Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 05/506/03. The contractual start date was in February 2007. The draft report began editorial review in May 2012 and was accepted for publication in April 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

All authors have completed the unified competing interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare Medicines for Children Research Network funding (MD); involvement in the Health Technology Assessment programme SLEEPS (Safety profiLe Efficacy and Equivalence in Paediatric intensive care Sedation) trial and royalties for acting as an editor of handbook of PIC (KM); payment from Baxter for a single advisory meeting and from GlaxoSmithKline for pip contributions (MP); and a grant awarded from the neonatal and paediatric pharmacists group for an in vitro study of drug compatibility (JP).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Macrae et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Hyperglycaemia is a common element of the early phase of the neuroendocrine response to stress which is observed following the onset of illness or injury in both adults and children, and is sometimes referred to as the diabetes of critical illness,1–4 as a result of accelerated glucose production and acute development of relative insulin resistance.

Stress has long been recognised as a programmed, co-ordinated and adaptive process conferring survival advantage which may, if prolonged, lead to secondary harm. 5 Stress hyperglycaemia was therefore usually explained as being an adaptive response whose purpose could potentially be beneficial by maintaining intravascular volume or increasing energy substrate delivery to vital organs, and it was not usually treated unless glucose levels were grossly and persistently elevated. These assumptions around the lack of harm from or benefits of stress hyperglycaemia have increasingly been questioned in the light of reports from a wide range of illnesses and populations which have shown hyperglycaemia to be related to worse clinical outcomes.

Myocardial infarction

In a meta-analysis,6 patients with acute myocardial infarction, and without diabetes mellitus, who had glucose concentrations in the range 6.1–8.0 mmol/l or higher had a 3.9-fold [95% confidence interval (CI) 2.9- to 5.4-fold] higher risk of death than patients who had lower glucose concentrations. Glucose concentrations higher than values in the range of 8.0–10.0 mmol/l on admission were associated with increased risk of congestive heart failure or cardiogenic shock.

Stroke

Capes et al. 7 conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature relating glucose levels in the interval immediately post stroke to the subsequent course. A comprehensive literature search was carried out to identify cohort studies reporting mortality and/or functional recovery after stroke in relation to admission glucose level. In total, 32 studies were identified, and predefined outcomes could be analysed for 26 of these. After stroke, the unadjusted relative risk (RR) of in-hospital or 30-day mortality associated with an admission glucose level above the range of 6–8 mmol/l was 3.07 (95% CI 2.50 to 3.79) in non-diabetic patients and 1.30 (95% CI 0.49 to 3.43) in diabetic patients. Non-diabetic stroke survivors whose admission glucose level was above the range of 6.7–8 mmol/l also had a greater risk of poor functional recovery (RR 1.41; 95% CI 1.16 to 1.73).

Head injury and multisystem trauma

Hyperglycaemia has been shown to be an independent predictor of poor outcomes in adults with head injury8 and in cases of multiple trauma. 9

Pulmonary function

Hyperglycaemia has been shown to be associated with diminished pulmonary function in adults, even in the absence of diabetes mellitus,10 and a range of risk factors for lung injury. 11

Gastrointestinal effects

Hyperglycaemia has been shown to be associated with delayed gastric emptying,12 decreased small bowel motility and increased sensation and cerebral-evoked potentials in response to a range of gastrointestinal stimuli in adult volunteers. 13–16

Infections

The in vitro responsiveness of leucocytes stimulated by inflammatory mediators is inversely correlated with glycaemic control. 17 This reduction in polymorphonuclear leucocyte responsiveness may contribute to the compromised host defence associated with sustained hyperglycaemia,17 and, indeed, hyperglycaemia has been shown to be associated with an increased rate of serious infections after adult cardiac18 and vascular surgery. 19

These studies, which associate poorer outcomes with patients with the highest levels of stress glycaemia, raise the question of whether high blood glucose levels simply identify the more severely ill patients, in whom worse outcomes are inevitable, or whether specific homeostatic or allostatic glycaemic dysfunction influences outcomes independently. If the latter were true, then perhaps measures to prevent or limit stress-induced hyperglycaemia would improve clinical outcomes.

Does hyperglycaemia matter for adults in the critically ill setting?

Although the importance of good glycaemic control has long been established in minimising complications of chronic hyperglycaemia in patients with diabetes mellitus,20,21 and a number of mechanisms for glucotoxicity identified,22 in the era up to the year 2000, a permissive approach was typically adopted when managing non-diabetic patients in intensive care settings. A very reasonable question, however, is Could shorter-term hyperglycaemia in non-diabetic populations be associated with clinically important adverse outcomes? Early reports from adult populations started to explore the possible association between acute stress-induced hyperglycaemia and outcome in both diabetic and non-diabetic patients.

Furnary et al. 18 noted that hyperglycaemia is associated with higher sternal wound infection rates following adult cardiac surgery and questioned whether more aggressive control of glycaemia might lead to lower infection rates. In a prospective study of 2467 consecutive diabetic patients who underwent open-heart surgical procedures, patients were classified into two sequential groups. The control group included 968 patients treated with sliding-scale-guided intermittent subcutaneous insulin injections. The study group included 1499 patients treated with a continuous intravenous insulin infusion in an attempt to maintain a blood glucose level of < 11.1 mmol/l. Compared with subcutaneous insulin injections, continuous intravenous insulin infusion induced a significant reduction in perioperative blood glucose levels, which was associated with a significant reduction in the incidence of deep-sternal wound infection in the continuous intravenous insulin infusion group [0.8% (12 of 1499) vs. 2.0% (19 of 968) in the intermittent subcutaneous insulin injection group; p = 0.01]. The use of perioperative, continuous intravenous insulin infusion in diabetic patients undergoing open-heart surgical procedures appeared to significantly reduce the incidence of major infections.

Malmberg et al. 23 randomly allocated patients with diabetes mellitus and acute myocardial infarction to intensive insulin therapy (n = 306) or standard treatment (controls, n = 314). The mean (range) follow-up was 3.4 (1.6–5.6) years. There were 102 (33%) deaths in the treatment group compared with 138 (44%) deaths in the control group (RR 0.72; 95% CI 0.55 to 0.92; p = 0.011). The effect was most pronounced among a predefined group that included 272 patients who had not received insulin treatment previously and who were at a low cardiovascular risk (0.49; 0.30 to 0.80; p = 0.004). Intensive insulin therapy improved survival in diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction. The effect seen at 1 year continued for at least 3.5 years, with an absolute reduction in mortality of 11%.

In 2001, Van den Berghe and colleagues from Leuven, Belgium,24 extended this approach to non-diabetic hyperglycaemic populations. They performed a single-centre randomised trial in adults undergoing intensive care following surgical procedures which showed that the use of insulin to tightly control blood glucose led to a reduction in mortality from 10.9% to 7.2%, and a significantly lower incidence of a range of important complications of critical illness including renal failure, infection, inflammation, anaemia and polyneuropathy and need for prolonged ventilatory support.

The same group undertook a similar trial in non-surgical, adult, critically ill patients25 and again found benefits from the control of blood glucose with intensive insulin therapy. Patients were randomly assigned to a regimen of strict normalisation of blood glucose (4.4–6.1 mmol/l) with use of insulin or conventional therapy whereby insulin was administered only when blood glucose levels exceeded 12 mmol/l, with the infusion tapered when the level fell below 10 mmol/l. In the intention-to-treat analysis of the 1200 patients, intensive care unit (ICU) and in-hospital mortality were not significantly altered by intensive insulin therapy; however, for those patients who stayed > 3 days in intensive care (an a priori subgroup), mortality was significantly reduced from 52.5% to 43% (p = 0.009). Morbidity was significantly reduced by intensive insulin therapy, with a lower incidence of renal injury and shorter length of mechanical ventilation and duration of hospital stay noted. For patients who stayed > 5 days in intensive care after trial entry, all morbidity end points were significantly improved in the intensive insulin therapy group.

Although the precise mechanisms by which different glucose control strategies might influence clinical outcomes had not been fully elucidated, the clinical effects of ‘tight glycaemic control’ (TGC) for adults in critical care appeared promising. As a result, TGC was widely adopted in adult critical care standards in the years following the publication of Van den Berghe et al. 2001 paper. 24

Stress hyperglycaemia in the critically ill child

Over 12,000 children are admitted to ICUs in England and Wales each year. 26 Hyperglycaemia occurs frequently during critical illness or after major surgery in children, with a reported incidence of up to 86%,3 but children in critical care may not respond to interventions in the same way as adults.

References to hyperglycaemia and its management in critically ill children were identified through searches in MEDLINE27 from 1990 to December 2006. Articles were also identified through searches of the authors’ own files. Only papers published in English were reviewed. The final reference list was generated on the basis of originality and relevance to the genesis of this research proposal. The search terms used were ‘glycaemia’, ‘control’, ‘insulin’, ‘critical illness’ and ‘intensive care’; the limits applied were ‘clinical trials’, ‘meta-analysis’, ‘randomised controlled trial’ and ‘humans’ and ‘age 0–18 years’. No randomised trials or meta-analyses of glycaemic control in childhood critical illness were identified.

The non-randomised studies identified included a number of reports of critically ill children receiving care in general,3,28,29 cardiac surgical,30,31 trauma9,32,33 and burns34 ICUs, all showing that high blood glucose levels occur frequently and that levels are significantly higher in children who die than in children who survive. As in adults, the occurrence of hyperglycaemia was associated with poorer outcomes including death, sepsis and longer length of intensive care stay for critically ill children.

Srinivasan et al. 3 studied the association of timing, duration and intensity of hyperglycaemia with mortality in critically ill children. The study had a retrospective, cohort design and included 152 critically ill children receiving vasoactive infusions or mechanical ventilation. A peak blood glucose of > 7 mmol/l occurred in 86% of patients. Non-survivors had a higher peak blood glucose [mean ± standard deviation (SD)] than survivors (17.3 ± 6.4 mmol/l vs. 11.4 ± 4.4 mmol/l, p < 0.001). Non-survivors had more intense hyperglycaemia during the first 48 hours in the paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) (7 ± 2.1 mmol/l) than survivors (6.4 ± 1.9 mmol/l, p < 0.05). Median blood glucose levels > 8.3 mmol/l were associated with a threefold increased risk of mortality compared with median levels of < 8.3 mmol/l. Univariate logistic regression analysis showed that peak blood glucose and the duration and intensity of hyperglycaemia were each associated with PICU mortality (p < 0.05). Multivariate modelling controlling for age and paediatric risk of mortality scores showed an independent association of peak blood glucose and duration of hyperglycaemia with PICU mortality (p < 0.05). This study demonstrated that hyperglycaemia is common among critically ill children. Peak blood glucose and duration of hyperglycaemia appear to be independently associated with mortality. The study was limited by its retrospective design, its single-centre location and the absence of cardiac surgical cases, a group which make up approximately 40% of paediatric intensive care (PIC) admissions in the UK.

Yates et al. 30 conducted a retrospective review of data from 184 children < 1 year of age who underwent major cardiac surgery over a 22-month period ending in August 2004. Factors analysed included peak glucose levels and duration of hyperglycaemia. The duration of hyperglycaemia was significantly longer in children who developed renal insufficiency, liver insufficiency and infection and those who required mechanical circulatory support or who died, and was associated with longer PICU and hospital lengths of stay (LOS).

Hall et al. 35 investigated the incidence of hyperglycaemia in infants with necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) and the relationship between glucose levels and outcome in these infants. Glucose measurements (n = 6508) in 95 neonates with confirmed NEC admitted to the surgical ICU were reviewed. Glucose levels ranged from 0.5 to 35.0 mmol/l; 69% of infants became hyperglycaemic (> 8 mmol/l) during their admission; and 32 infants died. The mortality rate tended to be higher in infants whose peak glucose concentration exceeded 11.9 mmol/l than in those with peak glucose concentrations of < 11.9 mmol/l, and the late (> 10 days after admission) mortality rate was significantly higher in the former infants (29% vs. 2%; p = 0.0009). Linear regression analysis indicated that peak glucose concentration was significantly related to LOS (p < 0.0001).

Branco et al. 29 showed an association between hyperglycaemia and increased mortality in children with septic shock. They prospectively studied children admitted to a regional PICU with septic shock refractory to fluid therapy over a period of 32 months. The peak glucose level in those with septic shock was 11.9 ± 5.4 mmol/l (mean ± SD), and the mortality rate was 49.1% (28/57). In non-survivors, the peak glucose level was 14.5 ± 6.1 mmol/l, which was higher (p < 0.01) than that found in survivors (9.3 ± 3.0 mmol/l). The RR of death in patients with peak glucose levels of ≥ 9.9 mmol/l was 2.59 (p = 0.012).

Faustino and Apkon28 demonstrated that hyperglycaemia occurs frequently among critically ill non-diabetic children and is associated with higher mortality and longer LOSs in PICUs. They performed a retrospective cohort study of 942 non-diabetic patients admitted to a PICU over a 3-year period. The prevalence of hyperglycaemia was based on initial PICU glucose measurement, peak value within 24 hours and peak value measured during PICU stay up to 10 days after the first measurement. Using three cut-off values (6.7, 8.3 and 11.1 mmol/l), the prevalence of hyperglycaemia was 16.7–75.0%. The RR for death increased for peak glucose within 24 hours of > 8.3 mmol/l (RR, 2.50; 95% CI 1.26 to 4.93) and peak glucose within 10 days of > 6.7 mmol/l (RR, 5.68; 95% CI 1.38 to 23.47).

Pham et al. 34 reviewed the records of children with ≥ 30% total body surface area burn injury admitted to a regional paediatric burn centre during two consecutive periods, during the first of which patients received ‘conventional insulin therapy’ (n = 31), and during the second of which they were managed with TGC (n = 33). Intensive insulin therapy was positively associated with survival and a reduced incidence of infections. The authors concluded that intensive insulin therapy to maintain normoglycaemia in severely burned children could be safely and effectively implemented in a paediatric burns unit and that this therapy seemed to lower infection rates and improve survival.

There was, therefore, mounting evidence to suggest that stress hyperglycaemia occurred in both neonates and children (as in adults). From adult studies, TGC appeared to offer the possibility of clinical benefits, particularly following surgery, but there was no convincing randomised controlled trial (RCT) evidence for children, whether or not admitted to PICUs following surgery. This was of particular importance as approximately one-third of admissions of children to UK PICUs are associated with surgery, in particular cardiac surgery.

Evidence on the cost-effectiveness of tight glycaemic control

The existing evidence on the clinical effectiveness of TGC is derived from studies in both critically ill adults and critically ill children. However, to inform whether or not the NHS should provide TGC rather than conventional management (CM) for critically ill children, it is important to consider whether or not the additional costs associated with implementing a TGC protocol are offset by subsequent reductions in resource use and improved health outcomes. Limited evidence suggests that any additional costs associated with implementing a TGC protocol may be relatively small. 36 A post-hoc analysis of the Van den Berge 2001 RCT24,37 for critically ill adults admitted for surgery reported that TGC can reduce ICU LOS, and hence hospital costs. 37 However, this study had several limitations. The study was not designed to measure costs; resource use after the initial hospital episode was not recorded; the study was undertaken in a single centre and lacked generalisability; and it is unclear whether the results apply to other patient groups (e.g. critically ill children, patients not admitted for surgery).

For critically ill children, any assessment of the effect of a TGC protocol compared with CM on resource use and costs is hindered by the lack of evidence from RCTs. The costs of each PICU bed-day are substantial (ranging from £1000 to £5000 per bed-day),38 so if TGC reduces PICU LOS then it would be anticipated to also reduce short-term costs (i.e. those incurred within 30 days of admission to the PICU). It is also plausible that TGC may have an effect on longer-term costs. A previous study reported that around 10% of PICU survivors had residual long-term disability (median follow-up of 3.5 years from initial admission). 39 Therefore, the long-term costs following PICU survival may be substantial, and may be increased if TGC increases PICU survival, or reduced if improved blood glucose control reduces morbidity. There is little available evidence on the net effect of TGC compared with CM on longer-term morbidity and hence costs, either in general or specifically for critically ill children.

The previous evidence, therefore, raises the hypotheses that TGC may have an impact on costs, both in the short term (e.g. 30 days post PICU admission) and in the longer term (e.g. 12 months post PICU admission). It would, therefore, seem important to consider the net effect of TGC on costs alongside any change in clinical outcomes. No previous study has considered the effect of TGC on health service costs for paediatric patients.

The Control of Hyperglycaemia in Paediatric intensive care (CHiP) trial, therefore, sought to address the question of whether or not a policy of strictly controlling blood glucose using insulin in children admitted to PIC reduces mortality and morbidity and is cost-effective.

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

The study was an individually randomised controlled open trial with two parallel arms. The allocation ratio was 1 : 1.

