Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/46/01. The contractual start date was in November 2012. The draft report began editorial review in April 2013 and was accepted for publication in September 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Leaviss et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Description of health problem

Tobacco smoking is a major cause of a number of chronic diseases, including heart disease and cancers, and is attributed as the leading cause of preventable deaths worldwide. 1,2 Smoking-related illnesses include every type of cancer except for skin cancer; cardiovascular, respiratory and digestive problems;3 amputation due to peripheral vascular disease;4 diabetes; cataracts; and impotence and reproductive problems. 5

Despite these statistics, nearly one-fifth of adults in the UK are regular cigarette smokers. Although the rate of cigarette smoking has been falling slowly since the mid-1990s, in 2010 the proportion of males over 16 years who were smokers was reported to be 21%. 6 In 2006–7, smoking-related ill-health cost the NHS £3.3B. 7 Stopping smoking is known to reduce the risk of smoking-related disease, but it is challenging. Without smoking cessation aids, only between 2% and 5% of quit attempts are successful. 8,9 Smoking cessation strategies have varied success rates.

Available smoking cessation interventions

Broadly speaking, there are two types of smoking cessation intervention: (1) those designed to prompt quit attempts and (2) those designed to assist with quit attempts. The current review focuses on the latter type. A number of pharmacological interventions exist that aid smoking cessation in terms of assisting quit attempts. These include nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), typical antidepressant medications such as bupropion hydrochloride and nicotinic receptor partial agonists such as varenicline, cytisine and dianicline. Behavioural support interventions have also been developed to assist with quit attempts. Recent Cochrane reviews have demonstrated behavioural support (group, individual and telephone counselling), single-product nicotine replacement therapy and bupropion hydrochloride to demonstrate similar effectiveness as smoking cessation aids. 10–14 Greater effect sizes have been reported for nicotine partial agonists such as varenicline and cytisine. 15

This review assesses the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of two nicotinic receptor partial agonists: varenicline and cytisine. Nicotinic receptor partial agonists offer a pharmacological method to aid smoking cessation. Varenicline (Champix or Chantix; Pfizer, UK) and cytisine (Tabex; Sopharma, Bulgaria) are included in this class of drug. These drugs act by relieving craving and withdrawal symptoms, while also blocking the reinforcing effects of nicotine if a cigarette is smoked. 16 Cytisine is a naturally occurring product, extracted from the seeds of the plant Cytisus laborinum L. (golden rain acacia). It has been used as an aid to smoking cessation in former socialist economies for over 40 years, although West et al. 17 report that it has been withdrawn from many of these countries following their entry into the European Union. It is manufactured by the Bulgarian pharmaceutical company Sopharma. Varenicline is a synthetic product developed by Pfizer, with a similar structure to cytisine. Like cytisine, varenicline is a partial agonist of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, with high affinity for α4β2 receptors, and is licensed for use as an aid to smoking cessation in the USA, Canada and across Europe including the UK. Although both varenicline and cytisine are used as aids to smoking cessation, Etter et al. 18 reported a dearth of scientific evidence on the properties of cytisine and its safety and efficacy profile. They provide an overview of the in vitro and in vivo profiles of both drugs. Cytisine is considerably less expensive than varenicline and, although costs vary between countries (Poland US$12 for a course, Russian Federation US$6 for a course), the cost of a course of cytisine is generally about 10–20% that of varenicline. 17 The standard dosage for varenicline according to the British National Formulary (BNF) is for adults over 18 years, the treatment to start with is usually 1–2 weeks before the target stop date (up to a maximum of 5 weeks before the target stop date). Initially, the dosage is 500 μg q.d. [quaque die (every day)] for 3 days, the dosage is increased to 500 μg b.i.d. [bis in die (twice a day)] for 4 days, followed by 1 mg b.i.d. for 11 weeks (the dose is reduced to 500 μg b.i.d. if it is not tolerated) and a 12-week course can be repeated in abstinent individuals to reduce the risk of relapse. 19 Although cytisine is not licensed for use in the UK or the USA, the usual starting dose is 1.5 mg six times daily. 20

Measurement of abstinence

Clinical trials of interventions for smoking cessation may use a range of outcome measurements to evaluate abstinence. The Russell Standard21 is a set of criteria widely used to define smoking abstinence. These guidelines were developed in response to results from smoking cessation trial data historically being reported in a number of different ways. The Russell Standard outlines criteria important to the measurement and reporting of outcome data in such trials. A full description of these criteria are found in West et al. 21 Regarding the measurement of abstinence, the criteria recommend a duration of 6 months or 12 months, either from a designated quit date or allowing for a predefined grace period. Shorter periods of abstinence are reported to be insufficient in their ability to accurately predict long-term cessation. Regarding the definition of abstinence, historically a number of methods of measuring abstinence have been used. These include continuous abstinence, defined as abstinence between quit day and follow-up; prolonged abstinence, defined as sustained abstinence after an initial grace period, or to a period of sustained abstinence between two follow-ups; point prevalence abstinence, defined as the prevalence of abstinence during a time window immediately preceding follow-up and repeated point prevalence abstinence, defined as point prevalence abstinence measured at two or more follow-ups between which smoking is allowed. 22 Abstinence is often biochemically verified by measurement of carbon monoxide (CO). However, CO is eliminated from the body in around 24 hours;15 therefore, abstinence cannot be verified for longer periods than this. The Russell Standard recommends that abstinence should be defined as ‘a self-report of smoking not more than five cigarettes from the start of the abstinence period, supported by a negative biochemical test at the final follow-up’. 21

Current service provision

Stop smoking clinics in the UK typically include the option to attend specialist one-to-one sessions with a trained stop smoking advisor, group sessions or drop-in sessions. 23 Clinics generally involve some form of assessment of current smoking behaviour and willingness to quit, including CO monitoring, prescription of some form of pharmacotherapy if desired (NRT, bupropion hydrochloride or varenicline) and behavioural support focused on managing withdrawal symptoms and preventing relapse (including preparing to quit, setting a quit date and making plans for situations where the client may be tempted to smoke). 24

Success rates for the NHS smoking cessation treatments

Eight hundred thousand smokers each year attempt cessation through the NHS stop smoking services. 25 In any given quit attempt 0.5% of smokers attempt cessation using varenicline with specialist individual behavioural support through NHS stop smoking clinics, 0.2% use varenicline with specialist group behavioural support, 0.1% use varenicline with specialist drop-in behavioural support and 2.8% obtain a prescription for varenicline in NHS settings (e.g. primary care, hospital). 23 The estimated 52-week continuous abstinence rates for NHS specialist individual behavioural support clinics are 15% when combined with NRT monotherapy, 20% with NRT combination therapy, 17% with bupropion hydrochloride and 24% with varenicline. The estimated 52-week continuous abstinence rates for NHS specialist group behavioural support clinics are 20% when combined with NRT monotherapy, 26% with NRT combination therapy, 23% with hydrochloride and 31% with varenicline. The estimated 52-week continuous abstinence rates for NHS specialist drop-in behavioural support clinics are 11% when combined with NRT monotherapy, 15% with NRT combination therapy, 13% with bupropion hydrochloride and 19% with varenicline. The estimated 52-week continuous abstinence rates for brief interventions in NHS settings (e.g. primary care, hospital) are 7% for NRT monotherapy, 10% for NRT combination therapy, 8% for bupropion hydrochloride and 12% for varenicline. 23

A recent Cochrane review of nicotinic receptor partial agonists as aids to smoking cessation showed a modest efficacy for cytisine over placebo in helping people to stop smoking, although the study reports low absolute quit rates for these trials. 15 The authors report a twofold increase in quit rates for varenicline over placebo. These analyses, comparing each drug with placebo, found no difference in their efficacy. The authors highlight that trials have now been conducted in real-world settings, for example in smokers with underlying diseases or medical conditions who might under ordinary circumstances be excluded from clinical trials, and report that the findings remain stable in these populations. A recent review of the efficacy and safety of cytisine found it to be an effective treatment for smoking cessation. 26 The review highlights the low cost of cytisine and suggests that licensing of this drug may therefore be warranted because of its potential public health benefit. No head-to-head trials between varenicline and cytisine were identified in either review and, to date, no indirect comparisons of the two drugs have been conducted in the absence of such trials.

Safety profile of varenicline

Concerns have been raised regarding the safety profile of varenicline. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued a series of warnings, resulting from post-marketing reports of increased risk of suicidal behaviour or depression, serious adverse cardiac events and gastrointestinal complaints including a recently added warning highlighting a small increased risk of certain cardiovascular events in smokers with pre-existing cardiac conditions. A meta-analysis of adverse gastrointestinal events by Leung et al. 27 showed an increased risk after treatment with varenicline. In a review of 10 trials, Tonstad et al. 28 found no evidence of a link between varenicline and serious neuropsychiatric events. Reviews by Singh et al. 29 and Prochaska30 report conflicting findings, with Singh et al. showing an increased risk of serious cardiovascular events after treatment with varenicline and Prochaska finding no evidence of a link. Cahill et al. 15 found a lack of trial evidence indicating serious adverse events for varenicline. However, the studies do not rule out the possibility of a link, in light of the FDA warnings. Data extracted from randomised control trials (RCTs) may not provide a comprehensive account of all possible adverse events – participants may be excluded for having a history of a number of relevant medical conditions, for example depression or cardiovascular disease. In addition, the follow-up time period of trials may not be long enough to sufficiently capture all relevant adverse events.

This assessment aimed to review the efficacy of varenicline and cytisine as an aid to smoking cessation by updating the Cahill et al. 15 review and to conduct indirect comparisons where appropriate. A mathematical model compared the cost-effectiveness of cytisine with varenicline in the context of NHS stopping smoking services. Recommendations regarding the need for a head-to-head trial were made.

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

This assessment addresses the question: what is the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cytisine compared with varenicline for smoking cessation? Specifically, the assessment will (i) review evidence on the clinical effectiveness and safety of cytisine in smoking cessation compared with varenicline; (ii) develop an economic model to estimate the cost-effectiveness of cytisine in the context of NHS smoking cessation services and (iii) provide recommendations based on the value of information analyses whether or not a head-to-head trial of cytisine and varenicline would represent an effective use of resources.

Decision problem

Population: adult smokers.

Intervention and relevant comparators: cytisine, a nicotinic receptor partial agonist, used as an aid in the treatment of smoking cessation, and varenicline, in any formulation. In the likely absence of data from head-to-head studies of cytisine with varenicline, any comparators (e.g. placebo, NRT, bupropion) were considered that would allow an indirect comparison or network meta-analysis.

Outcomes: the primary outcome was smoking cessation, as defined by the study’s strictest reported definition of abstinence, at a minimum of 6 months’ follow-up, i.e. continuous abstinence rate (CAR) data were used in preference to point prevalence abstinence (PPA) data where both were reported. 22 Secondary outcomes were adverse events. The four most frequently reported adverse events, as reported in the Cahill15 review, were analysed and these were nausea, headache, insomnia and abnormal dreams. Serious adverse events (SAEs) were also analysed.

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

The overall aims and objectives of this assessment were to:

-

Update the Cahill et al. 15 search to identify additional clinical effectiveness and safety data for cytisine compared with varenicline in helping people to stop smoking.

-

In the absence of head-to-head trials, conduct indirect treatment comparisons for efficacy and adverse events for cytisine compared with varenicline.

-

Model the cost-effectiveness of cytisine and varenicline within the context of NHS smoking cessation services.

-

Make recommendations for commissioning a full head-to-head trial of varenicline compared with cytisine.

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Methods for reviewing clinical effectiveness

Identification of studies

A good-quality recent Cochrane review evaluating the clinical effectiveness and safety profile of both cytisine and varenicline was identified. 15 This Cochrane review will be referred to subsequently as Cahill et al. 15 The current review aimed to use the data from Cahill et al. 15 to inform clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness analyses. An update of this search was conducted, which aimed to identify any recent studies evaluating the clinical effectiveness of varenicline or cytisine. The aim of the current review was to compare the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of varenicline and cytisine, but in the likely absence of head-to-head trials between cytisine and varenicline, any comparators were considered that would enable an indirect comparison, for example placebo, NRT and bupropion.

The search was conducted in January 2013 and the search strategy from Cahill et al. 15 was rerun for trials and systematic reviews in the period December 2011 to January 2013. Although dianicline was included in the Cahill et al. 15 searches, development of the drug has been discontinued and, therefore, will not be included in the comparisons for this report. This term was therefore excluded from the search. Additionally, a search was run for the terms Champix or Chantix (brand names for varenicline) with no date restrictions, in order to identify earlier trials using brand rather than generic names, as these terms were not included in Cahill et al. 15

The search was also rerun with a cost-effectiveness filter with no date restriction for cost-effectiveness literature. The purpose of the cost-effectiveness search was to obtain data to inform the model and no systematic review of this literature was conducted. Cost-effectiveness methods and analyses are reported in Chapter 4.

Searches were conducted by an information specialist (AC). Examples of each of the search strategies in MEDLINE are provided in Appendix 1.

The following electronic databases were searched for published and unpublished research evidence, from December 2011 to January 2013 for the efficacy searches and from database inception for the cost-effectiveness searches:

-

MEDLINE (Ovid) 1950–

-

EMBASE (Ovid) 1980–

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL; EBSCOhost) 1982–

-

The Cochrane Library including the Cochrane Systematic Reviews Database, Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database and NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) 1991–

-

Biological Abstracts (via Web of Science) 1969–

-

Science Citation Index (via Web of Science) 1900–

-

Social Science Citation Index (via Web of Science) 1956–

-

EconLit 1961–

-

Conference Proceedings Citation Index–Science (CPCI–S) (via Web of Science) 1990–

-

UK Clinical Trials Research Network (UKCRN) and the National Research Register archive (NRR)

-

Current Controlled Trials 1898–

-

ClinicalTrials.gov 1998–.

All citations were imported into Reference Manager (Thomson ResearchSoft, San Francisco, CA, USA) software and duplicates deleted.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

-

Study design: RCTs.

-

Intervention or comparators: cytisine, in any formulation; varenicline, in any formulation. In the likely absence of data from head-to-head studies of cytisine compared with varenicline, any other comparators (e.g. placebo, NRT, bupropion) were considered that would allow an indirect comparison.

-

Population: smokers.

-

The primary outcome was abstinence at a minimum 6 months’ follow-up.

Based on the above inclusion/exclusion criteria, study selection was conducted by two reviewers (JL and EEH). In the first instance titles and abstracts were examined for inclusion. Both reviewers independently screened all retrieved citations. Discrepancies between reviewers were discussed and any remaining disagreement resulted in retrieval of the full paper for further consideration. The full manuscripts of citations judged to be potentially relevant were retrieved and further assessed for inclusion. Any remaining discrepancies between reviewers at full-paper stage were discussed and, if no agreement could be reached, were resolved by referring to the review’s clinical experts. A table of studies excluded at full-paper stage with reasons for exclusion is presented in Appendix 3.

Data extraction

Data were extracted without blinding to either authors or journal. Data from studies included in the Cahill review15 were extracted directly from the review by one reviewer (JL or EEH). Data from studies included following the updated search were extracted by one reviewer (JL) and checked by a second (EEH). Any data for doses not reported in Cahill et al. 15 were extracted directly from the original papers. Efficacy data for newly included studies were calculated using the same method reported in Cahill et al. 15 – based on the numbers of people randomised to an intervention and excluding any deaths or untraceable moves in accordance with the Russell Standard. 31 Drop-outs or those patients lost to follow-up are treated as continuing smokers. It is beyond the scope of this short report to conduct a systematic review of adverse events for varenicline and cytisine, taking into account long-term observational studies. Therefore, this assessment will adopt the same approach to adverse events as the Cahill et al. 15 review, extracting this information from RCTs retrieved through an update of their efficacy search. Adverse events data were extracted on the basis of number of participants who had taken at least one dose of treatment. Data from the strictest reported measurement of smoking cessation were extracted for use in the analyses, i.e. 7-day PPA or CAR. Where studies reported both CAR and 7-day PPA, CAR data were extracted in preference to 7-day PPA22 and only data from studies measuring CAR were used in the network meta-analysis for efficacy. Data from both types of studies were used for adverse events analyses. Efficacy data from studies that reported only PPA were extracted with the purpose of conducting a sensitivity analysis for significant differences in results by method of outcome measurement. Adverse events data were extracted for the four most common adverse events, as identified in the Cahill review, and these were abnormal dreams, nausea, headache and insomnia. Data for SAEs were also extracted.

Critical appraisal strategy

Critical appraisals of the quality of studies, retrieved by the updated search, followed the same format as reported by Cahill,15 using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (Higgins et al). 32 Studies were critically appraised by JL or EEH and checked by the second reviewer. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion between reviewers. Quality assessments aimed to evaluate the risk of bias in the current evidence base for the clinical effectiveness of both varenicline and cytisine.

Methods of data synthesis

The continuous abstinence data and adverse events data including abnormal dreams, headache, insomnia, nausea and SAEs were synthesised using a network meta-analysis. The analysis combines evidence across studies in which there is at least one treatment in a study that is common to at least one other study.

A random (treatment) effects model was used to allow for heterogeneity in treatment effects between studies. The model assumed a fixed (i.e. unconstrained) baseline effect in each study so that treatment effects were estimated within study and combined across studies. All analyses were implemented in WinBUGS (MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK). 33

The continuous abstinence, abnormal dreams, headache, insomnia, nausea and SAEs data were modelled using a complementary log-log link function to allow for variation in duration of follow-up between studies (see Appendix 4). This assumes that the times to event follow an exponential distribution and, hence, that the treatment effect is constant over time. Although these are strong assumptions, they are expected to be better than assuming there is no effect of duration of follow-up.

Results of the network meta-analyses are reported in terms of the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% credible intervals (CrIs) relative to the baseline intervention (i.e. placebo). The posterior medians of the between-study standard deviations (SDs) together with their 95% CrIs are also presented.

Convergence of the models to their posterior distributions was assessed using the Gelman–Rubin convergence statistic. 34 Convergence occurred after 50,000 iterations for all outcome measures except for SAEs, which converged after 60,000 iterations. There was some suggestion of moderate autocorrelation between successive iterations of the Markov chains; to compensate for this the Markov chains were thinned every five iterations for continuous abstinence, nausea and SAEs, and every 10 iterations for abnormal dreams, headache and insomnia. Parameter estimates were based on 10,000 iterations of the Markov chains for continuous abstinence and nausea; 5000 iterations of the Markov chains for abnormal dreams, headache and insomnia and 8000 iterations of the Markov chains for SAEs to ensure that the Monte Carlo error was < 5% of the posterior SD. Although fewer samples would have been sufficient for estimating parameters for continuous abstinence, 10,000 samples were taken for the purpose of the expected value of sample information (EVSI).

The total residual deviance was used to assess formally whether or not the statistical model provided a reasonable representation of the sample data. The total residual deviance is the mean of the deviance under the current model minus the deviance for the saturated model, so that each data point should contribute about one to the deviance. 35

To enable the estimation of intervention-specific CARs, as required for the economic model, a separate random-effects meta-analysis was conducted on the placebo intervention arms. Absolute estimates of CARs were generated for each intervention by projecting the estimates of treatment effect (i.e. the log-hazard ratio) from the network meta-analysis onto the baseline CAR.

Results

Updated search

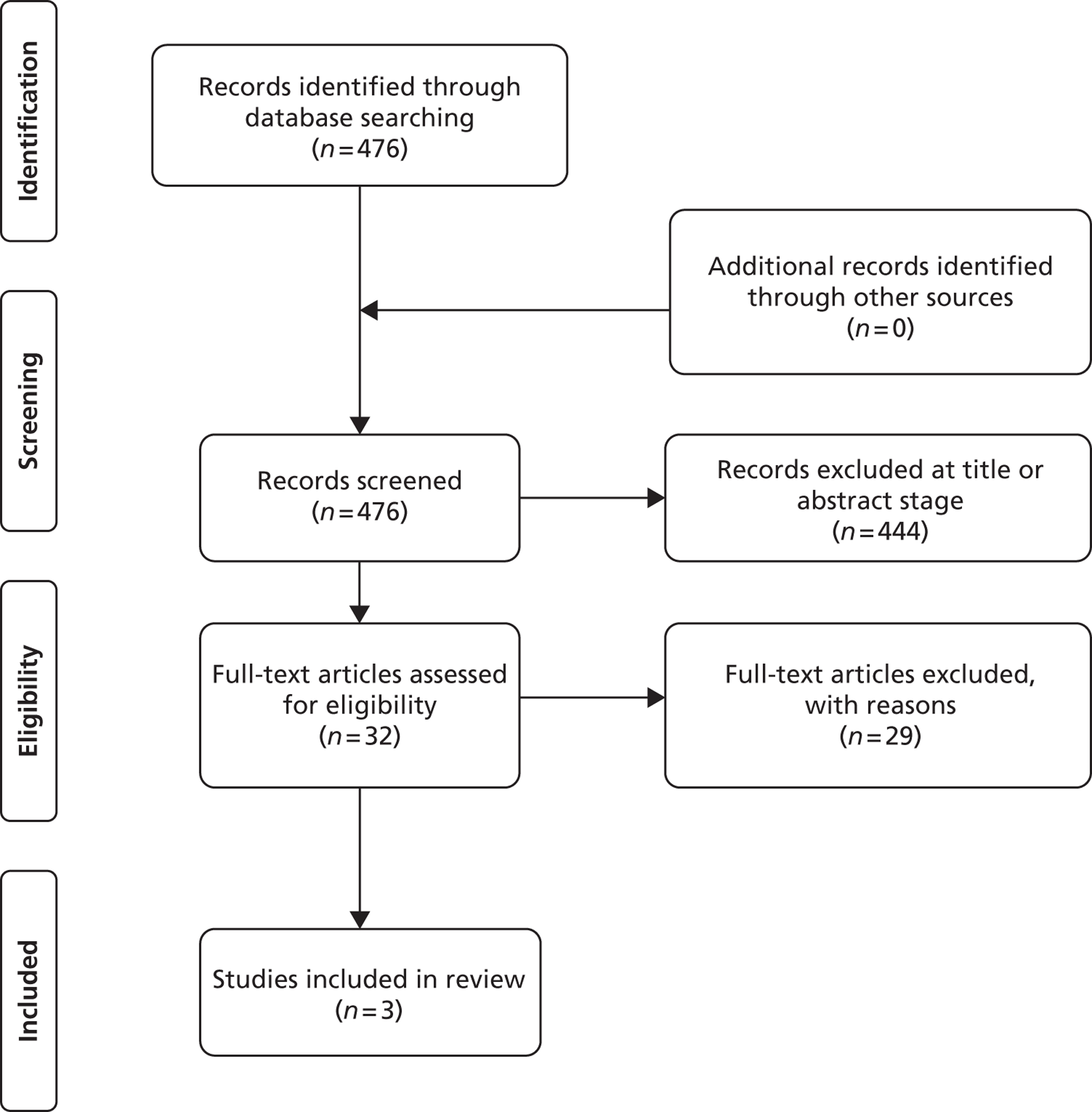

The updated bibliographic search for clinical effectiveness retrieved 476 papers. Figure 1 shows the results of this search. For the clinical effectiveness search, 32 full papers were retrieved after screening of titles and abstracts. After the reading of these full papers, a further 29 papers were excluded (reasons given in Appendix 3). Three papers were included from the updated search. 37–39 All three papers measured smoking cessation rates by PPA. The study reported in Cahill et al. 15 as Pfizer 201140 was identified in the updated search as now being a published paper. 41 There were no differences in reported data in the published paper. Data for efficacy and adverse events were extracted from all newly included studies.

FIGURE 1.

Study flow chart [adapted from Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e100009736].

Studies reported in the Cahill review

Cahill et al. 15 report 24 trials meeting their inclusion criteria. Their inclusion criteria considered any selective nicotinic receptor partial agonists, e.g. cytisine, varenicline, dianicline, or any other class of drug as they reach Phase III trial stage. Any comparators were considered, which included placebo, NRT, counselling and bupropion. RCTs of adult smokers were included. For outcomes, studies had to report a minimum of 6 months’ abstinence. Three of the reported trials evaluated cytisine, one trial evaluated dianicline and 20 trials evaluated varenicline. Four studies included in Cahill were not included in the current review for reasons outlined below.

Studies from Cahill not included in the current review

As the current review did not seek to evaluate dianicline as a result of its discontinuation, the trial evaluating dianicline reported in Cahill et al. 15 is not included here. Three studies of cytisine or varenicline that were included in the Cahill review (but not in their analyses) are not reported in the current review. Scharfenberg et al. 42 studied the efficacy of cytisine against placebo. In their review, Cahill et al. 15 reported the design and conduct of this early trial to be of indeterminate quality, using self-reported PPA and without biochemical verification. They therefore did not combine the results of this study with the two more recent cytisine studies. 17,43 Their sensitivity analysis combining these three trials indicated substantial heterogeneity between this older study and the newer ones. Therefore, this study has not been included in the current report. Two further studies from the Cahill review were not included in the current review. 44,45 Swan et al. 44 compared different counselling methods alongside varenicline treatment, with all groups receiving varenicline, and no non-treatment control groups. Tonstad45 studied varenicline as maintenance therapy, with both arms completing an initial course of varenicline before the comparison of varenicline and placebo for maintenance of the quit.

A summary of characteristics of all included studies is presented in Tables 1 and 2. A more detailed account of studies from the Cahill review is not provided in this update, but these characteristics are fully reported in Cahill et al. 15

| Study name | Country | n | Participants | Inclusion criteria | Intervention | Comparator | Smoking cessation (strictest definition) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vinnikov 200843 | Kyrgyzstan | 197 | Cytisine mean age 38.3 years, placebo 39.4 years; cytisine percentage male 99%, placebo 95%; cytisine mean years smoking 19.8 years, placebo 21.9 years | Aged > 20 years, smoked ≥ 15 cigarettes per day during the year prior to inclusion into the trial, had claimed high motivation to quit smoking and readiness to do so immediately and had no previous experience of cytisine use | Cytisine (1.5-mg tablets): six times daily (one every 2 hours) on days 1–3; five times per day on days 4–12; four times per day on days 13–16; three tablets per day on days 17–20; two tablets per day on days 21–22; one tablet per day on days 23–25 | Placebo: tablets same regimen | CO-validated CAR. Day 5, week 8. Day 5, week 26 |

| West 201117 | Poland | 740 | Cytisine mean age: 49.5 years, placebo 43.5 years; cytisine percentage male 49.5%, placebo 43.5%; cytisine mean years smoking 28.1 years, placebo 28.6 years | Adults who smoked ≥ 10 cigarettes per day, willing to attempt to stop smoking permanently | Cytisine (1.5-mg tablets): six times daily (one every 2 hours) on days 1–3; five times per day on days 4–12; four times per day on days 13–16; three tablets per day on days 17–20; two tablets per day on days 21–25 | Placebo: tablets same regimen | CO-validated abstinence (fewer than five cigarettes during preceding 6 months) 12 months after end of treatment |

| Study name | Country | n | Participants | Inclusion criteria | Intervention | Comparator | Smoking cessation (strictest definition) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aubin 200846 | Multinational (Belgium, France, the Netherlands, UK and the USA) | 757 (randomised), 746 (treated) | Varenicline: mean age 42.9 years, percentage male 48.4%, mean years smoking 25.9 years NRT: mean age 42.9 years, percentage male 50%, mean years smoking 25.2 years |

Smokers aged 18–75 years, smoking at least 15 cigarettes per day with no period of abstinence > 3 months in the previous year | Varenicline: 1 mg b.i.d. for 12 weeks, titrated during week 1 | Nicotine transdermal patch (21 mg weeks 2–6, 14 mg weeks 7–9, 7 mg weeks 10–11) | CO-confirmed CAR Varenicline: 9–12 weeks, 9–24 weeks, 9–52 weeks NRT: 8–11 weeks, 8–24 weeks, 8–52 weeks |

| Bolliger 201147 | Multinational (11 countries in Latin America, the Middle East and Africa) | 593 | Varenicline: mean age 43.1 years, percentage male 57.7%, mean years smoking 25.0 years Placebo: mean age 43.9 years, percentage male 65.7%, mean years smoking 26.8 years |

Smokers aged 18–75 years; motivated to stop smoking and had smoked a mean ≥ 10 cigarettes per day during the past 12 months; no cumulative period of abstinence > 3 months in the previous 12 months | Varenicline: 1 mg b.i.d. for 12 weeks, titrated during week 1 | Placebo: tablets same regimen | CO-validated CAR: 9–12 weeks, 9–24 weeks |

| de Dios 201238 | USA | 32 | Varenicline: mean age 45.7 years, percentage male 40% NRT: mean age 39.1 years, percentage male 54.5% Placebo: mean age 44.2 years, percentage male 45.5% |

Adult Latino light smokers ≤ 10 cigarettes per day for the past 3 months | Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 12 weeks, titrated during week 1 | Nicotine patch for 12 weeks: 14 mg for 4 weeks, tapering to 7 mg for 8 weeks Placebo: matched to varenicline regimen |

CO-validated 7-day PPA: 2 weeks, 1 month, 2 months, 3 months, 4 months, 6 months |

| Gonzales 200648 | USA (multicentre) | 1025 | Varenicline: mean age 42.5 years, percentage male 50%, mean years smoked 24.3 years Bupropion: mean age 42.0 years, percentage male 58.4%, mean years smoked 24.1 years Placebo: mean age 42.6 years, percentage male 54.1%, mean years smoked 24.7 years |

Smokers aged 18–75 years, smoking 10 or more cigarettes per day, had < 3 months of smoking abstinence in the past year, motivated to stop smoking | Varenicline: 1 mg b.i.d. for 12 weeks, titrated week 1 | Bupropion: SR for 12 weeks, 150 mg b.i.d. through week 12, titrated days 1–3 Placebo: tablets same regimen |

CO-validated CAR: 9–12 weeks, 9–24 weeks, 9–52 weeks |

| Heydari 201239 | Iran | 272 | Mean age: counselling, 42.2 years, varenicline 43.5 years, NRT 41.8 years. Percentages for individual group sex unclear. Mean years smoked not reported. NB study includes smokers of < 10 cigarettes per day | Smokers who attended the clinic for help in quitting | Varenicline: 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 8 weeks, titrated during week 1, plus counselling | NRT: 15 mg daily nicotine patches for 8 weeks, plus counselling Counselling only |

CO-verified ‘smoke-free’: 1 month, 6 months, 12 months |

| Jorenby 200616 | USA (multicentre) | 1027 | Varenicline: mean age 44.6 years, percentage male 55.2%, mean years smoked 27.1 years Bupropion: mean age 42.9 years, percentage male 60.2%, mean years smoked 25.4 years Placebo: mean age 42.3 years, percentage male 58.1%, mean years smoked 24.4 years |

Smokers aged 18–75 years, smoking 10 or more cigarettes per day, had < 3 months of smoking abstinence in the past year | Varenicline: 1 mg b.i.d. for 12 weeks, titrated during week 1 | Bupropion: sustained release 150 mg b.i.d. through week 12, titrated to full strength during week 1 Placebo: tablets matching regimen |

CO-validated CAR: 9–12: weeks, 9–24 weeks, 9–52 weeks |

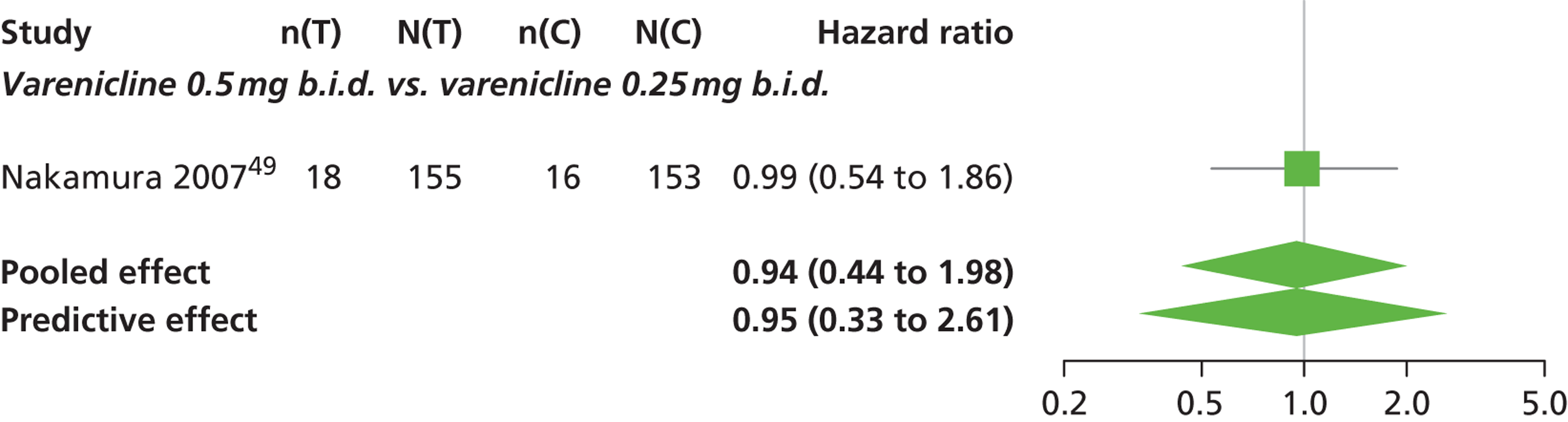

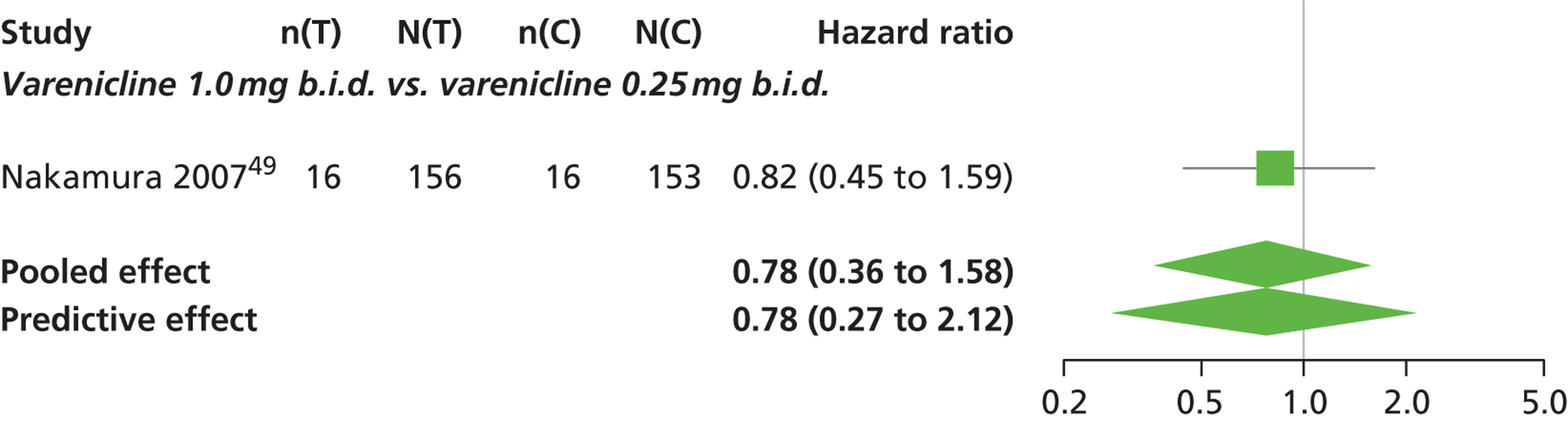

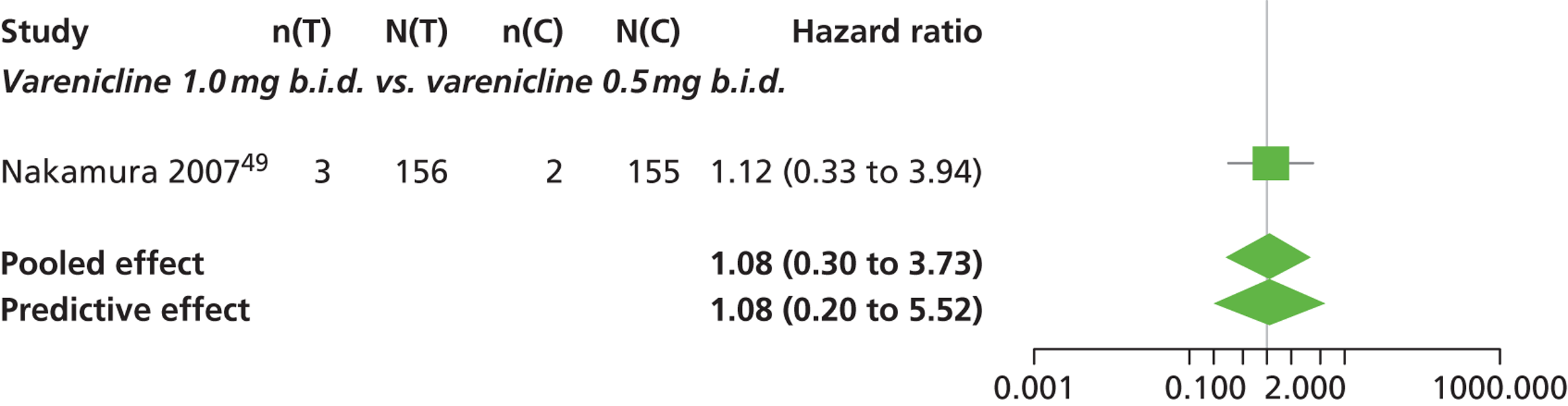

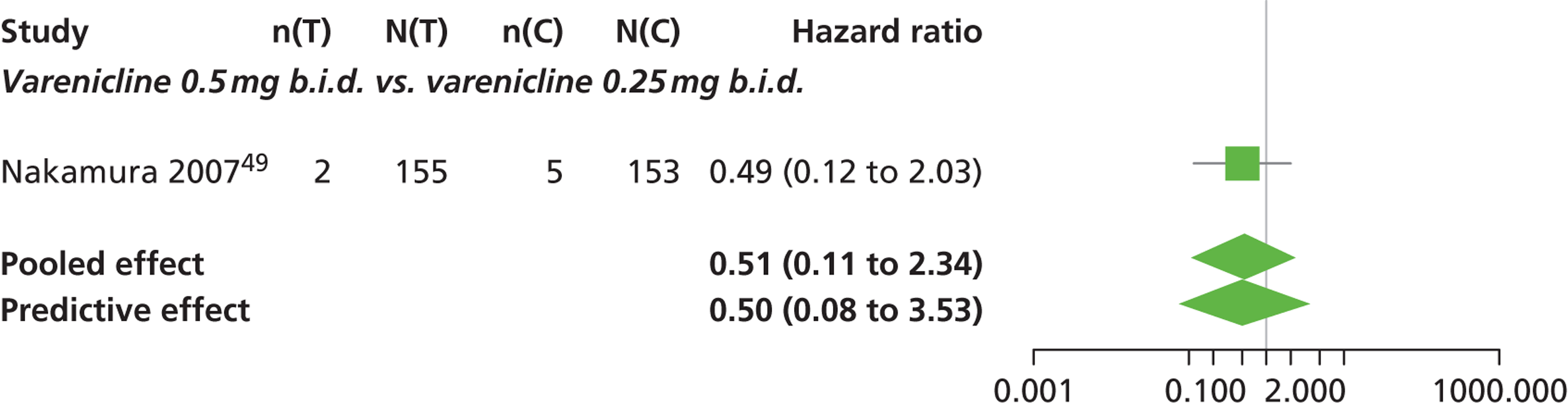

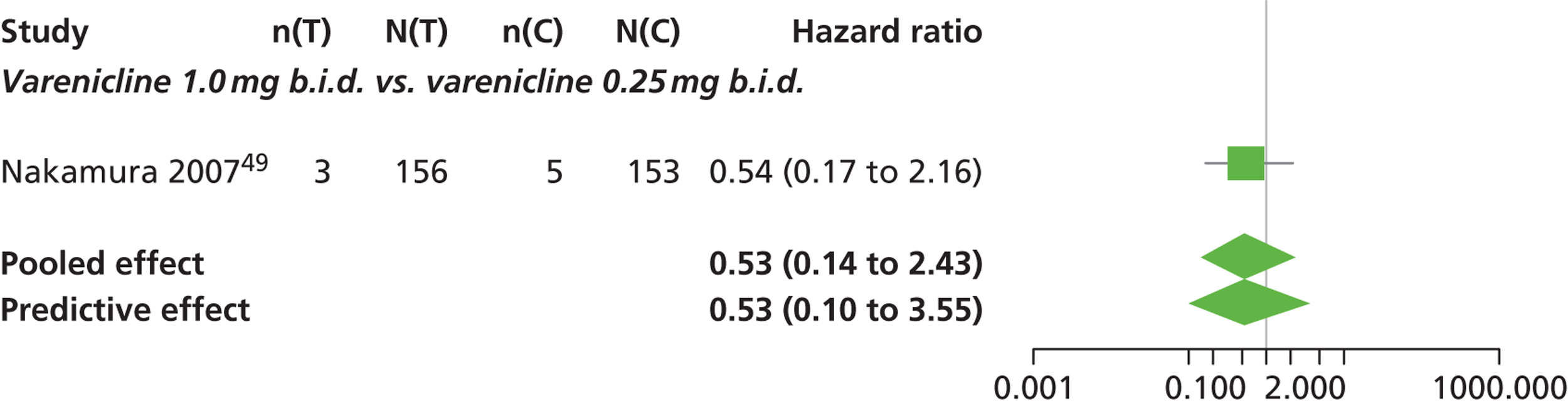

| Nakamura 200749 | Japan | 619 | Varenicline 0.25 mg (n = 128): mean age 40.2 years, percentage male 72.7%, mean years smoked 11.5 years Varenicline 0.5 mg (n = 128): mean age 39 years, percentage male 71.1%, mean years smoked 20.1 years Varenicline 1 mg (n = 130): mean age 40.1 years, percentage male 79.2%, mean years smoked 21.5 years Placebo (n = 129): mean age 39.9 years, percentage male 76%, mean years smoked 20.9 years |

