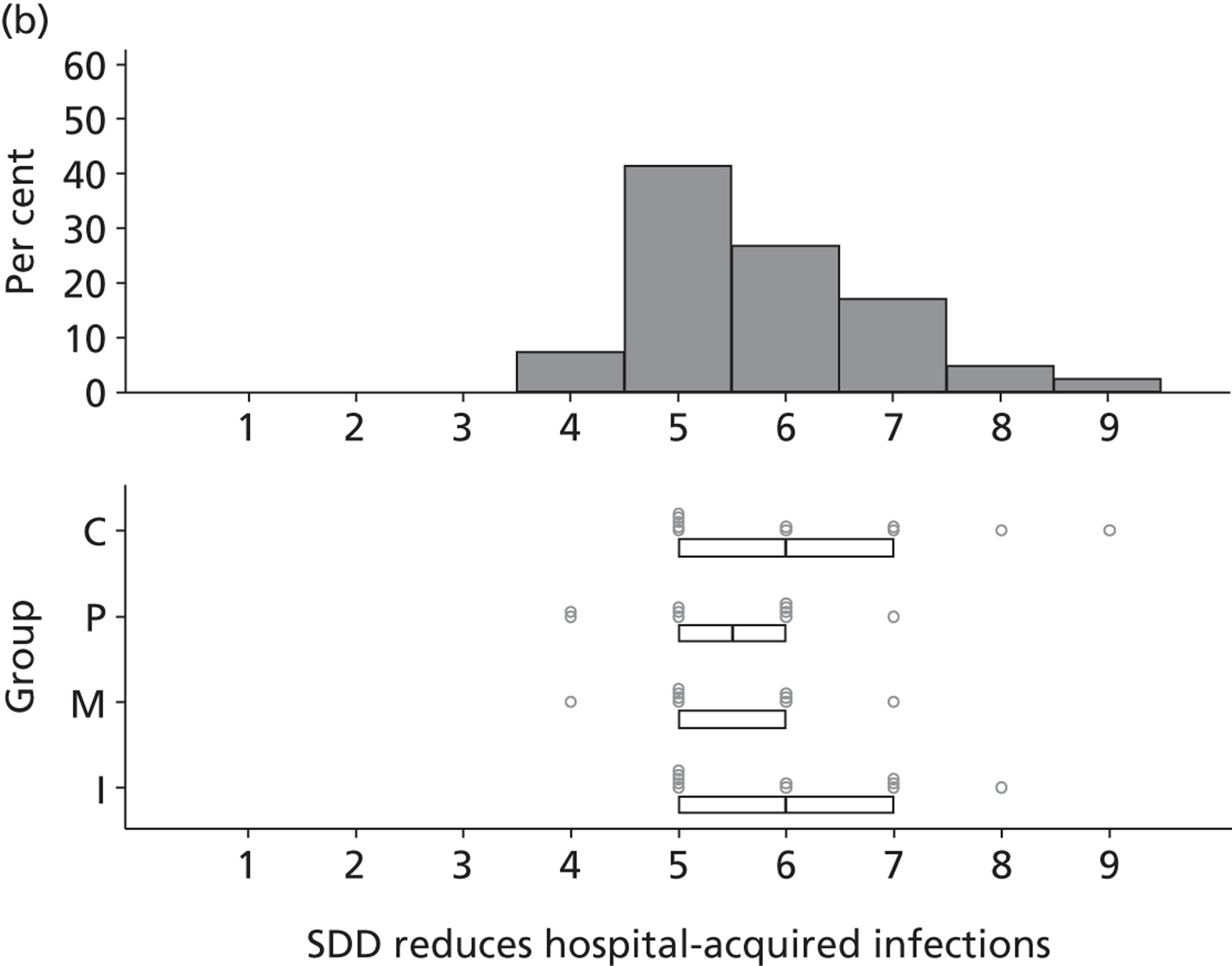

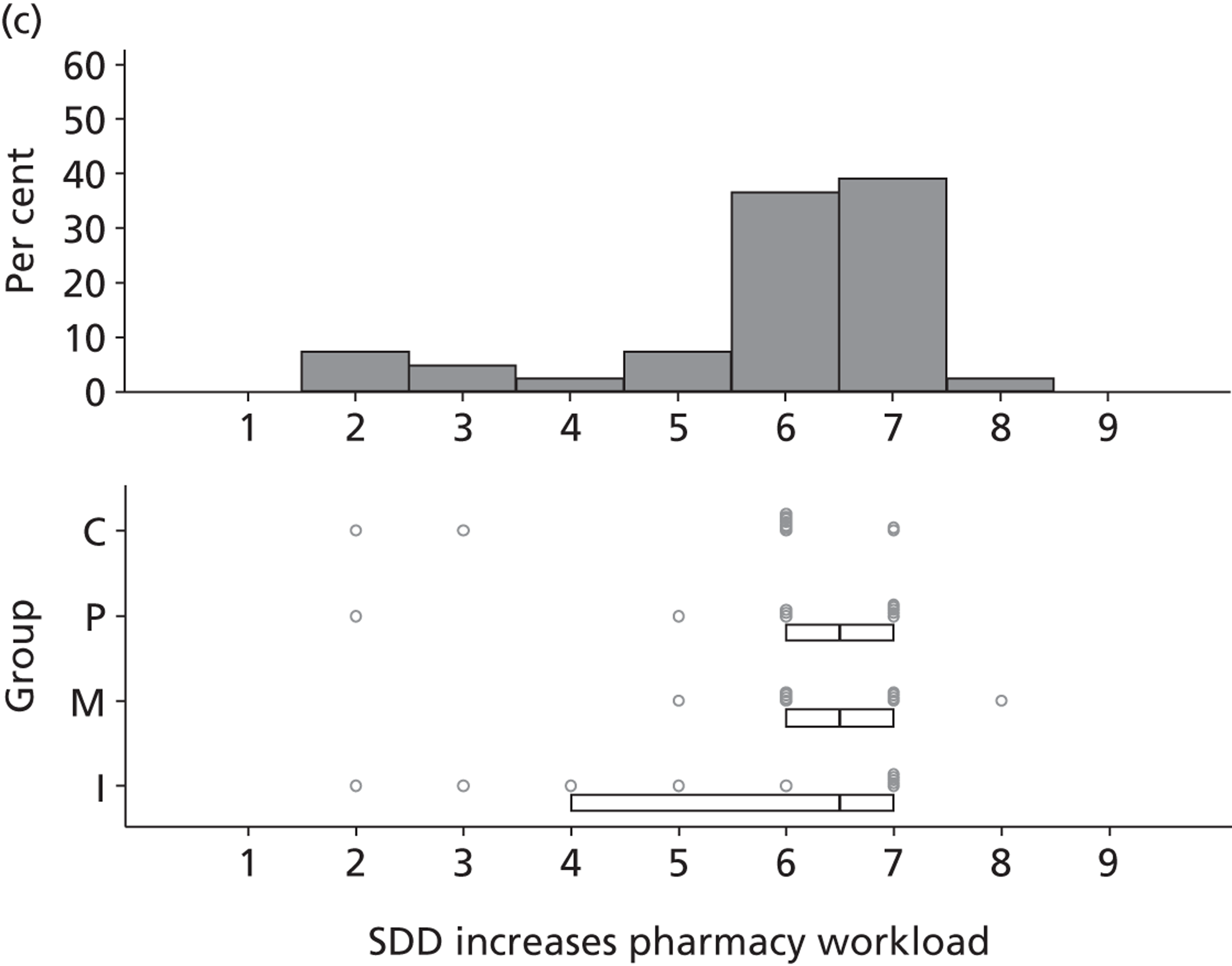

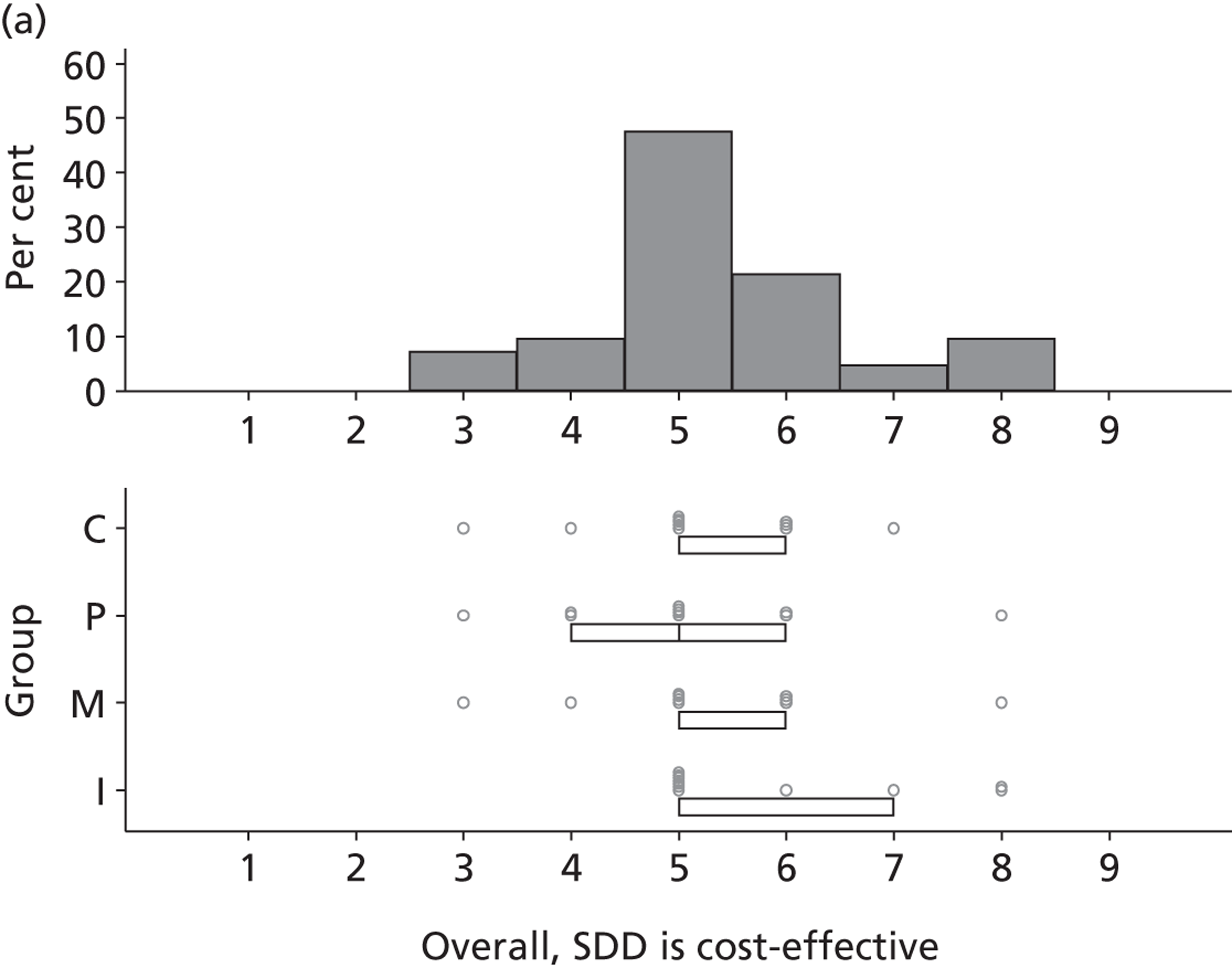

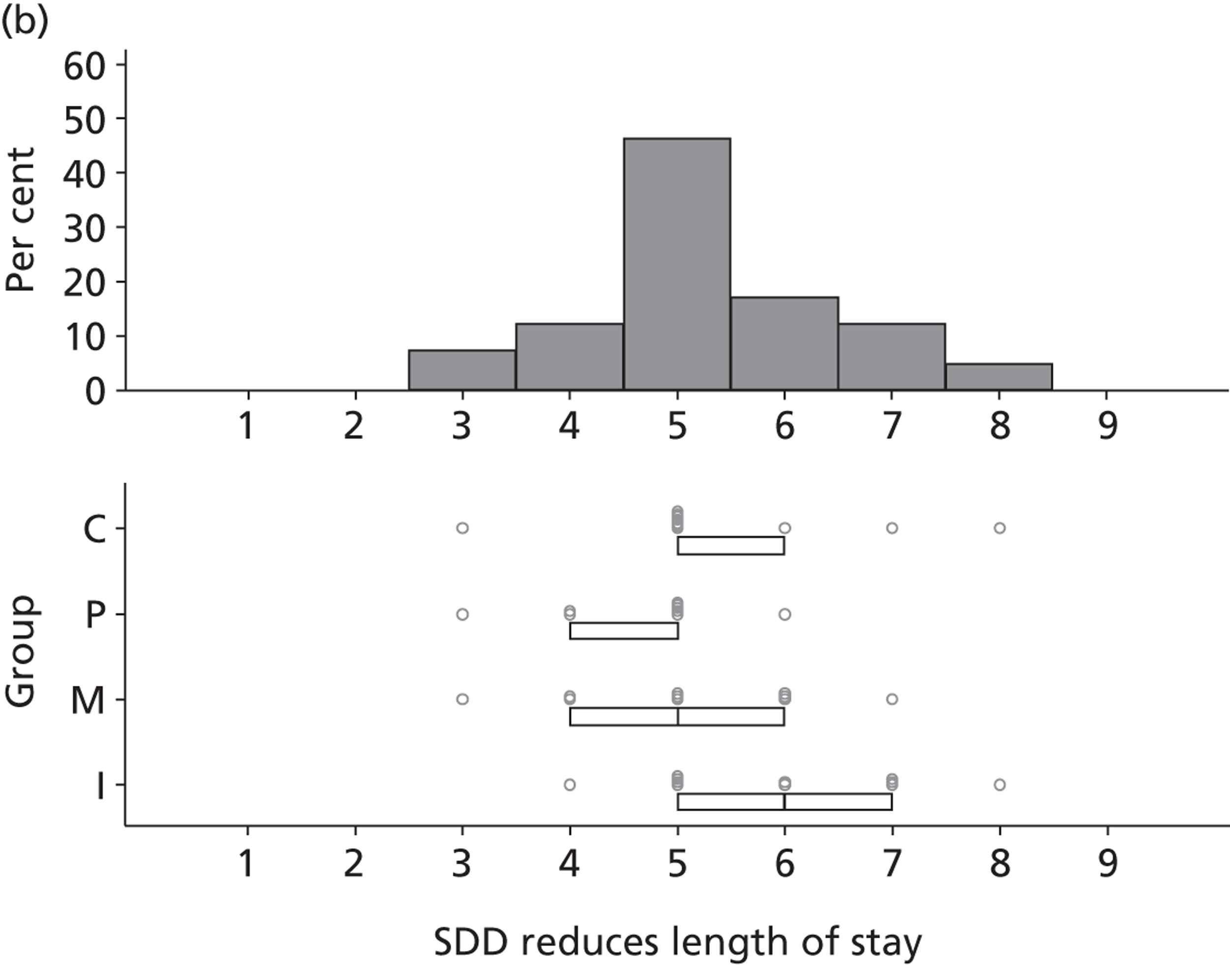