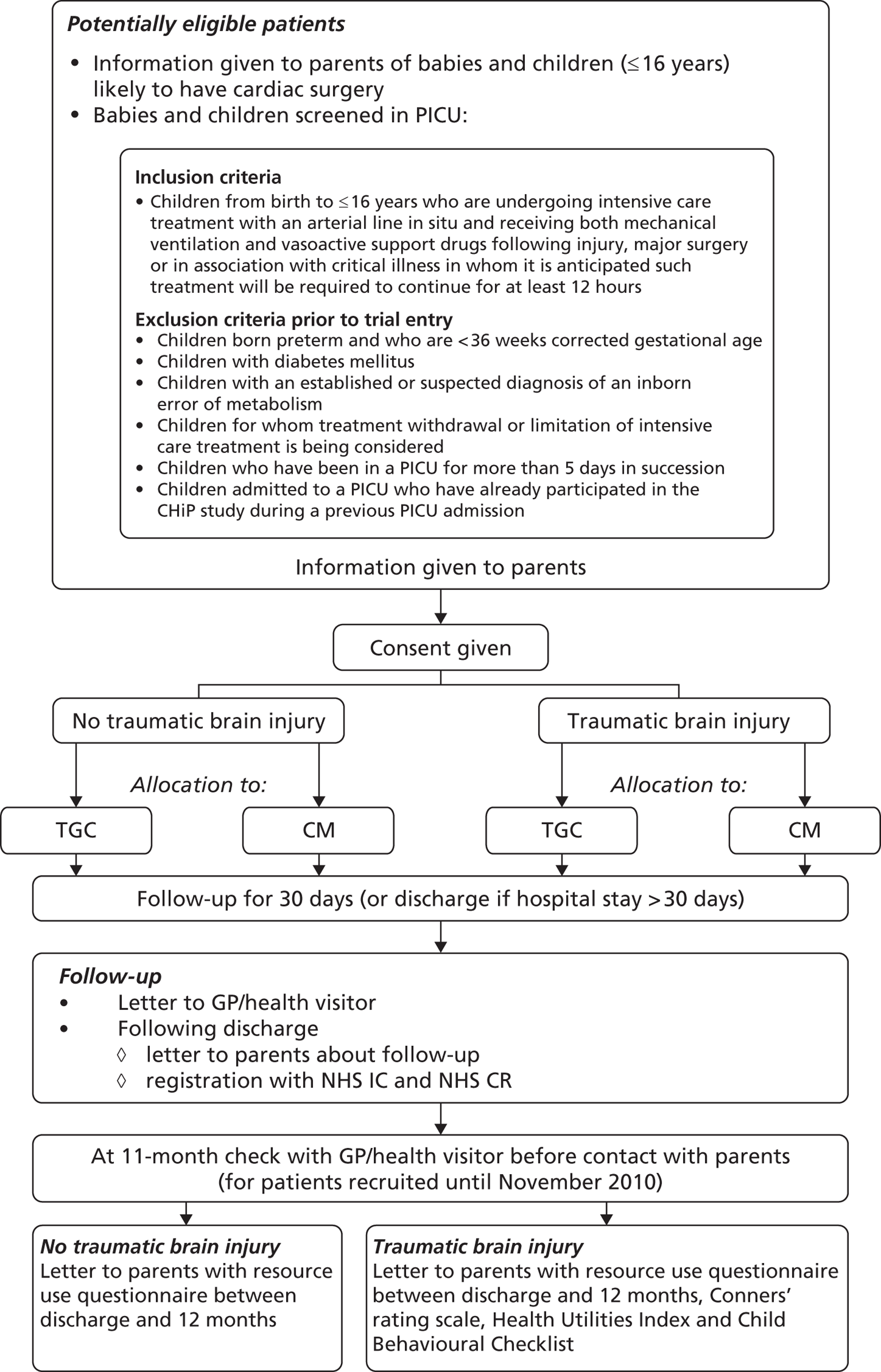

The planned flow of patients through the trial is summarised in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart summarising the planned flow of patients through the trial. CR, Central Register; GP, general practitioner; IC, Information Centre.

Primary hypothesis

The primary hypothesis was that TGC will increase the numbers of days alive and free of mechanical ventilation at 30 days post randomisation (VFD-30) for children aged ≤ 16 years on ventilatory support and receiving vasoactive drugs.

Secondary hypotheses

The secondary hypotheses were as follows:

-

TGC will lead to improvement in a range of complications associated with intensive care treatment.

-

TGC will be cost-effective.

-

The clinical effectiveness of TGC will be similar whether children were admitted to PICU following cardiac surgery or for other reasons.

-

The cost-effectiveness of TGC will be similar whether children were admitted to PICU following cardiac surgery or for other reasons.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

Included were children ≥ 36 weeks corrected gestational age and ≤ 16 years admitted to PICU who had an arterial line in situ and who were also receiving both mechanical ventilation and vasoactive drugs [catecholamines or similar (dopamine, dobutamine, adrenaline, noradrenaline), phosphodiesterase type III inhibitors (milrinone, enoximone), other vasopressors (vasopressin, phenylephrine or similar)] following injury, following major surgery or in association with critical illness, and in whom it was anticipated such treatment would be required to continue for at least 12 hours.

Exclusion criteria prior to trial entry

-

Children born preterm (< 36 weeks corrected gestational age).

-

Children with diabetes mellitus.

-

Children with an established or suspected diagnosis of an inborn error of metabolism.

-

Children for whom treatment withdrawal or limitation of intensive care treatment was being considered.

-

Children who had been in a PICU for > 5 consecutive days.

-

Children admitted to PICU who had already participated in the CHiP study during a previous PICU admission.

Consent

All parents/guardians of children in PICUs who wished to enter their child into the trial were asked by the principal investigator (PI) or delegated investigator to give consent. The trial team recognised that parents were likely to be stressed and anxious, and often had limited time to consider trial entry, but it was considered medically inappropriate to delay the start of treatment. Parents of children listed for cardiac surgery were given information about the trial preoperatively by the PI or delegated investigator, and this afforded families some additional time to think about participation. Provisional consent was sought at this time, and confirmed later if the child was admitted to the PICU. In addition, when possible, older children were given information by the PI or delegated investigator and, if they wished to enter the trial, were asked to assent to their participation in the study. Information sheets and consent forms are shown in Appendix 1.

Patients not entered into the trial received standard care.

Ethical approval

The trial (protocol version 1) was approved by the Brighton East Research Ethics Committee (07/Q1907/24) in 2007. Subsequent amendments are detailed in Appendix 2. The final substantive version (protocol version 6, 23 August 2010) is shown in Appendix 3, and the published version is in Appendix 4.

Allocation of patients

After inclusion in the study, children were randomised to one of two arms:

-

group 1 – CM

-

group 2 – TGC.

To reduce the risk of selection bias at trial entry, allocation was administered through a central computerised 24-hour, 7-day-a-week randomisation service established at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), with telephone backup if required. Minimisation was used, with the first child randomly allocated to a trial arm, and each subsequent child allocated randomly to a trial arm with a weighting in favour of the trial arm that minimises the imbalance on selected key prognostic factors.

The following factors were used:

-

centre

-

age ≤ 1 year compared with between 1 year and ≤ 16 years

-

admitted following cardiac surgery or not

-

for children who were admitted for cardiac surgery, risk-adjusted classification for congenital heart surgery (RACHS1)40 categories 1–4 compared with 5 or 6

-

for children who were not admitted for cardiac surgery, Paediatric Index of Mortality version 2 (PIM2) score at randomisation categorised by probabilities of death of < 5%, 5% to < 15% and ≥ 15%

-

accidental traumatic brain injury (TBI) or not.

Interventions

After inclusion in the study, children were randomised to one of two arms: arm 1 (CM) or arm 2 (TGC).

Arm 1: conventional management

Children in this arm were treated according to a standard approach to blood glucose management. Insulin was given by intravenous infusion in this group only if blood glucose levels exceeded 12 mmol/l on two blood samples taken at least 30 minutes apart and was discontinued once blood glucose fell to < 10 mmol/l.

The protocol for glucose control in this arm is shown in Appendix 3A.

Arm 2: tight glycaemic control

Children in this arm received insulin by intravenous infusion titrated to maintain a blood glucose level between the limits of 4 and 7.0 mmol/l.

The protocol for glucose control in this arm is shown in Appendix 3B.

The protocol for glucose control in arm 2 was carefully designed to achieve tight glucose control while minimising the risk of hypoglycaemia, the principal side effect of insulin therapy. Standard insulin solutions were used and changes in insulin infusion rates were guided by both the current glucose level and its rate of change from previous measurements. Blood glucose levels were routinely measured as in all ICUs using commercially available ‘point-of-care’ blood gas analysers, usually with extended biochemical panels, which utilise very small blood samples, producing results in approximately 1 minute. All of the hospitals in this study have laboratories registered with Clinical Pathology Accreditation (UK) Ltd. The NHS executive accreditation standards specify the requirement for the operation and management of chemical pathology, including the operation of a quality management system for all testing (see http://www.cpa-uk.co.uk). The CHiP protocol advised blood glucose testing using arterial rather than venous blood sampling.

Training in the use of the glucose control protocol was provided before the first patient was enrolled in each collaborating centre and for new staff throughout the trial. The clinical co-ordinating centre team liaised closely with local clinicians to ensure that glucose control algorithms were followed closely and safely.

Blinding

Following random allocation, care-givers and outcome assessors were no longer blind to allocation.

Outcome measures

Primary

Following the influential Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome NETwork (ARDSNET) study,41 VFD-30 was chosen as the primary outcome measure. Death is obviously an important outcome. Mechanical ventilation can be seen as a measure of disease severity, defining the need for complex intensive care. The concept of ventilator-free days (VFDs) brings together these two outcomes. Schoenfeld et al. 42 define VFDs as follows: VFD = 0 if the child dies before 30 days; VFD = 30 – x if the child is successfully weaned from ventilator within 30 days (where x is the number of days on ventilator); or VFD = 0 if the child is ventilated for ≥ 30 days. This use of organ-failure-free days to determine patient-related morbidity surrogate end points in paediatric trials has been supported by influential paediatric triallists in the current low-mortality paediatric critical care environment. 43

Secondary

Clinical outcomes at discharge from paediatric intensive care unit or 30 days (if at paediatric intensive care unit ≥ 30 days)

-

Death within 30 days of trial entry (or before discharge from hospital if duration of hospital stay was ≥ 30 days).

-

Number of days in PICU.

-

Duration of mechanical ventilation.

-

Duration of vasoactive drug usage.

-

Need for renal replacement therapy (RRT).

-

Bloodstream infection (positive cultures associated with two or more features of systemic inflammation or any positive blood culture for fungi).

-

Use of antibiotics for > 10 days.

-

Number of red cell transfusions.

-

Number of hypoglycaemic episodes either moderate (blood glucose < 2.5 mmol/l) or severe (blood glucose < 2.0 mmol/l).

-

Occurrence of seizures (clinical seizures requiring anticonvulsant therapy).

-

Number of children readmitted within 30 days of trial entry.

Thirty-day economic outcomes

-

Hospital LOS within 30 days of trial entry.

-

Hospital costs within 30 days of trial entry.

Twelve-month end points (resource use; survival; attention and behaviour in traumatic brain injury patients; costs)

-

Number of days in PICU, and hospital LOS.

-

Death within 12 months of trial entry.

-

Assessment of attention and behaviour in patients with TBI as measured by the Health Utilities Index [HUI®, Health Utilities Inc. (HUInc), Dundas, ON, Canada; www.healthutilities.com], the King’s outcome scale for childhood head injury (KOSCHI),46 the Child Behavioural Checklist (CBCL) (ASEBA, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT, USA; www.ASEBA.org) and the Conners’ rating scales revised – short version (CRS-R:S). 47

-

Hospital and community health service costs within 12 months of trial.

Lifetime cost-effectiveness

-

Cost per life-year (based on 12-month costs and survival for all cases).

-

Cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY).

-

Incremental net benefits (INB).

-

Cost per disability-free survivor (based on 12-month cost and outcomes data for subgroup with TBI).

Follow-up at 12 months

Parents were informed about the follow-up study at trial entry and asked to give consent for their children to be included. The trial manager at the data co-ordinating centre (DCC) wrote to parents following discharge from hospital to remind them about the follow-up, ask them whether or not they wished to receive the trial results and ask them to keep the DCC informed about any change of address. A separate letter was sent to bereaved parents.

At hospital discharge, parents were given a sample copy of a questionnaire (see Appendix 8) about service use post discharge, and a letter explaining that they would be sent and asked to complete the same questionnaire at the 12-month follow-up. To help the parents record and later recall use of any NHS services, at hospital discharge parents were also given a diary (see Appendix 5). The purpose of this diary was to allow parents to prospectively note resource use and to help them to remember it when the time came to complete the questionnaire. They were not asked to return the diary. After 11 months, following checks with the patient’s general practitioner (GP) to find out whether or not the patient was still alive, and whether or not the GP judged it was appropriate for the parents to receive the service-use questionnaire, the trial manager sent the questionnaire to the parents of those patients who met the eligibility criteria. For those parents who did not respond within 4 weeks, a first reminder was issued by post, and, if there was still no response after a further 4 weeks, the parent was contacted by telephone. Follow-up ended when a postal questionnaire was returned either complete or blank, when a refusal was obtained or after both reminders had been issued.

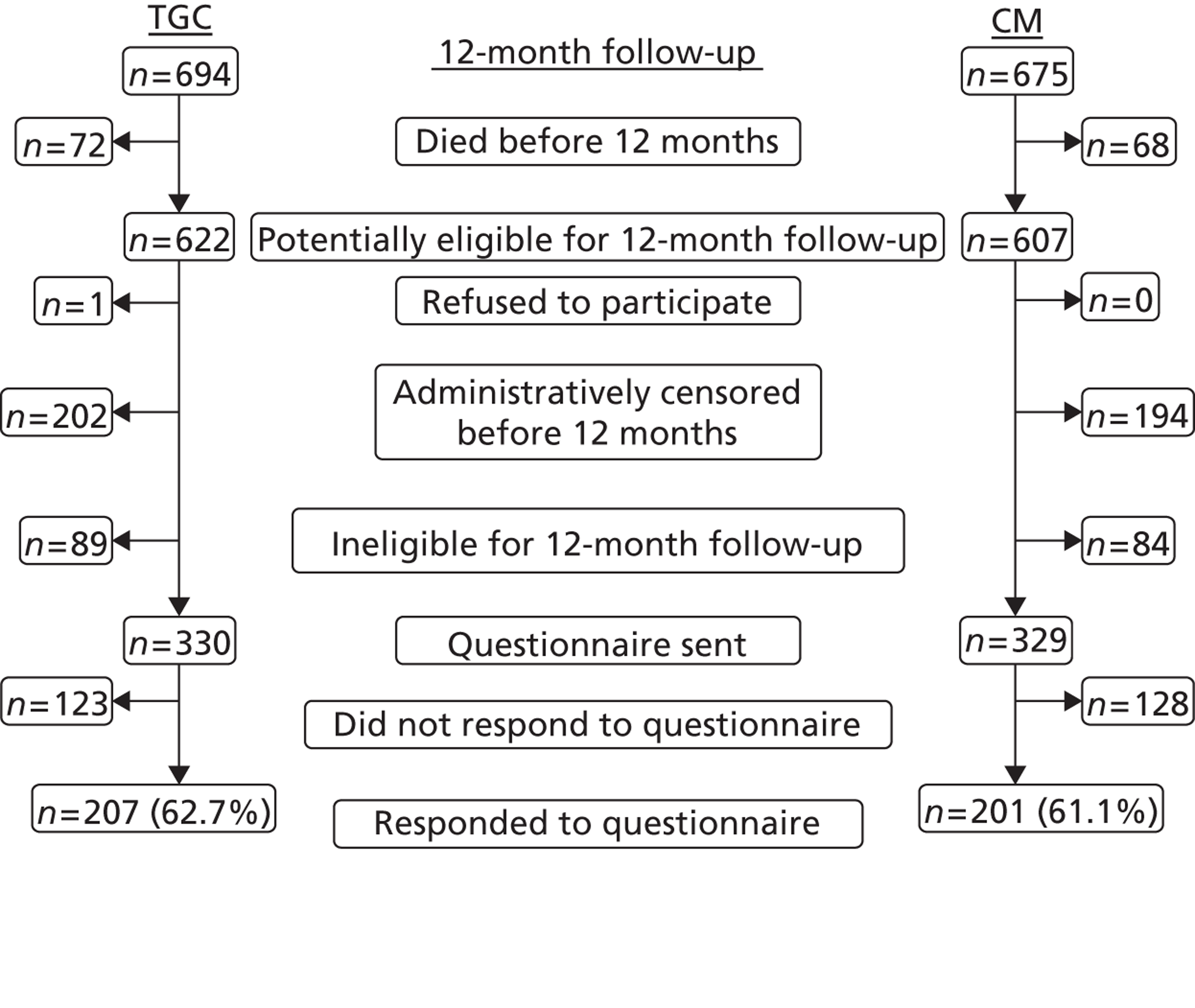

Because of the slower than expected recruitment rates, the funder, the National Institute for Health Research’s Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme, agreed a funding extension, but reduced the time period for which patients could be followed up, that is patients randomised after 30 October 2010 were ineligible for this 1-year follow-up. This also had implications for the analysis of total LOS and costs up to 12 months (see below).

Follow-up of traumatic brain injury subgroup

This subgroup is more likely to have longer-term morbidity. Although there were unlikely to be large numbers of such children in the trial, parents of children (aged ≥ 4 years) in this subgroup were asked to provide additional information at 12 months (for patients recruited until 2010), regarding overall health status, global neurological outcome, and attention and behavioural status. Further details are given in Appendix 6.

Survival up to 12 months

If parents gave their consent, all children who survived to hospital discharge were followed up for up to 12 months post randomisation to determine mortality using information from the participating PICUs, the children’s GPs or the NHS Information Centre and the NHS Central Register. The NHS number was used to ensure accurate linkage to national death registration using the ‘list cleaning’ service of the Medical Research Information Service at the NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care.

Adverse events and safety reporting

The Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Trust, as sponsor of this study, had the responsibility of ensuring arrangements were in place to record, notify, assess, report, analyse and manage adverse events in order to comply with Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004.

All sites involved in the study were expected to inform the chief investigator and lead research nurse of any serious adverse events (SAEs)/reactions within 24 hours so that appropriate safety reporting procedures could be followed by the sponsor.

It was therefore important that all site investigators involved in the study were aware of the reporting process and timelines. Details of the mandatory adverse event and safety reporting requirements are detailed in Appendix 3C.

Expected side effects

All adverse events judged by either the investigator or the sponsor as having a reasonable suspected causal relationship to insulin therapy qualified as adverse reactions. Whereas any suspected, unexpected, serious adverse reactions (SUSARs) involving insulin therapy were reported according to the timelines for SUSARs, expected side effects of insulin were reported in the annual safety report unless serious enough to warrant expedited reporting.