Smokers aged between 20–75 years. Motivated to stop smoking, smoking more than 10 cigarettes per day for previous year without a period of abstinence > 90 days | Varenicline at 3 doses: 0.25 mg b.i.d., 0.5 mg b.i.d., 1 mg b.i.d. 12 weeks of treatment, titrated during week 1 | Placebo: tablets matching regimen | CO-validated CAR: 9–12 weeks, 9–24 weeks, 9–52 weeks |

| Niaura 200850 | USA | 320 | Varenicline (n = 157): mean age 41.5 years, percentage male 50.3%, mean years smoked 24.9 years Placebo (n = 155): mean age 42.1 years, percentage male 53.5%, mean years smoked 25.7 years |

Healthy adult cigarette smokers, motivated to quit, aged 18–65 years, smoked at least 10 cigarettes per day with no period of abstinence > 3 months in the past year | Varenicline: 1 week dose titration up to 0.5 mg b.i.d. Participants then chose dosing schedule, at least one 0.5-mg tablet daily, no more than two 0.5-mg tablets b.i.d. | Placebo: same regimen | CO-validated CAR: 4–7 weeks, 9–12 weeks, 9–52 weeks |

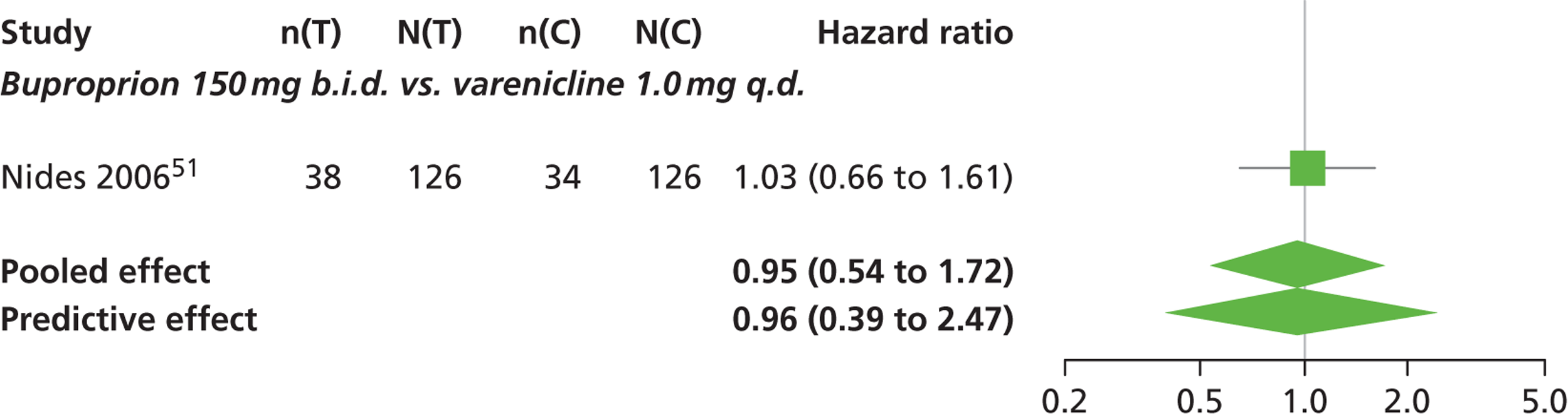

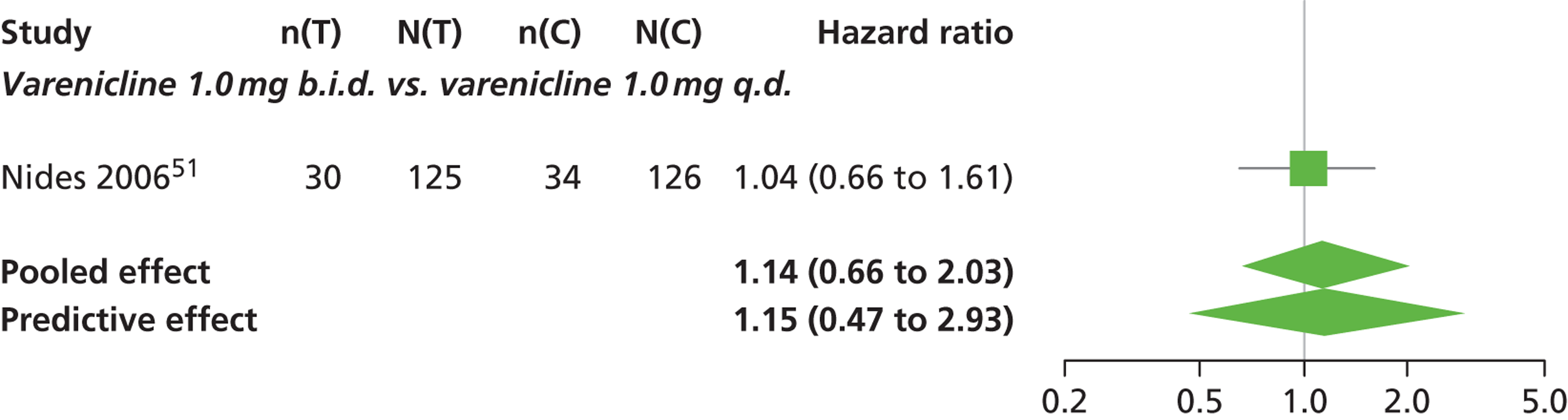

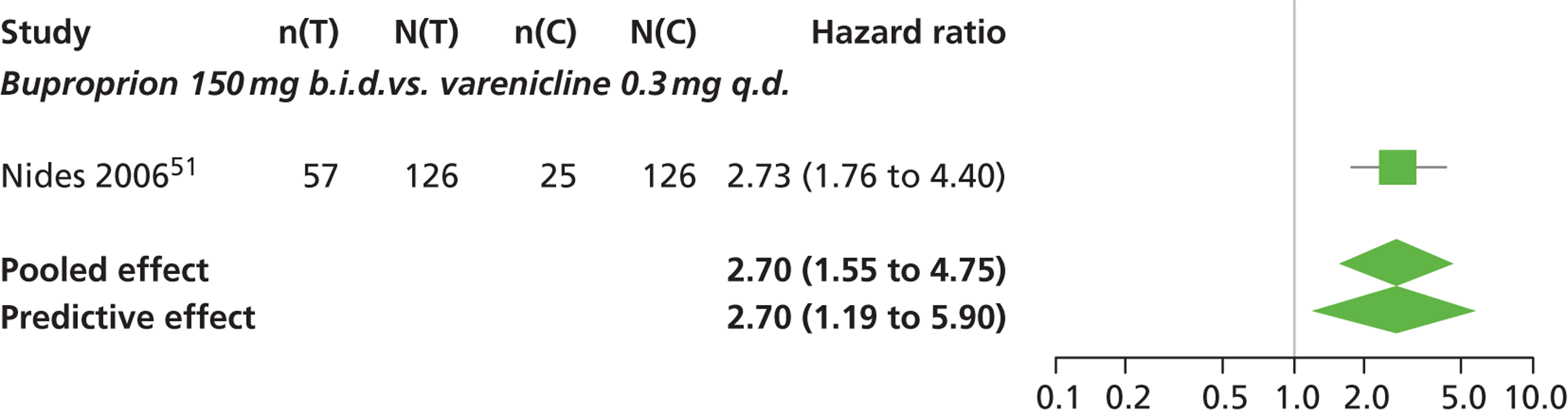

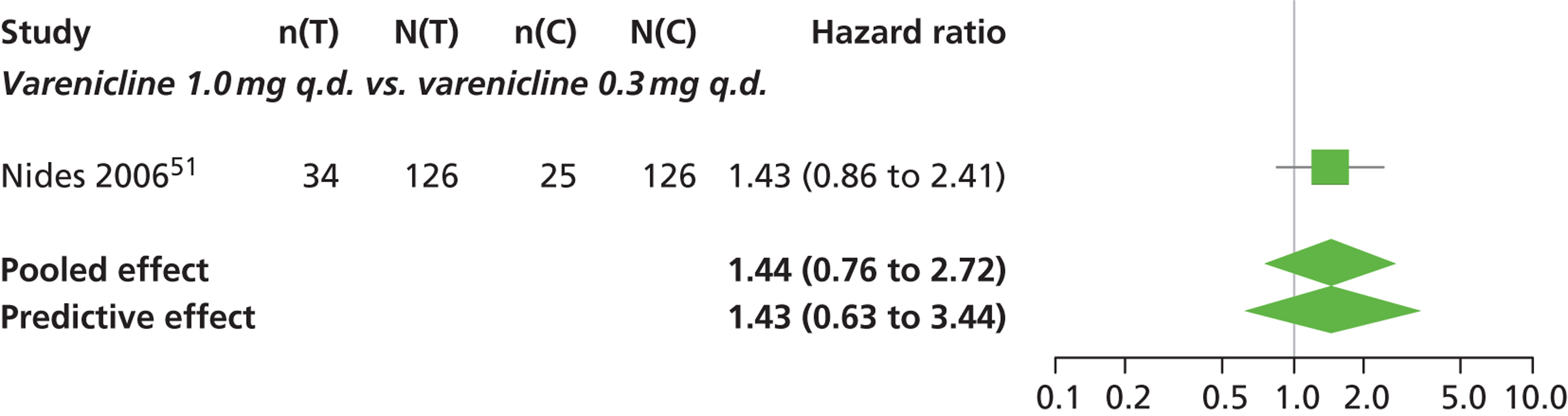

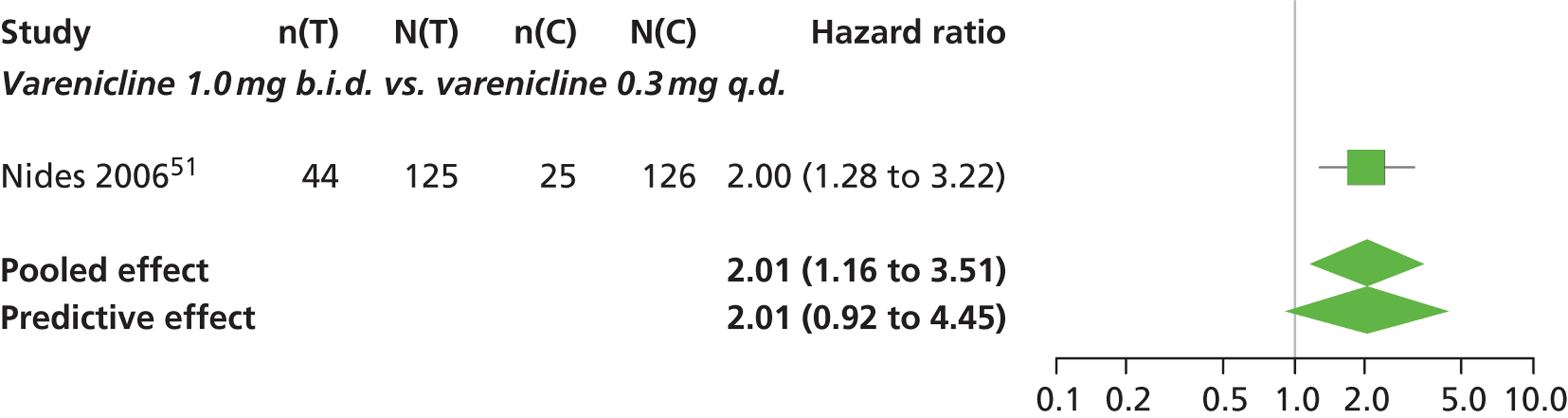

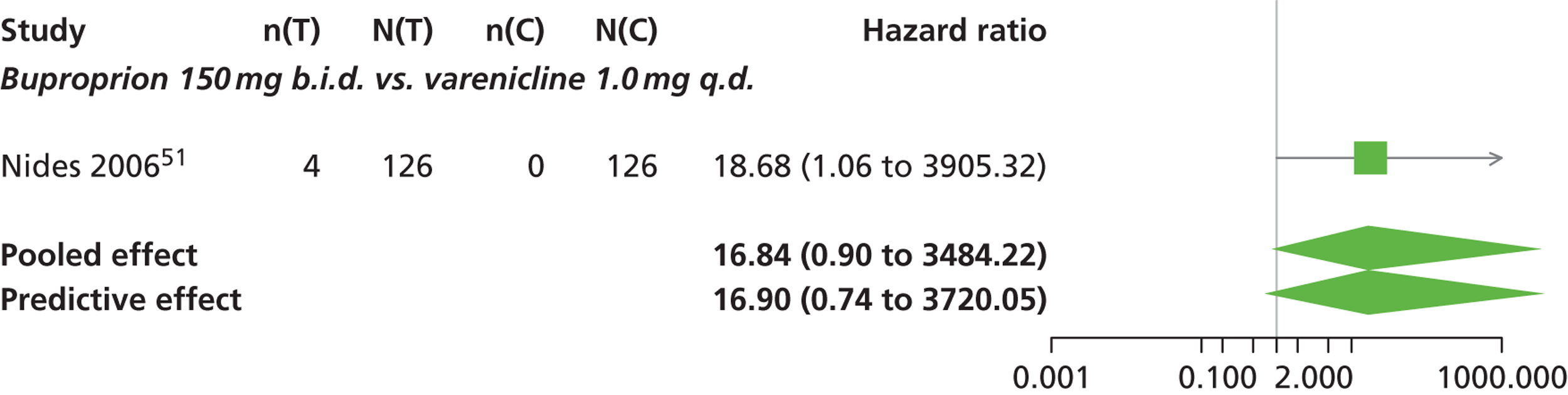

| Nides 200651 | USA | 638 | Varenicline 0.3 mg (n = 126): mean age 41.9 years, percentage male 50%, years smoked 24.6 years Varenicline 1.0 mg once per day (n = 126): mean age 42.9 years, percentage male 43.7%, mean years smoked 25.4 years Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. (n = 125): mean age 41.9 years, percentage male 50.4%, mean years smoked 23.4 years Bupropion hydrochloride (n = 126): mean age 40.5 years, percentage male 45.2%, mean years smoked 23.4 years Placebo (n = 123): mean age 41.6 years, percentage male 52.0%, mean years smoked 23.9 years |

Male and female smokers aged 18–65 years who were in good general health, required to have smoked an average 10 cigarettes per day during the previous year without a period of abstinence > 3 months | Varenicline at one of three dose regimens: 0.3 mg q.d., 1.0 mg q.d., or 1.0 mg b.i.d. Subjects dosed for 6 weeks, then received blinded placebo for week 7 | Bupropion hydrochloride: dosed for 7 weeks, titrated days 1–3 to 150 mg b.i.d. through week 7 Placebo: at matching regimen |

CO-validated 4-week abstinence for any part of treatment Continuous quit rate: 4–7 weeks, 2–12 weeks, 4–24 weeks, 4–52 weeks |

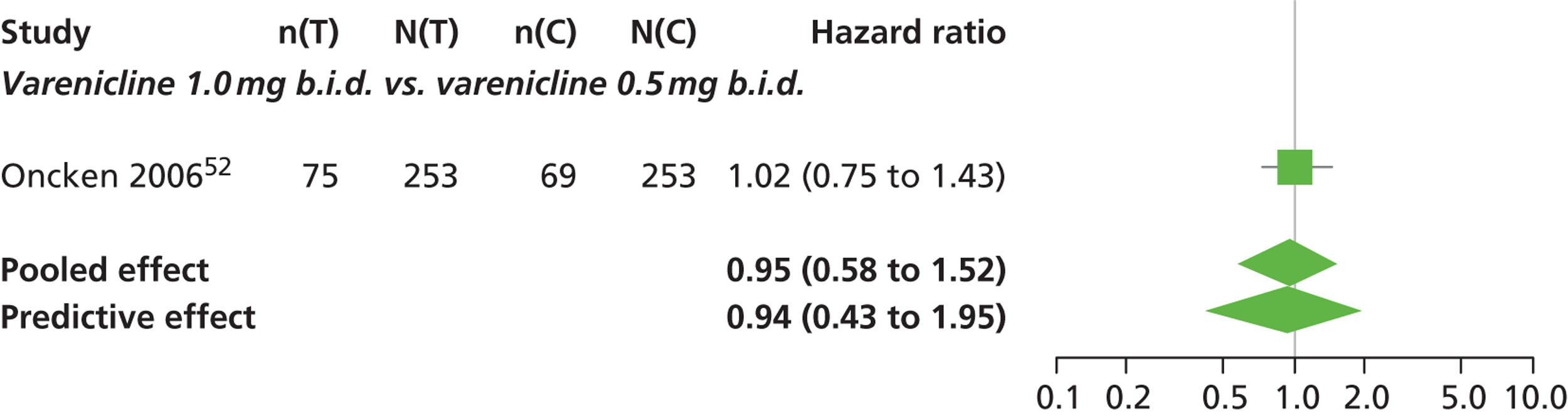

| Oncken 200652 | USA | 647 | Varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d. non-titrated: mean age 42.9 years, percentage male 45%, mean years smoked 26.0 years Varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d. titrated: mean age 43.5 years, percentage male 53.1%, mean years smoked 25 years Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. non-titrated: mean age 43.7 years, percentage male 48.8%, mean years smoked 25.7 years Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. titrated: mean age 42.2 years, percentage male 48.5%, mean years smoked 24.0 years Placebo: mean age 43.0 years, percentage male 51.9%, mean years smoked 25.3 years |

Healthy cigarette smokers aged 18–65 years, who smoked at least 10 cigarettes per day | Varenicline: 0.5 mg b.i.d. non-titrated (12 weeks); 0.5 mg b.i.d. titrated (0.5 mg q.d. for 1 week, then b.i.d. through 12 weeks); 1.0 mg b.i.d. non-titrated (12 weeks); 1.0 mg b.i.d. titrated (0.5 mg once a day for 3 days, 0.5 mg b.i.d. for 4 days, then 1.0 mg b.i.d. through 12 weeks) | Placebo: tablets b.i.d. for 12 weeks | CO-validated continuous 4-week abstinence: 4–7 weeks, 9–12 weeks Continuous-verified abstinence: 2–12 weeks, 9–52 weeks |

| Pfizer 2011 40/Williams 201241 | USA and Canada | 128 | Varenicline: male 65/85; age 18–34 years, n = 33; age 35–44 years, n = 10; age 45–64 years, n = 42 Placebo: male 33/43; age 18–34 years, n = 11; age 35–44 years, n = 9; age 45–64 years, n = 23 |

Aged 18–75 years, male and female, have a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and judged to be stable on psychiatric treatment. Current smokers, at least 15 cigarettes per day during the past year with no period of abstinence > 3 months in the past year. Motivated to stop smoking | Varenicline: 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 12 weeks, titrated during week 1 | Placebo: matching regimen | CO-validated PPA: 12 weeks, 24 weeks |

| Rennard 201253 | Multinational (14 countries) | 659 | Varenicline (n = 493): mean age 43.9 years, percentage male 60%, mean years smoked 26 years Placebo (n = 166): mean age 43.2 years, percentage male 59.6%, mean years smoked 24.6 |

Male and female smokers aged 18–75 years, who had smoked ≥ 10 cigarettes per day during the past year, with no period of abstinence > 3 months in the past year and who were motivated to stop smoking | Varenicline: 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 12 weeks, titrated during week 1 | Placebo: matching regimen | CO-validated CAR: 9–12 weeks, 9–24 weeks |

| Rigotti 201054 | Multinational (15 countries) | 714 | Varenicline: mean age 57 years, percentage male 75.2%, mean years smoked 40 years Placebo: mean age 55.9 years, percentage male 82.2%, mean years smoked 39 years |

Adults aged 35–75 years who had smoked > 10 cigarettes per day in the year prior to enrolment, wanted to stop smoking but had not tried to quit in the past 3 months. Had stable, documented CVD that had been diagnosed > 2 months. Eligible CVD diagnosis included history of myocardial infarction, coronary revascularisation, angina pectoris, peripheral arterial vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease | Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 12 weeks, titrated during week 1 | Placebo: matching regimen | CO-validated CAR: 9–12 weeks, 9–24 weeks, 9–52 weeks |

| Smith 201355 | Australia | 392 | Aged 20–75 years with smoking-related illnesses | Aged between 20–75 years recruited from hospital wards with smoking-related illnesses | Varenicline: 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 12 weeks, titrated during week 1, plus Quit South Australia counselling | Quit South Australia counselling alone | CAR < 5 cigarettes total: 2 weeks–12 months CO validation only in subset of participants |

| Steinberg 201156 | USA | 79 | Mean age overall: 51 years. Mean years smoking not reported Varenicline: age distribution ≤ 40 years, 12%; 41–50 years, 22%; 51–59 years, 35%; ≥ 60 years, 30%. Percentage male 60% Placebo: age distribution ≤ 40 years, 15%; 41–50 years, 33%; 51–59 years, 36%; ≥ 60 years, 15%. Percentage male 59% |

Patients admitted to the hospital who smoked ≥ 10 cigarettes per day within the past month, were not being discharged into a setting of forced abstinence (e.g. institutionalised) | Varenicline: 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 12 weeks, titrated during week 1 | Placebo: matching regimen | 7-day PPA: 4 weeks, 26 weeks, 12 weeks |

| Tashkin 201157 | Multinational (four countries) | 504 | Varenicline: mean age 57.2 years, percentage male 62.5%, mean years smoking 40.4 years Placebo: mean age 57.1 years, percentage male 62.2%, mean years smoking 40.6 years |

Adults aged ≥ 35 years with a clinical diagnosis of mild to moderate COPD, motivated to stop smoking, smoking an average of ≥ 10 cigarettes per day over the past year with no period of abstinence > 3 months over that time | Varenicline: 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 12 weeks, titrated during week 1 | Placebo: matching regimen | CO-validated CAR: 9–12 weeks, 9–24 weeks, 9–52 weeks |

| Tsai 200758 | Republic of Korea and Taiwan, province of China | 250 | Varenicline: mean age 39.7 years, percentage male 84.9%, mean years smoking 20.2 years Placebo: mean age 40.9 years, percentage male 92.7%, mean years smoking 22.1 years |

Male and female smokers aged 18–75 years, who had smoked ≥ 10 cigarettes per day during the past year, with no period of abstinence > 3 months in the past year, and who were motivated to stop smoking | Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 12 weeks, titrated during week 1 | Placebo: (no details reported) | CO-validated CAR: 9–12 weeks, 9–24 weeks |

| Tsukahara 201059 | Japan | 32 | Varenicline: mean age 45.4 years, percentage male 85.7%. mean years smoking 25.4 years Nicotine patch: mean age 46.8 years, percentage male 78.6%, mean years smoking 27.1 years |

Adult smokers who all wished to stop smoking immediately | Varenicline: 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 12 weeks, titrated during week 1 | Transdermal nicotine patch for 8 weeks, 52.5 mg for 4 weeks; 35 mg for 2 weeks; 17.5 mg for 2 weeks | CO-validated CAR: 9–12 weeks Self-reported CAR: 9–24 weeks |

| Wang 200960 | China, Singapore and Thailand | 333 | Varenicline: mean age 39.0 years, percentage male 96.4%, mean years smoking 20.5 years Placebo: mean age 38.5 years, percentage male 97.0%, mean years smoking 19.6 years |

Adults aged 18–75 years, smoked on average ≥ 10 cigarettes per day during the year prior to the screening visit with no period of abstinence > 3 months, motivated to stop smoking | Varenicline: 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 12 weeks, titrated during week 1 | Placebo: matching regimen | CO-validated CAR: 9–12 weeks, 9–24 weeks |

| Williams 200761 | USA and Australia | 377 | Varenicline: mean age 48.2 years, percentage male 50.6%, mean years smoking 30.7 years Placebo: mean age 46.6 years, percentage male 48.4%, mean years 29.9 years |

Adult smokers, aged 18–75 years, who had smoked an average of ≥ 10 cigarettes per day during the past year, with no period of abstinence > 3 months | Varenicline: 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 52 weeks, titrated during week 1 | Placebo: matching regimen | CO-validated 7-day PPA |

| Wong 201237 | Canada | 286 | Varenicline: mean age 51.9 years, percentage male 55% Placebo: mean age 53.3 years, percentage male 50.4% |

Adult patients 18 years or older who attended the preoperative clinic for surgery within 8–10 days, smoked a minimum of 10 cigarettes per day, with no period of abstinence > 3 months in the past year | Varenicline: 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 12 weeks, titrated during week 1 | Placebo: matching regimen | 7-day PPA CO-validated for some participants, but mailed in urinary cotinine validation for all: 3 months, 6 months, 12 months |

Description of studies from updated search

We found three additional studies that met our inclusion criteria, covering 590 participants. 37–39 All three studies were single-country studies, carried out in Canada, the USA, and Iran respectively. Wong et al. 37 conducted the study at two sites – both pre-operative clinics in hospitals in Canada. The Heydari et al. 39 study was set in tobacco cessation clinics in Iran and de Dios et al. 38 focused on Latino smokers in the USA. All studies evaluated varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. The duration of varenicline treatment for Wong et al. 37 and de Dios et al. 38 was 12 weeks, whereas for Heydari et al. 39 treatment duration was 8 weeks. Wong et al. 37 compared varenicline with placebo, while the remaining two studies had three arms: Heydari et al. 39 compared varenicline with nicotine patch or counselling and de Dios et al. 38 compared varenicline with nicotine patch or placebo. Wong et al. 37 only included adults who smoked more than 10 cigarettes per day, Heydari et al. 39 included smokers of both more or fewer than 10 cigarettes per day, and de Dios et al. 38 focused only on ‘light smokers’, i.e. those who smoked fewer than 10 cigarettes per day. Wong et al. 37 evaluated smoking cessation in a sample of patients who were due to undergo surgery.

Wong et al. 37 and de Dios et al. 38 measured smoking cessation using 7-day PPA. Heydari et al. 39 report their outcome measurement as being smoke free. An attempt to contact the authors to establish whether this was 7-day PPA or CAR failed and, therefore, we have made the conservative assumption that PPA was used. CO validation of smoking cessation outcomes was recorded in all three studies. Wong et al. 37 and Heydari et al. 39 followed up their participants for 12 months, while the longest follow-up for de Dios et al. 38 was 6 months. The target quit date for Heydari et al. 39 was day 14 of treatment, for Wong et al. 37 was 1 week after treatment began and in de Dios et al. 38 was not reported.

Risk of bias in included studies

A summary of the risk of bias judgements for all included studies is presented in Table 3. Support for judgements for quality assessments from Cahill et al. 15 is fully described in their review. Support for judgements of risk of bias for newly included studies is presented in Appendix 2. Both cytisine trials were judged to be of good quality. For varenicline trials, most studies were judged to be low risk for most of the risk of bias categories, although several studies were judged to have an unclear risk in one or more categories. For the newly included studies, Wong et al. 37 was assessed as low risk in all recorded categories of the Cochrane risk of bias tool. 32 De Dios et al. 38 was assessed as being unclear risk for both random sequence generation and allocation concealment as a result of unclear reporting, but was assessed as low risk for incomplete outcome data and selective reporting. Methods of randomisation, allocation concealment or blinding were not described in Heydari et al. ,39 and the study was therefore assessed as unclear risk for these categories. An assessment of low risk was given for incomplete outcome data as the authors report no dropouts from the study. Data on efficacy, the stated primary outcome, were reported and, therefore, the study was also assessed as low risk for this category.

| Study | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Selective reporting (reporting bias) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aVinnikov 200843 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Low risk |

| aWest 201117 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| bBolliger 201147 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| bGonzales 200648 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| bJorenby 200616 | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| bNakamura 200749 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | High risk |

| bNiaura 200850 | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| bNides 200651 | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk |

| bOncken 200652 | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| bPfizer 201140 | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | NR |

| bRennard 201253 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| bRigotti 201054 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| bSteinberg 201156 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Low risk |

| bTashkin 201157 | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk |

| bTsai 200758 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk |

| bWang 200960 | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk |

| bWilliams 200761 | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| bSmith 201355 | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | NR |

| bAubin 200846 | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| bTsukahara 201059 | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk |

| cHeydari 201239 | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| cWong 201237 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| cde Dios 201238 | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk |

Summary of data used in the network meta-analyses (cytisine and varenicline compared with placebo)

A full description of the data used for each meta-analysis for all interventions and comparators can be found in Appendix 5. Tables 4 and 5 present a summary of the CAR and adverse events data used in the analyses of cytisine and varenicline compared with placebo.

| Study | CAR | Abnormal dreams | Headache | Insomnia | Nausea | SAEs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytisine | Placebo | Cytisine | Placebo | Cytisine | Placebo | Cytisine | Placebo | Cytisine | Placebo | Cytisine | Placebo | |

| Vinnikov 200843 | 9/100 | 1/97 | – | – | 1/86 | 1/85 | – | – | 2/85 | 1/86 | – | – |

| West 201117 | 31/370 | 9/370 | – | – | 7/370 | 8/370 | – | – | 10/370 | 14/370 | 4/370 | 3/370 |

| Study | CAR | Abnormal dreams | Headache | Insomnia | Nausea | SAEs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Varenicline | Placebo | Varenicline | Placebo | Varenicline | Placebo | Varenicline | Placebo | Varenicline | Placebo | Varenicline | Placebo | |

| Bolliger 201147 | 157/394 | 26/199 | – | – | 64/390 | 24/198 | 50/390 | 13/198 | 103/390 | 16/198 | 11/394 | 2/199 |

| Niaura 200850 | 35/160 | 12/160 | – | – | 25/157 | 20/155 | 34/157 | 17/155 | 21/157 | 8/155 | 3/160 | 0/160 |

| Pfizer 201140/Williams 201241 | – | – | 6/84 | 43/4 | 9/84 | 8/43 | 8/84 | 2/43 | 20/84 | 6/43 | 5/85 | 4/43 |

| Rennard 201253 | 171/493 | 21/166 | 61/486 | 5/165 | 55/486 | 20/165 | 43/486 | 6/165 | 142/486 | 15/165 | 6/493 | 1/166 |

| Rigotti 201054 | 68/355 | 26/359 | 28/353 | 6/350 | 45/353 | 39/350 | 42/353 | 23/350 | 104/353 | 30/350 | 23/353 | 21/354 |

| Steinberg 201156 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 10/38 | 2/37 | 6/40 | 5/39 |

| Tashkin 201157 | 47/250 | 14/254 | 27/248 | 7/251 | 20/248 | 20/251 | 24/248 | 15/251 | 67/248 | 20/251 | 12/248 | 15/253 |

| Tsai 200758 | 59/126 | 27/124 | 7/126 | 1/124 | – | – | 19/126 | 17/124 | 55/126 | 14/124 | 3/126 | 3/124 |

| Smith 201355 | 61/196 | 42/196 | 12/196 | 2/196 | 12/196 | 3/196 | 10/196 | 4/196 | 32/196 | 3/196 | 6/119 | 3/117 |

| Aubin 200846 | 98/378 | 75/379 | 44/376 | 31/370 | 72/376 | 36/376 | 80/376 | 71/370 | 140/376 | 36/370 | 2/376 | 8/370 |

| Wang 200960 | 63/165 | 42/168 | – | – | 9/165 | 7/168 | 10/165 | 5/168 | 48/165 | 20/168 | 0/165 | 2/168 |

| Tsukahara 201059 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 6/14 | 2/14 | 4/14 | 0/14 | – | – |

| Wong 201237 | – | – | 3/151 | 0/135 | 5/151 | 0/135 | – | – | 20/151 | 5/135 | – | – |

| Heydari 201239 | – | – | 3/89 | 0/91 | – | – | – | – | 8/89 | 0/91 | – | – |

| Gonzales 200648 | 77/352 | 29/344 | 36/349 | 19/344 | 54/349 | 42/344 | 49/349 | 44/344 | 98/349 | 29/344 | 4/349 | 9/344 |

| Jorenby 200616 | 79/344 | 35/341 | 45/343 | 12/340 | 44/343 | 43/340 | 49/343 | 42/340 | 101/343 | 33/340 | 8/344 | 6/341 |

| Oncken 200652 | 58/259 | 5/129 | 46/253 | 6/121 | 59/253 | 21/121 | 75/253 | 14/121 | 97/253 | 18/121 | – | – |

| Nakamura 200749 | 56/156 | 35/154 | – | – | 16/156 | 4/154 | – | – | 38/156 | 12/154 | 3/156 | 3/154 |

| Nides 200651 | 18/127 | 6/127 | 19/125 | 10/123 | 30/125 | 33/123 | 44/125 | 27/123 | 65/125 | 23/123 | 1/125 | 0/127 |

Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Results

Continuous abstinence

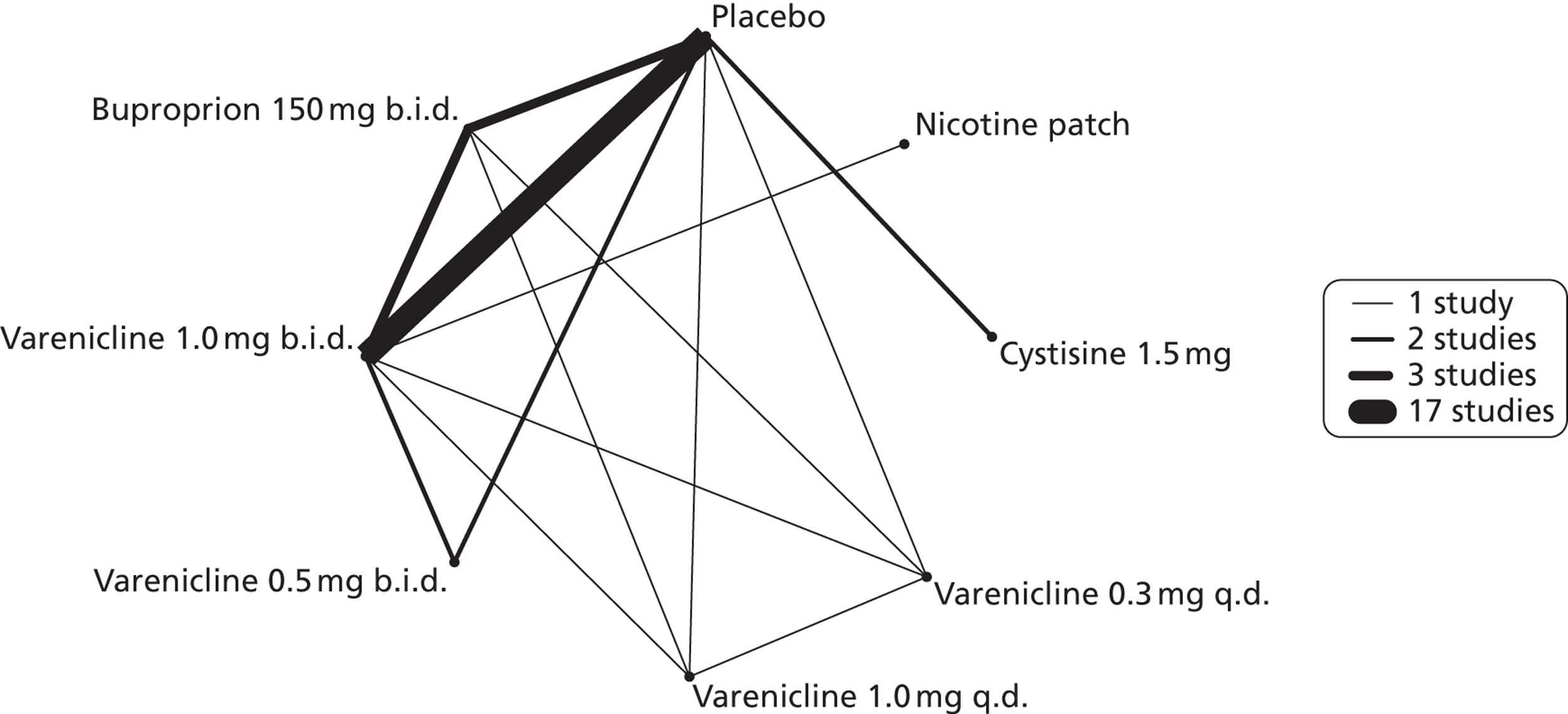

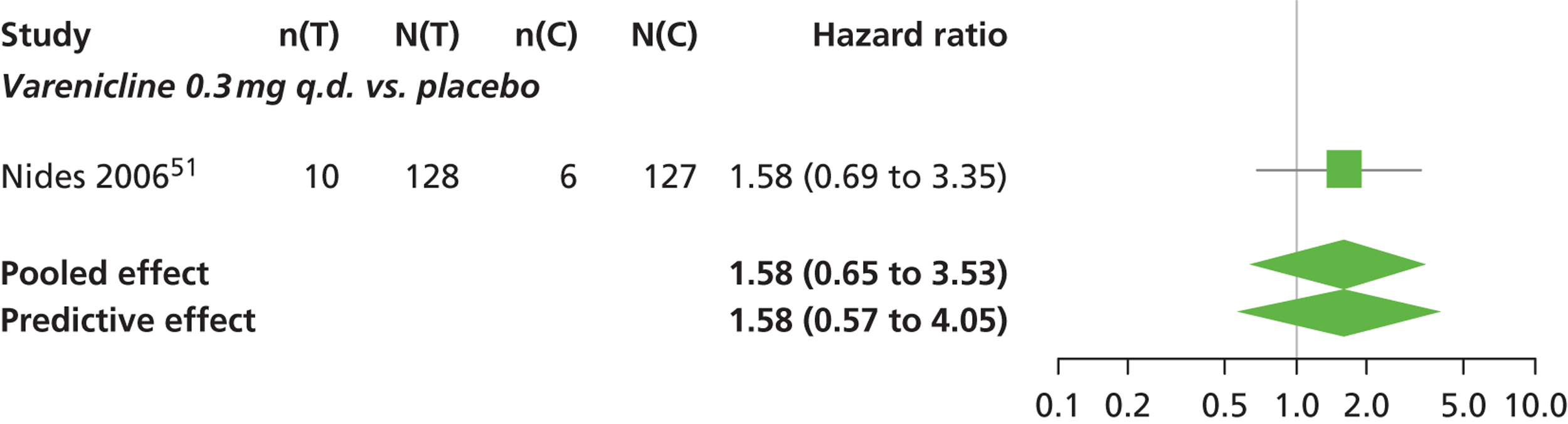

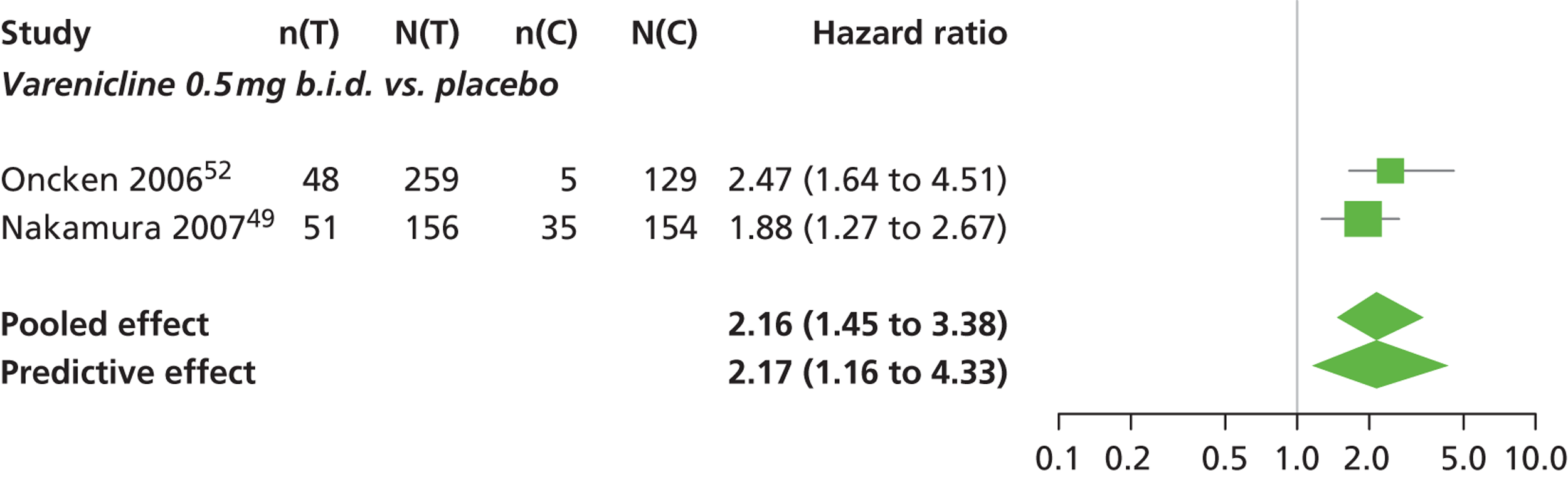

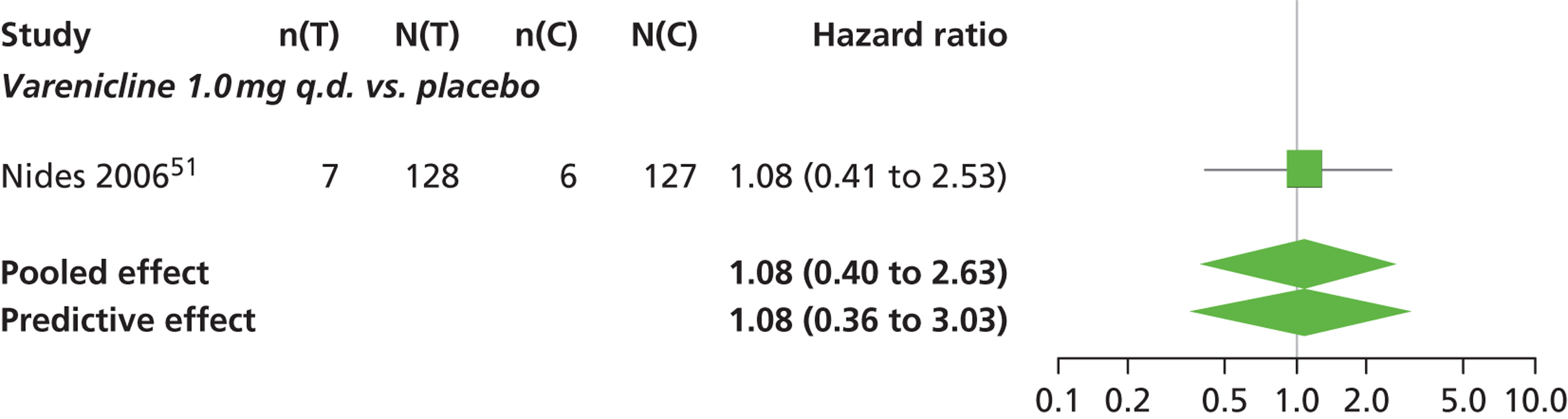

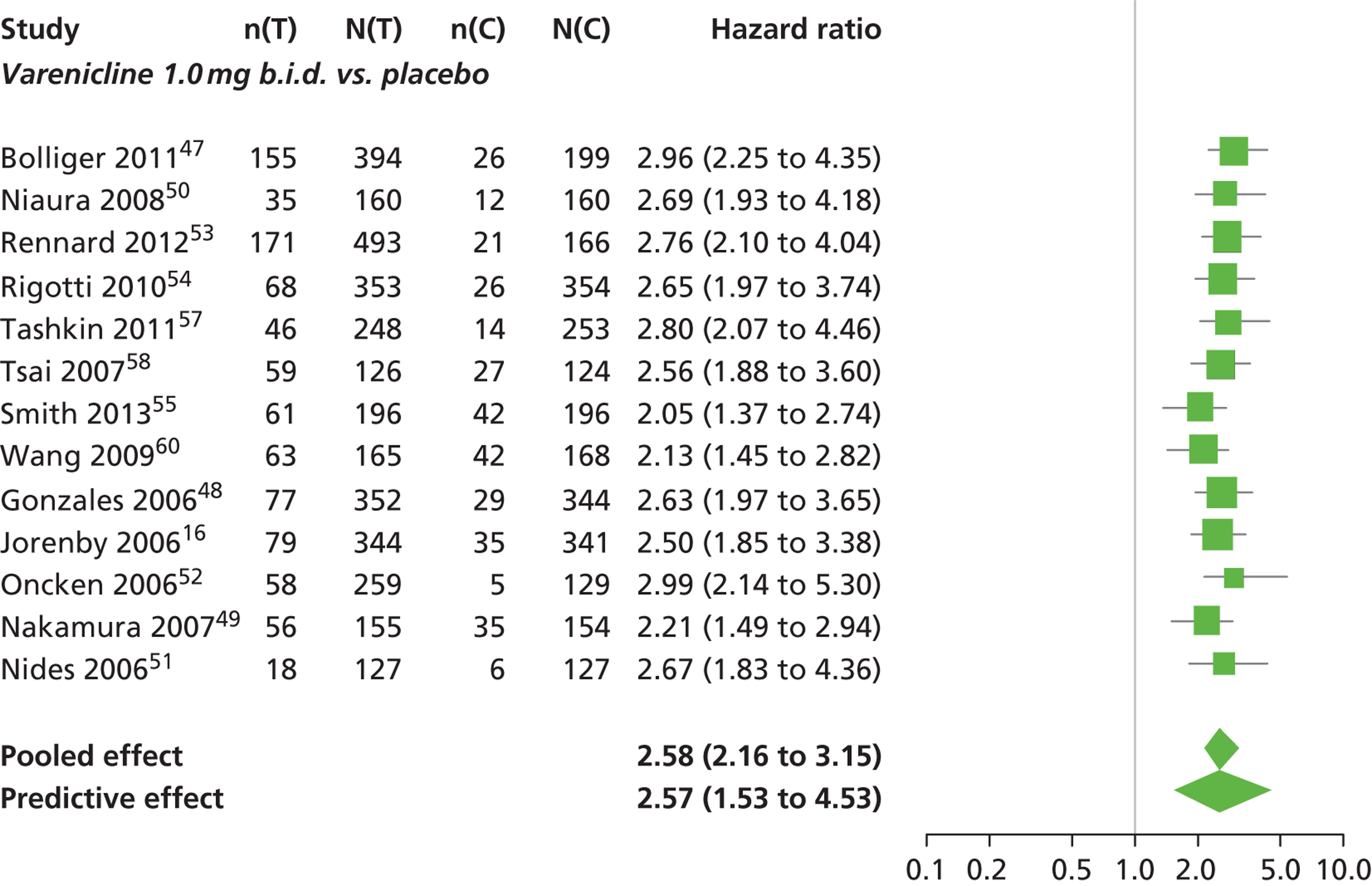

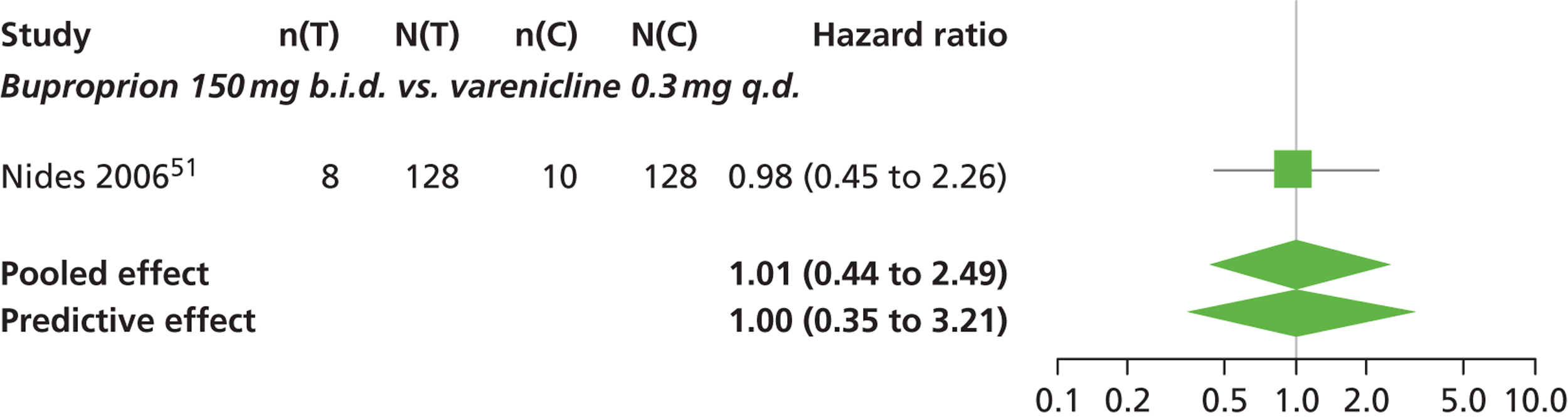

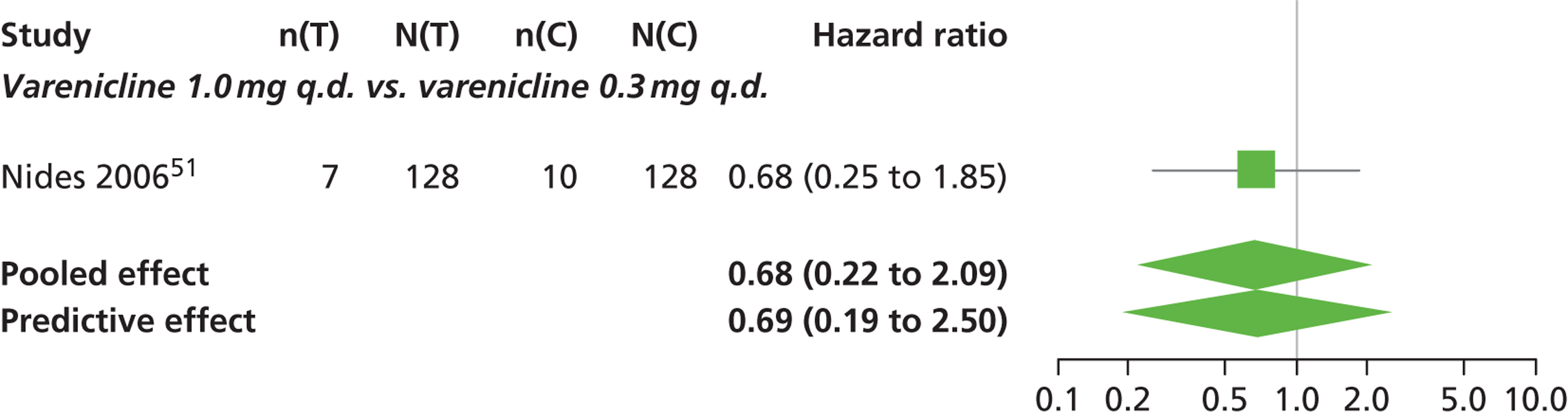

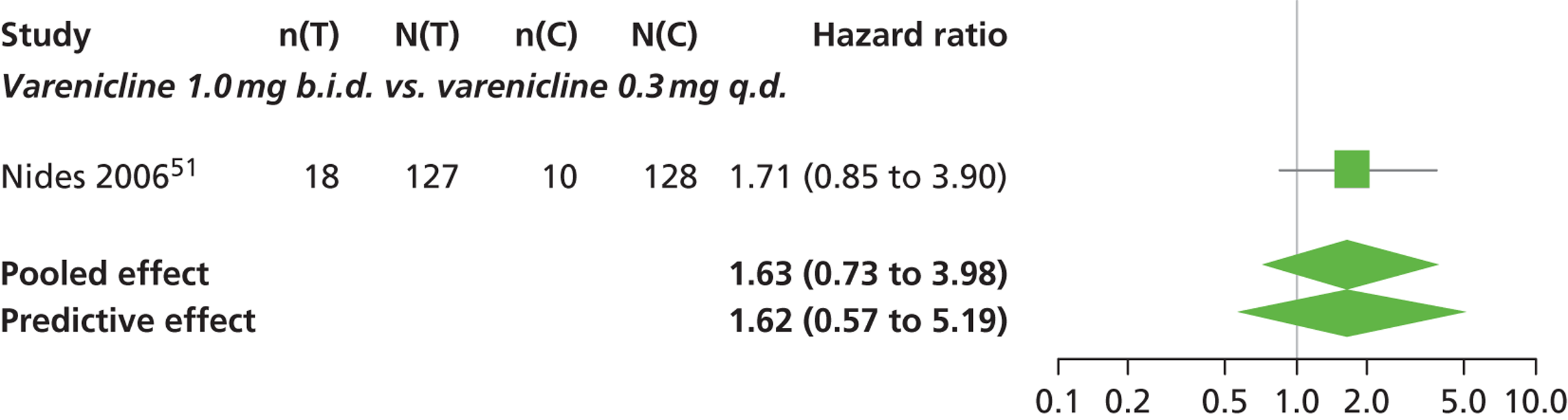

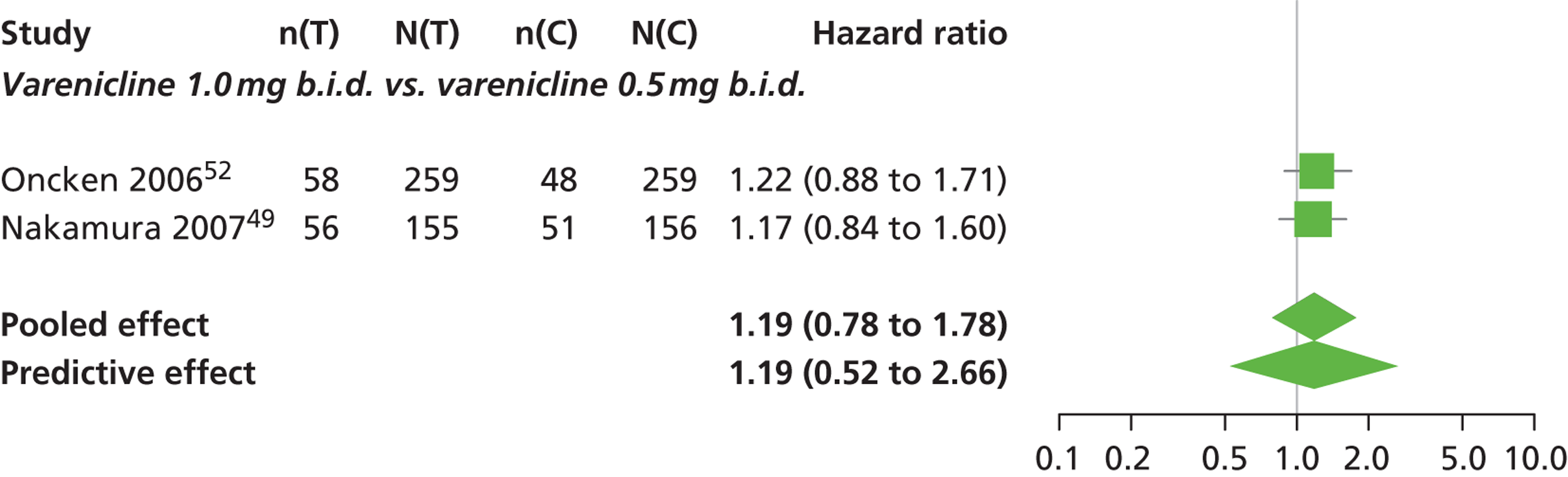

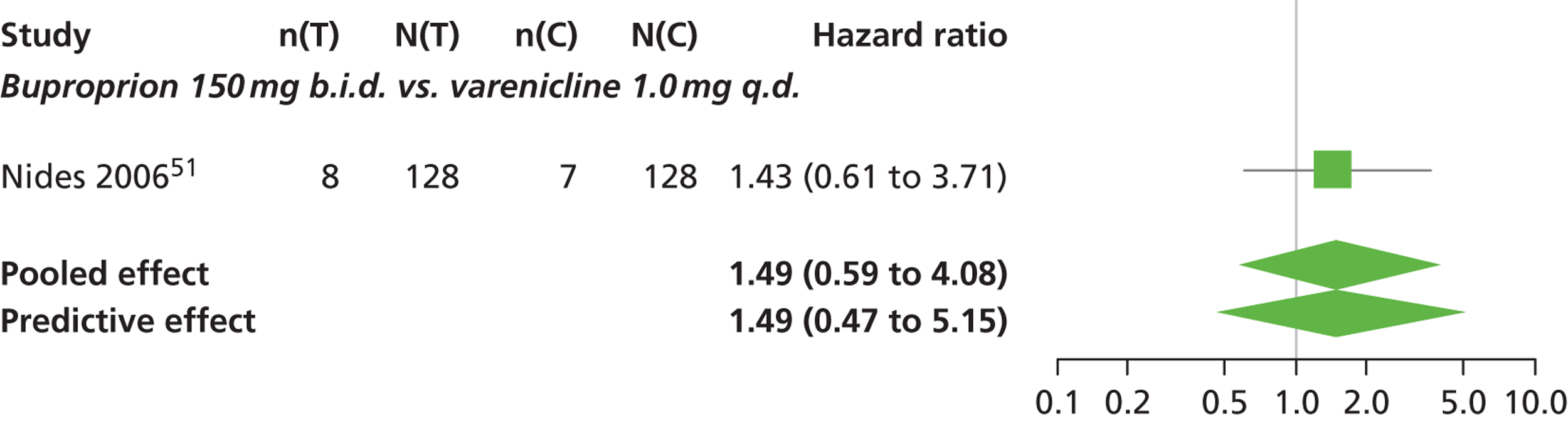

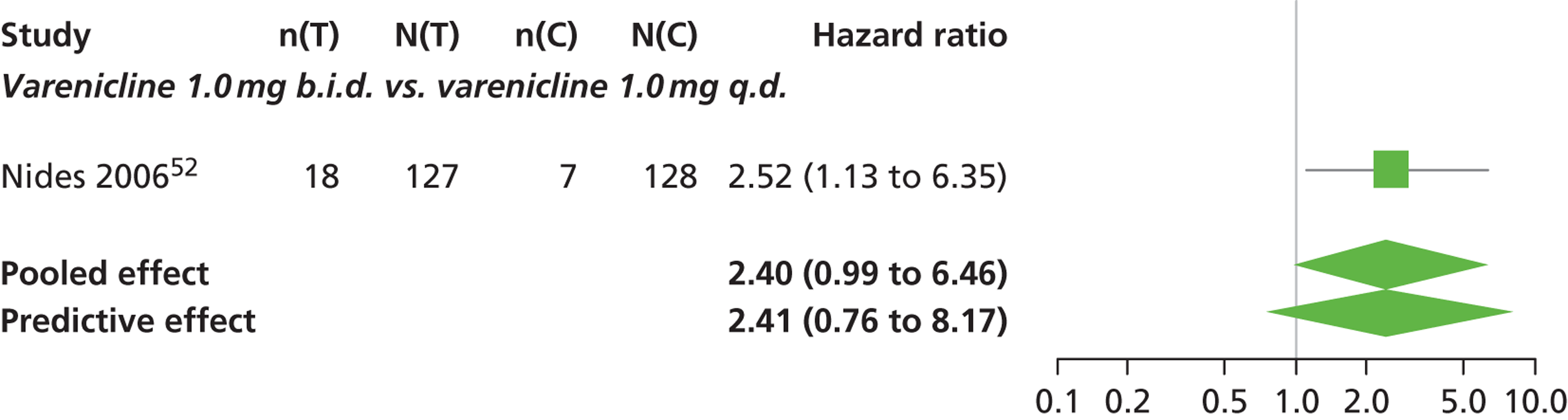

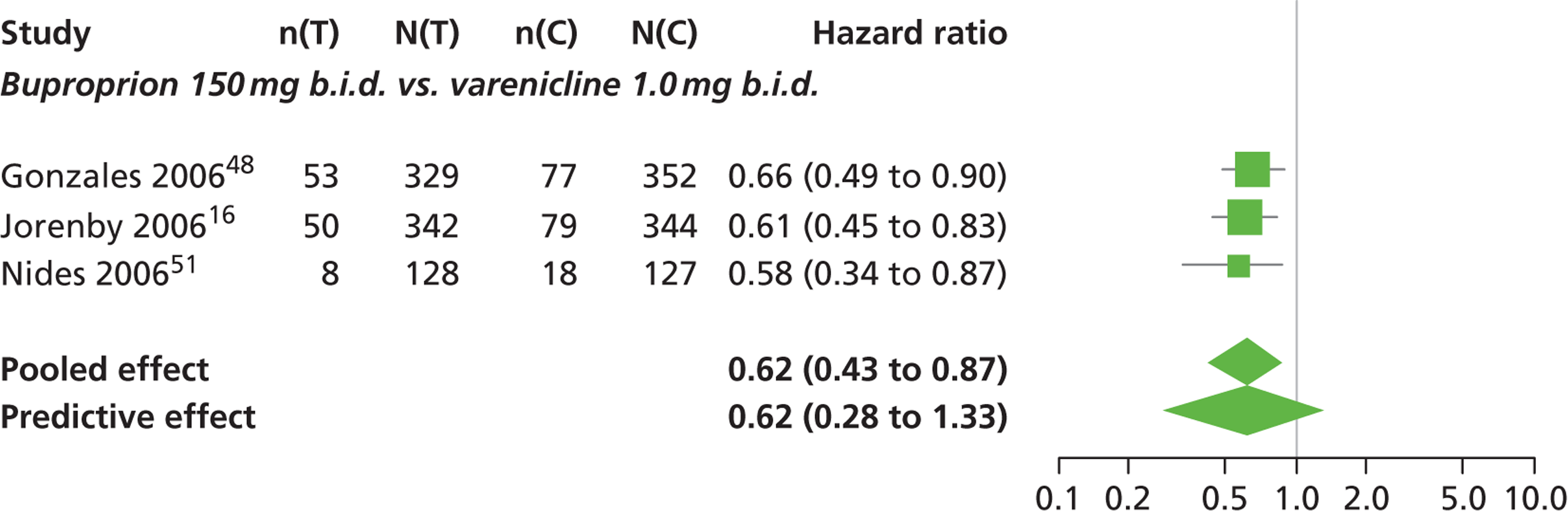

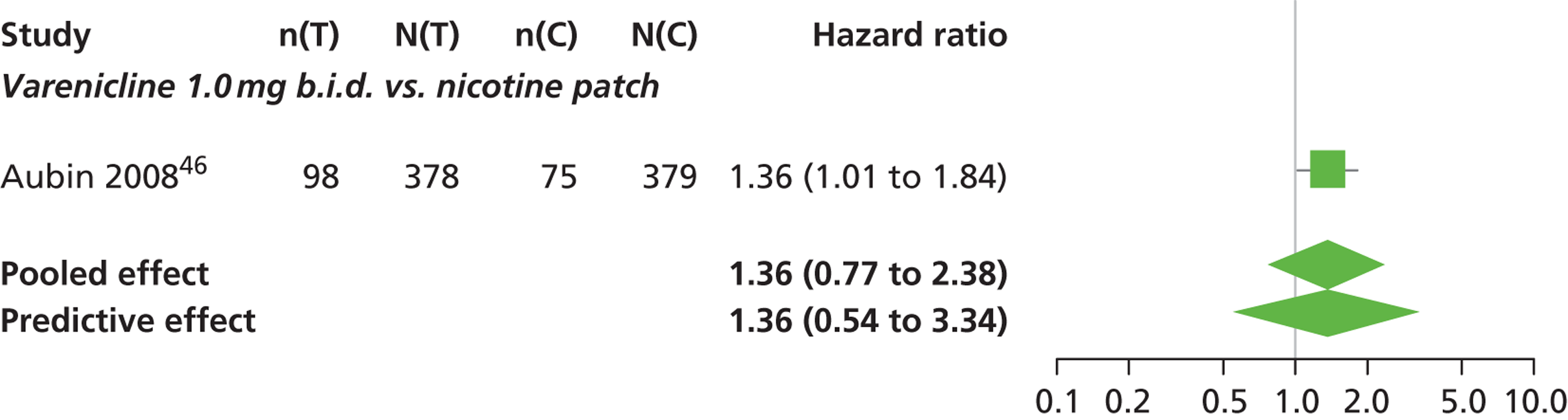

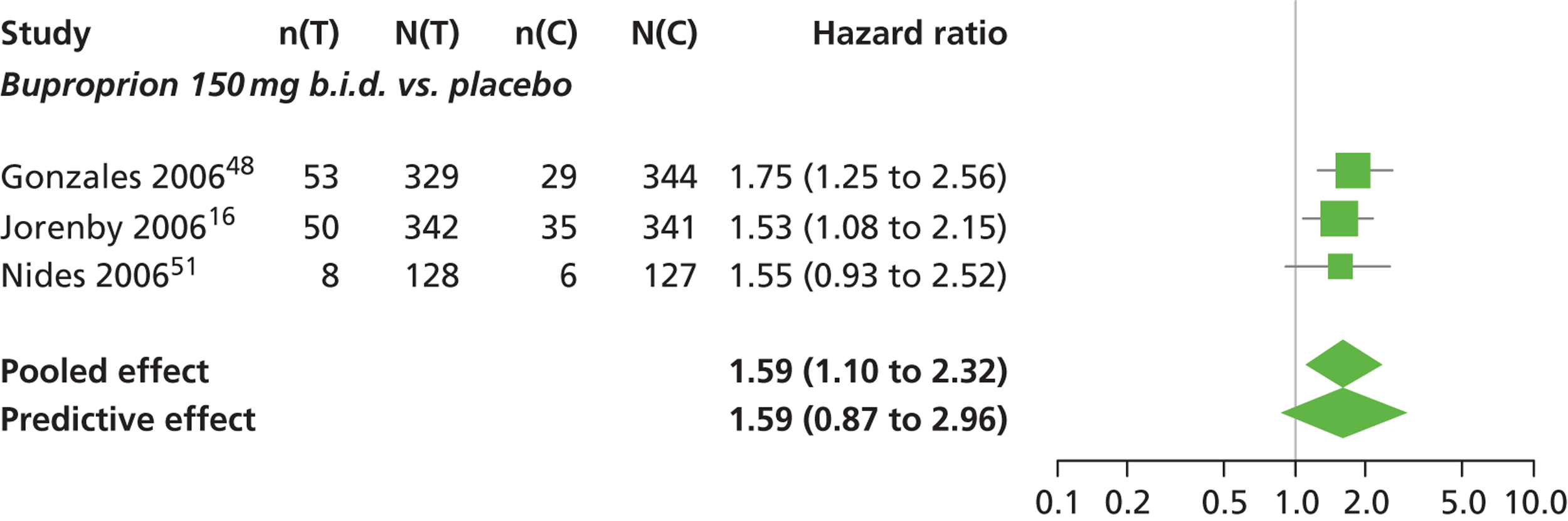

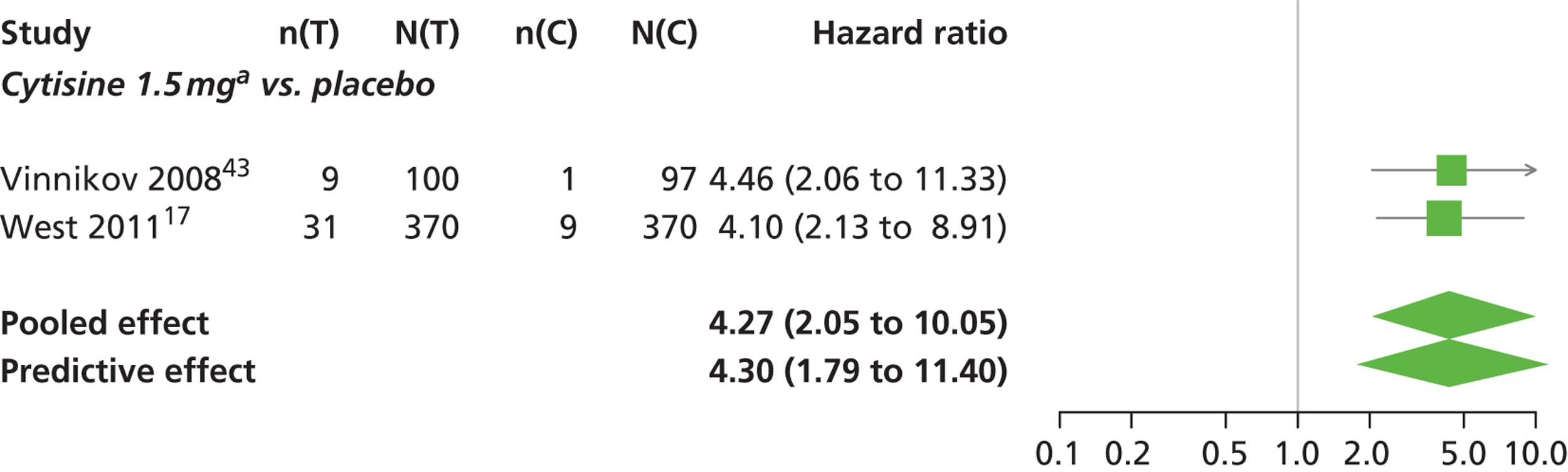

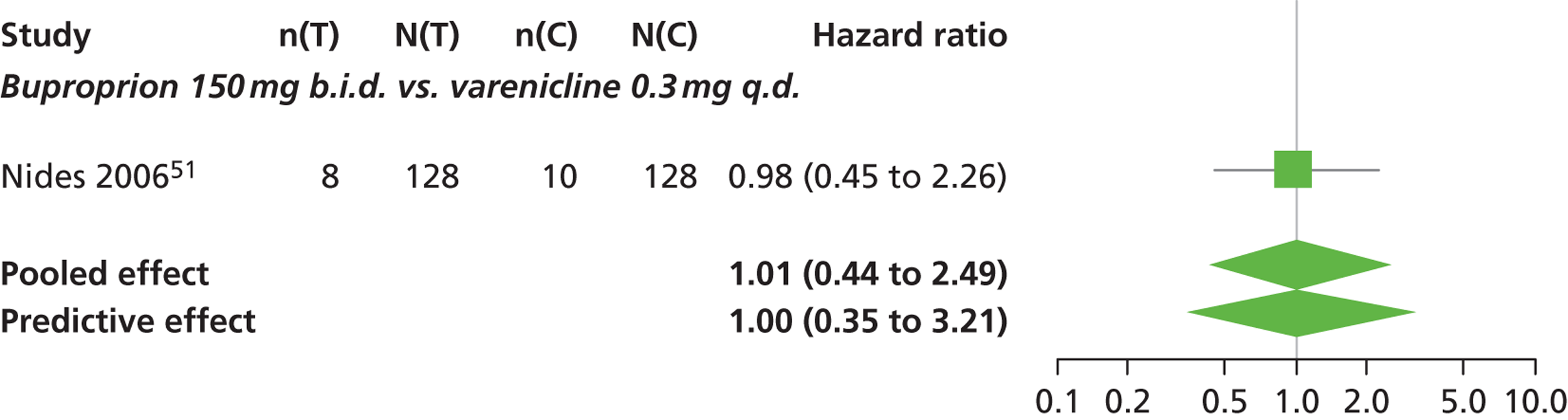

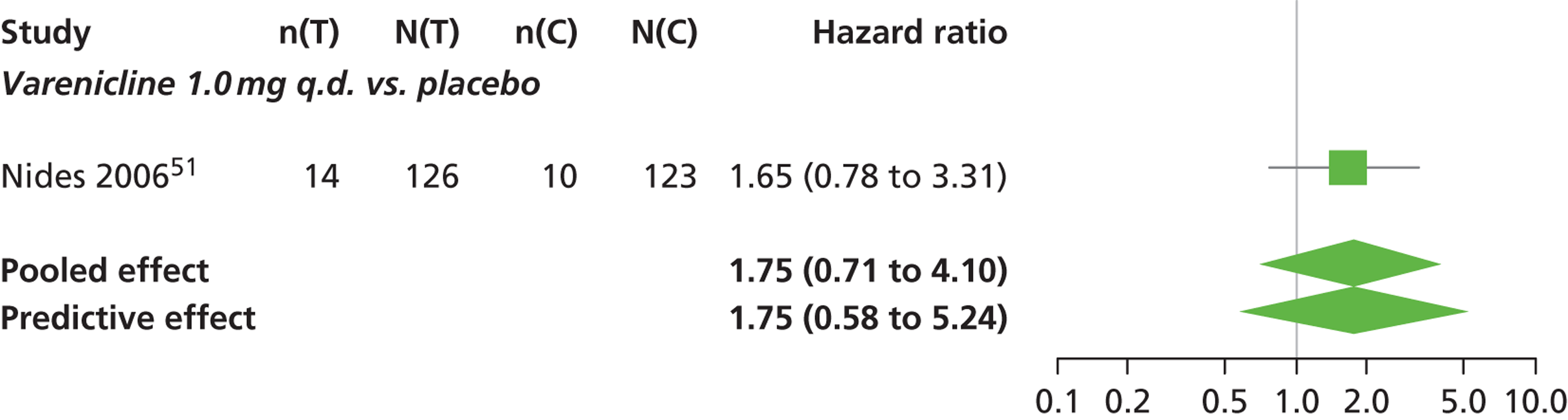

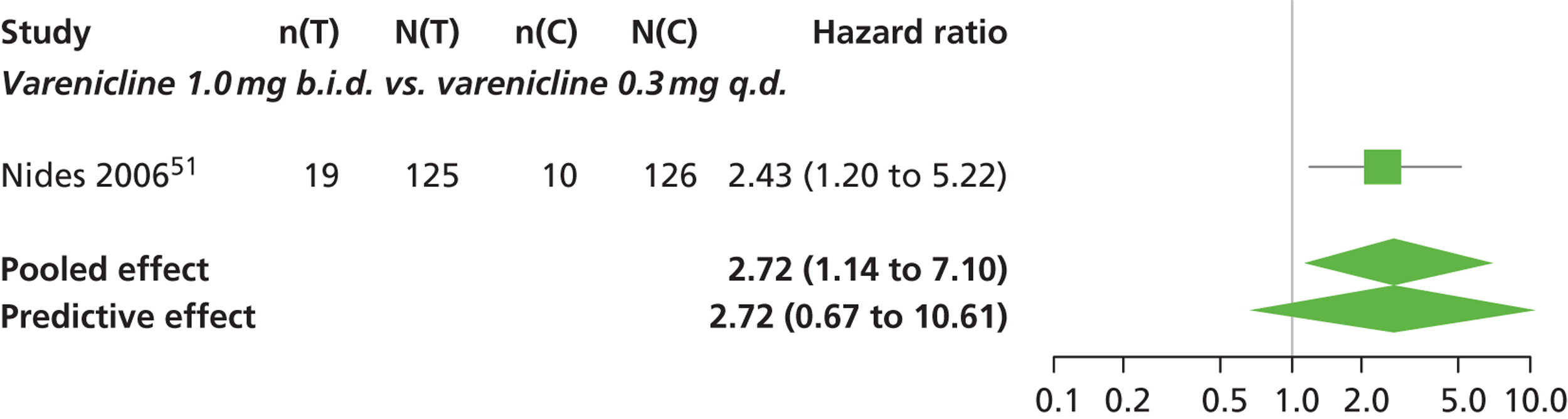

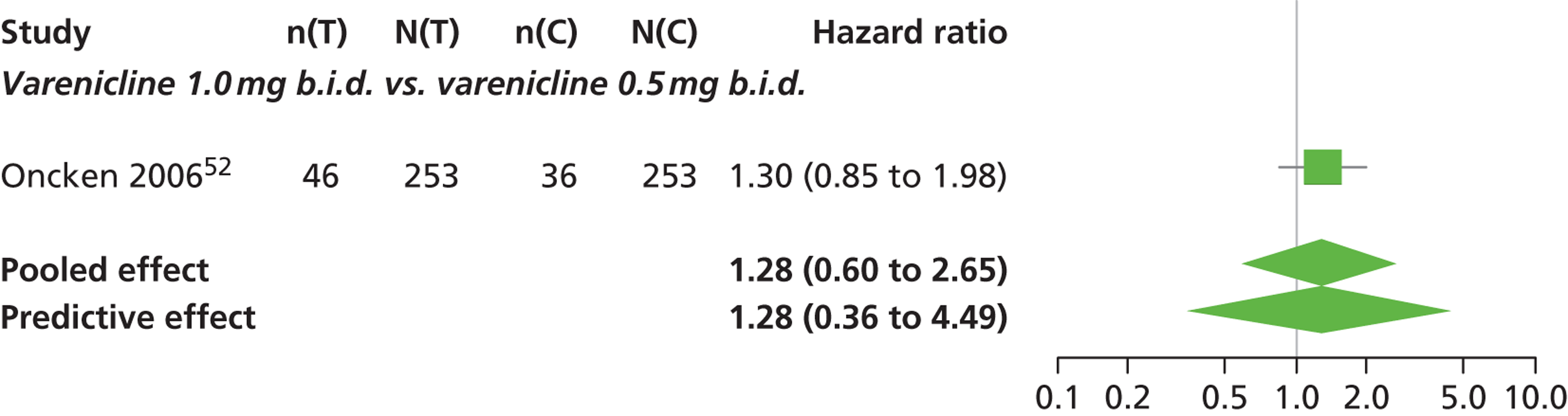

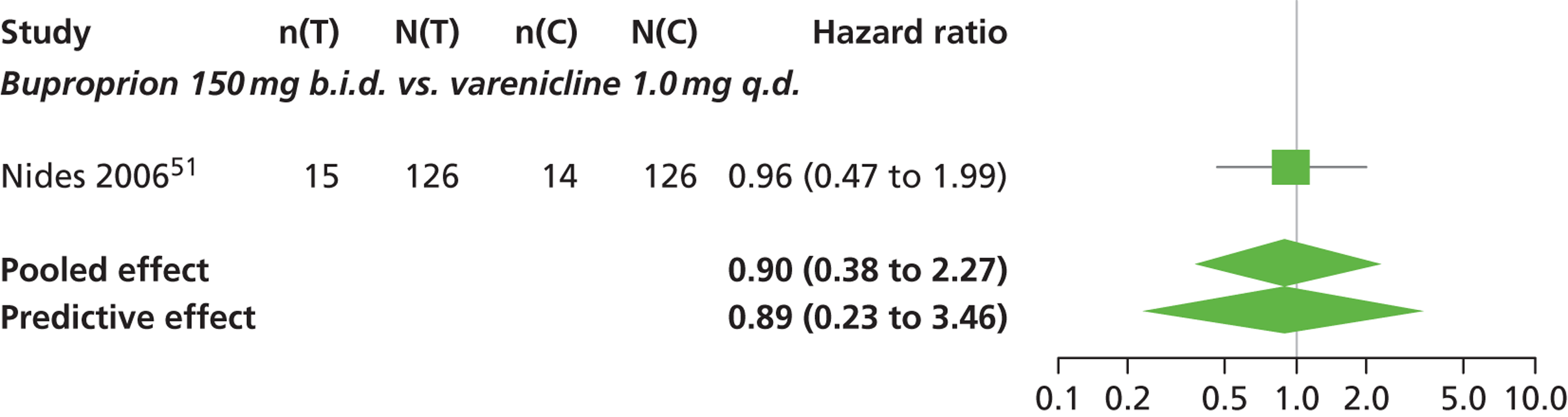

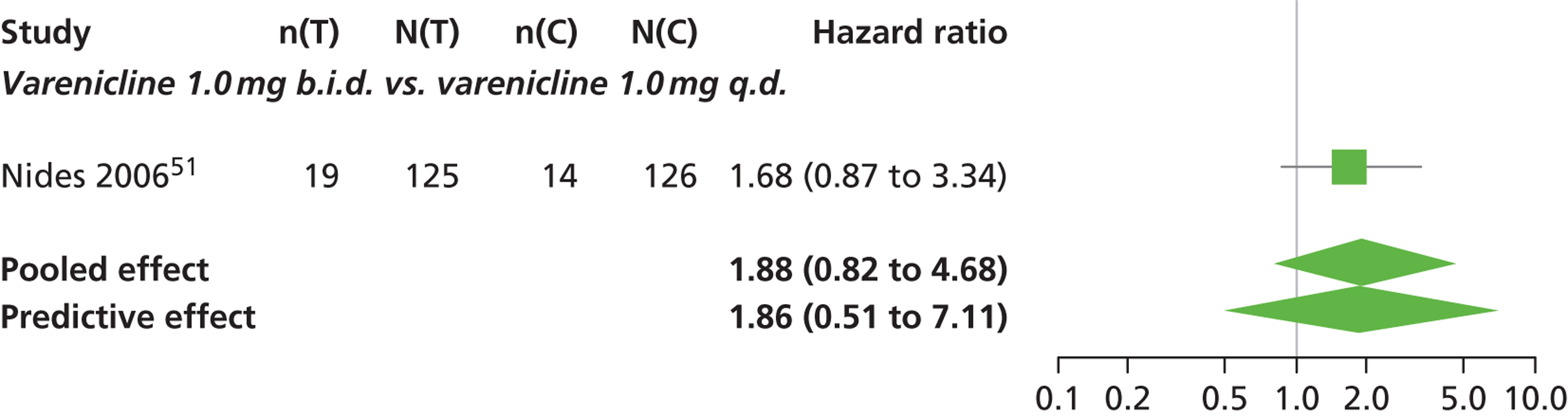

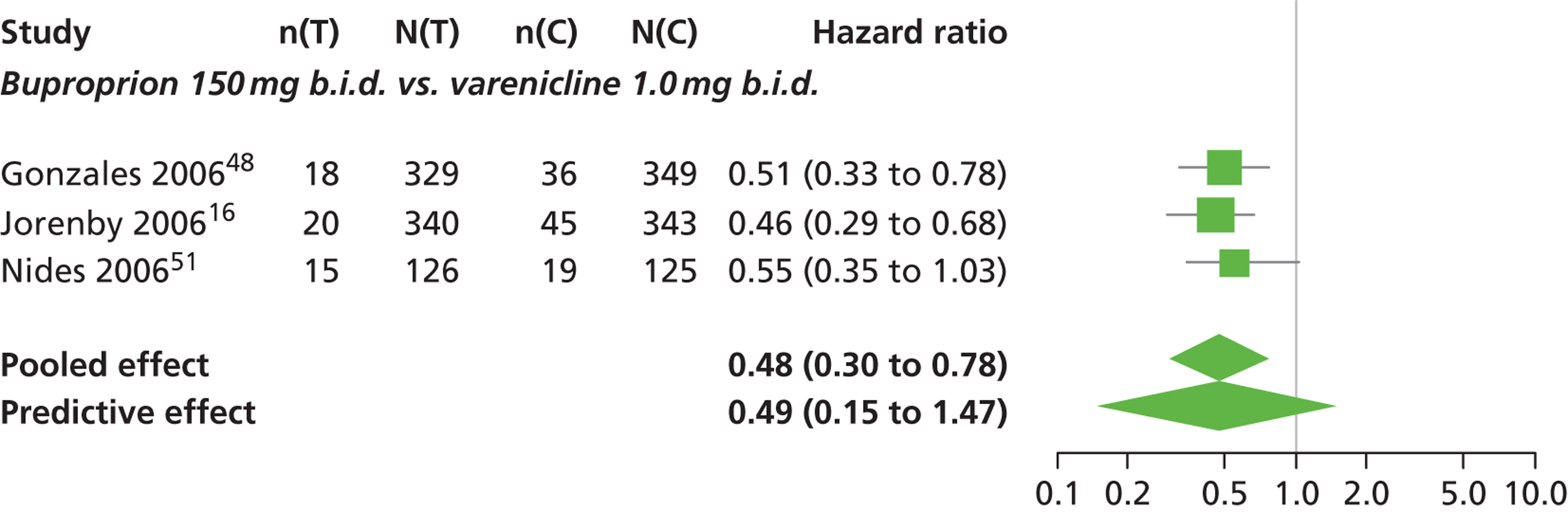

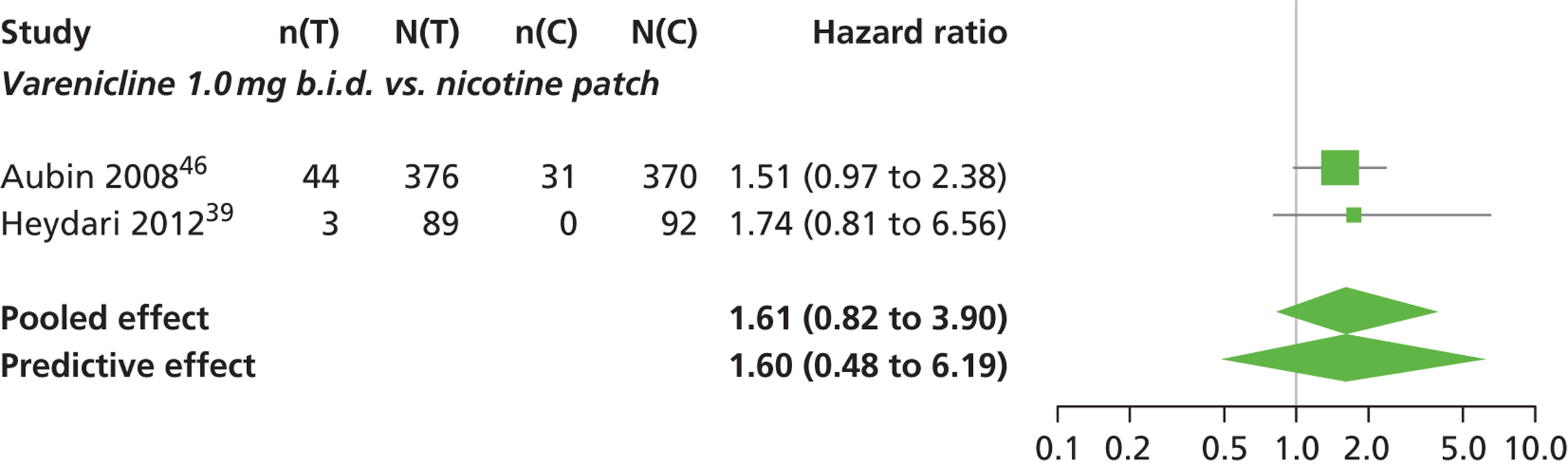

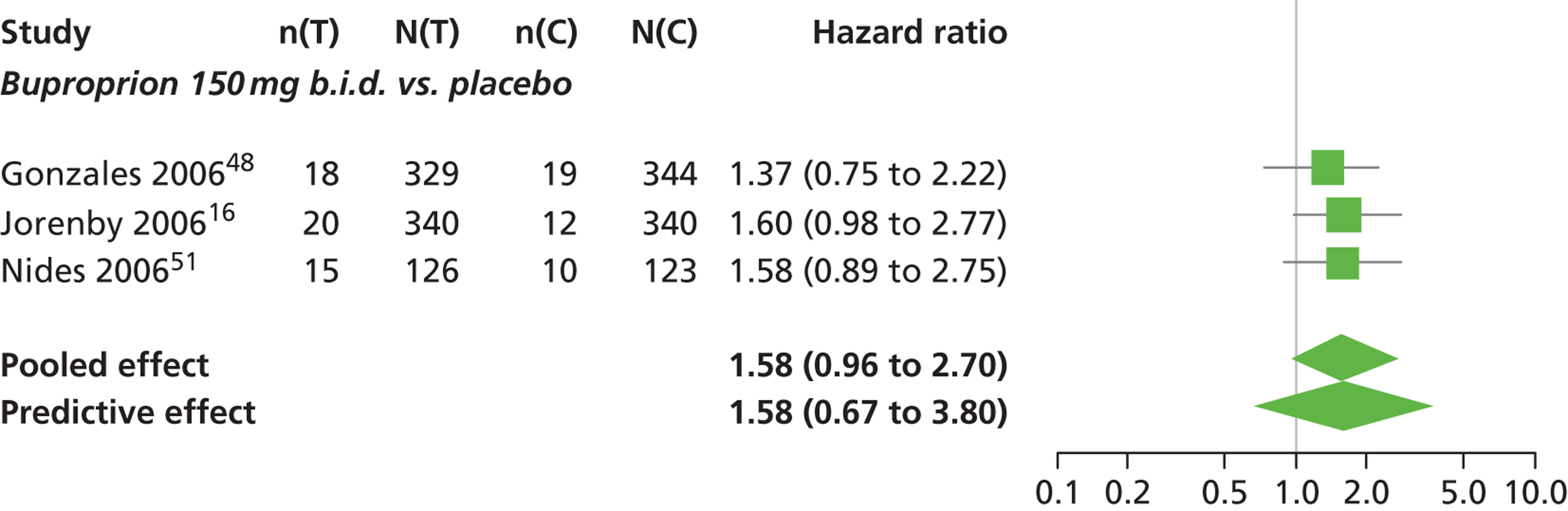

