Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 05/52/03. The contractual start date was in January 2010. The draft report began editorial review in May 2013 and was accepted for publication in October 2013. The project was jointly funded by the HTA programme and the European Commission. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

This report presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the HTA programme or the Department of Health.

Declared competing interests of authors

Both authors work for the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Evaluation, Trials and Studies Co-ordinating Centre. EUnetHTA project is supported by a grant from the European Commission. Both authors were members of the EUnetHTA Executive Committee from April 2008 until December 2012, which includes the period when this evaluation was undertaken. This committee had overall responsibility for the delivery of the EUnetHTA JA, of which the work described in this monograph is a part.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Woodford Guegan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

General introduction

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme [represented by the NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Co-ordinating Centre (NETSCC)] was invited to join the European network for Health Technology Assessment Joint Action (EUnetHTA JA) project 2010–12. Participation in this project was part-funded by the European Union (EU) Commission and the NIHR HTA programme.

The authors from NETSCC took on formal roles in three work packages under two broad activities.

Evaluation of the processes of the European network for Health Technology Assessment Joint Action project

It is important that such a project is appropriately evaluated and lessons learnt for future initiatives. A work package was included in the project to consider this and NETSCC was invited to lead it. This was our primary role within the EUnetHTA JA project.

The Directorate-General of the European Commission for Health and Consumers (DG SANCO) requires a process evaluation (rather than an outcome valuation) for all its funded projects. We undertook this role, but extended it slightly by offering some evaluation work to other work packages.

Informing clinical decision-makers about clinical research studies under development: development of a data set to inform a registry

Broadly speaking there are two methods for performing HTA: prospective clinical studies and retrospective systematic reviews. The majority of EU member organisations of the EUnetHTA JA perform only systematic reviews. In addition to these, the UK NIHR HTA programme has a strong history of conducting prospective clinical studies. The Netherlands also commissions such clinical studies and Norway, France, Italy and Portugal have mechanisms to request them. Having a database registry of planned prospective clinical studies would prevent duplication of effort and enable alignment of trial designs to produce more outcome data. It would also be of benefit to those EUnetHTA JA project participants who only perform systematic reviews – they would know when primary research was due to finish and could align the start of their systematic reviews accordingly. It is important that such a registry contains the appropriate data fields and the UK NIHR HTA programme led an activity to compile such a data set. This workstream was within the work package concerned with the production of additional evidence for new technologies [work package 7 (WP7)].

Both activities were performed by the NETSCC using the principles of project management and are described in detail in the following chapters.

Evaluation of the European network for Health Technology Assessment Joint Action project

Health technology assessment in the United Kingdom

Health technology assessment has been described as ‘the provision for health-care decision-makers of high-quality research information on the cost, clinical effectiveness and broader impact of health technologies. Health technologies are . . . all interventions offered to patients’. 1 The findings of applied research studies are vital in supporting an effective and efficient health system. 2

Early attempts to improve health-care decisions in the UK’s NHS were aided by the publication of Effectiveness and Efficiency: Random Reflections on Health Services by Cochrane in the early 1970s. 3 This influential book identified the lack of good-quality data to guide health decisions and highlighted the randomised controlled trial (RCT) as the most reliable assessment method. The UK’s NIHR Health Technology Assessment programme (formerly the NHS Health Technology Assessment programme) was established in the UK in 1993 with the purpose of producing such information for NHS clinicians. 1 It commissions both evidence syntheses and RCTs.

Previous European Union initiatives in health technology assessment

The EU Commission recognised HTA as a key tool in making health-care decisions. 4 It supported HTA-related studies in the 1980s and this continued throughout the 1990s and 2000s:

-

EUR-ASSESS 1994–7: This represented the first of a number of initiatives which aimed to form a European network for HTA. It investigated harmonisation of HTA methodology, priority-setting processes, strategies for disseminating results and issues on how to link the results of HTA to coverage. 5

-

HTA Europe 1997–8: The main activity of HTA Europe was to describe the HTA processes and health systems of all members of the European Union. These reports were published in the International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care. 6

-

ECHTA/ECAHI (the European Collaboration for Assessment of Health Interventions and Technology) 2000–2: This informal network provided the benefits of working together, sharing information, providing education and training and sharing methodologies. 7

European network for Health Technology Assessment 2006–8

In 2005 the EU called for proposals for projects to establish a European network for HTA. A group led by the Danish Board of Health was invited to bid for this work, with the goal of developing a set of tools to facilitate co-operation. Following this the EUnetHTA 2006–8 project was formed based on a contract funded by an EU grant. This project aimed to ‘create an effective and sustainable network for HTA across Europe that could develop and implement practical tools to provide reliable, timely, transparent and transferable information to contribute to HTAs in member states’. 8

Project structure

The project was divided into eight work packages co-ordinated by a secretariat:

-

co-ordination

-

communications

-

evaluation

-

common core HTA

-

adapting existing HTAs from one country into other settings

-

transferability of HTA to health policy

-

monitoring development for emerging new technologies and prioritisation of HTA

-

system to support HTA in member states with limited institutionalisation of HTA.

Thirty-four associated partners (contributing to the budget and receiving a share of the grant) and 30 collaborating partners (participating at their own expense) contributed to the project. A 3-year work plan was devised and followed. 8 Governance was through a steering committee (consisting of all associated partners) and an executive committee (consisting of all work package lead partners).

Project deliverables

The main project deliverables were practical tools for conducting HTA. The two tools of potentially immediate use to most HTA agencies were:

-

The core model: This is intended to serve as a platform to aid co-operation in developing a new HTA report. 9 It describes a number of domains (e.g. clinical, economic, etc.). The underlying idea is that different HTA organisations can prepare each domain then enter their findings into a central library. Each individual national organisation can then prepare its own local report for its own health economy by drawing mainly on material contained within the central library (with minor modifications to fit local idiosyncrasies).

-

The adaptation toolkit: This toolkit helps HTA practitioners convert a report between different health-care settings by working through a number of domains. 10,11

Evaluation of the European network for Health Technology Assessment 2006–8 project

Internal evaluation of the EUnetHTA project was an essential requirement of the EU and was the subject of work package 3. This had three objectives:

-

to provide an audit function during the project with regular feedback to the European Commission and the project organisation

-

to evaluate changes over time during the project period to show development towards the establishment of an effective and sustainable network

-

to summarise lessons learned to support the effectiveness and sustainability of the network in its next phase, from 2009 and onward.

The prospective evaluation consisted of three approaches: annual surveys of project participants, twice-yearly interviews with work package leads and documentary analysis of work packages. 12 It concluded that the project had been successful in developing tools that describe a standard for conducting and reporting HTAs and this should facilitate greater international collaboration. Support was evident for a future network. 12

The evaluation report included nine recommendations for a future sustainable network:

-

Secure funding, and maintain a dedicated co-ordinating secretariat.

-

Improve efficiency through an organisational structure made up of work packages managed by a core of dedicated partners, with less committed partners taking part as a wider review group.

-

Continue developing and evaluating the tools as necessary.

-

Involve people in the work to ensure commitment, a high level of knowledge and a broad basis for decision-making processes.

-

Encourage collaboration and communication among all parties to ensure coherence within groups and EUnetHTA.

-

Continue developing the communication platform and functionality of the clearinghouse to make EUnetHTA a central reference point for HTA in Europe.

-

Arrange face-to-face meetings, particularly at the start of group or committee work to strengthen social coherence and reach a common understanding of the work.

-

Evaluate the tools used in real setting and the technical communication platform.

-

English should continue to be the main language.

Evaluation of the European network for Health Technology Assessment collaboration

After the completion of the project at the end of 2008, a number of the partners decided to maintain the network and relationships which had been established over the previous 3 years. This collaboration was established by 25 founding partner organisations from 13 EU member states, Norway and Switzerland. The main output from this year was an application for funding to DG SANCO’s call for a joint action in the field of public health, which became the first EUnetHTA JA.