Hypoglycaemia is the principal side effect of insulin therapy. Moderate and severe hypoglycaemia were defined as a blood glucose < 2.5 mmol/l and < 2 mmol/l48 respectively. The insulin administration protocols aimed to achieve blood glucose control with the lowest possible incidence of hypoglycaemia and the avoidance of neuroglycopenia (hypoglycaemia associated with neurological symptoms and signs such as seizures and cerebral oedema). By definition, children in the TGC arm were at increased risk of hypoglycaemia because the target range in this arm of the study (i.e. blood glucose 4–7 mmol/l) was much closer to the trial’s predefined hypoglycaemic thresholds than the 10–12 mmol/l therapeutic window used as a target for the control of blood glucose in the CM arm of the study. The principal operating procedure used to avoid hypoglycaemia was blood glucose measurement every 30 minutes when insulin was first administered, and then every 45 minutes until blood glucose was controlled within the required range and stable glucose and insulin infusion rates were achieved, and then hourly once stabilised.

Insulin is reported to occasionally cause a rash which may be associated with itching.

Data collection

To minimise the data collection load for busy units, the trial collaborated with the Paediatric Intensive Care Audit Network (PICANet)49 to make best use of the established data collection infrastructure which exists in all PICUs in the UK. The PICANet data set included many of the items being used in the trial and these data were transmitted from the participating centres to the DCC electronically using strong encryption. The remaining short-term data items were collected locally by the research nurses, and those for the longer-term follow-up were collected separately by telephone and postal questionnaires. These data were used to report the mean number of inpatient days following readmissions after 30 days, and the mean outpatient and community service use at 12 months for all patients randomised. The main data collection forms, questionnaires and covering letters are shown in Appendix 7.

All case report form (CRF) data were double entered onto electronic database storage systems at the DCC.

Sample size

The primary outcome was VFD-30. A difference of 2 days in VFD-30 was considered clinically important. Information from PICANet from a sample of PICUs for 2003–4 provided estimates that the mean VFD-30 in cardiac patients is 26.7 days, with a SD of 4.2 days. The corresponding figures for non-cardiac patients were a mean of 22.7 days and a SD of 6.8 days. As the SD is estimated with error, to be conservative a SD nearer 5.5 days for the cardiac and 8 days for the non-cardiac patients was assumed. There were likely to be more non-cardiac than cardiac patients eligible for the trial. An overall SD across both cardiac and non-cardiac strata of 7 days was therefore assumed. Assuming this was the same in both trial arms, and taking a type I error of 1% (with a two-sided test), a total sample size of 750 patients would have 90% power to detect this difference. Although minimal loss to follow-up at 30 days could be assumed, there was the possibility of some non-compliance (some patients allocated to TGC not receiving this, and some allocated to CM being managed with TGC). The target size was therefore inflated to 1000 to take account of possible dilution of effect.

As information from PICANet indicated that there were differences in outcome between cardiac and non-cardiac patients, not merely in VFD-30 but also in 30-day mortality (3.4% vs. 20%) and mean duration of ventilation (3.7 vs. 8.0 days, survivors and non-survivors combined), the trial was powered to be able to detect whether or not any effect of tight glucose control differed between the cardiac and non-cardiac strata. To have 80% power for an interaction test to be able to detect a difference of 2 days in the effect of intervention between the strata at the 5% level of statistical significance, the sample size was increased to 1500. If the interaction test was positive, this size would allow assessment of the effect of TGC separately in the two strata.

Centres

The following PICUs in the UK planned to recruit patients into the CHiP trial: Birmingham Children’s Hospital; Bristol Royal Hospital for Children; Great Ormond Street Hospital; Leeds General Infirmary; University Hospitals of Leicester – Glenfield Hospital and Leicester Royal Infirmary; Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Trust (Royal Brompton Hospital); Royal Liverpool Children’s NHS Trust; Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital; St George’s Hospital; St Mary’s Hospital; Sheffield Children’s NHS Foundation Trust; Southampton General Hospital; and University Hospital of North Staffordshire.

Recruitment rate

There were estimated to be approximately 1300 eligible cardiac and 1550 eligible non-cardiac patients per year in collaborating PICUs at the start of the trial. About half of those eligible were anticipated to be recruited into the trial, predicting that the overall total sample size of 1500 would be accrued by September 2011.

Type of analysis for clinical outcomes at discharge from paediatric intensive care unit or at 30 days

Primary analyses were by intention to treat. For the primary outcome, linear regression models were used to estimate a mean difference in VFD-30 between the two arms of the trial. For the secondary outcomes, appropriate generalised linear models were used to examine the effect of the intervention. Odds ratios and mean differences are reported with 95% CIs. Where there was evidence of non-normality in the continuous outcome measures, non-parametric bootstrapping, with 1000 samples, was used to estimate the effect of the intervention50 and bias-corrected CIs are reported.

Secondary analyses included the following prespecified subgroup analyses: cardiac surgical compared with non-cardiac cases, age (< 1 year or between 1 and ≤ 16 years), TBI or not, RACHS1 (cardiac cases) (groups 1–4 vs. 5 and 6), PIM2 risk of mortality (non-cardiac cases) (categorised by probabilities of death of < 5%, between 5% and < 15% and ≥ 15%), run-in cases (first 100 randomised) compared with non-run-in cases. Likelihood ratio tests for interactions were used to assess whether or not there was any difference in the effect of the intervention in the different subgroups. Where stratified results are presented, the effects in the different strata are estimated directly from the regression model with the interaction term included.

Frequency of analysis

An independent Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) planned to review, in strict confidence, data from the trial approximately half-way through the recruitment period. The chair of the DMEC could also request additional meetings/analyses. In the light of these data, and other evidence from relevant studies, the DMEC would inform the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) if in their view:

-

There was proof that the data indicated that any part of the protocol under investigation was either clearly indicated or clearly contraindicated for either all patients or a particular subgroup of patients, using the Peto and Haybittle rule. 51,52

-

It was evident that no clear outcome would be obtained with the current trial design.

-

They had a major ethical or safety concern.

Except for those who supplied the confidential information, everyone (including the TSC, funders, collaborators and administrative staff) remained ignorant of the results of the interim analysis

Economic evaluation

Overview

Cost–consequence analyses were undertaken to assess whether or not any additional costs of achieving TGC were justified by subsequent reductions in hospitalisation costs and/or by improvements in patient outcomes. The evaluations were conducted in two phases: in the first phase, all hospital costs at 30 days post randomisation were compared across randomised arms alongside 30-day clinical outcomes; and, in the second phase, cost and outcomes at 12 months post randomisation were compared between arms, and used to project relative cost-effectiveness over the lifetime. This aspect of the costing study took the health and personal services perspective recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 53

Measurement of resource use up to 30 days post randomisation

The trial CRFs recorded the number of inpatient days for the index hospital episode following randomisation, up to day 30. Within this index hospital episode, the CRFs recorded the number of PICU days spent on the unit where the patient was randomised, and any subsequent PICU bed-days following transfers to other hospitals. The CRFs also recorded the LOS on general medical (GM) wards, both within the acute hospital where the patient was randomised and following transfer to other hospitals. The number of day-case admissions was also noted. The total LOS for the initial hospital episode was calculated as the sum of the LOS at PICUs and GM wards up to a maximum of 30 days following randomisation. Any readmissions within 30 days to the PICU where the child was randomised were also recorded. The LOS following these readmissions was added to the total number of days for the initial episode, to give the total hospital LOS up to 30 days post randomisation.

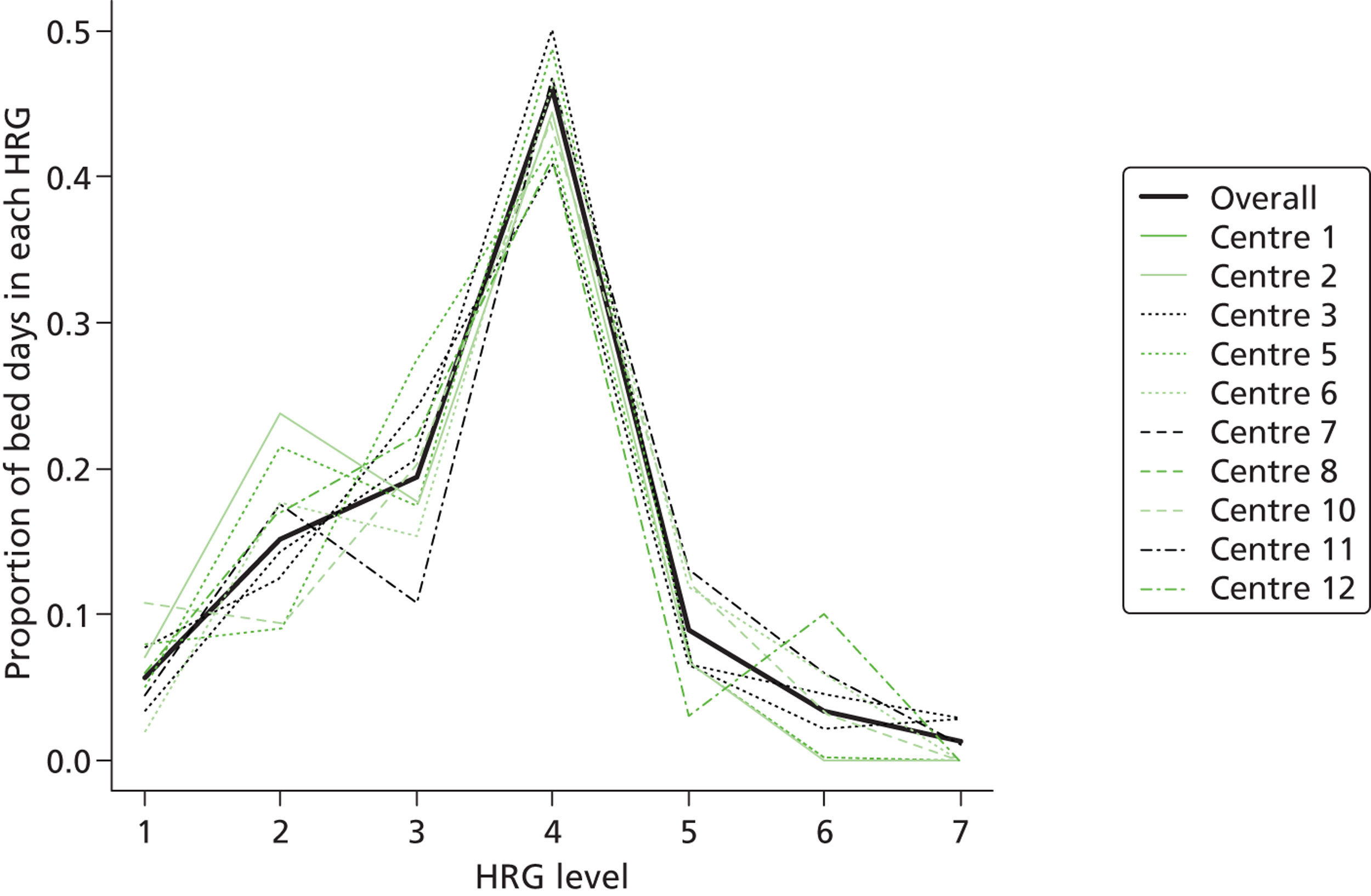

Data on the level of care for PICU bed-days were available through routine collection of the Paediatric Critical Care Minimum Data Set (PCCMDS)54 in 11 of the participating centres via the PICANet database. The PCCMDS consists of 32 items recorded for each PICU bed-day that can be used to define the level of care, that is the paediatric critical care health-care resource group (HRG). 55 The PCCMDS data items were extracted for each PICU bed-day after randomisation. Each PICU bed-day was then assigned to the appropriate HRG (HRG, version 4), using the HRG grouper. 55 [The HRG classification includes items for primary and secondary diagnosis, OPCS (Office of Population, Censuses and Surveys’ Classification of Surgical Operations and Procedures) codes for high-cost drugs, and fields for critical care activity.] Table 1 lists the HRG classifications for PIC with examples of procedures for each category. Figure 2 reports the distribution of PICU bed-days across HRG categories for the 8954 PICU bed-days that were grouped during the first 30 days, both overall and for each site. The most common HRG category was ‘intensive care basic enhanced’ [HRG level 4 (HRG4)]. For 1862 bed-days in the 11 sites that provided information, PCCMDS data were missing or incomplete, and, for three centres (254 bed-days), no PCCMDS information was available. All these bed-days were assigned to the modal HRG category (HRG4) (see Sensitivity analysis). For a total of 326 bed-days, the activity reported was categorised by the HRG grouper as ‘not critical care activity’, and designated as bed-days on GM wards.

| HRG Level | Critical care unit | Examples of procedures |

|---|---|---|

| HRG1 | HDU basic | ECG or CVP monitoring, oxygen therapy plus pulse oximetry |

| HRG2 | HDU advanced | Non-invasive ventilation, acute haemodialysis, vasoactive infusion (inotrope, vasodilator) |

| HRG3 | ICU basic | Invasive mechanical ventilation, or non-invasive ventilation + vasoactive infusion + haemofiltration |

| HRG4 | ICU basic enhanced | Invasive mechanical ventilation + vasoactive infusion, or advanced respiratory support |

| HRG5 | ICU advanced | Invasive mechanical ventilation or advanced respiratory support + haemofiltration |

| HRG6 | ICU advanced enhanced | Invasive mechanical ventilation or advanced respiratory support + burns > 79% BSA |

| HRG7 | ICU ECMO/ECLS | ECMO or ECLS, including VAD or aortic balloon pump |

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of paediatric critical care bed-days within 30 days post randomisation across HRG categorises for CHiP patients. Proportion of paediatric critical care bed-days within each HRG category, overall and by centre.

Unit costs

Unit costs were taken from the 2011 NHS Payments by Results (PbR) database, which includes reference costs returns from each NHS trust. 38 For all critical care admissions, each bed-day was costed with the corresponding unit cost per bed-day from the PbR database. 38 The unit cost of bed-days classified as ‘intensive care basic’ was taken as the average across all CHiP centres that returned reference costs for that HRG category (HRG3, Table 2) (see Sensitivity analysis). Few NHS trusts returned reference cost information for all seven paediatric critical care HRGs, so the relative unit costs for all HRGs apart from ‘intensive care basic’ (HRG3) were calculated by multiplying the unit costs for HRG 3 by the relative cost ratio from a previous detailed multicentre PICU costing study (see Sensitivity analysis). 56 This previous study assessed the relative staff input according to HRG category and reported the cost ratios listed (see Table 2). Table 2 reports the PICU costs taken for the base case and subsequent sensitivity analyses (SAs). The unit costs for GM bed-days and day-case admissions were taken from previous studies (Table 3). 58,59

| HRG | Cost ratios (NHS information centre) | PCC reference costs (n = 11 CHiP centres) | PCC reference cost for ICU basic weighted by cost ratios |

|---|---|---|---|

| HDU basic | 0.75 | 1112 | 1324 |

| HDU advanced | 0.91 | 1315 | 1607 |

| ICU basic | 1 | 1765 | 1765 |

| ICU basic enhanced | 1.22 | 2065 | 2154 |

| ICU advanced | 1.4 | 1998 | 2472 |

| ICU advanced enhanced | 2.12 | 3061 | 3743 |

| ICU ECMO/ECLS | 3.06 | 4026 | 5402 |

| Personal or social service | Unit costa |

|---|---|

| Hospital inpatient bed-day | 252 |

| Hospital outpatient visit | 147 |

| Day cases | 202 |

| GP contact | 47 |

| GP practice nurse contact | 11 |

| Health visitor contact | 11 |

| District nurse contact | 11 |

| Social worker contact | 9 |

| Speech and language therapist contact | 8 |

| Occupational therapist contact | 10 |

| Physiotherapist contact | 8 |

| Children’s disability team contact | 7 |

| Hospital discharge co-ordinator contact | 6 |

| Child psychologist contact | 15 |

| Dietitian contact | 8 |

| Mental health service contact | 27 |

| Specialist paediatric nurse contact | 14 |

| School nurse contact | 3 |

The base-case analysis assumed that all resource use required implementation of the TGC protocol or management of side effects and was recognised by the HRG categorisation, as including any additional resources could represent double-counting. A SA was also undertaken to investigate whether or not the results were robust to an alternative approach whereby the resources and unit costs of implementing the TGC protocol and managing hypoglycaemic events were considered as additional unit costs (see Sensitivity analysis). To inform these SAs, information was collected on the nurse time, clinical time, number of blood gas analyses and insulin required in managing a subsample of patients in either group during the first 48 hours in critical care after randomisation. Soluble insulin (Actrapid®, Novo Nordisk Limited) was assumed to be used over a 24-hour period, the unit costs of which were taken from the British National Formulary. 60 The additional resources required in managing patients who in the CRFs were recorded as having moderate or severe hypoglycaemic episodes were also considered. All unit costs were reported in 2010–11 prices.