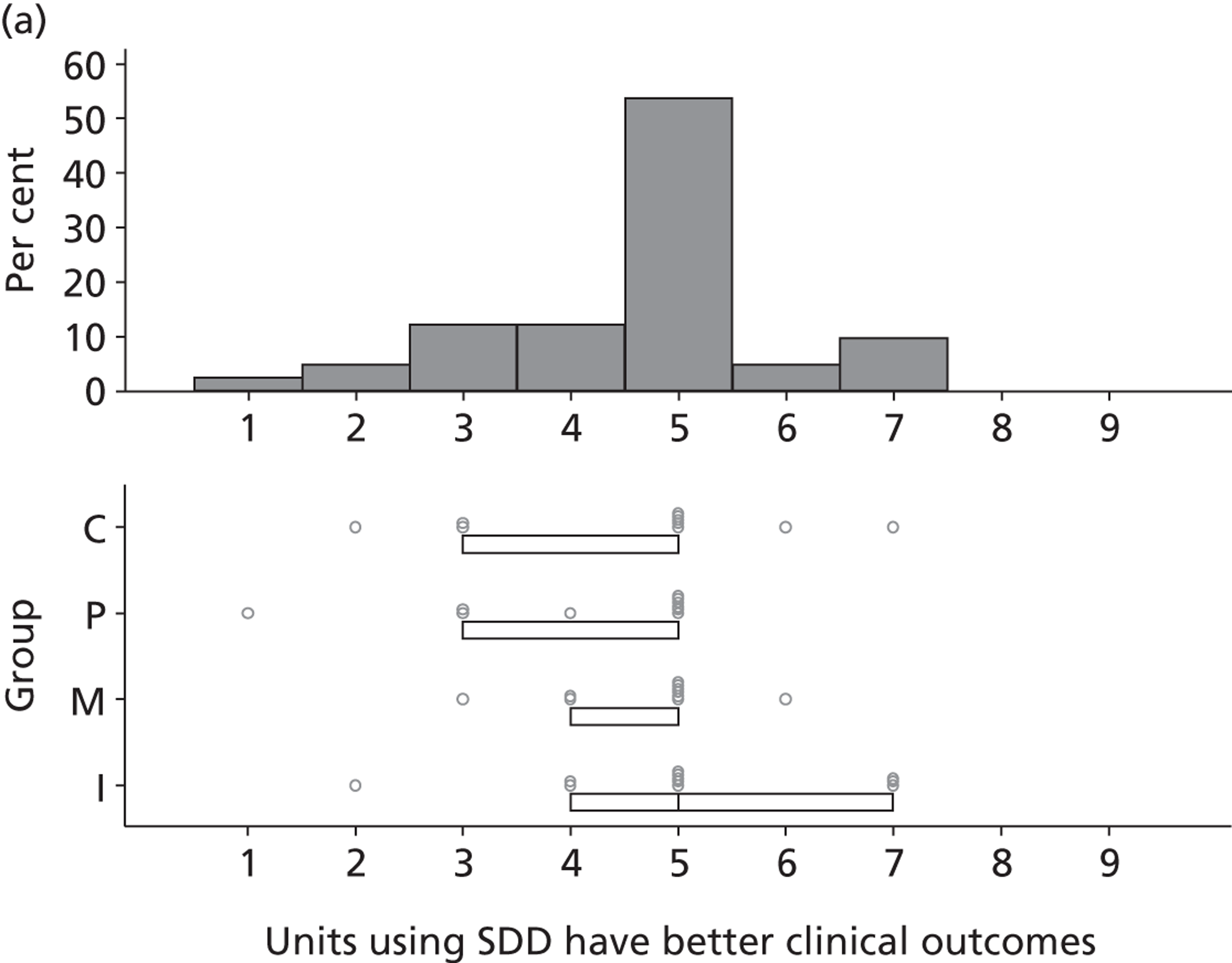

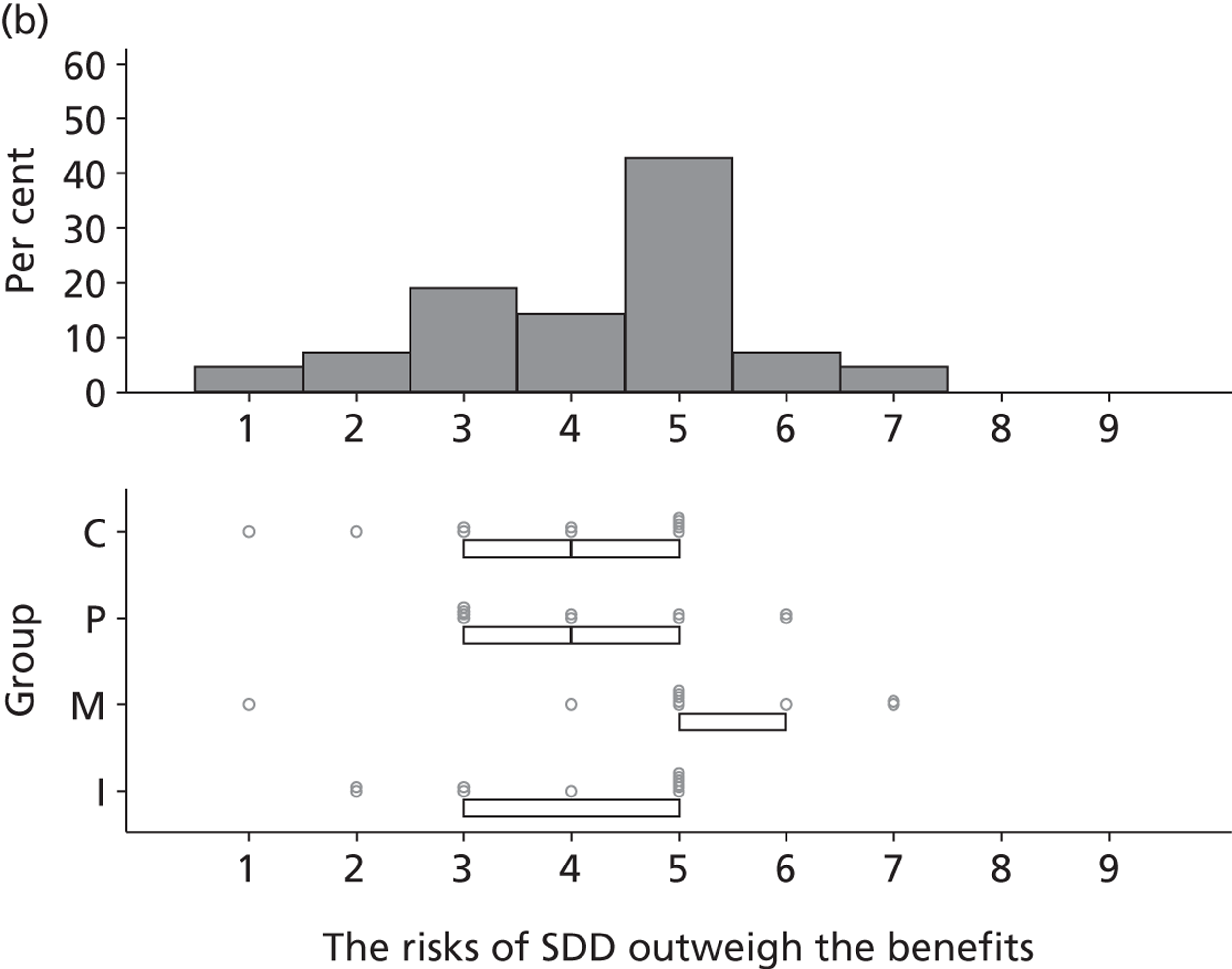

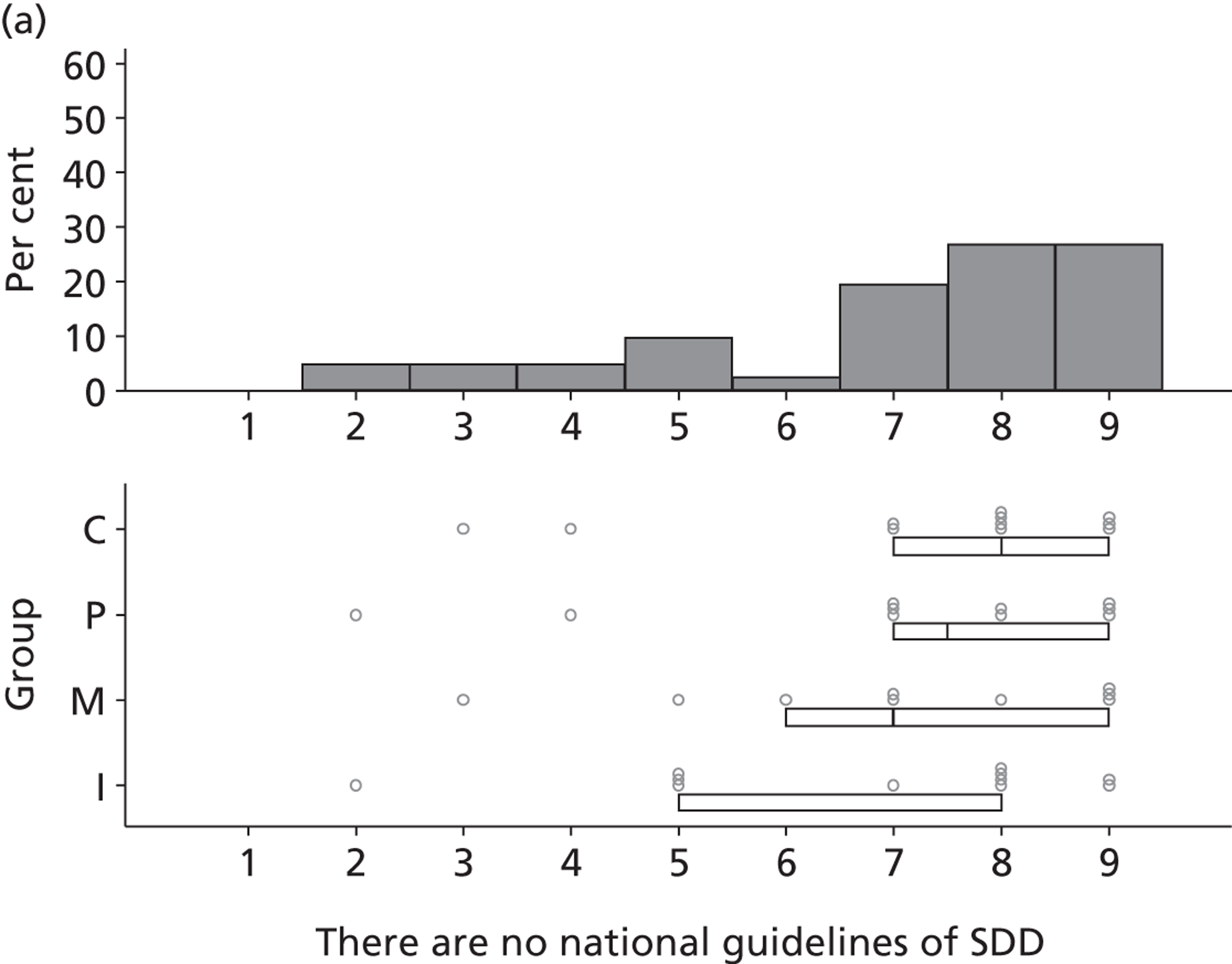

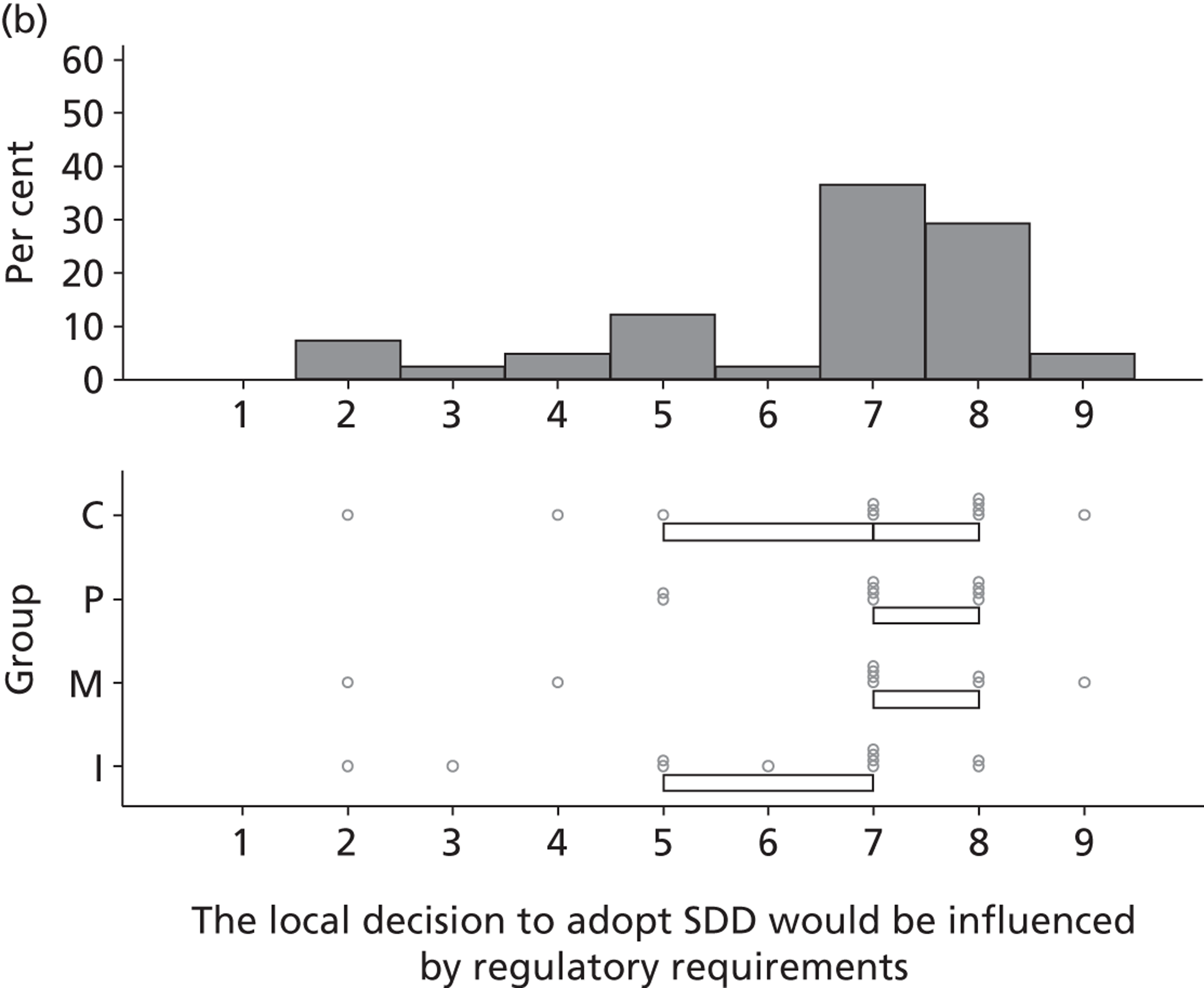

