Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/127/01. The contractual start date was in October 2011. The draft report began editorial review in April 2013 and was accepted for publication in August 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Robertson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

In this chapter we briefly discuss definitions, epidemiology and risks of obesity and possible benefits of reducing obesity in men. We show that men are under-represented in weight-loss programmes in developed countries and briefly discuss the growing literature on possible explanations. Evidence from qualitative and quantitative research is starting to accumulate on how men who are obese may be helped to lose weight, but there has been little systematic research to synthesise the evidence base. This project attempts to provide the current evidence base for engaging obese men with weight loss and provide pointers to designing successful services. The literature is still limited and we acknowledge that, although we would have liked to explore the effects of diversity, such as age, ethnic group, socioeconomic status, disability or sexual orientation, the evidence for these was sparse.

In this report we have tried to stick to accepted definitions of the words ‘sex’ and ‘gender’:1

The word ‘gender’ is used to define those characteristics of women and men that are socially constructed, while ‘sex’ refers to those that are biologically determined. People are born female or male but learn to be girls and boys who grow into women and men.

Definitions of obesity in men and women

A body mass index (BMI) of ≥ 30 kg/m2 [weight in kg/(height in m)2] is widely used to define obesity in both men and women, with a BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2 and < 30 kg/m2 defining overweight. The term ‘morbid obesity’ is used to denote a BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2. BMI is widely used as an easy practical measure to classify the degree of obesity, predict the risk of obesity-related diseases and identify individuals or communities at risk. However, BMI does not distinguish between differences in body composition affected by sex, physique or ethnicity. For example, men will have a lower percentage of fat than women of an equivalent BMI. 2

Waist circumference is also used to assess increased body fat, particularly intra-abdominal fat. Unlike BMI, waist circumference cut-offs for risks of disease are sex specific. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)3 has advised that both BMI and waist circumference should be used to assess the risk of health problems (such as type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, osteoarthritis) in people with a BMI of < 35 kg/m2; above this BMI, risk will be high irrespective of waist circumference ( Table 1 ).

| BMI (kg/m2) | Waist circumference | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lowa | Highb | Very highc | |

| Normal: < 25 | No increased risk | No increased risk | Increased risk |

| Overweight: 25 to < 30 | No increased risk | Increased risk | High risk |

| Obese: 30 to < 35 | Increased risk | High risk | Very high risk |

Demographics of obesity in men and women

Based on BMI, more men than women are overweight or obese in the UK and this difference is projected to continue. In the Health Survey for England 2011,4 65% of men had a BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2 whereas 58% of women fell into this category. As the prevalence of obesity continues to increase, it is likely that people who are overweight will become obese in the future. Thus, the Foresight report5 predicts that 36% of men and 28% of women will be obese by 2015 and 47% of men and 36% of women by 2025 in England. Figures from Wales6 (64% and 53%), Scotland7 (69.2% and 59.6%) and Northern Ireland8 (67% and 56%) show similar differences (men vs. women for overweight or obese respectively). In the UK, only in England do figures show that the prevalence of obesity in men is less than that in women,4 whereas in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales it is similar or higher in men. 6,7,8 However, morbid obesity tends to be less prevalent in men. 4,7 Worldwide, fewer men are obese than women but men have a higher BMI than women in high-income countries. 9

However, if waist circumference alone is used to define risks from obesity then women are more at risk, with 47% of women and 34% of men at risk in 2011 in England. 4 Using both BMI and waist circumference to define health risk, 18% of men had an increased risk, 15% had a high risk and 21% had a very high risk compared with 15%, 18% and 26% of women respectively. 4 Thus, measures of risk in men and women differ depending on the obesity measure used.

In England, the age-standardised prevalence of obesity and raised waist circumference for men and women was higher in households in lower quintiles than in households in higher quintiles of equivalised household income. 4 Some occupations, such as bus driving, may be at higher risk of obesity because of the work environment. 10 Work-related stress has different effects in men and women, increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes in obese women but not apparently for obese men. 11

Figures for different ethnic groups are not available from the recent Health Survey for England. 4 However, lower BMI and waist circumference cut-offs have been recommended for some ethnic groups, such as South Asian populations, as a measure of risk, particularly for type 2 diabetes, and have recently been recommended by NICE. 12 If existing BMI cut-offs are used, then data from the Health Survey for England from 200413 show lower prevalences of obesity in men from black African, Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Chinese groups.

In England the prevalence of overweight and obese individuals using BMI increases with age in men and women, with 29% of men and 32% of women aged ≥ 75 years being obese. 4

Risks of obesity in men and women

Collaborative analyses from 57 prospective studies, mainly from Western Europe and North America, with a mean recruitment age of 46 years, have found that mortality in both men and women is lowest for a baseline BMI of 22.5–25 kg/m2. 14 Each additional 5 kg/m2 was approximately associated with 30% higher overall mortality, 40% higher vascular mortality, 60–120% higher diabetic, renal and hepatic mortality, 20% higher respiratory disease mortality and 10% higher cancer mortality. Median survival was reduced by 2–4 years for a BMI of 30–35 kg/m2 and by 8–10 years for a BMI of 40–45 kg/m2. However, others have found that all-cause mortality does not appear to increase relative to normal weight until BMI is ≥ 35 kg/m2. 15

Pischon and colleagues16 found that waist circumference or waist-to-hip ratio enhanced the ability of BMI to predict risk of death in men and women in nine countries in Europe. However, the Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration17 found little difference in the ability of BMI, waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio to predict cardiovascular disease in men and women in developed countries, but BMI had greater reproducibility. Similarly, there was little difference in the ability of BMI or waist circumference to predict the risk of developing type 2 diabetes in men, which is so strongly associated with obesity. 18 However, Cameron and colleagues19 considered that including both waist and hip circumference together, rather than as a ratio, may improve risk prediction models for mortality and type 2 diabetes.

Positive associations have been found between increasing BMI and subsequent risk of death from liver, kidney, prostate, breast, endometrial and large bowel cancer. 14 Others have found strong associations between obesity in men and subsequent oesophageal, thyroid, colon and renal cancer. 20

Obesity is a risk factor for a very wide range of diseases impacting on health and quality of life. Men with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 and a waist circumference ≥ 102 cm have an increased risk of at least one symptom of impaired physical, psychological or sexual function, and these symptoms are also more likely in men with a raised waist circumference but a BMI of < 30 kg/m2. 21 Men who are overweight or obese in midlife also have a higher risk of frailty in old age. 22

Costs of obesity

Although the Foresight report5 predicted that future costs to the NHS of elevated BMI could be £6.4B per year by 2015 and £9.7B per year by 2050, no breakdown by sex was given, despite there being clear differences for the risk of diseases related to obesity, such as coronary heart disease and type 2 diabetes.

Benefits of weight loss in men and women

Although there are many diseases associated with obesity, it has been difficult to demonstrate that prevention or treatment of obesity reduces the risk of disease long term, despite beneficial changes in cardiovascular risk factors in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of lifestyle interventions. 23 The evidence for a reduction in mortality from long-term weight loss from cohort studies and randomised trials is strongest for both overweight or obese men and overweight or obese women with diabetes. 24 There is some evidence that intentional weight loss may reduce mortality in women, but benefits in men are not clear. 24 Maintaining or increasing physical activity seems to be particularly beneficial to survival. 25

Randomised trials of lifestyle interventions for weight loss have confirmed the long-term prevention of type 2 diabetes in men and women. 26 – 28 Randomised trials of weight-loss interventions in men and women have also shown significant reductions in blood pressure or cardiovascular events. 23

Under-representation of men in weight-loss programmes

Men are under-represented in randomised trials of weight-loss interventions and in health services and commercial programmes for weight loss. In a systematic review, Pagoto and colleagues29 found that only 27% of participants in randomised trials were men, although the percentage was higher in interventions for obesity with related comorbidities (36% men). There was also a trend towards lower participation by men in group formats (24%) compared with individual counselling (29%) or mail/e-mail/internet formats (34%); however, the male/female mix of the groups was not specified. In another systematic review, Moroshko and colleagues30 did not find sex to be a predictor of dropout in weight-loss interventions.

Services for the treatment of adults with obesity in the UK have consistently shown an under-representation of men. In the Counterweight programme in 65 general practices in seven UK regions, only 23% of participants were men. 31 Men made up only 27.6% of referrals to the NHS Glasgow and Clyde Weight Management Service and, once referred, women were slightly more likely to opt in (73.6% vs. 69.4%), but there was no significant difference in completion rates by sex. 32

Commercial programmes in the UK, such as Weight Watchers,33 Slimming World34 and LighterLife,35 and some NHS organisations have only recently started to evaluate men-only weight-loss groups. When services were not sex specific, men made up only 10.7% of 34,271 adults in a slimming on referral scheme between Slimming World and 77 primary care trusts or NHS trusts,36 and 10.5% of 29,326 adults referred from NHS primary care to Weight Watchers. 37 Thus, UK figures suggest that men may be even less likely to attend commercial weight-loss programmes than programmes provided by the NHS.

Two systematic reviews have examined the qualitative evidence on people’s views and experiences of weight management. 38,39 Most of the evidence came from studies with women or studies with groups of men and women in which the majority of participants were women. The authors did not specifically examine the evidence from male participants in these studies, or men compared with women, so it is unclear whether or not their conclusions can be applied to men. There is evidence that since 1999 increasing numbers of both men and women in the UK are failing to recognise that they are overweight or obese. 40 Men may be more likely than women to misperceive their weight, less likely to consider their body weight a risk for their health and less likely to consider managing or be actively trying to manage their weight. 41,42

Men’s attitudes to lifestyle behaviour change

Men may be more reluctant to change their current lifestyle than women43 and may be cynical about government health messages. 44 Media and other sociocultural influences may also encourage men to maintain a larger, more muscular, masculine body size. 45 Men could be less interested in gaining an ideal body weight, according to the medical definition, and more interested in physical activity and regaining fitness and a masculine body shape. 46 There may also be differences in the way that men and women view physical activity as a means of becoming stronger, fitter and healthier. 47

Weight-loss programmes and facilities, including commercial weight-loss programmes, could be seen as feminised spaces,46,47 and there is some evidence to suggest that men may prefer masculine spaces, such as their workplace, for such programmes. 48,49 Fear and embarrassment may particularly deter men from taking part in weight-loss programmes and could mean that talking to an advisor on a one-to-one basis, rather than working in a group, is preferred. 49 Some men have also cited that having a male advisor for lifestyle change is important in the health-care setting. 50

Men could be less interested in undertaking weight-loss diets, which are perceived as tasting poor and failing to satisfy the appetite. 44 Men could distance themselves from the feminised realm of dieting, in which women are viewed as the experts. 51

Previous evidence associated with weight-loss management programmes and men

Given that there are difficulties in encouraging men to undertake weight management, what is the evidence for improving their engagement in services and should weight-loss programmes be designed differently for men and women?

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence3 and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN)52 have not provided specific guidance for men, as opposed to women, for the prevention and treatment of obesity. NICE guidance on behaviour change interventions called for research on the cost-effectiveness of behaviour change interventions for men and women separately, but did not provide evidence on the effectiveness of lifestyle interventions separately by sex. 53

The Men’s Health Forum convened a conference in 2005 with 23 health and social policy researchers to discuss men and weight issues; the outcomes of this conference were subsequently published in a book entitled Hazardous Waist: Tackling Male Weight Problems. 54 Evidence of effective interventions was not reviewed, although several examples of innovative approaches in the UK were presented. The conference conclusions included a need to invest in ‘male-sensitive approaches’, that ‘men’s attitudes to weight and weight loss need to be more fully understood’ and that the ‘existing, broadly “unisex”, approach is failing men’ (pp. 218–19). 54

A systematic review was conducted by Robertson and colleagues55 in 2008 to explore the effectiveness of male-specific health-promoting interventions covering a wide range of health behaviours. However, it did not identify any intervention studies (at the time that the review was conducted) that had focused on men and weight management or weight loss.

More recently, Young and colleagues56 systematically reviewed men-only weight-loss or weight-maintenance interventions of any duration, limiting their review to the 18–65 years age group and people without obesity-related morbidity, for example diabetes. Only 12 of the 23 identified studies were RCTs and six included a follow-up of approximately a year or longer. Thirty-one different interventions were identified with a median weight loss of 6.25%. A high frequency of contact (three or more per month), group programmes, a mean age of ≤ 43 years in the sample and prescribing an energy-restricted diet were associated with greater programme effectiveness. Only five of the studies tested interventions that were specifically designed for men.

Aims of this project

The evidence briefly discussed in this chapter suggests that methods to engage men in services, and the services themselves, are currently not optimal. We set out to systematically review evidence-based management strategies for treating obesity in men and how to engage men with obesity in weight management programmes. Where we use the term ‘engagement’, this is to denote obese men deciding to start using services to help them lose weight.

We asked the following questions:

-

What works for obesity management for men?

-

How can men be engaged with services?

-

Should services for men and women be different?

Our overarching objective was to integrate the quantitative and qualitative evidence base by systematically reviewing:

-

the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions for obesity in men, and in men compared with women

-

the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions to engage men in their weight reduction

-

qualitative research with men about obesity management and with providers of such services for men.

This report is structured in the following way:

-

Chapter 2 presents the methods for the quantitative and qualitative systematic reviews and the mixed-methods synthesis of these reviews.

-

Chapter 3 presents the systematic review of RCTs of interventions [lifestyle and/or the UK licensed medication orlistat (a pharmaceutical agent to aid weight loss)] in any setting with men only who are obese with a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2 (or overweight with a BMI of ≥ 28 kg/m2 and with cardiac risk factors based on orlistat guidance) and with follow-up of at least 1 year. Chapter 3 also presents the systematic review of RCTs of interventions (as above) in any setting including both men and women who are obese with a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2 (or overweight with a BMI of ≥ 28 kg/m2 and with cardiac risk factors based on orlistat guidance) in which the results are presented separately for men and women in the same trial. We use trials with both men and women to look for differences in effectiveness.

-

Chapter 4 presents the results of the systematic review of interventions for men with obesity in the UK, of any setting, study design or duration. This includes data from UK studies with men and women in which data are presented separately for men and women. This chapter also contains details of the search carried out for the systematic review of studies to increase the engagement of men with obesity services; however, no studies fitting the inclusion criteria were found. However, information on engaging men with services is available and discussed in the first review in this chapter.

-

Chapter 5 presents the systematic review of economic evaluations of obesity interventions, including studies in which data were presented either for men only or for men compared with women.

-

Chapter 6 presents the systematic review of qualitative studies that have explored men’s engagement and experiences associated with weight management interventions linked to RCTs and other intervention studies. We also included qualitative studies on obesity from the UK that were not linked to interventions. This review focused on questions relating to the context of these interventions and well as their mechanisms and outcomes. The findings from the qualitative studies were combined with the findings from all of the quantitative reviews in a mixed-methods synthesis.

-

Chapter 7 presents our overall discussion of the results from all of the reviews.

-

Chapter 8 draws out the implications for health care and makes recommendations for future research.

Chapter 2 Methods

We undertook six systematic reviews as follows:

-

a systematic review of RCTs of interventions with men only

-

a systematic review of RCTs of interventions in which the results were presented separately for men and women in the same trial

-

a systematic review of interventions for men, or men and women compared, with obesity in the UK in any setting, using any study design and of any duration

-

a systematic review of interventions to increase the engagement of men with services for obesity management, using any study design

-

a systematic review of the cost-effectiveness of alternative strategies for the management of obesity in adult men

-

a systematic review of qualitative research with obese men, or obese men compared with obese women, and with health professionals and commercial organisations managing obesity.

We prepared a priori protocols detailing the objectives; types of study design, participants, interventions and outcomes considered; and the inclusion/exclusion criteria for all reviews. For quantitative reviews we followed methodological guidance recommended by The Cochrane Collaboration57 and Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. 58 Details of the methods used for the cost-effectiveness review are provided in Chapter 5 .

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Types of study

The systematic reviews of men only and men and women compared included RCTs or quasi-randomised trials (including trials with a cluster design) with a mean or median duration of ≥ 52 weeks for all groups. This duration of follow-up for data was to ensure that long-term weight-loss and weight-maintenance interventions were evaluated for their associated effects on weight- and obesity-related morbidities. 23 This was also the minimum duration of studies adopted by NICE for its review of obesity. 3

For the systematic review of UK interventions, any study design and duration were considered to include and evaluate as much UK-relevant research as possible. We included studies of men only and studies of men and women if data were presented separately for men.

For the systematic review of interventions to increase engagement, we included any study design that examined interventions to increase the engagement of men with services for obesity management.

Types of participants

Men aged ≥ 16 years were included, with no upper age limit. Participants in studies included in the systematic reviews of men only, men and women compared and UK interventions had to have a mean or median BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2 (or ≥ 28 kg/m2 with cardiac risk factors based on criteria for receiving orlistat). When body weight was reported instead of BMI, we calculated BMI using relevant population data for heights to assess study eligibility. 23 We recognised that the BMI of men targeted in systematic reviews of engagement and cost-effectiveness may not have been clearly stated.

Types of interventions and comparators

Systematic reviews of studies of men only, men and women compared and the UK interventions considered interventions in the form of orlistat (but not sibutramine or rimonabant, which no longer have UK licences), diet, physical activity, behaviour change techniques or combinations of any of these. For the reviews of men-only RCTs and RCTs of men and women compared, we considered any of these interventions along with placebo and ‘no treatment’ as comparators. For the systematic review of engagement we considered any form of intervention to increase the engagement of men with services for obesity management.

Setting

We considered all settings for the lifestyle and drug interventions, including hospitals, primary care, the community (including a community pharmacy), commercial organisations, the voluntary sector, leisure centres, workplaces, the internet and other digital domains, for example mobile phone networks. This is because there is increasing collaboration between the NHS and non-NHS organisations in the delivery of services. It may also be the case that increasing the participation of men in obesity services requires their engagement in settings outside primary and secondary care.

Types of outcome measures

We developed our rationale for outcome measurement from our existing knowledge of the topic area and in consultation with the project advisory group. Studies had to explicitly mention weight loss or weight-loss maintenance as a main outcome to be eligible for inclusion.

We considered the following types of outcome:

-

Primary outcome: weight change

-

Secondary outcomes:

-

waist circumference

-

cardiovascular risk factors [decreases in these are generally beneficial for cardiovascular risk, with the exception of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol]: total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), systolic and diastolic blood pressure

-

disease-specific outcomes (e.g. erectile function)

-

adverse events

-

quality of life outcomes

-

process outcomes (e.g. staff involvement, setting, type of intervention, timing, frequency, individual and/or group setting, couple or family setting, proportion recruited and dropping out, participants’ evaluations)

-

economic costs.

-

Exclusion criteria

We did not consider interventions including complementary therapy, for example acupuncture, or non-diet products promoted for weight loss available solely over the counter. Studies evaluating bariatric surgery or examining a combination of interventions, for example smoking cessation and weight loss at the same time, or examining men with obesity receiving psychotropic medication, with learning disabilities or with a diagnosed eating disorder, were also excluded.

Search strategies

For the search strategies there were no language restrictions and studies had to be set in societies relevant to the UK setting. We maintained the comprehensive electronic search conducted in MEDLINE and EMBASE in our previous systematic review23 of RCTs of lifestyle interventions for weight loss in obese adults with 1 year of follow-up. From our existing searches for this review and subsequent updates we identified approximately 800 potentially relevant reports, in any language, for full-text assessment for the review of men-only RCTs and RCTs of men and women compared. In addition to this search we conducted comprehensive electronic searches based on our existing search strategy to identify RCTs of interventions for obesity in men. To avoid unnecessary overlap with the pre-existing results from the review by Avenell and colleagues,23 the search strategy for reviews of men-only RCTs and RCTs of men and women compared excluded studies published before 2001.