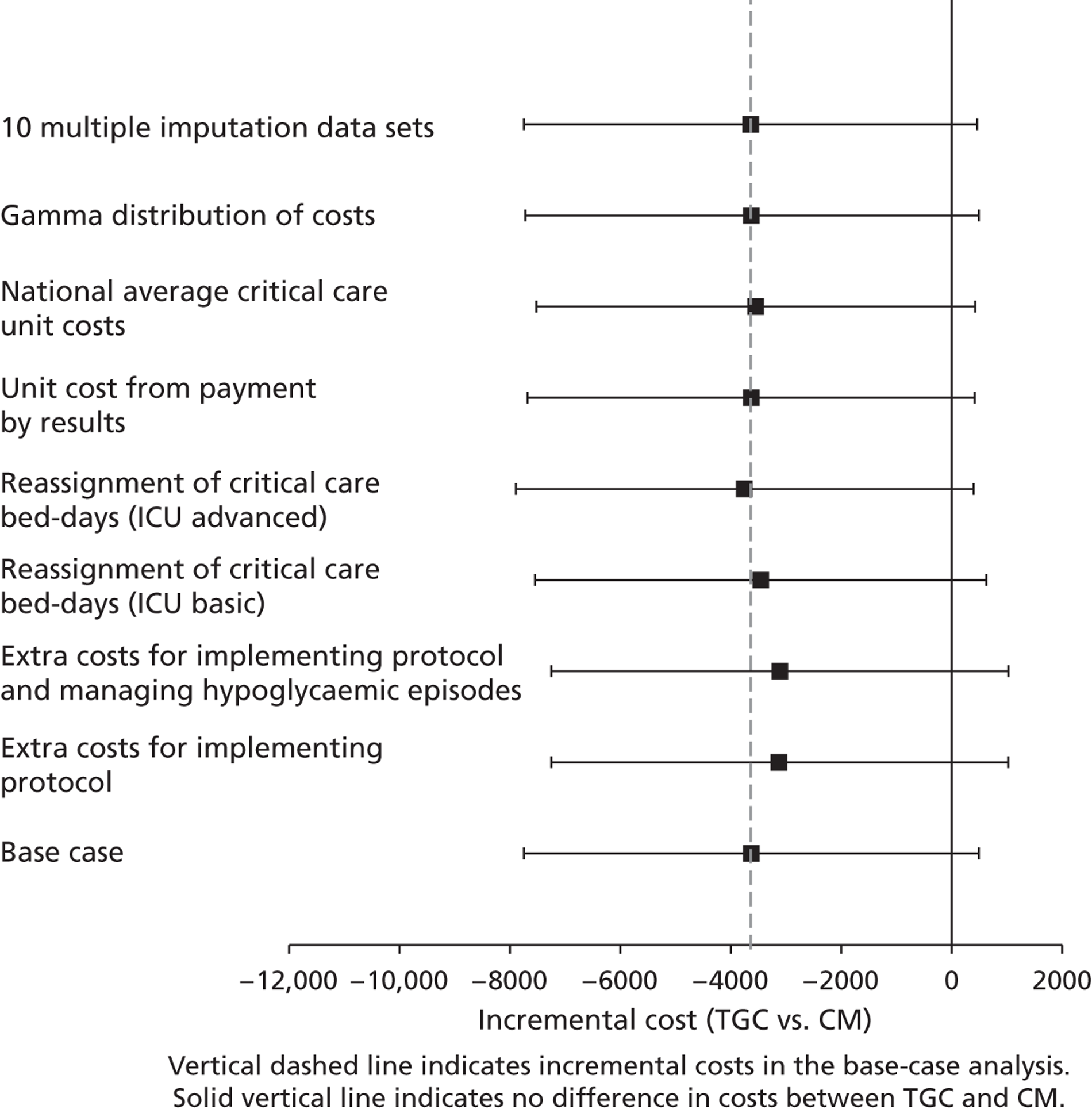

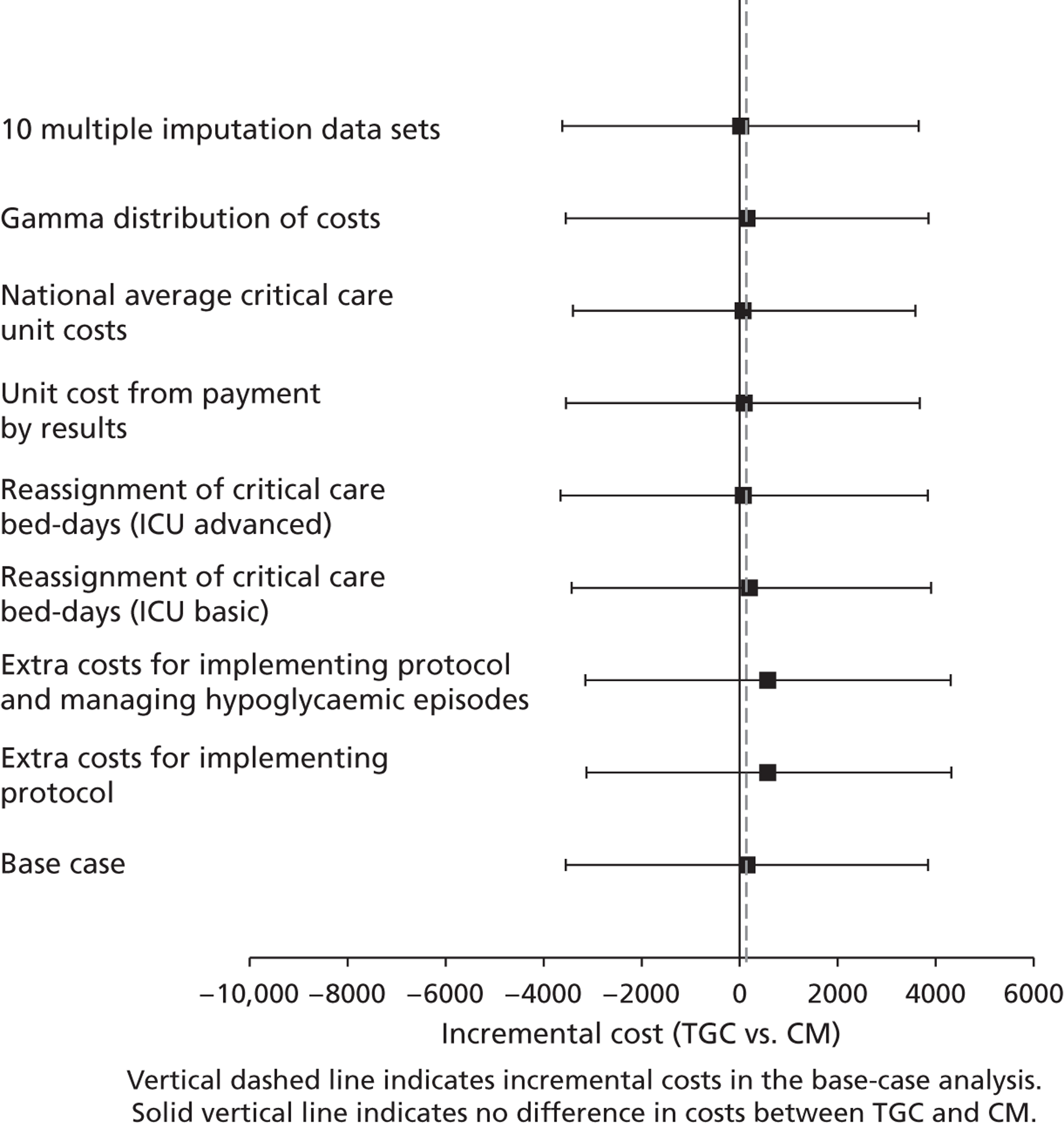

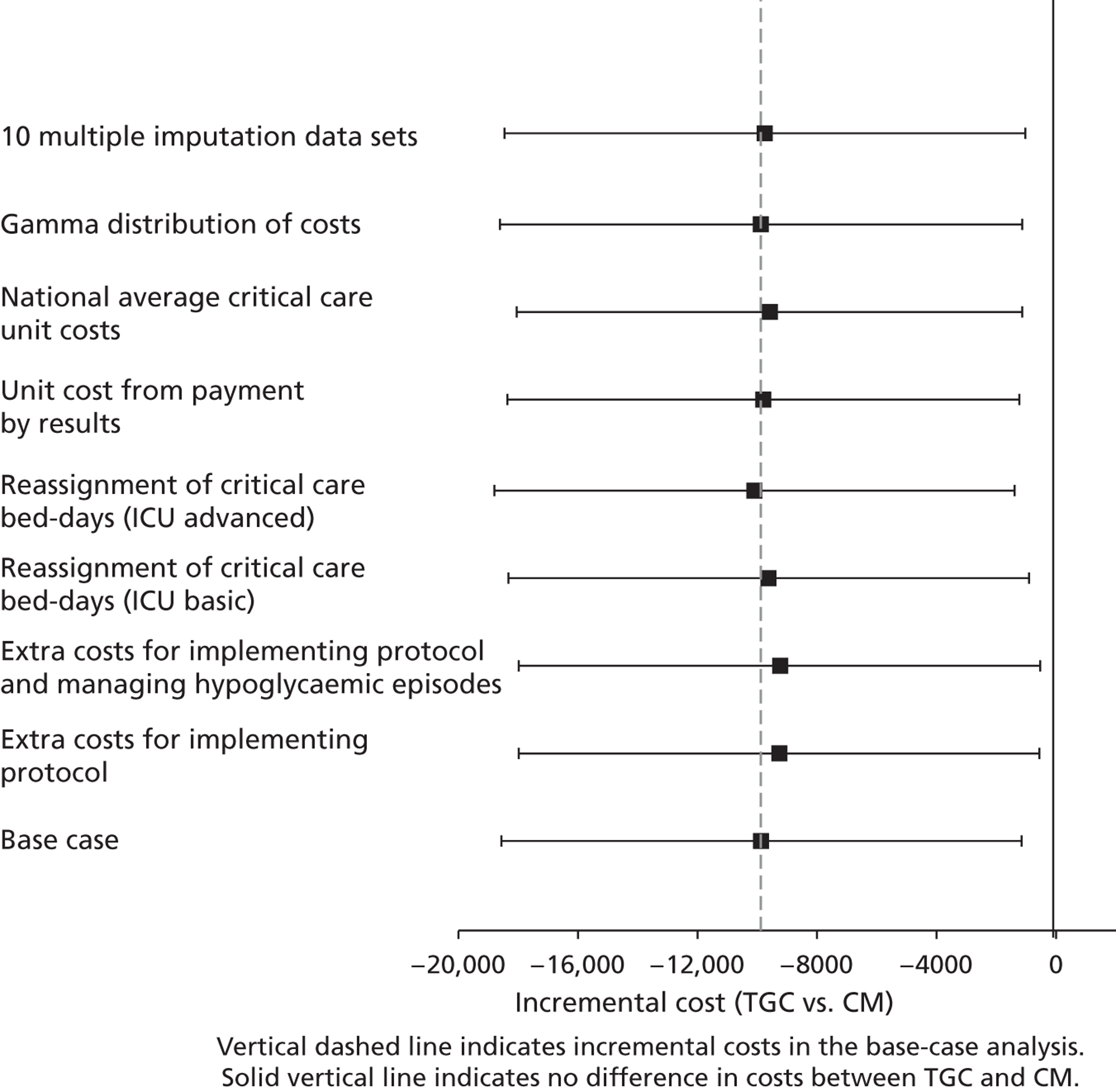

Statistical analysis for the 30-day economic end points

All the economic analyses were based on the treatment arms as randomly allocated (‘intention to treat’). Mean differences between treatment arms in resource use (e.g. total LOS summed across the index hospital episode and readmissions to PICU within 30 days) were reported for the overall cohort, and separately for subgroups admitted following either cardiac surgery (cardiac surgery) or no cardiac surgery (non-cardiac). Incremental costs were estimated as the mean difference (95% CI) in total costs at 30 days using ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analysis, with randomised arm as the only independent variable. To test the hypothesis that incremental costs differed according to cardiac surgery status, the OLS regression was repeated, including independent effects for randomised arm, cardiac surgery status and an interaction term for randomised arm by cardiac status. A likelihood ratio test was then employed to compare the model fit to that from an OLS model that included randomised arm and cardiac surgery status as independent effects. Finally, the above OLS regression models that included the interaction terms for randomised arm by cardiac status were used to report the incremental costs for each subgroup (cardiac surgery, non-cardiac).

Resource-use measurement between 30 days and 12 months post randomisation

Index hospital episode and readmissions to the paediatric intensive care unit within 30 days post randomisation

Information on PICU days and hospital LOS for up to 12 months was collected from the CHiP trial CRFs. For CHiP patients whose index hospital episode exceeded 30 days, the CRFs collected information on their continuing hospital stay up to a maximum of 12 months. The CRFs also noted any readmissions that were within 30 days to the PICU where the patient was randomised. For both initial hospital episodes and readmissions, the CRFs recorded subsequent transfers to other hospitals. For initial hospital admissions and readmissions, the CRFs distinguished between the total LOS in PIC and those on GM wards, and day cases. These data were used to report the total days in PIC and on GM wards up to 12 months. The last time point at which 12-month follow-up data were available from the CRFs was 31 March 2012, so, for patients randomised after 1 April 2011, it was possible that an index admission or a readmission was censored before 12 months post randomisation.

Other hospital and community service use

The postal questionnaires were used to collect information on hospital and community service use, from discharge from the index hospital episode up to 12 months post randomisation. This questionnaire was based on one previously developed for neonatal intensive care,61 and modified to include those items of service use most relevant to patients discharged from PIC. The items for the questionnaires were further amended following comments from a panel of parents from the Medicines for Children Research Network (MCRN). The final questionnaire is appended61 (see Appendix 8). The items considered covered readmissions to PIC other than those collected on the CRFs, readmissions to GM wards, outpatient visits, and contacts with the GP, practice nurse, health visitor, social worker, speech and language therapist and child psychologist.

Unit costs and calculation of total 12-month costs per patient

For PICU bed-days from 30 days to 12 months post randomisation, PCCMDS information was not available for categorising each bed-day into the appropriate HRG4 category. Each PICU bed-day was, therefore, assumed to be in the modal HRG4 category (intensive care basic enhanced) and assigned the corresponding unit cost. GM bed-days and outpatient and community service use were valued with national unit costs (see Table 3). Total costs for each patient were then calculated by summing the costs of all hospital and community health services used.

Statistical analysis for the 12-month end points (resource use, survival, costs)

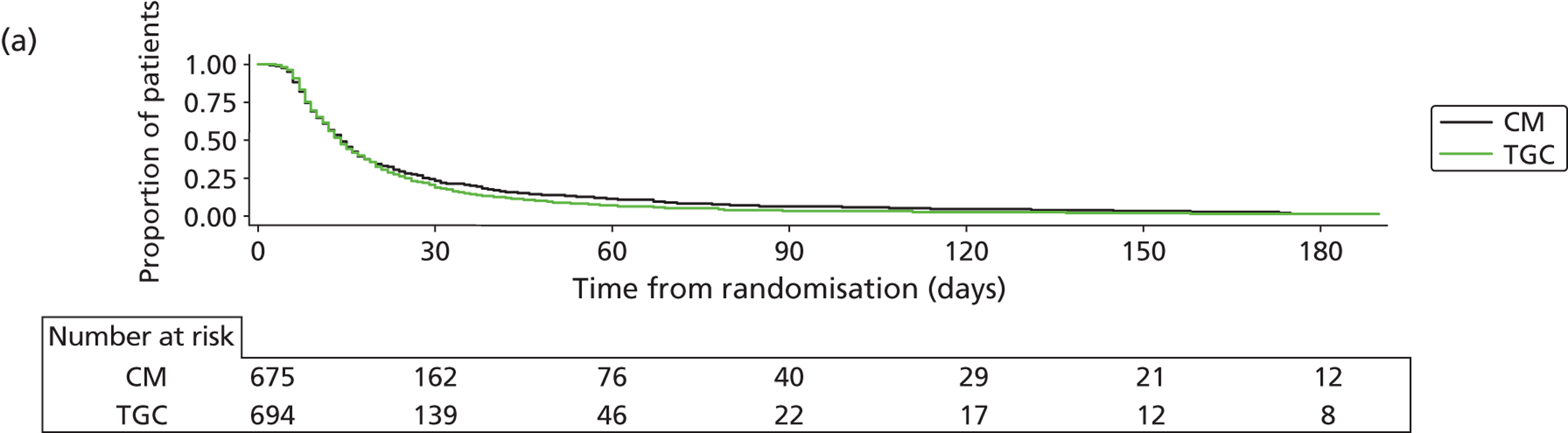

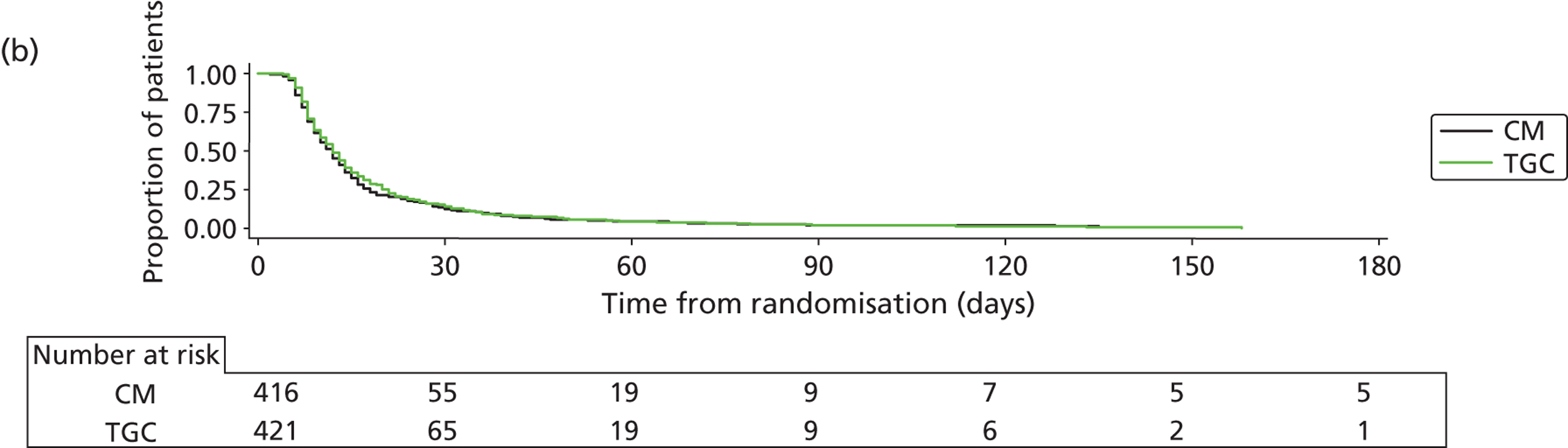

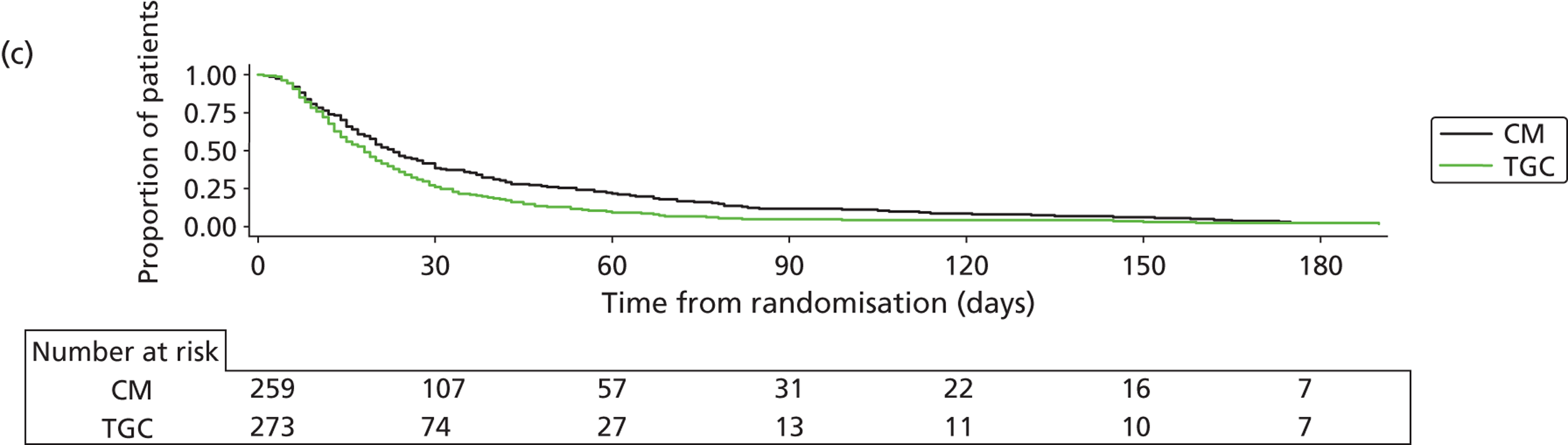

Mean differences in resource use (e.g. days in PICU, on GM wards and combined) between the randomised arms were reported. The proportion of patients still in hospital (index admission) was plotted for up to 12 months post randomisation. Each of these items was reported for the overall cohort and separately for those admitted for cardiac surgery or not.