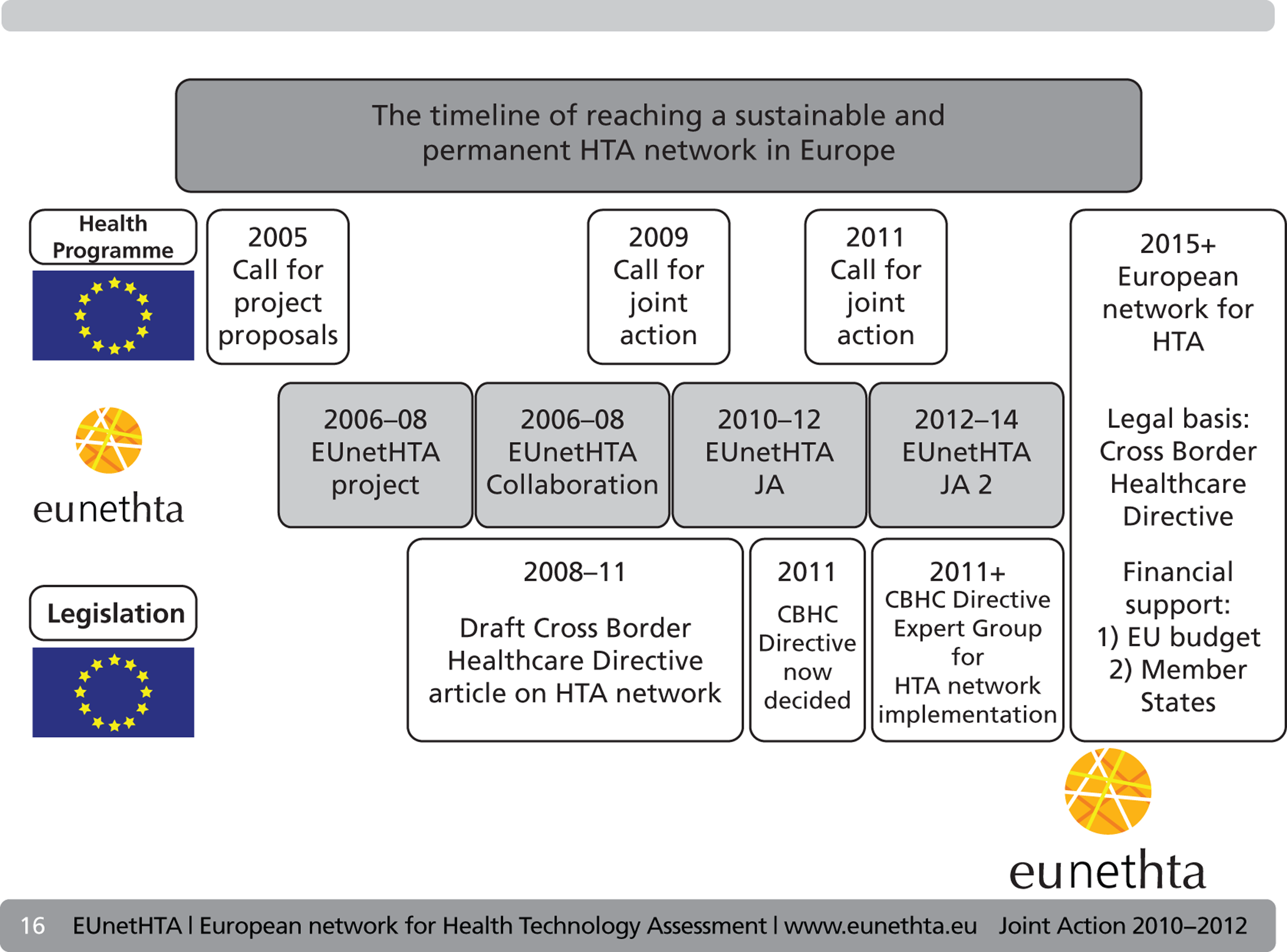

European network for Health Technology Assessment Joint Action: description of the project

The EUnetHTA JA was a further project funded by DG SANCO, with an overall aim of producing a self-sustaining ongoing European collaboration in HTA. It aimed to ‘ensure the completion and development of HTA in the EU, including work on relative effectiveness of drugs’. Collaboration between the EU Commission and member state-appointed HTA agencies resulted in the establishment of a 3-year joint action project (2010–12), which EUnetHTA was asked to perform. At its investure it was foreseen that sustainability following the project would be ensured through an EU directive. 8

The EUnetHTA JA project was based on a contract of a funding grant with the EU Commission DG SANCO (2009 23 02 – EUnetHTA Joint Action) which specified what it must achieve. The technical annex of the grant agreement described the action as ‘exchanging knowledge and best practice’ with the subaction, ‘Building on the expertise already developed in the field of health technology assessment, ensure the continuation and development of HTA in the EU, including work on relative effectiveness (RE) of drugs’. It is important to make explicit the context of EUnetHTA within local political procedures. The strategic position of the EUnetHTA JA is that ‘its outputs will be used to inform, but not mandate the content of national/regional/institutional HTA reports’. 13

Aims and objectives of the European network for Health Technology Assessment Joint Action project

The project had three aims:13

-

to facilitate the efficient use of resources available for HTA

-

to create a sustainable system of HTA knowledge sharing

-

to promote good practice in HTA methods and processes.

The overarching objective of the EUnetHTA JA was to ‘establish an effective and sustainable HTA collaboration in Europe that brings added value at the regional, national and European level’.

This was separated into three specific objectives:13

-

Development of a general strategy and a business model for sustainable European collaboration on HTA. Specifically, this involves constructing a business model for collaboration addressing the sustainability of the HTA collaboration within the EU.

-

Development of HTA tools and methods. Specifically, developing principles, methodological guidance and functional online tools and policies.

-

Application and field-testing of developed tools and methods. Specifically, testing and implementation of tools and methods.

Project participant health technology assessment agencies

At its commencement in autumn of 2012 the EUnetHTA JA comprised 38 government-appointed organisations from 26 EU member states, Norway and Croatia. Organisations who were members of the EUnetHTA JA were either associate partners (which received 50% funding from the EU grant and 50% from national resources) or collaborating partners (who participated in the project at their own expense). The main partner was the Danish Health and Medicines Authority, which also led the secretariat.

European network for Health Technology Assessment Joint Action: project structure

The work of the EUnetHTA JA was divided into eight work packages: three cross-cutting and five stand-alone ( Table 1 ).

| Work package | Title | Aim |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Co-ordination | To facilitate the achievement of the EUnetHTA JA general objective of putting into practice an effective and sustainable HTA collaboration in Europe that brings added value at the European, national and regional level |

| 2 | Communication | To facilitate coherent, effective and sustainable external communication of the EUnetHTA JA, where its aims, objectives, work in progress, results and final products are known to all partners, identified stakeholders and target groups in the EU and at a national regional level |

| 3 | Evaluation | To identify to what extent the individual work packages enable the EUnetHTA JA to meet its objective |

| 4 | Core model | Further development and testing of the core model developed in the project 2006–8 |

| 5 | Relative effectiveness assessment of pharmaceuticals | To apply the concepts developed in the core model to provide methods to test the relative effectiveness of pharmaceuticals |

| 6 | Information platform | Developing the tools and internal communication platform to support the other work packages |

| 7 | New technologies | To support collaboration on new technologies and to contribute to reducing duplication of work by:

|

| 8 | Business plan | Construction of a detailed business model for collaboration addressing the sustainability of the HTA collaboration within the EU |

All work packages had a lead partner agency that was responsible for submitting the 3-year work plan for the work package, delivering its deliverables and reporting via the annual technical reports. WP2, WP4, WP5 and WP7 also had a co-lead partner agency.

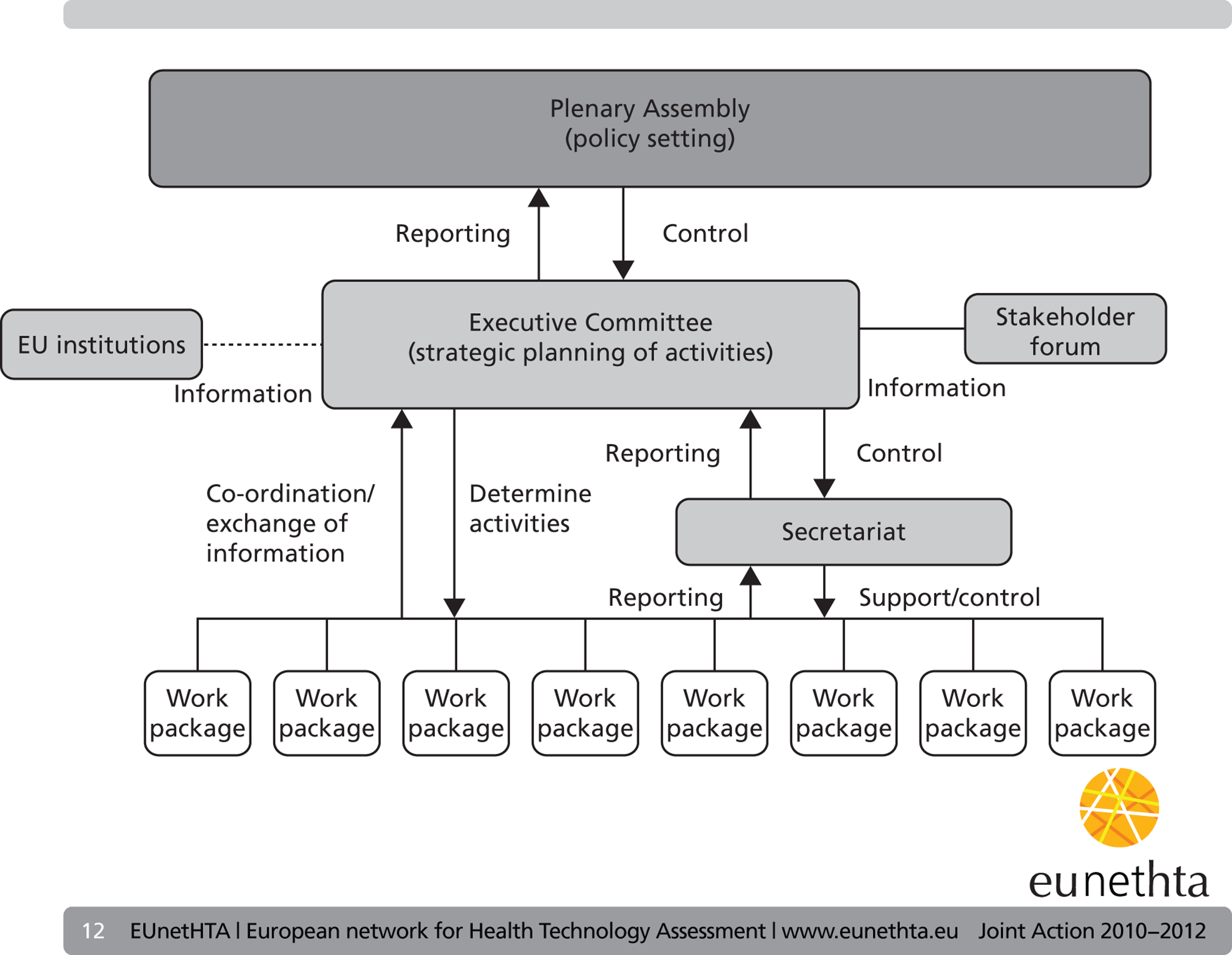

The governance structure is outlined in Figure 1 .