Highly sensitive electronic searches were undertaken to inform the reviews of UK interventions and interventions to increase engagement. The searches were designed to identify studies of interventions for obese men in the UK, studies of interventions to increase the engagement of men with obesity management services and qualitative research with obese men or obese men compared with obese women. The searches for all reviews were designed to identify systematic reviews and other background information relevant to the management of obesity in men. Additionally, a separate search was undertaken to identify studies examining the cost-effectiveness of interventions for obese men. The searches for each of the reviews were designed to be mutually exclusive, with the results of each new search being deduplicated against the results of the previous searches. Table 2 details the databases searched for each review.

| Database | Men-only RCTs | RCTs of men and women compared | UK interventions | Engagement | Cost-effectiveness | Qualitative research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEDLINE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| EMBASE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ |

| PsycINFO | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ |

| Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | – |

| Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) | – | – | – | ✓ | – | ✓ |

| Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) | – | – | – | – | – | ✓ |

| Anthropology Plus | – | – | – | – | – | ✓ |

| British Nursing Index | – | – | – | – | – | ✓ |

| Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) | – | – | ✓ | – | – | ✓ |

| Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) | – | – | – | – | ✓ | – |

| Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Social Science & Humanities (CPCI-SSH) | – | – | ✓ | – | – | ✓ |

| Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Registry (CEA Registry) | – | – | – | – | ✓ | – |

| Research Papers in Economics (RePEc) | – | – | – | – | ✓ | – |

| ClinicalTrials.gov | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| CenterWatch | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| Current Controlled Trials | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| International Clinical Trials Registry | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

The database searches were conducted over the following time periods:

-

MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations: 1948 to 30 July 2012

-

MEDLINE: 1948 to 2012 Week 31

-

EMBASE: 1980 to 2012 Week 31

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL): 1981 to July 2012

-

PsycINFO: 1800s to July 2012

-

Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI): 1970 to July 2012

-

Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Social Science & Humanities (CPCI-SSH): 1990 to July 2012

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL): The Cochrane Library, Issue 5, 2012

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR): The Cochrane Library, Issue 5, 2012

-

ClinicalTrials.gov: September 2011

-

CenterWatch: September 2011

-

Current Controlled Trials: September 2011

-

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry: September 2011

-

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA): 1987 to July 2012

-

Education Resources Information Center (ERIC): 1966 to July 2012

-

Anthropology Plus: 1957 to July 2012

-

British Nursing Index: 1994 to October 2011

-

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED): July 2012

-

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database: July 2012

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE): July 2012

-

Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC): 1979 to November 2011

-

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Registry (CEA Registry): January 2012

-

Research Papers in Economics (RePEc): January 2012.

Hand searching

Reference lists of all included studies were scanned to identify any additional potentially relevant reports. We also searched the internet for online weight-loss programmes specifically targeted at men (e.g. www.fatmanslim.com) and the Picker Institute and Joanna Briggs Institute websites for grey literature.

Other methods of ascertaining relevant information sources

When contact details were available, we contacted all authors of men-only RCTs to identify any qualitative or other relevant published or unpublished reports. Our advisory group members provided details of potentially relevant reports and further potentially useful contacts and information sources. Each of the Men’s Health Forum representatives included articles in their newsletters highlighting our project and providing details for readers to contact us with any relevant reports. The English Men’s Health Forum also publicised the project through its Twitter account. Furthermore, we contacted the Association for the Study of Obesity, Dietitians in Obesity Management and other commercial organisations to identify published and unpublished UK studies (see Appendix 1 ).

Quantitative reviews of randomised controlled trials and other intervention studies

Data extraction strategy

One reviewer (CR) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all identified items. Full-text copies of all potentially relevant reports were obtained and independently assessed for eligibility (CR assessed reviews of men-only RCTs, RCTs of men and women compared and interventions to increase engagement; AA assessed the review of UK interventions). One reviewer (CR) extracted details of study design, methods, participants, interventions and outcomes using a data extraction form (see Appendix 2 ). The data extraction was then checked by a second reviewer (AA) and any errors were corrected.