The effect of TGC compared with CM on 12-month mortality and cost was then reported, overall and for the cardiac and non-cardiac stratum. For a subsample of patients, 12-month health and community cost data were censored. Other patients were judged ineligible or did not respond to the 12-month service-use questionnaire. The cost data that were either censored or missing at 12 months were addressed with multiple imputation (MI). 62–64 The imputation models included baseline covariates, the number of ventilated days, total LOS and costs at 30 days, and information on 12-month costs for those individuals for whom this end point was observed. Each imputation model assumed that the data were ‘missing at random’, that is conditional on the variables included in each imputation model. 62 MI was employed based on predictive mean matching,65 which offers relative advantages when dealing with data, such as costs that have irregular distributions. 66

Incremental costs were estimated as the mean difference (95% CI) in total costs at 12 months post randomisation with OLS regression analysis. Incremental costs were reported both overall and for the cardiac and non-cardiac strata.

As the missingness pattern may differ across treatment groups, separate imputation models were specified for each comparator. Five imputed data sets were generated for the imputation models (see Sensitivity analysis). After imputation, the analytical models were applied to estimate incremental costs overall, and by subgroup to each imputed data set. Each of the resultant estimates was combined with Rubin’s formulae,62 which recognise uncertainty both within and between imputations. All MI models were implemented in R with multivariate imputation by chained equations. 67

Sensitivity analysis

The base-case cost analysis made the following assumptions that a priori were judged potentially important: (1) all relevant resource use relating to implementing the TGC protocol and managing side effects was recognised by the paediatric critical care HRG categorisation; (2) PICU bed-days for which PCCMDS data were missing or incomplete were in the HRG category for ‘basic enhanced intensive care’ (HRG4); (3) the cost ratios from a previous PICU costing study reflected the relative costs; (4) the average unit costs for HRG4 were taken just from CHiP sites; (5) the regression models had residuals that were normally distributed.

The following separate, univariate, SAs tested whether or not the results were robust to the following alternative assumptions.

-

Inclusion of the costs of implementing the TGC protocol and managing hypoglycaemic episodes as specific additional items. The HRG categorisation could be insensitive to the resource use required to implement the TGC protocol, and for managing hypoglycaemic episodes. SAs were therefore conducted that considered any additional staff times, blood gas analyses and insulin required for:

-

implementing the TGC protocol compared with CM

-

as for i. but also including any further costs for managing the moderate or severe hypoglycaemic episodes recorded.

-

-

Reassignment of PICU bed-days without HRG classification to either:

-

‘ICU basic’ (HRG3); or

-

‘ICU advanced’ (HRG5).

-

The unit costs for each level of care in PICU were taken directly from PbR. Rather than using the cost ratios, unit costs from PbR were used for each HRG level.

-

PICU costs were taken as national averages: the unit costs of PIC were taken as averages from all centres that returned the relevant costs in PbR including non-CHiP sites.

-

Assume gamma rather than normal distributions for costs at 30 days and 12 months. The assumption that costs are normally distributed may not be plausible,68 so here costs were allowed to follow a gamma distribution. 69

-

-

The MI was rerun with 10 imputations. In some circumstances, five imputations may be insufficient to test the impact of increasing the number of imputations; the imputation models were rerun but with 10 imputations.

For each SA, the effect of TGC compared with CM on 12-month costs was reported, overall and for the cardiac and non-cardiac subgroups.