FIGURE 1.

The governance structure of the EUnetHTA JA. (Reproduced from www.eunethta.eu with permission from EUnetHTA secretariat).

Executive committee

The executive committee was composed of the lead partners of the eight work packages, the chairperson of the plenary assembly (a non-voting member) and three elected members (from the EUnetHTA JA member agencies). This committee was the main executive body involved in strategic leadership of the project. Regular face-to-face meetings were held and e-meetings were held every 2 months.

Plenary assembly

The plenary assembly was the main governance and policy-setting body of the EUnetHTA JA. It was composed of the head of each partner organisation (or their representative). The chairperson was elected by plenary assembly members and ensured liaison between the executive committee and the plenary assembly. This annual meeting was of crucial importance because it represented the only meeting of all project organisations and its function was to agree policy.

The stakeholder forum

In formation of the EUnetHTA JA the EU Commission emphasised the importance of giving a greater focus to stakeholders than had been given during the EUnetHTA 2006–8 project. The stakeholder forum was established in 2010 to facilitate information exchange with the stakeholders and was part of the governance structure for the EUnetHTA JA.

European umbrella organisations, with four types of expertise, were invited to apply to join the stakeholder forum: industry, patients/consumers, providers and payers. Despite several attempts it was not possible to recruit experts to the health media category. Some eligible organisation that were approved for participation in the EUnetHTA JA stakeholder forum were not selected for the final list of the EUnetHTA JA stakeholder forum members because of the limitation of the number of seats per stakeholder group. These organisations received all the information that was circulated to members of the stakeholder forum. They were able to provide written comments on such documents through representative organisations on the forum or via the secretariat. Expertise was represented as follows.

Industry

-

The European Co-ordination Committee of the Radiological Electromedical and Healthcare IT Industry (COCIR).

-

The European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA).

-

The European Generic Medicines Association (EGA).

-

Eucomed.

Four organisations applied to be members of the stakeholder forum, but were unsuccessful in gaining a place:

-

Association of the European Self-Medication Industry (AESGP)

-

European Diagnostic Manufacturers Association (EDMA)

-

EuropaBio

-

The European Association of Pharmaceutical Full-line Wholesalers (GIRP).

Patients/consumers

-

The European Consumers’ Organisation (BEUC).

-

The European Cancer Patient Coalition (ECPC).

-

The European Patients’ Forum (EPF).

-

The European Rare Diseases Organisation (EURORDIS).

An additional organisation applied to join the EUnetHTA JA stakeholder forum, but was unsuccessful in gaining a place:

-

The European Federation of Neurological Associations (EFNA).

Providers

-

The Standing Committee of European Doctors (CPME).

-

European Hospital and Healthcare Federation (HOPE).

Payers

-

Association Internationale de la Mutualité (AIM).

-

European Social Insurance Platform (ESIP).

European network for Health Technology Assessment Joint Action: project deliverables

There were eleven project deliverables, which are shown in Table 2 .

| Number | Title | Description | Work package responsible | Month of delivery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | An online tool and service for producing, publishing, storing and retrieving HTA information | It facilitates the use of the paper-based HTA Core Model developed previously, allowing to produce, publish, store and retrieve core HTAs and other HTA information not included in core HTAs. It supports production of local reports using core HTAs | WP4 | December 2012 |

| HTA Core Model on screening | A new application of the HTA Core Model | WP4 | March 2011 | |

| 2 | A set of two core HTAs | Two completely new core HTAs on topics that are pertinent to several HTA agencies and that can be utilised when producing local HTA reports on the same topics | WP4 | December 2012 |

| 3 | A methodological guidance that will be appropriate for the assessment of relative effectiveness of pharmaceuticals | A common methodology for REA of pharmaceuticals consisting of a tutorial that describes the fundamental principles of REA and a toolbox that can be used in daily practice for REA in standardised fashion | WP5 | December 2012 |

| 4 | Operational web-based toolkit including database-containing information on evidence generation on new technologies | Database including information on:

|

WP7 | September 2012 |

| 5 | Quarterly communication protocol for information flow on ongoing/planned national assessments of same technologies | Protocols containing information on ongoing/planned national assessments of identical and therefore alerted topics, to facilitate the analysis of hindrances and chances of collaboration on specific topics | WP7 | December 2012 |

| 6 | IMS and the related documentation, processes and policies | The IMS provides a single point of access ensuring compatibility to resources that help to conduct HTA, with emphasis on automation of the content update processes | WP6 | September 2012 |

| 7 | Communication and dissemination plan | Building on the communication strategy developed during EUnetHTA 2006–8 project, an elaborated communication and dissemination plan will be written and implemented as part of the EUnetHTA JA | WP2 | June 2011 |

| 8 | Stakeholder policy | Development of a stakeholder involvement policy | WP1/WP8 | October 2010 |

| 9 | Collaboratively developed business model for sustainability | Development of a collaborative business model for sustainability | WP8 | December 2011 |

| 10 | A relative effectiveness assessment of a (group of) pharmaceutical(s) | As a part of methodological guidance development and in line with the core-HTA development | WP5 | March 2012 |

| 11 | Final report from the EUnetHTA JA | Final report including evaluation results | WP3 | December 2012 |

Tools

Tools were developed during the EUnetHTA JA to help the production of HTA reports and collaboration in HTA:

-

EUnetHTA Planned and Ongoing Projects Database (POP; Ludwig Boltzmann Institute, Vienna, Austria): This database was developed during the new technologies work package (WP7). It aims to reduce duplication in HTA production and to facilitate collaboration between HTA agencies. During 2010 it was available as an Microsoft Excel datasheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and was converted into a database in 2011. Access to the POP database was restricted to those EUnetHTA Partners who contributed data.

-

HTA Core Model: This online tool aims to help with the production, storage and utilisation of structured HTA information. It was developed during the EUnetHTA 2006–8 project and work continued in EUnetHTA JA in the HTA Core Model work package (WP4).

-

EVIdence DatabasE on New Technologies (EVIDENT): The EVIDENT was developed from the EUnetHTA Interafe to Facilitate Furthering of Evidence Level (EIFFEL) database which was developed during the EUnetHTA 2006–8 project. It allows the sharing of information about promising new health technologies, remaining evidence gaps, recommendations or requests for further information and additional data being collected.

Informing clinical decision-makers about clinical research studies under development: development of a data set to inform a registry

The number of clinical trials is increasing yearly and many are undertaken for regulatory purposes. These are explanatory in nature, thereby identifying whether or not an intervention can produce the desired effect under ideal conditions. 14 Such trials tend to be small in scale or involve investigational interventions which are not in wide clinical use. By their nature they take place within small communities of investigators. They are often funded by manufacturers or research charities – organisations with no wider responsibility beyond their shareholders or donors. 15

However, there is progressive growth and interest in pragmatic trials (and other prospective study designs) which are designed to deliver clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness information to directly inform policy, commissioning and clinical decision-makers. Pragmatic studies reflect the actual environment in which clinical practice occurs and create robust evidence to inform these decision-makers,16,17 including organisations such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK. These studies are often large and expensive – as they often involve active comparators and ‘soft’ concepts such as ‘usual care’ and ‘best current treatment’. 18 They are often commissioned through publicly funded research management organisations, such as the NIHR in the UK and, hence, these funders must consider taxpayer value for money in their decision-making processes. This is money which if not spent on medical research would, in all likelihood, have been spent on direct clinical care. It behoves such funders to be aware of the activities of their counterparts in other international funding agencies so as not to commission work when the answers would be available elsewhere.

For established, funded clinical trials the scenario is simple. All such studies should be entered into one of a number of international clinical trials registries, such as ClinicalTrials at the National Institute of Health and Current Controlled Trials. Among other benefits, this enables:

-

triallists to see what work is under way in their field

-

clinicians to identify trials in which they might like to take part or enrol their patients

-

reviewers and policy-makers to assess publication bias, by using registered trials as a denominator.

Some funders make this a condition of funding and many journals will only publish studies which have been prospectively registered. 19,20 A funder, therefore, only has to check a limited number of registries for overlapping studies to become aware of what is already under way in a field and decide if it is sufficiently similar to what is planned.