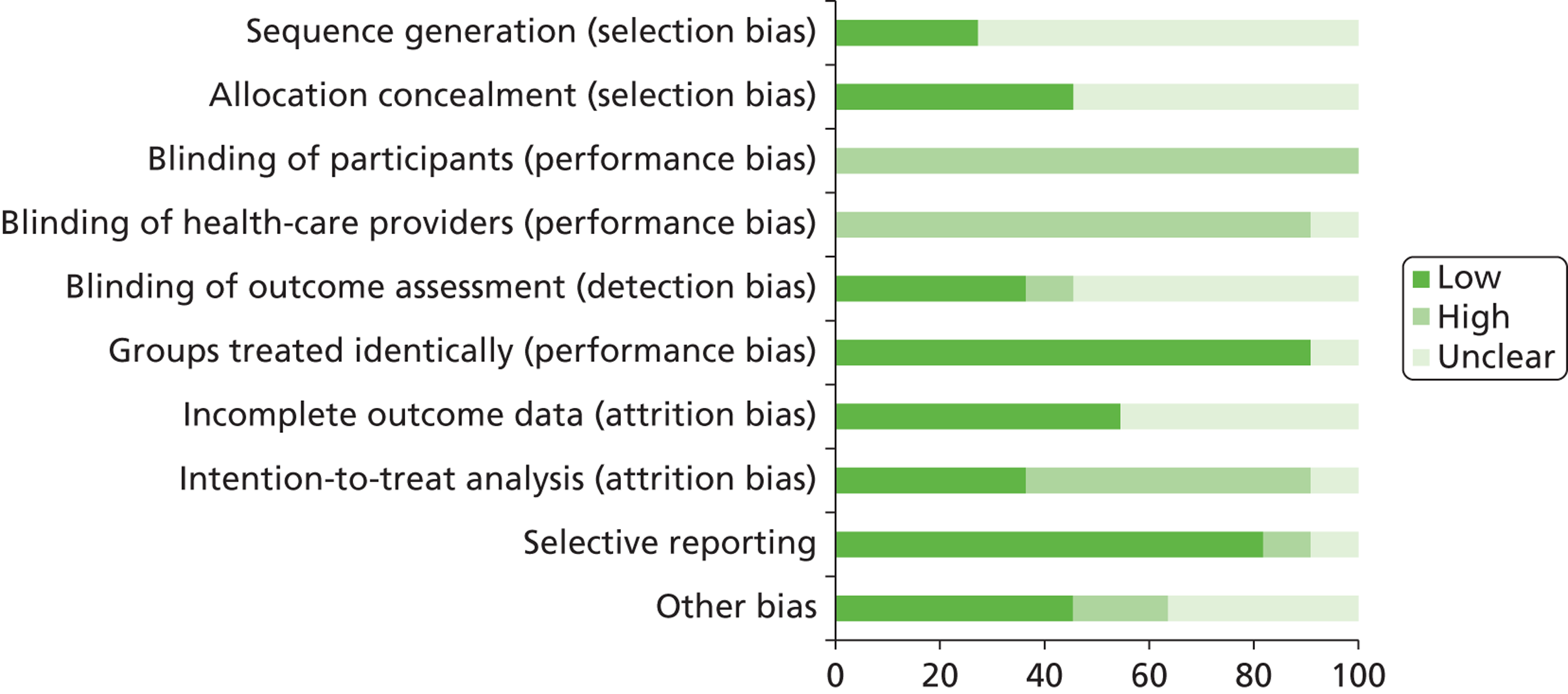

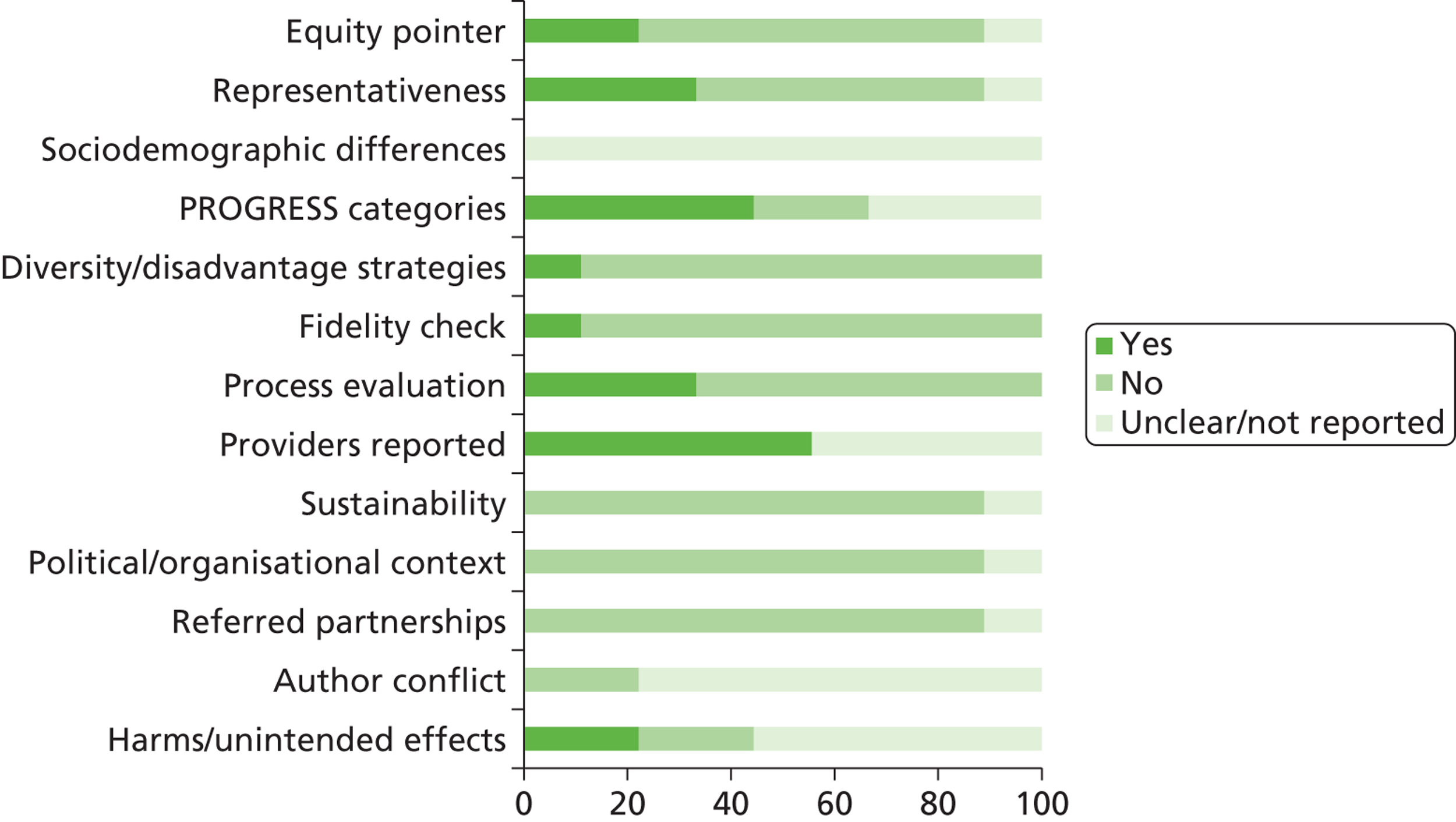

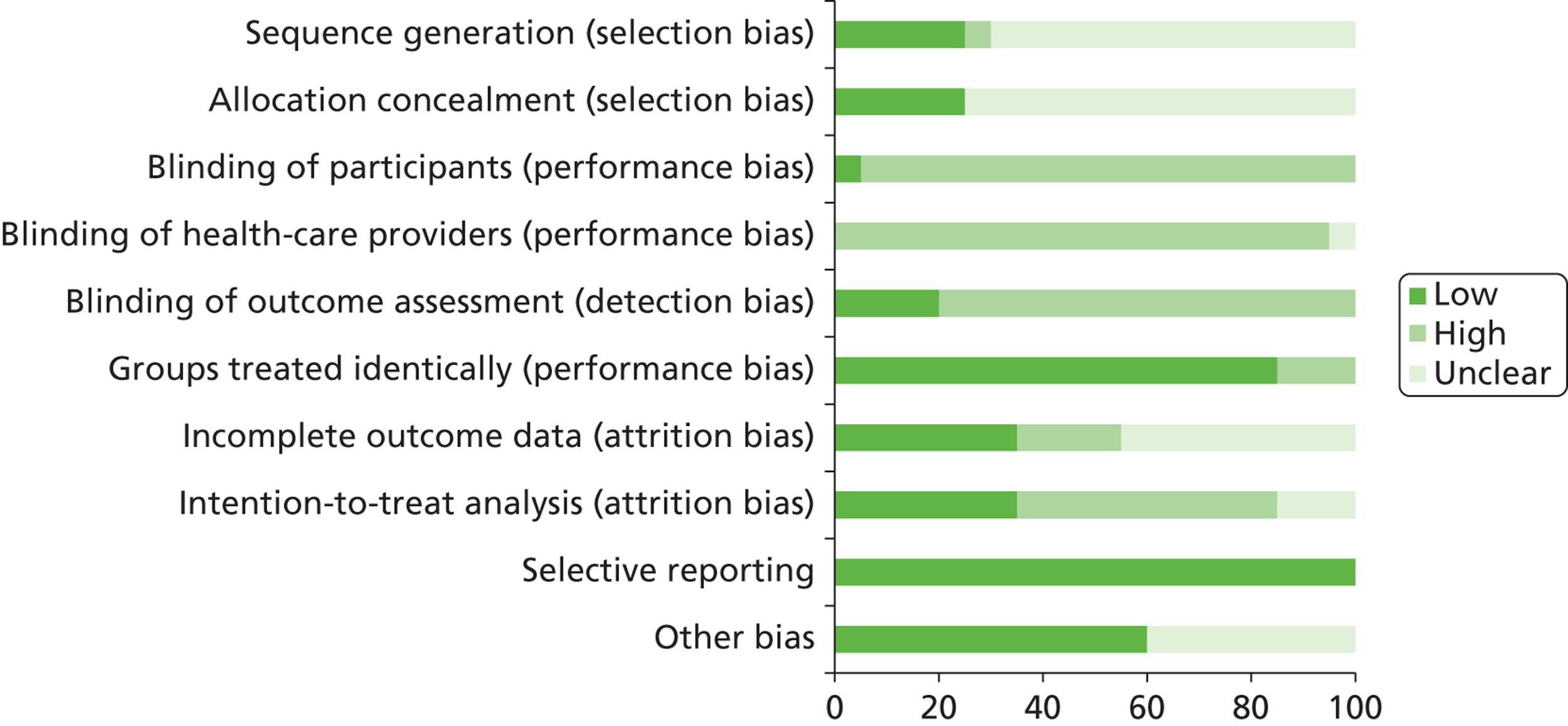

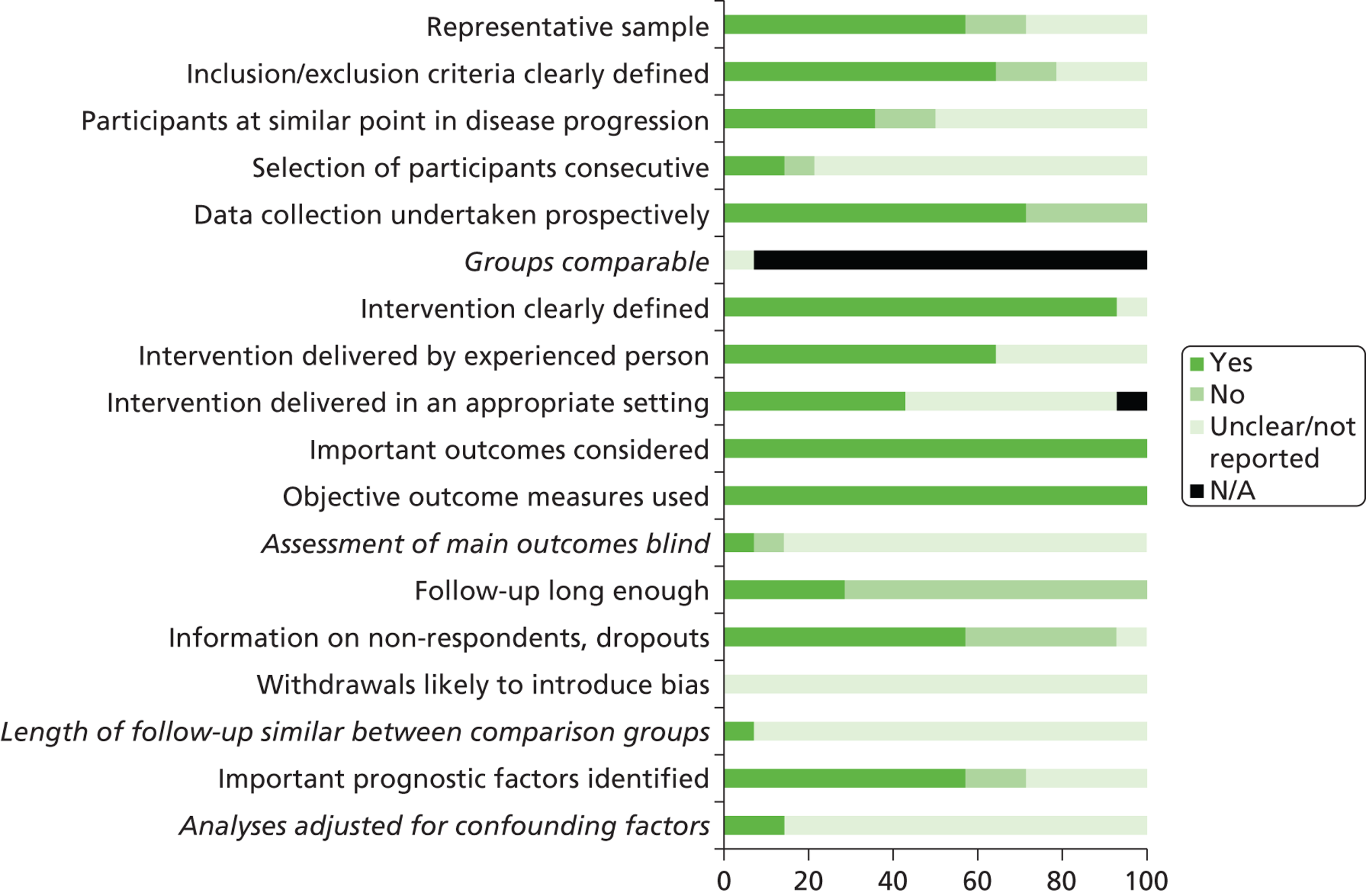

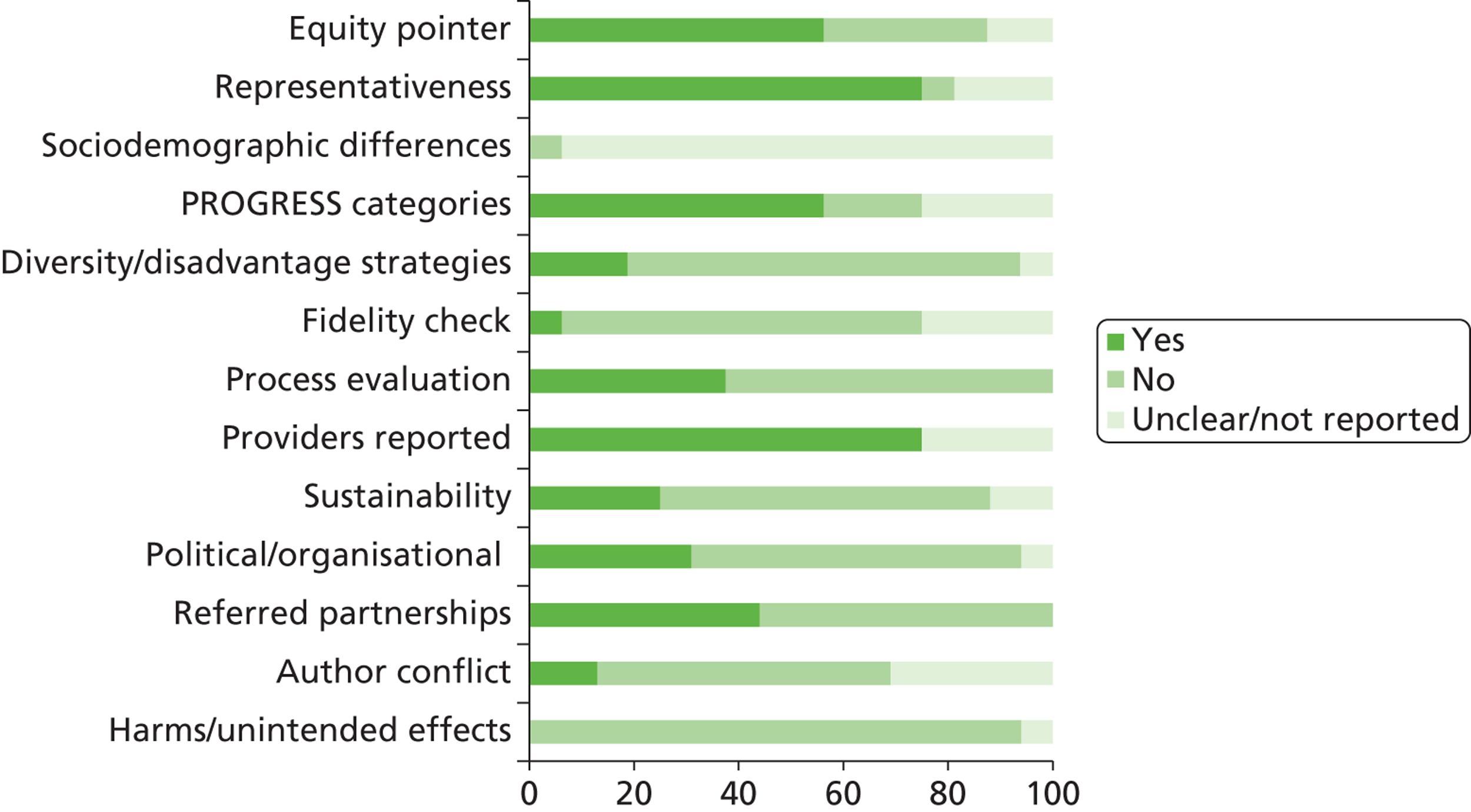

Quality assessment strategy

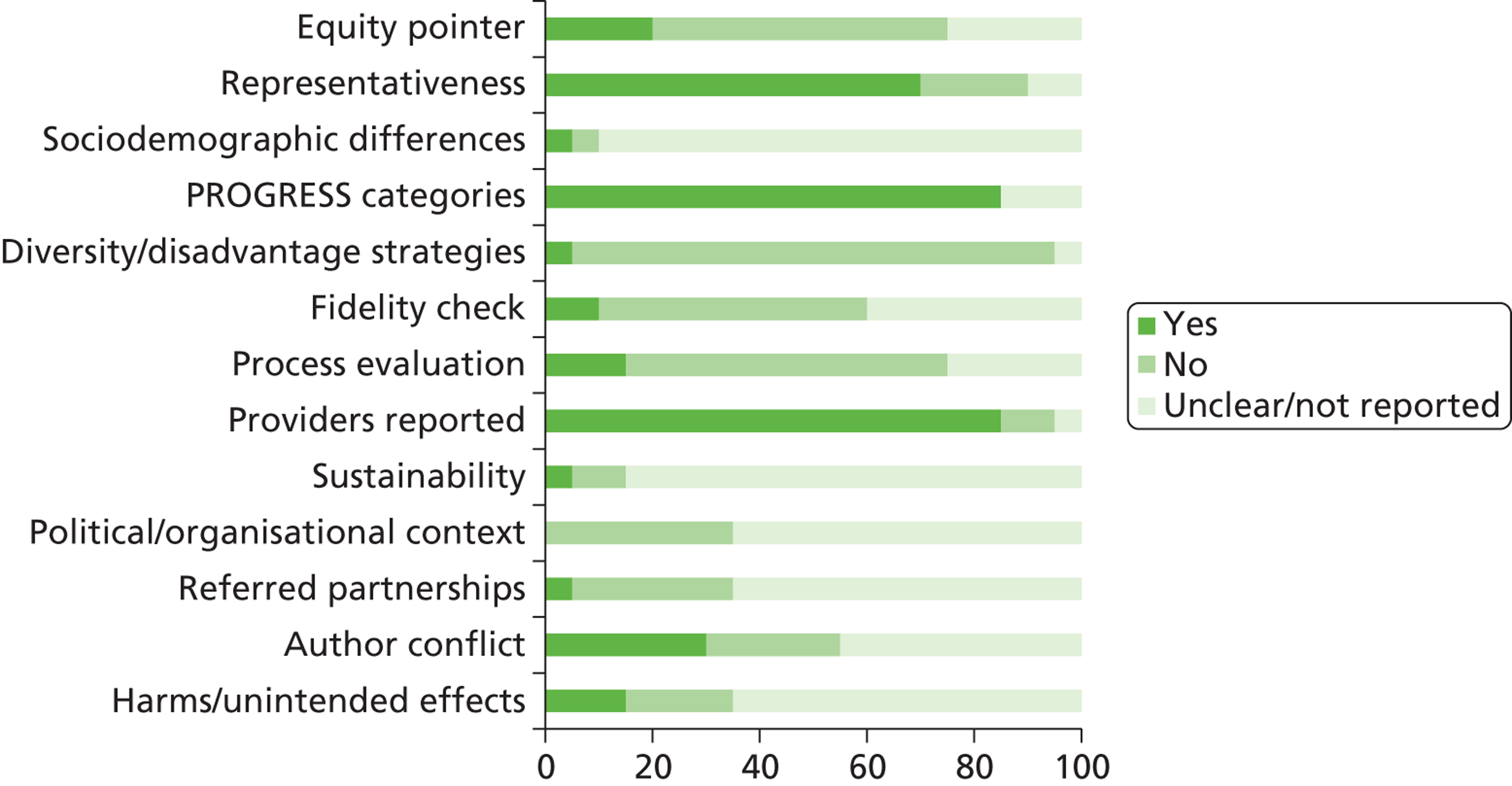

We assessed the methodological quality of included RCTs using The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias57 (see Appendix 3 ). We assessed the methodological quality of non-randomised comparative studies using a 17-item checklist, with the same checklist minus four questions used to assess the quality of case series (see Appendix 4 ). The checklist was developed for NICE through the Review Body for Interventional Procedures (ReBIP) and was adapted from several sources, including the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination’s guidance for those conducting or commissioning systematic reviews,58 Verhagen and colleagues,59 Downs and Black60 and the Generic Appraisal Tool for Epidemiology (GATE). 61 Individual items within these tools were rated as ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘unclear’ so that a rating of ‘yes’ denoted the optimal rating for methodological quality. Two reviewers independently assessed the quality of all included full-text primary studies. In addition, we used an adapted version of the Campbell & Cochrane Equity Methods Group checklist62 for each of the reviews to assess the effect of interventions reported in the included studies on disadvantaged groups and/or their impact on reducing socioeconomic inequalities (see Appendices 8 , 10 and 12 ). Individual items were worded as ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘unclear/not reported.’ Conference abstracts and poster presentations were excluded unless sufficient details were reported to carry out quality, equity and sustainability assessments (e.g. protocols, internal reports). Any disagreements or uncertainty were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers. A third reviewer acted as an arbitrator when consensus could not be reached.