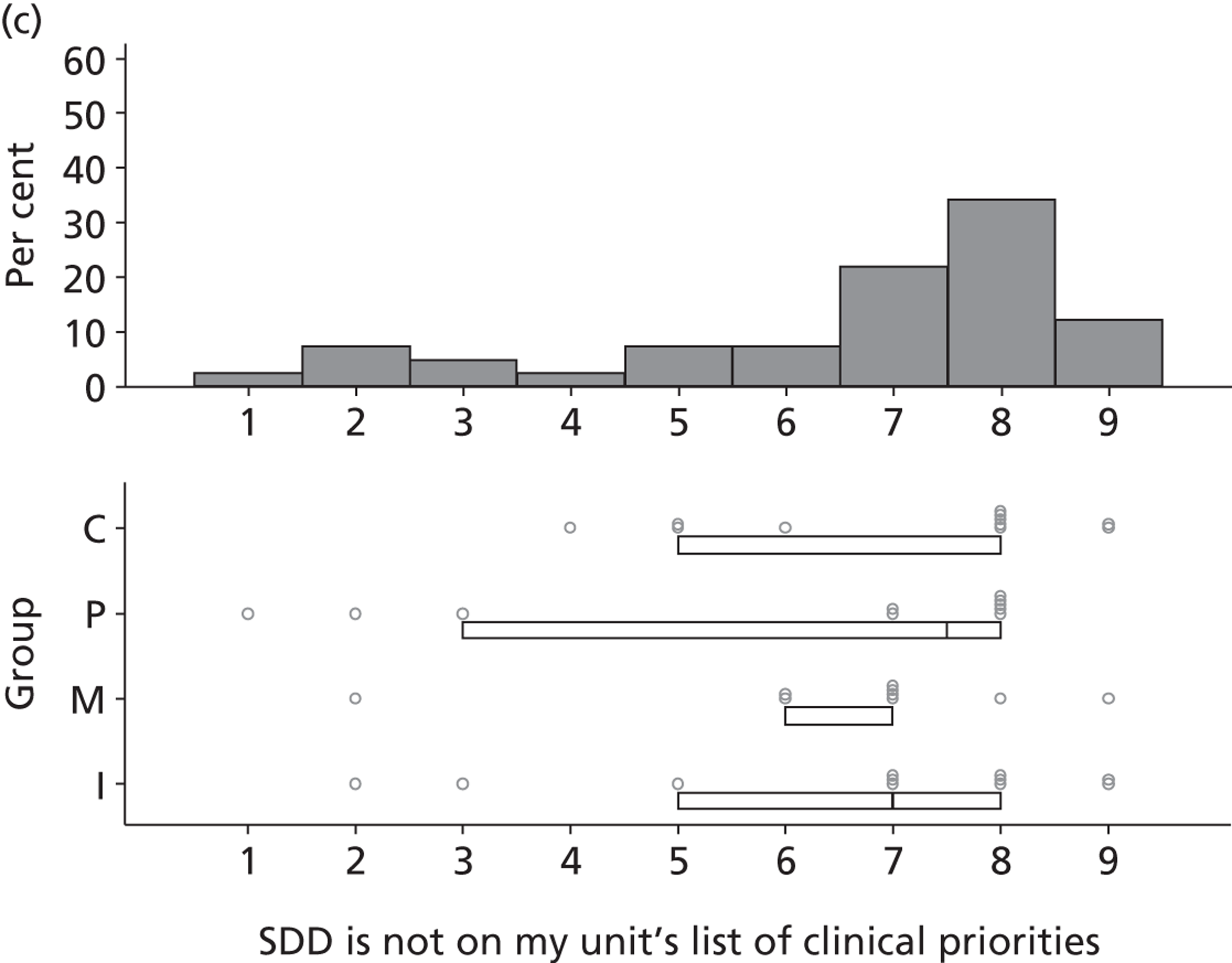

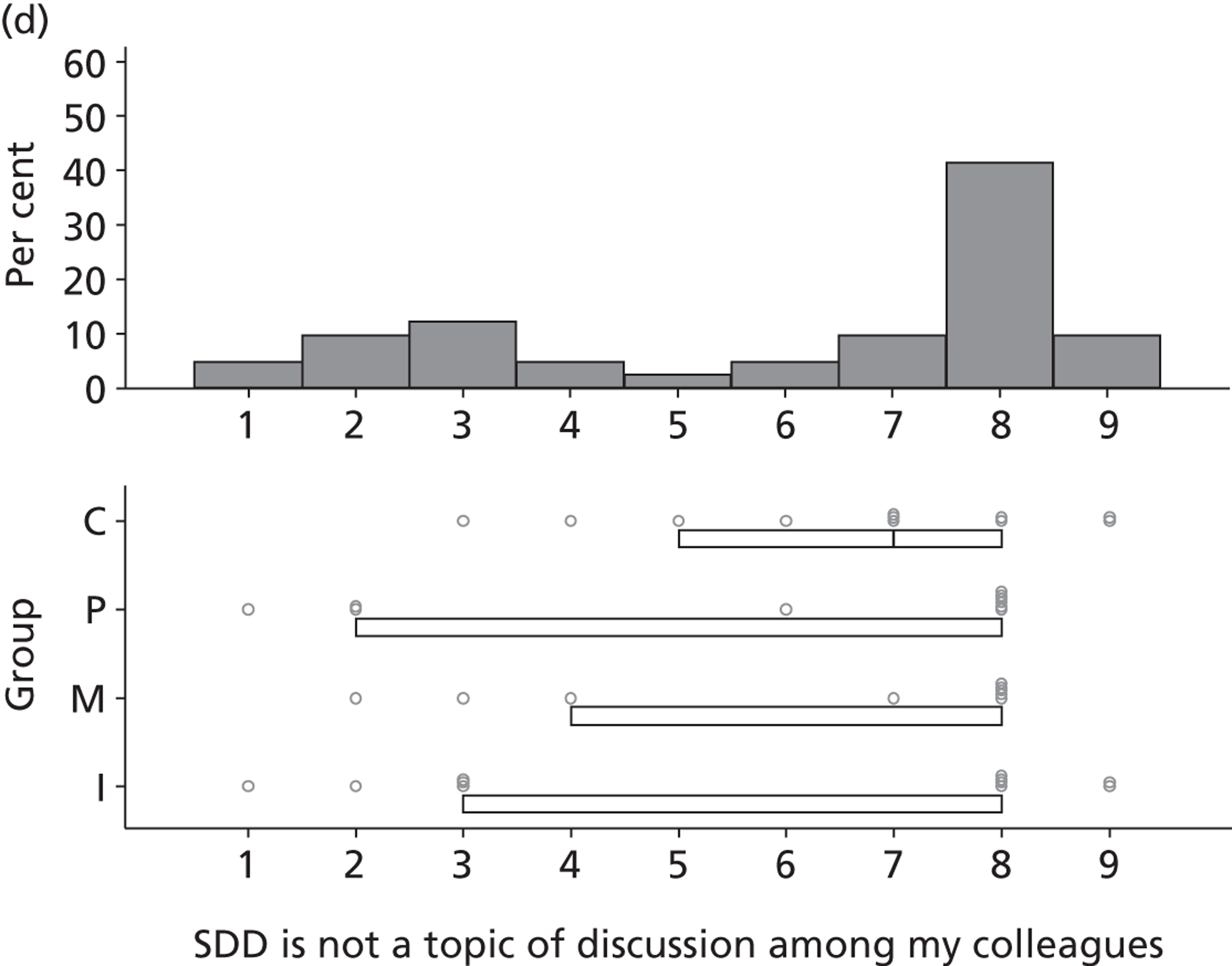

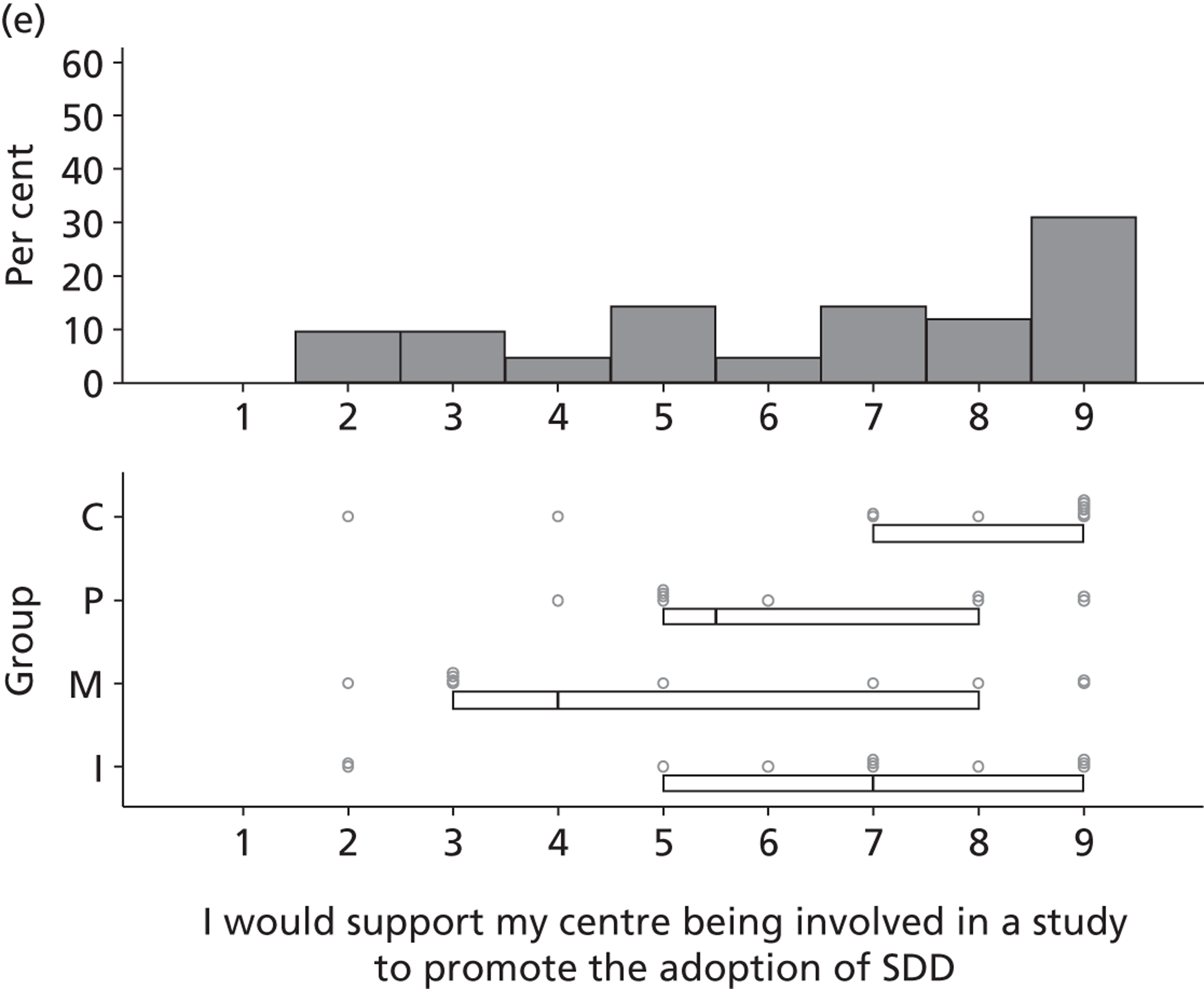

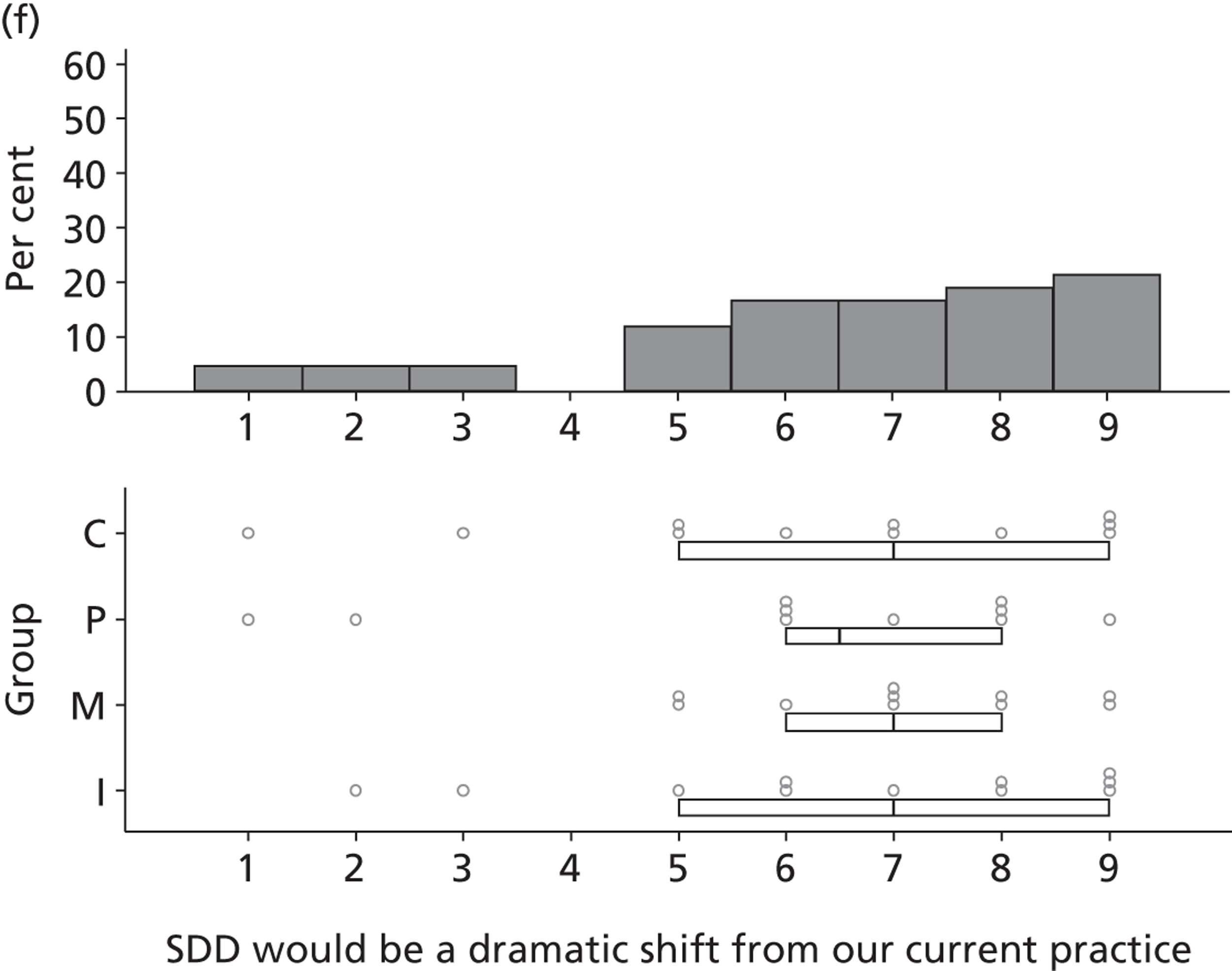