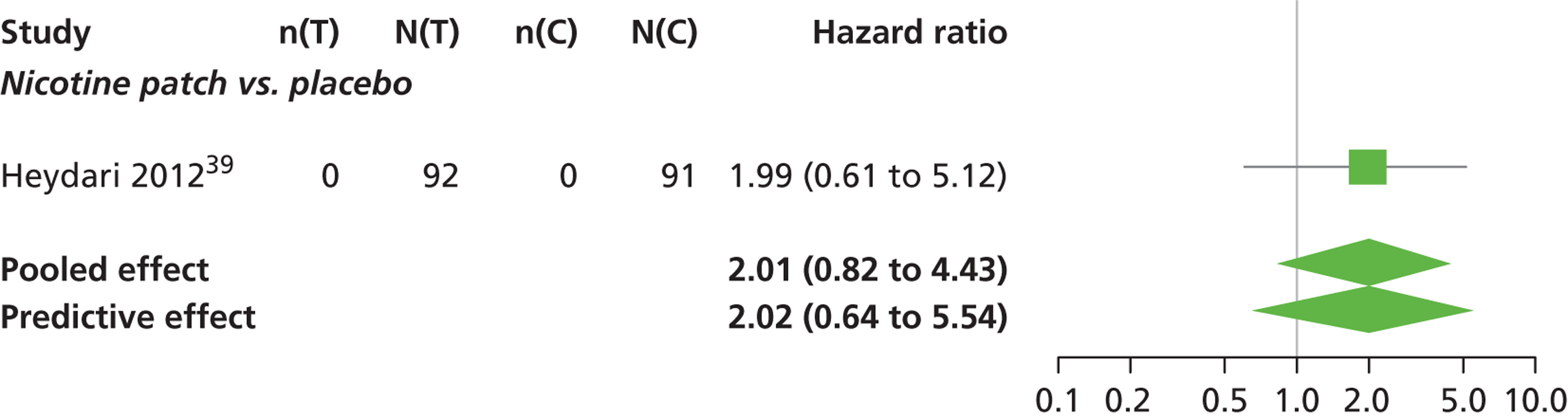

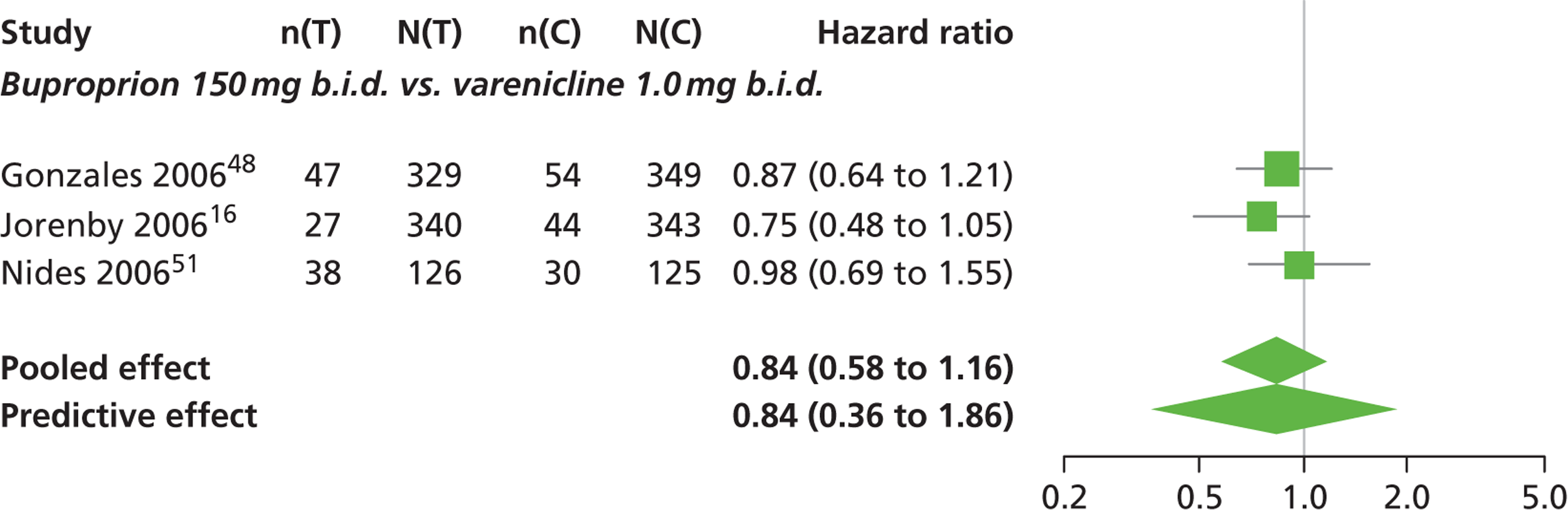

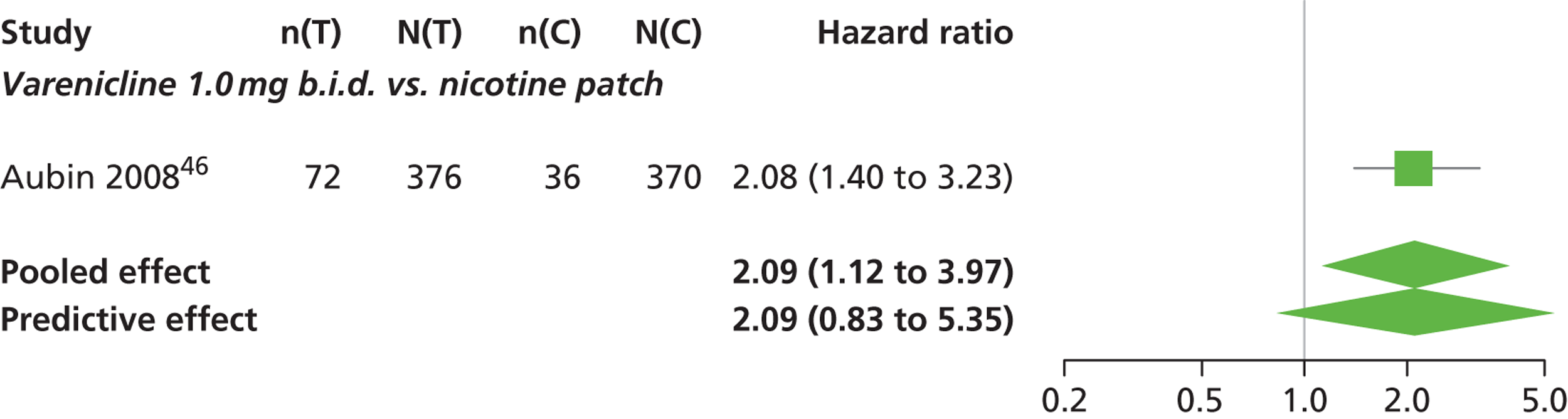

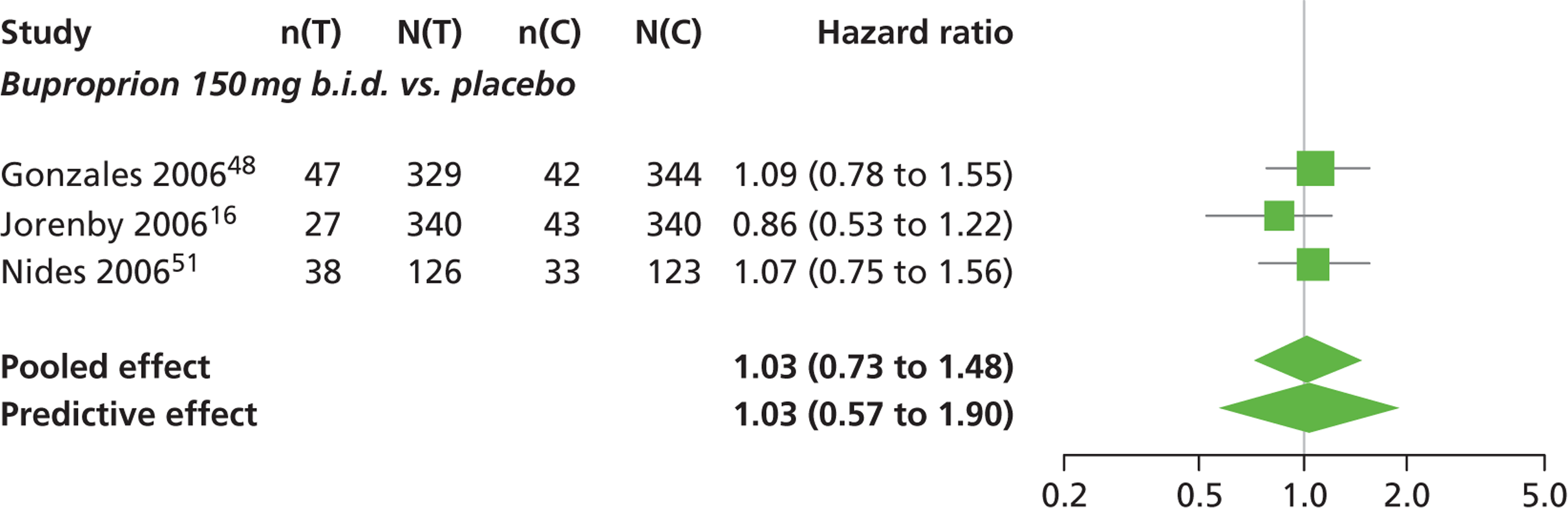

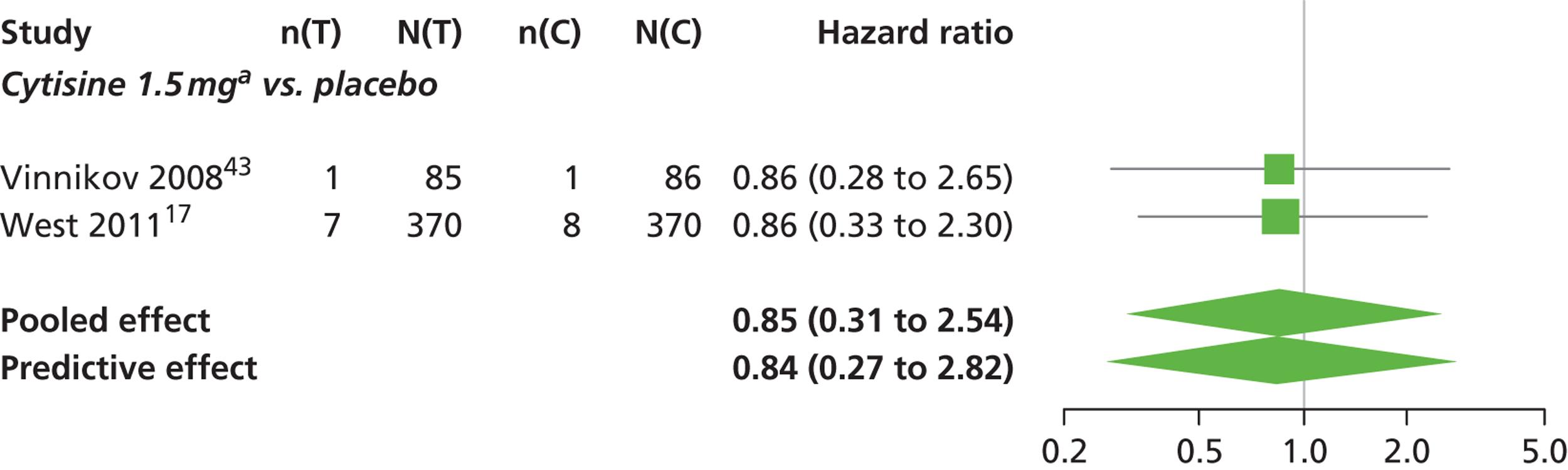

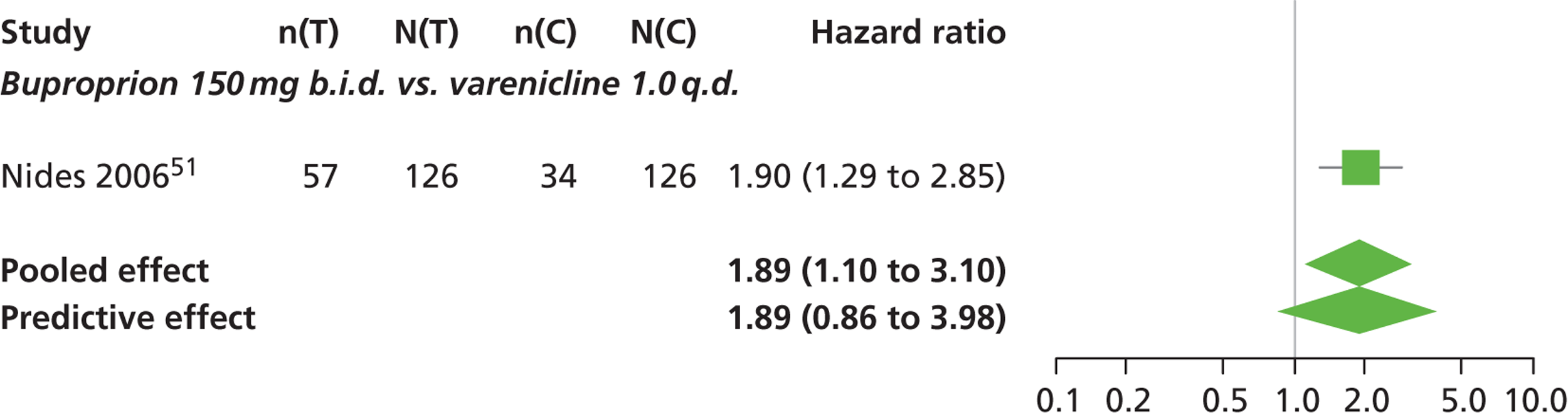

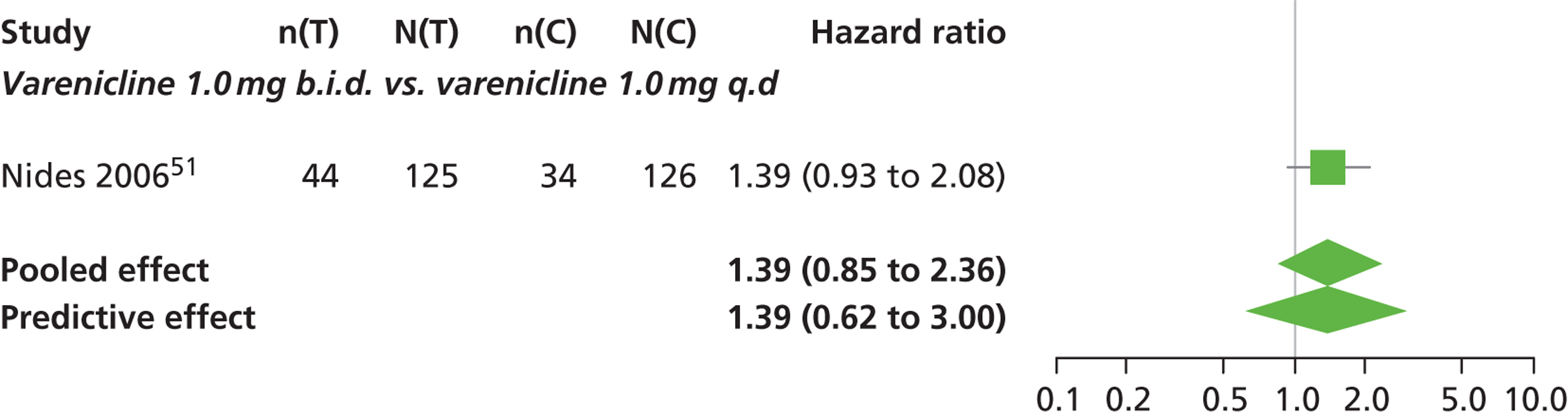

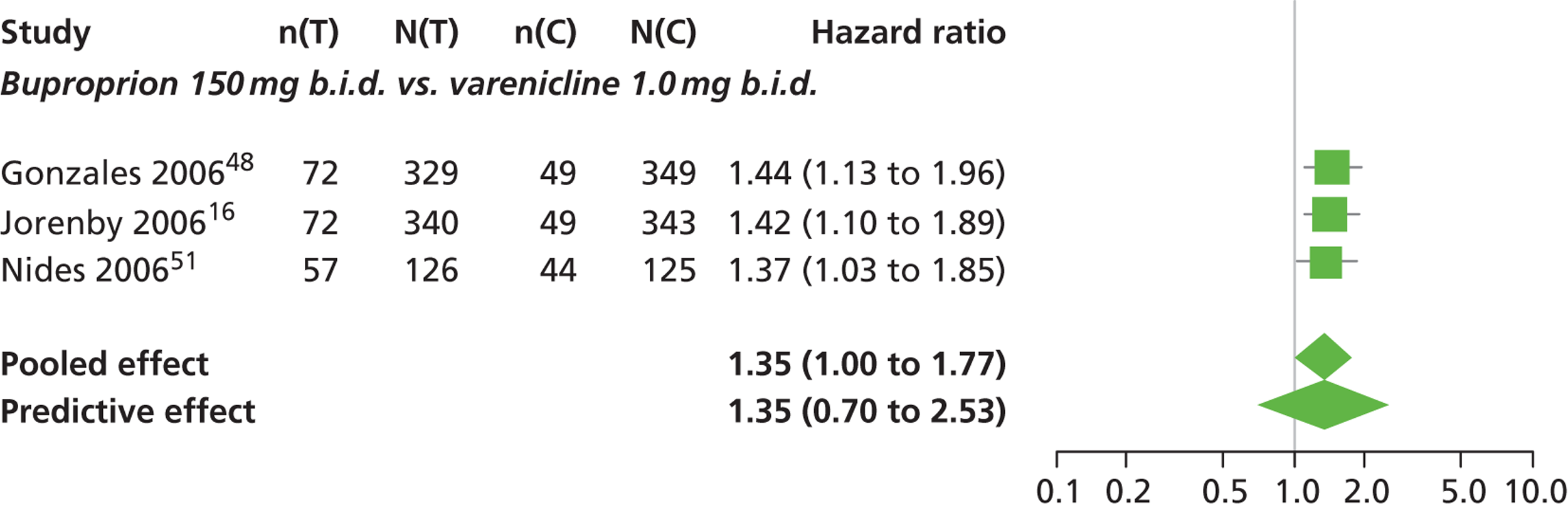

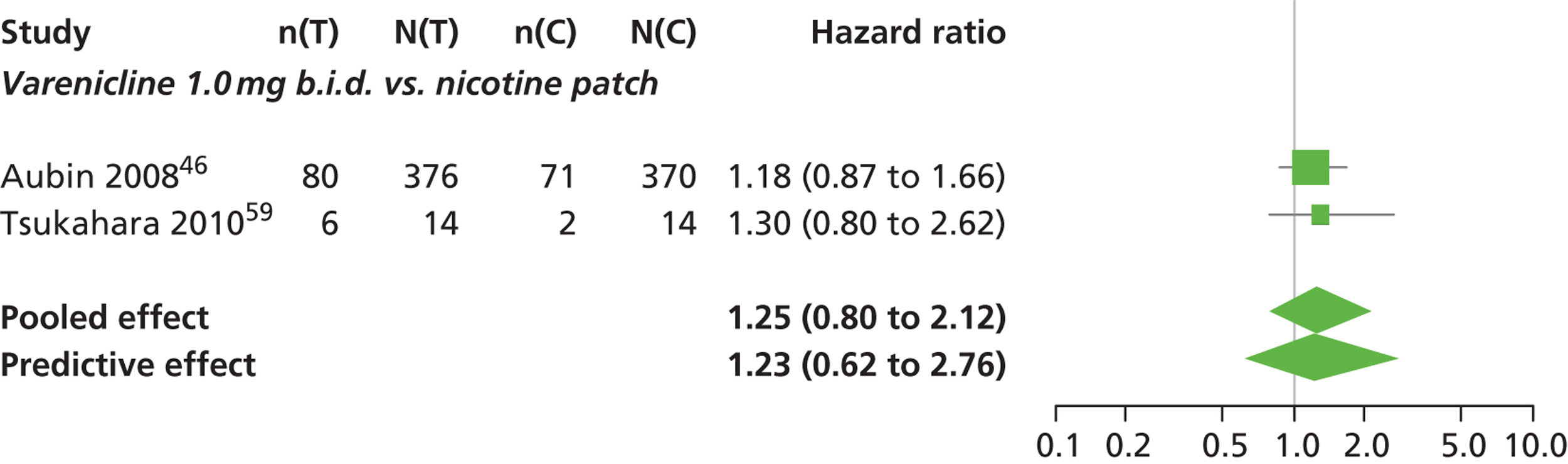

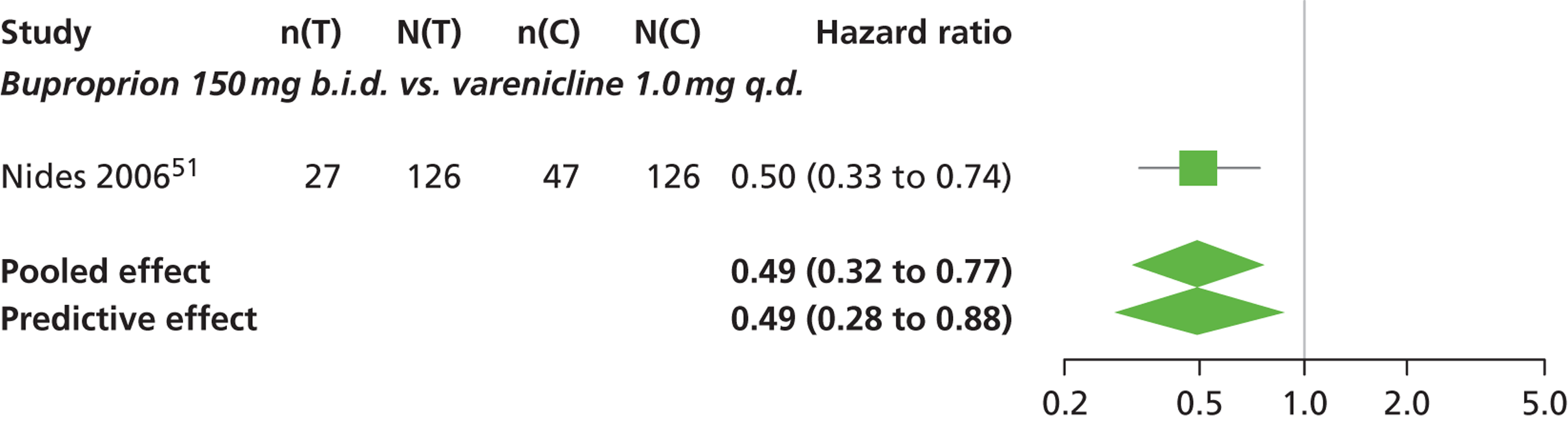

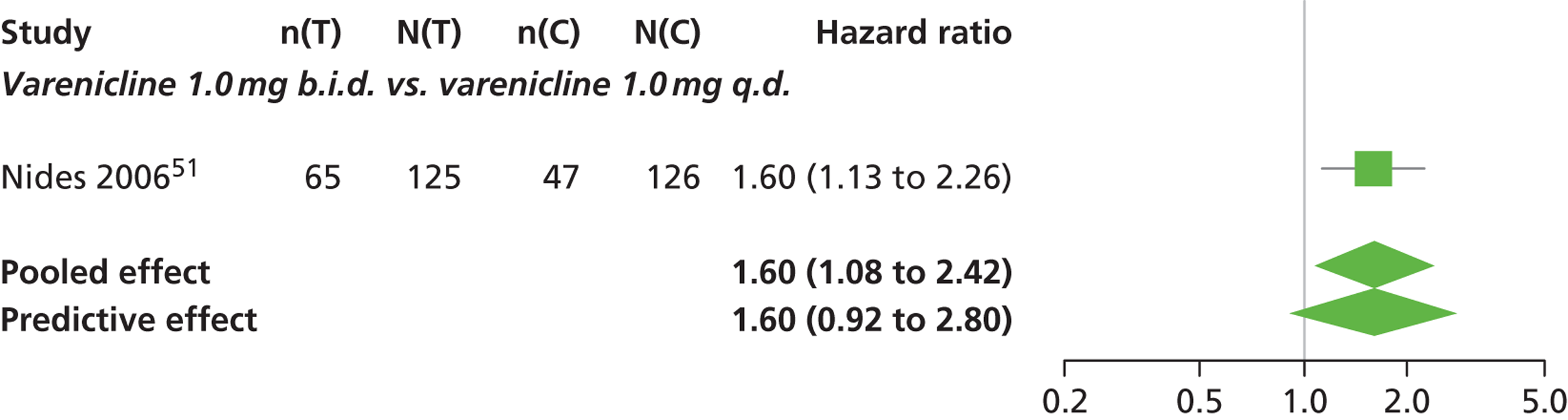

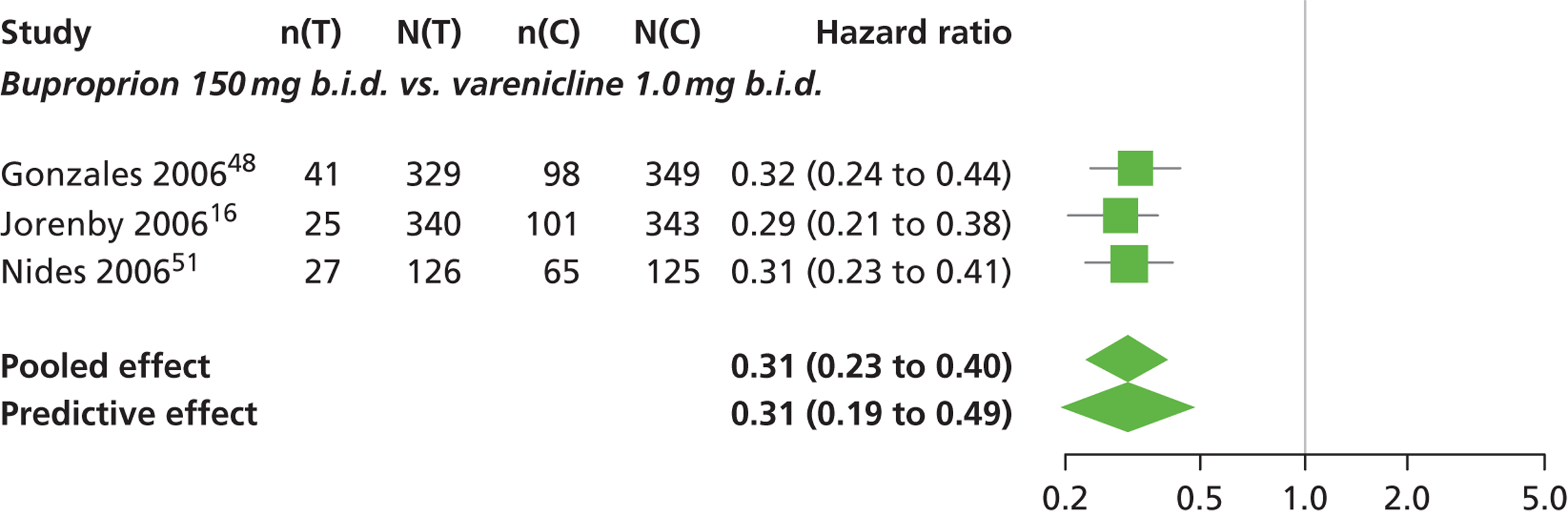

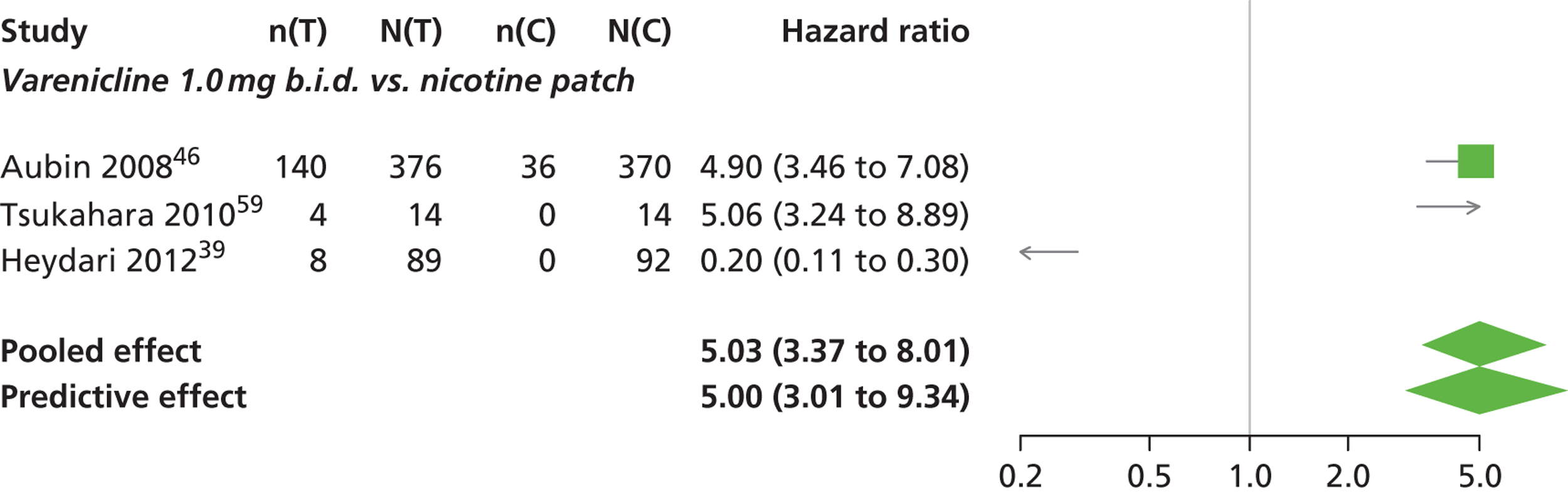

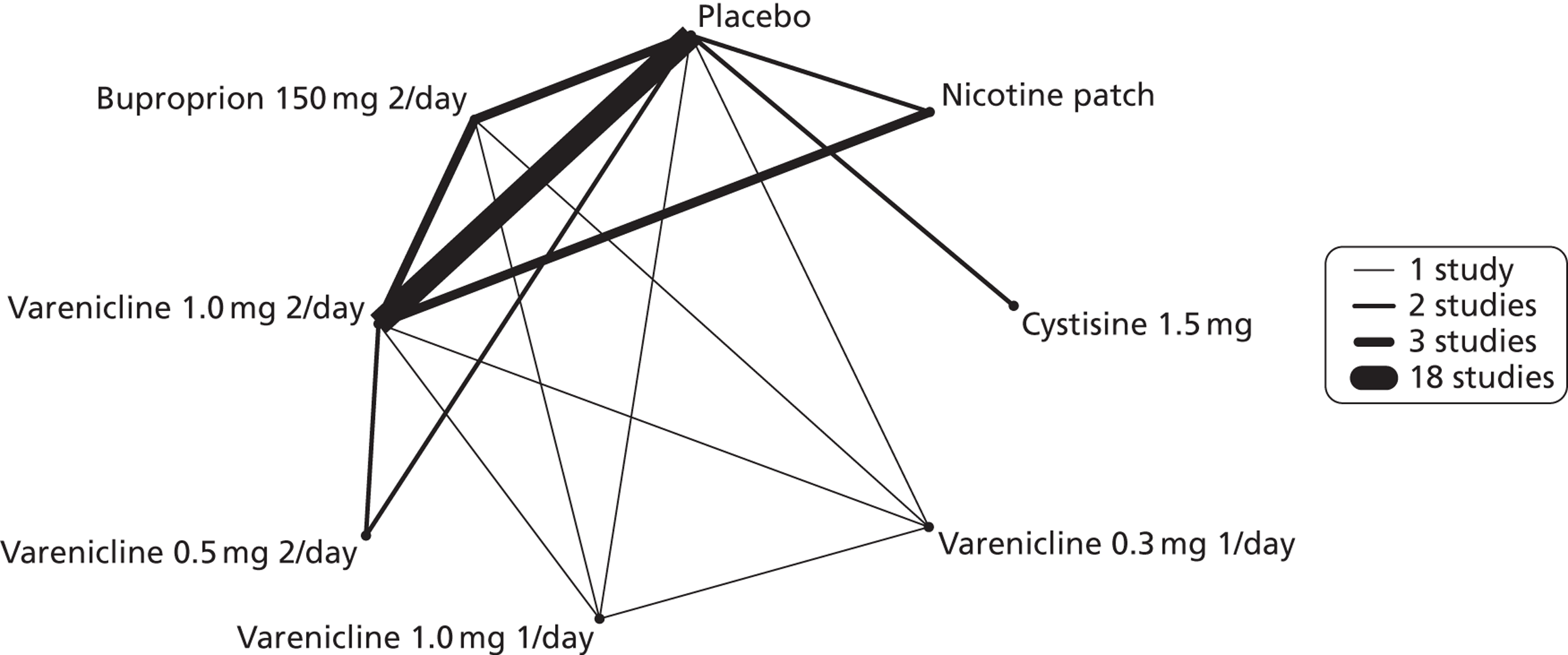

A network meta-analysis was used to compare the hazard of having continuous abstinence when treating with nicotine patch, cytisine 1.5 mg six times daily, varenicline 0.3 mg q.d., varenicline 1.0 mg q.d., varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d., varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. and bupropion hydrochloride 150 mg b.i.d. compared with placebo. A total of 16 studies comparing pairs, triplets or quintuplets of interventions provided information at various study durations. 16,17,43,46–55,57,58,60