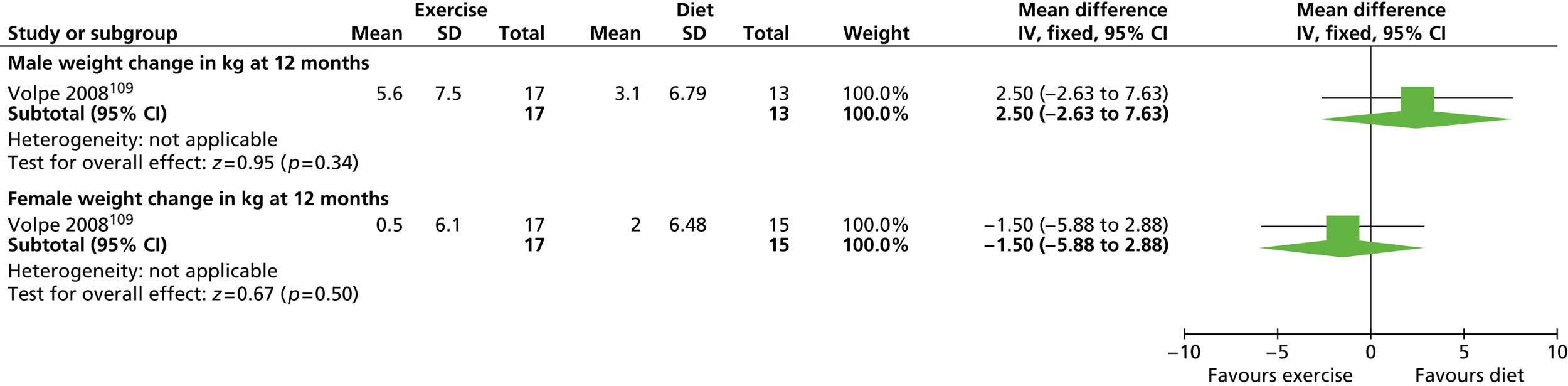

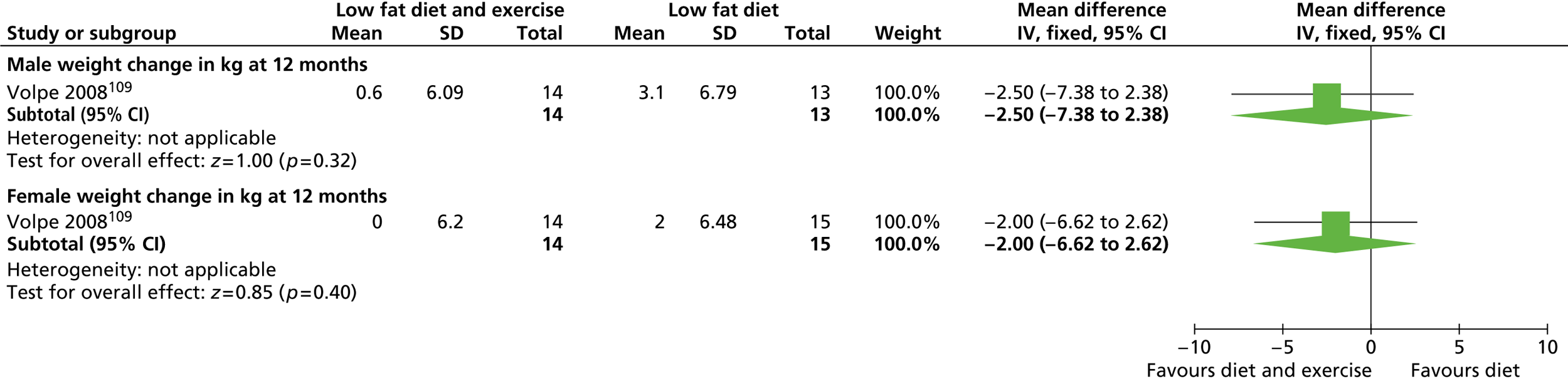

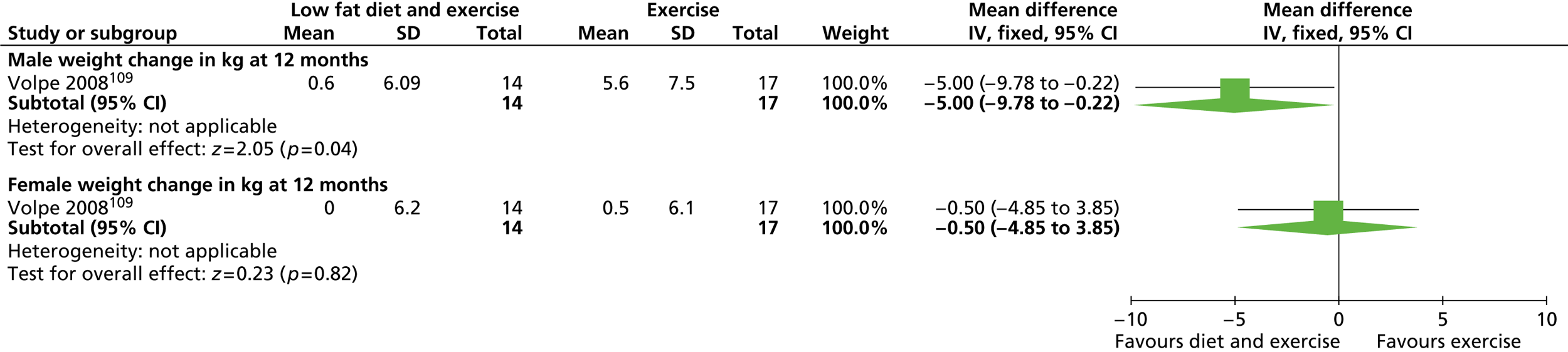

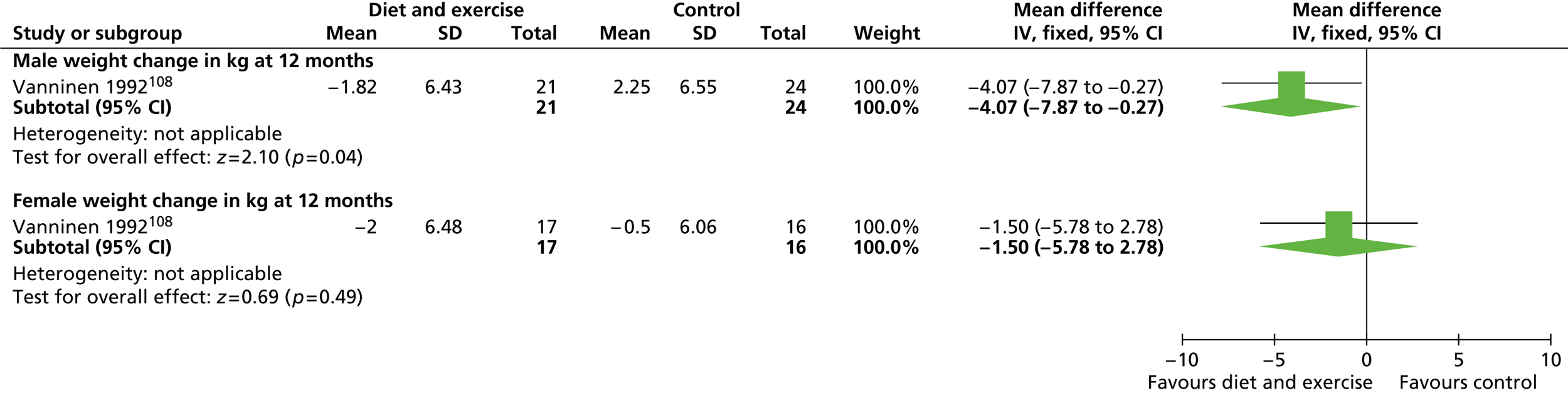

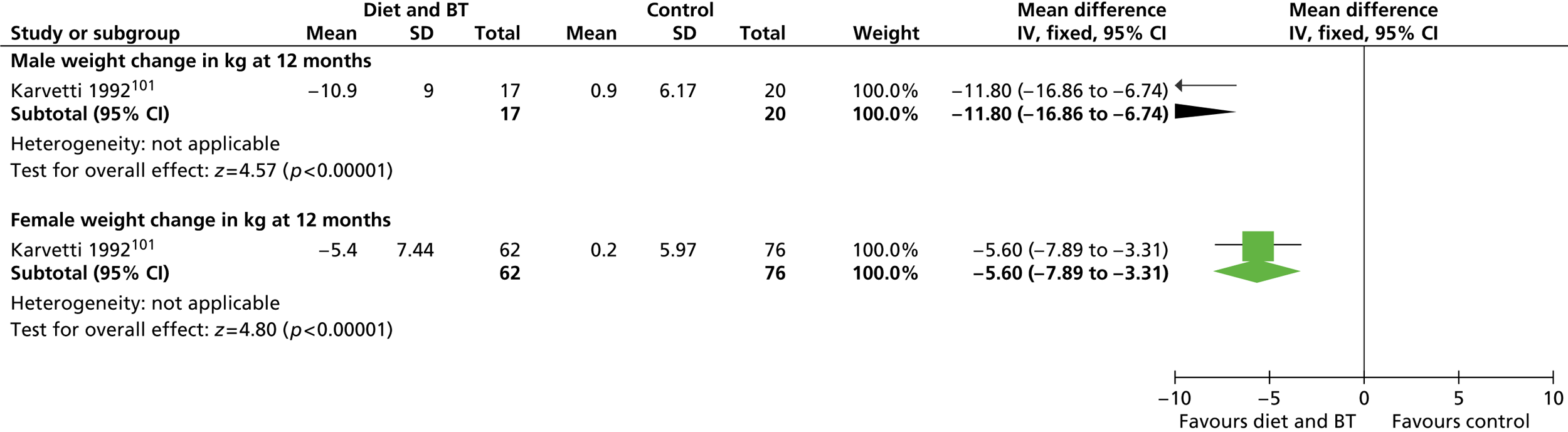

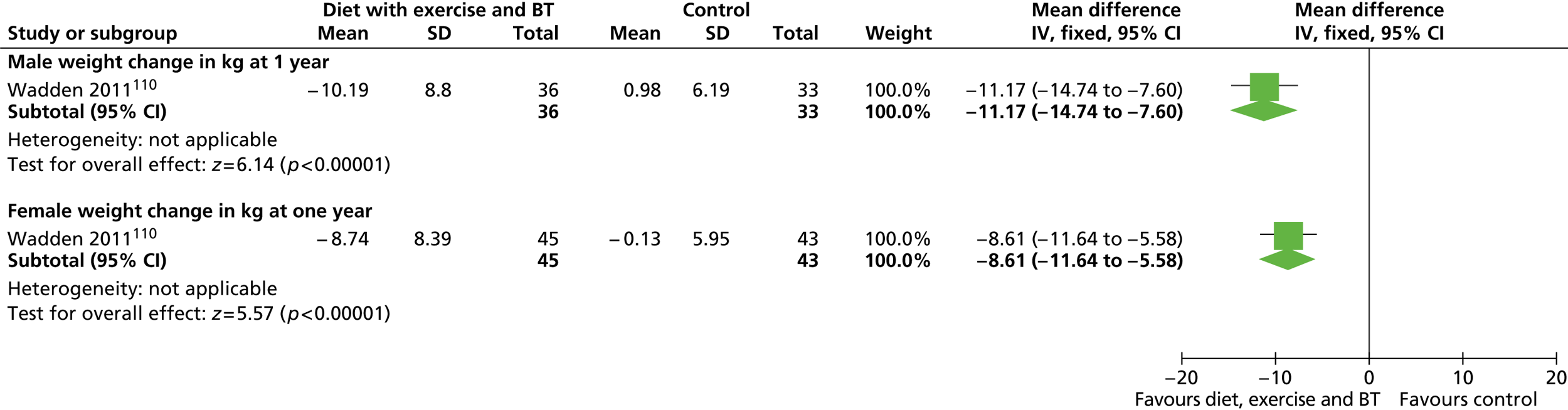

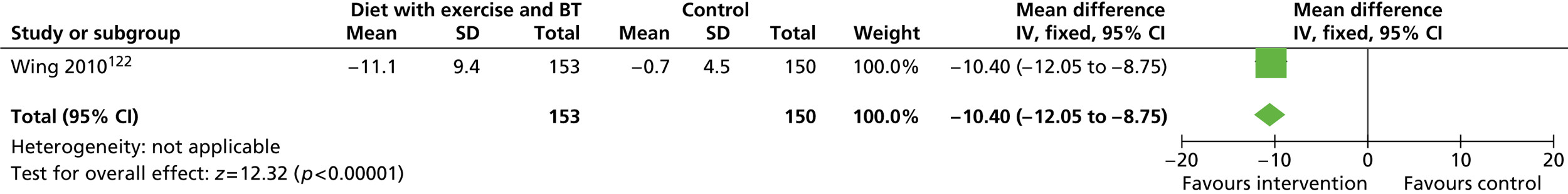

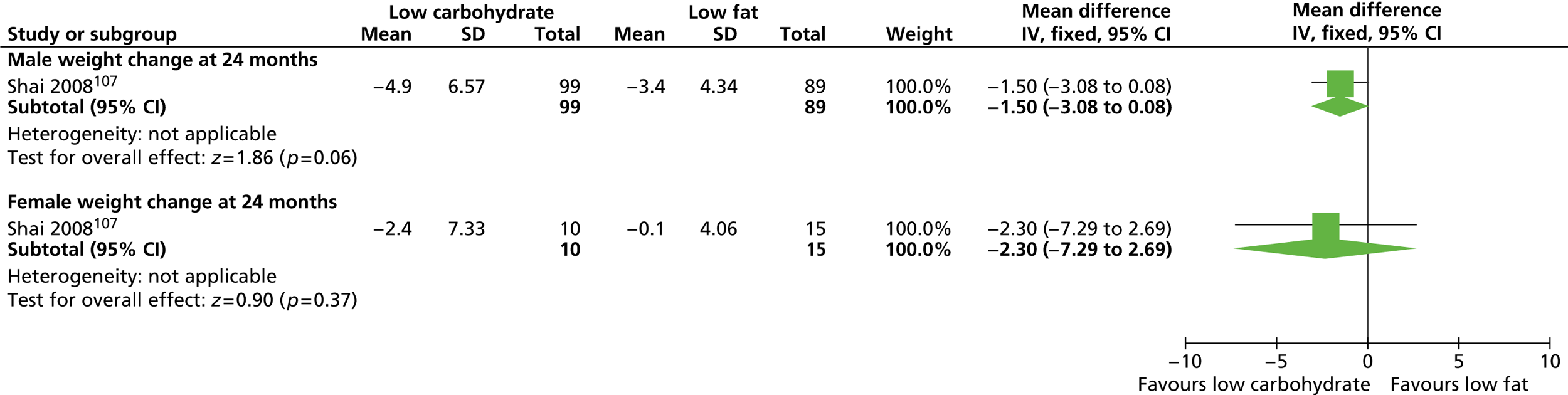

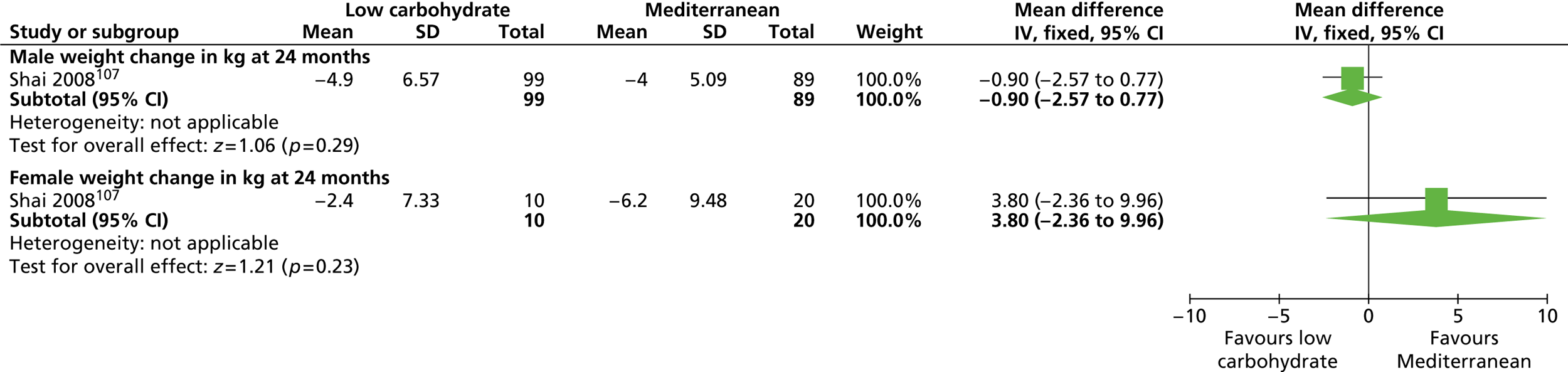

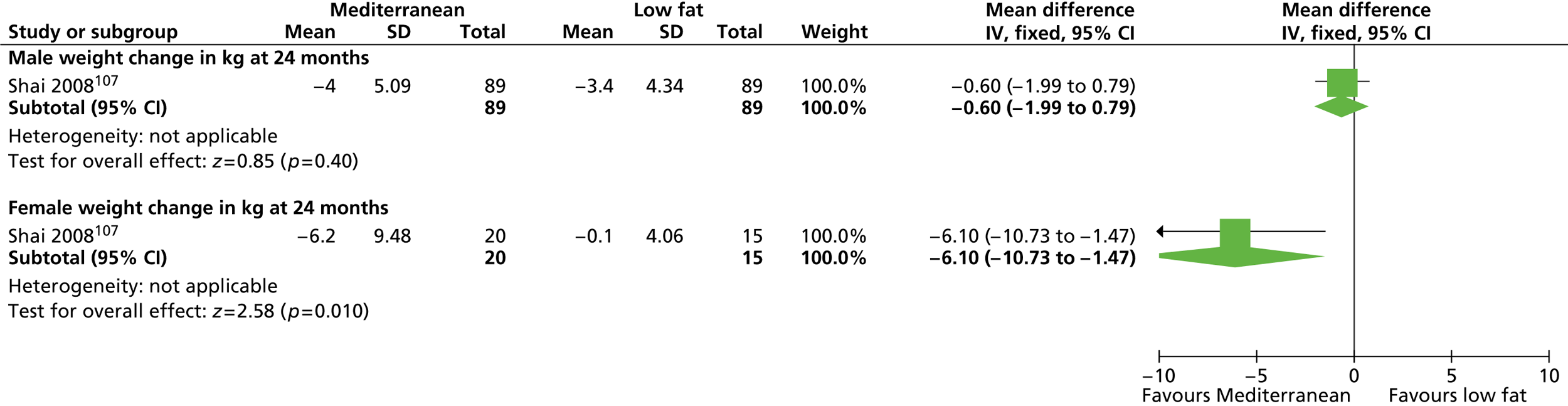

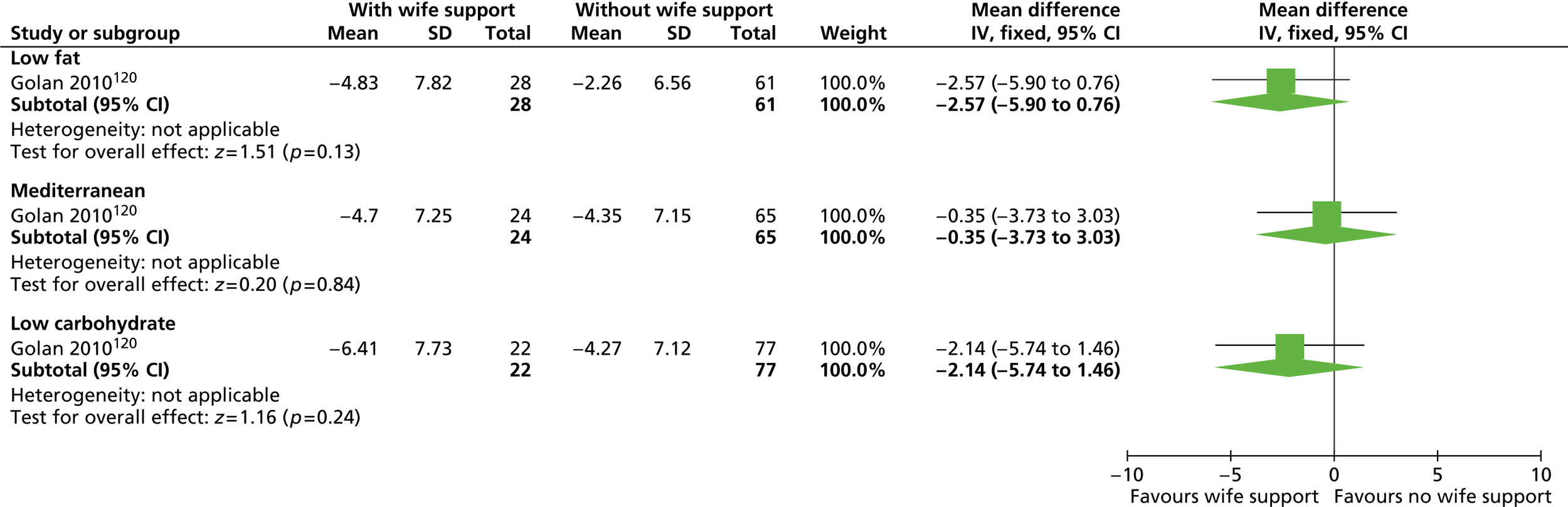

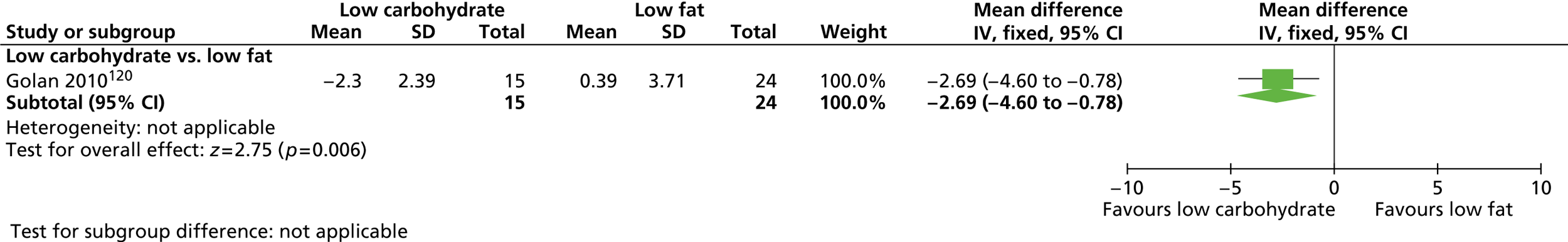

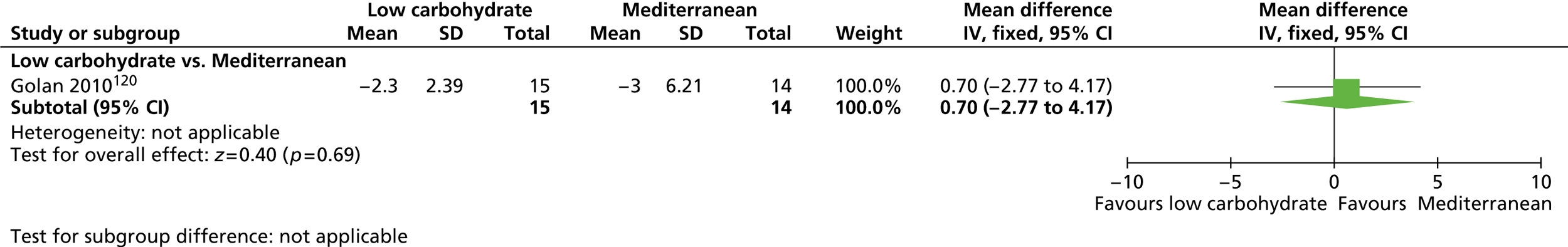

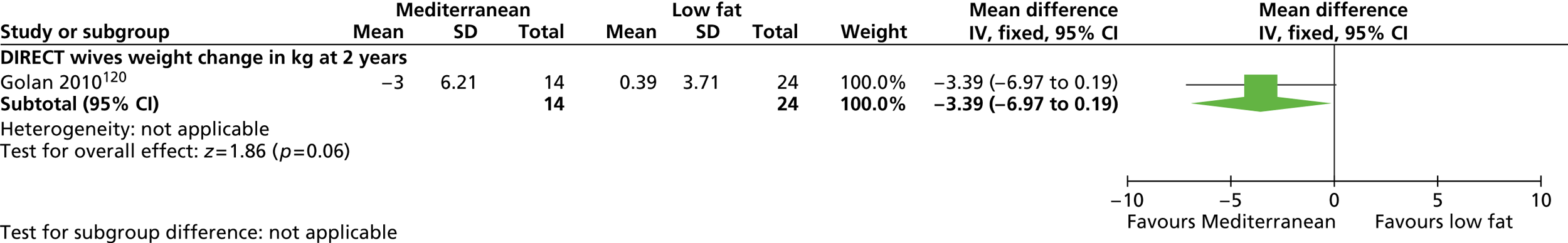

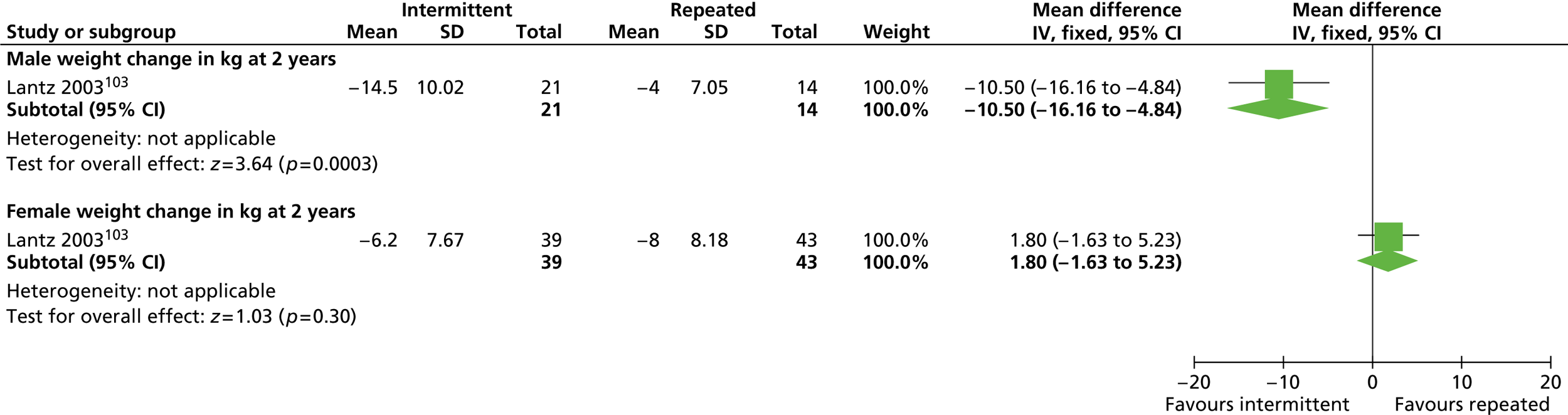

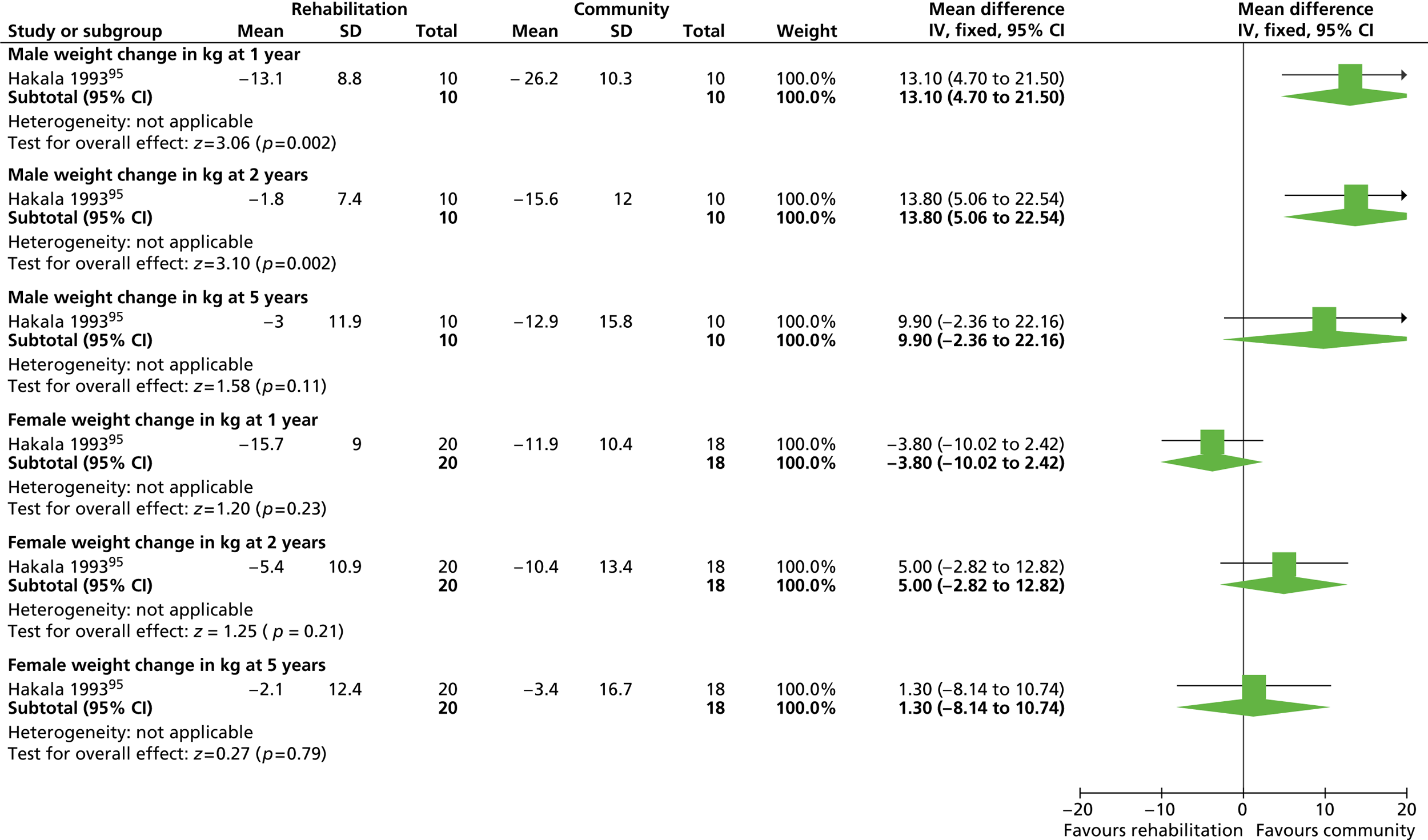

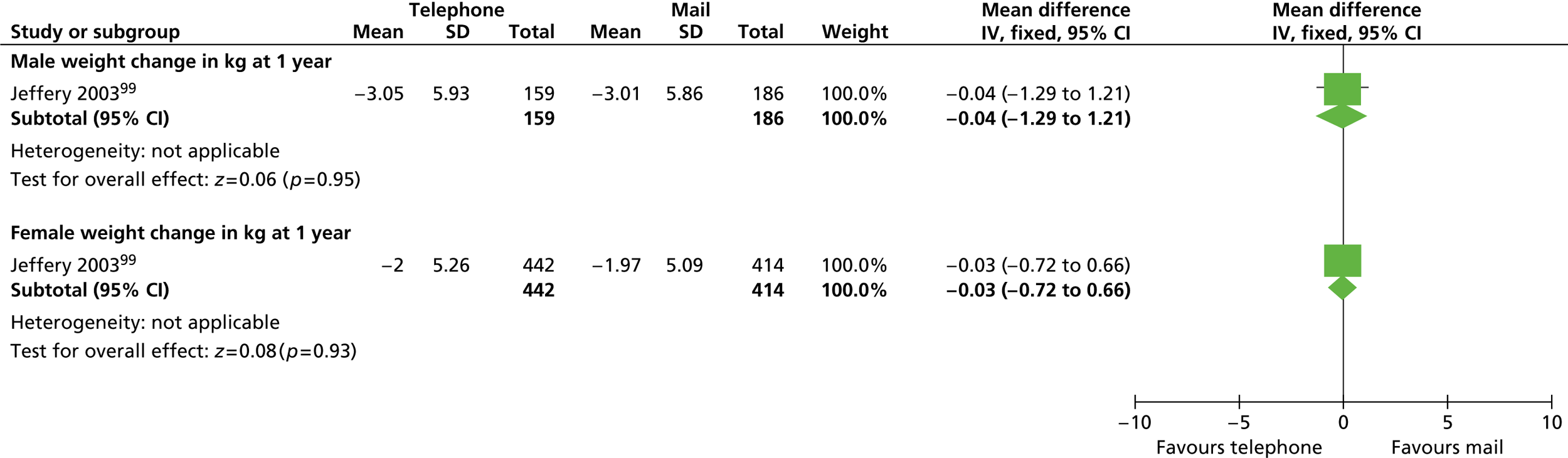

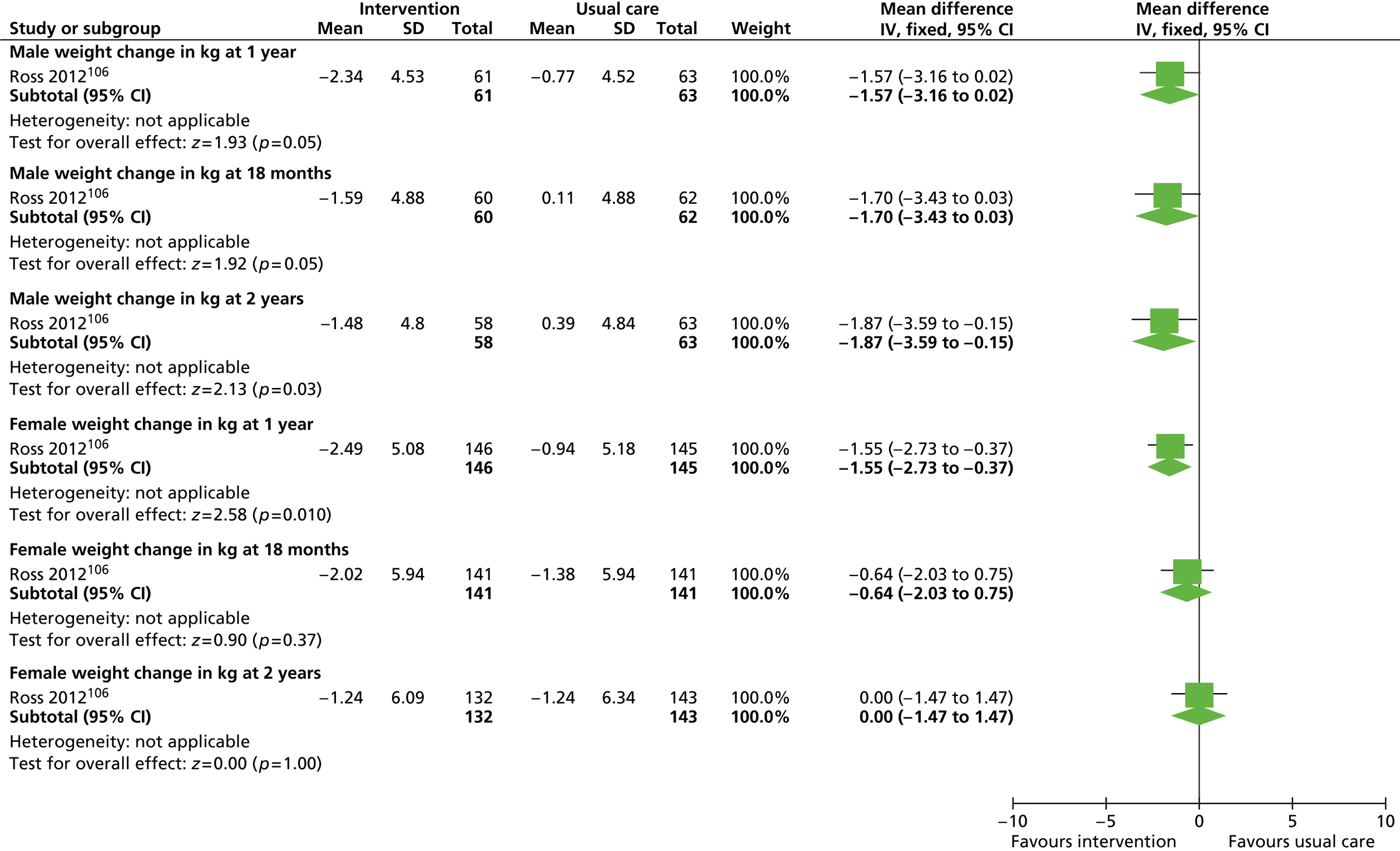

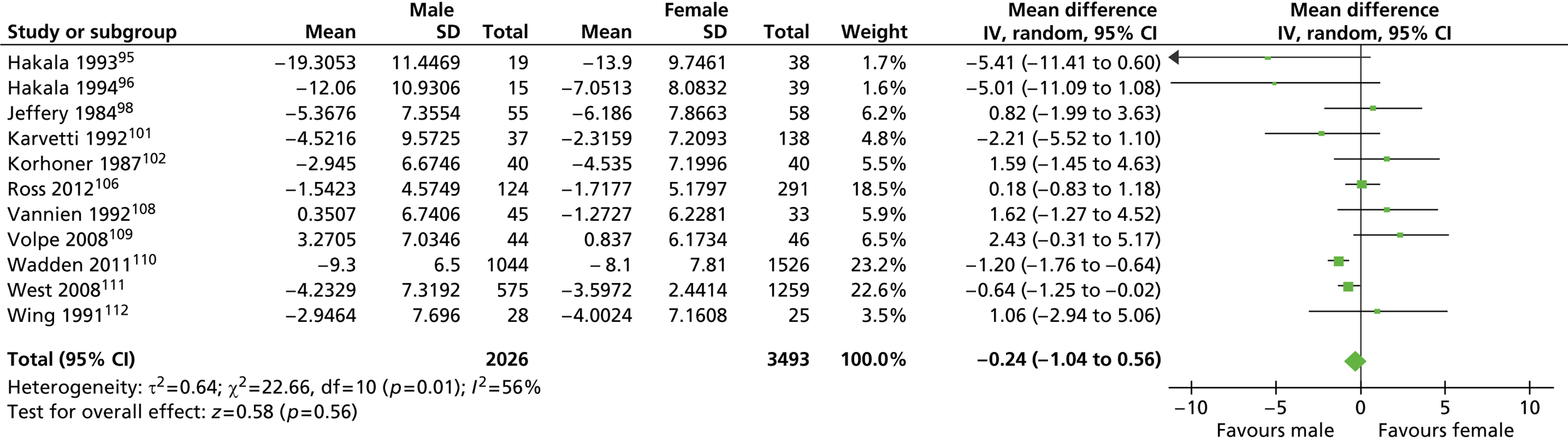

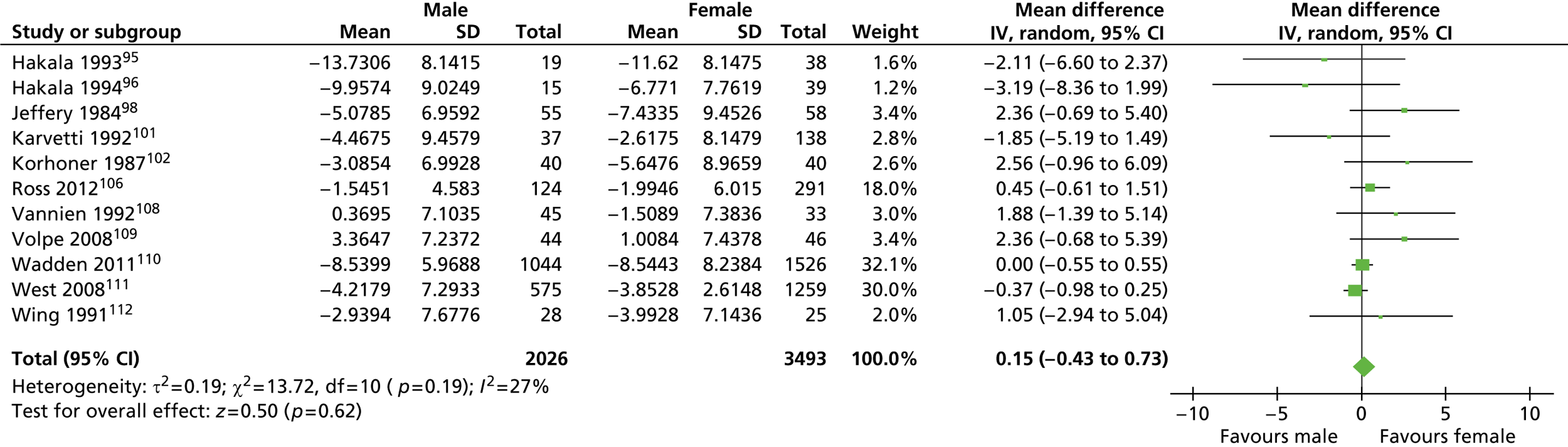

Data analysis

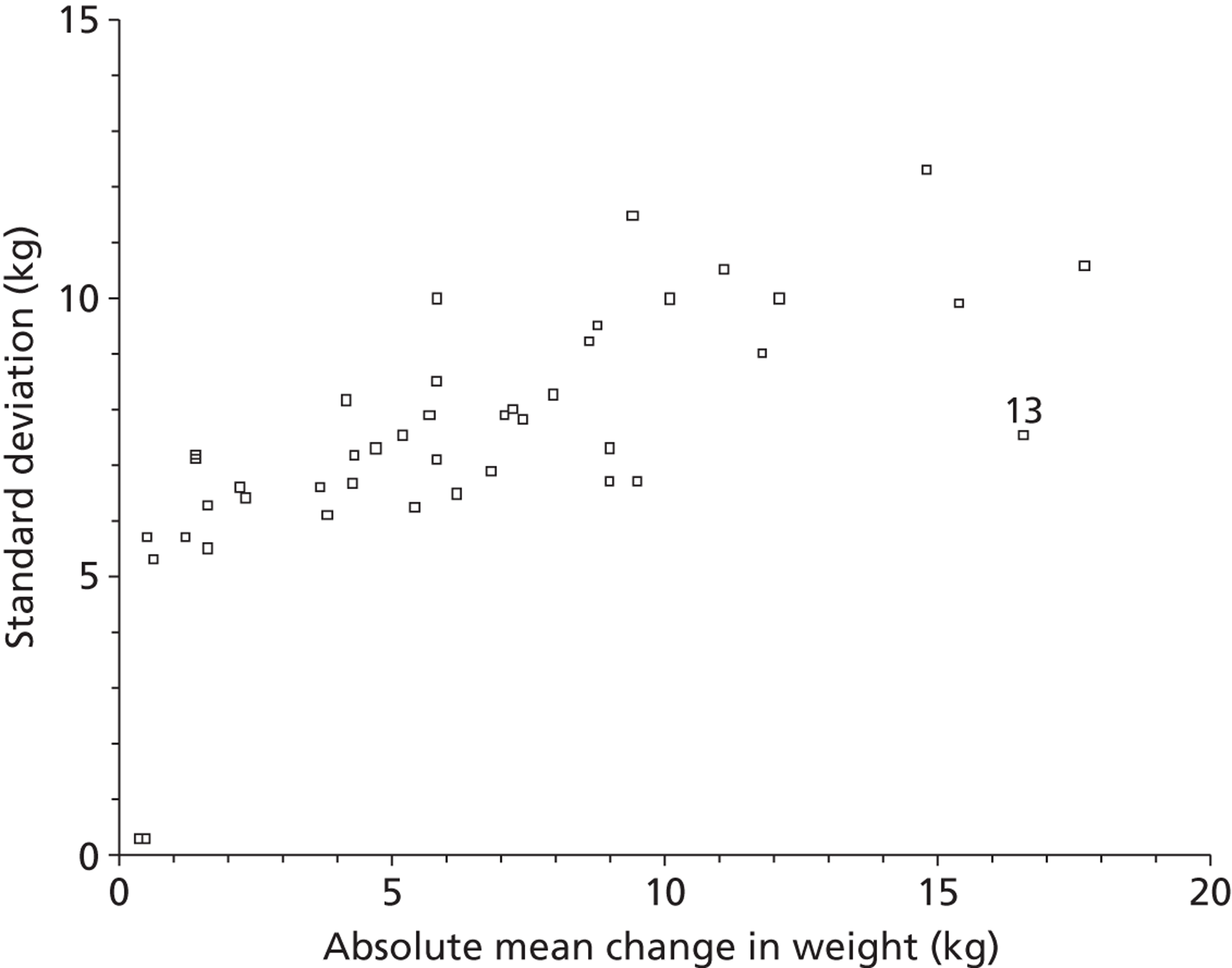

We imported data into Review Manager (RevMan) software (version 5.1; The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) for data synthesis. We reported means or changes in means or proportions between groups. For continuous outcomes we reported the mean difference or standardised mean difference (different scales for the same outcome) and for dichotomous data we presented the risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Because of the inherent heterogeneity in studies of obesity interventions, when study results could be quantitatively pooled we used random-effects meta-analysis throughout. For meta-analysis plots of only one study we used fixed effects. We used visual inspection and the I 2 statistic to assess heterogeneity in forest plots57 and planned funnel plot analysis to investigate reporting biases for forest plots with ≥ 10 studies.

We planned to explore the role of sex as a treatment modifier by conducting a meta-analysis of the treatment by sex interaction effect across trials in which outcomes were presented separately by sex,63 but this was not possible because of the heterogeneous nature of the interventions, particularly in terms of dietary calorie prescription. For statistics on the proportion of participants completing the study, only studies that reported the rate of dropout were included. The risk difference and its CI between men and women were calculated with the p-value.