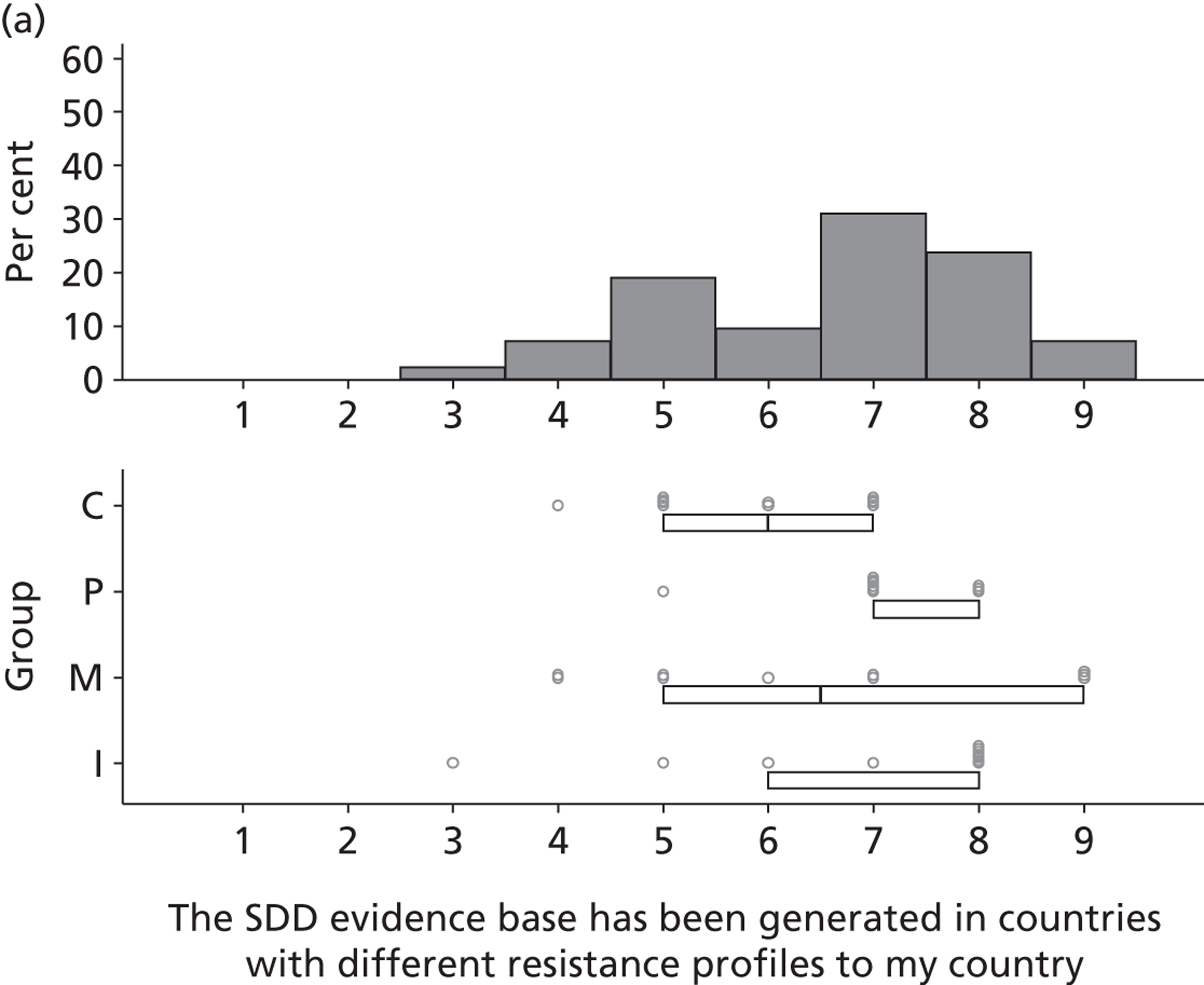

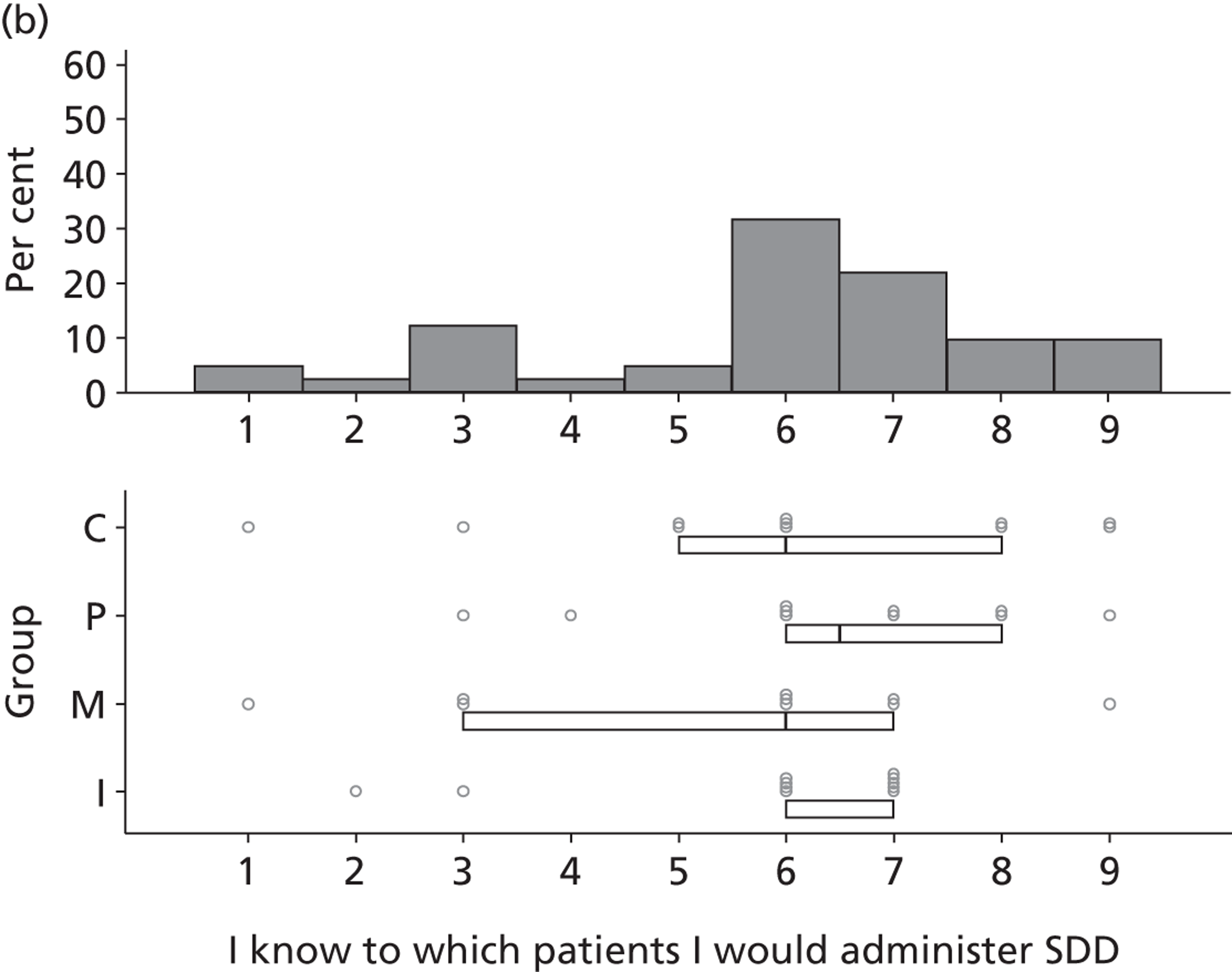

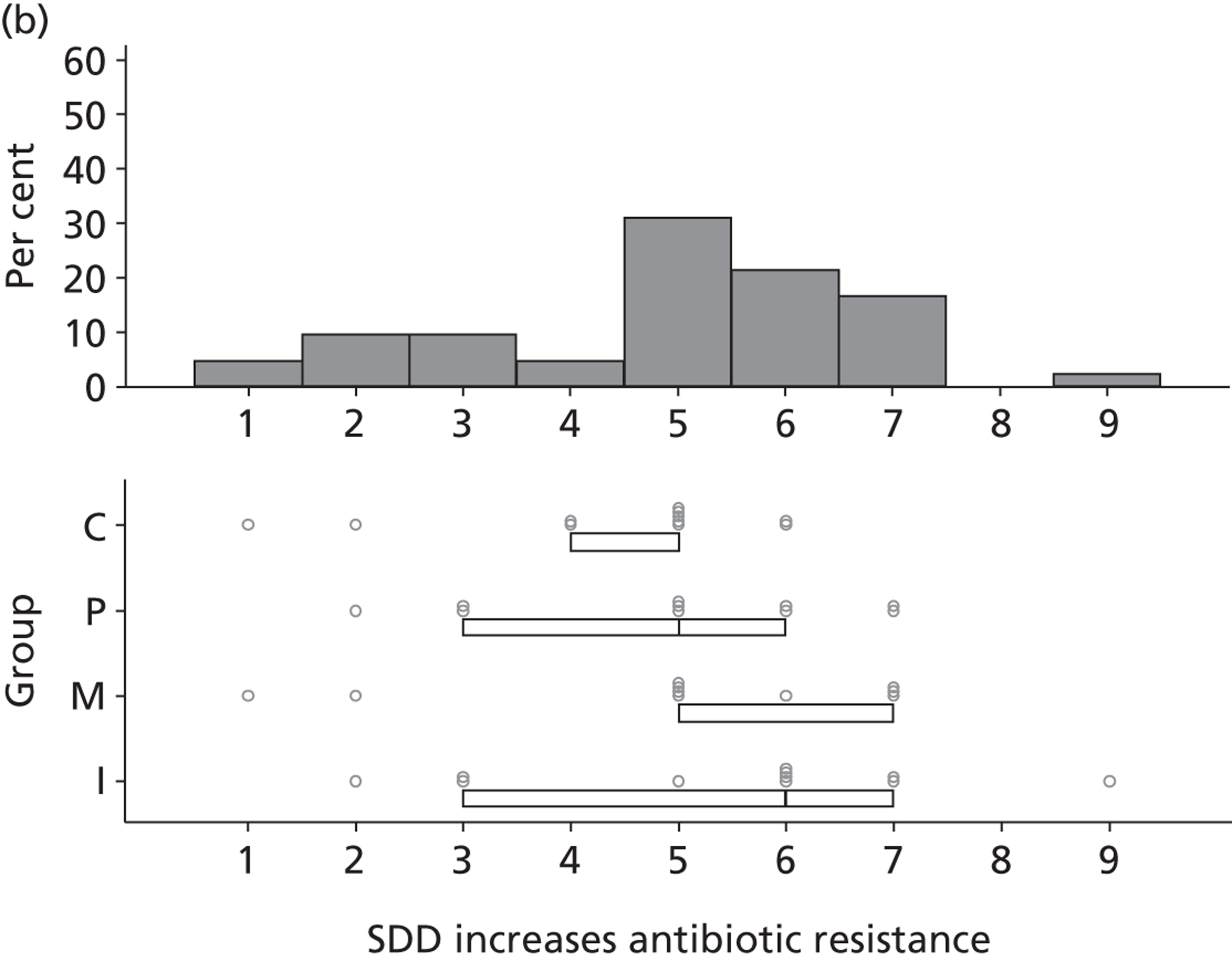