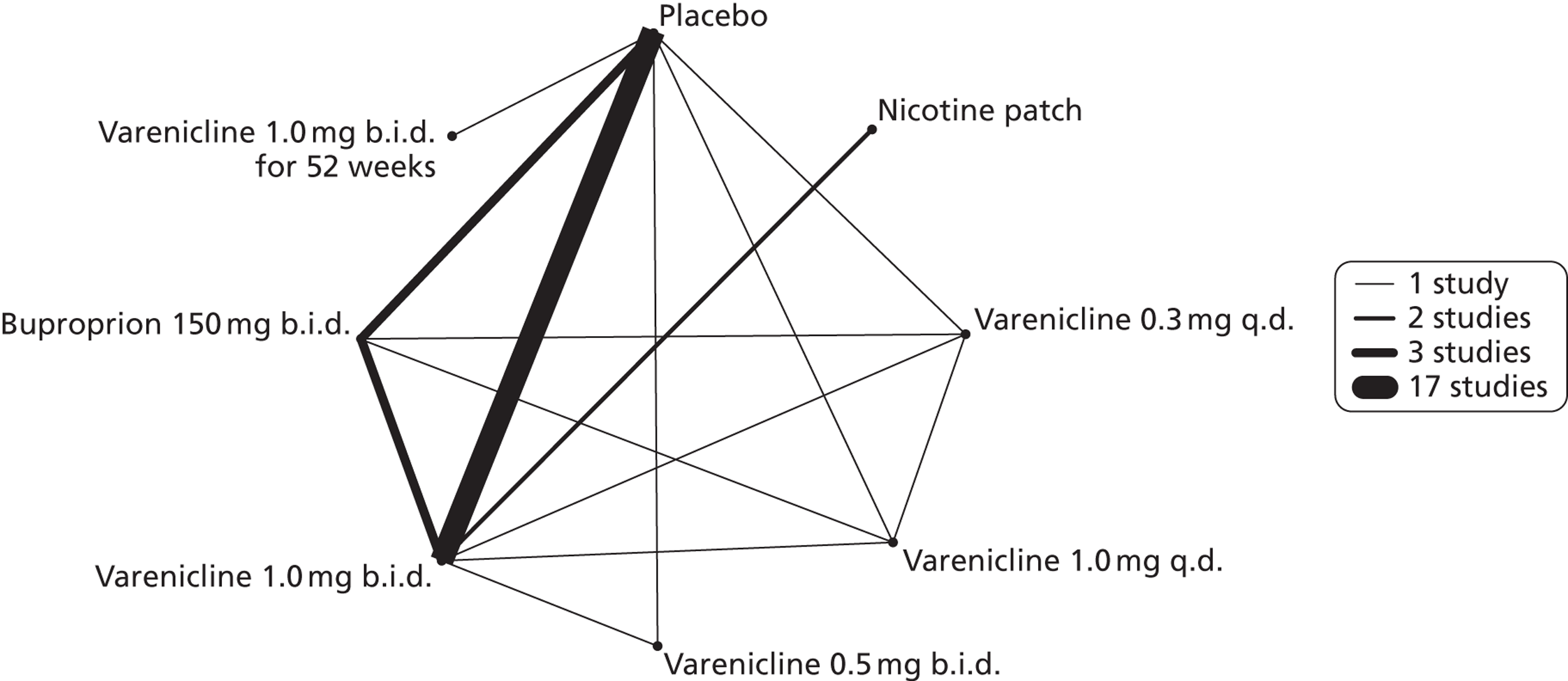

Figure 2 presents the network of evidence. A summary of all the trials (data) included in the network meta-analysis for continuous abstinence is provided (see Appendix 5, Table 38).

FIGURE 2.

Network diagram of different interventions for continuous abstinence. The nodes represent the interventions. Lines between nodes indicate when interventions have been compared. Different thicknesses of the lines represent the number of times that each pair of interventions has been compared.

The network meta-analysis model fitted the data well, with a total residual deviance close to the total number of data points included in the analysis. The total residual deviance was 40.99, which compared favourably with the 39 data points being analysed.

There was evidence of mild heterogeneity in treatment effects between studies (between-study heterogeneity SD 0.20, 95% CrI 0.02 to 0.45). All interventions apart from varenicline 0.3 mg q.d. and varenicline 1.0 mg q.d. were associated with a statistically significant effect on having continuous abstinence at a conventional 5% significance level relative to placebo. Cytisine 1.5 mg produced the greatest effect (HR 4.27, 95% CrI 2.05 to 10.05) relative to placebo (Table 6; see also Appendix 5, Figure 13). Cytisine 1.5 mg was the intervention with the highest probability of being the most effective intervention (p = 0.87) (Table 7).

| Intervention | Hazard ratio (95% CrI) |

|---|---|

| Nicotine patch | 1.89 (1.06 to 3.49) |

| Cytisine 1.5 mga | 4.27 (2.05 to 10.05) |

| Varenicline 0.3 mg q.d. | 1.58 (0.65 to 3.53) |

| Varenicline 1.0 mg q.d. | 1.08 (0.40 to 2.63) |

| Varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d. | 2.16 (1.54 to 3.38) |

| Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. | 2.58 (2.16 to 3.15) |

| Bupropion hydrochloride 150 mg b.i.d. | 1.59 (1.10 to 2.32) |

| Between-study SD | 0.20 (0.02 to 0.45) |

| Rank (b) | Treatment (j) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | Nicotine patch | Cytisine 1.5 mga | Varenicline 0.3 mg q.d. | Varenicline 1.0 mg q.d. | Varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d. | Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. | Bupropion hydrochloride 150 mg b.i.d. | |

| 1 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.87 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.61 | 0.00 |

| 3 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.37 | 0.27 | 0.03 |

| 4 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.28 | 0.05 | 0.16 |

| 5 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.01 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.38 |

| 6 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.33 |

| 7 | 0.42 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.26 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.10 |

| 8 | 0.48 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

Since repeated 7-day PPA may be used as a proxy for continuous abstinence,22 a sensitivity analysis was conducted including studies used measurement such as continuous abstinence or repeated 7-day PPA. Both the estimates and 95% CrIs of all treatment effects were similar to the results from the analysis including only studies that used continuous abstinence (see Appendix 5). However, the goodness of the model fit suggested that some studies, in particular those by Steinberg et al. ,56 Oncken et al. ,52 Heydari et al. 39 and de Dios et al. ,38 may come from a different model. The measurement used by Steinberg et al. ,56 Heydari et al. 39 and de Dios et al. 38 was the repeated 7-day PPA. Hence, the treatment effects were estimated using studies having continuous abstinence as the measurement and these were used in the economic model.

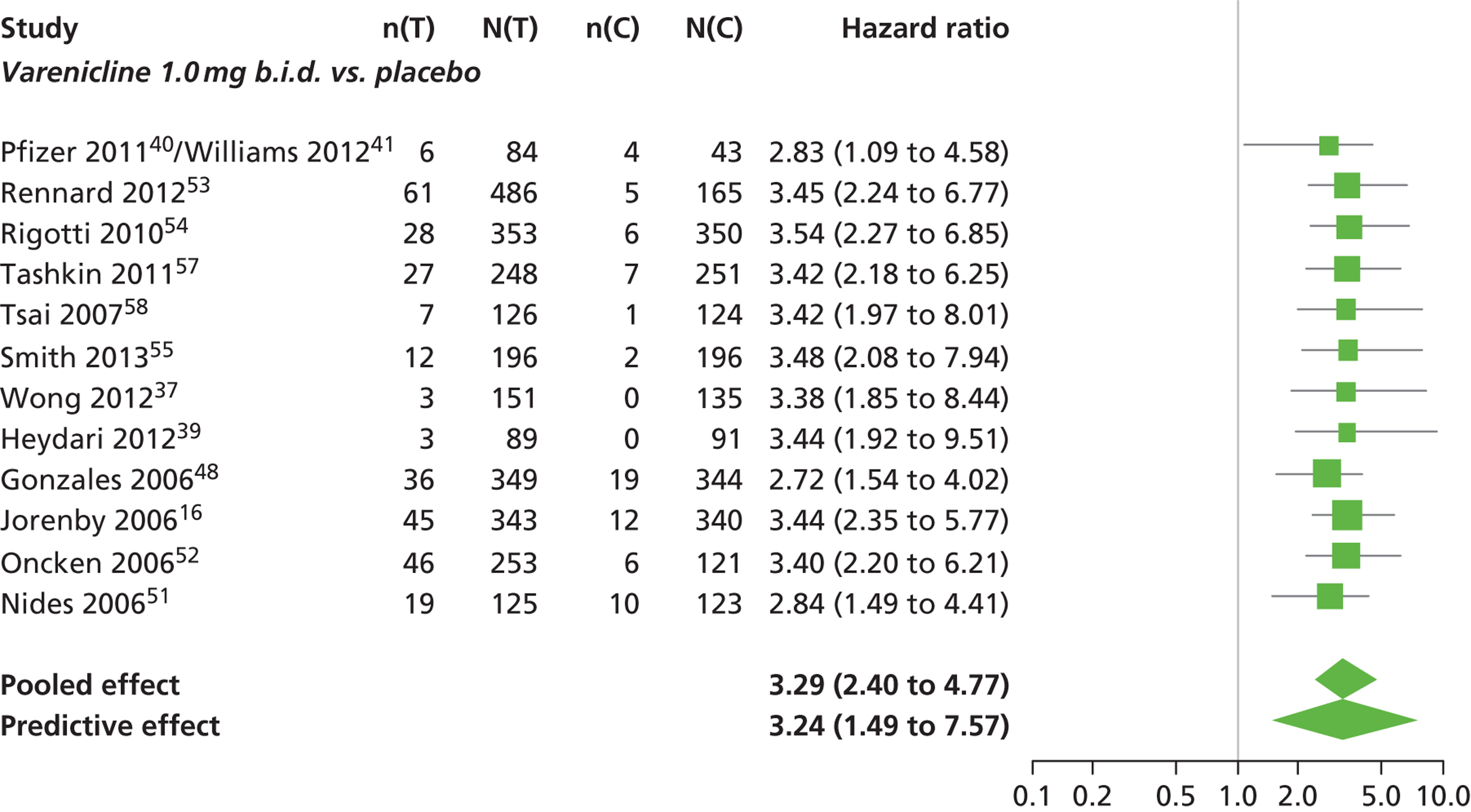

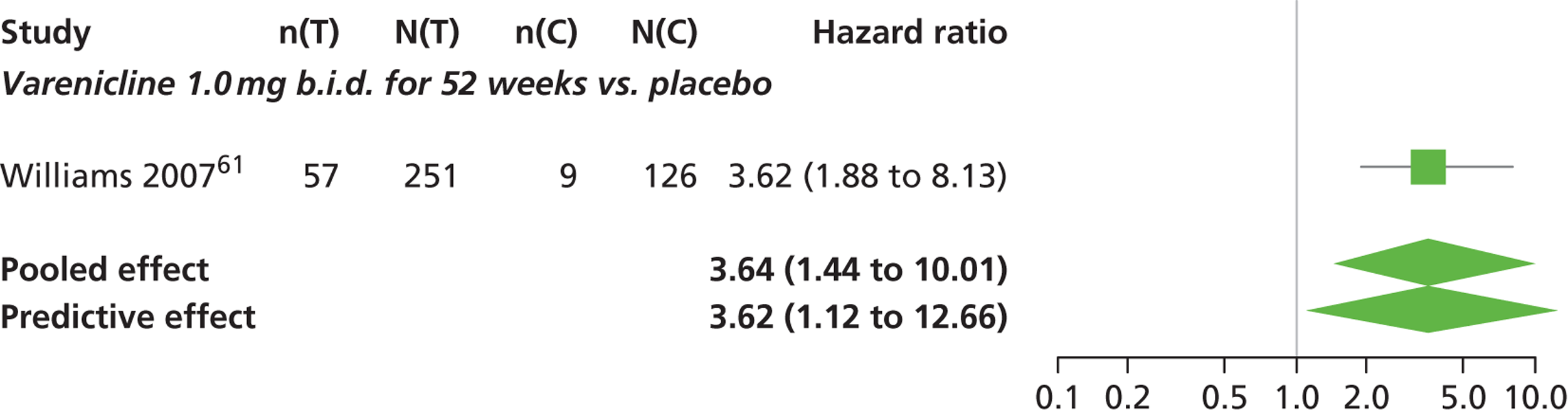

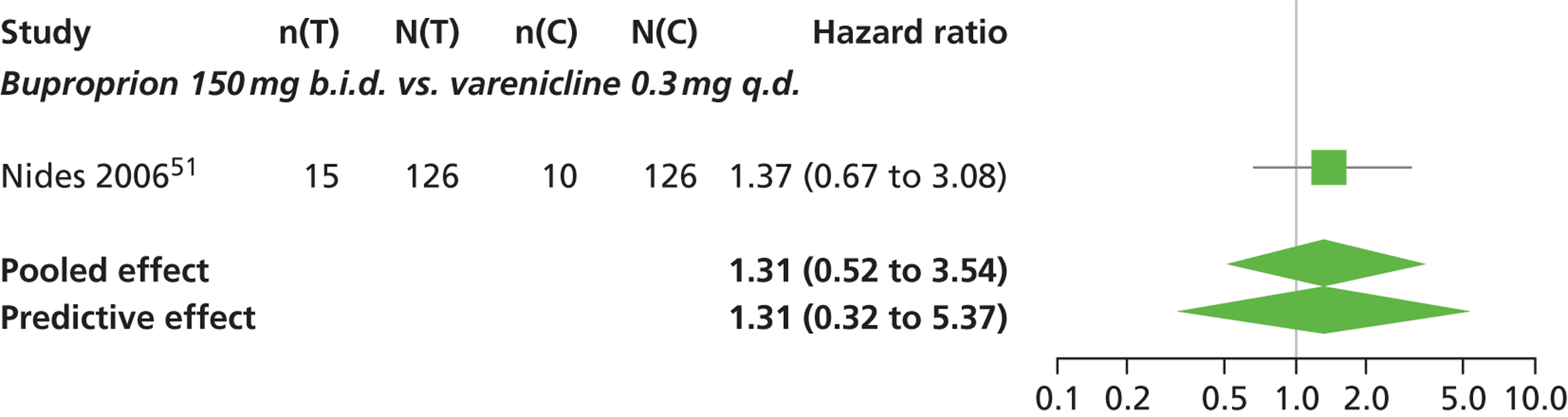

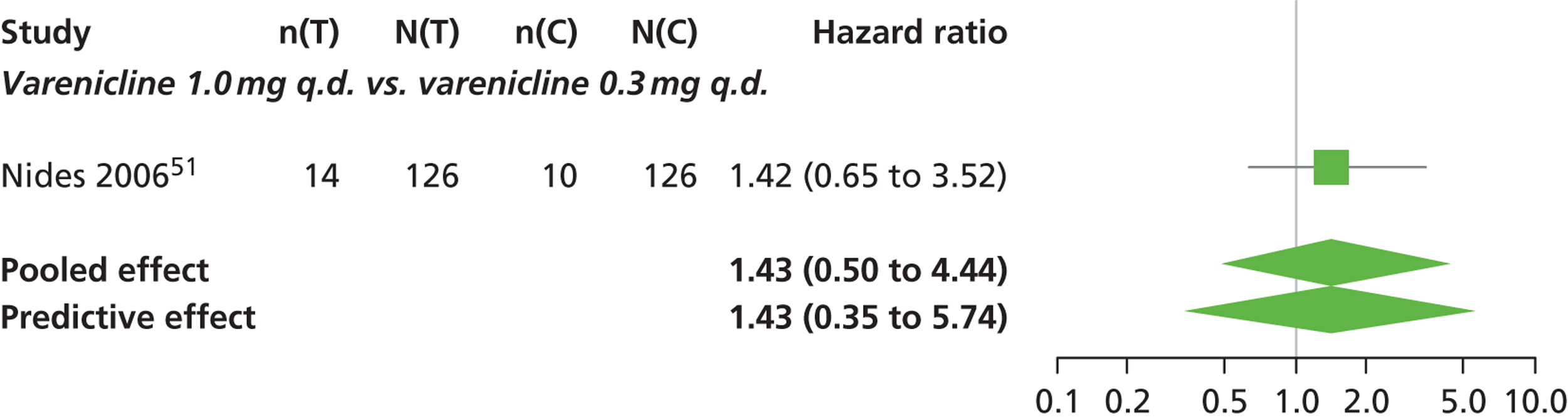

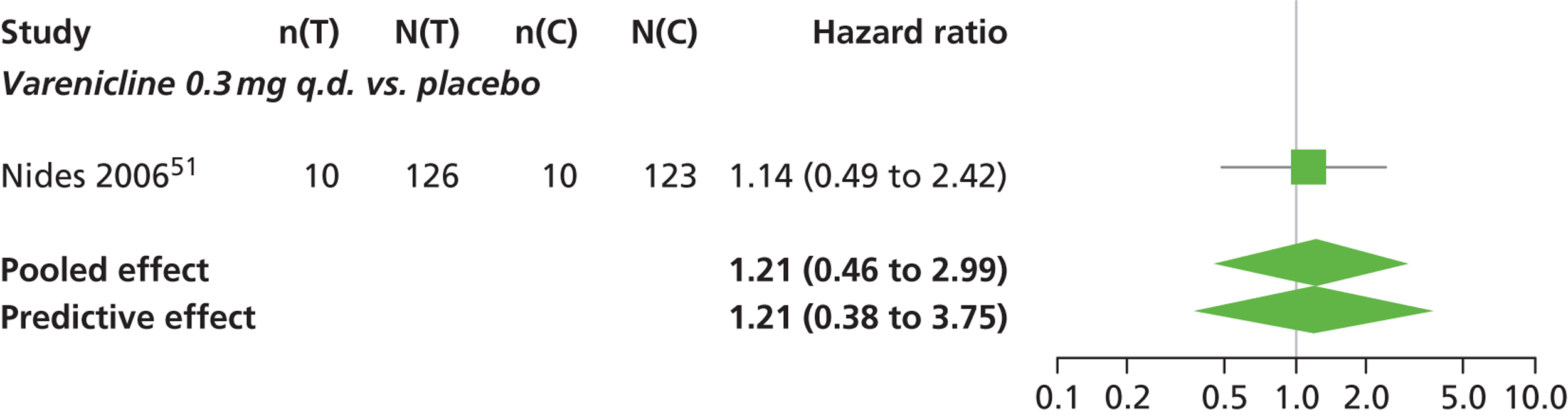

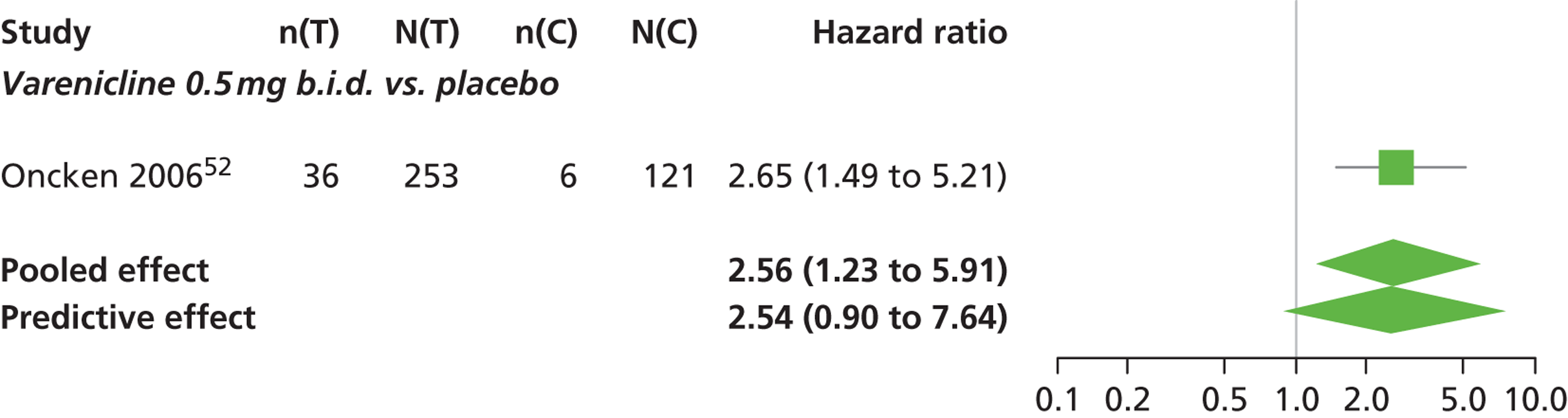

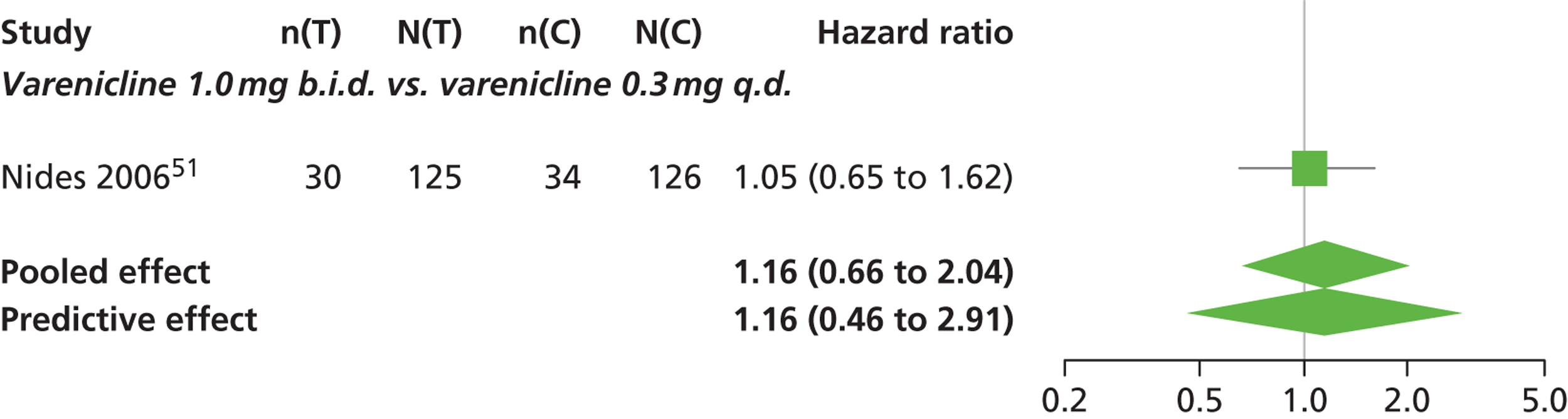

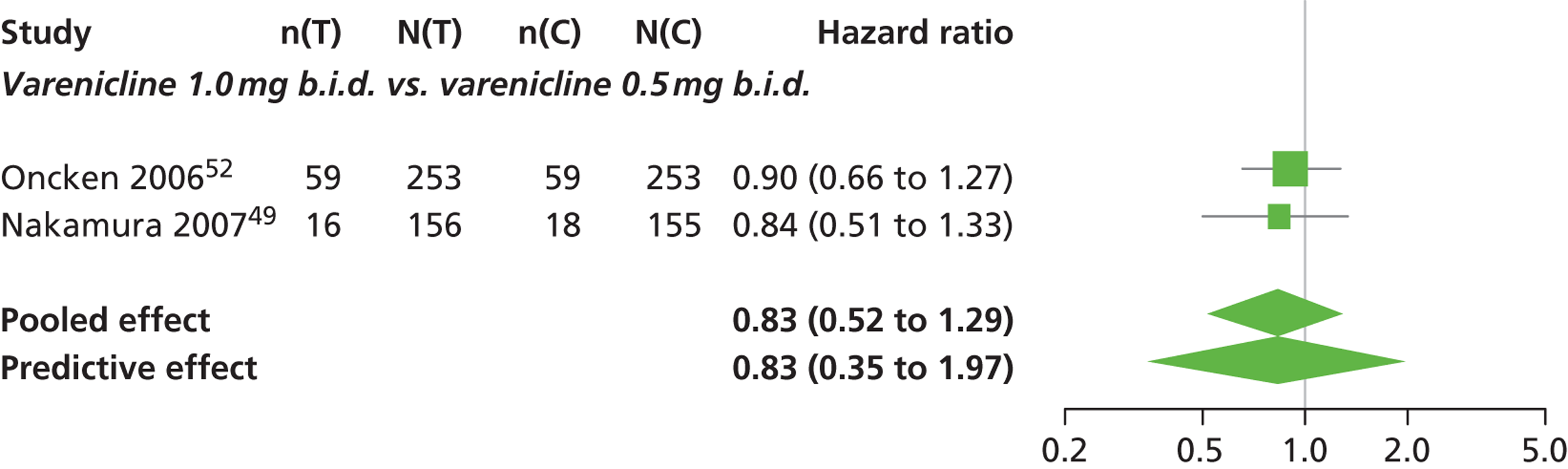

Abnormal dreams

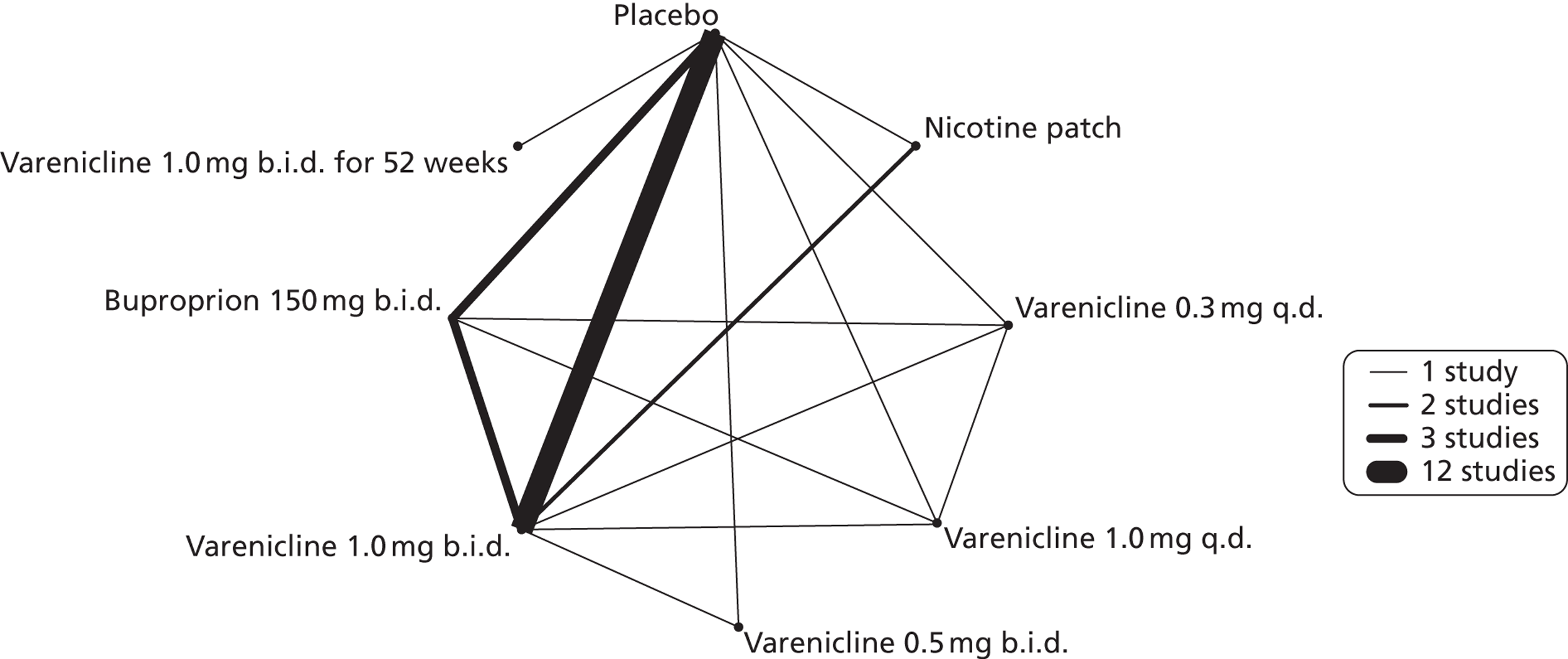

A network meta-analysis was used to compare the hazard of having abnormal dreams when treating with nicotine patch, varenicline 0.3 mg q.d., varenicline 1.0 mg q.d., varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d., varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d., bupropion hydrochloride 150 mg b.i.d. and varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 52 weeks or placebo. A total of 14 studies comparing pairs or triplets of interventions provided information at various study durations. 16,37,39,41,46,48,51–55,57,58,61 No data were available for cytisine for abnormal dreams.

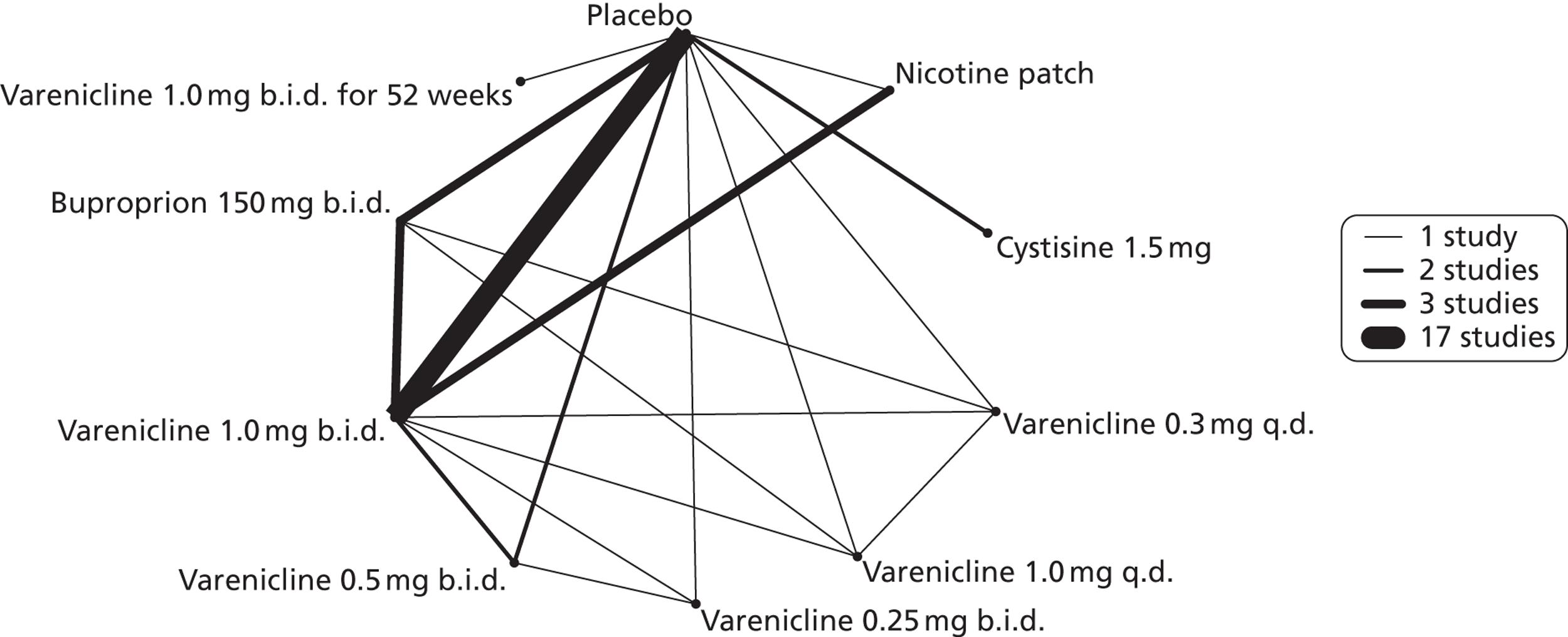

Figure 3 presents the network of evidence. A summary of all the trials (data) included in the network meta-analysis for abnormal dreams is provided (see Appendix 5, Table 39).

FIGURE 3.

Network diagram of different interventions for abnormal dreams. The nodes represent the interventions. Lines between nodes indicate when interventions have been compared. Different thicknesses of the lines represent the number of times that each pair of interventions has been compared.

The network meta-analysis model fitted the data reasonably well, with a total residual deviance close to the total number of data points included in the analysis. The total residual deviance was 37.98, which was slightly less than the 39 data points being analysed.