For the analysis of mean weight difference between men and women, the weighted mean difference (WMD) was calculated for both men and women when more than one group was reported. The standard deviation (SD) for the WMD was calculated using the formulae for calculating SD for grouped data. Studies with no baseline weight values were excluded from the analysis of weight difference. In the analysis of percentage weight loss the WMD was divided by the baseline weight. For each study the number of participants, the WMD of weight or percentage weight loss from baseline and its SD were entered into RevMan software. The random-effects model was used.

Subgroup analyses were planned to explore whether the effectiveness of interventions differed according to whether participants were selected on the basis of newly diagnosed or pre-existing obesity-related comorbidities (e.g. diabetes, hypertension). This was not possible because of the limited quantity of data and the heterogeneity of the studies. Sufficient data were not available to explore the effect of deprivation, age and ethnicity on effectiveness nor were there sufficient data to explore the effect of assumed values for weight on meta-analyses.

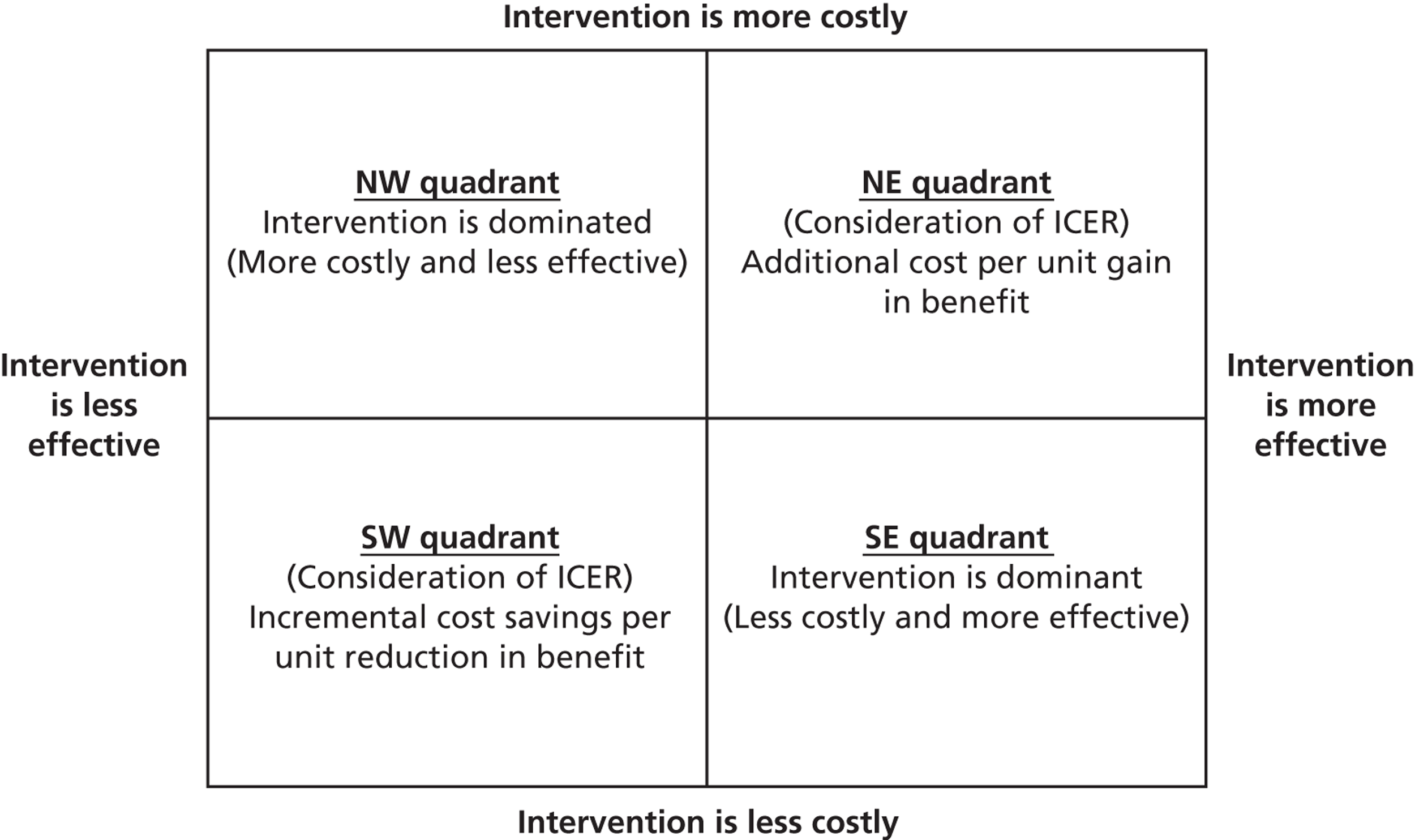

The methods for incorporating economics evidence into the reviews followed those recommended in The Cochrane Handbook. 57 A narrative synthesis is presented.

Integrated qualitative and quantitative evidence synthesis

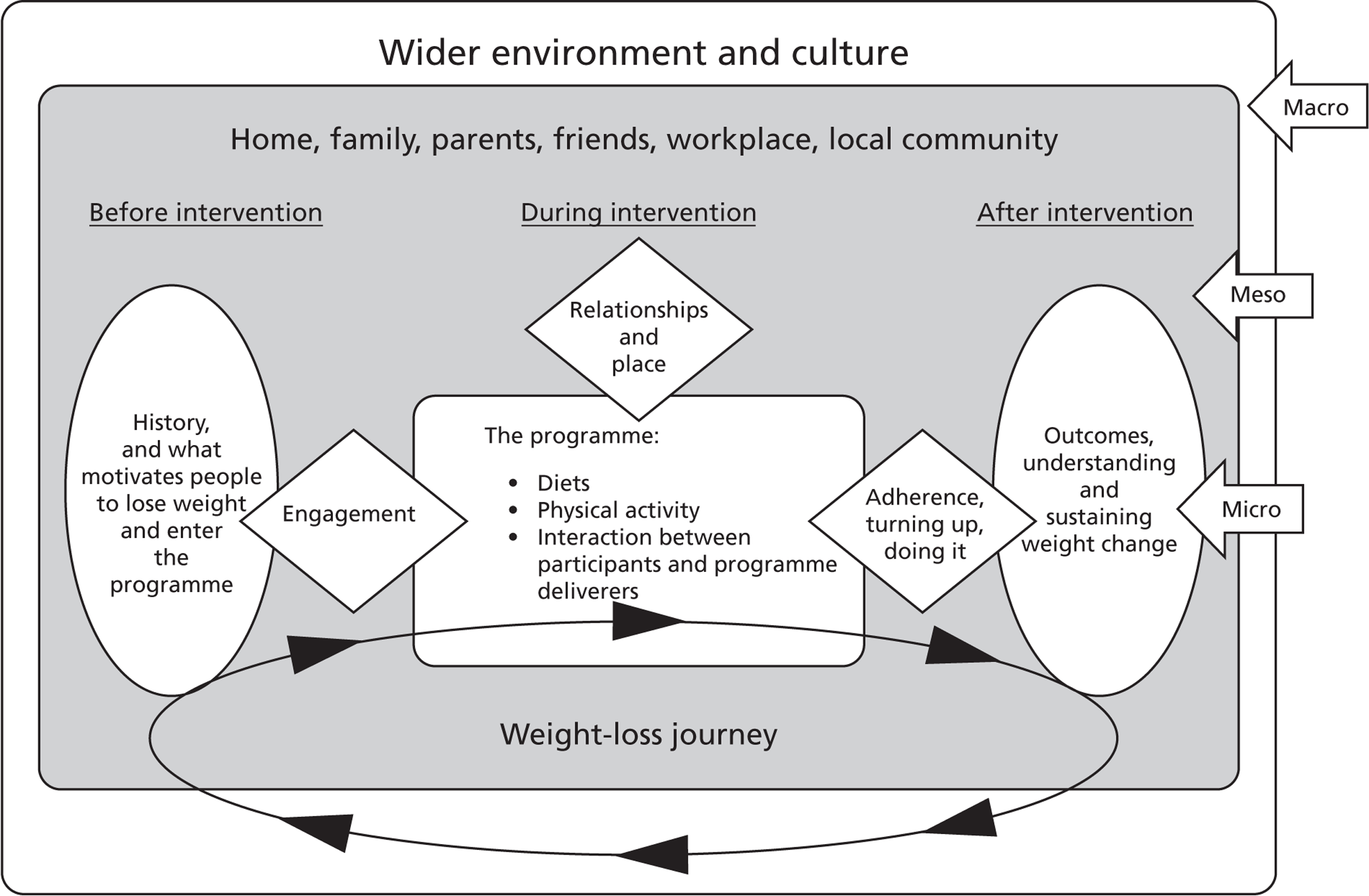

We undertook a realist integrated qualitative and quantitative evidence synthesis to investigate what weight management interventions work for men, with which men and under what circumstances. From a realist perspective, it is important to conceptualise any intervention intended to improve health by considering the:

-

context that an intervention/programme will be situated within so that factors that might inhibit or enhance its effectiveness can be identified

-

mechanisms of the intervention/programme and how the intended programme beneficiaries will interact and react to the intervention processes and mechanisms

-

outcomes, both positive and negative, that may arise from an individual’s engagement with the proposed intervention.