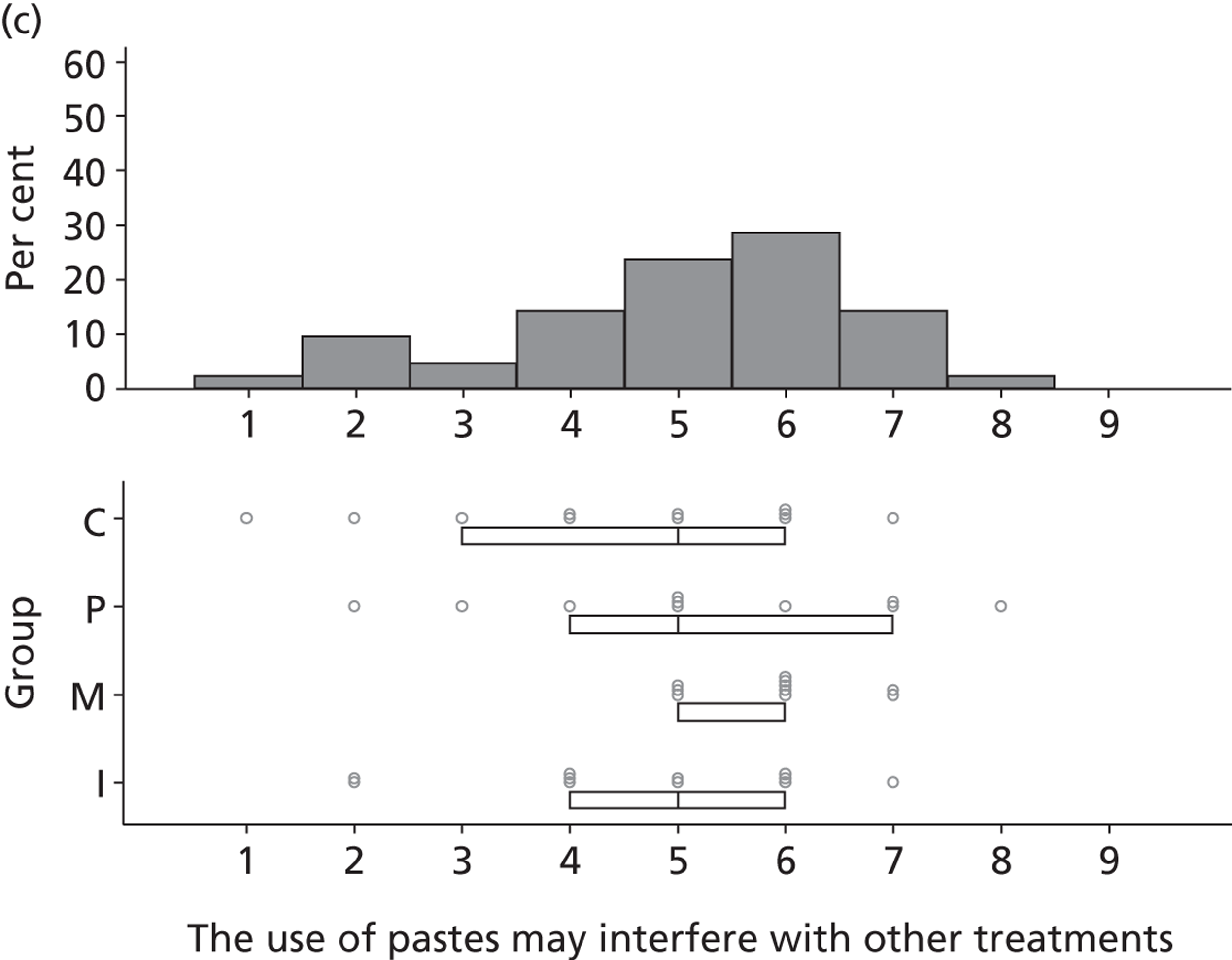

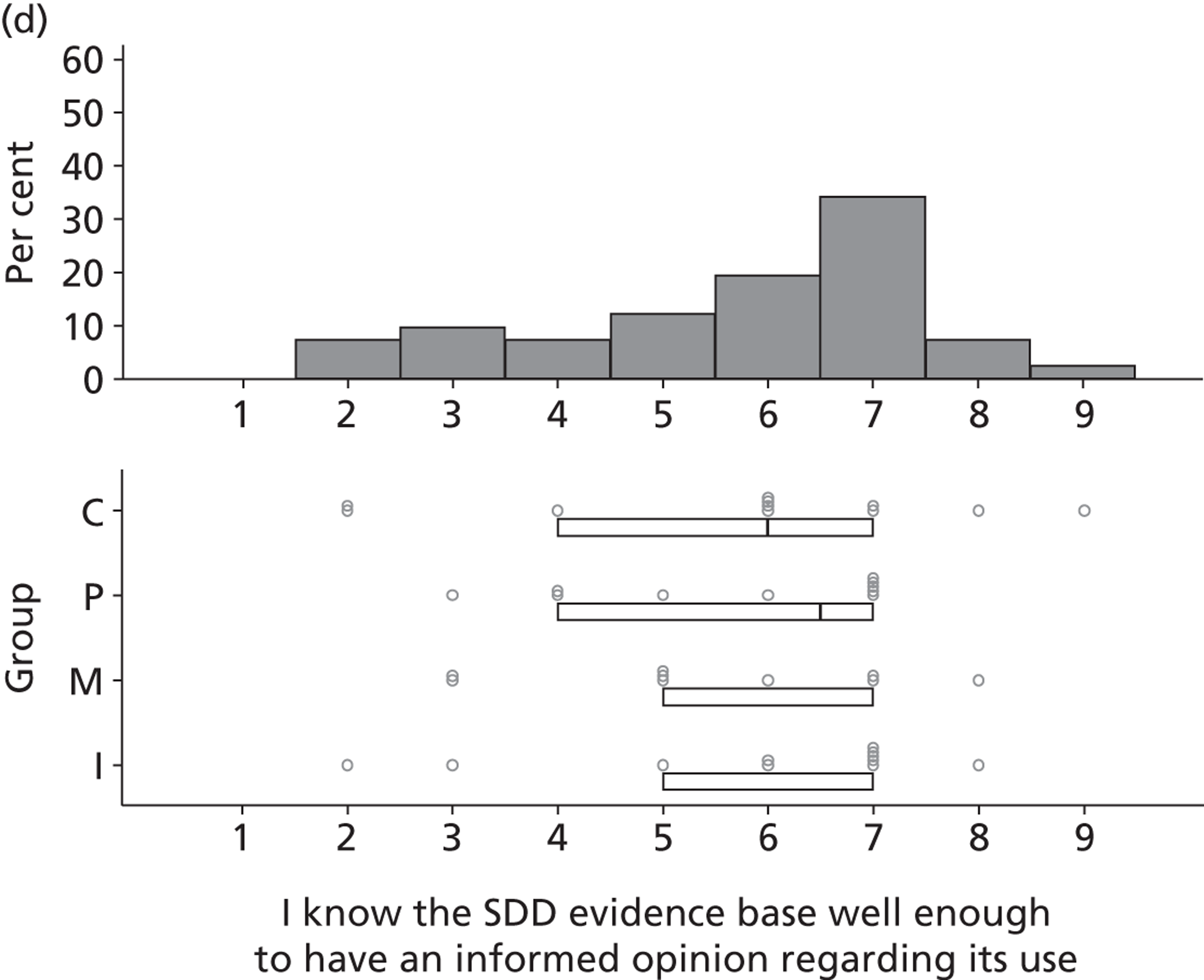

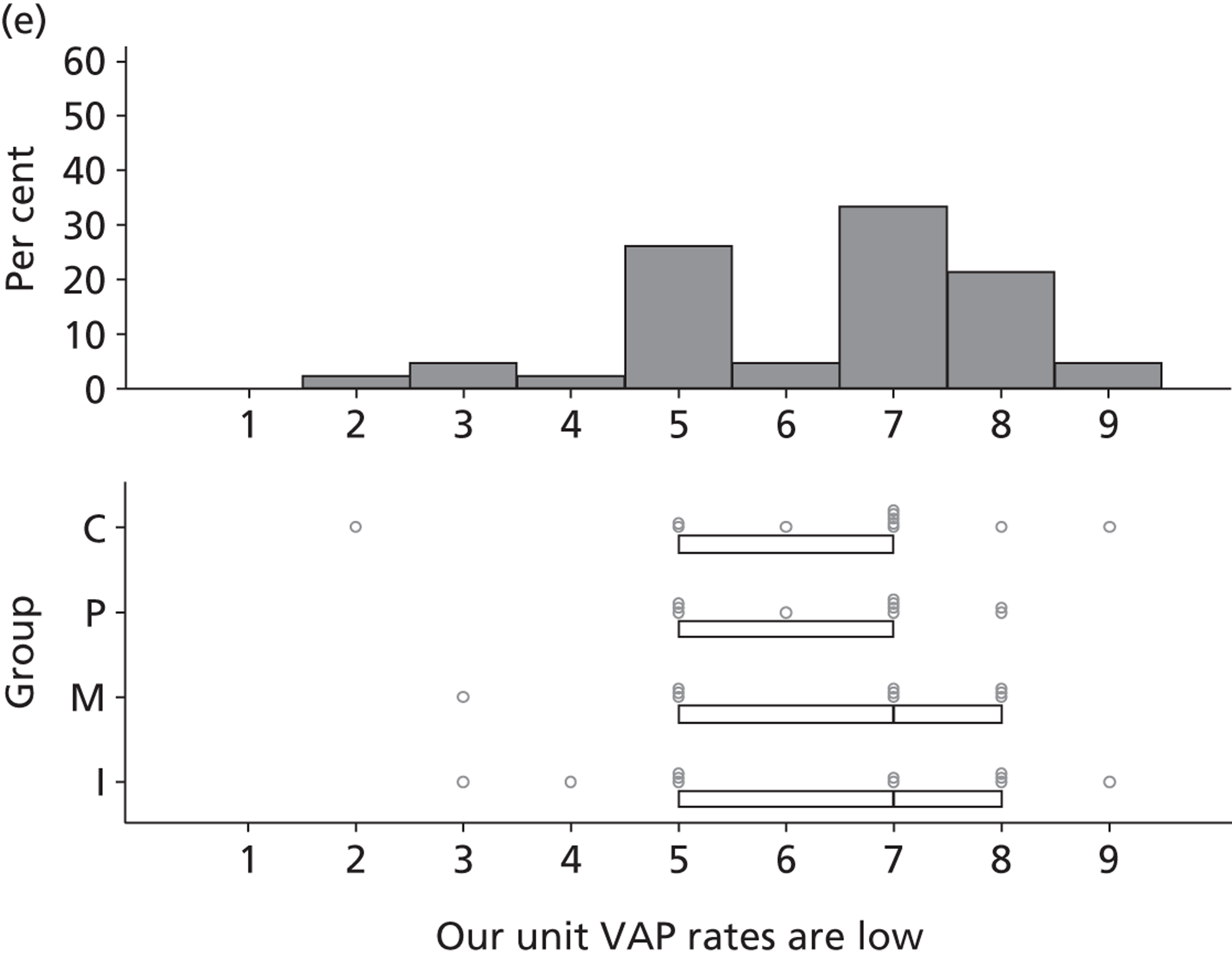

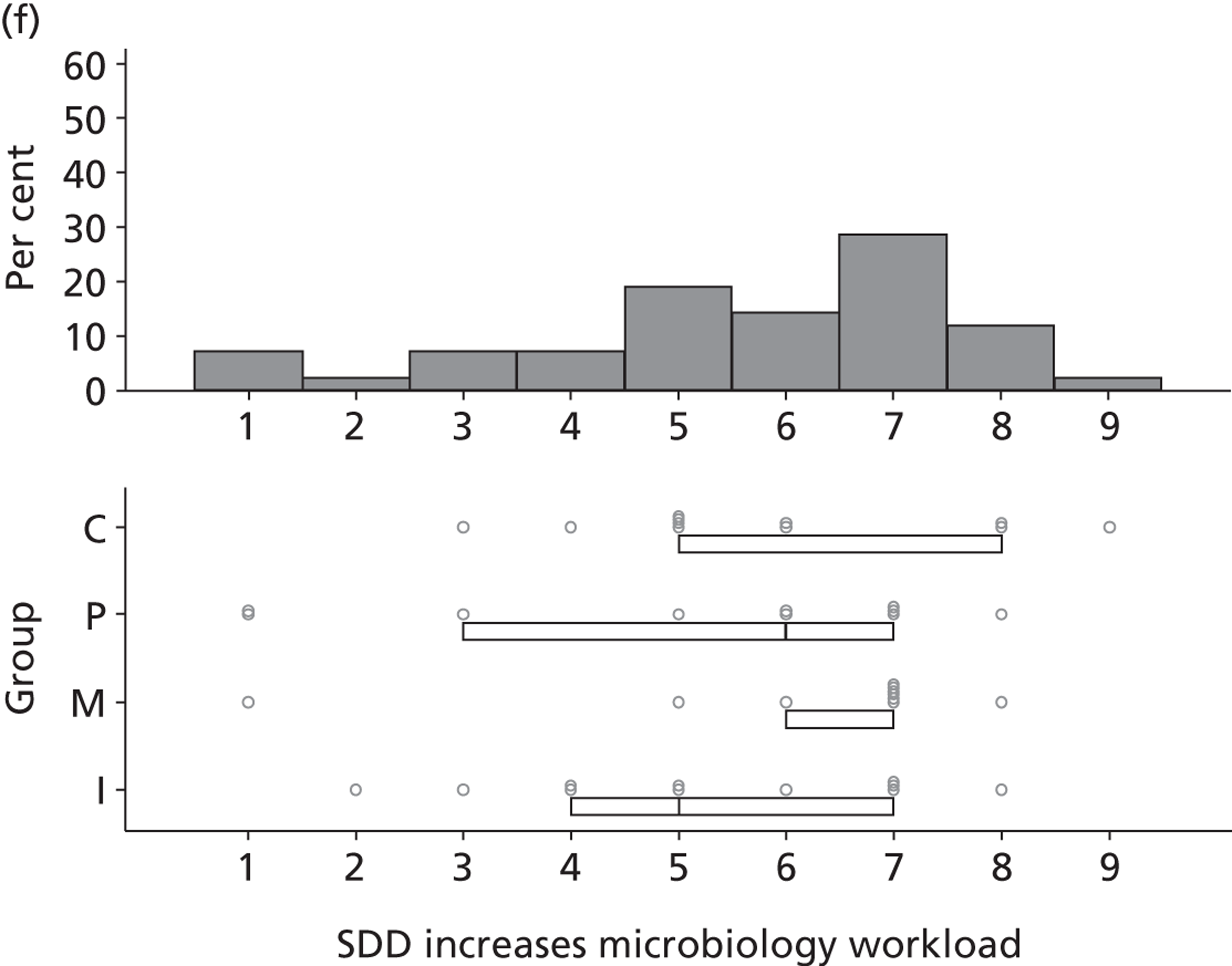