There was evidence of mild heterogeneity in treatment effects between studies (between-study heterogeneity SD 0.24, 95% CrI 0.02 to 0.74). Varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d., varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. and varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 52 weeks were associated with statistically significant effects of having abnormal dreams at a conventional 5% level relative to placebo. Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 52 weeks produced the greatest effect (HR 3.64, 95% CrI 1.44 to 10.01) relative to placebo (Table 8; see also Appendix 5, Figure 14). Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 52 weeks was the intervention with the highest probability of being the most likely intervention to be associated with abnormal dreams (p = 0.54) (Table 9).

| Intervention | Hazard ratio (95% CrI) |

|---|---|

| Nicotine patch | 2.01 (0.82 to 4.43) |

| Varenicline 0.3 mg q.d. | 1.21 (0.46 to 2.99) |

| Varenicline 1.0 mg q.d. | 1.75 (0.71 to 4.10) |

| Varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d. | 2.56 (1.23 to 5.91) |

| Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. | 3.29 (2.40 to 4.77) |

| Bupropion hydrochloride 150 mg b.i.d. | 1.58 (0.96 to 2.70) |

| Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 52 weeks | 3.64 (1.44 to 10.01) |

| Between-study SD | 0.24 (0.02 to 0.74) |

| Rank (b) | Treatment (j) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | Nicotine patch | Varenicline 0.3 mg q.d. | Varenicline 1.0 mg q.d. | Varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d. | Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. | Bupropion hydrochloride 150 mg b.i.d. | Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 52 weeks | |

| 1 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.54 |

| 2 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.19 | 0.51 | 0.01 | 0.16 |

| 3 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.13 |

| 4 | 0.00 | 0.28 | 0.06 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.08 |

| 5 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.31 | 0.05 |

| 6 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 0.02 |

| 7 | 0.32 | 0.08 | 0.29 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.01 |

| 8 | 0.58 | 0.03 | 0.31 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

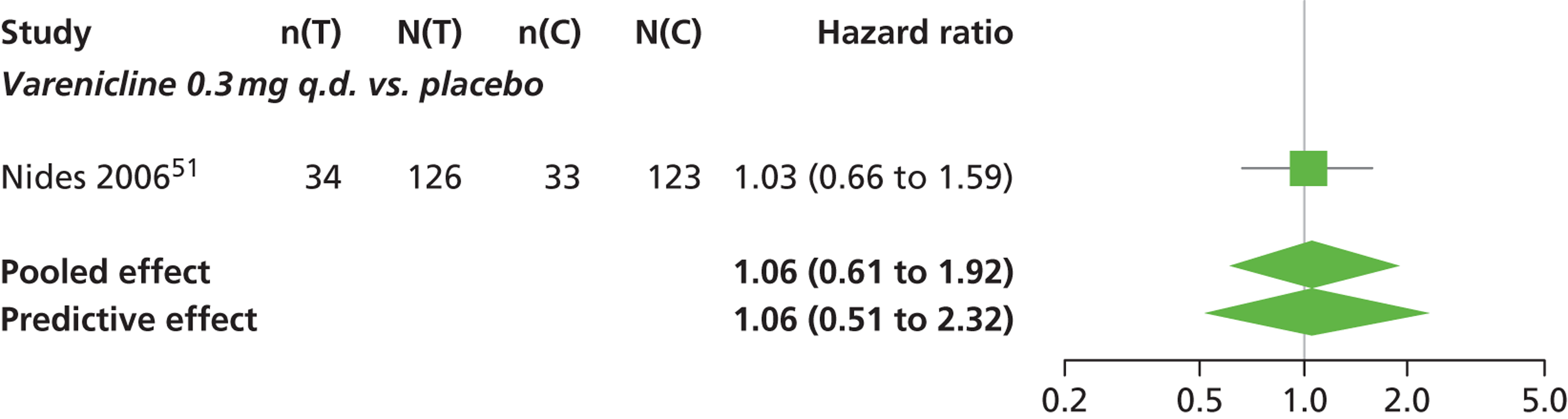

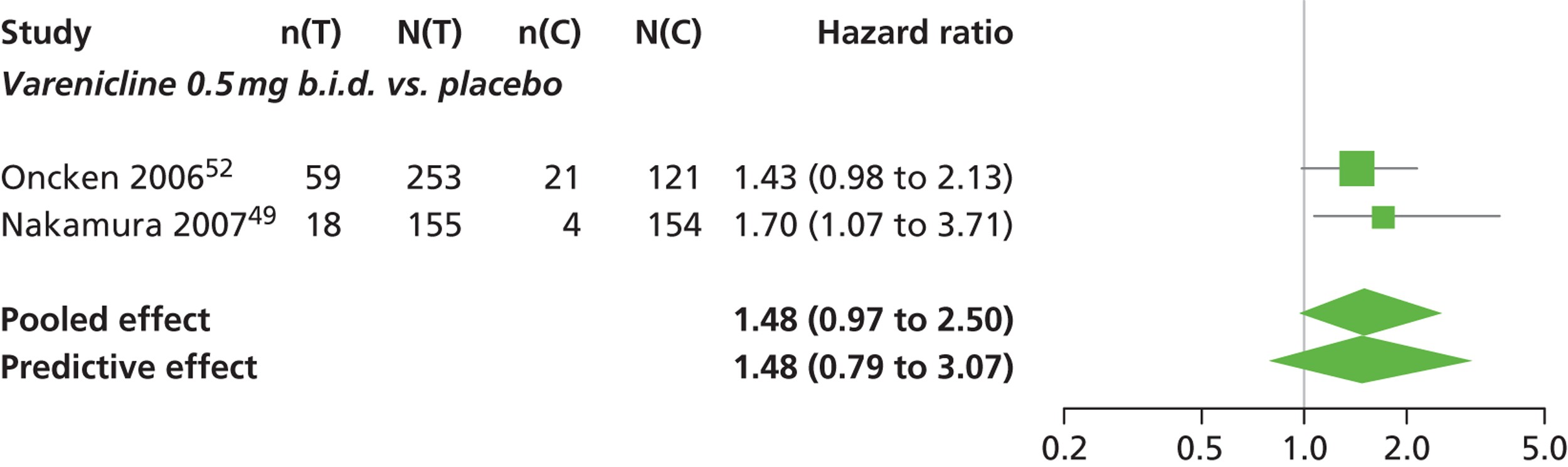

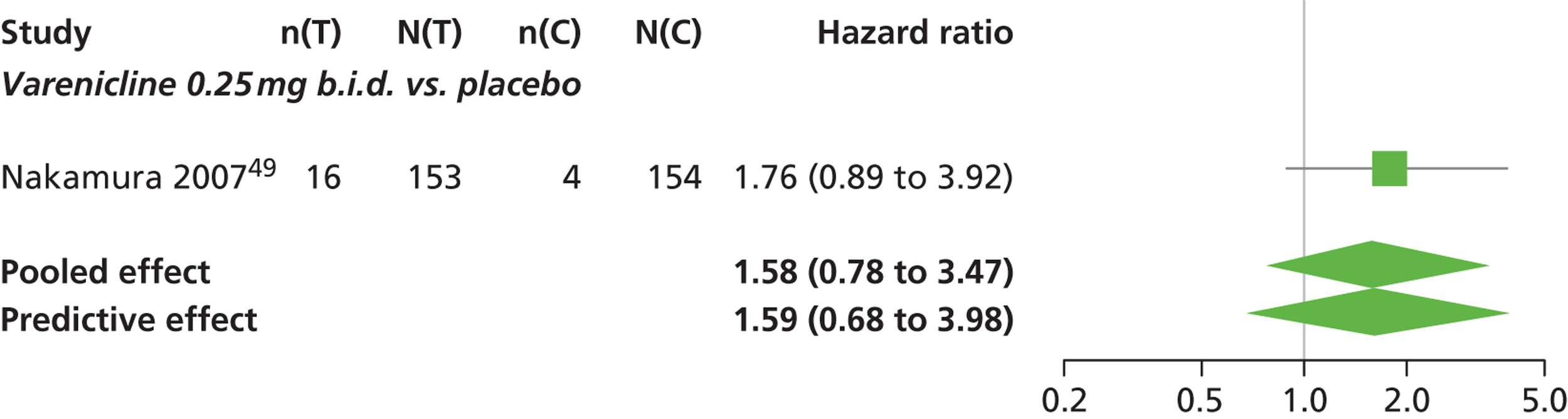

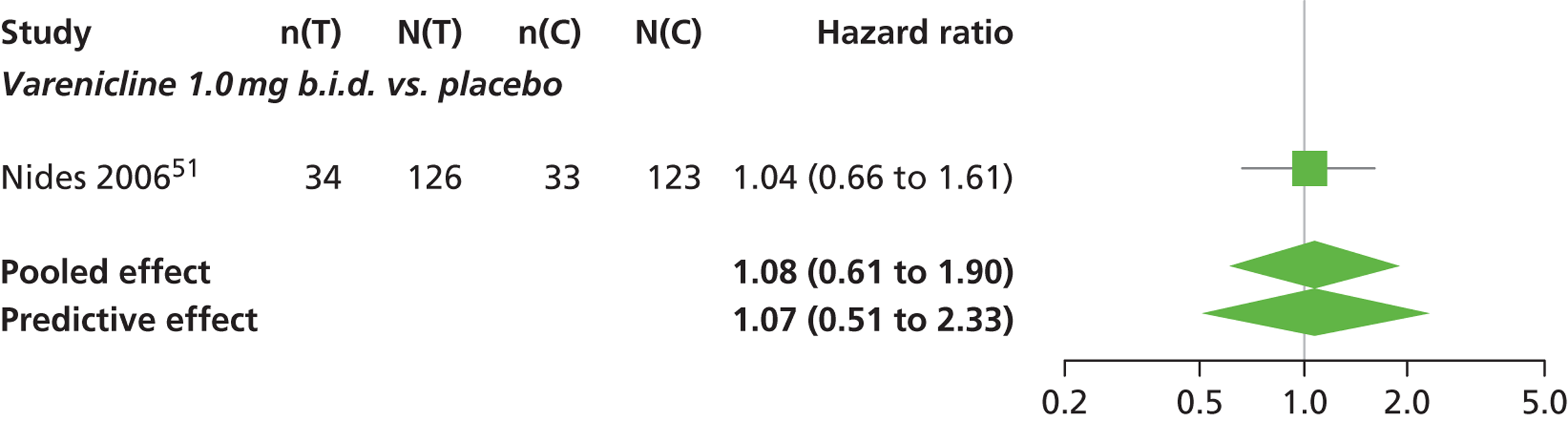

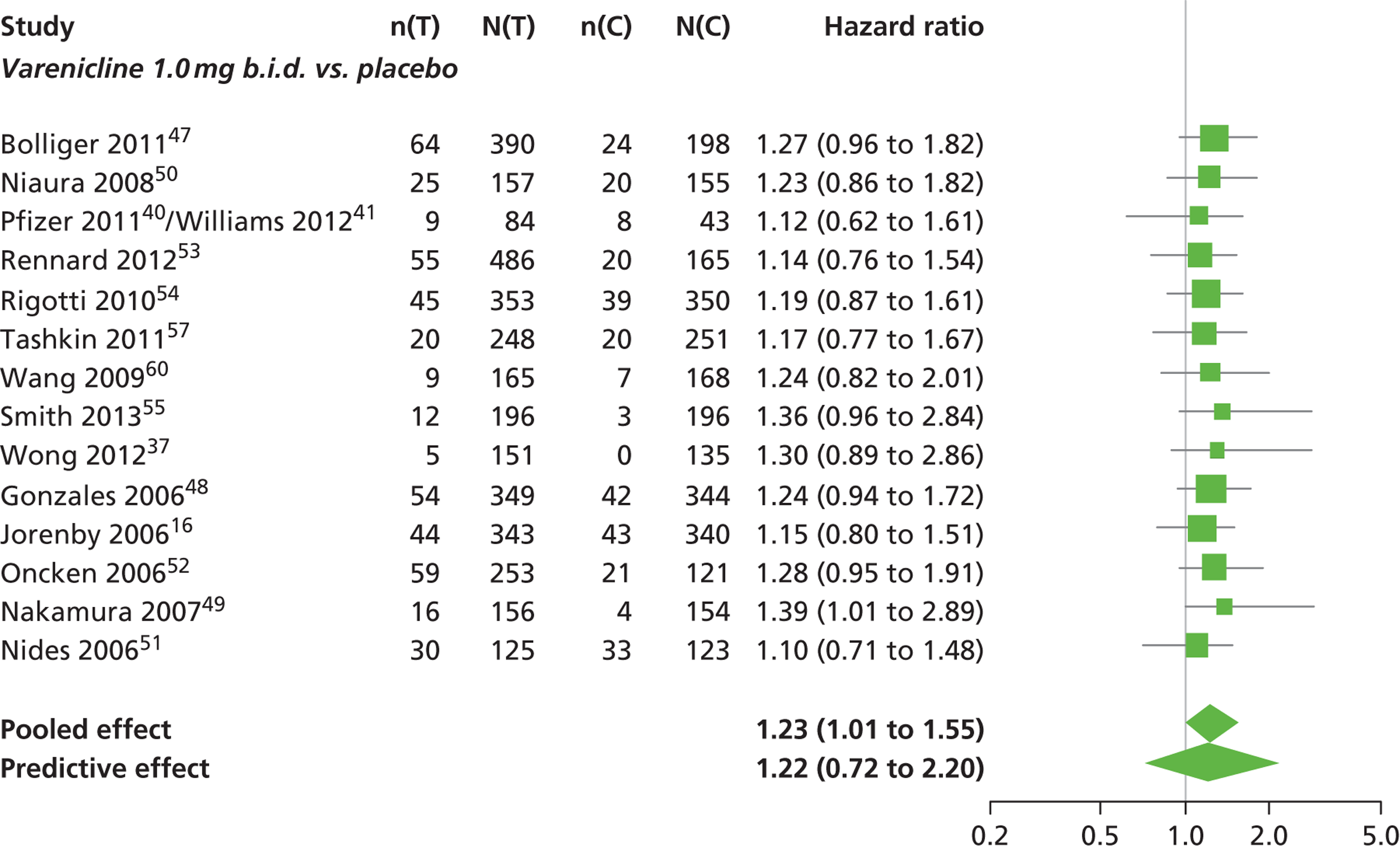

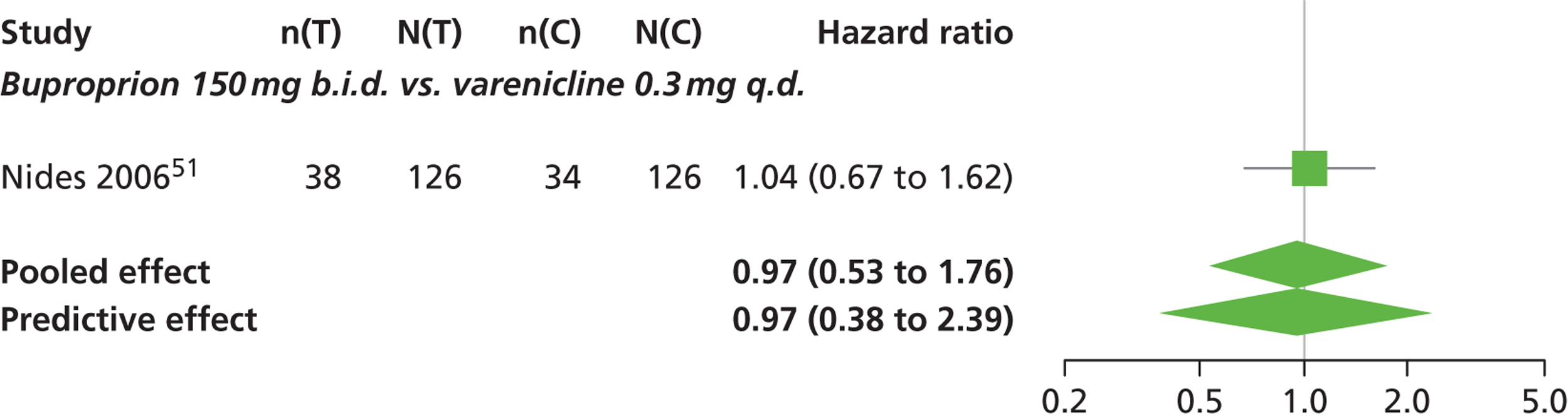

Headache

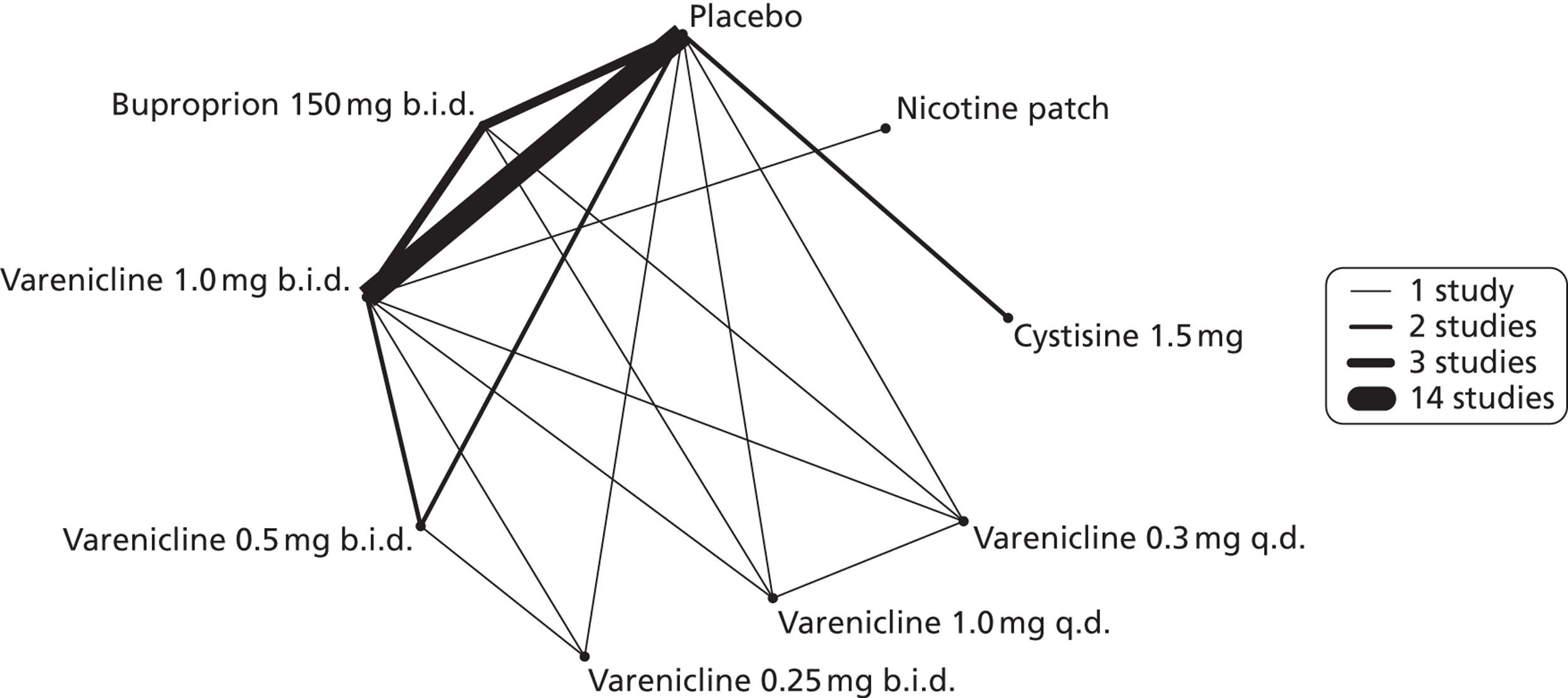

A network meta-analysis was used to compare the hazard of experiencing headaches when treating with nicotine patch, cytisine 1.5 mg, varenicline 0.3 mg q.d., varenicline 1.0 mg q.d., varenicline 0.25 mg b.i.d., varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d., varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. and bupropion hydrochloride 150 mg b.i.d. compared with placebo. A total of 17 studies comparing pairs, triplets, quadruplets or quintuplets of interventions provided information at various study durations. 16,17,37,41,43,46–55,58,61

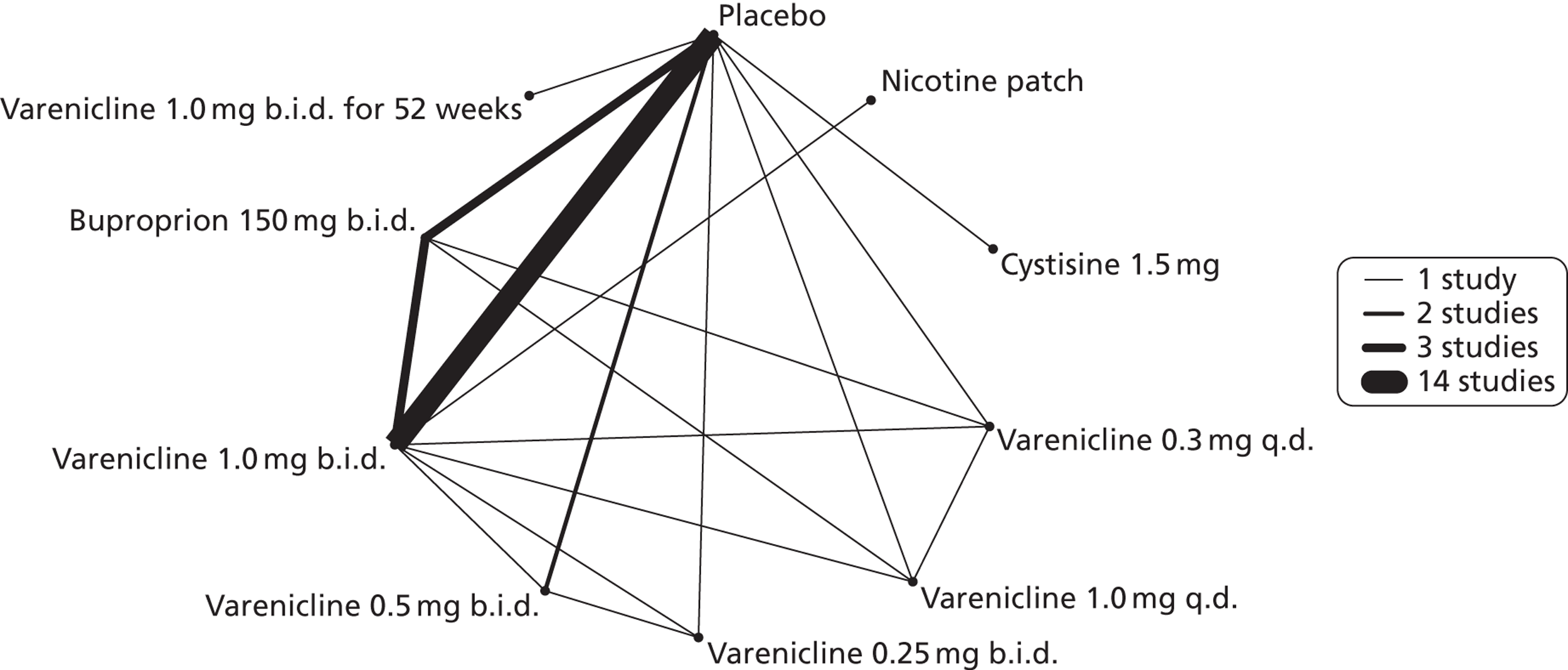

Figure 4 presents the network of evidence. A summary of all the trials (data) included in the network meta-analysis for headache is presented in Appendix 5, Table 40.

FIGURE 4.

Network diagram of different interventions for hazard of experiencing headaches. The nodes represent the interventions. Lines between nodes indicate when interventions have been compared. Different thicknesses of the lines represent the number of times that each pair of interventions has been compared.

The network meta-analysis model did not fit the data very well. The total residual deviance was 49.95, which was higher than would be expected given the 42 data points being analysed. In particular, the model did not fit the Smith et al. 55 and Nakamura et al. 49 studies particularly well. For Smith et al. 55 the model predicted six events in the placebo arm, which is twice as much as the number of events reported. For Nakamura et al. ,49 the model predicted nine events in the placebo arm, which is more than double the number of events reported in the study, which was only four. There was no obvious explanation in terms of the characteristics of the two studies, although we did not attempt a meta-regression because of limited available data.

There was evidence of mild heterogeneity in treatment effects between studies (between-study heterogeneity SD 0.19, 95% CrI 0.01 to 0.50). Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. was the only intervention associated with a statistically significant increase in the hazard of experiencing headaches at a conventional 5% significance level relative to placebo (HR 1.23, 95% CrI 1.01 to 1.55). Varenicline 0.25 mg b.i.d. produced the greatest effect (HR 1.58, 95% CrI 0.78 to 3.47) relative to placebo (Table 10; see also Appendix 5, Figure 15), although the treatment effect was not statistically significant at a conventional 5% significance level. Varenicline 0.25 mg b.i.d. was the intervention with the highest probability of being associated with headaches (p = 0.46) (Table 11).

| Intervention | Hazard ratio (95% CrI) |

|---|---|

| Nicotine patch | 0.59 (0.30 to 1.16) |

| Cytisine 1.5 mga | 0.85 (0.31 to 2.54) |

| Varenicline 0.3 mg q.d. | 1.06 (0.61 to 1.92) |

| Varenicline 1.0 mg q.d. | 1.08 (0.61 to 1.90) |

| Varenicline 0.25 mg b.i.d. | 1.58 (0.78 to 3.47) |

| Varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d. | 1.48 (0.97 to 2.50) |

| Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. | 1.23 (1.01 to 1.55) |

| Bupropion hydrochloride 150 mg b.i.d. | 1.03 (0.76 to 1.48) |

| Between-study SD | 0.19 (0.01 to 0.50) |

| Rank (b) | Treatment (j) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | Nicotine patch | Cytisine 1.5 mg | Varenicline 0.3 mg q.d. | Varenicline 1.0 mg q.d. | Varenicline 0.25 mg b.i.d. | Varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d. | Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. | Bupropion hydrochloride 150 mg b.i.d. | |

| 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.46 | 0.30 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 0.37 | 0.12 | 0.03 |

| 3 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.36 | 0.07 |

| 4 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.29 | 0.14 |

| 5 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.21 |

| 6 | 0.30 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.23 |

| 7 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.20 |

| 8 | 0.10 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.10 |

| 9 | 0.01 | 0.66 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

Nicotine patch and cytisine 1.5 mg were less likely than placebo to be associated with headache, although the effects were not statistically significant at a conventional 5% significance level. The HR for nicotine patch compared with placebo was 0.59 (95% CrI 0.30 to 1.16) and for cytisine 1.5 mg compared with placebo was 0.85 (95% CrI 0.31 to 2.54).

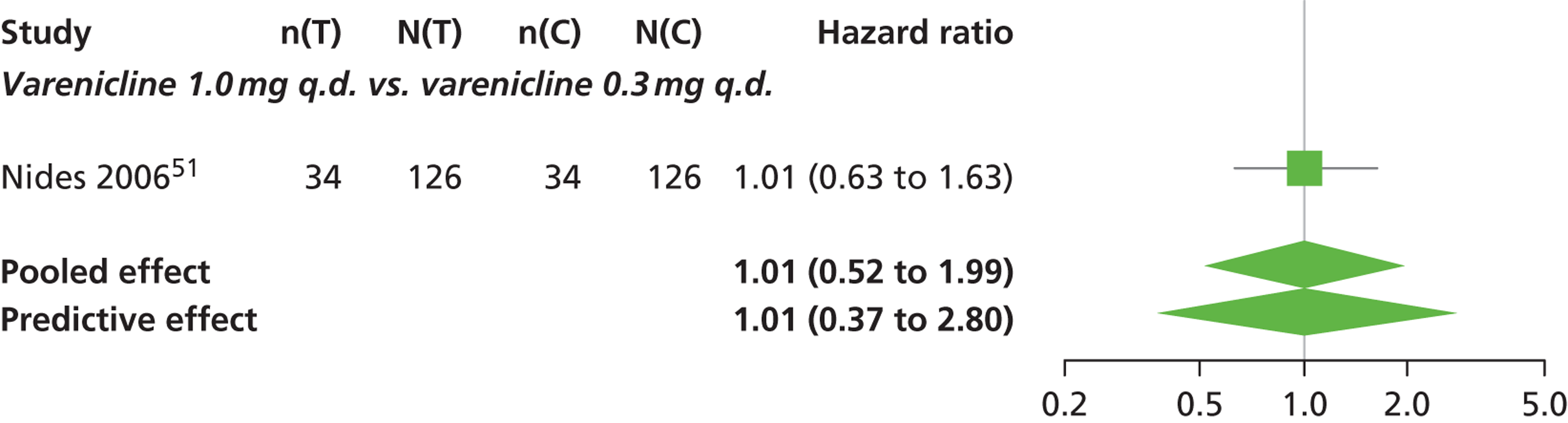

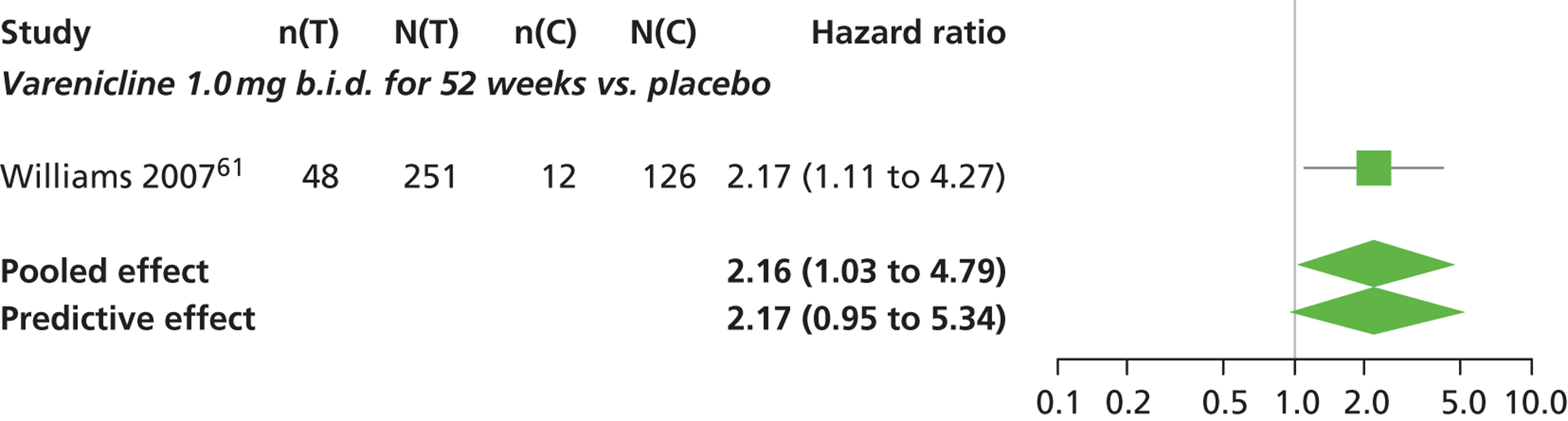

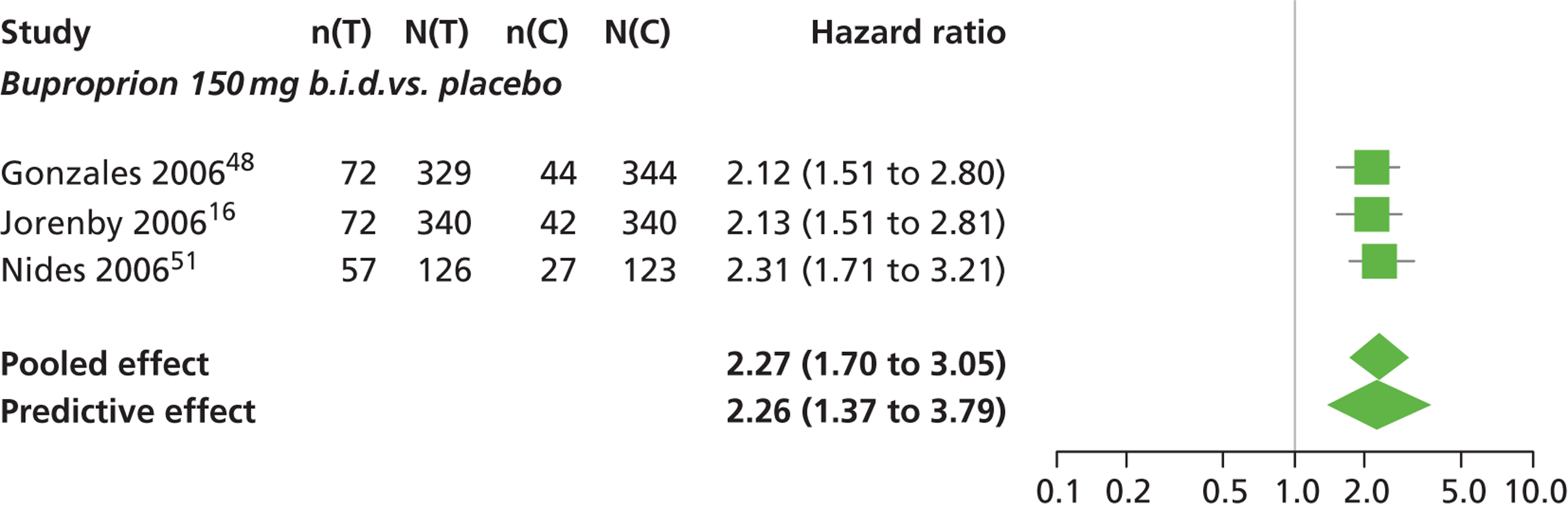

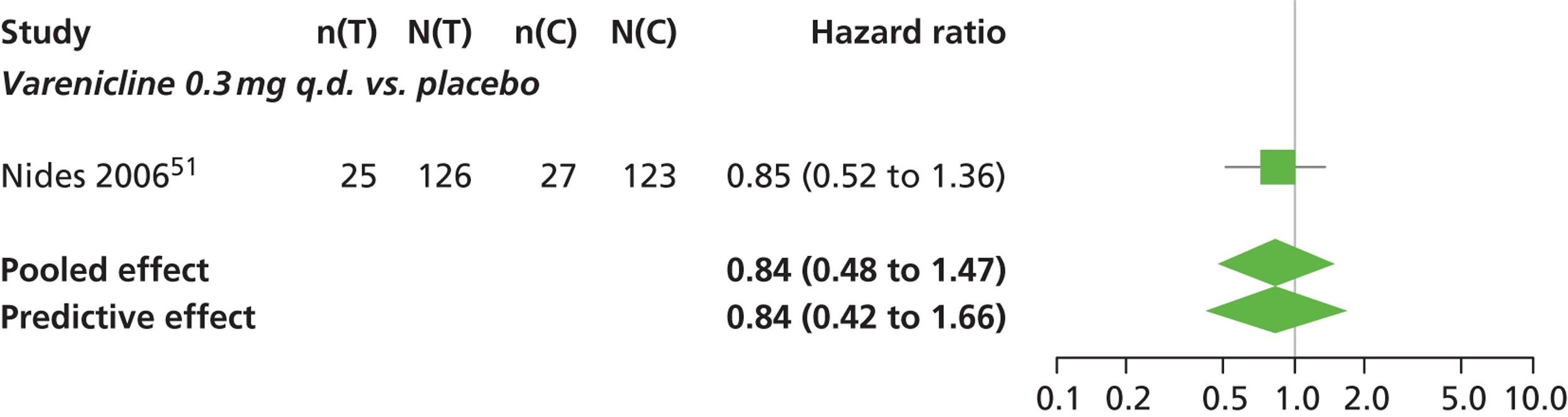

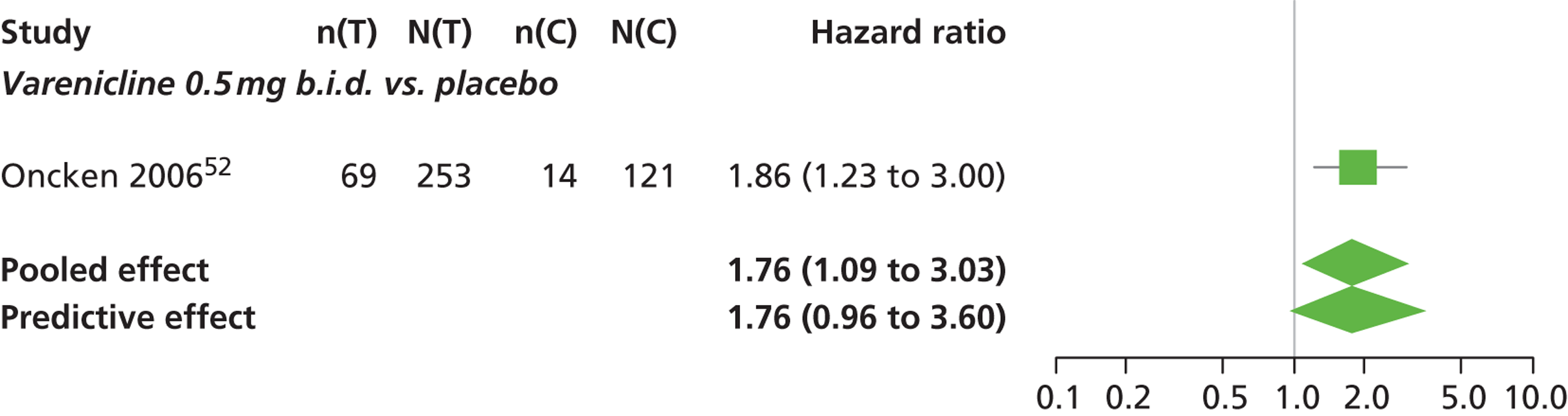

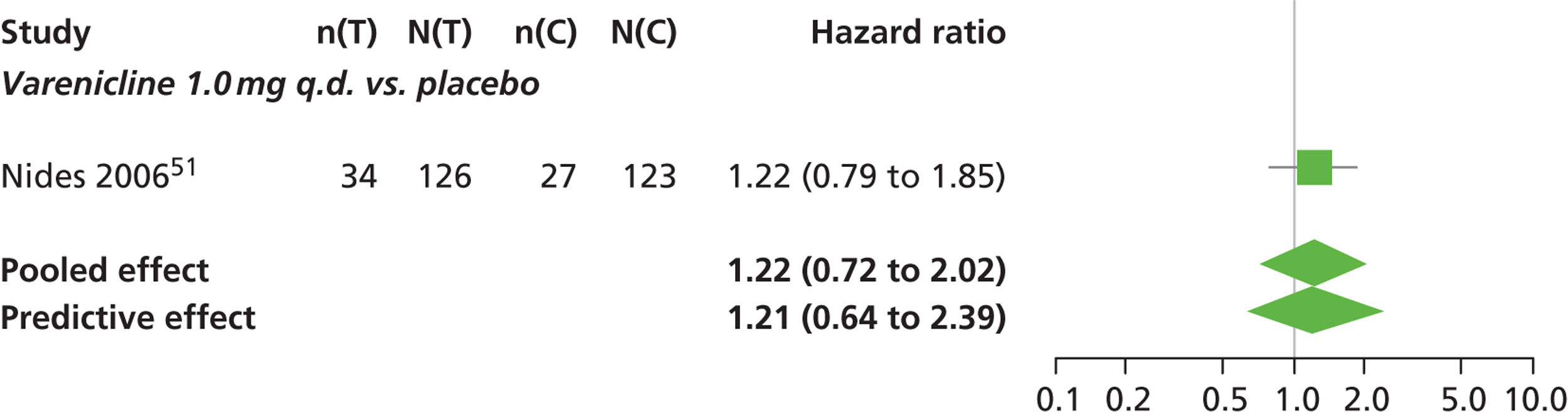

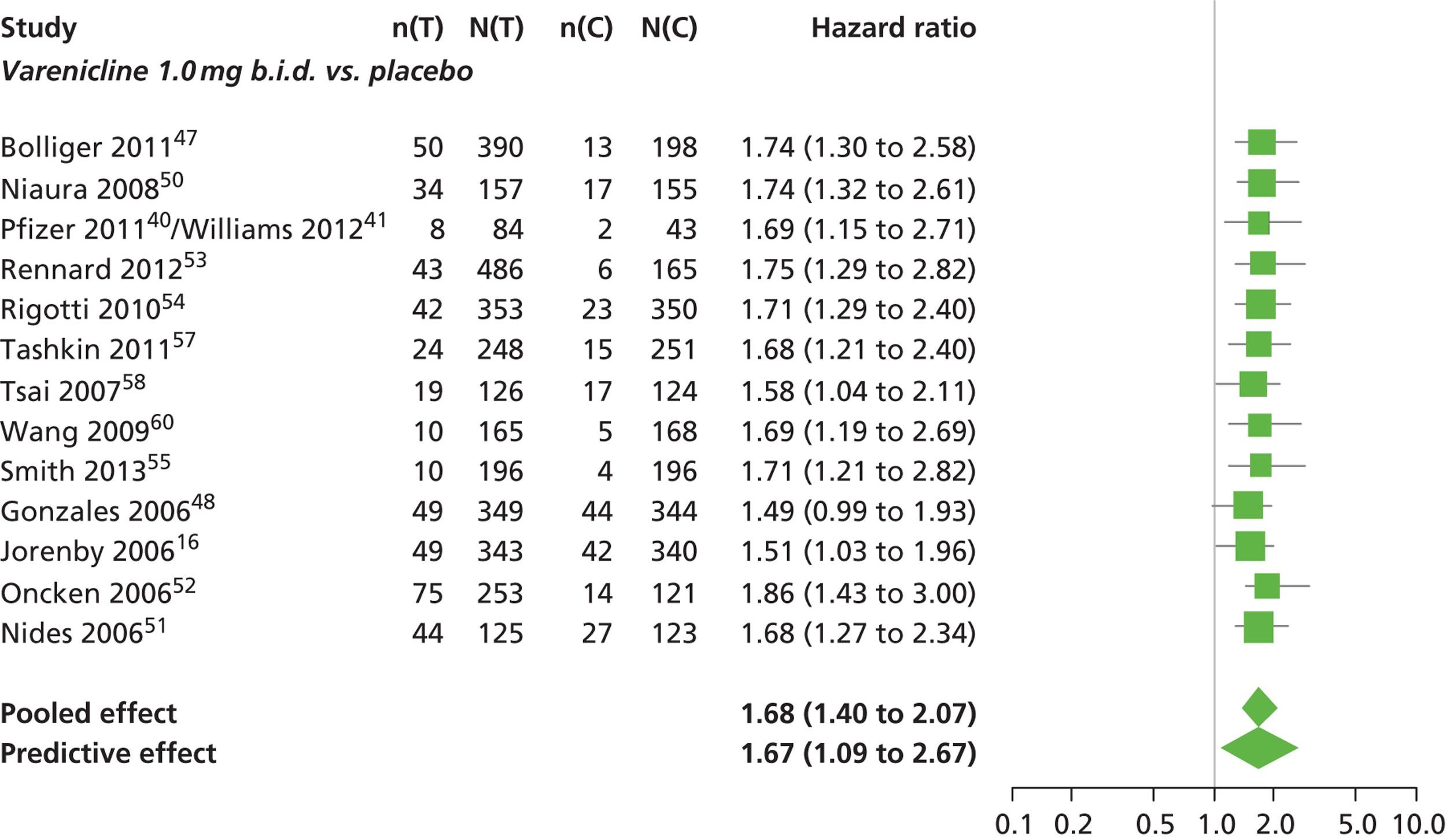

Insomnia

A network meta-analysis was used to compare the hazard of experiencing insomnia when treating with nicotine patch, varenicline 0.3 mg q.d., varenicline 1.0 mg q.d., varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d., varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d., bupropion hydrochloride 150 mg b.i.d. and varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 52 weeks. A total of 16 studies comparing pairs, triplets or quintuplets of interventions provided information at various study durations. 16,41,46–48,50–55,57–61

Figure 5 presents the network of evidence. A summary of all the trials (data) included in the network meta-analysis for insomnia is presented in Appendix 5, Table 41.

FIGURE 5.

Network diagram of different interventions for insomnia. The nodes represent the interventions. Lines between nodes indicate when interventions have been compared. Different thicknesses of the lines represent the number of times that each pair of interventions has been compared.

The network meta-analysis model fitted the data reasonably well, with a total residual deviance close to the total number of data points included in the analysis. The total residual deviance was 36.91, which was slightly less than the 38 data points being analysed.