A body of literature has emerged over recent years that has stressed the importance of considering public health problems (such as obesity) from a so-called socioecological perspective. 5,64 – 69 Hence, our methodological approach investigated issues relating to the macro-, meso- and micro-level influences that shape and influence men’s perspectives and experiences related to engaging with weight management programmes. By macro-level influences we mean the wider social, cultural, economic and political factors that overarch and influence the meso level of workplace, community, family, friends and peers, whereas micro level refers to the individual psychological and biological determinants of health and well-being.

A priori research questions

The primary aim of the evidence synthesis was to uncover how effective interventions work and to describe key intervention ingredients, processes and environmental and contextual factors that contribute to effectiveness. 70 We also aimed to identify the barriers and facilitators that men experience when engaging with a weight management intervention. Both deductive and inductive analytical approaches were employed throughout the review process and as such the following a priori research questions were developed to guide our initial investigation:

-

What are the best evidence-based management strategies for treating obesity in men?

-

How can men’s engagement in obesity services be improved?

In addition to these a priori research questions we also developed a series of 10 more detailed research questions that emerged inductively from the initial findings of the review of men-only RCTs (see Chapter 3 ) and also the expertise, knowledge and previous research of the chief investigator (AA) and principal investigators (FD, PH, EvT). Generating inductive research questions in this way is an inherent property of qualitative research and particularly of a grounded theory approach in which data collection and analysis proceed iteratively to confirm or refute an emerging theory:

-

How are men initially motivated to lose weight?

-

How are men attracted to taking part in the trial/intervention?

-

Are men consulted in the design of the intervention?

-

If it is found that interventions for men should be different from those for women, how should they be different and why?

-

Are group-based interventions for men found to be more effective for weight loss than those delivered to individual men?

-

Are certain features of diets found to be more attractive for obese men?

-

Are certain features of physical activity stated to be more attractive for obese men? How and why are these features more attractive?

-

What efforts are made to help men continue with the programme?

-

Do men state who they believe to be the best person/persons to deliver the intervention?

-

Are programmes deliberately involving partners/families more effective?

These questions were incorporated into our data extraction form (see Appendix 15 ) to code the data from studies linked to interventions to identify a priori themes. A full description of the data analysis cycle is provided in The analysis cycle and thematic synthesis.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included any study reporting qualitative research with obese men, or obese men in contrast to obese women. In addition we included qualitative data from both health professionals and commercial organisations involved in managing obesity. The search included studies published from 1990 onwards and no language restrictions were placed on any of the searches.

As stated above in the description of methods for quantitative reviews, the studies included men who were 16 years or over, with no upper age limit, who had a mean or median BMI of 30 kg/m2. We included data from qualitative and mixed method studies linked to the identified RCTs and linked to RCTs not included in the quantitative reviews for this report. We also included any qualitative data reported as part of papers reporting quantitative outcomes. Furthermore, we included data from qualitative studies linked to non-randomised intervention studies and qualitative data from studies that were not linked to any specific UK-based, men-only interventions that had reported on men’s experiences of weight-loss attempts.

Studies conducted in developed countries were included if they contributed relevance to the UK context and all settings for lifestyle and drug interventions were considered. These included workplaces, football and rugby clubs, primary care, the internet, and religious and community settings.

We did not consider studies where men were not included and where obesity and weight management were not the prime focus. In addition, studies that did not contain primary qualitative research with obese men were not considered.

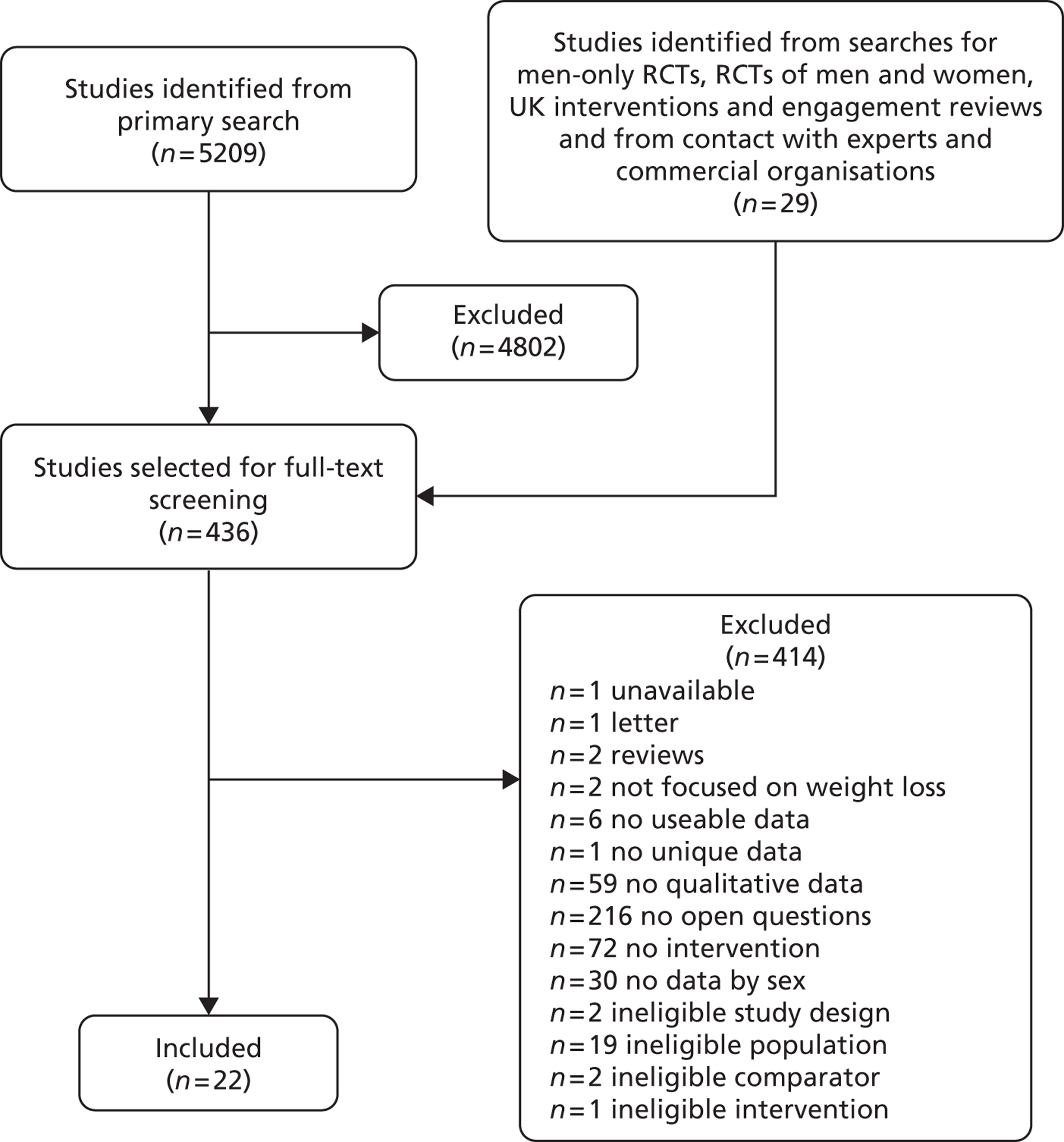

Identification of studies

The search methods for the review of qualitative studies have been reported earlier (see Search strategies). Two researchers independently screened abstracts for inclusion and all eligible study reports were entered into NVivo 9 qualitative data management software (QSR International, Southport, UK). Two researchers then grouped the final included studies into three categories:

-

qualitative and mixed-method studies linked to eligible RCTs, including any qualitative data reported as part of papers reporting quantitative outcomes

-

qualitative and mixed-method studies linked to ineligible RCTs and identified non-randomised intervention studies, including any qualitative data reported

-

UK-based qualitative studies not linked to any specific interventions that contained men-only samples.

Although it could be argued that separation of the studies into groups could cause further decontextualisation, as the focus of this project is to assess the evidence for weight management interventions, grouping the studies in this way assisted in the integration of the quantitative and qualitative review processes.

Data extraction strategy

For the studies linked to interventions, one reviewer (DA) used a data extraction form (see Appendix 15 ) to extract details of study design, methods, participants, interventions, findings, data pertaining to area and setting, and quality. Completed data extraction forms were checked by a second reviewer (either FD or EvT). Any disagreements over the interpretation of extracted data were discussed at group meetings. After agreement was reached the extraction forms were imported into NVivo 9 for analysis.

Following the analysis of the intervention study data, a further process of data extraction was applied to the nine theoretical studies not linked to interventions to investigate whether these studies contained data to confirm, refute or add any new thematic insights. Three researchers (DA, FD and EvT) screened three of the non-intervention studies each and extracted and inserted data into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (2007; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) containing our interpretive themes derived from the intervention study data as headings. Data extraction of the non-intervention studies was cross-checked by other researchers in the group.

Quality assessment strategy

There is a great diversity of approaches to data collection and data analysis within qualitative research and also a multiplicity of theoretical perspectives. This has made it difficult to develop consensus over which criteria are the most useful when assessing the quality of qualitative studies. 1,71,72 At present, some qualitative synthesis methods such as framework synthesis and thematic synthesis undertake highly specified forms of quality appraisal that can result in the exclusion of studies that are judged to be of poor methodological quality. However, other methods such as critical interpretive synthesis do not exclude papers as long as they meet basic relevance criteria. 73

With this in mind, there appears to be a growing argument amongst certain researchers72,74 – 77 that qualitative studies should not be excluded from qualitative evidence syntheses based on quality assessment. They argue that excluding studies because of methodological flaws or incomplete reporting may result in the loss of valuable new insights, whereas studies that are methodologically sound may suffer from poor interpretation of data, leading to an insufficient insight into the phenomenon under study. 76 In addition, Carroll and colleagues74 contend that a quality appraisal instrument can assess only what is reported in a publication; thus, aspects such as the style of journal or word limits may have a bearing on whether or not studies have adequate space to describe fully certain elements of a study that a quality assessment tool may be investigating. For example, Garip and Yardley39 note that papers published in medical journals were often rated poorly using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool78 because of the lack of space to provide full methodological details. We found these arguments against excluding studies to be convincing and therefore did not exclude any of the 13 qualitative studies linked to interventions on the basis of quality. Instead, we elected to formulate and apply a quality appraisal tool during the process of data extraction.

Our quality assessment tool was formulated following a consultation of the following critical appraisal checklists: CASP,78 the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research79 and the Joanna Briggs Institute Qualitative Assessment and Review Instrument. 80 We included criteria from these that we considered were key in terms of methodological rigour and also in terms of importance for our a priori research questions, which are specifically concerned with informing policy and practice.

The criteria that we selected were:

-

Aims and methods:

-

Research questions – stated explicitly or implicitly within the general text/topic guide? In what section(s) of the paper are questions mentioned? Are they prospective or retrospective?

-

Theoretical and epistemological perspective underpinning the qualitative research?

-

Theoretical perspective underpinning the intervention?

-

Qualitative methods used?

-

Data analysis technique and procedure?

-

-

Sample:

-

Sample size?

-

Sample characteristics?

-

Sample selection process?

-

Sample inclusion and exclusion criteria?

-

-

Reflexivity:

-

Evidence of researcher reflexivity?

-

-

Ethics:

-

Evidence of attention to ethical issues?

-

-

General criteria:

-

Are the findings adequately supported by the data presented?

-

Is there potential for a ‘charisma effect’ with this study? (this relates to the potential influence of the principal investigator)

-

Any other quality issues not covered by previous items?

-

The quality appraisal tool was integrated into the data extraction form and was applied by one researcher (DA). The quality assessments were subsequently cross-checked by another researcher (either FD or EvT). The findings and conclusions of our quality assessment are discussed in Chapter 6 .

The analysis cycle and thematic synthesis

We developed an analysis cycle that started with coding of the qualitative data from studies linked to interventions followed by the development of initial descriptive themes and finally the development of higher-order analytical and interpretive themes and concepts. This cyclical and iterative process was conducted to identify the promising ‘ingredients’ of interventions that are likely to be effective in male weight reduction, both in terms of essential and necessary contextual/environmental variables and intervention processes.

Development of a thematic index

To develop a thematic index, one researcher (DA) coded the findings reported in the included qualitative studies linked to interventions line by line for content and meaning and categorised these according to whether they corresponded to the a priori themes or whether they appeared to represent emergent themes unconnected to the a priori themes.

After undertaking this process for all studies linked to interventions the coding was cross-checked by another researcher (FD). The data then underwent a second importing process within NVivo 9 into framework matrices for comparison of the a priori and emergent themes for effective and non-effective interventions. Framework matrices were used to facilitate the use of the constant comparative method to search for patterns and relationships and assist with developing theory. All qualitative researchers (DA, FD, PH and EvT) then developed the descriptive thematic index over a series of meetings, with a tree structure of themes and subthemes to enable us to remain close to the reported study findings. The thematic framework was discussed at a meeting with the Men’s Health Forum representatives to ascertain service users’ perspectives. The qualitative researchers decided that one of the 10 a priori themes (‘Are programmes deliberately involving partners/families more effective?’) was not supported by the data and it was rejected. To develop a thematic index, one researcher (DA) coded the findings reported in the qualitative studies line by line.

The development of interpretive themes

We then generated a more refined set of interpretive themes from the a priori and emergent themes for the effective management of obesity in men and the barriers to and facilitators of engaging in weight management programmes. In meta-ethnography these are described as ‘third-order interpretations’. 81 Following the completion of the analytical cycle for studies linked to interventions, the theoretical studies not linked to interventions were then read to ascertain whether they provided disconfirming evidence or added any new perspectives and all relevant data from these studies were extracted. This process was conducted to test the robustness of the synthesis and has been recommended in previous narrative synthesis methods literature. 82

The final stage of the analysis involved integrating the qualitative findings with findings from the quantitative reviews. This was achieved through a process of in-depth reading of each results chapter by all members of the research group to identify where qualitative findings were supported or refuted by quantitative findings. The supporting or disconfirming quantitative data were then integrated into the findings.

Researcher perspectives

It is important to be aware of the researchers’ backgrounds and associated perspectives when interpreting our findings. DA is a health services researcher with a background in sociology and mixed-methods research methodologies. FD is a public health researcher with a background in health promotion and nursing, with an interest in health inequalities and the social determinants of health outcomes and behaviours. EvT is a medical sociologist with a background in qualitative and mixed-methods research and an interest in public health in general and health promotion in particular. PH is an academic general practitioner (GP) with expertise in qualitative and mixed-methods research, particularly when applied to RCTs of complex interventions. None of the qualitative researchers can be considered obese. Throughout the study reflexivity took place through weekly research team discussions until a consensus was reached.

Chapter 3 Systematic reviews of men-only randomised controlled trials and randomised controlled trials with data for men and women compared

In this chapter we present two systematic reviews. The first is a systematic review of RCTs of interventions (lifestyle and/or the UK-licensed medication orlistat) in any setting with men only who are obese with a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2 (or overweight with a BMI of ≥ 28 kg/m2 and cardiac risk factors based on orlistat guidance) and for which there are follow-up data for at least 1 year.

The second is a systematic review of RCTs of interventions (as above) in any setting with both men and women who are obese with a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2 (or overweight with a BMI of ≥ 28 kg/m2 and cardiac risk factors based on orlistat guidance) in which the results are presented separately for men and women in the same trial. We use trials with both men and women to look for differences in effectiveness.