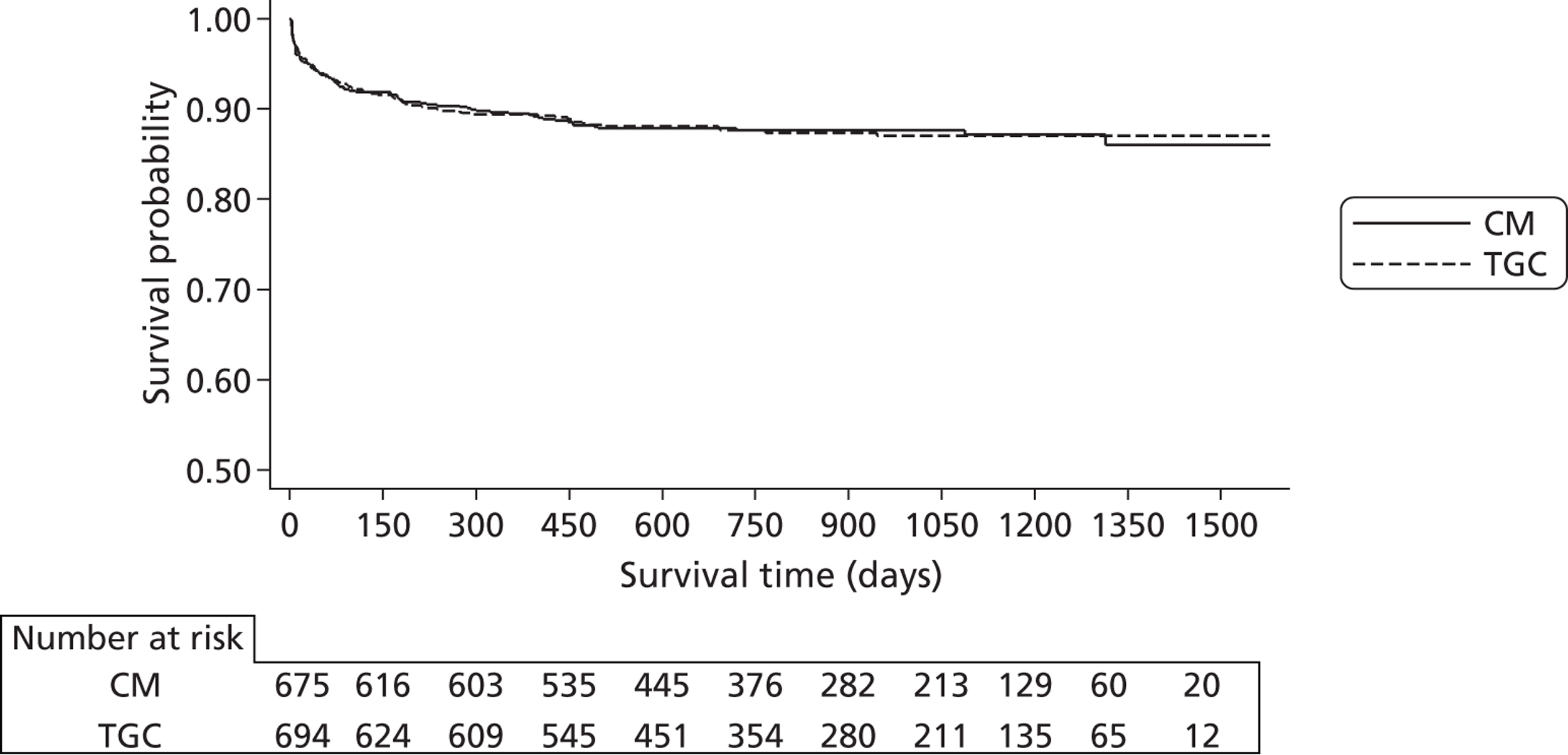

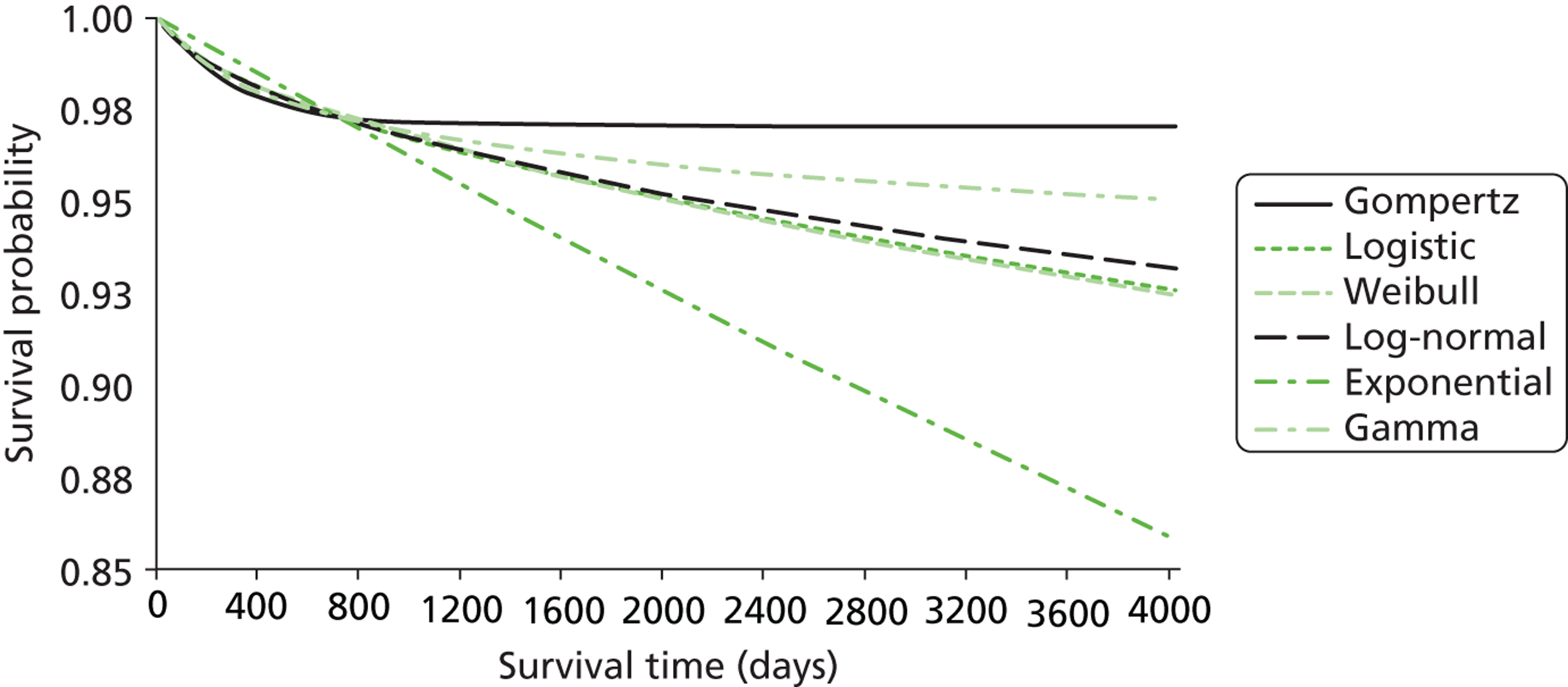

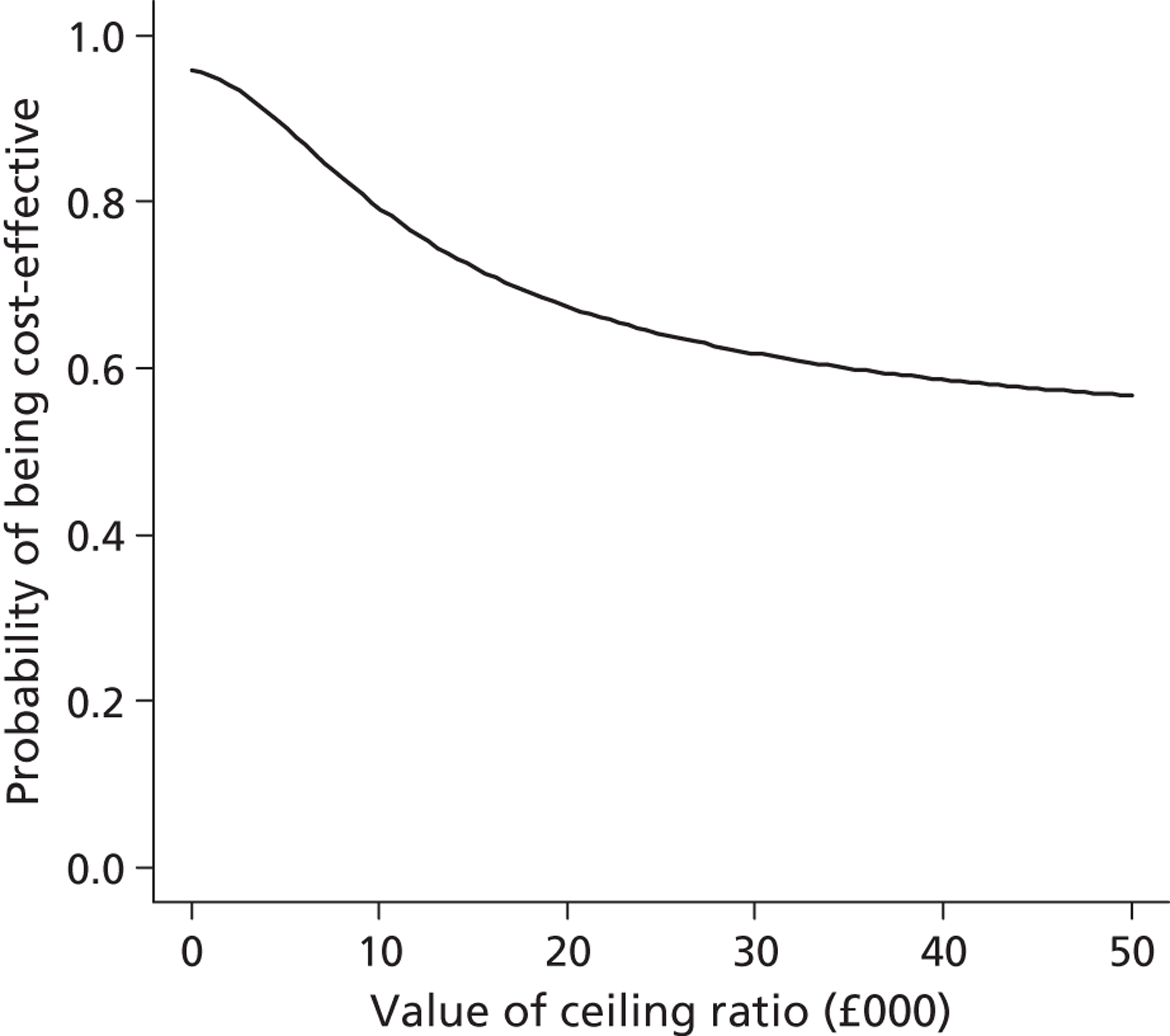

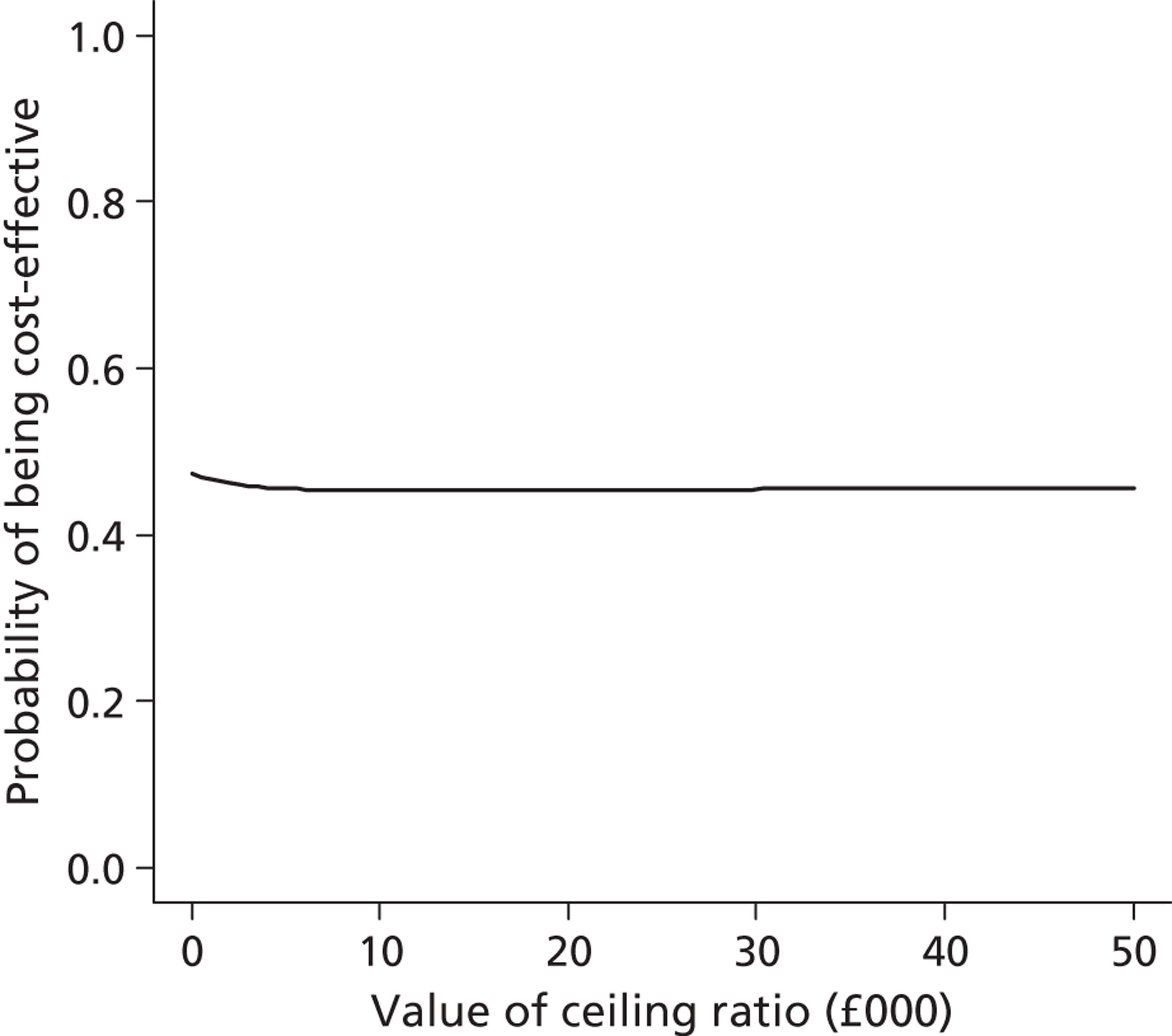

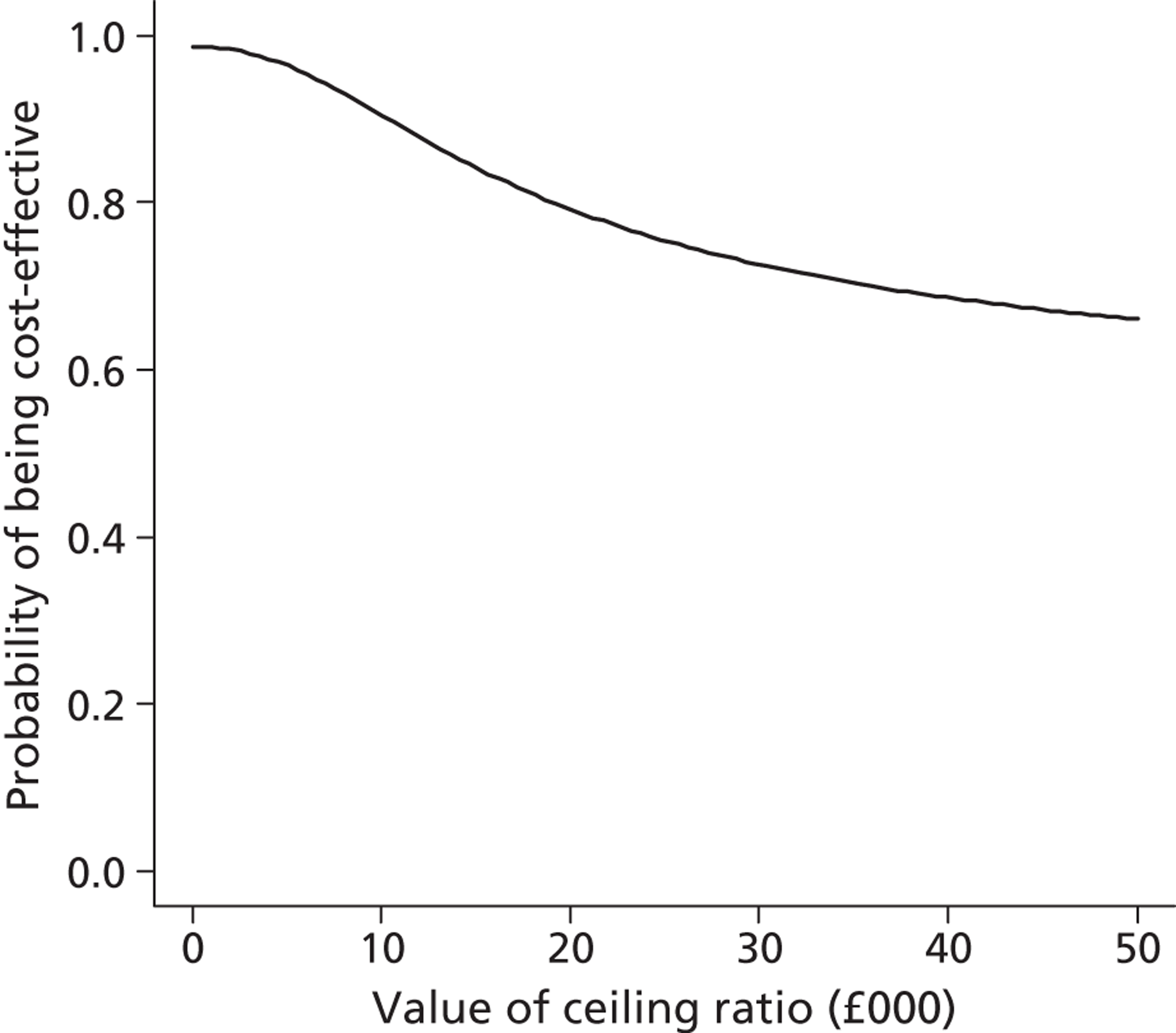

Lifetime cost-effectiveness analysis

The cost and outcome data collected at 1 year were used to project the impact of the intervention on longer-term costs and outcomes. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were plotted out to the maximum time of follow-up, overall and then separately for cardiac and non-cardiac cases. Alternative parametric functions were considered for extrapolating mortality up to 5 years, by fitting commonly recommended alternative distributions to the CHiP survival data, excluding the first 365 days post randomisation, as the event rate during this early period was anticipated to be atypical and not to provide an appropriate basis for extrapolation. The base-case analysis used the ‘most appropriate’ parametric survival curves judged according to which gave the best fit to the observed data and the most plausible extrapolation relative to the age- and gender-matched general population. 70 Survival extrapolations were considered for the first 5 years from randomisation, as this was anticipated to be the period over which the risk of death would be higher than that for the age- and gender-matched general population. After 5 years post randomisation, all-cause death rates were assumed to be that of the age- and gender-matched general population. The parametric extrapolations for years 1–5 were combined, applying all-cause death rates for years 6 onwards to report life expectancy for each CHiP patient observed to survive at 1 year. The projected life expectancy was used to report life-years following TGC compared with CM both overall and for the cardiac and non-cardiac strata.

Previous evidence suggests that a minority of PICU survivors may suffer from long-term disability and reductions in quality of life (QoL), and therefore QALYs were reported. QoL data were not collected for the patients who did not have TBI in the CHiP trial. Instead, information was used from a previous study that included a large sample of PICU patients with similar baseline characteristics to those of the patients of the CHiP study71 and reported QoL with the HUI questionnaire at 6 months after the index admission. The mean QoL from this previous study (0.73, on a scale anchored at 0, death, and 1, perfect health) was applied to weight each life-year of those CHiP patients predicted to be alive 12 months after randomisation.

To project costs attributable to the initial critical care admission for years 1–5, the inpatient, outpatient and community service costs reported from the service-use survey at 1 year were assumed to be maintained until the end of year 2. Previous studies have suggested that, between 3 and 4 years after the initial PICU admission, around 10% of survivors have relatively severe disability. Those predicted to survive in years 3–5 were, therefore, assumed to have incurred 10% of the mean costs reported at 12 months. Those patients who were observed or predicted to die before 12 months were assigned zero QALYs.

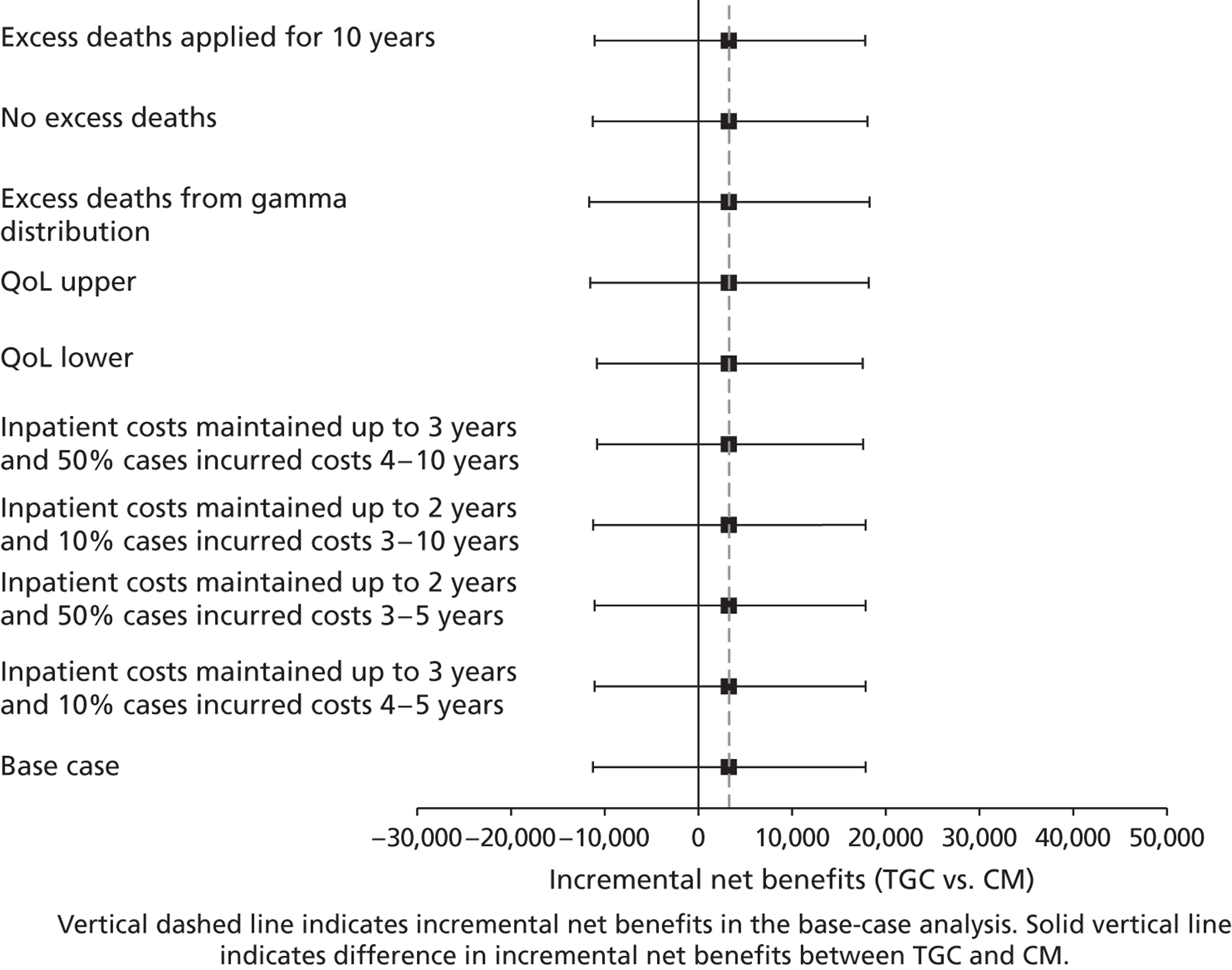

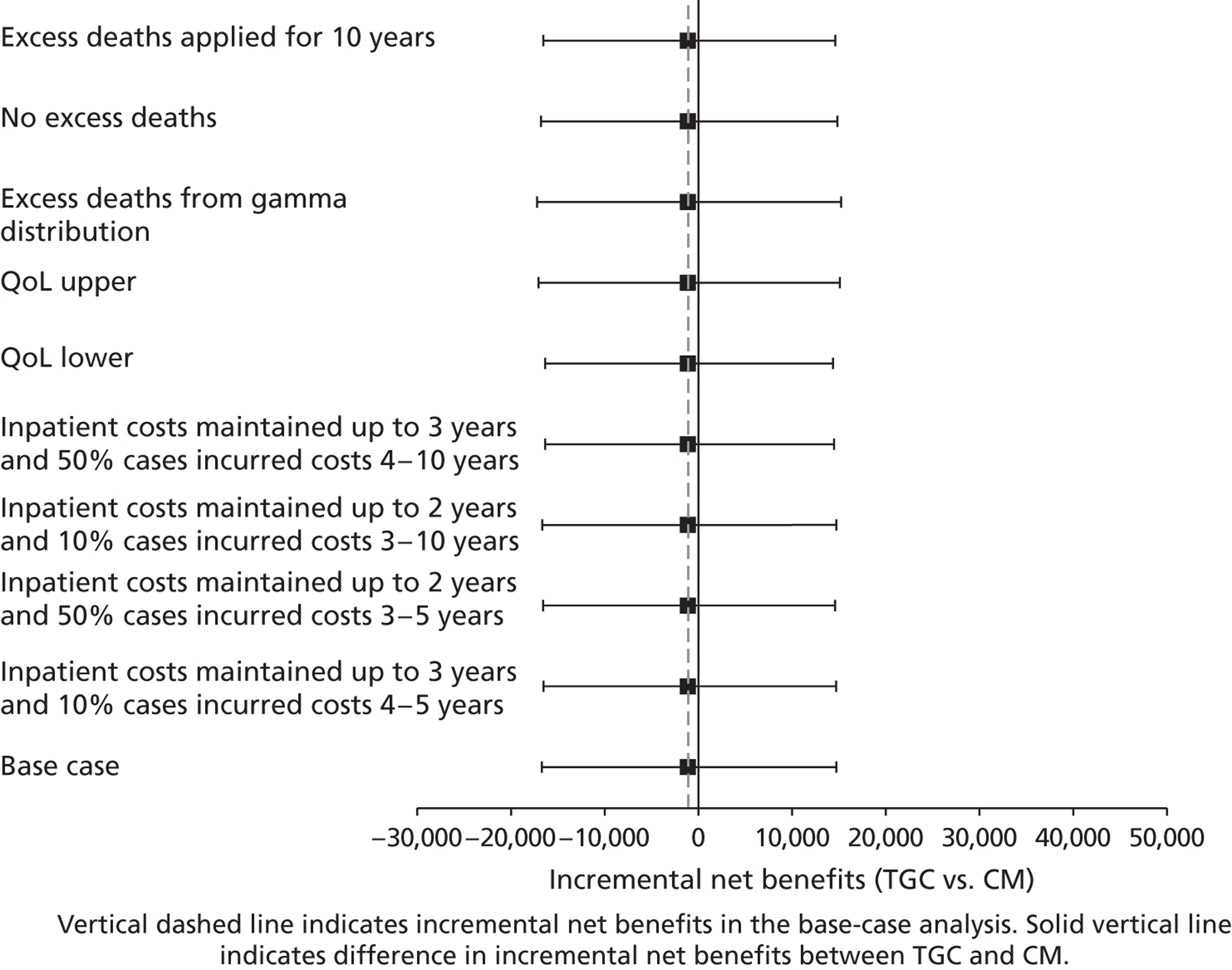

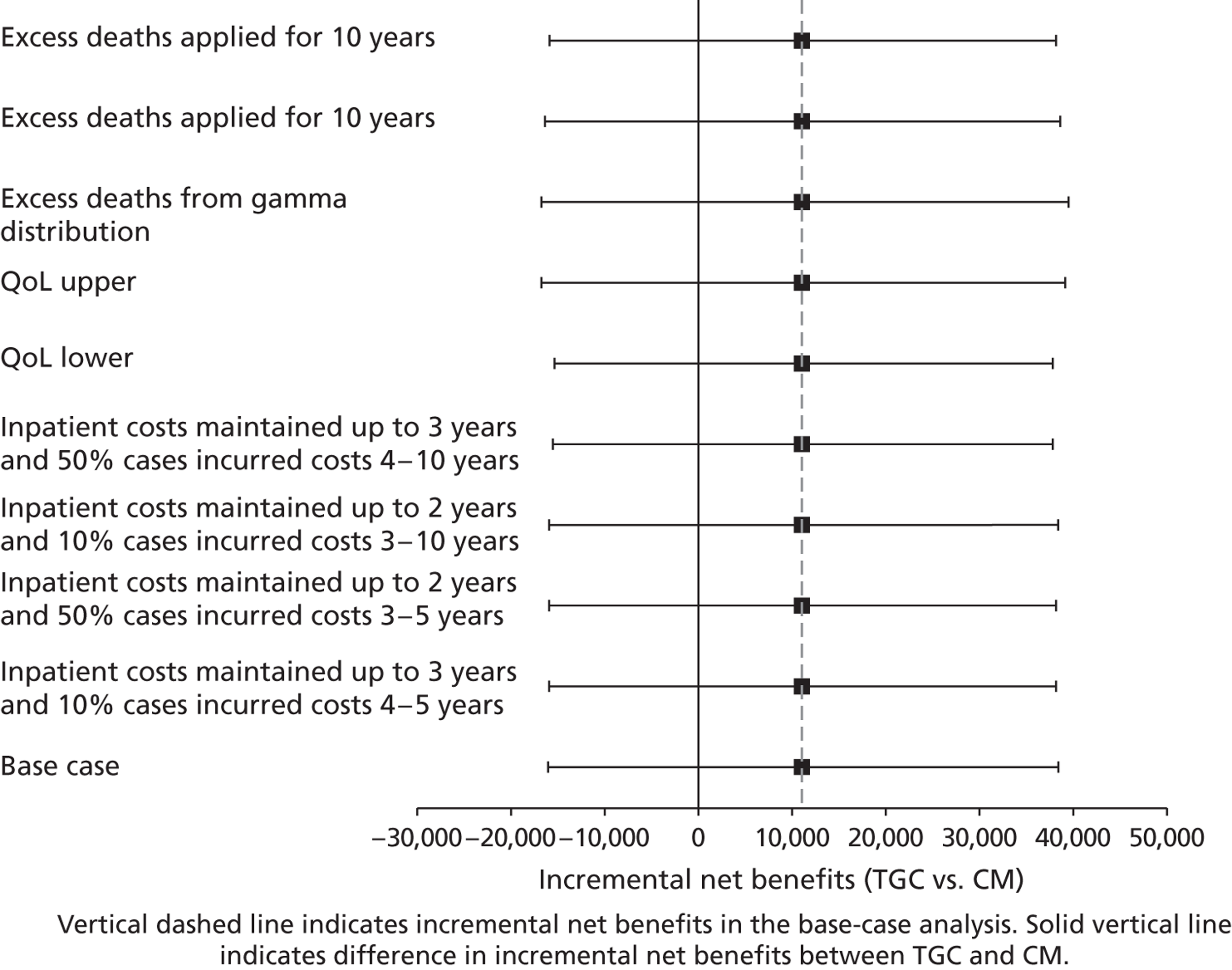

Lifetime incremental costs per life-year, and per QALY gained, were reported. INBs were calculated by valuing each QALY at the £20,000 per QALY threshold recommended by NICE. 53 All future costs and life-years were discounted at the recommended rate of 3.5%. 53 All incremental cost-effectiveness results are reported overall, and then for the cardiac and non-cardiac strata.