There was evidence of mild heterogeneity in treatment effects between studies (between-study heterogeneity SD 0.15, 95% CrI 0.00 to 0.40). Varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d., varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d., bupropion hydrochloride 150 mg b.i.d. and varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 52 weeks were associated with a statistically significant increase in the hazard of experiencing insomnia at a conventional 5% significance level relative to placebo. Bupropion hydrochloride 150 mg b.i.d. produced the greatest effect (HR 2.27 95% CrI 1.70 to 3.05) relative to placebo (Table 12; see also Appendix 5, Figure 16). Bupropion hydrochloride 150 mg b.i.d. was the intervention with the highest probability of being associated with insomnia (p = 0.45) (Table 13).

| Intervention | Hazard ratio (95% CrI) |

|---|---|

| Nicotine patch | 1.36 (0.79 to 2.20) |

| Varenicline 0.3 mg q.d. | 0.84 (0.48 to 1.47) |

| Varenicline 1.0 mg q.d. | 1.22 (0.72 to 2.02) |

| Varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d. | 1.76 (1.09 to 3.03) |

| Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. | 1.68 (1.40 to 2.07) |

| Bupropion hydrochloride 150 mg b.i.d. | 2.27 (1.70 to 3.05) |

| Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 52 weeks | 2.16 (1.03 to 4.79) |

| Between-study SD | 0.15 (0.00 to 0.40) |

| Rank (b) | Treatment (j) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | Nicotine patch | Varenicline 0.3 mg q.d. | Varenicline 1.0 mg q.d. | Varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d. | Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. | Bupropion hydrochloride 150 mg b.i.d. | Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 52 weeks | |

| 1 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.45 | 0.43 |

| 2 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.44 | 0.21 |

| 3 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.29 | 0.37 | 0.08 | 0.12 |

| 4 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.21 | 0.43 | 0.02 | 0.10 |

| 5 | 0.03 | 0.37 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.08 |

| 6 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.09 | 0.36 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| 7 | 0.53 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| 8 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.68 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

Varenicline 0.3 mg q.d. was less likely than placebo to be associated with insomnia, although the effect was not statistically significant at a conventional 5% significance level (HR 0.84, 95% CrI 0.48 to 1.47).

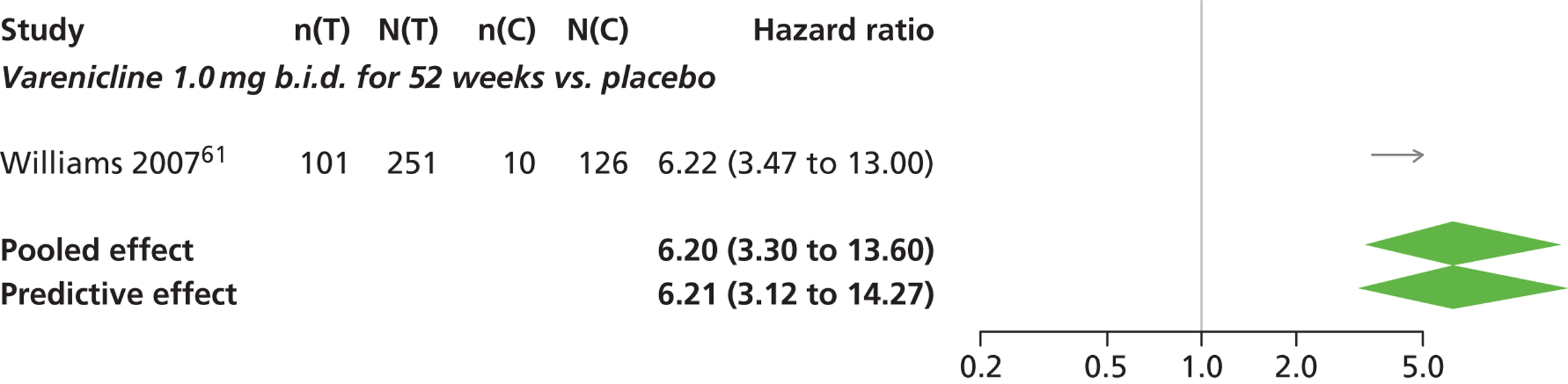

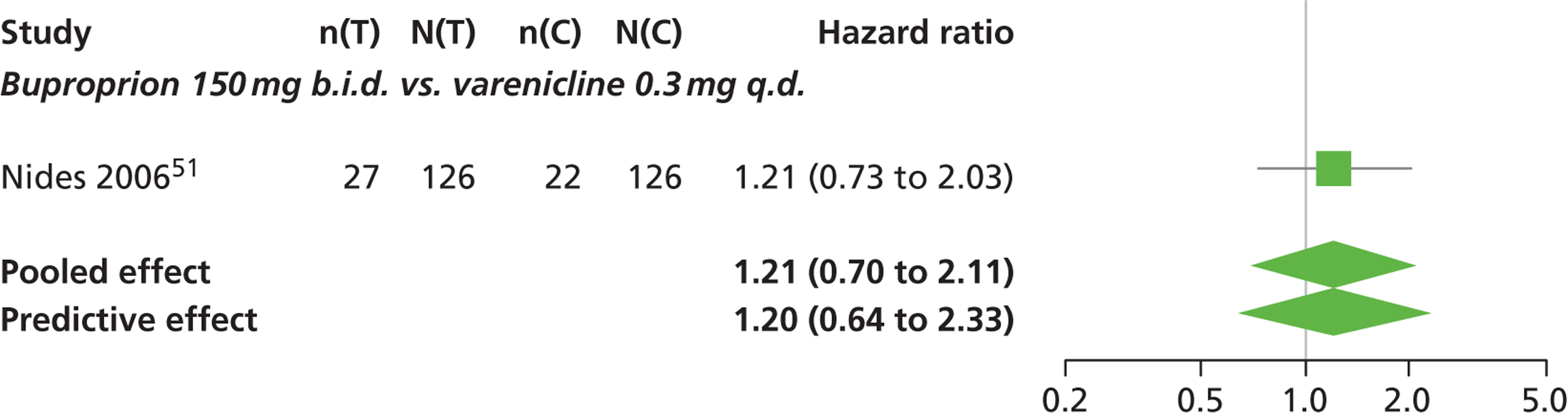

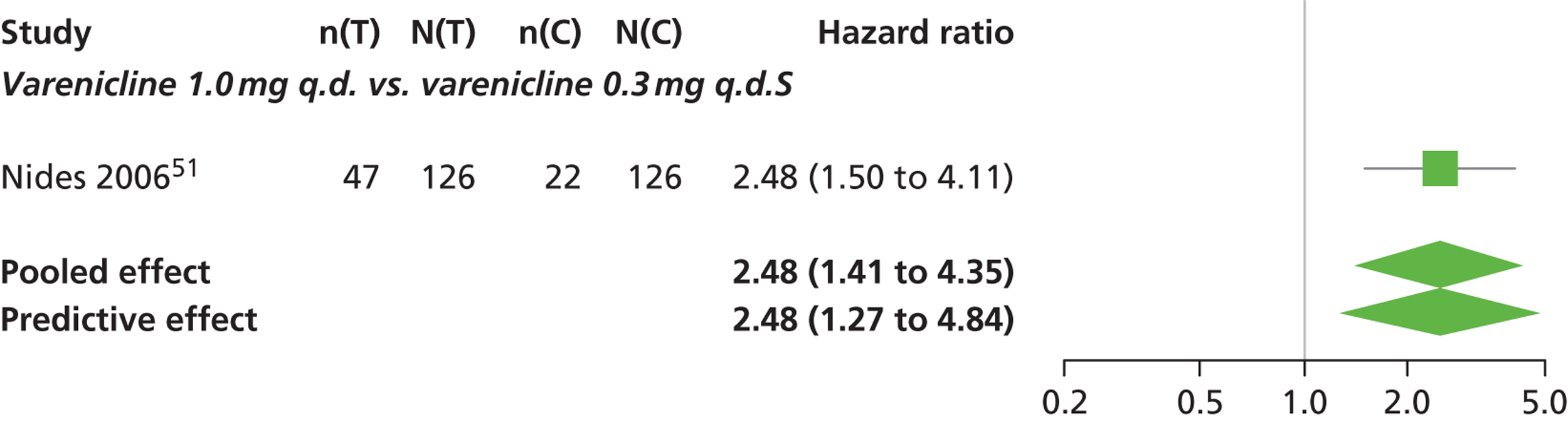

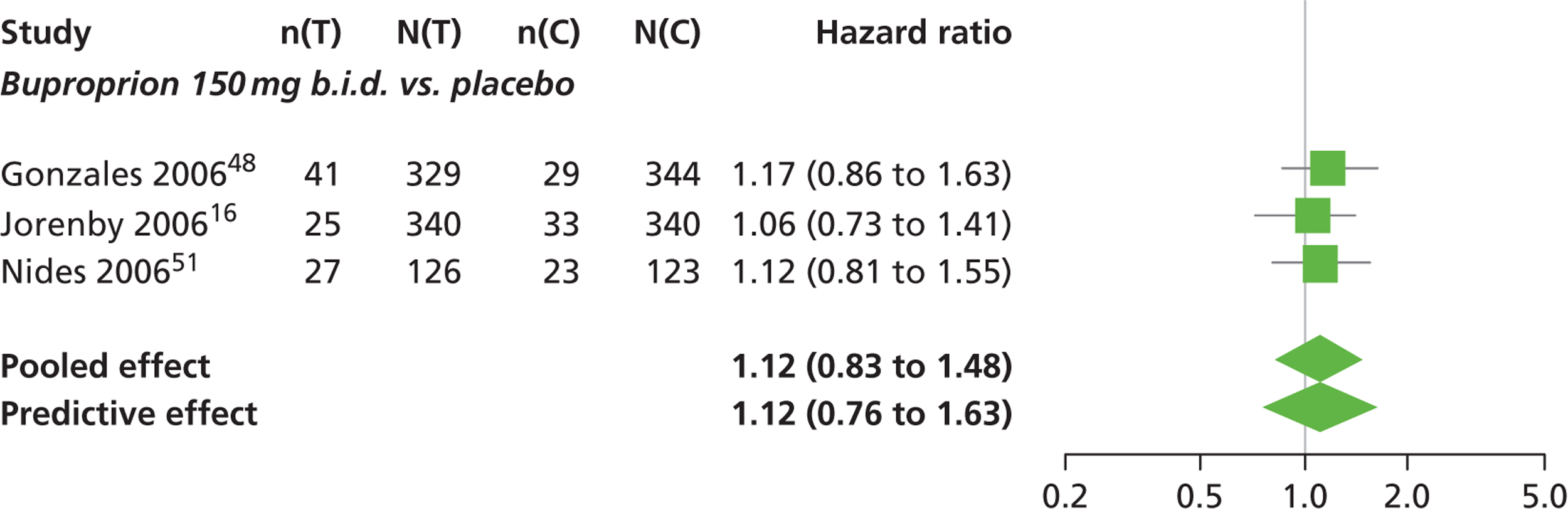

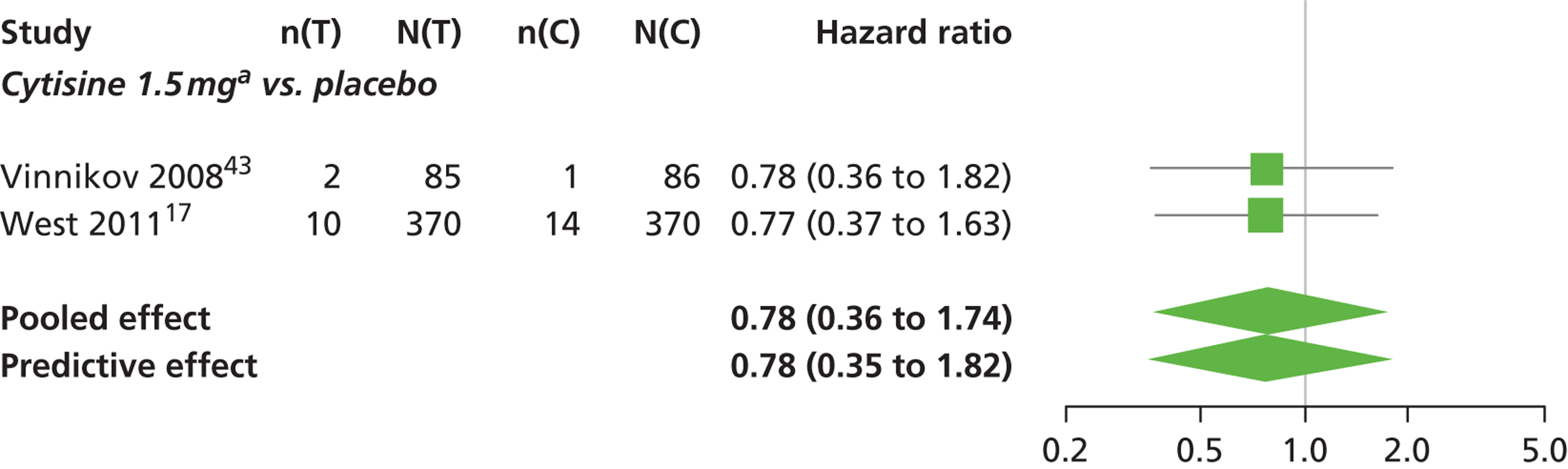

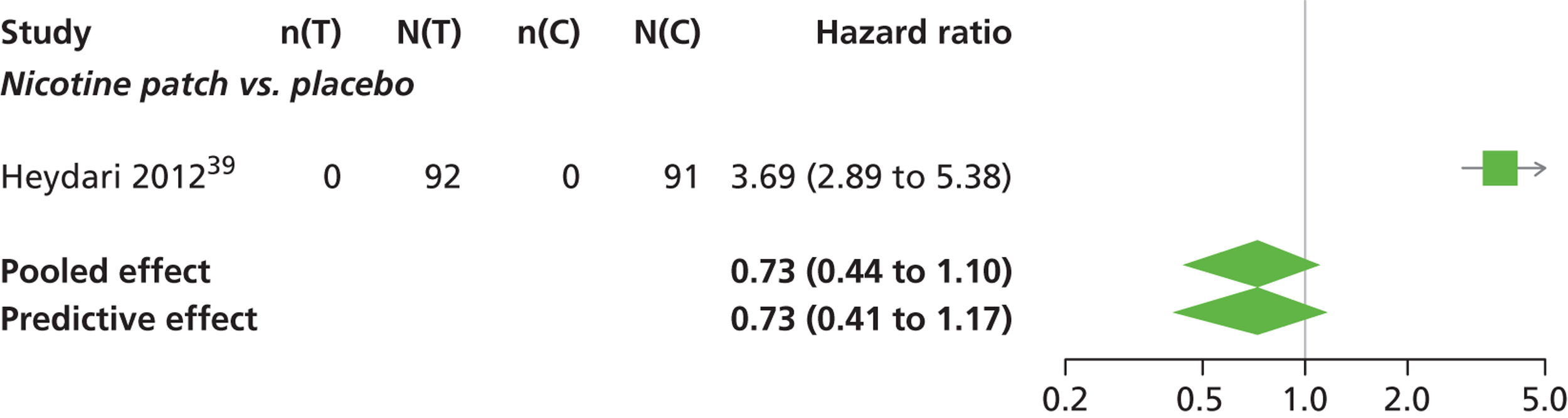

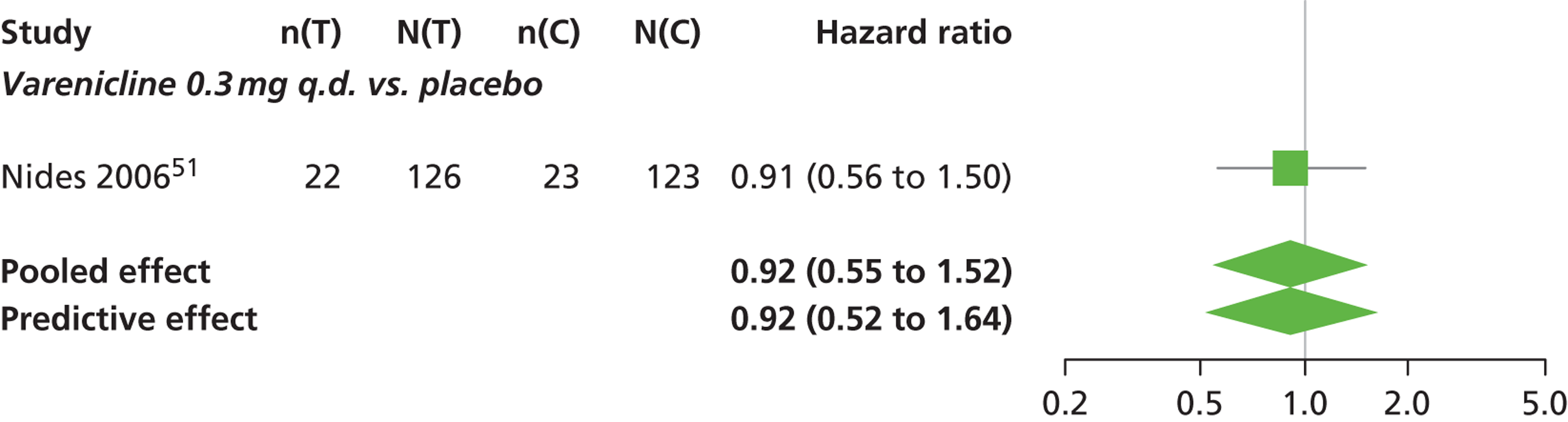

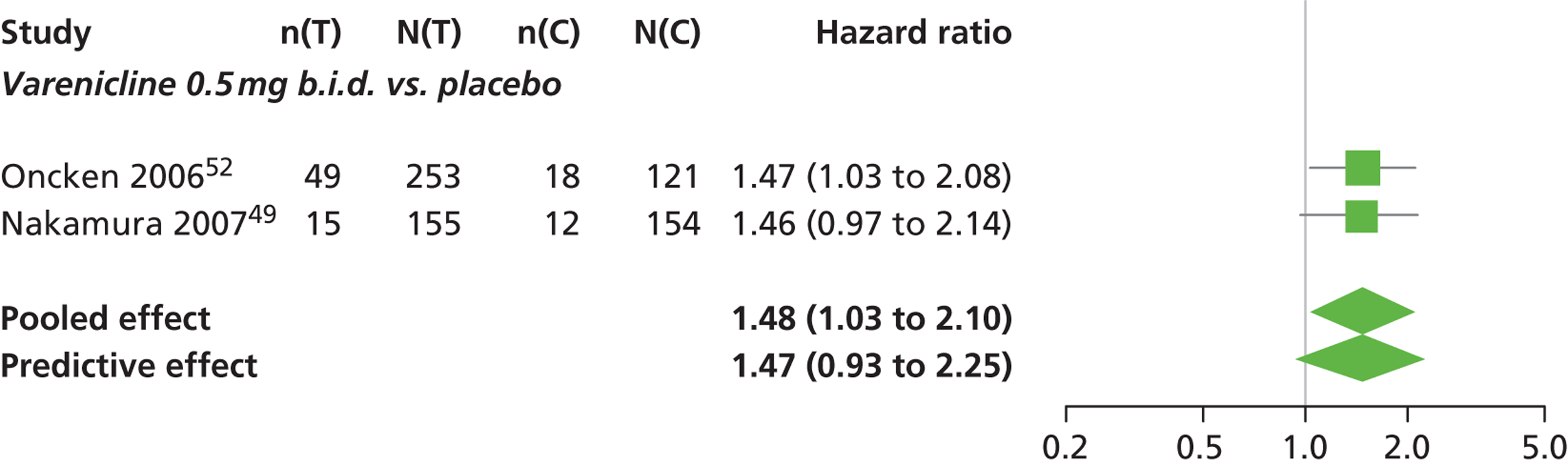

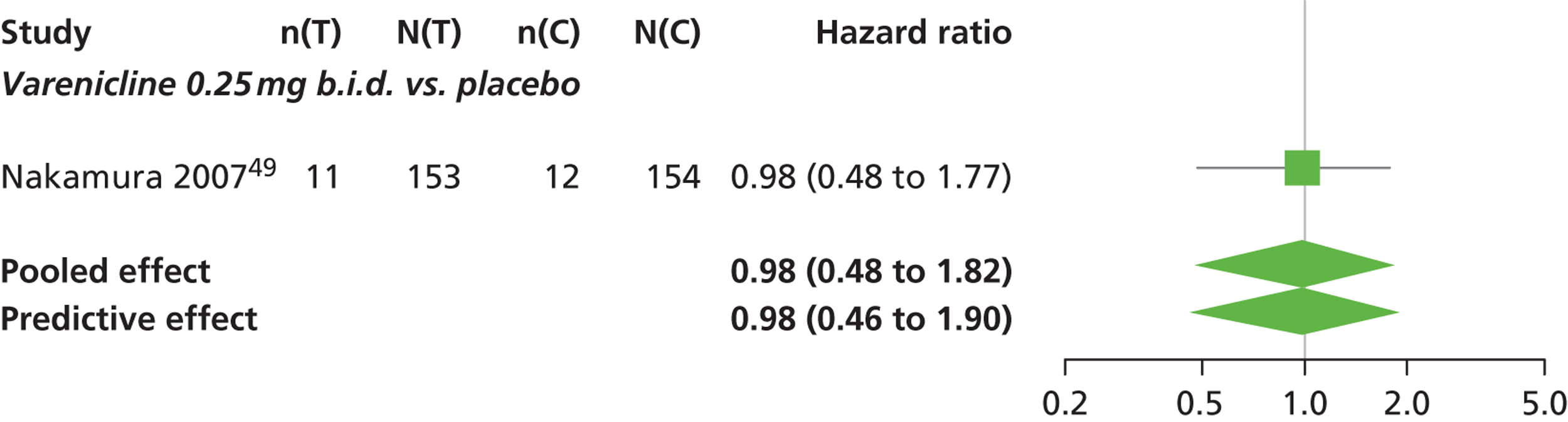

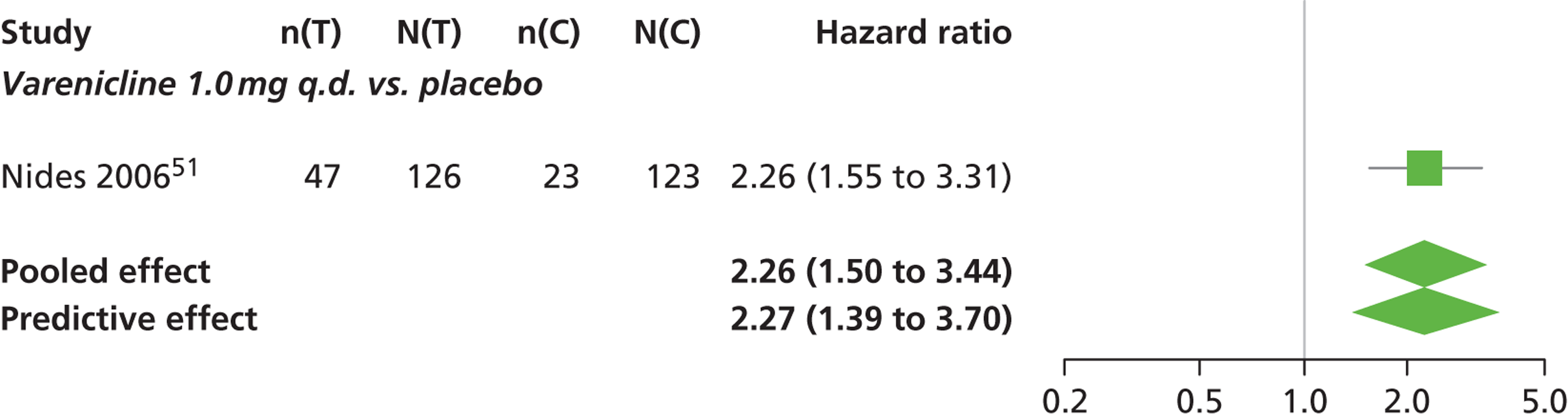

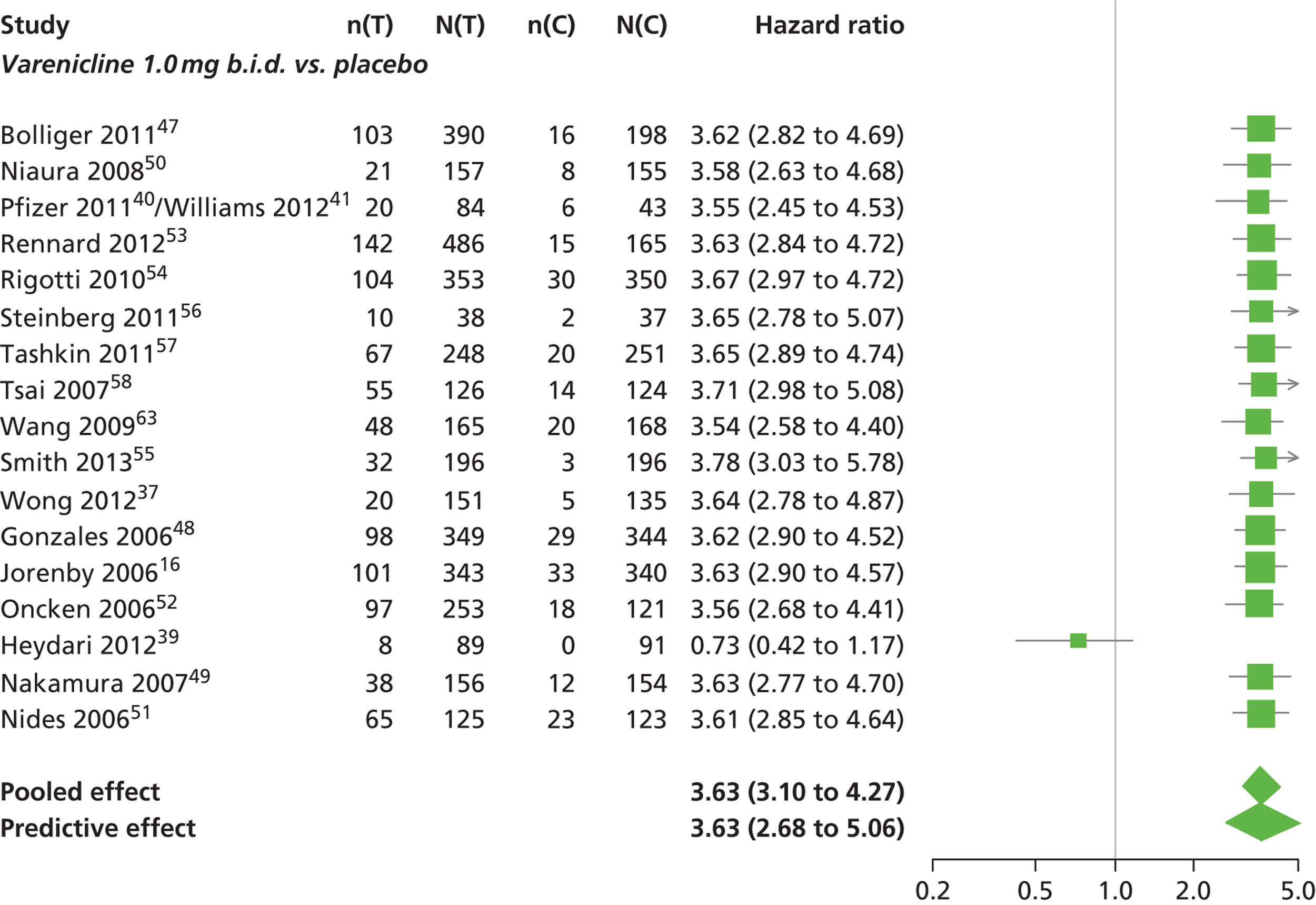

Nausea

A network meta-analysis was used to compare the hazard of experiencing nausea when treating with nicotine patch, cytisine 1.5 mg, varenicline 0.3 mg q.d., varenicline 1.0 mg q.d., varenicline 0.25 mg b.i.d., varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d., varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d., bupropion hydrochloride 150 mg b.i.d. and varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 52 weeks. A total of 22 studies comparing pairs, triplets, quadruplets or quintuplets of interventions provided information at various study durations. 16,17,37,39,41,43,46–61

Figure 6 presents the network of evidence. A summary of all the trials (data) included in the network meta-analysis for nausea is presented in Appendix 5, Table 42.

FIGURE 6.

Network diagram of different interventions for hazard of experiencing nausea. The nodes represent the interventions. Lines between nodes indicate when interventions have been compared. Different thicknesses of the lines represent the number of times that each pair of interventions has been compared.

The network meta-analysis model fitted the data reasonably well, with a total residual deviance close to the total number of data points included in the analysis. The total residual deviance was 55.20, which compared favourably with the 53 non-zero data points being analysed.

There was evidence of mild heterogeneity in treatment effects between studies (between-study heterogeneity SD 0.08, 95% CrI 0.00 to 0.29). Varenicline 1.0 mg q.d., varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d., varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d., bupropion hydrochloride 150 mg b.i.d. and varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 52 weeks were more likely than placebo to be associated with nausea. Varenicline 1.0 mg q.d., varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d., varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. and varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 52 weeks were associated with a statistically significant increase in the hazard of experiencing nausea at a conventional 5% significance level relative to placebo. Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 52 weeks produced the greatest effect (HR 6.20, 95% CrI 3.30 to 13.61) relative to placebo (Table 14; see also Appendix 5, Figure 17). Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 52 weeks was the intervention with the highest probability of being associated with nausea (p = 0.95) (Table 15).

| Intervention | Hazard ratio (95% CrI) |

|---|---|

| Nicotine patch | 0.73 (0.44 to 1.10) |

| Cytisine 1.5 mga | 0.78 (0.36 to 1.74) |

| Varenicline 0.3 mg q.d. | 0.92 (0.55 to 1.52) |

| Varenicline 1.0 mg q.d. | 2.26 (1.50 to 3.44) |

| Varenicline 0.25 mg b.i.d. | 0.98 (0.48 to 1.82) |

| Varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d. | 1.48 (1.03 to 2.10) |

| Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. | 3.63 (3.10 to 4.27) |

| Bupropion hydrochloride 150 mg b.i.d. | 1.12 (0.83 to 1.48) |

| Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 52 weeks | 6.20 (3.30 to 13.61) |

| Between-study SD | 0.08 (0.00 to 0.29) |

| Rank (b) | Treatment (j) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | Nicotine patch | Cytisine 1.5 mg | Varenicline 0.3 mg q.d. | Varenicline 1.0 mg q.d. | Varenicline 0.25 mg b.i.d. | Varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d. | Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. | Bupropion hydrochloride 150 mg b.i.d. | Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 52 weeks | |

| 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.95 |

| 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.94 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| 3 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.92 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 4 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.70 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.00 |

| 5 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.34 | 0.00 |

| 6 | 0.25 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.32 | 0.00 |

| 7 | 0.38 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.00 |

| 8 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.00 |

| 9 | 0.06 | 0.34 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| 10 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

Nicotine patch, cytisine 1.5 mg, varenicline 0.3 mg q.d. and varenicline 0.25 mg b.i.d. were less likely than placebo to be associated with nausea, although the effects were not statistically significant at a conventional 5% significance level.