Quantity of evidence

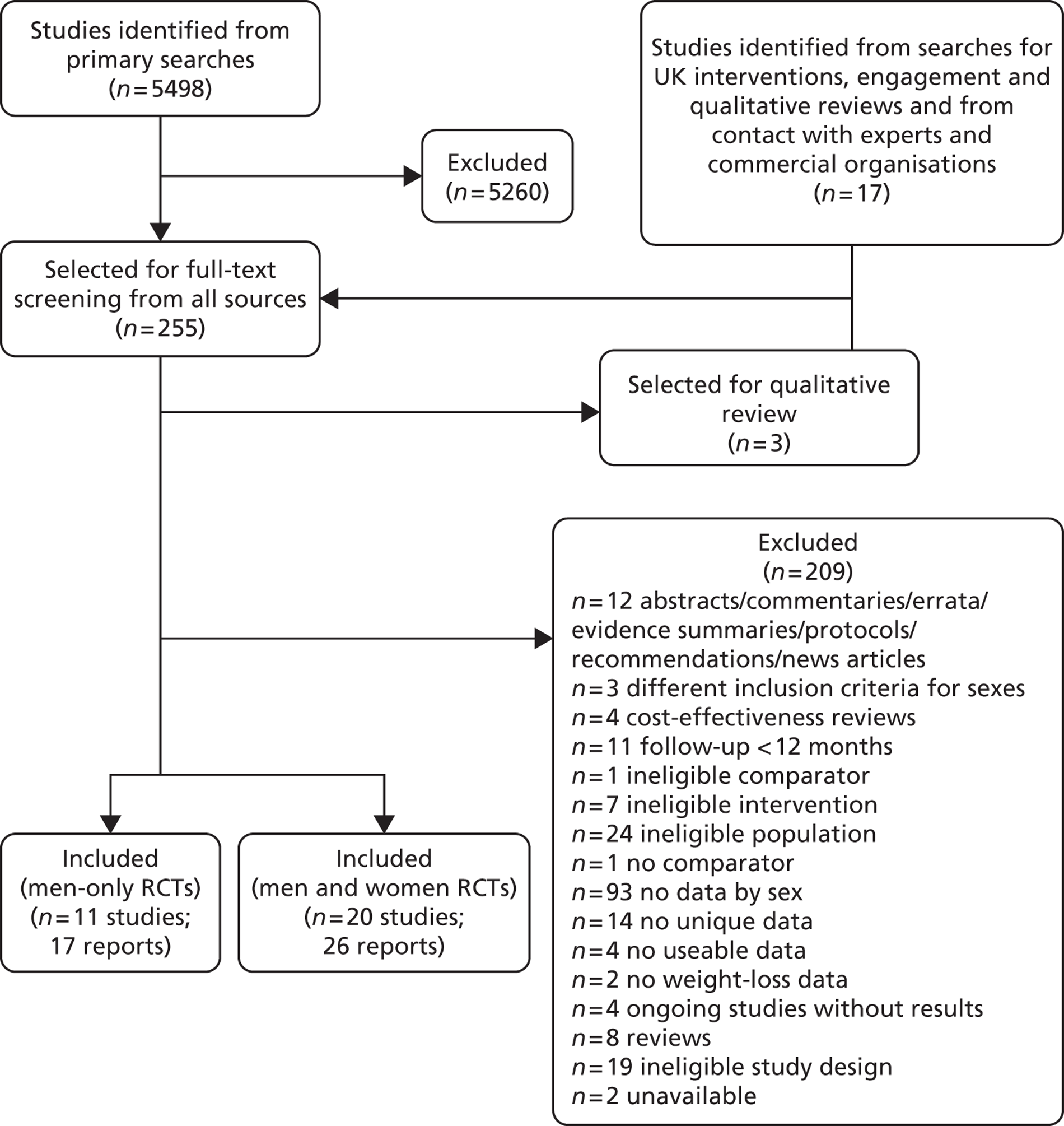

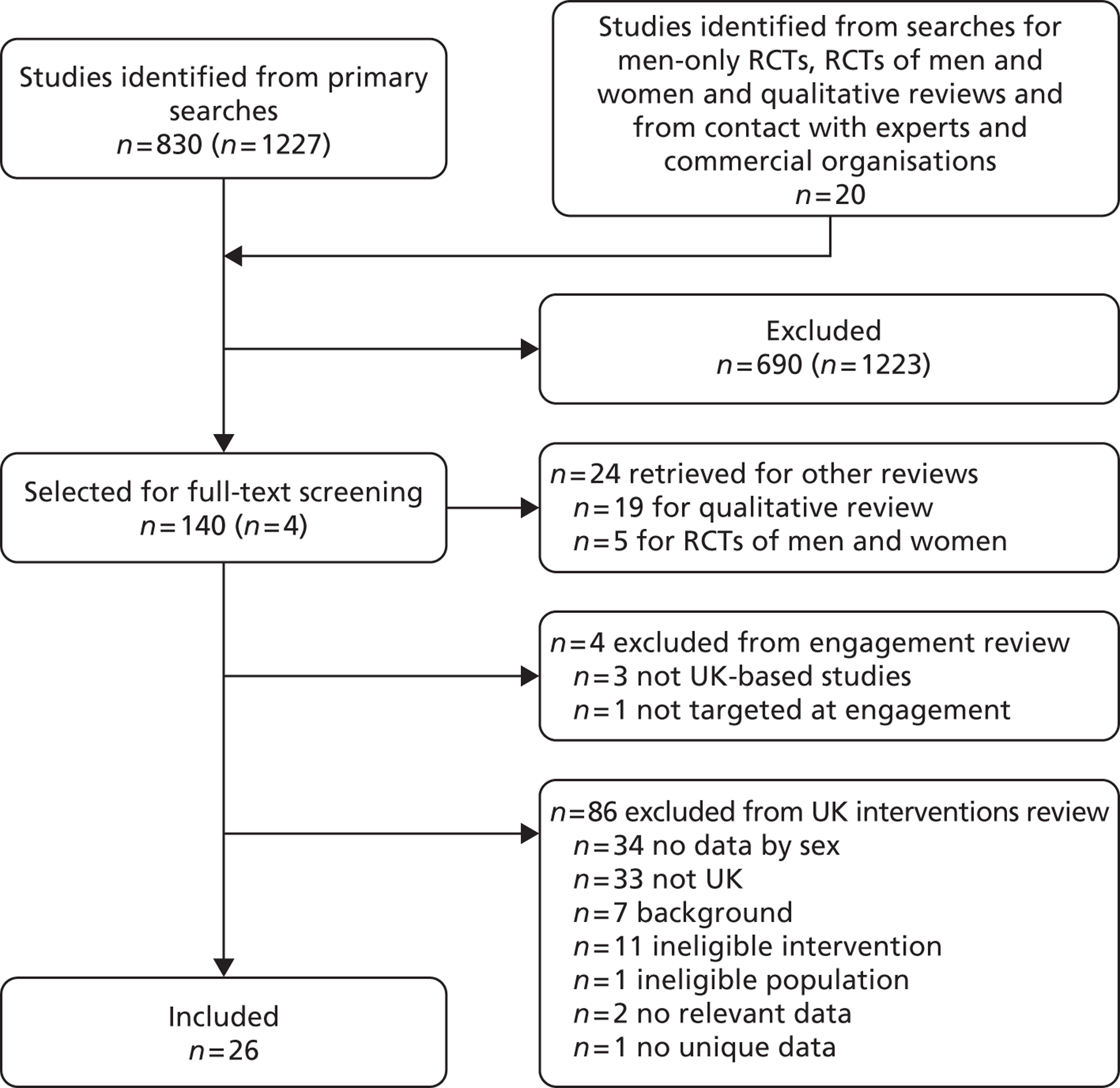

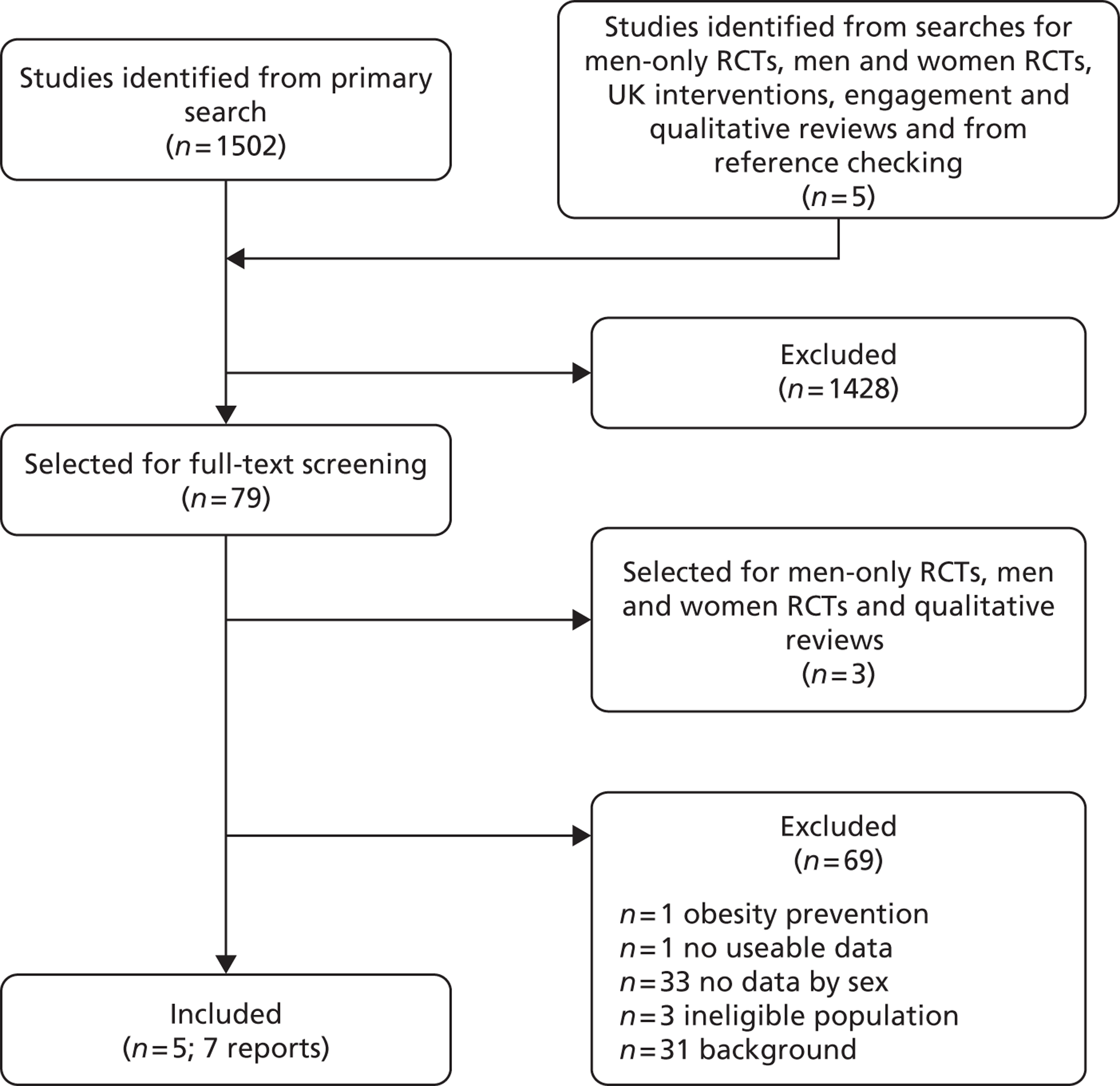

Our primary literature search identified 5498 potentially relevant titles and abstracts ( Figure 1 ). In addition to this, we identified 17 potentially relevant reports from other sources, such as commercial organisations and expert opinion. We selected 255 reports for full-text assessment, of which 11 RCTs83 – 93 were included in the review of men-only RCTs and 20 RCTs94 – 113 were included in the review of RCTs of men and women, along with six reports114 – 119 linked to the review of men-only RCTs and six reports120 – 125 linked to the review of RCTs of men and women.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of the number of potentially relevant reports and the numbers subsequently included and excluded from the reviews.

Review of men-only randomised controlled trials

Number and type of studies

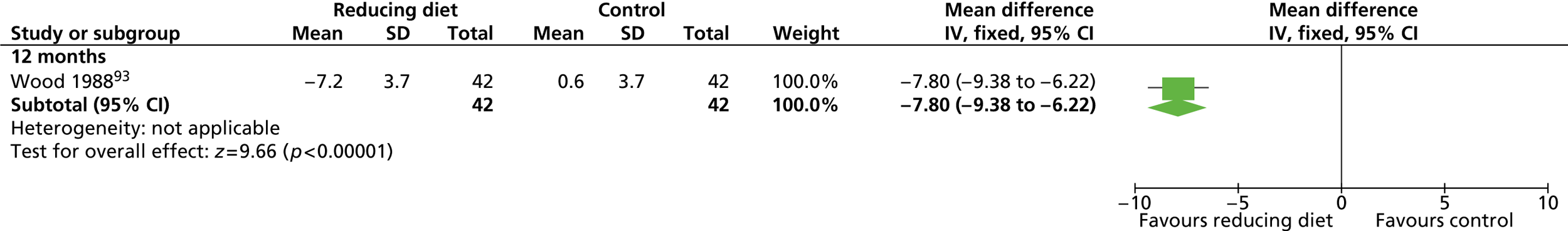

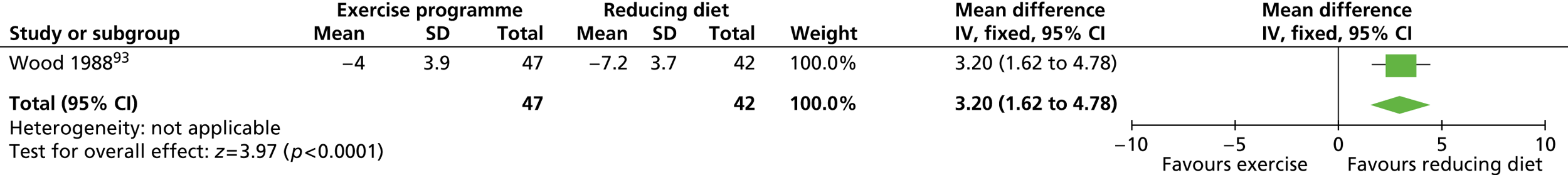

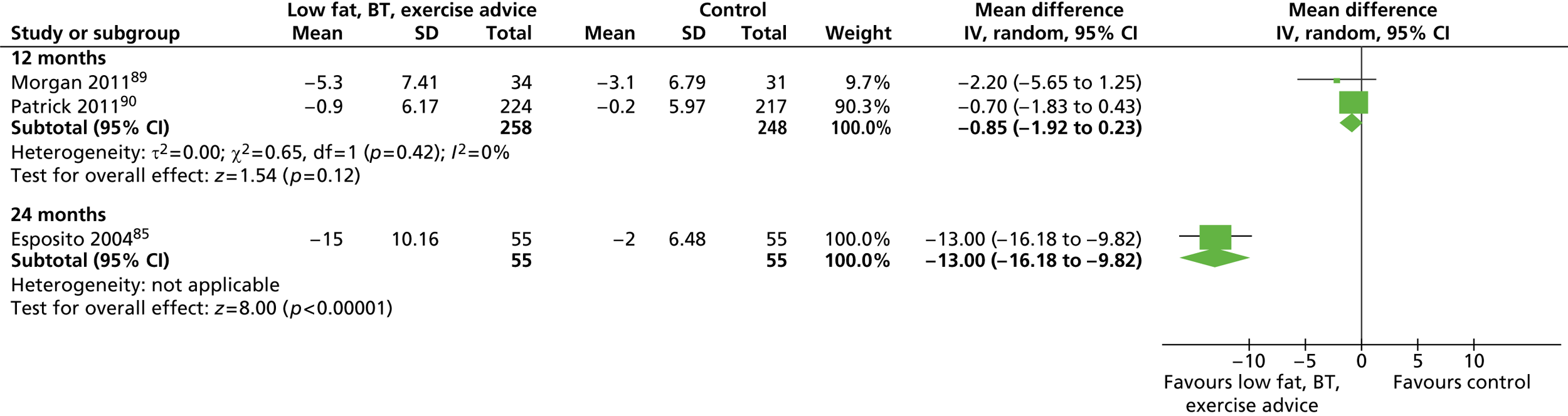

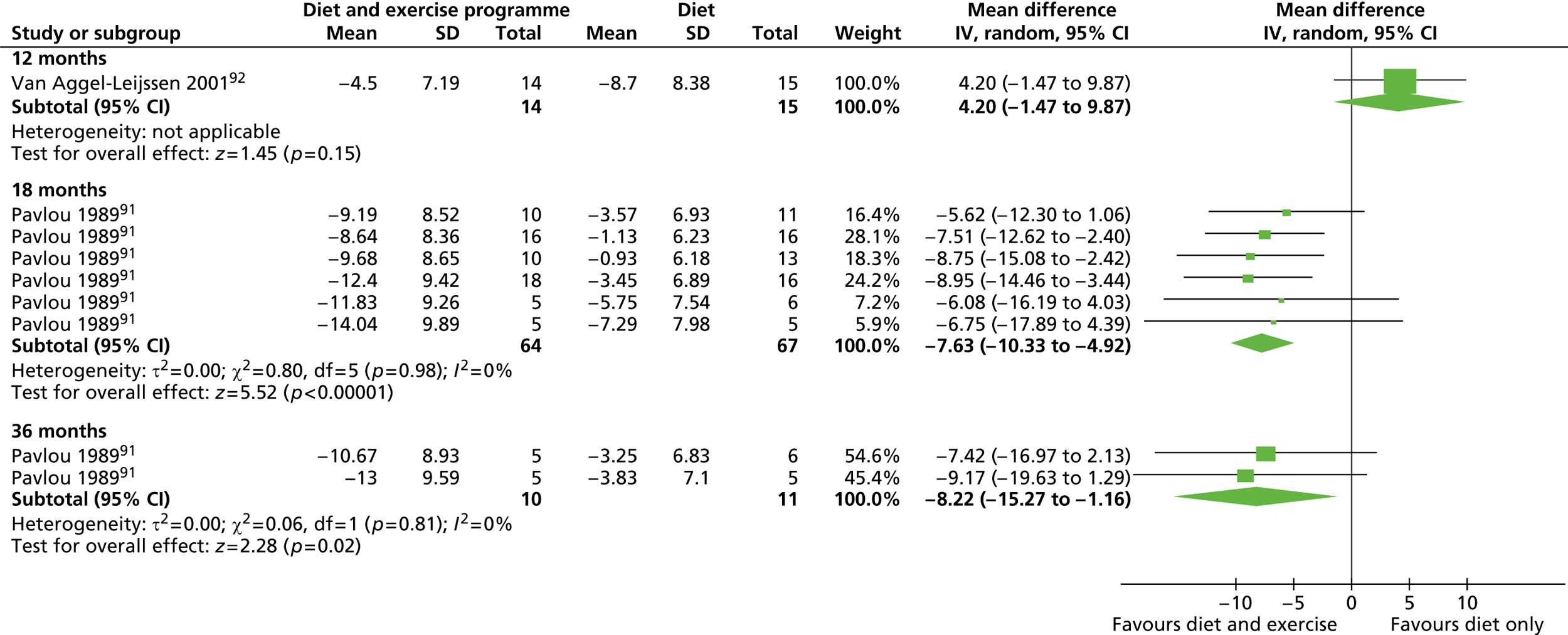

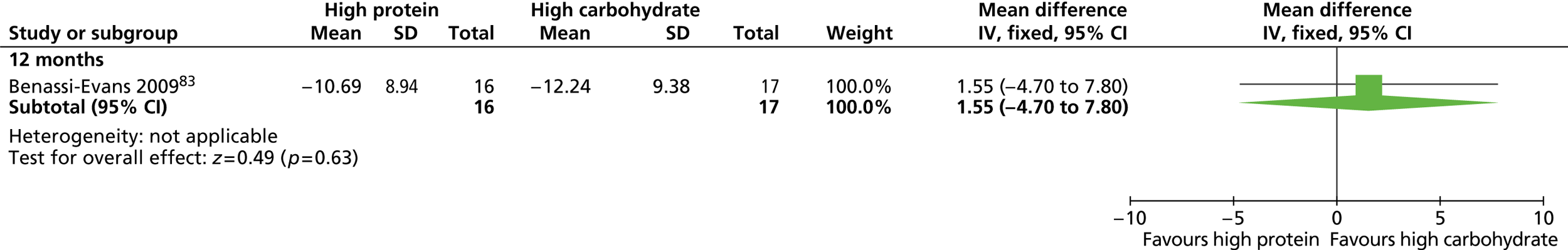

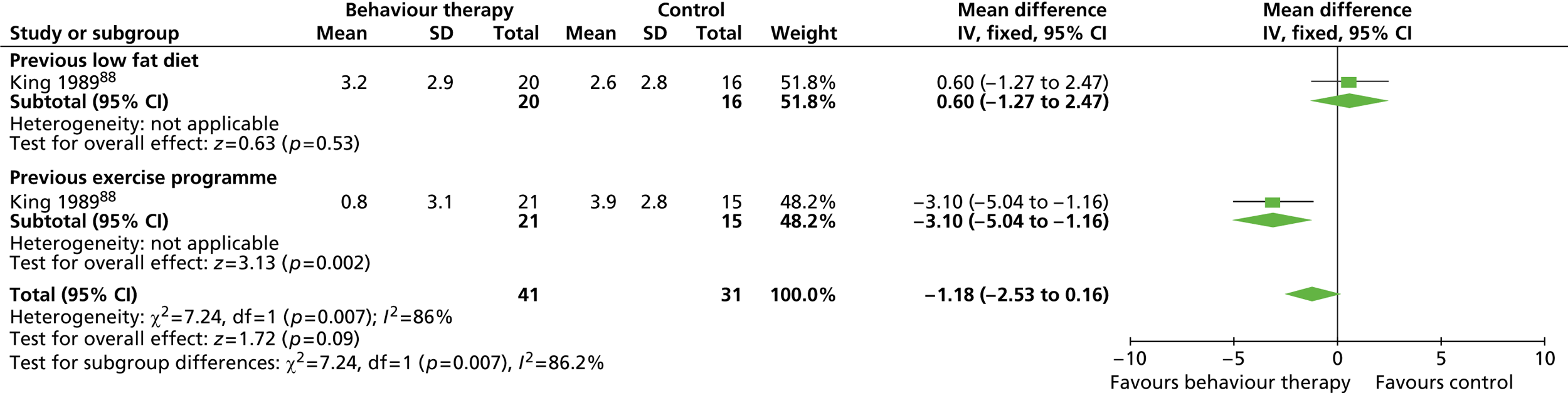

Eleven RCTs including men only were identified as eligible for inclusion, nine of which investigated weight-loss interventions. 83,85 – 87,89 – 93 One trial examined a reducing diet for weight loss. 93 Three trials investigated the type of reducing diet to use. 83,87,91 Three trials looked at the use of physical activity in weight reduction. 91 – 93 Three trials examined a diet plus behaviour therapy and exercise advice for weight loss. 85,89,90 Jeffery and colleagues86 investigated the use of various monetary contracts for individual or group weight loss. Two trials investigated exercise or behaviour change training for weight maintenance. 84,88 The weight-maintenance trial conducted by King and colleagues88 randomised men who had received active weight-loss interventions in the trial by Wood and colleagues. 93 This was the only weight-maintenance trial found that was linked to one of the eligible weight-loss intervention trials identified by our screening process. Details of the interventions investigated by the individual trials are presented in Table 3 . None of the trials reported involving male service users in the design of the intervention. The period of follow-up for all of the trials ranged from 12 to 36 months (median 15 months), with five trials83,88,89,92,93 having a follow-up period of 1 year only.

| Study ID | Participants | Interventions | Outcomes | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benassi-Evans 200983 | Location: One nutrition clinic in Adelaide, Australia Period of study: NR Inclusion criteria: Male, age 20–65 years, BMI 27–40 kg/m2, at least one cardiovascular disease risk factor other than obesity Exclusion criteria: History of metabolic or coronary disease, type 1 or 2 diabetes Age (years), mean (SEM): a: 54.94 (1.17); b: 52.94 (1.5) BMI (kg/m2), mean (SEM): a: 32.42 (0.79); b: 31.47 (0.96) Weight (kg), mean (SEM): a: 99.84 (2.45); b: 99.58 (3.61) Baseline comparability: Yes |