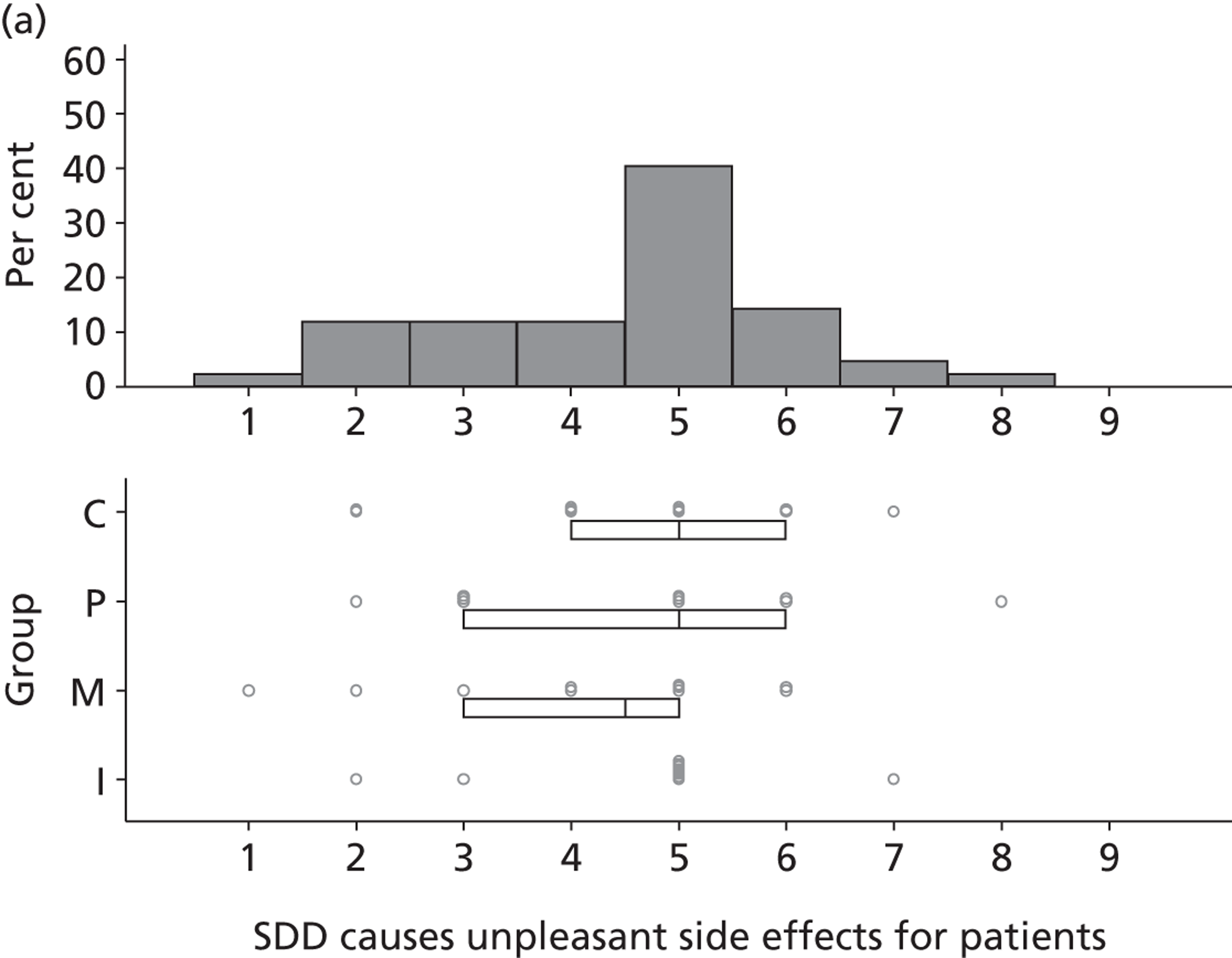

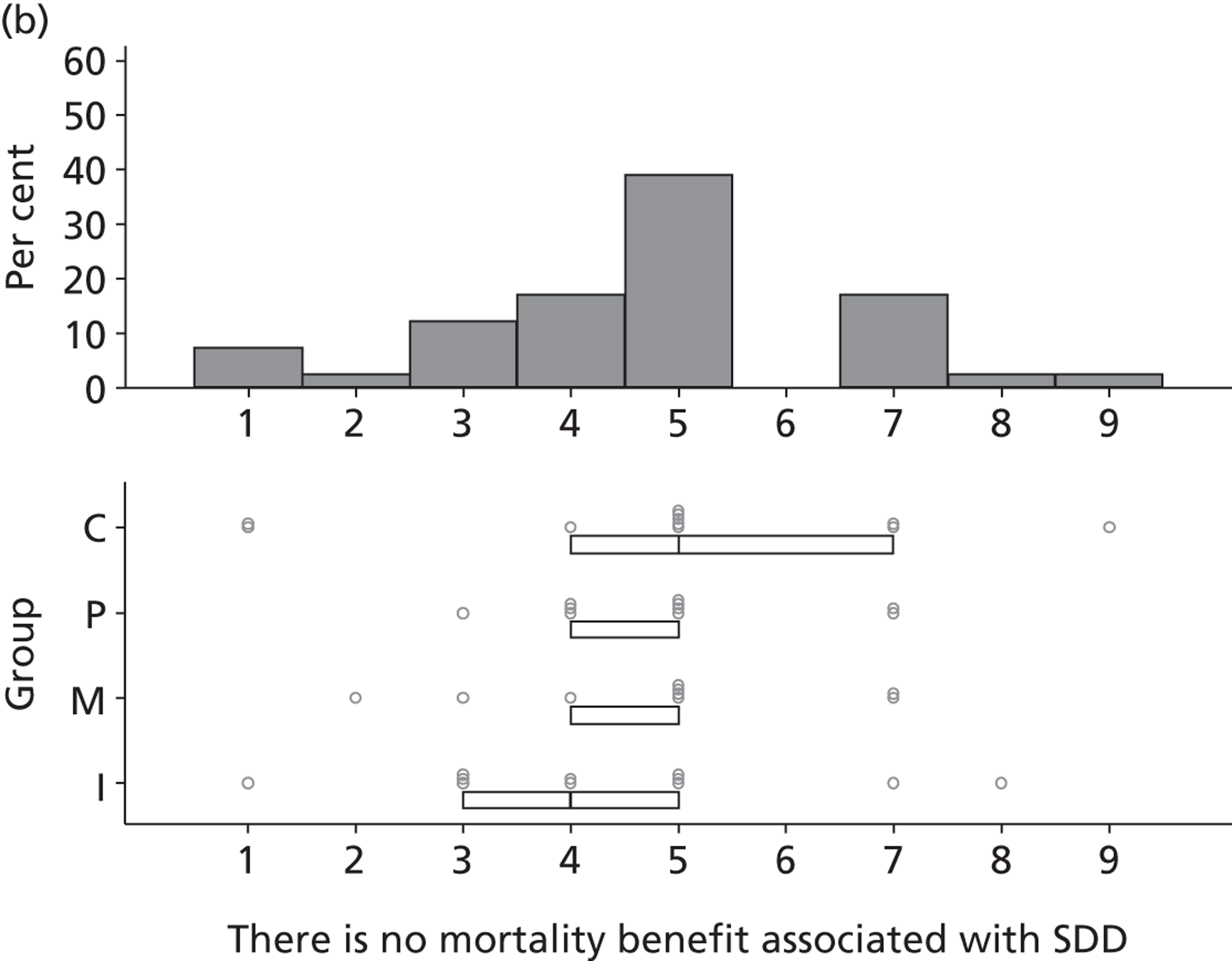

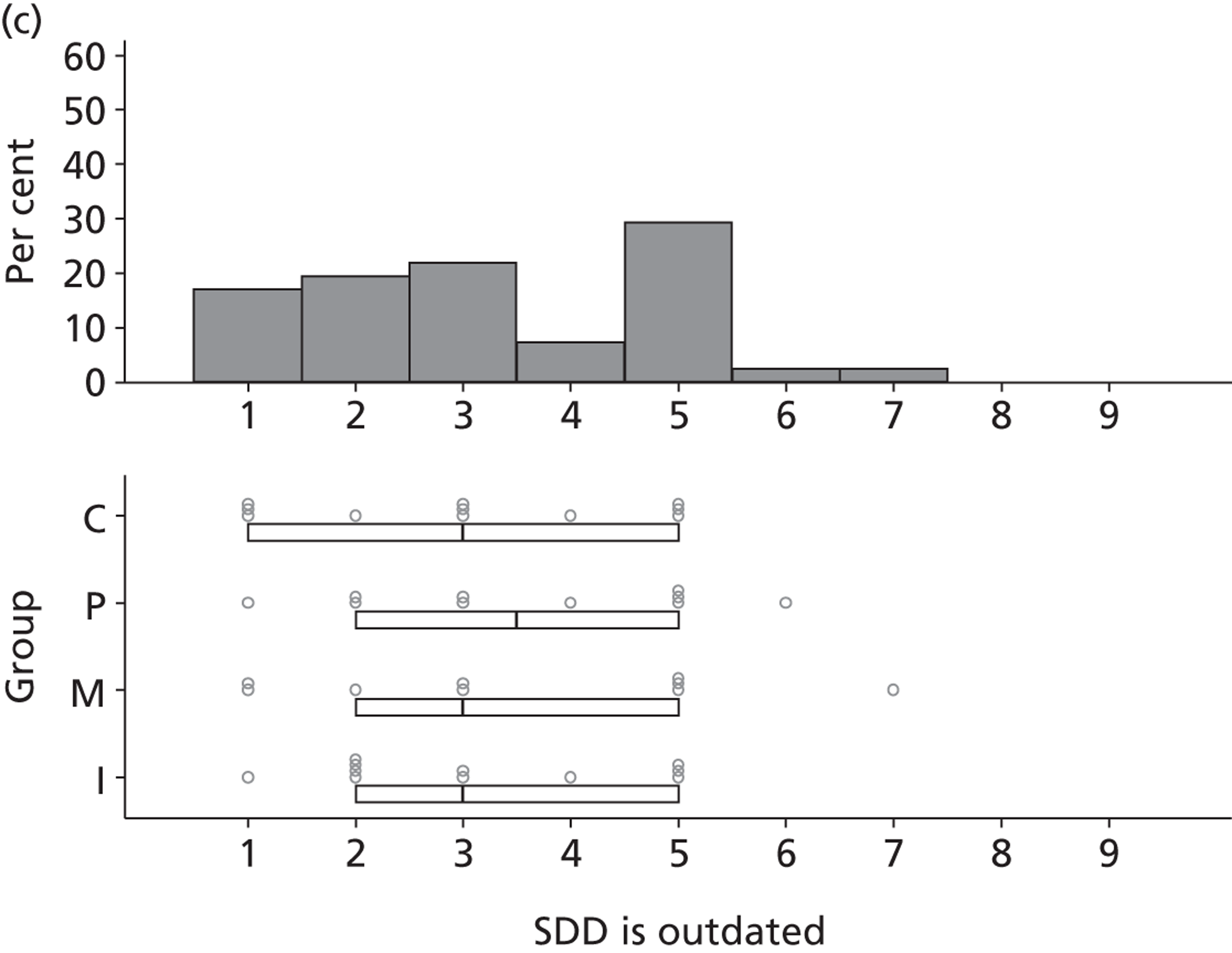

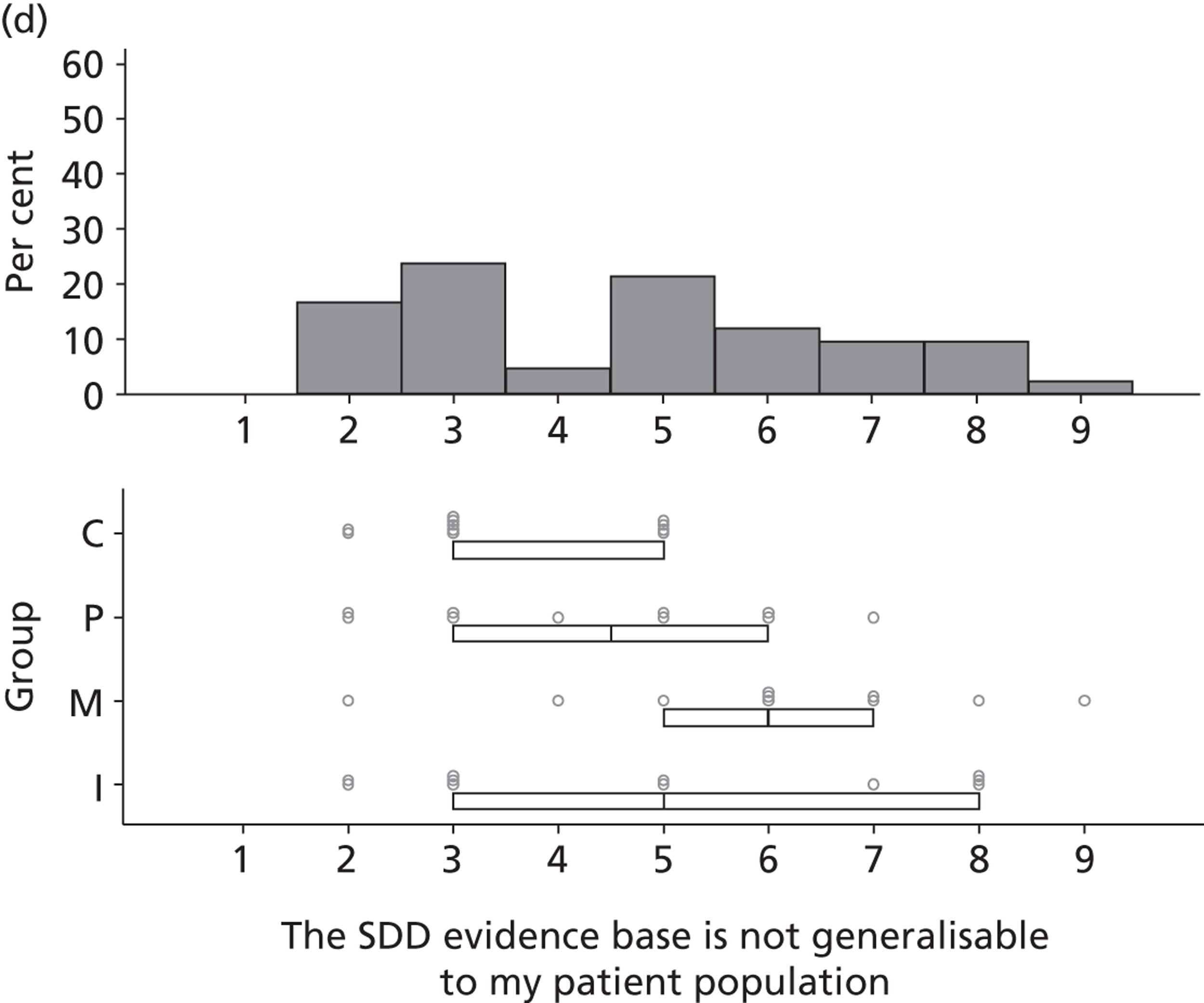