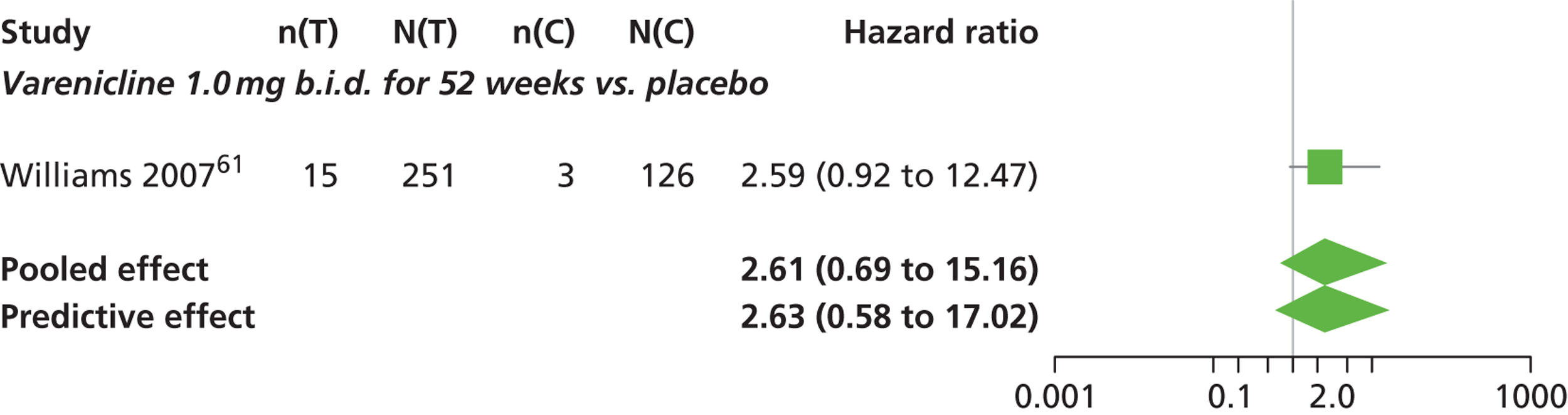

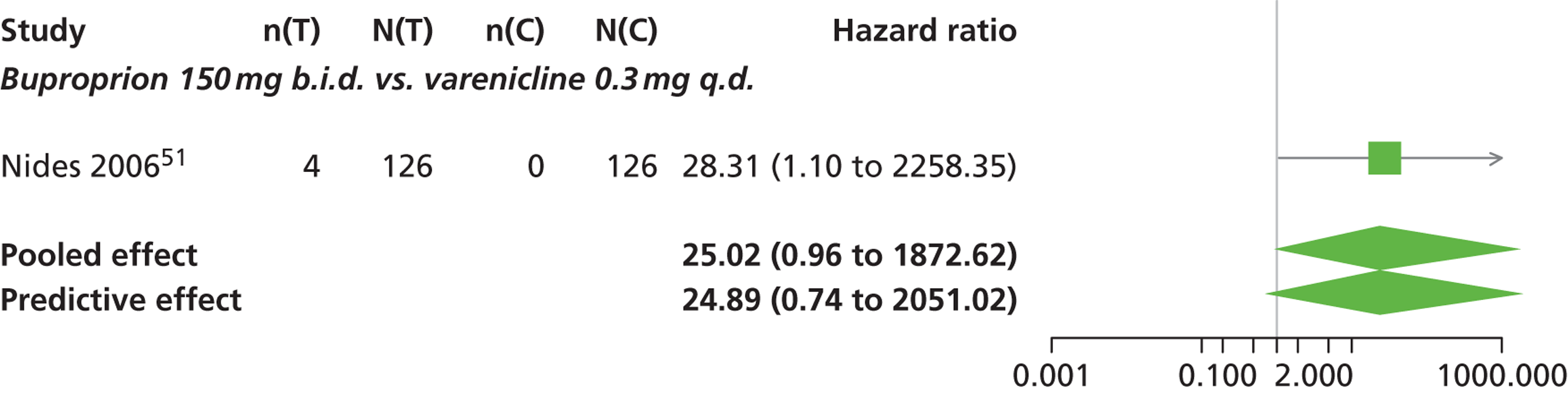

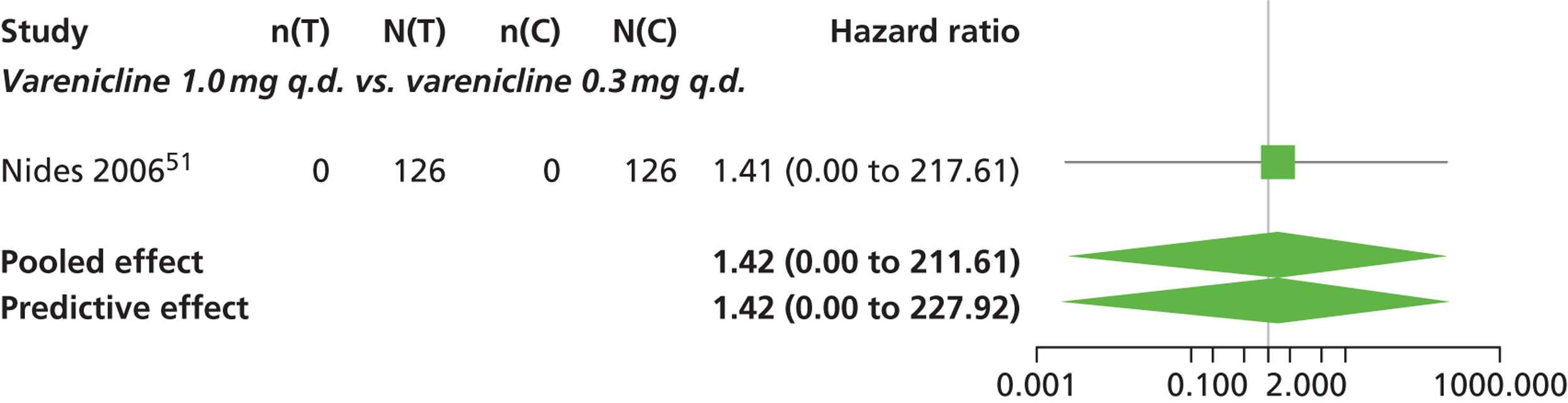

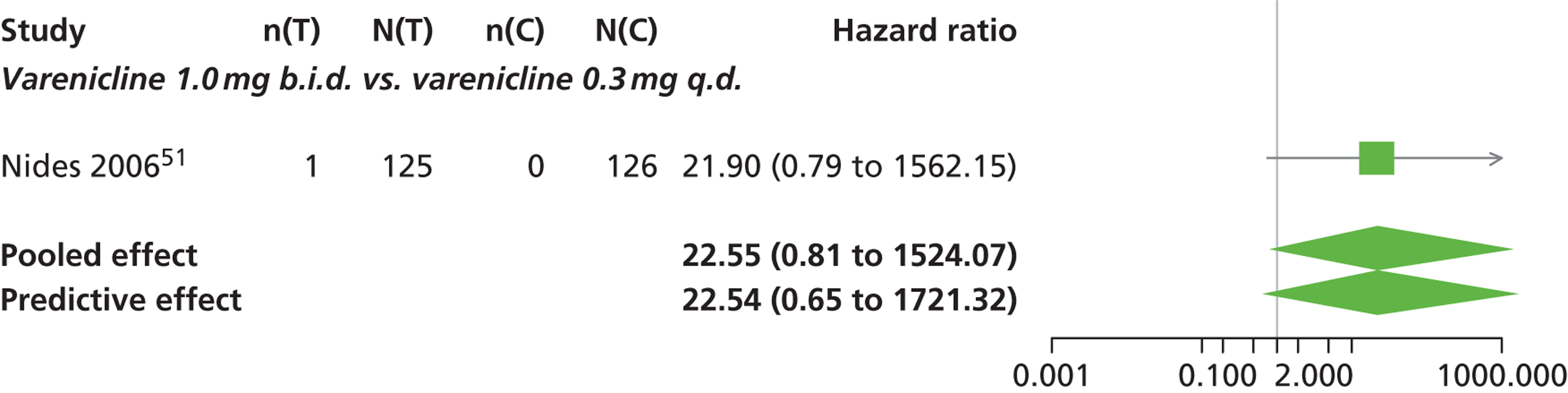

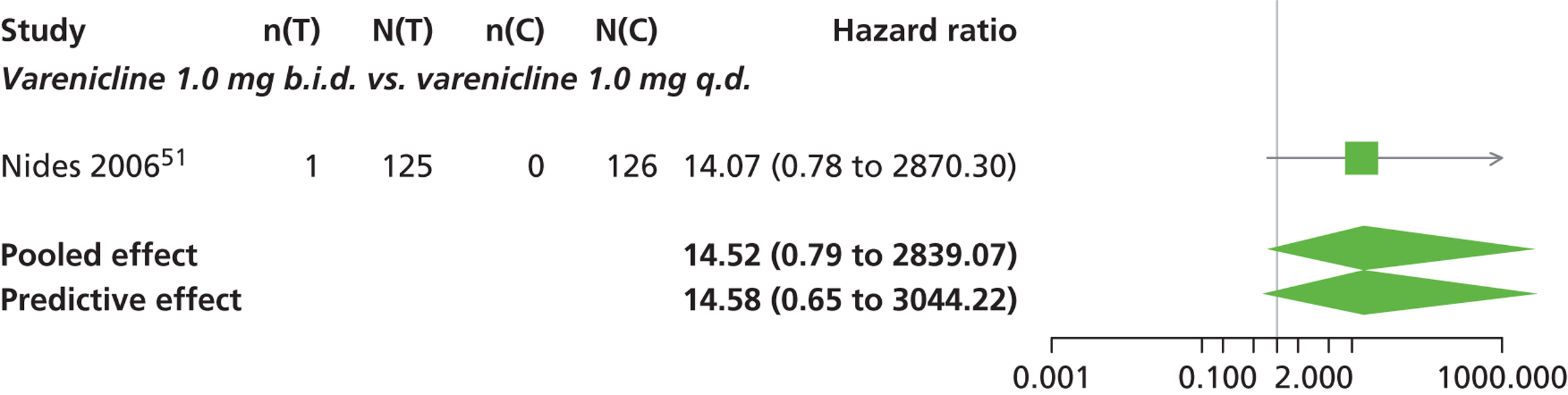

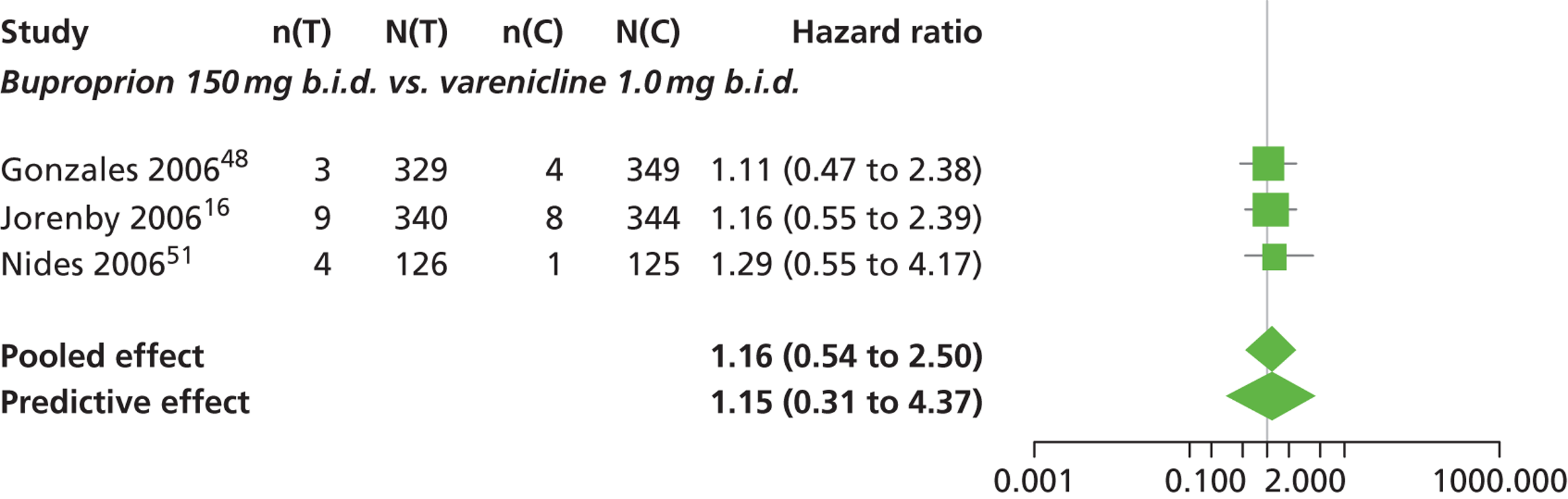

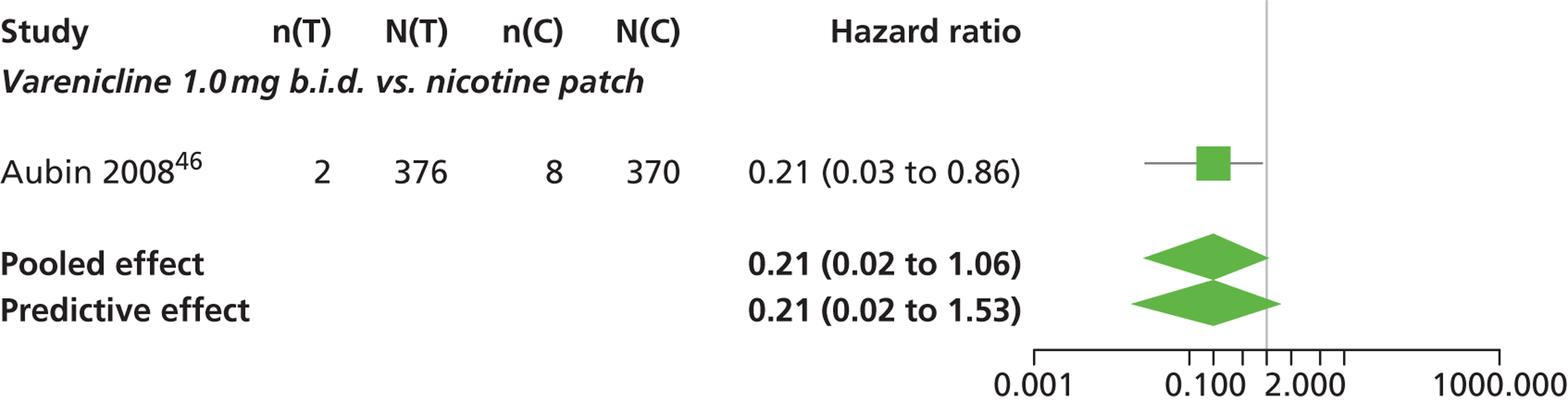

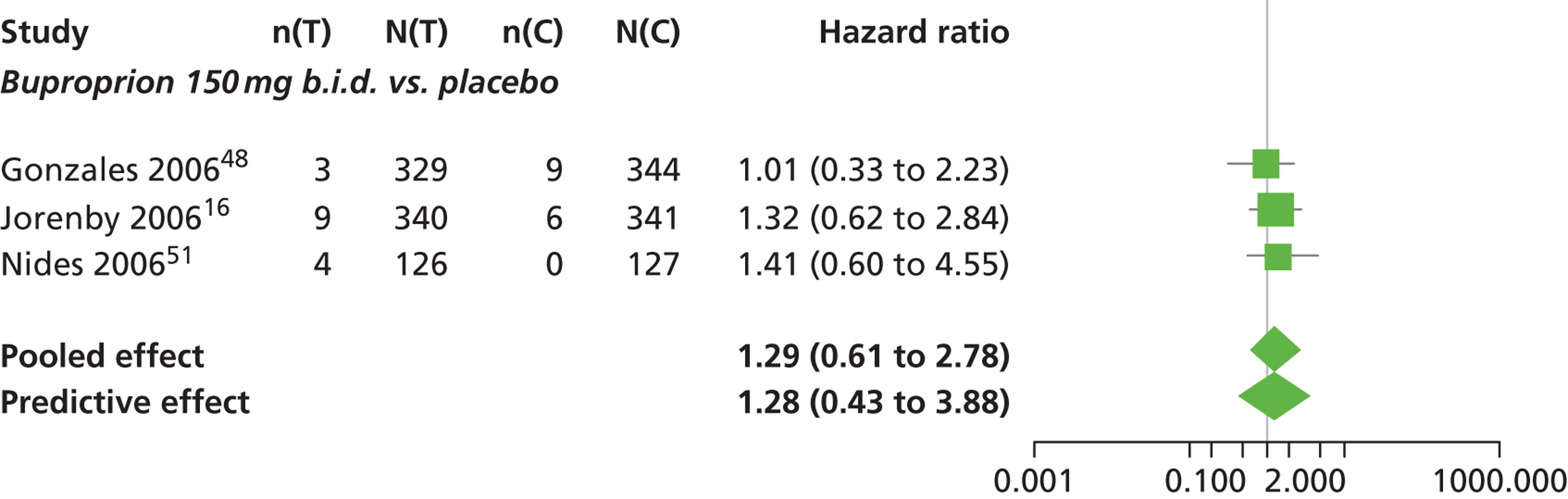

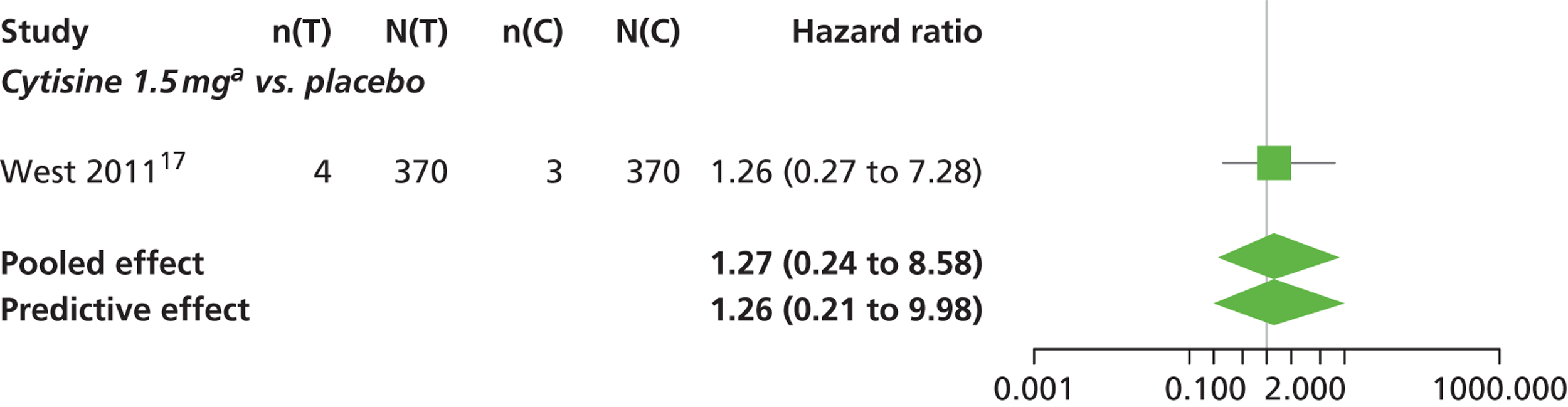

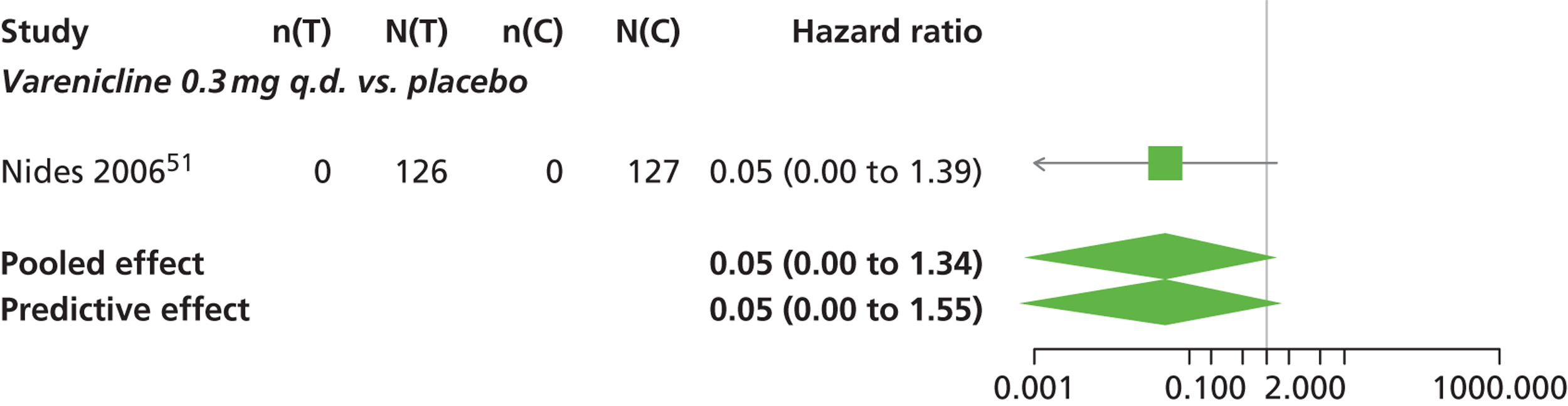

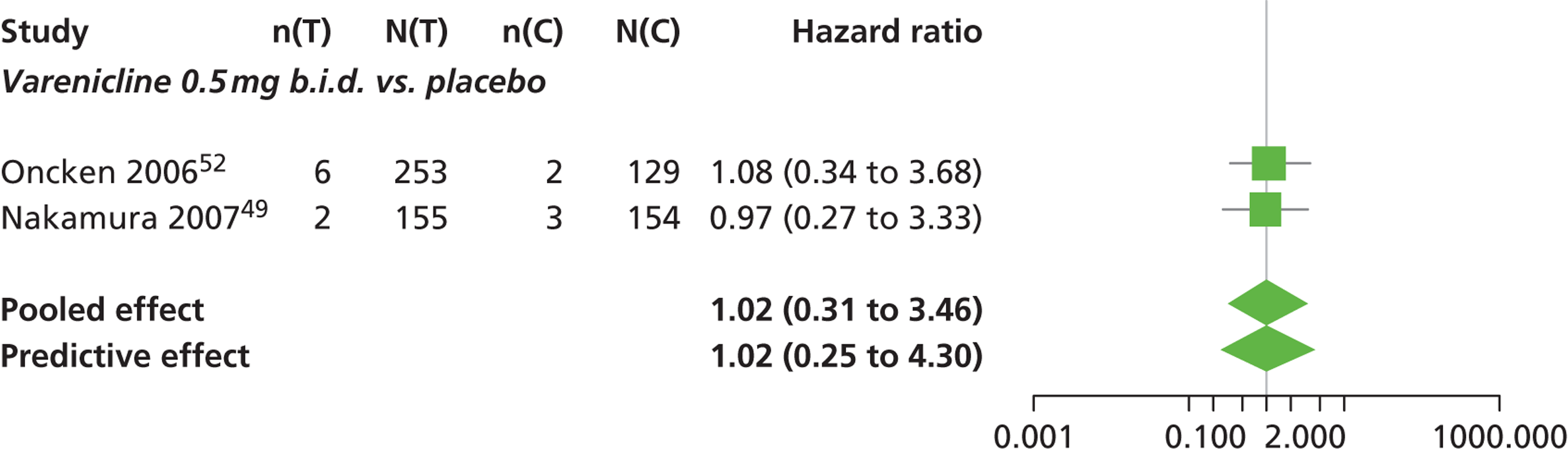

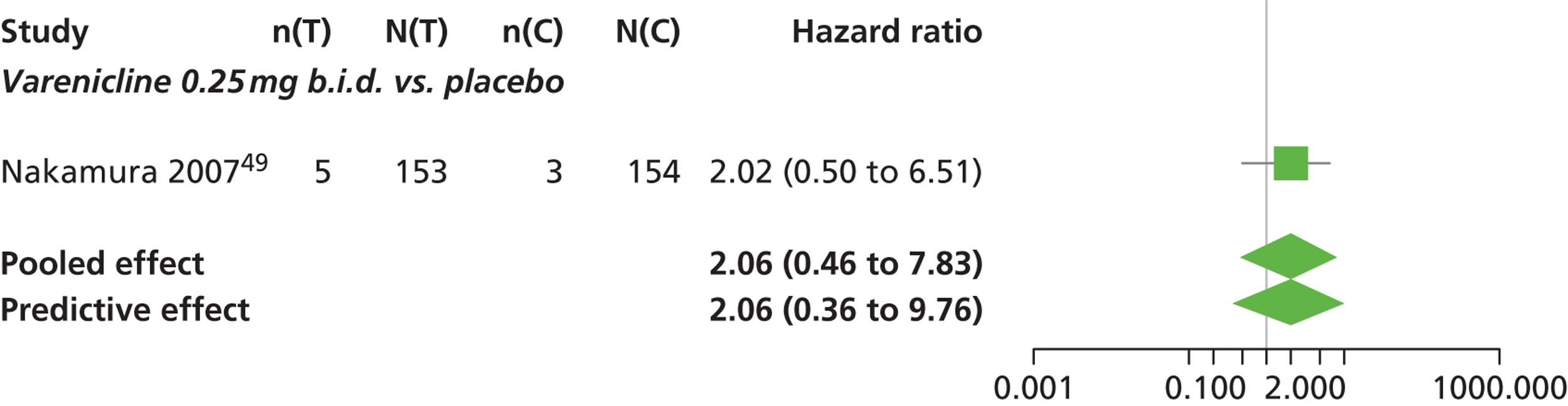

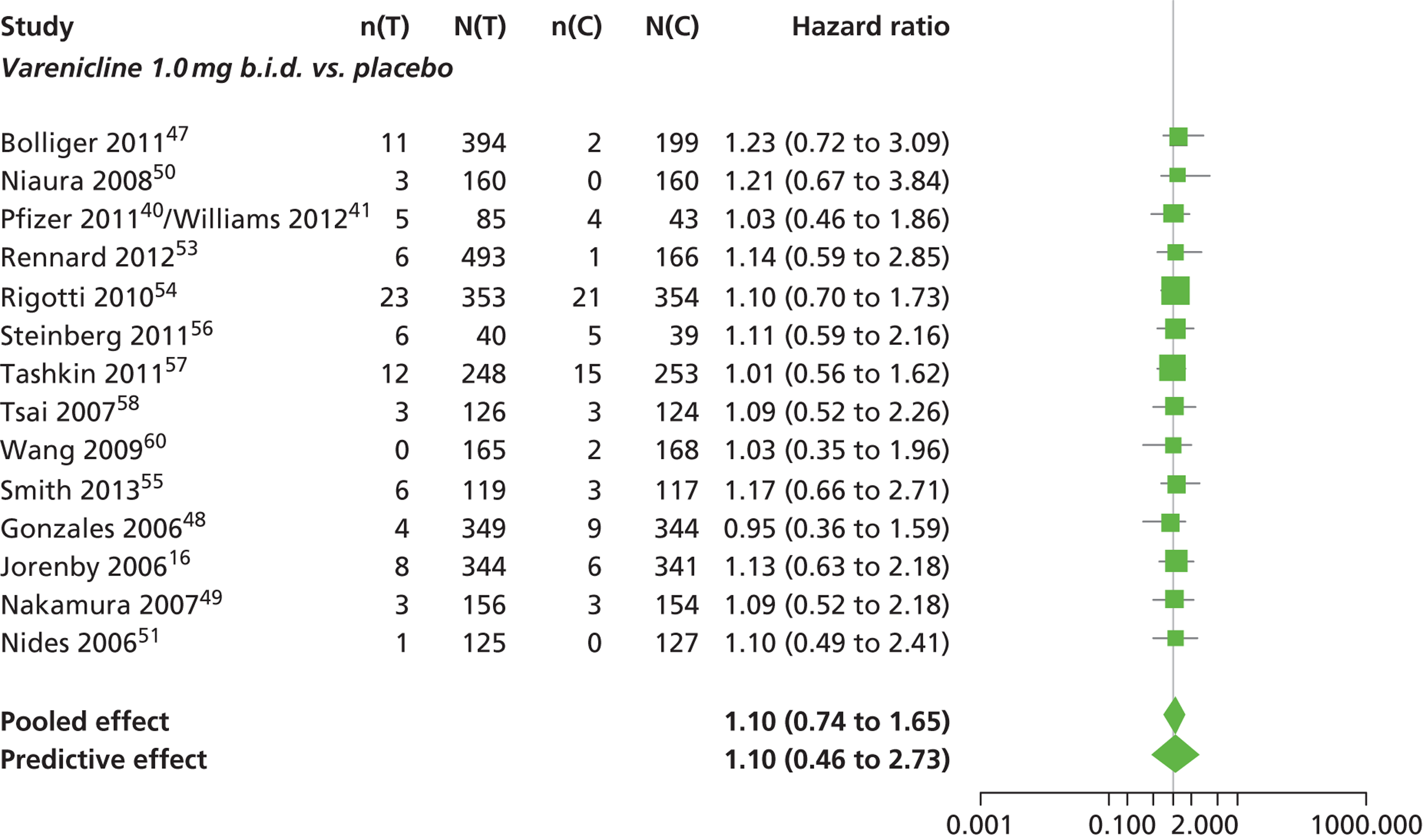

Serious adverse events

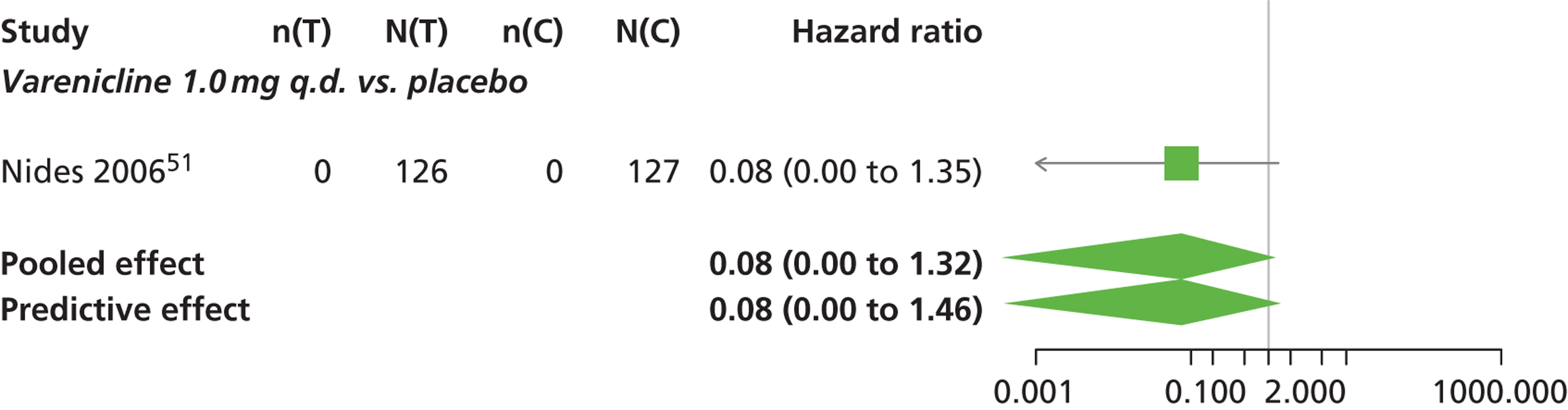

A network meta-analysis was used to compare the hazard of experiencing SAEs when treating with nicotine patch, cytisine 1.5 mg, varenicline 0.3 mg q.d., varenicline 1.0 mg q.d., varenicline 0.25 mg b.i.d., varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d., varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d., bupropion hydrochloride 150 mg b.i.d. and varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 52 weeks or placebo. A total of 18 studies comparing pairs, triplets, quadruplets or quintuplets of interventions provided information at various study durations. 16,17,41,46–58,60,61

Figure 7 presents the network of evidence. A summary of all the trials (data) included in the network meta-analysis for SAEs is presented in Appendix 5, Table 43.

FIGURE 7.

Network diagram of different interventions for risk of experiencing SAEs. The nodes represent the interventions. Lines between nodes indicate when interventions have been compared. Different thicknesses of the lines represent the number of times that each pair of interventions has been compared.

The network meta-analysis model fitted the data reasonably well, with a total residual deviance close to the total number of data points included in the analysis. The total residual deviance was 46.67, which compared favourably with the 43 data points being analysed.

There was evidence of mild heterogeneity in treatment effects between studies (between-study heterogeneity SD 0.25, 95% CrI 0.01 to 0.86). Nicotine patch, cytisine 1.5 mg, varenicline 0.25 mg b.i.d., varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d., varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d., bupropion hydrochloride 150 mg b.i.d. and varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 52 weeks were associated with a higher risk of experiencing SAEs relative to placebo.

Varenicline 0.3 mg q.d. and varenicline 1.0 mg q.d. weeks were associated with a lower risk of experiencing SAEs relative to placebo, although none of the treatment effects was statistically significant at a conventional 5% significance level.

Nicotine patch produced the greatest effect (HR 5.33, 95% CrI 0.98 to 45.21) relative to placebo (Table 16; see also Appendix 5, Figure 18). Nicotine patch was the intervention with the highest probability of being associated with SAEs (p = 0.62) (Table 17).

| Intervention | Hazard ratio (95% CrI) |

|---|---|

| Nicotine patch | 5.3 (0.98 to 45.21) |

| Cytisine 1.5 mga | 1.27 (0.24 to 8.58) |

| Varenicline 0.3 mg q.d. | 0.049 (0.00 to 1.34) |

| Varenicline 1.0 mg q.d. | 0.078 (0.00 to 1.32) |

| Varenicline 0.25 mg b.i.d. | 2.06 (0.46 to 7.83) |

| Varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d. | 1.02 (0.31 to 3.46) |

| Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. | 1.10 (0.74 to 1.65) |

| Bupropion hydrochloride 150 mg b.i.d. | 1.29 (0.61 to 2.78) |

| Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 52 weeks | 2.61 (0.69 to 15.16) |

| Between-study SD | 0.25 (0.01 to 0.86) |

| Rank (b) | Treatment (j) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | Nicotine patch | Cytisine 1.5 mga | Varenicline 0.3 mg q.d. | Varenicline 1.0 mg q.d. | Varenicline 0.25 mg b.i.d. | Varenicline 0.5 mg b.i.d. | Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. | Bupropion hydrochloride 150 mg b.i.d. | Varenicline 1.0 mg b.i.d. for 52 weeks | |

| 1 | 0.00 | 0.62 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.20 |

| 2 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.33 |

| 3 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.26 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.20 |

| 4 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.11 |

| 5 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.06 |

| 6 | 0.29 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.28 | 0.13 | 0.03 |

| 7 | 0.33 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.03 |

| 8 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.26 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.03 |

| 9 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| 10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.55 | 0.44 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

Strengths and limitations

A strength of the network meta-analysis is that it enabled a comprehensive comparison of all interventions of interest taking into account all available information. Parameters were estimated using a Bayesian framework which allowed for uncertainty in the estimate of the between-study SD and the ability to make probabilistic statements about the rankings of the interventions.

The continuous abstinence and adverse events data were modelled using a complementary log-log link function to allow for variation in the duration of follow-up between studies. This model assumes that the times to event follow an exponential distribution and, hence, that the treatment effect is constant over time. While these are strong assumptions, they are expected to be better than assuming there is no effect of duration of follow-up on the observed event rates.

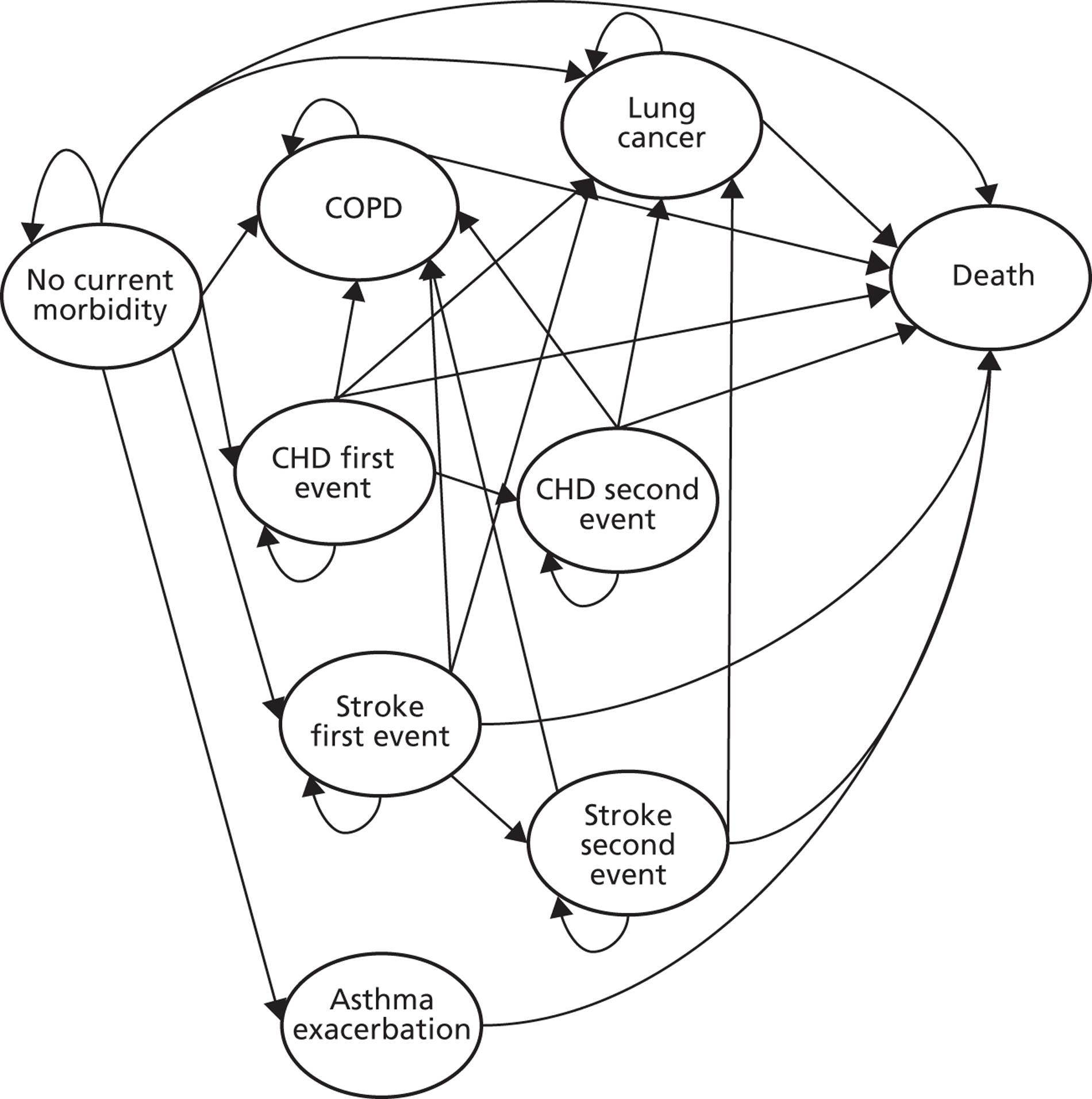

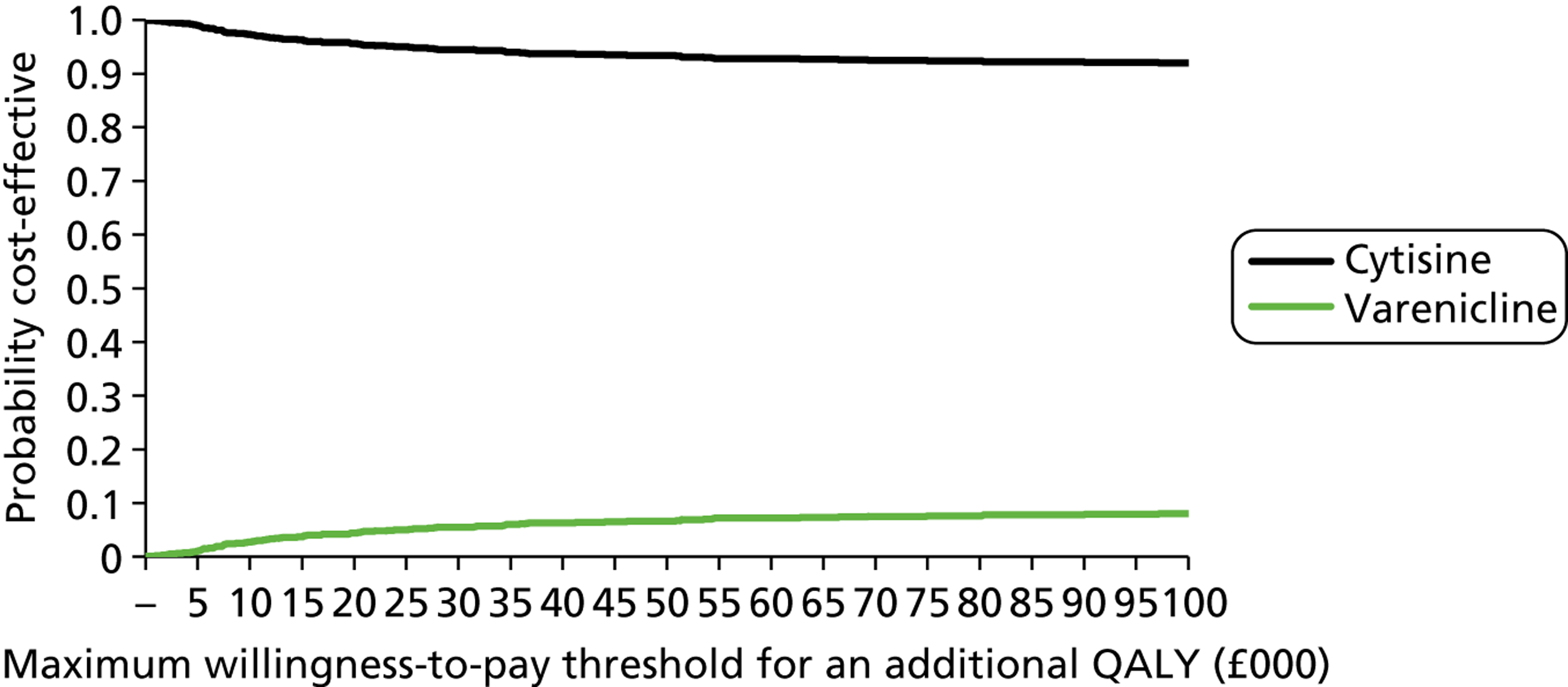

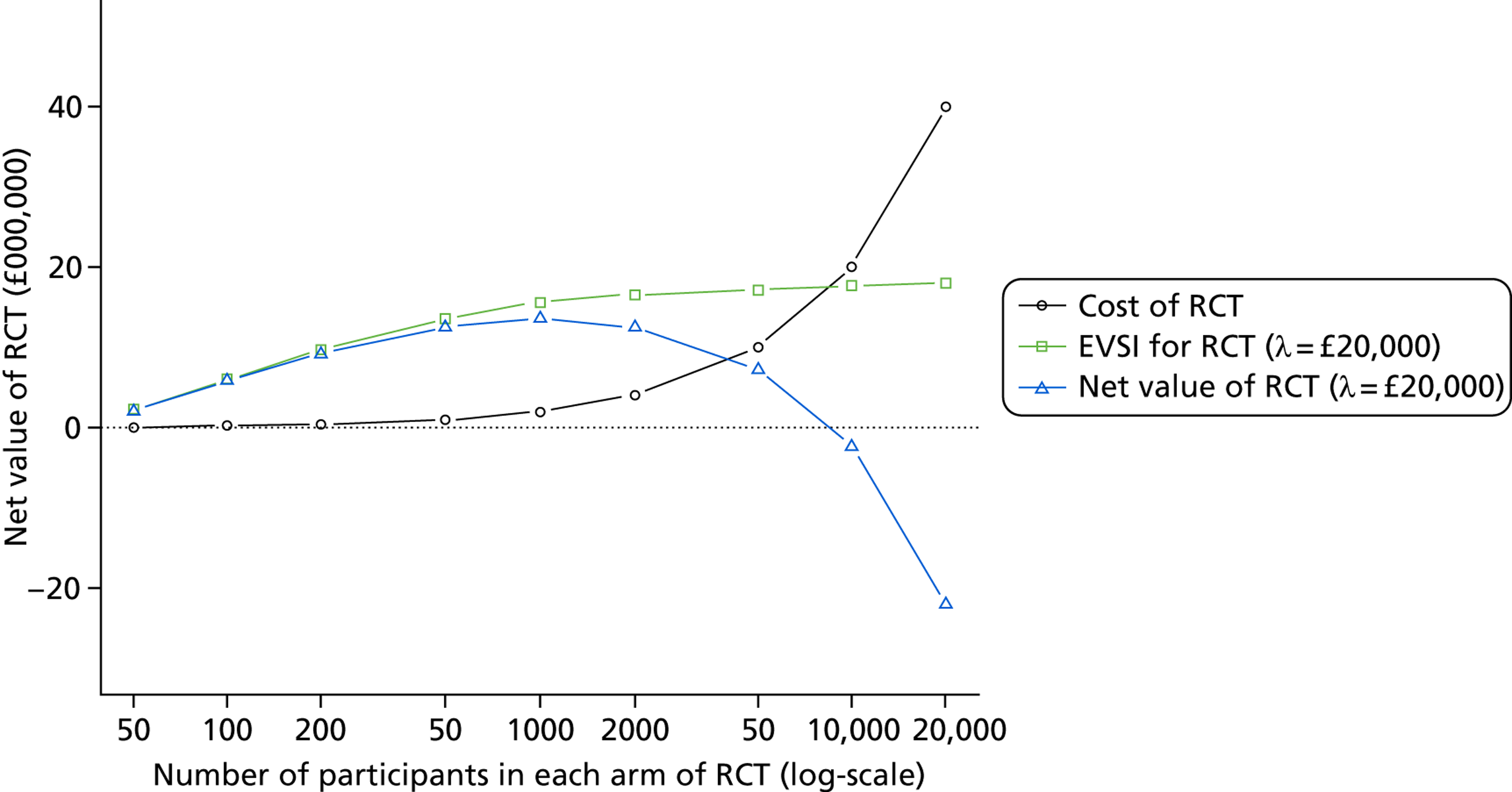

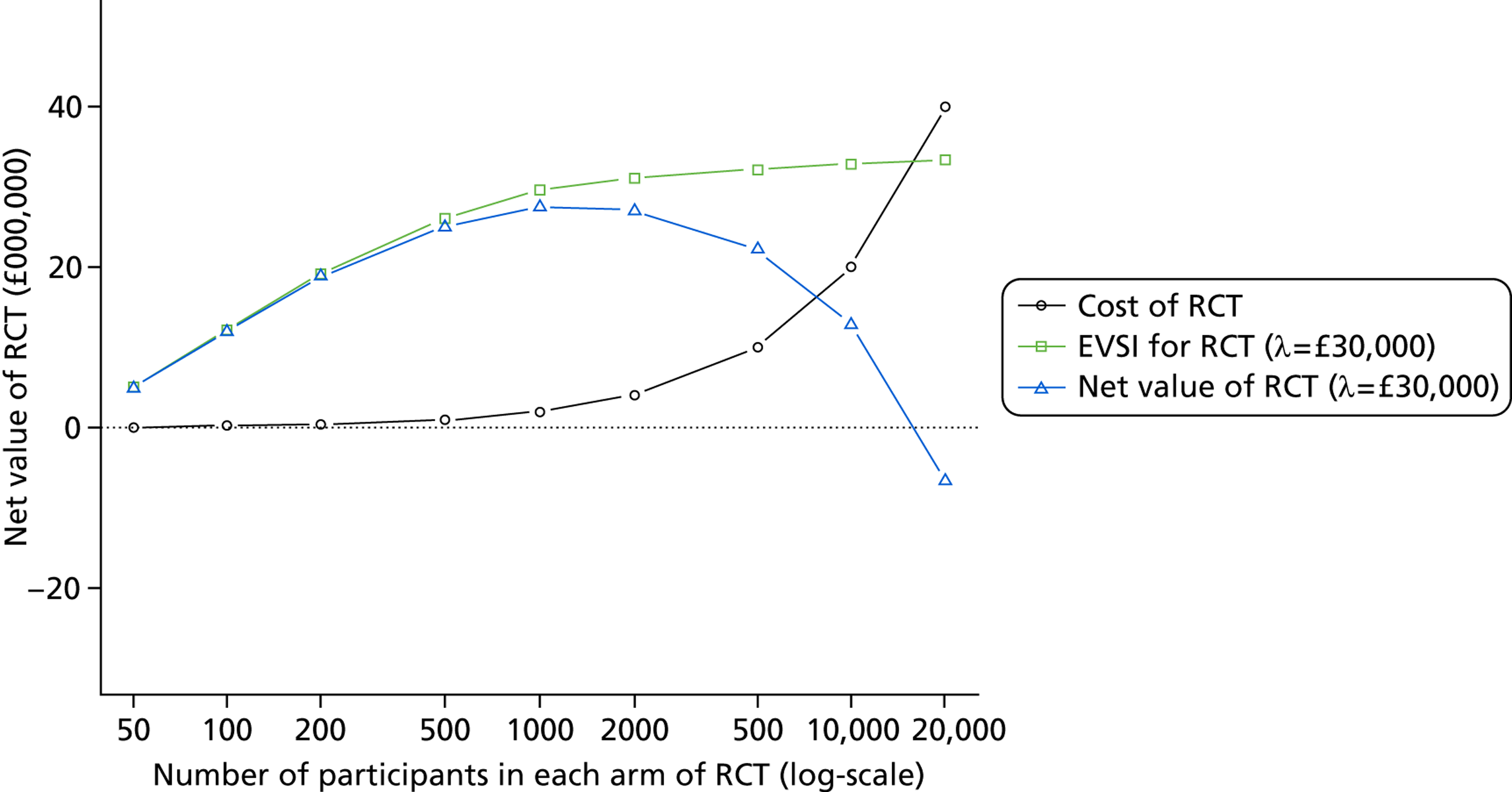

In practice, the exponential models fitted the data for each outcome measure reasonably well except for the headache data. There was no obvious reason for this in terms of study characteristics, although there were insufficient data to perform a meta-regression.