Description of interventions: a: High-protein (red meat) diet comprising 35% protein, 40% carbohydrate, 25% fat, 7 MJ with some adjustment in energy to achieve approximate weight loss of 1 kg per week b: High-carbohydrate diet comprising 17% protein, 58% carbohydrate, 25% fat, 7 MJ with some adjustment in energy to achieve approximate weight loss of 1 kg per week Timing of active intervention: a + b: 0–12 weeks intensive weight loss with fortnightly clinic visits followed by monthly weight-maintenance visits up to 1 year No. of times contacted: a + b: 15 No. allocated: a: 16; b: 17 No. completed: a: 16; b: 17 Dropout (%): 0 No. assessed: a: 16; b: 17 |

Length of follow-up: 1 year Outcome: Weight |

|

| Borg 2002,84 Kukkonen-Harjula 2005116 | Location: Single research clinic, Finland Period of study: NR Inclusion criteria: age 35–50 years, BMI 30–40 kg/m2, waist circumference > 100 cm, clinically healthy other than obesity Exclusion criteria: Regular medication, participation in leisure time exercise more than twice weekly, smoker, resting blood pressure > 160/105 mmHg Age (years), mean (SD): a + b + c: 42.6 (4.6) BMI (kg/m2) (after 2 months of very low-calorie diet and before randomisation), mean (SD): a: 33.1 (2.7); b: 33.3 (2.8); c: 32.4 (2.4) Weight (kg), mean (SD): a + b + c: 106.0 (9.9) Baseline comparability: Yes |

Description of interventions: All men participated in a 2-month weight reduction programme consisting of a very low energy diet (Nutrilett, Leiras Oy, Turku, Finland) of 2 MJ per day for 8 weeks followed by a low energy diet of 5 MJ per day. Men attended small group weekly meetings led by a nutritionist. Men were then randomised to groups a, b and c: a: Control: Men advised not to increase their physical activity b: Walking: An exercise instructor supervised one group training session per week – 10-minute warm-up + 45 minutes’ training + 5-minute cool down. Heart rate monitors used to ensure target training intensity of 60–70% maximum oxygen consumption. Energy expenditure per exercise session 1.7 MJ c: Resistance exercise: An exercise instructor supervised one group training session per week – 10-minute warm-up + 45 minutes’ training + 5-minute cool down. Resistance load set at 60–80% of one repetition maximum with eight repetitions and three sets in each exercise. Each session included six exercises aimed at large muscle groups. Energy expenditure per exercise session 1.2 MJ Men continued to meet weekly in small groups in their intervention group throughout the 6-month weight-maintenance phase. Men in all groups were given the same instruction to follow ad libitum a high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet and received written material. No special instructions for diet or physical activity were given during follow-up after the weight-maintenance period Timing of active intervention: 6 months (preceded by 2-month pretreatment phase) No. of times contacted: a: 24 times, weekly for 6 months; b + c: 96 times, with exercise sessions up to three times per week for 6 months No. allocated: a: 30; b: 30; c: 30 No. completed: a: 22; b: 20; c: 26 Dropout (%): a: 27; b: 33; c: 13 No. assessed: a: 22; b: 20; c: 26 |

Length of follow-up: 21 months Outcomes: BMI, WHR, LDL and HDL cholesterol, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose |

|

| Esposito 200485 | Location: One university hospital, Naples, Italy Period of study: 2000–3 Inclusion criteria: Age 35–55 years with erectile dysfunction (IIEF-5 score < 22), no participation in diet reduction programmes within previous 6 months, sedentary (< 1 hour per week physical activity), BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 Exclusion criteria: Diabetes mellitus/impaired glucose tolerance, impaired renal function/macroalbuminuria, pelvic trauma, prostatic disease, peripheral neuropathy, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, psychiatric problems, drug/alcohol abuse, taking medication for erectile dysfunction Age (years), mean (SD): a: 43 (5.1); b: 43.5 (4.8) BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD): a: 36.4 (2.3); b: 36.9 (2.5) Baseline comparability: Yes |

Description of interventions: a: General oral and written advice regarding healthy food choices and exercise given at baseline b: Group sessions led by a nutritionist and exercise trainer providing individually tailored advice about reducing calorie intake, goal setting and self-monitoring to achieve a 10% reduction in body weight. Dietary advice and guidance for increasing physical activity tailored to each individual man. Behavioural and psychological counselling offered. Diet composition per 1000 kcal comprised carbohydrate 50–60%, protein 15–20%, total fat < 30% and fibre 18 g Timing of active intervention: a + b: 2 years – monthly visits for year 1, bimonthly visits for year 2 No. of times contacted: a + b: 18 No. allocated: a: 55; b: 55 No. completed: a: 52; b: 52 Dropout (%): a: 5.5; b: 5.5 No. assessed: a: 55; b: 55 |

Length of follow-up: 2 years Outcomes: Weight, BMI, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, erectile function, glucose |

The trial objective was to determine the effect of weight loss and increased physical activity on erectile function in obese men |

| Jeffery 1983,86,114 Jeffery 1984117 | Location: One university research centre, MN, USA Period of study: 1974–5 Inclusion criteria: Age 35–75 years, self-reported body weight > 30 lb (13.6 kg) above ideal weight Exclusion criteria: Uncontrolled diabetes, heart disease, concurrent dietary or psychological treatment, self-report of six or more alcoholic drinks per day Age (years), mean: a: (i) 52.0, (ii) 53.8, (iii) 52.4; b: (i) 54.1, (ii) 50.5, (iii) 53.8 BMI (kg/m2), mean: a: (i) 30.5, (ii) 31.8, (iii) 32.8; b: (i) 31.0, (ii) 32.3, (iii) 32.7 Weight (kg), mean: a: (i) 93.07, (ii) 99.38, (iii) 104.83; b: (i) 96.17, (ii) 102.87, (iii) 107.86 Baseline comparability: Yes |

Description of interventions: All groups participated in a 15-week educational programme emphasising reduced eating and increased exercise equally. Three levels of monetary deposit were made at the first meeting a: Individual monetary contracts: (i) US$30, (ii) US$150, (iii) US$300 b: Group monetary contracts: (i) US$30, (ii) US$150, (iii) US$300 Refunds at a rate of US$1, US$5 or US$10 per pound, up to a maximum cumulative weight loss of 2 lb per week. Individual contracts based on individual weight loss. Group contracts based on average group weight loss Timing of active intervention: 0–15 weeks No. of times contacted: a + b: 16 No. allocated: a: (i) 16, (ii) 15, (iii) 14; b: (i) 17, (ii) 14, (iii) 13 No. completed: a: (i) 16, (ii) 14, (iii) 14; b: (i) 17, (ii) 13, (iii) 12 Dropout (%): a: 2.2; b: 4.5 No. assessed: a: (i) 16, (ii) 15, (iii) 14; b: (i) 17, (ii) 14, (iii) 13 |

Length of follow-up: 2 years Outcome: Weight |

1-year data reported in Jeffery et al.;86 2-year data reported in Jeffery et al. 117 |

| Khoo 201187 | Location: Community, Adelaide, Australia Period of study: June 2007–May 2008 Inclusion criteria: BMI > 30 kg/m2, waist circumference ≥ 102 cm, type 2 diabetes mellitus, HbA1c on diet or oral medication stable for 3 months ≤ 7% Exclusion criteria: Smoker, previous or current treatment for sexual problems or lower urinary tract symptoms, glomerular filtration rate < 60 ml per minute, alcohol > 500 g per week in previous 12 months Age (years), mean (SD): a: 58.1 (11.4); b: 62.3 (5.9) BMI: NR Weight (kg), mean (SD): a: 112.7 (19.2); b: 109.6 (14.9) Baseline comparability: Poorer IIEF-5 score in a |

Description of interventions: a: Low-calorie diet: Total intake of 900 kcal per day from two liquid meal replacements consumed daily (Kicstart, Pharmacy Health Solutions), providing a maximum of 450 kcal, 0.8 g protein per kg of ideal body weight and the recommended daily allowance of vitamins, minerals and omega 3 and 6 fatty acids, plus one other small meal. After 8 weeks men changed to follow b b: High-protein, low-fat diet: Daily energy reduction of approximately 600 kcal per day. Daily consumption of 300 g lean meat, poultry or fish, three servings of cereals/breads and low-fat dairy and two servings of fruit and vegetables All men received a written plan with diet information, a menu plan, recipes and advice for cooking and eating out and all maintained their usual daily activity levels Timing of active intervention: a + b: 1 year No. of times contacted: a + b: 16–29 No. allocated: a: 19; b:12 No. completed: a: 9; b: 7 Dropout (%): a: 52.63; b: 41.67 No. assessed: a: 9; b:7 |

Length of follow-up: 1 year Outcomes: Weight, waist circumference, erectile function, adverse events |

|

| Morgan 201189 | Location: One university centre, University of Newcastle, Australia Period of study: 2007–8 Inclusion criteria: BMI 25–37 kg/m2 Exclusion criteria: History of major medical problems preventing physical activity, recent weight loss of ≥ 4.5 kg, taking medications that might affect body weight Age (years), mean (SD): a: 34 (11.6), b: 37.5 (10.4) BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD): a: 30.5 (3.0), b: 30.6 (2.7) Weight (kg), mean (SD): a: 99.2 (13.7); b: 99.1 (12.2) Baseline comparability: Yes |

Description of interventions: a: Researcher delivered one 60-minute face-to-face weight-loss information session. Participants given a self-help weight-loss programme booklet b: Researcher delivered one 75-minute information session (60 minutes on weight loss + 15 minutes’ internet instruction). Participants given self-help weight-loss programme booklet and 3 months’ online support from the study website, Calorie King. Participants received personalised online feedback and responses to any questions posted on the website noticeboard, including anecdotes and weight-loss strategies for men Weight-loss information sessions in both groups covered instruction relating to the modification of diet and physical activity habits and behaviour change, based on Bandura’s social cognitive theory Timing of active intervention: 3 months No. of times contacted: a: four times for 3-monthly assessments; b: 11 times for 3-monthly assessments and seven feedback sessions No. allocated: a: 31; b: 34 No. completed: a: 20; b: 26 Dropout (%): a: 35.5; b: 23.5 No. assessed: a: 31; b: 34 |

Length of follow-up: 12 months Outcomes: Weight change, waist circumference, BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure |

|

| Patrick 201190 | Location: Universities of California, and San Diego, San Diego State, USA Period of study: February 2004–March 2005 Inclusion criteria: BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, age 25–55 years Exclusion criteria: NR Age (years), mean (SD): a: 42.8 (8.0); b: 44.9 (7.8) BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD): a: 34.3 (4.0); b: 34.2 (4.2) Weight (kg), mean (SD): a: 104.6 (15.3); b: 104.7 (15.3) Baseline comparability: Yes |

Description of interventions: a: Wait list/general internet advice: Participants given access to a website giving general male health advice that was unlikely to produce a change in diet or physical activity (e.g. stress, hair loss, worksite injury prevention). Men were given the option to swap to the weight-loss intervention after 12 months b: Internet-based diet and physical activity advice and behavioural support; based on social cognitive theory and informed by the behavioural determinants model and designed to improve diet and physical activity in five key areas to promote weight loss, rather than directly targeting calorie restriction: increase fruit and vegetable intake to five to nine servings per day, decrease saturated fat intake to ≤ 20 g per day, increase wholegrain intake to three or more servings per day, increase physical activity to > 10,000 steps per day using a pedometer for at least 5 days per week and participate in upper and lower body strength training at least twice per week Men met with a case manager to set goals at baseline and completed weekly web-based activities, including behaviour change skills and reading diet and physical activity information. Men also had the opportunity to e-mail study experts (dietitian, physical activity expert and a clinical psychologist). Both groups paid US$20 for completing 6 months and US$100 for completing 12 months Timing of active intervention: 12 months No. of times contacted: a: 3; b: 55 No. allocated: a: 217; b: 224 No. completed: a + b: 309 Dropout (%): a + b: 29.9 No. assessed: a: 217; b: 224 |

Length of follow-up: 12 months Outcomes: weight, BMI |

Trial conducted focus groups with men and two weight-loss experts to tailor the intervention for men (not published) |

| Pavlou 198991 (main trial) | Location: One university centre, Boston University Medical Centre, MA, USA Period of study: NR Inclusion criteria: Male, age 26–52 years, euthyroid, free from any physical, psychological or metabolic impairment Exclusion criteria: NR Age (years), mean (SD): a: 41.5 (7.59); b: 42.9 (6.63); c: 45.1 (10.0); d: 49.6 (8.4); e: 41.8 (10.44); f: 41.8 (7.57); g: 46.1 (9.33); h: 44.5 (9.6) (completers) BMI (kg/m2), mean: a: 32.54; b: 32.4; c: 32.07; d: 31.5; e: 30.13; f: 34.82; g: 31.89; h: 33.78 (completers) Weight (kg), mean, SEM (SD): a: 103.1, 3.1 (9.80); b: 105.0, 4.4 (14.59); c: 100.8, 2.3 (9.2); d: 98.8, 2.6 (10.4); e: 96.1, 3.3 (10.44); f: 103.0, 3.7 (13.34); g: 100.8, 2.3 (9.76); h: 105.7, 3.4 (13.6) (completers) Baseline comparability: Yes |

Description of interventions: Subjects were randomly assigned to four diets and exercise and non-exercise groups for 8 weeks Exercise consisted of a 90-minute supervised exercise programme three times a week from baseline to week 8, which consisted of 35–60 minutes of aerobic activity, e.g. walk–jog–run (70–85% max. heart rate), calisthenics and relaxation techniques. Non-exercise groups were instructed to continue normal daily activity and not to participate in any form of additional supervised and/or unsupervised physical activity during the initial 8 weeks a: Balanced caloric-deficit, low-calorie diet (BCDD). 1000 kcal per day selected from usual four food groups in quantities thought to meet basic requirements b: BCDD + exercise c: Protein-sparing modified fast, low carbohydrate (PSMF). Ketogenic diet of meat, fish and fowl used as only dietary source to provide equivalent of 1.2 g high biological value protein per kg of ideal body weight or 1000 kcal per day, no carbohydrate and all fat ingested from meat, fish and fowl. Participants prescribed 2.8 g potassium chloride daily d: PSMF + exercise e: DPC-70: A very low-calorie diet of 420 kcal powdered protein carbohydrate mix derived from calcium caseinate, egg albumin and fructose, formulated with vitamins and minerals to meet the US recommended dietary allowances (RDA) dissolved in water or other non-caloric liquid. Fat content zero. Participants instructed to consume five packets a day and to consume no other nutrients. Participants prescribed 2.8 g potassium chloride daily f: DPC-70 + exercise g: DPC 800: A very low-calorie diet of 800 kcal per day provided in powdered form consumed similarly to DPC-70, providing a complete mixture of nutrients and similar nutritionally to BCDD except for fewer calories h: DPC-800 + exercise All participants attended weekly education sessions up to week 8 that included behaviour modification, diet and general nutrition and exercise education. All participants were given multivitamins and daily food and activity records up to week 8. Non-caloric liquids, including coffee, were allowed in unrestricted amounts Timing of active intervention: 8 weeks + 18 months’ follow up No. of times contacted: a–h: 11 times, weekly 0–8 weeks then at 8 and 18 months No. allocated: 160 men (20 in each intervention group) No. completed: a: 10; b: 11; c: 16; d: 16; e: 10; f: 13; g: 18; h: 16 (18 months post treatment) Dropout (%): 31 (18 months) No. assessed: a: 10; b: 11; c: 16; d: 16; e: 10; f: 13; g: 18; h: 16 (18 months; completers) |

Length of follow-up: 18 months Outcomes: Weight, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, systolic and diastolic blood pressure |

|

| Pavlou 198991 (pilot) | Location: As above Period of study: As above Inclusion criteria: As above Exclusion criteria: As above Age (years), mean (SD): a: 49.2 (6.48); b: 44.8 (7.84); c: 46.1 (5.14); d: 48.1 (4.65) (data for completers) BMI (kg/m2), mean: a: 31.75; b: 31.92; c: 31.11; d: 30.4 (completers) Weight (kg), mean (SEM): a: 102.3 (2.1); b: 99.2 (4.2); c: 101.7 (3.1); d: 97.3 (4.1) Baseline comparability: Yes |

Description of interventions: As above but a, b, c and d only Timing of active intervention: 12 weeks No. of times contacted: 16 times, weekly 0–12 weeks and then at 6, 18 and 36 months No. allocated: a–d: 24 No. completed: a: 5; b: 6; c: 5; d: 5 (36 months post treatment) Dropout (%): 13 (36 months post treatment) No. assessed: a: 5; b: 6; c: 5; d: 5 (36 months post treatment) |

Length of follow-up: 162 weeks Outcome: Weight |

|

| van Aggel-Leijssen 2001,92 van Aggel-Leijssen 2002,118 Lejeune 2003119 | Location: One university research department, Maastricht, the Netherlands Period of study: Not reported Inclusion criteria: Good health, ≤ 2 hours per week of sports activities, stable body weight over previous 3 months (< 3 kg change) Exclusion criteria: Physically demanding job, taking medication known to influence measured variables Age (years), mean (SD): a: 38.6 (6.5); b: 39.3 (7.7) BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD): a: 32.0 (2.1); b: 32.6 (2.5) Weight (kg), mean (SD): a: 103.6 (11.7); b: 102.6 (9.8) Baseline comparability: Yes |

Description of interventions: a: 12-week energy restriction period followed by 40-week weight-maintenance period: Weeks 1–6: Very low energy diet of 2.1 MJ per day protein-enriched formula diet (Modifast, Novartis) consisting of 50 g carbohydrate, 52 g protein, 7 g fat Weeks 7–8: 1.4 MJ per day formula + 3.5 MJ per day free choice Weeks 9–10: 0.7 MJ per day formula + 4.9 MJ per day free choice Weeks 11–12: Participants received dietary instruction to stabilise their body weight and not to change their habitual activity pattern b: 12-week energy restriction period (as in a) combined with an exercise training programme [40% maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max.)] for 1 hour, four times a week – cycling, walking or aqua-jogging (three sessions supervised by a personal trainer in the lab and one session at home). Exercise training programme continued during the weight-maintenance period to week 52 Timing of active intervention: a: weeks 0–12; b: weeks 0–12 No. of times contacted: a: 12 times at weekly intervals; b: 168 times up to four times per week for 52 weeks No. allocated: a: 20; b: 20 No. completed: a: 15; b: 14 Dropout (%): a: 25; b: 30 No. assessed: a: 15; b: 14 |

Length of follow-up: 52 weeks Outcomes: Weight, BMI |

|

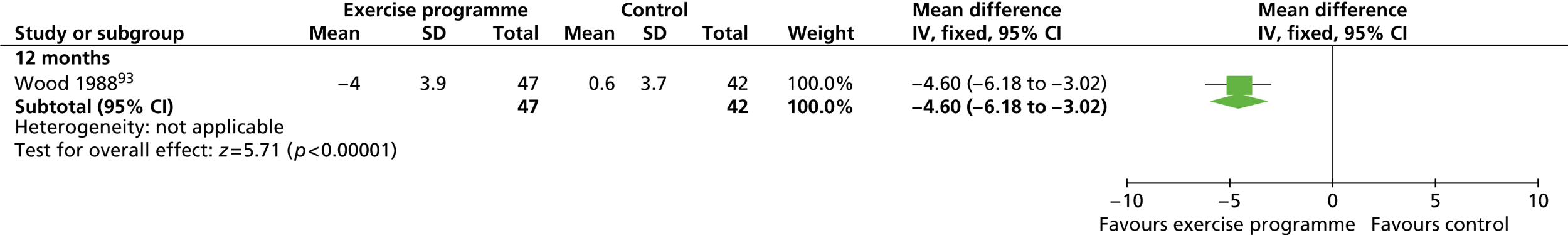

| Wood 1988,93 Fortmann 1988115 | Location: One research centre, Stanford, CA, USA Period of study: NR Inclusion criteria: 120–160% ideal body weight, non-smoker, plasma total cholesterol < 8.28 mmol/l, triglycerides < 5.65 mmol/l, normal electrocardiogram, alcohol intake less than four drinks per day, sedentary activity, weight stable (±5 lb) over the past year Exclusion criteria: Blood pressure > 160/100 mmHg, taking medications affecting lipids, plasma cholesterol > 300 mg/dl, triglycerides > 500 mg/dl, exercise three or more times per week Age (years), mean (SD): a: 45.2 (7.2); b: 44.2 (8.2); c: 44.1 (7.8) BMI: NR Weight (kg), mean (SD): a: 95.4 (10.6); b: 93.0 (8.8); c: 94.1 (8.6) Baseline comparability: Yes |