The scenario is much more complex for pragmatic trials when earlier in their gestation. A trial is effectively invisible outside the organisation which may fund it when it is anywhere in its life from a funder having an idea or receiving an application through to a short period of time after a funding decision. Importantly, this runs the risk of multiple funders accidentally spending their limited resource on similar studies – which, perversely, may not be similar enough to allow subsequent meta-analysis of outcomes. Existing registries go part way to addressing this need by allowing funders to identify trials that are under way. However, there remains a gap because there is no widely used registry that tracks trials in development. Therefore, funders run the risk of developing trials in parallel, which may have been avoided or ameliorated if they had been aware of parallel activity.

An example of limited alignment of outcome measures is illustrated by the SOLD (Synergism or Long Duration), PERSEPHONE (Phase III Randomized Study of Neoadjuvant or Adjuvant Trastuzumab (Herceptin®) in Women With HER2-Positive Early Breast Cancer) and PHARE (Protocol of Herceptin Adjuvant With Reduced Exposure, a Randomised Comparison of 6 Months vs 12 Months in All Women Receiving Adjuvant Herceptin) trials, which were all funded around 2006. 21,22 These studies all compared the use of various durations of trastuzumab (Herceptin®, Genentech), using patient relevant outcomes and were, in essence, pragmatic in design. The commissioned trials are comparatively ‘stand alone’. None of their primary outcomes were directly comparable – they used different measures, and those with similar measures assessed them at different end points. It is likely that had the agencies been aware of these trials in parallel development, they could have included appropriate outcome measures to facilitate meta-analysis or other comparison between them.

An example of what should be possible is the interaction between the CATT (Comparison of Age-Related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials) and IVAN [A randomised controlled trial (RCT) of alternative treatments to Inhibit VEGF in patients with Age-related choroidal Neovascularisation (IVAN)] trials. 23–25 These trials investigated the use of ranibizumab and bevacizumab (Avastin®, Genentech) in the management of wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Briefly, both agents are manufactured by the same drug company. Ranibizumab is licensed for the management of wet AMD and bevacizumab is not. Ranibizumab is approximately two orders of magnitude more expensive. There were good biological reasons to believe that both drugs would have similar clinical effectiveness in the management of wet AMD. Discussion between the trial teams during the design and set up of these trials led to an agreed set of primary and secondary outcome measures and a subsequent demonstration that neither drug is superior to the other. Given the hostility of the pharmaceutical industry towards these trials (and the implication of their findings for industry profit margins), the similar results demonstrated against the same outcome measures will give commissioners added confidence should they decide to commission a service based on the cheaper (and, hence, more cost-effective) agent.

There is, therefore, a need for a system to facilitate the identification of pending similar pragmatic studies by international trial funders. This would enable optimisation of scarce public resources – both financial, and in terms of patients and researchers. Desbiens suggested that a ‘Registry of Hypothesis’ should be developed and shared by the medical community. 26 It seems to us that such a registry is too far divorced from the reality of actual funding of a trial – there are many ideas but not all are worth committing resources to. In addition, to a funder, what is important is not who had an idea, but who else might be funding a relevant trial.

It was therefore considered that a registry of ‘trials which funders are considering’ could have potential for filling this gap, and led to several opportunities:

-

Funders could commit to one multinational study, rather than multiple smaller studies.

-

Funders could ensure that at least some outcome data in multiple studies would be directly comparable – thus facilitating meta-analysis.

-

On a global basis, this would facilitate an optimum distribution of trial funding, e.g. knowledge of what each funder had planned could facilitate interfunder discussion to obtain maximum value from the resources each had to contribute.

-

With an indicative map of possible trials, systematic reviewers may be able to better plan when to conduct updates of existing reviews.

-

Similarly, policy-makers may be able to plan when to consider updates of their guidance.

Such a registry could (indeed, should) include the hypothesis to be tested, therefore addressing Desbiens’ call for hypotheses to clearly be developed a priori. 26

We considered who such a registry should be aimed at and, specifically, who should register potential studies and who should have read access. The two options are funders and researchers. The incentives and disincentives are different for the two groups.

Funders are motivated to avoid unconscious duplication of funding and maximise the value of the overall research resource they control. They are, therefore, more likely to register studies they are considering with a registry and keep that information up to date.

A researcher might feel this, but is also driven to obtain funding for their own ideas and, hence, avoid the risk of having their research ideas copied by others. We considered that an individual researcher is less likely to submit their ideas to a public registry.

Therefore, we consider that a registry for pragmatic trials in development is more likely to work if the main adopting groups are trial funders.

Should a registry go ahead, consideration should be given to its performance characteristics, but also whether or not it contributes to the originally identified issues of reducing unconscious duplications and promoting discussion and potentially collaboration between funders.

Chapter 2 Methods

Evaluation of the processes of the European network for Health Technology Assessment Joint Action project

Evaluation approach

Internal evaluation process

Evaluation is an important facet of project management and evaluation of the EUnetHTA JA was a requirement of the EU. There are two types of evaluation: internal evaluation (performed by staff directly involved in the project work) and external evaluation (performed by an expert who is not involved in the project). The EU Commission had specified that the former approach should be used, as it had been used in the previous EUnetHTA 2006–8 project. As recommended in conducting evaluations of European projects, the evaluation plan was a key component and integrated within the EUnetHTA JA project from the beginning. 27

These activities were the subject of a specific work package [WP3 (Evaluation)], led by the NETSCC represented by Dr Eleanor Guegan and Dr Andrew Cook.

Strategic evaluation outcome

Rationale

Evaluation has been defined as, the ‘systematic assessment of the operation and/or the outcomes of a program or policy, compared with a set of explicit or implicit standards, as a means of contributing to the improvement of the program or policy’. 28 Such critical reflection can be performed retrospectively (after the programme has ended) or prospectively (designed at the start of the programme). A prospective methodology is the gold standard for evaluation research and was used to evaluate the EUnetHTA JA.

Project evaluation allows monitoring of the processes of the project and achievements against specified criteria for success. This enables assessment of the effectiveness and achievements of the project and the formation of ‘lessons learned’ recommendations to inform future projects. It also ensures accountability against project plans. 29 There are three main types of evaluation for projects:29

-

Formative evaluation: This ongoing evaluation starts early in the project and assesses the nature of the project, the needs that the project addresses and monitors the progress of the project. It identifies gaps in the content and operational aspects.

-

Process evaluation: This monitors the project to ensure it is being completed as designed and to the time schedule.

-

Summative evaluation: This is an overall assessment of the project’s achievements and the effectiveness of its processes. It is completed at the end of the project and provides evidence to support the performance of future projects.

The first stage in the evaluation process was creating a project evaluation plan. The main purpose of the evaluation was to identify to what extent the individual work packages enabled the EUnetHTA JA to meet its objectives. This included project participants’ and external stakeholders’ perception of the project processes and deliverables. Documentary review enabled identification about whether or not the deliverables had been produced by the work streams according to the work plan.

This evaluation was a systematic data collection designed to develop generalisable knowledge and to contribute to quality improvement of the EUnetHTA JA project:

-

The impact of the project was assessed by an outcome evaluation (identifying the success of delivering the stated project deliverables). However, it should be noted that, although it was possible to measure whether or not the outputs had been delivered in accordance with the work plan, assessment of their quality and cost–utility was beyond the scope of the evaluation agreed by the EU Commission.

-

The effectiveness of the project was evaluated by its processes (identifying the effectiveness of the processes employed during the project).

Evaluation questions

There were two primary evaluation questions:

-

Will the EUnetHTA JA achieve its overarching objective, and ultimately did it?

-

The overall objective was defined in the technical annex for the EUnetHTA JA as, ‘The overarching objective of the JA, including work on relative effectiveness of pharmaceuticals, is to put into practice an effective and sustainable HTA collaboration in Europe that brings added value at the European, national and regional level.’

-

This was assessed by whether or not an effective and sustainable HTA collaboration, not reliant on project funding, had been set up at the end of the EUnetHTA JA project.

-

-

Will the EUnetHTA JA achieve its specific objectives, and ultimately did it?

-

Three subobjectives were defined in the technical annex of the grant agreement for the EUnetHTA JA13 as:

-

– Development of a general strategy and a business model for sustainable European collaboration on HTA.

-

– Development of HTA tools and methods.

-

– Application and field-testing of developed tools and methods.

-

Documentary analysis was used to determine whether or not the work packages had produced their deliverables by the end of the EUnetHTA JA project.

-

A prospective evaluation strategy mapped out and evaluated how the activities and deliverables of the individual work packages supported the EUnetHTA JA objectives. The individual work packages within the EUnetHTA JA can themselves be seen as individual projects (with their own objectives, milestones and deliverables) contributing to the overall programme of work of the EUnetHTA JA. This means it was necessary to aggregate evaluation outcomes from the individual projects.

-

-

Questions were included in the questionnaires sent to participants to examine:

-

demographic information about the nature of participants, their organisations and the HTA information they produce

-

the setting-up process for the project

-

progress of the project in the interim year

-

administrative support and communication from the co-ordinating secretariat

-

the role of information technology in supporting the project

-

involvement of external stakeholders

-

the workings of the eight internal work packages

-

the planned follow-up project – European network for Health Technology Assessment Joint action 2 (EUnetHTA JA2).