Sensitivity analysis on lifetime cost-effectiveness analysis

The following further SAs were run to test the assumptions made in the lifetime analyses:

-

An alternative parametric extrapolation was used to project survival from year 1 to 5.

-

Excess mortality compared with the age- and gender-matched general population was assumed to remain for 10 rather than 5 years post randomisation, that is the parametric extrapolation was applied for years 1–10, and then applied for all-cause death rates.

-

It was assumed that trial patients were not subject to any excess mortality other than that of the age- and gender-matched general population.

-

Rather than assuming the mean QoL (0.73) from a previous study, the values given by the lower and upper 95% CIs around that mean (0.71 to 0.75) were assumed.

-

Alternative assumptions were made about the duration and magnitude of the costs:

-

For all patients who survived beyond 1 year, it was assumed that costs were maintained until the end of year 3 (rather than 2).

-

10% of costs were assumed to be maintained over years 3–10 rather than years 3–5.

-

The costs for years 2–5 were assumed to be 50% not 10% of those at 12 months.

-

i. to iii. above were combined.

-

For each of these SAs, the lifetime INBs of TGC compared with CM overall and for the cardiac and non-cardiac strata were reported.

Ancillary studies

In addition to the main study, the grant holders welcomed more detailed or complementary studies, provided that proposals were discussed in advance with the TSC and appropriate additional research ethics approval was sought. These will not be discussed further in this monograph.

Publication policy

To safeguard the integrity of the trial, data from this study were not presented in public or submitted for publication without requesting comments and receiving agreement from the TSC. The primary results of the trial will be published by the group as a whole in collaboration with local investigators and local investigators will be acknowledged. The success of the trial was dependent on the collaboration of many people. The results were, therefore, presented first to the trial local investigators. A summary of the results of the trial will be sent to parents of participating children on request and also made available on the trial website.

Organisation

A TSC (see Appendix 9) and a DMEC were established (see Appendix 10). Day-to-day management of the trial was overseen by a Trial Management Group (TMG) (see Appendix 11). Each participating centre identified a paediatric intensivist as a PI (see Appendix 12). Each participating centre was allocated funding (from the core trial grant, from the MCRN and/or from local Comprehensive Local Research Networks) for research nursing time, and employed or reallocated a research nurse to support all aspects of the trial at the local centre.

Confidentiality

Patients were identified by their trial number to ensure confidentiality. However, as the patients in the trial were contacted about the study results (and patients recruited until November 2010 were followed up for 12 months following randomisation), it was essential that the team at the DCC had the names and addresses of the trial participants recorded on the data collection forms in addition to the allocated trial number. Stringent precautions were taken to ensure confidentiality of names and addresses at the DCC.

The chief investigator and local investigators ensured conservation of records in areas to which access is restricted.

Audit

To ensure that the trial was conducted according to the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) and Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines, site audits were carried out on a random basis. The local investigator was required to demonstrate knowledge of the trial protocol and procedures and ICH and GCP. The accessibility of the site file to trial staff and its contents were checked to ensure all trial records were being properly maintained. Adherence to local requirements for consent was examined.

If the site had full compliance, the site visit form was signed by the lead research nurse. In the event of non-compliance, the DCC and/or the lead research nurse addressed the specific issues to ensure that relevant training and instruction were given.

The CHiP trial also passed an inspection by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) (August 2009).

Termination of the study

At the termination of planned recruitment, the DCC contacted all sites by telephone, email or fax in order to terminate all patient recruitment as quickly as possible. After all recruited patients had been followed until 30 days post randomisation (or hospital discharge if stay > 30 days), a declaration of the end of trial form was sent to EudraCT and the Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (MREC). The following documents will be archived in each site file and kept for at least 5 years: original consent forms, data forms, trial-related documents and correspondence. At the end of the analysis and reporting phase, the trial master files at the clinical co-ordinating centre and DCC will be archived for 15 years.

Funding

The costs for the study itself were covered by a grant from the HTA programme. Clinical costs were met by the NHS under existing contracts.

Indemnity

If there is negligent harm during the clinical trial, when the NHS body owes a duty of care to the person harmed, NHS indemnity covers NHS staff, medical academic staff with honorary contracts and those conducting the trial. NHS indemnity does not offer no-fault compensation.

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment

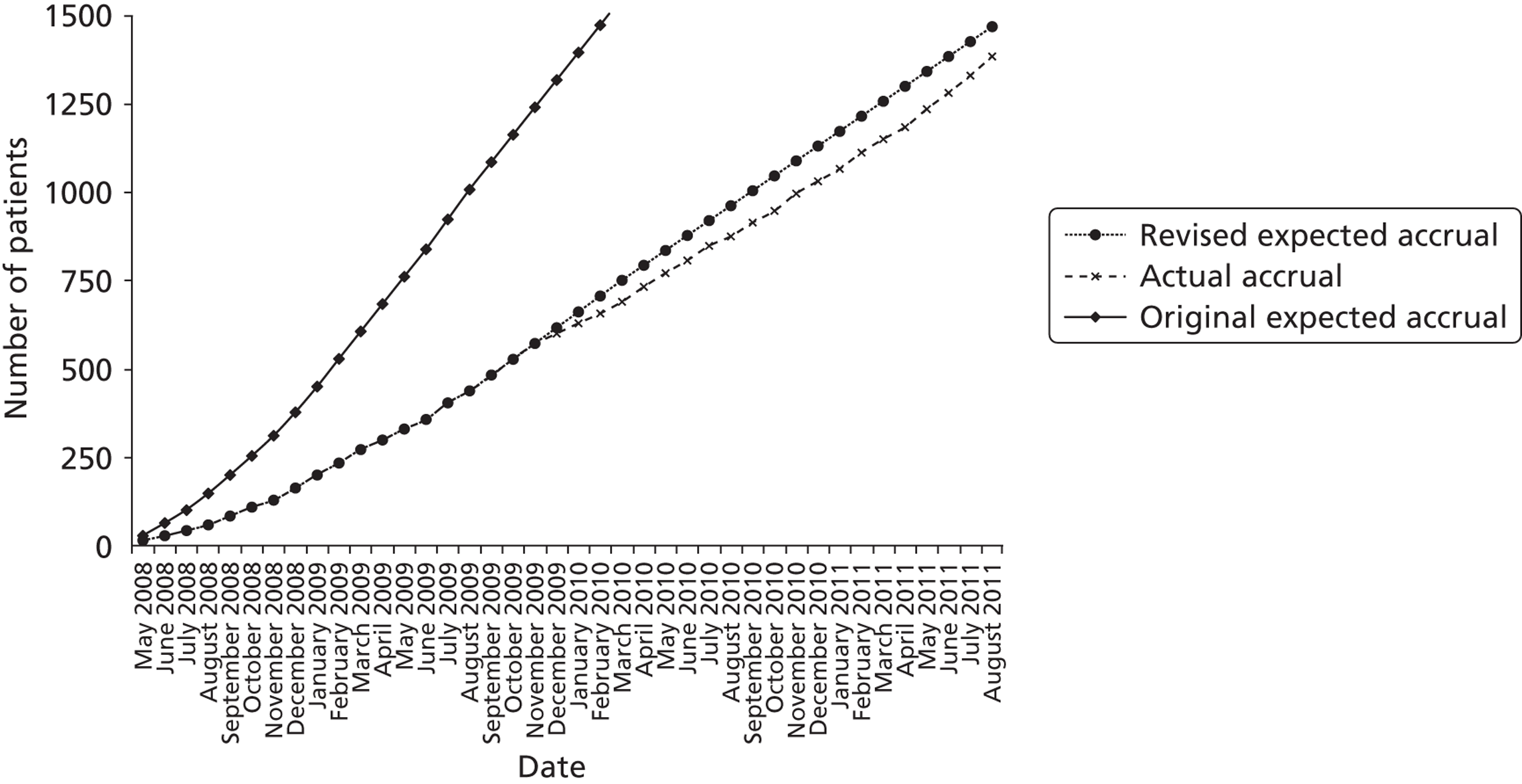

Trial recruitment began on 4 May 2008. As indicated in Chapter 2, recruitment was slower than expected. This was mainly a result of delays in trial initiation at some sites, clinical constraints and a ‘research learning curve’ in many of the participating units which had no previous experience of recruiting critically ill children to clinical trials. These delays necessitated an application to the HTA programme for an extension to the trial. The HTA programme granted funding to allow recruitment to be extended to allow the trial to achieve sufficient power (1500 children) to identify whether or not there was a differential effect for the primary end point (VFD-30) in the two strata (cardiac and non-cardiac).

The DMEC confidentially reviewed unblinded interim analyses on two occasions. In addition, they met to discuss SAEs and recruitment rates on three further occasions.

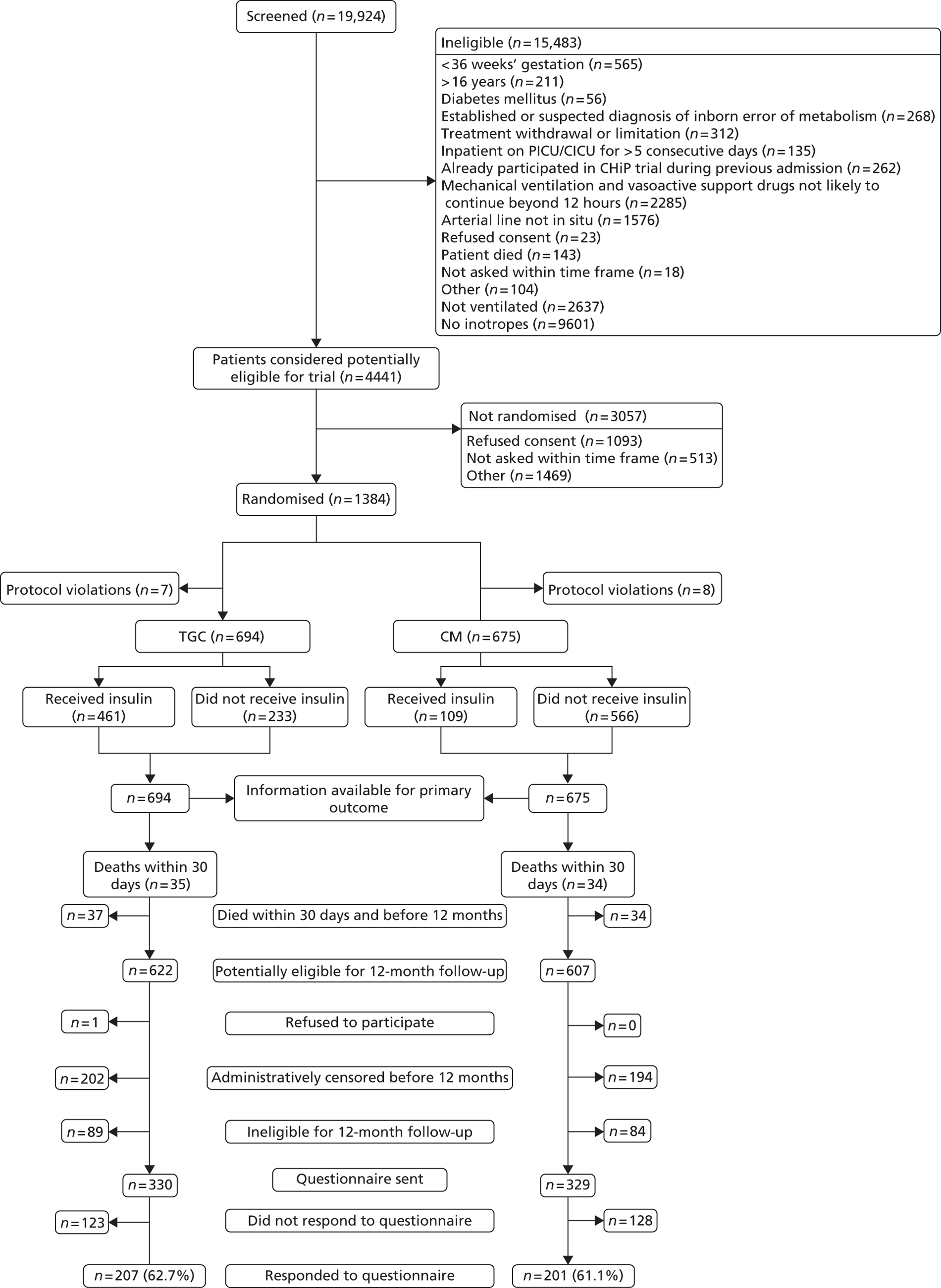

Recruitment closed on 31 August 2011, as agreed in the HTA funding. A total of 19,924 children were screened from 13 sites. Of these, 1384 were recruited and randomised (701 to TGC and 683 to CM). The reasons for non-recruitment are shown in Table 4. Of the 1384, 15 were subsequently found to be ineligible (Table 5), leaving 1369 eligible children (694 to TGC and 675 to CM) randomised into the trial – 91% of the original target of 1500. The flow of patients is shown in Figure 3 and cumulative recruitment in Figure 4. Recruitment by site is shown in Table 6.

| Reason not recruited | All screened, non-recruited patients N = 18,540 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n/N (%) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Inclusion criteria | > 16 years | 211 | 1.14 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mechanical ventilator and vasoactive drugs not likely to be continued for > 12 hours | 2285 | 12.32 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arterial line not in situ | 1576 | 8.50 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Not ventilated | 2637 | 14.22 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No inotropes | 9601 | 51.79 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Exclusion criteria | < 36 weeks corrected gestational age | 565 | 3.05 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 56 | 0.30 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Error of metabolism | 268 | 1.45 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Treatment withdrawal/limitation | 312 | 1.68 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| > 5 days on PICU | 135 | 0.73 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Already participated in CHiP | 262 | 1.41 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other | Refused consent | 1116 | 6.02 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Patient died | 143 | 0.77 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Not asked within time frame | 531 | 2.86 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other (further details in box below) | 1573 | 8.48 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Text responses for category

‘other’ Research nurse on leave/ill/unavailable (weekend) 322 ECMO/transplant 134 Language difficulties 127 In another trial/approached for another trial 116 Legal/social issues 109 No decision within time frame 97 PI – clinical decision 95 Parents not available/too upset 89 Transferred to another hospital 48 Non-TBI site 33 Other 403 ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. |

Research nurse on leave/ill/unavailable (weekend) | 322 | ECMO/transplant | 134 | Language difficulties | 127 | In another trial/approached for another trial | 116 | Legal/social issues | 109 | No decision within time frame | 97 | PI – clinical decision | 95 | Parents not available/too upset | 89 | Transferred to another hospital | 48 | Non-TBI site | 33 | Other | 403 | ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. | |||||||||||||||||

| Research nurse on leave/ill/unavailable (weekend) | 322 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ECMO/transplant | 134 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Language difficulties | 127 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In another trial/approached for another trial | 116 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legal/social issues | 109 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No decision within time frame | 97 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PI – clinical decision | 95 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parents not available/too upset | 89 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Transferred to another hospital | 48 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Non-TBI site | 33 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other | 403 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TGC arm | CM arm |

|---|---|

| During a monitoring visit it was found that this patient had not fully consented | During the final data analysis the trial statistician found that this patient actually met one of the exclusion criteria, i.e. he or she was in PICU for > 5 days before he or she was randomised |

| In response to a query it was found that this patient was recruited in error. He or she did not meet one of the eligibility criteria (taking vasoactive drugs) | During the final data analysis the trial statistician found that this patient actually met one of the exclusion criteria, i.e. he or she was in PICU for > 5 days before he or she was randomised |

| Patient randomised incorrectly, possibly met one of the exclusion criteria,as when randomised had suspected metabolic illness; therefore treatment was stopped early | During the final data analysis the trial statistician found that this patient actually met one of the exclusion criteria, i.e. he or she was in PICU for > 5 days before he or she was randomised |

| Parents had forgotten that their child had previously been in the trial; therefore he or she was not eligible for the trial | During the final data analysis the trial statistician found that this patient actually met one of the exclusion criteria, i.e. he or she was in PICU for > 5 days before he or she was randomised |

| Patient randomised in error: met the exclusion criterion of having an inborn error of metabolism (Refsum’s disease, which is a rare disorder of lipid metabolism) | Patient randomised in error: met the exclusion criterion of being in PICU for > 5 days but site did not realise until after randomised |

| During the final data analysis the trial statistician found that this patient actually met one of the exclusion criteria, i.e. he or she was in PICU for > 5 days before he or she was randomised | Patient randomised in error: met the exclusion criterion of being in PICU for > 5 days but site did not realise until after randomised |

| Patient randomised in error: did not meet the inclusion criterion of being on inotropes at randomisation | Patient randomised in error: met the exclusion criterion of having an inborn error of metabolism (Barth syndrome) |

| Patient randomised in error: did not meet the inclusion criterion of being on inotropes at randomisation |

FIGURE 3.