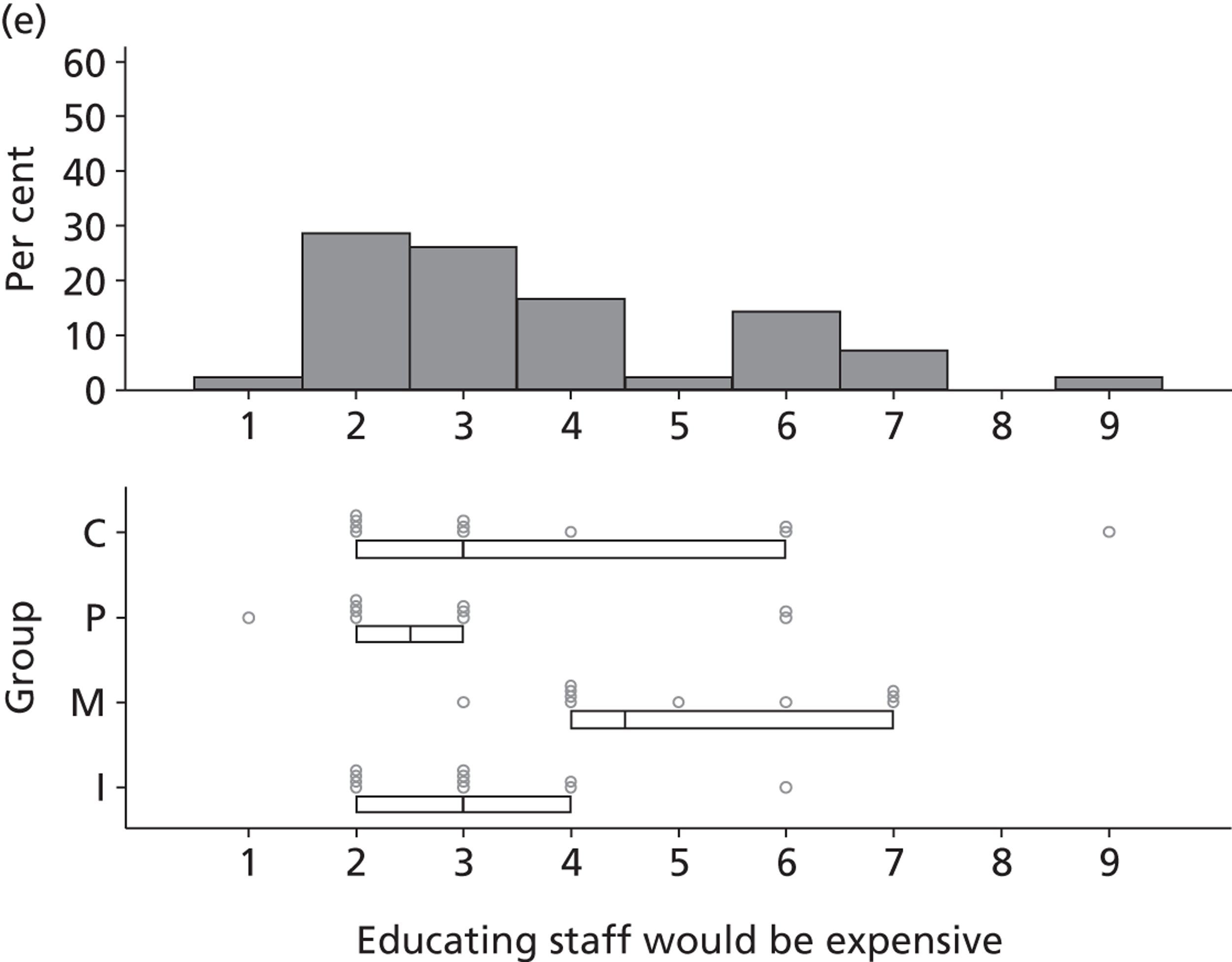

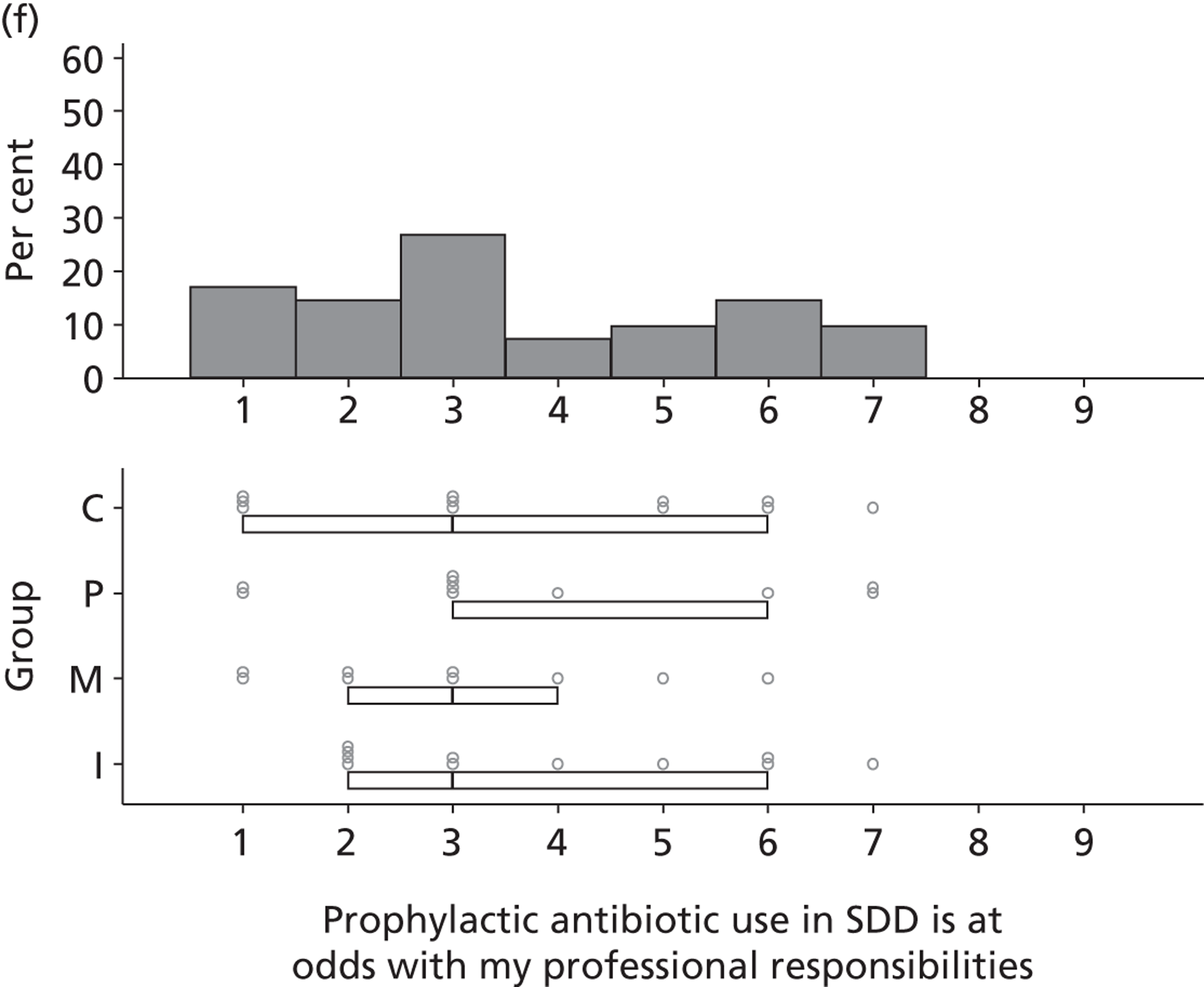

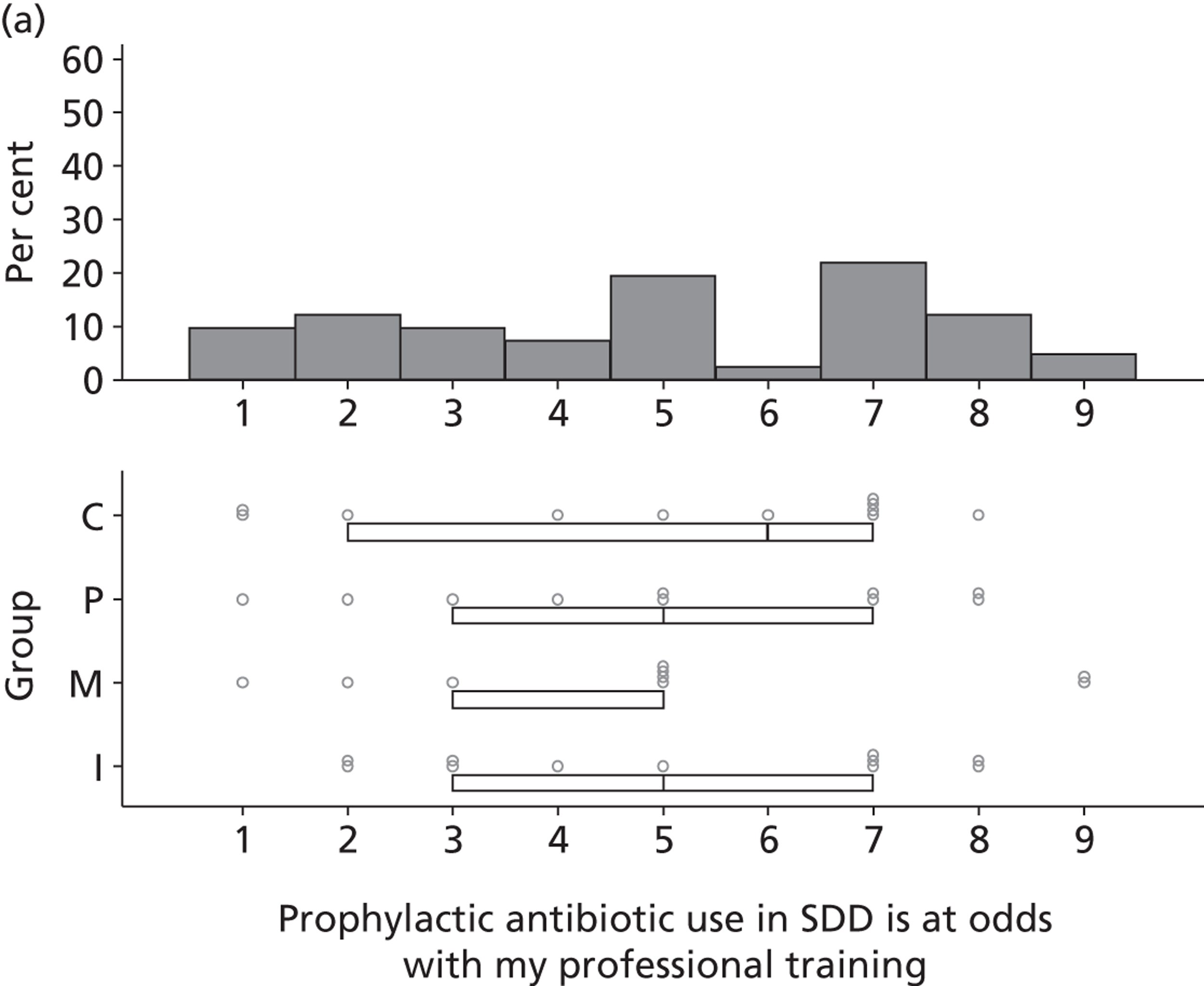

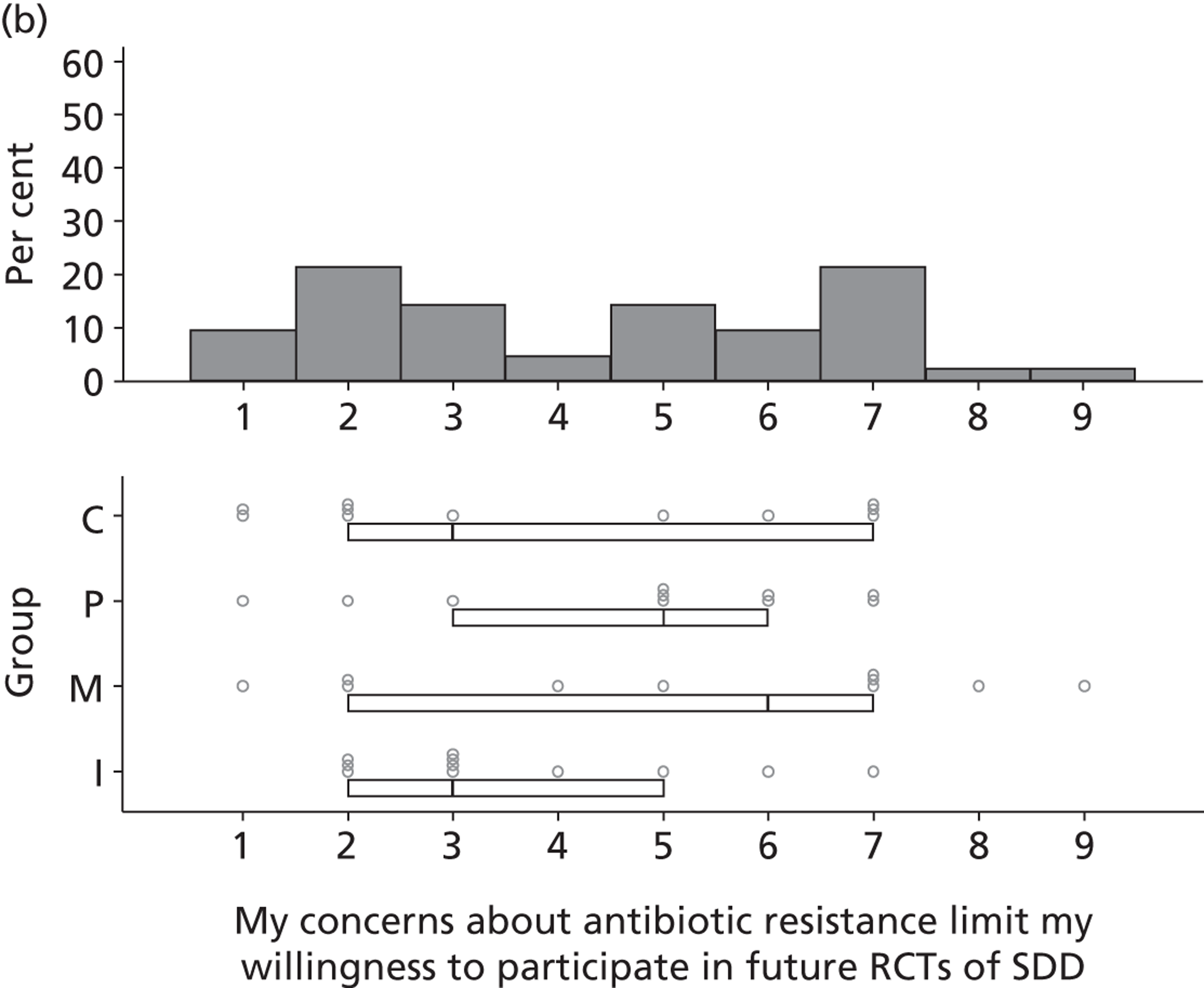

Most felt that further research was needed to address clinical uncertainties (see Table 9), in particular beliefs about the consequences of routine delivery of SDD.