Questions were included in the questionnaires sent to external stakeholders to examine:

-

the mechanisms of the stakeholder forum

-

the EUnetHTA JA project

-

the workings of the eight internal work packages

-

the planned follow-up project – EUnetHTA JA2.

Various terms were used in the evaluation and these are summarised in Box 1 .

Overarching objective: This was the main objective of the EUnetHTA JA and was assessed by whether or not an effective and sustainable HTA collaboration, not reliant on project funding, had been set up at the end of the EUnetHTA JA project.

Specific objectives: These were the secondary project objectives of the EUnetHTA JA and were assessed by documentary analysis of whether or not the specified deliverables had been produced.

Deliverables: These were the 11 specific deliverables (see Table 2 ) that the project committed to produce. Whether or not these had been delivered according to plan was assessed by documentary analysis of final technical reports submitted by work packages at the project end.

Performance indicators: These are criteria developed for evaluation of the overall success of the project.

Project impact: This was measured by evaluating whether or not the project’s overarching objective and specific objectives had been met and the deliverables produced. These were the specific performance indicators to enable judgement about the project’s impact.

Project effectiveness: This was measured by evaluating how well the project’s processes had worked. The specific performance indicators for this were assessment of communication within the project, administration by the co-ordinating secretariat, involvement of external stakeholders and management of the eight constituent work packages. Whether or not lessons had been learnt and progress made from the preceding EUnetHTA 2006–8 project was also evaluated.

Evaluation methodology

Possible evaluation methods

Several research instruments could have been used to perform the evaluation, such as interviews, focus groups, observations, case studies, questionnaires and document review, which are described below:

-

Interviews: This research methodology enables the probing of a topic with one interviewee to explore meanings and uncover new areas not anticipated at the outset of the research. 30 These can adhere strictly to a formalised interview schedule (structured) or allow divergence from a schedule to pursue an idea in more detail (semistructured). 30 They have the advantage of probing a subject in detail to obtain rich qualitative data, but are expensive and can be difficult to arrange. It would have been useful to have used this methodology in the evaluation to probe the questionnaire data in greater depth, but unfortunately this was beyond the resource agreed by the EU.

-

Focus groups: This is a form of group interview that generates data from the interaction of the group participants. 31 This has particular advantages in exploring the way people think and perceive things, with findings being generated as a result of group discussions. Like individual interviews, they allow the probing of qualitative data. However, they are expensive and it can be difficult to arrange all participants together in one location at a specified time to conduct the focus group. 31 It would have been useful to have employed this methodology in the evaluation, for instance with a group of stakeholders, but unfortunately this was beyond the resource agreed by the EU.

-

Observations: This methodology involves the researcher systematically watching people and events to discover behaviours and interactions in a setting, then describing and analysing what has been observed. 32 This allows identification of any discrepancies between what people say they do and what they actually do. This method was not considered appropriate for the current evaluation.

-

Case studies: This research methodology is used when broad questions need to be addressed in complex circumstances and it typically involves mixed methods of quantitative and qualitative methods. 33 The selection of sites is of key importance to this methodology. This method was not considered appropriate for the current evaluation.

-

Self-completion questionnaires: These confer several advantages for collection of data from project participants and external stakeholders: standardisation of question wording eliminates the possibility of interviewer bias, respondents are allowed to complete the questionnaire at their own convenience and a greater degree of confidentiality is provided than in interviews. 34 However, they also pose several disadvantages; they are difficult to design, are impersonal and inflexible and are dependent on having a valid sampling frame of the correct details of recipients. 27 They are often the only viable survey format when trying to obtain information from a large cohort of respondents that are within a geographically dispersed population. 35

-

Documentary review: This allows review of a project using documents routinely produced without artificially interfering with the project. This enables retrieval of contextual and historical information about a project. However, by definition this means that the data collection is limited and inflexible, and incomplete data might be encountered.

It was necessary to select which evaluation methods would be most appropriate and feasible within the economic, geographic and time restraints of the project. The methods chosen were self-completion questionnaires (owing to the international location and large number of evaluation participants) and documentary review. It would have been ideal to have also used key informant interviews to obtain richer, qualitative data about what was going well in the project, what could be improved and suggestions for improvement, etc. However, unfortunately, this was not possible owing to time and cost restraints (according to the scope of the evaluation agreed by the EU), and this is a major limitation of the methodology. This meant that it was unfortunately not possible to follow up non-respondents to questions with qualitative enquiry to interpret their views. This has meant that the reasons for non-response have been speculated but it was impossible to substantiate this.