A flow chart showing the flow of patients. Note that the information on vital status up to 12 months was available from the Office for National Statistics, aside from for 17 non-UK nationals.

FIGURE 4.

Cumulative recruitment – actual accrual vs. revised expected.

| Site | Screened (N) | Randomised [n (%)] |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Birmingham Children's Hospital | 3490 | 241 (6.9) |

| 2. Bristol Royal Hospital for Children | 1525 | 148 (9.7) |

| 3. Great Ormond Street Hospital | 3878 | 210 (5.4) |

| 4. Leeds General Infirmary | 278 | 3 (1.1) |

| 5. Royal Brompton Hospital | 1695 | 158 (9.3) |

| 6. Royal Liverpool Children's NHS Trust | 2145 | 164 (7.6) |

| 7. Royal Manchester Children's Hospital | 1806 | 75 (4.2) |

| 8. St Mary’s Hospital | 935 | 60 (6.4) |

| 9. Sheffield Children's NHS Foundation Trust | 320 | 22 (6.9) |

| 10. Southampton General Hospital | 2416 | 219 (9.1) |

| 11. University Hospital of North Staffordshire | 419 | 15 (3.6) |

| 12. University Hospitals of Leicester | 946 | 63 (6.7) |

| 14. St George's Hospital | 71 | 6 (8.5) |

| Total | 19,924 | 1384 |

Comparability at baseline

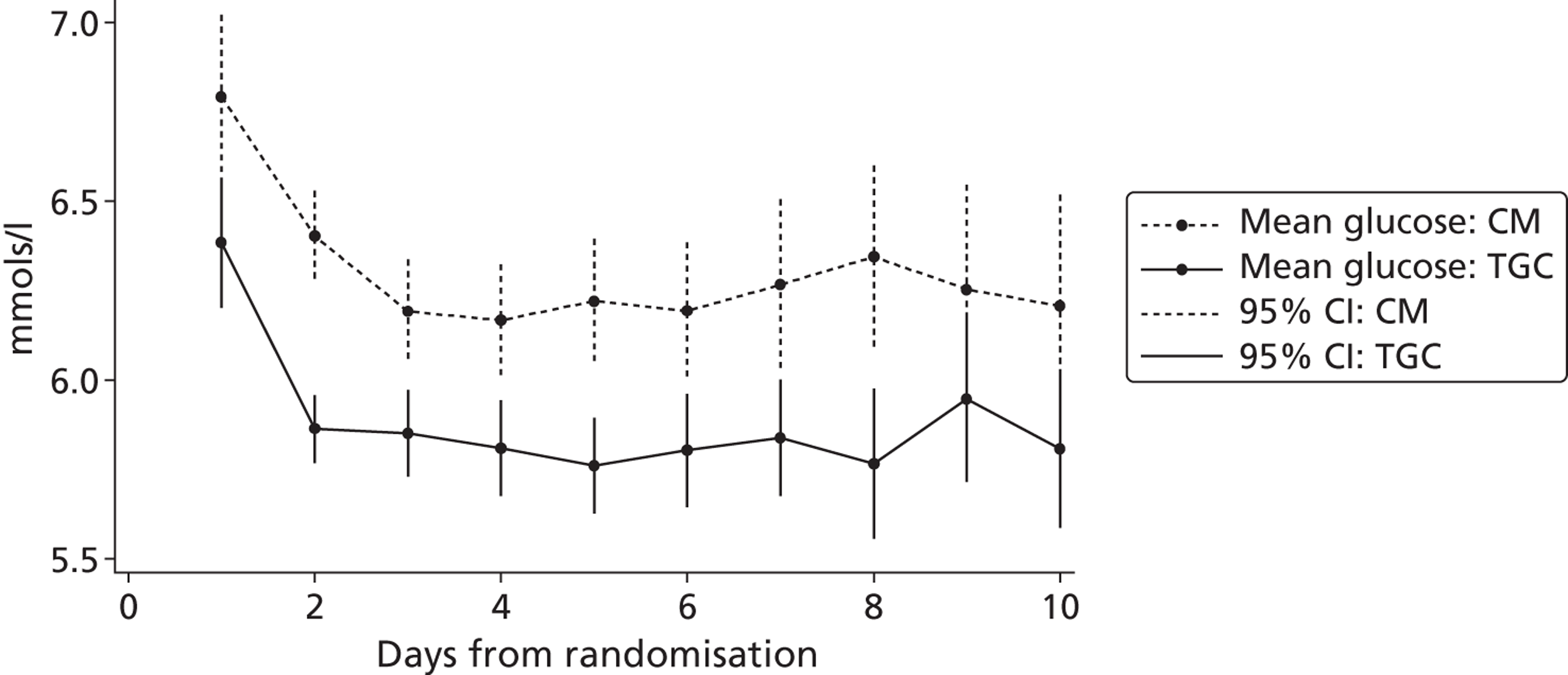

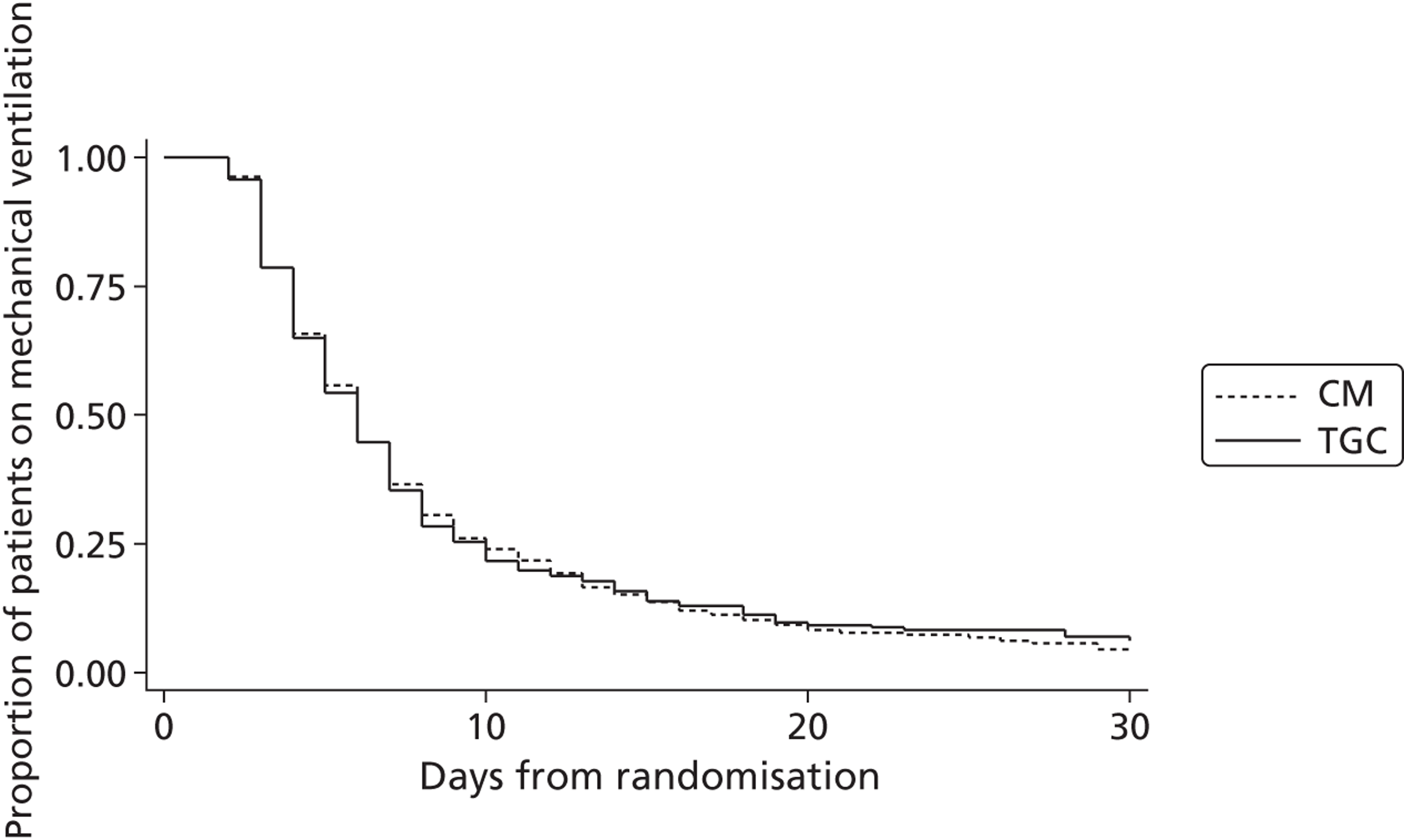

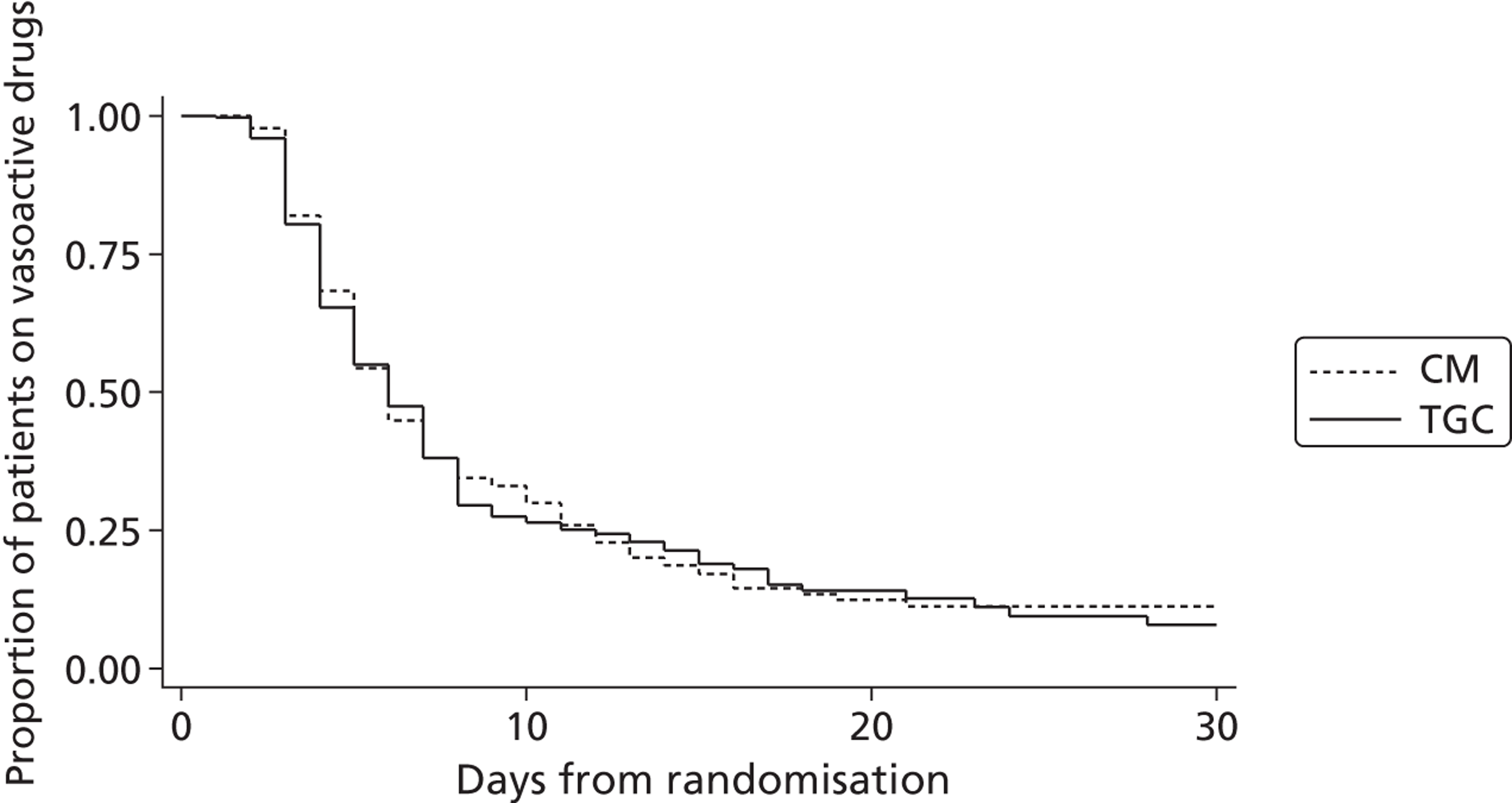

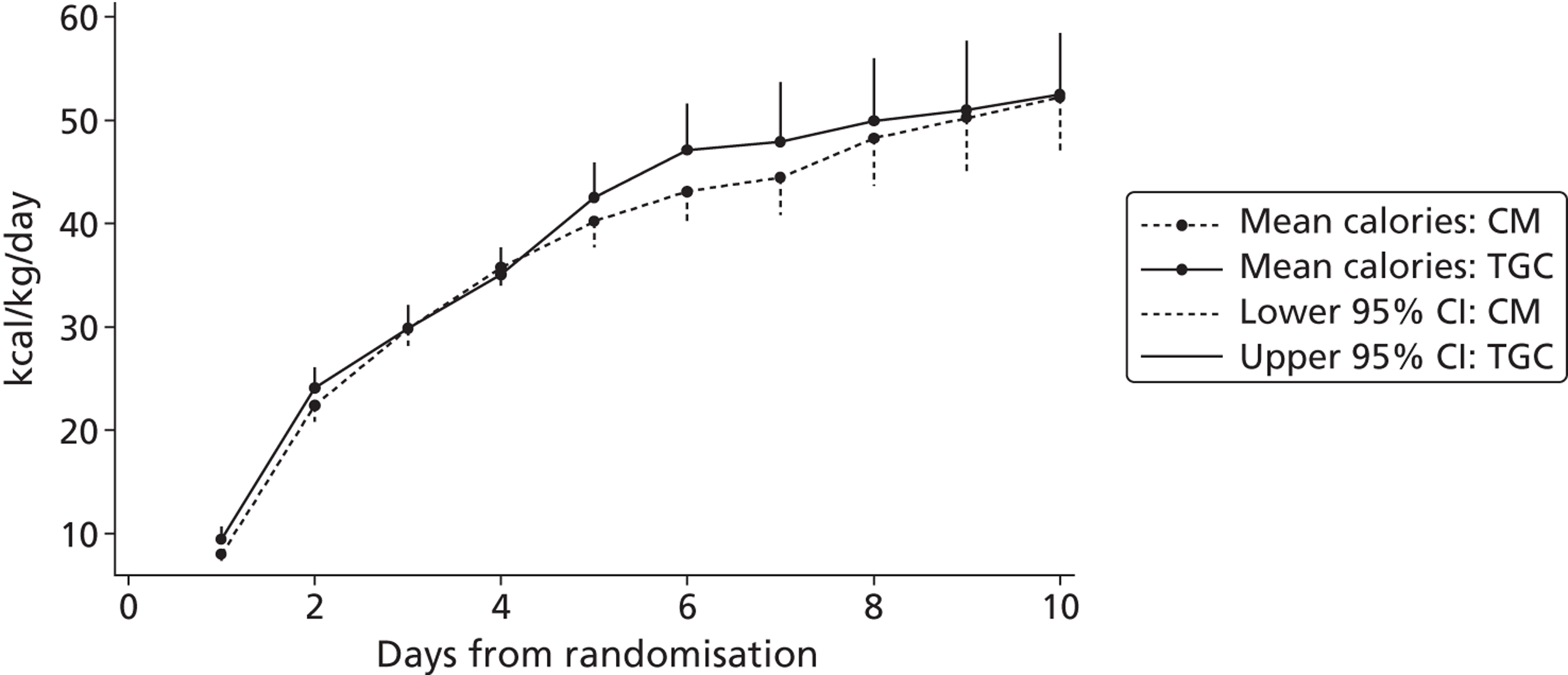

The characteristics of the children at baseline are shown in Table 7. The randomised groups were broadly comparable at trial entry. Sixty-two per cent were randomised within 1 day of admission to PICU. In terms of the prespecified stratifying factors, two-thirds were aged < 1 year, and 60% of the children were in the cardiac surgery stratum. Seven per cent of children in the cardiac surgery stratum were considered to be undergoing surgical procedures associated with a high risk of mortality (RACHS1 score 5 or 6), and 19% of children in the non-cardiac group had a PIM2 score indicative of a ≥ 15% risk of PICU mortality.