Self-completion questionnaires

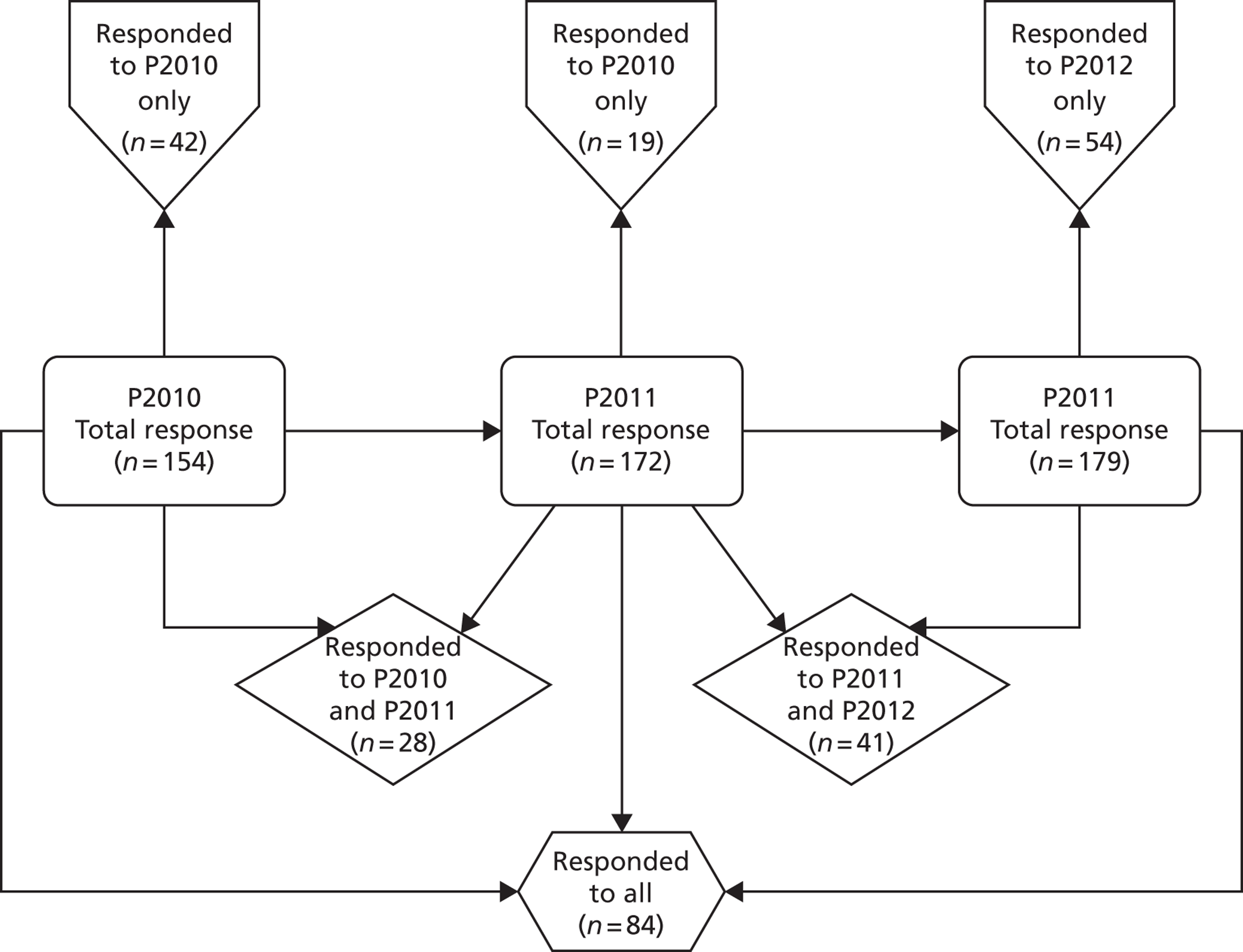

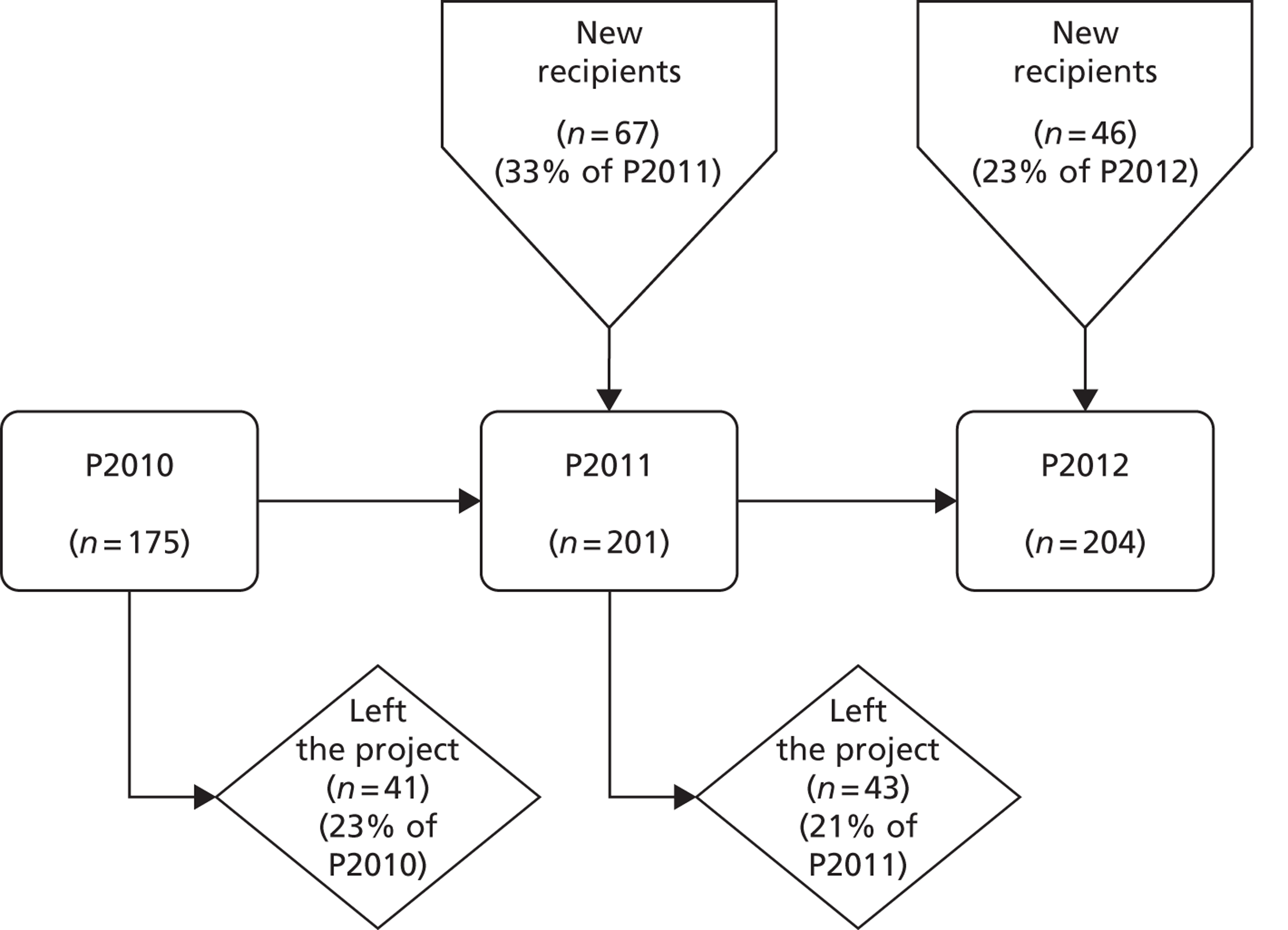

The evaluation participants were in two survey populations:

-

project participants – members of EUnetHTA JA partner organisations

-

external stakeholders.

This allowed triangulation of information between the project participants and external stakeholders for common topics. Participants at the annual policy-setting plenary assembly meeting were asked to evaluate the meeting.

-

Annual electronic surveys were sent to project participants and external stakeholders. In some cases the same questions were repeated in questionnaires of different years to allow some assessment of longitudinal data. However, evaluation of such longitudinal elements was severely limited because the large turnover of staff meant it was difficult to assess whether an element had changed over time or this change was due to the responses of different respondents.

-

Paper questionnaires were disseminated at each of the annual plenary assembly meetings which asked respondents to evaluate the meeting.

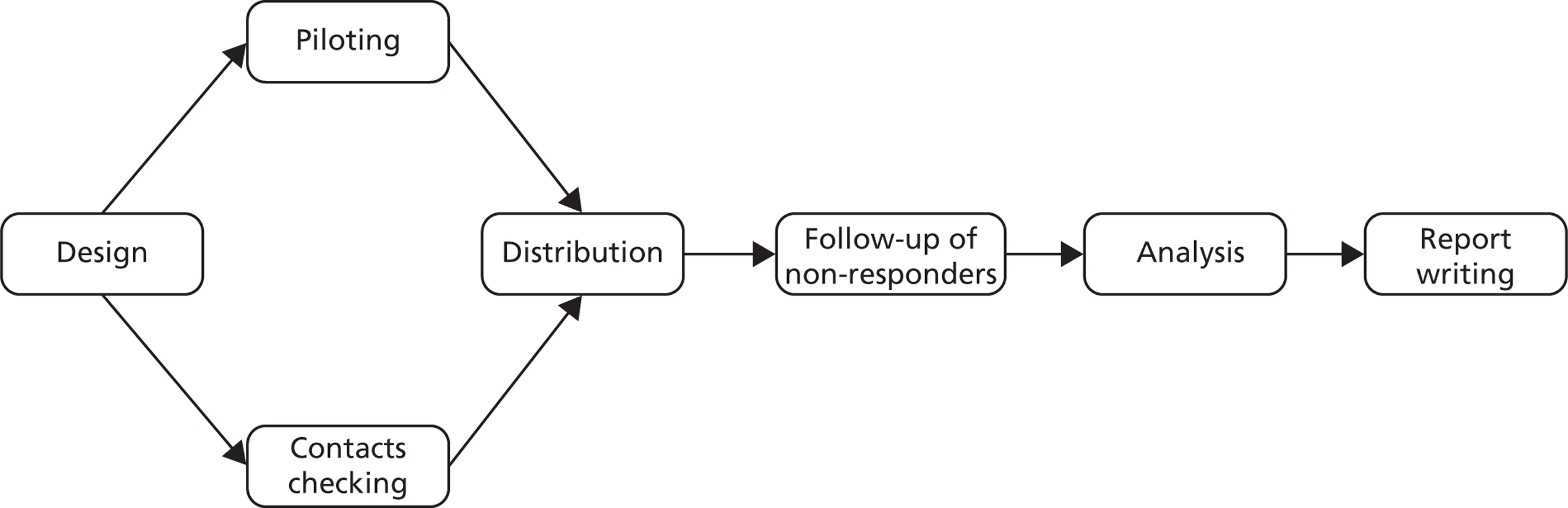

The process for each questionnaire followed the same schedule ( Figure 2 ).

FIGURE 2.

The processes followed for the questionnaires.

Compilation of questionnaire themes

The first stage in the design of a questionnaire is the preparation of a ‘questionnaire specification’ – a comprehensive list of every variable that must be measured. 36 In the current research these were the important aspects, or ‘dimensions of performance’, of the EUnetHTA JA project that needed to be measured. 27 In any evaluation it is impossible to assess all component parts of a project and, therefore, a conscious selection process was performed to consider what needed to be evaluated. Questions were then grouped into a series of ‘question modules’ each concerned with a particular variable, as recommended for survey design. 36 Attention was paid to the order of the individual questions within the question modules to ensure a logical sequence throughout the questionnaire.

Evaluation of the processes of the European network for Health Technology Assessment Joint Action project

A mapping exercise was undertaken to identify which aspects of the project should be assessed at the different time points. One of the objectives of the evaluation was to ‘generate maximum support for the work packages whilst actively seeking evaluation and monitoring solutions that minimise the burden’. This objective was met by decreasing the burden of answering extra questionnaires issued by different work packages. This was achieved by combining questions from other work packages into the questionnaires. The evaluation had been specifically contracted to include questions from the information management work package (WP6). As a courtesy it also included questions from the training strand of the WP8 work package in all three questionnaires and from the dissemination work package (WP2) in 2010. Extensive collaboration was undertaken with the leaders of these other EUnetHTA JA work packages to incorporate their questions. In addition, a questionnaire design workshop was held with participants of the WP6.

Evaluation was performed at three checkpoints within the project, i.e. baseline, interim and towards the end:

-

The formative evaluation started at the baseline of the project (month 6, June 2010). This incorporated the key processes of measuring and monitoring to enable identification of emerging issues, and feedback to the executive committee by evaluation reports. These reports were an appendix to the annual reporting mechanism. The baseline questionnaire captured expectations for the project, experiences during the set-up and identified early concerns about the project.

-

The interim evaluation (mid-term evaluation) of progress against the project plan was performed in month 18 of the project (June 2011). This identified progress against the plan and identified problems requiring corrective action, which were fed back to the executive committee.

-

The final annual questionnaire survey was performed in month 30 (June 2012). This was a towards-the-end evaluation to identify whether or not the objectives of the EUnetHTA JA had been met and flagged-up problems effectively resolved. A limitation of the evaluation was that the EU had requested this be completed before the end of the project.

Evaluation of the plenary assembly meetings

Following the process described above, a standard paper evaluation form was designed to measure participants’ attitudes about attributes of this policy-setting meeting. This was designed to consider:

-

whether or not the meeting met its objectives

-

satisfaction with the conference venue and facilities

-

what the best thing about the meeting was

-

what the worst thing about the meeting was

-

how the next year’s meeting could be improved.

Analysis of the ‘open’ questions from the 2010 survey allowed identification of themes. Therefore, the 2011 and 2012 surveys also included a grid of meeting attributes and Likert answer options to address these themes:

-

receiving meeting documents in advance

-

leadership of the meeting

-

relevance of items discussed

-

meeting and networking with colleagues

-

venue and meeting facilities

-

social event.

At the request of the secretariat, additional questions were included in the 2011 and 2012 surveys. These addressed:

-

when meeting documents were received

-

when meeting documents were read

-

input into developing the meeting agenda.

Question design

Broadly speaking, there are two types of questions that can be used in questionnaires: ‘closed’ questions and ‘open’ questions. Both types of questions were used in the questionnaires.

Closed questions have possible answers predefined by the survey designer and are analysed by frequency measures. They are several different formats: multiple choice, only one choice, Likert scale and matrix. They have the advantage of being easier to analyse than open questions. 37 Multiple-choice questions allowed various choices to be chosen as applicable or may only allow one answer. Likert questions requested respondents to indicate their response according to a predefined scale. However using closed questions means that respondents do not have the ability to provide their own response and, therefore, the richness of potential responses can be limited. 38 There is also the possibility that the answer options are biased and it is important to test this during the piloting phase. A limitation of closed questions is that respondents do not have the ability to explain their answers. 39 This aspect was considered in the design of the questionnaires in the evaluation. To counterbalance this potential problem, most closed questions also included a free-text box to allow respondents to explain their answer, if they wished. This type of question is classified as an ‘expansion’ open question. Such questions act as safety nets, explaining the results of closed questions and identifying new issues not covered by closed questions. 24

Open or free response questions allow respondents to provide their own answers and allow respondents to express their thoughts in their own language. 36 These enable respondents to explain their responses and provide qualitative data. Although these types of questions provide rich data they require more effort to analyse and this was factored into the analysis period. 39 The Cochrane systematic review about methods to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires identified that the odds of response were reduced by more than half when open questions are used. 40 It was important to be aware of this and to design the questionnaire to contain both open and closed questions. The majority of questions combined a closed question with an open question asking the participant to provide further detail about their response.

The questions included in the participant questionnaires are summarised below in Table 3 .

| Question topic | Question type | Baseline questionnaire (2010) | Interim questionnaire (2011) | Final questionnaire (2012) | Tracker question |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Professional expertise | Closed | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Gender | Closed | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Age | Closed | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Length in HTA | Open | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Membership of international HTA organisations | Closed | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| HTA practitioner | Closed | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Lead person | Closed | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Organisational expertise | Closed | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Organisational and HTA information | |||||

| Difficulties applying | Combined | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Sufficient funding | Combined | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Sufficient staff | Combined | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Succession planning | Combined | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| HTA information | Closed | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Setting-up process | |||||

| Achievement of objectives | Combined | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Set-up with EU | Combined | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Organisation into work packages | Combined | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Understand the aims of work packages | Closed | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Foundation as a sustainable collaboration | Combined | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Progress | |||||

| Achievement of objectives | Combined | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Foundation of a sustainable European collaboration | Combined | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Value added | Combined | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Concerns about work packages | Combined | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Evaluation | |||||

| Achievements | Combined | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Personal gain | Combined | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| External promotion | Open | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Administration and communication | |||||

| Secretariat leadership | Combined | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Secretariat administration | Combined | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Secretariat other activities | Combined | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Understood information needed | Combined | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Secretariat e-mails | Combined | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Project intranet | Combined | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| E-meetings | Combined | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Communication issues | Combined | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Communication methods | Combined | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Project conference | Combined | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Renewal of project identification | Combined | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Improvement of communication | Open | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Project challenges | Open | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Project benefits | Open | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Negative effects of participation | Combined | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Positive effects of participation | Combined | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Information technology | |||||

| Operating system | Closed | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Browser | Closed | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Software packages | Closed | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Communication systems | Closed | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Social media | Closed | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Smart phone/tablet | Closed | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Tools | |||||

| Use/awareness | Closed | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Priority for training | Closed | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Preferred training method | Closed | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Anticipated mobile use | Closed | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Barriers to tools | Closed | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Improvements to tools | Open | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Stopped using tools | Open | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Stakeholders | |||||

| Concerns | Open | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Benefits | Open | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| EUnetHTA JA2 | |||||

| Concerns | Combined | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Process | Combined | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Impact of planning | Combined | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Improvement | Open | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Use as a follow-up | Combined | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Main learning point | Open | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Involvement of stakeholders | Open | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Improvement of communication | Open | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Work packages | |||||

| WP1 | Combined | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| WP2 | Combined | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| WP3 | Combined | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| WP4 | Combined | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| WP5 | Combined | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| WP6 | Combined | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| WP7 | Combined | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| WP8 | Combined | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

The questions included in the external stakeholder questionnaires are summarised in Table 4 .

| Question topic | Question type | Baseline questionnaire (2010) | Interim questionnaire (2011) | Final questionnaire (2012) | Tracker question |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder forum | |||||

| Purpose of stakeholder forum | Open | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Fulfilment of purpose | Combined | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Awareness of stakeholder forum | Open | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Why applied for membership | Open | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Membership role as expected | Combined | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Role as a member of the forum | Open | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Role represents a good use of organisation’s time | Combined | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Benefits of membership | Open | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Challenges of membership | Open | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Effectiveness of the stakeholder advisory groups | Open | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Contributions to the project | Open | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Offer by membership | Open | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Setting up of the forum | Combined | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Comments about relevant documents | Open | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Comments about the meetings | Open | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Consideration of stakeholders’ views | Combined | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Feedback to stakeholders | Open | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Correct organisations included | Combined | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Concerns about involvement of stakeholders | Combined | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| EUnetHTA JA project | |||||

| Achieving objectives | Combined | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Organisational structure | Combined | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| A foundation for a European collaboration | Combined | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Functions of a European collaboration | Open | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Added value of a European collaboration | Combined | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Achievement of a European collaboration | Open | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Interactions of a European collaboration with stakeholders | Open | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Attendance at plenary assembly meeting | Combined | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| External project promotion | Combined | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Use of tools for HTA producers | Combined | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Would appreciate training in tools | Combined | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Holding a regular conference | Combined | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| EUnetHTA JA2 | |||||

| Consultation about planning | Combined | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Concerns about EUnetHTA JA2 | Combined | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Usefulness as a project follow-up | Combined | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Learning from EUnetHTA JA to inform EUnetHTA JA2 | Open | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Improvement of communication | Open | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Work packages | |||||

| WP4 | Combined | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| WP5 | Combined | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| WP7 | Combined | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

Attention was paid to the design and wording of the individual questions, according to recognised guidance:36,41

-

avoid long questions

-

avoid double-barrelled questions

-

avoid double negatives

-

ensure inclusion of ‘Don’t Know’ and ‘Not Applicable’ answer options where applicable

-

use simple words, avoid jargon, and avoid abbreviations

-

avoid ambiguous words

-

make questions specific

-

ensure all reasonable response alternatives are included.

Formatting

It is important that questionnaires are designed to be visually attractive as this has been shown to encourage high response rates. 39 In this respect, the layout and flow of the questionnaires was important and the ordering of questions needed to be logical.

Checking of recipient details

It was vital to have an accurate sampling frame for the questionnaires. This ensures that all relevant recipients have been surveyed and ensures integrity of the response rate calculation. It is difficult, but necessary, to differentiate between genuine non-responders and those recipients for whom an incorrect name or e-mail address has been used; therefore, the use of an accurate mailing is essential. 42

Evaluation of the processes of the European network for Health Technology Assessment Joint Action project

It was feasible to survey the entire population and, therefore, no selected sampling was required. An Excel database was obtained from the EUnetHTA JA secretariat which contained details of the EUnetHTA JA project participants in the individual project work packages. This was restructured into a comprehensive database of all the project participants using the following data fields:

-

first name

-

surname

-

e-mail address

-

organisation

-

membership of individual work packages.

The heads of each organisation were asked to confirm the validity of the information of their staff working for EUnetHTA JA. This feedback resulted in a fairly substantial refinement of the contact database.

A pre-notification e-mail was sent to all project participants in advance of sending them a questionnaire. This enabled the correction of any incorrect information and querying of e-mails for which ‘bounce backs’ were obtained. Pre-notification of survey recipients prior to the questionnaire send-out is a strategy that has been shown to increase response rate by 50%. 40 It emphasises the legitimacy of the questionnaire and communicates the value of response. 43 For the current study each recipient of a questionnaire was sent an e-mail 1 week before the send-out notifying them when the questionnaire would be sent to them, the importance of their completing it and the deadline for completion. This also served the purpose of checking e-mail addresses and correcting any errors about work package membership (in the case of project participants) or sending the survey to a nominated colleague instead (in the case of stakeholders).

Details of the representatives of the stakeholder organisations were also obtained from the EUnetHTA JA secretariat.

Evaluation of the plenary assembly meetings

All participants who attended a meeting were surveyed. Therefore, it was unnecessary to perform this stage because the recipients were physically in the room.

Piloting

One disadvantage of the use of self-completion questionnaires is that questions may remain non-completed, without the possibility of explanation. Therefore, time and effort must be spent on designing useful, unambiguous questions. It is important that both the reliability and validity of the questionnaire instrument is assured:

-

Reliability concerns how different people will interpret a question. For a question to be classified as ‘reliable’ respondents must interpret it in the same way and it must therefore be repeatable. 36

-

Validity concerns whether or not the questionnaire actually measures the data it intends to. 27

Before sending out the questionnaire to the recipients it is essential to pilot it on a representative sample first. This is a ‘quality assurance’ method to ensure that the questionnaire contains the correct spelling, is grammatically correct and has a good layout. It also aims to prevent any problems with comprehension and to ensure that the format of the overall survey instrument and individual questions are appropriate. 39 It was important to consider that this was a European project with participants communicating in the common language of English. This was therefore not the native language of the vast majority of participants. Special considerations must be given to the interpretation of question wording and answer options by respondents who are not native English speakers, ensuring the concept is properly understood. This meant that it was necessary to pilot the questionnaires with people who were non-native speakers of English, including those whose primary language was French, German or Spanish.

Evaluation of the processes of the European network for Health Technology Assessment Joint Action project

Questionnaires were piloted with members of the lead partner organisation who were non-native English speakers. Comments were also sought from members of the EUnetHTA JA executive committee and the European Commission. A design workshop was held with members of WP6 in 2010 and the lead partners of WP6 (French) and WP8 (Spanish) also piloted the questionnaires prior to the send-out.

Evaluation of the plenary assembly meetings

The form was piloted by members of the lead partner organisation.

Distribution

When disseminating a questionnaire it is necessary to choose between the possible distribution methods of postal, telephone or internet. Until the 2000s, the primary means of distribution of questionnaires was by face-to-face interviews or postal questionnaires and the advantages and disadvantages of these approaches have been discussed. 36,40,41 However, the 2000s saw the advent of new distribution methods such as e-mail and the internet. The earliest electronic questionnaires involved the distribution of a document [designed in Microsoft Word® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) or similar] by e-mail. The EUnetHTA 2006–8 project was also evaluated by questionnaire. However, these were sent by e-mail and the respondent required to record their responses on a Microsoft Word document and e-mail this back to the questionnaire administrator. The effort required in e-mailing the survey back may have contributed to the low response rates received for that questionnaire (23–26% over the years 2006, 2007 and 2008).

Evaluation of the processes of the European network for Health Technology Assessment Joint Action project

The choice of mode of transmission of the questionnaires in the current research was between postal mail, telephone, e-mail and web based. For this study the participants were geographically dispersed over Europe and, therefore, postal distribution was not a practical possibility owing to financial and logistical limitations. Telephone questionnaires were also impractical. A web-based questionnaire that could be completed at the convenience of the respondent was preferable and the recipients were familiar to e-mail communications and using the internet.

Web-based surveys offered several advantages compared with post for the current research: there was a significant cost reduction when considering the international survey population and a quicker turnaround time. 44 In addition to electronic transmission of surveys by e-mail, web-based applications enable automatic data collection. The design of web surveys may be more important than for print surveys. This is primarily because a web-based survey can be displayed differently to a respondent as a result of computer-related glitches and the coding system offers more design capabilities than print. 44 However, the increased ability for design capabilities must be used with some caution because too many design features may lead to overcomplication and a decreased response rate.

Different possible online survey platforms were investigated for the distribution of the questionnaires and SurveyMonkey.com® (Palo Alto, CA, USA) was selected for ease of use and function capability. A paid, professional account was selected from SurveyMonkey.com. 45 This enabled:

-

an unlimited number of questions and responses

-

a custom uniform resource locator (URL)

-

a branded survey with a logo – use of the EUnetHTA logo and colours

-

a survey completion progress bar

-

a custom redirect on survey completion – to the eunethta.net project page

-

a printable PDF version for sharing during design collaboration

-

importing e-mails into the ‘survey manager’ send-out function

-

easy tracking of non-respondents and distribution of follow-up e-mails.

Care was taken that the questionnaire invitations were not sent during the weekends and that the public holidays in the different European countries were avoided. As far as possible these invitations were not sent during the summer holiday season (particularly avoiding the month of August).

Evaluation of the plenary assembly meetings

The analysis of the annual EUnetHTA JA plenary assembly meetings was performed by anonymous self-completion paper questionnaires. These were included as part of the agenda pack given to the meeting participants. They were reminded to complete the questionnaire and hand it in at the end of the meeting.

Follow-up of non-respondents

It is important that as many recipients as possible submit their replies because the non-respondents might differ significantly to the respondents, thereby introducing bias into the results. 36 There seems to be no generalisable recommendation for an acceptable survey response rate. However, this should aim for the highest rate possible and above 50% has been deemed adequate. 34,46

It should be noted that the questionnaire recipients were all associated with the EUnetHTA JA project – either project participants or external stakeholders. Therefore, they had an implicit duty to respond to the questionnaires. However, it was still necessary to employ appropriate strategies to obtain a high response rate to limit bias. A review of methods to increase the response to postal and electronic questionnaires revealed that the odds of response were increased by more than one-quarter when non-respondents were adequately followed up. 40

Evaluation of the processes of the European network for Health Technology Assessment Joint Action project

The recipients had been given a guarantee of confidentiality but not anonymity. This meant that through using the SurveyMonkey.com online platform it was possible to send targeted reminder e-mails to non-respondents. These were personalised e-mails that contained a personal weblink to the questionnaire. E-mails were designed to include two strategies that have been shown to be effective in increasing response rate: each e-mail included a statement that indicated others had responded and provided a deadline for response. 40 Reminders were generally sent 1 week after the date requested for the questionnaire completion and non-respondents were requested to complete the questionnaire within 3 weeks. Two follow-up reminders were sent at 3-weekly intervals.

Evaluation of the plenary assembly meetings

Survey response was anonymous and there was no possibility of tracking non-respondents. Therefore, it was not possible to follow up non-respondents.

Analysis

The overall percentage response rate to questionnaires was calculated as:

It is important that the response rate to individual questions was also defined. The National Center for Education Statistics has stated that key items should achieve a response rate of at least 90%. 47 Accordingly, actual completion rates were shown for each individual question. Data from the two types of question were analysed:

-

The computer software program Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS®, version 19; IBM, New York, NY, USA) was used for the analysis of the quantitative questions. Descriptive statistics were included for categorical data, showing frequency and percentages.

-

Thematic analysis was performed on the qualitative data responses provided to the open questions. Such inductive reasoning involves analysing the data to generate ideas. 48 The grounded theory methodology was used to compare pieces of data to develop conceptualisations to create descriptive knowledge. 48 Topics were identified and clustered into themes. This qualitative analysis was performed by only one researcher owing to the resource limitation of the evaluation agreed with the EU. This has a limitation because it might have biased the results as only one person’s opinion was used. The software program NVivo® (Version 10; QSR International, Victoria, Australia) was used to help analyse the qualitative comments. When analysing open-ended questions it is important to outline the main themes and illustrate them as necessary with quotes36 and this was done in the individual survey reports that were submitted to the secretariat annually.

Report writing

Individual reports were written for each questionnaire. These individual questionnaire reports formed appendices to the technical report submitted to the EUnetHTA JA secretariat each year.

-

2010:

-

plenary assembly evaluation survey

-

EUnetHTA JA participants’ 2010 baseline survey

-

EUnetHTA JA stakeholder forum 2010 baseline survey

-

EUnetHTA JA for those that applied to join the stakeholder forum but were not successful 2010 baseline survey.

-

-

2011:

-

plenary assembly 2011 evaluation survey

-

EUnetHTA JA participants’ 2011 interim survey

-

EUnetHTA JA stakeholder forum 2011 interim survey.

-

-

2012:

-

plenary assembly 2012 evaluation survey

-

EUnetHTA JA participants’ 2012 final survey

-

EUnetHTA JA stakeholders’ 2012 final survey.

-

These reports were uploaded to the EUnetHTA JA members only intranet website. Reports were written as appropriate for work package leaders and tool developers. Articles were submitted to the EUnetHTA JA project e-newsletters to encourage response rates and to report questionnaire results.

Documentary analysis

Each of the eight individual work packages was responsible for writing a final technical report about its performance in the EUnetHTA JA and these were submitted to the secretariat in mid-January 2013. The secretariat was requested to send a copy of each report for analysis in this evaluation. The documentary analysis involved one of the researchers reading the report submitted by each work package and identifying whether or not the work package stated it had produced its deliverable (in accordance with the EUnetHTA JA Grant agreement). 13 This analysis was limited because budgetary restraints of the evaluation meant that it was performed by only one researcher. In addition, it consisted solely of whether or not a work package had self-reported that it had produced the deliverable, rather than an actual observation of the existence of a deliverable.

Informing clinical decision-makers about clinical research studies under development: development of a data set to inform a registry

The project was divided into three phases:

-

development of a data set on which to base a registry

-

assessment of the potential accuracy of that data set

-

building an electronic registry based on the developed data set.